DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-025-00511-7

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-13

الذكاء الاصطناعي وتكنولوجيا الاتصال في الأوساط الأكاديمية: تصورات أعضاء هيئة التدريس واعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي

aya.shata@unlv.edu

الملخص

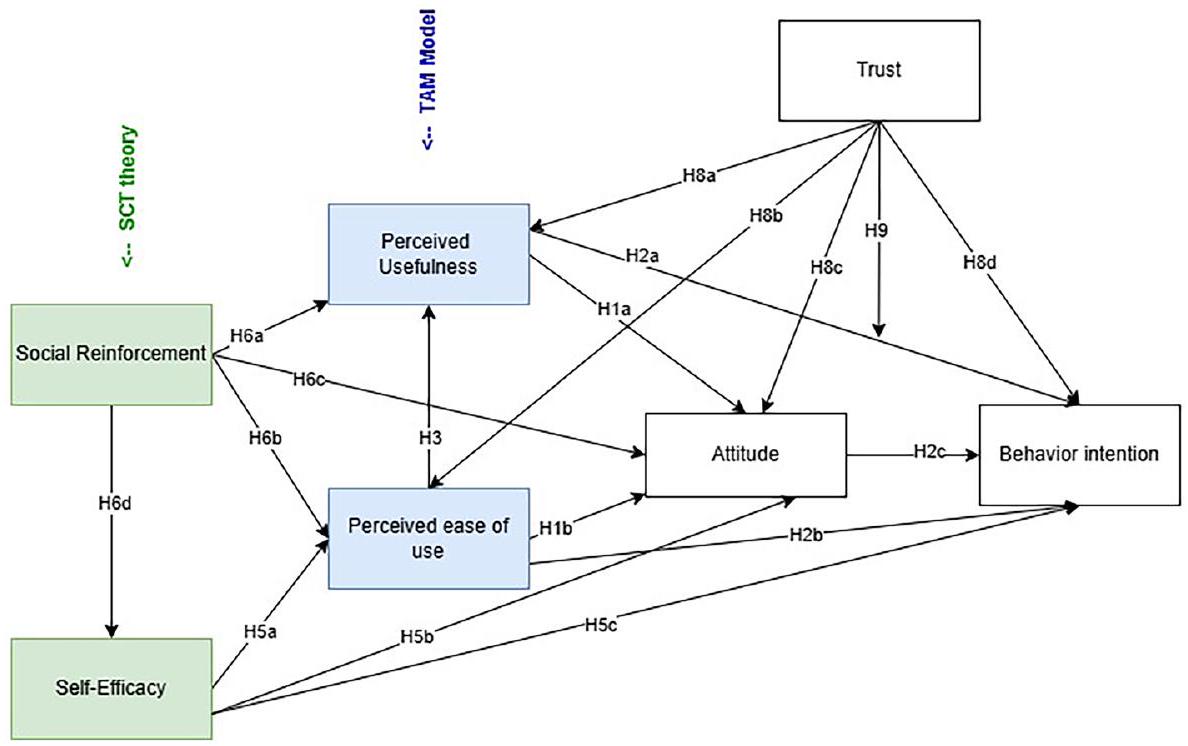

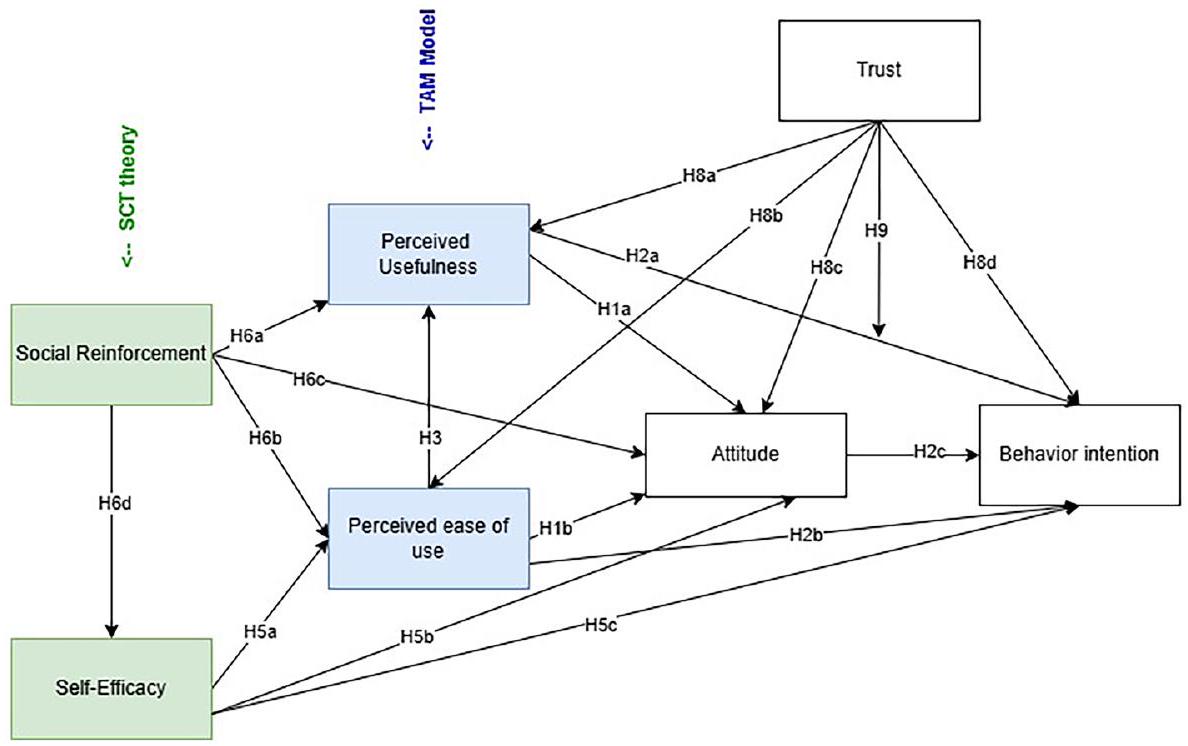

الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) يفتح عصرًا من التحول المحتمل في مجالات متعددة، خاصة في تكنولوجيا الاتصال التعليمية، مع أدوات مثل ChatGPT وغيرها من تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (GenAI). هذا الانتشار السريع واعتماد أدوات GenAI أثار اهتمامًا وقلقًا كبيرين بين أساتذة الجامعات، الذين يتعاملون مع الديناميات المتطورة في الاتصال الرقمي داخل الفصول الدراسية. ومع ذلك، فإن تأثير ونتائج GenAI في التعليم لا تزال غير مدروسة بشكل كاف. لذلك، تستخدم هذه الدراسة نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا (TAM) ونظرية التعلم الاجتماعي (SCT) كإطارات نظرية لاستكشاف تصورات أعضاء هيئة التدريس في التعليم العالي، والمواقف، والاستخدام، والدوافع، كعوامل أساسية تؤثر على اعتمادهم أو رفضهم لأدوات GenAI. تم إجراء استبيان بين أعضاء هيئة التدريس بدوام كامل في التعليم العالي (

المقدمة

مراجعة الأدبيات

الذكاء الاصطناعي في التعليم العالي

تتحسن بسرعة كما يتحسن فهمنا لكيفية ومتى نستخدم ChatGPT. الدراسة المذكورة أعلاه استخدمت ChatGPT الإصدار 3.5. وجدت دراسة تقارن بين ChatGPT الإصدار 3.5 و4.0 في امتحان الترخيص الطبي الأمريكي تحسنًا ملحوظًا. أظهر الإصدار 3.5 دقة قدرها

تصورات أعضاء هيئة التدريس والطلاب حول الذكاء الاصطناعي

اعتماد التكنولوجيا

الموقف

حيوية في تحديد ما إذا كانوا سيقبلون الابتكارات أم لا (ديفيس، 1989؛ غرانيتش ومارانغونيك، 2019). فيما يتعلق بالذكاء الاصطناعي، يمكن أن تؤثر مواقف الأفراد ومستويات راحتهم بشكل كبير على القبول والاندماج في مختلف جوانب نظام التعليم (باور وآخرون، 2024). تشير الدراسات الأولية إلى أن مواقف أعضاء هيئة التدريس تجاه Gen AI مختلطة (باور وآخرون، 2024). بينما يدرك غالبية أعضاء هيئة التدريس الإمكانية للتأثير الكبير، فإن هؤلاء الأساتذة أنفسهم أكثر دراية بالتكنولوجيا.

PEU/PU

الكفاءة الذاتية

التعزيز الاجتماعي

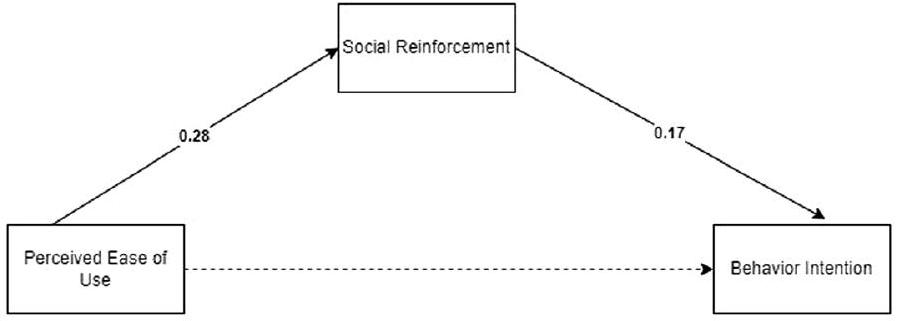

تعترف نظرية التعلم الاجتماعي المعرفي بقدرتنا المعززة على التعلم بالملاحظة والدور الحيوي للتفاعلات الاجتماعية (باندورا، 1999). من المحتمل أن تؤثر هذه القدرة، جنبًا إلى جنب مع النقاش الواسع، على تصورات المستخدمين ومواقفهم وكفاءتهم الذاتية تجاه استخدام GenAI. بما يتماشى مع الأعمال السابقة في اعتماد التكنولوجيا (فينكاتيش وآخرون، 2016)، نقوم بتشغيل التأثير الاجتماعي كتعزيز اجتماعي، مما يعكس تأثير آراء وسلوكيات الآخرين على قرار الفرد باستخدام التكنولوجيا.

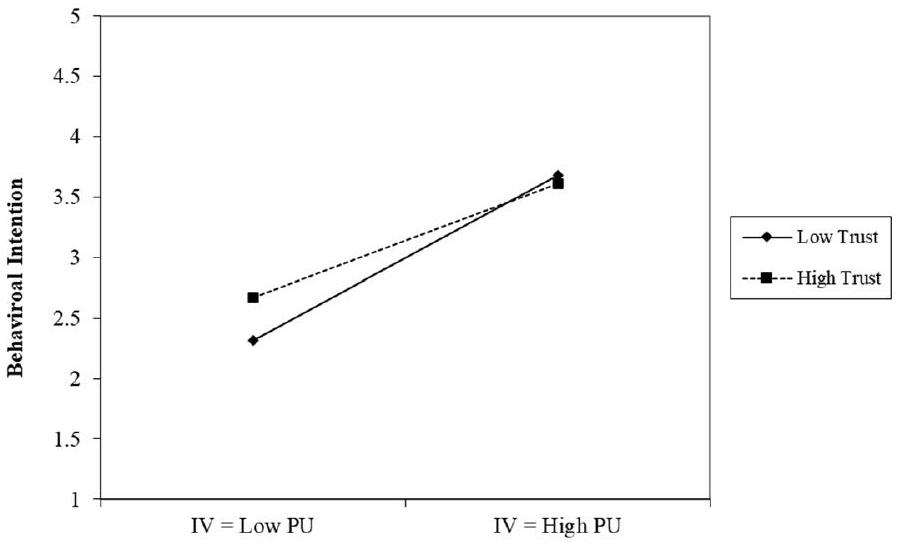

الثقة

الدراسة الحالية

أسئلة البحث المقترحة والافتراضات

طرق

المشاركون

الإجراءات

تدابير

خصائص العينة

أسئلة البحث

RQ2: ما هي العلاقة بين نموذج TAM (المنفعة المتصورة والسهولة المتصورة) ونموذج SCT (الكفاءة الذاتية والتعزيز الاجتماعي) في فهم اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي؟

RQ3: كيف يؤثر الثقة على العلاقة بين نموذج TAM (المنفعة المتوقعة وسهولة الاستخدام المتوقعة) ونموذج SCT (الكفاءة الذاتية والتعزيز الاجتماعي) في فهم اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي؟

النتائج

| الموقف | نية السلوك | |||

|

|

توقيع |

|

توقيع | |

| الفائدة المدركة | 0.655 | 0.000 | 0.347 | 0.000 |

| سهولة الاستخدام المدركة | 0.163 | 0.003 | – | 0.645 |

| الموقف | – | – | 0.462 | 0.000 |

تنبأت الفرضية الثالثة بمدى استخدام أساتذة الجامعات للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بناءً على سهولة الاستخدام المتوقعة. أظهرت النتائج أن النموذج كان ذا دلالة.

| الكفاءة الذاتية | تعزيز اجتماعي | ثقة | ||||

| ب | توقيع |

|

توقيع |

|

توقيع | |

| الفائدة المدركة | – | 0.551 | 0.348 | 0.000 | 0.525 | 0.000 |

| سهولة الاستخدام المدركة | 0.131 | 0.000 | 0.161 | 0.003 | 0.316 | 0.000 |

| الموقف | – | 0.113 | 0.335 | 0.000 | 0.630 | 0.000 |

| نية السلوك | – | 0.571 | 0.238 | 0.003 | 0.503 | 0.000 |

| ثقة | 0.072 | 0.011 | 0.232 | 0.001 | – | – |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | – | – | 0.357 | 0.042 | 0.466 | 0.011 |

| تعزيز اجتماعي | 0.061 | 0.042 | – | – | 0.254 | 0.001 |

نقاش

| رقم الفرضية | مسارات/علاقات الفرضيات | بيتا | قيمة P | نتيجة |

| H1-TAM | PU → Att | 0.655 |

|

مدعوم |

| PEU → انتباه | 0.163 |

|

مدعوم | |

| H2-TAM |

|

0.347 |

|

مدعوم |

| بيو → بي | – |

|

غير مدعوم | |

| Att → BI | 0.462 |

|

مدعوم | |

| H3-TAM | PEU → PU | 0.367 |

|

مدعوم |

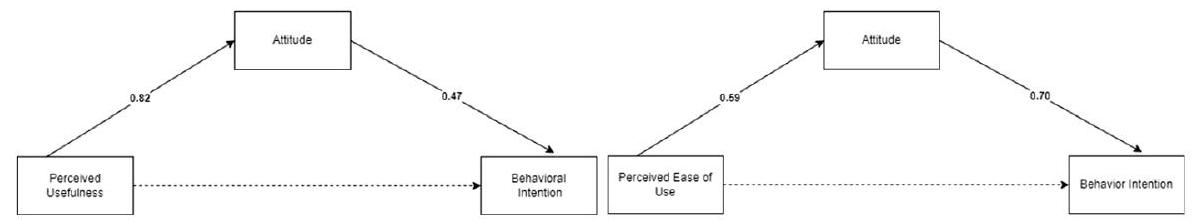

| الوساطة H4 | أAtt يتوسط | |||

|

|

0.39 |

|

مدعوم | |

| بيو → بي | 0.41 |

|

مدعوم | |

| الكفاءة الذاتية (SE) | SE → PEU | 0.131 |

|

مدعوم |

| SE → Att | – |

|

غير مدعوم | |

| SE → BI | – |

|

غير مدعوم | |

| H6-تعزيز اجتماعي (SR) |

|

0.348 |

|

مدعوم |

| SR → PEU | 0.161 |

|

مدعوم | |

| SR → انتباه | 0.335 |

|

مدعوم | |

| SR → SE | 0.357 |

|

مدعوم | |

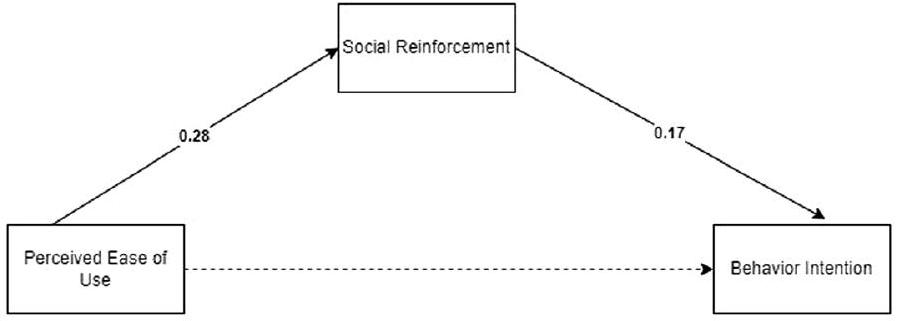

| H7- الوساطة | SR يتوسط | |||

| PEU → BI | 0.05 |

|

مدعوم | |

|

|

– |

|

غير مدعوم | |

| H8-ثقة (T) |

|

0.525 |

|

مدعوم |

| T → PEU | 0.316 |

|

مدعوم | |

|

|

0.630 |

|

مدعوم | |

|

|

0.503 |

|

مدعوم | |

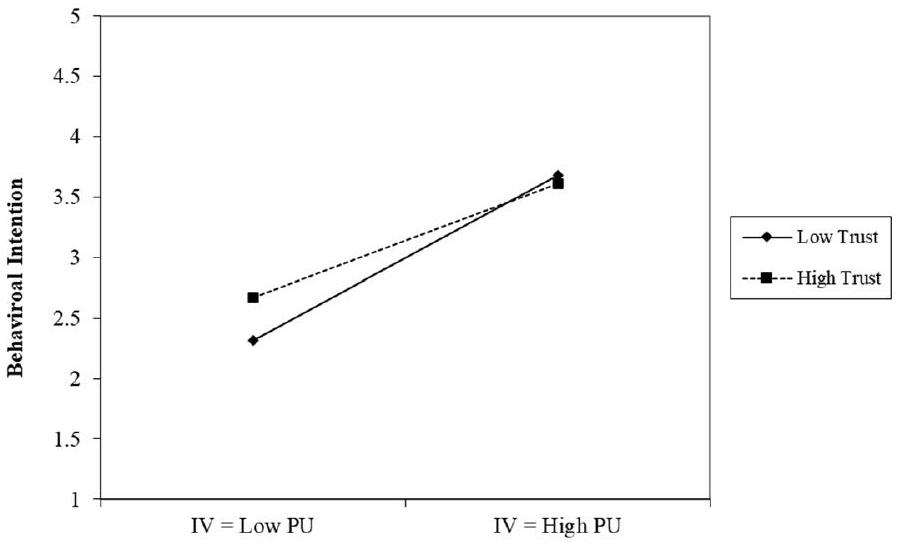

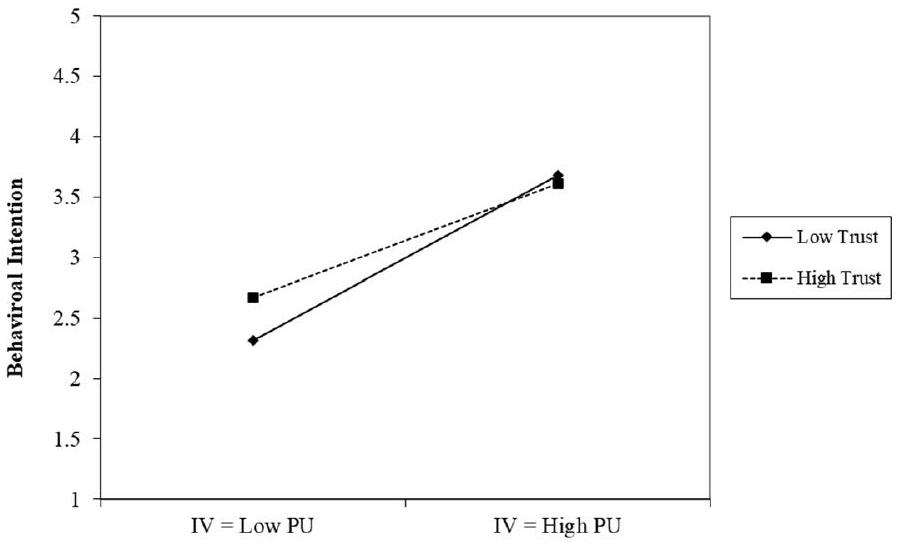

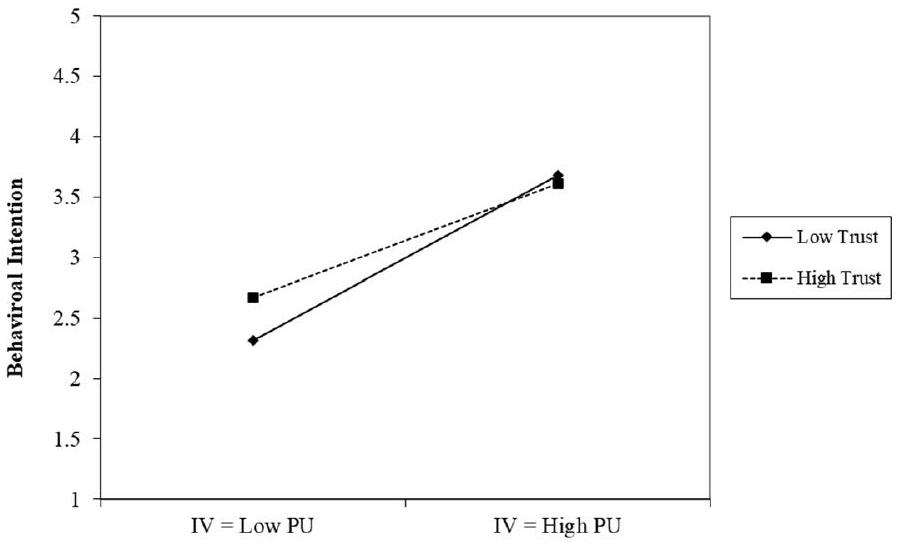

| اعتدال H9 | طن | |||

|

|

-0.21 |

|

مدعوم | |

| H10-الوساطة | توسط | |||

|

|

0.11 |

|

مدعوم |

تام

مع GenAI. على النقيض من ذلك، تُظهر الفائدة المدركة (PU) تأثيرًا قويًا على النوايا السلوكية لاستخدام GenAI، سواء بشكل مباشر أو غير مباشر من خلال المواقف.

ثقة

تعزيز اجتماعي

اقترب منه بحذر. وبالتالي، يمكن أن تؤثر التفاعلات الاجتماعية مع الأقران، والمحادثات، والتعليقات الإيجابية، والتجارب التي يشاركها الآخرون ضمن مجموعاتهم الاجتماعية، والنقاشات على المستويات الإدارية، والكليات، والجامعات جميعها على التصورات، والمواقف، واستخدام التكنولوجيا. وهذا يشير إلى أن التوقعات والسلوكيات لمجموعة اجتماعية يمكن أن تؤثر على ميول الفرد تجاه تكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي وقيمتها المدركة. إذا أصبح استخدام تكنولوجيا معينة شائعًا داخل مجتمع ما، فإن الأفراد يكونون أكثر عرضة لتبنيها.

الثقة والتعزيز الاجتماعي

الكفاءة الذاتية

الاستجابات العاطفية. تسلط هذه العوامل الضوء على تعقيد الكفاءة الذاتية، حيث تلعب التعزيز الاجتماعي والثقة أدوارًا مهمة في تشكيلها. وهذا يشير إلى أن الكفاءة الذاتية، على الرغم من أهميتها، ليست المحرك الوحيد للمواقف أو النوايا السلوكية، التي تتشكل بدلاً من ذلك من مجموعة أوسع بكثير من الاعتبارات.

الخاتمة

الآثار والدراسات المستقبلية والقيود

الملحق

| الاختصار | المصطلح |

| GenAI | الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي |

| PU | الفائدة المدركة |

| PEU | سهولة الاستخدام المدركة |

| TAM | نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا |

| UTAUT | النظرية الموحدة لقبول واستخدام التكنولوجيا |

| SCT | نظرية التعلم الاجتماعي |

| BI | النوايا السلوكية |

| Att | الموقف |

| SR | التعزيز الاجتماعي |

| SE | الكفاءة الذاتية |

| النموذج | المعاملات غير القياسية | المعاملات القياسية | t | Sig | |

| B | خطأ معياري | بيتا | |||

| (ثابت) | 0.226 | 0.268 | 0.844 | 0.400 | |

| PU | 0.749 | 0.061 | 0.655 | 12.221 | 0.000 |

| PEU | 0.235 | 0.077 | 0.163 | 3.040 | 0.003 |

| نموذج | المعاملات غير المعيارية | معاملات بيتا الموحدة | ت | توقيع | |

| ب | خطأ معياري | ||||

| (ثابت) | 1.139 | 0.258 | ٤.٤٢٤ | 0.000 | |

| بيو | 0.035 | 0.076 | 0.024 | 0.462 | 0.645 |

| PU | 0.399 | 0.079 | 0.347 | ٥.٠٦٥ | 0.000 |

| الموقف | 0.464 | 0.070 | 0.462 | 6.633 | 0.000 |

| نموذج | المعاملات غير المعيارية | المعاملات المعيارية | ت | توقيع | ||

| ب | خطأ معياري | بيتا | ||||

| 1 | (ثابت) | 1.613 | 0.298 | ٥.٤١٤ | 0.000 | |

| بيو | 0.471 | 0.086 | 0.367 | ٥.٤٨٧ | 0.000 | |

| المتغير التابع | معامل | ب | خطأ معياري | ت | توقيع | فترة الثقة 95% | |

| حد أدنى | حد أعلى | ||||||

| بي يو | اعتراض | 3.116 | 0.199 | 15.639 | 0.000 | ٢.٧٢٣ | ٣.٥٠٩ |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | 0.017 | 0.029 | 0.597 | 0.551 | -0.040 | 0.074 | |

| بيو | اعتراض | ٢.٥٣٨ | 0.143 | 17.710 | 0.000 | ٢.٢٥٥ | 2.820 |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | 0.131 | 0.021 | 6.334 | 0.000 | 0.090 | 0.172 | |

| أATT | اعتراض | ٣.١٠٢ | 0.226 | ١٣٫٧٠٠ | 0.000 | 2.655 | ٣.٥٤٨ |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | 0.052 | 0.033 | 1.593 | 0.113 | -0.012 | 0.117 | |

| ذكاء الأعمال | اعتراض | ٤.٠٢٠ | 0.229 | 17.569 | 0.000 | ٣.٥٦٩ | ٤.٤٧١ |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | 0.019 | 0.033 | 0.568 | 0.571 | -0.046 | 0.084 | |

| ريال سعودي | اعتراض | ٢.٢٢١ | 0.205 | 10.816 | 0.000 | 1.816 | ٢.٦٢٦ |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | 0.061 | 0.030 | 2.046 | 0.042 | 0.002 | 0.119 | |

| ثقة | اعتراض | 2.330 | 0.195 | 11.944 | 0.000 | 1.945 | ٢.٧١٥ |

| الكفاءة الذاتية | 0.072 | 0.028 | ٢.٥٦٤ | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.128 | |

| المتغير التابع | معامل | ب | خطأ معياري | ت | توقيع | فترة الثقة 95% | |

| حد أدنى | حد أعلى | ||||||

| PU | اعتراض | ٢.٣١٧ | 0.181 | 12.797 | 0.000 | 1.960 | ٢.٦٧٤ |

| تعزيز اجتماعي | 0.348 | 0.065 | ٥.٣٤٥ | 0.000 | 0.220 | 0.477 | |

| بيو | اعتراض | ٢.٩٧٣ | 0.150 | 19.797 | 0.000 | 2.677 | ٣.٢٦٩ |

| تعزيز اجتماعي | 0.161 | 0.054 | ٢.٩٨٤ | 0.003 | 0.055 | 0.268 | |

| أATT | اعتراض | ٢.٥٦٦ | 0.211 | 12.136 | 0.000 | ٢.١٤٩ | ٢.٩٨٣ |

| تعزيز اجتماعي | 0.335 | 0.076 | ٤.٤٠٠ | 0.000 | 0.185 | 0.485 | |

| ذكاء الأعمال | اعتراض | ٣.٥٢٠ | 0.218 | ١٦٫١٥٨ | 0.000 | ٣.٠٩٠ | ٣.٩٤٩ |

| تعزيز اجتماعي | 0.238 | 0.078 | ٣.٠٣٧ | 0.003 | 0.083 | 0.393 | |

| ثقة | اعتراض | ٢.١٩٤ | 0.187 | 11.701 | 0.000 | 1.824 | ٢.٥٦٤ |

| تعزيز اجتماعي | 0.232 | 0.067 | ٣.٤٤٧ | 0.001 | 0.099 | 0.366 | |

| SE | اعتراض | ٥.٦١٠ | 0.486 | 11.553 | 0.000 | ٤.٦٥٢ | 6.568 |

| تعزيز اجتماعي | 0.357 | 0.175 | 2.046 | 0.042 | 0.013 | 0.702 | |

| المتغير التابع | معامل | ب | خطأ معياري | ت | توقيع | فترة الثقة 95% | |

| حد أدنى | حد أعلى | ||||||

| بي يو | اعتراض | 1.756 | 0.183 | 9.580 | 0.000 | 1.395 | 2.118 |

| ثقة | 0.525 | 0.062 | 8.428 | 0.000 | 0.402 | 0.648 | |

| بيو | اعتراض | ٢.٥٠٩ | 0.156 | ١٦٫٠٧٤ | 0.000 | 2.201 | 2.817 |

| ثقة | 0.316 | 0.053 | ٥.٩٦١ | 0.000 | 0.212 | 0.421 | |

| أATT | اعتراض | 1.676 | 0.205 | 8.158 | 0.000 | 1.271 | ٢.٠٨١ |

| ثقة | 0.630 | 0.070 | 9.024 | 0.000 | 0.493 | 0.768 | |

| ذكاء الأعمال | اعتراض | ٢.٧٣٢ | 0.222 | 12.294 | 0.000 | 2.294 | ٣.١٧٠ |

| ثقة | 0.503 | 0.076 | 6.664 | 0.000 | 0.354 | 0.652 | |

| ريال سعودي | اعتراض | 1.905 | 0.217 | 8.773 | 0.000 | 1.477 | ٢.٣٣٣ |

| ثقة | 0.254 | 0.074 | ٣.٤٤٧ | 0.001 | 0.109 | 0.400 | |

| SE | اعتراض | ٥.٢٤١ | 0.534 | 9.810 | 0.000 | ٤.١٨٧ | ٦.٢٩٥ |

| ثقة | 0.466 | 0.182 | ٢.٥٦٤ | 0.011 | 0.107 | 0.824 | |

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

المصالح المتنافسة

تاريخ الاستلام: 25 أكتوبر 2024 تاريخ القبول: 10 فبراير 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 14 مارس 2025

References

Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2(1), 21-41. https:// doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X. 00024

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology, 51(2), 269-290. https://doi.org/10. 1111/1464-0597.00092

Barrett, A., & Pack, A. (2023). Not quite eye to A.I.: Student and teacher perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence in the writing process. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00427-0

Buskens, V. (2020). Spreading information and developing trust in social networks to accelerate diffusion of innovations. Trends in Food Science Technology, 106, 485-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2020.10.040

Chiu, T. K. F. (2024). Future research recommendations for transforming higher education with generative AI. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100197

Choung, H., David, P., & Ross, A. (2022). Trust in AI and its role in the acceptance of AI technologies. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 39(9), 1727-1739. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2050543

Compeau, D. R., & Higgins, C. A. (1995). Application of social cognitive theory to training for computer skills. Information Systems Research, 6(2), 118-143. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.6.2.118

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. M/S Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982-1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

Davis, F. D., Granić, A., & Marangunić, N. (2024). The technology acceptance model: 30 years of TAM. Springer International Publishing AG.

Granić, A., & Marangunić, N. (2019). Technology acceptance model in educational context: A systematic literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(5), 2572-2593. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 12864

Gupta, R., Nair, K., Mishra, M., Ibrahim, B., & Bhardwaj, S. (2024). Adoption and impacts of generative artificial intelligence: Theoretical underpinnings and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 4(1), 100232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2024.100232

Hartley, K., Hayak, M., & Ko, U. H. (2024). Artificial intelligence supporting independent student learning: An evaluative case study of ChatGPT and learning to code. Education Sciences, 14(2), 120.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

Holden, H., & Rada, R. (2011). Understanding the influence of perceived usability and technology self-efficacy on teachers’ technology acceptance. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 43(4), 343-367. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/15391523.2011.10782576

Labadze, L., Grigolia, M., & Machaidze, L. (2023). Role of AI chatbots in education: Systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s41239-023-00426-1

Lim, W. M., Gunasekara, A., Pallant, J. L., Pallant, J. I., & Pechenkina, E. (2023). Generative AI and the future of education: Ragnarök or reformation? A paradoxical perspective from management educators. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jime.2023.100790

Marikyan, D., Papagiannidis, S., & Stewart, G. (2023). Technology acceptance research: Meta-analysis. Journal of Information Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/01655515231191177

McClain, C. (2024). Americans’ use of ChatGPT is ticking up, but few trust its election information. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/03/26/americans-use-of-chatgpt-is-ticking-up-but-few-trust-its-election-information/

Mollick, E. (2024). Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI. Penguin Publishing Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest. com/lib/unlv/detail.action?docID=30848006

Motshegwe, M., & Batane, T. (2015). Factors influencing instructors’ attitudes toward technology integration. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange (JETDE). https://doi.org/10.18785/jetde.0801.01

Pan, X. (2020). Technology acceptance, technological self-efficacy, and attitude toward technology-based self-directed learning: Learning motivation as a mediator. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.564294

Roppelt, J. S., Kanbach, D. K., & Kraus, S. (2024). Artificial intelligence in healthcare institutions: A systematic literature review on influencing factors. Technology in Society, 76, 102443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102443

Rosen, L. D., Whaling, K., Carrier, L. M., Cheever, N. A., & Rokkum, J. (2013). The media and technology usage and attitudes scale: An empirical investigation. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2501-2511.

Shieh, A., Tran, B., He, G., Kumar, M., Freed, J. A., & Majety, P. (2024). Assessing ChatGPT 4.0’s test performance and clinical diagnostic accuracy on USMLE STEP 2 CK and clinical case reports. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 9330. https://doi.org/10. 1038/s41598-024-58760-x

Steiss, J., Tate, T., Graham, S., Cruz, J., Hebert, M., Wang, J., Moon, Y., Tseng, W., Warschauer, M., & Olson, C. (2024). Comparing the quality of human and ChatGPT feedback of students’ writing. Learning and Instruction, 91, 101894. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2024.101894

Tanantong, T., & Wongras, P. (2024). A UTAUT-based framework for analyzing users’ intention to adopt artificial intelligence in human resource recruitment: A case study of Thailand. Systems, 12(1), 28.

Trang, T. T. N., Chien Thang, P., Hai, L. D., Phuong, V. T., & Quy, T. Q. (2024). Understanding the adoption of artificial intelligence in journalism: An empirical study in vietnam. SAGE Open, 14(2), 21582440241255240. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 21582440241255241

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2016). Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A Synthesis and the Road Ahead (SSRN Scholarly Paper 2800121). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2800121

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

Wu, K., Zhao, Y., Zhu, Q., Tan, X., & Zheng, H. (2011). A meta-analysis of the impact of trust on technology acceptance model: Investigation of moderating influence of subject and context type. International Journal of Information Management, 31(6), 572-581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jijnfomgt.2011.03.004

Yusuf, A., Pervin, N., & Román-González, M. (2024). Generative AI and the future of higher education: A threat to academic integrity or reformation? Evidence from multicultural perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00453-6

ملاحظة الناشر

- © المؤلفون 2025. الوصول المفتوح. هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام والنسب 4.0 الدولية، التي تسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج بأي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد أُجريت. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمواد. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- أ. المتغير التابع: PU

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-025-00511-7

Publication Date: 2025-03-13

Artificial intelligence and communication technologies in academia: faculty perceptions and the adoption of generative AI

aya.shata@unlv.edu

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is ushering in an era of potential transformation in various fields, especially in educational communication technologies, with tools like ChatGPT and other generative AI (GenAI) applications. This rapid proliferation and adoption of GenAI tools have sparked significant interest and concern among college professors, who are dealing with evolving dynamics in digital communication within the classroom. Yet, the effect and implications of GenAI in education remain understudied. Therefore, this study employs the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) as theoretical frameworks to explore higher education faculty’s perceptions, attitudes, usage, and motivations, as the underlying factors that influence their adoption or rejection of GenAI tools. A survey was conducted among fulltime higher education faculty members (

Introduction

Literature review

Al in higher education

are improving rapidly as is our understanding of how and when to utilize ChatGPT. The study noted above utilized ChatGPT version 3.5. A study comparing ChatGPT version 3.5 with 4.0 on the United States Medical Licensing Exam found marked improvement. 3.5 demonstrated an accuracy of

Faculty and student perceptions of AI

Technology adoption

Attitude

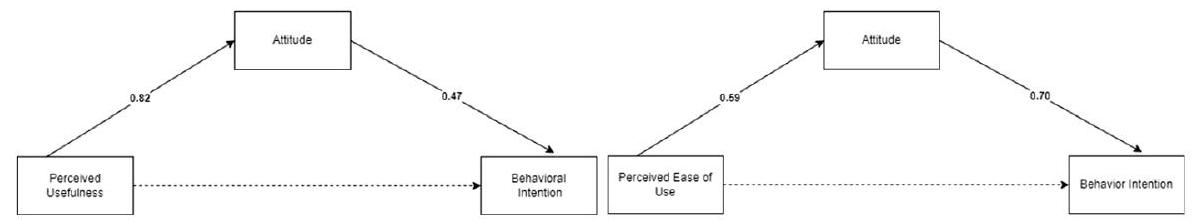

are crucial in determining whether or not they will embrace innovations (Davis, 1989; Granić & Marangunić, 2019). Regarding AI, individuals’ attitudes and comfort levels can greatly influence acceptance and integration into various aspects of the education system (Bower et al., 2024). Preliminary studies suggest that faculty attitudes toward Gen AI are mixed (Bower et al., 2024). While a majority of faculty perceive the potential for major impact, these same faculty are more familiar with the technology.

PEU/PU

Self-efficacy

Social reinforcement

negative attention. Social cognitive theory acknowledges our enhanced capacity for observational learning and the vital role of social interactions (Bandura, 1999). This capacity, combined with the widespread discussion, will likely influence users’ perceptions, attitudes, and self-efficacy toward using GenAI. In line with prior work in technology adoption (Venkatesh et al., 2016), we operationalize social influence as social reinforcement, reflecting the impact of others’ opinions and behaviors on an individual’s decision to use the technology.

Trust

Current study

Proposed research questions and hypotheses

Methods

Participants

Procedures

Measures

Sample characteristics

Research questions

RQ2: What is the relationship between the TAM model (PU and PEU) and the SCT (self-efficacy and social reinforcement) in understanding GenAI adoption?

RQ3: How does Trust influence the relationship between the TAM model (PU and PEU) and the SCT (self-efficacy and social reinforcement) in understanding GenAI adoption?

Results

| Attitude | Behavioral Intention | |||

|

|

Sig |

|

Sig | |

| Perceived usefulness | 0.655 | 0.000 | 0.347 | 0.000 |

| Perceived ease of use | 0.163 | 0.003 | – | 0.645 |

| Attitude | – | – | 0.462 | 0.000 |

The third hypothesis predicted College Professors’ PU of using GenAI from PEU. Results found that the model was significant

| Self-efficacy | Social reinforcement | Trust | ||||

| B | Sig |

|

Sig |

|

Sig | |

| Perceived usefulness | – | 0.551 | 0.348 | 0.000 | 0.525 | 0.000 |

| Perceived ease of use | 0.131 | 0.000 | 0.161 | 0.003 | 0.316 | 0.000 |

| Attitude | – | 0.113 | 0.335 | 0.000 | 0.630 | 0.000 |

| Behavior intention | – | 0.571 | 0.238 | 0.003 | 0.503 | 0.000 |

| Trust | 0.072 | 0.011 | 0.232 | 0.001 | – | – |

| Self-efficacy | – | – | 0.357 | 0.042 | 0.466 | 0.011 |

| Social reinforcement | 0.061 | 0.042 | – | – | 0.254 | 0.001 |

Discussion

| Hypothesis number | Hypothesis paths/ relations | Beta | P value | Result |

| H1-TAM | PU → Att | 0.655 |

|

Supported |

| PEU → Att | 0.163 |

|

Supported | |

| H2-TAM |

|

0.347 |

|

Supported |

| PEU → BI | – |

|

Not supported | |

| Att → BI | 0.462 |

|

Supported | |

| H3-TAM | PEU → PU | 0.367 |

|

Supported |

| H4-Mediation | Att mediates | |||

|

|

0.39 |

|

Supported | |

| PEU → BI | 0.41 |

|

Supported | |

| H5-Self-Efficacy (SE) | SE → PEU | 0.131 |

|

Supported |

| SE → Att | – |

|

Not Supported | |

| SE → BI | – |

|

Not Supported | |

| H6-Social Reinforcement (SR) |

|

0.348 |

|

Supported |

| SR → PEU | 0.161 |

|

Supported | |

| SR → Att | 0.335 |

|

Supported | |

| SR → SE | 0.357 |

|

Supported | |

| H7- Mediation | SR mediates | |||

| PEU → BI | 0.05 |

|

Supported | |

|

|

– |

|

Not Supported | |

| H8-Trust (T) |

|

0.525 |

|

Supported |

| T → PEU | 0.316 |

|

Supported | |

|

|

0.630 |

|

Supported | |

|

|

0.503 |

|

Supported | |

| H9-Moderation | Ton | |||

|

|

-0.21 |

|

Supported | |

| H10-Mediation | T mediate | |||

|

|

0.11 |

|

Supported |

TAM

with GenAI. In contrast, perceived usefulness (PU) demonstrates a strong influence on behavioral intentions to use GenAI, both directly and indirectly through attitudes.

Trust

Social reinforcement

approach it with caution. Thus, social interactions with peers, conversations and positive feedback and experiences shared by others within their social groups, and discussion within the departmental, college and university levels can all influence perceptions, attitudes and use of the technology. This suggests that expectations and behaviors of a social group can influence one’s disposition toward GenAI technology and its perceived value. If using a particular technology becomes common within a community, individuals are more likely to adopt it.

Trust and social reinforcement

Self-efficacy

emotional responses. These factors highlight the complexity of self-efficacy, with social reinforcement and trust playing significant roles in shaping it. This suggests that self-efficacy, while important, is not the sole driver of attitudes or behavioral intentions, which are instead shaped by a much wider range of considerations.

Conclusion

Implications, future studies, and limitations

Appendix

| Abbreviation | Term |

| GenAI | Generative artificial intelligence |

| PU | Perceived usefulness |

| PEU | Perceived ease of use |

| TAM | Technology acceptance model |

| UTAUT | Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology |

| SCT | Social cognitive theory |

| BI | Behavioral intention |

| Att | Attitude |

| SR | Social Reinforcement |

| SE | Self-efficacy |

| Model | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | t | Sig | |

| B | Std. error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 0.226 | 0.268 | 0.844 | 0.400 | |

| PU | 0.749 | 0.061 | 0.655 | 12.221 | 0.000 |

| PEU | 0.235 | 0.077 | 0.163 | 3.040 | 0.003 |

| Model | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients Beta | t | Sig | |

| B | Std. error | ||||

| (Constant) | 1.139 | 0.258 | 4.424 | 0.000 | |

| PEU | 0.035 | 0.076 | 0.024 | 0.462 | 0.645 |

| PU | 0.399 | 0.079 | 0.347 | 5.065 | 0.000 |

| Attitude | 0.464 | 0.070 | 0.462 | 6.633 | 0.000 |

| Model | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | t | Sig | ||

| B | Std. error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 1.613 | 0.298 | 5.414 | 0.000 | |

| PEU | 0.471 | 0.086 | 0.367 | 5.487 | 0.000 | |

| Dependent variable | Parameter | B | Std. Error | t | Sig | 95% Confidence interval | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| PU | Intercept | 3.116 | 0.199 | 15.639 | 0.000 | 2.723 | 3.509 |

| Self_Efficacy | 0.017 | 0.029 | 0.597 | 0.551 | -0.040 | 0.074 | |

| PEU | Intercept | 2.538 | 0.143 | 17.710 | 0.000 | 2.255 | 2.820 |

| Self_Efficacy | 0.131 | 0.021 | 6.334 | 0.000 | 0.090 | 0.172 | |

| Att | Intercept | 3.102 | 0.226 | 13.700 | 0.000 | 2.655 | 3.548 |

| Self_Efficacy | 0.052 | 0.033 | 1.593 | 0.113 | -0.012 | 0.117 | |

| BI | Intercept | 4.020 | 0.229 | 17.569 | 0.000 | 3.569 | 4.471 |

| Self_Efficacy | 0.019 | 0.033 | 0.568 | 0.571 | -0.046 | 0.084 | |

| SR | Intercept | 2.221 | 0.205 | 10.816 | 0.000 | 1.816 | 2.626 |

| Self_Efficacy | 0.061 | 0.030 | 2.046 | 0.042 | 0.002 | 0.119 | |

| Trust | Intercept | 2.330 | 0.195 | 11.944 | 0.000 | 1.945 | 2.715 |

| Self_Efficacy | 0.072 | 0.028 | 2.564 | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.128 | |

| Dependent variable | Parameter | B | Std. error | t | Sig | 95% Confidence interval | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| PU | Intercept | 2.317 | 0.181 | 12.797 | 0.000 | 1.960 | 2.674 |

| Social_Reinforcement | 0.348 | 0.065 | 5.345 | 0.000 | 0.220 | 0.477 | |

| PEU | Intercept | 2.973 | 0.150 | 19.797 | 0.000 | 2.677 | 3.269 |

| Social_Reinforcement | 0.161 | 0.054 | 2.984 | 0.003 | 0.055 | 0.268 | |

| Att | Intercept | 2.566 | 0.211 | 12.136 | 0.000 | 2.149 | 2.983 |

| Social_Reinforcement | 0.335 | 0.076 | 4.400 | 0.000 | 0.185 | 0.485 | |

| BI | Intercept | 3.520 | 0.218 | 16.158 | 0.000 | 3.090 | 3.949 |

| Social_Reinforcement | 0.238 | 0.078 | 3.037 | 0.003 | 0.083 | 0.393 | |

| Trust | Intercept | 2.194 | 0.187 | 11.701 | 0.000 | 1.824 | 2.564 |

| Social_Reinforcement | 0.232 | 0.067 | 3.447 | 0.001 | 0.099 | 0.366 | |

| SE | Intercept | 5.610 | 0.486 | 11.553 | 0.000 | 4.652 | 6.568 |

| Social_Reinforcement | 0.357 | 0.175 | 2.046 | 0.042 | 0.013 | 0.702 | |

| Dependent variable | Parameter | B | Std. error | t | Sig | 95% Confidence interval | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| PU | Intercept | 1.756 | 0.183 | 9.580 | 0.000 | 1.395 | 2.118 |

| Trust | 0.525 | 0.062 | 8.428 | 0.000 | 0.402 | 0.648 | |

| PEU | Intercept | 2.509 | 0.156 | 16.074 | 0.000 | 2.201 | 2.817 |

| Trust | 0.316 | 0.053 | 5.961 | 0.000 | 0.212 | 0.421 | |

| Att | Intercept | 1.676 | 0.205 | 8.158 | 0.000 | 1.271 | 2.081 |

| Trust | 0.630 | 0.070 | 9.024 | 0.000 | 0.493 | 0.768 | |

| BI | Intercept | 2.732 | 0.222 | 12.294 | 0.000 | 2.294 | 3.170 |

| Trust | 0.503 | 0.076 | 6.664 | 0.000 | 0.354 | 0.652 | |

| SR | Intercept | 1.905 | 0.217 | 8.773 | 0.000 | 1.477 | 2.333 |

| Trust | 0.254 | 0.074 | 3.447 | 0.001 | 0.109 | 0.400 | |

| SE | Intercept | 5.241 | 0.534 | 9.810 | 0.000 | 4.187 | 6.295 |

| Trust | 0.466 | 0.182 | 2.564 | 0.011 | 0.107 | 0.824 | |

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and material

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Competing interests

Received: 25 October 2024 Accepted: 10 February 2025

Published online: 14 March 2025

References

Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2(1), 21-41. https:// doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X. 00024

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology, 51(2), 269-290. https://doi.org/10. 1111/1464-0597.00092

Barrett, A., & Pack, A. (2023). Not quite eye to A.I.: Student and teacher perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence in the writing process. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00427-0

Buskens, V. (2020). Spreading information and developing trust in social networks to accelerate diffusion of innovations. Trends in Food Science Technology, 106, 485-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2020.10.040

Chiu, T. K. F. (2024). Future research recommendations for transforming higher education with generative AI. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100197

Choung, H., David, P., & Ross, A. (2022). Trust in AI and its role in the acceptance of AI technologies. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 39(9), 1727-1739. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2050543

Compeau, D. R., & Higgins, C. A. (1995). Application of social cognitive theory to training for computer skills. Information Systems Research, 6(2), 118-143. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.6.2.118

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. M/S Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982-1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

Davis, F. D., Granić, A., & Marangunić, N. (2024). The technology acceptance model: 30 years of TAM. Springer International Publishing AG.

Granić, A., & Marangunić, N. (2019). Technology acceptance model in educational context: A systematic literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(5), 2572-2593. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet. 12864

Gupta, R., Nair, K., Mishra, M., Ibrahim, B., & Bhardwaj, S. (2024). Adoption and impacts of generative artificial intelligence: Theoretical underpinnings and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 4(1), 100232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2024.100232

Hartley, K., Hayak, M., & Ko, U. H. (2024). Artificial intelligence supporting independent student learning: An evaluative case study of ChatGPT and learning to code. Education Sciences, 14(2), 120.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

Holden, H., & Rada, R. (2011). Understanding the influence of perceived usability and technology self-efficacy on teachers’ technology acceptance. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 43(4), 343-367. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/15391523.2011.10782576

Labadze, L., Grigolia, M., & Machaidze, L. (2023). Role of AI chatbots in education: Systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s41239-023-00426-1

Lim, W. M., Gunasekara, A., Pallant, J. L., Pallant, J. I., & Pechenkina, E. (2023). Generative AI and the future of education: Ragnarök or reformation? A paradoxical perspective from management educators. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jime.2023.100790

Marikyan, D., Papagiannidis, S., & Stewart, G. (2023). Technology acceptance research: Meta-analysis. Journal of Information Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/01655515231191177

McClain, C. (2024). Americans’ use of ChatGPT is ticking up, but few trust its election information. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/03/26/americans-use-of-chatgpt-is-ticking-up-but-few-trust-its-election-information/

Mollick, E. (2024). Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI. Penguin Publishing Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest. com/lib/unlv/detail.action?docID=30848006

Motshegwe, M., & Batane, T. (2015). Factors influencing instructors’ attitudes toward technology integration. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange (JETDE). https://doi.org/10.18785/jetde.0801.01

Pan, X. (2020). Technology acceptance, technological self-efficacy, and attitude toward technology-based self-directed learning: Learning motivation as a mediator. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.564294

Roppelt, J. S., Kanbach, D. K., & Kraus, S. (2024). Artificial intelligence in healthcare institutions: A systematic literature review on influencing factors. Technology in Society, 76, 102443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102443

Rosen, L. D., Whaling, K., Carrier, L. M., Cheever, N. A., & Rokkum, J. (2013). The media and technology usage and attitudes scale: An empirical investigation. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2501-2511.

Shieh, A., Tran, B., He, G., Kumar, M., Freed, J. A., & Majety, P. (2024). Assessing ChatGPT 4.0’s test performance and clinical diagnostic accuracy on USMLE STEP 2 CK and clinical case reports. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 9330. https://doi.org/10. 1038/s41598-024-58760-x

Steiss, J., Tate, T., Graham, S., Cruz, J., Hebert, M., Wang, J., Moon, Y., Tseng, W., Warschauer, M., & Olson, C. (2024). Comparing the quality of human and ChatGPT feedback of students’ writing. Learning and Instruction, 91, 101894. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2024.101894

Tanantong, T., & Wongras, P. (2024). A UTAUT-based framework for analyzing users’ intention to adopt artificial intelligence in human resource recruitment: A case study of Thailand. Systems, 12(1), 28.

Trang, T. T. N., Chien Thang, P., Hai, L. D., Phuong, V. T., & Quy, T. Q. (2024). Understanding the adoption of artificial intelligence in journalism: An empirical study in vietnam. SAGE Open, 14(2), 21582440241255240. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 21582440241255241

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2016). Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A Synthesis and the Road Ahead (SSRN Scholarly Paper 2800121). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2800121

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

Wu, K., Zhao, Y., Zhu, Q., Tan, X., & Zheng, H. (2011). A meta-analysis of the impact of trust on technology acceptance model: Investigation of moderating influence of subject and context type. International Journal of Information Management, 31(6), 572-581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jijnfomgt.2011.03.004

Yusuf, A., Pervin, N., & Román-González, M. (2024). Generative AI and the future of higher education: A threat to academic integrity or reformation? Evidence from multicultural perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00453-6

Publisher’s Note

- © The Author(s) 2025. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- a. Dependent variable: PU