DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02325-x

تاريخ النشر: 2025-05-07

تساهم الفئات ذات الدخل المرتفع بشكل غير متناسب في التغيرات المناخية المتطرفة على مستوى العالم

تم القبول: 24 مارس 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 7 مايو 2025

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

تستمر الظلم المناخي حيث يتحمل الأقل مسؤولية غالبًا أكبر الآثار، سواء بين الدول أو داخلها. هنا نوضح كيف أن انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة الناتجة عن الاستهلاك والاستثمارات المنسوبة إلى أغنى فئات السكان قد أثرت بشكل غير متناسب على تغير المناخ الحالي. نربط عدم المساواة في الانبعاثات خلال الفترة من 1990 إلى 2020 بالظواهر المناخية الإقليمية باستخدام إطار قائم على المحاكاة. نجد أن ثلثي (خمس) الاحترار يُعزى إلى الأغنى.

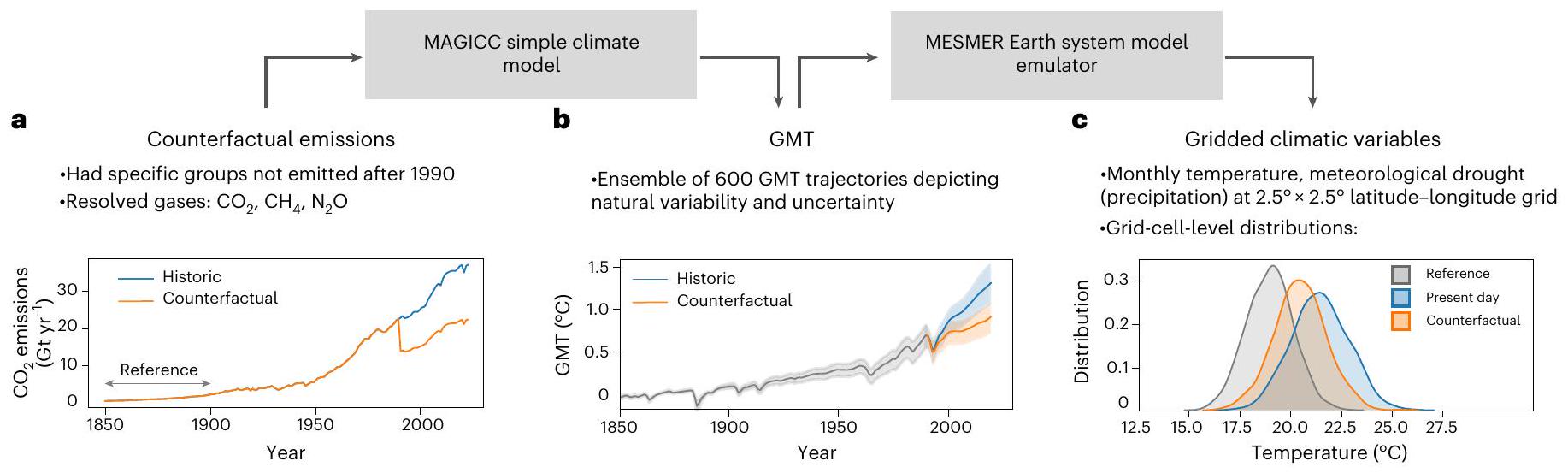

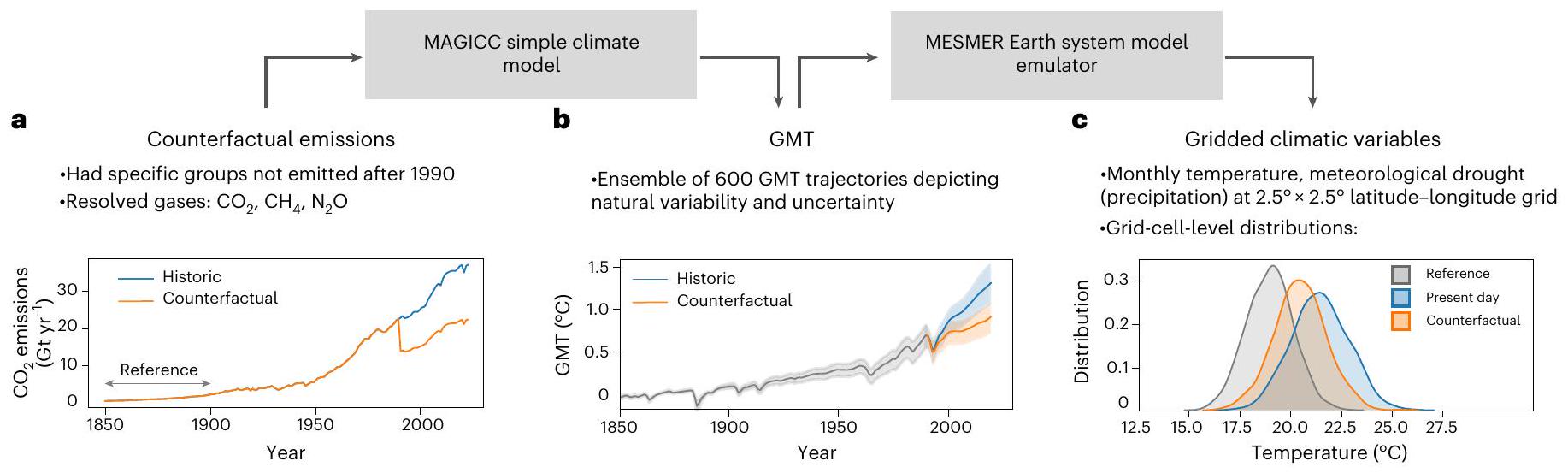

نُعزى بشكل منهجي التغيرات في مستويات درجة الحرارة العالمية المتوسطة (GMT) والتغيرات المناخية على مستوى خلايا الشبكة إلى الانبعاثات من مجموعات الثروة المختلفة. نستخدم نموذج تقييم تغير المناخ الناتج عن غازات الدفيئة (MAGICC).

مجموعات المنبع بعد عام 1990 (برتقالي). ب، مستويات متوسط درجة الحرارة العالمية للانبعاثات التاريخية والافتراضية (الخطوط الصلبة) جنبًا إلى جنب مع فترات الثقة من 5 إلى 95 (الأغلفة المظللة) المستمدة من 600 عضو في المجموعة. ج، التوزيعات المرجعية والحالية والافتراضية في خلية شبكة واحدة باستخدام درجة الحرارة كمثال.

عدم المساواة في المساهمات المنسوبة للاحتباس الحراري العالمي

واحد من خمسة) من مساهمات المجموعة المعنية في انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة المجمعة (الجدول التكميلي 2)، مما يبرز أهمية غير-

فترات الثقة ممثلة كخطوط عمودية. التقديرات تستند إلى 600 عضو في المجموعة. ج، التحليل الإقليمي لأفضل النتائج العالمية

فروقات كبيرة في الظروف القصوى المنسوبة على مستوى العالم

شمال غرب أمريكا وأوروبا الغربية والوسطى مقارنةً بمنطقة الأمازون وغرب وجنوب أفريقيا في الشكل 3c، d).

نسبة التأثيرات العابرة للحدود الناتجة عن الانبعاثات الإقليمية

نظائرها (الشكل 2). تظهر هذه الفجوة أيضًا على مستوى خلايا الشبكة: في الوسيط العالمي، تنبعث الانبعاثات من الأعلى

الأحداث تُنسب إلى مجموعة معينة من المنبعين. القيم في الأعمدة تشير إلى الأعداد الإضافية من الأحداث على مدار 100 عام. تم اشتقاق التقديرات الوسيطة من خلال حساب نتائج النسبة الوسيطة في كل خلية شبكية (مُقدرة من 15,000 عضو في المجموعة لكل منها) ثم حساب الإحصائيات عبر الخلايا الشبكية داخل كل منطقة.

ناتج عن القمة

نقاش

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

References

- Newman, R. & Noy, I. The global costs of extreme weather that are attributable to climate change. Nat. Commun. 14, 6103 (2023).

- Warner, K. & Weisberg, M. A funding mosaic for loss and damage. Science 379, 219-219 (2023).

- Chancel, L. Global carbon inequality over 1990-2019. Nat. Sustain. 5, 931-938 (2022).

- Wallemacq, P., Below, R. & McClean, D. Economic Losses, Poverty and Disasters: 1998-2017 (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2018); https://www.preventionweb.net/files/61119_ credeconomiclosses.pdf

- Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Burke, M. Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9808-9813 (2019).

- Hallegatte, S. & Rozenberg, J. Climate change through a poverty lens. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 250-256 (2017).

- Dhakal, S. et al. in Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) 215-294 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

- Mar, K. A., Unger, C., Walderdorff, L. & Butler, T. Beyond CO2 equivalence: the impacts of methane on climate, ecosystems, and health. Environ. Sci. Policy 134, 127-136 (2022).

- Beusch, L., Gudmundsson, L. & Seneviratne, S. I. Emulating Earth system model temperatures with MESMER: from global mean temperature trajectories to grid-point-level realizations on land. Earth Syst. Dynam. 11, 139-159 (2020).

- Meinshausen, M., Raper, S. C. & Wigley, T. M. Emulating coupled atmosphere-ocean and carbon cycle models with a simpler model, MAGICC6 – part 1: model description and calibration. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 1417-1456 (2011).

- Schöngart, S. Introducing the MESMER-M-TPv0.1.0 module: spatially explicit Earth system model emulation for monthly precipitation and temperature. EGUsphere 2024, 8283-8320 (2024).

- Otto, F. E. Attribution of extreme events to climate change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 48, 813-828 (2023).

- Stott, P. A., Stone, D. A. & Allen, M. R. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature 432, 610-614 (2004).

- Van Oldenborgh, G. J. et al. Pathways and pitfalls in extreme event attribution. Climatic Change 166, 13 (2021).

- Beusch, L. et al. Responsibility of major emitters for country-level warming and extreme hot years. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 7 (2022).

- Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. National attribution of historical climate damages. Climatic Change 172, 40 (2022).

- Trudinger, C. & Enting, I. Comparison of formalisms for attributing responsibility for climate change: non-linearities in the brazilian proposal approach. Climatic Change 68, 67-99 (2005).

- Otto, F. E., Skeie, R. B., Fuglestvedt, J. S., Berntsen, T. & Allen, M. R. Assigning historic responsibility for extreme weather events. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 757-759 (2017).

- De Polt, K. et al. Quantifying impact-relevant heatwave durations. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 104005 (2023).

- Seneviratne, S. et al. 2021: Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.), 1513-1766 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press 2021).

- Allen, M. R. et al. Indicate separate contributions of long-lived and short-lived greenhouse gases in emission targets. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 5 (2022).

- Cook, B.I. et al. Twenty-first century drought projections in the CMIP6 forcing scenarios. Earth Future 8, e2019EF001461 (2020).

- Wu, Y. et al. Hydrological projections under CMIP5 and CMIP6: sources and magnitudes of uncertainty. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 105, E59-E74 (2024).

- Chen, D. et al. 2021: Framing, context, and methods. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 147-286 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

- Yao, Y., Ciais, P., Viovy, N., Joetzjer, E. & Chave, J. How drought events during the last century have impacted biomass carbon in amazonian rainforests. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 747-762 (2023).

- Kumar, N. et al. Joint behaviour of climate extremes across India: past and future. J. Hydrol. 597, 126185 (2021).

- McKenna, C. M., Maycock, A. C., Forster, P. M., Smith, C. J. & Tokarska, K. B. Stringent mitigation substantially reduces risk of unprecedented near-term warming rates. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 126-131 (2021).

- IPCC Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

- Zeppetello, L. R. V., Battisti, D. S. & Baker, M. B. The physics of heat waves: what causes extremely high summertime temperatures? J. Clim. 35, 2231-2251 (2022).

- Chancel, L., Bothe, P. & Voituriez, T. The potential of wealth taxation to address the triple climate inequality crisis. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 5-7 (2024).

- Zucman, G. A Blueprint for a Coordinated Minimum Effective Taxation Standard for Utra-High-Net-Worth Individuals (Tax Observatory, 2024); https://www.taxobservatory.eu/www-site/ uploads/2024/06/report-g20-24_06_24.pdf

- Pachauri, S. et al. Fairness considerations in global mitigation investments. Science 378, 1057-1059 (2022).

- Bhattacharya, A., Songwe, V., Soubeyran, E. & Stern, N. Raising Ambition and Accelerating Delivery of Climate Finance (Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, 2024); https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/ uploads/2024/11/Raising-ambition-and-accelerating-delivery-of-climate-finance_Third-IHLEG-report.pdf

- Dibley, A. et al. Biases in ‘sustainable finance’ metrics could hinder lending to those that need it most. Nature 634, 294-297 (2024).

- Serdeczny, O. & Lissner, T. Research agenda for the loss and damage fund. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 412-412 (2023).

- Ogunbode, C. A. et al. Climate justice beliefs related to climate action and policy support around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 1144-1150 (2024).

- Berger, J. & Liebe, U. Effective climate action must address both social inequality and inequality aversion. npj Clim. Action 4, 1 (2025).

- Jézéquel, A. et al. Broadening the scope of anthropogenic influence in extreme event attribution. Environ. Res. Clim. 3, 042003 (2024).

- Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E. et al. Frontiers in attributing climate extremes and associated impacts. Front. Clim. 6, 1455023 (2024).

- Noy, I. et al. Event attribution is ready to inform loss and damage negotiations. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1279-1281 (2023).

- King, A. D., Grose, M. R., Kimutai, J., Pinto, I. & Harrington, L. J. Event attribution is not ready for a major role in loss and damage. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 415-417 (2023).

- Andrijevic, M. et al. Towards scenario representation of adaptive capacity for global climate change assessments. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 778-787 (2023).

- Smiley, K. T. et al. Social inequalities in climate change-attributed impacts of hurricane Harvey. Nat. Commun. 13, 3418 (2022).

- Jensen, L., Gerdener, H., Eicker, A., Kusche, J. & Fiedler, S. Observations indicate regionally misleading wetting and drying trends in CMIP6. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 249 (2024).

- Kim, Y.-H., Min, S.-K., Zhang, X., Sillmann, J. & Sandstad, M. Evaluation of the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble for climate extreme indices. Weather Clim. Extremes 29, 100269 (2020).

- Zimm, C. et al. Justice considerations in climate research. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 22-30 (2024).

- Kikstra, J. S., Mastrucci, A., Min, J., Riahi, K. & Rao, N. D. Decent living gaps and energy needs around the world. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 095006 (2021).

© The Author(s) 2025, corrected publication 2025

طرق

مسارات الانبعاثات المضادة للواقع

من

نهج النمذجة القائم على المحاكي

إطار النسبة

تعريف الحدث المتطرف

تحليل نماذج المناخ وتوليف المخاطر

المناخ مقارنة بمناخ افتراضي، ونسبة الفرق في القيم.

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Tirivarombo, S., Osupile, D. & Eliasson, P. Drought monitoring and analysis: standardised precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) and standardised precipitation index (SPI). Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C. 106, 1-10 (2018).

- Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Van der Schrier, G., Beguería, S., Azorin-Molina, C. & Lopez-Moreno, J.-I. Contribution of precipitation and reference evapotranspiration to drought indices under different climates. J. Hydrol. 526, 42-54 (2015).

- Santos, C. N. et al. Monthly potential evapotranspiration estimated using the Thornthwaite method with gridded climate datasets in southeastern brazil. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 155, 3739-3756 (2024).

- Sheffield, J., Wood, E. F. & Roderick, M. L. Little change in global drought over the past 60 years. Nature 491, 435-438 (2012).

- Nicholls, Z. R. J. et al. Reduced complexity model intercomparison project phase 1: introduction and evaluation of global-mean temperature response. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 5175-5190 (2020).

- IPCC: Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

- Gütschow, J. et al. The PRIMAP-hist national historical emissions time series. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 571-603 (2016).

- Zhang, B. et al. Consumption-based accounting of global anthropogenic

emissions. Earth Future 6, 1349-1363 (2018). - Meinshausen, M. et al. Greenhouse-gas emission targets for limiting global warming to

. Nature 458, 1158-1162 (2009). - Büning, H. & Trenkler, G. Nichtparametrische Statistische Methoden (Walter de Gruyter, 2013).

- Schoengart, S. Data accompanying publication “High-Income Groups Disproportionately Contribute to Climate Extremes Worldwide.”. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14860538 (2025).

- Schöngart, S. sarasita/mesmer-m-tp: MESMER-M-TP v0.1.0 – GMD Submission. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 11086167 (2024).

- Schöngart, S. sarasita/attribution: code version accompanying publication “High-Income Groups Disproportionately Contribute to Climate Extremes Worldwide.”. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 15011461 (2025).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

محفظة الطبيعة

آخر تحديث بواسطة المؤلفين: 13/03/2025

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

غير متوفر | مؤكد

□ حجم العينة بالضبط

بيان حول ما إذا كانت القياسات قد أُخذت من عينات متميزة أو ما إذا كانت نفس العينة قد تم قياسها عدة مرات

□ الاختبار الإحصائي المستخدم وما إذا كان ذو جانب واحد أو جانبين

يجب أن تُوصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ واصفًا التقنيات الأكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

□ وصف لجميع المتغيرات المرافقة التي تم اختبارها

□ وصف لأي افتراضات أو تصحيحات، مثل اختبارات الطبيعية والتعديل للمقارنات المتعددة

□

□ وصف كامل للمعلمات الإحصائية بما في ذلك الاتجاه المركزي (مثل المتوسطات) أو تقديرات أساسية أخرى (مثل معامل الانحدار) وَ التباين (مثل الانحراف المعياري) أو تقديرات مرتبطة بعدم اليقين (مثل فترات الثقة)

□ لاختبار الفرضية الصفرية، إحصائية الاختبار (على سبيل المثال،

□ لتحليل بايزي، معلومات حول اختيار الأوليات وإعدادات سلسلة ماركوف مونت كارلو

□ للتصاميم الهرمية والمعقدة، تحديد المستوى المناسب للاختبارات والتقارير الكاملة للنتائج

□ تقديرات أحجام التأثير (مثل حجم كوهين

تحتوي مجموعتنا على الإنترنت حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات حول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

البرمجيات والرموز

nature portfolio | ملخص التقرير مارس 2021

البيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الوصول، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا

المشاركون في البحث البشري

| التقارير حول الجنس والنوع | غير متاح | ||

| خصائص السكان | غير متاح | ||

| التوظيف |

|

||

| الإشراف الأخلاقي | غير متاح |

التقارير الخاصة بالمجال

□ علوم الحياة □ العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية

- العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

تصميم دراسة العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

n/a

□

التقارير للمواد والأنظمة والأساليب المحددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | الأساليب | ||

| غير متاح | المشاركة في الدراسة | غير متاح | المشاركة في الدراسة |

| – | □ |  |

□ |

| X | □ |  |

|

| X | □ | X | □ |

| X | □ | ||

| X | □ | ||

| V | □ | ||

المعهد الدولي لتحليل النظم التطبيقية (IIASA)، لاكسنبورغ، النمسا. معهد علوم الغلاف الجوي والمناخ، ETH زيورخ، زيورخ، سويسرا. IRIThesys، جامعة هومبولت في برلين، برلين، ألمانيا. موارد المناخ، ملبورن، فيكتوريا، أستراليا. مدرسة الجغرافيا، علوم الأرض والغلاف الجوي، جامعة ملبورن، ملبورن، فيكتوريا، أستراليا. البريد الإلكتروني: sarah.schoengart@env.ethz.ch

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02325-x

Publication Date: 2025-05-07

High-income groups disproportionately contribute to climate extremes worldwide

Accepted: 24 March 2025

Published online: 7 May 2025

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

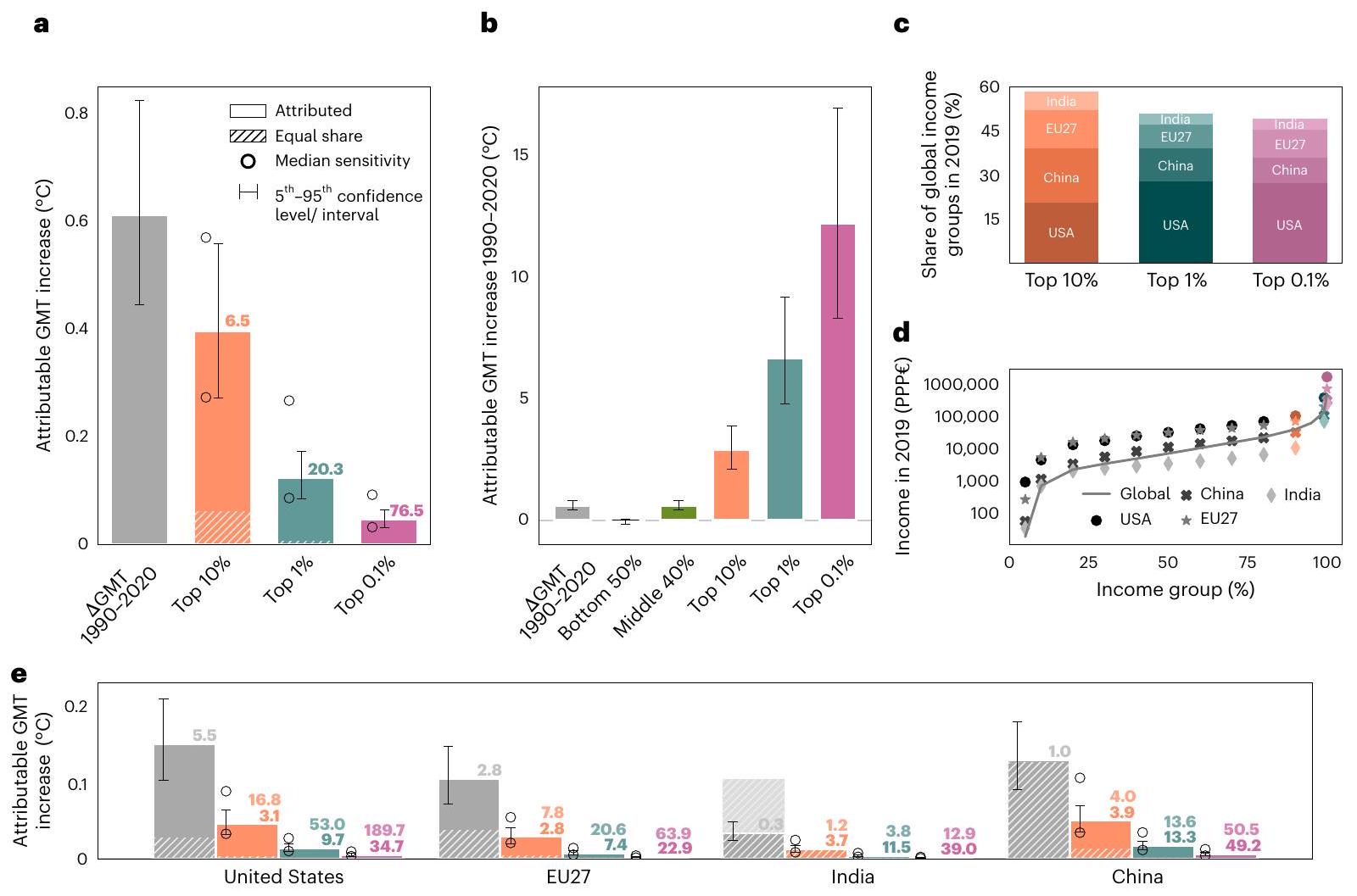

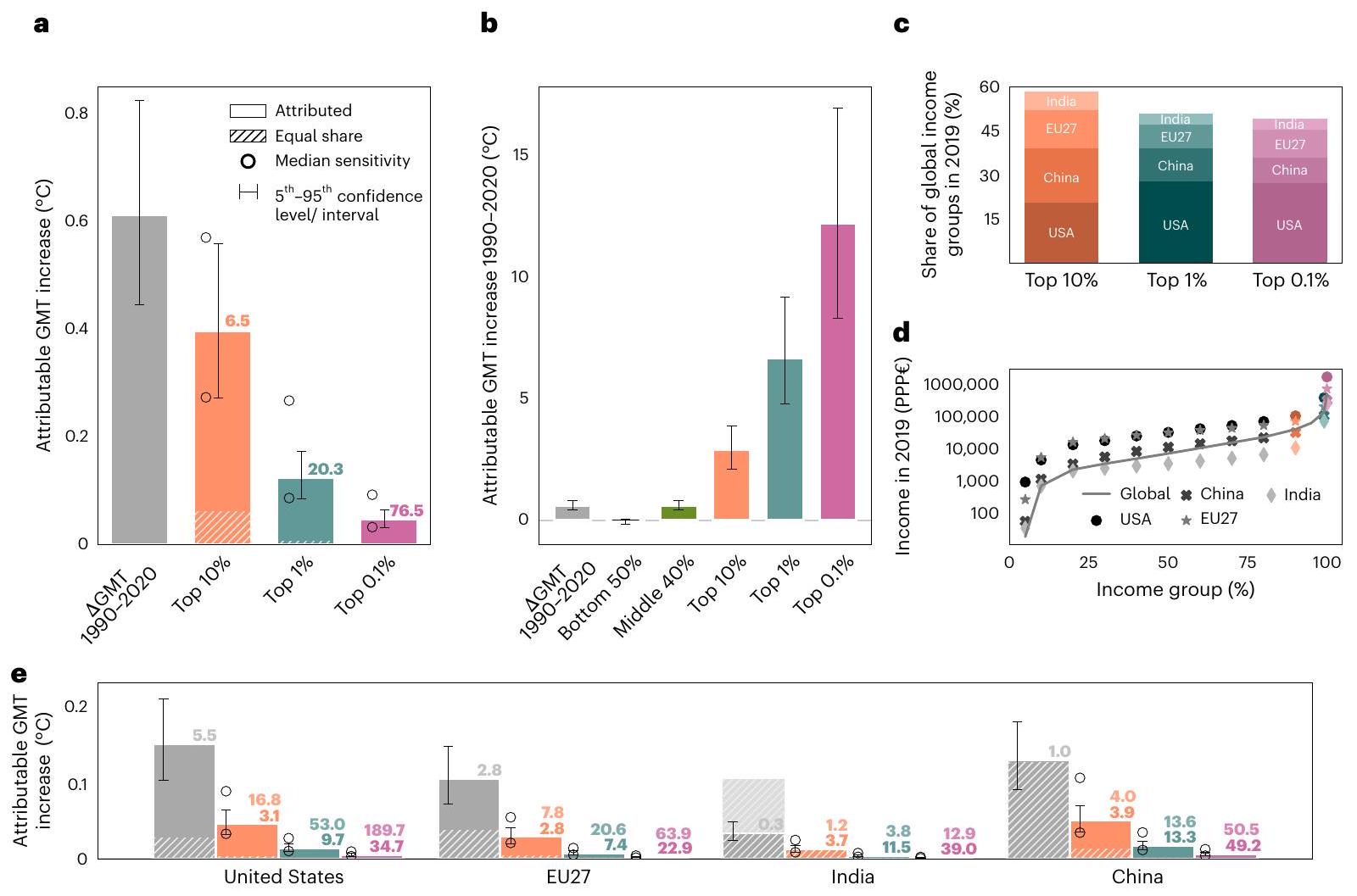

Climate injustice persists as those least responsible often bear the greatest impacts, both between and within countries. Here we show how GHG emissions from consumption and investments attributable to the wealthiest population groups have disproportionately influenced present-day climate change. We link emissions inequality over the period 1990-2020 to regional climate extremes using an emulator-based framework. We find that two-thirds (one-fifth) of warming is attributable to the wealthiest

systematically attribute changes in global mean temperature (GMT) levels and grid-cell-level climate extremes to emissions from different wealth groups. We use the Model for the Assessment of the Greenhouse Gas Induced Climate Change (MAGICC)

emitter groups after 1990 (orange).b, Median GMT levels for historic and counterfactual emissions pathways (solid lines) along with 5th-95th confidence intervals (shaded envelopes) derived from 600 ensemble members. c, Reference, present-day and counterfactual distributions at a single grid-cell using temperature as an example.

Inequality in attributed global warming contributions

one-fifth) than the respective group’s contributions to aggregated GHG basket emissions (Supplementary Table 2), underscoring the importance of non-

confidence intervals represented as vertical lines. Estimates are based on 600 ensemble members. c, Regional breakdown of the global top

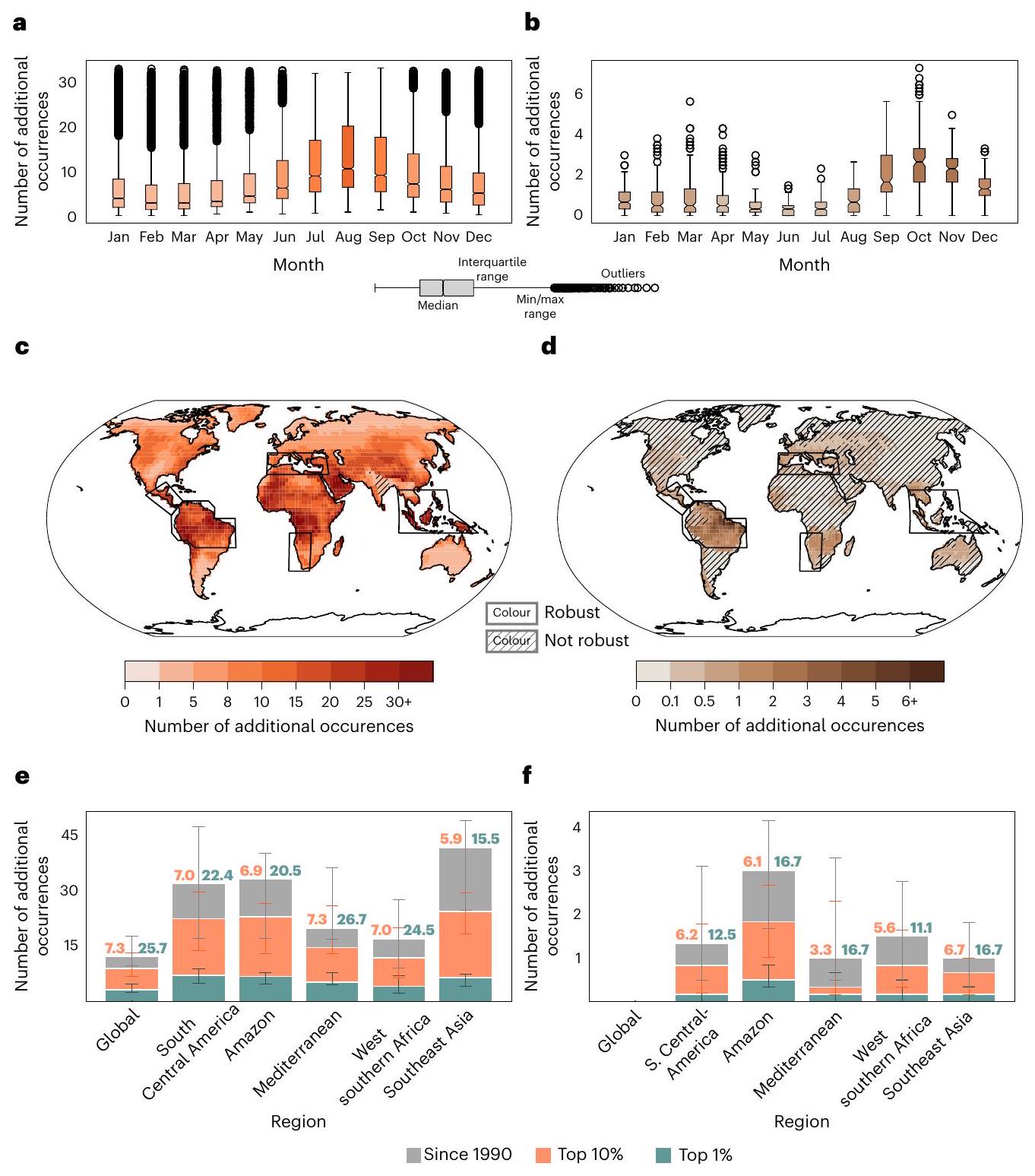

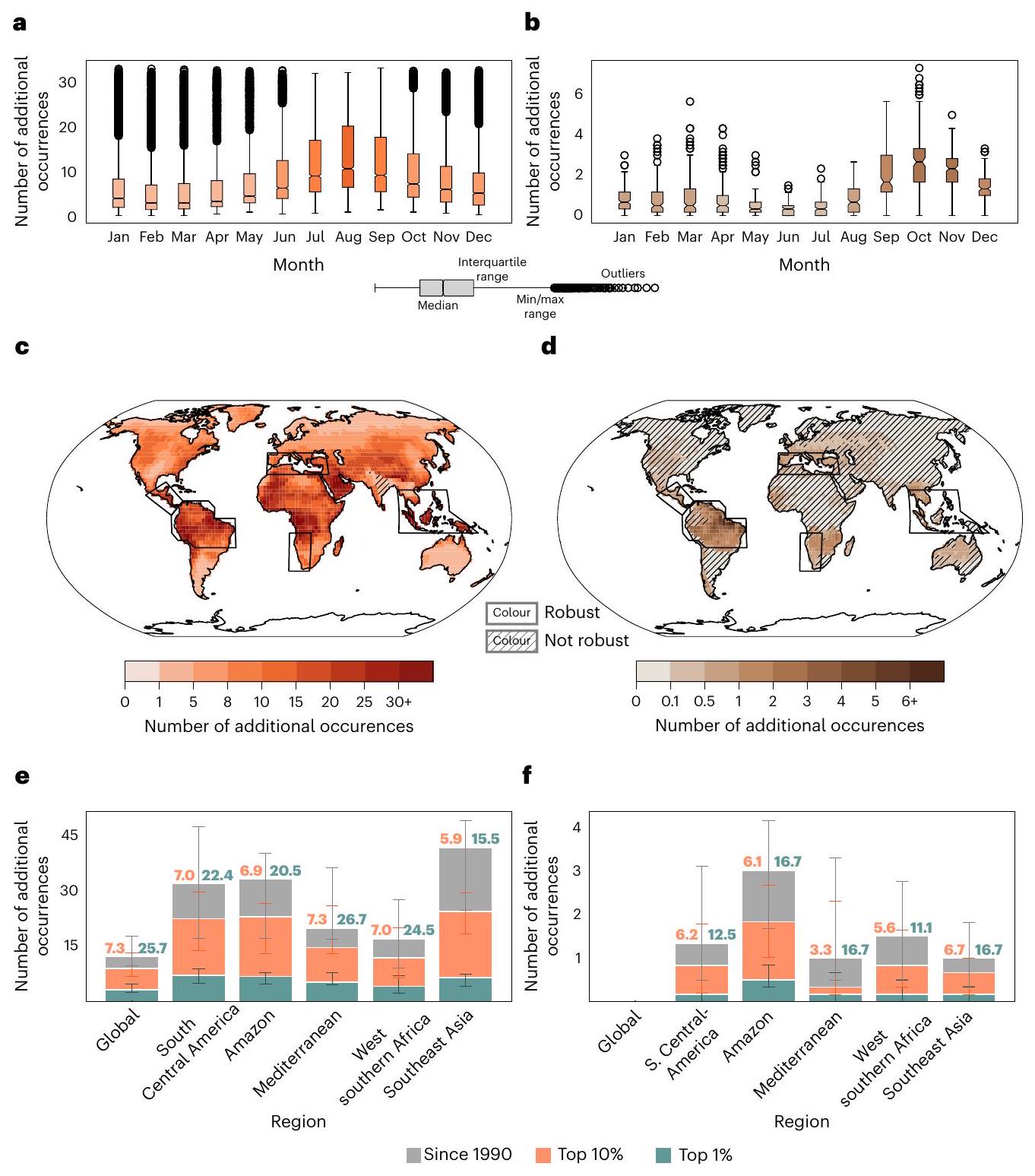

Major disparities in attributable extremes worldwide

western North America and west and central Europe compared with the Amazon region and west southern Africa in Fig. 3c,d).

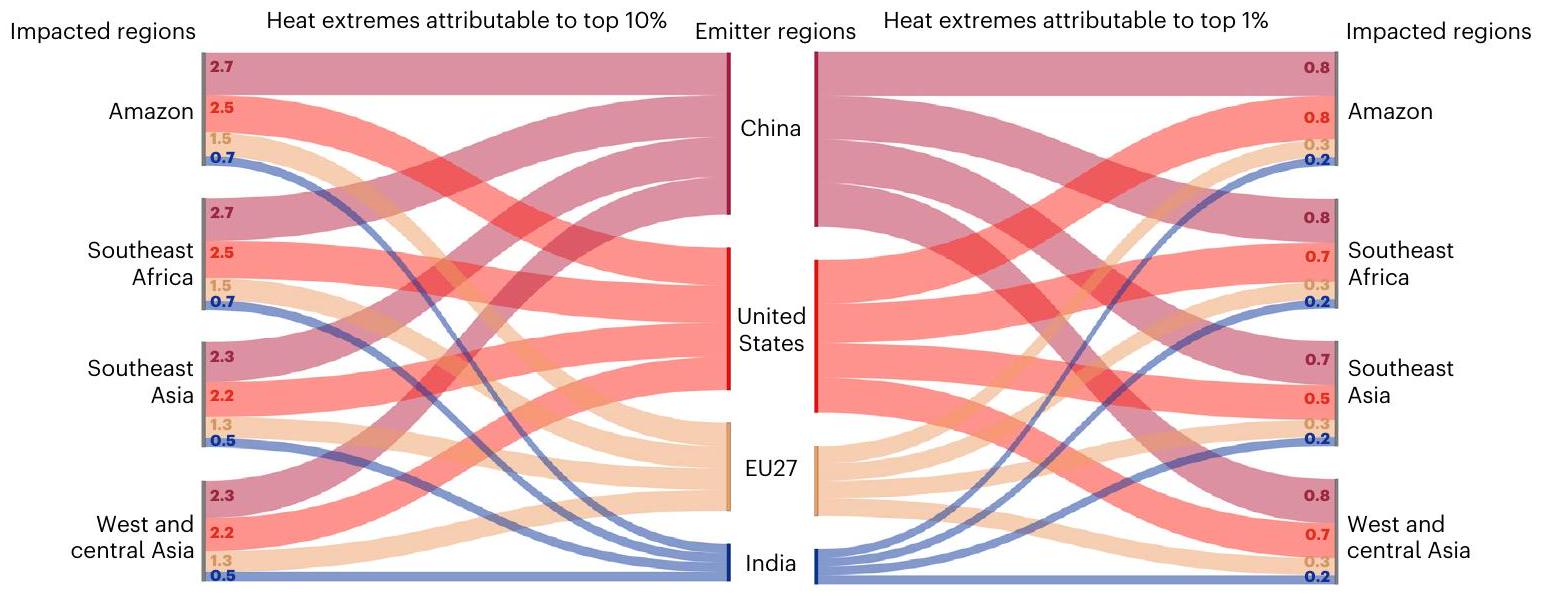

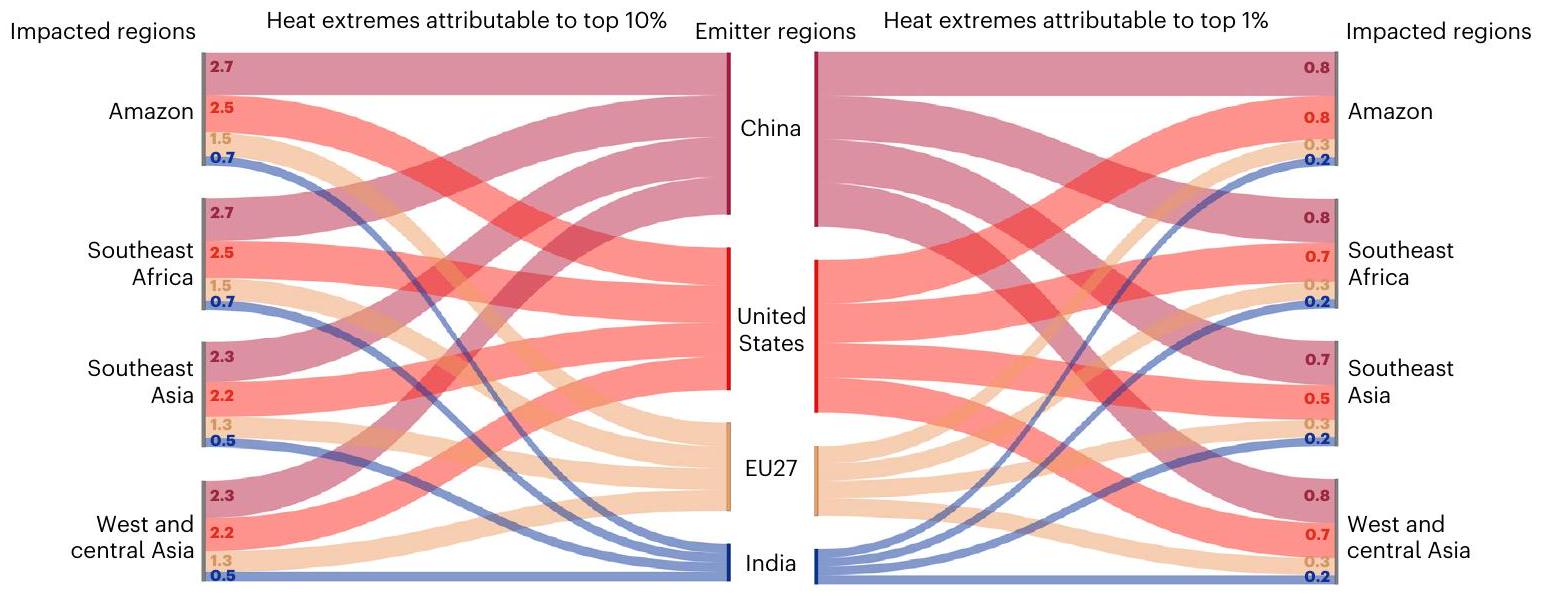

Attributing transboundary impacts of regional emissions

counterparts (Fig. 2). This disparity also appears at the grid-cell-level: in the global median, emissions from the top

events are attributable to a given emitter group. The values in the bars indicate the additional numbers of events over the course of 100 years. Median estimates were derived by first computing median attribution results at each grid cell (estimated from 15,000 ensemble members for each) and then computing statistics across grid cells within each region.

attributable to the top

Discussion

Online content

References

- Newman, R. & Noy, I. The global costs of extreme weather that are attributable to climate change. Nat. Commun. 14, 6103 (2023).

- Warner, K. & Weisberg, M. A funding mosaic for loss and damage. Science 379, 219-219 (2023).

- Chancel, L. Global carbon inequality over 1990-2019. Nat. Sustain. 5, 931-938 (2022).

- Wallemacq, P., Below, R. & McClean, D. Economic Losses, Poverty and Disasters: 1998-2017 (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2018); https://www.preventionweb.net/files/61119_ credeconomiclosses.pdf

- Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Burke, M. Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9808-9813 (2019).

- Hallegatte, S. & Rozenberg, J. Climate change through a poverty lens. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 250-256 (2017).

- Dhakal, S. et al. in Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) 215-294 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

- Mar, K. A., Unger, C., Walderdorff, L. & Butler, T. Beyond CO2 equivalence: the impacts of methane on climate, ecosystems, and health. Environ. Sci. Policy 134, 127-136 (2022).

- Beusch, L., Gudmundsson, L. & Seneviratne, S. I. Emulating Earth system model temperatures with MESMER: from global mean temperature trajectories to grid-point-level realizations on land. Earth Syst. Dynam. 11, 139-159 (2020).

- Meinshausen, M., Raper, S. C. & Wigley, T. M. Emulating coupled atmosphere-ocean and carbon cycle models with a simpler model, MAGICC6 – part 1: model description and calibration. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 1417-1456 (2011).

- Schöngart, S. Introducing the MESMER-M-TPv0.1.0 module: spatially explicit Earth system model emulation for monthly precipitation and temperature. EGUsphere 2024, 8283-8320 (2024).

- Otto, F. E. Attribution of extreme events to climate change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 48, 813-828 (2023).

- Stott, P. A., Stone, D. A. & Allen, M. R. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature 432, 610-614 (2004).

- Van Oldenborgh, G. J. et al. Pathways and pitfalls in extreme event attribution. Climatic Change 166, 13 (2021).

- Beusch, L. et al. Responsibility of major emitters for country-level warming and extreme hot years. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 7 (2022).

- Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. National attribution of historical climate damages. Climatic Change 172, 40 (2022).

- Trudinger, C. & Enting, I. Comparison of formalisms for attributing responsibility for climate change: non-linearities in the brazilian proposal approach. Climatic Change 68, 67-99 (2005).

- Otto, F. E., Skeie, R. B., Fuglestvedt, J. S., Berntsen, T. & Allen, M. R. Assigning historic responsibility for extreme weather events. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 757-759 (2017).

- De Polt, K. et al. Quantifying impact-relevant heatwave durations. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 104005 (2023).

- Seneviratne, S. et al. 2021: Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.), 1513-1766 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press 2021).

- Allen, M. R. et al. Indicate separate contributions of long-lived and short-lived greenhouse gases in emission targets. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 5 (2022).

- Cook, B.I. et al. Twenty-first century drought projections in the CMIP6 forcing scenarios. Earth Future 8, e2019EF001461 (2020).

- Wu, Y. et al. Hydrological projections under CMIP5 and CMIP6: sources and magnitudes of uncertainty. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 105, E59-E74 (2024).

- Chen, D. et al. 2021: Framing, context, and methods. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 147-286 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

- Yao, Y., Ciais, P., Viovy, N., Joetzjer, E. & Chave, J. How drought events during the last century have impacted biomass carbon in amazonian rainforests. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 747-762 (2023).

- Kumar, N. et al. Joint behaviour of climate extremes across India: past and future. J. Hydrol. 597, 126185 (2021).

- McKenna, C. M., Maycock, A. C., Forster, P. M., Smith, C. J. & Tokarska, K. B. Stringent mitigation substantially reduces risk of unprecedented near-term warming rates. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 126-131 (2021).

- IPCC Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

- Zeppetello, L. R. V., Battisti, D. S. & Baker, M. B. The physics of heat waves: what causes extremely high summertime temperatures? J. Clim. 35, 2231-2251 (2022).

- Chancel, L., Bothe, P. & Voituriez, T. The potential of wealth taxation to address the triple climate inequality crisis. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 5-7 (2024).

- Zucman, G. A Blueprint for a Coordinated Minimum Effective Taxation Standard for Utra-High-Net-Worth Individuals (Tax Observatory, 2024); https://www.taxobservatory.eu/www-site/ uploads/2024/06/report-g20-24_06_24.pdf

- Pachauri, S. et al. Fairness considerations in global mitigation investments. Science 378, 1057-1059 (2022).

- Bhattacharya, A., Songwe, V., Soubeyran, E. & Stern, N. Raising Ambition and Accelerating Delivery of Climate Finance (Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, 2024); https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/ uploads/2024/11/Raising-ambition-and-accelerating-delivery-of-climate-finance_Third-IHLEG-report.pdf

- Dibley, A. et al. Biases in ‘sustainable finance’ metrics could hinder lending to those that need it most. Nature 634, 294-297 (2024).

- Serdeczny, O. & Lissner, T. Research agenda for the loss and damage fund. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 412-412 (2023).

- Ogunbode, C. A. et al. Climate justice beliefs related to climate action and policy support around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 1144-1150 (2024).

- Berger, J. & Liebe, U. Effective climate action must address both social inequality and inequality aversion. npj Clim. Action 4, 1 (2025).

- Jézéquel, A. et al. Broadening the scope of anthropogenic influence in extreme event attribution. Environ. Res. Clim. 3, 042003 (2024).

- Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E. et al. Frontiers in attributing climate extremes and associated impacts. Front. Clim. 6, 1455023 (2024).

- Noy, I. et al. Event attribution is ready to inform loss and damage negotiations. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1279-1281 (2023).

- King, A. D., Grose, M. R., Kimutai, J., Pinto, I. & Harrington, L. J. Event attribution is not ready for a major role in loss and damage. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 415-417 (2023).

- Andrijevic, M. et al. Towards scenario representation of adaptive capacity for global climate change assessments. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 778-787 (2023).

- Smiley, K. T. et al. Social inequalities in climate change-attributed impacts of hurricane Harvey. Nat. Commun. 13, 3418 (2022).

- Jensen, L., Gerdener, H., Eicker, A., Kusche, J. & Fiedler, S. Observations indicate regionally misleading wetting and drying trends in CMIP6. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 249 (2024).

- Kim, Y.-H., Min, S.-K., Zhang, X., Sillmann, J. & Sandstad, M. Evaluation of the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble for climate extreme indices. Weather Clim. Extremes 29, 100269 (2020).

- Zimm, C. et al. Justice considerations in climate research. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 22-30 (2024).

- Kikstra, J. S., Mastrucci, A., Min, J., Riahi, K. & Rao, N. D. Decent living gaps and energy needs around the world. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 095006 (2021).

© The Author(s) 2025, corrected publication 2025

Methods

Counterfactual emissions pathways

from the

Emulator-based modelling approach

Attribution framework

Extreme event definition

Climate model analysis and hazard synthesis

climate as compared to a counterfactual climate, and attribute the difference in values.

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Tirivarombo, S., Osupile, D. & Eliasson, P. Drought monitoring and analysis: standardised precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) and standardised precipitation index (SPI). Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C. 106, 1-10 (2018).

- Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Van der Schrier, G., Beguería, S., Azorin-Molina, C. & Lopez-Moreno, J.-I. Contribution of precipitation and reference evapotranspiration to drought indices under different climates. J. Hydrol. 526, 42-54 (2015).

- Santos, C. N. et al. Monthly potential evapotranspiration estimated using the Thornthwaite method with gridded climate datasets in southeastern brazil. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 155, 3739-3756 (2024).

- Sheffield, J., Wood, E. F. & Roderick, M. L. Little change in global drought over the past 60 years. Nature 491, 435-438 (2012).

- Nicholls, Z. R. J. et al. Reduced complexity model intercomparison project phase 1: introduction and evaluation of global-mean temperature response. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 5175-5190 (2020).

- IPCC: Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

- Gütschow, J. et al. The PRIMAP-hist national historical emissions time series. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 571-603 (2016).

- Zhang, B. et al. Consumption-based accounting of global anthropogenic

emissions. Earth Future 6, 1349-1363 (2018). - Meinshausen, M. et al. Greenhouse-gas emission targets for limiting global warming to

. Nature 458, 1158-1162 (2009). - Büning, H. & Trenkler, G. Nichtparametrische Statistische Methoden (Walter de Gruyter, 2013).

- Schoengart, S. Data accompanying publication “High-Income Groups Disproportionately Contribute to Climate Extremes Worldwide.”. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14860538 (2025).

- Schöngart, S. sarasita/mesmer-m-tp: MESMER-M-TP v0.1.0 – GMD Submission. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 11086167 (2024).

- Schöngart, S. sarasita/attribution: code version accompanying publication “High-Income Groups Disproportionately Contribute to Climate Extremes Worldwide.”. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 15011461 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

natureportfolio

Last updated by author(s): 13/03/2025

Reporting Summary

Statistics

n/a |Confirmed

□ 【 The exact sample size

X A statement on whether measurements were taken from distinct samples or whether the same sample was measured repeatedly

□ The statistical test(s) used AND whether they are one- or two-sided

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

□ A description of all covariates tested

□ A description of any assumptions or corrections, such as tests of normality and adjustment for multiple comparisons

□

□ A full description of the statistical parameters including central tendency (e.g. means) or other basic estimates (e.g. regression coefficient) AND variation (e.g. standard deviation) or associated estimates of uncertainty (e.g. confidence intervals)

□ For null hypothesis testing, the test statistic (e.g.

□ For Bayesian analysis, information on the choice of priors and Markov chain Monte Carlo settings

□ For hierarchical and complex designs, identification of the appropriate level for tests and full reporting of outcomes

□ Estimates of effect sizes (e.g. Cohen’s

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

nature portfolio | reporting summary March 2021

Data

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

Human research participants

| Reporting on sex and gender | n/a | ||

| Population characteristics | n/a | ||

| Recruitment |

|

||

| Ethics oversight | n/a |

Field-specific reporting

□ Life sciences □ Behavioural & social sciences

- Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences study design

n/a

□

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | ||

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a | Involved in the study |

| – | □ |  |

□ |

| X | □ |  |

|

| X | □ | X | □ |

| X | □ | ||

| X | □ | ||

| V | □ | ||

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Laxenburg, Austria. Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETH Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland. IRIThesys, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Climate Resource, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. e-mail: sarah.schoengart@env.ethz.ch