DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2024.102777

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-23

الدور الرئيسي للابتكار والمرونة التنظيمية في تحسين أداء الأعمال: نهج مختلط الأساليب

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

ابتكار الخدمة

وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي

البحث المختلط

الملخص

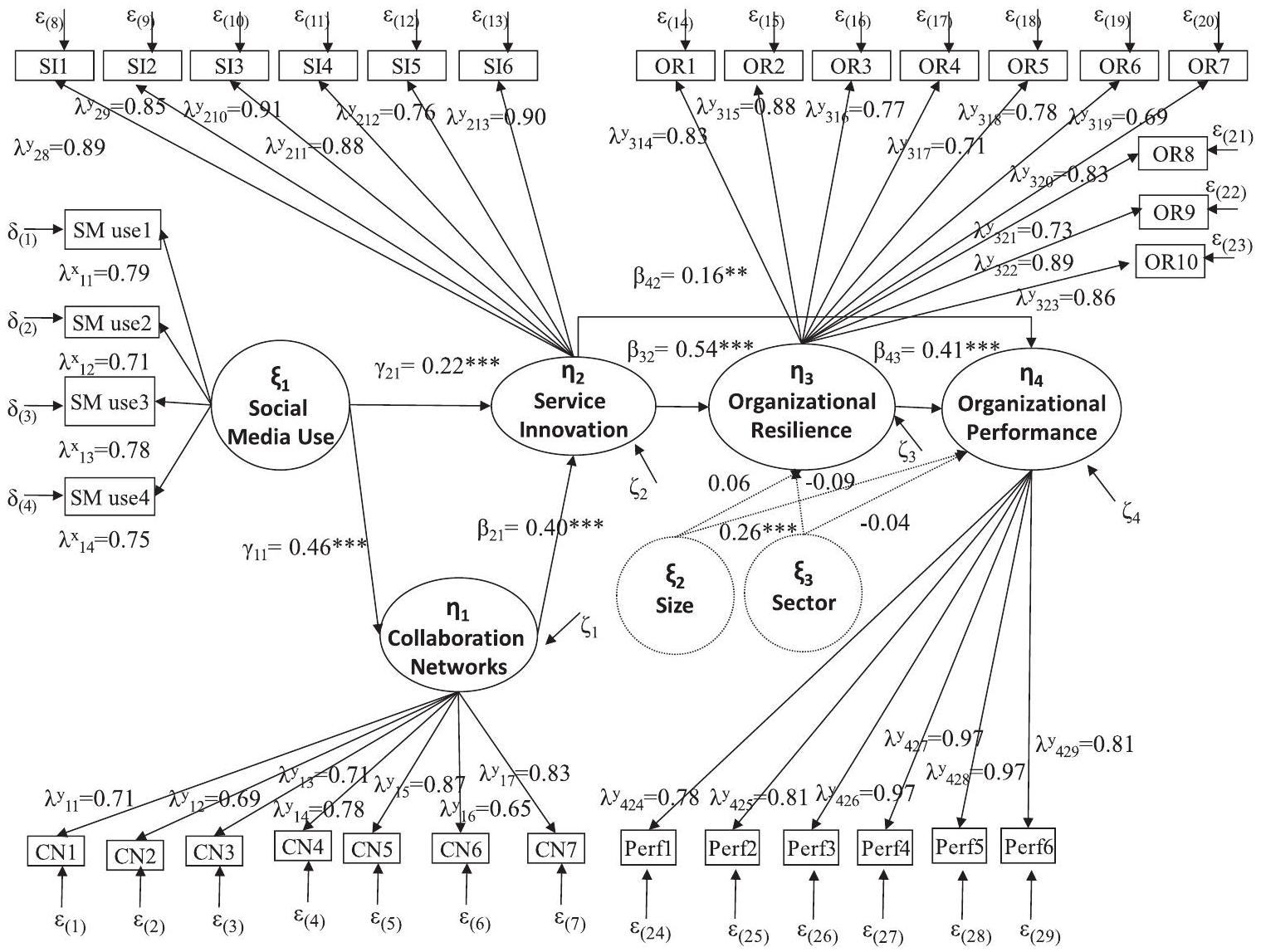

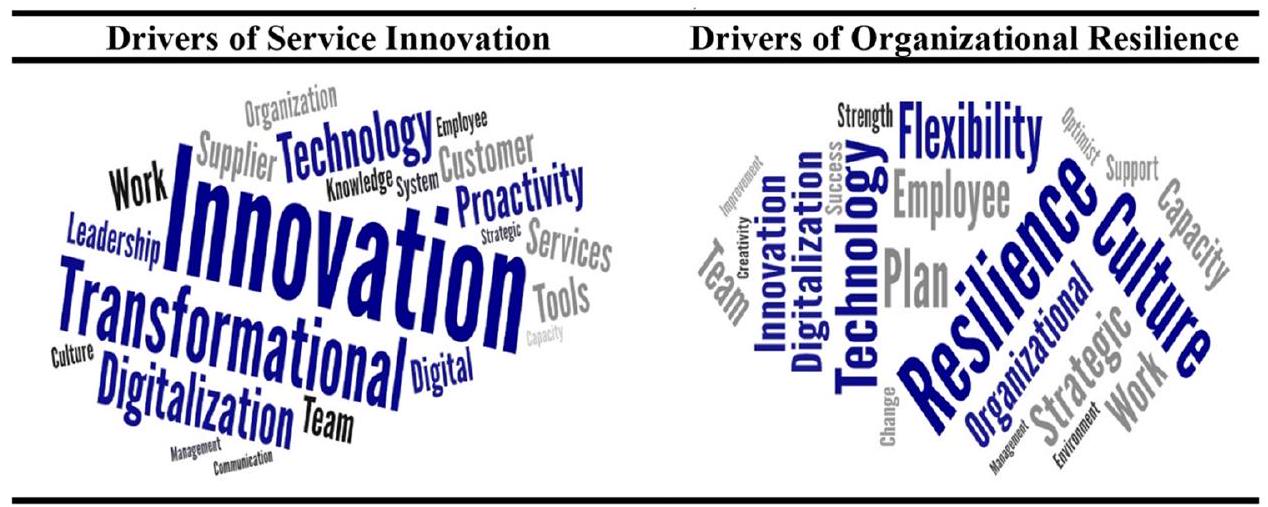

يتطلب بيئة اقتصادية غير مؤكدة ومعقدة من الشركات أن تتصرف بسرعة وتعيد ابتكار استراتيجيات أعمالها. لقد برز الابتكار كضرورة استراتيجية للتكيف مع تغييرات السوق والبقاء تنافسياً، بينما اكتسبت المرونة اهتماماً باعتبارها ضرورية للمنظمات للاستجابة بنجاح للضغوط البيئية الخارجية. على الرغم من أهمية هذه العوامل الاستراتيجية في البيئات غير المستقرة، إلا أن القليل من الأبحاث التجريبية قد حللتها. استناداً إلى نظرية القدرات الديناميكية، تفحص دراستنا دور ابتكار الخدمة ومرونة المنظمة في تعزيز أداء الأعمال باستخدام نهج مختلط من مرحلتين. أولاً، تم إجراء دراسة كمية لاختبار نموذج البحث المقترح باستخدام تحليل نمذجة المعادلات الهيكلية (SEM) مع عينة من 343 شركة خدمات في إسبانيا. ثانياً، تم إجراء تحليل نوعي مع 12 مقابلة مع مدراء لتقديم رؤى إضافية وفهم مفصل للظاهرة. تؤكد النتائج على الابتكار والمرونة كقدرات ديناميكية رئيسية للتعامل مع مشهد الأعمال المتغير والبقاء تنافسياً. تكشف نتائجنا أيضاً عن الأهمية الاستراتيجية للأدوات الرقمية (منصات وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي) والشبكات الخارجية كمحركات لابتكار الخدمة. يمكن للمديرين استخدام هذه النتائج للاستفادة من وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي للمشاركة في الشبكات التعاونية، وتعزيز الابتكار والمرونة، والنجاح في الأسواق المضطربة.

1. المقدمة

(بابادوبولوس وآخرون، 2020). ظهرت منصات مثل وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي (SM) كأدوات رقمية رئيسية لتعزيز التعاون مع الجهات الخارجية، مما يمكّن الشركات من جمع معلومات سوق قيمة لدعم أنشطة الابتكار (مونينجر وآخرون، 2022). لمواجهة التحديات الناشئة، يجب على الشركات توقع والتكيف مع الاتجاهات الجديدة من خلال تطوير منتجات وخدمات مبتكرة. وبالتالي، أصبح ابتكار الخدمة عاملاً أساسياً – بل إلزامياً – في تعزيز قدرة الشركات على التكيف مع التغيرات في بيئات الأعمال (هينونن وستراندفك، 2021). تظهر الأدلة أن الرقمنة والحلول التكنولوجية كانت حاسمة في دفع ابتكار المنظمات في مواجهة الأزمات الأخيرة (فورليانو وآخرون، 2023). على الرغم من أن البحث في هذا الموضوع يتزايد، إلا أن هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من المعرفة حول العمليات التي يمكن أن تستخدمها الشركات لاستغلال هذه الأدوات لتعزيز شبكات التعاون والابتكار (مونينجر وآخرون، 2022).

2. مراجعة الأدبيات

2.1. وجهة نظر القدرات الديناميكية

“الكفاءات للتعامل مع البيئات المتغيرة بسرعة.” تعكس القدرات الديناميكية بالتالي قدرة الشركة على تجديد كفاءاتها باستمرار للاستجابة بسرعة للظروف البيئية المتغيرة (جونيد وآخرون، 2023). تشير القدرات الديناميكية إلى قدرة المنظمة على التكيف والاستجابة للبيئات المتغيرة من خلال تنسيق ودمج الموارد والعمليات الداخلية والخارجية (عوض ومارتين-روخاس، 2023). أصبحت هذه القدرات مصدر قلق رئيسي للشركات اليوم لأنها تمكن الشركات من تحديد واكتساب وتحويل الموارد والقدرات بما يتماشى مع الظروف المتغيرة من أجل البقاء تنافسية (أمبروسيني وبومان، 2009؛ تييس وبيزانو، 1994). هذه القدرات مهمة بشكل خاص في قطاع الخدمات، حيث تتطور ديناميات السوق باستمرار. لكي تتمكن الشركات من تطوير خدمات جديدة في مثل هذا السياق غير المستقر، تحتاج إلى تطوير قدرات ديناميكية لتعزيز الابتكار في الخدمات (كيندستروم وآخرون، 2013).

2.2. ابتكار الخدمة، والتقنيات الرقمية، وشبكات التعاون

2.3. المرونة التنظيمية

السياقات. يُشتق المصطلح من اللاتينية resilire، والتي تعني الارتداد أو التعافي من اضطراب مفاجئ (Nielsen et al., 2023). تم تعريف المرونة التنظيمية على أنها قدرة الشركة على “توقع التهديدات المحتملة، والتعامل بفعالية مع الأحداث السلبية، والتكيف مع الظروف المتغيرة” (Duchek et al., 2020، ص. 220). تعكس قدرة المنظمة على التعامل مع الاضطرابات المفاجئة والتعافي منها من خلال التكيف والحفاظ على (أو تحسين) وظائف الشركة (Su & Junge, 2023). تمتلك الشركات المرنة ليس فقط القدرة على التعامل على المدى القصير للتعافي من الاضطرابات، ولكن أيضًا القدرات التكيفية على المدى الطويل لإحداث تغييرات عميقة في نماذج أعمالها بعد الأزمة (Li et al., 2021).

دراسات تجريبية حديثة تفحص الابتكار والمرونة في سياق رقمي.

| المؤلفون | المتغيرات المضمنة | تصميم البحث | بيانات | النتائج الرئيسية |

| بليتشفيلدت وفولانت (2021) | تنفيذ التكنولوجيا الرقمية، ابتكار المنتجات والخدمات، الميزة التنافسية (عائدات المبيعات). | التحليل الكمي (الارتباط). | بيانات ثانوية من 747 شركة صناعية. | تشير النتائج إلى أن الشركات التي تمتلك مستويات عالية من التقنيات الرقمية يمكنها تقديم ابتكارات أكثر جذرية في المنتجات والخدمات؛ مما يؤكد الدور الرئيسي لهذه التقنيات كعوامل مساعدة على الابتكار. |

| لي وآخرون (2021) | ممارسات مبتكرة لزيادة المرونة (أي، التعاون مع أطراف ثالثة، ابتكار خدمة العملاء). | التحليل النوعي (تحليل المحتوى). | 153 مصدر معلومات نصية من صناعة المطاعم. | تشير النتائج إلى نموذج مبتكر لإدارة الأزمات وتصف كيف عززت ممارسات مبتكرة معينة مرونة الأعمال خلال الجائحات. |

| دو وآخرون (2022) | مبادرات إدارة الابتكار (الدعم)، التعلم التنظيمي، المرونة التنظيمية، الابتكار. | التحليل الكمي (الانحدار وتحليل المسار). | استطلاع: 188 مديراً تنفيذياً من الشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة (عينة عبر الصناعات). | تؤكد النتائج أن مبادرات إدارة الابتكار أثرت بشكل إيجابي على مرونة المنظمة، مما عزز بدوره الابتكار. تكشف النتائج عن الدور الوسيط للتعلم التنظيمي في هذه العلاقات. |

| دوفبيتشوك (2022) | التعلم التنظيمي، القدرات الموجهة نحو الابتكار، المرونة الديناميكية، جودة خدمات اللوجستيات، أداء الشركة. | التحليل الكمي (الارتباط). | استطلاع: 113 شركة خدمات. | كانت القدرات المرتبطة بالتعلم التنظيمي والابتكار مرتبطة إيجابيًا بمستويات أعلى من المرونة خلال الجائحة. وكانت المرونة مرتبطة بجودة خدمة لوجستية أعلى وأداء تجاري أفضل. |

| براتونو (2022) | اضطراب تكنولوجيا المعلومات، الابتكار (تطوير المنتجات)، المرونة التنظيمية، التواصل التسويقي، الميزة التنافسية (الأداء). | التحليل الكمي (SEM). | استطلاع: 582 مديراً. | تظهر النتائج أن المرونة التنظيمية كان لها الأثر الأكثر أهمية على ميزة الشركات التنافسية. كما كان للابتكار تأثير إيجابي على أداء الشركات. |

| شيا وآخرون (2022) | شبكات الأعمال، قدرة المرونة التنظيمية، التعلم المزدوج، استخدام التقنيات الرقمية. | التحليل الكمي (الانحدار) | استطلاع: 409 شركات | في سياق الجائحة، تظهر النتائج كيف كان لشبكات الأعمال تأثير إيجابي على مرونة المنظمات. كما تؤكد النتائج أيضًا على الدور الوسيط لاستخدام التقنيات الرقمية في هذه العلاقة. |

| فورليانو وآخرون (2023) | التوجه التكنولوجي، نضج الاستراتيجية الرقمية والقدرة على التكيف مع كوفيد-19. | التحليل الكمي (SEM). | استطلاع: 186 شركة من قطاعات مختلفة. | تؤكد النتائج كيف أن التوجه التكنولوجي للشركة يؤثر بشكل إيجابي على نضج استراتيجيتها الرقمية، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة مرونة المنظمة. |

| جونيد وآخرون (2023) | قدرات الديناميكية لسلسلة التوريد، تكامل سلسلة التوريد، المرونة، الميزة التنافسية المستدامة، الأداء. | التحليل الكمي (SEM). | استطلاع: 325 محترفًا في صناعة الرعاية الصحية. | توضح النتائج كيف أن القدرات الديناميكية لسلسلة التوريد تحسن من تكامل سلسلة التوريد ومرونتها، مما يعزز الميزة التنافسية والأداء. |

| سانتوس وآخرون (2023) | التقنيات الرقمية، المرونة الريادية، أداء الشركة. | التحليل النوعي (النهج النوعي الاستقرائي). | 42 مقابلة مع رواد أعمال ناجحين. | ظهرت المنصات الرقمية والبنى التحتية كعوامل رئيسية لتعزيز المرونة خلال الجائحة. أدت مرونة الأعمال من خلال الرقمنة إلى تحسين الأداء المالي. |

| يوان وآخرون (2022) | المرونة التنظيمية، القدرة الاستيعابية | التحليل النوعي (دراسة حالة) | دراسة حالة فردية مع معلومات من شركة مشاركة قائمة على المنصة. | بالنظر إلى المرونة كعملية تكيف، تؤكد النتائج الدور الحاسم للقدرة الاستيعابية كالميسر الرئيسي للمرونة التنظيمية. |

تصميم البحث بأساليب مختلطة.

| مرحلة | إجراء | نتيجة | |||||||||

| جمع البيانات الكمية |

|

|

|||||||||

| تحليل البيانات الكمية |

|

|

|||||||||

| جمع البيانات النوعية |

|

– تم نسخ المقابلات والملاحظات. | |||||||||

| تحليل البيانات النوعية |

|

|

|||||||||

| دمج النتائج الكمية والنوعية | – دمج وشرح ومناقشة النتائج الكمية والنوعية. |

|

فهم مفصل للظاهرة (هولاندز وآخرون، 2023).

لتوفير نظرة أعمق حول الموضوعات الرئيسية التي تظهر في دراسة الابتكار والمرونة في السياق الرقمي، تلخص الجدول 1 الأبحاث التجريبية الحديثة حول هذا الموضوع.

3. تصميم البحث

نهج مختلط المعايير.

| جوانب الجودة | معايير الجودة | تفسير كيفية اتباع هذه الدراسة لإرشادات فينكاتيش وآخرون (2013) | |||||

| غرض نهج الطرق المختلطة | تحقيق كمي مهيمن متسلسل يتبعه تحليل نوعي أقل هيمنة. | تنقسم الدراسة إلى مرحلتين: 1) دراسة قائمة على الاستطلاع الكمي للتحقق من نموذج البحث المقترح واختبار الفرضيات المقترحة، و2) دراسة نوعية تتضمن مقابلات مع المديرين للتحقق من النتائج الكمية وإثرائها والحصول على فهم أعمق للظاهرة. | |||||

| جودة التصميم | ملاءمة التصميم. | استخدمت الدراسة دراسة كبيرة قائمة على الاستطلاع الكمي تلتها دراسة نوعية لمعالجة أسئلة البحث. كانت هذه الاستراتيجية لتصميم دراسة متسلسلة للتحقق من النتائج وتكملتها وإثراء الدراسة العامة ذات صلة بالظاهرة المعنية. | |||||

| ملاءمة التصميم. | كمي: | ||||||

| 1) العينة: تم اختيار عينة من الشركات المستجيبة بشكل عشوائي في إسبانيا. | |||||||

| ملاءمة تحليلية. | 1) اختيار المقابلين المناسبين: كان جميع المقابلين من مديري شركات الخدمات من قطاعات فرعية مختلفة في إسبانيا. | ||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| جودة التفسير | استنتاج كمي. |

|

|||||

| استنتاج نوعي | كانت جميع البنى والعلاقات التي تم الحصول عليها من خلال الدراسة النوعية معقولة، واعتبرت ذات صلة في الأدبيات الحديثة. | ||||||

| استنتاج تكاملي | تم تطوير نموذج بحث بناءً على الأدبيات ذات الصلة، وتم اختباره إحصائيًا استنادًا إلى عينة كمية من 343 شركة خدمات في إسبانيا. بعد ذلك، قمنا بإجراء دراسة نوعية، استنادًا إلى 12 مقابلة شبه منظمة، مما أتاح لنا تأكيد وإثراء النتائج التي تم الحصول عليها سابقًا. تشير التآزر بين النتائج الكمية والنوعية إلى مستوى مرضٍ من الفعالية التكاملي. |

وإنتاج “مجموعة أكبر من الآراء المتباينة و/أو التكميلية” (فينكاتيش وآخرون، 2016، ص. 437). تصميم الطرق المختلطة مناسب أيضًا بشكل خاص للتغلب على قيود البيانات المقطعية (ماير وآخرون، 2023). من خلال دمج نتائج الدراسات الكمية والنوعية، يمكن للباحثين تطوير استنتاجات ميتا، وهي الأصول الحاسمة لتحليل الطرق المختلطة، للحصول على رؤية كاملة (رايس وآخرون، 2022؛ فينكاتيش وآخرون، 2013).

الفرضيات، ثم توسيع النتائج الكمية من خلال دراسة نوعية (الدراسة 2). تقدم الجدول 2 المراحل المختلفة وتدفق تصميم البحث.

4. الدراسة 1: دراسة كمية

4.1. نظرة عامة

4.2. الخلفية النظرية وتطوير الفرضيات

في بيئة اليوم المعقدة وغير المؤكدة، يجب على الشركات المشاركة في شبكات تعاونية للعمل مع الشركاء والحصول على موارد قيمة (شي وآخرون، 2022). الابتكار التعاوني مهم بشكل خاص في صناعة الخدمات، حيث تجعل المنافسة الشديدة التعاون مع العملاء والموردين أحد الأصول العلائقية الرئيسية لابتكار الشركات (وانغ وآخرون، 2016). في الواقع، ساهمت الشبكات التجارية بشكل كبير في تكيف الشركات خلال جائحة كوفيد-19 من خلال توفير الوصول إلى موارد خارجية، بما في ذلك المعرفة (شي وآخرون، 2022).

تغيرات السوق من خلال تطوير خدمات جديدة. وبالتالي، يتم اقتراح الفرضية 2:

يتطلب التنافس في بيئات ديناميكية التكيف المستمر وتوليد أفكار مبتكرة (ماركوفيتش وآخرون، 2021). ولهذا الغرض، زادت المنظمات من اكتساب المعرفة من مصادر خارجية لتسريع عمليات الابتكار (ناتاليكيو وآخرون، 2018). توفر التعاون الخارجي خبرات إضافية لتكملة القاعدة الداخلية للشركات، مما يشجع على تطوير الابتكارات (نيفس ودياث-مينيسيس، 2018). في الواقع، تعتمد الابتكارات الخدمية أكثر من الابتكارات المنتجة على المعرفة الخارجية والتعاون، وتتطلب مشاركة أعمق من عملاء الشركات وشركاء النظام البيئي للخدمات الآخرين (لوتجن وآخرون، 2019).

H3. تؤثر شبكات التعاون بشكل إيجابي على ابتكار الخدمات.

H4. تؤثر الابتكارات في الخدمة بشكل إيجابي على مرونة المنظمة.

مثل هذا الابتكار ضروري للتعامل بنجاح مع البيئات المتقلبة لأنه يمكّن المنظمات من الحفاظ على الأداء وتحسينه في مواجهة الأحداث المدمرة.

استنادًا إلى نظرية القدرات الديناميكية، تعتبر دراستنا المرونة التنظيمية كقدرة ديناميكية تمكّن الشركات من التكيف بشكل أفضل مع بيئتها ومواجهة التحديات بنجاح أكبر (Beuren et al., 2022). تعزز المرونة التنظيمية الأداء ونجاح الأعمال، مما يمكّن المنظمات من الخروج من التحديات والاضطرابات الخارجية بشكل أقوى (Hollands et al., 2023).

الأداء المالي. لذلك يُقترح أن:

H6. تؤثر المرونة التنظيمية بشكل إيجابي على الأداء التنظيمي.

4.3. طرق البحث

4.3.1. جمع البيانات

تفاصيل فنية للبحث الكمي.

| المتغير | البيانات |

| القطاع | قطاع الخدمات |

| الموقع الجغرافي | إسبانيا |

| المنهجية | عينة عشوائية طبقية |

| عالم السكان | 3210 شركة |

| حجم العينة (% استجابة) | 950 (36.10%، 343) شركة |

| خطأ العينة | 5.0% |

| فترة جمع البيانات | يونيو إلى أكتوبر 2022 |

4.3.2. القياسات

تسليط الضوء على هذه المؤشرات من خلال مقارنتها بمؤشرات شركات المنافسين الرئيسيين (ممارسة شائعة في الدراسات الحديثة) (Martín-Rojas et al.، 2021). بينما اعتمدت الدراسات السابقة على تصورات المديرين لقياس أداء الشركة، شملت دراستنا أسئلة حول التقييمات الذاتية والموضوعية. حيثما كان ذلك ممكنًا، تم فحص الارتباطات بين البيانات، وكانت هذه عالية وذات دلالة. تم مقارنة الأداء التنظيمي للمنافسين المباشرين باستخدام مقياس من سبع نقاط (1 أسوأ بكثير – 7 أفضل بكثير). تم التحقق من صحة المقياس باستخدام CFA (

4.4. النتائج

4.4.1. نموذج القياس

المتغيرات التي تم اختبارها لعدم استجابة التحيز (المستجيبين المبكرين مقابل المستجيبين المتأخرين).

| خاصية | المستجيبون الأوائل | المستجيبون المتأخرون | الإحصائيات | ||

| معنى | الانحراف المعياري | معنى | الانحراف المعياري |

|

|

| حجم | 1.18 | 0.466 | 1.15 | 0.432 | 0.590 |

| قطاع | 1.86 | 0.910 | 1.91 | 0.935 | 0.668 |

| الإيرادات السنوية | ١٥٠٨.٩٥ | ٣٦٩٣.٢٥٥ | ١١٥٠.٥٢ | ٣٦٥٤٫٩٤ | 0.368 |

| نمو المبيعات | ٤.٨٥ | 1.70 | ٤.٩٤ | 1.66 | 0.647 |

| حصة السوق | ٤.٧١ | 1.63 | ٤.٨٧ | 1.54 | 0.348 |

| العائد على الاستثمار | ٤.٢٩ | 1.69 | ٤.٣١ | 1.68 | 0.922 |

| العائد على الأصول | ٤.٢١ | 1.65 | ٤.٢٦ | 1.63 | 0.754 |

| روس | ٤.٣٦ | 1.60 | ٤.٤٩ | 1.61 | 0.457 |

| العائد على حقوق الملكية | ٤.٨٩ | 1.49 | ٤.٩٦ | 1.48 | 0.635 |

مصفوفة المكونات المدوّرة للتدابير الاستراتيجية.

| عناصر | مكون | ||||

| 1 استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي | شبكتان للتعاون | 3 ابتكارات الخدمة | 4 المرونة التنظيمية | 5 أداء تنظيمي | |

| SMU1 | 0.745 | ||||

| SMU2 | 0.726 | ||||

| SMU3 | 0.713 | ||||

| SMU4 | 0.723 | ||||

| سي إن 1 | 0.605 | ||||

| CN2 | 0.648 | ||||

| CN3 | 0.705 | ||||

| CN4 | 0.745 | ||||

| CN5 | 0.810 | ||||

| CN6 | 0.616 | ||||

| CN7 | 0.788 | ||||

| SI1 | 0.813 | ||||

| SI2 | 0.784 | ||||

| SI3 | 0.830 | ||||

| SI4 | 0.798 | ||||

| SI5 | 0.683 | ||||

| SI6 | 0.821 | ||||

| R1 | 0.747 | ||||

| R2 | 0.791 | ||||

| R3 | 0.703 | ||||

| R4 | 0.642 | ||||

| R5 | 0.673 | ||||

| R6 | 0.609 | ||||

| R7 | 0.770 | ||||

| R8 | 0.683 | ||||

| R9 | 0.827 | ||||

| R10 | 0.794 | ||||

| OP1 | 0.782 | ||||

| OP2 | 0.780 | ||||

| أوب 3 | 0.858 | ||||

| OP4 | 0.858 | ||||

| أوب 5 | 0.854 | ||||

| OP6 | 0.789 | ||||

المتوسطات، والانحرافات المعيارية، والارتباطات، وفترات الثقة.

| متغير | معدل | س.د. | 1 | 2 | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ |

| 1. استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي | ٣.٢٥ | 1.53 | 1.000 | 0.33-0.55 | 0.31-0.53 | 0.03-0.27 | 0.30-0.52 | 0.31-0.65 | -0.23-0.03 |

| 2. شبكات التعاون | ٣.٤٥ | 1.47 | 0.36*** | 1.000 | 0.40-0.60 | 0.17-0.38 | 0.31-0.53 | 0.15-0.50 | -0.17-0.08 |

| 3. ابتكار الخدمة | 5.04 | 1.43 | 0.34*** | 0.50*** | 1.000 | 0.47-0.65 | 0.31-0.51 | -0.06-0.26 | -0.16-0.08 |

| 4. مرونة المنظمة | 5.56 | 1.16 | 0.13** | 0.28*** | 0.46*** | 1.000 | 0.46-0.63 | -0.03-0.31 | -0.24-0.01 |

| 5. أداء المنظمة | ٤.٥٩ | 1.45 | 0.32*** | 0.37*** | 0.41*** | 0.57*** | 1.000 | 0.18-0.50 | −0.26 − (−0.04) |

| 6. الحجم | 1.16 | 0.44 | 0.30*** | 0.19*** | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.20*** | 1.000 | −0.41 − (−0.01) |

| 7. القطاع | 1.89 | 0.92 | -0.08 | -0.02 | -0.03 | -0.12* | -0.12* | -0.11* | 1.000 |

تم تقديمها بترتيب عشوائي (بودساكوف وآخرون، 2003؛ بودساكوف وأورغان، 1986). لم يفسر أي مكون واحد معظم التباين، وكانت القيم الذاتية لعدة مكونات فوق الواحد (اختبار عامل هارمان)، وساءت الملاءمة في النموذج أحادي البعد (نموذج عامل واحد). كما أظهرت البيانات اختلافات تقل عن 0.200 بين مؤشرات العامل الكامن المشترك (من الدرجة الأولى) ونموذج البحث النظري مع جميع القياسات كمؤشرات. وبالتالي، تستبعد جميع الاختبارات تحيز الطريقة الشائعة كمشكلة تؤثر على بياناتنا (بو-لوسار وآخرون، 2009).

4.4.2. النموذج الهيكلي

نتائج نموذج القياس.

| متغير | عناصر |

|

|

صباحًا |

| استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي | SMU1 | 0.80*** (22.22) | 0.64 |

|

| SMU2 | 0.71*** (15.31) | 0.50 | AVE

|

|

| SMU3 | 0.77*** (20.47) | 0.59 | ||

| SMU4 | 0.76*** (20.96) | 0.57 | ||

| شبكات التعاون | سي إن 1 | 0.71*** (21.51) | 0.50 |

|

| CN2 | 0.72***(22.32) | 0.51 |

|

|

| CN3 | 0.71***(21.82) | 0.50 | ||

| CN4 | 0.73***(22.05) | 0.53 | ||

| CN5 | 0.88***(37.17) | 0.77 | ||

| CN6 | 0.72***(21.01) | 0.51 | ||

| CN7 | 0.84*** (30.48) | 0.70 | ||

| ابتكار الخدمة | SI1 | 0.89***(56.07) | 0.79 |

|

| SI2 | 0.85***(34.04) | 0.72 |

|

|

| SI3 | 0.91***(62.53) | 0.82 | ||

| SI4 | 0.88***(42.79) | 0.77 | ||

| SI5 | 0.76***(26.18) | 0.57 | ||

| SI6 | 0.90***(47.25) | 0.81 | ||

| المرونة التنظيمية | R1 | 0.83*** (32.89) | 0.68 |

|

| R2 | 0.88***(42.73) | 0.77 | AVE

|

|

| R3 | 0.77***(25.73) | 0.59 | ||

| R4 | 0.71***(19.69) | 0.50 | ||

| R5 | 0.78***(26.67) | 0.60 | ||

| R6 | 0.71***(21.17) | 0.50 | ||

| R7 | 0.88*** (24.37) | 0.77 | ||

| R8 | 0.78***(18.79) | 0.60 | ||

| R9 | 0.89***(40.67) | 0.79 | ||

| R10 | 0.86***(28.95) | 0.73 | ||

| أداء المنظمة | OP1 | 0.77*** (23.70) | 0.59 |

|

| OP2 | 0.80*** (30.95) | 0.64 | AVE

|

|

| OP3 | 0.97***(61.94) | 0.94 | ||

| OP4 | 0.97***(101.40) | 0.94 | ||

| أوب 5 | 0.97***(89.80) | 0.94 | ||

| OP6 | 0.81*** (23.71) | 0.65 | ||

| إحصائيات ملاءمة النموذج |

|

|||

بين الحجم وأداء المنظمة

5. الدراسة 2: دراسة نوعية

5.1. نظرة عامة

5.2. طريقة البحث

5.2.1. اختيار العينة

نتائج النموذج الهيكلي المقترح (التأثيرات المباشرة وغير المباشرة والإجمالية).

| – | التأثيرات المباشرة |

|

التأثيرات غير المباشرة |

|

التأثيرات الكلية |

|

فترة الثقة | ||

| أثر من | إلى | ||||||||

| استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي |

|

ابتكار الخدمة | 0.22*** | ٣.٣٠ | 0.18*** | ٤.٨٩ | 0.40*** | ٦.٦٠ | 0.05-0.21 (H1) |

| استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي |

|

شبكات التعاون | 0.46*** | ٦.٦٠ | 0.46*** | ٦.٩٠ | 0.24-0.44 (H2) | ||

| استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي |

|

المرونة التنظيمية | 0.22*** | ٥.٧٨ | 0.22*** | ٥.٧٨ | |||

| استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي |

|

أداء المنظمة | 0.15*** | ٤.٤١ | 0.15*** | ٤.٤١ | |||

| شبكات التعاون |

|

ابتكار الخدمة | 0.40*** | 6.59 | 0.40*** | 6.59 | 0.21-0.40 (H3) | ||

| شبكات التعاون |

|

المرونة التنظيمية | 0.22*** | 5.56 | 0.22*** | 5.56 | |||

| شبكات التعاون |

|

أداء المنظمة | 0.15*** | ٤.٣٨ | 0.15*** | ٤.٣٨ | |||

| ابتكار الخدمة |

|

المرونة التنظيمية | 0.54*** | 10.19 | 0.54*** | 10.19 | 0.36-0.53 (H4) | ||

| ابتكار الخدمة |

|

أداء المنظمة | 0.16** | 2.36 | 0.22*** | 5.13 | 0.38*** | 6.16 | 0.03-0.32 (H5) |

| المرونة التنظيمية |

|

أداء المنظمة | 0.41*** | 6.14 | 0.41*** | 6.14 | 0.40-0.77 (H6) | ||

| حجم |

|

المرونة التنظيمية | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 0.78 | |||

| حجم |

|

أداء المنظمة | 0.26*** | ٣.٥٦ | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.28*** | 3.66 | |

| قطاع |

|

المرونة التنظيمية | -0.09 | -1.58 | -0.09 | -1.58 | |||

| قطاع |

|

أداء المنظمة | -0.04 | -0.68 | -0.04 | -1.49 | -0.08 | -1.27 | |

|

|

|||||||||

مع كل مشارك لإجراء المقابلة. تقدم الجدول 11 المعلومات الديموغرافية للحالات المدروسة، استنادًا إلى خصائص المديرين والشركات. لحماية الخصوصية، تم إخفاء أسماء الشركات واستخدام رموز للإشارة إليها.

5.2.2. جمع البيانات

نموذج هيكلي مقترح مقابل نماذج إحصائية بديلة.

| وصف النموذج |

|

|

RMSEA | ECVI | إيه آي سي | NCP |

| 1. النموذج الهيكلي المقترح | 1580.44 | 0.074 | 5.09 | ١٧٤٢.٤٤ | ١٠٣١.٤٤ | |

| 2. استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي في ابتكار الخدمات | 1589.47 | 9.03 | 0.074 | 5.12 | ١٧٤٩.٤٧ | ١٠٣٩.٤٧ |

| 3. ابتكار الخدمة لتعزيز مرونة المنظمة | ١٦٥٨.٦٥ | 78.21 | 0.077 | 5.32 | 1818.65 | ١١٠٨.٦٥ |

| 4. مرونة المنظمة مقابل أداء المنظمة | ١٥٩٥.١٧ | 16.73 | 0.075 | 5.13 | ١٧٥٥.١٧ | ١٠٤٥.١٧ |

شكل مجمع للحفاظ على سرية كل من الشركة والمشارك في المقابلة.

5.2.3. تحليل البيانات

1) جمع البيانات من خلال نسخ المقابلات، والقراءة المتعمقة، وملاحظة الأفكار الأولية؛ 2) توليد الرموز الأولية من خلال تحديد الأفكار التي برزت في البداية وتطوير مخطط ترميز أولي من خلال مقارنة البيانات من المقابلات المختلفة؛ 3) البحث عن الموضوعات من خلال مقارنة مخطط الرموز الناتج بالأدبيات، وتقليل عدد الرموز الأولية من خلال تجميعها في مجالات أوسع؛ 4) فحص البيانات لتحديد ما إذا كانت تدعم الموضوعات الناشئة وكيف تختلف بعض الموضوعات عن الأخرى؛ 5) تعريف وتسميه الموضوعات من خلال تعريف الموضوعات والمواضيع الفرعية وتحديد شكلها النهائي؛ و 6) تحليل النتائج من خلال صياغة الأدلة وكتابة نتائج الدراسة.

5.3. النتائج: الاستنتاجات الميتا

5.3.1. الاستنتاجات الميتا: التأكيد والتصديق

ملف تعريف المستجيبين.

| الرموز | خصائص المديرين | خصائص الشركات | |||||

| الجنس | العمر | الوظيفة | الخبرة | عمر الشركة | النشاط | عدد.

|

|

| I#01 | أنثى | 57 | مدير أعمال | 29 | 21 | السياحة | 209 |

| I#02 | ذكر | 40 | مدير عام | 16 | 13 | السياحة | 150 |

| I#03 | ذكر | 56 | مدير عام | 23 | 50 | التعليم | 1015 |

| I#04 | أنثى | 41 | مدير موارد بشرية | 15 | 53 | المالية | 873 |

| I#05 | ذكر | 51 | مدير عام | 27 | 19 | التعليم | 126 |

| I#06 | أنثى | 59 | مدير عام | 20 | 49 | التعليم | 924 |

| I#07 | ذكر | 48 | مدير موارد بشرية | 19 | 23 | التكنولوجيا | 122 |

| I#08 | أنثى | 52 | مدير أعمال | 30 | 83 | التعليم | 132 |

| I#09 | ذكر | 45 | مدير عمليات | 24 | 66 | النقل | 610 |

| I#10 | ذكر | 44 | مدير عام | 12 | 46 | التوزيع | 102 |

| I#11 | ذكر | 41 | مدير عام | 6 | 40 | الرعاية الصحية | 104 |

| I#12 | ذكر | 52 | مدير عام | 15 | 30 | الرعاية الصحية | 120 |

5.3.2. الاستنتاجات الشاملة: رؤى تكميلية

الأداء التنظيمي. تعتبر الموارد البشرية من الأصول الرئيسية التي تلعب دورًا استراتيجيًا في الأداء التنظيمي. يجب على الشركات تعزيز المهارات الشخصية (مثل: الإبداع، التواصل، العمل الجماعي، الاستماع النشط، التعلم، التفكير، اتخاذ القرار، المرونة، الالتزام، التعاطف) لتحسين النتائج.

6. المناقشة

6.1. المساهمات النظرية والآثار

إدارة الشركات السياقات غير المؤكدة والاستجابة للضغوط البيئية (دو وآخرون، 2022). هذه النتيجة مهمة بشكل خاص لشركات الخدمات، التي يتغير سوقها باستمرار ويتطور. يمكّن كل من الابتكار والمرونة الشركات من توقع الفرص، واغتنامها، والتكيف بسرعة مع البيئة الديناميكية، مستغلين كل من الكفاءات الداخلية والخارجية الخاصة بالمؤسسة (دو وآخرون، 2022؛ مارتن-روخاس وآخرون، 2020). كما تعزز نتائجنا الافتراض بأن المرونة التنظيمية هي عملية ديناميكية وليست نتيجة (نيلسن وآخرون، 2023). وبالتالي، تظهر المرونة كقدرة أساسية للشركة، تعزز أداء الشركة في المناظر المتغيرة (أنور وآخرون، 2023). باختصار، تكمل نتائجنا وجهة نظر DC، حيث تمثل المتغيرات التي تم فحصها في نموذج البحث (استخدام SM، شبكات التعاون، الابتكار في الخدمات، المرونة التنظيمية) قدرات حاسمة تمكّن الشركات من التكيف والاستجابة بسرعة لضمان التنافسية في اقتصاد رقمي ناشئ (وارنر وويجر، 2019).

6.2. الآثار العملية

6.3. القيود وخطوط البحث المستقبلية

سياقات مضطربة، حيث التغيير هو الثابت الوحيد. استندت دراستنا إلى نظرية القدرات الديناميكية لتطوير نموذج بحث يتضمن الابتكار في الخدمات والمرونة التنظيمية كمتغيرات حاسمة في تعزيز أداء الشركات. تم اعتماد نهج مختلط متسلسل، باستخدام دراسة كمية للتحقق من صحة النموذج المقترح وتحليل نوعي لتقديم رؤى تكميلية حول الظاهرة المدروسة. تساهم النتائج في الأدبيات من خلال تأكيد أهمية الابتكار والمرونة كقدرات ديناميكية رئيسية للتعامل مع المشهد التجاري المتغير والبقاء تنافسيًا. كما تسلط نتائجنا الضوء على الأهمية المحددة لأدوات وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي وشبكات التعاون كمحركات مباشرة للابتكار في الخدمات وتوفر توجيهًا قيمًا لمساعدة المديرين على تحسين أداء الأعمال من خلال أن يصبحوا أكثر ابتكارًا ومرونة في سياقهم الرقمي اليوم.

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

شكر وتقدير

7. الخاتمة

الملحق 1. عناصر القياس

| المتغير | العناصر | الوصف | المؤلفون |

| استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي (SM) | SMU1 | فيسبوك. | تشودري وهاريغان (2014)؛ غاريدو-مورينو وآخرون (2018) |

| SMU2 | تويتر. | ||

| SMU3 | يوتيوب. | ||

| SMU4 | إنستغرام. | ||

| شبكات التعاون (CN) | CN1 | المشاركة في الأنشطة التي تهدف إلى الحصول على أفكار من العملاء الحقيقيين والمحتملين. | سيبيدا-كاريون وآخرون (2023)؛ أولترا وآخرون (2018) |

| CN2 | المشاركة في الأنشطة التي تهدف إلى الحصول على أفكار من الموردين الحقيقيين والمحتملين. | ||

| CN3 | المشاركة في الأنشطة التعاونية مع المنافسة. |

| المتغير | العناصر | الوصف | المؤلفون |

| CN4 | رعاية الأبحاث من قبل الجامعات ومراكز الأبحاث لتطوير مشاريع بحثية. | ||

| CN5 | شراكات بحثية مع شركات أخرى أو اتحادات البحث والتطوير. | ||

| CN6 | المشاركة والتعاون مع المستشارين والمستشارين. | ||

| CN7 | المشاركة في تجمعات أو شبكات الابتكار. | ||

| ابتكار الخدمة (SI) | SI1 | لقد زادت منتجاتنا وخدماتنا الجديدة المبتكرة المقدمة لعملائنا/زبائننا خلال السنوات الثلاث الماضية. | كالانتون وآخرون (2002)، فراج وآخرون (2015)؛ بالاثيوس-ماركيز وآخرون (2015) |

| SI3 | تسعى منظمتنا بشكل متكرر لتجربة أفكار جديدة للمنتجات والخدمات. | ||

| SI4 | تتميز منظمتنا بالإبداع في أساليب التشغيل (العمليات). | ||

| SI5 | تكون منظمتنا غالبًا الأولى في السوق مع منتجات وخدمات جديدة. | ||

| SI6 | في السنوات الأخيرة، قمنا بتطوير تغييرات وتحسينات في المنتجات والخدمات التي نقدمها لعملائنا. | ||

| المرونة التنظيمية (R) | R1 | تمكنت منظمتنا من التكيف مع التغييرات بسبب كوفيد-19. | كامبل-سيلز وستاين (2007)، كونور وديفيدسون (2003) |

| R2 | يمكن لمنظمتنا التعامل مع أي شيء يأتي كنتيجة لكوفيد-19. | ||

| R3 | تعاملت منظمتنا مع المشكلات المتعلقة بكوفيد-19 بمرونة ورأت الجانب الإيجابي منها. | ||

| R4 | لقد عزز التعامل مع الضغوط الناتجة عن كوفيد-19 منظمتنا. | ||

| R5 | بعد معاناة من صعوبة أو مرض خطير، مثل الوضع الوبائي العالمي، تمكنت منظمتنا من التعافي. | ||

| R6 | تمكنت المنظمة من تحقيق أهدافها على الرغم من عقبات كوفيد-19. | ||

| R7 | يمكن لمنظمتنا أن تبقى مركزة تحت الضغط الناتج عن كوفيد-19. | ||

| R8 | لم تثبط منظمتنا عزيمتها بسبب المشكلات أو الفشل. | ||

| R9 | كانت منظمتنا منظمة قوية في مواجهة الصعوبات المتعلقة بكوفيد-19. | ||

| R10 | تمكنت منظمتنا من إدارة النكسات بشكل صحيح، والأوضاع غير المستقرة أو غير السارة الناتجة عن الوباء. | ||

| الأداء التنظيمي (OP) | OP1 | نمو المبيعات. | مارتين-روخاس وآخرون (2020)؛ ميليان-ألسولا وآخرون (2020)؛ فينكاترامان ورامانوجام (1986) |

| OP2 | نمو حصة السوق. | ||

| OP3 | العائد على الاستثمار (ROI). | ||

| OP4 | العائد على الأصول (ROA). | ||

| OP5 | العائد على المبيعات (ROS). | ||

| OP6 | العائد على حقوق الملكية (ROE). | ||

| حجم القطاع | SIZE SECTOR | عدد الموظفين. النشاط الخدمي. | غارثيا-موراليس وآخرون (2006) مارتين-روخاس وآخرون (2021) |

الملحق 2. إحصائيات جودة الملاءمة (تحليل SEM)

GFI (مؤشر جودة الملاءمة): نسبة التباين التي تمثلها مصفوفة التغاير المقدرة.

NCP (معامل عدم المركزية المقدّر): مقياس بديل لـ

ECVI (مؤشر التحقق المتقاطع المتوقع): تقريب لجودة الملاءمة التي حققها النموذج المقدّر في عينة أخرى من نفس الحجم.

مقاييس الملاءمة التزايدية: مقارنة النموذج المقترح بنموذج مرجعي (نموذج فارغ: النموذج الحقيقي الذي يُتوقع أن تتفوق عليه بقية النماذج).

CFI (مؤشر الملاءمة المقارنة): يقارن ملاءمة نموذج مستهدف بملاءمة نموذج فارغ أو مستقل.

(يتواصل في الصفحة التالية)

(يتواصل)

NNFI (مؤشر الملاءمة غير المعيارية): يجمع بين مقياس الاقتصاد في نموذج مقارن بين النموذج الفارغ والنموذج المقترح (يفضل للعينات الصغيرة).

IFI (مؤشر الملاءمة التزايدية): يعدل NFI لدرجات الحرية وحجم العينة.

RFI (مؤشر الملاءمة النسبية): يقارن أداء النموذج المقترح بأداء نموذج فارغ لم يكن هناك ارتباط بين المتغيرات الملاحظة.

RMSEA (جذر متوسط مربع خطأ التقريب): ملاءمة مطلقة تعكس الملاءمة بين مصفوفة التباين-التغاير للمتغيرات الملاحظة والتباين المفترض من النموذج.

مقاييس ملاءمة الاقتصاد: الاقتصاد في نموذج هو الدرجة التي يحقق بها الملاءمة لكل معامل أو معلمة مقدرة.

لا يوجد اختبار إحصائي مرتبط بهذه المؤشرات، لذا فإن استخدامها أكثر ملاءمة عند مقارنة النماذج البديلة.

AIC (معيار معلومات أكايك): قياس مقارن بين النماذج ذات أعداد مختلفة من البنى.

CAIC (معيار معلومات أكايك المتسق): مشابه لـ AIC. ومع ذلك، فإن CAIC يفرض عقوبة إذا كان حجم العينة صغيرًا.

PGFI (مؤشر جودة الملاءمة الاقتصادية): إعادة تحديد لـ GFI بقيم عالية تعكس مزيدًا من الاقتصاد في النموذج.

الملحق 3. الاستنتاجات الميتا: التأكيد والتأكيد

| فرضية# | الفرضيات | الأدلة التمثيلية | ||||

| H1 | استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي يؤثر إيجابيًا على ابتكار الخدمة |

|

||||

| H2 | استخدام وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي يؤثر إيجابيًا على شبكات التعاون |

|

||||

| H3 | شبكات التعاون تؤثر إيجابيًا على ابتكار الخدمة |

|

||||

| H4 | ابتكار الخدمة يؤثر إيجابيًا على المرونة التنظيمية |

|

||||

| H5 | ابتكار الخدمة يؤثر إيجابيًا على الأداء التنظيمي |

|

||||

| H6 | المرونة التنظيمية تؤثر إيجابيًا على الأداء التنظيمي |

|

الملحق 4. الاستنتاجات الميتا: رؤى تكميلية

| استنتاج ميتا | أدلة تمثيلية | |||

| رؤية #1 |

|

|||

| رؤية #2 |

|

|||

| رؤية #3 |

|

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411-423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Anwar, A., Coviello, N., & Rouziou, M. (2023). Weathering a crisis: A multi-level analysis of resilience in young ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 47(3), 864-892. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587211046545

Armstrong, J., & Overton, T. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 4(3), 396-402. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150783

Avlonitis, G. J., Papastathopoulou, P. G., & Gounaris, S. P. (2001). An empirically-based typology of product innovativeness for new financial services: Success and failure scenarios. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 18(5), 324-342. https://doi. org/10.1111/1540-5885.1850324

Awad, J., & Martín-Rojas, R. (2023). Enhancing social responsibility and resilience through entrepreneurship and digital environment. In press, 1-17. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr. 2655

Ayala, J. C., & Manzano, G. (2010). Established business owners’ success: Influencing factors. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 15(3), 263-286. https://doi.org/ 10.1142/S1084946710001555

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Beuren, I. M., Dos Santos, V., & Theiss, V. (2022). Organizational resilience, job satisfaction and business performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 71(6), 2262-2279. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-03-2021-0158

Bhimani, H., Mention, A. L., & Barlatier, P. J. (2019). Social media and innovation: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 144, 251-269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.10.007

Blichfeldt, H., & Faullant, R. (2021). Performance effects of digital technology adoption and product & service innovation: A process-industry perspective. Technovation, 105 (102275), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102275

Borah, P. S., Iqbal, S., & Akhtar, S. (2022). Linking social media usage and SME’s sustainable performance: The role of digital leadership and innovation capabilities. Technology in Society, 68, Article 101900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. techsoc.2022.101900

Bou-Llusar, J. C., Escrig-Tena, A. B., Roca-Puig, V., & Beltrán-Martín, I. (2009). An empirical assessment of the EFQM excellence model: Evaluation as a TQM framework relative to the MBNQA model. Journal of Operations Management, 27(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2008.04.001

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bustinza, O. F., Vendrell-Herrero, F., Perez Arostegui, M. N., & Parry, G. (2019). Technological capabilities, resilience capabilities and organizational effectiveness. The International Journal of Human Resources Management, 30(8), 1370-1392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1216878

Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019-1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/ jts. 20271

Caputo, F., Cillo, V., Candelo, E., & Liu, Y. (2019). Innovation through digital revolution: The role of soft skills and Big Data in increasing firm performance. Management Decision, 57(8), 2032-2051. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2018-0833

Cepeda-Carrion, I., Ortega-Gutierrez, J., Garrido-Moreno, A., & Cegarra-Navarro, J. G. (2023). The mediating role of knowledge creation processes in the relationship between social media and open innovation. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 14, 1275-1297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-022-00949-4

Chandra, S., Shirish, A., & Srivastava, S. C. (2022). To be or not to be …human? Theorizing the role of human-like competencies in conversational artificial intelligence agents. Journal of Management Information Systems, 39(4), 969-1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2022.2127441

Chandran, V. G. R., Ahmed, T., Jebli, F., Josiassen, Al, & Lang, E. (2023). Developing innovation capability in the hotel industry, who and what is important? A mixed methods approach. Tourism Economics, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 13548166231179840

Chen, H., Chiang, R. H., & Storey, V. C. (2012). Business intelligence and analytics: From Big Data to big impact. MIS Quarterly, 36(4), 1165-1188. https://doi.org/10.2307/ 41703503

Choudhury, M., & Harrigan, P. (2014). CRM to social CRM: The integration of new technologies into customer relationship management. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 22(2), 149-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2013.876069

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CDRISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18, 76-82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da. 10113

Corral de Zubielqui, G., Fryges, H., & Jones, J. (2019). Social media, open innovation & HRM: Implications for performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 144, 334-347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.07.014

Corral de Zubielqui, G. C., & Jones, J. (2020). How and when social media affects innovation in startups: A moderated mediation model. Industrial Marketing Management, 85(2), 209-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.11.006

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. (1991). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behaviour. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7-24. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/104225879101600102

Do, H., Budhwar, P., Shipton, H., Nguyen, H. D., & Nguyen, B. (2022). Building organizational resilience, innovation through resource-based management initiatives, organizational learning and environmental dynamism. Journal of Business Research, 141, 808-821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.090

Dovbischuk, I. (2022). Innovation-oriented dynamic capabilities of logistics service providers, dynamic resilience and firm performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 33(2), 499-519. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/IJLM-01-2021-0059

Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, D. L., Coombs, C., Constantiou, I., Duan, Y., Edwards, J. S., & Upadhyay, N. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: Transforming education, work and life. International Journal of Information Management, 55(102211), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

ijinfomgt.2020.102211

Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Baabdullah, A. M., Ribeiro-Navarrete, D., Giannakis, M., AlDebei, M. M., Dennehy, D., Metri, B., Buahlis, D., Cheung, C. M. K., Conboy, K., Doyl, R., & Wamba, S. F. (2022). Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 66(102542), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2022.102542

Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Ismagilova, E., Aarts, G., Coombs, C., Crick, T., Duan, Y., Dwivedi, T., Edwards, J., Eirug, A., Galanos, V., Ilavarasan, P. V., Janssen, M., Jones, P., Kumar Kar, A., Kizgin, H., Kronemann, B., Lal, B., Lucini, B., Medaglia, R., & Williams, M. (2021b). Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 57(101994), 1-47. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jjinfomgt.2019.08.002

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10/11), 1105-1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266 (200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E

Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making social science matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again. Cambridge, TAS, Australia: Cambridge University Press,. https://doi. org/10.2307/1061731

Forliano, C., Bullini, L., Zardini, A., & Rossignoli, C. (2023). Technological orientation and organizational resilience to Covid-19: The mediating role of strategy’s digital maturity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 188(122288), 1-9. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122288

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Fraj, E., Matute, J., & Melero, I. (2015). Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: The role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tourism Management, 46, 30-42. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.05.009

García-Morales, V. J., Jiménez-Barrionuevo, M. M., & Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L. (2012). Transformational leadership influence on organizational performance through organizational learning and innovation. Journal of Business Research, 65(7), 1040-1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.03.005

García-Morales, V. J., Lloréns-Montes, F. J., & Verdú-Jover, A. J. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of organizational innovation and organizational learning in entrepreneurship. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 106(1-2), 21-42. https:// doi.org/10.1108/02635570610642940

García-Morales, V. J., Matías-Reche, F., & Verdu-Jover, A. (2011). Influence of internal communication on technological proactivity, organizational learning, and organizational innovation in the pharmaceutical sector. Journal of Communication, 61(1), 150-177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01530.x

Garrido-Moreno, A., Garcia-Morales, V., King, S., & Lockett, N. (2020). Social Media use and value creation in the digital landscape: A dynamic-capabilities perspective. Journal of Service Management, 31(3), 313-343. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-09-2018-0286

Garrido-Moreno, A., García-Morales, V., Lockett, N., & King, S. (2018). The missing link: Creating value with social media use in hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 94-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.03.008

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2016). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson,.

Heinonen, K., & Strandvik, T. (2021). Reframing service innovation: COVID-19 as catalyst for imposed service innovation. Journal of Service Management, 32(1), 101-112. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0161

Henderson, D. X., & Green, J. (2014). Using mixed methods to explore resilience, social connectedness, and resuspension among youth in a community-based alternative to suspension program. International Journal of Child, Youth, and Family Studies, 5(3), 423-446. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs.hendersondx. 532014

Hillmann, J., & Guenther, E. (2021). Organizational resilience: A valuable construct for management research? International Journal of Management Reviews, 23, 7-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr. 12239

Hollands, L., Haensse, L., & Lin-Hi, N. (2023). The How and Why of organizational resilience: A mixed-methods study on facilitators and consequences of organizational resilience throughout a crisis. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 1-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/00218863231165785

Huang, A., & Farboudi Jahromi, M. (2021). Resilience building in service firms during and post COVID-19. The Service Industries Journal, 41(1-2), 138-167. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/02642069.2020.1862092

Junaid, M., Zhang, Q., Cao, M., & Luqman, A. (2023). Nexus between technology enabled supply chain dynamic capabilities, integration, resilience, and sustainable

performance: An empirical examination of healthcare organizations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 196(122828), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. techfore.2023.122828

Kaplan, A., & Haenlin, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53, 59-68. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Kraus, S., Durst, S., Ferreira, J. J., Veiga, P., Kailer, N., & Weinmann, A. (2022). Digital transformation in business and management research: An overview of the current status quo. International Journal of Information Management, 63(102466), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102466

Kwayu, S., Abubakre, M., & Lal, B. (2021). The influence of informal social media practices on knowledge sharing and work processes within organizations. International Journal of Information Management, 58(102280), 1-9. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102280

Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Beck, T. E., & Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Human Resources Management Review, 21(3), 243-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. hrmr.2010.07.001

Li, B., Zhong, Y. Y., Zhang, T., & Hua, N. (2021). Transcending the COVID-19 crisis: Business resilience and innovation of the restaurant industry in China. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 49, 44-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jhtm.2021.08.024

Lütjen, H., Schultz, C., Tietze, F., & Urmetzer, F. (2019). Managing ecosystems for service innovation: A dynamic capability view. Journal of Business Research, 104, 506-519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.001

Maier, C., Thatcher, J. B., Grover, V., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2023). Cross-sectional research: A critical perspective, use cases, and recommendations for IS research. International Journal of Information Management, 70(102625), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijinfomgt.2023.102625

Markovic, S., Koporcic, N., Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M., Kadic-Maglajlic, S., Bagherzadeh, M., & Islam, N. (2021). Business-to-business open innovation: COVID19 lessons for small and medium-sized enterprises from emerging markets. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 170(120883), 1-5. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120883

Martín-Rojas, R., García-Morales, V. J., Garrido-Moreno, A., & Salmador-Sanchez, M. P. (2021). Social media use and the challenge of complexity: evidence from the technology sector. Journal of Business Research, 129, 621-640. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.026

Martín-Rojas, R., Garrido-Moreno, A., & Garcia-Morales, V. J. (2020). Fostering corporate entrepreneurship with the use of social media tools. Journal of Business Research, 112, 396-412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.072

Matarazzo, M., Penco, L., Profumo, G., & Quaglia, R. (2021). Digital transformation and customer value creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Journal of Business Research, 123, 642-656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbusres.2020.10.033

Melian-Alzola, Fernandez-Monroy, M., & Hidalgo-Peñate, M. (2020). Hotels in contexts of uncertainty: Measuring organisational resilience. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36(100747), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100747

Mention, A. L., Barlatier, P. J., & Josserand, E. (2019). Using social media to leverage and develop dynamic capabilities for innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 144, 242-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.03.003

Muninger, M.-I., Mahr, D., & Hammedi, W. (2022). Social media use: A review of innovation management practices. Journal of Business Research, 143, 140-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.039

Natalicchio, A., Petruzzelli, A. M., Cardinali, S., & Savino, T. (2018). Open innovation and the human resource dimension. Management Decision, 56(6), 1271-1284. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2017-0268

Newey, L. R., & Zahra, S. A. (2009). The evolving firm: How dynamic and operating capabilities interact to enable entrepreneurship. British Journal of Management, 20, 81-100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00614.x

Nielsen, J. A., Mahiassen, L., Benfeld, O., Madsen, S., Haslam, C., & Penttinen, E. (2023). Organizational resilience and digital resources: Evidence from responding to exogenous shock by going virtual. International Journal of Information Management, 73, Article 102687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102687

Niemimaa, M., Järveläinen, J., Hikkilä, M., & Heikkilä, J. (2019). Business continuity of business models: Evaluating the resilience of business models for contingencies. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 208-216. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jjinfomgt.2019.04.010

destination. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(6), 2537-2561. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2016-0341

Oltra, M. J., Flor, M. L., & Alfaro, J. A. (2018). Open innovation and firm performance: The role of organizational mechanisms. Business Process Management Journal, 24(3), 814-836. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-05-2016-0098

Ozanne, L. K., Chowdhury, M., Prayag, G., & Mollenkopf, D. A. (2022). SMEs navigating COVID-19: The influence of social capital and dynamic capabilities on organizational resilience. Industrial Marketing Management, 104, 116-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.indmarman.2022.04.009

Papadopoulos, T., Baltas, K. N., & Balta, M. E. (2020). The use of digital technologies by small and medium enterprises during COVID-19: Implications for theory and practice. International Journal of Information Management, 55(102192), 1-4. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102192

Papagiannidis, S., Harris, J., & Morton, D. (2020). WHO led the digital transformation of your company? A reflection of IT related challenges during the pandemic. International Journal of Information Management, 55(102166), 1-5. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jjinfomgt.2020.102166

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903. https://doi.org/10.1037/ 0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531-544. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/014920638601200408

Rakshit, S., Mondal, S., Islam, N., Jasimuddin, S., & Zhang, Z. (2021). Social media and the new product development during COVID-19: An integrated model for SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 170(120869), 1-15. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120869

Santos, S. C., Liguori, E. W., & Garvey, E. (2023). How digitalization reinvented entrepreneurial resilience during COVID-19. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 189, Article 122398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122398

Secundo, G., Del Vecchio, P., & Mele, G. (2021). Social media for entrepreneurship: Myth or reality? A structured literature review and a future research agenda. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 27(1), 149-177. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/IJEBR-07-2020-0453

Skare, M., De Obesso, M. M., & Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. (2023). Digital transformation and European small and medium enterprises (SMEs): A comparative study using digital economy and society index data. International Journal of Information Management, 68 (103594), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinfomgt.2022.102594

Su, W., & Junge, S. (2023). Unlocking the recipe for organizational resilience: A review and future research directions. European Management Journal. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.emj.2023.03.002

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319-1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj. 640

Teece, D. J., & Pisano, G. (1994). The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. Strategic Industrial and Corporate Change, 3(3), 537-556. https://doi.org/10.1093/ icc/3.3.537-a

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509-533. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

Venkatesh, V., Brown, S. A., & Bala, H. (2013). Bridging the qualitative-quantitative divide: Guidelines for conducting mixed methods research in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 37(1), 21-54. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.1.02

Venkatesh, V., Brown, S. A., & Sullivan, Y. W. (2016). Guidelines for conducting mixedmethods research: An extension and illustration. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17(7), 435-495. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais. 00433

Venkatraman, N., & Ramanujam, V. (1986). Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches. Academy of Management Review, 11 (4), 801-814. https://doi.org/10.2307/258398

Warner, K. S., & Wager, M. (2019). Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Longest Range Planning, 52 (3), 326-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.12.001

Westphal, J. D., & Fredickson, J. W. (2001). Who directs strategic change? Director experience, the selection of new CEOs, and change in corporate strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 1113-1137. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj. 205

Wu, Y., Jiao, Y., Xu, H., & Lyu, C. (2022). The more engagement, the better? The influence of supplier engagement on new product design in the social media context. International Journal of Information Management, 64(102475), 1-12. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2022.102475

Yuan, R., Luo, J., Liu, M. J., & Yu, J. (2022). Understanding organizational resilience in a platform-based sharing business: The role of absorptive capacity. Journal of Business Research, 141, 85-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.012

Zhu, Z., Zhao, M., Wu, X., Shi, S., & Leung, W. K. S. (2023). The dualistic view of challenge-hindrance technostress in accounting information systems: Technological antecedents and coping responses. International Journal of Information Management, 73(102681), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102681

- Corresponding author.

E-mail address: agarridom@uma.es (A. Garrido-Moreno).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2024.102777

Publication Date: 2024-03-23

The key role of innovation and organizational resilience in improving business performance: A mixed-methods approach

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Service innovation

Social media

Mixed-methods research

Abstract

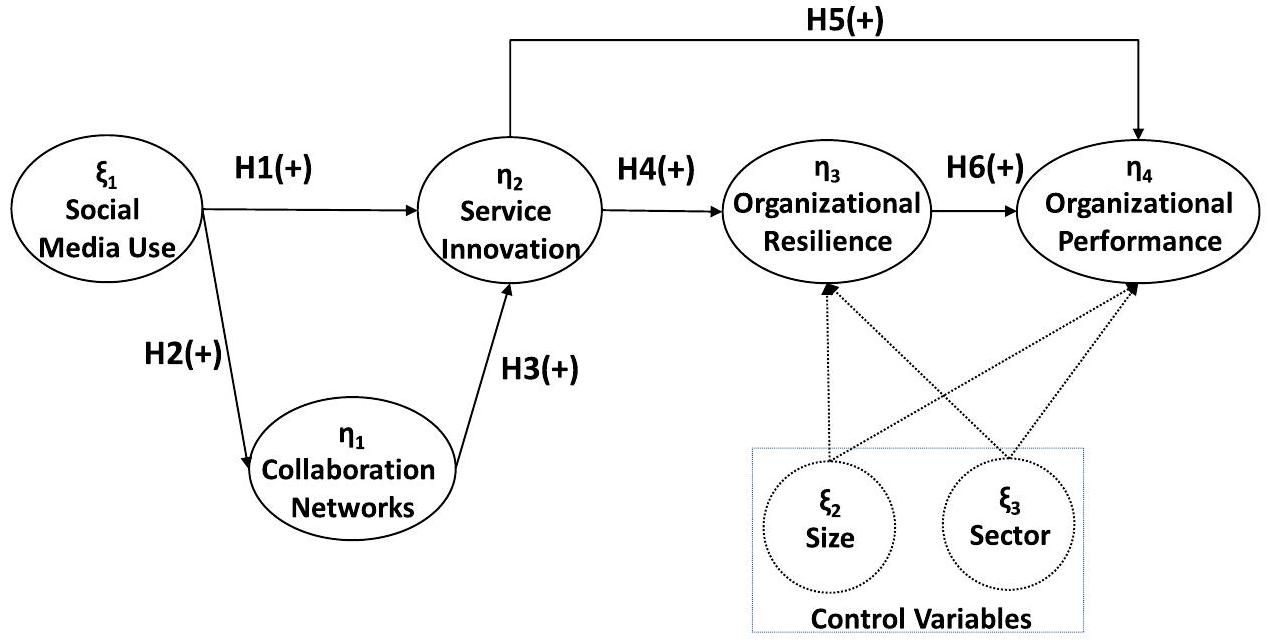

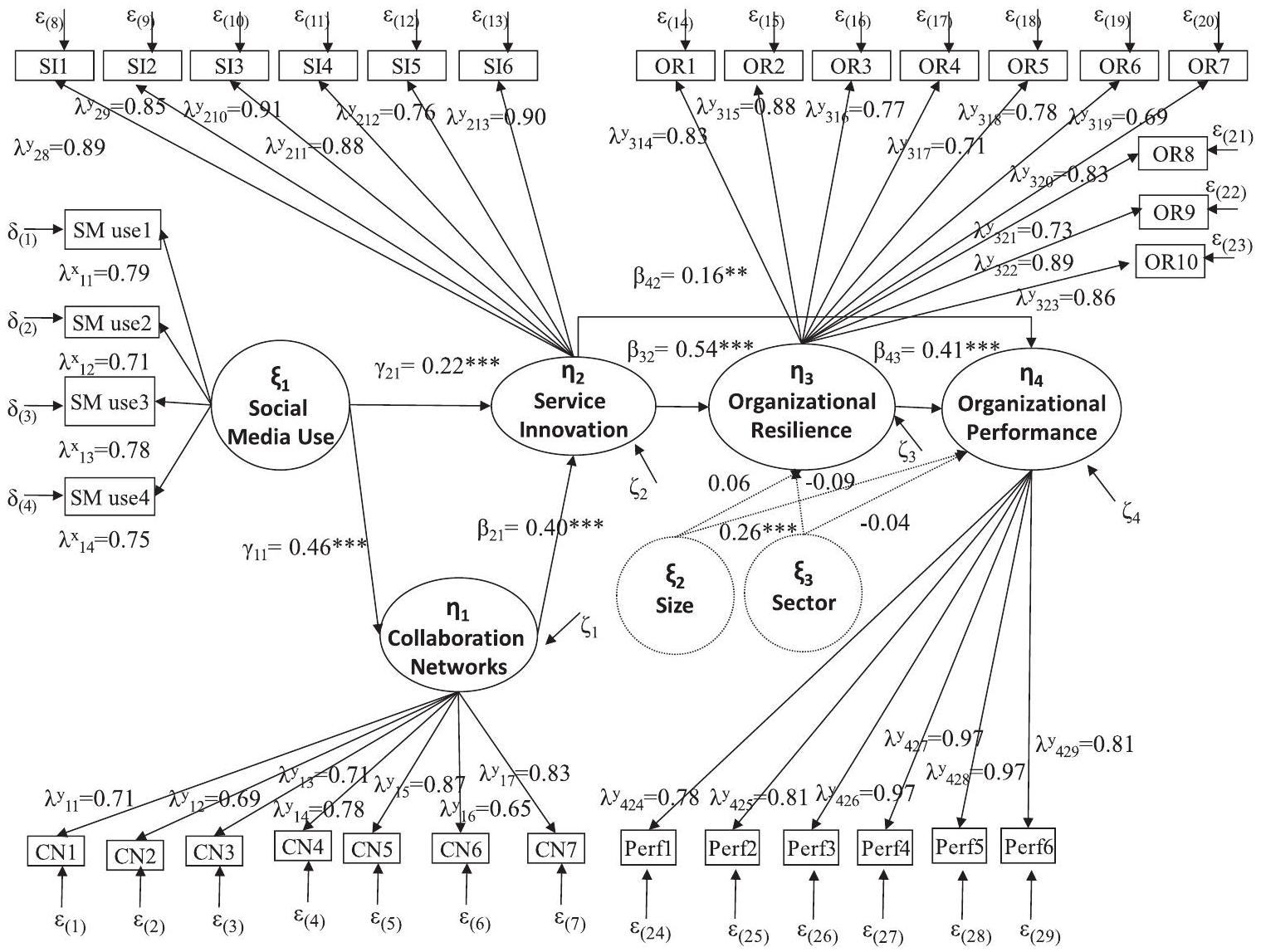

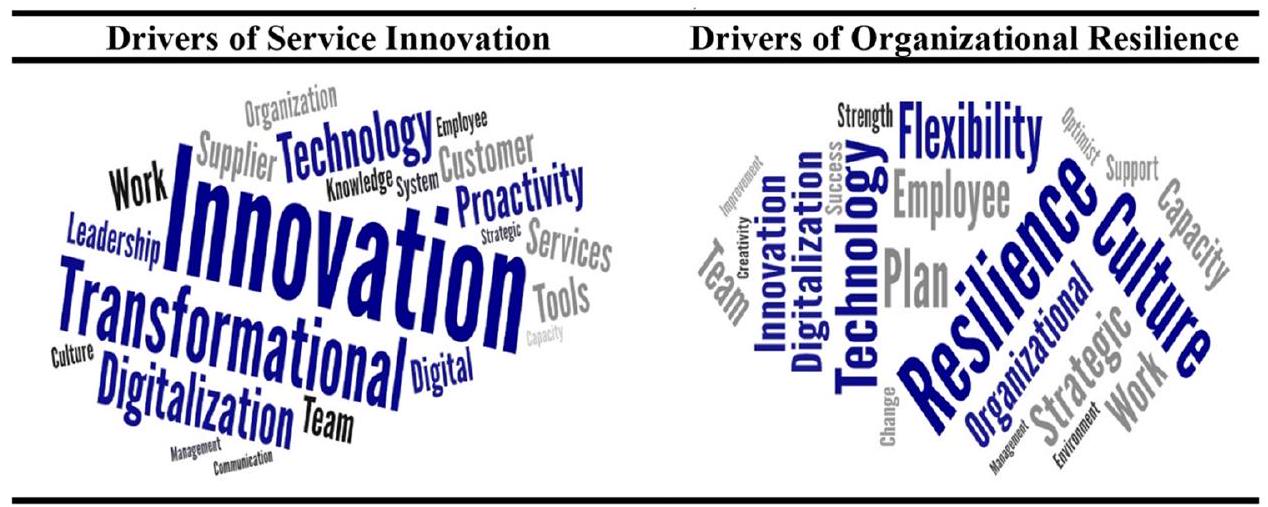

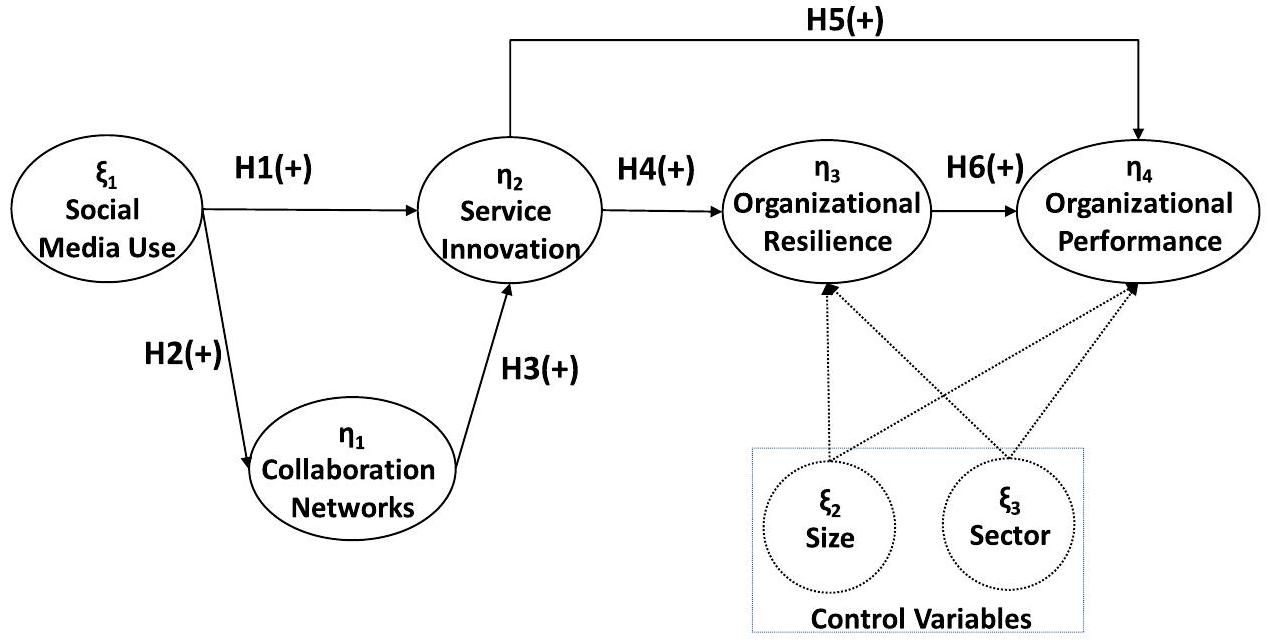

An uncertain and complex economic environment requires companies to act quickly and reinvent their business strategies. Innovation has emerged as a strategic imperative to adapt to market changes and remain competitive, while resilience has gained attention as essential for organizations to respond successfully to external environmental pressures. Despite these strategic factors’ importance in unstable environments, little empirical research has analyzed them. Drawing on dynamic capabilities’ theory, our study examines the role of service innovation and organizational resilience in enhancing business performance using a sequential two-stage mixed-methods approach. First, a quantitative study was conducted to test the proposed research model using structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis with a sample of 343 service companies in Spain. Second, a qualitative analysis was performed with 12 interviews with managers to provide additional insights and a detailed understanding of the phenomenon. The results confirm innovation and resilience as key dynamic capabilities to address a changing business landscape and remain competitive. Our findings also reveal the strategic importance of digital tools (social media platforms) and external networks as drivers of service innovation. Managers can use these findings to leverage social media to engage in collaborative networks, enhance innovation and resilience, and succeed in turbulent markets.

1. Introduction

(Papadopoulos et al., 2020). Platforms such as social media (SM) have emerged as key digital tools to promote collaboration with external actors, enabling firms to collect valuable market information to support innovation activities (Muninger et al., 2022). To address emerging challenges, risk, and turbulence, firms must anticipate and adjust to new trends by developing innovative products and services. Service innovation has thus become an essential-even mandatory-factor in fostering companies’ ability to adapt to changes in business environments (Heinonen & Strandvik, 2021). Evidence shows that digitalization and technological solutions have been critical in driving organizations’ innovativeness in coping with recent crises (Forliano et al., 2023). Although research on the topic is growing, more knowledge is needed on the processes by which firms can use these tools to foster collaboration networks and innovation (Muninger et al., 2022).

2. Literature review

2.1. Dynamic capabilities view

competences to address rapidly changing environments.” Dynamic capabilities thus reflect a firm’s ability to renew its competences continuously to respond rapidly to changing environmental conditions (Junaid et al., 2023). DC refers to the organization’s ability to adapt and respond to changing environments by coordinating and integrating internal and external resources and processes (Awad & Martín-Rojas, 2023). Those capabilities have become a key concern for businesses today as they enable firms to identify, acquire and transform resources and capabilities in line with changing conditions in order to remain competitive (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Teece & Pisano, 1994). These capabilities are especially important in the service sector, where market dynamics are constantly evolving. To be able to develop new services in such an unstable context, firms need to develop dynamic capabilities to foster service innovation (Kindström et al., 2013).

2.2. Service innovation, digital technologies, and collaboration networks

2.3. Organizational resilience

contexts. The term derives from the Latin resilire, which means to bounce back or recover from a sudden disturbance (Nielsen et al., 2023). Organizational resilience has been defined as the firm’s ability to “anticipate potential threats, to cope effectively with adverse events, and to adapt to changing conditions” (Duchek et al., 2020, p. 220). It reflects the organization’s ability to cope with and recover from sudden disruptions by adjusting and preserving (or improving) the firm’s functions (Su & Junge, 2023). Resilient firms possess not only the short-term coping capacity to recover from disturbances but also the long-term adaptative abilities to generate profound changes in their business models after the crisis (Li et al., 2021).

Recent empirical studies examining innovation and resilience in a digital context.

| Authors | Variables included | Research design | Data | Main findings |

| Blichfeldt and Faullant (2021) | Digital technology implementation, Product and service innovation, Competitive advantage (ROS). | Quantitative analysis (correlation). | Secondary data from 747 industrial firms. | Results indicate that firms with high levels of digital technologies can introduce more radical product and service innovations; corroborates key role of these technologies as catalysts for innovation. |

| Li et al. (2021) | Innovative practices to increase resilience (i. e., cooperation with third parties, customer service innovation). | Qualitative analysis (content analysis). | 153 textual information sources from the restaurant industry. | Findings propose an innovative crisis management model and describe how specific innovative practices enhanced business resilience during the pandemics. |

| Do et al. (2022) | Innovation management initiatives (support), Organizational learning, Organizational resilience, Innovation. | Quantitative analysis (regression and path analysis). | Survey: 188 CEOS from SMEs (cross-industry sample). | The results confirm that innovation management initiatives positively influenced organizational resilience, which in turn enhanced innovation. Findings reveal the mediating role of organizational learning in these relationships. |

| Dovbischuk (2022) | Organizational learning, Innovation-oriented capabilities, Dynamic resilience, Logistics service quality, Firm performance. | Quantitative analysis (correlation). | Survey: 113 service firms. | Organizational learning and innovationoriented capabilities were positively associated with higher levels of resilience during the pandemic. Resilience correlated with higher logistics service quality and better business performance. |

| Pratono (2022) | IT turbulence, Innovation (product development), Organizational resilience, Marketing communication, Competitive advantage (performance). | Quantitative analysis (SEM). | Survey: 582 managers. | Results show that organizational resilience exerted the most significant impact on firms’ competitive advantage. Innovation also had a positive effect on firm performance. |

| Xie et al. (2022) | Business networks, Organizational resilience capacity, Ambidextrous learning, Digital technologies use. | Quantitative analysis (regression) | Survey: 409 firms | In the context of the pandemic, results demonstrate how business networks had a positive impact on organizational resilience. Findings also confirm the moderating role of digital technologies use in this relationship. |

| Forliano et al. (2023) | Technological orientation, Maturity of the digital strategy and Resilience to Covid-19. | Quantitative analysis (SEM). | Survey: 186 firms from different sectors. | Results confirm how the technological orientation of a firm positively affects the maturity of its digital strategy, leading to higher organizational resilience. |

| Junaid et al. (2023) | Supply chain dynamic capabilities, Supply chain integration, Resilience, Sustainable competitive advantage, Performance. | Quantitative analysis (SEM). | Survey: 325 professionals of the healthcare industry. | Findings illustrate how Supply chain dynamic capabilities improve Supply chain integration and resilience, driving competitive advantage and performance. |

| Santos et al. (2023) | Digital technologies, Entrepreneurial resilience, Firm performance. | Qualitative analysis (inductive qualitative approach). | 42 interviews with successful entrepreneurs. | Digital platforms and infrastructures emerged as key enablers of resilience during the pandemic. Business resilience through digitalization led to better financial performance. |

| Yuan et al. (2022) | Organizational resilience, Absorptive capacity | Qualitative analysis (case study) | Single case study with information from a platform-based sharing company. | Considering resilience as an adaptive process, results confirm the crucial role of absorptive capacity as the main facilitator of organizational resilience. |

Mixed-methods research design.

| Phase | Procedure | Outcome | |||||||||

| Quantitative data collection |

|

|

|||||||||

| Quantitative data analysis |

|

|

|||||||||

| Qualitative data collection |

|

– Transcribed interviews and notes. | |||||||||

| Qualitative data analysis |

|

|

|||||||||

| Integration of quantitative and qualitative findings | – Integration, explanation and discussion of quantitative and qualitative findings. |

|

detailed understanding of the phenomenon (Hollands et al., 2023).

To provide deeper insight into the key themes emerging in the study of innovation and resilience in the digital context, Table 1 summarizes recent empirical research on the topic.

3. Research design

Mixed-methods approach and criteria.

| Quality aspects | Quality criteria | Explanation on how this study followed guidelines of Venkatesh et al. (2013) | |||||

| Purpose of mixedmethods approach | Sequential dominant quantitative investigation followed by a less-dominant qualitative analysis. | The study is divided into two phases: 1) quantitative survey-based study to verify proposed research model and test hypotheses proposed, and 2) qualitative study involving interviews with managers to validate and enrich quantitative results and obtain a richer understanding of the phenomenon. | |||||

| Design quality | Design appropriateness. | The study used a large quantitative survey-based study followed by a qualitative study to address the research questions. This strategy of designing a sequential study to validate and complement findings and ach richness to the overall study was relevant to the phenomenon of interest. | |||||

| Design adequacy. | Quantitative: | ||||||

| 1) Sampling: the sample of respondent firms was randomly selected in Spain. | |||||||

| Analytical adequacy. | 1) Selecting suitable interviewees: The interviewees were all managers of services firms from different subsectors in Spain. | ||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Explanation quality | Quantitative inference. |

|

|||||

| Qualitative inference | All constructs and relationships obtained through the qualitative study were plausible, and were considered relevant in recent literature. | ||||||

| Integrative inference | A research model was developed building on relevant literature, and was statistically tested drawing on a quantitative sample of 343 service firms in Spain. Subsequently, we performance a qualitative study, based on the 12 semi-structured interviews, which enabled us to corroborate and enrich the results previously obtained. The synergy between quantitative and qualitative results indicates a satisfactory level of integrative efficacy. |

and produce “a greater assortment of divergent and/or complementary views” (Venkatesh et al., 2016, p. 437). Mixed-methods design is also especially suited to overcoming the limitations of cross-sectional data (Maier et al., 2023). By integrating the findings of quantitative and qualitative studies, researchers can develop meta-inferences, the critical assets of mixed-methods analysis, to obtain a complete view (Reis et al., 2022; Venkatesh et al., 2013).

hypotheses, and then extending the quantitative findings through a qualitative study (Study 2). Table 2 presents the different phases and flow of the research design.

4. Study 1: quantitative study

4.1. Overview

4.2. Theoretical background and hypothesis development

In today’s complex and uncertain environment, companies must participate in collaborative networks to work with partners and gain valuable resources (Xie et al., 2022). Collaborative innovation is especially important in the service industry, where intense competition makes collaboration with customers and suppliers a key relational asset for companies’ innovation (Wang et al., 2016). In fact, business networks contributed significantly to companies’ adaptation during the Covid-19 pandemic by providing access to external resources, including knowledge (Xie et al., 2022).

market changes by developing new services. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is proposed:

Competing in dynamic environments requires constant adaptation to and generation of innovative ideas (Markovic et al., 2021). To this end, organizations have increased knowledge acquisition from external sources to accelerate innovation processes (Natalicchio et al., 2018). External collaboration provides additional expertise to complement firms’ internal base, encouraging development of innovations (Nieves & Diaz-Meneses, 2018). In fact, service innovations are more dependent than product innovation on external knowledge and collaboration, and require deeper involvement of firms’ customers and other service ecosystem partners (Lütjen et al., 2019).

H3. Collaboration networks positively affect service innovation.

H4. Service innovation positively affects organizational resilience.

2021). Such innovation is essential to coping successfully with volatile environments because it enables organizations to maintain and improve performance in the face of disruptive events (Dovbischuk, 2022).

Building on DC theory, our study considers organizational resilience as a DC that enables firms to adapt better to their environment and tackle challenges more successfully (Beuren et al., 2022). Organizational resilience improves performance and business success, enabling organizations to emerge strengthened from challenges and external disruptions (Hollands et al., 2023).

of financial performance. It is therefore proposed that:

H6. Organizational resilience positively affects organizational performance.

4.3. Research methods

4.3.1. Data collection

Technical details of the quantitative research.

| Variable | Data |

| Sector | Services sector |

| Geographic location | Spain |

| Methodology | Stratified random sampling |

| Universe of population | 3210 firms |

| Sample size (% response) | 950 (36.10%, 343) firms |

| Sampling error | 5.0% |

| Data collection period | June to October 2022 |

4.3.2. Measures

contextualized by comparing these indicators to those of their main competitor companies (common practice in recent studies) (Martín-Rojas et al., 2021). Whereas previous studies have relied on managers’ perceptions to measure company performance, ours included questions on subjective and objective ratings. Where possible, correlations among the data were examined, and these were high and significant. A seven-point Likert-type scale compared organizational performance of direct competitors ( 1 much worse – 7 much better). The scale was validated using CFA (

4.4. Results

4.4.1. Measurement model

Variables tested for non-response bias (early versus late respondents).

| Characteristic | Early Respondents | Late Respondents | Statistics | ||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|

|

| Size | 1.18 | 0.466 | 1.15 | 0.432 | 0.590 |

| Sector | 1.86 | 0.910 | 1.91 | 0.935 | 0.668 |

| Annual Turnover | 1508.95 | 3693.255 | 1150.52 | 3654.94 | 0.368 |

| Growth of Sales | 4.85 | 1.70 | 4.94 | 1.66 | 0.647 |

| Market share | 4.71 | 1.63 | 4.87 | 1.54 | 0.348 |

| ROI | 4.29 | 1.69 | 4.31 | 1.68 | 0.922 |

| ROA | 4.21 | 1.65 | 4.26 | 1.63 | 0.754 |

| ROS | 4.36 | 1.60 | 4.49 | 1.61 | 0.457 |

| ROE | 4.89 | 1.49 | 4.96 | 1.48 | 0.635 |

Rotated component matrix for strategic measures.

| Items | Component | ||||

| 1 Social Media Use | 2 Collaboration Networks | 3 Service Innovation | 4 Organizational Resilience | 5 Organizational Performance | |

| SMU1 | 0.745 | ||||

| SMU2 | 0.726 | ||||

| SMU3 | 0.713 | ||||

| SMU4 | 0.723 | ||||

| CN1 | 0.605 | ||||

| CN2 | 0.648 | ||||

| CN3 | 0.705 | ||||

| CN4 | 0.745 | ||||

| CN5 | 0.810 | ||||

| CN6 | 0.616 | ||||

| CN7 | 0.788 | ||||

| SI1 | 0.813 | ||||

| SI2 | 0.784 | ||||

| SI3 | 0.830 | ||||

| SI4 | 0.798 | ||||

| SI5 | 0.683 | ||||

| SI6 | 0.821 | ||||

| R1 | 0.747 | ||||

| R2 | 0.791 | ||||

| R3 | 0.703 | ||||

| R4 | 0.642 | ||||

| R5 | 0.673 | ||||

| R6 | 0.609 | ||||

| R7 | 0.770 | ||||

| R8 | 0.683 | ||||

| R9 | 0.827 | ||||

| R10 | 0.794 | ||||

| OP1 | 0.782 | ||||

| OP2 | 0.780 | ||||

| OP3 | 0.858 | ||||

| OP4 | 0.858 | ||||

| OP5 | 0.854 | ||||

| OP6 | 0.789 | ||||

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and confidence intervals.

| Variable | Mean | s.d. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1. Social Media Use | 3.25 | 1.53 | 1.000 | 0.33-0.55 | 0.31-0.53 | 0.03-0.27 | 0.30-0.52 | 0.31-0.65 | -0.23-0.03 |

| 2. Collaboration Networks | 3.45 | 1.47 | 0.36*** | 1.000 | 0.40-0.60 | 0.17-0.38 | 0.31-0.53 | 0.15-0.50 | -0.17-0.08 |

| 3. Service Innovation | 5.04 | 1.43 | 0.34*** | 0.50*** | 1.000 | 0.47-0.65 | 0.31-0.51 | -0.06-0.26 | -0.16-0.08 |

| 4. Org. Resilience | 5.56 | 1.16 | 0.13** | 0.28*** | 0.46*** | 1.000 | 0.46-0.63 | -0.03-0.31 | -0.24-0.01 |

| 5. Org. Performance | 4.59 | 1.45 | 0.32*** | 0.37*** | 0.41*** | 0.57*** | 1.000 | 0.18-0.50 | -0.26-(-0.04) |

| 6. Size | 1.16 | 0.44 | 0.30*** | 0.19*** | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.20*** | 1.000 | -0.41-(-0.01) |

| 7. Sector | 1.89 | 0.92 | -0.08 | -0.02 | -0.03 | -0.12* | -0.12* | -0.11* | 1.000 |

presented in random order (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). No single component explained most of the variance, several components’ eigenvalues were above one (Harman’s factor test), and fit worsened in the one-dimensional (one-factor model) model. The data also showed differences of less than 0.200 between indicators of the common latent (first-order) factor and the theoretical research model with all measures as indicators. All tests thus discount common method bias as a problem affecting our data (Bou-Llusar et al., 2009).

4.4.2. Structural model

Results of the measurement model.

| Variable | Items |

|

|

A.M. |

| Social Media Use | SMU1 | 0.80*** (22.22) | 0.64 |

|

| SMU2 | 0.71*** (15.31) | 0.50 | AVE

|

|

| SMU3 | 0.77*** (20.47) | 0.59 | ||

| SMU4 | 0.76*** (20.96) | 0.57 | ||

| Collaboration Networks | CN1 | 0.71*** (21.51) | 0.50 |

|

| CN2 | 0.72***(22.32) | 0.51 |

|

|

| CN3 | 0.71***(21.82) | 0.50 | ||

| CN4 | 0.73***(22.05) | 0.53 | ||

| CN5 | 0.88***(37.17) | 0.77 | ||

| CN6 | 0.72***(21.01) | 0.51 | ||

| CN7 | 0.84*** (30.48) | 0.70 | ||

| Service Innovation | SI1 | 0.89***(56.07) | 0.79 |

|

| SI2 | 0.85***(34.04) | 0.72 |

|

|

| SI3 | 0.91***(62.53) | 0.82 | ||

| SI4 | 0.88***(42.79) | 0.77 | ||

| SI5 | 0.76***(26.18) | 0.57 | ||

| SI6 | 0.90***(47.25) | 0.81 | ||

| Organizational Resilience | R1 | 0.83*** (32.89) | 0.68 |

|

| R2 | 0.88***(42.73) | 0.77 | AVE

|

|

| R3 | 0.77***(25.73) | 0.59 | ||

| R4 | 0.71***(19.69) | 0.50 | ||

| R5 | 0.78***(26.67) | 0.60 | ||

| R6 | 0.71***(21.17) | 0.50 | ||

| R7 | 0.88*** (24.37) | 0.77 | ||

| R8 | 0.78***(18.79) | 0.60 | ||

| R9 | 0.89***(40.67) | 0.79 | ||

| R10 | 0.86***(28.95) | 0.73 | ||

| Organizational Performance | OP1 | 0.77*** (23.70) | 0.59 |

|

| OP2 | 0.80*** (30.95) | 0.64 | AVE

|

|

| OP3 | 0.97***(61.94) | 0.94 | ||

| OP4 | 0.97***(101.40) | 0.94 | ||

| OP5 | 0.97***(89.80) | 0.94 | ||

| OP6 | 0.81*** (23.71) | 0.65 | ||

| Goodness of Fit Statistics |

|

|||

between size and organizational performance (

5. Study 2: qualitative study

5.1. Overview

5.2. Research method

5.2.1. Selection of the population

Proposed structural model results (direct, indirect, and total effects).

| – | Direct Effects |

|

Indirect Effects |

|

Total Effects |

|

Confidence Interval | ||

| Effect from | To | ||||||||

| Social Media Use |

|

Service Innovation | 0.22*** | 3.30 | 0.18*** | 4.89 | 0.40*** | 6.60 | 0.05-0.21 (H1) |

| Social Media Use |

|

Collaboration Networks | 0.46*** | 6.60 | 0.46*** | 6.90 | 0.24-0.44 (H2) | ||

| Social Media Use |

|

Org. Resilience | 0.22*** | 5.78 | 0.22*** | 5.78 | |||

| Social Media Use |

|

Org. Performance | 0.15*** | 4.41 | 0.15*** | 4.41 | |||

| Collaboration Networks |

|

Service Innovation | 0.40*** | 6.59 | 0.40*** | 6.59 | 0.21-0.40 (H3) | ||

| Collaboration Networks |

|

Org. Resilience | 0.22*** | 5.56 | 0.22*** | 5.56 | |||

| Collaboration Networks |

|

Org. Performance | 0.15*** | 4.38 | 0.15*** | 4.38 | |||

| Service Innovation |

|

Org. Resilience | 0.54*** | 10.19 | 0.54*** | 10.19 | 0.36-0.53 (H4) | ||

| Service Innovation |

|

Org. Performance | 0.16** | 2.36 | 0.22*** | 5.13 | 0.38*** | 6.16 | 0.03-0.32 (H5) |

| Org. Resilience |

|

Org. Performance | 0.41*** | 6.14 | 0.41*** | 6.14 | 0.40-0.77 (H6) | ||

| Size |

|

Org. Resilience | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 0.78 | |||

| Size |

|

Org. Performance | 0.26*** | 3.56 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.28*** | 3.66 | |

| Sector |

|

Org. Resilience | -0.09 | -1.58 | -0.09 | -1.58 | |||

| Sector |

|

Org. Performance | -0.04 | -0.68 | -0.04 | -1.49 | -0.08 | -1.27 | |

|

|

|||||||||

with each participant to conduct the interview. Table 11 presents the demographic information of the cases studied, based on the characteristics of the directors and companies. To protect confidentiality, the companies’ names were anonymized and codes were used to reference them.

5.2.2. Data collection

Proposed structural model against alternative statistical models.

| Model Description |

|

|

RMSEA | ECVI | AIC | NCP |

| 1. Proposed structural model | 1580.44 | 0.074 | 5.09 | 1742.44 | 1031.44 | |

| 2. W.R. Social media use to service innovation | 1589.47 | 9.03 | 0.074 | 5.12 | 1749.47 | 1039.47 |

| 3. W.R. Service innovation to org. resilience | 1658.65 | 78.21 | 0.077 | 5.32 | 1818.65 | 1108.65 |

| 4. W.R. Org. resilience to org. performance | 1595.17 | 16.73 | 0.075 | 5.13 | 1755.17 | 1045.17 |

aggregate form to maintain anonymity of both company and interviewee.

5.2.3. Data analysis

with the data through transcription of interviews, in-depth reading, and observation of initial ideas; 2) generation of initial codes by identifying the ideas that stood out initially and developing an initial coding scheme by comparing the data from the different interviews; 3) search for themes comparing the code scheme generated to the literature, reducing the number of initial codes by grouping them into broader areas; 4) examination of the data to determine whether they supported the emerging themes and how some themes differed from others; 5) definition and naming of themes by defining themes and subthemes and establishing their final form; and 6) analysis of results by formulating the evidence and writing up the study findings.

5.3. Results: meta-inferences

5.3.1. Meta-inferences: corroboration and confirmation

Respondents’ profile.

| Codes | Managers’ Characteristics | Firms’ Characteristics | |||||

| Gender | Age | Position | Experience | Firm Age | Activity | N.

|

|

| I#01 | Female | 57 | Business Manager | 29 | 21 | Tourism | 209 |

| I#02 | Male | 40 | General Manager | 16 | 13 | Tourism | 150 |

| I#03 | Male | 56 | General Manager | 23 | 50 | Education | 1015 |

| I#04 | Female | 41 | Human Resources Manager | 15 | 53 | Financial | 873 |

| I#05 | Male | 51 | General Manager | 27 | 19 | Education | 126 |

| I#06 | Female | 59 | General Manager | 20 | 49 | Education | 924 |

| I#07 | Male | 48 | Human Resources Manager | 19 | 23 | Technology | 122 |

| I#08 | Female | 52 | Business Manager | 30 | 83 | Education | 132 |

| I#09 | Male | 45 | Operational Manager | 24 | 66 | Transport | 610 |

| I#10 | Male | 44 | General Manager | 12 | 46 | Distribution | 102 |

| I#11 | Male | 41 | General Manager | 6 | 40 | Health care | 104 |

| I#12 | Male | 52 | General Manager | 15 | 30 | Health care | 120 |

5.3.2. Meta-inferences: complementary insights

organizational performance. Human resources are a key asset that play a strategic role in organizational performance. Firms should foster interpersonal skills (e.g., creativity, communication, teamwork, active listening, learning, thinking, decision making, flexibility, commitment, empathy) to improve results.

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical contributions and implications

firms can manage uncertain contexts and respond to environmental pressures (Do et al., 2022). This finding is especially important for service firms, whose market is continuously changing and evolving. Both innovation and resilience enable firms to anticipate, seize opportunities, and adapt rapidly to the dynamic environment, exploiting both internal and external enterprise-specific competences (Do et al., 2022; Martin-Rojas et al., 2020). Our findings also reinforce the assumption that organizational resilience is a dynamic process rather than an outcome (Nielsen et al., 2023). Resilience thus emerges as an essential capability of the firm, promoting firm performance in changing landscapes (Anwar et al., 2023). In sum, our results complement the DC view, as the variables examined in the research model (SM use, collaboration networks, service innovation, organizational resilience) represent critical capabilities that enable firms to adapt and respond quickly to ensure competitiveness in an emerging digital economy (Warner & Wager, 2019).

6.2. Implications for practice

6.3. Limitations and future research lines