DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47829-w

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38649721

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-22

تحليل ميتا عالمي حول تأثيرات التسميد العضوي وغير العضوي على المراعي والأراضي الزراعية

تم القبول: 15 أبريل 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 22 أبريل 2024

الملخص

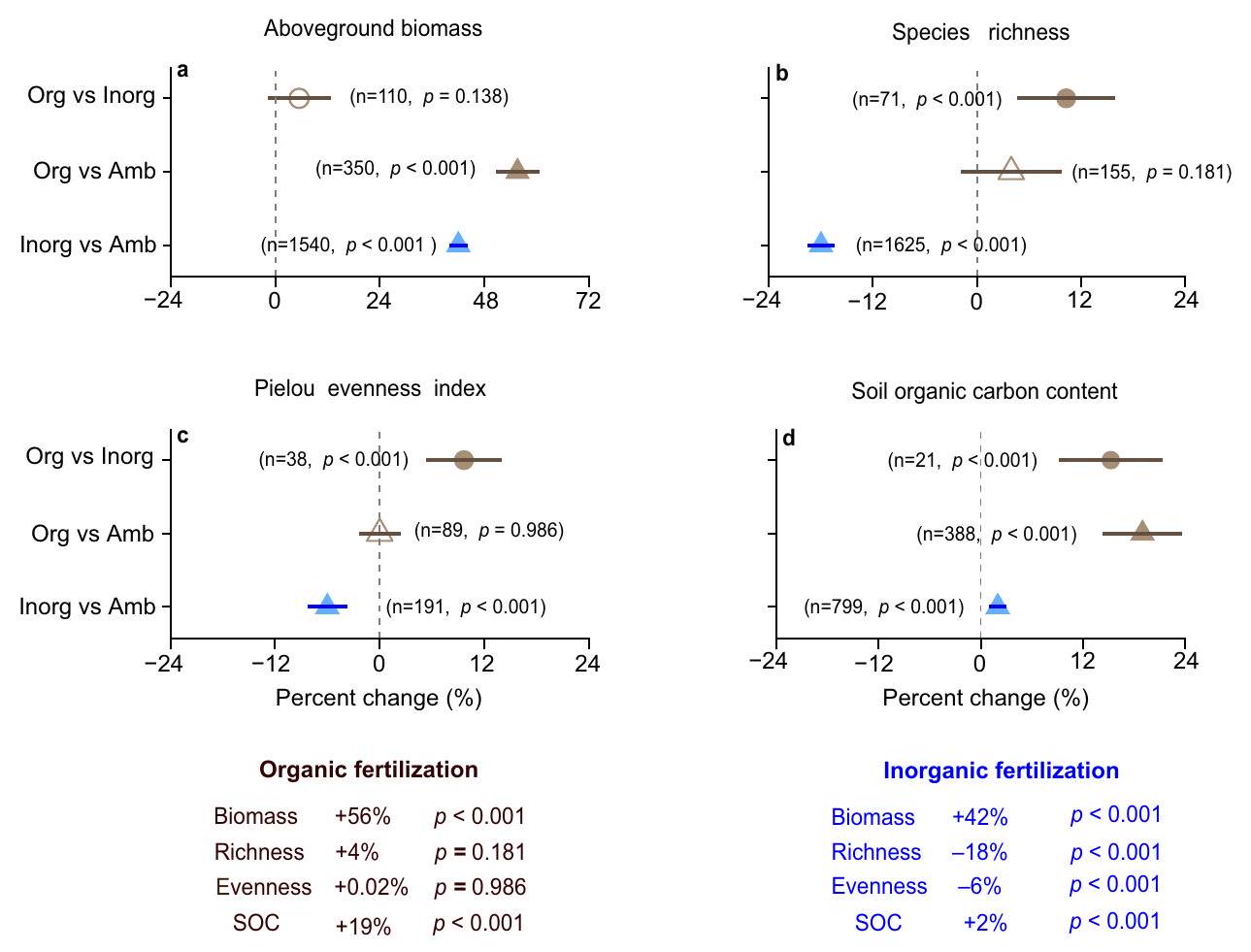

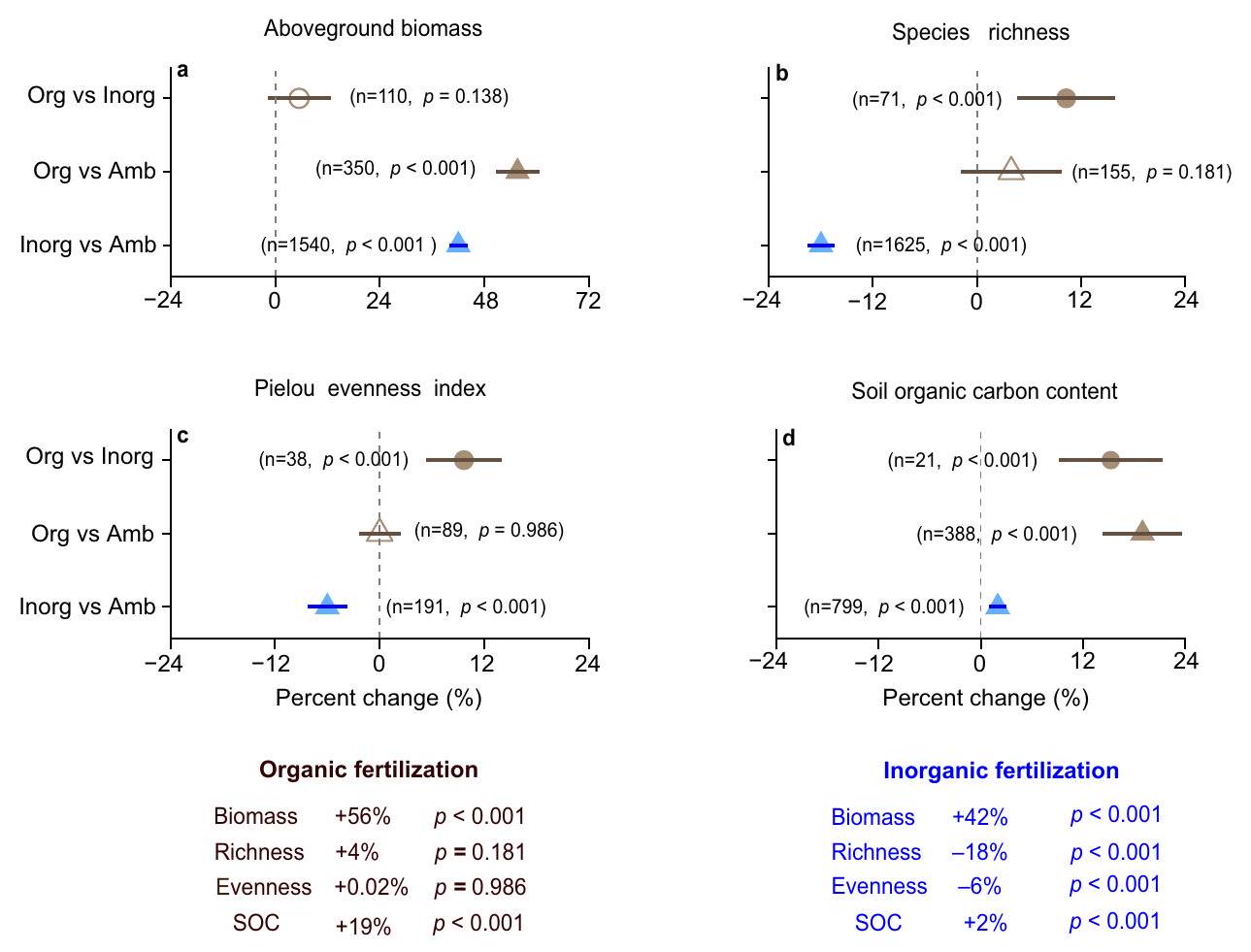

تلعب الحلول المستندة إلى الطبيعة دورًا مركزيًا في تحديد الممارسات الإدارية المثلى لمعالجة التحديات البيئية، بما في ذلك احتجاز الكربون والحفاظ على التنوع البيولوجي. يزيد التسميد غير العضوي من الكتلة الحيوية للنباتات فوق سطح الأرض ولكنه غالبًا ما يتسبب في تناقض مع فقدان تنوع النباتات. ومع ذلك، لا يزال غير واضح ما إذا كان التسميد العضوي، كحل محتمل مستند إلى الطبيعة، يمكن أن يغير هذا التناقض من خلال زيادة الكتلة الحيوية فوق سطح الأرض دون فقدان تنوع النباتات. هنا نجمع بيانات من 537 تجربة حول التسميد العضوي وغير العضوي عبر المراعي والأراضي الزراعية في جميع أنحاء العالم لتقييم استجابات الكتلة الحيوية فوق سطح الأرض، تنوع النباتات، والكربون العضوي في التربة (SOC). يزيد كل من التسميد العضوي وغير العضوي من الكتلة الحيوية فوق سطح الأرض من خلال

البحث المستهدف نحو نظم بيئية محددة وأهداف الحفظ

أنواع استخدام الأراضي التي غالبًا ما تتلقى مغذيات إضافية لزيادة الإنتاج، مثل المراعي والأراضي الزراعية. في الواقع، لقد أظهرت التسميد العضوي أنه يزيد من مخزونات الكربون العضوي في التربة بنحو

النتائج

الاستجابات العالمية للتسميد

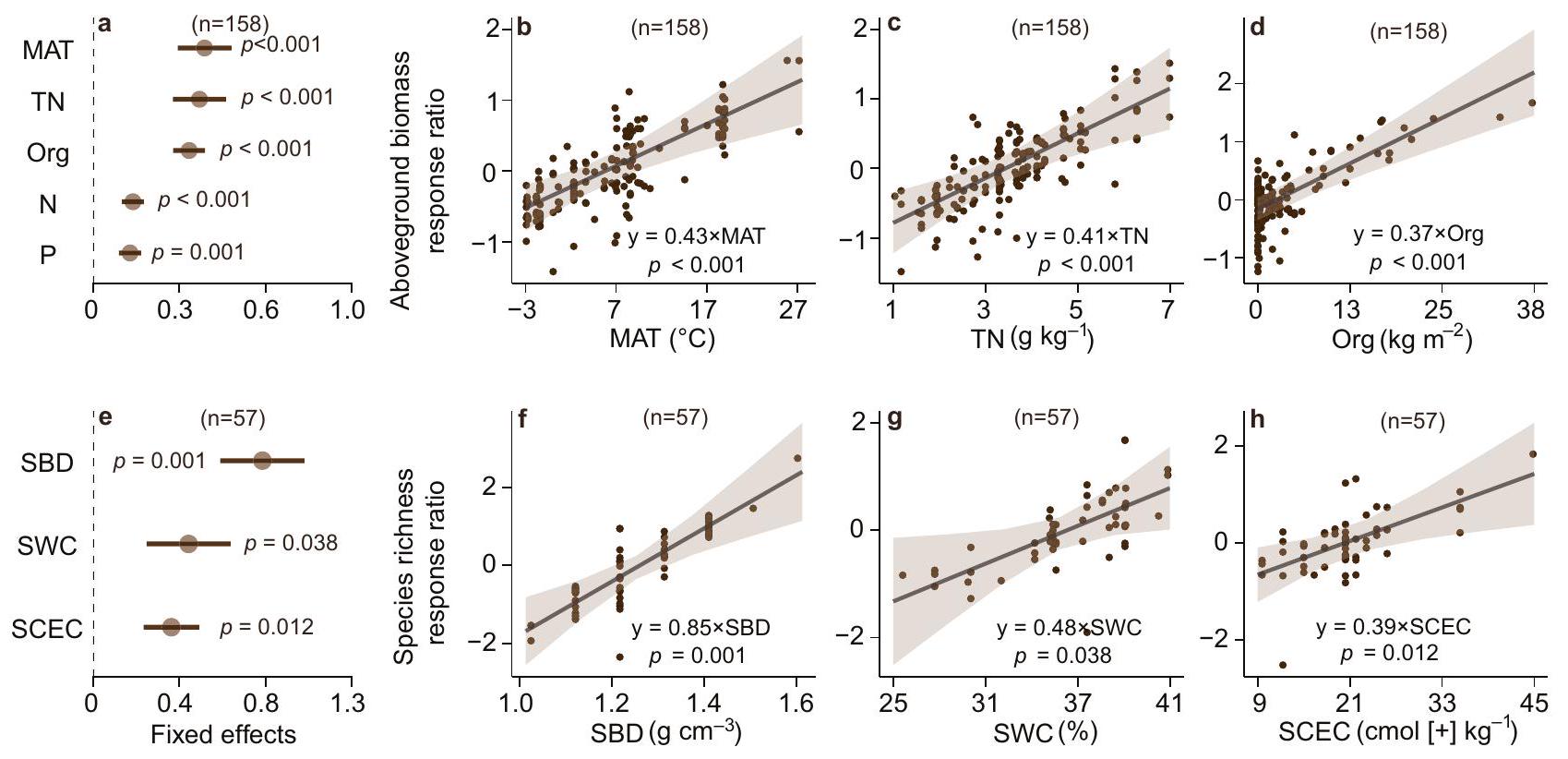

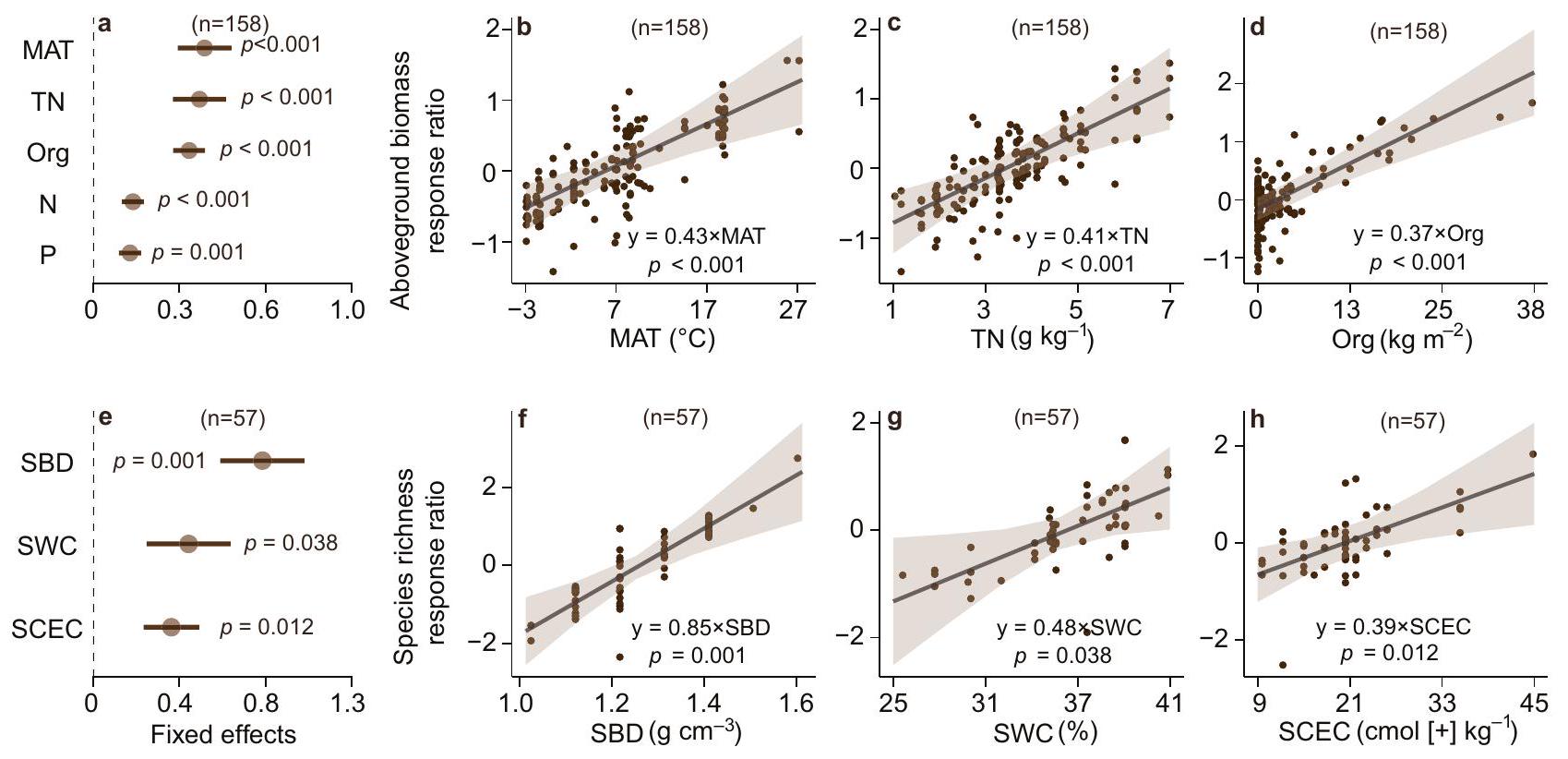

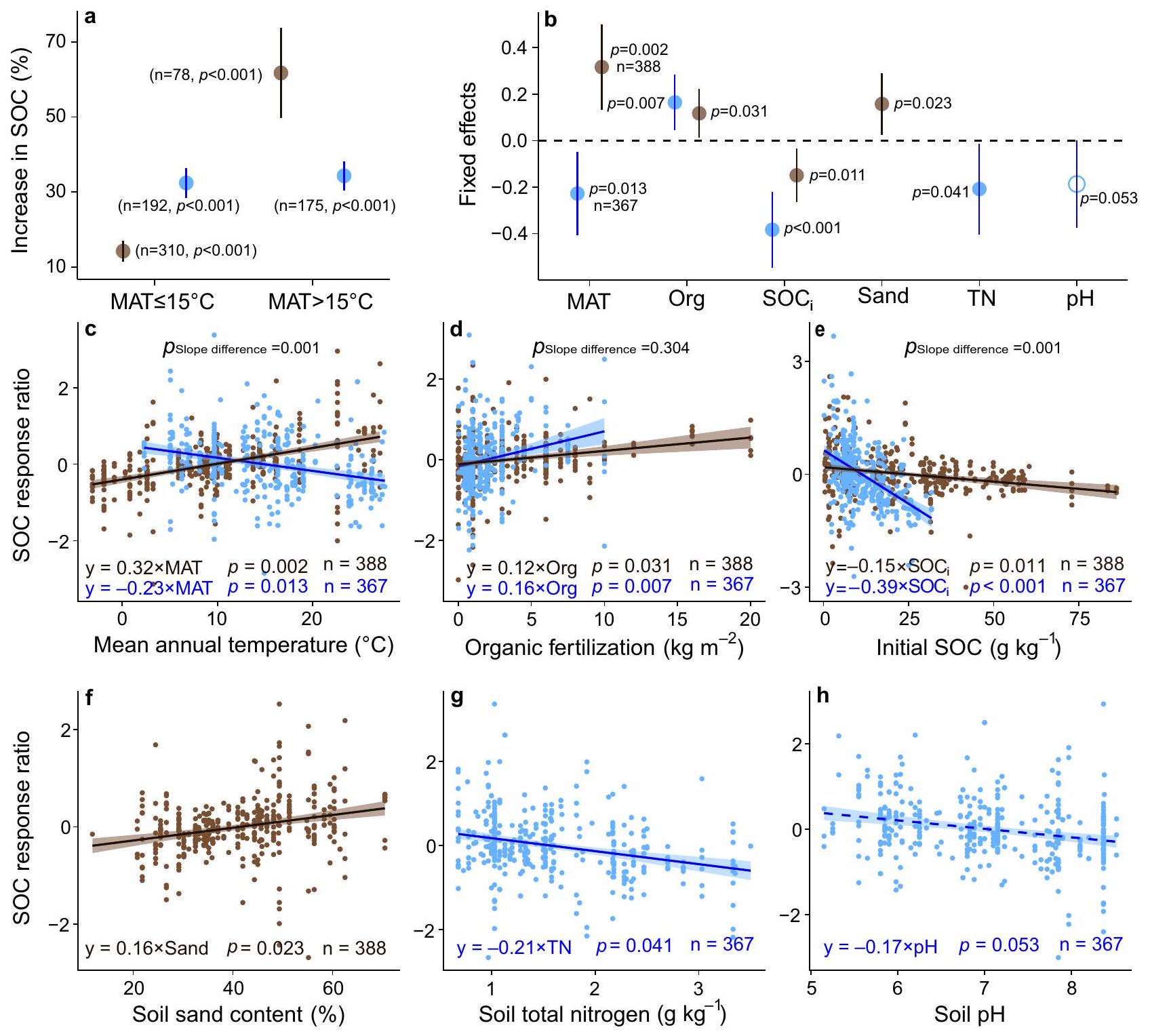

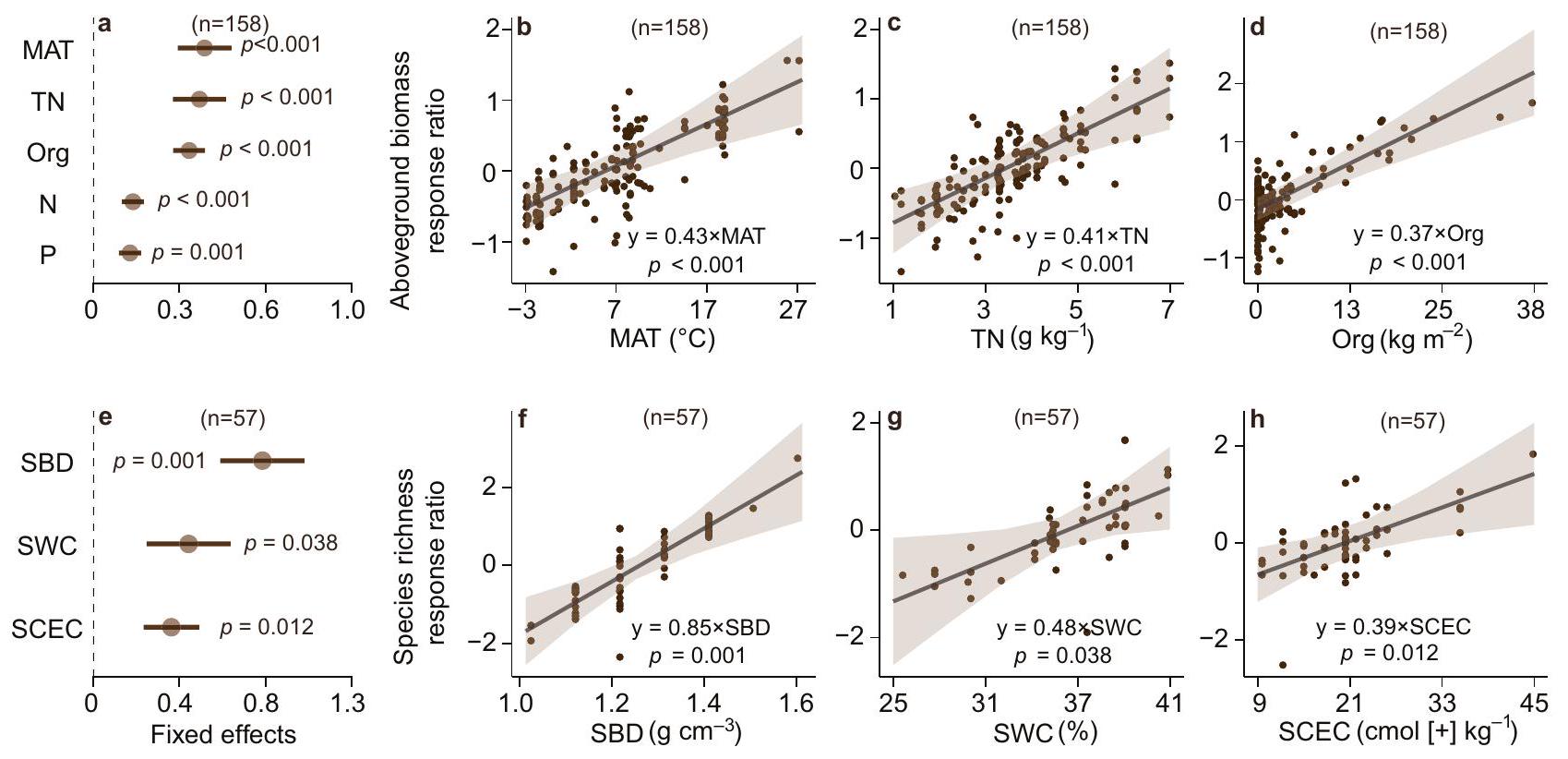

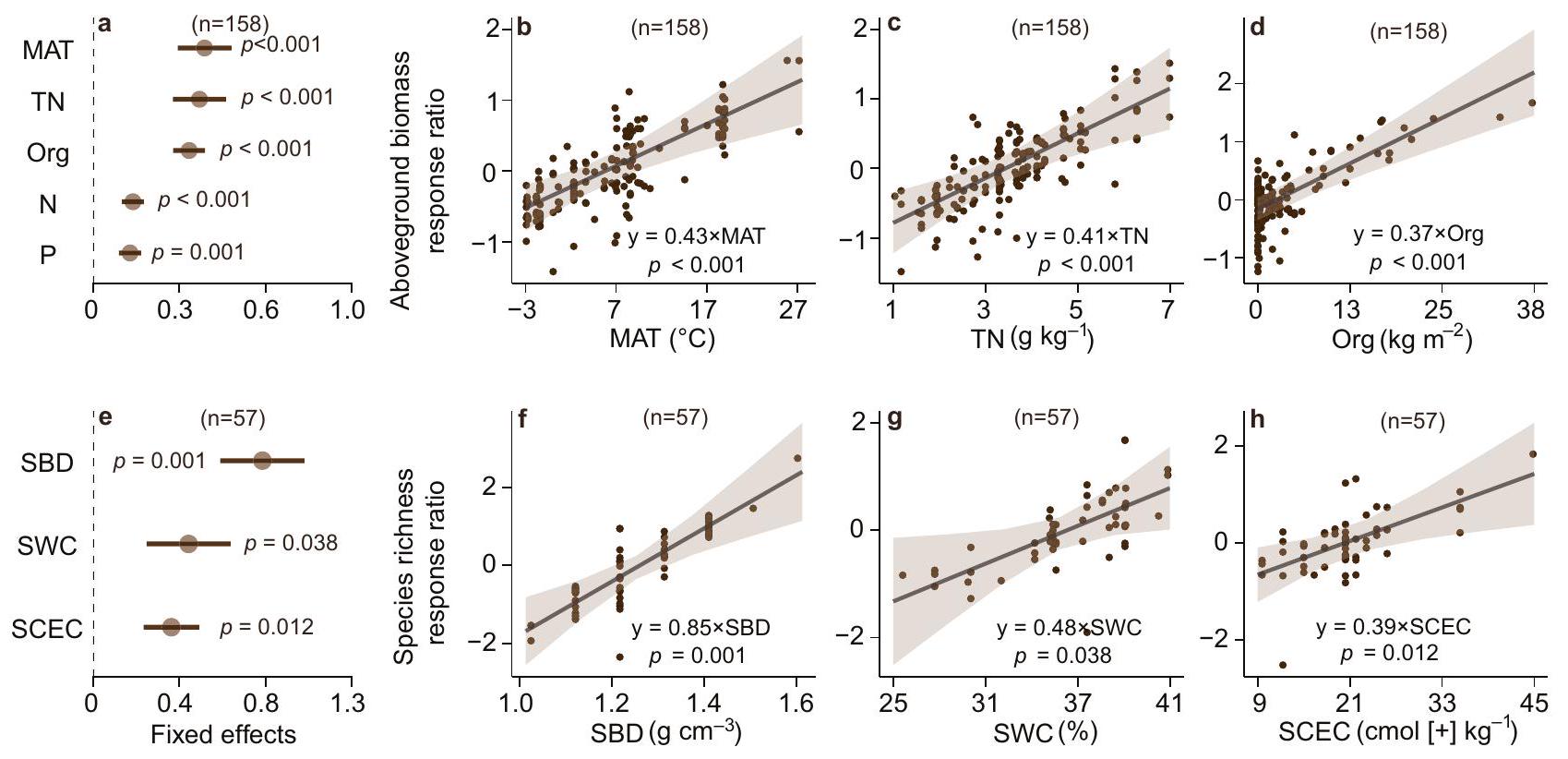

استجابات التسميد عبر التدرجات البيئية

مع الصفر (اختبار ذو طرفين،

التسميد (

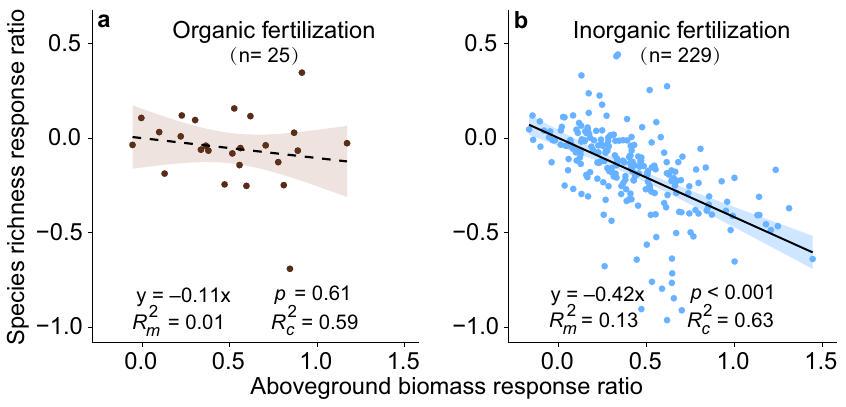

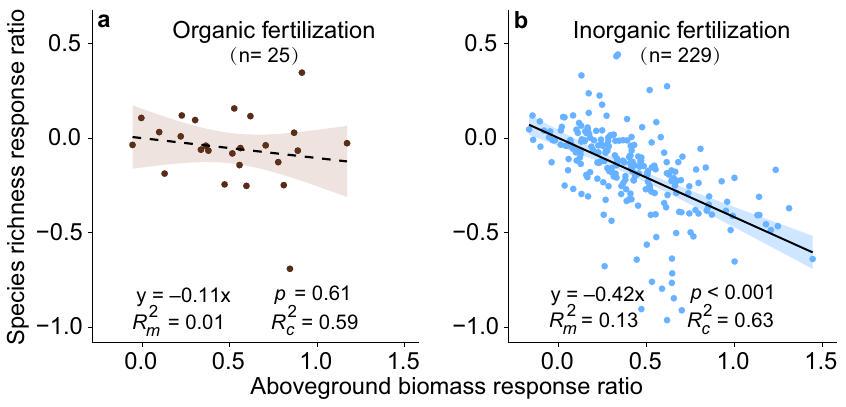

العلاقة بين إنتاج الكتلة الحيوية وتنوع النبات

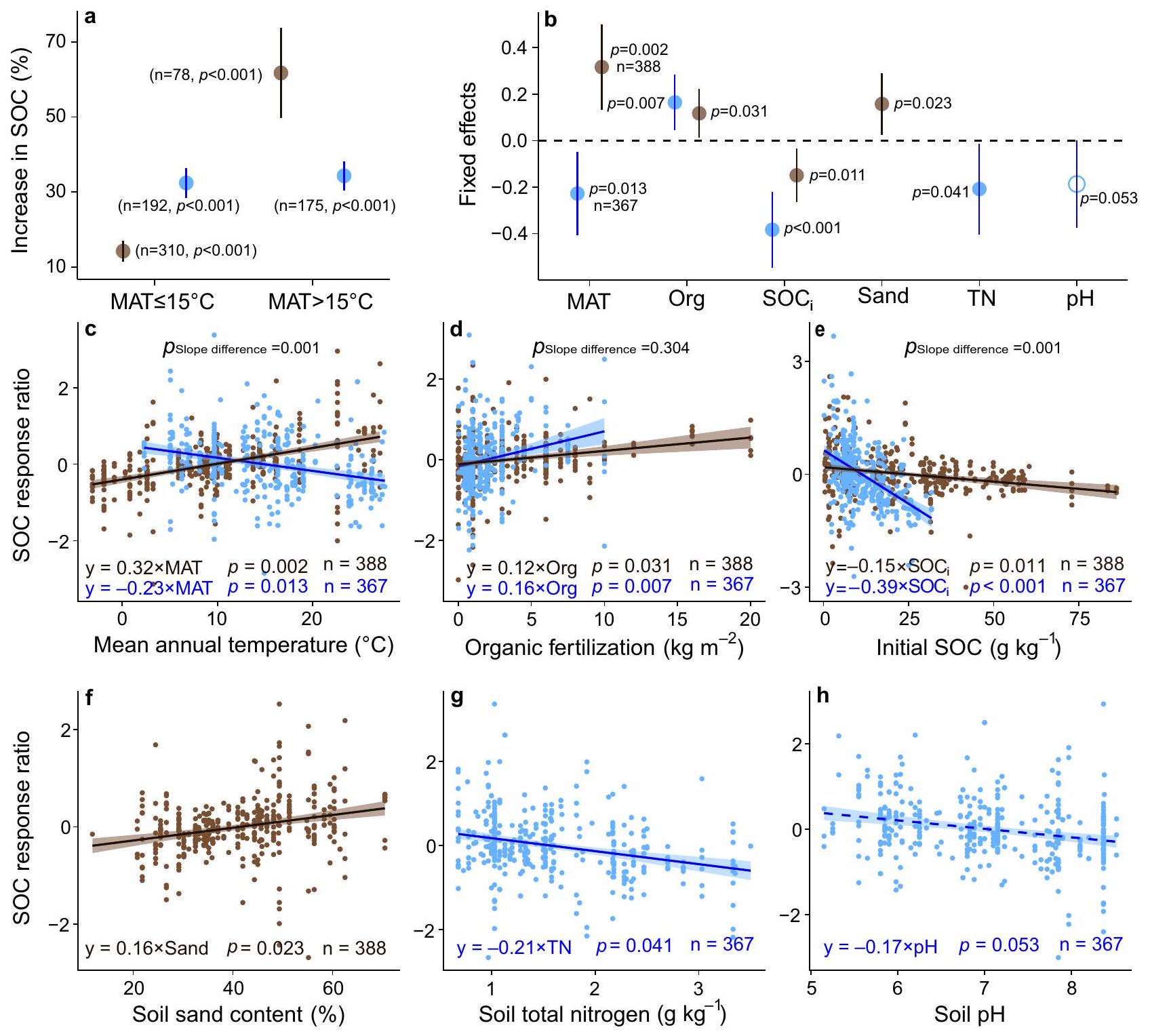

استجابات SOC للتسميد العضوي في المراعي والأراضي الزراعية

المراعي (

المناقشة

في

تمثيل المنحدرات

إضافة الفوسفور تؤدي إلى فقدان الأنواع

منحدرات

هامش الربح. كما اختبرنا تأثير جودة الأسمدة العضوية على استجابة الكربون العضوي في التربة

إنتاج الكتلة الحيوية وSOC دون التضحية بفقدان تنوع النباتات. بالمقارنة، أدى زيادة إنتاج الكتلة الحيوية فوق الأرض وتخزين الكربون في التربة إلى فقدان تنوع النباتات تحت التسميد غير العضوي. وبالتالي، يُفضل التسميد العضوي على التسميد غير العضوي لتحسين وظائف وخدمات نظام المراعي. زاد التسميد العضوي من تنوع النباتات في المراعي ذات الرطوبة العالية في التربة. علاوة على ذلك، قد يحسن التسميد العضوي البيئة التربوية لنمو النباتات، وبالتالي سيتجنب فقدان تنوع النباتات الناجم عن حموضة التربة وسمية الأمونيوم التي توجد عادة تحت التسميد غير العضوي. لذلك، نرى أن زيادة استخدام الأسمدة العضوية ستوفر حلاً طبيعياً مهماً لزيادة الإنتاجية وتخزين الكربون في التربة مع الحفاظ على تنوع النباتات.

طرق

جمع البيانات

تحليل ميتا

بلا أبعاد وتستخدم لوصف التغيرات النسبية بين العلاج والرقابة

استجابة الكتلة الحيوية وتنوع النباتات وSOC عبر تدرجات البيئة

كان أفضل نموذج مختلط خطي أيضًا من المتنبئين المهمين الذين تم تحديدهم بواسطة نموذج الغابة العشوائية (الشكل التوضيحي التكميلي 4).

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Rockstroem, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 619, 102-111 (2023).

- Seddon, N. et al. Understanding the value and limits of naturebased solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 375, 20190120 (2020).

- Griscom, B. W. et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11645-11650 (2017).

- Anderegg, W. et al. Climate-driven risks to the climate mitigation potential of forests. Science 368, eaaz7005 (2020).

- Li, H. et al. Nitrogen addition delays the emergence of an aridityinduced threshold for plant biomass. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwad242 (2023).

- Seabloom, E. W. et al. Increasing effects of chronic nutrient enrichment on plant diversity loss and ecosystem productivity over time. Ecology 102, e03218 (2021).

- Eskelinen, A., Harpole, W. S., Jessen, M.-T., Virtanen, R. & Hautier, Y. Light competition drives herbivore and nutrient effects on plant diversity. Nature 611, 301-305 (2022).

- Hautier, Y., Niklaus, P. A. & Hector, A. Competition for light causes plant biodiversity loss after eutrophication. Science 324, 636-638 (2009).

- Harpole, W. S. et al. Addition of multiple limiting resources reduces grassland diversity. Nature 537, 93-96 (2016).

- Band, N., Kadmon, R., Mandel, M. & DeMalach, N. Assessing the roles of nitrogen, biomass, and niche dimensionality as drivers of species loss in grassland communities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2112010119 (2022).

- Tilman, D. Resource Competition and Community Structure (Princeton University Press, 1982).

- Newman, E. I. Competition and diversity in herbaceous vegetation. Nature 244, 310 (1973).

- Harpole, W. S. & Tilman, D. Grassland species loss resulting from reduced niche dimension. Nature 446, 791-793 (2007).

- Farrer, E. C. & Suding, K. N. Teasing apart plant community responses to N enrichment: the roles of resource limitation, competition and soil microbes. Ecol. Lett. 19, 1287-1296 (2016).

- Stevens, C. J. et al. Nitrogen deposition threatens species richness of grasslands across Europe. Environ. Pollut. 158, 2940-2945 (2010).

- Crawley, M. J. et al. Determinants of species richness in the park grass experiment. Am. Nat. 165, 179-192 (2005).

- Britto, D. T. & Kronzucker, H. J.

toxicity in higher plants: a critical review. J. Plant Physiol. 159, 567-584 (2002). - Zhu, J., Zhang, Y., Yang, X., Chen, N. & Jiang, L. Synergistic effects of nitrogen and

enrichment on alpine grassland biomass and community structure. N. Phytol. 228, 1283-1294 (2020). - De Melo, T. R. et al. Biogenic aggregation intensifies soil improvement caused by manures. Soil Tillage Res. 190, 186-193 (2019).

- Cai, A. et al. Manure acts as a better fertilizer for increasing crop yields than synthetic fertilizer does by improving soil fertility. Soil Tillage Res. 189, 168-175 (2019).

- Tian, Q. et al. A novel soil manganese mechanism drives plant species loss with increased nitrogen deposition in a temperate steppe. Ecology 97, 65-74 (2016).

- Ryals, R., Eviner, V. T., Stein, C., Suding, K. N. & Silver, W. L. Grassland compost amendments increase plant production without changing plant communities. Ecosphere 7, e01270 (2016).

- Verma, P. et al. Variations in soil properties, species composition, diversity, and biomass of herbaceous species due to ruminant dung residue in a seasonally dry tropical environment of India. Trop. Grassl. -Forrajes Trop. 3, 112-128 (2015).

- Critchley, C. N. R. et al. Plant species richness, functional type and soil properties of grasslands and allied vegetation in English environmentally sensitive areas. Grass Forage Sci. 57, 82-92 (2002).

- Schmid, B. The species richness-productivity controversy. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17, 113-114 (2002).

- Stockmann, U. et al. The knowns, known unknowns and unknowns of sequestration of soil organic carbon. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 164, 80-99 (2013).

- Jobbágy, E. G. & Jackson, R. B. The vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its relation to climate and vegetation. Ecol. Appl. 10, 423-436 (2000).

- Brahim, N. et al. Soil OC and N stocks in the saline soil of tunisian gataaya oasis eight years after application of manure and compost. Land 11, 442 (2022).

- Keller, A. B. B. et al. Stronger fertilization effects on aboveground versus belowground plant properties across nine US grasslands. Ecology 104, e3891 (2023).

- Crowther, T. W. et al. Sensitivity of global soil carbon stocks to combined nutrient enrichment. Ecol. Lett. 22, 936-945 (2019).

- Doetterl, S. et al. Soil carbon storage controlled by interactions between geochemistry and climate. Nat. Geosci. 8, 780-783 (2015).

- Nuralykyzy, B. et al. Influence of land use types on soil carbon fractions in the Qaidam Basin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Catena 231, 107273 (2023).

- Wieder, W. R., Cleveland, C. C., Smith, W. K. & Todd-Brown, K. Future productivity and carbon storage limited by terrestrial nutrient availability. Nat. Geosci. 8, 441-444 (2015).

- Bai, Y. & Cotrufo, M. F. Grassland soil carbon sequestration: current understanding, challenges, and solutions. Science 377, 603-608 (2022).

- Gross, A. & Glaser, B. Meta-analysis on how manure application changes soil organic carbon storage. Sci. Rep. 11, 5516 (2021).

- Toth, G., Jones, A. & Montanarella, L. The LUCAS topsoil database and derived information on the regional variability of cropland topsoil properties in the European Union. Environ. Monit. Assess. 185, 7409-7425 (2013).

- Liu, Y. et al. Meta-analysis on the effects of types and levels of N, P, and K fertilization on organic carbon in cropland soils. Geoderma 437, 116580 (2023).

- Kan, Z.-R. et al. Mechanisms of soil organic carbon stability and its response to no-till: a global synthesis and perspective. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 693-710 (2022).

- White, R. P., Murray, S., Rohweder, M., Prince, S. & Thompson, K. Grassland ecosystems. (World Resources Institute Washington, DC, USA, 2000).

- Ma, J. et al. Assessing the impacts of agricultural managements on soil carbon stocks, nitrogen loss, and crop production-a modelling study in eastern Africa. Biogeosciences 19, 2145-2169 (2022).

- A, Y. et al. Vertical variations of soil water and its controlling factors based on the structural equation model in a semi-arid grassland. Sci. Total Environ. 691, 1016-1026 (2019).

- Zhang, Y. et al. Multi-decadal trends in global terrestrial evapotranspiration and its components. Sci. Rep. 6, 1-12 (2016).

- Kidd, J., Manning, P., Simkin, J., Peacock, S. & Stockdale, E. Impacts of 120 years of fertilizer addition on a temperate grassland ecosystem. PLoS One 12, e0174632 (2017).

- Rawls, W. J., Pachepsky, Y. A., Ritchie, J. C., Sobecki, T. M. & Bloodworth, H. Effect of soil organic carbon on soil water retention. Geoderma 116, 61-76 (2003).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Determining the harvest frequency to maintain grassland productivity and minimum nutrient removal from soil. Plant Soil 487, 79-91 (2023).

- Zhang, L. et al. Habitat heterogeneity induced by pyrogenic organic matter in wildfire-perturbed soils mediates bacterial community assembly processes. ISME J. 15, 1943-1955 (2021).

- CatenaElser, J. J. et al. Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1135-1142 (2007).

- Wassen, M. J., Venterink, H. O., Lapshina, E. D. & Tanneberger, F. Endangered plants persist under phosphorus limitation. Nature 437, 547-550 (2005).

- Venterink, H. O., Wassen, M. J., Verkroost, A. W. M. & de Ruiter, P. C. Species richness-productivity patterns differ between N -, P -, and K-limited wetlands. Ecology 84, 2191-2199 (2003).

- Gautam, A. et al. Responses of soil microbial community structure and enzymatic activities to long-term application of mineral fertilizer and beef manure. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 8, 100073 (2020).

- Du, Y. et al. Effects of manure fertilizer on crop yield and soil properties in China: a meta-analysis. Catena 193, 104617 (2020).

- Li, S. X., Wang, Z. H., Hu, T. T., Gao, Y. J. & Stewart, B. A. in Advances in Agronomy Vol. 101 (ed Donald L. Sparks) 123-181 (Academic Press, 2009).

- Naeem, M., Ansari, A. & Gill, S. Contaminants in Agriculture: Sources, Impacts and Management (Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, 2020).

- Rambaut, L.-A. E., Tillard, E., Vayssieres, J., Lecomte, P. & Salgado, P. Trade-off between short and long-term effects of mineral, organic or mixed mineral-organic fertilisation on grass yield of tropical permanent grassland. Eur. J. Agron. 141, 126635 (2022).

- Stevens, H. & Carson, W. Resource quantity, not resource heterogeneity, maintains plant diversity. Ecol. Lett. 5, 420-426 (2002).

- Taddesse, G., Peden, D., Abiye, A. & Wagnew, A. Effect of manure on grazing lands in Ethiopia, East African highlands. Mt. Res. Dev. 23, 156-160 (2003).

- Loydi, A. & Martin Zalba, S. Feral horses dung piles as potential invasion windows for alien plant species in natural grasslands. Plant Ecol. 201, 471-480 (2009).

- Ye, J.-S., Bradford, M. A., Maestre, F. T., Li, F.-M. & Garcia-Palacios, P. Compensatory thermal adaptation of soil microbial respiration rates in global croplands. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 34, e2019GB006507 (2020).

- Ye, J.-S., Bradford, M. A., Dacal, M., Maestre, F. T. & Garcia-Palacios, P. Increasing microbial carbon use efficiency with warming predicts soil heterotrophic respiration globally. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 3354-3364 (2019).

- Li, F. et al. Warming alters surface soil organic matter composition despite unchanged carbon stocks in a Tibetan permafrost ecosystem. Funct. Ecol. 34, 911-922 (2020).

- Chen, Y., Feng, J., Yuan, X. & Zhu, B. Effects of warming on carbon and nitrogen cycling in alpine grassland ecosystems on the Tibetan Plateau: a meta-analysis. Geoderma 370, 114363 (2020).

- Yan, Z. et al. Changes in soil organic carbon stocks from reducing irrigation can be offset fertilizer in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 266, 107539 (2022).

- Gaudare, U. et al. Soil organic carbon stocks potentially at risk of decline with organic farming expansion. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 719-725 (2023).

- Rui, Y. et al. Persistent soil carbon enhanced in Mollisols by well- managed grasslands but not annual grain or dairy forage cropping systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2118931119 (2022).

- Kallenbach, C. & Grandy, A. S. Controls over soil microbial biomass responses to carbon amendments in agricultural systems: ametaanalysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 144, 241-252 (2011).

- Hedges, L. V., Gurevitch, J. & Curtis, P. S. The meta-analysis of response ratios in experimental ecology. Ecology 80, 1150-1156 (1999).

- Murphy, G. E. P. & Romanuk, T. N. A meta-analysis of declines in local species richness from human disturbances. Ecol. Evol. 4, 91-103 (2014).

- Lajeunesse, M. J. On the meta-analysis of response ratios for studies with correlated and multi-group designs. Ecology 92, 2049-2055 (2011).

- Song, C., Peacor, S. D., Osenberg, C. W. & Bence, J. R. An assessment of statistical methods for nonindependent data in ecological meta-analyses. Ecology 101, e03184 (2020).

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1-48 (2010).

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in metaanalysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ-Br. Med. J. 315, 629-634 (1997).

- Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302-4315 (2017).

- Hengl, T. et al. SoilGrids1km-Global Soil Information Based on Automated Mapping. PLoS One 9, e105992 (2014).

- Munoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349-4383 (2021).

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H. & Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 8, 23-74 (2003).

- Warton, D. I., Wright, I. J., Falster, D. S. & Westoby, M. Bivariate linefitting methods for allometry. Biol. Rev. 81, 259-291 (2006).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47829-w.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© المؤلفون 2024

- (D) تحقق من التحديثات

المختبر الوطني الرئيسي لتحسين الأعشاب والأنظمة البيئية الزراعية، كلية البيئة، جامعة لانتشو، لانتشو 730000، الصين.

قسم البيولوجيا، جامعة نيو مكسيكو، ألبوكيركي، NM 87131، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. معهد هاي ميدوز البيئي، جامعة برينستون، برينستون، NJ، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. CSIC، وحدة البيئة العالمية CREAF-CSIC-UAB، برشلونة 08193، إسبانيا. CREAF، سيردانيولا ديل فاييس، برشلونة 08193، إسبانيا.

-البريد الإلكتروني: yejsh@lzu.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47829-w

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38649721

Publication Date: 2024-04-22

A global meta-analysis on the effects of organic and inorganic fertilization on grasslands and croplands

Accepted: 15 April 2024

Published online: 22 April 2024

Abstract

A central role for nature-based solution is to identify optimal management practices to address environmental challenges, including carbon sequestration and biodiversity conservation. Inorganic fertilization increases plant aboveground biomass but often causes a tradeoff with plant diversity loss. It remains unclear, however, whether organic fertilization, as a potential naturebased solution, could alter this tradeoff by increasing aboveground biomass without plant diversity loss. Here we compile data from 537 experiments on organic and inorganic fertilization across grasslands and croplands worldwide to evaluate the responses of aboveground biomass, plant diversity, and soil organic carbon (SOC). Both organic and inorganic fertilization increase aboveground biomass by

research targeted towards specific ecosystems and conservation objectives

land-use types that often receive additional nutrients to increase production, such as grasslands and croplands. Indeed, organic fertilization has been shown to increase SOC stocks by about

Results

Global mean responses to fertilization

Fertilization responses across environmental gradients

intervals do not overlap with zero (two-tailed test,

fertilization (

Relationship between biomass production and plant diversity

SOC responses to organic fertilization in grasslands and croplands

grasslands (

Discussion

in

represent slopes

phosphorus addition leads to species loss

slopes

profit margins. We also tested the impact of organic fertilizer quality on SOC response

biomass production and SOC without a tradeoff in plant diversity loss. By comparison, increased aboveground biomass production and soil carbon storage resulted in plant diversity loss under inorganic fertilization. As such, organic fertilization is favored over inorganic fertilization to improve grassland ecosystem functions and services. Organic fertilization increased plant diversity in grasslands with greater soil moisture. Moreover, organic fertilization may improve the soil environment for plant growth, and thus would avoid plant diversity loss caused by soil acidification and ammonium toxicity that is usually found under inorganic fertilization. Therefore, we argue that increasing the use of organic fertilizers would provide an important naturebased solution to increase productivity and soil carbon sequestration while conserving plant diversity.

Methods

Data collection

Meta-analysis

dimensionless and used to characterize the relative changes between treatment and control

Response of biomass, plant diversity and SOC across environment gradients

best linear mixed effects model were also significant predictors identified by a random forest model (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Rockstroem, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 619, 102-111 (2023).

- Seddon, N. et al. Understanding the value and limits of naturebased solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 375, 20190120 (2020).

- Griscom, B. W. et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11645-11650 (2017).

- Anderegg, W. et al. Climate-driven risks to the climate mitigation potential of forests. Science 368, eaaz7005 (2020).

- Li, H. et al. Nitrogen addition delays the emergence of an aridityinduced threshold for plant biomass. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwad242 (2023).

- Seabloom, E. W. et al. Increasing effects of chronic nutrient enrichment on plant diversity loss and ecosystem productivity over time. Ecology 102, e03218 (2021).

- Eskelinen, A., Harpole, W. S., Jessen, M.-T., Virtanen, R. & Hautier, Y. Light competition drives herbivore and nutrient effects on plant diversity. Nature 611, 301-305 (2022).

- Hautier, Y., Niklaus, P. A. & Hector, A. Competition for light causes plant biodiversity loss after eutrophication. Science 324, 636-638 (2009).

- Harpole, W. S. et al. Addition of multiple limiting resources reduces grassland diversity. Nature 537, 93-96 (2016).

- Band, N., Kadmon, R., Mandel, M. & DeMalach, N. Assessing the roles of nitrogen, biomass, and niche dimensionality as drivers of species loss in grassland communities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2112010119 (2022).

- Tilman, D. Resource Competition and Community Structure (Princeton University Press, 1982).

- Newman, E. I. Competition and diversity in herbaceous vegetation. Nature 244, 310 (1973).

- Harpole, W. S. & Tilman, D. Grassland species loss resulting from reduced niche dimension. Nature 446, 791-793 (2007).

- Farrer, E. C. & Suding, K. N. Teasing apart plant community responses to N enrichment: the roles of resource limitation, competition and soil microbes. Ecol. Lett. 19, 1287-1296 (2016).

- Stevens, C. J. et al. Nitrogen deposition threatens species richness of grasslands across Europe. Environ. Pollut. 158, 2940-2945 (2010).

- Crawley, M. J. et al. Determinants of species richness in the park grass experiment. Am. Nat. 165, 179-192 (2005).

- Britto, D. T. & Kronzucker, H. J.

toxicity in higher plants: a critical review. J. Plant Physiol. 159, 567-584 (2002). - Zhu, J., Zhang, Y., Yang, X., Chen, N. & Jiang, L. Synergistic effects of nitrogen and

enrichment on alpine grassland biomass and community structure. N. Phytol. 228, 1283-1294 (2020). - De Melo, T. R. et al. Biogenic aggregation intensifies soil improvement caused by manures. Soil Tillage Res. 190, 186-193 (2019).

- Cai, A. et al. Manure acts as a better fertilizer for increasing crop yields than synthetic fertilizer does by improving soil fertility. Soil Tillage Res. 189, 168-175 (2019).

- Tian, Q. et al. A novel soil manganese mechanism drives plant species loss with increased nitrogen deposition in a temperate steppe. Ecology 97, 65-74 (2016).

- Ryals, R., Eviner, V. T., Stein, C., Suding, K. N. & Silver, W. L. Grassland compost amendments increase plant production without changing plant communities. Ecosphere 7, e01270 (2016).

- Verma, P. et al. Variations in soil properties, species composition, diversity, and biomass of herbaceous species due to ruminant dung residue in a seasonally dry tropical environment of India. Trop. Grassl. -Forrajes Trop. 3, 112-128 (2015).

- Critchley, C. N. R. et al. Plant species richness, functional type and soil properties of grasslands and allied vegetation in English environmentally sensitive areas. Grass Forage Sci. 57, 82-92 (2002).

- Schmid, B. The species richness-productivity controversy. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17, 113-114 (2002).

- Stockmann, U. et al. The knowns, known unknowns and unknowns of sequestration of soil organic carbon. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 164, 80-99 (2013).

- Jobbágy, E. G. & Jackson, R. B. The vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its relation to climate and vegetation. Ecol. Appl. 10, 423-436 (2000).

- Brahim, N. et al. Soil OC and N stocks in the saline soil of tunisian gataaya oasis eight years after application of manure and compost. Land 11, 442 (2022).

- Keller, A. B. B. et al. Stronger fertilization effects on aboveground versus belowground plant properties across nine US grasslands. Ecology 104, e3891 (2023).

- Crowther, T. W. et al. Sensitivity of global soil carbon stocks to combined nutrient enrichment. Ecol. Lett. 22, 936-945 (2019).

- Doetterl, S. et al. Soil carbon storage controlled by interactions between geochemistry and climate. Nat. Geosci. 8, 780-783 (2015).

- Nuralykyzy, B. et al. Influence of land use types on soil carbon fractions in the Qaidam Basin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Catena 231, 107273 (2023).

- Wieder, W. R., Cleveland, C. C., Smith, W. K. & Todd-Brown, K. Future productivity and carbon storage limited by terrestrial nutrient availability. Nat. Geosci. 8, 441-444 (2015).

- Bai, Y. & Cotrufo, M. F. Grassland soil carbon sequestration: current understanding, challenges, and solutions. Science 377, 603-608 (2022).

- Gross, A. & Glaser, B. Meta-analysis on how manure application changes soil organic carbon storage. Sci. Rep. 11, 5516 (2021).

- Toth, G., Jones, A. & Montanarella, L. The LUCAS topsoil database and derived information on the regional variability of cropland topsoil properties in the European Union. Environ. Monit. Assess. 185, 7409-7425 (2013).

- Liu, Y. et al. Meta-analysis on the effects of types and levels of N, P, and K fertilization on organic carbon in cropland soils. Geoderma 437, 116580 (2023).

- Kan, Z.-R. et al. Mechanisms of soil organic carbon stability and its response to no-till: a global synthesis and perspective. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 693-710 (2022).

- White, R. P., Murray, S., Rohweder, M., Prince, S. & Thompson, K. Grassland ecosystems. (World Resources Institute Washington, DC, USA, 2000).

- Ma, J. et al. Assessing the impacts of agricultural managements on soil carbon stocks, nitrogen loss, and crop production-a modelling study in eastern Africa. Biogeosciences 19, 2145-2169 (2022).

- A, Y. et al. Vertical variations of soil water and its controlling factors based on the structural equation model in a semi-arid grassland. Sci. Total Environ. 691, 1016-1026 (2019).

- Zhang, Y. et al. Multi-decadal trends in global terrestrial evapotranspiration and its components. Sci. Rep. 6, 1-12 (2016).

- Kidd, J., Manning, P., Simkin, J., Peacock, S. & Stockdale, E. Impacts of 120 years of fertilizer addition on a temperate grassland ecosystem. PLoS One 12, e0174632 (2017).

- Rawls, W. J., Pachepsky, Y. A., Ritchie, J. C., Sobecki, T. M. & Bloodworth, H. Effect of soil organic carbon on soil water retention. Geoderma 116, 61-76 (2003).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Determining the harvest frequency to maintain grassland productivity and minimum nutrient removal from soil. Plant Soil 487, 79-91 (2023).

- Zhang, L. et al. Habitat heterogeneity induced by pyrogenic organic matter in wildfire-perturbed soils mediates bacterial community assembly processes. ISME J. 15, 1943-1955 (2021).

- CatenaElser, J. J. et al. Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1135-1142 (2007).

- Wassen, M. J., Venterink, H. O., Lapshina, E. D. & Tanneberger, F. Endangered plants persist under phosphorus limitation. Nature 437, 547-550 (2005).

- Venterink, H. O., Wassen, M. J., Verkroost, A. W. M. & de Ruiter, P. C. Species richness-productivity patterns differ between N -, P -, and K-limited wetlands. Ecology 84, 2191-2199 (2003).

- Gautam, A. et al. Responses of soil microbial community structure and enzymatic activities to long-term application of mineral fertilizer and beef manure. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 8, 100073 (2020).

- Du, Y. et al. Effects of manure fertilizer on crop yield and soil properties in China: a meta-analysis. Catena 193, 104617 (2020).

- Li, S. X., Wang, Z. H., Hu, T. T., Gao, Y. J. & Stewart, B. A. in Advances in Agronomy Vol. 101 (ed Donald L. Sparks) 123-181 (Academic Press, 2009).

- Naeem, M., Ansari, A. & Gill, S. Contaminants in Agriculture: Sources, Impacts and Management (Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, 2020).

- Rambaut, L.-A. E., Tillard, E., Vayssieres, J., Lecomte, P. & Salgado, P. Trade-off between short and long-term effects of mineral, organic or mixed mineral-organic fertilisation on grass yield of tropical permanent grassland. Eur. J. Agron. 141, 126635 (2022).

- Stevens, H. & Carson, W. Resource quantity, not resource heterogeneity, maintains plant diversity. Ecol. Lett. 5, 420-426 (2002).

- Taddesse, G., Peden, D., Abiye, A. & Wagnew, A. Effect of manure on grazing lands in Ethiopia, East African highlands. Mt. Res. Dev. 23, 156-160 (2003).

- Loydi, A. & Martin Zalba, S. Feral horses dung piles as potential invasion windows for alien plant species in natural grasslands. Plant Ecol. 201, 471-480 (2009).

- Ye, J.-S., Bradford, M. A., Maestre, F. T., Li, F.-M. & Garcia-Palacios, P. Compensatory thermal adaptation of soil microbial respiration rates in global croplands. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 34, e2019GB006507 (2020).

- Ye, J.-S., Bradford, M. A., Dacal, M., Maestre, F. T. & Garcia-Palacios, P. Increasing microbial carbon use efficiency with warming predicts soil heterotrophic respiration globally. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 3354-3364 (2019).

- Li, F. et al. Warming alters surface soil organic matter composition despite unchanged carbon stocks in a Tibetan permafrost ecosystem. Funct. Ecol. 34, 911-922 (2020).

- Chen, Y., Feng, J., Yuan, X. & Zhu, B. Effects of warming on carbon and nitrogen cycling in alpine grassland ecosystems on the Tibetan Plateau: a meta-analysis. Geoderma 370, 114363 (2020).

- Yan, Z. et al. Changes in soil organic carbon stocks from reducing irrigation can be offset fertilizer in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 266, 107539 (2022).

- Gaudare, U. et al. Soil organic carbon stocks potentially at risk of decline with organic farming expansion. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 719-725 (2023).

- Rui, Y. et al. Persistent soil carbon enhanced in Mollisols by well- managed grasslands but not annual grain or dairy forage cropping systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2118931119 (2022).

- Kallenbach, C. & Grandy, A. S. Controls over soil microbial biomass responses to carbon amendments in agricultural systems: ametaanalysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 144, 241-252 (2011).

- Hedges, L. V., Gurevitch, J. & Curtis, P. S. The meta-analysis of response ratios in experimental ecology. Ecology 80, 1150-1156 (1999).

- Murphy, G. E. P. & Romanuk, T. N. A meta-analysis of declines in local species richness from human disturbances. Ecol. Evol. 4, 91-103 (2014).

- Lajeunesse, M. J. On the meta-analysis of response ratios for studies with correlated and multi-group designs. Ecology 92, 2049-2055 (2011).

- Song, C., Peacor, S. D., Osenberg, C. W. & Bence, J. R. An assessment of statistical methods for nonindependent data in ecological meta-analyses. Ecology 101, e03184 (2020).

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1-48 (2010).

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in metaanalysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ-Br. Med. J. 315, 629-634 (1997).

- Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302-4315 (2017).

- Hengl, T. et al. SoilGrids1km-Global Soil Information Based on Automated Mapping. PLoS One 9, e105992 (2014).

- Munoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349-4383 (2021).

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H. & Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 8, 23-74 (2003).

- Warton, D. I., Wright, I. J., Falster, D. S. & Westoby, M. Bivariate linefitting methods for allometry. Biol. Rev. 81, 259-291 (2006).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47829-w.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© The Author(s) 2024

- (D) Check for updates

State Key Laboratory of Herbage Improvement and Grassland Agro-ecosystems, College of Ecology, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China.

Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA. High Meadows Environmental Institute, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA. CSIC, Global Ecology Unit CREAF-CSIC-UAB, Barcelona 08193, Spain. CREAF, Cerdanyola del Vallès, Barcelona 08193, Spain.

-e-mail: yejsh@lzu.edu.cn