DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-01768-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40011438

تاريخ النشر: 2025-02-26

تجديد العيوب المتعددة وإعادة بناء الطور للبيروفسكايتات ذات الأبعاد المنخفضة عبر الكلورة في الموقع من أجل ثنائيات الباعث الضوئي الأزرق العميق (454 نانومتر) الفعالة

الملخص

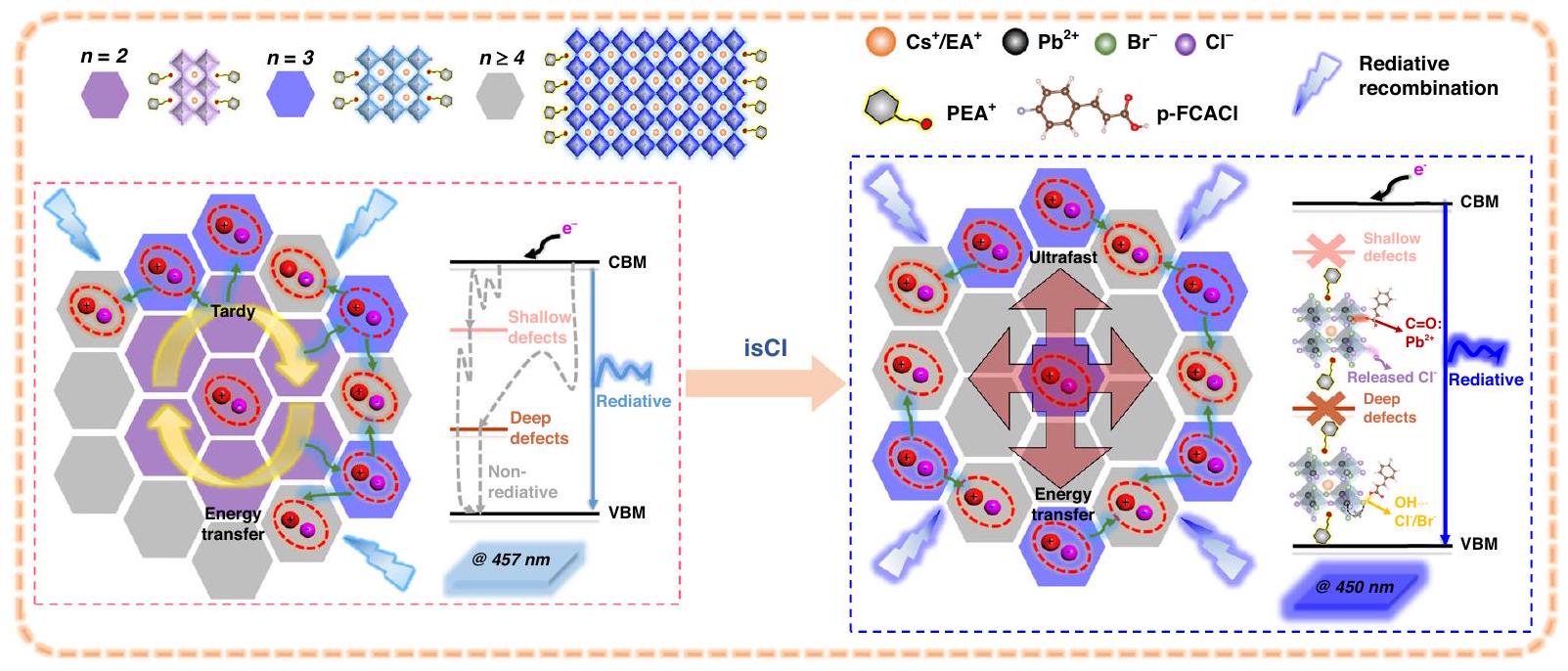

لا تزال ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من البيروفسكايت ذات اللون الأزرق الداكن (PeLEDs) المستندة إلى البيروفسكايتات ذات الأبعاد المخفضة (RDPs) تواجه بعض التحديات بما في ذلك إعادة التركيب غير الإشعاعي المعزز بالفخاخ، ونقل الإثارة البطيء، والانزياح غير المرغوب فيه في الطيف الكهروضوئي، مما يعيق تحقيق PeLEDs عالية الأداء. هنا، تم استخدام استراتيجية معالجة ما بعد الكلورة في الموقع (isCl) لتنظيم إعادة بناء الطور وتجديد العيوب المتعددة في RDPs، مما أدى إلى تبريد أفضل للحامل بمقدار 0.88 بيكوثانية، وطاقة ربط استثنائية للإثارة بمقدار 122.53 ميلي إلكترون فولت، وعائد كمي أعلى للضوء الفوتوني بنسبة 60.9% لأفلام RDP ذات الانبعاث الأزرق الداكن عند 450 نانومتر. يتم تحقيق تنظيم الطور من خلال الروابط الهيدروجينية المستمدة من الفلور التي تقلل من تكوين الجزيئات الصغيرة-

مقدمة

هناك بعض العوامل التي تعيق تطوير مصدري الضوء الأزرق الداكن. واحدة من القضايا الشائعة هي التوزيع غير المتجانس للطور لمختلف-

(عيوب الحالة السطحية)، تجمعات الرصاص-الرصاص، وعيوب الموقع المعاكس للرصاص-الهاليد (عيوب الحالة العميقة) الناتجة عن هجرة الأيونات السهلة بسبب تركيز الكلور العالي

هنا، نبلغ عن استراتيجية معالجة ما بعد التكلور في الموقع (isCl) من خلال استخدام كلوريد p-fluorocinnamoyl (p-FCACl) المذاب في مذيب مضاد لتنظيم حركيات تبلور RDPs بتركيبة من

النتائج

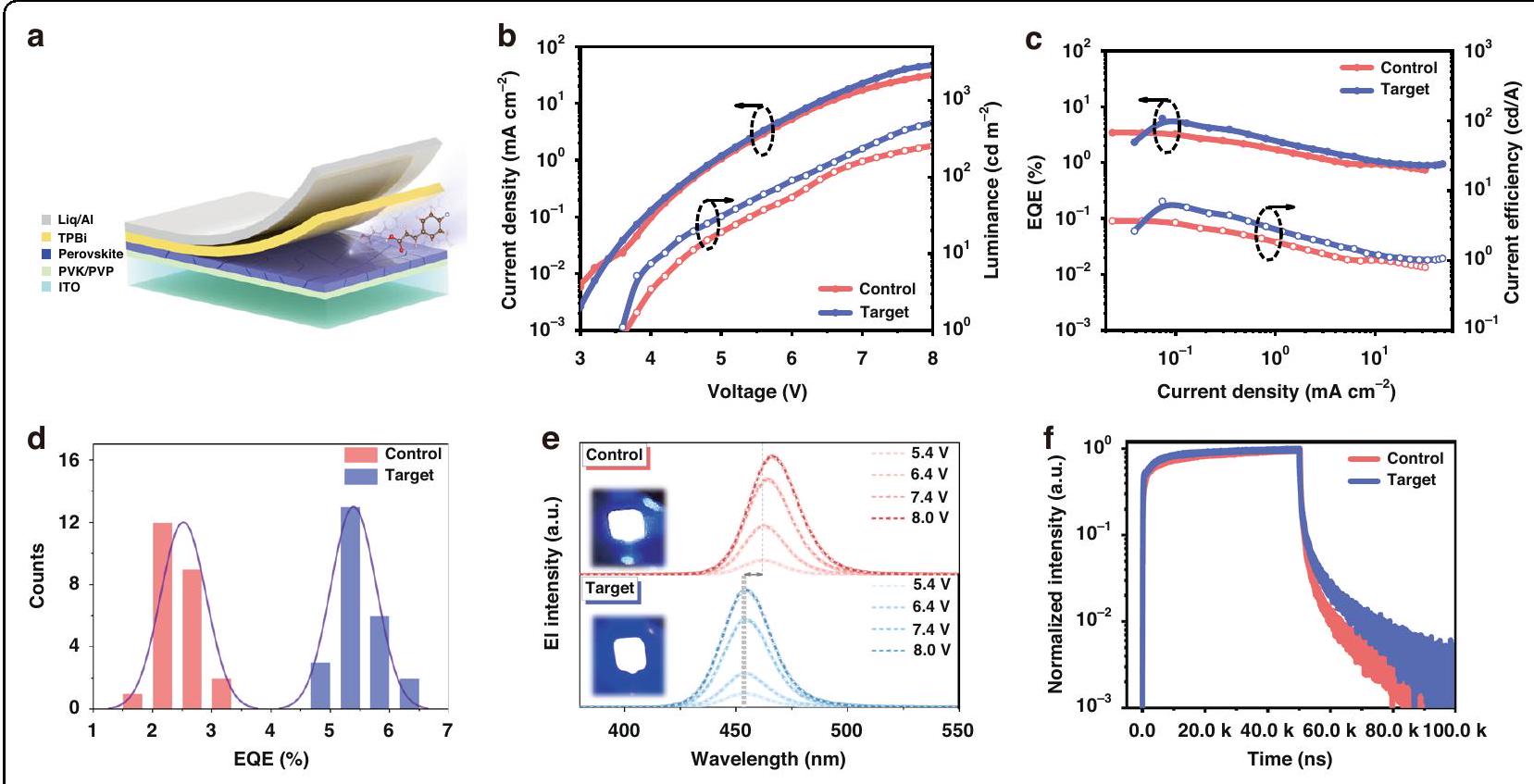

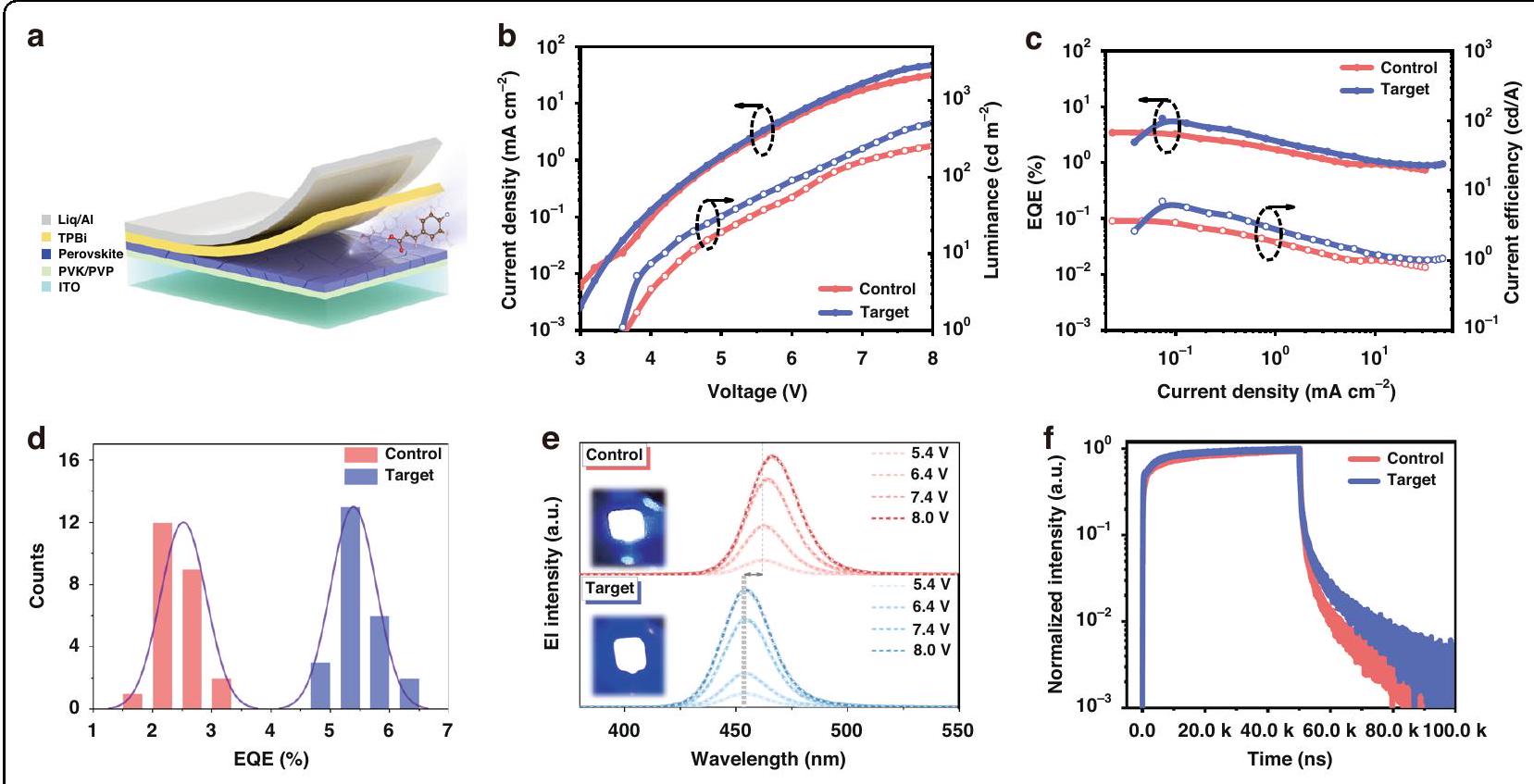

أداء الجهاز

كل طبقة في PeLED موضحة في الشكل S3 (المعلومات الداعمة) والشكل S4 (المعلومات الداعمة)، على التوالي.

كما هو موضح في الشكل 1e، من الجدير بالذكر أن جهاز الإضاءة العضوي القائم على الهاليد (isCl-0 PeLED) يظهر تحولًا واضحًا نحو الأطوال الموجية الأطول من 461 نانومتر إلى 466 نانومتر في طيف الإضاءة الكهربائية (EL) مع زيادة الجهد إلى 8.0 فولت، مصحوبًا بتوسيع عرض النطاق الكامل عند نصف الحد الأقصى (FWHM) بمقدار 26 نانومتر. بالمقابل، يظهر جهاز الإضاءة العضوي القائم على الهاليد (isCl-3 PeLED) طيف إضاءة كهربائية ثابت عند 454 نانومتر مع عرض نطاق ضيق بمقدار 24 نانومتر، مما يتوافق مع إحداثيات ثابتة من لجنة الإضاءة الدولية (CIE) تبلغ (0.149، 0.025) (الشكل S6a، b، المعلومات الداعمة). إن هذا التحسن المرضي في الاستقرار والانزياح الأزرق لطيف الإضاءة الكهربائية ناتج عن قمع هجرة أيونات الهاليد وإطلاق أيونات الكلوريد التي تزيد من فجوة الطاقة لمركبات RDPs. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم اختبار الاستقرار التشغيلي لجهاز الإضاءة العضوي القائم على الهاليد غير المغلف، وتظهر منحنيات الانحلال في الشكل S6c (المعلومات الداعمة)، مما يكشف أن جهاز الإضاءة العضوي القائم على الهاليد (isCl-3 PeLED) يظهر عمر نصف ممتد.

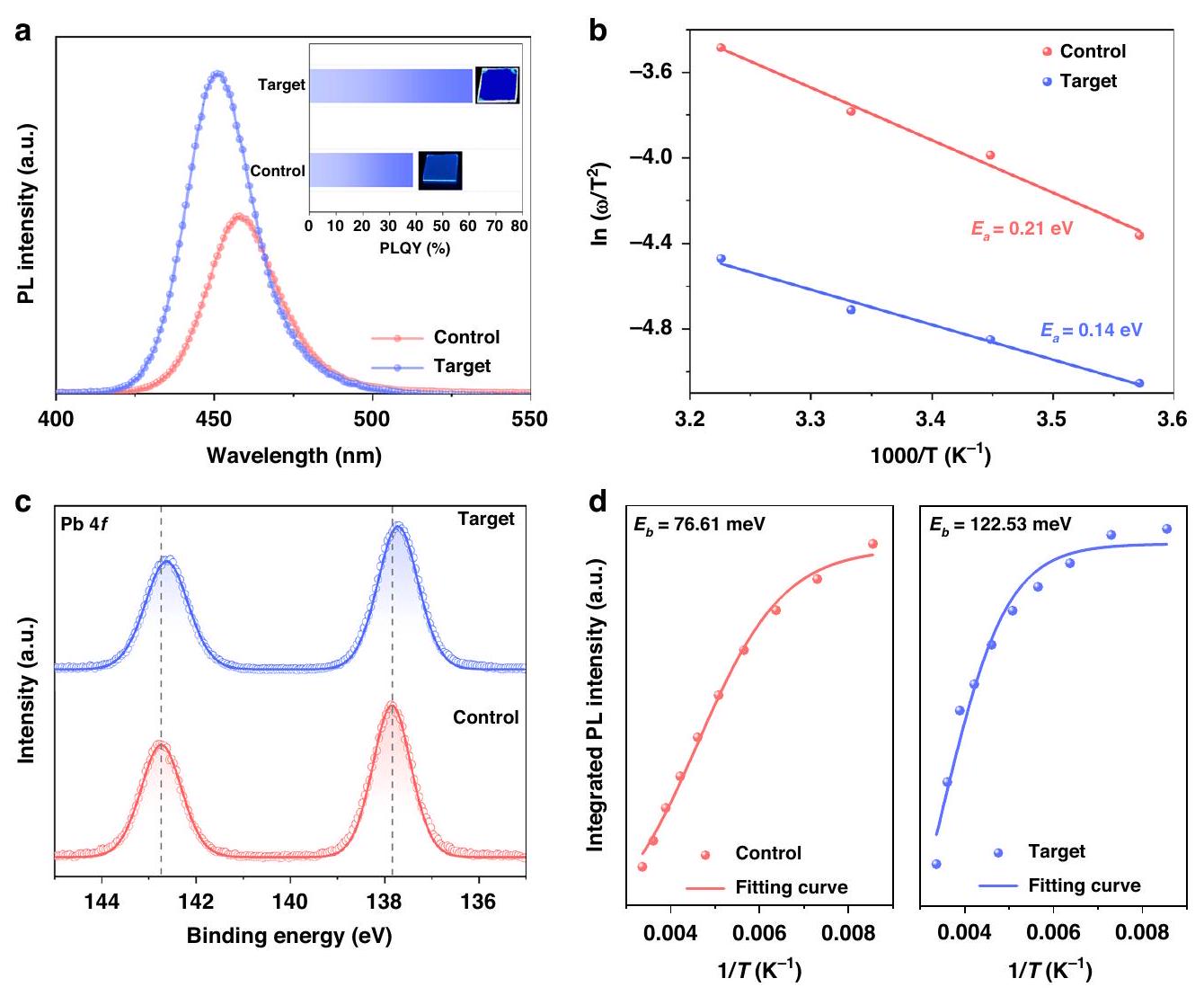

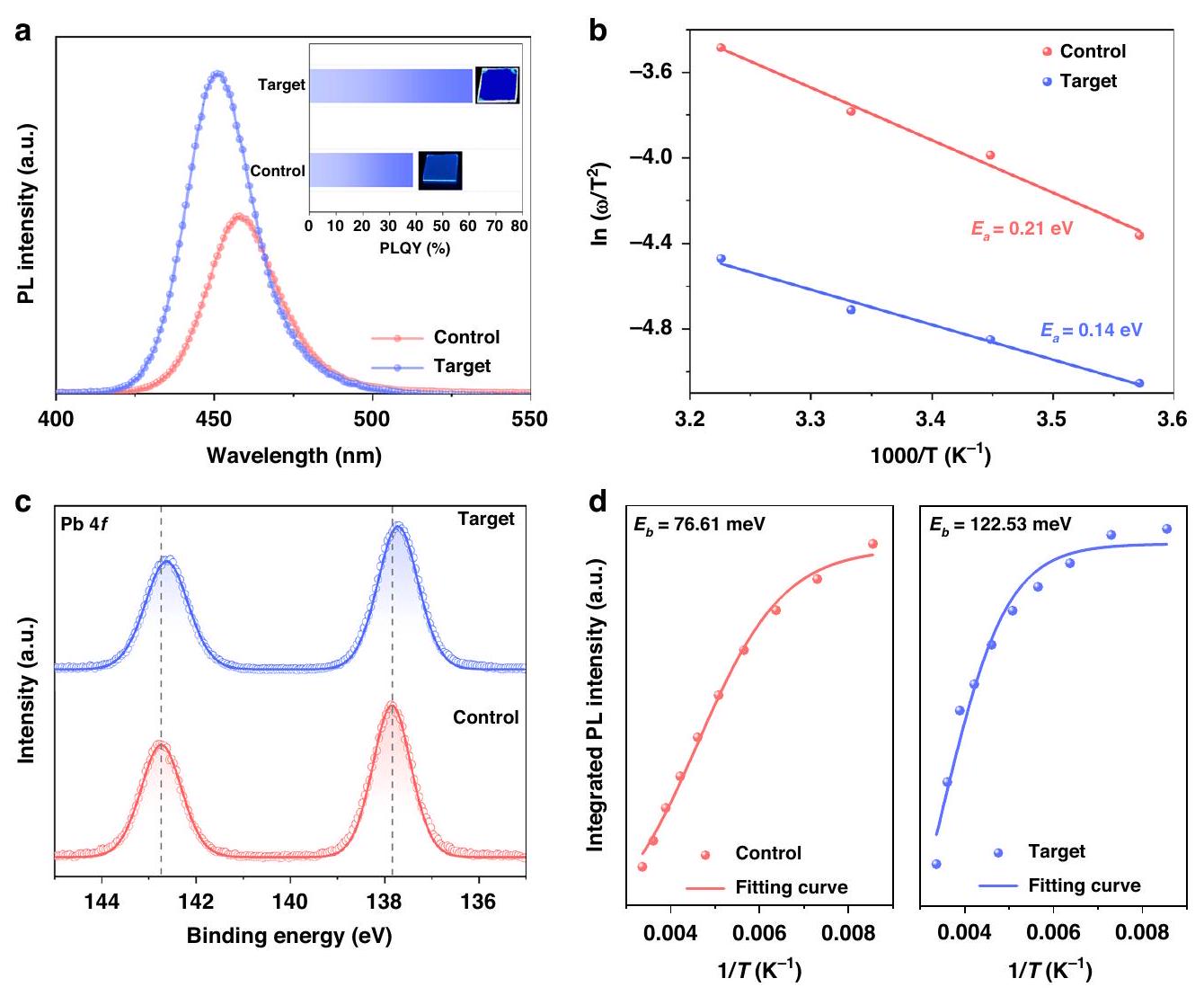

الخصائص البصرية الإلكترونية للبيروفسكايت ذات الأبعاد المخفضة

تم استخدام تقنيات التوصيف الطيفي الشاملة لفهم تأثيرات isCl. من خلال ضبط تركيز

(الشكل S8c، المعلومات الداعمة)، والذي يُعزى إلى زيادة طفيفة في العيوب بسبب ارتفاع

تم استخدام طيف القبول المعتمد على درجة الحرارة (AS) لتحليل توزيع الطاقة للعيوب، ويظهر طيف السعة-التردد المقابل في الشكل S9 (المعلومات الداعمة).

تم استخدام قياسات PL المعتمدة على درجة الحرارة للتحقيق في طاقة ارتباط الإثارة (

تظهر قياسات مجهر قوة بروب كيلفن (KPFM) (الشكل S12a، b، المعلومات الداعمة) زيادة ملحوظة في الجهد السطحي لعينة isCl-3، مما يشير إلى تحسين تجديد العيوب السطحية.

تمت دراسة استقرار الرطوبة لعينات isCl-0 و isCl-3 في الجو المحيط مع رطوبة نسبية (RH) من

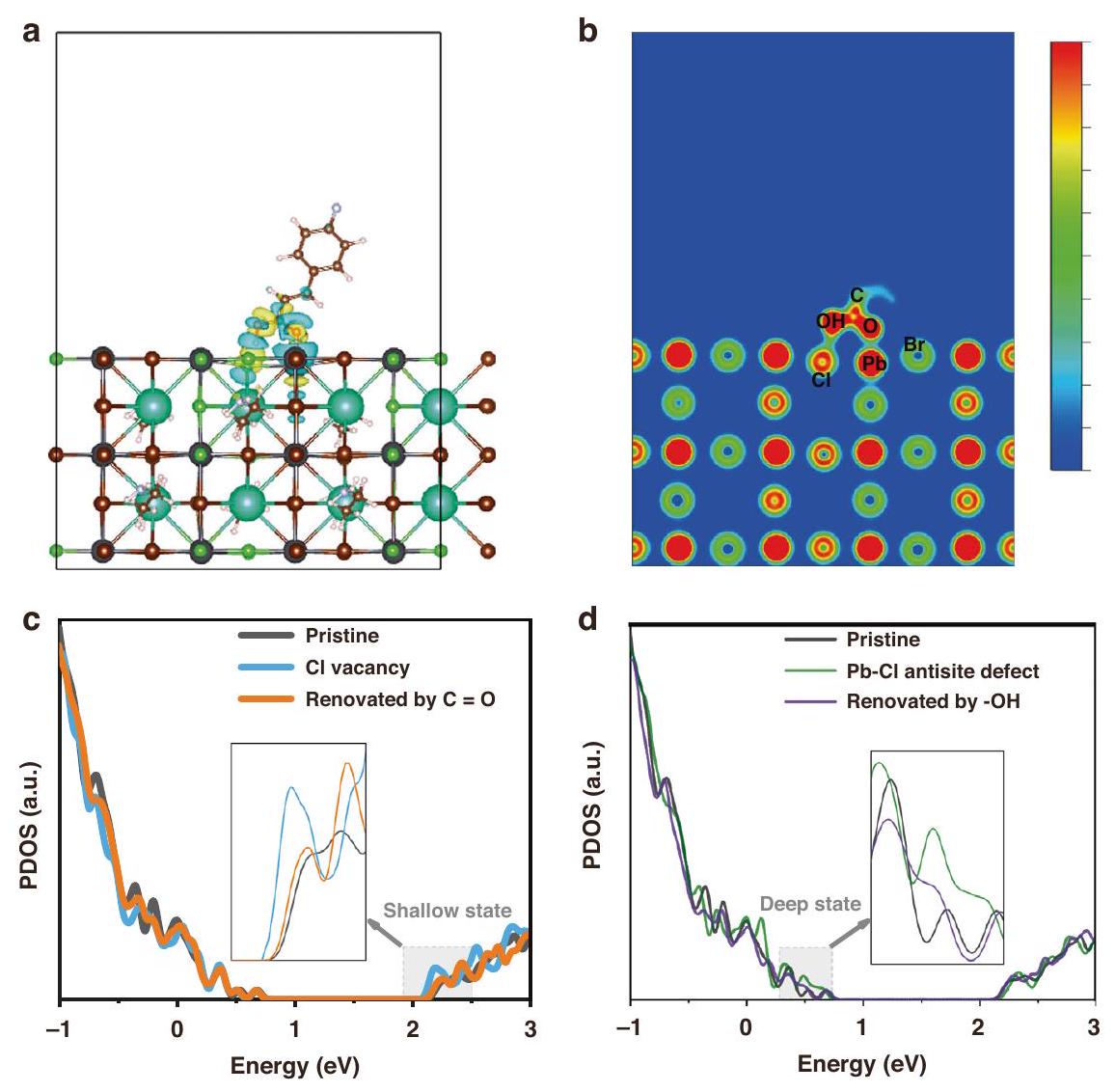

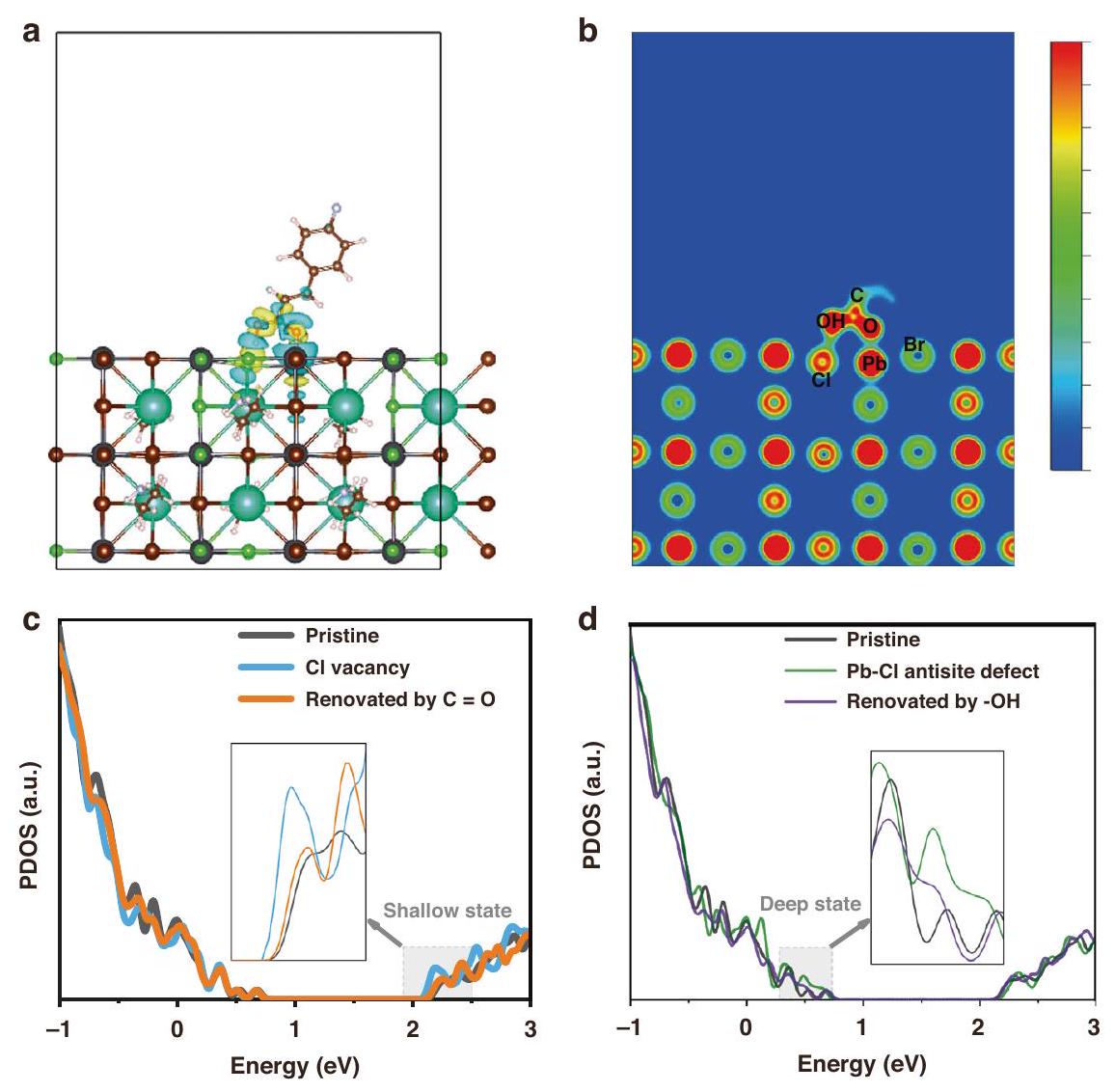

دراسة آلية تجديد العيوب المتعددة

كما ورد في الأدبيات السابقة، قد يؤدي هجرة أيونات الهاليد إلى إنشاء فراغات هاليد وعيوب مضادة لمواقع الرصاص-هاليد.

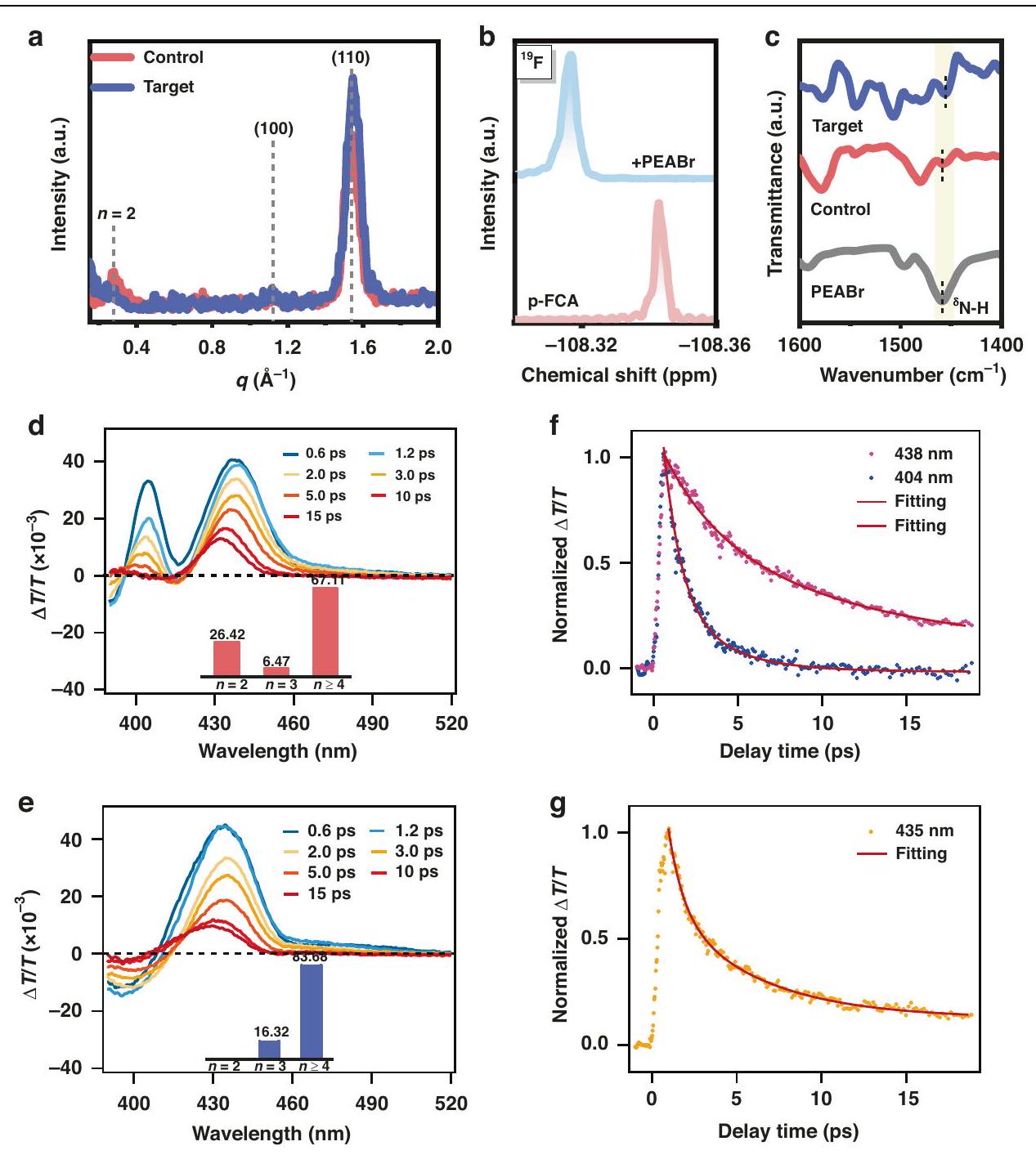

إعادة بناء الطور للبيروفسكيتات ذات الأبعاد المخفضة

القمع الفعال للصغار-

لفهم آلية تنظيم الطور،

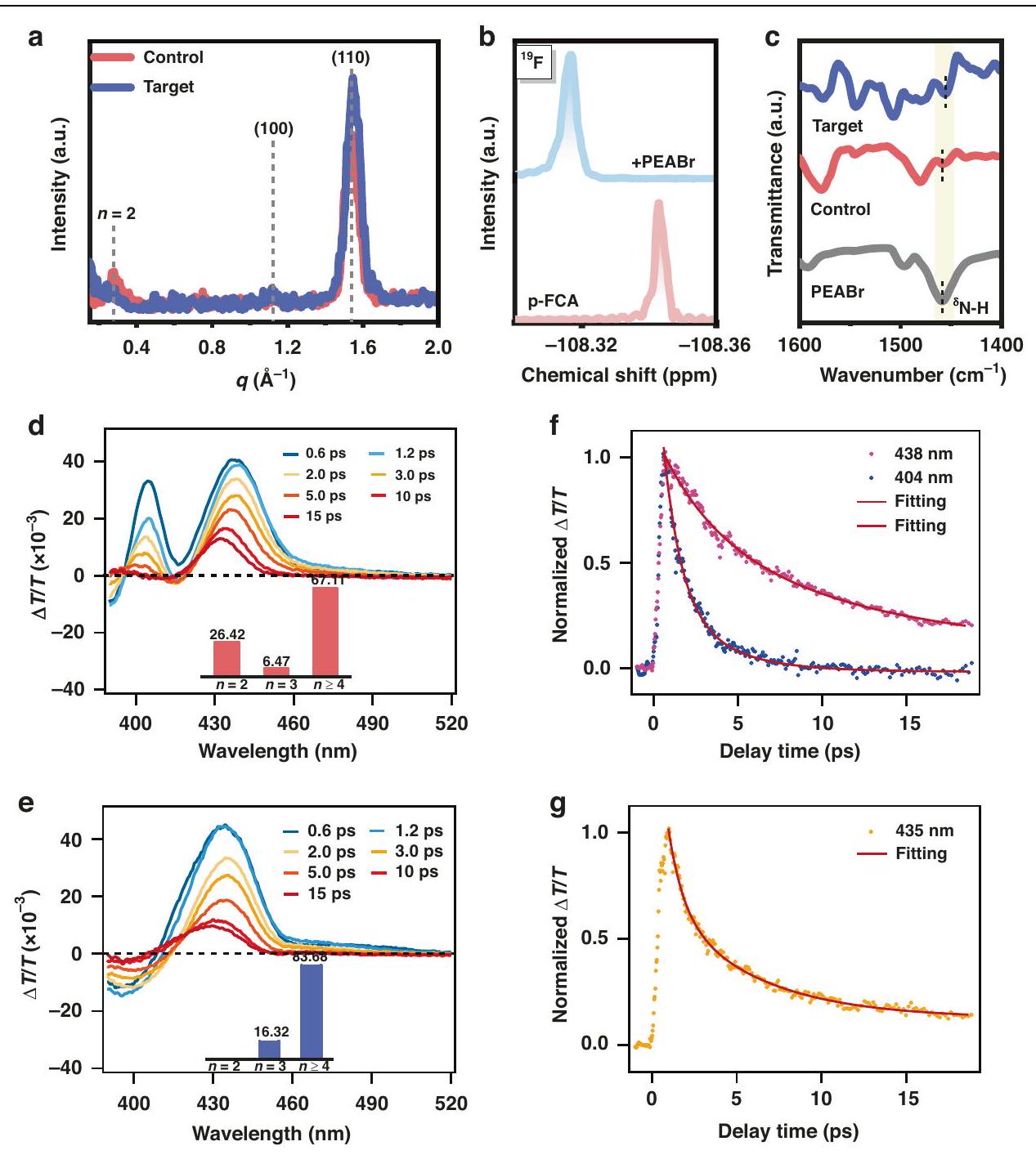

تم العثور على أن إعادة بناء الطور تؤثر بشكل كبير على ديناميات الحامل، كما كشفت طيفية الامتصاص العابر (TA). تقدم الشكل S20a و b (المعلومات الداعمة) خرائط الألوان TA لعينات isCl-0 و isCl-3. يتم تصوير طيف TA المقابل في أوقات تأخير مختلفة في الشكل 4d و e. بالنسبة لعينة isCl-0، تظهر قمم تلاشي الحالة الأساسية (GSB) المميزة في

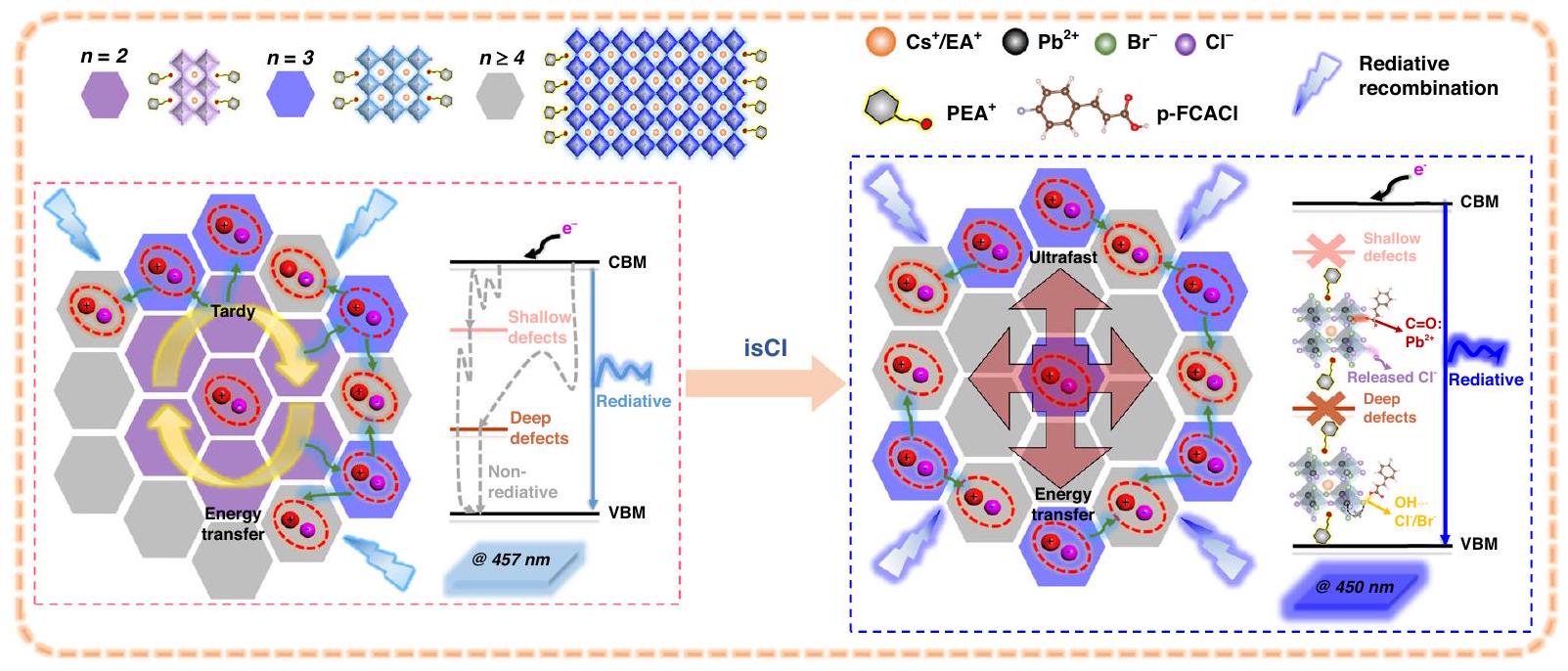

استنادًا إلى النتائج المذكورة أعلاه، يمكن الاستنتاج أن Cl يمكّن من تجديد عيوب متعددة سواء في الكتلة أو على سطح RDPs لتعزيز الإشعاعية.

موضحة في الشكل 5. خلال معالجة isCl، تجدد أيونات الكلور المحررة فراغات الهاليد سواء في الكتلة أو على سطح RDPs، مما يسهل توسيع فجوة الطاقة والانبعاث الأزرق. في الوقت نفسه، فإن

نقاش

المواد والطرق

المواد

كلوريد إيثيل أمين (EACl)، وأكسيد ثلاثي (4-فلوروفينيل) الفوسفور (TFPPO) من شركة شيان يوري سولار المحدودة. تم شراء 2،2’،2″-(1،3،5-بنزينيترييل)-تريس(1-فينيل-1-H-بنزيميدازول) (TPBi) وLiq من تكنولوجيا اللمعان. تم شراء كلوريد p-فلوروسينامويل (p-FCACl)، وحمض p-فلوروسيناميك (p-FCA)، و1،2-ثنائي كلورو إيثان (DCE) من العلّاء. تم استخدام جميع المواد الكيميائية مباشرة دون أي معالجة إضافية.

تحضير أفلام بيروفسكايت ذات الأبعاد المخفضة

تصنيع الجهاز

صندوق نيتروجين لتحضير طبقات PVK (المذابة في كلوريد البنزين،

توصيف الأفلام والأجهزة

حسابات DFT

الشكر والتقدير

تفاصيل المؤلف

توفر البيانات

تعارض المصالح

نُشر على الإنترنت: 26 فبراير 2025

References

- Deng, S. B. et al. Long-range exciton transport and slow annihilation in twodimensional hybrid perovskites. Nat. Commun. 11, 664 (2020).

- Chu, Z. M. et al. Blue light-emitting diodes based on quasi-two-dimensional perovskite with efficient charge injection and optimized phase distribution via an alkali metal salt. Nat. Electron. 6, 360-369 (2023).

- Yang, F. et al. Rational adjustment to interfacial interaction with carbonized polymer dots enabling efficient large-area perovskite light-emitting diodes. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 119 (2023).

- Yu, Y. et al. Red perovskite light-emitting diodes: recent advances and perspectives. Laser Photon. Rev. 17, 2200608 (2023).

- Yu, Y. et al. Regulating perovskite crystallization through interfacial engineering using a zwitterionic additive potassium sulfamate for efficient pure-blue lightemitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 136, e202319730 (2024).

- Karlsson, M. et al. Mixed halide perovskites for spectrally stable and highefficiency blue light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 12, 361 (2021).

- Cheng, L. et al. Multiple-quantum-well perovskites for high-performance lightemitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 32, 1904163 (2020).

- Zhang, L. J. et al. Manipulation of charge dynamics for efficient and bright blue perovskite light-emitting diodes with chiral ligands. Adv. Mater. 35, 2302059 (2023).

- Xia, Y. et al. Reduced confinement effect by isocyanate passivation for efficient sky-blue perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2208538 (2022).

10.Liu, S. C. et al. Zwitterions narrow distribution of perovskite quantum wells for blue light-emitting diodes with efficiency exceeding 15%. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208078 (2023). - Li, Y. H. et al. In situ hydrolysis of phosphate enabling sky-blue perovskite lightemitting diode with eqe approaching 16.32%. ACS Nano 18, 6513-6522 (2024).

- Tong, Y. F. et al. In situ halide exchange of cesium lead halide perovskites for blue light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207111 (2023).

- Wu, X. X. et al. Trap states in lead iodide perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 2089-2096 (2015).

- Yuan, S. et al. Efficient blue electroluminescence from reduced-dimensional perovskites. Nat. Photon. 18, 425-431 (2024).

- Guan, X. et al. Targeted elimination of tetravalent-Sn-induced defects for enhanced efficiency and stability in lead-free NIR-II perovskite LEDs. Nat. Commun. 15, 9913 (2024).

- Shen, Y. et al. Unveiling the carrier dynamics of perovskite light-emitting diodes via transient electroluminescence. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 7916-7923 (2024).

- Ma, D. X. et al. Chloride insertion-immobilization enables bright, narrowband, and stable blue-emitting perovskite diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5126-5134 (2020).

- Zou, G. R. et al. Color-stable deep-blue perovskite light-emitting diodes based on organotrichlorosilane post-treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2103219 (2021).

- Yuan, S. et al. Efficient and spectrally stable blue perovskite light-emitting diodes employing a cationic π-conjugated polymer. Adv. Mater. 33, 2103640 (2021).

- Zheng, X. P. et al. Defect passivation in hybrid perovskite solar cells using quaternary ammonium halide anions and cations. Nat. Energy 2, 17102 (2017).

- Zhang, C. C. et al. Perovskite films with reduced interfacial strains via a molecular-level flexible interlayer for photovoltaic application. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001479 (2020).

- Wang, T. et al. Deep defect passivation and shallow vacancy repair via an ionic silicone polymer toward highly stable inverted perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 4414-4424 (2022).

- Luo, X. Y. et al. Effects of local compositional heterogeneity in mixed halide perovskites on blue electroluminescence. Matter 7, 1054-1070 (2024).

- Zhang, J. et al. Sulfonic zwitterion for passivating deep and shallow level defects in perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2111578 (2022).

- Liu, Y. J. et al. A multifunctional additive strategy enables efficient pure-blue perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2302161 (2023).

- Qiu, J. M. et al. Robust molecular-dipole-induced surface functionalization of inorganic perovskites for efficient solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 1821-1830 (2022).

- Liu, X. X. et al. Full defects passivation enables

efficiency perovskite solar cells operating in air. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001958 (2020). - Xie, L. L. et al. Highly efficient synthesis of 4, 4-dimethylsterol oleates using acyl chloride method through esterification. Food Chem. 364, 130140 (2021).

- Filler, M. A. et al. Formation of surface-bound acyl groups by reaction of acyl halides on Ge (100)-

. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 4115-4124 (2006). - Han, D. Y. et al. Tautomeric mixture coordination enables efficient lead-free perovskite LEDs. Nature 622, 493-498 (2023).

- Schmidt, T., Lischka, K. & Zulehner, W. Excitation-power dependence of the near-band-edge photoluminescence of semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 45, 8989-8994 (1992).

- Wang, L. et al. Regulated perovskite crystallization for efficient blue lightemitting diodes via interfacial molecular network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401297 (2024).

- Li, X. Y. et al. Bright colloidal quantum dot light-emitting diodes enabled by efficient chlorination. Nat. Photon. 12, 159-164 (2018).

- Li, M. H. et al. High-efficiency perovskite solar cells with improved interfacial charge extraction by bridging molecules. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406532 (2024).

- Dong, J. C. et al. Deep-blue electroluminescence of perovskites with reduced dimensionality achieved by manipulating adsorption-energy differences. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210322 (2022).

- Wang, B. et al. Low-dimensional phase regulation to restrain non-radiative recombination for sky-blue perovskite LEDs with EQE exceeding 15%. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202219255 (2023).

- Wang, X. et al. Engineering fluorinated-cation containing inverted perovskite solar cells with an efficiency of

and improved stability towards humidity. Nat. Commun. 12, 52 (2021). - Liu, Y. et al. Wide-bandgap perovskite quantum dots in perovskite matrix for sky-blue light-emitting diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4009-4016 (2022).

- Chu, Z. M. et al. Large cation ethylammonium incorporated perovskite for efficient and spectra stable blue light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 11, 4165 (2020).

- Mei, X. Y. et al. In situ ligand compensation of perovskite quantum dots for efficient light-emitting diodes. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 4386-4396 (2023).

- Qi, Z. W. et al. Ligand-pinning induced size modulation of

perovskite quantum dots for red light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2405679 (2024). - Qiu, J. M. et al. Dipolar chemical bridge induced

perovskite solar cells with efficiency. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401751 (2024). - Fu, Y. X. et al. Insight into diphenyl phosphine oxygen-based molecular additives as defect passivators toward efficient quasi-2D perovskite lightemitting diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 10877-10884 (2023).

- Shen, Y. et al. Interfacial potassium-guided grain growth for efficient deepblue perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2006736 (2021).

- Sun, M. N. et al. Mixed 2D/3D perovskite with fine phase control modulated by a novel cyclopentanamine hydrobromide for better stability in lightemitting diodes. Chem. Eng. J. 393, 124787 (2020).

- Ma, D. X. et al. Distribution control enables efficient reduced-dimensional perovskite LEDs. Nature 599, 594-598 (2021).

- Yu, M. B. et al. Modulating phase distribution and passivating surface defects of quasi-2D perovskites via potassium tetrafluoroborate for light-emitting diodes. Chem. Eng. J. 450, 138021 (2022).

- Zhang, F. J. et al. High-performance blue perovskite light-emitting diodes enabled by synergistic effect of additives. Nano Lett. 24, 1268-1276 (2024).

- Wang, C.H. et al. Dimension control of in situ fabricated

nanocrystal films toward efficient blue light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 11, 6428 (2020).

- Correspondence: Gang Gao (gaogang@hit.edu.cn) or

Yong-Biao Zhao (yzhao@ynu.edu.cn) or Jiaqi Zhu (zhujq@hit.edu.cn)

National Key Laboratory of Science and Technology on Advanced Composites in Special Environments, Harbin Institute of Technology, 150080 Harbin, China

Zhengzhou Research Institute, Harbin Institute of Technology, 450046 Zhengzhou, China

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article These authors contributed equally: Mubing Yu, Tingxiao Qin

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-01768-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40011438

Publication Date: 2025-02-26

Multiple defects renovation and phase reconstruction of reduced-dimensional perovskites via in situ chlorination for efficient deep-blue ( 454 nm ) light-emitting diodes

Abstract

Deep-blue perovskite light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs) based on reduced-dimensional perovskites (RDPs) still face a few challenges including severe trap-assisted nonradiative recombination, sluggish exciton transfer, and undesirable bathochromic shift of the electroluminescence spectra, impeding the realization of high-performance PeLEDs. Herein, an in situ chlorination (isCl) post-treatment strategy was employed to regulate phase reconstruction and renovate multiple defects of RDPs, leading to superior carrier cooling of 0.88 ps , extraordinary exciton binding energy of 122.53 meV , and higher photoluminescence quantum yield of 60.9% for RDP films with deep-blue emission at 450 nm . The phase regulation is accomplished via fluorine-derived hydrogen bonds that suppress the formation of small-

Introduction

There are a few factors hindering the development of deep-blue RDP emitters. One common issue is the heterogeneous phase distribution of various-

(shallow-state defects), lead-lead clusters, and lead-halide antisite defects (deep-state defects) resulting from facile ion migration due to high chlorine concentration

Herein, we report an in situ chlorination (isCl) post-treatment strategy by utilizing p-fluorocinnamoyl chloride ( p -FCACl) dissolved in antisolvent to regulate the crystallization kinetics of RDPs with a composition of

Results

Device performance

each other layer in the PeLED are depicted in Fig. S3 (Supporting Information) and Fig. S4 (Supporting Information), respectively

As depicted in Fig. 1e, it is worth mentioning that the isCl-0 PeLED exhibits an obviously bathochromic shift from 461 nm to 466 nm in the EL spectra as the bias ramps up to 8.0 V accompanied by a widened full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 26 nm . In contrast, the isCl-3 PeLED shows unchanged EL spectra at 454 nm with a narrowed FWHM of 24 nm , corresponding to a stable Commission International de l’Elairage (CIE) coordinate of (0.149, 0.025) (Fig. S6a, b, Supporting Information). Such satisfactory enhancement in stability and blue-shift of the EL spectra results from the suppressed halide ion migration and released chloride ions enlarging the bandgap of RDPs. Besides, the operational stability of the unencapsulated PeLED was tested, and the decay curves are shown in Fig. S6c (Supporting Information), which reveals that the isCl-3 PeLED exhibits a prolonged halflifetime (

Optoelectronic properties of reduced-dimensional perovskites

Comprehensive spectroscopic characterization techniques were used to understand the effects of isCl. By tuning the concentration of

(Fig. S8c, Supporting Information), which is attributed to the slightly increased defects due to a higher

Temperature-dependent admittance spectra (AS) were used to analyze the energy distribution of defects, and the corresponding capacitance-frequency spectra are shown in Fig. S9 (Supporting Information)

Temperature-dependent PL measurements were utilized to investigate the exciton binding energy (

Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) measurements (Fig. S12a, b, Supporting Information) show a significant increase in the surface potential of the isCl-3 sample, indicating improved renovation of surface defects

The moisture stability of the isCl-0 and isCl-3 samples was investigated in the ambient atmosphere with relative humidity (RH) of

Mechanism study of multiple defects renovation

As reported by previous literature, halide ion migration may create halide vacancies and lead-halide antisite defects

Phase reconstruction of reduced-dimensional perovskites

the efficient suppression of small-

To understand the phase regulation mechanism,

Phase reconstruction was found to significantly alter the carrier dynamics, as revealed by transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy. Fig. S20a, b (Supporting Information) presents the TA color maps of the isCl-0 and isCl-3 samples. Corresponding TA spectra at various delay times are depicted in Fig. 4d, e. For the isCl-0 sample, distinct ground-state bleach (GSB) peaks at

Based on the above results, it can be concluded that is Cl enables the renovation of multiple defects both in the bulk and on the surface of RDPs to enhance radiative

depicted in Fig. 5. During isCl treatment, released chloride ions renovate halide vacancies both in bulk and on the surface of RDPs, which facilitates enlarged bandgap and blue-shifted emission. Meanwhile, the

Discussion

Materials and methods

Materials

ethylamine chloride (EACl), and Tri (4-fluorophenyl) phosphine oxide (TFPPO) were bought from Xi’an Yuri Solar Co., Ltd. 2,2′,2″-(1,3,5-Benzinetriyl)-tris(1-phenyl-1-H-benzimidazole) (TPBi) and Liq were purchased from Luminescence Technology. p-Fluorocinnamoyl chloride (p-FCACl), p-Fluorocinnamic acid (p-FCA), and 1, 2-dichloroethane (DCE) were purchased from Aladdin. All the chemicals were utilized directly without any further treatment.

Preparation of reduced-dimensional perovskite films

Device fabrication

nitrogen glovebox to prepare PVK layers (dissolved in chlorobenzene,

Films and device characterization

DFT calculations

Acknowledgements

Author details

Data availability

Conflict of interest

Published online: 26 February 2025

References

- Deng, S. B. et al. Long-range exciton transport and slow annihilation in twodimensional hybrid perovskites. Nat. Commun. 11, 664 (2020).

- Chu, Z. M. et al. Blue light-emitting diodes based on quasi-two-dimensional perovskite with efficient charge injection and optimized phase distribution via an alkali metal salt. Nat. Electron. 6, 360-369 (2023).

- Yang, F. et al. Rational adjustment to interfacial interaction with carbonized polymer dots enabling efficient large-area perovskite light-emitting diodes. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 119 (2023).

- Yu, Y. et al. Red perovskite light-emitting diodes: recent advances and perspectives. Laser Photon. Rev. 17, 2200608 (2023).

- Yu, Y. et al. Regulating perovskite crystallization through interfacial engineering using a zwitterionic additive potassium sulfamate for efficient pure-blue lightemitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 136, e202319730 (2024).

- Karlsson, M. et al. Mixed halide perovskites for spectrally stable and highefficiency blue light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 12, 361 (2021).

- Cheng, L. et al. Multiple-quantum-well perovskites for high-performance lightemitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 32, 1904163 (2020).

- Zhang, L. J. et al. Manipulation of charge dynamics for efficient and bright blue perovskite light-emitting diodes with chiral ligands. Adv. Mater. 35, 2302059 (2023).

- Xia, Y. et al. Reduced confinement effect by isocyanate passivation for efficient sky-blue perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2208538 (2022).

10.Liu, S. C. et al. Zwitterions narrow distribution of perovskite quantum wells for blue light-emitting diodes with efficiency exceeding 15%. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208078 (2023). - Li, Y. H. et al. In situ hydrolysis of phosphate enabling sky-blue perovskite lightemitting diode with eqe approaching 16.32%. ACS Nano 18, 6513-6522 (2024).

- Tong, Y. F. et al. In situ halide exchange of cesium lead halide perovskites for blue light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207111 (2023).

- Wu, X. X. et al. Trap states in lead iodide perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 2089-2096 (2015).

- Yuan, S. et al. Efficient blue electroluminescence from reduced-dimensional perovskites. Nat. Photon. 18, 425-431 (2024).

- Guan, X. et al. Targeted elimination of tetravalent-Sn-induced defects for enhanced efficiency and stability in lead-free NIR-II perovskite LEDs. Nat. Commun. 15, 9913 (2024).

- Shen, Y. et al. Unveiling the carrier dynamics of perovskite light-emitting diodes via transient electroluminescence. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 7916-7923 (2024).

- Ma, D. X. et al. Chloride insertion-immobilization enables bright, narrowband, and stable blue-emitting perovskite diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5126-5134 (2020).

- Zou, G. R. et al. Color-stable deep-blue perovskite light-emitting diodes based on organotrichlorosilane post-treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2103219 (2021).

- Yuan, S. et al. Efficient and spectrally stable blue perovskite light-emitting diodes employing a cationic π-conjugated polymer. Adv. Mater. 33, 2103640 (2021).

- Zheng, X. P. et al. Defect passivation in hybrid perovskite solar cells using quaternary ammonium halide anions and cations. Nat. Energy 2, 17102 (2017).

- Zhang, C. C. et al. Perovskite films with reduced interfacial strains via a molecular-level flexible interlayer for photovoltaic application. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001479 (2020).

- Wang, T. et al. Deep defect passivation and shallow vacancy repair via an ionic silicone polymer toward highly stable inverted perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 4414-4424 (2022).

- Luo, X. Y. et al. Effects of local compositional heterogeneity in mixed halide perovskites on blue electroluminescence. Matter 7, 1054-1070 (2024).

- Zhang, J. et al. Sulfonic zwitterion for passivating deep and shallow level defects in perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2111578 (2022).

- Liu, Y. J. et al. A multifunctional additive strategy enables efficient pure-blue perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2302161 (2023).

- Qiu, J. M. et al. Robust molecular-dipole-induced surface functionalization of inorganic perovskites for efficient solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 1821-1830 (2022).

- Liu, X. X. et al. Full defects passivation enables

efficiency perovskite solar cells operating in air. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001958 (2020). - Xie, L. L. et al. Highly efficient synthesis of 4, 4-dimethylsterol oleates using acyl chloride method through esterification. Food Chem. 364, 130140 (2021).

- Filler, M. A. et al. Formation of surface-bound acyl groups by reaction of acyl halides on Ge (100)-

. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 4115-4124 (2006). - Han, D. Y. et al. Tautomeric mixture coordination enables efficient lead-free perovskite LEDs. Nature 622, 493-498 (2023).

- Schmidt, T., Lischka, K. & Zulehner, W. Excitation-power dependence of the near-band-edge photoluminescence of semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 45, 8989-8994 (1992).

- Wang, L. et al. Regulated perovskite crystallization for efficient blue lightemitting diodes via interfacial molecular network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401297 (2024).

- Li, X. Y. et al. Bright colloidal quantum dot light-emitting diodes enabled by efficient chlorination. Nat. Photon. 12, 159-164 (2018).

- Li, M. H. et al. High-efficiency perovskite solar cells with improved interfacial charge extraction by bridging molecules. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406532 (2024).

- Dong, J. C. et al. Deep-blue electroluminescence of perovskites with reduced dimensionality achieved by manipulating adsorption-energy differences. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210322 (2022).

- Wang, B. et al. Low-dimensional phase regulation to restrain non-radiative recombination for sky-blue perovskite LEDs with EQE exceeding 15%. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202219255 (2023).

- Wang, X. et al. Engineering fluorinated-cation containing inverted perovskite solar cells with an efficiency of

and improved stability towards humidity. Nat. Commun. 12, 52 (2021). - Liu, Y. et al. Wide-bandgap perovskite quantum dots in perovskite matrix for sky-blue light-emitting diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4009-4016 (2022).

- Chu, Z. M. et al. Large cation ethylammonium incorporated perovskite for efficient and spectra stable blue light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 11, 4165 (2020).

- Mei, X. Y. et al. In situ ligand compensation of perovskite quantum dots for efficient light-emitting diodes. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 4386-4396 (2023).

- Qi, Z. W. et al. Ligand-pinning induced size modulation of

perovskite quantum dots for red light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2405679 (2024). - Qiu, J. M. et al. Dipolar chemical bridge induced

perovskite solar cells with efficiency. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401751 (2024). - Fu, Y. X. et al. Insight into diphenyl phosphine oxygen-based molecular additives as defect passivators toward efficient quasi-2D perovskite lightemitting diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 10877-10884 (2023).

- Shen, Y. et al. Interfacial potassium-guided grain growth for efficient deepblue perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2006736 (2021).

- Sun, M. N. et al. Mixed 2D/3D perovskite with fine phase control modulated by a novel cyclopentanamine hydrobromide for better stability in lightemitting diodes. Chem. Eng. J. 393, 124787 (2020).

- Ma, D. X. et al. Distribution control enables efficient reduced-dimensional perovskite LEDs. Nature 599, 594-598 (2021).

- Yu, M. B. et al. Modulating phase distribution and passivating surface defects of quasi-2D perovskites via potassium tetrafluoroborate for light-emitting diodes. Chem. Eng. J. 450, 138021 (2022).

- Zhang, F. J. et al. High-performance blue perovskite light-emitting diodes enabled by synergistic effect of additives. Nano Lett. 24, 1268-1276 (2024).

- Wang, C.H. et al. Dimension control of in situ fabricated

nanocrystal films toward efficient blue light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 11, 6428 (2020).

- Correspondence: Gang Gao (gaogang@hit.edu.cn) or

Yong-Biao Zhao (yzhao@ynu.edu.cn) or Jiaqi Zhu (zhujq@hit.edu.cn)

National Key Laboratory of Science and Technology on Advanced Composites in Special Environments, Harbin Institute of Technology, 150080 Harbin, China

Zhengzhou Research Institute, Harbin Institute of Technology, 450046 Zhengzhou, China

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article These authors contributed equally: Mubing Yu, Tingxiao Qin