DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-024-01794-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38212441

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-11

تأثيرات شبيهة بمضادات الاكتئاب للمواد النفسية في نموذج الفئران المعرضة لليأس المزمن: هل مستقبل 5-HT2A هو اللاعب الفريد؟

الملخص

اضطراب الاكتئاب الشديد (MDD) هو أحد أكثر الاضطرابات النفسية إعاقة في العالم. لا تزال العلاجات الأولى مثل مثبطات استرداد السيروتونين الانتقائية (SSRIs) تعاني من العديد من القيود، بما في ذلك مقاومة العلاج في

المقدمة

لعلاج MDD [4-7]. كشفت التجارب السريرية، التي كانت عمومًا صغيرة الحجم، أن جرعة واحدة أو جرعتين من السيلوسيبين تحفز تخفيفًا سريعًا (خلال ساعات) وطويل الأمد للأعراض الاكتئابية التي تستمر لعدة أسابيع وأحيانًا تصل إلى 12 شهرًا بعد العلاج [8، 9]. أظهرت تجربة سريرية أكبر من المرحلة 2 ب في المرضى الذين يعانون من نوبات اكتئابية شديدة ومقاومين للعلاجات التقليدية أجريت في 10 دول في أوروبا وأمريكا الشمالية مؤخرًا أن 30% من المرضى الذين تلقوا جرعة واحدة من السيلوسيبين (25 ملغ) بالاشتراك مع الدعم النفسي، شهدوا انخفاضًا سريعًا في الأعراض الاكتئابية استمر لمدة ثلاثة أسابيع بعد العلاج [10]. علاوة على ذلك، على عكس الكيتامين، لا تسبب المواد المهلوسة الاعتماد أو متلازمة الانسحاب [11] وتسبب آثارًا جانبية (قلق، تغيير في الإدراك، أو حالات ذهانية) فقط في نسبة صغيرة من المرضى [12]، مما يثير أملًا كبيرًا لعلاج المرضى الذين يعانون من MDD المرتبطة بأفكار/سلوكيات انتحارية.

المواد والأساليب الحيوانات

الأدوية والعلاجات

اختبارات سلوكية

تم قياس (المحدد على أنه عض الفأر للكرة الغذائية). استمرت جلسات الاختبار لمدة 10 دقائق. تم تخصيص القيمة القصوى (600 ثانية) للحيوانات التي لا تعض الكرة الغذائية خلال جلسة الاختبار. بعد عض الكرة الغذائية مباشرة، تم وضع الفئران في قفص اختبار يحتوي على كرة غذائية جديدة وموزونة. تم قياس كمية الكرة الغذائية التي تم تناولها لمدة 5 دقائق. ثم، تم إعادة الحيوانات إلى قفصها المنزلي مع الطعام والماء بحرية.

التحليل الإحصائي

النتائج

آثار شبيهة بمضادات الاكتئاب لـ 5-HT

إدارة الـ DOI أو السيلوسيبين إلى

تسبب القوارض [15، 29] والبشر [28، 30] تأثيرات سريعة وطويلة الأمد تشبه مضادات الاكتئاب في فئران CDM.

تُعزى التأثيرات الشبيهة بمضادات الاكتئاب لـ DOI و lisuride إلى 5-HT

تأثيرات شبيهة بمضادات الاكتئاب للسيلاسيبين مستقلة عن 5-HT

الجدول 1. المتوسط

| رقم الشكل | اختبار |

|

يعني

|

دقيق

|

قيمة F/H/W |

| 1ب | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 20 (10 ذكور/10 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 20 (

|

|

|

|||

| 20 (10 ذكور/10 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (

|

|

|

|||

| 1C | تحليل التباين الأحادي + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | 20 (

|

|

|

|

| 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 20 (

|

|

|

|||

| 20 (

|

|

|

|||

| 9 (

|

|

|

|||

| 1D | تحليل التباين الأحادي + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | 20 (

|

|

|

|

| 19 (

|

|

|

|||

| 20 (

|

|

|

|||

| 20 (10 ذكور/10 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (

|

|

|

|||

| 2A | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 17 (8 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 18 (

|

|

|

|||

| 8 (4 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 2B | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 19 (

|

|

|

|||

| 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (4 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 2C | تحليل التباين الأحادي + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (4 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 3A | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دن المتعددة | 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 17 (8 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 24 (12 ذكر/12 أنثى) |

|

|

|||

| 18 (

|

|

|

|||

| 3ب | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| ٢٤ (

|

|

|

|||

| ١٨ (

|

|

|

|||

| 3C | تحليل التباين الأحادي + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 24 (

|

|

|

|||

| 19 (

|

|

|

|||

| 4A | تحليل التباين ويلش + مقارنات دنيت المتعددة | 7 (4 ذكور/3 إناث) |

|

10.98 (3.000, 15.40) | |

| 7 (4 ذكور/3 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 4ب | تحليل التباين أحادي الاتجاه + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | ٧ (

|

|

|

|

| 7(4م/3ف) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 4C | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | ٧ (

|

|

|

|

| 7 (4 ذكور/3 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (

|

|

|

| رقم الشكل | اختبار |

|

يعني

|

دقيق

|

قيمة F/H/W |

| S1A | تحليل التباين ثنائي الاتجاه + مقارنات دنت المتعددة | بسيليو

|

|

||

| بسيليو

|

|

||||

| 6 (

|

بسيليو

|

|

|||

| 6 (3 ذكور/3 إناث) | معرف الكائن الرقمي

|

|

|||

| 6 (3 ذكور/3 إناث) | معرف الكائن الرقمي

|

|

|||

| ٦ (

|

معرف الكائن الرقمي

|

|

|||

| ليسو

|

|

||||

| ليسو

|

|

||||

| ليسو

|

|

||||

| S1B | تحليل التباين ثنائي الاتجاه + مقارنات دنت المتعددة | بسيليو

|

|

||

| 6 (

|

بسيليو

|

|

|||

| 6 (3 ذكور/3 إناث) | بسيليو

|

|

|||

| 6 (3 ذكور/3 إناث) | معرف الكائن الرقمي

|

|

|||

| معرف الوثيقة الرقمي

|

|

||||

| معرف الكائن الرقمي

|

|

||||

| S1C | تحليل التباين ثنائي الاتجاه + مقارنات دنت المتعددة | بسيليو

|

|

||

| 6 (3 ذكور/3 إناث) | بسيليو

|

|

|||

| 6 (3 ذكور/3 إناث) | بسيليو

|

|

|||

| 6 (3 ذكور/3 إناث) | معرف الكائن الرقمي

|

|

|||

| معرف الكائن الرقمي

|

|

||||

| معرف الكائن الرقمي

|

|

||||

| S2A | تحليل التباين الأحادي + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | 9 (5 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 8 (4 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (7 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| S2B | تحليل التباين أحادي الاتجاه + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | 9 (5 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 8 (4 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (7 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| S2C | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 9 (5 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 8 (4 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (7 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 30 (16 ذكر/14 أنثى) |

|

||||

| S2D | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دن المتعددة | 28 (16 ذكر/12 أنثى) |

|

|

|

| 24 (12 ذكر/12 أنثى) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (

|

|

|

|||

| 12 (8 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| S2E | تحليل التباين الأحادي + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | 30 (

|

|

|

|

| 30 (

|

|

|

|||

| ٢٤ (

|

|

|

|||

| 12 (

|

|

|

|||

| 12 (

|

|

|

|||

| S2F | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 30 (

|

|

|

|

| 30 (

|

|

|

|||

| 24 (12 ذكر/12 أنثى) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (8 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (

|

|

|

|||

| S4A | تحليل التباين الأحادي + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | 20 (10 ذكور/10 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (5 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

| رقم الشكل | اختبار |

|

متوسط

|

دقيق

|

قيمة F/H/W |

| S4B | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 20 (

|

|

|

|

| 9 (

|

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 8 (5 ذكور/3 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| S4C | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 20 (

|

|

|

|

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (5 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| S5A | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 9 (5 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 8 (4 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (7 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| S5B | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 7 (4 ذكور/3 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 7 (4 ذكور/3 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| S5C | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دُن المتعددة | 20 (10 ذكور/10 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 20 (11 ذكر/9 أنثى) |

|

|

|||

| 20 (10 ذكور/10 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (5 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| S5D | تحليل التباين الأحادي + مقارنات دانيه المتعددة | 19 (10 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 17 (8 ذكور/9 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 18 (

|

|

|

|||

| 8 (4 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 24 (12 ذكور/12 إناث) |

|

|

|||

| 18 (

|

|

|

|||

| S5E | اختبار كروسكال-واليس + مقارنات دن المتعددة | 11 (6 ذكور/5 إناث) |

|

|

|

| 11 (8 ذكور/3 إناث) |

|

p > 0.999 | |||

| 12 (8 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

p>0.999 | |||

| 12 (8 ذكور/4 إناث) |

|

|

تأثيرات شبيهة بمضادات الاكتئاب للسيلاسيبين في فئران CDM (الشكل التوضيحي S2D-F والجدول 1)، مما يشير إلى أنها مستقلة عن تنشيط مستقبلات D1 وD2.

الإدارة الدقيقة تحت الحادة لـ DOI أو السيلوسيبين تحفز تأثيرات شبيهة بمضادات الاكتئاب في فئران CDM

إما WAY100635، أو SCH23390 أو eticlopride (الشكل التوضيحي التكميلي S5D، E والجدول 1).

نقاش

أُلغي في

تأثيرات على الحالة المزاجية وبعض العمليات المعرفية، مثل الانتباه [40]، قمنا بالتحقيق في تأثير إدارة الجرعات الصغيرة اليومية من المخدرات النفسية على فئران CDM وأظهرنا أن هذا البروتوكول فعال مثل إدارة جرعة واحدة لتحفيز تأثيرات شبيهة بمضادات الاكتئاب. علاوة على ذلك، لم ينتج عن هذا البروتوكول زيادة في استهلاك الطعام لدى الفئران المعالجة بالسيلاسيبين، كما لوحظ بعد إدارة جرعة واحدة. هذه الملاحظة،

مع عدم وجود HTR بعد إعطاء جرعات صغيرة من المخدرات النفسية بشكل شبه مزمن، يدعم ذلك فائدته مقارنة بإعطاء جرعة واحدة.

REFERENCES

- WHO. Global Health Observatory data repository. WHO; 2020. https://apps.who. int/gho/data/node.home.

- Courtet P, Olie E, Debien C, Vaiva G. Keep socially (but not physically) connected and carry on: preventing suicide in the age of COVID-19. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81:20com13370.

- Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, Georgiou P, Fischell J, Elmer GI, et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature. 2016;533:481-6.

- Krystal JH, Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Charney DS, Duman RS. Ketamine: a paradigm shift for depression research and treatment. Neuron. 2019;101:774-8.

- Prouzeau D, Conejero I, Voyvodic PL, Becamel C, Abbar M, Lopez-Castroman J. Psilocybin efficacy and mechanisms of action in major depressive disorder: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022;24:573-81.

- Nichols DE. Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68:264-355.

- Carhart-Harris R, Giribaldi B, Watts R, Baker-Jones M, Murphy-Beiner A, Murphy R, et al. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1402-11.

- Nichols DE, Johnson MW, Nichols CD. Psychedelics as medicines: an emerging new paradigm. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;101:209-19.

- Nutt D, Erritzoe D, Carhart-Harris R. Psychedelic psychiatry’s brave new world. Cell. 2020;181:24-8.

- Goodwin GM, Aaronson ST, Alvarez O, Arden PC, Baker A, Bennett JC, et al. Singledose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1637-48.

- Johnson M, Richards W, Griffiths R. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:603-20.

- Strassman RJ. Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. A review of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1984;172:577-95.

- Halberstadt AL, Chatha M, Klein AK, Wallach J, Brandt SD. Correlation between the potency of hallucinogens in the mouse head-twitch response assay and their behavioral and subjective effects in other species. Neuropharmacology. 2020;167:107933.

- Preller KH, Herdener M, Pokorny T, Planzer A, Kraehenmann R, Stampfli P, et al. The fabric of meaning and subjective effects in LSD-induced states depend on serotonin 2A receptor activation. Curr Biol. 2017;27:451-7.

- Gonzalez-Maeso J, Weisstaub NV, Zhou M, Chan P, Ivic L, Ang R, et al. Hallucinogens recruit specific cortical 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated signaling pathways to affect behavior. Neuron. 2007;53:439-52.

- Vollenweider FX, Vollenweider-Scherpenhuyzen MF, Babler A, Vogel H, Hell D. Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3897-902.

- Hesselgrave N, Troppoli TA, Wulff AB, Cole AB, Thompson SM. Harnessing psilocybin: antidepressant-like behavioral and synaptic actions of psilocybin are independent of 5-HT2R activation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2022489118.

- Cameron LP, Patel SD, Vargas MV, Barragan EV, Saeger HN, Warren HT, et al. 5-HT2ARs mediate therapeutic behavioral effects of psychedelic tryptamines. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023;14:351-8.

- Sun P, Wang F, Wang L, Zhang Y, Yamamoto R, Sugai T, et al. Increase in cortical pyramidal cell excitability accompanies depression-like behavior in mice: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16464-72.

- Serchov T, Clement HW, Schwarz MK, lasevoli F, Tosh DK, Idzko M, et al. Increased signaling via adenosine A1 receptors, sleep deprivation, imipramine, and ketamine inhibit depressive-like behavior via induction of Homer1a. Neuron. 2015;87:549-62.

- David DJ, Samuels BA, Rainer Q, Wang JW, Marsteller D, Mendez I, et al. Neurogenesis-dependent and -independent effects of fluoxetine in an animal model of anxiety/depression. Neuron. 2009;62:479-93.

- Samuels B, Hen R. Novelty-Suppressed Feeding in the Mouse. In: Gould T, editor. Mood and Anxiety Related Phenotypes in Mice. Humana Press; 2011. p. 107-121.

- Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Jalfre M. Behavioral despair in mice: a primary screening test for antidepressants. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1977;229:327-36.

- Liu MY, Yin CY, Zhu LJ, Zhu XH, Xu C, Luo CX, et al. Sucrose preference test for measurement of stress-induced anhedonia in mice. Nat Protoc. 2018; 13:1686-98.

- Zhou QG, Zhu LJ, Chen C, Wu HY, Luo CX, Chang L, et al. Hippocampal neuronal nitric oxide synthase mediates the stress-related depressive behaviors of glucocorticoids by downregulating glucocorticoid receptor. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7579-90.

- Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, et al. Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Science. 2023;379:700-6.

- Parkes JD, Schachter M, Marsden CD, Smith B, Wilson A. Lisuride in parkinsonism. Ann Neurol. 1981;9:48-52.

- Verde G, Chiodini PG, Liuzzi A, Cozzi R, Favales F, Botalla L, et al. Effectiveness of the dopamine agonist lisuride in the treatment of acromegaly and pathological hyperprolactinemic states. J Endocrinol Invest. 1980;3:405-14.

- Halberstadt AL, Geyer MA. LSD but not lisuride disrupts prepulse inhibition in rats by activating the 5-HT(2A) receptor. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208:179-89.

- Schmidt LG, Kuhn S, Smolka M, Schmidt K, Rommelspacher H. Lisuride, a dopamine D2 receptor agonist, and anticraving drug expectancy as modifiers of relapse in alcohol dependence. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:209-17.

- Rickli A, Moning OD, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive tryptamines compared with classic hallucinogens. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:1327-37.

- Vollenweider FX, Vontobel P, Hell D, Leenders KL. 5-HT modulation of dopamine release in basal ganglia in psilocybin-induced psychosis in man-a PET study with [11C]raclopride. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:424-33.

- Madsen MK, Fisher PM, Burmester D, Dyssegaard A, Stenbaek DS, Kristiansen S, et al. Psychedelic effects of psilocybin correlate with serotonin 2 A receptor occupancy and plasma psilocin levels. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1328-34.

- Pedzich BD, Rubens S, Sekssaoui M, Pierre A, Van Schuerbeek A, Marin P, et al. Effects of a psychedelic 5-HT2A receptor agonist on anxiety-related behavior and fear processing in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47:1304-14.

- de la Fuente Revenga M, Zhu B, Guevara CA, Naler LB, Saunders JM, Zhou Z, et al. Prolonged epigenomic and synaptic plasticity alterations following single exposure to a psychedelic in mice. Cell Rep. 2021;37:109836.

- Desouza LA, Benekareddy M, Fanibunda SE, Mohammad F, Janakiraman B, Ghai U, et al. The hallucinogenic serotonin(2 A) receptor agonist, 2,5-Dimethoxy-4lodoamphetamine, promotes cAMP response element binding protein-dependent gene expression of specific plasticity-associated genes in the rodent neocortex. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021;14:790213.

- Barre A, Berthoux C, De Bundel D, Valjent E, Bockaert J, Marin P, et al. Presynaptic serotonin 2 A receptors modulate thalamocortical plasticity and associative learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1382-1391.

- Berthoux C, Barre A, Bockaert J, Marin P, Becamel C. Sustained activation of postsynaptic 5-HT2A receptors gates plasticity at prefrontal cortex synapses. Cereb Cortex. 2019;29:1659-69.

- Slifirski G, Krol M, Turlo J. 5-HT receptors and the development of new antidepressants. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9015.

- Kuypers KP, Ng L, Erritzoe D, Knudsen GM, Nichols CD, Nichols DE, et al. Microdosing psychedelics: More questions than answers? An overview and suggestions for future research. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33:1039-57.

- Cao D, Yu J, Wang H, Luo Z, Liu X, He L, et al. Structure-based discovery of nonhallucinogenic psychedelic analogs. Science. 2022;375:403-11.

- Kaplan AL, Confair DN, Kim K, Barros-Alvarez X, Rodriguiz RM, Yang Y, et al. Bespoke library docking for 5-HT(2A) receptor agonists with antidepressant activity. Nature. 2022;610:582-91.

- Dong C, Ly C, Dunlap LE, Vargas MV, Sun J, Hwang IW, et al. Psychedelic-inspired drug discovery using an engineered biosensor. Cell. 2021;184:2779-2792.e2718.

- Qu Y, Chang L, Ma L, Wan X, Hashimoto K. Rapid antidepressant-like effect of non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analog lisuride, but not hallucinogenic psychedelic DOI, in lipopolysaccharide-treated mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2023;222:173500.

- Pogorelov VM, Rodriguiz RM, Roth BL, Wetsel WC. The G protein biased serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonist lisuride exerts anti-depressant drug-like activities in mice. Front Mol Biosci. 2023;10:1233743.

- Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:563-7.

- Rosenblat JD, Leon-Carlyle M, Ali S, Husain MI, McIntyre RS. Antidepressant effects of psilocybin in the absence of psychedelic effects. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:395-6.

- Yaden DB, Griffiths RR. The subjective effects of psychedelics are necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:568-72.

شكر وتقدير

منح من CNRS وINSERM وجامعة مونبلييه. كان MS متلقيًا لزمالة دكتوراه من وزارة التعليم العالي والبحث الفرنسية.

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إعادة الطبع والإذن متاحة على http://www.nature.com/ إعادة الطبع

© المؤلفون 2024

معهد الجينوم الوظيفي، جامعة مونبلييه، المركز الوطني للبحث العلمي، المعهد الوطني للصحة والبحث الطبي، F-34094 مونبلييه، فرنسا. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: فيليب مارين، كارين بيكاميل. البريد الإلكتروني: carine.becamel@igf.cnrs.fr

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-024-01794-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38212441

Publication Date: 2024-01-11

Antidepressant-like effects of psychedelics in a chronic despair mouse model: is the

Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most disabling psychiatric disorders in the world. First-line treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) still have many limitations, including a resistance to treatment in

INTRODUCTION

to treat MDD [4-7]. Clinical trials, generally of small sizes, revealed that one or two doses of psilocybin induce fast (within hours) and prolonged alleviation of depressive symptoms that last several weeks and, sometimes, up to 12 months after the treatment [8, 9]. A larger phase 2 b clinical trial in patients with major depressive episodes and resistant to classical treatments conducted in 10 countries in Europe and North America recently showed that 30% of patients who received a single dose of psilocybin ( 25 mg ) in combination with psychological support, had a rapid reduction of depressive symptoms that persisted three weeks after the treatment [10]. Furthermore, unlike ketamine, psychedelics do not cause dependence or withdrawal syndrome [11] and induce side effects (anxiety, alteration of perception, or psychotic states) only in a small proportion of patients [12], thus raising a great hope for the treatment of patients with MDD associated to suicidal ideations/behaviors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Animals

Drugs and treatments

Behavioral tests

(defined as the mouse biting the pellet) was measured. The testing sessions lasted 10 min . The maximum value ( 600 s ) was attributed to animals that do not bite the pellet during the testing session. Immediately after biting the food pellet, mice were placed in a test cage containing a new, weighed food pellet. The amount of pellet eaten for 5 min was measured. Then, the animals were placed back in their home cage with food and water ad libitum [21, 22].

Statistical analysis

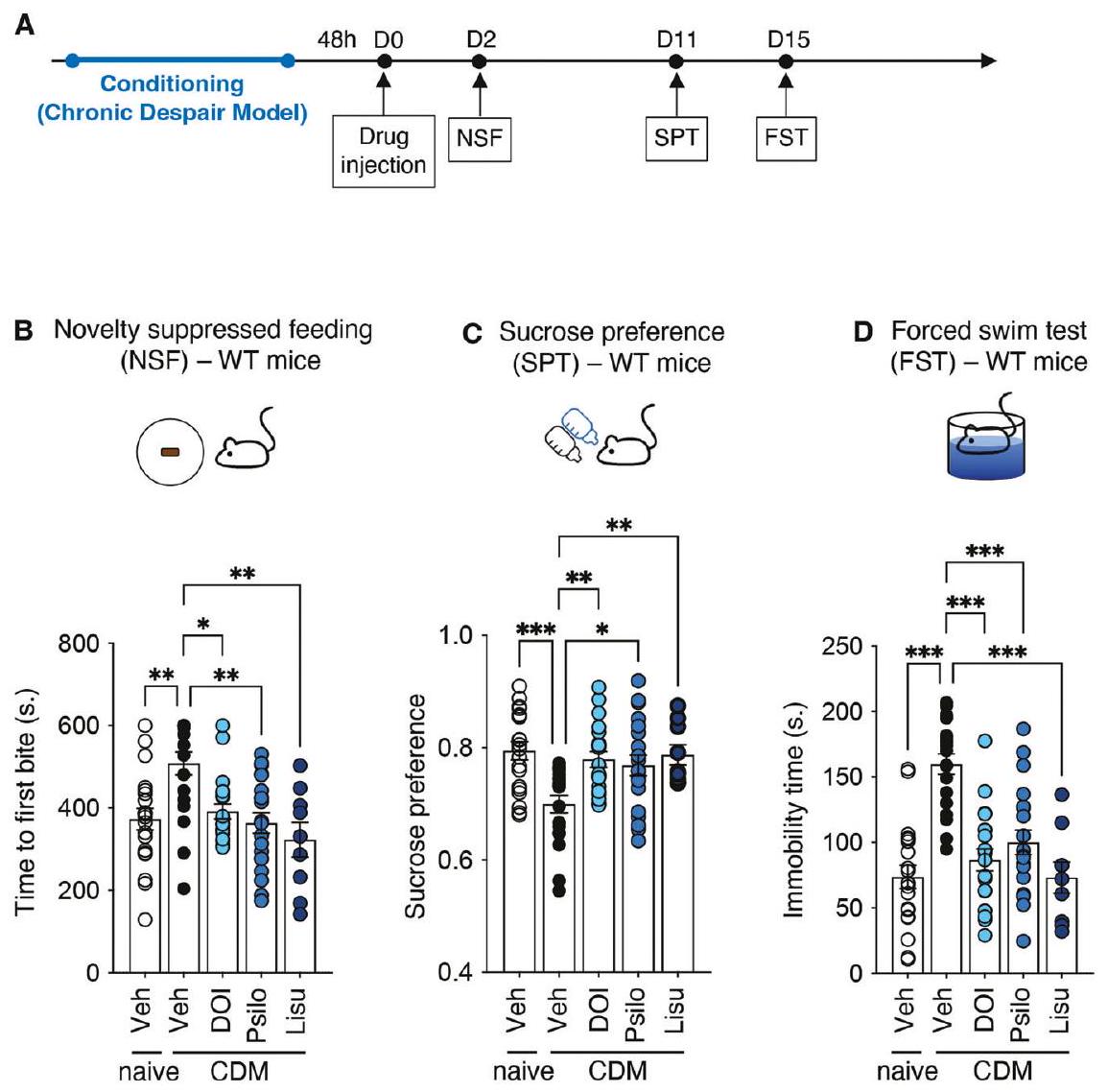

RESULTS

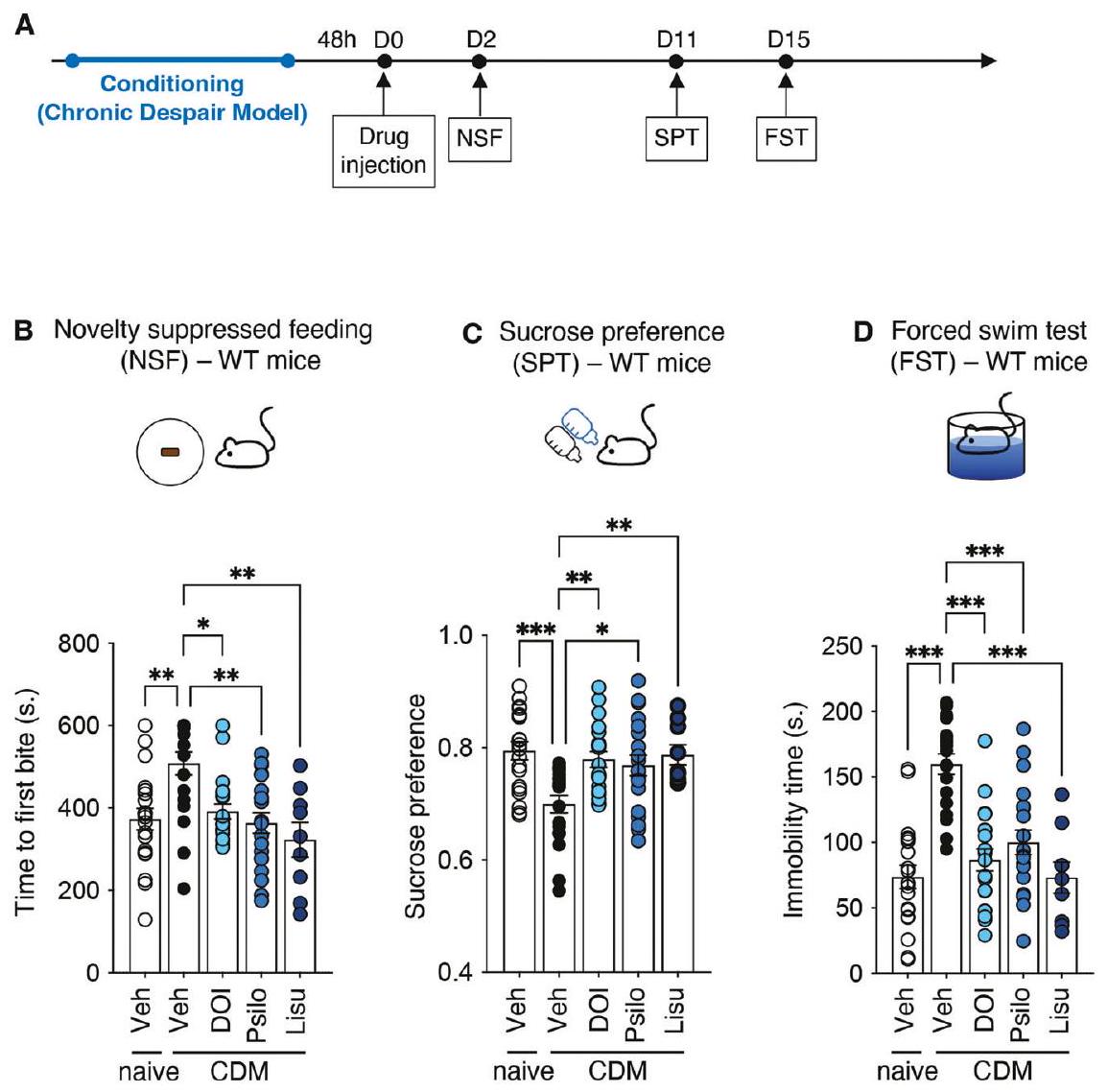

Antidepressant-like effects of 5-HT

administration of DOI or psilocybin to

rodents [15, 29] and humans [28, 30] induce rapid and prolonged antidepressant-like effects in CDM mice.

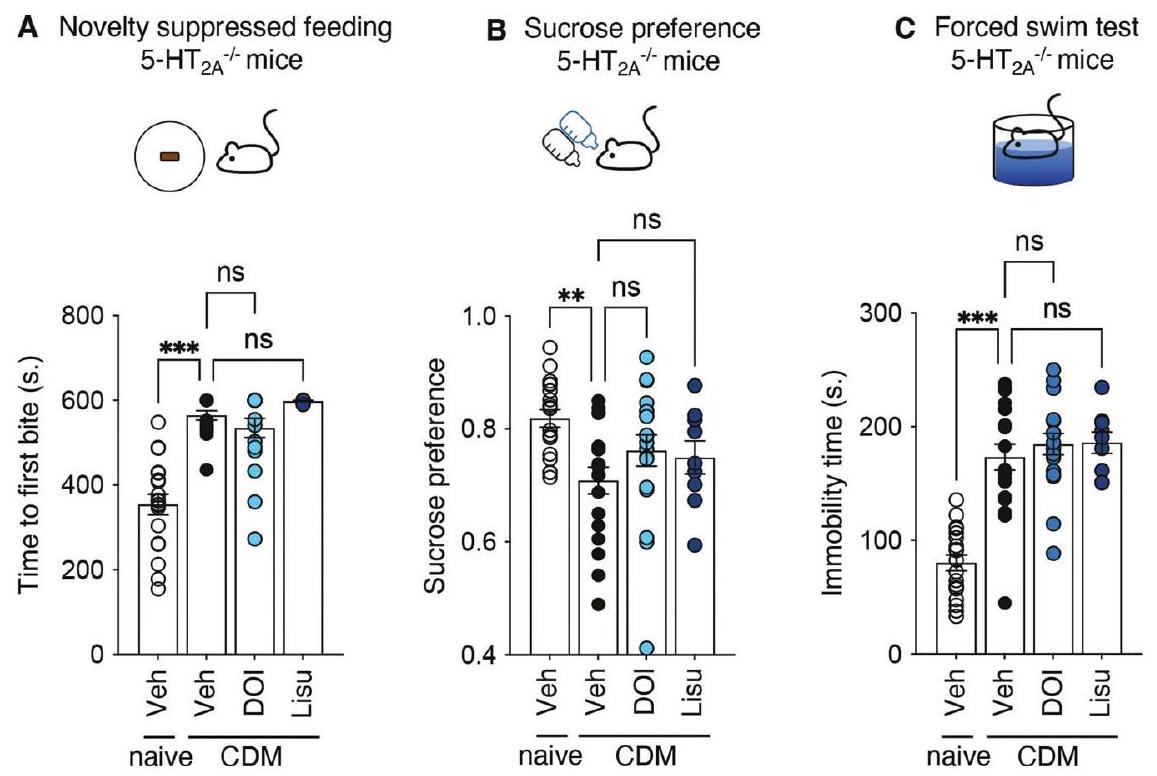

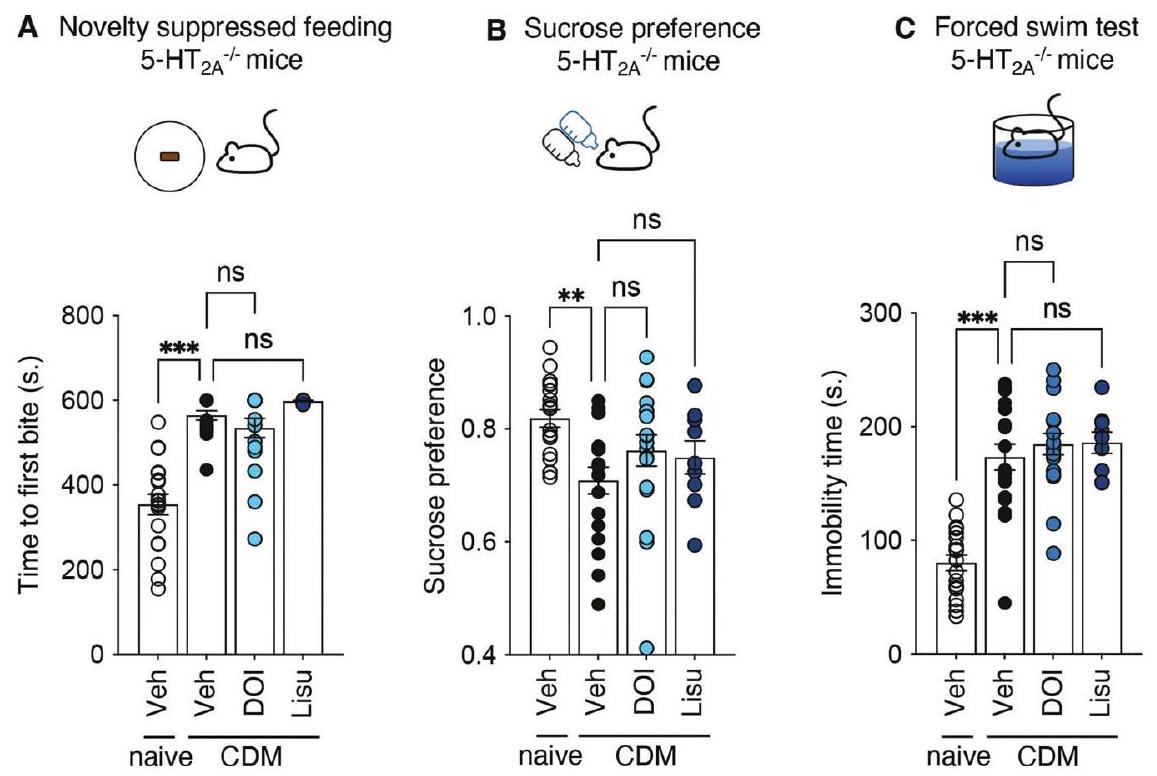

The antidepressant-like effects of DOI and lisuride are mediated by 5-HT

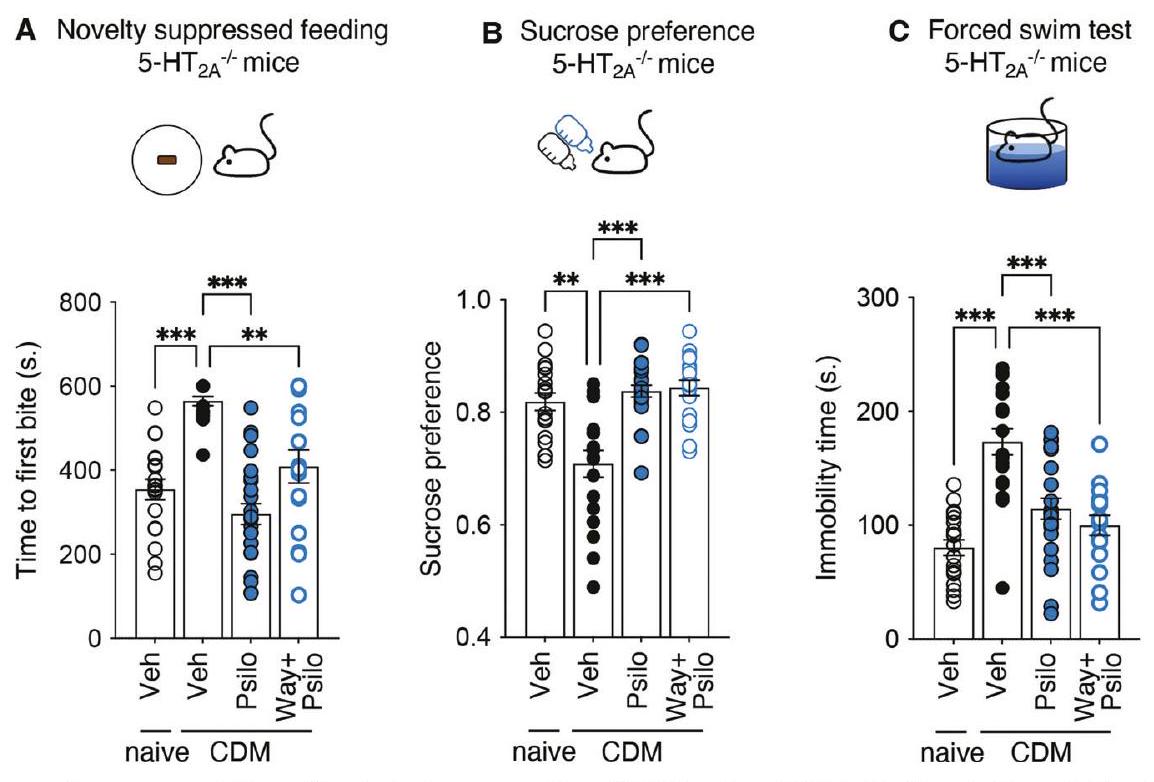

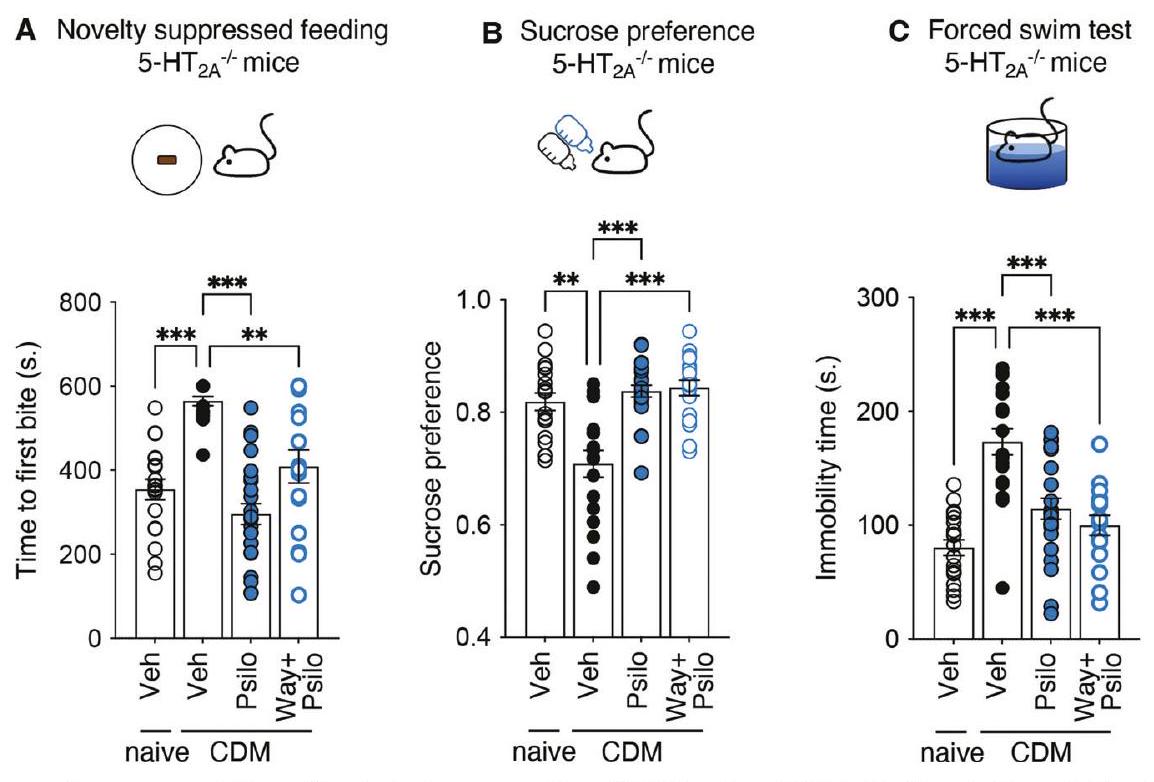

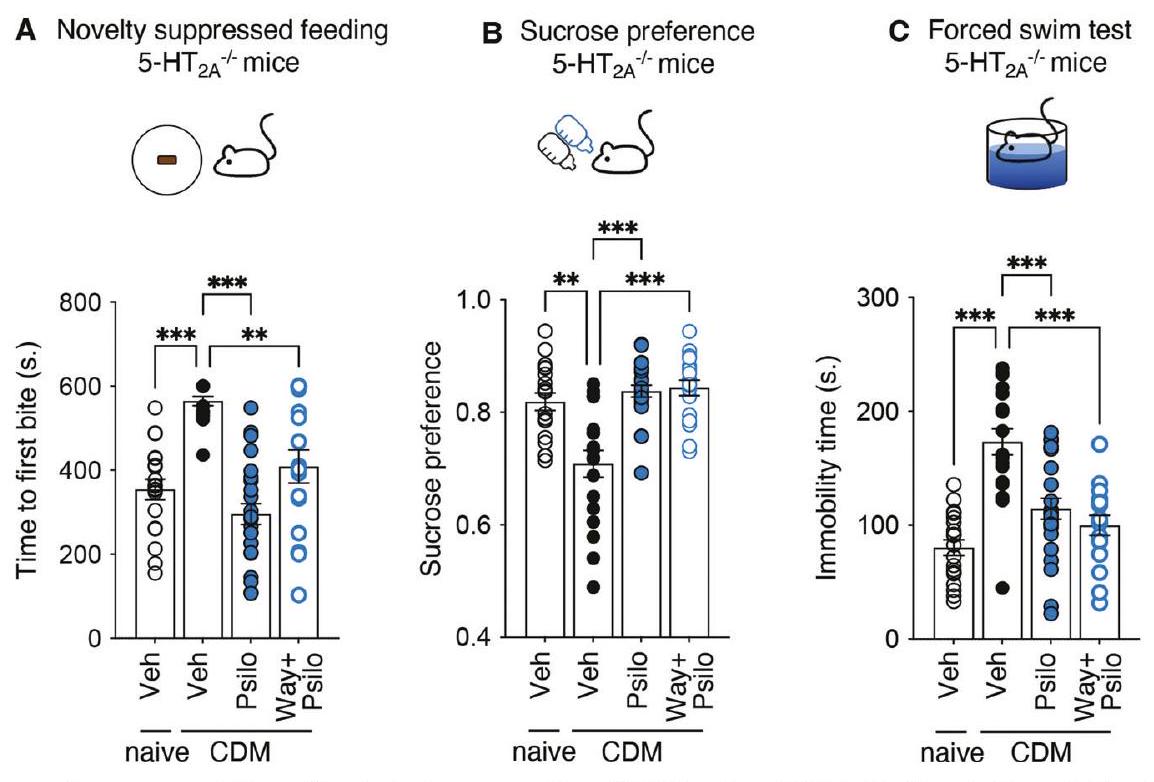

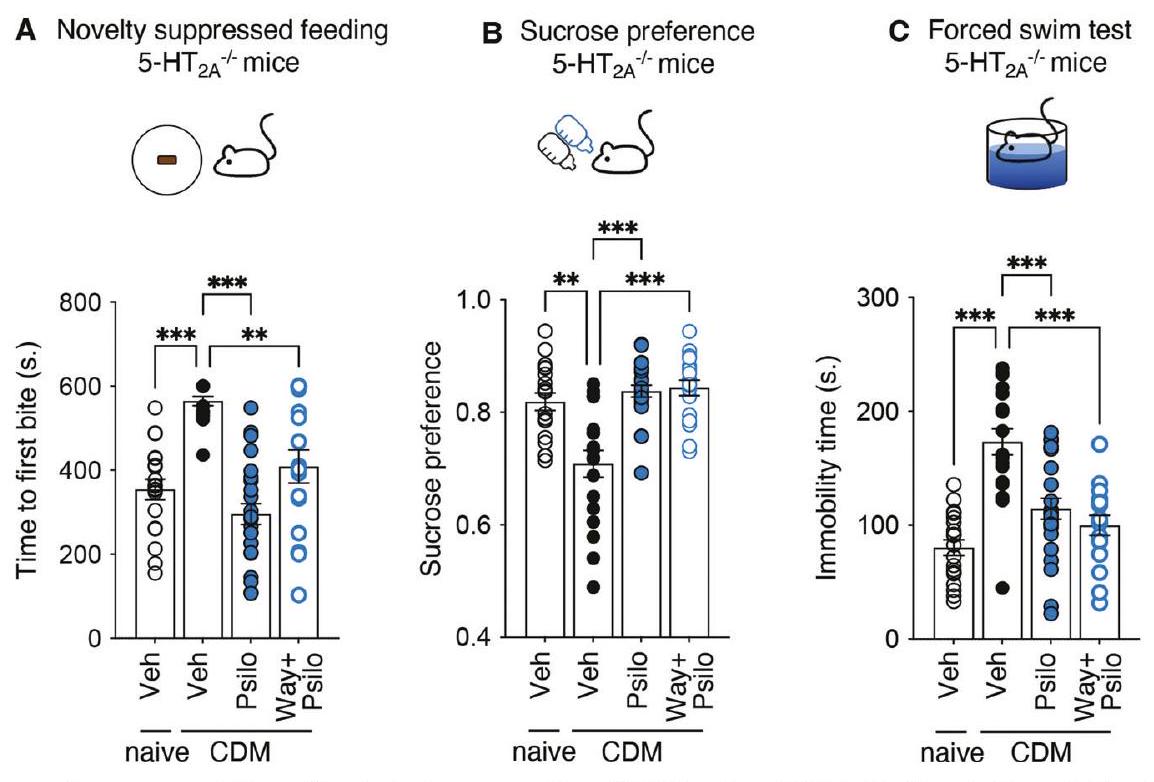

The antidepressant-like effects of psilocybin are independent of 5-HT

Table 1. Mean

| Figure number | Test |

|

Mean

|

Exact

|

F/H/W value |

| 1B | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 20 (10M/10F) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 20 (

|

|

|

|||

| 20 (10M/10F) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (

|

|

|

|||

| 1C | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 20 (

|

|

|

|

| 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 20 (

|

|

|

|||

| 20 (

|

|

|

|||

| 9 (

|

|

|

|||

| 1D | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 20 (

|

|

|

|

| 19 (

|

|

|

|||

| 20 (

|

|

|

|||

| 20 (10M/10F) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (

|

|

|

|||

| 2A | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|

| 17 (8M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 18 (

|

|

|

|||

| 8 (4M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| 2B | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|

| 19 (

|

|

|

|||

| 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (4M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 2C | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (4M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 3A | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|

| 17 (8M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 24 (12M/12F) |

|

|

|||

| 18 (

|

|

|

|||

| 3B | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 24 (

|

|

|

|||

| 18 (

|

|

|

|||

| 3C | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 24 (

|

|

|

|||

| 19 (

|

|

|

|||

| 4A | Welch ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 7 (4M/3F) |

|

10.98 (3.000, 15.40) | |

| 7 (4M/3F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 4B | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 7 (

|

|

|

|

| 7(4M/3F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 4C | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 7 (

|

|

|

|

| 7 (4M/3F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (

|

|

|

| Figure number | Test |

|

Mean

|

Exact

|

F/H/W value |

| S1A | Two-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | Psilo

|

|

||

| Psilo

|

|

||||

| 6 (

|

Psilo

|

|

|||

| 6 (3M/3F) | DOI

|

|

|||

| 6 (3M/3F) | DOI

|

|

|||

| 6 (

|

DOI

|

|

|||

| Lisu

|

|

||||

| Lisu

|

|

||||

| Lisu

|

|

||||

| S1B | Two-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | Psilo

|

|

||

| 6 (

|

Psilo

|

|

|||

| 6 (3M/3F) | Psilo

|

|

|||

| 6 (3M/3F) | DOI

|

|

|||

| DOI

|

|

||||

| DOI

|

|

||||

| S1C | Two-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | Psilo

|

|

||

| 6 (3M/3F) | Psilo

|

|

|||

| 6 (3M/3F) | Psilo

|

|

|||

| 6 (3M/3F) | DOI

|

|

|||

| DOI

|

|

||||

| DOI

|

|

||||

| S2A | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 9 (5M/4F) |

|

|

|

| 8 (4M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (7M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| S2B | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 9 (5M/4F) |

|

|

|

| 8 (4M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (7M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| S2C | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 9 (5M/4F) |

|

|

|

| 8 (4M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (7M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 30 (16M/14F) |

|

||||

| S2D | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 28 (16M/12F) |

|

|

|

| 24 (12M/12F) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (

|

|

|

|||

| 12 (8M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| S2E | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 30 (

|

|

|

|

| 30 (

|

|

|

|||

| 24 (

|

|

|

|||

| 12 (

|

|

|

|||

| 12 (

|

|

|

|||

| S2F | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 30 (

|

|

|

|

| 30 (

|

|

|

|||

| 24 (12M/12F) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (8M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (

|

|

|

|||

| S4A | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 20 (10M/10F) |

|

|

|

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (5M/4F) |

|

|

| Figure number | Test |

|

Mean

|

Exact

|

F/H/W value |

| S4B | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 20 (

|

|

|

|

| 9 (

|

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 8 (5M/3F) |

|

|

|||

| S4C | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 20 (

|

|

|

|

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (5M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| S5A | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 9 (5M/4F) |

|

|

|

| 8 (4M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| 12 (7M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| S5B | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 7 (4M/3F) |

|

|

|

| 7 (4M/3F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| 10 (5M/5F) |

|

|

|||

| S5C | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 20 (10M/10F) |

|

|

|

| 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 20 (11M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 20 (10M/10F) |

|

|

|||

| 9 (5M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| S5D | One-way ANOVA + Dunnett’s multiple comparisons | 19 (10M/9F) |

|

|

|

| 17 (8M/9F) |

|

|

|||

| 18 (

|

|

|

|||

| 8 (4M/4F) |

|

|

|||

| 24 (12M/12F) |

|

|

|||

| 18 (

|

|

|

|||

| S5E | Kruskal-Wallis + Dunn’s multiple comparisons | 11 (6M/5F) |

|

|

|

| 11 (8M/3F) |

|

p > 0.999 | |||

| 12 (8M/4F) |

|

p>0.999 | |||

| 12 (8M/4F) |

|

|

the antidepressant-like effects of psilocybin in CDM mice (Supplementary Fig. S2D-F and Table 1), suggesting that they are independent of D1 and D2 receptor activation.

Sub-chronic microdosing administration of DOI or psilocybin induce antidepressant-like effects in CDM mice

either WAY100635, or SCH23390 or eticlopride (Supplementary Fig. S5D, E and Table 1).

DISCUSSION

abolished in

effects on mood state and some cognitive processes, such as attention [40], we investigated the effect of daily microdosing administration of psychedelics to CDM mice and showed that this protocol is as efficient as a single dose administration to induce antidepressant-like effects. Furthermore, this protocol did not result in an increased food consumption in psilocybin-treated mice, as observed after a single administration. This observation,

together with the lack of HTR after sub-chronic microdosing psychedelic administration, supports its benefit over a single dose administration.

REFERENCES

- WHO. Global Health Observatory data repository. WHO; 2020. https://apps.who. int/gho/data/node.home.

- Courtet P, Olie E, Debien C, Vaiva G. Keep socially (but not physically) connected and carry on: preventing suicide in the age of COVID-19. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81:20com13370.

- Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, Georgiou P, Fischell J, Elmer GI, et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature. 2016;533:481-6.

- Krystal JH, Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Charney DS, Duman RS. Ketamine: a paradigm shift for depression research and treatment. Neuron. 2019;101:774-8.

- Prouzeau D, Conejero I, Voyvodic PL, Becamel C, Abbar M, Lopez-Castroman J. Psilocybin efficacy and mechanisms of action in major depressive disorder: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022;24:573-81.

- Nichols DE. Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68:264-355.

- Carhart-Harris R, Giribaldi B, Watts R, Baker-Jones M, Murphy-Beiner A, Murphy R, et al. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1402-11.

- Nichols DE, Johnson MW, Nichols CD. Psychedelics as medicines: an emerging new paradigm. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;101:209-19.

- Nutt D, Erritzoe D, Carhart-Harris R. Psychedelic psychiatry’s brave new world. Cell. 2020;181:24-8.

- Goodwin GM, Aaronson ST, Alvarez O, Arden PC, Baker A, Bennett JC, et al. Singledose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1637-48.

- Johnson M, Richards W, Griffiths R. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:603-20.

- Strassman RJ. Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. A review of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1984;172:577-95.

- Halberstadt AL, Chatha M, Klein AK, Wallach J, Brandt SD. Correlation between the potency of hallucinogens in the mouse head-twitch response assay and their behavioral and subjective effects in other species. Neuropharmacology. 2020;167:107933.

- Preller KH, Herdener M, Pokorny T, Planzer A, Kraehenmann R, Stampfli P, et al. The fabric of meaning and subjective effects in LSD-induced states depend on serotonin 2A receptor activation. Curr Biol. 2017;27:451-7.

- Gonzalez-Maeso J, Weisstaub NV, Zhou M, Chan P, Ivic L, Ang R, et al. Hallucinogens recruit specific cortical 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated signaling pathways to affect behavior. Neuron. 2007;53:439-52.

- Vollenweider FX, Vollenweider-Scherpenhuyzen MF, Babler A, Vogel H, Hell D. Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3897-902.

- Hesselgrave N, Troppoli TA, Wulff AB, Cole AB, Thompson SM. Harnessing psilocybin: antidepressant-like behavioral and synaptic actions of psilocybin are independent of 5-HT2R activation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2022489118.

- Cameron LP, Patel SD, Vargas MV, Barragan EV, Saeger HN, Warren HT, et al. 5-HT2ARs mediate therapeutic behavioral effects of psychedelic tryptamines. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023;14:351-8.

- Sun P, Wang F, Wang L, Zhang Y, Yamamoto R, Sugai T, et al. Increase in cortical pyramidal cell excitability accompanies depression-like behavior in mice: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16464-72.

- Serchov T, Clement HW, Schwarz MK, lasevoli F, Tosh DK, Idzko M, et al. Increased signaling via adenosine A1 receptors, sleep deprivation, imipramine, and ketamine inhibit depressive-like behavior via induction of Homer1a. Neuron. 2015;87:549-62.

- David DJ, Samuels BA, Rainer Q, Wang JW, Marsteller D, Mendez I, et al. Neurogenesis-dependent and -independent effects of fluoxetine in an animal model of anxiety/depression. Neuron. 2009;62:479-93.

- Samuels B, Hen R. Novelty-Suppressed Feeding in the Mouse. In: Gould T, editor. Mood and Anxiety Related Phenotypes in Mice. Humana Press; 2011. p. 107-121.

- Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Jalfre M. Behavioral despair in mice: a primary screening test for antidepressants. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1977;229:327-36.

- Liu MY, Yin CY, Zhu LJ, Zhu XH, Xu C, Luo CX, et al. Sucrose preference test for measurement of stress-induced anhedonia in mice. Nat Protoc. 2018; 13:1686-98.

- Zhou QG, Zhu LJ, Chen C, Wu HY, Luo CX, Chang L, et al. Hippocampal neuronal nitric oxide synthase mediates the stress-related depressive behaviors of glucocorticoids by downregulating glucocorticoid receptor. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7579-90.

- Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, et al. Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Science. 2023;379:700-6.

- Parkes JD, Schachter M, Marsden CD, Smith B, Wilson A. Lisuride in parkinsonism. Ann Neurol. 1981;9:48-52.

- Verde G, Chiodini PG, Liuzzi A, Cozzi R, Favales F, Botalla L, et al. Effectiveness of the dopamine agonist lisuride in the treatment of acromegaly and pathological hyperprolactinemic states. J Endocrinol Invest. 1980;3:405-14.

- Halberstadt AL, Geyer MA. LSD but not lisuride disrupts prepulse inhibition in rats by activating the 5-HT(2A) receptor. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208:179-89.

- Schmidt LG, Kuhn S, Smolka M, Schmidt K, Rommelspacher H. Lisuride, a dopamine D2 receptor agonist, and anticraving drug expectancy as modifiers of relapse in alcohol dependence. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:209-17.

- Rickli A, Moning OD, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive tryptamines compared with classic hallucinogens. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:1327-37.

- Vollenweider FX, Vontobel P, Hell D, Leenders KL. 5-HT modulation of dopamine release in basal ganglia in psilocybin-induced psychosis in man-a PET study with [11C]raclopride. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:424-33.

- Madsen MK, Fisher PM, Burmester D, Dyssegaard A, Stenbaek DS, Kristiansen S, et al. Psychedelic effects of psilocybin correlate with serotonin 2 A receptor occupancy and plasma psilocin levels. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1328-34.

- Pedzich BD, Rubens S, Sekssaoui M, Pierre A, Van Schuerbeek A, Marin P, et al. Effects of a psychedelic 5-HT2A receptor agonist on anxiety-related behavior and fear processing in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47:1304-14.

- de la Fuente Revenga M, Zhu B, Guevara CA, Naler LB, Saunders JM, Zhou Z, et al. Prolonged epigenomic and synaptic plasticity alterations following single exposure to a psychedelic in mice. Cell Rep. 2021;37:109836.

- Desouza LA, Benekareddy M, Fanibunda SE, Mohammad F, Janakiraman B, Ghai U, et al. The hallucinogenic serotonin(2 A) receptor agonist, 2,5-Dimethoxy-4lodoamphetamine, promotes cAMP response element binding protein-dependent gene expression of specific plasticity-associated genes in the rodent neocortex. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021;14:790213.

- Barre A, Berthoux C, De Bundel D, Valjent E, Bockaert J, Marin P, et al. Presynaptic serotonin 2 A receptors modulate thalamocortical plasticity and associative learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1382-1391.

- Berthoux C, Barre A, Bockaert J, Marin P, Becamel C. Sustained activation of postsynaptic 5-HT2A receptors gates plasticity at prefrontal cortex synapses. Cereb Cortex. 2019;29:1659-69.

- Slifirski G, Krol M, Turlo J. 5-HT receptors and the development of new antidepressants. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9015.

- Kuypers KP, Ng L, Erritzoe D, Knudsen GM, Nichols CD, Nichols DE, et al. Microdosing psychedelics: More questions than answers? An overview and suggestions for future research. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33:1039-57.

- Cao D, Yu J, Wang H, Luo Z, Liu X, He L, et al. Structure-based discovery of nonhallucinogenic psychedelic analogs. Science. 2022;375:403-11.

- Kaplan AL, Confair DN, Kim K, Barros-Alvarez X, Rodriguiz RM, Yang Y, et al. Bespoke library docking for 5-HT(2A) receptor agonists with antidepressant activity. Nature. 2022;610:582-91.

- Dong C, Ly C, Dunlap LE, Vargas MV, Sun J, Hwang IW, et al. Psychedelic-inspired drug discovery using an engineered biosensor. Cell. 2021;184:2779-2792.e2718.

- Qu Y, Chang L, Ma L, Wan X, Hashimoto K. Rapid antidepressant-like effect of non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analog lisuride, but not hallucinogenic psychedelic DOI, in lipopolysaccharide-treated mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2023;222:173500.

- Pogorelov VM, Rodriguiz RM, Roth BL, Wetsel WC. The G protein biased serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonist lisuride exerts anti-depressant drug-like activities in mice. Front Mol Biosci. 2023;10:1233743.

- Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:563-7.

- Rosenblat JD, Leon-Carlyle M, Ali S, Husain MI, McIntyre RS. Antidepressant effects of psilocybin in the absence of psychedelic effects. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:395-6.

- Yaden DB, Griffiths RR. The subjective effects of psychedelics are necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:568-72.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

grants from CNRS, INSERM, University of Montpellier. MS was a recipient of a Ph.D. fellowship from the French Government Ministry of Higher Education and Research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

COMPETING INTERESTS

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Reprints and permission information is available at http://www.nature.com/ reprints

© The Author(s) 2024

Institut de Génomique Fonctionnelle, Université de Montpellier, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, F-34094 Montpellier, France. These authors contributed equally: Philippe Marin, Carine Bécamel. email: carine.becamel@igf.cnrs.fr