DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08288-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39815097

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-15

تحويل الطاقة الكيميائية من خلال التحفيز بواسطة محرك جزيئي صناعي

تم الاستلام: 23 مايو 2024

تم القبول: 25 أكتوبر 2024

تم النشر على الإنترنت: 15 يناير 2025

الوصول المفتوح

الملخص

تظهر الخلايا مجموعة من الأنشطة الميكانيكية التي تولدها بروتينات المحرك المدعومة من خلال التحفيز

المحرك 1 (الشكل 1أ) هو نظير للمحرك الدوار المبلغ عنه سابقًا

أدى إلى تشكيل أنهدريد مؤقت (قسم المعلومات التكميلية 4.1)، مما يشير إلى أن التحولات الكيميائية الرئيسية من الحمض إلى الأنهدريد إلى الحمض في الدورة الكيميائية الميكانيكية

دمج جزيئات المحرك في إطار الجيل

التحيز الاتجاهي أثناء الوقود

أن نظام الوقود الكيرالي يولد تحيز دوران موجه مشابه في دورة المحرك الكيميائي للنموذج الجزيئي المدفوع بالتحفيز السابق

انكماش الجل المدعوم بالوقود

الشكل 2 | الانكماش الكلي للجيل-1 تحت تغذية كيميائية.

مخطط الجل قبل التعبئة

حتى بعد أن توقف الهلام عن الانكماش، استمرت عملية تحفيز ترطيب الكاربودي إيميد بواسطة المحركات المدمجة في الهلام طالما أن هناك وقود غير متفاعل متبقي أو إذا تم تجديد الوقود.

توصيف هلام مرتبط بالوقود

تشير جميع الميزات والقياسات الكلية والميكروسكوبية إلى أن انكماش الجل-1 تحت التغذية بالكاربودييميد الكيرالي ومروج التحلل المائي هو نتيجة للدوران الاتجاهي لجزيئات المحرك المدفوع بالتحفيز العضوي، مما يزيد من التشابك (الالتواء)

الكيمياء الميكانيكية عند قوة التوقف

تشغيل جزيئات المحرك في الاتجاه المعاكس

(قسم المعلومات التكميلية 6). تعكس مظهر المسام ذات القطر الميكرو متر التباينات الموجودة بشكل جوهري في مثل هذه الجل: المناطق ذات الكثافات الأعلى من المحركات تنتج المزيد من التشابكات عند التغذية، مما يترك فراغات (مسام) بينها.

تستمر دوران المحركات تحت التحفيز في الاتجاه الساعي مع عقارب الساعة ويبدأ الجل في الانكماش مرة أخرى، ليصل إلى حجم أدنى من

الهلام المتعاقد لتسريع هذه العملية هو نتيجة مباشرة لتحويل الطاقة من تفاعل الوقود إلى النفايات بواسطة تحفيز دوران المحرك خلال الانقباض الأول المدعوم بالوقود (الشكل 4c (نقاط البيانات الزرقاء)).

تحويل الطاقة من خلال عدم التماثل الحركي

سلوك الانكماش-التوسع-إعادة الانكماش المدعوم للهلام-1 عند التزويد المتكرر بأنظمة ذات تشيّع متعاكس (نقاط البيانات الزرقاء،

آلية حدوث ذلك واضحة تمامًا. حيث تحدث كلا التغيرات الشكلية الرئيسية في دورة التروس بين الأتروبيزومات المتناظرة ((+)-1 و(-)-1؛ (+)-1′ و(-)-1′)، لا يوجد هناك ضربة طاقة. إن العرض التجريبي لتحويل الطاقة الكيميائية لأداء عمل ضد حمل من خلال عدم التماثل الحركي يوفر توضيحًا آليًا بسيطًا لكيفية تمكن المحركات الجزيئية المدفوعة بالتحفيز من استخراج النظام من الفوضى.

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- شليوا، م. وويهلكي، ج. المحركات الجزيئية. ناتشر 422، 759-765 (2003).

- هوارد، ج. قوة البروتين. البيولوجيا الحالية 16، R517-R519 (2006).

- أستوميان، ر. د. عدم أهمية ضربة القوة بالنسبة للاتجاه، قوة التوقف، والكفاءة المثلى للآلات الجزيئية المدفوعة كيميائيًا. مجلة الفيزياء الحيوية. 108، 291-303 (2015).

- هوفمان، ب. م. كيف تستخرج المحركات الجزيئية النظام من الفوضى (مراجعة قضايا رئيسية). تقرير. تقدم. الفيزياء. 79، 032601 (2016).

- هوانغ، و. وكاربلوس، م. الأساس الهيكلي لآلية الضربة القوية مقابل آلية العتلة البراونية للبروتينات الحركية. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 116، 19777-19785 (2019).

- أمانو، س.، بورسلي، س.، لي، د. أ. وسون، ز. محركات كيميائية: دفع الأنظمة بعيدًا عن التوازن من خلال دورات تفاعل المحفز. نات. نانو تكنولوج. 16، 1057-1067 (2021).

- أمانو، س. وآخرون. استخدام التحفيز لدفع الكيمياء بعيدًا عن التوازن: ربط عدم التماثل الحركي، وضربات القوة ومبدأ كورتين-هاميت في رافعات براونية. ج. أم. كيم. سوس. 144، 20153-20164 (2022).

- سوييني، هـ. ل. وهدوس، أ. رؤى هيكلية ووظيفية حول آلية محرك الميوسين. مراجعة سنوية لعلم الأحياء الفيزيائية 39، 539-557 (2010).

- بورسلي، س.، كريدت، إ.، لي، د. أ. وروبرتس، ب. م. و. دوران اتجاهي مستقل مدفوع حول رابطة تساهمية مفردة. ناتشر 604، 80-85 (2022).

- أستوميان، ر. د. عدم التماثل الحركي والاتجاهية في الأنظمة الجزيئية غير المتوازنة. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناشونال. إيد. 63، e202306569 (2024).

- بورسلي، س.، لي، د. أ. وروبرتس، ب. م. و. العجلات الجزيئية والتماثل الحركي: إعطاء الكيمياء اتجاهًا. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إد. 63، e202400495 (2024).

- راجازون، ج. و برينس، ل. ج. استهلاك الطاقة في التجميع الذاتي المدفوع بالوقود الكيميائي. نات. نانو تكنولوجي. 13، 882-889 (2018).

- شوارز، ب. س.، تينا-سولسونا، م.، داي، ك. و بوكهوفن، ج. دورات التفاعل الحفاز المدفوعة بالكاربودييميد لتنظيم العمليات فوق الجزيئية. كيم. كوميونيك. 58، 1284-1297 (2022).

- سانغشاي، ت.، الشحيمي، س.، بينوتشيو، إ. وراغازون، ج. رافعات جزيئية صناعية: أدوات تمكّن العمليات الماصة للطاقة. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إيد. 62، e202309501 (2023).

- كومورا، ن.، زيلسترا، ر. و. ج.، فان ديلدن، ر. أ.، هارادا، ن. وفيرينغا، ب. ل. دوار جزيئي أحادي الاتجاه مدفوع بالضوء. ناتشر 401، 152-155 (1999).

- لي، د. أ.، وونغ، ج. ك. ي.، ديهز، ف. وزيربيتو، ف. دوران أحادي الاتجاه في دوار جزيئي متشابك ميكانيكياً. ناتشر 424، 174-179 (2003).

- غوينتر، م. وآخرون. دوران بتردد كيلوهيرتز مدعوم بأشعة الشمس لمحرك جزيئي قائم على الهيميثيوإنديجو. نات. كوميونيك. 6، 8406 (2015).

- ويلسون، م. ر. وآخرون. محرك صغير جزيئي يعمل بالوقود الكيميائي بشكل مستقل. ناتشر 534، 235-240 (2016).

- إيرباس-تشاكماك، س. وآخرون. محركات جزيئية دوارة وخطية مدفوعة بنبضات من وقود كيميائي. ساينس 358، 340-343 (2017).

- بوم، أ.-ك. وآخرون. محرك رافعة دوارة من أوريغامي الحمض النووي. ناتشر 607، 492-498 (2022).

- تشانغ، ل. وآخرون. محرك جزيئي كهربائي. ناتشر 613، 280-286 (2023).

- برير، ج. وآخرون. دوران أحادي الاتجاه مدفوع بالطاقة الحمراء عن

رابطة تحت السيطرة الإنزيمية. مسودة مسبقة فيhttps://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-tz8vc (2024). - سيريللي، ف.، لي، ج.-ف.، كاي، إ. ر. ولي، د. أ. رافعة معلومات جزيئية. ناتشر 445، 523-527 (2007).

- فنغ، ل. وآخرون. الامتصاص الميكانيكي النشط المدفوع بواسطة مضخات الكاسيت. العلوم 374، 1215-1221 (2021).

- أمانو، س.، فيلدن، س. د. ب. ولي، د. أ. مضخة جزيئية صناعية مدفوعة بالتحفيز. ناتشر 594، 529-534 (2021).

- بورسلي، س.، لي، د. أ. وروبرتس، ب. م. و. رافعة معلومات مزدوجة البوابة حركيًا مدفوعة ذاتيًا بواسطة ترطيب الكاربودييميد. ج. أم. كيم. سوس. 143، 4414-4420 (2021).

- توماس، د. وآخرون. الضخ بين المراحل باستخدام رافعة جزيئية تعمل بالوقود النبضي. نات. نانو تكنولوجي. 17، 701-707 (2022).

- كوررا، س. وآخرون. رؤى حركية وطاقة حول تشغيل مضخة فوق جزيئية مستقلة تعمل بالطاقة الضوئية في حالة عدم التوازن المبدد. نات. نانو تكنولوج. 17، 746-751 (2022).

- بينكس، ل. وآخرون. دور عدم التماثل الحركي وضربات القوة في رافعة المعلومات. كيم 9، 2902-2917 (2023).

- لي، ق. وآخرون. انكماش ماكروسكوبي لجيل ناتج عن الحركة المتكاملة لمحركات جزيئية مدفوعة بالضوء. نات. نانو تكنولوجي. 10، 161-165 (2015).

- فوي، ج. ت. وآخرون. التحكم المزدوج بالضوء في الآلات النانوية التي تدمج وحدات المحرك والمعدل. نات. نانو تكنولوجي. 12، 540-545 (2017).

- بيرو، أ.، وانغ، و.-ز.، بوهلر، إ.، مولان، إ. وجيوسيبوني، ن. تفعيل الانحناء للهيدروجيل من خلال دوران المحركات الجزيئية المدفوعة بالضوء. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إد. 62، e202300263 (2023).

- تينا-سولسونا، م. وآخرون. مواد فوق جزيئية غير متوازنة قابلة للتفكك بمدة حياة قابلة للتعديل. نات. كوميونيك. 8، 15895 (2017).

- كاريياوَسَم، ل. س. وهارتلي، س. س. التجميع المبدد لخلائط الأحماض الكربوكسيلية المائية المدعومة بالكاربودييميدات. مجلة الجمعية الأمريكية للكيمياء 139، 11949-11955 (2017).

- بورسلي، س.، لي، د. أ. وروبرتس، ب. م. و. وقود كيميائي للآلات الجزيئية. نات. كيم. 14، 728-738 (2022).

- ليانغ، ل. وأستروك، د. تفاعل الإضافة الدائرية بين الألكاين والأزيد المحفز بالنحاس (I) (CuAAC) ‘تفاعل النقر’ وتطبيقاته. نظرة عامة. مراجعات كيمياء التنسيق. 255، 2933-2945 (2011).

- هاجل، ج.، هارازتي، ت. وبوهيم، هـ. الانتشار والتفاعل في هيدروجيل PEG-DA. واجهات حيوية 8، 36 (2013).

- يافاري، ن. وأزيزيان، س. نموذج مختلط لديناميكا الانتشار والاسترخاء لتورم الهلاميات. ج. مول. ليك. 363، 119861 (2022).

- غوجون، أ. وآخرون. سلسلة دوائر دوارة ثنائية الاستقرار [c2] كمنشطات شبيهة بالعضلات قابلة للعكس في الجل النشط ميكانيكياً. مجلة الجمعية الأمريكية للكيمياء 139، 14825-14828 (2017).

- كولار-إيتي، ج.-ر. وآخرون. السلوك الميكانيكي للهلام القابل للانقباض المعتمد على المحركات الجزيئية المدفوعة بالضوء. نانو سكيل 11، 5197-5202 (2019).

- ساكاي، ت. وآخرون. تصميم وتصنيع هيدروجيل عالي القوة مع هيكل شبكة متجانس بشكل مثالي من الماكرو مونويمرات على شكل رباعي الأوجه. ماكرومولكيولز 41، 5379-5384 (2008).

- أشفريدج، ز. وآخرون. أهمية العقد: تشابكات جزيئية منظمة. مراجعات جمعية الكيمياء 51، 7779-7809 (2022).

- بايسي، م.، أورلانديني، إ. وويتنجتون، س. ج. التفاعل بين الالتواء والعقدة للبوليمرات المتورمة والمضغوطة. مجلة الكيمياء والفيزياء 131، 154902 (2009).

- هو، ل.، تشانغ، ق.، لي، إكس. وسيربي، م. ج. بوليمرات استجابة للمؤثرات للكشف والتحكم. مواد. أفق. 6، 1774-1793 (2019).

- هاوس، ج. ر. وآخرون. توليد الطاقة المتبادلة في عضلة صناعية مدفوعة كيميائيًا. نانو ليت. 6، 73-77 (2006).

- تشاتيرجي، م. ن.، كاي، إ. ر. ولي، د. أ. ما وراء المفاتيح: رفع جزيء طاقةً إلى الأعلى باستخدام آلة جزيئية مقسمة. ج. أم. كيم. سوس. 128، 4058-4073 (2006).

- بوكهوفن، ج.، هندريكسن، و. إ.، كوبر، ج. ج. م.، إيلكيما، ر. وفان إيش، ج. هـ. التجميع العابر للمواد النشطة المدعومة بتفاعل كيميائي. ساينس 349، 1075-1079 (2015).

- برونز، سي. جي. التقدم في حساء المعاني لتصنيف الآلات الجزيئية الاصطناعية. نات. نانو تكنولوجي. 17، 1231-1234 (2022).

(ج) المؤلفون 2025

طرق

طريقة تمثيلية لتكوين الجل-1

انكماش الوقود العام للجيل-1

AFM

(بروكر، ScanAsyst؛ ثابت الزنبرك لـ

قياسات الريولوجيا

توفر البيانات

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى نيكولاس جيوسيبوني أو ديفيد أ. لي.

تُعرب Nature عن شكرها لديسوكي آوكي، وجياوين تشين، والمراجعين الآخرين المجهولين، على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذا العمل.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints.

مقالة

مقالة

- ¹قسم الكيمياء، جامعة مانشستر، مانشستر، المملكة المتحدة. ²مدرسة الكيمياء والهندسة الجزيئية، جامعة شرق الصين العادية، شنغهاي، الصين. ³مجموعة أبحاث سامس، جامعة ستراسبورغ ومعهد شارل سادورن، ستراسبورغ، فرنسا.

معهد جامعة فرنسا (IUF)، باريس، فرنسا. البريد الإلكتروني:giuseppone@unistra.fr; david.leigh@manchester.ac.uk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08288-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39815097

Publication Date: 2025-01-15

Transducing chemical energy through catalysis by an artificial molecular motor

Received: 23 May 2024

Accepted: 25 October 2024

Published online: 15 January 2025

Open access

Abstract

Cells display a range of mechanical activities generated by motor proteins powered through catalysis

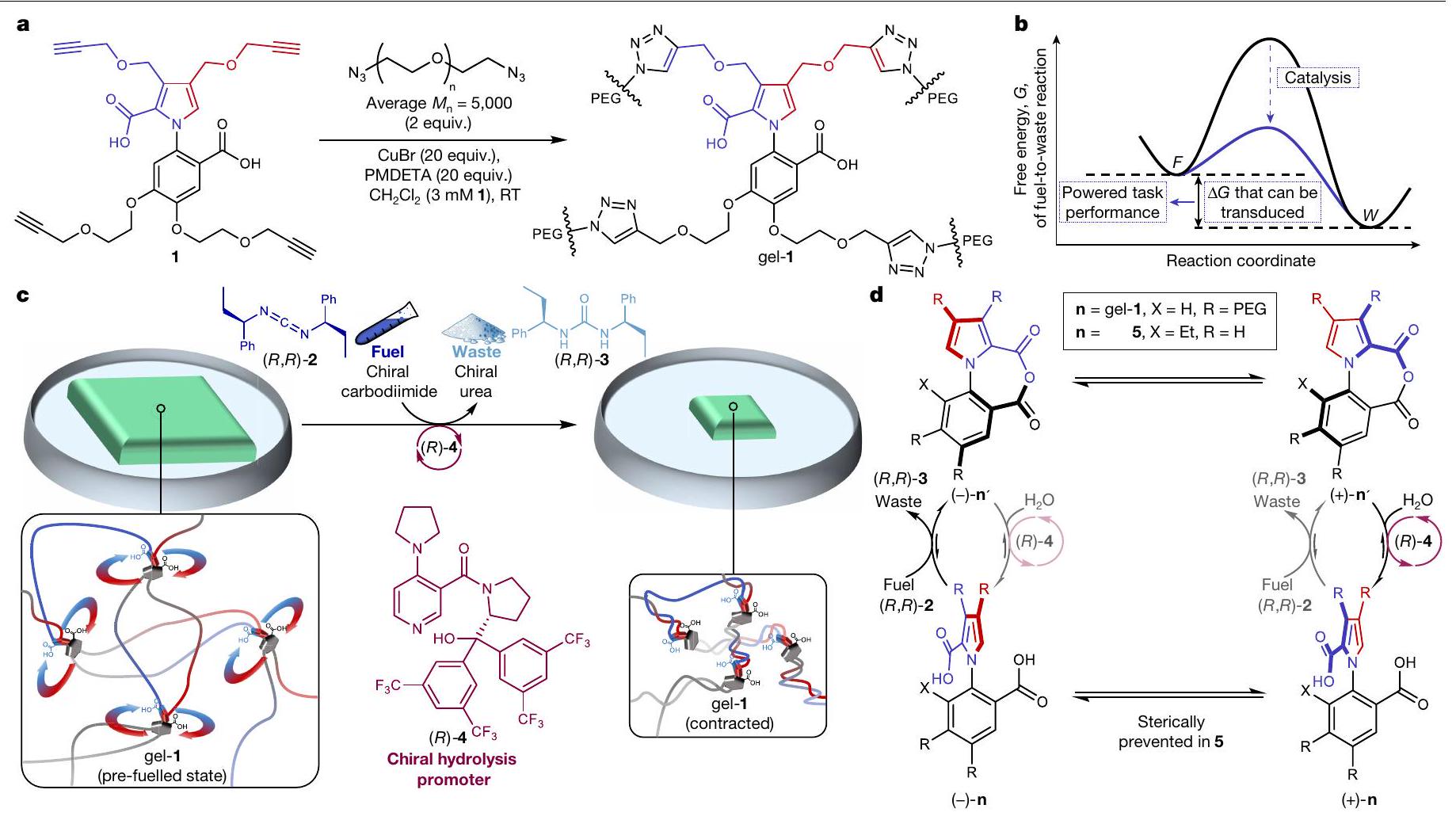

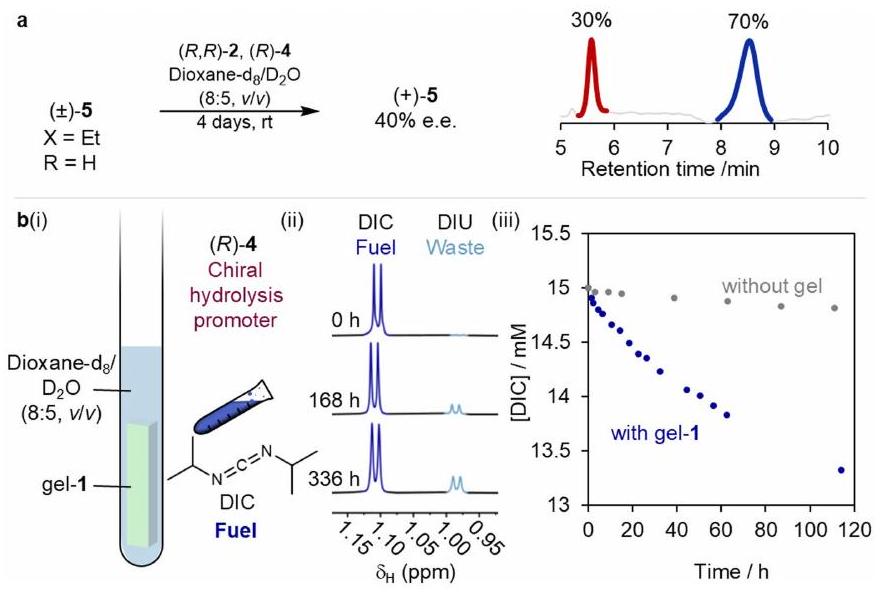

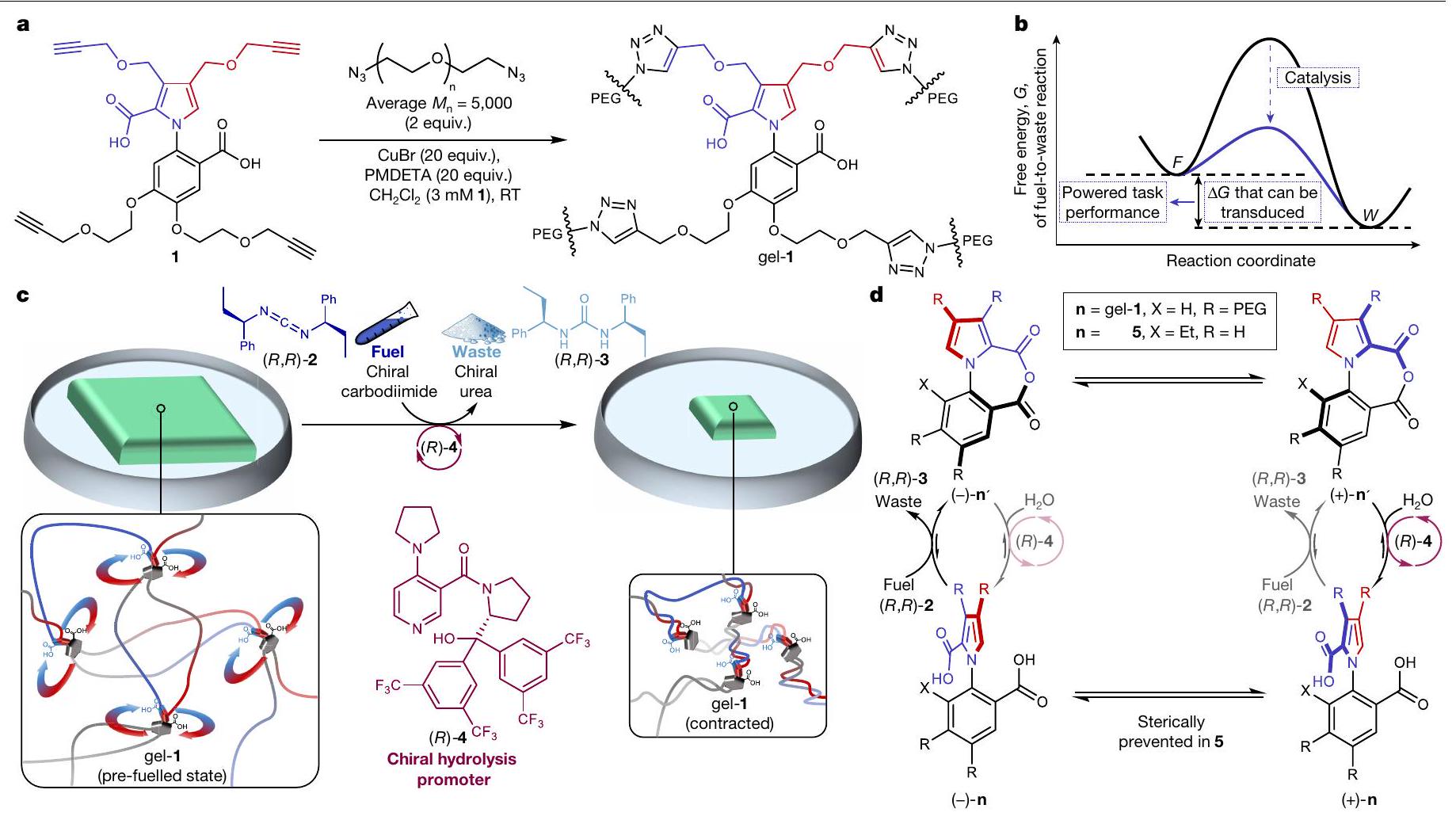

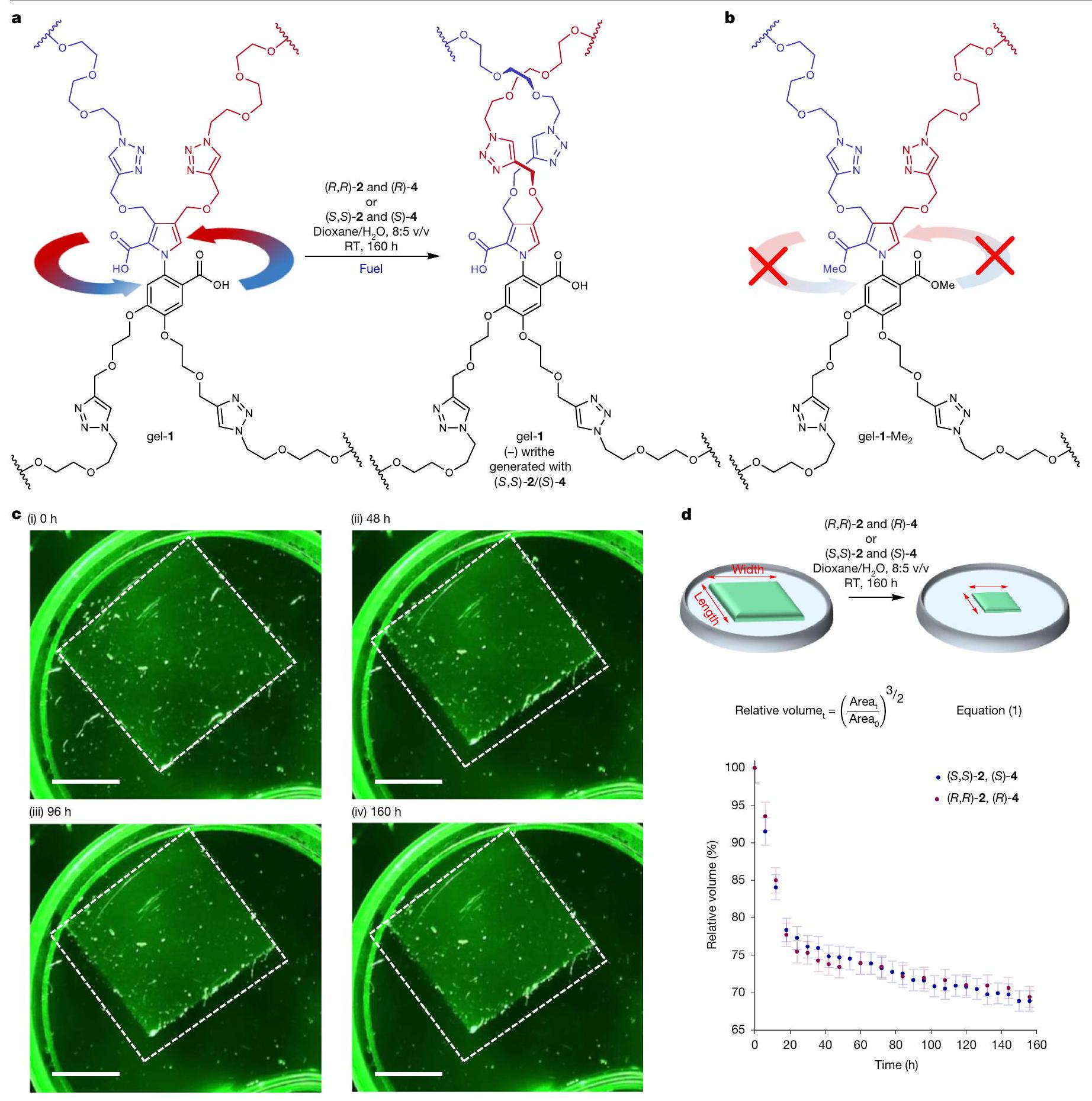

Motor 1 (Fig. 1a) is an analogue of the previously reported rotary motor

resulted in transient anhydride formation (Supplementary Information section 4.1), indicating that the key acid-to-anhydride-to-acid chemical transformations in the chemomechanical cycle

Motor-molecule incorporation into a gel framework

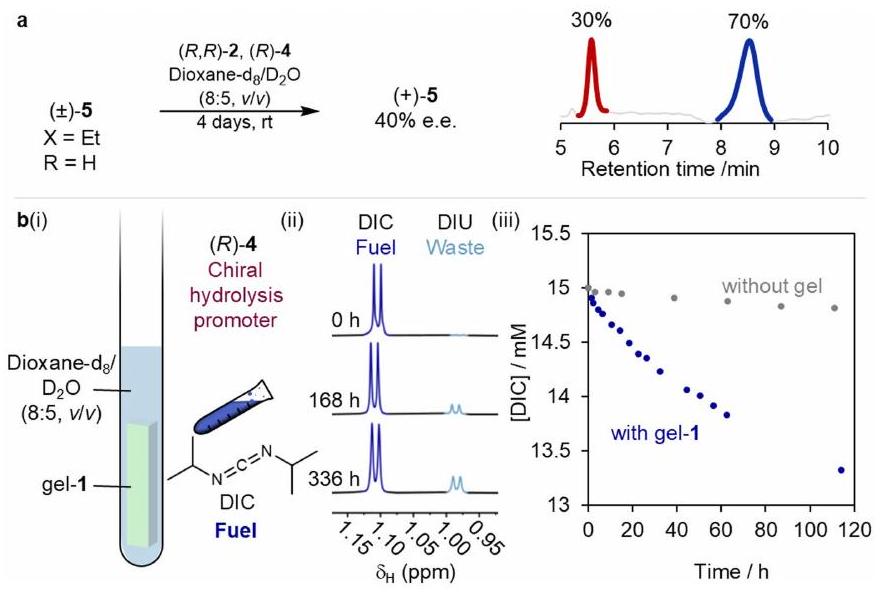

Directional bias during fuelling

that the chiral fuelling system generates similar directional rotational bias in the chemical engine cycle to the previous catalysis-driven motor molecule

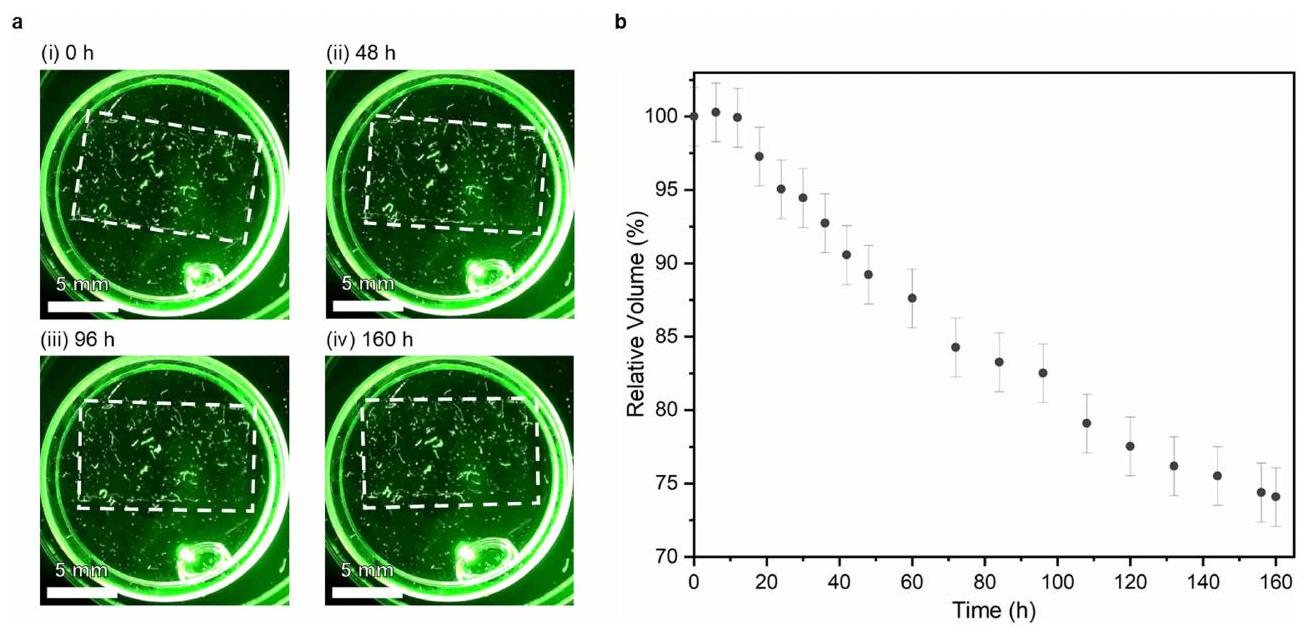

Fuelled gel contraction

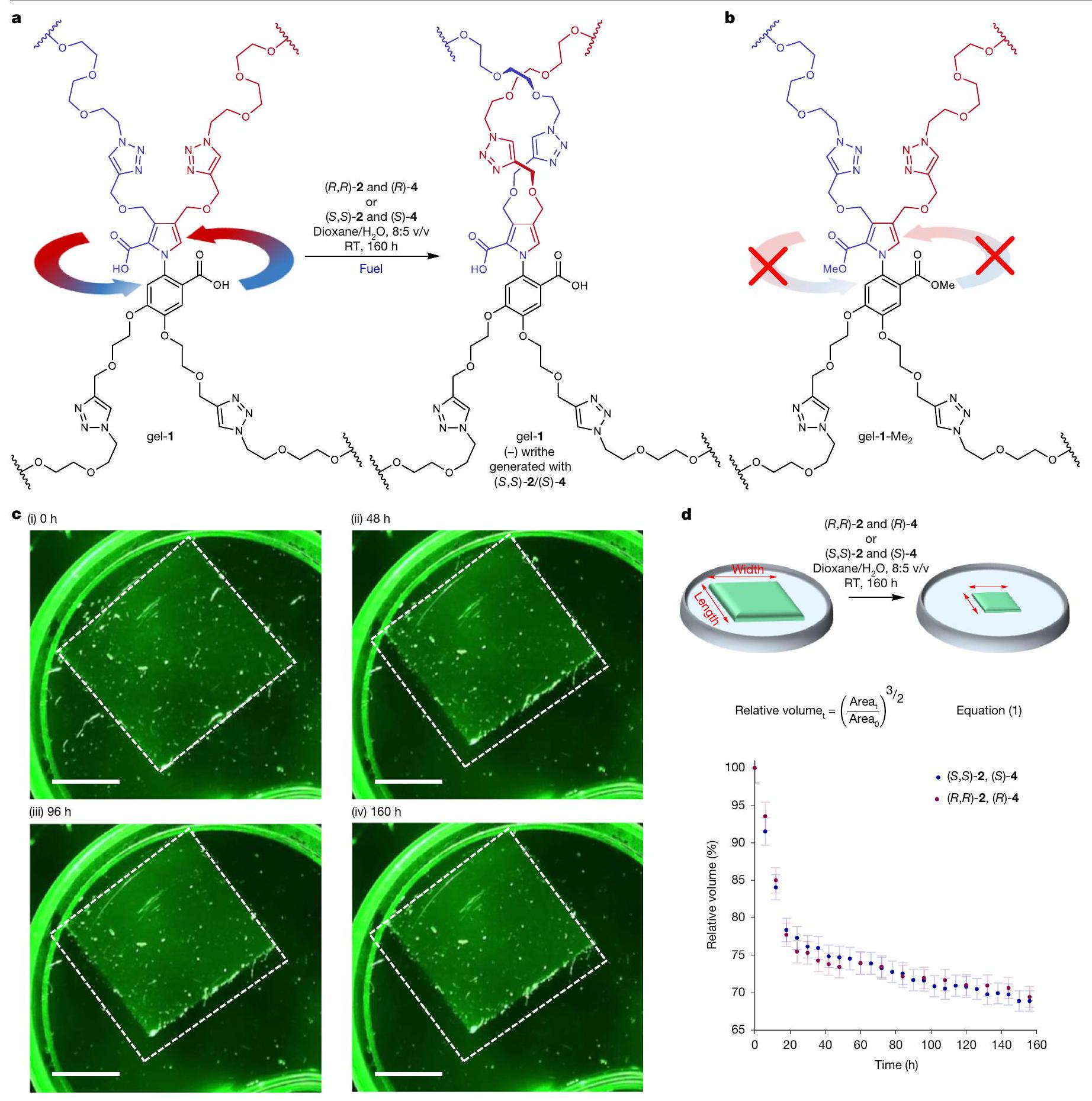

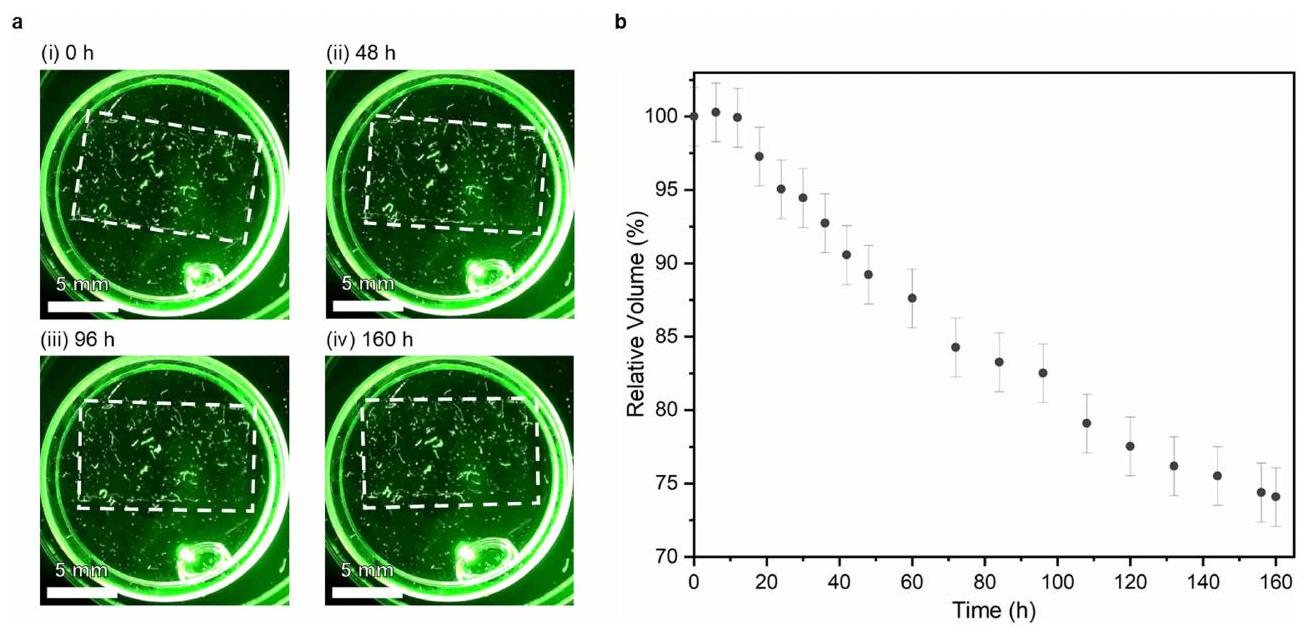

Fig. 2 | Macroscopic contraction of gel-1 under chemical fuelling.

outline of the gel before fuelling

equation (1) and Supplementary Information section 5.2). Even after the gel stopped contracting, the catalysis of carbodiimide hydration by the gel-embedded motors continued as long as unreacted fuel remained or if the fuel was replenished.

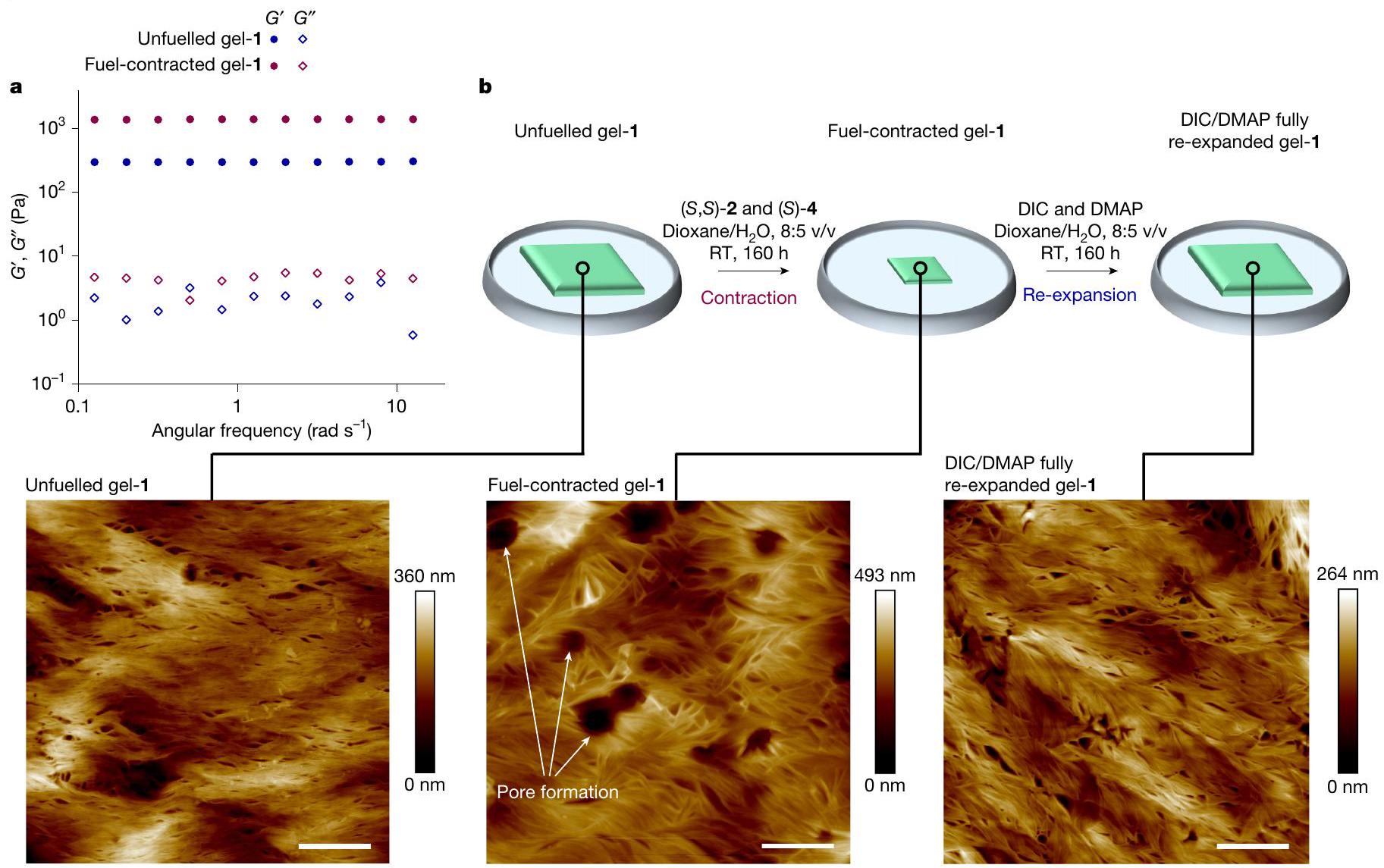

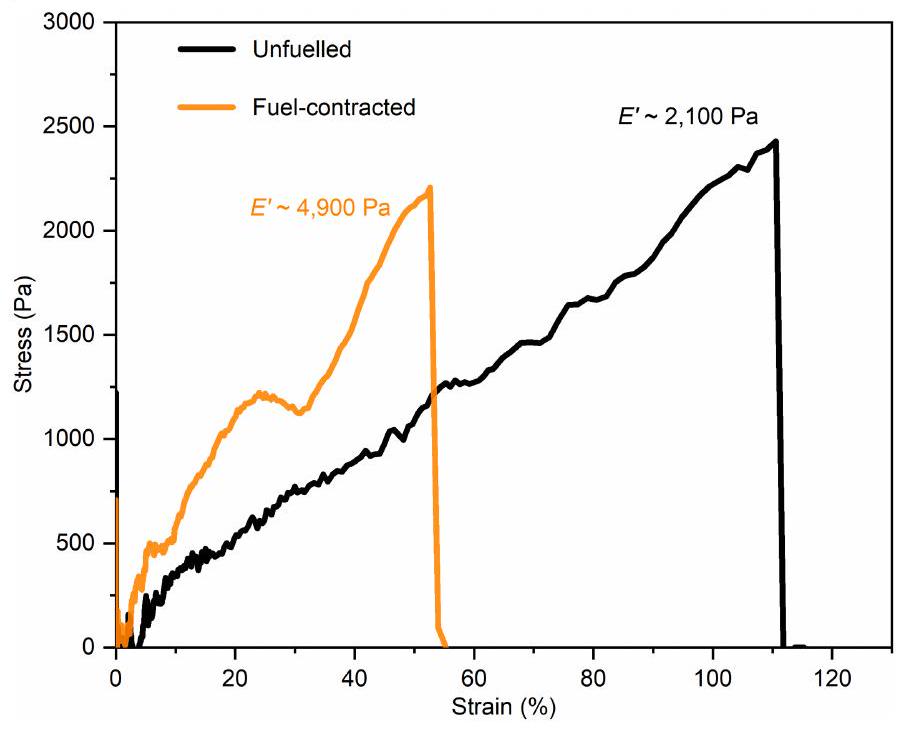

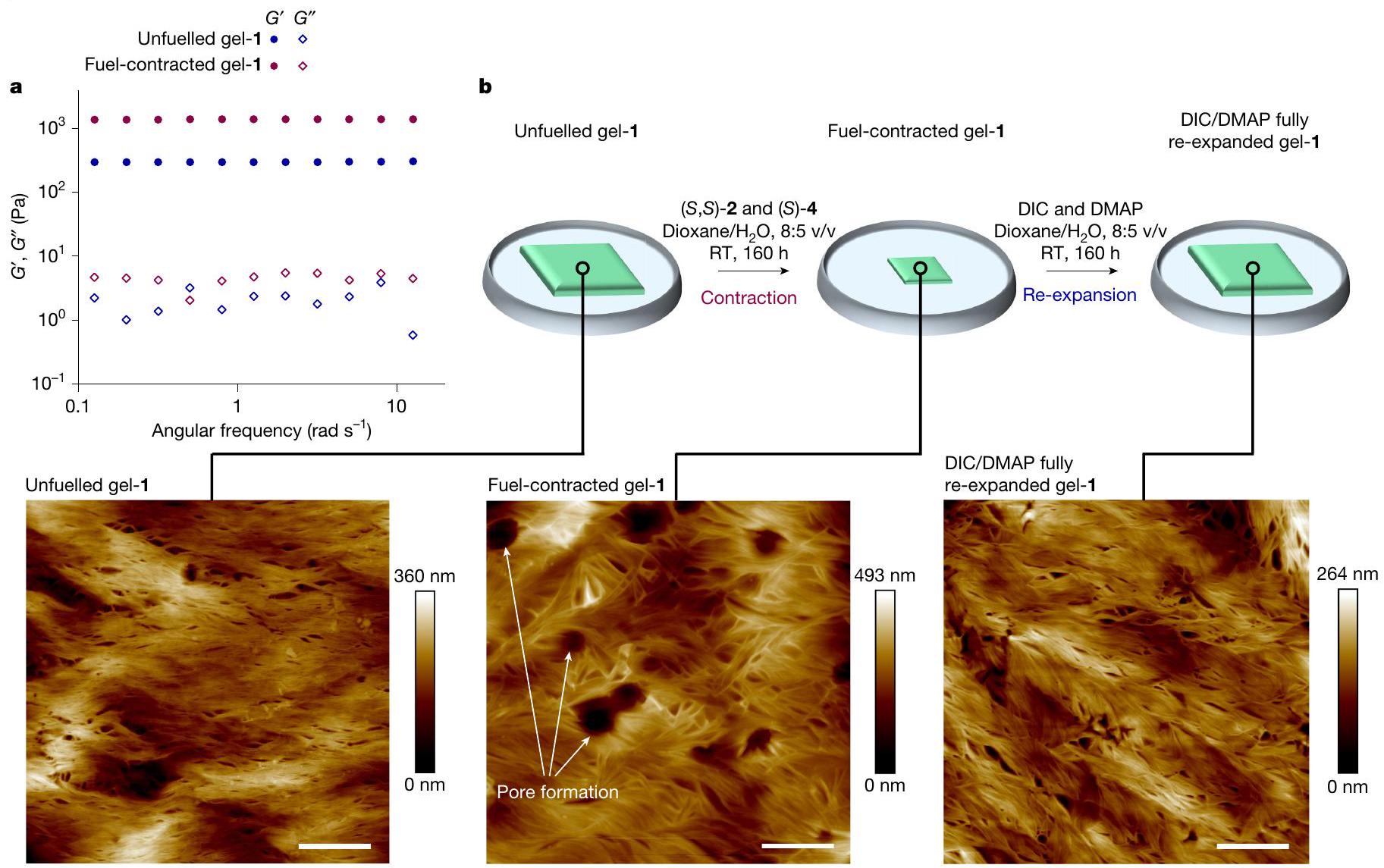

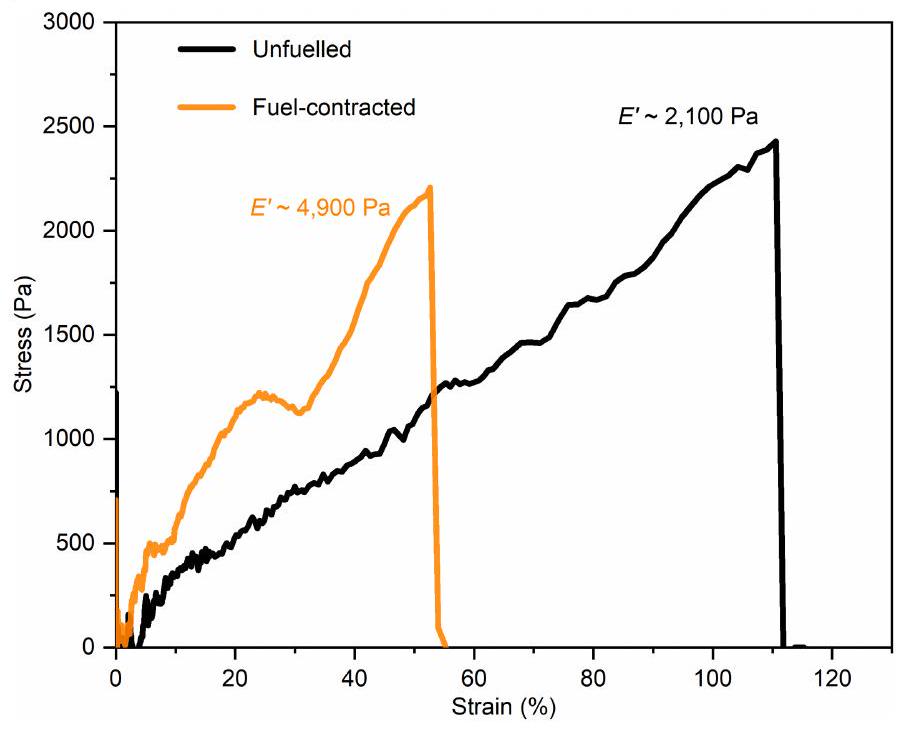

Fuel-contracted gel characterization

All the macroscopic and microscopic features and measurements are indicative that the contraction of gel-1 under fuelling with the chiral carbodiimide and hydrolysis promoter is a result of the organocatalysisdriven directional rotation of the motor molecules, increasing the entanglement (writhe

Chemomechanics at the stall force

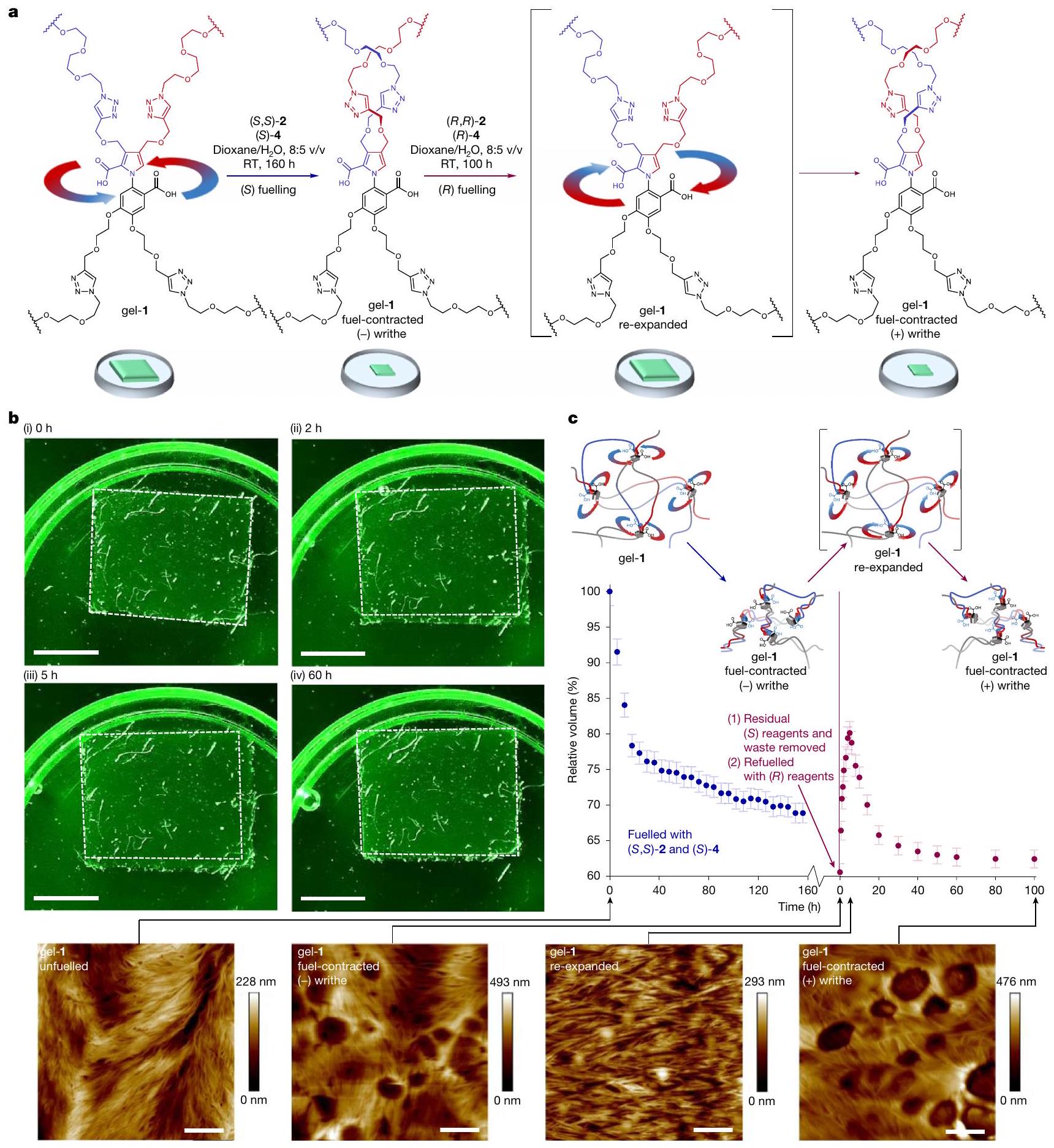

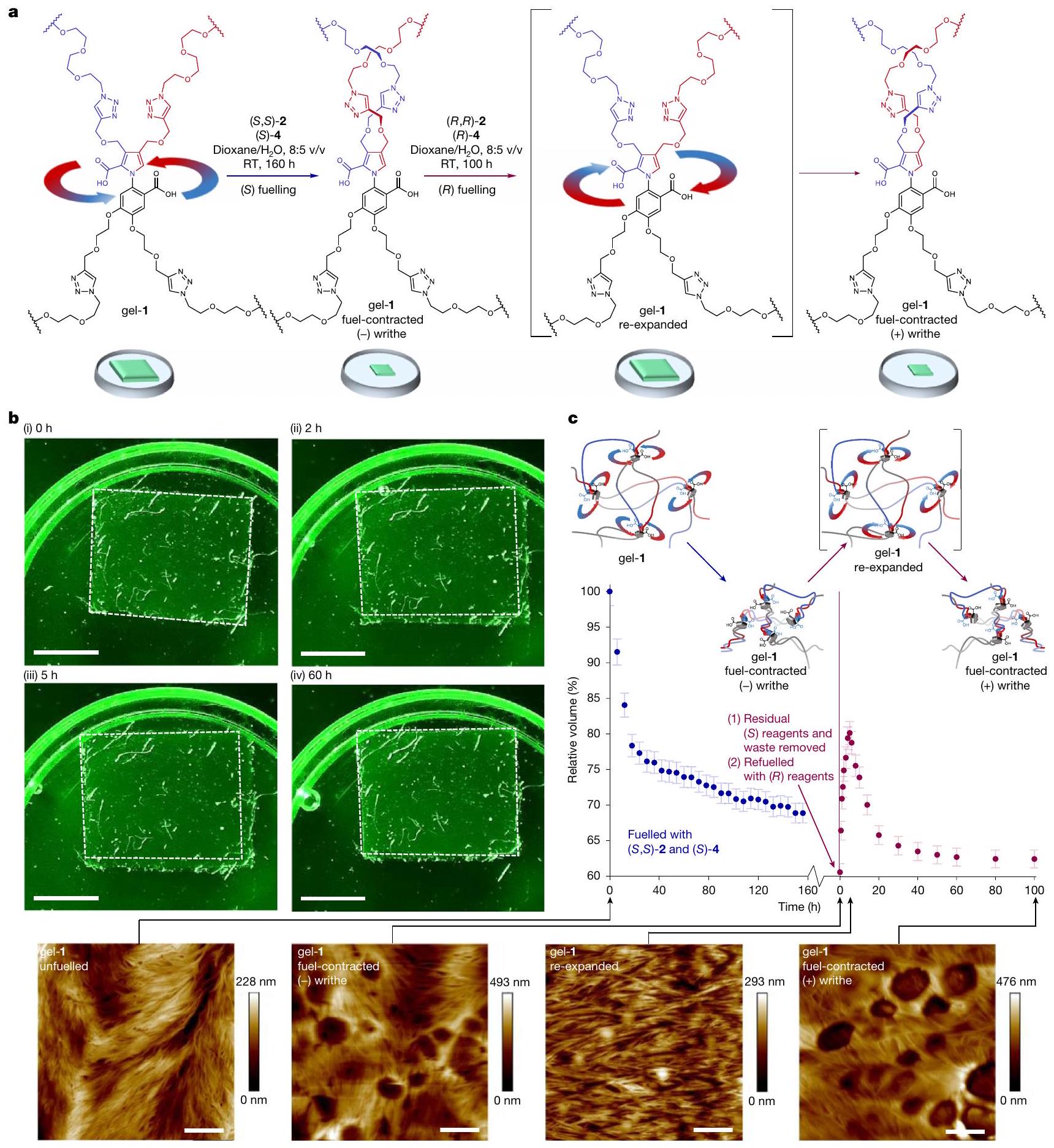

Powering the motor molecules in reverse

(Supplementary Information section 6). The appearance of the micrometre-diameter pores reflects heterogeneities that are intrinsically present in such gels: regions with higher densities of motors produce more entanglements on fuelling, leaving free space (pores) between them

rotation of the motors under catalysis continues in the clockwise direction and the gel begins to re-contract, reaching a minimum volume of

the contracted gel to accelerate this process is a direct result of energy being transduced from the fuel-to-waste reaction by motor rotational catalysis during the first fuelled contraction (Fig.4c (blue data points)).

Energy transduction through kinetic asymmetry

the powered contraction-expansion-re-contraction behaviour of gel-1 on successive fuelling with systems of opposite chirality (blue data points,

mechanism by which this happens is clearly apparent. As both key conformational changes in the ratcheting cycle occur between enantiomeric atropisomers ((+)-1 and (-)-1; (+)-1′ and (-)-1′), there is no power stroke. The experimental demonstration of the transduction of chemical energy to perform work against a load through kinetic asymmetry provides a minimalist mechanistic illustration of how catalysis-driven molecular motors can extract order from chaos

Online content

- Schliwa, M. & Woehlke, G. Molecular motors. Nature 422, 759-765 (2003).

- Howard, J. Protein power strokes. Curr. Biol. 16, R517-R519 (2006).

- Astumian, R. D. Irrelevance of the power stroke for the directionality, stopping force, and optimal efficiency of chemically driven molecular machines. Biophys. J. 108, 291-303 (2015).

- Hoffmann, P. M. How molecular motors extract order from chaos (a key issues review). Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 032601 (2016).

- Hwang, W. & Karplus, M. Structural basis for power stroke vs. Brownian ratchet mechanisms of motor proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19777-19785 (2019).

- Amano, S., Borsley, S., Leigh, D. A. & Sun, Z. Chemical engines: driving systems away from equilibrium through catalyst reaction cycles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1057-1067(2021).

- Amano, S. et al. Using catalysis to drive chemistry away from equilibrium: relating kinetic asymmetry, power strokes and the Curtin-Hammett principle in Brownian ratchets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 20153-20164 (2022).

- Sweeney, H. L. & Houdusse, A. Structural and functional insights into the Myosin motor mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 39, 539-557 (2010).

- Borsley, S., Kreidt, E., Leigh, D. A. & Roberts, B. M. W. Autonomous fuelled directional rotation about a covalent single bond. Nature 604, 80-85 (2022).

- Astumian, R. D. Kinetic asymmetry and directionality of nonequilibrium molecular systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202306569 (2024).

- Borsley, S., Leigh, D. A. & Roberts, B. M. W. Molecular ratchets and kinetic asymmetry: giving chemistry direction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400495 (2024).

- Ragazzon, G. & Prins, L. J. Energy consumption in chemical fuel-driven self-assembly. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 882-889 (2018).

- Schwarz, P. S., Tena-Solsona, M., Dai, K. & Boekhoven, J. Carbodiimide-fuelled catalytic reaction cycles to regulate supramolecular processes. Chem. Commun. 58, 1284-1297 (2022).

- Sangchai, T., Al Shehimy, S., Penocchio, E. & Ragazzon, G. Artificial molecular ratchets: tools enabling endergonic processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309501 (2023).

- Koumura, N., Zijlstra, R. W. J., van Delden, R. A., Harada, N. & Feringa, B. L. Light-driven monodirectional molecular rotor. Nature 401, 152-155 (1999).

- Leigh, D. A., Wong, J. K. Y., Dehez, F. & Zerbetto, F. Unidirectional rotation in a mechanically interlocked molecular rotor. Nature 424, 174-179 (2003).

- Guentner, M. et al. Sunlight-powered kHz rotation of a hemithioindigo-based molecular motor. Nat. Commun. 6, 8406 (2015).

- Wilson, M. R. et al. An autonomous chemically fuelled small-molecule motor. Nature 534, 235-240 (2016).

- Erbas-Cakmak, S. et al. Rotary and linear molecular motors driven by pulses of a chemical fuel. Science 358, 340-343 (2017).

- Pumm, A.-K. et al. A DNA origami rotary ratchet motor. Nature 607, 492-498 (2022).

- Zhang, L. et al. An electric molecular motor. Nature 613, 280-286 (2023).

- Berreur, J. et al. Redox-powered autonomous unidirectional rotation about a

bond under enzymatic control. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-tz8vc (2024). - Serreli, V., Lee, C.-F., Kay, E. R. & Leigh, D. A. A molecular information ratchet. Nature 445, 523-527 (2007).

- Feng, L. et al. Active mechanisorption driven by pumping cassettes. Science 374, 1215-1221 (2021).

- Amano, S., Fielden, S. D. P. & Leigh, D. A. A catalysis-driven artificial molecular pump. Nature 594, 529-534 (2021).

- Borsley, S., Leigh, D. A. & Roberts, B. M. W. A doubly kinetically-gated information ratchet autonomously driven by carbodiimide hydration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4414-4420 (2021).

- Thomas, D. et al. Pumping between phases with a pulsed-fuel molecular ratchet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 701-707 (2022).

- Corra, S. et al. Kinetic and energetic insights into the dissipative non-equilibrium operation of an autonomous light-powered supramolecular pump. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 746-751 (2022).

- Binks, L. et al. The role of kinetic asymmetry and power strokes in an information ratchet. Chem 9, 2902-2917 (2023).

- Li, Q. et al. Macroscopic contraction of a gel induced by the integrated motion of light-driven molecular motors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 161-165 (2015).

- Foy, J. T. et al. Dual-light control of nanomachines that integrate motor and modulator subunits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 540-545 (2017).

- Perrot, A., Wang, W.-Z., Buhler, E., Moulin, E. & Giuseppone, N. Bending actuation of hydrogels through rotation of light-driven molecular motors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202300263 (2023).

- Tena-Solsona, M. et al. Non-equilibrium dissipative supramolecular materials with a tunable lifetime. Nat. Commun. 8, 15895 (2017).

- Kariyawasam, L. S. & Hartley, C. S. Dissipative assembly of aqueous carboxylic acid anhydrides fueled by carbodiimides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11949-11955 (2017).

- Borsley, S., Leigh, D. A. & Roberts, B. M. W. Chemical fuels for molecular machinery. Nat. Chem. 14, 728-738 (2022).

- Liang, L. & Astruc, D. The copper(I)-catalyzed alkyne-azide cycloaddition (CuAAC) ‘click’ reaction and its applications. An overview. Coord. Chem. Rev. 255, 2933-2945 (2011).

- Hagel, J., Haraszti, T. & Boehm, H. Diffusion and interaction in PEG-DA hydrogels. Biointerphases 8, 36 (2013).

- Yavari, N. & Azizian, S. Mixed diffusion and relaxation kinetics model for hydrogels swelling. J. Mol. Liq. 363, 119861 (2022).

- Goujon, A. et al. Bistable [c2] daisy chain rotaxanes as reversible muscle-like actuators in mechanically active gels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 14825-14828 (2017).

- Colard-Itté, J.-R. et al. Mechanical behaviour of contractile gels based on light-driven molecular motors. Nanoscale 11, 5197-5202 (2019).

- Sakai, T. et al. Design and fabrication of a high-strength hydrogel with ideally homogeneous network structure from tetrahedron-like macromonomers. Macromolecules 41, 5379-5384 (2008).

- Ashbridge, Z. et al. Knotting matters: orderly molecular entanglements. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 7779-7809 (2022).

- Baiesi, M., Orlandini, E. & Whittington, S. G. Interplay between writhe and knotting for swollen and compact polymers. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 154902 (2009).

- Hu, L., Zhang, Q., Li, X. & Serpe, M. J. Stimuli-responsive polymers for sensing and actuation. Mater. Horiz. 6, 1774-1793 (2019).

- Howse, J. R. et al. Reciprocating power generation in a chemically driven synthetic muscle. Nano Lett. 6, 73-77 (2006).

- Chatterjee, M. N., Kay, E. R. & Leigh, D. A. Beyond switches: ratcheting a particle energetically uphill with a compartmentalized molecular machine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 4058-4073 (2006).

- Boekhoven, J., Hendriksen, W. E., Koper, G. J. M., Eelkema, R. & van Esch, J. H. Transient assembly of active materials fueled by a chemical reaction. Science 349, 1075-1079 (2015).

- Bruns, C. J. Moving forward in the semantic soup of artificial molecular machine taxonomy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 1231-1234 (2022).

(c) The Author(s) 2025

Methods

Representative method for formation of gel-1

General fuel contraction of gel-1

AFM

(Bruker, ScanAsyst; spring constant of

Rheology measurements

Data availability

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Nicolas Giuseppone or David A. Leigh.

Peer review information Nature thanks Daisuke Aoki, Jiawen Chen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

Article

Article

- ¹Department of Chemistry, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. ²School of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China. ³SAMS Research Group, Université de Strasbourg and Institut Charles Sadron, Strasbourg, France.

Institut Universitaire de France (IUF), Paris, France. e-mail: giuseppone@unistra.fr; david.leigh@manchester.ac.uk