المجلة: The Lancet، المجلد: 403، العدد: 10440

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00367-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38582094

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-03

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00367-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38582094

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-03

العبء العالمي لـ 288 سببًا للوفاة وتحليل العمر المتوقع في 204 دول وأقاليم و811 موقعًا دون وطني، 1990-2021: تحليل منهجي لدراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض 2021

811 موقعًا فرعيًا، 1990-2021: تحليل منهجي لدراسة عبء المرض العالمي 2021

متعاونون في أسباب الوفاة GBD 2021*

لانسيت 2024؛ 403: 2100-32

تم النشر على الإنترنت

3 أبريل 2024

https://doi.org/10.1016/

S0140-6736(24)00367-2

تم تصحيح هذه النشرة على الإنترنت. ظهرت النسخة المصححة لأول مرة فيthelancet.com في 19 أبريل 2024

انظر التعليق في الصفحة 1956

*المتعاونون مدرجون في نهاية المقال

تم النشر على الإنترنت

3 أبريل 2024

https://doi.org/10.1016/

S0140-6736(24)00367-2

تم تصحيح هذه النشرة على الإنترنت. ظهرت النسخة المصححة لأول مرة فيthelancet.com في 19 أبريل 2024

انظر التعليق في الصفحة 1956

*المتعاونون مدرجون في نهاية المقال

المراسلة إلى:

الأستاذ سيمون آي هاي، معهد قياسات الصحة والتقييم،

الأستاذ سيمون آي هاي، معهد قياسات الصحة والتقييم،

ملخص

الخلفية: يعد التقرير المنتظم والمفصل عن صحة السكان حسب سبب الوفاة أمرًا أساسيًا لاتخاذ قرارات الصحة العامة. تعتبر التقديرات الخاصة بالسبب لمعدلات الوفيات والآثار اللاحقة على العمر المتوقع عالميًا مقاييس قيمة لقياس التقدم في تقليل معدلات الوفيات. هذه التقديرات مهمة بشكل خاص بعد حدوث ارتفاعات كبيرة في الوفيات، مثل جائحة COVID-19. عند تحليلها بشكل منهجي، تسمح معدلات الوفيات والعمر المتوقع بمقارنات لنتائج أسباب الوفاة عالميًا وعلى مر الزمن، مما يوفر فهمًا دقيقًا لتأثير هذه الأسباب على السكان العالميين.

الطرق: تقدير تحليل أسباب الوفاة في دراسة عبء الأمراض والإصابات وعوامل الخطر (GBD) 2021 لمعدلات الوفيات وسنوات الحياة المفقودة (YLLs) من 288 سببًا للوفاة حسب العمر والجنس والموقع والسنة في 204 دول وأقاليم و811 موقعًا فرعيًا لكل سنة من 1990 حتى 2021. استخدم التحليل 56604 مصدر بيانات، بما في ذلك بيانات من التسجيل الحيوي والتشريح اللفظي بالإضافة إلى الاستطلاعات، والتعدادات، وأنظمة المراقبة، وسجلات السرطان، من بين أمور أخرى. كما هو الحال مع جولات GBD السابقة، تم تقدير معدلات الوفيات الخاصة بالسبب لمعظم الأسباب باستخدام نموذج مجموعة أسباب الوفاة – أداة نمذجة تم تطويرها لـ GBD لتقييم صلاحية التنبؤ خارج العينة لنماذج إحصائية مختلفة وتباديل المتغيرات المرافقة ودمج تلك النتائج لإنتاج تقديرات وفيات خاصة بالسبب مع استراتيجيات بديلة تم تكييفها لنمذجة الأسباب التي تفتقر إلى البيانات، أو التغيرات الكبيرة في الإبلاغ على مدار فترة الدراسة، أو علم الأوبئة غير العادي. تم حساب YLLs كمنتج لعدد الوفيات لكل سبب-عمر-جنس-موقع-سنة والعمر المتوقع القياسي عند كل عمر. كجزء من عملية النمذجة، تم توليد فترات عدم اليقين (UIs) باستخدام

النتائج: كانت الأسباب الرئيسية للوفيات الموحدة حسب العمر عالميًا هي نفسها في 2019 كما كانت في 1990؛ بالترتيب التنازلي، كانت هذه الأمراض القلبية الإقفارية، والسكتة الدماغية، ومرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن، والتهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي. في 2021، ومع ذلك، حلت COVID-19 محل السكتة الدماغية كسبب الوفاة الثاني الموحد حسب العمر، مع

وأصبحت هذه الأسباب للوفاة تتركز بشكل متزايد منذ 1990، عندما أظهر 44 سببًا فقط هذا النمط. يتم مناقشة ظاهرة التركيز بشكل استدلالي فيما يتعلق بالعدوى المعوية والتهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي، والملاريا، وفيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز، والاضطرابات حديثي الولادة، والسل، والحصبة.

وأصبحت هذه الأسباب للوفاة تتركز بشكل متزايد منذ 1990، عندما أظهر 44 سببًا فقط هذا النمط. يتم مناقشة ظاهرة التركيز بشكل استدلالي فيما يتعلق بالعدوى المعوية والتهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي، والملاريا، وفيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز، والاضطرابات حديثي الولادة، والسل، والحصبة.

التفسير: تم تعطيل المكاسب المستمرة في العمر المتوقع وتقليل العديد من الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة بسبب جائحة COVID-19، التي انتشرت آثارها السلبية بشكل غير متساوٍ بين السكان. على الرغم من الجائحة، كان هناك تقدم مستمر في مكافحة عدة أسباب ملحوظة للوفاة، مما أدى إلى تحسين العمر المتوقع العالمي على مدار فترة الدراسة. أظهرت كل من المناطق الفائقة السبع في GBD تحسنًا عامًا من 1990 إلى 2021، مما يخفي التأثير السلبي في سنوات الجائحة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن نتائجنا بشأن التباين الإقليمي في أسباب الوفاة التي تدفع الزيادات في العمر المتوقع تحمل فائدة واضحة للسياسات. تكشف تحليلات الاتجاهات المتغيرة في الوفيات أن عدة أسباب، كانت شائعة عالميًا، أصبحت الآن تتركز جغرافيًا بشكل متزايد. تقدم هذه التغييرات في تركيز الوفيات، جنبًا إلى جنب مع مزيد من التحقيق في المخاطر المتغيرة، والتدخلات، والسياسات ذات الصلة، فرصة مهمة لتعميق فهمنا لاستراتيجيات تقليل الوفيات. قد تكشف دراسة أنماط تركيز الوفيات عن مناطق تم تنفيذ تدخلات الصحة العامة الناجحة فيها. يمكن أن تساعد ترجمة هذه النجاحات إلى مواقع حيث تظل بعض أسباب الوفاة راسخة في إبلاغ السياسات التي تعمل على تحسين العمر المتوقع للناس في كل مكان.

التمويل: مؤسسة بيل وميليندا غيتس.

حقوق الطبع والنشر © 2024 المؤلفون. تم النشر بواسطة إلسفير المحدودة. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب ترخيص CC BY 4.0.

حقوق الطبع والنشر © 2024 المؤلفون. تم النشر بواسطة إلسفير المحدودة. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب ترخيص CC BY 4.0.

المقدمة

على مدى أكثر من ثلاثة عقود، كانت دراسة عبء الأمراض والإصابات وعوامل الخطر (GBD) تسجل وتحلل بشكل منهجي وشامل أسباب الوفاة البشرية مصنفة حسب العمر والجنس والزمن في جميع أنحاء العالم.

أسباب الوفاة ليست موزعة بشكل موحد بين السكان؛ بل إن التباين الكبير في الأسباب الرئيسية غالبًا ما يعكس اختلافات اجتماعية وجغرافية مهمة.

يوفر تحليلنا فرصة للإجابة على أسئلة وبائية مهمة كانت في طليعة النقاشات الصحية العالمية والعامة – مثل، ما هي الأسباب التي ساهمت في أكبر زيادة أو انخفاض في متوسط العمر المتوقع، وما هي المواقع التي تشهد تركيزات أكبر من أسباب الوفاة القابلة للتجنب، وكيف أثرت COVID-19 وغيرها من الوفيات المرتبطة بالجائحة (OPRM) على متوسط العمر المتوقع والعبء القاتل العام للأمراض؟ لا يزال التباين الإقليمي في العديد من الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة واضحًا في هذه التقديرات الأخيرة، مما يمثل فرصًا مهمة لإنشاء سياسة صحية مصممة لتحسين الفجوات وتخفيف تركيزات الوفيات.

يوفر GBD 2021 مجموعة محدثة وشاملة من العبء القاتل للأمراض ملخصة بمقاييس الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين ومقاييس سنوات الحياة المفقودة (YLLs) لـ 288 سببًا حسب العمر والجنس عبر 204 دول وأقاليم من 1990 إلى 2021، وهو تحديث للتقديرات المنشورة سابقًا التي تغطي 1990-2019. في هذه الدراسة، نقدم تركيزات الوفيات وتحليل تفكيك متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب أسباب الوفاة المختلفة ونوضح تأثير أسباب الوفاة على متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي والإقليمي والخاص بالبلد، بالإضافة إلى تسليط الضوء على المواقع الأكثر تأثرًا بعبء الوفيات الجغرافية المركزة. كما هو الحال مع النسخ السابقة من GBD، يتضمن هذا الدورة مصادر بيانات جديدة متاحة وطرق منهجية محسنة لإعادة تقدير السلسلة الزمنية بالكامل، مما يوفر تقديرات محدثة تتجاوز جميع منشورات GBD السابقة حول أسباب الوفاة. يتضمن GBD 2021 تقديرًا لعدة نماذج مختلفة لنتائج الأمراض والإصابات. تم إنتاج هذه المخطوطة كجزء من شبكة المتعاونين في GBD ووفقًا لبروتوكول GBD.

أسباب الوفاة ليست موزعة بشكل موحد بين السكان؛ بل إن التباين الكبير في الأسباب الرئيسية غالبًا ما يعكس اختلافات اجتماعية وجغرافية مهمة.

يوفر تحليلنا فرصة للإجابة على أسئلة وبائية مهمة كانت في طليعة النقاشات الصحية العالمية والعامة – مثل، ما هي الأسباب التي ساهمت في أكبر زيادة أو انخفاض في متوسط العمر المتوقع، وما هي المواقع التي تشهد تركيزات أكبر من أسباب الوفاة القابلة للتجنب، وكيف أثرت COVID-19 وغيرها من الوفيات المرتبطة بالجائحة (OPRM) على متوسط العمر المتوقع والعبء القاتل العام للأمراض؟ لا يزال التباين الإقليمي في العديد من الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة واضحًا في هذه التقديرات الأخيرة، مما يمثل فرصًا مهمة لإنشاء سياسة صحية مصممة لتحسين الفجوات وتخفيف تركيزات الوفيات.

يوفر GBD 2021 مجموعة محدثة وشاملة من العبء القاتل للأمراض ملخصة بمقاييس الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين ومقاييس سنوات الحياة المفقودة (YLLs) لـ 288 سببًا حسب العمر والجنس عبر 204 دول وأقاليم من 1990 إلى 2021، وهو تحديث للتقديرات المنشورة سابقًا التي تغطي 1990-2019. في هذه الدراسة، نقدم تركيزات الوفيات وتحليل تفكيك متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب أسباب الوفاة المختلفة ونوضح تأثير أسباب الوفاة على متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي والإقليمي والخاص بالبلد، بالإضافة إلى تسليط الضوء على المواقع الأكثر تأثرًا بعبء الوفيات الجغرافية المركزة. كما هو الحال مع النسخ السابقة من GBD، يتضمن هذا الدورة مصادر بيانات جديدة متاحة وطرق منهجية محسنة لإعادة تقدير السلسلة الزمنية بالكامل، مما يوفر تقديرات محدثة تتجاوز جميع منشورات GBD السابقة حول أسباب الوفاة. يتضمن GBD 2021 تقديرًا لعدة نماذج مختلفة لنتائج الأمراض والإصابات. تم إنتاج هذه المخطوطة كجزء من شبكة المتعاونين في GBD ووفقًا لبروتوكول GBD.

البحث في السياق

الأدلة قبل هذه الدراسة

قدمت دراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض والإصابات وعوامل الخطر (GBD) تحديثات منتظمة حول الأنماط المعقدة والاتجاهات في صحة السكان حول العالم منذ أول منشور لـ GBD في عام 1993. مع كل دورة تالية، كانت هناك تحديثات منهجية مهمة، ومجموعات بيانات جديدة مدرجة، وقائمة موسعة من الأسباب وعوامل الخطر والمواقع التي يتم إنتاج تقديرات عبء المرض لها. في عام 1993، تم الإبلاغ عن الوفيات وسنوات الحياة المفقودة (YLLs) لـ 107 فئات من الأمراض التي تغطي جميع أسباب الوفاة الممكنة، لثماني مناطق. في الدورة الأخيرة من GBD – GBD 2019 – تم إنتاج تقديرات الوفيات وYLLs لـ 286 سببًا للوفاة في 204 دول وأقاليم، بما في ذلك جميع الدول الأعضاء في منظمة الصحة العالمية، وللمواقع دون الوطنية في 21 دولة وإقليم، لكل عام من 1990 إلى 2019. على الرغم من أن العديد من المجموعات قد أبلغت عن الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين على المستوى الوطني، ومقاييس صحة السكان الأخرى، بما في ذلك تقارير إحصاءات الصحة العالمية لمنظمة الصحة العالمية، فإن GBD هو الجهد البحثي الأكثر تفصيلاً وشفافية حتى الآن. علاوة على ذلك، تم الإبلاغ عن تقديرات الوفيات المرتبطة بـ COVID-19 في 2020 و2021 من قبل عدة مصادر، بما في ذلك دراسات GBD التي قامت بتحديد الوفيات الزائدة بسبب الجائحة ضمن مجموعة من مواقع GBD. ومع ذلك، لم تقم أي منشورات سابقة بتحديد تأثير COVID-19 على متوسط العمر المتوقع، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار الطيف الكامل لوفيات الأمراض على مدى العقود الثلاثة الماضية، عبر جميع الدول والأقاليم. تقدم هذه الدراسة، للمرة الأولى، 288 سببًا للوفاة من 1990 إلى 2021، تكمل نتائج الوفيات لجميع الأسباب المقدمة في تحليل التركيبة السكانية لـ GBD 2021. مجتمعة، توفر هذه الدراسات رؤية شاملة لوفيات جميع الأسباب والوفيات المحددة بسبب معين من 1990 إلى 2021.

القيمة المضافة لهذه الدراسة

بالإضافة إلى تقييمات الوفيات لجميع الأسباب ومتوسط العمر المتوقع في المنشورات المرافقة لـ GBD 2021، توضح هذه التحليل الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين وتأثيرها على متوسط العمر المتوقع. تتضمن هذه الدراسة تحليل تفكيك شامل يوضح السبب الرئيسي للوفاة الذي يؤثر على متوسط العمر المتوقع على المستوى العالمي والإقليمي والوطني. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، نقدم أسباب الوفاة وYLLs لجميع الدول والأقاليم، مما يوفر لصانعي السياسات رؤى قيمة حول التباينات في الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين. هذه الدراسة هي أيضًا الأولى من نوعها التي تنشر تقديرات 2021 للوفيات المرتبطة بـ COVID-19 وYLLs لـ 204 دول وأقاليم في سياق العبء العالمي للأمراض. على الرغم من أن منشورات أخرى قد قدرت الوفيات بسبب COVID-19، إلا أن تلك الوفيات لم تتم مقارنتها سابقًا مع الوفيات من أسباب أخرى. من خلال نمذجة وفيات COVID-19 ضمن تسلسل هرمي

لأسباب وفاة متبادلة حصرية وشاملة، توفر هذه الدراسة لصانعي السياسات معلومات أساسية لوضع أولويات الصحة حول العالم. للحصول على رؤى أكثر شمولاً من متوسط العمر المتوقع، من الضروري تقسيمه إلى وفيات محددة حسب العمر، والتي تتأثر بمعدلات الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين. قمنا بفحص تأثير COVID-19 وأسباب الوفاة الأخرى على متوسط العمر المتوقع من خلال تفكيك أعداد الوفيات إلى معدلات الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين عبر أبعاد مختلفة، بما في ذلك الدولة أو الإقليم، المنطقة، السوبر-منطقة، وخمسة فترات زمنية متميزة: 1990-2000، 2000-2010، 2010-2019، 2019-2021، و1990-2021. وبالتالي، تمكنا من معايرة جائحة COVID-19 بشكل منهجي مقابل أسباب الوفيات الأخرى على مدى الفترة من 1990 إلى 2021. أخيرًا، حددت دراستنا عدة أسباب للوفاة التي أظهرت زيادة في التركيز الجغرافي بمرور الوقت – أي، أسباب لها تأثير غير متناسب ضمن منطقة جغرافية معينة مقارنة ببقية الملاحظات العالمية. يوفر هذا التحليل معلومات مهمة لصانعي السياسات حول التباين الإقليمي واللامساواة في الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين. أيضًا جديد في GBD 2021، نبلغ عن 12 سببًا إضافيًا للوفاة: COVID-19 والوفيات المرتبطة بالجائحة الأخرى، ارتفاع ضغط الدم الشرياني الرئوي، وتسعة أنواع من السرطان – ورم الكبد، لمفوما بوركيت، لمفوما غير هودجكين الأخرى، سرطان العين، ورم الشبكية، أنواع أخرى من سرطانات العين، الأنسجة الرخوة وساركوما أخرى خارج العظام، الورم الخبيث للعظام والغضاريف المفصلية، والورم العصبي والسرطانات الأخرى للخلايا العصبية المحيطية. تم تعزيز دقة تقدير الوفيات في الأطفال دون سن 5 سنوات من خلال إضافة أربع مجموعات عمرية جديدة: 1-5 أشهر، 6-11 شهرًا، 12-23 شهرًا، و2-4 سنوات.

لأسباب وفاة متبادلة حصرية وشاملة، توفر هذه الدراسة لصانعي السياسات معلومات أساسية لوضع أولويات الصحة حول العالم. للحصول على رؤى أكثر شمولاً من متوسط العمر المتوقع، من الضروري تقسيمه إلى وفيات محددة حسب العمر، والتي تتأثر بمعدلات الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين. قمنا بفحص تأثير COVID-19 وأسباب الوفاة الأخرى على متوسط العمر المتوقع من خلال تفكيك أعداد الوفيات إلى معدلات الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين عبر أبعاد مختلفة، بما في ذلك الدولة أو الإقليم، المنطقة، السوبر-منطقة، وخمسة فترات زمنية متميزة: 1990-2000، 2000-2010، 2010-2019، 2019-2021، و1990-2021. وبالتالي، تمكنا من معايرة جائحة COVID-19 بشكل منهجي مقابل أسباب الوفيات الأخرى على مدى الفترة من 1990 إلى 2021. أخيرًا، حددت دراستنا عدة أسباب للوفاة التي أظهرت زيادة في التركيز الجغرافي بمرور الوقت – أي، أسباب لها تأثير غير متناسب ضمن منطقة جغرافية معينة مقارنة ببقية الملاحظات العالمية. يوفر هذا التحليل معلومات مهمة لصانعي السياسات حول التباين الإقليمي واللامساواة في الوفيات المحددة بسبب معين. أيضًا جديد في GBD 2021، نبلغ عن 12 سببًا إضافيًا للوفاة: COVID-19 والوفيات المرتبطة بالجائحة الأخرى، ارتفاع ضغط الدم الشرياني الرئوي، وتسعة أنواع من السرطان – ورم الكبد، لمفوما بوركيت، لمفوما غير هودجكين الأخرى، سرطان العين، ورم الشبكية، أنواع أخرى من سرطانات العين، الأنسجة الرخوة وساركوما أخرى خارج العظام، الورم الخبيث للعظام والغضاريف المفصلية، والورم العصبي والسرطانات الأخرى للخلايا العصبية المحيطية. تم تعزيز دقة تقدير الوفيات في الأطفال دون سن 5 سنوات من خلال إضافة أربع مجموعات عمرية جديدة: 1-5 أشهر، 6-11 شهرًا، 12-23 شهرًا، و2-4 سنوات.

تداعيات جميع الأدلة المتاحة

تقدم دراستنا تحليلًا كاملًا لأسباب الوفاة في جميع أنحاء العالم وعلى مر الزمن، جنبًا إلى جنب مع الأنماط المتغيرة في متوسط العمر المتوقع الناتجة عن تلك الأسباب. لوحظ تزايد التركيز الجغرافي للوفيات للعديد من أسباب الوفاة، مما يبرز الفجوات بين المناطق والاختلافات الكبيرة في المساهمات المحددة لكل سبب في متوسط العمر المتوقع. على نطاق عالمي، توفر هذه المعلومات فرصة لفحص ما إذا كانت تخفيضات الوفيات كانت مرنة أمام ظهور جائحة جديدة. على المستوى الإقليمي، توفر التقديرات التي أنتجتها دراستنا تفاصيل مهمة حول التأثير المتطور لأسباب الوفاة بين الدول، مما يسمح برؤية حاسمة حول النجاح التفاضلي حسب الجغرافيا والوقت والسبب. الطبيعة الشاملة لتقدير أسباب الوفاة في GBD 2021 توفر فرصًا قيمة للتعلم من مكاسب وخسائر الوفيات، مما يساعد على تسريع التقدم في تقليل الوفيات.

الطرق

نظرة عامة

في GBD 2021، قمنا بإنتاج تقديرات لكل كمية وبائية ذات اهتمام لـ 288 سببًا للوفاة حسب العمر والجنس والموقع والسنة لـ 25 مجموعة عمرية من

الولادة حتى 95 عامًا وأكثر؛ للذكور والإناث وكلا الجنسين معًا؛ في 204 دول وأقاليم تم تجميعها في 21 منطقة وسبع مناطق عظمى؛ ولكل عام من 1990 إلى 2021. يتضمن GBD 2021 أيضًا تحليلات دون وطنية لـ 21 دولة وإقليم

(الملحق 1 القسم 2.1). توفر شبكة دولية من المتعاونين البيانات المتاحة وتراجعها وتحللها لتوليد هذه المقاييس؛ استند GBD 2021 إلى خبرة أكثر من 11000 متعاون من أكثر من 160 دولة وإقليم.

الولادة حتى 95 عامًا وأكثر؛ للذكور والإناث وكلا الجنسين معًا؛ في 204 دول وأقاليم تم تجميعها في 21 منطقة وسبع مناطق عظمى؛ ولكل عام من 1990 إلى 2021. يتضمن GBD 2021 أيضًا تحليلات دون وطنية لـ 21 دولة وإقليم

(الملحق 1 القسم 2.1). توفر شبكة دولية من المتعاونين البيانات المتاحة وتراجعها وتحللها لتوليد هذه المقاييس؛ استند GBD 2021 إلى خبرة أكثر من 11000 متعاون من أكثر من 160 دولة وإقليم.

اتبعت الطرق المستخدمة لتوليد هذه التقديرات عن كثب تلك المستخدمة في GBD 2019.

تشمل تقديرات أسباب الوفاة في GBD 2021 الموصوفة هنا الوفيات المحددة بالسبب ومقياس الوفاة المبكرة (YLLs). قمنا بحساب YLLs كعدد الوفيات لكل سبب-عمر-جنس-موقع-سنة مضروبًا في متوسط العمر المتوقع القياسي عند كل عمر (الملحق 1 القسم 6.3). يتم حساب متوسط العمر المتوقع القياسي من أدنى معدل وفيات محدد بالعمر بين الدول.

هرمية الأمراض والإصابات في GBD

يصنف GBD الأمراض والإصابات في هرمية تتكون من أربعة مستويات تشمل كل من الأسباب القاتلة وغير القاتلة. تشمل الأسباب في المستوى 1 ثلاث فئات واسعة

(الأمراض المعدية، والأمومية، والوليدية، والتغذوية [CMNN]؛ الأمراض غير المعدية [NCDs]؛ والإصابات) ويقوم المستوى 2 بتفكيك تلك الفئات إلى 22 مجموعة من الأسباب، والتي يتم تفكيكها بشكل أكبر إلى أسباب المستوى 3 والمستوى 4. على المستوى الأكثر تفصيلًا، يتم تقدير 288 سببًا قاتلًا. للحصول على قائمة كاملة بأسباب الوفاة حسب المستوى، انظر الملحق 1 (الجدول S2). بالنسبة لـ GBD 2021، نبلغ بشكل منفصل عن 12 سببًا للوفاة للمرة الأولى: COVID-19، OPRM، ارتفاع ضغط الدم الرئوي، وتسعة أنواع من السرطان: ورم الكبد، لمفوما بوركيت، لمفوما غير هودجكين الأخرى، سرطان العين، ورم الشبكية، سرطانات العين الأخرى، الأورام اللينة والأورام خارج العظام الأخرى، الورم الخبيث للعظام والغضاريف المفصلية، والورم العصبي والأورام الأخرى لخلايا الأعصاب الطرفية.

(الأمراض المعدية، والأمومية، والوليدية، والتغذوية [CMNN]؛ الأمراض غير المعدية [NCDs]؛ والإصابات) ويقوم المستوى 2 بتفكيك تلك الفئات إلى 22 مجموعة من الأسباب، والتي يتم تفكيكها بشكل أكبر إلى أسباب المستوى 3 والمستوى 4. على المستوى الأكثر تفصيلًا، يتم تقدير 288 سببًا قاتلًا. للحصول على قائمة كاملة بأسباب الوفاة حسب المستوى، انظر الملحق 1 (الجدول S2). بالنسبة لـ GBD 2021، نبلغ بشكل منفصل عن 12 سببًا للوفاة للمرة الأولى: COVID-19، OPRM، ارتفاع ضغط الدم الرئوي، وتسعة أنواع من السرطان: ورم الكبد، لمفوما بوركيت، لمفوما غير هودجكين الأخرى، سرطان العين، ورم الشبكية، سرطانات العين الأخرى، الأورام اللينة والأورام خارج العظام الأخرى، الورم الخبيث للعظام والغضاريف المفصلية، والورم العصبي والأورام الأخرى لخلايا الأعصاب الطرفية.

مصادر البيانات، المعالجة، والتقييم من أجل الاكتمال

تضمن قاعدة بيانات أسباب الوفاة في GBD 2021 مصادر البيانات التي تم تحديدها في الجولات السابقة من التقدير بالإضافة إلى 9248 مصدرًا جديدًا (الملحق 1 الجدول S5). قمنا بتضمين أنواع بيانات متعددة لالتقاط أوسع مجموعة من المعلومات، بما في ذلك تسجيل الوفيات والتشريح اللفظي لجميع الأسباب الـ 288 بالإضافة إلى الاستطلاعات، والتعداد، والمراقبة، وسجلات السرطان، وسجلات الشرطة، وقواعد البيانات مفتوحة المصدر، وأخذ عينات الأنسجة بشكل طفيف. لتوحيد هذه البيانات بحيث يمكن مقارنتها حسب السبب والعمر والجنس والموقع والوقت، قمنا بتطبيق مجموعة من تصحيحات معالجة البيانات. أولاً، تم تقسيم الوفيات التي تفتقر إلى بيانات عمر كافية لتقدير مجموعات أعمار GBD أو تفتقر إلى بيانات العمر والجنس لتعيين مجموعات أعمار GBD وكذلك الجنس (الملحق 1 القسم 3.5). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم إعادة توزيع الرموز غير المحددة، التي هي غير محددة، أو غير معقولة، أو متوسطة، بدلاً من رموز أسباب الوفاة الأساسية من التصنيف الدولي للأمراض، إلى أهداف مناسبة لتعيين السبب الأساسي للوفاة.

تقييم اكتمال البيانات يوضح التغطية من مصدر البيانات على الوفيات العامة للبلد. تم تقييم اكتمال بيانات تسجيل الوفيات والتشريح اللفظي – تقدير محدد لمصدر النسبة المئوية لإجمالي الوفيات المحددة بالسبب التي تم الإبلاغ عنها في موقع وسنة معينة – حسب سنة-موقع، وتم استبعاد المصادر التي كانت أقل من

انظر عبر الإنترنت للملحق 1

للحصول على مستودع قابل للبحث عن تفاصيل النموذج المحدد بالسبب انظرhttps://www.healthdata.org/gbd/methods-appendices-2021

للحصول على مستودع قابل للبحث عن تفاصيل النموذج المحدد بالسبب انظرhttps://www.healthdata.org/gbd/methods-appendices-2021

للحصول على مصادر بيانات GBD انظرhttps://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2021/sources

تحسينات في معالجة وتقدير بيانات أسباب الوفاة في GBD 2021

تعديلات للتغير العشوائي

في GBD 2021، قمنا بإجراء تحسينين رئيسيين على الأساليب المستخدمة لتقليل التباين العشوائي، والتي تؤثر بشكل أكبر على أسباب الوفاة ذات أحجام العينات الصغيرة. أولاً، قمنا بتحديث الخوارزمية البايزية المستخدمة في تقليل الضوضاء لهذه البيانات لتحسين الحفاظ على الاتجاهات الحقيقية في البيانات ذات أحجام العينات الكبيرة، وأضفنا معلومات إضافية من الاتجاهات الإقليمية للبيانات ذات أحجام العينات الصغيرة. ثانياً، تم تحديث الحد الأدنى غير الصفري، وهو أسلوب يعالج أشكال البيانات المشوهة والاتجاهات غير المنطقية الناتجة عن الأعداد الصغيرة عند تحويلها إلى مساحة اللوغاريتم، ليكون غير متغير مع الزمن ومستقلاً عن المدخلات السكانية. يمكن العثور على التفاصيل الكاملة لهذين التحسينين الرئيسيين، بالإضافة إلى تحسينات أخرى تعالج التباين العشوائي، في الملحق 1 (القسم 3.14).

تقدير COVID-19 و OPRM

قمنا باشتقاق تقديرات COVID-19 و OPRM من تحليل إجمالي الوفيات الزائدة بسبب جائحة COVID-19 من 1 يناير 2020 إلى 31 ديسمبر 2021. يتم تقديم التفاصيل الكاملة لتقدير الوفيات الزائدة، وفيات COVID-19، و OPRM في الملحق 1 (القسم 5). لتقدير الوفيات الزائدة، قمنا أولاً بتطوير قاعدة بيانات للوفيات بسبب جميع الأسباب حسب الأسبوع والشهر بعد أخذ تأخيرات الإبلاغ، والظواهر الشاذة مثل موجات الحر، وتحت تسجيل الوفيات في الاعتبار. بعد ذلك، قمنا بتطوير نموذج جماعي للتنبؤ بالوفيات المتوقعة في غياب جائحة COVID-19 للسنوات 2020 و2021. في تركيبات المواقع والأوقات التي تم استخدام البيانات لها في هذه النماذج، قمنا بتقدير الوفيات الزائدة على أنها الوفيات الملاحظة ناقص الوفيات المتوقعة. لتقدير الوفيات الزائدة لمواقع-سنوات بدون بيانات، قمنا بتطوير نموذج إحصائي للتنبؤ مباشرة بالوفيات الزائدة بسبب COVID-19، باستخدام متغيرات تتعلق بكل من جائحة COVID-19 ومقاييس صحة السكان الخلفية على مستوى السكان قبل ظهور SARS-CoV-2. تم نقل عدم اليقين عبر كل خطوة من خطوات إجراء التقدير هذا.

لإنتاج التقديرات النهائية لوفيات COVID-19 المستخدمة في GBD 2021، استخدمنا نهجًا مضادًا للواقع.

لإنتاج التقديرات النهائية لوفيات COVID-19 المستخدمة في GBD 2021، استخدمنا نهجًا مضادًا للواقع.

تقدّر الفرضيات المضادة عدد الوفيات إذا كانت معدلات اكتشاف العدوى عند أعلى قيمة تم ملاحظتها لكل موقع-سنة. باستخدام نسبة الفرضيات المضادة إلى الوفيات الزائدة ونسبة الوفيات المبلغ عنها بسبب COVID-19 إلى الوفيات الزائدة، قمنا بحساب نسبة إجمالي وفيات COVID-19 إلى الوفيات المبلغ عنها بسبب COVID-19 وضربنا هذا الرقم بعدد الوفيات المبلغ عنها بسبب COVID-19 للحصول على تقديراتنا النهائية لوفيات COVID-19.

لتفسير الزيادات في الوفيات الزائدة في عامي 2020 و2021 التي لم يمكن نسبها إلى أسباب معينة، قدمنا سببًا متبقيًا، OPRM. حددنا أربعة أسباب للوفاة – التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي، والحصبة، والملاريا، والسعال الديكي – على أنها مرتبطة بجائحة COVID-19 ولديها تقديرات موثوقة بما يكفي لعدم المساهمة في OPRM. وبالتالي، قمنا بحساب OPRM كالفارق بين الوفيات الزائدة ومجموع الوفيات الناتجة عن COVID-19 وهذه الأسباب الأربعة.

عرض تقديرات الوفيات حسب السبب

تُعطى تقديرات الوفيات المحددة بسبب في عام 2021 بعدد الوفيات ومعدلات موحدة العمر لكل 100000 نسمة، تم حسابها باستخدام هيكل السكان القياسي لمشروع عبء المرض.

تحليل متوسط العمر المتوقع

الهدف من تحليل تفكيك متوسط العمر المتوقع هو تحليل الفرق في متوسط العمر المتوقع حسب العمر والموقع، مع تحديد المساهمات من أسباب محددة (الملحق 1 القسم 7). قمنا بدراسة الاتجاهات الزمنية في الأسباب على مدى فترات زمنية مستمرة عبر مواقع مختلفة. كان هدفنا هو تحديد تأثير أسباب الوفاة على متوسط العمر المتوقع من خلال استخدام ثلاث خطوات رئيسية في التفكيك. في هذه الدراسة، بحثنا في أعلى 20 سببًا من المستوى 2 والمستوى 3 من أسباب الأمراض العالمية التي تساهم في تغيير متوسط العمر المتوقع. ثم تم دمج الأسباب المتبقية كـ “أخرى من الأمراض المعدية والأمومية” أو “أخرى من الأمراض غير المعدية”. كانت الخطوة الأولى تتعلق بتفكيك الفرق في متوسط العمر المتوقع حسب العمر. قمنا بحساب المساهمات الخاصة بالعمر لفهم التباين في متوسط العمر المتوقع عبر مجموعات عمرية مختلفة. في الخطوة الثانية، تم تفكيك كل مساهمة خاصة بالعمر إلى مساهمات خاصة بالأسباب والعمر. سمح هذا التحليل بتحديد الأسباب المحددة للوفاة التي ساهمت في الفروق في متوسط العمر المتوقع داخل كل مجموعة عمرية. أخيرًا، قمنا بتجميع المساهمات الخاصة بالأسباب والعمر عبر المجموعات العمرية لإنتاج مساهمات خاصة بالأسباب في الفرق العام.

في متوسط العمر المتوقع. قدمت هذه التجميعات فهماً شاملاً لكيفية مساهمة أسباب الوفاة المختلفة في التباينات الملحوظة في متوسط العمر المتوقع. من خلال تطبيق هذا النهج في التحليل، نحصل على رؤى حول التأثير النسبي لأسباب الوفاة المختلفة على التغيرات في متوسط العمر المتوقع حسب العمر والموقع.

في متوسط العمر المتوقع. قدمت هذه التجميعات فهماً شاملاً لكيفية مساهمة أسباب الوفاة المختلفة في التباينات الملحوظة في متوسط العمر المتوقع. من خلال تطبيق هذا النهج في التحليل، نحصل على رؤى حول التأثير النسبي لأسباب الوفاة المختلفة على التغيرات في متوسط العمر المتوقع حسب العمر والموقع.

حساب تركيز الوفيات

تشير الأسباب المركزة في GBD إلى الأسباب التي تظهر تأثيرًا غير متناسب في مجموعة جغرافية محددة من البيانات مقارنة ببقية الملاحظات العالمية. في GBD 2021، استخدمنا طريقتين مختلفتين لتحديد هذه الأسباب المركزة: معامل التباين وتركيز الوفيات.

معامل التباين

لكل سبب من أسباب GBD، قمنا بحساب معامل التباين باستخدام طرق إحصائية قياسية. يقيم هذا المقياس تباين السكان بالنسبة لمتوسطهم.

التباين لديه بيانات أقل تركيزًا حول المتوسط ويشير إلى احتمال أكبر لسبب مركّز.

التباين لديه بيانات أقل تركيزًا حول المتوسط ويشير إلى احتمال أكبر لسبب مركّز.

تركيز الوفيات

لتحديد تركيزات الوفيات – المواقع الجغرافية أو مجموعات المواقع ذات السكان المتأثرين بشكل غير متناسب بسبب معين، قمنا أولاً بحساب العدد الإجمالي للوفيات بجميع الأعمار ومن كلا الجنسين في عام 2021 حسب السبب في كل من المواقع الفرعية الـ 811، وقمنا بترتيب هذه المواقع حسب عدد الوفيات بترتيب تنازلي. ثم قمنا بحساب النسبة التراكمية للوفيات من خلال قسمة الوفيات التراكمية الخاصة بكل موقع على عدد الوفيات العالمية لكل سبب. عندما وصلت النسبة التراكمية إلى أو تجاوزت

| أسباب رئيسية 1990 | معدل الوفيات الموحد حسب العمر لكل 100000، 1990 | أسباب رئيسية 2019 | معدل الوفيات الموحد حسب العمر لكل 100000، 2019 | أسباب رئيسية 2021 | معدل الوفيات الموحد حسب العمر لكل 100000، 2021 |

| 1 مرض القلب الإقفاري | 158.9 (147.4 إلى 165.4) | 1 مرض القلب الإقفاري | 110.9 (102.5 إلى 116.9) | 1 مرض القلب الإقفاري | 108.7 (99.8 إلى 115.6) |

| دورة مزدوجة |

|

دورة مزدوجة | 89.3 (81.6 إلى 95.6) | 2 كوفيد-19 | 94.0 (89.2 إلى 100.0) |

| 3 مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | 71.9 (64.6 إلى 77.5) | 3 مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن |

|

3 ضربة | 87.4 (79.5 إلى 94.4) |

| 4 التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | 61.8 (57.0 إلى 66.8) | 4 التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي |

|

4 مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | ٤٥.٢ (٤٠.٧ إلى ٤٩.٨) |

| 5 أمراض الإسهال | 60.6 (46.7 إلى 79.6) | 5 اضطرابات حديثي الولادة | 30.7 (26.8 إلى 35.3) | 5 وفيات أخرى مرتبطة بالوباء | 32.3 (24.8 إلى 43.3) |

| 6 اضطرابات حديثي الولادة | ٤٦.٠ (٤٣.٥ إلى ٤٨.٩) | 6 مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | 25.0 (6.2 إلى 65.0) | 6 اضطرابات حديثي الولادة | 29.6 (25.3 إلى 34.4) |

| 7 السل | 40.0 (34.1 إلى 44.6) | 7 سرطان الرئة | 23.7 (21.8 إلى 25.8) | 7 التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | 28.7 (26.0 إلى 31.1) |

| 8 سرطان الرئة | 27.6 (26.1 إلى 29.0) | 8 داء السكري | 19.8 (18.5 إلى 20.8) | 8 مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | 25.2 (6.4 إلى 65.6) |

| 9 مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | 25.1 (6.0 إلى 66.1) | 9 مرض الكلى المزمن | 18.6 (16.9 إلى 19.8) | 9 سرطان الرئة |

|

| 10 تليف الكبد | ٢٤.٤ (٢٢.٣ إلى ٢٧.٥) | 10 أمراض الإسهال | 17.1 (12.4 إلى 23.2) | 10 داء السكري | 19.6 (18.2 إلى 20.8) |

| 11 سرطان المعدة |

|

11 تليف الكبد | 17.1 (15.9 إلى 18.5) | 11 مرض الكلى المزمن | 18.5 (16.7 إلى 19.9) |

| 12 إصابة على الطريق | 21.8 (20.9 إلى 22.8) | 12 مرض القلب الناتج عن ارتفاع ضغط الدم | 16.9 (14.1 إلى 18.6) | 12 تليف الكبد | 16.6 (15.2 إلى 18.2) |

| 13 مرض القلب الناتج عن ارتفاع ضغط الدم | 20.9 (17.1 إلى 23.3) | 13 إصابة على الطريق |

|

13 مرض القلب الناتج عن ارتفاع ضغط الدم | 16.3 (13.7 إلى 18.1) |

| 14 داء السكري | 18.2 (17.0 إلى 19.1) | 14 السل | 14.9 (13.7 إلى 16.4) | 14 أمراض الإسهال | 15.4 (10.9 إلى 20.9) |

| 15 سرطان القولون والمستقيم | 15.6 (14.5 إلى 16.3) | 15 سرطان القولون والمستقيم | 12.6 (11.6 إلى 13.4) | 15 إصابة على الطرق | 14.6 (13.6 إلى 15.6) |

| 16 عيوب خلقية | 15.2 (9.6 إلى 19.7) | 16 سرطان المعدة | 11.5 (9.9 إلى 12.9) | 16 السل | 14.0 (12.6 إلى 15.8) |

| 17 إيذاء النفس | 14.9 (12.8 إلى 15.8) | 17 شلال | 10.3 (8.8 إلى 11.2) | 17 سرطان القولون والمستقيم |

|

| 18 مرض الكلى المزمن | 14.9 (13.7 إلى 16.4) | 18 فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز | 9.8 (9.0 إلى 11.0) | 18 سرطان المعدة | 11.2 (9.6 إلى 12.6) |

| 19 ملاريا |

|

19 ملاريا | 9.3 (3.7 إلى 18.3) | 19 ملاريا | 10.5 (3.9 إلى 21.4) |

| 20 حصبة | 11.0 (3.9 إلى 22.6) | 20 إيذاء النفس | 9.2 (8.6 إلى 9.7) | 20 شلال | 9.9 (8.5 إلى 10.8) |

| 21 شلال | 10.9 (9.8 إلى 11.8) | 21 عيب خلقي | 8.9 (7.7 إلى 10.9) | 21 إيذاء النفس | 9.0 (8.3 إلى 9.6) |

| 34 فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز | 5.9 (4.5 إلى 7.8) | 67 حصبة | 1.4 (0.5 إلى 3.0) | 22 فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز | 8.7 (8.1 إلى 9.6) |

|

|

|

الشكل 1: الأسباب الرئيسية من المستوى 3 للوفيات العالمية ومعدل الوفيات المعدل حسب العمر لكل 100000 نسمة للذكور والإناث مجتمعة، 1990، 2019، و2021

يوضح الشكل 20 سببًا رئيسيًا للوفاة بترتيب تنازلي. الأسباب متصلة بخطوط بين الفترات الزمنية؛ تمثل الخطوط الصلبة زيادة أو تحول جانبي في الترتيب، بينما تمثل الخطوط المتقطعة انخفاضًا في الترتيب. COPD=مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن. سرطان الرئة=سرطان القصبة الهوائية والقصبات والرئة.

يوضح الشكل 20 سببًا رئيسيًا للوفاة بترتيب تنازلي. الأسباب متصلة بخطوط بين الفترات الزمنية؛ تمثل الخطوط الصلبة زيادة أو تحول جانبي في الترتيب، بينما تمثل الخطوط المتقطعة انخفاضًا في الترتيب. COPD=مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن. سرطان الرئة=سرطان القصبة الهوائية والقصبات والرئة.

انظر على الإنترنت للملحق 2

لرؤية وتنزيل التقديرات من أداة نتائج GBD، انظرhttps://www.vizhub. healthdata.org/gbd-results

لرؤية وتنزيل التقديرات من أداة نتائج GBD، انظرhttps://www.vizhub. healthdata.org/gbd-results

لاستكشاف تقديرات عبء الصحة باستخدام GBD Compare، انظرhttps://www.vizhub.healthdata. org/gbd-compare

لملخصات النتائج لكل سبب من أسباب الوفاة، انظر https:// www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/diseases-injuries-risks/نشرات المعلومات

لرمز الإحصائي انظرhttp://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd2021/code

تكرار الوفيات بين المواقع والسكان. بالإضافة إلى تحديد هذه التركيزات من الوفيات في عام 2021، قمنا بإعادة نفس التحليل لعام 1990. من خلال مقارنة النسب المعنية من السكان العالميين في هذين العامين، تمكنا من تمييز الأسباب التي أظهرت زيادة أو نقصان أو عدم تغيير في تركيزات الوفيات. كانت الأسباب المميزة في هذه الدراسة هي تلك التي تتميز بمعدل وفيات موحد حسب العمر أكبر من 0.5 لكل 100000 نسمة. الغرض من تقديم تركيزات الوفيات هو توضيح الأسباب التي تؤثر بشكل غير متناسب على مجموعات سكانية معينة، عندما كانت تلك الأسباب تؤثر سابقًا على أجزاء كبيرة من السكان. وبالتالي، لم نحسب تركيز الوفيات للأسباب التي تتوطن في مناطق معينة، حيث إن معدل الوفيات معروف بالفعل بأنه مركز بين أجزاء معينة من السكان العالميين. استبعدنا سببين متوطنين، وهما مرض فيروس إيبولا ومرض شاغاس، من هذا الحساب.

تكرار الوفيات بين المواقع والسكان. بالإضافة إلى تحديد هذه التركيزات من الوفيات في عام 2021، قمنا بإعادة نفس التحليل لعام 1990. من خلال مقارنة النسب المعنية من السكان العالميين في هذين العامين، تمكنا من تمييز الأسباب التي أظهرت زيادة أو نقصان أو عدم تغيير في تركيزات الوفيات. كانت الأسباب المميزة في هذه الدراسة هي تلك التي تتميز بمعدل وفيات موحد حسب العمر أكبر من 0.5 لكل 100000 نسمة. الغرض من تقديم تركيزات الوفيات هو توضيح الأسباب التي تؤثر بشكل غير متناسب على مجموعات سكانية معينة، عندما كانت تلك الأسباب تؤثر سابقًا على أجزاء كبيرة من السكان. وبالتالي، لم نحسب تركيز الوفيات للأسباب التي تتوطن في مناطق معينة، حيث إن معدل الوفيات معروف بالفعل بأنه مركز بين أجزاء معينة من السكان العالميين. استبعدنا سببين متوطنين، وهما مرض فيروس إيبولا ومرض شاغاس، من هذا الحساب.

ممارسات البحث والتقارير في GBD

تتوافق هذه الدراسة مع توصيات إرشادات الإبلاغ عن تقديرات الصحة الدقيقة والشفافة (GATHER؛ الملحق 1 الجدول S4).

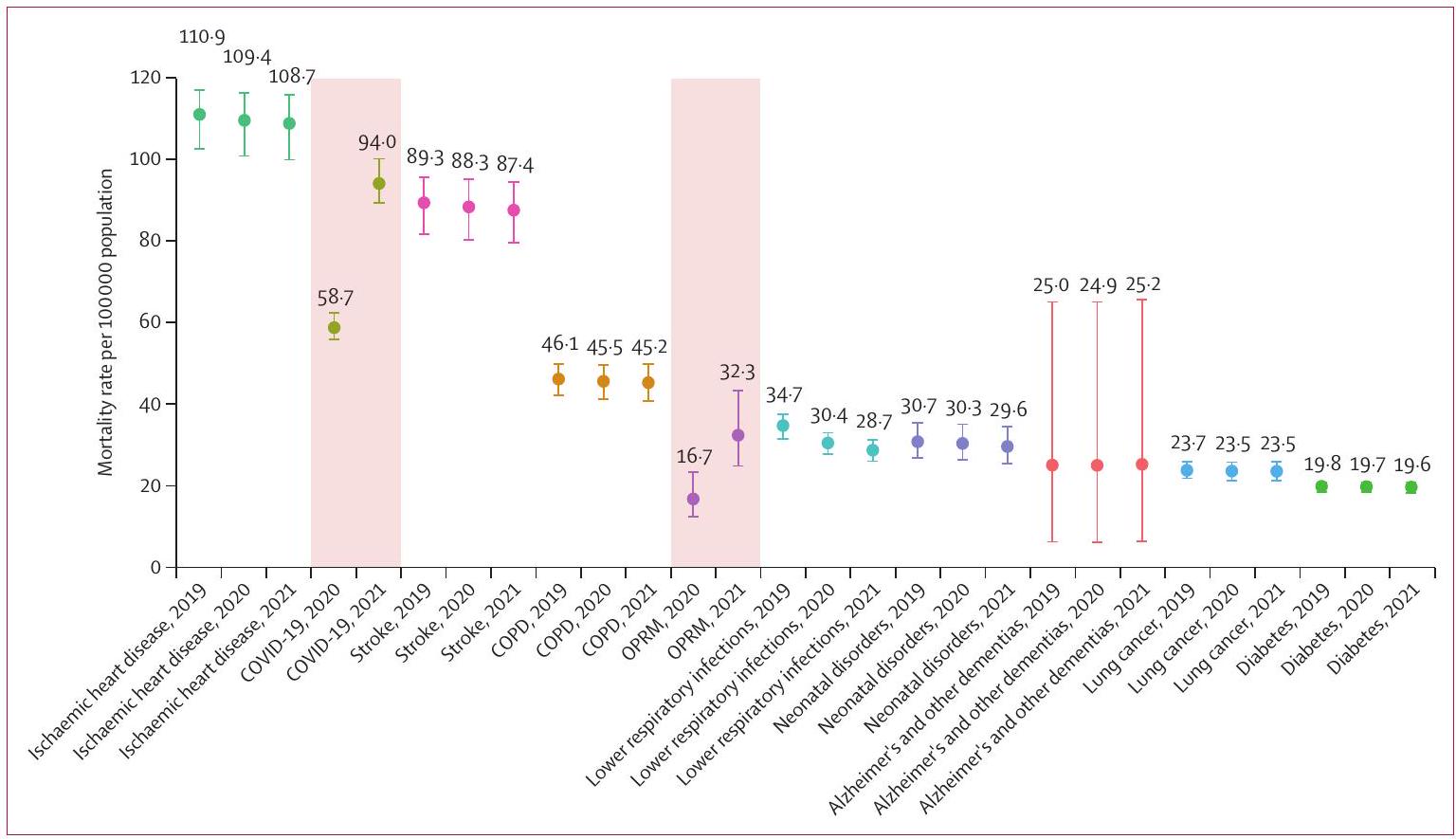

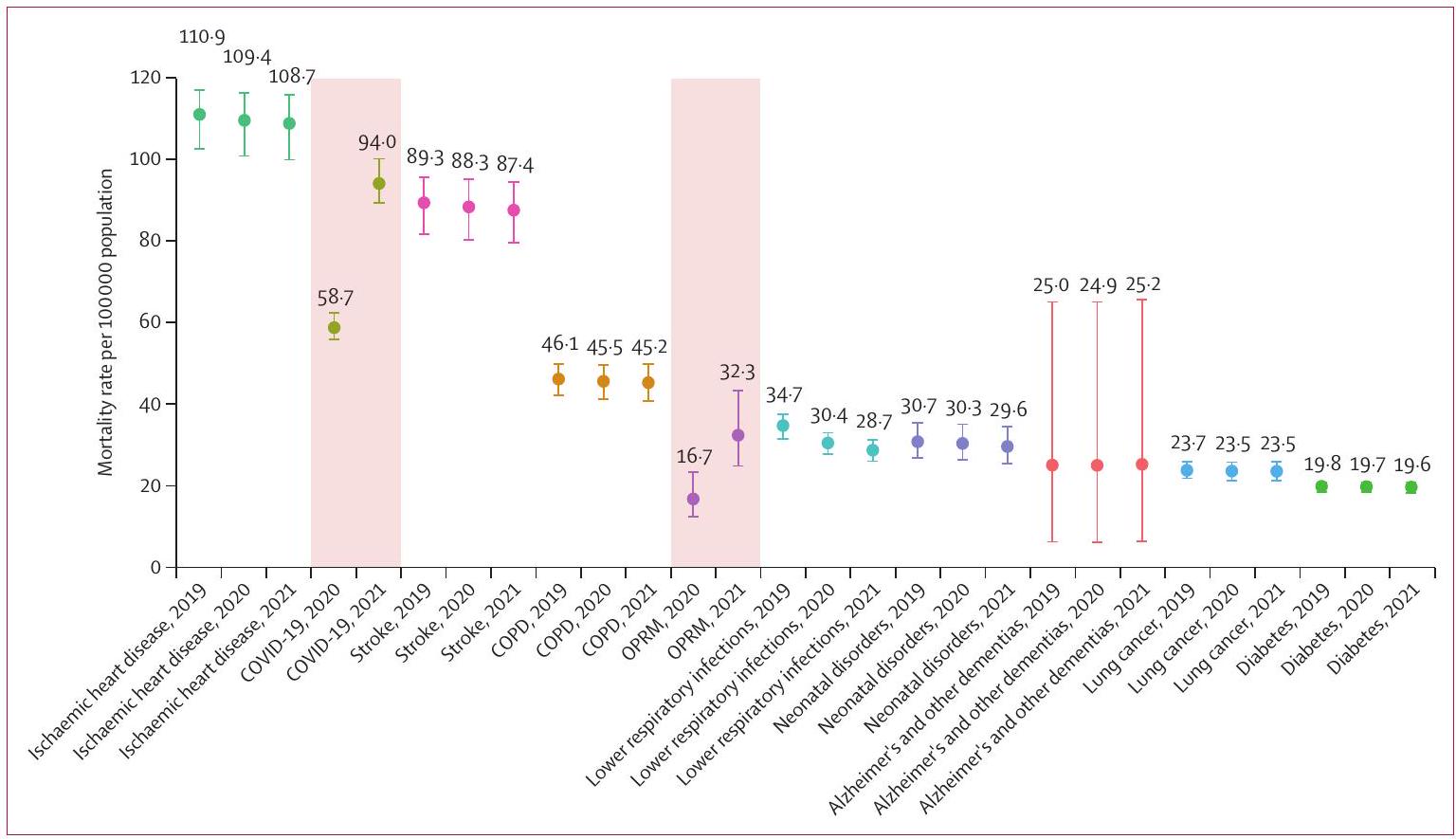

الشكل 2: معدل الوفيات الموحد حسب العمر لكل 100000 نسمة لأهم عشرة أسباب للوفاة من المستوى 3 على مستوى العالم، 2019-2021

مخطط الشوارب الذي فيه

مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن = COPD. وفيات أخرى مرتبطة بالوباء = OPRM.

مخطط الشوارب الذي فيه

مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن = COPD. وفيات أخرى مرتبطة بالوباء = OPRM.

دور مصدر التمويل

لم يكن للممول لهذه الدراسة أي دور في تصميم الدراسة، جمع البيانات، تحليل البيانات، تفسير البيانات، أو كتابة التقرير.

النتائج

يمكن الاطلاع على التقديرات الموضحة في المقال في الملحق 2. تتوفر النتائج التفصيلية لكل سبب من أسباب الوفاة في التحليل في شكل قابل للتنزيل من خلال أداة نتائج GBD ومن خلال الاستكشاف المرئي عبر الأداة الإلكترونية GBD Compare. تتوفر ملخصات النتائج لكل سبب من أسباب الوفاة المدرجة في التحليل عبر الإنترنت.

أسباب الوفاة العالمية

من 1990 إلى 2019، تراوحت نسبة التغير السنوي في الوفيات العالمية من جميع الأسباب بين

| عالمي | أوروبا الوسطى، أوروبا الشرقية، وآسيا الوسطى | دخل مرتفع | أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة البحر الكاريبي | شمال أفريقيا والشرق الأوسط | جنوب آسيا | جنوب شرق آسيا، شرق آسيا، وأوقيانوسيا | أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | |

| ٢٠٢٠ | ||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||

| سبب | مرض القلب الإقفاري | مرض القلب الإقفاري | مرض القلب الإقفاري | كوفيد-19 | مرض القلب الإقفاري | مرض القلب الإقفاري | جلطة | كوفيد-19 |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | ١٠٩.٤ (١٠٠.٧-١١٦.١) |

|

51.4 (45.1-54.6) | ١٣٣.٧ (

|

205.2 (182.7-225.6) |

|

|

158.9 (

|

| رقم | 8840000 (81800009360000) | ١٤١٠٠٠٠ (١٣١٠٠٠٠١٤٨٠٠٠) | ١٢٩٠٠٠٠ (١١١٠٠٠٠١٣٩٠٠٠) | 799000 (725 000869000) | 760000 (681000838000 | ١٩٦٠٠٠٠ (١٨٢٠٠٠٠٢١١٠٠٠) | ٣٤٦٠٠٠٠ (٣٠٣٠ ٠٠٠٣٨٨٠٠٠) | 659000 (615000706000) |

| 2 | سكتة دماغية | سكتة دماغية | كوفيد-19 | مرض القلب الإقفاري | كوفيد-19 | مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | مرض القلب الإقفاري | جلطة |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | ٨٨.٣ (٨٠.٢-٩٥.٠) |

|

41.8 (40.8-42.8) | 84.3 (77.2-89.4) |

|

١٠٤.١ (٩٢•٣-١١٧.٠) | 110.8 (97.3-124.6) | 126.2 (113.4-140.4) |

| رقم | 7140000 (6500 0007680000) | 726000 (675 000758000) | 930000 (908000952000) | 496000 (454000525000) | ٤٨٣٠٠٠ (٤١٥٠٠٠٥٣٧٠٠٠) | ١٢٣٠٠٠٠ (١٠٩٠ ٠٠٠١٣٧٠٠٠) | 2570000 (22600002880000) | 481000 (432000

|

| ٣ | ||||||||

| سبب | كوفيد-19 | كوفيد-19 | جلطة | سكتة دماغية | سكتة دماغية | كوفيد-19 | مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | مرض القلب الإقفاري |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | 58.7 (55.8-62.4) | 72.9 (64.1-81.7) | ٢٩.٠ (٢٤.٧-٣١.٢) | ٤٧.٥ (

|

١٠٣.٨ (٩٢•٠-١١٥•٦) |

|

66.9 (57.4-77.0) | 92.9 (83.1-103.0) |

| رقم | ٤٨٠٠٠٠٠ (٤٥٦٠٠٠٠٥١١٠٠٠) | 467000 (411000523000) | 764000 (636000830000) | 278000 (255000296000) | 370000 (329 000414000) | ١٣٢٠٠٠٠ (١٢٣٠ ٠٠٠

|

١٥٠٠٠٠٠ (١٢٩٠٠٠٠١٧٣٠٠٠) | 346000 (309 000388000) |

| ٤ | ||||||||

| سبب | مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | نتائج أخرى متعلقة بجائحة كوفيد-19 | مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | داء السكري | مرض القلب الناتج عن ارتفاع ضغط الدم | سكتة دماغية | سرطان القصبة الهوائية والشعب الهوائية والرئة | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

41.0 (

|

|

|

40.2 (

|

٨٣.٣ (٧٥.٧-٩٠.٤) | ٣٤.٨ (

|

٨٨.٥ (٧٧.٨-٩٨.٢) |

| رقم | ٣٦٥٠٠٠٠ (٣٣٢٠٠٠٠٣٩٧٠٠٠ | 264000 (212 000333000) | 774000 (1980001900000) | 217000 (202000231000) | 138000 (110 000160000) | ١٠٦٠٠٠٠ (٩٦٩ ٠٠٠١١٥٠٠٠) | 938000 (7830001110000) | 588000 (494000686000) |

| ٥ | ||||||||

| سبب | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | سرطان القصبة الهوائية والشعب الهوائية والرئة | سرطان القصبة الهوائية والشعب الهوائية والرئة | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | مرض الكلى المزمن | أمراض الإسهال | مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | الملاريا |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | 30.4 (27.7-32.9) |

|

25.9 (23.8-27.0) | 32.8 (

|

37.9 (

|

|

27.9 (6.76-74.8) | 67.9 (

|

| رقم | ٢٢٨٠٠٠٠ (٢٠٨٠٠٠٠٢٤٦٠٠٠) | 168000 (161000174000) | 581000 (526 000610000) | 187000 (169000200000) | 142000 (125000159000) | 591000 (381000

|

562000 (136000

|

713000 (2510001480000) |

| ٦ | ||||||||

| سبب | اضطرابات حديثي الولادة | تليف الكبد وأمراض الكبد المزمنة الأخرى | مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | مرض الكلى المزمن | نتائج أخرى متعلقة بجائحة كوفيد-19 | اضطرابات حديثي الولادة | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | السل |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

|

19.2 (16.9-20.3) | 30.9 (28.3-33.1) | 30.4 (

|

43.8 (

|

|

67.3 (56.7-77.8) |

| رقم | 1910000 (1650 0002200000 ) | 131000 (127000136000) | ٤٩٠٠٠٠ (٤٢٤٠٠٠٥٢٢٠٠٠) | 184000 (169000197000) | 121000 (46500207000) | 672000 (571000792000) | 424000 (378000469000) | 378000 (313000442000) |

| (الجدول 1 يستمر في الصفحة التالية) | ||||||||

مقالات

| عالمي | أوروبا الوسطى، أوروبا الشرقية، وآسيا الوسطى | دخل مرتفع | أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة البحر الكاريبي | شمال أفريقيا والشرق الأوسط | جنوب آسيا | جنوب شرق آسيا، شرق آسيا، وأوقيانوسيا | أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | |

| (مستمر من الصفحة السابقة) | ||||||||

| ٧ | ||||||||

| سبب | مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | سرطان القولون والمستقيم | مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | داء السكري | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | مرض القلب الناتج عن ارتفاع ضغط الدم | فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | 24.9 (6.16-65.0) | 20.8 (4.88-55.3) |

|

25.0 (

|

٢٩.٤ (٢٦.٤-٣٢.٣) | 40.0 (

|

|

65.8 (59.9-73.2) |

| ٨ | ||||||||

| سبب | سرطان القصبة الهوائية والشعب الهوائية والرئة | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | مرض الكلى المزمن | العنف بين الأفراد | مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | السل | سرطان المعدة | أمراض الإسهال |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

|

14.0 (

|

|

٢٦.٩ (٢٣.٩-٢٩.٧) |

|

18.4 (14•2-22•0) | 57.0 (

|

| رقم | 1970000 (17800002160000) | 96200 (91200101000) | 364000 (307000

|

147000 (140000 155000) | 92400 (82500102000) | ٥٠٩٠٠٠ (٤٥٠ ٠٠٠ ٥٩٧٠٠٠) | 491000 (380 000589000) | ٤٥٢٠٠٠ (٣٢٤٠٠٠

|

|

|

داء السكري | اعتلال عضلة القلب والتهاب عضلة القلب | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | نتائج أخرى متعلقة بجائحة كوفيد-19 | مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | داء السكري | إصابات الطرق | نتائج أخرى متعلقة بجائحة كوفيد-19 |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

19.2 (17.9-20.4) |

|

20.9 (10•3-33:3) | 25.7 (6.30-67.6) | 33.1 (29.8-36.0) | 15.7 (13.9-17.6) |

|

| رقم | 1630000 (15200001720000) | ١١٣٠٠٠ (١٠٥٠٠٠١٢١٠٠٠) | ٣٦١٠٠٠ (٣٠٦٠٠٠٣٩٠٠٠٠) | 125000 (59 600199000) | 73600 (17900198000) | ٤١٩٠٠٠ (٣٧٨ ٠٠٠٤٥٧٠٠٠) | ٣٨٠٠٠٠ (٣٣٥٠٠٠٤٢٩٠٠٠) | 245000 (159000339000) |

| 10 | ||||||||

| سبب | مرض الكلى المزمن | سرطان القولون والمستقيم | إيذاء النفس | مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | نتائج أخرى متعلقة بجائحة كوفيد-19 | مرض الكلى المزمن | اضطرابات حديثي الولادة |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | 18.6 (16.9-19.9) | 18.6 (17.6-19.4) | 10.9 (

|

20.8 (5.14-53.8) | 25.4 (

|

28.2 (

|

|

50.0 (

|

| رقم | ١٥٠٠٠٠٠ (١٣٦٠٠٠٠١٦١٠٠٠) | ١٢٢٠٠٠ (١١٥٠٠٠١٢٧٠٠٠) | 149000 (142000 153000) | 119000 (29200308000) | ١٠٣٠٠٠ (٩١٠٠٠١١٦٠٠٠) | 370000 (246 000514000) | ٣٧٦٠٠٠ (٣٣٣٠٠٠٤٢٠٠٠) | 889000 (749 0001050000 ) |

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||

| سبب | مرض القلب الإقفاري | مرض القلب الإقفاري | مرض القلب الإقفاري | كوفيد-19 | مرض القلب الإقفاري | كوفيد-19 | سكتة دماغية | كوفيد-19 |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | ١٠٨.٧ (٩٩•٨-١١٥•٦) | 213.6 (196•1-229•1) | 51.0 (44.9-54.2) | 195.4 (182.1-211.4) |

|

|

|

٢٧١.٠ (٢٥٠.١-٢٩٠.٧) |

| رقم | 8990000 (82900009550000) | ١٤١٠٠٠٠ (١٢٩٠ ٠٠٠١٥١٠٠٠) | ١٣١٠٠٠٠ (١١٢٠٠٠٠١٤٠٠٠٠) | ١٢٠٠٠٠٠ (١١١٠٠٠٠

|

769000 (679 000863000) | 2060000 (19800002170000) | ٣٥٥٠٠٠٠ (٣١٠٠ ٠٠٠٤٠٢٠٠٠) | ١١٥٠٠٠٠ (١٠٦٠٠٠٠١٢٤٠٠٠) |

|

|

كوفيد-19 | كوفيد-19 | كوفيد-19 | مرض القلب الإقفاري | كوفيد-19 | مرض القلب الإقفاري | مرض القلب الإقفاري | جلطة |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | 94.0 (89.2-100)

|

168.8 (150.6-186.1) | ٤٨.١ (٤٧.٤-٤٨.٨) | ٨٣.٨ (٧٥.٩-٩٠.٦) |

|

149.1 (

|

110.4 (94.9-124.6) |

|

| رقم | 7890000 (7490 0008400000) | ١١٠٠٠٠٠ (٩٨٢٠٠٠١٢١٠٠٠) | ١٠٧٠٠٠٠ (١٠٦٠٠٠٠١٠٩٠٠٠٠) | 504000 (457000545000) | 698000 (608000

|

١٩٩٠٠٠٠ (١٨٢٠٠٠٠٢١٦٠٠٠) | ٢٦٦٠٠٠٠ (٢٢٩٠٠٠٠٣٠٠٠٠٠) | 484000 (432000544000) |

| (الجدول 1 يستمر في الصفحة التالية) | ||||||||

| عالمي | أوروبا الوسطى، أوروبا الشرقية، وآسيا الوسطى | دخل مرتفع | أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة الكاريبي | شمال أفريقيا والشرق الأوسط | جنوب آسيا | جنوب شرق آسيا، شرق آسيا، وأوقيانوسيا | أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | ||||||||||

| (مستمر من الصفحة السابقة) | |||||||||||||||||

| ٣ | |||||||||||||||||

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | 87.4 (

|

١٠٩.٨ (

|

28.8 (

|

|

|

101.6 (90.3-114.2) | 66.6 (56.2-77.7) | 123.9 (87.7-159.5) | |||||||||

| رقم | 7250000 (66000007820000) | 725000 (671000770000) | 771000 (641000838000) | 279000 (254000301000) | 372000 (325000421000) | ١٢٣٠٠٠٠ (١١٠٠ ٠٠٠١٣٨٠٠٠) | ١٥٦٠٠٠٠ (١٣١٠٠٠٠١٨٢٠٠٠) | 584000 (418 000757000) | |||||||||

| ٤ | |||||||||||||||||

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

50.0 (

|

|

|

|

81.8 (

|

٣٤.٨ (٢٨.٨-٤١.١) | 92.8 (83.3-103.5) | |||||||||

| ٥ | ٣٧٢٠٠٠٠ (٣٣٦٠٠٠٠٤٠٩٠٠٠) | ٣٢١٠٠٠ (٢٢٣٠٠٠

|

792000 (2030001940000) | 236000 (135000355000) | 265000 (139 000414000) | ١٠٧٠٠٠٠ (٩٦٨٠٠٠١١٧٠٠٠) | 970000 (800 0001150000) | ٣٥٢٠٠٠ (٣١٦٠٠٠

|

|||||||||

| سبب | نتائج أخرى متعلقة بجائحة كوفيد-19 | سرطان القصبة الهوائية والشعب الهوائية والرئة | سرطان القصبة الهوائية والشعب الهوائية والرئة | داء السكري | مرض القلب الناتج عن ارتفاع ضغط الدم | نتائج أخرى متعلقة بجائحة كوفيد-19 | مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | |||||||||

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

|

25.9 (23.8-27.0) | ٣٦.٣ (

|

|

|

28.9 (7.41-78.6) | 85.4 (75.3-95.0) | |||||||||

| ٦ | 2690000 (20600003610000) | 167000 (157000176000) | 591000 (537000620000) | ٢٢١٠٠٠ (٢٠٢٠٠٠٢٣٩٠٠٠) | 138000 (109 000162000) | ٨٣٨٠٠٠ (٦٧٤٠٠٠١٠٢٠٠٠) | 608000 (1550001670000) | 563000 (472 000655000) | |||||||||

| سبب | اضطرابات حديثي الولادة | تليف الكبد وأمراض الكبد المزمنة الأخرى | مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | مرض الكلى المزمن | مرض الكلى المزمن | أمراض الإسهال | كوفيد-19 | الملاريا | |||||||||

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

|

|

30.7 (27.8-33.5) | 37.7 (

|

٤٧.٨ (

|

|

65.9 (

|

|||||||||

| رقم | ١٨٣٠٠٠٠ (١٥٧٠ ٠٠٠٢١٣٠٠٠) | 131000 (123 000138000) | 495000 (428 000527000) | 187000 (170 000204000) | 145000 (126000164000) | 573000 (372 000908000 ) | 606000 (425000974000) | 704000 (2650001400000) | |||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) | 28.7 (26.0-31.1) | 20.8 (4.94-55.6) | 14.7 (13.1-15.5) | 30.4 (27.0-33.3) |

|

|

|

65.8 (

|

|||||||||

| ٨ | 2180000 (19800002360000) | 137000 (32 500370000) | 348000 (304000372000) | 177000 (157000194000) | 116000 (102000129000) | 636000 (538000760000) | 431000 (384000482000) | ٣٧٣٠٠٠ (٣١٣٠٠٠

|

|||||||||

| سبب | مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | اعتلال عضلة القلب والتهاب عضلة القلب | مرض الكلى المزمن | مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | مرض القلب الناتج عن ارتفاع ضغط الدم | فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز | |||||||||

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

|

13.9 (

|

|

٢٦.٤ (

|

|

19.8 (

|

61.4 (

|

|||||||||

| رقم | 1960000 (499 0005120000) | ١١٢٠٠٠ (١٠٣٠٠٠١٢٢٠٠٠) | 368000 (310 000402000) | 145000 (130000156000) | 92700 (82000104000) | 516000 (451000584000) | ٤٧٠٠٠٠ (٣٣٣٠٠٠٥٧٥٠٠٠) | 515000 (467000583000) | |||||||||

| (الجدول 1 يستمر في الصفحة التالية) | |||||||||||||||||

مقالات

| عالمي | أوروبا الوسطى، أوروبا الشرقية، وآسيا الوسطى | دخل مرتفع | أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة الكاريبي | شمال أفريقيا والشرق الأوسط | جنوب آسيا | جنوب شرق آسيا، شرق آسيا، وأوقيانوسيا | أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | |

| (مستمر من الصفحة السابقة) | ||||||||

| 9 | ||||||||

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

|

11.9 (10.2-12.7) |

|

25.7 (6.22-66.8) |

|

18.1 (

|

54.4 (

|

| 10 | ||||||||

| سبب | داء السكري | التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي | إيذاء النفس | مرض الزهايمر وأنواع الخرف الأخرى | تليف الكبد وأمراض الكبد المزمنة الأخرى | داء السكري | إصابات الطرق | اضطرابات حديثي الولادة |

| معدل موحد العمر (لكل 100000 نسمة) |

|

|

10.8 (

|

20.8 (5•18-54•3) | 23.2 (20.2-26.8) | 32.8 (

|

|

٤٨.٦ (٤٠.٣-٥٨.١) |

| رقم | ١٦٦٠٠٠٠ (١٥٤٠٠٠٠١٧٦٠٠٠) | 82800 (77800-87500) | 148000 (141000152000) | 121000 (30300317000) | 99600 (86100116000) | 426000 (383000468000) | ٣٧٩٠٠٠ (٣٣١٠٠٠٤٣٠٠٠٠) | 873000 (724000

|

| الجدول 1: عدد الوفيات ومعدلات الوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر لأهم عشرة أسباب للوفاة من المستوى 3 في عامي 2020 و2021، على مستوى العالم وحسب المناطق الكبرى، لجميع الأعمار وللذكور والإناث معًا | ||||||||

إضافي

كوفيد-19 و OPRM

تظهر تقديراتنا أن 4.80 مليون

كانت معدلات الوفيات بسبب COVID-19 متغيرة بشكل كبير بين المناطق الكبرى في GBD (الجدول 1). في عام 2021، كانت الترتيبات من الأعلى إلى الأدنى هي: أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء (271.0 وفاة [250.1-290.7] لكل 100000 نسمة)؛ أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة البحر الكاريبي (195.4 وفاة [182.1-211.4] لكل 100000 نسمة)؛ شمال أفريقيا والشرق الأوسط (172.4 وفاة

كانت معدلات الوفيات بسبب COVID-19 متغيرة بشكل كبير بين المناطق الكبرى في GBD (الجدول 1). في عام 2021، كانت الترتيبات من الأعلى إلى الأدنى هي: أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء (271.0 وفاة [250.1-290.7] لكل 100000 نسمة)؛ أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة البحر الكاريبي (195.4 وفاة [182.1-211.4] لكل 100000 نسمة)؛ شمال أفريقيا والشرق الأوسط (172.4 وفاة

تفاوتت الوفيات الناتجة عن كل من COVID-19 و OPRM بشكل كبير حسب العمر، حيث تأثرت الفئات العمرية الأكبر بشكل غير متناسب (الجدول 2). كان لدى الأفراد الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 70-74 عامًا أعلى عدد من الوفيات الناتجة عن كل من COVID-19 و OPRM في عام 2020 ومرة أخرى في عام 2021. كانت أعلى نسبة من إجمالي الوفيات الناتجة عن COVID-19 موجودة في الفئة العمرية 40-44 عامًا، بينما حدثت أعلى معدل للوفيات في الفئة العمرية 95 عامًا وما فوق. كانت معدلات الوفيات الناتجة عن OPRM مرتفعة بين الفئات العمرية الأكبر وبين أصغر الفئات العمرية، مع معدل من

| الوفيات | الوفيات لكل 100000 نسمة | نسبة إجمالي الوفيات | |||||||||||||||||||

| كوفيد-19 2020 | كوفيد-19 2021 |

|

|

|

كوفيد-19 2021 |

|

|

كوفيد-19 2020 | كوفيد-19 2021 | نتائج أخرى متعلقة بجائحة كوفيد-19 2020 | نتائج أخرى متعلقة بجائحة كوفيد-19 2021 | ||||||||||

| حديثي الولادة المبكر | 0 | 1 | ٣٥١٨ | ٣٤٦٢ | 0.0 | <0.1 | 141.4 | 141.2 | 0.0% | <0.1٪ | 0.2% | 0.2% | |||||||||

| حديث الولادة المتأخر | ٣ | ٥ | 5069 | 5641 | <0.1 | 0.1 |

|

77.3 | <0.1٪ | <0.1٪ | 1.1٪ | 1.3% | |||||||||

| 1-5 أشهر | 170 | 287 | 24269 | ٢٦٦٤٧ | 0.3 | 0.5 | ٤٤.٤ | ٤٩.٦ | <0.1٪ | <0.1٪ | 3.1% | ٣.٦٪ | |||||||||

| 6-11 شهر | 234 | 394 | 20478 | ٣٠٨٨٣ | 0.4 | 0.6 | 31.7 | ٤٨.٩ | <0.1٪ | 0.1% | 3.5% |

|

|||||||||

| 12-23 شهر | 998 | 1644 | 19042 | ٣٠٥٥٠ | 0.8 | 1.3 | 14.5 | ٢٣.٨ | 0.2% | 0.3% | 3.7% | 6.2% | |||||||||

| 2-4 سنوات | ٨٥٠٠ | 14386 | 14730 | 23574 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 5.8 | 1.2٪ | ٢.١٪ | 2.0% | 3.4٪ | |||||||||

| 5-9 سنوات | 7052 | 11393 | ٥٣٧٧ | 8196 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.9% | 3.2% | 1.5% | ٢.٣٪ | |||||||||

| 10-14 سنة | 8553 | 14405 | 1588 | ٢٧١٥ | 1.3 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.8٪ | ٤.٨٪ | 0.5% | 0.9% | |||||||||

| 15-19 سنة | 17032 | ٢٦٨٥٢ | 5932 | 12576 | 2.8 |

|

1.0 | 2.0 | ٣.١٪ | ٤.٨٪ | 1.1٪ | ٢.٢٪ | |||||||||

| 20-24 سنة | 25528 | ٤٠٧٤٣ | 8219 | 17453 |

|

6.8 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 3.6% | ٥.٥٪ | 1.2٪ | ٢.٤٪ | |||||||||

| 25-29 سنة | 47857 | 78496 | 12581 | 28816 | 8.1 | 13.3 | 2.1 | ٤.٩ | 5.9% | 9.2% | 1.6% | 3.4% | |||||||||

| 30-34 سنة | 81232 | 137979 | 21625 | 49808 | 13.4 | 22.8 | 3.6 | 8.2 | ٧.٩٪ | 12.3% | ٢.١٪ |

|

|||||||||

| 35-39 سنة | ١١٢٢٢٨ | 195380 | 29877 | 69402 |

|

٣٤.٨ |

|

12.4 | 9.0% | 14.1٪ | ٢.٤٪ | ٥٫٠٪ | |||||||||

| 40-44 سنة | 165337 | 287099 | ٤٤٣٩١ | ١٠٢٠٤١ |

|

٥٧.٤ | 9.0 | ٢٠.٤ | 10.3% | 16.0% | 2.8% | 5.7% | |||||||||

| 45-49 سنة | ٢٠٧٩٤٠ | 355388 | 55989 | ١٢٤٨٩٩ | ٤٤.٠ | 75.1 | 11.8 | ٢٦.٤ | 10.1٪ | 15.7% | ٢.٧٪ | 5.5٪ | |||||||||

| 50-54 سنة | 253491 | 426785 | 67629 | 147651 | ٥٧.٧ | 95.9 | 15.4 | ٣٣.٢ | 9.1% | 14.0% | ٢.٤٪ | ٤.٨٪ | |||||||||

| 55-59 سنة | 336162 | 564508 | 90815 | 191441 | 87.5 |

|

٢٣.٦ | ٤٨.٤ | 9.0% | 13.8% | ٢.٤٪ | ٤.٧٪ | |||||||||

| 60-64 سنة | 460769 | 774879 | ١٢٥٤٣٣ | 262008 | ١٤٦.١ | 242.1 | ٣٩.٨ | 81.9 | 9.8% | 15.0% | ٢.٧٪ | 5•1% | |||||||||

| 65-69 سنة | 564371 | 957557 | 155431 | 321301 | ٢٠٩.٤ | ٣٤٧.١ | ٥٧.٧ | ١١٦.٥ | 9.4% | 14.5% | 2.6% | ٤.٩٪ | |||||||||

| 70-74 سنة | 585549 | 989888 | 156931 | ٣٢٥٢٩٥ | 298.7 | ٤٨٠.٩ | 80.1 | 158.0 | 8.8٪ | 13.2% | ٢.٤٪ | ٤.٣٪ | |||||||||

| 75-79 سنة | 539515 | 861796 | 135849 | 276402 | ٤١٧.١ | 653.4 | ١٠٥.٠ | ٢٠٩.٦ | ٧.٩٪ | 11.8% | 2.0% | 3.8٪ | |||||||||

| 80-84 سنة | ٥٥١٠١٤ | 888813 | 146084 | 277786 | ٦٣٨.٩ | ١٠١٤.٨ | ١٦٩.٤ | 317.2 | ٧.٥٪ | 11.3٪ | 2.0% | 3.5% | |||||||||

| 85-89 سنة | 427770 | 658875 | 106842 | 191824 | 959.3 |

|

239.6 | ٤١٩.٥ | 6.9% | 10.0% | 1.7% | 2.9% | |||||||||

| 90-94 سنة | 280605 | 426185 | 67297 | ١١٤٤٤٩ | ١٦٠٨.٩ | ٢٣٨٢.٣ | ٣٨٥.٩ | 639.8 | ٧.٥٪ | 10.8٪ | 1.8٪ | 2.9% | |||||||||

|

|

١٢٠١٧٣ | 174390 | 24074 | 42104 | ٢٢٩٨.٦ | ٣١٩٩.٦ |

|

٧٧٢.٥ | ٧.٨٪ | 10.7% | 1.6٪ | 2.6% | |||||||||

الجدول 2: عدد الوفيات، معدلات الوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر، ونسبة إجمالي الوفيات بسبب COVID-19 وغيرها من الوفيات المرتبطة بالوباء حسب العمر، على مستوى العالم

الأسباب الرئيسية لفقدان سنوات الحياة المعدلة حسب الإعاقة على مستوى العالم

تظهر أسباب الوفاة التي تتمتع بأعلى معدلات سنوات الحياة المفقودة المعدلة حسب العمر تحولًا في الاتجاهات الوبائية من الأمراض المعدية إلى الأمراض غير المعدية في المستوى الثالث من تسلسل الأسباب (الملحق 2 الشكل S2). على مستوى العالم، كانت الأسباب الثلاثة الرئيسية لسنوات الحياة المفقودة المعدلة حسب العمر في عام 1990 جميعها من الأمراض المعدية. مرتبة بترتيب تنازلي، كانت هذه الأسباب هي الاضطرابات الوليدية، والتهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي، وأمراض الإسهال. في عام 2019، ظلت الاضطرابات الوليدية السبب الرئيسي لسنوات الحياة المفقودة المعدلة حسب العمر، لكن السبب الثاني والثالث تم استبدالهما بالأمراض غير المعدية: مرض القلب الإقفاري (المصنف في المرتبة الثانية) والسكتة الدماغية (المصنفة في المرتبة الثالثة). في عام 2021، كان COVID-19 السبب الثاني الرئيسي لسنوات الحياة المفقودة المعدلة حسب العمر على مستوى العالم، مما جعل السببين الرئيسيين من الأمراض المعدية (مع الاضطرابات الوليدية في المرتبة الأولى)، بينما كان مرض القلب الإقفاري في المرتبة الثالثة. من بين الأسباب الرئيسية لسنوات الحياة المفقودة المعدلة حسب العمر، كانت الملاريا السبب الوحيد الذي أظهر زيادة في معدلات سنوات الحياة المفقودة المعدلة حسب العمر بين عامي 2019 و2021 (حيث كانت في المرتبة التاسعة في عام 2019 والسابعة في عام 2021).

تحليل متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي

لقد وجدنا اتجاهات إيجابية طويلة الأمد في متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي منذ أوائل التسعينيات، مع زيادات ثابتة تحدث في كل عقد بين عامي 1990 و2019 (الملحق 2 الجدول S4). إجمالاً، بلغ الزيادة العالمية في متوسط العمر المتوقع من 1990 إلى 2019

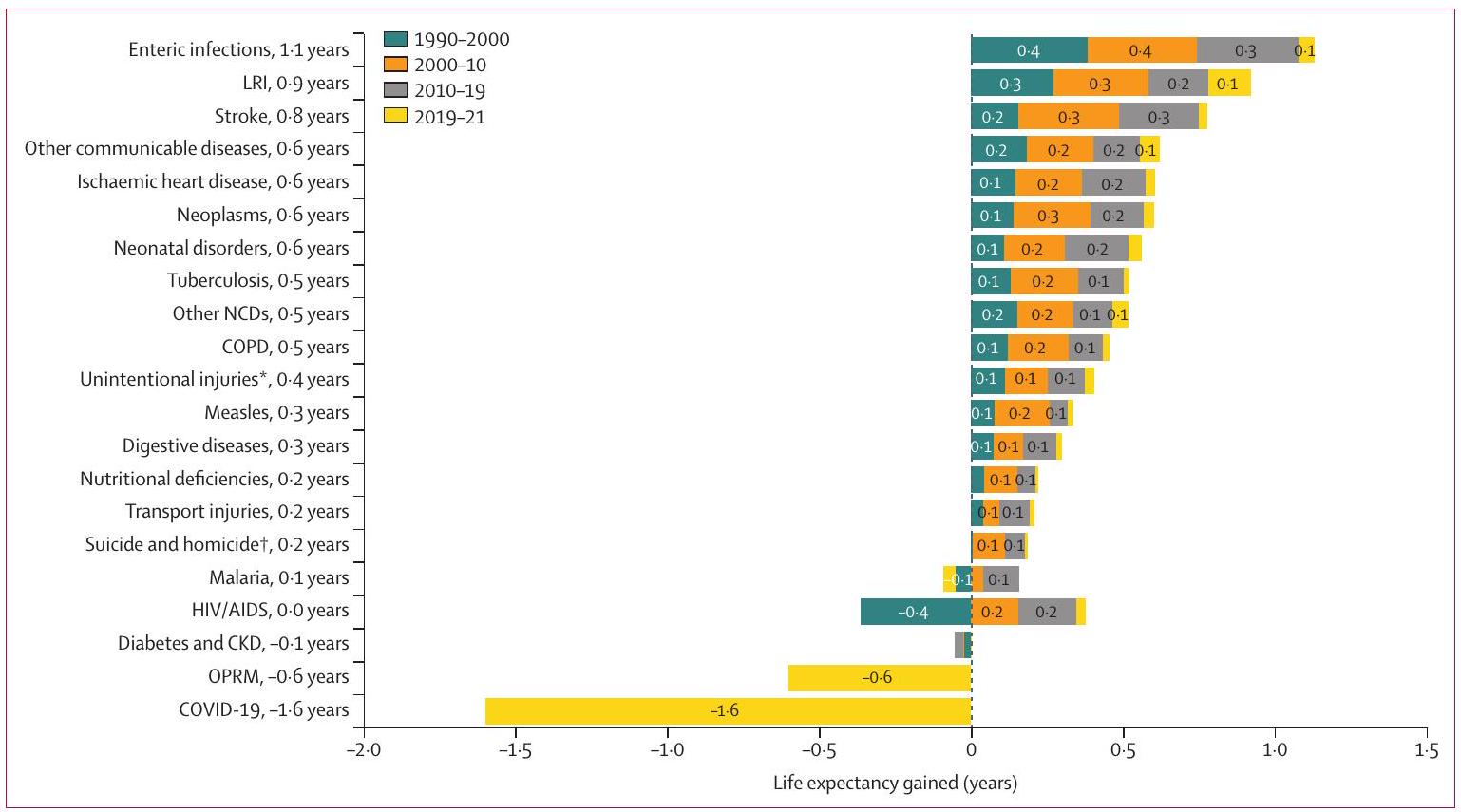

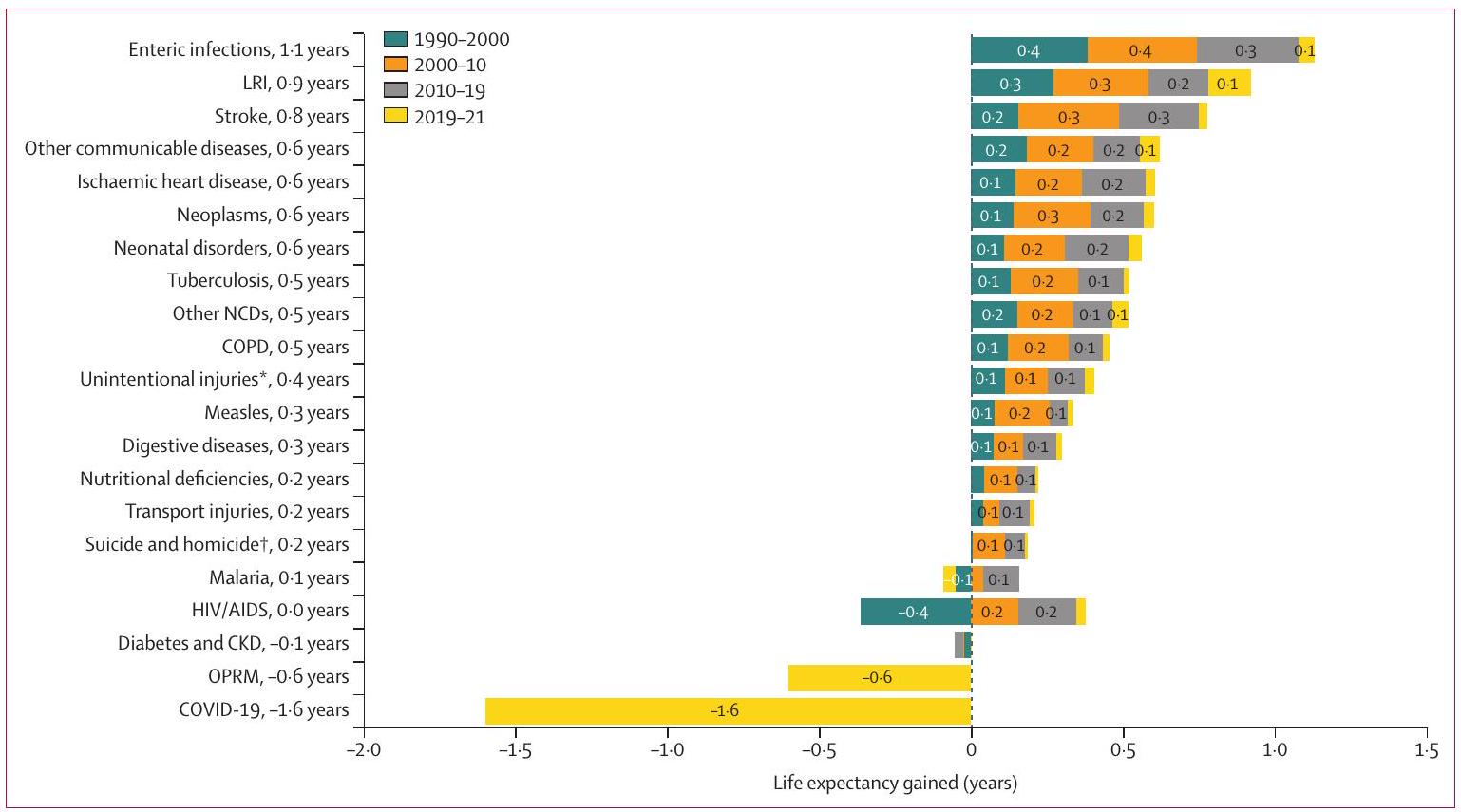

الشكل 3: التغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع الناتج عن الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة للذكور والإناث معًا، 1990-2000، 2000-2010، 2010-2019، و2019-2021، على مستوى العالم

تمثل كل صف التغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي من 1990 إلى 2021 بسبب سبب معين. يتم تقسيم التغير الكلي في متوسط العمر المتوقع بشكل أكبر بواسطة ألوان مختلفة لتمثيل التغيرات على مر الفترات الزمنية. يمثل الشريط إلى يمين 0 زيادة في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب التغيرات في الفترة الزمنية المعطاة، ويمثل الشريط إلى يسار 0 انخفاضًا في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب فترة زمنية معينة. لأغراض القراءة، لا يتم عرض التسميات التي تشير إلى تغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من 0.05 سنوات. CKD=مرض الكلى المزمن. COPD=مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن. LRI=عدوى الجهاز التنفسي السفلي. NCD=مرض غير معدي. OPRM=وفيات أخرى مرتبطة بالوباء. *لا تشمل الكوارث الطبيعية. †لا تشمل الحرب والإرهاب.

تمثل كل صف التغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي من 1990 إلى 2021 بسبب سبب معين. يتم تقسيم التغير الكلي في متوسط العمر المتوقع بشكل أكبر بواسطة ألوان مختلفة لتمثيل التغيرات على مر الفترات الزمنية. يمثل الشريط إلى يمين 0 زيادة في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب التغيرات في الفترة الزمنية المعطاة، ويمثل الشريط إلى يسار 0 انخفاضًا في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب فترة زمنية معينة. لأغراض القراءة، لا يتم عرض التسميات التي تشير إلى تغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من 0.05 سنوات. CKD=مرض الكلى المزمن. COPD=مرض الانسداد الرئوي المزمن. LRI=عدوى الجهاز التنفسي السفلي. NCD=مرض غير معدي. OPRM=وفيات أخرى مرتبطة بالوباء. *لا تشمل الكوارث الطبيعية. †لا تشمل الحرب والإرهاب.

في الوفيات الناتجة عن هذه الأمراض مسؤول عن زيادة كبيرة في متوسط العمر المتوقع بمقدار 1.1 سنة خلال 1990-2021، لكن هذه الزيادة كانت أكثر وضوحًا بين 1990 و2000 مقارنة بالفترات الزمنية الأخرى. التأثير الثاني الأكبر على زيادة متوسط العمر المتوقع يُعزى إلى تقليل الوفيات الناتجة عن عدوى الجهاز التنفسي السفلي، مما ساهم في زيادة قدرها 0.9 سنوات من متوسط العمر المتوقع من 1990 إلى 2021. تشمل العوامل الرائدة الأخرى انخفاض الوفيات الناتجة عن السكتة الدماغية، وأمراض CMNN، والوفيات حديثي الولادة، وأمراض القلب الإقفارية، والأورام، وكل منها زاد متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي بمقدار

تحليل متوسط العمر المتوقع على مستوى السوبر-منطقة، الإقليم، والدولة

شهدت كل من السبع سوبر-مناطق زيادة عامة في متوسط العمر المتوقع بين 1990 و2021، على الرغم من

أن التقدم في كل منها تأثر بشكل مختلف بـ COVID-19 (الأرقام 4، 5). أظهرت جنوب شرق آسيا، شرق آسيا، وأوقيانوسيا أعلى زيادة، مع تحسن صافي قدره 8.3 سنوات (

أن التقدم في كل منها تأثر بشكل مختلف بـ COVID-19 (الأرقام 4، 5). أظهرت جنوب شرق آسيا، شرق آسيا، وأوقيانوسيا أعلى زيادة، مع تحسن صافي قدره 8.3 سنوات (

تمت ملاحظة التأثير المختلف لـ COVID-19 على انخفاض متوسط العمر المتوقع عبر مناطق GBD (الشكل 6). على الرغم من أن معظم المناطق شهدت تحسينات عامة في متوسط العمر المتوقع بين 1990 و2021، حدث انخفاض في جنوب أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى، التي واجهت أكبر تأثير لفيروس نقص المناعة البشرية وكانت أيضًا

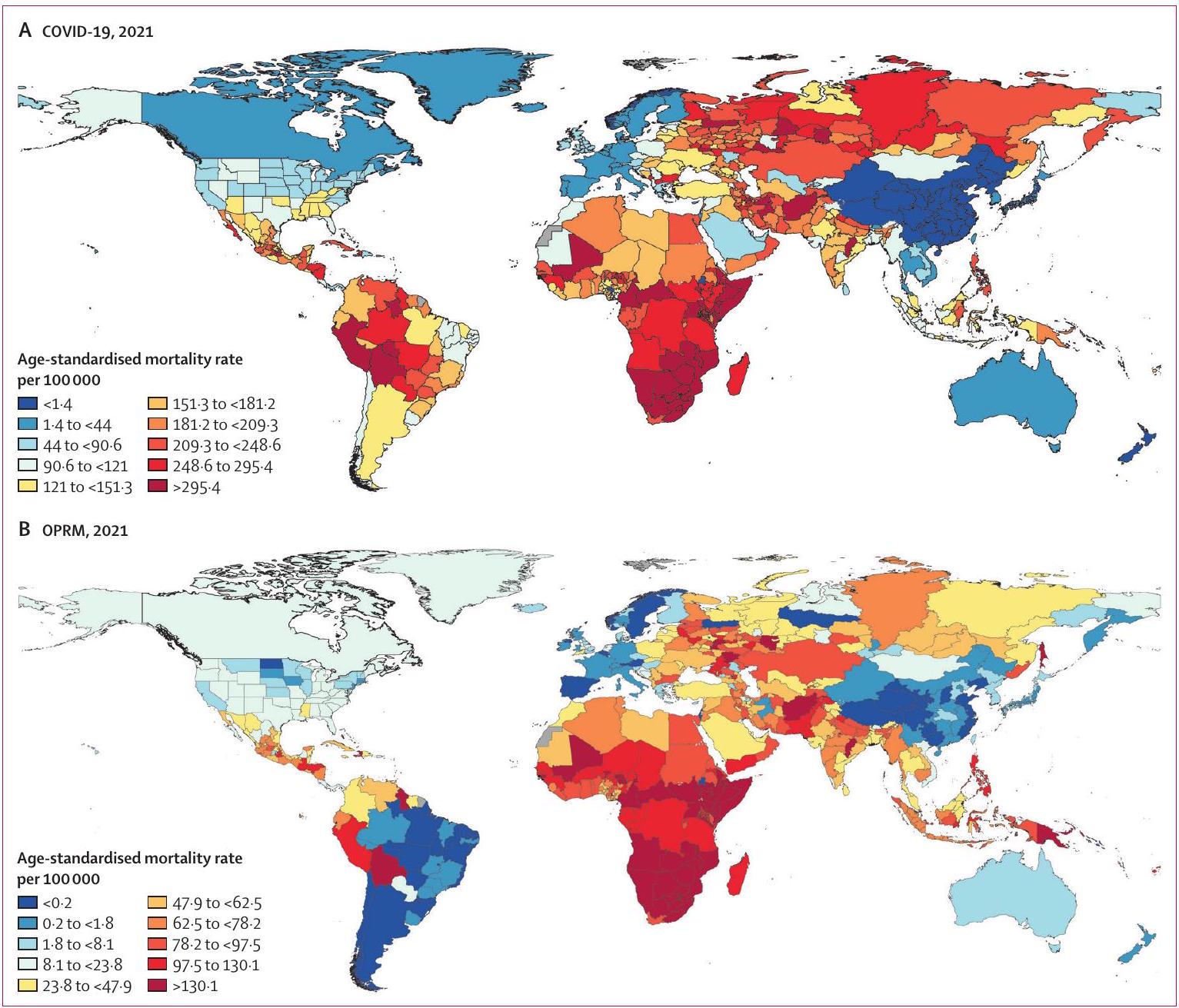

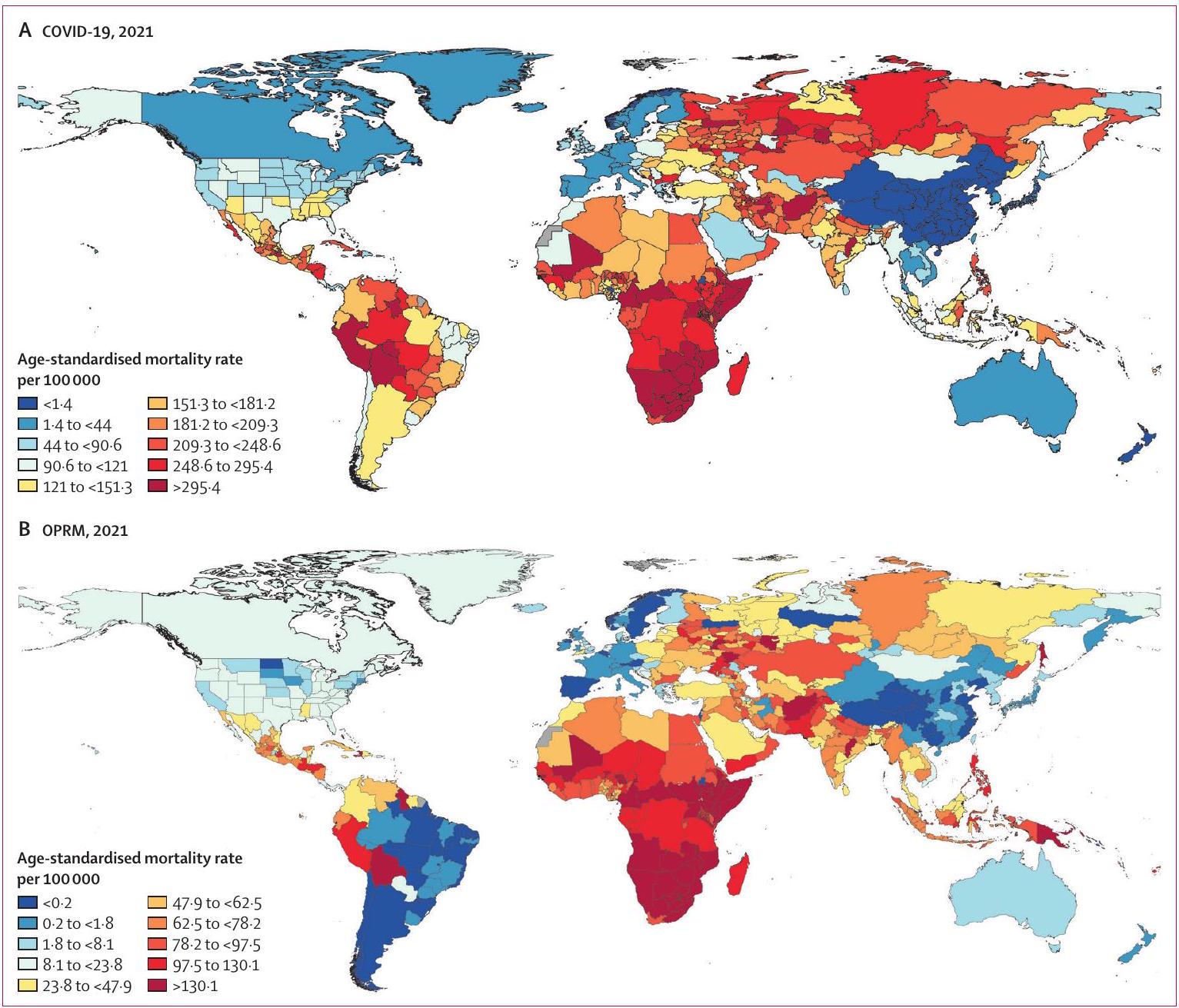

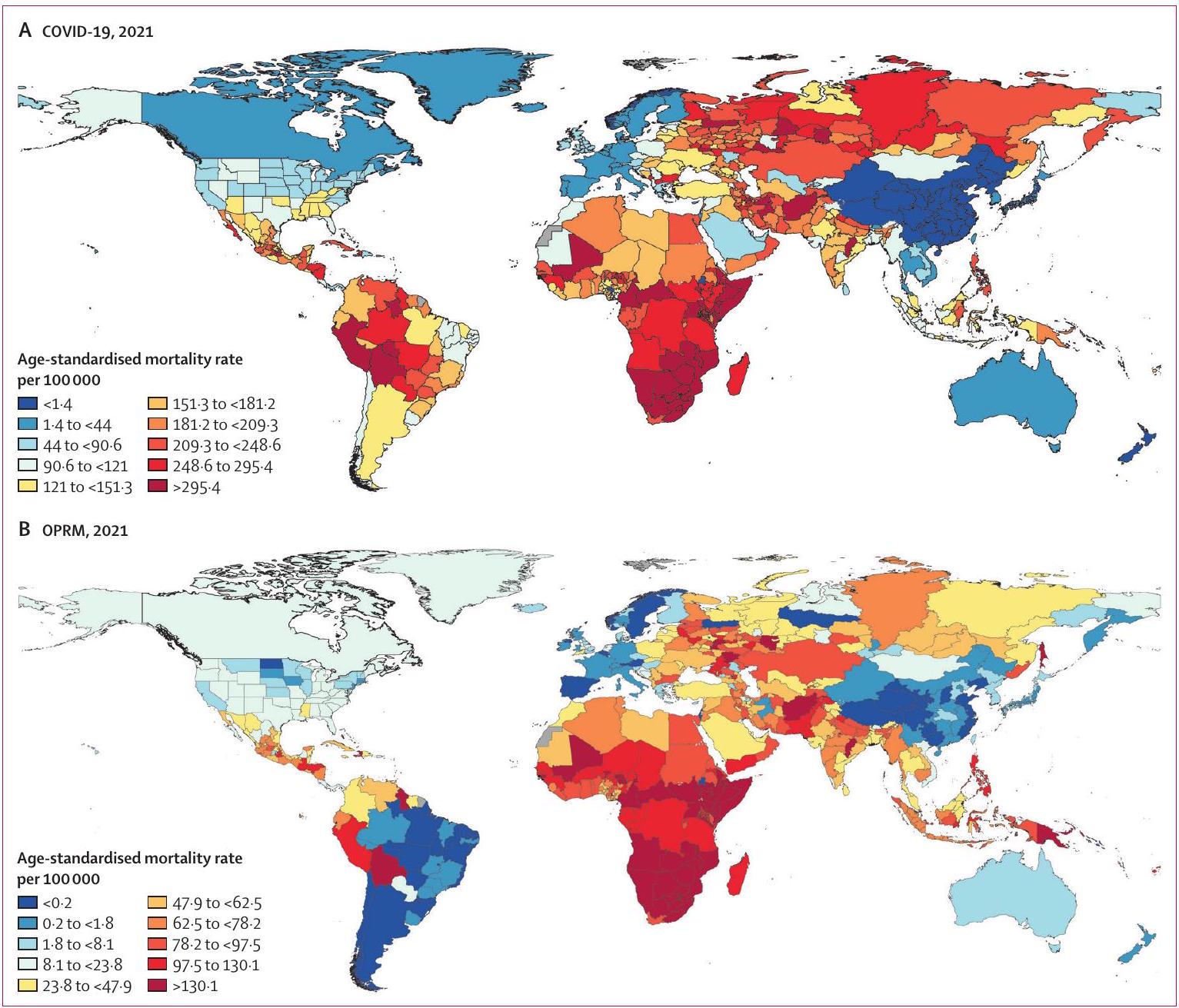

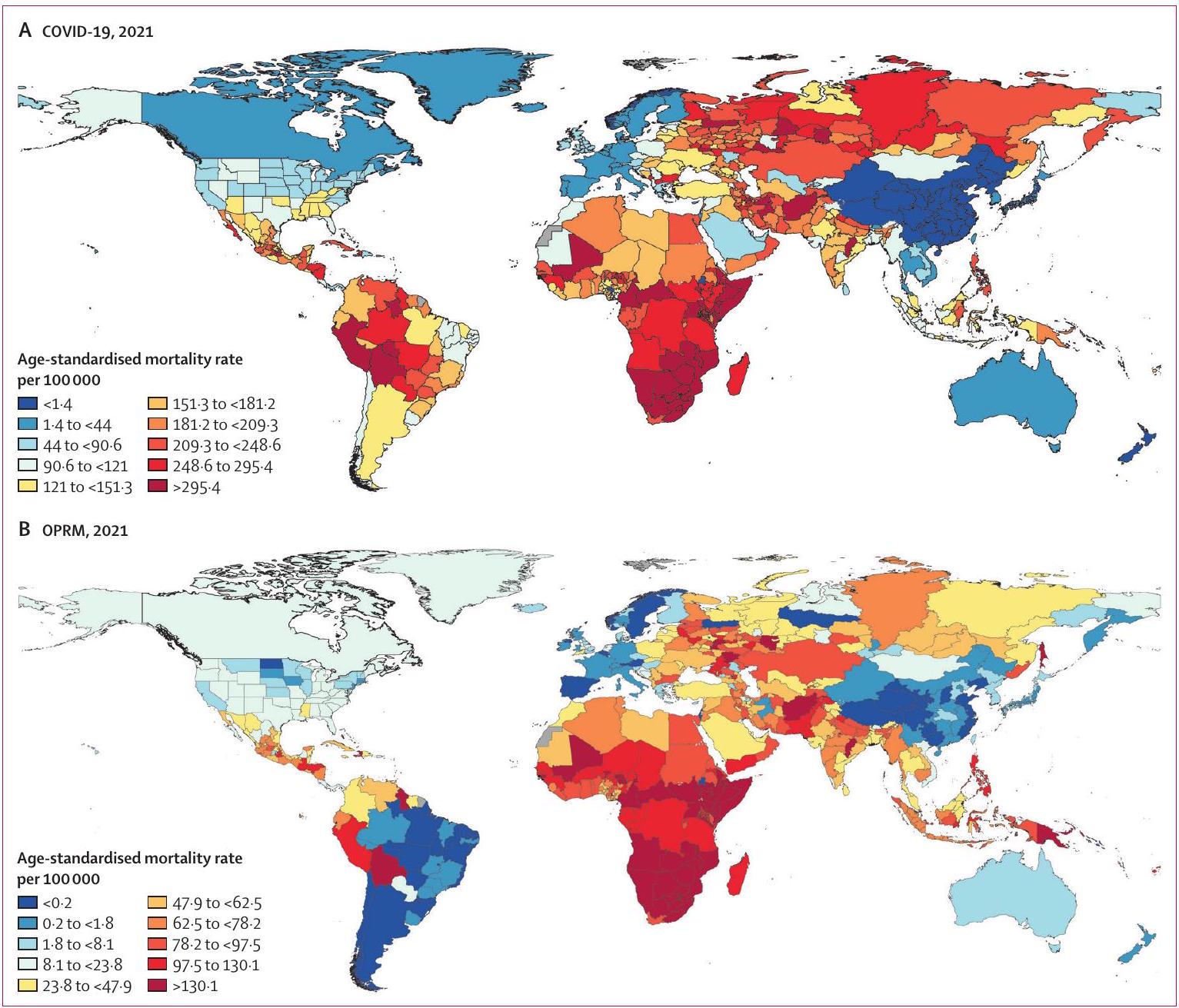

الشكل 4: معدل الوفيات المعدل حسب العمر بسبب COVID-19 وOPRM، 2021

خرائط الكوروبليث العالمية لـ COVID-19 (A) وOPRM (B) لعام 2021 التي تظهر تفاصيل دون الوطنية حيثما كان ذلك متاحًا. OPRM=وفيات أخرى مرتبطة بالوباء.

خرائط الكوروبليث العالمية لـ COVID-19 (A) وOPRM (B) لعام 2021 التي تظهر تفاصيل دون الوطنية حيثما كان ذلك متاحًا. OPRM=وفيات أخرى مرتبطة بالوباء.

الشكل 5: التغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع الناتج عن الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة بين السوبر-مناطق، 1990-2021

تمثل كل صف التغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع من 1990 إلى 2021 لسوبر-منطقة معينة. يمثل الشريط إلى يمين 0 زيادة في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب التغيرات في السبب المعطى، ويمثل الشريط إلى يسار 0 انخفاضًا في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب سبب معين. لأغراض القراءة، لا يتم عرض التسميات التي تشير إلى تغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من

تمثل كل صف التغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع من 1990 إلى 2021 لسوبر-منطقة معينة. يمثل الشريط إلى يمين 0 زيادة في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب التغيرات في السبب المعطى، ويمثل الشريط إلى يسار 0 انخفاضًا في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب سبب معين. لأغراض القراءة، لا يتم عرض التسميات التي تشير إلى تغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من

مقالات

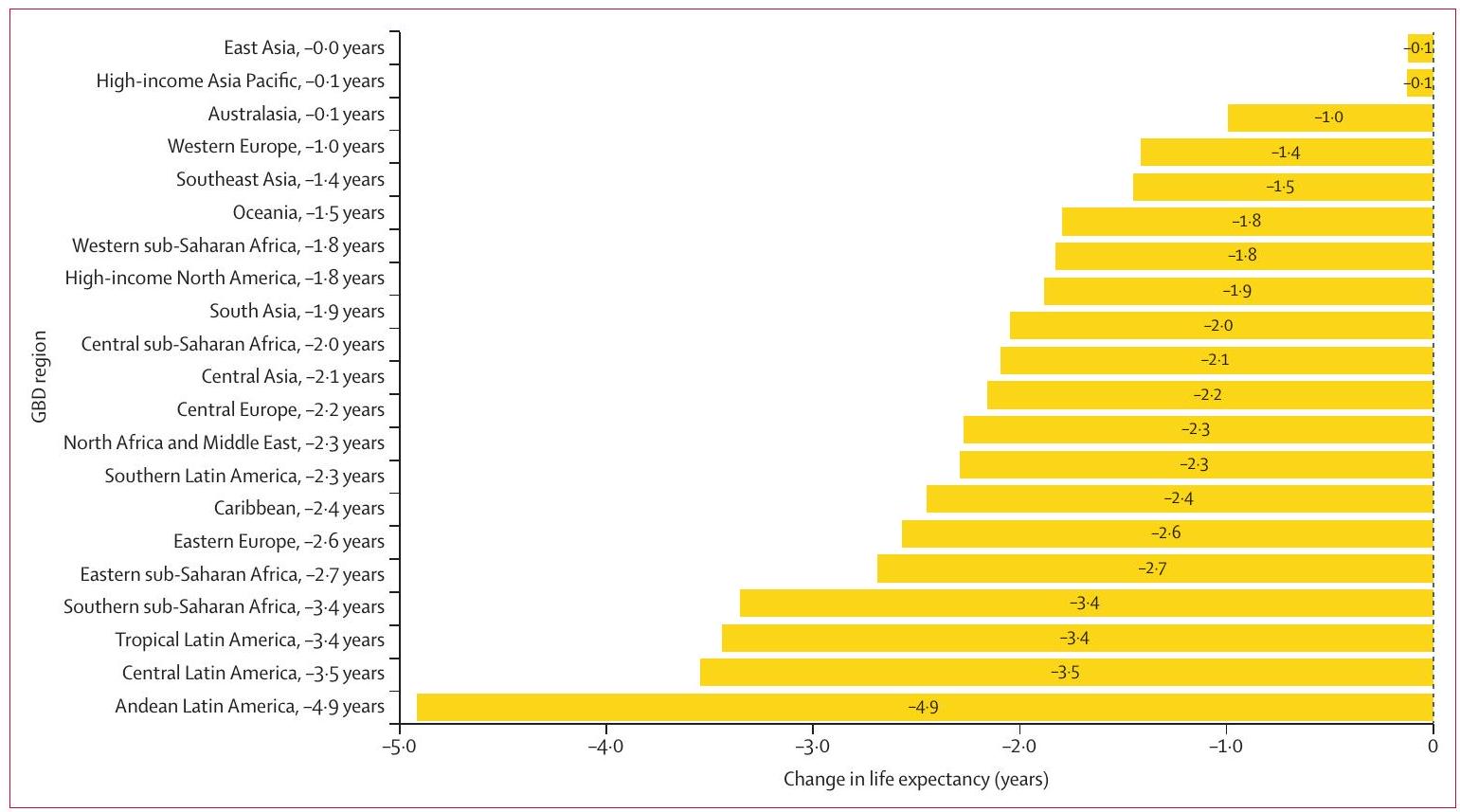

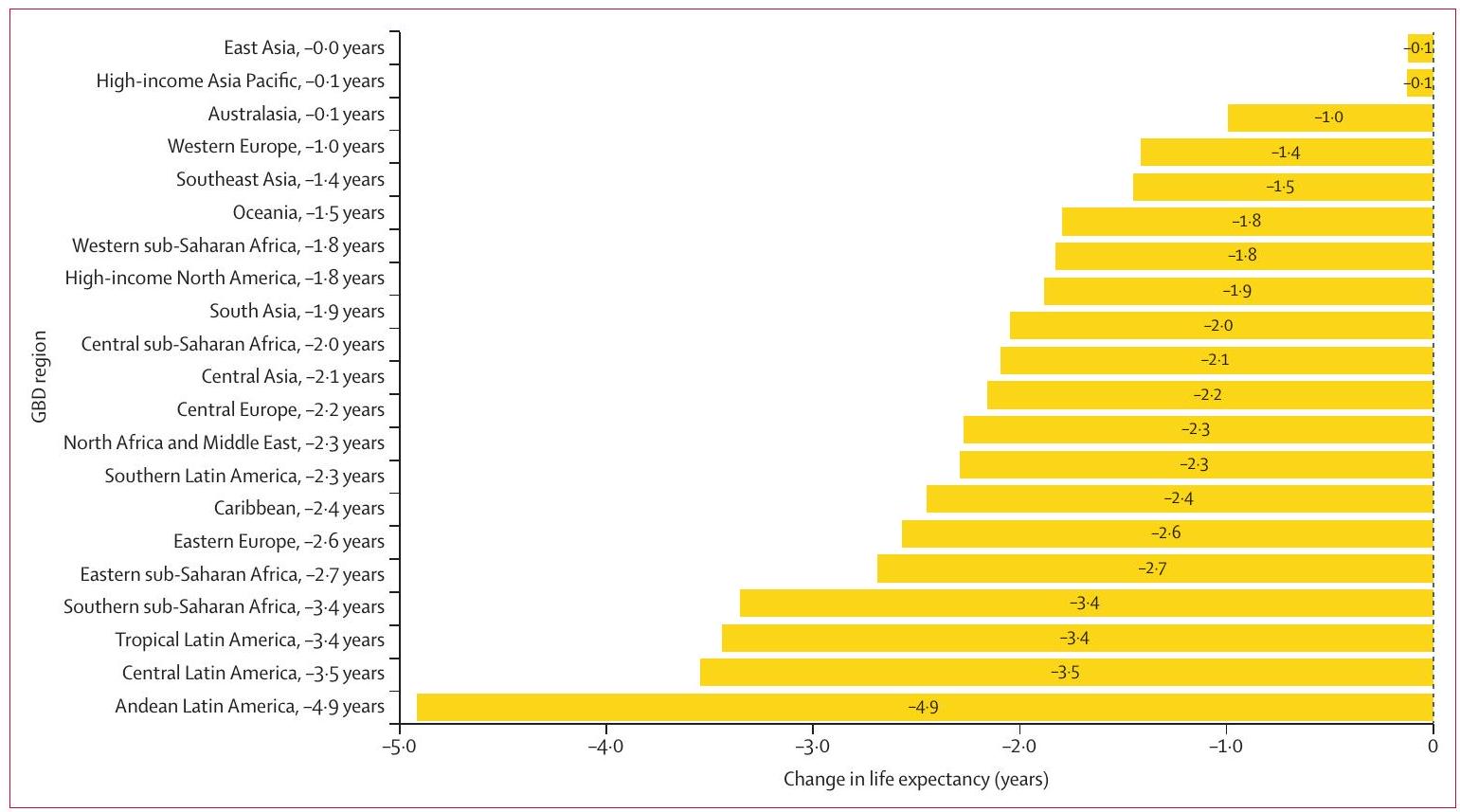

الشكل 6: تأثير COVID-19 على متوسط العمر المتوقع حسب منطقة GBD، 2019-21

لأغراض القراءة، لا يتم عرض التسميات التي تشير إلى تغير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من 0.05 سنوات. GBD=دراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض والإصابات وعوامل الخطر.

تأثرت بشدة بـ COVID-19. شمل الانخفاض العام في متوسط العمر المتوقع 4.3 سنوات (

كان لفيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز تأثير سلبي كبير على اتجاهات متوسط العمر المتوقع في جنوب أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى من 1990 إلى 2021 (الملحق 2 الشكل S27). على الرغم من التحسينات في كل من الفترات الزمنية 2000-2010، 2010-2019، و2019-2021، لم تتمكن هذه المنطقة من استعادة 9.0 سنوات التي فقدت خلال 1990-2000. على الرغم من أننا وجدنا انخفاضًا صافيًا في الوفيات بسبب فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز بين 2000 و2019، إلا أن التحسينات تباطأت بشكل كبير من 2019 إلى 2021، عندما تم الحصول على 0.2 سنوات فقط في متوسط العمر المتوقع نتيجة لتقليل وفيات فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز. على العكس من ذلك،

كانت أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الشرقية لديها أعلى مستوى من التعافي في متوسط العمر المتوقع بين المناطق، حيث زادت بمقدار 1.5 سنوات من متوسط العمر المتوقع على مدار فترة الدراسة بأكملها.

في عام 1990، كانت الوفيات المرتبطة بالملاريا لها تأثير ضئيل على متوسط العمر المتوقع في ثمانية من 21 منطقة GBD (الملحق 2 الشكل S13). بحلول عام 2021، ومع ذلك،

على المستوى الوطني، حدثت بعض من أعلى المكاسب في متوسط العمر المتوقع بين 1990 و2021 في المنطقة الشرقية من أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى (الملحق 2 الشكل S12). زاد متوسط العمر المتوقع في إثيوبيا بمقدار

تأثرت بشدة بـ COVID-19. شمل الانخفاض العام في متوسط العمر المتوقع 4.3 سنوات (

كان لفيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز تأثير سلبي كبير على اتجاهات متوسط العمر المتوقع في جنوب أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى من 1990 إلى 2021 (الملحق 2 الشكل S27). على الرغم من التحسينات في كل من الفترات الزمنية 2000-2010، 2010-2019، و2019-2021، لم تتمكن هذه المنطقة من استعادة 9.0 سنوات التي فقدت خلال 1990-2000. على الرغم من أننا وجدنا انخفاضًا صافيًا في الوفيات بسبب فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز بين 2000 و2019، إلا أن التحسينات تباطأت بشكل كبير من 2019 إلى 2021، عندما تم الحصول على 0.2 سنوات فقط في متوسط العمر المتوقع نتيجة لتقليل وفيات فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز. على العكس من ذلك،

كانت أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الشرقية لديها أعلى مستوى من التعافي في متوسط العمر المتوقع بين المناطق، حيث زادت بمقدار 1.5 سنوات من متوسط العمر المتوقع على مدار فترة الدراسة بأكملها.

في عام 1990، كانت الوفيات المرتبطة بالملاريا لها تأثير ضئيل على متوسط العمر المتوقع في ثمانية من 21 منطقة GBD (الملحق 2 الشكل S13). بحلول عام 2021، ومع ذلك،

على المستوى الوطني، حدثت بعض من أعلى المكاسب في متوسط العمر المتوقع بين 1990 و2021 في المنطقة الشرقية من أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى (الملحق 2 الشكل S12). زاد متوسط العمر المتوقع في إثيوبيا بمقدار

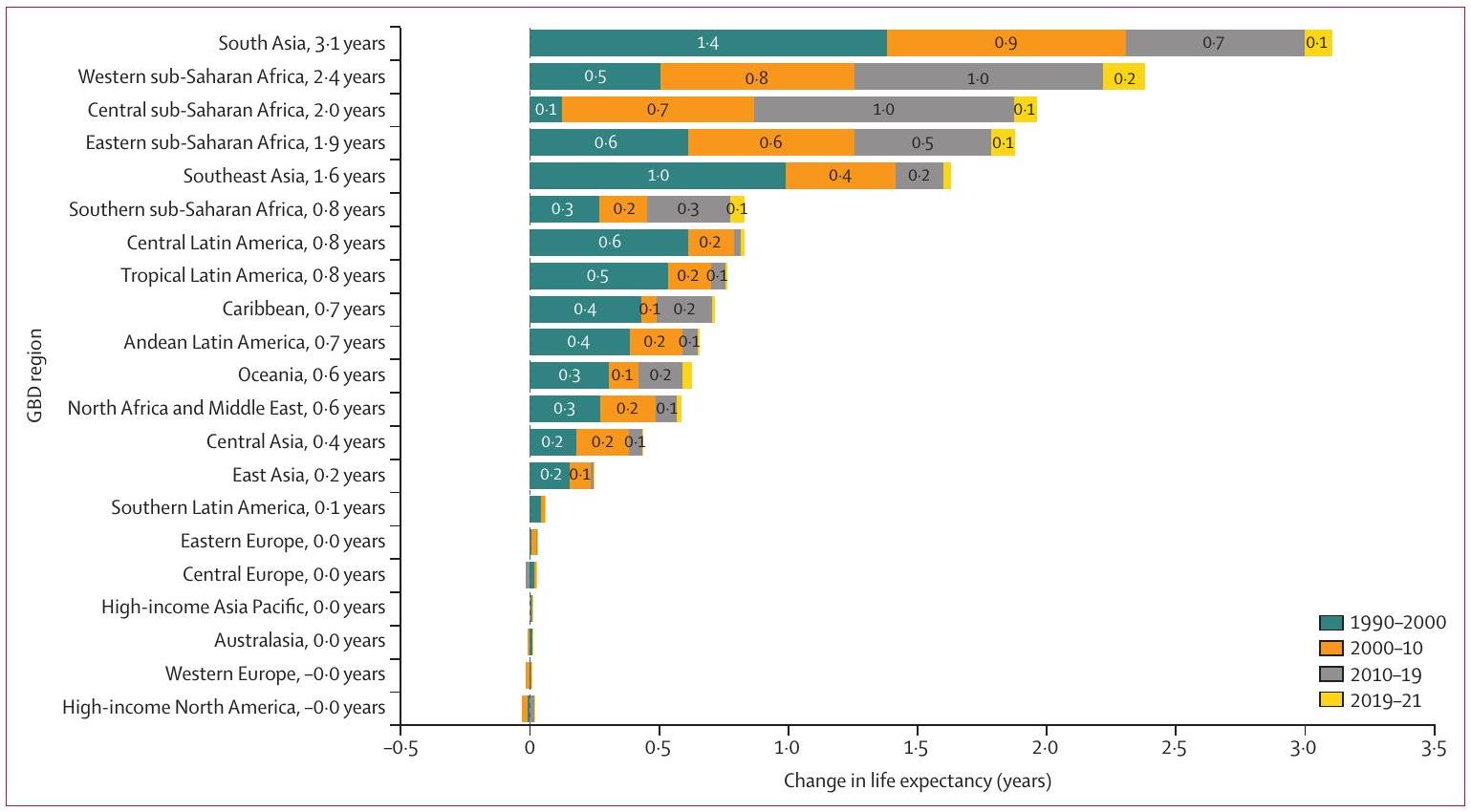

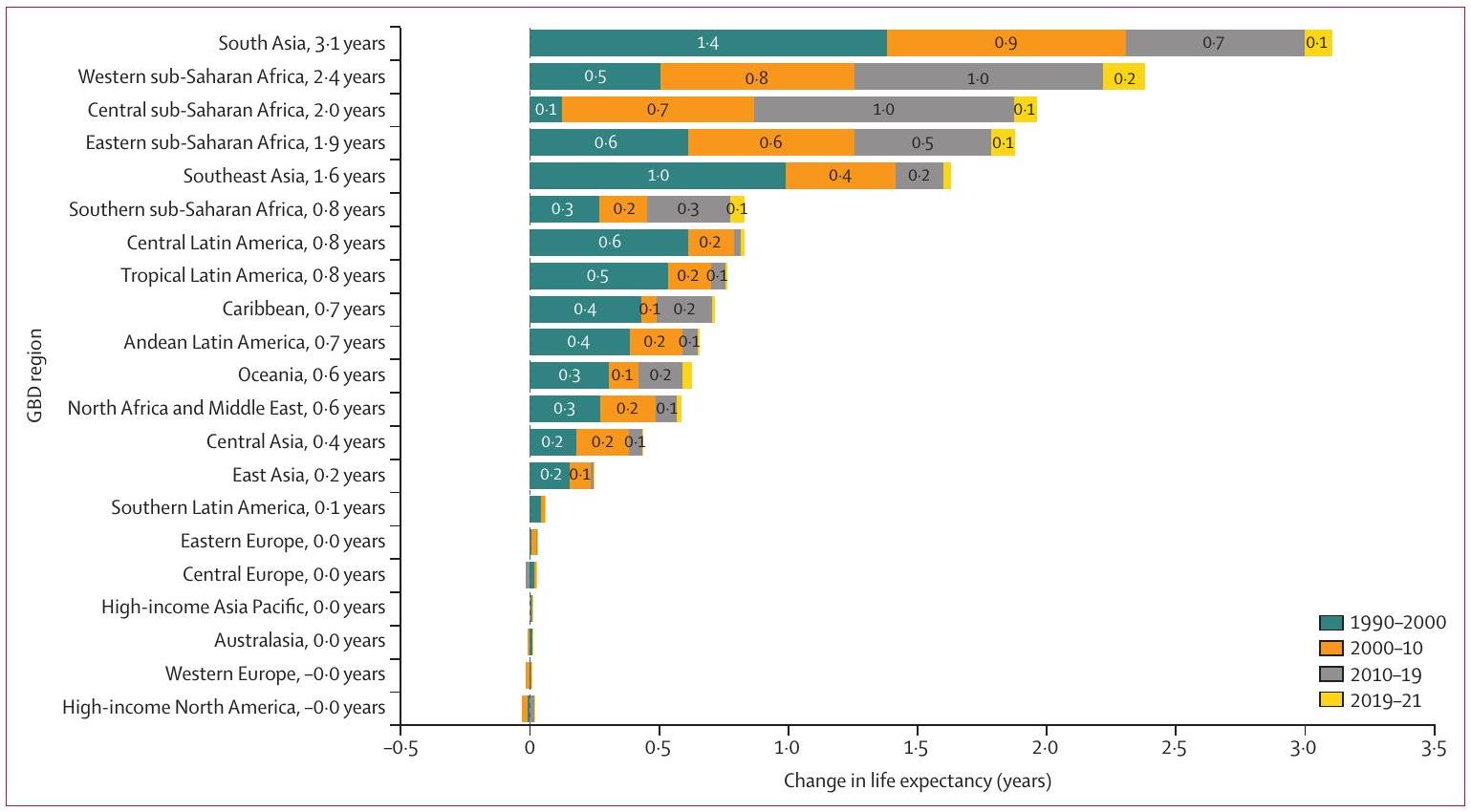

الشكل 7: تأثير الأمراض المعدية المعوية على متوسط العمر المتوقع حسب الفترة الزمنية ومنطقة GBD، 1990-2021

لتحسين القراءة، لا تظهر التسميات التي تشير إلى تغيير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من 0.05 سنة. GBD=عبء الأمراض العالمية، والإصابات، ودراسة عوامل الخطر.

لتحسين القراءة، لا تظهر التسميات التي تشير إلى تغيير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من 0.05 سنة. GBD=عبء الأمراض العالمية، والإصابات، ودراسة عوامل الخطر.

تأثير أمراض CMNN على متوسط العمر المتوقع واتجاهات تركيز الوفيات

بين أسباب CMNN، ظهرت عدة اتجاهات رئيسية في تأثيرها على متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي وتوزيع الوفيات مع مرور الوقت. أولاً، كان لانخفاض الوفيات بسبب الأمراض المعوية تأثير كبير على متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي، مع تباينات إقليمية ملحوظة (الشكل 7). مع تقدم 160 دولة وإقليم في تقليل الوفيات المرتبطة بأمراض CMNN، ظهر تركيز الوفيات. أصبحت الوفيات أكثر تركيزًا في دول أو مناطق معينة، واستمرت جنبًا إلى جنب مع التقدم المحرز في أجزاء أخرى من العالم. مثال توضيحي هو التحول في الوفيات بسبب الأمراض المعوية لدى الأطفال دون سن 5 سنوات، حيث

على اتجاهات متوسط العمر المتوقع، خاصة في جنوب الصحراء الأفريقية، ومع

ساهمت الانخفاضات في وفيات حديثي الولادة في زيادة قدرها

على اتجاهات متوسط العمر المتوقع، خاصة في جنوب الصحراء الأفريقية، ومع

ساهمت الانخفاضات في وفيات حديثي الولادة في زيادة قدرها

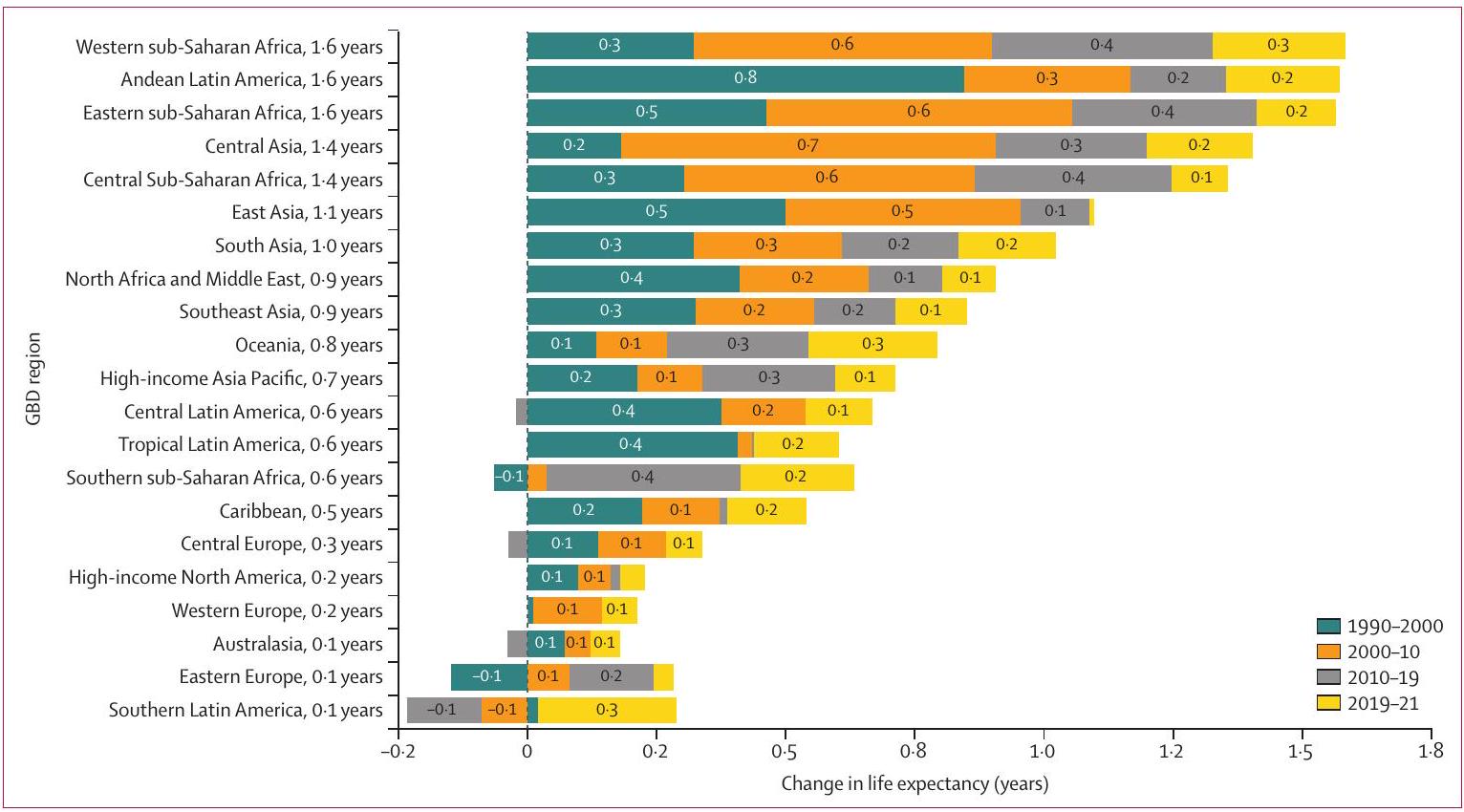

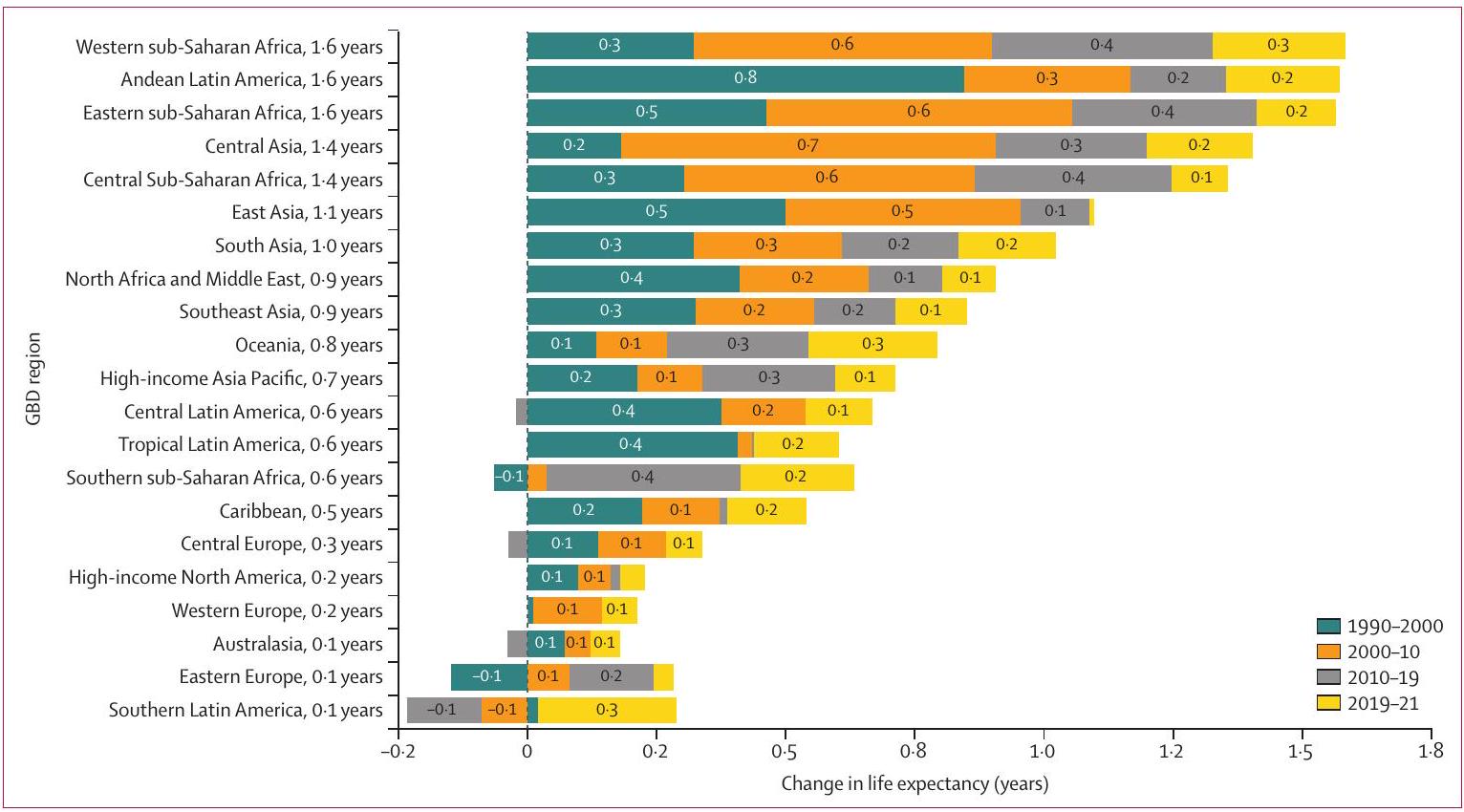

الشكل 8: تأثير العدوى التنفسية السفلية على متوسط العمر المتوقع حسب الفترة الزمنية ومنطقة GBD، 1990-2021

لتحسين القراءة، لا تظهر التسميات التي تشير إلى تغيير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من 0.05 سنة. GBD=عبء الأمراض العالمية، والإصابات، ودراسة عوامل الخطر.

لتحسين القراءة، لا تظهر التسميات التي تشير إلى تغيير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من 0.05 سنة. GBD=عبء الأمراض العالمية، والإصابات، ودراسة عوامل الخطر.

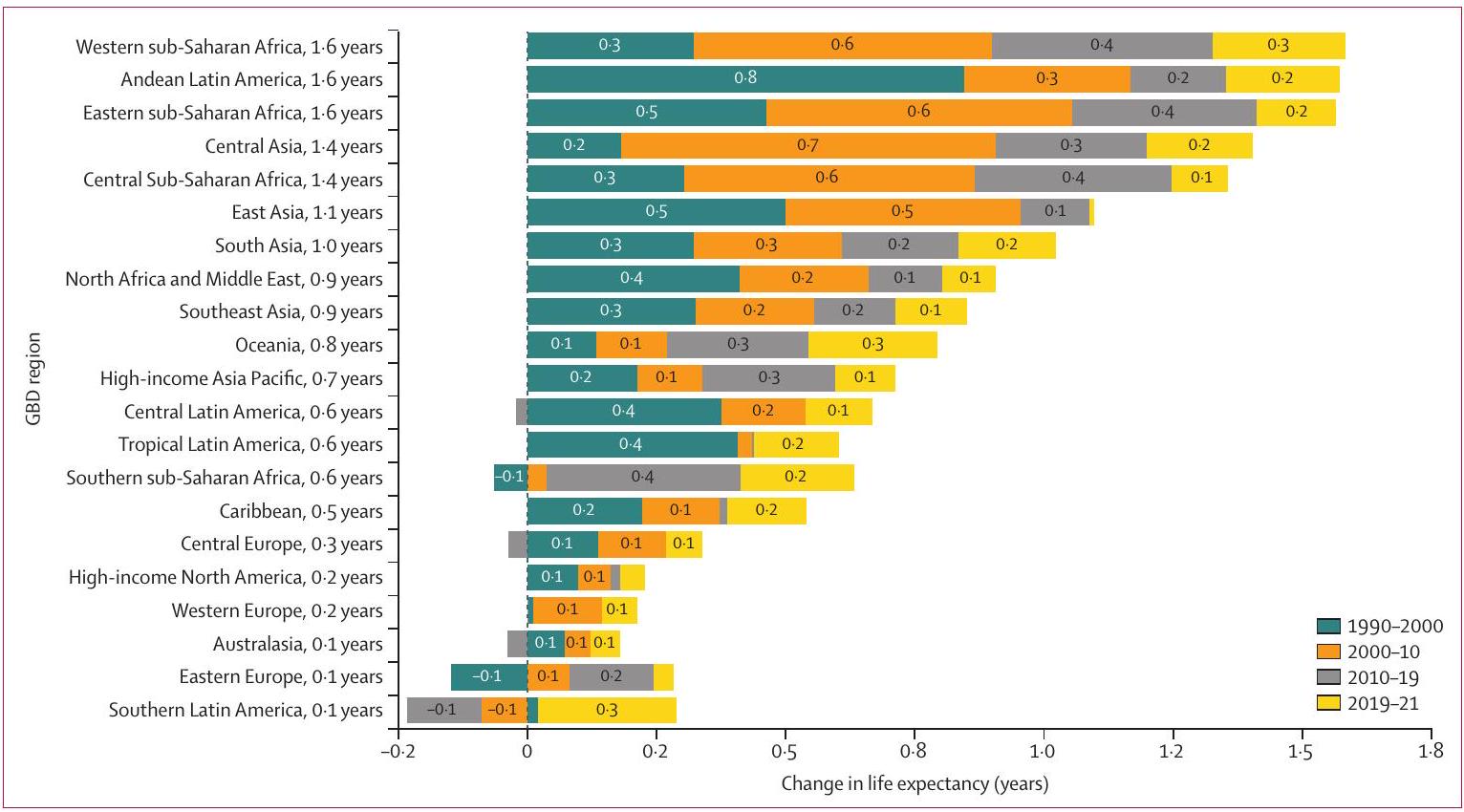

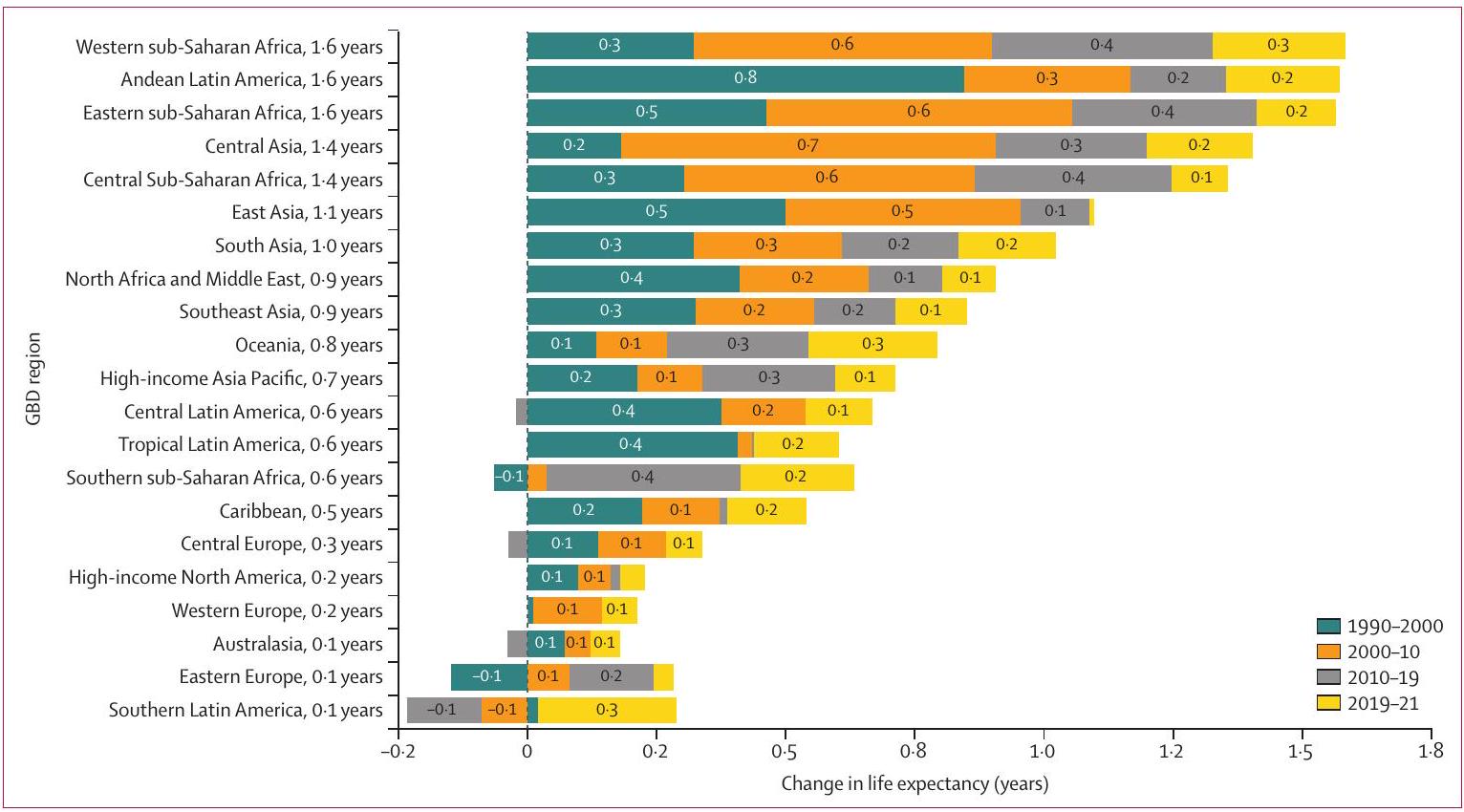

الشكل 9: التغيير في متوسط العمر المتوقع الناتج عن الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة بين مناطق GBD، 1990-2021

تمثل كل صف التغيير في متوسط العمر المتوقع من 1990 إلى 2021 لمنطقة GBD معينة. يمثل شريط إلى يمين 0 زيادة في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب التغيرات في السبب المعطى، ويمثل شريط إلى يسار 0 انخفاضًا في متوسط العمر المتوقع لسبب معين. لتحسين القراءة، لا تظهر التسميات التي تشير إلى تغيير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من 0.3 سنة. CKD=مرض الكلى المزمن. COPD=مرض الرئة الانسدادي المزمن. GBD=عبء الأمراض العالمية، والإصابات، ودراسة عوامل الخطر. LRI=العدوى التنفسية السفلية. NCD=مرض غير معدي. OPRM=وفيات أخرى مرتبطة بالوباء. *لا تشمل الحرب والإرهاب. †لا تشمل الكوارث الطبيعية.

تمثل كل صف التغيير في متوسط العمر المتوقع من 1990 إلى 2021 لمنطقة GBD معينة. يمثل شريط إلى يمين 0 زيادة في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب التغيرات في السبب المعطى، ويمثل شريط إلى يسار 0 انخفاضًا في متوسط العمر المتوقع لسبب معين. لتحسين القراءة، لا تظهر التسميات التي تشير إلى تغيير في متوسط العمر المتوقع أقل من 0.3 سنة. CKD=مرض الكلى المزمن. COPD=مرض الرئة الانسدادي المزمن. GBD=عبء الأمراض العالمية، والإصابات، ودراسة عوامل الخطر. LRI=العدوى التنفسية السفلية. NCD=مرض غير معدي. OPRM=وفيات أخرى مرتبطة بالوباء. *لا تشمل الحرب والإرهاب. †لا تشمل الكوارث الطبيعية.

شهدت أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء وآسيا الجنوبية زيادات ملحوظة. وجدنا تحولًا نحو تركيز الوفيات، مع

تأثير الأمراض غير المعدية على متوسط العمر المتوقع واتجاهات تركيز الوفيات

بين الأمراض غير المعدية، تعكس عدة نتائج تأثيرها على متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي وتركيز الوفيات. أدت الانخفاضات في السكتة الدماغية إلى مكسب ملحوظ في متوسط العمر المتوقع قدره 0.8 سنة، لكن وفيات السكتة الدماغية لم تكن مركزة، مع

تأثير الإصابات على متوسط العمر المتوقع واتجاهات تركيز الوفيات

كان لانخفاض إصابات النقل تأثير إيجابي على متوسط العمر المتوقع، مما ساهم في زيادة قدرها 0.2 سنة. ومع ذلك، كما هو الحال مع الأمراض غير المعدية، لم يكن تركيز وفيات إصابات النقل مرتفعًا، مع

تركيزًا قليلًا للوفيات، مع

تركيزًا قليلًا للوفيات، مع

المناقشة النتائج الرئيسية

لقد ظهرت جائحة COVID-19 كواحدة من أكثر الأحداث الصحية العالمية تحديدًا في التاريخ الحديث. تقدم تقديراتنا الشاملة الأخيرة للوفيات حسب السبب نظرة ثاقبة على المشهد العالمي للأمراض قبل وخلال العامين الأولين من الجائحة، كاشفة عن التغيرات المهمة في أنماط عبء المرض التي تلت ذلك. بعد أكثر من ثلاثة عقود من التحسينات المستمرة في متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي وانخفاض معدلات الوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر، عكست COVID-19 التقدم المستمر وأعاقت الاتجاهات في الانتقال الوبائي. باعتبارها السبب الثاني الرئيسي للوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر في عام 2021، كان لـ COVID-19 تأثير بارز على الانخفاض في متوسط العمر المتوقع العالمي الذي حدث. يوفر التأثير غير المتجانس للمرض عبر العالم رؤى مهمة لتحسين الاستعداد للجائحات المستقبلية وضمان تجهيز الدول بشكل عادل للاستجابة لتفشي الأمراض الجديدة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تمكننا تحليلاتنا للاتجاهات الجغرافية والزمنية في الوفيات من ملاحظة الأنماط المتغيرة في أسباب الوفاة على مستوى العالم. لقد أظهرت العديد من الأسباب نطاقًا جغرافيًا أقل – وهو انعكاس للجهود المخصصة والمستمرة للتخفيف من عبء بعض الأسباب، فضلاً عن التغيرات المحتملة في التعرض لعوامل الخطر.

جائحة كوفيد-19

ظهور وانتشار COVID-19 يتبع نمطًا مشابهًا من التباين الإقليمي الذي هو شائع بين العديد من الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة القابلة للاكتساب، حيث تحدث معدلات إصابة أعلى وزيادة في الوفيات في البيئات ذات الموارد المحدودة.

تؤكد المواقع على تعقيد الجائحة. ساهمت التأثيرات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية والسياسية المتنوعة في الاختلافات في معدلات الوفيات التي لوحظت بين المواقع. بشكل عام، كانت المناطق التي تتمتع بأنظمة رعاية صحية متقدمة ومرافق طبية قوية أكثر قدرة على إدارة الزيادات المفاجئة في عدد حالات COVID-19. بالمقابل، كانت المواقع التي تعاني من بنية تحتية صحية ضعيفة أقل تجهيزًا للتعامل مع الزيادة في الإصابات التي حدثت.

تظهر دراستنا أن COVID-19 كان واحدًا من الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة على مستوى العالم خلال العامين الأولين من الجائحة وتوفر فرصة لتحديد الفروق بين آثار المرض المباشرة وغير المباشرة على الوفيات بالإضافة إلى تأثيره على متوسط العمر المتوقع. كما تم التنبؤ به سابقًا،

تؤكد المواقع على تعقيد الجائحة. ساهمت التأثيرات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية والسياسية المتنوعة في الاختلافات في معدلات الوفيات التي لوحظت بين المواقع. بشكل عام، كانت المناطق التي تتمتع بأنظمة رعاية صحية متقدمة ومرافق طبية قوية أكثر قدرة على إدارة الزيادات المفاجئة في عدد حالات COVID-19. بالمقابل، كانت المواقع التي تعاني من بنية تحتية صحية ضعيفة أقل تجهيزًا للتعامل مع الزيادة في الإصابات التي حدثت.

تظهر دراستنا أن COVID-19 كان واحدًا من الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة على مستوى العالم خلال العامين الأولين من الجائحة وتوفر فرصة لتحديد الفروق بين آثار المرض المباشرة وغير المباشرة على الوفيات بالإضافة إلى تأثيره على متوسط العمر المتوقع. كما تم التنبؤ به سابقًا،

اتجاهات مهمة في متوسط العمر المتوقع

لقد ساهمت التقدمات على مدى العقود الثلاثة الماضية في الوقاية من الأمراض المعدية ومكافحتها في زيادة متوسط العمر المتوقع في العديد من الأماكن، مما زاد الحاجة إلى دعم السكان الذين يعيشون مع الأمراض غير المعدية.

لقد عوض فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز والعدوى التنفسية السفلية والعدوى المعوية بشكل ما عن الانخفاض، كما أن انخفاض متوسط العمر المتوقع قد تفاقم أيضًا بسبب زيادة معدلات الوفيات من أسباب أخرى، مثل مرض السكري وأمراض الكلى.

أظهر تأثير COVID-19 على متوسط العمر المتوقع درجات متفاوتة من الشدة، تتراوح من فقدان كبير قدره 4.9 سنوات في أمريكا اللاتينية الأنديزية إلى تغير طفيف تقريبًا في شرق آسيا. من 1990 إلى 2021، أدت التخفيضات في العديد من الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة إلى زيادات عامة في متوسط العمر المتوقع عبر معظم المناطق، على الرغم من الانتكاسات الكبيرة للعديد بسبب جائحة COVID-19. وجدنا أنه على الرغم من أن أمريكا اللاتينية الأنديزية شهدت أكبر انخفاض إقليمي في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب الجائحة، إلا أن التخفيضات العامة في متوسط العمر المتوقع عبر المنطقة تم تخفيفها من خلال التحسينات في أسباب أخرى، حيث كانت التخفيضات في معدلات الوفاة بسبب التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي والاضطرابات الوليدية مسؤولة عن زيادة في متوسط العمر المتوقع قدرها 2.6 سنوات بشكل عام بين 1990 و2021. وقد تم نسب التخفيضات الملحوظة في الاضطرابات الوليدية في العديد من دول أمريكا اللاتينية الأنديزية إلى التحسينات التي تم تحقيقها في تنفيذ استراتيجيات التدخل الفعالة في صحة الأم والوليد.

لقد تجاوزت نسبة الانخفاض في متوسط العمر المتوقع في جنوب الصحراء الكبرى الأفريقية المتوسط العالمي بفارق كبير، حيث انخفض بمقدار 3.4 سنوات بسبب COVID-19. على الرغم من أن متوسط العمر المتوقع في المنطقة تأثر بشكل كبير بجائحة COVID-19، إلا أن الانخفاض كان أيضًا ناتجًا عن معدلات الوفيات العالية بسبب فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز. كانت بعض الدول التي شهدت أعدادًا مرتفعة من الوفيات المرتبطة بالجائحة من بين تلك التي كانت تعاني بالفعل من معدلات مرتفعة من الأمراض المعدية الأخرى. navigated العديد من الدول في جنوب الصحراء الكبرى الأفريقية التحديات التي فرضتها الجائحة، إلى جانب تاريخ طويل من مكافحة بعض من أعلى معدلات انتشار فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز في العالم.

أظهر تأثير COVID-19 على متوسط العمر المتوقع درجات متفاوتة من الشدة، تتراوح من فقدان كبير قدره 4.9 سنوات في أمريكا اللاتينية الأنديزية إلى تغير طفيف تقريبًا في شرق آسيا. من 1990 إلى 2021، أدت التخفيضات في العديد من الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة إلى زيادات عامة في متوسط العمر المتوقع عبر معظم المناطق، على الرغم من الانتكاسات الكبيرة للعديد بسبب جائحة COVID-19. وجدنا أنه على الرغم من أن أمريكا اللاتينية الأنديزية شهدت أكبر انخفاض إقليمي في متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب الجائحة، إلا أن التخفيضات العامة في متوسط العمر المتوقع عبر المنطقة تم تخفيفها من خلال التحسينات في أسباب أخرى، حيث كانت التخفيضات في معدلات الوفاة بسبب التهابات الجهاز التنفسي السفلي والاضطرابات الوليدية مسؤولة عن زيادة في متوسط العمر المتوقع قدرها 2.6 سنوات بشكل عام بين 1990 و2021. وقد تم نسب التخفيضات الملحوظة في الاضطرابات الوليدية في العديد من دول أمريكا اللاتينية الأنديزية إلى التحسينات التي تم تحقيقها في تنفيذ استراتيجيات التدخل الفعالة في صحة الأم والوليد.

لقد تجاوزت نسبة الانخفاض في متوسط العمر المتوقع في جنوب الصحراء الكبرى الأفريقية المتوسط العالمي بفارق كبير، حيث انخفض بمقدار 3.4 سنوات بسبب COVID-19. على الرغم من أن متوسط العمر المتوقع في المنطقة تأثر بشكل كبير بجائحة COVID-19، إلا أن الانخفاض كان أيضًا ناتجًا عن معدلات الوفيات العالية بسبب فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز. كانت بعض الدول التي شهدت أعدادًا مرتفعة من الوفيات المرتبطة بالجائحة من بين تلك التي كانت تعاني بالفعل من معدلات مرتفعة من الأمراض المعدية الأخرى. navigated العديد من الدول في جنوب الصحراء الكبرى الأفريقية التحديات التي فرضتها الجائحة، إلى جانب تاريخ طويل من مكافحة بعض من أعلى معدلات انتشار فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز في العالم.

أنماط تركيز الوفيات حسب السبب

تقديرات تركيز الوفيات تعكس أنماط الأمراض المتغيرة بمرور الوقت، من الأمراض التي لها انتشار واسع إلى مجموعات جغرافية أكثر تقليصًا من السكان العالميين. تسلط هذه التغييرات الضوء على الفروق بين السكان وتقدمهم نحو تقليل الوفيات الناتجة عن الأمراض والإصابات. كما توفر هذه النتائج فرصة مهمة لتحسين كيفية تطبيق أفضل الممارسات الصحية العامة لتحقيق مزيد من تقليل الأمراض. بشكل عام، أدت الانخفاضات الواسعة في العديد من الأمراض المعدية إلى ظهور الوفيات الناتجة عن هذه الأسباب بشكل أكثر

توزيعات جغرافية مركزة في عام 2021 مقارنة بالأنماط التي لوحظت في عام 1990. إن درجة تركيز الوفيات التي قدرتها هذه الدراسة بسبب العدوى المعوية والالتهابات التنفسية السفلية والملاريا وفيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز والاضطرابات الوليدية والسل تعكس تقدمًا عالميًا كبيرًا في تقليل الوفيات الناتجة عن هذه الأسباب خلال فترة الدراسة، مما يبرز نجاح العديد من الحملات الصحية العامة والالتزامات العالمية والتحسينات في برامج الأمراض المعدية.

من الجدير بالذكر أن تقديراتنا تدعم النتائج السابقة

أظهرت العدوى المعوية تركيزًا كبيرًا للأمراض. كانت وفيات الأطفال دون سن الخامسة بسبب العدوى المعوية مركزة بشكل كبير في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء وآسيا الجنوبية. كانت الدول في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء وآسيا الجنوبية التي سجلت أعلى معدلات وفيات الأطفال دون سن الخامسة بسبب العدوى المعوية في عام 2021 تشمل تشاد وجنوب السودان وجمهورية إفريقيا الوسطى. هناك العديد من العوامل المساهمة التي يجب أخذها في الاعتبار عند دراسة كيفية تقليل العدوى المعوية في المواقع المتبقية المركزة. إلى جانب توفير محلول الإماهة الفموية ولقاحات الروتا فيروس، قد تكون التحسينات الحيوية في الصحة العامة مثل المياه والصرف الصحي والنظافة قد ساهمت في تقليل وفيات العدوى المعوية.

توزيعات جغرافية مركزة في عام 2021 مقارنة بالأنماط التي لوحظت في عام 1990. إن درجة تركيز الوفيات التي قدرتها هذه الدراسة بسبب العدوى المعوية والالتهابات التنفسية السفلية والملاريا وفيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز والاضطرابات الوليدية والسل تعكس تقدمًا عالميًا كبيرًا في تقليل الوفيات الناتجة عن هذه الأسباب خلال فترة الدراسة، مما يبرز نجاح العديد من الحملات الصحية العامة والالتزامات العالمية والتحسينات في برامج الأمراض المعدية.

من الجدير بالذكر أن تقديراتنا تدعم النتائج السابقة

أظهرت العدوى المعوية تركيزًا كبيرًا للأمراض. كانت وفيات الأطفال دون سن الخامسة بسبب العدوى المعوية مركزة بشكل كبير في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء وآسيا الجنوبية. كانت الدول في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء وآسيا الجنوبية التي سجلت أعلى معدلات وفيات الأطفال دون سن الخامسة بسبب العدوى المعوية في عام 2021 تشمل تشاد وجنوب السودان وجمهورية إفريقيا الوسطى. هناك العديد من العوامل المساهمة التي يجب أخذها في الاعتبار عند دراسة كيفية تقليل العدوى المعوية في المواقع المتبقية المركزة. إلى جانب توفير محلول الإماهة الفموية ولقاحات الروتا فيروس، قد تكون التحسينات الحيوية في الصحة العامة مثل المياه والصرف الصحي والنظافة قد ساهمت في تقليل وفيات العدوى المعوية.

موضوع واسع ومتكرر من هذه الدراسة هو أن تقليل العدوى المعوية ساهم في تحسين متوسط العمر المتوقع على مدى العقود القليلة الماضية. وقد حدثت الانخفاضات في وفيات الأطفال المرتبطة بأمراض الإسهال في العديد من مناطق أفريقيا.

لقد وجدت دراستنا أيضًا أن بعض الأمراض التي يمكن الوقاية منها باللقاحات، مثل الحصبة، قد أظهرت انخفاضات واسعة في معدلات الوفيات وكانت مركزة جغرافيًا. كانت وفيات الأطفال دون سن الخامسة بسبب الحصبة مركزة في غرب وشرق أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى. على الرغم من أن هناك عوامل متعددة تساهم في انخفاض عبء الأمراض المعدية، فإن التحسينات في وفيات الحصبة تعود إلى حد كبير إلى التوافر العالمي للقاح آمن وفعال ضد الحصبة، مما يوفر مناعة تدوم مدى الحياة، مع فعالية الجرعتين التي تتجاوز

بعض الأمراض المعدية، مثل فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز، أظهرت أيضًا تركيزًا في الوفيات. الوفيات الناتجة عن فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز

كانت تتركز بشكل كبير داخل منطقة جنوب الصحراء الكبرى في إفريقيا، وخاصة في جنوب منطقة جنوب الصحراء الكبرى. كانت الدول في منطقة جنوب الصحراء الكبرى التي سجلت أعلى معدل وفيات معيار العمر في عام 2021 تشمل ليسوتو، وإسواتيني، وبوتسوانا. وكانت الدول في منطقة جنوب الصحراء الكبرى التي سجلت أعلى معدلات وفيات الأطفال دون سن الخامسة بسبب فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية (HIV) في عام 2021 تشمل ليسوتو، وغينيا الاستوائية، وغينيا بيساو. تسلط هذه التركيزات الضوء على كيفية حملات السيطرة على فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية، والتدابير الوقائية،

لقد وجدت دراستنا أيضًا أن بعض الأمراض التي يمكن الوقاية منها باللقاحات، مثل الحصبة، قد أظهرت انخفاضات واسعة في معدلات الوفيات وكانت مركزة جغرافيًا. كانت وفيات الأطفال دون سن الخامسة بسبب الحصبة مركزة في غرب وشرق أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى. على الرغم من أن هناك عوامل متعددة تساهم في انخفاض عبء الأمراض المعدية، فإن التحسينات في وفيات الحصبة تعود إلى حد كبير إلى التوافر العالمي للقاح آمن وفعال ضد الحصبة، مما يوفر مناعة تدوم مدى الحياة، مع فعالية الجرعتين التي تتجاوز

بعض الأمراض المعدية، مثل فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز، أظهرت أيضًا تركيزًا في الوفيات. الوفيات الناتجة عن فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية/الإيدز

كانت تتركز بشكل كبير داخل منطقة جنوب الصحراء الكبرى في إفريقيا، وخاصة في جنوب منطقة جنوب الصحراء الكبرى. كانت الدول في منطقة جنوب الصحراء الكبرى التي سجلت أعلى معدل وفيات معيار العمر في عام 2021 تشمل ليسوتو، وإسواتيني، وبوتسوانا. وكانت الدول في منطقة جنوب الصحراء الكبرى التي سجلت أعلى معدلات وفيات الأطفال دون سن الخامسة بسبب فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية (HIV) في عام 2021 تشمل ليسوتو، وغينيا الاستوائية، وغينيا بيساو. تسلط هذه التركيزات الضوء على كيفية حملات السيطرة على فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية، والتدابير الوقائية،

في العديد من الدول ذات الدخل المرتفع، انخفض معدل وفيات حديثي الولادة بشكل عام بين عامي 1990 و2021، وأصبح أكثر تركيزًا مع مرور الوقت. كانت وفيات الاضطرابات حديثي الولادة في عام 2021 مركزة في منطقة جنوب الصحراء الكبرى في أفريقيا وجنوب آسيا.

على العكس، على الرغم من أن عبء العديد من الأمراض غير السارية قد انخفض أيضًا، إلا أن هذه الأسباب عادةً لم تتبع نفس نمط تركيز الوفيات الذي لوحظ في الأمراض المعدية. تؤكد هذه الاتجاهات على تمييز رئيسي في الديناميات المكانية للأمراض غير السارية مقارنة بالعديد من الأمراض المعدية. على الرغم من أن الأسباب غير السارية قد لا تظهر نفس درجة التركيز مثل الأسباب المعدية، إلا أن عبء الوفيات قد تغير في التوزيع، حيث انخفض مع مرور الوقت في البلدان والمناطق ذات الدخل المرتفع، بينما استمر في البلدان والمناطق ذات الدخل المنخفض. انخفضت معدلات الوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر بسبب الأمراض غير السارية في معظم المواقع داخل البلدان ذات الدخل المرتفع؛ أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة البحر الكاريبي؛ شمال أفريقيا والشرق الأوسط؛ وأوروبا الوسطى وأوروبا الشرقية وآسيا الوسطى بين عامي 1990 و2021. ومع ذلك، فإن الأمراض غير السارية في جنوب آسيا؛ أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى؛ ومنطقة جنوب شرق آسيا وشرق آسيا وأوقيانوسيا قد زادت أو

انخفضت بمستويات أقل بشكل ملحوظ في عام 2021 مقارنة بعام 1990. تشمل أمثلة على هذا الاتجاه مرض القلب الإقفاري، والأورام، والسكتة الدماغية، والتي انخفضت جميعها بشكل كبير خلال فترة الدراسة – على الرغم من أن تخفيضاتها كانت موزعة على نطاق واسع وليست مستهدفة مثل أسباب الأمراض غير السارية. تظهر هذه النتائج أن الأمراض غير السارية لا تبدو أنها تتحرك نحو مواقع جغرافية أكثر تركيزًا بمرور الوقت بنفس الطريقة التي تتحرك بها العديد من الأمراض السارية، مما قد يجعل التدخلات والسياسات أكثر تعقيدًا في التنفيذ.

انخفضت بمستويات أقل بشكل ملحوظ في عام 2021 مقارنة بعام 1990. تشمل أمثلة على هذا الاتجاه مرض القلب الإقفاري، والأورام، والسكتة الدماغية، والتي انخفضت جميعها بشكل كبير خلال فترة الدراسة – على الرغم من أن تخفيضاتها كانت موزعة على نطاق واسع وليست مستهدفة مثل أسباب الأمراض غير السارية. تظهر هذه النتائج أن الأمراض غير السارية لا تبدو أنها تتحرك نحو مواقع جغرافية أكثر تركيزًا بمرور الوقت بنفس الطريقة التي تتحرك بها العديد من الأمراض السارية، مما قد يجعل التدخلات والسياسات أكثر تعقيدًا في التنفيذ.

في النهاية، تعكس درجة تركيز الوفيات كل من التقدم المحرز في تقدم الرعاية الصحية والنقائص التي لا تزال قائمة في تنفيذها بشكل عادل. إن تركيز الأمراض هو دليل على وجود تدخلات وسياسات فعالة نجحت في تقليل عبء المرض في العديد من المواقع، ولكن لم يتم توزيع هذه الابتكارات بشكل عادل في جميع أنحاء العالم أو كانت غير فعالة في معالجة التحديات المحددة التي تواجهها بعض الفئات السكانية. لا يزال هناك حاجة عالمية لتحسين الوصول إلى التدخلات الجديدة واللقاحات، والاستثمار في تنفيذ السياسات الصحية العامة المعتمدة، ووضع استراتيجيات مع مراعاة المصادر الجغرافية للأمراض. يجب أن تستمر الجهود المستقبلية في التخفيف المستمر من الأمراض المعدية، مع التركيز على المواقع التي أصبحت فيها هذه الأسباب أكثر تركيزًا جغرافيًا، بينما يجب أيضًا بدء جهود لمكافحة الأسباب المزمنة في البيئات ذات الموارد المنخفضة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تعكس أنماط التركيز الجغرافي العالي بين الأسباب المعدية والتركيز الجغرافي المنخفض بين الأسباب المزمنة الانتقال الوبائي العالمي، حيث انخفضت معدلات الوفيات الناتجة عن الأمراض المعدية على مدار معظم سنوات دراستنا. إن زيادة تركيز سبب الوفاة، وخاصة الأمراض المعدية، توضح النجاح في التخفيف الذي يمكن تكييفه داخل البلدان والمناطق التي تم تحديد تركيز الوفيات فيها في دراستنا، مع إمكانية تقليل الوفيات بشكل كبير من تلك الأسباب.

القيود

لقد مكنت التقدمات المنهجية GBD 2021 من إنتاج تقديرات محددة للوفيات بشكل أسهل من النسخ السابقة؛ ومع ذلك، كما هو الحال مع أي دراسة من هذا النطاق، هناك عدة قيود مهمة يجب الاعتراف بها. يتم تفصيل القيود المحددة لكل سبب من أسباب الوفاة في GBD في الملحق 1 (القسم 3). هنا، نصف القيود المشتركة التي تنطبق عبر العديد من الأسباب. أولاً، يمكن أن تؤثر ندرة البيانات أو عدم موثوقية البيانات من مناطق معينة أو فترات زمنية أو مجموعات عمرية على دقة تقديراتنا، وخاصة جودة البيانات الضعيفة والتغطية من غرب وشرق وجنوب ووسط أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء وآسيا الجنوبية. ثانياً، تعتمد جودة بيانات أسباب الوفاة وبيانات التشريح اللفظي على شهادات الوفاة المرمزة بدقة وفقًا للمعايير الدولية التي وضعتها التصنيف الدولي للأمراض وهي

خاضع لممارسة الطبيب الذي يكمل شهادة الوفاة، والذي قد يكون قد تلقى تدريبًا لتسهيل قابلية المقارنة في الإبلاغ عن الأسباب الكامنة للوفاة أو لا. تتعقد هذه العملية أكثر بسبب الأمراض المصاحبة في وقت الوفاة، والتي قد تؤثر على دقة كل من مصادر تسجيل vital-registration و verbal-autopsy. إحدى الطرق الرئيسية لمعالجة البيانات في GBD هي إعادة تخصيص الوفيات التي تم تعيينها بشكل غير صحيح أو غير واضح – والتي تُعرف باسم النفايات.

تم توضيح الطرق المستخدمة لحساب COVID-19 بالكامل في المنشورات السابقة،

خاضع لممارسة الطبيب الذي يكمل شهادة الوفاة، والذي قد يكون قد تلقى تدريبًا لتسهيل قابلية المقارنة في الإبلاغ عن الأسباب الكامنة للوفاة أو لا. تتعقد هذه العملية أكثر بسبب الأمراض المصاحبة في وقت الوفاة، والتي قد تؤثر على دقة كل من مصادر تسجيل vital-registration و verbal-autopsy. إحدى الطرق الرئيسية لمعالجة البيانات في GBD هي إعادة تخصيص الوفيات التي تم تعيينها بشكل غير صحيح أو غير واضح – والتي تُعرف باسم النفايات.

تم توضيح الطرق المستخدمة لحساب COVID-19 بالكامل في المنشورات السابقة،

الاتجاهات المستقبلية

في النسخة القادمة من GBD، سنقوم بتضمين أكثر من 100 سنة موقعية من التسجيل الحيوي وأنواع بيانات أخرى تم الإبلاغ عنها منذ إنتاج تقديرات GBD 2021. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، سنواصل توسيع تقدير أسباب الوفاة من خلال تفكيك الفئات العامة لأسباب الوفاة إلى أسباب أكثر تفصيلاً حيثما كان ذلك متاحًا. تهدف هذه التحسينات إلى تعزيز دقة وتوقيت تقديرات الوفيات المرتبطة بـ COVID-19 وأسباب الوفاة الأخرى. كما نخطط لتبسيط نهجنا في تقدير الوفيات المرتبطة بـ COVID-19. بدلاً من فئة OPRM المتبقية المبلغ عنها في GBD 2021، سنستخدم جميع سنوات الموقع المتاحة من بيانات أسباب الوفاة لنسب الوفيات إلى أسباب محددة، مما يزيل هذه الفئة المتبقية. نتوقع أن تسهل هذه الطريقة الحصول على رؤى أكثر توقيتًا وقابلة للتنفيذ للتخطيط الصحي العام وصنع السياسات، خاصةً مع توقعنا لرؤية أنماط وفيات أكثر انتظامًا وقابلة للنمذجة في السنوات التي تلي الجائحة. من خلال هذه التقدمات، سنحسن من فائدة ودقة دراسة GBD كأداة لاستراتيجيات عامة فعالة.

الخاتمة