DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01479-1

تاريخ النشر: 2024-07-01

الزيادات المستمرة في الأكسجين الجوي وإنتاجية المحيطات في عصور النيوبرتوzoي والكامبري

تم القبول: 5 يونيو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 2 يوليو 2024

(د) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

يرتبط حدث الأكسجة السريع جيولوجيًا في النيو بروتيروزويك عادةً بظهور مجموعات الحيوانات البحرية في السجل الأحفوري. ومع ذلك، لا يزال هناك جدل حول الأدلة المستمدة من السجل الجيولوجي الكيميائي – إن وجدت – التي تقدم دعمًا قويًا لتحول مستمر في الأكسجين السطحي مباشرةً قبل ظهور الحيوانات. نقدم تحليلات التعلم الإحصائي لمجموعة كبيرة من البيانات الجيولوجية الكيميائية والسياق الجيولوجي المرتبط بها من السجل الرسوبي للنيو بروتيروزويك والباليوزويك، ثم نستخدم نمذجة نظام الأرض لربط الاتجاهات في تركيزات المعادن النادرة الحساسة للأكسدة والكربون العضوي بأكسجة محيطات الأرض وغلافها الجوي. لا نجد دليلًا على أكسجة محيطات الأرض بشكل كامل في أواخر عصر النيو بروتيروزويك. ومع ذلك، نقوم بإعادة بناء زيادة معتدلة على المدى الطويل في الأكسجين الجوي وإنتاجية المحيطات. كانت هذه التغيرات في نظام الأرض ستزيد من الأكسجين المذاب وإمدادات الغذاء في المواطن المائية الضحلة خلال الفترة الزمنية الجيولوجية الواسعة التي ظهرت فيها المجموعات الحيوانية الرئيسية لأول مرة. توفر هذه الطريقة بعضًا من أكثر الأدلة مباشرةً على المحركات الفسيولوجية المحتملة للإشعاع الكمبري، مع تسليط الضوء على أهمية أكسجة الباليوزويك اللاحقة في تطور نظام الأرض الحديث.

أن العديد من خطط الجسم الحيوانية والبيئات في العصر الكمبري لم تكن لتُسمح عند مستويات الأكسجين المنخفضة جداً

لا تتجاوز 1.5 مرة من نطاق الربعين من الحدود السفلية/العليا للصندوق، على التوالي؛ تشير النقاط إلى القيم الشاذة من نطاق الشعيرات. يقوم خوارزمية الوزن بوزن العينات بشكل عكسي بناءً على قربها المكاني والزماني من عينات أخرى في الوقت

وانحدار، في حين أن الغالبية العظمى من الحيوانات البحرية الحديثة وتلك المسجلة في السجل الأحفوري تعيش في بيئات الرفوف الضحلة. لذلك، فإن أكسجة هذه البيئات الضحلة هي التي ستتحكم في درجة الضغط الناجم عن نقص الأكسجين الذي تتعرض له الحيوانات البحرية. بينما يمكن أن تلعب ظروف حدود نظام الأرض مثل تكوين القارات دورًا رئيسيًا في أكسجة المحيطات العميقة العالمية على مدى فترات زمنية تصل إلى 10 ملايين سنة من خلال تأثيرها على دوران المحيطات.

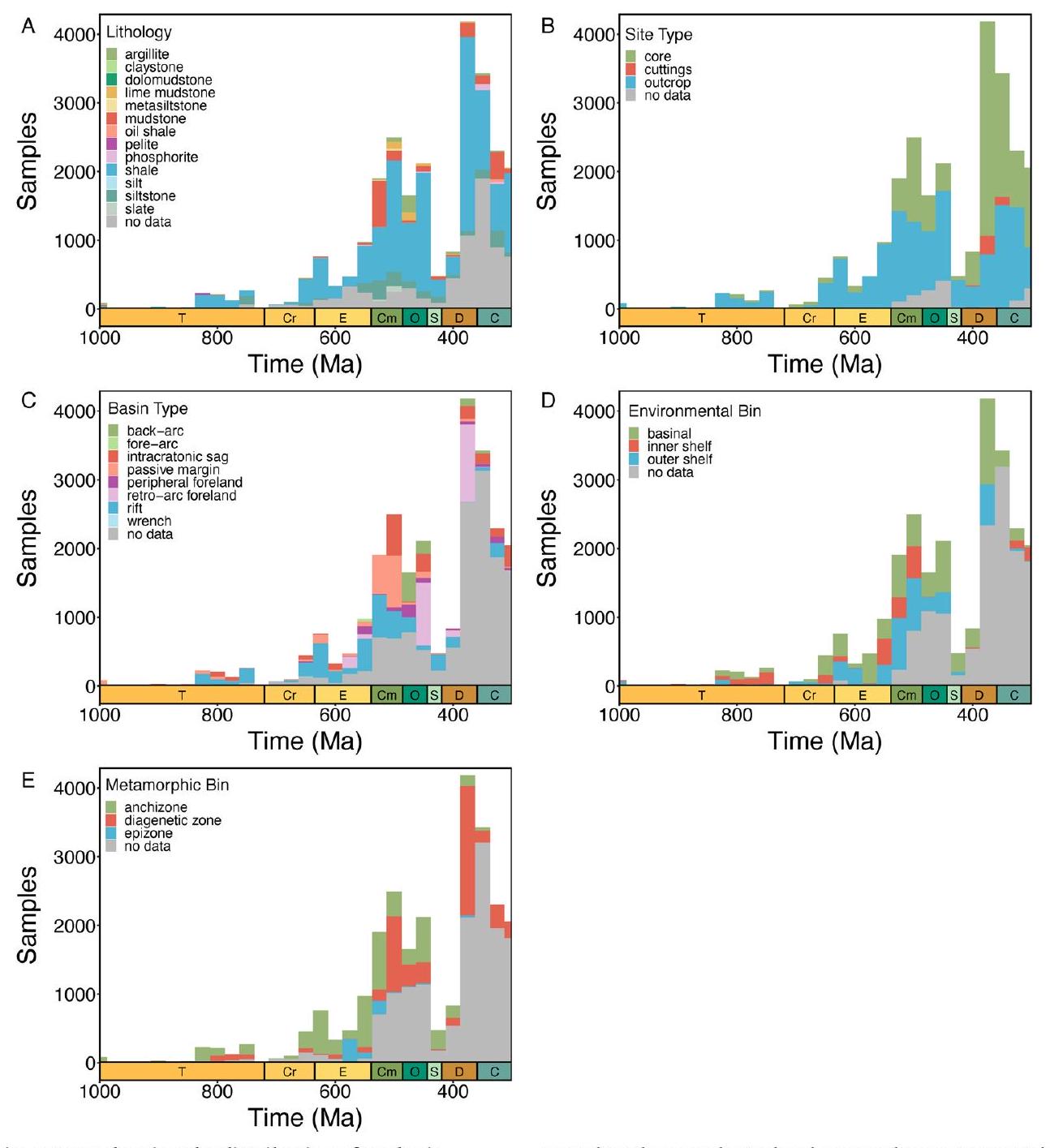

البيانات الجيوكيميائية والسياق الجيولوجي المرتبط بها التي تم تجميعها بواسطة مشروع الجيوكيمياء الرسوبية والبيئات القديمة

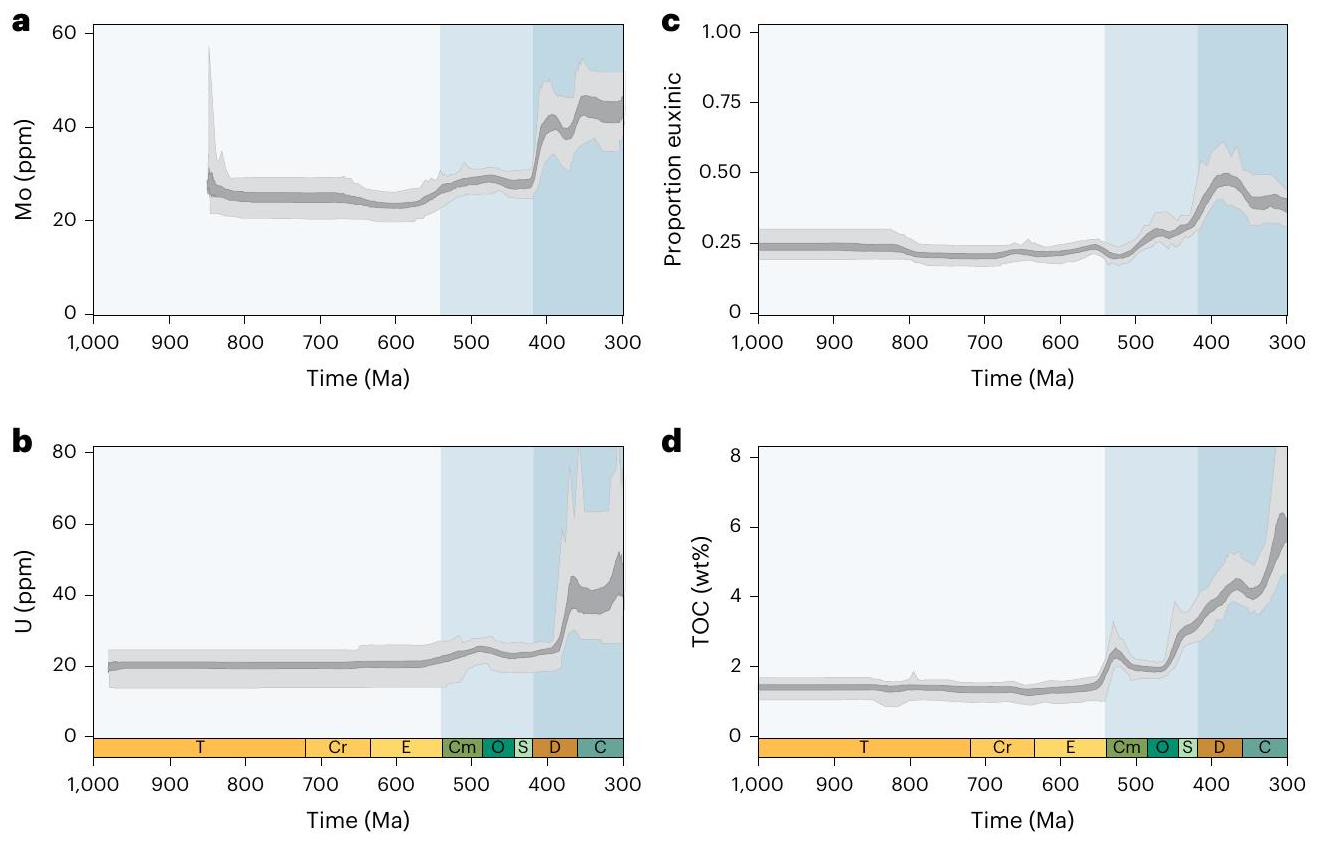

المؤشرات، مفصولة عن التعقيدات والتفاعلات المعقدة التي تؤثر على تفسيرات البيانات الرسوبية الخام. نستخدم إطار عمل مونت كارلو للغابات العشوائية (مع ضبط معلمات محددة لكل مؤشر؛ الطرق) لإنشاء تحليلات الاعتماد الجزئي التي تعزل التأثير الهامشي للوقت الجيولوجي على القيمة المتوسطة لكل مؤشر جيوكيميائي مع الحفاظ على جميع المتغيرات الجيولوجية والجيوكيميائية المربكة المحددة ثابتة. على الرغم من أن القيم المطلقة لهذه النتائج تعكس السجل الرسوبي المأخوذ، فإن الاتجاهات الاتجاهية الناتجة في هذه التحليلات التعليمية الإحصائية تمكننا من إعادة بناء التغيرات في الدورات البيوجيوكيميائية العالمية. لذلك، تتبع تحليلات الاعتماد الجزئي لدينا مخزونات المعادن في مياه البحر لعناصر الموليبدينوم (Mo) واليورانيوم (U)، ومستويات الكبريتيد في البيئات المأخوذة من الرف الساحلي والمنحدر لتحديد أنواع الحديد وتدفقات الكربون العضوي إلى البيئات المأخوذة من الرف الساحلي والمنحدر لمحتوى الكربون العضوي الكلي (TOC).

سجلات المؤشرات الجيوكيميائية

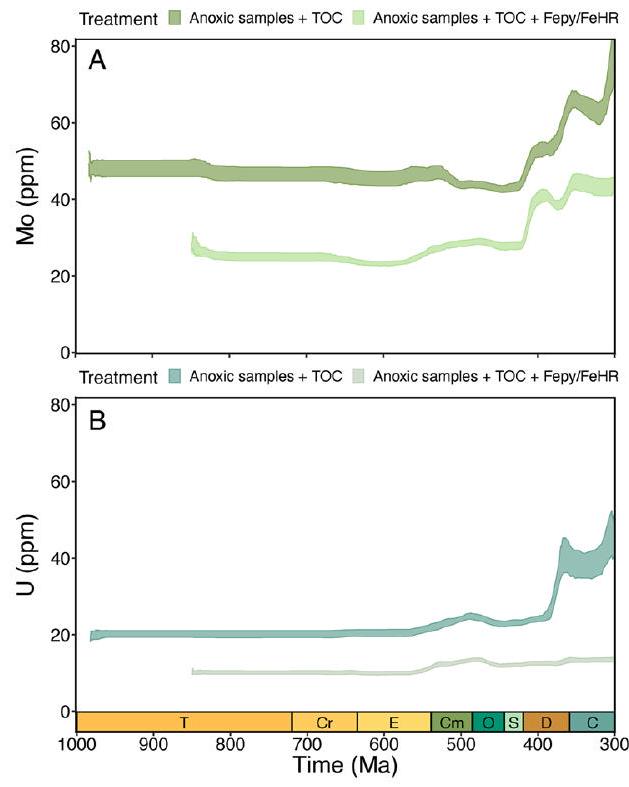

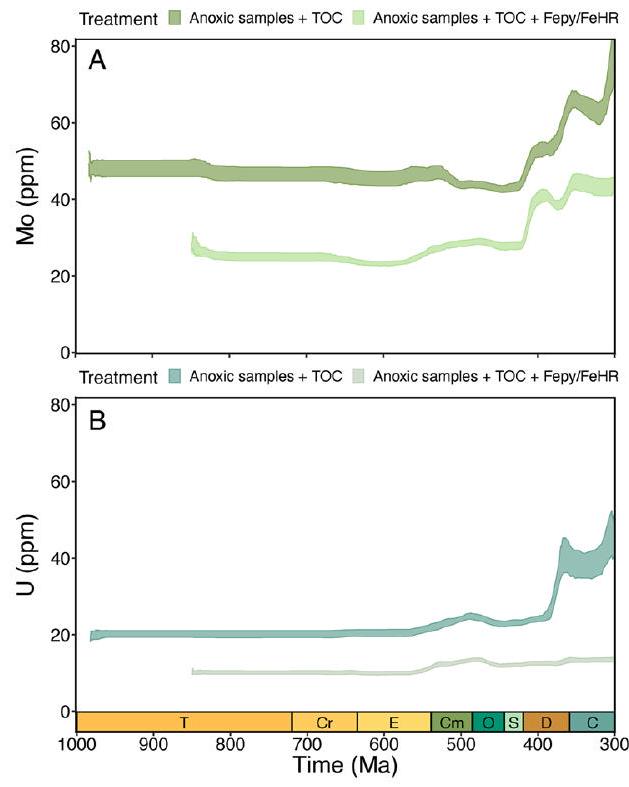

تعني القيم المعزولة، لكنها تنخفض بعد ذلك في العصر الباليوزي المبكر قبل أن ترتفع مرة أخرى في الديفوني (الشكل 1أ، ب). تظهر توزيعات كل من الموليبدينوم في الطين اليوكسي واليورانيوم في الطين اللاهوائي اتجاهات مماثلة عند أخذ التحيزات الزمنية والمكانية في الاعتبار. عندما يتم توحيد المعادن النادرة بالنسبة لمحتوى الكربون العضوي، يكون هناك ضجيج كبير في القيم المعزولة ولا يوجد اتجاه واضح خلال النيو بروتيروزويك والعصر الباليوزي المبكر، على الرغم من أن كل من Mo/TOC و U/TOC يزيدان في الديفوني المتأخر (الشكل 1ج، د؛ لاحظ العدد المنخفض من الوحدات المأخوذة لعينة Mo/TOC في الكربوني). لذلك، تشير هذه التحليلات وحدها إلى أنه لم يكن هناك زيادة كبيرة مستدامة في تركيزات الموليبدينوم أو اليورانيوم البحرية حتى الديفوني، مما يتناقض بشكل حاد مع التفسيرات السابقة لبيانات المعادن النادرة.

الاتجاهات البيوجيوكيميائية المفككة

مستويات المحيط الحالية (POL).

زيادة عابرة في تركيزات المعادن النادرة في أواخر النيوبرتوذوري تليها زيادات كبيرة في منتصف الباليوزوي (الشكل 2 أ، ب). تظل هذه الحالة قائمة عند استخدام بيانات تصنيف الحديد كبيانات تنبؤية بدلاً من عتبات (الشكل 3 من البيانات الموسعة)، مما يشير إلى قوة هذه الاتجاهات تجاه تفسيرات البروكسي المحددة (قارن المرجع 31). تختلف مسارات الموليبدينوم واليورانيوم قليلاً في التوقيتات ومعدلات التغيير، على الرغم من أن ربط التباينات الزمنية الدقيقة بحساسيات الأكسدة والاختزال الخاصة بالبروكسي سيتطلب اعتبارًا دقيقًا لتوزيعات عينات البروكسي. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن هذه التحليلات مصممة للتحقيق في التغيرات على مقاييس زمنية جيولوجية طويلة نسبيًا، وبالتالي لا يُتوقع أن تلتقط <

الدفن في بيئات خالية من الأكسجين مستقل عن التغيرات الزمنية في

الآثار المترتبة على الأكسجين والإنتاجية

نقاش

تم الحفاظ على سجلنا الأحفوري، كان هناك NOE (الأشكال 4 و 5). على وجه التحديد، تشير تحليلاتنا إلى أن المواطن البحرية الضحلة كانت على الأرجح تحت الأكسجين أو تعاني من نقص حاد في الأكسجين.

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

References

- Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T. & Planavsky, N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307-315 (2014).

- Farquhar, J., Bao, H. & Thiemens, M. Atmospheric influence of Earth’s earliest sulfur cycle. Science 289, 756-758 (2000).

- Crockford, P. W. et al. Triple oxygen isotope evidence for limited mid-Proterozoic primary productivity. Nature 559, 613-616 (2018).

- Kump, L. R. The rise of atmospheric oxygen. Nature 451, 277-278 (2008).

- Cole, D. B. et al. On the co-evolution of surface oxygen levels and animals. Geobiology 18, 260-281 (2020).

- Sperling, E. A., Knoll, A. H. & Girguis, P. R. The ecological physiology of Earth’s second oxygen revolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 46, 215-235 (2015).

- Stolper, D. A. & Keller, C. B. A record of deep-ocean dissolved

from the oxidation state of iron in submarine basalts. Nature 553, 323-327 (2018). - Sperling, E. A. et al. A long-term record of early to mid-Paleozoic marine redox change. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf4382 (2021).

- Dahl, T. W. et al. Devonian rise in atmospheric oxygen correlated to the radiations of terrestrial plants and large predatory fish. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17911-17915 (2010).

- Lu, W. et al. Late inception of a resiliently oxygenated upper ocean. Science 361, 174-177 (2018).

- Wallace, M. W. et al. Oxygenation history of the Neoproterozoic to early Phanerozoic and the rise of land plants. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 466, 12-19 (2017).

- Krause, A. J., Mills, B. J. W., Merdith, A. S., Lenton, T. M. & Poulton, S. W. Extreme variability in atmospheric oxygen levels in the late Precambrian. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm8191 (2022).

- Wei, G. Y. et al. Global marine redox evolution from the late Neoproterozoic to the early Paleozoic constrained by the integration of Mo and U isotope records. Earth Sci. Rev. 214, 103506 (2021).

- Sahoo, S. K. et al. Oceanic oxygenation events in the anoxic Ediacaran ocean. Geobiology 14, 457-468 (2016).

- Pohl, A. et al. Continental configuration controls ocean oxygenation during the Phanerozoic. Nature 608, 523-527 (2022).

- Sperling, E. A. & Stockey, R. G. The temporal and environmental context of early animal evolution: considering all the ingredients of an ‘explosion’. Integr. Comp. Biol. 58, 605-622 (2018).

- Berner, R. A. The Phanerozoic Carbon Cycle (Oxford Univ. Press, 2004); https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195173338.001.0001

- Tribovillard, N., Algeo, T. J., Lyons, T. & Riboulleau, A. Trace metals as paleoredox and paleoproductivity proxies: an update. Chem. Geol. 232, 12-32 (2006).

- Scott, C. et al. Tracing the stepwise oxygenation of the Proterozoic ocean. Nature 452, 456-459 (2008).

- Partin, C. A. et al. Large-scale fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric and oceanic oxygen levels from the record of

in shales. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 369-370, 284-293 (2013). - Sahoo, S. K. et al. Ocean oxygenation in the wake of the Marinoan glaciation. Nature 489, 546-549 (2012).

- Farrell, Ú. C. et al. The Sedimentary Geochemistry and Paleoenvironments Project. Geobiology 19, 545-556 (2021).

- Morford, J. L. & Emerson, S. The geochemistry of redox sensitive trace metals in sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 1735-1750 (1999).

- Poulton, S. W. & Canfield, D. E. Ferruginous conditions: a dominant feature of the ocean through Earth’s history. Elements 7, 107-112 (2011).

- Mehra, A. et al. Curation and analysis of global sedimentary geochemical data to inform Earth history. GSA Today 31, 4-9 (2021).

- Sperling, E. A. et al. Statistical analysis of iron geochemical data suggests limited late Proterozoic oxygenation. Nature 523, 451-454 (2015).

- Ridgwell, A. et al. Marine geochemical data assimilation in an efficient Earth system model of global biogeochemical cycling. Biogeosciences 4, 87-104 (2007).

- Stockey, R. G. et al. Persistent global marine euxinia in the early Silurian. Nat. Commun. 11, 1804 (2020).

- Ozaki, K. & Tajika, E. Biogeochemical effects of atmospheric oxygen concentration, phosphorus weathering, and sea-level stand on oceanic redox chemistry: implications for greenhouse climates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 373, 129-139 (2013).

- Cole, D. B., Ozaki, K. & Reinhard, C. T. Atmospheric oxygen abundance, marine nutrient availability, and organic carbon fluxes to the seafloor. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 36, e2021GB007052 (2022).

- Pasquier, V., Fike, D. A., Révillon, S. & Halevy, I. A global reassessment of the controls on iron speciation in modern sediments and sedimentary rocks: a dominant role for diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 335, 211-230 (2022).

- Alcott, L. J., Mills, B. J. W. & Poulton, S. W. Stepwise Earth oxygenation is an inherent property of global biogeochemical cycling. Science 366, 1333-1337 (2019).

- Brocks, J. J. The transition from a cyanobacterial to algal world and the emergence of animals. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2, 181-190 (2018).

- Laakso, T. A., Sperling, E. A., Johnston, D. T. & Knoll, A. H. Ediacaran reorganization of the marine phosphorus cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 11961-11967 (2020).

- Dahl, T. W. & Hammarlund, E. U. Do large predatory fish track ocean oxygenation? Commun. Integr. Biol. 4, 92-94 (2011).

- Boag, T. H., Gearty, W. & Stockey, R. G. Metabolic tradeoffs control biodiversity gradients through geological time. Curr. Biol. 31, 2906-2913.e3 (2021).

- Penn, J. L., Deutsch, C., Payne, J. L. & Sperling, E. A. Temperaturedependent hypoxia explains biogeography and severity of endPermian marine mass extinction. Science 362, eaat1327 (2018).

- Pohl, A. et al. Why the early Paleozoic was intrinsically prone to marine extinction. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg7679 (2023).

- Stockey, R. G., Pohl, A., Ridgwell, A., Finnegan, S. & Sperling, E. A. Decreasing Phanerozoic extinction intensity as a consequence of Earth surface oxygenation and metazoan ecophysiology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, 2021 (2021).

- Kocsis, Á. T., Reddin, C. J., Alroy, J. & Kiessling, W. The R package divDyn for quantifying diversity dynamics using fossil sampling data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 735-743 (2019).

- D’Antonio, M. P., Ibarra, D. E. & Boyce, C. K. Land plant evolution decreased, rather than increased, weathering rates. Geology 48, 29-33 (2020).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

طرق

معالجة البيانات

تحليل البوتستراب الموزون زمانيًا ومكانيًا

تحليلات الغابة العشوائية

يتم استنتاج الصخور، ثم يتم تعيين الصخور بشكل عشوائي. في نهج مونت كارلو الخاص بنا، يتم إجراء هذه التعيينات العشوائية للقيم 100 مرة لكل تحليل، مما يتوافق مع 100 نموذج غابة عشوائية منفصل لكل عملية بيولوجية كيميائية/بروكسي. ثم يتم تلخيص نتائج هذه النماذج الـ 100 كرسوم بيانية للاعتماد الجزئي ورسوم بيانية للصندوق لتصور عدم اليقين المرتبط بنماذج العمر الجيولوجي (الوصف يتبع) والعينات ذات البيانات الجزئية.

- أقسام تحتوي على بيانات الارتفاع/العمق

أ. يتم تعيين العينات بتقديرات عمرية متزايدة بشكل مستمر.

ب. يتم تعيين نفس تقدير العمر المفسر لجميع العينات.

يتم تعيين تقديرات العمر المفسرة للعينات في مجموعات أو خطوات. - أقسام بدون بيانات الارتفاع/العمق

أ. يتم تعيين العينات بتقديرات عمرية مترجمة تصاعديًا بشكل مستمر.

ب. يتم تعيين نفس تقدير العمر المفسر لجميع العينات.

يتم تعيين تقديرات العمر المفسرة للعينات في مجموعات أو خطوات. - أقسام تحتوي على عينة واحدة فقط

أ. العينة لها ارتفاع/عمق طبقي.

ب. العينة لا تحتوي على ارتفاع/عمق طبقي.

بيئة الأكسدة والترسيب؟ ومع ذلك، من المتوقع أن تمثل مخططات التأثيرات المحلية المتراكمة ونماذج تأثيرات الميزات المحلية بشكل أفضل متوسطات الغنى الرسوبي لكل فترة زمنية جيولوجية (دون، على سبيل المثال، توحيد التغيرات طويلة الأجل في متوسط الأكسدة المحلية) لأنها تأخذ في الاعتبار التغيرات في متغيرات التنبؤ الأخرى (في حالتنا، خصائص الصخور الرسوبية). وبالتالي، من غير المرجح أن تتبع بشكل مستقل التغيرات المحيطية وتغيرات نظام الأرض التي نحن مهتمون بالتحقيق فيها. نختار أيضًا تقديم مخططات الاعتماد الجزئي بدلاً من مخططات التوقع الشرطي الفردي لأن الأسئلة البحثية التي نتناولها في هذه الدراسة ذات طبيعة عالمية وتستفيد من التغيرات في المتوسطات العالمية التي يمكننا إعادة بنائها من تحليلات الاعتماد الجزئي، على الرغم من أن تحليلات التوقع الشرطي الفردي لديها إمكانيات مثيرة لتقديم رؤى جديدة حول مجموعات البيانات المحلية إلى الإقليمية. نقدم مخططات الاعتماد الجزئي كأغلفة، تلخص 100 نموذج غابة عشوائية في كل تحليل مونت كارلو (الشكل 2). يتم توليد الأغلفة المرسومة من خلال الاستيفاء الخطي لمخططات الاعتماد الجزئي الفردية الـ 100 التي تم إنشاؤها لكل تحليل على فترات زمنية قدرها 0.1 مليون سنة وحساب النسب المئوية الخامسة والعشرون والسبعون والتسعون من مجموعات مخططات الاعتماد الجزئي المستوفاة في كل خطوة زمنية. تُظهر طرق غابة مونت كارلو العشوائية الكاملة في ملفات R Markdown المرتبطة بنا (توفر الشيفرة).

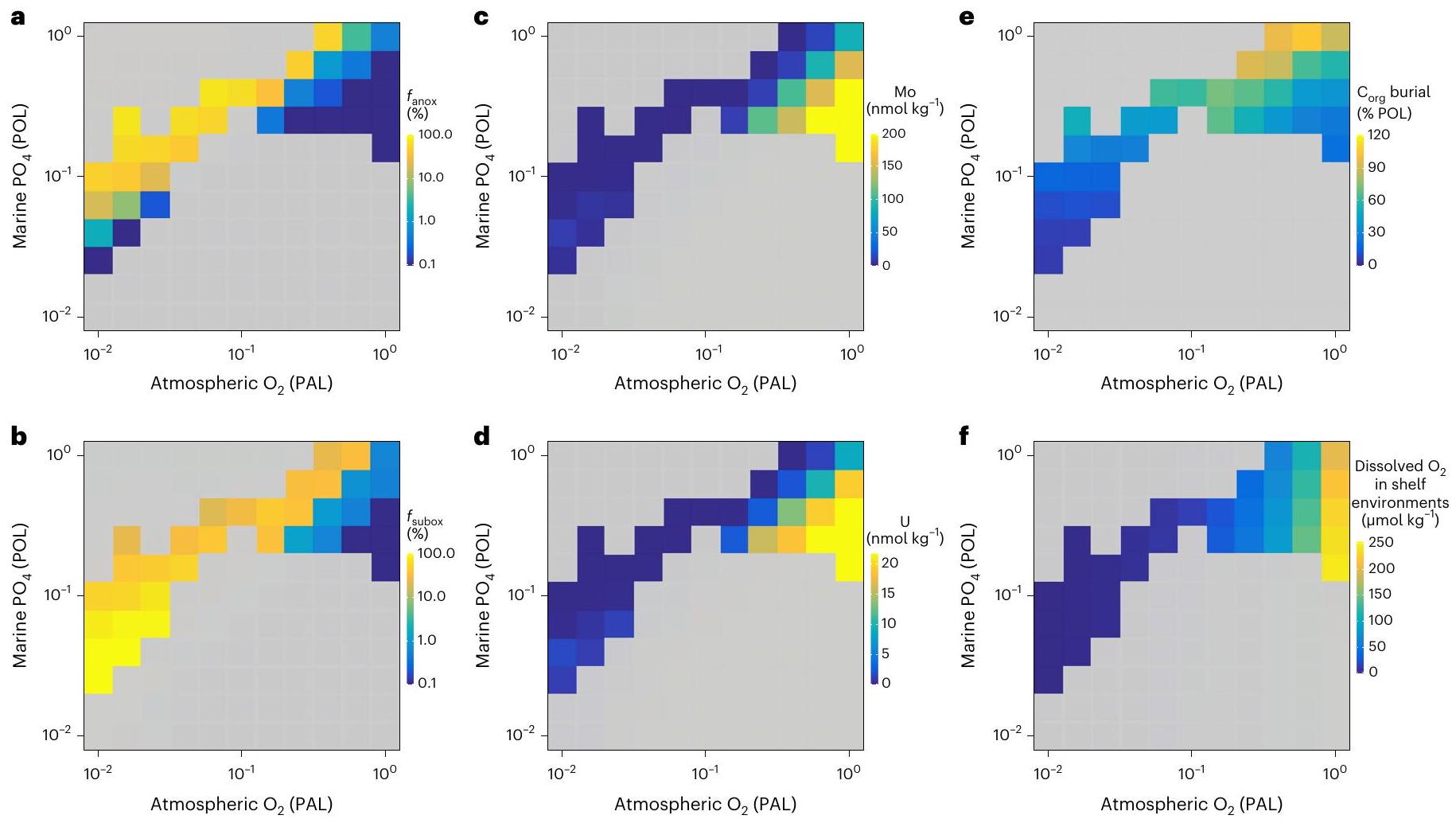

نمذجة نظام الأرض

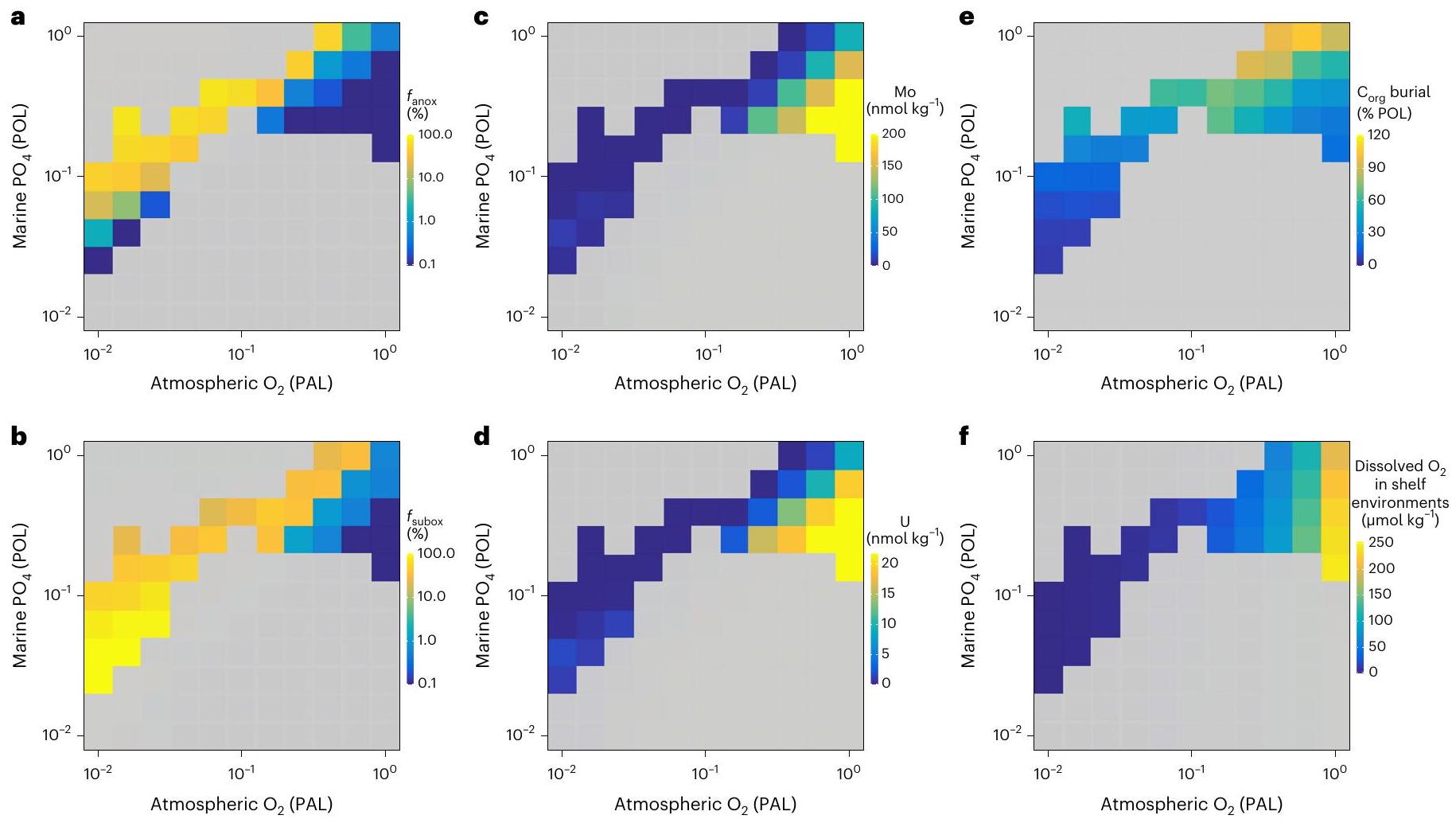

شبكة bathymetric خشنة نسبيًا ليست مناسبة تمامًا لحل بيئات المياه القاعية عبر الرفوف الضحلة المنحدرة بشدة بسبب التخفيف المكاني المطبق على إعادة بناء الجغرافيا القديمة عالية الدقة. لذلك، نحن نستخدم تقريبًا لبيئات الرف البحري (خلايا المحيط المجاورة للأرض في الطبقات الثلاث العليا من cGENIE ocean، وفقًا للمراجع 38،39)، أي أنها ليست معتمدة على شبكة bathymetric خشنة وبالتالي ليست عرضة لهذه القيود المكانية. تطبيقنا لـ cGENIE يمكّننا بالتالي من التقاط مناطق الحد الأدنى من الأكسجين المحددة جيدًا وفصل الأكسجة بين المياه الضحلة والعميقة لمجموعة من ظروف حدود نظام الأرض (الأشكال 3 و4 والشكل الممتد 7). هذه النتائج ليست متأثرة بالـ bathymetry المنحدرة للرفوف التي تتسم بها النماذج ذات التعقيد المتوسط. نظرًا لأن تدرجات bathymetric لبيئات المياه العميقة تكون أكثر ضحالة بكثير من الرفوف القارية، فإن التخفيف المكاني لا يؤثر بشكل كبير على تقديراتنا العالمية لعدم وجود الأكسجين في قاع البحر، والظروف شبه الأكسجينية والأكسجينية. لذلك، يتم استخدام هذه التقنية التقريبية فقط لنمذجة بيئات الرف.

الجو المستقر

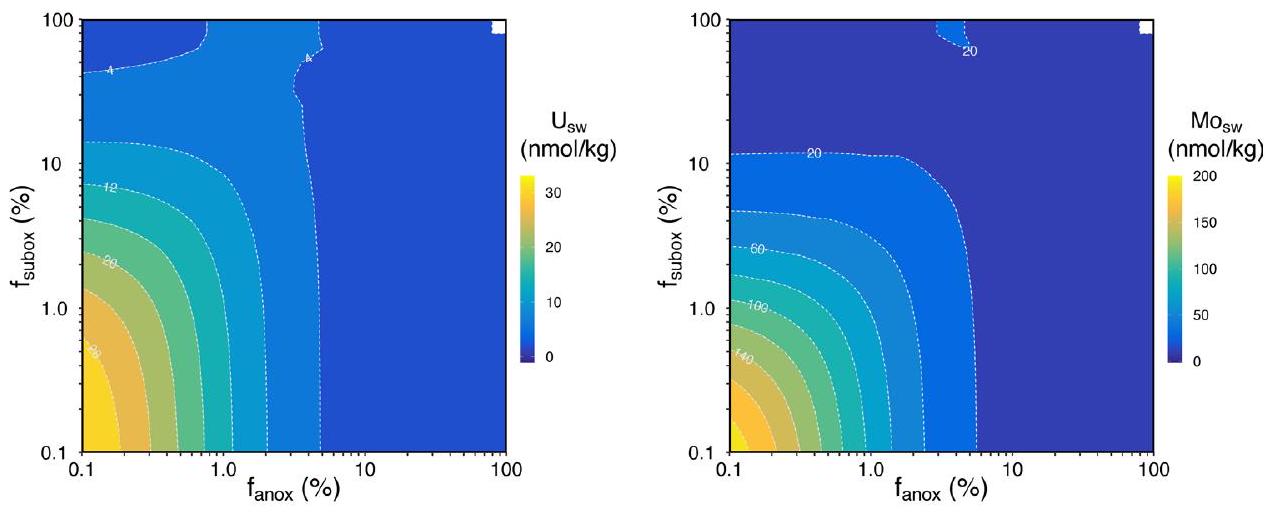

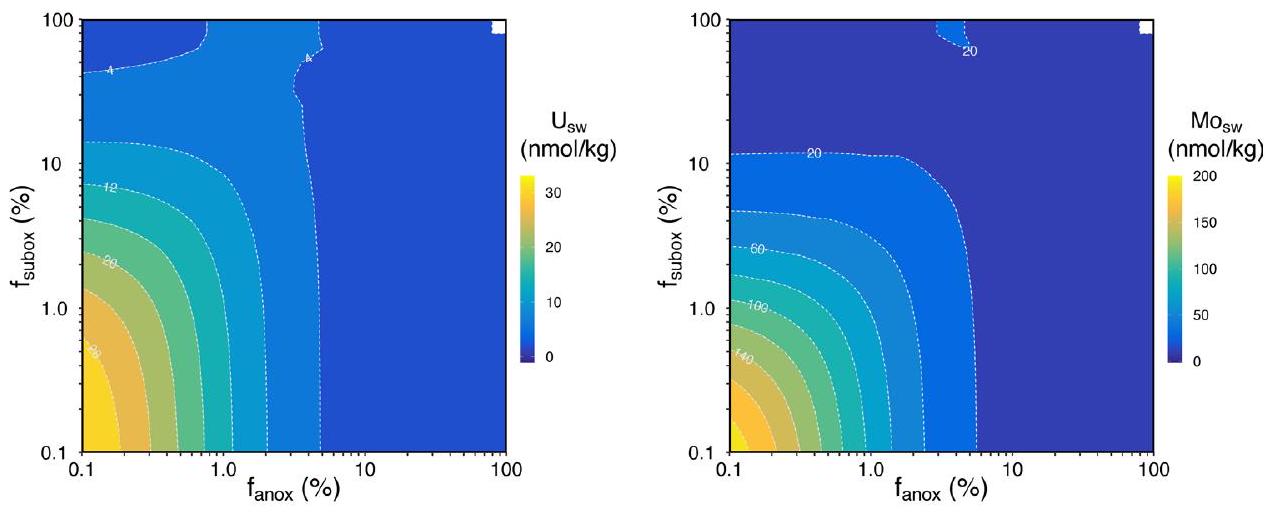

ميزان الكتلة للمعادن النادرة

، ولكن

دفن الكربون العضوي

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Raiswell, R. et al. The iron paleoredox proxies: a guide to the pitfalls, problems and proper practice. Am. J. Sci. 318, 491-526 (2018).

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning-A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable 2nd edn christophm.github.io/ interpretable-ml-book/ (2020).

- Reinhard, C. T. et al. The impact of marine nutrient abundance on early eukaryotic ecosystems. Geobiology 18, 139-151 (2020).

- Meyer, K. M., Ridgwell, A. & Payne, J. L. The influence of the biological pump on ocean chemistry: implications for long-term trends in marine redox chemistry, the global carbon cycle, and marine animal ecosystems. Geobiology 14, 207-219 (2016).

- Reinhard, C. T. et al. Proterozoic ocean redox and biogeochemical stasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 5357-5362 (2013).

- Stockey, R. Richardstockey/sgp.trace.metals: submission for publication. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 11426206 (2024).

- Ridgwell, A. et al. Derpycode/cgenie.muffin: v0.9.46. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 10041805 (2023).

- Ridgwell, A. et al. Derpycode/muffindoc: v0.9.35. Zenodo https:// doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7545814 (2023).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

M.A.L. وC.L. وD.K.L. وF.A.M. وJ.M.M. وN.T.M. وL.M.O. وB.O. وA.P. وS.E.P. وS.M.P. وS.W.P. وS.R.R. وA.D.R. وS.S. وE.F.S. وJ.V.S. وG.J.U. وT.W. وR.A.W. وC.R.W. وI.Y. وN.J.P. وE.A.S. قدموا معلومات سياق جيولوجي مفصلة حول العينات، وقدموا بيانات كيميائية غير منشورة وساعدوا في تفسير النتائج. كتب R.G.S. وE.A.S. المخطوطة، مع مناقشة مهمة ومساهمات من جميع المؤلفين.

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01479-1.

يمكن العثور على هذه المتغيرات المتعلقة بالسياق الجيولوجي والجغرافي في ويكي SGP (https://github.com/ufarrell/sgp_phase1/wiki/Database-description#geological-context).

تتوافق مع الوسيط للتوزيع لكل فترة زمنية؛ الحدود السفلية/العليا للصندوق تتوافق مع

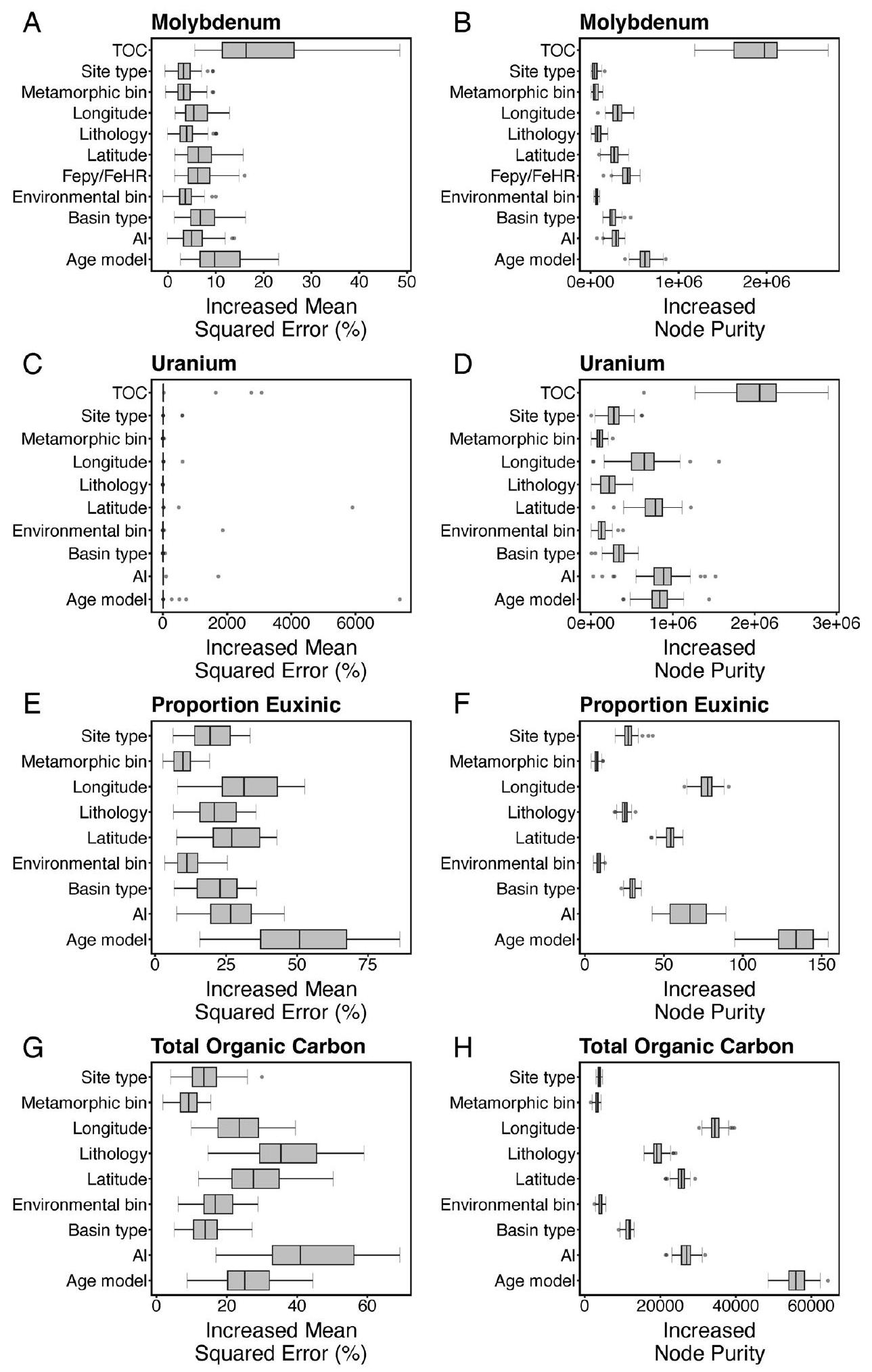

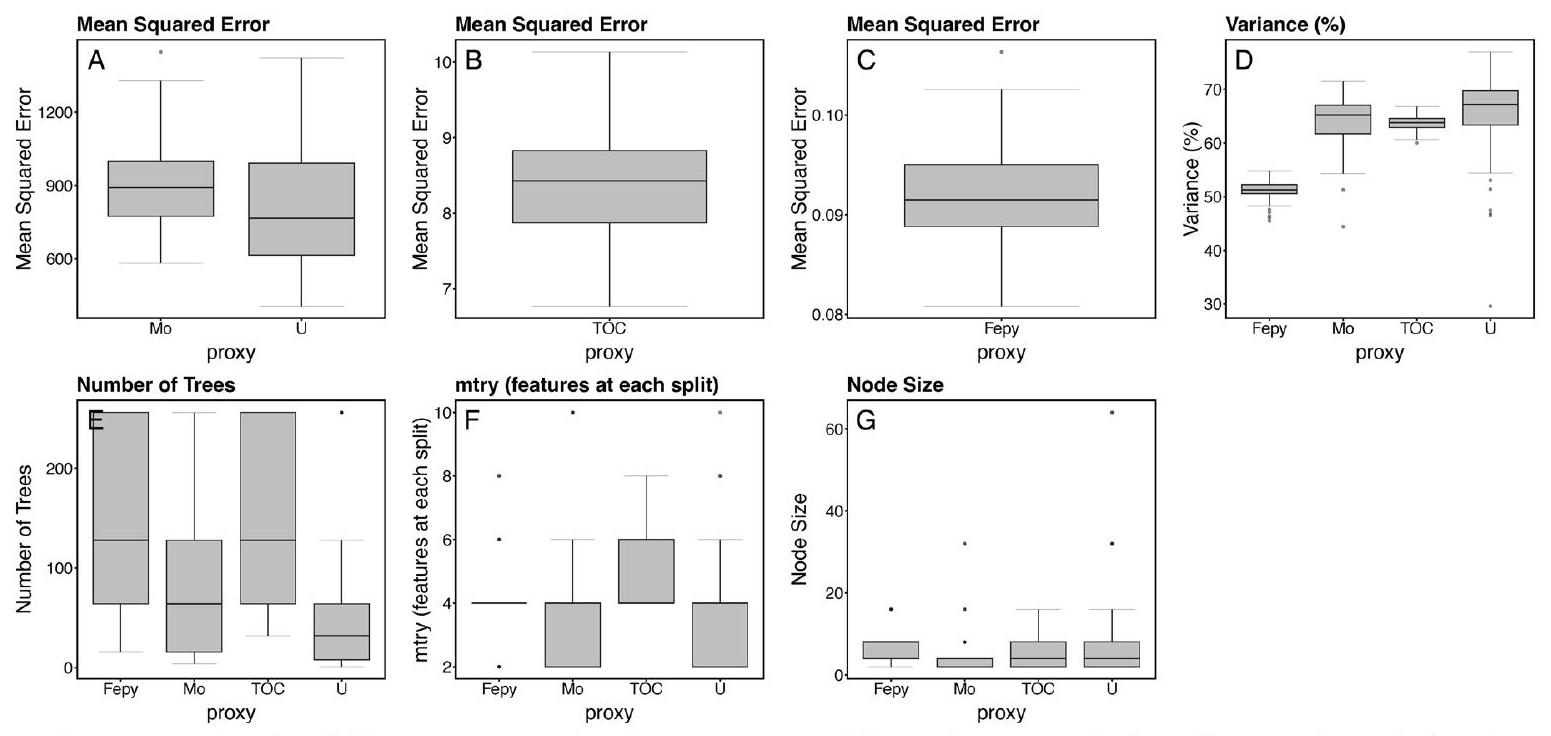

نموذج لكل وكيل. تُظهر اللوحة F قيمة mtry لأفضل نموذج ملائم لكل وكيل. تُظهر اللوحة G حجم العقدة لأفضل نموذج ملائم لكل وكيل. تتوافق خطوط الصندوق المركزية مع الوسيط للتوزيع لكل فترة زمنية؛ الحدود السفلية/ العلوية للصندوق تتوافق مع

تحليلات. يتم تلوين فلاتر الأكسدة والاختزال حسب كل وكيل. تمثل الأظرف

مع عمق إعادة التمعدن الحديث، D) التكوين القاري في العصر الكريوجيني-الإديكاراني قبل 3 ملايين سنة

| وكيل | تحليل | البيانات الجيوكيميائية المطلوبة | مرشحات | المتغيرات التنبؤية | وصف | شكل |

| مو | البوتستراب الموزون الزماني المكاني | مو، في إتش آر/في إتش تي، في إيه بي واي/في إتش آر | FeHR/FeT

|

غير متوفر | مو في الصخر الزيتي الأكسجيني فقط | 1أ |

| أنت | البوتستراب الموزون الزماني المكاني | U، [FeHR/FeT أو Fe/Al] | FeHR/FeT

|

غير متوفر | U في الصخر الزيتي الخالي من الأكسجين فقط | 1ب |

| مو/توك | البوتستراب الموزون الزماني المكاني | مو، في إتش آر/في إتش تي، في إيه بي واي/في إتش آر، تو سي | FeHR/FeT

|

غير متوفر | مو/توك في الصخر الزيتي الأكسجيني فقط | 1C |

| U/TOC | البوتستراب الموزون الزماني المكاني | U، [FeHR/FeT أو FelAl]، TOC | [FeHR/FeT

|

غير متوفر | U/TOC في الصخر الزيتي الخالي من الأكسجين فقط | 1D |

| نسبة الأكسجة | البوتستراب الموزون الزماني المكاني | FeHR/FeT، FePy/FeHR | FeHR/FeT

|

غير متوفر | نسبة الإيوكسين في الصخر الزيتي الخالي من الأكسجين فقط. (ترميز ثنائي يعتمد على FePy/FeHR) | 1E |

| فهرس المحتويات | البوتستراب الموزون الزماني المكاني | فهرس المحتويات | لا شيء | غير متوفر | نسبة الكربون العضوي الكلي في جميع الصخر الزيتي | 1F |

| مو | الغابة العشوائية | مو، في إتش آر/في إتش تي، في إيه بي واي/في إتش آر، تو سي | FeHR/FeT

|

نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية البيئة، TOC، FePy/FeHR، Al | عينات من بيئات خالية من الأكسجين فقط. التحكم في بيئة الترسيب، التغيرات بعد الترسيب، تحميل الكربون العضوي، المدخلات الحبيبية ومستويات الكبريتيدات. | 2A |

| أنت | الغابة العشوائية | U، [FeHR/FeT أو FelAl]، TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية البيئة، TOC، Al | عينات من بيئات خالية من الأكسجين فقط. التحكم في بيئة الترسيب، التغيرات بعد الترسيب، تحميل الكربون العضوي ومدخلات الحطام. | 2B |

| نسبة يوسينية | الغابة العشوائية | FeHR/FeT، FePy/FeHR | FeHR/FeT

|

نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية بيئية، الألمنيوم | عينات من بيئات خالية من الأكسجين فقط. التحكم في بيئة الترسيب، التغيرات بعد الترسيب ومدخلات الحطام. (ترميز ثنائي بناءً على FePy/FeHR) | 2C |

| فهرس المحتويات | الغابة العشوائية | فهرس المحتويات | لا شيء | نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية بيئية، أل | التحكم في بيئة الترسيب، التغيرات بعد الترسيب ومدخلات الحطام. | ثنائي الأبعاد |

| مو | الغابة العشوائية | مو، في إتش آر/في إتش تي، في إيه بي واي/في إتش آر، تو سي | لا شيء | نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية البيئة، TOC، FeHR/FeT، FePy/FeHR، Al | التحكم في بيئة الترسيب، التغيرات بعد الترسيب، تحميل الكربون العضوي، المدخلات الحبيبية، مستويات الحديد التفاعلي العالي ومستويات الكبريتيد. (اختبار تأثير استخدام قيم تمييز الحديد بدلاً من العتبات في التحليلات) | ممتد 3 |

| مو | الغابة العشوائية | مو، [FeHR/FeT أو FelAl]، TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية البيئة، TOC، Al | عينات من بيئات خالية من الأكسجين فقط. التحكم في بيئة الترسيب، التغيرات بعد الترسيب، تحميل الكربون العضوي وإدخال الحطام. | 6A الممتد |

| أنت | الغابة العشوائية | U، FeHR/FeT، FePy/FeHR، TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية البيئة، TOC، FePy/FeHR، Al | عينات من بيئات خالية من الأكسجين فقط. التحكم في بيئة الترسيب، التغيرات بعد الترسيب، تحميل الكربون العضوي، المدخلات الحبيبية ومستويات الكبريتيدات. | تمديد 6B |

| نسبة الأكسجة | الغابة العشوائية | FeHR/FeT، FePy/FeHR، TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية البيئة، TOC، Al | عينات من بيئات خالية من الأكسجين فقط. التحكم في بيئة الترسيب، التغيرات بعد الترسيب، تحميل الكربون العضوي ومدخلات الحطام. (ترميز ثنائي بناءً على FePy/FeHR) | تمديد 6 ج |

| فهرس المحتويات | الغابة العشوائية | TOC، [FeHR/FeT أو Fe/Al] | FeHR/FeT

|

نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية بيئية، الأل | عينات من بيئات خالية من الأكسجين فقط. تحكم في البيئة الترسيبية، والتغيرات بعد الترسيب، ومدخلات الحطام. | 6D الممتد |

| فهرس المحتويات | الغابة العشوائية | TOC، FeHR/FeT، FePy/FeHR | FeHR/FeT

|

نموذج العمر، نوع الموقع، حاوية التحول، نوع الحوض، خط عرض الموقع، خط طول الموقع، اسم الصخر، حاوية بيئية، FePy/FeHR، Al | عينات من بيئات خالية من الأكسجين فقط. التحكم في بيئة الترسيب، التغيرات بعد الترسيب، المدخلات الحبيبية ومستويات الكبريتيد. | 6D الممتد |

- البريد الإلكتروني: r.g.stockey@soton.ac.uk; esper@stanford.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01479-1

Publication Date: 2024-07-01

Sustained increases in atmospheric oxygen and marine productivity in the Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic eras

Accepted: 5 June 2024

Published online: 2 July 2024

(D) Check for updates

Abstract

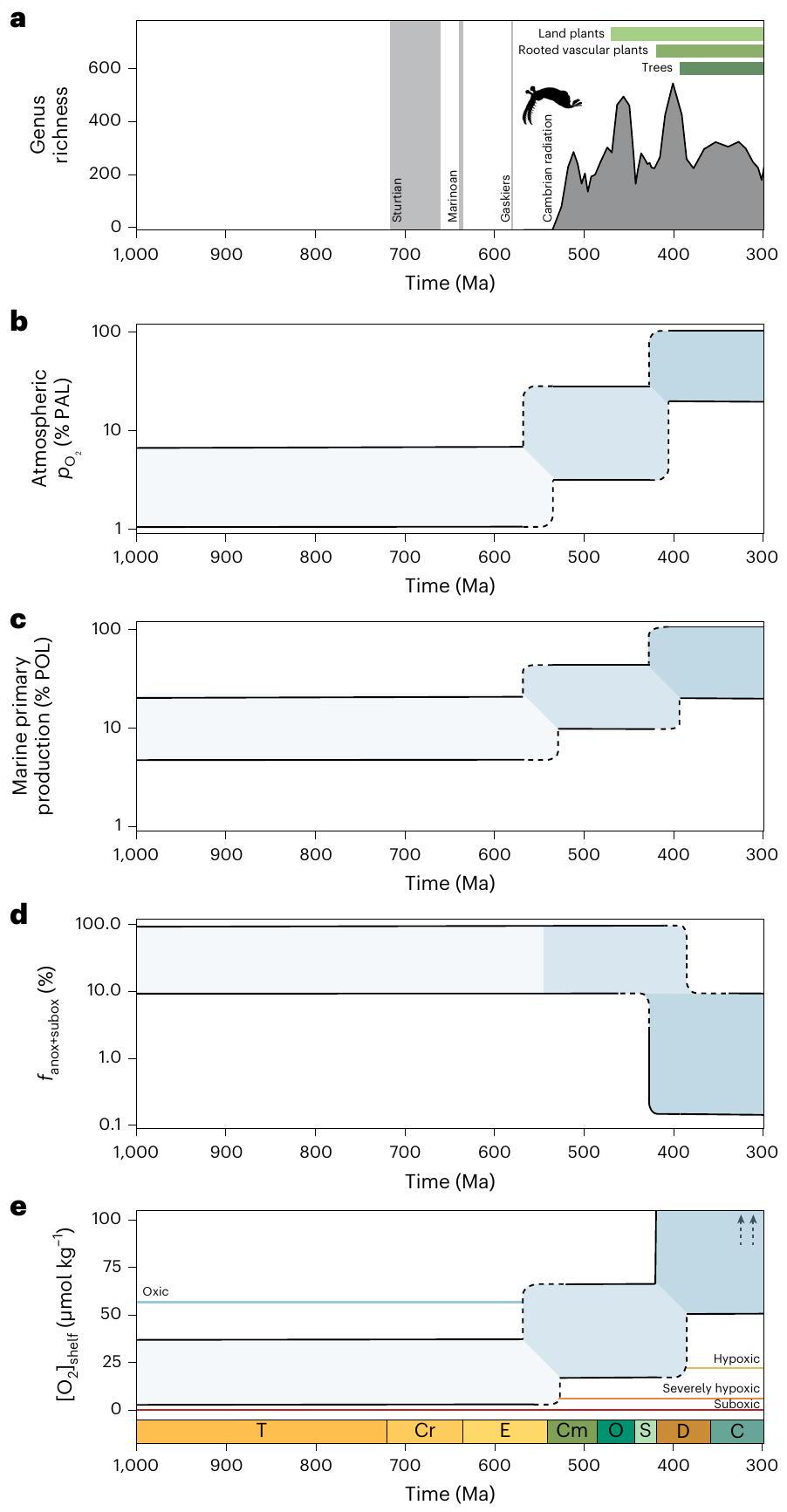

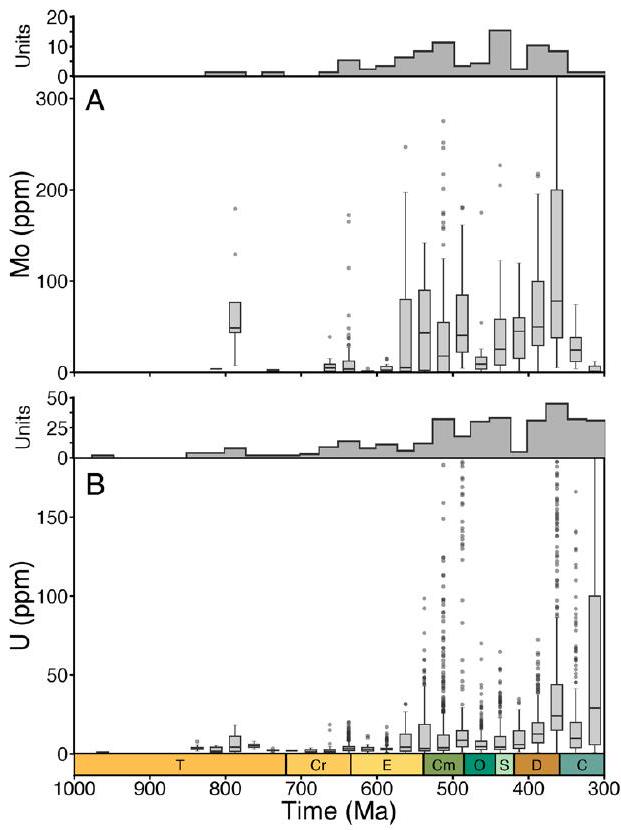

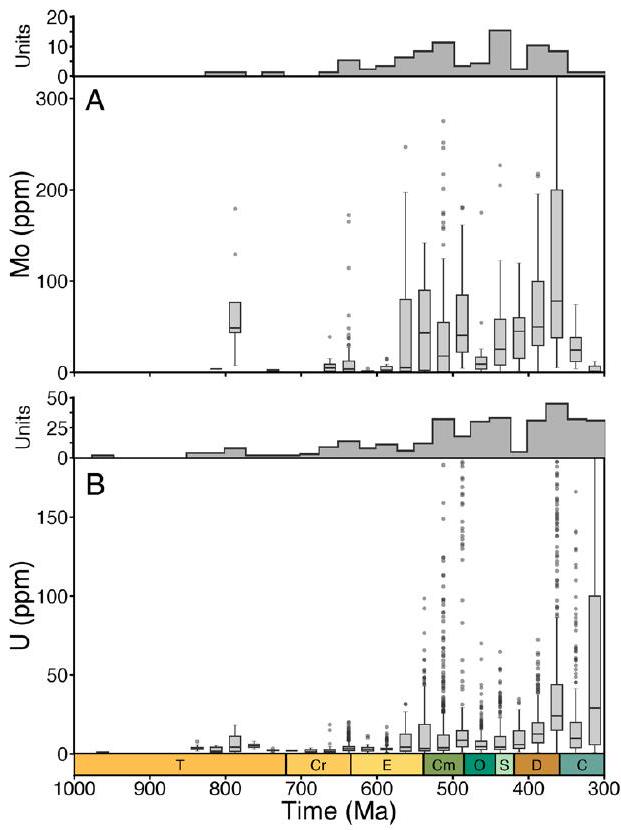

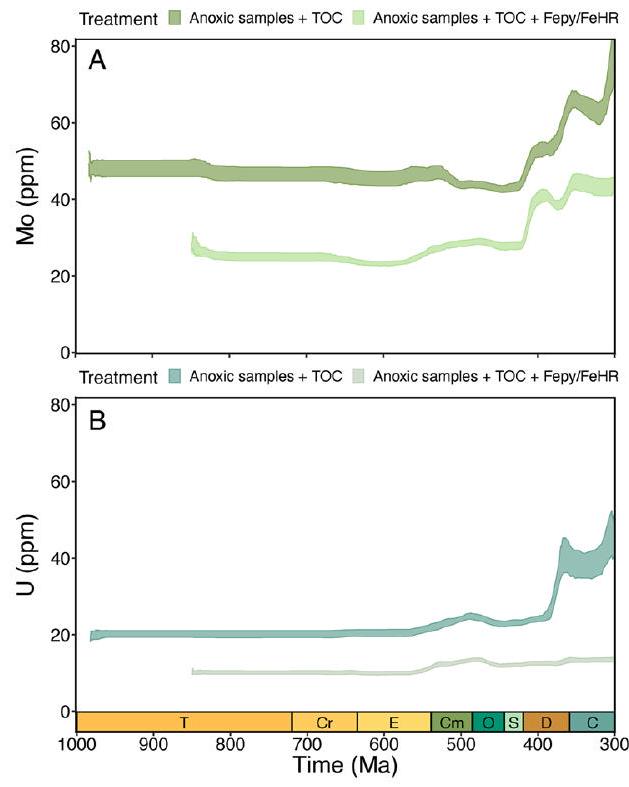

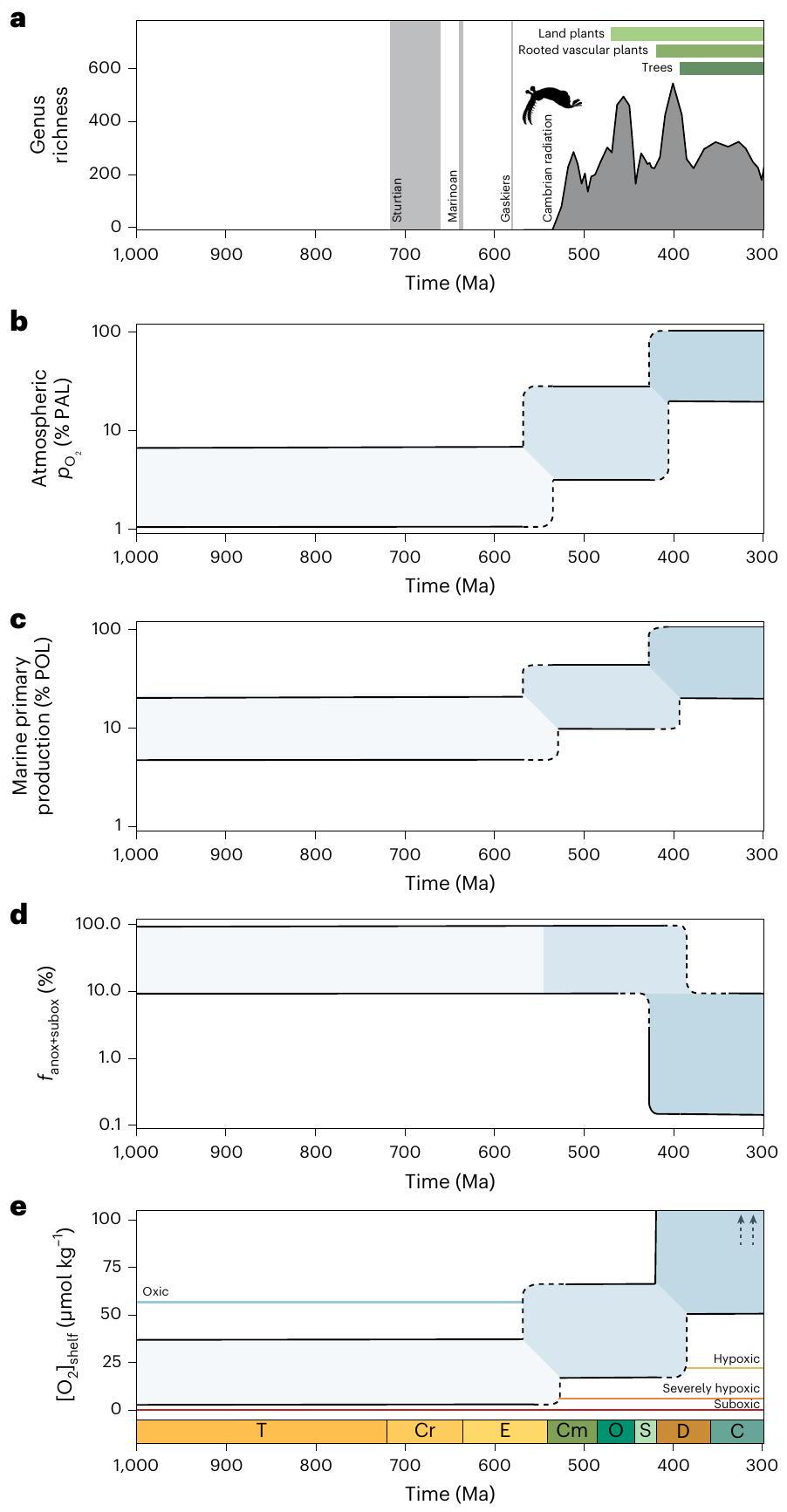

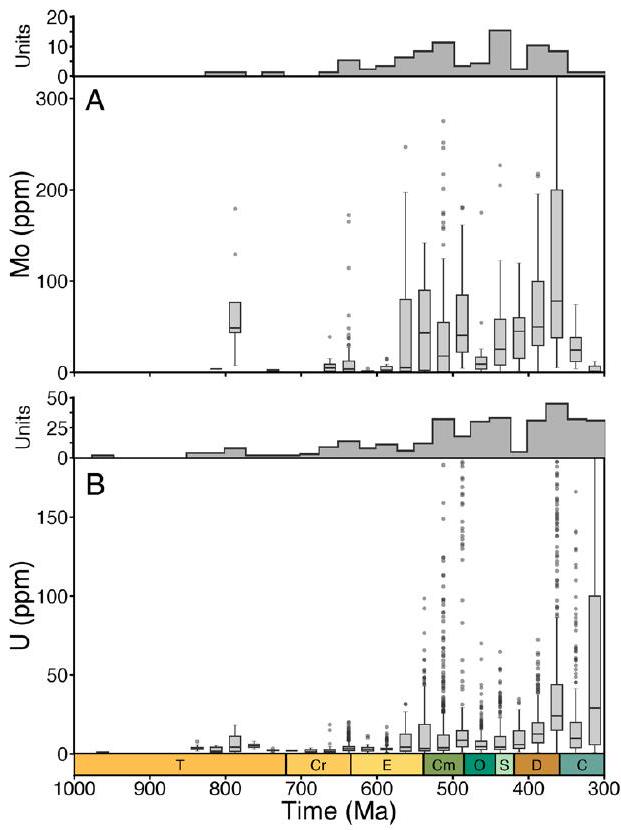

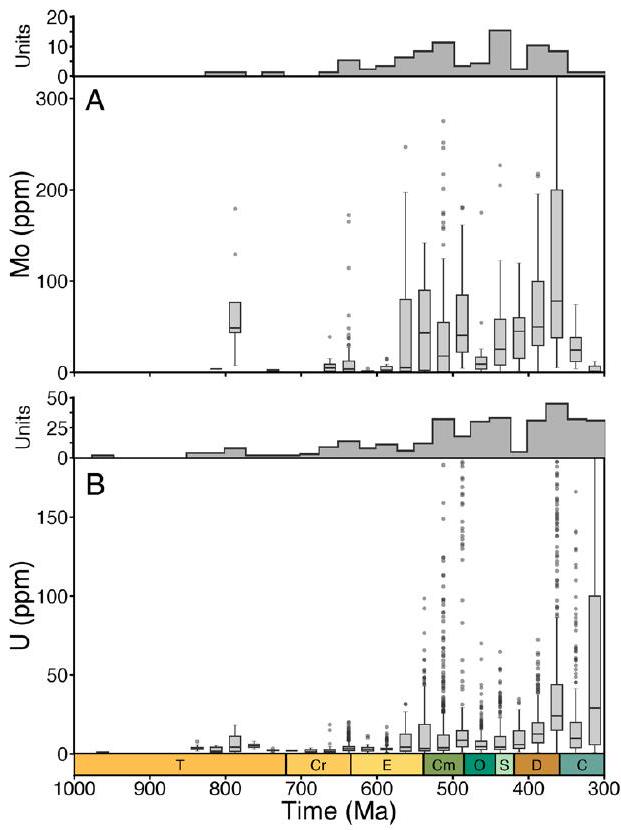

A geologically rapid Neoproterozoic oxygenation event is commonly linked to the appearance of marine animal groups in the fossil record. However, there is still debate about what evidence from the sedimentary geochemical record-if any-provides strong support for a persistent shift in surface oxygen immediately preceding the rise of animals. We present statistical learning analyses of a large dataset of geochemical data and associated geological context from the Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic sedimentary record and then use Earth system modelling to link trends in redox-sensitive trace metal and organic carbon concentrations to the oxygenation of Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. We do not find evidence for the wholesale oxygenation of Earth’s oceans in the late Neoproterozoic era. We do, however, reconstruct a moderate long-term increase in atmospheric oxygen and marine productivity. These changes to the Earth system would have increased dissolved oxygen and food supply in shallow-water habitats during the broad interval of geologic time in which the major animal groups first radiated. This approach provides some of the most direct evidence for potential physiological drivers of the Cambrian radiation, while highlighting the importance of later Palaeozoic oxygenation in the evolution of the modern Earth system.

that many Cambrian animal body plans and ecologies would not have been permitted at very low oxygen levels

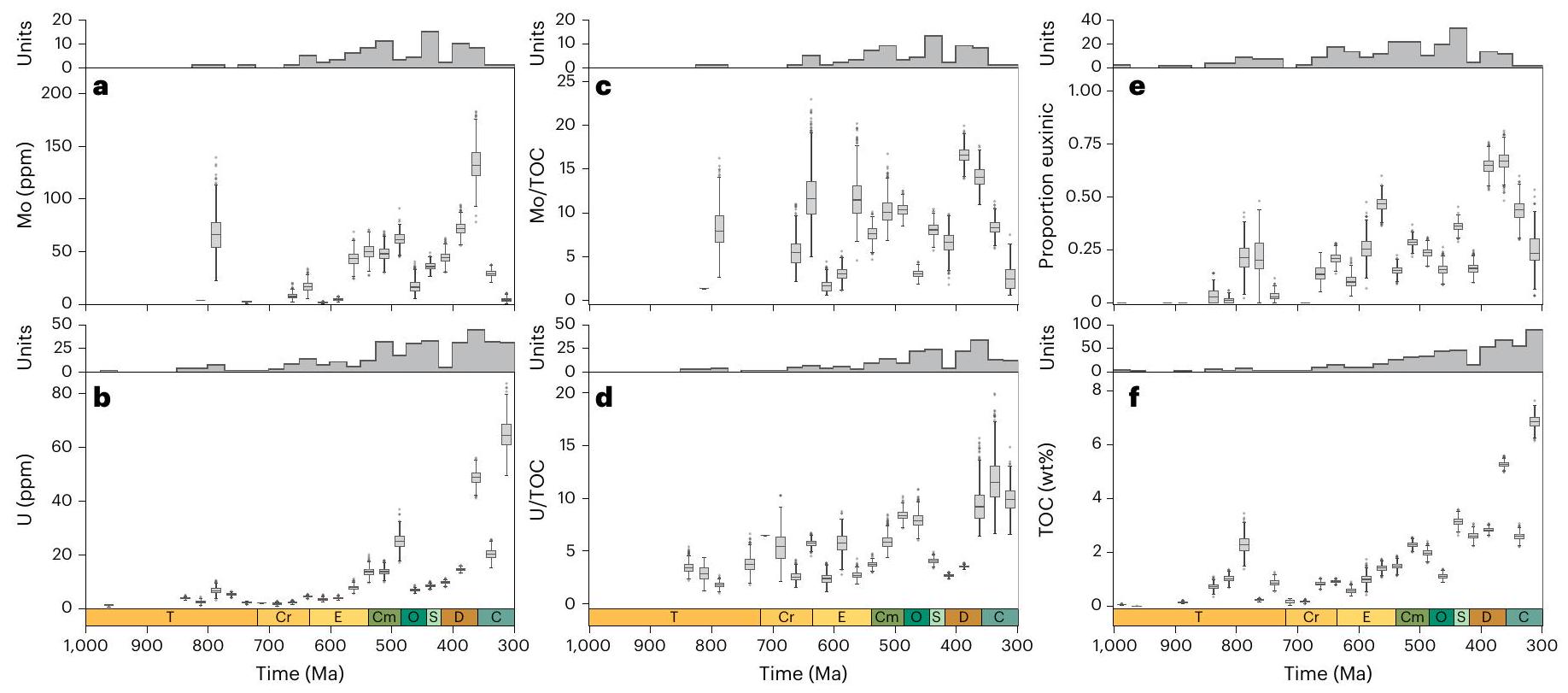

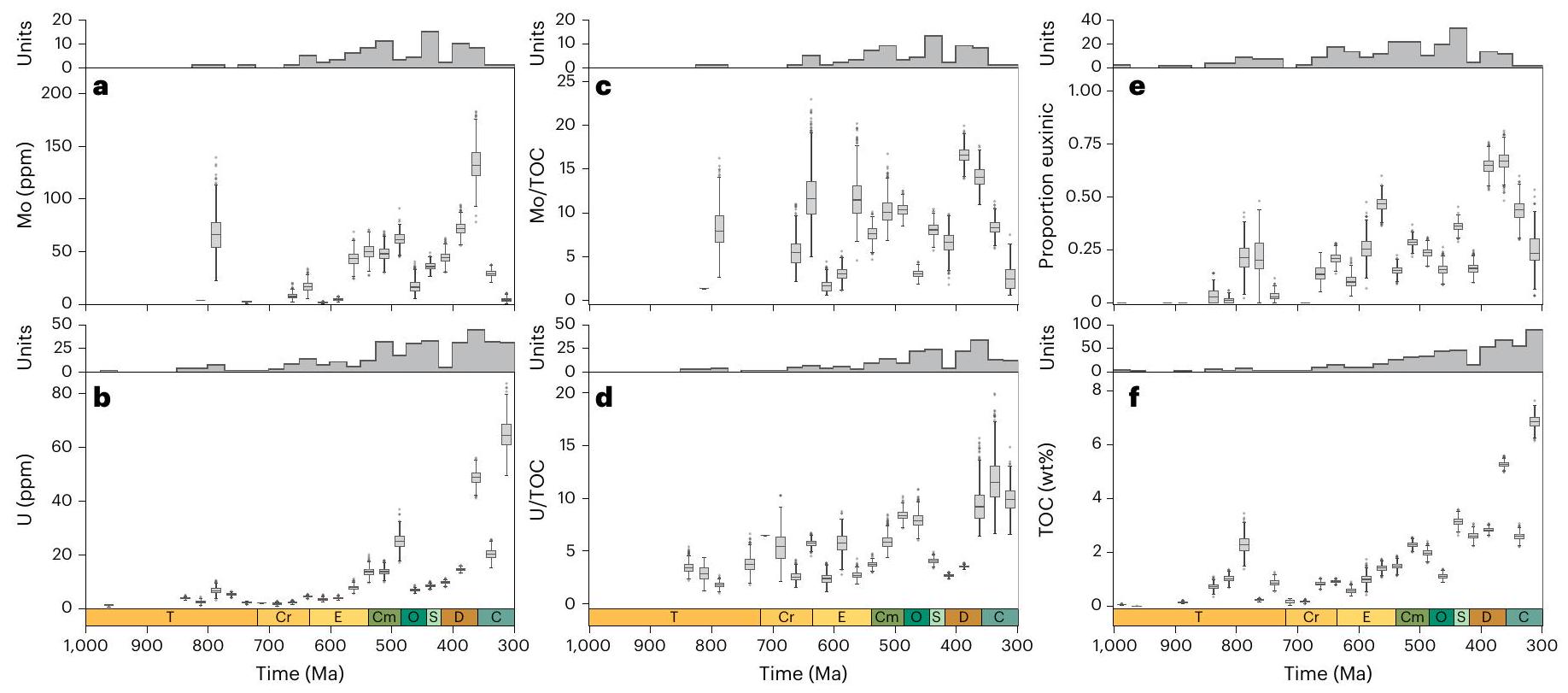

no further than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the lower/upper box boundary, respectively; points indicate outliers from the whisker range. The weighting algorithm inverse weights samples on the basis of their spatial and temporal proximity to other samples in the time

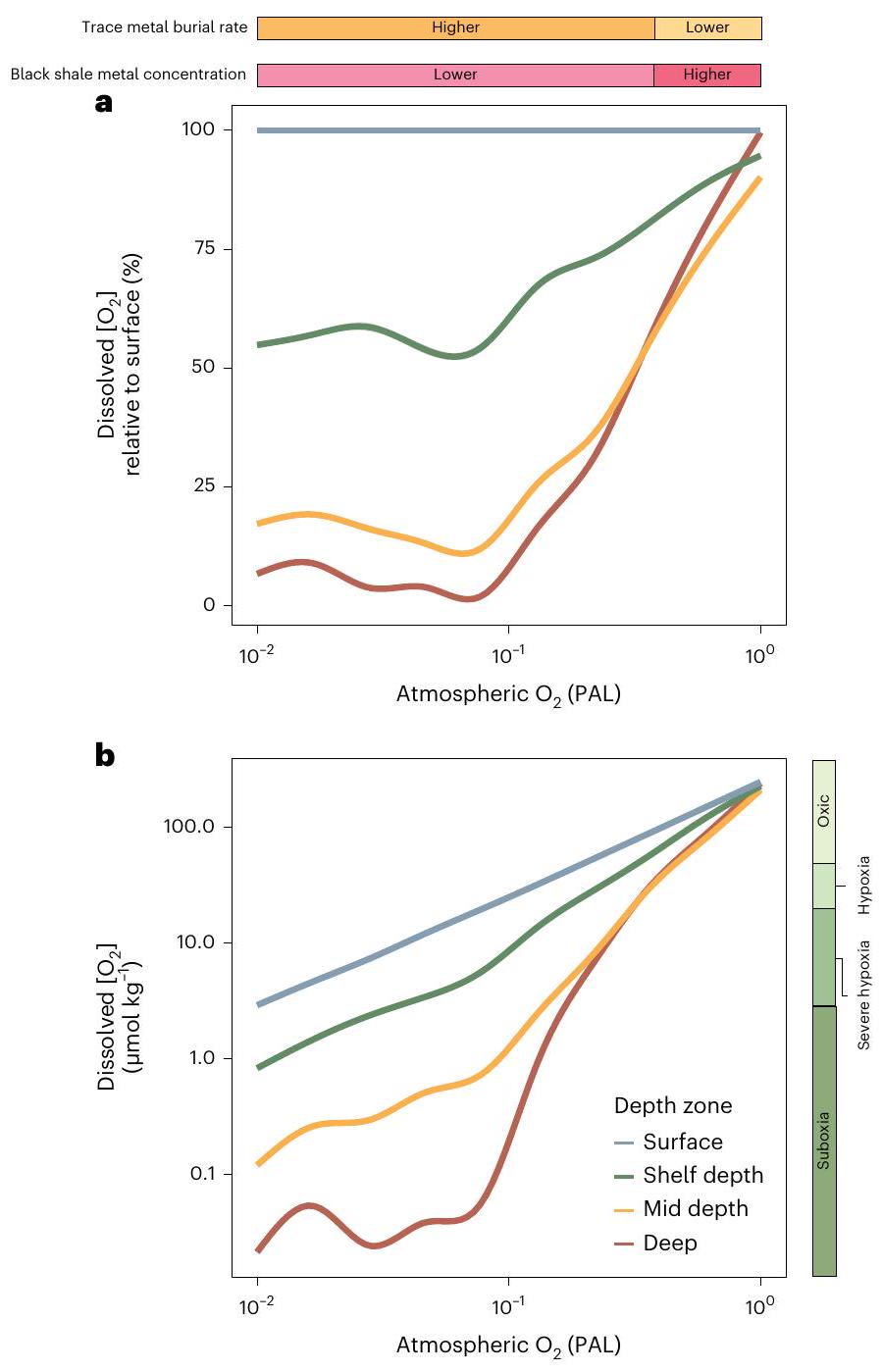

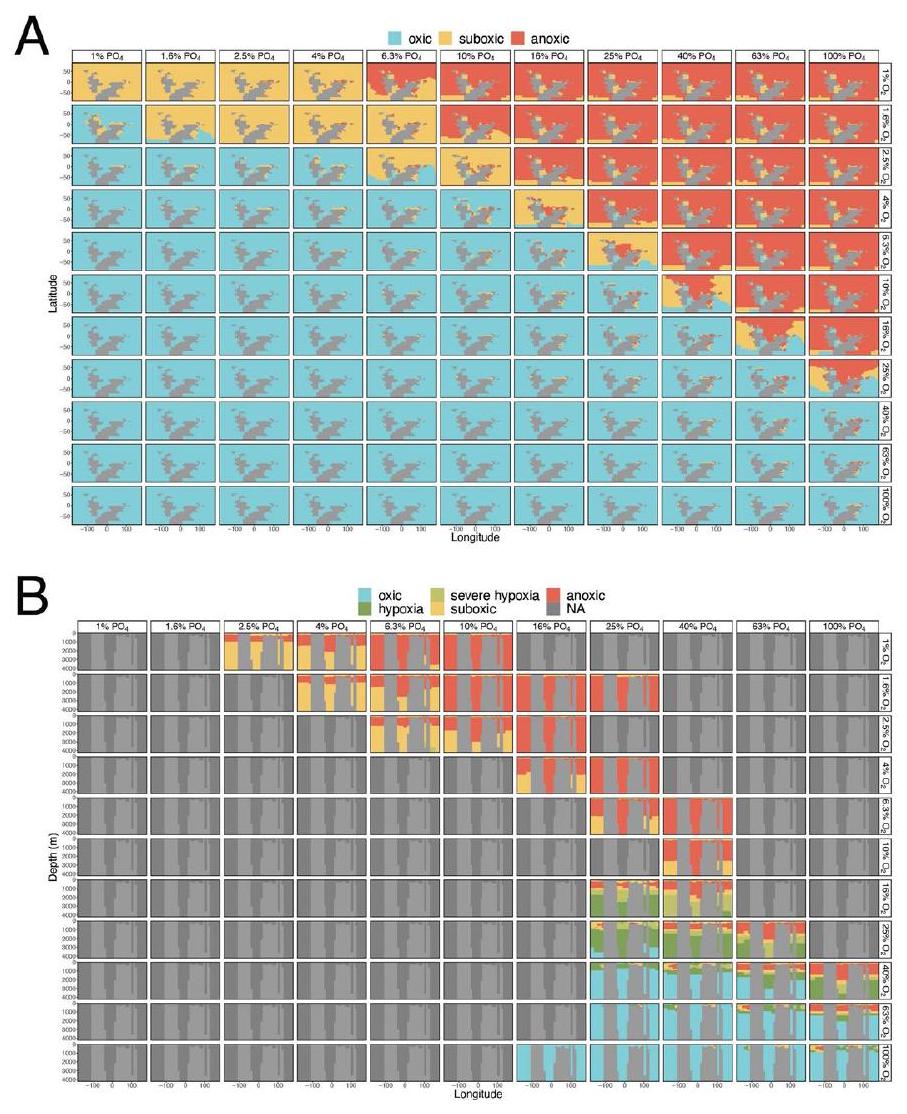

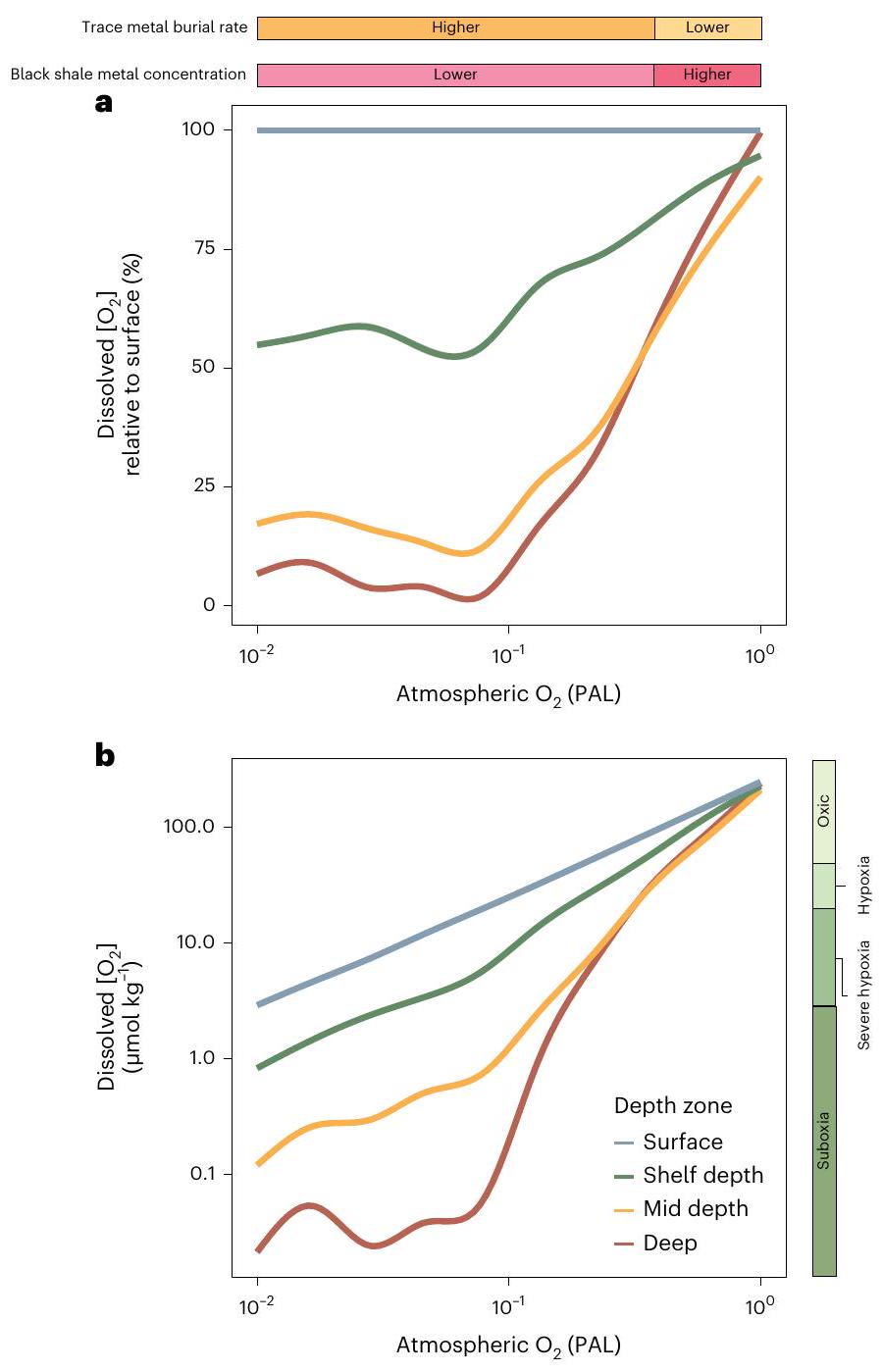

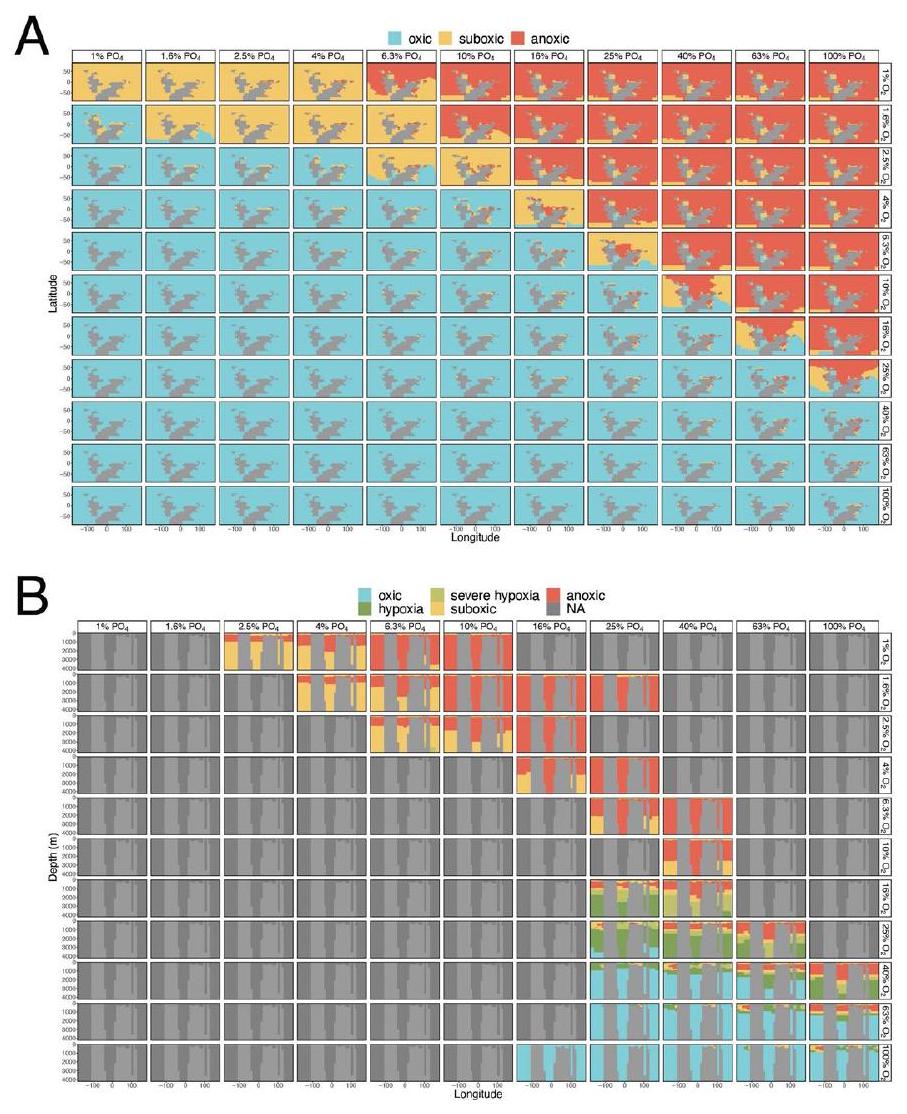

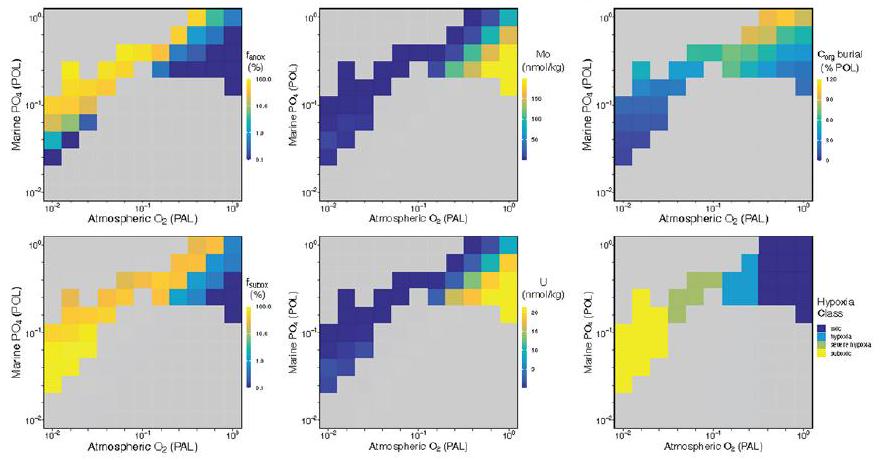

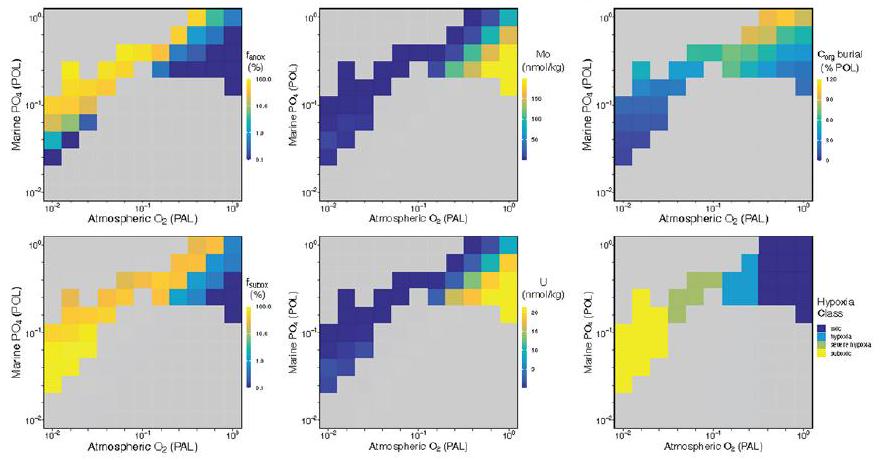

and slope, whereas the majority of modern marine animals and those recorded in the fossil record live in shallow shelf environments. It is therefore the oxygenation of these shallow environments that would control the degree of hypoxic stress experienced by marine animals. While Earth system boundary conditions such as continental configuration can play a major role in global deep-ocean oxygenation at 10 Myr timescales via impacts on ocean circulation

geochemical data and associated geological context assembled by the Sedimentary Geochemistry and Paleoenvironments Project

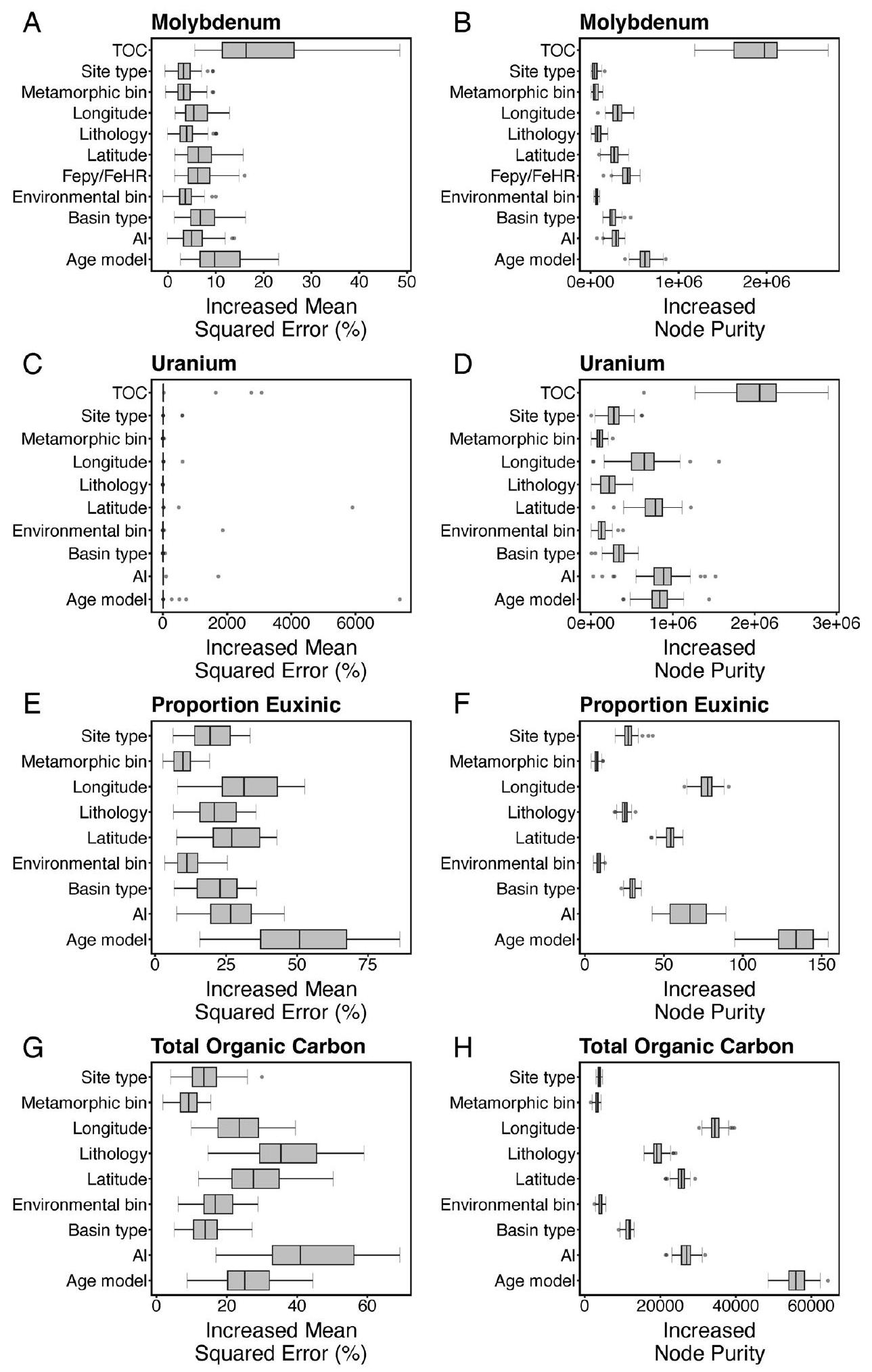

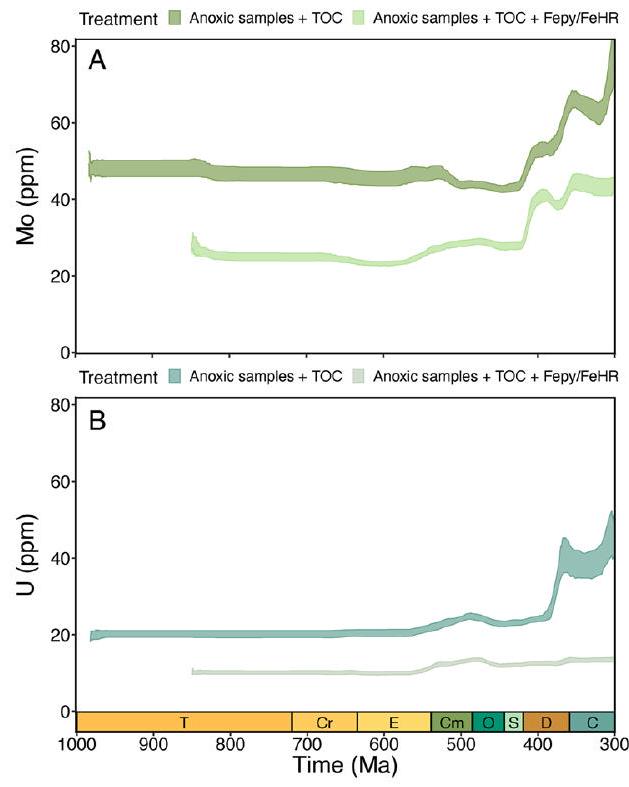

proxies, separated from the complex caveats and interactions that affect interpretations of raw sedimentary data. We use a Monte Carlo random forest framework (with proxy-specific hyperparameter tuning; Methods) to generate partial dependence analyses that isolate the marginal effect of geologic time on the mean value of each geochemical proxy with all identified confounding geochemical and geologic context variables held constant. Although the absolute magnitudes of these results reflect the sampled sedimentary record, the directional trends produced in these statistical learning analyses enable us to reconstruct changes in global biogeochemical cycles. Our partial dependence analyses therefore track seawater metal inventories for Mo and U, sulfide levels in sampled shelf-slope settings for iron speciation and organic carbon fluxes to sampled shelf-slope settings for TOC.

Geochemical proxy records

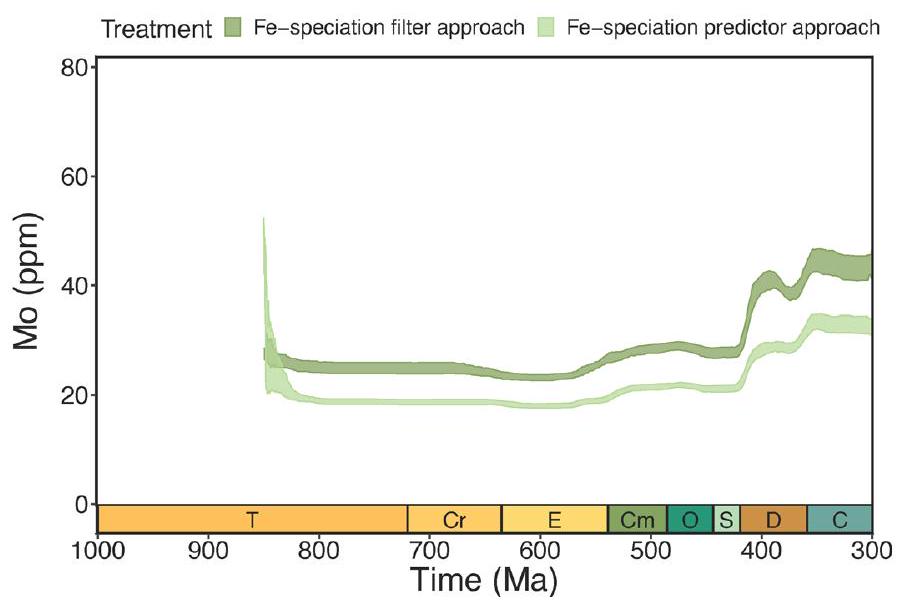

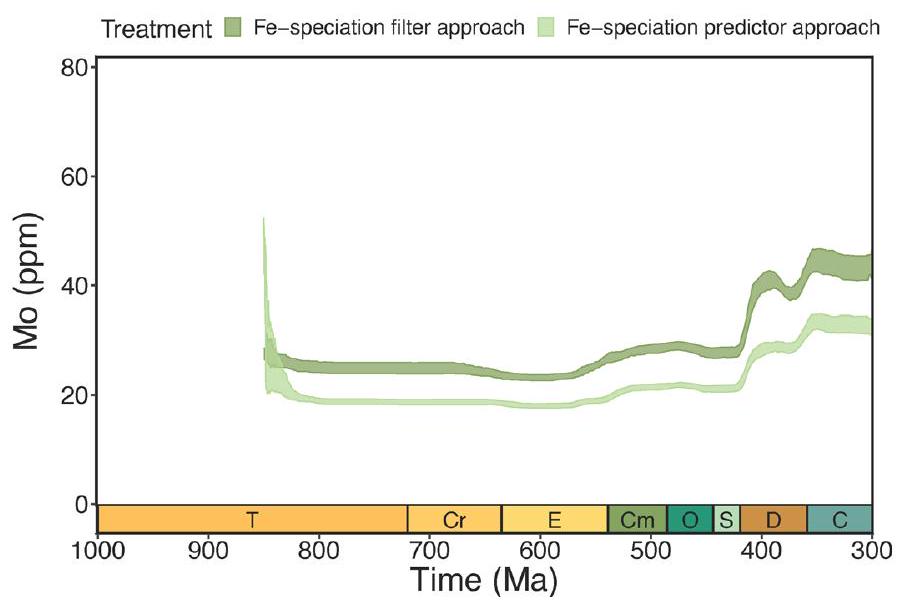

bootstrapped means, but they subsequently decrease in the early Palaeozoic before increasing again in the Devonian (Fig. 1a,b). Distributions of both Mo in euxinic shale and U in anoxic shale show similar trends when temporal and spatial sampling biases are accounted for. When trace metals are standardized to TOC, there is considerable noise in bootstrap means and no clear trend through the Neoproterozoic and early Palaeozoic, although both Mo/TOC and U/TOC increase in the later Devonian (Fig. 1c,d; note low number of units sampled for Mo/TOC in the Carboniferous). These analyses alone, therefore, suggest that there was no major sustained increase in marine Mo or U concentrations until the Devonian, contrasting sharply with previous interpretations of trace metal data.

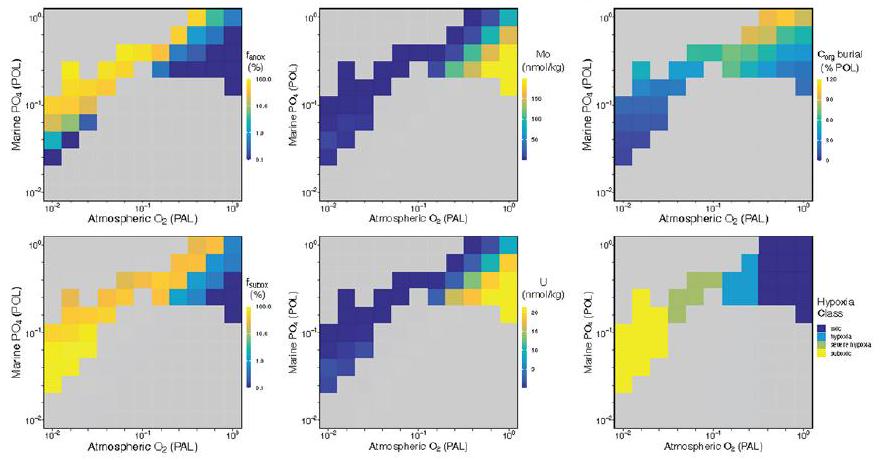

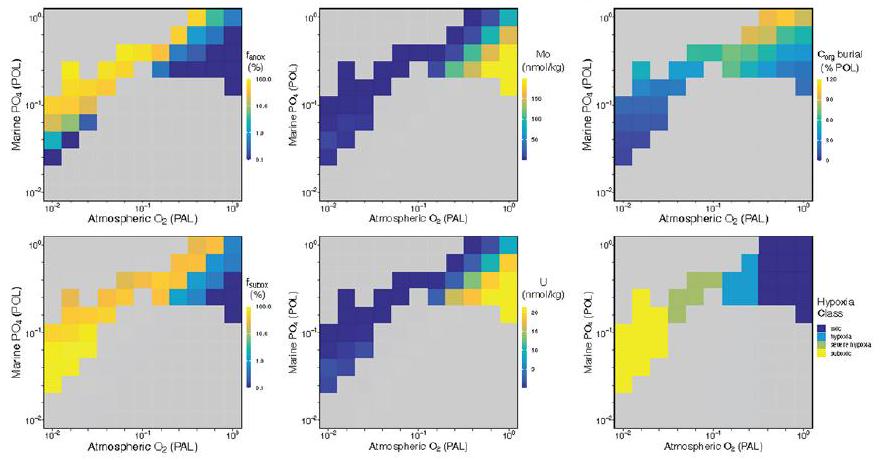

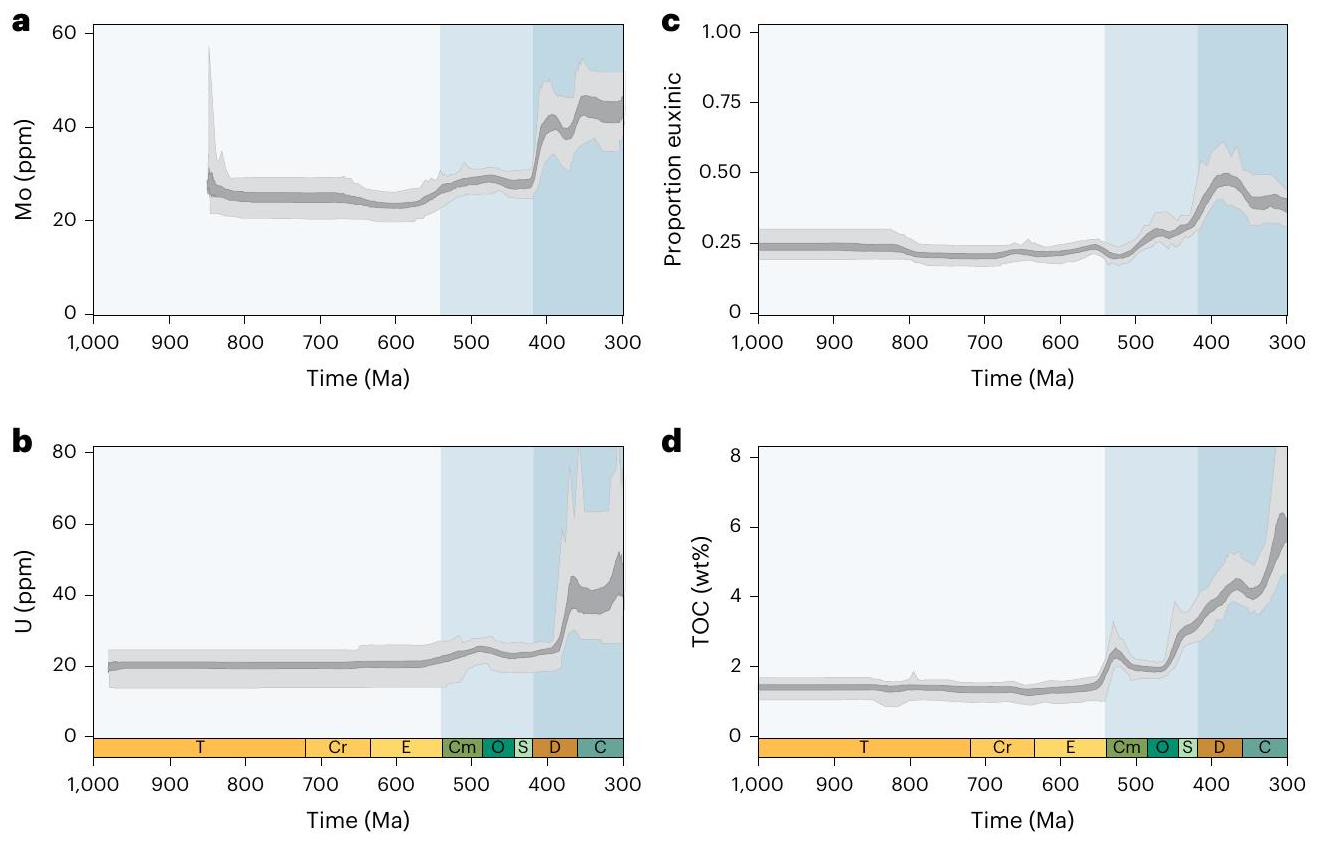

Deconvolved biogeochemical trends

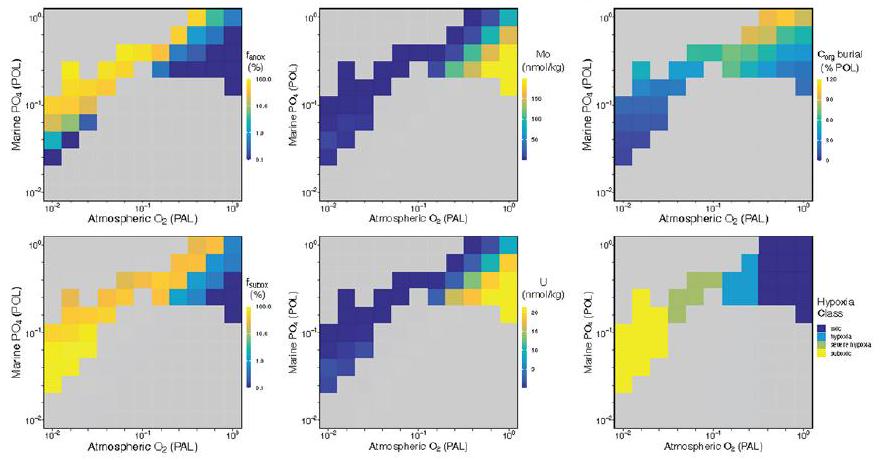

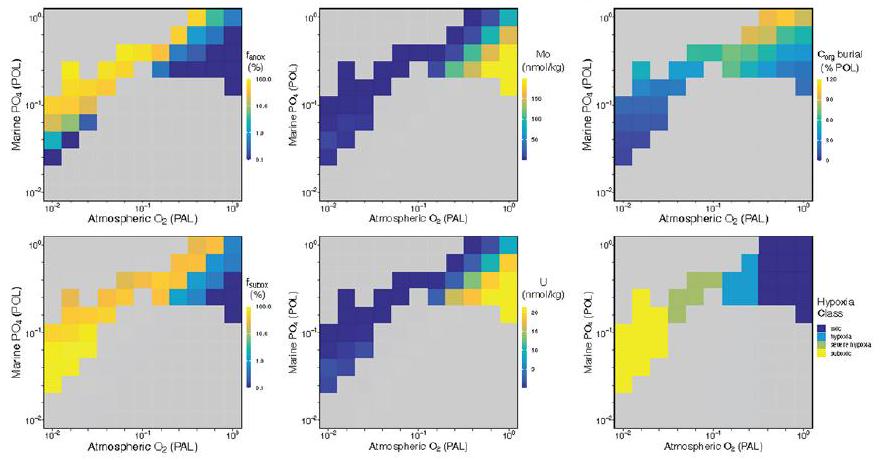

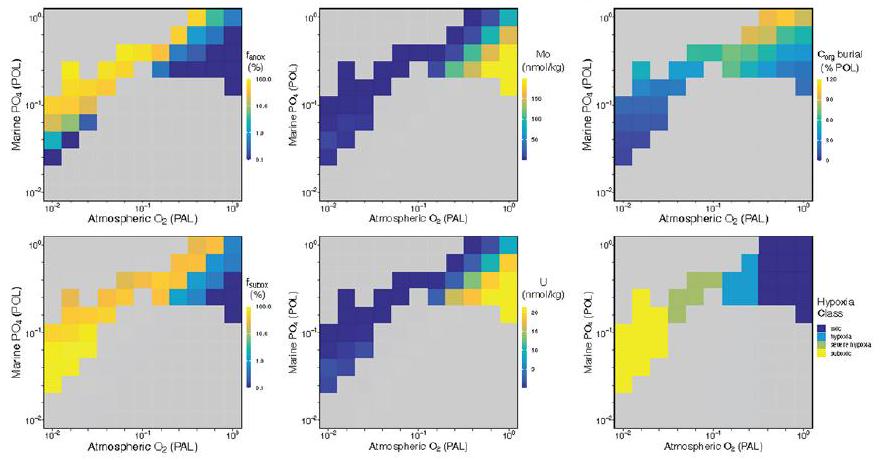

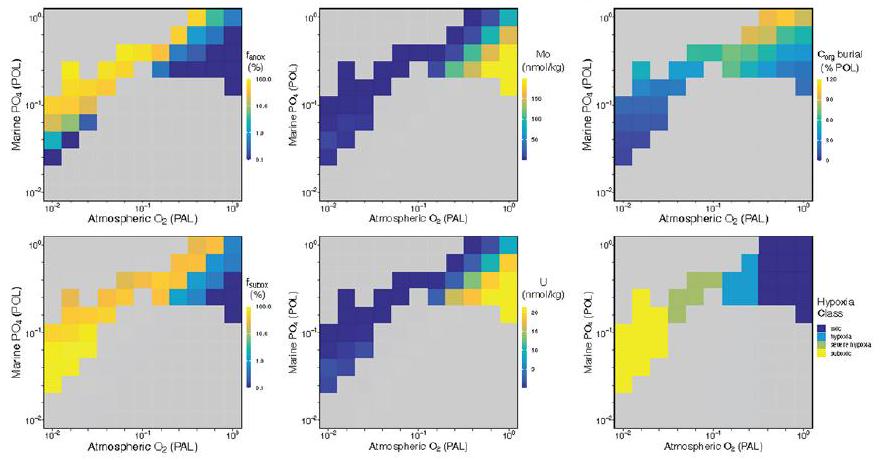

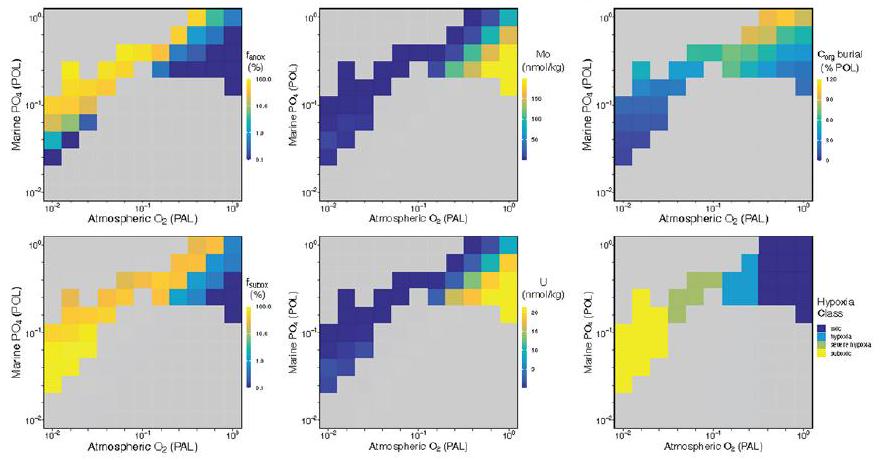

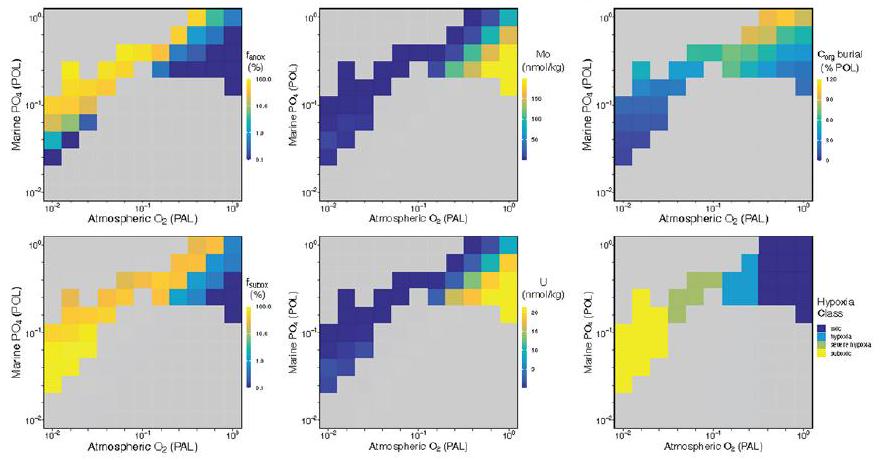

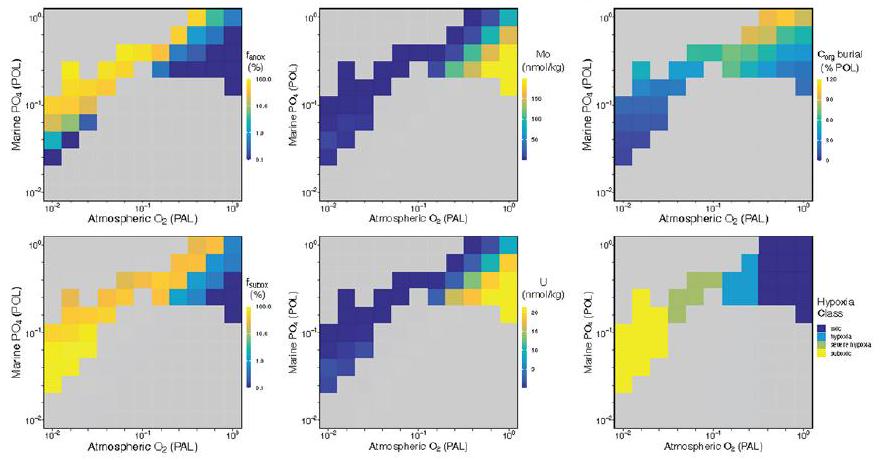

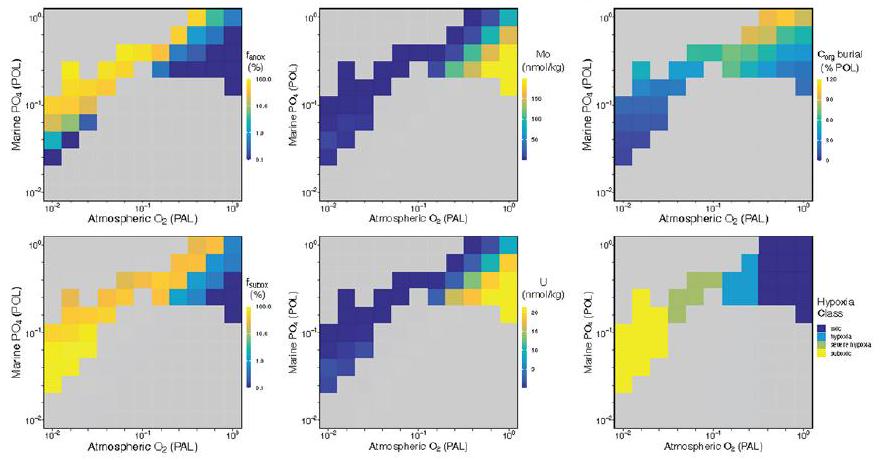

present oceanic levels (POL).

transient increases in trace metal concentrations in the late Neoproterozoic followed by major increases in the mid-Palaeozoic (Fig. 2a,b). This remains the case when iron speciation data are used as predictor data rather than thresholds (Extended Data Fig. 3), indicating the robustness of these trends to specific proxy interpretations (compare ref. 31). The trajectories of the Mo and U differ slightly in the timings and rates of change, although linking subtle temporal contrasts to proxy-specific redox sensitivities would require careful consideration of proxy sample distributions. Notably, these analyses are designed to investigate changes on relatively long geologic timescales and are therefore not expected to capture <

burial in anoxic settings independent of temporal changes in the

Implications for oxygen and productivity

Discussion

of our fossil record is preserved, there was an NOE (Figs. 4 and 5). Specifically, our analyses indicate that shallow marine habitats were probably suboxic or severely hypoxic (

Online content

References

- Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T. & Planavsky, N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307-315 (2014).

- Farquhar, J., Bao, H. & Thiemens, M. Atmospheric influence of Earth’s earliest sulfur cycle. Science 289, 756-758 (2000).

- Crockford, P. W. et al. Triple oxygen isotope evidence for limited mid-Proterozoic primary productivity. Nature 559, 613-616 (2018).

- Kump, L. R. The rise of atmospheric oxygen. Nature 451, 277-278 (2008).

- Cole, D. B. et al. On the co-evolution of surface oxygen levels and animals. Geobiology 18, 260-281 (2020).

- Sperling, E. A., Knoll, A. H. & Girguis, P. R. The ecological physiology of Earth’s second oxygen revolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 46, 215-235 (2015).

- Stolper, D. A. & Keller, C. B. A record of deep-ocean dissolved

from the oxidation state of iron in submarine basalts. Nature 553, 323-327 (2018). - Sperling, E. A. et al. A long-term record of early to mid-Paleozoic marine redox change. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf4382 (2021).

- Dahl, T. W. et al. Devonian rise in atmospheric oxygen correlated to the radiations of terrestrial plants and large predatory fish. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17911-17915 (2010).

- Lu, W. et al. Late inception of a resiliently oxygenated upper ocean. Science 361, 174-177 (2018).

- Wallace, M. W. et al. Oxygenation history of the Neoproterozoic to early Phanerozoic and the rise of land plants. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 466, 12-19 (2017).

- Krause, A. J., Mills, B. J. W., Merdith, A. S., Lenton, T. M. & Poulton, S. W. Extreme variability in atmospheric oxygen levels in the late Precambrian. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm8191 (2022).

- Wei, G. Y. et al. Global marine redox evolution from the late Neoproterozoic to the early Paleozoic constrained by the integration of Mo and U isotope records. Earth Sci. Rev. 214, 103506 (2021).

- Sahoo, S. K. et al. Oceanic oxygenation events in the anoxic Ediacaran ocean. Geobiology 14, 457-468 (2016).

- Pohl, A. et al. Continental configuration controls ocean oxygenation during the Phanerozoic. Nature 608, 523-527 (2022).

- Sperling, E. A. & Stockey, R. G. The temporal and environmental context of early animal evolution: considering all the ingredients of an ‘explosion’. Integr. Comp. Biol. 58, 605-622 (2018).

- Berner, R. A. The Phanerozoic Carbon Cycle (Oxford Univ. Press, 2004); https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195173338.001.0001

- Tribovillard, N., Algeo, T. J., Lyons, T. & Riboulleau, A. Trace metals as paleoredox and paleoproductivity proxies: an update. Chem. Geol. 232, 12-32 (2006).

- Scott, C. et al. Tracing the stepwise oxygenation of the Proterozoic ocean. Nature 452, 456-459 (2008).

- Partin, C. A. et al. Large-scale fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric and oceanic oxygen levels from the record of

in shales. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 369-370, 284-293 (2013). - Sahoo, S. K. et al. Ocean oxygenation in the wake of the Marinoan glaciation. Nature 489, 546-549 (2012).

- Farrell, Ú. C. et al. The Sedimentary Geochemistry and Paleoenvironments Project. Geobiology 19, 545-556 (2021).

- Morford, J. L. & Emerson, S. The geochemistry of redox sensitive trace metals in sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 1735-1750 (1999).

- Poulton, S. W. & Canfield, D. E. Ferruginous conditions: a dominant feature of the ocean through Earth’s history. Elements 7, 107-112 (2011).

- Mehra, A. et al. Curation and analysis of global sedimentary geochemical data to inform Earth history. GSA Today 31, 4-9 (2021).

- Sperling, E. A. et al. Statistical analysis of iron geochemical data suggests limited late Proterozoic oxygenation. Nature 523, 451-454 (2015).

- Ridgwell, A. et al. Marine geochemical data assimilation in an efficient Earth system model of global biogeochemical cycling. Biogeosciences 4, 87-104 (2007).

- Stockey, R. G. et al. Persistent global marine euxinia in the early Silurian. Nat. Commun. 11, 1804 (2020).

- Ozaki, K. & Tajika, E. Biogeochemical effects of atmospheric oxygen concentration, phosphorus weathering, and sea-level stand on oceanic redox chemistry: implications for greenhouse climates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 373, 129-139 (2013).

- Cole, D. B., Ozaki, K. & Reinhard, C. T. Atmospheric oxygen abundance, marine nutrient availability, and organic carbon fluxes to the seafloor. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 36, e2021GB007052 (2022).

- Pasquier, V., Fike, D. A., Révillon, S. & Halevy, I. A global reassessment of the controls on iron speciation in modern sediments and sedimentary rocks: a dominant role for diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 335, 211-230 (2022).

- Alcott, L. J., Mills, B. J. W. & Poulton, S. W. Stepwise Earth oxygenation is an inherent property of global biogeochemical cycling. Science 366, 1333-1337 (2019).

- Brocks, J. J. The transition from a cyanobacterial to algal world and the emergence of animals. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2, 181-190 (2018).

- Laakso, T. A., Sperling, E. A., Johnston, D. T. & Knoll, A. H. Ediacaran reorganization of the marine phosphorus cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 11961-11967 (2020).

- Dahl, T. W. & Hammarlund, E. U. Do large predatory fish track ocean oxygenation? Commun. Integr. Biol. 4, 92-94 (2011).

- Boag, T. H., Gearty, W. & Stockey, R. G. Metabolic tradeoffs control biodiversity gradients through geological time. Curr. Biol. 31, 2906-2913.e3 (2021).

- Penn, J. L., Deutsch, C., Payne, J. L. & Sperling, E. A. Temperaturedependent hypoxia explains biogeography and severity of endPermian marine mass extinction. Science 362, eaat1327 (2018).

- Pohl, A. et al. Why the early Paleozoic was intrinsically prone to marine extinction. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg7679 (2023).

- Stockey, R. G., Pohl, A., Ridgwell, A., Finnegan, S. & Sperling, E. A. Decreasing Phanerozoic extinction intensity as a consequence of Earth surface oxygenation and metazoan ecophysiology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, 2021 (2021).

- Kocsis, Á. T., Reddin, C. J., Alroy, J. & Kiessling, W. The R package divDyn for quantifying diversity dynamics using fossil sampling data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 735-743 (2019).

- D’Antonio, M. P., Ibarra, D. E. & Boyce, C. K. Land plant evolution decreased, rather than increased, weathering rates. Geology 48, 29-33 (2020).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Data processing

Spatial-temporal weighted bootstrap analysis

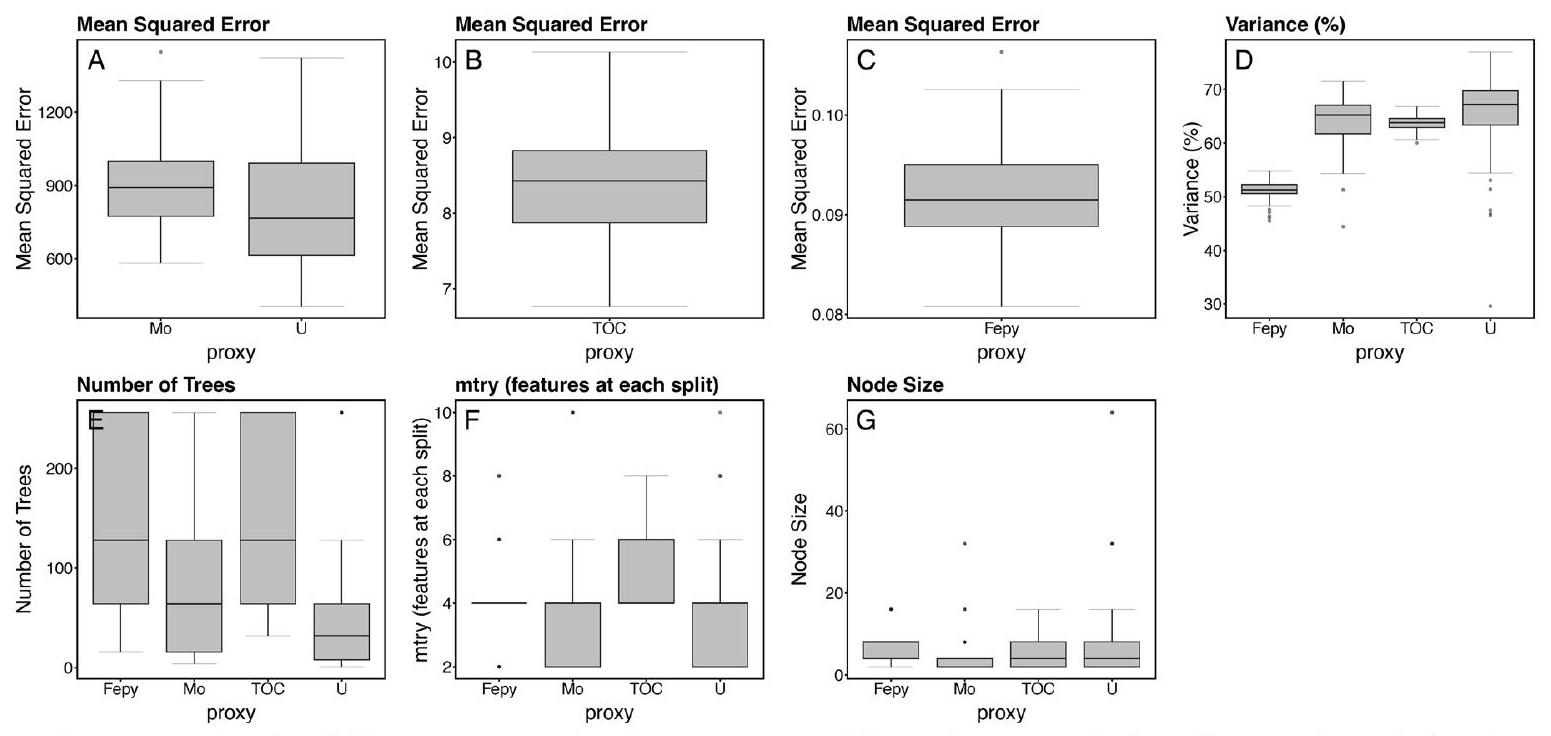

Random forest analyses

lithologies is imputed, and then lithology is randomly assigned. In our Monte Carlo approach, these random value assignments are conducted 100 times for each analysis, corresponding to 100 separate random forest models per proxy/biogeochemical process. The results of these 100 random forest models are then summarized as partial dependence plots and box plots to visualize the uncertainty associated with geologic age models (description follows) and samples with partial data.

- Sections with height/depth data

a. Samples are assigned continuously ascending interpreted age estimates.

b. Samples are all assigned the same interpreted age estimate.

c. Samples are assigned interpreted age estimates in clusters or steps. - Sections without height/depth data

a. Samples are assigned continuously ascending interpreted age estimates.

b. Samples are all assigned the same interpreted age estimate.

c. Samples are assigned interpreted age estimates in clusters or steps. - Sections with only one sample

a. Sample has stratigraphic height/depth.

b. Sample does not have stratigraphic height/depth.

redox and depositional environment? Accumulated local effects plots and other local feature effects models, however, would be expected to better represent average sedimentary enrichments for each geologic time interval (without, for example, standardizing for long-term variations in average local redox) because they do factor in changes in other predictor variables (in our case, characteristics of sedimentary rocks). Consequently, they are less likely to independently track the oceanographic and Earth system changes that we are most interested in investigating. We further choose to present partial dependence plots rather than individual conditional expectation plots because the research questions we address in this study are global in nature and benefit from the changes in global averages we can reconstruct from partial dependence analyses, although individual conditional expectation analyses have exciting potential to provide new insights into local-to-regional datasets. We present partial dependence plots as envelopes, summarizing the 100 random forest models in each Monte Carlo analysis (Fig. 2). The plotted envelopes are generated by linear interpolation of the 100 individual partial dependence plots generated per analysis at 0.1 Myr time intervals and computing the 5th, 25th, 75th and 95th percentiles of the interpolated partial dependence plot populations at each time step. Full Monte Carlo random forest methods are shown in our associated R Markdown files (Code availability).

Earth system modelling

relatively coarse bathymetric grid that is not well suited for explicitly resolving bottom-water environments across steeply sloping shallow shelves because of the spatial coarsening applied to higher-resolution palaeogeographic reconstructions. We therefore employ an approximation of marine shelf environments (ocean cells adjacent to land in the top three layers of the cGENIE ocean, following refs. 38,39), that is, not dependent on a coarsened bathymetric grid and therefore not vulnerable to these spatial limitations. Our application of cGENIE thus enables us to capture well-defined oxygen minimum zones and decoupling of shallow- and deep-water oxygenation for a range of Earth system boundary conditions (Figs. 3 and 4 and Extended Data Fig. 7). These results are not impacted by the coarsened shelf-slope bathymetry inherent to intermediate complexity models. As the bathymetric gradients of deep-water environments are much shallower than on continental shelves, spatial coarsening does not dramatically impact our global estimates of seafloor anoxia, suboxia and oxic conditions. This approximation technique is therefore employed only for modelling shelf environments.

Stable atmospheric

Trace metal mass balance

simulations, but

Organic carbon burial

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Raiswell, R. et al. The iron paleoredox proxies: a guide to the pitfalls, problems and proper practice. Am. J. Sci. 318, 491-526 (2018).

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning-A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable 2nd edn christophm.github.io/ interpretable-ml-book/ (2020).

- Reinhard, C. T. et al. The impact of marine nutrient abundance on early eukaryotic ecosystems. Geobiology 18, 139-151 (2020).

- Meyer, K. M., Ridgwell, A. & Payne, J. L. The influence of the biological pump on ocean chemistry: implications for long-term trends in marine redox chemistry, the global carbon cycle, and marine animal ecosystems. Geobiology 14, 207-219 (2016).

- Reinhard, C. T. et al. Proterozoic ocean redox and biogeochemical stasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 5357-5362 (2013).

- Stockey, R. Richardstockey/sgp.trace.metals: submission for publication. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 11426206 (2024).

- Ridgwell, A. et al. Derpycode/cgenie.muffin: v0.9.46. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 10041805 (2023).

- Ridgwell, A. et al. Derpycode/muffindoc: v0.9.35. Zenodo https:// doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7545814 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

M.A.L., C.L., D.K.L., F.A.M., J.M.M., N.T.M., L.M.O., B.O., A.P., S.E.P., S.M.P., S.W.P., S.R.R., A.D.R., S.S., E.F.S., J.V.S., G.J.U., T.W., R.A.W., C.R.W., I.Y., N.J.P. and E.A.S. provided detailed geological context information on samples, provided unpublished geochemical data and helped interpret results. R.G.S. and E.A.S. wrote the manuscript, with important discussion and contributions from all authors.

Competing interests

Additional information

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01479-1.

regarding these geological and geographic context variables can be found on the SGP wiki (https://github.com/ufarrell/sgp_phase1/wiki/Database-description#geological-context).

correspond to the median of the distribution for each time bin; lower/upper box boundaries correspond to the

model for each proxy. Panel F shows the mtry value for the best fit model for each proxy. Panel G shows the node size for the best fit model for each proxy. Central box lines correspond to the median of the distribution for each time bin; lower/ upper box boundaries correspond to the

analyses. Redox filters are color-coded for each proxy. Envelopes represent the

with modern remineralization depth,D) Cryogenian-Ediacaran continental configuration at 3 PAL

| Proxy | Analysis | Required geochemical data | Filters | Predictor variables | Description | Figure |

| Mo | Spatial-temporal weighted bootstrap | Mo, FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR | FeHR/FeT

|

N/A | Mo in euxinic shale only | 1A |

| U | Spatial-temporal weighted bootstrap | U, [FeHR/FeT OR Fe/Al] | FeHR/FeT

|

N/A | U in anoxic shale only | 1B |

| Mo/TOC | Spatial-temporal weighted bootstrap | Mo, FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR, TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

N/A | Mo/TOC in euxinic shale only | 1C |

| U/TOC | Spatial-temporal weighted bootstrap | U, [FeHR/FeT OR FelAl], TOC | [FeHR/FeT

|

N/A | U/TOC in anoxic shale only | 1D |

| Proportion euxinic | Spatial-temporal weighted bootstrap | FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR | FeHR/FeT

|

N/A | Proportion euxinic in anoxic shale only. (binary coding based on FePy/FeHR) | 1E |

| TOC | Spatial-temporal weighted bootstrap | TOC | None | N/A | TOC in all shales | 1F |

| Mo | Random Forest | Mo, FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR, TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, TOC, FePy/FeHR, Al | Samples from anoxic environments only. Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration, organic carbon loading, detrital input and sulfide levels. | 2A |

| U | Random Forest | U, [FeHR/FeT OR FelAl], TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, TOC, Al | Samples from anoxic environments only. Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration, organic carbon loading and detrital input. | 2B |

| Proportion euxinic | Random Forest | FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR | FeHR/FeT

|

Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, Al | Samples from anoxic environments only. Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration and detrital input. (binary coding based on FePy/FeHR) | 2C |

| TOC | Random Forest | TOC | None | Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, Al | Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration and detrital input. | 2D |

| Mo | Random Forest | Mo, FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR, TOC | None | Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, TOC, FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR, Al | Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration, organic carbon loading, detrital input, highly reactive iron levels and sulfide levels. (testing impact of using iron speciation values rather than thresholds in analyses) | Extended 3 |

| Mo | Random Forest | Mo, [FeHR/FeT OR FelAl], TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, TOC, Al | Samples from anoxic environments only. Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration, organic carbon loading and detrital input. | Extended 6A |

| U | Random Forest | U, FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR, TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, TOC, FePy/FeHR, Al | Samples from anoxic environments only. Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration, organic carbon loading, detrital input and sulfide levels. | Extended 6B |

| Proportion euxinic | Random Forest | FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR, TOC | FeHR/FeT

|

Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, TOC, Al | Samples from anoxic environments only. Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration, organic carbon loading and detrital input. (binary coding based on FePy/FeHR) | Extended 6 C |

| TOC | Random Forest | TOC, [FeHR/FeT OR Fe/Al] | FeHR/FeT

|

Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, Al | Samples from anoxic environments only. Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration and detrital input. | Extended 6D |

| TOC | Random Forest | TOC, FeHR/FeT, FePy/FeHR | FeHR/FeT

|

Age model, site type, metamorphic bin, basin type, site latitude, site longitude, lithology name, environmental bin, FePy/FeHR, Al | Samples from anoxic environments only. Control for depositional environment, post-depositional alteration, detrital input and sulfide levels. | Extended 6D |