DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114542

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-14

الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في إدارة الابتكار: لمحة عن تطورات البحث المستقبلية

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

دراسة دلفي

الإدارة

الابتكار

الملخص

تستعرض هذه الدراسة الفرص البحثية المستقبلية المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (GenAI) في إدارة الابتكار. لهذا الغرض، تجمع بين مراجعة الأدبيات الأكاديمية ونتائج دراسة دلفي التي تشمل أبرز علماء إدارة الابتكار. ظهرت عشرة مواضيع بحثية رئيسية يمكن أن توجه تطورات البحث المستقبلية عند تقاطع GenAI وإدارة الابتكار: 1) Gen AI وأنواع الابتكار؛ 2) GenAI، التصاميم السائدة وتطور التكنولوجيا؛ 3) الإبداع العلمي والفني والابتكارات المدعومة بـ GenAI؛ 4) الابتكارات المدعومة بـ GenAI وحقوق الملكية الفكرية؛ 5) GenAI وتطوير المنتجات الجديدة؛ 6) GenAI متعدد الأنماط/أحادي النمط ونتائج الابتكار؛ 7) GenAI، الوكالة والأنظمة البيئية؛ 8) صناع السياسات، المشرعين والسلطات المناهضة للاحتكار في تنظيم الابتكار المدعوم بـ GenAI؛ 9) إساءة الاستخدام والاستخدام غير الأخلاقي لـ GenAI مما يؤدي إلى ابتكار متحيز؛ و 10) التصميم التنظيمي والحدود للابتكار المدعوم بـ GenAI. تختتم الورقة بمناقشة كيف يمكن أن تُعلم هذه المواضيع التطور النظري في دراسات إدارة الابتكار.

1. المقدمة

2. مراجعة الأدبيات

2.1. الأسس النظرية، النقاشات الأخيرة، والتصورات حول الذكاء الاصطناعي في الإدارة

(1) أتمتة العمليات؛ (2) الرؤى المعرفية؛ و(3) التفاعل المعرفي. أتمتة العمليات – التي تُعرف أحيانًا بأتمتة العمليات الروبوتية (RPA) – هي أرخص وأسهل نوع من الذكاء الاصطناعي للتنفيذ؛ وبالتالي، فإنها عادةً ما تولد عائدًا مرتفعًا (وسريعًا) على الاستثمار. النوع الثاني، الرؤى المعرفية، يستخدم الخوارزميات وتعلم الآلة لاكتشاف الأنماط في كميات هائلة من البيانات وتفسير معانيها. أخيرًا، يستخدم التفاعل المعرفي روبوتات الدردشة المعتمدة على معالجة اللغة الطبيعية، والوكلاء الذكيين، وتعلم الآلة من أجل ربط الأشخاص داخل المنظمات وعبرها (مثل الموظفين والعملاء). قام هوانغ وراست (2021) بتصور وتمييز ثلاثة أنواع من الذكاء الاصطناعي: (1) الميكانيكي؛ (2) المفكر؛ و(3) العاطفي، والتي تتعامل على التوالي مع المهام الروتينية، القائمة على القواعد، والعاطفية (هوانغ وراست، 2021). يأتي الذكاء الاصطناعي الميكانيكي في شكل روبوتات، بينما يتخذ الذكاء الاصطناعي المفكر شكل وكلاء محادثة (مارياني وآخرون، 2022). بالاعتماد على عمل نيلسون (1971)، عرّف رايش وكراكوسكي (2021) الذكاء الاصطناعي بأنه مفهوم “يشير إلى الآلات التي تؤدي وظائف معرفية عادةً ما ترتبط بالعقول البشرية، مثل التعلم، والتفاعل، وحل المشكلات” (ص. 192). مستندين إلى نيلسون (2010)، الذي عرّف الذكاء الاصطناعي بأنه “النشاط المخصص لجعل الآلات ذكية” (ص. 13)، لاحظ كوكبورن وآخرون (2018) أن الذكاء الاصطناعي يغطي ثلاثة مجالات: الروبوتات، والأنظمة الرمزية، وأنظمة التعلم. فقط الأخيرة تمثل تقنية ذات غرض عام حقيقي يمكن أن تكون “طريقة للابتكار”. في الواقع، يسمح التعلم العميق للذكاء الاصطناعي بـ “توقع” الأحداث الفيزيائية والمنطقية بدقة ووضوح أعلى مقارنةً بالطرق الإحصائية التقليدية، مما قد يكون مفيدًا للبحث العلمي والسلوكي والتقني. اقترح باحثون آخرون (مثل، برينجولفسون وماكافي، 2014؛ دوجرتي وويلسون، 2018؛ دافنبورت ورونانكي، 2018) أن البشر والآلات يجب أن يتعاونوا، بدلاً من التنافس، من أجل مشاركة نقاط قوتهم التكميلية وتحقيق التعلم المتبادل (لا روش، 2017؛ رايش وكراكوسكي، 2021). بشكل عام، بينما يصر العديد من الباحثين على أنه لا يوجد تعريف مقبول عالميًا للذكاء الاصطناعي (ستراينب وآخرون، 2020)، بسبب عدم تعريف “الذكاء” بشكل رسمي (ورمزي) ، فإن مجال الإدارة لديه العديد من التعريفات العملية للذكاء الاصطناعي (انظر هوانغ وراست، 2021؛ نيلسون، 2010).

“الخيط المشترك بين هذه التعريفات هو القدرة المتزايدة للآلات على أداء أدوار ومهام محددة يتم تنفيذها حاليًا بواسطة البشر داخل مكان العمل والمجتمع بشكل عام” (دويفيدي وآخرون، 2022: ص. 2).

2.2. الأسس النظرية، النقاشات الحديثة، والتصورات حول الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في الإدارة

كانت تتطور مع مرور الوقت، ظهر تقاطع في بنية المحولات. تم تقديمها من قبل فاسواني وآخرون (2017) مع تطبيقات في معالجة اللغة الطبيعية، أصبحت بنية المحولات العمود الفقري السائد للنماذج التوليدية. على سبيل المثال، في مجال معالجة اللغة الطبيعية، تستخدم تمثيلات المشفرات ثنائية الاتجاه من المحولات (BERT) والمحولات المدربة مسبقًا التوليدية (GPTs) (مثل GPT-1 إلى GPT-4) بنية المحولات. تستخدم المحولات البصرية والمحولات السوين في مجال رؤية الكمبيوتر، كما تفعل تطبيقات تحويل النص إلى صورة مثل DALL-E. من المثير للاهتمام أن بنية المحولات تسمح بدمج نماذج مختلفة وبالتالي تمكين المهام متعددة الوسائط (أي، توليد أنواع مختلفة من المحتوى مثل الصور والموسيقى في وقت واحد).

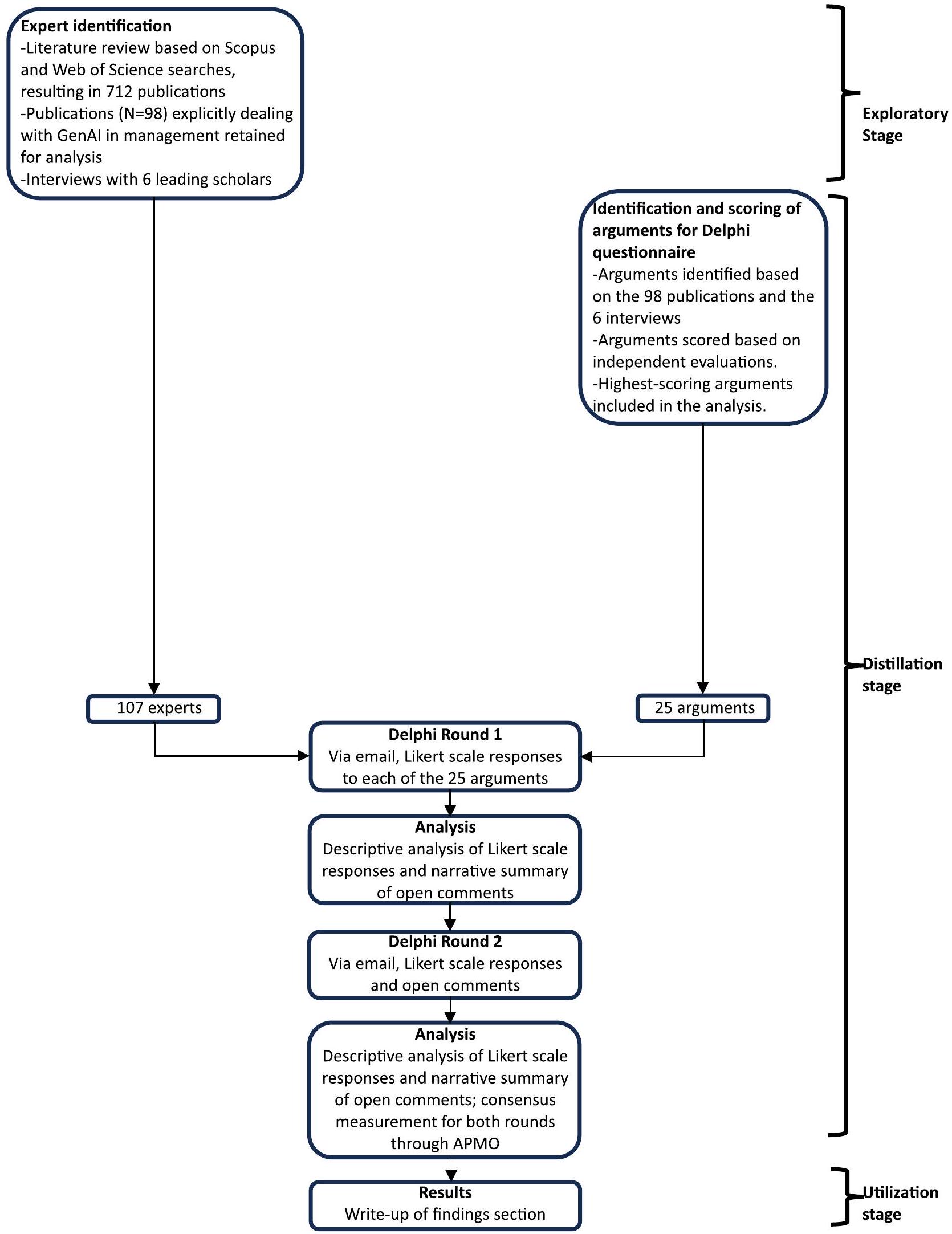

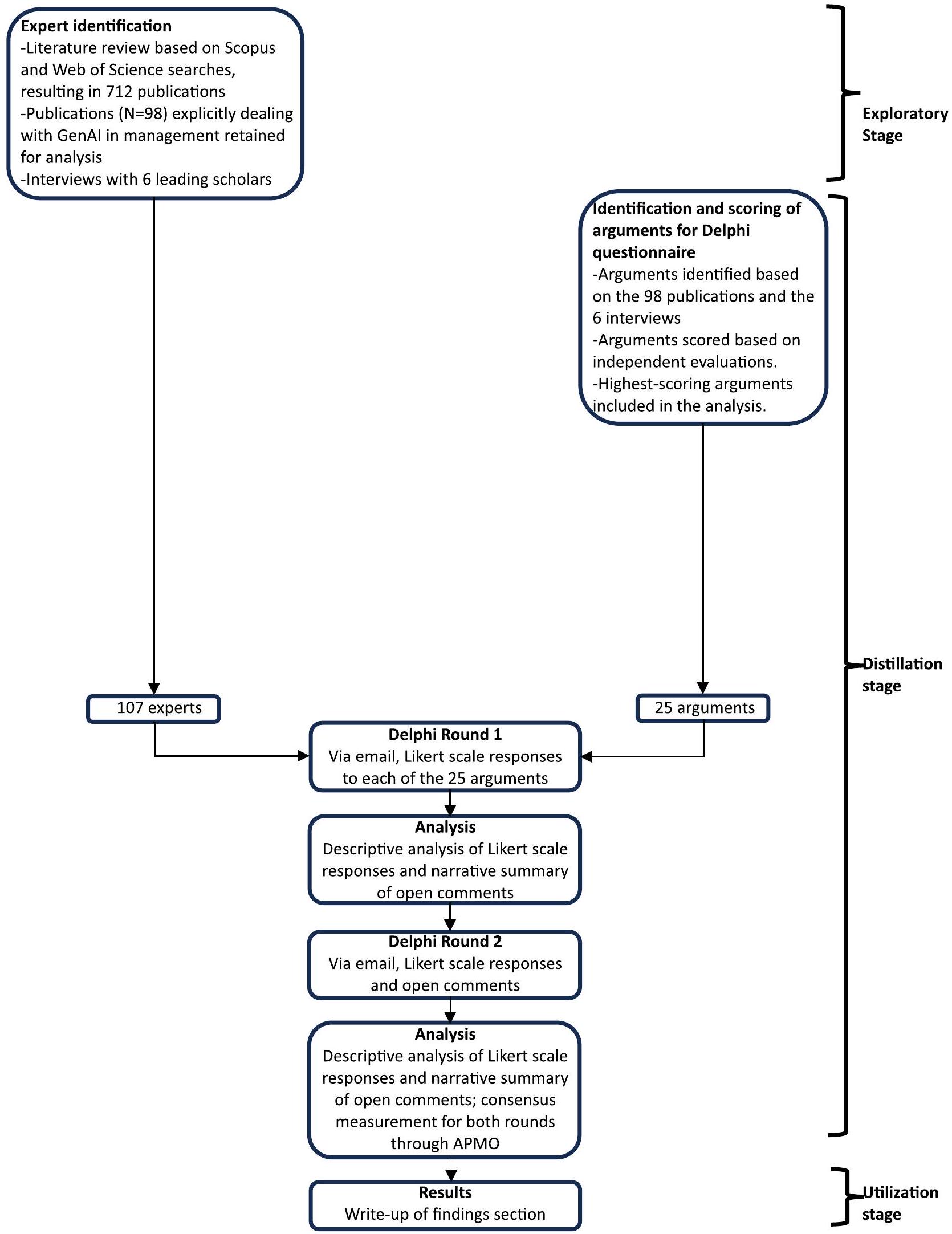

3. الطرق

3.1. مراجعة الأدبيات المستخدمة لدراسة دلفي

أو “ERNIE” أو “Bart” أو “T5” أو “Megatron” أو “Murf.ai أو Designs.ai” أو “Soundraw” أو “ChatFlash” أو “ChatSonic” أو “Scribe” أو “VEED” أو “Speechify” والعديد من الأسماء الخاصة الأخرى لـ GenAI. بينما قد لا تكون مجموعة الأسماء الخاصة بـ GenAI شاملة بالضرورة، إلا أنها واسعة بما يكفي لتغطية أنظمة GenAI الأكثر شيوعًا التي ذكرتها شركات الاستشارات التقنية الرائدة مثل غارتنر. علاوة على ذلك، عندما ظهرت الأسماء الخاصة بأشكال مختلفة، استخدمنا أكثر الأشكال انتشارًا (مثل حالة “DALL-E 2″، التي تُكتب أحيانًا كـ “DALL-E2”). كانت الكلمات الرئيسية المستخدمة لتغطية إدارة الابتكار هي “innovat*” و”manag*”.

3.2. دراسة دلفي

4. النتائج

4.1. النتائج من مراجعة الأدبيات

لهذا السبب، استخدمنا دراسات مراجعة الأدبيات والمقابلات لتطوير 25 عنصرًا من عناصر دلفي (انظر الجدول A. 1 في الملحق).

4.2. النتائج من دراسة دلفي

4.2.1. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي وأنواع الابتكار

4.2.2. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، التصاميم السائدة وتطور التكنولوجيا

النتائج المجمعة من الجولة الثانية (قيم موحدة الحجم).

| # | موضوع | حجة دلفي | أعارض بشدة | أختلف إلى حد ما | لا أوافق ولا أعارض | أوافق إلى حد ما | أوافق بشدة | غير قادر على التعليق | عدد الآراء |

| 1 | 1 | لن تؤدي الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي إلى تصور أنواع الابتكار التي تتجاوز التصنيفات الحالية للابتكار (مثل: المنتج/العملية، الجذري/التدريجي، المعماري/المكون، إلخ). | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | ٤٥.٥ ٪ | ٤٥.٥ ٪ | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 2 | 1 | قد يتأثر نموذج الأعمال بشكل كبير بوجود الذكاء الاصطناعي العام. | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 11.1 % | 33.3 % | 55.6 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ٣ | 2 | يمكن التقاط تطور أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي العام من خلال أطر تطور التكنولوجيا الحالية. | 10.0 % | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 80.0 % | 66.7 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ٥ | ٣ | ستُفهم الإبداع العلمي المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل مختلف عن الإبداع العلمي التقليدي. | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | 63.6 % | ١٨.٢ ٪ | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ٦ | ٣ | ستُفهم الإبداع الفني المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل مختلف عن الإبداع الفني التقليدي. | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 81.8 % | 18.2 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ٧ | ٤ | ستؤدي الذكاء الاصطناعي إلى تصور أشكال/أنواع جديدة من الملكية الفكرية (الحماية) في إدارة الابتكار | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | 10.0 % | 50.0 % | 30.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ٨ | ٤ | ستقوض GenAI الطريقة التي نفكر بها حاليًا في الملكية الفكرية في إدارة الابتكار | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | ٣٦.٤ ٪ | ٣٦.٤ ٪ | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 9 | ٥ | ستعدل GenAI الطريقة التي نفكر بها حاليًا في الاستراتيجيات المتعمدة مقابل الاستراتيجيات الناشئة في تطوير المنتجات الجديدة. | 9.1 % | 63.6 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 11 | ٥ | ستغير GenAI كيفية فهم الباحثين في الإدارة لفرق تطوير المنتجات الجديدة | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | ١٨.٢ ٪ | ٣٦.٤ ٪ | 27.3 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 12 | ٥ | ستغير GenAI كيفية تصور الباحثين في الإدارة للتجريب والتحقق. | 0.0 % | 11.1 % | 11.1 % | 33.3 % | ٤٤.٤ ٪ | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ١٣ | ٥ | ستغير الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي كيفية فهم الباحثين في الإدارة وتصوّرهم لاختبار المنتجات الجديدة. | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | ٢٠.٠ ٪ | ٤٠٫٠ ٪ | ٤٠٫٠ ٪ | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 14 | ٦ | من المحتمل أن يكون للذكاء الاصطناعي متعدد الأنماط تأثير إيجابي أكبر على ميزة الشركة المتبنية التنافسية مقارنةً بأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي أحادية النمط. | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | ٤٥.٥ ٪ | 27.3 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 15 | ٦ | من المحتمل أن يكون للذكاء الاصطناعي متعدد الأنماط تأثير إيجابي أكبر على أداء الابتكار للشركة المتبنية مقارنةً بأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي أحادية النمط. | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | ٢٠.٠ ٪ | ٤٠٫٠ ٪ | ٢٠.٠ ٪ | 10.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 16 | ٧ | ستجعل GenAI أبحاث إدارة الابتكار حول نظم المنصات أكثر صلة من ذي قبل | 0.0 % | 11.1 % | 11.1 % | 33.3 % | 44.4 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 17 | ٧ | من المرجح أن تكون الابتكارات المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي شكلًا مفتوحًا من الابتكار، بدلاً من أن تكون مغلقة. | 9.1 % | 27.3 % | ١٨.٢ ٪ | 18.2 % | ١٨.٢ ٪ | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| ١٨ | ٧ | ستغير GenAI كيفية فهم علماء إدارة الابتكار لوكالة أنشطة وعمليات الابتكار. | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | ١٨.٢ ٪ | ٣٦.٤ ٪ | ٣٦.٤ ٪ | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 19 | ٧ | ستغير تفاعلات البشر مع الذكاء الاصطناعي الابتكارات والعمليات. | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | ٤٠٫٠ ٪ | 50.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 20 | ٨ | سيحتاج صانعو السياسات والمشرعون إلى أطر جديدة لتنظيم الابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي. | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | ٤٤.٤ ٪ | 44.4 % | 11.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 21 | ٨ | يجب أن تكون سلطات مكافحة الاحتكار مجهزة بأطر جديدة لتطبيق اللوائح المتعلقة بالابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي. | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 27.3 % | ٣٦.٤ ٪ | ١٨.٢ ٪ | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| ٢٢ | 9 | يمكن أن يؤدي سوء استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي إلى نتائج ابتكارية متحيزة | 0.0 % | ٢٢.٢ ٪ | 11.1 % | ٤٤.٤ ٪ | 11.1 % | 11.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 23 | 9 | يمكن أن يؤدي الاستخدام غير الأخلاقي للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي إلى نتائج ابتكارية تفيد فقط مجموعة فرعية من أصحاب المصلحة. | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | ٤٥.٥ ٪ | 27.3 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| ٢٤ | 10 | من المحتمل أن تعدل GenAI الحدود التنظيمية | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | ٤٠٫٠ ٪ | 50.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ٢٥ | 10 | من المحتمل أن تعدل GenAI تصميم المنظمة والتنسيق | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | ٤٠٫٠ ٪ | 50.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

4.2.3. الإبداع العلمي والفني والابتكارات المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي

4.2.4. الابتكارات المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي وحقوق الملكية الفكرية

“ستبدأ الابتكارات التكنولوجية مثل تلك الموجودة هنا في الولايات المتحدة في تطوير قوانين تعدل بشكل كبير حقوق الطبع والنشر.” وقد اقترح نفس الخبراء أن الذكاء الاصطناعي العام سيؤدي إلى مفاهيم جديدة للملكية الفكرية (الحماية) في إدارة الابتكار. وقد اتفق العديد منهم على أن الحكومات بحاجة إلى أطر محدثة تسمح لأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي العام بالعمل بكامل طاقتها؛ حتى أن أحد الخبراء الأكثر راديكالية جادل بأن قانون حقوق الطبع والنشر الحالي “يجب أن يختفي” لتحقيق هذا الهدف. ومع ذلك، اقترح أقلية كبيرة من الخبراء أن الملكية الفكرية هنا لتبقى وبشكل كبير في شكلها الحالي (أي كبراءات اختراع، وعلامات تجارية وحقوق طبع ونشر). وقد ذكر هذه المجموعة الأخيرة من الخبراء أن مقدمي خدمات الذكاء الاصطناعي العام يجب أن يتعاونوا بدلاً من ذلك بشكل مستمر مع مكاتب براءات الاختراع وهيئات تنفيذ قانون حقوق الطبع والنشر.

4.2.5. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي وتطوير المنتجات الجديدة

غالبًا ما تكون الاستراتيجيات الناشئة مسألة حظ للموظفين والمديرين، على الرغم من أنه من الممكن أن تنتج الذكاء الاصطناعي العام حلولًا غير متوقعة من خلال عناصر مدمجة من “العشوائية الإيجابية”. يمكن أن تساعد هذه “العشوائية” الإيجابية في تعزيز قدرة البشر على تطوير أفكار غير تقليدية خلال عملية تطوير المنتجات الجديدة. علاوة على ذلك، جادل معظم الخبراء بأن الذكاء الاصطناعي العام سيغير كيفية تصور علماء الإدارة لفرق تطوير المنتجات الجديدة. في الواقع، ستحتاج الديناميات داخل فرق تطوير المنتجات الجديدة إلى التغيير لاستيعاب الزيادة في إدماج الآلات. كنتيجة لهذين النقطتين الأوليين (العشوائية الإيجابية التي تضخها أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي العام وفرق الابتكار الأكثر تنوعًا)، توقع معظم الخبراء أن علماء إدارة الابتكار سيعدلون الطريقة التي يتصورون بها ويصوغون بها عملية تطوير المنتجات الجديدة. في الواقع، ستؤثر التعاونات بين البشر وأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي العام على الهيكل والمدة والكفاءة في سير العمل. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، شعر معظم الخبراء أن الذكاء الاصطناعي العام سيمكن من تقنيات التجريب والتحقق في الوقت الحقيقي، مما يمكّن مديري الابتكار من تحويل أفكارهم بسرعة إلى منتجات/عمليات/نماذج أعمال. وبالمثل، سيحسن الذكاء الاصطناعي العام اختبار المنتجات الجديدة من خلال السماح بالتقاط ومعالجة تفضيلات واحتياجات المستهلكين في الوقت الحقيقي. على سبيل المثال، ذكر أحد الخبراء النمذجة الرقمية كوسيلة لاختبار المنتجات الجديدة بسرعة وبتكلفة منخفضة.

4.2.6. نتائج الابتكار في الذكاء الاصطناعي متعدد الأنماط/أحادي النمط

4.2.7. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، الوكالة والأنظمة البيئية

4.2.8. صناع السياسات، المشرعون والسلطات المعنية بمكافحة الاحتكار في تنظيم الابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي

4.2.9. إساءة الاستخدام والاستخدام غير الأخلاقي للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي مما يؤدي إلى ابتكار متحيز

الابتكار مع عدة عواقب ضارة، بما في ذلك الأضرار السمعة للأفراد والمنظمات، وفقدان الوظائف، وتشوهات في المنافسة السوقية، وانتشار المعلومات المضللة. ومع ذلك، تفتقر معظم الدول حاليًا إلى إطار تنظيمي يمكن أن يوفر الحماية ضد المحتوى الناتج عن إساءة استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. ثانياً، أشار الخبراء إلى أن أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي تولد بشكل متزايد معلومات مضللة (مثل المنشورات أو المراجعات المزيفة) التي يمكن أن تحيد – إن لم تعطل – اتخاذ القرارات من قبل المستهلكين والمديرين. يمكن أن يؤدي ذلك في النهاية إلى قرارات غير مثلى وخسائر كبيرة. أخيرًا، اتفق الخبراء على أن نماذج الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي يمكن أن تكون متحيزة ضد بعض الأفراد أو المجموعات، بناءً على ليس فقط بيانات تدريب النموذج، ولكن أيضًا غياب الضوابط الأخلاقية على خوارزميات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. وهذا يعني أن بعض مجموعات أصحاب المصلحة قد تستفيد بشكل غير متناسب من الابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي مقارنة بالآخرين. باختصار، تحتاج أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي إلى الامتثال للمعايير الأخلاقية لضمان أن تكون نتائج الابتكار أخلاقية وعادلة في حد ذاتها.

4.2.10. التصميم التنظيمي والحدود للابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي

5. المناقشة

5.1. GenAI وأنواع الابتكار

تصنيف للابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي.

|

أنواع الابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | أمثلة الأعمال وحالات الاستخدام | ||||

| ابتكار المنتج | ابتكار المنتجات المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي (GenAIProdI) استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي لتوليد منتج جديد أو تحسين منتج موجود |

|

||||

| ابتكار العمليات | ابتكار العمليات المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (GenAIProcI) استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لإنشاء عملية جديدة أو تحسين عملية قائمة |

|

||||

| ابتكار التسويق | ابتكار التسويق المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي (GenAIMarI) استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي لتحسين أنشطة التسويق |

|

|

أنواع الابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي | أمثلة الأعمال وحالات الاستخدام | ||

| الابتكار التنظيمي | الابتكار التنظيمي المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (GenAIOrgI) استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لتحسين ميزات التنظيم |

|

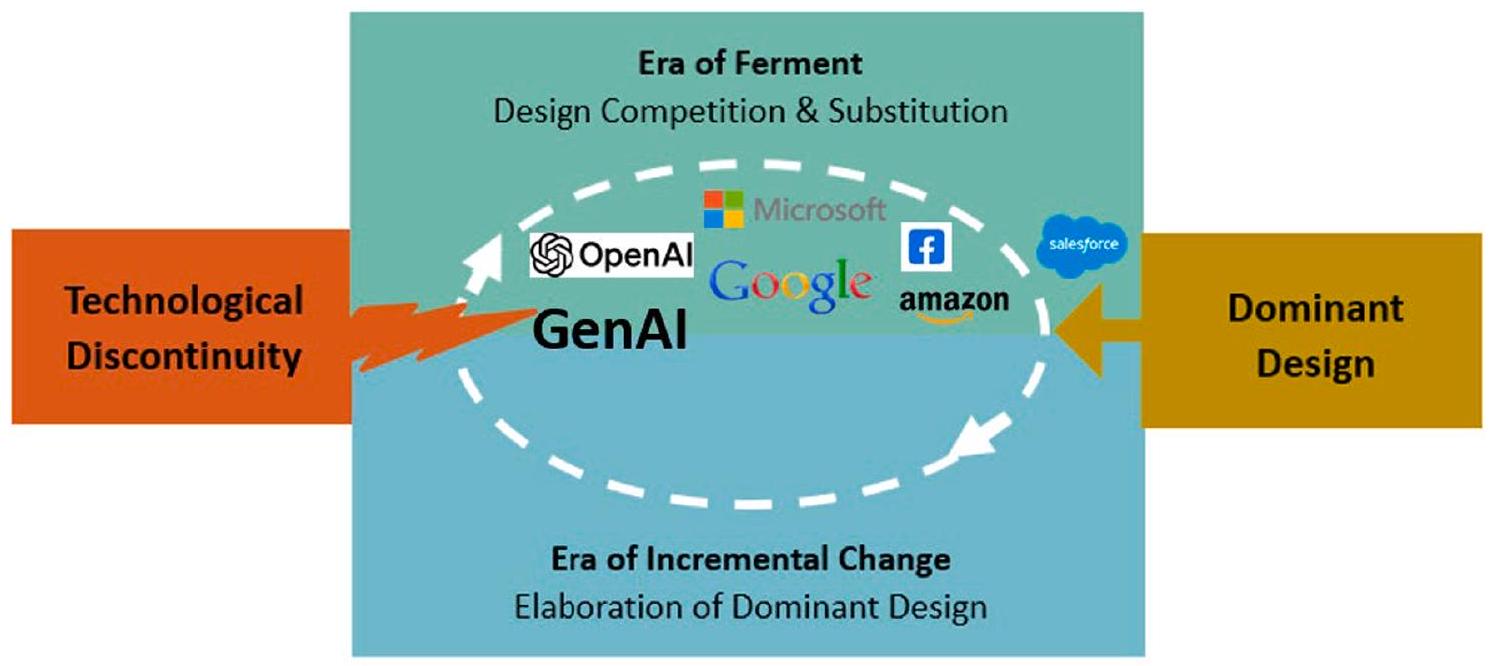

5.2. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، التصاميم السائدة وتطور التكنولوجيا

تصنيف الابتكار الجذري مقابل الابتكار التدريجي المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي.

|

أنواع الابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي | أمثلة الأعمال وحالات الاستخدام | |||||||

| ابتكار جذري |

|

|

|||||||

| الابتكار التدريجي |

|

|

لم يظهر المستخدمون بعد اهتمامًا بـ GenAI بالطريقة التي أظهرتها بها الشركات، ولكن الاستثمارات من الشركات التقنية الكبرى قد توسع السوق لأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي في السنوات الخمس المقبلة. ومع ذلك، فإن الهدف من توسيع السوق هو أيضًا ضمان أن الكمية المتزايدة من البيانات المتاحة يمكن أن تكون مناسبة لغرض التعلم العميق المدمج في أنظمة GenAI. سيتطلب ذلك أيضًا تطوير خوارزميات يمكنها فصل “الإشارة” عن “الضوضاء” (أي، تمييز البيانات الموثوقة عن غير الموثوقة)، بالإضافة إلى المعلومات الصحيحة من المعلومات المضللة. قد يتوجه المستخدمون إلى التكنولوجيا إذا حولت السلطة للابتكار بعيدًا عن الفنيين ذوي المهارات العالية إلى الأفراد الأقل مهارة.

5.3. الإبداع العلمي والفني والابتكارات المدعومة بـ GenAI

الفنية.

مؤخراً، جادل بعض العلماء بأن الذكاء الاصطناعي نفسه يمكن أن يكون مبدعًا بمعنى أنه قادر على إنتاج “أفكار جديدة للغاية، ولكن مناسبة، أو حلول للمشاكل، أو مخرجات أخرى” (أمابيلي، 2020: ص. 351). لذلك، قد تستكشف أبحاث إدارة الابتكار المستقبلية ما إذا كان GenAI مبدعًا بنفسه وإلى أي مدى يختلف إبداع GenAI عن الإبداع البشري من حيث محدداته. على سبيل المثال، قد يبحث العلماء في: الذاكرة البشرية مقابل ذاكرة GenAI؛ القدرة البشرية مقابل قدرة GenAI على النظر إلى المشاكل بطرق غير تقليدية؛ القدرة البشرية مقابل قدرة GenAI على تحليل أي الأفكار تستحق المتابعة؛ القدرة البشرية مقابل قدرة GenAI على التعبير عن تلك الأفكار للآخرين؛ ومعرفة المجال البشرية مقابل معرفة المجال لـ GenAI. قد تأخذ الأفكار الجديدة شكل أسئلة مثيرة للاهتمام بدلاً من مجرد حلول. قد يوسع GenAI مجموعة الاستفسارات المناسبة ويغير كيفية تشكيل المجتمعات العلمية والتقنية لأسئلة بحثها.

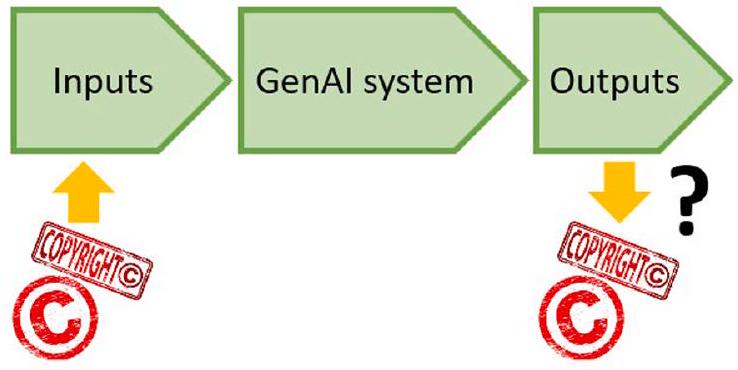

5.4. الابتكارات المدعومة بـ GenAI وحقوق الملكية الفكرية

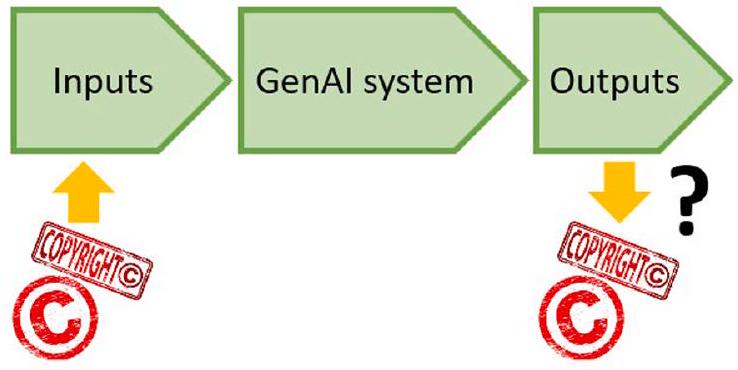

هل يجب أن تُشارك حقوق الطبع بين مهندس الطلب ونظام GenAI؟ من يجب أن يحصل على العائدات وفي أي شكل؟ كيف سيتم حماية المنتجات الجديدة الناتجة عن GenAI بموجب قوانين الملكية الفكرية؟ كيف يجب تعديل نماذج الأعمال لتعكس خلق القيمة من خلال أنظمة GenAI؟ نظرًا لأن GenAI من المحتمل أن يولد منتجات وعمليات جديدة أسرع من الأنظمة الأخرى، كيف يمكن لمكاتب براءات الاختراع تسريع عبء العمل الخاص بها لحماية ابتكارات GenAI؟

5.5. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي وتطوير المنتجات الجديدة

لقد أكدت الأبحاث أن إشراك العملاء في تطوير المنتجات الجديدة مهم بشكل خاص لأنهم لا يمثلون فقط مصدرًا للمعلومات، ولكنهم أيضًا يشكلون مطورين فعليين للمنتجات الجديدة (على سبيل المثال، من خلال تقنيات مثل اختبار بيتا والتطوير المرن؛ كوي وو، 2017). وقد اقترحت عدة دراسات أن الشركات يجب أن تركز جهودها في التطوير بشكل أساسي على مدخلات المستخدمين الرائدين (أي أولئك الذين يعبرون عن احتياجاتهم في وقت مبكر عن بقية السوق) بدلاً من عينة كبيرة من العملاء (هيرستات وفون هيبل، 1992). ولهذا الغرض، يسمح الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بمشاركة أكثر سلاسة للعملاء في تطوير المنتجات الجديدة. على سبيل المثال، يمكن للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي المحادثاتي أن يتعلم من المستخدمين، حيث يمكن للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي المحادثاتي (مثل ChatGPT وGPT-4) استخدام مدخلات العملاء لتشكيل نصوص جديدة. قد يفتح هذا آفاقًا بحثية جديدة، حيث قد تكتسب أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي تدريجيًا القدرة على تقييم المستخدمين بناءً على خبرتهم المثبتة في فئة معينة من المنتجات (مارياني ونمبسان، 2021) وبالتالي اكتشاف المستخدمين الرائدين (هيرستات وفون هيبل، 1992). باختصار، لدى الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي القدرة على التحدث إلى مجموعة أوسع من العملاء، وتمييز بين المستخدمين المتقدمين والمبتدئين.

5.6. نتائج الابتكار في GenAI متعددة الأنماط/أحادية النمط

5.7. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، الوكالة والأنظمة البيئية

من المحتمل أن تؤدي عملية دمج أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي العام إلى إنتاج شبكة كثيفة من الفاعلين والمساهمين – ليس جميعهم بشرًا – الذين سيتعاونون بشكل متزايد في السعي لتحقيق نتائج مبتكرة. وبالنتيجة، ستحدث الابتكارات المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي العام من خلال الوكالة الموزعة، حيث يمكن أن يكون الفاعلون بشرًا وآلات تتفاعل مع بعضها البعض لتفعيل عمليات الابتكار. سيتعين على أبحاث إدارة الابتكار المستقبلية دمج المفاهيم النظرية التي تلتقط كيف تتوزع وكالة الابتكار عبر عدة فاعلين (ليس فقط من حيث الأفراد البشر أو الآلات، ولكن أيضًا مجموعات من البشر و/أو الآلات). من خلال ذلك، نشجع علماء إدارة الابتكار على توسيع مفهوم أن وكالة الابتكار موزعة في البيئات الرقمية (نامبيسان، 2017).

5.8. صناع السياسات، المشرعون والسلطات المناهضة للاحتكار في تنظيم الابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي العام

لقد قضت الولايات المتحدة العقد الماضي تدعو إلى قانون تطوير الذكاء الاصطناعي وإنشاء وكالات حكومية لتصديق سلامة برامج الذكاء الاصطناعي (إيتزيوني وإيتزيوني، 2017). يبدو من الواضح أن صانعي السياسات سيلعبون دورًا حاسمًا في تشكيل البيئة التنظيمية للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. يبدو أن الاتحاد الأوروبي رائد في هذا الصدد – حيث اقترح قانون الذكاء الاصطناعي في عام 2021، والذي يضع إطارًا تنظيميًا لمقدمي ومستخدمي الذكاء الاصطناعي المحترفين عبر عدة قطاعات (باستثناء العسكرية/الدفاع) – بينما تتخلف معظم الدول غير الأعضاء في الاتحاد الأوروبي (تشاترجي وسرينيفاسولو، 2022). يصنف إطار عمل الاتحاد الأوروبي تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي حسب مخاطرها وينظمها وفقًا لذلك؛ يبدو أن دولًا أخرى (مثل البرازيل) تتبع نفس النهج، مما يشير إلى أن قانون الذكاء الاصطناعي قد يصبح معيارًا عالميًا (مشابهًا للائحة العامة لحماية البيانات). ومع ذلك، هناك العديد من القضايا المفتوحة التي يجب معالجتها: أولاً، يبدو غير واضح ما إذا كان سيتم تنظيم الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل مختلف عن أشكال الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخرى. نظرًا لأن نتائج الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي تعتمد على تجميع البيانات والمحتوى من مصادر متعددة، سيتعين على صانعي السياسات تطوير إطار تنظيمي جديد يمكنه وضع وإنفاذ قواعد الائتمان والنسب. من المحتمل أن يحتاج المشرعون في مجال الملكية الفكرية إلى العمل جنبًا إلى جنب مع مجموعات متعددة التخصصات من خبراء الذكاء الاصطناعي لتصميم قوانين تتعامل مع حقوق الملكية الفكرية المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، مما قد يعيد تشكيل – إن لم يكن إعادة كتابة – القوانين الحالية حول ملكية البيانات (كوكبورن وآخرون، 2018: ص. 41). على سبيل المثال، إذا كانت بيانات المستهلكين عبر الإنترنت تعود فقط للمستهلكين، فلن تتمكن الشركات من استخدامها لأغراض الابتكار في المنتجات. ثانيًا، في ظل هذه الحالة من عدم اليقين، يجب على الشركات الاستعداد داخليًا للامتثال للمعايير الجديدة (هاين وفلوريدي، 2022). ستحتاج بعض المنظمات إلى تشكيل لجان أخلاقية خاصة بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي تشرف على امتثال الشركة للمعايير وتقييمات المطابقة. من المؤكد أن اعتماد المعايير سيكون غير متساوٍ عبر الدول (والمنظمات)، بسبب السرعة التي تنشئ بها الحكومات المختلفة أطرًا تنظيمية ذات مغزى. بالتأكيد، سيتعين على مديري المنظمات التي لها قاعدة قانونية أو فروع في الاتحاد الأوروبي التصرف بسرعة استجابة لقانون الذكاء الاصطناعي، بالإضافة إلى التطورات الأخيرة والقادمة في قانون الخصوصية. ثالثًا، بالنسبة للولايات المتحدة بشكل خاص، كان من شبه المستحيل تسجيل براءات اختراع للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي وخوارزميات التعلم الآلي حتى قبل بضع سنوات (تشيسوم، 1985؛ تشودري، 2022)، ولكن الآن يمكن للمبتكرين تسجيل براءات اختراع لتسلسلات المراحل في الطرق. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن إيان جودفيل ورفاقه – الذين طوروا واحدة من هياكل الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (وهي الشبكات التنافسية التوليدية) – حصلوا مؤخرًا على براءات اختراع لعدة خوارزميات للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. ومع ذلك، لا يوضح قانون براءات الاختراع ما إذا كانت مخرجات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (مثل الجزيئات الجديدة، النصوص، الفيديوهات، الموسيقى، إلخ) قابلة للتسجيل كبراءات اختراع. تشير الحلقات السابقة إلى أن الابتكارات الجذرية في تقنيات وأدوات البحث – جنبًا إلى جنب مع القدرة المحدودة لمكاتب براءات الاختراع والأحكام القضائية غير المتسقة (إن لم تكن متناقضة) – يمكن أن تؤدي إلى فترات طويلة من عدم اليقين التي تقوض إصدار براءات اختراع جديدة وتعيق إنتاجية البحث. بالتأكيد، يجب توسيع قانون براءات الاختراع بشكل كبير ويمكن لعلماء إدارة الابتكار التفكير في ما إذا كانت نتائج الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي يمكن تسجيلها كبراءات اختراع وإلى أي مدى. رابعًا، يحتاج صانعو السياسات والمنظمون إلى تقييم قضايا التحيزات الخوارزمية وحماية المستهلك التي ترافق التعلم الآلي والتعلم العميق. على سبيل المثال: يمكن أن تضر التزييف العميق بسمعة الأفراد والمنظمات؛ استجابة عالمية أصبحت أكثر أهمية في ظل تزايد اعتماد أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. اقترح العلماء القانونيون تمرير تشريعات تعالج التمييز، والتشهير، والافتراء، وسرقة الهوية، والاحتيال، وانتحال صفة (المسؤولين الحكوميين)، والتزوير، والمخاطر السياسية (راي، 2021؛ ويسترلوند، 2019؛ وايلز، 2023). بالطبع، يجب صياغة مثل هذه اللوائح بعناية لتكون قابلة للتنفيذ ومقبولة (فاريش، 2020). علاوة على ذلك، يجب إنشاء مؤسسات دولية وتطوير معايير قوية لتنظيم التحيزات الخوارزمية، وحماية المستهلك و(خصوصًا) المعلومات المضللة الناتجة عن الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. خامسًا، سيؤثر الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل كبير على الاقتصاد العالمي من حيث نتائج الابتكار والإنتاجية، ولكن سيكون لهذا تأثير جانبي يتمثل في بعض إعادة هيكلة المنظمات، والأكثر قلقًا، الاضطرابات في سوق العمل. مع وجود الذكاء الاصطناعي الذي يخلق بالفعل عدم المساواة في الدخل (كيلي، 2021)، من الضروري أن يشارك المشرعون والنقابات العمالية في محادثة بناءة حول السياسات – مثل

دخل أساسي عالمي (بانيرجي وآخرون، 2019) – الذي يمكن أن يعوض الأضرار الناتجة عن التوظيف التي تسببها الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل عام وGenAI بشكل خاص. سادسًا، يفرض قانون الذكاء الاصطناعي (AIA) التزامات صارمة على الشركات التي تطور وتعمل وتستخدم أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي، بناءً على المخاطر المرتبطة بنظام الذكاء الاصطناعي نفسه (هيكمان وبترين، 2021؛ المنتدى الاقتصادي العالمي، 2022). وقد أكد بعض المعلقين أن قانون الذكاء الاصطناعي يفتقر إلى هياكل إنفاذ فعالة (إيبرس وآخرون، 2021)، ولا يحدد الذكاء الاصطناعي بدقة، ولا يخصص المسؤولية عن العواقب الضارة لاستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي (سماها وآخرون، 2021). ومع ذلك، يفرض القانون أعباء على الشركات التي تطور أو تعمل أو تستخدم أنظمة GenAI للابتكار، حيث إن انتهاك القانون يؤدي إلى عقوبات تصل إلى

5.9. إساءة الاستخدام والاستخدام غير الأخلاقي للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي مما يؤدي إلى ابتكار متحيز

قضايا الخصوصية بشكل كافٍ (ساورا وآخرون، 2022)، ناهيك عن تحديد إطار تنظيمي يوفر الحماية ضد التزييفات العميقة (موستاك وآخرون، 2023).

5.10. التصميم التنظيمي والحدود للابتكار المدعوم بـ GenAI

إدارتها.

فيما يتعلق بالتنسيق، من المحتمل أن يؤدي نشر GenAI إلى تقسيم العديد من مهام العمل إلى مهام فرعية أصغر يمكن الاستعانة بمصادر خارجية – ربما إلى سوق رقمي للمهام الصغيرة (مثل، أمازون ميكانيكال ترك، جوفوتو، كليك ووركر، بروليفك، أب وورك، كراود غورو) أو أي نظام GenAI (مثل، ChatGPT، Dall-E 2، Stable Diffusion، Midjourney). على مدار السنوات القليلة الماضية، أنشأت منظمات مختلفة أدوار تنظيمية داخلية (مثل، مدير الذكاء الاصطناعي أو بطل الذكاء الاصطناعي) وهياكل (مثل، مركز التميز للذكاء الاصطناعي) لإدارة مشاريع الذكاء الاصطناعي. من المحتمل أن تولد مشاريع GenAI استجابة مماثلة. ومع ذلك، تثار عدة أسئلة: i) كيف سيتفاعل مدراء الابتكار الحاليون مع الأدوار الجديدة المتعلقة بـ GenAI؟ ii) هل سيسمح لمدراء الابتكار الحاليين بالتفاعل مع أنظمة GenAI؟ iii) هل ستظهر توترات بين مدراء الابتكار الحاليين والأدوار الجديدة المتعلقة بـ GenAI، ومن سيتولى إدارة تلك التوترات؟ بشكل عام، سيتعين على المدراء الحاليين البدء في التعاون مع خبراء في التقنيات الرقمية (بما في ذلك تحليلات البيانات، تعلم الآلة، التعلم العميق، وأنظمة GenAI بشكل عام) وتكييف عملياتهم لتناسب تلك التفاعلات. قد تحتاج المنظمات أيضًا إلى إنشاء أقسام جديدة – إما داخل وظيفة البحث والتطوير التقليدية أو ربما كمراكز متعددة الوظائف – يمكن أن تدعم جهود الابتكار في الشركة. في الشركات متعددة الجنسيات، قد تؤسس إدارة البحث والتطوير منصة GenAI شاملة تخدم الشركات الفرعية الأجنبية (فيراريس وآخرون، 2021).

6. المساهمات النظرية

تتداخل العديد من هذه المواضيع من وجهة نظر مفاهيمية: على سبيل المثال، تشترك المواضيع الثلاثة المتعلقة بالإبداع المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، والملكية الفكرية وتطوير المنتجات الجديدة في التركيز على الأفراد والمنظمات التي تحاول خلق (“الإبداع” و”تطوير المنتجات الجديدة”) وملاءمة القيمة (“موضوع الملكية الفكرية”) من خلال استخدام أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لدعم قرارات وأنشطة الابتكار. من خلال مناقشة المواضيع العشر فيما يتعلق بالأدبيات والنظريات الموجودة، قدمنا عدة مساهمات في مجال إدارة الابتكار. على سبيل المثال، أثناء مناقشة موضوع التصاميم السائدة، قمنا بتوسيع نظرية إدارة الابتكار من خلال تطبيق أو توسيع الأطر المعمول بها (أندرسون وتوشمان، 1990؛ أوتر باك وأبرناثي، 1975). فيما يتعلق بموضوع الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي والإبداع، ربطنا عدة مفاهيم تتعلق بتخصصات مختلفة مثل علم النفس (مثل، تشيكسينتميهالي، 1975، 1997؛ ماكنون، 1965؛ ميدنيك، 1962؛ سولر، 1980)، وعلم وظائف الأعضاء (مثل، ليفي، 1961؛ رودس، 1961) وعلم الاجتماع (مثل، غيتزلز وجاكسون، 1961؛ ستراوس، 1968). بهذه الطريقة، قدمنا تأملات جديدة حول كيفية تقدم أبحاث إدارة الابتكار إلى ما هو أبعد من المفاهيم الحديثة لإبداع الذكاء الاصطناعي (أمالي، 2020)، مما يفتح آفاق جديدة للتأمل الفكري.

7. الخاتمة

بيان مساهمة المؤلفين

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

ملحق

خلفية الحجج المختارة لدراسة دلفي.

| # | الموضوع | حجة دلفي | المراجع أو المقابلات |

| 1 | 1 | لن يؤدي الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي إلى تصور أنواع الابتكار التي تتجاوز التصنيفات الحالية للابتكار (مثل، المنتج/ العملية، الجذري/ التدريجي، المعماري/ المكون، إلخ.) | مقابلات |

| 2 | 1 | قد يتم تعديل نموذج العمل بشكل كبير بسبب وجود الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي | كانباخ وآخرون (2023)، أكتار وآخرون (2023) |

| 3 | 2 | لم يظهر تصميم سائد بين أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بعد | سيرانو (2023)، مقابلات |

| 4 | 2 | يمكن التقاط تطور أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي من خلال الأطر الحالية لتطور التكنولوجيا | أغاروال وكابور (2023)، مقابلات |

| 5 | 3 | ستُفهم الإبداع العلمي المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل مختلف عن الإبداع العلمي التقليدي. | أمابيلي (2020)، مقابلات |

| ٦ | ٣ | ستُفهم الإبداع الفني المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل مختلف عن الإبداع الفني التقليدي. | أمابيلي (2020)، مقابلات |

| ٧ | ٤ | ستؤدي الذكاء الاصطناعي إلى تصور أشكال/أنواع جديدة من الملكية الفكرية (الحماية) في إدارة الابتكار | بيرس وآخرون (2023)، مقابلات |

| ٨ | ٤ | ستقوض GenAI الطريقة التي نفكر بها حاليًا في الملكية الفكرية في إدارة الابتكار | بيرس وآخرون (2023)، مقابلات |

| 9 | ٥ | ستعدل GenAI الطريقة التي نفكر بها حاليًا في الاستراتيجيات المتعمدة مقابل الاستراتيجيات الناشئة في تطوير المنتجات الجديدة. | المقابلات |

| 10 | ٥ | ستغير الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي كيفية فهم الباحثين في الإدارة وتصورهم لعملية تطوير المنتجات الجديدة. | جست وآخرون (2023)، مقابلات |

| 11 | ٥ | ستغير GenAI كيفية فهم الباحثين في الإدارة لفرق تطوير المنتجات الجديدة | المقابلات |

| 12 | ٥ | ستغير GenAI كيفية فهم الباحثين في الإدارة للتجريب والتحقق. | كانباخ وآخرون (2023) |

| ١٣ | ٥ | ستغير GenAI كيفية فهم الباحثين في الإدارة وتصوّرهم لاختبار المنتجات الجديدة. | كانباخ وآخرون (2023) |

| 14 | ٦ | من المحتمل أن يكون للذكاء الاصطناعي متعدد الأنماط تأثير أكثر إيجابية على ميزة الشركة المتبنية التنافسية مقارنةً بأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي أحادية النمط. | المقابلات |

| 15 | ٦ | من المحتمل أن يكون للذكاء الاصطناعي متعدد الأنماط تأثير إيجابي أكبر على أداء الابتكار للشركة المتبنية مقارنةً بأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي أحادية النمط. | المقابلات |

| 16 | ٧ | ستجعل GenAI أبحاث إدارة الابتكار حول نظم المنصات أكثر صلة من ذي قبل | أكتير وآخرون (2023) |

| 17 | ٧ | من المرجح أن تكون الابتكارات المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي العام شكلًا مفتوحًا، بدلاً من أن تكون شكلًا مغلقًا من الابتكار. | المقابلات |

| ١٨ | ٧ | ستغير GenAI كيفية فهم علماء إدارة الابتكار لوكالة أنشطة وعمليات الابتكار. | المقابلات |

| 19 | ٧ | ستغير تفاعلات البشر مع الذكاء الاصطناعي الابتكارات والعمليات. | هندريكسن (2023) |

| 20 | ٨ | سيحتاج صانعو السياسات والمشرعون إلى أطر جديدة لتنظيم الابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي. | المقابلات |

| 21 | ٨ | يجب أن تكون سلطات مكافحة الاحتكار مجهزة بأطر جديدة لتطبيق اللوائح المتعلقة بالابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي. | المقابلات |

| ٢٢ | 9 | يمكن أن يؤدي سوء استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي إلى نتائج ابتكارية متحيزة | بيرس وآخرون (2023)، مقابلات |

| 23 | 9 | يمكن أن يؤدي الاستخدام غير الأخلاقي للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي إلى نتائج ابتكارية تفيد فقط مجموعة فرعية من أصحاب المصلحة. | بيرس وآخرون (2023)، مقابلات |

| ٢٤ | 10 | من المحتمل أن تعدل GenAI الحدود التنظيمية | المقابلات |

| ٢٥ | 10 | من المحتمل أن تعدل الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي تصميم المنظمة وتنسيقها. | المقابلات |

النتائج المجمعة من الجولة الأولى (قيم بحجم مشترك).

| # | موضوع | حجة دلفي | أعارض بشدة | أختلف إلى حد ما | لا أوافق ولا أعارض | أوافق إلى حد ما | أوافق بشدة | غير قادر على التعليق | عدد الآراء |

| 1 | 1 | لن تؤدي الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي إلى تصور أنواع الابتكار التي تتجاوز التصنيفات الحالية للابتكار (مثل: المنتج/العملية، الجذري/التدريجي، المعماري/المكون، إلخ). | 0.0 % | ٥.٣ ٪ | 10.5 % | 31.6 % | 52.6 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 2 | 1 | قد يتغير نموذج الأعمال بشكل كبير بسبب وجود الذكاء الاصطناعي العام. | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 11.1 % | ٣٨.٩ ٪ | ٤٤.٤ ٪ | ٥.٦ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| ٣ | 2 | لم يظهر تصميم مهيمن بين أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بعد. | ٥.٣ ٪ | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 84.2 % | 10.5 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ٤ | 2 | يمكن التقاط تطور أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي العام من خلال أطر تطور التكنولوجيا الحالية. | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | 35.3 % | 52.9 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| ٥ | ٣ | ستُفهم الإبداع العلمي المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل مختلف عن الإبداع العلمي التقليدي. | 0.0 % | ٢٢.٢ ٪ | 11.1 % | 55.6 % | ٥.٦ ٪ | ٥.٦ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| ٦ | ٣ | ستُفهم الإبداع الفني المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل مختلف عن الإبداع الفني التقليدي. | 0.0 % | 10.5 % | 15.8 % | 63.2 % | ٥.٣ ٪ | ٥.٣ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| ٧ | ٤ | ستؤدي الذكاء الاصطناعي إلى تصور أشكال/أنواع جديدة من الملكية الفكرية (الحماية) في إدارة الابتكار | 5.3 % | 15.8 % | 5.3 % | ٣٦.٨ ٪ | 31.6 % | ٥.٣ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| ٨ | ٤ | ستقوض GenAI الطريقة التي نفكر بها حاليًا في الملكية الفكرية في إدارة الابتكار | ٥.٣ ٪ | ٢١.١ ٪ | 5.3 % | ٣٦.٨ ٪ | ٢٦.٣ ٪ | ٥.٣ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| 9 | ٥ | ستعدل GenAI الطريقة التي نفكر بها حاليًا في الاستراتيجيات المتعمدة مقابل الاستراتيجيات الناشئة في تطوير المنتجات الجديدة. | 16.7 % | 44.4 % | 5.6 % | 16.7 % | 11.1 % | ٥.٦ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| # | موضوع | حجة دلفي | أعارض بشدة | أختلف إلى حد ما | لا أوافق ولا أعارض | أوافق إلى حد ما | أوافق بشدة | غير قادر على التعليق | عدد الآراء |

| 10 | ٥ | ستغير GenAI كيفية فهم الباحثين في الإدارة وتصورهم لعملية تطوير المنتجات الجديدة | ٥.٦ ٪ | 33.3 % | 11.1 % | ٢٢.٢ ٪ | ٢٢.٢ ٪ | ٥.٦ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| 11 | ٥ | ستغير GenAI كيفية فهم الباحثين في الإدارة لفرق تطوير المنتجات الجديدة | 0.0 % | ٥.٦ ٪ | 11.1 % | ٤٤.٤ ٪ | 33.3 % | 5.6 % | 100.0 % |

| 12 | ٥ | ستغير GenAI كيفية تصور الباحثين في الإدارة للتجريب والتحقق. | 0.0 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | 11.8 % | 41.2 % | 41.2 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ١٣ | ٥ | ستغير الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي كيفية فهم الباحثين في الإدارة وتصوّرهم لاختبار المنتجات الجديدة. | 0.0 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | 11.8 % | 35.3 % | ٤٧.١ ٪ | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 14 | ٦ | من المحتمل أن يكون للذكاء الاصطناعي متعدد الأنماط تأثير إيجابي أكبر على ميزة الشركة المتبنية التنافسية مقارنةً بأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي أحادية النمط. | 0.0 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | 11.8 % | ٤٧.١ ٪ | 17.6 % | 17.6 % | 100.0 % |

| 15 | ٦ | من المحتمل أن يكون للذكاء الاصطناعي متعدد الأنماط تأثير إيجابي أكبر على أداء الابتكار للشركة المتبنية مقارنةً بالذكاء الاصطناعي أحادي النمط. | 0.0 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | 11.8 % | 52.9 % | 11.8 % | 17.6 % | 100.0 % |

| 16 | ٧ | ستجعل GenAI أبحاث إدارة الابتكار حول نظم المنصات أكثر صلة من ذي قبل | 0.0 % | ٥.٦ ٪ | ٥.٦ ٪ | 33.3 % | ٣٨.٩ ٪ | 16.7 % | 100.0 % |

| 17 | ٧ | من المرجح أن تكون الابتكارات المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي شكلًا مفتوحًا من الابتكار، بدلاً من أن تكون مغلقة. | 16.7 % | ٢٢.٢ ٪ | 16.7 % | 16.7 % | ٢٢.٢ ٪ | ٥.٦ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| 18 | ٧ | ستغير GenAI كيفية فهم علماء إدارة الابتكار لوكالة أنشطة وعمليات الابتكار. | 0.0 % | 5.3 % | ٢١.١ ٪ | 31.6 % | ٣٦.٨ ٪ | 5.3 % | 100.0 % |

| 19 | ٧ | ستغير تفاعلات البشر مع الذكاء الاصطناعي الابتكارات والعمليات. | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | ٥.٦ ٪ | 44.4 % | 50.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 20 | ٨ | سيحتاج صانعو السياسات والمشرعون إلى أطر جديدة لتنظيم الابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي. | 0.0 % | ٥.٦ ٪ | 0.0 % | 33.3 % | 50.0 % | 11.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 21 | ٨ | يجب أن تكون سلطات مكافحة الاحتكار مجهزة بأطر جديدة لتطبيق اللوائح المتعلقة بالابتكار المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي. | 0.0 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | ٢٣.٥ ٪ | 52.9 % | 11.8 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| ٢٢ | 9 | يمكن أن يؤدي سوء استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي إلى نتائج ابتكارية متحيزة | 0.0 % | 17.6 % | 11.8 % | 52.9 % | 11.8 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| 23 | 9 | الاستخدام غير الأخلاقي للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي يمكن أن ينتج نتائج ابتكارية تفيد فقط مجموعة فرعية من أصحاب المصلحة. | 0.0 % | ٥.٦ ٪ | 11.1 % | 44.4 % | ٣٣.٣ ٪ | ٥.٦ ٪ | 100.0 % |

| ٢٤ | 10 | من المحتمل أن تعدل GenAI الحدود التنظيمية | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | ٥.٦ ٪ | 44.4 % | 50.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| ٢٥ | 10 | من المحتمل أن تعدل الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي تصميم المنظمة والتنسيق. | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | ٥.٩ ٪ | ٤٧.١ ٪ | ٤٧.١ ٪ | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

References

Aimar, A., Palermo, A., & Innocenti, B. (2019). The role of 3D printing in medical applications: a state of the art. Journal of healthcare engineering, 2019.

Amabile, T. M. (2020). Creativity, artificial intelligence, and a world of surprises. Academy of Management Discoveries, 6(3), 351-354.

Amabile, T. M. (2018). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Routledge.

Anderson, P., & Tushman, M. L. (1990). Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: A cyclical model of technological change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(4), 604-633.

Bamberger, P. A. (2018). AMD-Clarifying what we are about and where we are going. Academy of Management Discoveries, 4(1), 1-10.

Banerjee, A., Niehaus, P., & Suri, T. (2019). Universal basic income in the developing world. Annual Review of Economics, 11, 959-983.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

Benbya, H., Davenport, T.H, Pachidi, S. (2020). Artificial Intelligence in Organizations: Current State and Future Opportunities, MIS Quarterly Executive: 19 (4). Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol19/iss4/4.

Bengio, Y., Ducharme, R., & Vincent, P. (2000). A neural probabilistic language model. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 13, 1-7 (available at) <https:// p roceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2000/file/728f206c2a01bf572b5940d7d9a8fa4cPape r.pdf >.

Bilgram, V., & Laarmann, F. (2023). Accelerating Innovation with Generative AI: AIaugmented Digital Prototyping and Innovation Methods. IEEE Engineering Management Review.

Bjarnason, T., & Jonsson, S. H. (2005). Contrast effects in perceived risk of substance use. Substance Use & Misuse, 40(1), 1733-1748.

Bouschery, S. G., Blazevic, V., & Piller, F. T. (2023). Augmenting human innovation teams with artificial intelligence: Exploring transformer-based language models. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 40(2), 139-153.

Bove, T. (2023). The A.I. revolution is here: ChatGPT could be the fastest-growing app in history and more than half of traders say it could disrupt investing the most. Fortunem. February 2, 2023. Available here: https://fortune.com/2023/02/02/ch atgpt-fastest-growing-app-in-history-could-revolutionize-trading/. Accessed 27.08.2023.

Brossard, M., Gatto, G., Gentile, A., Merle, T., & Wlezien, C. (2020). How generative design could reshape the future of product development. Mckinsey Co.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. WW Norton & Company.

Burger, B., Kanbach, D. K., Kraus, S., Breier, M., & Corvello, V. (2023). On the use of AIbased tools like ChatGPT to support management research. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(7), 233-241.

Cao, Y., Li, S., Liu, Y., Yan, Z., Dai, Y., Yu, P. S., & Sun, L. (2023). A comprehensive survey of ai-generated content (aigc): A history of generative ai from gan to chatgpt. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.04226.

Carnevalli, J. A., & Miguel, P. C. (2008). Review, analysis and classification of the literature on QFD-Types of research, difficulties and benefits. International Journal of Production Economics, 114(2), 737-754.

Chatterjee, S., & Ns, s.. (2022). Artificial intelligence and human rights: A comprehensive study from Indian legal and policy perspective. International Journal of Law and Management, 64(1), 110-134.

Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., Vrontis, D., Thrassou, A., & Ghosh, S. K. (2021). Adoption of artificial intelligence-integrated CRM systems in agile organizations in India. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 168, Article 120783.

Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business Press, Boston, MA.Chesbrough, H. W., & Appleyard, M. M. (2007). Open innovation and strategy. California Management Review, 50(1), 57-76.

Chisum, D. S. (1985). The patentability of algorithms. University of Pittsburgh Law Review, 47, 959.

Cho, H., & Schwarz, N. (2008). Of great art and untalented artists: Effort information and the flexible construction of judgmental heuristics. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 18 (3), 205-211.

Churchill, G. A., Jr., & Surprenant, C. (1982). An investigation into the determinants of customer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 491-504.

Clarysse, B., Wright, M., Bruneel, J., & Mahajan, A. (2014). Creating value in ecosystems: Crossing the chasm between knowledge and business ecosystems. Research Policy, 43 (7), 1164-1176.

Cooper, R. G., & Kleinschmidt, E. J. (1991). New product processes at leading industrial firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 20(2), 137-147.

Cockburn, I. M., Henderson, R., & Stern, S. (2018). The impact of artificial intelligence on innovation: An exploratory analysis. In The economics of artificial intelligence: An agenda (pp. 115-146). University of Chicago Press.

Croitoru, F. A., Hondru, V., Ionescu, R. T., & Shah, M. (2023). Diffusion models in vision: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. Harper Perennial, New York, 39, 1-16.

Csikzentimihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing flow in work and play. San Francisco/Washington/London.

Cui, A. S., & Wu, F. (2017). The impact of customer involvement on new product development: Contingent and substitutive effects. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 34(1), 60-80.

Dalkey, N., & Helmer, O. (1963). An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Science, 9(3), 458-467.

Daugherty, P. R., & Wilson, H. J. (2018). Human+ machine: Reimagining work in the age of AI. Harvard Business Press.

Davenport, T. H., & Ronanki, R. (2018). Artificial intelligence for the real world. Harvard Business Review, 96(1), 108-116.

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Kotlar, J., Magrelli, V., & Messeni Petruzzelli, A. (2018, July). Spanning temporal boundaries in pharmaceutical innovation: a process model. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2018, No. 1, p. 16625). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Delbecq, A. V., de Ven, A., & Gustafson, D. (1975). Group techniques for program planning. Glenview, Illinois: Scott Foresman.

Deng, J., & Lin, Y. (2022). The benefits and challenges of ChatGPT: An overview. Frontiers in Computing and Intelligent Systems, 2(2), 81-83.

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2018). Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1810.04805.

Dörr, N. K. (2015). Mapping the field of algorithmic journalism. Digital Journalism, 4(6), 700-722. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2015.1096748

Duchesneau, T. D., Cohn, S. F., & Dutton, J. E. (1979). A study of innovation in manufacturing. Determinants, Processes, and Methodological Issues, 1.

Durkheim, E. (1982). The rules of the sociological method. New York: Free Press.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Ismagilova, E., Aarts, G., Coombs, C., Crick, T., … Williams, M. D. (2021). Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 57, Article 101994.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Slade, E. L., & Wright, R. (2023). “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71, Article 102642.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Al-Debei, M. M., & Wamba, S. F. (2022). Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 66, Article 102542.

Ebers, M., Hoch, V. R., Rosenkranz, F., Ruschemeier, H., & Steinrötter, B. (2021). The european commission’s proposal for an artificial intelligence act-a critical assessment by members of the robotics and ai law society (rails). J, 4(4), 589-603.

Emmert-Streib, F., Yli-Harja, O., & Dehmer, M. (2020). Artificial intelligence: A clarification of misconceptions, myths and desired status. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 3, Article 524339.

Epstein, Z., Hertzmann, A., Investigators of Human Creativity, Akten, M., Farid, H., Fjeld, J., … & Smith, A. (2023). Art and the science of generative AI. Science, 380(6650), 1110-1111.

Ettlie, J. E. (1983). Organizational policy and innovation among suppliers to the food processing sector. Academy of Management journal, 26(1), 27-44.

Etzioni, A., & Etzioni, O. (2017). Should artificial intelligence be regulated?. Issues in Science and Technology (issues. org), Summer.

Farish, K. (2020). Do deepfakes pose a golden opportunity? Considering whether English law should adopt California’s publicity right in the age of the deepfake. Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 15(1), 40-48.

Ferràs-Hernández, X., Nylund, P. A., & Brem, A. (2023). The Emergence of Dominant Designs in Artificial Intelligence. California Management Review, 00081256231164362.

Floridi, L. (2023). AI as agency without intelligence: On ChatGPT, large language models, and other generative models. Philosophy & Technology, 36(1), 15.

Floridi, L., & Chiriatti, M. (2020). GPT-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds and Machines, 30, 681-694.

Floridi, L. (2013). The philosophy of information. OUP Oxford.

Foley, J. (2022). 14 deepfake examples that terrified and amused the internet. Creative Bloq. https://www.creativebloq.com/features/deepfake-example.

Forest, J., & Faucheux, M. (2011). Stimulating Creative Rationality to Stimulate Innovation. Creativity and Innovation Management, 20(3), 207-212.

Fosso Wamba, S., & Queiroz, M. M. (2021). Responsible artificial intelligence as a secret ingredient for digital health: Bibliometric analysis, insights, and research directions. Information Systems Frontiers, 1-16.

Gault, F. (2018). Defining and measuring innovation in all sectors of the economy. Research Policy, 47(3), 617-622.

Gaur, A., & Kumar, M. (2018). A systematic approach to conducting review studies: An assessment of content analysis in 25 years of IB research. Journal of World Business, 53(2), 280-289.

Getzels, J. W., & Jackson, P. W. (1961). Family environment and cognitive style: A study of the sources of highly intelligent and of highly creative adolescents. American Sociological Review, 351-359.

Goodfellow, I., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., … Bengio, Y. (2020). Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM, 63 (11), 139-144.

Gordon, T. J. (1994). The Delphi method. Washington, DC: American Council for the United Nations University.

Gragousian, D. (2022). How businesses should respond to the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act, World Economic Forum, Available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/ 02/how-businesses-should-respond-to-eu-artificial-intelligence-act/.

Graham, N., Hedges, R., Chiu, C., de La Chapelle, F., & van de Graaf, A. (2021, October 12). How can businesses protect themselves from deepfake attacks? Business Going Digital. https://www.businessgoing.digital/how-can-businesses-protect-themselves-from-deepfake-attacks/.

Graves, A., & Jaitly, N. (2014). Towards end-to-end speech recognition with recurrent neural networks. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 1764-1772). PMLR.

Griffin, A. (1992). Evaluating QFD’s use in US firms as a process for developing products. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 9(3), 171-187.

Grisoni, F., Huisman, B. J., Button, A. L., Moret, M., Atz, K., Merk, D., & Schneider, G. (2021). Combining generative artificial intelligence and on-chip synthesis for de novo drug design. Science Advances, 7(24), eabg3338.

Gursoy, D., Li, Y., & Song, H. (2023). ChatGPT and the hospitality and tourism industry: An overview of current trends and future research directions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 32(5), 579-592.

Haefner, N., Wincent, J., Parida, V., & Gassmann, O. (2021). Artificial intelligence and innovation management: A review, framework, and research agendar. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 162, Article 120392.

Hallowell, M. R., & Gambatese, J. A. (2010). Qualitative research: Application of the Delphi method to CEM research. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 136, 99-107.

Harrmann, L. K., Eggert, A., & Böhm, E. (2023). Digital technology usage as a driver of servitization paths in manufacturing industries. European Journal of Marketing, 57(3), 834-857.

Helfat, C. E., & Lieberman, M. B. (2002). The birth of capabilities: Market entry and the importance of pre-history. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(4), 725-760.

Hendriksen, C. (2023). AI for supply chain management: Disruptive innovation or innovative disruption? Journal of Supply Chain Management., 59(3), 65-76.

Herstatt, C., & Von Hippel, E. (1992). From experience: Developing new product concepts via the lead user method: A case study in a “low-tech” field. Journal of product innovation management, 9(3), 213-221.

Hickman, E., & Petrin, M. (2021). Trustworthy AI and corporate governance: The EU’s ethics guidelines for trustworthy artificial intelligence from a company law perspective. European Business Organization Law Review, 22, 593-625.

Hine, E., & Floridi, L. (2022). New deepfake regulations in China are a tool for social stability, but at what cost? Nature Machine Intelligence, 4(7), 608-610.

Hirsch, P. M. (1972). Processing fads and fashions: An organization-set analysis of cultural industry systems. American Journal of Sociology, 77(4), 639-659.

Hu, K. (2023). ChatGPT sets record for fastest-growing user base – analyst note. Reuters. Retrieved 28.6.2023 at https://www.reuters.com/technology/chatgpt-sets-record-fastest-growing-user-base-analyst-note-2023-02-01/.

Huang, M.-H., & Rust, R. T. (2021). Engaged to a robot? The role of AI in service. Journal of Service Research, 24(1), 30-41.

Huang, M. H., & Rust, R. T. (2018). Artificial intelligence in service. Journal of Service Research, 21(2), 155-172.

Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004). Strategy as ecology. Harvard Business Review, 82(3), 68-78.

IBM (2022). How to use AI to discover new drugs and materials with limited data. 13.04.2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022: https://research.ibm.com/blog/ai-discovery-with-limited-data.

Johnson, C. D., Bauer, B. C., & Niederman, F. (2021). The automation of management and business science. Academy of Management Perspectives, 35(2), 292-309.

Kanbach, D. K., Heiduk, L., Blueher, G., Schreiter, M., & Lahmann, A. (2023). The GenAI is out of the bottle: Generative artificial intelligence from a business model innovation perspective. Review of Managerial Science, 1-32.

Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2019). Siri, Siri, in my hand: Who’s the fairest in the land? On the interpretations, illustrations, and implications of artificial intelligence. Business Horizons, 62(1), 15-25.

Kapoor, P. (1987). Systems approach to documentary maritime fraud.

Keil, M., Tiwana, A., & Bush, A. A. (2002). Reconciling user and project manager perceptions of IT project risk: A Delphi study. Information Systems Journal, 12, 103-119.

Kietzmann, J., Lee, L. W., McCarthy, I. P., & Kietzmann, T. C. (2020). Deepfakes: Trick or treat? Business Horizons, 63(2), 135-146.

Koivisto, M., & Grassini, S. (2023). Best humans still outperform artificial intelligence in a creative divergent thinking task. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 13601.

Kruger, J., Lobschat, D., Van Boven, L., & Altermatt, T. W. (2004). The effort heuristic. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 91-98.

La Roche, J. (2017). November 16. IBM’s Rometty: The skills gap for tech jobs is “the essence of divide.” Yahoo! Finance. Retrieved from https://finance.yahoo.com/news /ibms-rometty-skills-gap-tech-jobs-essencedivide-175847484.html.

Lehman, D. W., O’Connor, K., Kovács, B., & Newman, G. E. (2019). Authenticity. Academy of Management Annals, 13(1), 1-42.

Leone, D., Schiavone, F., Appio, F. P., & Chiao, B. (2021). How does artificial intelligence enable and enhance value co-creation in industrial markets? An exploratory case study in the healthcare ecosystem. Journal of Business Research, 129, 849-859.

Levy, N. J. (1961). Notes on the creative process and the creative person. PsychiatricQuarterly, 35(1), 66-77.

Lobschat, L., Mueller, B., Eggers, F., Brandimarte, L., Diefenbach, S., Kroschke, M., & Wirtz, J. (2021). Corporate digital responsibility. Journal of Business Research, 122, 875-888.

Longoni, C., Fradkin, A., Cian, L., & Pennycook, G. (2022, June). News from generative artificial intelligence is believed less. 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 97-106).

Macdonald, N. (1954). Language translation by machine-a report of the first successful trial. Computers and Automation, 3(2), 6-10.

MacKinnon, D. W. (1965). Personality and the realization of creative potential. American Psychologist, 20(4), 273.

Marconi, F. (2020). Newsmakers. In Newsmakers. Columbia University Press.

Marcus, G. (2022). AI Platforms like ChatGPT Are Easy to Use but Also Potentially Dangerous. Scientific American, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ai-platforms-like-chatgpt-are-easy-to-use-but-also-potentially-dangerous/. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

Martineau, K. (2023). What is generative AI? IBM Research. Retrieved 26.6.2023 at https://research.ibm.com/blog/what-is-generative-AI.

Mariani, M. M., Machado, I., Magrelli, V., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2023). Artificial intelligence in innovation research: A systematic review, conceptual framework, and future research directions. Technovation, 102623.

Mariani, M. M., & Nambisan, S. (2021). Innovation analytics and digital innovation experimentation: The rise of research-driven online review platforms. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 172, 121009.

Mariani, M. M., Perez-Vega, R., & Wirtz, J. (2022). AI in marketing, consumer research and psychology: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Psychology & Marketing, 39(4), 755-776.

Mariani, M. M., & Wamba, S. F. (2020). Exploring how consumer goods companies innovate in the digital age: The role of big data analytics companies. Journal of Business Research, 121, 338-352.

Mednick, S. (1962). The associative basis of the creative process. Psychological Review, 69 (3), 220.

Mikolov, T., Karafiát, M., Burget, L., Cernocký, J., & Khudanpur, S. (2010). Recurrent neural network based language model. Interspeech, 2(3), 1045-1048.

Miller, L. E. (2006). Determining what could/should be: The Delphi technique and its application. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2006 Annual Meeting of the MidWestern Educational Research Association, Columbus, Ohio.

Mittelstadt, B. D., Allo, P., Taddeo, M., Wachter, S., & Floridi, L. (2016). The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data & Society, 3(2), 2053951716679679.

Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and prey: A new ecology of competition. Harvard Business Review, 71(3), 75-86.

Morley, J., Floridi, L., Kinsey, L., & Elhalal, A. (2020). From what to how: An initial review of publicly available AI ethics tools, methods and research to translate principles into practices. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(4), 2141-2168.

Nagendran, M., Chen, Y., Lovejoy, C. A., Gordon, A. C., Komorowski, M., Harvey, H., Maruthappu, M. (2020). Artificial intelligence versus clinicians: Systematic review of design, reporting standards, and claims of deep learning studies. The BMJ, 368.

Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029-1055.

Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1977). In search of a useful theory of innovation. In Innovation, Economic Change and Technology Policies: Proceedings of a Seminar on Technological Innovation held in Bonn, Federal Republic of Germany, April 5 to 9, 1976 (pp. 215-245). Birkhäuser Basel.

Nilsson, N. (2010). The quest for artificial intelligence: A history of ideas and achievements. Cambridge University Press.

Nijssen, E. J., Arbouw, A. R., & Commandeur, H. R. (1995). Accelerating new product development: A preliminary empirical test of a hierarchy of implementation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 12(2), 99-109.

Nilsson, N. J. (1971). Problem-solving methods in artificial intelligence. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Paschen, J., Wilson, M., & Ferreira, J. J. (2020). Collaborative intelligence: How human and artificial intelligence create value along the B2B sales funnel. Business Horizons, 63(3), 403-414.

Perez-Vega, R., Kaartemo, V., Lages, C. R., Razavi, N. B., & Männistö, J. (2021). Reshaping the contexts of online customer engagement behavior via artificial intelligence: A conceptual framework. Journal of Business Research, 129, 902-910.

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., & Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. Available at: https://www.mikecaptain. com/resources/pdf/GPT-1.pdf.

Raisch, S., & Krakowski, S. (2021). Artificial intelligence and management: The automation-augmentation paradox. Academy of Management Review, 46(1), 192-210.

Ray, A. (2021). Disinformation, deepfakes and democracies: The need for legislative reform. The University of New South Wales Law Journal, 44(3), 983-1013.

Rhodes, M. (1961). An analysis of creativity. The Phi delta kappan, 42(7), 305-310.

Samuelson, P. (2023). Generative AI meets copyright. Science, 381(6654), 158-161.

Saura, J. R., Ribeiro-Soriano, D., & Palacios-Marqués, D. (2022). Assessing behavioral data science privacy issues in government artificial intelligence deployment. Government Information Quarterly, 39(4), Article 101679.

Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1975). Scripts, plans, and knowledge. In IJCAI, 75, 151-157.

Schilling, M. A. (2023). Strategic management of technological innovation (7th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill.

Schilling, M. A. (2018). Quirky: The remarkable story of the traits, foibles, and genius of breakthrough innovators who changed the world. PublicAffairs.

Schilling, M. A. (2008). Strategic management of technological innovation (1st ed.). New York: McGraw Hill.

Schmenner, R. W. (1988). The merit of making things fast. MIT Sloan Management Review, 30(1), 11.

Schneider, J., Abraham, R., Meske, C., & Vom Brocke, J. (2022). Artificial intelligence governance for businesses. Information Systems Management. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/10580530.2022.2085825

Simon, H. A. (1991). Bounded rationality and organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 125-134.

Simon, H. A. (1984). Models of bounded rationality. Economic analysis and public policy. Boston: The MIT Press.

Skinner, R., Nelson, R. R., Chin, W. W., & Land, L. (2015). The Delphi method research strategy in studies of information systems. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 37, 31-63.

Smuha, N.A., Ahmed-Rengers, E., Harkens, A., Li, W., MacLaren, J., Piselli, R. & Yeung, K. (2021). How the EU Can Achieve Legally Trustworthy AI: A Response to the European Commission’s Proposal for an Artificial Intelligence Act (August 5, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3899991 or https://doi.org/ 10.2139/ssrn. 3899991.

Staw, B. M. (1990). An evolutionary approach to creativity and innovation. In M. A. West & J. L. Farr, Innovation and creativity at work: Psychological and organizational strategies (pp. 287-308).

Straus, M. A. (1968). Communication, creativity, and problem-solving ability of middleand working-class families in three societies. American Journal of Sociology, 73(4), 417-430.

Suler, J. R. (1980). Primary process thinking and creativity. Psychological Bulletin, 88(1), 144.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509-533.

Thomke, S. (2020). Building a culture of experimentation. Harvard Business Review, 98 (2), 40-47.

Tsamados, A., Aggarwal, N., Cowls, J., Morley, J., Roberts, H., Taddeo, M., & Floridi, L. (2021). The ethics of algorithms: Key problems and solutions. Ethics, Governance, and Policies in Artificial Intelligence, 97-123.

Utterback, J. M., & Abernathy, W. J. (1975). A dynamic model of process and product innovation. Omega, 3(6), 639-656.

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30.

Peterson, J. C., Uddenberg, S., Griffiths, T. L., Todorov, A., & Suchow, J. W. (2022). Deep models of superficial face judgments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(17).

Verganti, R., Vendraminelli, L., & Iansiti, M. (2020). Innovation and design in the age of artificial intelligence. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 37(3), 212-227.

Vieira, E., & Gomes, J. (2009). A comparison of Scopus and Web of Science for a typical university. Scientometrics, 81(2), 587-600.

Wamba-Taguimdje, S. L., Fosso Wamba, S., Kala Kamdjoug, J. R., & Tchatchouang Wanko, C. E. (2020). Influence of artificial intelligence (AI) on firm performance: The business value of AI-based transformation projects. Business Process Management Journal, 26(7), 1893-1924.

Wang, Y., Ma, H. S., Yang, J. H., & Wang, K. S. (2017). Industry 4.0: A way from mass customization to mass personalization production. Advances in Manufacturing, 5, 311-320.

Weizenbaum, J. (1966). ELIZA-a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the ACM, 9(1), 36-45.

Westerlund, M. (2019). The emergence of Deepfake technology: A review. Technology Innovation Management Review, 9(11), 40-53.

Wiles, J. (2023). Beyond ChatGPT: the future of generative AI for enterprises, 23.01.2023. Available at: https://www.gartner.com/en/articles/beyond-chatgpt-the-future-of-generative-ai-for-enterprises.

Wirtz, J., Kunz, W. H., Hartley, N., & Tarbit, J. (2023). Corporate digital responsibility in service firms and their ecosystems. Journal of Service Research, 26(2), 173-190.

Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. (1993). Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Academy of Management Review, 18(2), 293-321.

Wu, B., Nair, S., Martin-Martin, R., Fei-Fei, L., & Finn, C. (2021). Greedy hierarchical variational autoencoders for large-scale video prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 2318-2328).

Zahra, S. A., & Nambisan, S. (2012). Entrepreneurship and strategic thinking in business ecosystems. Business Horizons, 55(3), 219-222.

- Corresponding author at: Henley Business School, University of Reading Greenlands, Henley on Thames Oxfordshire, RG9 3AU, United Kingdom.

E-mail addresses: m.mariani@henley.ac.uk (M. Mariani), y.k.dwivedi@swansea.ac.uk (Y.K. Dwivedi).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114542

Publication Date: 2024-02-14

Generative artificial intelligence in innovation management: A preview of future research developments

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Delphi study

Management

Innovation

Abstract

This study outlines the future research opportunities related to Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) in innovation management. To this end, it combines a review of the academic literature with the results of a Delphi study involving leading innovation management scholars. Ten major research themes emerged that can guide future research developments at the intersection of GenAI and innovation management: 1) Gen AI and innovation types; 2) GenAI, dominant designs and technology evolution; 3) Scientific and artistic creativity and GenAI-enabled innovations; 4) GenAI-enabled innovations and intellectual property; 5) GenAI and new product development; 6) Multimodal/unimodal GenAI and innovation outcomes; 7) GenAI, agency and ecosystems; 8) Policymakers, lawmakers and anti-trust authorities in the regulation of GenAI-enabled innovation; 9) Misuse and unethical use of GenAI leading to biased innovation; and 10) Organizational design and boundaries for GenAIenabled innovation. The paper concludes by discussing how these themes can inform theoretical development in innovation management studies.

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical underpinnings, recent debate, and conceptualizations of AI in management

(1) process automation; (2) cognitive insights; and (3) cognitive engagement. Process automation-sometimes referred to as robotic process automation (RPA)-is the cheapest and easiest AI to implement; as such, it typically generates a high (and quick) return on investment. The second type, cognitive insights, deploys algorithms and machine learning to detect patterns in vast volumes of data and interpret their meaning. Finally, cognitive engagement employs natural language processing chatbots, intelligent agents, and machine learning in order to connect people within and across organizations (e.g., employees, customers). Huang and Rust (2021) similarly conceptualized and distinguished three types of artificial intelligence: (1) mechanical; (2) thinking; and (3) feeling AI, which respectively handle routine, rulebased, and emotional tasks (Huang and Rust, 2021). Mechanical AI comes in the guise of robots, while thinking AI takes the form of conversational agents (Mariani et al., 2022). Relying on work by Nilsson (1971), Raisch and Krakowski (2021) defined AI as a concept that “refers to machines performing cognitive functions that are usually associated with human minds, such as learning, interacting, and problem solving” (p. 192). Drawing on Nilsson (2010), who defined AI as “that activity devoted to making machines intelligent” (p. 13), Cockburn et al. (2018) observed that AI covers three areas: robotics, symbolic systems, and learning systems. Only the latter ones represent a truly general-purpose technology that can be “a method to innovate”. Indeed, deep learning allows AI to “predict” physical and logical events with higher precision and accuracy compared to traditional statistical methods, which could be a boon for scientific, behavioral and technical research. Other scholars (e.g., Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014; Daugherty & Wilson, 2018; Davenport and Ronanki, 2018) have suggested that humans and machines must collaborate, rather than compete, in order to share their complementary strengths and achieve mutual learning (La Roche, 2017; Raisch & Krakowski, 2021). Overall, while several scholars maintain that there is no universally accepted definition of AI (Streinb et al., 2020), due to “intelligence” not being formally (and mathematically) defined, the management field has access to many working definitions of AI (see Huang & Rust, 2021; Nilsson, 2010).

“common thread amongst these definitions is the increasing capability of machines to perform specific roles and tasks currently performed by humans within the workplace and society in general” (Dwivedi et al., 2022: p. 2).

2.2. Theoretical underpinnings, recent debate, and conceptualizations of GenAI in management

had been developing over time, an intersection emerged in the transformer architecture. Introduced by Vaswani et al. (2017) with applications to NLP, the transformer architecture has become the dominant backbone of generative models. For instance, in the area of NLP, Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) and Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPTs) (such as GPT-1 to GPT-4) deploy a transformer architecture. Vision Transformer and Swin Transformer utilize a transformer architecture in the area of CV, as does the text-to-image application DALL-E. Interestingly, the transformer architecture allows one to fuse different models and thereby enable multimodal tasks (i.e., simultaneously generating different types of content like images and music).

3. Methods

3.1. Literature review deployed for the Delphi study

or “ERNIE” or “Bart” or “T5” or “Megatron” or “Murf.ai” or “Designs.ai” or “Soundraw” or “ChatFlash” or “ChatSonic” or “Scribe” or “VEED” or “Speechify” and several other GenAI proper names. While the collection of proper GenAI names is not necessarily comprehensive, it is broad enough to cover the most popular GenAI systems mentioned by leading IT consultancy companies like Gartner. Moreover, when proper names appeared with different spellings, we used the most widespread spellings (like in the case of “DALL-E 2”, which is sometimes written as “DALL-E2”). The keywords deployed to cover innovation management were “innovat*” and “manag*”.

3.2. Delphi study

4. Findings

4.1. Findings from the literature review

this reason, we used the literature review studies and the interviews to develop the 25 Delphi items (see Table A. 1 in the Appendix).

4.2. Findings from the Delphi study

4.2.1. GenAI and innovation types

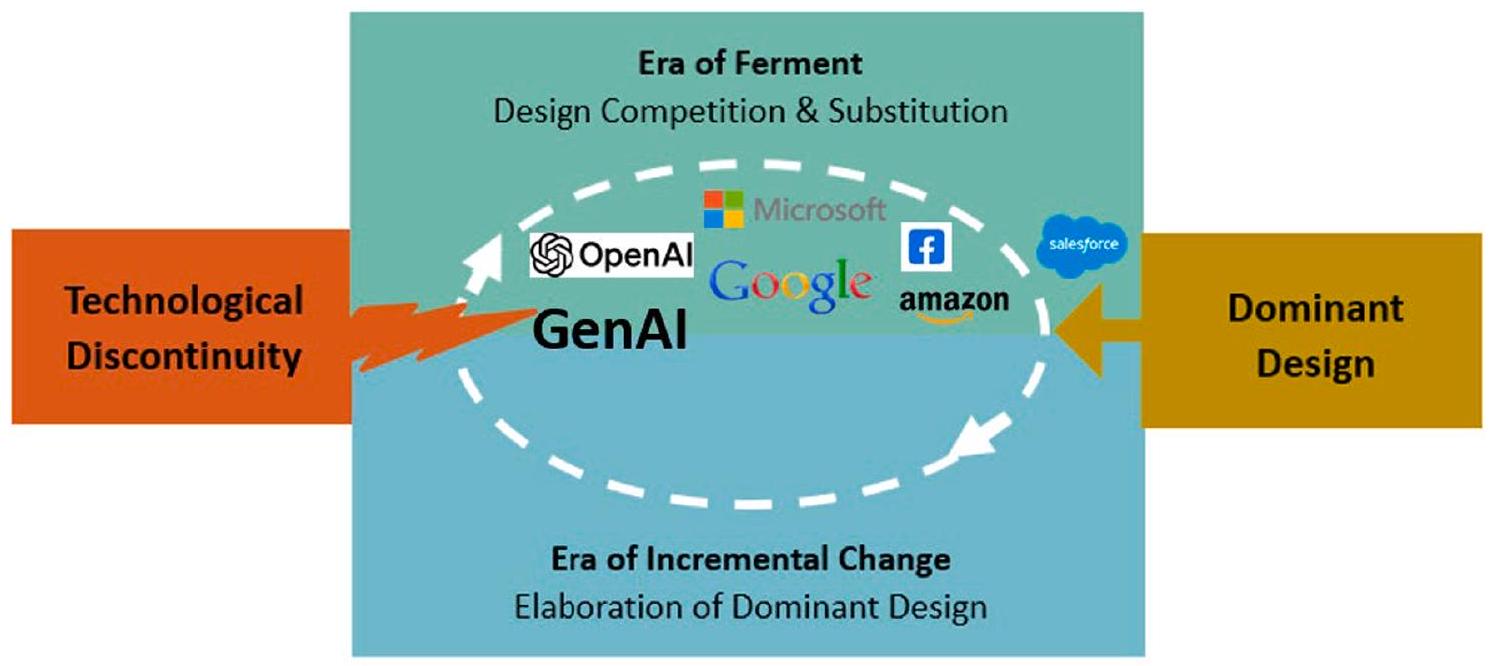

4.2.2. GenAI, dominant designs and technology evolution

Aggregated results from Round 2 (common sized values).

| # | Theme | Delphi argument | Strongly disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neither agree or disagree | Somewhat agree | Strongly agree | Unable to comment | Number of Opinions |

| 1 | 1 | GenAI will not lead to the conceptualization of innovation types that go beyond extant innovation taxonomies (e.g., product/ process, radical/incremental, architectural/component, etc.) | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 45.5 % | 45.5 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 2 | 1 | Business model innovation might be significantly modified by the presence of GenAI | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 11.1 % | 33.3 % | 55.6 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 3 | 2 | The evolution of GenAI systems can be captured through extant technology evolution frameworks | 10.0 % | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 80.0 % | 66.7 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 5 | 3 | GenAI-enabled scientific creativity will be conceptualized differently than traditional scientific creativity | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | 63.6 % | 18.2 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 6 | 3 | GenAI-enabled artistic creativity will be conceptualized differently than traditional artistic creativity | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 81.8 % | 18.2 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 7 | 4 | GenAI will lead to to the conceptualization of novel forms/types of intellectual property (protection) in innovation management | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | 10.0 % | 50.0 % | 30.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 8 | 4 | GenAI will undermine the way we currently conceptualize intellectual property in innovation management | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | 36.4 % | 36.4 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 9 | 5 | GenAI will modify the way we currently conceptualize deliberate vs. emergent strategies in New Product Development | 9.1 % | 63.6 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 11 | 5 | GenAI will change how management scholars construe New Product Development teams | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 18.2 % | 36.4 % | 27.3 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 12 | 5 | GenAI will change how management scholars construe and conceptualize experimentation and validation | 0.0 % | 11.1 % | 11.1 % | 33.3 % | 44.4 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 13 | 5 | GenAI will change how management scholars construe and conceptualize new product testing | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 20.0 % | 40.0 % | 40.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 14 | 6 | Multimodal GenAI is likely to have a more positive influence on the adopting firm’s competitive advantage than unimodal GenAI systems | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | 45.5 % | 27.3 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 15 | 6 | Multimodal GenAI is likely to have a more positive influence on the adopting firm’s innovation performance than unimodal GenAI systems | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | 20.0 % | 40.0 % | 20.0 % | 10.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 16 | 7 | GenAI will make innovation management research on platform ecosystems more relevant than before | 0.0 % | 11.1 % | 11.1 % | 33.3 % | 44.4 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 17 | 7 | GenAI-enabled innovation is more likely to be an open, rather than closed, form of innovation | 9.1 % | 27.3 % | 18.2 % | 18.2 % | 18.2 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 18 | 7 | GenAI will change how innovation management scholars make sense of agency of innovation activities and processes | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 18.2 % | 36.4 % | 36.4 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 19 | 7 | Human-GenAI interactions will change innovation activities and processes | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | 40.0 % | 50.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 20 | 8 | Policymakers and lawmakers will need novel frameworks to regulate GenAI-enabled innovation | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 44.4 % | 44.4 % | 11.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 21 | 8 | Anti-trust authorities should be equipped with new frameworks to enforce regulations related to GenAI-enabled innovation | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 27.3 % | 36.4 % | 18.2 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 22 | 9 | The misuse of GenAI can generate biased innovation outcomes | 0.0 % | 22.2 % | 11.1 % | 44.4 % | 11.1 % | 11.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 23 | 9 | The unethiical use of GenAI can generate innovation outcomes that benefit only a subset of stakeholders | 0.0 % | 9.1 % | 9.1 % | 45.5 % | 27.3 % | 9.1 % | 100.0 % |

| 24 | 10 | GenAI is likely to modify organizational boundaries | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | 40.0 % | 50.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

| 25 | 10 | GenAI is likely to modify organizational design and coordination | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 10.0 % | 40.0 % | 50.0 % | 0.0 % | 100.0 % |

4.2.3. Scientific and artistic creativity and GenAI-enabled innovations

4.2.4. GenAI-enabled innovations and intellectual property

technological innovation like here in the US – will start developing laws that significantly modify copyright.” Those same experts suggested that GenAI will lead to new conceptualizations of intellectual property (protection) in innovation management. Several agreed that governments need updated frameworks that allow GenAI systems to work at full capacity; the most radical expert even argued that current copyright law “should go away” in order to fulfil that goal. That said, a significant minority of experts suggested that intellectual property is here to stay and largely in its current form (i.e., as patents, trademarks and copyrights). This latter group of experts mentioned that GenAI providers should instead coordinate continuously with patent offices and copyright law enforcement bodies.

4.2.5. GenAI and new product development

emergent strategies are often a matter of serendipity for employees and managers, although it is possible for GenAI to produce unexpected solutions via embedded elements of “positive” randomness. That “positive” randomness could help amplify humans’ capacity to develop unconventional ideas during the NPD process. Furthermore, the majority of experts argued that GenAI will change how management scholars construe NPD teams. Indeed, the dynamics within NPD teams will need to change to accommodate the increasing inclusion of machines,. As a corollary of these first two points (“positive” randomness injected by GenAI systems and more diverse innovation teams), most of the experts expected that innovation management scholars would modify the way they construe and conceptualize the NPD process. Indeed, the collaborations between humans and GenAI systems will impact the structure, duration, and efficiency of workflows. Additionally, most experts felt that GenAI would enable more real-time experimentation and validation techniques, empowering innovation managers to quickly pivot their ideas into products/processes/business models. Likewise, GenAI would improve new product testing by allowing for real-time uptake and processing of consumer preferences and needs. For instance, one expert mentioned digital prototyping as a way to quickly and cheaply test new products.

4.2.6. Multimodal/unimodal GenAI and innovation outcomes

4.2.7. GenAI, agency and ecosystems

4.2.8. Policymakers, lawmakers and anti-trust authorities in the regulation of GenAI-enabled innovation

4.2.9. Misuse and unethical use of GenAI leading to biased innovation

innovation with several detrimental consequences, including reputational damages to individuals and organizations, job losses, distortions in market competition, and the spread of misinformation. However, most countries currently lack a regulatory framework that can offer protection against content generated through the misuse of GenAI. Secondly, the experts noted that GenAI systems are increasingly generating misinformation (e.g., fake posts or reviews) that can bias-if not paralyze-consumers’ and managers’ decision-making. This can eventually lead to suboptimal decisions and substantive losses. Lastly, the experts agreed that GenAI models can be biased against certain individuals or groups, based on not only the model’s training data, but also the absence of ethical controls on GenAI algorithms. This means that certain groups of stakeholders might disproportionately benefit from GenAI-enabled innovation compared to others. In short, GenAI systems need to comply with ethical standards in order to ensure that innovation outcomes are ethical and fair themselves.

4.2.10. Organizational design and boundaries for GenAI-enabled innovation

5. Discussion

5.1. GenAI and innovation types

A typology of GenAI-enabled innovation.

|

Types of GenAIenabled innovation | Business examples and use cases | ||||

| Product innovation | GenAI-enabled Product Innovation (GenAIProdI)GenAI used to generate a new product or improve an existing product |

|

||||

| Process innovation | GenAI-enabled Process Innovation (GenAIProcI)GenAI used to generate a new process or improve an existing process |

|

||||

| Marketing innovation | GenAI-enabled Marketing Innovation (GenAIMarI)GenAI used to improve marketing activities |

|

|

Types of GenAIenabled innovation | Business examples and use cases | ||

| Organizational innovation | GenAI-enabled Organizational Innovation (GenAIOrgI)GenAI used to improve organizational features |

|

5.2. GenAI, dominant designs and technology evolution

A Taxonomy of GenAI-enabled Radical vs. Incremental Innovation.

|

Types of GenAI-enabled innovation | Business examples and use cases | |||||||

| Radical innovation |

|

|

|||||||

| Incremental innovation |

|

|

Users have not yet shown interest in GenAI the way that businesses have, but investments from large tech firms may expand the market for AI systems in the next five years. However, the point of expanding the market is also ensuring that the increasing amount of available data can be made suitable for the purpose of deep learning that is embedded in GenAI systems. This will also require developing algorithms that can separate the “signal” from the “noise” (i.e., distinguish reliable from unreliable data), as well as factually true information from misinformation. Users may flock to the technology if it shifts the power to innovate away from highly skilled technicians to less skilled individuals.

5.3. Scientific and artistic creativity and GenAI-enabled innovations

artistic domains.