DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00681-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38649365

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-22

النظام الغذائي والميكروبيوم المعوي لدى مرضى باركنسون

الملخص

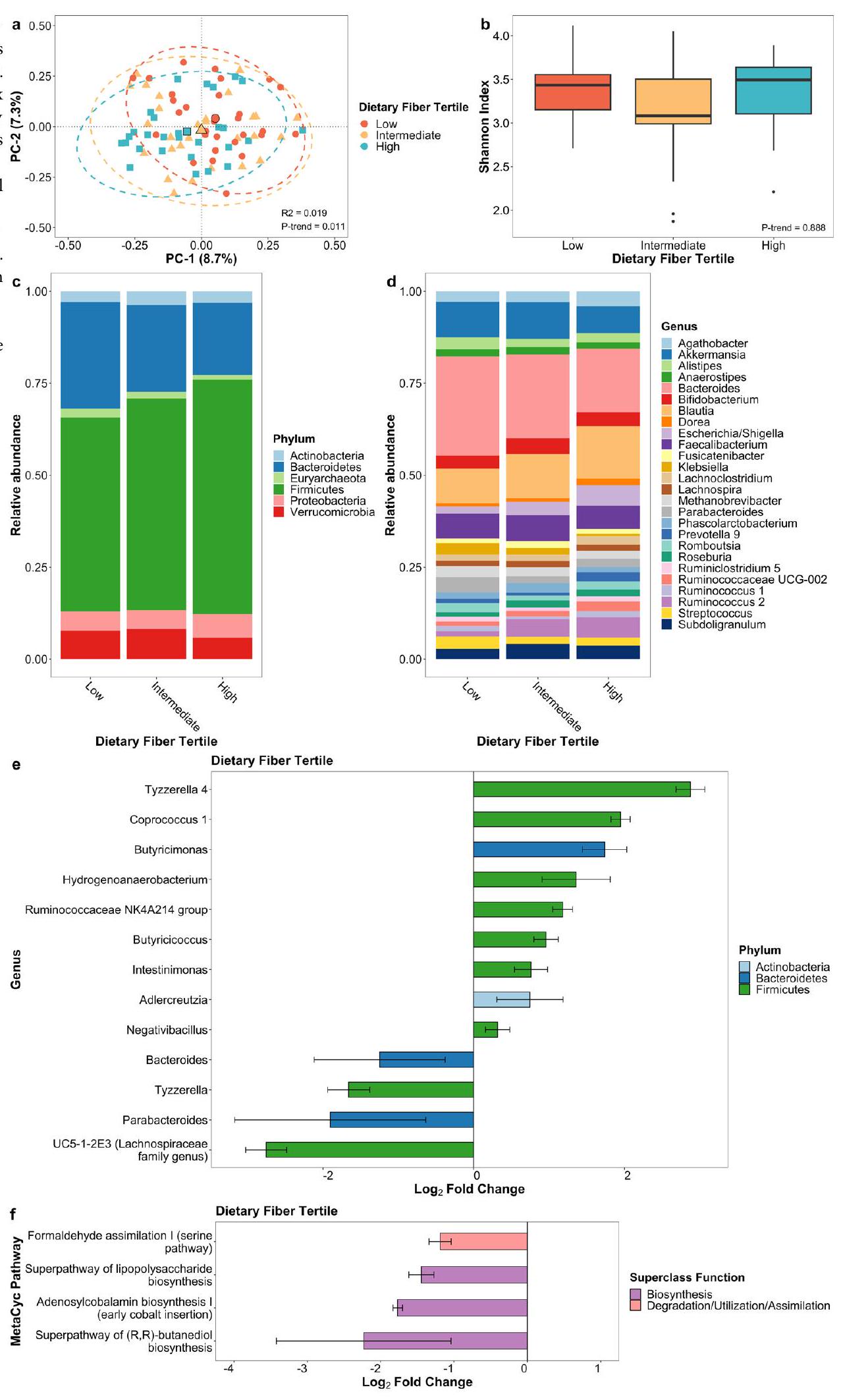

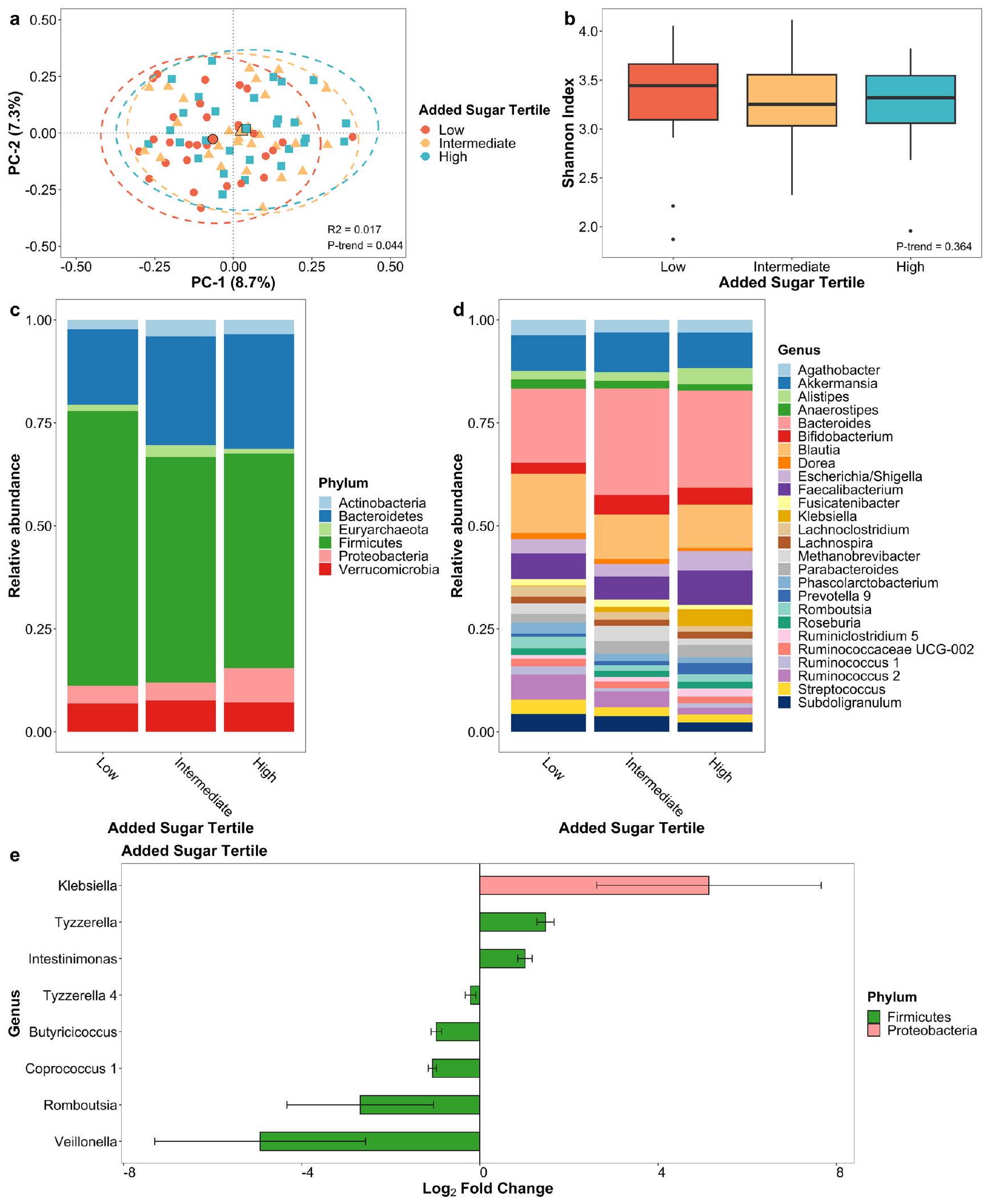

لقد تم اقتراح أن الميكروبات المعوية تؤثر على مرض باركنسون (PD) عبر محور الأمعاء-الدماغ. هنا، نفحص الارتباطات بين النظام الغذائي وتركيب الميكروبيوم المعوي ومساراته الوظيفية المتوقعة لدى مرضى PD. قمنا بتقييم الميكروبات المعوية في عينات البراز من 85 مريضًا بـ PD في وسط كاليفورنيا باستخدام تسلسل جين 16S rRNA. تم تقييم جودة النظام الغذائي من خلال حساب مؤشر الأكل الصحي 2015 (HEI-2015) بناءً على استبيان تاريخ النظام الغذائي II. قمنا بفحص ارتباطات جودة النظام الغذائي، والألياف، واستهلاك السكر المضاف مع تنوع الميكروبات، والتركيب، ووفرة الأنواع، والملفات الميتاجينومية المتوقعة، مع ضبط العمر، والجنس، والعرق/الاثنية، ومنصة التسلسل. كانت درجات HEI الأعلى واستهلاك الألياف مرتبطين بزيادة في البكتيريا المنتجة للزبدات المضادة للالتهابات المحتملة، مثل الأجناس Butyricicoccus وCoprococcus 1. على العكس، كان استهلاك السكر المضاف الأعلى مرتبطًا بزيادة في البكتيريا المحتملة المسببة للالتهابات، مثل الأجناس Klebsiella. اقترحت الميتاجينوميات التنبؤية أن الجينات البكتيرية المعنية في تخليق الليبوساكاريد انخفضت مع ارتفاع درجات HEI، بينما يشير الانخفاض المتزامن في الجينات المعنية في تحلل التورين إلى انخفاض الالتهاب العصبي. وجدنا أن النظام الغذائي الصحي، والألياف، واستهلاك السكر المضاف يؤثرون على تركيب الميكروبيوم المعوي ووظيفته الميتاجينومية المتوقعة لدى مرضى PD. وهذا يشير إلى أن النظام الغذائي الصحي قد يدعم الميكروبيوم المعوي الذي له تأثير إيجابي على خطر وتقدم مرض PD.

النتائج

خصائص المجموعة التحليلية

جودة النظام الغذائي

استهلاك الألياف الغذائية

تناول السكر المضاف

تحليل الحساسية

نقاش

| منخفض

|

HEI-2015 متوسط (

|

عالي

|

|

| العمر (بالسنوات) | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 75.6 (7.88) | 73.4 (8.55) | ٧٢.٥ (٩.٣٩) |

| نطاق | ٥٤-٨٨ | 51-86 | ٥٦-٩٠ |

| جنس | |||

| ذكر | 19 (65.5%) | 20 (71.4%) | 18 (64.3%) |

| أنثى | 10 (34.5%) | 8 (28.6%) | 10 (35.7%) |

| العرق/الاثنية | |||

| الأبيض غير اللاتيني | 24 (82.8%) | 22 (78.6%) | 23 (82.1%) |

| غير الأبيض أو اللاتيني | 5 (17.2%) | 6 (21.4%) | 5 (17.9%) |

| منصة | |||

| هاي سيك | ٢٦ (٨٩.٧٪) | 21 (75.0%) | 20 (71.4%) |

| مي سيك | 3 (10.3%) | 7 (25.0%) | 8 (28.6%) |

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم (BMI)

|

|||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | ٢٧.١ (٥.٥٦) | ٢٨.٥ (٥.٨٣) | 25.8 (5.11) |

| نطاق | 16.2-39.7 | 14-41.3 | 14.8-38.3 |

| التعليم (السنوات) | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 14.9 (2.50) | 14.5 (3.64) | 16.8 (4.77) |

| نطاق | 12-22 | ٤-٢٢ | ٤-٢٧ |

| حالة التدخين | |||

| أبداً | 17 (58.6%) | 19 (67.9%) | 17 (60.7%) |

| أبداً | 12 (41.4%) | 9 (32.1%) | 11 (39.3%) |

| تناول الكحول (غ/يوم) | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 2.59 (6.25) | 9.24 (17.7) | 3.95 (7.47) |

| نطاق | 0-26.4 | 0-76.8 | 0-28.3 |

| تناول الكافيين (ملغ/يوم) | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 147 (184) | 195 (308) | ٢٠٣ (٢٥٢) |

| نطاق | 2.67-611 | 2.96-1430 | 0.52-1020 |

| مدخول الطاقة (سعرة حرارية/يوم) | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 1940 (914) | ٢٠٨٠ (٨٦٦) | 1850 (811) |

| نطاق | ٦٢٧-٤٠٠٠ | 731-4430 | 653-4050 |

| العمر عند تشخيص مرض باركنسون (سنوات) | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 64.3 (9.04) | 64.7 (8.46) | 62.4 (11.1) |

| نطاق | 50-84 | 42-75 | 41-81 |

| مدة PD (بالسنوات) | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 10.2 (5.28) | 9.14 (3.78) | 9.79 (4.84) |

| نطاق | 4-20 | 3-20 | 2-20 |

| إمساك | |||

| لا | 8 (27.6%) | 13 (46.4%) | 14 (50.0%) |

| نعم | 21 (72.4%) | 15 (53.6%) | 14 (50.0%) |

| MDS-UPDRS IA | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 3.78 (3.11) | 3.77 (2.62) | 3.38 (2.98) |

| نطاق | 0-10 | 0-11 | 0-11 |

| MDS-UPDRS IB | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 11.6 (4.50) | 9.33 (4.95) | 9.47 (5.20) |

| نطاق | ٤-٢٢ | ٢-٢٤ | 1-21 |

| MDS-UPDRS II | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 17.5 (9.09) | 16.4 (7.80) | 14.8 (8.57) |

| نطاق | 1-41 | ٣-٤٠ | 2-40 |

| منخفض

|

HEI-2015 متوسط (

|

عالي

|

|

| MDS-UPDRS III | |||

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | ٢٨.٣ (١٢.٢) | ٢٨.٣ (١٠.٧) | ٢٤.٥ (١٣.٤) |

| نطاق | 11-58 | 8-51 | 3-58.2 |

(الجدول التكميلي 3). بشكل محدد، مع اتباع نظام غذائي أكثر صحة، لاحظنا انخفاضًا في وفرة البكتيريا المحتملة المسببة للالتهابات التي توجد عادة بكثرة في مرضى باركنسون مقارنةً بالضوابط. علاوة على ذلك، زاد النظام الغذائي الصحي لدى المشاركين في دراستنا من وفرة البكتيريا المحتملة المضادة للالتهابات التي تكون عادةً ناقصة في مرضى باركنسون مقارنةً بالضوابط. إحدى النتائج المترتبة على اكتشافاتنا هي أن الروابط السابقة المبلغ عنها بين الميكروبيوم ومرض باركنسون قد تكون ناتجة، على الأقل جزئيًا، عن الاختلافات الغذائية بين مرضى باركنسون والأشخاص الضوابط.

في الدماغ

أن نظامًا غذائيًا أفضل في مرضى باركنسون كان مرتبطًا بمستويات أعلى من الأجناس التابعة لعائلة رامينوكوكاسيا، مما قد يدعم استقلاب التورين ويؤدي إلى تقليل تدهور التورين بواسطة ميكروبات الأمعاء.

عند مستوى الجنس حسب تناول السكر المضاف بعد ضبطها حسب العمر والجنس والعرق ومنصة التسلسل. الأنواع في (هـ) مرتبطة بفئة تناول السكر المضاف التصنيفية عند

حجم، مما يحد من التحكم في المتغيرات المربكة وتحديد الأنواع الميكروبية الأقل انتشارًا، وتصميم مقطعي، مما لا يسمح لنا باستنتاج الزمنية أو السببية للعلاقات. لمعالجة هذه القيود واستكشاف تأثير النظام الغذائي والتفاعل بين النظام الغذائي والميكروبيوم على تقدم مرض باركنسون، يجب أن تستفيد الدراسات اللاحقة من بيانات طولية حول النظام الغذائي والميكروبيوم وتقدم المرض. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كانت المسارات الميتاجينومية مستندة إلى بيانات ميتاجينومية متوقعة وليست الميتاجينوم الفعلي. لذلك، يجب أن تأخذ الأبحاث المستقبلية في الاعتبار استخدام تسلسل شوتغن وعلوم الأيض لتوفير فهم أكثر قوة لتأثير النظام الغذائي على تركيب ووظيفة الميكروبيوم المعوي في مرض باركنسون. قد تؤدي أخطاء القياس المتأصلة في تقييمات DHQ II أيضًا إلى تصنيف خاطئ للتعرضات الغذائية. في المستقبل، نأمل أن نكون قادرين على تقييم استقرار جودة النظام الغذائي بمرور الوقت في مجموعة مرضانا، ولكن في الوقت الحالي يجب أن نفترض أن النظام الغذائي لم يتغير بشكل كبير خلال الفجوة بين تقييم النظام الغذائي وجمع البراز (متوسط 6 أشهر). أظهرت الأبحاث السابقة أن استقرار درجات HEI2015 المشتقة من DHQ مستقر على مدى فترة سنة واحدة

طرق

مجموعة الدراسة

تقييم النظام الغذائي والمتغيرات المصاحبة

مقياس لجودة النظام الغذائي. تعكس هذه الأداة التوصيات المستندة إلى إرشادات النظام الغذائي للأمريكيين 2015-2020 وتتكون من 13 مكونًا مع درجة إجمالية تتراوح من 0 (أسوأ) إلى 100 (أفضل) نقطة. تم التعبير عن درجة HEI كزيادة لكل نطاق ربعي (IQR).

جمع عينات البراز وقياسات الميكروبيوم

التحليل الإحصائي

تناول. لم تغير هذه العوامل النتائج المبلغ عنها أكثر من الحد الأدنى، وهذه الطريقة تتجنب مشاكل البيانات النادرة. كانت جميع الاختبارات الإحصائية ثنائية الجانب. كانت الأنواع والمسارات التي اعتبرناها مختلفة في الوفرة مرتبطة بالنظام الغذائي عند

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 22 أبريل 2024

References

- GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 459-480 (2019).

- Schapira, A. H. V., Chaudhuri, K. R. & Jenner, P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 509 (2017).

- Gao, X. et al. Prospective study of dietary pattern and risk of Parkinson disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86, 1486-1494 (2007).

- Liu, Y. H. et al. Diet quality and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a prospective study and meta-analysis. J. Parkinsons Dis. 11, 337-347 (2021).

- Molsberry, S. et al. Diet pattern and prodromal features of Parkinson disease. Neurology 95, e2095-e2108 (2020).

- Kwon, D. et al. Diet quality and Parkinson’s disease: Potential strategies for non-motor symptom management. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 115, 105816 (2023).

- Noble, E. E., Hsu, T. M. & Kanoski, S. E. Gut to brain dysbiosis: mechanisms linking western diet consumption, the microbiome, and cognitive impairment. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 11, 9 (2017).

- Obrenovich, M. E. M. Leaky Gut, Leaky Brain? Microorganisms 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms6040107 (2018).

- Lubomski, M. et al. The impact of device-assisted therapies on the gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 269, 780-795 (2022).

- Huang, B. et al. Gut microbiome dysbiosis across early Parkinson’s disease, REM sleep behavior disorder and their first-degree relatives. Nat. Commun. 14, 2501 (2023).

- Chen, Y., Xu, J. & Chen, Y. Regulation of neurotransmitters by the gut microbiota and effects on cognition in neurological disorders. Nutrients 13, 2099 (2021).

- Keshavarzian, A. et al. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1351-1360 (2015).

- O’Donovan, S. M. et al. Nigral overexpression of alpha-synuclein in a rat Parkinson’s disease model indicates alterations in the enteric nervous system and the gut microbiome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 32, e13726 (2020).

- Barichella, M. et al. Unraveling gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 34, 396-405 (2019).

- Heintz-Buschart, A. et al. The nasal and gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease and idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov. Disord. 33, 88-98 (2018).

- Hill-Burns, E. M. et al. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Mov. Disord. 32, 739-749 (2017).

- Unger, M. M. et al. Short chain fatty acids and gut microbiota differ between patients with Parkinson’s disease and age-matched controls. Parkinsonism Relat. D. 32, 66-72 (2016).

- Jackson, A. et al. Diet in Parkinson’s disease: critical role for the microbiome. Front. Neurol. 10, 1245 (2019).

- Palavra, N. C., Lubomski, M., Flood, V. M., Davis, R. L. & Sue, C. M. Increased added sugar consumption is common in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Nutr. 8, 628845 (2021).

- De Filippis, F. et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut 65, 1812-1821 (2016).

- Zhang, K. et al. Parkinson’s disease and the gut microbiome in rural California. J. Parkinsons Dis. 12, 2441-2452 (2022).

- Canani, R. B. et al. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 17, 1519-1528 (2011).

- Madore, C., Yin, Z., Leibowitz, J. & Butovsky, O. Microglia, lifestyle stress, and neurodegeneration. Immunity 52, 222-240 (2020).

- Elfil, M., Kamel, S., Kandil, M., Koo, B. B. & Schaefer, S. M. Implications of the gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 35, 921-933 (2020).

- Xie, A. J. et al. Bacterial butyrate in Parkinson’s disease is linked to epigenetic changes and depressive symptoms. Mov. Disord. 37, 1644-1653 (2022).

- Friedland, R. P. & Chapman, M. R. The role of microbial amyloid in neurodegeneration. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006654 (2017).

- Gerhardt, S. & Mohajeri, M. H. Changes of colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients 10, 708 (2018).

- Wallen, Z. D. et al. Metagenomics of Parkinson’s disease implicates the gut microbiome in multiple disease mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 13, 6958 (2022).

- Mehanna, M. et al. Study of the gut microbiome in Egyptian patients with Parkinson’s disease. BMC Microbiol 23, 196 (2023).

- Lin, C. H. et al. Altered gut microbiota and inflammatory cytokine responses in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 16, 129 (2019).

- Ghosh, S. S., Wang, J., Yannie, P. J. & Ghosh, S. Intestinal barrier dysfunction, LPS translocation, and disease development. J. Endocr. Soc. 4, bvz039 (2020).

- Ferrari, C. C. & Tarelli, R. Parkinson’s disease and systemic inflammation. Parkinsons Dis. 2011, 436813 (2011).

- Pietrucci, D. et al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in a selected population of Parkinson’s patients. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 65, 124-130 (2019).

- Engelborghs, S., Marescau, B. & De Deyn, P. P. Amino acids and biogenic amines in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 28, 1145-1150 (2003).

- Zhang, L. et al. Reduced plasma taurine level in Parkinson’s disease: association with motor severity and levodopa treatment. Int. J. Neurosci. 126, 630-636 (2016).

- Cui, C. et al. Gut microbiota-associated taurine metabolism dysregulation in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. mSphere 8, e0043123 (2023).

- Murakami, K., Livingstone, M. B. E., Fujiwara, A. & Sasaki, S. Reproducibility and relative validity of the Healthy Eating Index-2015 and Nutrient-Rich Food Index 9.3 estimated by comprehensive and brief diet history questionnaires in Japanese adults. Nutrients 11, 2540 (2019).

- Faith, J. J. et al. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science 341, 1237439 (2013).

- GBD Parkinson’s Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 17, 939-953 (2018).

- Kwon, D. et al. Diet quality and Parkinson’s disease: Potential strategies for non-motor symptom management. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 115, 105816 (2023).

- Willett, W. C., Howe, G. R. & Kushi, L. H. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 65, 1220S-1228S (1997).

- Tong, M., Jacobs, J. P., McHardy, I. H. & Braun, J. Sampling of intestinal microbiota and targeted amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes for microbial ecologic analysis. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 107, 7 4141-474111 (2014).

- Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581-583 (2016).

- Mallick, H. et al. Multivariable association discovery in populationscale meta-omics studies. Plos Comput Biol. 17, e1009442 (2021).

- Douglas, G. M. et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 685-688 (2020).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تفسير وجمع البيانات لدراسة PEG: ج.م.ب، أ.م.ك، ب.ر، ك.ز، أ.د.ف، إ.ر؛ جميع المؤلفين قرأوا ووافقوا على النسخة النهائية من المخطوطة.

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة علىhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00681-7.

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

- ¹قسم علم الأوبئة، كلية فيلدينغ للصحة العامة، جامعة كاليفورنيا، لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية.

قسم الأعصاب، كلية ديفيد غيفن للطب، جامعة كاليفورنيا، لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الأمراض الهضمية فاتي وتامار مانوكيان، قسم الطب، كلية ديفيد غيفن للطب، جامعة كاليفورنيا، لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: britz@ucla.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00681-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38649365

Publication Date: 2024-04-22

Diet and the gut microbiome in patients with Parkinson’s disease

Abstract

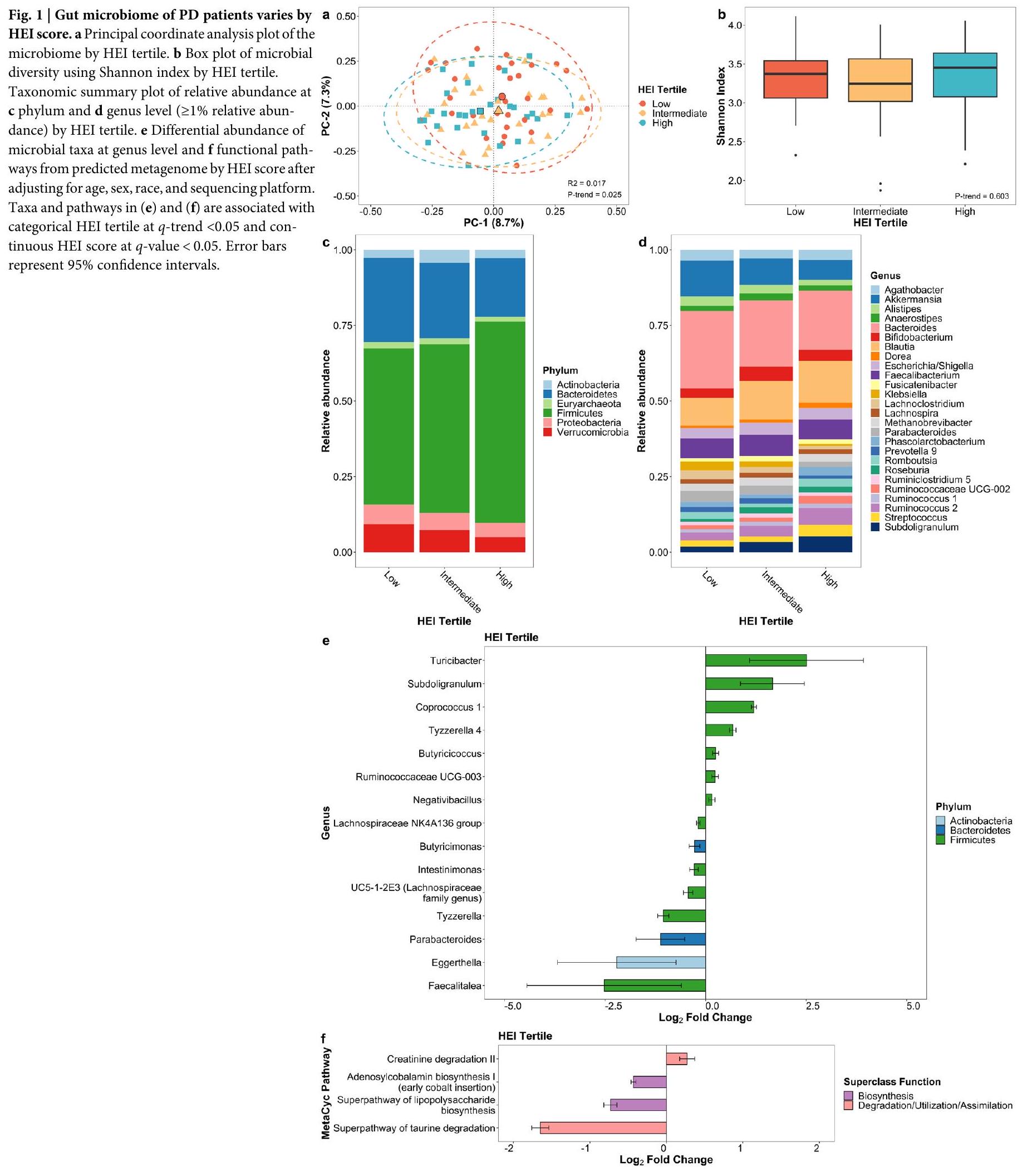

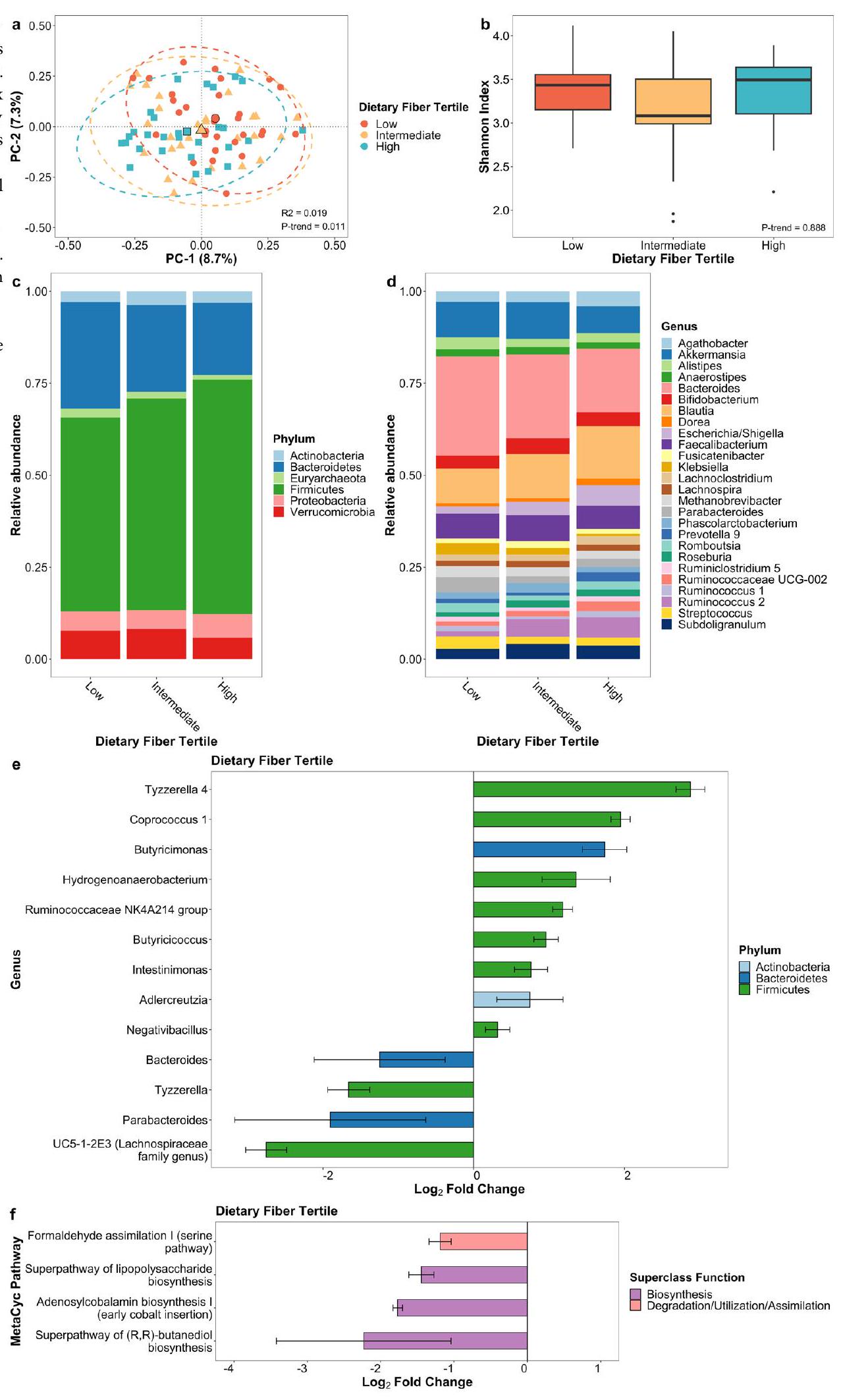

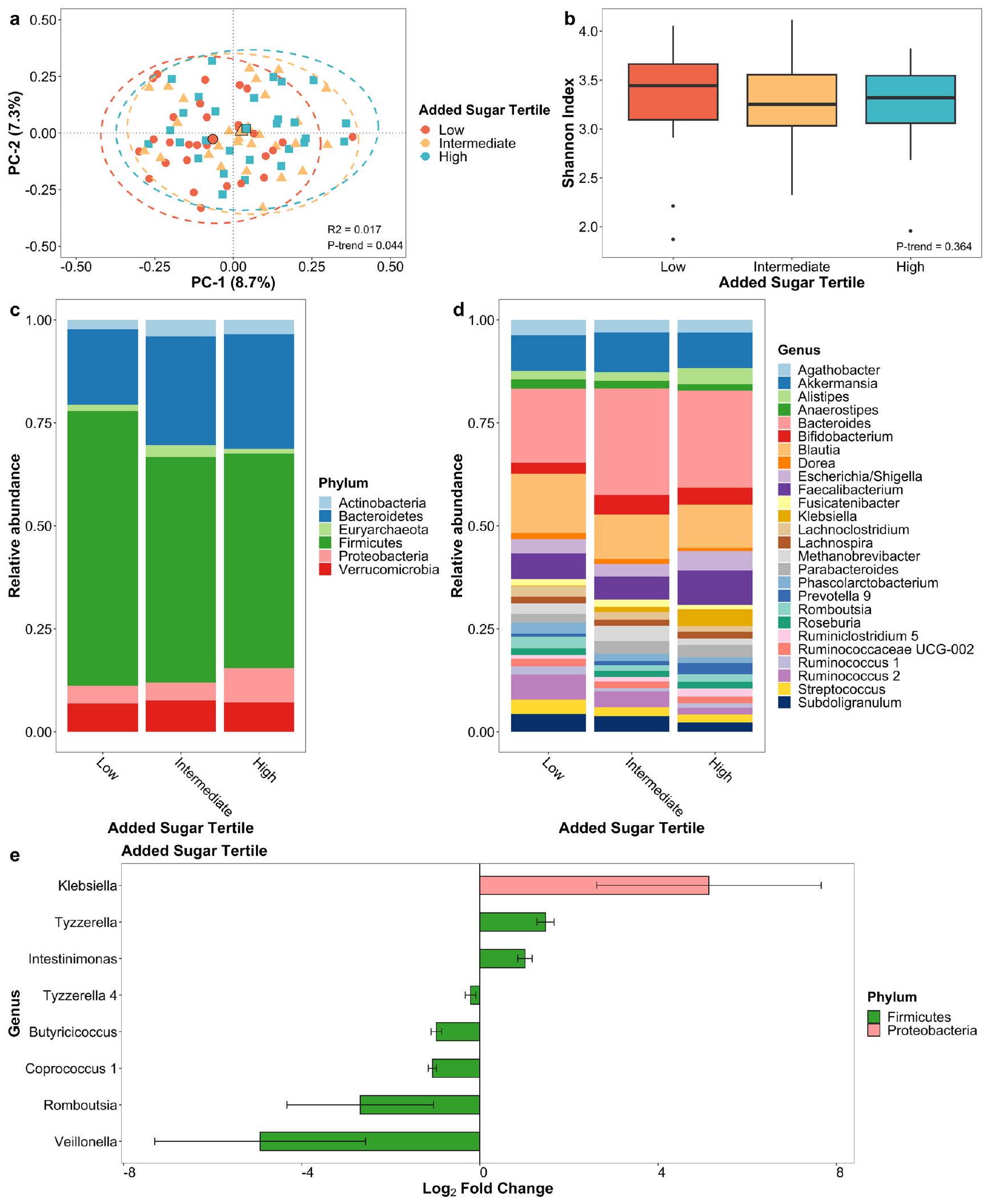

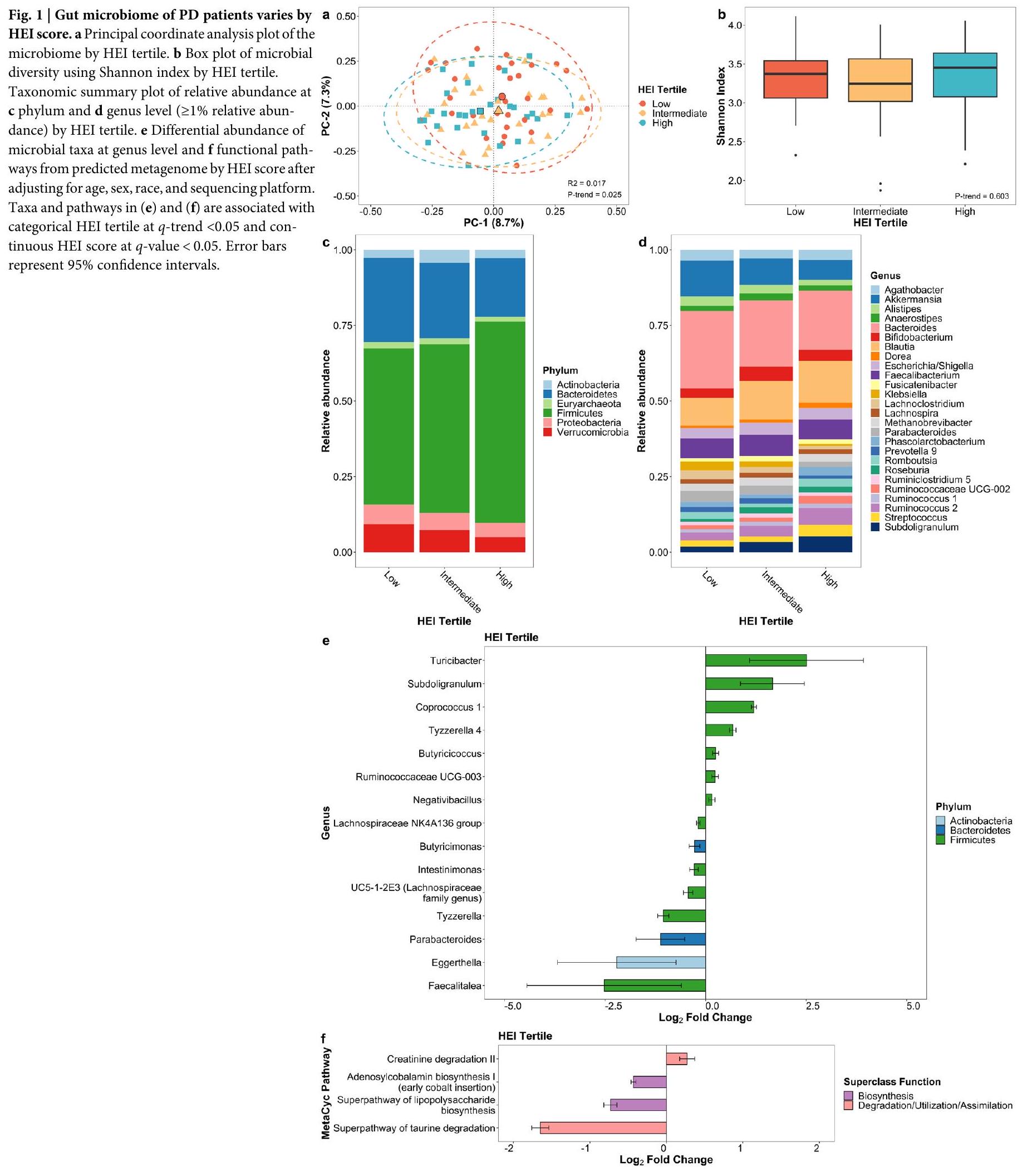

It has been suggested that gut microbiota influence Parkinson’s disease (PD) via the gut-brain axis. Here, we examine associations between diet and gut microbiome composition and its predicted functional pathways in patients with PD. We assessed gut microbiota in fecal samples from 85 PD patients in central California using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Diet quality was assessed by calculating the Healthy Eating Index 2015 (HEI-2015) based on the Diet History Questionnaire II. We examined associations of diet quality, fiber, and added sugar intake with microbial diversity, composition, taxon abundance, and predicted metagenomic profiles, adjusting for age, sex, race/ ethnicity, and sequencing platform. Higher HEI scores and fiber intake were associated with an increase in putative anti-inflammatory butyrate-producing bacteria, such as the genera Butyricicoccus and Coprococcus 1. Conversely, higher added sugar intake was associated with an increase in putative pro-inflammatory bacteria, such as the genera Klebsiella. Predictive metagenomics suggested that bacterial genes involved in the biosynthesis of lipopolysaccharide decreased with higher HEI scores, whereas a simultaneous decrease in genes involved in taurine degradation indicates less neuroinflammation. We found that a healthy diet, fiber, and added sugar intake affect the gut microbiome composition and its predicted metagenomic function in PD patients. This suggests that a healthy diet may support gut microbiome that has a positive influence on PD risk and progression.

Results

Analytic cohort characteristics

Diet quality

Dietary fiber intake

Added sugar intake

Sensitivity analysis

Discussion

| Low (

|

HEI-2015 Intermediate (

|

High (

|

|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 75.6 (7.88) | 73.4 (8.55) | 72.5 (9.39) |

| Range | 54-88 | 51-86 | 56-90 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 19 (65.5%) | 20 (71.4%) | 18 (64.3%) |

| Female | 10 (34.5%) | 8 (28.6%) | 10 (35.7%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White nonHispanic | 24 (82.8%) | 22 (78.6%) | 23 (82.1%) |

| Non-White or Hispanic | 5 (17.2%) | 6 (21.4%) | 5 (17.9%) |

| Platform | |||

| HiSeq | 26 (89.7%) | 21 (75.0%) | 20 (71.4%) |

| MiSeq | 3 (10.3%) | 7 (25.0%) | 8 (28.6%) |

| BMI (

|

|||

| Mean (SD) | 27.1 (5.56) | 28.5 (5.83) | 25.8 (5.11) |

| Range | 16.2-39.7 | 14-41.3 | 14.8-38.3 |

| Education (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.9 (2.50) | 14.5 (3.64) | 16.8 (4.77) |

| Range | 12-22 | 4-22 | 4-27 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 17 (58.6%) | 19 (67.9%) | 17 (60.7%) |

| Ever | 12 (41.4%) | 9 (32.1%) | 11 (39.3%) |

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.59 (6.25) | 9.24 (17.7) | 3.95 (7.47) |

| Range | 0-26.4 | 0-76.8 | 0-28.3 |

| Caffeine intake (mg/d) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 147 (184) | 195 (308) | 203 (252) |

| Range | 2.67-611 | 2.96-1430 | 0.52-1020 |

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1940 (914) | 2080 (866) | 1850 (811) |

| Range | 627-4000 | 731-4430 | 653-4050 |

| Age at PD diagnosis (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 64.3 (9.04) | 64.7 (8.46) | 62.4 (11.1) |

| Range | 50-84 | 42-75 | 41-81 |

| PD duration (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 10.2 (5.28) | 9.14 (3.78) | 9.79 (4.84) |

| Range | 4-20 | 3-20 | 2-20 |

| Constipation | |||

| No | 8 (27.6%) | 13 (46.4%) | 14 (50.0%) |

| Yes | 21 (72.4%) | 15 (53.6%) | 14 (50.0%) |

| MDS-UPDRS IA | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.78 (3.11) | 3.77 (2.62) | 3.38 (2.98) |

| Range | 0-10 | 0-11 | 0-11 |

| MDS-UPDRS IB | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.6 (4.50) | 9.33 (4.95) | 9.47 (5.20) |

| Range | 4-22 | 2-24 | 1-21 |

| MDS-UPDRS II | |||

| Mean (SD) | 17.5 (9.09) | 16.4 (7.80) | 14.8 (8.57) |

| Range | 1-41 | 3-40 | 2-40 |

| Low (

|

HEI-2015 Intermediate (

|

High (

|

|

| MDS-UPDRS III | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.3 (12.2) | 28.3 (10.7) | 24.5 (13.4) |

| Range | 11-58 | 8-51 | 3-58.2 |

(Supplementary Table 3). Specifically, with a healthier diet, we observed a reduction in the abundance of putative pro-inflammatory bacteria that are generally found to be enriched in PD patients compared to controls. Furthermore, a healthy diet in our study participants increased the abundance of putative anti-inflammatory bacteria that are typically depleted in PD patients compared to controls. One implication of our findings is that the previously reported microbiome associations with PD may have been due, at least partially, to dietary differences between PD patients and control subjects.

in the brain

that a better diet in PD patients was associated with higher levels of Ruminococcaceae family genera, which may support taurine metabolism and lead to reduced degradation of taurine by gut microbiota.

at genus level by added sugar intake after adjusting for age, sex, race, and sequencing platform. Taxa in (e) are associated with categorical added sugar intake tertile at

size, which limits confounder control and the identification of less prevalent microbial taxa, and the cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to infer temporality or causality of associations. To address these limitations and further explore the impact of diet and the interaction between diet and the microbiome on the progression of PD, subsequent studies should leverage longitudinal data on diet, microbiome, and disease progression. In addition, the metagenomic pathways were based on predicted metagenomic data and not the actual metagenome. Therefore, future research should consider using shotgun sequencing and metabolomics to provide a more robust understanding of the impact of diet on gut microbiome composition and function in PD. Measurement errors inherent in DHQ II assessments may also have led to the misclassification of dietary exposures. In the future, we hope to be able to evaluate the stability of diet quality over time in our patient cohort, but for now we have to assume that the diet did not change in a major way during the gap between diet assessment and stool collection (average 6 months). Previous research established that the stability of HEI2015 scores derived from the DHQ is stable over a 1 -year period

Methods

Study population

Diet and covariate assessment

a measure of diet quality. This instrument reflects recommendations based on the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines of Americans and consists of 13 components with a total score ranging from 0 (worst) to 100 (best) points. The HEI score was expressed as a per interquartile range (IQR) increase.

Fecal sample collection and microbiome measurements

Statistical analysis

intake. These factors did not change reported results more than minimally and this approach avoids sparse data issues. All statistical tests were twosided. Taxa and pathways we considered differential in abundance were associated with diet at a

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

Published online: 22 April 2024

References

- GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 459-480 (2019).

- Schapira, A. H. V., Chaudhuri, K. R. & Jenner, P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 509 (2017).

- Gao, X. et al. Prospective study of dietary pattern and risk of Parkinson disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86, 1486-1494 (2007).

- Liu, Y. H. et al. Diet quality and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a prospective study and meta-analysis. J. Parkinsons Dis. 11, 337-347 (2021).

- Molsberry, S. et al. Diet pattern and prodromal features of Parkinson disease. Neurology 95, e2095-e2108 (2020).

- Kwon, D. et al. Diet quality and Parkinson’s disease: Potential strategies for non-motor symptom management. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 115, 105816 (2023).

- Noble, E. E., Hsu, T. M. & Kanoski, S. E. Gut to brain dysbiosis: mechanisms linking western diet consumption, the microbiome, and cognitive impairment. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 11, 9 (2017).

- Obrenovich, M. E. M. Leaky Gut, Leaky Brain? Microorganisms 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms6040107 (2018).

- Lubomski, M. et al. The impact of device-assisted therapies on the gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 269, 780-795 (2022).

- Huang, B. et al. Gut microbiome dysbiosis across early Parkinson’s disease, REM sleep behavior disorder and their first-degree relatives. Nat. Commun. 14, 2501 (2023).

- Chen, Y., Xu, J. & Chen, Y. Regulation of neurotransmitters by the gut microbiota and effects on cognition in neurological disorders. Nutrients 13, 2099 (2021).

- Keshavarzian, A. et al. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1351-1360 (2015).

- O’Donovan, S. M. et al. Nigral overexpression of alpha-synuclein in a rat Parkinson’s disease model indicates alterations in the enteric nervous system and the gut microbiome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 32, e13726 (2020).

- Barichella, M. et al. Unraveling gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 34, 396-405 (2019).

- Heintz-Buschart, A. et al. The nasal and gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease and idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov. Disord. 33, 88-98 (2018).

- Hill-Burns, E. M. et al. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Mov. Disord. 32, 739-749 (2017).

- Unger, M. M. et al. Short chain fatty acids and gut microbiota differ between patients with Parkinson’s disease and age-matched controls. Parkinsonism Relat. D. 32, 66-72 (2016).

- Jackson, A. et al. Diet in Parkinson’s disease: critical role for the microbiome. Front. Neurol. 10, 1245 (2019).

- Palavra, N. C., Lubomski, M., Flood, V. M., Davis, R. L. & Sue, C. M. Increased added sugar consumption is common in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Nutr. 8, 628845 (2021).

- De Filippis, F. et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut 65, 1812-1821 (2016).

- Zhang, K. et al. Parkinson’s disease and the gut microbiome in rural California. J. Parkinsons Dis. 12, 2441-2452 (2022).

- Canani, R. B. et al. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 17, 1519-1528 (2011).

- Madore, C., Yin, Z., Leibowitz, J. & Butovsky, O. Microglia, lifestyle stress, and neurodegeneration. Immunity 52, 222-240 (2020).

- Elfil, M., Kamel, S., Kandil, M., Koo, B. B. & Schaefer, S. M. Implications of the gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 35, 921-933 (2020).

- Xie, A. J. et al. Bacterial butyrate in Parkinson’s disease is linked to epigenetic changes and depressive symptoms. Mov. Disord. 37, 1644-1653 (2022).

- Friedland, R. P. & Chapman, M. R. The role of microbial amyloid in neurodegeneration. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006654 (2017).

- Gerhardt, S. & Mohajeri, M. H. Changes of colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients 10, 708 (2018).

- Wallen, Z. D. et al. Metagenomics of Parkinson’s disease implicates the gut microbiome in multiple disease mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 13, 6958 (2022).

- Mehanna, M. et al. Study of the gut microbiome in Egyptian patients with Parkinson’s disease. BMC Microbiol 23, 196 (2023).

- Lin, C. H. et al. Altered gut microbiota and inflammatory cytokine responses in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 16, 129 (2019).

- Ghosh, S. S., Wang, J., Yannie, P. J. & Ghosh, S. Intestinal barrier dysfunction, LPS translocation, and disease development. J. Endocr. Soc. 4, bvz039 (2020).

- Ferrari, C. C. & Tarelli, R. Parkinson’s disease and systemic inflammation. Parkinsons Dis. 2011, 436813 (2011).

- Pietrucci, D. et al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in a selected population of Parkinson’s patients. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 65, 124-130 (2019).

- Engelborghs, S., Marescau, B. & De Deyn, P. P. Amino acids and biogenic amines in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 28, 1145-1150 (2003).

- Zhang, L. et al. Reduced plasma taurine level in Parkinson’s disease: association with motor severity and levodopa treatment. Int. J. Neurosci. 126, 630-636 (2016).

- Cui, C. et al. Gut microbiota-associated taurine metabolism dysregulation in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. mSphere 8, e0043123 (2023).

- Murakami, K., Livingstone, M. B. E., Fujiwara, A. & Sasaki, S. Reproducibility and relative validity of the Healthy Eating Index-2015 and Nutrient-Rich Food Index 9.3 estimated by comprehensive and brief diet history questionnaires in Japanese adults. Nutrients 11, 2540 (2019).

- Faith, J. J. et al. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science 341, 1237439 (2013).

- GBD Parkinson’s Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 17, 939-953 (2018).

- Kwon, D. et al. Diet quality and Parkinson’s disease: Potential strategies for non-motor symptom management. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 115, 105816 (2023).

- Willett, W. C., Howe, G. R. & Kushi, L. H. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 65, 1220S-1228S (1997).

- Tong, M., Jacobs, J. P., McHardy, I. H. & Braun, J. Sampling of intestinal microbiota and targeted amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes for microbial ecologic analysis. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 107, 7 4141-474111 (2014).

- Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581-583 (2016).

- Mallick, H. et al. Multivariable association discovery in populationscale meta-omics studies. Plos Comput Biol. 17, e1009442 (2021).

- Douglas, G. M. et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 685-688 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

interpretation, and data collection for PEG study: J.M.B., A.M.K., B.R., K.Z., A.D.F., I.R.; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00681-7.

© The Author(s) 2024

- ¹Department of Epidemiology, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, Los Angele, CA, USA.

Department of Neurology, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA, USA. The Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases, Department of Medicine, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA, USA. e-mail: britz@ucla.edu