DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2024.117627

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-29

تحليل نقدي لتقنيات الاستخراج الأخضر المستخدمة في النباتات: الاتجاهات والأولويات واستراتيجيات التحسين – مراجعة

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

الكيمياء الخضراء

المنتجات الطبيعية

تصميم التجربة

النباتات

تقييم دورة الحياة PLE

SFE

MAE

UAE

المحتويات

الملخص

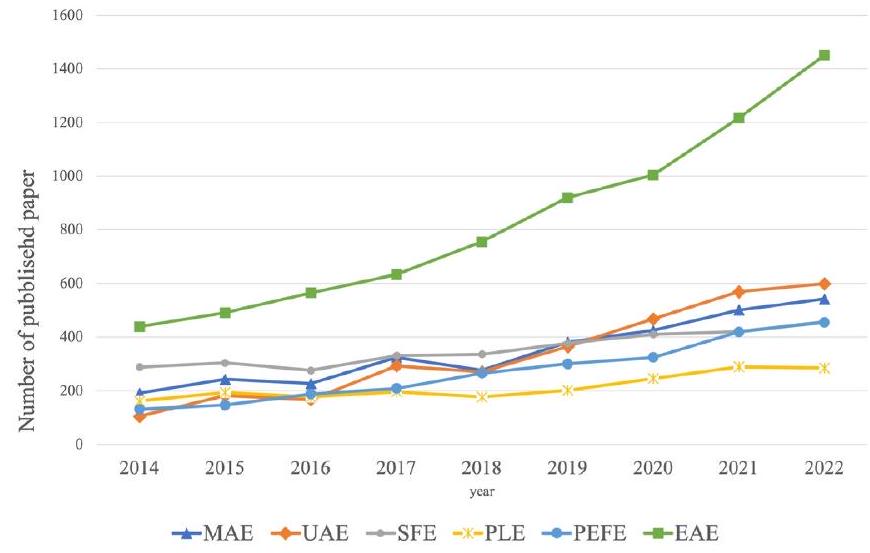

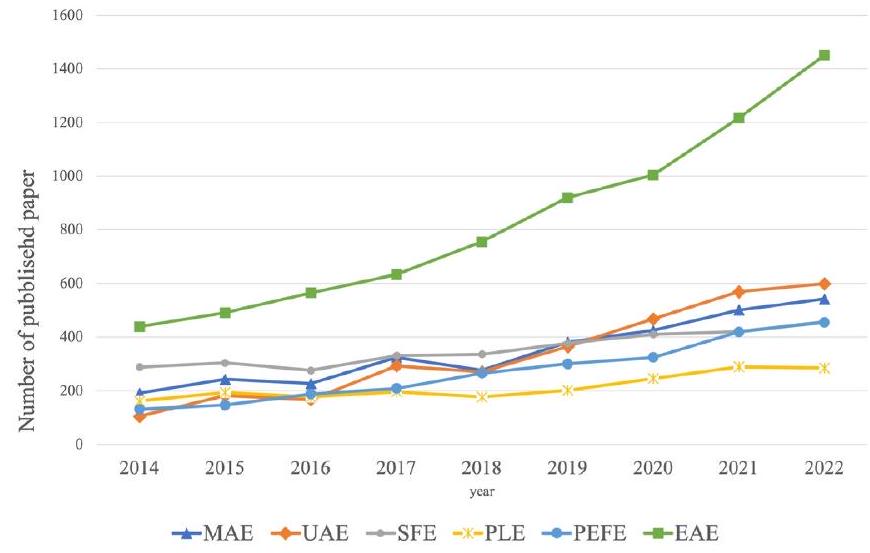

تستخدم النباتات على نطاق واسع وتُسوَّق كمكملات غذائية أو مستحضرات تجميل مع فوائد خاصة لصحة الإنسان. النباتات هي منتجات مصنوعة باستخدام مكونات طبيعية مستمدة من النباتات أو الطحالب أو الفطريات أو الطحالب. نظرًا لتوافر هذه المنتجات بسهولة، من الضروري ضمان سلامتها من خلال ضمان عدم وجود تلوث كيميائي أو ميكروبيولوجي. علاوة على ذلك، نظرًا لأن النباتات مستمدة من المنتجات الطبيعية، فإنها تتكون من مجموعة من الجزيئات تُسمى الفيتوكومبلكس، ومن المهم تطوير طرق موحدة لضمان قابليتها للتكرار. تضمن الأساليب التقليدية لاستخراج الفيتوكيميائيات، كما هو موصوف في المونوغراف أو الصيدلانيات للسلطات الدولية، سلامة المنتج مع مستويات منخفضة من الشوائب ومنتجات التحلل، ولكنها تستخدم كميات كبيرة من المذيبات العضوية مع أوقات طويلة، وتكاليف عالية وتأثير بيئي. يُفضل استخدام نهج الكيمياء الخضراء لتحسين سلامة المستهلك، وتحسين عملية الاستخراج والحفاظ على الحالة البيئية. يمكن تحقيق ذلك من خلال استخدام طرق استخراج متقدمة أثبتت فعاليتها في استخراج الجزيئات الطبيعية، مثل الاستخراج بمساعدة الميكروويف (MAE)، والاستخراج بمساعدة الموجات فوق الصوتية (UAE)، والاستخراج بالسوائل فوق الحرجة (SFE) والاستخراج السائل المضغوط (PLE) بالاقتران مع المذيبات GRAS أو المذيبات غير التقليدية، مثل المذيبات الطبيعية العميقة (NADES). في كيمياء المنتجات الطبيعية، تعتبر مرحلة الاستخراج خطوة أساسية وهي الأكثر مسؤولية عن الاستدامة البيئية. عادةً ما توجد العديد من المعلمات التي تحتاج إلى المراقبة والتحسين لضمان الظروف المثلى لهذه التقنيات. أكثر من نهج متغير واحد في كل مرة (OVAT) التجريبي، يتطلب تصميم التجارب (DoE) لفهم تأثيرات الأبعاد المتعددة وتفاعلات عوامل الإدخال على استجابات الإخراج لمرحلة الاستخراج. حتى الآن، لا توجد مقاييس محددة لمرحلة الاستخراج، لذلك، من الضروري تحديد المعلمات المسؤولة عن التأثير البيئي لمرحلة الاستخراج وتحسينها لزيادة الاستدامة البيئية للعملية التحليلية. توفر المراجعة الحالية تحليلًا نقديًا للإجراءات الحالية للاستخراج الأخضر في كيمياء المنتجات الطبيعية تهدف إلى تقديم رؤى حول استراتيجيات لتحسين كفاءة الاستخراج والاستدامة البيئية.

1. المقدمة

النباتات أو الطحالب أو الفطريات أو الطحالب. قنوات تسويق هذه المنتجات منتشرة إلى حد كبير من خلال التسويق المباشر وعبر الإنترنت مما يجعلها سهلة الوصول للمستهلكين. بينما تمتلك معظم هذه المنتجات تاريخًا طويلًا من الاستخدام في أوروبا، توجد بعض المخاوف بشأن سلامتها وجودتها. تشمل هذه المخاوف خطر التلوث الكيميائي أو الميكروبيولوجي والحاجة إلى ضمان أن تركيزات العوامل الحيوية النشطة ضمن حدود آمنة. في الاتحاد الأوروبي (EU) بدأت المناقشة حول تنظيم المنتجات النباتية في عام 2004، وفي عام 2009، أعدت اللجنة العلمية للهيئة الأوروبية لسلامة الغذاء (EFSA) وثيقة إرشادية لتقييم السلامة المتعلقة باستخدامها كمكونات في المكملات الغذائية و

“استخراج السوائل”، “تصميم التجارب”، “المذيبات الخضراء” و “تقييم دورة الحياة”. تم اختيار ما مجموعه 39 ورقة باللغة الإنجليزية لمناقشة البيانات. تم استبعاد الأوراق غير المتعلقة بمصفوفات النباتات وتلك التي تستخدم تقنيات استخراج غير مستدامة من البحث.

2. تحليل نقدي لطرق الاستخراج

2.1. الاتجاهات ونظرة عامة على طرق الاستخراج المتقدمة

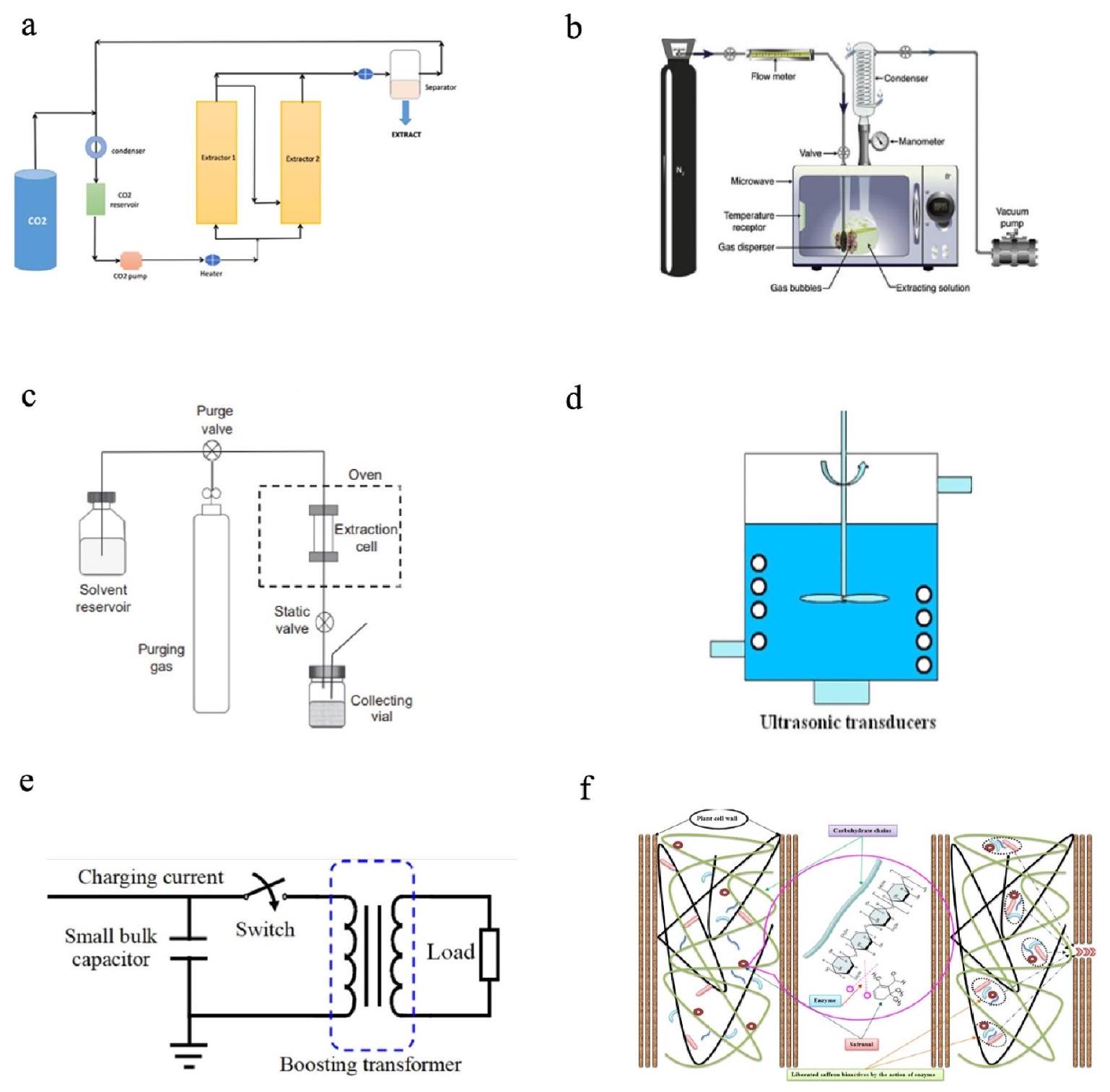

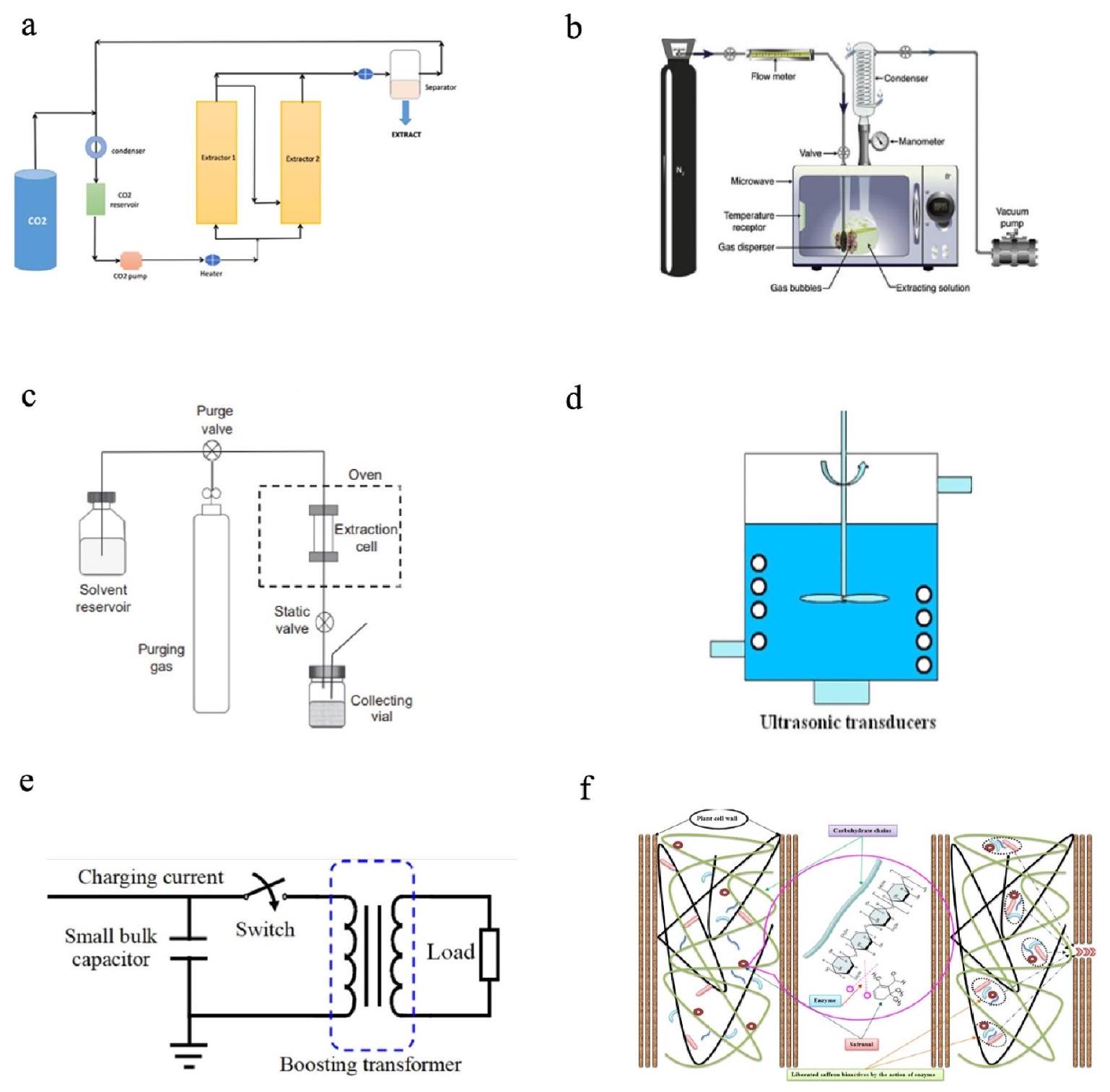

استخراج السوائل فوق الحرجة (SFE) هو تقنية فصل تُستخدم لاستخراج المكونات المرغوبة من مواد مختلفة باستخدام السوائل فوق الحرجة كمذيب للاستخراج. تستخدم SFE (الشكل 2) سوائل في حالة فوق حرجة، وهي حالة من المادة توجد فوق درجة حرارتها الحرجة وضغطها الحرجي حيث تظهر خصائص سائلة وغازية في آن واحد. كل غاز أو جزيء في حالة ضغط معينة و

مزايا وقيود تقنيات الاستخراج المحسّنة.

| تقنية الاستخراج | ميزة | عيب | المراجع | ||

| الاستخراج بمساعدة الميكروويف (MAE) | – وقت استخراج سريع – استهلاك منخفض للطاقة – تكاليف منخفضة للمعدات – لا حاجة للمذيب | – التسخين غير المنضبط للعينة قد يؤثر على كفاءة استخراج المركبات الحساسة للحرارة – استخراج غير انتقائي – عمق اختراق قصير للموجات الدقيقة عند زيادة الحجم | [20-22، 50] | ||

| استخراج السوائل فوق الحرجة (SFE) | -اختيارية عالية من خلال التحكم في درجة الحرارة والضغط المؤثرين على قوة الإذابة -نقل الكتلة وزيادة العائد من الاستخراج معززين بواسطة لزوجة منخفضة ومعدل انتشار مرتفع للسوائل فوق الحرجة -استعادة المركبات الحساسة للحرارة عند التشغيل في درجات حرارة معتدلة -تساعد إزالة الضغط عن الغاز في استعادة المركبات المستخرجة، حتى في وجود نسبة منخفضة من المذيب -إمكانية إعادة استخدام السائل فوق الحرجة. | -ارتفاع تكلفة المعدات -تعقيد تكوين النظام -مراقبة بيئية صارمة لإطلاق الغاز -انخفاض الانتقائية تجاه المركبات القطبية. | [8,15,51] | ||

| السائل المضغوط | – تقليل وقت الاستخراج؛ | – التكلفة العالية للمعدات | [28,52] | ||

| الاستخراج (PLE) |

|

– تحسين صارم لبارامترات الاستخراج مثل درجة الحرارة والضغط – التسخين لفترة طويلة قد يسبب تدهور المركبات الحساسة للحرارة | |||

| الاستخراج بمساعدة الموجات فوق الصوتية (UAE) | – استهلاك منخفض للطاقة – وقت استخراج سريع – كمية منخفضة من المذيب | [21, 33-35,53] | |||

| – استخراج غير انتقائي؛ – التدهور الحراري للمركب الحساس للحرارة؛ – تقدم عمر الأداة يقلل من شدة الموجات فوق الصوتية، مما يقلل من القابلية للتكرار | |||||

| الاستخراج بمساعدة الإنزيم (EAE) | – يستخدم الماء كمذيب. – مناسب لفصل المركبات المرتبطة. | – حساسية الإنزيم. – صعوبة في التوسع للتطبيقات الصناعية. – سعر الإنزيم المرتفع لحجم كبير من العينات | [40] | ||

| الاستخراج باستخدام مجال كهربائي نبضي (PEFE) | – وقت استخراج سريع – أداء عند درجات حرارة منخفضة – استخراج الجزيئات الحساسة للحرارة؛ | – تكاليف عالية للصيانة. – التحكم الدقيق في المعلمات. | [38] |

يسمح بتقليل التوتر السطحي، ولزوجة المذيب، مما يضمن معدل نقل كتلة أسهل وانتشارًا، ويقلل من وقت الاستخراج واستهلاك المذيب (الشكل 2) [28]. حتى الآن، تُعتبر تقنية الاستخراج السريع بالضغط (PLE) تقنية مستخدمة على نطاق واسع لتحسين عوائد الاستخراج واستعادة المركبات النشطة بيولوجيًا. نظرًا لوجود عدة معايير (درجة الحرارة، عدد الدورات، وقت الاستخراج وتركيب المذيب) يمكن أن تؤثر بشكل كبير على استخلاص PLE، من المهم تحسين العملية لتعظيم استعادة المركبات النشطة بيولوجيًا وتحسين كفاءة الاستخراج. قام تشادا وآخرون [30] بتحسين معايير PLE (

وقت أقل استهلاكًا، واستخدام أقل للمذيبات، ودرجات حرارة استخراج أقل مقارنة بتقنيات الاستخراج الأخرى؛ هذه المزايا تجعل PEFE طريقة جيدة للتطبيق الصناعي (الشكل 2). وجد سيغوفيا وآخرون (2015) أن PEFE زادت من المحتوى الكلي للفينولات وقيم قدرة امتصاص الجذور الحرة للأكسجين (ORAC) بـ

2.2. تقييم الاستدامة البيئية للاستخراجات الخضراء في كيمياء المنتجات الطبيعية

الكيمياء، وقد تم تحديدها كواحدة من الخطوات الأكثر أهمية من وجهة نظر GCA لأنها مسؤولة عن استهلاك المذيبات والطاقة والمواد القابلة للاستهلاك أو الأجهزة.

خطوة الاستخراج في كيمياء المنتجات الطبيعية، ولكن حتى الآن، تم تطبيقها فقط على تقييم استدامة الإجراءات التحليلية لتحديد الملوثات [65].

صديقة للبيئة لاستخراج البوليفينولات من أوراق المورينغا أوليفيرا [70].

2.3. معايير الاختيار للنباتات والمنتجات ذات الصلة

2.3.1. استخراج المركبات الطبيعية من النباتات

ووقت أطول للاستخراج لاسترداد عائد كبير من المركبات. بخلاف الاستخدام الكبير للإجراءات التقليدية لاسترداد البوليفينولات القياسية، تؤدي طرق الاستخراج المتقدمة إلى استخراج فعال بتكاليف أقل للبوليفينولات، مستردة أقصى عائد من البوليفينولات مع كمية أقل من المذيبات في وقت استخراج أقصر. أظهرت النتائج التجريبية المبلغ عنها أن التقنيات الخضراء أكثر فعالية في استرداد المستقلبات الثانوية. يمكن تخصيص مجموعة مناسبة من المذيبات الخضراء وتقنيات الاستخراج لأغراض محددة من خلال اعتماد تقنيات وظروف استخراج مناسبة للحصول على تركيبة مختلفة من المركبات الحيوية في المنتج النهائي من نفس المصفوفة.

الظروف المحسنة للاستخراج الانتقائي للنباتات باستخدام تقنيات الاستخراج الأخضر.

| المصفوفة | المركبات المستهدفة | تقنية الاستخراج | المعلمة المحددة | عائد الاستخراج | المرجع | |||||||

| بذور الجراناديل | زيت UFA | SFE-

|

|

24.97% | [84] | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| بذور الجراناديل | الفينولات | PLE |

|

|

[84] | |||||||

| R. officinalis | التربينات | SFE-

|

|

|

[95] | |||||||

| Scutellaria incarnata | الفينولات | UAE |

|

– | [96] | |||||||

| Scutellaria coccinea | الفينولات | UAE |

|

– | [96] | |||||||

| Scutellaria ventenatii | الفينولات | UAE |

|

– | [96] | |||||||

| Lippia citriodora | الفينيل بروبانيدات والفلافونويدات | SFE-

|

|

|

[97] | |||||||

| Syzygium cumini | الفينولات | UAE |

|

|

[98] | |||||||

| Beta vulgaris | الفينولات | UAE |

|

32.17% | [92] | |||||||

| Beta vulgaris | الفينولات | MAE | 10 دقيقة 600 واط | 37.04% | [92] | |||||||

| Beta vulgaris | الفينولات | PLE |

|

32.85% | [92] | |||||||

| Beta vulgaris | الفينولات | SFE-

|

|

28.84% | [92] | |||||||

| الجزر (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) | الكاروتينات | MAE |

|

19.2% | [99] | |||||||

| قشر المانجو (Mangifera indica L.) |

|

SFE-

|

|

|

[100] | |||||||

| منتجات الطماطم (Solanum lycopersicum) | ليكوبين | الإمارات العربية المتحدة |

|

|

[101] | |||||||

| منتجات ثانوية من اليقطين (Cucurbita maxima) |

|

الإمارات العربية المتحدة |

|

|

[102] | |||||||

| ديندرانثيما إنديكوم | الزيوت الأساسية | SFE |

|

9.37% | [103] | |||||||

| قرنفل، لحاء القرفة، قشور البرتقال والليمون، أوراق الكينا، بذور الهيل | الزيوت الأساسية | نظام استخراج يعتمد على الطاقة الشمسية (SEE) |

|

13.4-15.3% (برسيم)

|

[87] |

لوظائفها في صحة الإنسان مثل النشاط المضاد للأكسدة، والوقاية من السرطان، وتحسين حالة العين [86]. المذيبات التقليدية المستخدمة لاستخراج الكاروتينات من الأطعمة مصنوعة من

العلاج بالروائح [87]. يتم استعادة الزيوت عالية القيمة عادةً بواسطة طرق تقليدية مثل التقطير المائي (HD)، الضغط البارد، الإنفلاوراج، استخراج المذيبات، والتقطير المتزامن الذي يؤدي إلى كفاءة استخراج منخفضة، وتحلل حراري كبير أو تحلل مائي لمركبات الإستر غير المشبعة، والاحتمال لوجود مذيبات عضوية متبقية في الزيوت الأساسية [88]. من ناحية أخرى، تم تطوير طرق صديقة للبيئة لتحسين عملية استخراج الزيوت الأساسية. قدم استخراج ثاني أكسيد الكربون فوق الحرج من Dendranthema indicum، بالاشتراك مع التقطير الجزيئي الذي أجراه قوه وآخرون، 2022، عائد استخراج قدره

2.4. اختيار المذيب في الكيمياء الخضراء

2.4.1. التقنيات الخضراء وتركيبة المذيبات في النباتات الطبية

البيئة والصحة. الماء هو المذيب الأكثر أمانًا للاستخراج مع توافق بيولوجي، لكن القدرة على استخراج المركبات النشطة بيولوجيًا من النباتات محدودة جدًا. على الرغم من سلوكه، فإن ظروف درجات الحرارة والضغط في استخراج الماء تحت الحرج (SWE) حولت قطبية الماء نحو المذيبات العضوية الأقل قطبية وزادت بشكل محتمل من عائد استخراج المركبات ذات القطبية المتوسطة. وصف مارافيتش وآخرون، 2022، الملف الفينولي لاستخراج أوراق بنجر السكر (Beta vulgaris L.) وقدرة مضادات الأكسدة المرتبطة به تعتمد إلى حد كبير على تقنية الاستخراج المستخدمة والمذيبات. أظهر الفيتكسين أنه المركب الفينولي الأكثر وفرة الموجود في جميع الاستخراجات. تم التحقيق في مقارنة بين قدرة مضادات الأكسدة للاستخراجات من خلال DPPH وFRAP وABTS، مما يشير إلى أدنى نشاط مضاد للأكسدة للاستخراجات التي تم الحصول عليها من خلال الاستخراج الصلب/السائل مقارنة بتقنيات الاستخراج الأخرى. بشكل خاص، أظهر تأثير الماء في تقنية SWE كفاءة أعلى في درجة الحرارة الأعلى المختبرة.

3. تحسين عقلاني لمتغيرات الاستخراج

3.1. متغير واحد في كل مرة مقابل تصميم التجارب

من الممكن زيادة كفاءة عملية الاستخراج من خلال دمج تقنيات الاستخراج غير التقليدية المبتكرة مع تصميم تجريبي مناسب. هذا مهم بشكل خاص عندما تكون المصفوفة الابتدائية من أصل نباتي وبالتالي غنية بالمركبات الطبيعية. يمكن أن يضمن استخدام التصاميم التجريبية زيادة في الانتقائية الاستخراجية وزيادة في استرداد المكونات الوظيفية. كما يمكن أن تقلل التصاميم التجريبية من عدد التجارب المطلوبة، مما يقلل من التكلفة والوقت والأثر البيئي.

3.2. تصميم التجربة (DoE)

العملية، ولهذا السبب تتوفر حاليًا نماذج مختلفة للتحليل متعدد المتغيرات. على وجه الخصوص، يمكننا التمييز بين الطرق الخاصة بالتقييم الأولي للعوامل التي يجب أخذها بعين الاعتبار والطرق الخاصة بتحسين الاستجابة.

3.2.1. فحص العوامل الأولية

- تصميم كامل للعوامل

في هذا النموذج، يمثل الرقم 2 عدد المستويات وk هو عدد العوامل المدروسة. يُشار إليه للمتغيرات غير المستمرة. يسمح بتعريف تأثيرات وأهمية كل عامل وتفاعلاتهم. ومع ذلك، فإنه غير مناسب إذا كان عدد العوامل المدروسة مرتفعًا جدًا. ) [114,115]. – تصميم العوامل الكسرية ( ): هذا النموذج قابل للتطبيق عندما يؤدي تصميم التجارب الكامل (FFD) إلى عدد كبير جدًا من التجارب أو إذا كان يُشتبه في أن التفاعلات بين العوامل ضئيلة. في الواقع، يوفر FFD معلومات حول أهمية المتغيرات المستقلة ولكن ليس حول تفاعلاتها، حيث يتم الخلط بين تأثيرات العوامل الرئيسية وتلك الخاصة بتفاعلات العوامل [116]. – تصميم بلاكيت-بورمان: هذه طريقة بسيطة جدًا يمكن استخدامها لفحص العوامل. غالبًا ما يتم اختيارها بدقة بسبب بساطتها، مما يسمح بإجراء عدد قليل من التجارب. أيضًا، في هذه الحالة، لا يتم تقييم تفاعلات العوامل. خيار اقتصادي وفعال لتقييم قوة البيانات [117،118].

3.2.2. تحسين ظروف الاستخراج

- تصميم مركزي مركب (CCD): لديه تصميم تجريبي كامل أو جزئي بمستويين (والذي له ميزة لأنه يمكن أيضًا تشغيله كفحص)، وخمسة نقاط مركزية، ونقطتين محوريين. العيب في هذه الطريقة هو تطبيق التجارب مع جميع العوامل عند مستويات إيجابية وسلبية مع خطر أن تؤدي التجارب في ظروف قصوى إلى نتائج مضللة [119،120].

- مصفوفة دوهلرت: هي نهج اقتصادي ومرن وفعال لنمذجة البيانات التجريبية. ميزة مهمة في هذا التصميم هي إمكانية دراسة متغيرات مختلفة وأعداد مختلفة من مستويات نفس المصفوفة، مما يجعلها مناسبة بشكل خاص للدراسات التي يتم فيها اعتبار متغير واحد بشكل أكثر قربًا على عدد مختلف من المستويات. أخيرًا، يتطلب عددًا أقل من النقاط التجريبية، مما يجعله فعالًا واقتصاديًا جدًا مقارنةً بنماذج أخرى مثل تصميم CCD وتصميم بوكس-بينكن [121].

- تصميم العوامل بمستويات 3: تتطلب هذه الطريقة عددًا كبيرًا من التجارب للحصول على نموذج تربيعي وتتضمن تجارب مع جميع العوامل الإيجابية والسلبية. لا يمكن تطبيقها مع

[112].

تصميم بوكس-بينكن: نشأ في الستينيات كتعديل لخطة العوامل بمستويات 3 حيث يجب الحفاظ على عامل ما بالضرورة عند قيمته المتوسطة (نقطة الصفر) في كل تجربة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يتضمن هذا النموذج أيضًا على الأقل تجربة واحدة تكون فيها جميع العوامل عند القيمة “الصفرية”، وتسمى نقاط المركز. زيادة عدد نقاط المركز في تصميم تجريبي باستخدام نهج بوكس-بينكن يجعل من الممكن زيادة درجات الحرية، أي دقة البيانات التي تم الحصول عليها من خلال القدرة على تسليط الضوء على أي شذوذ أثناء تنفيذ التصميم التجريبي [122-124].

4. الخاتمة وآفاق المستقبل

المكونات، فإن مستخلصات النباتات لها تطبيقات عديدة في صناعة المكملات الغذائية ومستحضرات التجميل. من بين المنتجات النباتية المتزايدة الانتشار، تعتبر النباتات منتجات تعزز الصحة مع اهتمام متزايد في السوق. يرتبط استرداد المكونات النشطة من النباتات ومنتجاتها الثانوية بعملية الاستخراج التي توفر توازنًا بين أداء تقنيات الاستخراج والمذيبات المستخدمة كوسائط لنقل الكتلة من المصفوفة. توفر هذه المراجعة نظرة نقدية على إجراءات الاستخراج الخضراء الحالية في كيمياء المنتجات الطبيعية. كان هدفها هو تقديم تحديث حول استراتيجيات تحسين كفاءة الاستخراج والاستدامة البيئية.

تمويل

بيان مساهمة المؤلفين

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

توفر البيانات

شكر

References

[2] M.Y. Heng, S.N. Tan, J.W.H. Yong, E.S. Ong, Emerging green technologies for the chemical standardization of botanicals and herbal preparations, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 50 (2013) 1-10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2013.03.012.

[3] D.K. Singh, A. Sahu, S. Kumar, S. Singh, Critical review on establishment and availability of impurity and degradation product reference standards, challenges faced by the users, recent developments, and trends, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 101 (2018) 85-107, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2017.10.021.

[4] J.C. Prata, T. Rocha-Santos, A.I. Ribeiro, An introduction to the concept of One Health, One Heal. Integr. Approach to 21st Century Challenges to Heal (2022) 1-31, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822794-7.00004-6.

[5] S. Armenta, S. Garrigues, M. de la Guardia, The role of green extraction techniques in Green Analytical Chemistry, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 71 (2015) 2-8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2014.12.011.

[6] T. Belwal, S.M. Ezzat, L. Rastrelli, I.D. Bhatt, M. Daglia, A. Baldi, H.P. Devkota, I. E. Orhan, J.K. Patra, G. Das, C. Anandharamakrishnan, L. Gomez-Gomez, S. F. Nabavi, S.M. Nabavi, A.G. Atanasov, A critical analysis of extraction techniques used for botanicals: trends, priorities, industrial uses and optimization strategies, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 100 (2018) 82-102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. trac.2017.12.018.

[7] P. Yu, M.Y. Low, W. Zhou, Design of experiments and regression modelling in food flavour and sensory analysis: a review, Trends Food Sci. Technol. 71 (2018) 202-215, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.11.013.

[8] C. Picot-Allain, M.F. Mahomoodally, G. Ak, G. Zengin, Conventional versus green extraction techniques – a comparative perspective, Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 40 (2021) 144-156, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COFS.2021.02.009.

[9] T. Belwal, F. Chemat, P.R. Venskutonis, G. Cravotto, D.K. Jaiswal, I.D. Bhatt, H. P. Devkota, Z. Luo, Recent advances in scaling-up of non-conventional extraction techniques: learning from successes and failures, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 127 (2020) 115895, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TRAC.2020.115895.

[10] M. Garcia-Vaquero, G. Rajauria, B. Tiwari, Conventional extraction techniques: solvent extraction, Sustain. Seaweed Technol. Cultiv. Biorefinery, Appl. (2020) 171-189, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817943-7.00006-8.

[11] M. Ramos, A. Jiménez, M.C. Garrigós, Il-based advanced techniques for the extraction of value-added compounds from natural sources and food by-products, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 119 (2019) 115616, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. TRAC.2019.07.027.

[12] A.C. Diamanti, P.E. Igoumenidis, I. Mourtzinos, K. Yannakopoulou, V. T. Karathanos, Green extraction of polyphenols from whole pomegranate fruit using cyclodextrins, Food Chem. 214 (2017) 61-66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodchem.2016.07.072.

[13] S.P. Ishwarya, P. Nisha, Headway in Supercritical Extraction of Fragrances and Colors, Elsevier, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-100596-5.22677-2.

[14] C. Picot-Allain, M.F. Mahomoodally, G. Ak, G. Zengin, Conventional versus green extraction techniques – a comparative perspective, Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 40 (2021) 144-156, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2021.02.009.

[15] C. Da Porto, D. Decorti, A. Natolino, Water and ethanol as co-solvent in supercritical fluid extraction of proanthocyanidins from grape marc: a comparison and a proposal, J. Supercrit. Fluids 87 (2014) 1-8, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.supflu.2013.12.019.

[16] A. Rajaei, M. Barzegar, Y. Yamini, Supercritical fluid extraction of tea seed oil and its comparison with solvent extraction, Eur. Food Res. Technol. 220 (2005) 401-405, https://doi.org/10.1007/S00217-004-1061-8/TABLES/3.

[17] S. Zhao, D. Zhang, Supercritical CO2 extraction of Eucalyptus leaves oil and comparison with Soxhlet extraction and hydro-distillation methods, Sep. Purif. Technol. 133 (2014) 443-451, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEPPUR.2014.07.018.

[18] R. Martins, A. Barbosa, B. Advinha, H. Sales, R. Pontes, J. Nunes, Green extraction techniques of bioactive compounds: a state-of-the-art review, Process 11 (2023) 2255, https://doi.org/10.3390/PR11082255.

[19] D. De Vita, S. Lachowicz, W. Wi’sniewska, L. Lajoie, A.-S. Fabiano-Tixier, F. Chemat, Water as green solvent: methods of solubilisation and extraction of natural products-past, present and future solutions, Pharm. Times 15 (1507 15) (2022) 1507, https://doi.org/10.3390/PH15121507.

[20] F.G.C. Ekezie, D.W. Sun, J.H. Cheng, Acceleration of microwave-assisted extraction processes of food components by integrating technologies and applying emerging solvents: a review of latest developments, Trends Food Sci. Technol. 67 (2017) 160-172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.06.006.

[21] M. Vinatoru, T.J. Mason, I. Calinescu, Ultrasonically assisted extraction (UAE) and microwave assisted extraction (MAE) of functional compounds from plant materials, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 97 (2017) 159-178, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.trac.2017.09.002.

[22] R. Costa, The chemistry of mushrooms: a survey of novel extraction techniques targeted to chromatographic and spectroscopic screening, Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 49 (2016) 279-306, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63601-0.00009-0.

[23] A.M. Galan, I. Calinescu, A. Trifan, C. Winkworth-Smith, M. Calvo-Carrascal, C. Dodds, E. Binner, New insights into the role of selective and volumetric heating during microwave extraction: investigation of the extraction of polyphenolic compounds from sea buckthorn leaves using microwave-assisted extraction and conventional solvent extraction, Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 116 (2017) 29-39, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEP.2017.03.006.

[24] G. Silveira Da Rosa, S. Kranthi Vanga, Y. Gariepy, V. Raghavan, Comparison of Microwave, Ultrasonic and Conventional Techniques for Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Olive Leaves, Olea europaea L.), 2019, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ifset.2019.102234.

[25] Z. Rafiee, S.M. Jafari, M. Alami, M. Khomeiri, Microwave-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from olive leaves; a comparison with maceration, J. Anim. Plant Sci 21 (2011) 738.

[26] C.B.T. Pal, G.C. Jadeja, Microwave-assisted deep eutectic solvent extraction of phenolic antioxidants from onion (Allium cepa L.) peel: a Box-Behnken design approach for optimization, J. Food Sci. Technol. 56 (2019) 4211-4223, https:// doi.org/10.1007/S13197-019-03891-7/FIGURES/4.

[27] B. Zhang, R. Yang, C.Z. Liu, Microwave-assisted extraction of chlorogenic acid from flower buds of Lonicera japonica Thunb, Sep. Purif. Technol. 62 (2008) 480-483, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEPPUR.2008.02.013.

[28] G. Alvarez-Rivera, M. Bueno, D. Ballesteros-Vivas, J.A. Mendiola, E. Ibañez, Pressurized liquid extraction, Liq. Extr. (2019) 375-398, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-12-816911-7.00013-X.

[29] V. Kitrytė, A. Kavaliauskaitė, L. Tamkutė, M. Pukalskienė, M. Syrpas, P. Rimantas Venskutonis, Zero waste biorefining of lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) pomace into functional ingredients by consecutive high pressure and enzyme assisted extractions with green solvents, Food Chem. 322 (2020) 126767, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126767.

[30] P.S.N. Chada, P.H. Santos, L.G.G. Rodrigues, G.A.S. Goulart, J.D. Azevedo dos Santos, M. Maraschin, M. Lanza, Non-conventional techniques for the extraction of antioxidant compounds and lycopene from industrial tomato pomace (Solanum lycopersicum L.) using spouted bed drying as a pre-treatment, Food Chem. X 13 (2022) 100237, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOCHX.2022.100237.

[31] J. Viganó, I.Z. Brumer, P.A. de C. Braga, J.K. da Silva, M.R. Maróstica Júnior, F. G. Reyes Reyes, J. Martínez, Pressurized liquids extraction as an alternative process to readily obtain bioactive compounds from passion fruit rinds, Food Bioprod. Process. 100 (2016) 382-390, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. FBP.2016.08.011.

[32] A.P.D.F. Machado, J.L. Pasquel-Reátegui, G.F. Barbero, J. Martínez, Pressurized liquid extraction of bioactive compounds from blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L.) residues: a comparison with conventional methods, Food Res. Int. 77 (2015) 675-683, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODRES.2014.12.042.

[33] S. Bachtler, H.J. Bart, Increase the yield of bioactive compounds from elder bark and annatto seeds using ultrasound and microwave assisted extraction technologies, Food Bioprod. Process. 125 (2021) 1-13, https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.fbp.2020.10.009.

[34] L. Vernès, M. Vian, F. Chemat, Ultrasound and microwave as green tools for solidliquid extraction, Liq. Extr. (2019) 355-374, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816911-7.00012-8.

[35] C. Wen, J. Zhang, H. Zhang, C.S. Dzah, M. Zandile, Y. Duan, H. Ma, X. Luo, Advances in ultrasound assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from cash crops – a review, Ultrason. Sonochem. 48 (2018) 538-549, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.07.018.

[36] A.A. Jovanović, V.B. Đorđević, G.M. Zdunić, D.S. Pljevljakušić, K.P. Šavikin, D. M. Gođevac, B.M. Bugarski, Optimization of the extraction process of polyphenols from Thymus serpyllum L. herb using maceration, heat- and ultrasound-assisted techniques, Sep. Purif. Technol. 179 (2017) 369-380, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. SEPPUR.2017.01.055.

[37] S.A. Mousavi, L. Nateghi, M. Javanmard Dakheli, Y. Ramezan, Z. Piravi-Vanak, Maceration and ultrasound-assisted methods used for extraction of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity from Ferulago angulata, J. Food Process. Preserv. 46 (2022) e16356, https://doi.org/10.1111/JFPP. 16356.

[38] D. Niu, X.A. Zeng, E.F. Ren, F.Y. Xu, J. Li, M.S. Wang, R. Wang, Review of the application of pulsed electric fields (PEF) technology for food processing in China,

[39] F.J. Segovia, E. Luengo, J.J. Corral-Pérez, J. Raso, M.P. Almajano, Improvements in the aqueous extraction of polyphenols from borage (Borago officinalis L.) leaves by pulsed electric fields: pulsed electric fields (PEF) applications, Ind. Crops Prod. 65 (2015) 390-396, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. INDCROP.2014.11.010.

[40] F. Garavand, S. Rahaee, N. Vahedikia, S.M. Jafari, Different techniques for extraction and micro/nanoencapsulation of saffron bioactive ingredients, Trends Food Sci. Technol. 89 (2019) 26-44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.05.005.

[41] S.S. Nadar, P. Rao, V.K. Rathod, Enzyme assisted extraction of biomolecules as an approach to novel extraction technology: a review, Food Res. Int. 108 (2018) 309-330, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODRES.2018.03.006.

[42] O. Gligor, A. Mocan, C. Moldovan, M. Locatelli, G. Crișan, I.C.F.R. Ferreira, Enzyme-assisted extractions of polyphenols – a comprehensive review, Trends Food Sci. Technol. 88 (2019) 302-315, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. TIFS.2019.03.029.

[43] K.L. Nagendra Chari, D. Manasa, P. Srinivas, H.B. Sowbhagya, Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), Food Chem. 139 (2013) 509-514, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. FOODCHEM. 2013.01.099.

[44] J.M. Awika, L.W. Rooney, X. Wu, R.L. Prior, L. Cisneros-Zevallos, Screening methods to measure antioxidant activity of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and Sorghum products, J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 (2003) 6657-6662, https://doi.org/ 10.1021/JF034790I/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/JF034790IF00005.JPEG.

[45] J.E. Cacace, G. Mazza, Pressurized low polarity water extraction of lignans from whole flaxseed, J. Food Eng. 77 (2006) 1087-1095, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. JFOODENG.2005.08.039.

[46] S.M. Choudhari, L. Ananthanarayan, Enzyme aided extraction of lycopene from tomato tissues, Food Chem. 102 (2007) 77-81, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. FOODCHEM. 2006.04.031.

[47] A. Boulila, I. Hassen, L. Haouari, F. Mejri, I. Ben Amor, H. Casabianca, K. Hosni, Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from bay leaves (Laurus nobilis L.), Ind. Crops Prod. 74 (2015) 485-493, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. INDCROP.2015.05.050.

[48] F. Sahne, M. Mohammadi, G.D. Najafpour, A.A. Moghadamnia, Enzyme-assisted ionic liquid extraction of bioactive compound from turmeric (Curcuma longa L.): Isolation, purification and analysis of curcumin, Ind. Crops Prod. 95 (2017) 686-694, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INDCROP.2016.11.037.

[49] P. Nath, C. Kaur, S.G. Rudra, E. Varghese, Enzyme-assisted extraction of carotenoid-rich extract from red Capsicum (Capsicum annuum), Agric. Res. 5 (2016) 193-204, https://doi.org/10.1007/S40003-015-0201-7/FIGURES/8.

[50] K. Suktham, P. Daisuk, A. Shotipruk, Microwave-assisted extraction of antioxidative anthraquinones from roots of Morinda citrifolia L. (Rubiaceae): Errata and review of technological development and prospects, Sep. Purif. Technol. 256 (2021) 117844, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2020.117844.

[51] L. Valadez-Carmona, A. Ortiz-Moreno, G. Ceballos-Reyes, J.A. Mendiola, E. Ibáñez, Valorization of cacao pod husk through supercritical fluid extraction of phenolic compounds, J. Supercrit. Fluids 131 (2018) 99-105, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.09.011.

[52] A.M. Pavkovich, D.S. Bell, Extraction | Pressurized Liquid Extraction, third ed., Elsevier Inc., 2019 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409547-2.14407-5.

[53] S. Roohinejad, N. Nikmaram, M. Brahim, M. Koubaa, A. Khelfa, R. Greiner, Potential of Novel Technologies for Aqueous Extraction of Plant Bioactives, Elsevier Inc., 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809380-1.00016-4.

[54] A. Gałuszka, Z. Migaszewski, J. Namieśnik, The 12 principles of green analytical chemistry and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic of green analytical practices, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 50 (2013) 78-84, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. TRAC.2013.04.010.

[55] J.B. Zimmerman, P.T. Anastas, H.C. Erythropel, W. Leitner, Designing for a green chemistry future, Science (80-.) 367 (2020) 397-400, https://doi.org/10.1126/ SCIENCE.AAY3060/ASSET/8997170C-4499-4F22-A12F-B46943929ED6/ ASSETS/GRAPHIC/367_397_F3.JPEG.

[56] P. Jessop, Editorial: evidence of a significant advance in green chemistry, Green Chem. 22 (2020) 13-15, https://doi.org/10.1039/C9GC90119A.

[57] M. Sajid, J. Płotka-Wasylka, Green analytical chemistry metrics: a review, Talanta 238 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TALANTA.2021.123046.

[58] P.-Y. Liew, J.-Y. Yong, J. Jaromír Klemeš, H. Loong Lam, S.G. Papadaki, K. E. Kyriakopoulou, M.K. Krokida, Life cycle analysis of microalgae extraction techniques, Chem. Eng. Trans. 52 (2016) 1039-1044, https://doi.org/10.3303/ CET1652174.

[59] R.L. Lankey, P.T. Anastas, Life-cycle approaches for assessing green chemistry technologies, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 41 (2002) 4498-4502, https://doi.org/ 10.1021/IE0108191.

[60] M.S. Imam, M.M. Abdelrahman, How environmentally friendly is the analytical process? A paradigm overview of ten greenness assessment metric approaches for analytical methods, Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 38 (2023) e00202, https://doi. org/10.1016/J.TEAC.2023.E00202.

[61] A. Gałuszka, Z.M. Migaszewski, P. Konieczka, J. Namieśnik, Analytical Eco-Scale for assessing the greenness of analytical procedures, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 37 (2012) 61-72, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TRAC.2012.03.013.

[62] Y. Gaber, U. Törnvall, M.A. Kumar, M. Ali Amin, R. Hatti-Kaul, HPLC-EAT (Environmental Assessment Tool): a tool for profiling safety, health and environmental impacts of liquid chromatography methods, Green Chem. 13 (2011) 2021-2025, https://doi.org/10.1039/C0GC00667J.

[63] M.B. Hicks, W. Farrell, C. Aurigemma, L. Lehmann, L. Weisel, K. Nadeau, H. Lee, C. Moraff, M. Wong, Y. Huang, P. Ferguson, Making the move towards modernized greener separations: introduction of the analytical method greenness score (AMGS) calculator, Green Chem. 21 (2019) 1816-1826, https://doi.org/ 10.1039/C8GC03875A.

[64] S. Armenta, S. Garrigues, F.A. Esteve-Turrillas, M. de la Guardia, Green extraction techniques in green analytical chemistry, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 116 (2019) 248-253, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2019.03.016.

[65] W. Wojnowski, M. Tobiszewski, F. Pena-Pereira, E. Psillakis, AGREEprep analytical greenness metric for sample preparation, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 149 (2022) 116553, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TRAC.2022.116553.

[66] G. Barjoveanu, O.A. Pătrăuțanu, C. Teodosiu, I. Volf, Life cycle assessment of polyphenols extraction processes from waste biomass, Sci. Rep. 10110 (2020) 1-12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70587-w.

[67] P. Vauchel, C. Colli, D. Pradal, M. Philippot, S. Decossin, P. Dhulster, K. Dimitrov, Comparative LCA of ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from chicory grounds under different operational conditions, J. Clean. Prod. 196 (2018) 1116-1123, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2018.06.042.

[68] T. Ding, S. Bianchi, C. Ganne-Chédeville, P. Kilpeläinen, A. Haapala, T. Räty, Life cycle assessment of tannin extraction from spruce bark, IForest – Biogeosciences For 10 (2017) 807, https://doi.org/10.3832/IFOR2342-010.

[69] M. Salzano de Luna, G. Vetrone, S. Viggiano, L. Panzella, A. Marotta, G. Filippone, V. Ambrogi, Pine needles as a biomass resource for phenolic compounds: trade-off between efficiency and sustainability of the extraction methods by life cycle assessment, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11 (2023) 4670-4677, https://doi.org/ 10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c06698.

[70] V.M. Pappas, I. Samanidis, G. Stavropoulos, V. Athanasiadis, T. Chatzimitakos, E. Bozinou, D.P. Makris, S.I. Lalas, Analysis of five-extraction technologies’ environmental impact on the polyphenols production from Moringa oleifera leaves using the life cycle assessment tool based on ISO 14040, Sustain. Times 15 (2023) 2328, https://doi.org/10.3390/SU15032328/S1.

[71] J. Płotka-Wasylka, M. Rutkowska, K. Owczarek, M. Tobiszewski, J. Namieśnik, Extraction with environmentally friendly solvents, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 91 (2017) 12-25, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TRAC.2017.03.006.

[72] S. Fraterrigo Garofalo, F. Demichelis, G. Mancini, T. Tommasi, D. Fino, Conventional and ultrasound-assisted extraction of rice bran oil with isopropanol as solvent, Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 29 (2022) 100741, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. scp. 2022.100741.

[73] Y. Yao Chen, R. Walvekar, M. Khalid, J.M. Pringle, M.D. Murugan, L.H. Tee, K. S. Oh, Evaluation of the environment impact of extraction of bioactive compounds from Darcyodes rostrata using Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) using Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2120 (2021) 012005, https://doi.org/ 10.1088/1742-6596/2120/1/012005.

[74] G. Croxatto Vega, J. Sohn, J. Voogt, M. Birkved, S.I. Olsen, A.E. Nilsson, Insights from combining techno-economic and life cycle assessment – a case study of polyphenol extraction from red wine pomace, Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 167 (2021) 105318, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESCONREC.2020.105318.

[75] T.P. Rieseberg, A. Dadras, J.M.R. Fürst-Jansen, A. Dhabalia Ashok, T. Darienko, S. de Vries, I. Irisarri, J. de Vries, Crossroads in the evolution of plant specialized metabolism, Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 134 (2023) 37-58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. semcdb.2022.03.004.

[76] J. Azmir, I.S.M. Zaidul, M.M. Rahman, K.M. Sharif, A. Mohamed, F. Sahena, M.H. A. Jahurul, K. Ghafoor, N.A.N. Norulaini, A.K.M. Omar, Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: a review, J. Food Eng. 117 (2013) 426-436, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.01.014.

[77] P. Panja, Green extraction methods of food polyphenols from vegetable materials, Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 23 (2018) 173-182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cofs.2017.11.012.

[78] K. Carbone, V. Macchioni, G. Petrella, D.O. Cicero, Exploring the potential of microwaves and ultrasounds in the green extraction of bioactive compounds from Humulus lupulus for the food and pharmaceutical industry, Ind. Crops Prod. 156 (2020) 112888, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112888.

[79] S. Feng, L. Wang, T. Belwal, L. Li, Z. Luo, Phytosterols extraction from hickory (Carya cathayensis Sarg.) husk with a green direct citric acid hydrolysis extraction method, Food Chem. 315 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodchem.2020.126217.

[80] L. Schwingshackl, H. Heseker, E. Kiesswetter, B. Koletzko, Reprint of: dietary fat and fatty foods in the prevention of non-communicable diseases: a review of the evidence, Trends Food Sci. Technol. 130 (2022) 20-31, https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.tifs.2022.10.011.

[81] M. Wiesner, F.S. Hanschen, R. Maul, S. Neugart, M. Schreiner, S. Baldermann, Nutritional Quality of Plants for Food and Fodder, second ed., Elsevier, 2016 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394807-6.00128-3.

[82] S. Kazaz, R. Miray, L. Lepiniec, S. Baud, Plant monounsaturated fatty acids: diversity, biosynthesis, functions and uses, Prog. Lipid Res. 85 (2022), https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2021.101138.

[83] C. Cannavacciuolo, A. Napolitano, E.H. Heiss, V.M. Dirsch, S. Piacente, Portulaca oleracea, a rich source of polar lipids: chemical profile by LC-ESI/LTQOrbitrap/ MS/MSn and in vitro preliminary anti-inflammatory activity, Food Chem. 388 (2022) 132968, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132968.

[84] R. Vardanega, F.S. Fuentes, J. Palma, W. Bugueño-Muñoz, P. Cerezal-Mezquita, M.C. Ruiz-Domínguez, Valorization of granadilla waste (Passiflora ligularis, Juss.) by sequential green extraction processes based on pressurized fluids to obtain bioactive compounds, J. Supercrit. Fluids 194 (2023) 1-10, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.supflu.2022.105833.

[85] G. Britton, Getting to Know Carotenoids, first ed., Elsevier Inc., 2022 https://doi. org/10.1016/bs.mie.2022.04.005.

[86] G. Britton, Carotenoid research: history and new perspectives for chemistry in biological systems, Biochim. Biophys. Acta – Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1865 (2020) 158699, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158699.

[87] A.R. Al-Hilphy, A.H.K. Ahmed, M. Gavahian, H.H. Chen, F. Chemat, T.K.M. AlBehadli, M.Z. Mohd Nor, S. Ahmad, Solar energy-based extraction of essential oils from cloves, cinnamon, orange, lemon, eucalyptus, and cardamom: a clean energy technology for green extraction, J. Food Process. Eng. 45 (2022) e14038, https://doi.org/10.1111/JFPE. 14038.

[88] T. Guo, Q. Hao, Z. Nan, C. Wei, J. Liu, Green Extraction and Separation of Dendranthema Indicum Essential Oil by Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction Combined with Molecular Distillation, Elsevier, 2022. https://www.sciencedirec t.com/science/article/pii/S0959652622037805?casa_token=bsa1a FYJ1P4AAAAA:auoPadoJ332mZyH_tOd-LQ6XBnaUTqBYwqDZgeiMV9QENh EUdccIm6Gk_3i05Fmup29pFkmeivM. (Accessed 26 July 2023).

[89] Á. Santana-Mayor, R. Rodríguez-Ramos, A.V. Herrera-Herrera, B. SocasRodríguez, M.Á. Rodríguez-Delgado, Deep eutectic solvents. The new generation of green solvents in analytical chemistry, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 134 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2020.116108.

[90] C. Cannavacciuolo, S. Pagliari, J. Frigerio, C.M. Giustra, M. Labra, L. Campone, Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADESs) combined with sustainable extraction techniques: a review of the green chemistry approach in food analysis, Foods 12 (2023), https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12010056.

[91] C. Benoit, C. Virginie, The Use of NADES to Support Innovation in the Cosmetic Industry, Elsevier, 2021. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii /S0065229620300525?casa_token=iqdToUoEPq4AAAAA:rrGmzjs5lxZ71GBZ EMdi7PugYjokqUsEbcXoL9PnQ3GE1LJsDDqXmXA6VOnAjnJ7G3OKxG8jT_4. (Accessed 26 July 2023).

[92] N. Maravić, N. Teslić, D. Nikolić, I. Dimić, Z. Sereš, B. Pavlić, From agricultural waste to antioxidant-rich extracts: green techniques in extraction of polyphenols from sugar beet leaves, Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 28 (2022) 1-12, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scp.2022.100728.

[93] A. Stupar, V. Šeregelj, B.D. Ribeiro, L. Pezo, A. Cvetanović, A. Mišan, I. Marrucho, Recovery of

[94] L.M. de Souza Mesquita, L.S. Contieri, F.H.B. Sosa, R.S. Pizani, J. Chaves, J. Viganó, S.P.M. Ventura, M.A. Rostagno, Combining eutectic solvents and pressurized liquid extraction coupled in-line with solid-phase extraction to recover, purify and stabilize anthocyanins from Brazilian berry waste, Green Chem. 25 (2023) 1884-1897, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2GC04347E.

[95] J.C. Kessler, V. Vieira, I.M. Martins, Y.A. Manrique, P. Ferreira, R.C. Calhelha, A. Afonso, L. Barros, A.E. Rodrigues, M.M. Dias, Chemical and organoleptic properties of bread enriched with Rosmarinus officinalis L.: the potential of natural extracts obtained through green extraction methodologies as food ingredients, Food Chem. 384 (2022) 132514, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodchem.2022.132514.

[96] S. Porras, R. Saavedra, L. Sierra, R.G. Molecules, Chemical Characterization and Determination of the Antioxidant Properties of Phenolic Compounds in Three Scutellaria Sp. Plants Grown in Colombia, 2023. https://www.mdpi.com/ 1420-3049/28/8/3474. (Accessed 26 July 2023).

[97] F.J. Leyva-Jiménez, Á. Fernández-Ochoa, M. de la L. Cádiz-Gurrea, J. LozanoSánchez, R. Oliver-Simancas, M.E. Alañón, I. Castangia, A. Segura-Carretero, D. Arráez-Román, Application of response surface methodologies to optimize high-added value products developments: cosmetic formulations as an example, Antioxidants 11 (2022) 1552, https://doi.org/10.3390/ANTIOX11081552. Page 155211.

[98] M. Abdin, Y.S. Hamed, H. Muhammad, S. Akhtar, D. Chen, S. Mukhtar, Original Article Extraction Optimisation , Antioxidant Activity and Inhibition on a -amylase and Pancreatic Lipase of Polyphenols from the Seeds of Syzygium Cumini, 2019, pp. 2084-2093, https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.14112.

[99] P. Kaur, J. Subramanian, A. Singh, Green extraction of bioactive components from carrot industry waste and evaluation of spent residue as an energy source, Sci. Rep. 12 (2022) 1-16, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20971-5.

[100] A. del P. Sánchez-Camargo,E.I.-G. extraction, undefined 2017, Bioactives obtained from plants, seaweeds, microalgae and food by-products using pressurized liquid extraction and supercritical fluid extraction, Books.Google. ComA Del Pilar Sánchez-Camargo, E Ibáñez, A Cifuentes, M HerreroGreen Extr. Tech. Princ. Adv. Appl. 2017

[101] Y.P.A. Silva, T.A.P.C. Ferreira, G. Jiao, M.S. Brooks, Sustainable approach for lycopene extraction from tomato processing by-product using hydrophobic eutectic solvents, J. Food Sci. Technol. 56 (2019) 1649-1654, https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s13197-019-03618-8.

[102] A. Stupar, V. Šeregelj, B.D. Ribeiro, L. Pezo, A. Cvetanović, A. Mišan, I. Marrucho, Recovery of

[103] N. Guo, Ping-Kou, Y.W. Jiang, L.T. Wang, L.J. Niu, Z.M. Liu, Y.J. Fu, Natural deep eutectic solvents couple with integrative extraction technique as an effective approach for mulberry anthocyanin extraction, Food Chem. 296 (2019) 78-85, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2019.05.196.

[104] J. Jacyna, M. Kordalewska, M.J. Markuszewski, Design of Experiments in metabolomics-related studies: an overview, J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 164 (2019) 598-606, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2018.11.027.

[105] L. Barrentine, An Introduction to Design of Experiments, 2001. https://books.goo gle.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=-uqiEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&ots=njla 2wKDyi&sig=U3r2xRSgFt219NT1ZhLJGTmjTrQ. (Accessed 26 July 2023).

[106] D. Montgomery, Design and Analysis of Experiments, 2017. https://books.google. com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Py7bDgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&ots=X7y_o 5QOZ4&sig=b46B2BAgdUS-7jzyZS6wjmf_r1U. (Accessed 26 July 2023).

[107] N. Rahman, A. Raheem, Graphene oxide/Mg-Zn-Al layered double hydroxide for efficient removal of doxycycline from water: taguchi approach for optimization, J. Mol. Liq. 354 (2022) 118899, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. MOLLIQ.2022.118899.

[108] I. Pagano, L. Campone, R. Celano, A.L. Piccinelli, L. Rastrelli, Green nonconventional techniques for the extraction of polyphenols from agricultural food by-products: a review, J. Chromatogr. A 1651 (2021) 462295, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/J.CHROMA. 2021.462295.

[109] S. Pagliari, R. Celano, L. Rastrelli, E. Sacco, F. Arlati, M. Labra, L. Campone, Extraction of methylxanthines by pressurized hot water extraction from cocoa shell by-product as natural source of functional ingredient, LWT 170 (2022) 114115, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LWT.2022.114115.

[110] S. Pagliari, C.M. Giustra, C. Magoni, R. Celano, P. Fusi, M. Forcella, G. Sacco, D. Panzeri, L. Campone, M. Labra, Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of naturally occurring glucosinolates from by-products of Camelina sativa L. and their effect on human colorectal cancer cell line, Front. Nutr. 9 (2022) 901944, https://doi.org/10.3389/FNUT.2022.901944/BIBTEX.

[111] L.W. Condra, Reliability improvement with design of experiments, Reliab. Improv. with Des. Exp. (2018), https://doi.org/10.1201/9781482270846/ RELIABILITY-IMPROVEMENT-DESIGN-EXPERIMENT-LLOYD-CONDRA.

[112] S.L.C. Ferreira, M.M. Silva Junior, C.S.A. Felix, D.L.F. da Silva, A.S. Santos, J. H. Santos Neto, C.T. de Souza, R.A. Cruz Junior, A.S. Souza, Multivariate optimization techniques in food analysis – a review, Food Chem. 273 (2019) 3-8, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2017.11.114.

[113] R.K.-S. handbook of quantitative methods in psychology, undefined 2009, Experimental design, Torrossa.ComRE KirkSage Handb. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2009

[114] J.D. Kechagias, K.E. Aslani, N.A. Fountas, N.M. Vaxevanidis, D.E. Manolakos, A comparative investigation of Taguchi and full factorial design for machinability prediction in turning of a titanium alloy, Measurement 151 (2020) 107213, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MEASUREMENT.2019.107213.

[115] B. Durakovic, Design of experiments application, concepts, examples: state of the art, Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 5 (2017) 421-439, https://doi.org/10.21533/pen. v5i3.145.

[116] L.S. de Lima, M.D.M. Araujo, S.P. Quináia, D.W. Migliorine, J.R. Garcia, Adsorption modeling of

[117] S. Heydari, L. Zare, S. Eshagh Ahmadi, Removal of phenolphthalein by aspartame functionalized dialdehyde starch nano-composite and optimization by Plackett-Burman design, J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 18 (2021) 3417-3427, https://doi. org/10.1007/S13738-021-02275-Z/TABLES/9.

[118] R.L. Plackett, J.P. Burman, The design of optimum multifactorial experiments author(s), Biometrika 33 (1946) 305-325.

[119] M. Ahmadi, F. Vahabzadeh, B. Bonakdarpour, E. Mofarrah, M. Mehranian, Application of the central composite design and response surface methodology to the advanced treatment of olive oil processing wastewater using Fenton’s peroxidation, J. Hazard Mater. 123 (2005) 187-195, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. JHAZMAT. 2005.03.042.

[120] N. Pandey, C. Thakur, Statistical comparison of response surface methodology-based central composite design and hybrid central composite design for paper mill wastewater treatment by electrocoagulation, Process Integr. Optim. Sustain. 4 (2020) 343-359, https://doi.org/10.1007/S41660-020-00123W/FIGURES/9.

[121] U.M.F.M. Cerqueira, M.A. Bezerra, S.L.C. Ferreira, R. de Jesus Araújo, B.N. da Silva, C.G. Novaes, Doehlert design in the optimization of procedures aiming food analysis – a review, Food Chem. 364 (2021) 130429, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. FOODCHEM.2021.130429.

[122] S.L.C. Ferreira, R.E. Bruns, H.S. Ferreira, G.D. Matos, J.M. David, G.C. Brandão, E. G.P. da Silva, L.A. Portugal, P.S. dos Reis, A.S. Souza, W.N.L. dos Santos, BoxBehnken design: an alternative for the optimization of analytical methods, Anal. Chim. Acta 597 (2007) 179-186, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2007.07.011.

[123] S.F.C. Guerreiro, J.F.A. Valente, J.R. Dias, N. Alves, Box-behnken design a key tool to achieve optimized PCL/Gelatin Electrospun mesh, Macromol. Mater. Eng. 306 (2021) 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1002/mame. 202000678.

[124] N.M. Abd-El-Aziz, M.S. Hifnawy, A.A. El-Ashmawy, R.A. Lotfy, I.Y. Younis, Application of Box-Behnken design for optimization of phenolics extraction from Leontodon hispidulus in relation to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic activities, Sci. Rep. 12112 (2022) 1-16, https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-022-12642-2.

- Corresponding author.University of Milano-Bicocca Department of Biotechnology and Bioscience -BtBs- Piazza, Della Scienza 4, 20126, Milano, Italy

E-mail address: luca.campone@unimib.it (L. Campone).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2024.117627

Publication Date: 2024-02-29

Critical analysis of green extraction techniques used for botanicals: Trends, priorities, and optimization strategies-A review

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Green chemistry

Natural products

Design of experiment

Botanicals

Life cycle assessment PLE

SFE

MAE

UAE

Contents

Abstract

Botanicals are widely used and marketed as food supplements or cosmetics with particular benefits for human health. Botanicals are products manufactured using natural components derived from plants, algae, fungi or lichens. Given the easy accessibility of such products, it is essential to ensure their safety by guaranteeing the absence of chemical or microbiological contamination. Furthermore, since botanicals are derived from natural products, they consist of a set of molecules called a phytocomplex, and it is important to develop standardized methods to ensure their reproducibility. Traditional approaches to the extraction of phytochemicals, as described in the monographs or pharmacopoeias of international authorities, guarantee product integrity with low levels of impurities and degradation products, but use large quantities of organic solvents with long timescales, high costs and environmental impact. A green chemistry approach is preferable to improve consumer safety, improve the extraction process and preserve the environmental status. This can be achieved by using advanced extraction methods that have proven effective in the extraction of natural molecules, such as microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) and pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) combined with GRAS solvents or unconventional solvents, such as natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES). In the chemistry of natural products, the extraction phase is a fundamental step and the one most responsible for environmental sustainability. There are usually many parameters that need to be monitored and optimized to ensure the optimized conditions of these techniques. More than the empirical one variable at a time (OVAT) approach, Design of Experiments (DoE) is required to understand the effects of multidimensionality and interactions of input factors on the output responses of the extraction phase. To date, there are no specific metrics for the extraction phase, therefore, it is necessary to identify the parameters responsible for the environmental impact of the extraction phase and to optimize them in order to increase the eco-sustainability of the analytical process. The actual review provides a critical analysis of the current green extraction procedures in natural product chemistry aimed to provide insights into strategies to improve both extraction efficiency and ecosustainability.

1. Introduction

plants, algae, fungi or lichens. The market channels of these products are largely diffused through direct and online channel marketing making them easily accessible to consumers. While most of these products have a long history of use in Europe, some concerns exist about their safety and quality. These include the risk of chemical or microbiological contamination and the need to ensure that concentrations of bioactive agents are within safe limits. In the European Union (EU) the discussion about regulation of the botanical products started in 2004, and in 2009, EFSA’s Scientific Committee draw up a guidance document for the safety assessment related to the use as ingredients in food supplements and the

liquid extraction”, “experimental design”, “green solvents” and “life cycle assessment”. A total of 39 English language papers were selected for data discussion. Papers not related to plant matrices and those using non-sustainable extraction techniques were excluded from the search.

2. Critical analysis of extraction methods

2.1. Trends and overview of the advanced extraction methods

Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) is a separation technique used to extract desired components from various substances using supercritical fluids as the extracting solvent. SFE (Fig. 2) uses fluids in supercritical state, a state of matter that exists above its critical temperature and critical pressure where its exhibiting both liquid and gas-like properties [13]. Each gas or molecule in the specific condition of pressure and

Advantages and limitation of enhanced extraction techniques.

| Extraction technique | advantage | disadvantage | references | ||

| MicrowaveAssisted Extraction (MAE) | – Rapid extraction time -Low energy consumption -Low costs of the equipment -Solvent is not necessary | -Uncontrolled heating of sample may affect extraction efficiency of heat-labile compounds -Non-selective extraction -Short penetration depth of microwave upon scaling up | [20-22, 50] | ||

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | -High selectivity by the control of temperature and pressure affecting solvation power -Mass transfer and higher extraction yield enhanced by low viscosity and high diffusion rate of supercritical fluids -Recovery of heat-labile compounds operating at mild temperatures -Gas depressurization assists the recovery of extracted compounds, also in the presence of low ratio solvent -Recyclability of supercritical fluid. | -High cost of the equipment -Complex configuration of the system -Strict environmental monitoring for gas releasing -Low selectivity towards polar compounds. | [8,15,51] | ||

| Pressurized Liquid | -Reduced extraction time; | -high cost of the equipment | [28,52] | ||

| Extraction (PLE) |

|

-rigorous optimization of extraction parameters temperature and pressure -heating for a long time may cause the degradation of thermolabile compounds | |||

| UltrasoundAssisted Extraction (UAE) | -Low energy consumption -Rapid extraction time -Low amount of solvent | [21, 33-35,53] | |||

| -Non-selective extraction; -thermal degradation of the heat-labile compound; -the aging of the instrument decreases ultrasound intensity, thus reducing the reproducibility | |||||

| EnzymeAssisted Extraction (EAE) | -Uses water as solvent. -Suitable to separate bound compounds. | -Enzyme sensitivity. -Difficult to scale up to industrial applications. -Expensive price of enzyme for large volume of samples | [40] | ||

| Pulsed Eelctric Field Extraction (PEFE) | -Rapid extraction time -Low-temperature performance -Extraction of heat-lable molecules; | -High costs for maintenance. -Accurate control of parameters. | [38] |

allow the reduction of surface tension, viscosity of the solvent, ensuring an easier mass transfer rate and diffusion, and decreasing the extraction time and solvent consumption (Fig. 2) [28]. To date, PLE is a widely used technique to improve extraction yields and recovery of bioactive compounds. As there are several parameters (temperature, number of cycles, extraction time and solvent composition) that can significantly affect PLE extraction, it is important to optimize the process to maximise bioactive recovery and improve extraction efficiency. Chada et al. [30] optimized the PLE parameters (

less time-consuming, using less solvent, and lower temperatures of extraction compared with other extraction techniques; those advantages make PEFE a good method for industrial application (Fig. 2). Segovia et al. (2015) found that PEFE increased total phenolic content and oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) values by

2.2. Eco-sustainability assessment of green extractions in natural product chemistry

chemistry, and it has been identified as one of the most critical steps from the GCA point of view because it is responsible for the consumption of solvent, energy, and consumable materials or devices.

extraction step in natural product chemistry, but, to date, it has only been applied to the assessment of the sustainability of analytical procedures for the determination of contaminants [65].

environmentally friendly for the extraction of polyphenols from Moringa oleifera leaves [70].

2.3. Criteria of selection for botanicals and related products

2.3.1. Extraction of natural compounds from botanicals

and longer time of the extraction for the recovery considerable yield of compounds. Beyond the large use of conventional procedures for the standardized recovery of polyphenolics, the advanced extraction methods perform efficient and lower costs extraction of polyphenols recovering the maximum yield of polyphenols with less amount of solvent in a shorter extraction time [14,77]. Reported experimental results highlighted that green techniques are more effective in recovering secondary metabolites. A suitable combination of green solvents and extraction techniques can be tailored for specific purposes by adopting appropriate technologies and extraction conditions to obtain a different composition of bioactive compounds in the final product from the same matrix [78].

Optimized condition for the selective extraction of botanicals by green extraction techniques.

| Matrix | Target compounds | Extraction technique | Specific parameter | Extraction yield | reference | |||||||

| Granadilla seeds | UFA oil | SFE-

|

|

24.97% | [84] | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Granadilla seeds | Phenolics | PLE |

|

|

[84] | |||||||

| R. officinalis | Terpenes | SFE-

|

|

|

[95] | |||||||

| Scutellaria incarnata | Phenols | UAE |

|

– | [96] | |||||||

| Scutellaria coccinea | Phenols | UAE |

|

– | [96] | |||||||

| Scutellaria ventenatii | Phenols | UAE |

|

– | [96] | |||||||

| Lippia citriodora | Phenylpropanoids and flavonoids | SFE-

|

|

|

[97] | |||||||

| Syzygium cumini | Phenols | UAE |

|

|

[98] | |||||||

| Beta vulgaris | Phenols | UAE |

|

32.17% | [92] | |||||||

| Beta vulgaris | Phenols | MAE | 10 min 600 W | 37.04% | [92] | |||||||

| Beta vulgaris | Phenols | PLE |

|

32.85% | [92] | |||||||

| Beta vulgaris | Phenols | SFE-

|

|

28.84% | [92] | |||||||

| Carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) | Carotenoids | MAE |

|

19.2% | [99] | |||||||

| Mango peel (Mangifera indica L.) |

|

SFE-

|

|

|

[100] | |||||||

| Tomato by-products (Solanum lycopersicum) | Lycopene | UAE |

|

|

[101] | |||||||

| Pumpkin by-products (Cucurbita maxima) |

|

UAE |

|

|

[102] | |||||||

| Dendranthema indicum | Essential oils | SFE |

|

9.37% | [103] | |||||||

| cloves, cinnamon barks, orange and lemon peels, eucalyptus leaves, cardamom seeds | Essential oils | Solar energy-based extraction system (SEE) |

|

13.4-15.3% (clover),

|

[87] |

for their functions in human health as antioxidant activity, cancer-preventing, and eye condition improvement [86]. The conventional solvents used for the extraction of carotenoids from foods is made by

aromatherapy [87]. The recovery of the high-value oils is commonly obtained by conventional methods such as hydro distillation (HD), cold pressing, enfleurage, solvent extraction, and simultaneous distillation exerting low extraction efficiency, great thermal decomposition or hydrolysis of unsaturated ester compounds, and the possible residual organic solvents in essential oils [88]. On the other hand, green approaches were developed to optimize the process in the extraction of essential oils. The supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of Dendranthema indicum combined with the molecular distillation performed by Guo et al., 2022, provided an extraction yield of

2.4. Selection of the solvent in green chemistry

2.4.1. Green techniques and solvent combination in botanicals

environment, and health. Water is the safer extraction solvent with biological compatibility but the capacity in the extraction of plant bioactives is very limited. Despite its behaviour, the conditions of temperatures and pressure in subcritical water extraction (SWE) shifted water polarity towards less polar organic solvents and potentially increased extraction yield of compounds with intermediate polarity [92]. Maravìc et al., 2022 described the phenolic profile of sugar beet leaves extracts (Beta vulgaris L.) and related antioxidant capacity largely depended on the applied extraction technique and the solvents. Vitexin revealed the most abundant phenolic compound present in all extracts. The comparison between antioxidant capacity of the extracts was investigated through DPPH, FRAP and ABTS, indicating the lowest antioxidant activity of extracts obtained by solid/liquid extraction compared to other extraction techniques. In particular, the effect of water in the SWE technique revealed a higher efficiency in the higher tested temperature of

3. Rational optimization of extraction variables

3.1. One-variable-at-a-time vs. design of experiments

possible to maximise the efficiency of the extraction process by combining innovative unconventional extraction techniques with an appropriate experimental design. This is particularly important when the starting matrix is of plant origin and therefore rich in natural compounds. The use of experimental designs can ensure greater extractive selectivity and greater recovery of functional ingredients. Experimental designs can also reduce the number of experiments required, thereby reducing cost, time and environmental impact [97].

3.2. Design of experiment (DoE)

process, and for this reason different models for multivariate analysis are currently available. In particular, we can distinguish between methods for the preliminary evaluation of the factors to be considered and methods for the optimization of the response

3.2.1. Preliminary factors screening

- Full Factorial Design (

): in this model 2 represents number of levels and k is the number of factors investigated. Indicated for noncontinuous variables. It allows the effects and significance of each factor and their interactions to be defined. However, it is not suitable if the number of factors investigated is too high ( ) [114,115]. – Fractional factorial design ( ): this model is applicable when FFD would result in too large a number of experiments or if it is suspected that the interactions between factors are negligible. In fact, FFD provides information on the significance of the independent variables but not on their interactions, the effects of the main factors being confused with those of the interactions between factors [116]. – Plackett-Burman design: this is a very simple method that can be used for factor screening. It is often selected precisely because of its simplicity, which allows a small number of experiments to be performed. Also, in this case, factor interactions are not evaluated. Economical and efficient option for assessing the robustness of the data [117,118].

3.2.2. Optimization of extraction conditions

- Central Composite Design (CCD): has a full or fractional 2-level factorial design (which has an advantage because it can also be run as a screening), a central pento, and two axial points. The disadvantage of this approach is the application of experiments with all factors at positive and negative levels with the risk that runs with extreme conditions that may give misleading results [119,120].

- The Doehlert matrix: is an economical, versatile and efficient approach to modelling experimental data. An important feature of this design is the possibility of studying different variables and different numbers of levels of the same matrix, making it particularly suitable for studies in which one variable is considered more closely on a different number of levels. Finally, it requires a reduced number of experimental points, thus being very efficient and economical compared to other models such as the CCD and Box-Behnken design [121].

- The 3-level factor design: this approach requires a high number of experiments to obtain a quadratic model and involves experiments with all positive and negative factors. It cannot be applied with

[112].

Box-Behnken design: Originated in the 1960 s as a modification of the 3-level factorial plan in which a factor must necessarily be maintained at its mean value (zero point) in every experiment. In addition, this model also includes at least one experiment in which all factors are at the “zero” value, called center points. Increasing the number of center points in an experimental design using the BoxBehnken approach makes it possible to increase the degrees of freedom, namely the accuracy of the data obtained by being able to highlight any anomalies during the execution of the experimental design [122-124].

4. Conclusion and future perspectives

components, plants metabolites have numerous applications in nutraceutical and cosmetic industry. Among the rising diffused plant-based products, botanicals are health promoting products with increasing interest in market. The recovery of bioactive components from plants and their by-products is related to extraction process provided by a balance between the performance of extraction techniques and the solvents used as mass transfer media from the matrix. This review provides a critical insight into current green extraction procedure in the natural product chemistry. Its purpose was to provide updating on strategies for improving both extraction efficiency and eco-sustainability.

Funding

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Data availability

Acknowledgment

References

[2] M.Y. Heng, S.N. Tan, J.W.H. Yong, E.S. Ong, Emerging green technologies for the chemical standardization of botanicals and herbal preparations, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 50 (2013) 1-10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2013.03.012.

[3] D.K. Singh, A. Sahu, S. Kumar, S. Singh, Critical review on establishment and availability of impurity and degradation product reference standards, challenges faced by the users, recent developments, and trends, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 101 (2018) 85-107, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2017.10.021.

[4] J.C. Prata, T. Rocha-Santos, A.I. Ribeiro, An introduction to the concept of One Health, One Heal. Integr. Approach to 21st Century Challenges to Heal (2022) 1-31, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822794-7.00004-6.

[5] S. Armenta, S. Garrigues, M. de la Guardia, The role of green extraction techniques in Green Analytical Chemistry, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 71 (2015) 2-8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2014.12.011.

[6] T. Belwal, S.M. Ezzat, L. Rastrelli, I.D. Bhatt, M. Daglia, A. Baldi, H.P. Devkota, I. E. Orhan, J.K. Patra, G. Das, C. Anandharamakrishnan, L. Gomez-Gomez, S. F. Nabavi, S.M. Nabavi, A.G. Atanasov, A critical analysis of extraction techniques used for botanicals: trends, priorities, industrial uses and optimization strategies, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 100 (2018) 82-102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. trac.2017.12.018.

[7] P. Yu, M.Y. Low, W. Zhou, Design of experiments and regression modelling in food flavour and sensory analysis: a review, Trends Food Sci. Technol. 71 (2018) 202-215, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.11.013.

[8] C. Picot-Allain, M.F. Mahomoodally, G. Ak, G. Zengin, Conventional versus green extraction techniques – a comparative perspective, Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 40 (2021) 144-156, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COFS.2021.02.009.

[9] T. Belwal, F. Chemat, P.R. Venskutonis, G. Cravotto, D.K. Jaiswal, I.D. Bhatt, H. P. Devkota, Z. Luo, Recent advances in scaling-up of non-conventional extraction techniques: learning from successes and failures, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 127 (2020) 115895, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TRAC.2020.115895.

[10] M. Garcia-Vaquero, G. Rajauria, B. Tiwari, Conventional extraction techniques: solvent extraction, Sustain. Seaweed Technol. Cultiv. Biorefinery, Appl. (2020) 171-189, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817943-7.00006-8.

[11] M. Ramos, A. Jiménez, M.C. Garrigós, Il-based advanced techniques for the extraction of value-added compounds from natural sources and food by-products, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 119 (2019) 115616, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. TRAC.2019.07.027.

[12] A.C. Diamanti, P.E. Igoumenidis, I. Mourtzinos, K. Yannakopoulou, V. T. Karathanos, Green extraction of polyphenols from whole pomegranate fruit using cyclodextrins, Food Chem. 214 (2017) 61-66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodchem.2016.07.072.

[13] S.P. Ishwarya, P. Nisha, Headway in Supercritical Extraction of Fragrances and Colors, Elsevier, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-100596-5.22677-2.

[14] C. Picot-Allain, M.F. Mahomoodally, G. Ak, G. Zengin, Conventional versus green extraction techniques – a comparative perspective, Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 40 (2021) 144-156, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2021.02.009.

[15] C. Da Porto, D. Decorti, A. Natolino, Water and ethanol as co-solvent in supercritical fluid extraction of proanthocyanidins from grape marc: a comparison and a proposal, J. Supercrit. Fluids 87 (2014) 1-8, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.supflu.2013.12.019.

[16] A. Rajaei, M. Barzegar, Y. Yamini, Supercritical fluid extraction of tea seed oil and its comparison with solvent extraction, Eur. Food Res. Technol. 220 (2005) 401-405, https://doi.org/10.1007/S00217-004-1061-8/TABLES/3.

[17] S. Zhao, D. Zhang, Supercritical CO2 extraction of Eucalyptus leaves oil and comparison with Soxhlet extraction and hydro-distillation methods, Sep. Purif. Technol. 133 (2014) 443-451, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEPPUR.2014.07.018.

[18] R. Martins, A. Barbosa, B. Advinha, H. Sales, R. Pontes, J. Nunes, Green extraction techniques of bioactive compounds: a state-of-the-art review, Process 11 (2023) 2255, https://doi.org/10.3390/PR11082255.

[19] D. De Vita, S. Lachowicz, W. Wi’sniewska, L. Lajoie, A.-S. Fabiano-Tixier, F. Chemat, Water as green solvent: methods of solubilisation and extraction of natural products-past, present and future solutions, Pharm. Times 15 (1507 15) (2022) 1507, https://doi.org/10.3390/PH15121507.

[20] F.G.C. Ekezie, D.W. Sun, J.H. Cheng, Acceleration of microwave-assisted extraction processes of food components by integrating technologies and applying emerging solvents: a review of latest developments, Trends Food Sci. Technol. 67 (2017) 160-172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.06.006.

[21] M. Vinatoru, T.J. Mason, I. Calinescu, Ultrasonically assisted extraction (UAE) and microwave assisted extraction (MAE) of functional compounds from plant materials, TrAC – Trends Anal. Chem. 97 (2017) 159-178, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.trac.2017.09.002.

[22] R. Costa, The chemistry of mushrooms: a survey of novel extraction techniques targeted to chromatographic and spectroscopic screening, Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 49 (2016) 279-306, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63601-0.00009-0.

[23] A.M. Galan, I. Calinescu, A. Trifan, C. Winkworth-Smith, M. Calvo-Carrascal, C. Dodds, E. Binner, New insights into the role of selective and volumetric heating during microwave extraction: investigation of the extraction of polyphenolic compounds from sea buckthorn leaves using microwave-assisted extraction and conventional solvent extraction, Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 116 (2017) 29-39, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEP.2017.03.006.

[24] G. Silveira Da Rosa, S. Kranthi Vanga, Y. Gariepy, V. Raghavan, Comparison of Microwave, Ultrasonic and Conventional Techniques for Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Olive Leaves, Olea europaea L.), 2019, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ifset.2019.102234.

[25] Z. Rafiee, S.M. Jafari, M. Alami, M. Khomeiri, Microwave-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from olive leaves; a comparison with maceration, J. Anim. Plant Sci 21 (2011) 738.

[26] C.B.T. Pal, G.C. Jadeja, Microwave-assisted deep eutectic solvent extraction of phenolic antioxidants from onion (Allium cepa L.) peel: a Box-Behnken design approach for optimization, J. Food Sci. Technol. 56 (2019) 4211-4223, https:// doi.org/10.1007/S13197-019-03891-7/FIGURES/4.

[27] B. Zhang, R. Yang, C.Z. Liu, Microwave-assisted extraction of chlorogenic acid from flower buds of Lonicera japonica Thunb, Sep. Purif. Technol. 62 (2008) 480-483, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEPPUR.2008.02.013.

[28] G. Alvarez-Rivera, M. Bueno, D. Ballesteros-Vivas, J.A. Mendiola, E. Ibañez, Pressurized liquid extraction, Liq. Extr. (2019) 375-398, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-12-816911-7.00013-X.

[29] V. Kitrytė, A. Kavaliauskaitė, L. Tamkutė, M. Pukalskienė, M. Syrpas, P. Rimantas Venskutonis, Zero waste biorefining of lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) pomace into functional ingredients by consecutive high pressure and enzyme assisted extractions with green solvents, Food Chem. 322 (2020) 126767, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126767.

[30] P.S.N. Chada, P.H. Santos, L.G.G. Rodrigues, G.A.S. Goulart, J.D. Azevedo dos Santos, M. Maraschin, M. Lanza, Non-conventional techniques for the extraction of antioxidant compounds and lycopene from industrial tomato pomace (Solanum lycopersicum L.) using spouted bed drying as a pre-treatment, Food Chem. X 13 (2022) 100237, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOCHX.2022.100237.

[31] J. Viganó, I.Z. Brumer, P.A. de C. Braga, J.K. da Silva, M.R. Maróstica Júnior, F. G. Reyes Reyes, J. Martínez, Pressurized liquids extraction as an alternative process to readily obtain bioactive compounds from passion fruit rinds, Food Bioprod. Process. 100 (2016) 382-390, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. FBP.2016.08.011.

[32] A.P.D.F. Machado, J.L. Pasquel-Reátegui, G.F. Barbero, J. Martínez, Pressurized liquid extraction of bioactive compounds from blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L.) residues: a comparison with conventional methods, Food Res. Int. 77 (2015) 675-683, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODRES.2014.12.042.

[33] S. Bachtler, H.J. Bart, Increase the yield of bioactive compounds from elder bark and annatto seeds using ultrasound and microwave assisted extraction technologies, Food Bioprod. Process. 125 (2021) 1-13, https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.fbp.2020.10.009.

[34] L. Vernès, M. Vian, F. Chemat, Ultrasound and microwave as green tools for solidliquid extraction, Liq. Extr. (2019) 355-374, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816911-7.00012-8.

[35] C. Wen, J. Zhang, H. Zhang, C.S. Dzah, M. Zandile, Y. Duan, H. Ma, X. Luo, Advances in ultrasound assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from cash crops – a review, Ultrason. Sonochem. 48 (2018) 538-549, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.07.018.

[36] A.A. Jovanović, V.B. Đorđević, G.M. Zdunić, D.S. Pljevljakušić, K.P. Šavikin, D. M. Gođevac, B.M. Bugarski, Optimization of the extraction process of polyphenols from Thymus serpyllum L. herb using maceration, heat- and ultrasound-assisted techniques, Sep. Purif. Technol. 179 (2017) 369-380, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. SEPPUR.2017.01.055.

[37] S.A. Mousavi, L. Nateghi, M. Javanmard Dakheli, Y. Ramezan, Z. Piravi-Vanak, Maceration and ultrasound-assisted methods used for extraction of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity from Ferulago angulata, J. Food Process. Preserv. 46 (2022) e16356, https://doi.org/10.1111/JFPP. 16356.

[38] D. Niu, X.A. Zeng, E.F. Ren, F.Y. Xu, J. Li, M.S. Wang, R. Wang, Review of the application of pulsed electric fields (PEF) technology for food processing in China,

[39] F.J. Segovia, E. Luengo, J.J. Corral-Pérez, J. Raso, M.P. Almajano, Improvements in the aqueous extraction of polyphenols from borage (Borago officinalis L.) leaves by pulsed electric fields: pulsed electric fields (PEF) applications, Ind. Crops Prod. 65 (2015) 390-396, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. INDCROP.2014.11.010.

[40] F. Garavand, S. Rahaee, N. Vahedikia, S.M. Jafari, Different techniques for extraction and micro/nanoencapsulation of saffron bioactive ingredients, Trends Food Sci. Technol. 89 (2019) 26-44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.05.005.

[41] S.S. Nadar, P. Rao, V.K. Rathod, Enzyme assisted extraction of biomolecules as an approach to novel extraction technology: a review, Food Res. Int. 108 (2018) 309-330, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODRES.2018.03.006.

[42] O. Gligor, A. Mocan, C. Moldovan, M. Locatelli, G. Crișan, I.C.F.R. Ferreira, Enzyme-assisted extractions of polyphenols – a comprehensive review, Trends Food Sci. Technol. 88 (2019) 302-315, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. TIFS.2019.03.029.

[43] K.L. Nagendra Chari, D. Manasa, P. Srinivas, H.B. Sowbhagya, Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe), Food Chem. 139 (2013) 509-514, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. FOODCHEM. 2013.01.099.

[44] J.M. Awika, L.W. Rooney, X. Wu, R.L. Prior, L. Cisneros-Zevallos, Screening methods to measure antioxidant activity of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and Sorghum products, J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 (2003) 6657-6662, https://doi.org/ 10.1021/JF034790I/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/JF034790IF00005.JPEG.

[45] J.E. Cacace, G. Mazza, Pressurized low polarity water extraction of lignans from whole flaxseed, J. Food Eng. 77 (2006) 1087-1095, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. JFOODENG.2005.08.039.

[46] S.M. Choudhari, L. Ananthanarayan, Enzyme aided extraction of lycopene from tomato tissues, Food Chem. 102 (2007) 77-81, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. FOODCHEM. 2006.04.031.

[47] A. Boulila, I. Hassen, L. Haouari, F. Mejri, I. Ben Amor, H. Casabianca, K. Hosni, Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from bay leaves (Laurus nobilis L.), Ind. Crops Prod. 74 (2015) 485-493, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. INDCROP.2015.05.050.

[48] F. Sahne, M. Mohammadi, G.D. Najafpour, A.A. Moghadamnia, Enzyme-assisted ionic liquid extraction of bioactive compound from turmeric (Curcuma longa L.): Isolation, purification and analysis of curcumin, Ind. Crops Prod. 95 (2017) 686-694, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INDCROP.2016.11.037.

[49] P. Nath, C. Kaur, S.G. Rudra, E. Varghese, Enzyme-assisted extraction of carotenoid-rich extract from red Capsicum (Capsicum annuum), Agric. Res. 5 (2016) 193-204, https://doi.org/10.1007/S40003-015-0201-7/FIGURES/8.

[50] K. Suktham, P. Daisuk, A. Shotipruk, Microwave-assisted extraction of antioxidative anthraquinones from roots of Morinda citrifolia L. (Rubiaceae): Errata and review of technological development and prospects, Sep. Purif. Technol. 256 (2021) 117844, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2020.117844.

[51] L. Valadez-Carmona, A. Ortiz-Moreno, G. Ceballos-Reyes, J.A. Mendiola, E. Ibáñez, Valorization of cacao pod husk through supercritical fluid extraction of phenolic compounds, J. Supercrit. Fluids 131 (2018) 99-105, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.09.011.

[52] A.M. Pavkovich, D.S. Bell, Extraction | Pressurized Liquid Extraction, third ed., Elsevier Inc., 2019 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409547-2.14407-5.

[53] S. Roohinejad, N. Nikmaram, M. Brahim, M. Koubaa, A. Khelfa, R. Greiner, Potential of Novel Technologies for Aqueous Extraction of Plant Bioactives, Elsevier Inc., 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809380-1.00016-4.

[54] A. Gałuszka, Z. Migaszewski, J. Namieśnik, The 12 principles of green analytical chemistry and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic of green analytical practices, TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 50 (2013) 78-84, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. TRAC.2013.04.010.