DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-01146-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38172602

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-04

الفهم الحالي للميكروبيوم المرتبط بمرض الزهايمر والاستراتيجيات العلاجية

الملخص

مرض الزهايمر (AD) هو مرض تنكسي عصبي تقدمي قاتل. على الرغم من الجهود البحثية الهائلة لفهم هذا المرض المعقد، إلا أن الفيزيولوجيا المرضية الدقيقة للمرض ليست واضحة تمامًا. مؤخرًا، مضادات A

مقدمة

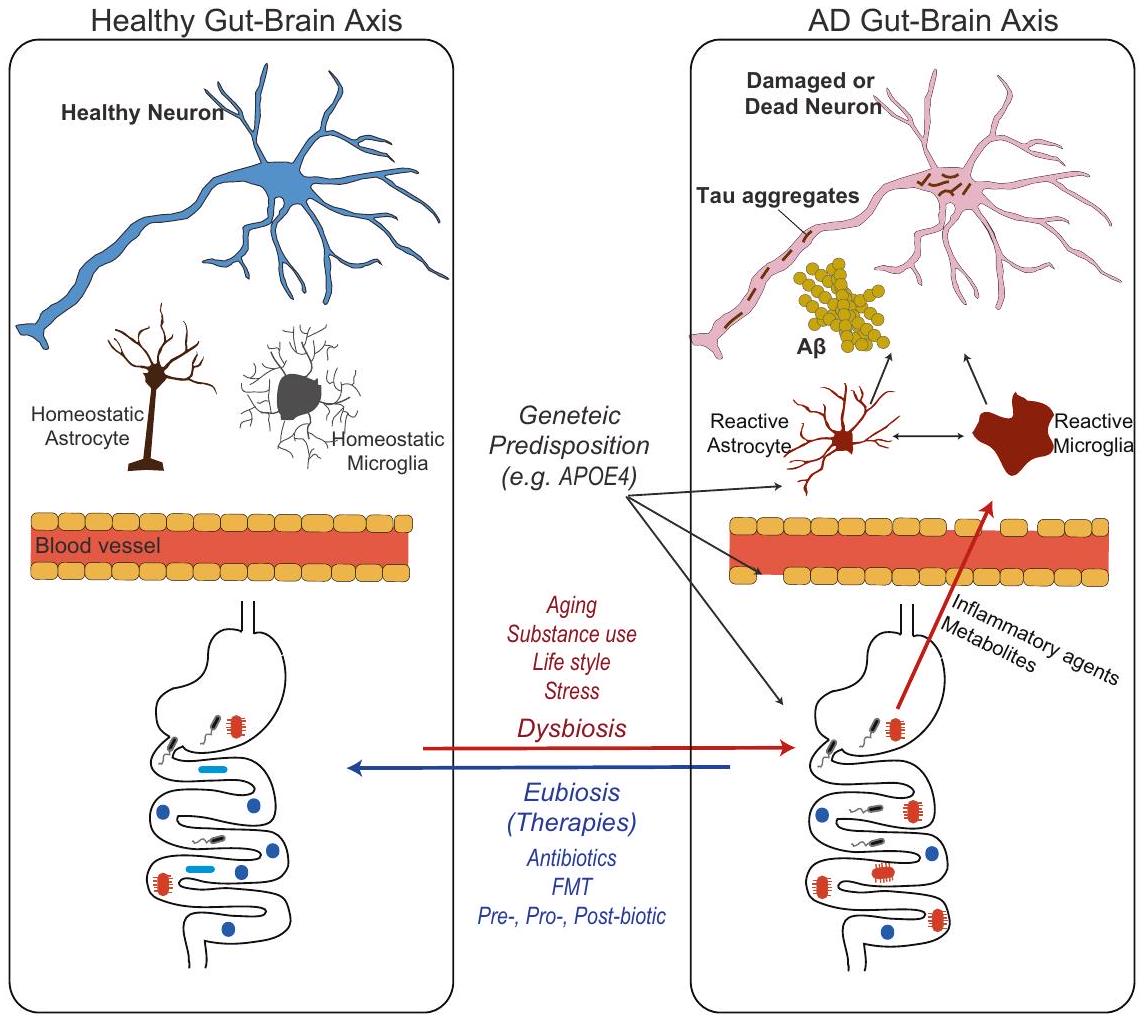

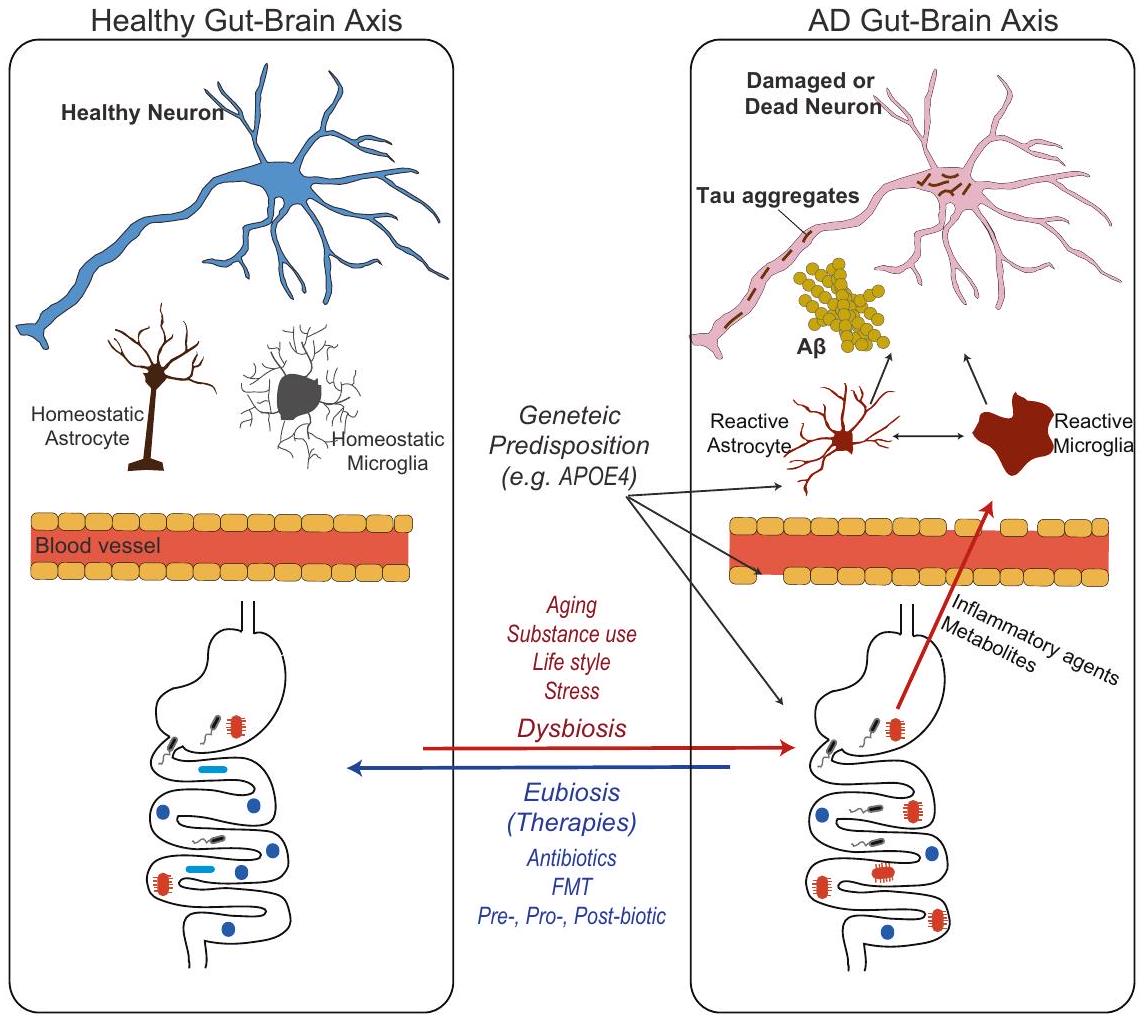

نظرة عامة على محور الميكروبيوتا-الأمعاء-الدماغ في مرض الزهايمر

توقيعات الميكروبيوتا المعوية المرتبطة بمرض الزهايمر. من ناحية أخرى، أدت التباينات والفشل في تحديد توقيعات تصنيفية واضحة مرتبطة بمرض الزهايمر إلى دفع المجال للتركيز على دراسة الأنشطة الوظيفية والتفاعلات للميكروبيوتا المعوية وعوامل أخرى تتجاوز التركيب التصنيفي (مثل علم الأيض).

الآليات الأساسية والالتهاب العصبي

لم يتضح المسار بعد. قد ينطوي تأثير الميكروبيوتا على مرض الزهايمر على مزيج من عدة مسارات وتفاعلات تساهم مجتمعة في أمراض الزهايمر بدلاً من مسار واحد فقط متورط في المحور. تطور الرأي حول دور الميكروبيوتا في المرض في اتجاهين مميزين في السنوات الأخيرة: (1) العدوى الميكروبية المباشرة في الجهاز العصبي المركزي و(2) المسارات غير المباشرة التي تشمل تعديل الجهاز المناعي المحيطي والجهاز الأيضي. تمثل هذه الاتجاهات وجهات نظر مختلفة وتؤكد على جوانب مميزة من علاقة ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء بالمرض.

العدوى الميكروبية المباشرة في الجهاز العصبي المركزي

المسار غير المباشر الذي ينظم الجهاز المناعي والأنظمة الأيضية الطرفية

مصحوبًا بانخفاض في أمراض الزهايمر (أي،

المستقلبات المشتقة من ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء: الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة وغيرها

الاختلافات الجينية للمضيف والفروق بين الجنسين

ما وراء الأمعاء والبكتيريا

يزيد من ترسيب اللويحات الشبيهة بمرض الزهايمر

الاستراتيجيات العلاجية

المضادات الحيوية

زرع الميكروبيوتا البرازية

البريبايوتكس، البروبيوتكس، والبروبيوتكس اللاحقة

يمكن للمضادات الحيوية أن يكون لها عواقب غير مقصودة على ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء، بما في ذلك اضطراب الميكروفلورا الطبيعية، مما يؤدي إلى نقص محتمل في العناصر الغذائية وإمكانية سيطرة مسببات الأمراض الانتهازية. وبالنظر إلى ذلك، فإن النهج البديل لإعادة تهيئة ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء غير المتوازنة هو إدخال البكتيريا المفيدة إلى الجهاز الهضمي. يتضمن هذا النهج استخدام البروبيوتيك (الكائنات الحية الدقيقة الحية التي، عند إعطائها بكميات كافية، تمنح فائدة صحية للمضيف؛ مثل بيفيدوباكتيريوم ولاكتوباسيلوس)، والبريبايوتكس (الألياف الخاصة التي تعزز نمو البكتيريا المفيدة؛ مثل الإينولين)، والبروبيوتيك (المواد التي تنتجها البكتيريا المفيدة أثناء نموها، والتي يمكن أن تفيد صحتنا مباشرة؛ مثل الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة).

بتمثيلها الأيضي. تساهم هذه العملية الأيضية المرتبطة بالميكروبيوتا في حالات صحية مختلفة من خلال إنتاج المستقلبات، وتخليق الفيتامينات، وتنظيم الجهاز المناعي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تؤدي هذه العمليات الأيضية أيضًا إلى تغييرات في تركيبة ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء، مما يعزز نمو البكتيريا المفيدة، ويؤثر على التنوع الميكروبي، ويؤثر على صحة المضيف

الخلاصة

لتعديل ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء بشكل أكثر انتقائية مفيدًا لتطوير الأساليب العلاجية: تشمل الأساليب التي تتضمن تغليف الميكروبات (حصر الخلايا الميكروبية داخل مصفوفة بوليمرية واقية)، والفيروسات البكتيرية (التي تستهدف وتزيل بكتيريا معينة بشكل انتقائي)، ومنظمات إنزيمات الميكروبات (التي تعدل نشاط إنزيمات ميكروبية محددة لإبطاء أو منع تفاعلات كيميائية حيوية معينة)، وميكروبات مهندسة حيويًا لإنتاج مستقلبات مفيدة، وهي في طور الظهور في هذا المجال. يمكن أن تؤدي هذه الأساليب إلى تدخلات ذات إطلاق محكم ومستهدف لاستعادة التوازن والوظيفة الميكروبية في الأمعاء بكفاءة.

REFERENCES

- Long, J. & Holtzman, D. M. Alzheimer disease: an update on pathobiology and treatment strategies. Cell 179, 312-339 (2019).

- Agirman, G., Yu, K. B. & Hsiao, E. Y. Signaling inflammation across the gut-brain axis. Science 374, 1087-1092 (2021).

- Seo, D. O. & Holtzman, D. M. Gut microbiota: from the forgotten organ to a potential key player in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 1232-1241 (2020).

- Moore, A. M., Mathias, M. & Valeur, J. Contextualising the microbiota-gut-brain axis in history and culture. Micro. Ecol. Health Dis. 30, 1546267 (2019).

- Bharti, R. & Grimm, D. G. Current challenges and best-practice protocols for microbiome analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 178-193 (2021).

- Cattaneo, A. et al. Association of brain amyloidosis with pro-inflammatory gut bacterial taxa and peripheral inflammation markers in cognitively impaired elderly. Neurobiol. Aging 49, 60-68 (2017).

- Vogt, N. M. et al. Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 7, 13537 (2017).

- Jemimah, S., Chabib, C. M. M., Hadjileontiadis, L. & AlShehhi, A. Gut microbiome dysbiosis in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 18, e0285346 (2023).

- Ferreiro, A. L. et al. Gut microbiome composition may be an indicator of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabo2984 (2023).

- Zhuang, Z. Q. et al. Gut microbiota is altered in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 63, 1337-1346 (2018).

- Brandscheid, C. et al. Altered gut microbiome composition and tryptic activity of the 5xFAD Alzheimer’s mouse model. J. Alzheimers Dis. 56, 775-788 (2017).

- Chen, C. et al. Gut microbiota regulate Alzheimer’s disease pathologies and cognitive disorders via PUFA-associated neuroinflammation. Gut 71, 2233-2252 (2022).

- Sun, B. L. et al. Gut microbiota alteration and its time course in a tauopathy mouse model. J. Alzheimers Dis. 70, 399-412 (2019).

- Ursell, L. K. et al. The interpersonal and intrapersonal diversity of humanassociated microbiota in key body sites. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129, 1204-1208 (2012).

- Human, M. P. C. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486, 207-214 (2012).

- Turnbaugh, P. J. et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 457, 480-484 (2009).

- Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K. & Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489, 220-230 (2012).

- Fetzer, I. et al. The extent of functional redundancy changes as species’ roles shift in different environments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14888-14893 (2015).

- Harach, T. et al. Reduction of Abeta amyloid pathology in APPPS1 transgenic mice in the absence of gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 7, 41802 (2017).

- Dodiya, H. B. et al. Sex-specific effects of microbiome perturbations on cerebral

amyloidosis and microglia phenotypes. J. Exp. Med. 216, 1542-1560 (2019). - Wang, X. L. et al. Helicobacter pylori filtrate impairs spatial learning and memory in rats and increases

-amyloid by enhancing expression of presenilin-2. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 66 (2014). - Kim, M. S. et al. Transfer of a healthy microbiota reduces amyloid and tau pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Gut 69, 283-294 (2020).

- Seo, D. O. et al. ApoE isoform- and microbiota-dependent progression of neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Science 379, eadd1236 (2023).

- Koyuncu, O. O., Hogue, I. B. & Enquist, L. W. Virus infections in the nervous system. Cell Host Microbe 13, 379-393 (2013).

- Itzhaki, R. F. et al. Microbes and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 51, 979-984 (2016).

- Seaks, C. E. & Wilcock, D. M. Infectious hypothesis of Alzheimer disease. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008596 (2020).

- Readhead, B. et al. Multiscale analysis of independent Alzheimer’s cohorts finds disruption of molecular, genetic, and clinical networks by human herpesvirus. Neuron 99, 64-82.e7 (2018).

- Tzeng, N. S. et al. Anti-herpetic medications and reduced risk of dementia in patients with herpes simplex virus infections-a nationwide, population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Neurotherapeutics 15, 417-429 (2018).

- Senejani, A. G. et al. Borrelia burgdorferi Co-Localizing with Amyloid Markers in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Tissues. J. Alzheimers Dis. 85, 889-903 (2022).

- Chacko, A. et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae can infect the central nervous system via the olfactory and trigeminal nerves and contributes to Alzheimer’s disease risk. Sci. Rep. 12, 2759 (2022).

- Dominy, S. S. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3333 (2019).

- Moir, R. D., Lathe, R. & Tanzi, R. E. The antimicrobial protection hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 1602-1614 (2018).

- Eimer, W. A. et al. Alzheimer’s disease-associated

-amyloid is rapidly seeded by herpesviridae to protect against brain infection. Neuron 99, 56-63.e3 (2018). - Wu, Y. et al. Microglia and amyloid precursor protein coordinate control of transient Candida cerebritis with memory deficits. Nat. Commun. 10, 685 (2019).

- Thapa, M. et al. Translocation of gut commensal bacteria to the brain. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.30.555630 (2023).

- Friedland, R. P. & Chapman, M. R. The role of microbial amyloid in neurodegeneration. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006654 (2017).

- Schäfer, K. H., Christmann, A. & Gries, M. Intra-gastrointestinal amyloid-

oligomers perturb enteric function and induce Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J. Physiol. 598, 4141-4142 (2020). - Jin, J. et al. Gut-derived

-amyloid: Likely a centerpiece of the gut-brain axis contributing to Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Gut Microbes 15, 2167172 (2023). - Shi, Y. & Holtzman, D. M. Interplay between innate immunity and Alzheimer disease: APOE and TREM2 in the spotlight. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 759-772 (2018).

- Brandebura, A. N., Paumier, A., Onur, T. S. & Allen, N. J. Astrocyte contribution to dysfunction, risk and progression in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 23-39 (2023).

- Erny, D. et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 965-977 (2015).

- Thion, M. S. et al. Microbiome influences prenatal and adult microglia in a sexspecific manner. Cell 172, 500-516.e16 (2018).

- Hanamsagar, R. et al. Generation of a microglial developmental index in mice and in humans reveals a sex difference in maturation and immune reactivity. Glia 66, 460 (2018).

- Matcovitch-Natan, O. et al. Microglia development follows a stepwise program to regulate brain homeostasis. Science 353, aad8670 (2016).

- Spichak, S. et al. Microbially-derived short-chain fatty acids impact astrocyte gene expression in a sex-specific manner. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 16, 100318 (2021).

- Erny, D. et al. Microbiota-derived acetate enables the metabolic fitness of the brain innate immune system during health and disease. Cell Metab. 33, 2260-2276.e7 (2021).

- Mezö, C. et al. Different effects of constitutive and induced microbiota modulation on microglia in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 8, 119 (2020).

- Dodiya, H. B. et al. Gut microbiota-driven brain

amyloidosis in mice requires microglia. J. Exp. Med. 219, e20200895 (2022). - Hou, K. et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 135 (2022).

- Marizzoni, M. et al. A peripheral signature of Alzheimer’s disease featuring microbiota-gut-brain axis markers. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 101 (2023).

- Bettcher, B. M., Tansey, M. G., Dorothée, G. & Heneka, M. T. Peripheral and central immune system crosstalk in Alzheimer disease-a research prospectus. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 17, 689-701 (2021).

- Minter, M. R. et al. Antibiotic-induced perturbations in gut microbial diversity influences neuro-inflammation and amyloidosis in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 30028 (2016).

- Köhler, C. A. et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 135, 373-387 (2017).

- Bell, R. D. et al. Apolipoprotein E controls cerebrovascular integrity via cyclophilin A. Nature 485, 512-516 (2012).

- Montagne, A. et al. APOE4 accelerates advanced-stage vascular and neurodegenerative disorder in old Alzheimer’s mice via cyclophilin A independently of amyloid-

. Nat. Aging 1, 506-520 (2021). - Tang, Y., Chen, Y., Jiang, H. & Nie, D. Short-chain fatty acids induced autophagy serves as an adaptive strategy for retarding mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 18, 602-618 (2011).

- den Besten, G. et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 54, 2325-2340 (2013).

- Boland, B. et al. Autophagy induction and autophagosome clearance in neurons: relationship to autophagic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 28, 6926-6937 (2008).

- Bonfili, L. et al. Microbiota modulation counteracts Alzheimer’s disease progression influencing neuronal proteolysis and gut hormones plasma levels. Sci. Rep. 7, 2426 (2017).

- Choi, H. & Mook-Jung, I. Functional effects of gut microbiota-derived metabolites in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 81, 102730 (2023).

- Dalile, B., Van Oudenhove, L., Vervliet, B. & Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 461-478 (2019).

- Smith, P. M. et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 341, 569-573 (2013).

- Arpaia, N. et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 504, 451-455 (2013).

- Alves de Lima, K. et al. Meningeal

T cells regulate anxiety-like behavior via IL17a signaling in neurons. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1421-1429 (2020). - van der Hee, B. & Wells, J. M. Microbial regulation of host physiology by shortchain fatty acids. Trends Microbiol. 29, 700-712 (2021).

- Sadler, R. et al. Short-chain fatty acids improve poststroke recovery via immunological mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 40, 1162-1173 (2020).

- McMurran, C. E. et al. The microbiota regulates murine inflammatory responses to toxin-induced CNS demyelination but has minimal impact on remyelination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25311-25321 (2019).

- Abdel-Haq, R. et al. A prebiotic diet modulates microglial states and motor deficits in a-synuclein overexpressing mice. Elife 11, e81453 (2022).

- Fernando, W. M. A. D. B. et al. Sodium butyrate reduces brain amyloid-

levels and improves cognitive memory performance in an Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mouse model at an early disease stage. J. Alzheimers Dis. 74, 91-99 (2020). - Jiang, Y., Li, K., Li, X., Xu, L. & Yang, Z. Sodium butyrate ameliorates the impairment of synaptic plasticity by inhibiting the neuroinflammation in 5XFAD mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 341, 109452 (2021).

- Cuervo-Zanatta, D. et al. Dietary fiber modulates the release of gut bacterial products preventing cognitive decline in an Alzheimer’s mouse model. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 43, 1595-1618 (2023).

- Killingsworth, J., Sawmiller, D. & Shytle, R. D. Propionate and Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 580001 (2020).

- Baloni, P. et al. Metabolic network analysis reveals altered bile acid synthesis and metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep. Med. 1, 100138 (2020).

- Connell, E. et al. Microbial-derived metabolites as a risk factor of age-related cognitive decline and dementia. Mol. Neurodegener. 17, 43 (2022).

- Vogt, N. M. et al. The gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N -oxide is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 10, 124 (2018).

- Maier, L. et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 555, 623-628 (2018).

- Rothschild, D. et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 555, 210-215 (2018).

- Parikh, I. J. et al. Murine gut microbiome association with APOE alleles. Front. Immunol. 11, 200 (2020).

- Maldonado Weng, J. et al. Synergistic effects of APOE and sex on the gut microbiome of young EFAD transgenic mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 47 (2019).

- Tran, T. T. T. et al. APOE genotype influences the gut microbiome structure and function in humans and mice: relevance for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. FASEB J. 33, 8221-8231 (2019).

- Vitek, M. P., Brown, C. M. & Colton, C. A. APOE genotype-specific differences in the innate immune response. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 1350-1360 (2009).

- Klein, S. L. & Flanagan, K. L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 626-638 (2016).

- Colton, C. A., Brown, C. M. & Vitek, M. P. Sex steroids, APOE genotype and the innate immune system. Neurobiol. Aging 26, 363-372 (2005).

- Hosang, L. et al. The lung microbiome regulates brain autoimmunity. Nature 603, 138-144 (2022).

- Seo, D. O., Boros, B. D. & Holtzman, D. M. The microbiome: a target for Alzheimer disease. Cell Res. 29, 779-780 (2019).

- Francino, M. P. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1543 (2015).

- Rakuša, E., Fink, A., Tamgüney, G., Heneka, M. T. & Doblhammer, G. Sporadic use of antibiotics in older adults and the risk of dementia: a nested case-control study based on German Health Claims Data. J. Alzheimers Dis. 93, 1329-1339 (2023).

- Hazan, S. Rapid improvement in Alzheimer’s disease symptoms following fecal microbiota transplantation: a case report. J. Int. Med. Res. 48, 300060520925930 (2020).

- Park, S. H. et al. Cognitive function improvement after fecal microbiota transplantation in Alzheimer’s dementia patient: a case report. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 37, 1739-1744 (2021).

- Park, S. H. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation can improve cognition in patients with cognitive decline and Clostridioides difficile infection. Aging (Albany NY) 14, 6449-6466 (2022).

- Akhgarjand, C., Vahabi, Z., Shab-Bidar, S., Etesam, F. & Djafarian, K. Effects of probiotic supplements on cognition, anxiety, and physical activity in subjects with mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 1032494 (2022).

- He, X. et al. The preventive effects of probiotic Akkermansia muciniphila on Dgalactose/AICI3 mediated Alzheimer’s disease-like rats. Exp. Gerontol. 170, 111959 (2022).

- Zhu, G., Zhao, J., Wang, G. & Chen, W. Bifidobacterium breve HNXY26M4 attenuates cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation by regulating the gut-brain axis in APP/PS1 mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 4646-4655 (2023).

- Bicknell, B. et al. Neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases and the gut-brain axis: the potential of therapeutic targeting of the microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9577 (2023).

- Lancaster, S. M. et al. Global, distinctive, and personal changes in molecular and microbial profiles by specific fibers in humans. Cell Host Microbe 30, 848-862.e7 (2022).

- Sonnenburg, J. L. & Bäckhed, F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 535, 56-64 (2016).

- Wang, X. et al. Sodium oligomannate therapeutically remodels gut microbiota and suppresses gut bacterial amino acids-shaped neuroinflammation to inhibit Alzheimer’s disease progression. Cell Res. 29, 787-803 (2019).

الشكر والتقدير

تضارب المصالح

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إعادة الطبع والإذن متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/ إعادة الطبع

© المؤلف(ون) 2023

قسم الأعصاب، مركز هوب للاضطرابات العصبية، مركز نايت لأبحاث مرض الزهايمر، كلية الطب بجامعة واشنطن، سانت لويس، ميزوري 63110، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: seo.biome@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-01146-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38172602

Publication Date: 2024-01-04

Current understanding of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated microbiome and therapeutic strategies

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a fatal progressive neurodegenerative disease. Despite tremendous research efforts to understand this complex disease, the exact pathophysiology of the disease is not completely clear. Recently, anti-A

INTRODUCTION

OVERVIEW OF THE MICROBIOTA-GUT-AD BRAIN AXIS

signatures of AD-associated gut microbiota. On the other hand, the inconsistency and failure to identify clear taxonomic signatures associated with AD have prompted the field to focus on investigating the functional activities and interactions of the gut microbiota and other factors beyond taxonomic composition (e.g., metabolomics).

UNDERLYING MECHANISMS AND NEUROINFLAMMATION

tract is not yet clear. The influence of the microbiota on AD might involve a combination of multiple pathways and interactions collectively contributing to AD pathologies rather than a single pathway involved in the axis. The view on the role of the microbiota in the disease has evolved in two distinct directions in recent years: (1) direct microbial infection in the central nervous system and (2) indirect pathways involving the modulation of the peripheral immune and metabolic systems. These directions represent different perspectives and emphasize distinct aspects of the gut microbiota-disease relationship.

Direct microbial infection in the central nervous system

Indirect pathway modulating the peripheral immune and metabolic systems

accompanying the reduction in AD pathologies (i.e.,

GUT MICROBIOTA-DERIVED METABOLITES: SCFAS AND OTHERS

HOST GENETIC VARIANTS AND SEX DIFFERENCES

BEYOND THE GUT AND BACTERIA

increases the deposition of AD-like plaques

THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES

Antibiotics

Fecal microbiota transplantation

Prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics

antibiotics can have unintended consequences on the gut microbiota, including a disruption of the normal microflora, leading to potential nutrient shortages and the possibility of opportunistic pathogens taking over. In consideration of this, an alternative approach to recondition the imbalanced gut microbiota is the introduction of beneficial bacteria to the GI tract. This approach involves the use of probiotics (live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host; e.g., Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus), prebiotics (special fibers that promote the growth of beneficial bacteria; e.g., inulin), and postbiotics (substances produced by beneficial bacteria during their growth, which can directly benefit our health; e.g., SCFAs).

metabolize them. This microbiota-associated metabolic process contributes to various health conditions by producing metabolites, synthesizing vitamins, and modulating the immune system. In addition, these metabolic processes also lead to changes in the gut microbiota composition, promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria, influencing microbial diversity, and affecting host health

CONCLUSION

techniques for modulating the gut microbiota more selectively would be beneficial for advancing therapeutic approaches: Approaches involving microbial encapsulation (enclosing microbial cells within a protective polymeric matrix), bacteriophages (selectively targeting and eliminating specific bacteria), microbial enzyme modulators (modulating the activity of specific microbial enzymes to slow down or prevent certain biochemical reactions), and other bioengineered microbes to produce beneficial metabolites are emerging in this field. These approaches could lead to controlled-release and targeted interventions to efficiently restore microbial balance and function in the gut.

REFERENCES

- Long, J. & Holtzman, D. M. Alzheimer disease: an update on pathobiology and treatment strategies. Cell 179, 312-339 (2019).

- Agirman, G., Yu, K. B. & Hsiao, E. Y. Signaling inflammation across the gut-brain axis. Science 374, 1087-1092 (2021).

- Seo, D. O. & Holtzman, D. M. Gut microbiota: from the forgotten organ to a potential key player in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 1232-1241 (2020).

- Moore, A. M., Mathias, M. & Valeur, J. Contextualising the microbiota-gut-brain axis in history and culture. Micro. Ecol. Health Dis. 30, 1546267 (2019).

- Bharti, R. & Grimm, D. G. Current challenges and best-practice protocols for microbiome analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 178-193 (2021).

- Cattaneo, A. et al. Association of brain amyloidosis with pro-inflammatory gut bacterial taxa and peripheral inflammation markers in cognitively impaired elderly. Neurobiol. Aging 49, 60-68 (2017).

- Vogt, N. M. et al. Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 7, 13537 (2017).

- Jemimah, S., Chabib, C. M. M., Hadjileontiadis, L. & AlShehhi, A. Gut microbiome dysbiosis in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 18, e0285346 (2023).

- Ferreiro, A. L. et al. Gut microbiome composition may be an indicator of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabo2984 (2023).

- Zhuang, Z. Q. et al. Gut microbiota is altered in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 63, 1337-1346 (2018).

- Brandscheid, C. et al. Altered gut microbiome composition and tryptic activity of the 5xFAD Alzheimer’s mouse model. J. Alzheimers Dis. 56, 775-788 (2017).

- Chen, C. et al. Gut microbiota regulate Alzheimer’s disease pathologies and cognitive disorders via PUFA-associated neuroinflammation. Gut 71, 2233-2252 (2022).

- Sun, B. L. et al. Gut microbiota alteration and its time course in a tauopathy mouse model. J. Alzheimers Dis. 70, 399-412 (2019).

- Ursell, L. K. et al. The interpersonal and intrapersonal diversity of humanassociated microbiota in key body sites. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129, 1204-1208 (2012).

- Human, M. P. C. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486, 207-214 (2012).

- Turnbaugh, P. J. et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 457, 480-484 (2009).

- Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K. & Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489, 220-230 (2012).

- Fetzer, I. et al. The extent of functional redundancy changes as species’ roles shift in different environments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14888-14893 (2015).

- Harach, T. et al. Reduction of Abeta amyloid pathology in APPPS1 transgenic mice in the absence of gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 7, 41802 (2017).

- Dodiya, H. B. et al. Sex-specific effects of microbiome perturbations on cerebral

amyloidosis and microglia phenotypes. J. Exp. Med. 216, 1542-1560 (2019). - Wang, X. L. et al. Helicobacter pylori filtrate impairs spatial learning and memory in rats and increases

-amyloid by enhancing expression of presenilin-2. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 66 (2014). - Kim, M. S. et al. Transfer of a healthy microbiota reduces amyloid and tau pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Gut 69, 283-294 (2020).

- Seo, D. O. et al. ApoE isoform- and microbiota-dependent progression of neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Science 379, eadd1236 (2023).

- Koyuncu, O. O., Hogue, I. B. & Enquist, L. W. Virus infections in the nervous system. Cell Host Microbe 13, 379-393 (2013).

- Itzhaki, R. F. et al. Microbes and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 51, 979-984 (2016).

- Seaks, C. E. & Wilcock, D. M. Infectious hypothesis of Alzheimer disease. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008596 (2020).

- Readhead, B. et al. Multiscale analysis of independent Alzheimer’s cohorts finds disruption of molecular, genetic, and clinical networks by human herpesvirus. Neuron 99, 64-82.e7 (2018).

- Tzeng, N. S. et al. Anti-herpetic medications and reduced risk of dementia in patients with herpes simplex virus infections-a nationwide, population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Neurotherapeutics 15, 417-429 (2018).

- Senejani, A. G. et al. Borrelia burgdorferi Co-Localizing with Amyloid Markers in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Tissues. J. Alzheimers Dis. 85, 889-903 (2022).

- Chacko, A. et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae can infect the central nervous system via the olfactory and trigeminal nerves and contributes to Alzheimer’s disease risk. Sci. Rep. 12, 2759 (2022).

- Dominy, S. S. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3333 (2019).

- Moir, R. D., Lathe, R. & Tanzi, R. E. The antimicrobial protection hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 1602-1614 (2018).

- Eimer, W. A. et al. Alzheimer’s disease-associated

-amyloid is rapidly seeded by herpesviridae to protect against brain infection. Neuron 99, 56-63.e3 (2018). - Wu, Y. et al. Microglia and amyloid precursor protein coordinate control of transient Candida cerebritis with memory deficits. Nat. Commun. 10, 685 (2019).

- Thapa, M. et al. Translocation of gut commensal bacteria to the brain. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.30.555630 (2023).

- Friedland, R. P. & Chapman, M. R. The role of microbial amyloid in neurodegeneration. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006654 (2017).

- Schäfer, K. H., Christmann, A. & Gries, M. Intra-gastrointestinal amyloid-

oligomers perturb enteric function and induce Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J. Physiol. 598, 4141-4142 (2020). - Jin, J. et al. Gut-derived

-amyloid: Likely a centerpiece of the gut-brain axis contributing to Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Gut Microbes 15, 2167172 (2023). - Shi, Y. & Holtzman, D. M. Interplay between innate immunity and Alzheimer disease: APOE and TREM2 in the spotlight. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 759-772 (2018).

- Brandebura, A. N., Paumier, A., Onur, T. S. & Allen, N. J. Astrocyte contribution to dysfunction, risk and progression in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 23-39 (2023).

- Erny, D. et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 965-977 (2015).

- Thion, M. S. et al. Microbiome influences prenatal and adult microglia in a sexspecific manner. Cell 172, 500-516.e16 (2018).

- Hanamsagar, R. et al. Generation of a microglial developmental index in mice and in humans reveals a sex difference in maturation and immune reactivity. Glia 66, 460 (2018).

- Matcovitch-Natan, O. et al. Microglia development follows a stepwise program to regulate brain homeostasis. Science 353, aad8670 (2016).

- Spichak, S. et al. Microbially-derived short-chain fatty acids impact astrocyte gene expression in a sex-specific manner. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 16, 100318 (2021).

- Erny, D. et al. Microbiota-derived acetate enables the metabolic fitness of the brain innate immune system during health and disease. Cell Metab. 33, 2260-2276.e7 (2021).

- Mezö, C. et al. Different effects of constitutive and induced microbiota modulation on microglia in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 8, 119 (2020).

- Dodiya, H. B. et al. Gut microbiota-driven brain

amyloidosis in mice requires microglia. J. Exp. Med. 219, e20200895 (2022). - Hou, K. et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 135 (2022).

- Marizzoni, M. et al. A peripheral signature of Alzheimer’s disease featuring microbiota-gut-brain axis markers. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 101 (2023).

- Bettcher, B. M., Tansey, M. G., Dorothée, G. & Heneka, M. T. Peripheral and central immune system crosstalk in Alzheimer disease-a research prospectus. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 17, 689-701 (2021).

- Minter, M. R. et al. Antibiotic-induced perturbations in gut microbial diversity influences neuro-inflammation and amyloidosis in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 30028 (2016).

- Köhler, C. A. et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 135, 373-387 (2017).

- Bell, R. D. et al. Apolipoprotein E controls cerebrovascular integrity via cyclophilin A. Nature 485, 512-516 (2012).

- Montagne, A. et al. APOE4 accelerates advanced-stage vascular and neurodegenerative disorder in old Alzheimer’s mice via cyclophilin A independently of amyloid-

. Nat. Aging 1, 506-520 (2021). - Tang, Y., Chen, Y., Jiang, H. & Nie, D. Short-chain fatty acids induced autophagy serves as an adaptive strategy for retarding mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 18, 602-618 (2011).

- den Besten, G. et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 54, 2325-2340 (2013).

- Boland, B. et al. Autophagy induction and autophagosome clearance in neurons: relationship to autophagic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 28, 6926-6937 (2008).

- Bonfili, L. et al. Microbiota modulation counteracts Alzheimer’s disease progression influencing neuronal proteolysis and gut hormones plasma levels. Sci. Rep. 7, 2426 (2017).

- Choi, H. & Mook-Jung, I. Functional effects of gut microbiota-derived metabolites in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 81, 102730 (2023).

- Dalile, B., Van Oudenhove, L., Vervliet, B. & Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 461-478 (2019).

- Smith, P. M. et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 341, 569-573 (2013).

- Arpaia, N. et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 504, 451-455 (2013).

- Alves de Lima, K. et al. Meningeal

T cells regulate anxiety-like behavior via IL17a signaling in neurons. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1421-1429 (2020). - van der Hee, B. & Wells, J. M. Microbial regulation of host physiology by shortchain fatty acids. Trends Microbiol. 29, 700-712 (2021).

- Sadler, R. et al. Short-chain fatty acids improve poststroke recovery via immunological mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 40, 1162-1173 (2020).

- McMurran, C. E. et al. The microbiota regulates murine inflammatory responses to toxin-induced CNS demyelination but has minimal impact on remyelination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25311-25321 (2019).

- Abdel-Haq, R. et al. A prebiotic diet modulates microglial states and motor deficits in a-synuclein overexpressing mice. Elife 11, e81453 (2022).

- Fernando, W. M. A. D. B. et al. Sodium butyrate reduces brain amyloid-

levels and improves cognitive memory performance in an Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mouse model at an early disease stage. J. Alzheimers Dis. 74, 91-99 (2020). - Jiang, Y., Li, K., Li, X., Xu, L. & Yang, Z. Sodium butyrate ameliorates the impairment of synaptic plasticity by inhibiting the neuroinflammation in 5XFAD mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 341, 109452 (2021).

- Cuervo-Zanatta, D. et al. Dietary fiber modulates the release of gut bacterial products preventing cognitive decline in an Alzheimer’s mouse model. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 43, 1595-1618 (2023).

- Killingsworth, J., Sawmiller, D. & Shytle, R. D. Propionate and Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 580001 (2020).

- Baloni, P. et al. Metabolic network analysis reveals altered bile acid synthesis and metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep. Med. 1, 100138 (2020).

- Connell, E. et al. Microbial-derived metabolites as a risk factor of age-related cognitive decline and dementia. Mol. Neurodegener. 17, 43 (2022).

- Vogt, N. M. et al. The gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N -oxide is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 10, 124 (2018).

- Maier, L. et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 555, 623-628 (2018).

- Rothschild, D. et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 555, 210-215 (2018).

- Parikh, I. J. et al. Murine gut microbiome association with APOE alleles. Front. Immunol. 11, 200 (2020).

- Maldonado Weng, J. et al. Synergistic effects of APOE and sex on the gut microbiome of young EFAD transgenic mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 47 (2019).

- Tran, T. T. T. et al. APOE genotype influences the gut microbiome structure and function in humans and mice: relevance for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. FASEB J. 33, 8221-8231 (2019).

- Vitek, M. P., Brown, C. M. & Colton, C. A. APOE genotype-specific differences in the innate immune response. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 1350-1360 (2009).

- Klein, S. L. & Flanagan, K. L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 626-638 (2016).

- Colton, C. A., Brown, C. M. & Vitek, M. P. Sex steroids, APOE genotype and the innate immune system. Neurobiol. Aging 26, 363-372 (2005).

- Hosang, L. et al. The lung microbiome regulates brain autoimmunity. Nature 603, 138-144 (2022).

- Seo, D. O., Boros, B. D. & Holtzman, D. M. The microbiome: a target for Alzheimer disease. Cell Res. 29, 779-780 (2019).

- Francino, M. P. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1543 (2015).

- Rakuša, E., Fink, A., Tamgüney, G., Heneka, M. T. & Doblhammer, G. Sporadic use of antibiotics in older adults and the risk of dementia: a nested case-control study based on German Health Claims Data. J. Alzheimers Dis. 93, 1329-1339 (2023).

- Hazan, S. Rapid improvement in Alzheimer’s disease symptoms following fecal microbiota transplantation: a case report. J. Int. Med. Res. 48, 300060520925930 (2020).

- Park, S. H. et al. Cognitive function improvement after fecal microbiota transplantation in Alzheimer’s dementia patient: a case report. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 37, 1739-1744 (2021).

- Park, S. H. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation can improve cognition in patients with cognitive decline and Clostridioides difficile infection. Aging (Albany NY) 14, 6449-6466 (2022).

- Akhgarjand, C., Vahabi, Z., Shab-Bidar, S., Etesam, F. & Djafarian, K. Effects of probiotic supplements on cognition, anxiety, and physical activity in subjects with mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 1032494 (2022).

- He, X. et al. The preventive effects of probiotic Akkermansia muciniphila on Dgalactose/AICI3 mediated Alzheimer’s disease-like rats. Exp. Gerontol. 170, 111959 (2022).

- Zhu, G., Zhao, J., Wang, G. & Chen, W. Bifidobacterium breve HNXY26M4 attenuates cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation by regulating the gut-brain axis in APP/PS1 mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 4646-4655 (2023).

- Bicknell, B. et al. Neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases and the gut-brain axis: the potential of therapeutic targeting of the microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9577 (2023).

- Lancaster, S. M. et al. Global, distinctive, and personal changes in molecular and microbial profiles by specific fibers in humans. Cell Host Microbe 30, 848-862.e7 (2022).

- Sonnenburg, J. L. & Bäckhed, F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 535, 56-64 (2016).

- Wang, X. et al. Sodium oligomannate therapeutically remodels gut microbiota and suppresses gut bacterial amino acids-shaped neuroinflammation to inhibit Alzheimer’s disease progression. Cell Res. 29, 787-803 (2019).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

COMPETING INTERESTS

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Reprints and permission information is available at http://www.nature.com/ reprints

© The Author(s) 2023

Department of Neurology, Hope Center for Neurological Disorders, Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA. email: seo.biome@gmail.com