DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49762-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38969643

تاريخ النشر: 2024-07-05

المتراكبات الميتاموادية المركبة من MOF/Fe ثنائية الأبعاد تتيح امتصاص الميكروويف فائق النطاق بشكل قوي

تم القبول: 11 يونيو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 05 يوليو 2024

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

نينغ

الملخص

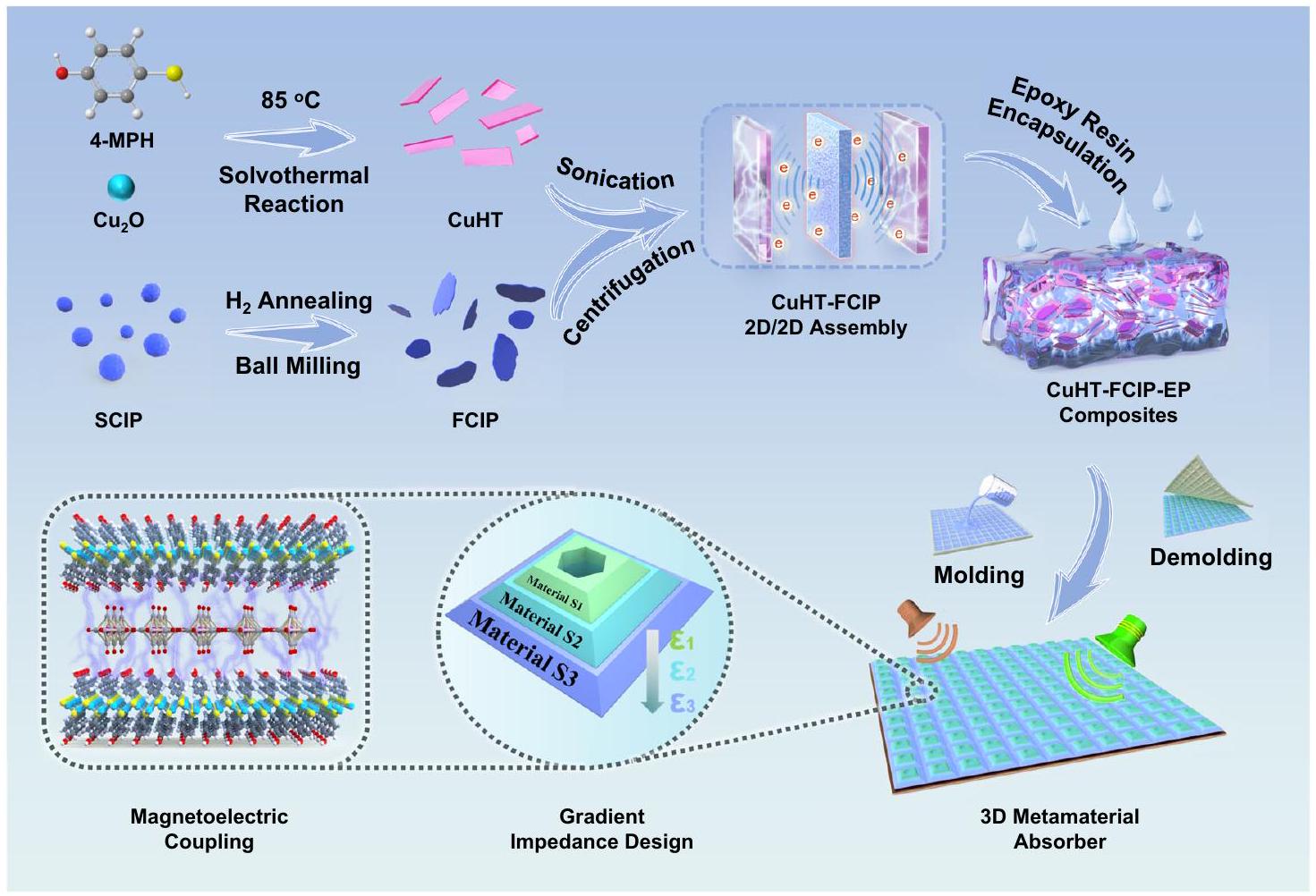

يجمع التصميم بين الهياكل الماكروسكوبية وتصميمات المواد الميكروسكوبية إمكانيات هائلة لتطوير ماصات الموجات الكهرومغناطيسية المتقدمة. هنا، نقترح تصميم مادة ميتا لمعالجة التحديات المستمرة في هذا المجال، بما في ذلك عرض النطاق الضيق، والعقبات في الترددات المنخفضة، وخاصة القضية الملحة للمتانة (أي، الحوادث المائلة والمستقطبة). يتميز ماصنا بإطار معدني عضوي شبه موصل/تجميع ثنائي الأبعاد من الحديد (CuHT-FCIP) مع وفرة من التوصيلات غير المتجانسة البلورية/البلورية وشبكات قوية من الاقتران المغناطيسي الكهربائي. يحقق هذا التصميم امتصاصًا ملحوظًا للموجات الكهرومغناطيسية عبر نطاق واسع (من 2 إلى 40 جيجاهرتز) بسماكة تبلغ 9.3 مم فقط. ومن الجدير بالذكر أنه يحافظ على أداء مستقر ضد الحوادث المائلة (ضمن

الميكروويف

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن الشكل البلوري المستقر والقابل للتعديل لمركبات MOF ذات الهيكل الثنائي الأبعاد (2D) الشبيه بالورقة، المصاحب لطريقة تحضير خالية من التحلل الحراري، يفتح آفاقًا جديدة لتطوير ممتصات المواد الميتامادية الفعالة والمتينة.

النتائج

تحضير مركبات CuHT-FCIP

j

تحكم في النمو والتبلور على طول المستوى البلوري المحدد. المنتجات الناتجة من CuHT لها شكل رقيق مستطيل ثنائي الأبعاد بمتوسط نسبة الطول إلى العرض حوالي 1.70 (الشكل 2a والشكل التكميلي 1). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يظهر CuHT خصائص شبه موصلة نموذجية، مع فجوة نطاق تبلغ 2.87 eV وموصلية كتلية لـ

(الشكل 2b). تشير هذه الخاصية الفريدة من نوعها أيضًا إلى توافق ممتاز بين CuHT و FCIP من حيث أدائهما المغناطيسي الكهربائي.

الأداء الكهرومغناطيسي لمركبات CuHT-FCIP-EP

fقد الرنين الطبيعي/التبادلي بين الطبقات (الشكل التكميلي 7). من ناحية أخرى، فإن الموصلية الكهربائية المنخفضة لـ FCIP نفسها تؤدي إلى عدم تطابق في الاقتران المغناطيسي الكهربائي سواء عند إضافتها بكميات زائدة أو غير كافية (الشكل التكميلي 8). لذلك، قد يكون محتوى FCIP حاسمًا في تعديل الأداء العام لامتصاص نظام مركب CuHT-FCIP.

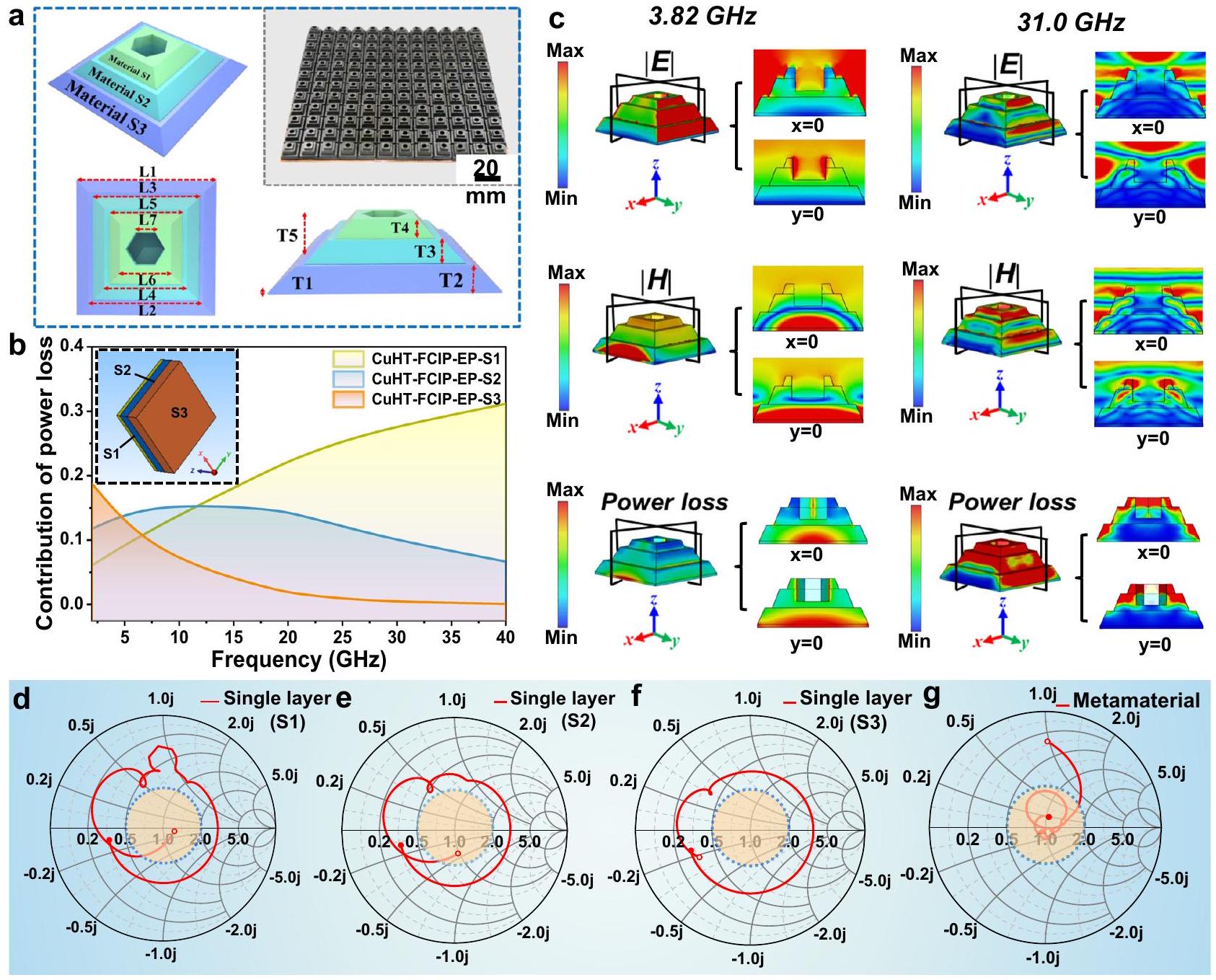

تصميم المادة الميتامادية CuHT-FCIP-EP

تتطابق وتترابط مساهمات الخسارة للمواد بشكل مثالي عبر نطاق الترددات المنخفضة

امتصاص المواد الميتامادية عند 3.82 جيجاهرتز و 31.0 جيجاهرتز. مخطط د-ج سميث للامتصاصات ذات الطبقة الواحدة والامتصاصات الميتامادية (يمثل الطرف الدائري الفارغ 2 جيجاهرتز، بينما يمثل الطرف الصلب 40 جيجاهرتز؛ المنطقة المظللة بالبرتقالي تمثل نطاق التذبذب من

وشكل إضافي رقم 13). يسمح الثقب السداسي بزيادة دخول الموجات الكهرومغناطيسية ذات التردد المنخفض. وبالتالي، عند 3.82 جيجاهرتز، تظهر المجالات الكهربائية والمغناطيسية توزيعًا مركزًا في الطبقة السفلية من المادة الميتامادية. وهذا يشير إلى أن مادة الطبقة السفلية (أي CuHT-FCIP-EP-S3) تعمل بشكل أساسي على امتصاص الموجات الكهرومغناطيسية في نطاق التردد المنخفض (شكل إضافي رقم 14). مع انخفاض الطول الموجي، تحدث تشوهات كبيرة في المجالات الكهربائية والمغناطيسية على سطح المادة، مما يشير إلى التأثيرات الهيكلية للمادة الميتامادية. تشير شدة المجالات الكهربائية والمغناطيسية القوية بالقرب من الخطوات وداخل الثقب السداسي إلى انكسارات حادة أو تشتت ثانوي في هذه المناطق. وبالتالي، من خلال دمج هياكل متعددة الطبقات ذات مقاومة متدرجة مع ثقوب سداسية، تحقق مادة CuHT-FCIP-EP الميتامادية امتصاصًا عريض النطاق من كل من فقدان المادة والتأثيرات الهيكلية. تتغلب هذه الآلية بفعالية على تأثير الجلد الذي تواجهه ممتصات الموجات الكهرومغناطيسية التقليدية ذات الطبقة الواحدة. كطريقة تمثيلية في الإلكترونيات، مخطط سميث

الرسم البياني)، وبالتالي تحقيق امتصاص مثالي. كما هو موضح في الشكل 4د-ز، تؤدي هذه الظواهر إلى تطابق مقاومة قريب من المثالي لمادة CuHT-FCIP-EP الميتامادية، وهو ما لا يمكن تحقيقه بواسطة المواد الميتامادية ذات المكون الواحد. لذلك، يسمح التصميم الهيكلي العقلاني للماص أن يظهر استجابة كهرومغناطيسية قريبة من المثالية، ولكنه يمتلك أيضًا آليات فقد متعددة، مما يعزز من قدرته على امتصاص الموجات الكهرومغناطيسية.

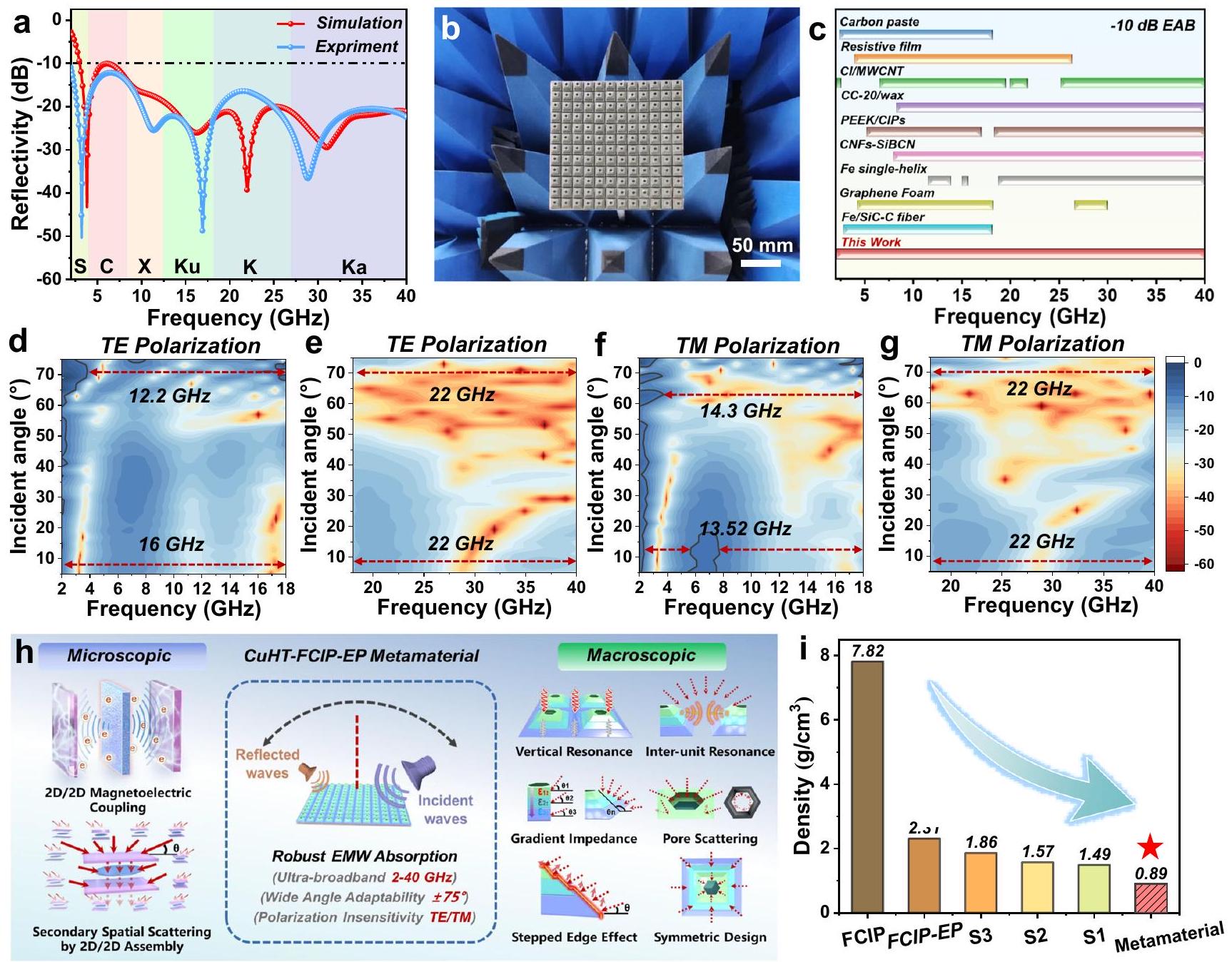

أداء امتصاص الموجات الكهرومغناطيسية لمادة CuHT-FCIP-EP الميتامادية

إلى

). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، بفضل تناظر C4 في تصميم الوحدة، يظهر ماص الميتامادة عدم حساسية للاستقطاب. يظهر CuHT-FCIP-EP الميتامادي أداء امتصاص متسق وفعال في وضع الاستقطاب المغناطيسي العرضي (TM) عبر زوايا السقوط ضمن

نقدم تصميمًا قويًا لماص الموجات الدقيقة يعتمد على آلية فقدان الربط المغناطيسي الكهربائي القوي ثنائي الأبعاد/ثنائي الأبعاد للمواد شبه الموصلة MOFs مع المواد المغناطيسية، بالإضافة إلى تصميم هيكل ميتا ثلاثي الأبعاد مع ترتيب مقاومة متدرج. في الأعمال السابقة، غالبًا ما تعمل ماصات الميتامادة في نطاقات دون الطول الموجي، تحت تردد قطع تحدده ثابت الشبكة. يكسر عملنا هذا الحد من خلال تقديم تصميم هيكل متدرج مسامي مصاحب مع تصميم مادة امتصاص قوية للربط المغناطيسي الكهربائي، مما يتيح ضبط عرض نطاق الامتصاص بشكل فعال. تظهر مادة CuHT-FCIP-EP الميتامادية امتصاصًا قريبًا من المثالية من 2 غيغاهرتز إلى 40 غيغاهرتز، مما يغطي جميع نطاقات التردد العالي 5G. بسبب إدخال المواد المغناطيسية، فإن سمك مادة CuHT-FCIP-EP الميتامادية هو فقط 9.3 مم، ومع ذلك، تظهر قوة امتصاص ممتازة (زاوية مائلة ضمن

مواد

جميع المواد المستخدمة في هذا العمل متوفرة في الملف التكميلي.

تم تصنيع الميزات لأول مرة. تم تصنيع المادة الميتامادية بناءً على عملية تشكيل متعددة الخطوات: (1) تم صب كمية محددة من راتنج CuHT-FCIP-EP-S1 غير المعالج بعناية في قالب مطاطي سيليكوني لملء الجزء السفلي من القالب (الطبقة العلوية من المادة الميتامادية). (2) بعد المعالجة لمدة ساعتين، تم صب راتنج CuHT-FCIP-EP-S2 غير المعالج بعناية في القالب المطاطي السيليكوني لملء الطبقة الوسطى. (3) بعد المعالجة لمدة ساعتين إضافيتين، تم صب راتنج CuHT-FCIP-EP-S3 غير المعالج بعناية في القالب المطاطي السيليكوني لملء بقية التجاويف (الطبقة السفلية من المادة الميتامادية). (4) أخيرًا، بعد ثلاث ساعات إضافية من المعالجة، تم الحصول على مواد ميتامادية CuHT-FCIP-EP مع تركيبات S1-S3 من الأعلى إلى الأسفل من خلال عملية إزالة القالب الكاملة.

توفر البيانات

References

- Lv, H. L. et al. Electromagnetic absorption materials: current progress and new frontiers. Prog. Mater. Sci. 127, 100946 (2022).

- Liang, J. et al. Defect-engineered graphene/

multilayer alternating core-shell nanowire membrane: a plainified hybrid for

broadband electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200141 (2022). - Asadchy, V. S. et al. Broadband reflectionless metasheets: frequency-selective transmission and perfect absorption. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031005 (2015).

- Choi, M. et al. A terahertz metamaterial with unnaturally high refractive index. Nature 470, 369-373 (2011).

- Xi, W. et al. Ultrahigh-efficient material informatics inverse design of thermal metamaterials for visible-infrared-compatible camouflage. Nat. Commun. 14, 4694 (2023).

- Jin, Y. et al. Infrared-reflective transparent hyperbolic metamaterials for use in radiative cooling windows. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2207940 (2023).

- Qu, S. C. et al. Conceptual-based design of an ultrabroadband microwave metamaterial absorber. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2110490118 (2021).

- Xing, R. et al. 3D printing of liquid-metal-in-ceramic metamaterials for high-efficient microwave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2307499 (2023).

- Lu, J. et al. Vat photopolymerization 3D printing gyroid metastructural SiOC ceramics achieving full absorption of X-band electromagnetic wave. Addit. Manuf. 78, 103827 (2023).

- Huang, M. et al. Heterogeneous interface engineering of Bi-Metal MOFs-derived

– ZnO -Fe@C microspheres via confined growth strategy toward superior electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2308898 (2023). - Zhai, N. et al. Interface engineering of heterogeneous

for high-efficient electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312237 (2023). - Yao, L. H. et al. Multifunctional nanocrystalline-assembled porous hierarchical material and device for integrating microwave absorption, electromagnetic interference shielding, and energy storage. Small 19, 2208101 (2023).

- Snyder, B. E. R. et al. A ligand insertion mechanism for cooperative

capture in metal-organic frameworks. Nature 613, 287 (2023). - Gao, X. et al. Specific-band electromagnetic absorbers derived from metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 498, 215465 (2024).

- Jiang, M. et al. Scalable 2D/2D assembly of ultrathin MOF/MXene sheets for stretchable and bendable energy storage devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312692 (2023).

- Zhou, P. et al. Strategies for enhancing the catalytic activity and electronic conductivity of MOFs-based electrocatalysts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 478, 214969 (2023).

- Qiao, J. et al. Non-magnetic bimetallic MOF-derived porous carbonwrapped

composites for efficient electromagnetic wave absorption. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 75 (2021). - Choi, S.-G. et al. MOF-derived carbon/ZnS nanoparticle composite interwoven with structural and conductive CNT scaffolds for ultradurable K-ion storage. Chem. Eng. J. 459, 141663 (2023).

- Liang, C. Y. et al. Boosting the optoelectronic performance by regulating exciton behaviors in a porous semiconductive metalorganic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2189-2196 (2022).

- Deng, X. L. et al. Conductive MOFs based on thiol-functionalized linkers: challenges, opportunities, and recent advances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 450, 214235 (2022).

- Liang, C. et al. Thermoplastic membranes incorporating semiconductive metal-organic frameworks: an advance on flexible X-ray detectors. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 59, 11856-11860 (2020).

- Dong, A. et al. Fine-tuning the electromagnetic parameters of 2D conjugated metal-organic framework semiconductors for antielectromagnetic interference in the Ku band. Chem. Eng. J. 444, 136574 (2022).

- Zang, Y. et al. Recent development on the alkaline earth MOFs (AEMOFs). Coord. Chem. Rev. 440, 213955 (2021).

- Ban, Q. et al. Polymer self-assembly guided heterogeneous structure engineering towards high-performance low-frequency electromagnetic wave absorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 650, 1434-1445 (2023).

- Hao, Z. et al. Two-dimensional confinement engineering of

nanosheets supported nano-cobalt for high-efficiency microwave absorption. Chem. Eng. J. 473, 145296 (2023). - Zhao, Y. et al. Interfacial engineering of a vertically stacked graphene/h-BN heterostructure as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen peroxide synthesis. Mater. Horiz. 10, 4930-4939 (2023).

- Zhao, Q. et al. Built-in electric field-assisted charge separation over carbon dots-modified

nanoplates for photodegradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 465, 164-171 (2019). - Hu, B. et al. Electronic modulation of the interaction between Fe single atoms and

for photocatalytic reduction. Catal. 12, 11860-11869 (2022). - Liu, G. et al. High-yield two-dimensional metal-organic framework derivatives for wideband electromagnetic wave absorption. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 13, 20459-20466 (2021).

- Yuan, M. et al. Remarkable magnetic exchange coupling via constructing Bi-magnetic interface for broadband lower-frequency microwave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2203161 (2022).

- Li, Q. et al. Graphene-enabled metasurface with independent amplitude and frequency controls in orthogonal polarization channels. Carbon 206, 260-267 (2023).

- Shu, J.-C. et al. Heterodimensional structure switching multispectral stealth and multimedia interaction devices. Adv. Sci. 10, 2302361 (2023).

- Tang, Z. et al. Synthesis of

Expanded Graphite with crystal/amorphous heterointerface and defects for electromagnetic wave absorption. Nat. Commun. 14, 5951 (2023). - Bao, Y. et al. Heterogeneous burr-like

MXene nanospheres for ultralow microwave absorption and satellite skin application. Chem. Eng. J. 473, 145409 (2023). - Wang, C. et al. Developments status of magnetic loss waveabsorbing materials. J. Silk 58, 27-34 (2021).

- He, L. et al. A four-narrowband terahertz tunable absorber with perfect absorption and high sensitivity. Mater. Res Bull. 170, 112572 (2024).

- Qu, N. et al. Multi-scale design of metal-organic framework metamaterials for broad-band microwave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2402923 (2024).

- Rozanov, K. N. Ultimate thickness to bandwidth ratio of radar absorbers. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 48, 1230-1234 (2000).

- Cong, L. et al. Highly flexible broadband terahertz metamaterial quarter-wave plate. Laser Photonics Rev. 8, 626-632 (2014).

- Wu, S. et al. Microwave meta-absorber by using Smith Chart. Micro. Opt. Technol. Lett. 66, e33957 (2024).

- Low, K.-H. et al. Highly conducting two-dimensional copper(I) 4-hydroxythiophenolate network. Chem. Commun. 46, 7328-7330 (2010).

- Jiang, H. J. et al. Ordered heterostructured aerogel with broadband electromagnetic wave absorption based on mesoscopic magnetic superposition enhancement. Adv. Sci. 10, 2301599 (2023).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49762-4.

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى رويزه شينغ أو جي كونغ.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

(ج) المؤلفون 2024

مختبر شاندونغ الرئيسي لعلوم البوليمرات والتكنولوجيا ومختبر وزارة التعليم الرئيسي لفيزياء المواد وكيميائها في الظروف الاستثنائية، كلية الكيمياء والهندسة الكيميائية، جامعة شمال غرب البوليتكنيك، شيان 710072، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: نينغ كوو، هانكسو سون. البريد الإلكتروني:rzxing@nwpu.edu.cn; كونغجيه@nwpu.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49762-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38969643

Publication Date: 2024-07-05

2D/2D coupled MOF/Fe composite metamaterials enable robust ultra-broadband microwave absorption

Accepted: 11 June 2024

Published online: 05 July 2024

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

Ning

Abstract

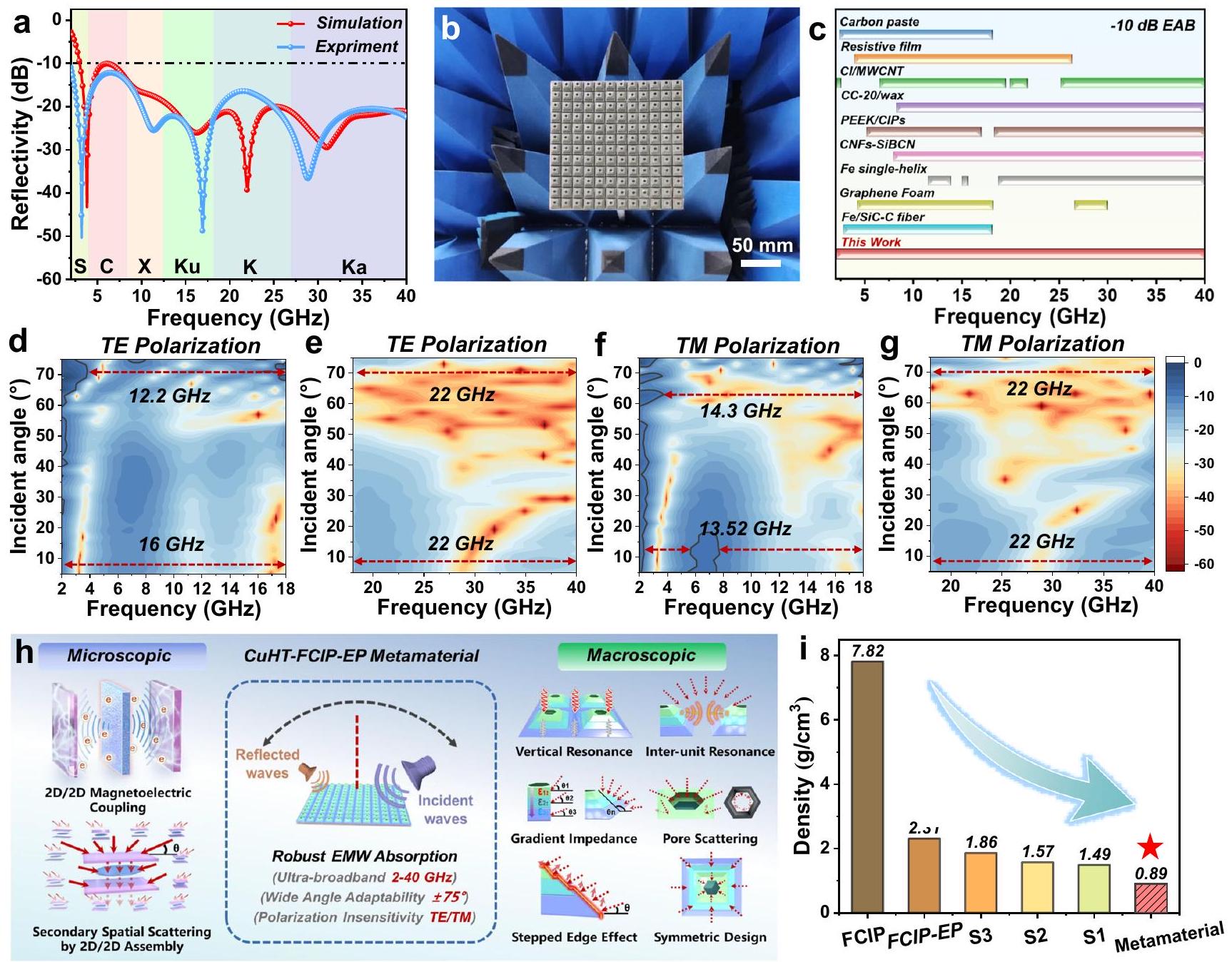

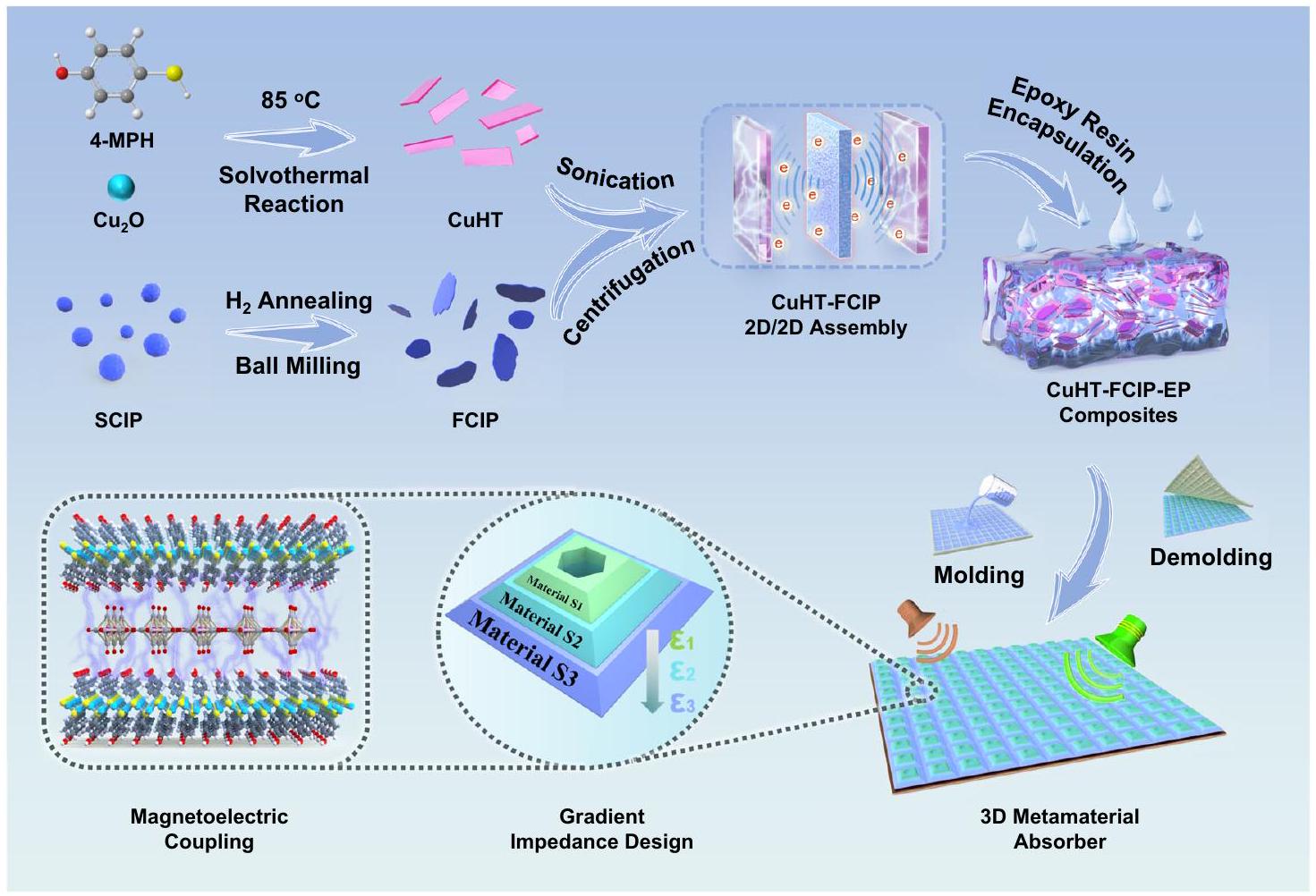

The combination between macroscopic structure designs and microscopic material designs offers tremendous possibilities for the development of advanced electromagnetic wave (EMW) absorbers. Herein, we propose a metamaterial design to address persistent challenges in this field, including narrow bandwidth, low-frequency bottlenecks, and, particularly, the urgent issue of robustness (i.e., oblique, and polarized incidence). Our absorber features a semiconductive metal-organic framework/iron 2D/2D assembly (CuHT-FCIP) with abundant crystal/crystal heterojunctions and strong magneto-electric coupling networks. This design achieves remarkable EMW absorption across a broad range ( 2 to 40 GHz ) at a thickness of just 9.3 mm . Notably, it maintains stable performance against oblique incidence (within

microwaves

addition, the stable and tunable crystal morphology of SC-MOFs, especially their two-dimensional (2D) sheet-like structure, attendant with a pyrolysis-free preparation method, opens up new opportunities for the development of efficient and robust EMW metamaterial absorbers.

Results

Preparation of CuHT-FCIP composites

j

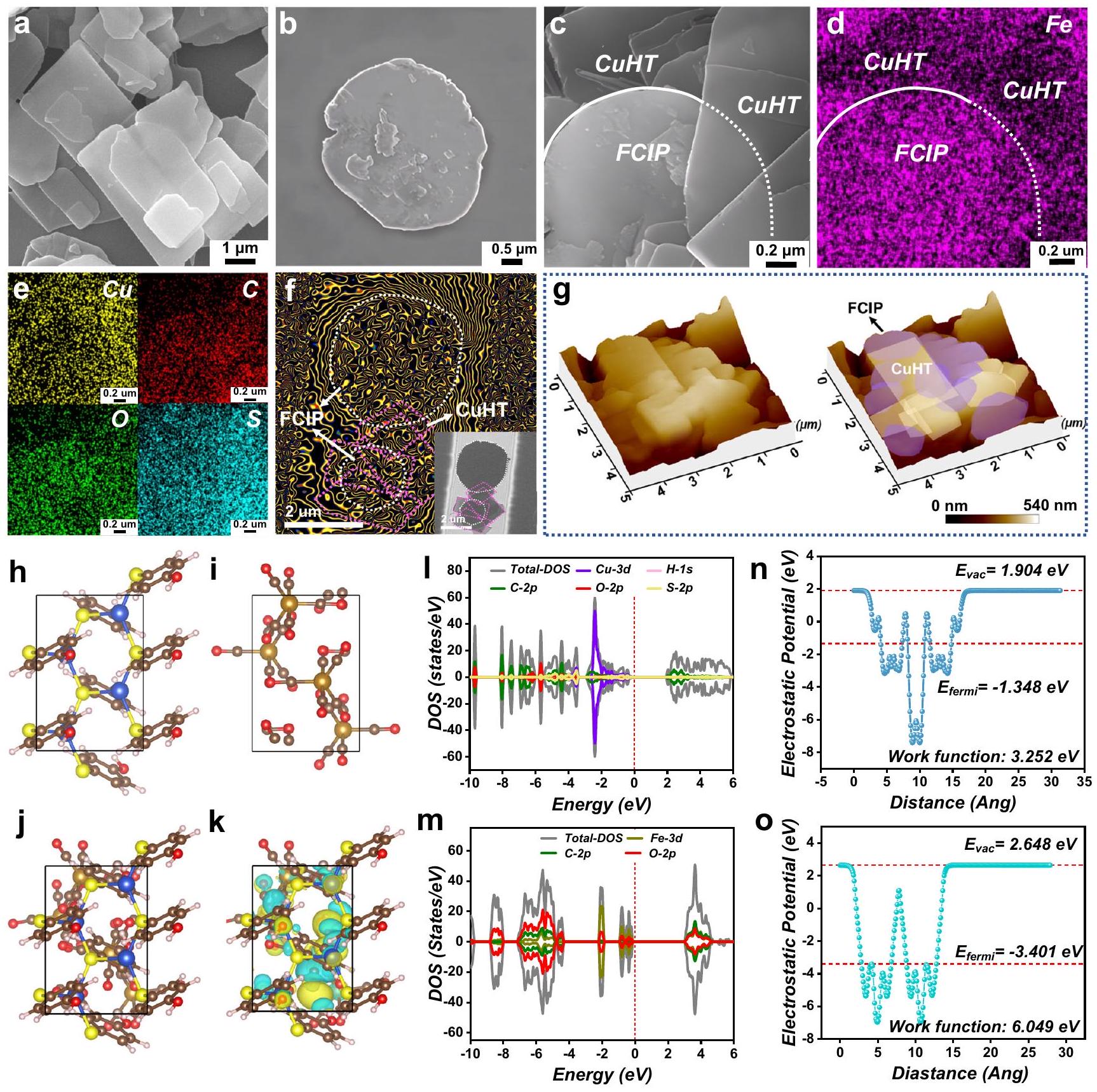

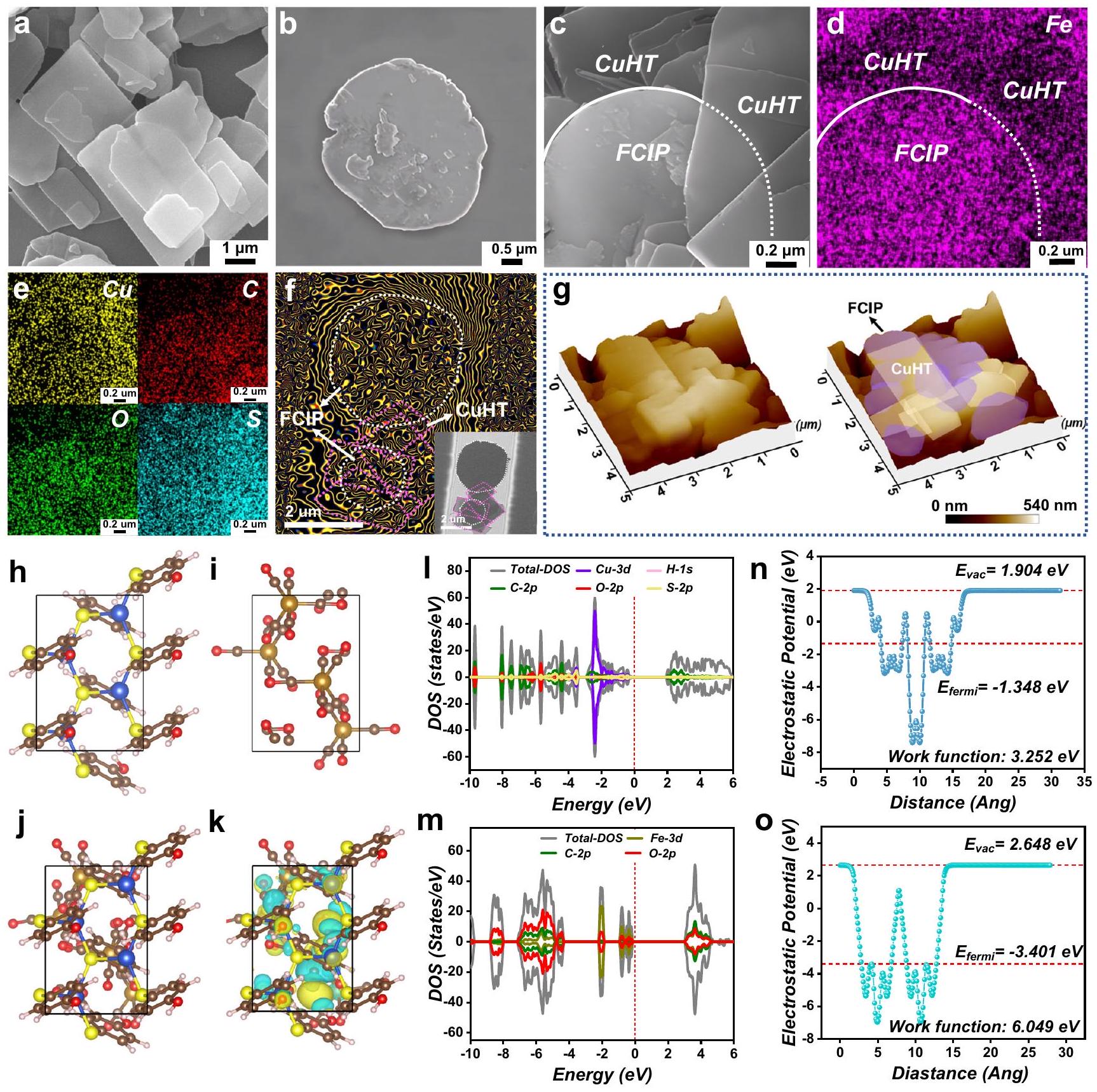

control the growth and nucleation along the specific crystal plane. The resulting CuHT products have a rectangular 2D flake morphology with an average length to width ratio of around 1.70 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, CuHT exhibits typical semiconductor properties, with a bandgap of 2.87 eV and a bulk conductivity of

(Fig. 2b). This unique morphology matching characteristic also indicates an excellent compatibility between CuHT and FCIP in terms of their magnetoelectric performance.

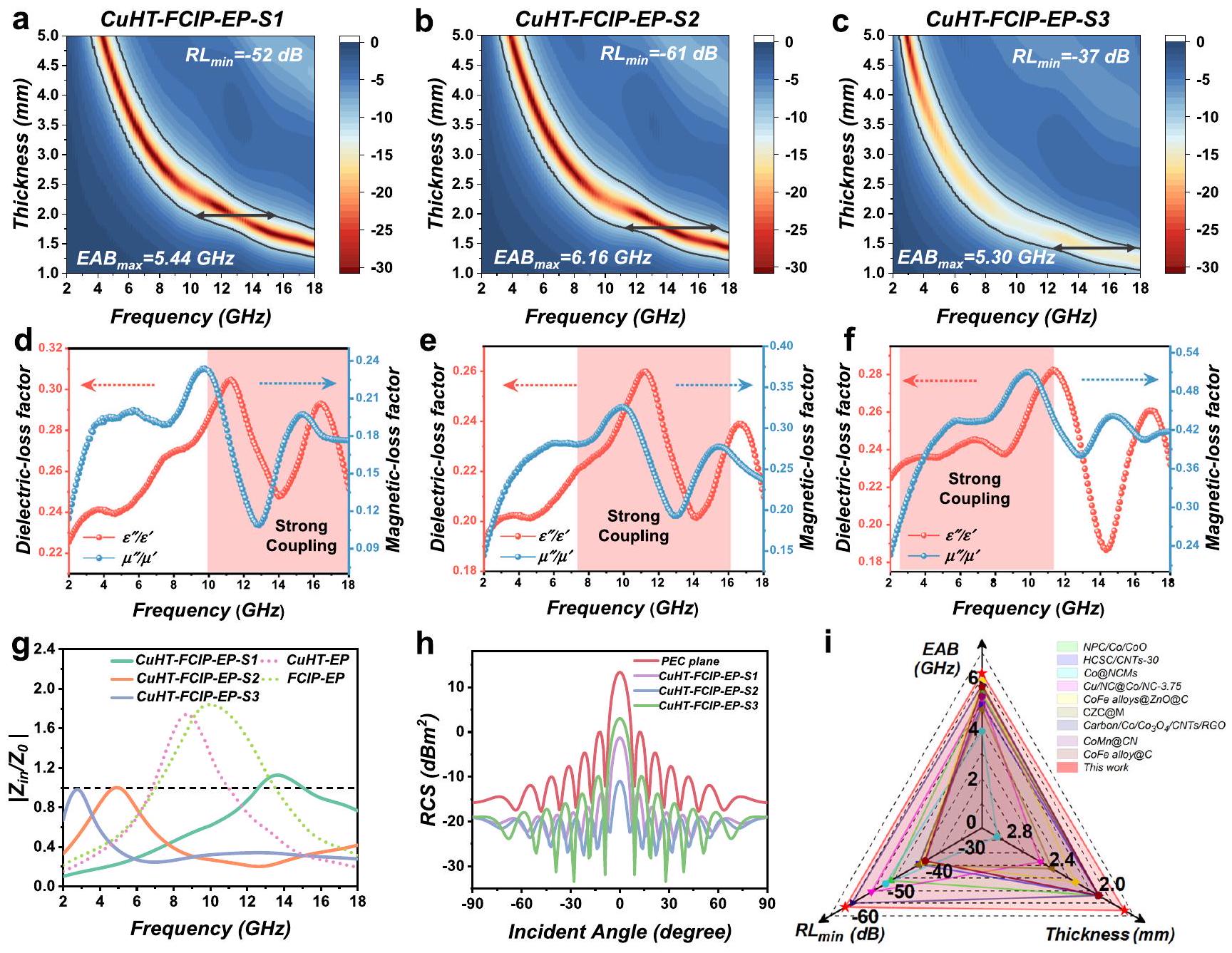

Electromagnetic performance of CuHT-FCIP-EP composites

enhances the interlayer magnetic natural/exchange resonance loss (Supplementary Fig. 7). On the other hand, the low electrical conductivity of FCIP itself results in a mismatch in magnetoelectric coupling either when added in excess or insufficient amounts (Supplementary Fig. 8). Therefore, the FCIP content could be crucial in modulating the overall absorption performance of the CuHT-FCIP composite system.

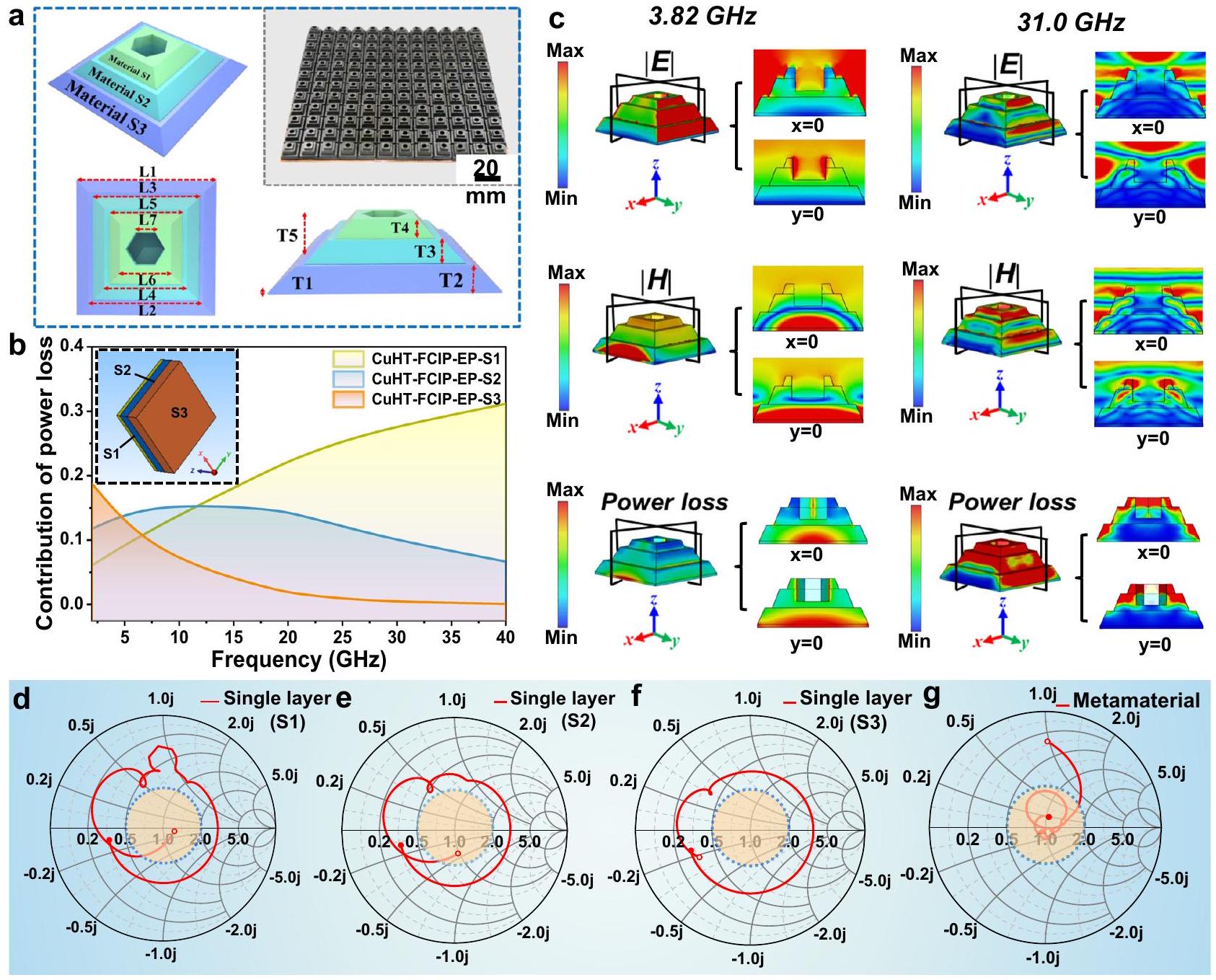

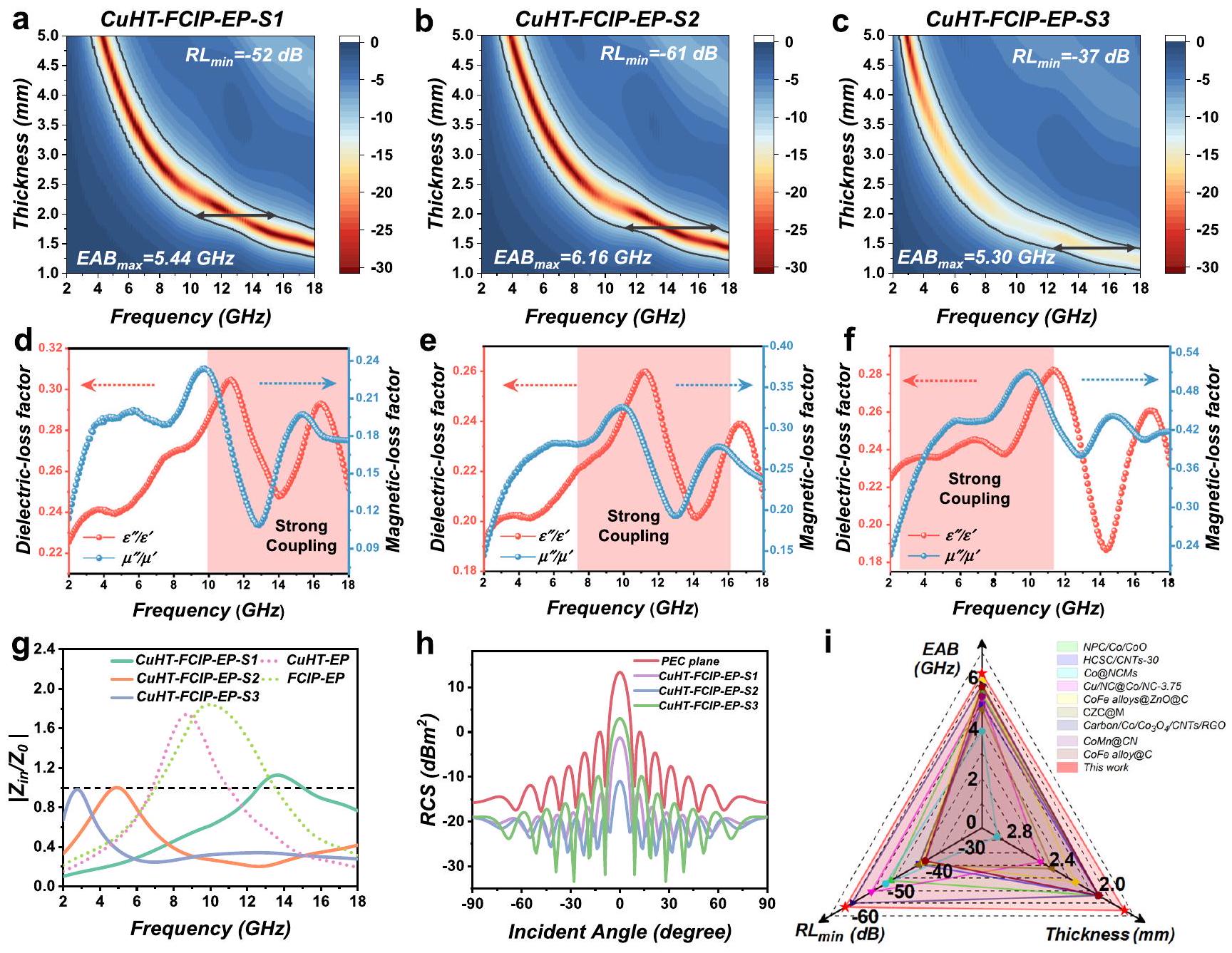

Design of the CuHT-FCIP-EP metamaterial

loss contributions of the overall material perfectly match and connect across the low-frequency range (

of the metamaterial absorber at 3.82 GHz and 31.0 GHz . d-g Smith chart of single-layer absorbers and metamaterial absorbers (the hollow circle end represents 2 GHz , while the solid end represents 40 GHz ; the orange shadowed region represents a fluctuation range of

and Supplementary Fig. 13). The honeycomb perforation enables increased entry of low-frequency EMWs. Consequently, at 3.82 GHz , the electric and magnetic fields exhibit a concentrated distribution in the bottom layer of the metamaterial. This suggests that the bottom layer material (i.e., CuHT-FCIP-EP-S3) primarily functions in absorbing EMWs at the low-frequency range (Supplementary Fig. 14). As the wavelength decreases, significant distortions occur in the electric and magnetic fields at the material’s surface, indicating the structural effects of the metamaterial. Strong electric and magnetic field intensities near the stepping and inside the honeycomb perforation suggest edge diffractions or secondary scattering in these areas. Thus, by combining gradient impedance multilayer structures with honeycomb perforations, the CuHT-FCIP-EP metamaterial achieves a broadband absorption from both material loss and structural effects. This mechanism effectively overcomes the skin effect faced by traditional single-layer EMW absorbers. As a representative technique in electronics, Smith Chart

the chart), thus achieving perfect absorption. As shown in the Fig. 4d-g, these phenomena result in a near-ideal impedance matching of the CuHT-FCIP-EP metamaterial, which is unattainable by single-component metamaterials. Therefore, a rational structural design allows the absorber to not only exhibit nearly ideal electromagnetic response but also simultaneously possess multiple loss mechanisms, thereby enhancing its EMW absorption capability.

EMW absorption performance of CuHT-FCIP-EP metamaterial

d-g Experimental reflectivity of metamaterial absorber at an oblique incidence with the incident angle ranging from

cavities that can induce additional secondary reflections at large incident angles, especially for shorter wavelength EMWs (Fig. 5h). This can be further confirmed by the significant decrease of RL at high-frequency ranges (

Discussion

Methods

Materials

features was first fabricated. The metamaterial was fabricated based on a multi-step molding process: (1) A specific amount of uncured CuHT-FCIP-EP-S1 resin was carefully poured into the silicone rubber mold to fill the bottom part of the mold (top layer of the metamaterial). (2) After curing for 2 h , the uncured CuHT-FCIP-EP-S2 resin was carefully poured into the silicone rubber mold to fill the middle layer. (3) After curing for another 2 h , the uncured CuHT-FCIP-EP-S3 resin was carefully poured into the silicone rubber mold to fill the rest cavities (bottom layer of the metamaterial). (4) Finally, after three additional hours of curing, CuHT-FCIP-EP metamaterials with S1-S3 combinations from top to the bottom were obtained by a complete demolding process.

Data availability

References

- Lv, H. L. et al. Electromagnetic absorption materials: current progress and new frontiers. Prog. Mater. Sci. 127, 100946 (2022).

- Liang, J. et al. Defect-engineered graphene/

multilayer alternating core-shell nanowire membrane: a plainified hybrid for

broadband electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200141 (2022). - Asadchy, V. S. et al. Broadband reflectionless metasheets: frequency-selective transmission and perfect absorption. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031005 (2015).

- Choi, M. et al. A terahertz metamaterial with unnaturally high refractive index. Nature 470, 369-373 (2011).

- Xi, W. et al. Ultrahigh-efficient material informatics inverse design of thermal metamaterials for visible-infrared-compatible camouflage. Nat. Commun. 14, 4694 (2023).

- Jin, Y. et al. Infrared-reflective transparent hyperbolic metamaterials for use in radiative cooling windows. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2207940 (2023).

- Qu, S. C. et al. Conceptual-based design of an ultrabroadband microwave metamaterial absorber. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2110490118 (2021).

- Xing, R. et al. 3D printing of liquid-metal-in-ceramic metamaterials for high-efficient microwave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2307499 (2023).

- Lu, J. et al. Vat photopolymerization 3D printing gyroid metastructural SiOC ceramics achieving full absorption of X-band electromagnetic wave. Addit. Manuf. 78, 103827 (2023).

- Huang, M. et al. Heterogeneous interface engineering of Bi-Metal MOFs-derived

– ZnO -Fe@C microspheres via confined growth strategy toward superior electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2308898 (2023). - Zhai, N. et al. Interface engineering of heterogeneous

for high-efficient electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312237 (2023). - Yao, L. H. et al. Multifunctional nanocrystalline-assembled porous hierarchical material and device for integrating microwave absorption, electromagnetic interference shielding, and energy storage. Small 19, 2208101 (2023).

- Snyder, B. E. R. et al. A ligand insertion mechanism for cooperative

capture in metal-organic frameworks. Nature 613, 287 (2023). - Gao, X. et al. Specific-band electromagnetic absorbers derived from metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 498, 215465 (2024).

- Jiang, M. et al. Scalable 2D/2D assembly of ultrathin MOF/MXene sheets for stretchable and bendable energy storage devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312692 (2023).

- Zhou, P. et al. Strategies for enhancing the catalytic activity and electronic conductivity of MOFs-based electrocatalysts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 478, 214969 (2023).

- Qiao, J. et al. Non-magnetic bimetallic MOF-derived porous carbonwrapped

composites for efficient electromagnetic wave absorption. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 75 (2021). - Choi, S.-G. et al. MOF-derived carbon/ZnS nanoparticle composite interwoven with structural and conductive CNT scaffolds for ultradurable K-ion storage. Chem. Eng. J. 459, 141663 (2023).

- Liang, C. Y. et al. Boosting the optoelectronic performance by regulating exciton behaviors in a porous semiconductive metalorganic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2189-2196 (2022).

- Deng, X. L. et al. Conductive MOFs based on thiol-functionalized linkers: challenges, opportunities, and recent advances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 450, 214235 (2022).

- Liang, C. et al. Thermoplastic membranes incorporating semiconductive metal-organic frameworks: an advance on flexible X-ray detectors. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 59, 11856-11860 (2020).

- Dong, A. et al. Fine-tuning the electromagnetic parameters of 2D conjugated metal-organic framework semiconductors for antielectromagnetic interference in the Ku band. Chem. Eng. J. 444, 136574 (2022).

- Zang, Y. et al. Recent development on the alkaline earth MOFs (AEMOFs). Coord. Chem. Rev. 440, 213955 (2021).

- Ban, Q. et al. Polymer self-assembly guided heterogeneous structure engineering towards high-performance low-frequency electromagnetic wave absorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 650, 1434-1445 (2023).

- Hao, Z. et al. Two-dimensional confinement engineering of

nanosheets supported nano-cobalt for high-efficiency microwave absorption. Chem. Eng. J. 473, 145296 (2023). - Zhao, Y. et al. Interfacial engineering of a vertically stacked graphene/h-BN heterostructure as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen peroxide synthesis. Mater. Horiz. 10, 4930-4939 (2023).

- Zhao, Q. et al. Built-in electric field-assisted charge separation over carbon dots-modified

nanoplates for photodegradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 465, 164-171 (2019). - Hu, B. et al. Electronic modulation of the interaction between Fe single atoms and

for photocatalytic reduction. Catal. 12, 11860-11869 (2022). - Liu, G. et al. High-yield two-dimensional metal-organic framework derivatives for wideband electromagnetic wave absorption. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 13, 20459-20466 (2021).

- Yuan, M. et al. Remarkable magnetic exchange coupling via constructing Bi-magnetic interface for broadband lower-frequency microwave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2203161 (2022).

- Li, Q. et al. Graphene-enabled metasurface with independent amplitude and frequency controls in orthogonal polarization channels. Carbon 206, 260-267 (2023).

- Shu, J.-C. et al. Heterodimensional structure switching multispectral stealth and multimedia interaction devices. Adv. Sci. 10, 2302361 (2023).

- Tang, Z. et al. Synthesis of

Expanded Graphite with crystal/amorphous heterointerface and defects for electromagnetic wave absorption. Nat. Commun. 14, 5951 (2023). - Bao, Y. et al. Heterogeneous burr-like

MXene nanospheres for ultralow microwave absorption and satellite skin application. Chem. Eng. J. 473, 145409 (2023). - Wang, C. et al. Developments status of magnetic loss waveabsorbing materials. J. Silk 58, 27-34 (2021).

- He, L. et al. A four-narrowband terahertz tunable absorber with perfect absorption and high sensitivity. Mater. Res Bull. 170, 112572 (2024).

- Qu, N. et al. Multi-scale design of metal-organic framework metamaterials for broad-band microwave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2402923 (2024).

- Rozanov, K. N. Ultimate thickness to bandwidth ratio of radar absorbers. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 48, 1230-1234 (2000).

- Cong, L. et al. Highly flexible broadband terahertz metamaterial quarter-wave plate. Laser Photonics Rev. 8, 626-632 (2014).

- Wu, S. et al. Microwave meta-absorber by using Smith Chart. Micro. Opt. Technol. Lett. 66, e33957 (2024).

- Low, K.-H. et al. Highly conducting two-dimensional copper(I) 4-hydroxythiophenolate network. Chem. Commun. 46, 7328-7330 (2010).

- Jiang, H. J. et al. Ordered heterostructured aerogel with broadband electromagnetic wave absorption based on mesoscopic magnetic superposition enhancement. Adv. Sci. 10, 2301599 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49762-4.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Ruizhe Xing or Jie Kong.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Macromolecular Science and Technology and MOE Key Laboratory of Materials Physics and Chemistry in Extraordinary Conditions, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an 710072, P. R. China. These authors contributed equally: Ning Qu, Hanxu Sun. e-mail: rzxing@nwpu.edu.cn; kongjie@nwpu.edu.cn