DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-024-01972-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38515134

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-21

تباين ومرونة خلايا T السامة: الآثار المترتبة على العلاج المناعي للسرطان

الملخص

تلعب الخلايا اللمفاوية التائية السامة للخلايا (CTLs) أدوارًا حاسمة في مكافحة الأورام، وتشمل مجموعات فرعية متنوعة بما في ذلك CD4+ وNK و

مقدمة

في السنوات الأخيرة، حاول الباحثون تحديد مجموعة من العلامات الخلوية التي يمكن أن تميز الخلايا التائية السامة للخلايا (CTLs) عن غيرها من خلايا المناعة، لكن لم يتم التوصل إلى توافق كامل بشأن هذه العلامات الخلوية [5]. بالإضافة إلى عدم وجود مجموعة متناسقة تمامًا من العلامات الحيوية، توجد التحديات التالية فيما يتعلق بالعلامات الخلوية للخلايا التائية السامة للخلايا. على سبيل المثال، فإن اللمفاويات التي تعبر عن جزيئات مرتبطة بالسُمية الخلوية لا تظهر بالضرورة سُمية خلوية [5]. علاوة على ذلك، وجد جونسون وآخرون أنه على الرغم من أنهم يعبرون عن جزيئات مرتبطة بالسُمية الخلوية،

تصنيفات خلايا T السامة

خلايا CTLs CD8+

CTLs CD4+

جميع الأنواع الفرعية من

iNK-CTLs

تعبّر خلايا iNKT عن مستقبلات TCR ثابتة تتكون من V

نشاط القتل المباشر ضد خلايا الورم [39، 40] ولكنه أيضًا يعدل خلايا المناعة الأخرى لتظهر نشاطًا مضادًا للورم بشكل غير مباشر [41]. على سبيل المثال، CD1d على سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا يحفز السمية الخلوية المعتمدة على خلايا iNKT [37]. وجد كونشي وآخرون أن

المؤشرات الحيوية الخلوية للخلايا التائية السامة

الجزيئات المرتبطة بسطح الخلية

بروتينات الليزوزوم LAMP-1 (CD107a) و LAMP-2 (CD107b)

جزيئات السطح المرتبطة بخلايا NK

فئران التقارير الفلورية [47]. يمكن تحديد خلايا CTLs CD4+ التي تعبر عن جينات مرتبطة بخلايا NK (مثل Nkg7 و Klrb1) من خلال تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية (scRNA-seq) لخلايا الدم البيضاء أحادية النواة في الدم المحيطي (PBMCs) [53]. وجدت دراسة أخرى تعتمد على scRNA-seq وجود خلايا CTLs CD4+ التي تعبر عن Gzmb و Nkg7 في سرطانات المثانة والكبد [54].

آخرون

إن توسيع خلايا T من نوع CD38+CD4+ مرتبط بشكل كبير بتقليل الطفيليات في الدم [60]. تم اقتراح CD26، وهو بروتين سكري معبر عنه على نطاق واسع ويملك نشاط ديوبيبتيديل ببتيداز IV (DPPIV)، كعلامة جديدة لخلايا CTLs من نوع CD4+ [61]. قد يكون تعبير CD56 مرتبطًا بحالة تنشيط اللمفاويات [62-64]. CD56+

الجزيئات المرتبطة بالخلايا

الجزيئات المرتبطة بالخارج الخلوي

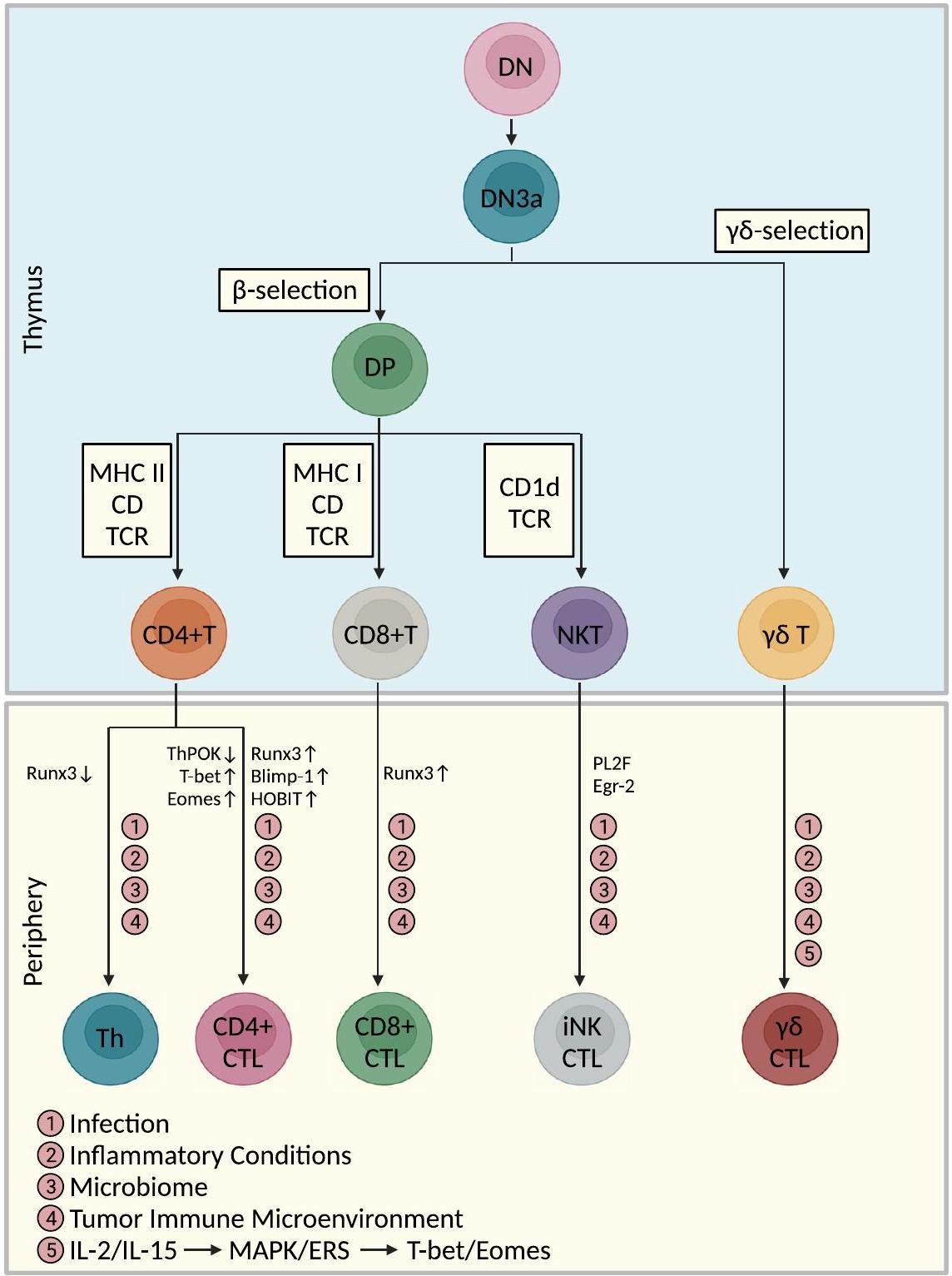

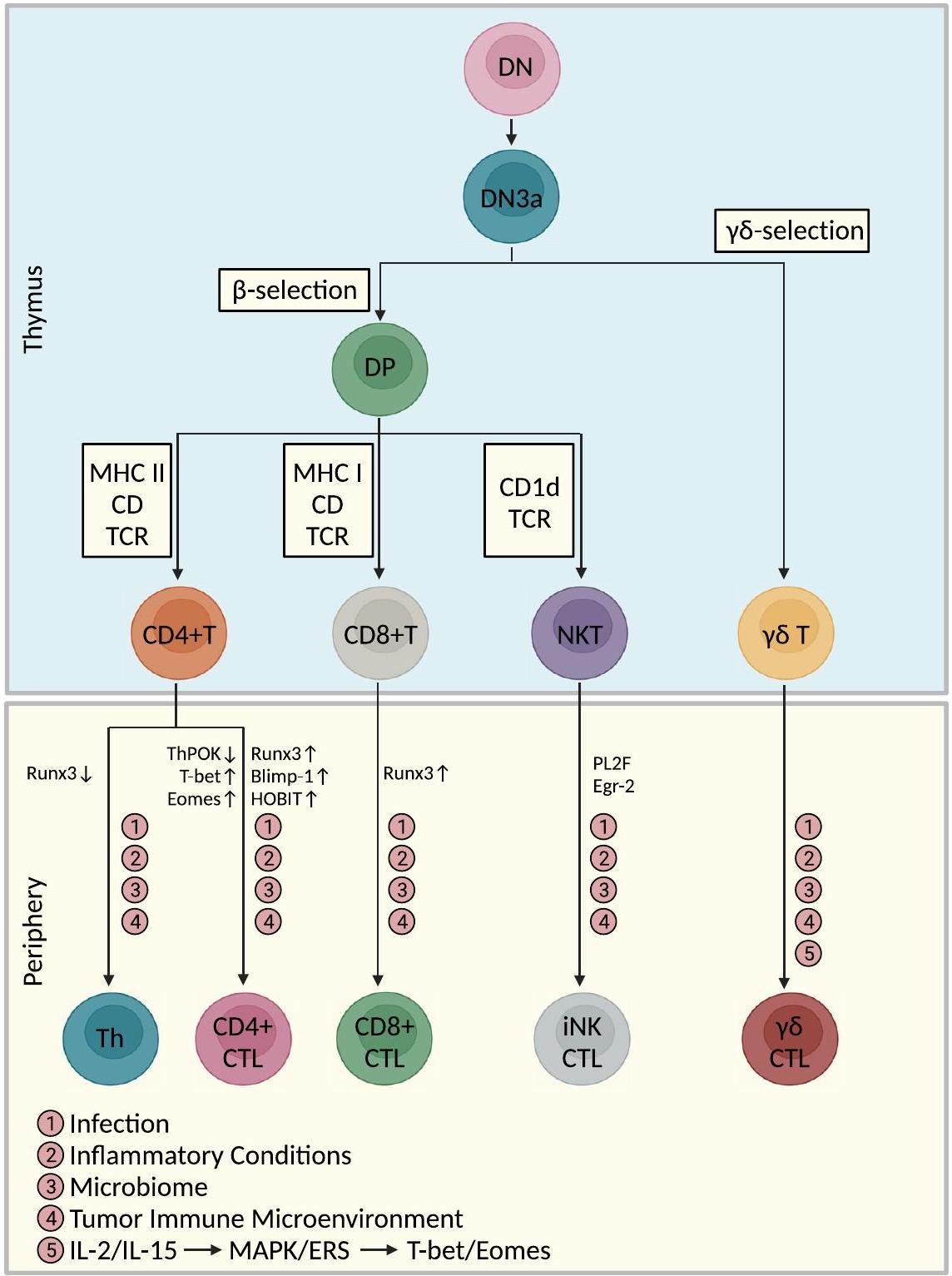

أصل ومسار تمايز خلايا CTLs

مسارات تمايز خلايا CTLs CD4+

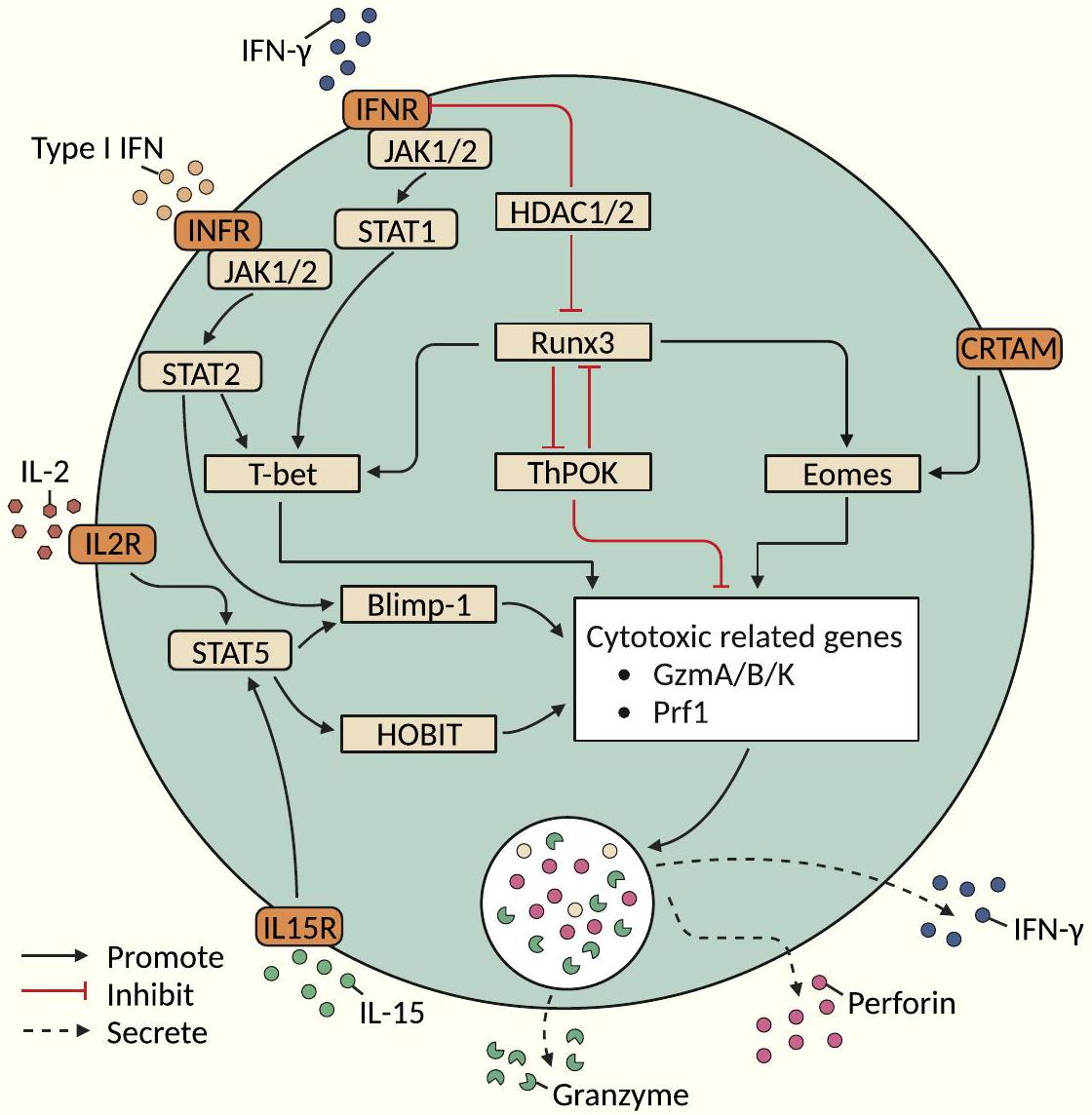

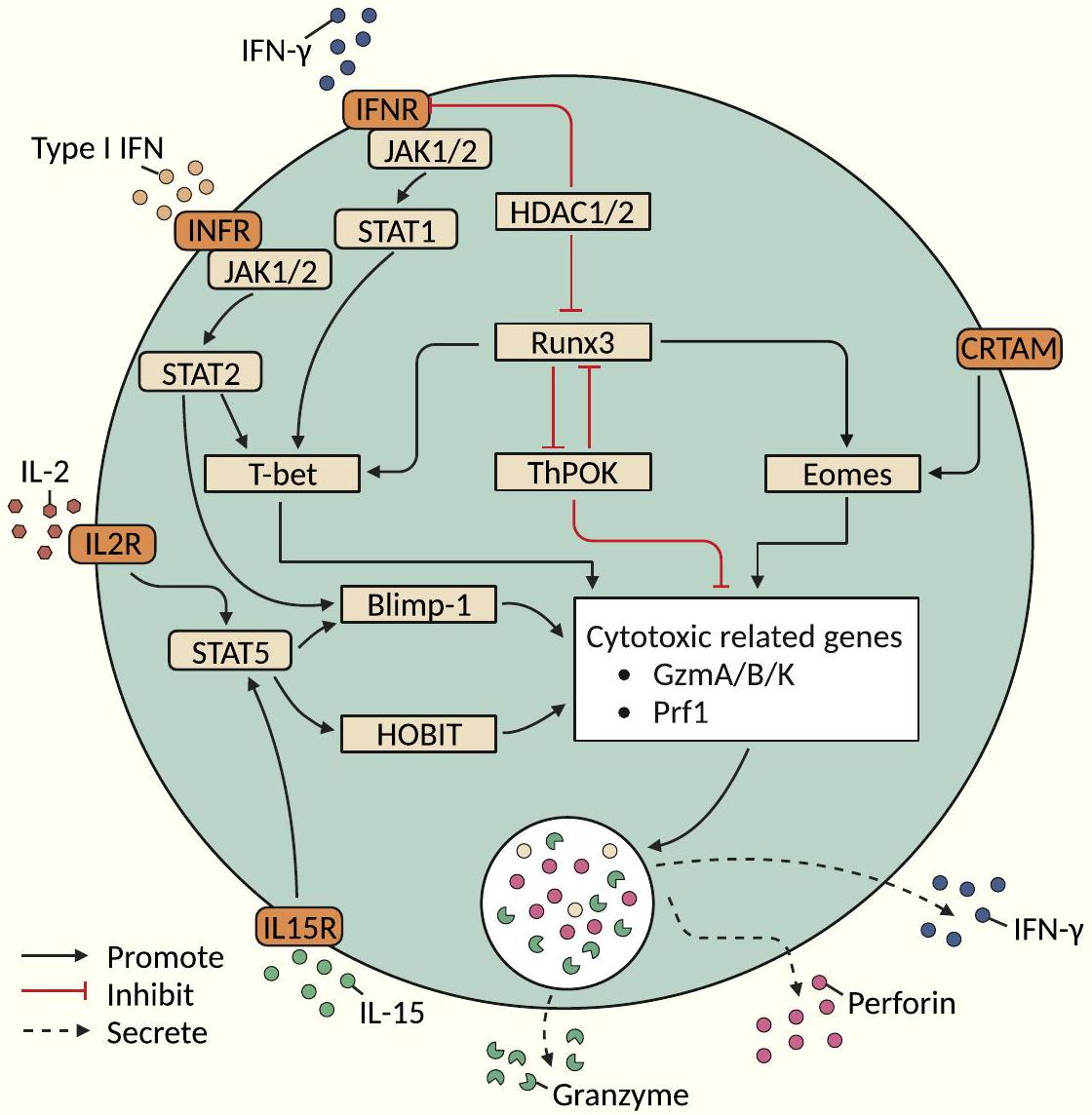

تم توضيحه. قد تكون عوامل النسخ التي تحفز التأثيرات السامة للخلايا في CD8+ CTLs [مثل T-bet، بروتين نضوج الخلايا اللمفاوية B المستحث (Blimp-1)، Eomes، عامل النسخ من عائلة RUNX 3 (Runx3)، عامل تحفيز الخلايا المساعدة POZKruppel (ThPOK)، ونظير Blimp-1 في الخلايا التائية (HOBIT)] متورطة في تمايز CD4+ CTLs، ولكن لا يزال هناك حاجة لمزيد من التحقق.

الاعتماد على إشارات TCR كحدث ابتدائي

الفوسفوريلation، التي في النهاية تتوسط تعبير الجرانزيم B والبرفورين في خلايا CD28-CD4+ T [79-81].

الإشارة من خلال CRTAM كمسار حدث ابتدائي

مسارات التعديل الوراثي فوق الجيني

تعمل كمنظم لنسخ الجينات [59]. تنشيط TCR مع IFN-

مسار تمايز خلايا CTLs CD8+

مسار التمايز

وظائف المؤثر (خاصة التفريغ/القدرة السامة للخلايا) لـ

مسارات تمايز خلايا iNK-CTLs

وظائف الخلايا التائية السامة للخلايا في مناعة الأورام

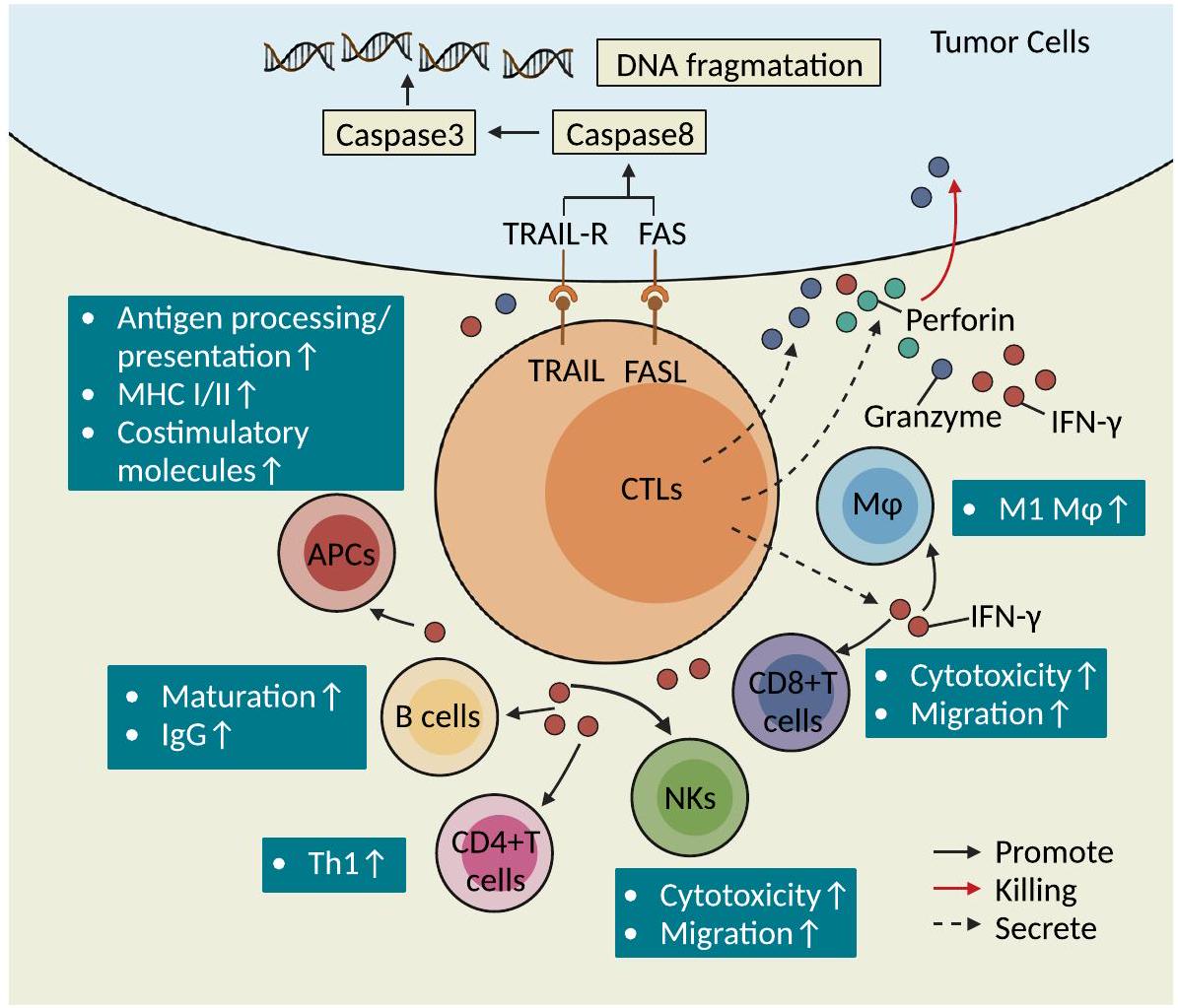

المناعة المضادة للأورام

ورم [95]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تعتبر خلايا CD4+ CTLs مؤشراً على نتيجة المرضى الذين يعانون من الأورام المعالجة بمثبطات المناعة [54، 96-99]. كما أظهرت الدراسات أن خلايا CD4+ CTLs مهمة في السيطرة على انتشار سرطان الرئة [76]. تقتل خلايا CD4+ T خلايا الميلانوما بطريقة مقيدة بمركب التوافق النسيجي الرئيسي من النوع الثاني (MHCII) بعد العلاج الواضح بخلايا CD4+ T محددة المستضد [16]. خلايا Th9/Th17 التي تم نقلها إلى المضيف بطريقة متسلسلة تحفز قتل الورم عن طريق إطلاق إنزيم غرانزيم B [100، 101]. خلايا CD4+ T التي تعبر عن كيموكين (CXCL)-13 (CXCL13) وجينات سامة للخلايا مرتبطة بزيادة ملحوظة في مدة البقاء الإجمالية (OS) لدى مرضى الميلانوما [102]. يمكن أن تتمايز خلايا CD4+ T الساذجة بشكل أكبر إلى خلايا CD4+ CTLs وتساعد في قتل خلايا الميلانوما في أجسام المضيفين الذين يعانون من نقص اللمفاويات [16]. حالياً، تركز الدراسات على وظيفة

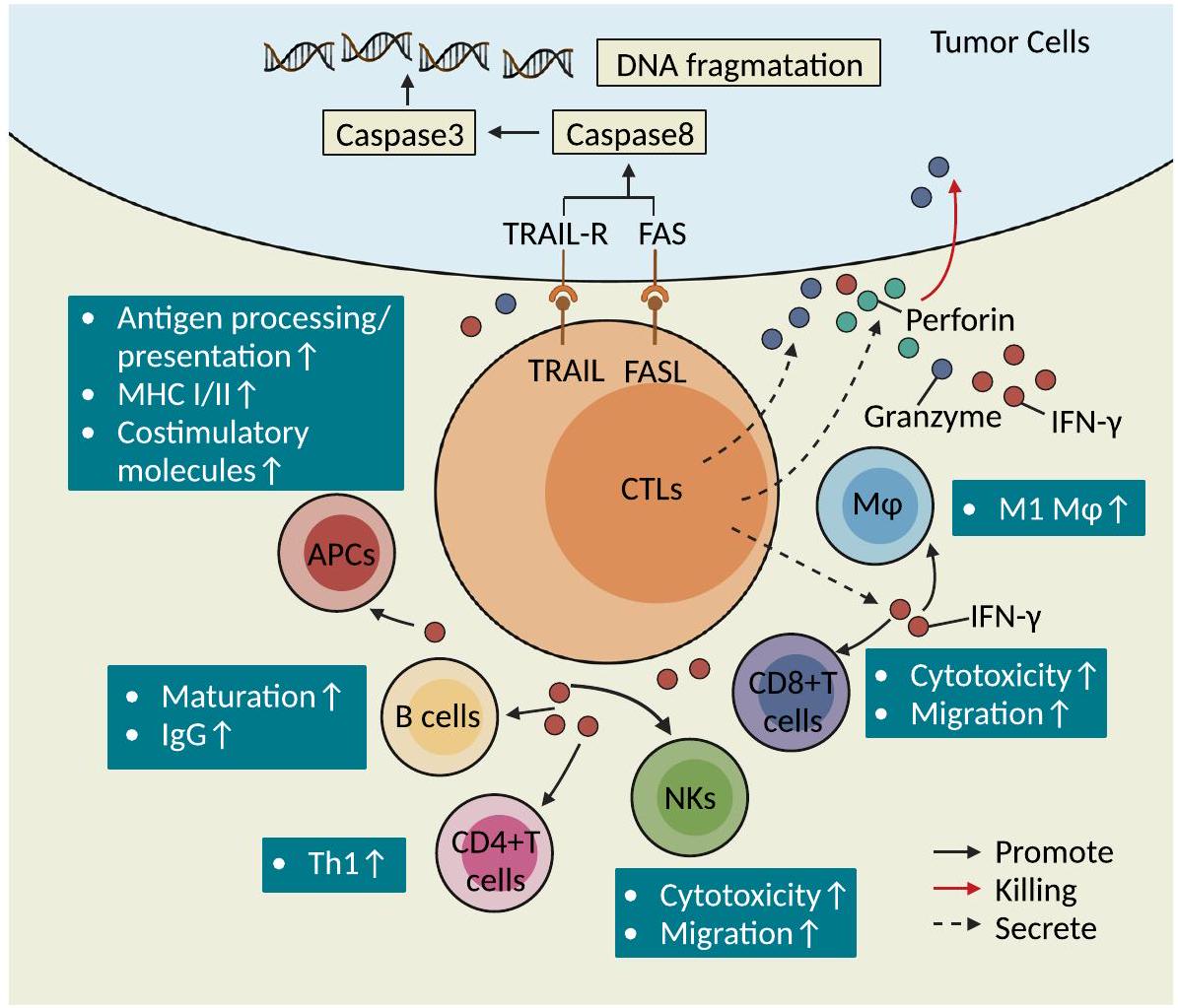

النتائج السريرية لدى مرضى سرطان المثانة وتسبب زيادة إفراز IFN-

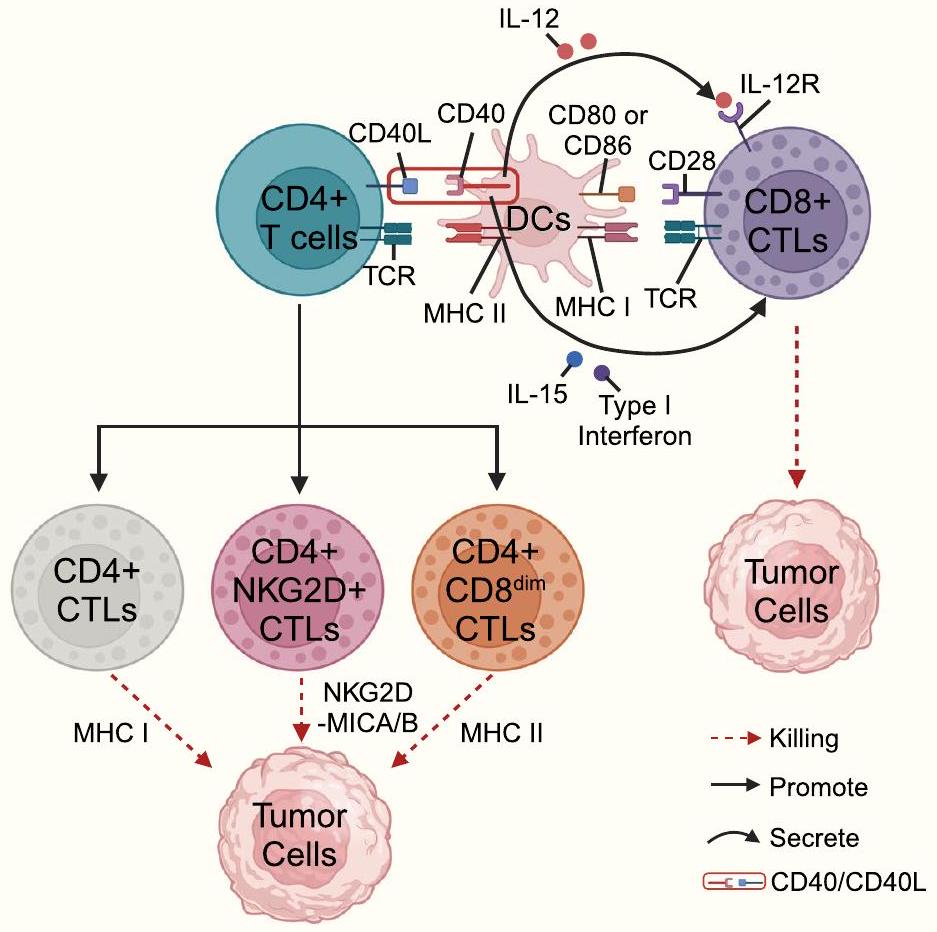

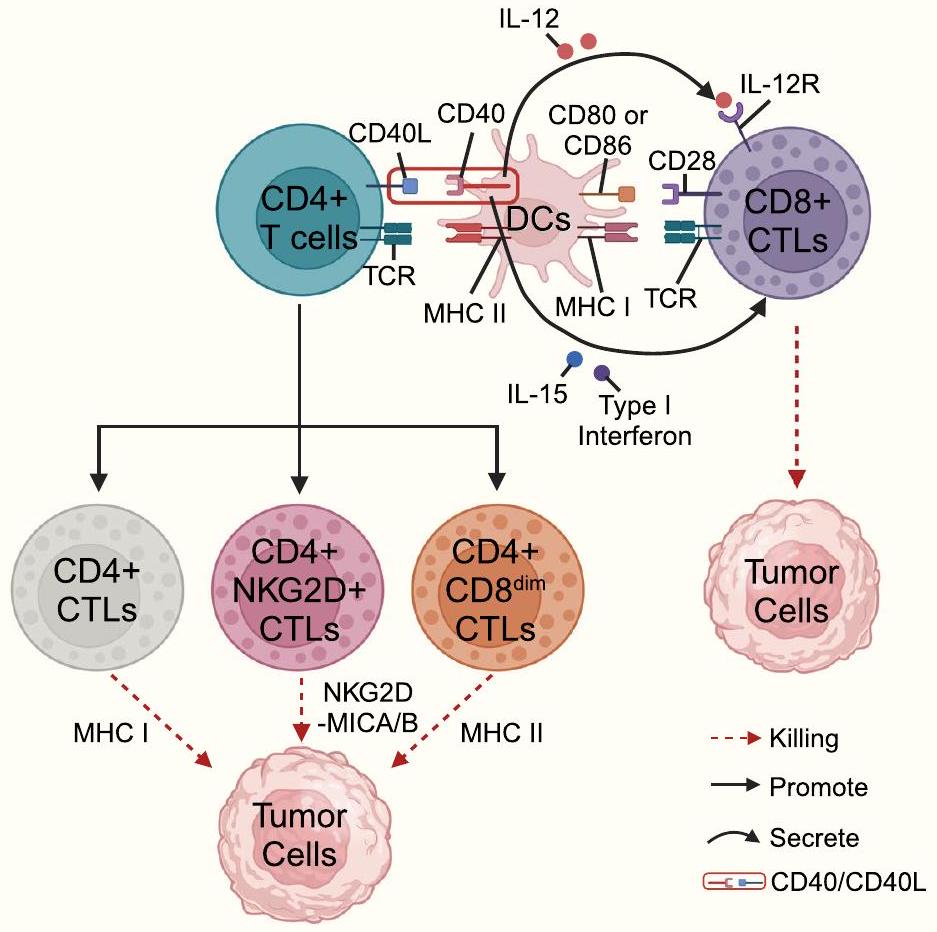

آثار القتل من نوع الليسوجيني المباشر

معقد الإشارة المميتة الناتج عن (FLIP) وفي النهاية موت الخلايا المبرمج بواسطة الكاسبيز 3 في الخلايا المستهدفة [18]. يرتبط TRAIL المعبر عنه على سطح خلايا CTLs بـ TRAIL-R على سطح الخلايا المستهدفة ويمكن أن يمارس تأثيرًا قاتلًا على خلايا الورم المقاومة لمسار Fas/FasL [106]. وجدت الدراسات الحديثة أن اختيار مسار الجرانزيم/البيرفورين ومسار مستقبلات الموت يعتمد على شدة الإشارة التحفيزية الخارجية والبيئة الدقيقة المحلية؛ على سبيل المثال، في ظل ظروف تتكون من تركيز عالٍ من مستضد معين وغياب IL-2، تفضل خلايا CTLs CD4+ اعتماد مسار Fas/FasL لقتل الخلايا المستهدفة، وفي ظل ظروف تتكون من تركيز منخفض من المستضد في وجود IL-2، تفضل خلايا CTLs CD4+ استخدام مسار القتل المعتمد على البيرفورين/الجرانزيم [109]. يمكن أن تقتل خلايا CTLs CD4+ خلايا الورم من خلال ثلاثة آليات محتملة (الشكل 4): أولاً، يمكن أن تتعرف خلايا CTLs CD4+ على المستضدات المتماثلة المعروضة بواسطة APCs وتفرز حبيبات لقتل الخلايا المستهدفة بطريقة تعتمد على MHC الفئة II؛ ثانيًا، يمكن أن تقوم خلايا CTLs CD4+ بزيادة تعبير NKG2D لقتل خلايا الورم بطريقة تعتمد على مسار NKG2D-MICA/B؛ ثالثًا، يمكن أن تقتل خلايا CTLs CD4+CD8dim التي تعبر عن مستويات منخفضة من CD8 (CD8dim) خلايا الورم بطريقة تعتمد على MHC الفئة I [55]. يمكن أن تبدأ خلايا T CD8+ تأثيرات سامة لاحقة عند التحفيز بالمستضد.

تنشيط مساعد للخلايا المناعية الأخرى

زيادة تنظيم وظائف معالجة المستضدات وعرضها في خلايا APCs. بالمقابل، IFN-

يمكن أن ترخص خلايا B لبدء وتنشيط الاستجابة المضادة للورم بفعالية [2].

تعزيز تكوين الأورام والتقدم

تحسين وظيفة السمية الخلوية للخلايا التائية السامة

تحسين السمية الخلوية للخلايا التائية السامة (CTLs) وتعزيز دورها في المناعة المضادة للأورام. أظهرت الدراسات أن السمية الخلوية للخلايا التائية السامة يمكن تحسينها أو تعزيزها من خلال تعديل مستوى تعبير السيتوكينات، وتقليل نسبة تسرب بعض الخلايا المناعية المحددة، وتعديل مستوى تعبير بعض الجزيئات في بيئة الورم، أو تغيير بعض المسارات الأيضية في الخلايا التائية السامة.

CTLs CD4+

خلايا CTLs CD8+

تقلل مستقبلات النفايات MARCO و IL37R من عدد خلايا Tregs وتستعيد السمية الخلوية والقدرة المضادة للورم لخلايا NK و CD8+ CTLs. يزيد Clec9A على cDC1 من التأثير السمي لخلايا CD8+ CTLs. يمكن أن يعزز تحسين استقلاب الأسيتات في خلايا CD8+ CTLs فعالية هذه الخلايا. أظهرت الدراسات أن LSD1 يشكل مجمعات نووية مع Eomes من خلايا CD8+ CTLs من مرضى الميلانوما وسرطان الثدي المقاوم للعلاج المناعي، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى تعطيل خلايا CD8+ CTLs، واستهداف فسفرة مسار LSD1 يمكن أن يزيد من السمية الخلوية لخلايا CD8+ CTLs. تظهر خلايا CD8+ CTLs المنشطة زيادة في مسار التحلل السكري وتتطلب إشارات CD28 المساعدة لإطالة مدة زيادة التحلل السكري؛ في نموذج فأر بدين لسرطان الثدي، يزيد تقليل STAT3 في خلايا CD8+ CTLs أو العلاج بمثبطات أكسدة الأحماض الدهنية من كل من التحلل السكري والوظيفة السامة لخلايا CD8+ CTLs (بما في ذلك IFN-

أسئلة مفتوحة

يجب إعادة التفكير في تعريف خلايا CTL.

تم إنشاء مؤشرات حيوية موحدة ومعيارية لتحديد الخلايا التائية السامة. من ناحية، بعض الخلايا التائية التي تعبر عن جزيئات مرتبطة بالوظيفة السامة لا تظهر بالضرورة وظيفة سامة. على سبيل المثال، خلايا CD8+ التائية التي تعبر عن GzmK وGzmB تظهر فقط قدرة سامة منخفضة جداً ولا تمارس سمية كافية لقتل الخلايا المستهدفة. من ناحية أخرى، لم يتم التعرف بعد بشكل متسق على علامات السمية مثل جزيئات التفريغ السام، والجينات المشفرة للجرانزيم والبرفورين، وعوامل النسخ المرتبطة بتمايز السمية، والعلامات المرتبطة بالإشارات الخلوية، وجزيئات مستقبلات سطح الخلايا القاتلة الطبيعية، وCRTAM، وعوامل النسخ (Eomes وRUNX3) من خلال دراسات مختلفة. لذلك، هناك حاجة إلى العديد من الدراسات المستقبلية لإثبات ما إذا كانت العلامات المحددة يمكن أن تصبح المعيار الذهبي لتحديد الخلايا التائية السامة.

يجب استكشاف الأنماط الفرعية الوظيفية لخلايا CTLs في أنواع خلايا T المختلفة بشكل أكبر

الجزيئات الرئيسية المعنية في تمايز أنواع مختلفة من خلايا CTL مثيرة للجدل

دور التعديلات التنظيمية الجينية غير الوراثية في وساطة تمايز خلايا CTLs من نوع CD4+ لا يزال محدودًا جدًا. من ناحية أخرى، فإن مسارات تمايز خلايا NK-CTL و V

لا يزال التوصيف المتعدد الأوميات لأنماط مختلفة من خلايا T السامة للخلايا غير واضح

العلاقة بين الميكروبات (داخل الورم أو المعوية) وخلايا T السامة للخلايا غير واضحة

لذلك، لا يزال يتعين معالجة هذه القضية وأن تكون محور الدراسات المستقبلية.

لم يتم بعد توضيح أنماط شيخوخة أنواع مختلفة من خلايا CTL واستراتيجيات عكس عملية شيخوخة خلايا CTL.

تنظيم الخلايا التائية السامة للخلايا (CTLs) على المستوى الإبيجينومي غير واضح

يمكن أن تساعد الاضطرابات الدوائية للمنظمات الجينية في نماذج الفئران في تقييم التأثير بشكل سببي على تراكم خلايا T السامة للخلايا، وتكوين الأنواع، والوظائف السامة داخل الأورام. من خلال رسم الخرائط للمناظر الجينية المرتبطة بتنوع خلايا T السامة للخلايا وضعفها، يمكننا تحديد أهداف دوائية جديدة لعكس البرمجة الجينية غير التكيفية وإعادة تنشيط المناعة المضادة للأورام. ستوفر أساليب متعددة الأوميات على مستوى الخلية الواحدة، التي تجمع بين ATAC-seq وChIP-seq وRNAseq، مزيدًا من الدقة في الدائرة الجينية التي تنظم تباين خلايا T السامة للخلايا ووظيفتها. أخيرًا، فإن توضيح التفاعلات بين التغيرات الجينية والشبكات النسخية والمسارات الأيضية يقدم رؤى على مستوى الأنظمة حول كيفية تشكيل الإشارات الخارجية لهوية خلايا T السامة للخلايا واللياقة التكيفية في بيئة الورم الدقيقة. سيساعد توضيح الأسس الجينية لخصائص خلايا T السامة للخلايا وقرارات المصير بشكل شامل في اكتشاف استراتيجيات جديدة لمكافحة ضعف خلايا T السامة للخلايا وتحسين العلاجات المناعية.

الاختصارات

| CTLs | الخلايا اللمفاوية التائية السامة للخلايا |

| قرص مضغوط | مجموعة التمايز |

| إن كيه | قاتل طبيعي |

|

|

خلايا تي غاما دلتا |

| تي سي آر | مستقبلات الخلايا التائية |

| APCs | خلايا تقديم المستضدات |

| خلايا جذعية Hematopoietic | خلايا جذعية دموية |

| CLPs | السلائف اللمفاوية المشتركة |

| iNKT | خلايا القاتل الطبيعي invariant |

| تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية | تسلسل RNA على مستوى الخلية الواحدة |

| تي إم إي | البيئة المجهرية للورم |

| إنترفيرون-

|

إنترفيرون غاما |

| STAT | موصل الإشارة ومفعل النسخ |

| روس | أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية |

| RCD | الموت الخلوي المنظم |

| مكافحة غسل الأموال | سرطان الدم النخاعي الحاد |

| كُلّ | سرطان الدم اللمفاوي الحاد |

| CRC | سرطان القولون والمستقيم |

| سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا | سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا |

| B-CLL | سرطان الدم اللمفاوي المزمن من نوع B |

| ADCC | السُميّة المعتمدة على الأجسام المضادة بواسطة الخلايا |

| RORyt | مستقبل اليتيم المرتبط بـ RAR-غاما |

| BCL6 | لمفوما الخلايا B 6 |

| HDAC | هيستون ديأسيتيلز |

| LSD1 | دي ميثيلاز 1 المحدد لليزين |

| تي-فك | تاليموجين لاهيرباربيفيك |

| إل | إنترلوكين |

| CXCR | مستقبل كيموكين (نمط C-X-C) |

| DCs | الخلايا الشجرية |

| تام | البلاعم المرتبطة بالورم |

| الوقت | البيئة المناعية للورم |

| TNFa | عامل نخر الورم ألفا |

| MHC | مجمع التوافق النسيجي الرئيسي |

| ث | خلايا المساعدة T |

| RUNX3 | عامل النسخ من عائلة RUNX 3 |

| إيومز | إيموسوديرمين |

| مصباح | بروتين سكري مرتبط بالغشاء الليزوزومي |

| بليمب-1 | بروتين النضوج المستحث بواسطة الخلايا اللمفاوية B-1 |

| رانكس 3 | عامل النسخ من عائلة RUNX 3 |

| ثبوك | عامل كروبل الشبيه بـ POZ المحفز للخلايا المساعدة |

| هوبيت | نظير بلينب-1 في خلايا T |

| CXCL | ليغاند كيموكين (C-X-C motif) |

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 21 مارس 2024

References

- Weigelin B, Friedl P.T cell-mediated additive cytotoxicity – death by multiple bullets. Trends Cancer. 2022;8:980-7.

- Nair S & Dhodapkar MV. Natural killer T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2017; 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017. 01178.

- de Miguel D, et al. Inflammatory cell death induced by cytotoxic lymphocytes: a dangerous but necessary liaison. FEBS J. 2022;289:4398-415.

- Martínez-Lostao L, Anel A, Pardo J. How do cytotoxic lymphocytes kill cancer cells? Clinical Cancer Res. 2015;21:5047-56.

- Venkatesh H, Tracy SI & Farrar MA. Cytotoxic CD4 T cells in the mucosa and in cancer. Front Immunol. 2023; 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu. 2023.1233261.

- Jonsson AH, et al. Granzyme K+ CD8 T cells form a core population in inflamed human tissue. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(649):eabo0686.

- Capitani N, Patrussi L & Baldari CT. Nature vs. Nurture: The two opposing behaviors of cytotoxic t lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222011221.

- Torres RM, Turner JA, D’Antonio M, Pelanda R, Kremer KN. Regulation of CD8 T-cell signaling, metabolism, and cytotoxic activity by extracellular Iysophosphatidic acid. Immunol Rev. 2023;317:203-22.

- Lisci M, Griffiths GM. Arming a killer: mitochondrial regulation of CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity. Trends Cell Biol. 2023;33:138-47.

- Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Shaping and reshaping CD8+ T-cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:107-19.

- Konduri V. et al. CD8+CD161+T-Cells: Cytotoxic Memory Cells With High Therapeutic Potential. Front Immunol. 2021; 11. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fimmu.2020.613204.

- Al Moussawy M & Abdelsamed HA. Non-cytotoxic functions of CD8 T cells: “repentance of a serial killer”. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi. org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1001129.

- Wagner H, Götze D, Ptschelinzew L, Röllinghoff M. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against I-region-coded determinants: in vitro evidence for a third histocompatibility locus in the mouse. J Exp Med. 1975;142:1477-87.

- Takeuchi A & Saito T. CD4 CTL, a cytotoxic subset of CD4 + T cells, their differentiation and function. Front Immunol. 2017; 8. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fimmu.2017.00194.

- Xie Y, et al. Naive tumor-specific CD4 + T cells differentiated in vivo eradicate established melanoma. J ExpMed. 2010;207:651-67.

- Quezada SA, et al. Tumor-reactive CD4+ T cells develop cytotoxic activity and eradicate large established melanoma after transfer into lymphopenic hosts. J Exp Med. 2010;207:637-50.

- van de Berg PJ, van Leeuwen EM, ten Berge IJ, van Lier R. Cytotoxic human CD4+ T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:339-43.

- Juno JA. et al. Cytotoxic CD4 T cells-friend or foe during viral infection? Front Immunol. 2017; 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00019.

- Freuchet A , et al. Identification of human exTreg cells as CD16+CD56+ cytotoxic CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2023;24:1748-61.

- Fisch P, et al. Gamma/delta T cell clones and natural killer cell clones mediate distinct patterns of non-major histocompatibility complexrestricted cytolysis. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1567-79.

- Silva-Santos B, Serre K, Norell H.

T cells in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:683-91. - Chitadze G, Oberg H-H, Wesch D, Kabelitz D. The Ambiguous role of

T lymphocytes in antitumor immunity. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:668-78. - Doherty DG, Dunne MR, Mangan BA, Madrigal-Estebas L. Preferential Th1 cytokine profile of phosphoantigen-stimulated human

cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:704941. - Mao

, et al. A new effect of IL-4 on human cells: promoting regulatory V T cells via IL-10 production and inhibiting function of V cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:217-28. - Caccamo N, et al. Differentiation, phenotype, and function of interleu-kin-17-producing human

cells. Blood. 2011;118:129-38. - Harmon C, et al.

cell dichotomy with opposing cytotoxic and wound healing functions in human solid tumors. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:1122-37. - Raverdeau M, Cunningham SP, Harmon C, Lynch L.

T cells in cancer: a small population of lymphocytes with big implications. Clin Transl Immunol. 2019;8:e01080. - Holderness J, Hedges JF, Ramstead A, Jutila MA. Comparative biology of

T cell function in humans, mice, and domestic animals. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2013;1:99-124. - Niu C, et al. In vitro analysis of the proliferative capacity and cytotoxic effects of ex vivo induced natural killer cells, cytokine-induced killer cells, and gamma-delta T cells. BMC Immunol. 2015;16:61.

- Pizzolato G, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing unveils the shared and the distinct cytotoxic hallmarks of human TCRV

and TCRV lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:11906-15. - Almeida AR, et al. Delta one T cells for immunotherapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical-grade expansion/differentiation and preclinical proof of concept. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5795-804.

- Halim L, Parente-Pereira AC, Maher J. Prospects for immunotherapy of acute myeloid leukemia using

T cells. Immunotherapy. 2017;9:111-4. - Fisher JPH, et al. Neuroblastoma killing properties of V

and negative T cells following expansion by artificial antigen-presenting cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5720-32. - Chan KF, Duarte JDG, Ostrouska S & Behren A.

Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment-Interactions With Other Immune Cells. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.894315. - Pont

, et al. The gene expression profile of phosphoantigen-specific human lymphocytes is a blend of a T-cell and NK-cell signatures. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:228-40. - Kratzmeier C, Singh S, Asiedu EB, Webb TJ. Current Developments in the Preclinical and Clinical use of Natural Killer T cells. Bio Drugs. 2023;37:57-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-022-00572-4.

- Nakashima, H. & Kinoshita, M. Antitumor Immunity Exerted by Natural Killer and Natural Killer T Cells in the Liver. J Clin Med. 2023; 12. https:// doi.org/10.3390/jcm12030866.

- Crosby CM, Kronenberg M. Tissue-specific functions of invariant natural killer T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:559-74. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41577-018-0034-2.

- Bassiri H, et al. iNKT cell cytotoxic responses control T-lymphoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:59-69.

- Perna SK, et al. Interleukin-7 Mediates Selective Expansion of Tumorredirected Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes (CTLs) without Enhancement of Regulatory T-cell Inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:131-9.

- Ihara F, et al. Regulatory T cells induce CD4- NKT cell anergy and suppress NKT cell cytotoxic function. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:1935-47.

- Konishi J, et al. The characteristics of human NKT cells in lung cancerCD1d independent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells by NKT cells and decreased human NKT cell response in lung cancer patients. Hum Immunol. 2004;65:1377-88.

- Díaz-Basabe A, et al. Human intestinal and circulating invariant natural killer T cells are cytotoxic against colorectal cancer cells via the perforingranzyme pathway. Mol Oncol. 2021;15:3385-403.

- Cachot A, et al. Tumor-specific cytolytic CD4 T cells mediate immunity against human cancer. Sci Adv. 2021;7(9):eabe3348.

- Hoeks C, Duran G, Hellings N & Broux B. When Helpers Go Above and Beyond: Development and Characterization of Cytotoxic CD4+ T Cells. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.951900.

- Peters PJ, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte granules are secretory lysosomes, containing both perforin and granzymes. J Exp Med. 1991;173(5):1099-109.

- Ng SS, et al. The NK cell granule protein NKG7 regulates cytotoxic granule exocytosis and inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1205-18.

- Cenerenti, M., Saillard, M., Romero, P. & Jandus, C. The Era of Cytotoxic CD4 T Cells. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu. 2022.867189.

- Fasth AER, Björkström NK, Anthoni M, Malmberg K-J, Malmström V. Activating NK-cell receptors co-stimulate CD4+CD28-T cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:378-87.

- Groh V, Brühl A, El-Gabalawy H, Nelson JL, Spies T. Stimulation of T cell autoreactivity by anomalous expression of NKG2D and its MIC ligands in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:9452-7.

- de Menthon M, et al. Excessive interleukin-15 transpresentation endows NKG2D + CD4 + T cells with innate-like capacity to lyse vascular endothelium in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s). Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2116-26.

- Broux B, et al. IL-15 Amplifies the Pathogenic Properties of CD4+CD28T Cells in Multiple Sclerosis. J Immunol. 2015;194:2099-109.

- Hashimoto K, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals expansion of cytotoxic CD4 T cells in supercentenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116:24242-51.

- Oh DY, et al. Intratumoral CD4+ T cells mediate anti-tumor cytotoxicity in human bladder cancer. Cell. 2020;181:1612-1625.e13.

- Wang B, Hu S, Fu X, Li L. CD4+ Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes in Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy. Adv Biol. 2023;7:2200169.

- Lin Y-C, et al. Murine cytotoxic CD4+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment are at a hyper-maturation stage of Th1 CD4 + T cells sustained by IL-12. Int Immunol. 2023;35:387-400.

- Marshall NB, et al. NKG2C/E Marks the Unique Cytotoxic CD4 T Cell Subset, ThCTL, Generated by Influenza Infection. J Immunol. 2017;198:1142-55.

- Takeuchi A, et al. CRT AM determines the CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte lineage. J Exp Med. 2016;213:123-38.

- Preglej T, Ellmeier W. CD4+ Cytotoxic T cells – Phenotype, Function and Transcriptional Networks Controlling Their Differentiation Pathways. Immunol Lett. 2022;247:27-42.

- Burel JG, et al. Reduced Plasmodium Parasite Burden Associates with CD38 + CD4 + T Cells Displaying Cytolytic Potential and Impaired IFN

Production. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005839. - Nelson MH , et al. Identification of human

cell populations with distinct antitumor activity. Sci Adv. 2023;6:eaba7443. - Van Acker HH, et al. Interleukin-15 enhances the proliferation, stimulatory phenotype, and antitumor effector functions of human gamma delta T cells. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:101.

- Liu Y, et al. Growth and activation of natural killer cells Ex Vivo from children with neuroblastoma for adoptive cell therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2132-43.

- Nörenberg J, Jaksó P, Barakonyi A. Gamma/Delta T Cells in the Course of Healthy Human Pregnancy: Cytotoxic Potential and the Tendency of CD8 Expression Make CD56+

T Cells a Unique Lymphocyte Subset. Front Immunol. 2021;11:596489. - Gruenbacher G, et al. Stress-related and homeostatic cytokines regulate Vү9V82 T-cell surveillance of mevalonate metabolism. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e953410.

- Alexander AAZ, et al. Isopentenyl pyrophosphate-activated CD56+

T lymphocytes display potent antitumor activity toward human squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4232-40. - Truong KL, et al. Killer-like receptors and GPR56 progressive expression defines cytokine production of human CD4+ memory T cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2263.

- Patil VS, et al. Precursors of human CD4 + cytotoxic T lymphocytes identified by single-cell transcriptome analysis. Sci Immunol. 2018;3(19):eaan8664.

- Tanemoto S , et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of human gut T cells identifies cytotoxic CD4+CD8A+T cells related to mouse CD4 cytotoxic T cells. Front Immunol. 2022;13:977117.

- Ciofani M, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. Determining

versus cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:657-63. - Pellicci DG, Koay H-F, Berzins SP. Thymic development of unconventional T cells: how NKT cells, MAIT cells and

T cells emerge. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:756-70. - Soghoian DZ & Streeck H. Cytolytic CD4 + T cells in viral immunity. Exp Rev Vacc. 2010; 9: 1453-1463. https://doi.org/10.1586/erv.10.132.

- Śledzińska A, et al. Regulatory T cells restrain interleukin-2- and Blimp-1-dependent acquisition of cytotoxic function by CD4 + T cells. Immunity. 2020;52:151-166.e6.

- Preglej T, et al. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 restrain CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte differentiation. JCI Insight. 2020;5(4):e133393.

- Hua L, et al. Cytokine-Dependent Induction of CD4 + T cells with Cytotoxic Potential during Influenza Virus Infection. J Virol. 2013;87:11884-93.

- Liu Q, et al. Tumor-Specific CD4+ T Cells Restrain Established Metastatic Melanoma by Developing Into Cytotoxic CD4-T Cells. Front Immunol. 2022;13:875718.

- Workman AM, Jacobs AK, Vogel AJ, Condon S, Brown DM. Inflammation Enhances IL-2 Driven Differentiation of Cytolytic CD4 T Cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89010.

- Brown DM, Kamperschroer C, Dilzer AM, Roberts DM, Swain SL. IL-2 and antigen dose differentially regulate perforin- and FasL-mediated cytolytic activity in antigen specific CD4+ T cells. Cell Immunol. 2009;257:69-79.

- Oja AE, et al. The transcription factor hobit identifies human cytotoxic CD4+T cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8:325.

- Mackay LK, et al. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science. 2016;1979(352):459-63.

- Alonso-Arias R, et al. IL-15 preferentially enhances functional properties and antigen-specific responses of CD4+CD28null compared to CD4+CD28+T cells. Aging Cell. 2011;10:844-52.

- Göschl L, et al. A T cell-specific deletion of HDAC1 protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Autoimmun. 2018;86:51-61.

- Boucheron N , et al.

cell lineage integrity is controlled by the histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:439-48. - Li X, Leung S, Qureshi S, Darnell JE, Stark GR. Formation of STAT1-STAT2 Heterodimers and Their Role in the Activation of IRF-1 Gene Transcription by Interferon-a(*). J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5790-4.

- Del Vecchio F. et al. Professional killers: The role of extracellular vesicles in the reciprocal interactions between natural killer, CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells and tumour cells. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021; 10. https://doi.org/10. 1002/jev2.12075.

- Taniuchi I. CD4 Helper and CD8 Cytotoxic T Cell Differentiation. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol.

- Park J-H, et al. Signaling by intrathymic cytokines, not T cell antigen receptors, specifies CD8 lineage choice and promotes the differentiation of cytotoxic-lineage T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:257-64.

- Hernández-Hoyos G, Anderson MK, Wang C, Rothenberg EV, Alberolalla J. GATA-3 expression is controlled by TCR signals and regulates CD4/ CD8 differentiation. Immunity. 2003;19:83-94.

- Joshi NS, et al. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8+T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281-95.

- Sharma RK, Chheda ZS, Jala VR, Haribabu B. Regulation of cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte trafficking to tumors by chemoattractants: implications for immunotherapy. Exp Rev Vacc. 2015;14:537-49.

- Ribot JC, Ribeiro ST, Correia DV, Sousa AE, Silva-Santos B. Human

thymocytes are functionally immature and differentiate into cytotoxic type 1 effector T cells upon IL-2/IL-15 signaling. J Immunol. 2014;192:2237-43. - Matsuda JL, George TC, Hagman J, Gapin L. Temporal dissection of T-bet functions. J Immunol. 2007;178:3457-65.

- Altman JB, Benavides AD, Das R & Bassiri H. Antitumor Responses of Invariant Natural Killer T Cells. J Immunol Res. 2015. 2015. https://doi. org/10.1155/2015/652875.

- Townsend MJ, et al. T-bet regulates the terminal maturation and homeostasis of NK and Valpha14i NKT cells. Immunity. 2004;20:477-94.

- Qi J, et al. Analysis of Immune Landscape Reveals Prognostic Significance of Cytotoxic CD4 + T Cells in the Central Region of pMMR CRC. Front Oncol. 2021;11:724232.

- Bonnal RJP, et al. Clonally expanded EOMES + Tr 1-like cells in primary and metastatic tumors are associated with disease progression. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:735-45.

- Germano G, et al. Cd4 t cell-dependent rejection of beta-2 microglobulin null mismatch repair-deficient tumors. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1844-59.

- Nagasaki J, et al. The critical role of CD4+ T cells in PD-1 blockade against MHC-II-expressing tumors such as classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020;4:4069-82.

- Oh DY, Fong L. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells in cancer: expanding the immune effector toolbox. Immunity. 2021;54:2701-11.

- Tilg H, Adolph TE, Gerner RR, Moschen AR. The intestinal microbiota in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:954-64.

- Marshall EA, et al. Emerging roles of Thelper 17 and regulatory T cells in lung cancer progression and metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:67.

- Veatch JR, et al. Neoantigen-specific CD4+ T cells in human melanoma have diverse differentiation states and correlate with CD8+T cell, macrophage, and B cell function. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:393-409.e9.

- Siegers GM & Lamb LS. Cytotoxic and regulatory properties of circulating

cells: A new player on the cell therapy field? Mol Ther. 2014; 22 1416-1422. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2014.104. - Ingram, Z. et al. Targeting natural killer t cells in solid malignancies. Cells. 2021; 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10061329.

- Kotov DI, Kotov JA, Goldberg MF, Jenkins MK. Many Th cell subsets have fas ligand-dependent cytotoxic potential. J Immunol. 2018;200:2004-12.

- Thomas WD, Hersey P. TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) induces apoptosis in fas ligand-resistant melanoma cells and mediates CD4 T cell killing of target cells. The J Immunol. 1998;161:2195-200.

- Zheng CF, et al. Cytotoxic CD4 + T cells use granulysin to kill Cryptococcus neoformans, and activation of this pathway is defective in HIV patients. Blood. 2006;109:2049-57.

- Voskoboinik I, Whisstock JC, Trapani JA. Perforin and granzymes: function, dysfunction and human pathology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:388-400.

- Brown DM. Cytolytic CD4 cells: direct mediators in infectious disease and malignancy. Cell Immunol. 2010;262:89-95.

- Borst J, Ahrends T, Bąbała N, Melief CJM, Kastenmüller W. CD4 + T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:635-47.

- He M , et al. CD5 expression by dendritic cells directs T cell immunity and sustains immunotherapy responses. Science (1979). 2023;379(6633):eabg2752.

- Lee D. et al. Human

T Cell subsets and their clinical applications for cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2022; 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ cancers14123005. - Caccamo N, Dieli F, Meraviglia S, Guggino G, Salerno A. Gammadelta T cell modulation in anticancer treatment. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10:27-36.

- Shissler SC, Lee MS & Webb TJ. Mixed signals: Co-stimulation in invariant natural killer T cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunol. 2017; 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01447.

- Kägi D, Ledermann B, Bürki K, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity and their role in immunological protection and pathogenesis in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:207-32.

- Alspach E, Lussier DM, Schreiber RD. Interferon

and its important roles in promoting and inhibiting spontaneous and therapeutic cancer immunity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019;11(3):a028480. - Gocher AM, Workman CJ & Vignali DAA. Interferon-

: teammate or opponent in the tumour microenvironment? Nat Rev Immunol. 2022; 22 158-172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-021-00566-3. - Gálvez NMS. et al. Type I natural killer T cells as key regulators of the immune response to infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2021; 34: 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00232-20.

- Shrestha N. et al. Regulation of Acquired Immunity by

T-Cell/Den-dritic-Cell Interactions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005; 1062: 79-94. - Ye

, et al. cells infiltrating hepatocellular carcinomas are activated and predictive of a better prognosis. Aging. 2019;11(20):8879-91. - Shen J, et al. A subset of CXCR5+CD8+T cells in the germinal centers from human tonsils and lymph nodes help B cells produce immunoglobulins. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2287.

- Gibbs BF, Sumbayev VV, Hoyer KK. CXCR5+CD8 T cells: Potential immunotherapy targets or drivers of immune-mediated adverse events? Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1034764.

- Le K-S, et al. CXCR5 and ICOS expression identifies a CD8 T-cell subset with TFH features in Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood Adv. 2018;2:1889-900.

- Chaudhry MS, Karadimitris A. Role and Regulation of CD1d in Normal and Pathological B Cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:4761-8.

- Colvin RA, Campanella GSV, Sun J & Luster AD. Intracellular Domains of CXCR3 That Mediate CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 Function*. J Biol Chem. 2004; 279: 30219-30227.

- Bolivar-Wagers S, Larson JH, Jin S & Blazar BR. Cytolytic CD4+ and CD8+ Regulatory T-Cells and Implications for Developing Immunotherapies to Combat Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.864748.

- Chen PP, et al. Alloantigen-specific type 1 regulatory T cells suppress through CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways and persist long-term in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(617):eabf5264.

- Magnani CF, et al. Killing of myeloid APCs via HLA class I, CD2 and CD226 defines a novel mechanism of suppression by human Tr1 cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1652-62.

- Roessner PM, et al. EOMES and IL-10 regulate antitumor activity of T regulatory type 1 CD4+T cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2021;35:2311-24.

- Chuang Y, Hung ME, Cangelose BK, Leonard JN. Regulation of the IL-10-driven macrophage phenotype under incoherent stimuli. Innate Immun. 2016;22:647-57.

- Mittal SK, Cho K-J, Ishido S, Roche PA. Interleukin 10 (IL-10)-mediated Immunosuppression: march-I induction regulates antigen presentation by macrophages but not dendritic cells*. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:27158-67.

- Tuomela K, Ambrose AR. & Davis DM. Escaping Death: How Cancer Cells and Infected Cells Resist Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.867098.

- Xu Y , et al. An engineered IL15 cytokine mutein fused to an anti-PD1 improves intratumoral T-cell function and antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9:1141-57.

- Meng F, Zhen S, Song B. HBV-specific CD4+ cytotoxic T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma are less cytolytic toward tumor cells and suppress CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor immunity. APMIS. 2017;125:743-51.

- Jacquier A, et al. Tumor infiltrating and peripheral CD4+ILT2+T cells are a cytotoxic subset selectively inhibited by HLA-G in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Lett. 2021;519:105-16.

- Dumont C , et al.

cells are an intratumoral cytotoxic population selectively inhibited by the immune-checkpoint HLA-G. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7:1619-32. - Akhmetzyanova I, et al. CD137 agonist therapy can reprogram regulatory T cells into cytotoxic CD4+ T cells with antitumor activity. J Immunol. 2016;196:484-92.

- van der Sluis TC, et al. OX40 agonism enhances PD-L1 checkpoint blockade by shifting the cytotoxic T cell differentiation spectrum. Cell Rep Med. 2023;4(3):100939.

- Yunger S, Geiger B, Friedman N, Besser MJ, Adutler-Lieber S. Modulating the proliferative and cytotoxic properties of patient-derived TIL by a synthetic immune niche of immobilized CCL21 and ICAM1. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1116328.

- Wang R, et al. CD40L-armed oncolytic herpes simplex virus suppresses pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by facilitating the tumor microenvironment favorable to cytotoxic T cell response in the syngeneic mouse model. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(1):e003809.

- Di Marco M, et al. Enhanced Expression of miR-181b in B Cells of CLL Improves the Anti-Tumor Cytotoxic T Cell Response. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:257.

- Schwartz AL, et al. Antisense targeting of CD47 enhances human cytotoxic T-cell activity and increases survival of mice bearing B16 melanoma when combined with anti-CTLA4 and tumor irradiation. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:1805-17.

- La Fleur L, et al. Targeting MARCO and IL37R on immunosuppressive macrophages in lung cancer blocks regulatory t cells and supports cytotoxic lymphocyte function. Cancer Res. 2021;81:956-67.

- Yan L, et al. Increased expression of Clec9A on cDC1s associated with cytotoxic CD8+ T cell response in COPD. Clin Immunol. 2022;242:109082.

- Leone RD, et al. Glutamine blockade induces divergent metabolic programs to overcome tumor immune evasion. Science. 2019;1979(366):1013-21.

- Li C , et al. The transcription factor Bhlhe40 programs mitochondrial regulation of resident CD8+ T cell fitness and functionality. Immunity. 2019;51:491-507.e7.

- Van Acker HH, Ma S, Scolaro T, Kaech SM, Mazzone M. How metabolism bridles cytotoxic CD8+ T cells through epigenetic modifications. Trends Immunol. 2021;42:401-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2021.03.006.

- Zhang C , et al. STAT3 activation-induced fatty acid oxidation in CD8+ T effector cells is critical for obesity-promoted breast tumor growth. Cell Metab. 2020;31:148-161.e5.

- Siegers GM, Dutta I, Lai R, Postovit LM. Functional plasticity of Gamma delta T cells and breast tumor targets in hypoxia. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1367.

- Jiang H, et al.

cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients present cytotoxic activity but are reduced in potency due to IL-2 and IL-21 pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;70:167-73. - Assy L, Khalil SM, Attia M, Salem ML. IL-12 conditioning of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from breast cancer patients promotes the zoledronate-induced expansion of

cells in vitro and enhances their cytotoxic activity and cytokine production. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;114:109402. - Gao Z, et al. Gamma delta T-cell-based immune checkpoint therapy: attractive candidate for antitumor treatment. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:31.

- Rigau M, Uldrich AP, Behren A. Targeting butyrophilins for cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2021;42:670-80.

- Zhu G , et al. Intratumour microbiome associated with the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and patient survival in cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2021;151:25-34.

- Perry LM, et al. Human soft tissue sarcomas harbor an intratumoral viral microbiome which is linked with natural killer cell infiltrate and prognosis. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11(1):e004285.

- Wang H , et al. The microbial metabolite trimethylamine N -oxide promotes antitumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Metab. 2022;34:581-594.e8.

- Zeng B, et al. The oral cancer microbiome contains tumor space-specific and clinicopathology-specific bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:942328.

- Varela-Eirín M, Demaria M. Cellular senescence. Curr Biol. 2022;32:R448-52.

- Hernandez-Segura A, Nehme J, Demaria M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:436-53.

- Choi YW, et al. Senescent tumor cells build a cytokine shield in colorectal cancer. Advanced Sci. 2021;8(4):2002497.

- Dock JN, Effros RB. Aging and Disease Role of CD8 T Cell replicative senescence in human aging and in HIV-mediated. Immunosenescence. 2011;2(5):382-97.

- Zelle-Rieser C, et al. T cells in multiple myeloma display features of exhaustion and senescence at the tumor site. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:116.

- Shosaku J. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of senescence in repetitively infected memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunology. 2018;153:253-67.

ملاحظة الناشر

شينغكون بينغ، أنكي لين، آيمين جيانغ وكانغ زانغ مؤلفون مشتركون. لقد ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي في هذا العمل ويتشاركون في تأليف العمل الأول.

*المراسلة:

كوان تشينغ

chengquan@csu.edu.cn

بينغ لو

luopeng@smu.edu.cn

يفينغ باي

baiyifeng@med.uestc.edu.cn

قسم الأشعة، مستشفى الشعب بمقاطعة سيتشوان، كلية الطب، جامعة علوم وتكنولوجيا الإلكترونيات في الصين، تشنغدو، الصين

قسم الأورام، مستشفى تشوجيانغ، جامعة الطب الجنوبية، قوانغتشو 510282، غوانغدونغ، الصين

قسم المسالك البولية، مستشفى تشانغهاي، جامعة الطب العسكري البحرية (الجامعة الطبية العسكرية الثانية)، شنغهاي، الصين

قسم الميكروبيولوجيا المرضية والمناعة، كلية العلوم الطبية الأساسية، جامعة شيان جياوتونغ، شيان 710061، شنشي، الصين

قسم جراحة الأعصاب، مستشفى شيانغيا، جامعة جنوب الوسط، تشانغشا 410008، هونان، الصين

المركز الوطني للبحوث السريرية لاضطرابات الشيخوخة، مستشفى شيانغيا، جامعة وسط جنوب الصين، هونان، الصين

قسم الأورام، مستشفى الشعب بمقاطعة سيتشوان، كلية الطب، جامعة العلوم والتكنولوجيا الإلكترونية في الصين، تشنغدو، الصين

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-024-01972-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38515134

Publication Date: 2024-03-21

CTLs heterogeneity and plasticity: implications for cancer immunotherapy

Abstract

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) play critical antitumor roles, encompassing diverse subsets including CD4+, NK, and

Introduction

In recent years, researchers have attempted to identify a set of cellular markers that can directly distinguish CTLs from other immune cells, but a full consensus on these cellular markers has not been reached [5]. In addition to the lack of a fully harmonized set of biomarkers, the following challenges exist with respect to cellular markers for CTLs. For example, lymphocytes that express molecules associated with cytotoxicity do not necessarily exhibit cytotoxicity [5]. Moreover, Jonsson et al. found that even though they express cytotoxicity-associated molecules,

Classifications of CTLs

CD8+ CTLs

CD4+ CTLs

All subtypes of

iNK-CTLs

iNKT expresses a constant TCR composed of V

direct killing activity against tumor cells [39, 40] but also modulate other immune cells to exhibit indirect antitumor activity [41]. For example, CD1d on NSCLC induces iNKT cell-mediated cytotoxicity [37]. Konishi et al. found that

Cellular biomarkers of CTLs

Cell surface-associated molecules

Lysosomal proteins LAMP-1 (CD107a) and LAMP-2 (CD107b)

NK-associated surface molecules

fluorescent reporter mice [47]. CD4+ CTLs expressing NK-related genes (e.g., Nkg7 and Klrb1) can be identified by scRNA-seq of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [53]. Another scRNA-seq-based study found the presence of CD4+ CTLs coexpressing Gzmb and Nkg7 in bladder and liver cancers [54].

Others

that CD38+CD4+ T-cell expansion is significantly correlated with a reduction in blood parasites [60]. CD26, a widely expressed glycoprotein with dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV) activity, has recently been proposed as a new marker for CD4+ CTLs [61]. CD56 expression may be correlated with the activation status of lymphocytes [62-64]. CD56+

Intracellular-related molecules

Extracellular-associated molecules

Origin and differentiation trajectory of CTLs

Differentiation pathways of CD4+ CTLs

clarified. Transcription factors that induce cytotoxic effects in CD8+ CTLs [e.g., T-bet, B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 (Blimp-1), Eomes, RUNX Family Transcription Factor 3 (Runx3), T-helper inducing POZKruppel like factor (ThPOK), and Homolog of Blimp-1 in T cells (HOBIT)] may be involved in the differentiation of CD4+ CTLs, but further validation is still needed

Dependence on TCR signaling as an initiating event

phosphorylation, which ultimately mediates the expression of granzyme B and perforin in CD28-CD4+ T cells [79-81].

Signaling through CRTAM as an initiating event pathway

Epigenetic modification pathways

further acts as a gene transcription regulator [59]. TCR activation with IFN-

Differentiation pathway of CD8+ CTLs

Differentiation pathway of

effector functions (especially degranulation/cytotoxic potential) of

Differentiation pathways of iNK-CTLs

Cellular functions of CTLs in tumor immunity

Antitumor immunity

tumor [95]. In addition, CD4+ CTLs are predictive of the outcome of patients with tumors treated with ICIs [54, 96-99]. CD4+ CTLs have also been shown to be important for controlling lung cancer metastasis [76]. CD4+ T cells kill melanoma cells in an MHCII-restricted manner after overt treatment with antigen-specific CD4+ T cells [16]. Th9/Th17 cells that were transferred to the host in a relayed manner induce tumor killing by releasing granzyme B [100, 101]. CD4+ T cells coexpressing chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)-13 (CXCL13) and cytotoxic genes are associated with a significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) time in melanoma patients [102]. Naïve CD4+ T cells can further differentiate into CD4+ CTLs and mediate the killing of melanoma cells in lymphocytopenic host bodies [16]. Currently, studies on the function of

clinical outcomes in bladder cancer patients and induces enhanced secretion of IFN-

Direct lysogenic-type killing effects

(FLIP)-induced death signaling complex and eventually caspase 3 -mediated apoptosis in target cells [18]. TRAIL expressed on the surface of CTLs binds to TRAIL-R on the surface of target cells and can exert a killing effect on tumor cells that are resistant to the Fas/FasL pathway [106]. Recent studies found that the granzyme/perforin pathway and death receptor-dependent pathway selection are affected by exogenous stimulus signal intensity and the local microenvironment; for example, under conditions consisting of a high concentration of a specific antigen and the absence of IL-2, CD4+ CTLs prefer to adopt the Fas/FasL pathway for the killing of target cells, and under conditions consisting of a low antigen concentration in the presence of IL-2, CD4+ CTLs prefer to utilize perforin/granzyme pathway-mediated killing [109]. CD4+ CTLs may kill tumor cells through three potential mechanisms (Fig. 4): First, CD4+ CTLs can recognize homologous antigens presented by APCs and secrete granules to kill target cells in the MHC class II-dependent manner; Second, CD4+ CTLs can upregulate NKG2D to kill tumor cells in the NKG2D-MICA/B pathway-dependent manner; Third, CD4+CD8dim CTLs expressing low levels of CD8 (CD8dim) can kill tumor cells in a MHC class I-dependent manner [55]. CD8+ T cells can initiate subsequent cytotoxic effects upon antigenic stimulation.

Adjuvant activation of other immune cells

upregulate the antigen processing and presentation functions of APCs. In contrast, IFN-

can license B cells to effectively initiate and activate the antitumor response [2].

Promotion of tumorigenesis and progression

Improving the cytotoxic function of CTLs

improving the cytotoxicity of CTLs and for enhancing the role of CTLs in antitumor immunity. Studies have shown that the cytotoxicity of CTLs could be improved or enhanced by modulating the expression level of cytokines, reducing the infiltration ratio of certain specific immune cells, modulating the expression level of certain molecules in the TIME, or altering certain metabolic pathways in CTLs.

CD4+ CTLs

CD8+ CTLs

scavenger receptors MARCO and IL37R reduces the number of Tregs and restores the cytotoxicity and antitumor capacity of NKs and CD8+ CTLs [143]. Clec9A on cDC1 increases the cytotoxic effect of CD8+ CTLs [144]. The enhancement of acetate metabolism in CD8+ CTLs could enhance the efficacy of CD8+ CTLs [145]. Studies have shown that LSD1 forms nuclear complexes with Eomes of CD8+ CTLs from immunotherapy-resistant melanoma and breast cancer patients, ultimately mediating dysfunction of CD8+ CTLs [146, 147], and targeting the phosphorylation of the LSD1 pathway can increase the cytotoxicity of CD8+ CTLs [147]. Activated CD8+ CTLs exhibit upregulation of the glycolytic pathway and require CD28 costimulatory signaling to prolong the duration of glycolytic upregulation; in an obese mouse model of breast cancer, the knockdown of STAT3 in CD8+ CTLs or treatment with inhibitors of fatty acid oxidation increases both glycolysis and the toxic function of CD8+ CTLs (including IFN-

Open questions

The definition of CTLs needs to be rethought

uniform and standardized biomarkers have been established for determining CTLs. On the one hand, some T cells expressing molecules related to cytotoxic function do not necessarily exhibit cytotoxic function. For example, CD8+ T cells expressing GzmK and GzmB only exhibit very low cytotoxicity potential and do not exert sufficient cytotoxicity to kill target cells. On the other hand, cytotoxicity markers such as cytotoxic degranulation molecules, granzyme- and perforin-encoding genes, cytotoxicity differentiation-associated transcription factors, markers associated with cellular signaling, NK cell surface receptor molecules, CRTAM, and transcription factors (Eomes and RUNX3) have not yet been consistently identified by different studies. Therefore, many future studies are needed to demonstrate whether specific markers can become the gold standard for determining CTLs.

The functional subtypes of CTLs in different T-cell subtypes need to be further explored

The key molecules involved in the differentiation of different CTLs are controversial

role of epigenetic regulatory modifications mediating the differentiation of CD4+ CTLs remains very limited. On the other hand, the differentiation pathways of NK-CTL and V

The multiomics characterization of different subtypes of CTLs remains unclear

The relationship between microorganisms (intratumoral or intestinal) and CTLs is unclear

explored. Therefore, this issue still needs to be addressed in and be the focus of future studies.

The aging patterns of different types of CTLs and strategies for reversing the aging process of CTLs have not yet been elucidated

The epigenetic regulation of CTLs is unclear

and pharmacological perturbation of epigenetic regulators in mouse models can help causally evaluate the impact on CTLs accumulation, subtype composition, and cytotoxic functions within tumors. By mapping epigenetic landscapes linked to CTLs heterogeneity and impairment, we can identify novel drug targets to reverse maladaptive epigenetic programming and reinvigorate anti-tumor immunity. Single-cell multi-omics approaches combining ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq and RNAseq will provide further resolution of the epigenetic circuitry orchestrating CTLs divergence and dysfunction. Finally, elucidating interactions between epigenetic alterations, transcriptional networks, and metabolic pathways offers systems-level insight into how extrinsic signals shape CTLs identity and adaptive fitness in the tumor microenvironment. Comprehensively elucidating the epigenetic underpinnings of CTLs properties and fate decisions will uncover new strategies to combat CTLs dysfunction and improve immunotherapies.

Abbreviatons

| CTLs | Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes |

| CD | Cluster of Differentiation |

| NK | Natural Killer |

|

|

Gamma Delta T cells |

| TCR | T-cell Receptor |

| APCs | Antigen-Presenting Cells |

| HSCs | Hematopoietic Stem Cells |

| CLPs | Common Lymphoid Progenitors |

| iNKT | Invariant Natural Killer T |

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell RNA Sequencing |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| IFN-

|

Interferon-gamma |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RCD | Regulated Cell Death |

| AML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| ALL | Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| B-CLL | B-Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| ADCC | Antibody-Dependent Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity |

| RORyt | RAR-related Orphan Receptor-gamma |

| BCL6 | B-Cell Lymphoma 6 |

| HDAC | Histone Deacetylase |

| LSD1 | Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 |

| T-VEC | Talimogene Laherparepvec |

| IL | Interleukin |

| CXCR | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) Receptor |

| DCs | Dendritic Cells |

| TAM | Tumor-Associated Macrophage |

| TIME | Tumor Immune Microenvironment |

| TNFa | tumour necrosis factor a |

| MHC | major histocompatibility complex |

| Th | T helper cells |

| RUNX3 | RUNX Family Transcription Factor 3 |

| Eomes | Eomesodermin |

| LAMP | lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein |

| Blimp-1 | B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 |

| Runx3 | RUNX Family Transcription Factor 3 |

| ThPOK | T-helper inducing POZ-Kruppel like factor |

| HOBIT | Homolog of Blimp-1 in T cells |

| CXCL | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand |

Acknowledgements

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 21 March 2024

References

- Weigelin B, Friedl P.T cell-mediated additive cytotoxicity – death by multiple bullets. Trends Cancer. 2022;8:980-7.

- Nair S & Dhodapkar MV. Natural killer T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2017; 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017. 01178.

- de Miguel D, et al. Inflammatory cell death induced by cytotoxic lymphocytes: a dangerous but necessary liaison. FEBS J. 2022;289:4398-415.

- Martínez-Lostao L, Anel A, Pardo J. How do cytotoxic lymphocytes kill cancer cells? Clinical Cancer Res. 2015;21:5047-56.

- Venkatesh H, Tracy SI & Farrar MA. Cytotoxic CD4 T cells in the mucosa and in cancer. Front Immunol. 2023; 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu. 2023.1233261.

- Jonsson AH, et al. Granzyme K+ CD8 T cells form a core population in inflamed human tissue. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(649):eabo0686.

- Capitani N, Patrussi L & Baldari CT. Nature vs. Nurture: The two opposing behaviors of cytotoxic t lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222011221.

- Torres RM, Turner JA, D’Antonio M, Pelanda R, Kremer KN. Regulation of CD8 T-cell signaling, metabolism, and cytotoxic activity by extracellular Iysophosphatidic acid. Immunol Rev. 2023;317:203-22.

- Lisci M, Griffiths GM. Arming a killer: mitochondrial regulation of CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity. Trends Cell Biol. 2023;33:138-47.

- Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Shaping and reshaping CD8+ T-cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:107-19.

- Konduri V. et al. CD8+CD161+T-Cells: Cytotoxic Memory Cells With High Therapeutic Potential. Front Immunol. 2021; 11. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fimmu.2020.613204.

- Al Moussawy M & Abdelsamed HA. Non-cytotoxic functions of CD8 T cells: “repentance of a serial killer”. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi. org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1001129.

- Wagner H, Götze D, Ptschelinzew L, Röllinghoff M. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against I-region-coded determinants: in vitro evidence for a third histocompatibility locus in the mouse. J Exp Med. 1975;142:1477-87.

- Takeuchi A & Saito T. CD4 CTL, a cytotoxic subset of CD4 + T cells, their differentiation and function. Front Immunol. 2017; 8. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fimmu.2017.00194.

- Xie Y, et al. Naive tumor-specific CD4 + T cells differentiated in vivo eradicate established melanoma. J ExpMed. 2010;207:651-67.

- Quezada SA, et al. Tumor-reactive CD4+ T cells develop cytotoxic activity and eradicate large established melanoma after transfer into lymphopenic hosts. J Exp Med. 2010;207:637-50.

- van de Berg PJ, van Leeuwen EM, ten Berge IJ, van Lier R. Cytotoxic human CD4+ T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:339-43.

- Juno JA. et al. Cytotoxic CD4 T cells-friend or foe during viral infection? Front Immunol. 2017; 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00019.

- Freuchet A , et al. Identification of human exTreg cells as CD16+CD56+ cytotoxic CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2023;24:1748-61.

- Fisch P, et al. Gamma/delta T cell clones and natural killer cell clones mediate distinct patterns of non-major histocompatibility complexrestricted cytolysis. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1567-79.

- Silva-Santos B, Serre K, Norell H.

T cells in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:683-91. - Chitadze G, Oberg H-H, Wesch D, Kabelitz D. The Ambiguous role of

T lymphocytes in antitumor immunity. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:668-78. - Doherty DG, Dunne MR, Mangan BA, Madrigal-Estebas L. Preferential Th1 cytokine profile of phosphoantigen-stimulated human

cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:704941. - Mao

, et al. A new effect of IL-4 on human cells: promoting regulatory V T cells via IL-10 production and inhibiting function of V cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:217-28. - Caccamo N, et al. Differentiation, phenotype, and function of interleu-kin-17-producing human

cells. Blood. 2011;118:129-38. - Harmon C, et al.

cell dichotomy with opposing cytotoxic and wound healing functions in human solid tumors. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:1122-37. - Raverdeau M, Cunningham SP, Harmon C, Lynch L.

T cells in cancer: a small population of lymphocytes with big implications. Clin Transl Immunol. 2019;8:e01080. - Holderness J, Hedges JF, Ramstead A, Jutila MA. Comparative biology of

T cell function in humans, mice, and domestic animals. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2013;1:99-124. - Niu C, et al. In vitro analysis of the proliferative capacity and cytotoxic effects of ex vivo induced natural killer cells, cytokine-induced killer cells, and gamma-delta T cells. BMC Immunol. 2015;16:61.

- Pizzolato G, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing unveils the shared and the distinct cytotoxic hallmarks of human TCRV

and TCRV lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:11906-15. - Almeida AR, et al. Delta one T cells for immunotherapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical-grade expansion/differentiation and preclinical proof of concept. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5795-804.

- Halim L, Parente-Pereira AC, Maher J. Prospects for immunotherapy of acute myeloid leukemia using

T cells. Immunotherapy. 2017;9:111-4. - Fisher JPH, et al. Neuroblastoma killing properties of V

and negative T cells following expansion by artificial antigen-presenting cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5720-32. - Chan KF, Duarte JDG, Ostrouska S & Behren A.

Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment-Interactions With Other Immune Cells. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.894315. - Pont

, et al. The gene expression profile of phosphoantigen-specific human lymphocytes is a blend of a T-cell and NK-cell signatures. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:228-40. - Kratzmeier C, Singh S, Asiedu EB, Webb TJ. Current Developments in the Preclinical and Clinical use of Natural Killer T cells. Bio Drugs. 2023;37:57-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-022-00572-4.

- Nakashima, H. & Kinoshita, M. Antitumor Immunity Exerted by Natural Killer and Natural Killer T Cells in the Liver. J Clin Med. 2023; 12. https:// doi.org/10.3390/jcm12030866.

- Crosby CM, Kronenberg M. Tissue-specific functions of invariant natural killer T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:559-74. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41577-018-0034-2.

- Bassiri H, et al. iNKT cell cytotoxic responses control T-lymphoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:59-69.

- Perna SK, et al. Interleukin-7 Mediates Selective Expansion of Tumorredirected Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes (CTLs) without Enhancement of Regulatory T-cell Inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:131-9.

- Ihara F, et al. Regulatory T cells induce CD4- NKT cell anergy and suppress NKT cell cytotoxic function. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:1935-47.

- Konishi J, et al. The characteristics of human NKT cells in lung cancerCD1d independent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells by NKT cells and decreased human NKT cell response in lung cancer patients. Hum Immunol. 2004;65:1377-88.

- Díaz-Basabe A, et al. Human intestinal and circulating invariant natural killer T cells are cytotoxic against colorectal cancer cells via the perforingranzyme pathway. Mol Oncol. 2021;15:3385-403.

- Cachot A, et al. Tumor-specific cytolytic CD4 T cells mediate immunity against human cancer. Sci Adv. 2021;7(9):eabe3348.

- Hoeks C, Duran G, Hellings N & Broux B. When Helpers Go Above and Beyond: Development and Characterization of Cytotoxic CD4+ T Cells. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.951900.

- Peters PJ, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte granules are secretory lysosomes, containing both perforin and granzymes. J Exp Med. 1991;173(5):1099-109.

- Ng SS, et al. The NK cell granule protein NKG7 regulates cytotoxic granule exocytosis and inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1205-18.

- Cenerenti, M., Saillard, M., Romero, P. & Jandus, C. The Era of Cytotoxic CD4 T Cells. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu. 2022.867189.

- Fasth AER, Björkström NK, Anthoni M, Malmberg K-J, Malmström V. Activating NK-cell receptors co-stimulate CD4+CD28-T cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:378-87.

- Groh V, Brühl A, El-Gabalawy H, Nelson JL, Spies T. Stimulation of T cell autoreactivity by anomalous expression of NKG2D and its MIC ligands in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:9452-7.

- de Menthon M, et al. Excessive interleukin-15 transpresentation endows NKG2D + CD4 + T cells with innate-like capacity to lyse vascular endothelium in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s). Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2116-26.

- Broux B, et al. IL-15 Amplifies the Pathogenic Properties of CD4+CD28T Cells in Multiple Sclerosis. J Immunol. 2015;194:2099-109.

- Hashimoto K, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals expansion of cytotoxic CD4 T cells in supercentenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116:24242-51.

- Oh DY, et al. Intratumoral CD4+ T cells mediate anti-tumor cytotoxicity in human bladder cancer. Cell. 2020;181:1612-1625.e13.

- Wang B, Hu S, Fu X, Li L. CD4+ Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes in Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy. Adv Biol. 2023;7:2200169.

- Lin Y-C, et al. Murine cytotoxic CD4+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment are at a hyper-maturation stage of Th1 CD4 + T cells sustained by IL-12. Int Immunol. 2023;35:387-400.

- Marshall NB, et al. NKG2C/E Marks the Unique Cytotoxic CD4 T Cell Subset, ThCTL, Generated by Influenza Infection. J Immunol. 2017;198:1142-55.

- Takeuchi A, et al. CRT AM determines the CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte lineage. J Exp Med. 2016;213:123-38.

- Preglej T, Ellmeier W. CD4+ Cytotoxic T cells – Phenotype, Function and Transcriptional Networks Controlling Their Differentiation Pathways. Immunol Lett. 2022;247:27-42.

- Burel JG, et al. Reduced Plasmodium Parasite Burden Associates with CD38 + CD4 + T Cells Displaying Cytolytic Potential and Impaired IFN

Production. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005839. - Nelson MH , et al. Identification of human

cell populations with distinct antitumor activity. Sci Adv. 2023;6:eaba7443. - Van Acker HH, et al. Interleukin-15 enhances the proliferation, stimulatory phenotype, and antitumor effector functions of human gamma delta T cells. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:101.

- Liu Y, et al. Growth and activation of natural killer cells Ex Vivo from children with neuroblastoma for adoptive cell therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2132-43.

- Nörenberg J, Jaksó P, Barakonyi A. Gamma/Delta T Cells in the Course of Healthy Human Pregnancy: Cytotoxic Potential and the Tendency of CD8 Expression Make CD56+

T Cells a Unique Lymphocyte Subset. Front Immunol. 2021;11:596489. - Gruenbacher G, et al. Stress-related and homeostatic cytokines regulate Vү9V82 T-cell surveillance of mevalonate metabolism. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e953410.

- Alexander AAZ, et al. Isopentenyl pyrophosphate-activated CD56+

T lymphocytes display potent antitumor activity toward human squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4232-40. - Truong KL, et al. Killer-like receptors and GPR56 progressive expression defines cytokine production of human CD4+ memory T cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2263.

- Patil VS, et al. Precursors of human CD4 + cytotoxic T lymphocytes identified by single-cell transcriptome analysis. Sci Immunol. 2018;3(19):eaan8664.

- Tanemoto S , et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of human gut T cells identifies cytotoxic CD4+CD8A+T cells related to mouse CD4 cytotoxic T cells. Front Immunol. 2022;13:977117.

- Ciofani M, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. Determining

versus cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:657-63. - Pellicci DG, Koay H-F, Berzins SP. Thymic development of unconventional T cells: how NKT cells, MAIT cells and

T cells emerge. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:756-70. - Soghoian DZ & Streeck H. Cytolytic CD4 + T cells in viral immunity. Exp Rev Vacc. 2010; 9: 1453-1463. https://doi.org/10.1586/erv.10.132.

- Śledzińska A, et al. Regulatory T cells restrain interleukin-2- and Blimp-1-dependent acquisition of cytotoxic function by CD4 + T cells. Immunity. 2020;52:151-166.e6.

- Preglej T, et al. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 restrain CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte differentiation. JCI Insight. 2020;5(4):e133393.

- Hua L, et al. Cytokine-Dependent Induction of CD4 + T cells with Cytotoxic Potential during Influenza Virus Infection. J Virol. 2013;87:11884-93.

- Liu Q, et al. Tumor-Specific CD4+ T Cells Restrain Established Metastatic Melanoma by Developing Into Cytotoxic CD4-T Cells. Front Immunol. 2022;13:875718.

- Workman AM, Jacobs AK, Vogel AJ, Condon S, Brown DM. Inflammation Enhances IL-2 Driven Differentiation of Cytolytic CD4 T Cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89010.

- Brown DM, Kamperschroer C, Dilzer AM, Roberts DM, Swain SL. IL-2 and antigen dose differentially regulate perforin- and FasL-mediated cytolytic activity in antigen specific CD4+ T cells. Cell Immunol. 2009;257:69-79.

- Oja AE, et al. The transcription factor hobit identifies human cytotoxic CD4+T cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8:325.

- Mackay LK, et al. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science. 2016;1979(352):459-63.

- Alonso-Arias R, et al. IL-15 preferentially enhances functional properties and antigen-specific responses of CD4+CD28null compared to CD4+CD28+T cells. Aging Cell. 2011;10:844-52.

- Göschl L, et al. A T cell-specific deletion of HDAC1 protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Autoimmun. 2018;86:51-61.

- Boucheron N , et al.

cell lineage integrity is controlled by the histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:439-48. - Li X, Leung S, Qureshi S, Darnell JE, Stark GR. Formation of STAT1-STAT2 Heterodimers and Their Role in the Activation of IRF-1 Gene Transcription by Interferon-a(*). J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5790-4.

- Del Vecchio F. et al. Professional killers: The role of extracellular vesicles in the reciprocal interactions between natural killer, CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells and tumour cells. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021; 10. https://doi.org/10. 1002/jev2.12075.

- Taniuchi I. CD4 Helper and CD8 Cytotoxic T Cell Differentiation. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol.

- Park J-H, et al. Signaling by intrathymic cytokines, not T cell antigen receptors, specifies CD8 lineage choice and promotes the differentiation of cytotoxic-lineage T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:257-64.

- Hernández-Hoyos G, Anderson MK, Wang C, Rothenberg EV, Alberolalla J. GATA-3 expression is controlled by TCR signals and regulates CD4/ CD8 differentiation. Immunity. 2003;19:83-94.

- Joshi NS, et al. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8+T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281-95.

- Sharma RK, Chheda ZS, Jala VR, Haribabu B. Regulation of cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte trafficking to tumors by chemoattractants: implications for immunotherapy. Exp Rev Vacc. 2015;14:537-49.

- Ribot JC, Ribeiro ST, Correia DV, Sousa AE, Silva-Santos B. Human

thymocytes are functionally immature and differentiate into cytotoxic type 1 effector T cells upon IL-2/IL-15 signaling. J Immunol. 2014;192:2237-43. - Matsuda JL, George TC, Hagman J, Gapin L. Temporal dissection of T-bet functions. J Immunol. 2007;178:3457-65.

- Altman JB, Benavides AD, Das R & Bassiri H. Antitumor Responses of Invariant Natural Killer T Cells. J Immunol Res. 2015. 2015. https://doi. org/10.1155/2015/652875.

- Townsend MJ, et al. T-bet regulates the terminal maturation and homeostasis of NK and Valpha14i NKT cells. Immunity. 2004;20:477-94.

- Qi J, et al. Analysis of Immune Landscape Reveals Prognostic Significance of Cytotoxic CD4 + T Cells in the Central Region of pMMR CRC. Front Oncol. 2021;11:724232.

- Bonnal RJP, et al. Clonally expanded EOMES + Tr 1-like cells in primary and metastatic tumors are associated with disease progression. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:735-45.

- Germano G, et al. Cd4 t cell-dependent rejection of beta-2 microglobulin null mismatch repair-deficient tumors. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1844-59.

- Nagasaki J, et al. The critical role of CD4+ T cells in PD-1 blockade against MHC-II-expressing tumors such as classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020;4:4069-82.

- Oh DY, Fong L. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells in cancer: expanding the immune effector toolbox. Immunity. 2021;54:2701-11.

- Tilg H, Adolph TE, Gerner RR, Moschen AR. The intestinal microbiota in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:954-64.

- Marshall EA, et al. Emerging roles of Thelper 17 and regulatory T cells in lung cancer progression and metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:67.

- Veatch JR, et al. Neoantigen-specific CD4+ T cells in human melanoma have diverse differentiation states and correlate with CD8+T cell, macrophage, and B cell function. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:393-409.e9.

- Siegers GM & Lamb LS. Cytotoxic and regulatory properties of circulating

cells: A new player on the cell therapy field? Mol Ther. 2014; 22 1416-1422. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2014.104. - Ingram, Z. et al. Targeting natural killer t cells in solid malignancies. Cells. 2021; 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10061329.

- Kotov DI, Kotov JA, Goldberg MF, Jenkins MK. Many Th cell subsets have fas ligand-dependent cytotoxic potential. J Immunol. 2018;200:2004-12.

- Thomas WD, Hersey P. TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) induces apoptosis in fas ligand-resistant melanoma cells and mediates CD4 T cell killing of target cells. The J Immunol. 1998;161:2195-200.

- Zheng CF, et al. Cytotoxic CD4 + T cells use granulysin to kill Cryptococcus neoformans, and activation of this pathway is defective in HIV patients. Blood. 2006;109:2049-57.

- Voskoboinik I, Whisstock JC, Trapani JA. Perforin and granzymes: function, dysfunction and human pathology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:388-400.

- Brown DM. Cytolytic CD4 cells: direct mediators in infectious disease and malignancy. Cell Immunol. 2010;262:89-95.

- Borst J, Ahrends T, Bąbała N, Melief CJM, Kastenmüller W. CD4 + T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:635-47.

- He M , et al. CD5 expression by dendritic cells directs T cell immunity and sustains immunotherapy responses. Science (1979). 2023;379(6633):eabg2752.

- Lee D. et al. Human

T Cell subsets and their clinical applications for cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2022; 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ cancers14123005. - Caccamo N, Dieli F, Meraviglia S, Guggino G, Salerno A. Gammadelta T cell modulation in anticancer treatment. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10:27-36.

- Shissler SC, Lee MS & Webb TJ. Mixed signals: Co-stimulation in invariant natural killer T cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunol. 2017; 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01447.

- Kägi D, Ledermann B, Bürki K, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity and their role in immunological protection and pathogenesis in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:207-32.

- Alspach E, Lussier DM, Schreiber RD. Interferon

and its important roles in promoting and inhibiting spontaneous and therapeutic cancer immunity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019;11(3):a028480. - Gocher AM, Workman CJ & Vignali DAA. Interferon-

: teammate or opponent in the tumour microenvironment? Nat Rev Immunol. 2022; 22 158-172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-021-00566-3. - Gálvez NMS. et al. Type I natural killer T cells as key regulators of the immune response to infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2021; 34: 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00232-20.

- Shrestha N. et al. Regulation of Acquired Immunity by

T-Cell/Den-dritic-Cell Interactions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005; 1062: 79-94. - Ye

, et al. cells infiltrating hepatocellular carcinomas are activated and predictive of a better prognosis. Aging. 2019;11(20):8879-91. - Shen J, et al. A subset of CXCR5+CD8+T cells in the germinal centers from human tonsils and lymph nodes help B cells produce immunoglobulins. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2287.

- Gibbs BF, Sumbayev VV, Hoyer KK. CXCR5+CD8 T cells: Potential immunotherapy targets or drivers of immune-mediated adverse events? Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1034764.

- Le K-S, et al. CXCR5 and ICOS expression identifies a CD8 T-cell subset with TFH features in Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood Adv. 2018;2:1889-900.

- Chaudhry MS, Karadimitris A. Role and Regulation of CD1d in Normal and Pathological B Cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:4761-8.

- Colvin RA, Campanella GSV, Sun J & Luster AD. Intracellular Domains of CXCR3 That Mediate CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 Function*. J Biol Chem. 2004; 279: 30219-30227.

- Bolivar-Wagers S, Larson JH, Jin S & Blazar BR. Cytolytic CD4+ and CD8+ Regulatory T-Cells and Implications for Developing Immunotherapies to Combat Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.864748.

- Chen PP, et al. Alloantigen-specific type 1 regulatory T cells suppress through CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways and persist long-term in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(617):eabf5264.

- Magnani CF, et al. Killing of myeloid APCs via HLA class I, CD2 and CD226 defines a novel mechanism of suppression by human Tr1 cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1652-62.

- Roessner PM, et al. EOMES and IL-10 regulate antitumor activity of T regulatory type 1 CD4+T cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2021;35:2311-24.

- Chuang Y, Hung ME, Cangelose BK, Leonard JN. Regulation of the IL-10-driven macrophage phenotype under incoherent stimuli. Innate Immun. 2016;22:647-57.

- Mittal SK, Cho K-J, Ishido S, Roche PA. Interleukin 10 (IL-10)-mediated Immunosuppression: march-I induction regulates antigen presentation by macrophages but not dendritic cells*. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:27158-67.

- Tuomela K, Ambrose AR. & Davis DM. Escaping Death: How Cancer Cells and Infected Cells Resist Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity. Front Immunol. 2022; 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.867098.

- Xu Y , et al. An engineered IL15 cytokine mutein fused to an anti-PD1 improves intratumoral T-cell function and antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9:1141-57.

- Meng F, Zhen S, Song B. HBV-specific CD4+ cytotoxic T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma are less cytolytic toward tumor cells and suppress CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor immunity. APMIS. 2017;125:743-51.

- Jacquier A, et al. Tumor infiltrating and peripheral CD4+ILT2+T cells are a cytotoxic subset selectively inhibited by HLA-G in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Lett. 2021;519:105-16.

- Dumont C , et al.

cells are an intratumoral cytotoxic population selectively inhibited by the immune-checkpoint HLA-G. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7:1619-32. - Akhmetzyanova I, et al. CD137 agonist therapy can reprogram regulatory T cells into cytotoxic CD4+ T cells with antitumor activity. J Immunol. 2016;196:484-92.

- van der Sluis TC, et al. OX40 agonism enhances PD-L1 checkpoint blockade by shifting the cytotoxic T cell differentiation spectrum. Cell Rep Med. 2023;4(3):100939.

- Yunger S, Geiger B, Friedman N, Besser MJ, Adutler-Lieber S. Modulating the proliferative and cytotoxic properties of patient-derived TIL by a synthetic immune niche of immobilized CCL21 and ICAM1. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1116328.

- Wang R, et al. CD40L-armed oncolytic herpes simplex virus suppresses pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by facilitating the tumor microenvironment favorable to cytotoxic T cell response in the syngeneic mouse model. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(1):e003809.

- Di Marco M, et al. Enhanced Expression of miR-181b in B Cells of CLL Improves the Anti-Tumor Cytotoxic T Cell Response. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:257.

- Schwartz AL, et al. Antisense targeting of CD47 enhances human cytotoxic T-cell activity and increases survival of mice bearing B16 melanoma when combined with anti-CTLA4 and tumor irradiation. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:1805-17.

- La Fleur L, et al. Targeting MARCO and IL37R on immunosuppressive macrophages in lung cancer blocks regulatory t cells and supports cytotoxic lymphocyte function. Cancer Res. 2021;81:956-67.

- Yan L, et al. Increased expression of Clec9A on cDC1s associated with cytotoxic CD8+ T cell response in COPD. Clin Immunol. 2022;242:109082.

- Leone RD, et al. Glutamine blockade induces divergent metabolic programs to overcome tumor immune evasion. Science. 2019;1979(366):1013-21.

- Li C , et al. The transcription factor Bhlhe40 programs mitochondrial regulation of resident CD8+ T cell fitness and functionality. Immunity. 2019;51:491-507.e7.

- Van Acker HH, Ma S, Scolaro T, Kaech SM, Mazzone M. How metabolism bridles cytotoxic CD8+ T cells through epigenetic modifications. Trends Immunol. 2021;42:401-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2021.03.006.

- Zhang C , et al. STAT3 activation-induced fatty acid oxidation in CD8+ T effector cells is critical for obesity-promoted breast tumor growth. Cell Metab. 2020;31:148-161.e5.

- Siegers GM, Dutta I, Lai R, Postovit LM. Functional plasticity of Gamma delta T cells and breast tumor targets in hypoxia. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1367.

- Jiang H, et al.

cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients present cytotoxic activity but are reduced in potency due to IL-2 and IL-21 pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;70:167-73. - Assy L, Khalil SM, Attia M, Salem ML. IL-12 conditioning of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from breast cancer patients promotes the zoledronate-induced expansion of

cells in vitro and enhances their cytotoxic activity and cytokine production. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;114:109402. - Gao Z, et al. Gamma delta T-cell-based immune checkpoint therapy: attractive candidate for antitumor treatment. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:31.

- Rigau M, Uldrich AP, Behren A. Targeting butyrophilins for cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2021;42:670-80.

- Zhu G , et al. Intratumour microbiome associated with the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and patient survival in cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2021;151:25-34.

- Perry LM, et al. Human soft tissue sarcomas harbor an intratumoral viral microbiome which is linked with natural killer cell infiltrate and prognosis. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11(1):e004285.

- Wang H , et al. The microbial metabolite trimethylamine N -oxide promotes antitumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Metab. 2022;34:581-594.e8.