DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57140-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40025011

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-01

تحفيز اختزال ثاني أكسيد الكربون بواسطة الضوء المرئي على مواقع الإنديوم المتوترة ذريًا في الهواء المحيط

تم القبول: 8 فبراير 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 01 مارس 2025

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

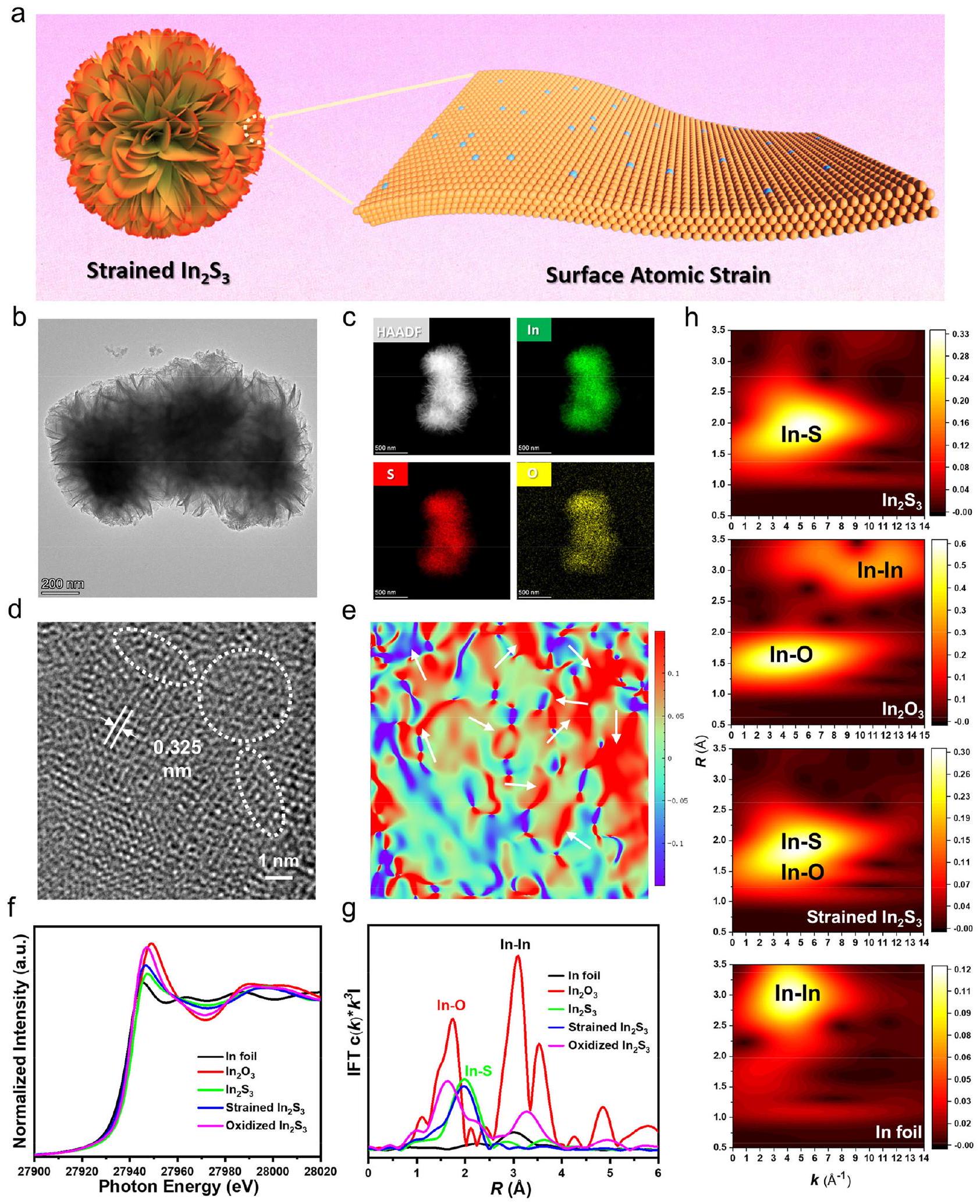

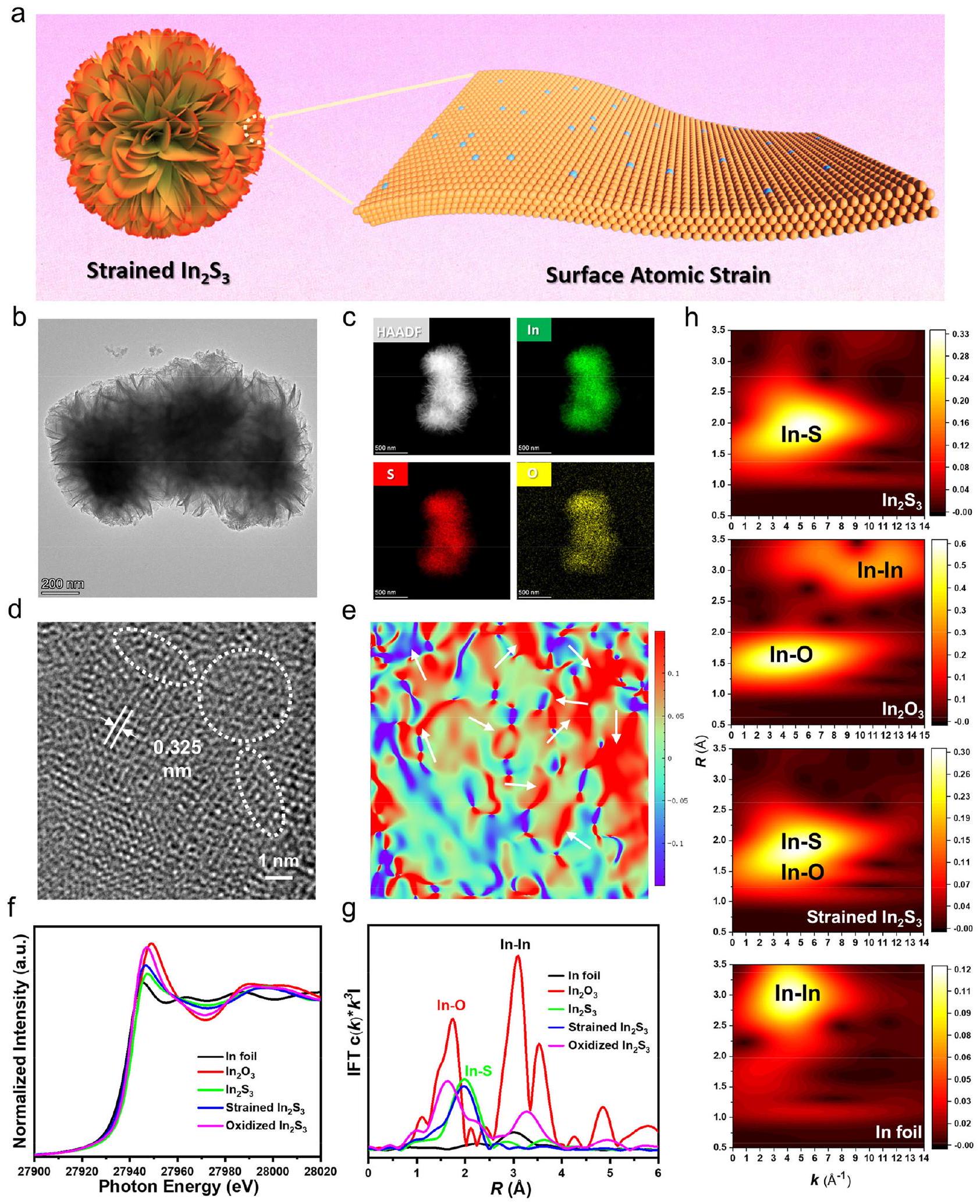

يقدم هندسة الإجهاد استراتيجية جذابة لتحسين الأداء التحفيزي الجوهري لمحفز غير متجانس. هنا، ننجح في إدخال إجهاد في كبريتيد الإنديوم الطبقي.

تستفيد التفاعلات الضوئية الحفازة من خلال تقديم عدد كبير من المواقع النشطة حفازياً. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن يؤدي الهيكل النانوي الرقيق لهذه المواد ثنائية الأبعاد إلى تقصير مسارات هجرة حوامل الشحنة الناتجة عن الضوء بشكل كبير، مما يقلل بشكل كبير من إعادة اتحاد الإلكترونات والثقوب ويحسن كفاءة فصل حوامل الشحنة. لتحسين أداء محفزات الكبريتيد المعدنية في التحفيز الضوئي، يوفر ضبط الهيكل الإلكتروني لمواقع المعادن من خلال هندسة الضغط استراتيجية فعالة.

صورة رسم خرائط الإجهاد على طول

إجهاد صغير النطاق على المستوى الذري (مجهد

مجموعة من القياسات الطيفية في الموقع وحسابات نظرية الكثافة (DFT)، التوتر الذري

تعزيز أداء اختزال ثاني أكسيد الكربون بشكل كبير تحت إضاءة الطيف الكامل/الضوء المرئي في كل من النقاء

النتائج والمناقشة

الخصائص الهيكلية للطبقات

تحفيز ضوئي

شرط الإشعاع الطيف الكامل في النقاء

ظهرت تحت إشعاع الطيف الكامل (الشكل 3f) أو إشعاع الضوء المرئي (الشكل 3g) وزادت كثافتها مع زيادة وقت الإشعاع الضوئي، بسبب زيادة تغطية * COOH (وهو وسيط حاسم لـ

رؤية النشاط الضوئي المحفز المتزايد

من المعروف جيدًا أن الزيادة في التردد

كشفت ملفات الطاقة الحرة المنحدرة أن تكوين *CO من *COOH كان أكثر تلقائية على المواد المتوترة.

نقاش

القياسات وحسابات DFT، مما أدى إلى تعزيز كبير في أداء اختزال CO2 الضوئي.

طرق

المواد

تركيب

تركيب المواد المتوترة

تركيب المؤكسد

تركيب

توصيف

تم قياس الإيزوثيرمات على جهاز Micromeritics ASAP2460. تم تسجيل استجابات التيار الضوئي العابر وطيف التحليل الكهربائي (EIS) للعينات على جهاز عمل كهربائي (CHI660C Instruments، الصين) بتكوين ثلاثي الأقطاب في

تحفيز ضوئي

التفاصيل الحاسوبية

توفر البيانات

References

- Xu, Y. et al. Engineering built-in electric field microenvironment of CQDs/g-

heterojunction for efficient photocatalytic reduction. Adv. Sci. e2403607 (2024). - Wang, L., Wang, D. & Li, Y. Single-atom catalysis for carbon neutrality. Carbon Energy 4, 1021-1079 (2022).

- Ou, H. et al. Carbon nitride photocatalysts with integrated oxidation and reduction atomic active centers for improved

conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202206579 (2022). - Vu, N. N., Kaliaguine, S. & Do, T. O. Critical aspects and recent advances in structural engineering of photocatalysts for sunlightdriven photocatalytic reduction of

into fuels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1901825 (2019). - Ou, M. et al. Amino-assisted anchoring of

perovskite quantum dots on porous for enhanced photocatalytic reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13570-13574 (2018). - Liu, L. et al. Tunable interfacial charge transfer in 2D-2D composite for efficient visible-light-driven

conversion. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300643 (2023). - Ouyang, T. et al. Dinuclear metal synergistic catalysis boosts photochemical

-to-CO conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 16480-16485 (2018). - Zhou, Y. et al. Engineering 2D photocatalysts toward carbon dioxide reduction. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003159 (2021).

- Zhao, Z. et al. Interfacial chemical bond and oxygen vacancyenhanced

CdSe-DETA S-scheme heterojunction for photocatalytic conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214470 (2023). - Zhang, X. et al. Photocatalytic conversion of diluted

into light hydrocarbons using periodically modulated multiwalled nanotube arrays. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12732-12735 (2012). - Wang, K. et al. Unlocking the charge-migration mechanism in SScheme junction for photoreduction of diluted

with high selectivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2309603 (2023). - Yin, S. et al. Boosting water decomposition by sulfur vacancies for efficient

photoreduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 1556-1562 (2022). - Wang, S., Guan, B. Y., Lu, Y. & Lou, X. W. D. Formation of hierarchical

heterostructured nanotubes for efficient and stable visible light reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17305-17308 (2017). - Xing, Z. et al. From one to two: in situ construction of an ultrathin 2D-2D closely bonded heterojunction from a single-phase monolayer nanosheet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 19715-19727 (2019).

- Wang, K. et al. Unveiling S-Scheme charge transfer pathways in

hybrid nanofiber photocatalysts for low-concentration hydrogenation. Solar RRL 7, 2200963 (2022). - Yu, F., Jing, X., Wang, Y., Sun, M. & Duan, C. Hierarchically porous metal-organic framework

interface for selective photocatalytic conversion of with into . Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 24849-24853 (2021). - Wang, K. et al. In situ-illuminated X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy investigation of S-Scheme

core-shell hybrid nanofibers for highly efficient solar-driven overall splitting. Solar RRL 6, 2200736 (2022). - Bie, C., Zhu, B., Xu, F., Zhang, L. & Yu, J. In situ grown monolayer N -doped graphene on CdS hollow spheres with seamless contact for photocatalytic

reduction. Adv. Mater. 31, e1902868 (2019). - Li, J. et al. Interfacial engineering of

nanowires promotes metallic photocatalytic reduction activity under near-infrared light irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6551-6559 (2021). - Liang, L. et al. Infrared light-driven

overall splitting at room temperature. Joule 2, 1004-1016 (2018). - Jiao, X. et al. Defect-mediated electron-hole separation in one-unitcell

layers for boosted solar-driven reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7586-7594 (2017). - Li, Y. et al. Plasmonic hot electrons from oxygen vacancies for infrared light-driven catalytic

reduction on . Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 910-916 (2021). - Zhu, S. et al. Selective

photoreduction into product enabled by charge-polarized metal pair sites. Nano Lett 21, 2324-2331 (2021). -

. et al. Selective visible-light-driven photocatalytic reduction to mediated by atomically thin layers. Nat. Energy 4, 690-699 (2019). - Wang, K. et al. Atomic-level insight of sulfidation-engineered Aur-ivillius-related

nanosheets enabling visible light lowconcentration conversion. Carbon Energy 5, e264 (2022). - Maiti, S. et al. Engineering electrocatalyst nanosurfaces to enrich the activity by inducing lattice strain. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3717-3756 (2021).

- He, H. et al. Interface chemical bond enhanced ions intercalated carbon nitride/CdSe-diethylenetriamine S-scheme heterojunction for photocatalytic

synthesis in pure water. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2315426 (2024). - Liu, L. et al. Synergistic polarization engineering on bulk and surface for boosting

photoreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18303-18308 (2021). - Li, A. et al. Three-phase photocatalysis for the enhanced selectivity and activity of

reduction on a hydrophobic surface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14549-14555 (2019). - Li, X. et al. Ultrathin conductor enabling efficient IR light

reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 423-430 (2019). - Liu, W. et al. Vacancy-cluster-mediated surface activation for boosting

chemical fixation. Chem. Sci. 14, 1397-1402 (2023). - Bellotti, P. & Glorius, F. Strain-release photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20716-20732 (2023).

- Yue, X., Cheng, L., Li, F., Fan, J. & Xiang, Q. Highly strained Bi-MOF on bismuth oxyhalide support with tailored intermediate adsorption/desorption capability for robust

photoreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208414 (2022). - Cao, X. et al. Engineering lattice disorder on a photocatalyst: photochromic BiOBr nanosheets enhance activation of aromatic C-H bonds via water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3386-3397 (2022).

- Wang, Z. & Zhou, G. Lattice-strain control of flexible Janus indium chalcogenide monolayers for photocatalytic water splitting. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 167-174 (2019).

- Miao, Y., Zhao, Y., Zhang, S., Shi, R. & Zhang, T. Strain engineering: a boosting strategy for photocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 34, e2200868 (2022).

- Feng, H. et al. Modulation of photocatalytic properties by strain in 2D BiOBr nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 27592-27596 (2015).

- Huo, W., Xu, W., Guo, Z., Zhang, Y. & Dong, F. Motivated surface reaction thermodynamics on the bismuth oxyhalides with lattice strain for enhanced photocatalytic NO oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 284, 119694 (2021).

- Dai, D. et al. Strain adjustment realizes the photocatalytic overall water splitting on tetragonal zircon

. Adv. Sci. 9, e2105299 (2022). - Zhong, Q. et al. Strain-modulated seeded growth of highly branched black Au superparticles for efficient photothermal conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 20513-20523 (2021).

- Cai, X. et al. Synergism of surface strain and interfacial polarization on Pd@Au core-shell cocatalysts for highly efficient photocatalytic

reduction over . J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 7350-7359 (2020). - Yan, Y. et al. Tensile strain-mediated spinel ferrites enable superior oxygen evolution activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24218-24229 (2023).

- Hou, Z. et al. Lattice-strain engineering for heterogenous electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 35, e2209876 (2023).

- Wei, K. et al. Strained zero-valent iron for highly efficient heavy metal removal. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200498 (2022).

- Sabbah, A. et al. Boosting photocatalytic

reduction in a heterostructure through strain-induced direct Z-scheme and a mechanistic study of molecular interaction thereon. Nano Energy 93, 106809 (2022). - Huang, H. et al. Noble-metal-free ultrathin MXene coupled with

nanoflakes for ultrafast photocatalytic reduction of hexavalent chromium. Appl. Catal. B 284, 119754 (2021). - Liu, Y. et al. Rapid room-temperature mechanosynthesis tensilestrained

for robust photomineralization. Catal. Commun. 177, 106638 (2023). - Hao, L. et al. Surface-halogenation-induced atomic-site activation and local charge separation for superb

photoreduction. Adv. Mater. 31, e1900546 (2019). - Li, X. et al. Atomically strained metal sites for highly efficient and selective photooxidation. Nano Lett. 23, 2905-2914 (2023).

- Xiao, Y., Yao, C., Su, C. & Liu, B. Nanoclusters for photoelectrochemical water splitting: bridging the photosensitizer and carrier transporter. EcoEnergy 1, 60-84 (2023).

- Di, J. et al. Isolated single atom cobalt in

atomic layers to trigger efficient photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 10, 2840 (2019). - Wu, X . et al. Identification of the active sites on metallic

nano-sea-urchin for atmospheric photoreduction under UV, visible, and near-infrared light illumination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202213124 (2023). - Zhang, H. et al. Isolated cobalt centers on

nanowires perform as a reaction switch for efficient photoreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 2173-2177 (2021).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

http://www.nature.com/reprints

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2025

- ¹كلية العلوم الحضرية والبيئية، مختبر هوبى الرئيسي لتحليل الملوثات وتقنية إعادة الاستخدام، جامعة هوبى العادية، هوانغشي، جمهورية الصين الشعبية.

معهد هنان للتكنولوجيا المتقدمة، جامعة تشنغتشو، تشنغتشو، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. قسم علوم المواد والهندسة، جامعة مدينة هونغ كونغ، منطقة هونغ كونغ الإدارية الخاصة، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. قسم الكيمياء، معهد هونغ كونغ للطاقة النظيفة (HKICE) ومركز الألماس الفائق والأفلام المتقدمة (COSDAF)، جامعة مدينة هونغ كونغ، منطقة هونغ كونغ الإدارية الخاصة، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. البريد الإلكتروني: وانغكاي@hbnu.edu.cn; junli2019@zzu.edu.cn; bliu48@cityu.edu.hk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57140-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40025011

Publication Date: 2025-03-01

Visible-light-driven

Accepted: 8 February 2025

Published online: 01 March 2025

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

Strain engineering offers an attractive strategy for improving intrinsic catalytic performance of a heterogeneous catalyst. Herein, we successfully create strain into layered indium sulfide (

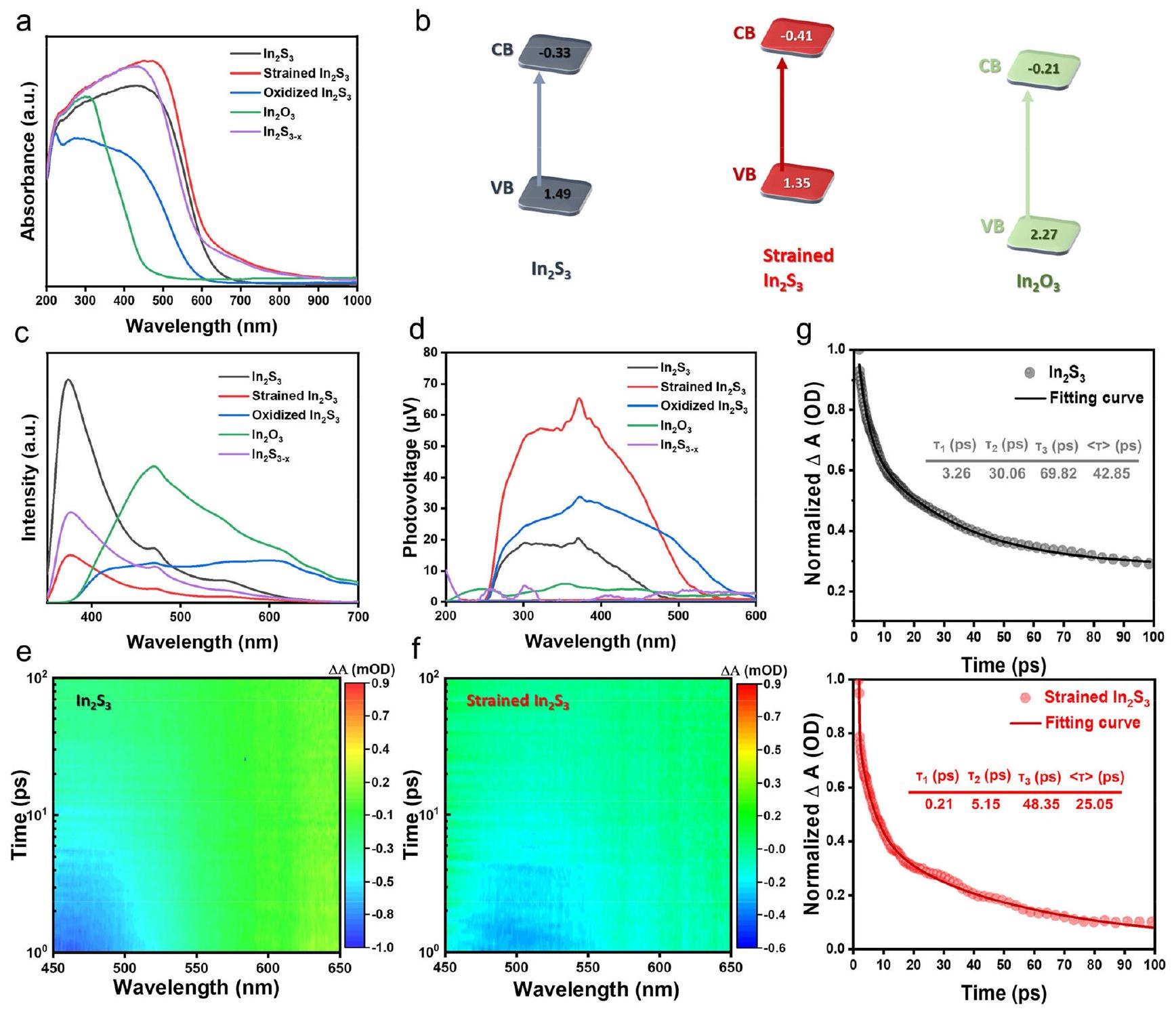

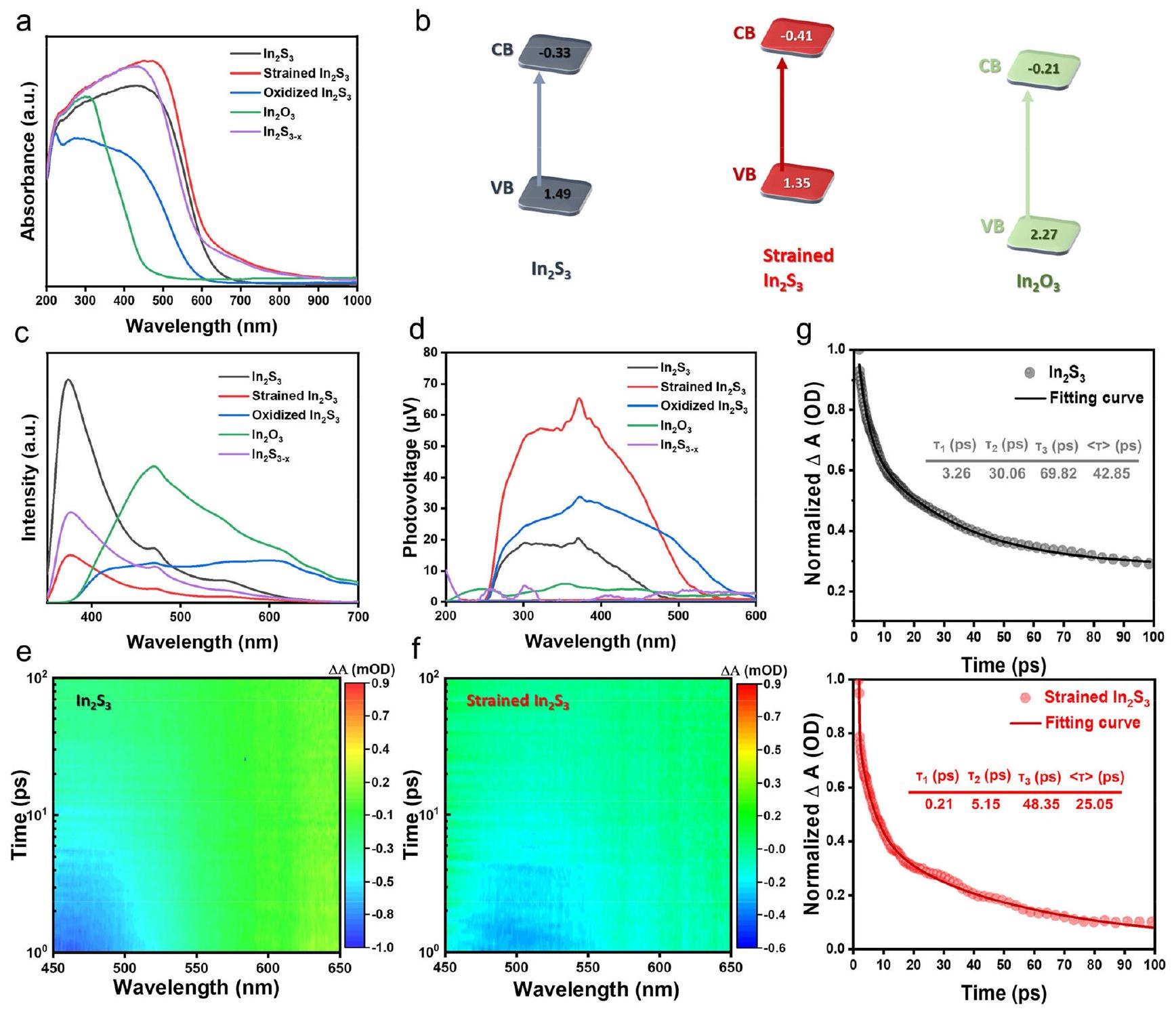

benefit photocatalytic reactions by offering a large number of catalytically active sites. Moreover, the ultrathin architecture of these 2D materials can also significantly shorten the migration pathways of photogenerated charge carriers, thereby substantially reducing electron-hole recombination and improving efficiency of charge carrier separation. To further improve the performance of metal sulfide photocatalysts in photocatalysis, tuning electronic structure of metal sites by strain engineering provides an effective strategy

strain mapping image along the

small-domain strain at the atomic scale (strained

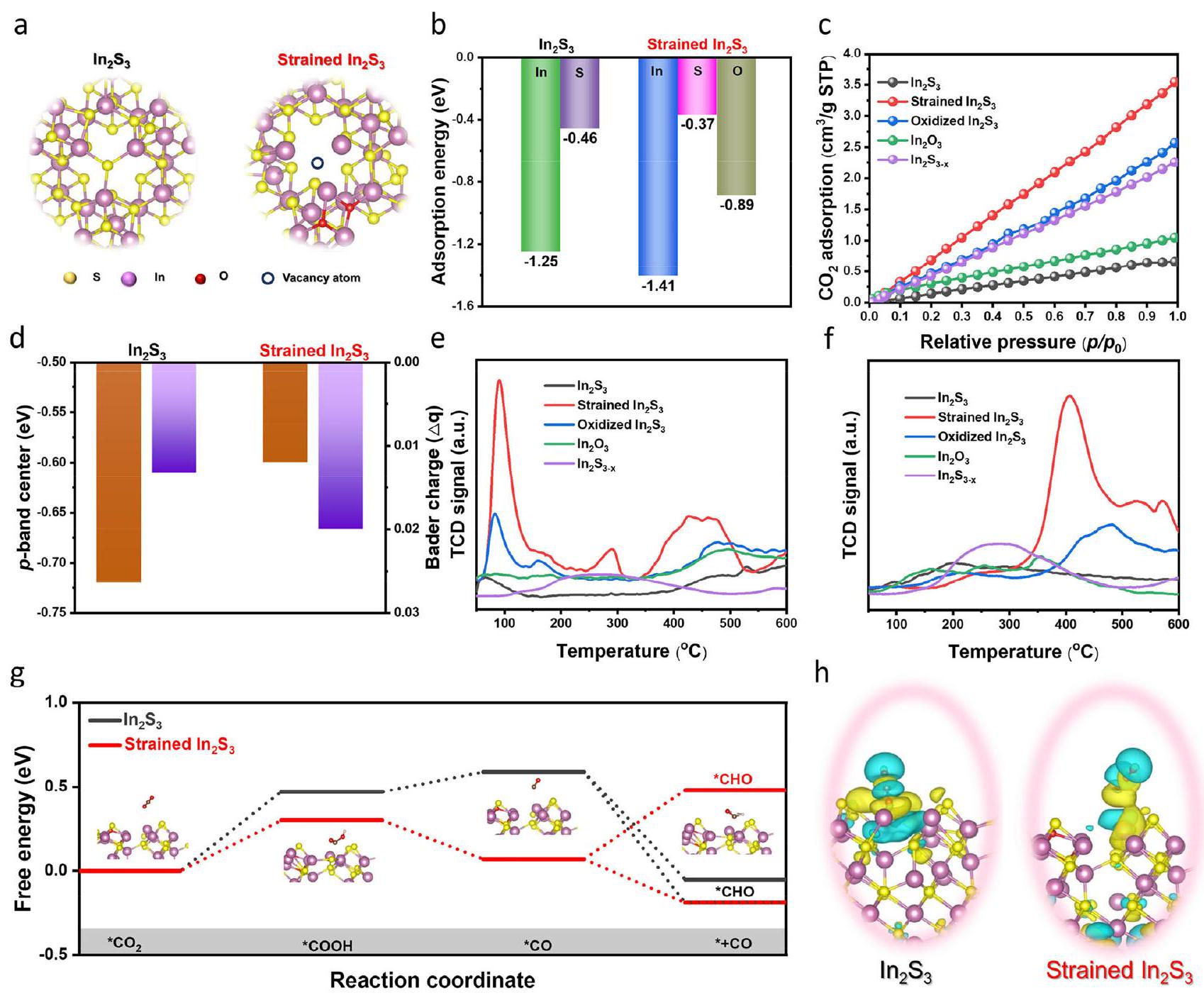

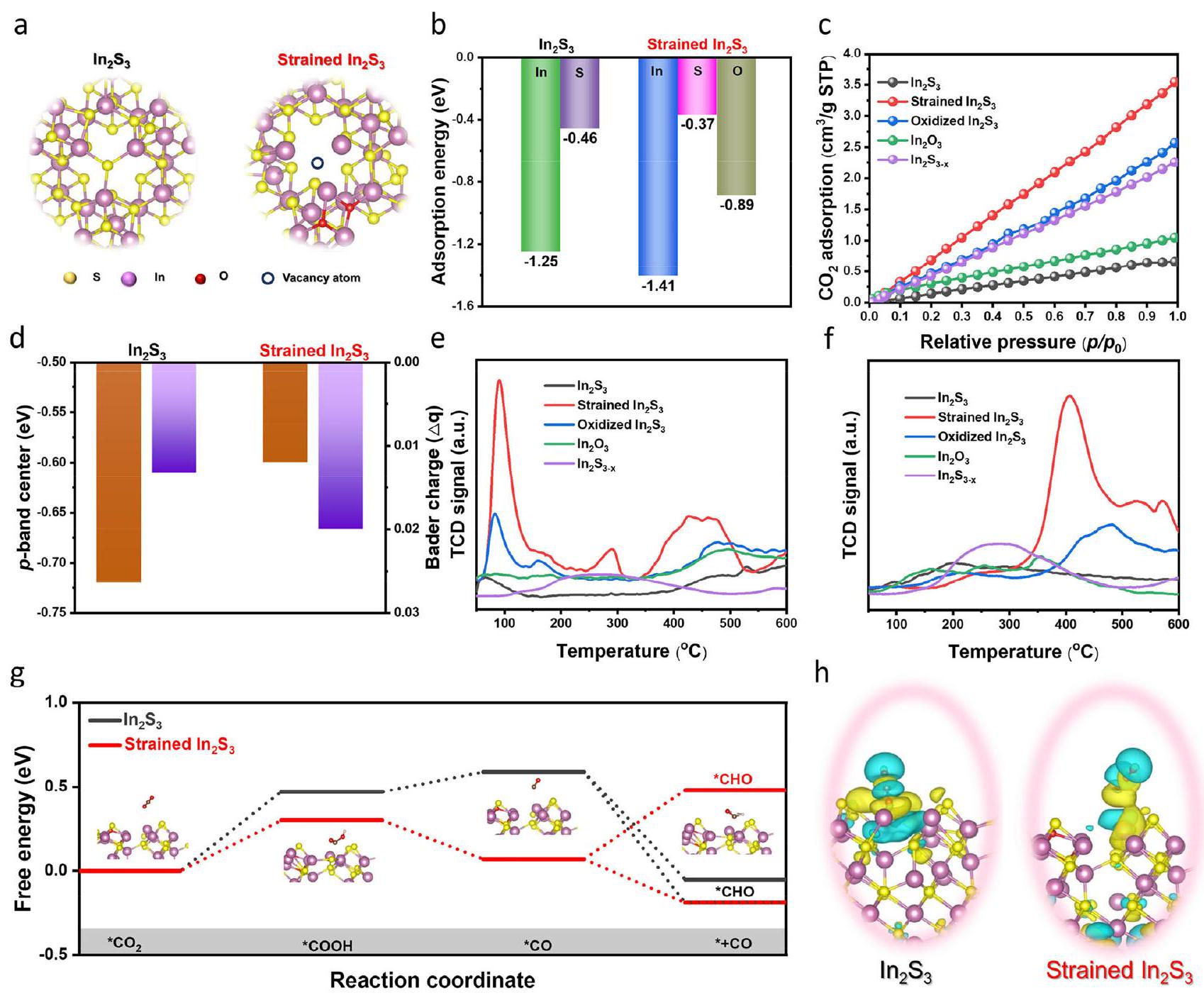

collection of in-situ spectroscopic measurements and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, the atomically strained

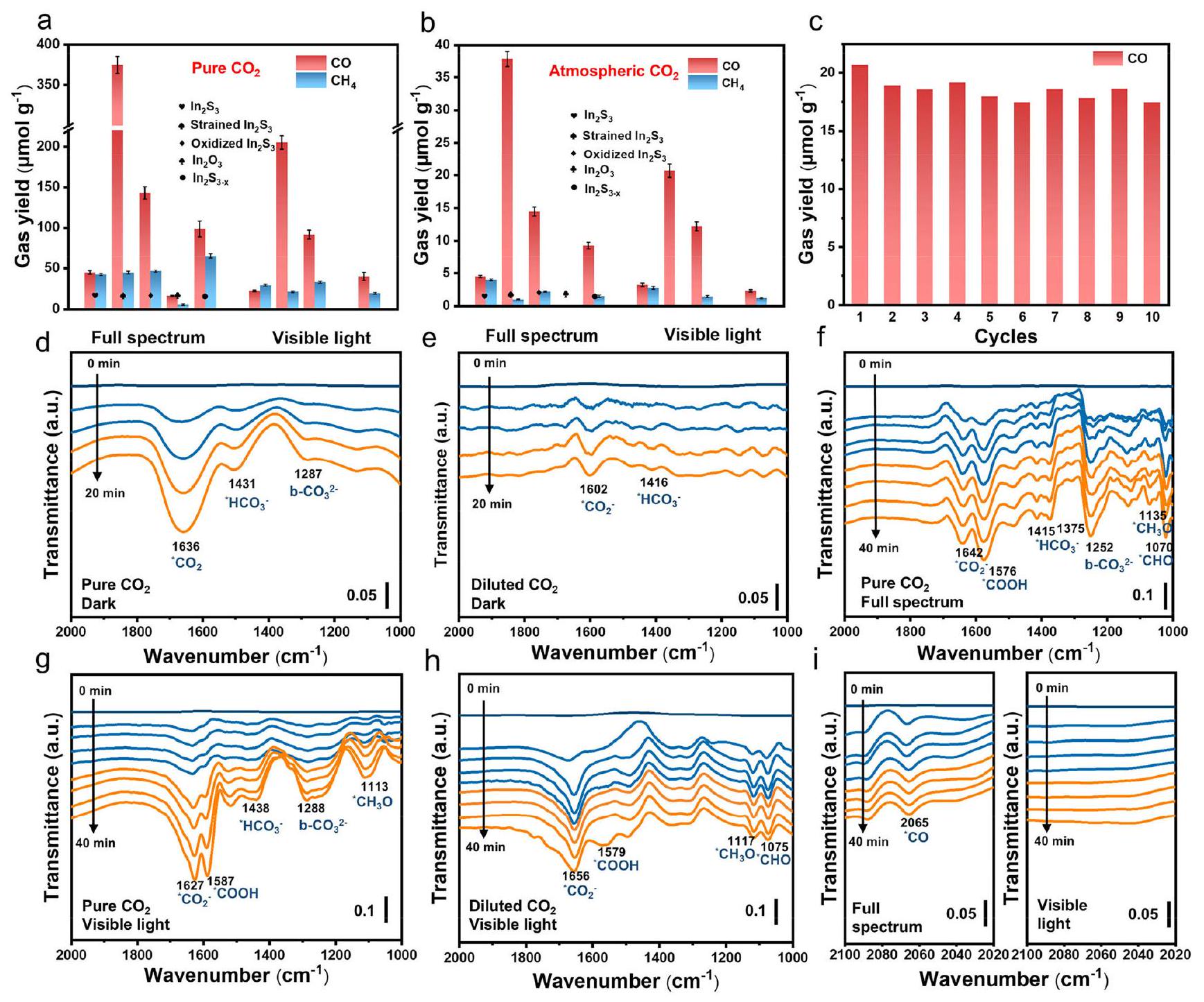

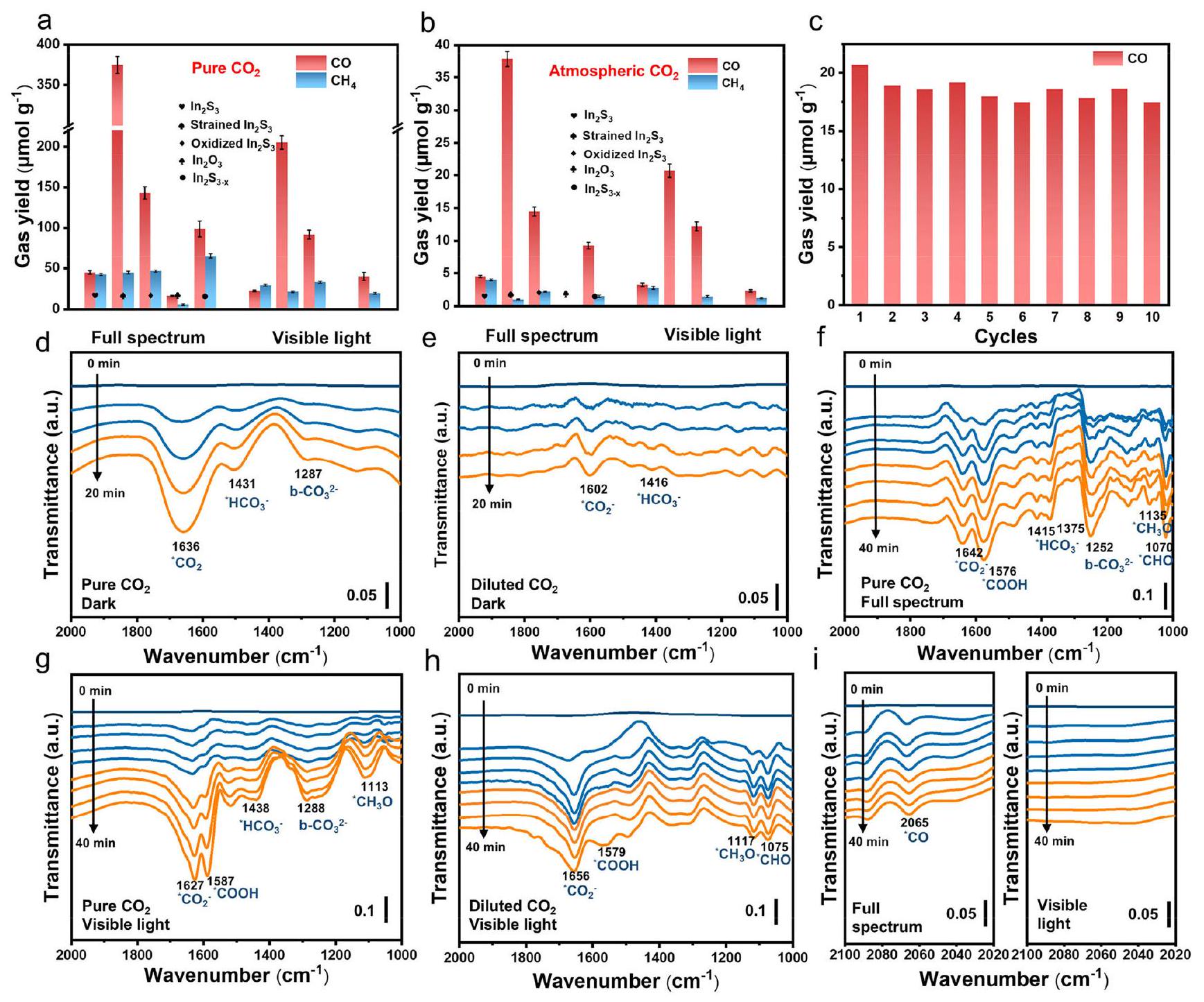

greatly enhancing CO2 photoreduction performance under full spectrum/visible light illumination in both pure

Results and discussion

Structural characterizations of layered

Photocatalytic

full spectrum irradiation condition in pure

appeared under full spectrum (Fig. 3f) or visible-light (Fig. 3g) irradiation and their intensities increased with increasing light irradiation time, due to increased coverage of * COOH (a crucial intermediate for

Insight of the increased photocatalytic activity

well established that the upshifted

the downhill free energy profiles revealed that the formation of *CO from *COOH was more spontaneous over strained

Discussion

measurements and DFT calculations, as a result, greatly boosting CO2 photoreduction performance.

Methods

Materials

Synthesis of

Synthesis of strained

Synthesis of oxidized

Synthesis of

Characterization

isotherms were measured on a Micromeritics ASAP2460. The transient photocurrent responses and the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) spectra of the samples were recorded on an electrochemical workstation (CHI660C Instruments, China) with a threeelectrode configuration in

Photocatalytic

Computational details

Data availability

References

- Xu, Y. et al. Engineering built-in electric field microenvironment of CQDs/g-

heterojunction for efficient photocatalytic reduction. Adv. Sci. e2403607 (2024). - Wang, L., Wang, D. & Li, Y. Single-atom catalysis for carbon neutrality. Carbon Energy 4, 1021-1079 (2022).

- Ou, H. et al. Carbon nitride photocatalysts with integrated oxidation and reduction atomic active centers for improved

conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202206579 (2022). - Vu, N. N., Kaliaguine, S. & Do, T. O. Critical aspects and recent advances in structural engineering of photocatalysts for sunlightdriven photocatalytic reduction of

into fuels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1901825 (2019). - Ou, M. et al. Amino-assisted anchoring of

perovskite quantum dots on porous for enhanced photocatalytic reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13570-13574 (2018). - Liu, L. et al. Tunable interfacial charge transfer in 2D-2D composite for efficient visible-light-driven

conversion. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300643 (2023). - Ouyang, T. et al. Dinuclear metal synergistic catalysis boosts photochemical

-to-CO conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 16480-16485 (2018). - Zhou, Y. et al. Engineering 2D photocatalysts toward carbon dioxide reduction. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003159 (2021).

- Zhao, Z. et al. Interfacial chemical bond and oxygen vacancyenhanced

CdSe-DETA S-scheme heterojunction for photocatalytic conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214470 (2023). - Zhang, X. et al. Photocatalytic conversion of diluted

into light hydrocarbons using periodically modulated multiwalled nanotube arrays. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12732-12735 (2012). - Wang, K. et al. Unlocking the charge-migration mechanism in SScheme junction for photoreduction of diluted

with high selectivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2309603 (2023). - Yin, S. et al. Boosting water decomposition by sulfur vacancies for efficient

photoreduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 1556-1562 (2022). - Wang, S., Guan, B. Y., Lu, Y. & Lou, X. W. D. Formation of hierarchical

heterostructured nanotubes for efficient and stable visible light reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17305-17308 (2017). - Xing, Z. et al. From one to two: in situ construction of an ultrathin 2D-2D closely bonded heterojunction from a single-phase monolayer nanosheet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 19715-19727 (2019).

- Wang, K. et al. Unveiling S-Scheme charge transfer pathways in

hybrid nanofiber photocatalysts for low-concentration hydrogenation. Solar RRL 7, 2200963 (2022). - Yu, F., Jing, X., Wang, Y., Sun, M. & Duan, C. Hierarchically porous metal-organic framework

interface for selective photocatalytic conversion of with into . Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 24849-24853 (2021). - Wang, K. et al. In situ-illuminated X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy investigation of S-Scheme

core-shell hybrid nanofibers for highly efficient solar-driven overall splitting. Solar RRL 6, 2200736 (2022). - Bie, C., Zhu, B., Xu, F., Zhang, L. & Yu, J. In situ grown monolayer N -doped graphene on CdS hollow spheres with seamless contact for photocatalytic

reduction. Adv. Mater. 31, e1902868 (2019). - Li, J. et al. Interfacial engineering of

nanowires promotes metallic photocatalytic reduction activity under near-infrared light irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6551-6559 (2021). - Liang, L. et al. Infrared light-driven

overall splitting at room temperature. Joule 2, 1004-1016 (2018). - Jiao, X. et al. Defect-mediated electron-hole separation in one-unitcell

layers for boosted solar-driven reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7586-7594 (2017). - Li, Y. et al. Plasmonic hot electrons from oxygen vacancies for infrared light-driven catalytic

reduction on . Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 910-916 (2021). - Zhu, S. et al. Selective

photoreduction into product enabled by charge-polarized metal pair sites. Nano Lett 21, 2324-2331 (2021). -

. et al. Selective visible-light-driven photocatalytic reduction to mediated by atomically thin layers. Nat. Energy 4, 690-699 (2019). - Wang, K. et al. Atomic-level insight of sulfidation-engineered Aur-ivillius-related

nanosheets enabling visible light lowconcentration conversion. Carbon Energy 5, e264 (2022). - Maiti, S. et al. Engineering electrocatalyst nanosurfaces to enrich the activity by inducing lattice strain. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3717-3756 (2021).

- He, H. et al. Interface chemical bond enhanced ions intercalated carbon nitride/CdSe-diethylenetriamine S-scheme heterojunction for photocatalytic

synthesis in pure water. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2315426 (2024). - Liu, L. et al. Synergistic polarization engineering on bulk and surface for boosting

photoreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18303-18308 (2021). - Li, A. et al. Three-phase photocatalysis for the enhanced selectivity and activity of

reduction on a hydrophobic surface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14549-14555 (2019). - Li, X. et al. Ultrathin conductor enabling efficient IR light

reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 423-430 (2019). - Liu, W. et al. Vacancy-cluster-mediated surface activation for boosting

chemical fixation. Chem. Sci. 14, 1397-1402 (2023). - Bellotti, P. & Glorius, F. Strain-release photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20716-20732 (2023).

- Yue, X., Cheng, L., Li, F., Fan, J. & Xiang, Q. Highly strained Bi-MOF on bismuth oxyhalide support with tailored intermediate adsorption/desorption capability for robust

photoreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208414 (2022). - Cao, X. et al. Engineering lattice disorder on a photocatalyst: photochromic BiOBr nanosheets enhance activation of aromatic C-H bonds via water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3386-3397 (2022).

- Wang, Z. & Zhou, G. Lattice-strain control of flexible Janus indium chalcogenide monolayers for photocatalytic water splitting. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 167-174 (2019).

- Miao, Y., Zhao, Y., Zhang, S., Shi, R. & Zhang, T. Strain engineering: a boosting strategy for photocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 34, e2200868 (2022).

- Feng, H. et al. Modulation of photocatalytic properties by strain in 2D BiOBr nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 27592-27596 (2015).

- Huo, W., Xu, W., Guo, Z., Zhang, Y. & Dong, F. Motivated surface reaction thermodynamics on the bismuth oxyhalides with lattice strain for enhanced photocatalytic NO oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 284, 119694 (2021).

- Dai, D. et al. Strain adjustment realizes the photocatalytic overall water splitting on tetragonal zircon

. Adv. Sci. 9, e2105299 (2022). - Zhong, Q. et al. Strain-modulated seeded growth of highly branched black Au superparticles for efficient photothermal conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 20513-20523 (2021).

- Cai, X. et al. Synergism of surface strain and interfacial polarization on Pd@Au core-shell cocatalysts for highly efficient photocatalytic

reduction over . J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 7350-7359 (2020). - Yan, Y. et al. Tensile strain-mediated spinel ferrites enable superior oxygen evolution activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24218-24229 (2023).

- Hou, Z. et al. Lattice-strain engineering for heterogenous electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 35, e2209876 (2023).

- Wei, K. et al. Strained zero-valent iron for highly efficient heavy metal removal. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200498 (2022).

- Sabbah, A. et al. Boosting photocatalytic

reduction in a heterostructure through strain-induced direct Z-scheme and a mechanistic study of molecular interaction thereon. Nano Energy 93, 106809 (2022). - Huang, H. et al. Noble-metal-free ultrathin MXene coupled with

nanoflakes for ultrafast photocatalytic reduction of hexavalent chromium. Appl. Catal. B 284, 119754 (2021). - Liu, Y. et al. Rapid room-temperature mechanosynthesis tensilestrained

for robust photomineralization. Catal. Commun. 177, 106638 (2023). - Hao, L. et al. Surface-halogenation-induced atomic-site activation and local charge separation for superb

photoreduction. Adv. Mater. 31, e1900546 (2019). - Li, X. et al. Atomically strained metal sites for highly efficient and selective photooxidation. Nano Lett. 23, 2905-2914 (2023).

- Xiao, Y., Yao, C., Su, C. & Liu, B. Nanoclusters for photoelectrochemical water splitting: bridging the photosensitizer and carrier transporter. EcoEnergy 1, 60-84 (2023).

- Di, J. et al. Isolated single atom cobalt in

atomic layers to trigger efficient photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 10, 2840 (2019). - Wu, X . et al. Identification of the active sites on metallic

nano-sea-urchin for atmospheric photoreduction under UV, visible, and near-infrared light illumination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202213124 (2023). - Zhang, H. et al. Isolated cobalt centers on

nanowires perform as a reaction switch for efficient photoreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 2173-2177 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

http://www.nature.com/reprints

(c) The Author(s) 2025

- ¹College of Urban and Environmental Sciences, Hubei Key Laboratory of Pollutant Analysis and Reuse Technology, Hubei Normal University, Huangshi, PR China.

Henan Institute of Advanced Technology, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, PR China. Department of Materials Science and Engineering, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, PR China. Department of Chemistry, Hong Kong Institute of Clean Energy (HKICE) & Center of Super-Diamond and Advanced Films (COSDAF), City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, PR China. e-mail: wangkai@hbnu.edu.cn; junli2019@zzu.edu.cn; bliu48@cityu.edu.hk