المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 14، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53335-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38316898

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-05

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53335-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38316898

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-05

افتح

المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي: القياس والارتباطات بالشخصية

لقد أصبح الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) جزءًا لا يتجزأ من العديد من التقنيات المعاصرة، مثل منصات الوسائط الاجتماعية، والأجهزة الذكية، وأنظمة اللوجستيات العالمية. في الوقت نفسه، تُظهر الأبحاث حول قبول الجمهور للذكاء الاصطناعي أن العديد من الناس يشعرون بالقلق بشأن إمكانيات هذه التقنيات – وهي ملاحظة تم ربطها بكل من المتغيرات الديموغرافية والاجتماعية الثقافية للمستخدمين (مثل العمر، والتعرض السابق للوسائط). ومع ذلك، بسبب القياسات المتباينة وغالبًا ما تكون عشوائية للمواقف المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، تظل الأدلة الحالية غير حاسمة. وبالمثل، لا يزال غير واضح ما إذا كانت المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي تتأثر أيضًا بسمات شخصية المستخدمين. استجابةً لهذه الفجوات البحثية، نقدم مساهمة مزدوجة. أولاً، نقدم استبيانًا جديدًا مستندًا إلى علم النفس (ATTARI-12) يلتقط المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي كهيكل واحد، مستقل عن السياقات أو التطبيقات المحددة. بعد أن لاحظنا موثوقية وصلاحية جيدة لمقياسنا الجديد عبر دراستين (

يعد الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) وعدًا لجعل حياة الإنسان أكثر راحة بكثير: قد يعزز التعاون بين الثقافات عبر أدوات الترجمة المتطورة، ويوجه العملاء عبر الإنترنت نحو المنتجات التي من المرجح أن يشتروا، أو ينفذ وظائف تبدو مملة للعمال البشر

من المهم أن الأفراد قد يختلفون في تقييمهم لهذه الفرص والمخاطر، وبالتالي، يحملون مواقف مختلفة تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. ومع ذلك، نلاحظ أن العلماء المهتمين بهذه الاختلافات غالبًا ما استخدموا نهجًا أساسيًا عشوائيًا لتقييم مواقف المشاركين تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي

هدف البحث 1: قياس المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي

بشكل عام، يُستخدم مصطلح الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) لوصف التقنيات التي يمكن أن تنفذ مهام قد يتوقع أن تتطلب ذكاءً بشريًا – أي، التقنيات التي تمتلك درجة معينة من الاستقلالية، والقدرة على التعلم والتكيف، والقدرة على التعامل مع كميات كبيرة من البيانات

لفهم استجابة المستخدمين – وقبولهم – للتكنولوجيا الذكية الاصطناعية بشكل أفضل. بالطبع، من أجل تحقيق هذا الهدف، من الضروري استخدام مقاييس نظرية ذات جودة نفسية عالية عند تقييم المواقف المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. علاوة على ذلك، يحتاج الباحثون إلى اتخاذ قرار بشأن ما إذا كانوا يريدون دراسة نوع محدد فقط من التطبيقات (مثل السيارات ذاتية القيادة أو الروبوتات الذكية) أو التركيز على الذكاء الاصطناعي كمفهوم تكنولوجي مجرد يمكن تطبيقه في العديد من الإعدادات المختلفة. بينما تتمتع كلا الطريقتين بمزايا لا يمكن إنكارها، يمكن القول إن قابلية المقارنة بين جهود البحث المختلفة – خاصة تلك الموجودة عند تقاطع تخصصات مختلفة – تستفيد بوضوح من الأخيرة، أي، التركيز التجريبي على المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي كمجموعة من القدرات التكنولوجية بدلاً من حالات الاستخدام المحددة.

تماشيًا مع هذا الحجة، أنتجت الجهود العلمية عدة مقاييس لتقييم المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي كمفهوم أكثر شمولية. تشمل هذه مقياس المواقف العامة تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي (GAAIS

لذا، استنادًا إلى النقص المحدد في مقياس أحادي البعد، موثوق نفسيًا، ولكنه اقتصادي، يلتقط الجوانب الإيجابية والسلبية لموقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي، كان هدفنا الأول هو تطوير مقياس يتجاوز هذه القيود. من أجل قابلية تطبيق واسعة بين التخصصات، ركزنا بشكل صريح على إنشاء مقياسنا على إدراك الذكاء الاصطناعي كمجموعة عامة من القدرات التكنولوجية، مستقلة عن تجسيدها المادي أو سياق استخدامها. لم يكن هذا المنظور مستندًا إلى الأبحاث الحديثة، التي أشارت إلى أن تقييم الناس للعقول الرقمية من المحتمل أن يتغير بمجرد دخول العوامل البصرية في اللعب

هدف البحث 2: فهم الارتباطات بين المواقف المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي وسمات الشخصية

حتى الآن، استكشفت معظم الدراسات حول قبول الجمهور للذكاء الاصطناعي دور المتغيرات الديموغرافية والاجتماعية الثقافية، كاشفة أن المخاوف بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي تبدو أكثر انتشارًا بين النساء، وكبار السن، والأقليات العرقية، والأفراد ذوي المستويات التعليمية المنخفضة

بعيدًا عن الفهم الكبير للمحددات الاجتماعية والثقافية المتعلقة بإعجاب أو عدم إعجاب الأفراد بتكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي، فإن المعرفة حول تأثير عوامل شخصية المستخدمين على مواقفهم المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي أقل بكثير. حسب علمنا، فإن عددًا قليلاً فقط من الدراسات العلمية قد تناولت هذه القضية، وقد أسفرت معظمها عن نتائج محدودة جدًا – إما من خلال التركيز على أنواع محددة جدًا من

لذلك، بناءً على العمل الذي تم مراجعته، كان هدفنا الثاني هو فحص عدة أبعاد شخصية مركزية كمتنبئات لمواقف الناس تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي، بما في ذلك الخمسة الكبار المعروفة.

نظرة عامة على الدراسات والتوقعات

في معالجة الاقتراحات البحثية الموضحة، نقدم ثلاث دراسات (انظر الجدول 1 للحصول على نظرة عامة موجزة عن الخصائص الرئيسية للدراسة). يمكن العثور على جميع المواد والبيانات التي تم الحصول عليها وأكواد التحليل لهذه الدراسات الثلاث في مستودع إطار العلوم المفتوحة لمشروعنا.https://osf.io/3j67a/تم جمع الموافقة المستنيرة من جميع المشاركين قبل أن يشاركوا في جهودنا البحثية.

الدراستان 1 و2 خدمتا بشكل رئيسي للتحقق من موثوقية وصلاحية مقياسنا الجديد للمواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي، ATTARI-12. وبالتالي، كانت هذه الدراسات موجهة بشكل رئيسي من خلال عدة خطوات تحليلية تفحص الخصائص الإحصائية لمقياسنا، بما في ذلك صلاحية التقارب، وموثوقية إعادة الاختبار، وقابلية التأثر بتحيز الرغبة الاجتماعية. في الدراسة 3، بدأنا بعد ذلك في ربط موقف المشاركين تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي (كما تم قياسه من خلال الاستبيان المطور) بالسمات الشخصية الأساسية والعوامل الديموغرافية. في هذه الدراسة الثالثة والأخيرة، سنفصل جميع الاعتبارات النظرية والافتراضات في ما يلي.

| الدراسة 1 | الدراسة 2 | الدراسة 3 | |

| نوع العينة | MTurk (الولايات المتحدة) | عينة الطالب | MTurk (الولايات المتحدة) |

| تركيز الدراسة | تطوير المقياس: الصلاحية العاملية، الموثوقية (الاتساق الداخلي)، صلاحية البناء | تطوير المقياس: الموثوقية (موثوقية إعادة الاختبار)، الصلاحية البنائية | مؤشرات الشخصية (الخمسة الكبار، مثلث الظلام، عقلية المؤامرة) |

| دراسة اللغة | الإنجليزية | ألماني | الإنجليزية |

| حجم العينة النهائي | ٤٩٠ | 166 (في الوقت 1)، 163 في الوقت 2، 150 في كلا الوقتين | 298 |

| القياسات | 1 | 2 (متابعة بعد أربعة إلى خمسة أسابيع) | 1 |

الجدول 1. نظرة عامة على الدراسات التي تم إجراؤها.

في مواجهة نقص النتائج السابقة المتعلقة بمؤشرات الشخصية تجاه المواقف المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، اعتبرنا أنه من المهم أن نؤسس تحقيقنا على رؤية أوسع لشخصية الإنسان. وقد قادنا هذا المنظور إلى تضمين نموذج الخمسة الكبار أولاً.

بالنسبة للانفتاح على التجربة – الذي يمكن تعريفه على أنه الميل إلى المغامرة، والفضول الفكري، والخيال – توقعنا وجود علاقة إيجابية واضحة مع المواقف المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. نظرًا لأن تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي تعد بالعديد من الإمكانيات الجديدة للمجتمع البشري، يجب أن يشعر الأشخاص المنفتحون على التجربة بمزيد من الحماس والفضول تجاه الابتكارات المعنية (وهذا ما تعكسه النتائج الأخيرة حول السيارات ذاتية القيادة).

H1 كلما زادت انفتاح الشخص على التجارب، زادت المواقف الإيجابية التي يحملها تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

يمكن وصف الضمير بأنه الميل إلى أن يكون الشخص مجتهدًا وفعالًا وحذرًا، وأن يتصرف بطريقة منضبطة أو حتى مثالية. نظرًا لأنه قد يكون من الصعب على البشر فهم الآليات الداخلية لنظام الذكاء الاصطناعي أو توقع سلوكه، يبدو من المحتمل أن الأشخاص ذوي الضمير سيعبرون عن آراء أكثر سلبية حول الذكاء الاصطناعي، وهو مفهوم تكنولوجي قد يجعل العالم أقل قابلية للفهم بالنسبة لهم.

يمكن وصف الضمير بأنه الميل إلى أن يكون الشخص مجتهدًا وفعالًا وحذرًا، وأن يتصرف بطريقة منضبطة أو حتى مثالية. نظرًا لأنه قد يكون من الصعب على البشر فهم الآليات الداخلية لنظام الذكاء الاصطناعي أو توقع سلوكه، يبدو من المحتمل أن الأشخاص ذوي الضمير سيعبرون عن آراء أكثر سلبية حول الذكاء الاصطناعي، وهو مفهوم تكنولوجي قد يجعل العالم أقل قابلية للفهم بالنسبة لهم.

H2 كلما زادت درجة الوعي الذاتي لدى الشخص، زادت المواقف السلبية التي يحملها تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

الصفة الثالثة من الصفات الخمس الكبرى، الانفتاح، تشمل الميل إلى الانخراط، والتحدث، والاجتماعية؛ ومن ثم، فإنها ترتبط سلبًا بالسلوك القلق والمقيد. استنادًا إلى هذا التعريف، ليس من المستغرب أن الأفراد المنفتحين أبلغوا عن مخاوف أقل بشأن التقنيات المستقلة في الدراسات السابقة.

الصفة الثالثة من الصفات الخمس الكبرى، الانفتاح، تشمل الميل إلى الانخراط، والتحدث، والاجتماعية؛ ومن ثم، فإنها ترتبط سلبًا بالسلوك القلق والمقيد. استنادًا إلى هذا التعريف، ليس من المستغرب أن الأفراد المنفتحين أبلغوا عن مخاوف أقل بشأن التقنيات المستقلة في الدراسات السابقة.

H3 كلما زادت انفتاحية الأشخاص، زادت المواقف الإيجابية التي يحملونها تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

تظهر الوداعة العالية في الميل إلى إظهار سلوك دافئ وتعاوني وطيب القلب. فيما يتعلق بالموضوع المطروح، تشير الأبحاث السابقة إلى أن الوداعة قد تكون مرتبطة (بشكل معتدل) بوجهات نظر إيجابية حول الأتمتة أو أنواع معينة من

تظهر الوداعة العالية في الميل إلى إظهار سلوك دافئ وتعاوني وطيب القلب. فيما يتعلق بالموضوع المطروح، تشير الأبحاث السابقة إلى أن الوداعة قد تكون مرتبطة (بشكل معتدل) بوجهات نظر إيجابية حول الأتمتة أو أنواع معينة من

H4 كلما زادت درجة توافق الشخص، زادت المواقف الإيجابية التي يحملها تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

السمة الأخيرة من سمات الخمسة الكبار، العصابية، مرتبطة بالسلوك الخجول والواعي للذات. الأشخاص الذين يحصلون على درجات عالية في هذه السمة يميلون إلى أن يكونوا أكثر عرضة للضغوط الخارجية ويواجهون صعوبة في التحكم في الدوافع العفوية. ماك دورمان وإنتيزاري

السمة الأخيرة من سمات الخمسة الكبار، العصابية، مرتبطة بالسلوك الخجول والواعي للذات. الأشخاص الذين يحصلون على درجات عالية في هذه السمة يميلون إلى أن يكونوا أكثر عرضة للضغوط الخارجية ويواجهون صعوبة في التحكم في الدوافع العفوية. ماك دورمان وإنتيزاري

H5 كلما زادت درجة العصابية لدى الشخص، زادت المواقف السلبية التي يحملها تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

على الرغم من أن الخمسة الكبار يُعتبرون مجموعة شاملة نسبيًا من سمات الشخصية البشرية، إلا أن الأبحاث قد أسفرت عن عدة مفاهيم أخرى تساعد في فهم الفروق بين الأفراد (وكيف ترتبط هذه الفروق بالمواقف والسلوكيات). ومن المهم، التطرق إلى الجوانب الأكثر سلبية في الطبيعة البشرية، حيث قام بولهاس وويليامز

على الرغم من أن الخمسة الكبار يُعتبرون مجموعة شاملة نسبيًا من سمات الشخصية البشرية، إلا أن الأبحاث قد أسفرت عن عدة مفاهيم أخرى تساعد في فهم الفروق بين الأفراد (وكيف ترتبط هذه الفروق بالمواقف والسلوكيات). ومن المهم، التطرق إلى الجوانب الأكثر سلبية في الطبيعة البشرية، حيث قام بولهاس وويليامز

الميكافيلية هي بُعد شخصي يتضمن صفات متلاعبة، قاسية، وغير أخلاقية. بالنسبة لموضوع بحثنا، تأملنا في فكرتين متعارضتين حول كيفية ارتباط هذه السمة بمواقف الذكاء الاصطناعي. من ناحية، تشير الأدبيات الحديثة إلى أن الأفراد الميكافليين قد يشعرون بقلق أقل بشأن الاستخدامات غير الأخلاقية للذكاء الاصطناعي وبدلاً من ذلك يركزون على قيمته النفعية، مما قد ينعكس في مواقف أكثر إيجابية.

H6 كلما زادت ميول الشخص الميكافيلية، زادت المواقف السلبية التي يحملها تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

الشخص الذي يحصل على درجات عالية في السيكوباتية من المحتمل أن يكون ميالًا لسلوكيات البحث عن الإثارة وقد يشعر فقط بقليل من القلق. على عكس التلاعب المتعمد الذي يتميز به الأشخاص الميكافيلليين، فإن سمة الشخصية السيكوباتية تتضمن ميولًا معادية اجتماعيًا أكثر اندفاعًا. بناءً على ذلك، افترضنا وجود علاقة إيجابية بين السيكوباتية والمواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي – لا سيما بالنظر إلى أن متغيرنا التابع سيتضمن أيضًا ردود فعل الناس العاطفية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتي ينبغي أن تكون أقل خوفًا بين أولئك الذين لديهم درجات عالية في السيكوباتية. افترضنا:

الشخص الذي يحصل على درجات عالية في السيكوباتية من المحتمل أن يكون ميالًا لسلوكيات البحث عن الإثارة وقد يشعر فقط بقليل من القلق. على عكس التلاعب المتعمد الذي يتميز به الأشخاص الميكافيلليين، فإن سمة الشخصية السيكوباتية تتضمن ميولًا معادية اجتماعيًا أكثر اندفاعًا. بناءً على ذلك، افترضنا وجود علاقة إيجابية بين السيكوباتية والمواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي – لا سيما بالنظر إلى أن متغيرنا التابع سيتضمن أيضًا ردود فعل الناس العاطفية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتي ينبغي أن تكون أقل خوفًا بين أولئك الذين لديهم درجات عالية في السيكوباتية. افترضنا:

H7 كلما زادت درجة نفسية الشخص، زادت المواقف الإيجابية التي يحملها تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

بشكل عام، يميل النرجسيون إلى إظهار سلوكيات أنانية وفخورة وغير متعاطفة، وغالبًا ما تكون مصحوبة بمشاعر العظمة والاستحقاق. بينما تشير بعض الأبحاث النوعية إلى أن الحواسيب الذكية قد توجه ضربة شديدة لـ”نرجسيتنا”.

بشكل عام، يميل النرجسيون إلى إظهار سلوكيات أنانية وفخورة وغير متعاطفة، وغالبًا ما تكون مصحوبة بمشاعر العظمة والاستحقاق. بينما تشير بعض الأبحاث النوعية إلى أن الحواسيب الذكية قد توجه ضربة شديدة لـ”نرجسيتنا”.

كلما زاد نرجسية الشخص، زادت المواقف الإيجابية التي يحملها تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

أخيرًا، انتقلنا إلى استكشاف متغير سلوكي على نطاق أصغر بكثير من التجريد، والذي بدا واعدًا لنا من منظور معاصر: عقلية المؤامرة لدى الناس. ترتبط هذه السمة الشخصية ارتباطًا وثيقًا بعدم الثقة العامة في الناس والمؤسسات والأنظمة السياسية بأكملها، وتركز على القابلية لنظريات المؤامرة، أي التفسيرات حول أحداث مشهورة تتحدى المنطق السليم أو الحقائق المقدمة علنًا.

أخيرًا، انتقلنا إلى استكشاف متغير سلوكي على نطاق أصغر بكثير من التجريد، والذي بدا واعدًا لنا من منظور معاصر: عقلية المؤامرة لدى الناس. ترتبط هذه السمة الشخصية ارتباطًا وثيقًا بعدم الثقة العامة في الناس والمؤسسات والأنظمة السياسية بأكملها، وتركز على القابلية لنظريات المؤامرة، أي التفسيرات حول أحداث مشهورة تتحدى المنطق السليم أو الحقائق المقدمة علنًا.

على الرغم من أنهم قد لا يكونون معروفين تمامًا مثل نظريات المؤامرة البارزة الأخرى (مثل، المتعلقة بـ

H9 كلما زادت درجة عقلية المؤامرة لدى الشخص، زادت المواقف السلبية التي يحملها تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

ختامًا للتحضير النظري لدراستنا، وضعنا فرضيات حول متغيرين ديموغرافيين أساسيين تم ربطهما سابقًا بالمواقف المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي في المنشورات العلمية. على وجه التحديد، وُجد أن النساء عمومًا يحملن مواقف أكثر سلبية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي مقارنة بالرجال، وهو ما يمكن تفسيره، من بين أسباب أخرى، بالحواجز الاجتماعية التي تحد من وصول النساء إلى (واهتمامهن بـ) المجالات التقنية.

ختامًا للتحضير النظري لدراستنا، وضعنا فرضيات حول متغيرين ديموغرافيين أساسيين تم ربطهما سابقًا بالمواقف المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي في المنشورات العلمية. على وجه التحديد، وُجد أن النساء عمومًا يحملن مواقف أكثر سلبية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي مقارنة بالرجال، وهو ما يمكن تفسيره، من بين أسباب أخرى، بالحواجز الاجتماعية التي تحد من وصول النساء إلى (واهتمامهن بـ) المجالات التقنية.

تمتلك النساء في H10 مواقف أكثر سلبية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي مقارنة بالرجال.

H11 الأفراد الأكبر سناً يحملون مواقف أكثر سلبية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي مقارنة بالأفراد الأصغر سناً.

H11 الأفراد الأكبر سناً يحملون مواقف أكثر سلبية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي مقارنة بالأفراد الأصغر سناً.

الدراسة 1

الهدف الأساسي من الدراسة 1 كان تطوير مقياس نفسي موثوق يكون (أ) أحادي البعد، (ب) يتضمن عناصر تعكس الأسس الثلاثة أو الجوانب للمواقف (المعرفية، العاطفية، السلوكية) التي وجهت أبحاث المواقف في علم النفس على مدى العقود الماضية.

في الخطوة الثانية، ناقش المؤلفون العناصر، واستبعدوا العناصر التي كانت غامضة في المحتوى، أو محددة جدًا من حيث هدف الموقف، أو تضمنت تداخلًا لغويًا كبيرًا مع عناصر أخرى. كانت المقياس المتبقي يتكون من اثني عشر عنصرًا، حيث تم تمثيل كل من الجوانب النفسية الثلاثة لمواقف البشر – المعرفية، والعاطفية، والسلوكية – بواسطة عنصرين إيجابيين وعنصرين سلبيين. ومع ذلك، كان من المتوقع أن تمثل جميع العناصر الاثني عشر عاملًا عامًا واحدًا: موقف الناس تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. يمكن العثور على المقياس الكامل (ATTARI-12) في الملحق.

للحصول على رؤى حول صلاحية مقياسنا الجديد، شملت الدراسة 1 أيضًا عناصر تتعلق بتطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي الأكثر تحديدًا. كنا نتوقع أن تكون المواقف العامة تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي كما تم قياسها بواسطة ATTARI-12 مرتبطة بشكل إيجابي بالمواقف المحددة تجاه المساعدين الشخصيين الإلكترونيين (مثل أليكسا) والمواقف تجاه الروبوتات. علاوة على ذلك، قمنا بتقييم ميل المشاركين لتقديم إجابات مرغوبة اجتماعيًا لتحديد ما إذا كان أداتنا الجديدة ستتأثر بتحيز الرغبة الاجتماعية. استنادًا إلى صياغتنا الدقيقة أثناء بناء المقياس، توقعنا أن تكون مواقف الناس تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي (وفقًا لـ ATTARI-12) غير مرتبطة بشكل كبير بالرغبة الاجتماعية. تم تسجيل الفرضيات وخطوات تحليل البيانات المخطط لها للدراسة 1 مسبقًا على https://aspredicted.org/8B5_GHZ (انظر أيضًا الملحق S1).

طريقة

بيان الأخلاقيات

في ألمانيا، لا يتطلب البحث النفسي موافقة أخلاقية مؤسسية طالما أنه لا يتضمن قضايا منظمة بموجب القانون.

المشاركون والإجراء

تحليلات القوة باستخدام semPower (الإصدار 2.0.1)

وفقًا لمعايير الاستبعاد المسجلة مسبقًا (أي، وقت الإكمال، الفشل في اجتياز واحد على الأقل من اختبارين للانتباه)، تم استبعاد 111 مشاركًا من تحليلاتنا. بشكل أكثر تحديدًا، أكمل 31 مشاركًا الاستبيان في أقل من

تدابير

المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. قمنا بتطبيق مقياس ATTARI-12 الذي تم إنشاؤه حديثًا، باستخدام تنسيق إجابة من خمسة نقاط لالتقاط ردود المشاركين.

المواقف تجاه المساعدين الصوتيين الشخصيين (PVA). أشار المشاركون إلى مواقفهم تجاه المساعدين الصوتيين الشخصيين من خلال ثلاثة عناصر تمييز دلالي (مع خمس نقاط تدرج) تم إنشاؤها لغرض هذه الدراسة (على سبيل المثال، “أكرهه – أحبه”؛ كرونباخ’s

المواقف تجاه الروبوتات. تم قياس التقييم العام للناس تجاه الروبوتات باستخدام ثلاثة عناصر تم استخدامها سابقًا في أبحاث قبول الروبوتات.

الرغبة الاجتماعية. تم قياس ميل المشاركين لتقديم إجابات مرغوبة اجتماعيًا باستخدام مقياس الرغبة الاجتماعية.

النتائج

تم توجيه تحليلنا لصلاحية العوامل من خلال الافتراض بأن العناصر تمثل بناءً واحدًا: موقف الناس تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. ولهذا الغرض، قمنا بمقارنة نماذج مختلفة، تتسم بتقييد أقل بشكل متزايد، في تحليل العوامل التأكيدي: النموذج الأول (أ) حدد عاملاً واحدًا، وبالتالي افترض أن الفروق الفردية في استجابات العناصر يمكن تفسيرها من خلال بناء موقف عام واحد. ومع ذلك، فإن هذا الافتراض غالبًا ما يكون قويًا جدًا في الممارسة العملية لأن جوانب المحتوى المحددة أو صياغة العناصر قد تؤدي إلى تعددية أبعاد طفيفة. لذلك، قام النموذج (ب) بتقدير هيكل ثنائي العوامل S-1 الذي، بالإضافة إلى العامل العام، شمل عاملين محددين متعامدين للعناصر المعرفية أو العاطفية. هذه العوامل المحددة التقطت التباين الفريد الناتج عن مجالي المحتوى الاثنين اللذين لم يتم حسابهما بواسطة عامل الموقف العام. وفقًا لما ذكره عيد وزملاؤه.

تم تلخيص جودة ملاءمة هذه النماذج في الجدول 2. باستخدام التوصيات المعتمدة لتفسير هذه المؤشرات.

|

|

|

CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | إيه آي سي | بيك | تعويض |

|

|

|

||

| (أ) | نموذج العامل الواحد | 434.77 | ٥٤ | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.08 | ١٤,٥٦٤ | ١٤٬٦٦٤ | ||||

| نماذج Bifactor S-1 مع عامل عالمي واحد وعوامل محددة متعامدة لـ … | ||||||||||||

| (ب) | جوانب المحتوى | 327.39 | ٤٦ | 0.89 | 0.14 | 0.07 | ١٤,٤١٢ | 1456 | (أ) | ١٠٢.٩٥ | ٨ | <0.001 |

| (ج) | نص العنصر | ١٠٩.٦٤ | ٤٨ | 0.98 | 0.06 | 0.03 | ١٤٠٨٦ | ١٤٢١٢ | (أ) | ٢٦٨.٣٥ | ٦ | <0.001 |

| (د) | جوانب المحتوى وصياغة العناصر | 93.91 | 40 | 0.98 | 0.06 | 0.03 | ١٤٠٧٦ | ١٤٢٣٦ | (ب) | 191.45 | ٦ | <0.001 |

| (ج) | ١٦.٠٧ | ٨ | 0.041 | |||||||||

الجدول 2. جودة الملاءمة لنماذج العوامل التأكيدية المتنافسة لـ ATTARI-12 (الدراسة 1؛ المشاركون في لوحة MTurk الأمريكية).

| عنصر | تحميل على العامل العام | تحميل على عامل محدد | التباين المتبقي |

| 1 | 0.79 (0.04)/0.84 | 0.26 | |

| 2 | 0.66 (0.05) /0.59 | 0.61 (0.06) /0.54 | 0.46 |

| ٣ | 0.81 (0.04) /0.77 | 0.45 | |

| ٤ | 0.66 (0.05) /0.57 | 0.54 (0.06) /0.48 | 0.58 |

| ٥ | 0.91 (0.04) /0.87 | 0.27 | |

| ٦ | 0.64 (0.05) /0.65 | 0.55 | |

| ٧ | 0.77 (0.05) /0.64 | 0.56 (0.06) /0.46 | 0.56 |

| ٨ | 0.55 (0.05) /0.48 | 0.52 (0.06) /0.45 | 0.75 |

| 9 | 0.71 (0.05) / 0.65 | 0.69 | |

| 10 | 0.67 (0.05) / 0.59 | 0.70 (0.06) / 0.61 | 0.37 |

| 11 | 0.95 (0.04) / 0.88 | 0.27 | |

| 12 | 0.84 (0.05) / 0.69 | 0.59 (0.06) / 0.48 | 0.43 |

الجدول 3. نمط تحميل العوامل لـ ATTARI-12 (الدراسة 1؛ المشاركون في لوحة MTurk الأمريكية). تم تقديم تحميلات العوامل غير المعيارية (مع الأخطاء المعيارية بين قوسين) / تحميلات العوامل المعيارية والتباينات المتبقية. تم تحديد العوامل الكامنة عن طريق تقييد تباينات العوامل الكامنة إلى 1.

عامل أو عامل الصياغة المحددة (انظر

تظهر النتائج الوصفية والارتباطية على المقياس المركب لـ ATTARI-12 في الجدول 4. كانت موثوقية المقياس من حيث الاتساق الداخلي ممتازة، حيث كانت قيمة كرونباخ

باختصار، قاس مقياس ATTARI-12 أحادية البعد المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي بطريقة موثوقة، وتؤكد مؤشرات الصلاحية البنائية المتقاربة (المواقف تجاه تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي المحددة) والمتباينة (الرغبة الاجتماعية) صلاحية المقياس.

| 1 | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | |||||||

| كرونباخ

|

M |

|

انحراف | كورت | |||||||

| 1 | أتاري-12 | 0.93 | 3.66 | 0.83 | -0.63 | 0.22 | – | ||||

| ٢ | الرغبة الاجتماعية | 0.85 | 8.74 | ٤.٢٤ | -0.25 | -0.87 | 0.037 | – | |||

| ٣ | الموقف تجاه PVAs | 0.94 | 3.72 | 1.09 | -0.81 | 0.02 | 0.599*** | 0.125** | – | ||

| ٤ | الموقف تجاه الروبوتات | 0.77 | 3.24 | 0.57 | -0.75 | 0.81 | 0.676*** | -0.021 | 0.435*** | ||

| ٥ | عمر | ٣٩.٧٨ | 11.06 | 0.81 | -0.08 | – 0.039 | 0.090* | -0.023 | -0.036 | ||

| ٦ | جنس | -0.087 | 0.042 | 0.099* | -0.058 |

|

|||||

الجدول 4. الإحصائيات الوصفية والارتباطات من الدرجة صفر (الدراسة 1؛ المشاركون في لوحة MTurk الأمريكية).

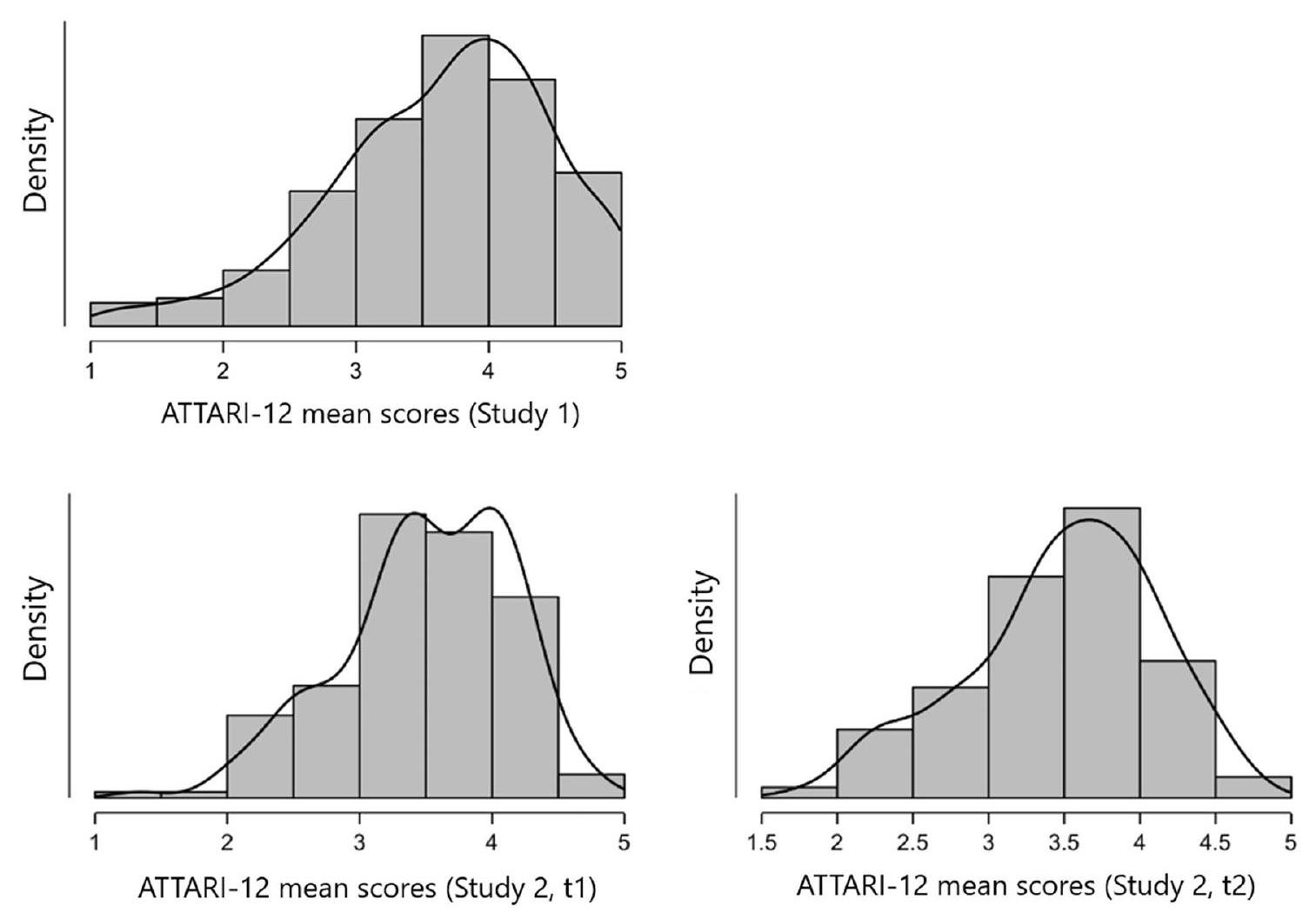

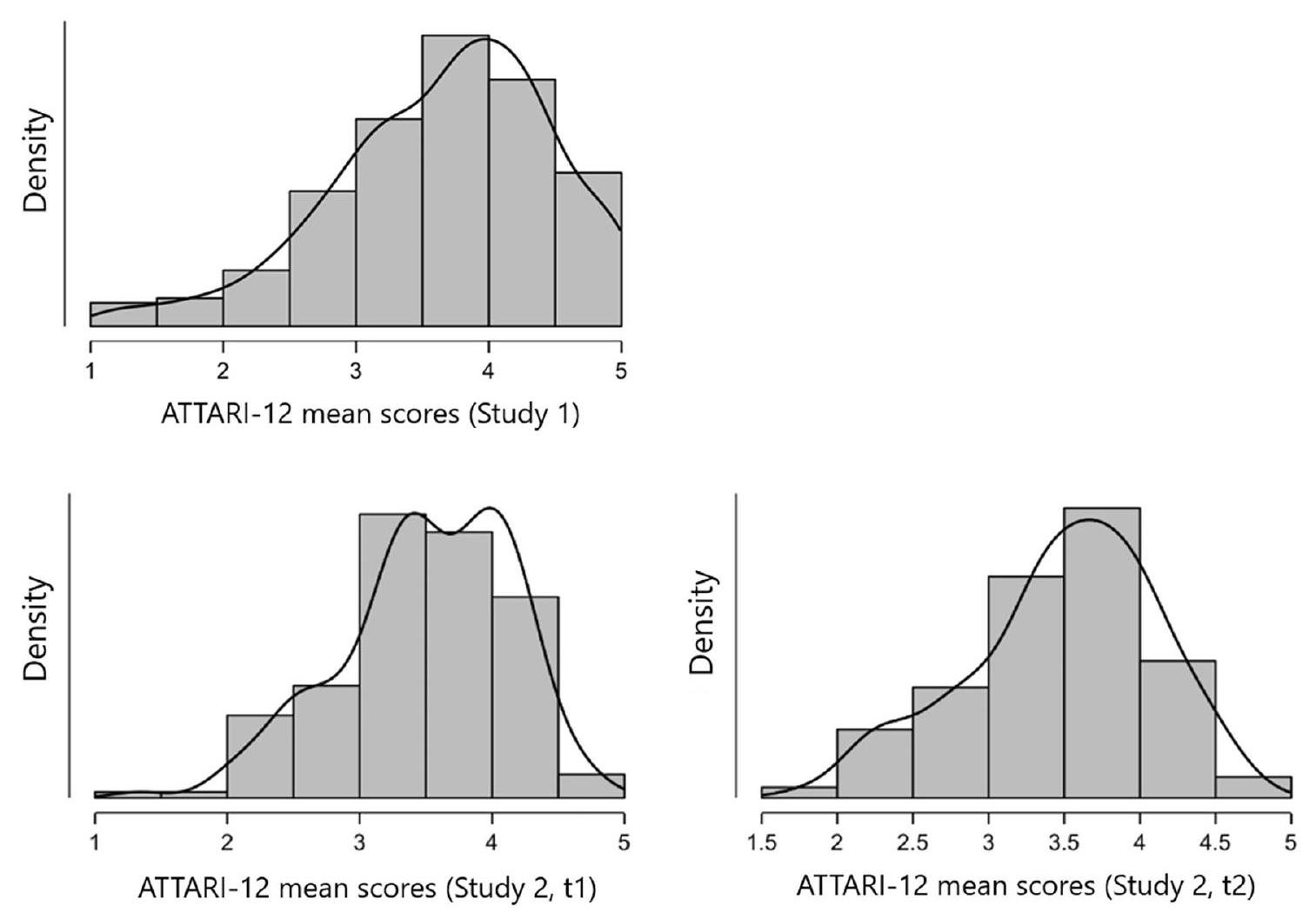

الشكل 1. توزيعات نتائج ATTARI-12 في الدراسة 1 والدراسة 2 (في الوقت 1 والوقت 2).

الدراسة 2

كان هدف الدراسة الثانية هو تطوير نسخة باللغة الألمانية من المقياس والحصول على مزيد من الفهم حول موثوقية المقياس وصحته. على وجه الخصوص، قمنا بفحص موثوقية إعادة الاختبار للمقياس، من خلال تقديم العناصر في نقطتين زمنيتين. كما قمنا بتقييم مدى رغبة المشاركين (طلاب الجامعات) في العمل مع (أو بدون) الذكاء الاصطناعي في مسيراتهم المهنية المستقبلية. كنا نتوقع وجود ارتباط إيجابي بين المتغير الأخير والمواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

طريقة

تكونت هذه الدراسة من جزئين، تم إجراؤهما عبر الإنترنت بمتوسط تأخير قدره 31.40 يومًا.

في الوقت 1، أجاب المشاركون على اختبار ATTARI-12، بالإضافة إلى أربعة عناصر قيست اهتمامهم بمهنة تتعلق بتكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي (كان هناك عنصران مشفران عكسيًا، مثل: “أفضل وظيفة لا يلعب فيها الذكاء الاصطناعي أي دور”). كانت العناصر تتضمن مقياسًا من 5 نقاط.

النتائج

تظهر النتائج الرئيسية في الجدول 5. كانت موثوقية النسخة الألمانية المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة من حيث الاتساق الداخلي جيدة جداً، معامل كرونباخ T1

الدراسة 3

بعد أن وجدنا دعمًا تجريبيًا لصحة مقياسنا الجديد، تابعنا هدفنا البحثي الرئيسي الثاني: استكشاف العلاقات المحتملة بين سمات الشخصية والمواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. لضمان الشفافية، قررنا تسجيل الدراسة 3 مسبقًا قبل جمع البيانات، بما في ذلك جميع الفرضيات والتحليلات المخطط لها.https://aspredicted.org/VRU_BJI).

طريقة

المشاركون

حساب مسبق لحجم العينة الأدنى بواسطة

| أتاري-12 T1 | أتاري-12 T2 | ||||||

| كرونباخ

|

M | SD | انحراف | كورت | |||

| أتاري-12 تي 1 | 0.90 | 3.51 | 0.64 | – 0.58 | 0.07 | – | |

| أATTARI-12 T2 | 0.89 | 3.49 | 0.63 | -0.48 | -0.24 | 0.804 | – |

| المهنة-الذكاء الاصطناعي T1 | 0.85 | 3.11 | 0.92 | -0.08 | -0.78 | 0.635 | 0.563 |

الجدول 5. الوصفيات والارتباطات من الدرجة صفر (الدراسة 2؛ طلاب الجامعات الألمان).

عند فحص البيانات المجمعة، تم اتخاذ عدة تدابير لاستبعاد عمال MTurk الذين تشير إجاباتهم إلى الاستجابة غير المبالية وغير المنتبهة. أولاً، طلبنا من جميع المشاركين تحديد أعمارهم وسنة ميلادهم في صفحتين منفصلتين من الاستبيان؛ إذا انحرفت هذه الإجابات بأكثر من عامين عن بعضها البعض، تم استبعاد المشارك.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، اعتبرنا في البداية استبعاد جميع المشاركين الذين ملأوا الاستبيان في أقل من أربع دقائق، وهو الحد الأدنى الذي قمنا بقياسه كوقت أدنى للاستجابة بانتباه. عند النظر إلى البيانات التي حصلنا عليها، كان من الممكن أن يؤدي ذلك إلى استبعاد 81 مشاركًا إضافيًا. ومع ذلك، حيث لاحظنا أن العديد من عمال MTurk قد أنهوا الاستبيان في أقل من أربع دقائق بقليل، قررنا تخفيف معيار الاستبعاد الأولي لدينا إلى مدة أدنى قدرها ثلاث دقائق، مما أدى إلى استبعاد

لذا، في الملخص، كانت عيّنتنا النهائية تتكون من 298 مشاركًا بمتوسط عمر 39.29 سنة.

إجراءات

تم تقديم جميع عناصر التدابير التالية على مقياس من 5 نقاط (

المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. لقياس المتغير الناتج الرئيسي، قمنا بتطبيق مقياس ATTARI-12 بنسخته الإنجليزية. أظهرت تحليل بياناتنا أن المقياس مرة أخرى حقق اتساقًا داخليًا ممتازًا في هذه المرة (ألفا كرونباخ

المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. لقياس المتغير الناتج الرئيسي، قمنا بتطبيق مقياس ATTARI-12 بنسخته الإنجليزية. أظهرت تحليل بياناتنا أن المقياس مرة أخرى حقق اتساقًا داخليًا ممتازًا في هذه المرة (ألفا كرونباخ

الخمس الكبار. تم تقييم الخمس الكبار باستخدام استبيان الخمس الكبار.

الثالوث المظلم

قمنا بتقييم سمات الشخصية الثلاثية المظلمة لدى المشاركين باستخدام مقياس الثلاثية المظلمة القصير (SD3).

عقلية المؤامرة

استبيان عقلية المؤامرة

النتائج

الجدول 6 يلخص المعلومات الوصفية والارتباطات من الدرجة صفر بين جميع متغيرات الدراسة. في المتوسط، كانت مواقف المشاركين المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي إيجابية قليلاً،

مع تحديد تحليل البيانات الرئيسي لدينا ليشمل الانحدار المتعدد، تأكدنا أولاً من تلبية جميع الافتراضات اللازمة.

| متغير | M | SD | 1 | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| 1 | عمر | ٣٩.٢٩ | 11.08 | – | |||||||||||

| 2 | جنس

|

-0.23*** | – | ||||||||||||

| ٣ | أتاري-12 | 3.60 | 0.81 | -0.12* | 0.04 | – | |||||||||

| ٤ | الانفتاح على التجربة | ٣.٥٦ | 0.74 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.14* | – | ||||||||

| ٥ | الضمير الحي | 3.97 | 0.72 | 0.25*** | – 0.12* | 0.08 |

|

– | |||||||

| ٦ | الانفتاح | 2.77 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.27*** | 0.25*** | – | ||||||

| ٧ | الود | 3.77 | 0.73 |

|

-0.15** | 0.22*** |

|

|

0.16** | – | |||||

| ٨ | العصابية | ٢.٦٤ | 1.01 | -0.13* | -0.10 | -0.07 | -0.14* | -0.60*** | -0.44

|

-0.53*** | – | ||||

| 9 | المكيافيلية | 2.88 | 0.81 | -0.19** | 0.17** | -0.11 | -0.05 | -0.25*** | 0.07 | -0.50*** | 0.25*** | – | |||

| 10 | علم النفس المرضي | ٢.١٩ | 0.77 | -0.25*** |

|

-0.12* | -0.02 | -0.36*** |

|

-0.50*** | 0.14* |

|

– | ||

| 11 | النرجسية | ٢.٥٠ | 0.74 | -0.15** |

|

-0.06 | 0.23** | -0.03 |

|

-0.18** | -0.16** |

|

0.62*** | – | |

| 12 | عقلية المؤامرة | 3.36 | 0.94 | -0.08 | -0.06 |

|

0.06 | -0.07 | 0.07 |

|

0.15* |

|

|

|

– |

الجدول 6. الإحصائيات الوصفية والارتباطات لمتغيرات الدراسة (الدراسة 3؛ المشاركون في لوحة MTurk الأمريكية).

ملاحظة.

| الخطوة 1 | الخطوة 2 | الخطوة 3 | الخطوة 4 | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| عمر | – 0.12 | -1.96 | – 0.15* | -2.52 | -0.16** | – 2.68 | – 0.17** | -2.86 |

| جنس

|

0.01 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.07 | 1.15 | 0.04 | 0.68 |

| الانفتاح على التجربة | 0.09 | 1.53 | 0.10 | 1.67 | 0.11 | 1.85 | ||

| الضمير الحي | – 0.01 | 0.09 | -0.03 | -0.35 | -0.01 | -0.15 | ||

| الانفتاح | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.85 | ||

| الود |

|

3.95 | 0.25** | 3.12 |

|

3.34 | ||

| العصابية | 0.08 | 1.01 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 1.24 | ||

| المكيافيلية | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 1.08 | ||||

| علم النفس المرضي | -0.06 | -0.64 | -0.05 | -0.49 | ||||

| النرجسية | -0.09 | – 1.02 | -0.05 | -0.60 | ||||

| عقلية المؤامرة | -0.22*** | -3.68 | ||||||

|

|

0.02 | (0.08***) | (0.01) | (0.04***) | ||||

الجدول 7. الانحدار الهرمي الذي يتنبأ بمواقف المشاركين تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي (الدراسة 3).

خمسة) أسفر عن نتيجة مهمة،

القيمة التنبؤية للخمس الكبار

استجابةً للفرضيات H1 إلى H5، وجهنا انتباهنا أولاً إلى أبعاد الشخصية الخمسة الكبرى. استنادًا إلى الخطوة الثانية من الانحدار، التي كانت مصممة لتضمين هذه المتغيرات، وُجد أن التوافق فقط هو الذي تنبأ بشكل كبير بمواقف المشاركين تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

القيمة التنبؤية للثالوث المظلم

بالانتقال إلى السمات الشخصية المظلمة مثل الميكافيلية، والاعتلال النفسي، والنرجسية (كما تم إدخاله خلال الخطوة 3)، نلاحظ أن أيًا من المتنبئين الثلاثة لم يقترب من العتبة التقليدية للدلالة الإحصائية. وبالتالي، لا يمكننا قبول الفرضيات H6 إلى H8؛ وفقًا لبياناتنا، لم تكن السمات الشخصية الأكثر شرًا تنبؤية بمواقف الناس العامة تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

القيمة التنبؤية لعقلية المؤامرة

في ختام تحقيقنا في التأثيرات الشخصية، ركزنا على عقلية المؤامرة لدى المشاركين كما أضيفت خلال الخطوة النهائية من الانحدار. وجدنا أن هذه المتغيرات ظهرت كمتنبئ ذو دلالة أخرى،

القيمة التنبؤية للعمر والجنس

أخيرًا، تم استكشاف تأثير عمر المشاركين وجنسهم على مواقفهم تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. لهذا الغرض، ركزنا على نموذج الانحدار النهائي لدينا مع جميع المتنبئين المدخلين في المعادلة. بينما ظل تأثير الجنس غير ذي دلالة، تم فحص أن العمر الأعلى كان مرتبطًا بشكل كبير بتدني الدرجات في مقياس ATTARI-12، أي، بمزيد من الإدراكات، والمشاعر، والنوايا السلوكية السلبية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي (

نقاش عام

في عالم تشكله التقنيات المستقلة التي من المفترض أن تجعل الحياة البشرية أكثر أمانًا وصحة وراحة، من المهم فهم كيف يقيم الناس مفهوم التكنولوجيا الذكية الاصطناعية – وتحديد العوامل التي تفسر التباين الملحوظ بين الأفراد في هذا الصدد. وبالتالي، بدأ المشروع الحالي لاستكشاف دور السمات الشخصية الأساسية كمتنبئين بمواقف الناس المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. من أجل بناء بحثنا على قياس صالح وموثوق للنتيجة المعنية، قمنا أولاً بتطوير استبيان جديد – ATTARI-12 – وأكدنا جودته النفسية عبر دراستين. مميزين أداتنا عن البدائل الموجودة، نلاحظ أن مقياسنا أحادي البعد يقيم المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي على طيف كامل بين النفور والحماس. علاوة على ذلك، تتضمن عناصر ATTARI-12 الثالوث الكلاسيكي للموقف البشري (الإدراك، العاطفة، السلوك)، وبالتالي تظهر كطريقة مفهومية سليمة لقياس تقييم الناس للذكاء الاصطناعي. أخيرًا، نظرًا لأن تعليمات ATTARI-12 لا تركز على حالات استخدام محددة بل على فهم أوسع للذكاء الاصطناعي كمجموعة من القدرات التكنولوجية، نعتقد أنه قد يكون مناسبًا للاستخدام عبر العديد من التخصصات والإعدادات البحثية المختلفة.

باستخدام قياسنا الجديد المطور، انتقلنا إلى هدف بحثنا الثاني: التحقيق في الروابط المحتملة بين مواقف الأفراد المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي وسماتهم الشخصية. بشكل محدد، ركزنا على تصنيفين مركزيين من مجال علم نفس الشخصية (الخمسة الكبار، الثلاثي المظلم)، بالإضافة إلى عقلية المؤامرة كصفة ذات صلة معاصرة عالية. من خلال هذه الوسائل، وجدنا تأثيرات كبيرة لاثنين من المتنبئين الشخصيين المستكشفين: كانت الصداقة (واحدة من سمات الخمسة الكبار) مرتبطة بشكل كبير بمواقف أكثر إيجابية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي، بينما تنبأت عقلية المؤامرة الأقوى بالعكس. نعتقد أن كلا من هذين الاكتشافين قد يقدمان دلالات مثيرة للباحثين والمطورين ومستخدمي التكنولوجيا المستقلة.

بعد شخصية عادة ما تترافق مع نظرة متفائلة للحياة

يمكن تقديم حجة مشابهة بشكل مدهش عند تناول العامل الشخصي الثاني الذي حقق دلالة ملحوظة في تحليلاتنا، أي، عقلية المؤامرة لدى الناس. حسب التعريف، هذه الصفة الشخصية مرتبطة أيضًا بإدراكات الثقة (أو بالأحرى، نقصها)، وهو مفهوم يتردد صداه في نتائجنا: كلما عبر المشاركون عن شكوكهم بشأن الحكومات، والمنظمات، والتغطية الإخبارية ذات الصلة (كما تشير إليه عناصر مثل “أعتقد أن العديد من الأمور المهمة جدًا تحدث في العالم، والتي لا يتم إبلاغ الجمهور عنها أبدًا”)، كلما كانت مواقفهم تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي أكثر سلبية. في قراءتنا، يوضح هذا كيف تؤثر الشفافية والموثوقية المدركة بشكل حاسم على قبول الجمهور للذكاء الاصطناعي؛ تمامًا كما أن وجود شخصية ودودة وسهلة التصديق تنبأت بمواقف أكثر إيجابية، فإن الميل للاشتباه في قوى شريرة على الساحة العالمية مرتبط بوجهات نظر أكثر سلبية حول التكنولوجيا المستقلة.

على المستوى المجتمعي، نعتقد أن تحديدنا لمعتقدات المؤامرة كعقبة أمام مواقف الذكاء الاصطناعي هو نتيجة في الوقت المناسب بشكل خاص، حيث يرتبط بالنقاش المستمر حول الأخبار الزائفة في المجتمع الحديث. في السنوات القليلة الماضية، بدأ العديد من الناس في التوجه إلى وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي كمصدر للأخبار والتعليم، مما مهد الطريق لانتشار غير عادي للمعلومات المضللة

قد تتزايد بسهولة في المجال الرقمي. من المؤكد أن الادعاء الملحوظ في وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي بأن لقاحات COVID-19 حقن سرًا تكنولوجيا النانو الذكية الاصطناعية في المرضى غير الراغبين

قد تتزايد بسهولة في المجال الرقمي. من المؤكد أن الادعاء الملحوظ في وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي بأن لقاحات COVID-19 حقن سرًا تكنولوجيا النانو الذكية الاصطناعية في المرضى غير الراغبين

استنادًا إلى الحجج المقدمة، من المنطقي أن يعتمد النجاح في اعتماد التقنيات الذكية على نطاق واسع أيضًا على ما إذا كان يمكن دحض النظريات ما بعد الحقيقة حول الذكاء الاصطناعي علنًا. لتحقيق ذلك، قد يكون من الضروري زيادة ثقة الجمهور، ليس فقط في مفهوم الذكاء الاصطناعي نفسه، ولكن أيضًا في المنظمات والأنظمة التي تستخدمه. على سبيل المثال، قد يسعى المطورون إلى تعليم المستخدمين حول قدرات وحدود التقنيات المستقلة بطريقة مفهومة، بينما قد تسعى الشركات إلى وضع سياسات وإفصاحات أكثر سهولة. في الوقت نفسه، نلاحظ أن التغلب على المخاوف والشكوك المتأصلة حول الذكاء الاصطناعي سيظل على الأرجح تحديًا كبيرًا في المستقبل؛ ونتوقع أن تستمر التعقيدات والتطورات الكبيرة في الحواسيب الذكية في توفير أرض خصبة لنظريات المؤامرة. كما لا يمكن استبعاد أن المحاولات لجعل الذكاء الاصطناعي أكثر شفافية في المستقبل قد تؤدي أيضًا إلى نتائج عكسية، حيث قد يفسر منظرو المؤامرة هذه المحاولات كدليل فعلي على وجود مؤامرة في المقام الأول. علاوة على ذلك، فإن حقيقة أن الأفلام والبرامج التلفزيونية الشعبية تقدم غالبًا التكنولوجيا المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي بطريقة خطيرة أو مخيفة (على سبيل المثال، في وسائل الإعلام الخيالية الديستوبية

بعيدًا عن الدلالات المثيرة التي تقدمها مؤشرات الشخصية الهامة، أظهرت عدة سمات أخرى تم فحصها عدم وجود ارتباط كبير بمواقف المشاركين تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. على وجه التحديد، وجدنا أن ثلاثة من الخمسة الكبار (الضمير الحي، الانفتاح، والعصابية) وجميع متغيرات الثالوث المظلم لم تكن كافية لشرح التباين الملحوظ في درجات ATTARI-12 التي تم الحصول عليها. مع الأخذ في الاعتبار النتائج المذكورة أعلاه، يشير هذا إلى أن شخصية المستخدم قد تكون لها إمكانيات قيمة ولكن محدودة لشرح قبول الجمهور لتكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي. بطبيعتها كسمات شاملة على مستوى ميتا، قد تكون بعض أبعاد الخمسة الكبار مجردة جدًا للتعامل مع الفروق الدقيقة التي تميز تجارب الناس مع – ومواقفهم تجاه – تكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي. على سبيل المثال، قد ينطوي كون الشخص أكثر انفتاحًا على جوانب تزيد من قبول الذكاء الاصطناعي (مثل كونه أقل قلقًا وتقييدًا بشكل عام) وتقلل منه (مثل تقدير الاتصال الاجتماعي الحقيقي مع البشر الآخرين، والذي قد يتعرض للتحدي من قبل تكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي الجديدة). وبالمثل، قد تكون السمات الشخصية الأكثر انحرافًا المدرجة في الثالوث المظلم مرتبطة برؤى إيجابية وسلبية تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي، مما يمنع التنبؤ الكبير في اتجاه معين. تمامًا كما يمكن رؤية العديد من الإمكانيات التي تقدمها التكنولوجيا الذكية الجديدة كأدوات مفيدة للتلاعب أو تعزيز الذات، مما يشير إلى ارتباط إيجابي بالمكيافيلية والنرجسية – قد تثير أيضًا مخاوف بين الأشخاص الذين يحصلون على درجات عالية في هذه السمات، حيث قد تجعل الذكاء الاصطناعي من الصعب التصرف بدوافع خبيثة بطريقة غير مكتشفة أو مقبولة جيدًا.

القيود والاتجاهات المستقبلية

نود أن نشير إلى القيود المهمة التي يجب أخذها بعين الاعتبار عند تفسير النتائج المقدمة لمشروعنا، وخاصة الدراسة الثالثة والأخيرة التي كانت تهدف إلى معالجة فرضياتنا الرئيسية. على الرغم من أننا قمنا بتجنيد عينة متنوعة نسبيًا من حيث العمر والجنس والخلفية الاجتماعية والاقتصادية – وطبقنا عدة تدابير لضمان جودة البيانات العالية – فإن بياناتنا حول العلاقة بين مواقف الذكاء الاصطناعي وشخصية المستخدم تستند إلى مجموعة واحدة فقط من المشاركين. علاوة على ذلك، نظرًا لأن عينة دراستنا الثالثة تم تجنيدها بنفس الطريقة المستخدمة في الدراسة الأولى (MTurk)، لا يمكننا استبعاد أن بعض المشاركين قد شاركوا في كلا الجهدين البحثيين (على الرغم من أنه، استنادًا إلى مجموعة المشاركين الكبيرة جدًا في اللوحة المختارة، نعتبر أنه من غير المحتمل للغاية حدوث استجابات مكررة). وبالتالي، يُشجع على جهود التكرار مع عينات مختلفة من أجل تعزيز الأدلة المستخلصة. ولا سيما، يتعلق هذا بتجنيد عينات ذات توزيع جنسي أكثر توازنًا، حيث أسفرت عملية تجنيدنا عن أغلبية ملحوظة من المشاركين الذكور. أيضًا، بالنظر إلى أن العوامل الاجتماعية والاقتصادية والتعليمية تؤثر بشكل ملحوظ على آراء الناس تجاه التكنولوجيا (لا سيما فيما يتعلق بالذكاء الاصطناعي؛ انظر

على هذا النحو، نقترح إجراء دراسات مع عينات من ثقافات مختلفة من أجل تحديد ما إذا كانت نتائجنا متسقة عبر الحدود الوطنية. مؤخرًا، أبلغت دراسة تركزت على عينة من المشاركين الكوريين الجنوبيين أيضًا عن ارتباطات إيجابية بين المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي وأبعاد الخمسة الكبرى من الشخصية، خاصة فيما يتعلق بالاجتماعية ووظائف الأنظمة المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي.

السعي، أو الخوف من الفقدان، يمكن أن يكون مفيدًا أيضًا للحصول على فهم شامل للاختلافات بين الأفراد فيما يتعلق بمواقف الناس تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

السعي، أو الخوف من الفقدان، يمكن أن يكون مفيدًا أيضًا للحصول على فهم شامل للاختلافات بين الأفراد فيما يتعلق بمواقف الناس تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يجب الإشارة إلى أن الأبحاث المستقبلية في هذا الموضوع يمكن أن تستفيد بوضوح من تقييم الجوانب السياقية والدافعية التي تؤثر على آراء المشاركين حول الذكاء الاصطناعي بخلاف خصائص شخصياتهم. على سبيل المثال، تشير الأبحاث الحديثة إلى أن الآراء حول التكنولوجيا المتطورة تتأثر بشكل كبير بالتعرض السابق لوسائط الخيال العلمي.

الخاتمة

في مشروعنا، بحثنا في المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي كمقياس مركب لأفكار الناس ومشاعرهم ونواياهم السلوكية. سعيًا لتكملة الأبحاث السابقة التي ركزت أكثر على قبول تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي المتخصصة، أنشأنا واستخدمنا مقياسًا جديدًا أحادي البعد: ATTARI-12. نحن واثقون من أن المقياس المطور قد يكون الآن أداة مفيدة للتعامل عمليًا مع الذكاء الاصطناعي كظاهرة على مستوى ماكرو، والتي – على الرغم من احتوائها على مجموعة من البرامج والتطبيقات المختلفة – تتحد من خلال عدة أسس مشتركة. في توقعنا، يمكن أن يتم تطبيق المقياس الذي تم إنشاؤه حتى عند ظهور تقنيات ذكاء اصطناعي جديدة وغير متوقعة، حيث يركز أكثر على المبادئ الأساسية بدلاً من القدرات المحددة. بالنسبة للممارسين والمطورين، قد تكون هذه النظرة مفيدة بشكل خاص، مما يشير إلى أن استجابة الأفراد لتقنية الذكاء الاصطناعي الجديدة (مثل العملاء أو الموظفين) لن تكون مدفوعة فقط بالميزات المحددة لتقنية معينة، ولكن أيضًا بموقف عام تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. وبالمثل، نأمل أن تتمكن الجهود السوسيوديموغرافية واسعة النطاق (مثل استبيانات الرأي الوطنية) من الاستفادة من المقياس المقدم.

بعيدًا عن ذلك، أنشأنا روابط مهمة بين المواقف العامة تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي وسمتين شخصيتين مختارتين. في رأينا، فإن الارتباط الملحوظ مع عقلية المؤامرة لدى المشاركين يحمل أهمية ملحوظة في عالمنا المتزايد التعقيد. إذا لم يتمكن مطورو الذكاء الاصطناعي من إيجاد طرق مناسبة لجعل تقنيتهم تبدو غير ضارة للمراقبين (خصوصًا لأولئك الذين يميلون إلى البحث عن تفسيرات ما بعد الحقائق)، فقد يصبح من الصعب بشكل متزايد إنشاء ابتكارات على نطاق أوسع. ومع ذلك، نؤكد أن المواقف السلبية والاعتراضات ضد تقنية الذكاء الاصطناعي ليست بالضرورة غير مبررة؛ لذا، عند توعية الجمهور بتقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي، يجب تشجيع الناس على التفكير في كل من المخاطر والفوائد المحتملة. لتقليل خطر ظهور نظريات مؤامرة جديدة، نشجع أيضًا المحترفين في الصناعة على أن يكونوا شفافين قدر الإمكان عند تقديم ابتكاراتهم للجمهور.

أخيرًا، نقترح أن العمل اللاحق ضروري تمامًا لتفصيل مساهمتنا الحالية. بينما نظل مقتنعين بأن قياس المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي كمجموعة عامة من القدرات التكنولوجية هو أمر جدير بالاهتمام، يمكن أن تأتي نتائج أكثر ملموسة من تضمين ثنائية نظرية ظهرت مؤخرًا في مجال التفاعل بين الإنسان والآلة.

توفر البيانات

يمكن العثور على جميع المواد والبيانات التي تم الحصول عليها وأكواد التحليل للدراسات الثلاث المبلغ عنها في مستودع إطار العلوم المفتوحة الخاص بالمشروع (https://osf.io/3j67a/).

الملحق

مقياس المواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي (ATTARI-12)، النسخة الإنجليزية

التعليمات: في ما يلي، نحن مهتمون بمواقفك تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI). يمكن للذكاء الاصطناعي تنفيذ مهام تتطلب عادةً الذكاء البشري. إنه يمكّن الآلات من الإحساس والعمل والتعلم والتكيف بطريقة مستقلة تشبه الإنسان. قد يكون الذكاء الاصطناعي جزءًا من جهاز كمبيوتر أو منصة عبر الإنترنت – ولكنه يمكن أيضًا أن يُواجه في مجموعة متنوعة من الأجهزة الأخرى مثل الروبوتات.

قائمة العناصر:

| الصياغة | الجانب | القيمة | |

| 1 | سيجعل الذكاء الاصطناعي هذا العالم مكانًا أفضل. | معرفي | إيجابي |

| 2 | لدي مشاعر سلبية قوية تجاه

|

عاطفي | سلبي (معكوس) |

| 3 | أريد استخدام تقنيات تعتمد على

|

سلوكي | إيجابي |

| 4 | لدى الذكاء الاصطناعي المزيد من العيوب مقارنة بالمزايا. | معرفي | سلبي (معكوس) |

| 5 | أتطلع إلى مستقبل

|

عاطفي | إيجابي |

| 6 |

|

معرفي | إيجابي |

| 7 | أفضل التقنيات التي لا تحتوي على

|

سلوكي | سلبي (معكوس) |

| الصياغة | الجانب | القيمة | |

| 8 | أخاف من

|

عاطفي | سلبي (معكوس) |

| 9 | أفضل اختيار تقنية تحتوي على

|

سلوكي | إيجابي |

| 10 | يخلق الذكاء الاصطناعي مشاكل بدلاً من حلها. | معرفي | سلبي (معكوس) |

| 11 | عندما أفكر في

|

عاطفي | إيجابي |

| 12 | أفضل تجنب التقنيات التي تعتمد على

|

سلوكي | سلبي (معكوس) |

تم الاستلام: 3 أغسطس 2023؛ تم القبول: 31 يناير 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 05 فبراير 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 05 فبراير 2024

References

- Grewal, D., Roggeveen, A. L. & Nordfält, J. The future of retailing. J. Retail. 93(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2016.12.008 (2017).

- Vanian, J. Artificial Intelligence will Obliterate These Jobs by 2030 (Fortune, 2019). https://fortune.com/2019/11/19/artificial-intel ligence-will-obliterate-these-jobs-by-2030/.

- Ivanov, S., Kuyumdzhiev, M. & Webster, C. Automation fears: Drivers and solutions. Technol. Soc. 63, 101431. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.techsoc.2020.101431 (2020).

- Waytz, A. & Norton, M. I. Botsourcing and outsourcing: Robot, British, Chinese, and German workers are for thinking-not feeling—jobs. Emotion 14, 434-444. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036054 (2014).

- Gherheş, V. Why are we afraid of artificial intelligence (AI)?. Eur. Rev. Appl. Sociol. 11(17), 6-15. https://doi.org/10.1515/eras-2018-0006 (2018).

- Liang, Y. & Lee, S. A. Fear of autonomous robots and artificial intelligence: Evidence from national representative data with probability sampling. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 9, 379-384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-017-0401-3 (2017).

- Fast, E., & Horvitz, E. Long-term trends in the public perception of artificial intelligence. In Proceedings of the 31st AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence pp. 963-969 (AAAI Press, 2016).

- Thorp, H. H. ChatGPT is fun, but not an author. Science 379(6630), 313. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg7879 (2023).

- Lobera, J., Fernández Rodríguez, C. J. & Torres-Albero, C. Privacy, values and machines: Predicting opposition to artificial intelligence. Commun. Stud. 71(3), 448-465. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2020.1736114 (2020).

- Laakasuo, M. et al. The dark path to eternal life: Machiavellianism predicts approval of mind upload technology. Pers. Individ. Differ. 177, 110731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110731 (2021).

- Qu, W., Sun, H. & Ge, Y. The effects of trait anxiety and the big five personality traits on self-driving car acceptance. Transportation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-020-10143-7 (2020).

- Kaplan, J. Artificial Intelligence: What Everyone Needs to Know. (Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Schepman, A. & Rodway, P. Initial validation of the general attitudes towards Artificial Intelligence Scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 1, 100014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2020.100014 (2020).

- Sindermann, C. et al. Assessing the attitude towards artificial intelligence: Introduction of a short measure in German, Chinese, and English language. Künstliche Intelligenz 35(1), 109-118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13218-020-00689-0 (2020).

- Wang, Y. Y., & Wang, Y. S. Development and validation of an artificial intelligence anxiety scale: An initial application in predicting motivated learning behavior. Interact. Learn. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1674887 (2019).

- Kieslich, K., Lünich, M. & Marcinkowski, F. The Threats of Artificial Intelligence Scale (TAI): Development, measurement and test over three application domains. Int. J. Soc. Robot. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-020-00734-w (2021).

- Stein, J.-P., Liebold, B. & Ohler, P. Stay back, clever thing! Linking situational control and human uniqueness concerns to the aversion against autonomous technology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 95, 73-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.021 (2019).

- Rosenberg, M. J., & Hovland, C. I. Attitude Organization and Change: An Analysis of Consistency Among Attitude Components (Yale University Press, 1960).

- Zanna, M. P. & Rempel, J. K. Attitudes: A new look at an old concept. In Attitudes: Their Structure, Function, and Consequences (eds Fazio, R. H. & Petty, R. E.) 7-15 (Psychology Press, 2008).

- Stein, J.-P., Appel, M., Jost, A. & Ohler, P. Matter over mind? How the acceptance of digital entities depends on their appearance, mental prowess, and the interaction between both. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 142, 102463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020. 102463 (2020).

- McClure, P. K. “You’re fired”, says the robot. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 36(2), 139-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317698637 (2017).

- Gillath, O. et al. Attachment and trust in artificial intelligence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 115, 106607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb. 2020.106607 (2021).

- Young, K. L. & Carpenter, C. Does science fiction affect political fact? Yes and no: A survey experiment on “Killer Robots”. Int. Stud. Q. 62(3), 562-576. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqy028 (2018).

- Gnambs, T. & Appel, M. Are robots becoming unpopular? Changes in attitudes towards autonomous robotic systems in Europe. Comput. Hum. Behav. 93, 53-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.045 (2019).

- Horstmann, A. C. & Krämer, N. C. Great expectations? Relation of previous experiences with social robots in real life or in the media and expectancies based on qualitative and quantitative assessment. Front. Psychol. 10, 939. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg. 2019.00939 (2019).

- Sundar, S. S., Waddell, T. F. & Jung, E. H. The Hollywood robot syndrome: Media effects on older adults’ attitudes toward robots and adoption intentions. Paper presented at the 11th Annual ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Christchurch, New Zealand (2016).

- Chien, S.-Y., Sycara, K., Liu, J.-S. & Kumru, A. Relation between trust attitudes toward automation, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, and Big Five personality traits. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 60(1), 841-845. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541931213 601192 (2016).

- MacDorman, K. F. & Entezari, S. Individual differences predict sensitivity to the uncanny valley. Interact. Stud. 16(2), 141-172. https://doi.org/10.1075/is.16.2.01mac (2015).

- Oksanen, A., Savela, N., Latikka, R. & Koivula, A. Trust toward robots and artificial intelligence: An experimental approach to Human-Technology interactions online. Front. Psychol. 11, 3336. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568256 (2020).

- Wissing, B. G. & Reinhard, M.-A. Individual differences in risk perception of artificial intelligence. Swiss J. Psychol. 77(4), 149-157. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000214 (2018).

- Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. Four ways five factors are basic. Pers. Individ. Differ. 13, 653-665. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I (1992).

- Paulhus, D. L. & Williams, K. M. The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Pers. 36, 556-563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6 (2002).

- Bruder, M., Haffke, P., Neave, N., Nouripanah, N. & Imhoff, R. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: Conspiracy mentality questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 4, 225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225 (2013).

- Imhoff, R. et al. Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6(3), 392-403. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41562-021-01258-7 (2022).

- Nettle, D. & Penke, L. Personality: Bridging the literatures from human psychology and behavioural ecology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 365(1560), 4043-4050. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0061 (2010).

- Poropat, A. E. A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychol. Bull. 135(2), 322-338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014996 (2009).

- Kaplan, A. D., Sanders, T. & Hancock, P. A. The relationship between extroversion and the tendency to anthropomorphize robots: A bayesian analysis. Front. Robot. AI 5, 135. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2018.00135 (2019).

- Kaufman, S. B., Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E. & Tsukayama, E. The light vs. Dark triad of personality: Contrasting two very different profiles of human nature. Front. Psychol. 10, 467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467 (2019).

- LeBreton, J. M., Shiverdecker, L. K. & Grimaldi, E. M. The Dark Triad and workplace behavior. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5(1), 387-414. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104451 (2018).

- Feldstein, S. The Global Expansion of AI Surveillance. Carnegie Endowment for International Piece. https://carnegieendowment. org/files/WP-Feldstein-AISurveillance_final1.pdf (2019).

- Malabou, C. Morphing Intelligence: From IQ Measurement to Artificial Brains (Columbia University Press, 2019).

- Swami, V., Chamorro-Premuzic, T. & Furnham, A. Unanswered questions: A preliminary investigation of personality and individual difference predictors of 9/11 conspiracist beliefs. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 24, 749-761. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1583 (2010).

- Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. G. Who falls for fake news? The roles of bullshit receptivity, overclaiming, familiarity, and analytic thinking. J. Pers. 88(2), 185-200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy. 12476 (2019).

- Shakarian, A. The Artificial Intelligence Conspiracy (2016).

- McEvoy, J. Microchips, Magnets and Shedding: Here are 5 (Debunked) Covid Vaccine Conspiracy Theories Spreading Online (Forbes, 2021). https://www.forbes.com/sites/jemimamcevoy/2021/06/03/microchips-and-shedding-here-are-5-debunked-covid-vacci ne-conspiracy-theories-spreading-online/

- De Vynck, G., & Lerman, R. Facebook and YouTube Spent a Year Fighting Covid Misinformation. It’s Still Spreading (The Washington Post, 2021). https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/07/22/facebook-youtube-vaccine-misinformation/.

- González, F., Yu, Y., Figueroa, A., López, C., & Aragon, C. Global reactions to the Cambridge Analytica scandal: A cross-language social media study. In Proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web Conference 799-806. ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/33085 60.3316456 (2019).

- Joyce, M. & Kirakowski, J. Measuring attitudes towards the internet: The general internet attitude scale. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 31, 506-517. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2015.1064657 (2015).

- Bartneck, C., Lütge, C., Wagner, A., & Welsh, S. An Introduction to Ethics in Robotics and AI (Springer, 2021).

- German Research Foundation. Statement by an Ethics Committee. https://www.dfg.de/en/research_funding/faq/faq_humanities_ social_science/index.html (2023).

- German Psychological Society. Berufsethische Richtlinien [Work Ethical Guidelines]. https://www.dgps.de/fileadmin/user_upload/ PDF/Berufsetische_Richtlinien/BER-Foederation-20230426-Web-1.pdf (2022).

- Jobst, L. J., Bader, M. & Moshagen, M. A tutorial on assessing statistical power and determining sample size for structural equation models. Psychol. Methods 28(1), 207-221. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000423 (2023).

- Stöber, J. The Social Desirability Scale-17 (SDS-17): Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and relationship with age. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 17(3), 222-232. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.17.3.222 (2001).

- Eid, M., Geiser, C., Koch, T. & Heene, M. Anomalous results in G-factor models: Explanations and alternatives. Psychol. Methods 22, 541-562. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000083 (2017).

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H. & Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 8(2), 23-74 (2003).

- Rodriguez, A., Reise, S. P. & Haviland, M. G. Evaluating bifactor models: Calculating and interpreting statistical indices. Psychol. Methods 21(2), 137-150. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000045 (2016).

- Kennedy, R. et al. The shape of and solutions to the MTurk quality crisis. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 8(4), 614-629. https://doi.org/10. 1017/psrm. 2020.6 (2020).

- Peer, E., Vosgerau, J. & Acquisti, A. Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 46(4), 1023-1031. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0434-y (2013).

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P. & Soto, C. J. Paradigm shift to the integrative Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (eds John, O. P. et al.) 114-158 (Guilford Press, 2008).

- Jones, D. N. & Paulhus, D. L. Introducing the Short Dark Triad (SD3): A brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment 21(1), 28-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191113514105 (2014).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics (SAGE, 2013).

- Baranski, E., Sweeny, K., Gardiner, G. & Funder, D. C. International optimism: Correlates and consequences of dispositional optimism across 61 countries. J. Pers. 89(2), 288-304. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy. 12582 (2020).

- Sharpe, J. P., Martin, N. R. & Roth, K. A. Optimism and the Big Five factors of personality: Beyond neuroticism and extraversion. Pers. Individ. Differ. 51(8), 946-951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.033 (2011).

- Steel, G. D., Rinne, T. & Fairweather, J. Personality, nations, and innovation. Cross-Cult. Res. 46(1), 3-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1069397111409124 (2011).

- McCarthy, M. H., Wood, J. V. & Holmes, J. G. Dispositional pathways to trust: Self-esteem and agreeableness interact to predict trust and negative emotional disclosure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 113(1), 95-116. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000093 (2017).

- Lazer, D. M. J. et al. The science of fake news. Science 359(6380), 1094-1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998 (2018).

- Stecula, D. A. & Pickup, M. Social media, cognitive reflection, and conspiracy beliefs. Front. Polit. Sci. 3, 62. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fpos.2021.647957 (2021).

- van Prooijen, J. W. Why education predicts decreased belief in conspiracy theories. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 31(1), 50-58. https:// doi.org/10.1002/acp. 3301 (2016).

- Scheibenzuber, C., Hofer, S. & Nistor, N. Designing for fake news literacy training: A problem-based undergraduate online-course. Comput. Hum. Behav. 121, 106796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106796 (2021).

- Sindermann, C., Schmitt, H. S., Rozgonjuk, D., Elhai, J. D. & Montag, C. The evaluation of fake and true news: On the role of intelligence, personality, interpersonal trust, ideological attitudes, and news consumption. Heliyon 7(3), e06503. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06503 (2021).

- Park, J. & Woo, S. E. Who likes artificial intelligence? Personality predictors of attitudes toward artificial intelligence. J. Psychol. 156(1), 68-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2021.2012109 (2022).

- McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Jr. Personality trait structure as a human universal. Am. Psychol. 52(5), 509-516. https://doi.org/10. 1037/0003-066X.52.5.509 (1997).

- Rogoza, R. et al. Structure of Dark Triad Dirty Dozen across eight world regions. Assessment 28(4), 1125-1135. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1073191120922611 (2020).

- Gurven, M., von Rueden, C., Massenkoff, M., Kaplan, H. & Lero Vie, M. How universal is the Big Five? Testing the five-factor model of personality variation among forager-farmers in the Bolivian Amazon. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104(2), 354-370. https://doi. org/10.1037/a0030841 (2013).

- Lee, K. & Ashton, M. C. Psychometric properties of the HEXACO-100. Assessment 25, 543-556. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731 91116659134 (2018).

- Thielmann, I. et al. The HEXACO-100 across 16 languages: A Large-Scale test of measurement invariance. J. Pers. Assess. 102(5), 714-726. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2019.1614011 (2019).

- Mara, M. & Appel, M. Science fiction reduces the eeriness of android robots: A field experiment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 48, 156-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.007 (2015).

- Laakasuo, M. et al. What makes people approve or condemn mind upload technology? Untangling the effects of sexual disgust, purity and science fiction familiarity. Palgrave Commun. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0124-6 (2018).

- Latikka, R., Savela, N., Koivula, A. & Oksanen, A. Attitudes toward robots as equipment and coworkers and the impact of robot autonomy level. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 13(7), 1747-1759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-020-00743-9 (2021).

- Appel, M., Izydorczyk, D., Weber, S., Mara, M. & Lischetzke, T. The uncanny of mind in a machine: Humanoid robots as tools, agents, and experiencers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 102, 274-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.031 (2020).

- Gray, K. & Wegner, D. M. Feeling robots and human zombies: Mind perception and the uncanny valley. Cognition 125, 125-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2012.06.007 (2012).

- Grundke, A., Stein, J.-P. & Appel, M. Mind-reading machines: Distinct user responses to thought-detecting and emotion-detecting robots. Technol. Mind Behav. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/U52KM (2021).

- Yuan, K. H. & Bentler, P. M. Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with non-normal missing data. Sociol. Methodol. 30(1), 165-200. https://doi.org/10.1111/0081-1750.00078 (2000).

- Satorra, A. & Bentler, P. M. Ensuring positiveness of the scaled difference chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika 75, 243-248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y (2010).

مساهمات المؤلفين

J.-P.S.: التصور، المنهجية، التحقيق، التحليل الرسمي، تنسيق البيانات، الكتابة (المسودة الأصلية)، الكتابة (المراجعة والتحرير).T.M.: التصور، المنهجية، التحقيق، تنسيق البيانات، الكتابة (المراجعة والتحرير).T.G.: المنهجية، التحقيق، التحليل الرسمي، تنسيق البيانات، الكتابة (المراجعة والتحرير).F.H.: التصور، المنهجية، التحقيق، الكتابة (المراجعة والتحرير).M.A.: التصور، المنهجية، التحليل الرسمي، تنسيق البيانات، الكتابة (المسودة الأصلية)، الكتابة (المراجعة والتحرير)، الإشراف.

التمويل

تم تمكين وتنظيم تمويل الوصول المفتوح بواسطة مشروع DEAL.

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

المعلومات التكميلية تحتوي النسخة عبر الإنترنت على مواد تكميلية متاحة على https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-024-53335-2.

يجب توجيه المراسلات وطلبات المواد إلى J.-P.S.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي 4.0 الدولية، التي تسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو تنسيق، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر ائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© المؤلفون 2024

© المؤلفون 2024

قسم علم نفس الإعلام، معهد أبحاث الإعلام، جامعة كمنيتز للتكنولوجيا، طريق ثورينجر 11، 09126 كمنيتز، ألمانيا. علم نفس الاتصال والإعلام الجديد، معهد الإنسان-الكمبيوتر-الإعلام، جامعة فيورزبورغ، فيورزبورغ، ألمانيا. معهد لايبنيز لمسارات التعليم، بامبرغ، ألمانيا. البريد الإلكتروني: jpstein@phil.tu-chemnitz.de

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 14, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53335-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38316898

Publication Date: 2024-02-05

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53335-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38316898

Publication Date: 2024-02-05

OPEN

Attitudes towards AI: measurement and associations with personality

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become an integral part of many contemporary technologies, such as social media platforms, smart devices, and global logistics systems. At the same time, research on the public acceptance of AI shows that many people feel quite apprehensive about the potential of such technologies-an observation that has been connected to both demographic and sociocultural user variables (e.g., age, previous media exposure). Yet, due to divergent and often ad-hoc measurements of AI-related attitudes, the current body of evidence remains inconclusive. Likewise, it is still unclear if attitudes towards AI are also affected by users’ personality traits. In response to these research gaps, we offer a two-fold contribution. First, we present a novel, psychologically informed questionnaire (ATTARI-12) that captures attitudes towards AI as a single construct, independent of specific contexts or applications. Having observed good reliability and validity for our new measure across two studies (

Artificial intelligence (AI) promises to make human life much more comfortable: It may foster intercultural collaboration via sophisticated translating tools, guide online customers towards the products they are most likely going to buy, or carry out jobs that feel tedious to human workers

Crucially, individuals may differ regarding their evaluation of such chances and risks, and in turn, hold different attitudes towards AI. However, we note that scholars interested in these differences often used a basic ad-hoc approach to assess participants’ AI attitudes

Research objective 1: measuring attitudes towards AI

Broadly speaking, the term artificial intelligence (AI) is used to describe technologies that can execute tasks one may expect to require human intelligence-i.e., technologies that possess a certain degree of autonomy, the capacity for learning and adapting, and the ability to handle large amounts of data

better understand users’ response to-and acceptance of-artificially intelligent technology. Of course, in order to achieve this goal, it is essential to employ theoretically sound measures of high psychometric quality when assessing AI-related attitudes. Furthermore, researchers need to decide whether they want to examine only a specific type of application (such as self-driving cars or intelligent robots) or focus on AI as an abstract technological concept that can be applied to many different settings. While both approaches have undeniable merit, it may be argued that the comparability of different research efforts-especially those situated at the intersection of different disciplines-clearly benefits from the latter, i.e., an empirical focus on attitudes towards AI as a set of technological capabilities instead of concrete use cases.

In line with this argument, scientific efforts have produced several measures to assess attitudes towards AI as a more overarching concept. These include the General Attitudes Towards Artificial Intelligence Scale (GAAIS

Hence, based on the identified lack of a one-dimensional, psychometrically sound, yet economic measure that captures both positive and negative aspects of the attitude towards AI, our first aim was to develop a scale that overcomes these limitations. For the sake of broad interdisciplinary applicability, we explicitly focused the creation of our scale on the perception of AI as a general set of technological capabilities, independent of its physical embodiment or use context. This perspective was not least informed by recent research, which indicated that people’s evaluation of digital ‘minds’ is likely to change once visual factors come into play

Research objective 2: understanding associations between AI-related attitudes and personality traits

Thus far, most studies on public AI acceptance have explored the role of demographic and sociocultural variables, revealing that concerns about AI seem to be more prevalent among women, the elderly, ethnic minorities, and individuals with lower levels of education

Apart from considerable insight into the sociocultural predictors of (dis-)liking AI technology, much less is known about the impact of users’ personality factors on their AI-related attitudes. To our knowledge, only a handful of scientific studies have actually addressed this issue, and most of them have yielded rather limited results-either by focusing on very specific types of

Therefore, building upon the reviewed work, our second objective was to scrutinize several central personality dimensions as predictors for people’s AI-related attitudes, including the well-known Big Five

Overview of studies and predictions

Addressing the outlined research propositions, we present three studies (see Table 1 for a brief overview of main study characteristics). All materials, obtained data, and analysis codes for these three studies can be found in our project’s Open Science Framework repository (https://osf.io/3j67a/). Informed consent was collected from all participants before they took part in our research efforts.

Studies 1 and 2 mainly served to investigate the reliability and validity of our new attitudes towards AI scale, the ATTARI-12. Hence, these studies were mainly guided by several analytical steps examining the statistical properties of our measure, including its convergent validity, re-test reliability, and susceptibility to social desirability bias. In Study 3, we then set out to connect participants’ attitude towards AI (as measured by the developed questionnaire) to fundamental personality traits and demographic factors. For this third and final study, we will detail all theoretical considerations and hypotheses in the following.

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | |

| Sample type | MTurk (US) | Student sample | MTurk (US) |

| Study focus | Scale development: Factorial validity, reliability (internal consistency), construct validity | Scale development: Reliability (re-test reliability), construct validity | Personality predictors (Big Five, Dark Triad, conspiracy mentality) |

| Study language | English | German | English |

| Final sample size | 490 | 166 (at Time 1), 163 at Time 2, 150 at both times | 298 |

| Measurements | 1 | 2 (four to five week follow-up) | 1 |

Table 1. Overview of the conducted studies.

Faced with a lack of previous findings regarding personality predictors of AI-related attitudes, we deemed it important to anchor our investigation in a broader view at human personality. This perspective led us to first include the Big Five model

For openness to experience-which can be defined as the tendency to be adventurous, intellectually curious, and imaginative-we expected a clear positive relationship to AI-related attitudes. Since AI technologies promise many new possibilities for human society, people who are open to experience should feel more excited and curious about the respective innovations (this is mirrored by recent findings on self-driving cars

H1 The higher a person’s openness for experience, the more positive attitudes they hold towards AI.

Conscientiousness can be described as the inclination to be diligent, efficient, and careful, and to act in a disciplined or even perfectionist manner. Considering that it may be difficult for humans to understand the inner workings of an AI system or to anticipate its behavior, it seems likely that conscientious people would express more negative views about AI, a technological concept that might make the world less comprehensible for them

Conscientiousness can be described as the inclination to be diligent, efficient, and careful, and to act in a disciplined or even perfectionist manner. Considering that it may be difficult for humans to understand the inner workings of an AI system or to anticipate its behavior, it seems likely that conscientious people would express more negative views about AI, a technological concept that might make the world less comprehensible for them

H2 The higher a person’s conscientiousness, the more negative attitudes they hold towards AI.

The third of the Big Five traits, extraversion, encompasses the tendency to be out-going, talkative, and gregarious; in turn, it is negatively related to apprehensive and restrained behavior. Based on this definition, it comes as no surprise that extroverted individuals reported fewer concerns about autonomous technologies in previous studies

The third of the Big Five traits, extraversion, encompasses the tendency to be out-going, talkative, and gregarious; in turn, it is negatively related to apprehensive and restrained behavior. Based on this definition, it comes as no surprise that extroverted individuals reported fewer concerns about autonomous technologies in previous studies

H3 The higher people’s extraversion, the more positive attitudes they hold towards AI.

High agreeableness manifests itself in the proclivity to show warm, cooperative, and kind-hearted behavior. Regarding the topic at hand, previous research suggests that agreeableness might be (moderately) correlated with positive views about automation or specific types of

High agreeableness manifests itself in the proclivity to show warm, cooperative, and kind-hearted behavior. Regarding the topic at hand, previous research suggests that agreeableness might be (moderately) correlated with positive views about automation or specific types of

H4 The higher a person’s agreeableness, the more positive attitudes they hold towards AI.

The last Big Five trait, neuroticism, is connected to self-conscious and shy behavior. People with high scores in this trait tend to be more vulnerable to external stressors and have trouble controlling spontaneous impulses. MacDorman and Entezari

The last Big Five trait, neuroticism, is connected to self-conscious and shy behavior. People with high scores in this trait tend to be more vulnerable to external stressors and have trouble controlling spontaneous impulses. MacDorman and Entezari

H5 The higher a person’s neuroticism, the more negative attitudes they hold towards AI.

Although the Big Five are considered a relatively comprehensive set of human personality traits, research has yielded several other concepts that serve to make sense of interpersonal differences (and how they relate to attitudes and behaviors). Importantly, tapping into more negatively connotated aspects of human nature, Paulhus and Williams

Although the Big Five are considered a relatively comprehensive set of human personality traits, research has yielded several other concepts that serve to make sense of interpersonal differences (and how they relate to attitudes and behaviors). Importantly, tapping into more negatively connotated aspects of human nature, Paulhus and Williams

Machiavellianism is a personality dimension that encompasses manipulative, callous, and amoral qualities. For our research topic, we contemplated two opposing notions as to how this trait could relate to AI attitudes. On the one hand, recent literature suggests that Machiavellian individuals might feel less concerned about amoral uses of AI and instead focus on its utilitarian value, which may reflect in more positive attitudes

H6 The higher a person’s Machiavellianism, the more negative attitudes they hold towards AI.

A person scoring high on psychopathy is likely prone to thrill-seeking behavior and may experience only little anxiety. Unlike the deliberate manipulations typical for Machiavellian people, the psychopathic personality trait involves much more impulsive antisocial tendencies. Based on this, we came to assume a positive relationship between psychopathy and attitudes towards AI—not least considering that our dependent variable would also involve people’s emotional reactions towards AI, which should turn out less fearful among those high in psychopathy. We assumed:

A person scoring high on psychopathy is likely prone to thrill-seeking behavior and may experience only little anxiety. Unlike the deliberate manipulations typical for Machiavellian people, the psychopathic personality trait involves much more impulsive antisocial tendencies. Based on this, we came to assume a positive relationship between psychopathy and attitudes towards AI—not least considering that our dependent variable would also involve people’s emotional reactions towards AI, which should turn out less fearful among those high in psychopathy. We assumed:

H7 The higher a person’s psychopathy, the more positive attitudes they hold towards AI.

Broadly speaking, narcissists tend to show egocentric, proud, and unempathetic behavior, which is often accompanied by feelings of grandeur and entitlement. Whereas some qualitative research suggests that intelligent computers might deal a severe “blow to our narcissism” (

Broadly speaking, narcissists tend to show egocentric, proud, and unempathetic behavior, which is often accompanied by feelings of grandeur and entitlement. Whereas some qualitative research suggests that intelligent computers might deal a severe “blow to our narcissism” (

H8 The higher a person’s narcissism, the more positive attitudes they hold towards AI.

Lastly, we proceeded to the exploration of a dispositional variable on a notably smaller scale of abstraction, which appeared promising to us from a contemporary perspective: people’s conspiracy mentality. Strongly related to general distrust in people, institutions, and whole political systems, this personality trait focuses on the susceptibility to conspiracy theories, i.e., explanations about famous events that defy common sense or publicly presented facts

Lastly, we proceeded to the exploration of a dispositional variable on a notably smaller scale of abstraction, which appeared promising to us from a contemporary perspective: people’s conspiracy mentality. Strongly related to general distrust in people, institutions, and whole political systems, this personality trait focuses on the susceptibility to conspiracy theories, i.e., explanations about famous events that defy common sense or publicly presented facts

Although they might not be quite as well-known as other prominent conspiracy theories (e.g., concerning the

H9 The higher a person’s level of conspiracy mentality, the more negative attitudes they hold towards AI.

Concluding the theoretical preparation of our study, we devised hypotheses on two basic demographic variables that were previously connected to AI-related attitudes in scientific publications. Specifically, it has been found that women typically hold more negative attitudes towards AI than men, which may, among other causes, be explained by societal barriers that limit women’s access to (and interest in) technical domains

Concluding the theoretical preparation of our study, we devised hypotheses on two basic demographic variables that were previously connected to AI-related attitudes in scientific publications. Specifically, it has been found that women typically hold more negative attitudes towards AI than men, which may, among other causes, be explained by societal barriers that limit women’s access to (and interest in) technical domains

H10 Women hold more negative attitudes towards AI than men.

H11 Older individuals hold more negative attitudes towards AI than younger individuals.

H11 Older individuals hold more negative attitudes towards AI than younger individuals.

Study 1

The goal underlying Study 1 was to develop a psychometrically sound scale that was (a) one-dimensional, (b) incorporated items reflecting the three bases or facets of attitudes (cognitive, affective, behavioral) that have guided attitude research in psychology for the last decades

In a second step, the authors discussed the items, and excluded items that were ambiguous in content, too specific in terms of attitude target, or involved too much linguistic overlap with other items. The remaining scale consisted of twelve items, with each of the three psychological facets of human attitudes-cognitive, affective, and behavioral-being represented by two positively and two negatively worded items. Nevertheless, all twelve items were expected to represent one general factor: People’s attitude towards AI. The full scale (ATTARI-12) can be found in the Appendix.

To gain insight into the validity of our new scale, Study 1 further included items on more specific AI applications. We expected that general attitudes towards AI as measured by the ATTARI-12 would be positively associated with specific attitudes towards electronic personal assistants (e.g., Alexa) and attitudes towards robots. Moreover, we assessed participants’ tendency to give socially desirable answers to establish whether our novel instrument would be affected by social desirability bias. Based on our careful wording during the construction of the scale, we expected that people’s attitude towards AI (per the ATTARI-12) would not be substantially related to social desirability. The hypotheses and planned data analysis steps for Study 1 were preregistered at https:// aspredicted.org/8B5_GHZ (see also Supplement S1).

Method

Ethics statement

In Germany, institutional ethics approval is not required for psychological research as long as it does not involve issues regulated by law

Participants and procedure

Power analyses with semPower (Version 2.0.1

Following preregistered exclusion criteria (i.e., completion time, failing at least one of two attention checks), 111 participants were excluded from our analyses. More specifically, 31 participants completed the questionnaire in less than

Measures

Attitudes towards artificial intelligence. We applied the newly created ATTARI-12, using a five-point answer format to capture participants’ responses (

Attitudes towards personal voice assistants (PVA). Participants indicated their attitudes towards PVAs on three semantic differential items (with five gradation points) that were created for the purpose of this study (e.g., “hate it-love it”; Cronbach’s

Attitudes towards robots. People’s general assessment of robots was measured with three items that were previously used in robot acceptance research

Social desirability. Participants’ tendency to give socially desirable answers was measured with the Social Desirability Scale

Results

Our analysis of factorial validity was guided by the assumption that the items represent a single construct: People’s attitude towards AI. To this end, we compared different, increasingly less restrictive, models in a confirmatory factor analysis: The first model (a) specified a single factor and, thus, assumed that individual differences in item responses could be explained by a single, general attitude construct. However, this assumption is often too strong in practice because specific content facets or item wording might lead to minor multidimensionality. Therefore, Model (b) estimated a bifactor S-1 structure that, in addition to the general factor, included two orthogonal specific factors for the cognitive or affective items. These specific factors captured the unique variance resulting from the two content domains that were not accounted by the general attitude factor. Following Eid and colleagues

The goodness of fit of these models are summarized in Table 2. Using established recommendations for the interpretation of these fit indices

|

|

|

CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | BIC | Comp |

|

|

|

||

| (a) | Single factor model | 434.77 | 54 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 14,564 | 14,664 | ||||

| Bifactor S-1 models with one global factor and orthogonal specific factors for … | ||||||||||||

| (b) | Content facets | 327.39 | 46 | 0.89 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 14,412 | 1456 | (a) | 102.95 | 8 | <0.001 |