DOI: https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.rv22015

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38220184

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-13

تدخين السجائر ومرض القلب والأوعية الدموية الناتج عن تصلب الشرايين

الملخص

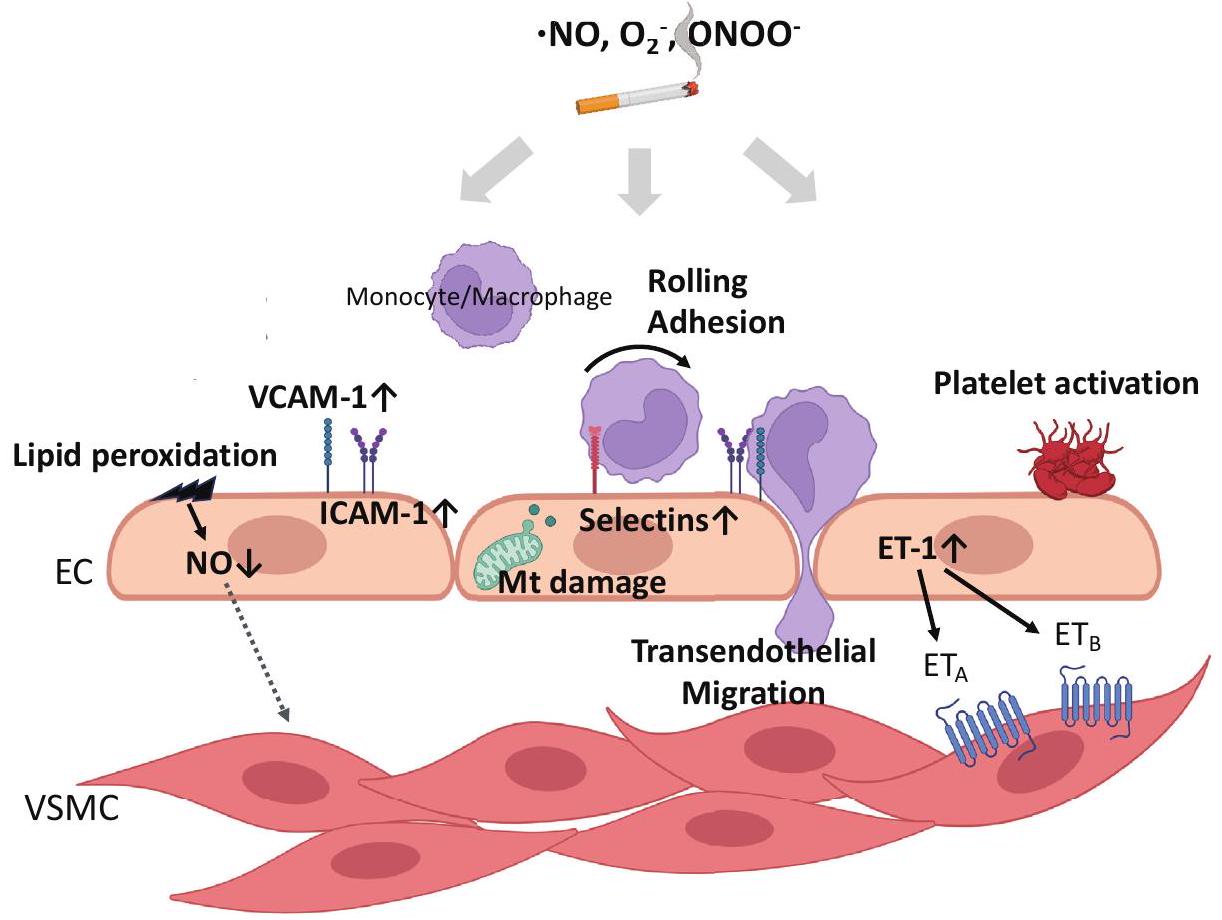

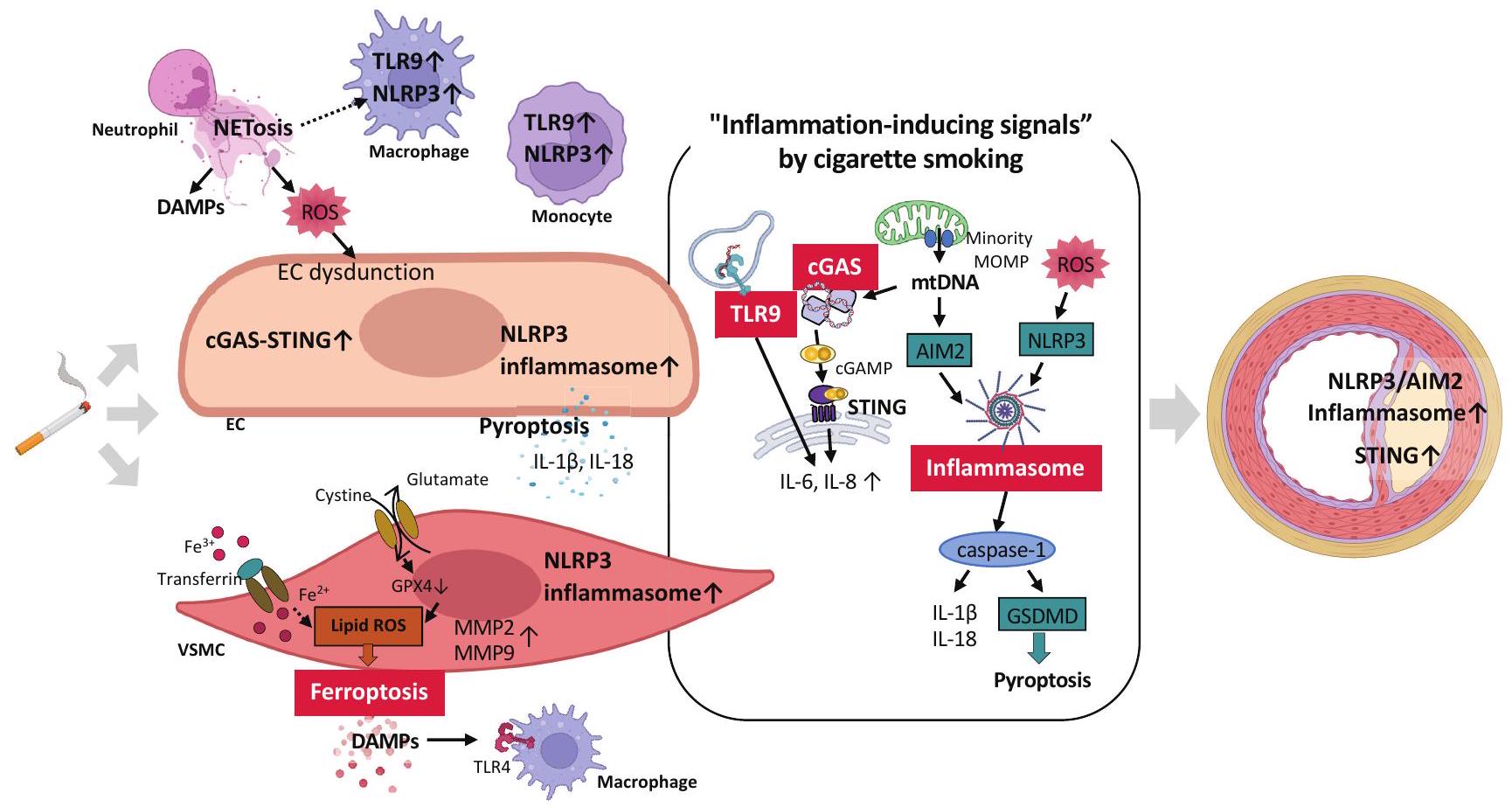

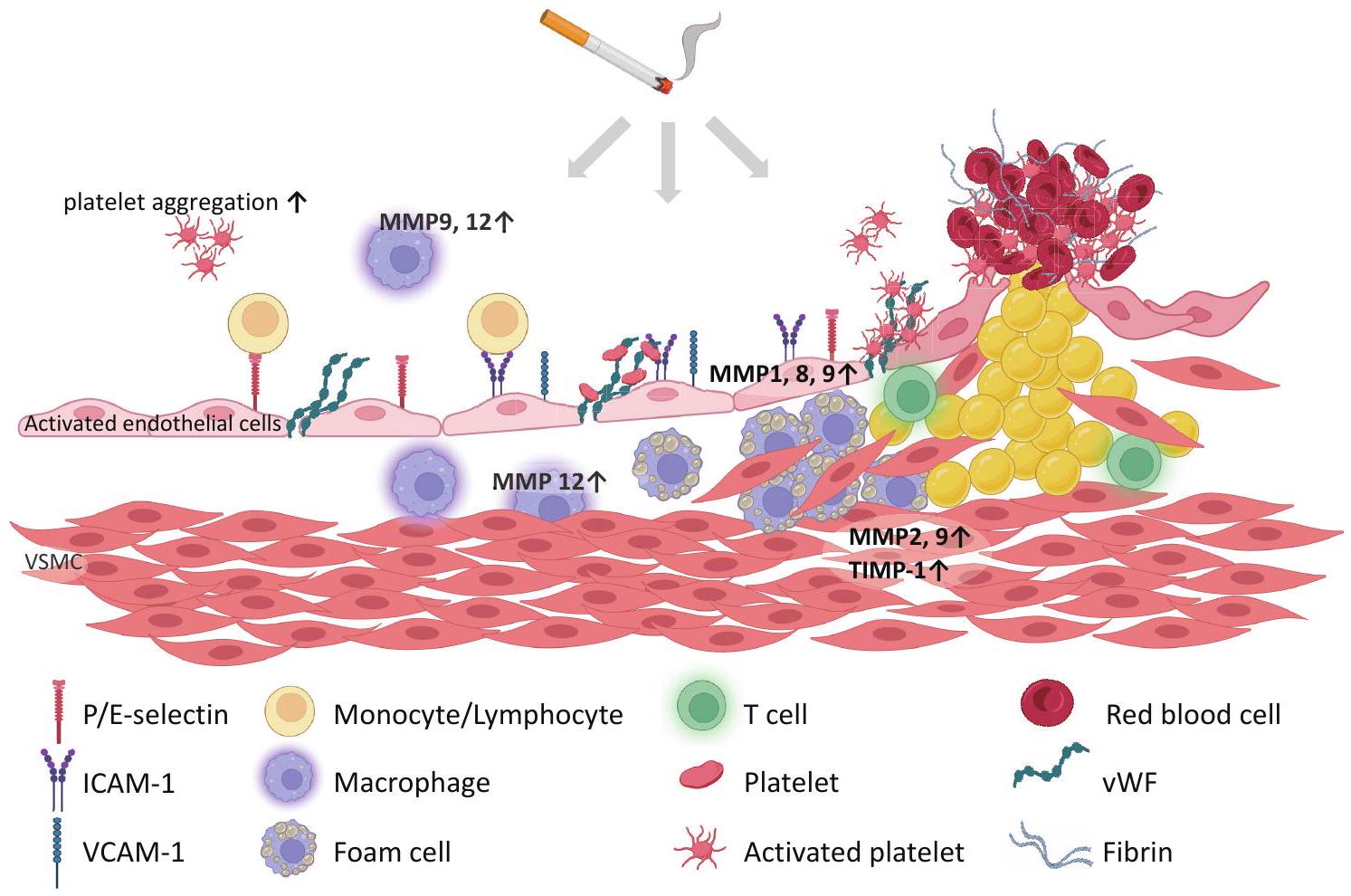

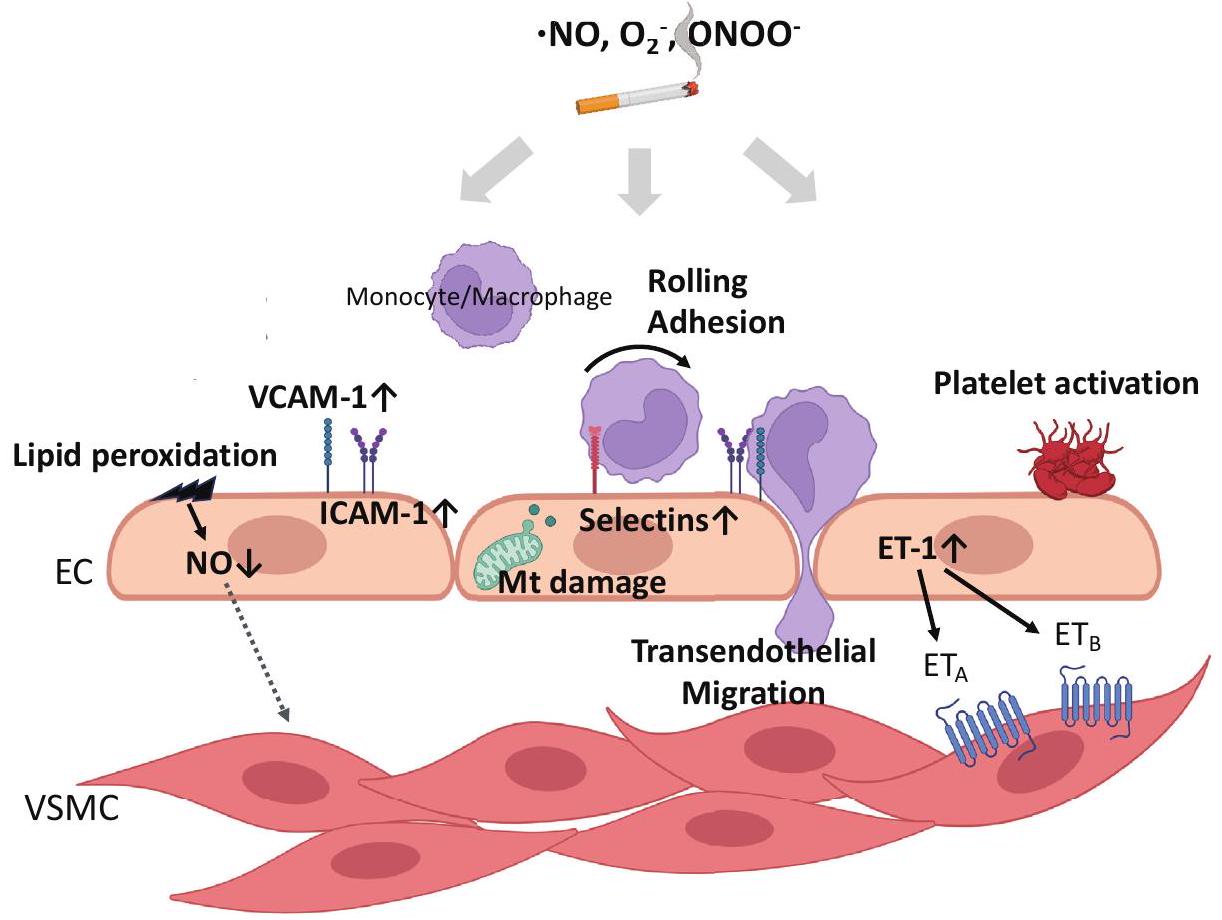

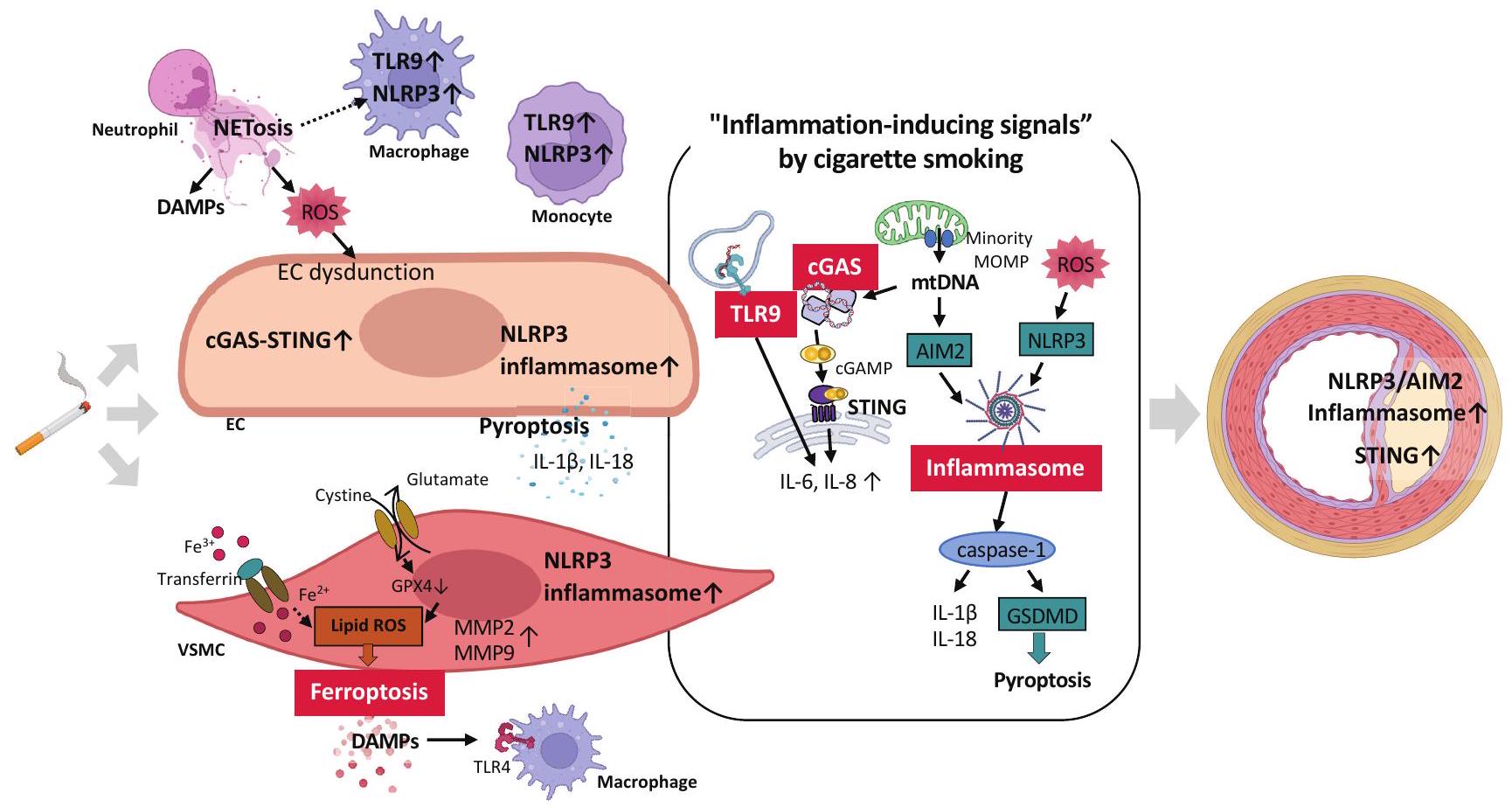

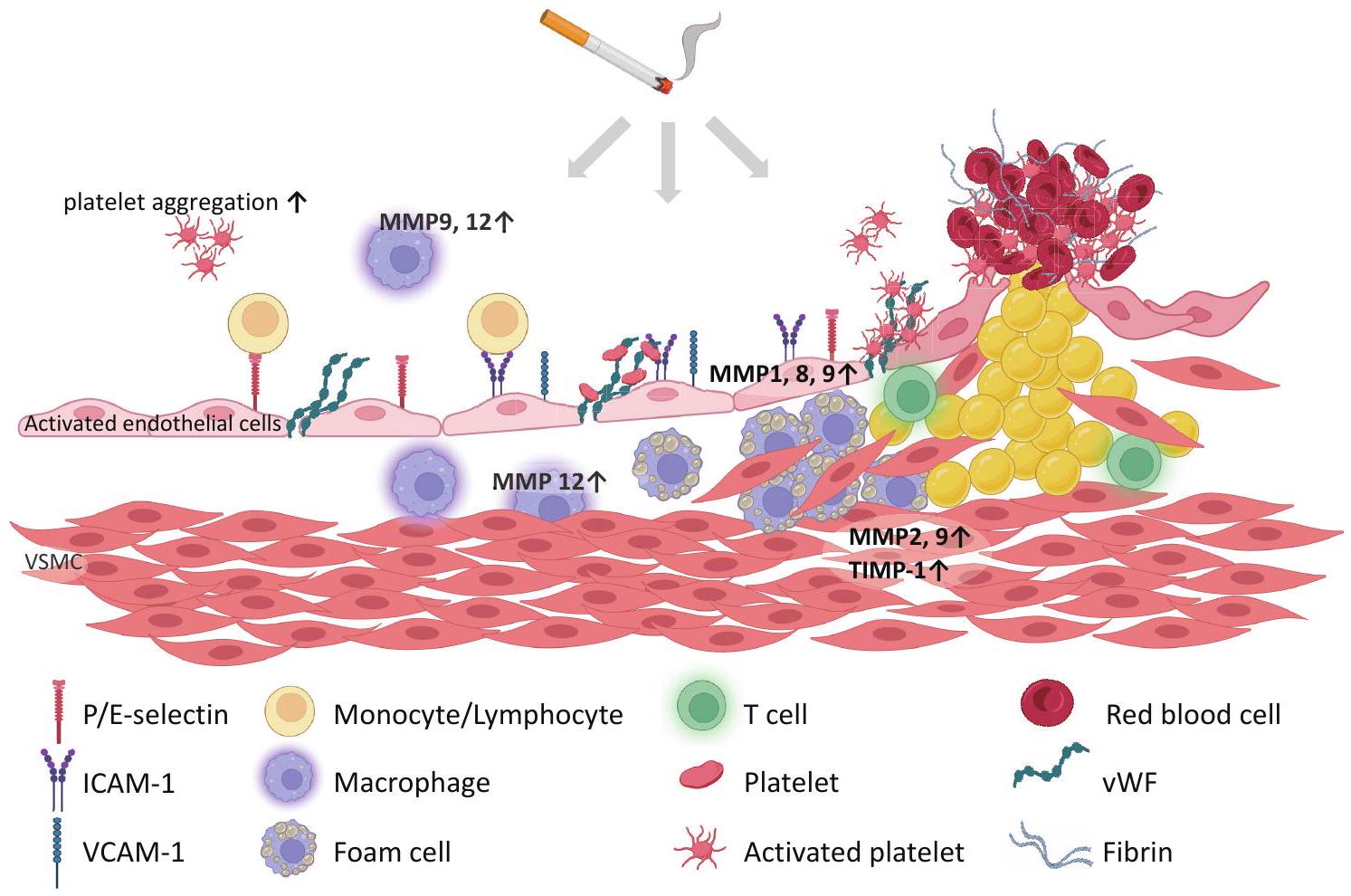

تأثيرات تدخين السجائر الضارة على صحة القلب والأوعية الدموية، وخاصة تصلب الشرايين والتخثر، مثبتة جيدًا، وتستمر الآليات الأكثر تفصيلًا في الظهور. تعتبر خلل وظيفة البطانة، الالتهاب، والتخثر كأسباب أساسية للتأثيرات الضارة للتدخين. يؤدي دخان السجائر إلى خلل في وظيفة البطانة، مما يؤدي إلى ضعف توسيع الأوعية وتنظيم التجلط. تشمل العوامل المساهمة في خلل وظيفة البطانة انخفاض التوافر الحيوي لأكسيد النيتريك، وزيادة مستويات الأنيون الفائق، وإطلاق الإندوتيلين. الالتهاب المزمن لجدار الأوعية هو آلية مركزية لتصلب الشرايين الناتج عن التدخين. يرفع التدخين بشكل نظامي علامات الالتهاب ويحفز التعبير عن جزيئات الالتصاق والسيتوكينات في أنسجة مختلفة. تلعب مستقبلات التعرف على الأنماط وجزيئات الأنماط المرتبطة بالضرر أدوارًا حاسمة في الآلية الكامنة وراء الالتهاب الناتج عن التدخين. يُظهر تلف الحمض النووي الناتج عن التدخين وتنشيط المناعة الفطرية، مثل نازعة البيرين 3 (NLRP3)، وسانتاز GMP-AMP الحلقي (cGAS)-محفز جينات الإنترفيرون (STING)، ومستقبلات Toll-like 9، أنها تعزز التعبير عن السيتوكينات الالتهابية. يؤثر الإجهاد التأكسدي والالتهاب الناتج عن دخان السجائر على التصاق الصفائح الدموية وتجمعها وتجلطها عبر زيادة جزيئات الالتصاق. علاوة على ذلك، يؤثر على سلسلة التجلط وتوازن التحلل الفيبريني، مما يسبب تكوين الجلطة. تساهم ميتالوبروتيناز المصفوفة في ضعف اللويحات والأحداث الأثروجلطية. يؤثر التدخين على الخلايا الالتهابية وجزيئات الالتصاق مما يزيد من خطر الأثروجلطة. بشكل جماعي، يؤثر التعرض لدخان السجائر بشكل عميق على وظيفة البطانة، والالتهاب، والتخثر، مما يساهم في تطور وتقدم تصلب الشرايين وأمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية الأثروجلطية. فهم هذه الآليات المعقدة يبرز الحاجة الملحة للإقلاع عن التدخين لحماية صحة القلب والأوعية الدموية. تستعرض هذه المراجعة الشاملة الآليات المتعددة الأوجه التي يساهم بها التدخين في هذه الحالات المهددة للحياة.

1. المقدمة

التدخين بالسجائر

2. خلل وظيفة البطانة

مع تأثيرات مضادة لتصلب الشرايين ومضادة للتجمع، مثل NO والبروستاسيكلين، وبالتالي فهي عضو ديناميكي للغاية تمتلك خصائص مضادة للالتهاب، ومضادة للتخثر، وموسعة للأوعية. يؤدي التعرض لدخان السجائر إلى خلل في وظيفة البطانة، والذي يعتبر أول مظاهر تصلب الشرايين، مما يؤدي إلى ضعف التنظيم والصيانة لتوسيع الأوعية وتنظيم التجلط

أفاد آخرون أن خلايا البطانة الوعائية المزروعة في وسط زراعة مدعوم بمصل المدخنين أظهرت انخفاضًا في إنتاج NO، وانخفاضًا في نشاط eNOS، وزيادة في إنتاج ROS الداخلي مقارنةً بغير المدخنين، والتي تم استعادتها بواسطة أدوية مضادة للأكسدة

إلى زيادة في

3. الالتهاب

تم ذكره لاحقًا، أظهرت التجارب التي أجريت في المختبر أن CSE يزيد من تعبير IL-6 و IL-8

تصلب الشرايين. على سبيل المثال، يؤدي تثبيط تنشيط TLR9 باستخدام أوليغوديوكسي نيوكليوتيدات تنظيمية مناعية إلى تحويل مرونة البلعميات إلى بلعميات مضادة للالتهابات ويثبط تشكيل لويحات تصلب الشرايين

خلايا العضلات الملساء وزيادة تجنيد البلعميات داخل اللويحات

وأدى نسيج الشريان الأورطي للفئران إلى زيادة إنتاج الجذور الحرة للأكسجين، وتنشيط إنزيم NLRP3، وارتفاع مستوى بروتين CRP.

يكون مرتفعًا لدى المدخنين الذين يعانون من مرض الشريان التاجي

إنزيم سينثاز GMP-AMP الحلقي (cGAS)، المعروف بأنه مستشعر للحمض النووي السيتوزولي، يتم تفعيله ليس فقط بواسطة الحمض النووي المشتق من مسببات الأمراض ولكن أيضًا بواسطة الحمض النووي الداخلي. يتم التعبير عنه في خلايا متنوعة، بما في ذلك الخلايا الدبقية الصغيرة، الخلايا العصبية، الخلايا الكبدية، وحيدات النوى المحيطية، والخلايا الشجرية، البلعميات، والخلايا القلبية الوعائية، مثل الخلايا البطانية، خلايا العضلات الملساء الوعائية، خلايا القلب، والخلايا الليفية.

أكسدة الدهون

خلايا شبيهة بالعدلات مشتقة من خلايا HL-60

4. التأثيرات التخثرية

تم الإبلاغ عن دخان السجائر

مستقبل الفبرينوجين الجليكوبروتين IIb/IIIa، مقارنة بغير المدخنين

البلاعم البشرية ونشاط MMP المحفز بطريقة تعتمد على الإجهاد التأكسدي في آفات تصلب الشرايين المتقدمة

5. الاستنتاجات وآفاق المستقبل

الشكر والتقدير

المصالح المتنافسة

References

- Outline of Health, Labour and Welfare Statistics 2022. 2022

- Ezzati M, Henley SJ, Thun MJ, Lopez AD: Role of smoking in global and regional cardiovascular mortality. Circulation, 2005; 112: 489-497

- Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Odell PM, Kannel WB: An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation, 1991; 83: 356-362

- Iso H, Date C, Yamamoto A, Toyoshima H, Watanabe Y, Kikuchi S, Koizumi A, Wada Y, Kondo T, Inaba Y,

5) Smith CJ, Fischer TH: Particulate and vapor phase constituents of cigarette mainstream smoke and risk of myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis, 2001; 158: 257267

6) Csordas A, Bernhard D: The biology behind the atherothrombotic effects of cigarette smoke. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2013; 10: 219-230

7) Barua RS, Ambrose JA: Mechanisms of coronary thrombosis in cigarette smoke exposure. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2013; 33: 1460-1467

8) Kobayashi Y, Sakai C, Ishida T, Nagata M, Nakano Y, Ishida M: Mitochondrial DNA is a key driver in cigarette smoke extract-induced IL-6 expression. Hypertens Res, 2023; doi: 10.1038/s41440-023-01463-z. ePub ahead of print

9) Messner B, Bernhard D: Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2014; 34: 509-515

10) Jaén RI, Val-Blasco A, Prieto P, Gil-Fernández M, Smani T, López-Sendón JL, Delgado C, Boscá L, FernándezVelasco M: Innate Immune Receptors, Key Actors in Cardiovascular Diseases. JACC Basic Transl Sci, 2020; 5: 735-749

11) Zindel J, Kubes P: DAMPs, PAMPs, and LAMPs in Immunity and Sterile Inflammation. Annu Rev Pathol, 2020; 15: 493-518

12) Sampilvanjil A, Karasawa T, Yamada N, Komada T, Higashi T, Baatarjav C, Watanabe S, Kamata R, Ohno N, Takahashi M: Cigarette smoke extract induces ferroptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2020; 318: H508-h518

13) Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ye T, Yang L, Shen Y, Li H: Ferroptosis Signaling and Regulators in Atherosclerosis. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021; 9: 809457

14) Fuster V, Moreno PR, Fayad ZA, Corti R, Badimon JJ: Atherothrombosis and high-risk plaque: part I: evolving concepts. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2005; 46: 937-954

15) Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, Spiegelhalter DJ, Miller OI, Sullivan ID, Lloyd JK, Deanfield JE: Noninvasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet, 1992; 340: 1111-1115

16) Johnson HM, Gossett LK, Piper ME, Aeschlimann SE, Korcarz CE, Baker TB, Fiore MC, Stein JH: Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on endothelial function: 1 -year outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010; 55: 1988-1995

17) Otsuka R, Watanabe H, Hirata K, Tokai K, Muro T, Yoshiyama M, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J: Acute effects of passive smoking on the coronary circulation in healthy young adults. Jama, 2001; 286: 436-441

18) Rahman MM, Laher I: Structural and functional alteration of blood vessels caused by cigarette smoking: an overview of molecular mechanisms. Curr Vasc Pharmacol, 2007; 5: 276-292

19) Heitzer T, Just H, Münzel T: Antioxidant vitamin C improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic smokers.

20) Heitzer T, Brockhoff C, Mayer B, Warnholtz A, Mollnau H, Henne S, Meinertz T, Münzel T: Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in chronic smokers: evidence for a dysfunctional nitric oxide synthase. Circ Res, 2000; 86: E36-41

21) Barua RS, Ambrose JA, Srivastava S, DeVoe MC, EalesReynolds LJ: Reactive oxygen species are involved in smoking-induced dysfunction of nitric oxide biosynthesis and upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: an in vitro demonstration in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Circulation, 2003; 107: 2342-2347

22) Kayyali US, Budhiraja R, Pennella CM, Cooray S, Lanzillo JJ, Chalkley R, Hassoun PM: Upregulation of xanthine oxidase by tobacco smoke condensate in pulmonary endothelial cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2003; 188: 59-68

23) Jaimes EA, DeMaster EG, Tian RX, Raij L: Stable compounds of cigarette smoke induce endothelial superoxide anion production via NADPH oxidase activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2004; 24: 1031-1036

24) Miró O, Alonso JR, Jarreta D, Casademont J, UrbanoMárquez A, Cardellach F: Smoking disturbs mitochondrial respiratory chain function and enhances lipid peroxidation on human circulating lymphocytes. Carcinogenesis, 1999; 20: 1331-1336

25) Ueda K, Sakai C, Ishida T, Morita K, Kobayashi Y, Horikoshi Y, Baba A, Okazaki Y, Yoshizumi M, Tashiro S, Ishida M: Cigarette smoke induces mitochondrial DNA damage and activates cGAS-STING pathway: application to a biomarker for atherosclerosis. Clin Sci (Lond), 2023; 137: 163-180

26) Suski JM, Lebiedzinska M, Bonora M, Pinton P, Duszynski J, Wieckowski MR: Relation Between Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and ROS Formation. In: Palmeira CM, Moreno AJ, eds. Mitochondrial Bioenergetics: Methods and Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2012: 183-205

27) Lavi S, Prasad A, Yang EH, Mathew V, Simari RD, Rihal CS, Lerman LO, Lerman A: Smoking is associated with epicardial coronary endothelial dysfunction and elevated white blood cell count in patients with chest pain and early coronary artery disease. Circulation, 2007; 115: 2621-2627

28) Barbieri SS, Zacchi E, Amadio P, Gianellini S, Mussoni L, Weksler BB, Tremoli E: Cytokines present in smokers’ serum interact with smoke components to enhance endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res, 2011; 90: 475483

29) Wang H, Chen H, Fu Y, Liu M, Zhang J, Han S, Tian Y, Hou H, Hu Q: Effects of Smoking on InflammatoryRelated Cytokine Levels in Human Serum. Molecules, 2022; 27

30) Hussein BJ, Atallah HN, AL-Dahhan NAA: Salivary levels of Interleukin-6, Interleukin-8 and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha in Smokers Aged 35-46 Years with Dental Caries Disease. Medico Legal Update, 2020; 20: 14641470

31) Jefferis BJ, Lowe GD, Welsh P, Rumley A, Lawlor DA, Ebrahim S, Carson C, Doig M, Feyerabend C, McMeekin

32) Bernhard D, Csordas A, Henderson B, Rossmann A, Kind M, Wick G: Cigarette smoke metal-catalyzed protein oxidation leads to vascular endothelial cell contraction by depolymerization of microtubules. Faseb j, 2005; 19: 1096-1107

33) Sundar IK, Chung S, Hwang JW, Lapek JD, Jr., Bulger M, Friedman AE, Yao H, Davie JR, Rahman I: Mitogenand stress-activated kinase 1 (MSK1) regulates cigarette smoke-induced histone modifications on NF-

34) Hansson GK, Libby P, Schönbeck U, Yan ZQ: Innate and adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Circ Res, 2002; 91: 281-291

35) Ishida M, Sakai C, Ishida T: Role of DNA damage in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J Cardiol, 2023; 81: 331336

36) Shaw AC, Goldstein DR, Montgomery RR: Agedependent dysregulation of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol, 2013; 13: 875-887

37) Takeuchi O, Akira S: Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell, 2010; 140: 805-820

38) Roshan MH, Tambo A, Pace NP: The Role of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Int J Inflam, 2016; 2016: 1532832

39) Miggin SM, O’Neill LA: New insights into the regulation of TLR signaling. J Leukoc Biol, 2006; 80: 220-226

40) Banchereau J, Pascual V: Type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Immunity, 2006; 25: 383-392

41) Ma C, Ouyang Q, Huang Z, Chen X, Lin Y, Hu W, Lin L: Toll-Like Receptor 9 Inactivation Alleviated Atherosclerotic Progression and Inhibited Macrophage Polarized to M1 Phenotype in ApoE-/- Mice. Dis Markers, 2015; 2015: 909572

42) Krogmann AO, Lüsebrink E, Steinmetz M, Asdonk T, Lahrmann C, Lütjohann D, Nickenig G, Zimmer S: Proinflammatory Stimulation of Toll-Like Receptor 9 with High Dose CpG ODN 1826 Impairs Endothelial Regeneration and Promotes Atherosclerosis in Mice. PLoS One, 2016; 11: e0146326

43) Li J, Huynh L, Cornwell WD, Tang MS, Simborio H, Huang J, Kosmider B, Rogers TJ, Zhao H, Steinberg MB, Thu Thi Le L, Zhang L, Pham K, Liu C, Wang H: Electronic Cigarettes Induce Mitochondrial DNA Damage and Trigger TLR9 (Toll-Like Receptor 9)-Mediated Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2021; 41: 839-853

44) Takahashi M: NLRP3 inflammasome as a key driver of vascular disease. Cardiovasc Res, 2022; 118: 372-385

45) Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JP: The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol, 2019; 19: 477-489

46) Kumari P, Russo AJ, Shivcharan S, Rathinam VA: AIM2 in health and disease: Inflammasome and beyond. Immunol Rev, 2020; 297: 83-95

47) Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G,

48) Usui F, Shirasuna K, Kimura H, Tatsumi K, Kawashima A, Karasawa T, Hida S, Sagara J, Taniguchi S, Takahashi M : Critical role of caspase-1 in vascular inflammation and development of atherosclerosis in Western diet-fed apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2012; 425: 162-168

49) Hendrikx T, Jeurissen ML, van Gorp PJ, Gijbels MJ, Walenbergh SM, Houben T, van Gorp R, Pöttgens CC, Stienstra R, Netea MG, Hofker MH, Donners MM, Shiri-Sverdlov R: Bone marrow-specific caspase-1/11 deficiency inhibits atherosclerosis development in Ldlr(-/-) mice. Febs j, 2015; 282: 2327-2338

50) Paulin N, Viola JR, Maas SL, de Jong R, FernandesAlnemri T, Weber C, Drechsler M, Döring Y, Soehnlein O: Double-Strand DNA Sensing Aim2 Inflammasome Regulates Atherosclerotic Plaque Vulnerability. Circulation, 2018; 138: 321-323

51) Pan J, Han L, Guo J, Wang X, Liu D, Tian J, Zhang M, An F: AIM2 accelerates the atherosclerotic plaque progressions in ApoE-/- mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2018; 498: 487-494

52) Mehta S, Dhawan V: Exposure of cigarette smoke condensate activates NLRP3 inflammasome in THP-1 cells in a stage-specific manner: An underlying role of innate immunity in atherosclerosis. Cell Signal, 2020; 72: 109645

53) Yao Y, Mao J, Xu S, Zhao L, Long L, Chen L, Li D, Lu S: Rosmarinic acid inhibits nicotine-induced C-reactive protein generation by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation in smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol, 2019; 234: 1758-1767

54) Wu X, Zhang H, Qi W, Zhang Y, Li J, Li Z, Lin Y, Bai X, Liu X, Chen X, Yang H, Xu C, Zhang Y, Yang B: Nicotine promotes atherosclerosis via ROS-NLRP3mediated endothelial cell pyroptosis. Cell Death Dis, 2018; 9: 171

55) Mehta S, Vijayvergiya R, Dhawan V: Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly is associated with smoking status of patients with coronary artery disease. Int Immunopharmacol, 2020; 87: 106820

56) Hong

57) Pham PT, Fukuda D, Nishimoto S, Kim-Kaneyama JR, Lei XF, Takahashi Y, Sato T, Tanaka K, Suto K, Kawabata Y, Yamaguchi K, Yagi S, Kusunose K, Yamada H, Soeki T, Wakatsuki T, Shimada K, Kanematsu Y, Takagi Y, Shimabukuro M, Setou M, Barber GN, Sata M: STING, a cytosolic DNA sensor, plays a critical role in atherogenesis: a link between innate immunity and chronic inflammation caused by lifestyle-related diseases. Eur Heart J, 2021; 42: 4336-4348

58) Li M, Wang ZW, Fang LJ, Cheng SQ, Wang X, Liu NF: Programmed cell death in atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. Cell Death Dis, 2022; 13: 467

59) Yu Y, Yan Y, Niu F, Wang Y, Chen X, Su G, Liu Y, Zhao X, Qian L, Liu P, Xiong Y: Ferroptosis: a cell death connecting oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Discov, 2021; 7: 193

60) Wen Q, Liu J, Kang R, Zhou B, Tang D: The release and activity of HMGB1 in ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2019; 510: 278-283

61) Moschonas IC, Tselepis AD: The pathway of neutrophil extracellular traps towards atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Atherosclerosis, 2019; 288: 9-16

62) Hidalgo A, Libby P, Soehnlein O, Aramburu IV, Papayannopoulos V, Silvestre-Roig C: Neutrophil extracellular traps: from physiology to pathology. Cardiovasc Res, 2022; 118: 2737-2753

63) Sano M, Maejima Y, Nakagama S, Shiheido-Watanabe Y, Tamura N, Hirao K, Isobe M, Sasano T: Neutrophil extracellular traps-mediated Beclin-1 suppression aggravates atherosclerosis by inhibiting macrophage autophagy. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022; 10: 876147

64) Cornel JH, Becker RC, Goodman SG, Husted S, Katus H, Santoso A, Steg G, Storey RF, Vintila M, Sun JL, Horrow J, Wallentin L, Harrington R, James S: Prior smoking status, clinical outcomes, and the comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in acute coronary syndromesinsights from the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Am Heart J, 2012; 164: 334

65) Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT, Liang YH, Smialek J, Virmani R: Coronary risk factors and plaque morphology in men with coronary disease who died suddenly. N Engl J Med, 1997; 336: 1276-1282

66) Levine PH: An acute effect of cigarette smoking on platelet function. A possible link between smoking and arterial thrombosis. Circulation, 1973; 48: 619-623

67) Hawkins RI: Smoking, platelets and thrombosis. Nature, 1972; 236: 450-452

68) Caponnetto P, Russo C, Di Maria A, Morjaria JB, Barton S, Guarino F, Basile E, Proiti M, Bertino G, Cacciola RR, Polosa R: Circulating endothelial-coagulative activation markers after smoking cessation: a 12 -month observational study. Eur J Clin Invest, 2011; 41: 616-626

69) Blache D: Involvement of hydrogen and lipid peroxides in acute tobacco smoking-induced platelet hyperactivity. Am J Physiol, 1995; 268: H679-685

70) Tell GS, Grimm RH, Jr., Vellar OD, Theodorsen L: The relationship of white cell count, platelet count, and hematocrit to cigarette smoking in adolescents: the Oslo Youth Study. Circulation, 1985; 72: 971-974

71) Imaizumi T, Satoh K, Yoshida H, Kawamura Y, Hiramoto M, Takamatsu S: Effect of cigarette smoking on the levels of platelet-activating factor-like lipid(s) in plasma lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis, 1991; 87: 47-55

72) Togna AR, Latina V, Orlando R, Togna GI: Cigarette smoke inhibits adenine nucleotide hydrolysis by human platelets. Platelets, 2008; 19: 537-542

73) Ichiki K, Ikeda H, Haramaki N, Ueno T, Imaizumi T: Long-term smoking impairs platelet-derived nitric oxide release. Circulation, 1996; 94: 3109-3114

74) Della Corte A, Tamburrelli C, Crescente M, Giordano L, D’Imperio M, Di Michele M, Donati MB, De Gaetano G, Rotilio D, Cerletti C: Platelet proteome in healthy

volunteers who smoke. Platelets, 2012; 23: 91-105

75) FitzGerald GA, Oates JA, Nowak J: Cigarette smoking and hemostatic function. Am Heart J, 1988; 115: 267271

76) Hioki H, Aoki N, Kawano K, Homori M, Hasumura Y, Yasumura T, Maki A, Yoshino H, Yanagisawa A, Ishikawa K : Acute effects of cigarette smoking on plateletdependent thrombin generation. Eur Heart J, 2001; 22: 56-61

77) Markuljak I, Ivankova J, Kubisz P: Thrombomodulin and von Willebrand factor in smokers and during smoking. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol (1978), 1995; 37: 137-139

78) Lippi G, Franchini M, Targher G: Arterial thrombus formation in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2011; 8: 502-512

79) Hansson GK, Libby P, Tabas I: Inflammation and plaque vulnerability. J Intern Med, 2015; 278: 483-493

80) Newby AC: Metalloproteinases and vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques. Trends Cardiovasc Med, 2007; 17: 253-258

81) Perlstein TS, Lee RT: Smoking, metalloproteinases, and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2006; 26: 250-256

82) Churg A, Wang X, Wang RD, Meixner SC, Pryzdial EL, Wright JL: Alpha1-antitrypsin suppresses TNF-alpha and MMP-12 production by cigarette smoke-stimulated macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2007; 37: 144151

83) Takimoto-Sato M, Suzuki M, Kimura H, Ge H, Matsumoto M, Makita H, Arai S, Miyazaki T, Nishimura M, Konno S: Apoptosis inhibitor of macrophage (AIM)/ CD5L is involved in the pathogenesis of COPD. Respir Res, 2023; 24: 201

84) Nordskog BK, Blixt AD, Morgan WT, Fields WR, Hellmann GM: Matrix-degrading and pro-inflammatory changes in human vascular endothelial cells exposed to cigarette smoke condensate. Cardiovasc Toxicol, 2003; 3: 101-117

85) Carty CS, Soloway PD, Kayastha S, Bauer J, Marsan B, Ricotta JJ, Dryjski M: Nicotine and cotinine stimulate secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and affect expression of matrix metalloproteinases in cultured

human smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Surg, 1996; 24: 927934; discussion 934-925

86) O’Toole TE, Zheng YT, Hellmann J, Conklin DJ, Barski O, Bhatnagar A: Acrolein activates matrix metalloproteinases by increasing reactive oxygen species in macrophages. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2009; 236: 194201

87) Henning RJ: Particulate matter air pollution is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Curr Probl Cardiol, 2023: 102094

88) Bouki KP, Katsafados MG, Chatzopoulos DN, Psychari SN, Toutouzas KP, Charalampopoulos AF, Sakkali EN, Koudouri AA, Liakos GK, Apostolou TS: Inflammatory markers and plaque morphology: an optical coherence tomography study. Int J Cardiol, 2012; 154: 287-292

89) Palmer RM, Stapleton JA, Sutherland G, Coward PY, Wilson RF, Scott DA: Effect of nicotine replacement and quitting smoking on circulating adhesion molecule profiles (sICAM-1, sCD44v5, sCD44v6). Eur J Clin Invest, 2002; 32: 852-857

90) Komiyama M, Takanabe R, Ono K, Shimada S, Wada H, Yamakage H, Satoh-Asahara N, Morimoto T, Shimatsu A, Takahashi Y, Hasegawa K: Association between monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and blood pressure in smokers. J Int Med Res, 2018; 46: 965-974

91) Ambrose JA, Barua RS: The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2004; 43: 1731-1737

92) Bielinski SJ, Berardi C, Decker PA, Kirsch PS, Larson NB, Pankow JS, Sale M, de Andrade M, Sicotte H, Tang W, Hanson NQ, Wassel CL, Polak JF, Tsai MY: P-selectin and subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis: the MultiEthnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis, 2015; 240: 3-9

93) Cacciola RR, Guarino F, Polosa R: Relevance of endothelial-haemostatic dysfunction in cigarette smoking. Curr Med Chem, 2007; 14: 1887-1892

94) Jennings LK: Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost, 2009; 102: 248257

- Address for correspondence: Mari Ishida, Department of Cardiovascular Physiology and Medicine, Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan E-mail: mari@hiroshima-u.ac.jp

Received: October 31, 2023 Accepted for publication: December 1, 2023

Copyright@2024 Japan Atherosclerosis Society

This article is distributed under the terms of the latest version of CC BY-NC-SA defined by the Creative Commons Attribution License.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.rv22015

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38220184

Publication Date: 2024-01-13

Cigarette Smoking and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

Abstract

The detrimental effects of cigarette smoking on cardiovascular health, particularly atherosclerosis and thrombosis, are well established, and more detailed mechanisms continue to emerge. As the fundamental pathophysiology of the adverse effects of smoking, endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and thrombosis are considered to be particularly important. Cigarette smoke induces endothelial dysfunction, leading to impaired vascular dilation and hemostasis regulation. Factors contributing to endothelial dysfunction include reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide, increased levels of superoxide anion, and endothelin release. Chronic inflammation of the vascular wall is a central pathogenesis of smoking-induced atherosclerosis. Smoking systemically elevates inflammatory markers and induces the expression of adhesion molecules and cytokines in various tissues. Pattern recognition receptors and damage-associated molecular patterns play crucial roles in the mechanism underlying smoking-induced inflammation. Smoking-induced DNA damage and activation of innate immunity, such as the NLRP3 inflammasome, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway, and Toll-like receptor 9, are shown to amplify inflammatory cytokine expression. Cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and inflammation influence platelet adhesion, aggregation, and coagulation via adhesion molecule upregulation. Furthermore, it affects the coagulation cascade and fibrinolysis balance, causing thrombus formation. Matrix metalloproteinases contribute to plaque vulnerability and atherothrombotic events. The impact of smoking on inflammatory cells and adhesion molecules further intensifies the risk of atherothrombosis. Collectively, exposure to cigarette smoke exerts profound effects on endothelial function, inflammation, and thrombosis, contributing to the development and progression of atherosclerosis and atherothrombotic cardiovascular diseases. Understanding these intricate mechanisms highlights the urgent need for smoking cessation to protect cardiovascular health. This comprehensive review investigates the multifaceted mechanisms through which smoking contributes to these life-threatening conditions.

1. Introduction

attributed to cigarette smoking

2. Endothelial Dysfunction

vasodilators with anti-atherosclerotic and antiaggregatory effects, such as NO and prostacyclin, and thus is a highly dynamic organ possessing antiinflammatory, antithrombotic, and vasodilatory properties. Exposure to cigarette smoke leads to endothelial dysfunction, which is considered as the earliest manifestation of atherosclerosis, resulting in impaired regulation and maintenance of vascular dilation and hemostasis

al. reported that vascular endothelial cells cultured in a culture medium supplemented with smoker’s serum exhibited decreased NO production, decreased eNOS activity, and increased endogenous ROS production compared with nonsmokers, which were restored by antioxidant drugs

dysfunction leads to an increase in

3. Inflammation

mentioned later, experiments conducted in vitro have demonstrated that CSE increases the expression of IL-6 and IL-8

atherosclerosis. For example, inhibition of TLR9 activation using immune-regulatory oligodeoxynucleotides transforms macrophage plasticity into anti-inflammatory macrophages and suppresses atherosclerotic plaque formation

smooth muscle cells and increased macrophage recruitment within the plaques

and rat aortic tissues resulted in increased ROS production, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and CRP elevation

be elevated in smokers with CAD

Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), known as a cytosolic DNA sensor, is activated not only by pathogen-derived DNA but also by endogenous DNA. It is expressed in various cells, including microglia, neurons, hepatocytes, peripheral monocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages, and cardiovascular cells, such as endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, cardiomyocytes, and fibroblasts

lipid peroxidation

neutrophil-like cells derived from HL-60 cells

4. Thrombotic Effects

to cigarette smoke has been reported

fibrinogen receptor glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, compared with nonsmokers

human macrophages and stimulated MMP activity in an oxidative stress-dependent manner in advanced atherosclerotic lesions

5. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Acknowledgements

Competing Interests

References

- Outline of Health, Labour and Welfare Statistics 2022. 2022

- Ezzati M, Henley SJ, Thun MJ, Lopez AD: Role of smoking in global and regional cardiovascular mortality. Circulation, 2005; 112: 489-497

- Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Odell PM, Kannel WB: An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation, 1991; 83: 356-362

- Iso H, Date C, Yamamoto A, Toyoshima H, Watanabe Y, Kikuchi S, Koizumi A, Wada Y, Kondo T, Inaba Y,

5) Smith CJ, Fischer TH: Particulate and vapor phase constituents of cigarette mainstream smoke and risk of myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis, 2001; 158: 257267

6) Csordas A, Bernhard D: The biology behind the atherothrombotic effects of cigarette smoke. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2013; 10: 219-230

7) Barua RS, Ambrose JA: Mechanisms of coronary thrombosis in cigarette smoke exposure. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2013; 33: 1460-1467

8) Kobayashi Y, Sakai C, Ishida T, Nagata M, Nakano Y, Ishida M: Mitochondrial DNA is a key driver in cigarette smoke extract-induced IL-6 expression. Hypertens Res, 2023; doi: 10.1038/s41440-023-01463-z. ePub ahead of print

9) Messner B, Bernhard D: Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2014; 34: 509-515

10) Jaén RI, Val-Blasco A, Prieto P, Gil-Fernández M, Smani T, López-Sendón JL, Delgado C, Boscá L, FernándezVelasco M: Innate Immune Receptors, Key Actors in Cardiovascular Diseases. JACC Basic Transl Sci, 2020; 5: 735-749

11) Zindel J, Kubes P: DAMPs, PAMPs, and LAMPs in Immunity and Sterile Inflammation. Annu Rev Pathol, 2020; 15: 493-518

12) Sampilvanjil A, Karasawa T, Yamada N, Komada T, Higashi T, Baatarjav C, Watanabe S, Kamata R, Ohno N, Takahashi M: Cigarette smoke extract induces ferroptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2020; 318: H508-h518

13) Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ye T, Yang L, Shen Y, Li H: Ferroptosis Signaling and Regulators in Atherosclerosis. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021; 9: 809457

14) Fuster V, Moreno PR, Fayad ZA, Corti R, Badimon JJ: Atherothrombosis and high-risk plaque: part I: evolving concepts. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2005; 46: 937-954

15) Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, Spiegelhalter DJ, Miller OI, Sullivan ID, Lloyd JK, Deanfield JE: Noninvasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet, 1992; 340: 1111-1115

16) Johnson HM, Gossett LK, Piper ME, Aeschlimann SE, Korcarz CE, Baker TB, Fiore MC, Stein JH: Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on endothelial function: 1 -year outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010; 55: 1988-1995

17) Otsuka R, Watanabe H, Hirata K, Tokai K, Muro T, Yoshiyama M, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J: Acute effects of passive smoking on the coronary circulation in healthy young adults. Jama, 2001; 286: 436-441

18) Rahman MM, Laher I: Structural and functional alteration of blood vessels caused by cigarette smoking: an overview of molecular mechanisms. Curr Vasc Pharmacol, 2007; 5: 276-292

19) Heitzer T, Just H, Münzel T: Antioxidant vitamin C improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic smokers.

20) Heitzer T, Brockhoff C, Mayer B, Warnholtz A, Mollnau H, Henne S, Meinertz T, Münzel T: Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in chronic smokers: evidence for a dysfunctional nitric oxide synthase. Circ Res, 2000; 86: E36-41

21) Barua RS, Ambrose JA, Srivastava S, DeVoe MC, EalesReynolds LJ: Reactive oxygen species are involved in smoking-induced dysfunction of nitric oxide biosynthesis and upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: an in vitro demonstration in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Circulation, 2003; 107: 2342-2347

22) Kayyali US, Budhiraja R, Pennella CM, Cooray S, Lanzillo JJ, Chalkley R, Hassoun PM: Upregulation of xanthine oxidase by tobacco smoke condensate in pulmonary endothelial cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2003; 188: 59-68

23) Jaimes EA, DeMaster EG, Tian RX, Raij L: Stable compounds of cigarette smoke induce endothelial superoxide anion production via NADPH oxidase activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2004; 24: 1031-1036

24) Miró O, Alonso JR, Jarreta D, Casademont J, UrbanoMárquez A, Cardellach F: Smoking disturbs mitochondrial respiratory chain function and enhances lipid peroxidation on human circulating lymphocytes. Carcinogenesis, 1999; 20: 1331-1336

25) Ueda K, Sakai C, Ishida T, Morita K, Kobayashi Y, Horikoshi Y, Baba A, Okazaki Y, Yoshizumi M, Tashiro S, Ishida M: Cigarette smoke induces mitochondrial DNA damage and activates cGAS-STING pathway: application to a biomarker for atherosclerosis. Clin Sci (Lond), 2023; 137: 163-180

26) Suski JM, Lebiedzinska M, Bonora M, Pinton P, Duszynski J, Wieckowski MR: Relation Between Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and ROS Formation. In: Palmeira CM, Moreno AJ, eds. Mitochondrial Bioenergetics: Methods and Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2012: 183-205

27) Lavi S, Prasad A, Yang EH, Mathew V, Simari RD, Rihal CS, Lerman LO, Lerman A: Smoking is associated with epicardial coronary endothelial dysfunction and elevated white blood cell count in patients with chest pain and early coronary artery disease. Circulation, 2007; 115: 2621-2627

28) Barbieri SS, Zacchi E, Amadio P, Gianellini S, Mussoni L, Weksler BB, Tremoli E: Cytokines present in smokers’ serum interact with smoke components to enhance endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res, 2011; 90: 475483

29) Wang H, Chen H, Fu Y, Liu M, Zhang J, Han S, Tian Y, Hou H, Hu Q: Effects of Smoking on InflammatoryRelated Cytokine Levels in Human Serum. Molecules, 2022; 27

30) Hussein BJ, Atallah HN, AL-Dahhan NAA: Salivary levels of Interleukin-6, Interleukin-8 and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha in Smokers Aged 35-46 Years with Dental Caries Disease. Medico Legal Update, 2020; 20: 14641470

31) Jefferis BJ, Lowe GD, Welsh P, Rumley A, Lawlor DA, Ebrahim S, Carson C, Doig M, Feyerabend C, McMeekin

32) Bernhard D, Csordas A, Henderson B, Rossmann A, Kind M, Wick G: Cigarette smoke metal-catalyzed protein oxidation leads to vascular endothelial cell contraction by depolymerization of microtubules. Faseb j, 2005; 19: 1096-1107

33) Sundar IK, Chung S, Hwang JW, Lapek JD, Jr., Bulger M, Friedman AE, Yao H, Davie JR, Rahman I: Mitogenand stress-activated kinase 1 (MSK1) regulates cigarette smoke-induced histone modifications on NF-

34) Hansson GK, Libby P, Schönbeck U, Yan ZQ: Innate and adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Circ Res, 2002; 91: 281-291

35) Ishida M, Sakai C, Ishida T: Role of DNA damage in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J Cardiol, 2023; 81: 331336

36) Shaw AC, Goldstein DR, Montgomery RR: Agedependent dysregulation of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol, 2013; 13: 875-887

37) Takeuchi O, Akira S: Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell, 2010; 140: 805-820

38) Roshan MH, Tambo A, Pace NP: The Role of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Int J Inflam, 2016; 2016: 1532832

39) Miggin SM, O’Neill LA: New insights into the regulation of TLR signaling. J Leukoc Biol, 2006; 80: 220-226

40) Banchereau J, Pascual V: Type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Immunity, 2006; 25: 383-392

41) Ma C, Ouyang Q, Huang Z, Chen X, Lin Y, Hu W, Lin L: Toll-Like Receptor 9 Inactivation Alleviated Atherosclerotic Progression and Inhibited Macrophage Polarized to M1 Phenotype in ApoE-/- Mice. Dis Markers, 2015; 2015: 909572

42) Krogmann AO, Lüsebrink E, Steinmetz M, Asdonk T, Lahrmann C, Lütjohann D, Nickenig G, Zimmer S: Proinflammatory Stimulation of Toll-Like Receptor 9 with High Dose CpG ODN 1826 Impairs Endothelial Regeneration and Promotes Atherosclerosis in Mice. PLoS One, 2016; 11: e0146326

43) Li J, Huynh L, Cornwell WD, Tang MS, Simborio H, Huang J, Kosmider B, Rogers TJ, Zhao H, Steinberg MB, Thu Thi Le L, Zhang L, Pham K, Liu C, Wang H: Electronic Cigarettes Induce Mitochondrial DNA Damage and Trigger TLR9 (Toll-Like Receptor 9)-Mediated Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2021; 41: 839-853

44) Takahashi M: NLRP3 inflammasome as a key driver of vascular disease. Cardiovasc Res, 2022; 118: 372-385

45) Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JP: The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol, 2019; 19: 477-489

46) Kumari P, Russo AJ, Shivcharan S, Rathinam VA: AIM2 in health and disease: Inflammasome and beyond. Immunol Rev, 2020; 297: 83-95

47) Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G,

48) Usui F, Shirasuna K, Kimura H, Tatsumi K, Kawashima A, Karasawa T, Hida S, Sagara J, Taniguchi S, Takahashi M : Critical role of caspase-1 in vascular inflammation and development of atherosclerosis in Western diet-fed apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2012; 425: 162-168

49) Hendrikx T, Jeurissen ML, van Gorp PJ, Gijbels MJ, Walenbergh SM, Houben T, van Gorp R, Pöttgens CC, Stienstra R, Netea MG, Hofker MH, Donners MM, Shiri-Sverdlov R: Bone marrow-specific caspase-1/11 deficiency inhibits atherosclerosis development in Ldlr(-/-) mice. Febs j, 2015; 282: 2327-2338

50) Paulin N, Viola JR, Maas SL, de Jong R, FernandesAlnemri T, Weber C, Drechsler M, Döring Y, Soehnlein O: Double-Strand DNA Sensing Aim2 Inflammasome Regulates Atherosclerotic Plaque Vulnerability. Circulation, 2018; 138: 321-323

51) Pan J, Han L, Guo J, Wang X, Liu D, Tian J, Zhang M, An F: AIM2 accelerates the atherosclerotic plaque progressions in ApoE-/- mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2018; 498: 487-494

52) Mehta S, Dhawan V: Exposure of cigarette smoke condensate activates NLRP3 inflammasome in THP-1 cells in a stage-specific manner: An underlying role of innate immunity in atherosclerosis. Cell Signal, 2020; 72: 109645

53) Yao Y, Mao J, Xu S, Zhao L, Long L, Chen L, Li D, Lu S: Rosmarinic acid inhibits nicotine-induced C-reactive protein generation by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation in smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol, 2019; 234: 1758-1767

54) Wu X, Zhang H, Qi W, Zhang Y, Li J, Li Z, Lin Y, Bai X, Liu X, Chen X, Yang H, Xu C, Zhang Y, Yang B: Nicotine promotes atherosclerosis via ROS-NLRP3mediated endothelial cell pyroptosis. Cell Death Dis, 2018; 9: 171

55) Mehta S, Vijayvergiya R, Dhawan V: Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly is associated with smoking status of patients with coronary artery disease. Int Immunopharmacol, 2020; 87: 106820

56) Hong

57) Pham PT, Fukuda D, Nishimoto S, Kim-Kaneyama JR, Lei XF, Takahashi Y, Sato T, Tanaka K, Suto K, Kawabata Y, Yamaguchi K, Yagi S, Kusunose K, Yamada H, Soeki T, Wakatsuki T, Shimada K, Kanematsu Y, Takagi Y, Shimabukuro M, Setou M, Barber GN, Sata M: STING, a cytosolic DNA sensor, plays a critical role in atherogenesis: a link between innate immunity and chronic inflammation caused by lifestyle-related diseases. Eur Heart J, 2021; 42: 4336-4348

58) Li M, Wang ZW, Fang LJ, Cheng SQ, Wang X, Liu NF: Programmed cell death in atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. Cell Death Dis, 2022; 13: 467

59) Yu Y, Yan Y, Niu F, Wang Y, Chen X, Su G, Liu Y, Zhao X, Qian L, Liu P, Xiong Y: Ferroptosis: a cell death connecting oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Discov, 2021; 7: 193

60) Wen Q, Liu J, Kang R, Zhou B, Tang D: The release and activity of HMGB1 in ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2019; 510: 278-283

61) Moschonas IC, Tselepis AD: The pathway of neutrophil extracellular traps towards atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Atherosclerosis, 2019; 288: 9-16

62) Hidalgo A, Libby P, Soehnlein O, Aramburu IV, Papayannopoulos V, Silvestre-Roig C: Neutrophil extracellular traps: from physiology to pathology. Cardiovasc Res, 2022; 118: 2737-2753

63) Sano M, Maejima Y, Nakagama S, Shiheido-Watanabe Y, Tamura N, Hirao K, Isobe M, Sasano T: Neutrophil extracellular traps-mediated Beclin-1 suppression aggravates atherosclerosis by inhibiting macrophage autophagy. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022; 10: 876147

64) Cornel JH, Becker RC, Goodman SG, Husted S, Katus H, Santoso A, Steg G, Storey RF, Vintila M, Sun JL, Horrow J, Wallentin L, Harrington R, James S: Prior smoking status, clinical outcomes, and the comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in acute coronary syndromesinsights from the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Am Heart J, 2012; 164: 334

65) Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT, Liang YH, Smialek J, Virmani R: Coronary risk factors and plaque morphology in men with coronary disease who died suddenly. N Engl J Med, 1997; 336: 1276-1282

66) Levine PH: An acute effect of cigarette smoking on platelet function. A possible link between smoking and arterial thrombosis. Circulation, 1973; 48: 619-623

67) Hawkins RI: Smoking, platelets and thrombosis. Nature, 1972; 236: 450-452

68) Caponnetto P, Russo C, Di Maria A, Morjaria JB, Barton S, Guarino F, Basile E, Proiti M, Bertino G, Cacciola RR, Polosa R: Circulating endothelial-coagulative activation markers after smoking cessation: a 12 -month observational study. Eur J Clin Invest, 2011; 41: 616-626

69) Blache D: Involvement of hydrogen and lipid peroxides in acute tobacco smoking-induced platelet hyperactivity. Am J Physiol, 1995; 268: H679-685

70) Tell GS, Grimm RH, Jr., Vellar OD, Theodorsen L: The relationship of white cell count, platelet count, and hematocrit to cigarette smoking in adolescents: the Oslo Youth Study. Circulation, 1985; 72: 971-974

71) Imaizumi T, Satoh K, Yoshida H, Kawamura Y, Hiramoto M, Takamatsu S: Effect of cigarette smoking on the levels of platelet-activating factor-like lipid(s) in plasma lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis, 1991; 87: 47-55

72) Togna AR, Latina V, Orlando R, Togna GI: Cigarette smoke inhibits adenine nucleotide hydrolysis by human platelets. Platelets, 2008; 19: 537-542

73) Ichiki K, Ikeda H, Haramaki N, Ueno T, Imaizumi T: Long-term smoking impairs platelet-derived nitric oxide release. Circulation, 1996; 94: 3109-3114

74) Della Corte A, Tamburrelli C, Crescente M, Giordano L, D’Imperio M, Di Michele M, Donati MB, De Gaetano G, Rotilio D, Cerletti C: Platelet proteome in healthy

volunteers who smoke. Platelets, 2012; 23: 91-105

75) FitzGerald GA, Oates JA, Nowak J: Cigarette smoking and hemostatic function. Am Heart J, 1988; 115: 267271

76) Hioki H, Aoki N, Kawano K, Homori M, Hasumura Y, Yasumura T, Maki A, Yoshino H, Yanagisawa A, Ishikawa K : Acute effects of cigarette smoking on plateletdependent thrombin generation. Eur Heart J, 2001; 22: 56-61

77) Markuljak I, Ivankova J, Kubisz P: Thrombomodulin and von Willebrand factor in smokers and during smoking. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol (1978), 1995; 37: 137-139

78) Lippi G, Franchini M, Targher G: Arterial thrombus formation in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2011; 8: 502-512

79) Hansson GK, Libby P, Tabas I: Inflammation and plaque vulnerability. J Intern Med, 2015; 278: 483-493

80) Newby AC: Metalloproteinases and vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques. Trends Cardiovasc Med, 2007; 17: 253-258

81) Perlstein TS, Lee RT: Smoking, metalloproteinases, and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2006; 26: 250-256

82) Churg A, Wang X, Wang RD, Meixner SC, Pryzdial EL, Wright JL: Alpha1-antitrypsin suppresses TNF-alpha and MMP-12 production by cigarette smoke-stimulated macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2007; 37: 144151

83) Takimoto-Sato M, Suzuki M, Kimura H, Ge H, Matsumoto M, Makita H, Arai S, Miyazaki T, Nishimura M, Konno S: Apoptosis inhibitor of macrophage (AIM)/ CD5L is involved in the pathogenesis of COPD. Respir Res, 2023; 24: 201

84) Nordskog BK, Blixt AD, Morgan WT, Fields WR, Hellmann GM: Matrix-degrading and pro-inflammatory changes in human vascular endothelial cells exposed to cigarette smoke condensate. Cardiovasc Toxicol, 2003; 3: 101-117

85) Carty CS, Soloway PD, Kayastha S, Bauer J, Marsan B, Ricotta JJ, Dryjski M: Nicotine and cotinine stimulate secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and affect expression of matrix metalloproteinases in cultured

human smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Surg, 1996; 24: 927934; discussion 934-925

86) O’Toole TE, Zheng YT, Hellmann J, Conklin DJ, Barski O, Bhatnagar A: Acrolein activates matrix metalloproteinases by increasing reactive oxygen species in macrophages. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2009; 236: 194201

87) Henning RJ: Particulate matter air pollution is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Curr Probl Cardiol, 2023: 102094

88) Bouki KP, Katsafados MG, Chatzopoulos DN, Psychari SN, Toutouzas KP, Charalampopoulos AF, Sakkali EN, Koudouri AA, Liakos GK, Apostolou TS: Inflammatory markers and plaque morphology: an optical coherence tomography study. Int J Cardiol, 2012; 154: 287-292

89) Palmer RM, Stapleton JA, Sutherland G, Coward PY, Wilson RF, Scott DA: Effect of nicotine replacement and quitting smoking on circulating adhesion molecule profiles (sICAM-1, sCD44v5, sCD44v6). Eur J Clin Invest, 2002; 32: 852-857

90) Komiyama M, Takanabe R, Ono K, Shimada S, Wada H, Yamakage H, Satoh-Asahara N, Morimoto T, Shimatsu A, Takahashi Y, Hasegawa K: Association between monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and blood pressure in smokers. J Int Med Res, 2018; 46: 965-974

91) Ambrose JA, Barua RS: The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2004; 43: 1731-1737

92) Bielinski SJ, Berardi C, Decker PA, Kirsch PS, Larson NB, Pankow JS, Sale M, de Andrade M, Sicotte H, Tang W, Hanson NQ, Wassel CL, Polak JF, Tsai MY: P-selectin and subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis: the MultiEthnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis, 2015; 240: 3-9

93) Cacciola RR, Guarino F, Polosa R: Relevance of endothelial-haemostatic dysfunction in cigarette smoking. Curr Med Chem, 2007; 14: 1887-1892

94) Jennings LK: Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost, 2009; 102: 248257

- Address for correspondence: Mari Ishida, Department of Cardiovascular Physiology and Medicine, Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan E-mail: mari@hiroshima-u.ac.jp

Received: October 31, 2023 Accepted for publication: December 1, 2023

Copyright@2024 Japan Atherosclerosis Society

This article is distributed under the terms of the latest version of CC BY-NC-SA defined by the Creative Commons Attribution License.