المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 15، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90313-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40016413

تاريخ النشر: 2025-02-27

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90313-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40016413

تاريخ النشر: 2025-02-27

افتح

تحقيق تأثير المذيبات المتبادلة على أداء الامتزاز لمركبات Ce-MOFs تجاه الأصباغ العضوية

تعتبر MOFs القائمة على السيريم (Ce-MOFs) مواد مسامية جذابة تظهر هياكل متنوعة، وثبات حراري وكيميائي ممتاز، وخصائص مسامية قابلة للتعديل، وطرق تركيب بسيطة مفيدة لتطبيقات معالجة مياه الصرف. لذلك، في العمل الحالي، قمنا بتخليق سلسلة من Ce-MOFs من خلال طريقة تركيب سريعة وصديقة للبيئة في درجة حرارة الغرفة باستخدام الماء كمذيب صديق للبيئة. تم استخدام أربعة مذيبات مختلفة بما في ذلك الإيثانول، والكلوروفورم، والأسيتون، والميثانول في عملية تبادل المذيبات لتعديل خصائص Ce-MOFs المُعدة. تم دراسة تأثير المذيبات المختلفة على الهيكل البلوري، والهيكل المسامي، والثبات الحراري، وشكل السطح لـ Ce-MOFs بشكل منهجي. وُجد أن المذيبات المتبادلة يمكن أن تؤثر بشكل كبير على الخصائص الكيميائية والفيزيائية لـ Ce-MOFs المُعدة. يؤدي استخدام الإيثانول كمذيب تبادلي إلى إنتاج MOF بلوري عالي الجودة يتمتع بأعلى مساحة سطح.

الكلمات الرئيسية: التخليق الأخضر، تفعيل فعال، امتصاص الصبغة، MOFs المعتمدة على السيريوم، تبادل المذيبات

نظرًا للنمو السكاني العالمي والتصنيع، تم إنتاج كميات كبيرة من المياه العادمة التي تحتوي على ملوثات مختلفة مثل أيونات المعادن الثقيلة، والأصباغ العضوية، والأدوية، والمبيدات الحشرية، وما إلى ذلك، مما يشكل تحديات بيئية كبيرة.

نظرًا للنمو السكاني العالمي والتصنيع، تم إنتاج كميات كبيرة من المياه العادمة التي تحتوي على ملوثات مختلفة مثل أيونات المعادن الثقيلة، والأصباغ العضوية، والأدوية، والمبيدات الحشرية، وما إلى ذلك، مما يشكل تحديات بيئية كبيرة.

من بين تقنيات المعالجة المتطورة المختلفة، حققت طريقة الامتزاز شهرة بسبب كفاءتها من حيث التكلفة، وفعاليتها، وسهولة تشغيلها، واستخدام مجموعة متنوعة من مواد الامتزاز، وغيرها.

تعتبر المواد القائمة على الزركونيوم (Zr-MOFs) اليوم مواد واعدة لمعالجة مياه الصرف الصحي.

وقد تم دراسة ومشتقاته بشكل متكرر لإزالة الملوثات المختلفة من الماء

بعد ذلك، درست مجموعات بحثية مختلفة النشاط التحفيزي لمركبات Ce-UiO-66 MOFs في مجالات مختلفة.

بالإضافة إلى الاستقرار الهيكلي لمواد الامتصاص المستخدمة في تطبيقات معالجة مياه الصرف، فإن الطرق الاصطناعية المستدامة والصديقة للبيئة التي تكون فعالة من حيث الطاقة والبيئة والاقتصاد تعتبر ضرورية للغاية. حتى الآن، تم تطوير استراتيجيات اصطناعية مختلفة لتخليق MOFs Ce-UiO-66، بعضها سريع وبسيط وصديق للبيئة، ويتم في ظروف محيطية دون استخدام كميات كبيرة من المذيبات العضوية.

خلال عملية تخليق MOFs، يتم حبس جزيئات المذيب والمواد الأولية غير المتفاعلة بشكل لا مفر منه داخل مسام MOFs المُعدة.

ومع ذلك، لا توجد تقارير في الأدبيات تركز بشكل منهجي على تأثيرات المذيبات المتبادلة على الخصائص الفيزيائية والكيميائية لمركبات الإطار المعدني العضوي المعتمد على السيريوم (Ce-MOFs). وبالتالي، في العمل الحالي، قمنا بتخليق سلسلة من Ce-MOFs من خلال طريقة تخليق سريعة وصديقة للبيئة في درجة حرارة الغرفة باستخدام الماء كمذيب. تم استخدام أربعة مذيبات ذات نقطة غليان منخفضة مختلفة مثل الإيثانول، والكلوروفورم، والأسيتون، والميثانول في عملية تبادل المذيبات لتعديل خصائص Ce-MOFs المُعدة. تم دراسة تأثير المذيبات المتبادلة المختلفة على الهيكل البلوري، والهيكل المسامي، والثبات الحراري، وشكل السطح لـ Ce-MOFs بشكل منهجي. أخيرًا، تم استخدام Ce-MOFs المُعدة كمواد ماصة لإزالة الأصباغ الكاتيونية والأنيونية بكفاءة من الماء. كشفت النتائج أن المذيب المتبادل له تأثير كبير على الخصائص المسامية وكذلك أداء امتصاص الأصباغ لـ Ce-MOFs.

التجارب

المواد

ماء أحادي الصوديوم بيركلورات

تركيب MOFs من السيريوم

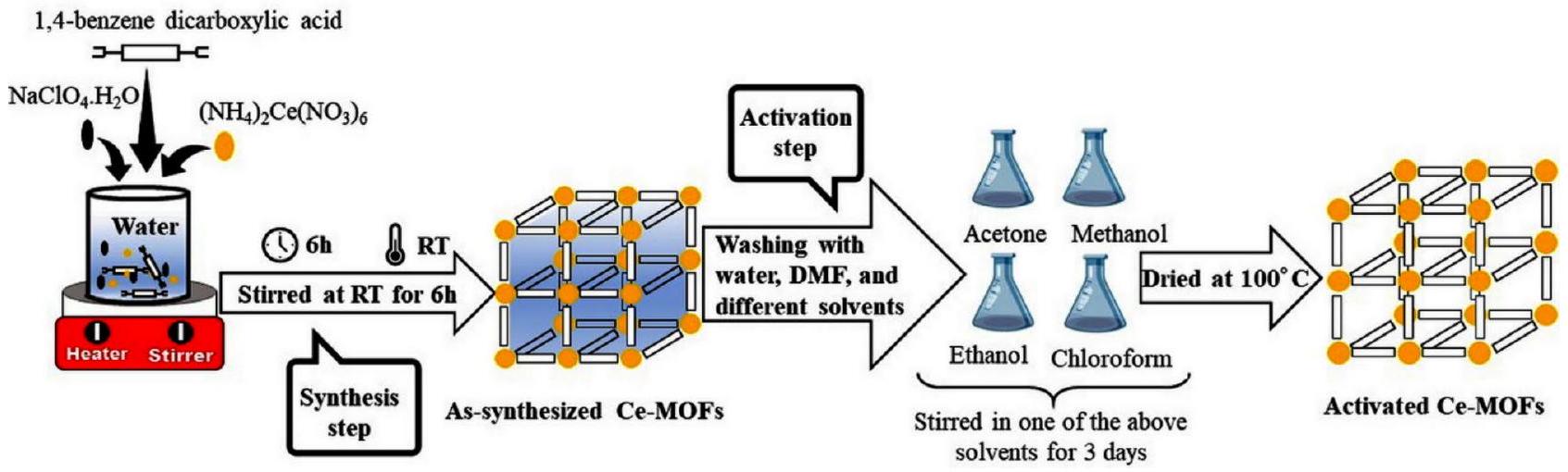

تم تحضير Ce-MOFs بطريقة صديقة للبيئة وفقًا لإجراءاتنا السابقة مع بعض التعديلات.

تفعيل Ce-MOFs

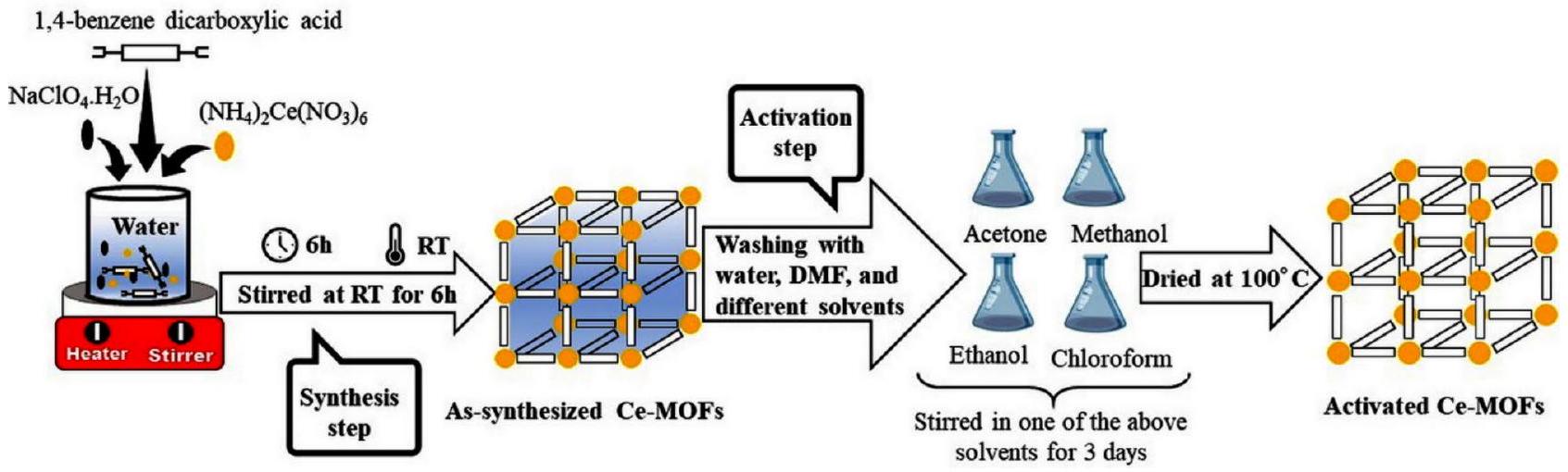

كما هو موضح في الشكل 1، تم غسل جزيئات Ce-MOFs المحضرة ثلاث مرات بالماء لإزالة

الشكل 1. توضيح تخطيطي لتحضير وتفعيل Ce-MOFs.

| MOFs | مذيبات التبادل | عائد

|

جهد زيتا (ملي فولت) | مساحة السطح

|

متوسط قطر المسام (نانومتر) | حجم المسام

|

| سي-موف-1 | – |

|

|

٥٩٢ | 2.97 | 0.4401 |

| سي-موف-2 | الإيثانول |

|

|

843 | ٣.٥٧ | 0.7518 |

| سي-موف-3 | ميثانول |

|

|

618 | 3.29 | 0.5095 |

| سي-موف-4 | أسيتون |

|

|

605 | 2.85 | 0.4079 |

| سي-موف-5 | كلوروفورم |

|

|

642 | 2.40 | 0.3857 |

الجدول 1. خصائص مركبات Ce-MOFs المحضرة.

تجارب الامتزاز

تم إجراء جميع تجارب الامتزاز في ظروف محيطية باستخدام محاليل CR و MG. تم اختيار هذه الأصباغ العضوية المختلفة كأصباغ نموذجية للتحقيق في تأثير معلمات مختلفة (مثل وقت الاتصال، التركيز الابتدائي، الرقم الهيدروجيني، تركيز الملح، ودرجة الحرارة) على أداء الإزالة للمنتج المحضر.

في الذي،

توصيف

تمت دراسة العينات التي تم تحضيرها وتفعيلها بشكل كامل باستخدام تحليلات مختلفة، حيث تم تقديم التفاصيل في الملف التكميلي.

النتائج والمناقشة

توصيف الـ Ce-MOFs المُعدة

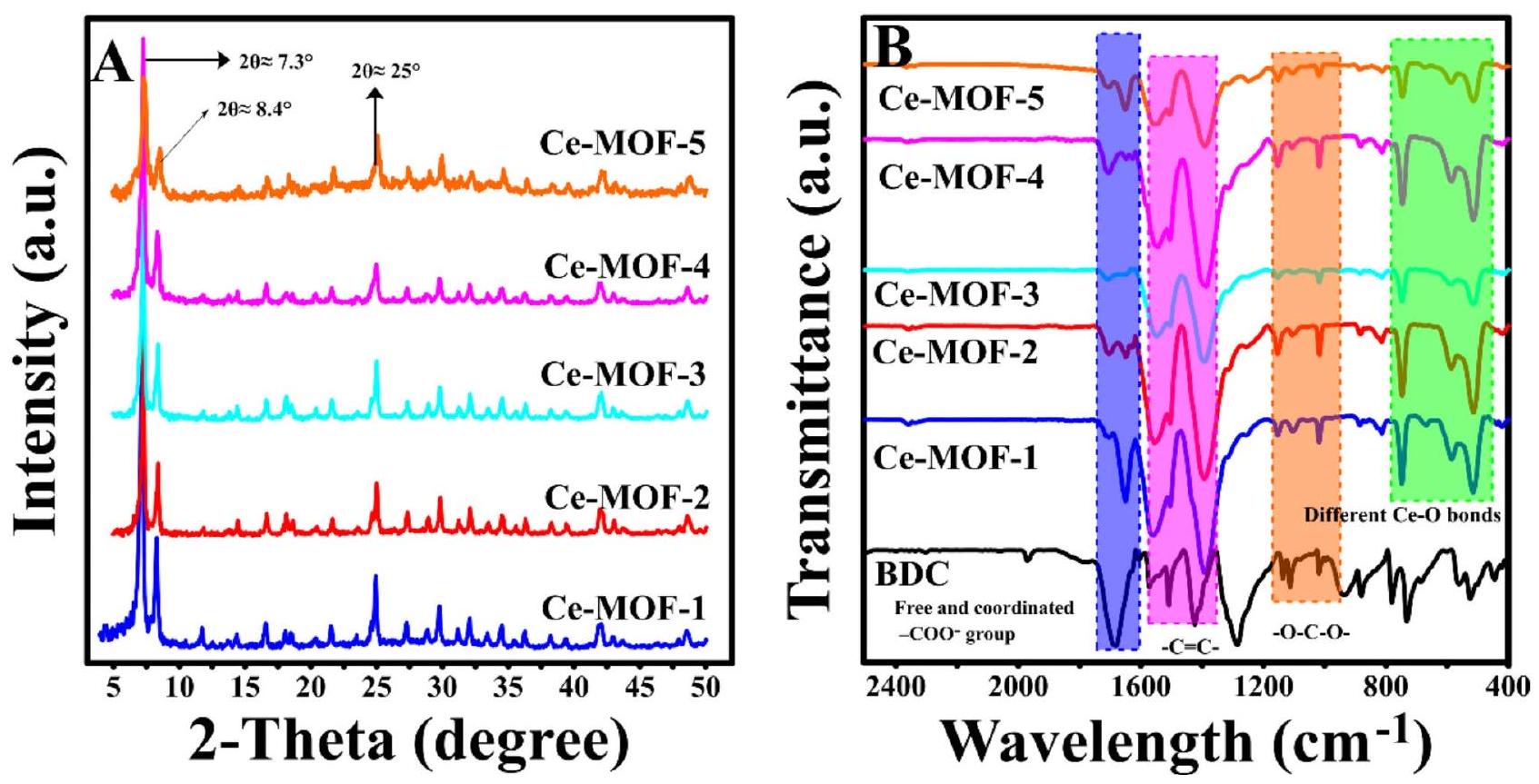

تحليلات XRD و FTIR

لإزالة المذيبات ذات نقطة الغليان العالية بكفاءة

لإزالة المذيبات ذات نقطة الغليان العالية بكفاءة

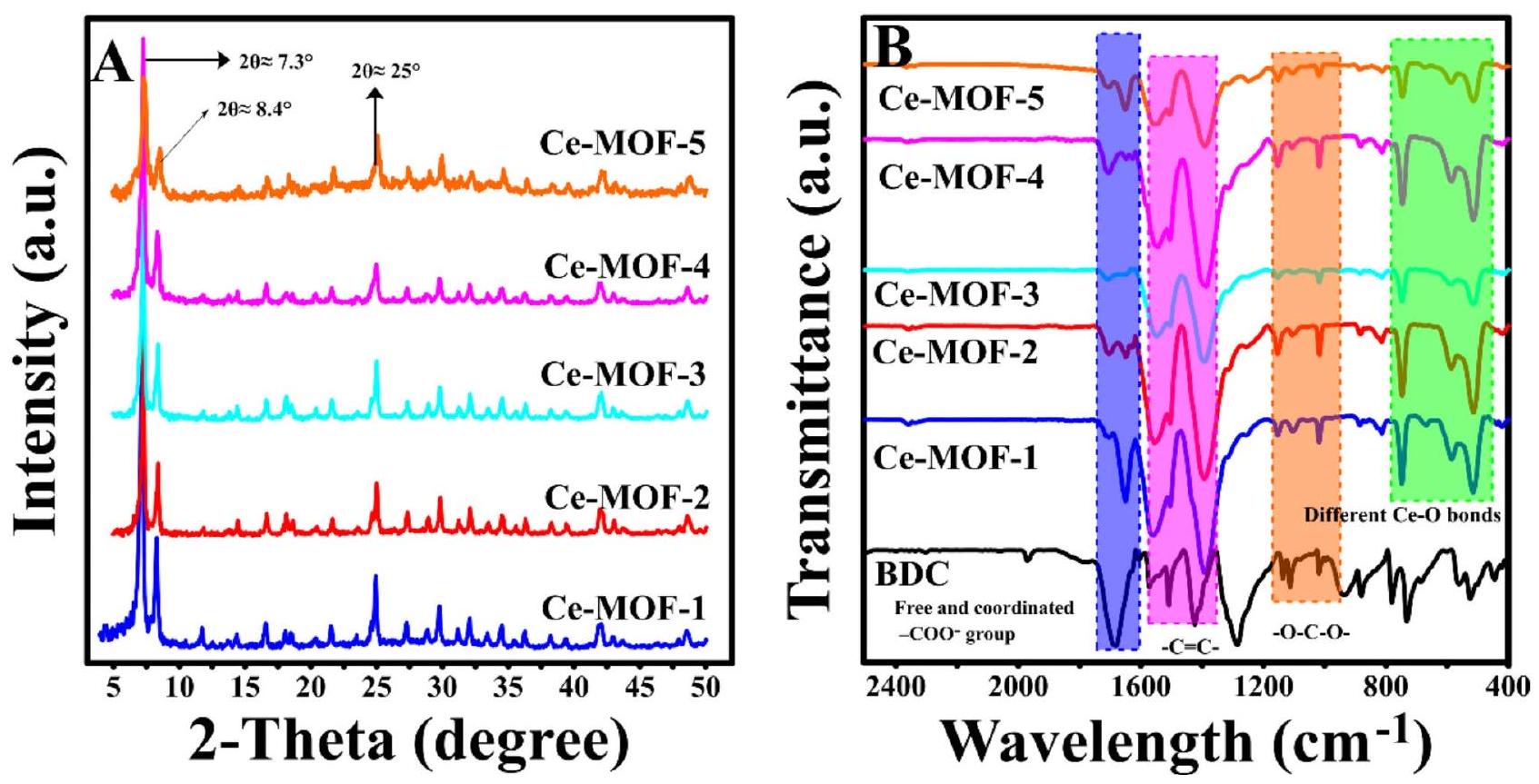

الشكل 2. (أ) أنماط حيود الأشعة السينية و (ب) طيف الأشعة تحت الحمراء لتحضير Ce-MOFs.

في شدة النسب، فإن أنماط XRD لجميع مركبات Ce-MOFs المحضرة هي نفسها وتتوافق جيدًا مع الأدبيات.

علاوة على ذلك، فإن طيف FTIR (الشكل 2B) لمركبات Ce-MOFs المحضرة متشابه نسبيًا ومماثل للأدبيات.

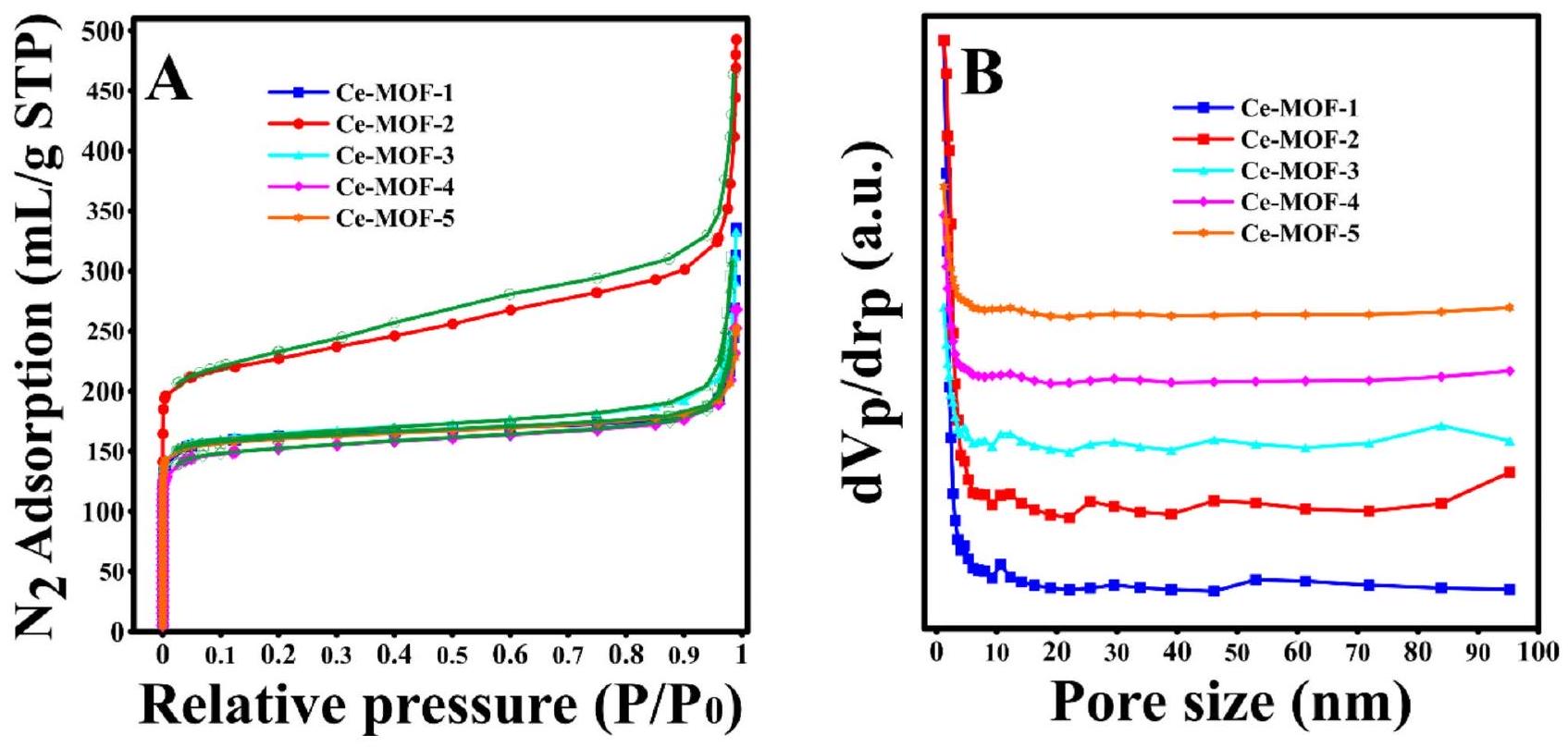

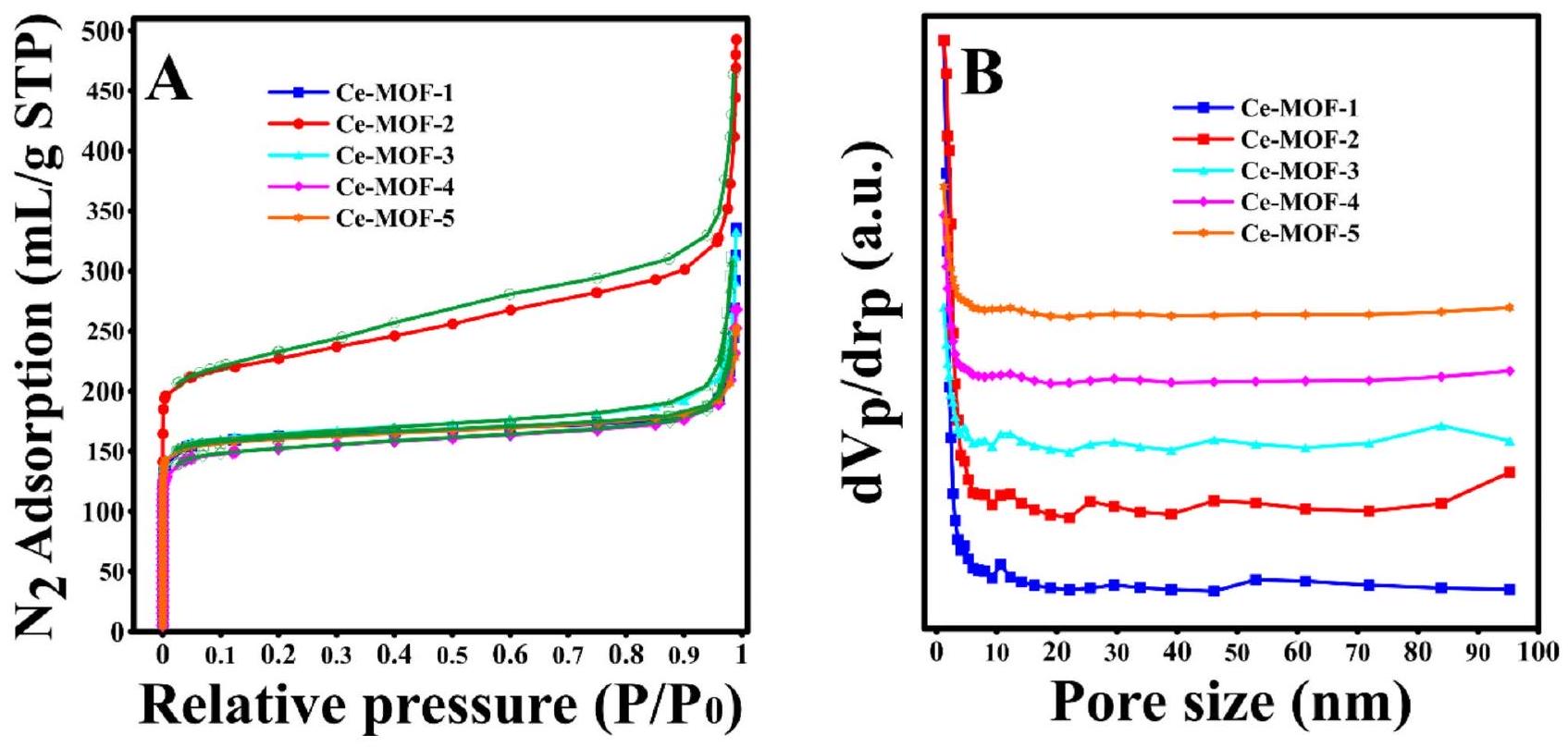

تحليلات امتصاص النيتروجين وإزالة النيتروجين

لتحديد تأثير عملية تبادل المذيبات على المسامية في Ce-MOFs، تم تحليل الخصائص المسامية لـ Ce-MOFs التي تم تصنيعها من خلال امتصاص وإزالة النيتروجين عند 77 كلفن، حيث تم عرض النتائج المستخلصة في الشكل 3. أظهرت المنحنيات الخاصة بالعينة التي تم تصنيعها (Ce-MOF-1) والعينات التي تم تنشيطها بواسطة الإيثانول، الميثانول، الكلوروفورم، والأسيتون منحنيات من النوع الرابع وفقًا لتصنيف IUPAC، مما يدل على وجود مسام متوسطة نموذجية في هيكل هذه المواد.

تبلغ المساحات السطحية وفقًا لطريقة BET لمركبات Ce-MOFs المحضرة ترتيب Ce-MOF-1

الشكل 3. (أ) إيزوثرم امتصاص النيتروجين وإزالة النيتروجين و (ب) توزيع حجم المسام لـ CeMOFs المحضرة. (تظهر الخطوط الخضراء الإزالة).

لم يظهر فقط أكبر مساحة سطحية و حجم مسام إجمالي، بل أظهر أيضًا أكبر قطر متوسط للمسام، وهو ما يفيد في امتصاص ملوثات المياه.

ترتيب الزيادة في مساحة السطح للعينات المنشطة هو عكس ما هو متوقع لنقاط غليان المذيبات المستخدمة، وزادت مساحة السطح تقريبًا مع زيادة نقاط غليان المذيبات المتبادلة. بينما كان من المتوقع أن تزيد المساحة السطحية المحددة لـ MOFs المحضرة مع انخفاض نقطة غليان المذيبات المتبادلة. وبناءً عليه، فإن الإيثانول الذي له أعلى نقطة غليان (79

عامل آخر مهم يمكن أن يتحكم في كفاءة عملية تبادل المذيبات هو القدرة على تبادل جزيئات المذيب للتنسيق مع مراكز المعادن المفتوحة المحتملة لـ

كما لوحظ من الجدول 1، فإن الإيثانول هو أفضل مذيب لعملية تبادل المذيبات مما يؤدي إلى تكوين Ce-MOF-2 بأعلى مساحة سطحية. علاوة على ذلك، تم ملاحظة نتيجة مماثلة أيضًا من قبل داي وآخرون.

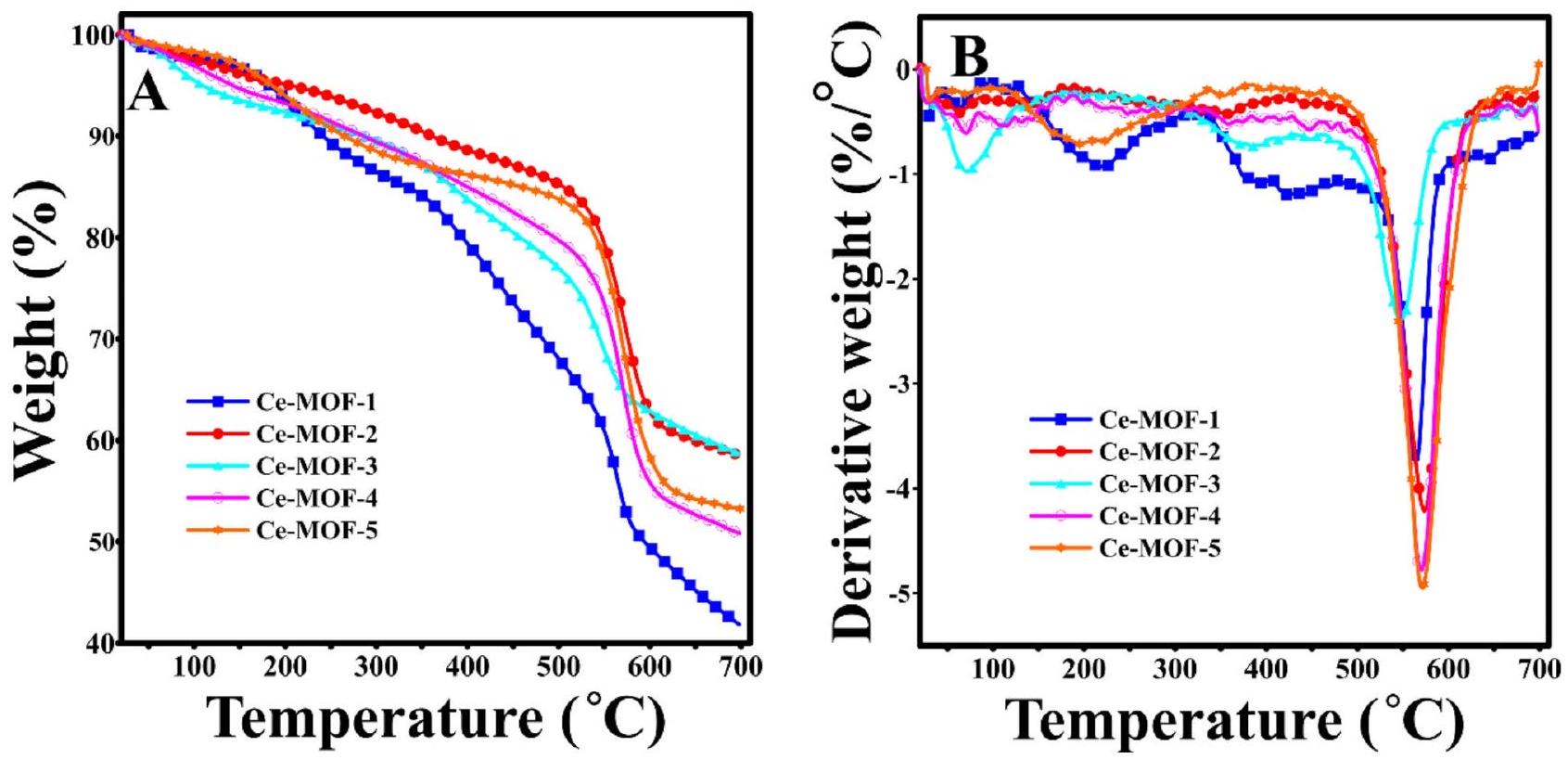

تحليل الوزن الحراري

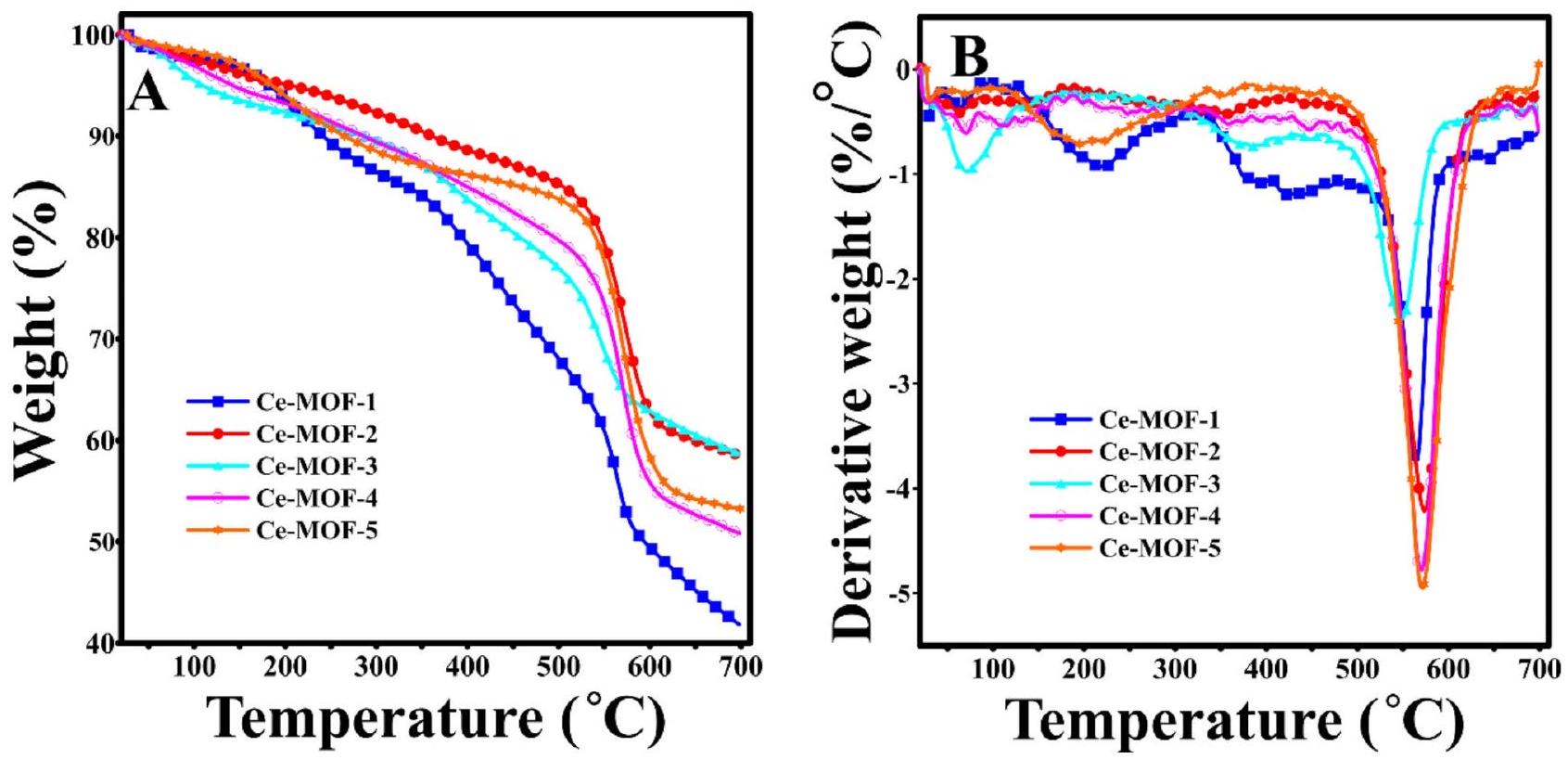

نظرًا لأن الاستقرار الحراري هو عامل مهم للمواد الممتصة القائمة على MOF المسامي، تم إجراء تحليل الوزن الحراري للتحقيق في تأثير المذيبات المتبادلة على الاستقرار الحراري لـ Ce-MOFs المحضرة.

الشكل 4. (أ) ملفات TGA و (ب) ملفات DTG لـ Ce-MOFs المحضرة.

كما لوحظ من الشكل 4، أظهرت جميع Ce-MOFs المحضرة عدة خسائر في الوزن من درجة حرارة الغرفة إلى 500

تتعلق خسارة الوزن الملحوظة عند أكثر من

حدثت أعلى خسارة في الوزن عند درجة حرارة أعلى من

كانت النتائج المستخلصة من ملفات TGA (الشكل 4A) و DTG (الشكل 4B) لـ Ce-MOFs المحضرة متوافقة تمامًا مع النتائج المستخلصة من إيزوثرم امتصاص النيتروجين وإزالة النيتروجين. وبناءً عليه، عندما كانت عملية التبادل ناجحة وتم تبادل جزيئات ذات نقاط غليان أعلى مع مذيبات ذات نقاط غليان منخفضة، ستتكون MOFs ذات محتويات رماد متبقية عالية ومساحة سطحية عالية. نتيجة لنجاح تبادل الجزيئات الضيفية مع الإيثانول، أظهر Ce-MOF-2 أعلى محتويات رماد متبقية وكذلك أعلى مسامية. بينما، من بين العينات المنشطة، أظهر Ce-MOF-4 أقل محتويات رماد متبقية وكذلك أقل مساحة سطحية، بسبب القدرة المنخفضة للأسيتون كمذيب تبادل لإزالة الجزيئات الضيفية داخل مسام MOFs.

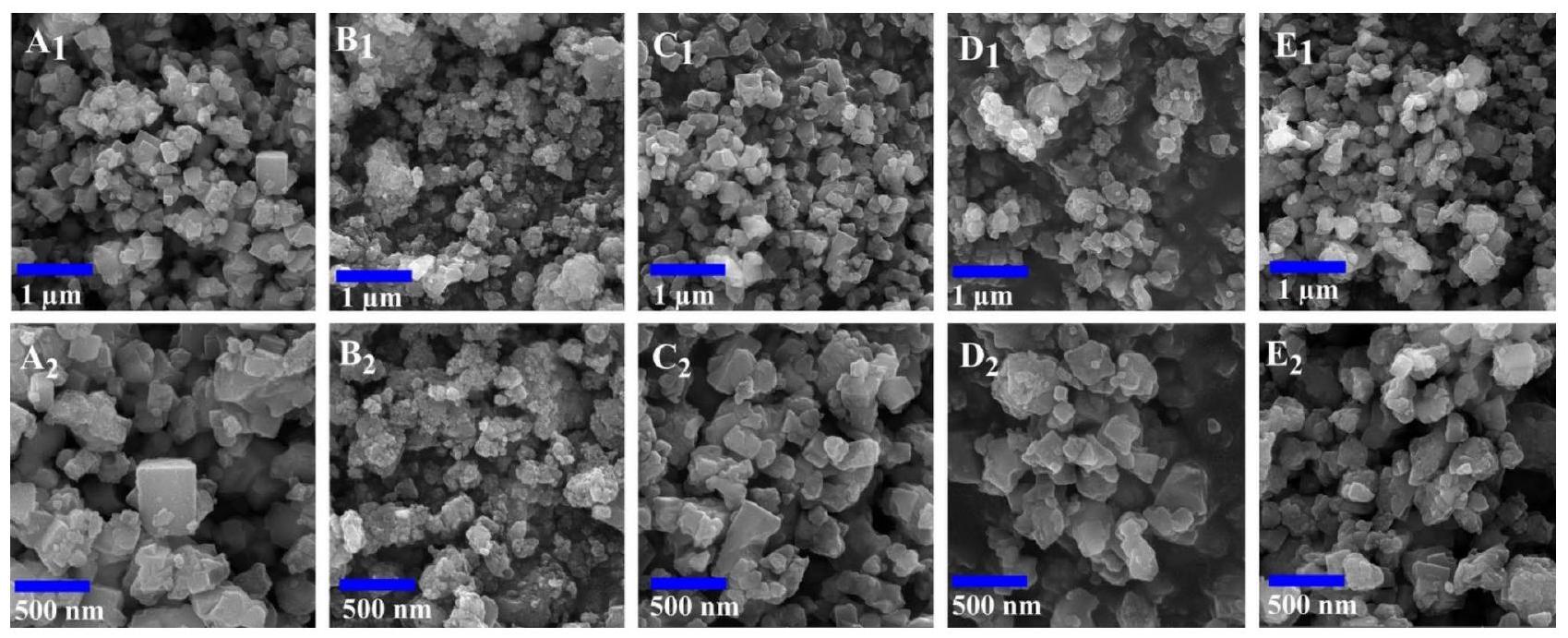

تحليل FESEM

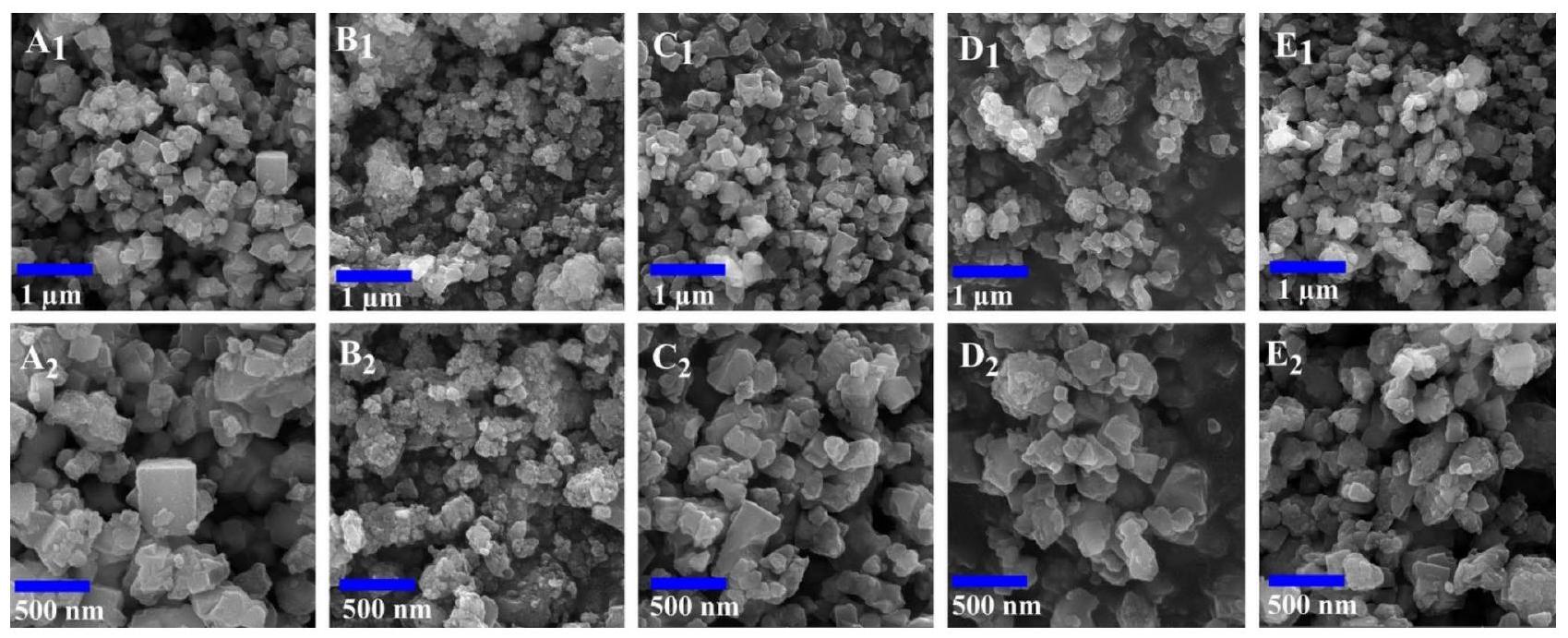

تظهر الشكل 5 صور FESEM لـ Ce-MOFs المحضرة التي تم تنشيطها بمذيبات تبادل مختلفة. شكل جميع Ce-MOFs المحضرة متشابه نسبيًا وأحجام جزيئاتها أصغر من 500 نانومتر، مما يشير إلى أن مذيب التبادل ليس له تأثير كبير على شكل الجزيئات النهائية. من الواضح أن معظم العينات المحضرة تحتوي على جزيئات كروية ذات شكل غير منتظم تتجمع معًا.

تجارب الامتصاص

تأثير المذيبات المتبادلة على أداء الامتصاص لـ Ce-MOFs

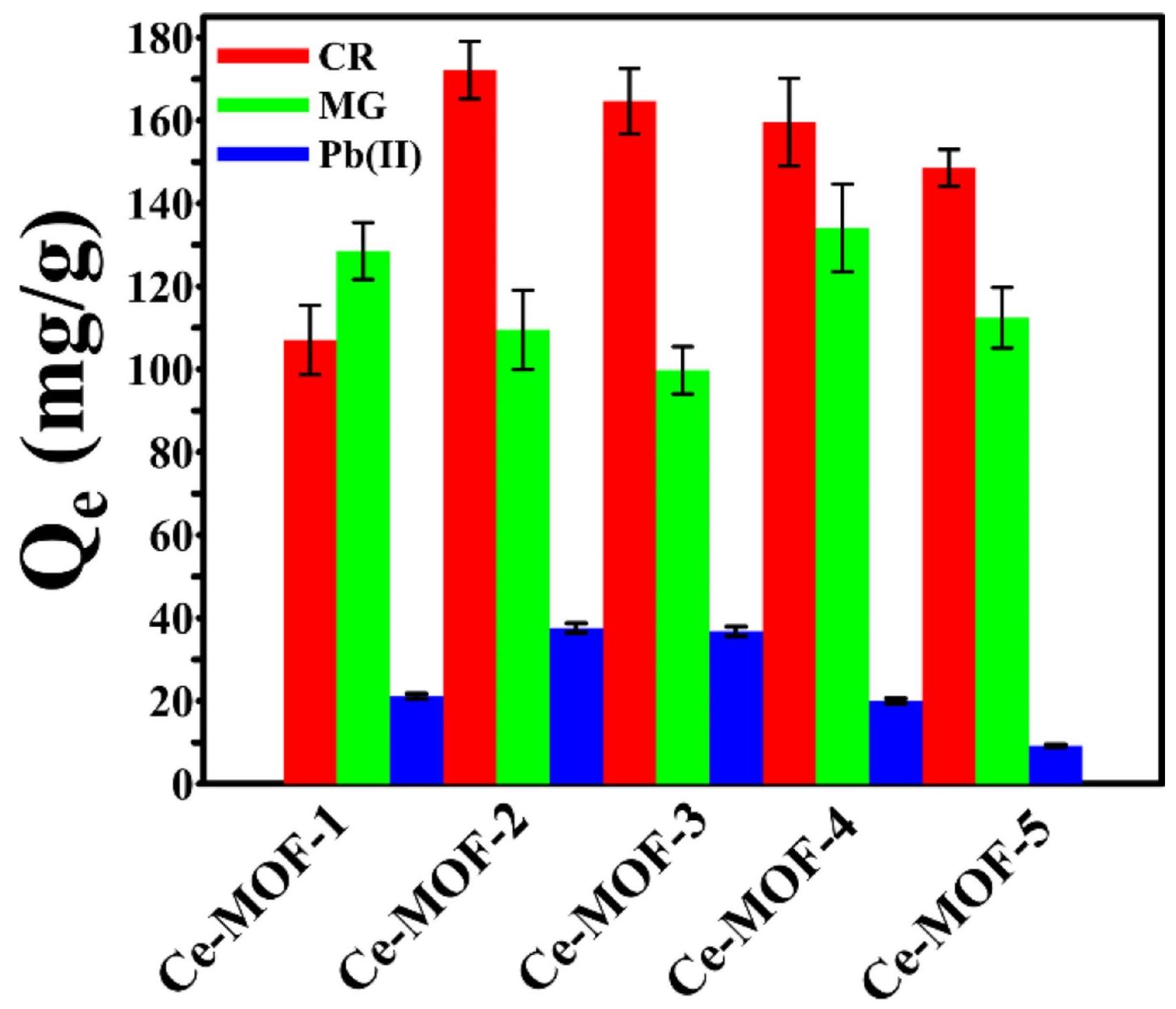

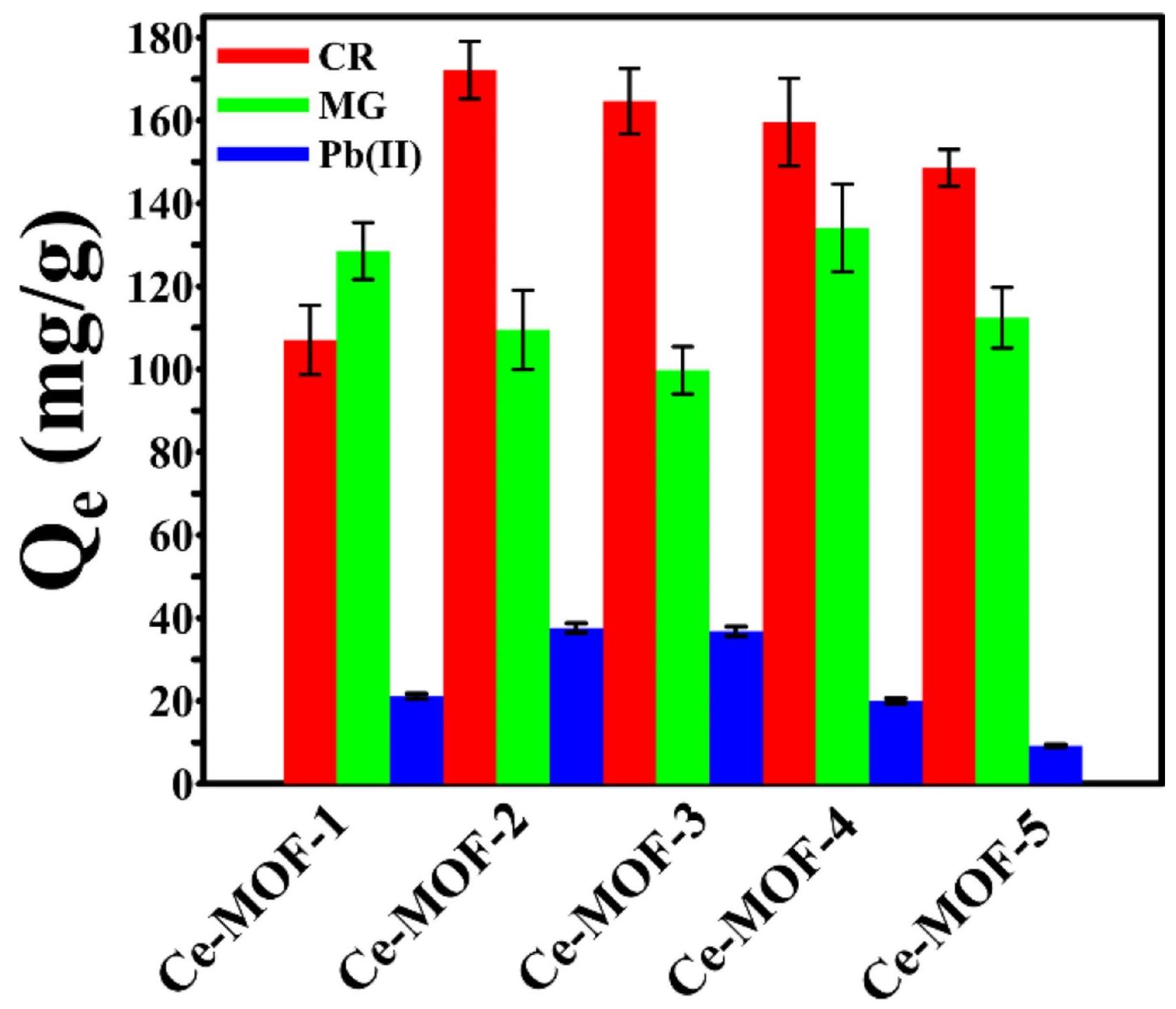

لتقييم أداء الامتصاص لـ Ce-MOFs المحضرة، تم تحليل سعات الامتصاص لجميع Ce-MOFs تجاه الأصباغ العضوية (CR كصبغة أنيونية، و MG كصبغة كاتيونية) وأيونات المعادن الثقيلة (

لتقييم أداء الامتصاص لـ Ce-MOFs المحضرة، تم تحليل سعات الامتصاص لجميع Ce-MOFs تجاه الأصباغ العضوية (CR كصبغة أنيونية، و MG كصبغة كاتيونية) وأيونات المعادن الثقيلة (

الشكل 5. صور FESEM لـ

بين

ومع ذلك، لم تكن قدرتها على الامتزاز تجاه كلا الصبغتين العضويتين متسقة تمامًا مع مساحاتها السطحية. قدرة الامتزاز لهذه المواد العضوية المعدنية (MOFs) تجاه صبغة CR السالبة هي بترتيب Ce-MOF-2.

ومع ذلك، فإن ترتيب سعة امتصاص MG هو Ce-MOF-4

دراسة الحركيات والإيزوثرمات لعملية الامتزاز

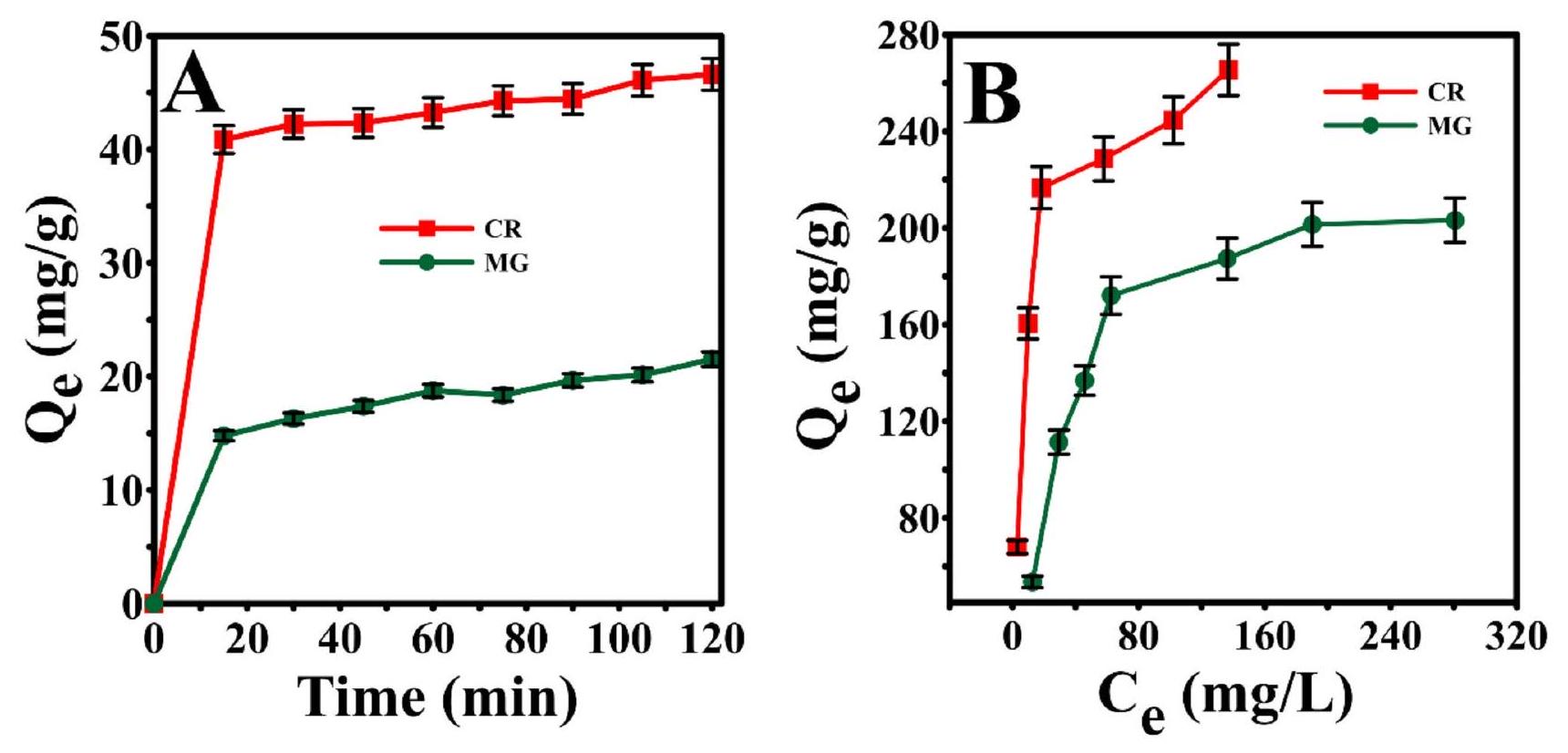

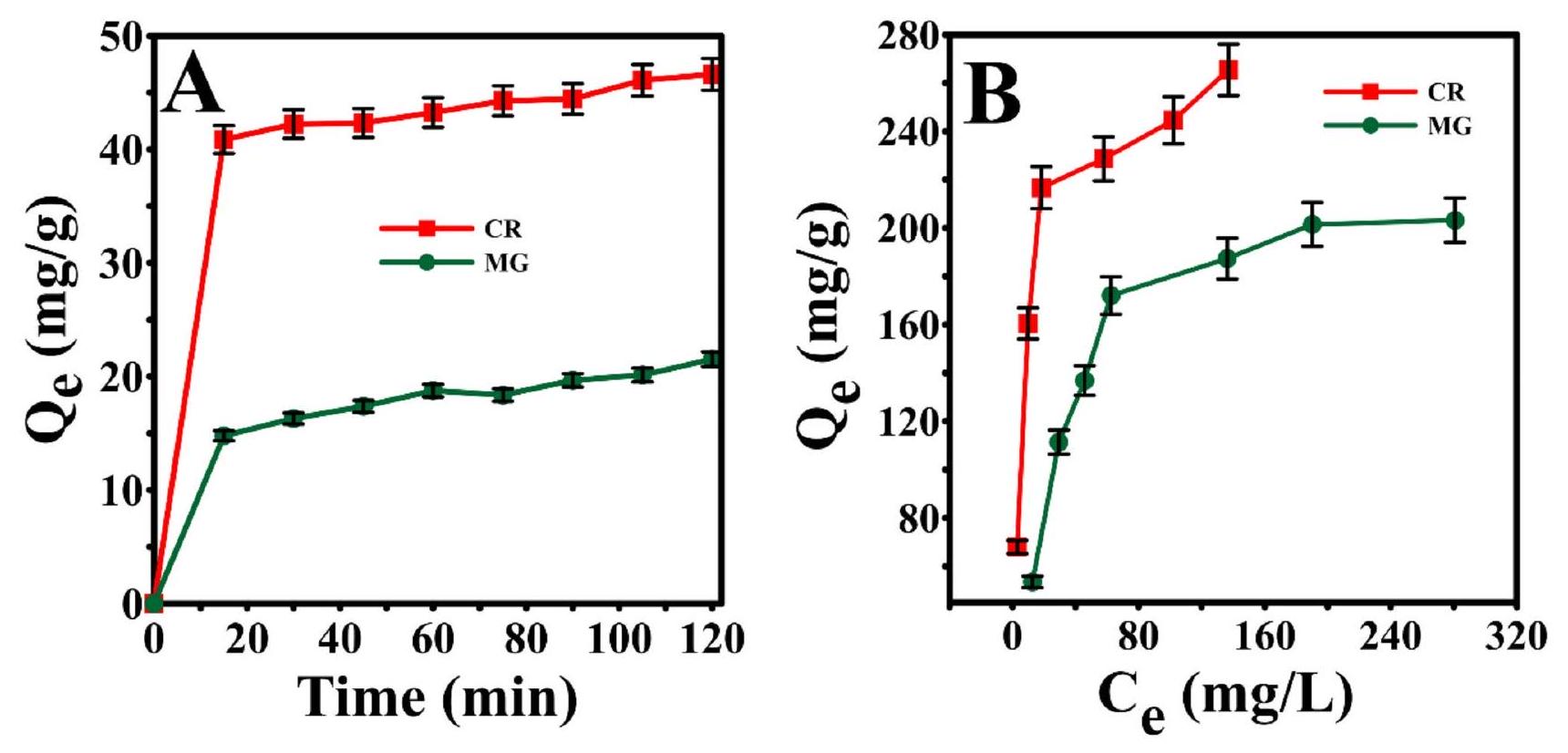

ديناميكا وخصائص الامتزاز للصبغات هما من المعايير المهمة لتقييم أداء الامتزاز للمواد الماصة. لذلك، لتقييم كفاءة إزالة Ce-MOF-4 تجاه كل من صبغتي CR وMG بشكل أفضل وفهم آليات الامتزاز، تم دراسة ديناميات الامتزاز وخصائص الامتزاز لجزيئات CR وMG على Ce-MOF-4. تعرض الشكل 7A تأثير زمن التلامس على سعة الامتزاز لصبغتي CR وMG على Ce-MOF-4. أدى الشحنة السطحية الإيجابية لـ Ce-MOF-4 (الجدول 1) إلى امتصاص جزيئات CR السالبة. بسبب التشتت الجيد لجزيئات المادة الماصة داخل محلول CR، لا توجد قيود كبيرة على نقل الكتلة لجزيئات CR من محلول الصبغة إلى سطح جزيئات MOF. نتيجة لمثل هذه الظواهر، تغير لون محلول CR بسرعة من البرتقالي الداكن إلى الأصفر الفاتح وانخفضت تركيزه بسرعة بناءً على شدة الامتصاص لطيف UV-Vis (الشكل S1).

ومع ذلك، أظهرت حركية الامتزاز لصبغة MG الكاتيونية على Ce-MOF-4 أن إزالة صبغة MG ليست فعالة جداً، ويرجع ذلك أساساً إلى الشحنة السطحية الإيجابية للامتصاص التي تزيد من التنافر الكهروستاتيكي لجزيئات MG الكاتيونية مع المواقع النشطة المشحونة إيجابياً في Ce-MOF-4. تم تحليل حركية الامتزاز لكل من الصبغات العضوية على Ce-MOF-4 باستخدام ثلاثة نماذج حركية مثل النموذج من الدرجة الأولى الزائفة، والنموذج من الدرجة الثانية الزائفة، وانتشار الجزيئات الداخلية، حيث كشفت النتائج المستخلصة أن البيانات كانت متوافقة بشكل معقول مع نموذج الحركية من الدرجة الثانية الزائفة.

الشكل 6. أداء الامتزاز لمركبات Ce-MOFs المحضرة تجاه CR و MG و

حوالي 0.0047 و

تمت دراسة كفاءات الإزالة لـ Ce-MOF-4 تجاه هذه الأصباغ بشكل إضافي من خلال إجراء إيزوثيرم الامتصاص (الشكل 7B). أشارت منحنيات الإيزوثيرم لكلا الصبغين إلى أن سعة الامتصاص زادت مع زيادة التركيز الابتدائي للأصباغ، وكانت السعات القصوى للامتصاص 265.48 و

دراسة تأثير المعلمات الأخرى المؤثرة على أداء الامتزاز

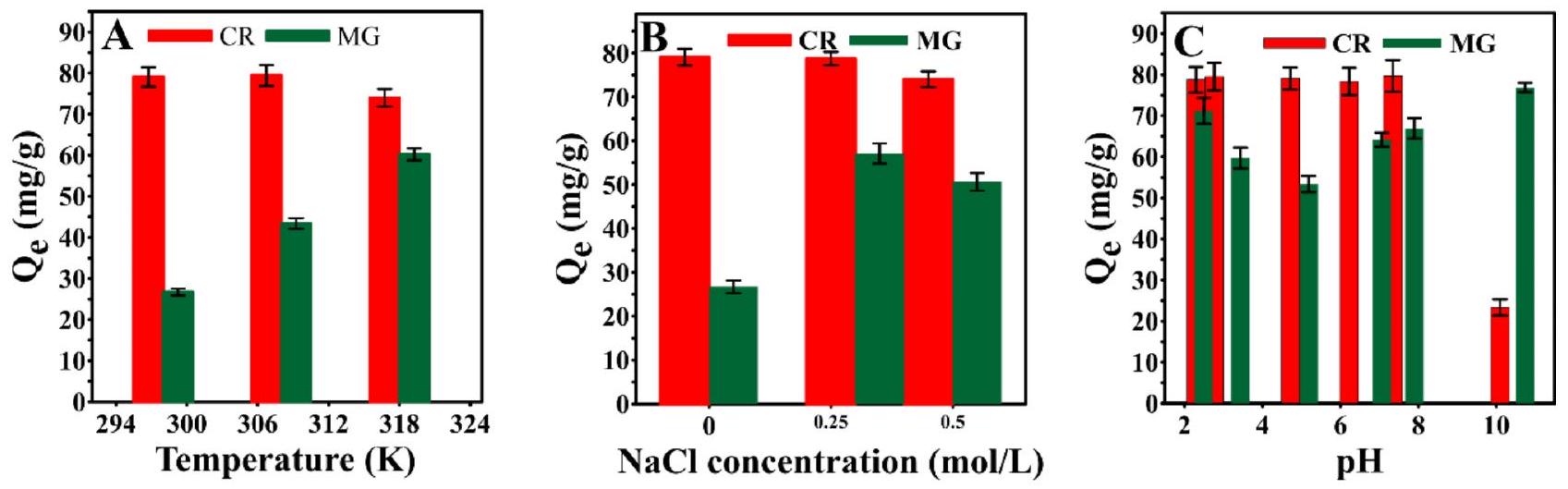

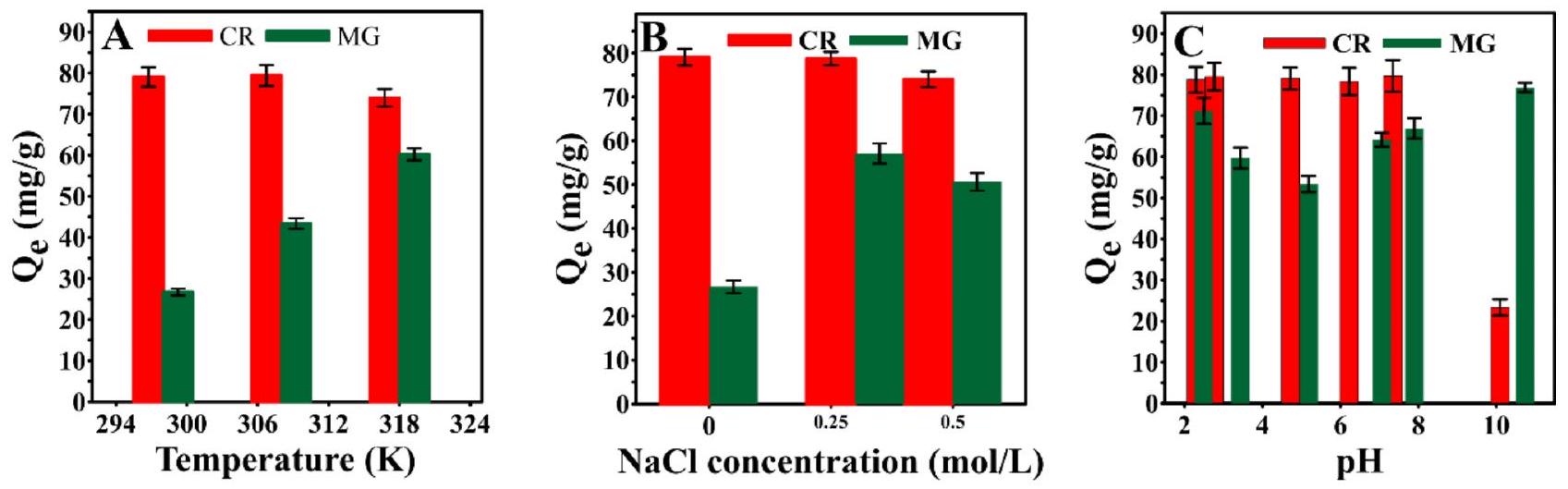

لتوضيح سلوك امتصاص الصبغة لـ Ce-MOF-4، تم إجراء تجارب امتصاص إضافية عند درجات حرارة مختلفة، وتركيزات ملح مختلفة، ودرجات حموضة مختلفة. يتم توضيح أداء الامتصاص لـ Ce-MOF-4 تحت ظروف متنوعة في الشكل 8. من الواضح من الشكل 8A أن درجة حرارة الامتصاص لم يكن لها تأثير كبير على سعة امتصاص CR على Ce-MOF-4. سعة امتصاص CR

الشكل 7. (أ) حركيات الامتزاز و (ب) منحنيات الامتزاز لامتزاز CR و MG على Ce-MOF-4.

| النماذج الحركية | المعلمات المحسوبة | صبغات | |

| إم جي | سي آر | ||

| زائف من الدرجة الأولى |

|

0.9545 | 0.7902 |

|

|

0.017 | 0.022 | |

|

|

8.74 | 9.95 | |

| الترتيب الزائف من الدرجة الثانية |

|

0.9910 | 0.9981 |

|

|

0.0037 | 0.0047 | |

|

|

٢٢.٦٢ | ٤٧.٦٢ | |

|

|

21.52 | ٤٦.٦١ | |

| انتشار داخل الجسيمات |

|

0.9680 | 0.9497 |

|

|

0.8795 | 0.792 | |

| ج (

|

11.42 | ٣٧.٥١ | |

الجدول 2. المعلمات الثابتة لنماذج حركية مختلفة لامتصاص صبغات CR و MG على Ce-MOF-4.

انخفض قليلاً من 79.07 إلى

تمت ملاحظة نتائج مماثلة أيضًا من خلال حساب معلمات الامتزاز الديناميكية الحرارية (الجدول 4)، باستخدام مخطط فان’t هوف (الشكل S4). تم حساب تغير الطاقة الحرة غيبس السلبية (

يمكن أن يكون لوجود أيونات مختلفة في مياه الصرف الصحي تأثيرات ملحوظة على أداء الامتصاص للمواد الماصة. وبالتالي، تم تقييم تأثير تركيز NaCl على سعة الامتصاص لـ CR و MG. نظريًا، عندما يكون تفاعل الممتص والممتص عليه جذابًا، قد يقلل وجود أيونات مختلفة من أداء الامتصاص، بينما إذا كان التفاعل طاردًا، فإن أداء الامتصاص يتحسن مع إضافة أملاح مختلفة.

| نماذج الإيزوثرم | المعلمات المحسوبة | صبغات | |

| إم جي | سي آر | ||

| لانغموير |

|

0.9944 | 0.9963 |

|

|

0.032 | 0.125 | |

|

|

227.27 | ٢٧٠.٢٧ | |

|

|

٢٠٣.١٥ | ٢٦٥.٤٨ | |

| ودود |

|

0.8465 | 0.8136 |

|

|

٢٥.٦٩ | ٦٤.٦٥ | |

|

|

٢.٤٩ | 3.22 | |

| تمبكين |

|

0.9345 | 0.9048 |

|

|

50.97 | 53.17 | |

|

|

0.33 | ٢.٥٠ | |

| دوبيين-رادوشكيفيتش |

|

0.9132 | 0.9428 |

|

|

178.52 | 229.66 | |

| ب (

|

|

|

|

الجدول 3. المعلمات المحسوبة للآيزوثرم لامتصاص CR و MG على Ce-MOF-4.

الشكل 8. تأثير (أ) درجة الحرارة، (ب) تركيز NaCl، و(ج) الرقم الهيدروجيني على قدرة الامتزاز لـ Ce-MOF-4 تجاه صبغات CR وMG.

| درجة الحرارة (ك) |

|

|

|

| سي آر | |||

| 298 | -74.79 | -198.51 | -15.64 |

| ٣٠٣ | -13.66 | ||

| 318 | -11.67 | ||

| إم جي | |||

| 298 | 70.96 | 243.72 | -1.67 |

| ٣٠٣ | -4.11 | ||

| 318 | -6.54 | ||

الجدول 4. المعلمات الديناميكية الحرارية المقاسة لامتصاص CR و MG على Ce-MOF-4.

في وجود NaCl، ويظهر القيمة القصوى لـ

تمت دراسة تأثير الرقم الهيدروجيني على أداء الامتزاز لـ Ce-MOF-4 من خلال تغيير الرقم الهيدروجيني لمحلول الصبغة من 2 إلى 11 باستخدام محاليل مخففة من HCl و NaOH (الشكل 8C). لم يظهر سعة الامتزاز لـ Ce-MOF-4 تغييرًا كبيرًا عند الأرقام الهيدروجينية الأقل من 8، حيث يكون للامتزاز شحنة سطحية إيجابية ويمكنه التفاعل مع جزيئات CR المشحونة سلبًا. ومع ذلك، عند الأرقام الهيدروجينية الأعلى، انخفضت كفاءة الإزالة بسبب وجود تنافر كهربائي قوي بين جزيئات CR والمواقع المشحونة سلبًا لجزيئات Ce-MOF-4.

ومع ذلك، لوحظ أن Ce-MOF-4 يمكنه امتصاص جزيئات CR حتى في الظروف القلوية القوية.

على عكس صبغة CR، تتأثر سعة الامتصاص لـ MG بشكل كبير بـ pH المحلول، حيث انخفضت نسبة امتصاصه مع زيادة pH، ثم أظهرت زيادة كبيرة في المحلول القلوي. عند pH المنخفض، عندما يكون MG في شكله المحايد ولدى Ce-MOF-4 مواقع مشحونة إيجابيًا، لا توجد تفاعلات كهربائية بين المادتين. لذلك، في هذه الحالة يمكن لجزيئات MG التفاعل مع الممتز.

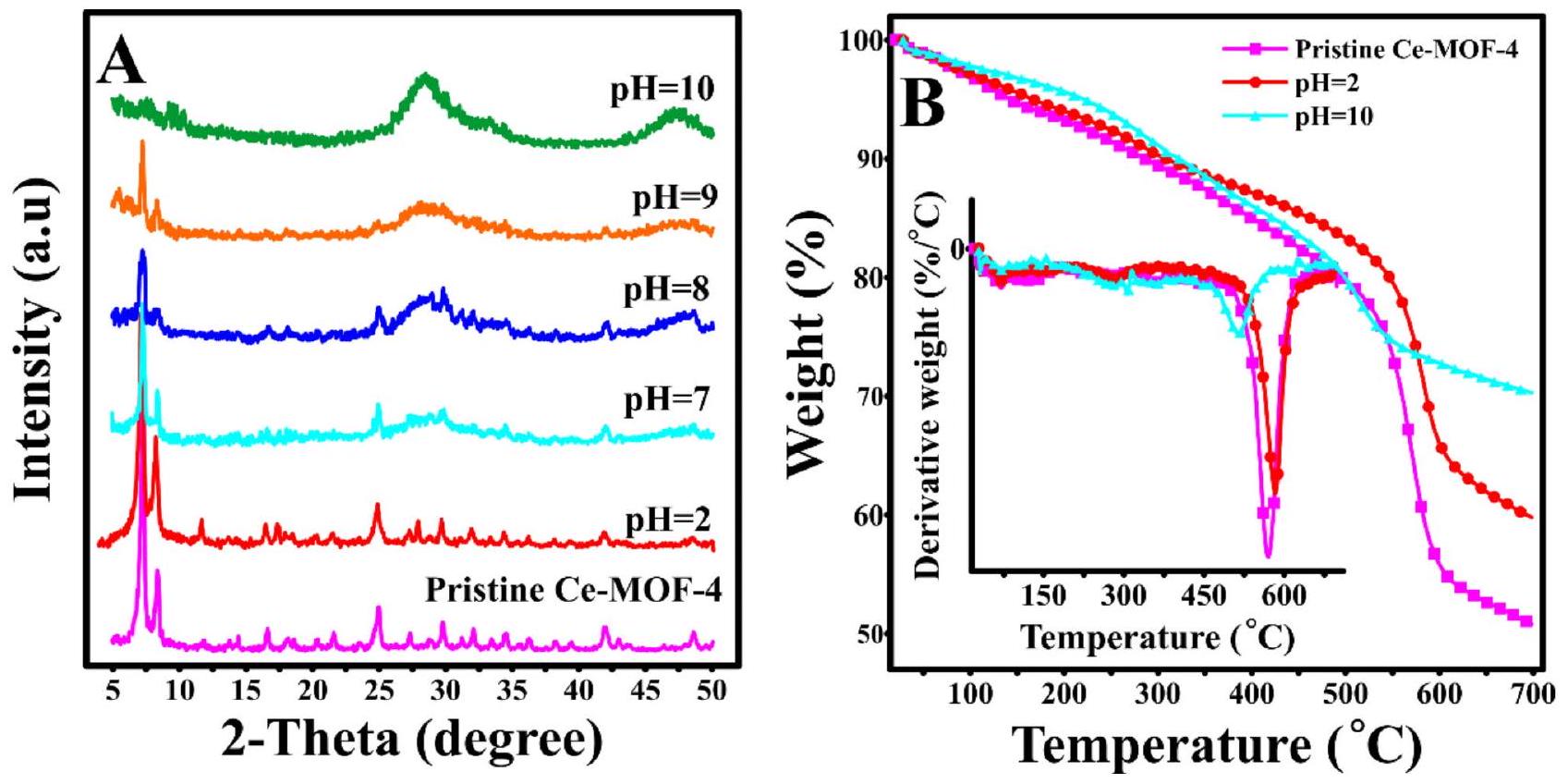

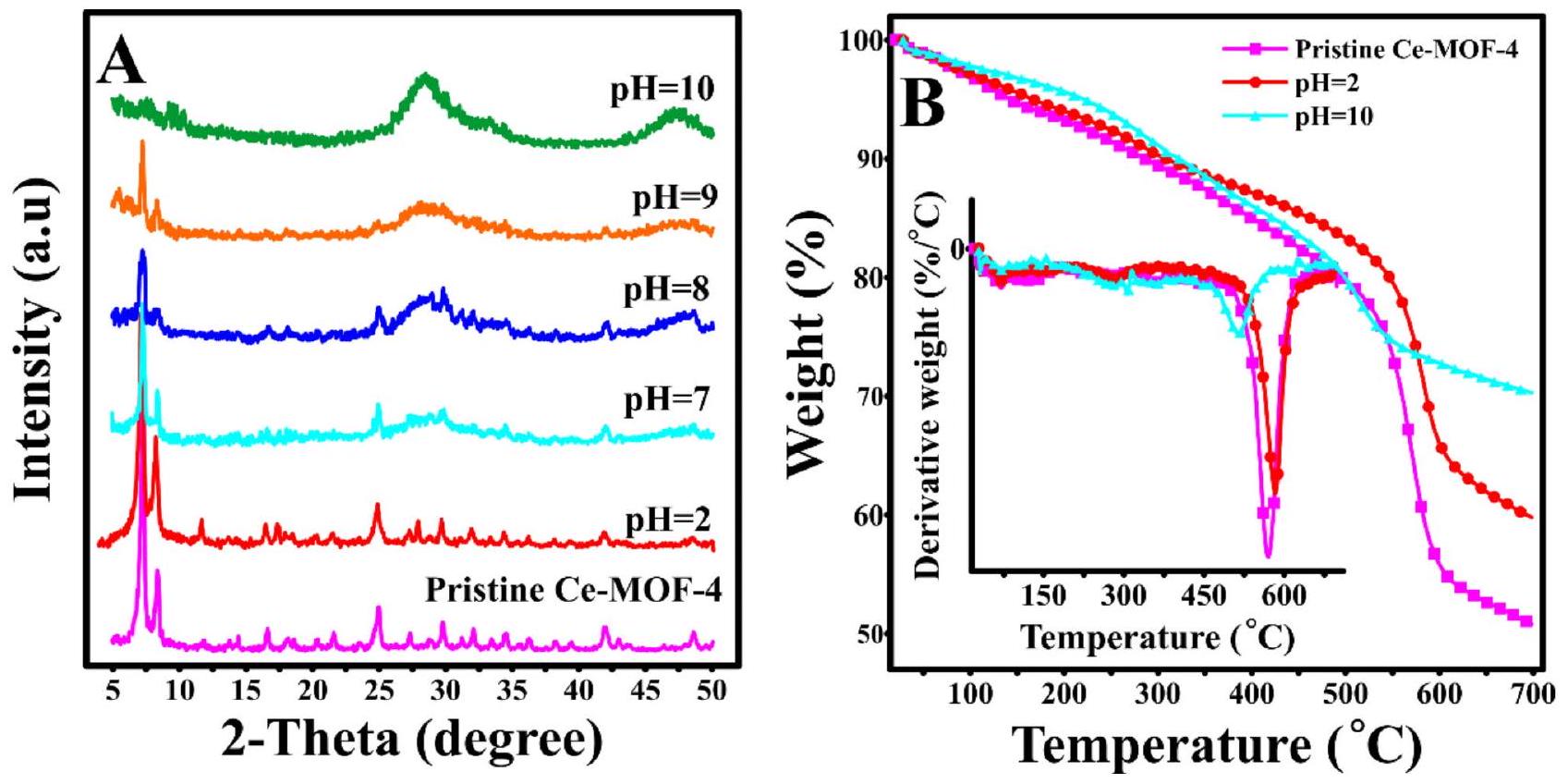

دراسة الاستقرار الهيكلي لـ Ce-MOF-4

استقرار الماء لمواد الامتصاص القائمة على MOF هو أحد المعايير الحاسمة التي يمكن أن تحدد أداء الامتصاص للمواد الماصة في تطبيقات معالجة المياه العادمة على المدى الطويل. لأن جزيئات الماء يمكن أن تعزز تفاعل التحلل المائي لـ MOFs وتؤدي إلى تدهور هياكل MOF.

تم تقييم الاستقرار الهيدروليتي لـ Ce-MOF-4 من خلال غمر جزيئات MOF في محلول مائي بقيم pH مختلفة (من 2 إلى 10) لمدة 3 ساعات. تم ضبط قيم pH الأولية للمحاليل المائية عن طريق إضافة محاليل HCl أو NaOH. تم فصل جزيئات Ce-MOF-4 المنقوعة عن طريق الطرد المركزي، وغسلها عدة مرات بالماء لتحييد pH الخاص بها، وأخيرًا تم تجفيفها عند

كما هو متوقع، تم تدمير الهيكل البلوري لـ Ce-MOF-4 بالكامل في المحاليل القلوية.

الشكل 9. (أ) أنماط حيود الأشعة السينية و (ب) ملفات تحليل الوزن الحراري لـ Ce-MOF-4 في درجات حموضة مختلفة.

تمت ملاحظة اتجاهات مماثلة أيضًا في إيزوثرمات امتصاص وإطلاق النيتروجين لكل من العينات المعالجة في المحاليل الحمضية والقاعدية (الشكل S5). تم تقليل مساحة السطح وفقًا لطريقة BET للعينة المنقوعة في pH 10 بشكل كبير من 605 إلى

ومع ذلك، فإن العينات المعالجة مع المحاليل الحمضية والقاعدية لا تزال تظهر أداءً جيدًا في الامتزاز تجاه كلا الصبغتين العضويتين. وبناءً عليه، تم تقليل سعة امتصاص CR لـ Ce-MOF-4 من 79.1 إلى

تمت دراسة تأثير pH المحلول على الاستقرار الحراري لـ Ce-MOF-4 بواسطة TGA. تُظهر الشكل 9B أن ملفات TGA للعينات المعالجة مشابهة نسبيًا لمركبات MOF الأصلية. قد يكون ظهور بعض خطوات تقليل الوزن الضعيفة الجديدة بسبب التغيرات الهيكلية. من الواضح أن الاستقرار الحراري للعينة المنقوعة في محلول قاعدي

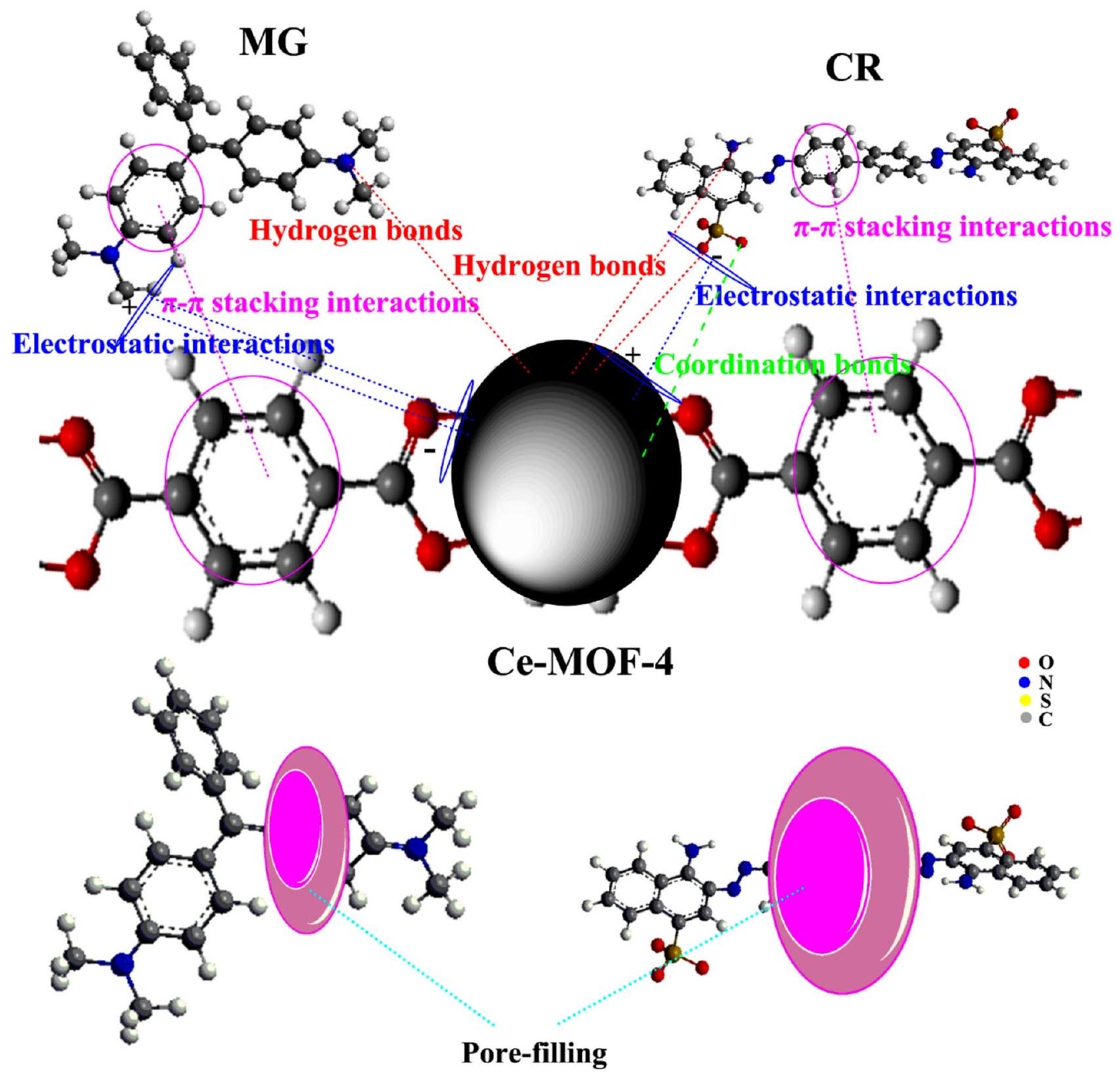

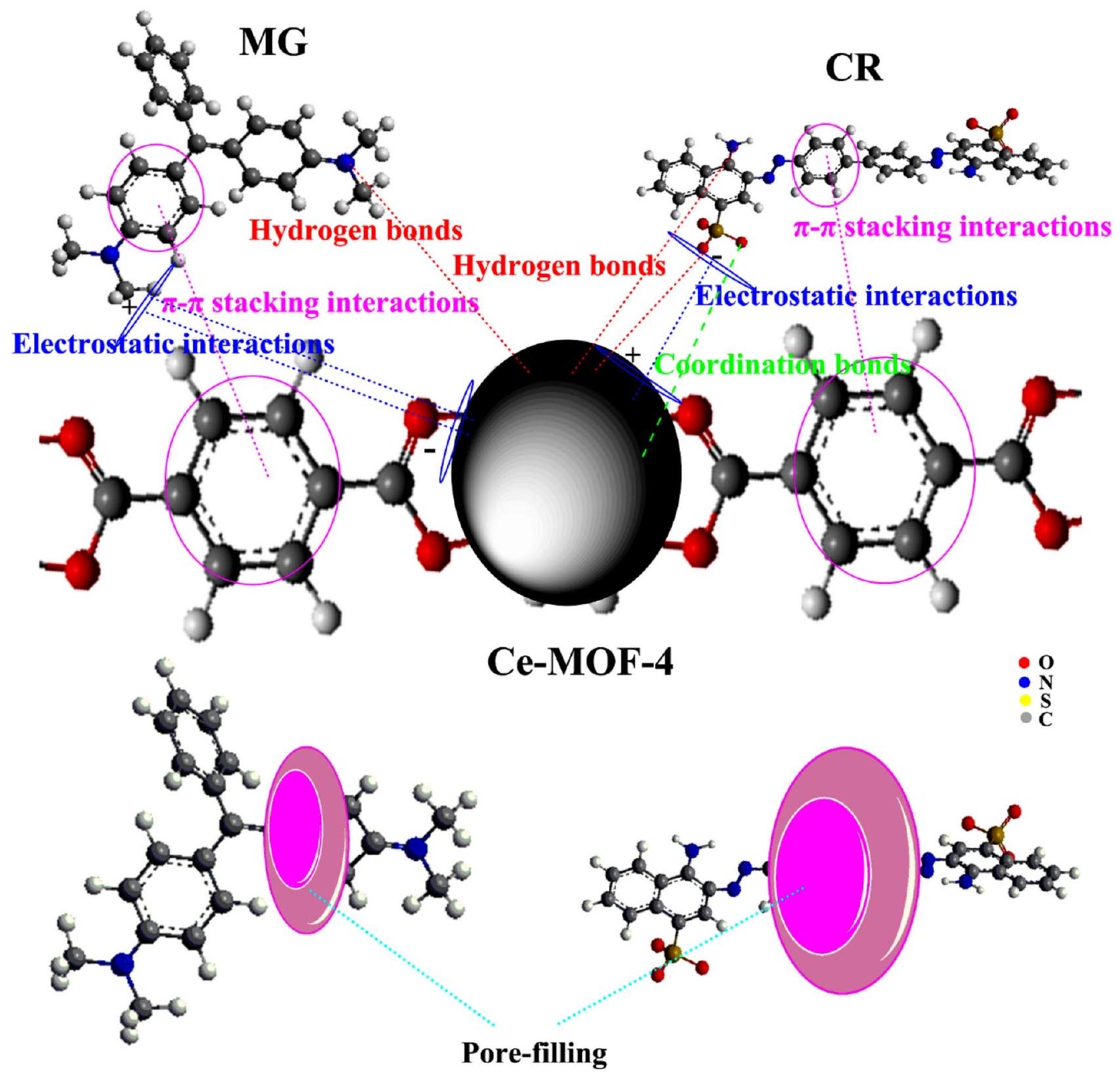

آليات الامتزاز

تم تحليل آليات الامتزاز لصبغات CR و MG على Ce-MOF-4 باستخدام تحليل الجهد الكهربائي، FTIR، و FESEM. وفقًا للنتائج التي تم الحصول عليها من الأقسام السابقة، يمكن توقع أن وجود تفاعل كهربائي بين المواقع النشطة لمركبات MOFs وجزيئات الصبغة هو أحد الآليات الحرجة للامتزاز. كما هو موضح في الشكل 10، فإن الأنيونات

تظهر طيف FTIR لـ Ce-MOF-4 بعد امتصاص صبغات CR و MG (الشكل S6) عدة قمم امتصاص جديدة تتعلق بالمجموعات الوظيفية لجزيئات الصبغة، مما يؤكد أن جزيئات الصبغة تم امتصاصها على سطح Ce-MOF-4. وتم تأكيد وجود هذه الصبغات على سطح Ce-MOF-4 من خلال صور التحليل الطيفي بالأشعة السينية المشتتة للطاقة (EDS) (الشكل S7). وتكوين روابط هيدروجينية بين

| MOFs | مساحة السطح

|

متوسط قطر المسام (نانومتر) | حجم المسام

|

| سي-موف-4 النقي | 605 | 2.85 | 0.4079 |

| Ce-MOF-4 في pH 2 | 86 | 15.63 | 0.3375 |

| Ce-MOF-4 في pH 10 | 187 | ٥.٩٩ | 0.2802 |

| CR المعاد تدويره Ce-MOF-4 | 511 | 3.56 | 0.4548 |

| MG المعاد تدويره Ce-MOF-4 | 410 | ٤.١٩ | 0.4301 |

الجدول 5. الخصائص المسامية لـ Ce-MOF-4، المعالج بالأحماض/القلويات، و Ce-MOF-4 المعاد تدويره.

الشكل 10. توضيح تخطيطي لآليات الامتزاز المحتملة

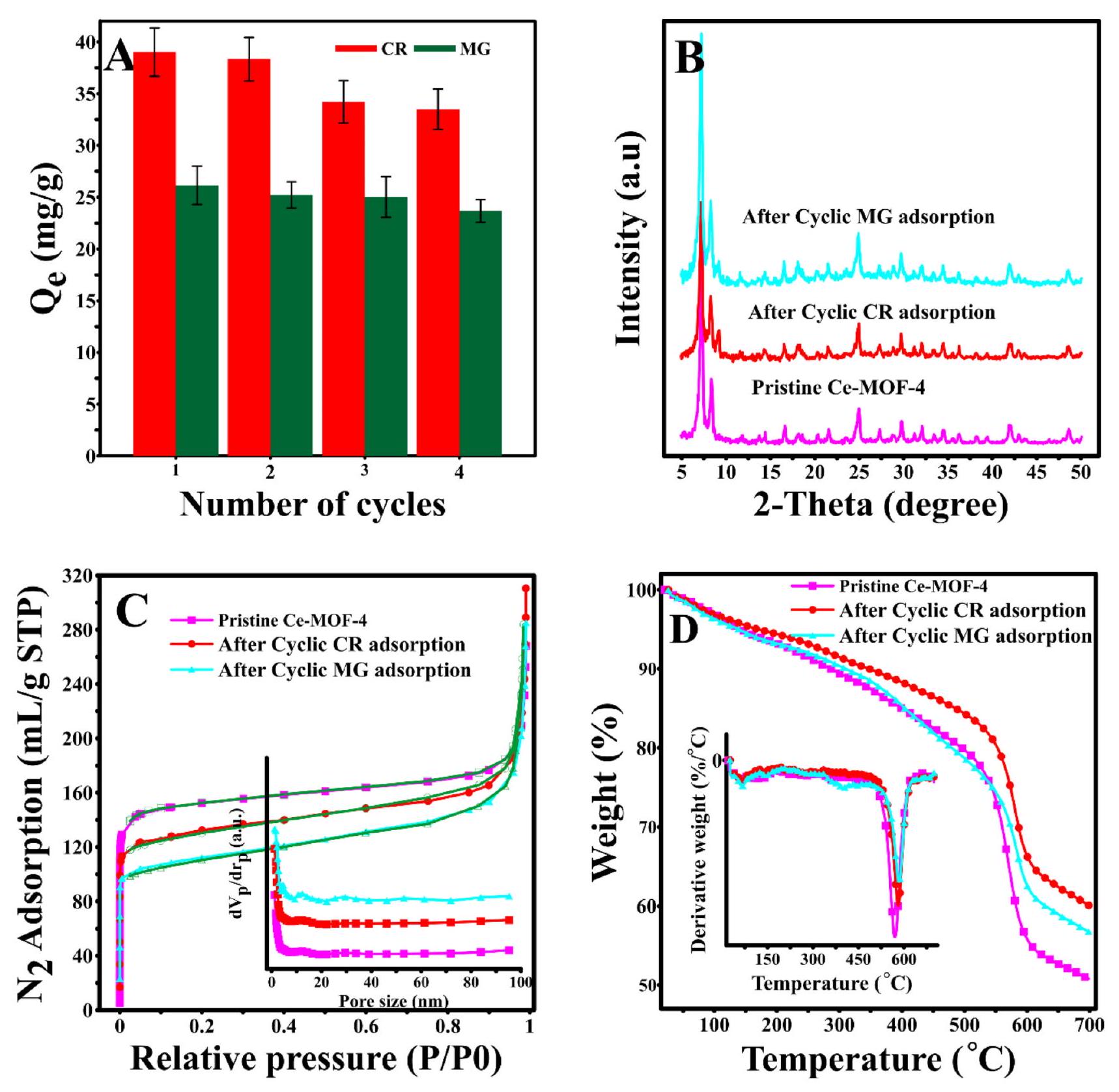

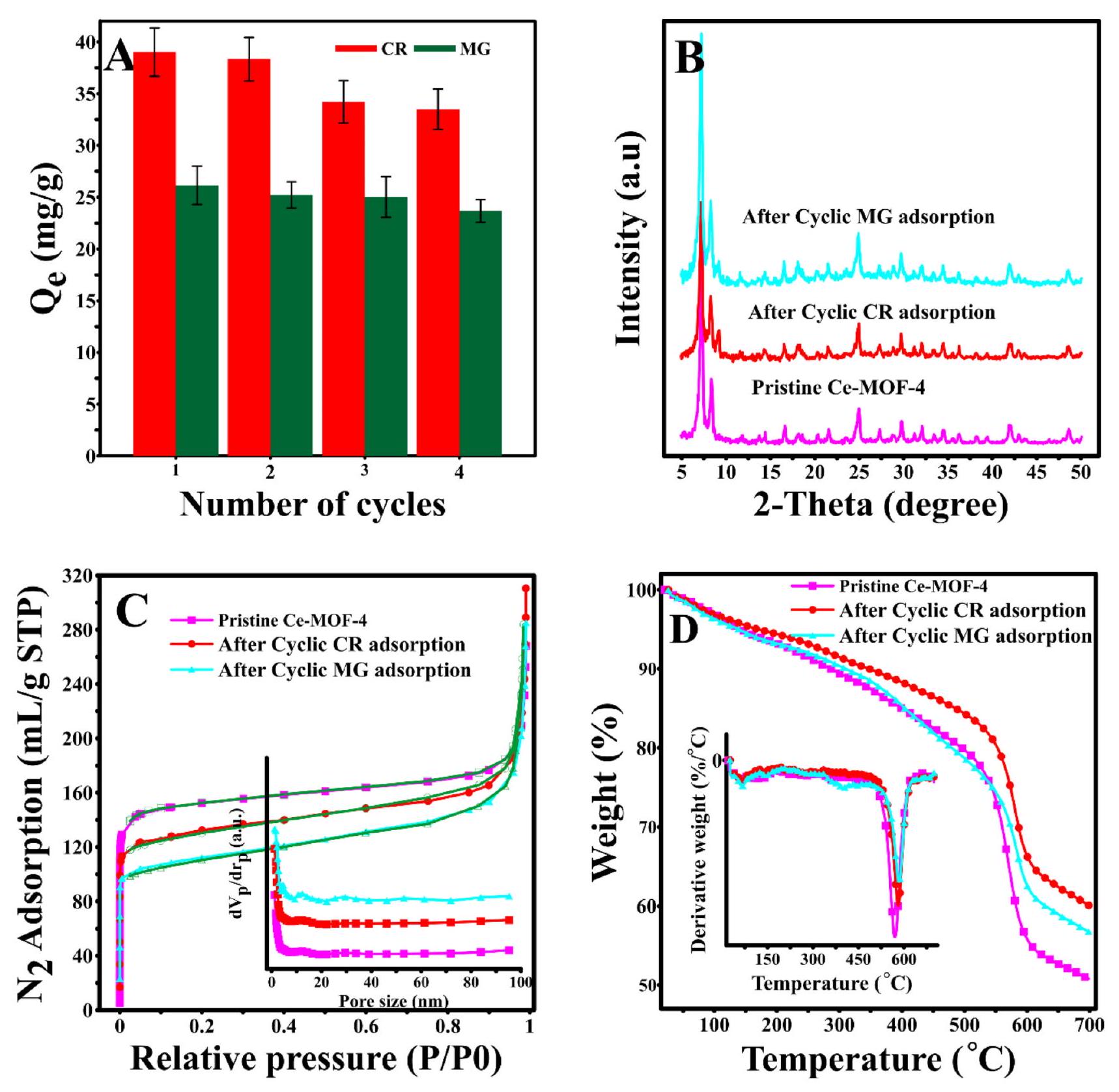

إمكانية إعادة الاستخدام والاستقرار الهيكلي

تمت دراسة قدرة التجديد وإعادة التدوير لـ Ce-MOF-4 أيضًا لأنها ضرورية جدًا لتطبيقات معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي العملية. وبناءً عليه، تم dispersing Ce-MOF-4 المحمّل بالصبغة في محلول إيثانول قلوي (يحتوي على NaOH) وتم تحريكه لمدة ساعتين لإطلاق الصبغات الممتصة. بعد ذلك، تم تنشيط العينة المستعادة وتطبيقها لدورة امتصاص-إزالة أخرى. يمكن ملاحظة أن Ce-MOF-4 يمكن استعادته لمدة أربع دورات متتالية من الامتصاص والإزالة دون انخفاض ملحوظ في أدائه في الامتصاص تجاه كل من الصبغات العضوية (الشكل 11A). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كما هو موضح في الشكل 11B، ظل الهيكل البلوري لـ Ce-MOF-4 مستقرًا بعد أربع دورات. والأهم من ذلك، تؤكد منحنيات امتصاص النيتروجين وإزالة النيتروجين (الشكل 11C) وملفات TGA (الشكل 11D) للعينات المعاد تدويرها على الاستقرار الهيكلي لهذا MOF خلال عمليات الامتصاص والإزالة الدورية. تشير جميع هذه النتائج إلى أن Ce-MOF-4 يمكن أن يكون مرشحًا واعدًا لتطبيقات معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي العملية.

الخاتمة

تم إعداد سلسلة من Ce-MOFs وتفعيلها بواسطة مذيبات تبادل مختلفة مثل الإيثانول، الكلوروفورم، الأسيتون، والميثانول. تتراوح مساحات السطح لـ Ce-MOFs المعدة في ترتيب Ce-MOF-1.

الشكل 11. (أ) تجربة إعادة استخدام Ce-MOF-4 لصبغات CR وMG. (ب) أنماط XRD، (ج) منحنيات امتصاص وإزالة النيتروجين، و(د) ملفات TGA للعينات المعاد تدويرها.

موف-1

توفر البيانات

جميع البيانات المتعلقة بهذه الدراسة مدرجة في المخطوطة وملف المعلومات الداعمة أو متاحة عند الطلب من المؤلف المراسل.

تاريخ الاستلام: 17 ديسمبر 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 12 فبراير 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 27 فبراير 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 27 فبراير 2025

References

- Bashir, N. et al. Green-synthesized silver nanoparticle-enhanced nanofiltration mixed matrix membranes for high-performance water purification. Sci. Rep. 15, 1001. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83801-w (2025).

- Mirzaei, R. et al. Innovative cross-linked Electrospun PVA/MOF nanocomposites for removal of cefixime antibiotic. Sci. Rep. 15, 83. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84818-x (2025).

- Kayani, K. F. Bimetallic metal-organic frameworks (BMOFs) for dye removal: a review. RSC Adv. 14, 31777-31796. https://doi.or g/10.1039/D4RA06626J (2024).

- Nazir, M. A. et al. Synthesis of bimetallic Mn@ZIF-8 nanostructure for the adsorption removal of methyl orange dye from water. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 165, 112294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112294 (2024).

- Eleryan, A. et al. Isothermal and kinetic screening of methyl red and methyl orange dyes adsorption from water by Delonix regia biochar-sulfur oxide (DRB-SO). Sci. Rep. 14, 13585. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63510-0 (2024).

- Molavi, H. et al. 3D-Printed MOF monoliths: fabrication strategies and environmental applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-024-01487-1 (2024).

- Shiri, M., Hosseinzadeh, M., Shiri, S. & Javanshir, S. Adsorbent based on MOF-5/cellulose aerogel composite for adsorption of organic dyes from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 14, 15623. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65774-y (2024).

- Mohammadi, A. et al. Novel ZIF-8/CNC nanohybrid with an interconnected structure: toward a sustainable adsorbent for efficient removal of cd(II) ions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 16, 3862-3875. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c15524 (2024).

- Noor, T., Raffi, U., Iqbal, N., Yaqoob, L. & Zaman, N. Kinetic evaluation and comparative study of cationic and anionic dyes adsorption on zeolitic imidazolate frameworks based metal organic frameworks. Mater. Res. Express. 6, 125088. https://doi.org/10 .1088/2053-1591/ab5bdf (2019).

- Ahmad, U. et al. ZIF-8 composites for the removal of Wastewater pollutants. ChemistrySelect 9, e202401719. https://doi.org/10.10 02/slct. 202401719 (2024).

- Sudarsan, S., Murugesan, G., Varadavenkatesan, T., Vinayagam, R. & Selvaraj, R. Efficient adsorptive removal of Congo Red dye using activated carbon derived from Spathodea campanulata flowers. Sci. Rep. 15, 1831. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-8603 2-9 (2025).

- Ahmadijokani, F. et al. COF and MOF hybrids: Advanced materials for Wastewater Treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2305527. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202305527 (2024).

- Molavi, H. et al. Wastewater treatment using nanodiamond and related materials. J. Environ. Manage. 349, 119349. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119349 (2024).

- Singh, S. et al. Metal organic frameworks for wastewater treatment, renewable energy and circular economy contributions. npj Clean. Water. 7, 124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00408-4 (2024).

- Ahmadijokani, F. et al. UiO-66 metal-organic frameworks in water treatment: a critical review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 125, 100904 (2022).

- Mirzaei, K., Jafarpour, E., Shojaei, A., Khasraghi, S. S. & Jafarpour, P. An investigation on the influence of highly acidic media on the microstructural stability and dye adsorption performance of UiO-66. Appl. Surf. Sci. 618, 156531 (2023).

- He, H. H. et al. Yolk-Shell and Hollow Zr/Ce-UiO-66 for manipulating selectivity in Tandem reactions and photoreactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 17164-17175 (2023).

- Zaremba, O., Andreo, J. & Wuttke, S. The chemistry behind room temperature synthesis of hafnium and cerium UiO-66 derivatives. Inorg. Chem. Front. 9, 5210-5216 (2022).

- Lammert, M. et al. Cerium-based metal organic frameworks with UiO-66 architecture: synthesis, properties and redox catalytic activity. Chem. Commun. 51, 12578-12581(2015).

- Wu, X. P., Gagliardi, L. & Truhlar, D. G. Cerium metal-organic framework for photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7904-7912 (2018).

- Farrag, M. In situ preparation of palladium nanoclusters in cerium metal-organic frameworks Ce-MOF-808, Ce-UiO-66 and CeBTC as nanoreactors for room temperature Suzuki cross-coupling reaction. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 312, 110783 (2021).

- Zhang, Y., Zeng, X., Jiang, X., Chen, H. & Long, Z. Ce-based UiO-66 metal-organic frameworks as a new redox catalyst for atomic spectrometric determination of Se (VI) and colorimetric sensing of hg (II). Microchem. J. 149, 103967 (2019).

- Rego, R. M. et al. Cerium based UiO-66 MOF as a multipollutant adsorbent for universal water purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 125941 (2021).

- Molavi, H. Cerium-based metal-organic frameworks: synthesis, properties, and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 527, 216405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2024.216405 (2025).

- Molavi, H. & Salimi, M. S. Green synthesis of Cerium-based metal-Organic Framework (Ce-UiO-66 MOF) for Wastewater Treatment. Langmuir 39, 17798-17807. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c02384 (2023).

- Li, K., Yang, J. & Gu, J. Salting-in species induced self-assembly of stable MOFs. Chem. Sci. 10, 5743-5748 (2019).

- Yassin, J. M., Taddesse, A. M. & Sanchez-Sanchez, M. Room temperature synthesis of high-quality ce (IV)-based MOFs in water. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 324, 111303 (2021).

- Jin, H. G. et al. Room temperature aqueous synthesis of ce (IV)-MOFs with UiO-66 architecture and their photocatalytic decarboxylative oxygenation of arylacetic acids. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 346, 112257 (2022).

- Campanelli, M. et al. Solvent-free synthetic route for Cerium (IV) metal-organic frameworks with UiO-66 architecture and their photocatalytic applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11, 45031-45037 (2019).

- Otun, K. O. Temperature-controlled activation and characterization of iron-based metal-organic frameworks. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 507, 119563 (2020).

- Andrés, M. A. et al. Solvent-exchange process in MOF ultrathin films and its effect on CO2 and methanol adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 590, 72-81 (2021).

- Zhang, X., Zhan, Z., Li, Z. & Di, L. Thermal activation of CuBTC MOF for CO oxidation: the effect of activation atmosphere. Catalysts 7, 106 (2017).

- Yang, Y. et al. Significant improvement of surface area and CO 2 adsorption of Cu-BTC via solvent exchange activation. RSC Adv. 3, 17065-17072 (2013).

- Zeleňák, V. et al. Large and tunable magnetocaloric effect in gadolinium-organic framework: tuning by solvent exchange. Sci. Rep. 9, 15572 (2019).

- Tati, A., Ahmadipouya, S., Molavi, H., Mousavi, S. A. & Rezakazemi, M. Efficient removal of organic dyes using electrospun nanofibers with Ce-based UiO-66 MOFs. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 266, 115584 (2023).

- Mohammadnejad, M. & Alizadeh, S. MnFe2O4-NH2-HKUST-1, MOF magnetic composite, as a novel sorbent for efficient dye removal: fabrication, characterization and isotherm studies. Sci. Rep. 14, 9048. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59727-8 (2024).

- Huang, F. P. et al. Solvent effects on the structures and magnetic properties of two doubly interpenetrated metal-organic frameworks. Dalton Trans. 44, 6593-6599 (2015).

- Ghadim, E. E., Walker, M. & Walton, R. I. Rapid synthesis of cerium-UiO-66 MOF nanoparticles for photocatalytic dye degradation. Dalton Trans. 52, 11143-11157. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3DT00890H (2023).

- Rad, F. A. & Rezvani, Z. Preparation of cubane-1, 4-dicarboxylate-Zn-Al layered double hydroxide nanohybrid: comparison of structural and optical properties between experimental and calculated results. RSC Adv. 5, 67384-67393 (2015).

- Li, Y. et al. Boosting the rhodamine B adsorption of bimetallic

: effect of valence states of cerium precursor. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 357, 112628 (2023). - Ramezanzadeh, M., Ramezanzadeh, B., Bahlakeh, G., Tati, A. & Mahdavian, M. Development of an active/barrier bi-functional anti-corrosion system based on the epoxy nanocomposite loaded with highly-coordinated functionalized zirconium-based nanoporous metal-organic framework (Zr-MOF). Chem. Eng. J. 408, 127361 (2021).

- Yazaydın, A. O. et al. Enhanced CO2 adsorption in metal-organic frameworks via occupation of open-metal sites by coordinated water molecules. Chem. Mater. 21, 1425-1430 (2009).

- Li, J. R., Kuppler, R. J. & Zhou, H. C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477-1504 (2009).

- Dai, S. et al. Room temperature design of ce(iv)-MOFs: from photocatalytic HER and OER to overall water splitting under simulated sunlight irradiation. Chem. Sci. 14, 3451-3461. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2SC05161C (2023).

- He, J. et al. Ce (III) nanocomposites by partial thermal decomposition of

for effective phosphate adsorption in a wide pH range. Chem. Eng. J. 379, 122431 (2020). - Amesimeku, J., Zhao, Y., Li, K. & Gu, J. Rapid synthesis of hierarchical cerium-based metal organic frameworks for carbon dioxide adsorption and selectivity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater., 112658 (2023).

- Karimi, M. et al. Additive-free aerobic C-H oxidation through a defect-engineered Ce-MOF catalytic system. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 322, 111054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2021.111054 (2021).

- Deng, S. Q. et al. An anionic nanotubular metal-Organic Framework for high-capacity dye adsorption and dye degradation in darkness. Inorg. Chem. 58, 13979-13987 (2019).

- Far, H. S. et al. PPI-dendrimer-functionalized magnetic metal-organic framework (Fe3O4@ MOF@ PPI) with high adsorption capacity for sustainable wastewater treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12, 25294-25303 (2020).

- Louaer, S., Wang, Y. & Guo, L. Fast synthesis and size control of gibbsite nanoplatelets, their pseudomorphic dehydroxylation, and efficient dye adsorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 5, 9648-9655 (2013).

- Abbasi, S., Nezafat, Z., Javanshir, S., Aghabarari, B. & Bionanocomposite MIL-100(Fe)/Cellulose as a high-performance adsorbent for the adsorption of methylene blue. Sci. Rep. 14, 14497. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65531-1 (2024).

- El Jery, A. et al. Isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamic mechanism of methylene blue dye adsorption on synthesized activated carbon. Sci. Rep. 14, 970. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50937-0 (2024).

- Mirzaei, K., Jafarpour, E., Shojaei, A. & Molavi, H. Facile synthesis of Polyaniline@UiO-66 nanohybrids for efficient and Rapid Adsorption of Methyl Orange from Aqueous Media. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61, 11735-11746. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.2c009 19 (2022).

- Samiey, B. & Toosi, A. R. Adsorption of malachite green on silica gel: effects of NaCl, pH and 2-propanol. J. Hazard. Mater. 184, 739-745 (2010).

- Lammert, M., Glißmann, C. & Stock, N. Tuning the stability of bimetallic ce (IV)/Zr (IV)-based MOFs with UiO-66 and MOF-808 structures. Dalton Trans. 46, 2425-2429 (2017).

- Bǔžek, D., Demel, J. & Lang, K. Zirconium metal-organic framework UiO-66: stability in an aqueous environment and its relevance for organophosphate degradation. Inorg. Chem. 57, 14290-14297 (2018).

شكر وتقدير

يود المؤلفون أن يشكروا نائب البحث في معهد الدراسات المتقدمة في العلوم الأساسية (IASBS) على تقديم الدعم المالي لهذا البحث. كما تم دعم هذا العمل مالياً من قبل مؤسسة العلوم الوطنية الإيرانية (INSF) برقم المنحة: 4038000. يقدر المؤلفون دعمهم بامتنان.

مساهمات المؤلفين

نعترف بأن جميع المؤلفين ساهموا في هذه المراجعة، بما في ذلك التحقيق، جمع الموارد، جمع البيانات، معالجة النتائج، التركيب، التوصيف، تنسيق البيانات، تحليل النتائج، التحقيق، الكتابة، المراجعة وتحرير المخطوطة. قام المؤلف المراسل حسين ملافي بتوجيه اتجاه بحثنا وكتابتنا، والإشراف، ومراجعة الكتابة، وتحرير المسودة الأصلية.

إعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

المعلومات التكميلية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على مواد تكميلية متاحة على https://doi.org/1

يجب توجيه المراسلات وطلبات المواد إلى H.M.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام غير التجاري، والتي تسمح بأي استخدام غير تجاري، ومشاركة، وتوزيع، وإعادة إنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح إذا قمت بتعديل المادة المرخصة. ليس لديك إذن بموجب هذه الرخصة لمشاركة المواد المعدلة المشتقة من هذه المقالة أو أجزاء منها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommo ns.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

© المؤلفون 2025

© المؤلفون 2025

- قسم الكيمياء، معهد الدراسات المتقدمة في العلوم الأساسية (IASBS)، زنجان 45137-66731، إيران. ® البريد الإلكتروني: h.molavi@iasbs.ac.ir

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 15, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90313-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40016413

Publication Date: 2025-02-27

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90313-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40016413

Publication Date: 2025-02-27

OPEN

Investigation the effect of exchange solvents on the adsorption performances of CeMOFs towards organic dyes

Cerium-based MOFs (Ce-MOFs) are regarded as attractive porous materials showing various structures, excellent thermal and chemical stability, tunable porous properties, and simple synthetic methods that are useful for wastewater treatment applications. Hence, in the present work, we synthesized a series of Ce-MOFs through a fast and green synthetic method at room temperature using water as a green solvent. Four different solvents including ethanol, chloroform, acetone, and methanol were used in the solvent-exchange process to engineer the properties of prepared Ce-MOFs. The influence of different exchange solvents on the crystalline structure, porous structure, thermal stability, and surface morphology of Ce-MOFs was studied systematically. It was found that exchange solvents can significantly affect the chemical and physical properties of prepared Ce-MOFs. Using ethanol as an exchange solvent results in the production of highly crystalline MOF that has the highest surface area (

Keywords Green synthesis, Efficient activation, Dye adsorption, Ce-based MOFs, Solvent-exchange

Owing to the global population and industrialization, a large amount of wastewater containing different pollutants such as heavy metal ions, organic dyes, drugs, pesticides, etc., has been produced, which poses significant environmental challenges

Owing to the global population and industrialization, a large amount of wastewater containing different pollutants such as heavy metal ions, organic dyes, drugs, pesticides, etc., has been produced, which poses significant environmental challenges

Among, different developed treatment technologies, the adsorption method has achieved prominence because of its cost-efficiency, effectiveness, simple operation, applying a variety of adsorbent materials, etc

Zirconium-based MOFs (Zr-MOFs) are today regarded as promising materials for wastewater treatment

and its derivatives have been frequently studied for the removal of various contaminants from water

After that, different research groups studied the catalytic activity of Ce-UiO-66 MOFs in different fields

Besides the structural stability of adsorbent materials for wastewater treatment applications, sustainable and green synthetic methods that are energetical, environmental, and economic are very essential. Hitherto, different synthetic strategies have been developed for the synthesis of Ce-UiO-66 MOFs, some of which are quick, simple, green, and at ambient conditions without using a large volume of organic solvents

During the synthesis process of MOFs, solvent molecules and unreacted precursors are unavoidably trapped within the pores of prepared MOFs

However, there is no report in the literature that systematically focuses on the effects of exchange solvents on the physicochemical properties of Ce-MOFs. Thus, in the present work, we synthesized a series of Ce-MOFs through a fast and green synthetic method at room temperature using water as a solvent. Four different low boiling point solvents such as ethanol, chloroform, acetone, and methanol were used in the solvent-exchange process to engineer the properties of prepared Ce-MOFs. The influence of different exchange solvents on the crystalline structure, porous structure, thermal stability, and surface morphology of Ce-MOFs was studied systematically. Finally, the prepared Ce-MOFs were utilized as adsorbent to efficiently remove both cationic and anionic dyes from water. The results revealed that the exchange solvent has a significant effect on the porous properties as well as the dye adsorption performances of Ce-MOFs.

Experiments

Materials

Sodium perchlorate monohydrate (

Synthesis of Ce-MOFs

The Ce-MOFs were prepared via a green method according to our previous procedure with some modifications

Activation of Ce-MOFs

As shown in Fig. 1, the as-prepared Ce-MOFs particles were washed with water three times to remove

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of the preparation and activation of Ce-MOFs.

| MOFs | Exchange solvents | Yield

|

Zeta potential (mV) | Surface area (

|

Average pore diameter (nm) | Pore volume (

|

| Ce-MOF-1 | – |

|

|

592 | 2.97 | 0.4401 |

| Ce-MOF-2 | Ethanol |

|

|

843 | 3.57 | 0.7518 |

| Ce-MOF-3 | Methanol |

|

|

618 | 3.29 | 0.5095 |

| Ce-MOF-4 | Acetone |

|

|

605 | 2.85 | 0.4079 |

| Ce-MOF-5 | Chloroform |

|

|

642 | 2.40 | 0.3857 |

Table 1. The properties of the prepared Ce-MOFs.

Adsorption experiments

All the adsorption experiments were performed at ambient conditions using CR and MG solutions. These different organic dyes were selected as model dyes to investigate the effect of different parameters (e.g., contact time, initial concentration, pH , salt concentration, and temperature) on the removal performance of the prepared

in which,

Characterization

The as-synthesized and activated samples were completely characterized using different analyses, in which the details were presented in the Supplementary file.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the prepared Ce-MOFs

XRD and FTIR analyses

To efficiently remove the high boiling point solvents (

To efficiently remove the high boiling point solvents (

Fig. 2. (A) XRD patterns and (B) FTIR spectra of the prepared Ce-MOFs.

in the relative intensities, the XRD patterns of all prepared Ce-MOFs are the same and agree well with the literature

Furthermore, the FTIR spectra (Fig. 2B) of the prepared Ce-MOFs are relatively the same and similar to the literature

Nitrogen adsorption and desorption analyses

To determine the effect of the solvent-exchange process on the porosity of Ce-MOFs, the porous properties of the synthesized Ce-MOFs were analyzed by nitrogen adsorption and desorption at 77 K , in which the obtained results are shown in Fig. 3. The isotherms of as-synthesized sample (Ce-MOF-1) and samples activated by ethanol, methanol, chloroform, and acetone exhibited type IV curves based on the IUPAC classification, indicating the presence of typical mesopores in the structure of these

The BET surface areas of the prepared Ce-MOFs are in the order of Ce-MOF-1

Fig. 3. (A) Nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms and (B) pore size distribution of the prepared CeMOFs. (The green lines show desorption).

not only exhibited the highest BET surface area and total pore volume, but also showed the highest average pore diameter, which all are beneficial for the adsorption of water pollutants.

The order of increment in the surface area of the activated samples is unexpectedly opposite to the boiling points of used solvents, and the surface area nearly increased with increasing the boiling points of exchange solvents. While, it was expected that the specific surface area of the prepared MOFs would increase with the decrease in the boiling point of the exchange solvents. Accordingly, ethanol with the highest boiling point ( 79

Another important factor that can control the efficiency of the solvent-exchange process is the ability to exchange solvent molecules to coordinate with the possible open metal centers of

As observed from Table 1, ethanol is the best solvent for the solvent-exchange process resulting in the formation of Ce-MOF-2 with the highest surface area. Moreover, a similar result was also observed by Dai et al.

Thermogravimetric analysis

Since, thermal stability is an important factor for porous MOF-based adsorbents, thermogravimetric analysis was carried out to investigate the influence of exchange solvents on the thermal stability of prepared Ce-MOFs.

Fig. 4. (A) TGA and (B) DTG profiles of the prepared Ce-MOFs.

As observed from Fig. 4, all prepared Ce-MOFs exhibited several weight losses from ambient temperature to 500

The weight loss observed at above

The highest weight loss occurred at a temperature higher than

The results obtained from the TGA (Fig. 4A) and DTG (Fig. 4B) profiles of the prepared Ce-MOFs were well consistent with the results obtained from the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms. Accordingly, when the exchange process was successful and higher boiling point molecules were exchanged with low boiling point solvents, the MOFs with high residual ash contents and high surface area would be formed. As a result of the successful exchange of guest molecules with ethanol, Ce-MOF-2 exhibited the highest residual ash contents as well as the highest porosity. While, among the activated samples, Ce-MOF-4 showed the lowest residual ash contents as well as the lowest surface area, due to the low ability of acetone as an exchange solvent for removing guest molecules within the pores of MOFs.

FESEM analysis

Figure 5 exhibits the FESEM images of the prepared Ce-MOFs that were activated with different exchange solvents. The morphology of all prepared Ce-MOFs is relatively the same and their particle sizes are smaller than 500 nm , suggesting that the exchange solvent doesn’t have a significant effect on the morphology of final particles. It is clear that most of the prepared samples have spherical particles with irregular morphology that are aggregated together.

Adsorption experiments

Effect of exchange solvents on the adsorption performance of Ce-MOFs

To assess the adsorption performance of prepared Ce-MOFs, the adsorption capacities of all Ce-MOFs towards organic dyes (CR as anionic dye, and MG as cationic dye) and heavy metal ions (

To assess the adsorption performance of prepared Ce-MOFs, the adsorption capacities of all Ce-MOFs towards organic dyes (CR as anionic dye, and MG as cationic dye) and heavy metal ions (

Fig. 5. FESEM images of

between

However, their adsorption capacity toward both organic dyes was not completely consistent with their surface areas. The adsorption capacity of these MOFs toward anionic CR dye is in the order of Ce-MOF-2

However, the order of MG adsorption capacity is Ce-MOF-4

Study the kinetics and isotherms of adsorption

Kinetics and isotherm of dye adsorption are two of the main important parameters for the evaluation of the adsorption performance of adsorbents. Thus, to better evaluate the removal efficiency of Ce-MOF-4 toward both CR and MG dyes and understand the adsorption mechanisms, adsorption kinetics, and isotherms of CR and MG molecules on Ce-MOF-4 were studied. Figure 7A displays the impact of contact time on the adsorption capacity of CR and MG dyes over Ce-MOF-4. The positive surface charge of Ce-MOF-4 (Table 1) resulted in the adsorption of anionic CR molecules. Because of the good dispersion of adsorbent particles within the CR solution, there is no significant mass transfer limitation for CR molecules from the dye solution onto the surface of MOF particles. As a result of such phenomena, the color of CR solution was rapidly changed from dark orange to light yellow and its concentration reduced rapidly based on the absorption intensity of UV-Vis spectra (Fig. S1).

However, the adsorption kinetics of cationic MG dye on Ce-MOF-4 exhibited that the removal of MG dye is not so efficient, mainly due to the positive surface charge of adsorbent that increases the electrostatic repulsion of cationic MG molecules with the positively charged active sites of Ce-MOF-4. The adsorption kinetics of both organic dyes on Ce-MOF-4 were analyzed using three kinetic models such as pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and intra-particle diffusion, in which the obtained results revealed that the data were reasonably in accord with the pseudo-second-order kinetic model

Fig. 6. Adsorption performance of prepared Ce-MOFs toward CR, MG, and

about 0.0047 and

The removal efficiencies of Ce-MOF-4 toward these dyes were further investigated by performing adsorption isotherms (Fig. 7B). The isotherm curves of both dyes indicated that the adsorption capacity increased with increasing the initial concentration of dyes, and the maximum adsorption capacities of 265.48 and

Study the effect of other influencing parameters on adsorption performance

To elucidate the dye adsorption behavior of Ce-MOF-4, further adsorption experiments were performed at different temperatures, different salt concentrations, and different pHs . The adsorption performance of Ce -MOF-4 under various conditions is depicted in Fig. 8. It is clear from Fig. 8A that the adsorption temperature didn’t have a significant impact on the adsorption capacity of CR over Ce-MOF-4. The CR adsorption capacity

Fig. 7. (A) Adsorption kinetics and (B) Adsorption isotherms for adsorption of CR and MG over Ce-MOF-4.

| Kinetic models | Calculated parameters | Dyes | |

| MG | CR | ||

| Pseudo-first-order |

|

0.9545 | 0.7902 |

|

|

0.017 | 0.022 | |

|

|

8.74 | 9.95 | |

| Pseudo-second-order |

|

0.9910 | 0.9981 |

|

|

0.0037 | 0.0047 | |

|

|

22.62 | 47.62 | |

|

|

21.52 | 46.61 | |

| Intra-particle diffusion |

|

0.9680 | 0.9497 |

|

|

0.8795 | 0.792 | |

| C (

|

11.42 | 37.51 | |

Table 2. Constant parameters of different kinetic models for the adsorption of CR and MG dyes onto the Ce-MOF-4.

slightly reduced from 79.07 to

Similar results were also observed by calculating the thermodynamic adsorption parameters (Table 4), using the van’t Hoff plot (Fig. S4). The calculated negative Gibbs free energy change (

The presence of different ions in wastewater can have remarkable impacts on the adsorption performance of adsorbents. Thus, the influence of NaCl concentration on the adsorption capacity of CR and MG was evaluated. In theory, when the adsorbate-adsorbent interaction is attractive, the presence of different ions may reduce the adsorption performance, whereas if the interaction is repulsive the adsorption performance is enhanced with the addition of different salts

| Isotherm models | Calculated parameters | Dyes | |

| MG | CR | ||

| Langmuir |

|

0.9944 | 0.9963 |

|

|

0.032 | 0.125 | |

|

|

227.27 | 270.27 | |

|

|

203.15 | 265.48 | |

| Freundlich |

|

0.8465 | 0.8136 |

|

|

25.69 | 64.65 | |

|

|

2.49 | 3.22 | |

| Tempkin |

|

0.9345 | 0.9048 |

|

|

50.97 | 53.17 | |

|

|

0.33 | 2.50 | |

| Dubinin-Radushkevich |

|

0.9132 | 0.9428 |

|

|

178.52 | 229.66 | |

| B (

|

|

|

|

Table 3. Calculated isotherm parameters for adsorption of CR and MG onto the Ce-MOF-4.

Fig. 8. Effect of (A) temperature, (B) NaCl concentration, and (C) pH on the adsorption capacity of Ce-MOF-4 toward CR and MG dyes.

| Temperature (K) |

|

|

|

| CR | |||

| 298 | -74.79 | -198.51 | -15.64 |

| 303 | -13.66 | ||

| 318 | -11.67 | ||

| MG | |||

| 298 | 70.96 | 243.72 | -1.67 |

| 303 | -4.11 | ||

| 318 | -6.54 | ||

Table 4. The measured thermodynamic parameters for adsorption of CR and MG onto the Ce-MOF-4.

in the presence of NaCl , and shows the maximum value of

The impact of pH on the adsorption performance of Ce-MOF-4 was also investigated by changing the pH of the dye solution from 2 to 11 using diluted HCl and NaOH solutions (Fig. 8C). The CR adsorption capacity of Ce-MOF-4 didn’t show a significant change at pHs lower than 8, where the adsorbent has a positive surface charge and can interact with the negatively charged CR molecules. However, at higher pH , its removal efficiency decreased due to the presence of strong electrostatic repulsion between CR molecules and negatively charged sites of Ce-MOF-4 particles

Nevertheless, it was observed that the Ce-MOF-4 can adsorb CR molecules even at strong basic conditions

Contrary to CR dye, the adsorption capacity of MG over Ce-MOF-4 is dramatically affected by solution pH , in which its uptake decreased with increasing pH , then showed a high increment at the basic solution. At lower pH , when MG is in its neutral form and Ce-MOF-4 has positively charged sites, there is no electrostatic interaction between both materials. Therefore, at this condition MG molecules can interact with the adsorbent via

Study the structural stability of Ce-MOF-4

The water stability of MOF-based adsorbent materials is one of the critical parameters that can determine the adsorption performance of adsorbents for long-time wastewater treatment applications. Because water molecules can promote the hydrolysis reaction of MOFs and result in the deterioration of MOF structures

The hydrolytic stability of Ce-MOF-4 was evaluated by immersing the MOF particles into an aqueous solution with different pH values (from 2 to 10 ) for 3 h . The initial pH values of aqueous solutions were adjusted by adding HCl or NaOH solutions. The soaked Ce -MOF-4 particles were separated by centrifugation, washed several times with water to neutralize their pH , and finally dried at

As expected, the crystalline structure of Ce-MOF-4 was completely decomposed in basic solutions (

Fig. 9. (A) XRD patterns and (B) TGA profiles of Ce-MOF-4 in different pHs.

Similar trends were also observed in the nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms of both treated samples in acidic and basic solutions (Fig. S5). The BET surface area of the sample soaked in pH 10 was significantly reduced from 605 to

However, the treated samples with acidic and basic solutions still exhibited good adsorption performances toward both organic dyes. Accordingly, the CR adsorption capacity of Ce-MOF-4 was reduced from 79.1 to

The impact of solution pH on the thermal stability of Ce-MOF-4 was investigated by TGA. Figure 9B shows that the TGA profiles of treated samples are relatively similar to pristine MOFs. The observation of some new weak weight reduction steps may be due to structural changes. It is obvious that the thermal stability of the sample soaked in a basic solution

Adsorption mechanisms

The adsorption mechanisms of CR and MG dyes over Ce-MOF-4 were analyzed using zeta potential, FTIR, and FESEM analyses. According to the obtained results from the above sections, it can be expected that the presence of electrostatic interaction between active sites of MOFs and dye molecules is one of the critical adsorption mechanisms. As shown in Fig. 10, the anionic

The FTIR spectra of Ce-MOF-4 after adsorption of CR and MG dyes (Fig. S6) show several new absorption peaks that are related to the functional groups of dye molecules, confirming that dye molecules are adsorbed onto the surface of Ce-MOF-4. The presence of these dyes on the surface of Ce-MOF-4 was further evidenced by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) images (Fig. S7). The formation of hydrogen bonds between the

| MOFs | Surface area (

|

Average pore diameter (nm) | Pore volume (

|

| Pristine Ce-MOF-4 | 605 | 2.85 | 0.4079 |

| Ce-MOF-4 in pH 2 | 86 | 15.63 | 0.3375 |

| Ce-MOF-4 in pH 10 | 187 | 5.99 | 0.2802 |

| CR recycled Ce-MOF-4 | 511 | 3.56 | 0.4548 |

| MG recycled Ce-MOF-4 | 410 | 4.19 | 0.4301 |

Table 5. The porous properties of Ce-MOF-4, acid/base-treated, and recycled Ce-MOF-4.

Fig. 10. Schematic illustration of the possible adsorption mechanisms of

Reusability and structural stability

The regeneration and recycling ability of Ce-MOF-4 were also investigated because they are very essential for practical wastewater treatment applications. Accordingly, the dye-loaded Ce-MOF-4 was dispersed into an alkaline ethanol (containing NaOH ) solution and stirred for 2 h to release the adsorbed dyes. Subsequently, the recovered sample was activated and applied for another adsorption-desorption cycle. It can be observed that Ce-MOF-4 could be recovered for at least four consecutive adsorption-desorption cycles without a remarkable reduction in its adsorption performance toward both organic dyes (Fig. 11A). Additionally, as shown in Fig. 11B, the crystalline structure of Ce-MOF-4 remained stable after four cycles. More importantly, the nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms (Fig. 11C) and TGA (Fig. 11D) profiles of recycled samples confirm the structural stability of this MOF during cyclic adsorption-desorption processes. All of these results indicate that Ce-MOF-4 can be a promising candidate for practical wastewater treatment applications.

Conclusion

Herein, a series of Ce-MOFs was prepared and activated by different exchange solvents like ethanol, chloroform, acetone, and methanol. The surface areas of the prepared Ce-MOFs are in the order of Ce-MOF-1

Fig. 11. (A) Reusability experiment of Ce-MOF-4 for CR and MG dyes. (B) XRD patterns, (C) nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms, and (D) TGA profiles of recycled samples.

MOF-1

Data availability

All data relevant to this study are included in the manuscript and supporting information file or are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Received: 17 December 2024; Accepted: 12 February 2025

Published online: 27 February 2025

Published online: 27 February 2025

References

- Bashir, N. et al. Green-synthesized silver nanoparticle-enhanced nanofiltration mixed matrix membranes for high-performance water purification. Sci. Rep. 15, 1001. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83801-w (2025).

- Mirzaei, R. et al. Innovative cross-linked Electrospun PVA/MOF nanocomposites for removal of cefixime antibiotic. Sci. Rep. 15, 83. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84818-x (2025).

- Kayani, K. F. Bimetallic metal-organic frameworks (BMOFs) for dye removal: a review. RSC Adv. 14, 31777-31796. https://doi.or g/10.1039/D4RA06626J (2024).

- Nazir, M. A. et al. Synthesis of bimetallic Mn@ZIF-8 nanostructure for the adsorption removal of methyl orange dye from water. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 165, 112294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112294 (2024).

- Eleryan, A. et al. Isothermal and kinetic screening of methyl red and methyl orange dyes adsorption from water by Delonix regia biochar-sulfur oxide (DRB-SO). Sci. Rep. 14, 13585. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63510-0 (2024).

- Molavi, H. et al. 3D-Printed MOF monoliths: fabrication strategies and environmental applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-024-01487-1 (2024).

- Shiri, M., Hosseinzadeh, M., Shiri, S. & Javanshir, S. Adsorbent based on MOF-5/cellulose aerogel composite for adsorption of organic dyes from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 14, 15623. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65774-y (2024).

- Mohammadi, A. et al. Novel ZIF-8/CNC nanohybrid with an interconnected structure: toward a sustainable adsorbent for efficient removal of cd(II) ions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 16, 3862-3875. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c15524 (2024).

- Noor, T., Raffi, U., Iqbal, N., Yaqoob, L. & Zaman, N. Kinetic evaluation and comparative study of cationic and anionic dyes adsorption on zeolitic imidazolate frameworks based metal organic frameworks. Mater. Res. Express. 6, 125088. https://doi.org/10 .1088/2053-1591/ab5bdf (2019).

- Ahmad, U. et al. ZIF-8 composites for the removal of Wastewater pollutants. ChemistrySelect 9, e202401719. https://doi.org/10.10 02/slct. 202401719 (2024).

- Sudarsan, S., Murugesan, G., Varadavenkatesan, T., Vinayagam, R. & Selvaraj, R. Efficient adsorptive removal of Congo Red dye using activated carbon derived from Spathodea campanulata flowers. Sci. Rep. 15, 1831. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-8603 2-9 (2025).

- Ahmadijokani, F. et al. COF and MOF hybrids: Advanced materials for Wastewater Treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2305527. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202305527 (2024).

- Molavi, H. et al. Wastewater treatment using nanodiamond and related materials. J. Environ. Manage. 349, 119349. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119349 (2024).

- Singh, S. et al. Metal organic frameworks for wastewater treatment, renewable energy and circular economy contributions. npj Clean. Water. 7, 124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00408-4 (2024).

- Ahmadijokani, F. et al. UiO-66 metal-organic frameworks in water treatment: a critical review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 125, 100904 (2022).

- Mirzaei, K., Jafarpour, E., Shojaei, A., Khasraghi, S. S. & Jafarpour, P. An investigation on the influence of highly acidic media on the microstructural stability and dye adsorption performance of UiO-66. Appl. Surf. Sci. 618, 156531 (2023).

- He, H. H. et al. Yolk-Shell and Hollow Zr/Ce-UiO-66 for manipulating selectivity in Tandem reactions and photoreactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 17164-17175 (2023).

- Zaremba, O., Andreo, J. & Wuttke, S. The chemistry behind room temperature synthesis of hafnium and cerium UiO-66 derivatives. Inorg. Chem. Front. 9, 5210-5216 (2022).

- Lammert, M. et al. Cerium-based metal organic frameworks with UiO-66 architecture: synthesis, properties and redox catalytic activity. Chem. Commun. 51, 12578-12581(2015).

- Wu, X. P., Gagliardi, L. & Truhlar, D. G. Cerium metal-organic framework for photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7904-7912 (2018).

- Farrag, M. In situ preparation of palladium nanoclusters in cerium metal-organic frameworks Ce-MOF-808, Ce-UiO-66 and CeBTC as nanoreactors for room temperature Suzuki cross-coupling reaction. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 312, 110783 (2021).

- Zhang, Y., Zeng, X., Jiang, X., Chen, H. & Long, Z. Ce-based UiO-66 metal-organic frameworks as a new redox catalyst for atomic spectrometric determination of Se (VI) and colorimetric sensing of hg (II). Microchem. J. 149, 103967 (2019).

- Rego, R. M. et al. Cerium based UiO-66 MOF as a multipollutant adsorbent for universal water purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 125941 (2021).

- Molavi, H. Cerium-based metal-organic frameworks: synthesis, properties, and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 527, 216405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2024.216405 (2025).

- Molavi, H. & Salimi, M. S. Green synthesis of Cerium-based metal-Organic Framework (Ce-UiO-66 MOF) for Wastewater Treatment. Langmuir 39, 17798-17807. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c02384 (2023).

- Li, K., Yang, J. & Gu, J. Salting-in species induced self-assembly of stable MOFs. Chem. Sci. 10, 5743-5748 (2019).

- Yassin, J. M., Taddesse, A. M. & Sanchez-Sanchez, M. Room temperature synthesis of high-quality ce (IV)-based MOFs in water. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 324, 111303 (2021).

- Jin, H. G. et al. Room temperature aqueous synthesis of ce (IV)-MOFs with UiO-66 architecture and their photocatalytic decarboxylative oxygenation of arylacetic acids. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 346, 112257 (2022).

- Campanelli, M. et al. Solvent-free synthetic route for Cerium (IV) metal-organic frameworks with UiO-66 architecture and their photocatalytic applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11, 45031-45037 (2019).

- Otun, K. O. Temperature-controlled activation and characterization of iron-based metal-organic frameworks. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 507, 119563 (2020).

- Andrés, M. A. et al. Solvent-exchange process in MOF ultrathin films and its effect on CO2 and methanol adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 590, 72-81 (2021).

- Zhang, X., Zhan, Z., Li, Z. & Di, L. Thermal activation of CuBTC MOF for CO oxidation: the effect of activation atmosphere. Catalysts 7, 106 (2017).

- Yang, Y. et al. Significant improvement of surface area and CO 2 adsorption of Cu-BTC via solvent exchange activation. RSC Adv. 3, 17065-17072 (2013).

- Zeleňák, V. et al. Large and tunable magnetocaloric effect in gadolinium-organic framework: tuning by solvent exchange. Sci. Rep. 9, 15572 (2019).

- Tati, A., Ahmadipouya, S., Molavi, H., Mousavi, S. A. & Rezakazemi, M. Efficient removal of organic dyes using electrospun nanofibers with Ce-based UiO-66 MOFs. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 266, 115584 (2023).

- Mohammadnejad, M. & Alizadeh, S. MnFe2O4-NH2-HKUST-1, MOF magnetic composite, as a novel sorbent for efficient dye removal: fabrication, characterization and isotherm studies. Sci. Rep. 14, 9048. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59727-8 (2024).

- Huang, F. P. et al. Solvent effects on the structures and magnetic properties of two doubly interpenetrated metal-organic frameworks. Dalton Trans. 44, 6593-6599 (2015).

- Ghadim, E. E., Walker, M. & Walton, R. I. Rapid synthesis of cerium-UiO-66 MOF nanoparticles for photocatalytic dye degradation. Dalton Trans. 52, 11143-11157. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3DT00890H (2023).

- Rad, F. A. & Rezvani, Z. Preparation of cubane-1, 4-dicarboxylate-Zn-Al layered double hydroxide nanohybrid: comparison of structural and optical properties between experimental and calculated results. RSC Adv. 5, 67384-67393 (2015).

- Li, Y. et al. Boosting the rhodamine B adsorption of bimetallic

: effect of valence states of cerium precursor. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 357, 112628 (2023). - Ramezanzadeh, M., Ramezanzadeh, B., Bahlakeh, G., Tati, A. & Mahdavian, M. Development of an active/barrier bi-functional anti-corrosion system based on the epoxy nanocomposite loaded with highly-coordinated functionalized zirconium-based nanoporous metal-organic framework (Zr-MOF). Chem. Eng. J. 408, 127361 (2021).

- Yazaydın, A. O. et al. Enhanced CO2 adsorption in metal-organic frameworks via occupation of open-metal sites by coordinated water molecules. Chem. Mater. 21, 1425-1430 (2009).

- Li, J. R., Kuppler, R. J. & Zhou, H. C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477-1504 (2009).

- Dai, S. et al. Room temperature design of ce(iv)-MOFs: from photocatalytic HER and OER to overall water splitting under simulated sunlight irradiation. Chem. Sci. 14, 3451-3461. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2SC05161C (2023).

- He, J. et al. Ce (III) nanocomposites by partial thermal decomposition of

for effective phosphate adsorption in a wide pH range. Chem. Eng. J. 379, 122431 (2020). - Amesimeku, J., Zhao, Y., Li, K. & Gu, J. Rapid synthesis of hierarchical cerium-based metal organic frameworks for carbon dioxide adsorption and selectivity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater., 112658 (2023).

- Karimi, M. et al. Additive-free aerobic C-H oxidation through a defect-engineered Ce-MOF catalytic system. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 322, 111054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2021.111054 (2021).

- Deng, S. Q. et al. An anionic nanotubular metal-Organic Framework for high-capacity dye adsorption and dye degradation in darkness. Inorg. Chem. 58, 13979-13987 (2019).

- Far, H. S. et al. PPI-dendrimer-functionalized magnetic metal-organic framework (Fe3O4@ MOF@ PPI) with high adsorption capacity for sustainable wastewater treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12, 25294-25303 (2020).

- Louaer, S., Wang, Y. & Guo, L. Fast synthesis and size control of gibbsite nanoplatelets, their pseudomorphic dehydroxylation, and efficient dye adsorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 5, 9648-9655 (2013).

- Abbasi, S., Nezafat, Z., Javanshir, S., Aghabarari, B. & Bionanocomposite MIL-100(Fe)/Cellulose as a high-performance adsorbent for the adsorption of methylene blue. Sci. Rep. 14, 14497. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65531-1 (2024).

- El Jery, A. et al. Isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamic mechanism of methylene blue dye adsorption on synthesized activated carbon. Sci. Rep. 14, 970. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50937-0 (2024).

- Mirzaei, K., Jafarpour, E., Shojaei, A. & Molavi, H. Facile synthesis of Polyaniline@UiO-66 nanohybrids for efficient and Rapid Adsorption of Methyl Orange from Aqueous Media. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61, 11735-11746. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.2c009 19 (2022).

- Samiey, B. & Toosi, A. R. Adsorption of malachite green on silica gel: effects of NaCl, pH and 2-propanol. J. Hazard. Mater. 184, 739-745 (2010).

- Lammert, M., Glißmann, C. & Stock, N. Tuning the stability of bimetallic ce (IV)/Zr (IV)-based MOFs with UiO-66 and MOF-808 structures. Dalton Trans. 46, 2425-2429 (2017).

- Bǔžek, D., Demel, J. & Lang, K. Zirconium metal-organic framework UiO-66: stability in an aqueous environment and its relevance for organophosphate degradation. Inorg. Chem. 57, 14290-14297 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Research Deputy of Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Science (IASBS) for providing financial support for this research. This work was also financially supported by the Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) with grant No: 4038000. The authors gratefully appreciate their support.

Author contributions

We acknowledge that all authors contributed to this review, including investigation, resources collection, data collection, results processing, synthesis, characterization, data curation, results analysis, investigation, writing, review and editing the manuscript. Corresponding author Hossein Molavi guided our research direction and writing, supervision, writing-review, and editing the original draft.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/1

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to H.M.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommo ns.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2025

© The Author(s) 2025

- Department of Chemistry, Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Science (IASBS), Zanjan 45137-66731, Iran. ® email: h.molavi@iasbs.ac.ir