DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-023-00886-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38225620

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-15

القيادة الملتزمة ورفاهية الممرضين: دور بيئة العمل والدافع للعمل – دراسة مقطعية

الملخص

خلفية تشير الأدبيات الصحية إلى أن سلوك القيادة له تأثير عميق على رفاهية الممرضين المتعلقة بالعمل. ومع ذلك، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من البحث لفهم أفضل، وقياس، وتحليل مفاهيم القيادة والرفاهية، وفهم الآليات النفسية الكامنة وراء هذه العلاقة. يجمع هذا البحث بين نظرية تحديد الذات ونظرية متطلبات العمل والموارد، ويهدف إلى دراسة العلاقة بين القيادة الجذابة والإرهاق والانخراط في العمل بين الممرضين من خلال التركيز على آليتين تفسيريتيين: الخصائص الوظيفية المدركة (متطلبات العمل والموارد) والدافع الداخلي. الطرق تم إجراء مسح مقطعي لـ 1117 ممرض رعاية مباشرة (معدل الاستجابة = 25%) من 13 مستشفى عام للرعاية الحادة في بلجيكا. تم استخدام أدوات موثوقة لقياس تصورات الممرضين حول القيادة الجذابة، والإرهاق، والانخراط في العمل، والدافع الداخلي، ومتطلبات العمل وموارد العمل. تم إجراء نمذجة المعادلات الهيكلية لاختبار النموذج المفترض الذي افترض وساطة تسلسلية لخصائص العمل والدافع الداخلي في العلاقة بين القيادة الجذابة ورفاهية الممرضين المتعلقة بالعمل. النتائج أظهرت تحليل العوامل التأكيدية ملاءمة جيدة لنموذج القياس. تقدم النتائج دعمًا للنموذج المفترض، مما يشير إلى أن القيادة الجذابة مرتبطة بتحسين الرفاهية، كما يتضح من زيادة الانخراط في العمل، وتقليل الإرهاق. أظهرت النتائج أيضًا أن هذه العلاقة تتوسطها تصورات الممرضين حول موارد العمل والدافع الداخلي. من الجدير بالذكر أنه بينما وسّطت متطلبات العمل العلاقة بين القيادة الجذابة ورفاهية الممرضين، أصبحت العلاقة غير ذات دلالة عند تضمين الدافع الداخلي كوسيط ثانٍ.

الاستنتاجات تعزز القيادة الجذابة بيئة عمل ملائمة لطاقم التمريض، مما يعود بالنفع ليس فقط على دافعهم للعمل ولكن أيضًا على رفاهيتهم المتعلقة بالعمل. القيادة الجذابة وموارد العمل هي جوانب قابلة للتعديل في منظمات الرعاية الصحية. ستساعد التدخلات التي تهدف إلى تطوير سلوكيات القيادة الجذابة بين قادة التمريض وبناء موارد العمل منظمات الرعاية الصحية على خلق ظروف عمل ملائمة لممرضاتهم.

تسجيل التجربة: الدراسة الموصوفة هنا ممولة بموجب برنامج أفق 2020 للبحث والابتكار التابع للاتحاد الأوروبي من 2020 إلى 2023 (اتفاقية المنحة 848031). بروتوكول Magnet4Europe مسجل في سجل ISRCTN (ISRCTN10196901).

المقدمة

على الرغم من الأهمية المعترف بها على نطاق واسع للقيادة في خلق أماكن عمل صحية، فإن الغالبية العظمى من دراسات القيادة قد أهملت إلى حد كبير تأثيرها على النتائج المتعلقة بالصحة، مثل الإرهاق والانخراط في العمل، في الغالب لصالح أداء العمل أو رضا العمل [7]. علاوة على ذلك، قدّرت الأبحاث السابقة القيادة (غير الكافية) كعامل دافع في تطوير رفاهية الموظف وسوء الصحة، جزئيًا بسبب سوء التصور أو القياس أو التحليل للقيادة والإرهاق [11]. على سبيل المثال، قيمت الدراسات السابقة الإرهاق كظاهرة أحادية البعد من خلال التركيز فقط على بُعد الإرهاق العاطفي من مقياس الإرهاق ماسلاش (MBI) [12]. يُعتبر MBI الأداة الأكثر استخدامًا لتقييم الإرهاق المهني؛ ومع ذلك، تم انتقاده كثيرًا بسبب عيوب مفاهيمية وعملية ونفسية [13]. وبالمثل، اعتبرت معظم أبحاث الإرهاق سلوك القيادة ضيقًا (مثل الدعم الاجتماعي) بدلاً من كونه مفهومًا شاملًا ومتعدد الأبعاد [14]. فيما يتعلق بالقيادة، تم انتقاد مفاهيم القيادة السابقة، وخاصة القيادة التحويلية، لأنها تفتقر إلى أساس نظري ووصف مفصل للعمليات الكامنة [15، 16]. وفقًا لذلك، لا يزال هناك الكثير من الجدل في الأدبيات حول العمليات (الدافعية) الكامنة التي من خلالها تؤثر القيادة على رفاهية الموظف [10، 17].

في الدراسة الحالية، يتركز البحث على مفهوم القيادة الجذابة (EL) [11، 18] الذي يتم قياسه وفهمه من خلال تصورات الممرضين. مستندًا إلى نظرية تحديد الذات (SDT، [19])، يبني بحثنا على فرضية أن مكان العمل المليء بالموارد كما

يدركه الموظفون ليس مفيدًا فقط لصحتهم ولكن أيضًا لدافعهم للعمل. من خلال إلهام وتقوية وربط وتمكين الموظفين، يُفترض أن القادة الجذابين يوازنون بين متطلبات العمل ومواردهم بطريقة تضمن بقائهم أصحاء ومتحمسين ومنتجين وراضين [11]. يتماشى هذا مع الأبحاث التي تشير إلى أن القادة، بما في ذلك القادة الجذابين، يؤثرون بشكل غير مباشر على رفاهية تابعيهم من خلال تشكيل تصوراتهم لبيئة عملهم (أي، في شكل تقليل متطلبات العمل وتحسين موارد العمل) [6، 7، 11]. تفترض SDT أيضًا أن الموظفين يؤدون ويشعرون بتحسن عندما يكون دافعهم ذاتيًا بطبيعته (أي، داخلي). وبالتالي، يوفر مكان العمل الذي يشعر فيه الموظفون بدعم كافٍ، ويتلقون تعليقات عالية الجودة، ولديهم فرص للتطوير المهني، الوقود المطلوب لتحقيق الدافع الأمثل ويؤدي إلى الأداء والرفاهية المثلى [20،21].

الخلفية النظرية وفرضيات الدراسة نموذج القيادة JD-R

“الجهد البدني أو العقلي المستمر” [23]، وبالتالي يُقال إنها تستنزف طاقة الموظفين. بالمقابل، تُعتبر موارد العمل الجوانب الإيجابية في الوظيفة “التي هي إما/أو (1) وظيفية في تحقيق أهداف العمل، (2) تقلل من متطلبات العمل والتكاليف الفسيولوجية والنفسية المرتبطة بها، (3) تحفز النمو الشخصي والتعلم والتطور” [23]. يُفترض أن موارد العمل لديها إمكانات تحفيزية حيث قد لا تعزز فقط الانخراط في العمل ولكن أيضًا تقلل من الإرهاق. في هذه الدراسة، يتركز الاهتمام على كل من الجانب السلبي (الإرهاق) والجانب الإيجابي (الانخراط في العمل) من الرفاهية المتعلقة بالعمل حيث يظهر سلوك القيادة علاقات مختلفة مع هذه المفاهيم [7، 25]. يُعرف الإرهاق بأنه حالة من الإرهاق العقلي المرتبط بالعمل، والتي تتميز بالتعب الشديد، وانخفاض القدرة على تنظيم العمليات المعرفية والعاطفية، والابتعاد العقلي [13]. نظرًا لمواجهة مستويات عالية من عبء العمل وضغوط العمل الأخرى بشكل متكرر، يُعتبر الممرضون في خطر مرتفع للإرهاق [26]. بالمقابل، يشير الانخراط في العمل إلى حالة ذهنية إيجابية ومرضية تتعلق بالعمل، تتميز بالنشاط (أي مستوى عالٍ من الطاقة والمرونة العقلية أثناء العمل)، والتفاني (الذي يشير إلى شعور بالأهمية، والحماس، والتحدي)، والانغماس (كون الشخص مركزًا ومشغولًا بسعادة في عمله) [24، 27]. أظهرت دراسة انتشار واسعة النطاق حول الانخراط في العمل في 30 دولة أوروبية أن الموظفين في وظائف الخدمة الإنسانية مثل الرعاية الصحية أبلغوا عن مستويات أعلى من الانخراط في العمل مقارنة بالموظفين في أنواع أخرى من الصناعات [28].

وفقًا لنموذج القيادة JD-R، تعتبر القيادة واحدة من العوامل الفريدة وتلعب دورًا حاسمًا في كل من عملية تدهور الصحة وعملية التحفيز. بعبارة أخرى، القادة الذين يشجعون ويقدمون ملاحظات داعمة، والذين يظهرون التقدير، قد يوفرون للممرضين موارد كافية وبالتالي يؤثرون إيجابيًا على صحتهم ورفاههم (أي، عملية التحفيز). على النقيض من ذلك، القادة الذين يفشلون في تقديم ملاحظات بناءة، والذين يظهرون دعمًا أقل، أو الذين يمارسون سيطرة وضغطًا غير مبرر على موظفيهم قد يساهمون بشكل كبير في مشاعر التوتر مما يقلل من الرفاهية الفردية (أي، عملية تدهور الصحة) بسبب تقليل الموارد وزيادة المطالب. تدعم الأبحاث التجريبية هذا الافتراض. على سبيل المثال، وجد نيلسن وآخرون أن خصائص العمل المختلفة (مثل وضوح الدور، وفرص التطوير) كانت وسيطًا في العلاقة بين القيادة ورفاهية المهنيين الصحيين. بنفس السياق، أفاد شوفلي أن القيادة الفعالة مرتبطة إيجابيًا بالانخراط في العمل من خلال موارد العمل (مثل تنوع المهام، وضوح الدور) ومرتبطة سلبًا بالإرهاق من خلال تقليل مطالب العمل.

العبء الزائد، المطالب العاطفية). وقد تم دعم هذه النتائج بشكل أكبر في دراسة أجريت على طاقم التمريض [32].

الدافع الذاتي في نموذج القيادة JD-R

من المتوقع أن تزدهر الدوافع الذاتية للممرضين. ومن ثم، من خلال تمكينهم وتقويتهم وإلهامهم وربطهم، يُعتبر القادة المشاركون قادرين على خلق ظروف عمل ملائمة تتميز بمشاعر الاستقلالية والكفاءة والمعنى والترابط، مما سيزيد بدوره من الدوافع الذاتية للممرضين. من المحتمل أن تؤدي هذه التجربة إلى مستويات أعلى من الانخراط في العمل والرفاهية. وقد ركزت الدراسات السابقة بشكل أساسي على مفهوم القيادة التحولية. ومع ذلك، فإن البحث في القيادة المتمكنة جديد نسبيًا ولم يتم البحث فيه على نطاق واسع بعد. ومع ذلك، تدعم الأبحاث المستندة إلى نظرية الدوافع الذاتية عمومًا هذا الافتراض. على سبيل المثال، تُظهر مراجعة تحليلية شاملة أن بيئة العمل التي يدعم فيها القادة موظفيهم للعمل بشكل مستقل ليست مفيدة فقط لتلبية احتياجات الموظفين الأساسية، ولكن أيضًا لدوافعهم (الذاتية). بينما وجد الباحثون أن دعم استقلالية القائد كان مرتبطًا إيجابيًا بالدافع الذاتي، إلا أنه أظهر، من ناحية أخرى، ارتباطات سلبية مع ضغوط الموظفين (مثل الإرهاق وضغوط العمل). تدعم هذه النتائج ما وجده سليمب وآخرون الذين أجروا مراجعة تحليلية شاملة لـ 72 دراسة حول العمليات التحفيزية ونتائج دعم استقلالية القائد في مكان العمل – سلوكيات قد تكون أيضًا نموذجية للقيادة المتمكنة. علاوة على ذلك، أظهر فيرنيت وآخرون أن القيادة (التحولية) كانت مرتبطة بشكل كبير برفاهية الممرضين من خلال المساهمة في ظروف عمل ملائمة والدوافع الذاتية.

الهدف والفرضيات

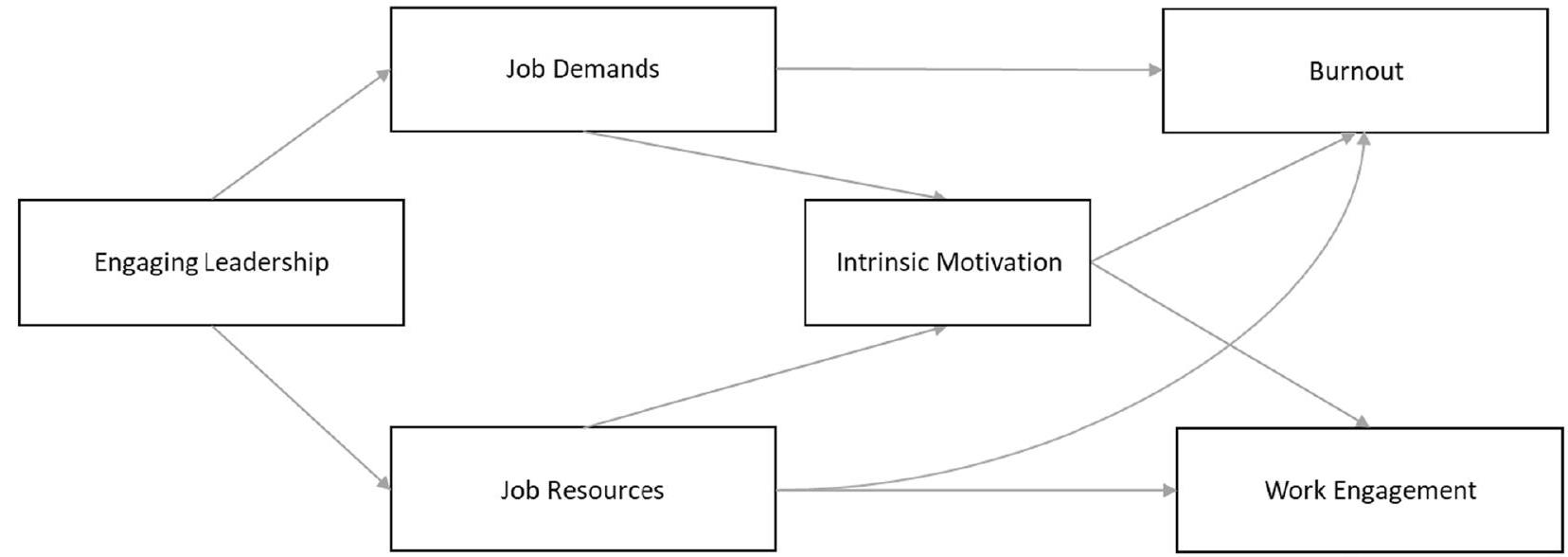

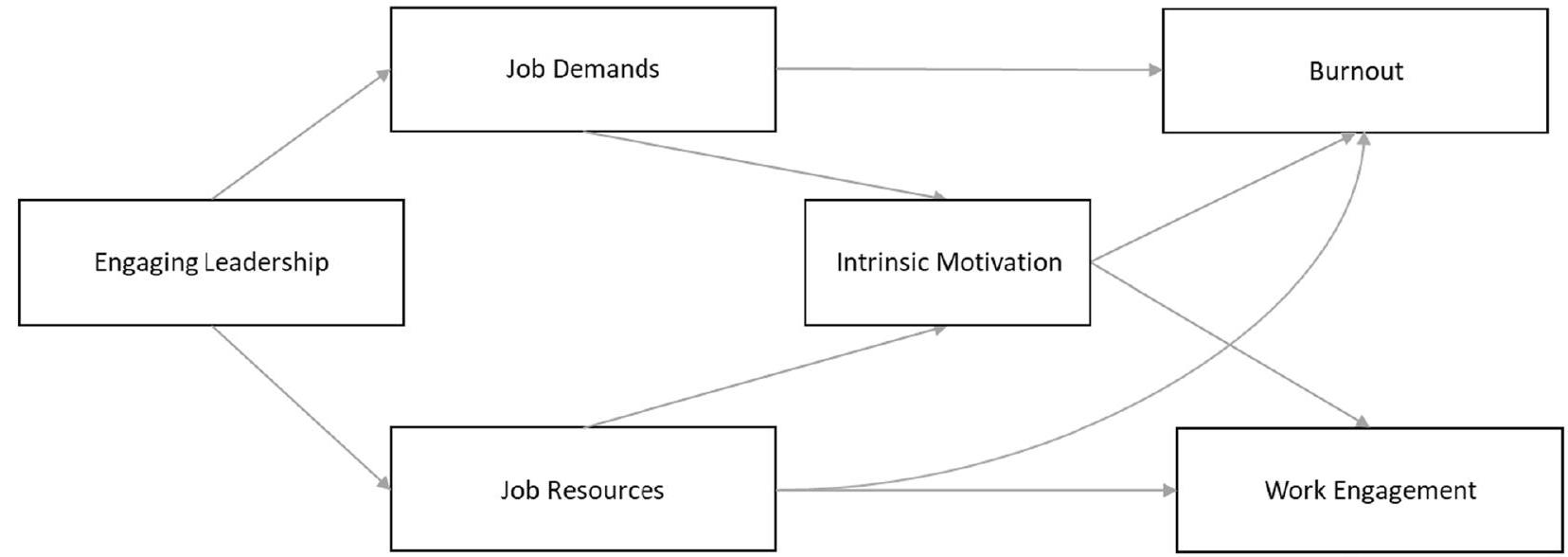

إذا (أ) دعم القادة الممرضين لتحقيق التوازن بين موارد العمل ومتطلبات العمل و(ب) رعى دافعهم الداخلي من خلال تحسين ظروف العمل، فمن المتوقع أن يؤثر القادة المشاركون على الضغط المتعلق بالعمل الذي يشعر به الممرضون ورفاهيتهم (أي تقليل مستويات الاحتراق النفسي وزيادة الانخراط في العمل). النموذج المقترح موضح في الشكل 1. الفرضيات هي كما يلي:

طرق البحث

التصميم والإعداد

جمع البيانات

المشاركون

القياسات

القيادة الجذابة

(ملهم). كانت قيمة ألفا كرونباخ للمقياس الكلي للقيادة الجذابة 0.96.

متطلبات العمل والموارد

الدافع الداخلي

الإرهاق

الانخراط في العمل

المتغيرات المرافقة

تحليل البيانات

بعد ذلك، تم تقييم النموذج الهيكلي المفترض. تم تطبيق تقنية Bootstrap مع إجراء إعادة أخذ عينات من 1000 عينة Bootstrap لتحديد التقدير النقطي وفترة الثقة المصححة والمسرعة بنسبة 95% (CI) للتأثير غير المباشر الكلي والخاص [51، 52]. يُوصى بتقنية Bootstrap حيث أن التأثير غير المباشر (ناتج معاملات المتغير التنبؤي والمتغير الوسيط) ليس موزعًا بشكل طبيعي [53]. يتم الإشارة إلى فترة الثقة المعاد تشكيلها (مستوى أدنى من فترة الثقة – مستوى أعلى من فترة الثقة، LLCI – ULCI) التي لا تشمل القيمة الصفرية على أنها ذات دلالة إحصائية. كما هو موضح في الشكل 1، لم نفترض وجود علاقات مباشرة بين القيادة الجذابة والدافع الداخلي، أو بين القيادة الجذابة والإرهاق والانخراط في العمل.

بدلاً من ذلك، تم الافتراض أن هذه العلاقات تفسر من خلال متطلبات العمل والموارد. وفقًا لـ هايز [51]، فإن وجود ارتباط كبير بين المتغير التنبؤي والنتيجة ليس شرطًا ضروريًا أو كافيًا للوساطة. ومع ذلك، تمت إضافة المسارات المباشرة من القيادة الجذابة إلى كل متغير نتيجة أيضًا في SEM. يتم توثيق أي ارتباطات مباشرة بين المتغيرات المدرجة في هذه الدراسة في المواد التكميلية لهذه الدراسة (الملف الإضافي 1: الملحق 1).

النتائج

تحليل العوامل التأكيدية

| المفهوم (عدد العناصر) | معنى | SD | الارتباطات | |||||||

| 1 | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | |||

| 1. الجنس | – | – | 1 | |||||||

| 2. العمر | 40 | 12 | -0.059* | 1 | ||||||

| 3. القيادة الجذابة (12) | 3.49 | 0.81 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 1 | |||||

| 4. متطلبات العمل (10) | ٣.٣٠ | 0.48 | -0.039 | -0.009 | -0.302** | 1 | ||||

| 5. موارد العمل (13) | ٣.٤٠ | 0.48 | 0.039 | 0.032 | 0.565** | -0.405** | 1 | |||

| 6. الدافع الداخلي (3) | 3.80 | 0.62 | 0.047 | -0.139** | 0.247** | -0.213** | 0.456** | 1 | ||

| 7. الانخراط في العمل (3) | 3.49 | 0.67 | 0.061 | 0.086** | 0.341** | -0.348** | 0.527** | 0.497** | 1 | |

| 8. الإرهاق (12) | 2.18 | 0.57 | 0.023 | -0.104** | -0.315** | 0.589** | -0.468** | -0.347** | -0.591** | 1 |

نتائج تحليل الوساطة

| فرضية | مؤشر | وسيط | نتيجة |

|

|

LLCI | ULCI |

| 1أ | القيادة الجذابة | متطلبات العمل | الإرهاق | -0.218 | 0.000 | -0.272 | -0.176 |

| 1ب | القيادة الجذابة | مطالب العمل | الانخراط في العمل | 0.064 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.100 |

| 2أ | القيادة الجذابة | موارد العمل | الانخراط في العمل | 0.260 | 0.000 | 0.192 | 0.342 |

| 2ب | القيادة الجذابة | موارد العمل | الإرهاق | -0.183 | 0.000 | -0.262 | -0.121 |

| 3a | القيادة الجذابة | متطلبات العمل | الدافع الداخلي | 0.011 | 0.457 | -0.018 | 0.040 |

| 3ب | القيادة الجذابة | موارد العمل | الدافع الداخلي | 0.368 | 0.000 | 0.286 | 0.457 |

| 4أ | القيادة الجذابة | مطالب العمل والدافع الداخلي | الإرهاق | -0.002 | 0.461 | -0.007 | 0.003 |

| 4ب | القيادة الجذابة | مطالب العمل والدافع الداخلي | الانخراط في العمل | 0.003 | 0.462 | -0.005 | 0.012 |

| 5أ | القيادة الجذابة | موارد العمل والدافع الداخلي | الانخراط في العمل | 0.104 | 0.000 | 0.070 | 0.144 |

| 5ب | القيادة الجذابة | موارد العمل والدافع الداخلي | الإرهاق | -0.058 | 0.000 | -0.095 | -0.032 |

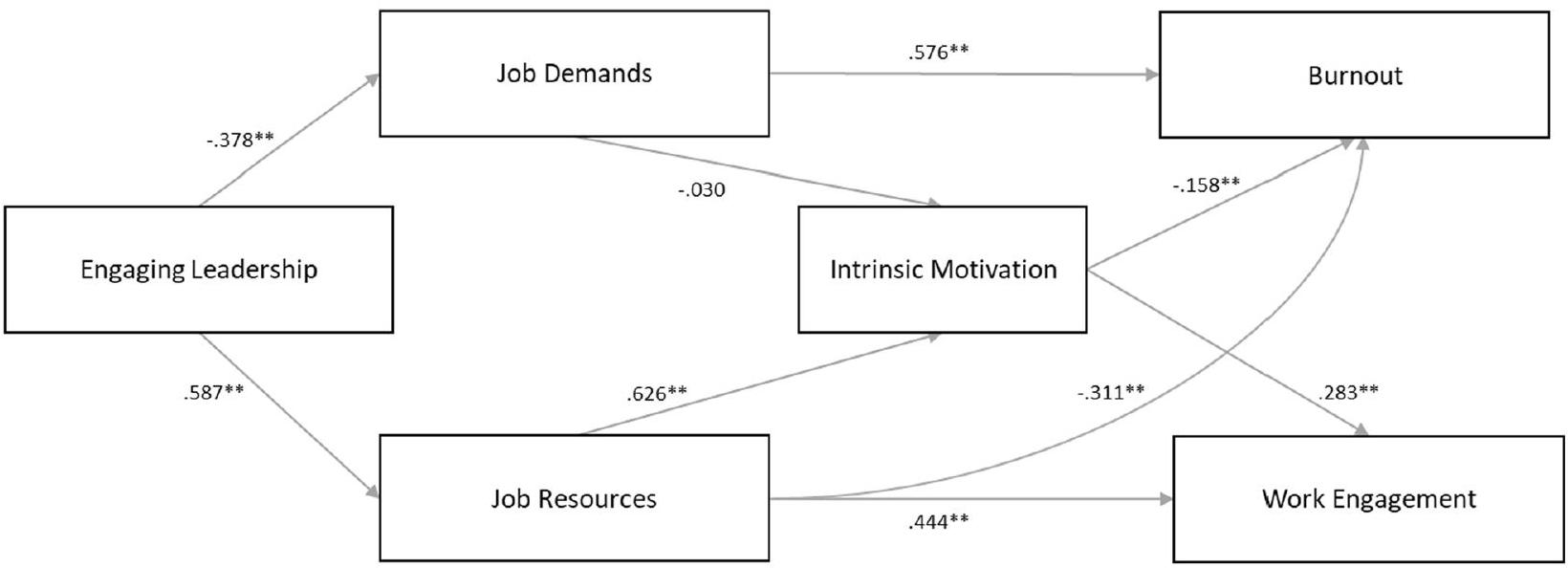

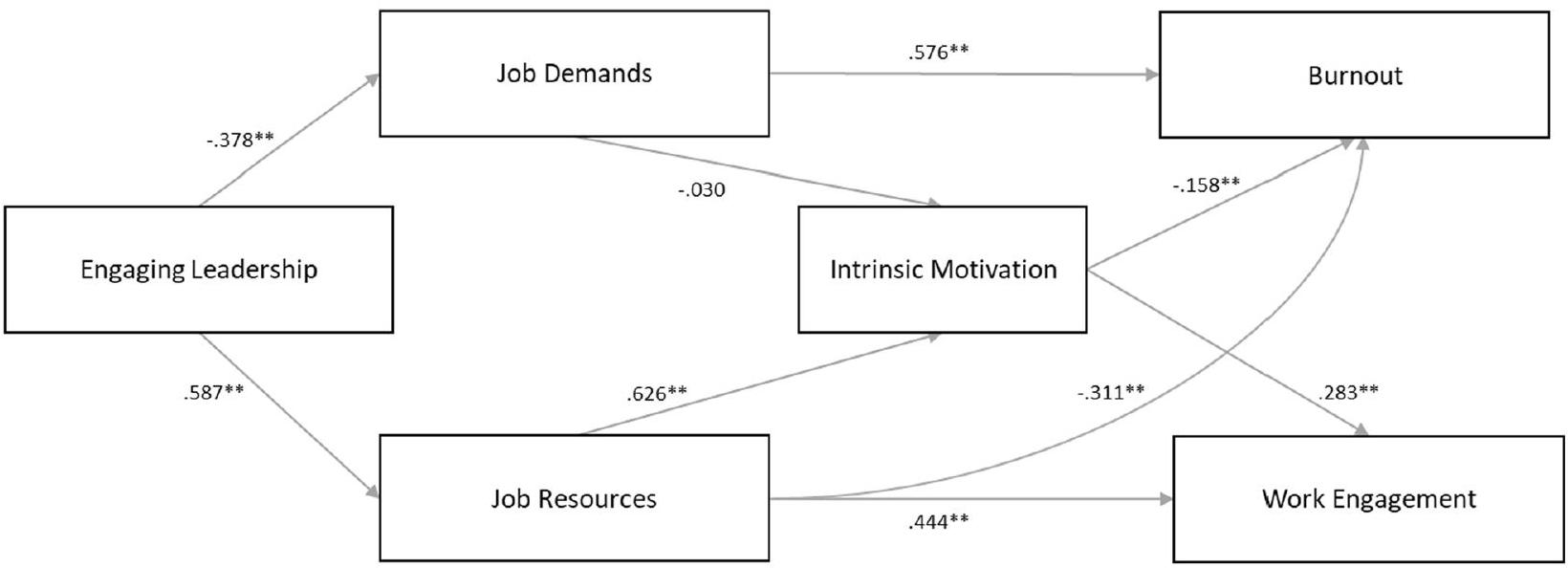

إلى فترة الثقة bootstrap 95% (0.035، 0.100). تؤكد هذه النتائج H1a و H1b.

بعد ذلك، تم افتراض أن العلاقة بين القيادة الأخلاقية والدافع الداخلي تتوسطها متطلبات العمل (H3a) وموارد العمل (H3b). وقد تم ملاحظة الارتباط غير المباشر بين القيادة الأخلاقية والدافع الداخلي من خلال متطلبات العمل.

تنص مجموعة الفرضيات التالية لدينا على أن متطلبات العمل والدافع الداخلي يتوسطان العلاقة بين القيادة العاطفية (EL) والإرهاق (H4a) والانخراط في العمل (H4b). وجدنا أن التأثير غير المباشر للقيادة العاطفية على الإرهاق من خلال متطلبات العمل والدافع الداخلي

نقاش

تدعم النتائج المستخلصة من نمذجة المعادلات الهيكلية إلى حد كبير هذا النموذج: يمكن للقادة الملتزمين تشكيل تصورات الممرضين عن عملهم وخلق بيئة عمل تتميز بمزيد من الموارد وأقل من المطالب. على وجه الخصوص، من خلال توفير الموارد الوظيفية الكافية للممرضين، لا يقوم هؤلاء القادة فقط برعاية دافعهم الداخلي ولكن أيضًا يعززون شعورهم بالرفاهية (أي، تقليل مستويات الاحتراق النفسي وزيادة الانخراط في العمل).

عملية في الممرضات، مما يثير شعورًا بالاستمتاع والرضا أثناء أداء عملهم [55]. علاوة على ذلك، كما هو موضح في العينة الحالية، من المحتمل أن تشعر الممرضات بمزيد من الانخراط في العمل (H5a)، بينما من غير المحتمل أن يتطور لديهن مشاعر الإرهاق (H5b). تضيف هذه الدراسة إلى الأدلة المتزايدة على نموذج JD-R وSDT من خلال إظهار أن سلوك القيادة له تأثير عميق على تصورات الممرضات لبيئة عملهن، ودافعهن للعمل، ورفاههن المتعلق بالعمل.

على عكس توقعاتنا، لم نجد أي تأثير وسطي لمتطلبات العمل والدافع الداخلي في العلاقة بين القيادة الأخلاقية وإرهاق الممرضين (H4a) والانخراط في العمل (H4b). على الرغم من أن متطلبات العمل وسّعت العلاقة بين القيادة الأخلاقية ورفاهية الممرضين، إلا أن العلاقة أصبحت غير ذات دلالة عندما تم تضمين الدافع الداخلي كوسيط ثانٍ. بشكل عام، تتماشى هذه النتائج مع دراسة حديثة أجراها كوهين وآخرون [21]. في عينة من 1729 ممرضًا يقدمون الرعاية المباشرة في بلجيكا، بحث المؤلفون في الدور الوسيط للدافع الداخلي في العلاقة بين متطلبات العمل وموارد العمل مع رفاهية الممرضين المتعلقة بالعمل. أظهرت النتائج أن الدافع الداخلي لم يكن وسيطًا في العلاقة بين متطلبات العمل ورفاهية الممرضين. بنفس السياق، لم يظهر الدافع الداخلي أي ارتباطات مع متطلبات العمل بشكل عام. فيما يتعلق بالدراسة الحالية، تدفع نتائجنا إلى مزيد من الاستكشاف للجوانب المحددة للقيادة الأخلاقية، حيث قد لا تكون فعالة في التنبؤ بالارتباطات بين متطلبات العمل والدافع الداخلي مع رفاهية الممرضين المتعلقة بالعمل. ومع ذلك، هناك تفسير آخر محتمل وهو أن العلاقة بين متطلبات العمل ورفاهية الممرضين تتأثر بأنواع أخرى من الدوافع، مثل التنظيم الخارجي، كشكل من أشكال الدافع المسيطر. يرتب نظرية الدافع الذاتي أشكالًا مختلفة من الدافع على طول استمرارية من التحديد الذاتي، تتراوح من الدافع الأكثر سيطرة إلى الدافع الأكثر استقلالية. بينما يكون الشكل الأكثر استقلالية من الدافع، أي الدافع الداخلي، في أحد طرفي الاستمرارية، يكون الشكل الأكثر سيطرة من الدافع (أي التنظيم الخارجي) في الطرف الآخر من الطيف. يحدث التنظيم الخارجي عندما يشارك الموظفون في سلوك أو نشاط معين لأسباب آلية بحتة، مثل الحصول على المكافآت، أو تجنب العقاب، أو ببساطة لأنهم يتعرضون لضغوط من المتطلبات. في الواقع، أظهرت الأبحاث السابقة والأدلة التحليلية التراكمية أن التنظيم الخارجي، وخاصة عدم الدافع (أي نقص الدافع، حيث يظهر الموظفون عدم اهتمام أو انخراط في أداء مهمة)، يؤثر سلبًا فقط على أداء الموظف، مما يؤدي إلى الضغوط النفسية والإرهاق [36، 37]. قد يشير هذا إلى أن الدافع المستقل والمسيطر أو عدم الدافع مرتبطان عكسيًا بوظيفة الموظفين النفسية. ومع ذلك، فإن الأدلة التجريبية حول التأثيرات الفردية لأنواع الدوافع المختلفة نادرة.

وما زالت هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من البحث لفهم دافع الموظفين في مكان العمل بشكل كامل [37].

القيود

قد تقدم رؤى قيمة حول تصوراتهم لبيئة العمل السريرية.

الآثار العملية

الخاتمة

الاختصارات

| CFA | تحليل العوامل التأكيدية |

| EL | القيادة التحويلية |

| نموذج JD-R | نموذج متطلبات العمل والموارد |

| SDT | نظرية تحديد الذات |

| SEM | نمذجة المعادلات الهيكلية |

معلومات إضافية

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر على الإنترنت: 15 يناير 2024

References

- Buchan J, Aiken L. Solving nursing shortages: a common priority. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:3262-8.

- Lu H, Zhao Y, While A. Job satisfaction among hospital nurses: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;94:21-31.

- Janssen PPM, De Jonge J, Bakker AB. Specific determinants of intrinsic work motivation, burnout and turnover intentions: a study among nurses. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29:1360-9.

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39:223-9.

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski JA, Busse R, Clarke H, et al. Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Aff. 2001;20:43-53.

- Skakon J, Nielsen K, Borg V, Guzman J. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work Stress. 2010;24:107-39.

- Inceoglu I, Thomas G, Chu C, Plans D, Gerbasi A. Leadership behavior and employee well-being: an integrated review and a future research agenda. Leadersh Q. 2018;29:179-202.

- Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Reinius M, Griffiths P. Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18:1-17.

- Rahmadani VG, Schaufeli WB. Engaging leaders foster employees’ wellbeing at work. 2020;5:1-7.

- Cummings GG, Tate K, Lee S, Wong CA, Paananen T, Micaroni SPM, et al. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;85:19-60.

- Schaufeli W. Engaging leadership in the job demands-resources model. Career Dev Int. 2015;20:446-63.

- Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, Hammarström A, Hogstedt C, Marteinsdottir I, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1-13.

- Schaufeli WB, Desart S, De Witte H. Burnout assessment tool (Bat)development, validity, and reliability. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1-21.

- Kanste O , Kyngäs H, Nikkilä J. The relationship between multidimensional leadership and burnout among nursing staff. J Nurs Manag. 2007;15:731-9.

- van Knippenberg D, Sitkin SB. A critical assessment of charismatic-transformational leadership research: back to the drawing board? Acad Manag Ann. 2013;7:1-60.

- Bormann KC, Rowold J. Construct proliferation in leadership style research: reviewing pro and contra arguments. Organ Psychol Rev. 2018;8:149-73.

- Nielsen K, Randall R, Yarker J, Brenner SO. The effects of transformational leadership on followers’ perceived work characteristics and psychological well-being: a longitudinal study. Work Stress. 2008;22:16-32.

- Schaufeli W. Engaging leadership: how to promote work engagement? Front Psychol. 2021;12:1-10.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68-78.

- Deci EL, Olafsen AH, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2017;4:19-43.

- Kohnen D, De Witte H, Schaufeli WB, Dello S, Bruyneel L, Sermeus W. What makes nurses flourish at work? How the perceived clinical work environment relates to nurse motivation and well-being: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2023;104567.

- de Beer LT, Schaufeli WB, De Witte H, Hakanen JJ, Shimazu A, Glaser J, et al. Measurement invariance of the burnout assessment tool (Bat) across seven cross-national representative samples. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1-14.

- Demerouti E, Nachreiner F, Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB. The job demandsresources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:499-512.

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J Organ Behav. 2004;25:293-315.

- Arnold KA. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: a review and directions for future research. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22:381-93.

- Woo T, Ho R, Tang A, Tam W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;123:9-20.

- Schaufeli W, Salanova M, González-romá V, Bakker A. The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3:71-92.

- Hakanen JJ, Ropponen A, De Witte H, Schaufeli WB. Testing demands and resources as determinants of vitality among different employment contract groups. A study in 30 European countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4951.

- Rahmadani VG, Schaufeli WB, Stouten J, Zhang Z, Zulkarnain Z. Engaging leadership and its implication for work engagement and job outcomes at the individual and team level: a multi-level longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:776.

- Engelbrecht AS, Heine G, Mahembe B. Integrity, ethical leadership, trust and work engagement. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2017;38:368-79.

- Van Dierendonck D, Borrill C, Haynes C, Stride C. Leadership behavior and subordinate well-being. J Occup Health Psychol. 2004;9:165-75.

- Lewis HS, Cunningham CJL. Linking nurse leadership and work characteristics to nurse burnout and engagement. Nurs Res. 2016;65:13-23.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25:54-67.

- Xue H, Luo Y, Luan Y, Wang N. A meta-analysis of leadership and intrinsic motivation: examining relative importance and moderators. Front Psychol. 2022;13.

- Eyal O, Roth G. Principals’ leadership and teachers’ motivation. J Educ Adm. 2011;49:256-75.

- Fernet C, Trépanier SG, Austin S, Gagné M, Forest J. Transformational leadership and optimal functioning at work: on the mediating role of employees’ perceived job characteristics and motivation. Work Stress. 2015;29:11-31.

- Van den Broeck A, Howard JL, Van Vaerenbergh Y, Leroy H, Gagné M. Beyond intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis on selfdetermination theory’s multidimensional conceptualization of work motivation. Organ Psychol Rev. 2021;11:240-73.

- Slemp GR, Kern ML, Patrick KJ, Ryan RM. Leader autonomy support in the workplace: a meta-analytic review. Motiv Emot. 2018;42:706-24.

- Sermeus W, Aiken LH, Ball J, Bridges J, Bruyneel L, Busse R, et al. A workplace organisational intervention to improve hospital nurses’ and physicians’ mental health: study protocol for the Magnet4Europe wait list cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e059159.

- Regulation P. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Regulation. 2016;679:2016.

- De Jonge J, Van Breukelen GJP, Landeweerd JA, Nijhuis FJN. Comparing group and individual level assessments of job characteristics in testing the job demand-control model: a multilevel approach. Hum Relations. 1999;52:95-122.

- Schaufeli WB. Applying the job demands-resources model: a’how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organ Dyn. 2017;46:120-32.

- Tremblay MA, Blanchard CM, Taylor S, Pelletier LG, Villeneuve M. Work extrinsic and intrinsic motivation scale: its value for organizational psychology research. Can J Behav Sci. 2009;41:213-26.

- Hadžibajramović E, Schaufeli W, De Witte H. Shortening of the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)-from 23 to 12 items using content and Rasch analysis. BMC Public Health BioMed Central. 2022;22:1-16.

- Schaufeli WB, Shimazu A, Hakanen J, Salanova M, De Witte H. An ultrashort measure for work engagement: the UWES-3 validation across five countries. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2019;35:577-91.

- IBM. IBM Corp. Released 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2021.

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus. Handb item response theory. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2017. p. 507-18.

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull. 1988;103:411.

- van de Schoot R, Lugtig P, Hox J. A checklist for testing measurement invariance. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2012;9:486-92.

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1-55.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Third Edn. Guilford Publications; 2022.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis—model numbers. Guilford publications: Guilford Press; 2013.

- Stride CB, Gardner SE, Catley N, Thomas F. Mplus code for mediation, moderation and moderated mediation models (1 to 80). 2017. p. 1-767.

- Cohen P, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. UK: Psychology Press; 2014.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11:227-68.

- de Koning R, Egiz A, Kotecha J, Ciuculete AC, Ooi SZY, Bankole NDA, et al. Survey fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of neurosurgery survey response rates. Front Surg. 2021;8:690680.

- Timmins F, Ottonello G, Napolitano F, Musio ME, Calzolari M, Gammone

, et al. The state of the science-the impact of declining response rates by nurses in nursing research projects. J Clin Nurs. 2023; e9-11. - Fisher GG, Matthews RA, Gibbons AM. Developing and investigating the use of single-item measures in organizational research. J Occup Health Psychol. 2016;21:3-23.

- Conway JM. Method variance and method bias in industrial and organizational psychology. In: Handbook of research methods in industrial and organizational psychology. USA: Wiley; 2008. p. 344-65.

- Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Deci EL, Ryan RM, Duda JL, et al. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: a metaanalysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7:325-40.

- van Tuin L, Schaufeli WB, van Rhenen W, Kuiper RM. Business results and well-being: an engaging leadership intervention study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1-18.

- Su YL, Reeve J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educ Psychol Rev. 2011;23:159-88.

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Sanz-Vergel AI. Burnout and work engagement: the JDR approach. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2014;1:389-411.

- Gordon HJ, Demerouti E, Le Blanc PM, Bakker AB, Bipp T, Verhagen MAMT. Individual job redesign: job crafting interventions in healthcare. J Vocat Behav. 2018;104:98-114.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

دوروثيا كوهين

dorothea.kohnen@kuleuven.be

القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقالة - **الارتباط ذو دلالة عند مستوى 0.01 (ذو طرفين)، تم ترميز الجنس

ذكر و أنثى. نطاق المقياس لجميع المتغيرات هو

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-023-00886-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38225620

Publication Date: 2024-01-15

Engaging leadership and nurse well-being: the role of the work environment and work motivation-a cross-sectional study

Abstract

Background Healthcare literature suggests that leadership behavior has a profound impact on nurse work-related well-being. Yet, more research is needed to better conceptualize, measure, and analyse the concepts of leadership and well-being, and to understand the psychological mechanisms underlying this association. Combining Self-Determination and Job Demands-Resources theory, this study aims to investigate the association between engaging leadership and burnout and work engagement among nurses by focusing on two explanatory mechanisms: perceived job characteristics (job demands and resources) and intrinsic motivation. Methods A cross-sectional survey of 1117 direct care nurses (response rate = 25%) from 13 general acute care hospitals in Belgium. Validated instruments were used to measure nurses’ perceptions of engaging leadership, burnout, work engagement, intrinsic motivation and job demands and job resources. Structural equation modeling was performed to test the hypothesised model which assumed a serial mediation of job characteristics and intrinsic motivation in the relationship of engaging leadership with nurse work-related well-being. Results Confirmatory factor analysis indicated a good fit of the measurement model. The findings offer support for the hypothesized model, indicating that engaging leadership is linked to enhanced well-being, as reflected in increased work engagement, and reduced burnout. The results further showed that this association is mediated by nurses’ perceptions of job resources and intrinsic motivation. Notably, while job demands mediated the relationship between EL and nurses’ well-being, the relationship became unsignificant when including intrinsic motivation as second mediator.

Conclusions Engaging leaders foster a favourable work environment for nursing staff which is not only beneficial for their work motivation but also for their work-related well-being. Engaging leadership and job resources are modifiable aspects of healthcare organisations. Interventions aimed at developing engaging leadership behaviours among nursing leaders and building job resources will help healthcare organisations to create favourable working conditions for their nurses.

Trial Registration: The study described herein is funded under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme from 2020 to 2023 (Grant Agreement 848031). The protocol of Magnet4Europe is registered in the ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN10196901).

Introduction

Despite the widely acknowledged importance of leadership in creating healthy workplaces, the majority of leadership studies have largely neglected its impact on health-related outcomes, such as burnout and work engagement, mostly in favour of job performance or job satisfaction [7]. Even more, previous research has underestimated (inadequate) leadership as a driving factor in the development of employee well-being and ill-health, partly because of poor conceptualization, measurement, or analysis of leadership and burnout [11]. For instance, earlier studies assessed burnout rather as a one-dimensional construct by solely focusing on the emotional exhaustion dimension of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [12]. The MBI is the most widely used instrument to assess occupational burnout; however, it has been frequently criticized because of conceptual, practical and psychometric shortcomings [13]. Similarly, most burnout research considered leadership behavior as rather narrow (e.g., by social support) instead of a comprehensive, multidimensional concept [14]. In relation to leadership, previous leadership concepts, particularly transformational leadership, have been criticized, because they lack a theoretical foundation and detailed description of the underlying processes [15, 16]. Accordingly, there is still much debate in the literature about the (motivational) underlying processes through which leaders influence employee well-being [10, 17].

In the present study, the focus is on the concept of engaging leadership (EL) [11, 18] which is measured and understood through the perceptions of nurses. Rooted in Self-Determination theory (SDT, [19]), our research builds on the premise that a resourceful workplace as

perceived by employees is not only beneficial for their health but also for their work motivation. By inspiring, strengthening, connecting, and empowering employees, engaging leaders are supposed to balance their follower’s job demands and resources in such a way that they remain healthy, motivated, productive, and satisfied [11]. This resonates with research indicating that leaders, including engaging leaders, indirectly influence their followers’ well-being by shaping their perceptions of their work environment (i.e., in the form of reduced job demands and improved job resources) [6, 7, 11]. SDT further posits that employees perform and feel better when their motivation is autonomous in nature (i.e., intrinsic). A workplace where employees experience sufficient support, receive high-quality feedback, and have opportunities for professional development, therefore, provides the fuel required for optimal motivation and leads to optimal functioning and well-being [20,21].

Theoretical background and study hypotheses The JD-R leadership model

sustained physical or mental effort” [23] and, therefore, are said to drain employees’ energy. By contrast, job resources are considered as the positive aspects of the job “that are either/or (1) functional in achieving work goals, (2) reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, (3) stimulate personal growth, learning, and development” [23]. Job resources are assumed to have motivational potential as they may not only promote work engagement but also reduce burnout. In this study, the focus is on both the negative aspect (burnout) and positive aspect (work engagement) of job-related well-being as leadership behaviour shows to have differential relationships with these constructs [7, 25]. Burnout is defined as a work-related state of mental exhaustion, which is characterized by extreme tiredness, reduced ability to regulate cognitive and emotional processes, and mental distancing [13]. Being repeatedly confronted with heavy levels of workload and other work-related stressors, nurses are considered at a high risk of burnout [26]. In contrast, work engagement refers to a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor (i.e., high level of energy and mental resilience while working), dedication (referring to a sense of significance, enthusiasm, and challenge), and absorption (being focused and happily engrossed in one’s work) [24, 27]. A large-scale prevalence study of work engagement in 30 European countries revealed that employees in human service jobs such as health care reported higher levels of work engagement than employees in other types of industries [28].

Following the JD-R leadership model, leadership is one of the unique antecedents and plays a decisive role in both the health impairment and motivational process [11, 29]. In other words, leaders who encourage and give supportive feedback, and who show recognition, may provide nurses with sufficient resources and thereby positively influence their health and well-being (i.e., the motivational process) [9, 30]. In contrast, leaders who fail to provide constructive feedback, who show less support, or who exert undue control and pressure on their staff may-due to reduced resources and increased demands-contribute substantially to feelings of stress reducing individual well-being (i.e., the health impairment process) [31]. Empirical research supports this assumption. For instance, Nielsen et al. [17] found that various work characteristics (e.g., role clarity, opportunities for development) mediated the relationship between leadership and health professionals’ well-being. In a similar vein, Schaufeli [11] reported that EL is positively associated with work engagement through job resources (e.g., task variation, role clarity) and negatively associated with burnout through reduced job demands (e.g., work

overload, emotional demands). These results were further supported in a study among nursing staff [32].

Intrinsic motivation in the JD-R leadership model

which nurses’ intrinsic motivation is expected to flourish. Hence, by empowering, strengthening, inspiring, and connecting, engaging leaders are considered to create favourable working conditions characterized by feelings of autonomy, competence, meaning, and relatedness which in turn will increase nurses’ intrinsic motivation. This experience is likely to result in higher levels of work engagement and well-being. Previous studies have mainly focused on the concept of transformational leadership. Research on EL is, however, relatively new and has not widely been researched yet. Nevertheless, SDT-based research generally supports this assumption [35, 36]. For instance, a meta-analytic review shows that a work environment where leaders support their employees to work autonomously is not only beneficial for the satisfaction of employees’ basic needs but also for their (intrinsic) motivation [37]. While the researchers found that leader autonomy support was positively related to intrinsic motivation, it showed, on the other hand, negative associations with employees’ distress (i.e., burnout and work stress). These findings find support by Slemp et al. [38] who conducted a meta-analytic review of 72 studies on the motivational processes and consequences of leader autonomy support in the workplace-behaviours that may be also typical of EL. Furthermore, Fernet et al. [36] showed that (transformational) leadership was significantly related to nurse well-being by contributing to favourable working conditions and intrinsic motivation.

Objective and hypotheses

leaders (a) support nurses to balance their job resources and job demands and (b) nurture their intrinsic motivation through improved working conditions, it is expected that engaging leaders influence nurses’ workrelated perceived strain and well-being (i.e., reduced levels of burnout and increased work engagement). The proposed model is shown in Fig. 1. The hypotheses are as follows:

Methods

Design and setting

Data collection

Participants

Measures

Engaging leadership

(inspiring). The value of Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale of EL was 0.96.

Job demands and resources

Intrinsic motivation

Burnout

Work engagement

Covariates

Data analysis

Next, the hypothesised structural model was evaluated. Bootstrapping was applied with a resample procedure of 1000 bootstrap samples to determine the point estimate and bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence interval (CI) of the total and specific indirect effect [51, 52]. Bootstrapping is recommended as the indirect effect (the product of the coefficients of the predictor and mediator variable) is not normally distributed [53]. A bootstrapped confidence interval (lower level of confidence interval – upper level of confidence interval, LLCI – ULCI) that does not include the null value is indicated as statistically significant. As shown in Fig. 1, we did not hypothesise direct relationships between EL and intrinsic motivation, or between EL and burnout and work

engagement. Rather, it was assumed that these relationships are explained through job demands and resources. Following Hayes [51], a significant association between the predictor and the outcome is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition of mediation. Yet, the direct paths from EL to each outcome variable were also added in the SEM. Any direct associations among the variables included in this study are documented in the supplementary material of this study (Additional file 1: Appendix 1).

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

| Concept (# of items) | Mean | SD | Correlations | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| 1. Gender | – | – | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Age | 40 | 12 | -0.059* | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Engaging Leadership (12) | 3.49 | 0.81 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 1 | |||||

| 4. Job Demands (10) | 3.30 | 0.48 | -0.039 | -0.009 | -0.302** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Job Resources (13) | 3.40 | 0.48 | 0.039 | 0.032 | 0.565** | -0.405** | 1 | |||

| 6. Intrinsic Motivation (3) | 3.80 | 0.62 | 0.047 | -0.139** | 0.247** | -0.213** | 0.456** | 1 | ||

| 7. Work Engagement (3) | 3.49 | 0.67 | 0.061 | 0.086** | 0.341** | -0.348** | 0.527** | 0.497** | 1 | |

| 8. Burnout (12) | 2.18 | 0.57 | 0.023 | -0.104** | -0.315** | 0.589** | -0.468** | -0.347** | -0.591** | 1 |

Results of the mediation analysis

| Hypothesis | Predictor | Mediator | Outcome |

|

|

LLCI | ULCI |

| 1a | Engaging Leadership | Job demands | Burnout | -0.218 | 0.000 | -0.272 | -0.176 |

| 1b | Engaging Leadership | Job demands | Work engagement | 0.064 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.100 |

| 2a | Engaging Leadership | Job resources | Work engagement | 0.260 | 0.000 | 0.192 | 0.342 |

| 2b | Engaging Leadership | Job resources | Burnout | -0.183 | 0.000 | -0.262 | -0.121 |

| 3a | Engaging Leadership | Job demands | Intrinsic motivation | 0.011 | 0.457 | -0.018 | 0.040 |

| 3b | Engaging Leadership | Job resources | Intrinsic motivation | 0.368 | 0.000 | 0.286 | 0.457 |

| 4a | Engaging Leadership | Job demands and intrinsic motivation | Burnout | -0.002 | 0.461 | -0.007 | 0.003 |

| 4b | Engaging Leadership | Job demands and Intrinsic motivation | Work engagement | 0.003 | 0.462 | -0.005 | 0.012 |

| 5a | Engaging Leadership | Job resources and intrinsic motivation | Work engagement | 0.104 | 0.000 | 0.070 | 0.144 |

| 5b | Engaging Leadership | Job resources and intrinsic motivation | Burnout | -0.058 | 0.000 | -0.095 | -0.032 |

to the bootstrap CI 95% (0.035, 0.100). These results confirm H1a and H1b.

Next, it was hypothesised that the relationship of EL with intrinsic motivation is mediated by job demands (H3a) and job resources (H3b). The observed indirect association between EL and intrinsic motivation via job demands (

Our next set of hypotheses stated that job demands and intrinsic motivation mediate the relationship of EL with burnout (H4a) and work engagement (H4b). We found that the indirect effect of EL on burnout via job demands and intrinsic motivation (

Discussion

results from the structural equation modeling largely support this model: engaging leaders can shape nurses’ perceptions of their work and create a work environment that is characterized by more resources and fewer demands. Particularly, by providing nurses with sufficient job resources such leaders do not only nurture their intrinsic motivation but also foster their perceived wellbeing (i.e., reduced levels of burnout and increased work engagement).

process in nurses, inducing a sense of enjoyment and satisfaction while performing their job [55]. Even more, as illustrated in the current sample, nurses are likely to feel more engaged at work (H5a), while they are less likely to develop feelings of burnout (H5b). This study adds to the accumulating evidence of the JD-R model and SDT by showing that leadership behavior has a profound impact on nurses’ perceptions of their work environment, their work motivation, and work-related well-being.

Contrary to our expectations, we found no mediating effect of job demands and intrinsic motivation in the relationship of EL with nurses’ burnout (H4a) and work engagement (H4b). Although job demands mediated the relationship between EL and nurses’ well-being, the relationship became unsignificant when including intrinsic motivation as second mediator. Overall, these findings align with a recent study by Kohnen et al. [21]. In a sample of 1729 direct care nurses in Belgium, the authors investigated the mediating role of intrinsic motivation in the relationship of job demands and job resources with nurse work-related well-being. The results showed that intrinsic motivation did not mediate the relationship of job demands with nurse well-being. In a similar vein, intrinsic motivation showed no associations with job demands in general. In relation to the current study, our findings prompt further exploration into the specific aspects of EL, as it may not be effectively predicting the associations of job demands and intrinsic motivation with nurses’ work-related well-being. Yet, another possible explanation is that the relationship between job demands and nurse well-being is influenced by other types of motivation, such as external regulation, as a form of controlled motivation. SDT arranges different forms of motivation along a continuum of self-determination, ranging from more controlled to more autonomous motivation. While the most autonomous form of motivation, i.e., intrinsic motivation, is at one extreme of the continuum, the most controlled form of motivation (i.e., external regulation) is at the other end of the spectrum. External regulation occurs when employees engage in a certain behavior or activity for purely instrumental reasons, such as to obtain rewards, to avoid punishment, or simply because they are being pressured by demands. Indeed, previous research and meta-analytic evidence demonstrated that external regulation, and particularly amotivation (i.e., lack of motivation, employees shows no interest or engagement in performing a task), exerted only negative influence on employee functioning, leading to distress and burnout [36, 37]. This may suggest that autonomous and controlled motivation or amotivation are inversely associated with employees’ psychological functioning. However, empirical evidence on the individual effects of the different motivational types is scarce

and more research is needed to fully understand employees’ motivation in the workplace [37].

Limitations

might offer valuable insights into their perceptions of the clinical work environment.

Implications for practice

Conclusion

Abbreviations

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| EL | Engaging leadership |

| JD-R model | Job demands-resources model |

| SDT | Self-determination theory |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 15 January 2024

References

- Buchan J, Aiken L. Solving nursing shortages: a common priority. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:3262-8.

- Lu H, Zhao Y, While A. Job satisfaction among hospital nurses: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;94:21-31.

- Janssen PPM, De Jonge J, Bakker AB. Specific determinants of intrinsic work motivation, burnout and turnover intentions: a study among nurses. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29:1360-9.

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39:223-9.

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski JA, Busse R, Clarke H, et al. Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Aff. 2001;20:43-53.

- Skakon J, Nielsen K, Borg V, Guzman J. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work Stress. 2010;24:107-39.

- Inceoglu I, Thomas G, Chu C, Plans D, Gerbasi A. Leadership behavior and employee well-being: an integrated review and a future research agenda. Leadersh Q. 2018;29:179-202.

- Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Reinius M, Griffiths P. Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18:1-17.

- Rahmadani VG, Schaufeli WB. Engaging leaders foster employees’ wellbeing at work. 2020;5:1-7.

- Cummings GG, Tate K, Lee S, Wong CA, Paananen T, Micaroni SPM, et al. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;85:19-60.

- Schaufeli W. Engaging leadership in the job demands-resources model. Career Dev Int. 2015;20:446-63.

- Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, Hammarström A, Hogstedt C, Marteinsdottir I, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1-13.

- Schaufeli WB, Desart S, De Witte H. Burnout assessment tool (Bat)development, validity, and reliability. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1-21.

- Kanste O , Kyngäs H, Nikkilä J. The relationship between multidimensional leadership and burnout among nursing staff. J Nurs Manag. 2007;15:731-9.

- van Knippenberg D, Sitkin SB. A critical assessment of charismatic-transformational leadership research: back to the drawing board? Acad Manag Ann. 2013;7:1-60.

- Bormann KC, Rowold J. Construct proliferation in leadership style research: reviewing pro and contra arguments. Organ Psychol Rev. 2018;8:149-73.

- Nielsen K, Randall R, Yarker J, Brenner SO. The effects of transformational leadership on followers’ perceived work characteristics and psychological well-being: a longitudinal study. Work Stress. 2008;22:16-32.

- Schaufeli W. Engaging leadership: how to promote work engagement? Front Psychol. 2021;12:1-10.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68-78.

- Deci EL, Olafsen AH, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2017;4:19-43.

- Kohnen D, De Witte H, Schaufeli WB, Dello S, Bruyneel L, Sermeus W. What makes nurses flourish at work? How the perceived clinical work environment relates to nurse motivation and well-being: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2023;104567.

- de Beer LT, Schaufeli WB, De Witte H, Hakanen JJ, Shimazu A, Glaser J, et al. Measurement invariance of the burnout assessment tool (Bat) across seven cross-national representative samples. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1-14.

- Demerouti E, Nachreiner F, Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB. The job demandsresources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:499-512.

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J Organ Behav. 2004;25:293-315.

- Arnold KA. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: a review and directions for future research. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22:381-93.

- Woo T, Ho R, Tang A, Tam W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;123:9-20.

- Schaufeli W, Salanova M, González-romá V, Bakker A. The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3:71-92.

- Hakanen JJ, Ropponen A, De Witte H, Schaufeli WB. Testing demands and resources as determinants of vitality among different employment contract groups. A study in 30 European countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4951.

- Rahmadani VG, Schaufeli WB, Stouten J, Zhang Z, Zulkarnain Z. Engaging leadership and its implication for work engagement and job outcomes at the individual and team level: a multi-level longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:776.

- Engelbrecht AS, Heine G, Mahembe B. Integrity, ethical leadership, trust and work engagement. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2017;38:368-79.

- Van Dierendonck D, Borrill C, Haynes C, Stride C. Leadership behavior and subordinate well-being. J Occup Health Psychol. 2004;9:165-75.

- Lewis HS, Cunningham CJL. Linking nurse leadership and work characteristics to nurse burnout and engagement. Nurs Res. 2016;65:13-23.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25:54-67.

- Xue H, Luo Y, Luan Y, Wang N. A meta-analysis of leadership and intrinsic motivation: examining relative importance and moderators. Front Psychol. 2022;13.

- Eyal O, Roth G. Principals’ leadership and teachers’ motivation. J Educ Adm. 2011;49:256-75.

- Fernet C, Trépanier SG, Austin S, Gagné M, Forest J. Transformational leadership and optimal functioning at work: on the mediating role of employees’ perceived job characteristics and motivation. Work Stress. 2015;29:11-31.

- Van den Broeck A, Howard JL, Van Vaerenbergh Y, Leroy H, Gagné M. Beyond intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis on selfdetermination theory’s multidimensional conceptualization of work motivation. Organ Psychol Rev. 2021;11:240-73.

- Slemp GR, Kern ML, Patrick KJ, Ryan RM. Leader autonomy support in the workplace: a meta-analytic review. Motiv Emot. 2018;42:706-24.

- Sermeus W, Aiken LH, Ball J, Bridges J, Bruyneel L, Busse R, et al. A workplace organisational intervention to improve hospital nurses’ and physicians’ mental health: study protocol for the Magnet4Europe wait list cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e059159.

- Regulation P. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Regulation. 2016;679:2016.

- De Jonge J, Van Breukelen GJP, Landeweerd JA, Nijhuis FJN. Comparing group and individual level assessments of job characteristics in testing the job demand-control model: a multilevel approach. Hum Relations. 1999;52:95-122.

- Schaufeli WB. Applying the job demands-resources model: a’how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organ Dyn. 2017;46:120-32.

- Tremblay MA, Blanchard CM, Taylor S, Pelletier LG, Villeneuve M. Work extrinsic and intrinsic motivation scale: its value for organizational psychology research. Can J Behav Sci. 2009;41:213-26.

- Hadžibajramović E, Schaufeli W, De Witte H. Shortening of the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)-from 23 to 12 items using content and Rasch analysis. BMC Public Health BioMed Central. 2022;22:1-16.

- Schaufeli WB, Shimazu A, Hakanen J, Salanova M, De Witte H. An ultrashort measure for work engagement: the UWES-3 validation across five countries. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2019;35:577-91.

- IBM. IBM Corp. Released 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2021.

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus. Handb item response theory. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2017. p. 507-18.

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull. 1988;103:411.

- van de Schoot R, Lugtig P, Hox J. A checklist for testing measurement invariance. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2012;9:486-92.

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1-55.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Third Edn. Guilford Publications; 2022.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis—model numbers. Guilford publications: Guilford Press; 2013.

- Stride CB, Gardner SE, Catley N, Thomas F. Mplus code for mediation, moderation and moderated mediation models (1 to 80). 2017. p. 1-767.

- Cohen P, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. UK: Psychology Press; 2014.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11:227-68.

- de Koning R, Egiz A, Kotecha J, Ciuculete AC, Ooi SZY, Bankole NDA, et al. Survey fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of neurosurgery survey response rates. Front Surg. 2021;8:690680.

- Timmins F, Ottonello G, Napolitano F, Musio ME, Calzolari M, Gammone

, et al. The state of the science-the impact of declining response rates by nurses in nursing research projects. J Clin Nurs. 2023; e9-11. - Fisher GG, Matthews RA, Gibbons AM. Developing and investigating the use of single-item measures in organizational research. J Occup Health Psychol. 2016;21:3-23.

- Conway JM. Method variance and method bias in industrial and organizational psychology. In: Handbook of research methods in industrial and organizational psychology. USA: Wiley; 2008. p. 344-65.

- Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Deci EL, Ryan RM, Duda JL, et al. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: a metaanalysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7:325-40.

- van Tuin L, Schaufeli WB, van Rhenen W, Kuiper RM. Business results and well-being: an engaging leadership intervention study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1-18.

- Su YL, Reeve J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educ Psychol Rev. 2011;23:159-88.

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Sanz-Vergel AI. Burnout and work engagement: the JDR approach. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2014;1:389-411.

- Gordon HJ, Demerouti E, Le Blanc PM, Bakker AB, Bipp T, Verhagen MAMT. Individual job redesign: job crafting interventions in healthcare. J Vocat Behav. 2018;104:98-114.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Dorothea Kohnen

dorothea.kohnen@kuleuven.be

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article - **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed), gender was coded

male and female. The range of scale for all variables is