DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw-2024-0073

تاريخ النشر: 2025-04-28

المجتمعات في عملية العولمة

تم الاستلام في 2 أغسطس 2024؛ تم القبول في 2 أبريل 2025؛

تم النشر على الإنترنت في 28 أبريل 2025

الملخص

يعتمد الكثير من العمل على موقع الصناعة، والتدويل، والابتكار على أبحاث على مستوى الشركات أو الشبكات الشركات، ولكنه لا يأخذ في الاعتبار دور المجتمعات المهنية القائمة على الصناعة التي يمكن أن تكون حاسمة في توفير الوصول إلى المعرفة، والموارد، والشبكات الشخصية. هذه المجتمعات، التي يصل عدد أعضائها إلى ما هو أبعد من الشركات نفسها، هي مكونات لا غنى عنها في الأنشطة اليومية للشركات، ومع ذلك غالبًا ما يتم تجاهلها عند التحقيق في سلوك الشركات. تركز هذه الورقة من جهة على دور المجتمعات المحلية والأفراد الذين يشكلونها، ومن جهة أخرى على كيفية ارتباطها بالمجتمعات الدولية وكيف تصبح facilitators حاسمة لعمليات التدويل. من منظور التفاعل المشترك، نستكشف دور المجتمعات المهنية المحلية والواجهات المحلية-العالمية التي يتم إنشاؤها في عمليات التدويل، وكيف يمكن أن يرتبط هذا النشاط المحلي بالتنمية الإقليمية. في مناقشة مفاهيمية، نقترح أن المجتمعات المهنية المحلية وروابطها بالمجتمعات المحلية-الدولية هي حاسمة للقدرة على الانخراط في مشاريع التدويل. من هذا، نناقش عددًا من الأسئلة ذات الصلة: أولاً، من هم أعضاء المجتمعات المهنية المحلية وكيف يخلقون المعرفة؟ ثانيًا، كيف تتطور المجتمعات المهنية المحلية وما هي القوى الدافعة التي تكمن وراء نموها؟ ثالثًا، ما هي الشروط اللازمة لتكاثر المجتمعات المهنية المحلية؟ نختتم بالتأكيد على أن العلاقة المتبادلة بين المجتمعات المحلية والدولية هي ميزة حاسمة لبيئة مرنة تسهل نجاح الشركات في عملية التدويل، وأن هذا التفاعل الإيجابي بين الشركات وبيئتها يؤثر أيضًا على

1 المقدمة: الشركات، المجتمعات وواجهاتها المحلية-العالمية

الإدارة (براون ودوجيد 1991؛ كنور سيتينا 1999؛ وينجر 1998؛ لمراجعة، انظر روبرتس 2017)، من المدهش أن الكثير من الأدبيات ذات الصلة تركز على إنشاء وصيانة الشبكات بين الشركات دون التدقيق في الدور المحدد لهذه المجتمعات المهنية الأساسية، وقدراتها وأفعالها التي هي في صميم التنافسية وتكاثر الاقتصاديات الإقليمية (للاستثناءات، انظر باتهلت ولي 2020؛ كوهين وآخرون 2014؛ لي 2014؛ مونتيرو وبيركنشو 2017). إن هذه المجتمعات المهنية المحلية أو المعتمدة على الصناعة (للاختصار، يُشار إليها هنا فقط بالمجتمعات المحلية) – ليست فقط في التجمعات ولكن في الاقتصاديات الإقليمية بشكل عام – هي في صميم استفسارنا المفاهيمي.

| اسم الكيان المجتمعي | نوع المجتمع | طبيعة نوع المجتمع والعلاقة بين الأنواع |

| الشبكات الاجتماعية | تجمعات فضفاضة من الفاعلين المرتبطين بروابط من أنواع مختلفة | قد تتطور الروابط بين الفاعلين بسبب الروابط المعاملاتية، أو بعض المصالح المتبادلة أو الأنشطة المشتركة، أو تحركات الأفراد – ويمكن تعزيزها من خلال أشكال مختلفة من القرب |

| المجتمعات المهنية | تجمعات من المحترفين من أنواع مختلفة، من المهن ذات الصلة التي تجتمع للمساهمة في مشاريع الأعمال في صناعة معينة | تحديد متعمد والمشاركة الطوعية في مجتمع يتشارك أعضاؤه الاهتمام والخبرة في مجموعة متنوعة من أنواع الخبرة المتخصصة التي تحتاجها لدعم مشاريع الأعمال الدولية في سياق صناعي معين |

| مجتمعات الممارسة | تجمعات متماسكة من الأفراد المشاركين والبارعين في بعض المجالات المشتركة من الممارسة | تحديد متعمد والمشاركة الطوعية في مجتمع يتميز بالتزامات مشتركة ومتبادلة لتطوير مجال ممارسة قائم على الصناعة |

| المجتمعات المعرفية | تجمعات متماسكة من الأفراد ذوي المبادئ والقيم المشتركة في تطوير وتطبيق بعض المجالات المشتركة من المعرفة | تحديد متعمد والمشاركة الطوعية في مجتمع مبني على أساس قوي في مجموعة من المعرفة في مجال خبرة قائم على الصناعة محدد، مع التزام مشترك لتطوير تلك المجموعة من المعرفة مع مرور الوقت |

| المجتمعات المعرفية | تجمعات متماسكة من مجتمعات الممارسة، والمجتمعات المعرفية، والمجتمعات الافتراضية التي تطور فهمًا متبادلًا ومتسقًا لمجال مشترك من المعرفة | تحديد متعمد والمشاركة الطوعية في مجتمع يتشارك ويطور المعرفة في مجال مشترك يجمع بين المعرفة (الممارسة) والفهم (التفسير العلمي أو المفهومي) في سياق صناعي معين |

| المجتمعات المهنية المحلية | تجمعات متماسكة من الأفراد المتواجدين في منطقة أو مجتمعات معرفة محلية، تمثل عبر الصناعة وتعكس تخصص المنطقة | التعريف بمجتمع محدد مكانيًا يتركز في الصناعات الرئيسية للتخصص في منطقة معينة، ويطور أفضل الممارسات ويتبادل المعرفة، غالبًا ما يعتمد على خلفيات وتجارب مشتركة، ويتناغم مع السياق المؤسسي المحلي؛ تندمج المجتمعات المحلية مع مجتمعات الممارسة والمجتمعات المعرفية في مجالات أقوى الصناعات في المنطقة |

| المجتمعات المهنية الدولية | تجمعات متماسكة من الأفراد المنتشرين جغرافيًا في بعض المجالات المشتركة من الخبرة القائمة على الصناعة، الذين يتفاعلون بانتظام مع الآخرين في تطوير خبرة متقدمة قد تكون ذات اهتمام عبر سياقات مكانية مختلفة | التعريف بمجتمع محدد بالمجال في سياق صناعي معين، مع التزام مشترك لتطوير وتطبيق أفضل الخبرات في المجال، وغالبًا ما يرتبط أو ينظم حول بعض الجمعيات المهنية الدولية؛ تؤسس المجتمعات الدولية قنوات لنشر أفضل المعرفة والممارسات في مجال عبر الفضاء؛ يمكن أن تتصل المجتمعات المحلية بمجموعة مختارة من المجتمعات الدولية المتوافقة مع نطاق تخصص الصناعة المحلية |

| التقسيمات الوطنية للمجتمعات المهنية الدولية | تجمعات متماسكة من الأفراد داخل مجتمع مهني دولي في بلد إقامة مشترك، يتفاعلون مع الآخرين على المستوى الوطني وكذلك دوليًا | التعريف بمجتمع محدد بالمجال نشط في جمع الخبرات حول نوع معين من المشاريع الصناعية في بلد معين؛ غالبًا ما يرتبط بتقسيم وطني لجمعية مهنية دولية، مما يسهل الروابط بين المجتمع الدولي المعني والمجتمعات المحلية في البلد المعني |

| المجتمعات العابرة للحدود | تجمعات متماسكة من الأفراد التي تظهر خلال عمليات العولمة حيث تندمج المجتمعات المحلية مع المجتمعات الدولية وتطور قدرات عابرة للحدود | التعريف بمجتمع محدد بالمجال في سياق صناعي معين، حيث يتعاون أعضاء من مجتمعات محلية مختارة مباشرة في دعم مشاريع الأعمال الدولية، وفي نشر المعرفة حول العلاقة بين المشاريع التي يتم تنفيذها في مواقع مختلفة |

تحليلنا للمجتمعات المهنية وليست جزءًا من التحليل نفسه.

المعرفة أو الخبرة في مشاريع التدويل ليست محدودة بهذا فقط، بل تمتد إلى مجالات أوسع بكثير. المعرفة ذات الصلة تتعلق بالعديد من القضايا التي تتعلق بتنفيذ واستمرار عمليات التدويل، مثل المعرفة بالسياق القانوني والمؤسسي، أو السياق اللغوي والثقافي لدول ومناطق معينة، وكيف تختلف الممارسات والتطبيقات عبر سياقات صناعية أو سوقية مختلفة (Bathelt و Li 2020). نحن نعتبر مشاريع التدويل ناجحة عندما تقوم الشركات بإنشاء أو الحفاظ على أو توسيع وجودها في الأسواق الدولية وتكون قادرة على النمو من خلال ذلك. بشكل إجمالي، فإن التدويل له تأثير فوري على التنمية الإقليمية وهو مرتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا بها.

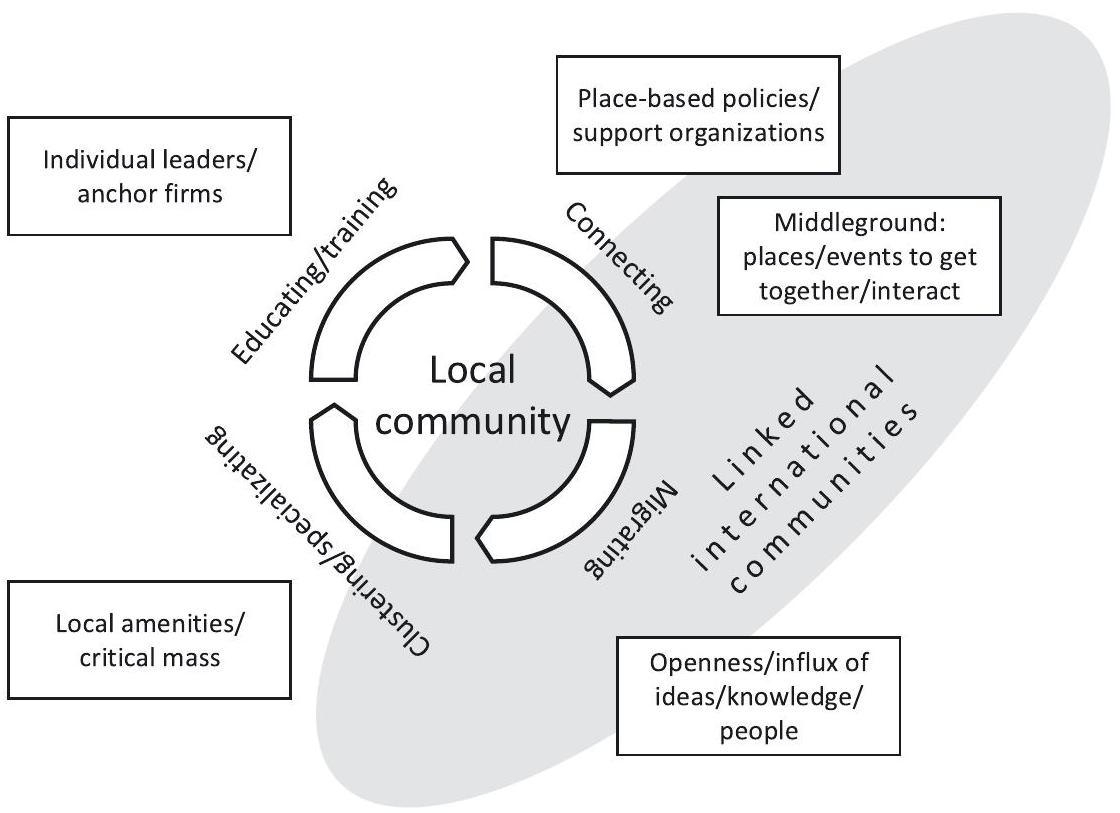

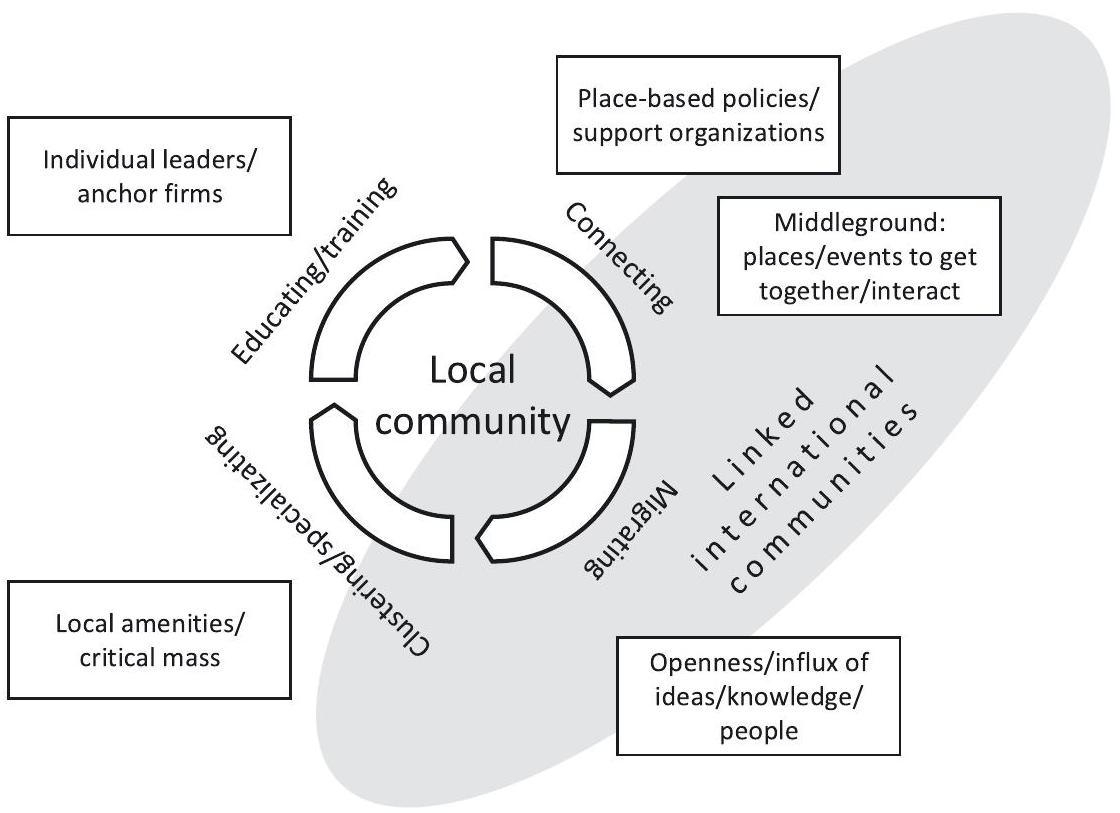

شروط إعادة إنتاج المجتمعات المهنية المحلية. يُقال إن عمليات التغذية الراجعة المستدامة تدعم عندما تصل المجتمعات المهنية المحلية إلى كتلة حرجة، وتتوفر لديها المرافق المحلية، وعندما تكون مفتوحة لتدفق المعرفة والأشخاص الجدد، وتكون لديها سياسات قائمة على المكان ومنظمات دعم، وقادة فرديون وشركات رائدة، و/أو عندما تُنشئ أرضية وسطى حيث يمكن لأعضاء المجتمع الاجتماع. يختتم القسم 6 بتسليط الضوء على الروابط بين المجتمعات المهنية المحلية والدولية، التي تغيرت مع مرور الوقت، مما يخلق منظورًا ديناميكيًا لتطورها المشترك. العلاقة المتبادلة بين المجتمعات المحلية والدولية هي ميزة حاسمة لبيئة مرنة تسهل النجاح المؤسسي في عملية العولمة، وهذه التفاعلات المواتية بين الشركات وبيئتها تعزز أيضًا آفاق التنمية في المناطق الحضرية التي تقع فيها.

إطار مفاهيمي: المجتمعات المهنية المحلية والدولية في عملية العولمة

يشاركون في التجارة عبر الحدود ويستثمرون في الخارج (هاكانسون 1979؛ يوهانسون وفالني 1977؛ فالني ويوهانسون 2013). في المراحل اللاحقة من التطور، قد تطور الشركات الأكثر نضجًا هيكل إنتاج متعدد الجنسيات (دونينغ ولوندان 2008)، وتصل إلى الأسواق الأجنبية بمنتجات مخصصة وتستفيد من الروابط المعرفية الدولية لدعم أنشطة الابتكار الخاصة بها في مواقع متخصصة أو مراكز حضرية (كانتويل 2009).

نحو حل مشكلات محددة أو التعاون في الشبكات (Cantwell و Piscitello 1999). بالنسبة للشركات التي تستثمر في بلد مختلف، تساعد الروابط بين المجتمع المحلي والمجتمع الدولي في تسهيل الوصول إلى الشركات والشبكات في المنطقة المضيفة، مما يمكّن الشركات التابعة بمرور الوقت من المشاركة في البيئة المعرفية المحلية للمنطقة المضيفة (Malecki 2009). على هذا النحو، تساعد واجهات المجتمع المحلي-الدولي في تشكيل الروابط عبر المجتمعات وفي النهاية الروابط بين الشركات التي تعتبر ضرورية للتغلب على عبء الشركات من الخارج من الشبكات المحلية (Johanson و Vahlne 2009).

المجتمعات المهنية المحلية: من هم وكيف يخلقون المعرفة؟

على درجة من الألفة المؤسسية والترابط بين المنطقة التي يقيمون فيها وبلدانهم الأصلية. تعتمد هذه القدرة أيضًا على ما إذا كانت المجموعات المهاجرة قد حققت كتلة حرجة محليًا (Buchholz 2021؛ Kloosterman 2010؛ Sandoz et al. 2022؛ Shukla و Cantwell 2018).

حتى لو لم يعرفوا بعضهم البعض شخصيًا أو لديهم أي روابط مباشرة.

كيف تتطور وتنمو المجتمعات المهنية المحلية ذات القدرات العابرة للحدود؟

الادعاء بأن هذه هي المحركات الوحيدة لتطوير المجتمع المحلي، هناك على الأقل أربع قوى دافعة تلعب دورًا حاسمًا في ظهورها ونموها، والتي تسود في بعض مناطق المدن: الاتصال، التعليم/التدريب، الهجرة والتجمع/التخصص (الشكل 1):

(1) الاتصال. الاتصال هو دافع قوي بشكل خاص لتطوير المجتمع في المدن العالمية/العالمية التي تعتبر مواقع رئيسية لظهور ونمو المجتمعات المهنية المحلية. تتميز بتركيز كبير لمقرات الشركات متعددة الجنسيات في المالية والخدمات المعتمدة على المعرفة والتصنيع وتطور روابط وثيقة مع مدن عالمية أخرى وكذلك مع المدن الثانوية التي تصبح مواقع للفروع التي تقوم بوظائف التصنيع والخدمات (ساسن 2001؛ تايلور وديرودر 2004). تمارس المدن العالمية/العالمية الهيمنة والسيطرة من خلال الشبكات والاتصالات التي تقيمها مع مجموعة واسعة من المواقع الدولية. تطور هذه الهيمنة حيث تتمكن من توظيف وتدريب وجذب المتخصصين ذوي القدرات العابرة للحدود في الحوكمة وخلق المعرفة (فلوريدا 2002). تطور المدن العالمية/العالمية مجتمعات مهنية كبيرة، مرتبطة بشكل كبير بالمجتمعات الدولية ولديها روابط قوية عبر المجتمعات المحلية. يعتمد اتصالها العالي على الشبكات الشخصية التي يقيمها أعضاء المجتمع خلال مسيرتهم المهنية/التقنية مع مختلف أصحاب العمل المتعددين الجنسيات، بالإضافة إلى العضوية في جمعيات مهنية دولية/منتديات إنترنت وممارسات مشتركة لاستخدام نفس مصادر المعرفة الم codified (مثل المجلات المهنية). إن الاتساع والعمق العالي في الاتصال، سواء للشركات أو لأعضاء المجتمع، هو ما يدفع نمو المجتمعات المحلية في هذه المدن ويعزز قدراتها العابرة للحدود (كانويل وزمان 2018، 2024).

(2) التعليم/التدريب. يلعب التعليم/التدريب دورًا مميزًا في تطوير المجتمع في مناطق المدن التي تحتوي على مرافق بحث وتعليم عالي معروفة ومرموقة. من خلال التعليم/التدريب المستمر، تظهر وتنمو المجتمعات المهنية المحلية في هذه الأماكن، بشرط أن يكون هناك قاعدة اقتصادية محلية حيث يمكن لخريجي الدفعات العثور على عمل. في معظم الصناعات، تعتبر المعرفة الجامعية حاسمة لتمكين الوصول إلى المجتمعات المعرفية الدولية، خاصة عندما تشارك الشركات في أبحاث متقدمة وتكتسب الشرعية في هذه المجتمعات (بافيت 1991). تجذب الأماكن التي تحتوي على جامعات بحثية محلية قوية عددًا كبيرًا من الطلاب الدوليين في برامج الأعمال والهندسة والعلوم التي يمكن أن تحفز عمليات بدء التشغيل والتدوير إذا كان هناك تطابق جيد بين التركيز التعليمي والتركيبة القطاعية للاقتصاد المحلي (برامويل وولف 2008). بينما

(3) الهجرة. الهجرة هي قوة دافعة مهمة أخرى، من خلالها يمكن أن تتطور المجتمعات المهنية المحلية. قد تطور المناطق الحضرية التي تضم أعدادًا كبيرة من المهاجرين و/أو العمال المهاجرين مجتمعات محلية ديناميكية وملحوظة تجذب المهنيين من مجتمعات محلية أخرى للارتباط بالمعرفة الإقليمية. قد يعزز ذلك المجتمع المحلي ويحسن الروابط مع المجتمعات الدولية، مما يؤدي إلى عملية تطوير مجتمع تعزز نفسها بنفسها. مثل النيو أرجونات، قد يستفيد المهاجرون الذين لديهم خلفية مهنية مسبقة أو بعد تلقي التدريب في دول المقصد من الروابط الوثيقة مع

بلد المنشأ لإنشاء أعمال جديدة تربط بين الاقتصادين، مستغلة تداخلها المزدوج في سياقات ثقافية مختلفة (هارتمان وفيليب 2022؛ كلوسمان وآخرون 1966؛ بورتس ومارتينيز 2020؛ ساندوز وآخرون 2022). بالإضافة إلى تحفيز ريادة الأعمال، يمكن أن تعمل الهجرة بمعنى أوسع كدافع لتطوير المجتمعات مما يساعد على الحفاظ على الروابط الدولية المستمرة (كاي وآخرون 2021؛ هاجرو وآخرون 2021؛ شوكلا وكانويل 2018). هناك محفزات متعددة لكيفية توليد تنوع المهاجرين لتأثيرات إيجابية على أسواق العمل المحلية (كيميني وكوك 2018)؛ من خلال التفاعل/التعلم، والتكامل، وعمليات التخصص، فضلاً عن تأثيرات التعرض، يمكن للمهاجرين تعزيز أسواق العمل وزيادة تنافسية الشركات المحلية (بوشهولز 2021).

(4) التجميع/التخصص. تعتبر قوة دافعة مهمة لتطوير المجتمع مرتبطة بمجموعات صناعية قوية ودرجة عالية من التخصص. تمتلك المناطق الحضرية المقابلة فرصًا متعددة للتوسع دوليًا والوصول إلى أسواق جديدة من خلال استراتيجيات النسخ/التعزيز والربط المستندة إلى المزايا التنافسية (Bathelt و Li 2022؛ Bathelt وآخرون 2004؛ Giuliani و Bell 2005؛ Kerr و Robert-Nicoud 2020؛ Porter 1990). عبر سياقات صناعية مختلفة، يبدو أن التجميع الاقتصادي/التخصص يعد دافعًا مهمًا، في الواقع شبه طبيعي، للمجتمعات المهنية المحلية القوية التي تطور قدرات عبر وطنية. في المجموعات الناشئة الصغيرة، قد يتم ذلك في البداية من خلال عمليات التجربة والخطأ، ولكن مع نمو المجموعات ونضوجها (Fornahl وآخرون.

تجعل تنافسيتها المتزايدة وسمعتها الدولية من السهل جذب المواهب من المجتمعات البعيدة ومن خلال الروابط المجتمعية الدولية. مرة أخرى، ترتبط قدرات المجتمع المحلي ونجاح الشركات المحلية في التدويل بطريقة تفاعلية. كما هو الحال في المدن العالمية، غالبًا ما تتميز المراكز الحضرية الكبيرة بوجود بيئات صناعية متعددة أو تجمعات (Crevoisier 2001) وبالتالي تطور مجتمعات محلية كبيرة ومتنوعة مع محافظ مهارات متخصصة واسعة. تشكل هذه المجتمعات أسواق عمل جذابة للغاية للمواهب، وفي الوقت نفسه، مواقع جذابة للشركات في الصناعات ذات الصلة (Krugman 1991). لا تطور هذه الأماكن فقط بيئات معرفية محلية ديناميكية وغنية مع إمكانات ابتكار داخلي عالية، بل تبني أيضًا قنوات عالمية مع تجمعات متطورة أخرى في الخارج وتصبح وجهات ذات أولوية لروابط الاستثمار من التجمعات الأجنبية (Bathelt و Li 2022؛ Owen-Smith و Powell 2004).

من مجتمع مهني محلي صغير، يشجع على المزيد من العولمة وينشط التنمية الإقليمية. ومع ذلك، على عكس السياقات الحضرية التي تم مناقشتها سابقًا، قد تفتقر المجتمعات المحلية في المناطق العادية إلى التغذية الراجعة الفعالة ومحفزات النمو وقد تكون عرضة للخطر حيث تعتمد وجودها على عدد قليل من الشركات وأعضاء موظفيها.

5 كيف تعيد المجتمعات المهنية المحلية إنتاج نفسها؟

في الوقت نفسه، لها تأثيرات إيجابية مباشرة على التنمية الإقليمية (باتهلت وبوخولز 2019) من خلال توجيه الطلب الإضافي والمعرفة الجديدة إلى المناطق الأصلية. من ناحية، تدعم العولمة المستمرة النمو المستمر للصناعات الإقليمية وتدفع نحو مزيد من التخصص في المناطق الأصلية (بيركنشو وسولفيل 2000؛ سولفيل وبيركنشو 2000). من ناحية أخرى، يولد هذا هيكل حوافز يشجع على نمو المجتمعات المحلية ويدفع نحو مزيد من العولمة. وبالتالي، تؤدي عمليات الربط إلى توسيع المجتمعات المهنية المحلية (باتهلت وآخرون 2023).

المدن-المناطق ذات الاقتصاد المتنوع التي لا تمتلك مجتمعات محلية متطورة بشكل جيد، ولا القدرات اللازمة لتطويرها. على سبيل المثال، قد تدعم السياسات الوطنية الصناعية والابتكارية نمو صناعات معينة وتوفر إعانات للبنية التحتية الجديدة وقدرات البحث لتعزيز تطوير وتخصص المجتمعات المحلية. غالبًا ما يركز هدف هذه السياسات على القدرة التنافسية الدولية للشركات وبالتالي تستفيد بشكل أساسي المناطق التكنولوجية القائمة. بالمقابل، قد تؤثر سياسات التعليم والهجرة التي تركز على تطوير المهارات المتقدمة وجذب العمالة المؤهلة من الخارج بشكل جغرافي أوسع، وإن كان بطريقة غير مباشرة. يمكن أن تؤثر السياسات ذات الصلة بشكل إيجابي على تطوير المدن-المناطق الأصغر والثانوية إذا تم تنفيذها باستراتيجيات قائمة على المكان تستهدف الاحتياجات والإمكانات المحددة لهذه المواقع (Iammarino et al. 2019). بشكل غير مباشر أو مباشر، يمكن أن تدعم السياسات المستهدفة إعادة إنتاج المجتمعات المهنية المحلية وتساعد في تعزيز القدرات العابرة للحدود.

6 الخاتمة: تطور الروابط بين المجتمعات المهنية المحلية والدولية

عمليات العولمة للشركات في أي منطقة حضرية رئيسية. كلما كانت الروابط بين المجتمعات المحلية والدولية في مكان ما أفضل، زادت فوائد مشاريع العولمة للشركات من تسهيل أنشطة المجتمع (Bathelt و Li 2020). لهذه العمليات تأثير حاسم على نمو المنطقة الأصلية (Buchholz et al. 2020)، حيث تعزز تطوير المجتمع وتخلق بيئة مواتية لمزيد من العولمة ومزيد من التنمية الإقليمية. في التجمعات الابتكارية والمناطق الحضرية الكبرى، نشهد تطوير مجتمعات مهنية محلية قوية تسير جنبًا إلى جنب مع عولمة الشركات، وفي الواقع، تصبح محركات رئيسية لكل من عمليات النمو المستمر للشركات والازدهار الإقليمي، بينما قد تواجه الشركات في المناطق الحضرية الأصغر التي تفتقر إلى المجتمعات الكبرى المزيد من المخاطر والصراعات على المدى الطويل.

أخلاقيات البحث: غير قابلة للتطبيق.

الموافقة المستنيرة: غير قابلة للتطبيق.

مساهمات المؤلفين: ساهم كلا المؤلفين بالتساوي في الورقة.

استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، الذكاء الاصطناعي وتعلم الآلة

الأدوات: لم يتم استخدام أي أدوات من هذا القبيل في أي مرحلة من مراحل عملية البحث وفي كتابة الورقة.

تضارب المصالح: يصرح المؤلفون بعدم وجود تضارب في المصالح.

تمويل البحث: لم يتم الإعلان عن أي تمويل.

توفر البيانات: غير قابل للتطبيق.

References

Agrawal, A. and Cockburn, I. (2003). The anchor tenant hypothesis: exploring the role of large, local, R & D-intensive firms in regional innovation systems. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 21: 1227-1253.

Amin, A. and Cohendet, P. (2004). Architectures of knowledge: firms, capabilities, and communities. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Asheim, B.T. (1999). Interactive learning and localised knowledge in globalising learning economies. Geojournal 49: 345-352.

Bathelt, H. and Buchholz, M. (2019). Outward foreign-direct investments as a catalyst of urban-regional income development? Evidence from the United States. Econ. Geogr. 95: 442-466.

Bathelt, H., Cantwell, J.A., and Mudambi, R. (2018). Overcoming frictions in transnational knowledge flows: challenges of connecting, sense-making and integrating. J. Econ. Geogr. 18: 1001-1022.

Bathelt, H. and Cohendet, P. (2014). The creation of knowledge: local building, global accessing and economic development – toward an agenda. J. Econ. Geogr. 14: 869-882.

Bathelt, H. and Henn, S. (2025). Creating knowledge over distance: the role of temporary proximity. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bathelt, H. and Li, P. (2020). Processes of building cross-border knowledge pipelines. Res. Pol. 49: 103928.

Bathelt, H. and Li, P. (2022). The interplay between location and strategy in a turbulent age. Glob. Strateg. J. 12: 451-471.

Bathelt, H. and Sydow, J. (2025). Thoughtlet – Beyond temporary organizations: trade fairs as temporary markets, clusters and community gatherings. Proj. Manag. J. 56.

Bathelt, H., Buchholz, M., and Cantwell, J.A. (2023). OFDI activity and urban-regional development cycles: a co-evolutionary perspective. Compet. Rev. 33: 512-533.

Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., and Maskell, P. (2004). Clusters and knowledge: local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 28: 31-56.

Belderbos, R., Castellani, D., Du, H.S., and Lee, G.H. (2024). Internal versus external agglomeration advantages in investment location choice: the role of global cities’ international connectivity. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 55: 745-763.

Bernard, A.B. and Moxnes, A. (2018). Networks and trade. Ann. Rev. Econ. 10: 65-85.

Berns, J.P., Gondo, M., and Sellar, C. (2021). Whole country-of-origin network development abroad. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 52: 479-503.

Birkinshaw, J. and Sölvell, Ö. (2000). Leading-edge multinationals and leading-edge clusters. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 33: 3-9.

Boland, R.J. and Tenkasi, R.V. (1995). Perspective making and perspective taking in communities of knowing. Organ. Sci. 6: 350-372.

Boschma, R.A. (2005). Proximity and innovation: a critical assessment. Reg. Stud. 39: 61-74.

Bramwell, A. and Wolfe, D.A. (2008). Universities and regional economic development: the entrepreneurial University of Waterloo. Res. Pol. 37: 1175-1187.

Breschi, S. and Lissoni, F. (2001). Knowledge spillovers and local innovation systems: a critical survey. Ind. Corp. Change 10: 975-1005.

Brown, J.S. and Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovating. Organ. Sci. 2: 40-57.

Buchholz, M. (2021). Immigrant diversity, integration and worker productivity: uncovering the mechanisms behind ‘diversity spillover’ effects. J. Econ. Geogr. 21: 261-285.

Buchholz, M., Bathelt, H., and Cantwell, J.A. (2020). Income divergence and global connectivity of U.S. urban regions. J. Int. Bus. Policy 3: 229-248.

Cano-Kollmann, M., Mudambi, R., and Tavares-Lehmann, A. (2022). The geographical dispersion of inventor networks in peripheral economies. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 49-63.

Cantwell, J.A. (1989). Technological innovation and multinational corporations. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

Cantwell, J.A. (1995). The globalisation of technology: what remains of the product cycle model? Camb. J. Econ. 19: 155-174.

Cantwell, J.A. (2009). Location and the multinational enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 40: 35-41.

Cantwell, J.A., Dunning, J.H., and Lundan, S.M. (2010). An evolutionary approach to understanding international business activity: the co-evolution of MNEs and the institutional environment. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 41: 567-586.

Cantwell, J. and Iammarino, S. (2003). Multinational corporations and European regional systems of innovation. Routledge, London, New York.

Cantwell, J.A. and Janne, O.E.M. (1999). Technological globalisation and innovative centres: the role of corporate technological leadership and locational hierarchy. Res. Pol. 28: 119-144.

Cantwell, J. and Piscitello, L. (1999). The emergence of corporate international networks for the accumulation of dispersed technological competences. Manag. Int. Rev. 39: 123-147.

Cantwell, J. and Shukla, P. (2025). Spatial development of technological knowledge and the evolution of international business activity across technological paradigms. Int. Bus. Rev. 34: 102356.

Cantwell, J. and Spadevecchia, A. (2023). Which actors drove national patterns of technological specialization into the science-based age? The British experience, 1918-1932. Ind. Corp. Change 32: 622-646.

Cantwell, J. and Zaman, S. (2018). Connecting local and global technological knowledge sourcing. Compet. Rev. 28: 277-294.

Cantwell, J. and Zaman, S. (2024). International knowledge connectivity and the increasing concentration of innovation in major global cities. J. Econ. Geogr. 24: 421-446.

Chandler, A.D. (1984). The emergence of managerial capitalism. Bus. Hist. Rev. 58: 473-503.

Clark, G. (2022). Agency, sentiment, and risk and uncertainty: fears of job loss in 8 European countries. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 3-17.

Coe, N.M. and Bunnell, T.G. (2003). ‘Spatializing’ knowledge communities: towards a conceptualization of transnational innovation networks. Glob. Netw. 3: 437-456.

Cohendet, P. (2022). Architectures of the commons: collaborative spaces and innovation. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 36-48

Cohendet, P., Grandadam, D., and Simon, L. (2010). The anatomy of the creative city. Ind. Innov. 17: 91-111.

Cohendet, P., Grandadam, D., Simon, L., and Capdevila, I. (2014). Epistemic communities, localization and the dynamics of knowledge creation. J. Econ. Geogr. 14: 929-954.

Cohendet, P., Parmentier, G., and Simon, L. (2017). Managing knowledge, creativity, and innovation. In: Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S., and Simon, L. (Eds.). The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA, pp. 197-214.

Collings, D.G., Scullion, H., and Caligiuri, P.M. (2019). Global talent management. Routledge, London.

Crane, D. (2022). Invisible colleges: diffusion of knowledge in scientific communities. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Crevoisier, O. (2001). Der Ansatz des kreativen Milieus: Bestandsaufnahme und Forschungsperspektiven am Beispiel urbaner Milieus (The creative milieu: state of the art, research perspectives and the case of urban milieus). ZFW – Z. Wirtschaftsgeogr. 45: 246-256.

de Groot, E., Endedijk, M.D., Jaarsma, A.D.C., Simons, P.R.-J., and van Beukelen, P. (2014). Critically reflective dialogues in learning communities of professionals. Stud. Cont. Educ. 36: 15-37.

de Solla Price, D.J. and Beaver, D. (1966). Collaboration in an invisible college. Am. Psychol. 21: 1011-1018.

DiMaggio, P.J. and Powell, W.W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 48: 147-160.

Dunning, J.H. (1983). Changes in the level and structure of international production: the last one hundred years. In: Casson, M.C. (Ed.). The growth of international business. Allen and Unwin, London, pp. 84-139.

Dunning, J.H. (1993). Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Addison-Wesley, Wokingham.

Dunning, J.H. (2000). The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. Int. Bus. Rev. 9: 163-190.

Dunning, J.H. and Lundan, S.M. (2008). Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA.

Evren, Y. and Odabaş, E. (2024). Towards a comprehensive agency-based resilience approach: myopia and hypermetropia in the Turkish wine industry. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 68: 81-95.

Faulconbridge, J.R. (2007). Relational networks of knowledge production in transnational law firms. Geoforum 38: 925-940.

Faulconbridge, J.R. (2010). TNCs as embedded social communities: transdisciplinary perspectives. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 6: 273-290.

Faulconbridge, J.R., Folke Henriksen, L.F., and Seabrooke, L. (2021). How professional actions connect and protect. J. Prof. Organ. 8: 214-227.

Feldman, M. (2003). The locational dynamics of the US biotech industry: knowledge externalities and the anchor hypothesis. Ind. Innov. 10: 311-329.

Fitzsimmons, S.R., Miska, C., and Stahl, G.K. (2011). Multicultural employees: global business’ untapped resource. Org. Dyn. 40: 199-206.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class: and how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. Basic Books, New York.

Fornahl, D., Henn, S., and Menzel, M.-P. (Eds.) (2010). Emerging clusters: theoretical, empirical and political perspectives in the initial stage of cluster evolution. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA.

Forsgren, M., Holm, U., and Johanson, J. (2006). Managing the embedded multinational: a business network view. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA.

Fuchs, M., Henn, S., Franz, M., and Mudambi, R. (Eds.) (2017). Managing culture and interspace in cross-border investments: building a global company. Routledge, Abingdon.

Gertler, M.S. (2003). Tacit knowledge and the economic geography of context, or the undefinable tacitness of being (there). J. Econ. Geogr. 3: 75-99.

Giuliani, E. and Bell, M. (2005). The micro-determinants of mess-level learning and innovation: evidence from a Chilean wine cluster. Res. Pol. 34: 47-68.

Goerzen, A., Asmussen, C.G., and Nielsen, B.B. (2013). Global cities and multinational enterprise location strategy. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 44: 427-450.

Grillitsch, M. and Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 44: 704-723.

Hajiro, A., Brewster, C., Haak-Saheem, W., and Morley, M.J. (2023). Global migration: implications for international business scholarship. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 54: 1134-1150.

Hajro, A., Caprar, D.V., Zikic, J., and Stahl, G. (2021). Global migrants: understanding the implications for international business and management. J. World Bus. 56: 101192.

Håkanson, L. (1979). Towards a theory of location and corporate growth. In: Hamilton, F.E.I. and Linge, G.J.R. (Eds.). Spatial analysis, industry and the industrial environment. Volume i: industrial systems. Wiley, Chichester, pp. 115-138.

Hamida, L.M. (2013). Are there regional spillovers from FDI in the Swiss manufacturing industry? Int. Bus. Rev. 22: 754-769.

Harrington, B. and Seabrooke, L. (2020). Transnational professionals. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 46: 399-417.

Hartmann, C. and Philipp, R. (2022). Lost in space? Refugee entrepreneurship and cultural diversity in spatial contexts. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 151-171.

Henn, S. and Bathelt, H. (2017). Transnational entrepreneurs and innovation. In: Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S., and Simon, L. (Eds.). The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA, pp. 638-651.

Henn, S. and Bathelt, H. (2018). Cross-cluster knowledge fertilization, cluster emergence and the generation of buzz. Ind. Corp. Change 27: 449-466.

Hess, C. and Ostrom, E. (2003). Ideas, artefacts and facilities: information as a common pool resource. Law Contemp. Probl. 66: 111-146.

Hitt, M.A., Li, D., and Xu, K. (2016). International strategy: from local to global and beyond. J. World Bus. 51: 58-73.

Iammarino, S., Rodríguez-Pose, A., and Storper, M. (2019). Regional inequality in Europe: evidence, theory and policy implications. J. Econ. Geogr. 19: 273-298.

Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E. (1977). The internationalisation process of the firm – a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 8: 23-32.

Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: from liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 40: 1411-1431.

Kemeny, T. and Cooke, A. (2018). Spillovers from immigrant diversity in cities. J. Econ. Geogr. 18: 213-245.

Kennedy, P. (2004). Making global society: friendship networks among transnational professionals in the building design industry. Glob. Netw. 4: 157-179.

Kerr, W.R. and Kominers, S.D. (2015). Agglomerative forces and cluster shapes. Rev. Econ. Stat. 97: 877-899.

Kerr, W.R. and Robert-Nicoud, F. (2020). Tech clusters. J. Econ. Perspect. 34: 50-76.

Kloosterman, R., van der Leun, J., and Rath, R. (1999). Mixed embeddedness: (in)formal economic activities and immigrant businesses in the Netherlands. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 23: 252-266.

Knorr Cetina, K. (1999). Epistemic cultures: how the sciences make sense. Chicago University Press, Chicago.

Krugman, P. (1991). Geography and trade. Leuven University Press, Leuven; MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Lamoreaux, N.R. and Sokoloff, K.L. (2001). Market trade in patents and the rise of a class of specialized inventors in the 19th-century United States. Am. Econ. Rev. 91: 39-44.

Li, P. (2014). Horizontal vs. vertical learning: divergence and diversification of leading firms in Hangji toothbrush cluster, China. Reg. Stud. 48: 1227-1241.

Li, P. (2017a). Horizontal learning. In: Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S., and Simon, L. (Eds.). The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA, pp. 392-404.

Li, P. (2017b). Family networks for learning and knowledge creation in developing regions. In: Glückler, J., Lazega, E., and Hammer, I. (Eds.). Knowledge and networks. Springer, Berlin, pp. 67-84.

Li, P. (2018). A tale of two clusters: knowledge and emergence. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 30: 822-847.

Lorenzen, M. and Mudambi, R. (2013). Clusters, connectivity and catch-up: Bollywood and Bangalore in the global economy. J. Econ. Geogr. 13: 501-534.

Lorenzen, M., Mudambi, R., and Schotter, A. (2020). International connectedness and local disconnectedness: MNE strategy, city-regions and disruption. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 51: 1199-1222.

Malecki, E.J. (2009). Geographical environments for entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 7: 175-190.

Martinez-Vazquez, J. and Vaillancourt, F. (Eds.) (2008). Public policy for regional development. Routledge, London.

Maskell, P., Bathelt, H., and Malmberg, A. (2006). Building global knowledge pipelines: the role of temporary clusters. Eur. Plan. Stud. 14: 997-1013.

Monteiro, F. and Birkinshaw, J. (2017). The external knowledge sourcing process in multinational corporations. Strateg. Manag. J. 38: 342-362.

Murmann, J.P. (2003). Knowledge and competitive advantage: the coevolution of firms, technology, and national institutions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Murmann, J.P. (2013). The coevolution of industries and important features of their environments. Organ. Sci. 24: 58-78.

Nelson, R.R. (1989). What is private and what is public about technology? Sci. Technol. Hum. Val. 14: 229-241.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Oughton, C., Landabaso, M., and Morgan, K. (2002). The regional innovation paradox: innovation policy and industrial policy. J. Technol. Tran. 27: 97-110, .

Owen-Smith, J. and Powell, W.W. (2004). Knowledge networks as channels and conduits: the effects of spillovers in the Boston biotechnology community. Organ. Sci. 15: 2-21.

Pavitt, K.L.R. (1991). What makes basic research economically useful? Res. Pol. 20: 109-119.

Porter, M.E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Free Press, New York.

Portes, A. and Martinez, B.P. (2020). They are not all the same: immigrant enterprises, transnationalism, and development. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 46: 1991-2007.

Portes, A. and Sensenbrenner, J. (1993). Embeddedness and immigration: notes on the social determinants of economic action. Am. J. Sociol. 98: 1320-1350.

Potts, J. (2019). Innovation commons: the origin of economic growth. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Rappa, M.A. and Debackere, K. (1992). Technological communities and the diffusion of knowledge. R D Manag. 22: 209-220.

Rauch, J.E. (1999). Networks versus markets in international trade. J. Int. Econ. 48:7-35.

Roberts, J. (2017). Community, creativity and innovation. In: Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S., and Simon, L. (Eds.). The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA, pp. 342-359.

Sandoz, L., Mittmasser, C., Riaño, Y., and Piguet, E. (2022). A review of transnational migrant entrepreneurship: perspectives on unequal spatialities. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 137-150.

Sassen, S. (2001). The global city: New York, London, Tokyo. 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Saxenian, A. (2006). The New Argonauts: regional advantage in a global economy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Saxenian, A. and Sabel, C. (2008). Roepke lecture in economic geography – Venture capital in the ‘periphery’: the New Argonauts, global search, and local institution building. Econ. Geogr. 84: 379-394.

Shukla, P. and Cantwell, J. (2016). Migrants and the foreign expansion of firms. Rutgers Bus. Rev. 1: 44-56.

Shukla, P. and Cantwell, J. (2018). Migrants and multinational firms: the role of institutional affinity and connectedness in FDI. J. World Bus. 53: 835-849.

Shukla, P. and Cantwell, J. (2023). Skilled migrants: stimulating knowledge creation and flows in firms. In: Mockaitis, A.I. (Ed.). Palgrave handbook of global migration in international business. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 355-384.

Sölvell, Ö. and Birkinshaw, J. (2000). Multinational enterprises and the knowledge economy: leveraging global practices. In: Dunning, J. (Ed.). Regions, globalization and the knowledge-based economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 82-106.

Storper, M. (1997). The regional world: territorial development in a global economy. Guilford Press, New York.

Storper, M. and Venables, A.J. (2004). Buzz: face-to-face contact and the urban economy. J. Econ. Geogr. 4: 351-370.

Styhre, A. (2016). Knowledge sharing in professions: roles and identity in expert communities. Routledge, London.

Taylor, P.J. and Derudder, B. (2004). World city network: a global urban analysis. Routledge, London.

Teece, D.J. (1993). The dynamics of industrial capitalism: perspectives on Alfred Chandler’s scale and scope. J. Econ. Lit. 31: 199-225.

Vahlne, J.-E. and Johanson, J. (2013). The Uppsala model on evolution of the multinational business enterprise – from internalization to coordination of networks. Int. Mark. Rev. 30: 189-210.

Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Acad. Manag. J. 38: 341-363.

- *Corresponding author: Harald Bathelt, Department of Geography and Planning, University of Toronto, Sidney Smith Hall, 100 St. George Street, Toronto, ON M5S 3G3, Canada, E-mail: harald.bathelt@utoronto.ca.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0938-1765

John A. Cantwell, Rutgers Business School and Division of Global Affairs, Rutgers University, 1 Washington Park, Newark, NJ 07102, USA, E-mail: cantwell@business.rutgers.edu.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8638-0961 - 1 Communities are similarly under-conceptualized in the global-value-chain and global-production-network literature.

2 Their supportive role in knowledge acquisition, creativity and innovation has been well-explored (Cohendet et al. 2017), but depends on the context and purpose of the community (Roberts 2017). - 3 Note that this kind of technological community might be thought of as an innovation commons (Potts 2019), which builds on conceptualizations by Ostrom (1990).

- 4 These national subdivisions may have a community life of their own as their reproduction is shaped by national institutional contexts with specific regulations, practices and traditions (Berns et al. 2021). A primary role of these subdivisions in internationalization processes is to link local communities with international communities. In some instances, where a country is itself sufficiently large and diverse in character and internationally connected, these national subdivisions (for instance in the case of some American associations) may have the character of de facto international communities. In internationalization processes, foreign chapters of these subdivisions can sometimes operate like extensions of local communities abroad.

- 5 Local communities are not only important in vertical value-chainrelated knowledge transfers but also in horizontal learning processes. Li (2017a) identifies four crucial mechanisms that stimulate such processes: socially embedded learning, labor mobility, interaction and monitoring, and collective invention.

- 6 We might refer to the individuals that develop transnational capabilities or have these based on prior lived experience as transnational professional communities (Faulconbridge 2010; Faulconbridge et al. 2021; Saxenian 2006). Members of such transnational communities, as we define them, collaborate with others across selected locations based on kinship/friendship relations or shared experience (Bathelt and Li 2020; Kennedy 2004). They tend to be more self-referential and cohesive, with access being more narrowly regulated than in local and international communities.

7 These local-global interfaces are temporary organizations (sometimes organized by international business associations) where local community members can make contact with other local communities and through which future transaction networks may be forged (Bathelt and Henn 2025; Li 2017a). Such events also play an important role in the reproduction of international communities (Bathelt and Sydow 2025). - 8 When trying to access to business networks in the host economy, efforts to build connections between the local professional communities at both ends play an essential role, yet it is surprising that the international business literature largely maintains a firm perspective in its analysis and does not focus on the supporting role of communities (Belderbos et al. 2024; Goerzen et al. 2013; Lorenzen et al. 2020).

- 9 In debates about the role of various proximities in regional development (Boschma 2005), these community effects are imperfectly captured since geographical proximity is a category that is too broad and organizational proximity too narrow. Within a regional context, it is the local professional community that drives interaction in knowledge and practice, while interaction that occurs within firm boundaries (within or between firms) is merely a subset of overall community interaction.

- 10 In a local commons, organized by a local community (as opposed to firms), resources – including potentially public knowledge – are

- pooled communally to ensure the collective action needed to support the development of new business opportunities (Hess and Ostrom 2003; Potts 2019).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw-2024-0073

Publication Date: 2025-04-28

Communities in the internationalization process

Received August 2, 2024; accepted April 2, 2025;

published online April 28, 2025

Abstract

Much of the work on industrial location, internationalization and innovation is based on firm- or firm-network-level research, but does not consider the role of industry-based professional communities that can be crucial in providing access to knowledge, resources and personal networks. These communities, whose membership reaches well beyond firms themselves, are indispensable components of firms’ everyday activities, yet are often overlooked when investigating firm behavior. This paper focuses on the one hand on the role of local communities and those individuals that form them, and on the other hand on how they link with international communities and become crucial facilitators of internationalization processes. In a co-evolutionary perspective, we investigate the role of local professional communities and the localglobal interfaces that are created in internationalization processes, and how such localized activity may be associated with regional development. In a conceptual discussion, we propose that local professional communities and their local-international community connections are crucial to the capacity to engage in internationalization projects. From this, we discuss a number of related questions: First, who are the members of local professional communities and how do they create knowledge? Second, how do local professional communities develop and what are the driving forces that underlie their growth? Third, what are the conditions for the reproduction of local professional communities? We conclude by highlighting that the interrelationship between local and international communities is a critical feature of a permissive environment that facilitates corporate success in the internationalization process, and this favorable interaction between firms and their environment equally impacts

1 Introduction: firms, communities and their local-global interfaces

management (Brown and Duguid 1991; Knorr Cetina 1999; Wenger 1998; for an overview, see Roberts 2017), it is surprising that much of the related literature focuses on the creation and maintenance of networks between firms without scrutinizing the specific role of these underlying professional communities, their capabilities and their actions that are at the very core of the competitiveness and reproduction of regional economies (for exceptions, see Bathelt and Li 2020; Cohendet et al. 2014; Li 2014; Monteiro and Birkinshaw 2017). It is these local industrial or industrybased professional communities (for brevity, also referred to hereafter just as local communities) – not just in clusters but in regional economies more generally – that are at the core of our conceptual inquiry.

| Name of communal entity | Type of community | Nature of community type and relationship between types |

| Social networks | Loose constellations of actors linked by ties of various kinds | Inter-actor ties may develop due to transactional linkages, or some mutual interests or common activities, or personnel movements – and be enhanced by different forms of proximity |

| Professional communities | Groupings of professionals of various kinds, from relevant professions that come together to contribute to business projects in a given industry | Intentional identification with and voluntary participation in a community whose members share an interest and experience in a variety of types of specialized expertise that are needed to support international business projects in a given industry context |

| Communities of practice | Coherent groupings of individuals engaged and proficient in some common domain of practice | Intentional identification with and voluntary participation in a community characterized by shared and reciprocal commitments to develop an industry-based domain of practice |

| Epistemic communities | Coherent groupings of individuals with shared principles and values in the development and application of some common domain of knowledge | Intentional identification with and voluntary participation in a community built upon a strong foundation in a body of knowledge in a specific industry-based domain of expertise, with a shared commitment to develop that body of knowledge over time |

| Knowing communities | Coherent groupings of communities of practice, epistemic and virtual communities that develop a mutual, coherent understanding of a common domain of knowledge | Intentional identification with and voluntary participation in a community that shares and develops knowledge in a common domain that combines know-how (practice) with know-why (understanding and scientific or conceptual interpretation) in some given industry context |

| Local professional communities | Coherent groupings of individuals co-located in a region or localized knowing communities, having a cross-industry representation which reflects the specialization of the region | Identification with a spatially defined community concentrated in the main industries of specialization in a region, developing best practice and exchanging knowledge, often relying on shared backgrounds and experiences, and in tune with the local institutional context; local communities fuse together communities of practice and epistemic communities in the domains of the strongest industries in the region |

| International professional communities | Coherent groupings of geographically dispersed individuals in some common domain of industry-based expertise, who regularly interact with others in the development of frontier expertise of potential interest across various spatial contexts | Identification with a domain-defined community in some particular industrial setting, having a shared commitment to develop and apply the best expertise in the domain, often linked to or organized around some international professional associations; international communities establish channels for the dissemination of the best knowledge and practice in a domain across space; local communities can connect to a select set of international communities concordant with the range of local industry specialization |

| National subdivisions of international professional communities | Coherent groupings of individuals within an international professional community in a common country of residence, who interact with others at a national level as well as internationally | Identification with a domain-defined community that is active in bringing together expertise on a certain kind of industry-specific projects in a given country; often linked to a national subdivision of an international professional association, which facilitates connections between the relevant international community and local communities in the country in question |

| Transnational communities | Coherent groupings of individuals that emerge during internationalization processes as local communities merge with international communities and develop transnational capabilities | Identification with a domain-defined community in a given industrial context, in which members of select local communities collaborate directly in their support of international business projects, and in disseminating knowledge about the relationship between projects undertaken in different locations |

our analysis of professional communities and not part of the analysis themselves.

knowledge of or experience in internationalization projects as such, but ranges far more widely. Relevant knowledge relates to many issues which are germane to the implementation and continuation of internationalization processes, such as knowledge about the legal and institutional, or linguistic and cultural context of particular countries and regions, and about how practices and applications vary across different industry or market contexts (Bathelt and Li 2020). We view internationalization projects as successful when firms establish, maintain or extend an international market presence and are able to grow through this. In aggregate form, internationalization then has an immediate impact on regional development and is closely connected to it.

conditions for the reproduction of local professional communities. It is argued that self-sustaining feedback process are supported when local professional communities reach a critical mass, have local amenities, when they are open for an influx of new knowledge and people, have placebased policies and support organizations, individual leaders and anchor firms, and/or when they establish a middleground where community members can get together. Section 6 concludes by highlighting the linkages between local and international professional communities, which have changed over time, thus creating a dynamic perspective of their co-evolution. The interrelationship between local and international communities is a critical feature of a permissive environment that facilitates corporate success in the internationalization process, and this favorable interaction between firms and their environment equally favors the development prospects of the city-regions where they are located.

2 Conceptual framework: local and international professional communities in the internationalization process

they engage in cross-border trade and make investments abroad (Håkanson 1979; Johanson and Vahlne 1977; Vahlne and Johanson 2013). In the later stages of development, more mature firms may develop a multinational production structure (Dunning and Lundan 2008), access foreign markets with customized products and utilize international knowledge connections to support their innovation activities in specialized locations or urban centers (Cantwell 2009).

toward specific problem-solving or collaboration in networks (Cantwell and Piscitello 1999). For firms that invest in a different country, links between the local and international community help facilitate access to firms and networks in the host region, thus enabling affiliates over time to participate in the host region’s local knowledge ecology (Malecki 2009). As such, local-international community interfaces help forge cross-community and eventually interfirm linkages that are instrumental to overcoming firms’ liability of outsidership from local networks (Johanson and Vahlne 2009).

3 Local professional communities: who are they and how do they create knowledge?

processes depends on the degree of institutional affinity and connectedness between the region in which they reside and their countries of origin. This capacity also depends on whether migrant populations have achieved a critical mass locally (Buchholz 2021; Kloosterman 2010; Sandoz et al. 2022; Shukla and Cantwell 2018).

even if they do not know one another personally or have any direct ties.

4 How do local professional communities with transnational capabilities develop and grow?

claiming these are the only drivers of local community development, there are at least four driving forces that play a decisive role in their emergence and growth, which are prevalent in certain city-regions: connectivity, education/training, migrating and clustering/specialization (Figure 1):

(1) Connecting. Connecting is a particularly strong driver of community development in global/world cities that are prime locations for the emergence and growth of local professional communities. They are characterized by a large concentration of headquarters of multinational firms in finance, knowledge-intensive services and manufacturing and develop close linkages with other global cities as well as with secondary cities that become locations of subsidiaries with manufacturing and service functions (Sassen 2001; Taylor and Derudder 2004). Global/world cities exercise dominance and control through the networks and connections they establish with a broad set of international locations. They develop this dominance as they are able to actively recruit, train and attract specialists with transnational governance and knowledge creation capabilities (Florida 2002). Global/world cities develop large professional communities, which are highly connected with international communities and have strong cross-local community linkages. Their high connectivity is based on personal networks that community members establish during their managerial/technical career with different multinational employers, as well as on membership in international professional associations/Internet forums and shared practices of utilizing the same codified knowledge sources (e.g. professional magazines). It is the high breadth and depth in connectivity, both of firms and community members, which drives the growth of local communities in these cities and strengthens their transnational capabilities (Cantwell and Zaman 2018, 2024).

(2) Educating/training. Educating/training plays a distinct role for community development in city-regions with well-known, prestigious research and higher-education facilities. It is through continuous educating/training that local professional communities emerge and grow in these places, subject to having a local economic base where cohorts of graduates can find work. In most industries, university knowledge is crucial to enable access to international epistemic communities, especially when firms engage in advanced research and gain legitimacy in these communities (Pavitt 1991). Places with strong local research universities attract a large international student body in business, engineering and science programs that can trigger start-up and spin-off processes if there is a good match between the educational focus and the sectoral composition of the local economy (Bramwell and Wolfe 2008). While university

(3) Migrating. Migrating is another important driving force, through which local professional communities can develop. City-regions with large immigrant and/or migrant populations may thus develop significant, dynamic local communities that draw professionals from other local communities to connect to the regional knowledge base. This may strengthen the local community and improve linkages with international communities, thus resulting in a self-reinforcing process of community development. Like the New Argonauts, immigrants with a pre-existing professional background or after receiving training in their destination countries may utilize close linkages with their

country of origin to establish new businesses that connect both economies, exploiting their double-embeddedness in different cultural contexts (Hartmann and Philipp 2022; Kloosterman et al. 1966; Portes and Martinez 2020; Sandoz et al. 2022). Beyond triggering entrepreneurship, migrating can act in a broader sense as a driver of the development of communities which helps sustain ongoing international linkages (Cai et al. 2021; Hajro et al. 2021; Shukla and Cantwell 2018). There are multiple triggers of how immigrant diversity can generate positive spillover effects on local labor markets (Kemeny and Cooke 2018); through interaction/learning, complementarity and niching processes, as well as exposure effects, immigrants can strengthen labor markets and increase local firms’ competitiveness (Buchholz 2021).

(4) Clustering/specializing. An important driving force of community development is associated with strong industry clusters and a high degree of specialization. Corresponding city-regions have manifold opportunities to expand internationally and access new markets through replicating/augmenting and connecting strategies based on competitive advantages (Bathelt and Li 2022; Bathelt et al. 2004; Giuliani and Bell 2005; Kerr and Robert-Nicoud 2020; Porter 1990). Across different industry contexts, economic clustering/specializing seems to be an important, in fact almost natural, driver of strong local professional communities that develop transnational capabilities. In small emerging clusters, this may proceed initially through trial-and-error processes but, as clusters grow and mature (Fornahl et al.

2010), their increasing competitiveness and international reputation make it easy to attract talent from distant communities and through international community linkages. Again, the capabilities of the local community and the local firms’ successful internationalization are connected in a reflexive manner. As in the case of global/world cities, large urban centers are often characterized by multiple industrial milieus or clusters (Crevoisier 2001) and thus develop large diversified local communities with broad specialized skill portfolios. They form highly attractive labor markets for talent and are, at the same time, attractive locations for firms in related industries (Krugman 1991). Not only do these places develop dynamic and rich localized knowledge ecologies with high internal innovation potential, they also build global pipelines with other sophisticated clusters abroad and become priority destinations of investment linkages from foreign clusters (Bathelt and Li 2022; Owen-Smith and Powell 2004).

of a small local professional community, encourage more internationalization and stimulate regional development. As opposed to the urban contexts discussed before, however, the local communities in normal regions may lack effective feedback and growth triggers and be vulnerable as their existence depends on a few firms and their staff members.

5 How do local professional communities reproduce themselves?

same time, have direct positive effects on regional development (Bathelt and Buchholz 2019) by channeling additional demand and new knowledge into home regions. On the one hand, ongoing internationalization supports the continued growth of regional industries and drives further specialization in the home regions (Birkinshaw and Sölvell 2000; Sölvell and Birkinshaw 2000). On the other hand, this generates an incentive structure that encourages both the growth of local communities and drives further internationalization. Connecting processes thus lead to an expansion of local professional communities (Bathelt et al. 2023).

city-regions with a diversified economy that neither have well-developed local communities, nor the capabilities necessary to develop them. For instance, national industrial and innovation policies may support the growth of specific industries and provide subsidies for new infrastructure and research capacity to promote the development and specialization of local communities. The focus of these policies is often on firms’ international competitiveness and therefore primarily benefits existing technology regions. In contrast, education and migration policies that focus on the development of advanced skills and attract qualified labor from abroad may have a broader geographical effect, albeit in a more indirect fashion. Related policies can positively impact the development of smaller and secondary city-regions if implemented with place-based strategies that target the specific needs and potentials of these locations (Iammarino et al. 2019). Indirectly or directly, targeted policies can support the reproduction of local professional communities and help strengthen transnational capabilities.

6 Conclusion: evolving linkages between local and international professional communities

internationalization processes of firms in any major cityregion. The better the connectedness between local and international communities in a place, the more firms’ internationalization projects can benefit from facilitating community activities (Bathelt and Li 2020). These internationalization processes have a critical impact on home-region growth (Buchholz et al. 2020), as they strengthen community development and create a favorable environment for future internationalization and further regional development. In innovative clusters and major city-regions, we are witnessing the development of strong local professional communities that go hand in hand with firm internationalization and, in fact, become major drivers of both continued corporate growth processes and regional prosperity, while firms in smaller city-regions without major communities may have more risks and struggles in the long run.

Research ethics: Not applicable.

Informed consent: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Both authors contributed equally to the paper.

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning

Tools: No such tools were used in any stage of the research process and in writing the paper.

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interests.

Research funding: None declared.

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Agrawal, A. and Cockburn, I. (2003). The anchor tenant hypothesis: exploring the role of large, local, R & D-intensive firms in regional innovation systems. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 21: 1227-1253.

Amin, A. and Cohendet, P. (2004). Architectures of knowledge: firms, capabilities, and communities. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Asheim, B.T. (1999). Interactive learning and localised knowledge in globalising learning economies. Geojournal 49: 345-352.

Bathelt, H. and Buchholz, M. (2019). Outward foreign-direct investments as a catalyst of urban-regional income development? Evidence from the United States. Econ. Geogr. 95: 442-466.

Bathelt, H., Cantwell, J.A., and Mudambi, R. (2018). Overcoming frictions in transnational knowledge flows: challenges of connecting, sense-making and integrating. J. Econ. Geogr. 18: 1001-1022.

Bathelt, H. and Cohendet, P. (2014). The creation of knowledge: local building, global accessing and economic development – toward an agenda. J. Econ. Geogr. 14: 869-882.

Bathelt, H. and Henn, S. (2025). Creating knowledge over distance: the role of temporary proximity. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bathelt, H. and Li, P. (2020). Processes of building cross-border knowledge pipelines. Res. Pol. 49: 103928.

Bathelt, H. and Li, P. (2022). The interplay between location and strategy in a turbulent age. Glob. Strateg. J. 12: 451-471.

Bathelt, H. and Sydow, J. (2025). Thoughtlet – Beyond temporary organizations: trade fairs as temporary markets, clusters and community gatherings. Proj. Manag. J. 56.

Bathelt, H., Buchholz, M., and Cantwell, J.A. (2023). OFDI activity and urban-regional development cycles: a co-evolutionary perspective. Compet. Rev. 33: 512-533.

Bathelt, H., Malmberg, A., and Maskell, P. (2004). Clusters and knowledge: local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 28: 31-56.

Belderbos, R., Castellani, D., Du, H.S., and Lee, G.H. (2024). Internal versus external agglomeration advantages in investment location choice: the role of global cities’ international connectivity. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 55: 745-763.

Bernard, A.B. and Moxnes, A. (2018). Networks and trade. Ann. Rev. Econ. 10: 65-85.

Berns, J.P., Gondo, M., and Sellar, C. (2021). Whole country-of-origin network development abroad. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 52: 479-503.

Birkinshaw, J. and Sölvell, Ö. (2000). Leading-edge multinationals and leading-edge clusters. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 33: 3-9.

Boland, R.J. and Tenkasi, R.V. (1995). Perspective making and perspective taking in communities of knowing. Organ. Sci. 6: 350-372.

Boschma, R.A. (2005). Proximity and innovation: a critical assessment. Reg. Stud. 39: 61-74.

Bramwell, A. and Wolfe, D.A. (2008). Universities and regional economic development: the entrepreneurial University of Waterloo. Res. Pol. 37: 1175-1187.

Breschi, S. and Lissoni, F. (2001). Knowledge spillovers and local innovation systems: a critical survey. Ind. Corp. Change 10: 975-1005.

Brown, J.S. and Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovating. Organ. Sci. 2: 40-57.

Buchholz, M. (2021). Immigrant diversity, integration and worker productivity: uncovering the mechanisms behind ‘diversity spillover’ effects. J. Econ. Geogr. 21: 261-285.

Buchholz, M., Bathelt, H., and Cantwell, J.A. (2020). Income divergence and global connectivity of U.S. urban regions. J. Int. Bus. Policy 3: 229-248.

Cano-Kollmann, M., Mudambi, R., and Tavares-Lehmann, A. (2022). The geographical dispersion of inventor networks in peripheral economies. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 49-63.

Cantwell, J.A. (1989). Technological innovation and multinational corporations. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

Cantwell, J.A. (1995). The globalisation of technology: what remains of the product cycle model? Camb. J. Econ. 19: 155-174.

Cantwell, J.A. (2009). Location and the multinational enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 40: 35-41.

Cantwell, J.A., Dunning, J.H., and Lundan, S.M. (2010). An evolutionary approach to understanding international business activity: the co-evolution of MNEs and the institutional environment. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 41: 567-586.

Cantwell, J. and Iammarino, S. (2003). Multinational corporations and European regional systems of innovation. Routledge, London, New York.

Cantwell, J.A. and Janne, O.E.M. (1999). Technological globalisation and innovative centres: the role of corporate technological leadership and locational hierarchy. Res. Pol. 28: 119-144.

Cantwell, J. and Piscitello, L. (1999). The emergence of corporate international networks for the accumulation of dispersed technological competences. Manag. Int. Rev. 39: 123-147.

Cantwell, J. and Shukla, P. (2025). Spatial development of technological knowledge and the evolution of international business activity across technological paradigms. Int. Bus. Rev. 34: 102356.

Cantwell, J. and Spadevecchia, A. (2023). Which actors drove national patterns of technological specialization into the science-based age? The British experience, 1918-1932. Ind. Corp. Change 32: 622-646.

Cantwell, J. and Zaman, S. (2018). Connecting local and global technological knowledge sourcing. Compet. Rev. 28: 277-294.

Cantwell, J. and Zaman, S. (2024). International knowledge connectivity and the increasing concentration of innovation in major global cities. J. Econ. Geogr. 24: 421-446.

Chandler, A.D. (1984). The emergence of managerial capitalism. Bus. Hist. Rev. 58: 473-503.

Clark, G. (2022). Agency, sentiment, and risk and uncertainty: fears of job loss in 8 European countries. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 3-17.

Coe, N.M. and Bunnell, T.G. (2003). ‘Spatializing’ knowledge communities: towards a conceptualization of transnational innovation networks. Glob. Netw. 3: 437-456.

Cohendet, P. (2022). Architectures of the commons: collaborative spaces and innovation. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 36-48

Cohendet, P., Grandadam, D., and Simon, L. (2010). The anatomy of the creative city. Ind. Innov. 17: 91-111.

Cohendet, P., Grandadam, D., Simon, L., and Capdevila, I. (2014). Epistemic communities, localization and the dynamics of knowledge creation. J. Econ. Geogr. 14: 929-954.

Cohendet, P., Parmentier, G., and Simon, L. (2017). Managing knowledge, creativity, and innovation. In: Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S., and Simon, L. (Eds.). The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA, pp. 197-214.

Collings, D.G., Scullion, H., and Caligiuri, P.M. (2019). Global talent management. Routledge, London.

Crane, D. (2022). Invisible colleges: diffusion of knowledge in scientific communities. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Crevoisier, O. (2001). Der Ansatz des kreativen Milieus: Bestandsaufnahme und Forschungsperspektiven am Beispiel urbaner Milieus (The creative milieu: state of the art, research perspectives and the case of urban milieus). ZFW – Z. Wirtschaftsgeogr. 45: 246-256.

de Groot, E., Endedijk, M.D., Jaarsma, A.D.C., Simons, P.R.-J., and van Beukelen, P. (2014). Critically reflective dialogues in learning communities of professionals. Stud. Cont. Educ. 36: 15-37.

de Solla Price, D.J. and Beaver, D. (1966). Collaboration in an invisible college. Am. Psychol. 21: 1011-1018.

DiMaggio, P.J. and Powell, W.W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 48: 147-160.

Dunning, J.H. (1983). Changes in the level and structure of international production: the last one hundred years. In: Casson, M.C. (Ed.). The growth of international business. Allen and Unwin, London, pp. 84-139.

Dunning, J.H. (1993). Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Addison-Wesley, Wokingham.

Dunning, J.H. (2000). The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. Int. Bus. Rev. 9: 163-190.

Dunning, J.H. and Lundan, S.M. (2008). Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA.

Evren, Y. and Odabaş, E. (2024). Towards a comprehensive agency-based resilience approach: myopia and hypermetropia in the Turkish wine industry. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 68: 81-95.

Faulconbridge, J.R. (2007). Relational networks of knowledge production in transnational law firms. Geoforum 38: 925-940.

Faulconbridge, J.R. (2010). TNCs as embedded social communities: transdisciplinary perspectives. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 6: 273-290.

Faulconbridge, J.R., Folke Henriksen, L.F., and Seabrooke, L. (2021). How professional actions connect and protect. J. Prof. Organ. 8: 214-227.

Feldman, M. (2003). The locational dynamics of the US biotech industry: knowledge externalities and the anchor hypothesis. Ind. Innov. 10: 311-329.

Fitzsimmons, S.R., Miska, C., and Stahl, G.K. (2011). Multicultural employees: global business’ untapped resource. Org. Dyn. 40: 199-206.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class: and how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. Basic Books, New York.

Fornahl, D., Henn, S., and Menzel, M.-P. (Eds.) (2010). Emerging clusters: theoretical, empirical and political perspectives in the initial stage of cluster evolution. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA.

Forsgren, M., Holm, U., and Johanson, J. (2006). Managing the embedded multinational: a business network view. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA.

Fuchs, M., Henn, S., Franz, M., and Mudambi, R. (Eds.) (2017). Managing culture and interspace in cross-border investments: building a global company. Routledge, Abingdon.

Gertler, M.S. (2003). Tacit knowledge and the economic geography of context, or the undefinable tacitness of being (there). J. Econ. Geogr. 3: 75-99.

Giuliani, E. and Bell, M. (2005). The micro-determinants of mess-level learning and innovation: evidence from a Chilean wine cluster. Res. Pol. 34: 47-68.

Goerzen, A., Asmussen, C.G., and Nielsen, B.B. (2013). Global cities and multinational enterprise location strategy. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 44: 427-450.

Grillitsch, M. and Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 44: 704-723.

Hajiro, A., Brewster, C., Haak-Saheem, W., and Morley, M.J. (2023). Global migration: implications for international business scholarship. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 54: 1134-1150.

Hajro, A., Caprar, D.V., Zikic, J., and Stahl, G. (2021). Global migrants: understanding the implications for international business and management. J. World Bus. 56: 101192.

Håkanson, L. (1979). Towards a theory of location and corporate growth. In: Hamilton, F.E.I. and Linge, G.J.R. (Eds.). Spatial analysis, industry and the industrial environment. Volume i: industrial systems. Wiley, Chichester, pp. 115-138.

Hamida, L.M. (2013). Are there regional spillovers from FDI in the Swiss manufacturing industry? Int. Bus. Rev. 22: 754-769.

Harrington, B. and Seabrooke, L. (2020). Transnational professionals. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 46: 399-417.

Hartmann, C. and Philipp, R. (2022). Lost in space? Refugee entrepreneurship and cultural diversity in spatial contexts. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 151-171.

Henn, S. and Bathelt, H. (2017). Transnational entrepreneurs and innovation. In: Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S., and Simon, L. (Eds.). The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA, pp. 638-651.

Henn, S. and Bathelt, H. (2018). Cross-cluster knowledge fertilization, cluster emergence and the generation of buzz. Ind. Corp. Change 27: 449-466.

Hess, C. and Ostrom, E. (2003). Ideas, artefacts and facilities: information as a common pool resource. Law Contemp. Probl. 66: 111-146.

Hitt, M.A., Li, D., and Xu, K. (2016). International strategy: from local to global and beyond. J. World Bus. 51: 58-73.

Iammarino, S., Rodríguez-Pose, A., and Storper, M. (2019). Regional inequality in Europe: evidence, theory and policy implications. J. Econ. Geogr. 19: 273-298.

Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E. (1977). The internationalisation process of the firm – a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 8: 23-32.

Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: from liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 40: 1411-1431.

Kemeny, T. and Cooke, A. (2018). Spillovers from immigrant diversity in cities. J. Econ. Geogr. 18: 213-245.

Kennedy, P. (2004). Making global society: friendship networks among transnational professionals in the building design industry. Glob. Netw. 4: 157-179.

Kerr, W.R. and Kominers, S.D. (2015). Agglomerative forces and cluster shapes. Rev. Econ. Stat. 97: 877-899.

Kerr, W.R. and Robert-Nicoud, F. (2020). Tech clusters. J. Econ. Perspect. 34: 50-76.

Kloosterman, R., van der Leun, J., and Rath, R. (1999). Mixed embeddedness: (in)formal economic activities and immigrant businesses in the Netherlands. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 23: 252-266.

Knorr Cetina, K. (1999). Epistemic cultures: how the sciences make sense. Chicago University Press, Chicago.

Krugman, P. (1991). Geography and trade. Leuven University Press, Leuven; MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Lamoreaux, N.R. and Sokoloff, K.L. (2001). Market trade in patents and the rise of a class of specialized inventors in the 19th-century United States. Am. Econ. Rev. 91: 39-44.

Li, P. (2014). Horizontal vs. vertical learning: divergence and diversification of leading firms in Hangji toothbrush cluster, China. Reg. Stud. 48: 1227-1241.

Li, P. (2017a). Horizontal learning. In: Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S., and Simon, L. (Eds.). The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA, pp. 392-404.

Li, P. (2017b). Family networks for learning and knowledge creation in developing regions. In: Glückler, J., Lazega, E., and Hammer, I. (Eds.). Knowledge and networks. Springer, Berlin, pp. 67-84.

Li, P. (2018). A tale of two clusters: knowledge and emergence. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 30: 822-847.

Lorenzen, M. and Mudambi, R. (2013). Clusters, connectivity and catch-up: Bollywood and Bangalore in the global economy. J. Econ. Geogr. 13: 501-534.

Lorenzen, M., Mudambi, R., and Schotter, A. (2020). International connectedness and local disconnectedness: MNE strategy, city-regions and disruption. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 51: 1199-1222.

Malecki, E.J. (2009). Geographical environments for entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 7: 175-190.

Martinez-Vazquez, J. and Vaillancourt, F. (Eds.) (2008). Public policy for regional development. Routledge, London.

Maskell, P., Bathelt, H., and Malmberg, A. (2006). Building global knowledge pipelines: the role of temporary clusters. Eur. Plan. Stud. 14: 997-1013.

Monteiro, F. and Birkinshaw, J. (2017). The external knowledge sourcing process in multinational corporations. Strateg. Manag. J. 38: 342-362.

Murmann, J.P. (2003). Knowledge and competitive advantage: the coevolution of firms, technology, and national institutions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Murmann, J.P. (2013). The coevolution of industries and important features of their environments. Organ. Sci. 24: 58-78.

Nelson, R.R. (1989). What is private and what is public about technology? Sci. Technol. Hum. Val. 14: 229-241.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Oughton, C., Landabaso, M., and Morgan, K. (2002). The regional innovation paradox: innovation policy and industrial policy. J. Technol. Tran. 27: 97-110, .

Owen-Smith, J. and Powell, W.W. (2004). Knowledge networks as channels and conduits: the effects of spillovers in the Boston biotechnology community. Organ. Sci. 15: 2-21.

Pavitt, K.L.R. (1991). What makes basic research economically useful? Res. Pol. 20: 109-119.

Porter, M.E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Free Press, New York.

Portes, A. and Martinez, B.P. (2020). They are not all the same: immigrant enterprises, transnationalism, and development. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 46: 1991-2007.

Portes, A. and Sensenbrenner, J. (1993). Embeddedness and immigration: notes on the social determinants of economic action. Am. J. Sociol. 98: 1320-1350.

Potts, J. (2019). Innovation commons: the origin of economic growth. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Rappa, M.A. and Debackere, K. (1992). Technological communities and the diffusion of knowledge. R D Manag. 22: 209-220.

Rauch, J.E. (1999). Networks versus markets in international trade. J. Int. Econ. 48:7-35.

Roberts, J. (2017). Community, creativity and innovation. In: Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S., and Simon, L. (Eds.). The Elgar companion to innovation and knowledge creation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, Northampton, MA, pp. 342-359.

Sandoz, L., Mittmasser, C., Riaño, Y., and Piguet, E. (2022). A review of transnational migrant entrepreneurship: perspectives on unequal spatialities. ZFW – Adv. Econ. Geogr. 66: 137-150.

Sassen, S. (2001). The global city: New York, London, Tokyo. 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Saxenian, A. (2006). The New Argonauts: regional advantage in a global economy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Saxenian, A. and Sabel, C. (2008). Roepke lecture in economic geography – Venture capital in the ‘periphery’: the New Argonauts, global search, and local institution building. Econ. Geogr. 84: 379-394.

Shukla, P. and Cantwell, J. (2016). Migrants and the foreign expansion of firms. Rutgers Bus. Rev. 1: 44-56.

Shukla, P. and Cantwell, J. (2018). Migrants and multinational firms: the role of institutional affinity and connectedness in FDI. J. World Bus. 53: 835-849.

Shukla, P. and Cantwell, J. (2023). Skilled migrants: stimulating knowledge creation and flows in firms. In: Mockaitis, A.I. (Ed.). Palgrave handbook of global migration in international business. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 355-384.