DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07460-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38811739

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-29

تسريع إعادة التركيب الإشعاعي من أجل مصابيح LED بيروفسكايت الفعالة

تاريخ الاستلام: 9 ديسمبر 2023

تم القبول: 24 أبريل 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 29 مايو 2024

الوصول المفتوح

الملخص

إن الطلب المتزايد على مصابيح ثنائية الفينيل (LEDs) ذات الكفاءة العالية والإضاءة الأكثر سطوعًا في تطبيقات العرض المسطح والإضاءة الصلبة قد عزز البحث في البيروفسكايت ثلاثي الأبعاد (3D). تتميز هذه المواد بحركية شحن عالية وانخفاض في تدهور الكفاءة الكمومية.

تتدلى. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تشكل البيروفسكايت ثلاثي الأبعاد بشكل طبيعي هياكل منفصلة على مقياس دون الميكرومتر، مما يؤدي إلى كفاءة أعلى في إخراج الضوء تفوق

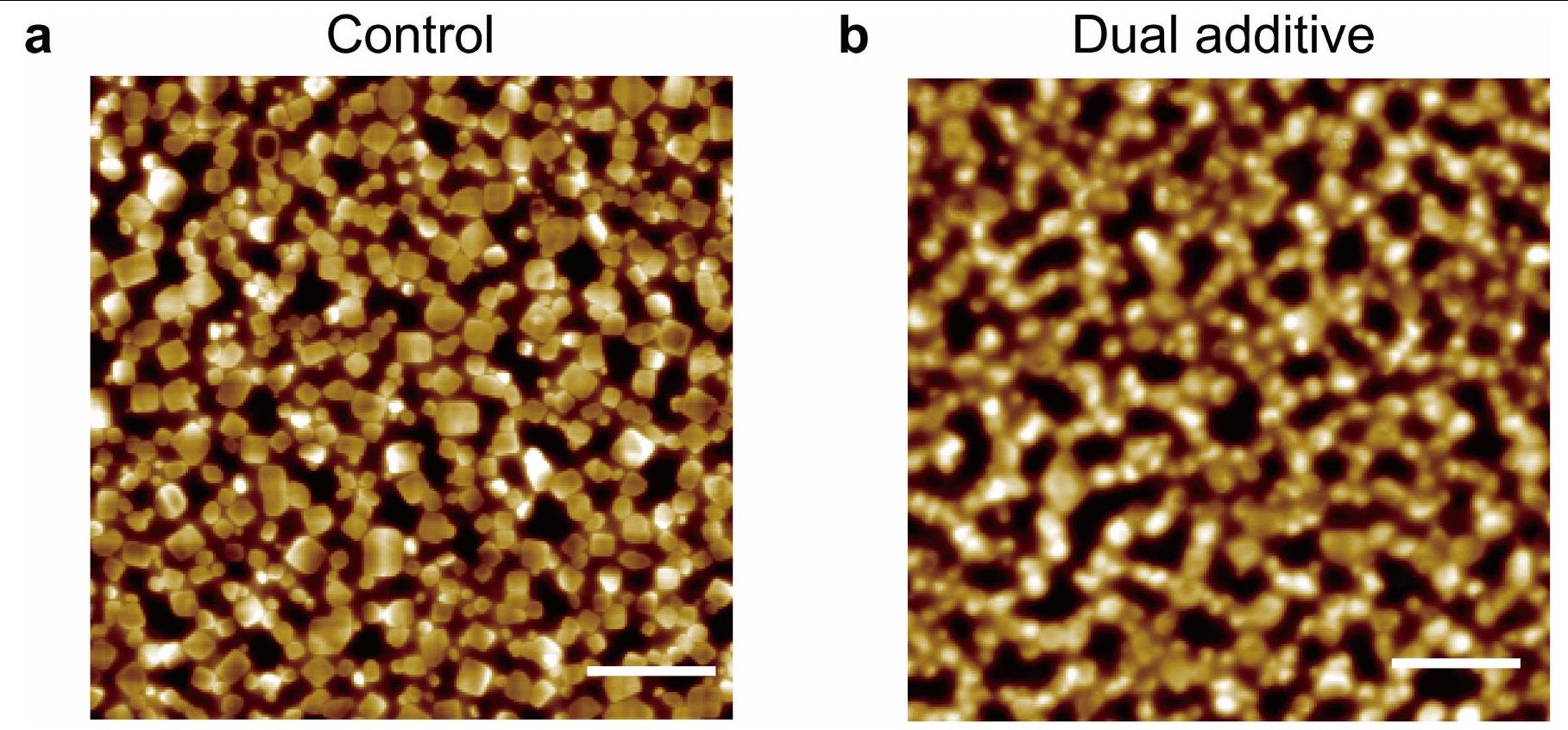

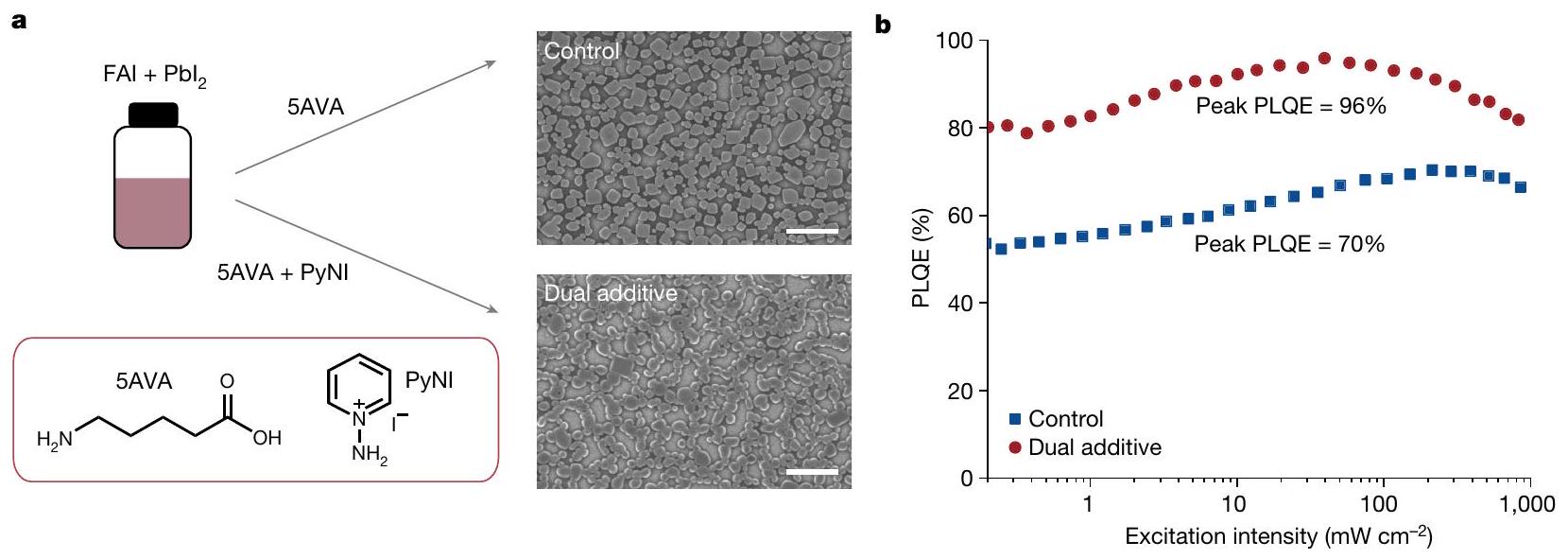

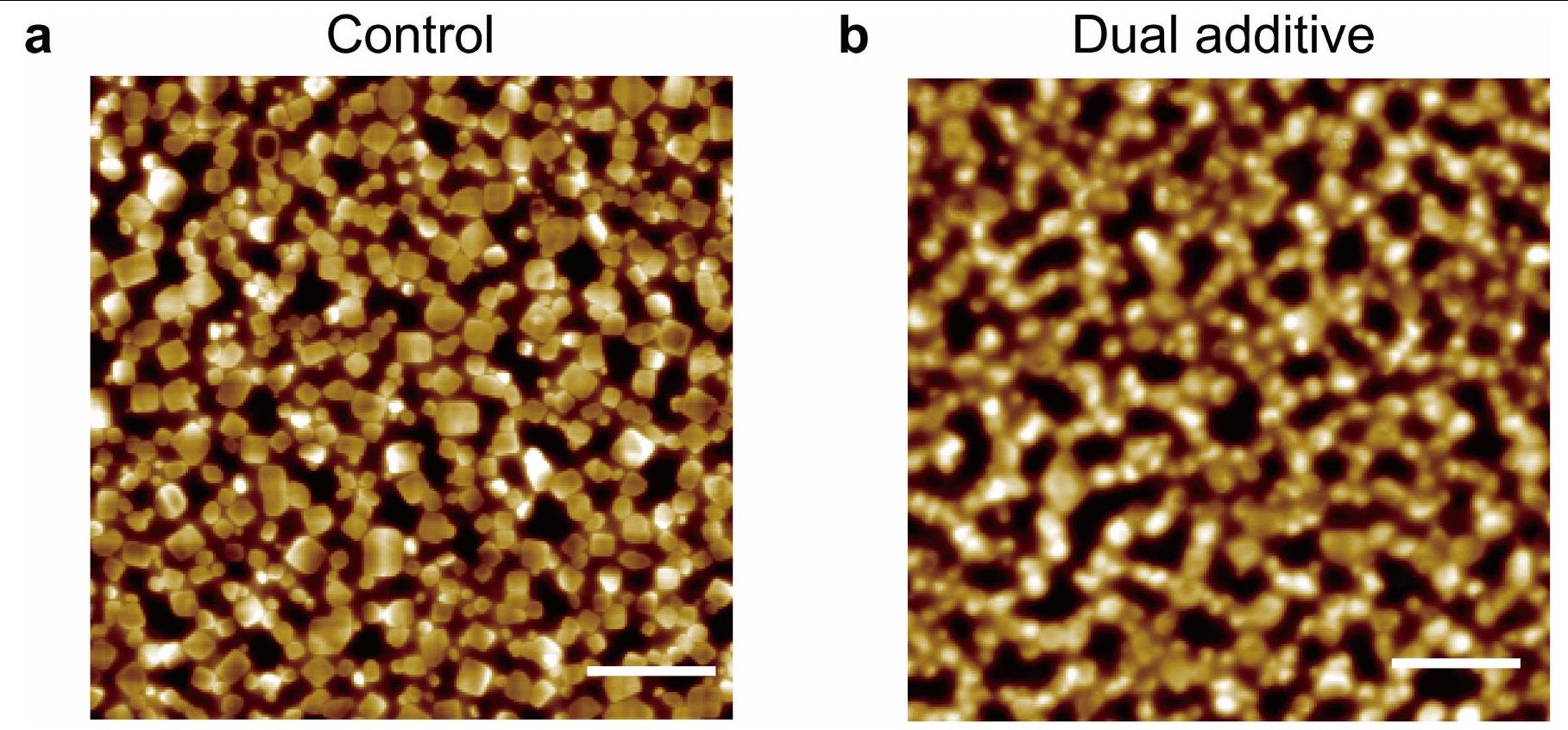

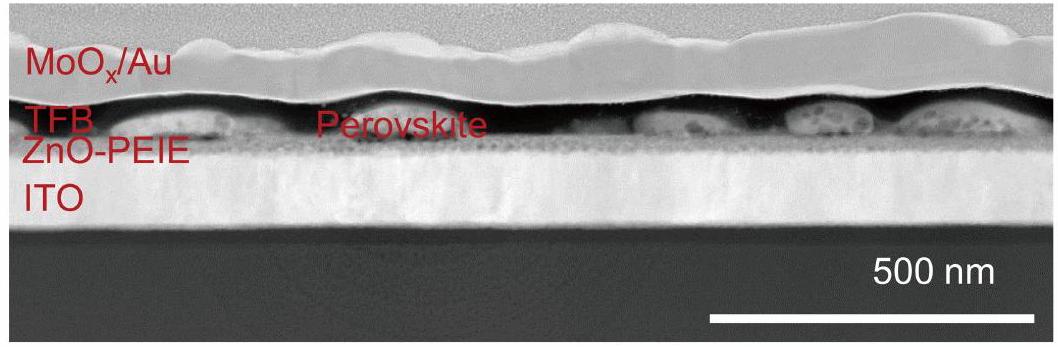

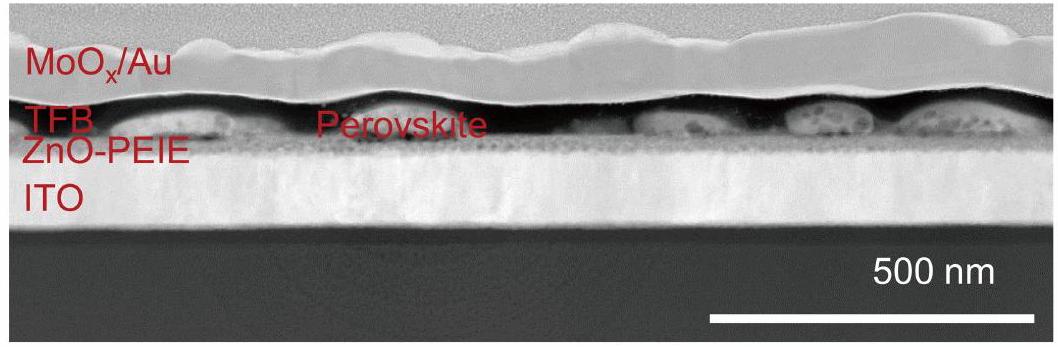

تصنيع أفلام البيروفسكايت وصور SEM للبيروفسكايت الضابط (مع 5AVA) والبيروفسكايت ذو الإضافات المزدوجة (مع 5AVA وPyNI). قضبان القياس،

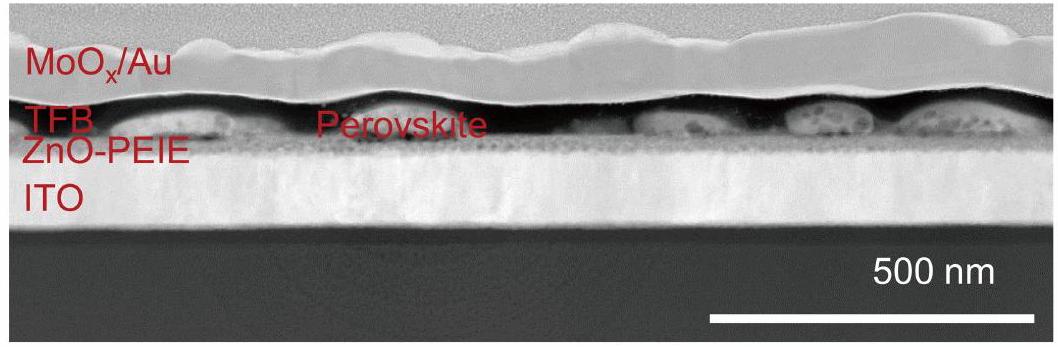

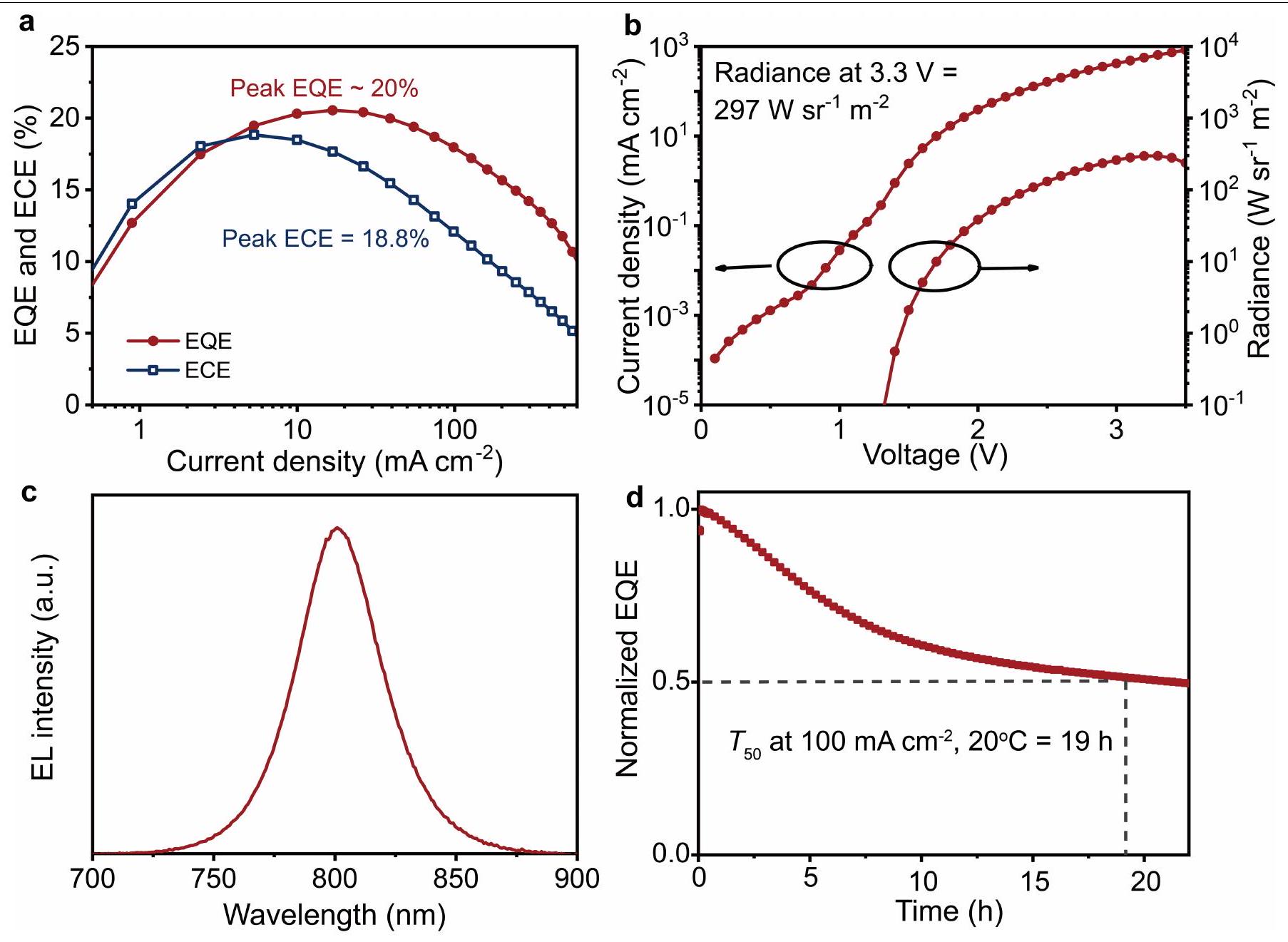

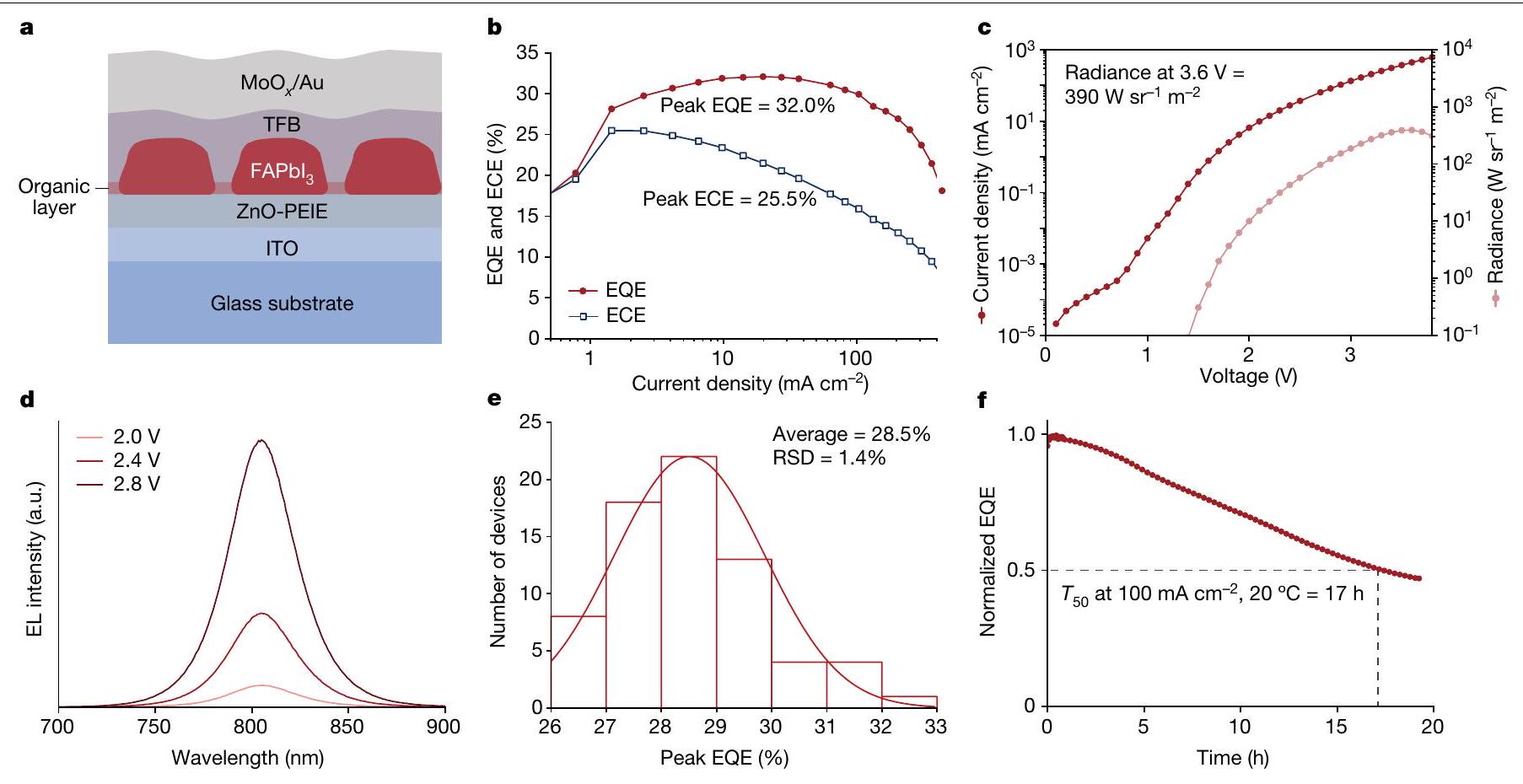

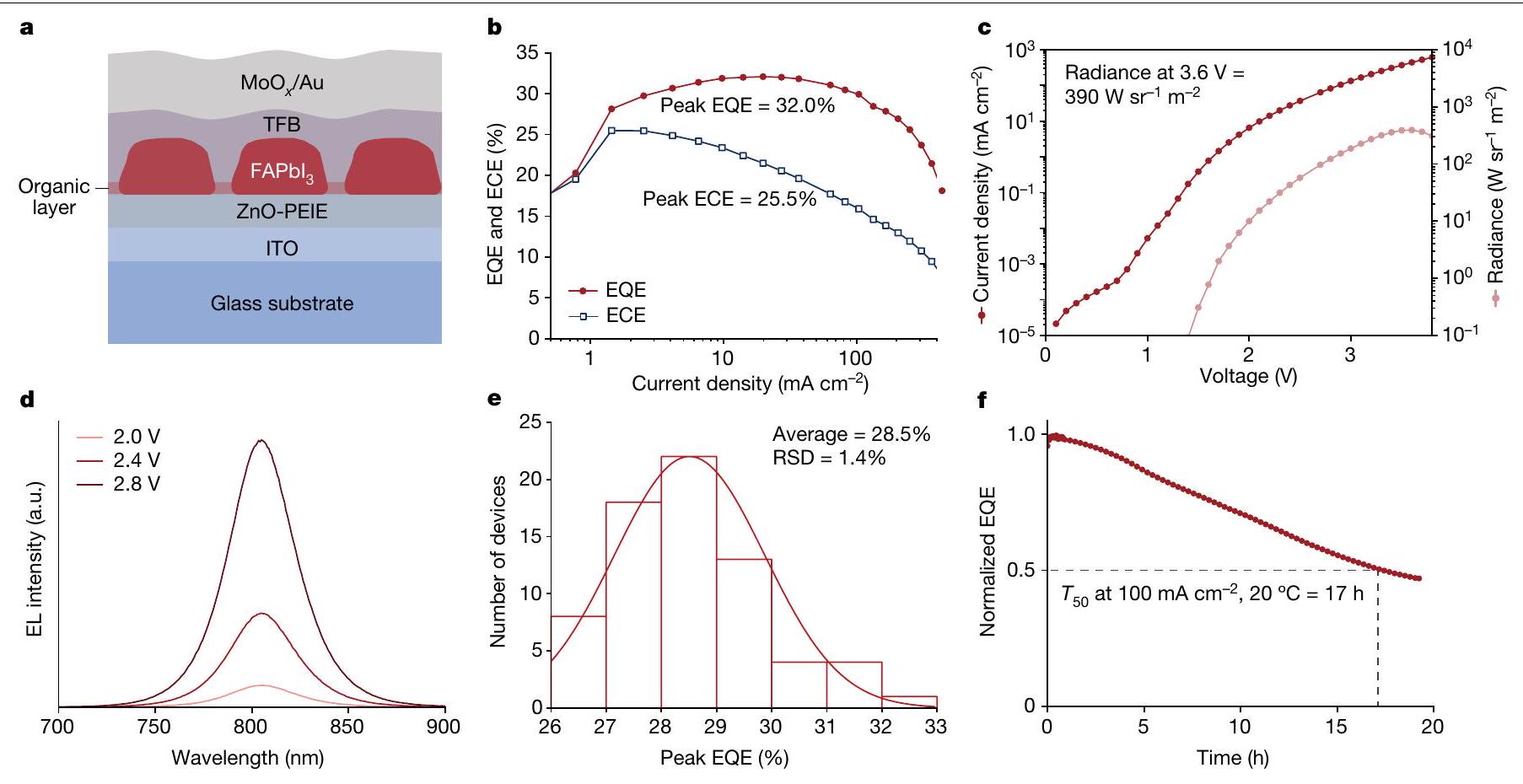

جهود مختلفة. هـ، رسم بياني لتوزيع قيم الذروة EQE. تظهر الإحصائيات من 70 جهازًا متوسط قيمة الذروة EQE

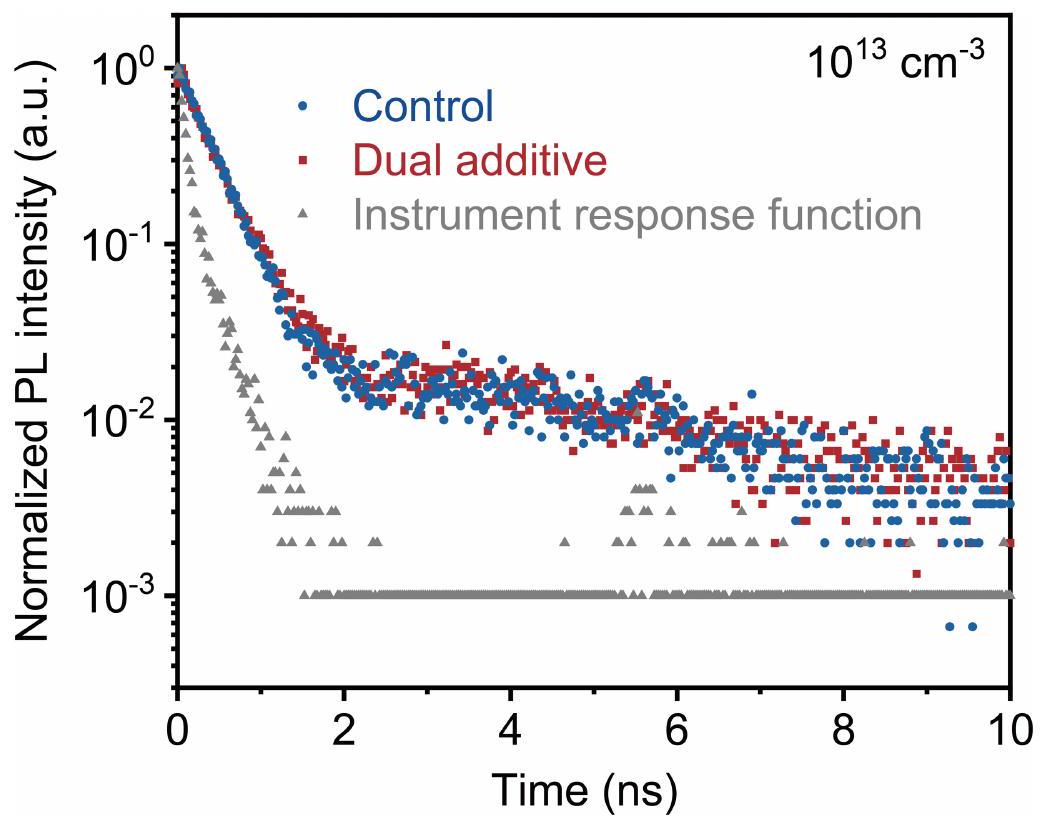

على الفور بعد التحفيز فائق السرعة (fs)، الذي يمكنه تحديد كثافة الحاملات المعتمدة على شدة الانبعاث الضوئي بدقة

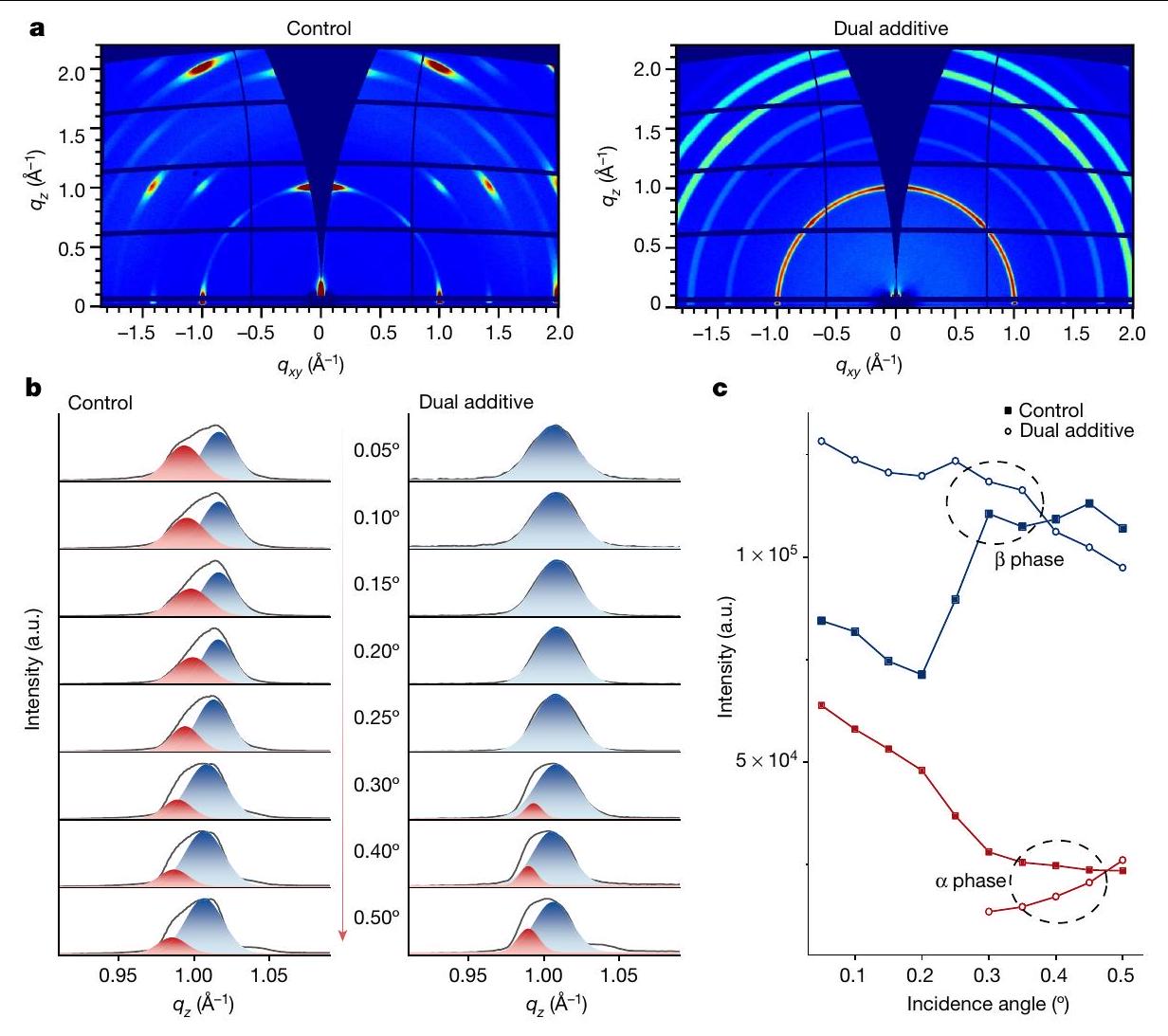

تشير الزوايا إلى اكتشاف البيروفسكايت الكتلي. نظرًا لتباعد الشبكة المميز (

حلل

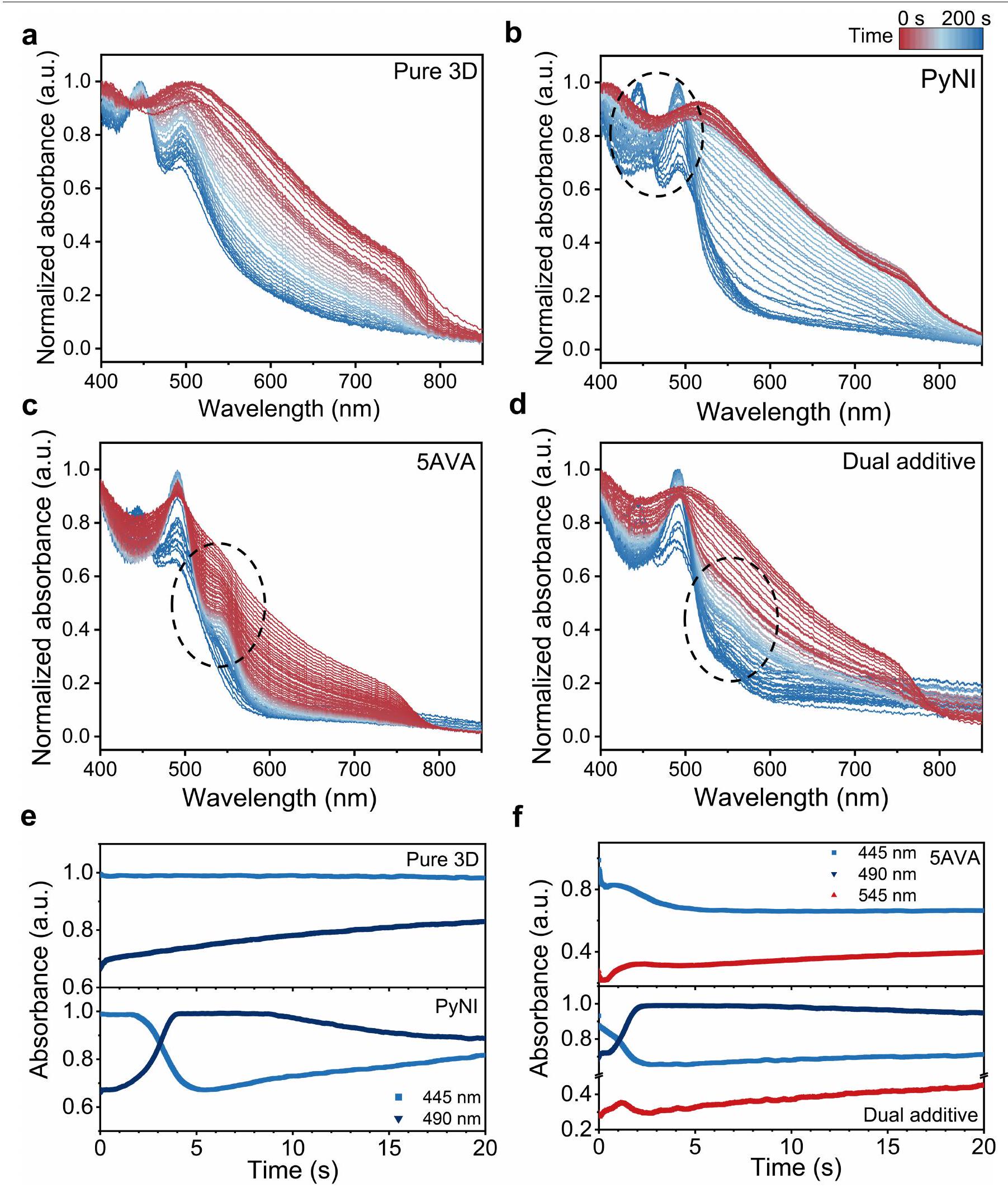

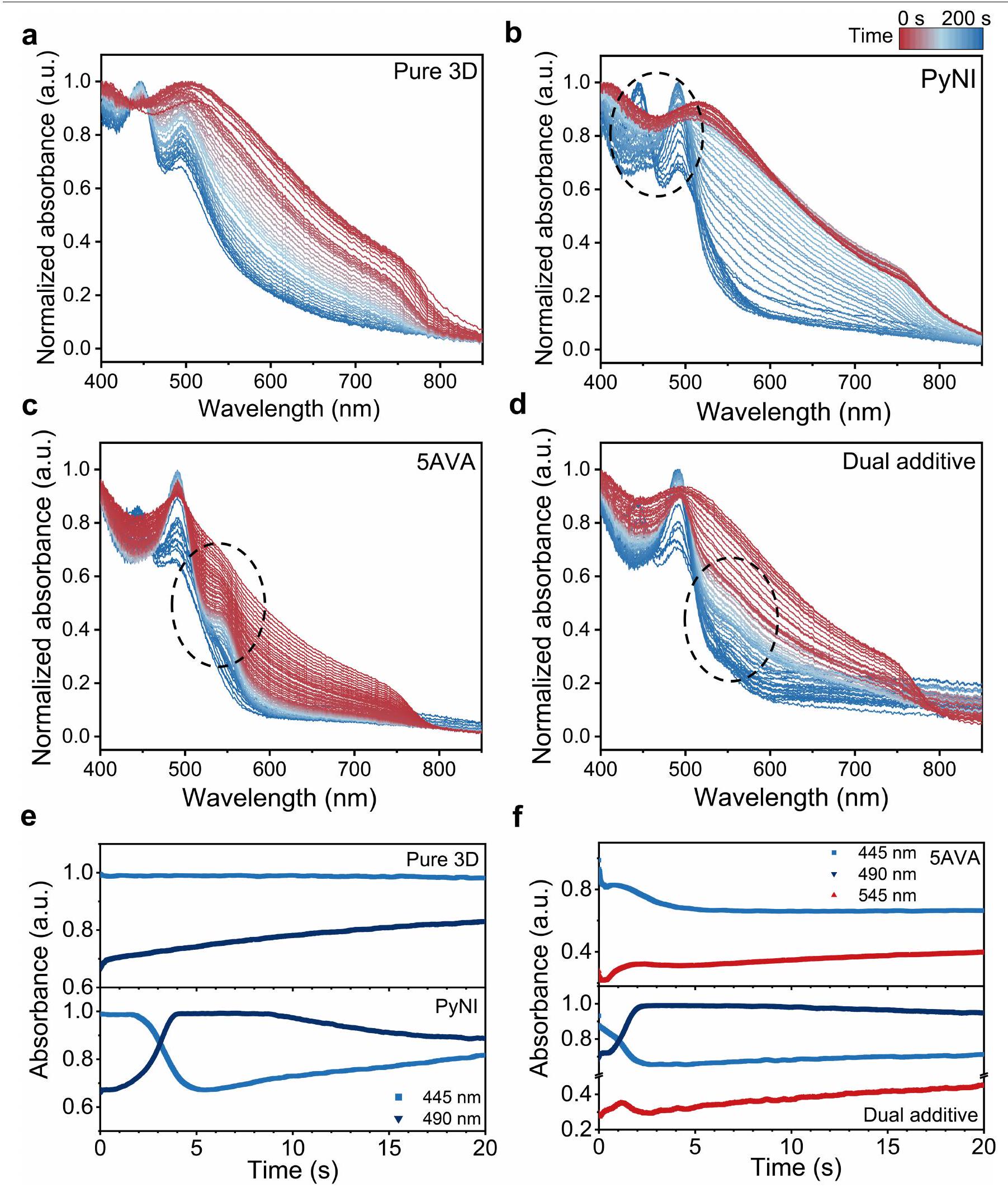

لتحقيق كيفية تأثير الإضافات المزدوجة على زيادة نسبة الطور الرباعي، قمنا بإجراء قياسات طيف الامتصاص في الموقع خلال عملية تلدين الفيلم (الشكل البياني الممتد 8). نلاحظ أن فيلم البيروفسكايت الذي يحتوي على إضافة PyNI فقط يظهر قمم امتصاص سائدة عند

يمكن أن تسهل PyNI تحويل

لتحقيق LEDs بسجل EQE غير مسبوق من

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- كاو، ي. وآخرون. ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من البيروفسكايت تعتمد على هياكل تتشكل بشكل تلقائي بمقياس دون الميكرومتر. ناتشر 562، 249-253 (2018).

-

التمرير الجزيئي العقلاني لثنائيات الصمام الثنائي الباعث للضوء من البيروفسكايت عالية الأداء. نات. فوتونيكس 13، 418-424 (2019). - زو، ل. وآخرون. كشف النمو الموجه المدعوم بالإضافات لبلورات البيروفسكايت من أجل ثنائيات الباعث الضوئي عالية الأداء. نات. كوميونيك. 12، 5081 (2021).

- سون، ي. وآخرون. ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من البيروفيسكايت الساطعة والمستقرة في نطاق الأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة. ناتشر 615، 830-835 (2023).

- كارلسون، م. وآخرون. بيروفسكيت الهاليد المختلط من أجل ثنائيات الباعث الضوئي الزرقاء ذات الكفاءة العالية والثبات الطيفي. نات. كوميونيك. 12، 361 (2021).

- فانغ، ز. وآخرون. تمرير مزدوج لعيوب البيروفسكايت لمصادر الضوء مع كفاءة كمية خارجية تتجاوز 20%. مواد وظيفية متقدمة. 30، 1909754 (2020).

- لي، ج. وآخرون. ثنائيات ضوء عضوية مضيئة فوسفورية زرقاء داكنة ذات سطوع وكفاءة عالية جداً. نات. ماتير. 15، 92-98 (2016).

- وانغ، ن. وآخرون. ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من البيروفسكايت المستندة إلى آبار الكم المتعددة المنظمة ذاتياً المعالجة بالحلول. نات. فوتونيكس 10، 699-704 (2016).

- تشاو، ب. وآخرون. ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من هياكل مختلطة من البيروفيسكايت والبوليمر ذات الكفاءة العالية. نات. فوتونيكس 12، 783-789 (2018).

- شياو، ز. وآخرون. ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من البيروفسكايت بكفاءة تحتوي على بلورات بحجم النانومتر. نات. فوتونيكس 11، 108-115 (2017).

- زوه، و. وآخرون. تقليل تراجع الكفاءة في ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من البيروفسكايت عالية السطوع. نات. كوم. 9، 608 (2018).

- تشاو، إكس. وتان، ز.-ك. ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من البيروفسكايت في نطاق الأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة ذات المساحة الكبيرة. نات. فوتونيكس 14، 215-218 (2020).

- زينغ، ج. وآخرون. تجاوز إعادة التركيب الثنائي الجزيئي البطيء في بيروكسيدات الرصاص الهاليدية من أجل الإضاءة الكهربائية. نات. كوميونيك. 8، 14558 (2017).

- لي، ن.، جيا، ي.، قوه، ي. وزهاو، ن. هجرة الأيونات في ثنائيات الباعث الضوئي من البيروفسكايت: الآلية، الخصائص، وهندسة المواد والأجهزة. مواد متقدمة. 34، 2108102 (2022).

- سترنكز، س. د. وآخرون. ديناميات إعادة التركيب في البيروفسكايت العضوي غير العضوي: الإثارات، الشحنات الحرة، وحالات تحت الفجوة. فيز. ريف. أبليد. 2، 034007 (2014).

- روف، ف. وآخرون. دراسات تعتمد على درجة الحرارة لطاقة ارتباط الإثارة وقمع الانتقال الطوري في (Cs، FA، MA) Pb(I، Br)

بيروفسكيت. APL Mater. 7، 031113 (2019). - سابا، م.، كوتشي، ف.، مورا، أ. وبونجيوفاني، ج. خصائص الحالة المثارة للبيروفسكايت الهجينة. أكاديمي. كيم. ريس. 49، 166-173 (2016).

- تشو، ج.، دوبوز، ج. ت. وكامات، ب. ف. ديناميات إعادة تركيب حاملات الشحنة في البيروفسكايتات ثنائية الأبعاد من هاليدات الرصاص. ج. فيز. كيم. ليتر. 11، 2570-2576 (2020).

- هو، ي. وآخرون. ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من البيروفيسكايت بكفاءة كمية داخلية قريبة من الوحدة عند درجات حرارة منخفضة. مواد متقدمة. 33، 2006302 (2021).

- وانغ، ل.، وانغ، ك. وزو، ب. الخصائص الهيكلية والبصرية المستحثة بالضغط لمركب بروميد الرصاص القائم على البيروفيسكايت العضوي المعدني. رسائل ج. فيز. كيم. 7، 2556-2562 (2016).

- زو، هـ. وآخرون. التحول الطوري الناتج عن الضغط وهندسة فجوة الطاقة لبلورات نانو بيروفسكايت يوديد الرصاص الفورمامي. ج. فيز. كيم. رسائل. 9، 4199-4205 (2018).

- وو، ب. وآخرون. تمييز كينتيك إعادة التركيب السطحية والداخلية لبلورات البيروفيسكايت العضوية-الغير عضوية. مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 6، 1600551 (2016).

- تشين، م. وآخرون. التلاعب بمسار تبلور البيروفسكايت المختلط الذي تم الكشف عنه بواسطة GIWAXS في الموقع. مواد متقدمة. 31، 1901284 (2019).

- فابيني، د. هـ. وآخرون. الخصائص الهيكلية والبصرية القابلة للعودة والتوسع الحراري الإيجابي الكبير في يوديد الرصاص من نوع البيروفكسايت فوراميدينيوم. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناشونال إد. 55، 15392-15396 (2016).

- تشن، ت. وآخرون. أصل العمر الطويل لحاملات الشحنة عند حافة النطاق في البيروفسكايتات العضوية غير العضوية لليوديد الرصاص. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 114، 7519-7524 (2017).

- داي، إكس. وآخرون. ثنائيات الباعث للضوء عالية الأداء المعالجة بالحلول والمبنية على النقاط الكمومية. ناتشر 515، 96-99 (2014).

- تشن، ف. وآخرون. طبقات نقل الثقوب مزدوجة الطبقة المعالجة بالحلول لثنائيات الباعث للضوء من النقاط الكمومية الخالية من الكادميوم عالية الكفاءة. أوبت. إكسبريس 28، 6134-6145 (2020).

- سانشيز، أ. و. ب.، سيلفا، م. أ. ت.، دا، كورديرو، ن. ج. أ.، أوربانو، أ. ولورينسو، س. أ. تأثير المراحل الوسيطة على الخصائص البصرية لـ

-غني بيروفسكايت هجين عضوي غير عضوي. فيز. كيم. كيم. فيز. 21، 5253-5261 (2019). - لي، ج. وديباك، ف. ل. ملاحظات حركية في الموقع على نوى البلورات ونموها. مراجعة الكيمياء 122، 16911-16982 (2022).

- يانغ، ب. وآخرون. تأثيرات الإجهاد على خلايا الشمسية من البيروفسكايت الهاليدي. مراجعة الجمعية الكيميائية 51، 7509-7530 (2022).

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2024

طرق

محلول سلفي بيروفسكايت

تصنيع الفيلم والأجهزة

توصيف الجهاز

توصيف الفيلم

لـ PL في زمن الصفر (

مع مدة نبضة تبلغ 100 فيمتوثانية، ومعدل تكرار قدره 1 كيلو هرتز وطول موجي قدره 800 نانومتر. تم تغذية هذا المضخم بواسطة مذبذب Coherent Vitesse.

قياس STEM

قياس GIWAXS

توفر البيانات

مقالة

b

صور STEM لفيلم البيروفسكايت ثنائي الإضافة مع أنماط خطوط كيكوتشي في مناطق مختلفة. مقياس الرسم، 100 نانومتر.

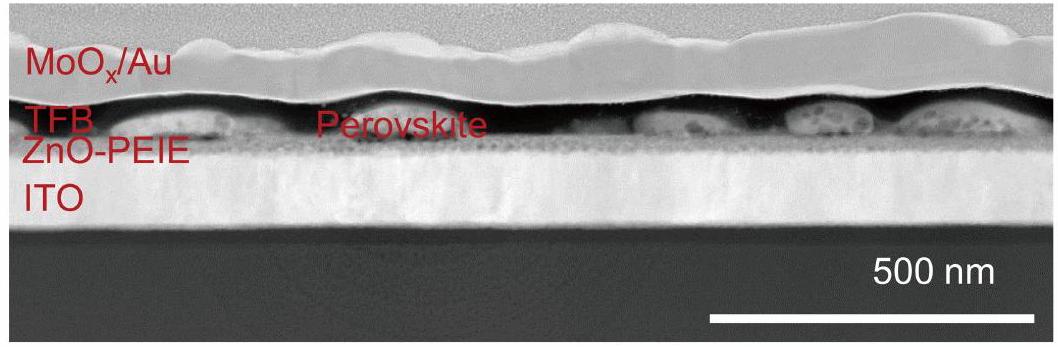

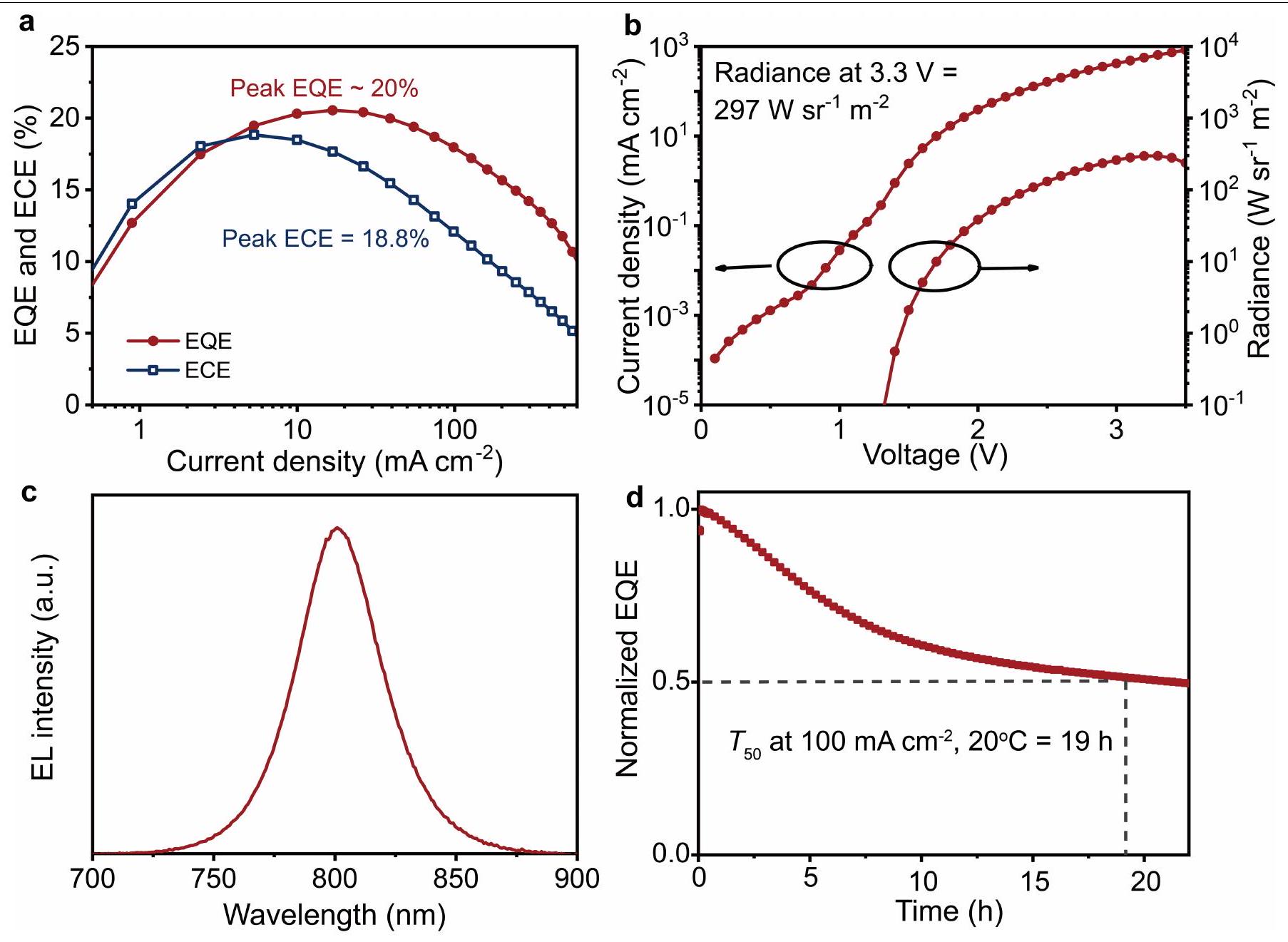

الكفاءة الكمية المعتمدة على الكثافة وECE. ب، اعتماد كثافة التيار والإشعاع على جهد الانحياز (أقصى إشعاع هو

استقرار الجهاز مقاس عند كثافة تيار ثابتة من

مقالة

مقالة

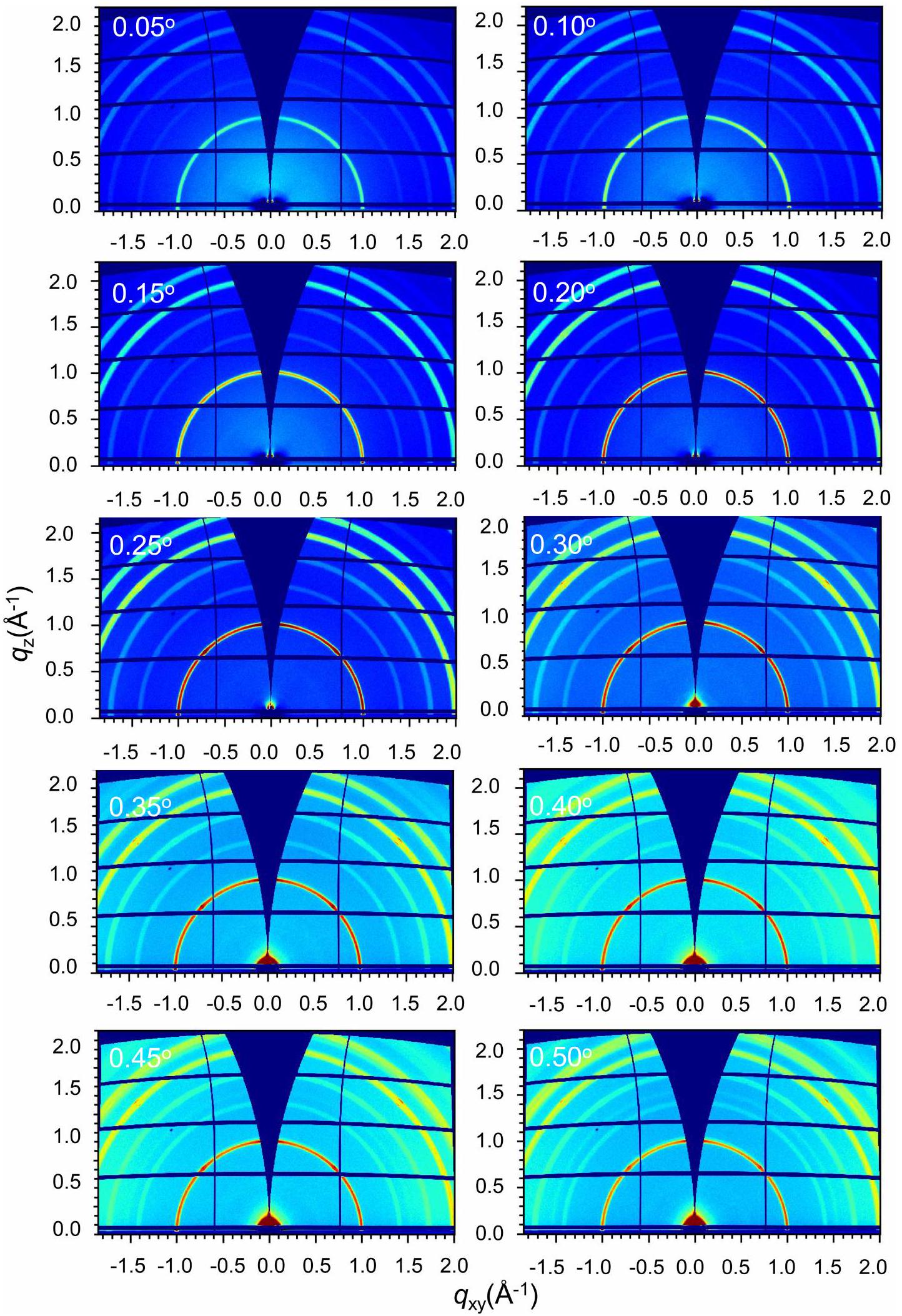

الشكل 6 من البيانات الموسعة | أنماط GIWAXS ثنائية الأبعاد لفيلم البيروفسكايت الضابط بزاويا سقوط مختلفة. زوايا السقوط لـ

| عينة | كثافة الحاملات (

|

|

|

|

|

| مضاف مزدوج |

|

|

|

|

0.995 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.994 | |

|

|

|

|

|

0.992 | |

|

|

|

|

|

0.991 | |

| تحكم |

|

|

|

|

0.991 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.994 | |

|

|

|

|

|

0.994 | |

|

|

|

|

|

0.993 |

المختبر الرئيسي للإلكترونيات المرنة (KLOFE)، معهد المواد المتقدمة (IAM) ومدرسة الإلكترونيات المرنة (التقنيات المستقبلية)، جامعة نانجينغ للتكنولوجيا، نانجينغ، الصين. معهد مضيق الإلكترونيات المرنة (SIFE، تقنيات المستقبل)، جامعة فوجيان العادية، فوزهو، الصين. مدرسة الميكروإلكترونيات، جامعة فودان، شنغهاي، الصين. مركز المجهر الإلكتروني، المختبر الوطني الرئيسي لمواد السيليكون، كلية علوم المواد والهندسة، جامعة تشجيانغ، هانغتشو، الصين. معهد الفيزياء التطبيقية وهندسة المواد، جامعة ماكاو، ماكاو، الصين. المختبر الوطني الرئيسي للبصريات المتطرفة والأدوات، كلية العلوم البصرية والهندسة، المركز الدولي للبحوث في الفوتونيات المتقدمة، جامعة تشجيانغ، هانغتشو، الصين. مختبر مضيق الإلكترونيات المرنة (SLoFE)، فوزهو، الصين. معهد الإلكترونيات المرنة (IFE)، جامعة شمال غرب البوليتكنيك (NPU)، شيان، الصين. مختبر MIIT الرئيسي للإلكترونيات المرنة (KLoFE)، جامعة شمال غرب البوليتكنيك (NPU)، شيان، الصين. مدرسة الإلكترونيات المرنة (SoFE)، جامعة صن يات-sen، شنتشن، الصين. كلية علوم المواد والهندسة، جامعة تشانغتشو، تشانغتشو، الصين. مدرسة الميكروإلكترونيات وهندسة التحكم، جامعة تشانغتشو، تشانغتشو، الصين. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: مينغ مينغ لي، يينغ قوه يانغ، تشي يوان قوانغ. البريد:iamlzhu@njtech.edu.cn; vc@nwpu.edu.cn; iamjpwang@njtech.edu.cn - الشكر والتقدير تم دعم هذا العمل مالياً من قبل البرنامج الوطني الرئيسي للبحث والتطوير في الصين (2022YFA1204800)، ومؤسسة العلوم الطبيعية الوطنية في الصين (62288102، 62134007، 52373220، 52233011 و62375124) ودوائر العلوم والتكنولوجيا في مقاطعة جيانغسو (BE2022023 وBK20220010). نشكر خطوط الأشعة BLO2U2 وBL17B1 وBL19U2 في منشأة الإشعاع المتزامن في شنغهاي (SSRF) على توفير وقت الأشعة ونظام مساعدة تجارب المستخدمين في SSRF على مساعدتهم.مساهمات المؤلفين: كان لدى ج. و. الفكرة وصمم التجارب. أشرف ل. زهو، و. هـ. و ج. و. على العمل. قام م. ل.، و. هـ.، و. ز.، و. ي. كاي، و. ي. كاو بتنفيذ تصنيع الجهاز والتوصيفات. أجرى ز. ك.، و. ل.، و. ف. ل. التوصيفات باستخدام SEM. قام ز. ل. بإجراء التوصيفات باستخدام STEM، تحت إشراف هـ. ت. قام ي. ي. و. هـ. بإجراء قياسات وتحليل GIWAXS. أجرى ز. ك.، و. س.، و. ج. م.، و. ي. م. و. ق. ب. القياسات البصرية تحت إشراف ج. و. و. ج. إكس. قام ج. ج. بإجراء محاكاة بصرية للجهاز. قام ج. و.، و. زهو، و. م. ل. و ز. ك. بتحليل البيانات. كتبت و. زهو المسودة الأولى من المخطوطة. قدم ج. و.، و. ق. ب. و ن. و. مراجعات كبيرة. ناقش جميع المؤلفين النتائج وعلقوا على المخطوطة.المصالح المتنافسة يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إضافية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على مواد إضافية متاحة علىhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07460-7.

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى لين زو، وي هاي، أو جيانبو وانغ.

معلومات مراجعة الأقران تشكر Nature المراجعين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذا العمل.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07460-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38811739

Publication Date: 2024-05-29

Acceleration of radiative recombination for efficient perovskite LEDs

Received: 9 December 2023

Accepted: 24 April 2024

Published online: 29 May 2024

Open access

Abstract

The increasing demands for more efficient and brighter thin-film light-emitting diodes (LEDs) in flat-panel display and solid-state lighting applications have promoted research into three-dimensional (3D) perovskites. These materials exhibit high charge mobilities and low quantum efficiency droop

droop. Furthermore, 3D perovskites can naturally form discrete, sub-micrometre-scale structures, leading to an enhanced light outcoupling efficiency greater than

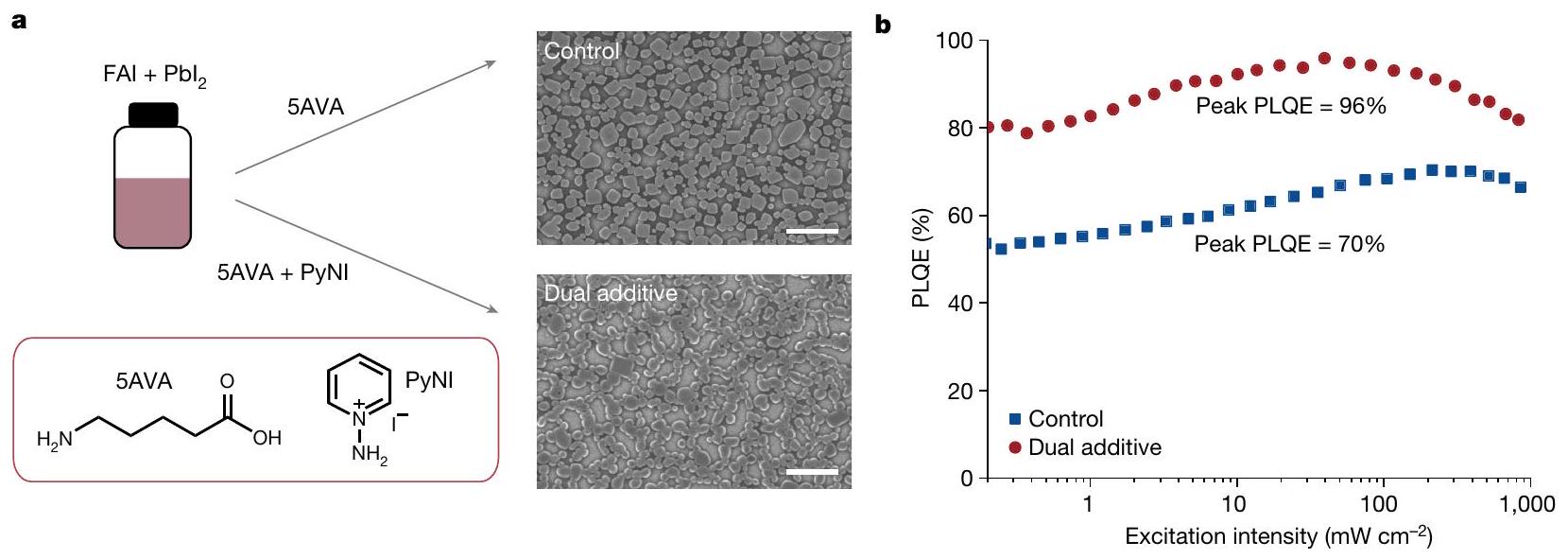

a, Fabrication of perovskite films and SEM images of control perovskite (with 5AVA) and dual-additive perovskite (with 5AVA and PyNI). Scale bars,

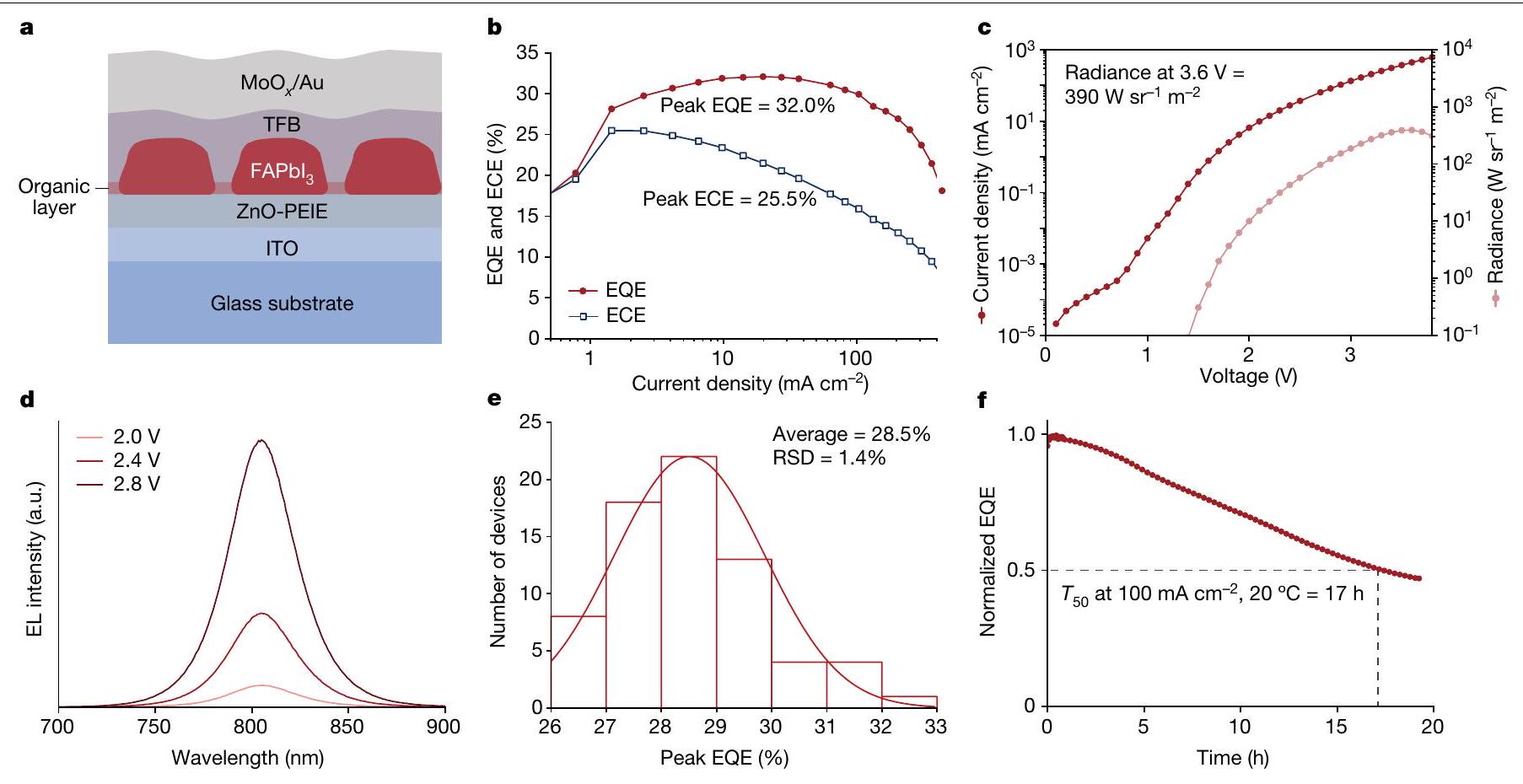

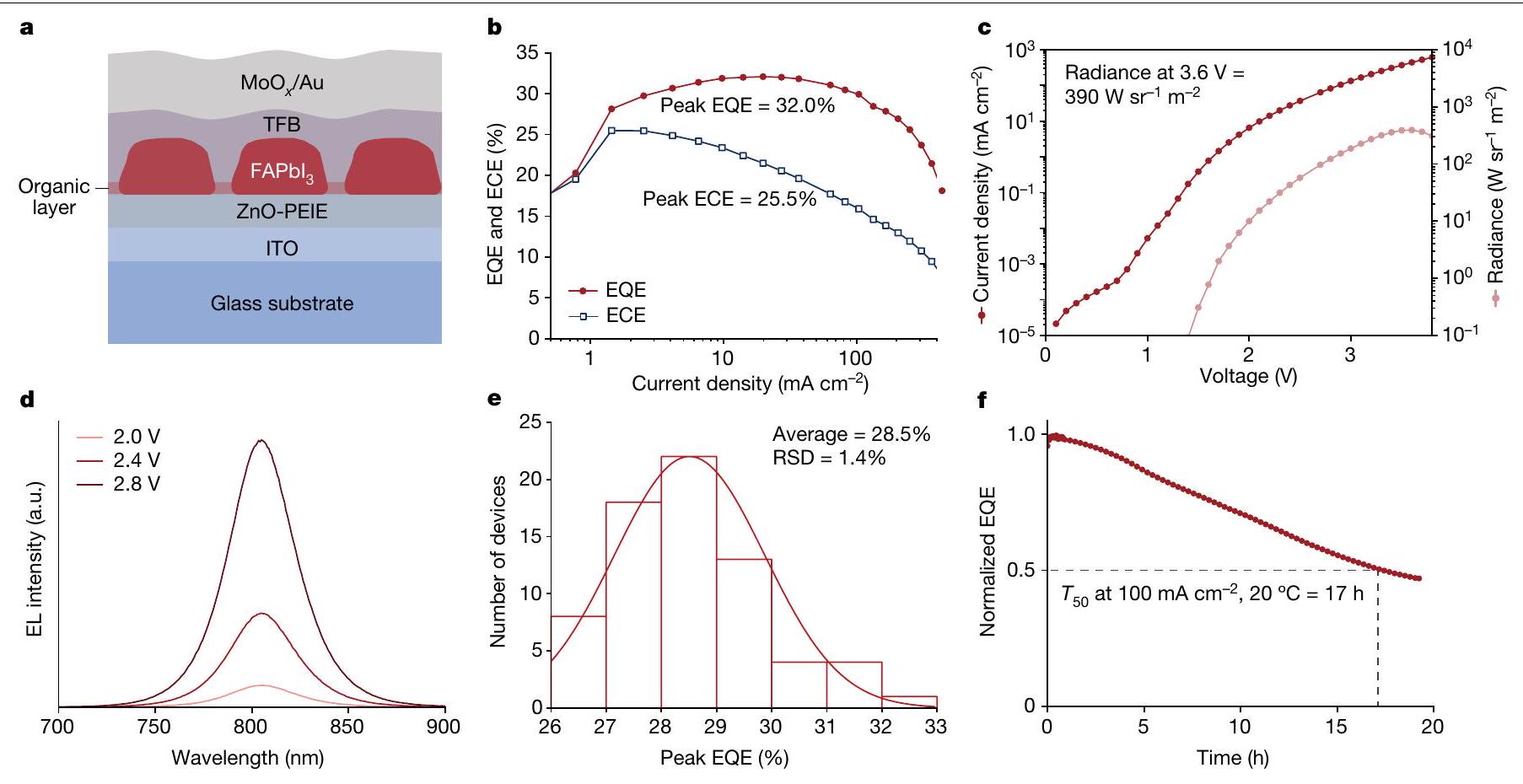

various voltages. e, Histogram of peak EQEs. Statistics from 70 devices show an average peak EQE of

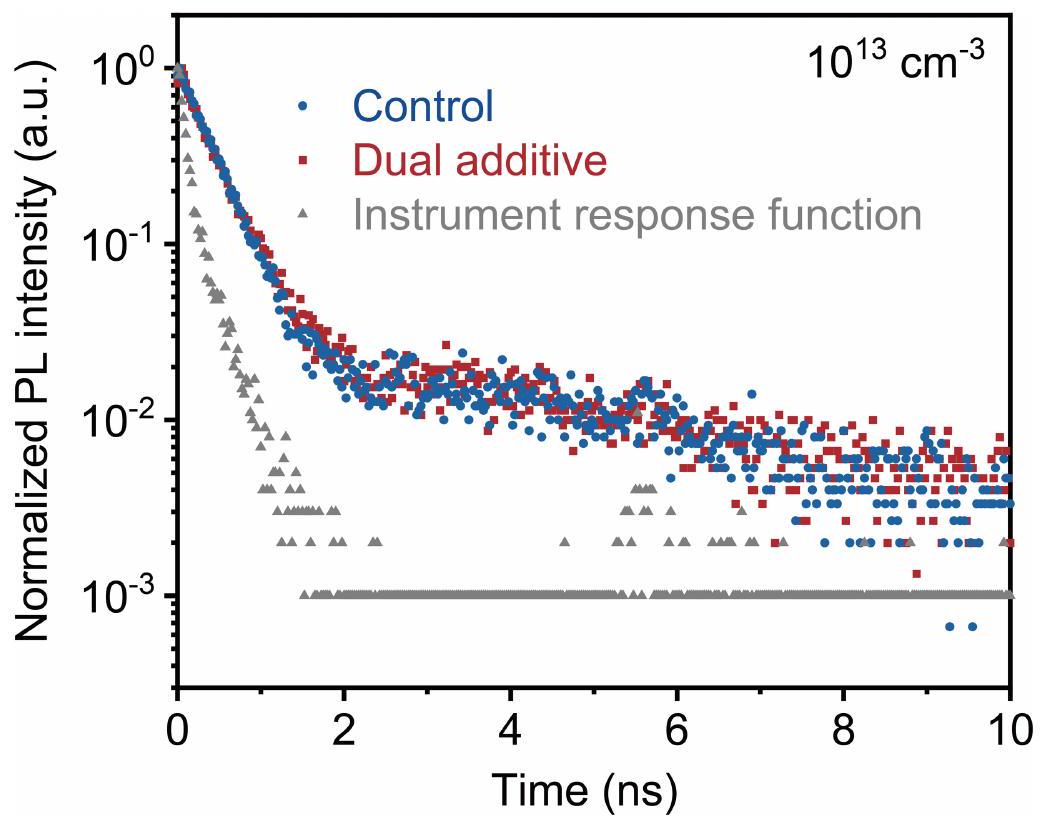

immediately after the ultra-fast (fs) excitation, which can precisely determine the carrier-density-dependent PL intensity

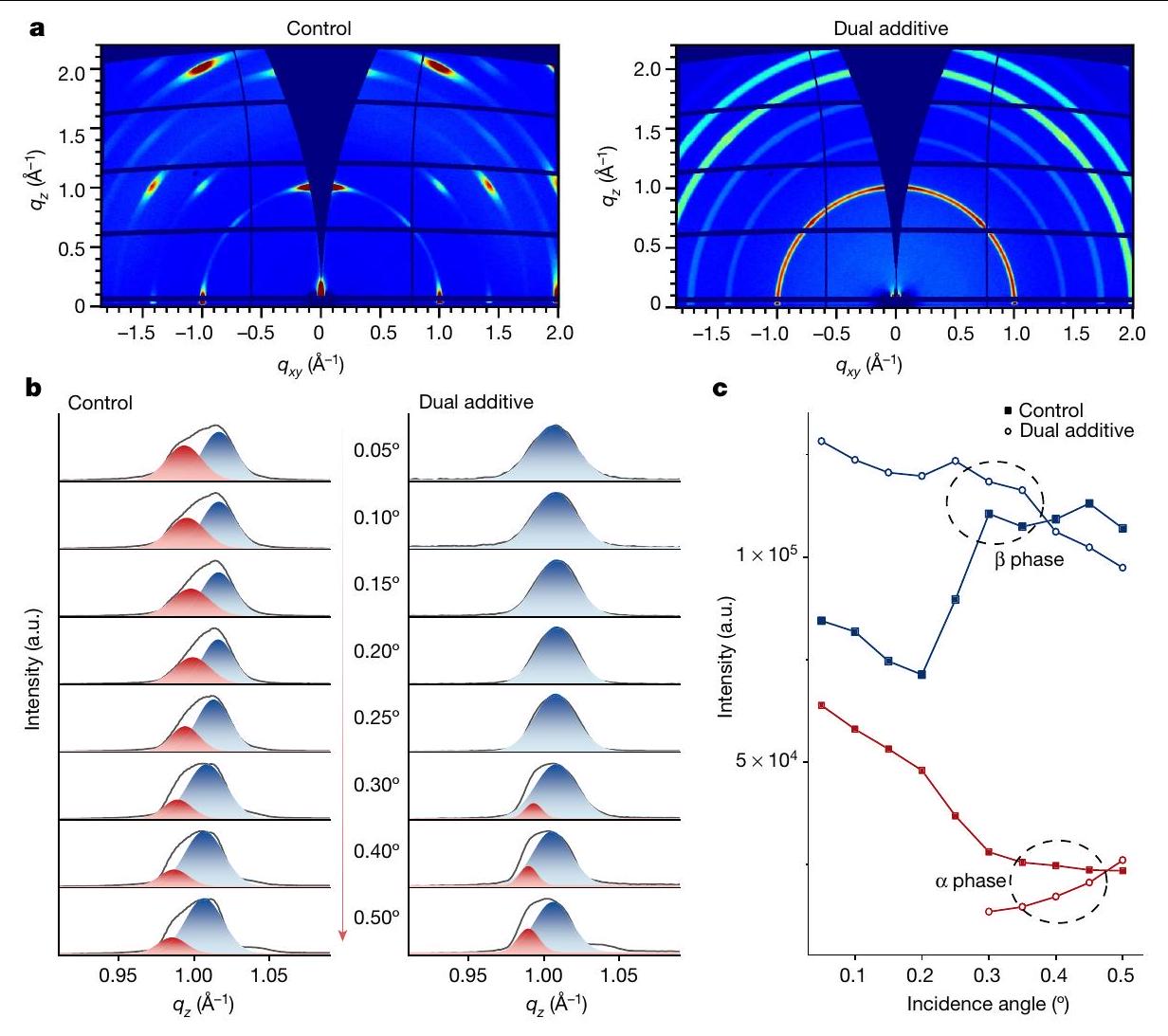

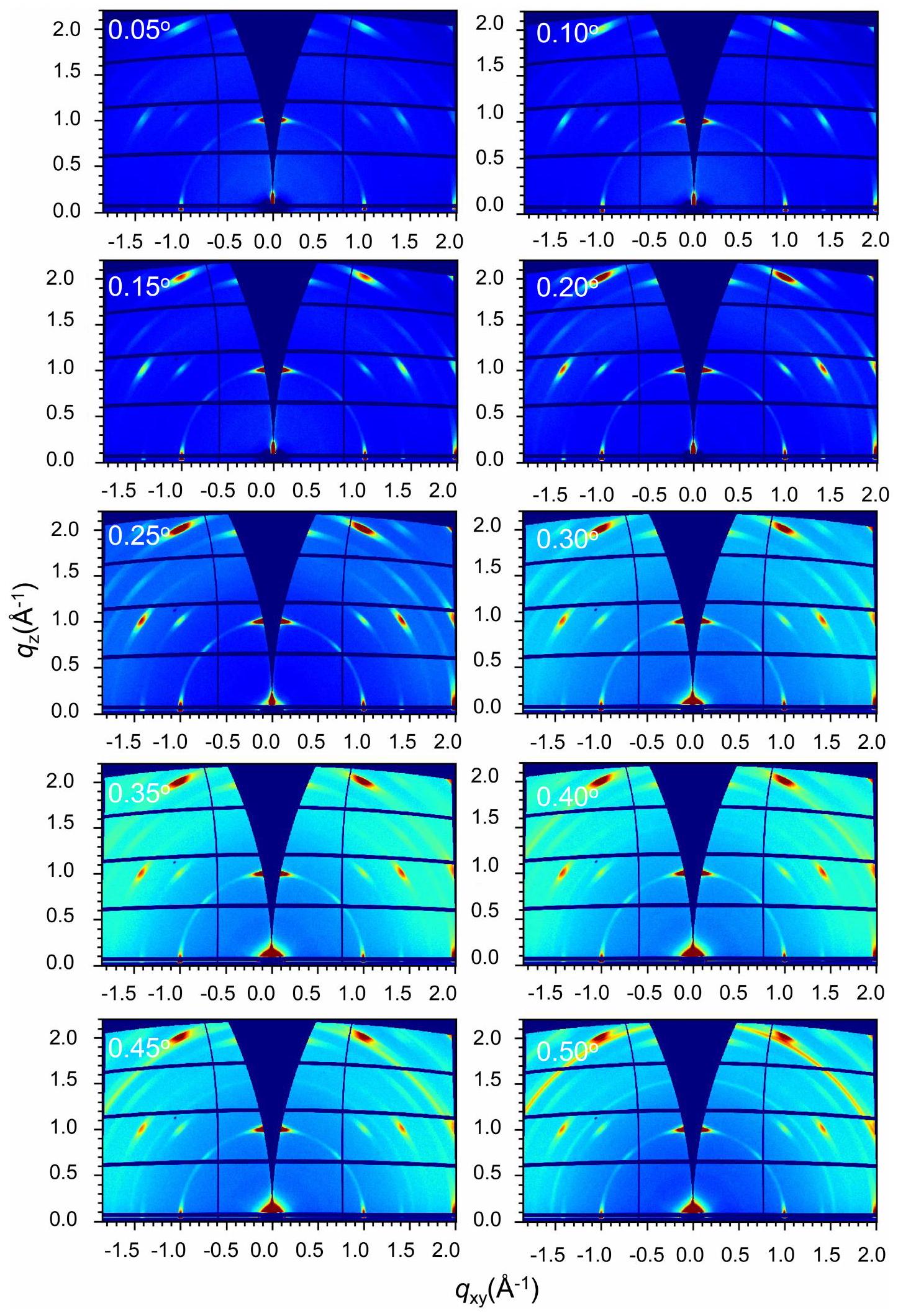

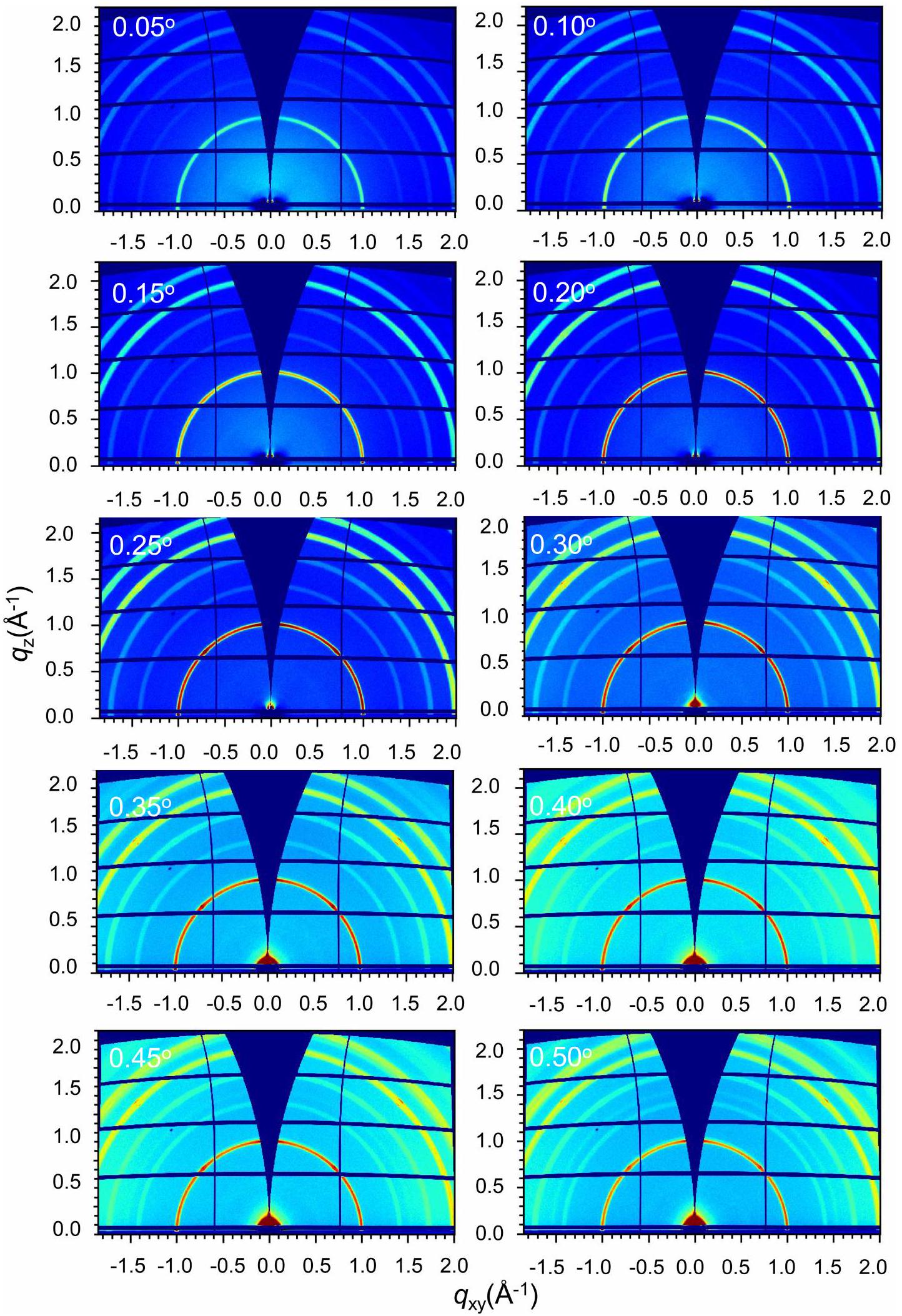

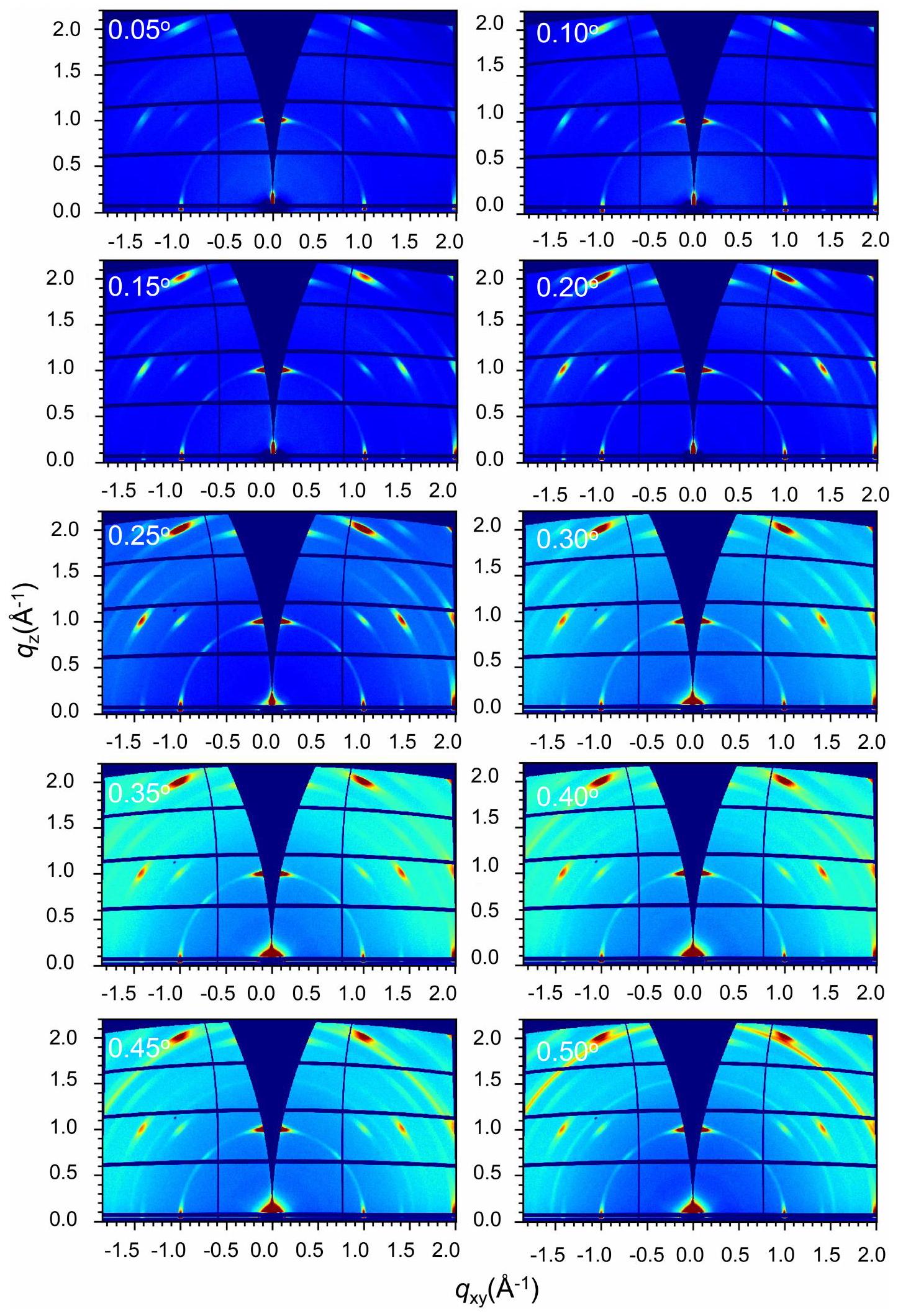

angles indicate the detection of bulk perovskite. Owing to the distinct lattice spacings (

analysed the

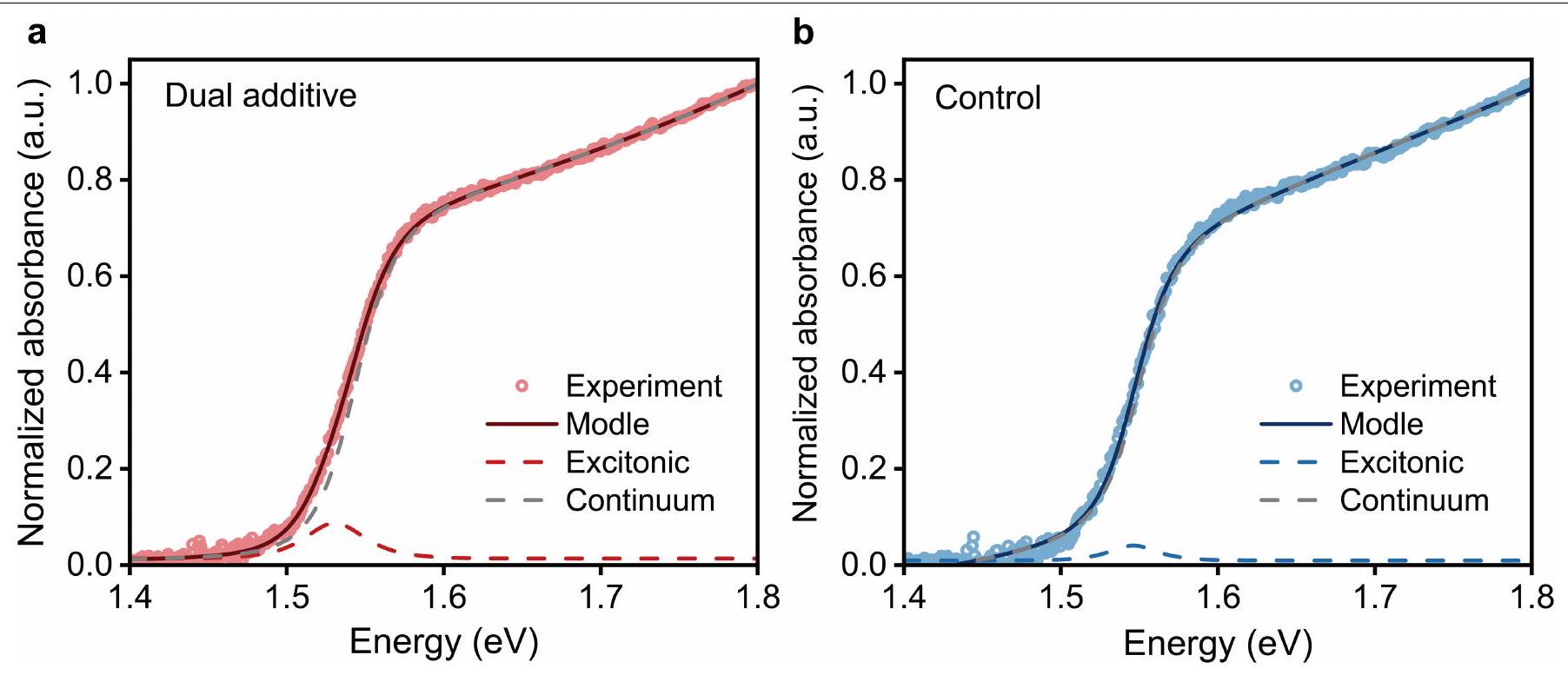

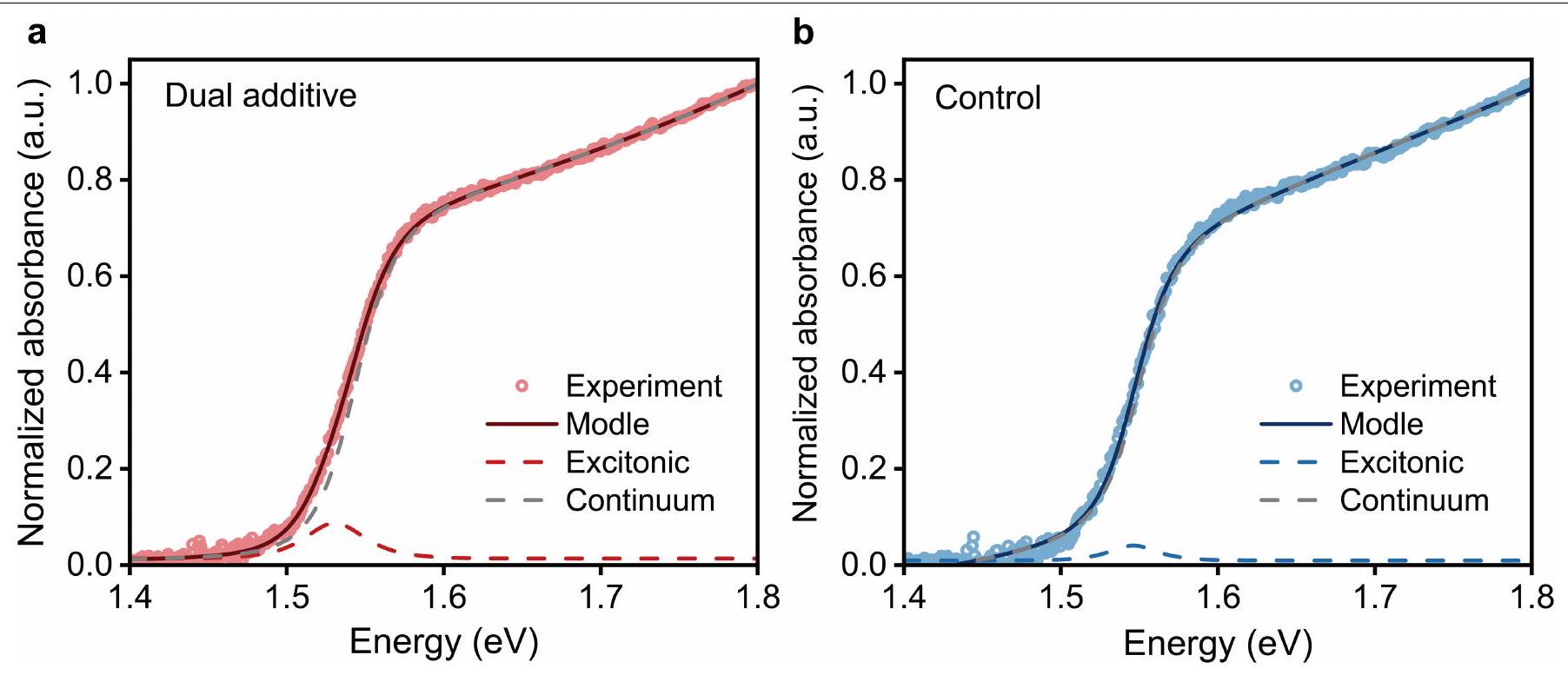

To investigate how the dual additives can induce an increased proportion of the tetragonal phase, we conducted in situ absorption-spectra measurements during the film-annealing process (Extended Data Fig. 8). We observe that PyNI-additive-alone perovskite film exhibits dominant absorption peaks at

that PyNI can facilitate the conversion of

us to realize LEDs with an unprecedented EQE record of

Online content

- Cao, Y. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes based on spontaneously formed submicrometre-scale structures. Nature 562, 249-253 (2018).

-

al. Rational molecular passivation for high-performance perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photonics 13, 418-424 (2019). - Zhu, L. et al. Unveiling the additive-assisted oriented growth of perovskite crystallite for high performance light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 12, 5081 (2021).

- Sun, Y. et al. Bright and stable perovskite light-emitting diodes in the near-infrared range. Nature 615, 830-835 (2023).

- Karlsson, M. et al. Mixed halide perovskites for spectrally stable and high-efficiency blue light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 12, 361 (2021).

- Fang, Z. et al. Dual passivation of perovskite defects for light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 20%. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909754 (2020).

- Lee, J. et al. Deep blue phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes with very high brightness and efficiency. Nat. Mater. 15, 92-98 (2016).

- Wang, N. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes based on solution-processed self-organized multiple quantum wells. Nat. Photonics 10, 699-704 (2016).

- Zhao, B. et al. High-efficiency perovskite-polymer bulk heterostructure light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photonics 12, 783-789 (2018).

- Xiao, Z. et al. Efficient perovskite light-emitting diodes featuring nanometre-sized crystallites. Nat. Photonics 11, 108-115 (2017).

- Zou, W. et al. Minimising efficiency roll-off in high-brightness perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 9, 608 (2018).

- Zhao, X. & Tan, Z.-K. Large-area near-infrared perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photonics 14, 215-218 (2020).

- Xing, G. et al. Transcending the slow bimolecular recombination in lead-halide perovskites for electroluminescence. Nat. Commun. 8, 14558 (2017).

- Li, N., Jia, Y., Guo, Y. & Zhao, N. Ion migration in perovskite light-emitting diodes: mechanism, characterizations, and material and device engineering. Adv. Mater. 34, 2108102 (2022).

- Stranks, S. D. et al. Recombination kinetics in organic-inorganic perovskites: excitons, free charge, and subgap states. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2, 034007 (2014).

- Ruf, F. et al. Temperature-dependent studies of exciton binding energy and phase-transition suppression in (Cs, FA, MA) Pb(I, Br)

perovskites. APL Mater. 7, 031113 (2019). - Saba, M., Quochi, F., Mura, A. & Bongiovanni, G. Excited state properties of hybrid perovskites. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 166-173 (2016).

- Cho, J., DuBose, J. T. & Kamat, P. V. Charge carrier recombination dynamics of two-dimensional lead halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 2570-2576 (2020).

- He, Y. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes with near unit internal quantum efficiency at low temperatures. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006302 (2021).

- Wang, L., Wang, K. & Zou, B. Pressure-induced structural and optical properties of organometal halide perovskite-based formamidinium lead bromide. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 2556-2562 (2016).

- Zhu, H. et al. Pressure-induced phase transformation and band-gap engineering of formamidinium lead iodide perovskite nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 4199-4205 (2018).

- Wu, B. et al. Discerning the surface and bulk recombination kinetics of organic-inorganic halide perovskite single crystals. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1600551 (2016).

- Qin, M. et al. Manipulating the mixed-perovskite crystallization pathway unveiled by in situ GIWAXS. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901284 (2019).

- Fabini, D. H. et al. Reentrant structural and optical properties and large positive thermal expansion in perovskite formamidinium lead iodide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 15392-15396 (2016).

- Chen, T. et al. Origin of long lifetime of band-edge charge carriers in organic-inorganic lead iodide perovskites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 7519-7524 (2017).

- Dai, X. et al. Solution-processed, high-performance light-emitting diodes based on quantum dots. Nature 515, 96-99 (2014).

- Chen, F. et al. Solution-processed double-layered hole transport layers for highly-efficient cadmium-free quantum-dot light-emitting diodes. Opt. Express 28, 6134-6145 (2020).

- Sanches, A. W. P., Silva, M. A. T., da, Cordeiro, N. J. A., Urbano, A. & Lourenço, S. A. Effect of intermediate phases on the optical properties of

-rich organicinorganic hybrid perovskite. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 5253-5261 (2019). - Li, J. & Deepak, F. L. In situ kinetic observations on crystal nucleation and growth. Chem. Rev. 122, 16911-16982 (2022).

- Yang, B. et al. Strain effects on halide perovskite solar cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 7509-7530 (2022).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Perovskite precursor solution

Film and device fabrication

Device characterization

Film characterization

For the zero-time PL (

with a pulse duration of 100 fs , repetition rate of 1 kHz and wavelength of 800 nm . This amplifier was seeded by a Coherent Vitesse oscillator. The

STEM measurement

GIWAXS measurement

Data availability

Article

b

b, STEM images of the dual-additive perovskite film with Kikuchi line patterns in various regions. Scale bar, 100 nm .

density-dependent EQE and ECE. b, Dependence of current density and radiance on bias voltage (the maximum radiance is

d, Stability of the device measured at a constant current density of

Article

Article

Extended Data Fig. 6|2D GIWAXS patterns of control perovskite film with various incidence angles. The incidence angles of

| Sample | Carrier density (

|

|

|

|

|

| Dual additive |

|

|

|

|

0.995 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.994 | |

|

|

|

|

|

0.992 | |

|

|

|

|

|

0.991 | |

| Control |

|

|

|

|

0.991 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.994 | |

|

|

|

|

|

0.994 | |

|

|

|

|

|

0.993 |

Key Laboratory of Flexible Electronics (KLOFE), Institute of Advanced Materials (IAM) & School of Flexible Electronics (Future Technologies), Nanjing Tech University, Nanjing, China. Strait Institute of Flexible Electronics (SIFE, Future Technologies), Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, China. School of Microelectronics, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. Center of Electron Microscopy, State Key Laboratory of Silicon Materials, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. Institute of Applied Physics and Materials Engineering, University of Macau, Macau, China. State Key Laboratory of Extreme Photonics and Instrumentation, College of Optical Science and Engineering, International Research Center for Advanced Photonics, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. Strait Laboratory of Flexible Electronics (SLoFE), Fuzhou, China. Institute of Flexible Electronics (IFE), Northwestern Polytechnical University (NPU), Xi’an, China. MIIT Key Laboratory of Flexible Electronics (KLoFE), Northwestern Polytechnical University (NPU), Xi’an, China. School of Flexible Electronics (SoFE), Sun Yat-sen University, Shenzhen, China. School of Materials Science and Engineering, Changzhou University, Changzhou, China. School of Microelectronics and Control Engineering, Changzhou University, Changzhou, China. These authors contributed equally: Mengmeng Li, Yingguo Yang, Zhiyuan Kuang. mail: iamlzhu@njtech.edu.cn; vc@nwpu.edu.cn; iamjpwang@njtech.edu.cn - Acknowledgements This work is financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1204800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62288102, 62134007, 52373220, 52233011 and 62375124) and the Jiangsu Provincial Departments of Science and Technology (BE2022023 and BK20220010). We thank the beamlines BLO2U2, BL17B1 and BL19U2 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) for providing the beam time and User Experiment Assist System of the SSRF for their help.Author contributions J.W. had the idea for and designed the experiments. L. Zhu, W.H. and J.W. supervised the work. M.L., C.H., L.Ze., Y. Cai and Y. Cao carried out the device fabrication and characterizations. Z.K., J.L. and F.L. conducted the SEM characterizations. Z.L. carried out the STEM characterizations, under the supervision of H.T. Y.Y. and C.H. carried out the GIWAXS measurement and analysis. Z.K., S.W., C.M., Y.M. and Q.P. conducted the optical measurements under the supervision of J.W. and G.X. J.G. carried out optical simulations of the device. J.W., L. Zhu, M.L. and Z.K. analysed the data. L. Zhu wrote the first draft of the manuscript. J.W., Q.P. and N.W. provided substantial revisions. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.Competing interests The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07460-7.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Lin Zhu, Wei Huang or Jianpu Wang.

Peer review information Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.