DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14010153

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38200884

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-02

انتشار الآفات المؤلمة في الأصابع وعوامل الخطر المرتبطة بالتهاب الجلد الرقمي، والقرحات، ومرض الخط الأبيض في مزارع الأبقار السويسرية

تمت المراجعة: 16 ديسمبر 2023

تم القبول: 27 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر: 2 يناير 2024

الملخص

كان الهدف الأول من هذه الدراسة هو حساب انتشار الآفات المؤلمة للأصابع (الآفات “التحذيرية”; ALs) في قطعان الألبان السويسرية وعمليات الأبقار والعجول على مدى فترة دراسة مدتها ثلاث سنوات. تم تضمين الآفات التالية في الحساب: المرحلة M2 من التهاب الجلد الرقمي (DD M2)، القرح (U)، الشقوق في الخط الأبيض (WLF) ذات الشدة المتوسطة والعالية، الخراجات في الخط الأبيض (WLA)، الفلغمون بين الأصابع (IP) وتورم التاج و/أو المصباح (SW). بين فبراير 2020 وفبراير 2023، تم تسجيل اضطرابات الأصابع إلكترونيًا خلال عمليات التقليم الروتينية بواسطة 40 مقلم حوافر مدرب تدريبًا خاصًا في مزارع الأبقار السويسرية المشاركة في البرنامج الوطني لصحة الحوافر. تتكون مجموعة البيانات المستخدمة من أكثر من 35,000 ملاحظة من حوالي 25,000 بقرة من 702 قطيع. بينما على مستوى القطيع، كانت الآفة التحذيرية السائدة الموثقة في عام 2022 هي U مع

1. المقدمة

إلى انخفاض في حدوث ALs مع مرور الوقت. علاوة على ذلك، توقعنا تحديد عوامل الخطر المتعلقة بخصائص القطيع، وإدارة صحة الحوافر، وخصائص الأبقار الفردية المرتبطة بارتفاع انتشار DD.

2. المواد والأساليب

2.1. منطقة الدراسة والسكان المدروسين

2.2. تسجيل البيانات الإلكترونية

وفحص اضطرابات الأصابع أثناء التقليم بقيمة كابا

2.3. إدارة البيانات

2.4. التحليلات الإحصائية

تم استخدام البيانات التي تم الوصول إليها في 28 نوفمبر 2023. يتم وصف المتغيرات الفئوية من خلال توزيعات التكرار، ويتم تلخيص المتغيرات المستمرة كوسيط ونطاق ربعي. بالنسبة لتحليلات عوامل الخطر، تم إجراء تحليلين منفصلين للنتائج ذات الاهتمام. كانت النتائج (1) القطعان المتأثرة بـ DD أو U أو WL و (2) الأبقار المتأثرة بـ DD أو U أو WL. تم تصنيف النتائج كمتغيرات ثنائية (قطيع/بقرة متأثرة مقابل غير متأثرة)، وتم تحليل كل متغير محتمل باستخدام نموذج انحدار لوجستي أحادي المتغير لكل مرض (أي ثلاثة نماذج لكل من مستوى القطيع ومستوى البقرة). فقط المتغيرات التي تظهر

3. النتائج

3.1. خصائص القطيع والأبقار

| خصائص على مستوى القطيع | سنة

|

سنة

|

سنة

|

|||

| % (ن) | الوسيط (Q1-Q3)

|

% (ن) | الوسيط (Q1-Q3)

|

% (ن) | الوسيط (Q1-Q3)

|

|

| نظام الإنتاج | ||||||

| عمليات الأبقار والعجول | 11.9 (18) | 12.9 (65) | 13.8 (77) | |||

| حجم القطيع

|

٢٦ (١٦.٥-٤٠) | ٢٦ (١٨-٤٠) | ٢٦ (١٨-٣٩) | |||

| نوع السكن | ||||||

| حظيرة الربط | 42.4 (64) | ٤١.٦ (٢٠٩) | ٣٩.٩ (٢٢٣) | |||

| حظيرة مجانية | 57.6 (87) | 58.4 (294) | 60.1 (336) | |||

| السلالة السائدة (قطعان الألبان) | ||||||

| هولشتاين فريزيان | ٣٣.١ (٤٤) | 32.2 (141) | ٣٣.٤ (١٦١) | |||

| آخر | 66.9 (89) | 67.8 (297) | 66.6 (321) | |||

| قصات القطيع سنويًا

|

||||||

|

|

٨٨.٧ (١٣٤) | 68.2 (343) | 61.4 (343) | |||

|

|

11.3 (17) | 30.4 (153) | ٣٦.٥ (٢٠٤) | |||

|

|

0.0 (0) | 1.4 (7) | 2.1 (12) | |||

| رعي الجبال | ||||||

| نعم | ٤٤.٤ (٦٧) | 53.9 (271) | 51.2 (286) | |||

| لا | 55.6 (84) | ٤٦.١ (٢٣٢) | ٤٨.٨ (٢٧٣) | |||

| المشاركة في برنامج RAUS

|

91.4 (138) | 94.8 (477) | 95.3 (533) | |||

| القطعان المجهزة لكل مقص أظافر | 8 (4-11.5) | 10 (6-19) | 10 (6-22) | |||

| موسم التقليم

|

||||||

| موسم الإسكان | 40.4 (61) | 65.0 (327) | 69.4 (388) | |||

| موسم الرعي | ٥٩.٦ (٩٠) | ٣٥.٠ (١٧٦) | 30.6 (171) | |||

| مسجلو مشذبات الحوافر | 19 | 37 | ٣٥ | |||

| خصائص مستوى البقر | سنة

|

سنة

|

سنة

|

|||

| % (ن) | الوسيط (Q1-Q3)

|

% (ن) | الوسيط (Q1-Q3)

|

% (ن) | الوسيط (Q1-Q3)

|

|

| نظام الإنتاج | ||||||

| أبقار الألبان | 90.6 (4118) |

|

|

|||

| الأبقار المرضعة

|

9.4 (428) | 10.5 (1625) | 10.5 (1786) | |||

| نسبة الأبقار المقتطعة لكل قطيع

|

100 (95.7-100) | 100 (94.1-100) | 100 (95.5-100) | |||

| الأبقار المجهزة لكل مقص أظافر | 205 (135-309) | 348 (135-573) | ٣٢٩ (١٨٢-٦٣٩) | |||

| 420 قطيع ألبان و13,735 بقرة ألبان | |

| خاصية | الوسيط (Q1-Q3)

|

| مستوى القطيع

|

|

| إنتاج الحليب لمدة 305 أيام (كجم) | 7702 (6765-8668) |

| التكافؤ | 3 (2.6-3.4) |

| مدة الرضاعة (يوم) | 346 (331-366) |

| فترة التزاوج | 401 (385-418) |

| مستوى البقر | |

| إنتاج الحليب (كجم)

|

25.8 (20.2-32.3) |

| التكافؤ

|

3 (2-4) |

| مدة الرضاعة (يوم)

|

316 (270-369) |

| فترة التزاوج (يوم)

|

٣٨٨ (٣٦٠-٤٣٧) |

|

|

|

-

أحدث تسجيل للحليب قبل تقليم القطيع. أحدث فترة إرضاع.

3.2. انتشار الآفات المنبهة

| انتشار القطيع | انتشار داخل القطيع | انتشار الأبقار | |||||||||||||

| سنة

|

٢٠٢٠ | ٢٠٢١ | 2022 | ٢٠٢٠ | ٢٠٢١ | ٢٠٢٢ | ٢٠٢٠ | ٢٠٢١ | ٢٠٢٢ | ||||||

| إجمالي عدد التحليلات | 151 | 503 | ٥٥٩ | 151 | 503 | ٥٥٩ | 4546 | 15,418 | ١٦,٩٥٩ | ||||||

| إحصائيات توزيع البيانات | % | الوسيط | نطاق التداخل الربعي

|

نطاق | الوسيط | نطاق التداخل الربعي

|

نطاق | الوسيط | نطاق التداخل الربعي

|

نطاق | % | ||||

| المرحلة M2 من التهاب الجلد الرقمي | 41.1 | ٣٩.٦ | ٣٦.٣ | ٤.١ | 19.1 | 0-55.0 | 2.8 | 16.7 | 0-58.1 | 0.0 | 11.4 | 0-50.3 | ٧.٩ | 6.1 | ٥.٤ |

| خُرَاج بين الأصابع | ٥.٣ | 6.6 | ٤.٠ | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-11.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-18.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-9.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| تورم التاج و/أو المصباح | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-4.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| قرحات

|

67.5 | ٥٦.٧ | 50.3 | ٤.٢ | 9.0 | 0-50.0 | 2.9 | ٦.٥ | 0-30.8 | 1.3 | ٥.٤ | 0-35.9 | ٥.٩ | ٤.٦ | 3.7 |

| قرحة باطن القدم | ٥٥.٠ | ٤٨.١ | ٤٤.٠ | 2.7 | ٦.٥ | 0-25.0 | 0.0 | ٥.٣ | 0-30.8 | 0.0 | ٤.٢ | 0-33.3 | 2.6 | ٣.٥ | 2.9 |

| قرحة المصباح | 19.9 | 15.7 | 13.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-25.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-18.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| قرحة إصبع القدم | 10.6 | ٤.٦ | ٤.٥ | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-14.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-5.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| نخر الأصابع | ٥.٣ | ٥.٤ | ٤.٥ | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-5.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-6.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| شدة شق الخط الأبيض II/III | ٤٥.٠ | 42.1 | ٣٨.١ | 6.8 | 19.1 | 0-47.2 | 7.2 | 13.9 | 0-39.2 | ٥.٥ | ١٣.٢ | 0-35.1 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| خراج الخط الأبيض | 31.8 | ٢٧.٨ | ٢٥.٦ | 0.0 | ٢.٥ | 0-25.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0-28.6 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0-22.2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| آفة الإنذار

|

86.1 | 79.0 | ٧٥.٩ | 11.5 | 16.6 | 0-66.1 | 9.4 | 12.8 | 0-57.2 | 8.0 | ١٣.٢ | 0-53.7 | 18.1 | 14.2 | 12.2 |

| 113 فبراير إلى 12 فبراير من العام التالي.

|

|||||||||||||||

3.3. عوامل الخطر للالتهاب الجلدي الرقمي، والقرحات، ومرض الخط الأبيض

| مؤشر | التهاب الجلد الرقمي | |||||

| فصل | العدد (ن) | مريض (اسم) | نسبة الأرجحية |

|

|

|

| مستوى القطيع | ||||||

| الإسكان | حظيرة الربط | 194 | 62 | 0.25 | 0.15-0.41 | <0.001 |

| حظيرة مجانية | 226 | 147 | مرجع | |||

| رعي الجبال | نعم | 221 | ٨٨ | 0.49 | 0.31-0.77 | 0.002 |

| لا | 199 | 121 | مرجع | |||

| السلالة السائدة | هولشتاين فريزيان | ١٢٥ | 97 | ٥.٠٣ | 3.00-8.66 | <0.001 |

| آخر | ٢٩٥ | ١١٢ | مرجع | |||

| قصات القطيع سنويًا | 2 | 1.64 | 1.03-2.64 | 0.039 | ||

| فترة بين الولادات (يوم) | 2 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.005 | ||

| مستوى البقر | ||||||

| الإسكان | حظيرة الربط | ٤٢٢٨ | 170 | 0.44 | 0.31-0.63 | <0.001 |

| حظيرة مجانية | 9507 | 1442 | مرجع | |||

| سلالة | هولشتاين فريزيان | 6072 | 1112 | 1.63 | 1.37-1.94 | <0.001 |

| آخر | 7663 | ٥٠٠ | مرجع | |||

| التكافؤ | 2 | 0.97 | 0.94-1.00 | 0.046 | ||

| مؤشر | قرحات | |||||

| فصل | العدد (ن) | مريض (اسم) | نسبة الأرجحية | فترة الثقة 95%

|

|

|

| مستوى القطيع | ||||||

| فترة بين الولادات (يوم) | 2 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.012 | ||

| مدة الرضاعة (يوم) | <339 | ١٧٥ | 66 | 0.43 | 0.25-0.76 | 0.003 |

| ٣٤٠-٣٦٠ | ١١٨ | 67 | 0.79 | 0.45-1.40 | 0.419 | |

| >360 | 127 | 85 | مرجع | |||

| مستوى البقر | ||||||

| الإسكان | حظيرة الربط | ٤٢٢٨ | 180 | 1.47 | 1.11-1.96 | 0.008 |

| حظيرة مجانية | 9507 | ٣٣٢ | مرجع | |||

| موسم التقليم

|

فترة السكن | 9022 | ٢٠٠ | 0.65 | 0.50-0.85 | 0.002 |

| فترة الرعي | 4713 | ٣١٢ | مرجع | |||

| التكافؤ | 2 | 1.36 | 1.31-1.41 | <0.001 | ||

| مؤشر | مرض الخط الأبيض | |||||

| فصل | العدد (ن) | مريض (اسم) | نسبة الأرجحية | فترة الثقة 95%

|

|

|

| مستوى القطيع | ||||||

| الإسكان | حظيرة الربط | 194 | ١١٥ | 0.20 | 0.11-0.34 | <0.001 |

| حظيرة مجانية | 226 | ١٩٧ | مرجع | |||

| مستوى البقر | ||||||

| الإسكان | حظيرة الربط | ٤٢٢٨ | ٢٧٨ | 0.40 | 0.32-0.50 | <0.001 |

| سلالة | حظيرة مجانية | 9507 | 1199 | مرجع | ||

| هولشتاين فريزيان | 6072 | 573 | 0.71 | 0.61-0.84 | <0.001 | |

| آخر | 7663 | 904 | مرجع | |||

| موسم التقليم

|

فترة السكن | 9022 | 596 | 0.55 | 0.44-0.67 | <0.001 |

| فترة الرعي | 4713 | ٨٨١ | مرجع | |||

| مدة الرضاعة (يوم) | <339 | 4140 | ٤٣٨ | 0.81 | 0.69-0.95 | 0.008 |

| ٣٤٠-٣٦٠ | 5731 | 584 | 0.89 | 0.78-1.03 | 0.119 | |

| >360 | 3864 | ٤٥٣ | مرجع | |||

| التكافؤ | ٣ | 1.30 | 1.27-1.33 | <0.001 | ||

3.3.1. عوامل الخطر على مستوى القطيع

3.3.2. عوامل المخاطر على مستوى الأبقار

4. المناقشة

في دراسة سابقة، ولكن نظرًا لأنهم لم يركزوا على ALs، تم إعادة حساب النسب المئوية لذلك العام [1]. تحتوي الدراسة الحالية على أكبر مجموعة بيانات إلكترونية حول صحة الأصابع في الماشية السويسرية، مع أكثر من 35,000 ملاحظة من حوالي 25,000 بقرة من أكثر من 700 مزرعة. ضمنت تطبيق معايير شاملة صارمة أننا اعتبرنا فقط تقليمات القطيع الكاملة.

4.1. تطور الانتشار للفترة 2020-2023

الحاجة إلى تحسين وعي المزارعين بالآفات المؤلمة والعرج الناتج [37]. عند مقارنة بيانات الانتشار مع تلك من دراسات أخرى، من المهم أن نأخذ في الاعتبار أن عوامل إدارة القطيع والظروف المناخية، بالإضافة إلى متطلبات التدريب وطرق جمع البيانات، تختلف. لذلك، تم تقديم أطلس صحة الحوافر من ICAR لوضع معايير تدريب دولية وضمان قابلية مقارنة البيانات [1،25،38]. ومع ذلك، فإن معدلات انتشار الآفات المبلغ عنها على مستوى الأبقار لـ DD M2 عند

4.2. عوامل المخاطر

4.2.1. التهاب الجلد الرقمي

يمكن أن يتم نقل DD عبر معدات تقليم المخالب [36،40]. أفاد باير وآخرون (2023) بتطبيق منخفض للتدابير الحيوية الخارجية والداخلية خلال تقليم المخالب الروتيني في مقصات المخالب السويسرية، مما قد يفسر أيضًا نتائجنا [41]. ومع ذلك، فإن مزايا التقليم الروتيني المتكرر تفوق العيوب، لأن حدوث اضطرابات المخالب المرتبطة بالقرون يمكن أن يقلل [37]. ومع ذلك، يجب أخذ قابلية نقل المرض المعدي وتنفيذ تدابير الأمان الحيوي المناسبة في الاعتبار [41]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد تقوم المزارع التي تعاني من انتشار أعلى لـ DD بإجراء جلسات تقليم للقطيع بشكل أكثر تكرارًا لمنع اضطرابات الأصابع، مما يؤدي وفقًا لذلك إلى اكتشاف أكثر تكرارًا ولكن أيضًا إلى مزيد من العلاج لمثل هذه الآفات [36،40].

4.2.2. القرحات

تجاوزت 180 يومًا) بما يصل إلى 71 يومًا [38]. وهذا يتماشى مع نتائج أوليشنويكز وجاسكوفسكي (2015) وبيكالهو وآخرون (2007)، الذين أبلغوا عن مدى ممتد يتراوح بين 20 إلى 40 يومًا من الولادة إلى الحمل [49،50]. يمكن أن تؤثر إصابات الحوافر مثل U على نشاط المبيض من خلال الألم عن طريق زيادة مستويات الكورتيزول، مما يمكن أن يتداخل مع دورة الشبق ويطيل فترة الأنوستروس [38،51]. علاوة على ذلك، أفاد هاجمان ويوغا (2015) ولينامو وآخرون (2009) ومانسكي (2002) أن خطر U يزداد بين 61 و150 يومًا من الرضاعة، حيث تزداد ضغوط الرضاعة وتؤثر سلبًا على درجة حالة الجسم [35،52،53]. ومن الجدير أيضًا أن نأخذ في الاعتبار أن العديد من الأبقار التي لديها فترة رضاعة طويلة جدًا تنتمي إلى مجموعة الأبقار التي لم تعد تُلقح وتُحلب حتى يتم استبعادها، لذا لم تعد تُعطى الأولوية لتقليم الحوافر من قبل المزارع، مما قد يزيد من خطر U.

4.2.3. مرض الخط الأبيض

5. الاستنتاجات

(أدريان شتاينر) وC.S.; تنسيق البيانات، A.F. وJ.B. وC.S.; إعداد المسودة الأصلية، A.F.; مراجعة الكتابة والتحرير، A.S. (أدريان شتاينر) وC.S. وJ.B. وM.W.R. وJ.W. وA.S. (ألانينا سارباخ) وA.F.; التصوير، A.F.; الإشراف، A.S. (أدريان شتاينر) وC.S.; إدارة المشروع، A.S. (أدريان شتاينر) وC.S. وM.W.R.; الحصول على التمويل، A.S. (أدريان شتاينر) وC.S. وM.W.R. جميع المؤلفين قرأوا ووافقوا على النسخة المنشورة من المخطوطة.

الشكر والتقدير: نتقدم بالشكر الخاص لمقدمي خدمات تقليم الحوافر المشاركين، والمزارعين، والمنظمات، وخاصةً إلى أنكي ريجلي (Qualitas AG، زوغ، سويسرا) لتوفيرها موارد البحث. كما نتوجه بالشكر للمؤسسات المنظمة للمشروع: الجمعية السويسرية لمقدمي خدمات تقليم الحوافر، وجمعية مربي الماشية السويسرية، والجمعية السويسرية لصحة المجترات.

References

- Jury, A.; Syring, C.; Becker, J.; Locher, I.; Strauss, G.; Ruiters, M.; Steiner, A. Prevalence of claw disorders in Swiss cattle farms. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2021, 163, 779-790. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvergnas, M.; Strabel, T.; Rzewuska, K.; Sell-Kubiak, E. Claw disorders in dairy cattle: Effects on production; welfare and farm economics with possible prevention methods. Livest. Sci. 2019, 222, 54-64. [CrossRef]

- Solano, L.; Barkema, H.W.; Mason, S.; Pajor, E.A.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Orsel, K. Prevalence and distribution of foot lesions in dairy cattle in Alberta; Canada. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 6828-6841. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.; Bernhard, J.; Syring, C.; Steiner, A. Establishment of key indicators and limit values for assessment of claw health of cattle in Switzerland. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2021, 163, 43-56. [CrossRef]

- Heringstad, B.; Egger-Danner, C.; Charfeddine, N.; Pryce, J.E.; Stock, K.F.; Kofler, J.; Sogstad, A.M.; Holzhauer, M.; Fiedler, A.; Müller, K.; et al. Invited review: Genetics and claw health: Opportunities to enhance claw health by genetic selection. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4801-4821. [CrossRef]

- Kofler, J.; Pesenhofer, R.; Landl, G.; Somerfeld-Stur, I.; Peham, C. Monitoring of dairy cow claw health status in 15 herds using the computerised documentation program Claw Manager and digital parameters. Tierarztl. Prax. Ausg. G. Grosstiere/Nutztiere 2013, 41, 31-44. [CrossRef]

- Bielfeldt, J.C.; Badertscher, R.; Tölle, K.H.; Krieter, J. Risk factors influencing lameness and claw disorders in dairy cows. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 95, 265-271. [CrossRef]

- Whay, H.; Shearer, J.K. The Impact of Lameness on Welfare of the Dairy Cow. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2017, 33, 153-164. [CrossRef]

- Huxley, J.N. Impact of lameness and claw lesions in cows on health and production. Livest. Sci. 2013, 156, 64-70. [CrossRef]

- Browne, N.; Hudson, C.D.; Crossley, R.E.; Sugrue, K.; Huxley, J.N.; Conneely, M. Hoof lesions in partly housed pasture-based dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 9038-9053. [CrossRef]

- Mostert, P.F.; van Middelaar, C.E.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Bokkers, E.A.M. The impact of foot lesions in dairy cows on greenhouse gas emissions of milk production. Agric. Syst. 2018, 167, 206-212. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; White, E.; Holden, N.M. The effect of lameness on the environmental performance of milk production by rotational grazing. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 172, 143-150. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, J.; Steiner, A.; Kohler, S.; Koller-Bähler, A.; Wüthrich, M.; Reist, M. Lameness and foot lesions in Swiss dairy cows: I. Prevalence. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2014, 156, 71-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofler, J.; Suntinger, M.; Mayerhofer, M.; Linke, K.; Maurer, L.; Hund, A.; Fiedler, A.; Duda, J.; Egger-Danner, C. Benchmarking Based on Regularly Recorded Claw Health Data of Austrian Dairy Cattle for Implementation in the Cattle Data Network (RDV). Animals 2022, 12, 808. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöström, K.; Fall, N.; Blanco-Penedo, I.; Duval, J.E.; Krieger, M.; Emanuelson, U. Lameness prevalence and risk factors in organic dairy herds in four European countries. Livest. Sci. 2018, 208, 44-50. [CrossRef]

- Chapinal, N.; Barrientos, A.K.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Galo, E.; Weary, D.M. Herd-level risk factors for lameness in freestall farms in the northeastern United States and California. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 318-328. [CrossRef]

- Barker, Z.E.; Leach, K.A.; Whay, H.R.; Bell, N.J.; Main, D.C.J. Assessment of lameness prevalence and associated risk factors in dairy herds in England and Wales. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 93, 932-941. [CrossRef]

- Haskell, M.J.; Rennie, L.J.; Bowell, V.A.; Bell, M.J.; Lawrence, A.B. Housing System, Milk Production; and Zero-Grazing Effects on Lameness and Leg Injury in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 4259-4266. [CrossRef]

- Sogstad, Å.M.; Fjeldaas, T.; Østerås, O.; Plym Forshell, K. Prevalence of claw lesions in Norwegian dairy cattle housed in tie stalls and free stalls. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005, 70, 191-209. [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Steiner, A.; Kohler, S.; Koller-Bähler, A.; Wüthrich, M.; Reist, M. Lameness and foot lesions in Swiss dairy cows: II. Risk factors. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2014, 156, 79-89. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, G.; Stucki, D.; Jury, A.; Locher, I.; Syring, C.; Ruiters, M.; Steiner, A. Evaluation of a novel training course for hoof trimmers to participate in a Swiss national cattle claw health monitoring programme. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2021, 163, 189-201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.; Welham Ruiters, M.; Syring, C.; Steiner, A. Improvement of claw health of cattle in Switzerland. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2020, 162, 285-292. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesamt für Landwirtschaft BLW (Federal Agricultural Office). Ressourcenprogramm. 2022. Available online: https://www. blw.admin.ch/blw/de/home/instrumente/ressourcen–und-gewaesserschutzprogramm/ressourcenprogramm.html (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Weber, J.; Becker, J.; Syring, C.; Welham Ruiters, M.; Locher, I.; Bayer, M.; Schüpbach-Regula, G.; Steiner, A. Farm-level risk factors for digital dermatitis in dairy cows in mountainous regions. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 1341-1350. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger-Danner, C.; Nielsen, P.; Fiedler, A.; Müller, K.; Fjeldaas, T.; Döpfer, D.; Daniel, V.; Bergsten, C.; Cramer, G.; Christen, A.-M.; et al. ICAR Claw Health Atlas, 2nd ed.; International Committee for Animal Recording (ICAR): Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://www.icar.org/ICAR_Claw_Health_Atlas.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Kofler, J.; Fiedler, A.; Charfeddine, N.; Capion, N.; Fjeldaas, T.; Cramer, G.; Bell, N.J.; Müller, K.E.; Christen, A.-M.; Thomas, G.; et al. ICAR Claw Health Atlas-Appendix 1: Digital Dermatitis Stages (M-stages). 2019. Available online: https://www.icar.org/ Documents/ICAR-Claw-Health-Atlas-Appendix-1-DD-stages-M-stages.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Kofler, J. Klauenerkrankungen—Erkennung, Ursachen und Maßnahmen—Alarmerkrankungen. In Klauengesundheit im Griff—Mit System und Voraussicht—Ein Leitfaden für die Praxis; Ländliches Fortbildungsinstitut (LFI): Vienna, Austria, 2021; pp. 16-36.

- Swiss Federal Office for Agriculture. Tierwohlbeiträge (BTS/RAUS/Weidebeitrag). Available online: https://www.blw.admin. ch/blw/de/home/instrumente/direktzahlungen/produktionssystembeitraege23/tierwohlbeitraege1.html (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Bergsten, C.; Carlsson, J.; Jansson Mörk, M. Influence of grazing management on claw disorders in Swedish freestall dairies with mandatory grazing. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 6151-6162. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SFSO Swiss Federal Statistical Office; Agriculture and Food. Neuchâtel. 2022. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/ asset/en/22906539 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Gieseke, D.; Lambertz, C.; Gauly, M. Relationship between herd size and measures of animal welfare on dairy cattle farms with freestall housing in Germany. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 7397-7411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango-Sabogal, J.; Desrochers, A.; Lacroix, R.; Christen, A.; Dufour, S. Prevalence of foot lesions in Québec dairy herds from 2015 to 2018. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11659-11675. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capion, N.; Raundal, P.; Foldager, L.; Thompsen, P.T. Status of claw recordings and claw health in Danish dairy cattle from 2013 to 2017. Vet. J. 2021, 277, 105749. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276-282. [CrossRef]

- Häggman, J.; Juga, J. Effects of cow-level and herd-level factors on claw health in tied and loose-housed dairy herds in Finland. Livest. Sci. 2015, 181, 200-209. [CrossRef]

- Holzhauer, M.; Hardenberg, C.; Bartels, C.J.M.; Frankena, K. Herd- and Cow-Level Prevalence of Digital Dermatitis in The Netherlands and Associated Risk Factors. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 580-588. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.B.; Ramanoon, S.Z.; Mansor, R.; Syed-Hussain, S.S.; Shaik Mossadeq, W.M. Claw Trimming as a Lameness Management Practice and the Association with Welfare and Production in Dairy Cows. Animals 2020, 10, 1515. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charfeddine, N.; Pérez-Cabal, M.A. Effect of claw disorders on milk production; fertility; and longevity; and their economic impact in Spanish Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 653-665. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, G.; Lissemore, K.D.; Guard, C.L.; Leslie, K.E.; Kelton, D.F. Herd- and Cow-Level Prevalence of Foot Lesions in Ontario Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 3888-3895. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlén, L.; Hunter Holmøy, I.; Nødtvedt, A.; Sogstad, A.M.; Fjeldaas, T. A case-control study regarding factors associated with digital dermatitis in Norwegian dairy herds. Acta Vet. Scand. 2022, 64, 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, M.; Strauss, G.; Syring, C.; Ruiters, M.; Becker, J.; Steiner, A. Implementation of biosecurity measures by hoof trimmers in Switzerland. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2023, 165, 307-320. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, G.; Lissemore, K.D.; Guard, C.L.; Leslie, K.E.; Kelton, D.F. Herd-level risk factors for seven different foot lesions in Ontario Holstein cattle housed in tie stalls or free stalls. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 1404-1411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, M.A.; O’Connell, N.E. Digital dermatitis in dairy cows: A review of risk factors and potential sources of between-animal variation in susceptibility. Animals 2015, 5, 512-535. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relun, A.; Lehebel, A.; Chesnin, A.; Guatteo, R.; Bareille, N. Association between digital dermatitis lesions and test-day milk yield of Holstein cows from 41 French dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 2190-2200. [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.J.; Murray, R.D.; Carter, S.D. Bovine digital dermatitis: Current concepts from laboratory to farm. Vet. J. 2016, 211, 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Somers, J.G.C.J.; Frankena, K.; Noordhuizen-Stassen, E.N.; Metz, J.H.M. Risk factors for digital dermatitis in dairy cows kept in cubicle houses in The Netherlands. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005, 71, 11-21. [CrossRef]

- McLellan, K.K.; Weary, D.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Effects of free-choice pasture access on lameness recovery and behavior of lame dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 6845-6857. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gernand, E.; Rehbein, P.; von Borstel, U.U.; König, S. Incidences of and genetic parameters for mastitis, claw disorders, and common health traits recorded in dairy cattle contract herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 2144-2156. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olechnowicz, J.; Jaśkowski, J.M. Associations between different degrees of lameness in early lactation and the fertility of dairy cows. Med. Weter. 2015, 71, 36-40.

- Bicalho, R.C.; Vokey, F.; Erb, H.N.; Guard, C.L. Visual locomotion scoring in the first seventy days in milk: Impact on pregnancy and survival. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 4586-4591. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbarino, E.J.; Hernandez, J.A.; Shearer, J.K.; Risco, C.A.; Thatcher, W.W. Effect of Lameness on Ovarian Activity in Postpartum Holstein Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 4123-4131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liinamo, A.E.; Laakso, M.; Ojala, M. Environmental and genetic effects on claw disorders in Finnish dairy cattle. In Breeding for Robustness in Cattle; Klopcic, M., Reents, R., Philipsson, J., Kuipers, A., Eds.; EAAP Publication: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 126, pp. 169-179.

- Manske, T.; Hultgren, J.; Bergsten, C. Prevalence and interrelationships of hoof lesions and lameness in Swedish dairy cows. Prev. Vet. Med. 2002, 54, 247-263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, L.; Barkema, H.W.; Pajor, E.A.; Mason, S.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Zaffino Heyerhoff, J.C.; Nash, C.G.R.; Haley, D.B.; Vasseur, E.; Pellerin, D.; et al. Prevalence of lameness and associated risk factors in Canadian Holstein-Friesian cows housed in freestall barns. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 6978-6991. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lischer, C.; Steiner, A.; Geyer, H.; Friedli, K.; Ossent, P.; Nuss, K. Klauenpflege. Ein Handbuch zur Klauenpflege beim Rind, 4th ed.; Edition-lmz: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 114-120.

- Bernhard, J.K.; Vidondo, B.; Ackermann, R.L.; Rediger, R.; Stucki, D.; Müller, K.E.; Steiner, A. Slightly and Moderately Lame Cows in Tie Stalls Behave Differently from Non-lame Controls. A Matched Case-Control Study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 594825. [CrossRef]

- Greenough, P.R. Bovine Laminitis and Lameness: A Hands-on Approach; Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 55-69.

- Cook, N.B.; Nordlund, K.V.; Oetzel, G.R. Environmental Influences on Claw Horn Lesions Associated with Laminitis and Subacute Ruminal Acidosis in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 36-46. [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, A.; Maierl, J.; Nuss, K. Erkrankungen der Klauen und Zehen des Rindes, 2nd ed.; Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019; pp. 130-137. [CrossRef]

- Overton, M.W.; Sischo, W.M.; Temple, G.D.; Moore, D.A. Using Time-Lapse Video Photography to Assess Dairy Cattle Lying Behavior in a Free-Stall Barn. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 2407-2413. [CrossRef]

- Holzhauer, M.; Hardenberg, C.; Bartels, C.J.M. Herd and cow-level prevalence of sole ulcers in The Netherlands and associatedrisk factors. Prev. Vet. Med. 2008, 85, 125-135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, N.J.; Knowles, T.G.; Whay, H.R.; Main, D.J.; Webster, A.J. The development, implementation and testing of a lameness control programme based on HACCP principles and designed for heifers on dairy farms. Vet. J. 2009, 180, 178-188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, A.D.; St. Jean, G.; Steiner, A. Bovine Surgery and Lameness, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 208-268. [CrossRef]

- Shearer, J.K.; van Amstel, S.R. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Sole Ulcers and White Line Disease. Food Anim. Pract. 2017, 33, 283-300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, L.G.; O’Connell, N.E.; McCoy, M.A.; Keady, T.W.J.; Kilpatrick, D.J. Effects of breed and production system on lameness parameters in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 2174-2182. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Lundström, K. Influence of breed, age, bodyweight and season on digital disease and hoof size in dairy cows. Zentbl. Vetmed. 1981, 28, 141-151. [CrossRef]

February to 12 February of the following year. Q1 th percentile; Q3 th percentile. Cows in cow-calf operations. of the cows were trimmed. February to 12 February of the following year. IQR interquartile range. Distribution of different types of ulcers in the herds and cows analysed. In some herds and cows, more than one type of ulcer can occur. Herds and cows with at least one alarm lesion present at routine trimming. Alarm lesions analysed include all lesions listed in the table. 95% confidence interval. Metric variable. Housing period: 1 January to 30 June (60-day transition period included); grazing period: 1 July to 31 December (60-day transition period included).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14010153

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38200884

Publication Date: 2024-01-02

Prevalence of Painful Lesions of the Digits and Risk Factors Associated with Digital Dermatitis, Ulcers and White Line Disease on Swiss Cattle Farms

Revised: 16 December 2023

Accepted: 27 December 2023

Published: 2 January 2024

Abstract

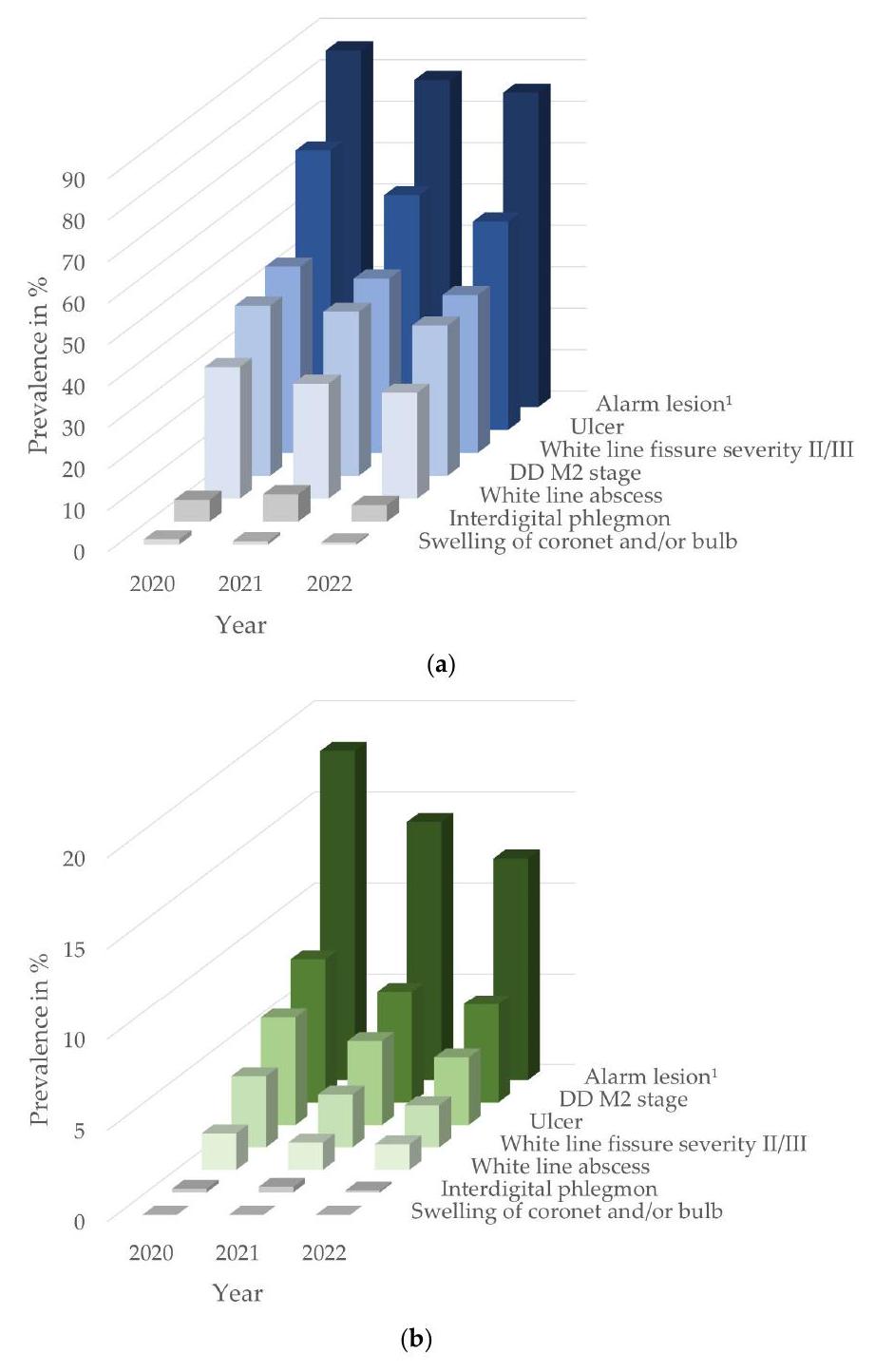

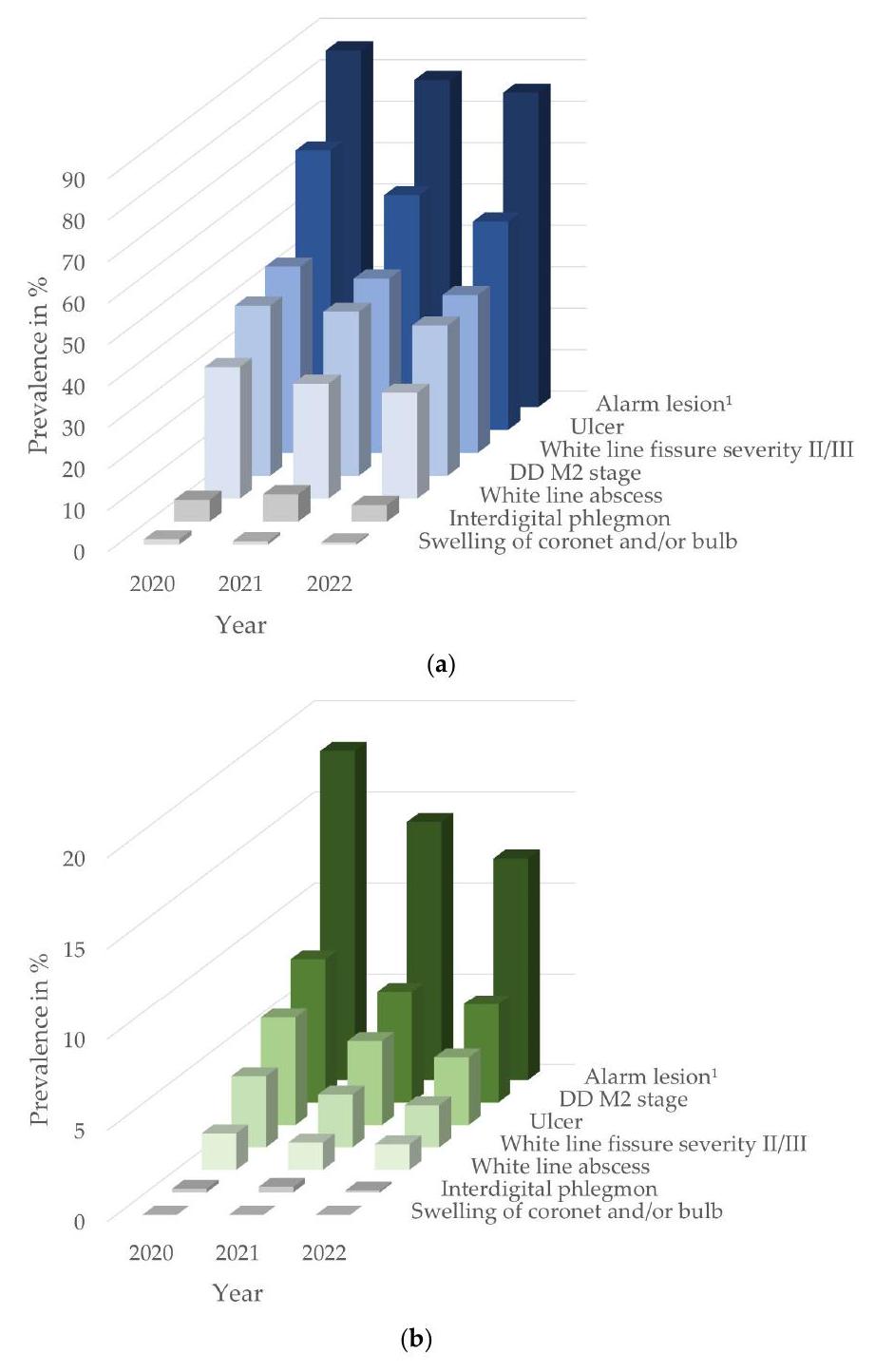

The first aim of this study was to calculate the prevalence of painful lesions of the digits (“alarm” lesions; ALs) in Swiss dairy herds and cow-calf operations over a three-year study period. The following ALs were included in the calculation: the M2 stage of digital dermatitis (DD M2), ulcers (U), white line fissures (WLF) of moderate and high severity, white line abscesses (WLA), interdigital phlegmon (IP) and swelling of the coronet and/or bulb (SW). Between February 2020 and February 2023, digit disorders were electronically recorded during routine trimmings by 40 specially trained hoof trimmers on Swiss cattle farms participating in the national claw health programme. The data set used consisted of over 35,000 observations from almost 25,000 cows from 702 herds. While at the herd-level, the predominant AL documented in 2022 was U with

1. Introduction

to a decrease in the occurrence of ALs over time. Furthermore, we expected to identify risk factors referring to herd characteristics, claw health management and individual cow characteristics related to high prevalences of DD,

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Study Population

2.2. Electronical Data Recording

and the examination of digit disorders during trimming with a kappa value

2.3. Data Management

2.4. Statistical Analyses

accessed on 28 November 2023) were used. Categorical variables are described by frequency distributions, and continuous variables are summarised as the median and interquartile range. For the risk factor analyses, two separate analyses for the outcomes of interest were performed. The outcomes were (i) herds affected by DD, U or WL and (ii) cows affected by DD, U or WL. The outcomes were classified as binary (herd/cow affected vs. not affected), and each potential predictor variable was analysed with a respective univariable logistic regression model for each disease (i.e., three models each for the herd-level and cow-level). Only variables showing a

3. Results

3.1. Herd and Cow Characteristics

| Herd-Level Characteristic | Year

|

Year

|

Year

|

|||

| % (n) | Median (Q1-Q3)

|

% (n) | Median (Q1-Q3)

|

% (n) | Median (Q1-Q3)

|

|

| Production system | ||||||

| Cow-calf operations | 11.9 (18) | 12.9 (65) | 13.8 (77) | |||

| Herd size

|

26 (16.5-40) | 26 (18-40) | 26 (18-39) | |||

| Housing type | ||||||

| Tie stall | 42.4 (64) | 41.6 (209) | 39.9 (223) | |||

| Free stall | 57.6 (87) | 58.4 (294) | 60.1 (336) | |||

| Predominant breed (dairy herds) | ||||||

| Holstein Friesian | 33.1 (44) | 32.2 (141) | 33.4 (161) | |||

| Other | 66.9 (89) | 67.8 (297) | 66.6 (321) | |||

| Herd trimmings per year

|

||||||

|

|

88.7 (134) | 68.2 (343) | 61.4 (343) | |||

|

|

11.3 (17) | 30.4 (153) | 36.5 (204) | |||

|

|

0.0 (0) | 1.4 (7) | 2.1 (12) | |||

| Mountain pasturing | ||||||

| Yes | 44.4 (67) | 53.9 (271) | 51.2 (286) | |||

| No | 55.6 (84) | 46.1 (232) | 48.8 (273) | |||

| Participating in the RAUS Programme

|

91.4 (138) | 94.8 (477) | 95.3 (533) | |||

| Trimmed herds per hoof trimmer | 8 (4-11.5) | 10 (6-19) | 10 (6-22) | |||

| Trimming season

|

||||||

| Housing season | 40.4 (61) | 65.0 (327) | 69.4 (388) | |||

| Grazing season | 59.6 (90) | 35.0 (176) | 30.6 (171) | |||

| Recording hoof trimmers | 19 | 37 | 35 | |||

| Cow-Level Characteristic | Year

|

Year

|

Year

|

|||

| % (n) | Median (Q1-Q3)

|

% (n) | Median (Q1-Q3)

|

% (n) | Median (Q1-Q3)

|

|

| Production system | ||||||

| Dairy cows | 90.6 (4118) |

|

|

|||

| Suckler cows

|

9.4 (428) | 10.5 (1625) | 10.5 (1786) | |||

| Percentage of trimmed cows per herd trimming

|

100 (95.7-100) | 100 (94.1-100) | 100 (95.5-100) | |||

| Trimmed cows per hoof trimmer | 205 (135-309) | 348 (135-573) | 329 (182-639) | |||

| 420 Dairy Herds and 13,735 Dairy Cows | |

| Characteristic | Median (Q1-Q3)

|

| Herd-Level

|

|

| 305-day milk yield (kg) | 7702 (6765-8668) |

| Parity | 3 (2.6-3.4) |

| Lactation length (d) | 346 (331-366) |

| Intercalving period | 401 (385-418) |

| Cow-Level | |

| Milk yield (kg)

|

25.8 (20.2-32.3) |

| Parity

|

3 (2-4) |

| Lactation length (d)

|

316 (270-369) |

| Intercalving period (d)

|

388 (360-437) |

|

|

|

-

Most recent milk recording before herd trimming. Most recent lactation.

3.2. Prevalence of Alarm Lesions

| Herd Prevalence | Within-Herd Prevalence | Cow Prevalence | |||||||||||||

| Year

|

2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||||

| Total number analysed | 151 | 503 | 559 | 151 | 503 | 559 | 4546 | 15,418 | 16,959 | ||||||

| Data distribution statistic | % | Median | IQR

|

Range | Median | IQR

|

Range | Median | IQR

|

Range | % | ||||

| M2 stage of digital dermatitis | 41.1 | 39.6 | 36.3 | 4.1 | 19.1 | 0-55.0 | 2.8 | 16.7 | 0-58.1 | 0.0 | 11.4 | 0-50.3 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 5.4 |

| Interdigital phlegmon | 5.3 | 6.6 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-11.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-18.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-9.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Swelling of coronet and/or bulb | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-4.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ulcers

|

67.5 | 56.7 | 50.3 | 4.2 | 9.0 | 0-50.0 | 2.9 | 6.5 | 0-30.8 | 1.3 | 5.4 | 0-35.9 | 5.9 | 4.6 | 3.7 |

| Sole ulcer | 55.0 | 48.1 | 44.0 | 2.7 | 6.5 | 0-25.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 0-30.8 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0-33.3 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 2.9 |

| Bulb ulcer | 19.9 | 15.7 | 13.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-25.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-18.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Toe ulcer | 10.6 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-14.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-5.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Toe necrosis | 5.3 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-5.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0-6.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| White line fissure severity II/III | 45.0 | 42.1 | 38.1 | 6.8 | 19.1 | 0-47.2 | 7.2 | 13.9 | 0-39.2 | 5.5 | 13.2 | 0-35.1 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| White line abscess | 31.8 | 27.8 | 25.6 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0-25.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0-28.6 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0-22.2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Alarm lesion

|

86.1 | 79.0 | 75.9 | 11.5 | 16.6 | 0-66.1 | 9.4 | 12.8 | 0-57.2 | 8.0 | 13.2 | 0-53.7 | 18.1 | 14.2 | 12.2 |

| 113 February to 12 February of the following year.

|

|||||||||||||||

3.3. Risk Factors for Digital Dermatitis, Ulcers, and White Line Disease

| Predictor | Digital Dermatitis | |||||

| Class | Count (n) | Diseased (n) | Odds Ratio |

|

|

|

| Herd-Level | ||||||

| Housing | Tie stall | 194 | 62 | 0.25 | 0.15-0.41 | <0.001 |

| Free stall | 226 | 147 | Ref | |||

| Mountain pasturing | Yes | 221 | 88 | 0.49 | 0.31-0.77 | 0.002 |

| No | 199 | 121 | Ref | |||

| Predominant breed | Holstein Friesian | 125 | 97 | 5.03 | 3.00-8.66 | <0.001 |

| Other | 295 | 112 | Ref | |||

| Herd trimmings per year | 2 | 1.64 | 1.03-2.64 | 0.039 | ||

| Intercalving period (d) | 2 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.005 | ||

| Cow-Level | ||||||

| Housing | Tie stall | 4228 | 170 | 0.44 | 0.31-0.63 | <0.001 |

| Free stall | 9507 | 1442 | Ref | |||

| Breed | Holstein Friesian | 6072 | 1112 | 1.63 | 1.37-1.94 | <0.001 |

| Other | 7663 | 500 | Ref | |||

| Parity | 2 | 0.97 | 0.94-1.00 | 0.046 | ||

| Predictor | Ulcers | |||||

| Class | Count (n) | Diseased (n) | Odds ratio | 95% CI

|

|

|

| Herd-Level | ||||||

| Intercalving period (d) | 2 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.02 | 0.012 | ||

| Lactation length (d) | <339 | 175 | 66 | 0.43 | 0.25-0.76 | 0.003 |

| 340-360 | 118 | 67 | 0.79 | 0.45-1.40 | 0.419 | |

| >360 | 127 | 85 | Ref | |||

| Cow-Level | ||||||

| Housing | Tie stall | 4228 | 180 | 1.47 | 1.11-1.96 | 0.008 |

| Free stall | 9507 | 332 | Ref | |||

| Trimming season

|

Housing period | 9022 | 200 | 0.65 | 0.50-0.85 | 0.002 |

| Grazing period | 4713 | 312 | Ref | |||

| Parity | 2 | 1.36 | 1.31-1.41 | <0.001 | ||

| Predictor | White Line Disease | |||||

| Class | Count (n) | Diseased (n) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI

|

|

|

| Herd-Level | ||||||

| Housing | Tie stall | 194 | 115 | 0.20 | 0.11-0.34 | <0.001 |

| Free stall | 226 | 197 | Ref | |||

| Cow-Level | ||||||

| Housing | Tie stall | 4228 | 278 | 0.40 | 0.32-0.50 | <0.001 |

| Breed | Free stall | 9507 | 1199 | Ref | ||

| Holstein Friesian | 6072 | 573 | 0.71 | 0.61-0.84 | <0.001 | |

| Other | 7663 | 904 | Ref | |||

| Trimming season

|

Housing period | 9022 | 596 | 0.55 | 0.44-0.67 | <0.001 |

| Grazing period | 4713 | 881 | Ref | |||

| Lactation length (d) | <339 | 4140 | 438 | 0.81 | 0.69-0.95 | 0.008 |

| 340-360 | 5731 | 584 | 0.89 | 0.78-1.03 | 0.119 | |

| >360 | 3864 | 453 | Ref | |||

| Parity | 3 | 1.30 | 1.27-1.33 | <0.001 | ||

3.3.1. Herd-Level Risk Factors

3.3.2. Cow-Level Risk Factors

4. Discussion

in a previous study, but as they did not focus on ALs, the prevalences for that year were recalculated [1]. The present study contains the largest electronical data set on the health of the digits in Swiss cattle, with over 35,000 observations from almost 25,000 cows from over 700 farms. The implementation of stringent inclusion criteria ensured that we considered complete herd trimmings only (

4.1. Prevalence Development for 2020-2023

the need to improve farmers’ awareness of painful lesions and resulting lameness [37]. When comparing the prevalence data with those from other studies, it is important to keep in mind that not only herd management factors and climatic conditions but also training requirements and data collection methods differ. Therefore, the ICAR Claw Health Atlas was introduced to set international training standards and ensure the comparability of data [1,25,38]. However, reported lesion prevalences at the cow-level for DD M2 at

4.2. Risk Factors

4.2.1. Digital Dermatitis

with DD can potentially be transmitted via claw trimming equipment [36,40]. Bayer et al. (2023) reported low implementation of external and internal biosafety measures during routine trimming in Swiss hoof trimmers, which could also explain our findings [41]. However, the advantages of frequent routine trimming outweigh the disadvantages, because the incidence of horn associated claw disorders can be reduced [37]. Nevertheless, the transmissibility of the infectious disease and the implementation of adequate biosafety measures must be considered [41]. Additionally, farms with higher DD prevalences may perform more frequent herd trimming sessions to prevent digit disorders, which accordingly leads to more frequent detection but also more treatment of such lesions [36,40].

4.2.2. Ulcers

exceeded 180 d) by up to 71 days [38]. This is in line with the findings of Olechnowicz and Jaskowski (2015) and Bicalho et al. (2007), who reported an extended range of 20 to 40 days from calving to conception [ 49,50 ]. Claw lesions such as U can affect ovarian activity through pain by increasing cortisol levels, which can interfere with the oestrus cycle and prolong the anoestrus period [38,51]. Furthermore, Häggman and Juga (2015), Liinamo et al. (2009) and Manske (2002) reported that the risk of U increases between 61 and 150 days of lactation, as lactational stress increases and negatively affects the body condition score [35,52,53]. It is also worth considering that many cows with a very long lactation period belong to the group of cows that are no longer inseminated and milked until being culled, so they are no longer prioritised for claw trimming by the farmer, which may then increase the risk of U.

4.2.3. White Line Disease

5. Conclusions

(Adrian Steiner) and C.S.; data curation, A.F., J.B. and C.S.; writing-original draft preparation, A.F.; writing-review and editing, A.S. (Adrian Steiner), C.S., J.B., M.W.R., J.W., A.S. (Analena Sarbach) and A.F. visualization, A.F.; supervision, A.S. (Adrian Steiner) and C.S.; project administration, A.S. (Adrian Steiner), C.S. and M.W.R.; funding acquisition, A.S. (Adrian Steiner), C.S. and M.W.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks are due to the participating hoof trimmers, farmers and organisations, especially to Anke Regli (Qualitas AG, Zug, Switzerland), for providing research resources. Our thanks also go to the organising project institutions: the Swiss Association of Hoof Trimmers, the Swiss Cattle Breeders’ Association and the Swiss Association for Ruminant Health.

References

- Jury, A.; Syring, C.; Becker, J.; Locher, I.; Strauss, G.; Ruiters, M.; Steiner, A. Prevalence of claw disorders in Swiss cattle farms. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2021, 163, 779-790. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvergnas, M.; Strabel, T.; Rzewuska, K.; Sell-Kubiak, E. Claw disorders in dairy cattle: Effects on production; welfare and farm economics with possible prevention methods. Livest. Sci. 2019, 222, 54-64. [CrossRef]

- Solano, L.; Barkema, H.W.; Mason, S.; Pajor, E.A.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Orsel, K. Prevalence and distribution of foot lesions in dairy cattle in Alberta; Canada. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 6828-6841. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.; Bernhard, J.; Syring, C.; Steiner, A. Establishment of key indicators and limit values for assessment of claw health of cattle in Switzerland. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2021, 163, 43-56. [CrossRef]

- Heringstad, B.; Egger-Danner, C.; Charfeddine, N.; Pryce, J.E.; Stock, K.F.; Kofler, J.; Sogstad, A.M.; Holzhauer, M.; Fiedler, A.; Müller, K.; et al. Invited review: Genetics and claw health: Opportunities to enhance claw health by genetic selection. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4801-4821. [CrossRef]

- Kofler, J.; Pesenhofer, R.; Landl, G.; Somerfeld-Stur, I.; Peham, C. Monitoring of dairy cow claw health status in 15 herds using the computerised documentation program Claw Manager and digital parameters. Tierarztl. Prax. Ausg. G. Grosstiere/Nutztiere 2013, 41, 31-44. [CrossRef]

- Bielfeldt, J.C.; Badertscher, R.; Tölle, K.H.; Krieter, J. Risk factors influencing lameness and claw disorders in dairy cows. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 95, 265-271. [CrossRef]

- Whay, H.; Shearer, J.K. The Impact of Lameness on Welfare of the Dairy Cow. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2017, 33, 153-164. [CrossRef]

- Huxley, J.N. Impact of lameness and claw lesions in cows on health and production. Livest. Sci. 2013, 156, 64-70. [CrossRef]

- Browne, N.; Hudson, C.D.; Crossley, R.E.; Sugrue, K.; Huxley, J.N.; Conneely, M. Hoof lesions in partly housed pasture-based dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 9038-9053. [CrossRef]

- Mostert, P.F.; van Middelaar, C.E.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Bokkers, E.A.M. The impact of foot lesions in dairy cows on greenhouse gas emissions of milk production. Agric. Syst. 2018, 167, 206-212. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; White, E.; Holden, N.M. The effect of lameness on the environmental performance of milk production by rotational grazing. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 172, 143-150. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, J.; Steiner, A.; Kohler, S.; Koller-Bähler, A.; Wüthrich, M.; Reist, M. Lameness and foot lesions in Swiss dairy cows: I. Prevalence. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2014, 156, 71-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofler, J.; Suntinger, M.; Mayerhofer, M.; Linke, K.; Maurer, L.; Hund, A.; Fiedler, A.; Duda, J.; Egger-Danner, C. Benchmarking Based on Regularly Recorded Claw Health Data of Austrian Dairy Cattle for Implementation in the Cattle Data Network (RDV). Animals 2022, 12, 808. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöström, K.; Fall, N.; Blanco-Penedo, I.; Duval, J.E.; Krieger, M.; Emanuelson, U. Lameness prevalence and risk factors in organic dairy herds in four European countries. Livest. Sci. 2018, 208, 44-50. [CrossRef]

- Chapinal, N.; Barrientos, A.K.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Galo, E.; Weary, D.M. Herd-level risk factors for lameness in freestall farms in the northeastern United States and California. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 318-328. [CrossRef]

- Barker, Z.E.; Leach, K.A.; Whay, H.R.; Bell, N.J.; Main, D.C.J. Assessment of lameness prevalence and associated risk factors in dairy herds in England and Wales. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 93, 932-941. [CrossRef]

- Haskell, M.J.; Rennie, L.J.; Bowell, V.A.; Bell, M.J.; Lawrence, A.B. Housing System, Milk Production; and Zero-Grazing Effects on Lameness and Leg Injury in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 4259-4266. [CrossRef]

- Sogstad, Å.M.; Fjeldaas, T.; Østerås, O.; Plym Forshell, K. Prevalence of claw lesions in Norwegian dairy cattle housed in tie stalls and free stalls. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005, 70, 191-209. [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Steiner, A.; Kohler, S.; Koller-Bähler, A.; Wüthrich, M.; Reist, M. Lameness and foot lesions in Swiss dairy cows: II. Risk factors. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2014, 156, 79-89. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, G.; Stucki, D.; Jury, A.; Locher, I.; Syring, C.; Ruiters, M.; Steiner, A. Evaluation of a novel training course for hoof trimmers to participate in a Swiss national cattle claw health monitoring programme. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2021, 163, 189-201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.; Welham Ruiters, M.; Syring, C.; Steiner, A. Improvement of claw health of cattle in Switzerland. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2020, 162, 285-292. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesamt für Landwirtschaft BLW (Federal Agricultural Office). Ressourcenprogramm. 2022. Available online: https://www. blw.admin.ch/blw/de/home/instrumente/ressourcen–und-gewaesserschutzprogramm/ressourcenprogramm.html (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Weber, J.; Becker, J.; Syring, C.; Welham Ruiters, M.; Locher, I.; Bayer, M.; Schüpbach-Regula, G.; Steiner, A. Farm-level risk factors for digital dermatitis in dairy cows in mountainous regions. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 1341-1350. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger-Danner, C.; Nielsen, P.; Fiedler, A.; Müller, K.; Fjeldaas, T.; Döpfer, D.; Daniel, V.; Bergsten, C.; Cramer, G.; Christen, A.-M.; et al. ICAR Claw Health Atlas, 2nd ed.; International Committee for Animal Recording (ICAR): Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://www.icar.org/ICAR_Claw_Health_Atlas.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Kofler, J.; Fiedler, A.; Charfeddine, N.; Capion, N.; Fjeldaas, T.; Cramer, G.; Bell, N.J.; Müller, K.E.; Christen, A.-M.; Thomas, G.; et al. ICAR Claw Health Atlas-Appendix 1: Digital Dermatitis Stages (M-stages). 2019. Available online: https://www.icar.org/ Documents/ICAR-Claw-Health-Atlas-Appendix-1-DD-stages-M-stages.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Kofler, J. Klauenerkrankungen—Erkennung, Ursachen und Maßnahmen—Alarmerkrankungen. In Klauengesundheit im Griff—Mit System und Voraussicht—Ein Leitfaden für die Praxis; Ländliches Fortbildungsinstitut (LFI): Vienna, Austria, 2021; pp. 16-36.

- Swiss Federal Office for Agriculture. Tierwohlbeiträge (BTS/RAUS/Weidebeitrag). Available online: https://www.blw.admin. ch/blw/de/home/instrumente/direktzahlungen/produktionssystembeitraege23/tierwohlbeitraege1.html (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Bergsten, C.; Carlsson, J.; Jansson Mörk, M. Influence of grazing management on claw disorders in Swedish freestall dairies with mandatory grazing. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 6151-6162. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SFSO Swiss Federal Statistical Office; Agriculture and Food. Neuchâtel. 2022. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/ asset/en/22906539 (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Gieseke, D.; Lambertz, C.; Gauly, M. Relationship between herd size and measures of animal welfare on dairy cattle farms with freestall housing in Germany. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 7397-7411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango-Sabogal, J.; Desrochers, A.; Lacroix, R.; Christen, A.; Dufour, S. Prevalence of foot lesions in Québec dairy herds from 2015 to 2018. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11659-11675. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capion, N.; Raundal, P.; Foldager, L.; Thompsen, P.T. Status of claw recordings and claw health in Danish dairy cattle from 2013 to 2017. Vet. J. 2021, 277, 105749. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276-282. [CrossRef]

- Häggman, J.; Juga, J. Effects of cow-level and herd-level factors on claw health in tied and loose-housed dairy herds in Finland. Livest. Sci. 2015, 181, 200-209. [CrossRef]

- Holzhauer, M.; Hardenberg, C.; Bartels, C.J.M.; Frankena, K. Herd- and Cow-Level Prevalence of Digital Dermatitis in The Netherlands and Associated Risk Factors. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 580-588. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.B.; Ramanoon, S.Z.; Mansor, R.; Syed-Hussain, S.S.; Shaik Mossadeq, W.M. Claw Trimming as a Lameness Management Practice and the Association with Welfare and Production in Dairy Cows. Animals 2020, 10, 1515. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charfeddine, N.; Pérez-Cabal, M.A. Effect of claw disorders on milk production; fertility; and longevity; and their economic impact in Spanish Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 653-665. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, G.; Lissemore, K.D.; Guard, C.L.; Leslie, K.E.; Kelton, D.F. Herd- and Cow-Level Prevalence of Foot Lesions in Ontario Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 3888-3895. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlén, L.; Hunter Holmøy, I.; Nødtvedt, A.; Sogstad, A.M.; Fjeldaas, T. A case-control study regarding factors associated with digital dermatitis in Norwegian dairy herds. Acta Vet. Scand. 2022, 64, 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, M.; Strauss, G.; Syring, C.; Ruiters, M.; Becker, J.; Steiner, A. Implementation of biosecurity measures by hoof trimmers in Switzerland. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2023, 165, 307-320. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, G.; Lissemore, K.D.; Guard, C.L.; Leslie, K.E.; Kelton, D.F. Herd-level risk factors for seven different foot lesions in Ontario Holstein cattle housed in tie stalls or free stalls. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 1404-1411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, M.A.; O’Connell, N.E. Digital dermatitis in dairy cows: A review of risk factors and potential sources of between-animal variation in susceptibility. Animals 2015, 5, 512-535. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relun, A.; Lehebel, A.; Chesnin, A.; Guatteo, R.; Bareille, N. Association between digital dermatitis lesions and test-day milk yield of Holstein cows from 41 French dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 2190-2200. [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.J.; Murray, R.D.; Carter, S.D. Bovine digital dermatitis: Current concepts from laboratory to farm. Vet. J. 2016, 211, 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Somers, J.G.C.J.; Frankena, K.; Noordhuizen-Stassen, E.N.; Metz, J.H.M. Risk factors for digital dermatitis in dairy cows kept in cubicle houses in The Netherlands. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005, 71, 11-21. [CrossRef]

- McLellan, K.K.; Weary, D.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Effects of free-choice pasture access on lameness recovery and behavior of lame dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 6845-6857. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gernand, E.; Rehbein, P.; von Borstel, U.U.; König, S. Incidences of and genetic parameters for mastitis, claw disorders, and common health traits recorded in dairy cattle contract herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 2144-2156. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olechnowicz, J.; Jaśkowski, J.M. Associations between different degrees of lameness in early lactation and the fertility of dairy cows. Med. Weter. 2015, 71, 36-40.

- Bicalho, R.C.; Vokey, F.; Erb, H.N.; Guard, C.L. Visual locomotion scoring in the first seventy days in milk: Impact on pregnancy and survival. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 4586-4591. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbarino, E.J.; Hernandez, J.A.; Shearer, J.K.; Risco, C.A.; Thatcher, W.W. Effect of Lameness on Ovarian Activity in Postpartum Holstein Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 4123-4131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liinamo, A.E.; Laakso, M.; Ojala, M. Environmental and genetic effects on claw disorders in Finnish dairy cattle. In Breeding for Robustness in Cattle; Klopcic, M., Reents, R., Philipsson, J., Kuipers, A., Eds.; EAAP Publication: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 126, pp. 169-179.

- Manske, T.; Hultgren, J.; Bergsten, C. Prevalence and interrelationships of hoof lesions and lameness in Swedish dairy cows. Prev. Vet. Med. 2002, 54, 247-263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, L.; Barkema, H.W.; Pajor, E.A.; Mason, S.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Zaffino Heyerhoff, J.C.; Nash, C.G.R.; Haley, D.B.; Vasseur, E.; Pellerin, D.; et al. Prevalence of lameness and associated risk factors in Canadian Holstein-Friesian cows housed in freestall barns. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 6978-6991. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lischer, C.; Steiner, A.; Geyer, H.; Friedli, K.; Ossent, P.; Nuss, K. Klauenpflege. Ein Handbuch zur Klauenpflege beim Rind, 4th ed.; Edition-lmz: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 114-120.

- Bernhard, J.K.; Vidondo, B.; Ackermann, R.L.; Rediger, R.; Stucki, D.; Müller, K.E.; Steiner, A. Slightly and Moderately Lame Cows in Tie Stalls Behave Differently from Non-lame Controls. A Matched Case-Control Study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 594825. [CrossRef]

- Greenough, P.R. Bovine Laminitis and Lameness: A Hands-on Approach; Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 55-69.

- Cook, N.B.; Nordlund, K.V.; Oetzel, G.R. Environmental Influences on Claw Horn Lesions Associated with Laminitis and Subacute Ruminal Acidosis in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 36-46. [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, A.; Maierl, J.; Nuss, K. Erkrankungen der Klauen und Zehen des Rindes, 2nd ed.; Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019; pp. 130-137. [CrossRef]

- Overton, M.W.; Sischo, W.M.; Temple, G.D.; Moore, D.A. Using Time-Lapse Video Photography to Assess Dairy Cattle Lying Behavior in a Free-Stall Barn. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 2407-2413. [CrossRef]

- Holzhauer, M.; Hardenberg, C.; Bartels, C.J.M. Herd and cow-level prevalence of sole ulcers in The Netherlands and associatedrisk factors. Prev. Vet. Med. 2008, 85, 125-135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, N.J.; Knowles, T.G.; Whay, H.R.; Main, D.J.; Webster, A.J. The development, implementation and testing of a lameness control programme based on HACCP principles and designed for heifers on dairy farms. Vet. J. 2009, 180, 178-188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, A.D.; St. Jean, G.; Steiner, A. Bovine Surgery and Lameness, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 208-268. [CrossRef]

- Shearer, J.K.; van Amstel, S.R. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Sole Ulcers and White Line Disease. Food Anim. Pract. 2017, 33, 283-300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, L.G.; O’Connell, N.E.; McCoy, M.A.; Keady, T.W.J.; Kilpatrick, D.J. Effects of breed and production system on lameness parameters in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 2174-2182. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Lundström, K. Influence of breed, age, bodyweight and season on digital disease and hoof size in dairy cows. Zentbl. Vetmed. 1981, 28, 141-151. [CrossRef]

February to 12 February of the following year. Q1 th percentile; Q3 th percentile. Cows in cow-calf operations. of the cows were trimmed. February to 12 February of the following year. IQR interquartile range. Distribution of different types of ulcers in the herds and cows analysed. In some herds and cows, more than one type of ulcer can occur. Herds and cows with at least one alarm lesion present at routine trimming. Alarm lesions analysed include all lesions listed in the table. 95% confidence interval. Metric variable. Housing period: 1 January to 30 June (60-day transition period included); grazing period: 1 July to 31 December (60-day transition period included).