DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51034-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39107273

تاريخ النشر: 2024-08-06

الميزات الأساسية للتيار الضعيف من أجل تحسين ممتاز لتقليل أكاسيد النيتروجين على المحفز القائم على الفاناديوم أحادي الذرة

تم القبول: 25 يوليو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 06 أغسطس 2024

الملخص

تواجه المجتمع البشري مشاكل متزايدة الخطورة تتعلق بتلوث البيئة ونقص الطاقة، وحتى الآن، تحقيق مستوى عالٍ

يتفاعل

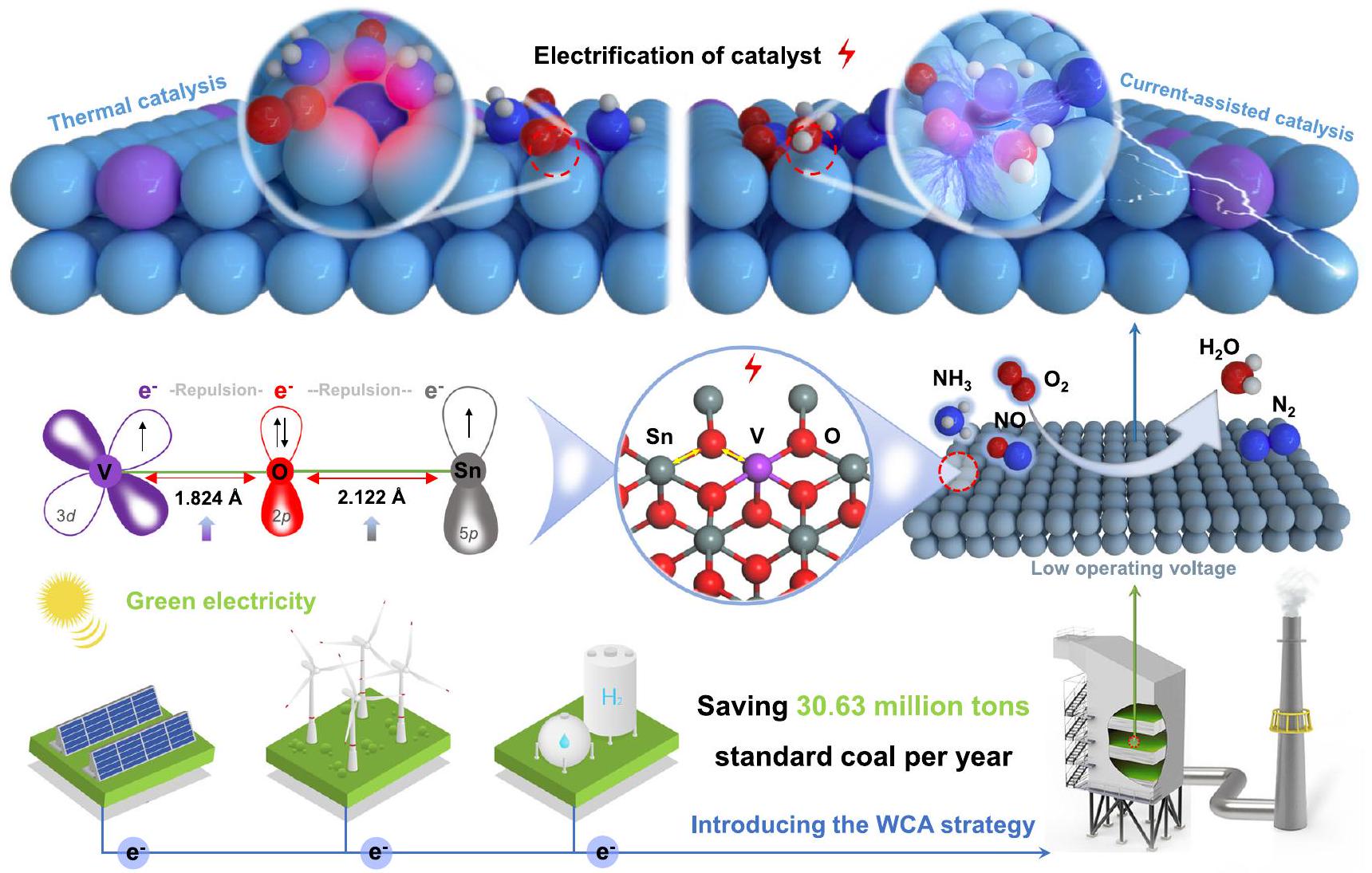

في تجارب مطيافية الانعكاس المنتشر بالأشعة تحت الحمراء باستخدام تحويل فورييه (DRIFTS)، تم استخدام الدراسات الحركية لتوضيح آلية الاستراتيجية. على المستوى المجهري، تم دراسة تأثيرات هجرة الإلكترونات على طاقة الربط والروابط الكيميائية من خلال تجارب XPS في الموقع وحسابات نظرية الكثافة الوظيفية (DFT). وقد كشفت هذه الدراسات بعمق عن آلية تعزيز التحفيز باستخدام استراتيجية WCA. باختصار، أكدت الدراسة على الدور الهام الذي تلعبه استراتيجية WCA في تعزيز النشاط عند درجات الحرارة المنخفضة للغاية ووضحت الآلية التحفيزية تحت استراتيجية WCA من منظور سلوك الإلكترونات والروابط الكيميائية.

النتائج والمناقشة

توصيف عملية تحسين المحفز

تحديد

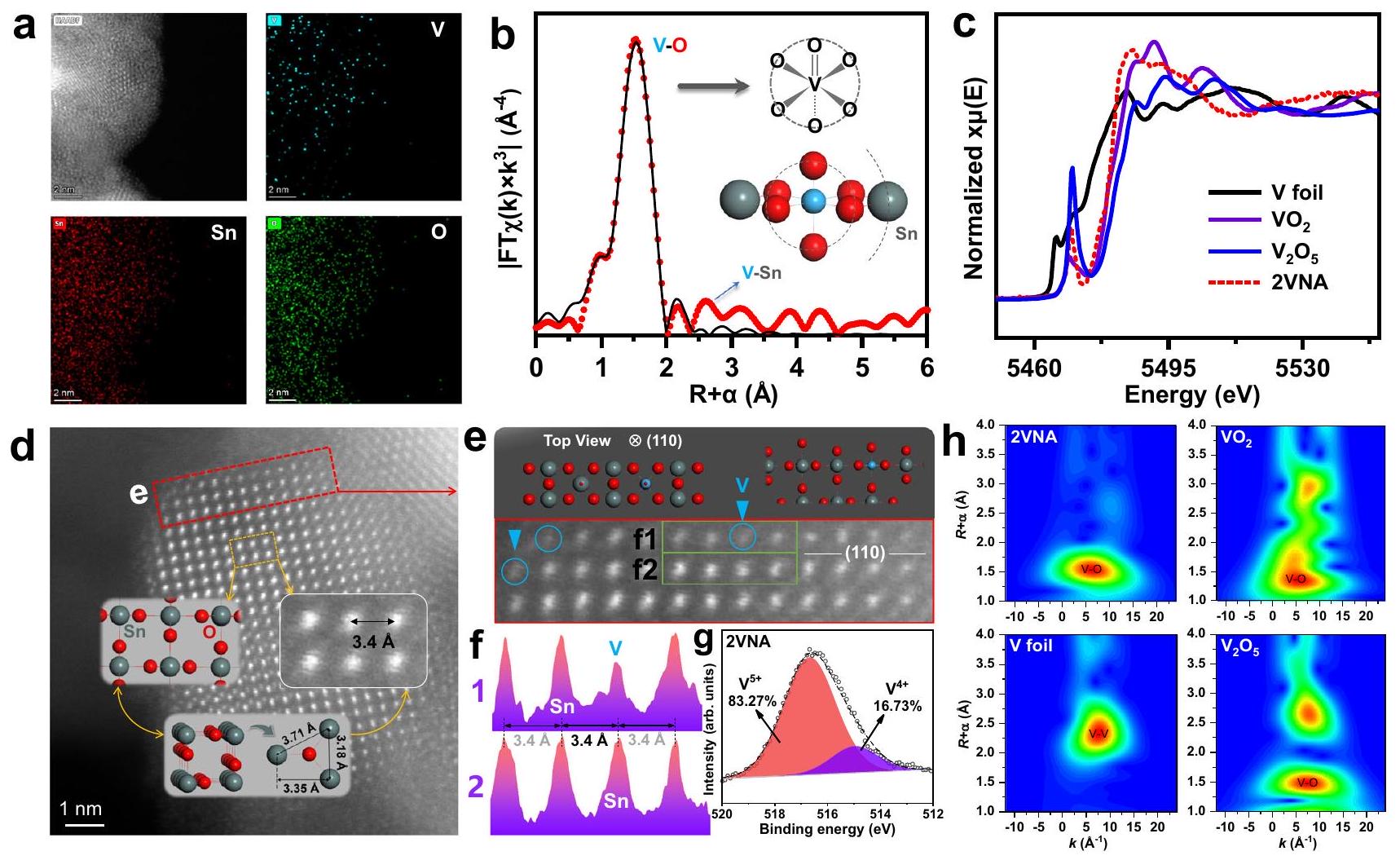

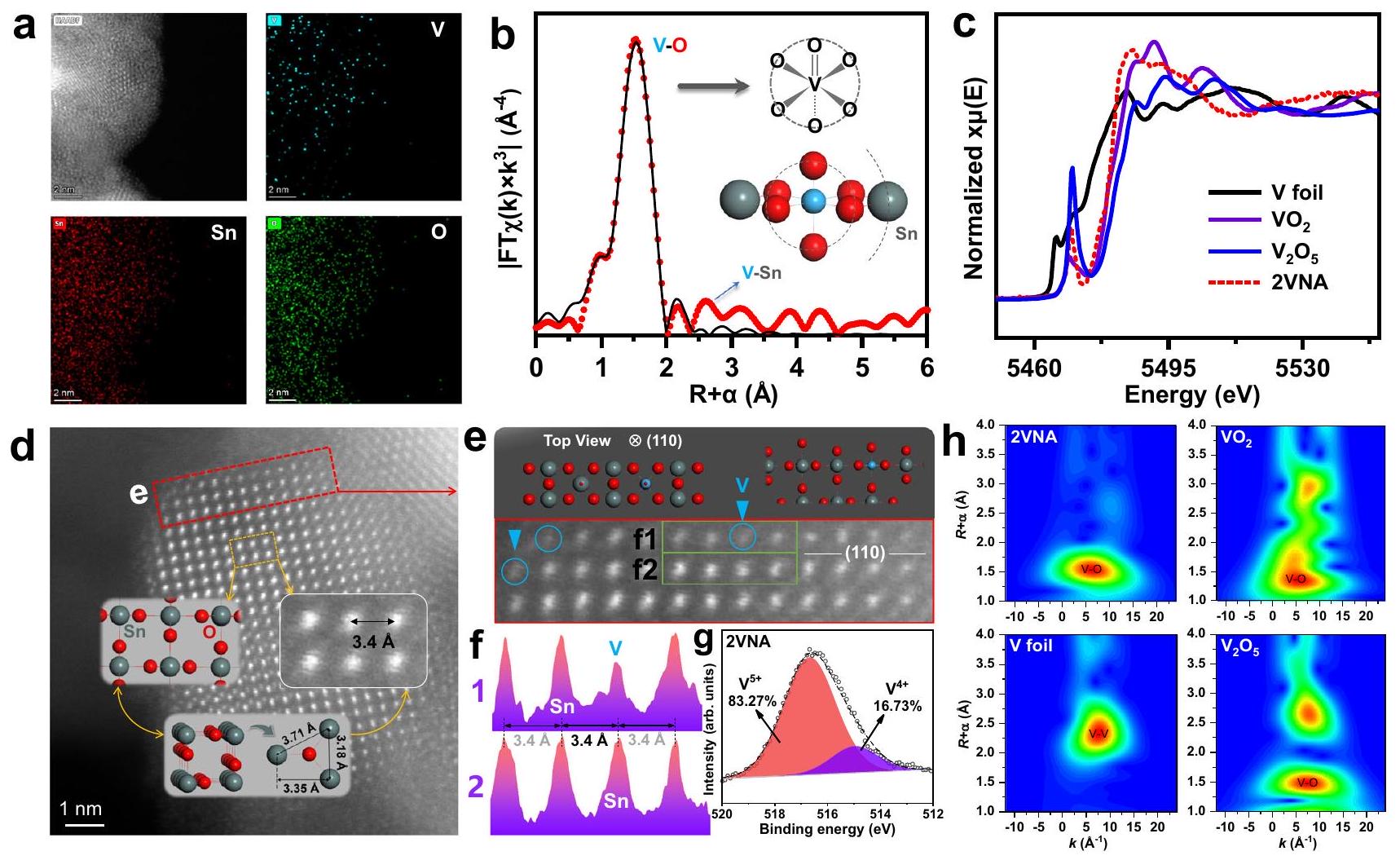

صورة HAADF TEM ورسم خرائط EDS لمحفز 2VNA. شريط القياس، 2 نانومتر؛ شريط القياس في صور رسم خرائط EDS،

المسافة متوافقة مع القيمة النظرية، مما يشير إلى أن هيكل محفز 2VNA ظل متسقًا مع الهيكل لـ

نشاط تحفيزي ممتاز تحت استراتيجية WCA

مرتبط سلبًا مع درجة الحرارة (موضح في الشكل S14). يمكن تحويل الطاقة بين أشكال مختلفة

استقرار

الاستراتيجية. من منظور توفير الطاقة، استهلكت استراتيجية WCA فقط

المحفزات التجارية والمبلغ عنها لـ SCR عند نفس أو أعلى WHSV. بناءً على النتائج المذكورة أعلاه، تم الاستنتاج أن الاستراتيجية قللت من استهلاك الطاقة وحسنت النشاط التحفيزي

مع المجال الحراري الخارجي.

توصيف الآلية الميكروسكوبية تحت استراتيجية WCA

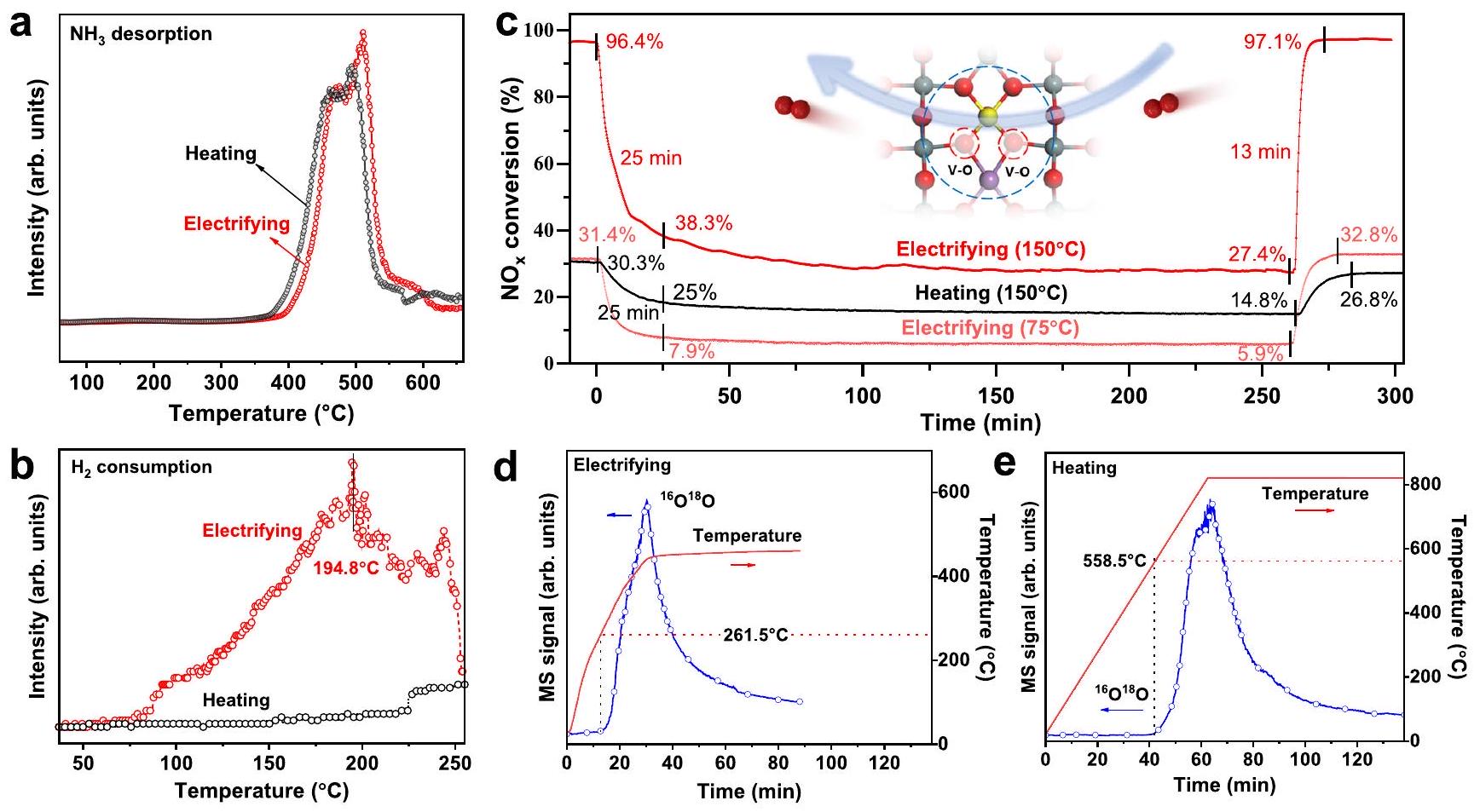

. بالاقتران مع

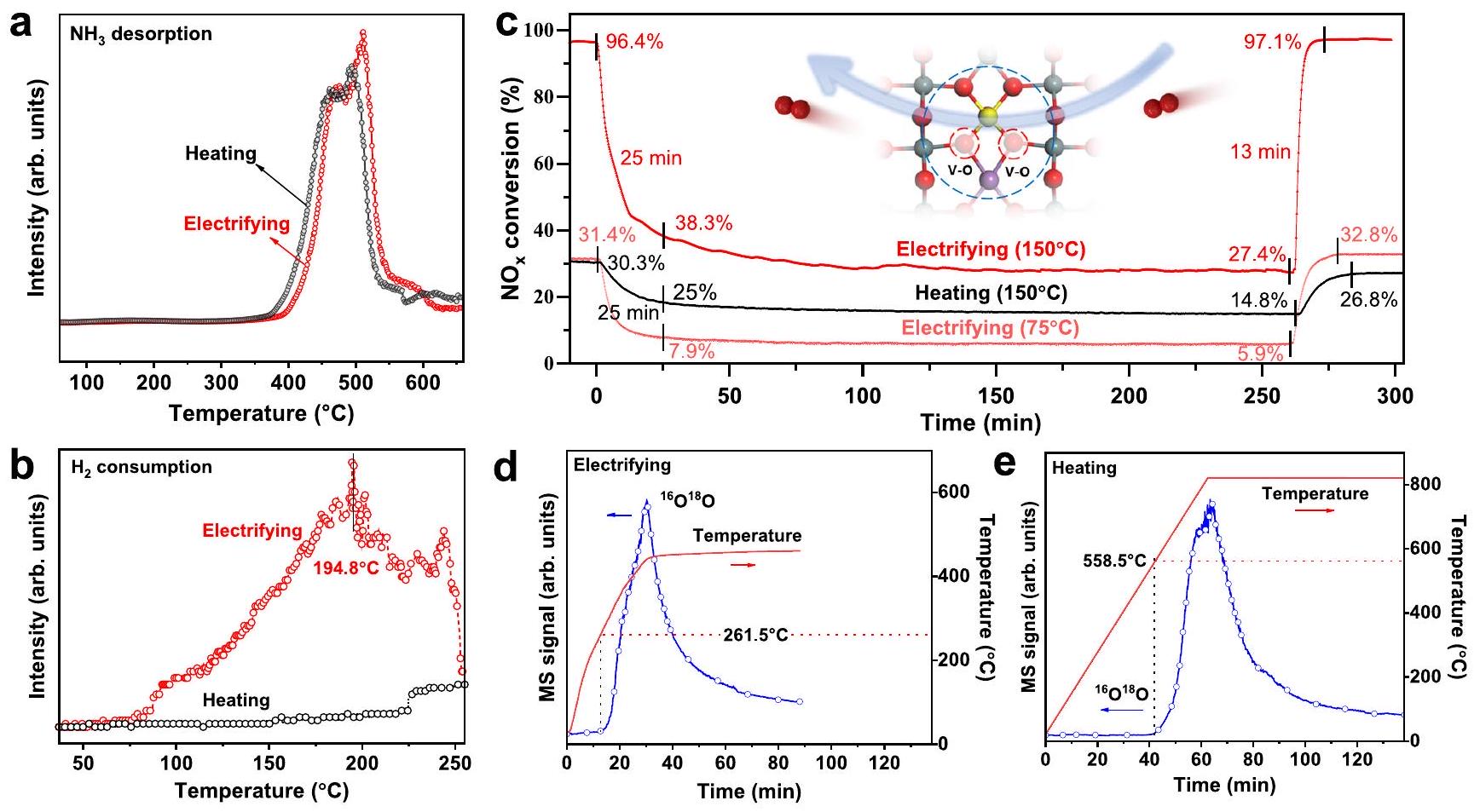

TPR تحت الاستراتيجيتين، على التوالي. استراتيجية WCA بدون المجال الحراري الخارجي (الكهرباء)، التسخين البسيط في الفرن. ج تجارب الأكسجين العابر: تم قطع الأكسجين عند 0 دقيقة واستؤنف عند حوالي 260 دقيقة تحت الاستراتيجيتين. تم الحفاظ على التجارب عند درجات حرارة مختلفة (

توصيف الآلية الميكروسكوبية تحت استراتيجية WCA

أكسجين الشبكة

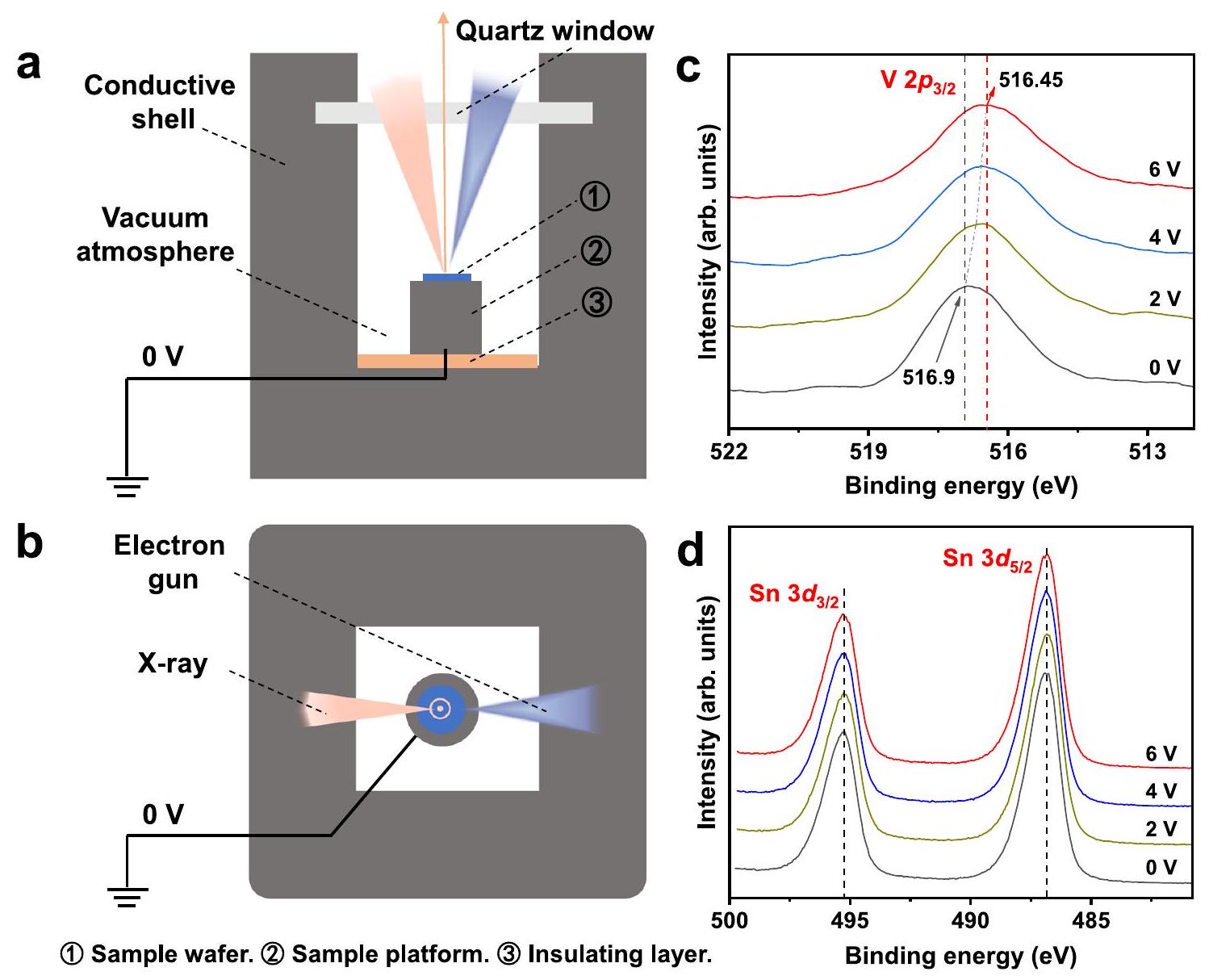

تم تحبيبه، وتم تطبيق تيارات مختلفة تحت ظروف فراغ، جهد التشغيل لـ

في التجارب في الحالة غير الموصلة (الشكل S22 والشكل 3b؛ الشكل S25 والشكل 5d)، يمكن رؤية أن وجود التيار الكهربائي كان مفتاح استراتيجية WCA.

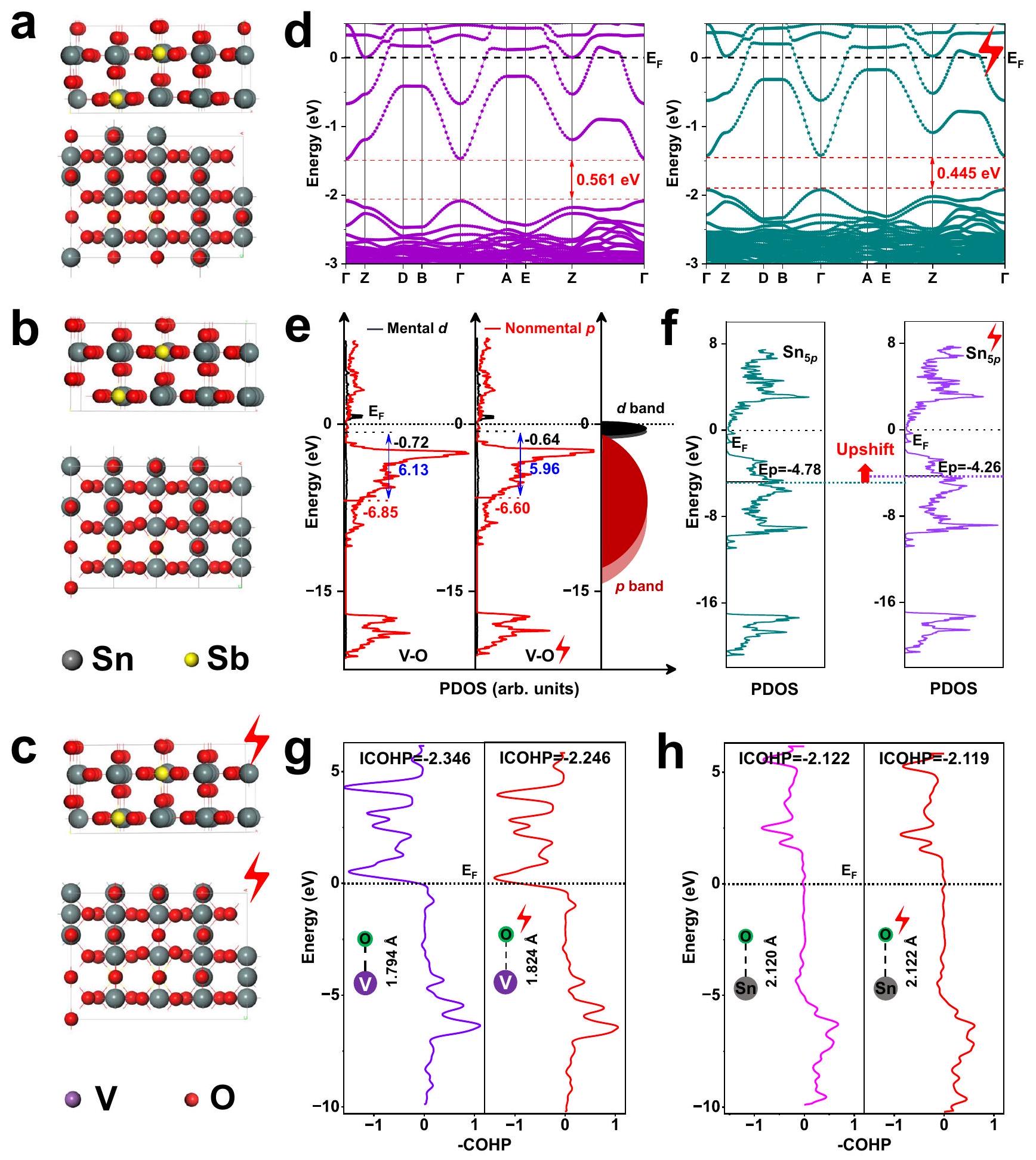

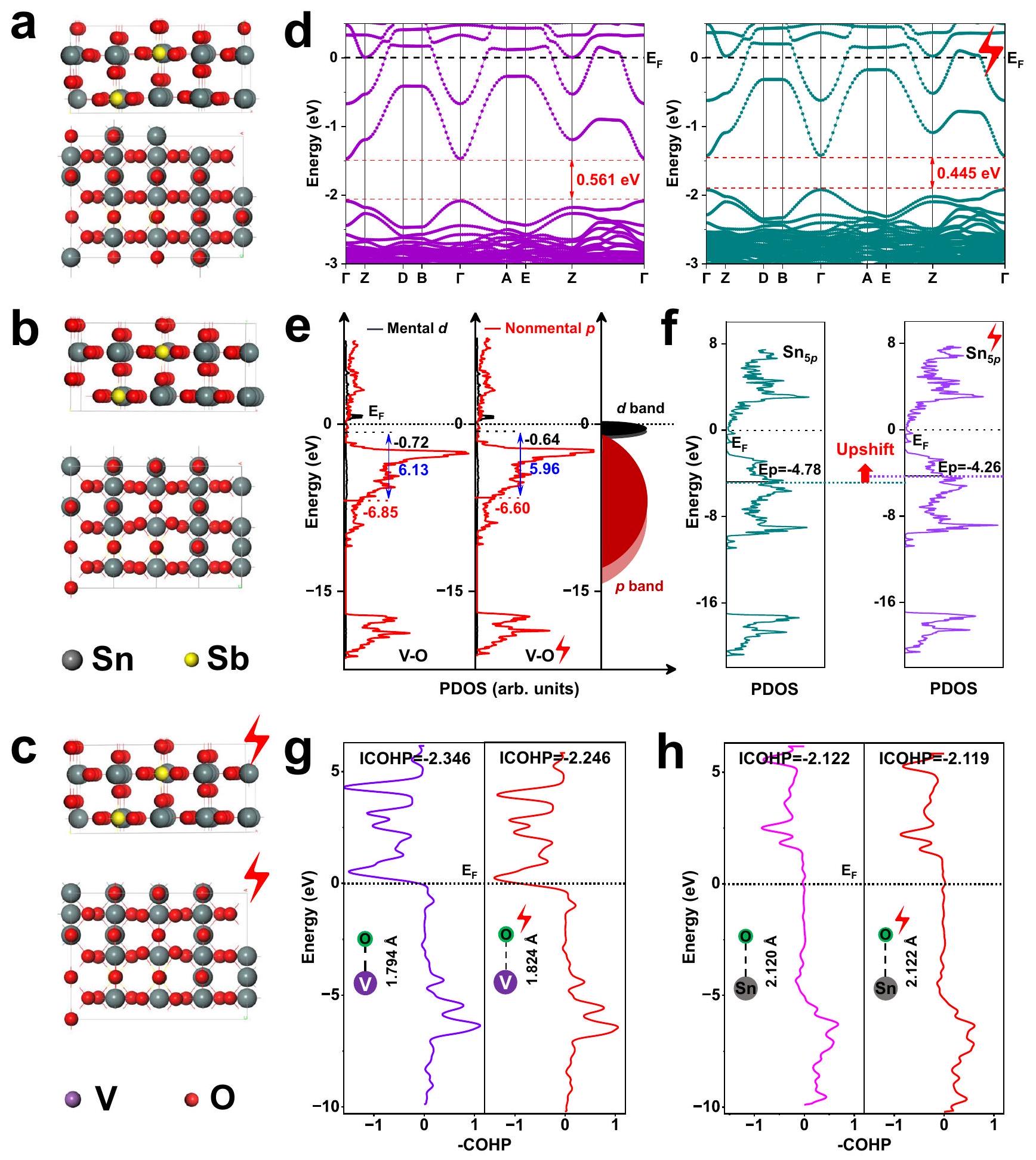

حساب DFT

أشارت إلى أن هجرة الإلكترونات أدت إلى ارتفاع طاقة الحالات المرتبطة وزيادة في نسبة المدارات المضادة للرابطة.

(ب، ج) 2VA. تحليل مقارن لأداء محفز 2VA قبل وبعد

تطبيق المجال الكهربائي عبر حسابات DFT: التوصيفات بما في ذلك (ب، ج) الهيكل البلوري، (د) هيكل النطاق، (هـ، و) كثافة الحالات، و(ز، ح) COHP. تم ضبط المجال الكهربائي على

تم اختبار النشاط تحت استراتيجية WCA (أو ما يسمى CA). أظهرت النتائج أن ECWC لعبت دورًا كبيرًا في استراتيجية WCA، وكانت فعالة جدًا لـ

البيانات المتعلقة بتوفير الطاقة تُقدّر وفقًا لانبعاثات غاز العادم السنوية ونسبة

الانتقائية)، وكان المحفز يتمتع بثبات ممتاز. تم تمييز تجارب DRIFTS في الموقع والدراسات الحركية تحت استراتيجية WCA، ووجد أن ECWC عزز بشكل كبير الاصطدامات الفعالة للجزيئات التفاعلية وتحلل المنتجات الوسيطة (النتريت، النترات). أظهرت تجارب الأكسجين العابر وتبادل الأكسجين النظائري أن ECWC عزز إنتاج وتحلل

تطبيق أنظمة التحفيز عند درجات حرارة منخفضة وتعزيز تطوير كهربائية المحفزات. يوفر هذا العمل استراتيجية جديدة لتحقيق نشاط أكبر مع استهلاك أقل للطاقة ويمكن أن يلعب دورًا إيجابيًا جدًا في تعزيز تحقيق الحياد الكربوني العالمي.

طرق

تركيب عينة

تقييم المحفز

تم حساب الشروط بواسطة الصيغ (1) و (2) على التوالي.

توصيف

WCA

فرن. المعالجة المسبقة في الأرجون عند

WCA

DRIFTS في الموقع

XPS في الموقع

تجارب تبادل الأكسجين النظائري

التفاصيل الحاسوبية

يستخدم على نطاق واسع لشرح التبادل والتفاعل بين المحفز والاختزال التحفيزي الانتقائي للأمونيا

توفر البيانات

References

- Lai, J. et al. A perspective on the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NO with

by supported catalysts. ACS Catal. 8, 6537-6551 (2018). - Han, L. et al. Selective catalytic reduction of

with by using novel catalysts: state of the art and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 119, 10916-10976 (2019). - He, G. et al. Superior oxidative dehydrogenation performance toward

determines the excellent low-temperature -SCR activity of Mn-based catalysts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 6995-7003 (2021). - Luo, L. et al. Recent advances in external fields-enhanced electrocatalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301276 (2023).

- Liu, H. et al. Active hydrogen-controlled

electroreduction: from mechanism understanding to catalyst design. Innov. Mater. 2, 100058 (2024). - Ma, Y. et al. Photothermal-magnetic synergistic effects in an electrocatalyst for efficient water splitting under optical-magnetic fields. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303741 (2023).

- Mei, X. et al. Decreasing the catalytic ignition temperature of diesel soot using electrified conductive oxide catalysts. Nat. Catal. 4, 1002-1011 (2021).

- Wismann, S. T. et al. Electrified methane reforming: a compact approach to greener industrial hydrogen production. Science 364, 756-759 (2019).

- Dou, L. et al. Enhancing

methanation over a metal foam structured catalyst by electric internal heating. Chem. Commun. 56, 205-208 (2020). - Chang, J. et al. Electrothermal water-gas shift reaction at room temperature with a silicomolybdate-based palladium single-atom catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218265 (2023).

- Chen, Z. et al. Metallic W/WO

solid-acid catalyst boosts hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline electrolyte. Nat. Commun. 14, 5363 (2023). - Yang, Y. et al. O-coordinated W-Mo dual-atom catalyst for pH universal electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba6586 (2020).

- Liu, H. et al. Eliminating over-oxidation of ruthenium oxides by niobium for highly stable electrocatalytic oxygen evolution in acidic media. Joule 7, 558-573 (2023).

- Qu, W. et al. Single-atom catalysts reveal the dinuclear characteristic of active sites in NO selective reduction with

. Nat. Commun. 11, 1532 (2020). - Luo, R. et al. Role of delocalized electrons on the doping effect in vanadia. Chem 9, 2255-2266 (2023).

- Qu, W. et al. An atom-pair design strategy for optimizing the synergistic electron effects of catalytic sites in NO selective reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212703 (2022).

- Chen, S. et al. Coverage-dependent behaviors of vanadium oxides for chemical looping oxidative dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22072-22079 (2020).

- Muñoz, M. et al. Continuous cauchy wavelet transform analyses of EXAFS spectra: a qualitative approach. Am. Mineral. 88, 694-700 (2003).

- Funke, H. et al. Wavelet analysis of extended x -ray absorption fine structure data. Phys. Rev. B 71, 094110 (2005).

- Timoshenko, J. et al. Wavelet data analysis of EXAFS spectra. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 920-925 (2009).

- Ek, M. et al. Visualizing atomic-scale redox dynamics in vanadium oxide-based catalysts. Nat. Commun. 8, 305 (2017).

- Fan, X. et al. From theory to experiment: cascading of thermocatalysis and electrolysis in oxygen evolution reactions. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 343-348 (2022).

- Yang, B. et al. Accelerating

electroreduction to multicarbon products via synergistic electric-thermal field on copper nanoneedles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3039-3049 (2022). - Li, X. et al. Microenvironment modulation of single-atom catalysts and their roles in electrochemical energy conversion. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb6833 (2020).

- Guan, D. et al. Light/electricity energy conversion and storage for a hierarchical porous

@CNT/SS cathode towards a flexible Li battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19518-19524 (2020). - Huang, H. et al. Kinetics of selective catalytic reduction of NO with

on Fe-ZSM-5 catalyst. Appl. Catal. Gen. 235, 241-251 (2002). -

. et al. Formation of active sites on transition metals through reaction-driven migration of surface atoms. Science 380, 70-76 (2023). - Ding, Y. et al. Pulsed electrocatalysis enables the stabilization and activation of carbon-based catalysts towards

production. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 316, 121688 (2022). - Liu, Y. et al. DRIFT Studies on the selectivity promotion mechanism of Ca-modified

catalysts for lowtemperature NO reduction with . J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 16582-16592 (2012). - Hadjiivanov, K. I. et al. Identification of neutral and charged

surface species by IR spectroscopy. Catal. Rev. 42, 71-144 (2000). - Yang, S. et al. Mechanism of

formation during the lowtemperature selective catalytic reduction of NO with over Mn-Fe spinel. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 10354-10362 (2014). - Jiang, C. et al. Data-driven interpretable descriptors for the structure-activity relationship of surface lattice oxygen on doped vanadium oxides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202206758 (2022).

- Fang, Y. et al. Dual activation of molecular oxygen and surface lattice oxygen in single atom

catalyst for CO oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202212273 (2022). - Topsøe, N.-Y. et al. Mechanism of the selective catalytic reduction of nitric oxide by ammonia elucidated by in situ on-line fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Science 265, 1217-1219 (1994).

- Hajar, Y. et al. Isotopic oxygen exchange study to unravel noble metal oxide/support interactions: the case of

and IrO nanoparticles supported on and YSZ. ChemCatChem 12, 2548-2555 (2020). - Wang, X. et al. Atomic-scale insights into surface lattice oxygen activation at the spinel/perovskite interface of

. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11720-11725 (2019). - Yi, D. et al. Regulating charge transfer of lattice oxygen in single-atom-doped titania for hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 132, 15989-15993 (2020).

- Lai, J. et al. Opening the black box: insights into the restructuring mechanism to steer catalytic performance. Innov. Mater. 1, 100020 (2023).

- Xiong, L. et al. Octahedral gold-silver nanoframes with rich crystalline defects for efficient methanol oxidation manifesting a COpromoting effect. Nat. Commun. 10, 3782 (2019).

- Wang, B. et al. Zinc-assisted cobalt ditelluride polyhedra inducing lattice strain to endow efficient adsorption-catalysis for high-energy lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 34, 2204403 (2022).

- Zheng, T. et al. Intercalated iridium diselenide electrocatalysts for efficient pH-universal water splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14764-14769 (2019).

- Gu, H. et al. Adjacent single-atom irons boosting molecular oxygen activation on

. Nat. Commun. 12, 5422 (2021). - Zang, Y. et al. Directing isomerization reactions of cumulenes with electric fields. Nat. Commun. 10, 4482 (2019).

- Yang, J. et al. High-efficiency V-Mediated

photocatalyst for PMS activation: modulation of energy band structure and enhancement of surface reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 339, 123149 (2023). - Zheng, C. et al. Enhanced active-site electric field accelerates enzyme catalysis. Nat. Chem. 15, 1715-1721 (2023).

- Zhao, S. et al. Structural transformation of highly active metal-organic framework electrocatalysts during the oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Energy 5, 881-890 (2020).

- Zhou, J. et al. Deciphering the modulation essence of

bands in Cobased compounds on Li-S chemistry. Joule 2, 2681-2693 (2018). - Gao, D. et al. Reversing free-electron transfer of

cocatalyst for optimizing antibonding-orbital occupancy enables high photocatalytic H2 evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e2O23O4559 (2023). - Huang, Z. et al. Interplay between remote single-atom active sites triggers speedy catalytic oxidation. Chem 8, 3008-3017 (2022).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15-50 (1996).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169-11186 (1996).

- Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558-561 (1993).

- Perdew, J. P. et al. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865-3868 (1996).

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787-1799 (2006).

- Grimme, S. et al. Dispersion-corrected mean-field electronic structure methods. Chem. Rev. 116, 5105-5154 (2016).

- Maintz, S. et al. Analytic projection from plane-wave and PAW wave functions and application to chemical-bonding analysis in solids. J. Comput. Chem. 34, 2557-2567 (2013).

- Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 59, 1758-1775 (1999).

- Deringer, V. L. & Tchougr, A. L. Crystal Orbital Hamilton Population (COHP) analysis as projected from plane-wave basis sets. J. Phys. Chem. A. 115, 5461-5466 (2011).

- Maintz, S. et al. Lobster: a tool to extract chemical bonding from plane-wave based DFT. J. Comput. Chem. 37, 1030-1035 (2016).

شكر وتقدير

من مقاطعة جيانغشي للعلماء الشباب المتميزين (20232ACB213004 (Y.Z.))، مؤسسة جيانغشي للعلوم الطبيعية (20212BAB213032 (K.L.))، جمعية تعزيز الابتكار للشباب من الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم (2018263 (Y.Z.))، خطة “الألفين المزدوجة” لمقاطعة جيانغشي (jxsq2020101047 (Y.Z.)) ومشاريع البحث من أكاديمية غانجيانغ للابتكار، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم (E355COO1 (Y.Z.) وE490C004 (K.L.)).

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

- (ن) تحقق من التحديثات

أكاديمية غانجيانغ للابتكار، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، رقم 1، طريق أكاديمية العلوم، غانتشو 341000، الصين. جامعة العلوم والتكنولوجيا الصينية، هيفي 230026، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي للمعادن النادرة، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، غانتشو 341000، الصين. شركة هانغتشو يانكيو لتكنولوجيا المعلومات المحدودة، هانغتشو 310003، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي للدولة لاستغلال موارد المعادن النادرة، معهد تشانغتشون للكيمياء التطبيقية، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، تشانغتشون 130022، الصين. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: دايينغ تشنغ، كايجيه ليو. البريد الإلكتروني: liukaijie@gia.cas.cn; yibozhang@gia.cas.cn; songsy@ciac.ac.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51034-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39107273

Publication Date: 2024-08-06

Essential features of weak current for excellent enhancement of

Accepted: 25 July 2024

Published online: 06 August 2024

Abstract

Human society is facing increasingly serious problems of environmental pollution and energy shortage, and up to now, achieving high

reacts

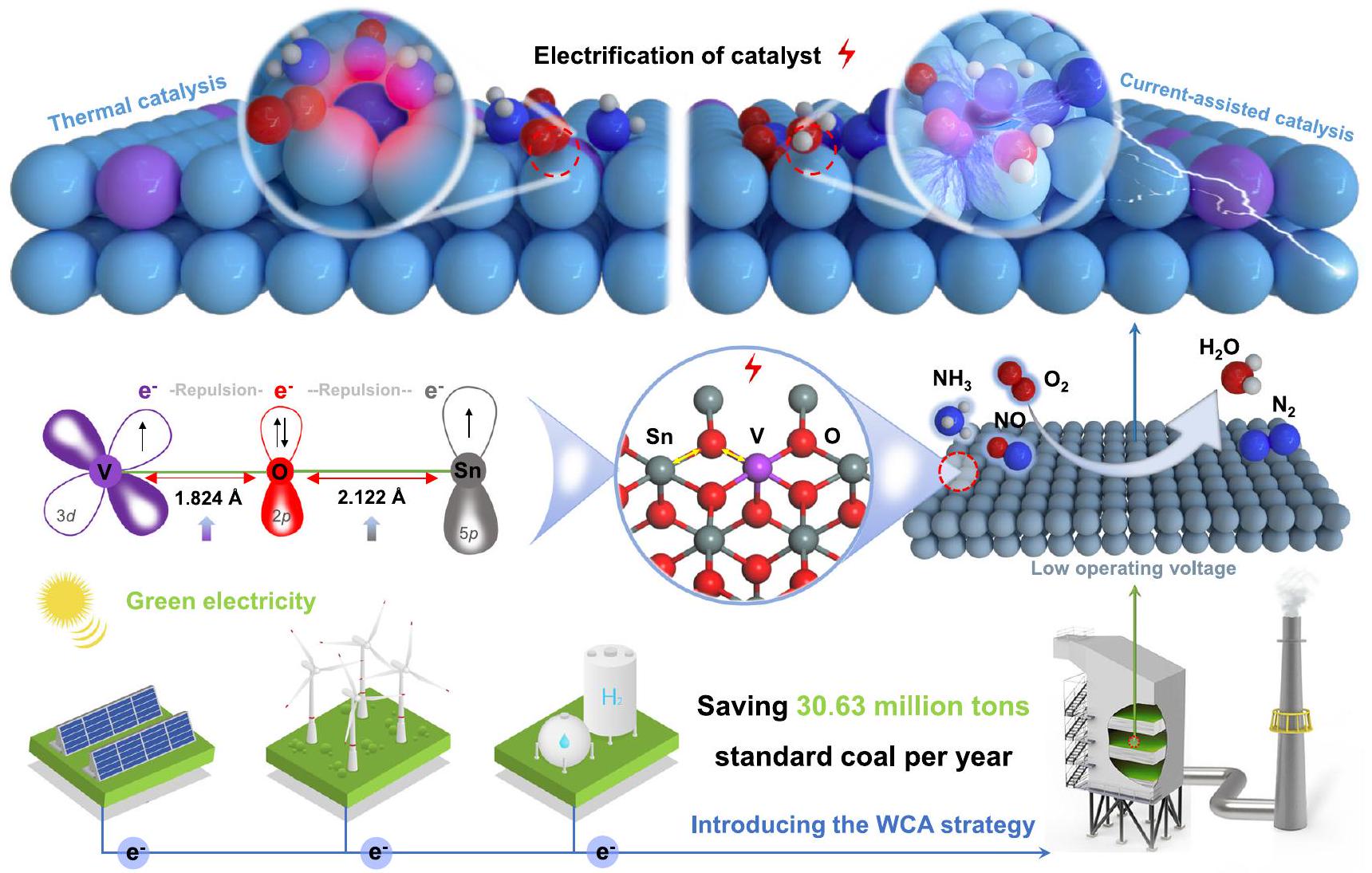

in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) experiments, and kinetic studies were used to elucidate the mechanism of the strategy. At the microscopic level, the effects of electron migration on binding energy and chemical bonds were studied by the in situ XPS experiments and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. That deeply revealed the mechanism of WCA enhancement catalysis. In summary, the work confirmed the significant role played by the WCA strategy in enhancing ultra-lowtemperature activity and elucidated the catalytic mechanism under the WCA strategy from the perspective of electron behavior and chemical bonds.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the catalyst optimization process

Identification of

a HAADF TEM image and EDS mappings of the 2VNA catalyst. Scale bar, 2 nm ; Scale bar in the EDS mapping images,

spacing aligned with the theoretical value, indicating that the structure of the 2VNA catalyst remained consistent with the structure of

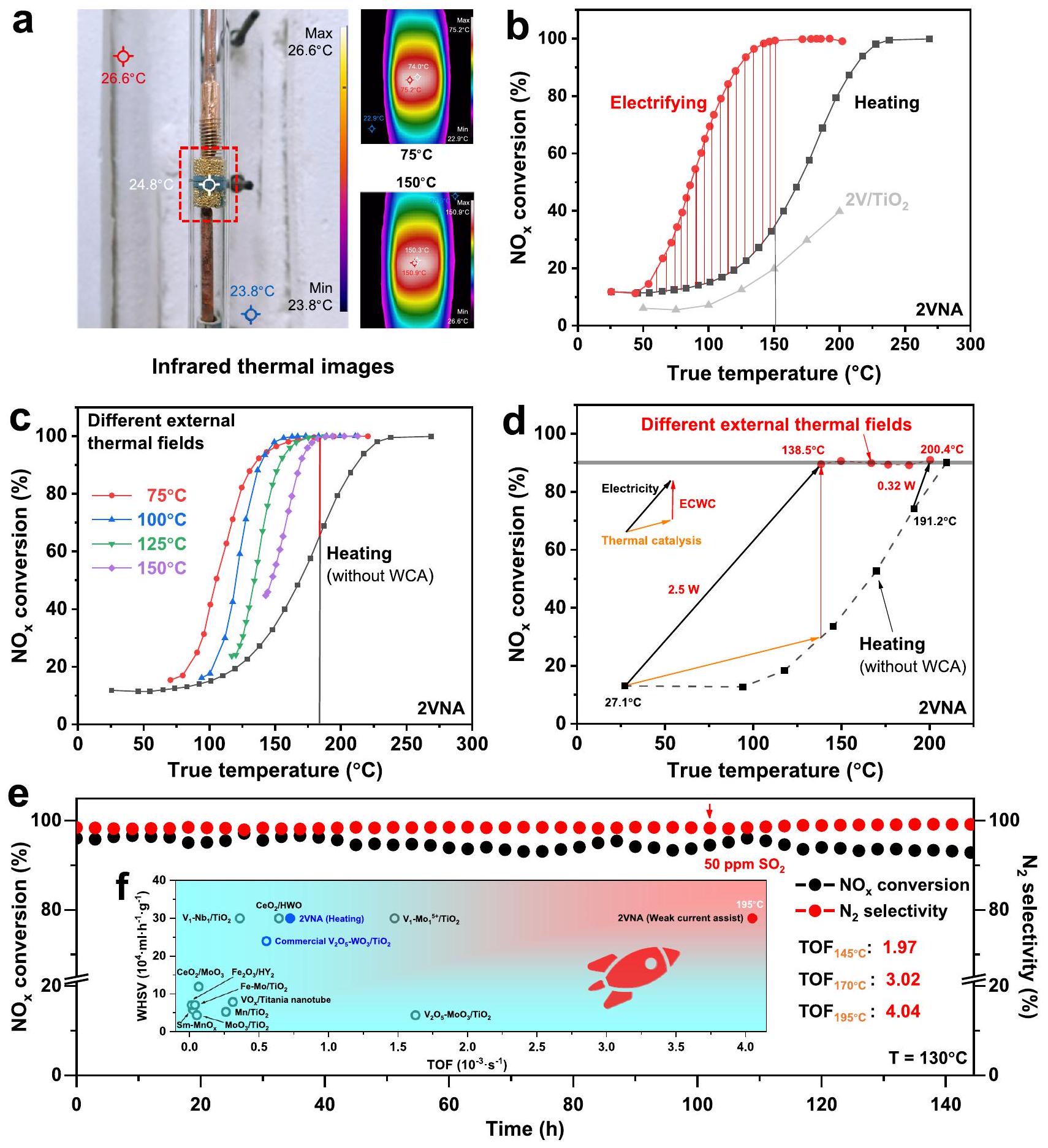

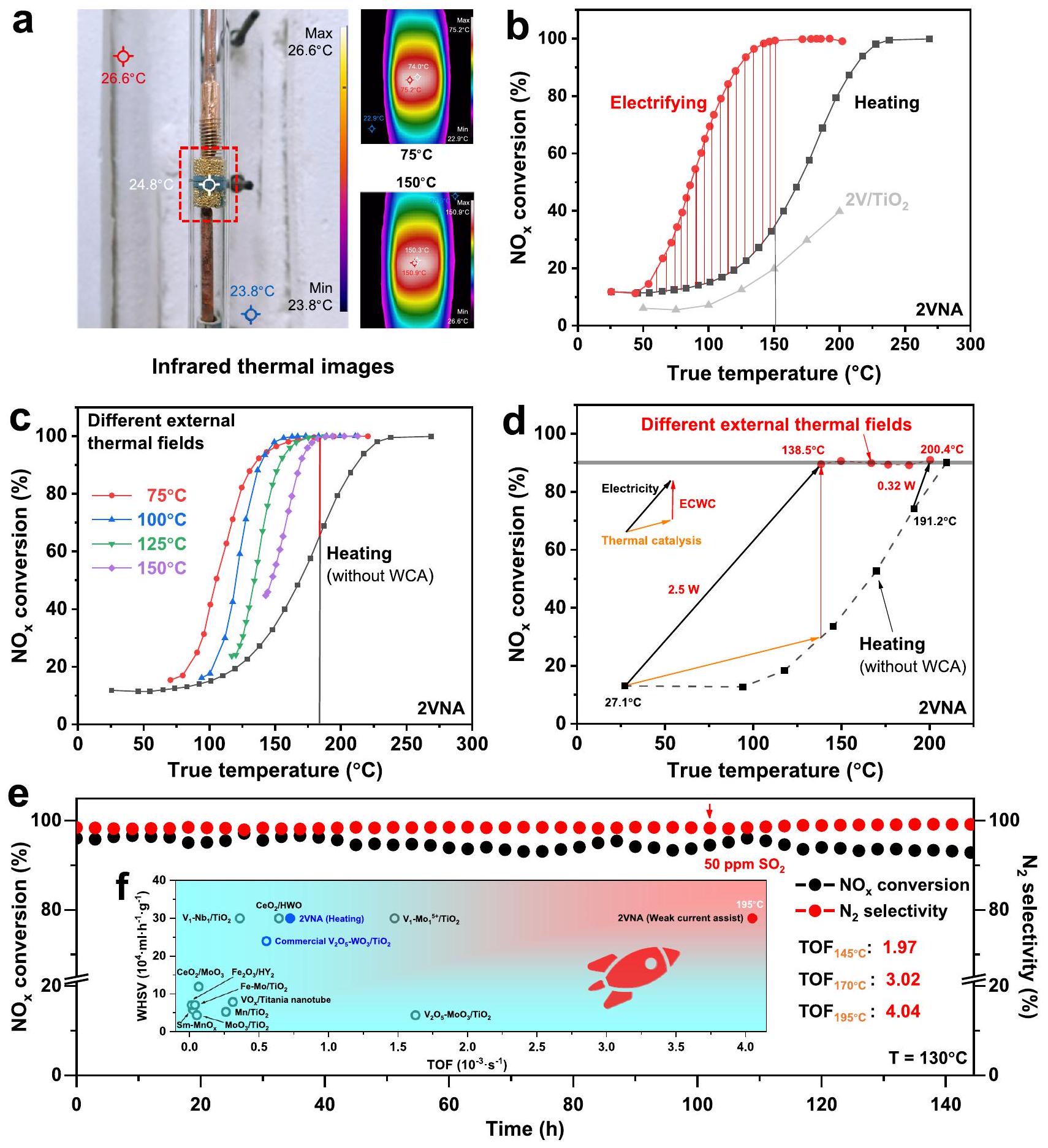

Excellent catalytic activity under the WCA strategy

negatively correlated with the temperature (shown in Fig. S14). The energy can be converted between different forms

e Stability of

the strategy. From an energy-saving perspective, the WCA strategy consumed only

commercial and reported SCR catalysts at the same or higher WHSV. Based on the above results, it was concluded that the strategy reduced energy consumption and improved catalytic activity

strategy with the external thermal field.

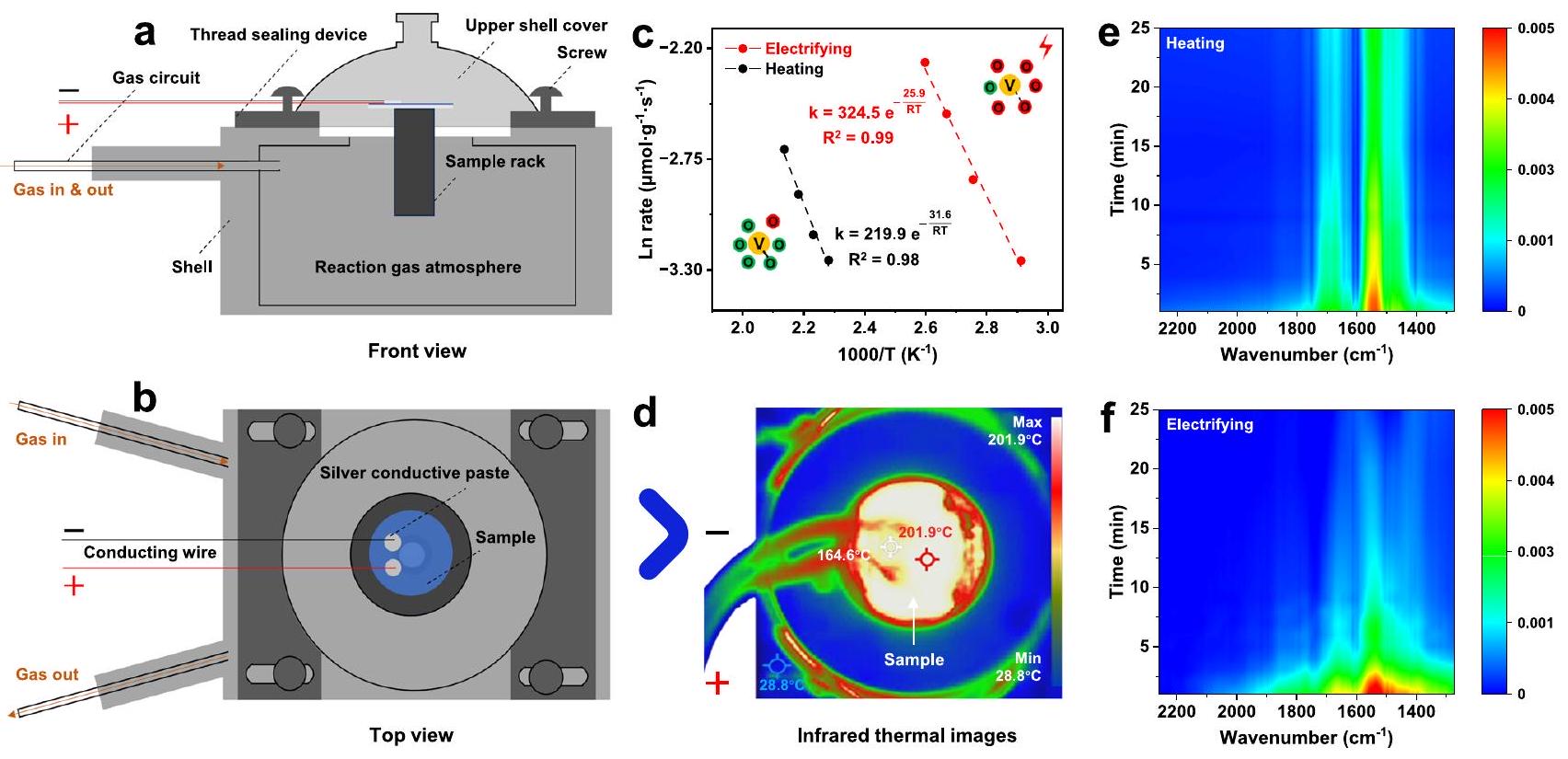

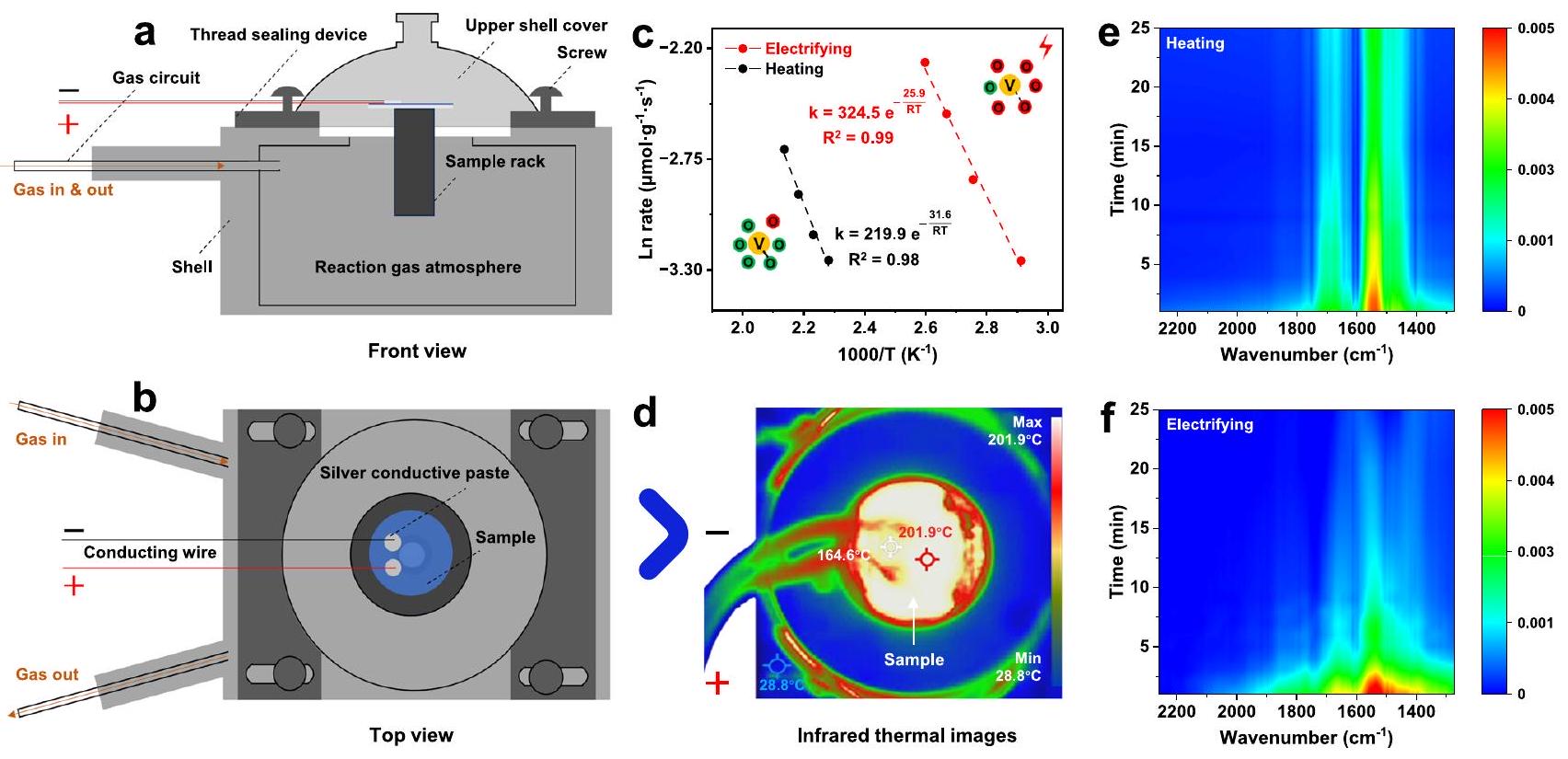

Characterization of mesoscopic mechanism under the WCA strategy

kinetics data, it was evident that the ECWC could activate more inert sites, facilitate the decomposition of intermediate products like bridged monodentate nitrite and bidentate nitrate, and eventually enhance the SCR reaction.

temperatures (

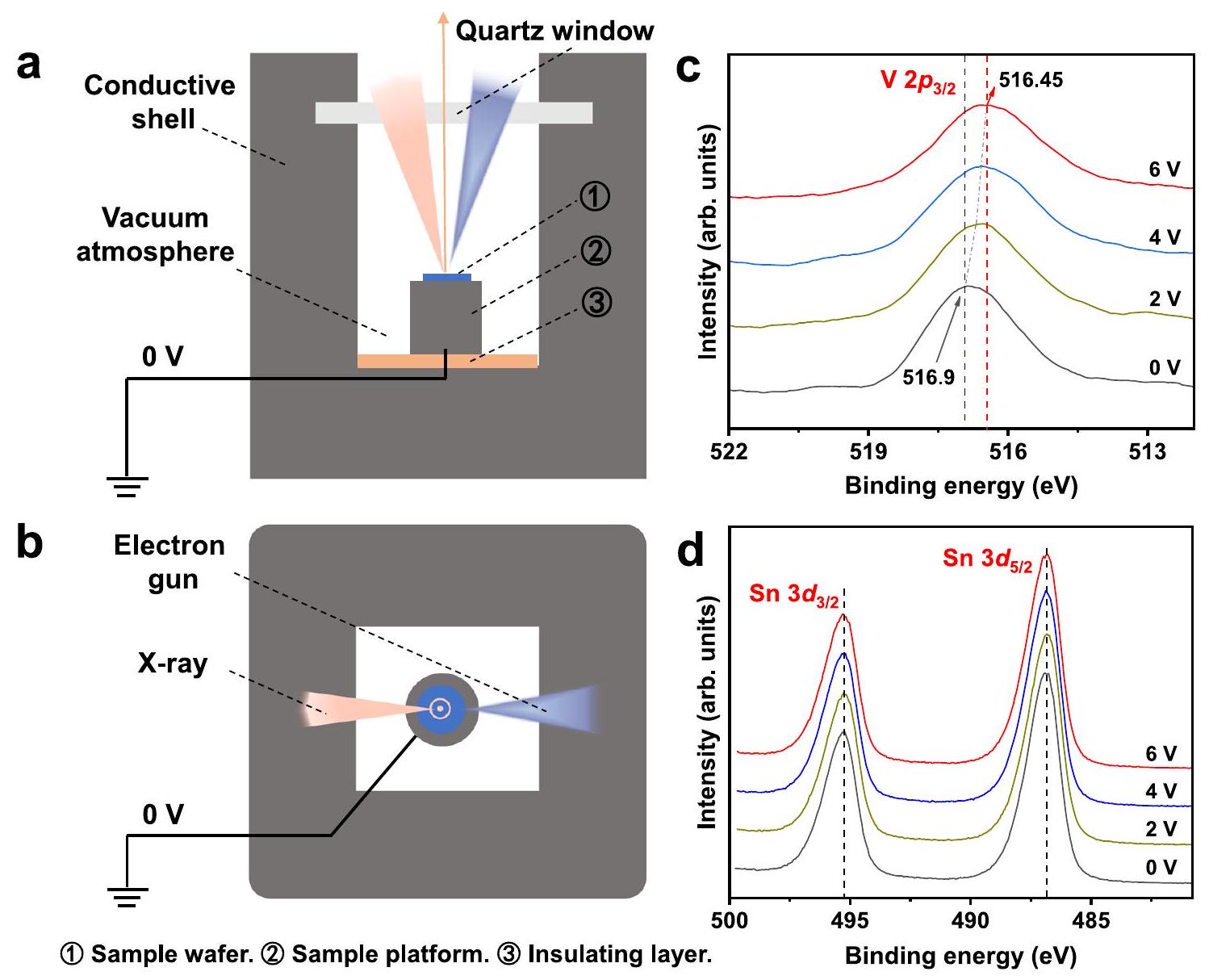

Characterization of the microcosmic mechanism under the WCA strategy

lattice oxygen (

was tableted, and different current were applied under vacuum conditions, the operating voltages of

experiments in the non-conducting state (Fig. S22 and Fig. 3b; Fig. S25 and Fig. 5d), it could be seen that the existence of electric current was the key of WCA strategy.

DFT calculation

indicated that electron migration resulted in an elevation of the energy of bonded states and an increase in the proportion of antibonding orbitals

(b, c) 2VA. Comparative analysis of the 2VA catalyst performance before and after

electric field application via DFT calculations: characterizations including (b, c) crystalline structure, (d) band Structure, (e, f) density of states, and (g, h) COHP. The electric field is set to

activity was tested under the WCA (or called CA) strategy. The results showed that the ECWC played a significant role in the WCA strategy, and it was very effective for

calculations. Energy-saving data is estimated according to the annual flue gas emissions and the proportion of

selectivity), and the catalyst had excellent stability. In-situ DRIFTS experiments and kinetic studies were characterized under the WCA strategy, and it was found that ECWC significantly promoted the effective collisions of reactive molecules and the decomposition of intermediate products (nitrite, nitrate). Oxygen transient and isotope oxygen exchange experiments showed that ECWC promoted the production and decomposition of

application of low-temperature catalytic systems and promote the development of catalyst electrification. This work provides a new strategy for achieving greater activity with less energy consumption and can play a very positive role in promoting the realization of global carbon neutrality.

Methods

Sample synthesis

Catalyst evaluation

conditions were calculated by formulas (1) and (2), respectively.

Characterization

WCA

furnace. Pretreatment in Ar at

WCA

In situ DRIFTS

In situ XPS

Isotopic oxygen exchange experiments

Computational details

is widely used to explain the exchange-correlation between the catalyst and selective catalytic reduction of ammonia

Data availability

References

- Lai, J. et al. A perspective on the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NO with

by supported catalysts. ACS Catal. 8, 6537-6551 (2018). - Han, L. et al. Selective catalytic reduction of

with by using novel catalysts: state of the art and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 119, 10916-10976 (2019). - He, G. et al. Superior oxidative dehydrogenation performance toward

determines the excellent low-temperature -SCR activity of Mn-based catalysts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 6995-7003 (2021). - Luo, L. et al. Recent advances in external fields-enhanced electrocatalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301276 (2023).

- Liu, H. et al. Active hydrogen-controlled

electroreduction: from mechanism understanding to catalyst design. Innov. Mater. 2, 100058 (2024). - Ma, Y. et al. Photothermal-magnetic synergistic effects in an electrocatalyst for efficient water splitting under optical-magnetic fields. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303741 (2023).

- Mei, X. et al. Decreasing the catalytic ignition temperature of diesel soot using electrified conductive oxide catalysts. Nat. Catal. 4, 1002-1011 (2021).

- Wismann, S. T. et al. Electrified methane reforming: a compact approach to greener industrial hydrogen production. Science 364, 756-759 (2019).

- Dou, L. et al. Enhancing

methanation over a metal foam structured catalyst by electric internal heating. Chem. Commun. 56, 205-208 (2020). - Chang, J. et al. Electrothermal water-gas shift reaction at room temperature with a silicomolybdate-based palladium single-atom catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218265 (2023).

- Chen, Z. et al. Metallic W/WO

solid-acid catalyst boosts hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline electrolyte. Nat. Commun. 14, 5363 (2023). - Yang, Y. et al. O-coordinated W-Mo dual-atom catalyst for pH universal electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba6586 (2020).

- Liu, H. et al. Eliminating over-oxidation of ruthenium oxides by niobium for highly stable electrocatalytic oxygen evolution in acidic media. Joule 7, 558-573 (2023).

- Qu, W. et al. Single-atom catalysts reveal the dinuclear characteristic of active sites in NO selective reduction with

. Nat. Commun. 11, 1532 (2020). - Luo, R. et al. Role of delocalized electrons on the doping effect in vanadia. Chem 9, 2255-2266 (2023).

- Qu, W. et al. An atom-pair design strategy for optimizing the synergistic electron effects of catalytic sites in NO selective reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212703 (2022).

- Chen, S. et al. Coverage-dependent behaviors of vanadium oxides for chemical looping oxidative dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22072-22079 (2020).

- Muñoz, M. et al. Continuous cauchy wavelet transform analyses of EXAFS spectra: a qualitative approach. Am. Mineral. 88, 694-700 (2003).

- Funke, H. et al. Wavelet analysis of extended x -ray absorption fine structure data. Phys. Rev. B 71, 094110 (2005).

- Timoshenko, J. et al. Wavelet data analysis of EXAFS spectra. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 920-925 (2009).

- Ek, M. et al. Visualizing atomic-scale redox dynamics in vanadium oxide-based catalysts. Nat. Commun. 8, 305 (2017).

- Fan, X. et al. From theory to experiment: cascading of thermocatalysis and electrolysis in oxygen evolution reactions. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 343-348 (2022).

- Yang, B. et al. Accelerating

electroreduction to multicarbon products via synergistic electric-thermal field on copper nanoneedles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3039-3049 (2022). - Li, X. et al. Microenvironment modulation of single-atom catalysts and their roles in electrochemical energy conversion. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb6833 (2020).

- Guan, D. et al. Light/electricity energy conversion and storage for a hierarchical porous

@CNT/SS cathode towards a flexible Li battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19518-19524 (2020). - Huang, H. et al. Kinetics of selective catalytic reduction of NO with

on Fe-ZSM-5 catalyst. Appl. Catal. Gen. 235, 241-251 (2002). -

. et al. Formation of active sites on transition metals through reaction-driven migration of surface atoms. Science 380, 70-76 (2023). - Ding, Y. et al. Pulsed electrocatalysis enables the stabilization and activation of carbon-based catalysts towards

production. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 316, 121688 (2022). - Liu, Y. et al. DRIFT Studies on the selectivity promotion mechanism of Ca-modified

catalysts for lowtemperature NO reduction with . J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 16582-16592 (2012). - Hadjiivanov, K. I. et al. Identification of neutral and charged

surface species by IR spectroscopy. Catal. Rev. 42, 71-144 (2000). - Yang, S. et al. Mechanism of

formation during the lowtemperature selective catalytic reduction of NO with over Mn-Fe spinel. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 10354-10362 (2014). - Jiang, C. et al. Data-driven interpretable descriptors for the structure-activity relationship of surface lattice oxygen on doped vanadium oxides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202206758 (2022).

- Fang, Y. et al. Dual activation of molecular oxygen and surface lattice oxygen in single atom

catalyst for CO oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202212273 (2022). - Topsøe, N.-Y. et al. Mechanism of the selective catalytic reduction of nitric oxide by ammonia elucidated by in situ on-line fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Science 265, 1217-1219 (1994).

- Hajar, Y. et al. Isotopic oxygen exchange study to unravel noble metal oxide/support interactions: the case of

and IrO nanoparticles supported on and YSZ. ChemCatChem 12, 2548-2555 (2020). - Wang, X. et al. Atomic-scale insights into surface lattice oxygen activation at the spinel/perovskite interface of

. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11720-11725 (2019). - Yi, D. et al. Regulating charge transfer of lattice oxygen in single-atom-doped titania for hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 132, 15989-15993 (2020).

- Lai, J. et al. Opening the black box: insights into the restructuring mechanism to steer catalytic performance. Innov. Mater. 1, 100020 (2023).

- Xiong, L. et al. Octahedral gold-silver nanoframes with rich crystalline defects for efficient methanol oxidation manifesting a COpromoting effect. Nat. Commun. 10, 3782 (2019).

- Wang, B. et al. Zinc-assisted cobalt ditelluride polyhedra inducing lattice strain to endow efficient adsorption-catalysis for high-energy lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 34, 2204403 (2022).

- Zheng, T. et al. Intercalated iridium diselenide electrocatalysts for efficient pH-universal water splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14764-14769 (2019).

- Gu, H. et al. Adjacent single-atom irons boosting molecular oxygen activation on

. Nat. Commun. 12, 5422 (2021). - Zang, Y. et al. Directing isomerization reactions of cumulenes with electric fields. Nat. Commun. 10, 4482 (2019).

- Yang, J. et al. High-efficiency V-Mediated

photocatalyst for PMS activation: modulation of energy band structure and enhancement of surface reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 339, 123149 (2023). - Zheng, C. et al. Enhanced active-site electric field accelerates enzyme catalysis. Nat. Chem. 15, 1715-1721 (2023).

- Zhao, S. et al. Structural transformation of highly active metal-organic framework electrocatalysts during the oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Energy 5, 881-890 (2020).

- Zhou, J. et al. Deciphering the modulation essence of

bands in Cobased compounds on Li-S chemistry. Joule 2, 2681-2693 (2018). - Gao, D. et al. Reversing free-electron transfer of

cocatalyst for optimizing antibonding-orbital occupancy enables high photocatalytic H2 evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e2O23O4559 (2023). - Huang, Z. et al. Interplay between remote single-atom active sites triggers speedy catalytic oxidation. Chem 8, 3008-3017 (2022).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15-50 (1996).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169-11186 (1996).

- Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558-561 (1993).

- Perdew, J. P. et al. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865-3868 (1996).

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787-1799 (2006).

- Grimme, S. et al. Dispersion-corrected mean-field electronic structure methods. Chem. Rev. 116, 5105-5154 (2016).

- Maintz, S. et al. Analytic projection from plane-wave and PAW wave functions and application to chemical-bonding analysis in solids. J. Comput. Chem. 34, 2557-2567 (2013).

- Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 59, 1758-1775 (1999).

- Deringer, V. L. & Tchougr, A. L. Crystal Orbital Hamilton Population (COHP) analysis as projected from plane-wave basis sets. J. Phys. Chem. A. 115, 5461-5466 (2011).

- Maintz, S. et al. Lobster: a tool to extract chemical bonding from plane-wave based DFT. J. Comput. Chem. 37, 1030-1035 (2016).

Acknowledgements

of Jiangxi Province for Distinguished Young Scholars (20232ACB213004 (Y.Z.)), Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20212BAB213032 (K.L.)), Youth Innovation Promotion Association of Chinese Academy of Sciences (2018263 (Y.Z.)), Jiangxi Province “Double Thousand Plan” (jxsq2020101047 (Y.Z.)) and the Research Projects of Ganjiang Innovation Academy, Chinese Academy of Sciences (E355COO1 (Y.Z.) and E490C004 (K.L.)).

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024

- (n) Check for updates

Ganjiang Innovation Academy, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No.1, Science Academy Road, Ganzhou 341000, China. University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China. Key Laboratory of Rare Earths, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Ganzhou 341000, China. Hangzhou Yanqu Information Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou 310003, China. State Key Laboratory of Rare Earth Resource Utilization, Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun 130022, China. These authors contributed equally: Daying Zheng, Kaijie Liu. e-mail: liukaijie@gia.cas.cn; yibozhang@gia.cas.cn; songsy@ciac.ac.cn