DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2024.103063

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-25

بناء المرونة الريادية خلال الأزمات باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي: دراسة تجريبية على الشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

التوجه الريادي

المرونة الريادية

اضطراب السوق

وجه القدرة الديناميكية

الملخص

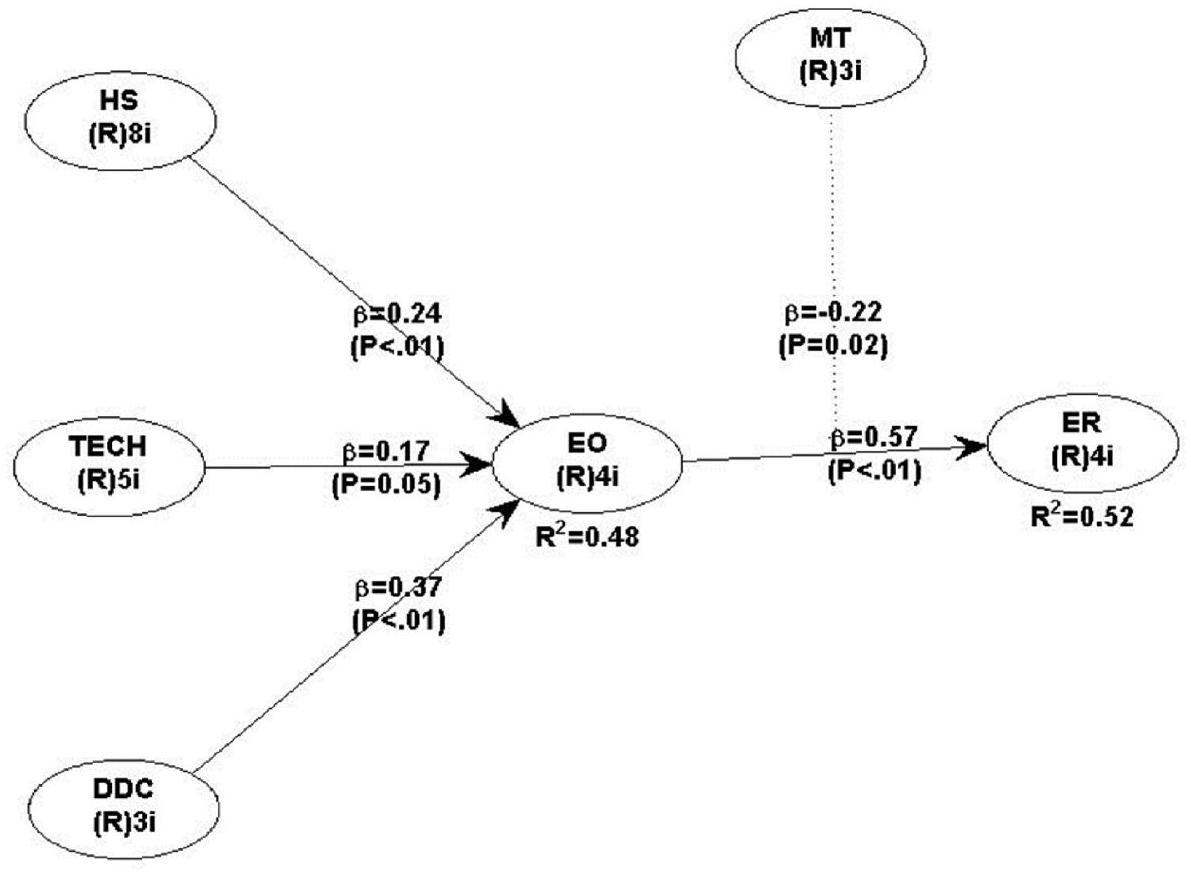

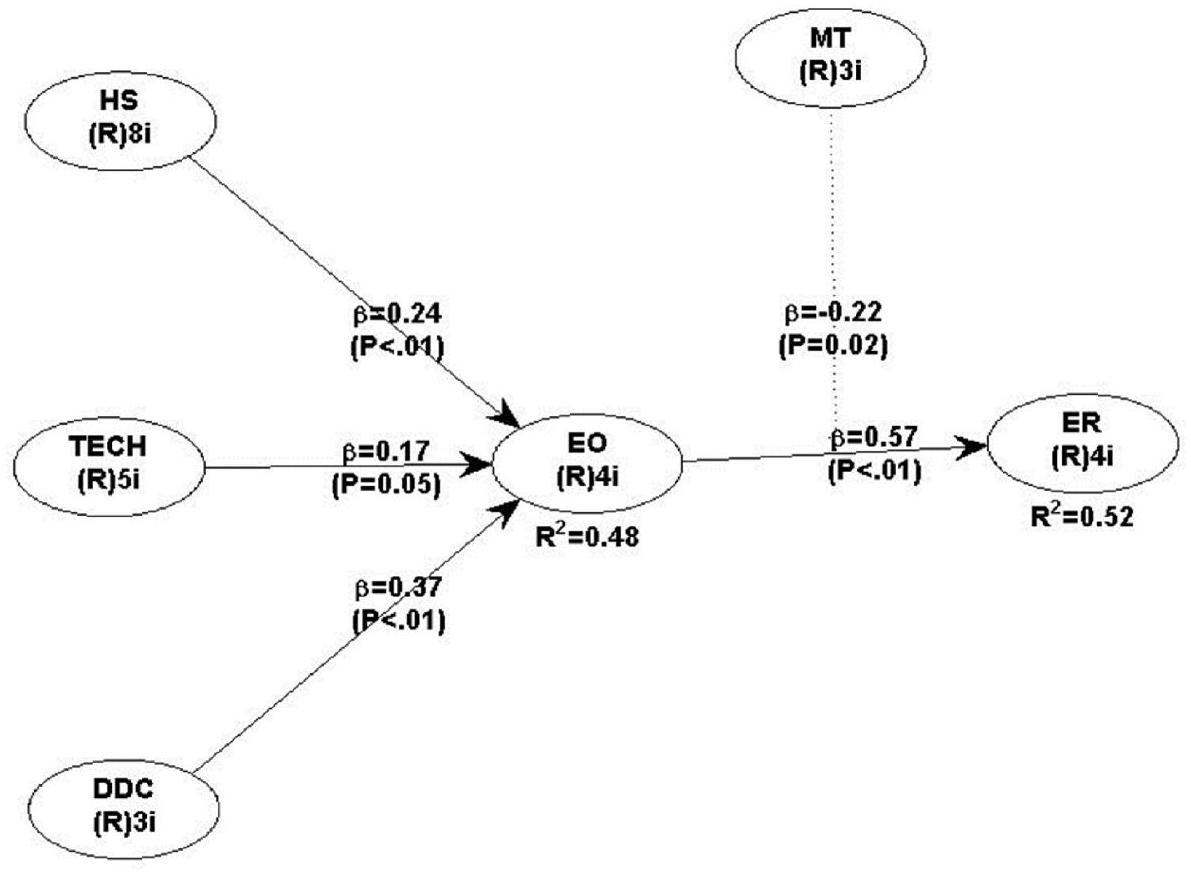

مؤخراً، حظيت الذكاء الاصطناعي العام باهتمام كبير عبر مختلف قطاعات المجتمع، حيث جذب اهتمام الشركات الصغيرة بسبب قدرته على السماح لها بإعادة تقييم نماذج أعمالها باستثمار minimal. لفهم كيف استخدمت الشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة أدوات قائمة على الذكاء الاصطناعي العام للتكيف مع مستوى الاضطراب العالي في السوق الناتج عن جائحة COVID-19، والأزمات الجيوسياسية، وتباطؤ الاقتصاد، أجرت الباحثون دراسة تجريبية. على الرغم من أن الذكاء الاصطناعي العام يتلقى مزيدًا من الاهتمام، لا يزال هناك نقص في الدراسات التجريبية التي تحقق في كيفية تأثيره على التوجه الريادي للشركات وقدرتها على تنمية المرونة الريادية في ظل الاضطراب السوقي. تقدم معظم الأدبيات أدلة قصصية. لمعالجة هذه الفجوة البحثية، أسس المؤلفون نموذجهم النظري وفرضيات البحث على الرؤية الطارئة للقدرات الديناميكية. اختبروا فرضيات البحث باستخدام بيانات مقطعية من أداة استبيان تم اختبارها مسبقًا، والتي أسفرت عن 87 استجابة قابلة للاستخدام من الشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة في فرنسا. استخدم المؤلفون نمذجة المعادلات الهيكلية القائمة على التباين باستخدام برنامج WarpPLS 7.0 التجاري لاختبار النموذج النظري. تشير نتائج الدراسة إلى أن الذكاء الاصطناعي العام والتوجه الريادي لهما تأثير كبير على بناء المرونة الريادية كقدرات ديناميكية أعلى وأدنى. ومع ذلك، فإن الاضطراب السوقي له تأثير معتدل سلبي على المسار الذي يربط بين التوجه الريادي والمرونة الريادية. تشير النتائج إلى أن الافتراض بأن الاضطراب السوقي العالي سيكون له آثار إيجابية على القدرات الديناميكية والميزة التنافسية ليس دائمًا صحيحًا، وأن الافتراض الخطي لا ينطبق، وهو ما يتماشى مع افتراضات بعض العلماء. تقدم نتائج الدراسة مساهمات كبيرة للرؤية الطارئة للقدرات الديناميكية وتفتح آفاق بحث جديدة تتطلب مزيدًا من التحقيق في العلاقة غير الخطية للاضطراب السوقي.

1. المقدمة

2022).

رواد الأعمال في اتخاذ قرارات مستنيرة كانت تعتبر سابقًا صعبة. وبالتالي، فإن هذه الفجوة البحثية تمثل فرصة لتوسيع النقاش النظري حول ريادة الأعمال. كانت المناقشات المبكرة حول ريادة الأعمال تركز على ثلاثة أبعاد رئيسية: الإدارة العليا، الهيكل التنظيمي، ومبادرات الدخول الجديدة (ويلز وآخرون، 2020). ومع ذلك، لا تزال الأدبيات حول مكونات ريادة الأعمال بحاجة إلى استكشاف (أندرسون وآخرون، 2015). نقترح سؤال البحث (RQ1) لمعالجة هذه الفجوة البحثية المحتملة، بهدف التحقيق في تأثير أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي على ريادة الأعمال.

تعتبر التوجه الريادي (EO)، الذي يحدد الموقف الاستراتيجي للمنظمة تجاه ريادة الأعمال، أمرًا حيويًا في تطوير والحفاظ على المرونة الريادية خلال أوقات الأزمات (زيغان وآخرون، 2022). وهذا يشير إلى أن الشركات التي تتبنى عقلية ريادية وميلاً للمخاطرة المحسوبة تكون أكثر قدرة على التنقل والتغلب على التحديات التي تطرأ نتيجة الأزمات (شارما وآخرون، 2024). هناك انقسام حديث بين العلماء في إدارة الاستراتيجيات وريادة الأعمال يتعلق باستخدام وجهة نظر القدرة الديناميكية لفحص التوجه الريادي كقدرة ديناميكية (زهرة وآخرون، 2006؛ أندرسون وآخرون، 2009). تدعو هذه المناقشة إلى وجهة النظر الشرطية للقدرة الديناميكية، حيث تفترض أن فعالية القدرات الديناميكية لا تعتمد فقط على الروتين التنظيمي ولكن أيضًا على النشر السياقي لهذه القدرات (ليفينثال، 2011؛ سيرمون وهيت، 2009؛ شيلكي، 2014). وقد جادل العلماء بأن قابلية التكيف التنظيمي تتأثر، إلى حد ما، بالقوى البيئية (هريبينيك وجويس، 1985؛ شيلكي، 2014)، حيث تظهر تقلبات السوق كمتغير سياقي محوري محتمل في تفسير آثار القدرات الديناميكية (وانغ وآخرون، 2015). ومع ذلك، لم تستكشف الدراسات الحالية بعد كيف تؤثر تقلبات السوق (MT) على العلاقة بين EO وER. لمعالجة هذه الفجوات البحثية، نطرح سؤالنا البحثي الثاني.

RQ2: كيف يقوم التحويل الآلي بتعديل المسار الذي يربط بين ريادة الأعمال والنتائج الاقتصادية؟

المرونة في عصر الذكاء الاصطناعي. ثانياً، يُظهر كيف تساهم الدراسة في الرؤية الطارئة لوجهة نظر القدرة الديناميكية. في جوهرها، تقدم الدراسة رؤى قيمة وتساهم في النقاش المستمر عند تقاطع التحول الرقمي، وريادة الأعمال، والإدارة الاستراتيجية.

2. النظريات الأساسية

2.1. القدرات الديناميكية

2.2. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (Gen AI)

الصناعات، مثل الترفيه والتسويق والإعلانات (كانباخ وآخرون، 2024). التطبيقات المحتملة للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي واسعة النطاق وبعيدة المدى، ومن المتوقع أن تلعب دورًا كبيرًا في تشكيل مستقبل التكنولوجيا والابتكار في السنوات القادمة (فوسو وامبا وآخرون، 2023). لدى تكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي القدرة على إحداث ثورة في طريقة عمل الشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة والشركات الصغيرة من خلال تزويدها بأدوات تحليلية قوية لمساعدتها على البقاء تنافسية (عبادي، 2023). مع قدراتها المتقدمة، يمكن لهذه التكنولوجيا أن تساعد الشركات الصغيرة في إعداد تحليلات مقارنة مفصلة لمنافسيها، والصناعة، وديناميات السوق (مانورو وآخرون، 2023). يمكن أن تساعد هذه المعلومات الشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة في اتخاذ قرارات مستنيرة بشأن مسار عملها الحالي والمستقبلي واستغلال الفرص الجديدة (براساد أغراوال، 2023). من خلال الاستفادة من الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، يمكن للشركات الصغيرة أن تحقق ميزة تنافسية وتسريع نموها في بيئة الأعمال المتطورة بسرعة (وي وباردو، 2022؛ دويفيدي وآخرون، 2023).

2.3. التوجه الريادي (EO)

2.4. المرونة الريادية (ER)

2.5. اضطراب السوق (MT)

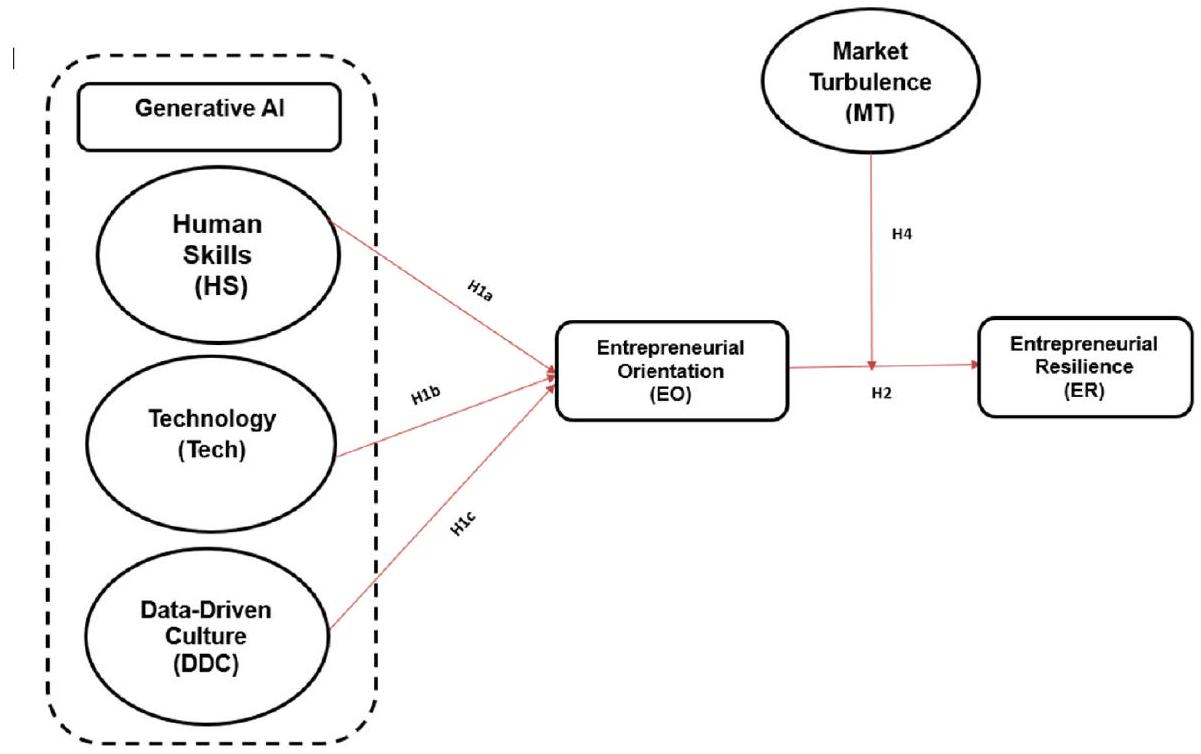

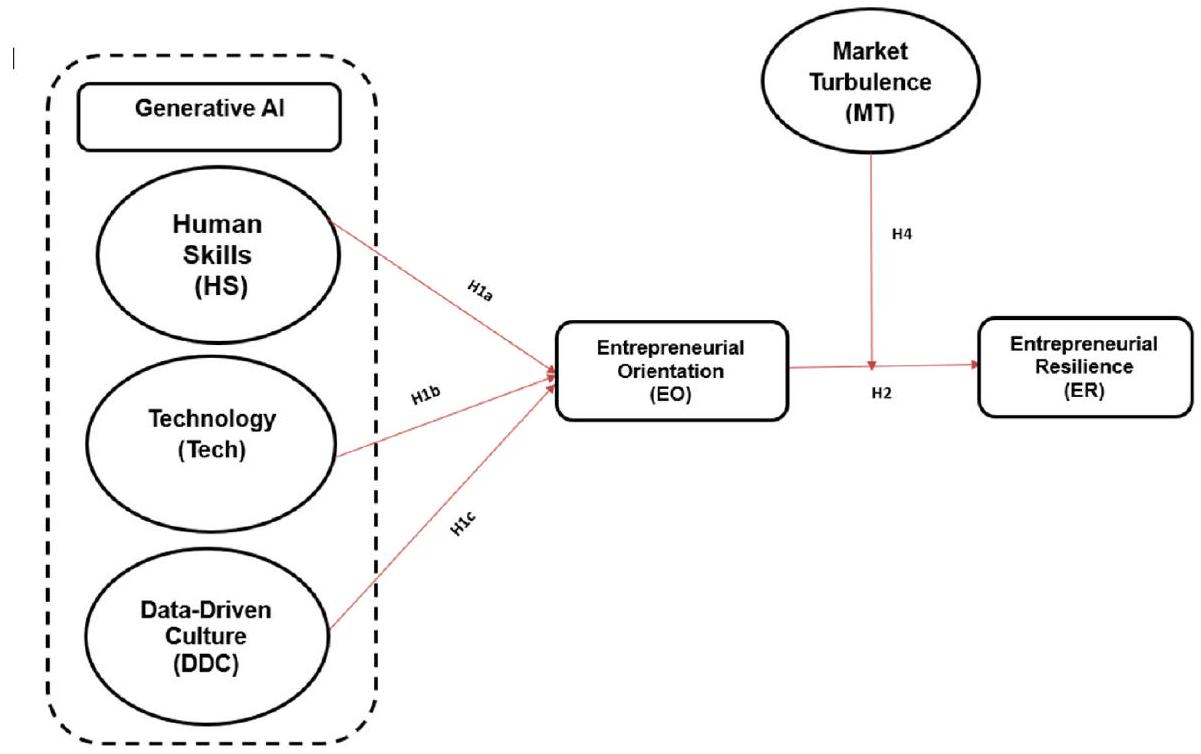

3. النموذج النظري وفرضيات البحث

3.1. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (Gen AI) وتوجه ريادة الأعمال (EO)

علاوة على ذلك، فإن تقدم التكنولوجيا، بما في ذلك كل من الأجهزة والبرامج، هو حجر الزاوية في إنشاء وصيانة البنية التحتية للذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (كانباخ وآخرون، 2024). لقد سهلت وتيسرت توفر مرافق الحوسبة السحابية والتقنيات المتقدمة استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (الحمدي وآخرون، 2024). توفر الحوسبة السحابية موارد قابلة للتوسع وفعالة من حيث التكلفة، مما يمكّن من نشر نماذج الذكاء الاصطناعي بسرعة وتوسيعها (غوباخلو وآخرون، 2024). لقد عززت التقنيات المتقدمة، مثل الحوسبة عالية الأداء والخوارزميات الفعالة، تطوير وتنفيذ الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، مما يعزز الثقة في إمكانيات تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي عبر مختلف الصناعات (الحمدي وآخرون، 2024؛ غوباخلو وآخرون، 2024). ومن ثم، يمكننا افتراض ذلك.

3.2. التوجه الريادي (EO) والمرونة الريادية

تستجيب هذه الشركات للتغيرات البيئية وتتغلب على التحديات (لومبكين وديس، 2001؛ كوسا وآخرون، 2022). هذه الشركات أكثر تكيفًا وموارد ومرونة (بينكو وآخرون، 2023). لذلك، تساهم ريادة الأعمال بشكل كبير في بناء المرونة المؤسسية، وهي القدرة على التعافي من النكسات، والتعلم من الفشل، والحفاظ على النجاح على المدى الطويل (زيغان وآخرون، 2022؛ كريشنان وآخرون، 2022؛ خورانا وآخرون، 2022).

3.3. التأثير الوسيط للتوجه الريادي

تسلسل قدرات الذكاء الاصطناعي العام والعمليات الخارجية.

H3a. التوجه الريادي يتوسط تأثير المهارات البشرية على المرونة الريادية.

3.4. تأثير تقلبات السوق على العلاقة بين التوجه الريادي (EO) والمرونة الريادية (ER)

تشير “الاضطرابات السوقية” إلى التغيرات غير المتوقعة والمفاجئة في ظروف السوق وتفضيلات العملاء التي تؤثر على الأعمال التجارية بجميع أحجامها (سون وغوفيند، 2017). تقدم الأدبيات الحالية مناقشتين حول تأثير الاضطرابات السوقية على العلاقة بين القدرات الديناميكية والميزة التنافسية (كاشوي وآخرون، 2018). الآراء متباينة، مع وجود ارتباط ضئيل (تشو وآخرون، 2019). يناقش مجموعة من الباحثين ما إذا كان ينبغي على المنظمات الاستثمار في بناء القدرات الديناميكية (هيلفات وآخرون، 2009؛ زهراء وآخرون، 2006)، بينما يجادل آخرون بأن القدرات الحالية قد لا تكون كافية لمواجهة الطلبات السريعة التطور في السوق (أولريش وسمول وود، 2004؛ شيلكي، 2014).

4. تصميم البحث

4.1. التدابير

4.1.1. الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (Gen AI)

4.1.2. التوجه الريادي (EO)

4.1.3. المرونة الريادية (ER)

قياس هذه الأبعاد، يوفر مقياسنا المقترح تقييمًا أكثر دقة وقابلية للتنفيذ للمرونة الريادية. يمكن أن يساعد المؤسسات الصغيرة والمتوسطة وأصحاب المصلحة في تحديد نقاط قوتهم وضعفهم، وتحديد أولويات استثماراتهم وتدخلاتهم، وتعزيز قدرتهم على البقاء والنمو والتأثير على المدى الطويل.

4.1.4. اضطراب السوق (MT)

4.2. جمع البيانات

تركيب العينة (

| القطاع | العينة | % |

| الرعاية الصحية | 22 | 25.29 |

| الأغذية الزراعية | 29 | 33.33 |

| تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات | 17 | 19.54 |

| السلع والخدمات البيئية | 10 | 11.49 |

| خدمات الأمن | 9 | 10.34 |

| وظيفة المستجيب | ||

| رئيس قسم البحث والتطوير | 23 | 26.44 |

| مدير تطوير الأعمال | 18 | 20.69 |

| رئيس الأعمال | 27 | 31.03 |

| مدير العلاقات | 19 | 21.84 |

5. تحليلات البيانات والنتائج

5.1. نموذج القياس

5.2. انحياز الطريقة الشائعة (CMB)

تحميلات عناصر القياس، موثوقية التركيب المقياسي ومتوسط التباين المستخرج

| بناء | عناصر | أحمال العوامل | التباين | خطأ | SCR | AVE |

| HS (

|

HS1 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.94 | 0.65 |

| HS2 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.46 | |||

| إتش إس 3 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.26 | |||

| إتش إس 4 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.34 | |||

| HS5 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 | |||

| HS6 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.34 | |||

| HS7 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 | |||

| HS8 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.43 | |||

| تكنولوجيا (

|

تكنولوجيا 2 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.85 | 0.54 |

| تِك 3 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.41 | |||

| تكنولوجيا 4 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.41 | |||

| تِك6 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.45 | |||

| TECH7 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.52 | |||

| دي دي سي (

|

دي دي سي 1 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.86 | 0.67 |

| دي دي سي 4 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.29 | |||

| دي دي سي 5 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.39 | |||

| EO (

|

EO1 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.83 | 0.55 |

| EO2 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.36 | |||

| EO3 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.37 | |||

| EO4 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.65 | |||

| غرفة الطوارئ (

|

ER1 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.89 | 0.67 |

| ER2 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.31 | |||

| ER3 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.30 | |||

| ER4 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.30 | |||

| MT (

|

MT1 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.90 | 0.76 |

| MT2 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.18 | |||

| MT3 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 |

صحة التمييز

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| إتش إس | 0.79 | |||||

| تكنولوجيا | 0.55 | 0.74 | ||||

| دي دي سي | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.82 | |||

| EO | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.74 | ||

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.82 | |

| MT | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.87 |

قيم HTMT (جيدة إذا كانت)

| HS | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| HS | ||||||

| تكنولوجيا | 0.87 | |||||

| دي دي سي | 0.61 | 0.80 | ||||

| EO | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.87 | |||

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.93 | ||

| MT | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.80 | |

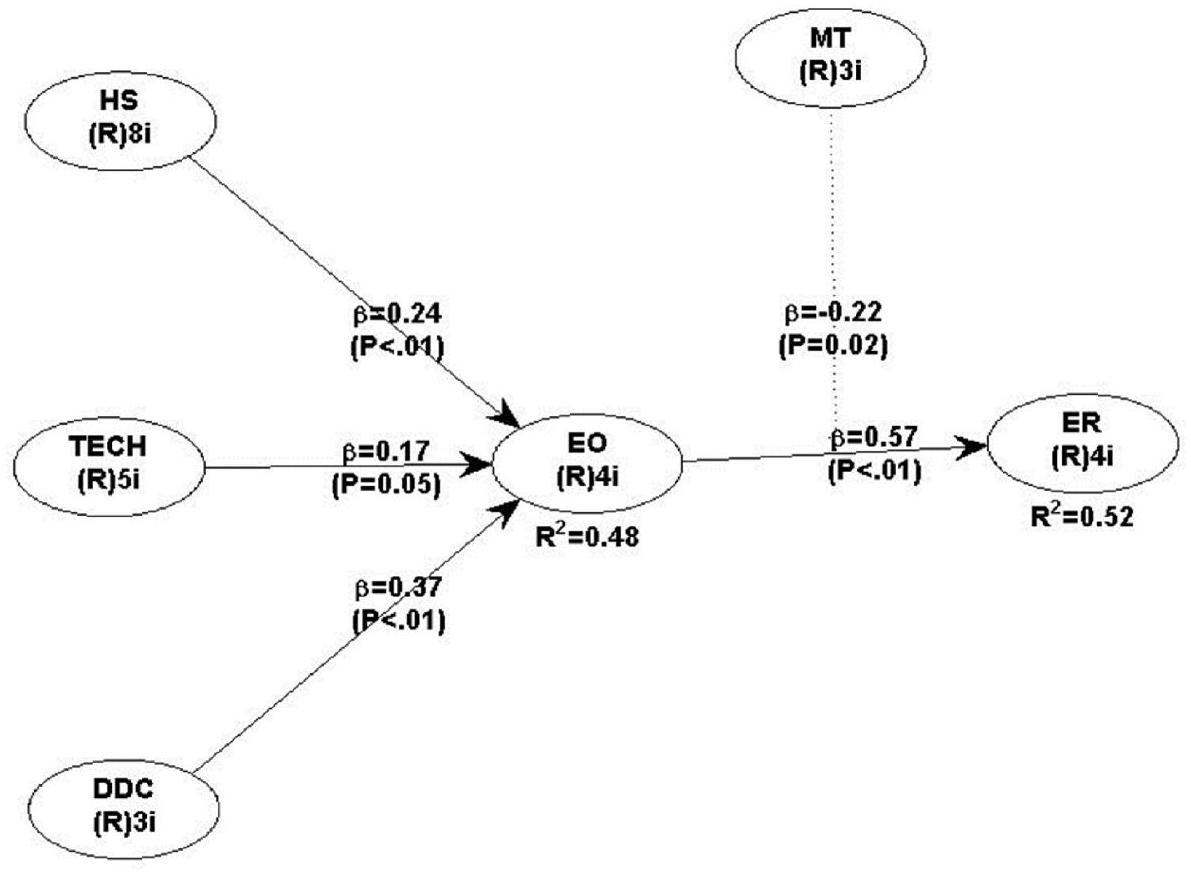

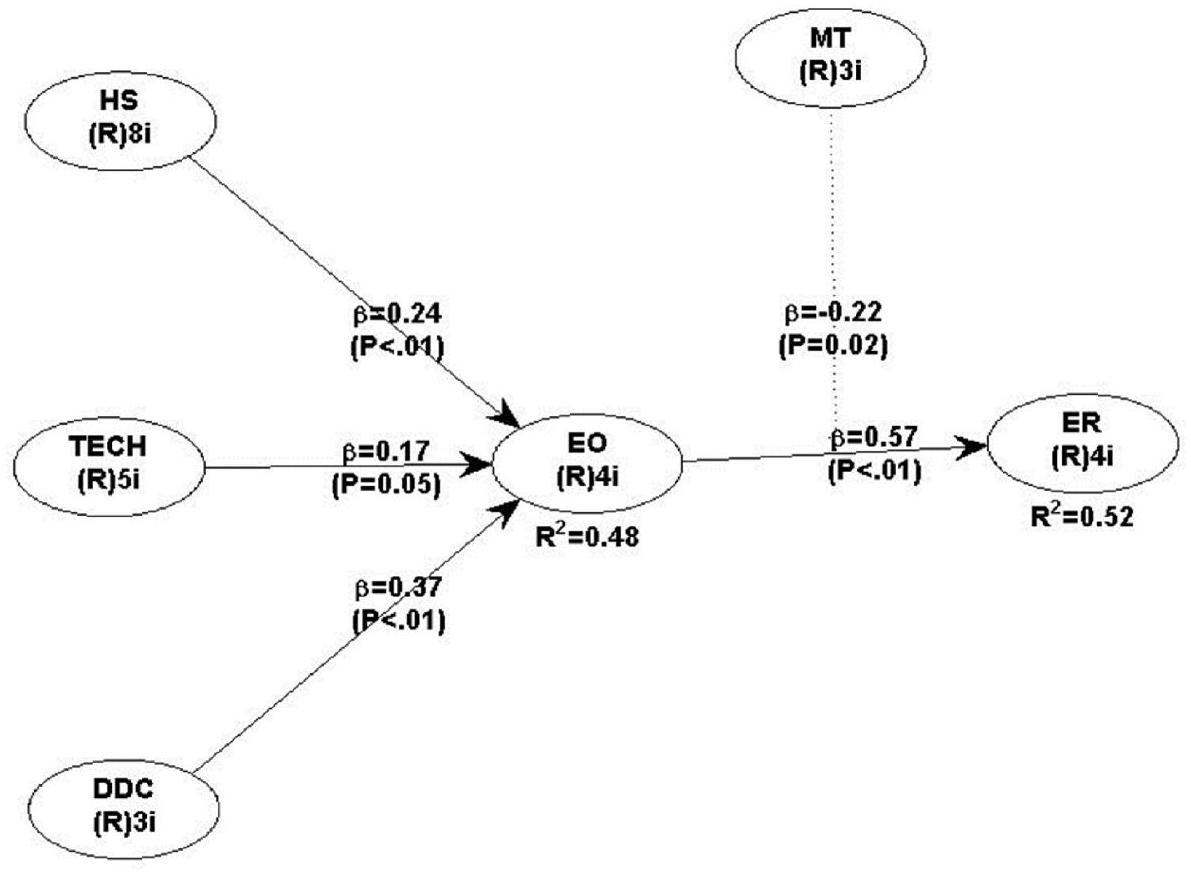

5.3. اختبار الفرضيات

| اختبار الفرضيات (

|

|||||

| الفرضية | المتغير الدافع | المتغير الناتج |

|

قيمة p | النتائج |

| H1a | HS | EO | 0.24 | <0.01 | مدعوم |

| H1b | TECH | EO | 0.17 | <0.05 | مدعوم |

| H1c | DDC | EO | 0.37 | <0.01 | مدعوم |

| H2 | EO | ER | 0.57 | <0.01 | مدعوم |

| H3 | EO*MT | ER | -0.22 | <0.02 | غير مدعوم |

مجموع التأثيرات غير المباشرة، مقاطع المسار، قيم P، الأخطاء المعيارية، وأحجام التأثير (

6. المناقشات

أن EO تؤثر بقوة على ER في ظل اضطراب السوق العالي. تتعارض هذه النتيجة مع بعض العلماء الذين يجادلون بأن الديناميكية العالية تعزز تأثير EO على ER (بولوه ورينكو، 2013) لكنها تتماشى مع آخرين يقترحون أن اضطراب السوق العالي قد لا يؤثر إيجابياً على القدرات الديناميكية والميزة التنافسية (شيلكي، 2014).

6.1. الآثار النظرية

تحمل أهمية خاصة. لقد كان التوجه الريادي لفترة طويلة نقطة محورية في نظرية ريادة الأعمال. ومع ذلك، فإن التقاطع غير المستكشف نسبيًا بين Gen AI وتأثيره على التوجه الريادي يتطلب استكشافًا تجريبيًا أكثر صرامة لتوسيع النطاق النظري بشكل فعال. نعتقد أن مساهمتنا قد لعبت دورًا متواضعًا في تعزيز النقاش المستمر عند تقاطع نظرية ريادة الأعمال والابتكار التكنولوجي. لقد قدمت جهودنا وجهات نظر جديدة، وسلطت الضوء على قضايا حاسمة، ووفرت رؤى قيمة أثرت النقاش في هذه المجالات.

6.2. الآثار المترتبة على المديرين

6.3. الآثار المترتبة على صانعي السياسات

6.4. قيود الدراسة واتجاهات البحث المستقبلية

نهج القدرة الديناميكية، الذي يعد أمرًا حيويًا لتحقيق الميزة التنافسية وER (Ferreira وآخرون، 2022). ومع ذلك، نعترف بأن افتراضات القدرة الديناميكية قد لا تنطبق في جميع الأزمات (Dubey وآخرون، 2023). كما نعتبر نظرية معالجة المعلومات التنظيمية (OIPT) التي قدمها غالبراث (1974)، والتي تؤكد على دور OIPT في التعامل مع عدم اليقين البيئي وتحسين الأداء. من منظور OIPT، قد يتطلب اضطراب السوق (MT) معالجة المعلومات من ظروف السوق غير المؤكدة، مما يحفز المنظمات على البحث عن معرفة جديدة وتعزيز اتخاذ القرار، وبالتالي تعزيز المرونة الريادية.

7. ملاحظات ختامية

تشير ريادة الأعمال إلى القدرة على الاستجابة والتكيف بفعالية مع الأعمال في مواجهة التحديات وعدم اليقين (كوربر وماكنوتون، 2018). تستخدم ريادة الأعمال بفعالية موقفًا رياديًا لتعزيز التكنولوجيا وأداء الأعمال (سيو وبارك، 2022). تدرس هذه الدراسة المرونة كاستجابة لاضطرابات السوق وتحقق في كيفية زراعة الشركات الناجحة للمرونة من خلال الرقمنة والتقدم التكنولوجي خلال الجائحة. بشكل أكثر دقة، نكشف عن الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي وتوجه ريادة الأعمال الذي يستخدمه رواد الأعمال لزراعة المرونة الريادية وتحويل أعمالهم بسرعة. بحثنا أيضًا في كيفية تأثير اضطراب السوق على العلاقات بين الانضمام إلى ريادة الأعمال والمرونة الريادية. تقدم دراستنا مساهمتين في مجال القدرات الديناميكية. يوفر عملنا أدلة تجريبية تدعم المبدأين النظريين الأساسيين للقدرات الديناميكية. تكشف دراستنا أن الجمع بين الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي وتوجه ريادة الأعمال له تأثير ملحوظ وبناء على المرونة الريادية. لقد أثبتنا بنجاح التأثير المعتدل لاضطراب السوق كفكرة ثانية.

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

توفر البيانات

الملحق أ. مقاييس القياس

| مقياس | عناصر |

| المهارات البشرية (HS) | يمتلك موظفو تكنولوجيا المعلومات لدينا مهارات كافية في معالجة البيانات وتحليلها (HS1) |

| نحن نوفر لموظفي تكنولوجيا المعلومات لدينا التدريب اللازم للتعامل مع تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (HS2) | |

| نقوم بتوظيف فريق تكنولوجيا المعلومات لدينا بناءً على المتطلبات الأخيرة لمهارات الذكاء الاصطناعي (HS3) | |

| يمتلك موظفو تكنولوجيا المعلومات لدينا خبرة عمل مناسبة لتلبية متطلبات وظائفهم (HS4) | |

| استنادًا إلى معرفتهم التجارية، يستخدم مديرونا مدخلات قائمة على الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لاتخاذ قرارات مناسبة (HS5) | |

| يعمل مديرونا مع فريق تكنولوجيا المعلومات، والموظفين الآخرين، والعملاء لفهم الفرص أو التهديدات التي يمكن معالجتها باستخدام حلول الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (HS6) | |

| مديرونا لديهم فهم عميق للأعمال (HS7) | |

| مديرونا لديهم إحساس جيد بمكان تطبيق الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (HS8) | |

| رئيس فريق تكنولوجيا المعلومات الذي يقود الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لديه مهارات قيادية قوية (HS9) | |

| يمكن لمديرينا توقع احتياجات الأعمال المستقبلية للمديرين الوظيفيين والموردين والعملاء وتصميم حلول الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدية بشكل استباقي لدعم هذه الاحتياجات (HS10) | |

| التكنولوجيا (TECH) | لقد أنشأنا بنى تحتية قابلة للتوسع لتخزين البيانات (TECH1) |

| مقياس | عناصر |

| ثقافة قائمة على البيانات (DDC) | لقد استثمرنا في خدمات السحابة المتقدمة لتمكين قدرات الذكاء الاصطناعي المعقدة من خلال استدعاءات API بسيطة (مثل خدمات مايكروسوفت المعرفية، جوجل كلاود) |

| لقد استثمرنا في الحوسبة الموزعة والمتوازية لمعالجة بيانات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (TECH 3) | |

| لقد استكشفنا بنية الذكاء الاصطناعي لضمان تأمين البيانات من البداية إلى النهاية باستخدام تكنولوجيا متطورة (TECH 4) | |

| لقد خصصنا الأموال المطلوبة لترقية قدرات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لدينا (TECH 5) | |

| نحن نستثمر في توظيف فرق لدعم مبادرات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (TECH 6) | |

| نعتقد أنه يجب منح الوقت الكافي لتطوير قدرات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (TECH 7) | |

| نعتبر البيانات والمخرجات التي تم الحصول عليها من خلال الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي كأصل (DDC1) | |

| نستند في قراراتنا إلى البيانات بدلاً من الحدس (DDC2) | |

| نحن نفضل البيانات على الحدس عند اتخاذ القرارات (DDC3) | |

| نقوم بتقييم وتحسين قواعد العمل باستمرار استجابةً للرؤى المستخلصة من الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بعد تقييم دقيق من قبل مديري الأعمال لدينا (DDC4) | |

| نحن ندرب موظفينا باستمرار على اتخاذ القرارات بناءً على رؤى مدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي (DDC5) | |

| التوجه الريادي (EO) | نعتقد أن المستوى العالي من عدم اليقين في السوق هو فرصة لنا (EO1) |

| نحن متفائلون للغاية لأننا نؤمن بالحصول على ميزة من الاضطراب (EO2) | |

| نحن نؤمن ببناء نهج لإدارة المخاطر (EO3) | |

| الأعضاء الكبار في المنظمة يدعمون بشدة مبادرة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (EO4) | |

| المرونة الريادية (ER) | يمكننا التكيف مع أي تغييرات ديناميكية (ER1) |

| نحن مصممون على تحقيق أهدافنا على الرغم من أي مستوى من العقبات التي نواجهها (ER2) | |

| نحن لا نخشى الفشل لأن الفشل يساعد على تصحيح أخطائنا ويسمح لنا باتخاذ قرارات أفضل في المستقبل (ER3) | |

| سنتعافى بسرعة من الفشل الأولي (ER4) | |

| اضطراب السوق (MT) | العملاء أصبحوا أكثر تطلبًا مع مرور الوقت (MT1) |

| المنافسة في سوقنا شرسة | |

| التكنولوجيا في صناعتنا تتغير بسرعة (MT3) |

| التأثيرات غير المباشرة للمسارات ذات القطاعين | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.035 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.064 | ||

| عدد المسارات ذات القطاعين | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.318 | 0.287 | 0.484 | 0.194 | ||

| الأخطاء المعيارية للتأثيرات غير المباشرة للمسارات ذات الشقين | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.075 | 0.074 | ||

| أحجام التأثيرات للتأثيرات غير المباشرة للمسارات ذات القطاعين | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.026 | 0.031 | 0.002 | 0.053 | ||

| مجموعات التأثيرات غير المباشرة | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.035 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.064 | ||

| عدد المسارات للتأثيرات غير المباشرة | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.318 | 0.287 | 0.484 | 0.194 | ||

| الأخطاء المعيارية لمجموعات التأثيرات غير المباشرة | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.075 | 0.074 | ||

| أحجام التأثيرات لمجموعات التأثيرات غير المباشرة | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.026 | 0.031 | 0.002 | 0.053 | ||

| التأثيرات الكلية | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| EO | 0.207 | 0.246 | 0.018 | 0.375 | ||

| غرفة الطوارئ | 0.035 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.17 | 0.777 | |

| عدد المسارات للتأثيرات الكلية | ||||||

| إتش إس | تكنولوجيا | دي دي سي | EO | غرفة الطوارئ | MT | |

| EO | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| غرفة الطوارئ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

References

J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2023.2240744.

Alalwan, A.A., Baabdullah, A.M., Fetais, A.H.M., Algharabat, R.S., Raman, R., Dwivedi, Y.K., 2023. SMEs entrepreneurial finance-based digital transformation: towards innovative entrepreneurial finance and entrepreneurial performance. Ventur. Cap. 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2023.2195127.

Alhammadi, A., Shayea, I., El-Saleh, A.A., Azmi, M.H., Ismail, Z.H., Kouhalvandi, L., Saad, S.A., 2024. Artificial intelligence in 6G wireless networks: opportunities, applications, and challenges. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2024 (1), 8845070.

Al-Thaqeb, S.A., Algharabali, B.G., Alabdulghafour, K.T., 2022. The pandemic and economic policy uncertainty. Int. J. Finance Econ. 27 (3), 2784-2794.

Anderson, B.S., Covin, J.G., Slevin, D.P., 2009. Understanding the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and strategic learning capability: an empirical investigation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 3 (3), 218-240.

Anderson, B.S., Kreiser, P.M., Kuratko, D.F., Hornsby, J.S., Eshima, Y., 2015. Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial orientation. Strat. Manag. J. 36 (10), 1579-1596.

Anwar, A., Coviello, N., Rouziou, M., 2023. Weathering a crisis: a multi-level analysis of resilience in young ventures. Entrep. Theory Pract. 47 (3), 864-892.

Armstrong, J.S., Overton, T.S., 1977. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Market. Res. 14 (3), 396-402.

Balta, M.E., Papadopoulos, T., Spanaki, K., 2023. Business model pivoting and digital technologies in turbulent environments. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. https:// doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2023-0210.

Bankins, S., Ocampo, A.C., Marrone, M., Restubog, S.L.D., Woo, S.E., 2023. A multilevel review of artificial intelligence in organizations: implications for organizational behavior research and practice. J. Organ. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2735.

Baron, R.M., Kenny, D.A., 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173.

Benitez, J., Henseler, J., Castillo, A., Schuberth, F., 2020. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Inf. Manag. 57 (2), 103168.

Berry, A.J., Sweeting, R., Goto, J., 2006. The effect of business advisers on the performance of SMEs. J. Small Bus. Enterprise Dev. 13 (1), 33-47.

Berthon, P., Yalcin, T., Pehlivan, E., Rabinovich, T., 2024. Trajectories of AI technologies: insights for managers. Bus. Horiz. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. bushor.2024.03.002.

Boyer, K.K., Swink, M.L., 2008. Empirical elephants-Why multiple methods are essential to quality research in operations and supply chain management. J. Oper. Manag. 26 (3), 338-344.

Budhwar, P., Chowdhury, S., Wood, G., Aguinis, H., Bamber, G.J., Beltran, J.R., et al., 2023. Human resource management in the age of generative artificial intelligence: perspectives and research directions on ChatGPT. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 33 (3), 606-659.

Bullough, A., Renko, M., 2013. Entrepreneurial resilience during challenging times. Bus. Horiz. 56 (3), 343-350.

Castro, M.P., Zermeño, M.G.G., 2021. Being an entrepreneur post-COVID-19-resilience in times of crisis: a systematic literature review. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 13 (4), 721-746.

Chalmers, D., MacKenzie, N.G., Carter, S., 2021. Artificial intelligence and entrepreneurship: implications for venture creation in the fourth industrial revolution. Entrep. Theory Pract. 45 (5), 1028-1053.

Chaston, I., Sadler-Smith, E., 2012. Entrepreneurial cognition, entrepreneurial orientation and firm capability in the creative industries. Br. J. Manag. 23 (3), 415-432.

Chatterjee, S., Gupta, S.D., Upadhyay, P., 2020. Technology adoption and entrepreneurial orientation for rural women: evidence from India. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 160, 120236.

Chaudhary, S., Dhir, A., Meenakshi, N., Christofi, M., 2024. How small firms build resilience to ward off crises: a paradox perspective. Enterpren. Reg. Dev. 36 (1-2), 182-207.

Chen, K.H., Wang, C.H., Huang, S.Z., Shen, G.C., 2016. Service innovation and new product performance: the influence of market-linking capabilities and market turbulence. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 172, 54-64.

Chen, B., Wu, Z., Zhao, R., 2023. From fiction to fact: the growing role of generative AI in business and finance. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 21 (4), 471-496.

Chirumalla, K., 2021. Building digitally-enabled process innovation in the process industries: a dynamic capabilities approach. Technovation 105, 102256.

Churchill Jr., G.A., 1979. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Market. Res. 16 (1), 64-73.

Ciampi, F., Demi, S., Magrini, A., Marzi, G., Papa, A., 2021. Exploring the impact of big data analytics capabilities on business model innovation: the mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. J. Bus. Res. 123, 1-13.

Clausen, T., Korneliussen, T., 2012. The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and speed to the market: the case of incubator firms in Norway. Technovation 32 (9-10), 560-567.

Cohen, J., 1988. Set correlation and contingency tables. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 12 (4), 425-434.

Corner, P.D., Singh, S., Pavlovich, K., 2017. Entrepreneurial resilience and venture failure. Int. Small Bus. J. 35 (6), 687-708.

Dahles, H., Susilowati, T.P., 2015. Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Ann. Tourism Res. 51, 34-50.

Donthu, N., Gustafsson, A., 2020. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. J. Bus. Res. 117, 284-289.

Dubey, R., Bryde, D.J., Dwivedi, Y.K., Graham, G., Foropon, C., Papadopoulos, T., 2023. Dynamic digital capabilities and supply chain resilience: The role of government effectiveness. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 258, 108790.

Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., Childe, S.J., Bryde, D.J., Giannakis, M., Foropon, C., et al., 2020. Big data analytics and artificial intelligence pathway to operational performance under the effects of entrepreneurial orientation and environmental dynamism: a study of manufacturing organisations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 226, 107599.

Dwivedi, Y.K., Hughes, L., Ismagilova, E., Aarts, G., Coombs, C., Crick, T., et al., 2021. Artificial Intelligence (AI): multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 57, 101994.

Eisenhardt, K.M., Martin, J.A., 2000. Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strat. Manag. J. 21 (10-11), 1105-1121.

Fainshmidt, S., Pezeshkan, A., Lance Frazier, M., Nair, A., Markowski, E., 2016. Dynamic capabilities and organizational performance: a meta-analytic evaluation and extension. J. Manag. Stud. 53 (8), 1348-1380.

Fatoki, O., 2018. The impact of entrepreneurial resilience on the success of small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Sustainability 10 (7), 2527.

Faquet, R., Malarde, V., 2020. Digitalisation in France’s business sector. TresorEconomics 271 (November), 1-8. https://www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr/Articles/ df17a219-238e-4b52-90f3-e294fbda02f0/files/8ec8a48e-a30e-4479-865e-bce6ce22 63dd. (Accessed 15 October 2023).

Fellnhofer, K., 2023. Positivity and higher alertness levels facilitate discovery: Longitudinal sentiment analysis of emotions on Twitter. Technovation 122, 102409.

Ferreira, J.J., Cruz, B., Veiga, P.M., 2022. Knowledge strategies and digital technologies maturity: effects on small business performance. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 1-19.

Ferreras-Méndez, J.L., Olmos-Penuela, J., Salas-Vallina, A., Alegre, J., 2021. Entrepreneurial orientation and new product development performance in SMEs: the mediating role of business model innovation. Technovation 108, 102325.

Filippo, C., Vito, G., Irene, S., Simone, B., Gualtiero, F., 2024. Future applications of generative large language models: a data-driven case study on ChatGPT. Technovation 133, 103002.

Flynn, B.B., Sakakibara, S., Schroeder, R.G., Bates, K.A., Flynn, E.J., 1990. Empirical research methods in operations management. J. Oper. Manag. 9 (2), 250-284.

Fornell, C., Larcker, D.F., 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18 (1), 39-50.

Fosso Wamba, S., 2022. Impact of artificial intelligence assimilation on firm performance: the mediating effects of organizational agility and customer agility. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 67, 102544.

Fosso Wamba, F., Queiroz, M.M., Jabbour, C.J.C., Shi, C.V., 2023. Are both generative AI and ChatGPT game changers for 21st-Century operations and supply chain excellence? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 265, 109015.

Fosso Wamba, F., Queiroz, M.M., Trinchera, L., 2024. The role of artificial intelligenceenabled dynamic capability on environmental performance: the mediation effect of a data-driven culture in France and the USA. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 268, 109131.

Frick, N.R., Mirbabaie, M., Stieglitz, S., Salomon, J., 2021. Maneuvering through the stormy seas of digital transformation: the impact of empowering leadership on the AI readiness of enterprises. J. Decis. Syst. 30 (2-3), 235-258.

Galbraith, J.R., 1974. Organization design: An information processing view. Interfaces 4 (3), 28-36.

Giuggioli, G., Pellegrini, M.M., 2022. Artificial intelligence as an enabler for entrepreneurs: a systematic literature review and an agenda for future research. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 29 (4), 816-837.

Gottschalck, N., Branner, K., Rolan, L., Kellermanns, F., 2021. Cross-level effects of entrepreneurial orientation and ambidexterity on the resilience of small business owners. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00472778.2021.2002878.

Grover, V., Sabherwal, R., 2020. Making sense of the confusing mix of digitalization, pandemics, and economics. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 55, 102234.

Gupta, M., George, J.F., 2016. Toward the development of a big data analytics capability. Inf. Manag. 53 (8), 1049-1064.

Hadjielias, E., Christofi, M., Tarba, S., 2022. Contextualizing small business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from small business owner-managers. Small Bus. Econ. 59 (4), 1351-1380.

Hansen, E.B., Bøgh, S., 2021. Artificial intelligence and internet of things in small and medium-sized enterprises: a survey. J. Manuf. Syst. 58, 362-372.

Hayes, A.F., Preacher, K.J., 2010. Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivariate Behavioural Research 45 (4), 627-660.

Helfat, C.E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M., Singh, H., Teece, D., Winter, S.G., 2009. Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations. John Wiley & Sons.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., 2015. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 43, 115-135.

Hillmann, J., Guenther, E., 2021. Organizational resilience: a valuable construct for management research? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 23 (1), 7-44.

Holmström, J., Carroll, N., 2024. How organizations can innovate with generative AI. Bus. Horiz. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2024.02.010.

Hrebiniak, L.G., Joyce, W.F., 1985. Organizational adaptation: strategic choice and environmental determinism. Adm. Sci. Q. 30 (3), 336-349.

Hughes, M., Hughes, P., Hodgkinson, I., Chang, Y.Y., Chang, C.Y., 2022. Knowledgebased theory, entrepreneurial orientation, stakeholder engagement, and firm performance. Strateg. Entrep. J. 16 (3), 633-665.

Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H., Smith, K.M., 2018. Marketing survey research best practices: evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 46, 92-108.

Iborra, M., Safón, V., Dolz, C., 2020. What explains the resilience of SMEs? Ambidexterity capability and strategic consistency. Long. Range Plan. 53 (6), 101947.

Iyengar, D., Nilakantan, R., Rao, S., 2021. On entrepreneurial resilience among microentrepreneurs in the face of economic disruptions… A little help from friends. J. Bus. Logist. 42 (3), 360-380.

Jantunen, A., Puumalainen, K., Saarenketo, S., Kyläheiko, K., 2005. Entrepreneurial orientation, dynamic capabilities and international performance. J. Int. Enterpren. 3, 223-243.

Jiang, W., Chai, H., Shao, J., Feng, T., 2018. Green entrepreneurial orientation for enhancing firm performance: a dynamic capability perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 198, 1311-1323.

Kachouie, R., Mavondo, F., Sands, S., 2018. Dynamic marketing capabilities view on creating market change. Eur. J. Market. 52 (5/6), 1007-1036.

Kalubanga, M., Gudergan, S., 2022. The impact of dynamic capabilities in disrupted supply chains-the role of turbulence and dependence. Ind. Market. Manag. 103, 154-169.

Kam-Sing Wong, S., 2014. Impacts of environmental turbulence on entrepreneurial orientation and new product success. Eur. J. Innovat. Manag. 17 (2), 229-249.

Kanbach, D.K., Heiduk, L., Blueher, G., Schreiter, M., Lahmann, A., 2024. The GenAI is out of the bottle: generative artificial intelligence from a business model innovation perspective. Review of Managerial Science 18 (4), 1189-1220.

Kar, A.K., Varsha, P.S., Rajan, S., 2023. Unravelling the impact of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) in industrial applications: a review of scientific and grey literature. Global J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 24 (4), 659-689.

Ketokivi, M.A., Schroeder, R.G., 2004. Perceptual measures of performance: fact or fiction? J. Oper. Manag. 22 (3), 247-264.

Kirtley, J., O’Mahony, S., 2023. What is a pivot? Explaining when and how entrepreneurial firms decide to make strategic change and pivot. Strat. Manag. J. 44 (1), 197-230.

Khurana, I., Dutta, D.K., Ghura, A.S., 2022. SMEs and digital transformation during a crisis: the emergence of resilience as a second-order dynamic capability in an entrepreneurial ecosystem. J. Bus. Res. 150, 623-641.

Kock, N., 2014. Advanced mediating effects tests, multi-group analyses, and measurement model assessments in PLS-based SEM. Int. J. e-Collaboration 10 (1), 1-13.

Kock, A., Gemünden, H.G., 2021. How entrepreneurial orientation can leverage innovation project portfolio management. R D Manag. 51 (1), 40-56.

Kock, N., Hadaya, P., 2018. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: the inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J. 28 (1), 227-261.

Kolupaieva, I., Tiesheva, L., 2023. Asymmetry and convergence in the development of digital technologies in the EU countries. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 18 (3), 687-716.

Korber, S., McNaughton, R., 2018. Resilience and entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Entrepren. Behav. Res. 24 (7), 1129-1154.

Kraus, S., Rigtering, J.C., Hughes, M., Hosman, V., 2012. Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: a quantitative study from The Netherlands. Review of Managerial Science 6, 161-182.

Kreiser, P.M., Davis, J., 2010. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: the unique impact of innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking. J. Small Bus. Enterpren. 23 (1), 39-51.

Krishnan, C.S.N., Ganesh, L.S., Rajendran, C., 2022. Entrepreneurial Interventions for crisis management: lessons from the Covid-19 Pandemic’s impact on entrepreneurial ventures. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 72, 102830.

Kusa, R., Duda, J., Suder, M., 2022. How to sustain company growth in times of crisis: the mitigating role of entrepreneurial management. J. Bus. Res. 142, 377-386.

Lamine, W., Fayolle, A., Jack, S., Audretsch, D., 2023. Impact of digital technologies on entrepreneurship: Taking stock and looking forward. Technovation 126, 102823.

Leppäaho, T., Ritala, P., 2022. Surviving the coronavirus pandemic and beyond: unlocking family firms’ innovation potential across crises. Journal of Family Business Strategy 13 (1), 100440.

Levinthal, D.A., 2011. A behavioral approach to strategy-what’s the alternative? Strat. Manag. J. 32 (13), 1517-1523.

Li, L., Tong, Y., Wei, L., Yang, S., 2022. Digital technology-enabled dynamic capabilities and their impacts on firm performance: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Inform. Manag. 59 (8), 103689.

Liang, H., Saraf, N., Hu, Q., Xue, Y., 2007. Assimilation of enterprise systems: the effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Q. 31 (1), 59-87.

Li, D.Y., Liu, J., 2014. Dynamic capabilities, environmental dynamism, and competitive advantage: evidence from China. J. Bus. Res. 67 (1), 2793-2799.

Lindell, M.K., Whitney, D.J., 2001. Accounting for common method variance in crosssectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 86 (1), 114-121.

Lumpkin, G.T., Dess, G.G., 1996. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 21 (1), 135-172.

Lumpkin, G.T., Dess, G.G., 2001. Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: the moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. J. Bus. Ventur. 16 (5), 429-451.

MacKenzie, S.B., Podsakoff, P.M., 2012. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. Journal of Retailing 88 (4), 542-555.

Mahotra, A., Majchrzak, A., 2024. Digital innovations in crowdsourcing using AI tools. Technovation 133, 102997.

Manley, S.C., Hair, J.F., Williams, R.I., McDowell, W.C., 2021. Essential new PLS-SEM analysis methods for your entrepreneurship analytical toolbox. Int. Enterpren. Manag. J. 17, 1805-1825.

Mannuru, N.R., Shahriar, S., Teel, Z.A., Wang, T., Lund, B.D., Tijani, S., et al., 2023. Artificial intelligence in developing countries: the impact of generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies for development. Inf. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 02666669231200628.

Martinelli, E., Tagliazucchi, G., Marchi, G., 2018. The resilient retail entrepreneur: dynamic capabilities for facing natural disasters. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 24 (7), 1222-1243.

Marquis, C., Raynard, M., 2015. Institutional strategies in emerging markets. Acad. Manag. Ann. 9 (1), 291-335.

Matsuno, K., Mentzer, J.T., Özsomer, A., 2002. The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and market orientation on business performance. J. Market. 66 (3), 18-32.

McElheran, K., Li, J.F., Brynjolfsson, E., Kroff, Z., Dinlersoz, E., Foster, L., Zolas, N., 2024. AI adoption in America: who, what, and where. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. https://doi. org/10.1111/jems.12576.

McGee, J.E., Terry, R.P., 2022. COVID-19 as an external enabler: the role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial orientation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2127746.

Mikalef, P., Gupta, M., 2021. Artificial intelligence capability: conceptualization, measurement calibration, and empirical study on its impact on organizational creativity and firm performance. Inf. Manag. 58 (3), 103434.

Miklian, J., Hoelscher, K., 2022. SMEs and exogenous shocks: a conceptual literature review and forward research agenda. Int. Small Bus. J. 40 (2), 178-204.

Mthanti, T.S., Urban, B., 2014. Effectuation and entrepreneurial orientation in hightechnology firms. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 26 (2), 121-133.

Moqbel, M., Guduru, R., Harun, A., 2020. Testing mediation via indirect effects in PLSSEM: a social networking site illustration. Data Analysis Perspectives Journal 1 (3), 1-6.

Norbäck, P.-J., Persson, L., 2024. Why generative AI can make creative destruction more creative but less destructive. Small Bus. Econ. 63 (1), 349-377.

Obschonka, M., Audretsch, D.B., 2020. Artificial intelligence and big data in entrepreneurship: a new era has begun. Small Bus. Econ. 55, 529-539.

Ostrom, A.L., Field, J.M., Fotheringham, D., Subramony, M., Gustafsson, A., Lemon, K.N., et al., 2021. Service research priorities: managing and delivering service in turbulent times. J. Serv. Res. 24 (3), 329-353.

Parmar, R., Mackenzie, I., Cohn, D., Gann, D., 2014. The new patterns of innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 92 (1), 2-11.

Penco, L., Profumo, G., Serravalle, F., Viassone, M., 2023. Has COVID-19 pushed digitalisation in SMEs? The role of entrepreneurial orientation. J. Small Bus. Enterprise Dev. 30 (2), 311-341.

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., Podsakoff, N.P., 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5), 879-903.

Prasad Agrawal, K., 2023. Towards adoption of Generative AI in organizational settings. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2023.2240744.

continuity and growth. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 13 (4), 497-524.

Raisch, S., Fomina, K., 2024. Combining human and artificial intelligence: hybrid problem-solving in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. https://doi.org/10.5465/ amr.2021.0421.

Rank, O.N., Strenge, M., 2018. Entrepreneurial orientation as a driver of brokerage in external networks: exploring the effects of risk taking, proactivity, and innovativeness. Strateg. Entrep. J. 12 (4), 482-503.

Rizomyliotis, I., Kastanakis, M.N., Giovanis, A., Konstantoulaki, K., Kostopoulos, I., 2022. “How mAy I help you today?” The use of AI chatbots in small family businesses and the moderating role of customer affective commitment. J. Bus. Res. 153, 329-340.

Salvato, C., Sargiacomo, M., Amore, M.D., Minichilli, A., 2020. Natural disasters as a source of entrepreneurial opportunity: family business resilience after an earthquake. Strateg. Entrep. J. 14 (4), 594-615.

Santos, S.C., Liguori, E.W., Garvey, E., 2023. How digitalization reinvented entrepreneurial resilience during COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 189, 122398.

Schiuma, G., Schettini, E., Santarsiero, F., Carlucci, D., 2022. The transformative leadership compass: six competencies for digital transformation entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 28 (5), 1273-1291.

Seo, R., Park, J.H., 2022. When is interorganizational learning beneficial for inbound open innovation of ventures? A contingent role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation 116, 102514.

Sharma, G.D., Kraus, S., Liguori, E., Bamel, U.K., Chopra, R., 2024. Entrepreneurial challenges of COVID-19: Re-thinking entrepreneurship after the crisis. J. Small Bus. Manag. 62 (2), 824-846.

Shepherd, D.A., Saade, F.P., Wincent, J., 2020. How to circumvent adversity? Refugeeentrepreneurs’ resilience in the face of substantial and persistent adversity. J. Bus. Ventur. 35 (4), 105940.

Shepherd, D.A., Majchrzak, A., 2022. Machines augmenting entrepreneurs: opportunities (and threats) at the Nexus of artificial intelligence and entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 37 (4), 106227.

Shet, S.V., Poddar, T., Samuel, F.W., Dwivedi, Y.K., 2021. Examining the determinants of successful adoption of data analytics in human resource management-A framework for implications. J. Bus. Res. 131, 311-326.

Shore, A.P., Pittaway, L., Bortolotti, T., 2023. From negative emotions to personal growth: failure and reentry into entrepreneurship. Br. J. Manag. (in press).

Si, S., Hall, J., Suddaby, R., Ahlstrom, D., Wei, J., 2023. Technology, entrepreneurship, innovation and social change in digital economics. Technovation 119, 102484.

SIA, 2023. The AI Effect: Two-Thirds of Small Businesses to Try Generative AI over Next 12 Months; 44% Plan to Cut Hiring. Available at: https://www2.staffingindustry.co m/Editorial/Daily-News/The-AI-effect-Two-thirds-of-small-businesses-to-try-gene rative-AI-over-next-12-months-44-plan-to-cut-hiring-65715. (Accessed 8 January 2024).

Sirmon, D.G., Hitt, M.A., 2009. Contingencies within dynamic managerial capabilities: interdependent effects of resource investment and deployment on firm performance. Strat. Manag. J. 30 (13), 1375-1394.

Srinivasan, R., Swink, M., 2018. An investigation of visibility and flexibility as complements to supply chain analytics: an organizational information processing theory perspective. Prod. Oper. Manag. 27 (10), 1849-1867.

Sun, W., Govind, R., 2017. Product market diversification and market emphasis: impacts on firm idiosyncratic risk in market turbulence. Eur. J. Market. 51 (7/8), 1308-1331.

Taherizadeh, A., Beaudry, C., 2023. An emergent grounded theory of AI-driven digital transformation: Canadian SMEs’ perspectives. Ind. Innovat. 30 (9), 1244-1273.

Teece, D.J., Pisano, G., Shuen, A., 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strat. Manag. J. 18 (7), 509-533.

Teece, D.J., 2007. Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strat. Manag. J. 28 (13), 1319-1350.

Teece, D.J., 2016. Dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial management in large organizations: toward a theory of the (entrepreneurial) firm. Eur. Econ. Rev. 86, 202-216.

Thukral, E., 2021. COVID-19: small and medium enterprises challenges and responses with creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Strat. Change 30 (2), 153-158.

Townsend, D.M., Hunt, R.A., 2019. Entrepreneurial action, creativity, & judgment in the age of artificial intelligence. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 11, e00126.

Tran, H., Murphy, P.J., 2023. Generative artificial intelligence and entrepreneurial performance. J. Small Bus. Enterprise Dev. 30 (5), 853-856.

Tsai, K.H., Yang, S.Y., 2013. Firm innovativeness and business performance: the joint moderating effects of market turbulence and competition. Ind. Market. Manag. 42 (8), 1279-1294.

Ulrich, D., Smallwood, N., 2004. Capitalizing on capabilities. Harv. Bus. Rev. 82 (6), 119-127.

Upadhyay, N., Upadhyay, S., Al-Debei, M.M., Baabdullah, A.M., Dwivedi, Y.K., 2023. The influence of digital entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial orientation on intention of family businesses to adopt artificial intelligence: examining the mediating role of business innovativeness. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 29 (1), 80-115.

van Dun, C., Moder, L., Kratsch, W., Röglinger, M., 2023. ProcessGAN: supporting the creation of business process improvement ideas through generative machine learning. Decis. Support Syst. 165, 113880.

Wales, W.J., Gupta, V.K., Mousa, F.T., 2013. Empirical research on entrepreneurial orientation: an assessment and suggestions for future research. Int. Small Bus. J. 31 (4), 357-383.

Wales, W.J., Covin, J.G., Monsen, E., 2020. Entrepreneurial orientation: the necessity of a multilevel conceptualization. Strateg. Entrep. J. 14 (4), 639-660.

Wang, G., Dou, W., Zhu, W., Zhou, N., 2015. The effects of firm capabilities on external collaboration and performance: the moderating role of market turbulence. J. Bus. Res. 68 (9), 1928-1936.

Wang, M.C., Chen, P.C., Fang, S.C., 2021. How environmental turbulence influences firms’ entrepreneurial orientation: the moderating role of network relationships and organizational inertia. J. Bus. Ind. Market. 36 (1), 48-59.

Wei, R., Pardo, C., 2022. Artificial intelligence and SMEs: how can B2B SMEs leverage AI platforms to integrate AI technologies? Ind. Market. Manag. 107, 466-483.

Wiklund, J., Shepherd, D., 2003. Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strat. Manag. J. 24 (13), 1307-1314.

Williams, T.A., Gruber, D.A., Sutcliffe, K.M., Shepherd, D.A., Zhao, E.Y., 2017. Organizational response to adversity: fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Acad. Manag. Ann. 11 (2), 733-769.

Winter, S.G., 2003. Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strat. Manag. J. 24 (10), 991-995.

Wu, F., Yeniyurt, S., Kim, D., Cavusgil, S.T., 2006. The impact of information technology on supply chain capabilities and firm performance: a resource-based view. Ind. Market. Manag. 35 (4), 493-504.

Xia, Q., Xie, Y., Hu, S., Song, J., 2024. Exploring how entrepreneurial orientation improve firm resilience in digital era: findings from sequential mediation and FsQCA. Eur. J. Innovat. Manag. 27 (1), 96-112.

Zahra, S.A., Sapienza, H.J., Davidsson, P., 2006. Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: a review, model and research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 43 (4), 917-955.

Zhang, J.A., O’Kane, C., Chen, G., 2020. Business ties, political ties, and innovation performance in Chinese industrial firms: the role of entrepreneurial orientation and environmental dynamism. J. Bus. Res. 121, 254-267.

Zhou, J., Mavondo, F.T., Saunders, S.G., 2019. The relationship between marketing agility and financial performance under different levels of market turbulence. Ind. Market. Manag. 83, 31-41.

Zighan, S., Abualqumboz, M., Dwaikat, N., Alkalha, Z., 2022. The role of entrepreneurial orientation in developing SMEs resilience capabilities throughout COVID-19. Int. J. Enterpren. Innovat. 23 (4), 227-239.

an Associate Editor of Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, and as guest editor of a SI on post Covid-19 at International Journal of Logistics Management.

- Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: A.P.Shore@ljmu.ac.uk (A. Shore), M.Tiwari@hull.ac.uk (M. Tiwari), priyankat@regenesys.net (P. Tandon), c.foropon@montpellier-bs.com (C. Foropon).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2024.103063

Publication Date: 2024-06-25

Building entrepreneurial resilience during crisis using generative AI: An empirical study on SMEs

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Entrepreneurial orientation

Entrepreneurial resilience

Market turbulence

Dynamic capability view

Abstract

Recently, Gen AI has garnered significant attention across various sectors of society, particularly capturing the interest of small business due to its capacity to allow them to reassess their business models with minimal investment. To understand how small and medium-sized firms have utilised Gen AI-based tools to cope with the market’s high level of turbulence caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical crises, and economic slowdown, researchers have conducted an empirical study. Although Gen AI is receiving more attention, there remains a dearth of empirical studies that investigate how it influences the entrepreneurial orientation of firms and their ability to cultivate entrepreneurial resilience amidst market turbulence. Most of the literature offers anecdotal evidence. To address this research gap, the authors have grounded their theoretical model and research hypotheses in the contingent view of dynamic capability. They tested the research hypotheses using cross-sectional data from a pre-tested survey instrument, which yielded 87 useable responses from small and medium enterprises in France. The authors used variance-based structural equation modelling with the commercial WarpPLS 7.0 software to test the theoretical model. The study’s findings suggest that Gen AI and EO have a significant influence on building entrepreneurial resilience as higher-order and lower-order dynamic capabilities. However, market turbulence has a negative moderating effect on the path that joins entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial resilience. The results suggest that the assumption that high market turbulence will have positive effects on dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage is not always true, and the linear assumption does not hold, which is consistent with some scholars’ assumptions. The study’s results offer significant contributions to the contingent view of dynamic capabilities and open new research avenues that require further investigation into the non-linear relationship of market turbulence.

1. Introduction

2022).

entrepreneurs in making informed decisions previously deemed arduous. Thus, this research gap presents an opportunity to broaden the theoretical debate surrounding EO. Early discussions on EO centred on three primary dimensions: top management, organisational structure, and new entry initiatives (Wales et al., 2020). Yet, the literature on the components of EO remains ripe for exploration (Anderson et al., 2015). We propose research question (RQ1) to address this potential research gap, aiming to investigate the impact of Gen AI tools on EO.

Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), delineating an organisation’s strategic stance towards entrepreneurship, is crucial in developing and maintaining entrepreneurial resilience during times of crisis (Zighan et al., 2022). This suggests that businesses that embrace an entrepreneurial mindset and a propensity for calculated risk-taking are better equipped to navigate and overcome challenges brought about by crises (Sharma et al., 2024). A recent divergence among scholars in strategic management and entrepreneurship pertains to employing the dynamic capability view for examining entrepreneurial orientation as a dynamic capability (Zahra et al., 2006; Anderson et al., 2009). This debate advocates for the contingent view of dynamic capability, positing that the efficacy of dynamic capabilities is not solely dependent on organisational routines but also the contextual deployment of these capabilities (Levinthal, 2011; Sirmon and Hitt, 2009; Schilke, 2014). Scholars have argued that organisational adaptability is, to some extent, influenced by environmental forces (Hrebiniak and Joyce, 1985; Schilke, 2014), with market turbulence emerging as a potentially pivotal contextual variable in explaining the effects of dynamic capabilities (Wang et al., 2015). Nonetheless, extant studies have yet to explore how market turbulence (MT) moderates the path linking EO and ER. To address these research gaps, we pose our second research question.

RQ2: How does the MT moderate the path joining EO and ER?

resilience in the Gen AI era. Secondly, it demonstrates how the study contributes to the contingent view of the dynamic capability perspective. In essence, the study provides valuable insights and contributes to the ongoing debate at the intersection of digital transformation, entrepreneurship, and strategic management.

2. Underpinning theories

2.1. Dynamic capabilities

2.2. Generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI)

industries, such as entertainment, marketing, and advertising (Kanbach et al., 2024). The potential applications of Gen AI are vast and far-reaching, and it is expected to play a significant role in shaping the future of technology and innovation in the coming years (Fosso Wamba et al., 2023). Gen AI technology has the potential to revolutionise the way SMEs and micro-firms operate by providing them with powerful analytical tools to help them stay competitive (Abaddi, 2023). With its advanced capabilities, this technology can assist small businesses in preparing detailed comparative analyses of their competitors, industry, and market dynamics (Mannuru et al., 2023). This information can help SMEs make informed decisions about their present and future course of action and take advantage of new opportunities (Prasad Agrawal, 2023). By leveraging Gen AI, small businesses can gain a competitive edge and accelerate their growth in a rapidly evolving business landscape (Wei and Pardo, 2022; Dwivedi et al., 2023).

2.3. Entrepreneurial orientation (EO)

2.4. Entrepreneurial resilience (ER)

2.5. Market turbulence (MT)

3. Theoretical model and research hypotheses

3.1. Generative AI (Gen AI) and entrepreneurial orientation (EO)

Moreover, the progress of technology, encompassing both hardware and software, is a cornerstone in establishing and maintaining the infrastructure for Generative AI (Kanbach et al., 2024). The availability of cloud computing facilities and advanced technologies has facilitated and empowered the use of Generative AI (Alhammadi et al., 2024). Cloud computing offers scalable and cost-effective resources, enabling AI models’ swift deployment and scaling (Ghobakhloo et al., 2024). Advanced technologies, such as high-performance computing and efficient algorithms, have further enhanced the development and execution of Generative AI, instilling confidence in the potential of AI applications across various industries (Alhammadi et al., 2024; Ghobakhloo et al., 2024). Hence, we can hypothesise it as.

3.2. Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and entrepreneurial resilience

respond to environmental changes and overcome challenges (Lumpkin and Dess, 2001; Kusa et al., 2022). These companies are more adaptable, resourceful, and resilient (Penco et al., 2023). Therefore, EO significantly contributes to building ER, which is the ability to bounce back from setbacks, learn from failures, and sustain long-term success (Zighan et al., 2022; Krishnan et al., 2022; Khurana et al., 2022).

3.3. The mediating effect of entrepreneurial orientation

sequence of Gen AI and EO capabilities.

H3a. Entrepreneurial orientation mediates the effect of human skills on entrepreneurial resilience.

3.4. Moderating effect of market turbulence on the path joining entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and entrepreneurial resilience (ER)

“Market turbulence” refers to unpredictable and abrupt changes in market conditions and customer preferences that impact businesses of all sizes (Sun and Govind, 2017). Existing literature presents two debates on the effect of market turbulence on the link between dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage (Kachouie et al., 2018). The views are divergent, with little correlation (Zhou et al., 2019). One group of researchers debates whether organisations should invest in building dynamic capabilities (Helfat et al., 2009; Zahra et al., 2006), while others argue that existing capabilities might not suffice to match fast-evolving market demands (Ulrich and Smallwood, 2004; Schilke, 2014).

4. Research design

4.1. Measures

4.1.1. Generative AI (Gen AI)

4.1.2. Entrepreneurial orientation (EO)

4.1.3. Entrepreneurial resilience (ER)

measuring these dimensions, our proposed scale provides a more nuanced and actionable assessment of entrepreneurial resilience. It can help SMEs and stakeholders identify their strengths and weaknesses, prioritise their investments and interventions, and enhance their long-term viability, growth, and impact.

4.1.4. Market turbulence (MT)

4.2. Data collection

Sample Composition (

| Sector | Sample | % |

| Healthcare | 22 | 25.29 |

| Agrifood | 29 | 33.33 |

| ICT | 17 | 19.54 |

| Environmental goods and service | 10 | 11.49 |

| Security Services | 9 | 10.34 |

| Position of the respondent | ||

| Head of R&D | 23 | 26.44 |

| Business Development Manager | 18 | 20.69 |

| Business Head | 27 | 31.03 |

| Relationship Manager | 19 | 21.84 |

5. Data analyses and results

5.1. Measurement model

5.2. Common method bias (CMB)

Loadings of measurement items, Scale Composite Reliability and Average Variance Extracted (

| Construct | Items | Factor loadings | Variance | Error | SCR | AVE |

| HS (

|

HS1 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.94 | 0.65 |

| HS2 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.46 | |||

| HS3 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.26 | |||

| HS4 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.34 | |||

| HS5 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 | |||

| HS6 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.34 | |||

| HS7 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 | |||

| HS8 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.43 | |||

| TECH (

|

TECH2 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.85 | 0.54 |

| TECH3 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.41 | |||

| TECH4 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.41 | |||

| TECH6 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.45 | |||

| TECH7 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.52 | |||

| DDC (

|

DDC1 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 0.86 | 0.67 |

| DDC4 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.29 | |||

| DDC5 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.39 | |||

| EO (

|

EO1 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.83 | 0.55 |

| EO2 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.36 | |||

| EO3 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.37 | |||

| EO4 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.65 | |||

| ER (

|

ER1 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.89 | 0.67 |

| ER2 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.31 | |||

| ER3 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.30 | |||

| ER4 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.30 | |||

| MT (

|

MT1 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.90 | 0.76 |

| MT2 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.18 | |||

| MT3 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 |

Discriminant validity (

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| HS | 0.79 | |||||

| TECH | 0.55 | 0.74 | ||||

| DDC | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.82 | |||

| EO | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.74 | ||

| ER | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.82 | |

| MT | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.87 |

HTMT values (good if

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| HS | ||||||

| TECH | 0.87 | |||||

| DDC | 0.61 | 0.80 | ||||

| EO | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.87 | |||

| ER | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.93 | ||

| MT | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.80 | |

5.3. Hypothesis testing

| Hypotheses testing (

|

|||||

| Hypothesis | Driving variable | Outcome Variable |

|

pvalue | Results |

| H1a | HS | EO | 0.24 | <0.01 | supported |

| H1b | TECH | EO | 0.17 | <0.05 | supported |

| H1c | DDC | EO | 0.37 | <0.01 | supported |

| H2 | EO | ER | 0.57 | <0.01 | supported |

| H3 | EO*MT | ER | -0.22 | <0.02 | Not supported |

the sum of indirect effects, path segments, P values, standard errors, and effect sizes (

6. Discussions

that EO strongly influences ER under high market turbulence. This finding contrasts with some scholars who argue that high dynamism enhances EO’s effect on ER (Bullough and Renko, 2013) but aligns with others who suggest high market turbulence may not positively influence dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage (Schilke, 2014).

6.1. Implications for theory

hold particular importance. Entrepreneurial orientation has long been a focal point within entrepreneurship theory. However, the comparatively unexplored intersection of Gen AI and its influence on entrepreneurial orientation requires a more rigorous empirical exploration to effectively broaden the theoretical scope. We believe that our contribution has played a modest role in advancing the ongoing discussion at the intersection of entrepreneurship theory and technological innovation. Our efforts have introduced new perspectives, drawn attention to critical issues, and provided valuable insights that have enriched the discourse in these fields.

6.2. Implications for managers

6.3. Implications for policymakers

6.4. Limitations of the study and future research direction

dynamic capability approach, which is crucial for attaining competitive advantage and ER (Ferreira et al., 2022). However, we acknowledge that dynamic capability assumptions may not apply in all crises (Dubey et al., 2023). We also consider the Organisational Information Processing Theory (OIPT) by Galbraith (1974), which emphasises the role of OIPT in dealing with environmental uncertainty and improving performance. From the OIPT perspective, market turbulence (MT) may necessitate processing information from uncertain market conditions, motivating organisations to seek new knowledge and enhance decision-making, thereby fostering entrepreneurial resilience.

7. Concluding remarks

entrepreneurship refers to the capacity to respond and effectively adjust a business in the face of challenges and unpredictability (Korber and McNaughton, 2018). EO effectively uses an entrepreneurial attitude to enhance technology and business performance (Seo and Park, 2022). This study examines resilience as a reaction to market turbulence and investigates how accomplished businesses cultivate resilience through digitalisation and technological advancements within the pandemic. More precisely, we uncover the Gen AI and entrepreneurial orientation entrepreneurs employ to cultivate entrepreneurial resilience and rapidly transform their businesses. We investigated further how MT influences the relationships between joining EO and ER. Our study makes two contributions to the field of DCV. Our work offers empirical evidence that supports the two fundamental theoretical principles of dynamic capabilities. Our study reveals that combining Gen AI and EO has a notable and constructive impact on entrepreneurial resilience. We have successfully demonstrated the moderating influence of market turbulence as the second notion.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Data availability

Appendix A. Measurement Scales

| Scale | Items |

| Human Skills (HS) | Our IT staff possess adequate skills in processing data and analysing them (HS1) |

| We provide our IT staff with the required training to deal with Generative AI applications (HS2) | |

| We hire our IT team based on recent requirements for AI skills (HS3) | |

| Our IT staff have suitable work experience to fulfil their job (HS4) | |

| Based on their business knowledge, our managers use Generative AI-based inputs to make appropriate decisions (HS5) | |

| Our managers work with the IT team, other employees, and customers to understand the opportunities or threats that can be addressed using Generative AI solutions (HS6) | |

| Our managers have an in-depth understanding of business (HS7) | |

| Our managers have a good sense of where to apply Generative AI (HS8) | |

| The IT team head leading the Generative AI has strong leadership skills (HS9) | |

| Our managers can anticipate the future business needs of functional managers, suppliers and customers and proactively design Generative AI solutions to support these needs (HS10) | |

| Technology (TECH) | We have built scalable data storage infrastructures (TECH1) |

| Scale | Items |

| Data-Driven Culture (DDC) | We have invested in advanced cloud services to allow complex AI abilities on simple API calls (e.g., Microsoft Cognitive Services, Google Cloud |

| We have invested in distributed and parallel computing for Generative AI data processing (TECH 3) | |

| We have explored AI infrastructure to ensure that data is secured from end to end with state-of-the-art technology (TECH 4) | |

| We have allocated the desired funds to upgrade our Generative AI capabilities (TECH 5) | |

| We are investing in recruiting teams to support the Generative AI initiatives (TECH 6) | |

| We believe that sufficient time must be given to develop Generative AI capabilities (TECH 7) | |

| We consider data and output obtained through Generative AI as an asset (DDC1) | |

| We base our decisions on data rather than on instinct (DDC2) | |

| We give preference to data over intuition while making decisions (DDC3) | |

| We continuously assess and improve the business rules in response to insights extracted from Generative AI after careful evaluation by our business managers (DDC4) | |

| We continuously coach our employees to make decisions based on AI-driven insights (DDC5) | |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) | We believe that the high level of uncertainty in the market is an opportunity for us (EO1) |

| We are highly positive as we believe in gaining an advantage out of turbulence (EO2) | |

| We believe in building a risk management approach (EO3) | |

| The senior members of the organisation are highly supportive of the Generative AI initiative (EO4) | |

| Entrepreneurial Resilience (ER) | We can adapt to any dynamic changes (ER1) |

| We are determined to achieve our goals despite any level of obstacles we face (ER2) | |

| We fear no failures as failures help to correct our mistakes and allow us to make better decisions in future (ER3) | |

| We will bounce quickly from initial failures (ER4) | |

| Market Turbulence (MT) | Customers are becoming far more demanding with time (MT1) |

| Competition in our market is cutthroat (MT2) | |

| The technology in our industry is changing rapidly (MT3) |

| Indirect effects for paths with 2 segments | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 0.035 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.064 | ||

| Number of paths with 2 segments | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 0.318 | 0.287 | 0.484 | 0.194 | ||

| Standard errors of indirect effects for paths with 2 segments | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.075 | 0.074 | ||

| Effect sizes of indirect effects for paths with 2 segments | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 0.026 | 0.031 | 0.002 | 0.053 | ||

| Sums of indirect effects | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 0.035 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.064 | ||

| Number of paths for indirect effects | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 0.318 | 0.287 | 0.484 | 0.194 | ||

| Standard errors for sums of indirect effects | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.075 | 0.074 | ||

| Effect sizes for sums of indirect effects | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| ER | 0.026 | 0.031 | 0.002 | 0.053 | ||

| Total effects | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| EO | 0.207 | 0.246 | 0.018 | 0.375 | ||

| ER | 0.035 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.17 | 0.777 | |

| Number of paths for total effects | ||||||

| HS | TECH | DDC | EO | ER | MT | |

| EO | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ER | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

References

J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2023.2240744.

Alalwan, A.A., Baabdullah, A.M., Fetais, A.H.M., Algharabat, R.S., Raman, R., Dwivedi, Y.K., 2023. SMEs entrepreneurial finance-based digital transformation: towards innovative entrepreneurial finance and entrepreneurial performance. Ventur. Cap. 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2023.2195127.

Alhammadi, A., Shayea, I., El-Saleh, A.A., Azmi, M.H., Ismail, Z.H., Kouhalvandi, L., Saad, S.A., 2024. Artificial intelligence in 6G wireless networks: opportunities, applications, and challenges. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2024 (1), 8845070.

Al-Thaqeb, S.A., Algharabali, B.G., Alabdulghafour, K.T., 2022. The pandemic and economic policy uncertainty. Int. J. Finance Econ. 27 (3), 2784-2794.

Anderson, B.S., Covin, J.G., Slevin, D.P., 2009. Understanding the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and strategic learning capability: an empirical investigation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 3 (3), 218-240.

Anderson, B.S., Kreiser, P.M., Kuratko, D.F., Hornsby, J.S., Eshima, Y., 2015. Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial orientation. Strat. Manag. J. 36 (10), 1579-1596.

Anwar, A., Coviello, N., Rouziou, M., 2023. Weathering a crisis: a multi-level analysis of resilience in young ventures. Entrep. Theory Pract. 47 (3), 864-892.

Armstrong, J.S., Overton, T.S., 1977. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Market. Res. 14 (3), 396-402.

Balta, M.E., Papadopoulos, T., Spanaki, K., 2023. Business model pivoting and digital technologies in turbulent environments. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. https:// doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2023-0210.

Bankins, S., Ocampo, A.C., Marrone, M., Restubog, S.L.D., Woo, S.E., 2023. A multilevel review of artificial intelligence in organizations: implications for organizational behavior research and practice. J. Organ. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2735.

Baron, R.M., Kenny, D.A., 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173.

Benitez, J., Henseler, J., Castillo, A., Schuberth, F., 2020. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Inf. Manag. 57 (2), 103168.

Berry, A.J., Sweeting, R., Goto, J., 2006. The effect of business advisers on the performance of SMEs. J. Small Bus. Enterprise Dev. 13 (1), 33-47.

Berthon, P., Yalcin, T., Pehlivan, E., Rabinovich, T., 2024. Trajectories of AI technologies: insights for managers. Bus. Horiz. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. bushor.2024.03.002.

Boyer, K.K., Swink, M.L., 2008. Empirical elephants-Why multiple methods are essential to quality research in operations and supply chain management. J. Oper. Manag. 26 (3), 338-344.

Budhwar, P., Chowdhury, S., Wood, G., Aguinis, H., Bamber, G.J., Beltran, J.R., et al., 2023. Human resource management in the age of generative artificial intelligence: perspectives and research directions on ChatGPT. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 33 (3), 606-659.

Bullough, A., Renko, M., 2013. Entrepreneurial resilience during challenging times. Bus. Horiz. 56 (3), 343-350.

Castro, M.P., Zermeño, M.G.G., 2021. Being an entrepreneur post-COVID-19-resilience in times of crisis: a systematic literature review. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 13 (4), 721-746.

Chalmers, D., MacKenzie, N.G., Carter, S., 2021. Artificial intelligence and entrepreneurship: implications for venture creation in the fourth industrial revolution. Entrep. Theory Pract. 45 (5), 1028-1053.

Chaston, I., Sadler-Smith, E., 2012. Entrepreneurial cognition, entrepreneurial orientation and firm capability in the creative industries. Br. J. Manag. 23 (3), 415-432.

Chatterjee, S., Gupta, S.D., Upadhyay, P., 2020. Technology adoption and entrepreneurial orientation for rural women: evidence from India. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 160, 120236.

Chaudhary, S., Dhir, A., Meenakshi, N., Christofi, M., 2024. How small firms build resilience to ward off crises: a paradox perspective. Enterpren. Reg. Dev. 36 (1-2), 182-207.

Chen, K.H., Wang, C.H., Huang, S.Z., Shen, G.C., 2016. Service innovation and new product performance: the influence of market-linking capabilities and market turbulence. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 172, 54-64.

Chen, B., Wu, Z., Zhao, R., 2023. From fiction to fact: the growing role of generative AI in business and finance. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 21 (4), 471-496.

Chirumalla, K., 2021. Building digitally-enabled process innovation in the process industries: a dynamic capabilities approach. Technovation 105, 102256.

Churchill Jr., G.A., 1979. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Market. Res. 16 (1), 64-73.

Ciampi, F., Demi, S., Magrini, A., Marzi, G., Papa, A., 2021. Exploring the impact of big data analytics capabilities on business model innovation: the mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. J. Bus. Res. 123, 1-13.

Clausen, T., Korneliussen, T., 2012. The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and speed to the market: the case of incubator firms in Norway. Technovation 32 (9-10), 560-567.

Cohen, J., 1988. Set correlation and contingency tables. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 12 (4), 425-434.

Corner, P.D., Singh, S., Pavlovich, K., 2017. Entrepreneurial resilience and venture failure. Int. Small Bus. J. 35 (6), 687-708.

Dahles, H., Susilowati, T.P., 2015. Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Ann. Tourism Res. 51, 34-50.

Donthu, N., Gustafsson, A., 2020. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. J. Bus. Res. 117, 284-289.

Dubey, R., Bryde, D.J., Dwivedi, Y.K., Graham, G., Foropon, C., Papadopoulos, T., 2023. Dynamic digital capabilities and supply chain resilience: The role of government effectiveness. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 258, 108790.

Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., Childe, S.J., Bryde, D.J., Giannakis, M., Foropon, C., et al., 2020. Big data analytics and artificial intelligence pathway to operational performance under the effects of entrepreneurial orientation and environmental dynamism: a study of manufacturing organisations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 226, 107599.

Dwivedi, Y.K., Hughes, L., Ismagilova, E., Aarts, G., Coombs, C., Crick, T., et al., 2021. Artificial Intelligence (AI): multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 57, 101994.

Eisenhardt, K.M., Martin, J.A., 2000. Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strat. Manag. J. 21 (10-11), 1105-1121.

Fainshmidt, S., Pezeshkan, A., Lance Frazier, M., Nair, A., Markowski, E., 2016. Dynamic capabilities and organizational performance: a meta-analytic evaluation and extension. J. Manag. Stud. 53 (8), 1348-1380.

Fatoki, O., 2018. The impact of entrepreneurial resilience on the success of small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Sustainability 10 (7), 2527.

Faquet, R., Malarde, V., 2020. Digitalisation in France’s business sector. TresorEconomics 271 (November), 1-8. https://www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr/Articles/ df17a219-238e-4b52-90f3-e294fbda02f0/files/8ec8a48e-a30e-4479-865e-bce6ce22 63dd. (Accessed 15 October 2023).

Fellnhofer, K., 2023. Positivity and higher alertness levels facilitate discovery: Longitudinal sentiment analysis of emotions on Twitter. Technovation 122, 102409.

Ferreira, J.J., Cruz, B., Veiga, P.M., 2022. Knowledge strategies and digital technologies maturity: effects on small business performance. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 1-19.

Ferreras-Méndez, J.L., Olmos-Penuela, J., Salas-Vallina, A., Alegre, J., 2021. Entrepreneurial orientation and new product development performance in SMEs: the mediating role of business model innovation. Technovation 108, 102325.

Filippo, C., Vito, G., Irene, S., Simone, B., Gualtiero, F., 2024. Future applications of generative large language models: a data-driven case study on ChatGPT. Technovation 133, 103002.

Flynn, B.B., Sakakibara, S., Schroeder, R.G., Bates, K.A., Flynn, E.J., 1990. Empirical research methods in operations management. J. Oper. Manag. 9 (2), 250-284.

Fornell, C., Larcker, D.F., 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18 (1), 39-50.

Fosso Wamba, S., 2022. Impact of artificial intelligence assimilation on firm performance: the mediating effects of organizational agility and customer agility. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 67, 102544.

Fosso Wamba, F., Queiroz, M.M., Jabbour, C.J.C., Shi, C.V., 2023. Are both generative AI and ChatGPT game changers for 21st-Century operations and supply chain excellence? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 265, 109015.

Fosso Wamba, F., Queiroz, M.M., Trinchera, L., 2024. The role of artificial intelligenceenabled dynamic capability on environmental performance: the mediation effect of a data-driven culture in France and the USA. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 268, 109131.

Frick, N.R., Mirbabaie, M., Stieglitz, S., Salomon, J., 2021. Maneuvering through the stormy seas of digital transformation: the impact of empowering leadership on the AI readiness of enterprises. J. Decis. Syst. 30 (2-3), 235-258.

Galbraith, J.R., 1974. Organization design: An information processing view. Interfaces 4 (3), 28-36.

Giuggioli, G., Pellegrini, M.M., 2022. Artificial intelligence as an enabler for entrepreneurs: a systematic literature review and an agenda for future research. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 29 (4), 816-837.

Gottschalck, N., Branner, K., Rolan, L., Kellermanns, F., 2021. Cross-level effects of entrepreneurial orientation and ambidexterity on the resilience of small business owners. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00472778.2021.2002878.

Grover, V., Sabherwal, R., 2020. Making sense of the confusing mix of digitalization, pandemics, and economics. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 55, 102234.

Gupta, M., George, J.F., 2016. Toward the development of a big data analytics capability. Inf. Manag. 53 (8), 1049-1064.

Hadjielias, E., Christofi, M., Tarba, S., 2022. Contextualizing small business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from small business owner-managers. Small Bus. Econ. 59 (4), 1351-1380.