DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-023-01567-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38168610

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-02

الطبقة الخارجية المتصلبة ضرورية لتحمل الطماطم للجفاف

تم القبول: 23 أكتوبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 2 يناير 2024

(د) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

تدمج جذور النباتات الإشارات البيئية مع التطور باستخدام تحكم مكاني زمني دقيق. يتضح ذلك في ترسيب السوبرين، وهو حاجز انتشار أبلاستيكي، ينظم تدفق الماء والمواد المذابة والغازات، وهو قابل للتكيف مع البيئة. يُعتبر السوبرين علامة مميزة لتمايز الأندوديرم، لكنه غائب في الأندوديرم للطماطم. بدلاً من ذلك، يوجد السوبرين في الإكسوديرم، وهو نوع من الخلايا غير موجود في الكائن النموذجي أرابيدوبسيس ثاليانا. هنا نوضح أن شبكة تنظيم السوبرين تحتوي على نفس الأجزاء التي تحفز إنتاج السوبرين في الإكسوديرم للطماطم والأندوديرم لأرابيدوبسيس. على الرغم من هذا الاستخدام المشترك لمكونات الشبكة، فقد خضعت الشبكة لإعادة توصيل لتحفيز تعبير مكاني مميز مع مساهمات مميزة من جينات معينة. توضح التحليلات الجينية الوظيفية لعامل النسخ MYB92 في الطماطم وإنزيم ASFT أهمية السوبرين الإكسوديرمي لاستجابة النبات لنقص الماء وأن الحاجز الإكسوديرمي يؤدي وظيفة مكافئة لتلك الخاصة بالأندوديرم ويمكن أن يعمل بدلاً منها.

تم توضيح تخليق السوبرين والتنظيم النسخي لهذه العملية التخليقية باستخدام الأدمة الجذرية لنبات الأرابيدوبسيس كنموذج.

استجابة لنقص المياه. حددنا وحدة تعبير مشترك للجينات المحتملة المتعلقة بالسوبرين، بما في ذلك المنظمات النسخية، وقمنا بالتحقق من صحة هؤلاء المرشحين من خلال إنشاء خطوط جذر شعر الطماطم متعددة الطفرات باستخدام CRISPR-Cas9 بواسطة Rhizobium rhizogenes.

النتائج

تطور وتركيب الإكسوديرميس المكسو بالسبيرين

إنزيمات التخليق الحيوي للسوبيرين والمنظمات النسخية

توصيف النسخ في جذور M82 بالإضافة إلى الجذور من 76 خط إدخال طماطم مشتق من

أطلس جذور الطماطم على مستوى الخلية الواحدة لرسم خريطة الإكسوديرميس

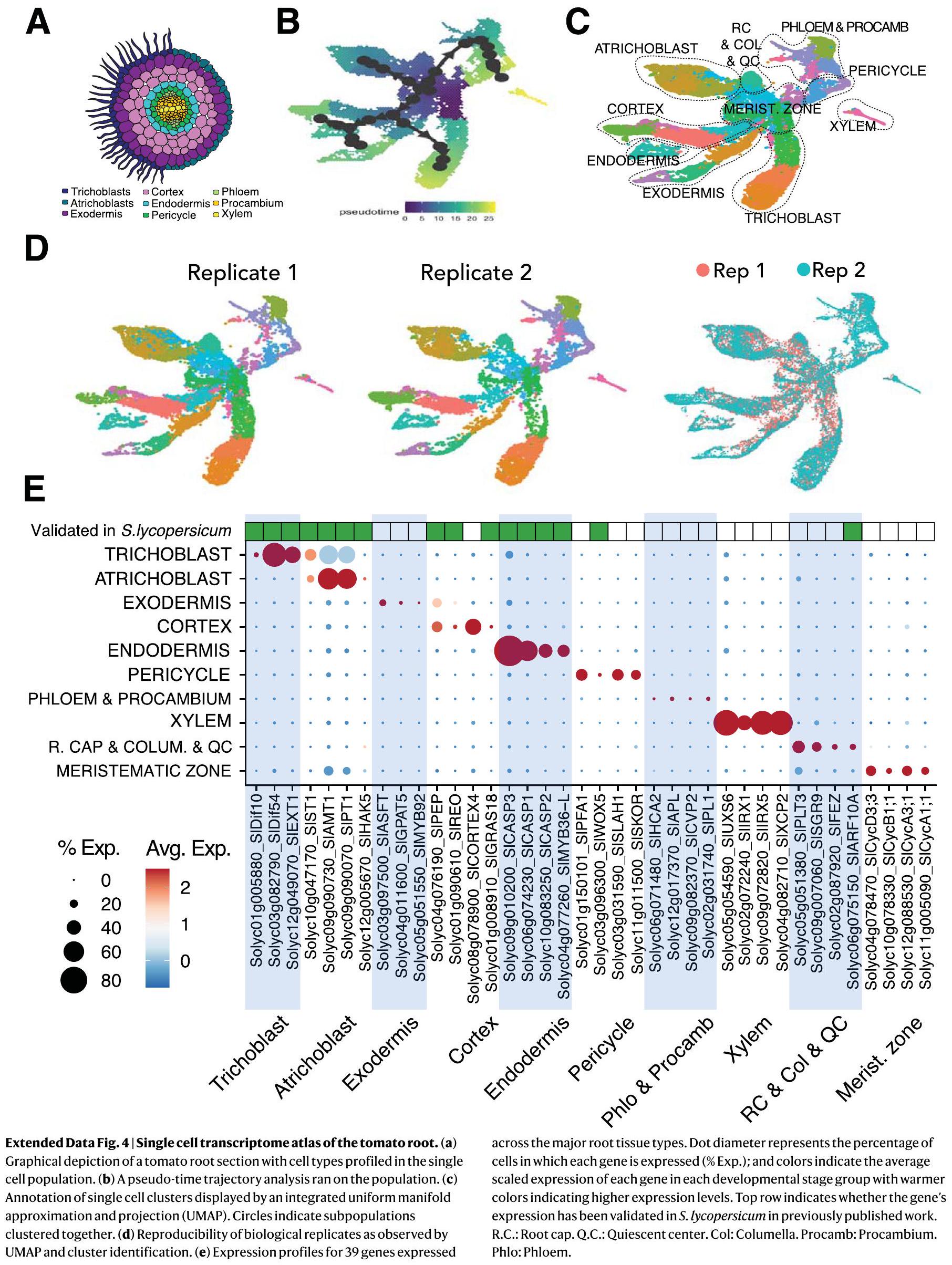

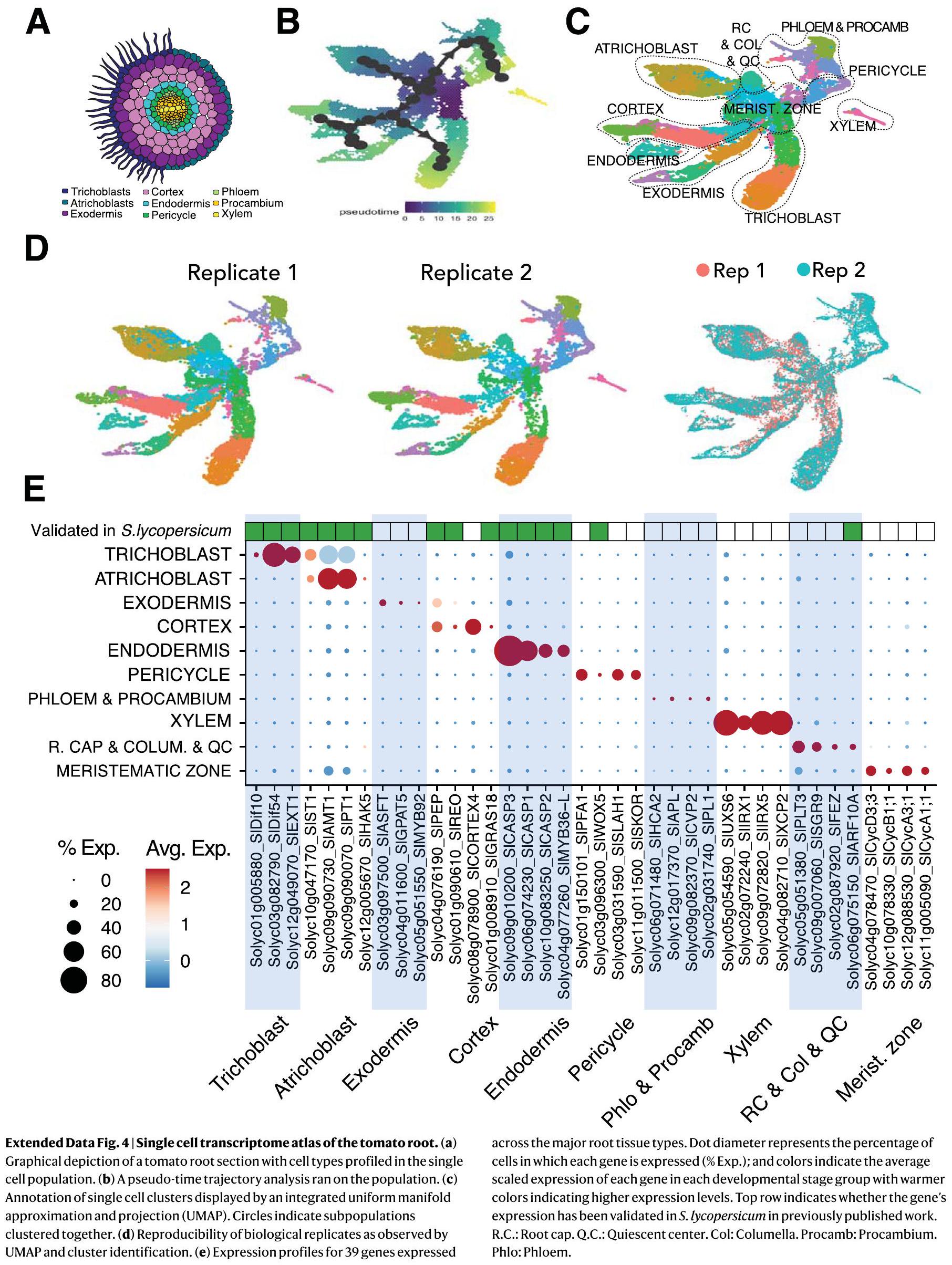

تم ترسيب السوبرين. لتحسين مجموعة الجينات المرتبطة بالسوبرين المرشحة، قمنا بإجراء تحليل التعبير الجيني على مستوى الخلية الواحدة لجذر الطماطم. استخدمنا منصة 10X Genomics scRNA-seq لتحليل أكثر من 20,000 خلية جذر. جمعنا الأنسجة من جذور الطماطم الأولية (M82) التي تبلغ من العمر 7 أيام حتى 3 سم من الطرف لتضمين المنطقة التي يتم فيها ملاحظة ترسيب السوبرين في البداية. تم إنشاء مصفوفات التعبير الجيني باستخدام cellranger وتم تحليلها في Seurat. بمجرد معالجة البيانات مسبقًا وتصفيتها من القطرات ذات الجودة المنخفضة، تم تحليل النسخ الجينية عالية الجودة لـ 22,207 خلية. بعد التطبيع، استخدمنا التجميع غير المراقب لتحديد تجمعات خلوية متميزة (الشكل الممتد 4). ثم تم تعيين هوية نوع الخلية لهذه التجمعات الخلوية باستخدام الأساليب التالية: قمنا أولاً بتقدير التداخل مع مجموعات النسخ الغنية بنوع الخلية الموجودة من جذر الطماطم.

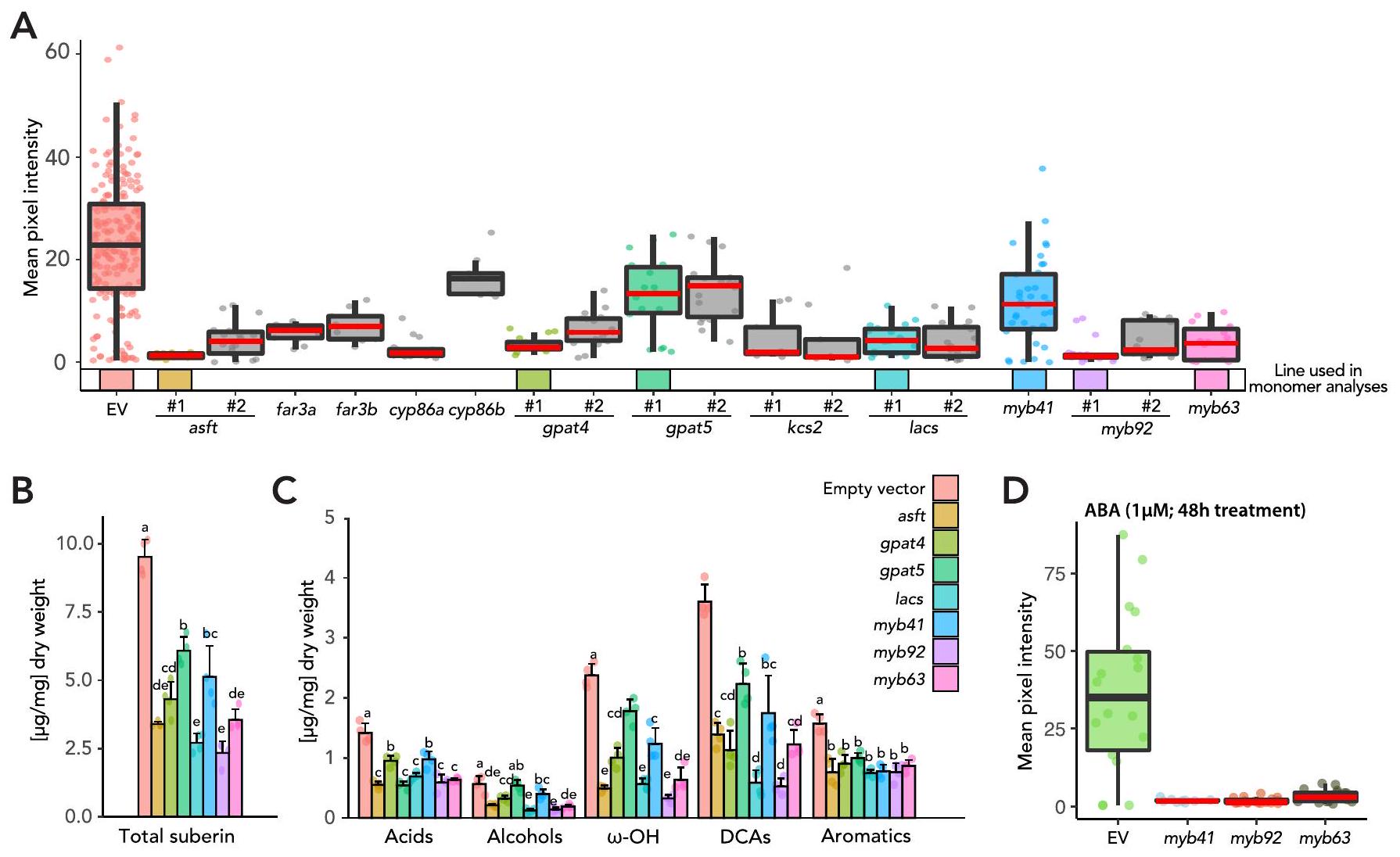

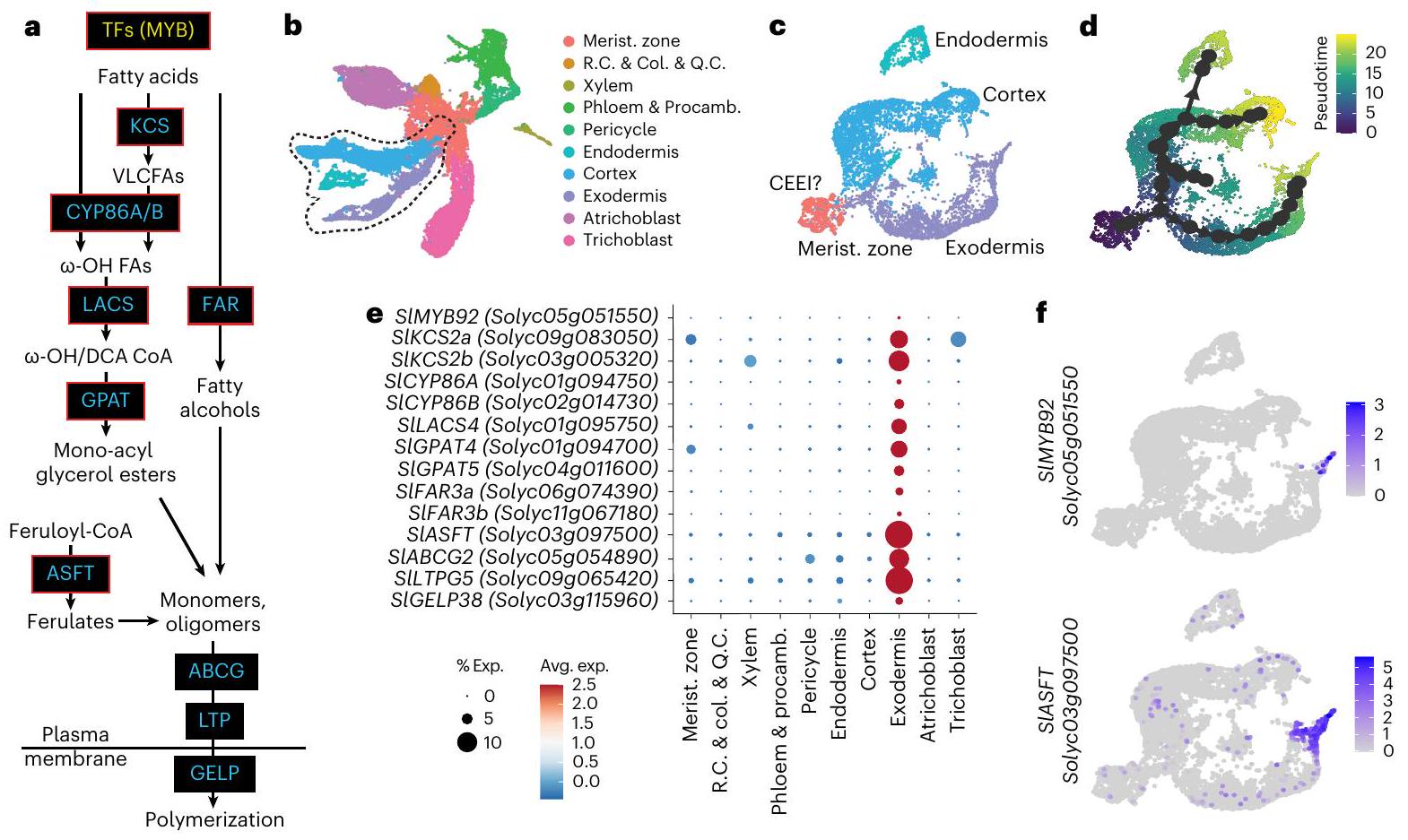

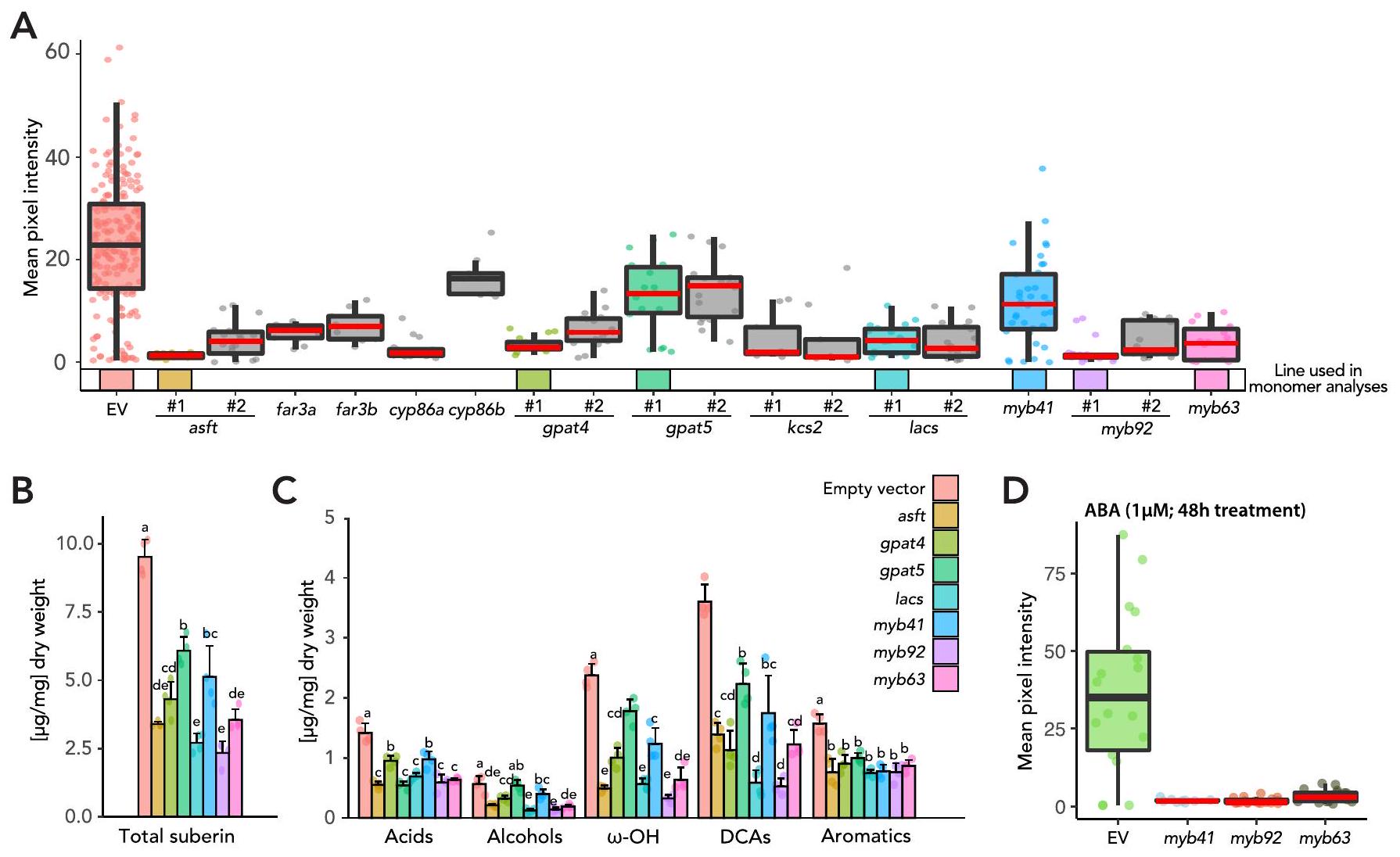

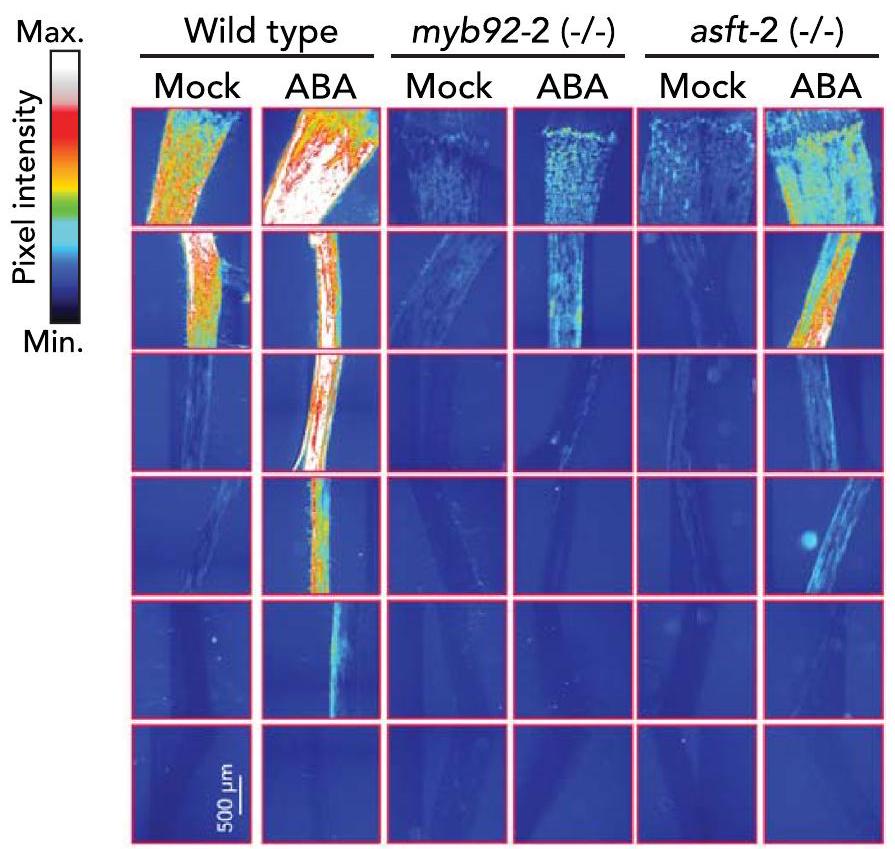

تم تحديد مجموعة الخلايا المرتبطة بمسارات التطور الثلاثة (CEEI) (الشكل 2c، d). ضمن هذه المسارات الثلاثة المرتبطة، قمنا بتحديد الخلايا التي كانت فيها إنزيمات تخليق السوبرين والجهات التنظيمية المحتملة معبرة بشكل عالٍ (الجدول التكميلي 3). من بين هذه، أظهرت النسخ الجينية لـ SIASFT (Solyc03g097500)، واثنين من FAR (SIFAR3A: Solyc06g074390؛ SIFAR3B: Solyc11g067190)، واثنين من CYP86 (SICYPB86A: Solyc01g094750؛ SICYP86B1: Solyc02g014730)، واثنين من KCS2 (SIKCS2a: Solyc09g083050 و SIKCS2b: Solyc03g005320)، واثنين من GPAT (SIGPAT4: Solyc01g094700؛ SlGPAT5: Solyc04g011600) وواحد من LACS (SILACS4: Solyc01g095750) تعبيرًا مقيدًا عند أقصى حافة من مسار التطور الإكسودرمي (الشكل 2e، f، والأشكال التكملية 2 و 3). قمنا بإنشاء تقرير نسخي يتكون من محفز SIASFT مرتبط ببروتين الفلورسنت الأخضر (GFP) المحلي في النواة وأكدنا أن تعبيره مقيد بالإكسودرم باستخدام جذور شعرية (الشكل البياني الممتد 5)، بما يتماشى مع تحليلنا على مستوى الخلية الواحدة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، من بين ثلاثة عوامل نسخ تم الإشارة إليها سابقًا (SIMYB41، SIMYB63 و SIMYB92)، أظهر فقط SIMYB92 تعبيرًا محددًا ومقيدًا في الخلايا عند طرف مسار الإكسودرم (الشكل 2f والأشكال التكملية 3). بناءً على بيانات التعبير المشترك ومسار الخلايا، كانت هذه الجينات مرشحة محتملة لتنظيم النسخ الخاص بالسوبرين وإنزيمات تخليق السوبرين.

إسقاط الجينات المرشحة يعطل ترسيب السوبرين

في تصنيف الأنسجة، أظهر جميع الطفرات باستثناء طفرة slcyp86b انخفاضًا في السوبرين (الشكل 3ب). تم الحصول على تأكيد إضافي لانخفاض مستويات السوبرين من خلال تحليل الأيض لمونومرات السوبرين في الطفرات slgpat5 و slgpat4 و slasft و sllacs و slmyb92 (الشكل التمديدي 6). وشملت هذه الانخفاض الجماعي لمكونات حمض الفيروليك وحمض السينا بيك؛ الأحماض الدهنية (C20 و C22 و C24)،

كلا من ارتباط جدار الخلية والتصاق بين الطبقات، و

قمنا بمعالجة جذور slmyb92 و slasft بـ

تغيير ترسيب السوبيرين يؤثر على استجابة نقص المياه

نقاش

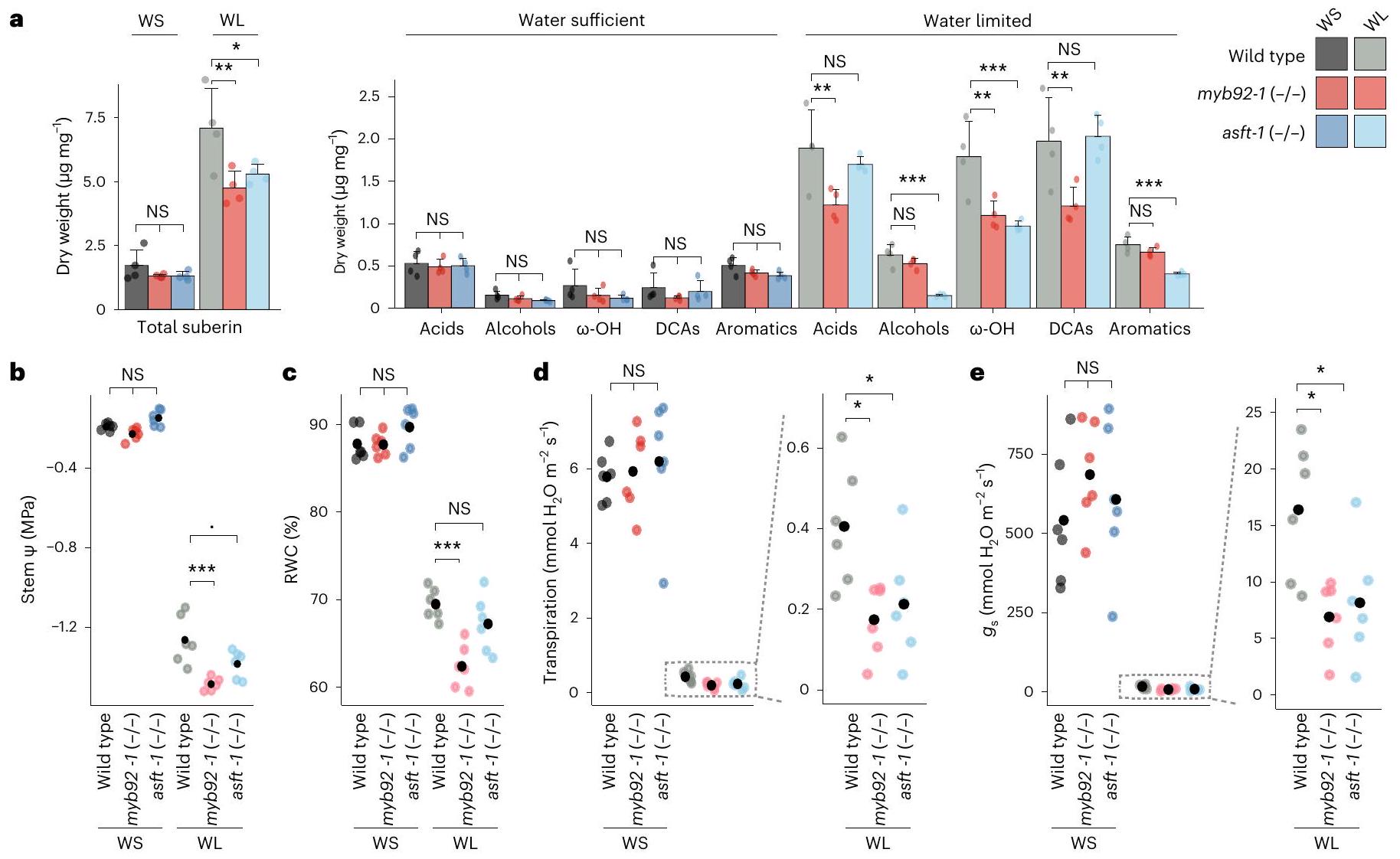

الإيزومرات الفيرولات والكومارات. تشير أشرطة الخطأ إلى الانحراف المعياري. ب-هـ، مخططات نقطية للقيم المسجلة لإمكانات الماء في الساق (الساق

الطفرات في الأليلات slmyb92 و slasft واختبارات ABA، يؤثر هذا العامل النسخي وإنزيم التخليق الحيوي على أنماط ترسيب السوبرين المرتبطة بالتطور ووساطة ABA (الشكل 3c، d). ستحدد التحليلات الإضافية للأليلات الطافرة لعوامل النسخ SIMYB41 و SIMYB62 في الطماطم ما إذا كانت التنظيم المتناسق للتطور والاستجابة للضغط في تخليق السوبرين هو القاعدة بالنسبة للسوبرين الخارجي. الدرجة التي يعتمد بها هذا التنظيم على إشارات ABA، كما هو الحال في الأرابيدوبسيس.

بما في ذلك المناطق الجذرية التي تحتوي على سوبيرين غير ناضج. يُعرف AtMYB92 أيضًا بتنظيم تطور الجذور الجانبية في الأرابيدوبسيس جنبًا إلى جنب مع نظيره القريب.

لأهمية السوبيرين في علاقات المياه. هذه الطفرات، باستثناء هورست-2، لديها مستويات أعلى

طرق

المواد النباتية وظروف النمو

مع

تحويل الطماطم

تحليل التعبير الجيني لجذور M82 تحت ضغط الجفاف والفيضانات

معالجة وتحليل بيانات تسلسل RNA للسكان تحت ظروف الجفاف ونقص المياه وخطوط الإدخال

توليد تراكيب كريسبر للطماطم

توليد بناء تقرير النسخ SIASFT الذي يقود GFP موضعي في النواة

توليد وتحليل الطفرات باستخدام كريسبر-كاس9

اختبار نقص المياه

كلوروفورم:ميثانول الطازج (

اختبار ABA

تحليل شبكة التعبير المشترك

عزل البروتوبلاست وتسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية

الجينات المستحثة بواسطة البروتوبلاست

تحليل النسخ الجيني على مستوى الخلية الواحدة

ملف مع تسلسلات عضيات (الميتوكوندريا والبلاستيدات) مضافة. تم تصفية الجينات المستحثة بواسطة البروتوبلاست (الجدول التكميلي 2)، والجينات التي تحتوي على عدّ في 3 خلايا أو أقل، والخلايا ذات الجودة المنخفضة التي تحتوي على أقل من 500 معرف جزيئي فريد (UMIs) والخلايا التي تحتوي على أكثر من 1% من عدّ UMIs التي تنتمي إلى جينات العضيات. ثم تم تطبيع البيانات باستخدام Seurat (الإصدار 4.0.5).

تسمية تجمعات الخلايا المفردة

O2 = مجموع العلامات التي تتداخل مع جميع الكتل الأخرى مجموع (

تم تكرار هذه العملية للعلامات المتداخلة الثانية والثالثة الأعلى حتى تم تصحيح

تحليل المسار

التحليل الهيستوكيميائي والتصويري

وتم صبغها بلون الأنيليين الأزرق

تحليل مونومر السوبيرين

ميكروسكوبية الإلكترون الناقل

شبكة

بناء شجرة النشوء والتطور

الإحصائيات وإمكانية التكرار

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

References

- Baxter, I. et al. Root suberin forms an extracellular barrier that affects water relations and mineral nutrition in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000492 (2009).

- Thomas, R. et al. Soybean root suberin: anatomical distribution, chemical composition, and relationship to partial resistance to Phytophthora sojae. Plant Physiol. 144, 299-311 (2007).

- Barberon, M. et al. Adaptation of root function by nutrient-induced plasticity of endodermal differentiation. Cell 164, 447-459 (2016).

- Molina, I., Li-Beisson, Y., Beisson, F., Ohlrogge, J. B. & Pollard, M. Identification of an Arabidopsis feruloyl-coenzyme A transferase required for suberin synthesis. Plant Physiol. 151, 1317-1328 (2009).

- Serra, O. & Geldner, N. The making of suberin. New Phytol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph. 18202 (2022).

- Franke, R. et al. The DAISY gene from Arabidopsis encodes a fatty acid elongase condensing enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of aliphatic suberin in roots and the chalaza-micropyle region of seeds. Plant J. 57, 80-95 (2009).

- Domergue, F. et al. Three Arabidopsis fatty acyl-coenzyme A reductases, FAR1, FAR4, and FAR5, generate primary fatty alcohols associated with suberin deposition. Plant Physiol. 153, 1539-1554 (2010).

- Compagnon, V. et al. CYP86B1 is required for very long chain omega-hydroxyacid and alpha, omega -dicarboxylic acid synthesis in root and seed suberin polyester. Plant Physiol. 150, 1831-1843 (2009).

- Höfer, R. et al. The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 CYP86A1 encodes a fatty acid

-hydroxylase involved in suberin monomer biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2347-2360 (2008). - Beisson, F., Li, Y., Bonaventure, G., Pollard, M. & Ohlrogge, J. B. The acyltransferase GPAT5 is required for the synthesis of suberin in seed coat and root of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 351-368 (2007).

- Gou, J.-Y., Yu, X.-H. & Liu, C.-J. A hydroxycinnamoyltransferase responsible for synthesizing suberin aromatics in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 18855-18860 (2009).

- Serra, O. et al. A feruloyl transferase involved in the biosynthesis of suberin and suberin-associated wax is required for maturation and sealing properties of potato periderm. Plant J. 62, 277-290 (2010).

- Ursache, R. et al. GDSL-domain proteins have key roles in suberin polymerization and degradation. Nat. Plants 7, 353-364 (2021).

- Shukla, V. et al. Suberin plasticity to developmental and exogenous cues is regulated by a set of MYB transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2101730118 (2021).

- Kosma, D. K. et al. AtMYB41 activates ectopic suberin synthesis and assembly in multiple plant species and cell types. Plant J. 80, 216-229 (2014).

- Cohen, H., Fedyuk, V., Wang, C., Wu, S. & Aharoni, A. SUBERMAN regulates developmental suberization of the Arabidopsis root endodermis. Plant J. 102, 431-447 (2020).

- Lashbrooke, J. et al. MYB107 and MYB9 homologs regulate suberin deposition in angiosperms. Plant Cell 28, 2097-2116 (2016).

- Gou, M. et al. The MYB107 transcription factor positively regulates suberin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 173, 1045-1058 (2017).

- Enstone, D. E., Peterson, C. A. & Ma, F. Root endodermis and exodermis: structure, function, and responses to the environment. J. Plant Growth Regul. 21, 335-351 (2002).

- Perumalla, C. J., Peterson, C. A. & Enstone, D. E. A survey of angiosperm species to detect hypodermal Casparian bands. I. Roots with a uniseriate hypodermis and epidermis. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 103, 93-112 (1990).

- Barberon, M. The endodermis as a checkpoint for nutrients. New Phytol. 213, 1604-1610 (2017).

- Geldner, N. The endodermis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 531-558 (2013).

- Kajala, K. et al. Innovation, conservation, and repurposing of gene function in root cell type development. Cell 184, 3333-3348.e19 (2021).

- Ron, M. et al. Hairy root transformation using Agrobacterium rhizogenes as a tool for exploring cell type-specific gene expression and function using tomato as a model. Plant Physiol. 166, 455-469 (2014).

- Naseer, S. et al. Casparian strip diffusion barrier in Arabidopsis is made of a lignin polymer without suberin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10101-10106 (2012).

- Franke, R. et al. Apoplastic polyesters in Arabidopsis surface tissues-a typical suberin and a particular cutin. Phytochemistry 66, 2643-2658 (2005).

- Kolattukudy, P. E., Kronman, K. & Poulose, A. J. Determination of structure and composition of suberin from the roots of carrot, parsnip, rutabaga, turnip, red beet, and sweet potato by combined gas-liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Plant Physiol. 55, 567-573 (1975).

- Legay, S. et al. MdMyb93 is a regulator of suberin deposition in russeted apple fruit skins. New Phytol. 212, 977-991 (2016).

- Gong, P. et al. Transcriptional profiles of drought-responsive genes in modulating transcription signal transduction, and biochemical pathways in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 3563-3575 (2010).

- Eshed, Y., Abu-Abied, M., Saranga, Y. & Zamir, D. Lycopersicon esculentum lines containing small overlapping introgressions from L. pennellii. Theor. Appl. Genet. 83, 1027-1034 (1992).

- Gur, A. et al. Yield quantitative trait loci from wild tomato are predominately expressed by the shoot. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122, 405-420 (2011).

- Toal, T. W. et al. Regulation of root angle and gravitropism. G3 8, 3841-3855 (2018).

- Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 559 (2008).

- Du, H. et al. The evolutionary history of R2R3-MYB proteins across 50 eukaryotes: new insights into subfamily classification and expansion. Sci. Rep. 5, 11037 (2015).

- Saelens, W., Cannoodt, R., Todorov, H. & Saeys, Y. A comparison of single-cell trajectory inference methods. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 547-554 (2019).

- Bucher, M., Schroeer, B., Willmitzer, L. & Riesmeier, J. W. Two genes encoding extensin-like proteins are predominantly expressed in tomato root hair cells. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 497-508 (1997).

- Bucher, M. et al. The expression of an extensin-like protein correlates with cellular tip growth in tomato. Plant Physiol. 128, 911-923 (2002).

- Howarth, J. R., Parmar, S., Barraclough, P. B. & Hawkesford, M. J. A sulphur deficiency-induced gene, sdi1, involved in the utilization of stored sulphate pools under sulphur-limiting conditions has potential as a diagnostic indicator of sulphur nutritional status. Plant Biotechnol. J. 7, 200-209 (2009).

- von Wirén, N. et al. Differential regulation of three functional ammonium transporter genes by nitrogen in root hairs and by light in leaves of tomato. Plant J. 21, 167-175 (2000).

- Gómez-Ariza, J., Balestrini, R., Novero, M. & Bonfante, P. Cell-specific gene expression of phosphate transporters in mycorrhizal tomato roots. Biol. Fertil. Soils 45, 845-853 (2009).

- Nieves-Cordones, M., Alemán, F., Martínez, V. & Rubio, F. The Arabidopsis thaliana HAK5 K+ transporter is required for plant growth and

acquisition from low solutions under saline conditions. Mol. Plant 3, 326-333 (2010). - Jones, M. O. et al. The promoter from SIREO, a highly-expressed, root-specific Solanum lycopersicum gene, directs expression to cortex of mature roots. Funct. Plant Biol. 35, 1224-1233 (2008).

- Ho-Plágaro, T., Molinero-Rosales, N., Fariña Flores, D., Villena Díaz, M. & García-Garrido, J. M. Identification and expression analysis of GRAS transcription factor genes involved in the control of arbuscular mycorrhizal development in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 268 (2019).

- Li, P. et al. Spatial expression and functional analysis of Casparian strip regulatory genes in endodermis reveals the conserved mechanism in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 832 (2018).

- Bouzroud, S. et al. Auxin Response Factors (ARFs) are potential mediators of auxin action in tomato response to biotic and abiotic stress (Solanum lycopersicum). PLoS ONE 13, eO193517 (2018).

- Shahan, R. et al. A single-cell Arabidopsis root atlas reveals developmental trajectories in wild-type and cell identity mutants. Dev. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2022.01.008 (2022).

- Andersen, T. G. et al. Tissue-autonomous phenylpropanoid production is essential for establishment of root barriers. Curr. Biol. 31, 965-977.e5 (2021).

- Hosmani, P. S. et al. Dirigent domain-containing protein is part of the machinery required for formation of the lignin-based Casparian strip in the root. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14498-14503 (2013).

- Calvo-Polanco, M. et al. Physiological roles of Casparian strips and suberin in the transport of water and solutes. New Phytol. 232, 2295-2307 (2021).

- Beisson, F., Li-Beisson, Y. & Pollard, M. Solving the puzzles of cutin and suberin polymer biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 329-337 (2012).

- Zhu, J.-K. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 247-273 (2002).

- Raghavendra, A. S., Gonugunta, V. K., Christmann, A. & Grill, E. ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 395-401 (2010).

- Gibbs, D. J. et al. AtMYB93 is a novel negative regulator of lateral root development in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 203, 1194-1207 (2014).

- Zimmermann, H. M., Hartmann, K., Schreiber, L. & Steudle, E. Chemical composition of apoplastic transport barriers in relation to radial hydraulic conductivity of corn roots (Zea mays L.). Planta 210, 302-311 (2000).

- Steudle, E. Water uptake by roots: effects of water deficit. J. Exp. Bot. 51, 1531-1542 (2000).

- Thompson, A. The new plants that could save us from climate change. Popular Mechanics https://www. popularmechanics.com/science/green-tech/a14000753/ the-plants-that-could-save-us-from-climate-change/ (2017).

- Pillay, I. & Beyl, C. Early responses of drought-resistant and -susceptible tomato plants subjected to water stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 9, 213-219 (1990).

- Gur, A. & Zamir, D. Unused natural variation can lift yield barriers in plant breeding. PLoS Biol. 2, e245 (2004).

- Holbein, J. et al. Root endodermal barrier system contributes to defence against plant-parasitic cyst and root-knot nematodes. Plant J. 100, 221-236 (2019).

- Kashyap, A. et al. Induced ligno-suberin vascular coating and tyramine-derived hydroxycinnamic acid amides restrict Ralstonia solanacearum colonization in resistant tomato. New Phytol. 234, 1411-1429 (2022).

- Salas-González, I. et al. Coordination between microbiota and root endodermis supports plant mineral nutrient homeostasis. Science 371, eabd0695 (2021).

- To, A. et al. AtMYB92 enhances fatty acid synthesis and suberin deposition in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant J. 103, 660-676 (2020).

- Reynoso, M. A. et al. Evolutionary flexibility in flooding response circuitry in angiosperms. Science 365, 1291-1295 (2019).

- Townsley, B. T., Covington, M. F., Ichihashi, Y., Zumstein, K. & Sinha, N. R. BrAD-seq: Breath Adapter Directional sequencing: a streamlined, ultra-simple and fast library preparation protocol for strand specific mRNA library construction. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 366 (2015).

- Krueger, F. Trim Galore (Babraham Bioinformatics, 2012).

- Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 525-527 (2016).

- Bari, V. K. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE 8 in tomato provides resistance against the parasitic weed Phelipanche aegyptiaca. Sci. Rep. 9, 11438 (2019).

- Karimi, M., Bleys, A., Vanderhaeghen, R. & Hilson, P. Building blocks for plant gene assembly. Plant Physiol. 145, 1183-1191 (2007).

- Sade, N., Galkin, E. & Moshelion, M. Measuring Arabidopsis, tomato and barley leaf relative water content (RWC). Bio-Protocol 5, e1451-e1451 (2015).

- Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F. & Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 495-502 (2015).

- Ron, M. et al. Identification of novel loci regulating interspecific variation in root morphology and cellular development in tomato. Plant Physiol. 162, 755-768 (2013).

- Scrucca, L., Fop, M., Murphy, T. B. & Raftery, A. E. mclust 5: clustering, classification and density estimation using Gaussian finite mixture models. R J. 8, 289-317 (2016).

- Kremer, J. R., Mastronarde, D. N. & McIntosh, J. R. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116, 71-76 (1996).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-023-01567-x.

يتضمن مواد إضافية متاحة في

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-023-01567-x.

www.nature.com/reprints.

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

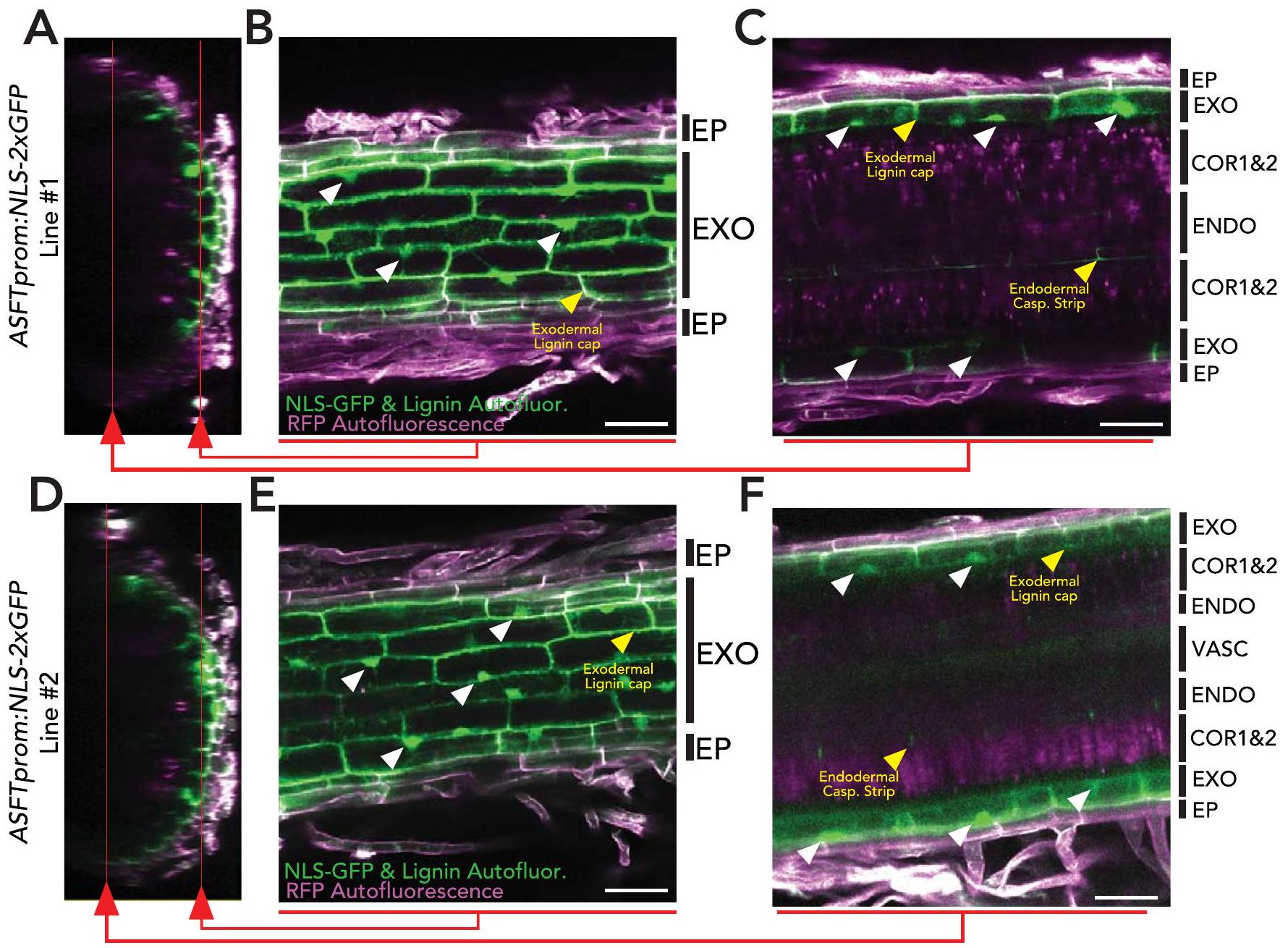

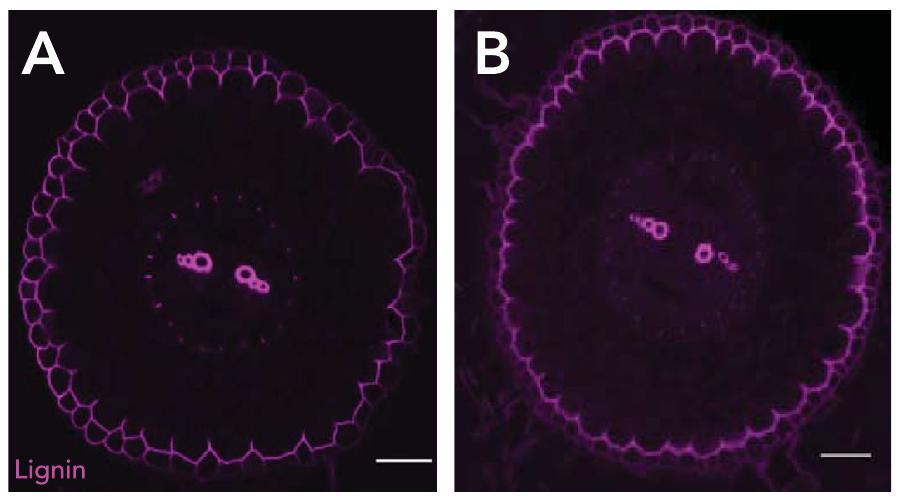

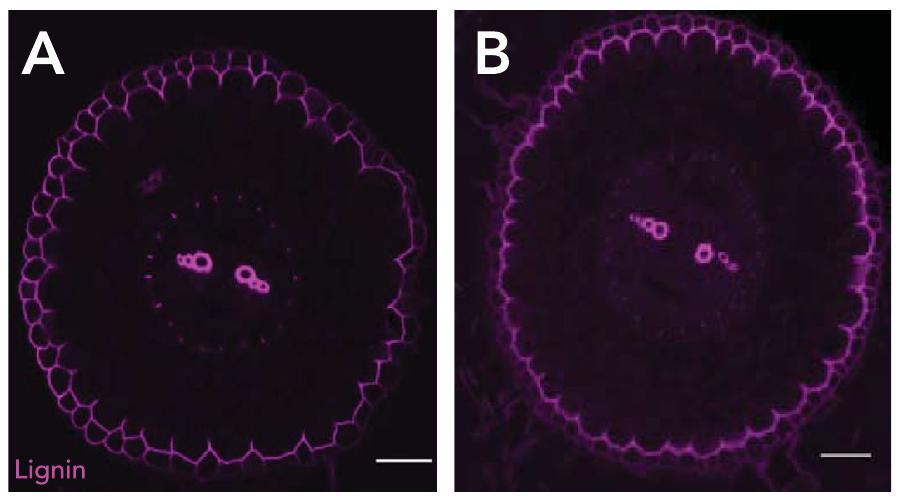

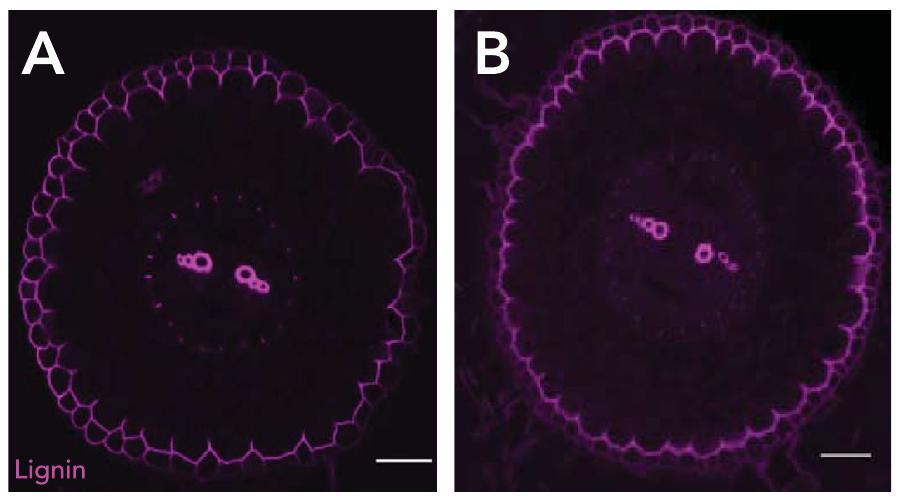

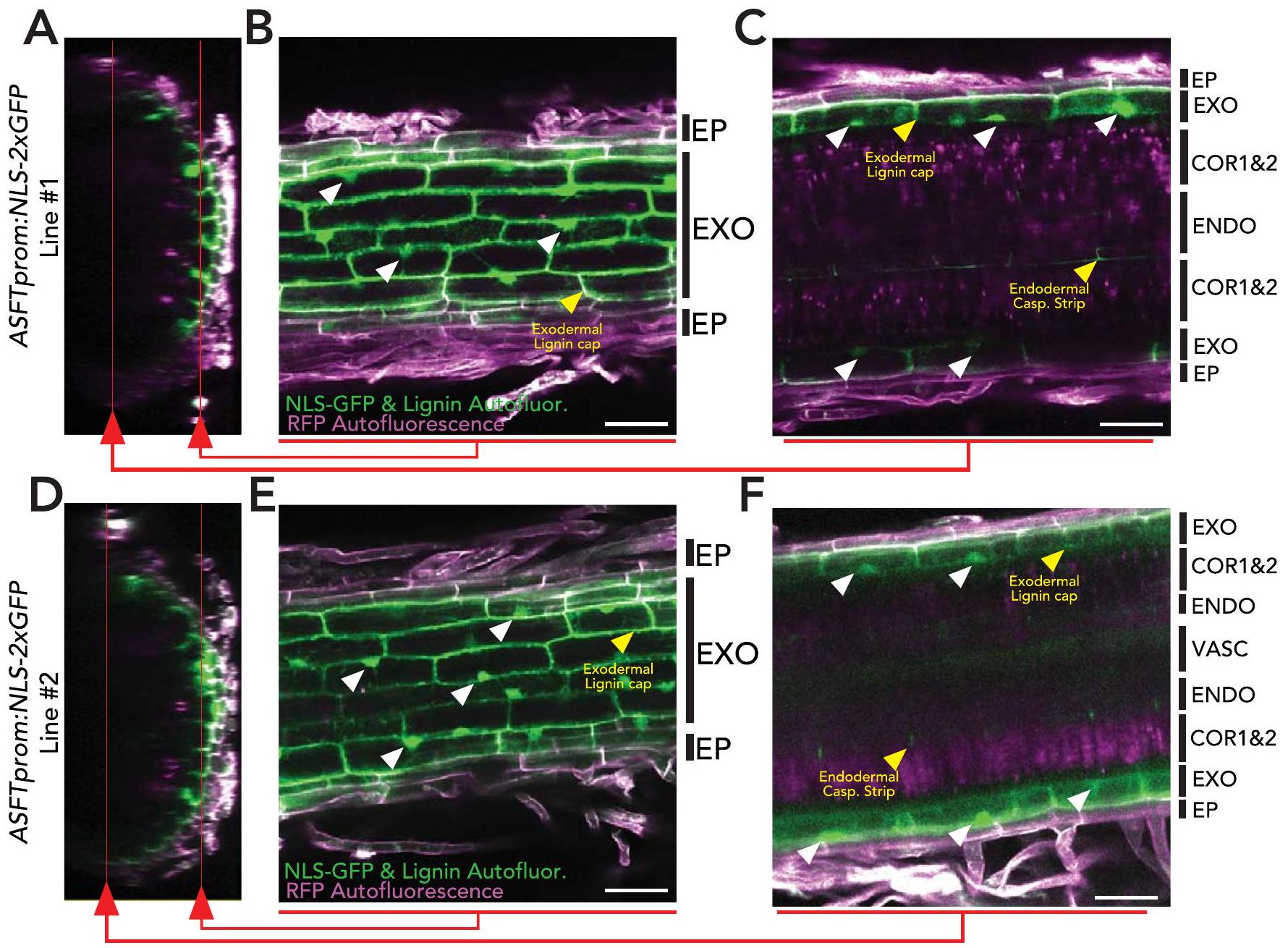

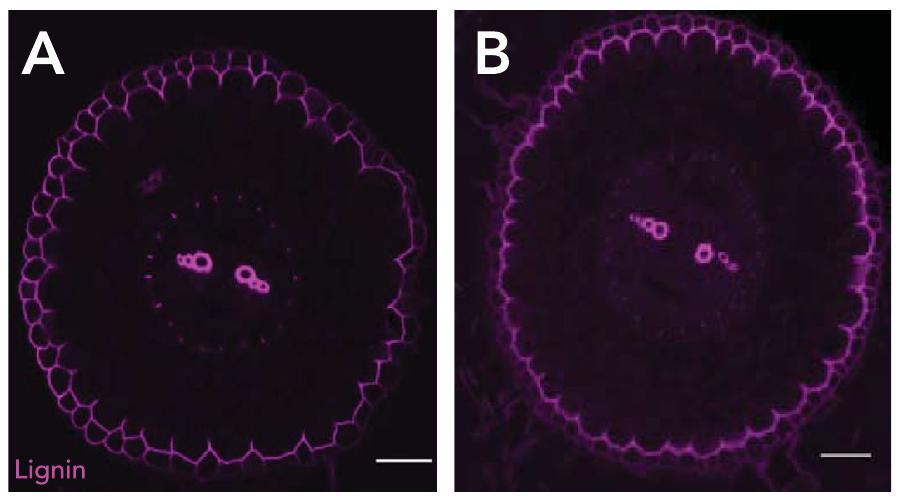

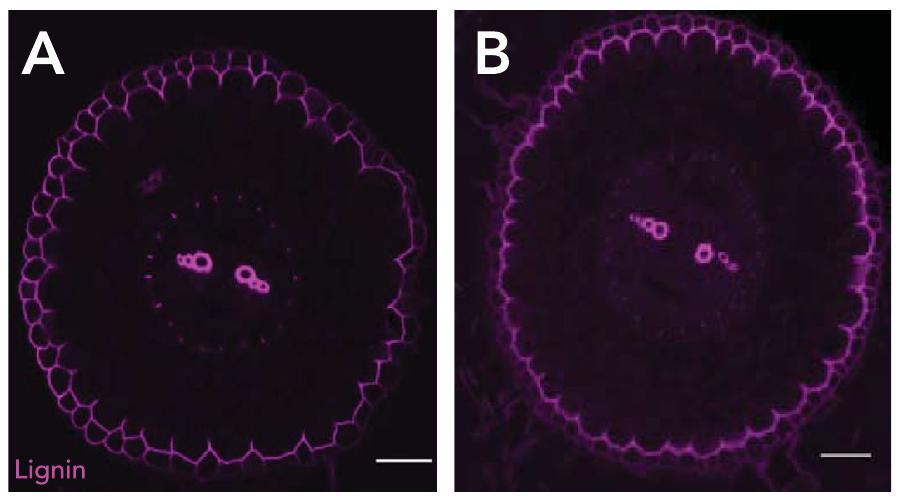

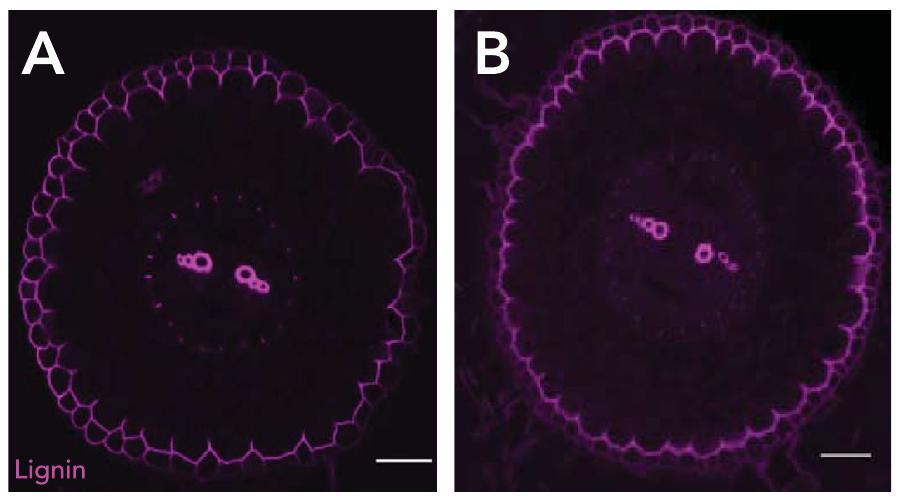

طبقات الخلايا البشرة والإكسوديرم. الأسهم البيضاء تشير إلى بعض النوى المعلمة بـ GFP في الإكسوديرم. الأسهم الصفراء تشير إلى الفلورية الذاتية لللجنين في القمة القطبية للإكسوديرم. (C و F) مقطع طولي من المستوى السفلي لكتل الز-، يظهر البشرة، الإكسوديرم، طبقات القشرة 1 و 2، والإندوديرم. الأسهم البيضاء تشير إلى النوى المعلمة بـ GFP في الإكسوديرم. الأسهم الصفراء تشير إلى الفلورية الذاتية لللجنين في القمة القطبية للإكسوديرم وشريط كاسبارين الإندوديرم. EP: البشرة؛ EXO: الإكسوديرم؛ COR1&2: طبقة القشرة 1 و 2؛ ENDO: الإندوديرم، VASC: الأوعية.

ملطخة بالفوشين الأساسي. ج. مقطع عرضي لطفرات الجذر الشعري myb63 ملطخة بالفوشين الأساسي. د. مقطع عرضي لـ

محفظة الطبيعة

آخر تحديث من المؤلف(ين): 16 أكتوبر 2023

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

يجب أن تُوصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ واصفًا التقنيات الأكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

للتصاميم الهرمية والمعقدة، تحديد المستوى المناسب للاختبارات والتقارير الكاملة عن النتائج

تقديرات أحجام التأثير (مثل حجم تأثير كوهين)

تحتوي مجموعتنا على الإنترنت حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات تتناول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

البرمجيات والشيفرة

جمع البيانات

لم يتم استخدام أي برنامج لجمع البيانات.

قص الشعر RNASEQ: TrimGalore!(v0.6.6); المحاذاة الزائفة: Kallisto v0.43.1 و v0.46.2; التجميع والتعبير المشترك: حزمة R WGCNA v1.70; معالجة البيانات: R v4.1.3; الرسم: ggplot2 v3.3.6. الخلية المفردة: التعيين: cellranger v1.1.0; المعالجة والتحليل: Seurat v4.0.5; صور TEM: EM-MENU v4.0 و IMOD v4.11;

بيانات

يجب أن تتضمن جميع المخطوطات بيانًا حول توفر البيانات. يجب أن يوفر هذا البيان المعلومات التالية، حيثما ينطبق:

- رموز الانضمام، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا

مشاركون في الأبحاث البشرية

| التقارير عن الجنس والنوع الاجتماعي | غير متوفر |

| خصائص السكان | غير متوفر |

| التوظيف | غير متوفر |

| رقابة الأخلاقيات | غير متوفر |

التقارير المتخصصة في المجال

علوم الحياة العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

لنسخة مرجعية من الوثيقة بجميع الأقسام، انظرnature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

تصميم دراسة العلوم الحياتية

| حجم العينة | استخدمنا ثلاث نسخ بيولوجية لتحليل RNA-Seq وأكثر من 20,000 خلية عبر جولتين في تقنيات النسخ الجيني أحادي الخلية 10X، وفقًا للممارسات الشائعة في هذا المجال. تم الإشارة إلى أحجام العينات للتجارب في الأساطير والنص. تم تحليل كل تحليل على الأقل مع ثلاث نسخ بيولوجية، وجولتين من التجارب. أسفرت النسخ البيولوجية عن نتائج مماثلة. لم يتم استخدام أي طريقة إحصائية لتحديد حجم العينة مسبقًا. عمومًا، تم اختيار حجم العينة تجريبيًا، بناءً على الخبرة السابقة حول مدى كبر حجم العينة الذي يجب أن يكون للحصول على نتيجة قابلة للتكرار وذات دلالة إحصائية على الأرجح. |

| استثناءات البيانات | لم يتم استبعاد أي بيانات من التحليل. |

| التكرار | تم إجراء ما لا يقل عن 3 تكرارات بيولوجية ودورتين مستقلتين من التجارب لكل تجربة لتقييم الجودة وقابلية تكرار الإجراء والأهمية الإحصائية. يتم تقديم عدد التكرارات في أساطير الأشكال حيثما كان ذلك مناسبًا. |

| التوزيع العشوائي | تم تعيين النباتات عشوائيًا إلى أنظمة كافية من المياه أو محدودة المياه لتجارب الجفاف. تم توزيع الأواني عشوائيًا حول غرفة النمو وتم خلطها كل يومين أثناء الري طوال مدة التجارب. عند التعامل مع طفرات CRISPR، سواء في الجذور المستقرة أو الشعرية، تم أخذ عدة أليلات مستقلة لتقليل التحيز ومخاطر التأثيرات غير المستهدفة. |

| عمى | تم إجراء تجارب النسخ الجيني دون معرفة مسبقة بنتيجة التجربة، وبالتالي لم يتم تطبيق التعمية. تم جمع وتحليل البيانات المتعلقة بالنمط الظاهري والتحليل المجهري من قبل عدة باحثين بشكل مستقل مع نتائج مشابهة. تم جمع بيانات تجربة الجفاف بشكل فعال وبطريقة عمياء من قبل باحثين مختلفين يقومون بأخذ عينات عشوائية دون معرفة مسبقة بإعداد العينة، وتم تسجيل القراءات في جهاز LICOR، وفقط بعد جمع البيانات تم تنزيلها وتحليلها. |

التقارير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | طرق | ||

| غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة | غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة |

| إكس |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

علم الحفريات وعلم الآثار |  |

تصوير الأعصاب باستخدام الرنين المغناطيسي |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| شر | البحث ذو الاستخدام المزدوج الذي يثير القلق | ||

قسم بيولوجيا النباتات ومركز الجينوم، جامعة كاليفورنيا، ديفيس، ديفيس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. إشارات النبات والبيئة، معهد البيولوجيا البيئية، جامعة أوترخت، أوترخت، هولندا. مدرسة علوم النبات والبيئة، جامعة فيرجينيا تك، بلاكسبرغ، فيرجينيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم بيولوجيا النباتات الجزيئية، جامعة لوزان، لوزان، سويسرا. مرفق المجهر الإلكتروني، جامعة لوزان، لوزان، سويسرا. معهد علم النبات الخلوي والجزيئي، جامعة راينيش فريدريش فيلهلم، بون، ألمانيا. قسم بيولوجيا النباتات، جامعة كاليفورنيا، ديفيس، ديفيس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز بيولوجيا خلايا النباتات، قسم علم النبات وعلوم النباتات، جامعة كاليفورنيا، ريفرسايد، ريفرسايد، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علوم النبات، جامعة كاليفورنيا، ديفيس، ديفيس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. العنوان الحالي: قسم البيولوجيا التطورية والبيئية، كلية العلوم الطبيعية، معهد التطور، جامعة حيفا، حيفا، إسرائيل. الراحلة: شارون غراي. البريد الإلكتروني: sbrady@ucdavis.edu - تم إيداع بيانات تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية والكمية في GEO: GSE212405.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-023-01567-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38168610

Publication Date: 2024-01-02

A suberized exodermis is required for tomato drought tolerance

Accepted: 23 October 2023

Published online: 2 January 2024

(D) Check for updates

Abstract

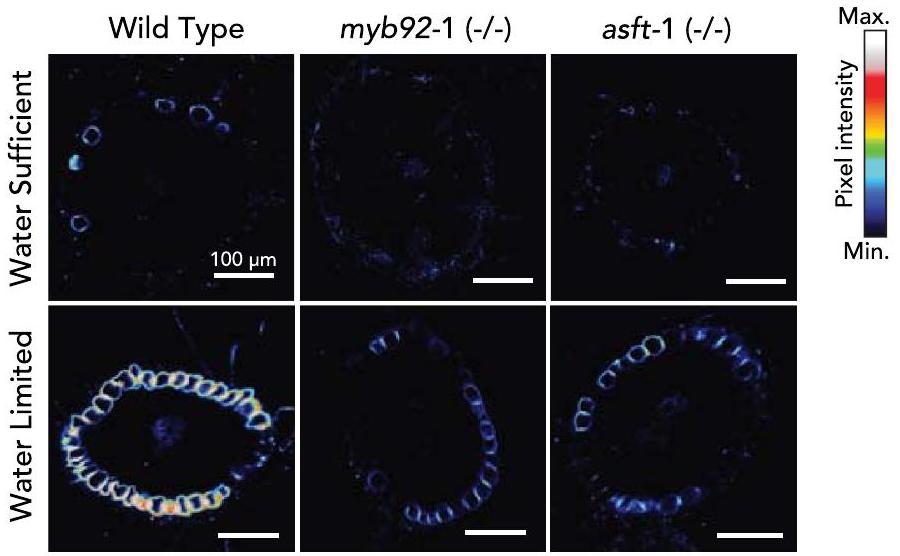

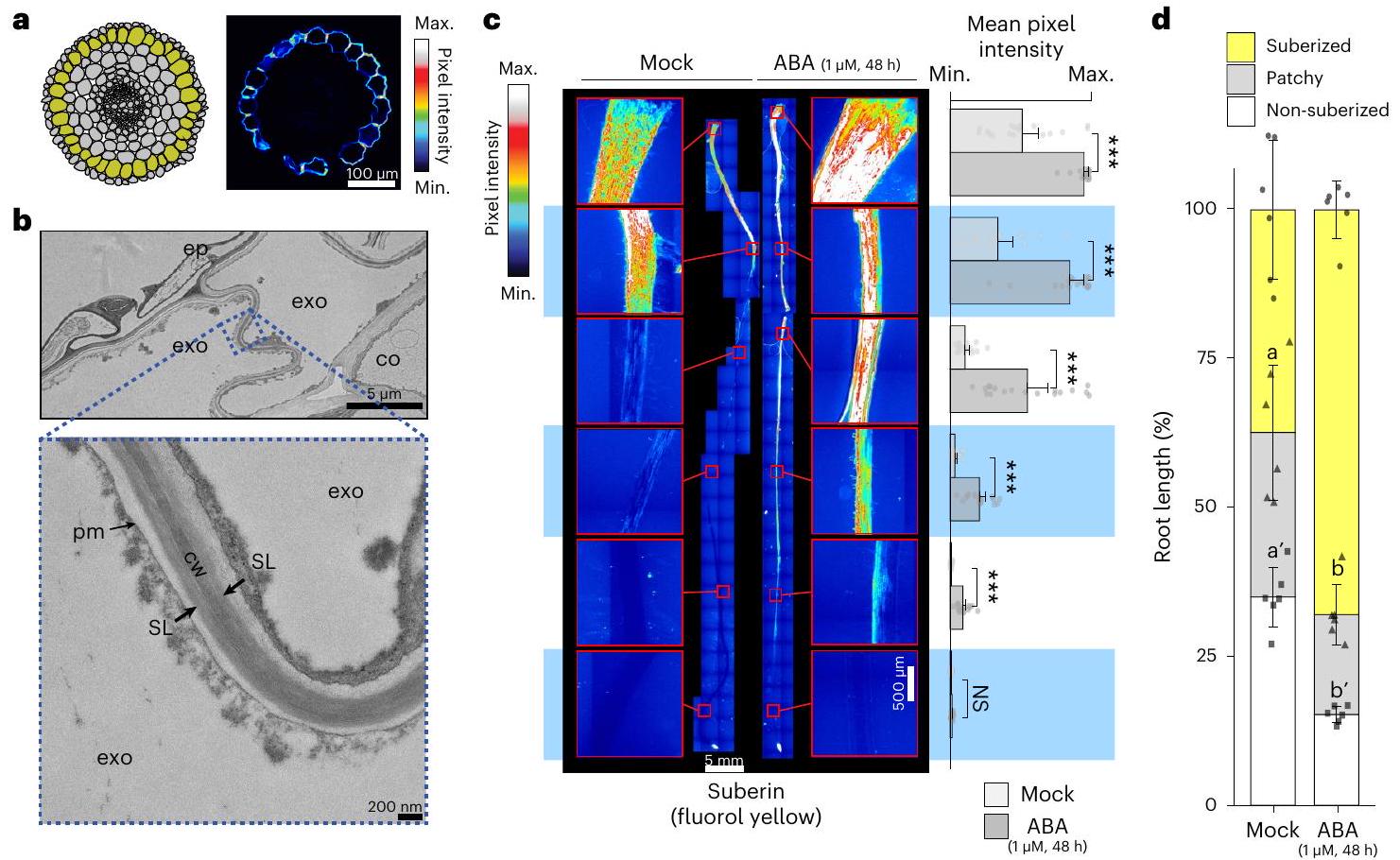

Plant roots integrate environmental signals with development using exquisite spatiotemporal control. This is apparent in the deposition of suberin, an apoplastic diffusion barrier, which regulates flow of water, solutes and gases, and is environmentally plastic. Suberin is considered a hallmark of endodermal differentiation but is absent in the tomato endodermis. Instead, suberin is present in the exodermis, a cell type that is absent in the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana. Here we demonstrate that the suberin regulatory network has the same parts driving suberin production in the tomato exodermis and the Arabidopsis endodermis. Despite this co-option of network components, the network has undergone rewiring to drive distinct spatial expression and with distinct contributions of specific genes. Functional genetic analyses of the tomato MYB92 transcription factor and ASFT enzyme demonstrate the importance of exodermal suberin for a plant water-deficit response and that the exodermal barrier serves an equivalent function to that of the endodermis and can act in its place.

with suberin biosynthesis and the transcriptional regulation of this biosynthetic process have been elucidated using the Arabidopsis root endodermis as a model.

response to water deficit. We identified a co-expression module of potential suberin-related genes, including transcriptional regulators, and validated these candidates by generating multiple CRISPR-Cas9 mutated tomato hairy root lines using Rhizobium rhizogenes

Results

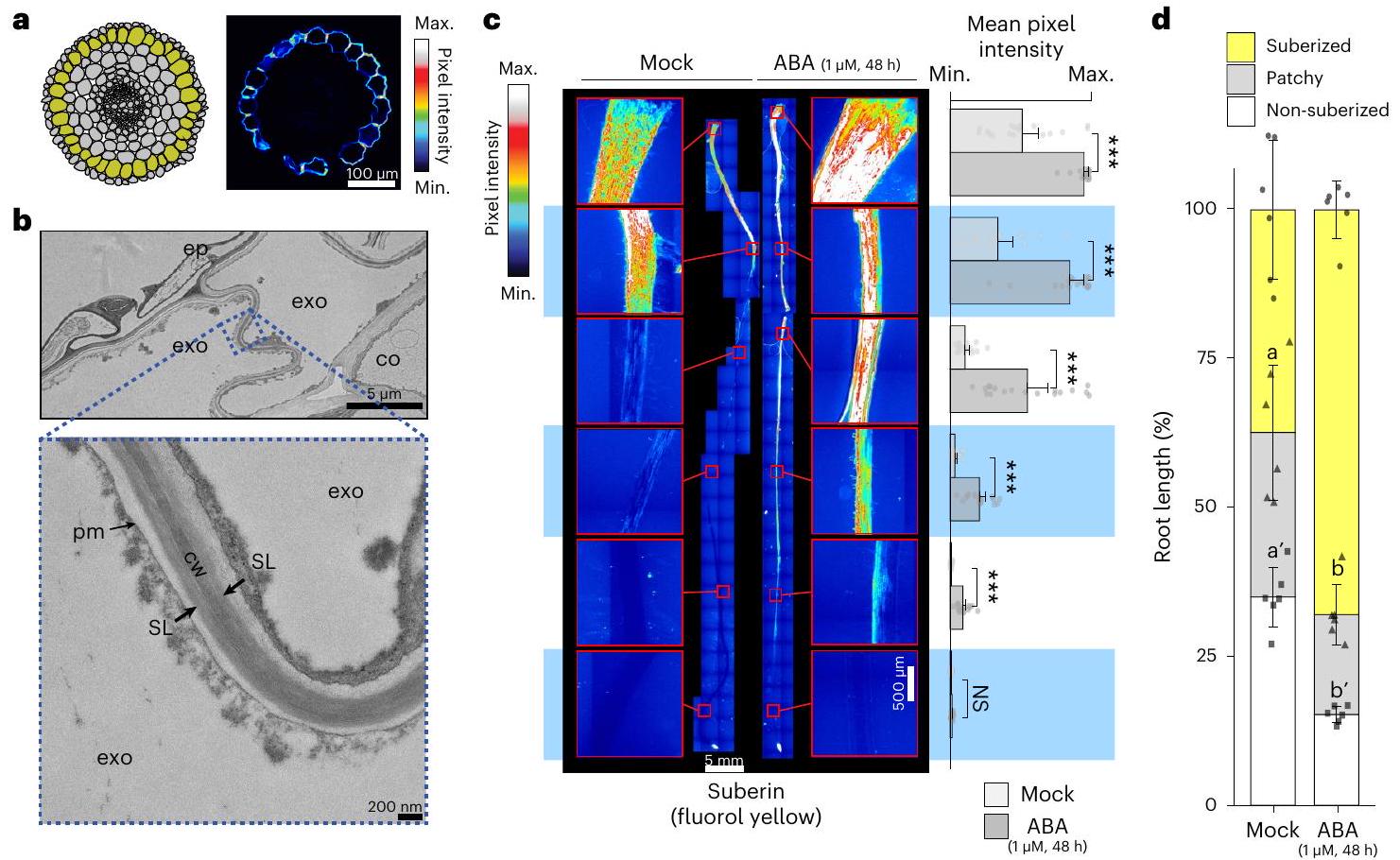

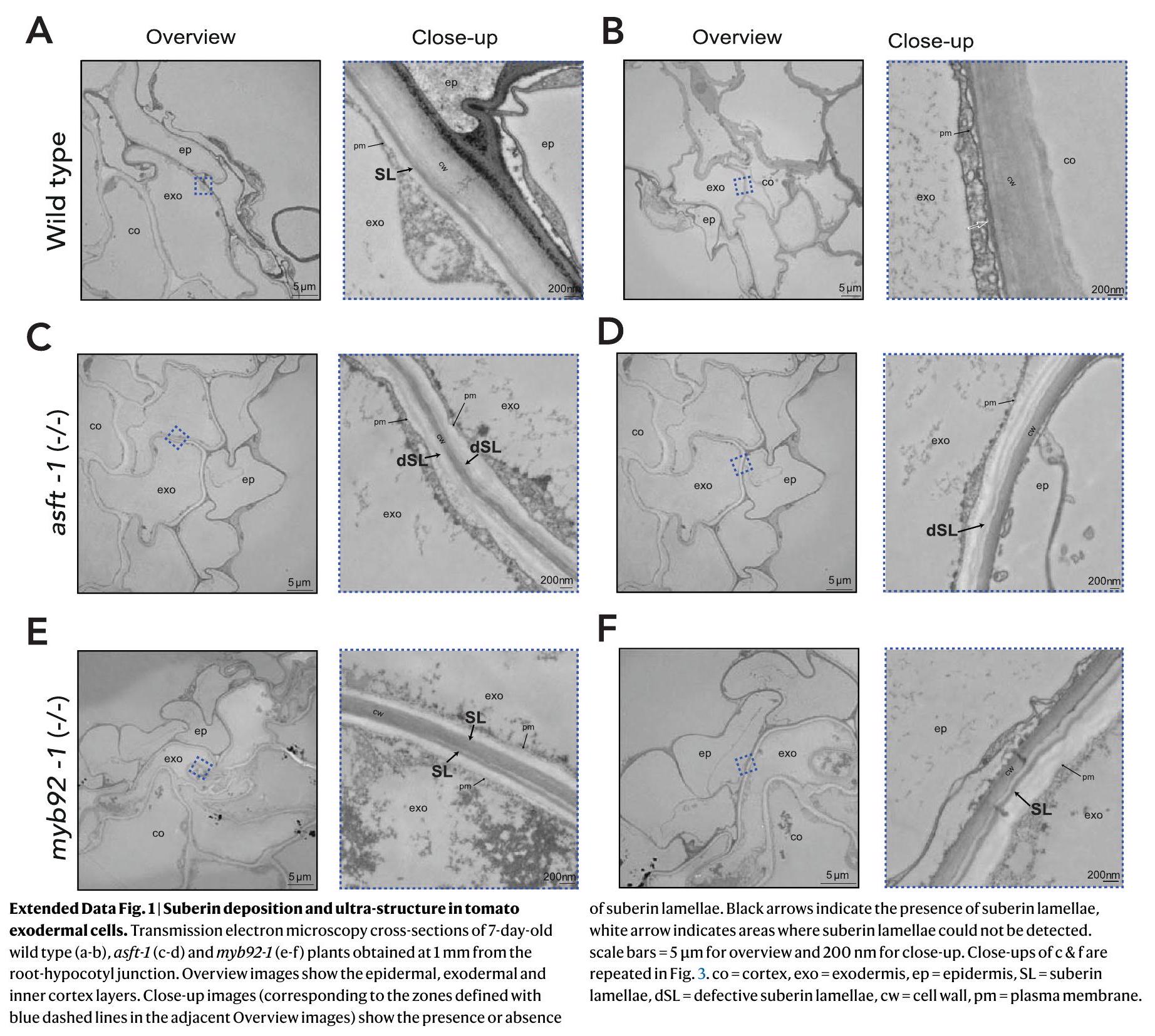

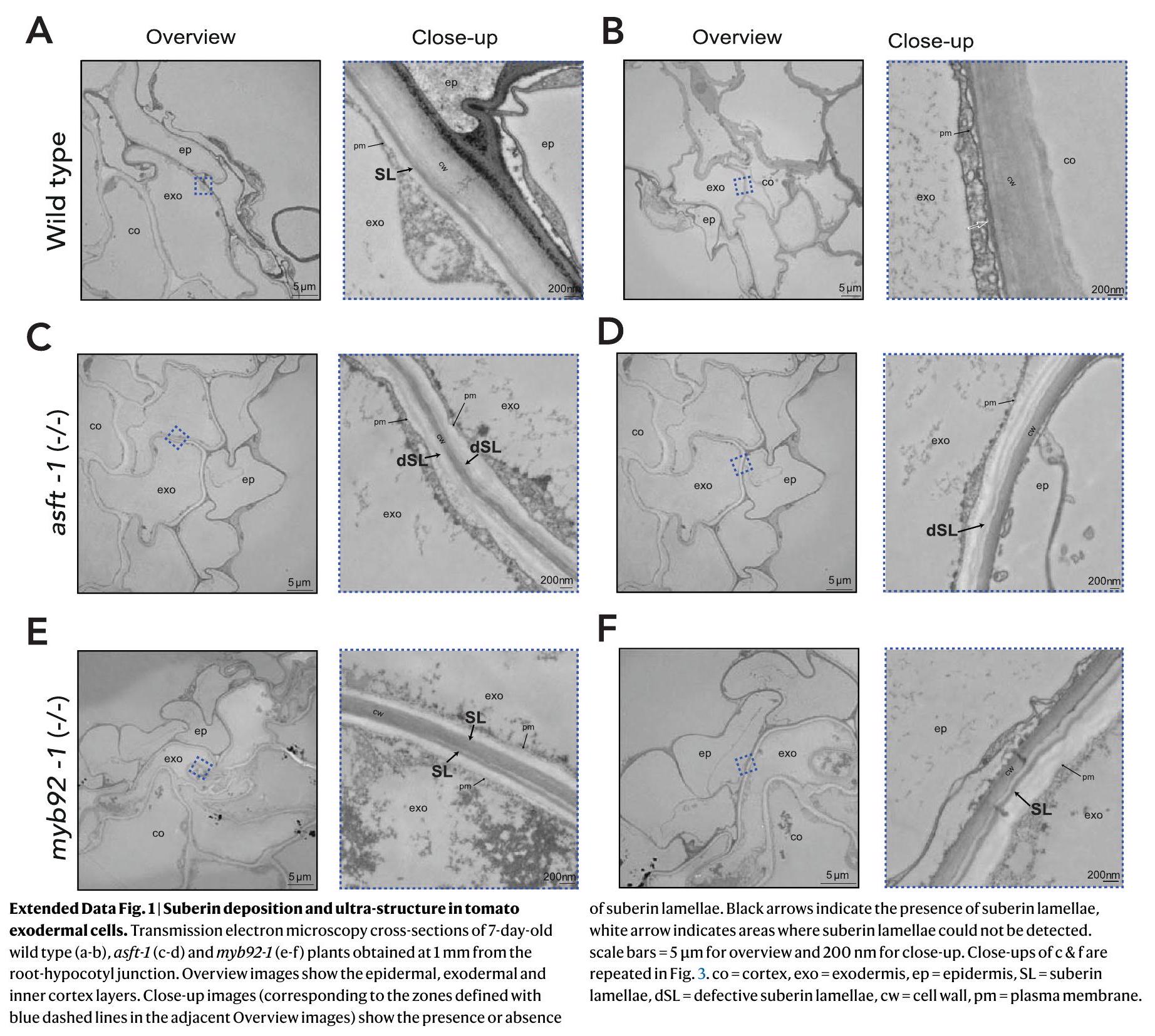

Development and composition of the suberized exodermis

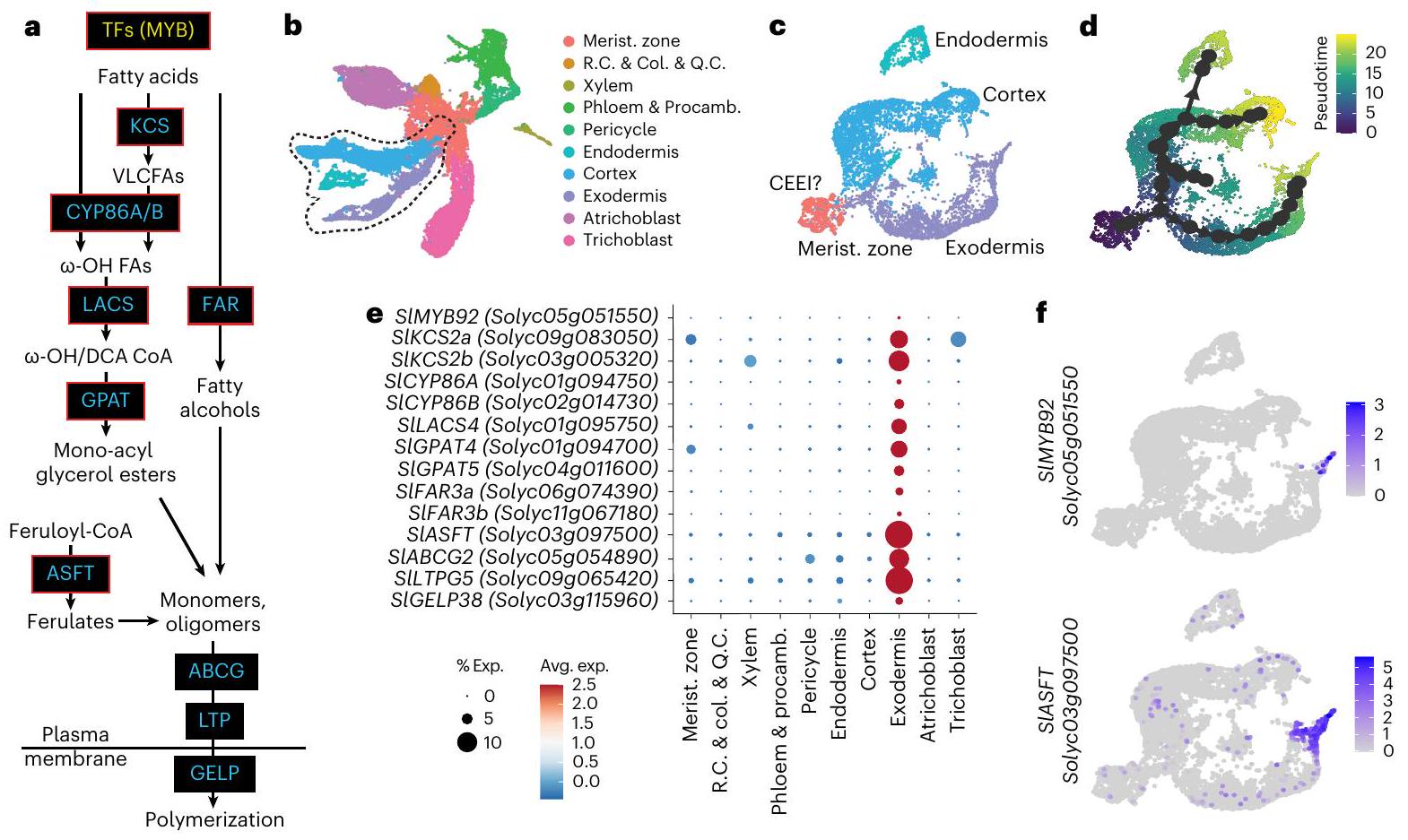

Suberin biosynthetic enzymes and transcriptional regulators

profiling transcription in M82 roots as well as across roots from 76 tomato introgression lines derived from

A single-cell tomato root atlas to map the exodermis

suberin is deposited. To refine the candidate suberin-associated gene set, we conducted single-cell transcriptome profiling of the tomato root. We used the 10X Genomics scRNA-seq platform to profile over 20,000 root cells. We collected tissue from 7 -day-old primary roots of tomato (M82) seedlings up to 3 cm from the tip to include the region where suberin deposition is initially observed. Gene expression matrices were generated using cellranger and analysed in Seurat. Once the data were pre-processed and filtered for low-quality droplets, the remaining high-quality transcriptomes of 22,207 cells were analysed. After normalization, we used unsupervised clustering to identify distinct cell populations (Extended Data Fig. 4). These cell clusters were then assigned a cell type identity using the following approaches: We first quantified the overlap with existing cell type-enriched transcript sets from the tomato root

cortex-endodermal-exodermalinitial (CEEI) population (Fig.2c,d). Within these three associated trajectories, welocalized the cells in which the suberin biosynthetic enzymes and putative regulators were highly expressed (Supplementary Table 3). Of these, transcripts of SIASFT (Solyc03g097500), two FAR(SIFAR3A:Solyc06g074390;SIFAR3B:Solyc11g067190), two CYP86 (SICYPB86A: Solyc01g094750; SICYP86B1: Solyc02g014730), two KCS2 (SIKCS2a:Solyc09g083050 and SIKCS2b:Solyc03g005320), two GPAT(SIGPAT4:Solyc01g094700;SlGPAT5:Solyc04g011600) and one LACS(SILACS4: Solyc01g095750) showed restricted expression at the furthest edge of the exodermal developmental trajectory (Fig. 2e,f, and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). We generated a transcriptional reporter composed of the SIASFT promoter fused to nuclear-localized green fluorescent protein (GFP) and corroborated that its expression is restricted to the exodermis using hairy roots (Extended Data Fig. 5), in agreement with our single-cell analysis. In addition, of the three transcription factors previously noted (SIMYB41, SIMYB63and SIMYB92), only SIMYB92showed specific and restricted expression in cells at the tip of the exodermal trajectory (Fig.2 fand Supplementary Fig.3). On the basis of the co-expression and cellular trajectory data, these genes served as likely candidates for an exodermal suberintranscriptional regulator and suberin biosynthetic enzymes.

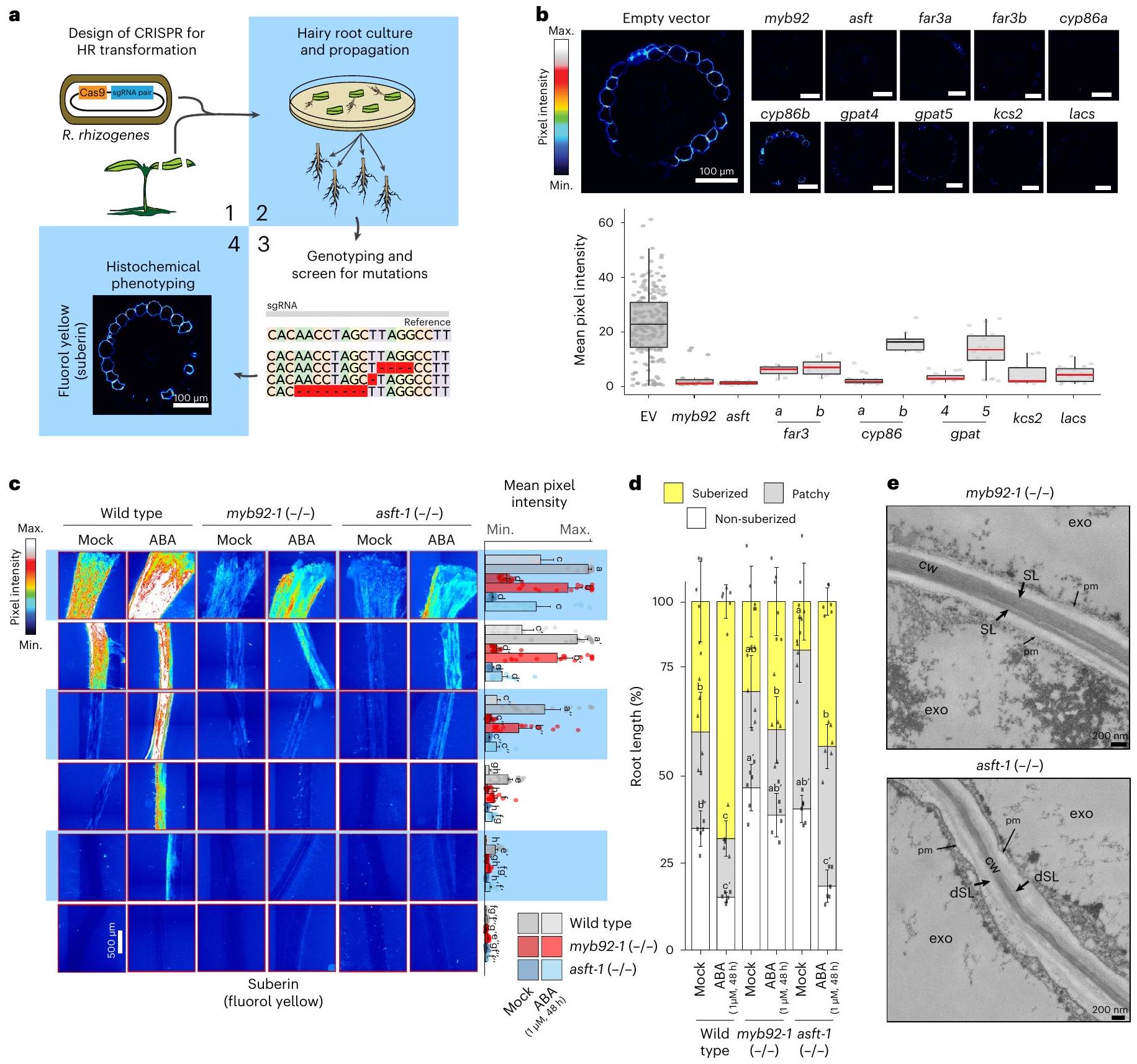

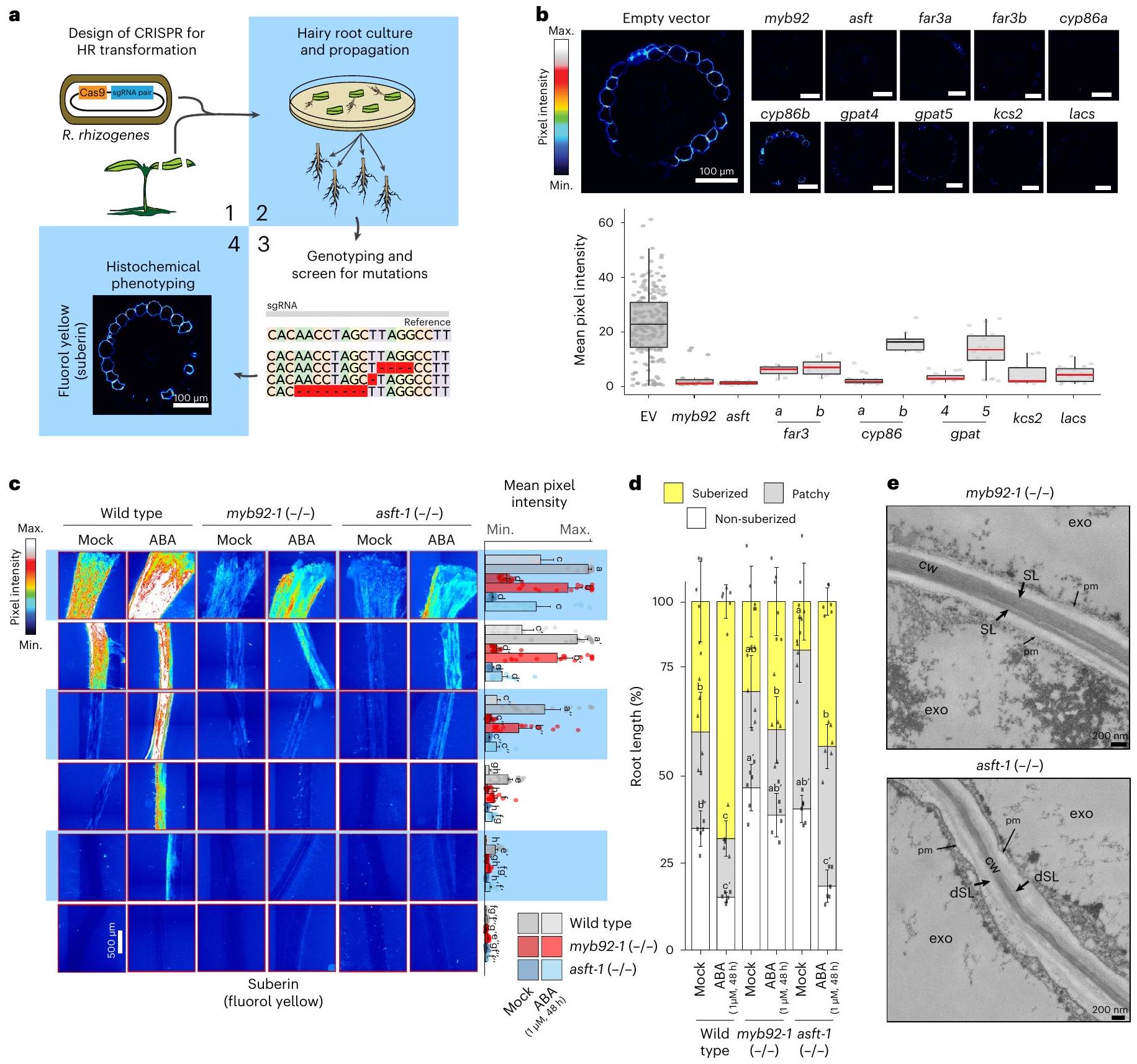

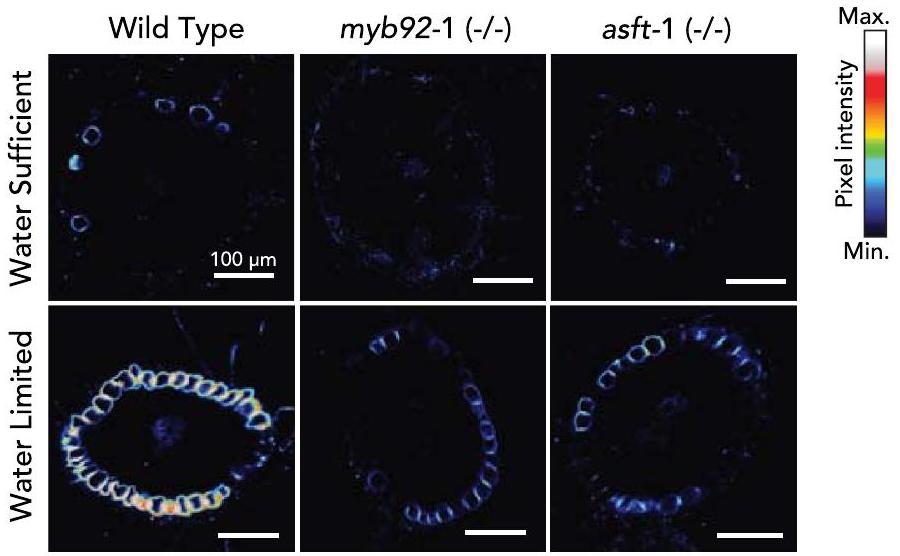

Knockout of candidate genes disrupt suberin deposition

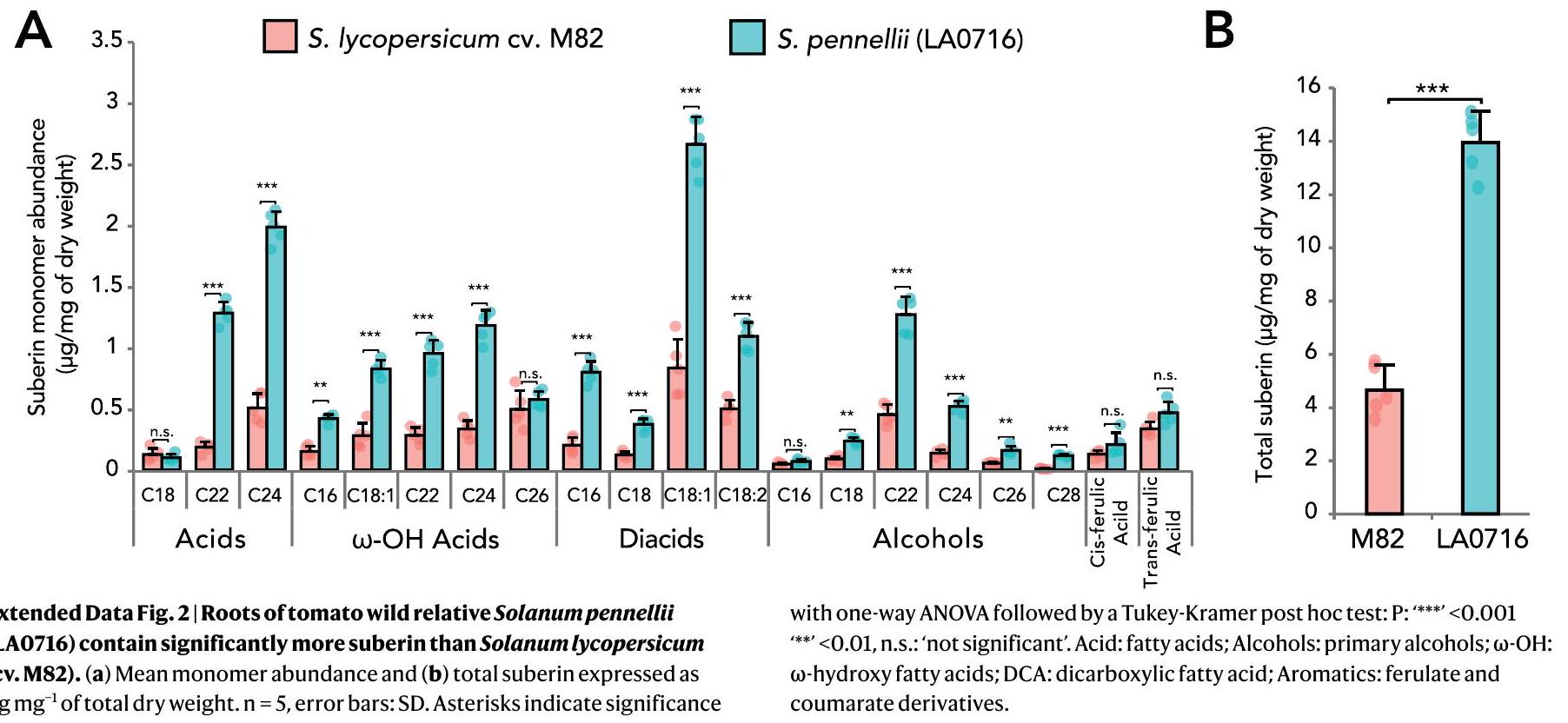

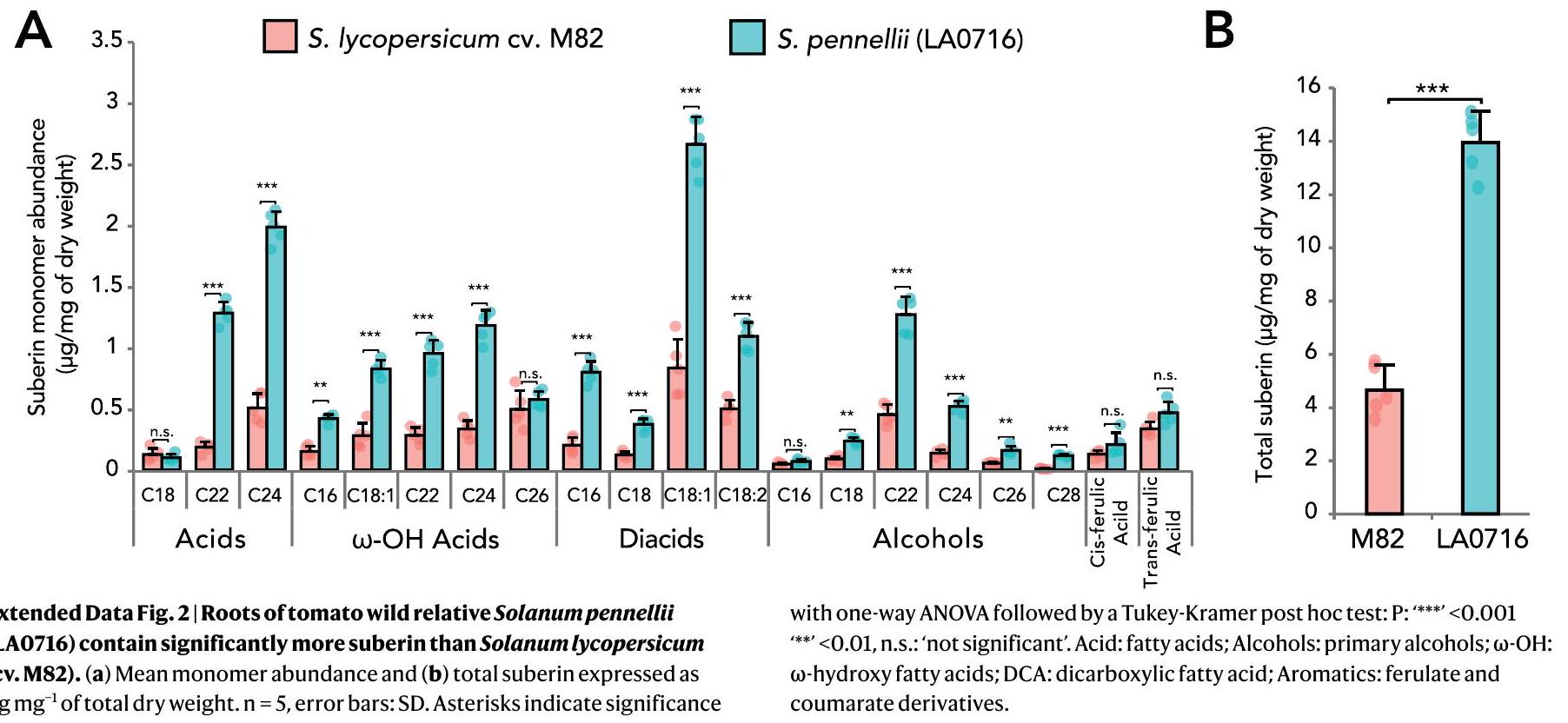

the histological phenotyping, all but the slcyp86b mutant showed a decrease in suberin (Fig.3b). Further confirmation of decreased suberin levels were obtained by suberin monomer metabolic profiling in the slgpat5, slgpat4, slasft, sllacs and slmyb92 mutants (Extended Data Fig. 6). These included collective reduction of ferulic acid and sinapic acid aromatic components; fatty acids (C20, C22, C24),

both cell wall attachment and inter-lamella adhesion, and

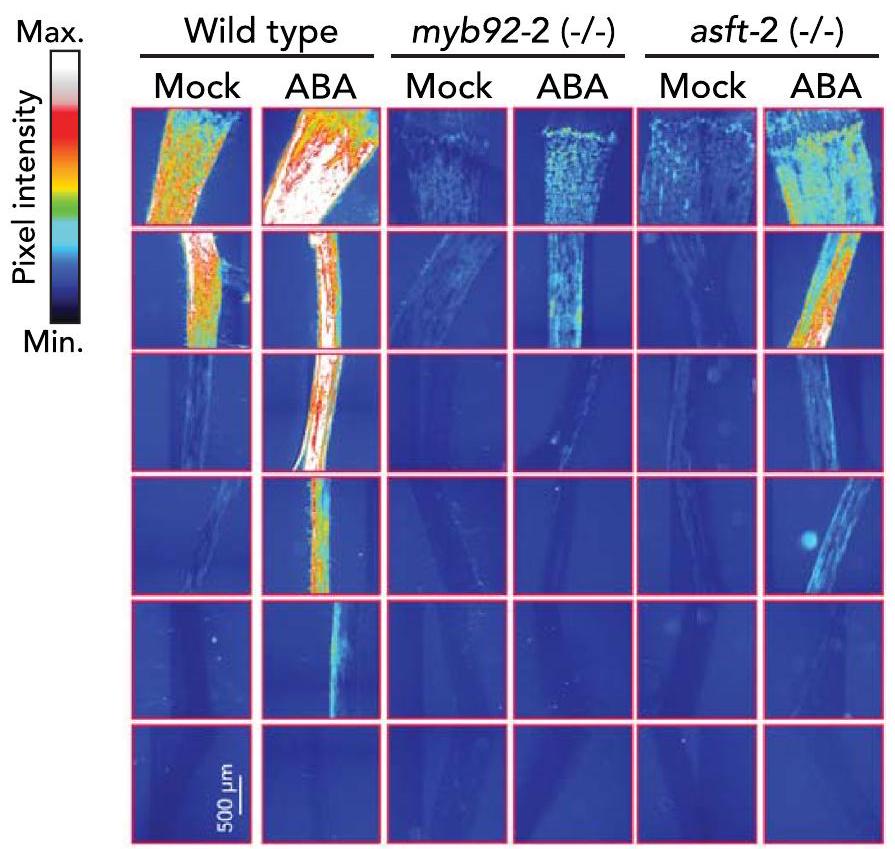

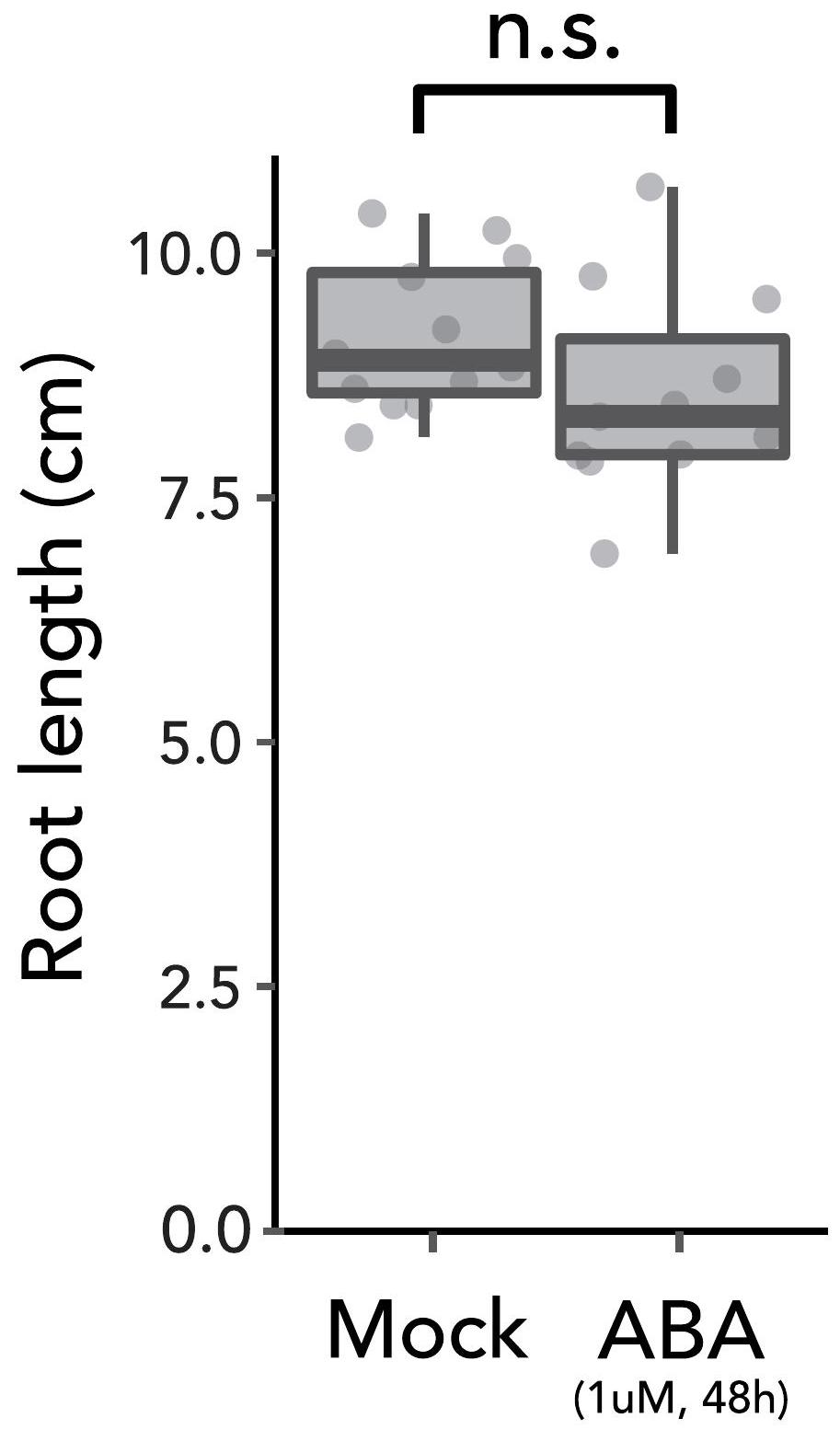

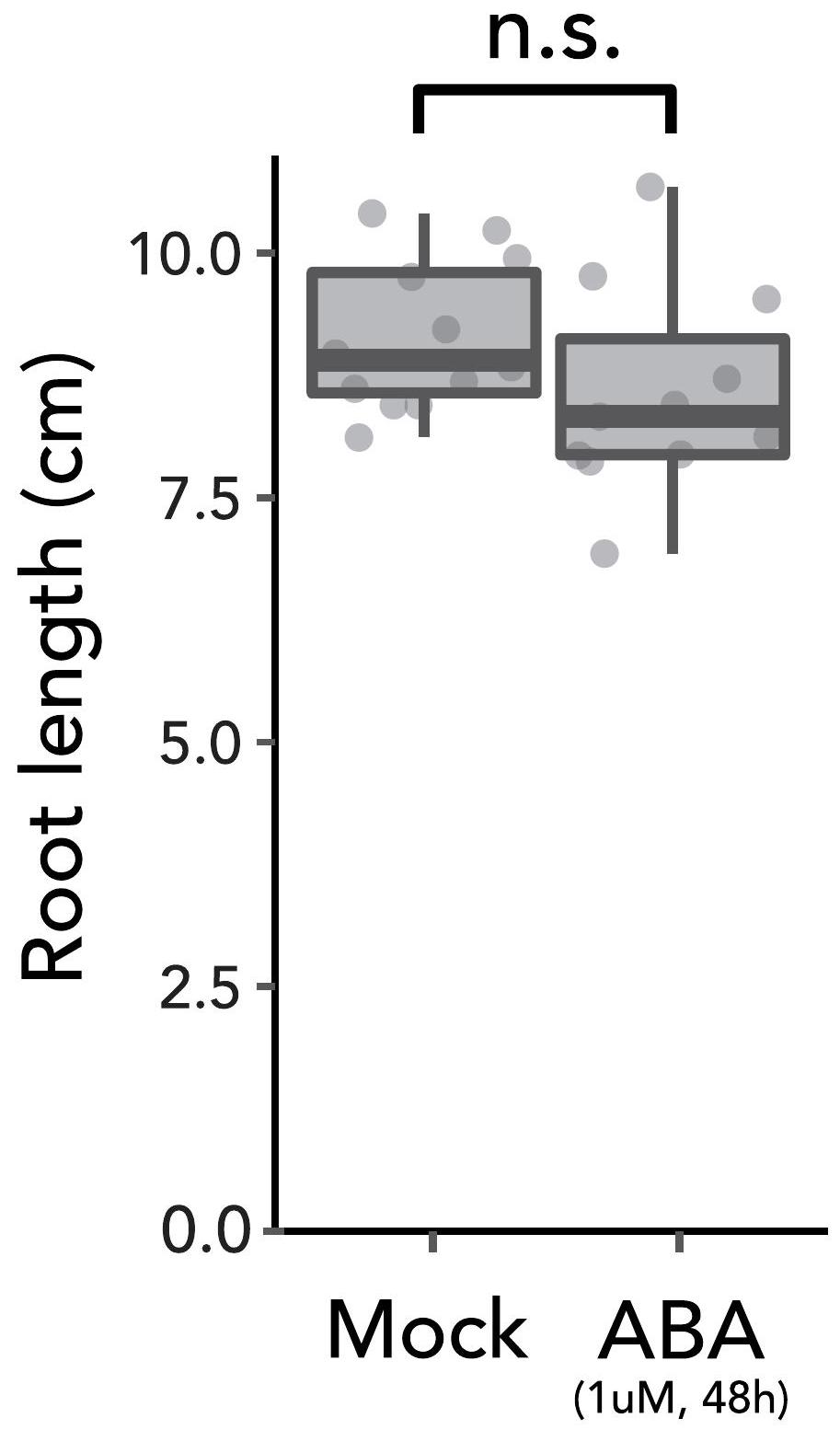

we treated slmyb92 and slasft roots with

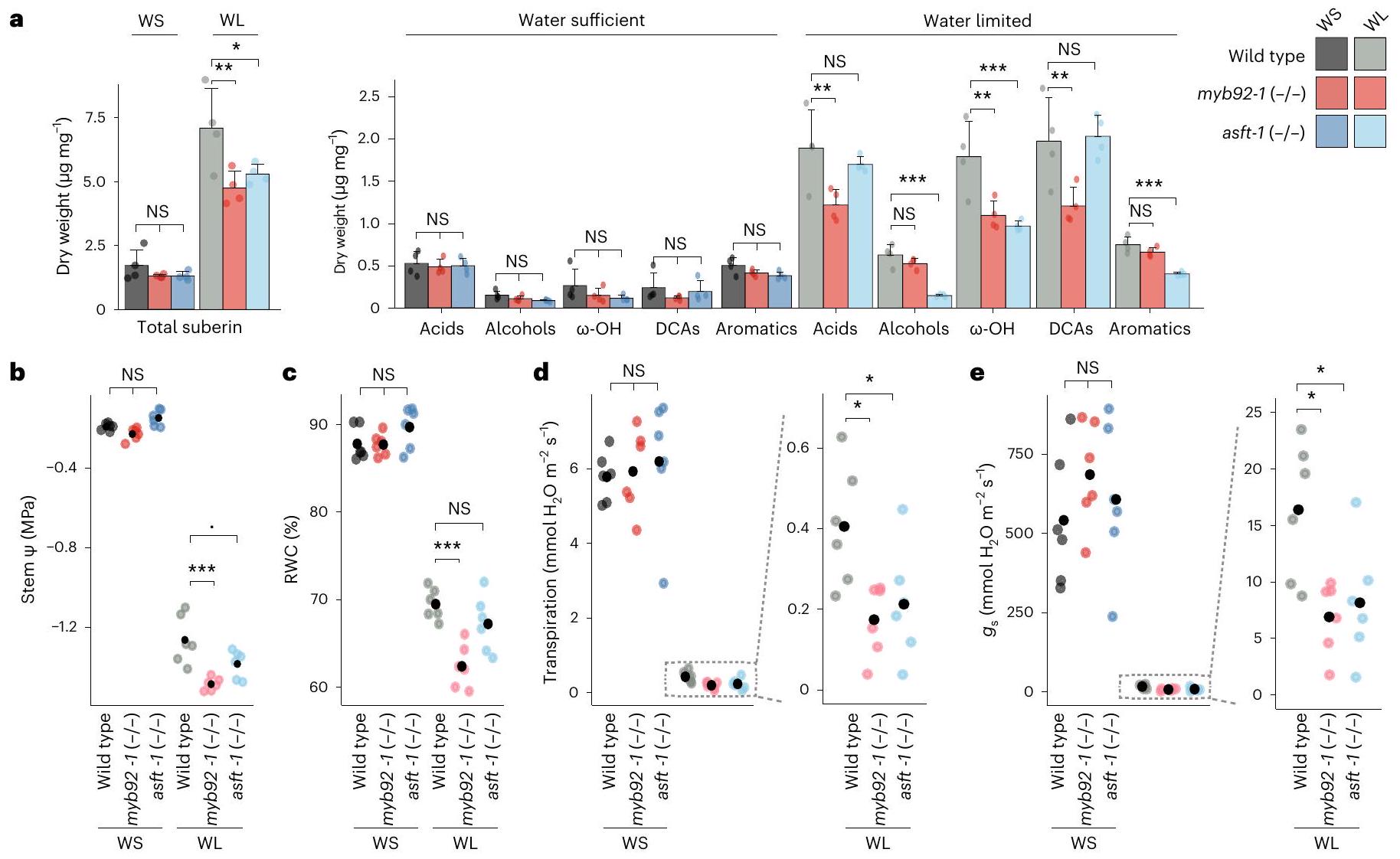

Impaired suberin deposition alters water limitation response

Discussion

ferulate and coumarate isomers. Error bars denote s.d. b-e, Dot plots of recorded values for stem water potential (stem

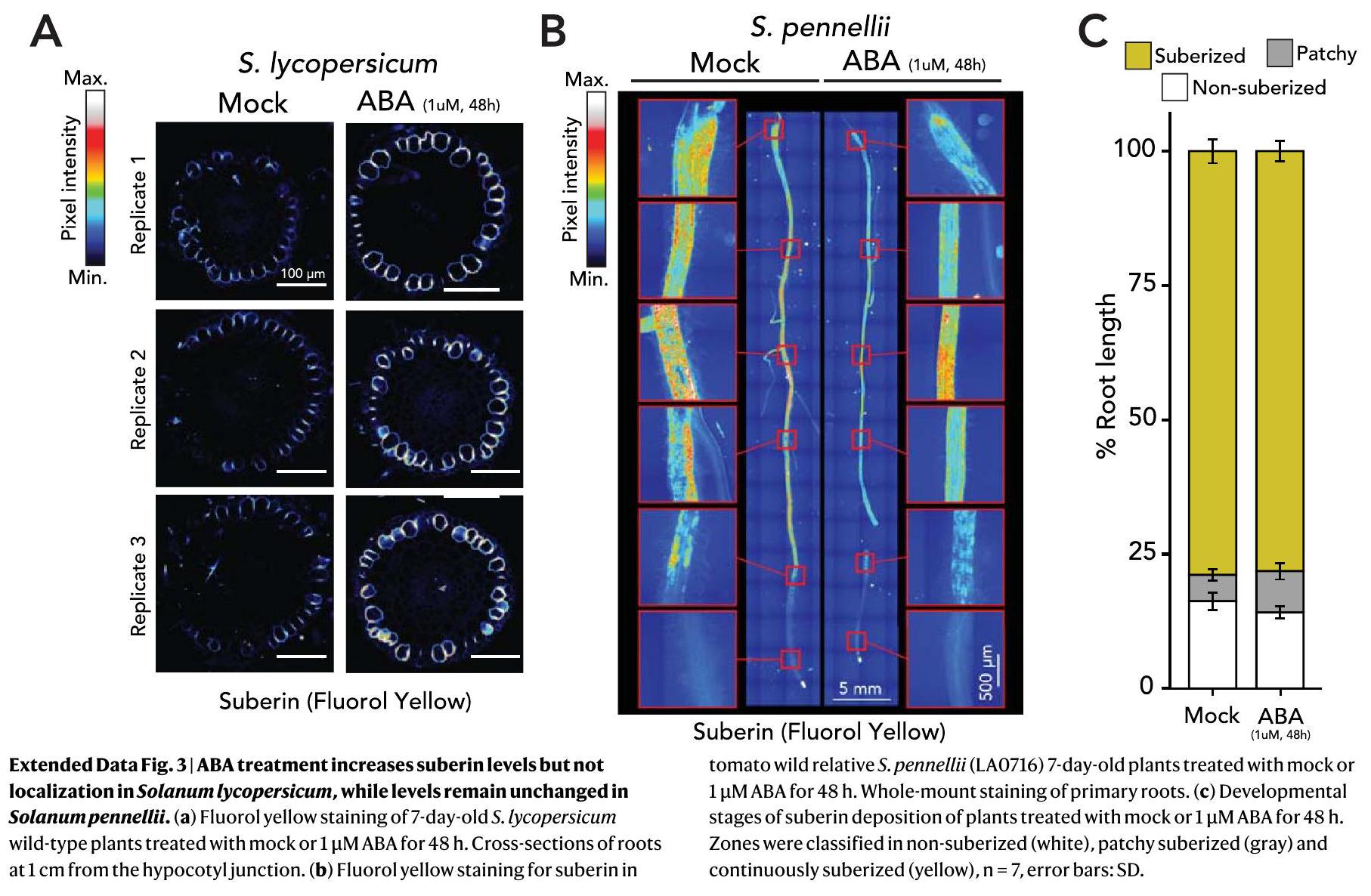

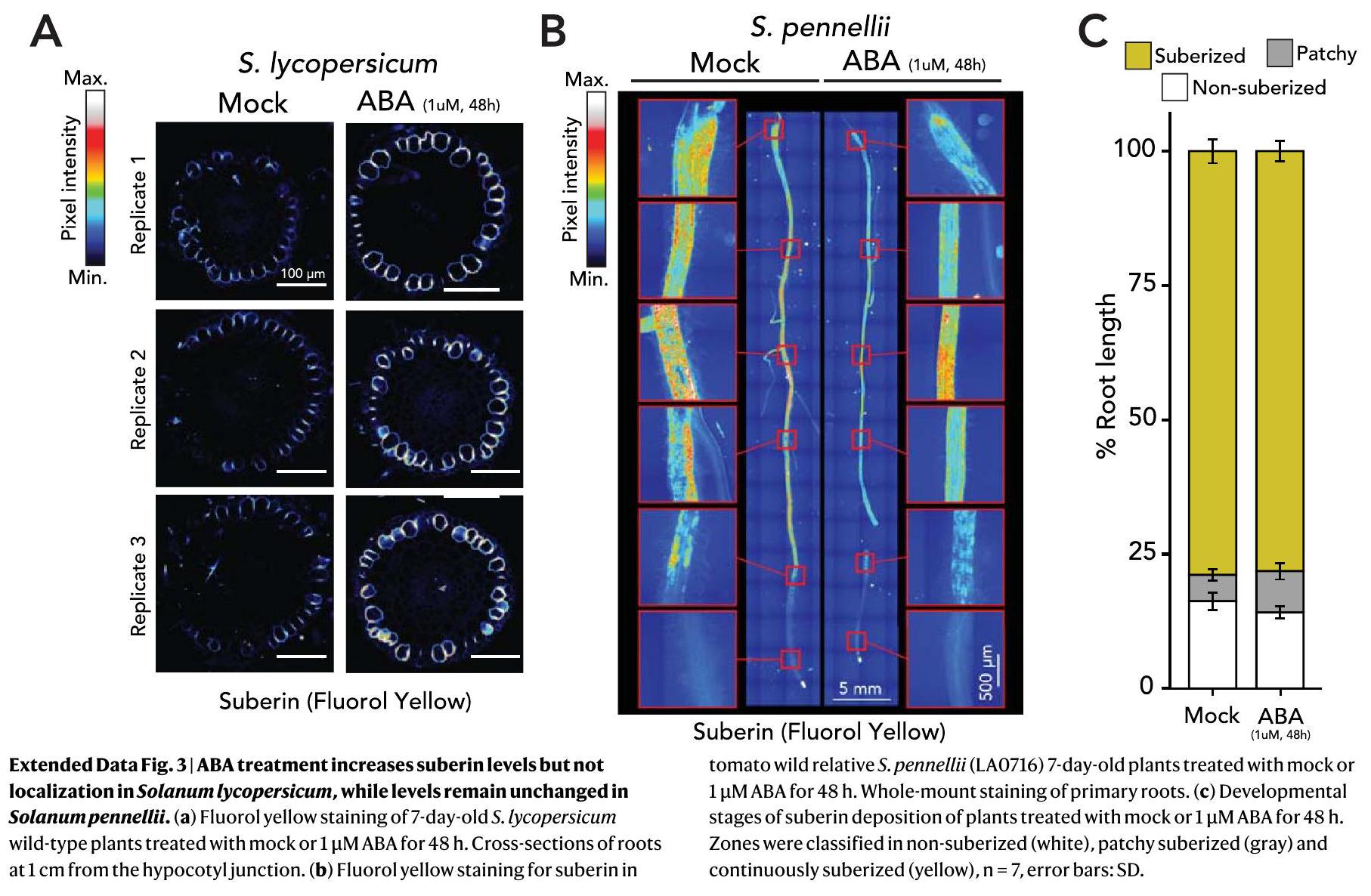

slmyb92 and slasft mutant alleles and the ABA assays, this transcription factor and biosynthetic enzyme influence both developmental and ABA-mediated suberin deposition patterns (Fig. 3c,d). Further analyses of mutant alleles of the tomato SIMYB41 and SIMYB62 transcription factors will determine whether a coordinated developmental and stress-inducible regulation of suberin biosynthesis is the norm for exodermal suberin. The degree to which this regulation is dependent on ABA signalling, as it is in Arabidopsis

including root areas with immature suberin. AtMYB92 is also known to regulate lateral root development in Arabidopsis together with its close orthologue

for the importance of suberin in water relations. These mutants, except for horst-2, have higher

Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

with

Tomato transformation

Transcriptome profiling of M82 roots under drought and waterlogging stress

RNA-seq data processing and analysis for drought, water deficit and introgression line population

Generation of tomato CRISPR constructs

Generation of the SIASFT transcriptional reporter construct driving a nuclear-localized GFP

CRISPR-Cas9 mutant generation and analysis

Water-deficit assay

fresh chloroform:methanol (

ABA assay

Co-expression network analysis

Protoplast isolation and scRNA-seq

Protoplasting-induced genes

Single-cell transcriptome analysis

file with organellar (mitochondria and plastid) sequences appended. Protoplasting-induced (Supplementary Table 2) genes, genes with counts in 3 cells or less, low-quality cells that contained <500 unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and cells with >1% UMI counts belonging to organelle genes were filtered out. Data were then normalized using Seurat (v.4.0.5)

Single-cell cluster annotation

O2 = sum of markers that overlap with all other clusters sum (

This process was repeated for the second and third highest overlapping markers until the corrected

Trajectory analysis

Histochemical and imaging analysis

and counterstained with aniline blue (

Suberin monomer analysis

Transmission electron microscopy

grid

Phylogenetic tree construction

Statistics and reproducibility

Reporting summary

Data availability

References

- Baxter, I. et al. Root suberin forms an extracellular barrier that affects water relations and mineral nutrition in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000492 (2009).

- Thomas, R. et al. Soybean root suberin: anatomical distribution, chemical composition, and relationship to partial resistance to Phytophthora sojae. Plant Physiol. 144, 299-311 (2007).

- Barberon, M. et al. Adaptation of root function by nutrient-induced plasticity of endodermal differentiation. Cell 164, 447-459 (2016).

- Molina, I., Li-Beisson, Y., Beisson, F., Ohlrogge, J. B. & Pollard, M. Identification of an Arabidopsis feruloyl-coenzyme A transferase required for suberin synthesis. Plant Physiol. 151, 1317-1328 (2009).

- Serra, O. & Geldner, N. The making of suberin. New Phytol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph. 18202 (2022).

- Franke, R. et al. The DAISY gene from Arabidopsis encodes a fatty acid elongase condensing enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of aliphatic suberin in roots and the chalaza-micropyle region of seeds. Plant J. 57, 80-95 (2009).

- Domergue, F. et al. Three Arabidopsis fatty acyl-coenzyme A reductases, FAR1, FAR4, and FAR5, generate primary fatty alcohols associated with suberin deposition. Plant Physiol. 153, 1539-1554 (2010).

- Compagnon, V. et al. CYP86B1 is required for very long chain omega-hydroxyacid and alpha, omega -dicarboxylic acid synthesis in root and seed suberin polyester. Plant Physiol. 150, 1831-1843 (2009).

- Höfer, R. et al. The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 CYP86A1 encodes a fatty acid

-hydroxylase involved in suberin monomer biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2347-2360 (2008). - Beisson, F., Li, Y., Bonaventure, G., Pollard, M. & Ohlrogge, J. B. The acyltransferase GPAT5 is required for the synthesis of suberin in seed coat and root of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 351-368 (2007).

- Gou, J.-Y., Yu, X.-H. & Liu, C.-J. A hydroxycinnamoyltransferase responsible for synthesizing suberin aromatics in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 18855-18860 (2009).

- Serra, O. et al. A feruloyl transferase involved in the biosynthesis of suberin and suberin-associated wax is required for maturation and sealing properties of potato periderm. Plant J. 62, 277-290 (2010).

- Ursache, R. et al. GDSL-domain proteins have key roles in suberin polymerization and degradation. Nat. Plants 7, 353-364 (2021).

- Shukla, V. et al. Suberin plasticity to developmental and exogenous cues is regulated by a set of MYB transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2101730118 (2021).

- Kosma, D. K. et al. AtMYB41 activates ectopic suberin synthesis and assembly in multiple plant species and cell types. Plant J. 80, 216-229 (2014).

- Cohen, H., Fedyuk, V., Wang, C., Wu, S. & Aharoni, A. SUBERMAN regulates developmental suberization of the Arabidopsis root endodermis. Plant J. 102, 431-447 (2020).

- Lashbrooke, J. et al. MYB107 and MYB9 homologs regulate suberin deposition in angiosperms. Plant Cell 28, 2097-2116 (2016).

- Gou, M. et al. The MYB107 transcription factor positively regulates suberin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 173, 1045-1058 (2017).

- Enstone, D. E., Peterson, C. A. & Ma, F. Root endodermis and exodermis: structure, function, and responses to the environment. J. Plant Growth Regul. 21, 335-351 (2002).

- Perumalla, C. J., Peterson, C. A. & Enstone, D. E. A survey of angiosperm species to detect hypodermal Casparian bands. I. Roots with a uniseriate hypodermis and epidermis. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 103, 93-112 (1990).

- Barberon, M. The endodermis as a checkpoint for nutrients. New Phytol. 213, 1604-1610 (2017).

- Geldner, N. The endodermis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 531-558 (2013).

- Kajala, K. et al. Innovation, conservation, and repurposing of gene function in root cell type development. Cell 184, 3333-3348.e19 (2021).

- Ron, M. et al. Hairy root transformation using Agrobacterium rhizogenes as a tool for exploring cell type-specific gene expression and function using tomato as a model. Plant Physiol. 166, 455-469 (2014).

- Naseer, S. et al. Casparian strip diffusion barrier in Arabidopsis is made of a lignin polymer without suberin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10101-10106 (2012).

- Franke, R. et al. Apoplastic polyesters in Arabidopsis surface tissues-a typical suberin and a particular cutin. Phytochemistry 66, 2643-2658 (2005).

- Kolattukudy, P. E., Kronman, K. & Poulose, A. J. Determination of structure and composition of suberin from the roots of carrot, parsnip, rutabaga, turnip, red beet, and sweet potato by combined gas-liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Plant Physiol. 55, 567-573 (1975).

- Legay, S. et al. MdMyb93 is a regulator of suberin deposition in russeted apple fruit skins. New Phytol. 212, 977-991 (2016).

- Gong, P. et al. Transcriptional profiles of drought-responsive genes in modulating transcription signal transduction, and biochemical pathways in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 3563-3575 (2010).

- Eshed, Y., Abu-Abied, M., Saranga, Y. & Zamir, D. Lycopersicon esculentum lines containing small overlapping introgressions from L. pennellii. Theor. Appl. Genet. 83, 1027-1034 (1992).

- Gur, A. et al. Yield quantitative trait loci from wild tomato are predominately expressed by the shoot. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122, 405-420 (2011).

- Toal, T. W. et al. Regulation of root angle and gravitropism. G3 8, 3841-3855 (2018).

- Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 559 (2008).

- Du, H. et al. The evolutionary history of R2R3-MYB proteins across 50 eukaryotes: new insights into subfamily classification and expansion. Sci. Rep. 5, 11037 (2015).

- Saelens, W., Cannoodt, R., Todorov, H. & Saeys, Y. A comparison of single-cell trajectory inference methods. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 547-554 (2019).

- Bucher, M., Schroeer, B., Willmitzer, L. & Riesmeier, J. W. Two genes encoding extensin-like proteins are predominantly expressed in tomato root hair cells. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 497-508 (1997).

- Bucher, M. et al. The expression of an extensin-like protein correlates with cellular tip growth in tomato. Plant Physiol. 128, 911-923 (2002).

- Howarth, J. R., Parmar, S., Barraclough, P. B. & Hawkesford, M. J. A sulphur deficiency-induced gene, sdi1, involved in the utilization of stored sulphate pools under sulphur-limiting conditions has potential as a diagnostic indicator of sulphur nutritional status. Plant Biotechnol. J. 7, 200-209 (2009).

- von Wirén, N. et al. Differential regulation of three functional ammonium transporter genes by nitrogen in root hairs and by light in leaves of tomato. Plant J. 21, 167-175 (2000).

- Gómez-Ariza, J., Balestrini, R., Novero, M. & Bonfante, P. Cell-specific gene expression of phosphate transporters in mycorrhizal tomato roots. Biol. Fertil. Soils 45, 845-853 (2009).

- Nieves-Cordones, M., Alemán, F., Martínez, V. & Rubio, F. The Arabidopsis thaliana HAK5 K+ transporter is required for plant growth and

acquisition from low solutions under saline conditions. Mol. Plant 3, 326-333 (2010). - Jones, M. O. et al. The promoter from SIREO, a highly-expressed, root-specific Solanum lycopersicum gene, directs expression to cortex of mature roots. Funct. Plant Biol. 35, 1224-1233 (2008).

- Ho-Plágaro, T., Molinero-Rosales, N., Fariña Flores, D., Villena Díaz, M. & García-Garrido, J. M. Identification and expression analysis of GRAS transcription factor genes involved in the control of arbuscular mycorrhizal development in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 268 (2019).

- Li, P. et al. Spatial expression and functional analysis of Casparian strip regulatory genes in endodermis reveals the conserved mechanism in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 832 (2018).

- Bouzroud, S. et al. Auxin Response Factors (ARFs) are potential mediators of auxin action in tomato response to biotic and abiotic stress (Solanum lycopersicum). PLoS ONE 13, eO193517 (2018).

- Shahan, R. et al. A single-cell Arabidopsis root atlas reveals developmental trajectories in wild-type and cell identity mutants. Dev. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2022.01.008 (2022).

- Andersen, T. G. et al. Tissue-autonomous phenylpropanoid production is essential for establishment of root barriers. Curr. Biol. 31, 965-977.e5 (2021).

- Hosmani, P. S. et al. Dirigent domain-containing protein is part of the machinery required for formation of the lignin-based Casparian strip in the root. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14498-14503 (2013).

- Calvo-Polanco, M. et al. Physiological roles of Casparian strips and suberin in the transport of water and solutes. New Phytol. 232, 2295-2307 (2021).

- Beisson, F., Li-Beisson, Y. & Pollard, M. Solving the puzzles of cutin and suberin polymer biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 329-337 (2012).

- Zhu, J.-K. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 247-273 (2002).

- Raghavendra, A. S., Gonugunta, V. K., Christmann, A. & Grill, E. ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 395-401 (2010).

- Gibbs, D. J. et al. AtMYB93 is a novel negative regulator of lateral root development in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 203, 1194-1207 (2014).

- Zimmermann, H. M., Hartmann, K., Schreiber, L. & Steudle, E. Chemical composition of apoplastic transport barriers in relation to radial hydraulic conductivity of corn roots (Zea mays L.). Planta 210, 302-311 (2000).

- Steudle, E. Water uptake by roots: effects of water deficit. J. Exp. Bot. 51, 1531-1542 (2000).

- Thompson, A. The new plants that could save us from climate change. Popular Mechanics https://www. popularmechanics.com/science/green-tech/a14000753/ the-plants-that-could-save-us-from-climate-change/ (2017).

- Pillay, I. & Beyl, C. Early responses of drought-resistant and -susceptible tomato plants subjected to water stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 9, 213-219 (1990).

- Gur, A. & Zamir, D. Unused natural variation can lift yield barriers in plant breeding. PLoS Biol. 2, e245 (2004).

- Holbein, J. et al. Root endodermal barrier system contributes to defence against plant-parasitic cyst and root-knot nematodes. Plant J. 100, 221-236 (2019).

- Kashyap, A. et al. Induced ligno-suberin vascular coating and tyramine-derived hydroxycinnamic acid amides restrict Ralstonia solanacearum colonization in resistant tomato. New Phytol. 234, 1411-1429 (2022).

- Salas-González, I. et al. Coordination between microbiota and root endodermis supports plant mineral nutrient homeostasis. Science 371, eabd0695 (2021).

- To, A. et al. AtMYB92 enhances fatty acid synthesis and suberin deposition in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant J. 103, 660-676 (2020).

- Reynoso, M. A. et al. Evolutionary flexibility in flooding response circuitry in angiosperms. Science 365, 1291-1295 (2019).

- Townsley, B. T., Covington, M. F., Ichihashi, Y., Zumstein, K. & Sinha, N. R. BrAD-seq: Breath Adapter Directional sequencing: a streamlined, ultra-simple and fast library preparation protocol for strand specific mRNA library construction. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 366 (2015).

- Krueger, F. Trim Galore (Babraham Bioinformatics, 2012).

- Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 525-527 (2016).

- Bari, V. K. et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE 8 in tomato provides resistance against the parasitic weed Phelipanche aegyptiaca. Sci. Rep. 9, 11438 (2019).

- Karimi, M., Bleys, A., Vanderhaeghen, R. & Hilson, P. Building blocks for plant gene assembly. Plant Physiol. 145, 1183-1191 (2007).

- Sade, N., Galkin, E. & Moshelion, M. Measuring Arabidopsis, tomato and barley leaf relative water content (RWC). Bio-Protocol 5, e1451-e1451 (2015).

- Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F. & Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 495-502 (2015).

- Ron, M. et al. Identification of novel loci regulating interspecific variation in root morphology and cellular development in tomato. Plant Physiol. 162, 755-768 (2013).

- Scrucca, L., Fop, M., Murphy, T. B. & Raftery, A. E. mclust 5: clustering, classification and density estimation using Gaussian finite mixture models. R J. 8, 289-317 (2016).

- Kremer, J. R., Mastronarde, D. N. & McIntosh, J. R. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116, 71-76 (1996).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-023-01567-x.

contains supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-023-01567-x.

www.nature.com/reprints.

© The Author(s) 2024

the epidermal and exodermal cell layers. White arrows indicate some of the GFP-tagged nuclei in the exodermis. Yellow arrows indicate the lignin autofluorescence of the exodermal polar cap. (C and F) Longitudinal section of a bottom plane of the z-stacks, showing the epidermis, exodermis, cortex layers 1 and 2, and endodermis. White arrows indicate the GFP-tagged nuclei in the exodermis. Yellow arrows indicate the lignin autofluorescence of the exodermal polar cap and the endodermal Casparian Strip. EP: Epidermis; EXO: Exodermis; COR1&2: Cortex layer 1 and 2; ENDO: Endodermis, VASC: Vasculature.

stained with basic fuchsin. c. Cross section of myb63 hairy root mutant stained with basic fuchsin. d. Cross section of

natureportfolio

Last updated by author(s): Oct 16, 2023

Reporting Summary

Statistics

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

For hierarchical and complex designs, identification of the appropriate level for tests and full reporting of outcomes

Estimates of effect sizes (e.g. Cohen’s

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

Data collection

No software was used for data collection.

RNASEQ Trimming: TrimGalore!(v0.6.6); Pseado-aligmnment: Kallisto v0.43.1 and v0.46.2; Clusterin and co-expression: WGCNA R package v1.70; Data handling: R v4.1.3 ;Plotting: ggplot2 v3.3.6. SINGLE CELL: Mapping: cellranger v1.1.0; Processing and analysis: Seurat v4.0.5; TEM images: EM-MENU v4. 0 & IMOD v4.11;

Data

All manuscripts must include a data availability statement. This statement should provide the following information, where applicable:

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

Human research participants

| Reporting on sex and gender | NA |

| Population characteristics | NA |

| Recruitment | NA |

| Ethics oversight | NA |

Field-specific reporting

Life sciences Behavioural & social sciences Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

For a reference copy of the document with all sections, see nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

Life sciences study design

| Sample size | We used three biological replicates for RNA-Seq and over 20,000 cells across two rounds on 10X single cell transcriptomics, following common practice in the field. Sample sizes for experiments are indicated in the legends and text. Each analysis was analyzed at least with three biological replicates, and two rounds of experimentation. Biological replicates yielded similar results. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Generally sample size was chosen empirically, based on prior experience of how big a sample size must be to most probably obtain a reproducible, statistically significant result. |

| Data exclusions | No data was excluded from the analysis. |

| Replication | At least 3 biological replicates and two independent rounds of experimentation were performed for each experiment to assess quality, repeatability of a procedure, and statistical significance. Number of repeats is provided in the figure legends where appreciate |

| Randomization | Plants were randomly assigned to water-sufficient or water-limited regimes for the drought experiments. Pots were distributed randomly around the growth chamber and shuffled every other day during watering for the duration of the experiments. When dealing with CRISPR mutants, both in stable and hairy roots, several independent alleles were taken to minimize bias and risk of off-target effects. |

| Blinding | Transcriptomics experiments were carried out without prior knowledge of experimental outcome, thus, blinding was not applied. Phenotype and confocal analysis were collected and quantified by several researchers independently with similar outcomes. Drought experiment data collection was performed effectively blind by different researchers sampling randomly without prior knowledge of the sample set-up, readings were recorded in the LICOR, and only after collection data was downloaded, parsed out and analyzed. |

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | ||

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a | Involved in the study |

| X |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Palaeontology and archaeology |  |

MRI-based neuroimaging |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| 凶 | Dual use research of concern | ||

Department of Plant Biology and Genome Center, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA. Plant-Environment Signaling, Institute of Environmental Biology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands. School of Plant and Environmental Sciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA. Department of Plant Molecular Biology, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. Electron Microscopy Facility, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. Institute of Cellular and Molecular Botany, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany. Department of Plant Biology, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA. Center for Plant Cell Biology, Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA, USA. Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA. Present address: Department of Evolutionary and Environmental Biology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Institute of Evolution, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel. Deceased: Sharon Gray. e-mail: sbrady@ucdavis.edu - Single-cell and bulk RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO: GSE212405.