المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 14، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62381-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38811645

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-29

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62381-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38811645

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-29

تحليل الاتجاهات الزمنية والمكانية لعبء الاكتئاب من جميع الأسباب استنادًا إلى دراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض (GBD) لعام 2019

تعتبر الاضطرابات النفسية مساهمًا رئيسيًا في العبء العالمي للأمراض. وغالبًا ما تؤدي إلى زيادة معدل الانخفاض البدني

هناك أدلة على أن الاكتئاب يعرض الأفراد للإصابة بالنوبات القلبية والسكري وأن الإصابة بهذه الأمراض تزيد من فرص تطوير الاكتئاب. العديد من عوامل الخطر، مثل الوضع الاجتماعي المنخفض، وإساءة استخدام الكحول، والضغط النفسي، مسؤولة عن تطوير الأمراض النفسية

التكاليف الاقتصادية لهذه المشاكل الصحية هائلة. وفقًا لدراسة جديدة، ستصل التكاليف المالية الإجمالية للمرض النفسي على مستوى العالم إلى

تعتبر الاضطرابات النفسية معروفة كمساهم رئيسي في العبء العالمي للأمراض، حيث تمثل 1566.2 سنة من الحياة المعدلة حسب الإعاقة (DALYs) لكل 100,000 من السكان العالميين في 2019. من بين هذه، شكلت الاضطرابات الاكتئابية (اضطراب الاكتئاب الشديد [MDD] والاضطراب المزاجي المستمر) النسبة الأكثر أهمية من DALYs للاضطرابات النفسية

الاكتئاب، الذي تصنفه منظمة الصحة العالمية كأكبر مساهم في الإعاقة العالمية

تقدم دراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض (GBD) بيانات مفصلة عن مجموعة واسعة من الأمراض لـ 204 دول في 21 منطقة مختلفة حول العالم

طرق البحث

مصادر البيانات

البيانات المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة متاحة على أداة نتائج GBD لتبادل البيانات الصحية العالمية (http://ghdx. healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool). قدرت GBD 2019 معدل الإصابة، والانتشار، والوفيات، وسنوات الحياة مع الإعاقة (YLDs)، وسنوات الحياة المفقودة (YLLs)، وDALYs لـ 369 مرضًا وإصابة، للذكور والإناث، و23 مجموعة عمرية، و204 دول وأقاليم تم تجميعها جغرافيًا في 21 منطقة منذ عام 1990

التصنيف والتعريفات

الاضطرابات الاكتئابية، MDD، والاضطراب المزاجي المستمر

في التصنيف الدولي للأمراض، الإصدار العاشر (ICD-10)، تم تصنيف الاضطرابات الاكتئابية إلى مجموعتين رئيسيتين: اضطراب الاكتئاب الشديد (MDD) والاضطراب المزاجي المستمر. لذلك، في دراسة GBD، تم تضمين كل من MDD والاضطراب المزاجي المستمر في فئة الاضطرابات الاكتئابية. MDD هو اضطراب اكتئابي دوري قد يتكرر طوال حياة الفرد، مع اختلاف شدة كل تكرار. الاضطراب المزاجي المستمر هو اضطراب اكتئابي بطيء وخفيف مستمر مع أعراض أقل شدة من تلك الخاصة بـ MDD، ولكن مع مسار يتميز بالاستمرارية. تم تضمين الحالات التي استوفت معايير التشخيص لـ MDD والاضطراب المزاجي المستمر وفقًا لدليل التشخيص والإحصاء (DSM) وICD (دليل التشخيص والإحصاء) في نموذج مرض البحث GBD

في التصنيف الدولي للأمراض، الإصدار العاشر (ICD-10)، تم تصنيف الاضطرابات الاكتئابية إلى مجموعتين رئيسيتين: اضطراب الاكتئاب الشديد (MDD) والاضطراب المزاجي المستمر. لذلك، في دراسة GBD، تم تضمين كل من MDD والاضطراب المزاجي المستمر في فئة الاضطرابات الاكتئابية. MDD هو اضطراب اكتئابي دوري قد يتكرر طوال حياة الفرد، مع اختلاف شدة كل تكرار. الاضطراب المزاجي المستمر هو اضطراب اكتئابي بطيء وخفيف مستمر مع أعراض أقل شدة من تلك الخاصة بـ MDD، ولكن مع مسار يتميز بالاستمرارية. تم تضمين الحالات التي استوفت معايير التشخيص لـ MDD والاضطراب المزاجي المستمر وفقًا لدليل التشخيص والإحصاء (DSM) وICD (دليل التشخيص والإحصاء) في نموذج مرض البحث GBD

SDI

يعتبر SDI مقياسًا تجميعيًا يقيس تنمية دولة أو منطقة، يجمع بين بيانات معدل الخصوبة الإجمالي للإناث تحت 25 عامًا، ومستوى التعليم المتوسط للإناث البالغات 15 عامًا وما فوق، والدخل الفردي. تصنف قاعدة بيانات GBD 2019 العالم إلى خمسة أنواع من المناطق بناءً على مؤشر SDI: منخفض SDI (

يعتبر SDI مقياسًا تجميعيًا يقيس تنمية دولة أو منطقة، يجمع بين بيانات معدل الخصوبة الإجمالي للإناث تحت 25 عامًا، ومستوى التعليم المتوسط للإناث البالغات 15 عامًا وما فوق، والدخل الفردي. تصنف قاعدة بيانات GBD 2019 العالم إلى خمسة أنواع من المناطق بناءً على مؤشر SDI: منخفض SDI (

مؤشر التنمية البشرية (HDI)

مؤشر التنمية البشرية هو مؤشر تجميعي يقيس مستوى التنمية الاقتصادية والاجتماعية لدول الأعضاء في الأمم المتحدة ويتكون من ثلاثة متغيرات أساسية: متوسط العمر المتوقع، والتحصيل التعليمي، وجودة الحياة. حصلنا على بيانات مؤشر التنمية البشرية لعام 2019 من تقرير التنمية البشرية لبرنامج الأمم المتحدة الإنمائي لاستكشاف العلاقة بين مؤشر التنمية البشرية ومعدل الإصابة وDALYs.https://hdr.undp.org/en/compoالموقع/HDI، تم الوصول إليه في 27 مارس 2022

ASR

معدل موحد حسب العمر (ASR) هو مؤشر شائع في علم الأوبئة. عندما يختلف تركيب الفئات العمرية بين عدة مجموعات مقارنة، فإن المعدل الخام للمجموعات المقارنة المباشرة سيؤدي إلى تحيز لأنه لا يشير إلى ما إذا كان معدل الإصابة المرتفع في منطقة معينة ناتجًا عن اختلافات في تركيب العمر، وعادة ما يكون من الضروري مقارنة المعدلات بعد التوحيد.

تم حساب معدل العمر القياسي بناءً على الصيغة التالية:

معدل العمر الموحد لكل 100,000 نسمة يساوي مجموع نواتج المعدلات الخاصة بالعمر (wi، حيث

السكان القياسيين المرجعيين المختارين ثم مقسومًا على مجموع أوزان السكان القياسيين

السكان القياسيين المرجعيين المختارين ثم مقسومًا على مجموع أوزان السكان القياسيين

EAPC

يوفر EAPC نهجًا معترفًا به لتوصيف ASR باستخدام نموذج انحدار يقوم بت quantifying متوسط معدل التغير السنوي خلال فترة محددة، مع تمثيل علامات الزائد والناقص اتجاه التغير. تم استخدام خط الانحدار لتقدير اللوغاريتم الطبيعي للمعدل (أي،

استراتيجية تحليلية

قمنا بتصوير التغيرات في انتشار وعبء مرض الاكتئاب في 204 دول تغطي 21 منطقة متميزة خلال فترة الدراسة. شملت مؤشرات التحليل الحدوث وDALYs. تم حساب معدل الانتشار القياسي مع الأخذ في الاعتبار الهيكل السكاني العالمي المتوسط من 2000 إلى 2025 كهيكل سكاني قياسي.

اللجنة الأخلاقية

كانت الدراسة متوافقة مع إرشادات الإبلاغ عن تقديرات الصحة بدقة وشفافية، وقد استعرضت لجنة المراجعة المؤسسية بجامعة واشنطن ووافقت على إعفاء من الموافقة المستنيرة لدراسة GBD 2019.

النتائج

منذ عام 1990 حتى 2019، زادت حالات الاضطراب الاكتئابي من 182,183,358

من حيث الأنواع الفرعية للاكتئاب، كانت نسبة حدوث الاكتئاب الشديد أكثر انتشارًا بكثير من الاكتئاب المزمن.

عبء الاكتئاب العالمي ومعدل الوفيات المرتبطة به حسب 21 منطقة من مناطق العبء العالمي للأمراض

زاد عدد الأفراد الذين يعانون من اضطرابات الاكتئاب في جميع مناطق SDI الخمس من عام 1990 حتى عام 2019 (انظر الجدول التكميلي S1a). ومع ذلك، انخفض معدل الإصابة القياسي المعدل حسب العمر في فئة SDI العالية والمتوسطة (EAPC

| خصائص | الحالات (95% فاصل الثقة) | سنوات الحياة المعدلة حسب الإعاقة (95% فاصل الثقة) | |||||||||||

| رقم | ASR | EAPC | رقم | ASR | EAPC | ||||||||

| عالمي |

|

3588.25 (3152.714060.42) |

|

46,863,642 (32,929,36363,797,315) | 577.75 (405.79-788.88) |

|

|||||||

| جنس | |||||||||||||

| ذكر |

|

2750.27 (2419.663104.07) |

|

18,183,102 (12,682,04724,947,035) | ٤٥٢.١٧ (٣١٦.٧٩-٦١٨.١٣) |

|

|||||||

| أنثى |

|

4416.34 (3886.95015.49) |

|

28,680,540 (20,155,77339,319,358) | 702.08 (492.3-963.58) |

|

|||||||

| فئة | |||||||||||||

| الاضطرابات الاكتئابية |

|

3588.25 (3152.714060.42) |

|

46,863,642 (32,929,36363,797,315) | 577.75 (405.79-788.88) | – 0.24% (- 0.31 إلى – 0.16) | |||||||

| اضطراب الاكتئاب الشديد |

|

٣٣٩٧.٤٨ (٢٩٧٨.٦٦٣٨٦٦.٩٧) |

|

٣٧,٢٠٢,٧٤٢ (٢٥,٦٥٠,٢٠٥٥١,٢١٧,٠٤٢) | 459.59 (315.19-634.72) | – 0.32% (- 0.41 إلى – 0.22) | |||||||

| الاكتئاب المزمن |

|

190.77 (158.69-229.44) | 0.08% (0.07-0.09) | 9,660,901 (6,311,56614,421,787) | 118.16 (77.31-176.65) | 0.09% (0.08-0.1) | |||||||

| مؤشر اجتماعي ديموغرافي | |||||||||||||

| مؤشر التنمية البشرية العالي | 44,711,792 (39,796,76150,166,003) | 4013.63 (3545.484550.43) | 0.31% (0.18-0.44) | 7,025,129 (4,955,2009,506,636) | 626.84 (438.47-852.48) | 0.23% (0.14-0.33) | |||||||

| SDI مرتفع-متوسط | 53,642,569 (47,529,70660,307,945) | 3184.21 (2809.63583.66) | – 0.5% (-0.57 إلى – 0.43) | 8,896,917 (6,247,98612,123,142) | 523.01 (367.02-713.05) |

|

|||||||

| مؤشر التنمية المستدامة المتوسط | 80,760,069 (71,066,73291,500,542) | 3139 (2765.35-3540.43) | – 0.2% (- 0.28 إلى – 0.13) | 13,541,947 (9,515,93518,454,507) | 521.68 (366.8-709.93) |

|

|||||||

| مؤشر التنمية البشرية المنخفضة والمتوسطة | 70,155,480 (61,292,23779,973,480) | 4180.3 (3660.974740.48) |

|

11,026,538 (7,715,89815,191,253) | 654.34 (458.32-897.85) | – 0.51% (- 0.66 إلى – 0.36) | |||||||

| مؤشر التنمية البشرية المنخفض | 40,743,981 (34,959,15747,317,678) | 4770.22 (4142.245461.66) | – 0.38% (- 0.5 إلى – 0.26) | 6,345,789 (4,316,6238,788,145) | 738.87 (514.681011.24) |

|

|||||||

| منطقة | |||||||||||||

| أمريكا اللاتينية الأنديزية | 1,809,802 (1,561,7072,084,373) | 2886.58 (2499.393315.19) |

|

290,671 (198,567403,423) | 462.07 (318.12-640.03) | – 0.25% (-0.29 إلى – 0.21) | |||||||

| أسترالاسيا | 1,539,866 (1,329,8481,771,752) | 5079.18 (4368.055925.8) | 0.07% (-0.06-0.21) | ٢٣٧,٥٦٤ (١٦٤,١٦٩٣٣٠,٣١١) | 777.82 (538.621094.07) | 0.07% (-0.05-0.2) | |||||||

| الكاريبي | 2,156,062 (1,859,1212,484,561) | 4336.17 (3737.425007.13) |

|

327,025 (226,095450,595) | 657.19 (454.07-905.93) | – 0.49% (-0.54 إلى – 0.43) | |||||||

| آسيا الوسطى | 2,980,970 (2,577,9063,464,935) | ٣٣٢٧.٤٢ (٢٨٨٨.٦٦٣٨٢٥.٣٦) | – 0.19% (- 0.21 إلى – 0.16) | ٤٨٦,٦٠٠ (٣٣٤,٥١٨,٦٧٩,٨٤٠) | 534.9 (372.57-741.82) | – 0.16% (- 0.18 إلى – 0.13) | |||||||

| أوروبا الوسطى | 3,557,074 (3,134,2834,043,451) | 2436.8 (2132.452771.69) |

|

596,440 (420,305816,082) | 413.89 (290.54-572.31) | – 0.54% (- 0.6 إلى – 0.48) | |||||||

| أمريكا الوسطى | 9,412,732 (8,221,932 10,719,231) | ٣٦٧٥٫٧٨ (٣٢١٩٫٦٥٤١٨١٫٩٦) | 0.34% (0.3-0.37) | 1,447,181 (1,009,4081,981,151) | 563.62 (392.72-771.17) | 0.31% (0.28-0.34) | |||||||

| وسط أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | 6,714,339 (5,590,5218,062,124) | 6646.94 (5680.57819.84) | – 0.17% (- 0.18 إلى – 0.15) | 1,010,267 (681,6331,430,655) | 1000.16 (682.151397.69) | – 0.12% (- 0.14 إلى – 0.11) | |||||||

| شرق آسيا | 42,235,926 (37,513,97947,555,038) | 2292.26 (2043.672562.45) | – 0.8% (- 0.97 إلى – 0.64) | 7,802,555 (5,472,93910,767,864) | 415.98 (291.93-573.46) | – 0.67% (- 0.78 إلى – 0.56) | |||||||

| أوروبا الشرقية | 9,150,637 (7,960,74910,432,658) | ٣٥٤٦.٨ (٣٠٧٦.٠٨٤٠٦٢.٨٢) |

|

1,442,695 (1,013,9901,986,605) | 562.24 (391.45-771.76) | – 0.46% (-0.54 إلى – 0.38) | |||||||

| شرق أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | 16,013,047 (13,725,94418,554,113) | 5466.48 (4781.026234.48) | – 0.32% (- 0.39 إلى – 0.26) | 2,510,165 (1,702,2083,475,451) | 845.4 (589.89-1154.93) | – 0.26% (-0.32 إلى – 0.21) | |||||||

| آسيا والمحيط الهادئ ذات الدخل المرتفع | 5,193,652 (4,652,1185,735,090) | 2320.99 (2063.542600.8) | 0.4% (0.27-0.53) | 812,255 (572,7411,104,805) | 365.65 (253.57-499.26) | 0.31% (0.2-0.43) | |||||||

| أمريكا الشمالية ذات الدخل المرتفع | 18,459,876 (16,429,39320,674,357) | ٤٨٨٥.١٦ (٤٣٠٨.٤٨٥٥٣٢.٤٤) | 0.62% (0.32-0.92) | 2,864,089 (2,023,9363,872,481) | 753.77 (525.531023.69) | 0.43% (0.2-0.66) | |||||||

| شمال أفريقيا والشرق الأوسط | 31,006,695 (26,270,01936,438,429) | 5098.6 (4378.865947.72) | 0.06% (0.03-0.09) | 4,767,774 (3,261,4706,600,677) | 781.06 (535.181075.62) | 0.06% (0.03-0.08) | |||||||

| أوقيانوسيا | 328,505 (274,947393,381) | ٢٧١١.٥٩ (٢٣٠٦.٢٦٣١٩٣.١٧) |

|

56,577 (38,501-80,206) | 476.09 (325.58-663.22) |

|

|||||||

| جنوب آسيا | 71,998,403 (62,917,27181,675,123) | 4179.15 (3668.724727.18) |

|

11,188,435 (7,828,80815,283,076) | 645.08 (452.66-877.7) |

|

|||||||

| جنوب شرق آسيا | 14,451,056 (12,506,180 16,471,186) | 2060.52 (1797.73-2341) | – 0.19% (- 0.25 إلى – 0.14) | 2,753,223 (1,898,4603,795,437) | 389.23 (270.38-536.55) | – 0.13% (- 0.16 إلى – 0.09) | |||||||

| أمريكا اللاتينية الجنوبية | 2,362,146 (2,089,2972,658,887) | ٣٣١٣.٥٥ (٢٩٢٥.٦٢٣٧٤٥.٤٥) | – 0.42% (- 0.5 إلى – 0.34) | 359,571 (249,695491,681) | 503.29 (349.65-690.9) | – 0.42% (- 0.5 إلى – 0.34) | |||||||

| جنوب الصحراء الكبرى الأفريقية | 3,344,012 (2,915,2693,791,826) | 4552.32 (4015.915105.97) | 0.13% (0.03-0.24) | 524,604 (368,831,719,717) | 705.61 (497.87-958.57) | 0.09% (-0.01-0.19) | |||||||

مستمر

| خصائص | الحالات (95% فاصل الثقة) | سنوات الحياة المعدلة حسب الإعاقة (95% فاصل الثقة) | ||||

| رقم | ASR | EAPC | رقم | ASR | EAPC | |

| أمريكا اللاتينية الاستوائية | 10,928,342 (9,746,995 12,123,340) | ٤٥٦٠.١٦ (٤٠٨٤.٤٣-٥٠٥٨) |

|

1,652,267 (1,159,7742,244,114) | 686.08 (482.44-932.46) |

|

| أوروبا الغربية | 22,312,186 (19,873,592 25,015,077) | 4347.46 (3841.954912.74) |

|

3,463,005 (2,438,3494,706,017) | 677.2 (475.01-929.5) | – 0.09% (- 0.11 إلى – 0.06) |

| غرب أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | 14,230,414 (12,217,18116,431,648) | 4407.3 (3851.355021.82) |

|

2,270,679 (1,552,6453,123,065) | 693.84 (485.18-949.29) |

|

الجدول 1. العبء العالمي لاضطراب الاكتئاب في عام 2019 لكلا الجنسين و27 منطقة، مع معدل التغير السنوي المتوقع من 1990 إلى 2019.

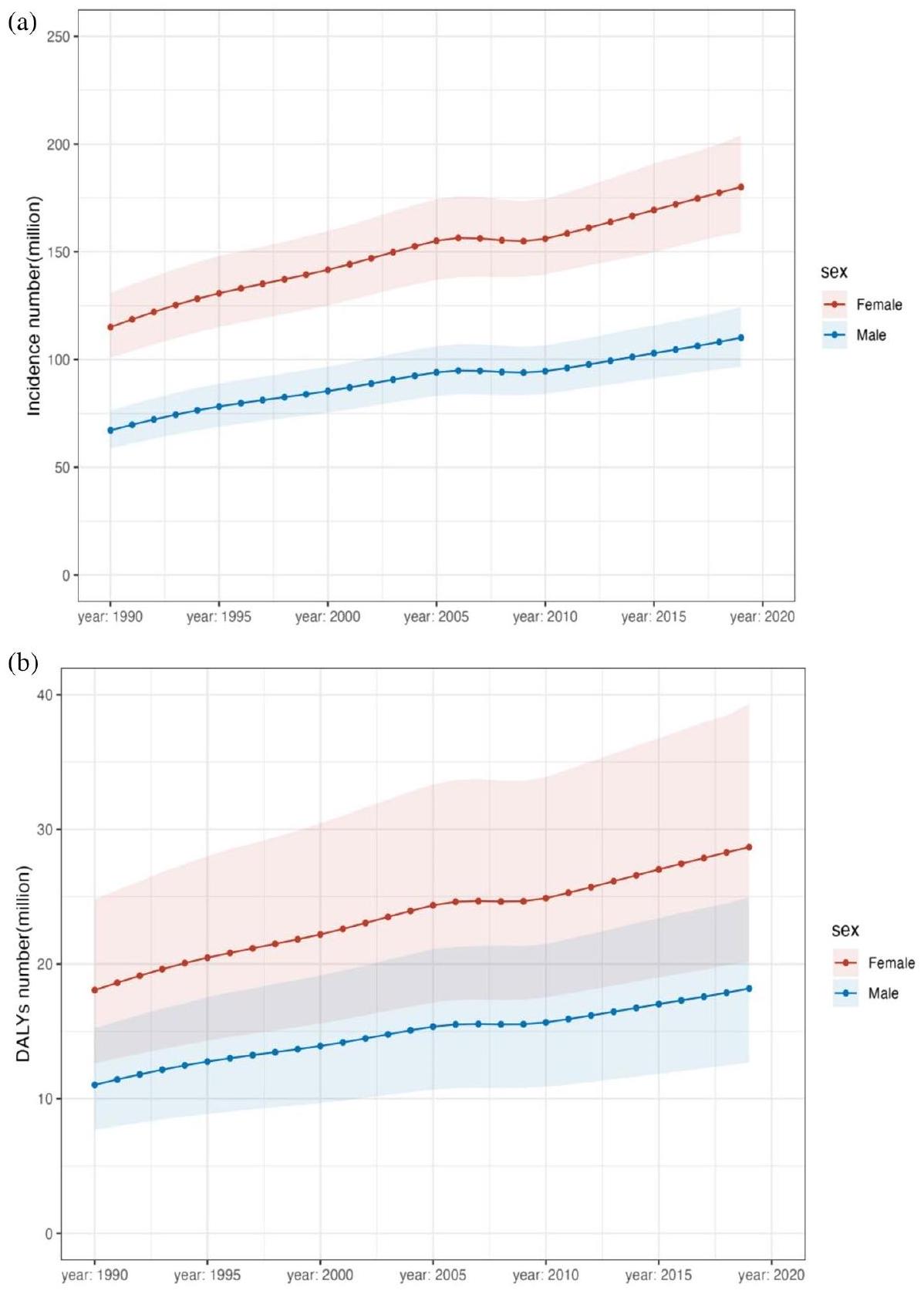

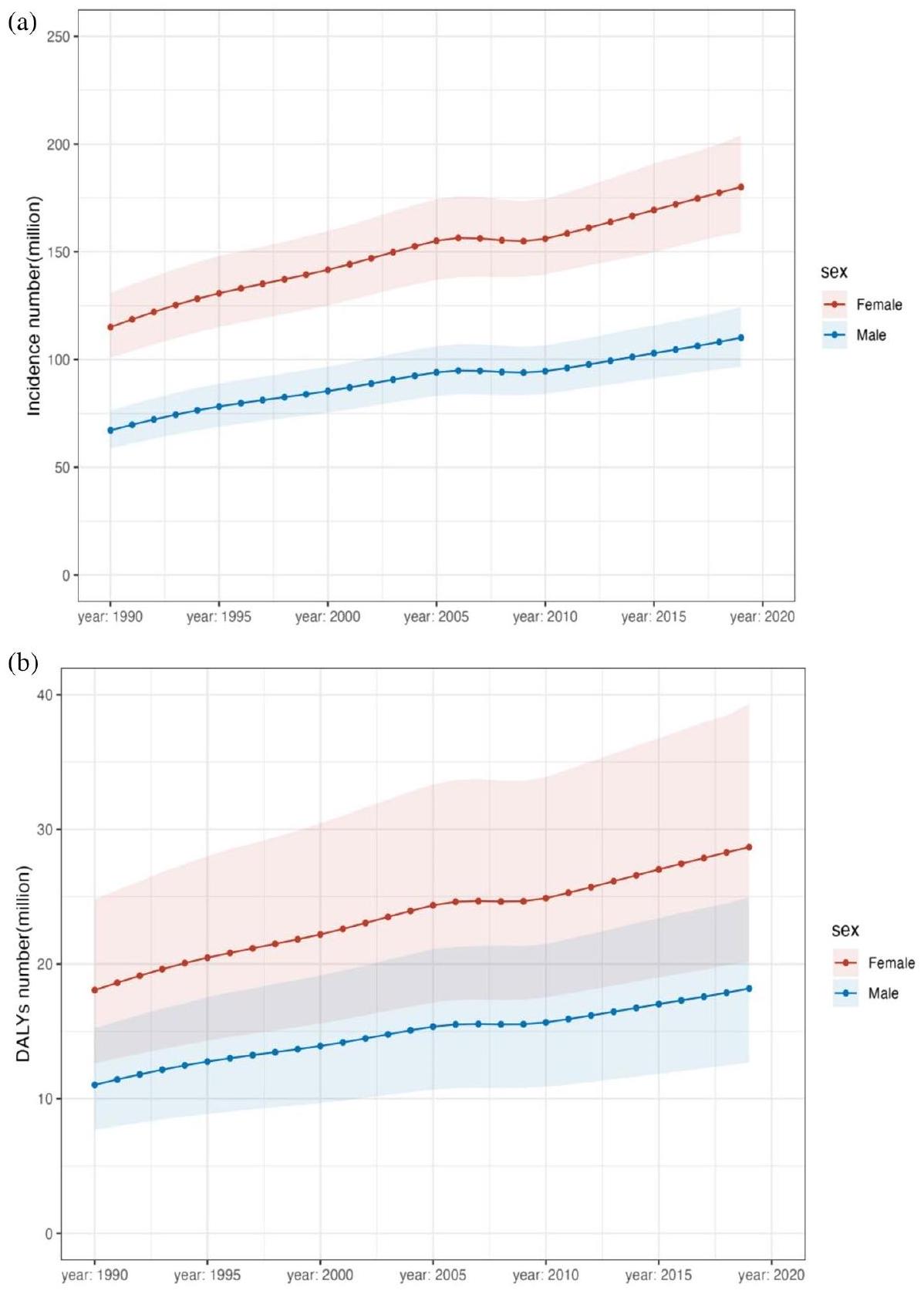

الشكل 1. الاتجاه الزمني لحدوث الاكتئاب العالمي (أ) وعدد سنوات الحياة المعدلة حسب الإعاقة (ب) للاكتئاب.

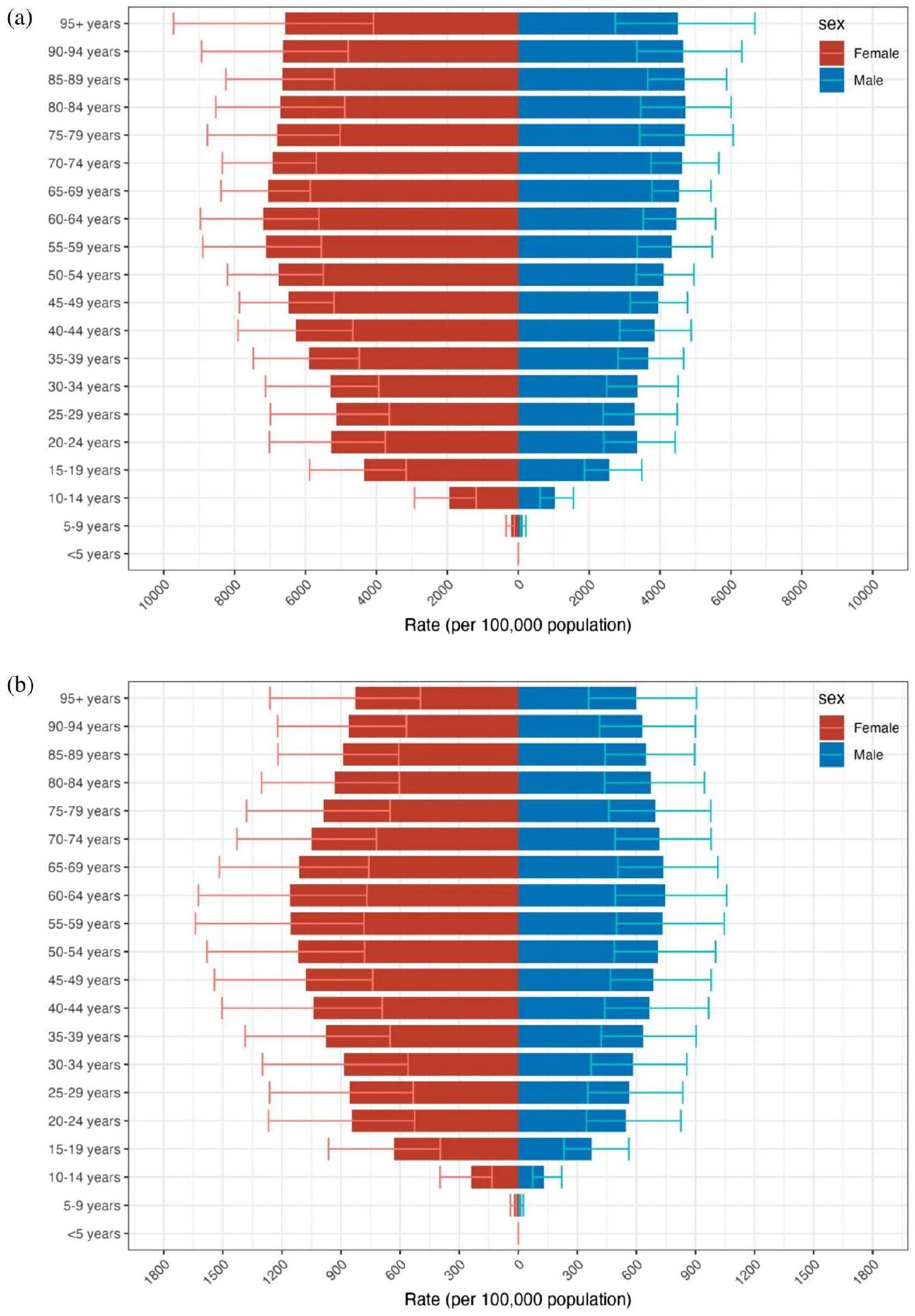

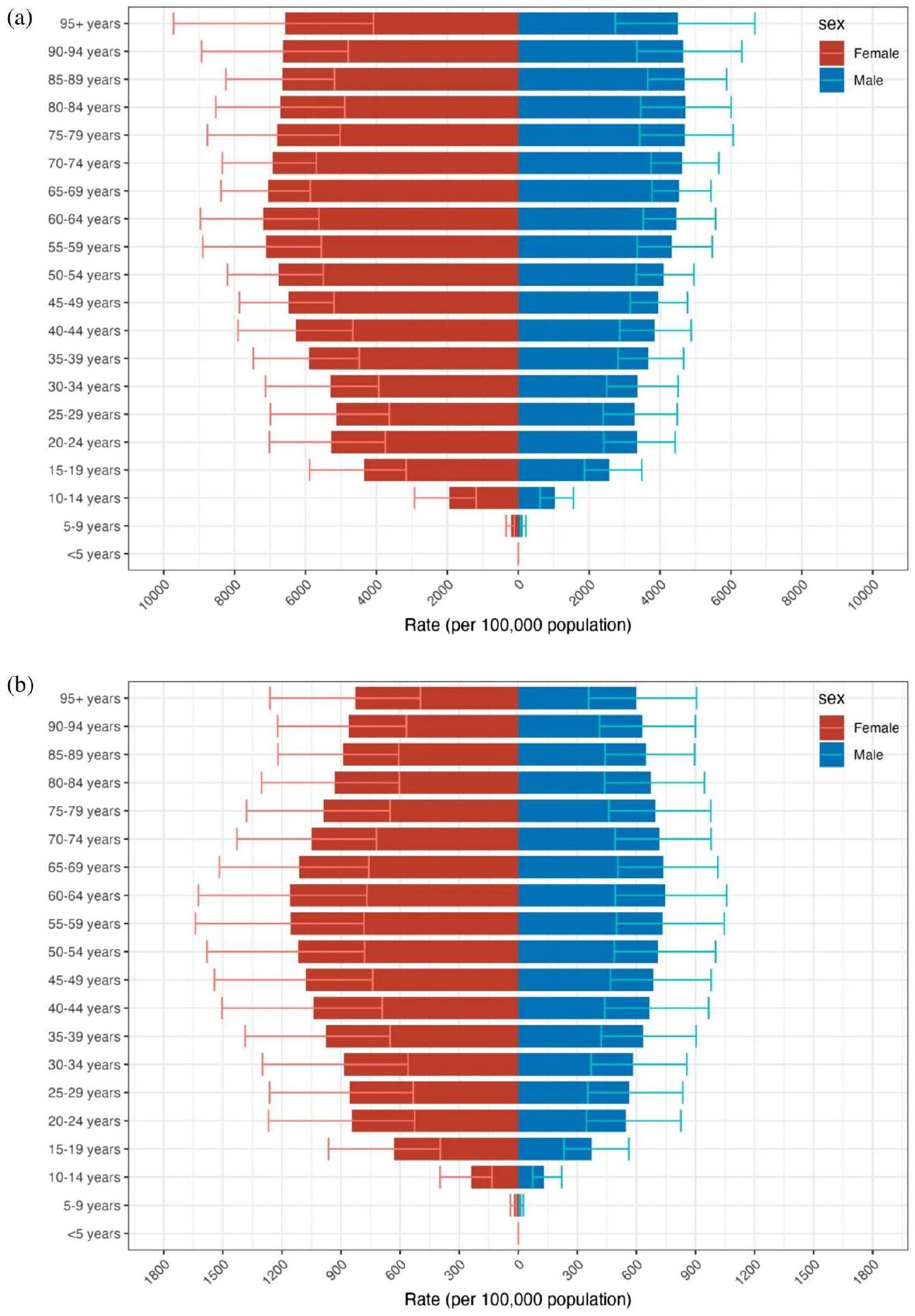

الشكل 2. معدل الإصابة الموحد حسب العمر (أ) ومعدل سنوات الحياة المعدلة حسب الإعاقة الموحد حسب العمر (ب) لاتجاهات توزيع الجنس والعمر.

(الجدول 1، الجدول التكميلي S1b). انخفض ASDR في فئة SDI المتوسطة العالية (EAPC

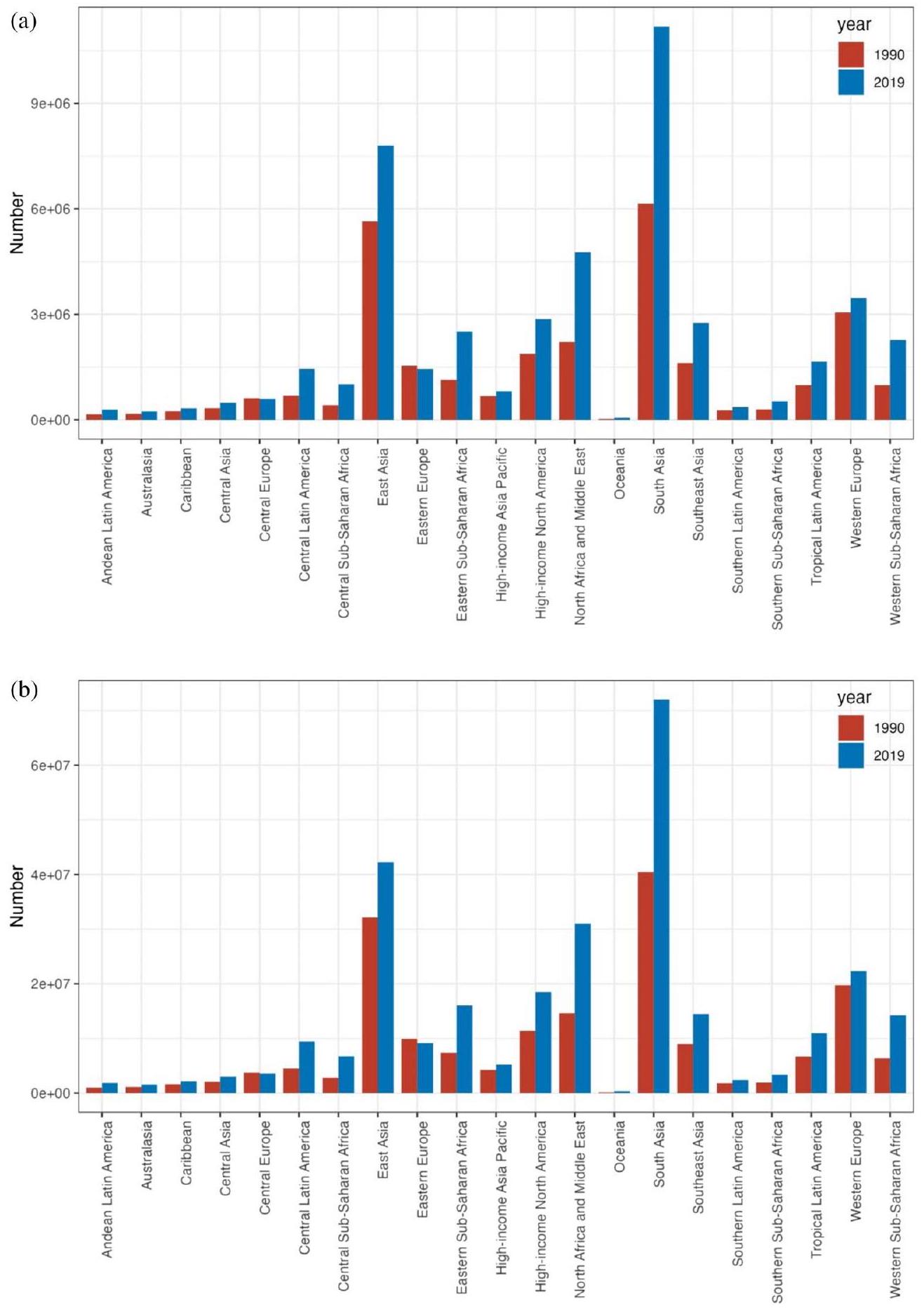

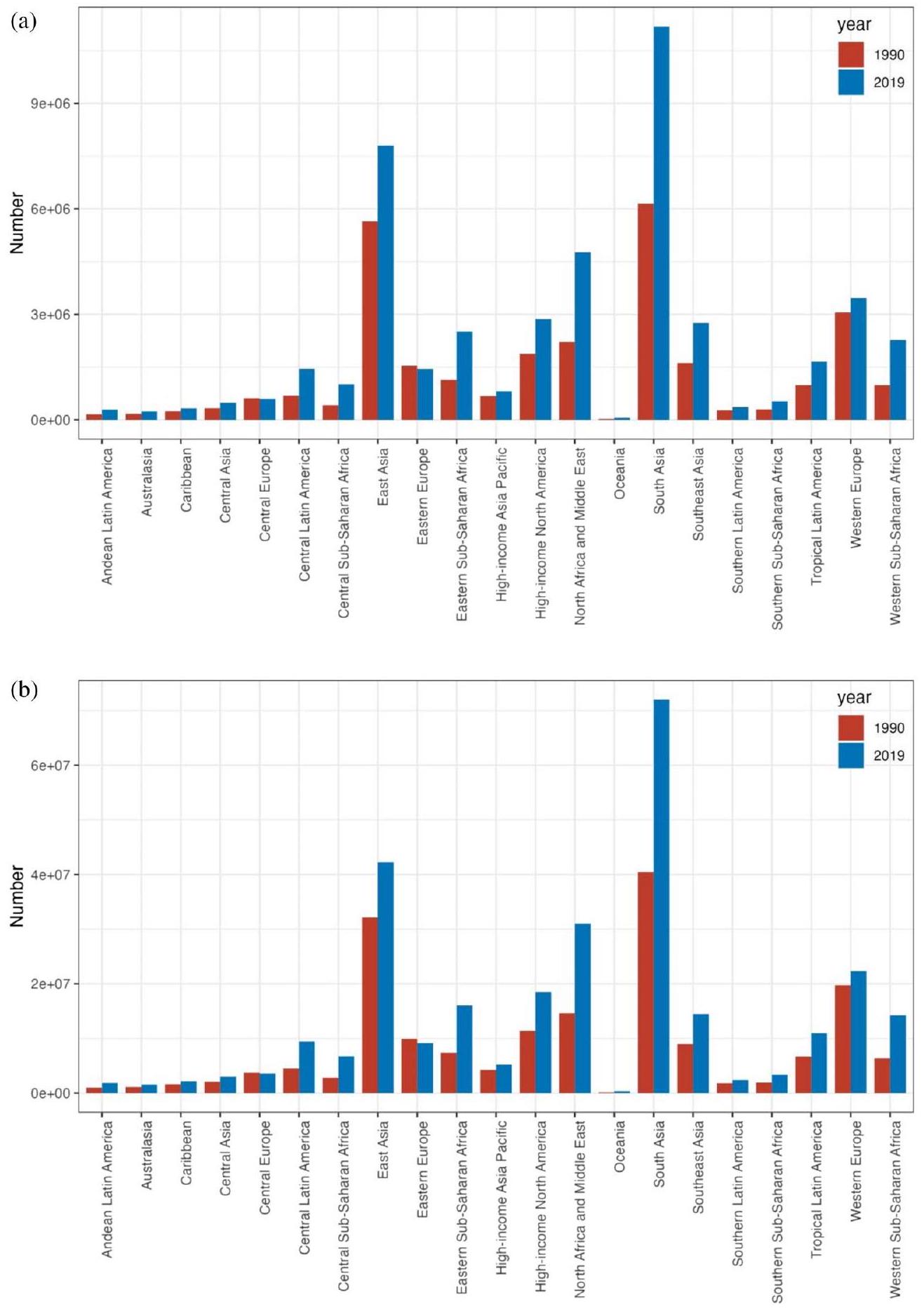

زاد معدل الاضطرابات الاكتئابية في جميع المناطق، مع انخفاض فقط في وسط وشرق أوروبا (انظر الشكل 3أ). شهدت وسط أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى أعلى معدل للزيادة.

الشكل 3. حالات الاكتئاب (أ) وDALYs (ب) على المستوى الإقليمي. العمود الأيسر في كل مجموعة هو بيانات الحالات في عام 1990 والعمود الأيمن في عام 2019.

1.13-1.21)، حيث كان الانخفاض الأكثر وضوحًا في أوروبا الشرقية (

نمت سنوات الحياة المعدلة حسب الإعاقة (DALYs) المرتبطة بالاضطرابات الاكتئابية في جميع المناطق الجغرافية، مع انخفاض فقط في وسط وشرق أوروبا (انظر الشكل 3ب). وكان أكبر زيادة قد حدثت في وسط أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء.

أفريقيا

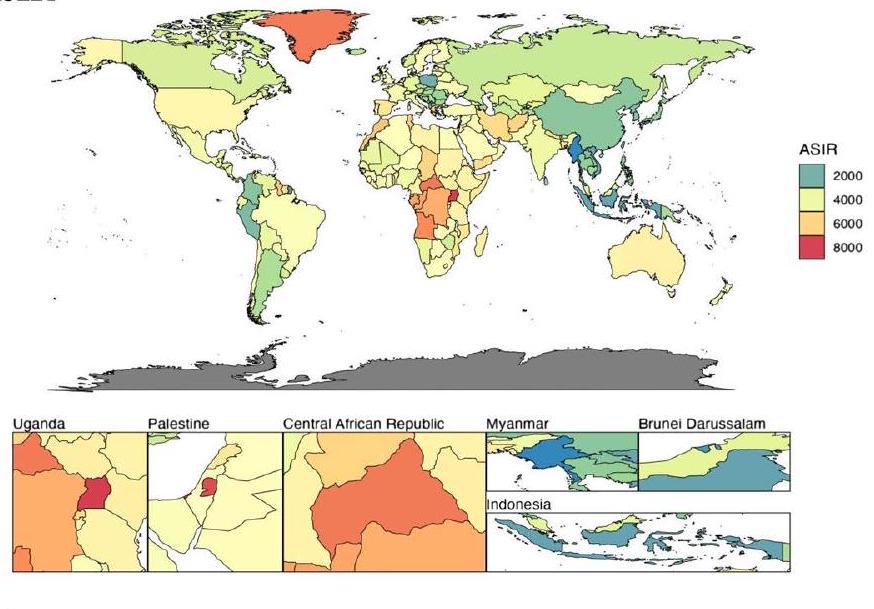

عبء الاكتئاب العالمي ومعدل الوفيات المرتبطة به عبر 204 دول وإقليم

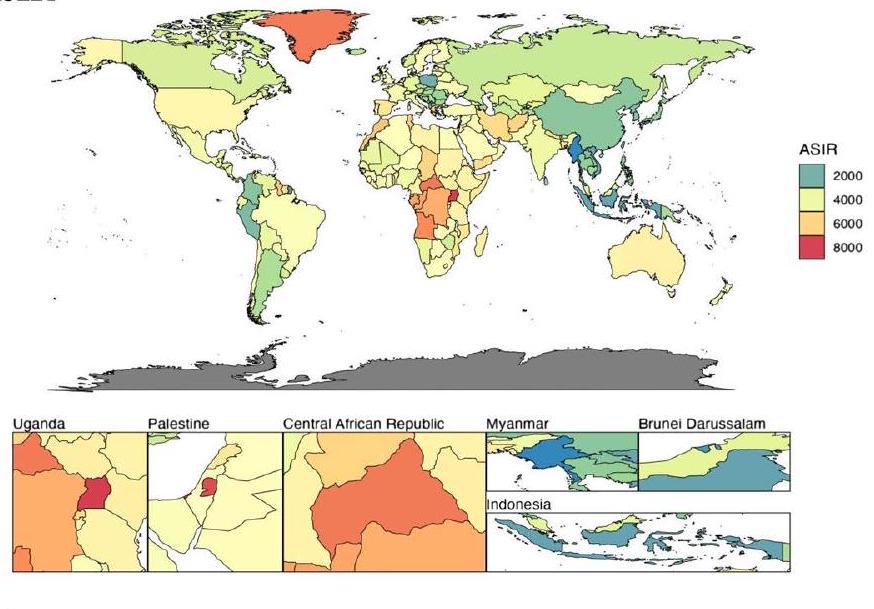

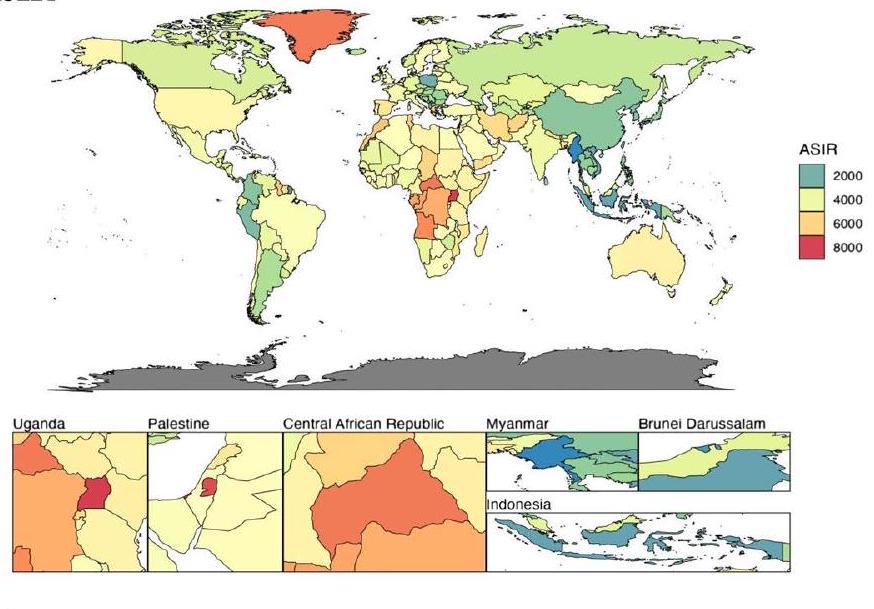

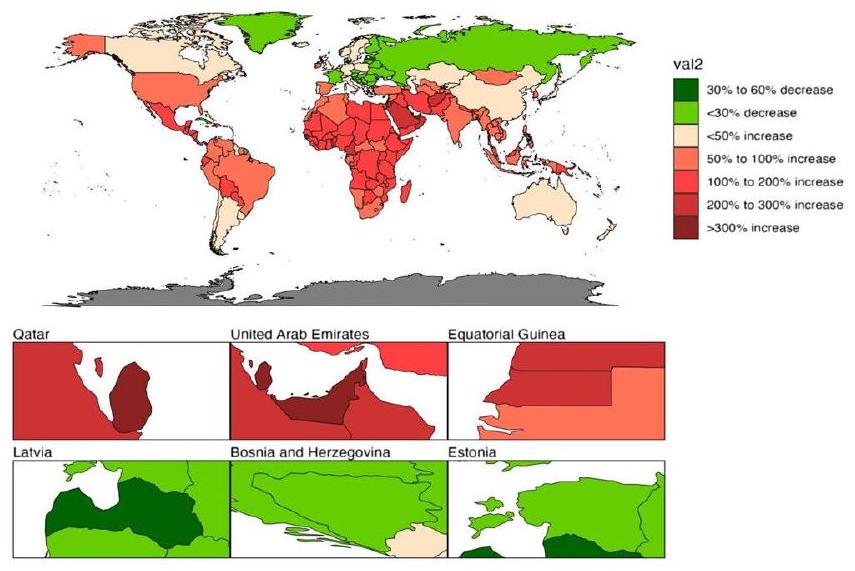

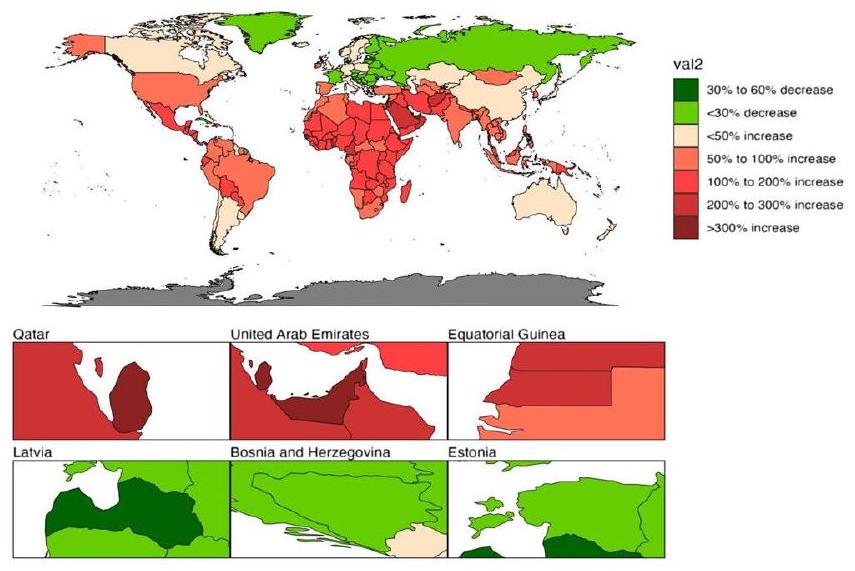

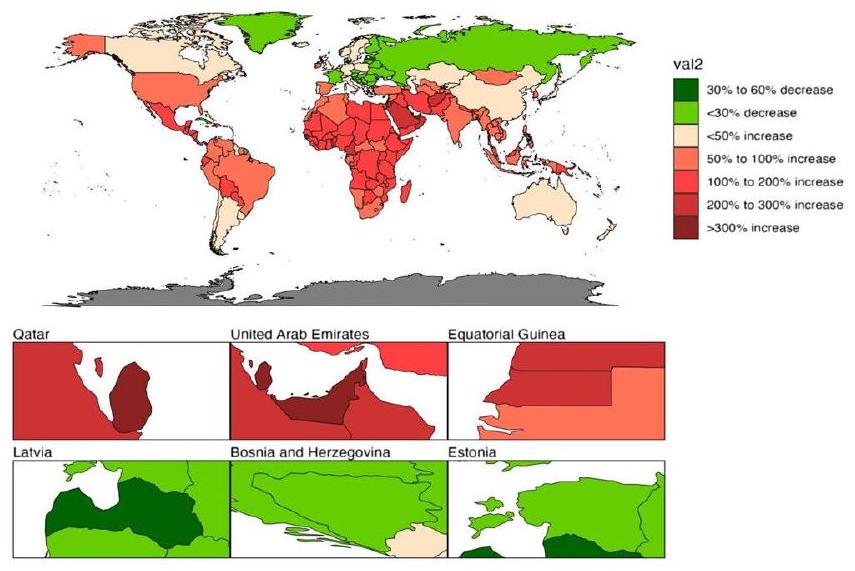

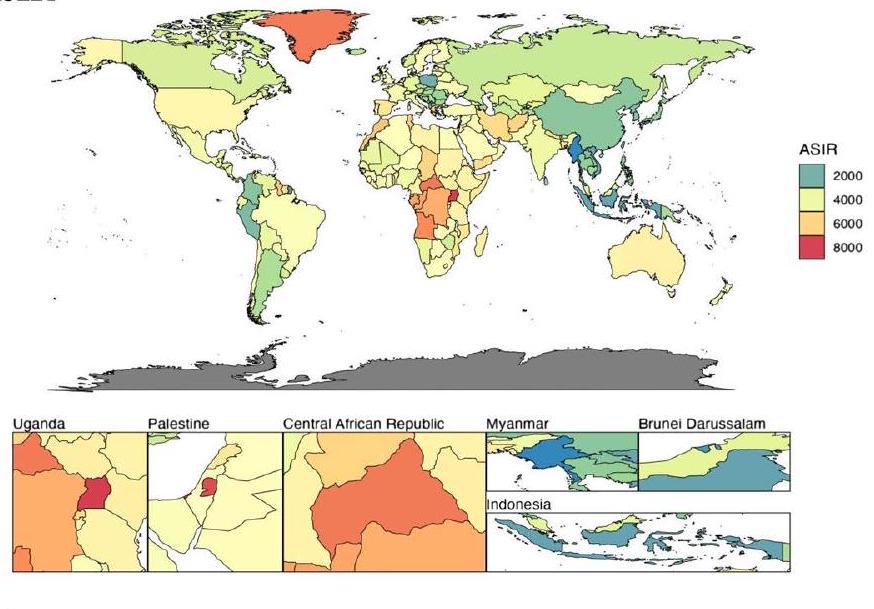

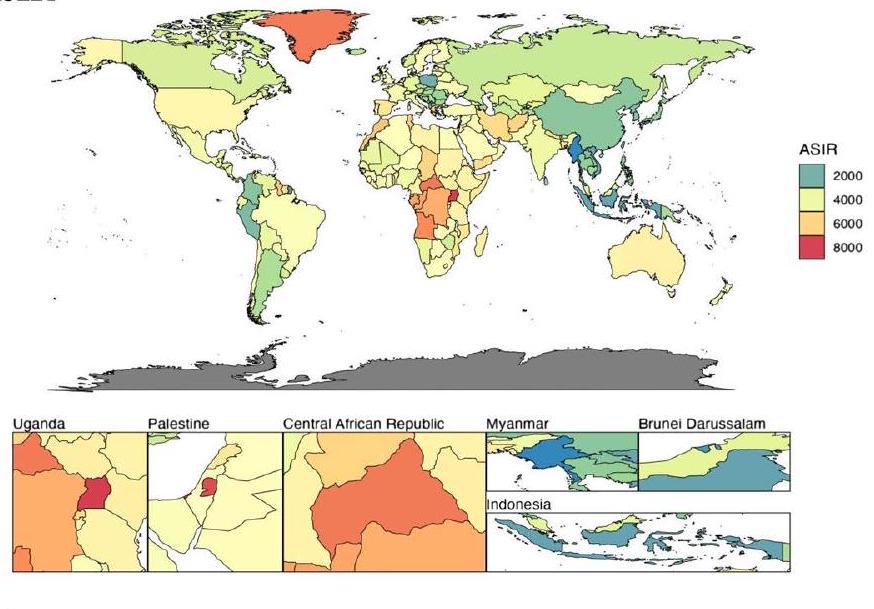

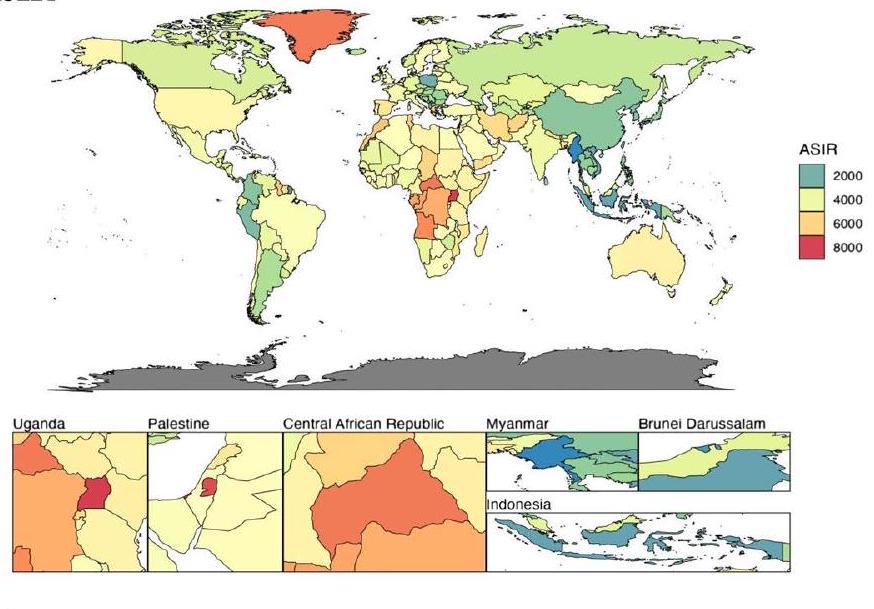

تفاوت معدل الإصابة القياسي للاكتئاب بشكل كبير عبر 204 دولة وإقليم في عام 2019 (انظر الشكل 4أ، الجدول التكميلي S2أ). كان معدل الإصابة القياسي الأعلى في أوغندا (8062.76، 95% فترة الثقة 6946.5-9436.97)، تليها فلسطين (7864.2،

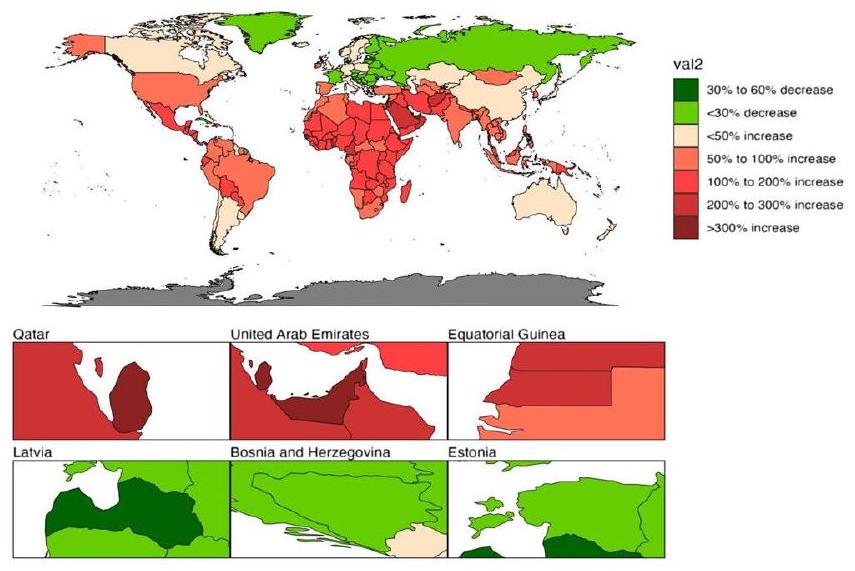

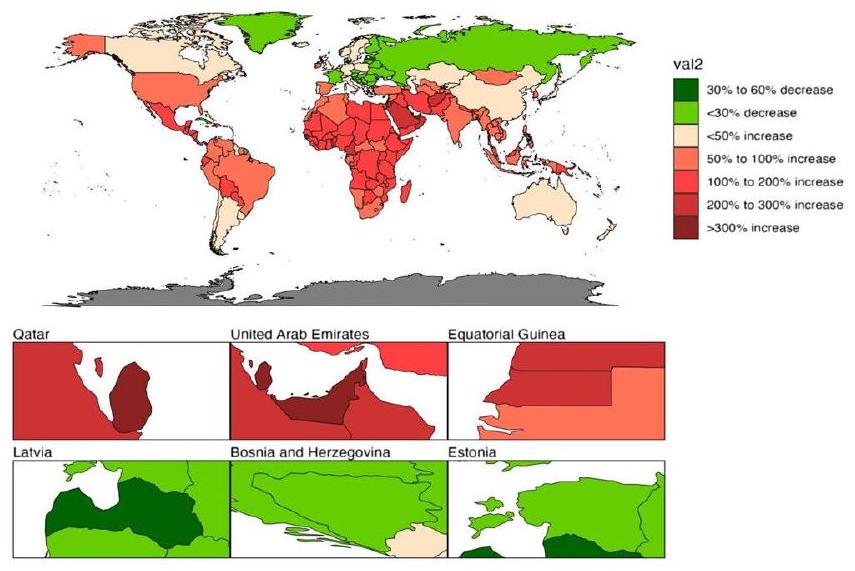

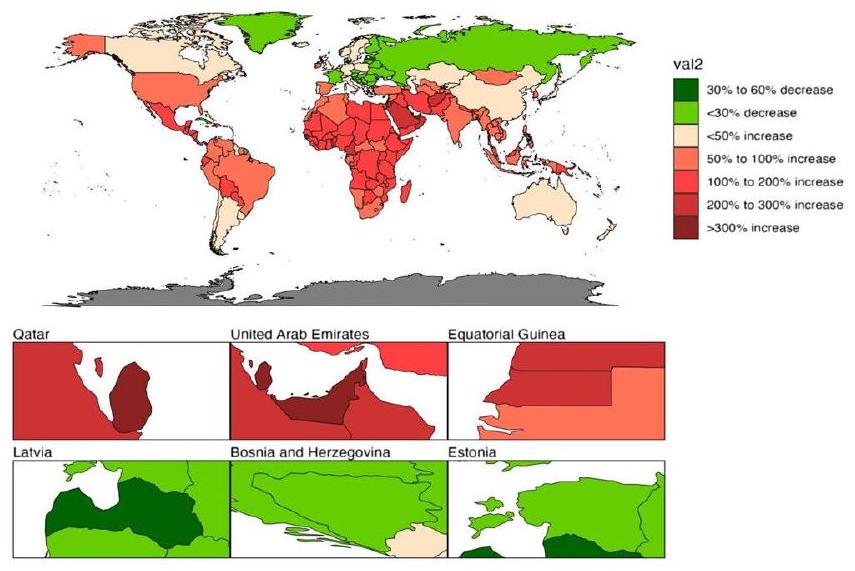

نمت نسبة الاكتئاب على مستوى العالم بـ

من بين 204 دولة وإقليم، حدث أكبر ارتفاع في معدل الوفيات المعدل حسب العمر (ASIR) في إسبانيا (EAPC

ترابط SDI مع العبء العالمي للاضطرابات الاكتئابية

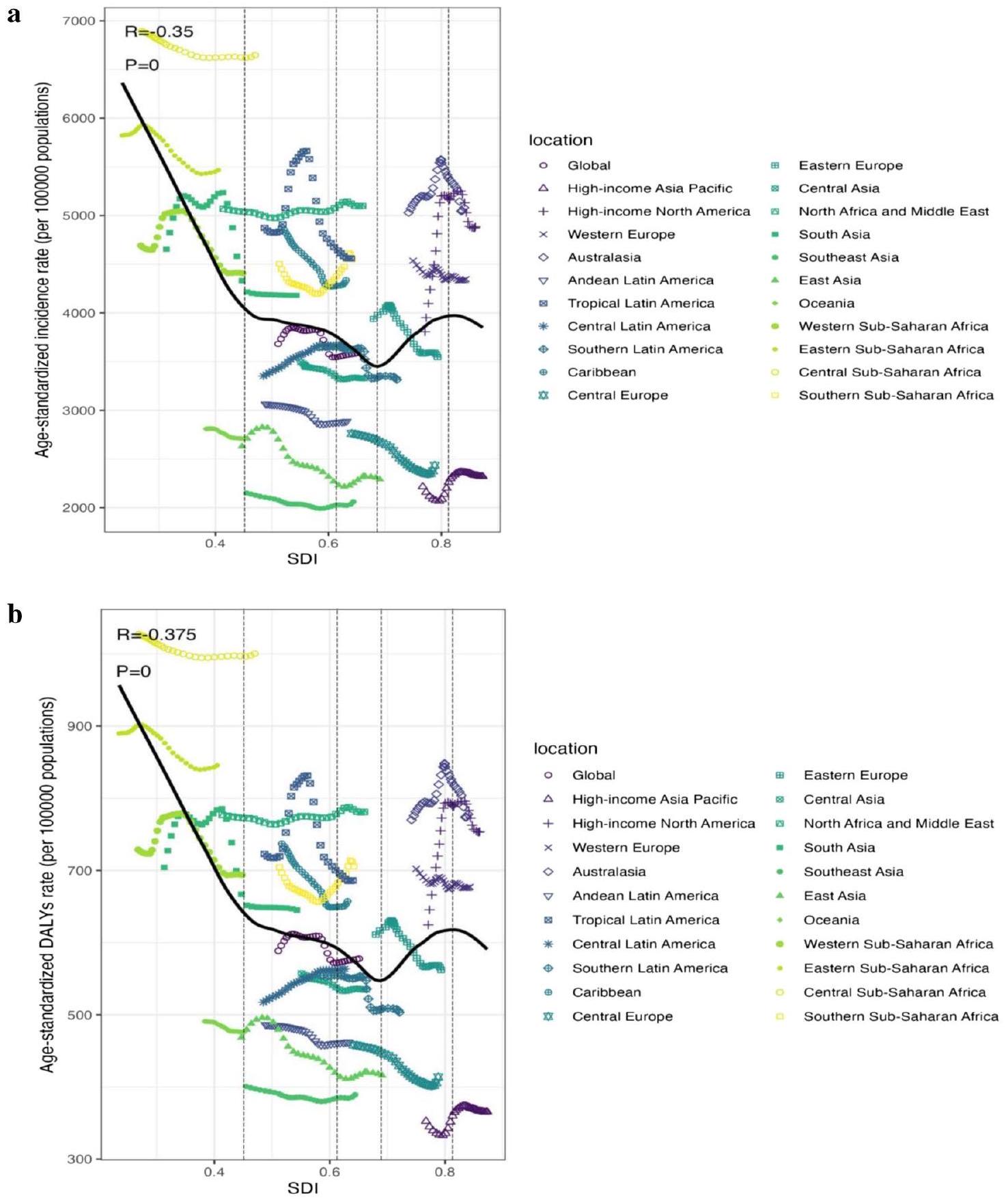

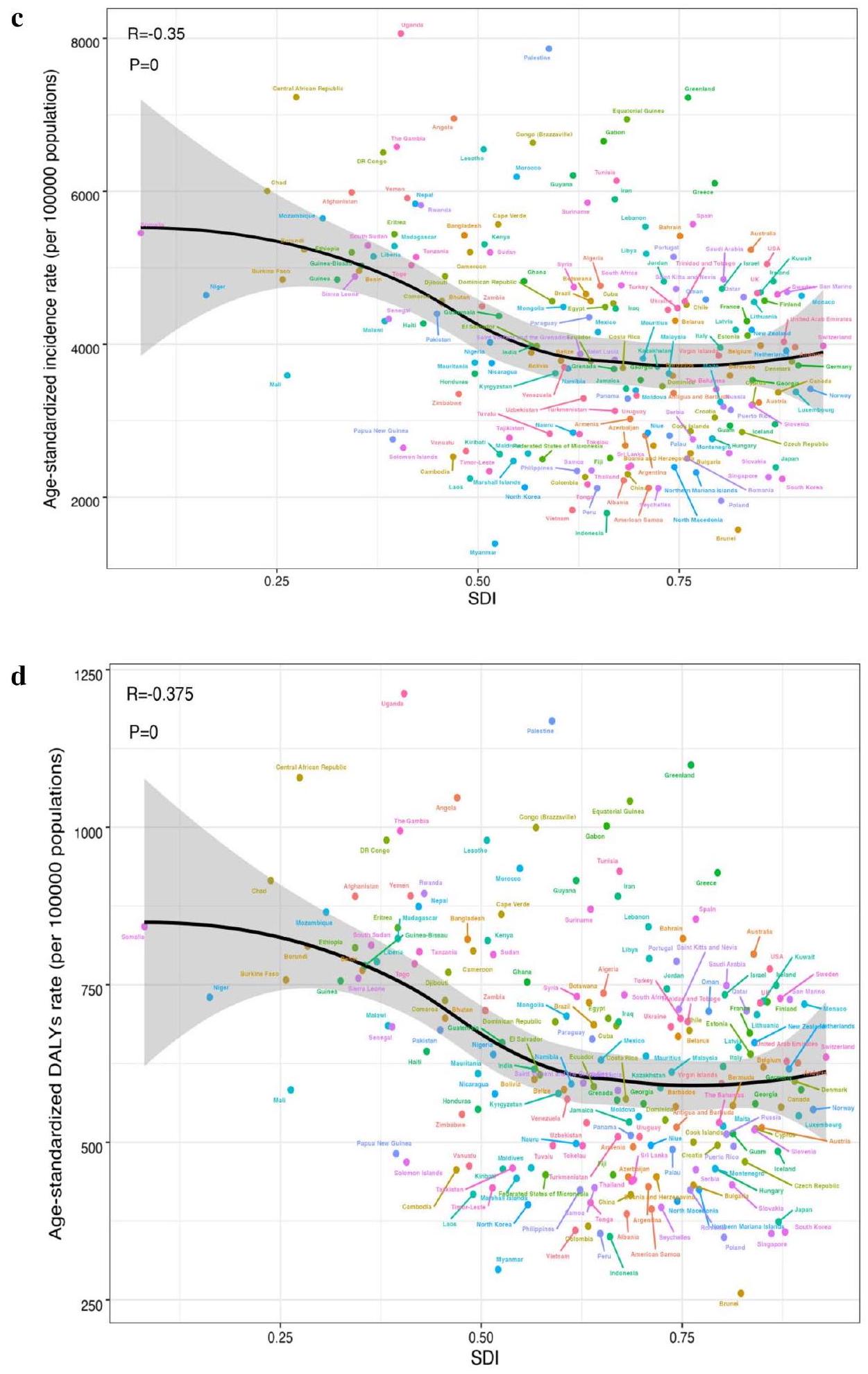

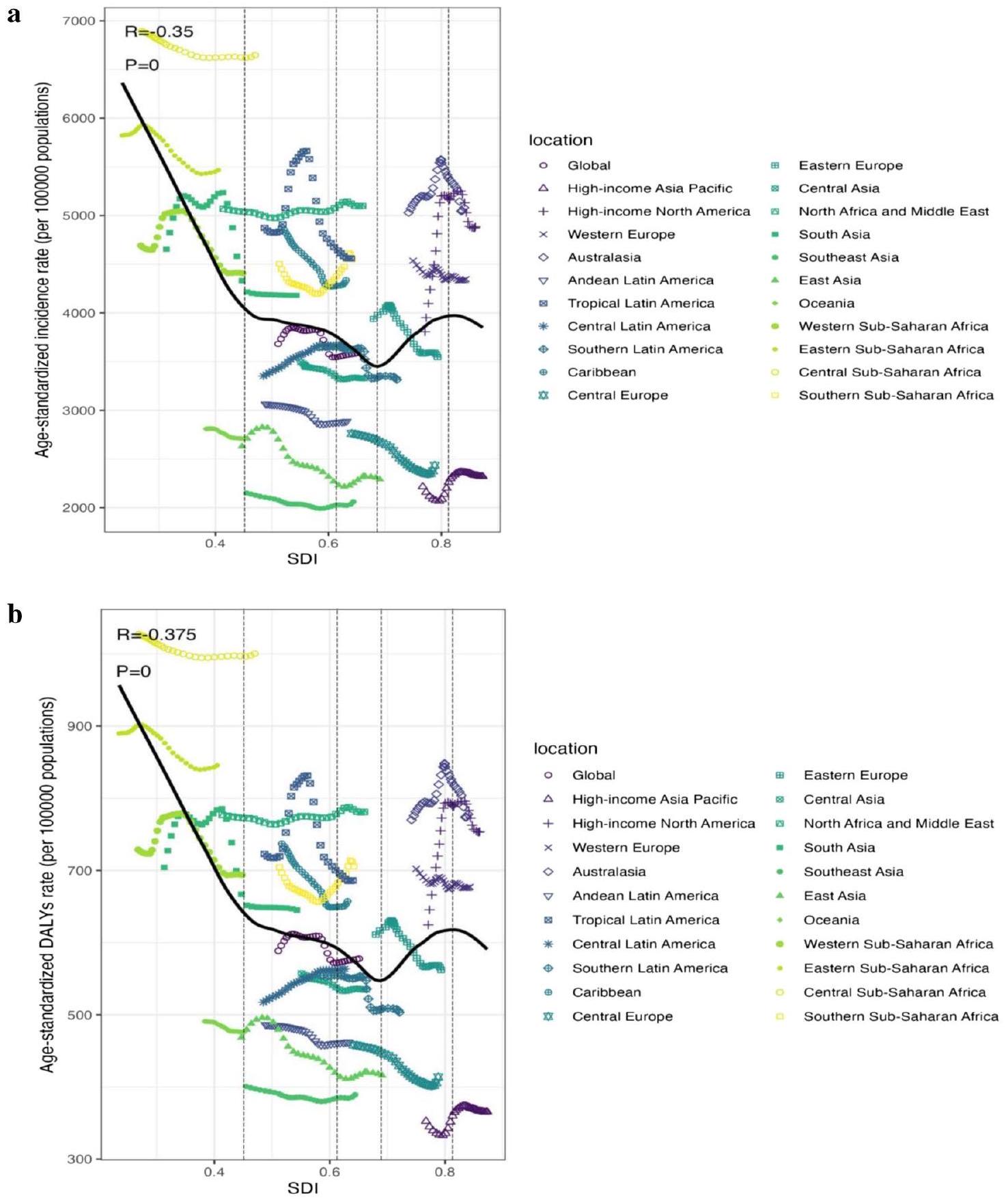

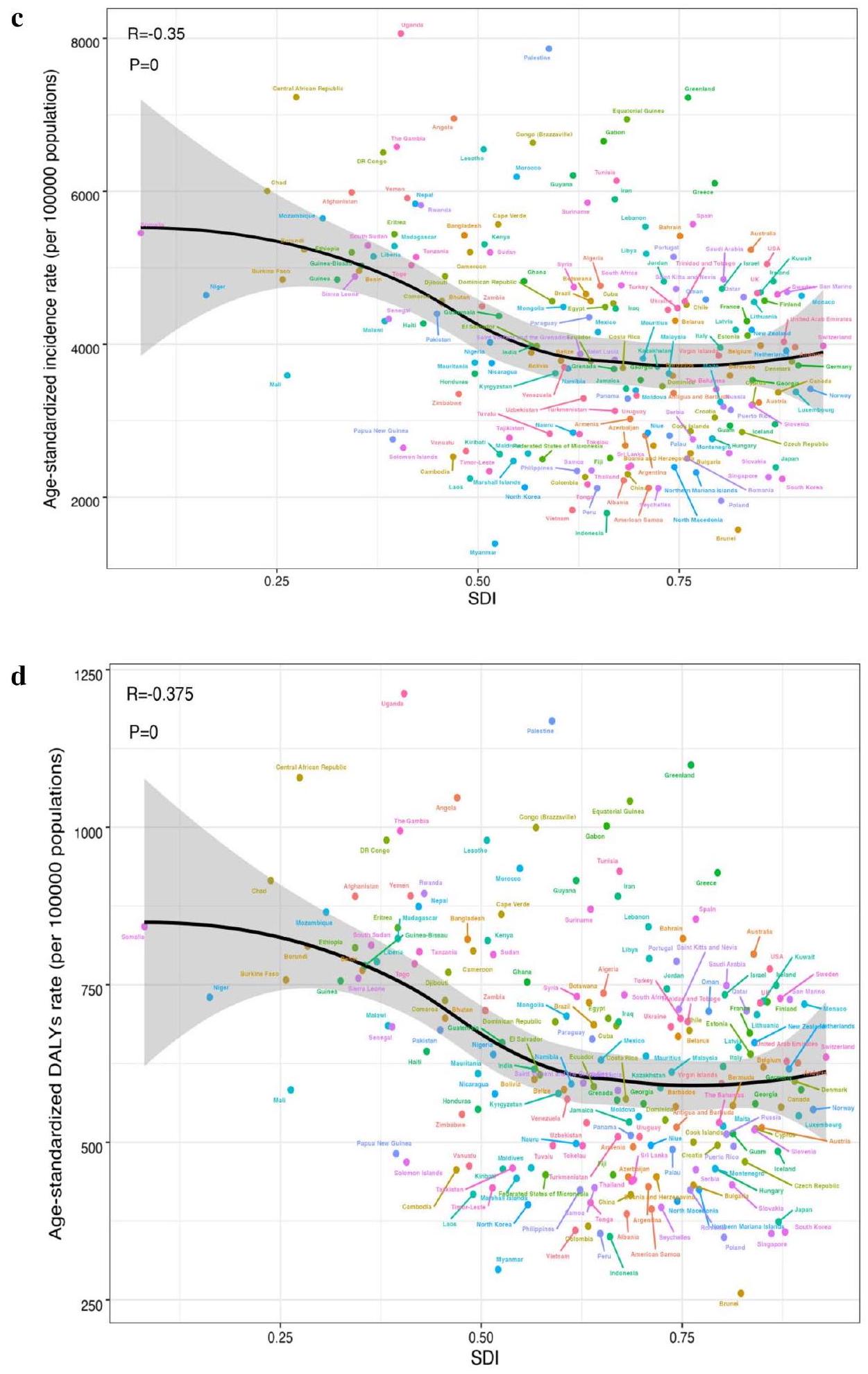

تمت ملاحظة ترابط كبير بين SDI وانتشار الاكتئاب وأيضًا بين SDI وDALYs، كما هو موضح في الشكل 5. تجاوز عدد من المناطق المستويات المتوقعة من الانتشار، بما في ذلك وسط أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء وأسترالاسيا، بينما انخفض عدد من المناطق عن المستويات المتوقعة من الانتشار، بما في ذلك جنوب شرق آسيا والمناطق ذات الدخل المرتفع في آسيا والمحيط الهادئ (انظر الشكل 5a).

من بين 204 دولة وإقليم تم التعرف على ارتباطها بـ SDI لعام 2019، كان لدى معظمها ارتباط سلبي مع SDI، مع وجود عدد قليل من الدول أعلى أو أقل بكثير من المستوى المتوقع. كانت أوغندا وفلسطين أعلى بكثير من المتوقع، بينما كانت ميانمار وبروناي أقل بكثير من المتوقع (انظر الشكل 5c).

انخفضت DALYs في العديد من المناطق مع ارتفاع SDI، باستثناء بعض المناطق. على سبيل المثال، انخفض معدل DALYs في غرب أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء لفترة قصيرة، ثم ارتفع، ثم استمر في الانخفاض، مكونًا منحنى U مقلوب. ظل معدل DALYs في أمريكا اللاتينية الاستوائية، التي لديها تصنيف SDI منخفض-متوسط، مستقرًا في البداية، ثم زاد، قبل أن ينخفض بشكل حاد. ظل معدل DALYs في أمريكا اللاتينية الجنوبية، التي لديها تصنيف SDI متوسط، مستقرًا في البداية، ثم انخفض، ثم استمر في الاستقرار. ارتفع معدل DALYs في شرق أوروبا، التي لديها SDI مرتفع-متوسط، قليلاً، ثم انخفض بشكل حاد، وظل مستقرًا لفترة، ثم انخفض قليلاً. انخفضت النسب العالية من SDI في المناطق ذات الدخل المرتفع في آسيا والمحيط الهادئ لفترة قصيرة ثم ارتفعت، قبل أن تنخفض قليلاً (انظر الشكل 5b).

منذ عام 1990 إلى 2019، كانت معدلات DALY التي تم الحصول عليها في المناطق ذات تصنيف SDI العالي، مثل غرب أوروبا، متسقة إلى حد كبير مع التوقعات. ومع ذلك، خلال فترة الدراسة، استمرت بعض المناطق (مثل، آسيا والمحيط الهادئ ذات الدخل المرتفع) في الحصول على DALYs أقل بكثير من المتوقع، بينما استمرت مناطق أخرى (مثل أسترالاسيا وأمريكا الشمالية ذات الدخل المرتفع) في الحصول على DALYs أعلى من المتوقع (انظر الشكل 5b). على مستوى الدولة خلال عام 2019، وباتباع نمط مشابه لارتباط المرض وSDI، كان هناك ترابط سلبي ملحوظ بين DALYs وSDI، مع بعض الاستثناءات (

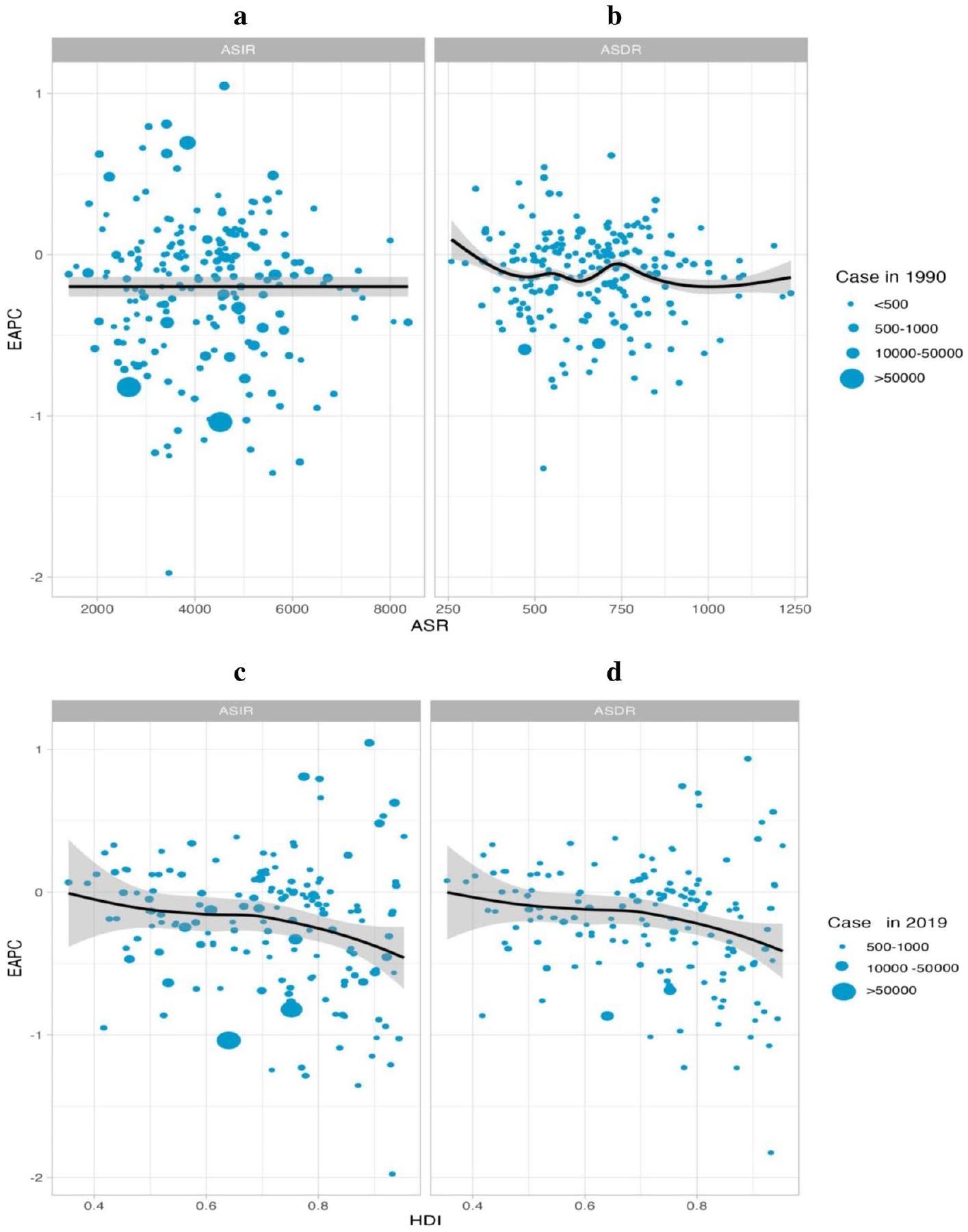

العلاقة بين HDI والعبء العالمي للاضطرابات الاكتئابية

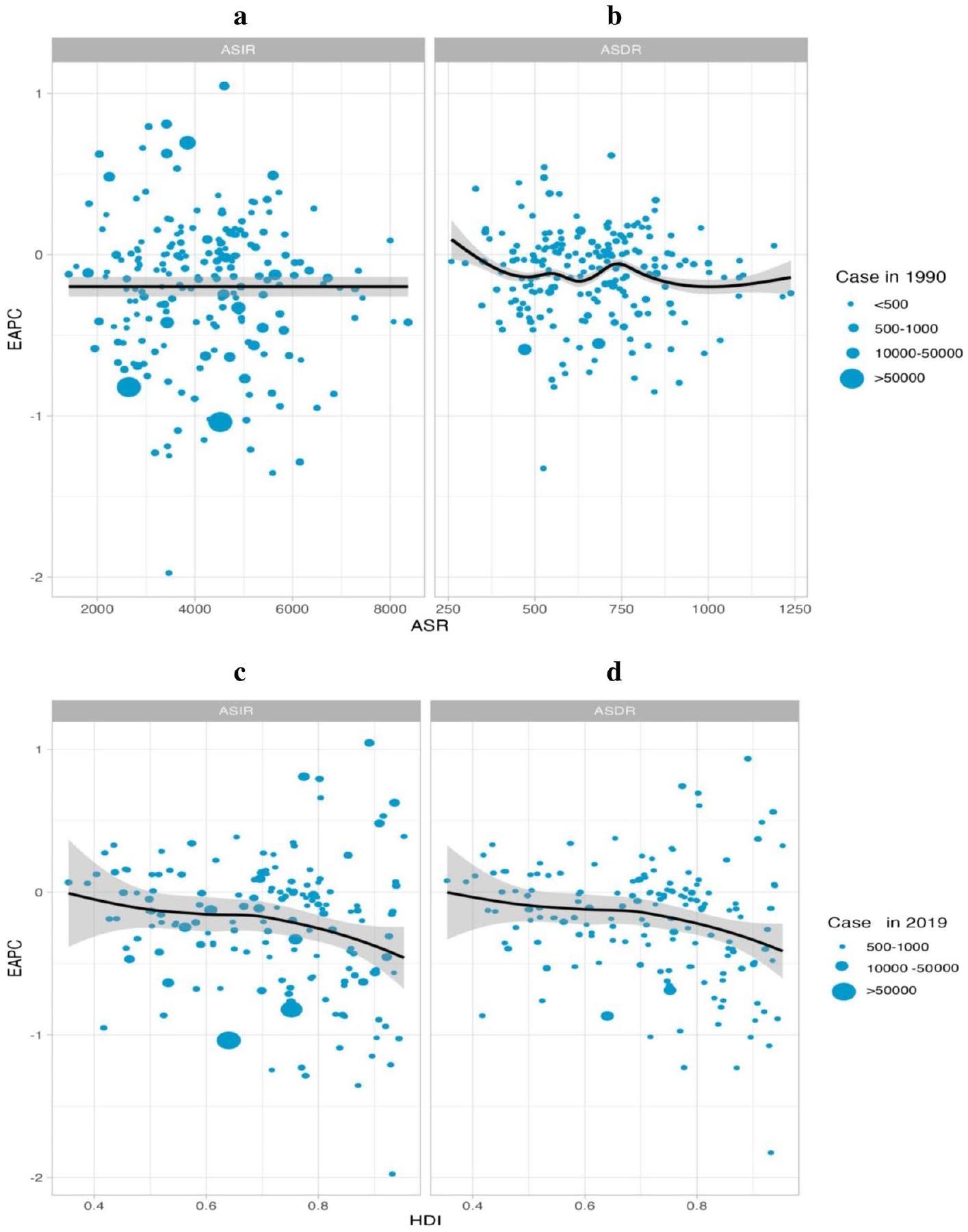

لم يتم العثور على علاقة كبيرة بين EAPC لمرض 1990 والمرض (

) (انظر الشكل 6b).

a1. ASIR

a2. ASDR

b1. التغيير (الحالات)

)).

b2. التغيير (DALYs)

c1. EAPC (الحالات)

c2. EAPC (DALYs)

الشكل 4. (مستمر)

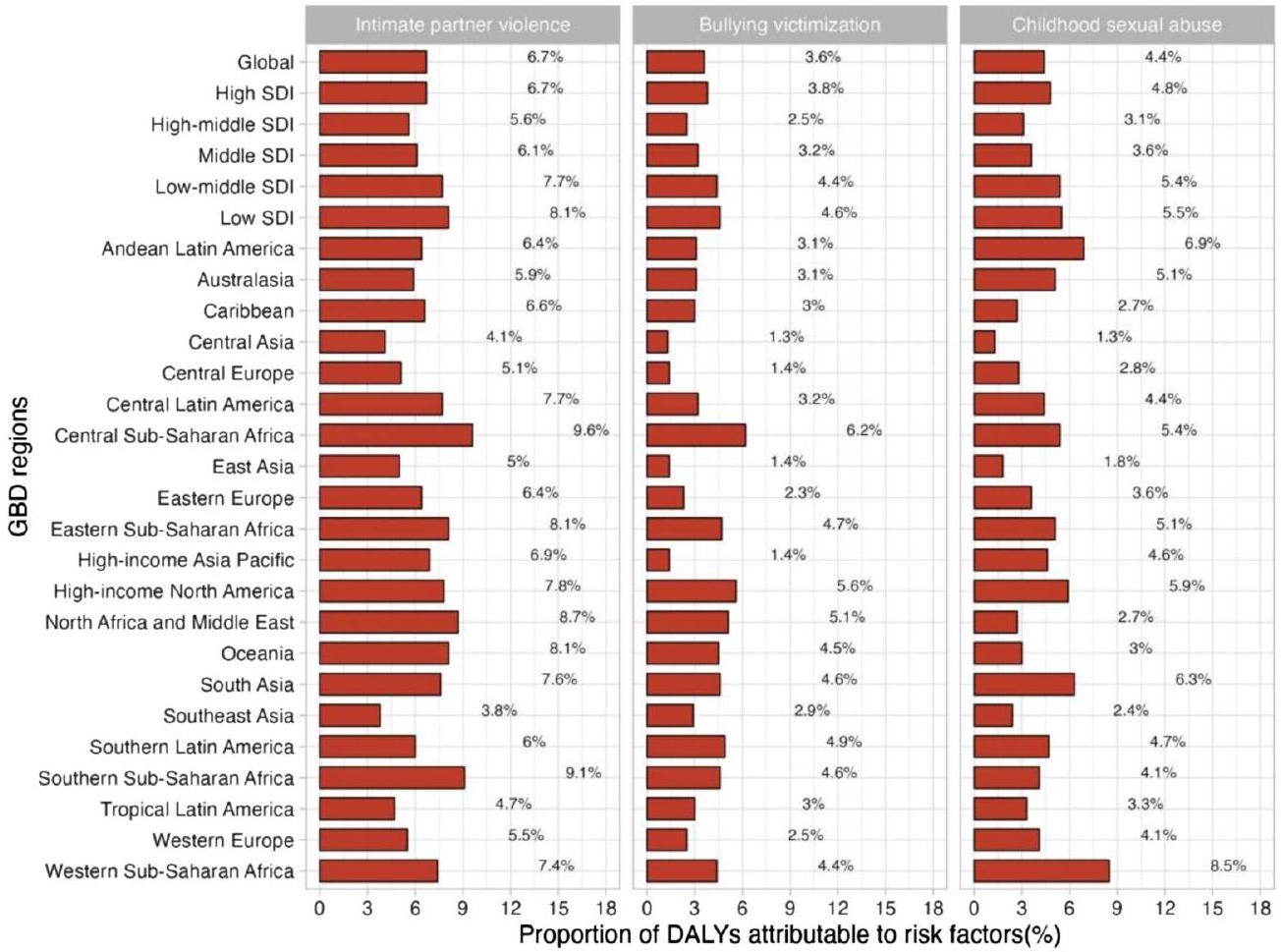

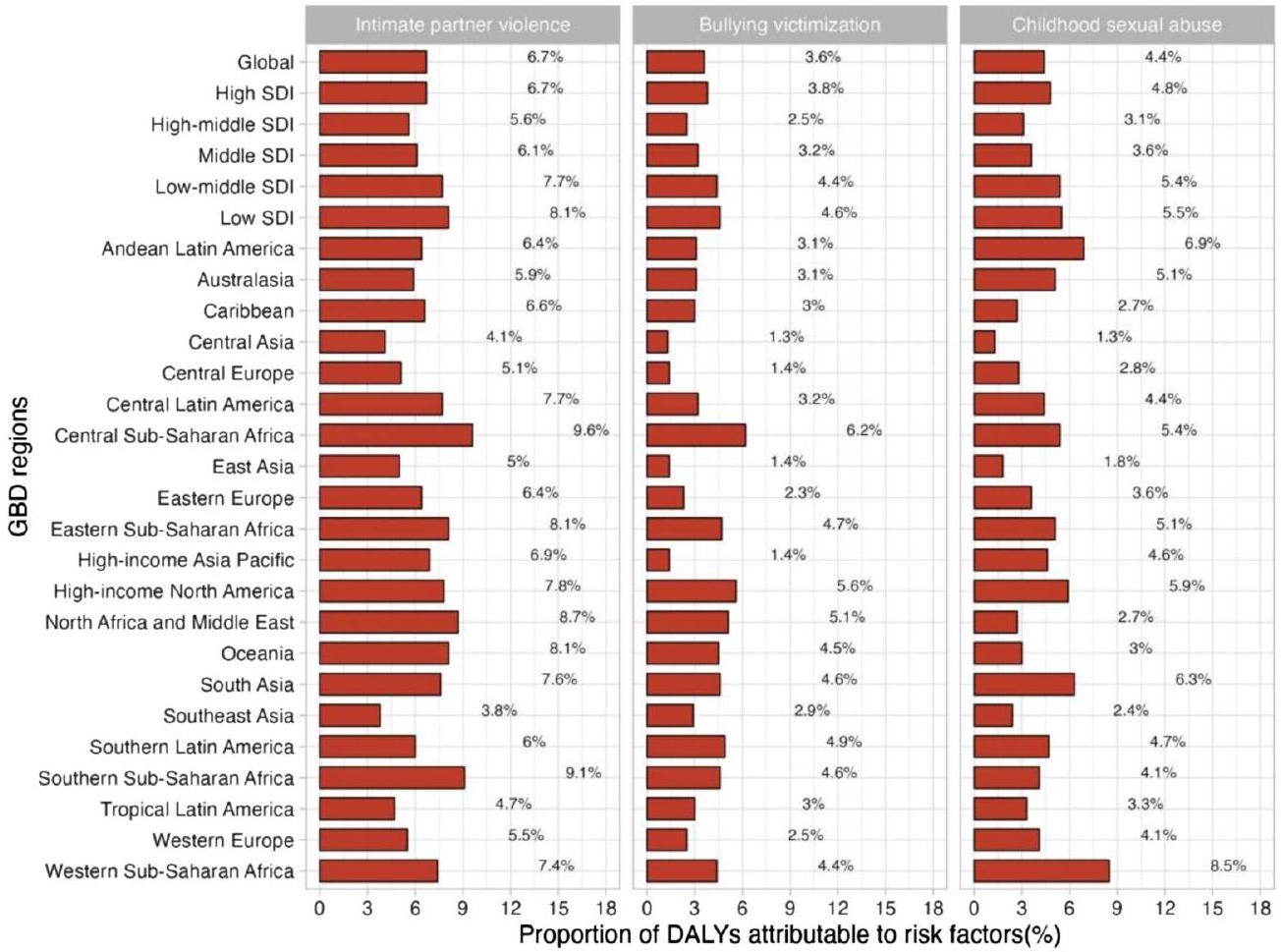

عوامل خطر الاضطرابات الاكتئابية

). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كانت مساهمة التنمر

الشكل 5. معدل الحدوث الموحد حسب العمر (أ) ومعدل DALYs الموحد حسب العمر (ب) للاكتئاب لـ 21 منطقة GBD و204 دولة وإقليم (ج، د) حسب مؤشر السند الاجتماعي (SDI)، 1990-2019 (تشير الخط الأسود إلى الترابط بين جميع مناطق SDI ومعدل الحدوث أو القيمة المتوقعة لـ DALY).

من DALYs كانت منسوبة إلى الاعتداء الجنسي في الطفولة) وأقل في وسط آسيا. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لوجود ثلاثة عوامل خطر فقط ذات صلة بالاضطرابات الاكتئابية بين دراسة GBD، فإن النسبة المئوية لـ DALYs الناتجة عن هذه العوامل الثلاثة تظل صغيرة عند النظر إليها ككل، مما يعني أن هناك حاجة لمزيد من الدراسة حول التأثيرات الرئيسية للاكتئاب.

نقاش

. تقدم هذه الدراسة العبء العالمي للاكتئاب من خلال بيانات GBD، مع التركيز على الاتجاهات الزمنية والتوزيع المكاني للاكتئاب من 1990 إلى 2019، مع تركيز خاص على EAPC. نتيجة

الشكل 5. (مستمر)

. تشير نتائج هذه الدراسة إلى أن العبء العام للاكتئاب قد زاد بسرعة خلال ثلاثة عقود، لكن الزيادة لم تكن متساوية عبر الفئات العمرية أو الجنس أو المناطق

الشكل 6. EAPCs للاضطرابات الاكتئابية على المستوى العالمي والإقليمي والوطني. (أ) الترابط بين EAPC ومعدل الحدوث الموحد حسب العمر للاكتئاب و(ب) معدل DALYs في عام 1990. (ج، د) الترابط بين EAPC وHDI في عام 2019. تمثل الدوائر الدول المتاحة على بيانات HDI. تزداد حجم الدائرة مع حالات الاضطرابات الاكتئابية. تم اشتقاق

مع تحسن مستويات المعيشة للناس، يرتفع الطلب على الخدمات الطبية أيضًا، خاصة مع التركيز المتزايد على الصحة النفسية، وفي هذه الحالة، زادت أيضًا الحاجة إلى خدمات الصحة النفسية. من المهم أيضًا ملاحظة أن التحسين المستمر لأدوات فحص الاكتئاب قد جعل من الممكن للمؤسسات الطبية والوكالات الحكومية الحصول على بيانات أكثر شمولاً ودقة. تشير أبحاثنا إلى أن الاكتئاب الشديد (MDD) يمثل نسبة كبيرة من حالات الاكتئاب وهو الفئة النفسية الأكثر انتشارًا للاكتئاب، وهو ما يتماشى مع نتائج دراسة أجراها لي وآخرون في عام 2022.

الشكل 7. نسبة سنوات الحياة المعدلة للإعاقة (DALYs) الناتجة عن العنف من الشريك الحميم، وضحية التنمر، وسوء المعاملة الجنسية في الطفولة، لـ 21 منطقة من GBD، 2019.

تظهر أبحاثنا أن الإناث لديهن معدلات أعلى من الاكتئاب وDALYs مقارنة بالذكور عبر جميع الفئات العمرية. كانت معدلات انتشار وDALYs الاكتئاب هي الأعلى بين الأشخاص الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين

تشير تقاريرنا إلى أن معدلات نوعي الاكتئاب الفرعيين، الاكتئاب المزمن (dysthymia) والاكتئاب الشديد (MDD)، ظلت مستقرة إلى حد كبير على الصعيدين العالمي والإقليمي خلال فترة الدراسة، حيث يعاني معظم المرضى من MDD. قدرت دراسة الصحة النفسية العالمية انتشار MDD السنوي بـ

تشير النتائج إلى أن الكثافة السكانية النسبية في أوغندا وارتفاع انتشار الأمراض الاستوائية، مثل الملاريا، والإيدز، وفيروس إيبولا، ومرض النوم، والتهاب الكبد الفيروسي، والسل، قد تكون مرتبطة بأعلى معدل عالمي لـ ASR وASDR للاكتئاب. على الرغم من أن ذروة الوباء في أوغندا، التي كانت واحدة من أعلى معدلات انتشار فيروس HIV في العالم، قد مرت وانخفضت نسبة الحالات الجديدة في السنوات الأخيرة، إلا أن عدد الأشخاص المصابين بالفيروس والذين يعيشون مع المرض لا يزال مرتفعًا، خاصة في المناطق الريفية. يعاني الأشخاص المصابون بفيروس HIV من التحيز الاجتماعي والتمييز، مما يمكن أن يؤدي إلى البطالة، والفقر، وتفكك الأسرة، ومشاكل جسدية ونفسية قد تؤدي إلى انخفاض تقدير الذات، وانخفاض المزاج، وحتى الاكتئاب

تم تحديد أكبر زيادة في الاكتئاب وDALYs في قطر، تليها الإمارات العربية المتحدة وغينيا الاستوائية. لوحظت زيادات كبيرة في الاكتئاب وDALYs في المناطق ذات SDI المتوسط-المرتفع وSDI العالي. قد يكون ذلك لأن مستوى التنمية الاقتصادية والتعليم في هذه المناطق مرتفع نسبيًا، والضغط الاجتماعي الناتج عن السكان أكبر، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة انتشار الاكتئاب. وجدت الدراسات أن الأفراد بمستويات تعليم مختلفة لديهم مستويات مختلفة من القدرة المعرفية. يؤثر مستوى التعليم على الاكتئاب لدى الأفراد ويمكن أن يؤثر أيضًا على الأزواج

من التنمية الاقتصادية، زاد الضغط الاجتماعي الذي يعاني منه الناس. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن الدولة التي شهدت أكبر انخفاض في الاكتئاب وDALYs كانت لاتفيا، تليها البوسنة والهرسك، وإستونيا

من التنمية الاقتصادية، زاد الضغط الاجتماعي الذي يعاني منه الناس. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن الدولة التي شهدت أكبر انخفاض في الاكتئاب وDALYs كانت لاتفيا، تليها البوسنة والهرسك، وإستونيا

زاد ASIR وASDR بشكل أكبر في إسبانيا، تليها المكسيك وماليزيا. يُبلغ عن أن هذه الدول لديها دخل اقتصادي أعلى ومؤشرات سكانية اجتماعية، مما يؤكد إحصائياتنا. ومع ذلك، من حيث ASR، كان أكبر انخفاض في ASIR في سنغافورة، ثم سريلانكا وسلوفينيا؛ وكان أكبر انخفاض في ASDR في سنغافورة وكوبا وإستونيا

تشير التحليلات الإضافية للعلاقة بين المرض والعوامل السكانية الاجتماعية والجغرافية إلى أن الاكتئاب أكثر وضوحًا من حيث الحدوث في البلدان ذات SDI العالي والدخل المرتفع، بينما يكون عبء الاكتئاب أعلى بكثير في البلدان ذات الدخل المنخفض وSDI المنخفض.

في الختام، يختلف عبء الاكتئاب عبر المناطق لعدة أسباب. تشمل هذه الأسباب مستوى التنمية الاقتصادية لكل منطقة، ومستوى التعليم، ومستوى التطور الطبي والقدرة على تشخيص المرض، بالإضافة إلى مستوى الأهمية الذي تعطيه الحكومات للمرض

لمنع الاكتئاب والسيطرة عليه بشكل فعال، يجب على الحكومات دعم الأبحاث المتعلقة بالاكتئاب مع اتخاذ خطوات مناسبة لمعالجة الاكتئاب بشكل فعال. على سبيل المثال، يجب عليهم تعزيز التعليم حول الوقاية والعلاج، وتحسين القدرة على التشخيص المبكر والعلاج القياسي، وإنشاء تدابير خدمات الصحة النفسية للفئات الرئيسية، وإجراء التدخل النفسي في الوقت المناسب

أجرت هذه الدراسة أكثر تقييم شامل لعبء الاكتئاب حتى الآن. تم الحصول على جميع البيانات المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة من قاعدة بيانات GBD، التي تقدم حجم عينة كبير وجودة بيانات عالية، مما يمنح هذه الدراسة ميزة واضحة من حيث موثوقية البيانات. بينما تم إجراء العديد من الأبحاث حول انتشار الاكتئاب في GBD 2019، فإن الغالبية العظمى من هذه الدراسات تقيم الحالة باستخدام نهج تحليل العمر-الفترة-الجيل، وتختلف مناطق دراستها، وأهداف دراستها، وأنواع الاكتئاب التي تركز عليها. على سبيل المثال، استخدم لي وآخرون نهج تحليل العمر-الفترة-الجيل لدراسة انتشار الاكتئاب بين المراهقين في منطقة غرب المحيط الهادئ

الخاتمة

لا تزال الاكتئاب تمثل تحديًا خطيرًا على مستوى العالم، ويظل عبء المرض ثقيلًا. من خلال تحليل العبء العالمي للاكتئاب، توضح هذه الدراسة الوضع الحالي للاكتئاب في مختلف البلدان وتوفر أساسًا مرجعيًا علميًا للحكومات لوضع استراتيجيات فعالة ونشطة للوقاية والعلاج. يجب على الدول، وخاصة تلك التي تعاني من عبء مرتفع من الاكتئاب، تعزيز التعليم في مجال الصحة النفسية بقوة، والوقاية بنشاط من عوامل الخطر، واعتماد تدخلات مستهدفة لرفع مستوى الوعي بالاكتئاب بين سكانها، وفي الوقت نفسه، الدعوة إلى إصلاح الأنظمة ذات الصلة وإزالة الحواجز السياسية من أجل تحسين الوقاية والعلاج من الاضطرابات النفسية.

توفر البيانات

يمكن العثور على مجموعة البيانات التي تم إنشاؤها لهذه الدراسة في GBD علىhttp://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

تاريخ الاستلام: 20 سبتمبر 2023؛ تاريخ القبول: 16 مايو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 29 مايو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 29 مايو 2024

References

- Lawrence, D., Kisely, S. & Pais, J. The epidemiology of excess mortality in people with mental illness. Can. J. Psychiatry. 55, 752-760. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371005501202 (2010).

- Scott, K. M. et al. Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 150-158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688 (2016).

- Wahlbeck, K., Westman, J., Nordentoft, M., Gissler, M. & Laursen, T. M. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: Life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 199, 453-458. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085100 (2011).

- Scott, K. M. et al. Associations between DSM-IV mental disorders and subsequent heart disease onset: beyond depression. Int. J. Cardiol. 168, 5293-5299 (2013).

- Piao, J. et al. Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 31(1827-1845), 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00787-022-02040-4(2022)(Epub (2022).

- Thomas, S. P. World Health Assembly adopts comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan for 2013-2020. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 34, 723-724. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2013.831260 (2013).

- Upthegrove, R., Marwaha, S. & Birchwood, M. Depression and schizophrenia: Cause, consequence, or trans-diagnostic issue?. Schizophr. Bull. 43, 240-244. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbw097 (2017).

- Kessler, R. C. et al. The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 18, 23-33. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1121189x00001421 (2009).

- Wang, P. S. et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet 370, 841-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7 (2007).

- Piao, J. et al. Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 31, 1827-1845. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00787-022-02040-4. [Epub2022July14] (2022).

- GBD. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 137-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21) 00395-3 (2022).

- Cui, R. Editorial: A systematic review of depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 13, 480. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159×1304150 831123535 (2015).

- Luo, Y., Zhang, S., Zheng, R., Xu, L. & Wu, J. Effects of depression on heart rate variability in elderly patients with stable coronary artery disease. J. Evid. Based Med. 11, 242-245. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm. 12310 (2018).

- Seligman, F. & Nemeroff, C. B. The interface of depression and cardiovascular disease: Therapeutic implications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1345, 25-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas. 12738 (2015).

- Smith, K. Mental health: A world of depression. Nature 515, 181. https://doi.org/10.1038/515180a (2014).

- Stringaris, A. Editorial: What is depression?. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatr. 58, 1287-1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12844 (2017).

- Gross, M. Silver linings for patients with depression?. Curr. Biol. 24, R851-R854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.059 (2014).

- Ménard, C., Hodes, G. E. & Russo, S. J. Pathogenesis of depression: Insights from human and rodent studies. Neuroscience 321, 138-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.053 (2016).

- Solmi, M. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of autism spectrum disorder from 1990 to 2019 across 204 countries. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 4172-4180 (2022).

- Liu, Q. et al. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 126, 134-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002 (2020).

- Peng, H. et al. The global, national, and regional burden of dysthymia from 1990 to 2019: Insights from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. J. Affect. Disord. 333, 524-526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.024 (2023).

- GBD. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223-1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 (2020).

- Hong, C. et al. Global trends and regional differences in the burden of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder attributed to bullying victimisation in 204 countries and territories, 1999-2019: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 31, e85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000683 (2022).

- Ren, X. et al. Burden of depression in China, 1990-2017: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. J. Affect. Disord. 268, 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.011 (2020).

- Dai, H. et al. The global burden of disease attributable to high body mass index in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. PLOS Med. 17, e1003198. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed. 1003198 (2020).

- Hankey, B. F. et al. Partitioning linear trends in age-adjusted rates. Cancer Causes Control 11, 31-35. https://doi.org/10.1023/a: 1008953201688 (2000).

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 396, 1204-1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(20)30925-9 (2020).

- Yue, T., Zhang, Q., Li, G. & Qin, H. Global burden of nutritional deficiencies among children under 5 years of age from 2010 to 2019. Nutrients 14, 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132685 (2022).

- Liu, Q. et al. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr Res. 126, 134-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002 (2019).

- Ogbo, F. A., Mathsyaraja, S., Koti, R. K., Perz, J. & Page, A. The burden of depressive disorders in South Asia, 1990-2016: findings from the global burden of disease study. BMC Psychiatry 18, 333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1918-1 (2018).

- Li, S. et al. Sex difference in global burden of major depressive disorder: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Front. Psychiatry. 21(13), 789305. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.789305 (2022).

- Keita, G. P. Psychosocial and cultural contributions to depression in women: Considerations for women midlife and beyond. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 13(Supp 9), 12-15 (2007).

- Patel, V., Rodrigues, M. & DeSouza, N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: A study of mothers in Goa India. Am. J. Psychiatr. 159(1), 43-47 (2002).

- Trivedi, J. K., Sareen, H. & Dhyani, M. Rapid urbanization-its impact on mental health: A south Asian perspective. Indian J. Psychiatry. 50(3), 161 (2008).

- Ahmad, O. B. et al. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. GPE Discussion Paper Series: No 31, 10-12. https://cdn. who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/gpe_discussion_paper_series_paper31_2001_age_ standardization_rates.pdf (2001).

- Ferrari, A. J. et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLOS Med. 10, e1001547. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547 (2013).

- Bachner-Melman, R., Watermann, Y., Lev-Ari, L. & Zohar, A. H. Associations of self-repression with disordered eating and symptoms of other psychopathologies for men and women. J. Eat. Disord. 10, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00569-y (2022).

- Kessler, R. C. et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289, 3095-3105. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.23.3095 (2003).

- Bromet, E. et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 9, 90 (2011).

- Sheehan, D. V. et al. Restoring function in major depressive disorder: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 215, 299-313 (2017).

- Malhi, G. S. & Mann, J. J. Depression. Lancet 392, 2299-2312 (2018).

- Yang, L. et al. The effects of psychological stress on depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 13, 494-504. https://doi.org/10.2174/15701 59×1304150831150507 (2015).

- Ironson, G., Henry, S. M. & Gonzalez, B. D. Impact of stressful death or divorce in people with HIV: A prospective examination and the buffering effects of religious coping and social support. J. Health Psychol. 25, 606-616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317 726151 (2020).

- Junqueira, P., Bellucci, S., Rossini, S. & Reimão, R. Women living with HIV/AIDS: Sleep impairment, anxiety and depression symptoms. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 66, 817-820. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-282×2008000600008 (2008).

- Lee, J. Pathways from education to depression. J. Cross. Cult. Gerontol. 26, 121-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-011-9142-1 (2011).

- Alonso, J. et al. Treatment gap for anxiety disorders is global: Results of the World Mental Health Surveys in 21 countries. Depress. Anxiety 35, 195-208. https://doi.org/10.1002/da. 22711 (2018).

- Perez, M. I. et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder misdiagnosis among mental healthcare providers in Latin America. J. Obsessive Compuls. Relat. Disord. 32, 100693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2021.100693 (2022).

- Li, Z. B. et al. Burden of depression in adolescents in the Western Pacific Region from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study. Psychiatry Res. 336, 115889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2024.115889 (2024).

- Xu, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence trends of depressive disorder, 1990-2019: An age-period-cohort analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 88, 51-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2024.03. 003 (2024) (Epub 2024 Mar 16).

- Hong, C. et al. Global trends and regional differences in the burden of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder attributed to bullying victimisation in 204 countries and territories, 1999-2019: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 28(31), e85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000683 (2022).

- Yang, F. et al. Thirty-year trends of depressive disorders in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis. Psychiatry Res. 328, 115433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115433 (2023) (Epub 2023 Aug 27).

- Baca, E., Lázaro, J. & Hernández-Clemente, J. C. Historical perspectives of the role of Spain and Portugal in today’s status of psychiatry and mental health in Latin America. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 22, 311-316. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2010.501165 (2010).

- Mullins, N. & Lewis, C. M. Genetics of depression: Progress at last. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 19, 43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0803-9 (2017).

- McGrath, J. J. et al. Comorbidity within mental disorders: A comprehensive analysis based on 145990 survey respondents from 27 countries. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 29, e153. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000633 (2020).

- Plana-Ripoll, O. et al. Nature and prevalence of combinations of mental disorders and their association with excess mortality in a population-based cohort study. World Psychiatry 19, 339-349. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps. 20802 (2020).

مساهمات المؤلفين

قام JL بإجراء التحليلات الإحصائية وكتب المخطوطة. حل YL المشكلات التقنية أثناء التحليلات الإحصائية وشارك في تصور وتصميم الدراسة، وتفسير النتائج. ساهم WM في تصور وتصميم الـدراسة.يوتيوبوشارك JZ في تصميم الدراسة وقام بتقييم المخطوطة بشكل نقدي ومراجعتها. ساهم جميع المؤلفين في المقالة ووافقوا على النسخة المقدمة.

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إضافية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على مواد إضافية متاحة علىhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62381-9.

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى Y.T. أو J.Z.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينجر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينجر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي النسب 4.0 الدولية، التي تسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج بأي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد أُجريت. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمواد. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فسيتعين عليك الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

كلية الصحة العامة، جامعة شاندونغ الطبية، تاييوان، شانشي، الصين. الكلية الطبية السريرية الثانية، جامعة نانتشانغ، نانتشانغ، جيانغشي، الصين. البريد الإلكتروني:tycarth@163.com; zjzhong4183@163.com - © المؤلف(ون) 2024

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 14, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62381-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38811645

Publication Date: 2024-05-29

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62381-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38811645

Publication Date: 2024-05-29

Temporal and spatial trend analysis of all-cause depression burden based on Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 study

Mental disorders are a major contributor to the global burden of disease. It commonly results in a higher incidence of physical decline

There is evidence that depression predisposes individuals to myocardial infection and diabetes and having these illnesses increases the chances of developing depression. Many risk factors, such as low social status, alcohol abuse, and stress, are responsible for the development of mental illnesses

The economic costs of these health problems are enormous. According to a new study, the total financial costs of mental illness worldwide will reach

Mental disorders are recognized as a major contributor to the global burden of disease, accounting for 1566.2 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per 100,000 of the global population in 2019. Among these, depressive disorders (major depressive disorder [MDD] and dysthymia) constituted the most significant proportion of mental disorder DALYs

depression, which the WHO ranks it as the greatest contributor to global disability

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study offers detailed data on a wide range of diseases for 204 countries in 21 different regions worldwide

Methods

Data sources

The data utilized in this study are available on the Global Health Data Exchange GBD Results Tool (http://ghdx. healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool). GBD 2019 estimated incidence, prevalence, mortality, years lived with disability (YLDs), years of life lost (YLLs), and DALYs for 369 diseases and injuries, for males and females, 23 age groups, 204 countries and territories that were geographically grouped into 21 regions from 1990 onwards

Classification and definitions

Depressive disorders, MDD, and dysthymia

In the International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision (ICD-10), depressive disorders were categorised into two main groups: major depressive disorder (MDD) and dysthymia. Therefore, in the GBD study, both MDD and dysthymia were included in the category of depressive disorders. MDD is an episodic depressive disorder that may recur throughout an individual’s life, with each recurrence varying in severity. Dysthymia is a slow and mild persistent depressive disorder with symptoms less severe than those of MDD, but with a course characterised by persistence. Cases that met the diagnostic criteria for MDD and dysthymia according to the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) and ICD (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) were included in the GBD research disease model

In the International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision (ICD-10), depressive disorders were categorised into two main groups: major depressive disorder (MDD) and dysthymia. Therefore, in the GBD study, both MDD and dysthymia were included in the category of depressive disorders. MDD is an episodic depressive disorder that may recur throughout an individual’s life, with each recurrence varying in severity. Dysthymia is a slow and mild persistent depressive disorder with symptoms less severe than those of MDD, but with a course characterised by persistence. Cases that met the diagnostic criteria for MDD and dysthymia according to the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) and ICD (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) were included in the GBD research disease model

SDI

The SDI is an aggregative metric that measures the development of a country or region, combining data on the total fertility rate for females under 25, the average level of education of females aged 15 and over, and per capita income. The GBD 2019 database categorises the world into five types of regions based on the SDI index: low-SDI (

The SDI is an aggregative metric that measures the development of a country or region, combining data on the total fertility rate for females under 25, the average level of education of females aged 15 and over, and per capita income. The GBD 2019 database categorises the world into five types of regions based on the SDI index: low-SDI (

Human development index (HDI)

HDI is an aggregative indicator that measure the level of economic and social development of United Nations Member States and consists of three basic variables: life expectancy, educational attainment, and quality of life. We obtained the 2019 HDI data from the United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Report to explore the association of the HDI and the EAPC for incidence and DALYs (https://hdr.undp.org/en/compo site/HDI, accessed on March 27, 2022)

ASR

Age-standardized rate (ASR) is a common indicator in epidemiology. When the composition of age structure is different between several comparison groups, the crude rate of direct comparison groups will lead to bias because it does not indicate whether the high incidence rate in a particular area is due to differences in age composition, and it is usually necessary to compare rates after standardization

The age-standardized rate was calculated on the basis of the following formula:

The age-standardized rate per 100,000 population is equal to the sum of the products of age-specific rates (wi, where

selected reference standard population and then divided by the sum of the standard population weights

selected reference standard population and then divided by the sum of the standard population weights

EAPC

The EAPC provides a well-recognized approach of characterizing ASR using a regression model that quantifies the average annual rate of change during a specific period, with the plus and minus signs representing the direction of change. The regression line was used to estimate the natural logarithm of the rate (i.e.,

Analytic strategy

We depicted changes in the prevalence and burden of disease of depression in 204 nations covering 21 distinct regions during the study period. The analysis indices included incidence and DALYs. The ASR was calculated considering the average population structure of the world from 2000 to 2025 as the standard population structure

Ethical committee

The study was compliant with the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting, and the University of Washington Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the waiver of informed consent for GBD 2019.

Results

Since 1990 to 2019, depressive disorder cases have grown from 182,183,358 (

In terms of the subtypes of depression, the incidence of MDD was much more prevalent than dysthymia at

Global burden and EAPC of depressive disorders by 21 GBD regions

Individuals with depressive disorders increased in all five SDI regions from 1990 through 2019 (see Supplementary Table S1a). However, the ASIR decreased in the high-middle-SDI (EAPC

| Characteristics | Incidence (95% UI) | DALYs (95% UI) | |||||||||||

| Number | ASR | EAPC | Number | ASR | EAPC | ||||||||

| Global |

|

3588.25 (3152.714060.42) |

|

46,863,642 (32,929,36363,797,315) | 577.75 (405.79-788.88) |

|

|||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Male |

|

2750.27 (2419.663104.07) |

|

18,183,102 (12,682,04724,947,035) | 452.17 (316.79-618.13) |

|

|||||||

| Female |

|

4416.34 (3886.95015.49) |

|

28,680,540 (20,155,77339,319,358) | 702.08 (492.3-963.58) |

|

|||||||

| Category | |||||||||||||

| Depressive disorders |

|

3588.25 (3152.714060.42) |

|

46,863,642 (32,929,36363,797,315) | 577.75 (405.79-788.88) | – 0.24% (- 0.31 to – 0.16) | |||||||

| Major depressive disorder |

|

3397.48 (2978.663866.97) |

|

37,202,742 (25,650,20551,217,042) | 459.59 (315.19-634.72) | – 0.32% (- 0.41 to – 0.22) | |||||||

| Dysthymia |

|

190.77 (158.69-229.44) | 0.08% (0.07-0.09) | 9,660,901 (6,311,56614,421,787) | 118.16 (77.31-176.65) | 0.09% (0.08-0.1) | |||||||

| Socio- demographic index | |||||||||||||

| High SDI | 44,711,792 (39,796,76150,166,003) | 4013.63 (3545.484550.43) | 0.31% (0.18-0.44) | 7,025,129 (4,955,2009,506,636) | 626.84 (438.47-852.48) | 0.23% (0.14-0.33) | |||||||

| High- middle SDI | 53,642,569 (47,529,70660,307,945) | 3184.21 (2809.63583.66) | – 0.5% (-0.57 to – 0.43) | 8,896,917 (6,247,98612,123,142) | 523.01 (367.02-713.05) |

|

|||||||

| Middle SDI | 80,760,069 (71,066,73291,500,542) | 3139 (2765.35-3540.43) | – 0.2% (- 0.28 to – 0.13) | 13,541,947 (9,515,93518,454,507) | 521.68 (366.8-709.93) |

|

|||||||

| Low-middle SDI | 70,155,480 (61,292,23779,973,480) | 4180.3 (3660.974740.48) |

|

11,026,538 (7,715,89815,191,253) | 654.34 (458.32-897.85) | – 0.51% (- 0.66 to – 0.36) | |||||||

| Low SDI | 40,743,981 (34,959,15747,317,678) | 4770.22 (4142.245461.66) | – 0.38% (- 0.5 to – 0.26) | 6,345,789 (4,316,6238,788,145) | 738.87 (514.681011.24) |

|

|||||||

| Region | |||||||||||||

| Andean Latin America | 1,809,802 (1,561,7072,084,373) | 2886.58 (2499.393315.19) |

|

290,671 (198,567403,423) | 462.07 (318.12-640.03) | – 0.25% (-0.29 to – 0.21) | |||||||

| Australasia | 1,539,866 (1,329,8481,771,752) | 5079.18 (4368.055925.8) | 0.07% (-0.06-0.21) | 237,564 (164,169330,311) | 777.82 (538.621094.07) | 0.07% (-0.05-0.2) | |||||||

| Caribbean | 2,156,062 (1,859,1212,484,561) | 4336.17 (3737.425007.13) |

|

327,025 (226,095450,595) | 657.19 (454.07-905.93) | – 0.49% (-0.54 to – 0.43) | |||||||

| Central Asia | 2,980,970 (2,577,9063,464,935) | 3327.42 (2888.663825.36) | – 0.19% (- 0.21 to – 0.16) | 486,600 (334,518679,840) | 534.9 (372.57-741.82) | – 0.16% (- 0.18 to – 0.13) | |||||||

| Central Europe | 3,557,074 (3,134,2834,043,451) | 2436.8 (2132.452771.69) |

|

596,440 (420,305816,082) | 413.89 (290.54-572.31) | – 0.54% (- 0.6 to – 0.48) | |||||||

| Central Latin America | 9,412,732 (8,221,93210,719,231) | 3675.78 (3219.654181.96) | 0.34% (0.3-0.37) | 1,447,181 (1,009,4081,981,151) | 563.62 (392.72-771.17) | 0.31% (0.28-0.34) | |||||||

| Central Sub-Saharan Africa | 6,714,339 (5,590,5218,062,124) | 6646.94 (5680.57819.84) | – 0.17% (- 0.18 to – 0.15) | 1,010,267 (681,6331,430,655) | 1000.16 (682.151397.69) | – 0.12% (- 0.14 to – 0.11) | |||||||

| East Asia | 42,235,926 (37,513,97947,555,038) | 2292.26 (2043.672562.45) | – 0.8% (- 0.97 to – 0.64) | 7,802,555 (5,472,93910,767,864) | 415.98 (291.93-573.46) | – 0.67% (- 0.78 to – 0.56) | |||||||

| Eastern Europe | 9,150,637 (7,960,74910,432,658) | 3546.8 (3076.084062.82) |

|

1,442,695 (1,013,9901,986,605) | 562.24 (391.45-771.76) | – 0.46% (-0.54 to – 0.38) | |||||||

| Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa | 16,013,047 (13,725,94418,554,113) | 5466.48 (4781.026234.48) | – 0.32% (- 0.39 to – 0.26) | 2,510,165 (1,702,2083,475,451) | 845.4 (589.89-1154.93) | – 0.26% (-0.32 to – 0.21) | |||||||

| High-income Asia Pacific | 5,193,652 (4,652,1185,735,090) | 2320.99 (2063.542600.8) | 0.4% (0.27-0.53) | 812,255 (572,7411,104,805) | 365.65 (253.57-499.26) | 0.31% (0.2-0.43) | |||||||

| High-income North America | 18,459,876 (16,429,39320,674,357) | 4885.16 (4308.485532.44) | 0.62% (0.32-0.92) | 2,864,089 (2,023,9363,872,481) | 753.77 (525.531023.69) | 0.43% (0.2-0.66) | |||||||

| North Africa and Middle East | 31,006,695 (26,270,01936,438,429) | 5098.6 (4378.865947.72) | 0.06% (0.03-0.09) | 4,767,774 (3,261,4706,600,677) | 781.06 (535.181075.62) | 0.06% (0.03-0.08) | |||||||

| Oceania | 328,505 (274,947393,381) | 2711.59 (2306.263193.17) |

|

56,577 (38,501-80,206) | 476.09 (325.58-663.22) |

|

|||||||

| South Asia | 71,998,403 (62,917,27181,675,123) | 4179.15 (3668.724727.18) |

|

11,188,435 (7,828,80815,283,076) | 645.08 (452.66-877.7) |

|

|||||||

| Southeast Asia | 14,451,056 (12,506,18016,471,186) | 2060.52 (1797.73-2341) | – 0.19% (- 0.25 to – 0.14) | 2,753,223 (1,898,4603,795,437) | 389.23 (270.38-536.55) | – 0.13% (- 0.16 to – 0.09) | |||||||

| Southern Latin America | 2,362,146 (2,089,2972,658,887) | 3313.55 (2925.623745.45) | – 0.42% (- 0.5 to – 0.34) | 359,571 (249,695491,681) | 503.29 (349.65-690.9) | – 0.42% (- 0.5 to – 0.34) | |||||||

| Southern Sub-Saharan Africa | 3,344,012 (2,915,2693,791,826) | 4552.32 (4015.915105.97) | 0.13% (0.03-0.24) | 524,604 (368,831719,717) | 705.61 (497.87-958.57) | 0.09% (-0.01-0.19) | |||||||

Continued

| Characteristics | Incidence (95% UI) | DALYs (95% UI) | ||||

| Number | ASR | EAPC | Number | ASR | EAPC | |

| Tropical Latin America | 10,928,342 (9,746,99512,123,340) | 4560.16 (4084.43-5058) |

|

1,652,267 (1,159,7742,244,114) | 686.08 (482.44-932.46) |

|

| Western Europe | 22,312,186 (19,873,59225,015,077) | 4347.46 (3841.954912.74) |

|

3,463,005 (2,438,3494,706,017) | 677.2 (475.01-929.5) | – 0.09% (- 0.11 to – 0.06) |

| Western Sub-Saharan Africa | 14,230,414 (12,217,18116,431,648) | 4407.3 (3851.355021.82) |

|

2,270,679 (1,552,6453,123,065) | 693.84 (485.18-949.29) |

|

Table 1. Global burden of depressive disorder in 2019 for both sexes and 27 regions, with EAPC from 1990 and 2019.

Figure 1. Temporal trend of global incidence (a) and DALYs (b) number of depressive disorders.

Figure 2. Age-standardized incidence rate (a) and age-standardized DALYs rate (b) trends of sex and age distribution.

(Table 1, Supplementary Table S1b). ASDR decreased in the high-middle-SDI (EAPC

The incidence of depressive disorders grew in all regions, with a decline only in Central and Eastern Europe (see Fig. 3a). Central Sub-Saharan Africa saw the maximum rate of increase (

Figure 3. The incident cases (a) and DALYs (b) of depression at a regional level. The left column in each group is case data in 1990 and the right column in 2019.

1.13-1.21), with the decline being most marked in Eastern Europe (

DALYs corresponding to depressive disorders grown in all geographical regions, with a decline only in Central and Eastern Europe (see Fig. 3b). The largest increase was occurred in Central Sub-Saharan Africa (

Africa

Global burden and EAPC of depressive disorders across 204 countries and territories

The ASIR for depression varied dramatically across 204 countries and territories in 2019 (see Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table S2a). The ASIR was highest in Uganda (8062.76, 95% UI 6946.5-9436.97), followed by Palestine (7864.2,

The global incidence of depression grew by

Among the 204 countries and territories, the greatest rise of ASIR occurred in Spain (EAPC

The correlation of SDI with the global burden of depressive disorders

Substantial correlation was observed among the SDI and depression prevalence and also among the SDI and DALYs, as illustrated in Fig. 5. A number of regions exceeded the expected levels of prevalence, including Central Sub-Saharan Africa and Australasia, while a number of regions fell below the expected levels of prevalence, including South-East Asia and the high-income regions Asia and the Pacific (see Fig. 5a).

Of the 204 countries and territories whose association with the 2019 SDI was recognised, most had a negative association with the SDI, with a few countries significantly above or below the expected level. Uganda and Palestine were significantly higher than expected, while Myanmar and Brunei were significantly lower than expected (see Fig. 5c).

DALYs declined in many areas as the SDI became higher, with the exception of certain regions. For instance, the DALYs rate in Western Sub-Saharan Africa fell briefly, then rose, and then kept falling, forming an inverted U-curve. The DALYs rate of Tropical Latin America, which has a low-middle SDI rank, remained stable at first, then increased, before declining sharply. The rate of Southern Latin America, which has a middle SDI rank, remained stable at first, then decreased, and then continued to remain stable. The DALYs rate of Eastern Europe, which has a high-middle SDI, rose slightly, then fell sharply, remained stable for a period, and then fell slightly. High SDI ratios in high-income Asia-Pacific regions fell briefly and then rose, before falling slightly (see Fig. 5b).

Since 1990 to 2019, the DALY rates obtained in high SDI-ranking regions, such as Western Europe, were mostly consistent with expectations. However, during the study period, some regions (e.g., high-income Asia-Pacific) continued to have DALYs far lower than expected, while others (e.g., Australasia and high-income North America) continued to have DALYs higher than expected (see Fig. 5b). At the country level during 2019, following a similar pattern to the association of morbidity and SDI, there was a marked adverse correlation between DALYs and SDI, with a few exceptions (

The relationship between the HDI and the global burden of depressive disorders

No significant relationship was found between the EAPC for 1990 morbidity and morbidity (

a1. ASIR

a2. ASDR

b1. Change (Incidence)

Figure 4. The global disease burden of depression for both sexes in 204 countries and territories. (a1) The ASIR of depression in 2019; (a2) the ASDR of depression in 2019; (b1) the relative change in incident cases of depression between 1990 and 2019; (b2) the relative change in DALYs number of depression between 1990 and 2019; (c1) the EAPC of depression ASIR from 1990 to 2019; (c2) the EAPC of depression ASDR from 1990 to 2019. ASIR age-standardized incidence rate,

b2. Change(DALYs)

c1. EAPC(Incidence)

c2. EAPC(DALYs)

Figure 4. (continued)

Risk factors of depressive disorders

For the world as a whole, a small fraction of DALYs were ascribed to the three risk factors for which GBD estimates were obtainable, of which

Figure 5. Age-standardized incidence rate (a) and age-standardized DALYs rate (b) for depression for 21 GBD regions and 204 countries and territories (c,d) by Socio-demographic Index(SDI),1990-2019 (the black line indicates the correlation between all SDI regions and the incidence rate or DALY expected value).

vicitimisation was greatest in Central Sub-Saharan Africa (

Discussion

Depression, as a serious public health problem, is associated with adverse health outcomes and reduced lifeexpectancy

Figure 5. (continued)

the study offers an important reference value for all regional governments when formulating relevant prevention and treatment measures for depression

The outcomes of this study suggest that the overall burden of depression has increased rapidly within three decades, but the increase has not been uniform across age groups, sexes, or regions

Figure 6. The EAPCs of depressive disorders at global, regional and national level. (a) The correlation between EAPC and age-standardized rate of depressive disorders incidence and (b) DALYs rate in 1990. (c,d) The correlation between EAPC and HDI in 2019. The circles represent countries that were available on HDI data. The size of circle is increased with the cases of depressive disorders cases. The

of people’s living standards, the demand for medical services is also rising, especially the increasing emphasis on mental health, in this case, the search for mental health services has also increased. It is also important to note that the continuous improvement of depression screening tools has made it possible for medical institutions and government agencies to obtain more comprehensive and accurate data. Our research suggests that MDD accounts for a large proportion of depression cases and is the most prevalent psychiatric category of depression, a finding which aligns with those of a 2022 study by Li et al.

Figure 7. Proportion of depressive disorders DALYs attributable to intimate partner violence, bullying victimization, and childhood sexual abuse, for 21 GBD regions, 2019.

Our research shows that females have higher rates of depression and DALYs than males across all age groups. The prevalence and DALYs rates of depression were highest in people aged

Our reports indicate that the rates of the two subtypes of depression, dysthymia and major depressive disorders, have remained largely stable globally and regionally over the study period, with the majority of patients suffering from MDD. The World Mental Health Survey estimated the annual prevalence of MDD to be

The findings suggest that Uganda’s relatively concentrated population and high prevalence of tropical diseases, malaria, AIDS, Ebola virus, sleeping sickness, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis may be associated with its highest global ASR and ASDR for depression. Although the peak of the epidemic in Uganda, which had one of the world’s highest HIV prevalence rates, has passed and the rate of new cases has diminished in recent years, the number of people infected with the virus and living with the disease remains high, especially in rural areas. People living with HIV experience social prejudice and discrimination, which can lead to unemployment, poverty, family disintegration, and physical and psychological problems that can lead to low self-esteem, low mood, and even depression

The most significant rise in depression and DALYs was identified in Qatar, with the United Arab Emirates and Equatorial Guinea next. Significant increases in depression and DALYs were observed in the medium-high SDI and high-SDI regions. It could be because the level of economic development and education in these regions is relatively high, and the social pressure generated by residents is greater, leading to the increased prevalence of depression. Studies have found that individuals with different education levels have different levels of cognitive ability. Education level influences depression in individuals and can also impact spouses

of economic development, the more social stress people experience. Notably, the country with the most decline in depression and DALYs was Latvia, followed by Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Estonia

of economic development, the more social stress people experience. Notably, the country with the most decline in depression and DALYs was Latvia, followed by Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Estonia

The ASIR and ASDR increased the most in Spain, followed by Mexico and Malaysia. These countries are reported to have higher economic incomes and sociodemographic indices, which confirm our statistics. However, in terms of ASR, the greatest decline in ASIR was in Singapore, then Sri Lanka and Slovenia; and the maximum decline in ASDR was in Singapore, Cuba, and Estonia

Further analysis of the relationship between illness and sociodemographic and geographic factors suggests that depression is more pronounced in terms of incidence in high-SDI and high-income countries, while the burden of depression is significantly higher in low-income and low-SDI countries.

In conclusion, the burden of depression varies across regions for a number of reasons. These include each region’s level of economic development, level of education, level of medical development and capacity to diagnose the illness, as well as the level of importance that governments attach to the illness

To effectively prevent and control depression, governments must support depression-related research while taking appropriate steps to effectively address depression. For example, they should strengthen education on prevention and treatment, improve the capacity for early diagnosis and standardised treatment, establish mental health service measures for key populations, and carry out psychological intervention in a timely manner

This study performed the most comprehensive assessment of the depression burden to date. All the data used in this study were obtained from the GBD database, which offers a large sample size and high data quality, offering this study a distinct advantage in terms of data reliability. While numerous research have been conducted on the prevalence of depression in GBD 2019, the majority of these studies evaluate the condition using the age-period-cohort analytic approach, and their study regions, study objects, and focus subtypes of depression vary. Li et al., for instance, used the age-period cohort analytic approach to study the prevalence of depression among teenagers in the Western Pacific region

Conclusion

Depression remains a serious challenge worldwide, and its burden of disease remains heavy. By analysing the global burden of depression, this study clarifies the current situation of depression in various countries and provides a scientific reference basis for governments to formulate active and effective prevention and treatment strategies. Countries, especially those with a high burden of depression, must vigorously strengthen mental health education, actively prevent risk factors, and adopt targeted interventions to raise the level of awareness of depression among their populations, and concurrently, call for the reform of the relevant systems and the elimination of policy barriers to better prevent and treat mental health disorders

Data availability

The dataset generated for this study can be found in the GBD at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

Received: 20 September 2023; Accepted: 16 May 2024

Published online: 29 May 2024

Published online: 29 May 2024

References

- Lawrence, D., Kisely, S. & Pais, J. The epidemiology of excess mortality in people with mental illness. Can. J. Psychiatry. 55, 752-760. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371005501202 (2010).

- Scott, K. M. et al. Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 150-158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688 (2016).

- Wahlbeck, K., Westman, J., Nordentoft, M., Gissler, M. & Laursen, T. M. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: Life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 199, 453-458. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085100 (2011).

- Scott, K. M. et al. Associations between DSM-IV mental disorders and subsequent heart disease onset: beyond depression. Int. J. Cardiol. 168, 5293-5299 (2013).

- Piao, J. et al. Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 31(1827-1845), 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00787-022-02040-4(2022)(Epub (2022).

- Thomas, S. P. World Health Assembly adopts comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan for 2013-2020. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 34, 723-724. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2013.831260 (2013).

- Upthegrove, R., Marwaha, S. & Birchwood, M. Depression and schizophrenia: Cause, consequence, or trans-diagnostic issue?. Schizophr. Bull. 43, 240-244. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbw097 (2017).

- Kessler, R. C. et al. The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 18, 23-33. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1121189x00001421 (2009).

- Wang, P. S. et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet 370, 841-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7 (2007).

- Piao, J. et al. Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 31, 1827-1845. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00787-022-02040-4. [Epub2022July14] (2022).

- GBD. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 137-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21) 00395-3 (2022).

- Cui, R. Editorial: A systematic review of depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 13, 480. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159×1304150 831123535 (2015).

- Luo, Y., Zhang, S., Zheng, R., Xu, L. & Wu, J. Effects of depression on heart rate variability in elderly patients with stable coronary artery disease. J. Evid. Based Med. 11, 242-245. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm. 12310 (2018).

- Seligman, F. & Nemeroff, C. B. The interface of depression and cardiovascular disease: Therapeutic implications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1345, 25-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas. 12738 (2015).

- Smith, K. Mental health: A world of depression. Nature 515, 181. https://doi.org/10.1038/515180a (2014).

- Stringaris, A. Editorial: What is depression?. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatr. 58, 1287-1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12844 (2017).

- Gross, M. Silver linings for patients with depression?. Curr. Biol. 24, R851-R854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.059 (2014).

- Ménard, C., Hodes, G. E. & Russo, S. J. Pathogenesis of depression: Insights from human and rodent studies. Neuroscience 321, 138-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.053 (2016).

- Solmi, M. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of autism spectrum disorder from 1990 to 2019 across 204 countries. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 4172-4180 (2022).

- Liu, Q. et al. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 126, 134-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002 (2020).

- Peng, H. et al. The global, national, and regional burden of dysthymia from 1990 to 2019: Insights from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. J. Affect. Disord. 333, 524-526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.024 (2023).

- GBD. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223-1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 (2020).

- Hong, C. et al. Global trends and regional differences in the burden of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder attributed to bullying victimisation in 204 countries and territories, 1999-2019: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 31, e85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000683 (2022).

- Ren, X. et al. Burden of depression in China, 1990-2017: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. J. Affect. Disord. 268, 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.011 (2020).

- Dai, H. et al. The global burden of disease attributable to high body mass index in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. PLOS Med. 17, e1003198. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed. 1003198 (2020).

- Hankey, B. F. et al. Partitioning linear trends in age-adjusted rates. Cancer Causes Control 11, 31-35. https://doi.org/10.1023/a: 1008953201688 (2000).

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 396, 1204-1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(20)30925-9 (2020).

- Yue, T., Zhang, Q., Li, G. & Qin, H. Global burden of nutritional deficiencies among children under 5 years of age from 2010 to 2019. Nutrients 14, 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132685 (2022).

- Liu, Q. et al. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr Res. 126, 134-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002 (2019).

- Ogbo, F. A., Mathsyaraja, S., Koti, R. K., Perz, J. & Page, A. The burden of depressive disorders in South Asia, 1990-2016: findings from the global burden of disease study. BMC Psychiatry 18, 333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1918-1 (2018).

- Li, S. et al. Sex difference in global burden of major depressive disorder: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Front. Psychiatry. 21(13), 789305. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.789305 (2022).

- Keita, G. P. Psychosocial and cultural contributions to depression in women: Considerations for women midlife and beyond. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 13(Supp 9), 12-15 (2007).

- Patel, V., Rodrigues, M. & DeSouza, N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: A study of mothers in Goa India. Am. J. Psychiatr. 159(1), 43-47 (2002).

- Trivedi, J. K., Sareen, H. & Dhyani, M. Rapid urbanization-its impact on mental health: A south Asian perspective. Indian J. Psychiatry. 50(3), 161 (2008).

- Ahmad, O. B. et al. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. GPE Discussion Paper Series: No 31, 10-12. https://cdn. who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/gpe_discussion_paper_series_paper31_2001_age_ standardization_rates.pdf (2001).

- Ferrari, A. J. et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLOS Med. 10, e1001547. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547 (2013).

- Bachner-Melman, R., Watermann, Y., Lev-Ari, L. & Zohar, A. H. Associations of self-repression with disordered eating and symptoms of other psychopathologies for men and women. J. Eat. Disord. 10, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00569-y (2022).

- Kessler, R. C. et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289, 3095-3105. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.23.3095 (2003).

- Bromet, E. et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 9, 90 (2011).

- Sheehan, D. V. et al. Restoring function in major depressive disorder: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 215, 299-313 (2017).

- Malhi, G. S. & Mann, J. J. Depression. Lancet 392, 2299-2312 (2018).

- Yang, L. et al. The effects of psychological stress on depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 13, 494-504. https://doi.org/10.2174/15701 59×1304150831150507 (2015).

- Ironson, G., Henry, S. M. & Gonzalez, B. D. Impact of stressful death or divorce in people with HIV: A prospective examination and the buffering effects of religious coping and social support. J. Health Psychol. 25, 606-616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317 726151 (2020).

- Junqueira, P., Bellucci, S., Rossini, S. & Reimão, R. Women living with HIV/AIDS: Sleep impairment, anxiety and depression symptoms. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 66, 817-820. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-282×2008000600008 (2008).

- Lee, J. Pathways from education to depression. J. Cross. Cult. Gerontol. 26, 121-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-011-9142-1 (2011).

- Alonso, J. et al. Treatment gap for anxiety disorders is global: Results of the World Mental Health Surveys in 21 countries. Depress. Anxiety 35, 195-208. https://doi.org/10.1002/da. 22711 (2018).

- Perez, M. I. et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder misdiagnosis among mental healthcare providers in Latin America. J. Obsessive Compuls. Relat. Disord. 32, 100693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2021.100693 (2022).

- Li, Z. B. et al. Burden of depression in adolescents in the Western Pacific Region from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study. Psychiatry Res. 336, 115889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2024.115889 (2024).

- Xu, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence trends of depressive disorder, 1990-2019: An age-period-cohort analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 88, 51-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2024.03. 003 (2024) (Epub 2024 Mar 16).

- Hong, C. et al. Global trends and regional differences in the burden of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder attributed to bullying victimisation in 204 countries and territories, 1999-2019: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 28(31), e85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000683 (2022).

- Yang, F. et al. Thirty-year trends of depressive disorders in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis. Psychiatry Res. 328, 115433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115433 (2023) (Epub 2023 Aug 27).

- Baca, E., Lázaro, J. & Hernández-Clemente, J. C. Historical perspectives of the role of Spain and Portugal in today’s status of psychiatry and mental health in Latin America. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 22, 311-316. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2010.501165 (2010).

- Mullins, N. & Lewis, C. M. Genetics of depression: Progress at last. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 19, 43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0803-9 (2017).

- McGrath, J. J. et al. Comorbidity within mental disorders: A comprehensive analysis based on 145990 survey respondents from 27 countries. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 29, e153. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000633 (2020).

- Plana-Ripoll, O. et al. Nature and prevalence of combinations of mental disorders and their association with excess mortality in a population-based cohort study. World Psychiatry 19, 339-349. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps. 20802 (2020).

Author contributions

JL performed the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. YL solved technical problems during the statistical analyses and participated in the conceptualization and design of the study, and the interpretation of the results. WM contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study.YT and JZ participated in the design of the study and critically evaluated and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-024-62381-9.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y.T. or J.Z.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

College of Public Health, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China. Second Clinical Medical College, Nanchang University, Nanchang, Jiangxi, China. email: tycarth@163.com; zjzhong4183@163.com - © The Author(s) 2024