DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01668-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38161204

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-01

العلاج التكاملي باستخدام الجسيمات النانوية متعددة الوظائف للأمراض البشرية

الملخص

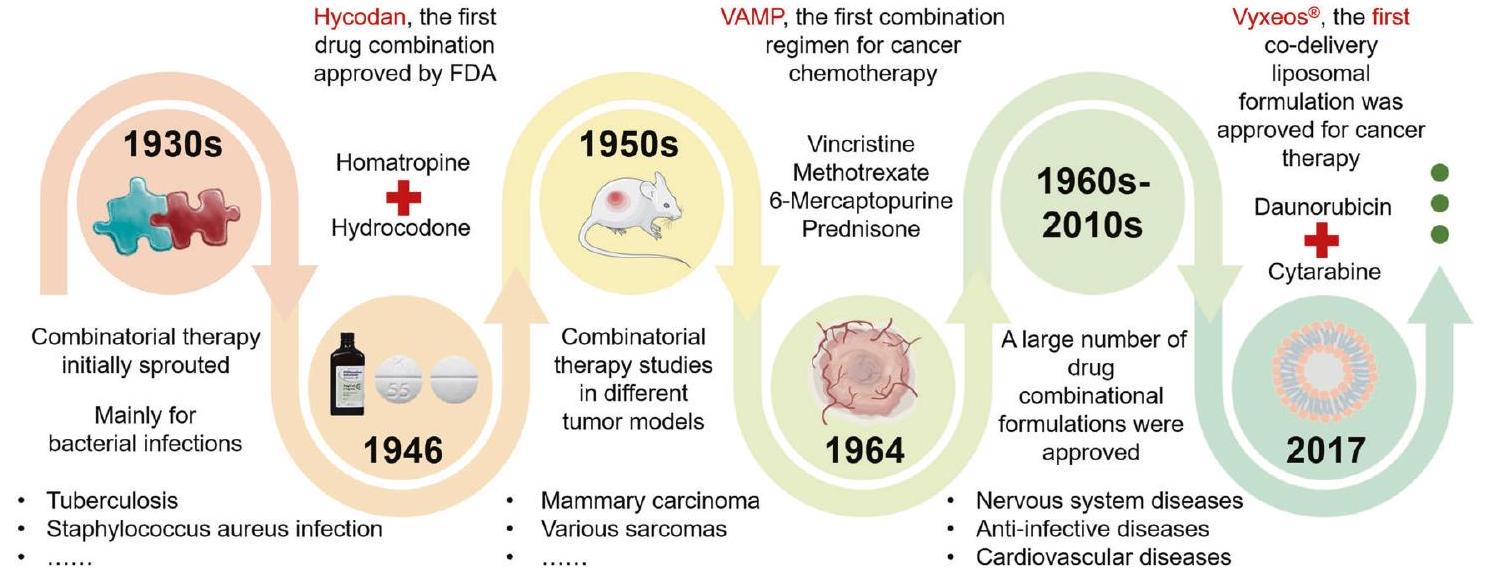

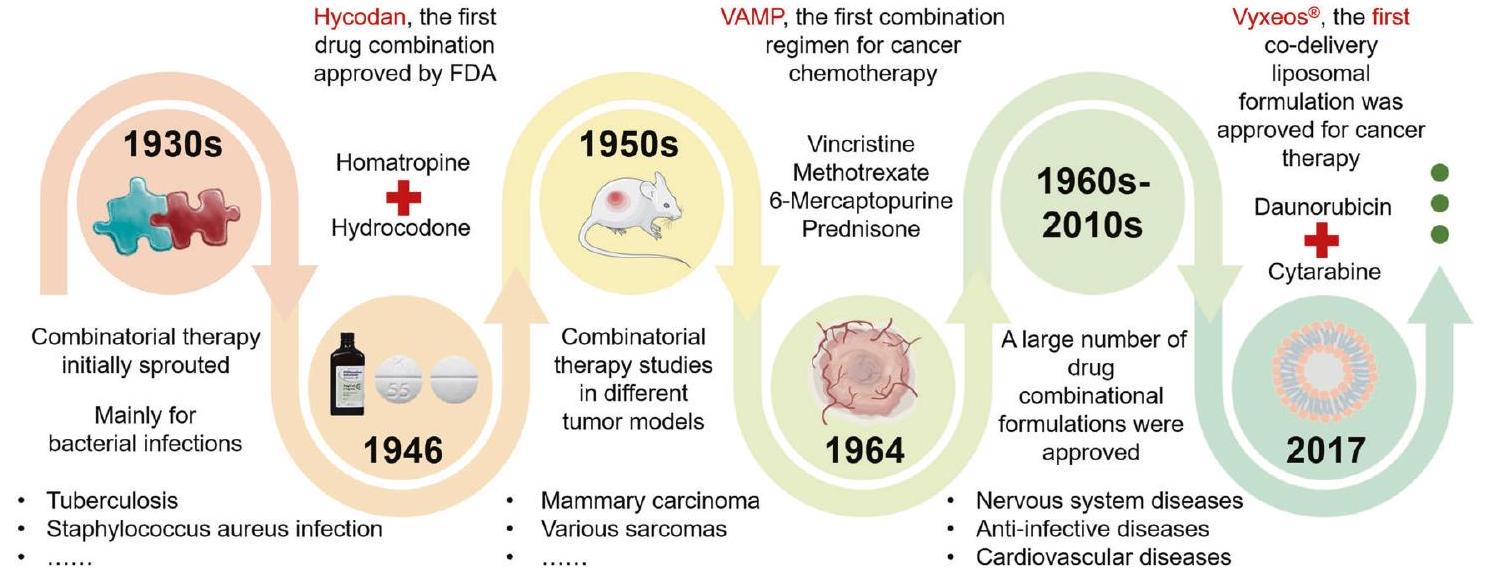

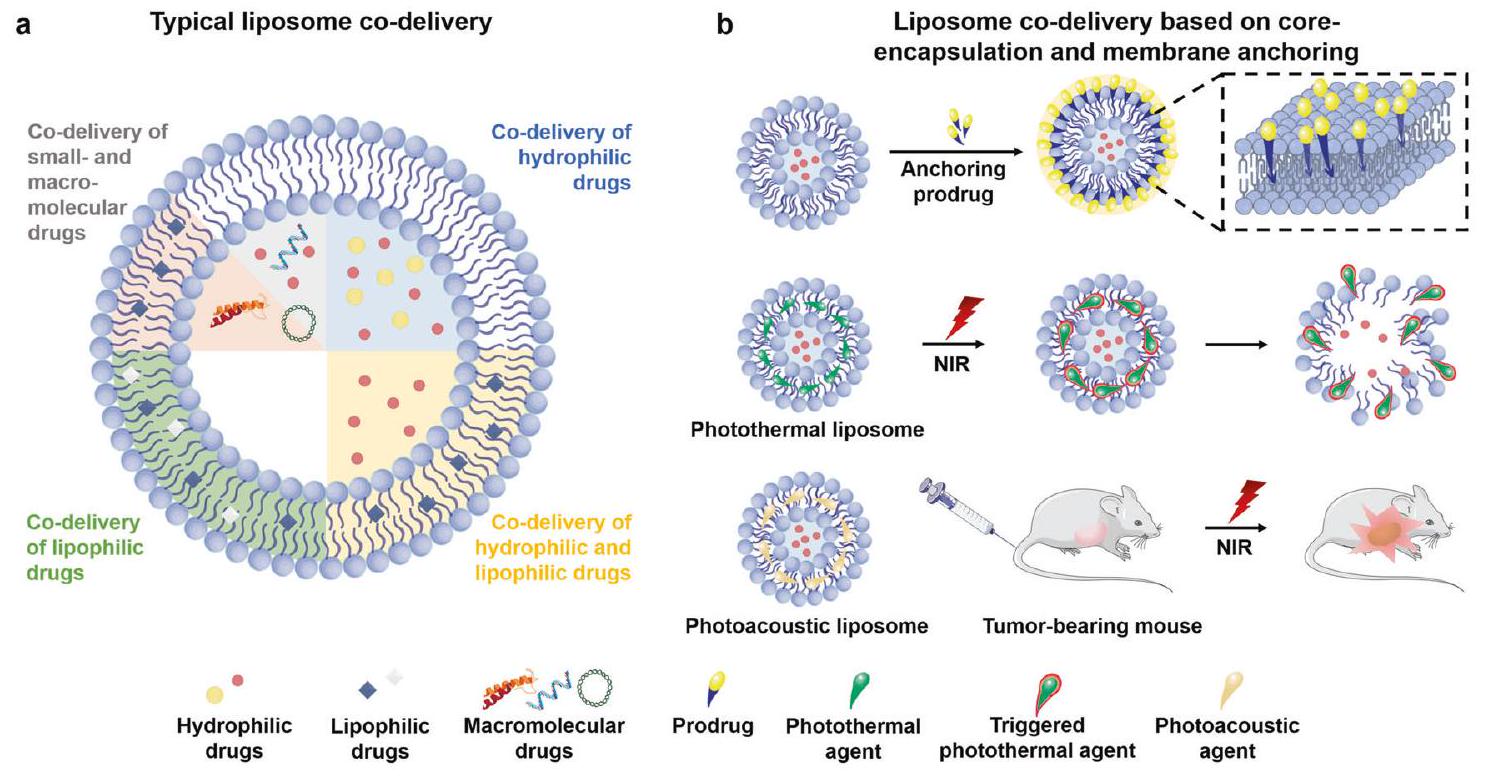

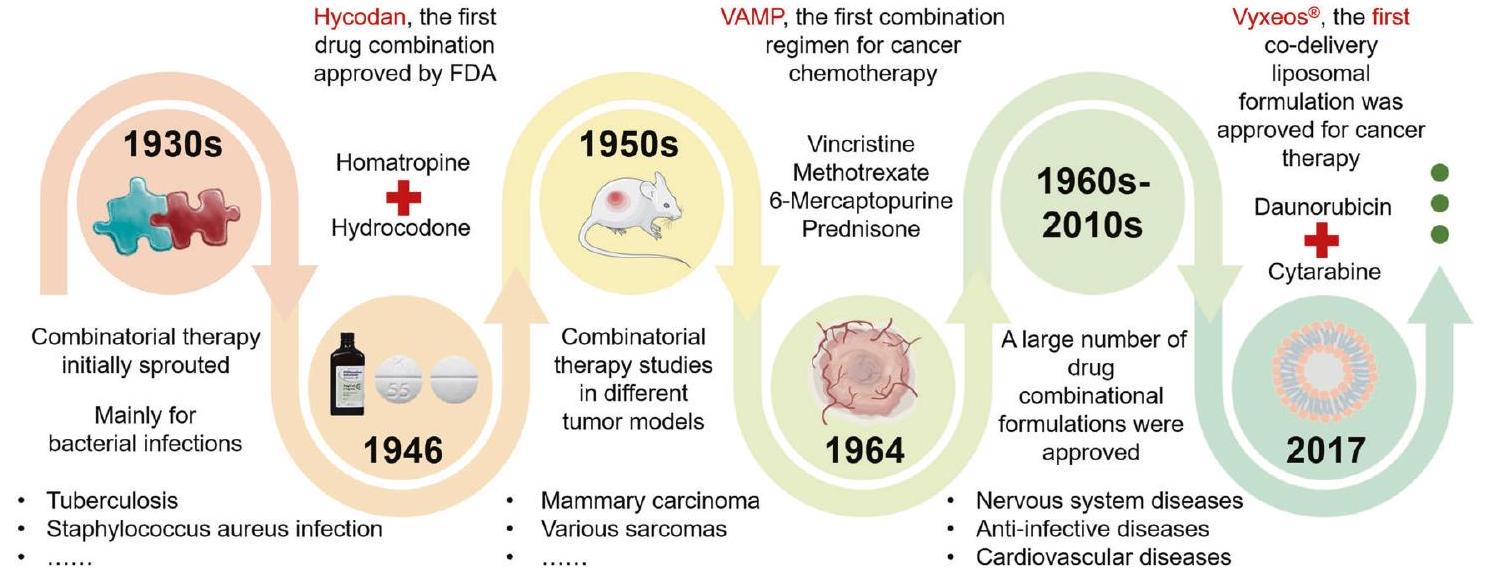

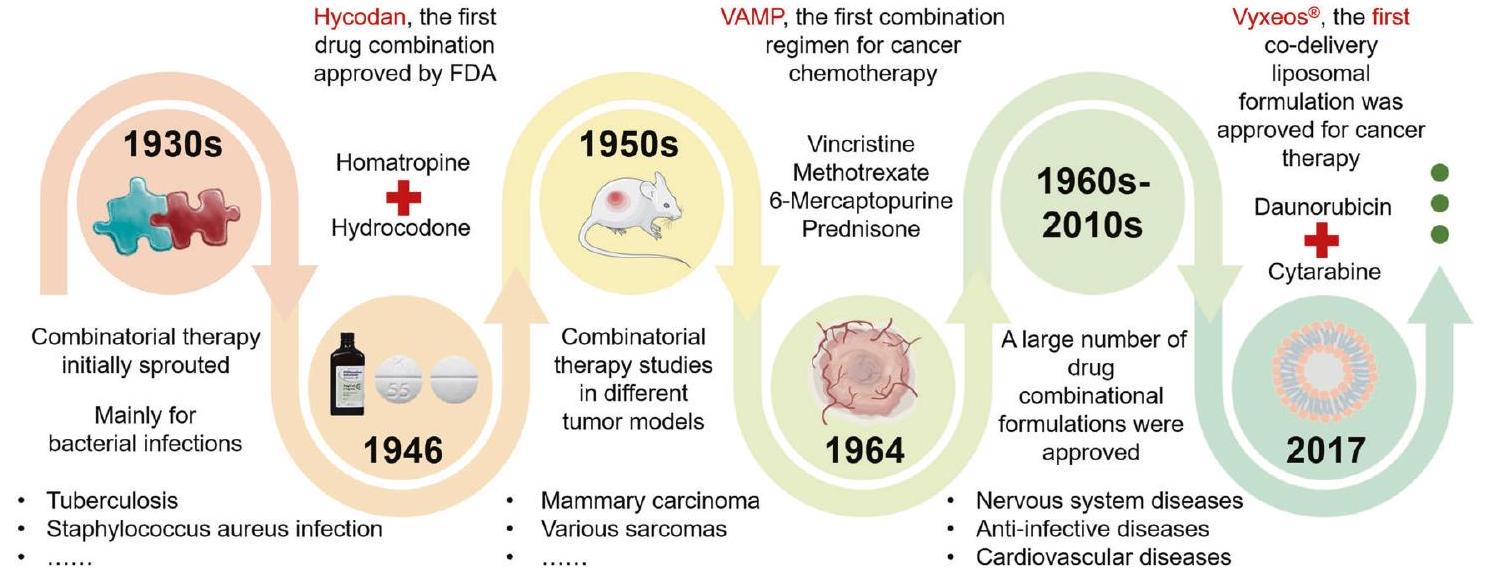

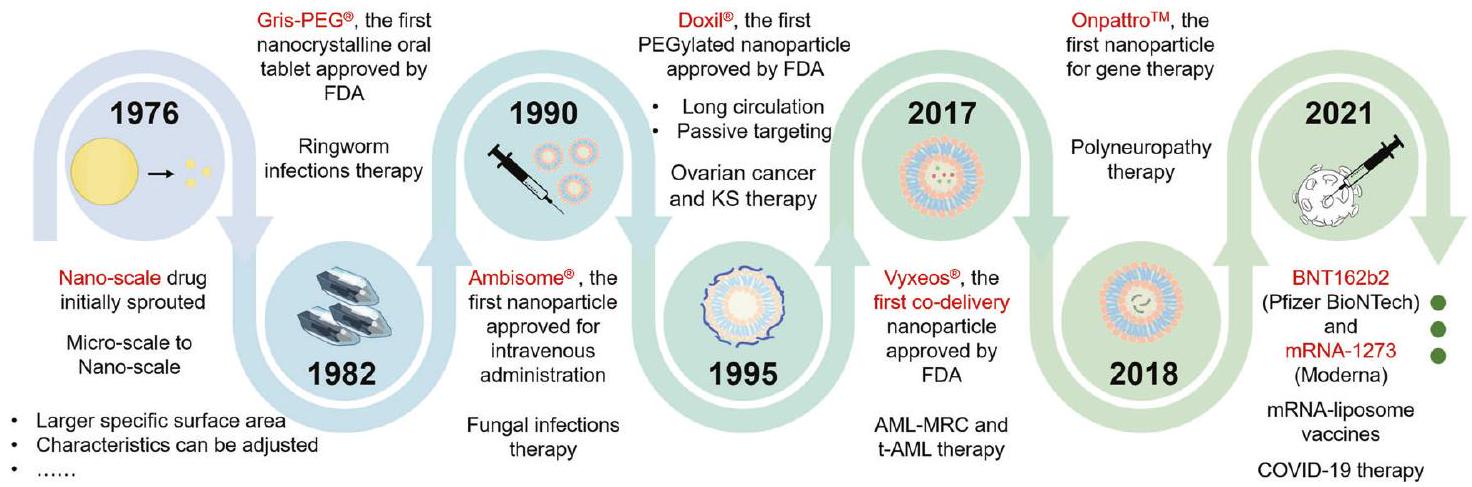

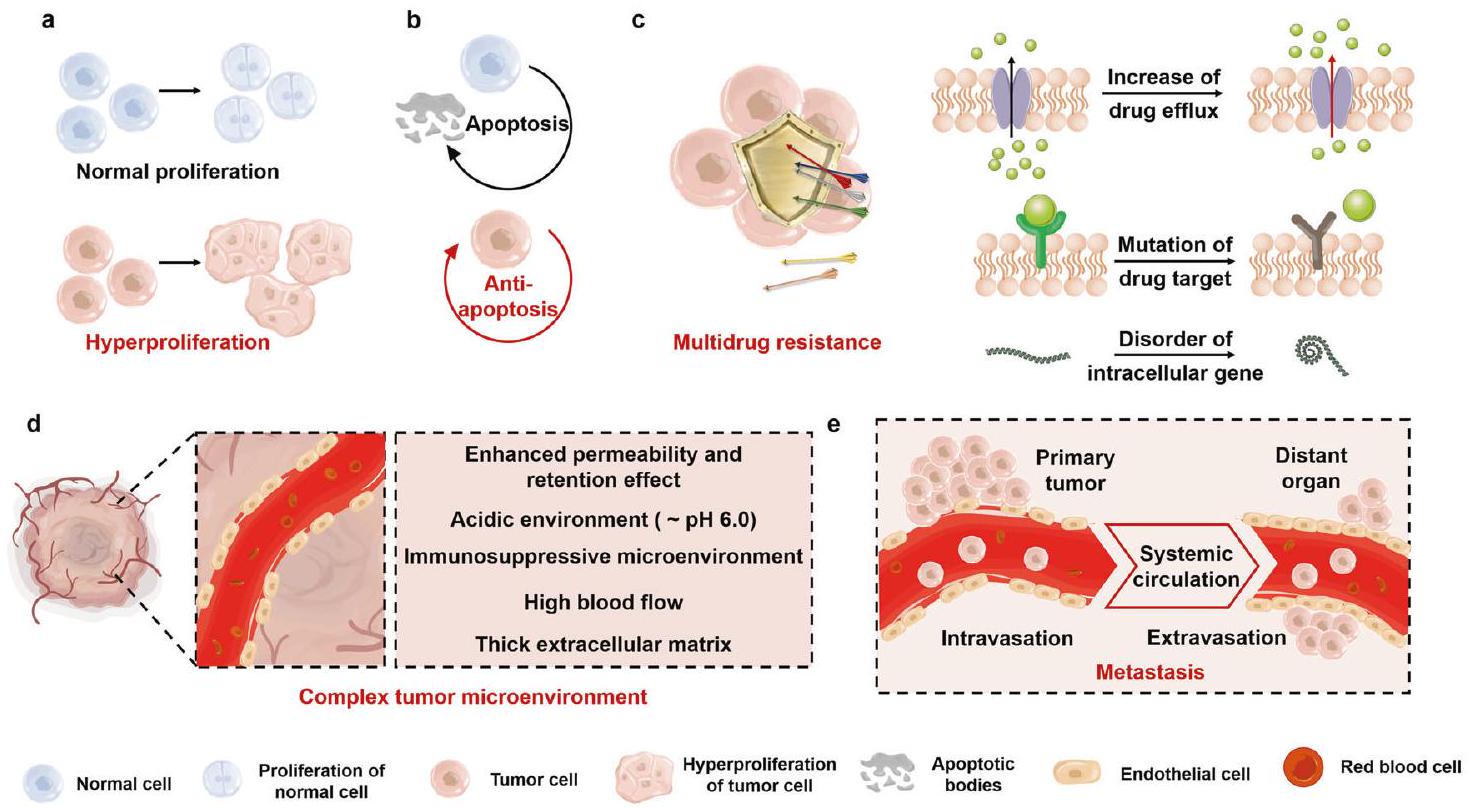

دمج العلاج الدوائي الحالي أمر أساسي في تطوير عوامل علاجية جديدة للوقاية من الأمراض وعلاجها. في الدراسات قبل السريرية، تم إثبات التأثير المشترك لبعض الأدوية المعروفة في علاج أمراض بشرية واسعة النطاق. ونظراً للتأثيرات التآزرية من خلال استهداف مسارات مرضية مختلفة والمزايا مثل تقليل جرعة الإعطاء، وتقليل السمية، وتخفيف مقاومة الدواء، يتم الآن السعي للعلاج التراكبي من خلال توصيل العوامل العلاجية لمكافحة الأمراض السريرية الكبرى مثل السرطان، تصلب الشرايين، ارتفاع ضغط الدم الرئوي، التهاب عضلة القلب، التهاب المفاصل الروماتويدي، أمراض الأمعاء الالتهابية، الاضطرابات الأيضية والأمراض التنكسية العصبية. يشمل العلاج التراكبي دمج أو توصيل مشترك لدوائين أو أكثر لعلاج مرض معين. أنظمة توصيل الدواء المعتمدة على الجسيمات النانوية، مثل الجسيمات النانوية الليبوزومية، الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية والنانوكريستالات، تحظى باهتمام كبير في العلاج التراكبي لمجموعة واسعة من الاضطرابات بسبب توصيل الدواء المستهدف، وإطلاق الدواء الممتد، وثبات الدواء الأعلى لتجنب الإزالة السريعة في المناطق المصابة. تلخص هذه المراجعة الأهداف المختلفة للأمراض، وتركيبات الأدوية المعتمدة قبل السريرية أو السريرية، وتطوير الجسيمات النانوية متعددة الوظائف للعلاج التراكبي، وتؤكد على استراتيجيات العلاج التراكبي القائمة على توصيل الدواء لعلاج الأمراض السريرية الشديدة. في النهاية، نناقش تحديات تطوير التوصيل المشترك للجسيمات النانوية والترجمة السريرية، ونقدم مقاربات محتملة لمعالجة القيود. تقدم هذه المراجعة نظرة شاملة على أحدث التطورات والتحديات في تطوير العلاج التراكبي المعتمد على الجسيمات النانوية لأمراض الإنسان.

مقدمة

نظام NPS متعدد الوظائف

تغيير في حجم الجسيمات. مقارنة بالجسيمات ذات الحجم الميكروني، تمتلك الجسيمات النانوية مساحة سطحية نوعية أكبر، ويمكن تعديل خصائص المواد المستخدمة في تكوين الجسيمات وفقًا لحجم وشكل الجسيمات النانوية على المستوى النانوي.

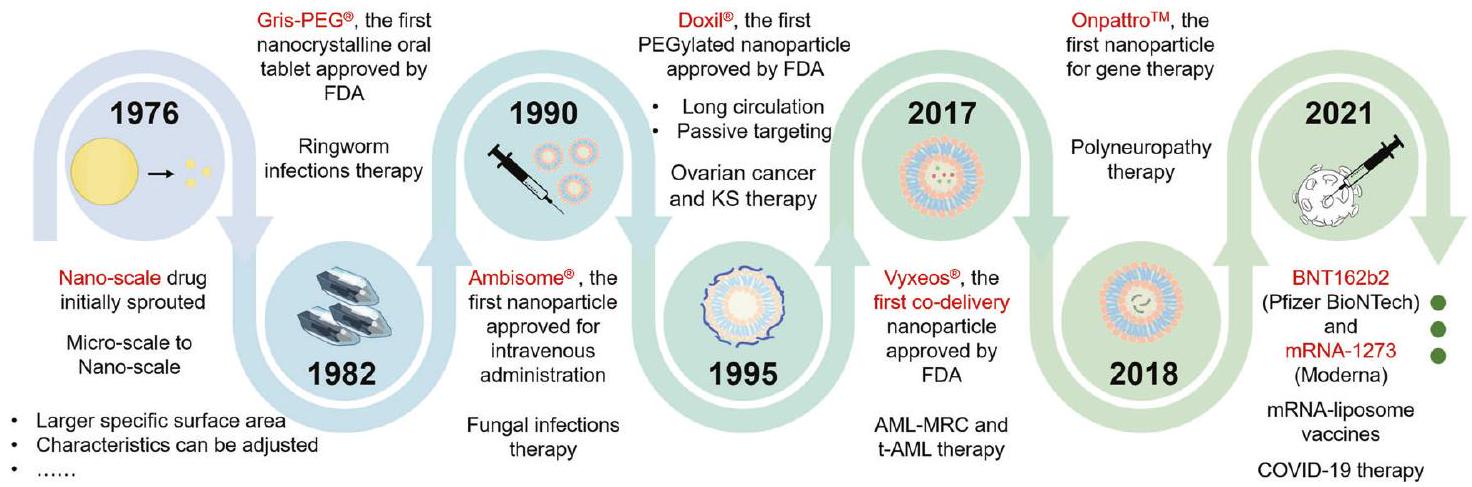

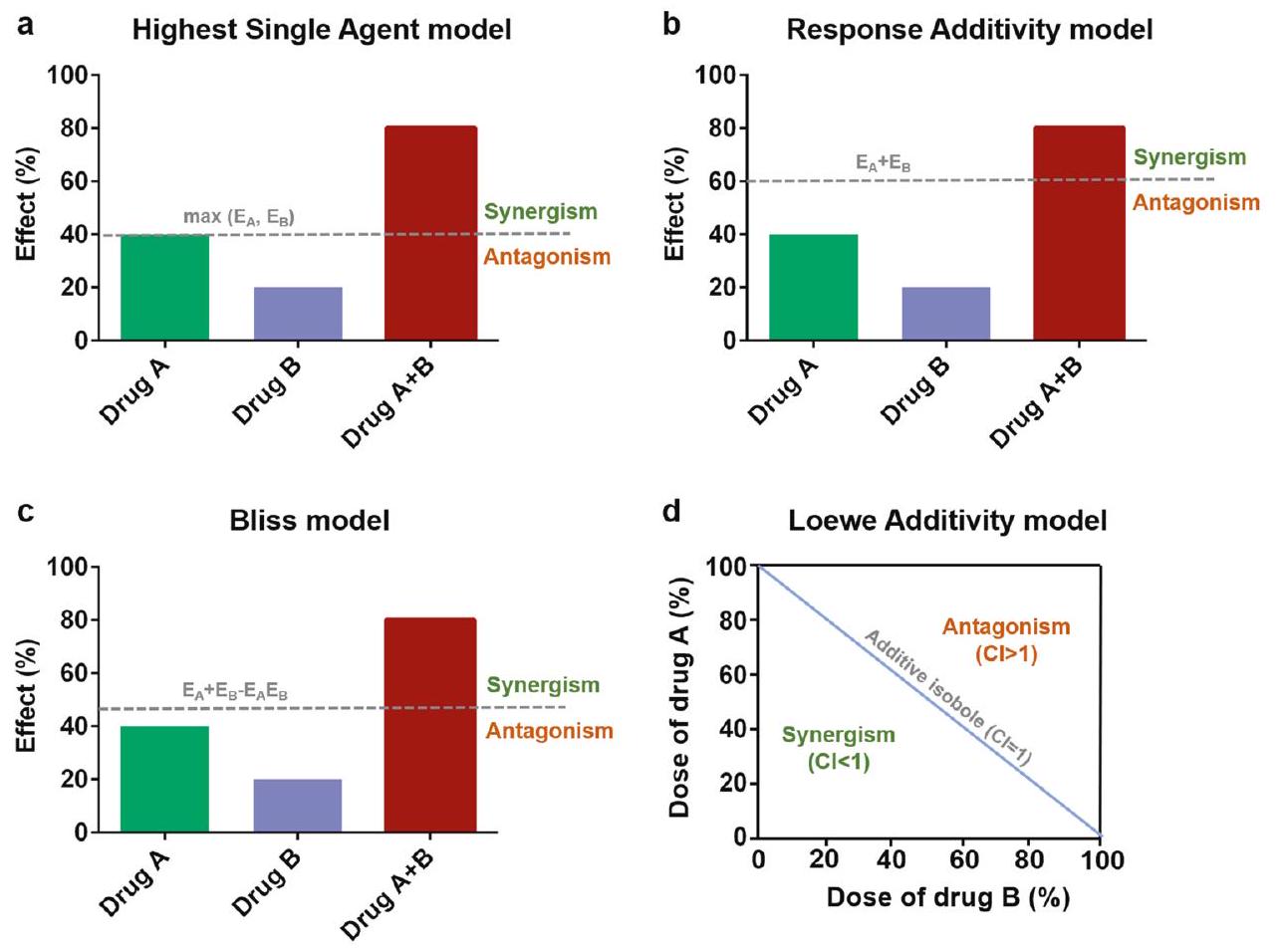

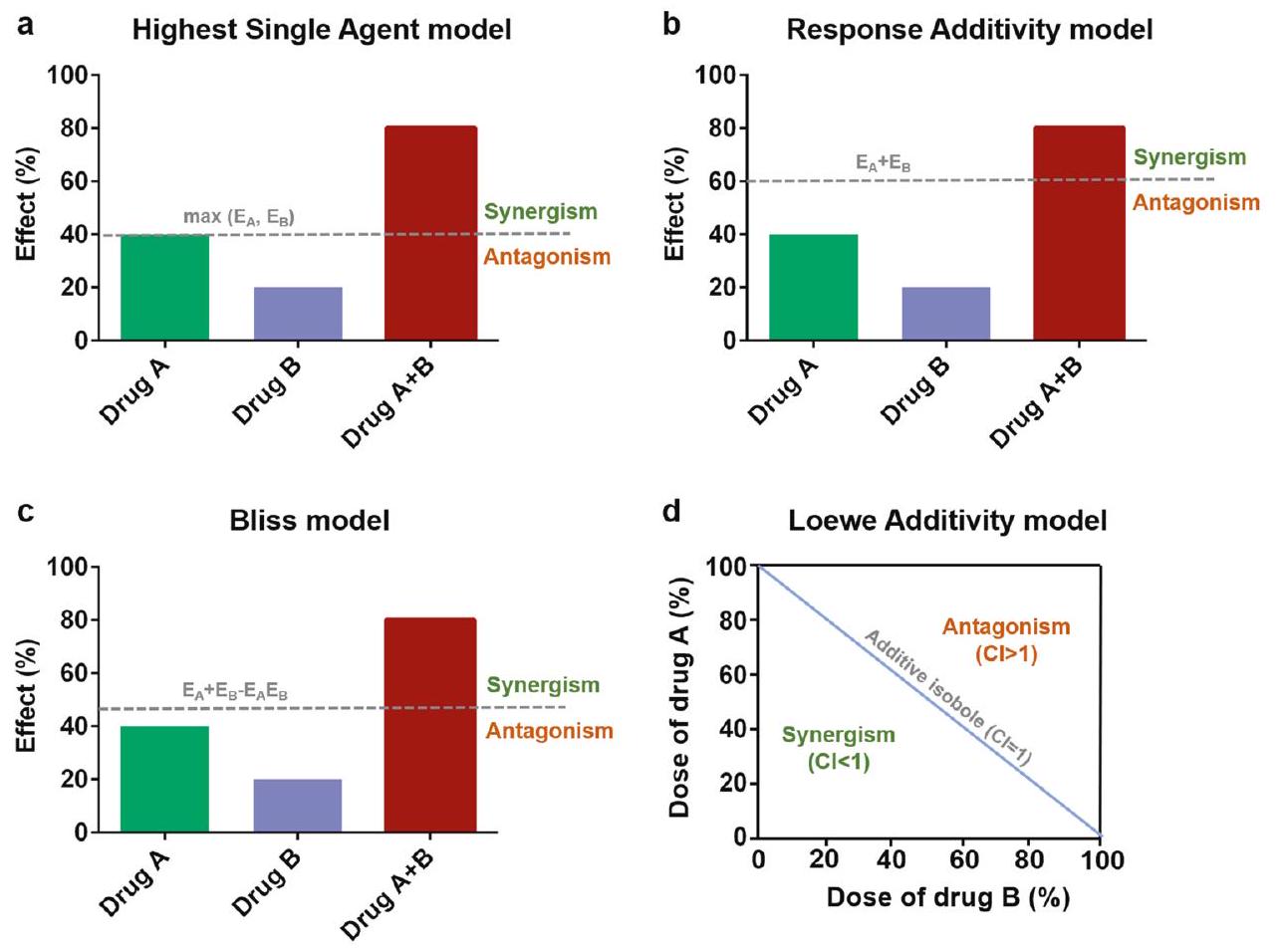

نماذج تقييم تأثيرات التوليف

منحنيات التأثير ذات الجرعة الخطية والتي ليست الحالة العامة. النموذج الأكثر شيوعًا المبني على التأثير هو نموذج الاستقلالية لبليس.

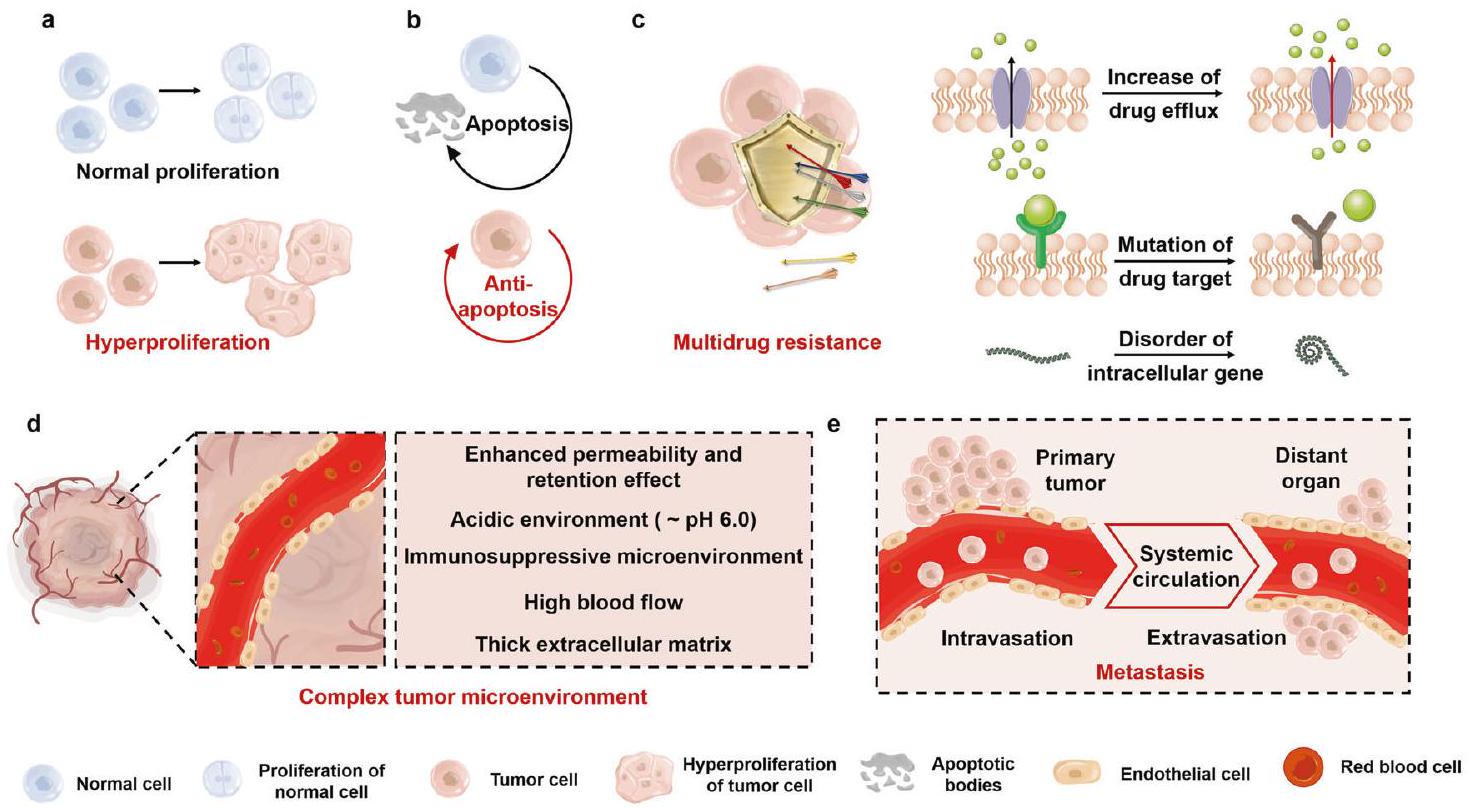

السرطان

أهداف علاج السرطان

الإجهاد الداخلي والخارجي عبر استجابة مضادة للأكسدة تُعرف بإشارة Nrf2-بروتين Kelch المشابه لـ ECH-1 (Keap1).

| دمج أو توصيل الأدوية معًا | المدة الزمنية | أعداد المرضى | الفعالية | مرحلة الدراسة | المراجع | معلومات إضافية | ||||

|

٣.٨ سنوات |

|

أطال بشكل ملحوظ الوقت حتى PSA.

|

المرحلة 3 | – | NCT01695135 | ||||

| دوكسيتاكسيل + سونيتينيب مقابل دوكسيتاكسيل | ٢.٨ سنوات |

|

زاد بشكل ملحوظ نسبة استجابات المشاركين الموضوعية مع الاستجابة الكاملة والاستجابة الجزئية.

|

المرحلة 3 | – | NCT00393939 | ||||

|

٥.٤ سنوات |

|

تحسن كبير في البقاء بدون تقدم المرض والبقاء الكلي.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٤٨٥،٤٨٦ | خط العرض NCT01715285 | ||||

| لاباتينيب + تراستوزوماب مقابل لاباتينيب | ٤.٥ سنوات |

|

تمديد البقاء بدون تقدم المرض، تحسين أو الحفاظ على جودة الحياة المتعلقة بالصحة على المدى القريب، متوسط البقاء على قيد الحياة 4.5 أشهر. | المرحلة 3 | ٤٨٧,٤٨٨ | EGF104900 NCT00320385 | ||||

| أناستروزول + فولفسترنت مقابل أناستروزول | ٤ سنوات |

|

زيادة البقاء على المدى الطويل. | المرحلة 3 | ٤٨٩ | NCT00075764 | ||||

|

18 أسبوعًا |

|

محمل جيدًا | المرحلة الثانية | ٤٩٠ | – | ||||

|

٣.٢ سنة |

|

انخفاض مؤشرات الورم، وارتفاع مستوى المناعة (

|

– | ٤٩١ | – | ||||

|

سنتان |

|

زاد المعدل الفعّال الإجمالي بمقدار

|

– | ٤٩٢ | – | ||||

| أزاسيتيدين + إيفوسيدينيب مقابل أزاسيتيدين + دواء وهمي | سنتان |

|

زيادة كبيرة في البقاء خاليًا من الأحداث.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٤٩٣ | NCT03173248 | ||||

| سنتان |

|

تقدم ملحوظ في البقاء بدون تقدم المرض (

|

المرحلة 3 | ٤٩٤ | NCT02425891 | |||||

|

28 يومًا |

|

الفعالية المضادة للأورام ضد الأورام الصلبة المتقدمة | المرحلة 1 | ٤٩٥ | – | ||||

| CPX-351: داونوروبيسين وسيتارابين في شكل ليبوسومات مقابل

|

فترة العلاج 30 يومًا؛ المتابعة 5 سنوات. | CPX-351 (

|

بعد متابعة لمدة 5 سنوات، تحسنت البقاء الكلي مع CPX-351 مقارنة بـ 7+3 | المرحلة 3 | ١٩٬١٠٠٬٤٩٦ | NCT01696084 | ||||

|

٤ سنوات |

|

تقدم كبير في البقاء بدون تقدم المرض.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٤٩٧ | NCT02470585 | ||||

| نيفولوماب + إيبيليموماب مقابل إيبيليموماب أو نيفولوماب | ٥ سنوات |

|

أظهر الجمع تفوقًا في البقاء الكلي لمدة 5 سنوات، والبقاء بدون تقدم المرض، ومعدل الاستجابة الكلي، مع ملف أمان أفضل مقارنة بالمجموعات الأخرى. | المرحلة 3 | ٤٩٨٬٤٩٩ | NCT01844505 |

العديد من الجزيئات المثبطة العكسية، بما في ذلك نقاط التفتيش المناعية.

تنقسم الأورام إلى أورام حميدة وأورام خبيثة وفقًا لقدرتها على الغزو والانتشار. الاستئصال الجراحي لإزالة الورم بالكامل هو الاستراتيجية الرئيسية للأورام الحميدة. بالمقابل، يعتمد اختيار العلاج للأورام الخبيثة على مرحلة تطور المرض. غالبًا ما يُستخدم العلاج الجراحي الذي يمكنه استئصال الآفات المحلية بشكل جذري في المرحلة المبكرة.

النهج المبلغ عنه بشكل شائع. مستوى ROS في خلايا الورم أعلى بحوالي 10 أضعاف من الخلايا الطبيعية.

توصيل DOX و pDNA باستخدام مشتقات الكيتوزان الأمفيبيلية.

استراتيجية “إعادة توظيف الأدوية”. “إعادة توظيف الأدوية” هي نهج علاجي شائع في علاج السرطان.

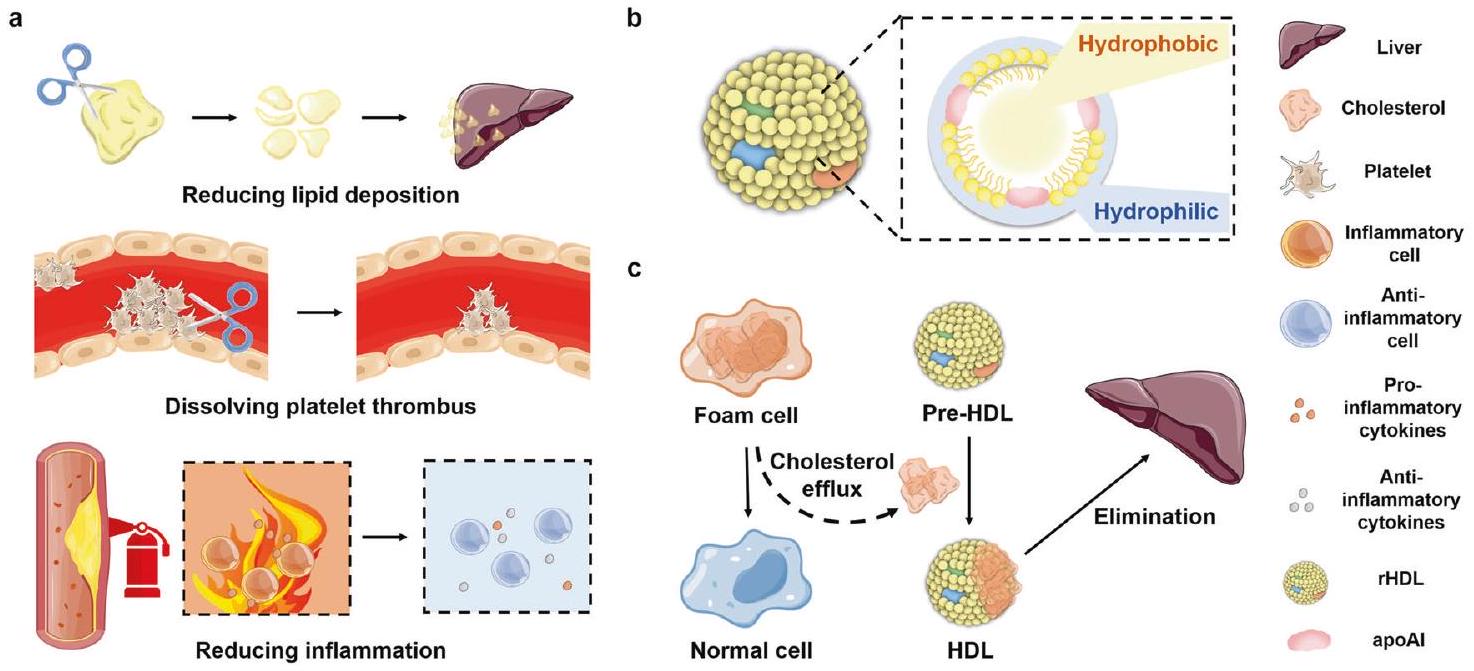

تصلب الشرايين (AS)

الأهداف لعلاج التصلب الجانبي الضموري

البلعميات الكبيرة وتنتج إنزيمات MMPs، مما يؤدي إلى تحلل الغطاء الليفي. زيادة عدم استقرار اللويحات التصلبية الوعائية الضعيفة، التي تنفجر في النهاية وتشكل جلطة دموية، هو أيضًا سبب مهم للأحداث الإقفارية.

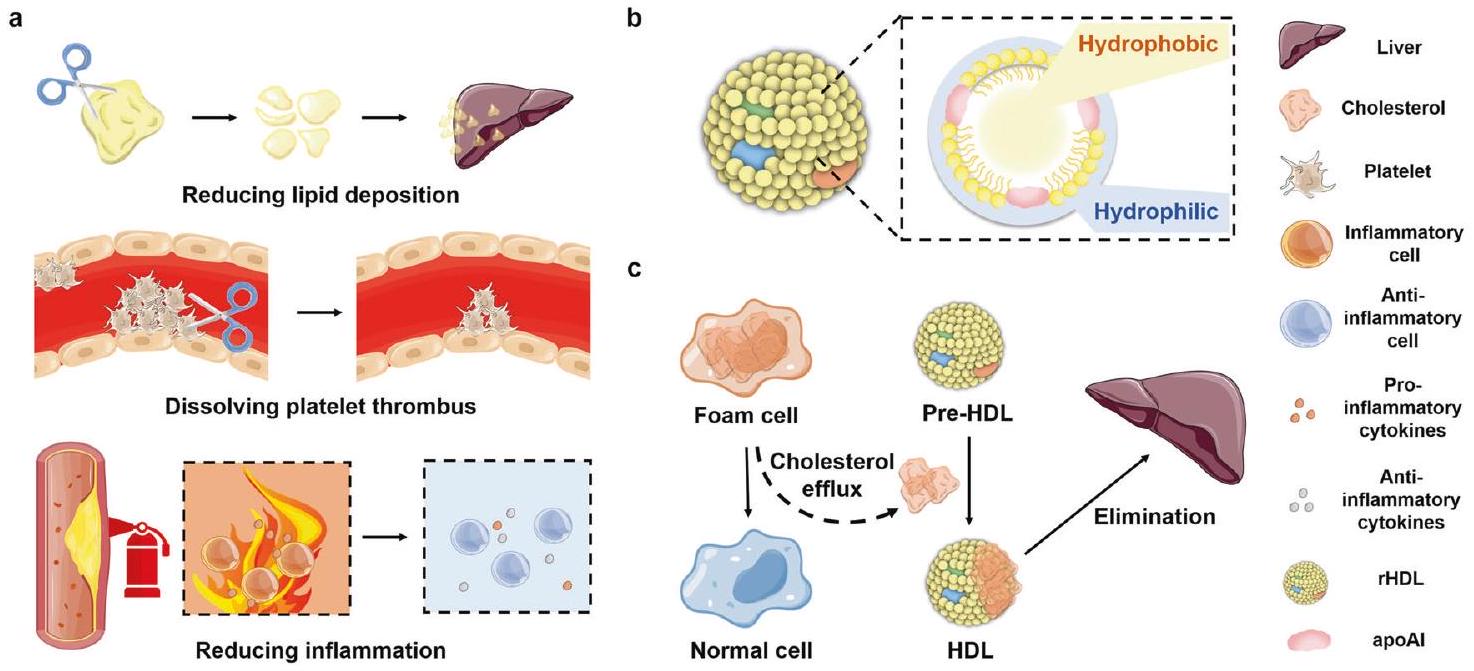

دمج استراتيجيات العلاج. تُظهر الطرق العلاجية الأساسية لتصلب الشرايين في الشكل 7. تقليل امتصاص الدهون وتعزيز تدفق الكوليسترول هما الإجراءان الأكثر مباشرة لتأخير تقدم وتطور تصلب الشرايين.

الجدول 2. البحوث السريرية حول استراتيجيات الدمج والتوصيل المشترك ضد تصلب الشرايين

| دمج أو توصيل الأدوية معًا | المدة | أعداد المرضى | الفعالية | مرحلة الدراسة | المراجع | معلومات إضافية | ||||

| أسبرين + ريفاروكسابان مقابل أسبرين + دواء وهمي | ٣.٢ سنة | ريفاروكسابان (

|

حدثت أحداث النتائج الأولية لأمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية في عدد أقل من المرضى في مجموعة ريفاروكسابان مقارنة بمجموعة الدواء الوهمي.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٠٠٬٥٠١ | NCT01776424 | ||||

| إزيتيميب + حمض بيمبيدويك مقابل إزيتيميب + دواء وهمي | ١٧ أسبوعًا | حمض بيمبيدويك (

|

خفض حمض بيمبيدويك LDL-C بنسبة

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٠٢ | NCT03001076 | ||||

| ستاتين + إزيتيميب + نياسبان مقابل ستاتين + دواء وهمي | سنتان |

|

تم تقليل الكوليسترول غير المرتبط بالبروتين الدهني عالي الكثافة بشكل كبير عند 12 شهرًا من العلاج الثلاثي مقارنة بالعلاج الأحادي.

|

المرحلة 4 | ٥٠٣ | NCT00687076 | ||||

| أتورفاستاتين + إزيتيميب مقابل أتورفاستاتين + دواء وهمي | 12 أسبوعًا | إزيتيميب

|

انخفاض LDL-C.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٠٤ | – | ||||

| إيفاسيترايب + الستاتينات مقابل إيفاسيترايب | 12 أسبوعًا | الستاتينات (

|

مزيج من إيفاسيترايب والستاتين خفض LDL-C.

|

المرحلة 2 | ٥٠٥ | NCT01105975 | ||||

| أتورفاستاتين + لوفازا مقابل أتورفاستاتين + دواء وهمي | 16 أسبوعًا | لوفازا (

|

انخفاض كبير في مستويات الكوليسترول غير المرتبط بالبروتين الدهني عالي الكثافة الوسيط.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٠٦ | NCT00435045 | ||||

| سيلوستازول + إل-كارنيتين مقابل سيلوستازول + دواء وهمي | ٠.٥ سنة | إل-كارنيتين (

|

كان هناك زيادة في PWT بنسبة

|

المرحلة 4 | ٥٠٧ | NCT00822172 | ||||

| حمض بيمبيدويك + إزيتيميب مقابل حمض بيمبيدويك أو إزيتيميب | 12 أسبوعًا |

|

انخفاض كبير في LDL-C.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٠٨ | NCT03337308 | ||||

| العلاج الدوائي الأمثل + أليروكوماب مقابل العلاج الدوائي الأمثل + الدواء الوهمي | ٦٢ أسبوعًا | أليروكوماب (

|

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٠٩ | أوديسي كومبو I NCT01644175 | ||||

|

٨٩ أسبوعًا | أليروكوماب (

|

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥١٠ | أوديسي طويل الأمد NCT01507831 |

نقل الكوليسترول العكسي المعزز المستهدف (RCT). ومع ذلك، يؤدي تنشيط مستقبلات LXRs الجهازية إلى تراكم مفرط لتكوين الدهون في الكبد وآثار جانبية، مثل تكوين الدهون الكبدي وارتفاع ثلاثي الغليسريد في الدم.

أظهرت الدراسات أن القضبان النانوية يمكنها استهداف اللويحات وتقليل ضغط الدم بأكثر من

ارتفاع ضغط الشريان الرئوي (PAH)

العلاجات التقليدية المرتبطة بارتفاع ضغط الشريان الرئوي تستهدف ثلاث مسارات إشارية مرتبطة بتوسيع الأوعية الدموية: الإندوثيلين، أكسيد النيتريك (NO)، والبروستاسايكلين.

توسيع الأوعية الدموية للشُرَيينات الرئوية وتقييد تجمع الصفائح الدموية وتكاثر خلايا العضلات الملساء.

دمج استراتيجيات العلاج. مقارنة بالعلاج الأحادي، يُعتبر دمج العلاجات تفضيلاً أكثر قيمة لإدارة المرضى المصابين بارتفاع ضغط الشريان الرئوي، حيث يمكنه استهداف عدم استقرار عدة مسارات بيولوجية حيوية في الشرايين الرئوية في الوقت نفسه وتخفيف الأعراض المرتبطة باضطراب ارتفاع ضغط الشريان الرئوي.

| مرض | دمج أو توصيل الأدوية معًا | المدة الزمنية | أعداد المرضى | الفعالية | مرحلة الدراسة | المراجع | معلومات إضافية | ||

| ارتفاع ضغط الشريان الرئوي | إيبوبروستينول + سيلدينافيل مقابل إيبوبروستينول + دواء وهمي | ٢.٦ سنوات | سيلدينافيل (

|

زيادة معدلة مقابل الدواء الوهمي بمقدار 28.8 مترًا (

|

– | ٥١١ | – | ||

| ماسيتينتان + تادالافيل + سيليكسبيج مقابل ماسيتينتان + تادالافيل + دواء وهمي | ٤ سنوات | سيليكسبيج (

|

يتم تقليل خطر تطور المرض (حتى نهاية فترة المراقبة الرئيسية) مع العلاج الثلاثي الأولي مقارنة بالعلاج المزدوج الأولي. | المرحلة 4 | ٥١٢ | تريتون NCT02558231 | |||

| سيلدينافيل + بوسنتان مقابل سيلدينافيل + دواء وهمي | ٧.٢ سنوات | بوسنتان (

|

|

المرحلة 4 | ٥١٣ | COMPASS-2 NCT00303459 | |||

| 3 أو 10 ملغ ماكيتنتان مقابل الدواء الوهمي (63.7% يتلقون دواء الدراسة مع علاج آخر مثل مثبطات PDE5، أو البروستانويد المستنشق أو الفموي) | ٣.٨ سنوات | ماسيتينتان (

|

خفض جرعة 10 ملغ من ماكيتنتان خطر حدوث أحداث M/M بنسبة 45%.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥١٤ | سيرافين NCT00660179 | |||

| سيليكسبيج (80% بالاقتران مع ERA، PDE5، أو كلاهما) | ٤.٣ سنوات |

|

خفض خطر حدوث حدث وفاة/مرض بنسبة 40%.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥١٥ | جريفون NCT01106014 | |||

| تادالافيل + أمبريسينتان مقابل العلاج الأحادي بأي من العاملين | ٣.٧ سنوات |

|

خفض خطر الفشل السريري بنسبة 50٪.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥١٦ | طموح NCT01178073 | |||

| تريبروستينيل + بيرابروست مقابل تريبروستينيل + دواء وهمي | ٦.٨ سنوات | بيرابروست (

|

عدد أقل من المشاركين شهد تدهورًا سريريًا. | المرحلة 3 | – | NCT01908699 | |||

| سيلدينافيل + سيتاكسنتان مقابل سيلدينافيل + دواء وهمي | ٢.٣ سنوات | سيتاكسنتان (

|

زاد مدى المشي خلال 6 دقائق بشكل ملحوظ في الأسبوع 12.

|

المرحلة 3 | – | NCT00795639 | |||

| سيتاكسنتان + سيلدينافيل مقابل سيتاكسنتان + دواء وهمي | ١.٨ سنة | سيلدينافيل (

|

لم يتم تحقيق هدف PEP. زادت مسافة المشي لمدة 6 دقائق بشكل ملحوظ في الأسبوع 12.

|

المرحلة 3 | – | NCT00796666 | |||

| تريبروستينيل (50% بالاقتران مع ERA أو PDE5 أو كلاهما) | ٤.٢ سنة | تريبروستينيل (

|

لم يتم تحقيق هدف PEP. زادت مسافة المشي لمدة 6 دقائق في الأسبوع 12. | المرحلة 3 | ٥١٧ | فريدوم-سي NCT00325442 | |||

| 1.5 ملغ أو 2.5 ملغ ريوسيغوات مقابل الدواء الوهمي (50% من المشاركين تم علاجهم مسبقًا بمثبط مستقبلات الأندوتيلين أو نظير البروستاسايكلين) | ٣.٥ سنوات | ريوسيجوات (

|

زاد التغير في مسافة المشي لمدة 6 دقائق

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥١٨ | NCT00810693 | |||

| إيبوبروستينول + سيلدينافيل مقابل إيبوبروستينول + دواء وهمي | ٣ سنوات | سيلدينافيل (

|

تحسنت أو تم الحفاظ على مسافة المشي لمدة 6 دقائق في

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥١٩ | أولي NCT00159861 | |||

| ماكد | بريدنيزون + أزاثيوبرين مقابل بريدنيزون + دواء وهمي | ٠.٥ سنة | أزاثيوبرين (

|

بالمقارنة مع الخط الأساسي، أدى الجمع بين البريدنيزون والأزاثيوبرين إلى تحسن كبير في نسبة القذف البطيني الأيسر وتقليل أبعاد وحجوم البطين الأيسر. | – | ٢٧٤ | تيميك | ||

| الجلوبيولين المناعي + السيكلوسبورين مقابل الجلوبيولين المناعي | ٣ سنوات | الجلوبيولين المناعي + السيكلوسبورين (

|

أدى الجمع بين الغلوبولين المناعي والسيكلوسبورين إلى تقليل حدوث تشوهات الشرايين التاجية.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٢٧٩ | كايسا CCT-B-2503 | |||

| جاما جلوبولين + فوسفات الكرياتين + العلاج الروتيني مقابل العلاج الروتيني | ٠.٥ سنوات | جاما جلوبولين + فوسفات الكرياتين + العلاج الروتيني (

|

التركيبة زادت بشكل كبير من معدل الاستجابة (

|

– | ٢٨٠ | – |

| الجدول 3. تابع | |||||||||

| مرض | دمج أو توصيل الأدوية معًا | المدة الزمنية | أعداد المرضى | الفعالية | مرحلة الدراسة | المراجع | معلومات إضافية | ||

| را | ميثوتركسيت + MP-435 مقابل ميثوتركسيت + دواء وهمي | ١.٨ سنة | MP-435 (

|

زاد المزيج بشكل كبير من معدل الاستجابة لمعيار ACR 20، وقلل من حدوث الأحداث الضائرة الخطيرة. | المرحلة الثانية | – | NCT01143337 | ||

| ميثوتركسيت

|

1.2 سنة | سيكوكينوماب (

|

لم يتم تحقيق PEP. تخفيف الأعراض بعد العلاج طويل الأمد بـ 150 ملغ من سيكوكينوماب. | المرحلة 2 | ٥٢٠٬٥٢١ | NCT00928512 | |||

| ميثوتركسيت

|

سنة واحدة | أداليموماب (

|

(أ) تحقيق معايير استجابة ACR20:

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٢٢ | DE019 NCT00195702 | |||

| ميثوتركسيت + أداليموماب مقابل ميثوتركسيت + دواء وهمي | ١.٦ سنوات | أداليموماب (

|

تحقيق sLDA. | المرحلة 4 | ٥٢٣ | أوبتيما NCT00420927 | |||

| أداليموماب + ميثوتركسيت مقابل أداليموماب أو ميثوتركسيت | سنتان |

|

أدى الجمع إلى تحسين كبير في الوظائف البدنية وجودة الحياة المتعلقة بالصحة لدى المرضى.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٢٤ | بريميير NCT00195663 | |||

| ميثوتركسيت + جوليموماب مقابل ميثوتركسيت + دواء وهمي | 48 أسبوعًا | جوليموماب (

|

التركيبة حسّنت بشكل كبير استجابة ACR 20 و DAS 28.

|

المرحلة 3 | – | NCT01248780 | |||

| ميثوتركسات + 100، 150 ملغ بيفيسيتينيب مقابل ميثوتركسات + دواء وهمي | 52 أسبوعًا | 100 ملغ بيفيسيتينيب (

|

التركيبة حسّنت بشكل كبير استجابة ACR 20.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٢٥ | NCT02305849 | |||

| ميثوتركسيت + باريستينيب مقابل ميثوتركسيت + دواء وهمي | ٥٢ أسبوعًا | باريسيتينيب (

|

التركيبة حسّنت بشكل كبير استجابة ACR 20 و mTSS.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٢٦ | NCT01710358 | |||

| ميثوتركسيت + سيرتوليزوماب بيغول مقابل ميثوتركسيت + دواء وهمي | 52 أسبوعًا | سيرتوليزوماب بيغول

|

التركيبة حققت بشكل ملحوظ عددًا أكبر من المرضى مع sREM و sLDA.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٢٧ | NCT01519791 | |||

| مرض التهاب الأمعاء | أزاثيوبرين + إنفليكسيماب مقابل أزاثيوبرين + دواء وهمي | ٠.٧ سنة | إنفليكسيماب (

|

المزيج

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٢٨ | SONIC NCT00094458 | ||

| حمض 5-أمينوساليسيليك + بوديزونيد مقابل حمض 5-أمينوساليسيليك + دواء وهمي | ٨ أسابيع | بوديزونيد (

|

المزيج

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٢٩ | NCT01532648 | |||

| فرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية | أتورفاستاتين + ميثيل بريدنيزولون مقابل ميثيل بريدنيزولون | ٠.٧٥ سنة |

|

حسّن الجمع بين العلاجات نتائج مرض جريفز المداري لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من مرض نشط متوسط إلى شديد في العين مع فرط كوليسترول الدم. | المرحلة الثانية | ٥٣٠ | NCT03110848 | ||

| ميثيمازول + السيلينيوم + كالسيفيديول مقابل ميثيمازول | ٠.٨ سنة |

|

التركيبة حسّنت الفعالية المبكرة لفرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية. | – | ٣٧٤ | EUDRACT2017-005050-11 | |||

| ريتوكسيماب + دواء مضاد للغدة الدرقية من نوع الثيوأميد (ATD) | سنتان |

|

يمكن لريتوكسيماب أن يساعد علاج مضادات الغدة الدرقية في تخفيف فرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية الناتج عن مرض جريفز لدى الشباب. | المرحلة الثانية | ٥٣١ | ISRCTN20381716 | |||

| ريتوكسيماب + دواء مضاد للغدة الدرقية | سنتان |

|

أدى الجمع إلى تحسن في تراجع فرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية في مرض جريفز لدى المرضى الشباب. | المرحلة الثانية | ٥٣٢ | ISRCTN20381716 | |||

| مايكوفينولات + ميثيل بريدنيزولون مقابل ميثيل بريدنيزولون | ٠.٧ سنة | مايكوفينولات

|

حسّن الجمع معدل الشفاء لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من التهاب العين الجريفزي النشط من الدرجة المتوسطة إلى الشديدة. | – | ٥٣٣ | مينغو يودراكت2008-002123-93 | |||

| الجدول 3. تابع | ||||||||

| مرض | دمج أو توصيل الأدوية معًا | المدة | أعداد المرضى | الفعالية | مرحلة الدراسة | المراجع | معلومات إضافية | |

| داء السكري | أسبرين + ريفاروكسابان مقابل أسبرين + دواء وهمي | ٣ سنوات | لا داء السكري (

|

أظهر المزيج فائدة خاصة في الأفراد المصابين بداء السكري. (2.7% مقابل 1.0%)؛

|

المرحلة 3 | ٥٣٤ | NCT01776424 | |

| ميتفورمين + فيلداجليبتين مقابل ميتفورمين + دواء وهمي | ٥ سنوات |

|

لوحظ انخفاض في الخطر النسبي لوقت الفشل الأولي للعلاج في المجموعة المركبة في المرحلة المبكرة (نسبة المخاطر 0.51؛ فترة الثقة 95 بالمئة (0.45-0.58؛)

|

المرحلة 4 | ٥٣٥ | NCT01528254 | ||

| إمباجليفلوزين + مدرات البول العروقية مقابل إمباجليفلوزين + الدواء الوهمي | ٦ أسابيع |

|

زاد المزيج من حجم البول خلال 24 ساعة دون زيادة الصوديوم في البول. | المرحلة 4 | ٥٣٦ | NCT03226457 | ||

| دورزاجليتين + ميتفورمين مقابل الدواء الوهمي + ميتفورمين | ٤ سنوات |

|

أنتج المزيج تحكمًا فعالًا في نسبة السكر في الدم مع تحمل جيد وملف أمان في مرضى السكري من النوع الثاني.

|

المرحلة 3 | ٤٠٩ | NCT03141073 | ||

| ميلادي | ChEls + ميمانتين | ٤ سنوات |

|

التركيبة قللت من التدهور المعرفي والوظيفي. | – | ٥٣٧ | – | |

| ريفاستيجمين + ميمانتين | ٠.٥ سنة |

|

الحُزمة حافظت على الوظائف العالمية والمعرفية والنتائج السلوكية. | المرحلة 4 | ٥٣٨ | NCT00305903 | ||

| ماسوبيردين + دونيبيزيل + ميمانتين مقابل الدواء الوهمي | ٠.٥ سنة | ماسوبيردين (

|

الإعطاء المتزامن لماسبيردين أثر سلبًا مع ميمانتين، لذا من الضروري إجراء المزيد من الأبحاث على ماسبيردين. | المرحلة 2 | ٥٣٩ | NCT02580305 | ||

| مرض باركنسون | هلام ليفودوبا-كاربيدوبا المعوي (LCIG) | سنة و2 أشهر |

|

أدى الجمع إلى تقليل عدد الأعراض غير الحركية وتقلبات الحركة لدى مرضى باركنسون المتقدمين. | المرحلة 3 | ٥٤٠ | NCT01736176 | |

| كاربيدوبا (25 ملغ) + ليفودوبا

|

٠.٧ سنة |

|

المزيج حسّن الأعراض، دون زيادة خطر المشاكل الحركية. | المرحلة 3 | ٥٤١ | NCT00134966 | ||

| كاربيدوبا + ليفودوبا | ٣.٥ أشهر |

|

أظهرت التركيبة أدلة أولية على الفعالية، وكانت آمنة وقابلة للتنفيذ لمرض باركنسون. | المرحلة 2 | ٥٤٢ | NCT02577523 | ||

| التصلب الجانبي الضموري | سيليكوكسيب + كرياتين + مينوسكلين | ٦ أسابيع |

|

أدى الجمع إلى تحسين كبير في الحماية ضد فقدان الخلايا العصبية الحركية في القرن الأمامي. | المرحلة الثانية | ٥٤٣ | NCT00919555 | |

| تريوميك (دولوتيغرافير 50 ملغ، أباكافير 600 ملغ، لاميفودين 300 ملغ) | ٥.٥ أشهر |

|

يمكن أن يكون نشاط العناصر القابلة للنقل هدفًا علاجيًا لأمراض التاو البشرية. | المرحلة الثانية | ٥٤٤ | NCT02868580 | ||

(خلايا العضلات الملساء للشريان الرئوي) يمكنها أيضًا إفراز عوامل مؤيدة للالتهاب مختلفة بشكل مباشر (IL-1

التهاب عضلة القلب (MCD)

أهداف علاج MCD

استراتيجيات للعلاج التراكبي باستخدام MCD

المرضى الذين لا يستطيعون تحمل الأزا بسبب اضطراب في الكبد، يُعتبر الميثوتركسيت (MTX) بديلاً. على سبيل المثال، تم إثبات أن الجمع بين الميثوتركسيت والبريدنيزون يعالج بشكل فعال مرض MCD المناعي الذاتي السلبي للفيروس.

التهاب المفاصل الروماتويدي (RA)

أهداف علاج التهاب المفاصل الروماتويدي

إلى مجرى الدم، مما يسبب التهابًا جهازيًا، في حين أنها تحفز إصابة المفاصل المحلية عن طريق زيادة إنتاج MMP وتنشيط الخلايا الهادمة للعظم.

العلاج التراكمي المبلغ عنه بشكل شائع، مما يوضح فعالية MTX. ومع ذلك، لا يزال الآلية الجزيئية لهذه التأثيرات التآزرية غير واضحة. قد تفيد الدراسات الآلية الإضافية في ترجمتها.

مرض التهاب الأمعاء (IBD)

أهداف علاج مرض التهاب الأمعاء

بين الخلايا الالتهابية والعوامل المؤيدة للالتهاب. عندما تتجمع الخلايا البلعمية، والخلايا المتعادلة، والخلايا التغصنية داخل الأجزاء الملتهبة من الأمعاء، يحدث زيادة في نفاذية الأمعاء للجزيئات الكبيرة، والجزيئات، والخلايا.

استراتيجيات للعلاج التراكمي لمرض التهاب الأمعاء (IBD)

كبت التعبير عن TNFa، في حين قلل IL-22 من العوامل المسببة للالتهاب وعزز شفاء الغشاء المخاطي في نموذج التهاب القولون التقرحي. قام آيب وزملاؤه بتغليف الأدوية المضادة للالتهاب ومضادات الأكسدة، الميزالازين والكركمين، داخل الليبوسومات وغطوها بـ Eudragit-S100، مما منح الليبوسومات إطلاقًا موجهًا نحو القولون.

فرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية

فرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية، والتي تُستخدم بالتبادل. التعرض المفرط لهرمون الغدة الدرقية في الأنسجة يُسمى التسمم الدرقي، في حين أن فرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية هو اضطراب مرتبط بالإفراز المفرط لهرمون الغدة الدرقية. على الرغم من أن مصطلحي فرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية والتسمم الدرقي يُستخدمان أحيانًا بالتبادل، من الضروري فهم الفروقات بينهما.

أهداف علاج فرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية

تم تعزيز أمراض المناعة الذاتية عن طريق حجب مستقبل FcRn؛ وأظهرت الفئران التي تفتقر إلى FcRn مقاومة لأمراض المناعة الذاتية.

على مر السنين، تم علاج فرط نشاط الغدة الدرقية بطريقتين، اعتمادًا على السبب الكامن وراءه، بما في ذلك العلاجات العرضية والعلاجات الحاسمة.

السكري

مستوى الجلوكوز في الدم في الجسم.

أهداف علاج مرض السكري

مثل الأنسولين في الجهاز الهضمي، صمم العلماء عدة جسيمات نانوية، بما في ذلك جسيمات السيليكا المسامية (MSNs)، الليبوزومات، جسيمات الذهب النانوية والجسيمات البوليمرية. ومع ذلك، يمكن استغلال أنظمة التوصيل المشترك للأدوية لتبسيط نظم العلاج وتحسين التزام المرضى. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن الاستفادة من الجسيمات النانوية لتوصيل العلاجات الجينية المضادة للسكري والببتيدات معًا. على الرغم من المزايا المحتملة، تم الإبلاغ عن عدد قليل من الدراسات قبل السريرية التي تحقق في التركيبات المضادة للسكري التي يتم توصيلها بواسطة الجسيمات النانوية.

الأمراض التنكسية العصبية (NDS)

الأهداف لعلاج ND

يبقى النهج ضد الأمراض العصبية التنكسية تحديًا، نظرًا لعدم وضوح سبب البداية والمسببات وحاجز الدم-الدماغ الذي يعيق توصيل الدواء إلى الدماغ (الشكل 8).

استراتيجيات للعلاج التوافقي غير المحدد

تقليل تجمع الأميلويد-بيتا، مما يحسن التعلم المكاني ووظيفة الذاكرة في فئران مرض الزهايمر. تم التوصية على نطاق واسع بدمج الهرمون العصبي الحامي، اللبتين، والعامل المضاد للالتهابات، البيوجليتازون، لعلاج الأمراض العصبية التنكسية، بما في ذلك مرض الزهايمر والتصلب الجانبي الضموري.

الاستنتاجات والآفاق

تدفق الدم، تأثير EPR، والمستقبلات المعبر عنها بشكل عالي على الأنسجة أو الخلايا المستهدفة. على سبيل المثال، يمكن للجسيمات النانوية ذات الشكل القضيبى استهداف البروتين الكهفي المعبر عنه بشكل عالي على الخلايا البطانية وتحسين توصيل السيتوسول عن طريق تقليل احتجازها في الحويصلات الداخلية. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن للجسيمات النانوية دمج أنظمة علاجية مختلفة للعلاج التراكبي. على سبيل المثال، يمكن الجمع بفعالية بين العلاج الكيميائي والعلاج بالحرارة الضوئية باستخدام أنظمة توصيل الدواء لعلاج السرطان أو تصلب الشرايين. بالنسبة للأمراض المحددة التي يصعب تشخيصها في الوقت الحقيقي، فإن التوصيل المشترك لعامل التشخيص والدواء العلاجي إلى موقع الآفة يتيح المراقبة في الوقت الحقيقي للعملية المرضية لموقع الآفة أثناء العلاج، مما يدمج بين التشخيص والعلاج.

الإنتاج، ومراقبة الجودة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، على الرغم من أن العديد من الجسيمات النانوية قد ثبت أنها تستهدف الآفات المرضية وتحسن فعالية العلاج، إلا أن أقل من

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلف

معلومات إضافية

REFERENCES

- He, C., Tang, Z., Tian, H. & Chen, X. Co-delivery of chemotherapeutics and proteins for synergistic therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 98, 64-76 (2016).

- Da Silva, C. et al. Combinatorial prospects of nano-targeted chemoimmunotherapy. Biomaterials 83, 308-320 (2016).

- Shim, G. et al. Nanoformulation-based sequential combination cancer therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 115, 57-81 (2017).

- Zhang, Z. et al. Overcoming cancer therapeutic bottleneck by drug repurposing. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5, 113 (2020).

- Shrestha, B., Tang, L. & Romero, G. Nanoparticles-mediated combination therapies for cancer treatment. Adv. Ther. 2, 1900076 (2019).

- Chen, L. et al. Stepwise co-delivery of an enzyme and prodrug based on a multiresponsive nanoplatform for accurate tumor therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 6, 6262-6268 (2018).

- Guo, M., Sun, X., Chen, J. & Cai, T. Pharmaceutical cocrystals: A review of preparations, physicochemical properties and applications. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 2537-2564 (2021).

- Gurunathan, S., Kang, M.-H., Qasim, M. & Kim, J.-H. Nanoparticle-mediated combination therapy: Two-in-one approach for cancer. Int J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3264 (2018).

- Ashrafizadeh, M. et al. Hyaluronic acid-based nanoplatforms for doxorubicin: A review of stimuli-responsive carriers, co-delivery and resistance suppression. Carbohyd Polym. 272, 118491 (2021).

- Wu, R. et al. Combination chemotherapy of lung cancer-co-delivery of docetaxel prodrug and cisplatin using aptamer-decorated lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 14, 2249 (2020).

- Li, Y. et al. Cocrystallization-like strategy for the codelivery of hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs in a single carrier material formulation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 32, 3071-3075 (2021).

- Baby, T. et al. Microfluidic synthesis of curcumin loaded polymer nanoparticles with tunable drug loading and pH-triggered release. J. Colloid Inter. Sci. 594, 474-484 (2021).

- Cao, Z. et al. pH-and enzyme-triggered drug release as an important process in the design of anti-tumor drug delivery systems. Biomed. Pharmacother. 118, 109340 (2019).

- Liu, R. et al. Theranostic nanoparticles with tumor-specific enzyme-triggered size reduction and drug release to perform photothermal therapy for breast cancer treatment. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 9, 410-420 (2019).

- Xie, X. et al. Ag nanoparticles cluster with pH-triggered reassembly in targeting antimicrobial applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2000511 (2020).

- Du, X. et al. Cytosolic delivery of the immunological adjuvant Poly I: C and cytotoxic drug crystals via a carrier-free strategy significantly amplifies immune response. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 3272-3285 (2021).

- Teng, C. et al. Intracellular codelivery of anti-inflammatory drug and anti-miR 155 to treat inflammatory disease. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 10, 1521-1533 (2020).

- Zhang, S., Langer, R. & Traverso, G. Nanoparticulate drug delivery systems targeting inflammation for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Nano Today 16, 82-96 (2017).

- Krauss, A. C. et al. FDA Approval Summary:(Daunorubicin and cytarabine) liposome for injection for the treatment of adults with high-risk acute myeloid LeukemiaFDA Approval:(Daunorubicin and Cytarabine). Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 2685-2690 (2019).

- Couvreur, P. Nanoparticles in drug delivery: past, present and future. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 65, 21-23 (2013).

- Birrenbach, G. & Speiser, P. Polymerized micelles and their use as adjuvants in immunology. J. Pharm. Sci. 65, 1763-1766 (1976).

- Chou, L. Y., Ming, K. & Chan, W. C. Strategies for the intracellular delivery of nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 233-245 (2011).

- Wang, R. et al. Strategies for the design of nanoparticles: starting with longcirculating nanoparticles, from lab to clinic. Biomater. Sci. 9, 3621-3637 (2021).

- Stone, N. R., Bicanic, T., Salim, R. & Hope, W. Liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome

): a review of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, clinical experience and future directions. Drugs 76, 485-500 (2016). - Lister, J. Amphotericin B lipid complex (Abelcet

) in the treatment of invasive mycoses: the North American experience. Eur. J. Haematol. 56, 18-23 (1996). - Zylberberg, C. & Matosevic, S. Pharmaceutical liposomal drug delivery: a review of new delivery systems and a look at the regulatory landscape. Drug Deliv. 23, 3319-3329 (2016).

- Rivankar, S. An overview of doxorubicin formulations in cancer therapy. J. Can. Res Ther. 10, 853-858 (2014).

- Rizzardinl, G., Pastecchia, C., Vigevanl, G. M. & Miiella, A. M. Stealth liposomal doxorubicin or bleomycin/vincristine for the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: 17. J. Acq lmm Def. 14, A20 (1997).

- Dinndorf, P. A. et al. FDA drug approval summary: pegaspargase (Oncaspar®) for the first-line treatment of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Oncologist 12, 991-998 (2007).

- Cammas, S. et al. Thermo-responsive polymer nanoparticles with a core-shell micelle structure as site-specific drug carriers. J. Control Release 48, 157-164 (1997).

- Stella, B. et al. Design of folic acid-conjugated nanoparticles for drug targeting. J. Pharm. Sci. 89, 1452-1464 (2000).

- Urits, I. et al. A review of patisiran (ONPATTRO

) for the treatment of polyneuropathy in people with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. NeurTher 9, 301-315 (2020). - Thapa, R. K. & Kim, J. O. Nanomedicine-based commercial formulations: Current developments and future prospects. J. Pharm. Investig. 53, 19-33 (2023).

- Yuan, S. & Chen, H. Mathematical rules for synergistic, additive, and antagonistic effects of multi-drug combinations and their application in research and development of combinatorial drugs and special medical food combinations. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 8, 136-141 (2019).

- Chen, D. et al. Systematic synergy modeling: understanding drug synergy from a systems biology perspective. BMC Syst. Biol. 9, 1-10 (2015).

- Niu, J., Straubinger, R. M. & Mager, D. E. Pharmacodynamic Drug-Drug Interactions. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 105, 1395-1406 (2019).

- Caesar, L. K. & Cech, N. B. Synergy and antagonism in natural product extracts: when

does not equal 2. Nat. Prod. Rep. 36, 869-888 (2019). - Nøhr-Nielsen, A. et al. Pharmacodynamic modelling reveals synergistic interaction between docetaxel and SCO-101 in a docetaxel-resistant triple negative breast cancer cell line. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 148, 105315 (2020).

- Rodríguez-Vázquez, G. O. et al. Synergistic interactions of cytarabineadavosertib in leukemic cell lines proliferation and metabolomic endpoints. Biomed. Pharmacother. 166, 115352 (2023).

- Liu, Z. et al. Pharmacokinetic synergy from the taxane extract of Taxus chinensis improves the bioavailability of paclitaxel. Phytomedicine 22, 573-578 (2015).

- Wang, H. & Huang, Y. Combination therapy based on nano codelivery for overcoming cancer drug resistance. Med Drug Discov. 6, 100024 (2020).

- Tardi, P. et al. In vivo maintenance of synergistic cytarabine: daunorubicin ratios greatly enhances therapeutic efficacy. Leuk. Res. 33, 129-139 (2009).

- Foucquier, J. & Guedj, M. Analysis of drug combinations: current methodological landscape. Pharm. Res Perspect. 3, e00149 (2015).

- Wooten, D. J. et al. MuSyC is a consensus framework that unifies multi-drug synergy metrics for combinatorial drug discovery. Nat. Commun. 12, 4607 (2021).

- Duarte, D. & Vale, N. Evaluation of synergism in drug combinations and reference models for future orientations in oncology. Curr Res Pharm. Drug Discov. 3, 100110 (2022).

- Vakil, V. & Trappe, W. Drug combinations: mathematical modeling and networking methods. Pharmaceutics 11, 208 (2019).

- Li, Y. et al. Protease-triggered bioresponsive drug delivery for the targeted theranostics of malignancy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 2220-2242 (2021).

- Bejarano, L., Jordāo, M. J. & Joyce, J. A. Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 11, 933-959 (2021).

- Xiao, Y. & Yu, D. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharm. Therapeut. 221, 107753 (2021).

- Romanini, A. et al. First-line chemotherapy with epidoxorubicin, paclitaxel, and carboplatin for the treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol. Oncol. 89, 354-359 (2003).

- Ye, F. et al. Advances in nanotechnology for cancer biomarkers. Nano Today 18, 103-123 (2018).

- Jin, C., Wang, K., Oppong-Gyebi, A. & Hu, J. Application of nanotechnology in cancer diagnosis and therapy-a mini-review. Int J. Med Sci. 17, 2964 (2020).

- Chaturvedi, V. K., Singh, A., Singh, V. K. & Singh, M. P. Cancer nanotechnology: A new revolution for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Curr. Drug Metab. 20, 416-429 (2019).

- Yang, S. et al. Paying attention to tumor blood vessels: cancer phototherapy assisted with nano delivery strategies. Biomaterials 268, 120562 (2021).

- Liu, J. et al. A DNA-based nanocarrier for efficient gene delivery and combined cancer therapy. Nano Lett. 18, 3328-3334 (2018).

- Qian, K., Yan, B. & Xiong, Y. The application of chemometrics for efficiency enhancement and toxicity reduction in cancer treatment with combined therapy. Curr. Drug Deliv. 18, 679-687 (2021).

- Partridge, A. H., Burstein, H. J. & Winer, E. P. Side effects of chemotherapy and combined chemohormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. JNCI Monogr. 2001, 135-142 (2001).

- Lebaron, S. et al. Chemotherapy side effects in pediatric oncology patients: Drugs, age, and sex as risk factors. Med Pediatr. Oncol. 16, 263-268 (1988).

- Lee, A. & Djamgoz, M. B. Triple negative breast cancer: emerging therapeutic modalities and novel combination therapies. Cancer Treat. Rev. 62, 110-122 (2018).

- Sang, W., Zhang, Z., Dai, Y. & Chen, X. Recent advances in nanomaterial-based synergistic combination cancer immunotherapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 3771-3810 (2019).

- Walsh, J. H., Karnes, W., Cuttitta, F. & Walker, A. Autocrine growth factors and solid tumor malignancy. West. J. Med. 155, 152 (1991).

- Drozdov, I. et al. Autoregulatory effects of serotonin on proliferation and signaling pathways in lung and small intestine neuroendocrine tumor cell lines. Cancer 115, 4934-4945 (2009).

- Semenza, G. L. Hypoxia-inducible factors: mediators of cancer progression and targets for cancer therapy. Trends Pharm. Sci. 33, 207-214 (2012).

- Shang, P. et al. VEGFR2-targeted antibody fused with IFNamut regulates the tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer and exhibits potent anti-tumor and anti-metastasis activity. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 420-433 (2021).

- Intlekofer, A. M. & Finley, L. W. Metabolic signatures of cancer cells and stem cells. Nat. Metab. 1, 177-188 (2019).

- Zhu, J. & Thompson, C. B. Metabolic regulation of cell growth and proliferation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 436-450 (2019).

- Lee, D.-Y., Song, M.-Y. & Kim, E.-H. Role of oxidative stress and Nrf2/ keap1 signaling in colorectal cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives with phytochemicals. Antioxidants 10, 743 (2021).

- Taguchi, K. & Yamamoto, M. The KEAP1-NRF2 system as a molecular target of cancer treatment. Cancers 13, 46 (2020).

- Cha, H.-Y. et al. Downregulation of Nrf2 by the combination of TRAIL and Valproic acid induces apoptotic cell death of TRAIL-resistant papillary thyroid cancer cells via suppression of Bcl-xL. Cancer Lett. 372, 65-74 (2016).

- Foo, B. J.-A., Eu, J. Q., Hirpara, J. L. & Pervaiz, S. Interplay between mitochondrial metabolism and cellular redox state dictates cancer cell survival. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 1341604 (2021).

- Missiroli, S. et al. Cancer metabolism and mitochondria: Finding novel mechanisms to fight tumours. EBioMedicine 59, 102943 (2020).

- Singh, P. & Lim, B. Targeting apoptosis in cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 24, 273-284 (2022).

- Singh, R., Letai, A. & Sarosiek, K. Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: the balancing act of BCL-2 family proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 175-193 (2019).

- Castle, V. P. et al. Expression of the apoptosis-suppressing protein bcl-2, in neuroblastoma is associated with unfavorable histology and

amplification. Am. J. Pathol. 143, 1543 (1993). - Raffo, A. J. et al. Overexpression of bcl-2 protects prostate cancer cells from apoptosis in vitro and confers resistance to androgen depletion in vivo. Cancer Res. 55, 4438-4445 (1995).

- Wang, M. & Su, P. The role of the Fas/FasL signaling pathway in environmental toxicant-induced testicular cell apoptosis: An update. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 64, 93-102 (2018).

- Ivanisenko, N. V. et al. Regulation of extrinsic apoptotic signaling by c-FLIP: towards targeting cancer networks. Trends Cancer 8, 190-209 (2022).

- Zheng, Y., Ma, L. & Sun, Q. Clinically-relevant ABC transporter for anti-cancer drug resistance. Front Pharmacol. 12, 648407 (2021).

- Wang, J. Q. et al. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in cancer: A review of recent updates. JEBM 14, 232-256 (2021).

- Gupta, S. K., Singh, P., Ali, V. & Verma, M. Role of membrane-embedded drug efflux ABC transporters in the cancer chemotherapy. Oncol. Rev. 14, 448 (2020).

- Sharma, P. & Allison James, P. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 348, 56-61 (2015).

- Passardi, A., Canale, M., Valgiusti, M. & Ulivi, P. Immune checkpoints as a target for colorectal cancer treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1324 (2017).

- Anderson, T. S. et al. Disrupting cancer angiogenesis and immune checkpoint networks for improved tumor immunity. Semin Cancer Biol. 86, 981-996 (2022).

- Li, N. et al. Adverse and unconventional reactions related to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 108, 108803 (2022).

- Khair, D. O. et al. Combining immune checkpoint inhibitors: Established and emerging targets and strategies to improve outcomes in melanoma. Front Immunol. 10, 453 (2019).

- Bonati, L. & Tang, L. Cytokine engineering for targeted cancer immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 62, 43-52 (2021).

- Mughees, M. et al. Chemokines and cytokines: Axis and allies in prostate cancer pathogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 86, 497-512 (2022).

- Malik, D., Mahendiratta, S., Kaur, H. & Medhi, B. Futuristic approach to cancer treatment. Gene 805, 145906 (2021).

- Baskar, R., Lee, K. A., Yeo, R. & Yeoh, K.-W. Cancer and radiation therapy: current advances and future directions. Int J. Med. Sci. 9, 193 (2012).

- DeVita, V. T. Jr & Chu, E. A history of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 68, 8643-8653 (2008).

- Wahida, A. et al. The coming decade in precision oncology: six riddles. Nat. Rev. Cancer 23, 43-54 (2023).

- Liu, R. et al. Advances of nanoparticles as drug delivery systems for disease diagnosis and treatment. Chin. Chem. Lett. 34, 107518 (2022).

- Deshpande, P. P., Biswas, S. & Torchilin, V. P. Current trends in the use of liposomes for tumor targeting. Nanomedicine 8, 1509-1528 (2013).

- He, K. & Tang, M. Safety of novel liposomal drugs for cancer treatment: Advances and prospects. Chem. Biol. Interact. 295, 13-19 (2018).

- Saraf, S. et al. Advances in liposomal drug delivery to cancer: An overview. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Tec. 56, 101549 (2020).

- Fan, Y. & Zhang, Q. Development of liposomal formulations: From concept to clinical investigations. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 8, 81-87 (2013).

- Sousa, I. et al. Liposomal therapies in oncology: does one size fit all? Cancer Chemoth Pharm. 82, 741-755 (2018).

- Cooper, T. M. et al. Phase I/II study of CPX-351 followed by fludarabine, cytarabine, and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor for children with relapsed acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 2170 (2020).

- Feldman, E. J. et al. Phase I study of a liposomal carrier (CPX-351) containing a synergistic, fixed molar ratio of cytarabine (Ara-C) and daunorubicin (DNR) in advanced leukemias. Blood 112, 2984 (2008).

- Lin, T. L. et al. Older adults with newly diagnosed high-risk/secondary AML who achieved remission with CPX-351: phase 3 post hoc analyses. Blood Adv. 5, 1719-1728 (2021).

- Lim, W.-S. et al. Leukemia-selective uptake and cytotoxicity of CPX-351, a synergistic fixed-ratio cytarabine: daunorubicin formulation, in bone marrow xenografts. Leuk. Res. 34, 1214-1223 (2010).

- Blagosklonny, M. V. “Targeting the absence” and therapeutic engineering for cancer therapy. Cell Cycle 7, 1307-1312 (2008).

- Sun, Y. et al. Co-delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs and cell cycle regulatory agents using nanocarriers for cancer therapy. Sci. China Mater. 64, 1827-1848 (2021).

- Li, F. et al. Co-delivery of VEGF siRNA and Etoposide for Enhanced Antiangiogenesis and Anti-proliferation Effect via Multi-functional Nanoparticles for

105. Nakamura, H. & Takada, K. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: Current findings and future directions. Cancer Sci. 112, 3945-3952 (2021).

106. Kohan, R. et al. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: A paradox between pro-and anti-tumour activities. Cancer Chemoth Pharm. 86, 1-13 (2020).

107. ArulJothi, K. et al. Implications of reactive oxygen species in lung cancer and exploiting it for therapeutic interventions. Med Oncol. 40, 43 (2022).

108. Sarmiento-Salinas, F. L. et al. Reactive oxygen species: Role in carcinogenesis, cancer cell signaling and tumor progression. Life Sci. 284, 119942 (2021).

109. Ghoneum, A. et al. Redox homeostasis and metabolism in cancer: a complex mechanism and potential targeted therapeutics. Int J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3100 (2020).

110. Antunes, F. & Cadenas, E. Cellular titration of apoptosis with steady state concentrations of H 2 O 2 : submicromolar levels of H 2 O 2 induce apoptosis through Fenton chemistry independent of the cellular thiol state. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 30, 1008-1018 (2001).

111. Tang, J. et al. Co-delivery of doxorubicin and P-gp inhibitor by a reductionsensitive liposome to overcome multidrug resistance, enhance anti-tumor efficiency and reduce toxicity. Drug Deliv. 23, 1130-1143 (2016).

112. Mirzaei, S. et al. Advances in understanding the role of P-gp in doxorubicin resistance: Molecular pathways, therapeutic strategies, and prospects. Drug Discov. 27, 436-455 (2022).

113. Wang, Y. et al. Paclitaxel derivative-based liposomal nanoplatform for potentiated chemo-immunotherapy. J. Control Release 341, 812-827 (2022).

114. Zhang, J. et al. Small molecules regulating reactive oxygen species homeostasis for cancer therapy. Med Res Rev. 41, 342-394 (2021).

115. Zong, Q. et al. Self-amplified chain-shattering cinnamaldehyde-based poly (thioacetal) boosts cancer chemo-immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 154, 97-107 (2022).

116. Boafo, G. F. et al. Targeted co-delivery of daunorubicin and cytarabine based on the hyaluronic acid prodrug modified liposomes. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 4600-4604 (2022).

117. Lv, Y. et al. Nanoplatform assembled from a CD44-targeted prodrug and smart liposomes for dual targeting of tumor microenvironment and cancer cells. Acs Nano. 12, 1519-1536 (2018).

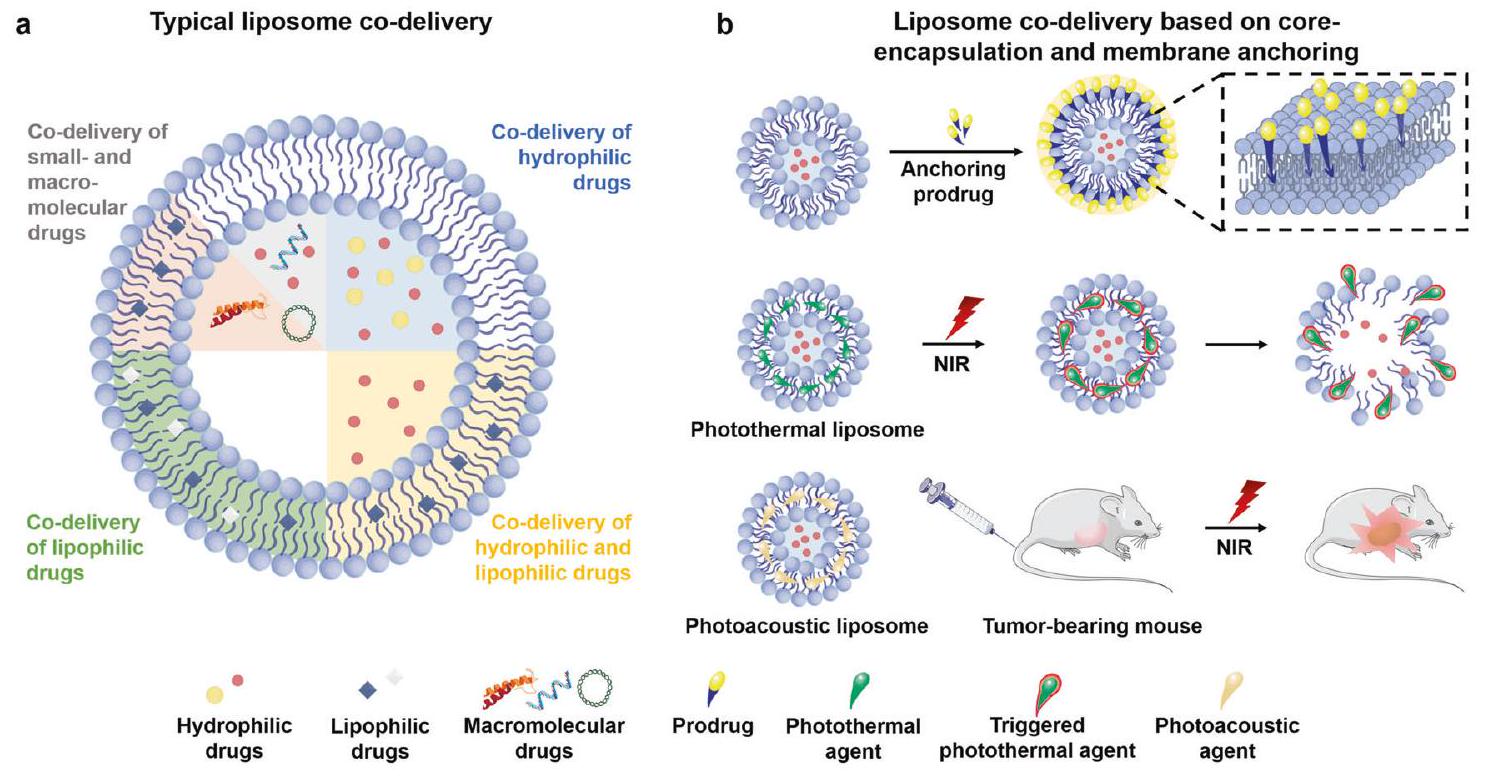

118. Xiao, Q. et al. Liposome-based anchoring and core-encapsulation for combinatorial cancer therapy. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 4191-4196 (2022).

119. Mei, K.-C. et al. Liposomal Delivery of Mitoxantrone and a Cholesteryl Indoximod Prodrug Provides Effective Chemo-immunotherapy in Multiple Solid Tumors. ACS Nano. 14, 13343-13366 (2020).

120. Xiao, Q. et al. Improving cancer immunotherapy via co-delivering checkpoint blockade and thrombospondin-1 downregulator. Acta Pharma Sin. B. 13, 3503-3517 (2022).

121. Yu, J. et al. Combining PD-L1 inhibitors with immunogenic cell death triggered by chemo-photothermal therapy via a thermosensitive liposome system to stimulate tumor-specific immunological response. Nanoscale 13, 12966-12978 (2021).

122. Mukherjee, A., Bisht, B., Dutta, S. & Paul, M. K. Current advances in the use of exosomes, liposomes, and bioengineered hybrid nanovesicles in cancer detection and therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. 43, 2759-2776 (2022).

123. Xu, Z. et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Resp. Med. 8, 420-422 (2020).

124. Zheng, Y. et al. Recent progress in sono-photodynamic cancer therapy: From developed new sensitizers to nanotechnology-based efficacy-enhancing strategies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 2197-2219 (2021).

125. Tarantino, P. et al. Antibody-drug conjugates: Smart chemotherapy delivery across tumor histologies. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72, 165-182 (2022).

126. Fu, Z. et al. Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 93 (2022).

127. Baah, S., Laws, M. & Rahman, K. M. Antibody-drug conjugates-A tutorial review. Molecules 26, 2943 (2021).

128. Baron, J. & Wang, E. S. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Rev. Clin. Phar. 11, 549-559 (2018).

129. Jin, Y. et al. Stepping forward in antibody-drug conjugate development. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 229, 107917 (2022).

130. Shi, F. et al. Disitamab vedotin: a novel antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Drug Deliv. 29, 1335-1344 (2022).

131. Deeks, E. D. Disitamab vedotin: first approval. Drugs 81, 1929-1935 (2021).

132. Nicolaou, K. C. & Rigol, S. The role of organic synthesis in the emergence and development of antibody-drug conjugates as targeted cancer therapies. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 58, 11206-11241 (2019).

133. Wiedemeyer, W. R. et al. ABBV-011, a novel, calicheamicin-based antibody-drug conjugate, targets SEZ6 to eradicate small cell lung cancer tumors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 21, 986 (2022).

134. Jabr-Milane, L. S., van Vlerken, L. E., Yadav, S. & Amiji, M. M. Multi-functional nanocarriers to overcome tumor drug resistance. Cancer Treat. Rev. 34, 592-602 (2008).

135. Baguley, B. C. Multiple drug resistance mechanisms in cancer. Mol. Biotechnol. 46, 308-316 (2010).

136. Iyer, A. K., Duan, Z. & Amiji, M. M. Nanodelivery Systems for Nucleic Acid Therapeutics in Drug Resistant Tumors. Mol. Pharm. 11, 2511-2526 (2014).

137. Tonissen, K. F. & Poulsen, S.-A. Carbonic anhydrase XII inhibition overcomes P-glycoprotein-mediated drug resistance: A potential new combination therapy in cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 4, 343-355 (2021).

138. Chen, S., Deng, J. & Zhang, L.-M. Cationic nanoparticles self-assembled from amphiphilic chitosan derivatives containing poly (amidoamine) dendrons and deoxycholic acid as a vector for co-delivery of doxorubicin and gene. Carbohyd Polym. 258, 117706 (2021).

139. Lee, M. J. et al. Sequential application of anticancer drugs enhances cell death by rewiring apoptotic signaling networks. Cell 149, 780-794 (2012).

140. Vickers, N. J. Animal communication: when i’m calling you, will you answer too? Curr. Biol. 27, R713-R715 (2017).

141. Wu, M. et al. Photoresponsive nanovehicle for two independent wavelength light-triggered sequential release of P-gp shRNA and doxorubicin to optimize and enhance synergistic therapy of multidrug-resistant cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 19416-19427 (2018).

142. Fares, J. et al. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5, 1-17 (2020).

143. Dana, H. et al. CAR-T cells: Early successes in blood cancer and challenges in solid tumors. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 1129-1147 (2021).

144. Tang, T. et al. Harnessing the layer-by-layer assembly technique to design biomaterials vaccines for immune modulation in translational applications. Biomater. Sci. 7, 715-732 (2019).

145. Garris, C. S. et al. Successful anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapy requires T celldendritic cell crosstalk involving the cytokines IFN-

146. Sun, D. et al. A cyclodextrin-based nanoformulation achieves co-delivery of ginsenoside Rg3 and quercetin for chemo-immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 12, 378-393 (2022).

147. Kroemer, G., Galluzzi, L., Kepp, O. & Zitvogel, L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev. Immunol 31, 51-72 (2013).

148. Zhu, M. et al. Co-delivery of tumor antigen and dual toll-like receptor ligands into dendritic cell by silicon microparticle enables efficient immunotherapy against melanoma. J. Control Release 272, 72-82 (2018).

149. Ashburn, T. T. & Thor, K. B. Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 673-683 (2004).

150. Turanli, B. et al. Systems biology based drug repositioning for development of cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 68, 47-58 (2021).

151. Turanli, B. et al. Discovery of therapeutic agents for prostate cancer using genome-scale metabolic modeling and drug repositioning. EBioMedicine 42, 386-396 (2019).

152. Mohammadi, E. et al. Applications of genome-wide screening and systems biology approaches in drug repositioning. Cancers 12, 2694 (2020).

153. Wu, Z., Li, W., Liu, G. & Tang, Y. Network-Based Methods for Prediction of DrugTarget Interactions. Front Pharmacol. 9, 1134 (2018).

154. Wang, P., Shen, Y. & Zhao, L. Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with aspirin and 5-fluororacil enable synergistic antitumour activity through the modulation of NF-кB/COX-2 signalling pathway. IET Nanobiotechnol. 14, 479-484 (2020).

155. Song, Y. et al. Recent advances in targeted stimuli-responsive nano-based drug delivery systems combating atherosclerosis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 1705-1717 (2022).

156. Murray, C. J. & Lopez, A. D. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349, 1498-1504 (1997).

157. Hopkins, P. N. & Williams, R. R. A survey of 246 suggested coronary risk factors. Atherosclerosis 40, 1-52 (1981).

158. Kannel, W. B. & Wilson, P. W. An update on coronary risk factors. Med Clin. N. Am. 79, 951-971 (1995).

159. Saigusa, R., Winkels, H. & Ley, K. T cell subsets and functions in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 387-401 (2020).

160. Allahverdian, S. et al. Smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity in atherosclerosis. Cardiovascular Res. 114, 540-550 (2018).

161. Wolf, D. & Ley, K. Immunity and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 124, 315-327 (2019).

162. Paone, S., Baxter, A. A., Hulett, M. D. & Poon, I. K. Endothelial cell apoptosis and the role of endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles in the progression of atherosclerosis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 76, 1093-1106 (2019).

163. Zahid, M. K. et al. Role of macrophage autophagy in atherosclerosis: modulation by bioactive compounds. Biochem J. 478, 1359-1375 (2021).

164. Custodio-Chablé, S. J., Lezama, R. A. & Reyes-Maldonado, E. Platelet activation as a trigger factor for inflammation and atherosclerosis. Cirugía y. cirujanos. 88, 233-243 (2020).

165. Lordan, R., Tsoupras, A. & Zabetakis, I. Platelet activation and prothrombotic mediators at the nexus of inflammation and atherosclerosis: Potential role of antiplatelet agents. Blood Rev. 45, 100694 (2021).

166. Marchio, P. et al. Targeting early atherosclerosis: a focus on oxidative stress and inflammation. Oxid. Med Cell Longev. 2019, 8563845 (2019).

167. Raggi, P. et al. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and therapeutic interventions. Atherosclerosis 276, 98-108 (2018).

168. Volobueva, A., Zhang, D., Grechko, A. V. & Orekhov, A. N. Foam cell formation and cholesterol trafficking and metabolism disturbances in atherosclerosis. Cor et. Vasa 61, e48-e54 (2018).

169. Kwak, B., Mulhaupt, F., Myit, S. & Mach, F. Statins as a newly recognized type of immunomodulator. Nat. Med. 6, 1399-1402 (2000).

170. Gotto, A. M. Jr. Statin therapy: where are we? Where do we go next? Am. J. Cardiol. 87, 13-18 (2001).

171. Grundy, S. M. Alternative approaches to cholesterol-lowering therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 90, 1135-1138 (2002).

172. Jia, J. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of statins in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 10, 6793-6803 (2021).

173. Alder, M. et al. A meta-analysis assessing additional LDL-C reduction from addition of a bile acid sequestrant to statin therapy. Am. J. Med. 133, 1322-1327 (2020).

174. Lee, M. et al. Association between intensity of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction with statin-based therapies and secondary stroke prevention: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Neurol. 79, 349-358 (2022).

175. Saxon, D. R. & Eckel, R. H. Statin intolerance: a literature review and management strategies. Prog. Cardiovasc Dis. 59, 153-164 (2016).

176. Okada, K. et al. Long-term effects of ezetimibe-plus-statin therapy on lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol levels as compared with double-dose statin therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 224, 454-456 (2012).

177. Park, S.-W. Intestinal and hepatic niemann-pick c1-like 1. Diabetes Metab. J. 37, 240-248 (2013).

178. Ah, Y.-M., Jeong, M. & Choi, H. D. Comparative safety and efficacy of low-or moderate-intensity statin plus ezetimibe combination therapy and highintensity statin monotherapy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Plos one 17, e0264437 (2022).

179. Hibi, K. et al. Effects of ezetimibe-statin combination therapy on coronary atherosclerosis in acute coronary syndrome. Circ. J. 82, 757-766 (2018).

180. Hong, N. et al. Comparison of the effects of ezetimibe-statin combination therapy on major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with and without diabetes: a meta-analysis. Endocrinol. Metab. 33, 219-227 (2018).

181. Sabatine, M. S. PCSK9 inhibitors: clinical evidence and implementation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 155-165 (2019).

182. Gallego-Colon, E., Daum, A. & Yosefy, C. Statins and PCSK9 inhibitors: A new lipid-lowering therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 878, 173114 (2020).

183. Pradhan, A. D., Aday, A. W., Rose, L. M. & Ridker, P. M. Residual inflammatory risk on treatment with PCSK9 inhibition and statin therapy. Circulation 138, 141-149 (2018).

184. Wallentin, L. et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1045-1057 (2009).

185. Wiviott, S. D. et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2001-2015 (2007).

186. Olie, R. H., van der Meijden, P. E. & Ten Cate, H. The coagulation system in atherothrombosis: Implications for new therapeutic strategies. Thromb. Haemost. 2, 188-198 (2018).

187. Khan, S. U. et al. PCSK9 inhibitors and ezetimibe with or without statin therapy for cardiovascular risk reduction: a systematic review and network metaanalysis. Brit Med J. 377, e069116 (2022).

188. Rached, F. & Santos, R. D. Beyond statins and PCSK9 inhibitors: updates in management of familial and refractory hypercholesterolemias. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 23, 1-9 (2021).

189. Kong, P. et al. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 131 (2022).

190. Samuel, M. & Tardif, J.-C. Lessons learned from large Cardiovascular Outcome Trials targeting inflammation in cardiovascular disease (CANTOS, CIRT, COLCOT and LoDoCo2). Future Cardiol. 17, 411-414 (2021).

191. Everett, B. M. et al. Inhibition of interleukin-1

192. Xepapadaki, E. et al. The antioxidant function of HDL in atherosclerosis. Angiology 71, 112-121 (2020).

193. Assmann, G. & Gotto, A. M. Jr HDL cholesterol and protective factors in atherosclerosis. Circulation 109, III-8-III-14 (2004).

194. Maisch, B. & Alter, P. Treatment options in myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy. Herz 43, 423-430 (2018).

195. Chen, J. et al. High density lipoprotein mimicking nanoparticles for atherosclerosis. Nano Converg. 7, 1-14 (2020).

196. Ou, L.-c, Zhong, S., Ou, J.-s & Tian, J.-w Application of targeted therapy strategies with nanomedicine delivery for atherosclerosis. Acta Pharm. Sin. 42, 10-17 (2021).

197. Motamed, S., Hosseini Karimi, S. N., Hooshyar, M. & Mehdinavaz Aghdam, R. Advances in nanocarriers as drug delivery systems in Atherosclerosis therapy. JUFGNSM 54, 198-210 (2021).

198. He, J. et al. Shuttle/sink model composed of

199. He, J. et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-responsive size-reducible nanoassemblies for deeper atherosclerotic plaque penetration and enhanced macrophage-targeted drug delivery. Bioact. Mater. 19, 115-126 (2023).

200. He, J. et al. Anchoring

201. Vickers, K. C. et al. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 423-433 (2011).

202. Tabet, F. et al. HDL-transferred microRNA-223 regulates ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells. Nat. Commun. 5, 1-14 (2014).

203. Wiese, C. B. et al. Dual inhibition of endothelial miR-92a-3p and miR-489-3p reduces renal injury-associated atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 282, 121-131 (2019).

204. Schultz, J. R. et al. Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Gene Dev. 14, 2831-2838 (2000).

205. Im, S.-S. & Osborne, T. F. Liver x receptors in atherosclerosis and inflammation. Circ. Res. 108, 996-1001 (2011).

206. Guo, Y. et al. Synthetic High-Density Lipoprotein-Mediated Targeted Delivery of Liver X Receptors Agonist Promotes Atherosclerosis Regression. EBioMedicine 28, 225-233 (2018).

207. Xiao, Q. et al. Biological drug and drug delivery-mediated immunotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 941-960 (2021).

208. Sheng, J. et al. Targeted therapy of atherosclerosis by zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 nanoparticles loaded with losartan potassium via simultaneous lipid-scavenging and anti-inflammation. J. Mater. Chem. B. 10, 5925-5937 (2022).

209. Zhao, R. et al. A ROS-Responsive Simvastatin Nano-Prodrug and its FibronectinTargeted Co-Delivery System for Atherosclerosis Treatment. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 14, 25080-25092 (2022).

210. Opriessnig, P., Silbernagel, G., Krassnig, S. & Reishofer, G. Magnetic resonance microscopy diffusion tensor imaging of collagen fibre bundles stabilizing an atherosclerotic plaque of the common carotid artery. Eur. Heart J. 39, 3337-3337 (2018).

211. Li, X. et al. Liposomal codelivery of inflammation inhibitor and collagen protector to the plaque for effective anti-atherosclerosis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 34, 107483 (2022).

212. Humbert, M. et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: results from a national registry. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care. 173, 1023-1030 (2006).

213. Maron, B. A. et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: diagnosis, treatment, and novel advances. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care. 203, 1472-1487 (2021).

214. Naeije, R., Richter, M. J. & Rubin, L. J. The physiological basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 59, 2102334 (2022).

215. Zoulikha, M., Huang, F., Wu, Z. & He, W. COVID-19 inflammation and implications in drug delivery. J. Control Release 346, 260-274 (2022).

216. Mclaughlin, V. V. et al. Treatment goals of pulmonary hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 42, 95-105 (2014).

217. Galiè, N. et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 53, 1801889 (2019).

218. Evans, C. E. et al. Endothelial cells in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 58, 2003957 (2021).

219. Kunder, S. K. Pharmacotherapy of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. In Introduction to Basics of Pharmacology and Toxicology (eds Paul, A., Anandabaskar, N., & Mathaiyan, J., Raj, G. M.) (Springer, Singapore, 2021).

220. Dai, Y. et al. Immunotherapy of endothelin-1 receptor type A for pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 2567-2580 (2019).

221. de Lima-Seolin, B. G. et al. Bucindolol attenuates the vascular remodeling of pulmonary arteries by modulating the expression of the endothelin-1 A receptor in rats with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Biomed. Pharmacother. 99, 704-714 (2018).

222. Lan, N. S., Massam, B. D., Kulkarni, S. S. & Lang, C. C. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: pathophysiology and treatment. Diseases 6, 38 (2018).

223. Hoeper, M. M. et al. Switching to riociguat versus maintenance therapy with phosphodiesterase- 5 inhibitors in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (REPLACE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Resp. Med. 9, 573-584 (2021).

224. Prins, K. W. et al. Repurposing medications for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: what’s old is new again. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e011343 (2019).

225. Beghetti, M. et al. Treatment of pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension: A focus on the NO-sGC-cGMP pathway. Pediatr. Pulm. 54, 1516-1526 (2019).

226. Angalakuditi, M. et al. Treatment patterns and resource utilization and costs among patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension in the United States. J. Med Econ. 13, 393-402 (2010).

227. Galie, N., Palazzini, M. & Manes, A. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: from the kingdom of the near-dead to multiple clinical trial meta-analyses. Eur. Heart J. 31, 2080-2086 (2010).

228. Yang, Y. et al. Discovery of highly selective and orally available benzimidazolebased phosphodiesterase 10 inhibitors with improved solubility and pharmacokinetic properties for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 10, 2339-2347 (2020).

229. Halliday, S. J. et al. Clinical and genetic associations with prostacyclin response in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 8, 2045894018800544 (2018).

230. Gąsecka, A. et al. Prostacyclin analogues inhibit platelet reactivity, extracellular vesicle release and thrombus formation in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Clin. Med. 10, 1024 (2021).

231. Lambers, C. et al. Mechanism of anti-remodelling action of treprostinil in human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. PLoS One 13, e0205195 (2018).

232. Lindegaard Pedersen, M. et al. The prostacyclin analogue treprostinil in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 126, 32-42 (2020).

233. Spaczyńska, M., Rocha, S. F. & Oliver, E. Pharmacology of pulmonary arterial hypertension: an overview of current and emerging therapies. ACS Pharm. Transl. 3, 598-612 (2020).

234. Nakamura, K. et al. Current treatment strategies and nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery systems for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5885 (2019).

235. Bai, Y., Sun, L., Hu, S. & Wei, Y. Combination therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a meta-analysis. Cardiology 120, 157-165 (2011).

236. Fox, B. D. et al. Combination therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 32, 1520-1530 (2016).

237. Ghofrani, H.-A. & Humbert, M. The role of combination therapy in managing pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. Rev. 23, 469-475 (2014).

238. Galiè, N. et al. Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 834-844 (2015).

239. Lajoie, A. C. et al. Combination therapy versus monotherapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: a meta-analysis. Lancet Resp. Med. 4, 291-305 (2016).

240. Sitbon, O. et al. Initial dual oral combination therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 1727-1736 (2016).

241. Gruenig, E. et al. Acute hemodynamic effects of single-dose sildenafil when added to established bosentan therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the COMPASS-1 study. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 49, 1343-1352 (2009).

242. McLaughlin, V. V. et al. Randomized study of adding inhaled iloprost to existing bosentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care. 174, 1257-1263 (2006).

243. Said, K. Riociguat: patent-1 study. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2014, 21 (2014).

244. McLaughlin, V. et al. Effect of Bosentan and Sildenafil Combination Therapy on Morbidity and Mortality in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH): Results From the COMPASS-2 Study. Chest 146, 860A-860A (2014).

245. Maron, B. A. & Galiè, N. Diagnosis, treatment, and clinical management of pulmonary arterial hypertension in the contemporary era: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 1, 1056-1065 (2016).

246. Shimokawa, H. & Satoh, K. 2015 ATVB Plenary Lecture: translational research on rho-kinase in cardiovascular medicine. Arterioscl Throm Vas. 35, 1756-1769 (2015).

247. Gupta, V. et al. Liposomal fasudil, a rho-kinase inhibitor, for prolonged pulmonary preferential vasodilation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Control Release 167, 189-199 (2013).

248. Rashid, J. et al. Fasudil and DETA NONOate, loaded in a peptide-modified liposomal carrier, slow PAH progression upon pulmonary delivery. Mol. Pharm. 15, 1755-1765 (2018).

249. Gupta, N. et al. Cocktail of superoxide dismutase and fasudil encapsulated in targeted liposomes slows PAH progression at a reduced dosing frequency. Mol. Pharm. 14, 830-841 (2017).

250. Qi, L. et al. Fasudil dichloroacetate (FDCA), an orally available agent with potent therapeutic efficiency on monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension rats. Bioorg. Med Chem. Lett. 29, 1812-1818 (2019).

251. Yang, Y. et al. Investigational pharmacotherapy and immunotherapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension: An update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 129, 110355 (2020).

252. Costa, J. et al. Inflammatory response of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells exposed to oxidative and biophysical stress. Inflammation 41, 1250-1258 (2018).

253. Mamazhakypov, A. et al. The role of chemokines and chemokine receptors in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Brit J. Pharmacol. 178, 72-89 (2021).

254. Dreymueller, D. et al. Smooth muscle cells relay acute pulmonary inflammation via distinct ADAM17/ErbB axes. J. Immunol. 192, 722-731 (2014).

255. Teng, C. et al. Targeted delivery of baicalein-p53 complex to smooth muscle cells reverses pulmonary hypertension. J. Control Release 341, 591-604 (2022).

256. Savai, R. et al. Pro-proliferative and inflammatory signaling converge on FoxO1 transcription factor in pulmonary hypertension. Nat. Med. 20, 1289-1300 (2014).

257. Tschöpe, C., Cooper, L. T., Torre-Amione, G. & Van Linthout, S. Management of myocarditis-related cardiomyopathy in adults. Circ. Res. 124, 1568-1583 (2019).

258. Basso, C. Myocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1488-1500 (2022).

259. Caforio, A. L. P., Malipiero, G., Marcolongo, R. & Iliceto, S. Myocarditis: A Clinical Overview. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 19, 63 (2017).

260. Caforio, A. L. et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur. Heart J. 34, 2636-2648 (2013).

261. Ammirati, E. et al. Clinical presentation and outcome in a contemporary cohort of patients with acute myocarditis: multicenter Lombardy registry. Circulation 138, 1088-1099 (2018).

262. Seko, Y. et al. Restricted usage of T cell receptor V alpha-V beta genes in infiltrating cells in the hearts of patients with acute myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 96, 1035-1041 (1995).

263. Godeny, E. K. & Gauntt, C. In situ immune autoradiographic identification of cells in heart tissues of mice with coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. Am. J. Pathol. 129, 267 (1987).

264. Hua, X. & Song, J. Immune cell diversity contributes to the pathogenesis of myocarditis. Heart Fail Rev. 24, 1019-1030 (2019).

265. Seko, Y. et al. Expression of perforin in infiltrating cells in murine hearts with acute myocarditis caused by coxsackievirus B3. Circulation 84, 788-795 (1991).

266. Leone, O., Pieroni, M., Rapezzi, C. & Olivotto, I. The spectrum of myocarditis: from pathology to the clinics. Virchows Arch. 475, 279-301 (2019).

267. Rivadeneyra, L. et al. Role of neutrophils in CVB3 infection and viral myocarditis. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 125, 149-161 (2018).

268. Alu, A. et al. The role of lysosome in regulated necrosis. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 10, 1880-1903 (2020).

269. Jensen, L. D. & Marchant, D. J. Emerging pharmacologic targets and treatments for myocarditis. Pharm. Therapeut. 161, 40-51 (2016).

270. Myers, J. M. et al. Cardiac myosin-Th17 responses promote heart failure in human myocarditis. JCI insight 1, e85851 (2016).

271. Higashitani, K. et al. Rituximab and mepolizumab combination therapy for glucocorticoid-resistant myocarditis related to eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod. Rheumatol. Case 6, 87-92 (2022).

272. Winter, M.-P. et al. Immunomodulatory treatment for lymphocytic myocarditisa systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 23, 573-581 (2018).

273. Wojnicz, R. et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled study for immunosuppressive treatment of inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy: two-year follow-up results. Circulation 104, 39-45 (2001).

274. Frustaci, A., Russo, M. A. & Chimenti, C. Randomized study on the efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy in patients with virus-negative inflammatory cardiomyopathy: the TIMIC study. Eur. Heart J. 30, 1995-2002 (2009).

275. Campochiaro, C. et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate for the treatment of autoimmune virus-negative myocarditis: a case series. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 27, e143-e146 (2021).

276. Song, T., Jones, D. M. & Homsi, Y. Therapeutic effect of anti-IL-5 on eosinophilic myocarditis with large pericardial effusion. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, bcr-2016218992 (2017).

277. Yen, C.-Y. et al. Role of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in the survival rate of pediatric patients with acute myocarditis: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Sci. Rep. 9, 10459 (2019).

278. Wei, X., Fang, Y. & Hu, H. Glucocorticoid and immunoglobulin to treat viral fulminant myocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 41, 2122-2122 (2020).

279. Hamada, H. et al. Efficacy of primary treatment with immunoglobulin plus ciclosporin for prevention of coronary artery abnormalities in patients with Kawasaki disease predicted to be at increased risk of non-response to intravenous immunoglobulin (KAICA): a randomised controlled, open-label, blindedendpoints, phase 3 trial. Lancet 393, 1128-1137 (2019).

280. Li, J. H., Li, T. T., Wu, X. S. & Zeng, D. L. Effect of gamma globulin combined with creatine phosphate on viral myocarditis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 13, 3682-3688 (2021).

281. Lee, G. et al. Curcumin attenuates the scurfy-induced immune disorder, a model of IPEX syndrome, with inhibiting Th1/Th2/Th17 responses in mice. Phytomedicine 33, 1-6 (2017).

282. Liu, R. et al. Curcumin alleviates isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis through inhibition of autophagy and activation of mTOR. Eur. Rev. Med Pharm. Sci. 22, 7500-7508 (2018).

283. Luthra, P. M., Singh, R. & Chandra, R. Therapeutic uses ofCurcuma longa (turmeric). Indian J. Clin. Bioche. 16, 153-160 (2001).

284. Hernández, M., Wicz, S., Santamaría, M. H. & Corral, R. S. Curcumin exerts antiinflammatory and vasoprotective effects through amelioration of NFATdependent endothelin-1 production in mice with acute Chagas cardiomyopathy. Mem. I Oswaldo Cruz. 113, e180171 (2018).

285. Hernández, M., Wicz, S. & Corral, R. S. Cardioprotective actions of curcumin on the pathogenic NFAT/COX-2/prostaglandin E2 pathway induced during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Phytomedicine 23, 1392-1400 (2016).

286. Hernández, M. et al. Dual chemotherapy with benznidazole at suboptimal dose plus curcumin nanoparticles mitigates Trypanosoma cruzi-elicited chronic cardiomyopathy. Parasitol. Int. 81, 102248 (2021).

287. Wu, M.-Y. et al. Pharmacological insights into autophagy modulation in autoimmune diseases. Acta Pharma Sin. B. 11, 3364-3378 (2021).

288. McInnes, I. B. & Schett, G. Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 389, 2328-2337 (2017).

289. Siouti, E. & Andreakos, E. The many facets of macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 165, 152-169 (2019).

290. Butola, L. K., Anjanker, A., Vagga, A. & Kaple, M. N. Endogenous factor and pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis: an autoimmune disease from decades. Int J. Cur Res Rev. 12, 34-40 (2020).

291. Koenders, M. I. & van den Berg, W. B. Novel therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Trends Pharm. Sci. 36, 189-195 (2015).

292. Alghasham, A. & Rasheed, Z. Therapeutic targets for rheumatoid arthritis: Progress and promises. Autoimmunity 47, 77-94 (2014).

293. Pirmardvand Chegini, S., Varshosaz, J. & Taymouri, S. Recent approaches for targeted drug delivery in rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis and treatment. Artif. Cell Nanomed. B. 46, 502-514 (2018).

294. Kesharwani, D., Paliwal, R., Satapathy, T. & Paul, S. D. Rheumatiod arthritis: an updated overview of latest therapy and drug delivery. J. Pharmacopunct. 22, 210 (2019).

295. Wang, S. et al. Recent Advances in Nanotheranostics for Treat-to-Target of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Adv. Health. Mater. 9, 1901541 (2020).

296. Wang, Q., Qin, X., Fang, J. & Sun, X. Nanomedicines for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: State of art and potential therapeutic strategies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 1158-1174 (2021).

297. Drosos, A. A., Pelechas, E. & Voulgari, P. V. Treatment strategies are more important than drugs in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 39, 1363-1368 (2020).

298. Donahue, K. E. et al. Comparative effectiveness of combining MTX with biologic drug therapy versus either MTX or biologics alone for early rheumatoid arthritis in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern Med. 34, 2232-2245 (2019).

299. Yang, M. et al. Nanotherapeutics relieve rheumatoid arthritis. J. Control Release 252, 108-124 (2017).

300. Yuan, F. et al. Development of macromolecular prodrug for rheumatoid arthritis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64, 1205-1219 (2012).

301. Buch, M., Bingham, S., Bryer, D. & Emery, P. Long-term infliximab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: subsequent outcome of initial responders. Rheumatology 46, 1153-1156 (2007).

302. Listing, J. et al. Infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum.-US. 52, 3403-3412 (2005).

303. Dolati, S. et al. Utilization of nanoparticle technology in rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 80, 30-41 (2016).

304. Yu, Z. et al. Nanomedicines for the delivery of glucocorticoids and nucleic acids as potential alternatives in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Wires Nanomed. Nanobi. 12, e1630 (2020).

305. Yu, K. et al. Layered dissolving microneedles as a need-based delivery system to simultaneously alleviate skin and joint lesions in psoriatic arthritis. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 505-519 (2021).

306. Janakiraman, K. et al. Development of methotrexate and minocycline loaded nanoparticles for the effective treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. AAPS PharmSciTech. 21, 34 (2020).

307. Chen, X. et al. Targeted hexagonal Pd nanosheet combination therapy for rheumatoid arthritis via the photothermal controlled release of MTX. J. Mater. Chem. B. 7, 112-122 (2019).

308. Wang, Y. et al. Enhanced therapeutic effect of RGD-modified polymeric micelles loaded with low-dose methotrexate and nimesulide on rheumatoid arthritis. Theranostics 9, 708 (2019).

309. Son, A. R. et al. Direct chemotherapeutic dual drug delivery through intraarticular injection for synergistic enhancement of rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Sci. Rep. 5, 14713 (2015).

310. Shen, Q. et al. Sinomenine hydrochloride loaded thermosensitive liposomes combined with microwave hyperthermia for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J. Pharm. 576, 119001 (2020).

311. Park, J. S. et al. The use of anti-COX2 siRNA coated onto PLGA nanoparticles loading dexamethasone in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Biomaterials 33, 8600-8612 (2012).

312. Duan, W. & Li, H. Combination of NF-kB targeted siRNA and methotrexate in a hybrid nanocarrier towards the effective treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 16, 58 (2018).

313. Wang, Q. et al. Targeting NF-kB signaling with polymeric hybrid micelles that codeliver siRNA and dexamethasone for arthritis therapy. Biomaterials 122, 10-22 (2017).

314. Hao, F. et al. Hybrid micelles containing methotrexate-conjugated polymer and co-loaded with microRNA-124 for rheumatoid arthritis therapy. Theranostics 9, 5282 (2019).

315. Yin, N. et al. A novel indomethacin/methotrexate/MMP-9 siRNA in situ hydrogel with dual effects of anti-inflammatory activity and reversal of cartilage disruption for the synergistic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Nanoscale 12, 8546-8562 (2020).

316. DK, P. Inflanain bowel diease. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 417-429 (2002).

317. Abraham, C. & Cho, J. H. Mechanisms of disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 2066-2078 (2009).

318. Graham, D. B. & Xavier, R. J. Pathway paradigms revealed from the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 578, 527-539 (2020).

319. Cui, G. & Yuan, A. A systematic review of epidemiology and risk factors associated with Chinese inflammatory bowel disease. Front Med. 5, 183 (2018).

320. Axelrad, J. E., Cadwell, K. H., Colombel, J.-F. & Shah, S. C. The role of gastrointestinal pathogens in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Ther. Adv. Gastroenter. 14, 17562848211004493 (2021).

321. Ahlawat, S. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: tri-directional relationship between microbiota, immune system and intestinal epithelium. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 47, 254-273 (2021).

322. Veenbergen, S. et al. IL-10 signaling in dendritic cells controls IL-1

323. Bernardo, D., Chaparro, M. & Gisbert, J. P. Human intestinal dendritic cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 62, 1700931 (2018).

324. Leppkes, M. & Neurath, M. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel diseases-update 2020. Pharm. Res. 158, 104835 (2020).

325. Lee, A. et al. Dexamethasone-loaded polymeric nanoconstructs for monitoring and treating inflammatory bowel disease. Theranostics 7, 3653 (2017).

326. Na, Y. R., Stakenborg, M., Seok, S. H. & Matteoli, G. Macrophages in intestinal inflammation and resolution: a potential therapeutic target in IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastro Hepat. 16, 531-543 (2019).

327. Fredericks, E. & Watermeyer, G. De-escalation of biological therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: Benefits and risks. S Afr. Med J. 109, 745-749 (2019).

328. Peyrin-Biroulet, L. et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110, 1324-1338 (2015).

329. Xiao, Q. et al. The effects of protein corona on in vivo fate of nanocarriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 186, 114356 (2022).

330. Sandborn, W. J. Strategies for targeting tumour necrosis factor in IBD. Best. Pr. Res Cl. Gastroenterol 17, 105-117 (2003).

331. Privitera, G. et al. Combination therapy in inflammatory bowel disease-from traditional immunosuppressors towards the new paradigm of dual targeted therapy. Autoimmun. Rev. 20, 102832 (2021).

332. Papa, A. et al. Biological therapies for inflammatory bowel disease: controversies and future options. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharm. 2, 391-403 (2009).

333. Sokol, H. et al. Usefulness of co-treatment with immunomodulators in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with scheduled infliximab maintenance therapy. Gut 59, 1363-1368 (2010).

334. Dohos, D. et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the effects of immunomodulator or biological withdrawal from mono-or combination therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharm. Ther. 53, 220-233 (2021).

335. van Schaik, T. et al. Influence of combination therapy with immune modulators on anti-TNF trough levels and antibodies in patients with IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 20, 2292-2298 (2014).