DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43994-024-00177-3

تاريخ النشر: 2024-07-11

تأمين مستقبل مستدام: تهديد تغير المناخ للزراعة، والأمن الغذائي، وأهداف التنمية المستدامة

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

الملخص

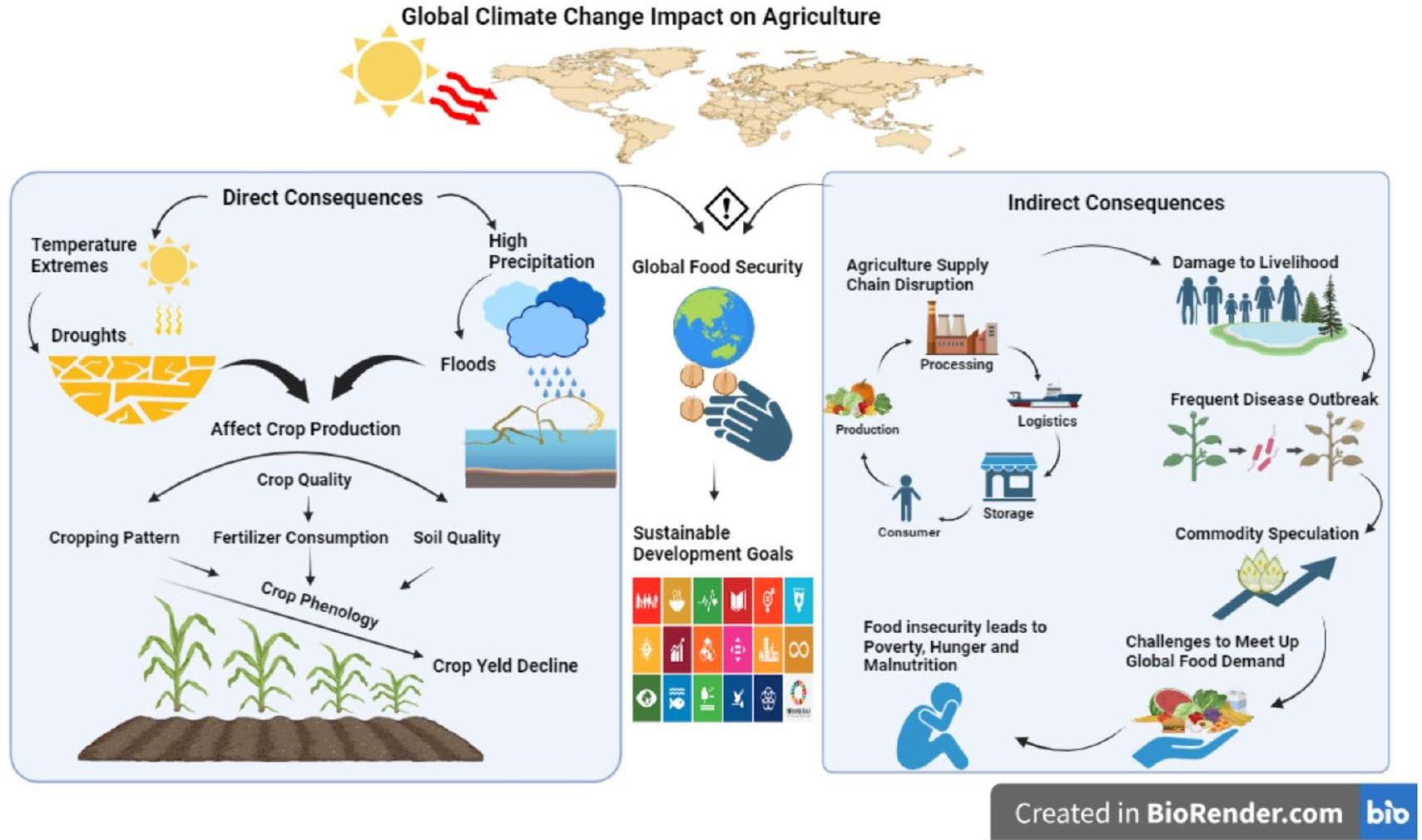

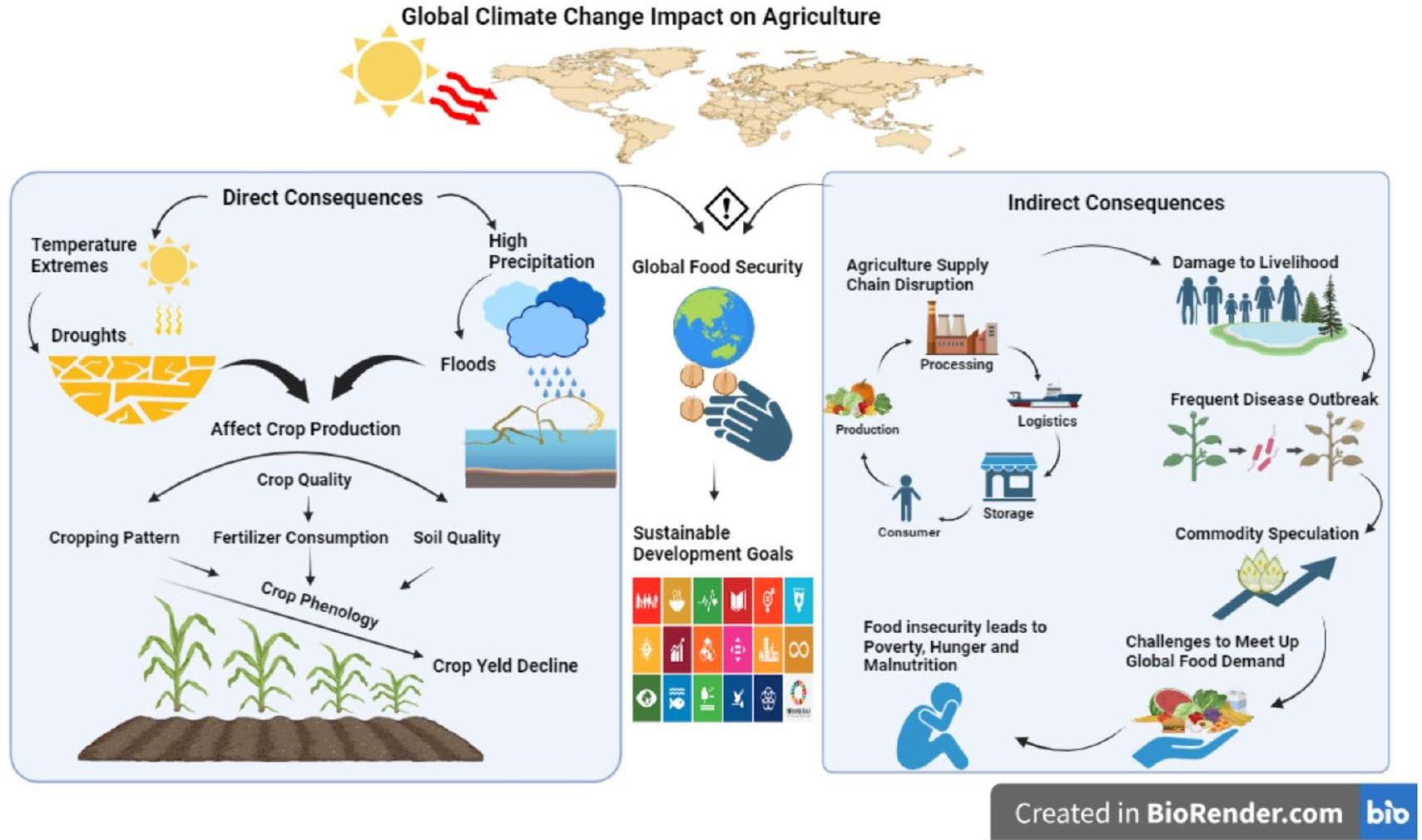

يشكل تغيير المناخ تهديدًا مستمرًا للأمن الغذائي ونظام إنتاج الزراعة. يواجه قطاع الزراعة تحديات شديدة في تحقيق أهداف التنمية المستدامة بسبب الآثار المباشرة وغير المباشرة التي تفرضها التغيرات المناخية المستمرة. على الرغم من أن العديد من الصناعات تواجه تحدي تغير المناخ، إلا أن تأثيره على صناعة الزراعة كبير. لقد أثارت التغيرات المناخية غير المنطقية مخاوف عامة ملحة، حيث أن الإنتاج الكافي والإمدادات الغذائية تحت تهديد مستمر. يتعرض نظام إنتاج الغذاء لتهديد سلبي بسبب تغير الأنماط المناخية مما يزيد من خطر الفقر الغذائي. وقد أدى ذلك إلى حالة مقلقة بشأن أنماط الأكل العالمية، لا سيما في البلدان التي تلعب فيها الزراعة دورًا كبيرًا في اقتصاداتها ومستويات إنتاجيتها. يركز هذا الاستعراض على العواقب المتدهورة لتغيير المناخ مع التأكيد الأساسي على قطاع الزراعة وكيف تؤثر الأنماط المناخية المتغيرة على الأمن الغذائي بشكل مباشر أو غير مباشر. لقد وضعت التحولات المناخية والتغير الناتج في نطاقات درجات الحرارة بقاء وصلاحية العديد من الأنواع في خطر، مما زاد من فقدان التنوع البيولوجي من خلال تقلب الهياكل البيئية بشكل متزايد. تؤدي التأثيرات غير المباشرة لتغير المناخ إلى انخفاض جودة الغذاء وارتفاع تكاليفه بالإضافة إلى أنظمة توزيع الغذاء غير الكافية. يبرز الجزء الختامي من الاستعراض التركيز على تنفيذ السياسات الهادفة إلى التخفيف من آثار تغير المناخ، على المستويين الإقليمي والعالمي. تم جمع بيانات هذه الدراسة من منظمات بحثية مختلفة، وصحف، وأوراق سياسات، ومصادر أخرى لمساعدة القراء في فهم القضية. كما تم تحليل تنفيذ السياسات الذي أظهر أن انخراط الحكومة أمر لا غنى عنه للتقدم على المدى الطويل للأمة، لأنه سيضمن المساءلة الصارمة عن الأدوات واللوائح التي تم تنفيذها سابقًا لإنشاء سياسة مناخية متطورة. لذلك، من الضروري تقليل أو التكيف مع آثار تغير المناخ لأنه، لضمان البقاء العالمي، يتطلب معالجة هذه المخاطر العالمية التزامًا جماعيًا عالميًا للتخفيف من عواقبها الوخيمة.

1 تغير المناخ – النظرة العالمية

1.1 تغير المناخ – تهديد مقلق للزراعة

2 العواقب المباشرة لتغير المناخ على الزراعة

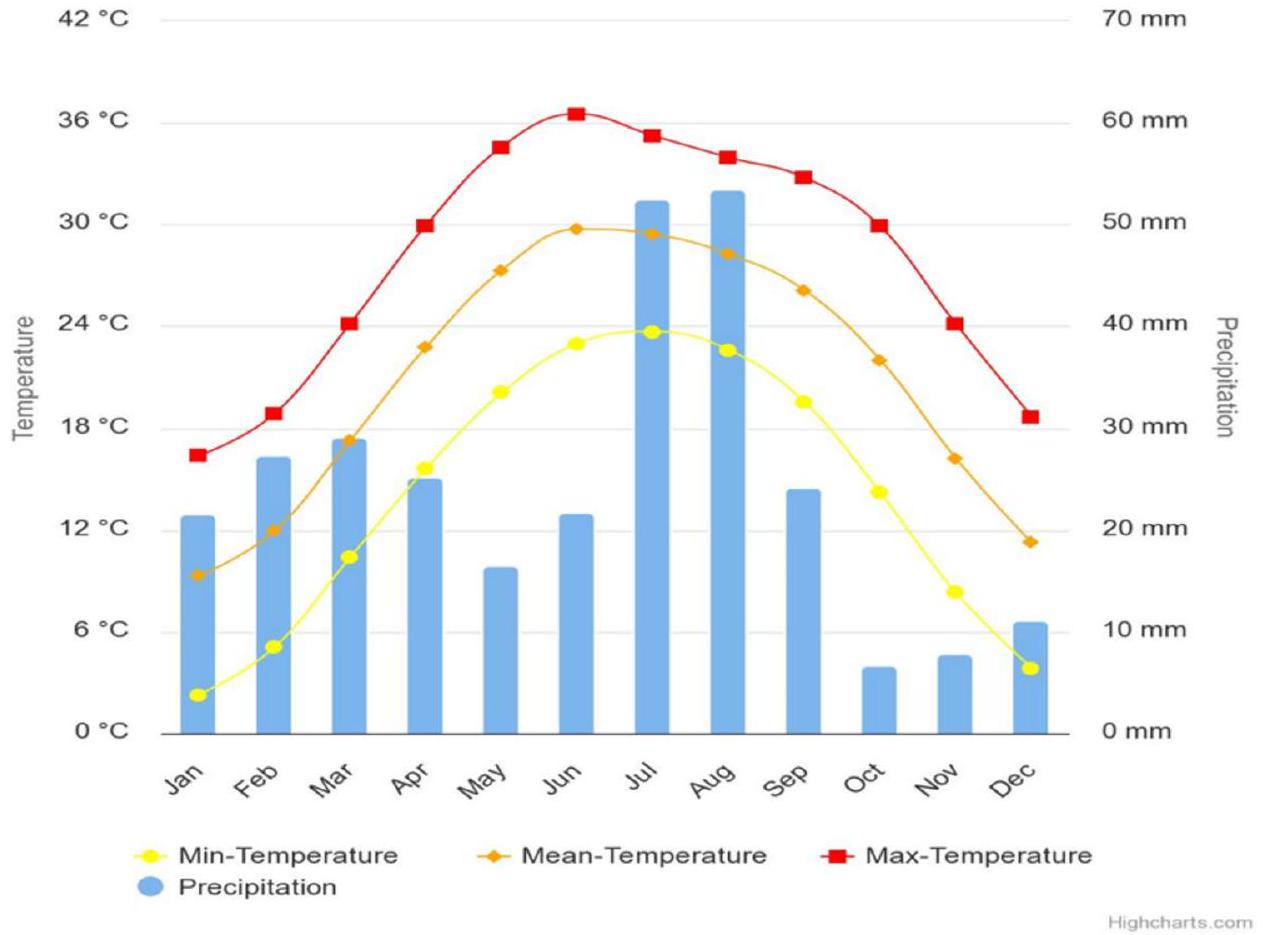

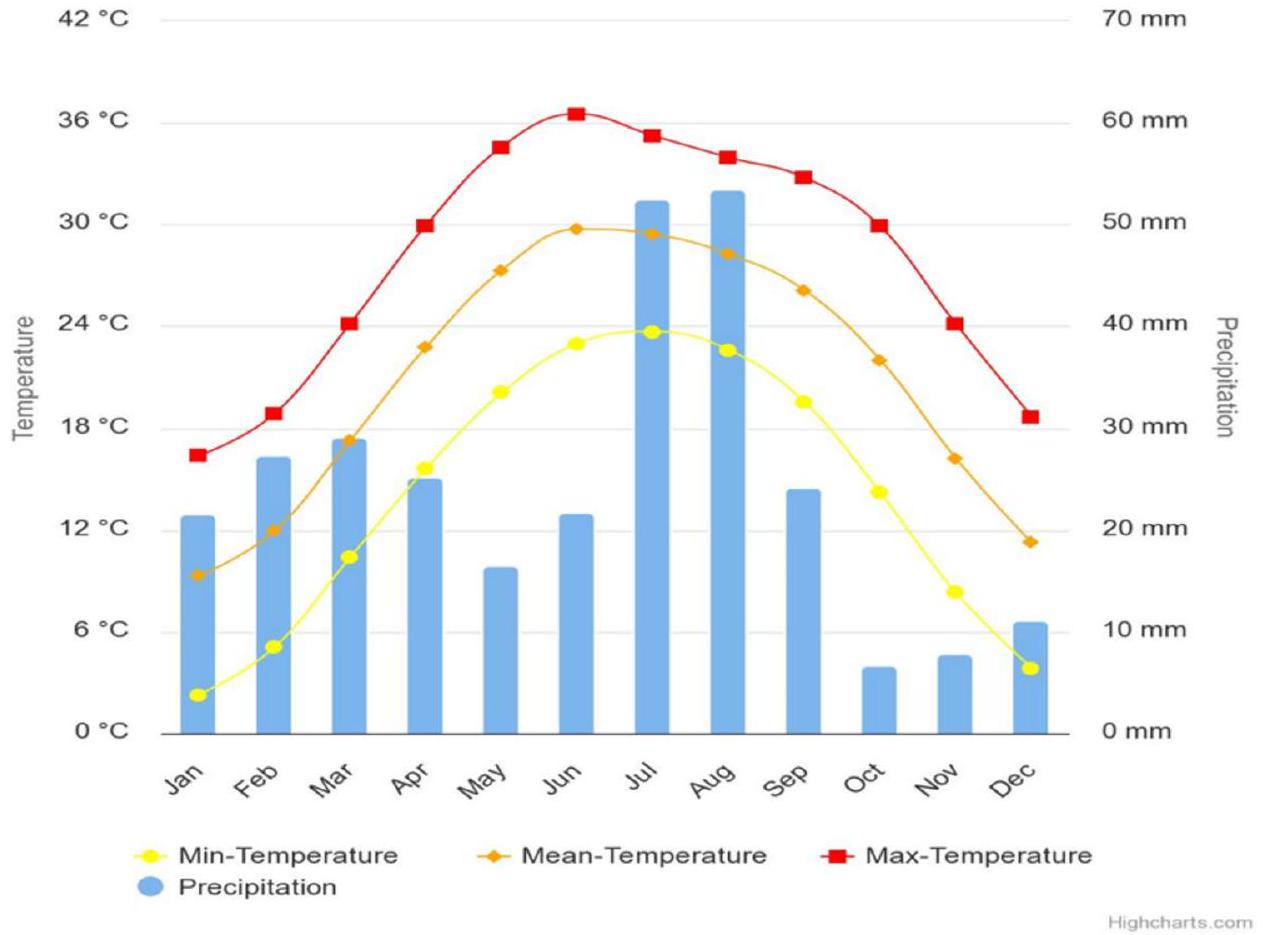

2.1 تغييرات درجة الحرارة

ارتفاع في درجة الحرارة، مما له عواقب سلبية مثل ذوبان الأنهار الجليدية. من الضروري تقليل انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة لمنع درجة حرارة الأرض من تجاوز

2.2 تغييرات الهطول

تتعرض العديد من الدول [103]. سكان المناطق الريفية، وخاصة في الدول النامية، غالبًا ما يكونون عرضة للفيضانات لأن لديهم موارد أقل وقدرة تكيف أقل [90]. التغيرات البيئية والمناخية هي المسؤولة بشكل أساسي عن شدة وكثافة كوارث الفيضانات [61، 62]. إن التعرف بشكل غير دقيق على كيفية تأثير الظروف المناخية المختلفة على الأنظمة الزراعية لن يؤدي فقط إلى إلحاق الضرر بالإنتاج الغذائي والسلامة، بل سيعيق أيضًا الجهود الرامية إلى تعزيز التنمية المستدامة والقضاء على الفقر [52]. يمكن أن تتسبب التغيرات الجذرية في أنماط هطول الأمطار في أضرار للبنية التحتية وفقدان زراعي. لقد تسببت الجفاف في انخفاض الإنتاجية الزراعية والأمن الغذائي في العديد من المناطق، بينما أدت الأمطار غير العادية إلى تدهور المحاصيل الناضجة. أظهرت دراسة حديثة في إثيوبيا أن انخفاض غلات الذرة والتيف كان نتيجة لزيادة تقلبات هطول الأمطار [105]. وبالمثل، أدى انخفاض هطول الأمطار في منطقة جنوب الصحراء الأفريقية إلى انخفاض إنتاجية الذرة، حيث أدى انخفاض هطول الأمطار إلى تقليل غلات محصول الذرة، الذي يعد الغذاء الأساسي في المنطقة [20]. من بين أهم آثار التغير المناخي العالمي في باكستان هو زيادة تكرار الفيضانات وشدتها. وفقًا لتقرير صادر عن البنك الدولي، تحتل باكستان مرتبة بين الدول الأكثر عرضة للفيضانات على مستوى العالم [13]. في عام 2022، شهدت البلاد عدة فيضانات كبيرة كانت الأسوأ في تاريخ البلاد، مما تسبب في أضرار كبيرة للمحاصيل القائمة بما في ذلك القمح والأرز والدخن والدخن وقصب السكر والقطن، خاصة في مقاطعتي السند وبلوشستان [1]. هذه الأضرار في المحاصيل تسببت في

2.3 تغيير في جودة التربة واستهلاك الأسمدة

3 عواقب غير مباشرة لتغير المناخ الضار

3.1 انخفاض الإنتاج الزراعي: السياق العالمي مقابل المحلي

من القمح والأرز والذرة [118]. تتأثر المناطق الاستوائية بشكل أكبر بالتغيرات المناخية بشكل عام لأن المحاصيل في المناطق الاستوائية لديها درجات حرارة مثالية أعلى، وبالتالي فهي أكثر عرضة للإجهاد الناتج عن ارتفاع درجات الحرارة [69]. بالإضافة إلى درجة الحرارة وهطول الأمطار، تعتبر الرطوبة وسرعة الرياح متغيرات إضافية تؤثر على الإنتاجية الزراعية. لقد زادت شعبية تطبيق خوارزميات التعلم الآلي في أبحاث المحاصيل وأبحاث تغير المناخ. أظهر هان وآخرون [46] أنه عندما يتعلق الأمر بتقدير إنتاج القمح الشتوي في الصين، فإن نهج الغابة العشوائية يتفوق على كل من الانحدار باستخدام العمليات الغاوسية وآلة الدعم الناقل. وجد زهي وآخرون [123] أن المدخلات التكنولوجية حاسمة لإنتاج الصين من القمح والأرز والذرة باستخدام خوارزمية أشجار الانحدار المعززة. وقد وُجد أن العديد من نماذج المحاصيل تشير إلى أن المناخ يمثل بين 39 و

للفيضانات الكبيرة والجفاف المطول، وذلك أساسًا بسبب عدم انتظام موسم الرياح الموسمية وهطول الأمطار السنوي. وبالتالي، فإن الزراعة في باكستان، وأمن المياه، وأمن الفيضانات، وأمن الطاقة معرضة باستمرار للتغيرات المناخية [67]. علاوة على ذلك، فإن المحاصيل التي تشكل فقط

3.2 الاضطراب في سلسلة الإمداد

| المحاصيل | % تغيير | ||

| 2020 | 2050 | 2080 | |

| قمح | -3.3 | -11.0 | -27.0 |

| أرز | 0 | -0.8 | -19.0 |

| ذرة | -2.4 | -3.3 | -43.0 |

| المصدر: ماتي | تغير العالم | بنك المعرفة | |

| بوابة: | الزراعة | نموذج | |

| IIASA. | http://sdwebx.world | ||

| bank. org/climateportal/ index.cfm?page=country- | |||

3.3 تفشي الأمراض المتكررة

بزيادة مستويات ثاني أكسيد الكربون في الغلاف الجوي، وارتفاع درجات الحرارة، وتغير توفر المياه، وزيادة تكرار الأحداث المناخية المتطرفة. مع زيادة رطوبة الهواء، يصبح الفطر Sclerotinia sclerotiorum أكثر مرضية؛ حيث يصل نمو الأمراض في نباتات الخس إلى ذروته عندما تصل الرطوبة النسبية في الهواء إلى

3.4 ارتفاع أسعار الغذاء/المضاربة على السلع

3.5 المخاطر على سلامة وأمن الغذاء: تحدي تلبية الطلب العالمي على الغذاء

في عواقب أخرى لتغير المناخ، مثل زيادة تكرار الأحداث المناخية المتطرفة (مثل موجات الحرارة القوية، والفيضانات، والجفاف الشديد). يمكن أن يكون لهذه التأثيرات تأثير ضار على إنتاج المحاصيل وكذلك القطاعات الأخرى المعنية في إنتاج الغذاء، مما يؤدي إلى تقليل إمدادات الغذاء وزيادة انعدام الأمن الغذائي [71].

3.6 العواقب على أهداف التنمية المستدامة

ملاءمة الأراضي للزراعة حيث تشهد المناطق المرتفعة زيادة في إنتاج المحاصيل، بينما قد تشهد المناطق المنخفضة انخفاضًا في غلات المحاصيل [56]. المحاصيل الرئيسية الأخرى في باكستان بما في ذلك القطن والذرة وقصب السكر والبقوليات تعاني أيضًا مؤخرًا من معدلات نمو بطيئة ومشوهة للغاية [1]. جنبًا إلى جنب مع مشكلة انعدام الأمن الغذائي المتزايدة، فإن الأداء غير المنتظم لنمو مثل هذه المحاصيل المهمة يمكن أن يقلل ليس فقط من الدخل المحلي والوظائف ولكن أيضًا يؤثر سلبًا على أداء الأعمال الإنتاجية ذات الصلة.

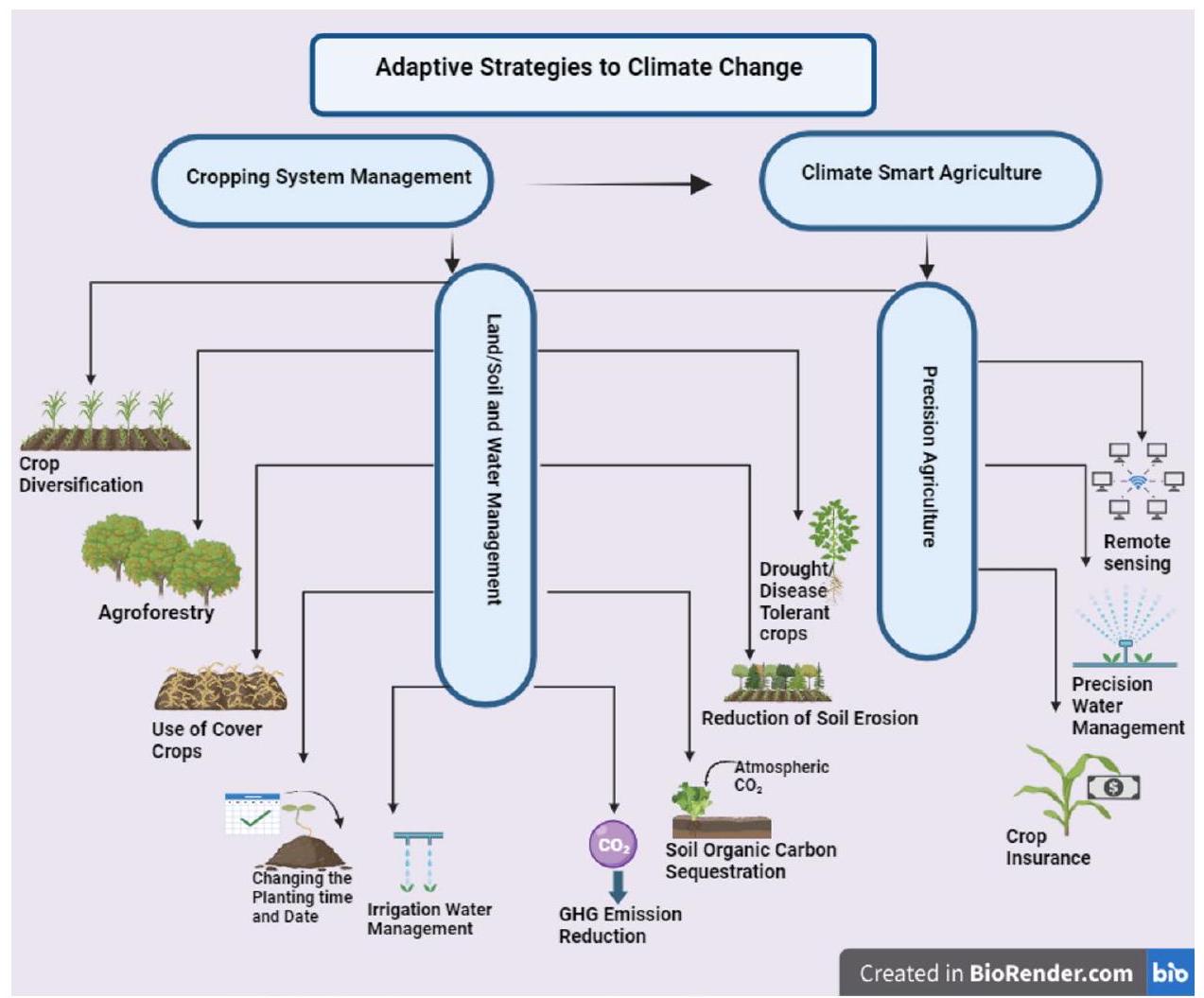

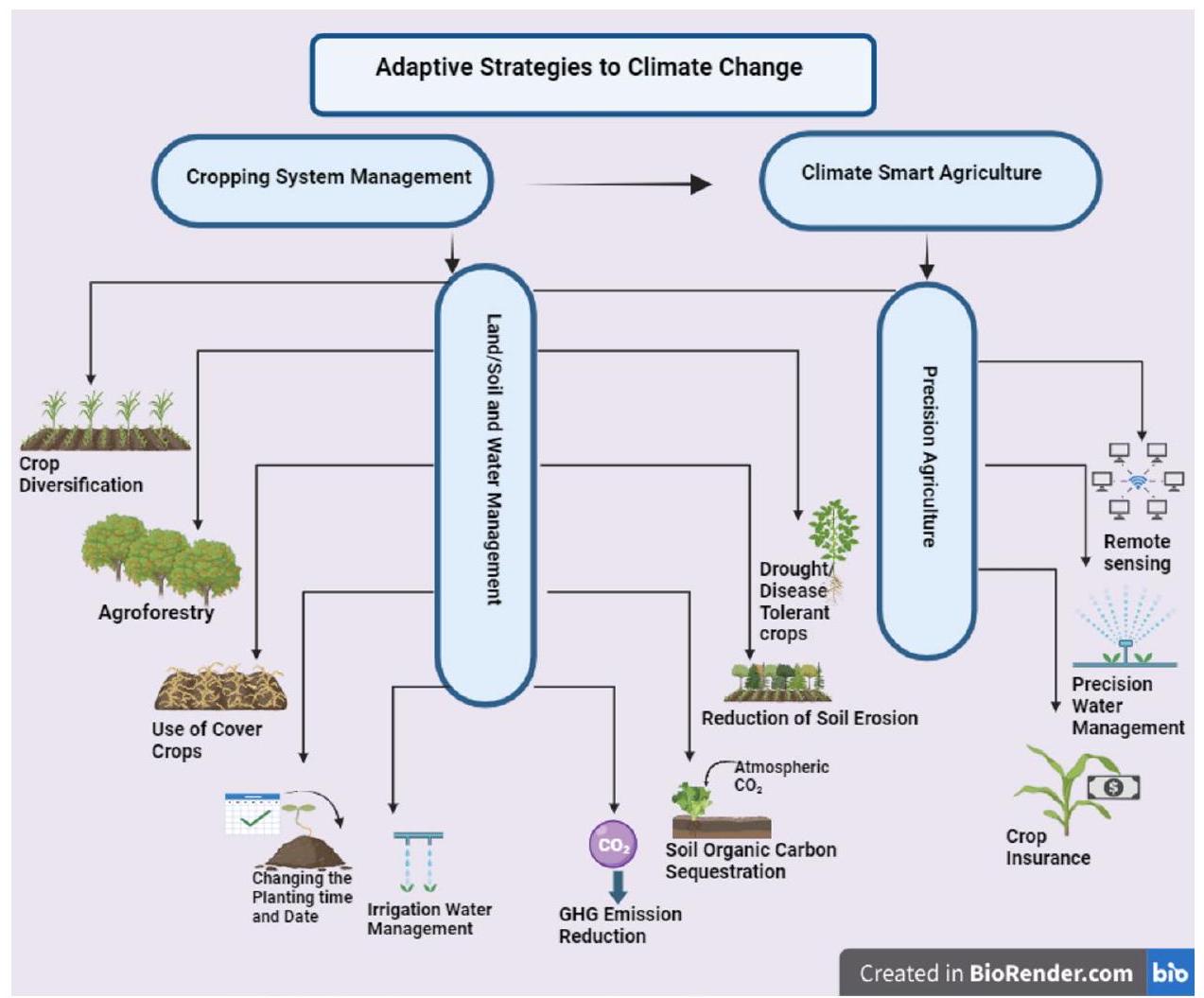

4 استراتيجيات التخفيف والتكيف المحتملة

4.1 إدارة الممارسات الزراعية

4.2 إدارة الأراضي/التربة والمياه

الحفاظ على خدمات النظام البيئي الإضافية وتعزيز المرونة أمام الصدمات كعناصر أساسية لتحقيق زيادة الإنتاجية. قد تشمل أساليب الزراعة المستدامة طرقًا متكاملة لإدارة الآفات وخصوبة التربة، واستخدام أفضل وأكثر كفاءة للمياه والمواد الغذائية. تم التعرف على إدارة التربة كواحدة من أهم الاستراتيجيات للتكيف مع تغير المناخ، حيث تحتوي التربة على جميع العناصر الغذائية اللازمة للنمو الزراعي [107]. أدت زيادة التباين في المناخ والظواهر الجوية القاسية مثل الأمطار الغزيرة والرياح القوية إلى تسريع تآكل التربة. لذلك، يجب اعتماد استراتيجيات إدارة فعالة لتقليل الاضطراب في التربة. في المناطق شبه الجافة، لمواجهة تآكل التربة الناتج عن الرياح، يتم استخدام زراعة الأشجار وإنشاء الحواجز؛ كما تستخدم المناطق الرطبة والساحلية بشكل متكرر تغطية النباتات، وتقلبات التربة، وحواجز الرياح. تساعد زراعة الحدائق على المدرجات وجمع المياه في المناطق الجبلية في السيطرة على تآكل التربة [30]. يمكن أن تتفاعل أنظمة الزراعة مع الإجهاد المائي، والمياه الزائدة الناتجة عن الأمطار غير المناسبة، ودرجات الحرارة القصوى من خلال التحول إلى الحد الأدنى من الحراثة مع الاحتفاظ بالمخلفات. كما أشار سابكوتا وآخرون [91]، يمكن زيادة إنتاجية مياه الري، مقارنة بالأنظمة الزراعية التقليدية من خلال

درجة الحرارة بواسطة

4.3 تنويع المحاصيل، تحسين نظام الزراعة

4.4 احتجاز الكربون العضوي في التربة (SOC)

4.5 الزراعة الذكية المناخية المحسّنة

تعتبر خدمات التأمين، وتحذيرات الطقس، وتسوية الأراضي بالليزر (LLL) من أكثر تقنيات الزراعة المستدامة استخدامًا. في المقابل، يفضل المزارعون في منطقة السهول الجانبية الغربية الزراعة المباشرة، وتسوية الأراضي بالليزر، والزراعة بدون حراثة، وتزامن الري مع تأمين المحاصيل.

4.6 تطوير أصناف مقاومة

4.7 الاستشعار عن بُعد وتصوير الأقمار الصناعية للتنبؤ بالمستقبل للأنظمة البيئية المعرضة للخطر

كما أن جودة المياه الجوفية. علاوة على ذلك، تم اكتشاف أن المناطق المتأثرة بالصقيع تزداد مع درجة حرارة السطح، والتبخر، ونسبة السحب، والارتفاع، والانحدار، والاتجاه. تم توقع خريطة استخدام الأراضي/غطاء الأرض والتغيرات المرتبطة بها باستخدام نموذج الخلايا الآلية ماركوف (CA_Markov) على صور الأقمار الصناعية متعددة التواريخ من Sentinel 2A وLandsat Oli-8 وETM التي تم جمعها في 2017 و2013 و2003، على التوالي. علاوة على ذلك، تم دمج معادلة فقدان التربة العالمية المنقحة (RUSLE) في نظام نظم المعلومات الجغرافية لتقدير فقدان التربة ولتvisualize خطر التآكل لسنوات معينة. وقد أظهرت هذه التقنية فعاليتها في توقع التغيرات في استخدام الأراضي وتقدير حجم فقدان التربة بدقة في المستقبل. ومع ذلك، توفر الاستشعار عن بعد وتصوير الأقمار الصناعية بيانات قيمة لرصد وتحليل وتوقع تأثيرات تغير المناخ على الزراعة. تعزز هذه الأدوات فهمنا للتغيرات البيئية، وتساعد في اتخاذ القرارات، وتمكن من اتخاذ تدابير استباقية للحفاظ على توفر الغذاء وممارسات الزراعة الصديقة للبيئة في ظل تغير المناخ.

4.8 تأمين المحاصيل

مساحة 1.33 هكتار [92]. يتلقى المزارعون تعويضًا يصل إلى

5 تنفيذ السياسات على المستوى العالمي والإقليمي

بالوضع المحلي مقارنة بالمنظمات الخارجية. هناك حاجة ماسة لمعالجة التناقضات في التخطيط والسياسة الحكومية. لاحظت الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ [55] أن عدم كفاية المعرفة لتحفيز الاستجابات التكيفية هو من بين عدة ظواهر تتطلب الانتباه. الوضع في باكستان هو الأسوأ في هذا الصدد، وفقاً لـ IPCC [55]، الذي استنتج أن تنفيذ السياسات كان مقيداً نسبياً ويواجه صعوبات متنوعة. للتعامل مع الآثار الدقيقة لتغير المناخ، تتطلب مختلف القطاعات تطوير خطط شاملة ومتعددة الأبعاد على الفور [55].

6 آفاق المستقبل

توفر البيانات: جميع البيانات التي تم إنشاؤها أو تحليلها خلال هذه الدراسة مدرجة في هذه المقالة المنشورة.

الإقرارات

الموافقة الأخلاقية: غير قابلة للتطبيق.

الموافقة على النشر: غير قابلة للتطبيق.

References

- Abbas S (2022) Climate change and major crop production: evidence from Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(4):5406-5414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16041-4

- Abbass K, Qasim MZ, Song H, Murshed M, Mahmood H, Younis I (2022) A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(28):42539-42559

- Adnan M, Khan MA, Basir A, Fahad S, Nasar J, Imran, Alharbi S, Ghoneim AM, Yu G-H, Saleem MH (2023) Biochar as soil amendment for mitigating nutrients stress in crops. Sustainable agriculture reviews 61: biochar to improve crop production and decrease plant stress under a changing climate. Springer, Cham, pp 123-140

- Ahmed I, Ullah A, ur Rahman MH, Ahmad B, Wajid SA, Ahmad A, Ahmed S (2019) Climate change impacts and adaptation strategies for agronomic crops. In: Climate change and agriculture. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/INTECHOPEN. 82697

- Ahmed M, Suphachalasai S (2014) Assessing the costs of climate change and adaptation in South Asia. Asian Development Bank, Mandaluyong

- Ali A, Rahut DB (2020) Localized floods, poverty and food security : empirical evidence from rural Pakistan. Hydrology 7(1):1-15

- Anwar A, Younis M, Ullah I (2020) Impact of urbanization and economic growth on CO2 emission: a case of far east Asian countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(7):2531

- Arifeen M (2017) Effective execution of crop insurance policy required. Pakistan and Gulf Economist

- Aryal JP, Sapkota TB, Khurana R, Khatri-Chhetri A, Rahut DB, Jat ML (2020) Climate change and agriculture in South Asia: adaptation options in smallholder production systems. Environ Dev Sustain 22(6):5045-5075

- Asghar AJ, Cheema AM, Hameed MI, Qasim S (2021) The critical junction between CPEC, agriculture and climate

change. LUMS Centre for Chinese Studies. Retrieved from https://ccls.lums.edu.pk/sites/default/files/2023-01/the_criti cal_junction_between_cpec_agriculture_and_climate_change. pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2022 - Azani N, Ghaffar MA, Suhaimi H, Azra MN, Hassan MM, Jung LH, Rasdi NW (2021) The impacts of climate change on plankton as live food: a review. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 869(1):012005

- Bandara JS, Cai Y (2014) The impact of climate change on food crop productivity, food prices and food security in South Asia. Econ Anal Policy 44(4):451-465

- Bank, T. W. (2022). Pakistan: Flood damages and economic losses over USD 30 billion and reconstruction needs over USD 16 billion – New assessment.

- Bawazeer S, Rauf A, Nawaz T, Khalil AA, Javed MS, Muhammad N, Shah MA (2021) Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities. Green Process Synth 10(1):882-892

- Biber-Freudenberger L, Ziemacki J, Tonnang HE, Borgemeister C (2016) Future risks of pest species under changing climatic conditions. PLoS ONE 11(4):e0153237

- Bradshaw C, Eyre D, Korycinska A, Li C, Steynor A, Kriticos D (2024) Climate change in pest risk assessment: interpretation and communication of uncertainties. EPPO Bull 54:4-19. https:// doi.org/10.1111/epp. 12985

- Brempong MB, Amankwaa-Yeboah P, Yeboah S, Owusu Danquah E, Agyeman K, Keteku AK, Addo-Danso A, Adomako J (2023) Soil and water conservation measures to adapt cropping systems to climate change facilitated water stresses in Africa. Front Sustain Food Syst. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022. 1091665

- Cell CC (2009) Crop insurance as a risk management strategy in Bangladesh. Ministry of Environment and Forests. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Department of Environment, Dhaka

- Chaloner T, Gurr S, Bebber D (2021) Plant pathogen infection risk tracks global crop yields under climate change. Nat Clim Change 11(8):710-715

- Chapman S, Birch CE, Pope E, Sallu S, Bradshaw C, Davie J, Marsham JH (2020) Impact of climate change on crop suitability in sub-Saharan Africa in parameterized and convection-permitting regional climate models. Environ Res Lett. https://doi.org/ 10.1088/1748-9326/ab9daf

- Chaudhry QUZ (2017) Climate change profile of Pakistan. Asian Development Bank

- Chaudhry S, Sidhu GPS (2022) Climate change regulated abiotic stress mechanisms in plants: a comprehensive review. Plant Cell Rep 41(1):1-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-021-02759-5

- Chen C, Ota N, Wang B, Fu G, Fletcher A (2023) Adaptation to climate change through strategic integration of long fallow into cropping system in a dryland Mediterranean-type environment. Sci Total Environ 880:163230

- Chivenge P, Mabhaudhi T, Modi AT, Mafongoya P (2015) The potential role of neglected and underutilised crop species as future crops under water scarce conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(6):5685-5711

- Cradock-Henry NA, Blackett P, Hall M, Johnstone P, Teixeira E, Wreford A (2020) Climate adaptation pathways for agriculture: insights from a participatory process. Environ Sci Policy 107:66-79

- Davidson DJ (2018) Rethinking adaptation: emotions, evolution, and climate change. Nat Cult 13(3):378-402

- Dawood MF, Moursi YS, Abdelrhim AS, Hassan AA (2024) Investigation of ecology, molecular, and host-pathogen interaction of rice blast pathogen and management approaches.

28. Dembedza VP, Chopera P, Mapara J, Macheka L (2022) Impact of climate change-induced natural disasters on intangible cultural heritage related to food: a review. J Ethn Foods 9(1):32

29. Deutsch CA, Tewksbury JJ, Tigchelaar M, Battisti DS, Merrill SC, Huey RB, Naylor RL (2018) Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science 361(6405):916-919

30. Dmuchowski W, Baczewska-d AH, Gworek B (2024) The role of temperate agroforestry in mitigating climate change: a review. For Policy Econ 159(August 2023):103136. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2023.103136

31. Eckardt NA, Ainsworth EA, Bahuguna RN, Broadley MR, Busch W, Carpita NC, Castrillo G, Chory J, Dehaan LR, Duarte CM, Henry A, Jagadish SVK, Langdale JA, Leakey ADB, Liao JC, Lu KJ, McCann MC, McKay JK, Odeny DA et al (2023) Climate change challenges, plant science solutions. Plant Cell 35(1):24-66. https://doi.org/10.1093/plcel1/koac303

32. El Jazouli A, Barakat A, Khellouk R, Rais J, El Baghdadi M (2019) Remote sensing and GIS techniques for prediction of land use land cover change effects on soil erosion in the high basin of the Oum Er Rbia River (Morocco). Remote Sens Appl Soc Environ 13:361-374

33. Elahi E, Khalid Z, Tauni MZ, Zhang H, Lirong X (2022) Extreme weather events risk to crop-production and the adaptation of innovative management strategies to mitigate the risk: a retrospective survey of rural Punjab, Pakistan. Technovation 117:102255. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TECHNOVATION. 2021.102255

34. Elbasiouny H, El-Ramady H, Elbehiry F, Rajput VD, Minkina T, Mandzhieva S (2022) Plant nutrition under climate change and soil carbon sequestration. Sustainability 14(2):914. https:// doi.org/10.3390/SU14020914

35. Fahad S, Adnan M, Zhou R, Nawaz T, Saud S (2024) Biocharassisted remediation of contaminated soils under changing climate. Elsevier, Amsterdam

36. FAO (2021) FAO. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#rankings/ countries_by_commodity

37. Farooq MS, Uzaiir M, Raza A, Habib M, Xu Y, Yousuf M, Ramzan Khan M (2022) Uncovering the research gaps to alleviate the negative impacts of climate change on food security: a review. Front Plant Sci 13:2334

38. Galanakis CM (2023) The ‘vertigo’ of the food sector within the triangle of climate change, the post-pandemic world, and the Russian-Ukrainian war. Foods 12(4):721

39. Gasparini K, Rafael DD, Peres LEP, Ribeiro DM, Zsögön A (2024) Agriculture and food security in the era of climate change. Digital agriculture: a solution for sustainable food and nutritional security. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 47-58

40. Gbadeyan OJ, Muthivhi J, Linganiso LZ, Deenadayalu N (2024) Decoupling economic growth from carbon emissions: a transition towards low carbon energy systems-a critical review. https:// doi.org/10.20944/preprints202402.1085.v1

41. Godde CM, Mason-D’Croz D, Mayberry DE, Thornton PK, Herrero

42. Gojon A, Cassan O, Bach L, Lejay L, Martin A (2023) The decline of plant mineral nutrition under rising

43. GOP (2016) BAEF Climate Change Adaptation Report-II. Technology needs assessment fro climate change adaptation barrier analysis and enabling framework

44. Guja MM, Bedeke SB (2024) Smallholders’ climate change adaptation strategies: exploring effectiveness and opportunities

to be capitalized. Environ Dev Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10668-024-04750-y

45. Gupta J, Roy D, Thakur IS, Kumar M (2022) Environmental DNA insights in search of novel genes/taxa for production of biofuels and biomaterials. Biomass Biofuels Biochem. https:// doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823500-3.00015-7

46. Han J, Zhang Z, Cao J, Luo Y, Zhang L, Li Z, Zhang J (2020) Prediction of winter wheat yield based on multi-source data and machine learning in China. Remote Sens 12(2):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12020236

47. Hanif S, Hayat MK, Zaheer M, Raza H, Ain QU (2024) Cornous biology impact of climate change on agriculture production and strategies to overcome. May. https://doi.org/10. 37446/corbio/ra/2.2.2024.1-7

48. Haq SU, Boz I, Shahbaz P (2021) Adoption of climate-smart agriculture practices and differentiated nutritional outcome among rural households: a case of Punjab province, Pakistan. Food Secur 13:913-931

49. Hassan MA, Xiang C, Farooq M, Muhammad N, Yan Z, Hui X, Yuanyuan K, Bruno AK, Lele Z, Jincai L (2021) Cold stress in wheat: plant acclimation responses and management strategies. Front Plant Sci 12:1234. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPLS.2021. 676884/BIBTEX

50. Hegerl GC, Brönnimann S, Cowan T, Friedman AR, Hawkins E, Iles C, Müller W, Schurer A, Undorf S (2019) Causes of climate change over the historical record. Environ Res Lett 14(12):123006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab4557

51. Higgens RF, Pries CH, Virginia RA (2021) Trade-offs between wood and leaf production in Arctic shrubs along a temperature and moisture gradient in West Greenland. Ecosystems 24(3):652-666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-020-00541-4

52. Huong NTL, Yao S, Fahad S (2018) Assessing household livelihood vulnerability to climate change: the case of Northwest Vietnam. Hum Ecol Risk Assess Int J 25(5):1157-1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/10807039.2018.1460801

53. Hussain M, Butt AR, Uzma F, Ahmed R, Irshad S, Rehman A, Yousaf B (2020) A comprehensive review of climate change impacts, adaptation, and mitigation on environmental and natural calamities in Pakistan. Environ Monit Assess 192(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-019-7956-4

54. Lee H., Calvin K, Dasgupta D, Krinmer G, Mukherji A, Thorne P, Zommers Z (2023). Synthesis report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), Longer report. IPCC.

55. IPCC (2021) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Summary for policymakers. In: Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth. Assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

56. IPCC (2023) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: synthesis report (SYR) of the IPCC sixth assessment report (AR6). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (Panmao Zhai)

57. Islam MM, Ahamed T, Matsushita S, Noguchi R (2024) A damage-based crop insurance system for flash flooding: a satellite remote sensing and econometric approach. Climate change perspective in agriculture in remote sensing application II. Springer Nature, Singapore, pp 121-163

58. Jatav HS, Rajput VD, Minkina T, Van Hullebusch ED, Dutta A (2024) Agroforestry to combat global challenges (issue March). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-981-99-7282-1

59. Karimi V, Karami E, Keshavarz M (2018) Climate change and agriculture: Impacts and adaptive responses in Iran. J Integr Agric 17(1):1-15

60. Kazemi Garajeh M, Salmani B, Zare Naghadehi S, Valipoori Goodarzi H, Khasraei A (2023) An integrated approach of

remote sensing and geospatial analysis for modeling and predicting the impacts of climate change on food security. Sci Rep 13(1):1057

61. Khan I, Lei H, Shah AA, Khan I, Muhammad I (2021) Climate change impact assessment, flood management, and mitigation strategies in Pakistan for sustainable future. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28(23):29720-29731. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11356-021-12801-4/FIGURES/7

62. Khan N, Jhariya MK, Raj A, Banerjee A, Meena RS (2021) Soil carbon stock and sequestration: implications for climate change adaptation and mitigation. Ecological intensification of natural resources for sustainable agriculture. Springer, Singapore, pp 461-489. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4203-3_ 13/COVER

63. Khangura R, Ferris D, Wagg C, Bowyer J (2023) Regenerative agriculture-a literature review on the practices and mechanisms used to improve soil health. Sustainability (Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032338

64. Korres NE, Norsworthy JK, Tehranchian P, Gitsopoulos TK, Loka DA, Oosterhuis DM, Palhano M (2016) Cultivars to face climate change effects on crops and weeds: a review. Agron Sustain Dev 36:1-22

65. Kubik Z, Mirzabaev A, May J (2023) Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics (issue January). In: Zimmermann KF (ed). Springer Nature, Cham. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-3-319-57365-6

66. Kumar L, Chhogyel N, Gopalakrishnan T, Hasan MK, Jayasinghe SL, Kariyawasam CS, Kogo BK, Ratnayake S (2022) Climate change and future of agri-food production. Future foods: global trends, opportunities, and sustainability challenges. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 49-79. https://doi.org/10. 1016/B978-0-323-91001-9.00009-8

67. Lodhi S, Ayyubi MS, Hayat S, Iqbal Z (2024) Unravelling the effects of climate change on agriculture of pakistan: an exploratory analysis. Qlantic J Soc Sci 5(2):142-158. https:// doi.org/10.55737/qjss. 791319404

68. Magesa BA, Mohan G, Matsuda H, Melts I, Kefi M, Fukushi K (2023) Understanding the farmers’ choices and adoption of adaptation strategies, and plans to climate change impact in Africa: a systematic review. Climate Services 30(October 2022):100362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2023.100362

69. Malhi GS, Kaur M, Kaushik P (2021) Impact of climate change on agriculture and its mitigation strategies: a review. Sustainability (Switzerland) 13(3):1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su130 31318

70. McClelland SC, Paustian K, Schipanski ME (2021) Management of cover crops in temperate climates influences soil organic carbon stocks: a meta-analysis. Ecol Appl 31(3):e02278

71. Mirón IJ, Linares C, Díaz J (2023) The influence of climate change on food production and food safety. Environ Res 216:114674

72. Mottaleb KA, Rejesus RM, Murty MVR, Mohanty S, Li T (2017) Benefits of the development and dissemination of cli-mate-smart rice: ex ante impact assessment of drought-tolerant rice in South Asia. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change 22:879-901

73. Murthy CS, Choudhary KK, Pandey V, Srikanth P, Ramasubramanian S, Kumar GS, Nemani R (2024) Transformative crop insurance solution with big earth data: Implementation for potato crops in India. Clim Risk Manag. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.crm.2024.100622

74. Northrup DL, Basso B, Wang MQ, Morgan CL, Benfey PN (2021). Novel technologies for emission reduction complement conservation agriculture to achieve negative emissions from row-crop production. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(28):e2022666118

75. Nawaz T, Gu L, Fahad S, Saud S, Bleakley B, Zhou R (2024) Exploring sustainable agriculture with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria and nanotechnology. Molecules 29(11):2534

76. Nawaz T, Gu L, Fahad S, Saud S, Harrison MT, Zhou R (2024) Sustainable protein production through genetic engineering of cyanobacteria and use of atmospheric

77. Nawaz T, Gu L, Fahad S, Saud S, Hassan S, Harrison MT, Liu K, Zhou R (2024) Unveiling the antioxidant capacity of fermented foods and food microorganisms: a focus on cyanobacteria. J Umm Al-Qura Univ Appl Sci 10(1):232-243

78. Nawaz T, Saud S, Gu L, Khan I, Fahad S, Zhou R (2024) Cyanobacteria: harnessing the power of microorganisms for plant growth promotion, stress alleviation, and phytoremediation in the era of sustainable agriculture. Plant Stress 11:100399

79. Nawaz T, Gu L, Gibbons J, Hu Z, Zhou R (2024) Bridging nature and engineering: protein-derived materials for bio-inspired applications. Biomimetics 9(6):373

80. Nazir MJ, Li G, Nazir MM, Zulfiqar F, Siddique KHM, Iqbal B, Du D (2024) Harnessing soil carbon sequestration to address climate change challenges in agriculture. Soil Till Res 237(Novenber 2023):105959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2023.105959

81. Northrup DL, Basso B, Wang MQ, Morgan CL, Benfey PN (2021) Novel technologies for emission reduction complement conservation agriculture to achieve negative emissions from rowcrop production. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(28):e2022666118

82. Ogle SM, Alsaker C, Baldock J, Bernoux M, Breidt FJ, McConkey B, Vazquez-Amabile GG (2019) Climate and soil characteristics determine where no-till management can store carbon in soils and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Sci Rep 9(1):11665

83. Paustian K, Larson E, Kent J, Marx E, Swan A (2019) Soil C sequestration as a biological negative emission strategy. Front Clim. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2019.00008

84. Powlson DS, Stirling CM, Thierfelder C, White RP, Jat ML (2016) Does conservation agriculture deliver climate change mitigation through soil carbon sequestration in tropical agroecosystems? Agr Ecosyst Environ 220:164-174

85. Praveen B, Sharma P (2019) A review of literature on climate change and its impacts on agriculture productivity. J Public Aff 19(4):e1960. https://doi.org/10.1002/PA. 1960

86. Qamer FM, Ahmad B, Abbas S, Hussain A, Salman A, Muhammad S, Nawaz M, Shrestha S, Iqbal B, Thapa S (2022) The 2022 Pakistan floods Assessment of crop losses in Sindh Province. pp 1-24. https://doi.org/10.53055/ICIMOD. 1015

87. Quandt A, Grafton D, Gorman K, Dawson PM, Ibarra C, Mayes E, Paderes P (2023) Mitigation and adaptation to climate change in San Diego County, California. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change 28(1):7

88. Raihan A, Pavel MI, Muhtasim DA, Farhana S, Faruk O, Paul A (2023) The role of renewable energy use, technological innovation, and forest cover toward green development: Evidence from Indonesia. Innov Green Dev 2(1):100035. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/J.IGD.2023.100035

89. Raza A, Razzaq A, Mehmood SS, Zou X, Zhang X, Lv Y, Xu J (2019) Impact of climate change on crops adaptation and strategies to tackle its outcome: a review. Plants 8(2):34. https://doi. org/10.3390/plants8020034

90. Rehman A, Batool Z, Ma H, Alvarado R, Oláh J (2024) Climate change and food security in South Asia: the importance of renewable energy and agricultural credit. Human Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02847-3

91. Sapkota TB, Jat ML, Aryal JP, Jat RK, Khatri-Chhetri A (2015) Climate change adaptation, greenhouse gas mitigation and economic profitability of conservation agriculture: Some examples from cereal systems of Indo-Gangetic Plains. J Integr Agric 14(8):1524-1533

92. Shakya S, Gyawali, DR, Gurung JK, Regmi PP (2013) A trailblazer in adopting climate smart practices: one cooperative’s success story. https://ccafs.cgiar.org/es/blog/trailblazer-adopt ing-climate-smart-practices-one-cooperative%e2,80

93. Sheikh ZA, Ashraf S, Weesakul S, Ali M, Hanh NC (2024) Impact of climate change on farmers and adaptation strategies in Rangsit, Thailand. Environ Chall 15(December 2023):100902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2024.100902

94. Shivanna KR (2022) Climate change and its impact on biodiversity and human welfare. Proc Indian Natl Sci Acad 88(2):160171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43538-022-00073-6

95. Shrestha S (2019) Effects of climate change in agricultural insect pest. Acta Sci Agric 3:74-80

96. Siddiq A (2017) Climate change profile of Pakistan. https://doi. org/10.22617/TCS178761

97. Siyal GEA (2018). Farmers see room for improvement in crop loan insurance scheme. The Express Tribune, Pakistan. https:// tribune.com.pk/story/1657400/2-farmers-see-room-impro vement-croploan-insurance-scheme/

98. Sorgho R, Quiñonez CAM, Louis VR, Winkler V, Dambach P, Sauerborn R, Horstick O (2020) Climate change policies in 16 West African countries: a systematic review of adaptation with a focus on agriculture, food security, and nutrition. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(23):8897

99. Sturrock RN, Frankel SJ, Brown AV, Hennon PE, Kliejunas JT, Lewis KJ, Worrall JJ, Woods AJ (2011) Climate change and forest diseases. Plant Pathol 60:133-149

100. Suhaeb FW, Tamrin S (2024) Community adaptation strategies to climate change: towards sustainable social development. Migrat Lett 2:943-953

101. Sun H, Wang Y, Wang L (2024) Impact of climate change on wheat production in China. Eur J Agron 153:127066

102. Syed A, Raza T, Bhatti TT, Eash NS (2022) Climate Impacts on the agricultural sector of Pakistan: risks and solutions. Environ Chall 6:100433

103. Syldon P, Shrestha BB, Miyamoto M, Tamakawa K, Nakamura S (2024) Assessing the impact of climate change on flood inundation and agriculture in the Himalayan Mountainous Region of Bhutan. J Hydrol Region Stud 52:101687. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.ejrh.2024.101687

104. Szyniszewska AM, Akrivou A, Björklund N, Boberg J, Bradshaw C, Damus M, Gardi C, Hanea A, Kriticos J, Maggini R, Musolin DL (2024) Beyond the present: how climate change is relevant to pest risk analysis. EPPO Bull 54:20-37. https://doi.org/10.1111/ epp. 12986

105. Temesgen H, Wu W, Legesse A, Yirsaw E (2021) Modeling and prediction of effects of land use change in an agroforestry dominated southeastern Rift-Valley escarpment of Ethiopia. Remote Sens Appl Soc Environ 21:100469. https://doi.org/10.1016/J. RSASE.2021.100469

106. Tesfaye K, Zaidi PH, Gbegbelegbe S, Boeber C, Rahut DB, Getaneh F, Stirling C (2017) Climate change impacts and potential benefits of heat-tolerant maize in South Asia. Theor Appl Climatol 130:959-970

107. Timsina J (2024) Agriculture-livestock-forestry Nexus in Asia: Potential for improving farmers’ livelihoods and soil health, and adapting to and mitigating climate change. Agric Syst 218:104012

108. Tume SJP, Mairomi WH, Awazi NP (2024) Rainfall reliability and maize production in the Bamenda Highlands of Cameroon.

109. Uddin ME, Kebreab E (2020) Impact of food and climate change on pastoral industries. Fronti Sustain Food Syst 4:543403

110. UNCDD (2017) Global land outlook. UNCDD, Bonn

111. Yanagi M (2024) Climate change impacts on wheat production: Reviewing challenges and adaptation strategies. Adv Resour Res 4(1):89-107

112. Yin F, Sun Z, You L, Müller D (2024). Determinants of changes in harvested area and yields of major crops in China. Food Secur 16(2):339-351

113. Vinke K, Martin MA, Adams S, Baarsch F, Bondeau A, Coumou D, Svirejeva-Hopkins A (2017) Climatic risks and impacts in South Asia: extremes of water scarcity and excess. Reg Environ Change 17:1569-1583

114. Wang SW, Lee WK, Son Y (2017) An assessment of climate change impacts and adaptation in South Asian agriculture. Int J Clim Change Strateg Manag 9(4):517-534

115. Wieder WR, Sulman BN, Hartman MD, Koven CD, Bradford MA (2019) Arctic soil governs whether climate change drives global losses or gains in soil carbon. Geophys Res Lett 46(24):14486-14495. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085543

116. Xu X, Pei J, Xu Y, Wang J (2020) Soil organic carbon depletion in global Mollisols regions and restoration by management practices: a review. J Soils Sediments 20(3):1173-1181. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02557-3

117. Yanagi M (2024) Climate change impacts on wheat production: reviewing challenges and adaptation strategies. 4(1):89-107. https://doi.org/10.5098/arr.4.1

118. Yin F, Sun Z, You L, Müller D (2024) Determinants of changes in harvested area and yields of major crops in China. Food Secur 16(2):339-351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-023-01424-x

119. You Y, Ting M, Biasutti M (2024) Climate warming contributes to the record-shattering 2022 Pakistan rainfall. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00630-4

120. Yu L, Shi H, Wu H, Hu X, Ge Y, Yu L, Cao W (2024) The role of climate change perceptions in sustainable agricultural development: evidence from conservation tillage technology adoption in Northern China. Land 13(5):705. https://doi.org/10.3390/land1 3050705

121. Zheng B, Chen K, Li B, Li Y, Shi L, Fan H (2024) Climate change impacts on precipitation and water resources in Northwestern China. Front Environ Sci 12(April):1-12. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1377286

122. Zheng H, Ma W, He Q (2024) Climate-smart agricultural practices for enhanced farm productivity, income, resilience, and greenhouse gas mitigation: a comprehensive review. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11027-024-10124-6

123. Zhi J, Cao X, Zhang Z, Qin T, Qi L, Ge L, Fu X (2022) Identifying the determinants of crop yields in China since 1952 and its policy implications. Agric For Meteorol 327:109216

المؤلفون والانتماءات

أنام سليم

shah_fahad80@yahoo.com

شاه سعود

saudhort@gmail.com

أنام سليم

anam.saleem@live.com

صبية أنور

sobiaamalik9@gmail.com

توفيق نواز

taufiq.nawaz@jacks.sdstate.edu

تنزيل الرحمن

Tanzeel.htm13@gmail.com

محمد ناصر رشيد خان

nasirrasheed219@gmail.com

توكير نواز

nawaztouqir25@gmail.com

3 كلية العلوم الطبيعية، جامعة ولاية داكوتا الجنوبية، بروكينغز، SD 57007، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

4 قسم الزراعة، جامعة عبد الوالي خان، مردان، باكستان

8 قسم العلوم السياسية، جامعة عبد الوالي خان، مردان، باكستان

- معلومات المؤلفين الموسعة متاحة في الصفحة الأخيرة من المقالة

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43994-024-00177-3

Publication Date: 2024-07-11

Securing a sustainable future: the climate change threat to agriculture, food security, and sustainable development goals

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

Climate alteration poses a consistent threat to food security and agriculture production system. Agriculture sector encounters severe challenges in achieving the sustainable development goals due to direct and indirect effects inflicted by ongoing climate change. Although many industries are confronting the challenge of climate change, the impact on agricultural industry is huge. Irrational weather changes have raised imminent public concerns, as adequate output and food supplies are under a continuous threat. Food production system is negatively threatened by changing climatic patterns thereby increasing the risk of food poverty. It has led to a concerning state of affairs regarding global eating patterns, particularly in countries where agriculture plays a significant role in their economies and productivity levels. The focus of this review is on deteriorating consequences of climate alteration with the prime emphasis on agriculture sector and how the altering climatic patterns affect food security either directly or indirectly. Climate shifts and the resultant alteration in the temperature ranges have put the survival and validity of many species at risk, which has exaggerated biodiversity loss by progressively fluctuating the ecological structures. The indirect influence of climate variation results in poor quality and higher food costs as well as insufficient systems of food distribution. The concluding segment of the review underscores the emphasis on policy implementation aimed at mitigating the effects of climate change, both on a regional and global scale. The data of this study has been gathered from various research organizations, newspapers, policy papers, and other sources to aid readers in understanding the issue. The policy execution has also been analyzed which depicted that government engrossment is indispensable for the long-term progress of nation, because it will guarantee stringent accountability for the tools and regulations previously implemented to create state-of-the-art climate policy. Therefore, it is crucial to reduce or adapt to the effects of climate change because, in order to ensure global survival, addressing this worldwide peril necessitates a collective global commitment to mitigate its dire consequences.

1 Climate change-global outlook

1.1 Climate change-alarming threat to agriculture

2 Direct consequences of climate change on agriculture

2.1 Temperature changes

rise in temperature, which has negative consequences for instance melting glaciers [66]. It is imperative to curtail greenhouse gas emissions to prevent the Earth’s temperature from surpassing a

2.2 Precipitation changes

many countries [103]. Rural residents, especially in developing nations, are frequently vulnerable to floods because they have lesser resources as well as adaptive capacity [90]. Ecological and climatic changes are primarily responsible for the severity and intensity of flood disasters [61, 62]. Inaccurately recognizing how different climatic conditions affect agricultural systems will not only negatively damage food production and safety but also obstruct attempts to enhance sustainable development and eliminate poverty [52]. The drastic changes in precipitation patterns can cause infrastructure damage and agricultural loss. Droughts have caused a decrease in agricultural productivity and food security in numerous regions while unusual rainfalls have deteriorated the ripe crops. A recent study in Ethiopia reported that decreased maize and teff yields resulted from increased rainfall variability [105]. Likewise, reduced rainfall in SubSaharan African region led to lesser maize productivity, decreased precipitation has resulted in a reduction in maize crop yields, which is the main staple food in the region [20]. Among the most important impacts of global climate alteration in Pakistan is the escalation in flood frequency and intensity. According to a report by the World Bank, Pakistan ranks among the nation’s most susceptible to flooding globally [13]. In 2022, the country has experienced several major floods which were the worst in the country’s history, which caused significant harm to standing crops including wheat, rice, millet, sorghum, sugar cane and cotton particularly in Sindh and Baluchistan provinces [1]. These crop damages caused

2.3 Alteration in soil quality and fertilizer consumption

3 Indirect consequences of adverse climate change

3.1 Reduced agriculture output: global vs local context

of wheat, rice, and maize [118]. Tropical areas are more influenced by climate shifts overall because crops of tropical areas have higher temperature optimums, thus are more vulnerable to elevated temperature stress [69]. In addition to temperature and precipitation, humidity and wind speed are additional variables that impact agricultural productivity. The application of machine learning algorithms in crop research and climate change research has been growing in popularity. Han et al. [46], demonstrated that when it comes to estimating China’s winter wheat production, the Random Forest approach outperforms both Gaussian Process Regression and Support Vector Machine. Zhi et al. [123] found that technology inputs are critical to China’s output of wheat, rice, and maize using the boosted regression trees algorithm. Numerous crop models have been found to indicate that the climate accounts for between 39 and

significant floods and prolonged droughts mainly because of irregularities in the monsoon season and annual rainfall Thus, Pakistan’s agriculture, water security, flood security, and energy security are consistently vulnerable to climatic shifts [67]. Moreover, crops that make up only

3.2 Disruption in supply chain

| Crops | % change | ||

| 2020 | 2050 | 2080 | |

| Wheat | -3.3 | -11.0 | -27.0 |

| Rice | 0 | -0.8 | -19.0 |

| Maize | -2.4 | -3.3 | -43.0 |

| Source: mate | World Change | Bank CliKnowledge | |

| Portal: | Agriculture | Model | |

| IIASA. | http://sdwebx.world | ||

| bank. org/climateportal/ index.cfm?page=country- | |||

3.3 Frequent disease outbreak

impacted by rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, rising temperatures, altered water availability, and an increase in the frequency of extreme weather events. As air humidity increases, the fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum becomes more pathogenic; disease growth in lettuce plants peaks when air relative humidity reaches

3.4 Spiked food prices/commodity speculation

3.5 Risks to food safety and security: challenge to meet up global food demand

of other consequences of climate change, like a rise in the frequency of extreme weather events (like powerful heat waves, floods, and severe droughts). These effects could have a harmful effect on crop output as well the other sectors involved in the production of food, thus leading to reduce in food supply and enhanced food insecurity [71].

3.6 Consequences on sustainable development goals

land suitability for farming with high-altitude experiences increased crop production, while low-altitude areas may see a decline in crop yields [56]. Other key crops of Pakistan including cotton, maize, sugar cane and pulses are also recently experiencing extremely slow and skewed growth rates [1]. Along with the growing issue of food insecurity, the irregular growth performance of such important crops can not only lower domestic income and employment but also impair the performance of related production businesses.

4 Possible mitigation and adaptive strategies

4.1 Managing agricultural practices

4.2 Land/soil and water management

preserving additional ecosystem services and fortifying resilience to shocks as essential components for achieving heightened productivity Sustainable agriculture approaches might include integrated methods for managing pests and soil fertility, better and efficient use of water and nutrients. Soil management has been recognized as one of the most important strategies for coping with climate change, since soil contains all the nutrients needed for agricultural growth [107]. Rising variability in the climate and harsh weather phenomenon such as torrential downpours and powerful winds, hastened the soil destruction. Therefore, effective management strategies must be adopted to minimize the soil disruption. In semi-arid regions, to counteract wind-driven soil erosion, planting trees and creating hedgerows are used; humid and coastal areas also frequently use vegetation cover, contour soil turns over, and contour windbreaks. Terrace gardening and water harvesting in mountainous areas assist control soil erosion [30]. Cropping systems can react to water stress, extra water from untimely rainfall, and extreme temperatures by switching to minimal tillage while retaining residue. As indicated by Sapkota et al. [91], the productivity of irrigation water can be increased, compared to traditional agricultural systems by

temperature by

4.3 Crop diversification, cropping system optimization

4.4 Sequestration of soil organic carbon (SOC)

4.5 Climate smart optimized agriculture

insurance, weather warning services, and laser land levelling (LLL) are the most widely used CSA technologies. In contrast, farmers in the western IGP prefer direct sowing, LLL, zero tillage and synchronization irrigation with crop insurance [9].

4.6 Developing resilient varieties

4.7 Remote sensing and satellite imaging for future prediction for vulnerable ecosystem

well as quality of ground water. Furthermore, it was discovered that areas affected with frost increase with LST, evapotranspiration, cloud ratio, elevation, slope and aspect [60]. The land use/land cover map and associated change detections were predicted using the Cellular Automata Markov (CA_Markov) model on multidate satellite images from Sentinel 2A, Landsat Oli-8, and ETM collected in 2017, 2013 and 2003, respectively. Furthermore, Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) was incorporated into GIS system to estimate loss of soil and to visualize the danger of erosion for certain years. This technique was shown to be effective for predicting LUCC and precisely estimating the volume of soil losses in the future [32]. Nevertheless, remote sensing and satellite imaging provide valuable data for monitoring, analyzing, and predicting climate change impacts on agriculture. These tools enhance our understanding of environmental changes, assist in decision-making, and enable proactive measures to maintain availability of food and eco-friendly agricultural practices amidst climate change [32].

4.8 Crop insurance

as 1.33 ha [92]. Farmers receive reimbursement for up to

5 Policy execution at global and regional level

about local situation compared to external organizations. Urgent attention is required to address inconsistencies in government planning and policy. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [55] noted that the inadequacy of knowledge to prompt adaptive responses is among several phenomena requiring attention. The situation in Pakistan are the worst in this regard, according to the IPCC [55], which deduced that policy execution and implementation have been comparatively constrained and confront various difficulties. To deal with the micro-level effects of climate change, various sectors require immediate development of comprehensive and multifaceted plans [55].

6 Future perspectives

Data availability All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethical approval Not applicable.

Consent to publish Not applicable.

References

- Abbas S (2022) Climate change and major crop production: evidence from Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(4):5406-5414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16041-4

- Abbass K, Qasim MZ, Song H, Murshed M, Mahmood H, Younis I (2022) A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(28):42539-42559

- Adnan M, Khan MA, Basir A, Fahad S, Nasar J, Imran, Alharbi S, Ghoneim AM, Yu G-H, Saleem MH (2023) Biochar as soil amendment for mitigating nutrients stress in crops. Sustainable agriculture reviews 61: biochar to improve crop production and decrease plant stress under a changing climate. Springer, Cham, pp 123-140

- Ahmed I, Ullah A, ur Rahman MH, Ahmad B, Wajid SA, Ahmad A, Ahmed S (2019) Climate change impacts and adaptation strategies for agronomic crops. In: Climate change and agriculture. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/INTECHOPEN. 82697

- Ahmed M, Suphachalasai S (2014) Assessing the costs of climate change and adaptation in South Asia. Asian Development Bank, Mandaluyong

- Ali A, Rahut DB (2020) Localized floods, poverty and food security : empirical evidence from rural Pakistan. Hydrology 7(1):1-15

- Anwar A, Younis M, Ullah I (2020) Impact of urbanization and economic growth on CO2 emission: a case of far east Asian countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(7):2531

- Arifeen M (2017) Effective execution of crop insurance policy required. Pakistan and Gulf Economist

- Aryal JP, Sapkota TB, Khurana R, Khatri-Chhetri A, Rahut DB, Jat ML (2020) Climate change and agriculture in South Asia: adaptation options in smallholder production systems. Environ Dev Sustain 22(6):5045-5075

- Asghar AJ, Cheema AM, Hameed MI, Qasim S (2021) The critical junction between CPEC, agriculture and climate

change. LUMS Centre for Chinese Studies. Retrieved from https://ccls.lums.edu.pk/sites/default/files/2023-01/the_criti cal_junction_between_cpec_agriculture_and_climate_change. pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2022 - Azani N, Ghaffar MA, Suhaimi H, Azra MN, Hassan MM, Jung LH, Rasdi NW (2021) The impacts of climate change on plankton as live food: a review. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 869(1):012005

- Bandara JS, Cai Y (2014) The impact of climate change on food crop productivity, food prices and food security in South Asia. Econ Anal Policy 44(4):451-465

- Bank, T. W. (2022). Pakistan: Flood damages and economic losses over USD 30 billion and reconstruction needs over USD 16 billion – New assessment.

- Bawazeer S, Rauf A, Nawaz T, Khalil AA, Javed MS, Muhammad N, Shah MA (2021) Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities. Green Process Synth 10(1):882-892

- Biber-Freudenberger L, Ziemacki J, Tonnang HE, Borgemeister C (2016) Future risks of pest species under changing climatic conditions. PLoS ONE 11(4):e0153237

- Bradshaw C, Eyre D, Korycinska A, Li C, Steynor A, Kriticos D (2024) Climate change in pest risk assessment: interpretation and communication of uncertainties. EPPO Bull 54:4-19. https:// doi.org/10.1111/epp. 12985

- Brempong MB, Amankwaa-Yeboah P, Yeboah S, Owusu Danquah E, Agyeman K, Keteku AK, Addo-Danso A, Adomako J (2023) Soil and water conservation measures to adapt cropping systems to climate change facilitated water stresses in Africa. Front Sustain Food Syst. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022. 1091665

- Cell CC (2009) Crop insurance as a risk management strategy in Bangladesh. Ministry of Environment and Forests. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Department of Environment, Dhaka

- Chaloner T, Gurr S, Bebber D (2021) Plant pathogen infection risk tracks global crop yields under climate change. Nat Clim Change 11(8):710-715

- Chapman S, Birch CE, Pope E, Sallu S, Bradshaw C, Davie J, Marsham JH (2020) Impact of climate change on crop suitability in sub-Saharan Africa in parameterized and convection-permitting regional climate models. Environ Res Lett. https://doi.org/ 10.1088/1748-9326/ab9daf

- Chaudhry QUZ (2017) Climate change profile of Pakistan. Asian Development Bank

- Chaudhry S, Sidhu GPS (2022) Climate change regulated abiotic stress mechanisms in plants: a comprehensive review. Plant Cell Rep 41(1):1-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-021-02759-5

- Chen C, Ota N, Wang B, Fu G, Fletcher A (2023) Adaptation to climate change through strategic integration of long fallow into cropping system in a dryland Mediterranean-type environment. Sci Total Environ 880:163230

- Chivenge P, Mabhaudhi T, Modi AT, Mafongoya P (2015) The potential role of neglected and underutilised crop species as future crops under water scarce conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(6):5685-5711

- Cradock-Henry NA, Blackett P, Hall M, Johnstone P, Teixeira E, Wreford A (2020) Climate adaptation pathways for agriculture: insights from a participatory process. Environ Sci Policy 107:66-79

- Davidson DJ (2018) Rethinking adaptation: emotions, evolution, and climate change. Nat Cult 13(3):378-402

- Dawood MF, Moursi YS, Abdelrhim AS, Hassan AA (2024) Investigation of ecology, molecular, and host-pathogen interaction of rice blast pathogen and management approaches.

28. Dembedza VP, Chopera P, Mapara J, Macheka L (2022) Impact of climate change-induced natural disasters on intangible cultural heritage related to food: a review. J Ethn Foods 9(1):32

29. Deutsch CA, Tewksbury JJ, Tigchelaar M, Battisti DS, Merrill SC, Huey RB, Naylor RL (2018) Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science 361(6405):916-919

30. Dmuchowski W, Baczewska-d AH, Gworek B (2024) The role of temperate agroforestry in mitigating climate change: a review. For Policy Econ 159(August 2023):103136. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2023.103136

31. Eckardt NA, Ainsworth EA, Bahuguna RN, Broadley MR, Busch W, Carpita NC, Castrillo G, Chory J, Dehaan LR, Duarte CM, Henry A, Jagadish SVK, Langdale JA, Leakey ADB, Liao JC, Lu KJ, McCann MC, McKay JK, Odeny DA et al (2023) Climate change challenges, plant science solutions. Plant Cell 35(1):24-66. https://doi.org/10.1093/plcel1/koac303

32. El Jazouli A, Barakat A, Khellouk R, Rais J, El Baghdadi M (2019) Remote sensing and GIS techniques for prediction of land use land cover change effects on soil erosion in the high basin of the Oum Er Rbia River (Morocco). Remote Sens Appl Soc Environ 13:361-374

33. Elahi E, Khalid Z, Tauni MZ, Zhang H, Lirong X (2022) Extreme weather events risk to crop-production and the adaptation of innovative management strategies to mitigate the risk: a retrospective survey of rural Punjab, Pakistan. Technovation 117:102255. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TECHNOVATION. 2021.102255

34. Elbasiouny H, El-Ramady H, Elbehiry F, Rajput VD, Minkina T, Mandzhieva S (2022) Plant nutrition under climate change and soil carbon sequestration. Sustainability 14(2):914. https:// doi.org/10.3390/SU14020914

35. Fahad S, Adnan M, Zhou R, Nawaz T, Saud S (2024) Biocharassisted remediation of contaminated soils under changing climate. Elsevier, Amsterdam

36. FAO (2021) FAO. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#rankings/ countries_by_commodity

37. Farooq MS, Uzaiir M, Raza A, Habib M, Xu Y, Yousuf M, Ramzan Khan M (2022) Uncovering the research gaps to alleviate the negative impacts of climate change on food security: a review. Front Plant Sci 13:2334

38. Galanakis CM (2023) The ‘vertigo’ of the food sector within the triangle of climate change, the post-pandemic world, and the Russian-Ukrainian war. Foods 12(4):721

39. Gasparini K, Rafael DD, Peres LEP, Ribeiro DM, Zsögön A (2024) Agriculture and food security in the era of climate change. Digital agriculture: a solution for sustainable food and nutritional security. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 47-58

40. Gbadeyan OJ, Muthivhi J, Linganiso LZ, Deenadayalu N (2024) Decoupling economic growth from carbon emissions: a transition towards low carbon energy systems-a critical review. https:// doi.org/10.20944/preprints202402.1085.v1

41. Godde CM, Mason-D’Croz D, Mayberry DE, Thornton PK, Herrero

42. Gojon A, Cassan O, Bach L, Lejay L, Martin A (2023) The decline of plant mineral nutrition under rising

43. GOP (2016) BAEF Climate Change Adaptation Report-II. Technology needs assessment fro climate change adaptation barrier analysis and enabling framework

44. Guja MM, Bedeke SB (2024) Smallholders’ climate change adaptation strategies: exploring effectiveness and opportunities

to be capitalized. Environ Dev Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10668-024-04750-y

45. Gupta J, Roy D, Thakur IS, Kumar M (2022) Environmental DNA insights in search of novel genes/taxa for production of biofuels and biomaterials. Biomass Biofuels Biochem. https:// doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823500-3.00015-7

46. Han J, Zhang Z, Cao J, Luo Y, Zhang L, Li Z, Zhang J (2020) Prediction of winter wheat yield based on multi-source data and machine learning in China. Remote Sens 12(2):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12020236

47. Hanif S, Hayat MK, Zaheer M, Raza H, Ain QU (2024) Cornous biology impact of climate change on agriculture production and strategies to overcome. May. https://doi.org/10. 37446/corbio/ra/2.2.2024.1-7

48. Haq SU, Boz I, Shahbaz P (2021) Adoption of climate-smart agriculture practices and differentiated nutritional outcome among rural households: a case of Punjab province, Pakistan. Food Secur 13:913-931

49. Hassan MA, Xiang C, Farooq M, Muhammad N, Yan Z, Hui X, Yuanyuan K, Bruno AK, Lele Z, Jincai L (2021) Cold stress in wheat: plant acclimation responses and management strategies. Front Plant Sci 12:1234. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPLS.2021. 676884/BIBTEX

50. Hegerl GC, Brönnimann S, Cowan T, Friedman AR, Hawkins E, Iles C, Müller W, Schurer A, Undorf S (2019) Causes of climate change over the historical record. Environ Res Lett 14(12):123006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab4557

51. Higgens RF, Pries CH, Virginia RA (2021) Trade-offs between wood and leaf production in Arctic shrubs along a temperature and moisture gradient in West Greenland. Ecosystems 24(3):652-666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-020-00541-4

52. Huong NTL, Yao S, Fahad S (2018) Assessing household livelihood vulnerability to climate change: the case of Northwest Vietnam. Hum Ecol Risk Assess Int J 25(5):1157-1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/10807039.2018.1460801

53. Hussain M, Butt AR, Uzma F, Ahmed R, Irshad S, Rehman A, Yousaf B (2020) A comprehensive review of climate change impacts, adaptation, and mitigation on environmental and natural calamities in Pakistan. Environ Monit Assess 192(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-019-7956-4

54. Lee H., Calvin K, Dasgupta D, Krinmer G, Mukherji A, Thorne P, Zommers Z (2023). Synthesis report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), Longer report. IPCC.

55. IPCC (2021) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Summary for policymakers. In: Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth. Assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

56. IPCC (2023) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: synthesis report (SYR) of the IPCC sixth assessment report (AR6). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (Panmao Zhai)

57. Islam MM, Ahamed T, Matsushita S, Noguchi R (2024) A damage-based crop insurance system for flash flooding: a satellite remote sensing and econometric approach. Climate change perspective in agriculture in remote sensing application II. Springer Nature, Singapore, pp 121-163

58. Jatav HS, Rajput VD, Minkina T, Van Hullebusch ED, Dutta A (2024) Agroforestry to combat global challenges (issue March). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-981-99-7282-1

59. Karimi V, Karami E, Keshavarz M (2018) Climate change and agriculture: Impacts and adaptive responses in Iran. J Integr Agric 17(1):1-15

60. Kazemi Garajeh M, Salmani B, Zare Naghadehi S, Valipoori Goodarzi H, Khasraei A (2023) An integrated approach of

remote sensing and geospatial analysis for modeling and predicting the impacts of climate change on food security. Sci Rep 13(1):1057

61. Khan I, Lei H, Shah AA, Khan I, Muhammad I (2021) Climate change impact assessment, flood management, and mitigation strategies in Pakistan for sustainable future. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28(23):29720-29731. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11356-021-12801-4/FIGURES/7

62. Khan N, Jhariya MK, Raj A, Banerjee A, Meena RS (2021) Soil carbon stock and sequestration: implications for climate change adaptation and mitigation. Ecological intensification of natural resources for sustainable agriculture. Springer, Singapore, pp 461-489. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4203-3_ 13/COVER

63. Khangura R, Ferris D, Wagg C, Bowyer J (2023) Regenerative agriculture-a literature review on the practices and mechanisms used to improve soil health. Sustainability (Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032338

64. Korres NE, Norsworthy JK, Tehranchian P, Gitsopoulos TK, Loka DA, Oosterhuis DM, Palhano M (2016) Cultivars to face climate change effects on crops and weeds: a review. Agron Sustain Dev 36:1-22

65. Kubik Z, Mirzabaev A, May J (2023) Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics (issue January). In: Zimmermann KF (ed). Springer Nature, Cham. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-3-319-57365-6

66. Kumar L, Chhogyel N, Gopalakrishnan T, Hasan MK, Jayasinghe SL, Kariyawasam CS, Kogo BK, Ratnayake S (2022) Climate change and future of agri-food production. Future foods: global trends, opportunities, and sustainability challenges. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 49-79. https://doi.org/10. 1016/B978-0-323-91001-9.00009-8

67. Lodhi S, Ayyubi MS, Hayat S, Iqbal Z (2024) Unravelling the effects of climate change on agriculture of pakistan: an exploratory analysis. Qlantic J Soc Sci 5(2):142-158. https:// doi.org/10.55737/qjss. 791319404

68. Magesa BA, Mohan G, Matsuda H, Melts I, Kefi M, Fukushi K (2023) Understanding the farmers’ choices and adoption of adaptation strategies, and plans to climate change impact in Africa: a systematic review. Climate Services 30(October 2022):100362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2023.100362

69. Malhi GS, Kaur M, Kaushik P (2021) Impact of climate change on agriculture and its mitigation strategies: a review. Sustainability (Switzerland) 13(3):1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su130 31318

70. McClelland SC, Paustian K, Schipanski ME (2021) Management of cover crops in temperate climates influences soil organic carbon stocks: a meta-analysis. Ecol Appl 31(3):e02278

71. Mirón IJ, Linares C, Díaz J (2023) The influence of climate change on food production and food safety. Environ Res 216:114674

72. Mottaleb KA, Rejesus RM, Murty MVR, Mohanty S, Li T (2017) Benefits of the development and dissemination of cli-mate-smart rice: ex ante impact assessment of drought-tolerant rice in South Asia. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change 22:879-901

73. Murthy CS, Choudhary KK, Pandey V, Srikanth P, Ramasubramanian S, Kumar GS, Nemani R (2024) Transformative crop insurance solution with big earth data: Implementation for potato crops in India. Clim Risk Manag. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.crm.2024.100622

74. Northrup DL, Basso B, Wang MQ, Morgan CL, Benfey PN (2021). Novel technologies for emission reduction complement conservation agriculture to achieve negative emissions from row-crop production. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(28):e2022666118

75. Nawaz T, Gu L, Fahad S, Saud S, Bleakley B, Zhou R (2024) Exploring sustainable agriculture with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria and nanotechnology. Molecules 29(11):2534

76. Nawaz T, Gu L, Fahad S, Saud S, Harrison MT, Zhou R (2024) Sustainable protein production through genetic engineering of cyanobacteria and use of atmospheric

77. Nawaz T, Gu L, Fahad S, Saud S, Hassan S, Harrison MT, Liu K, Zhou R (2024) Unveiling the antioxidant capacity of fermented foods and food microorganisms: a focus on cyanobacteria. J Umm Al-Qura Univ Appl Sci 10(1):232-243

78. Nawaz T, Saud S, Gu L, Khan I, Fahad S, Zhou R (2024) Cyanobacteria: harnessing the power of microorganisms for plant growth promotion, stress alleviation, and phytoremediation in the era of sustainable agriculture. Plant Stress 11:100399

79. Nawaz T, Gu L, Gibbons J, Hu Z, Zhou R (2024) Bridging nature and engineering: protein-derived materials for bio-inspired applications. Biomimetics 9(6):373

80. Nazir MJ, Li G, Nazir MM, Zulfiqar F, Siddique KHM, Iqbal B, Du D (2024) Harnessing soil carbon sequestration to address climate change challenges in agriculture. Soil Till Res 237(Novenber 2023):105959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2023.105959

81. Northrup DL, Basso B, Wang MQ, Morgan CL, Benfey PN (2021) Novel technologies for emission reduction complement conservation agriculture to achieve negative emissions from rowcrop production. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(28):e2022666118

82. Ogle SM, Alsaker C, Baldock J, Bernoux M, Breidt FJ, McConkey B, Vazquez-Amabile GG (2019) Climate and soil characteristics determine where no-till management can store carbon in soils and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Sci Rep 9(1):11665

83. Paustian K, Larson E, Kent J, Marx E, Swan A (2019) Soil C sequestration as a biological negative emission strategy. Front Clim. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2019.00008

84. Powlson DS, Stirling CM, Thierfelder C, White RP, Jat ML (2016) Does conservation agriculture deliver climate change mitigation through soil carbon sequestration in tropical agroecosystems? Agr Ecosyst Environ 220:164-174

85. Praveen B, Sharma P (2019) A review of literature on climate change and its impacts on agriculture productivity. J Public Aff 19(4):e1960. https://doi.org/10.1002/PA. 1960

86. Qamer FM, Ahmad B, Abbas S, Hussain A, Salman A, Muhammad S, Nawaz M, Shrestha S, Iqbal B, Thapa S (2022) The 2022 Pakistan floods Assessment of crop losses in Sindh Province. pp 1-24. https://doi.org/10.53055/ICIMOD. 1015

87. Quandt A, Grafton D, Gorman K, Dawson PM, Ibarra C, Mayes E, Paderes P (2023) Mitigation and adaptation to climate change in San Diego County, California. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change 28(1):7

88. Raihan A, Pavel MI, Muhtasim DA, Farhana S, Faruk O, Paul A (2023) The role of renewable energy use, technological innovation, and forest cover toward green development: Evidence from Indonesia. Innov Green Dev 2(1):100035. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/J.IGD.2023.100035

89. Raza A, Razzaq A, Mehmood SS, Zou X, Zhang X, Lv Y, Xu J (2019) Impact of climate change on crops adaptation and strategies to tackle its outcome: a review. Plants 8(2):34. https://doi. org/10.3390/plants8020034

90. Rehman A, Batool Z, Ma H, Alvarado R, Oláh J (2024) Climate change and food security in South Asia: the importance of renewable energy and agricultural credit. Human Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02847-3

91. Sapkota TB, Jat ML, Aryal JP, Jat RK, Khatri-Chhetri A (2015) Climate change adaptation, greenhouse gas mitigation and economic profitability of conservation agriculture: Some examples from cereal systems of Indo-Gangetic Plains. J Integr Agric 14(8):1524-1533

92. Shakya S, Gyawali, DR, Gurung JK, Regmi PP (2013) A trailblazer in adopting climate smart practices: one cooperative’s success story. https://ccafs.cgiar.org/es/blog/trailblazer-adopt ing-climate-smart-practices-one-cooperative%e2,80

93. Sheikh ZA, Ashraf S, Weesakul S, Ali M, Hanh NC (2024) Impact of climate change on farmers and adaptation strategies in Rangsit, Thailand. Environ Chall 15(December 2023):100902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2024.100902

94. Shivanna KR (2022) Climate change and its impact on biodiversity and human welfare. Proc Indian Natl Sci Acad 88(2):160171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43538-022-00073-6

95. Shrestha S (2019) Effects of climate change in agricultural insect pest. Acta Sci Agric 3:74-80

96. Siddiq A (2017) Climate change profile of Pakistan. https://doi. org/10.22617/TCS178761

97. Siyal GEA (2018). Farmers see room for improvement in crop loan insurance scheme. The Express Tribune, Pakistan. https:// tribune.com.pk/story/1657400/2-farmers-see-room-impro vement-croploan-insurance-scheme/

98. Sorgho R, Quiñonez CAM, Louis VR, Winkler V, Dambach P, Sauerborn R, Horstick O (2020) Climate change policies in 16 West African countries: a systematic review of adaptation with a focus on agriculture, food security, and nutrition. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(23):8897

99. Sturrock RN, Frankel SJ, Brown AV, Hennon PE, Kliejunas JT, Lewis KJ, Worrall JJ, Woods AJ (2011) Climate change and forest diseases. Plant Pathol 60:133-149

100. Suhaeb FW, Tamrin S (2024) Community adaptation strategies to climate change: towards sustainable social development. Migrat Lett 2:943-953

101. Sun H, Wang Y, Wang L (2024) Impact of climate change on wheat production in China. Eur J Agron 153:127066

102. Syed A, Raza T, Bhatti TT, Eash NS (2022) Climate Impacts on the agricultural sector of Pakistan: risks and solutions. Environ Chall 6:100433

103. Syldon P, Shrestha BB, Miyamoto M, Tamakawa K, Nakamura S (2024) Assessing the impact of climate change on flood inundation and agriculture in the Himalayan Mountainous Region of Bhutan. J Hydrol Region Stud 52:101687. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.ejrh.2024.101687

104. Szyniszewska AM, Akrivou A, Björklund N, Boberg J, Bradshaw C, Damus M, Gardi C, Hanea A, Kriticos J, Maggini R, Musolin DL (2024) Beyond the present: how climate change is relevant to pest risk analysis. EPPO Bull 54:20-37. https://doi.org/10.1111/ epp. 12986

105. Temesgen H, Wu W, Legesse A, Yirsaw E (2021) Modeling and prediction of effects of land use change in an agroforestry dominated southeastern Rift-Valley escarpment of Ethiopia. Remote Sens Appl Soc Environ 21:100469. https://doi.org/10.1016/J. RSASE.2021.100469

106. Tesfaye K, Zaidi PH, Gbegbelegbe S, Boeber C, Rahut DB, Getaneh F, Stirling C (2017) Climate change impacts and potential benefits of heat-tolerant maize in South Asia. Theor Appl Climatol 130:959-970

107. Timsina J (2024) Agriculture-livestock-forestry Nexus in Asia: Potential for improving farmers’ livelihoods and soil health, and adapting to and mitigating climate change. Agric Syst 218:104012

108. Tume SJP, Mairomi WH, Awazi NP (2024) Rainfall reliability and maize production in the Bamenda Highlands of Cameroon.

109. Uddin ME, Kebreab E (2020) Impact of food and climate change on pastoral industries. Fronti Sustain Food Syst 4:543403

110. UNCDD (2017) Global land outlook. UNCDD, Bonn

111. Yanagi M (2024) Climate change impacts on wheat production: Reviewing challenges and adaptation strategies. Adv Resour Res 4(1):89-107

112. Yin F, Sun Z, You L, Müller D (2024). Determinants of changes in harvested area and yields of major crops in China. Food Secur 16(2):339-351

113. Vinke K, Martin MA, Adams S, Baarsch F, Bondeau A, Coumou D, Svirejeva-Hopkins A (2017) Climatic risks and impacts in South Asia: extremes of water scarcity and excess. Reg Environ Change 17:1569-1583

114. Wang SW, Lee WK, Son Y (2017) An assessment of climate change impacts and adaptation in South Asian agriculture. Int J Clim Change Strateg Manag 9(4):517-534

115. Wieder WR, Sulman BN, Hartman MD, Koven CD, Bradford MA (2019) Arctic soil governs whether climate change drives global losses or gains in soil carbon. Geophys Res Lett 46(24):14486-14495. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085543

116. Xu X, Pei J, Xu Y, Wang J (2020) Soil organic carbon depletion in global Mollisols regions and restoration by management practices: a review. J Soils Sediments 20(3):1173-1181. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02557-3

117. Yanagi M (2024) Climate change impacts on wheat production: reviewing challenges and adaptation strategies. 4(1):89-107. https://doi.org/10.5098/arr.4.1

118. Yin F, Sun Z, You L, Müller D (2024) Determinants of changes in harvested area and yields of major crops in China. Food Secur 16(2):339-351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-023-01424-x

119. You Y, Ting M, Biasutti M (2024) Climate warming contributes to the record-shattering 2022 Pakistan rainfall. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00630-4

120. Yu L, Shi H, Wu H, Hu X, Ge Y, Yu L, Cao W (2024) The role of climate change perceptions in sustainable agricultural development: evidence from conservation tillage technology adoption in Northern China. Land 13(5):705. https://doi.org/10.3390/land1 3050705

121. Zheng B, Chen K, Li B, Li Y, Shi L, Fan H (2024) Climate change impacts on precipitation and water resources in Northwestern China. Front Environ Sci 12(April):1-12. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1377286

122. Zheng H, Ma W, He Q (2024) Climate-smart agricultural practices for enhanced farm productivity, income, resilience, and greenhouse gas mitigation: a comprehensive review. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11027-024-10124-6

123. Zhi J, Cao X, Zhang Z, Qin T, Qi L, Ge L, Fu X (2022) Identifying the determinants of crop yields in China since 1952 and its policy implications. Agric For Meteorol 327:109216

Authors and Affiliations

Anam Saleem

shah_fahad80@yahoo.com

Shah Saud

saudhort@gmail.com

Anam Saleem

anam.saleem@live.com

Sobia Anwar

sobiaamalik9@gmail.com

Taufiq Nawaz

taufiq.nawaz@jacks.sdstate.edu

Tanzeel Ur Rahman

Tanzeel.htm13@gmail.com

Muhammad Nasir Rasheed Khan

nasirrasheed219@gmail.com

Touqir Nawaz

nawaztouqir25@gmail.com

3 College of Natural Sciences, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD 57007, USA

4 Department of Agriculture, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Mardan, Pakistan

8 Department of Political Science, Abdul Wali Khan University, Mardan, Pakistan

- Extended author information available on the last page of the article