DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-024-02697-2

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-21

الفحص السريع واكتشاف مثبطات ستيرويل-CoA ديساتوراز 1 (SCD1) من الزنجبيل وفعاليتها في تحسين مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي

© المؤلفون 2024

الملخص

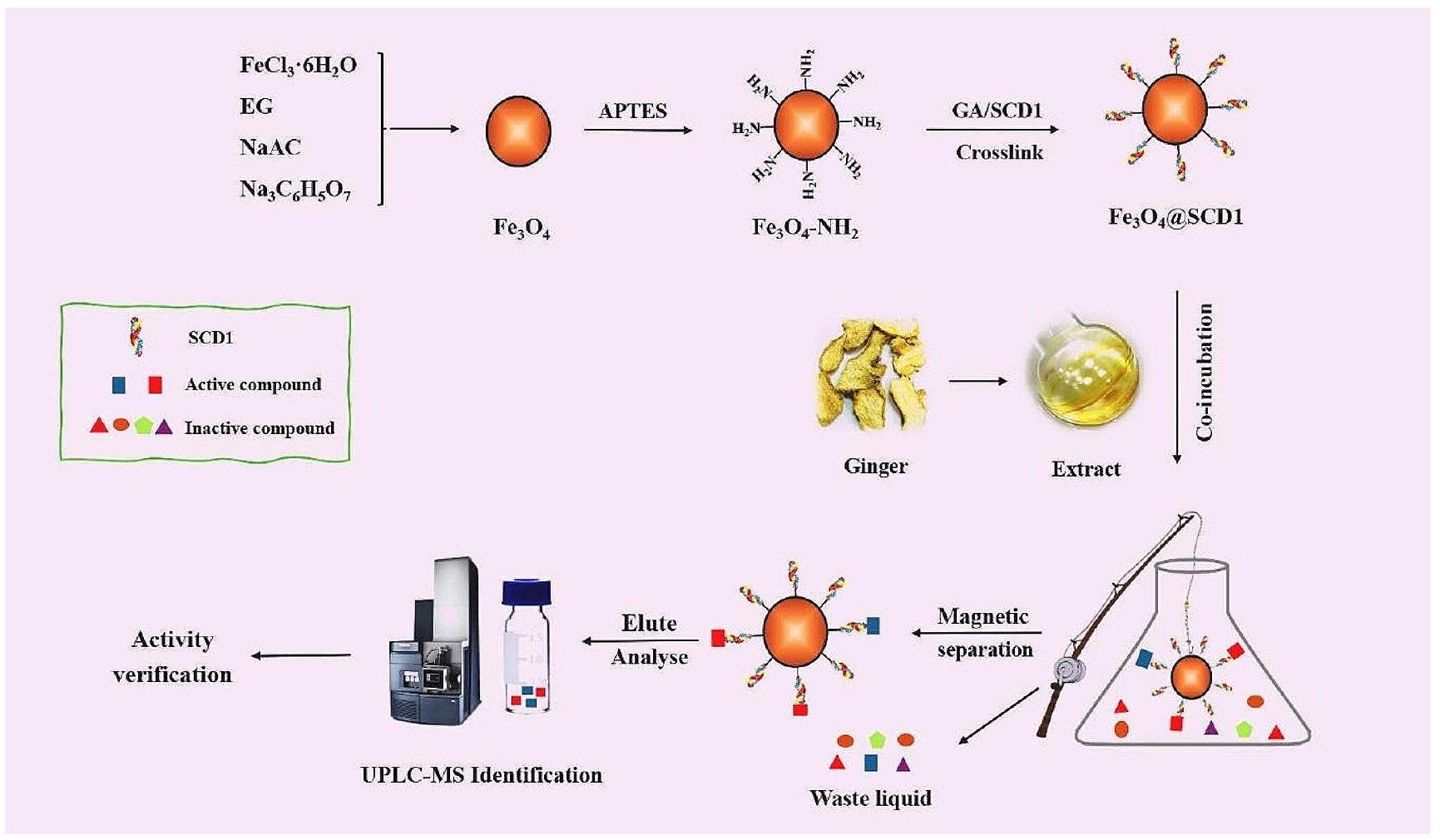

مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي هو حالة مزمنة شائعة في الأيض، ولا توجد أدوية معتمدة متاحة لها. كتوابل ودواء تقليدي صيني، يمكن أن يكون الزنجبيل مفيدًا في تقليل أعراض مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي. على الرغم من أن مكوناته النشطة وآليات عمله غير معروفة، إلا أن هناك نقصًا في الأبحاث حولها. الغرض من هذه الدراسة هو تحضير المغنتيت.

مقدمة

أعلى في المرضى البدينين الذين يعانون من مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي مقارنة بالمرضى البدينين الذين لا يعانون من مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي. لذلك، يبدو من المحتمل أن نشاط SCD1 الكبدي مرتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا بمرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي، وقد تم إثبات أن تثبيط SCD1 بشكل خاص في الكبد يخفف من تقدم الكبد الدهني. وقد أظهرت الدراسات أن SCD1 أيضًا يشارك في أكسدة الدهون داخل الخلايا وأن كتم أو تثبيط تعبير SCD1 يزيد من الأحماض الدهنية داخل الخلايا.

المواد والأساليب

الإجراءات التجريبية العامة

المادة النباتية

تحضير الاستخراج

تركيب المواد

رابط مع بروتين SCD1 للحصول على

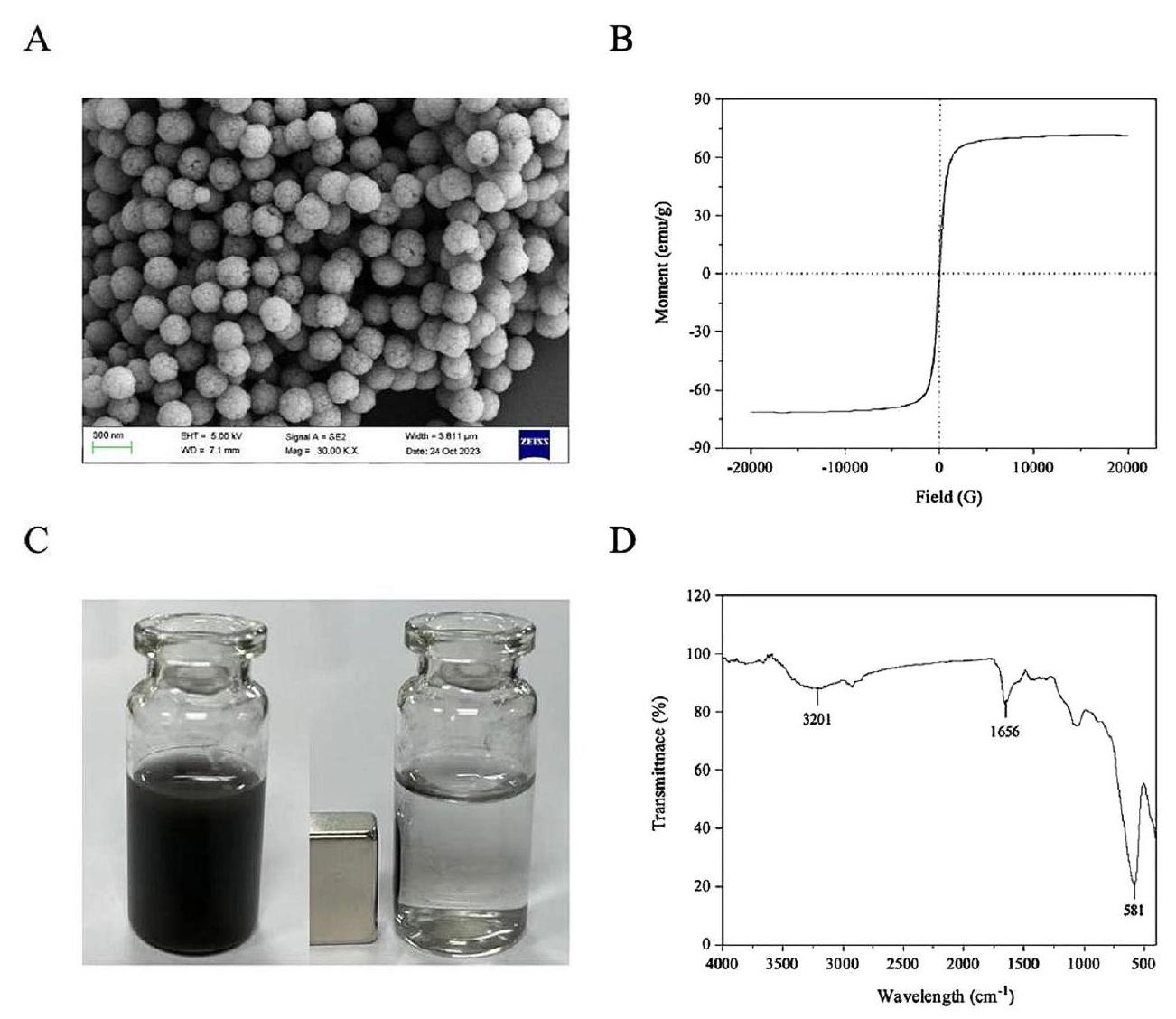

توصيف المواد

الفحص السريع للمكونات النشطة

تحليل UPLC-MS/MS

الربط الجزيئي

زراعة الخلايا

اختبار حيوية الخلايا

بناء نموذج ترسيب الدهون

تحديد محتوى الدهون الثلاثية داخل الخلايا

صبغة الزيت الأحمر 0

تحليل البيانات

النتائج

توصيف المواد

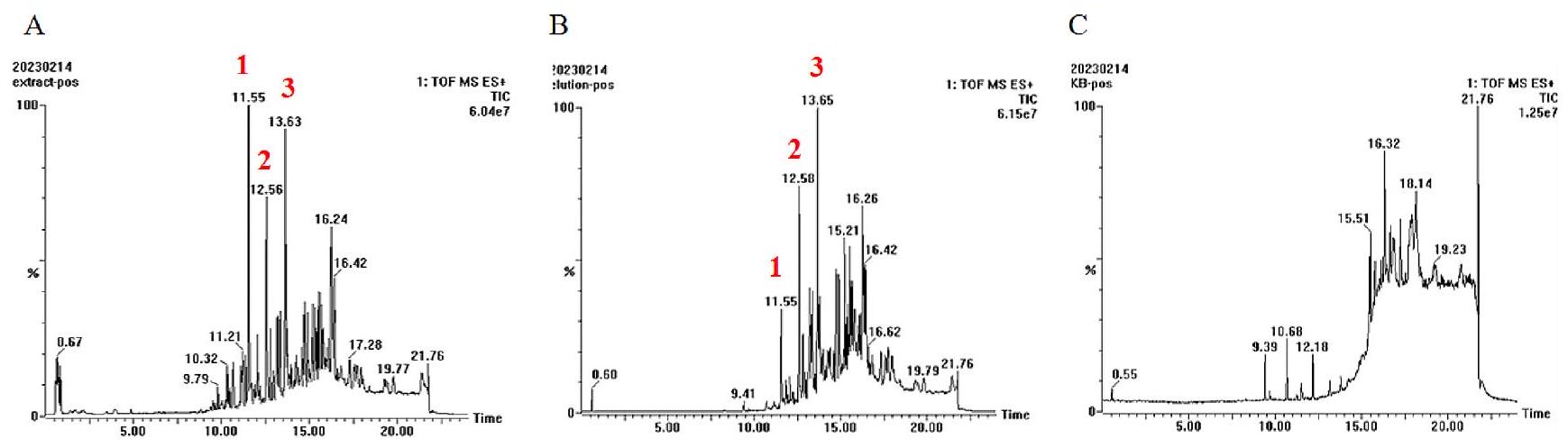

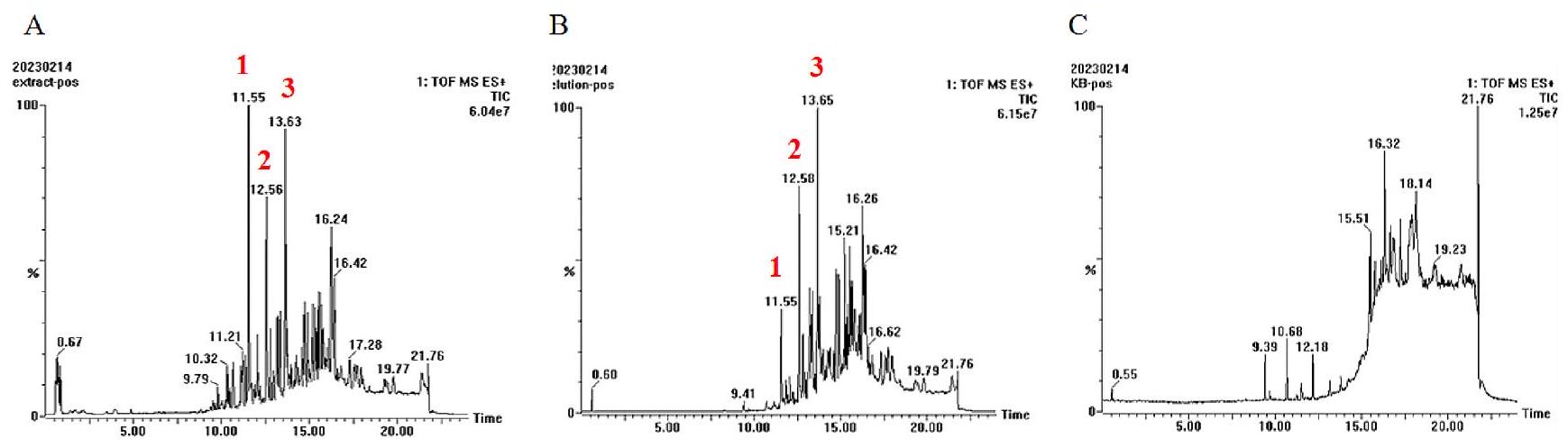

تحليل المكونات لمثبطات SCD1 المحتملة في مستخلص الزنجبيل

أظهرت أكبر استجابة، مما يشير إلى أنها قد تكون لديها ميول أكبر تجاه SCD1.

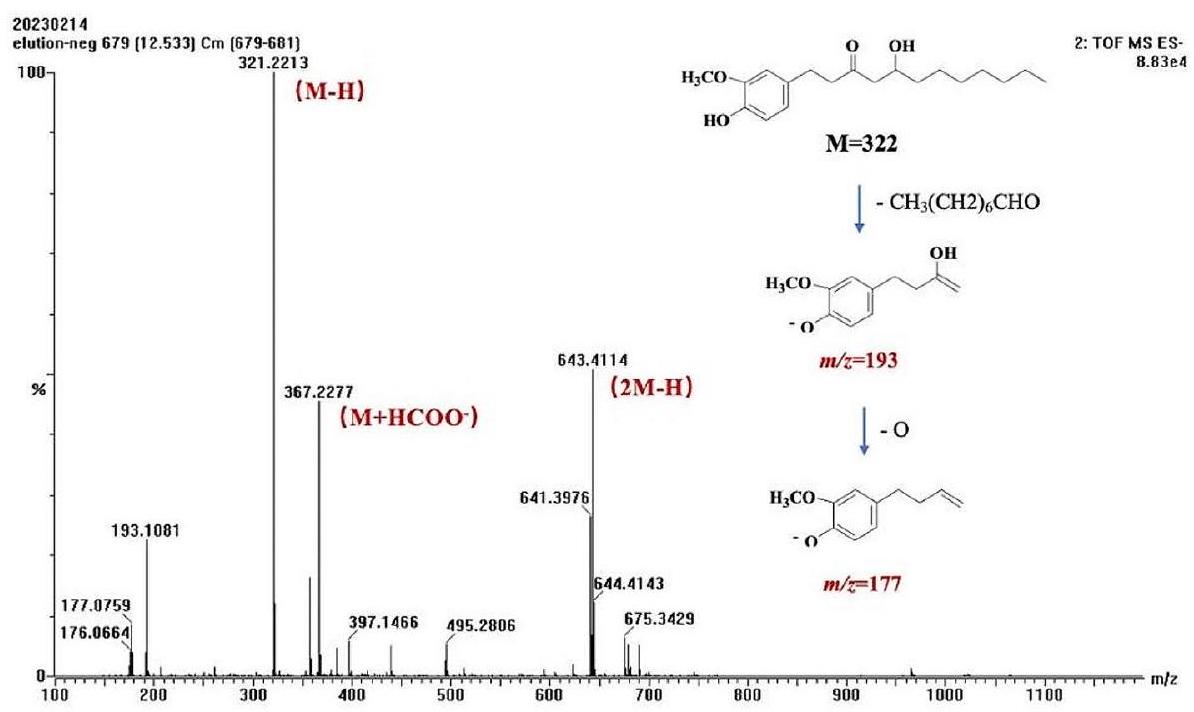

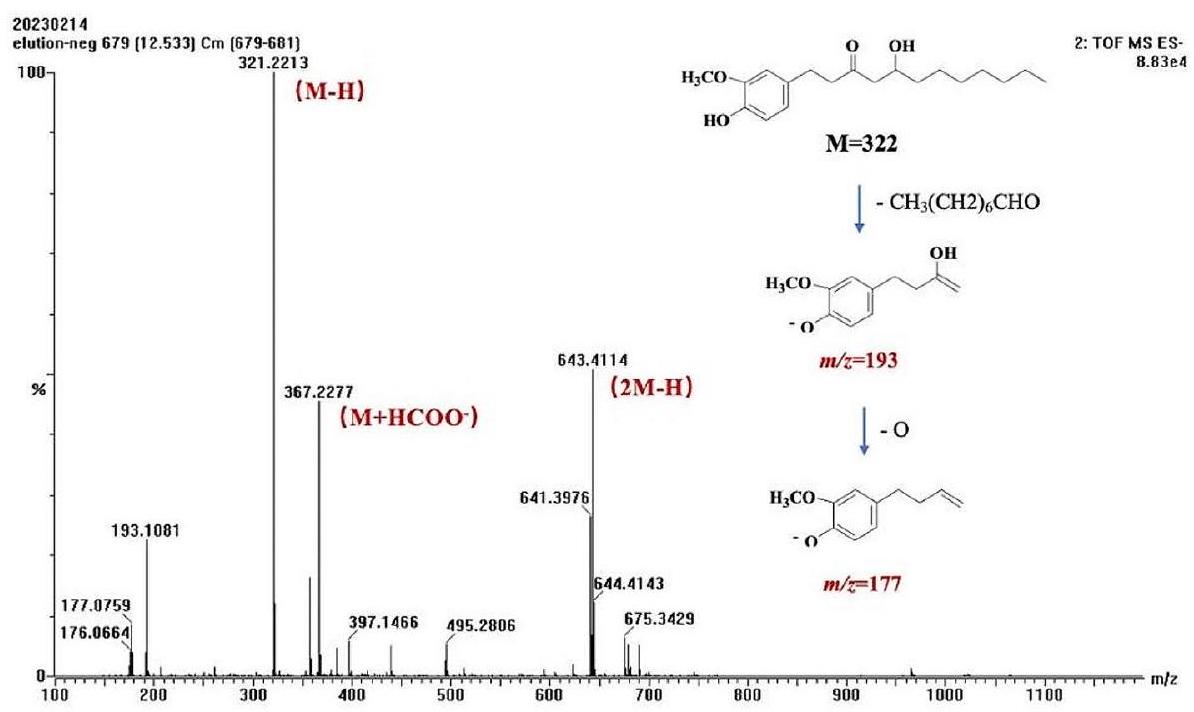

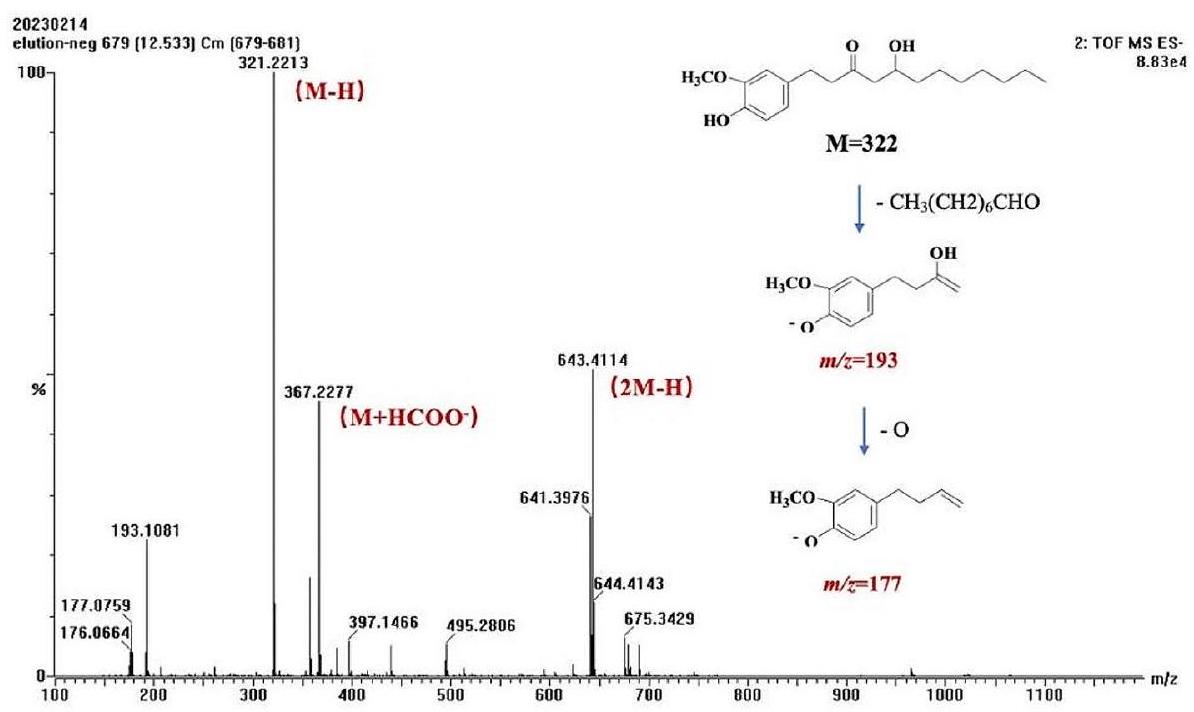

تم إظهار أيون الكتلة/الشحنة 179.0848 كإشارة تفتت تم توليدها بواسطة أيون السلف بعد أن فقد المكون الألكيلي المحايد.

تنبؤ وضع الارتباط للمكونات النشطة المحتملة

يظهر أن Asn144 وAsp152 في الجيب النشط لـ SCD1 [73]. وهذا يشير إلى أن 6-جينجيرول و8-جينجيرول و10-جينجيرول تحتوي على مواقع ارتباط تقع في الجيب التحفيزي لـ SCD1 وقادرة على الارتباط به مباشرة.

المكون المستهدف يحسن تراكم الدهون في الخلايا الكبدية

أ

ب

نقاش

من FFA؛

لقد تم تقسيمها عند MS (الشكل 4). قد يكون هناك سبب لذلك لأن الزنجبيل نفسه لا يتمتع باستقرار حراري جيد [82]. إنه ينتج منتج أكسي كيتون تحت ظروف درجة حرارة مرتفعة و/أو بيئة حمضية، نتيجة لامتلاكه عدم استقرار.

المعالجة بتركيزات مختلفة من المركبات؛

تنظيم تكوين الدهون، أكسدة الأحماض الدهنية، الإجهاد التأكسدي، والخلل الوظيفي الميتوكوندري [57]. بالمقابل، تشير تقارير قليلة جدًا إلى أن مكونات أخرى من الزنجبيل تساهم في تحسين مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي. أظهرت الدراسة الحالية أن الزنجبيل يحتوي على مركب جديد (10-زنجبيلول) يزيد من تراكم الدهون في الكبد من خلال العمل المباشر لـ SCD1. توفر الدراسة الحالية مستوى إضافيًا من الفهم للآلية التي من خلالها يحسن الزنجبيل مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي وتساهم أيضًا في اكتشاف مكونات نشطة جديدة يمكن أن تحسن مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي. من الضروري

إجراء دراسات إضافية حول الآلية الدقيقة التي من خلالها يحسن 10-زنجبيلول مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي في تجارب الحيوانات لتحديد تأثيره الدقيق.

خصائص مضادة للأورام [87]. أظهرت عدة دراسات حديثة أن الجمع بين 6-زنجبيلول وسيسبلاتين يحفز موت الخلايا المبرمج في خلايا سرطان المبيض ويثبط تكوين الأوعية بشكل أكثر فعالية من أي دواء بمفرده [88]. هناك أدلة على أن 10-زنجبيلول له نشاط مضاد للأورام من خلال عدة مسارات [89، 90]، بما في ذلك PI3K/Akt وMAPK. على الرغم من ذلك، لا يبدو أن الزنجبيلول له تأثير مباشر على SCD1، والذي يمكن أن يكون أيضًا آلية العمل المضادة للأورام لهذه الفئة من المركبات.

الاستنتاجات

المشروع (رقم المنحة 2023MD744147). تم تمويل البحث من قبل جامعة الطائف، الطائف، المملكة العربية السعودية (TU-DSPP-2024-21).

الإعلانات

References

- J. Zhang, B. Zhang, C. Pu, J. Cui, K. Huang, H. Wang, Y. Zhao, Nanoliposomal Bcl-xL proteolysis-targeting chimera enhances anti-cancer effects on cervical and breast cancer without on-target toxicities. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 78 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1007/s42114-023-00649-w

- U. Malik, D. Pal, Cancer-fighting isoxazole compounds: Sourcing Nature’s potential and synthetic Advancements- A Comprehensive Review. ES Food Agrofor. 15, 1052 (2024). https://doi. org/10.30919/esfaf1052

- M. Sudhi, V.K. Shukla, D.K. Shetty, V. Gupta, A.S. Desai, N. Naik, B.M.Z. Hameed, Advancements in bladder Cancer Management: a Comprehensive Review of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications. Eng. Sci. 26, 1003 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es1003

- Z. Ou, Z. Li, Y. Gao, W. Xing, H. Jia, H. Zhang, N. Yi, Novel triazole and morpholine substituted bisnaphthalimide: synthesis, photophysical and G-quadruplex binding properties. J. Mol. Struct. 1185, 27-37 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. molstruc.2019.02.073

- Z. Ou, Y. Qian, Y. Gao, Y. Wang, G. Yang, Y. Li, K. Jiang, X. Wang, Photophysical, G-quadruplex DNA binding and cytotoxic properties of terpyridine complexes with a naphthalimide ligand. RSC Adv. 6, 36923-36931 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/ C6RA01441K

- Q. Ban, J. Du, W. Sun, J. Chen, S. Wu, J. Kong, Intramolecular copper-containing hyperbranched polytriazole assemblies for label-free Cellular Bioimaging and Redox-Triggered Copper Complex Delivery. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 39, 1800171 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/marc. 201800171

- T. Bai, J. Du, J. Chen, X. Duan, Q. Zhuang, H. Chen, J. Kong, Reduction-responsive dithiomaleimide-based polymeric micelles for controlled anti-cancer drug delivery and bioimaging.

8. D. Bhargava, P. Rattanadecho, K. Jiamjiroch, Microwave imaging for breast Cancer detection – A Comprehensive review. Eng. Sci. Press. (2024). https://doi.org/10.30919/es31116

9. L. Xiao, W. Xu, L. Huang, J. Liu, G. Yang, Nanocomposite pastes of gelatin and cyclodextrin-grafted chitosan nanoparticles as potential postoperative tumor therapy. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00575-3

10. D.S. Uplaonkar, V. Virupakshappa, N. Patil, An efficient Discrete Wavelet transform based partial Hadamard feature extraction and hybrid neural network based Monarch Butterfly optimization for liver tumor classification. Eng. Sci. 16, 354-365 (2021). https:// doi.org/10.30919/es8d594

11. S. Wu, K. Zhao, J. Wang, N.N. Liu, K.D. Nie, L.M. Qi, L.A. Xia, Recent advances of tanshinone in regulating autophagy for medicinal research. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1059360 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1059360

12. X. Duan, J. Chen, Y. Wu, S. Wu, D. Shao, J. Kong, Drug selfdelivery systems based on Hyperbranched Polyprodrugs towards Tumor Therapy. Chem. Aian J. 13, 939-943 (2018). https://doi. org/10.1002/asia. 201701697

13. E. Sharifi, F. Reisi, S. Yousefiasl, F. Elahian, S.P. Barjui, R. Sartorius, N. Fattahi, E.N. Zare, N. Rabiee, E.P. Gazi, A.C. Paiva-Santos, P. Parlanti, M. Gemmi, G.-R. Mobini, M. Hash-emzadeh-Chaleshtori, De P. Berardinis, I. Sharifi, V. Mattoli, P. Makvandi, Chitosan decorated cobalt zinc ferrite nanoferrofluid composites for potential cancer hyperthermia therapy: anti-cancer activity, genotoxicity, and immunotoxicity evaluation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 191 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00768-4

14. W. Chen, X. Li, C. Liu, J. He, M. Qi, Y. Sun, B. Shi, H. Sepehrpour, H. Li, W. Tian, (2020)

15. V.K. Shukla, M. Sudhi, D.K. Shetty, S. Banthia, P. Chandrasekar, N. Naik, B.M.Z. Hameed, S.G. Balakrishnan JM, Transforming disease diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review of AI-driven urine analysis in clinical mdicine. Eng. Sci. 26, 1009 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es1009

16. S. Zhao, G. Yue, X. Liu, S. Qin, B. Wang, P. Zhao, A.J. Ragauskas, M. Wu, X. Song, Lignin-based carbon quantum dots with high fluorescence performance prepared by supercritical catalysis and solvothermal treatment for tumor-targeted labeling. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 73 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00645-0

17. M. Ghomi, E.N. Zare, H. Alidadi, N. Pourreza, A. Sheini, N. Rabiee, V. Mattoli, X. Chen, P. Makvandi, A multifunctional bioresponsive and fluorescent active nanogel composite for breast cancer therapy and bioimaging. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 51 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00613-0

18. S. Zhang, Y. Hou, H. Chen, Z. Liao, J. Chen, B.B. Xu, J. Kong, Reduction-responsive amphiphilic star copolymers with longchain hyperbranched poly(

19. W. Chen, J. He, H. Li, X. Li, W. Tian, A quinolone derivativebased organoplatinum(II) metallacycle supramolecular selfdelivery nanocarrier for combined cancer therapy. Supramol. Chem. 32, 597-604 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/10610278.2 020.1846739

20. Q. Tan, Q.F. He, Z. Peng, X. Zeng, Y.Z. Liu, D. Li, S. Wang, J.W. Wang, Topical rhubarb charcoal-crosslinked chitosan/ silk fibroin sponge scaffold for the repair of diabetic ulcers improves hepatic lipid deposition in

signalling pathway. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 52 (2024). https://doi. org/10.1186/s12944-024-02041-z

21. R. Loomba, S.L. Friedman, G.I. Shulman, Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell. 184, 2537-2564 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.015

22. P. Wu, S. Liang, Y. He, R. Lv, B. Yang, M. Wang, C. Wang, Y. Li, X. Song, W. Sun, Network pharmacology analysis to explore mechanism of Three Flower Tea against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with experimental support using high-fat dietinduced rats. Chin. Herb. Med. 14, 273-282 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.chmed.2022.03.002

23. X. Dai, J. Feng, Y. Chen, S. Huang, X. Shi, X. Liu, Y. Sun, Traditional Chinese medicine in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: molecular insights and therapeutic perspectives. Chin. Med. 16, 68 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-021-00469-4

24. Y. Liu, J. Wang, J. Chen, Q. Yuan, Y. Zhu, Ultrasensitive iontronic pressure sensor based on rose-structured ionogel dielectric layer and compressively porous electrodes. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 210 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00765-7

25. W. Jiang, X. Zhang, P. Liu, Y. Zhang, W. Song, D.-G. Yu, X. Lu , Electrospun healthcare nanofibers from medicinal liquor of Phellinus Igniarius. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 5, 3045-3056 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00551-x

26. N. Goswami, S. Raj, D. Thakral, J.F. Arias-Gonzãi Les JLa-G, Flores-Albornoz, E.A. Asnate-Salazar, D. Kapila, S. Yadav, S. Kumar, Intrusion detection system for IoT-based Healthcare Intrusions with Lion-salp-swarm-optimization algorithm: Meta-heuristic-Enabled Hybrid Intelligent Approach. Eng. Sci. 25, 933 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es933

27. S. Sahu, S. Sharma, M.S. Al, A. Shrivastava, P. Gupta, K. Hait M, Impact of Mucormycosis on Health of Covid patients: a review. ES Food Agrofor. 13, 939 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esfaf939

28. P. Gupta, S. Biswas, A.K. Chaturwedi, U. Janghel, G. Tamrakar, R. Verma, M. Hait, Health Impact of Ground Water Sample and its Effect on Flora of Kanker District, Chhattisgarh, India. ES Food Agrofor. 13, 940 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esfaf940

29. SC. Izah, L. Sylva, M. Hait, Cronbach’s Alpha: A Cornerstone in Ensuring Reliability and Validity in Environmental Health Assessment. ES Energy & Environ. 3, 1057 (2024). https://doi. org/10.30919/esee31057

30. X. Wang, Y. Qi, Z. Hu, L. Jiang, F. Pan, Z. Xiang, Z. Xiong, W. Jia, J. Hu, W. Lu,

31. J. Liu, K. Liu, X. Pan, K. Bi, F. Zhou, P. Lu, M. Lei, A flexible semidry electrode for long-term, high-quality electrocardiogram monitoring. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 13 (2022). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00596-y

32. Y. Shen, W. Yang, F. Hu, X. Zheng, Y. Zheng, H. Liu, H. Algadi, K. Chen, Ultrasensitive wearable strain sensor for promising application in cardiac rehabilitation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 21 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00610-3

33. A. Huang, Y. Guo, Y. Zhu, T. Chen, Z. Yang, Y. Song, P. Wasnik, H. Li, S. Peng, Z. Guo, X. Peng, Durable washable wearable antibacterial thermoplastic polyurethane/carbon nanotube@silver nanoparticles electrospun membrane strain sensors by multiconductive network. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 101 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00684-7

34. Q. Xu, Z. Wu, W. Zhao, M. He, N. Guo, L. Weng, Z. Lin, M.F.A. Taleb, M.M. Ibrahim, M.V. Singh, J. Ren, Z.M. El-Bahy, Strategies in the preparation of conductive polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels for applications in flexible strain sensors, flexible supercapacitors,

and triboelectric nanogenerator sensors: an overview. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 203 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00783-5

35. O.S.S.S. Chowdary, N. Naik, V. Patil, K. Adhikari, B.M.Z. Hameed, B.P. Rai, B.K. Somani, 5G technology is the future of Healthcare: opening up a New Horizon for Digital Transformation in Healthcare Landscape. ES Gen. 2, 1010 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.30919/esg1010

36. B. Fei, D. Wang, N. Almasoud, H. Yang, J. Yang, T.S. Alomar, B. Puangsin, B.B. Xu, H. Algadi, Z.M. El-Bahy, Z. Guo, Z. Shi, Bamboo fiber strengthened poly(lactic acid) composites with enhanced interfacial compatibility through a multi-layered coating of synergistic treatment strategy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 249, 126018 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126018

37. B. Fei, H. Yang, J. Yang, D. Wang, H. Guo, H. Hou, S. Melhi, B.B. Xu, H.K. Thabet, Z. Guo, Z. Shi, Sustainable compressionmolded bamboo fibers/poly(lactic acid) green composites with excellent UV shielding performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2024.03.074

38. S. Ge, G. Zheng, Y. Shi, Z. Zhang, A. Jazzar, X. He, S. Donkor, Z. Guo, D. Wang, B.B. Xu, Facile fabrication of high-strength biocomposite through

39. D. Wang, H. Yang, J. Yang, B. Wang, P. Wasnik, B.B. Xu, Z. Shi, Efficient visible light-induced photodegradation of industrial lignin using silver- CuO catalysts derived from Cu -metal organic framework. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 138 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00708-2

40. Y. Yang, L. Zhang, J. Zhang, Y. Ren, H. Huo, X. Zhang, K. Huang, M. Rezakazemi, Z. Zhang, Fabrication of environmentally, high-strength, fire-retardant biocomposites from smalldiameter wood lignin in situ reinforced cellulose matrix. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 140 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00721-5

41. M. Culebras, G.A. Collins, A. Beaucamp, H. Geaney, M.N. Collins, Lignin/Si Hybrid Carbon nanofibers towards highly efficient sustainable Li-ion anode materials. Eng. Sci. 17, 195-203 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d608

42. Y. Tian, L. Zhong, X. Sheng, X. Zhang, Corrosion inhibition property and promotion of green basil leaves extract materials on

43. R. Scaffaro, A. Maio, M. Gammino, Hybrid biocomposites based on polylactic acid and natural fillers from Chamaerops humilis dwarf palm and Posidonia oceanica leaves. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 5, 1988-2001 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00534-y

44. X.-Y. Ye, Y. Chen, J. Yang, H.-Y. Yang, D.-W. Wang, B.B. Xu, J. Ren, D. Sridhar, Z. Guo, Z.-J. Shi, Sustainable wearable infrared shielding bamboo fiber fabrics loaded with antimony doped tin oxide/silver binary nanoparticles. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 106 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00683-8

45. S. Rakesh, A.K. Pandey, A. Roy, Assessment of secondary metabolites, In-Vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of root of Argemone mexicana L. ES Food Agrofor. 15, 1007 (2024). https://doi.org/10.30919/esfaf1007

46. J. Cai, S. Xi, C. Zhang, X. Li, M.H. Helal, Z.M. El-Bahy, M.M. Ibrahim, H. Zhu, M.V. Singh, P. Wasnik, B.B. Xu, Z. Guo, H. Algadi, J. Guo, Overview of biomass valorization: case study of nanocarbons, biofuels and their derivatives. J. Agric. Food Res. 14, 100714 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr. 2023.100714

47. K. Zhao, X.Y. Wu, G.Q. Han, L. Sun, C.W. Zheng, H. Hou, Z.M. El-Bahy, C. Qian, M. Kallel, H. Algadi, Z.H. Guo, Z.J. Shi, Phyllostachys nigra (Lodd. Ex Lindl.) Derived polysaccharide with enhanced glycolipid metabolism regulation and mice gut

microbiome. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 257, 128588 (2024). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128588

48. A. Kaur, M.V. Singh, N. Bhatt, S. Arora, A. Shukla, Exploration of Chemical Composition and Biological activities of the essential oil from Ehretia acuminata R. Br. Fruit. ES Food Agrofor. 15, 1068 (2024). https://doi.org/10.30919/esfaf1068

49. D. Pal, S. Thakur, T. Sahu, M. Hait, Exploring the Anticancer potential and phytochemistry of Moringa oleifera: a multi-targeted Medicinal Herb from Nature. ES Food Agrofor. 14, 982 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esfaf982

50. K. Sur, A. Kispotta, N.N. Kashyap, AK. Das, J. Dutta, M. Hait, G. Roymahapatra, R. Jain, T. Akitsu, Physicochemical, Phytochemical and Pharmacognostic Examination of Samanea saman. ES Food Agrofor. 14, 1011 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esfaf1011

51. J. Xu, R. Liu, L. Wang, A. Pranovich, J. Hemming, L. Dai, C. Xu, C. Si, Towards a deep understanding of the biomass fractionation in respect of lignin nanoparticle formation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 214 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00797-z

52. B. Wang, Y. Kuang, M. Li, X. Wang, X. Zhang, Q. Rao, B. Yuan, S. Yang, Magnetic surface molecularly imprinted polymers for efficient selective recognition and targeted separation of daidzein. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 196 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1007/s42114-023-00775-5

53. T.L. Ersedo, T.A. Teka, S.F. Forsido, E. Dessalegn, J.A. Adebo, M. Tamiru, T. Astatkie, Food flavor enhancement, preservation, and bio-functionality of ginger (Zingiber officinale): a review. Int. J. Food Prop. 26, 928-951 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/10942 912.2023.2194576

54. M. Crichton, S. Marshall, W. Marx, E. Isenring, A. Lohning, Therapeutic health effects of ginger (Zingiber officinale): updated narrative review exploring the mechanisms of action. Nutr. Rev. 81, 1213-1224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuac115

55. Z. Peng, Y. Zeng, Q. Tan, Q.F. He, S. Wang, J.W. Wang, 6-Gingerol alleviates ectopic lipid deposition in skeletal muscle by regulating CD36 translocation and mitochondrial function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 708, 149786 (2024). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.149786

56. J. Ahn, H. Lee, C.H. Jung, S.Y. Ha, H.D. Seo, Y.I. Kim, T. Ha, 6-Gingerol ameliorates hepatic steatosis via

57. J. Li, S. Wang, L. Yao, P. Ma, Z. Chen, T.L. Han, C. Yuan, J. Zhang, L. Jiang, L. Liu, D. Ke, C. Li, J. Yamahara, Y. Li, J. Wang, 6-gingerol ameliorates age-related hepatic steatosis: Association with regulating lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 362, 125-135 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2018.11.001

58. U. Sen, C. Coleman, T. Sen, Stearoyl coenzyme a desaturase-1: multitasker in cancer, metabolism, and ferroptosis. Trends Cancer. 9, 480-489 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2023.03.003

59. J. Wang, L. Wang, X.J. Zhang, P. Zhang, J. Cai, Z.G. She, H. Li , Recent updates on targeting the molecular mediators of NAFLD. J. Mol. Medicine-Jmm. 101, 101-124 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s00109-022-02282-4

60. S.M. Jeyakumar, A. Vajreswari, Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1: a potential target for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease?-perspective on emerging experimental evidence. World J. Hepatol. 14, 168179 (2022). https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i1. 168

61. D. Bhattacharya, B. Basta, J.M. Mato, A. Craig, D. FernandezRamos, F. Lopitz-Otsoa, D. Tsvirkun, L. Hayardeny, V. Chandar, R.E. Schwartz, A. Villanueva, S.L. Friedman, Aramchol downregulates stearoyl CoA-desaturase 1 in hepatic stellate cells to attenuate cellular fibrogenesis. Jhep Rep. 3, 100237 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100237

62. V. Ratziu, De L. Guevara, R. Safadi, F. Poordad, F. Fuster, J. Flores-Figueroa, M. Arrese, A.L. Fracanzani, D. Ben Bashat, K. Lackner, T. Gorfine, S. Kadosh, R. Oren, M. Halperin, L. Hayardeny, R. Loomba, S. Friedman, A.I.S. Group, A.J. Sanyal, Aramchol in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Nat. Med. 27, 1825-1835 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01495-3

63. M.G. Carnuta, M. Deleanu, T. Barbalata, L. Toma, M. Raileanu, A.V. Sima, C.S. Stancu, Zingiber officinale extract administration diminishes steroyl-CoA desaturase gene expression and activity in hyperlipidemic hamster liver by reducing the oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Phytomedicine. 48, 62-69 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2018.04.059

64. Q. Li, L.M. Qi, K. Zhao, W. Ke, T.T. Li, L.A. Xia, Integrative quantitative and qualitative analysis for the quality evaluation and monitoring of Danshen medicines from different sources using HPLC-DAD and NIR combined with chemometrics. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 932855 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.932855

65. Y.Y. Zhu, W. Xiang, Y. Shen, Y.A. Jia, Y.S. Zhang, L.S. Zeng, J.X. Chen, Y. Zhou, X. Xue, X.Z. Huang, L. Xu, New butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor derived from mulberry twigs, a kind of agricultural byproducts. Ind. Crops Prod. 187, 115535 (2022). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115535

66. M. Nodehi, A. Kiasadr, G. Babaee Bachevanlo, Modified glassy carbon electrode with mesoporous Silica-Metformin/MultiWalled carbon nanotubes as a biosensor for ethinylestradiol detection. Mater. Chem. Horizons. 1, 219-230 (2022). https://doi. org/10.22128/mch.2022.601.1024

67. Y. Niu, X. Li, C. Wu, Z. Shi, X. Lin, H.M.A. Mahmoud, E.M.A. Widaa, H. Algadi, B.B. Xu, Z. Wang, Chemical composition, pharmacodynamic activity of processed Aconitum Brachypodum Diels., and molecular docking analysis of its active target. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 75 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00640-5

68. G. Roymahapatra, S. Pradhan, S. Sato, D. Nakane, M. Hait, S. Bhattacharyya, R. Saha, T. Akitsu, Computational study on Docking of Laccase and Cyanide-Bridged Ag-Cu Complex for Designing the Improved Biofuel Cell Cathode. ES Energy Environ. 21, 957 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee957

69. M.I. Abdjan, N.S. Aminah, A.N. Kristanti, I. Siswanto, M.A. Saputra, Y. Takaya, Pharmacokinetic, DFT modeling, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation approaches: Diptoindonesin A as a potential inhibitor of Sirtuin-1. Eng. Sci. 21, 794 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d794

70. H. Long, S. Ryu, X.-L. Zheng, L.-S. Zhang, L.-Y. Li, Z.-S. Zhang, Peptide L1H9 derived from the interaction of structural human rhomboid family 1 and

71. R.C. Shivamurthy, S.R.B.H.S.K. Brn M, S S, S EN, Comparative Genomics based putative drug targets identification, homology modeling, virtual screening and molecular Docking studies in Chlamydophila Pneumoniae. Eng. Sci. 19, 125-135 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d645

72. X.W. Shi, L. Xu, J.Q. Zhang, J.F. Mo, P. Zhuang, L. Zheng, Oxyresveratrol from mulberry branch extract protects HUVECs against oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced oxidative injury via activation of the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway. J. Funct. Foods. 100, 105371 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2022.105371

73. Y. Huang, H. Wang, H. Wang, R. Wen, X. Geng, T. Huang, J. Shi, X. Wang, J. Wang, Structure-based virtual screening of natural products as potential stearoyl-coenzyme a desaturase 1 (SCD1) inhibitors. Comput. Biol. Chem. 86, 107263 (2020). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2020.107263

74. Y. Yi, C. Zhao, H.L. Shindume, J. Ren, L. Chen, H. Hou, M.M. Ibrahim, Z.M. El-Bahy, Z. Guo, Z. Zhao, J. Gu, Enhanced

electromagnetic wave absorption of magnetite-spinach derived carbon composite. Colloids Surf., a 694, 134149 (2024). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.134149

75. I. Galarreta-Rodriguez, A. Lopez-Ortega, E. Garayo, J.J. BeatoLópez, La P. Roca, V. Sanchez-Alarcos, V. Recarte, C. GómezPolo, J.I. Pérez-Landazábal, Magnetically activated 3D printable polylactic acid/polycaprolactone/magnetite composites for magnetic induction heating generation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 102 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00687-4

76. K. Zhou, Y. Sheng, W. Guo, L. Wu, H. Wu, X. Hu, Y. Xu, Y. Li, M. Ge, Y. Du, X. Lu, J. Qu, Biomass porous carbon/polyethylene glycol shape-stable phase change composites for multisource driven thermal energy conversion and storage. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 34 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00620-1

77. J. Lu, Y. Yang, Y. Zhong, Q. Hu, B. Qiu, The study on activated Carbon, Magnetite, Polyaniline and Polypyrrole Development of Methane Production Improvement from Wastewater Treatment. ES Food Agrofor. 10, 30-38 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esfaf802

78. E.A. Dil, A.H. Doustimotlagh, H. Javadian, A. Asfaram, M. Ghaedi, Nano-sized

79. Y. Tao, X.H. Gu, W.D. Li, B.C. Cai, Fabrication and evaluation of magnetic phosphodiesterase-5 linked nanoparticles as adsorbent for magnetic dispersive solid-phase extraction of inhibitors from Chinese herbal medicine prior to ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 1532, 58-67 (2018). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.chroma.2017.11.062

80. F.S. Feng, W. Xiang, H. Gao, Y.A. Jia, Y.S. Zhang, L.S. Zeng, J.X. Chen, X.Z. Huang, L. Xu, Rapid screening of nonalkaloid alpha-glucosidase inhibitors from a Mulberry twig extract using enzyme-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles coupled with UPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 70, 11958-11966 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.2c03435

81. X. Xu, Y. Guo, M. Chen, N. Li, Y. Sun, S. Ren, J. Xiao, D. Wang, X. Liu, Y. Pan, Hypoglycemic activities of flowers of Xanthoceras sorbifolia and identification of anti-oxidant components by off-line UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS-free radical scavenging detection. Chin. Herb. Med. 16, 151-161 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. chmed.2022.11.009

82. L. Zhong, R. Wang, Q.H. Wen, J. Li, J.W. Lin, X.A. Zeng, The interaction between bovine serum albumin and [6]-,[8]- and [10]-gingerol: an effective strategy to improve the solubility and stability of gingerol. Food Chem. 372, 131280 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131280

83. K.R. Kou, X.Q. Wang, R.Y. Ji, L. Liu, Y.N. Qiao, Z.X. Lou, C.Y. Ma, S.M. Li, H.X. Wang, C.T. Ho, Occurrence, biological activity and metabolism of 6-shogaol. Food Funct. 9, 1310-1327 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7fo01354j

84. S.M. Sang, H.D. Snook, F.S. Tareq, Y. Fasina, Precision research on Ginger: the type of ginger matters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 8517-8523 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c03888

85. S. Salaramoli, S. Mehri, F. Yarmohammadi, S.I. Hashemy, H. Hosseinzadeh, The effects of ginger and its constituents in the prevention of metabolic syndrome: a review. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 25, 664-674 (2022). https://doi.org/10.22038/ IJBMS.2022.59627.13231

86. J. Chen, S. Lv, B. Huang, X. Ma, S. Fu, Y. Zhao, Upregulation of SCD1 by ErbB2 via LDHA promotes breast cancer cell migration and invasion. Med. Oncol. 40, 40 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12032-022-01904-8

87. Y. Zhang, Z. Gu, J. Wan, X. Lou, S. Liu, Y. Wang, Y. Bian, F. Wang, Z. Li, Z. Qin, Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase-1 dependent lipid droplets accumulation in cancer-associated fibroblasts facilitates the progression of lung cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 6114-6128 (2022). https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs. 74924

88. Z. Salari, A. Khosravi, E. Pourkhandani, E. Molaakbari, E. Salarkia, A. Keyhani, I. Sharifi, H. Tavakkoli, S. Sohbati, S. Dabiri, G. Ren, M. Shafie’ei, The inhibitory effect of 6-gingerol and cisplatin on ovarian cancer and antitumor activity: In silico, in vitro, and in vivo. Frontiers in oncology 13, 1098429 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1098429

89. M.K. Ediriweera, J.Y. Moon, Y.T.K. Nguyen, S.K. Cho, 10-Gingerol targets lipid rafts associated PI3K/Akt signaling in radioresistant triple negative breast cancer cells. Molecules. 25, 3164 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25143164

90. J.H. Joo, S.S. Hong, Y.R. Cho, D.W. Seo, 10-Gingerol inhibits proliferation and invasion of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through suppression of akt and p38(MAPK) activity. Oncol. Rep. 35, 779-784 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2015.4405

91. M. Miyazaki, W.C. Man, J.M. Ntambi, Targeted disruption of stearoyl-CoA desaturasel gene in mice causes atrophy of sebaceous and meibomian glands and depletion of wax esters in the eyelid. J. Nutr. 131, 2260-2268 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1093/ jn/131.9.2260

92. Z. Zhang, N.A. Dales, M.D. Winther, Opportunities and challenges in developing stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase-1 inhibitors as novel therapeutics for human disease. J. Med. Chem. 57, 5039-5056 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/jm401516c

93. M.L.E. Macdonald, Van M. Eck, R.B. Hildebrand, B.W.C. Wong, N. Bissada, P. Ruddle, A. Kontush, H. Hussein, M.A. Pouladi, M.J. Chapman, C. Fievet, Van T.J.C. Berkel, B. Staels, B.M. Mcmanus, M.R. Hayden, Despite antiatherogenic metabolic characteristics, SCD1-deficient mice have increased inflammation and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 29, 341-347 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.108.181099

94. T. Iida, M. Ubukata, I. Mitani, Y. Nakagawa, K. Maeda, H. Imai, Y. Ogoshi, T. Hotta, S. Sakata, R. Sano, H. Morinaga, T. Negoro, S. Oshida, M. Tanaka, T. Inaba, Discovery of potent liver-selective stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1) inhibitors, thiazole-4-acetic acid derivatives, for the treatment of diabetes, hepatic steatosis, and obesity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 158, 832-852 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.09.003

- Zhanhu Guo

zhanhu.guo@northumbria.ac.uk

Wei Xiang

xiangwei@cqctcm.edu.cn

Jianwei Wang

wjwcq68@163.com

Chongqing Key Laboratory of Traditional Chinese Medicine for Prevention and Cure of Metabolic Diseases, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China

Chongqing college of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chongqing 402760, China - 3 Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, Pharmaceutical Analysis, KU Leuven – University of Leuven, Herestraat 49, O&N2, PB 923, Leuven 3000, Belgium4 College of Material Science and Chemical Engineering, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming 650224, China

5 Department of Mechanical and Civil Engineering, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST, UK

6 Department of Chemistry, College of Science, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif 21944, Saudi Arabia

7 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Nasr City, Cairo 11884, Egypt

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-024-02697-2

Publication Date: 2024-06-21

Rapid screening and sensing of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) inhibitors from ginger and their efficacy in ameliorating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

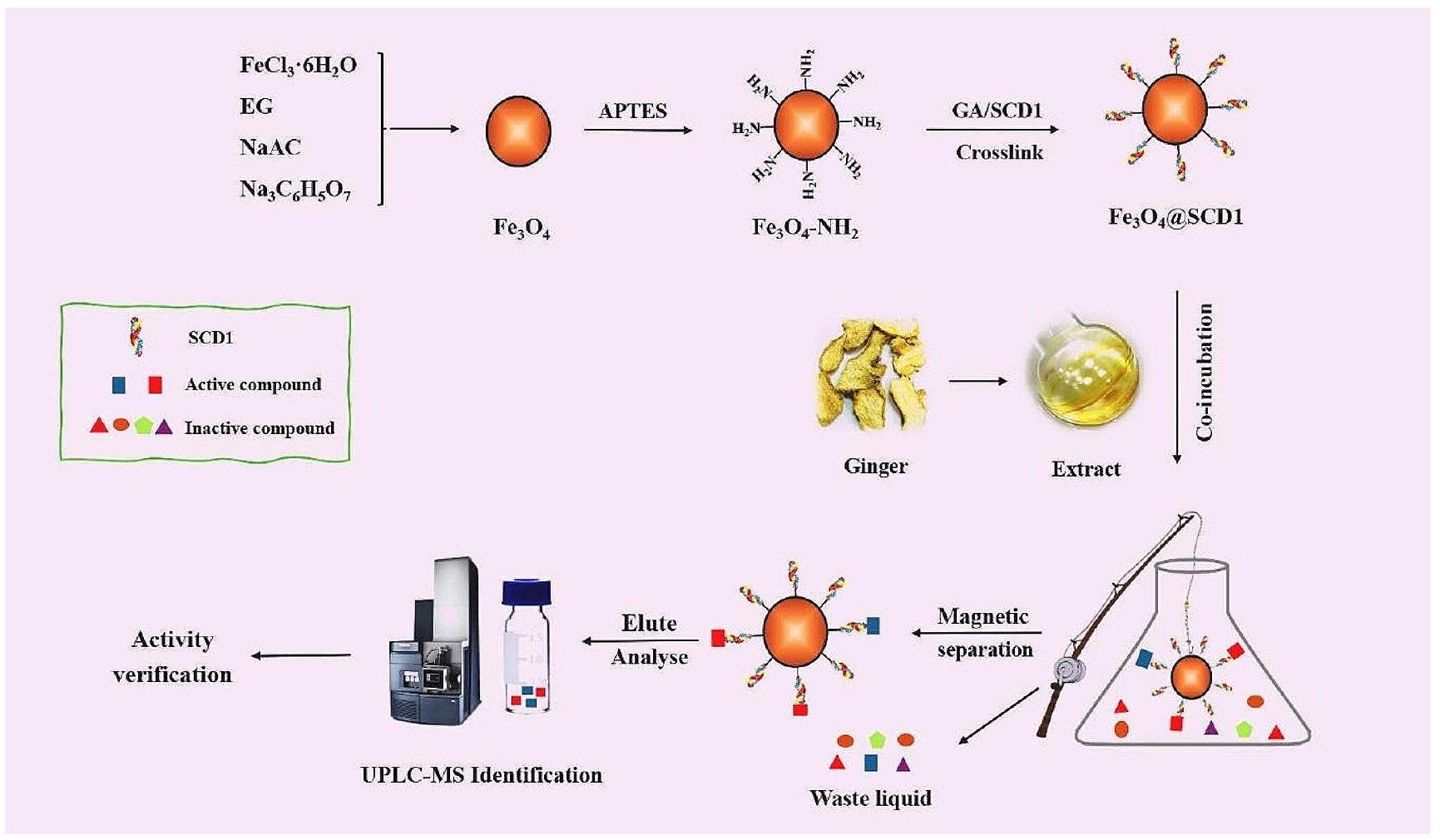

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a prevalent chronic metabolic condition, for which no approved medications are available. As a condiment and traditional Chinese medicine, ginger can be useful in reducing the symptoms of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Although its active ingredients and mechanisms of action are unknown, there is a lack of research on them. The purpose of this study is to prepare magnetite

Introduction

higher in obese patients with NAFLD in comparison to obese patients without NAFLD. Therefore, it seems likely that hepatic SCD1 activity is closely linked to NAFLD, and it has been demonstrated that hepatic-specific inhibition of SCD1 attenuates the progression of hepatic steatosis [60]. Studies have demonstrated that SCD1 is also involved in the oxidation of fats within cells and that silencing or inhibiting SCD1 expression increases intracellular fatty acid

Materials and methods

General experimental procedures

Plant material

Extraction preparation

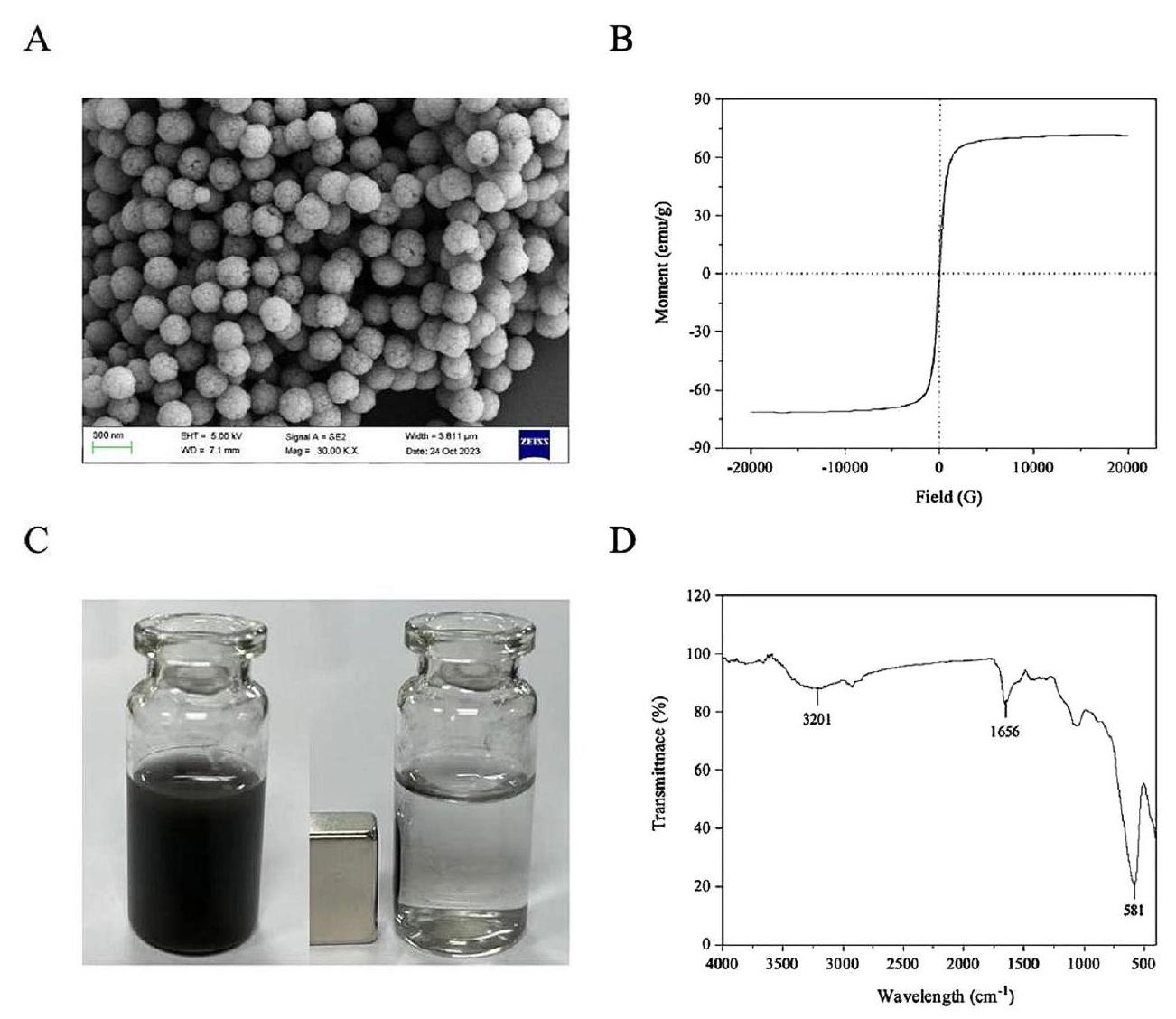

Synthesis of materials

crosslink with the SCD1 protein to obtain

Characterization of materials

Rapid screening of active ingredients

UPLC-MS/MS analysis

Molecular docking

Cell culture

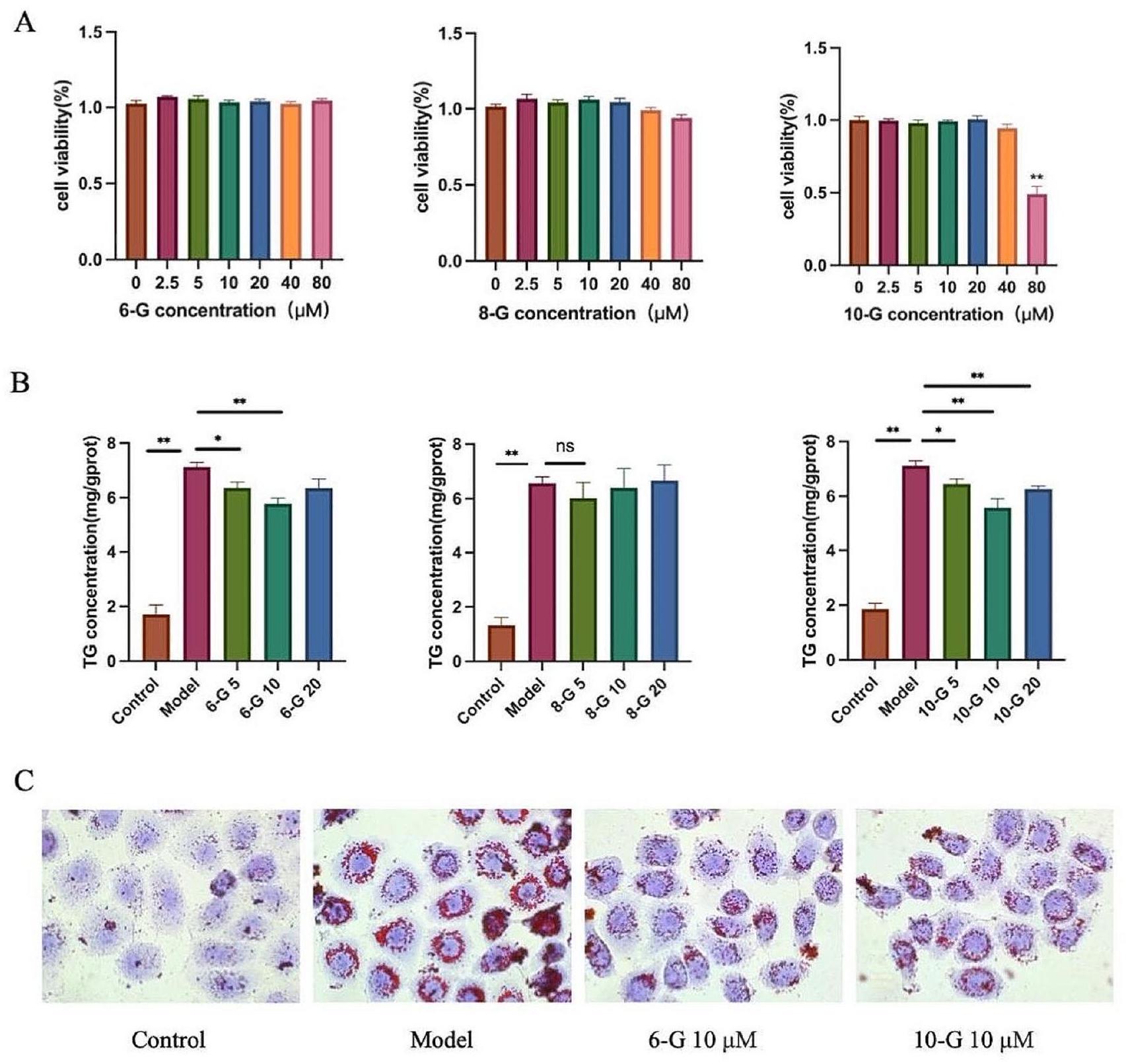

Cell viability assay

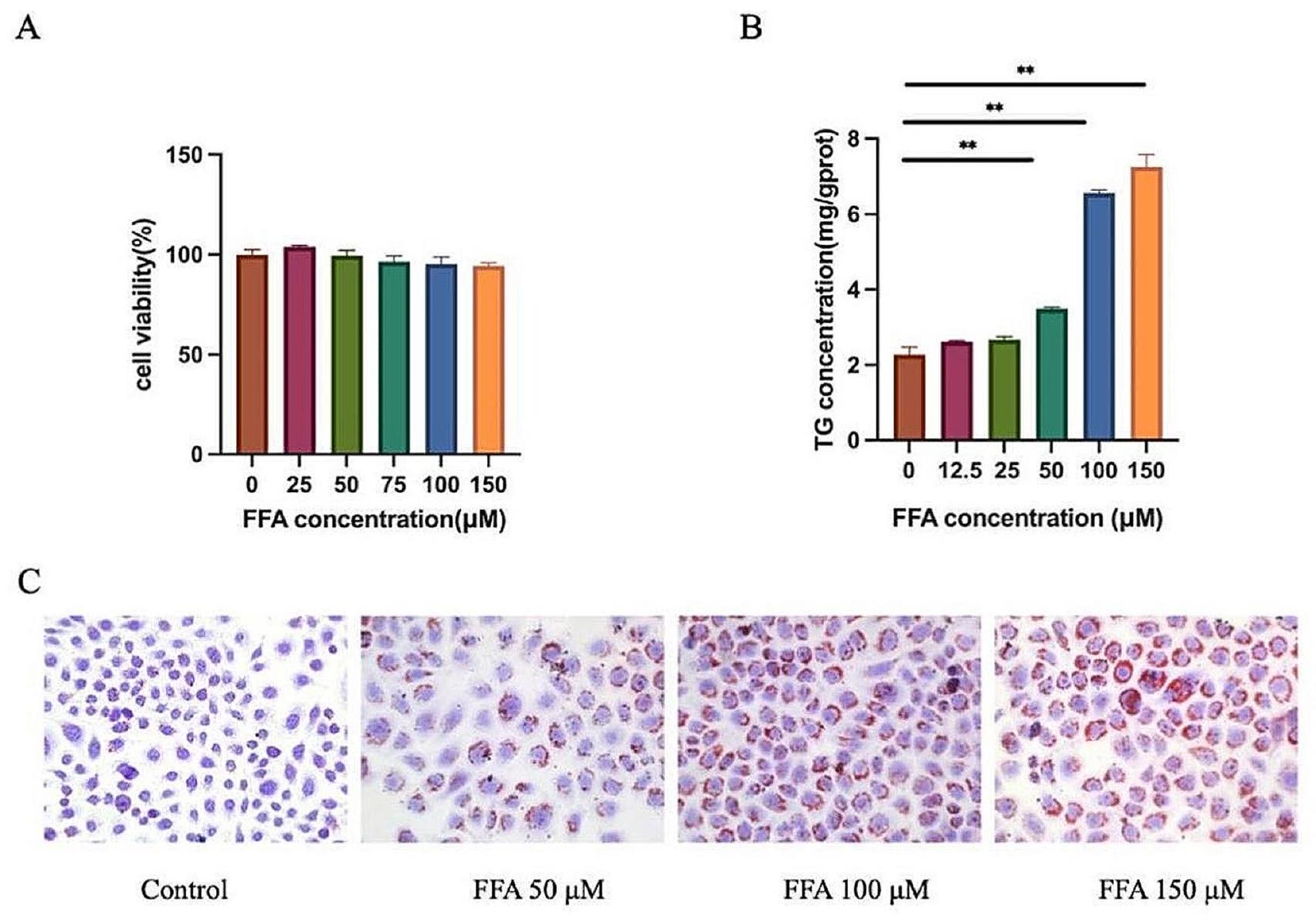

Lipid deposition model construction

Determination of intracellular triglyceride content

Oil red 0 staining

Data analysis

Results

Characterization of materials

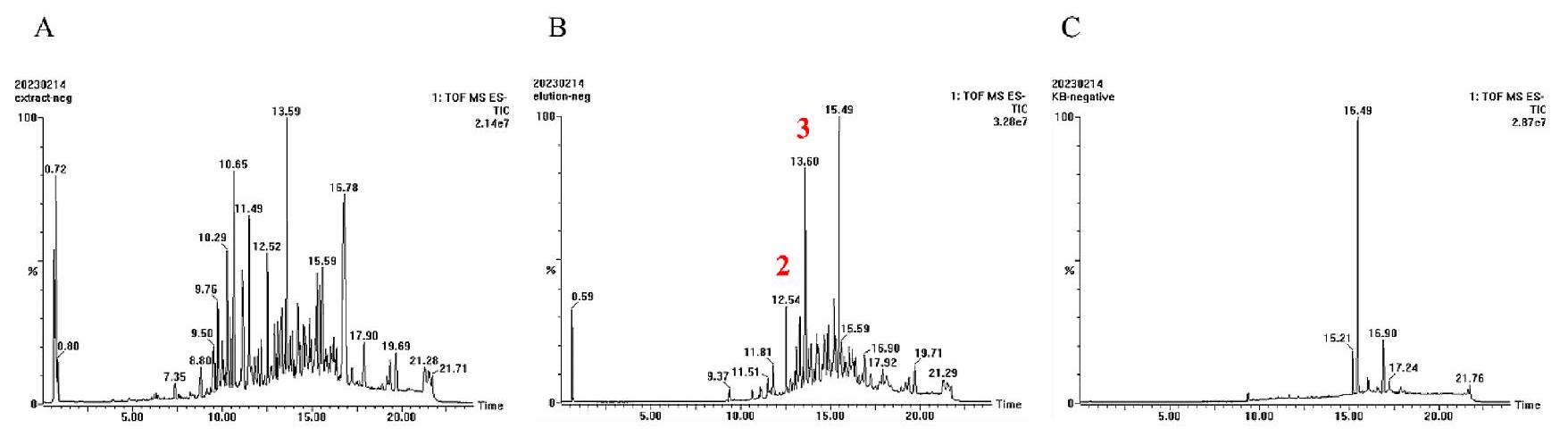

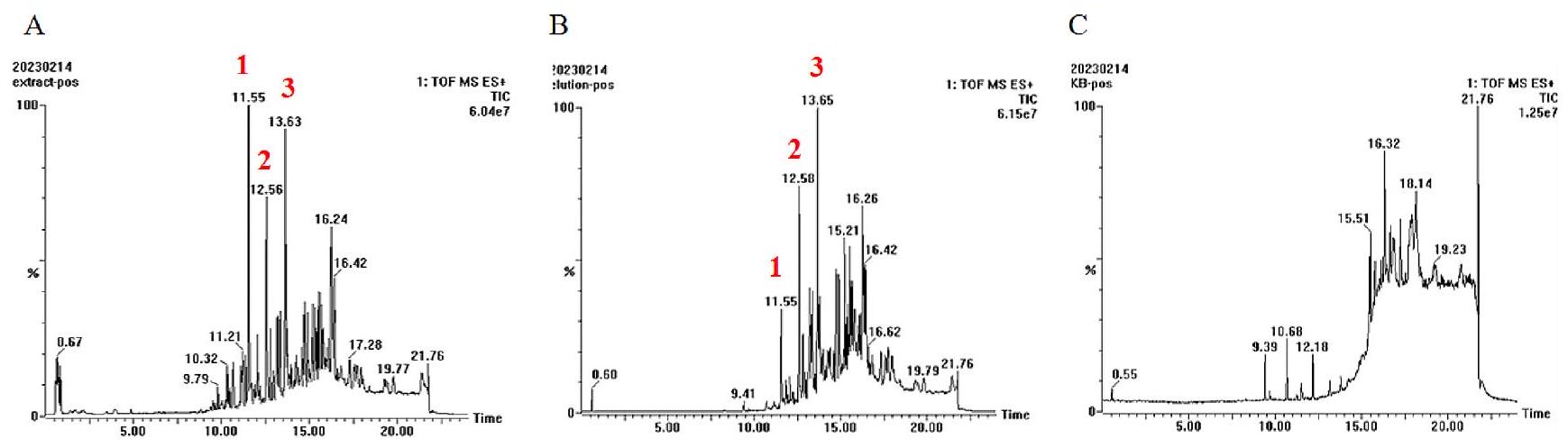

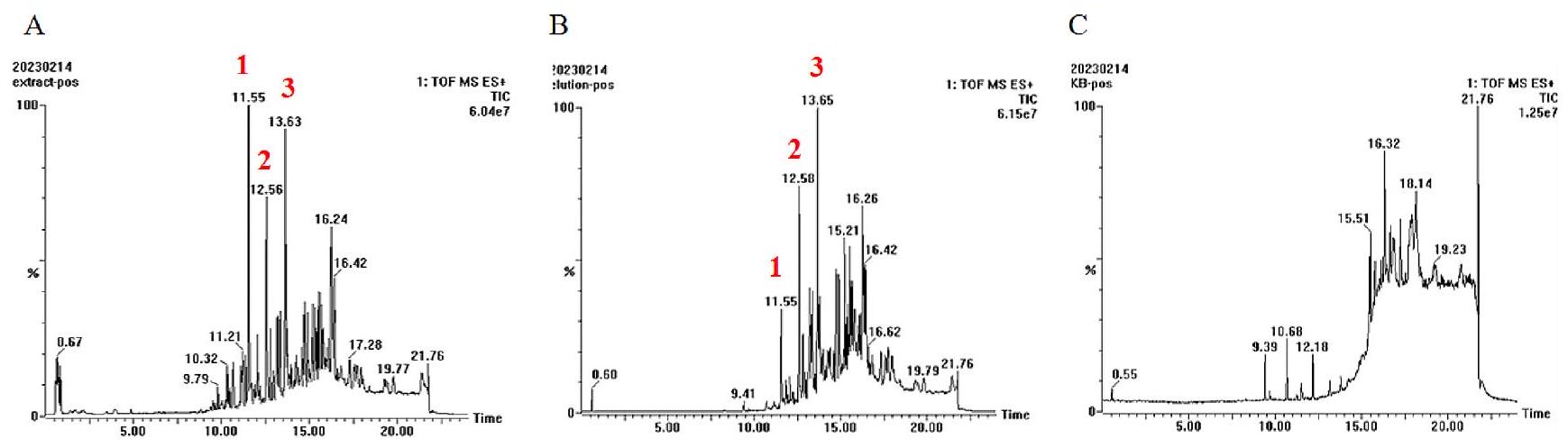

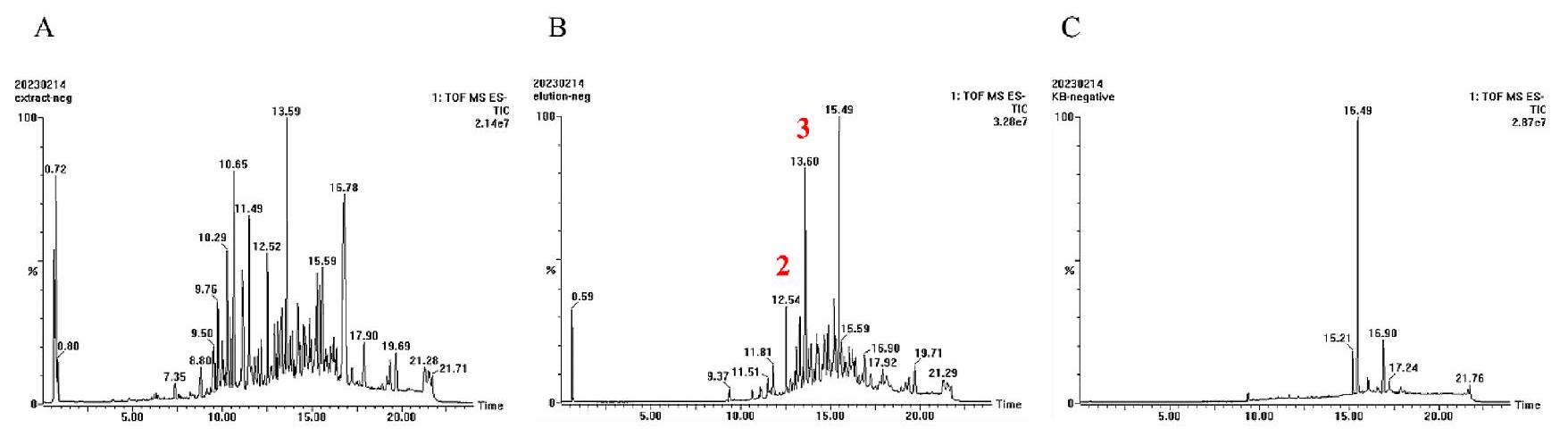

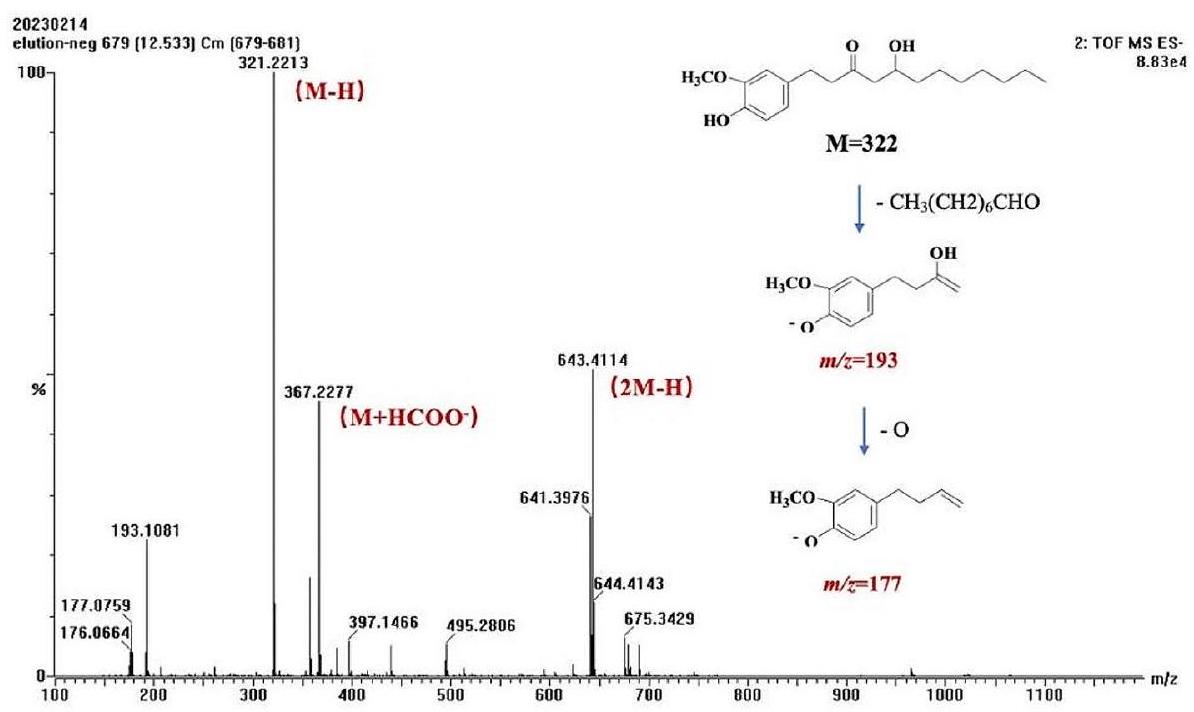

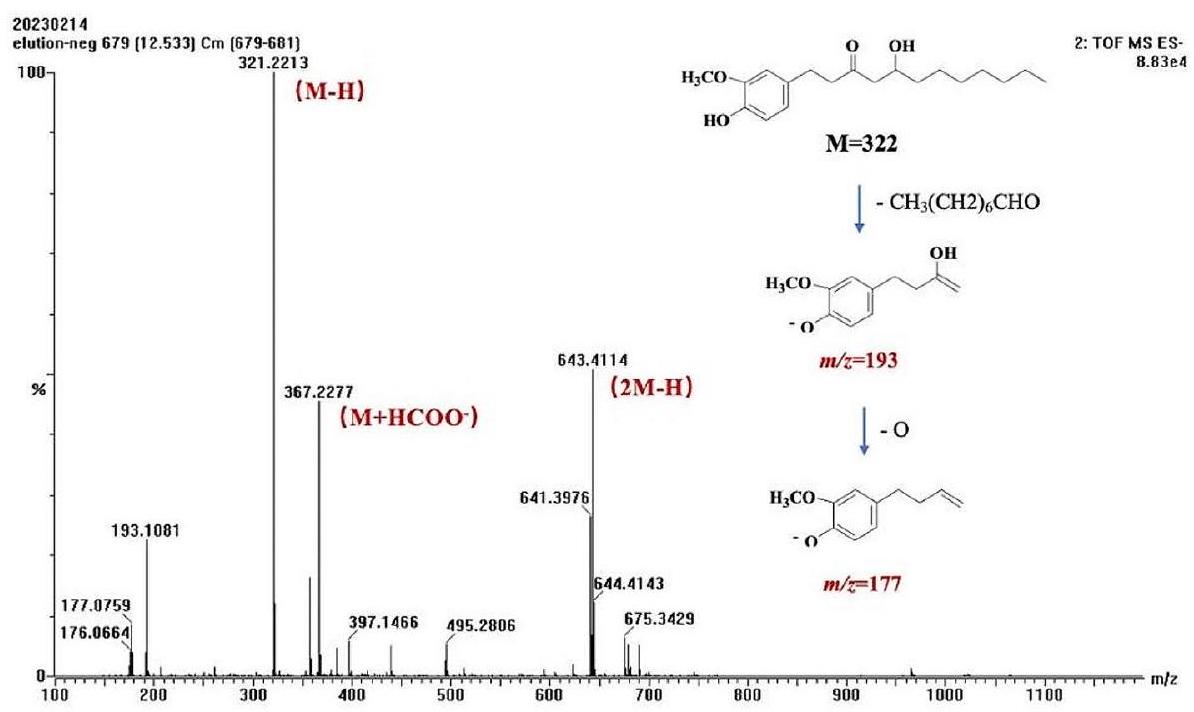

Component analysis of SCD1 potential inhibitors in ginger extract

demonstrated the greatest response, suggesting that it may have a greater affinity for SCD1.

ion m/z 179.0848 was shown to be the fragmentation signal generated by the precursor ion after it lost the neutral alkyl component

Prediction of the binding mode of potential active ingredients

on Asn144 and Asp152 in the active pocket of SCD1 [73]. This suggests that 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, and 10-gingerol have binding sites located in the catalytic pocket of SCD1 that are capable of directly binding to it.

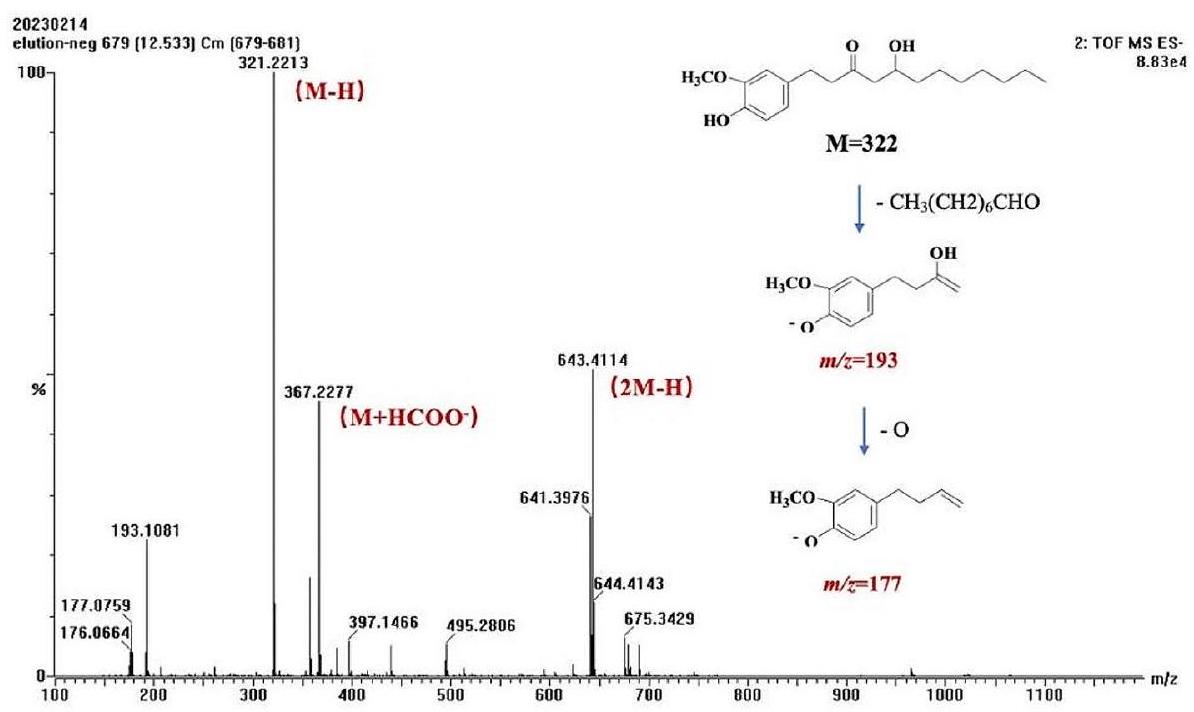

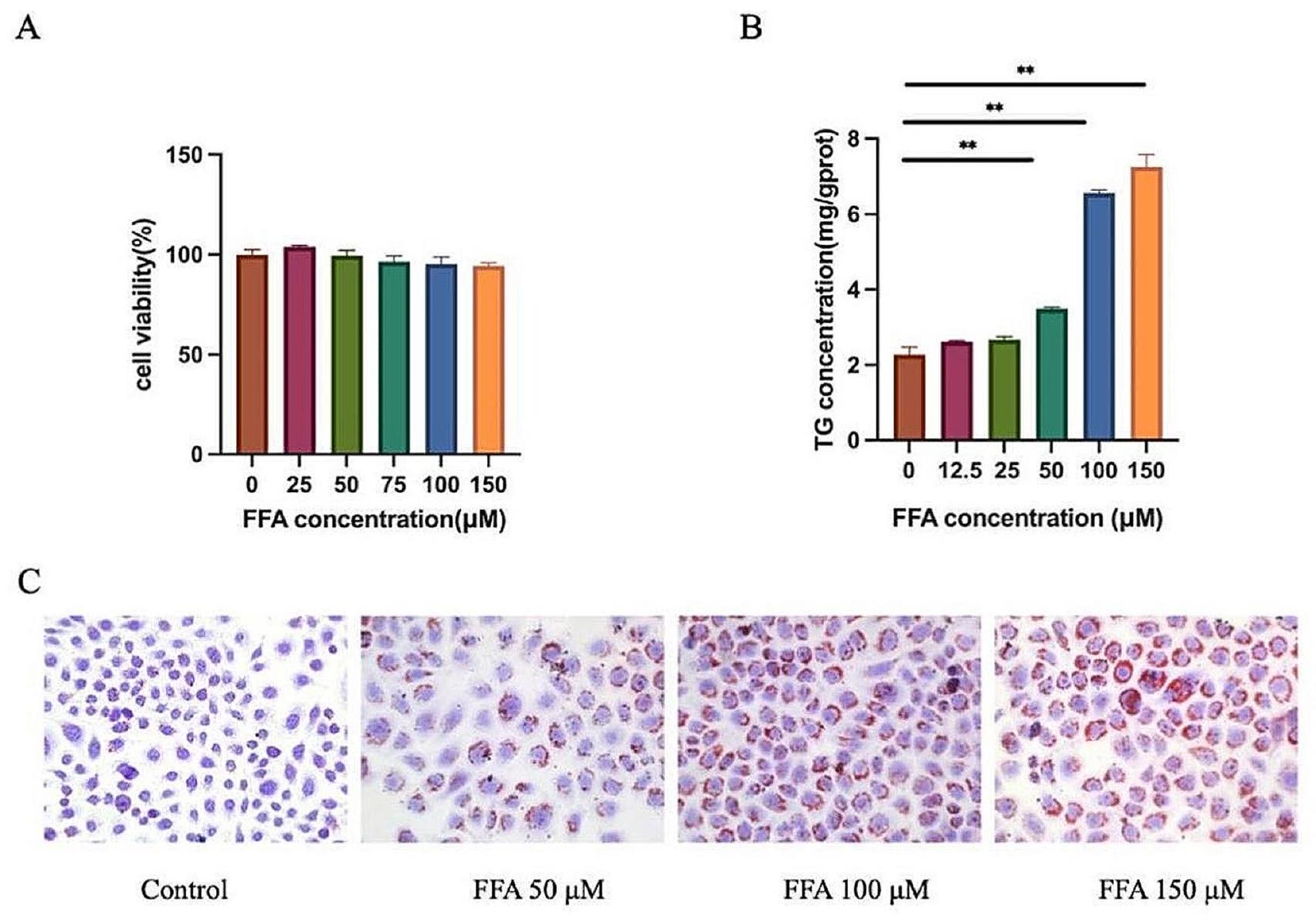

Target component ameliorates lipid accumulation in hepatocytes

A

B

Discussion

of FFA;

they had been cleaved at the MS (Fig. 4). There may be a reason for this because gingerols themselves do not have good thermal stability [82]. It yields an oxyketone product under conditions of elevated temperature and/or acidic environment, as a result of possessing an instability of the

treated with different concentrations of compounds;

regulating lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction [57]. In contrast, very few reports suggest that other components of ginger contribute to the improvement of NAFLD. The present study has demonstrated that ginger contains a new compound (10-gingerol) that increases hepatic lipid accumulation through the direct action of SCD1. The present study provides an additional level of insight into the mechanism, by which ginger improves NAFLD and also contributes to the discovery of new active ingredients that can improve NAFLD. It is

necessary to undertake further studies on the exact mechanism, by which 10 gingerol improves NAFLD in animal experiments to determine its exact effect.

antitumor properties [87]. Several recent studies have demonstrated that the combination of 6-gingerol and cisplatin induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells and inhibits angiogenesis more effectively than either drug alone [88]. There is evidence that 10-gingerol has anti-tumor activity through several pathways [89, 90], including PI3K/Akt and MAPK. Despite this, gingerols do not appear to have a direct effect on SCD1, which can also be the mechanism of anti-tumor action of this class of compounds.

Conclusions

project (grant number 2023MD744147). The research was funded by Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia (TU-DSPP-2024-21).

Declarations

References

- J. Zhang, B. Zhang, C. Pu, J. Cui, K. Huang, H. Wang, Y. Zhao, Nanoliposomal Bcl-xL proteolysis-targeting chimera enhances anti-cancer effects on cervical and breast cancer without on-target toxicities. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 78 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1007/s42114-023-00649-w

- U. Malik, D. Pal, Cancer-fighting isoxazole compounds: Sourcing Nature’s potential and synthetic Advancements- A Comprehensive Review. ES Food Agrofor. 15, 1052 (2024). https://doi. org/10.30919/esfaf1052

- M. Sudhi, V.K. Shukla, D.K. Shetty, V. Gupta, A.S. Desai, N. Naik, B.M.Z. Hameed, Advancements in bladder Cancer Management: a Comprehensive Review of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications. Eng. Sci. 26, 1003 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es1003

- Z. Ou, Z. Li, Y. Gao, W. Xing, H. Jia, H. Zhang, N. Yi, Novel triazole and morpholine substituted bisnaphthalimide: synthesis, photophysical and G-quadruplex binding properties. J. Mol. Struct. 1185, 27-37 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. molstruc.2019.02.073

- Z. Ou, Y. Qian, Y. Gao, Y. Wang, G. Yang, Y. Li, K. Jiang, X. Wang, Photophysical, G-quadruplex DNA binding and cytotoxic properties of terpyridine complexes with a naphthalimide ligand. RSC Adv. 6, 36923-36931 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/ C6RA01441K

- Q. Ban, J. Du, W. Sun, J. Chen, S. Wu, J. Kong, Intramolecular copper-containing hyperbranched polytriazole assemblies for label-free Cellular Bioimaging and Redox-Triggered Copper Complex Delivery. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 39, 1800171 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/marc. 201800171

- T. Bai, J. Du, J. Chen, X. Duan, Q. Zhuang, H. Chen, J. Kong, Reduction-responsive dithiomaleimide-based polymeric micelles for controlled anti-cancer drug delivery and bioimaging.

8. D. Bhargava, P. Rattanadecho, K. Jiamjiroch, Microwave imaging for breast Cancer detection – A Comprehensive review. Eng. Sci. Press. (2024). https://doi.org/10.30919/es31116

9. L. Xiao, W. Xu, L. Huang, J. Liu, G. Yang, Nanocomposite pastes of gelatin and cyclodextrin-grafted chitosan nanoparticles as potential postoperative tumor therapy. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00575-3

10. D.S. Uplaonkar, V. Virupakshappa, N. Patil, An efficient Discrete Wavelet transform based partial Hadamard feature extraction and hybrid neural network based Monarch Butterfly optimization for liver tumor classification. Eng. Sci. 16, 354-365 (2021). https:// doi.org/10.30919/es8d594

11. S. Wu, K. Zhao, J. Wang, N.N. Liu, K.D. Nie, L.M. Qi, L.A. Xia, Recent advances of tanshinone in regulating autophagy for medicinal research. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1059360 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1059360

12. X. Duan, J. Chen, Y. Wu, S. Wu, D. Shao, J. Kong, Drug selfdelivery systems based on Hyperbranched Polyprodrugs towards Tumor Therapy. Chem. Aian J. 13, 939-943 (2018). https://doi. org/10.1002/asia. 201701697

13. E. Sharifi, F. Reisi, S. Yousefiasl, F. Elahian, S.P. Barjui, R. Sartorius, N. Fattahi, E.N. Zare, N. Rabiee, E.P. Gazi, A.C. Paiva-Santos, P. Parlanti, M. Gemmi, G.-R. Mobini, M. Hash-emzadeh-Chaleshtori, De P. Berardinis, I. Sharifi, V. Mattoli, P. Makvandi, Chitosan decorated cobalt zinc ferrite nanoferrofluid composites for potential cancer hyperthermia therapy: anti-cancer activity, genotoxicity, and immunotoxicity evaluation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 191 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00768-4

14. W. Chen, X. Li, C. Liu, J. He, M. Qi, Y. Sun, B. Shi, H. Sepehrpour, H. Li, W. Tian, (2020)

15. V.K. Shukla, M. Sudhi, D.K. Shetty, S. Banthia, P. Chandrasekar, N. Naik, B.M.Z. Hameed, S.G. Balakrishnan JM, Transforming disease diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review of AI-driven urine analysis in clinical mdicine. Eng. Sci. 26, 1009 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es1009

16. S. Zhao, G. Yue, X. Liu, S. Qin, B. Wang, P. Zhao, A.J. Ragauskas, M. Wu, X. Song, Lignin-based carbon quantum dots with high fluorescence performance prepared by supercritical catalysis and solvothermal treatment for tumor-targeted labeling. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 73 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00645-0

17. M. Ghomi, E.N. Zare, H. Alidadi, N. Pourreza, A. Sheini, N. Rabiee, V. Mattoli, X. Chen, P. Makvandi, A multifunctional bioresponsive and fluorescent active nanogel composite for breast cancer therapy and bioimaging. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 51 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00613-0

18. S. Zhang, Y. Hou, H. Chen, Z. Liao, J. Chen, B.B. Xu, J. Kong, Reduction-responsive amphiphilic star copolymers with longchain hyperbranched poly(

19. W. Chen, J. He, H. Li, X. Li, W. Tian, A quinolone derivativebased organoplatinum(II) metallacycle supramolecular selfdelivery nanocarrier for combined cancer therapy. Supramol. Chem. 32, 597-604 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/10610278.2 020.1846739

20. Q. Tan, Q.F. He, Z. Peng, X. Zeng, Y.Z. Liu, D. Li, S. Wang, J.W. Wang, Topical rhubarb charcoal-crosslinked chitosan/ silk fibroin sponge scaffold for the repair of diabetic ulcers improves hepatic lipid deposition in

signalling pathway. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 52 (2024). https://doi. org/10.1186/s12944-024-02041-z

21. R. Loomba, S.L. Friedman, G.I. Shulman, Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell. 184, 2537-2564 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.015

22. P. Wu, S. Liang, Y. He, R. Lv, B. Yang, M. Wang, C. Wang, Y. Li, X. Song, W. Sun, Network pharmacology analysis to explore mechanism of Three Flower Tea against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with experimental support using high-fat dietinduced rats. Chin. Herb. Med. 14, 273-282 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.chmed.2022.03.002

23. X. Dai, J. Feng, Y. Chen, S. Huang, X. Shi, X. Liu, Y. Sun, Traditional Chinese medicine in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: molecular insights and therapeutic perspectives. Chin. Med. 16, 68 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-021-00469-4

24. Y. Liu, J. Wang, J. Chen, Q. Yuan, Y. Zhu, Ultrasensitive iontronic pressure sensor based on rose-structured ionogel dielectric layer and compressively porous electrodes. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 210 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00765-7

25. W. Jiang, X. Zhang, P. Liu, Y. Zhang, W. Song, D.-G. Yu, X. Lu , Electrospun healthcare nanofibers from medicinal liquor of Phellinus Igniarius. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 5, 3045-3056 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00551-x

26. N. Goswami, S. Raj, D. Thakral, J.F. Arias-Gonzãi Les JLa-G, Flores-Albornoz, E.A. Asnate-Salazar, D. Kapila, S. Yadav, S. Kumar, Intrusion detection system for IoT-based Healthcare Intrusions with Lion-salp-swarm-optimization algorithm: Meta-heuristic-Enabled Hybrid Intelligent Approach. Eng. Sci. 25, 933 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es933

27. S. Sahu, S. Sharma, M.S. Al, A. Shrivastava, P. Gupta, K. Hait M, Impact of Mucormycosis on Health of Covid patients: a review. ES Food Agrofor. 13, 939 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esfaf939

28. P. Gupta, S. Biswas, A.K. Chaturwedi, U. Janghel, G. Tamrakar, R. Verma, M. Hait, Health Impact of Ground Water Sample and its Effect on Flora of Kanker District, Chhattisgarh, India. ES Food Agrofor. 13, 940 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esfaf940

29. SC. Izah, L. Sylva, M. Hait, Cronbach’s Alpha: A Cornerstone in Ensuring Reliability and Validity in Environmental Health Assessment. ES Energy & Environ. 3, 1057 (2024). https://doi. org/10.30919/esee31057

30. X. Wang, Y. Qi, Z. Hu, L. Jiang, F. Pan, Z. Xiang, Z. Xiong, W. Jia, J. Hu, W. Lu,

31. J. Liu, K. Liu, X. Pan, K. Bi, F. Zhou, P. Lu, M. Lei, A flexible semidry electrode for long-term, high-quality electrocardiogram monitoring. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 13 (2022). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00596-y

32. Y. Shen, W. Yang, F. Hu, X. Zheng, Y. Zheng, H. Liu, H. Algadi, K. Chen, Ultrasensitive wearable strain sensor for promising application in cardiac rehabilitation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 21 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00610-3

33. A. Huang, Y. Guo, Y. Zhu, T. Chen, Z. Yang, Y. Song, P. Wasnik, H. Li, S. Peng, Z. Guo, X. Peng, Durable washable wearable antibacterial thermoplastic polyurethane/carbon nanotube@silver nanoparticles electrospun membrane strain sensors by multiconductive network. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 101 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00684-7

34. Q. Xu, Z. Wu, W. Zhao, M. He, N. Guo, L. Weng, Z. Lin, M.F.A. Taleb, M.M. Ibrahim, M.V. Singh, J. Ren, Z.M. El-Bahy, Strategies in the preparation of conductive polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels for applications in flexible strain sensors, flexible supercapacitors,

and triboelectric nanogenerator sensors: an overview. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 203 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00783-5

35. O.S.S.S. Chowdary, N. Naik, V. Patil, K. Adhikari, B.M.Z. Hameed, B.P. Rai, B.K. Somani, 5G technology is the future of Healthcare: opening up a New Horizon for Digital Transformation in Healthcare Landscape. ES Gen. 2, 1010 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.30919/esg1010

36. B. Fei, D. Wang, N. Almasoud, H. Yang, J. Yang, T.S. Alomar, B. Puangsin, B.B. Xu, H. Algadi, Z.M. El-Bahy, Z. Guo, Z. Shi, Bamboo fiber strengthened poly(lactic acid) composites with enhanced interfacial compatibility through a multi-layered coating of synergistic treatment strategy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 249, 126018 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126018

37. B. Fei, H. Yang, J. Yang, D. Wang, H. Guo, H. Hou, S. Melhi, B.B. Xu, H.K. Thabet, Z. Guo, Z. Shi, Sustainable compressionmolded bamboo fibers/poly(lactic acid) green composites with excellent UV shielding performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2024.03.074

38. S. Ge, G. Zheng, Y. Shi, Z. Zhang, A. Jazzar, X. He, S. Donkor, Z. Guo, D. Wang, B.B. Xu, Facile fabrication of high-strength biocomposite through

39. D. Wang, H. Yang, J. Yang, B. Wang, P. Wasnik, B.B. Xu, Z. Shi, Efficient visible light-induced photodegradation of industrial lignin using silver- CuO catalysts derived from Cu -metal organic framework. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 138 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00708-2

40. Y. Yang, L. Zhang, J. Zhang, Y. Ren, H. Huo, X. Zhang, K. Huang, M. Rezakazemi, Z. Zhang, Fabrication of environmentally, high-strength, fire-retardant biocomposites from smalldiameter wood lignin in situ reinforced cellulose matrix. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 140 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00721-5

41. M. Culebras, G.A. Collins, A. Beaucamp, H. Geaney, M.N. Collins, Lignin/Si Hybrid Carbon nanofibers towards highly efficient sustainable Li-ion anode materials. Eng. Sci. 17, 195-203 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d608

42. Y. Tian, L. Zhong, X. Sheng, X. Zhang, Corrosion inhibition property and promotion of green basil leaves extract materials on

43. R. Scaffaro, A. Maio, M. Gammino, Hybrid biocomposites based on polylactic acid and natural fillers from Chamaerops humilis dwarf palm and Posidonia oceanica leaves. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 5, 1988-2001 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00534-y

44. X.-Y. Ye, Y. Chen, J. Yang, H.-Y. Yang, D.-W. Wang, B.B. Xu, J. Ren, D. Sridhar, Z. Guo, Z.-J. Shi, Sustainable wearable infrared shielding bamboo fiber fabrics loaded with antimony doped tin oxide/silver binary nanoparticles. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 106 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00683-8

45. S. Rakesh, A.K. Pandey, A. Roy, Assessment of secondary metabolites, In-Vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of root of Argemone mexicana L. ES Food Agrofor. 15, 1007 (2024). https://doi.org/10.30919/esfaf1007

46. J. Cai, S. Xi, C. Zhang, X. Li, M.H. Helal, Z.M. El-Bahy, M.M. Ibrahim, H. Zhu, M.V. Singh, P. Wasnik, B.B. Xu, Z. Guo, H. Algadi, J. Guo, Overview of biomass valorization: case study of nanocarbons, biofuels and their derivatives. J. Agric. Food Res. 14, 100714 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr. 2023.100714

47. K. Zhao, X.Y. Wu, G.Q. Han, L. Sun, C.W. Zheng, H. Hou, Z.M. El-Bahy, C. Qian, M. Kallel, H. Algadi, Z.H. Guo, Z.J. Shi, Phyllostachys nigra (Lodd. Ex Lindl.) Derived polysaccharide with enhanced glycolipid metabolism regulation and mice gut

microbiome. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 257, 128588 (2024). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128588

48. A. Kaur, M.V. Singh, N. Bhatt, S. Arora, A. Shukla, Exploration of Chemical Composition and Biological activities of the essential oil from Ehretia acuminata R. Br. Fruit. ES Food Agrofor. 15, 1068 (2024). https://doi.org/10.30919/esfaf1068

49. D. Pal, S. Thakur, T. Sahu, M. Hait, Exploring the Anticancer potential and phytochemistry of Moringa oleifera: a multi-targeted Medicinal Herb from Nature. ES Food Agrofor. 14, 982 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esfaf982

50. K. Sur, A. Kispotta, N.N. Kashyap, AK. Das, J. Dutta, M. Hait, G. Roymahapatra, R. Jain, T. Akitsu, Physicochemical, Phytochemical and Pharmacognostic Examination of Samanea saman. ES Food Agrofor. 14, 1011 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esfaf1011

51. J. Xu, R. Liu, L. Wang, A. Pranovich, J. Hemming, L. Dai, C. Xu, C. Si, Towards a deep understanding of the biomass fractionation in respect of lignin nanoparticle formation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 214 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00797-z

52. B. Wang, Y. Kuang, M. Li, X. Wang, X. Zhang, Q. Rao, B. Yuan, S. Yang, Magnetic surface molecularly imprinted polymers for efficient selective recognition and targeted separation of daidzein. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 196 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1007/s42114-023-00775-5

53. T.L. Ersedo, T.A. Teka, S.F. Forsido, E. Dessalegn, J.A. Adebo, M. Tamiru, T. Astatkie, Food flavor enhancement, preservation, and bio-functionality of ginger (Zingiber officinale): a review. Int. J. Food Prop. 26, 928-951 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/10942 912.2023.2194576

54. M. Crichton, S. Marshall, W. Marx, E. Isenring, A. Lohning, Therapeutic health effects of ginger (Zingiber officinale): updated narrative review exploring the mechanisms of action. Nutr. Rev. 81, 1213-1224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuac115

55. Z. Peng, Y. Zeng, Q. Tan, Q.F. He, S. Wang, J.W. Wang, 6-Gingerol alleviates ectopic lipid deposition in skeletal muscle by regulating CD36 translocation and mitochondrial function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 708, 149786 (2024). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.149786

56. J. Ahn, H. Lee, C.H. Jung, S.Y. Ha, H.D. Seo, Y.I. Kim, T. Ha, 6-Gingerol ameliorates hepatic steatosis via

57. J. Li, S. Wang, L. Yao, P. Ma, Z. Chen, T.L. Han, C. Yuan, J. Zhang, L. Jiang, L. Liu, D. Ke, C. Li, J. Yamahara, Y. Li, J. Wang, 6-gingerol ameliorates age-related hepatic steatosis: Association with regulating lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 362, 125-135 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2018.11.001

58. U. Sen, C. Coleman, T. Sen, Stearoyl coenzyme a desaturase-1: multitasker in cancer, metabolism, and ferroptosis. Trends Cancer. 9, 480-489 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2023.03.003

59. J. Wang, L. Wang, X.J. Zhang, P. Zhang, J. Cai, Z.G. She, H. Li , Recent updates on targeting the molecular mediators of NAFLD. J. Mol. Medicine-Jmm. 101, 101-124 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s00109-022-02282-4

60. S.M. Jeyakumar, A. Vajreswari, Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1: a potential target for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease?-perspective on emerging experimental evidence. World J. Hepatol. 14, 168179 (2022). https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i1. 168

61. D. Bhattacharya, B. Basta, J.M. Mato, A. Craig, D. FernandezRamos, F. Lopitz-Otsoa, D. Tsvirkun, L. Hayardeny, V. Chandar, R.E. Schwartz, A. Villanueva, S.L. Friedman, Aramchol downregulates stearoyl CoA-desaturase 1 in hepatic stellate cells to attenuate cellular fibrogenesis. Jhep Rep. 3, 100237 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100237

62. V. Ratziu, De L. Guevara, R. Safadi, F. Poordad, F. Fuster, J. Flores-Figueroa, M. Arrese, A.L. Fracanzani, D. Ben Bashat, K. Lackner, T. Gorfine, S. Kadosh, R. Oren, M. Halperin, L. Hayardeny, R. Loomba, S. Friedman, A.I.S. Group, A.J. Sanyal, Aramchol in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Nat. Med. 27, 1825-1835 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01495-3

63. M.G. Carnuta, M. Deleanu, T. Barbalata, L. Toma, M. Raileanu, A.V. Sima, C.S. Stancu, Zingiber officinale extract administration diminishes steroyl-CoA desaturase gene expression and activity in hyperlipidemic hamster liver by reducing the oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Phytomedicine. 48, 62-69 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2018.04.059

64. Q. Li, L.M. Qi, K. Zhao, W. Ke, T.T. Li, L.A. Xia, Integrative quantitative and qualitative analysis for the quality evaluation and monitoring of Danshen medicines from different sources using HPLC-DAD and NIR combined with chemometrics. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 932855 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.932855

65. Y.Y. Zhu, W. Xiang, Y. Shen, Y.A. Jia, Y.S. Zhang, L.S. Zeng, J.X. Chen, Y. Zhou, X. Xue, X.Z. Huang, L. Xu, New butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor derived from mulberry twigs, a kind of agricultural byproducts. Ind. Crops Prod. 187, 115535 (2022). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115535

66. M. Nodehi, A. Kiasadr, G. Babaee Bachevanlo, Modified glassy carbon electrode with mesoporous Silica-Metformin/MultiWalled carbon nanotubes as a biosensor for ethinylestradiol detection. Mater. Chem. Horizons. 1, 219-230 (2022). https://doi. org/10.22128/mch.2022.601.1024

67. Y. Niu, X. Li, C. Wu, Z. Shi, X. Lin, H.M.A. Mahmoud, E.M.A. Widaa, H. Algadi, B.B. Xu, Z. Wang, Chemical composition, pharmacodynamic activity of processed Aconitum Brachypodum Diels., and molecular docking analysis of its active target. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 75 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00640-5

68. G. Roymahapatra, S. Pradhan, S. Sato, D. Nakane, M. Hait, S. Bhattacharyya, R. Saha, T. Akitsu, Computational study on Docking of Laccase and Cyanide-Bridged Ag-Cu Complex for Designing the Improved Biofuel Cell Cathode. ES Energy Environ. 21, 957 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee957

69. M.I. Abdjan, N.S. Aminah, A.N. Kristanti, I. Siswanto, M.A. Saputra, Y. Takaya, Pharmacokinetic, DFT modeling, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation approaches: Diptoindonesin A as a potential inhibitor of Sirtuin-1. Eng. Sci. 21, 794 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d794

70. H. Long, S. Ryu, X.-L. Zheng, L.-S. Zhang, L.-Y. Li, Z.-S. Zhang, Peptide L1H9 derived from the interaction of structural human rhomboid family 1 and

71. R.C. Shivamurthy, S.R.B.H.S.K. Brn M, S S, S EN, Comparative Genomics based putative drug targets identification, homology modeling, virtual screening and molecular Docking studies in Chlamydophila Pneumoniae. Eng. Sci. 19, 125-135 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d645

72. X.W. Shi, L. Xu, J.Q. Zhang, J.F. Mo, P. Zhuang, L. Zheng, Oxyresveratrol from mulberry branch extract protects HUVECs against oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced oxidative injury via activation of the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway. J. Funct. Foods. 100, 105371 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2022.105371

73. Y. Huang, H. Wang, H. Wang, R. Wen, X. Geng, T. Huang, J. Shi, X. Wang, J. Wang, Structure-based virtual screening of natural products as potential stearoyl-coenzyme a desaturase 1 (SCD1) inhibitors. Comput. Biol. Chem. 86, 107263 (2020). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2020.107263

74. Y. Yi, C. Zhao, H.L. Shindume, J. Ren, L. Chen, H. Hou, M.M. Ibrahim, Z.M. El-Bahy, Z. Guo, Z. Zhao, J. Gu, Enhanced

electromagnetic wave absorption of magnetite-spinach derived carbon composite. Colloids Surf., a 694, 134149 (2024). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.134149

75. I. Galarreta-Rodriguez, A. Lopez-Ortega, E. Garayo, J.J. BeatoLópez, La P. Roca, V. Sanchez-Alarcos, V. Recarte, C. GómezPolo, J.I. Pérez-Landazábal, Magnetically activated 3D printable polylactic acid/polycaprolactone/magnetite composites for magnetic induction heating generation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 102 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00687-4

76. K. Zhou, Y. Sheng, W. Guo, L. Wu, H. Wu, X. Hu, Y. Xu, Y. Li, M. Ge, Y. Du, X. Lu, J. Qu, Biomass porous carbon/polyethylene glycol shape-stable phase change composites for multisource driven thermal energy conversion and storage. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 34 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00620-1

77. J. Lu, Y. Yang, Y. Zhong, Q. Hu, B. Qiu, The study on activated Carbon, Magnetite, Polyaniline and Polypyrrole Development of Methane Production Improvement from Wastewater Treatment. ES Food Agrofor. 10, 30-38 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esfaf802

78. E.A. Dil, A.H. Doustimotlagh, H. Javadian, A. Asfaram, M. Ghaedi, Nano-sized

79. Y. Tao, X.H. Gu, W.D. Li, B.C. Cai, Fabrication and evaluation of magnetic phosphodiesterase-5 linked nanoparticles as adsorbent for magnetic dispersive solid-phase extraction of inhibitors from Chinese herbal medicine prior to ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 1532, 58-67 (2018). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.chroma.2017.11.062

80. F.S. Feng, W. Xiang, H. Gao, Y.A. Jia, Y.S. Zhang, L.S. Zeng, J.X. Chen, X.Z. Huang, L. Xu, Rapid screening of nonalkaloid alpha-glucosidase inhibitors from a Mulberry twig extract using enzyme-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles coupled with UPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 70, 11958-11966 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.2c03435

81. X. Xu, Y. Guo, M. Chen, N. Li, Y. Sun, S. Ren, J. Xiao, D. Wang, X. Liu, Y. Pan, Hypoglycemic activities of flowers of Xanthoceras sorbifolia and identification of anti-oxidant components by off-line UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS-free radical scavenging detection. Chin. Herb. Med. 16, 151-161 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. chmed.2022.11.009

82. L. Zhong, R. Wang, Q.H. Wen, J. Li, J.W. Lin, X.A. Zeng, The interaction between bovine serum albumin and [6]-,[8]- and [10]-gingerol: an effective strategy to improve the solubility and stability of gingerol. Food Chem. 372, 131280 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131280

83. K.R. Kou, X.Q. Wang, R.Y. Ji, L. Liu, Y.N. Qiao, Z.X. Lou, C.Y. Ma, S.M. Li, H.X. Wang, C.T. Ho, Occurrence, biological activity and metabolism of 6-shogaol. Food Funct. 9, 1310-1327 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7fo01354j

84. S.M. Sang, H.D. Snook, F.S. Tareq, Y. Fasina, Precision research on Ginger: the type of ginger matters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 8517-8523 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c03888

85. S. Salaramoli, S. Mehri, F. Yarmohammadi, S.I. Hashemy, H. Hosseinzadeh, The effects of ginger and its constituents in the prevention of metabolic syndrome: a review. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 25, 664-674 (2022). https://doi.org/10.22038/ IJBMS.2022.59627.13231

86. J. Chen, S. Lv, B. Huang, X. Ma, S. Fu, Y. Zhao, Upregulation of SCD1 by ErbB2 via LDHA promotes breast cancer cell migration and invasion. Med. Oncol. 40, 40 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12032-022-01904-8

87. Y. Zhang, Z. Gu, J. Wan, X. Lou, S. Liu, Y. Wang, Y. Bian, F. Wang, Z. Li, Z. Qin, Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase-1 dependent lipid droplets accumulation in cancer-associated fibroblasts facilitates the progression of lung cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 6114-6128 (2022). https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs. 74924

88. Z. Salari, A. Khosravi, E. Pourkhandani, E. Molaakbari, E. Salarkia, A. Keyhani, I. Sharifi, H. Tavakkoli, S. Sohbati, S. Dabiri, G. Ren, M. Shafie’ei, The inhibitory effect of 6-gingerol and cisplatin on ovarian cancer and antitumor activity: In silico, in vitro, and in vivo. Frontiers in oncology 13, 1098429 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1098429

89. M.K. Ediriweera, J.Y. Moon, Y.T.K. Nguyen, S.K. Cho, 10-Gingerol targets lipid rafts associated PI3K/Akt signaling in radioresistant triple negative breast cancer cells. Molecules. 25, 3164 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25143164

90. J.H. Joo, S.S. Hong, Y.R. Cho, D.W. Seo, 10-Gingerol inhibits proliferation and invasion of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through suppression of akt and p38(MAPK) activity. Oncol. Rep. 35, 779-784 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2015.4405

91. M. Miyazaki, W.C. Man, J.M. Ntambi, Targeted disruption of stearoyl-CoA desaturasel gene in mice causes atrophy of sebaceous and meibomian glands and depletion of wax esters in the eyelid. J. Nutr. 131, 2260-2268 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1093/ jn/131.9.2260

92. Z. Zhang, N.A. Dales, M.D. Winther, Opportunities and challenges in developing stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase-1 inhibitors as novel therapeutics for human disease. J. Med. Chem. 57, 5039-5056 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/jm401516c

93. M.L.E. Macdonald, Van M. Eck, R.B. Hildebrand, B.W.C. Wong, N. Bissada, P. Ruddle, A. Kontush, H. Hussein, M.A. Pouladi, M.J. Chapman, C. Fievet, Van T.J.C. Berkel, B. Staels, B.M. Mcmanus, M.R. Hayden, Despite antiatherogenic metabolic characteristics, SCD1-deficient mice have increased inflammation and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 29, 341-347 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.108.181099

94. T. Iida, M. Ubukata, I. Mitani, Y. Nakagawa, K. Maeda, H. Imai, Y. Ogoshi, T. Hotta, S. Sakata, R. Sano, H. Morinaga, T. Negoro, S. Oshida, M. Tanaka, T. Inaba, Discovery of potent liver-selective stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1) inhibitors, thiazole-4-acetic acid derivatives, for the treatment of diabetes, hepatic steatosis, and obesity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 158, 832-852 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.09.003

- Zhanhu Guo

zhanhu.guo@northumbria.ac.uk

Wei Xiang

xiangwei@cqctcm.edu.cn

Jianwei Wang

wjwcq68@163.com

Chongqing Key Laboratory of Traditional Chinese Medicine for Prevention and Cure of Metabolic Diseases, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China

Chongqing college of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chongqing 402760, China - 3 Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, Pharmaceutical Analysis, KU Leuven – University of Leuven, Herestraat 49, O&N2, PB 923, Leuven 3000, Belgium4 College of Material Science and Chemical Engineering, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming 650224, China

5 Department of Mechanical and Civil Engineering, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST, UK

6 Department of Chemistry, College of Science, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif 21944, Saudi Arabia

7 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Nasr City, Cairo 11884, Egypt