DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-024-00701-7

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-27

تشات جي بي تي وتوتر التكنولوجيا والتعليم: تطبيق نظرية الفضيلة السياقية على الأداة المعرفية

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

الملخص

وفقًا لعلم الأخلاق المعرفي، فإن الهدف الرئيسي من التعليم هو تطوير الشخصية المعرفية للطلاب (بريتشارد، 2014، 2016). نظرًا لانتشار الأدوات التكنولوجية مثل ChatGPT وغيرها من نماذج اللغة الكبيرة لحل المهام المعرفية، كيف ينبغي أن تدمج الممارسات التعليمية استخدام هذه الأدوات دون تقويض الشخصية المعرفية للطلاب؟ بريتشارد

1 المقدمة

1.1 الإبستمولوجيا الفضائلية في التعليم وتوتر التكنولوجيا والتعليم

حل بريتشارد للتوتر بين التكنولوجيا والتعليم

“مناهضة الفردية.” يعتبر الأول العمليات المعرفية للمواضيع داخلية تمامًا وغير قابلة للتوسيع بواسطة الموارد التكنولوجية، بينما يعتبر الثاني أنها قابلة للتوسيع من خلال الاجتماعية.

3 قيود حل بريتشارد

(Pritchard, 2013, 2016، ص. 117-118). وبالتالي، فإن المعلم الملتزم بنظرية المعرفة الممتدة سيتطلب من طلابه الانخراط بشكل نقدي في استخدام الأدوات من خلال نشر مجموعة من المهارات النقدية والفضائل المعرفية، بدلاً من الاعتماد بشكل سلبي على الأداة التي تمارس درجة محدودة من الوكالة المعرفية. لذلك، حتى لو لم يتم دائمًا تلبية شروط التمديد المعرفي، فإن هذا النهج التعليمي يدفع نحو استخدامات فضيلة معرفية للتكنولوجيا.

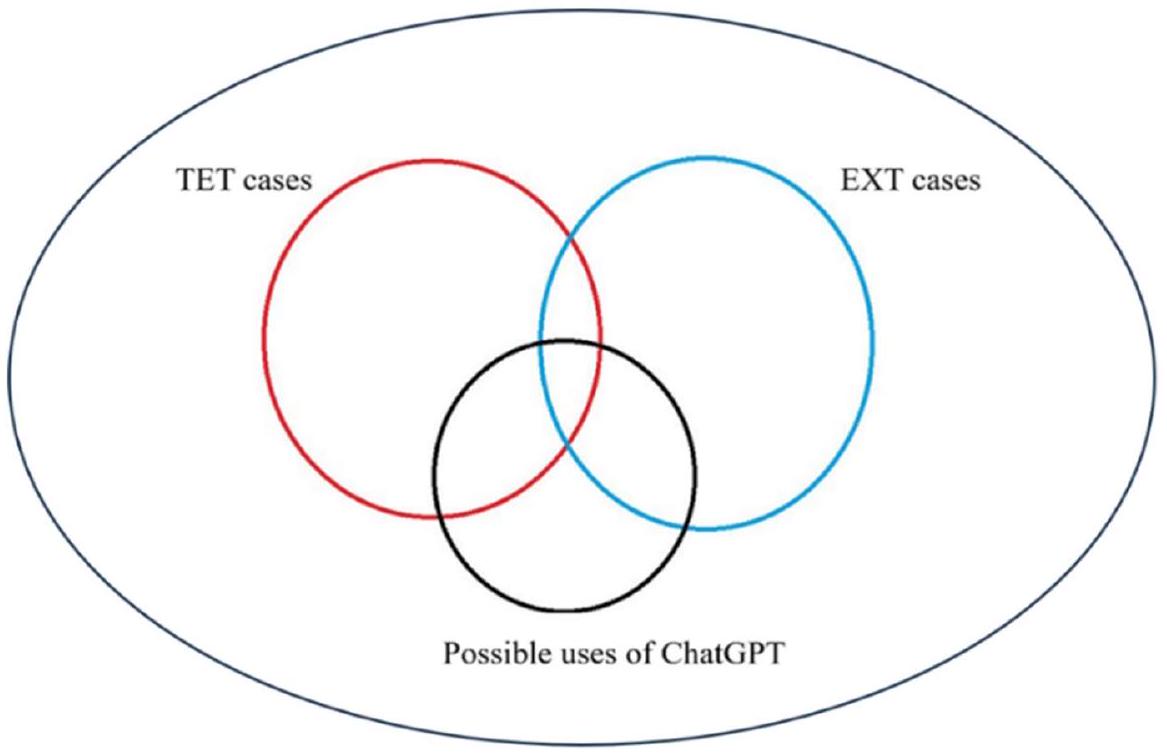

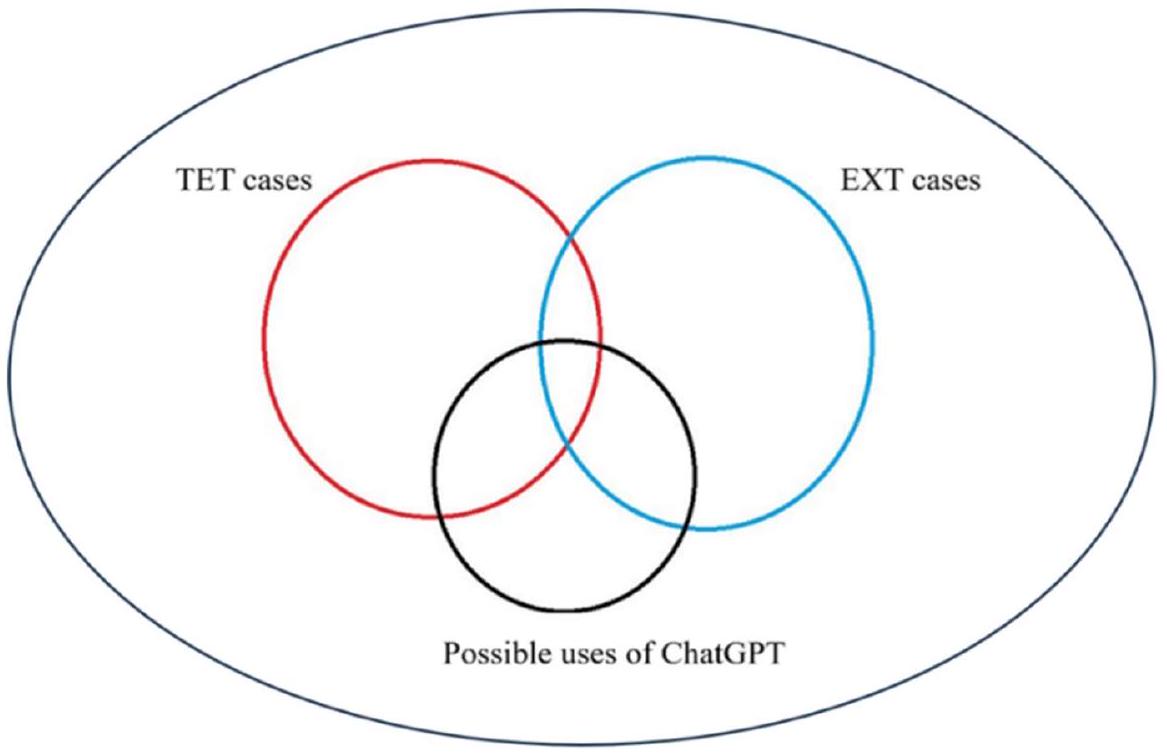

تتناول هذه القضايا والتي تنطبق على أشكال استخدام الأدوات (EMB) التي استبعدها حل بريتشارد. ستعتبر هذه الإطار EXT حالة خاصة من استخدام الأدوات التي يمكن أن تنطبق في بعض الظروف وستقدم توصيفًا دقيقًا لمختلف أنواع الأنظمة المعرفية (المضمنة والممتدة) التي تفسر الديناميات الداخلية بين المكونات المعتمدة على الدماغ والمكونات المعتمدة على التكنولوجيا للشخصية المعرفية.

4 نظرية الفضيلة السياقية في الإبستمولوجيا المطبقة على ChatGPT كأداة معرفية

4.1 شات جي بي تي كأداة معرفية

الأشياء المادية التي تم إنشاؤها أو تعديلها للمساهمة في إكمال مهمة معرفية، مما يوفر لنا تمثيلات نستخدمها كبديل أو كجزء من أو لتكملة عملياتنا المعرفية، وبالتالي تعديل المهمة المعرفية الأصلية أو إنشاء مهمة جديدة. (فازولي، 2017، ص. 681)

- تقدم ‘القطع المعرفية التأسيسية’ مساهمة ضرورية لإكمال المهمة المعرفية، التي لا يمكن إكمالها فقط من خلال العمليات المعرفية القائمة على الدماغ دون مساهمة الأداة.

- تُكمل ‘القطع المعرفية التكميلية’ عملية معرفية قائمة على الدماغ

بطريقة تجعل 1) الوكيل يمارس درجة كبيرة من الوكالة المعرفية المعتمدة على الدماغ، موكلاً إلى الأداة فقط مكونًا محدودًا من العمل لإكمال المهمة المعرفية؛ و 2) يمكن أن تُنفذ المهمة المعرفية بواسطة العملية المعرفية المعتمدة على الدماغ X بشكل مستقل عن مساهمة الأداة. - تُكمل ‘القطع المعرفية البديلة’ عملية معرفية قائمة على الدماغ X بطريقة تجعل 1) الوكيل يمارس درجة دنيا من الوكالة المعرفية القائمة على الدماغ، موكلاً إلى الأداة معظم العمل لإكمال المهمة المعرفية؛ و 2) يمكن أداء المهمة المعرفية بواسطة عملية قائمة على الدماغ.

بشكل مستقل عن مساهمة الأثر.

إذا كان جهازًا صناعيًا، فسيعمل كأداة معرفية تشكلية للتوجيه المكاني. ومع ذلك، يمكن أن ينطوي استخدام الأداة على أنواع مختلفة من العلاقات في الوقت نفسه.

| المساهمة البديلة لنظام تحديد المواقع العالمي (GPS) في مهمة ‘التوجيه المكاني’ | |

| أقصى تفويض للعمل المعرفي إلى الأداة. | ممارسة الحد الأدنى من درجة الوكالة المعرفية القائمة على الدماغ المطلوبة لقراءة المعلومات لرسم مؤشرات الأثر في البيئة الخارجية. |

| المساهمة الأساسية لنظام تحديد المواقع العالمي (GPS) في المهمة الفرعية ‘قراءة النص’ | |

| المساهمة الأثرية الضرورية لإكمال المهمة المعرفية. | ممارسة الوكالة المعرفية القائمة على الدماغ المطلوبة لإكمال المهمة المعرفية. |

- الهيكلية الممتدة: نظام إدراكي موسع يقوم على الأقل بعملية إدراكية موسعة

وفيها لا يمكن للوكيل أن يؤدي ويظهر الوكالة المعتمدة على الدماغ لإكمال العملية المعرفية X بشكل مستقل عن مساهمة الأداة. - التكميلي-EXT: نظام إدراكي موسع يقوم على الأقل بعملية إدراكية موسعة

بطريقة تجعل

- يؤدي الوكيل درجة كبيرة من الوكالة المعرفية المستندة إلى الدماغ لإكمال العملية المعرفية X ، باستخدام المورد التكنولوجي لأداء جزء جزئي فقط من العمل المعرفي اللازم لـ X ؛

- يمكن للوكيل أداء وعرض العملية المعرفية المستندة إلى الدماغ

بشكل مستقل عن مساهمة الأداة.

- بديل-EXT: نظام معرفي موسع يقوم على الأقل بأداء العملية المعرفية الموسعة

بطريقة تجعل

- الوكيل يؤدي فقط درجة دنيا من الوكالة المعرفية المستندة إلى الدماغ لأداء العملية المعرفية

، باستخدام المورد التكنولوجي لأداء معظم العمل المعرفي اللازم لـ X . - يمكن للوكيل أداء وعرض العملية المعرفية المستندة إلى الدماغ

بشكل مستقل عن مساهمة الأداة.

4.2 نظرية المعرفة الفضيلة السياقية، المقايضات المعرفية، والأدوات المعرفية

لتمديدات الإدراك التي تلبيها هذه الأداة، لا تبدو كحلول مرضية. الخيار الأول غير كافٍ لأننا يجب أن ندرب الطلاب على مواجهة الظروف الواقعية التي تتضمن استخدام أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدية بطرق معرفية فضيلة. من ناحية أخرى، قد تحترم الاستخدامات المحددة لـ ChatGPT شروط EXT لمجموعة معينة من القدرات المعرفية مما يمنع تطوير الفضائل الفكرية. وبالتالي، يحتاج المعلمون إلى تقييم، وتجربة، وتوزيع استراتيجيات وأنشطة تعليمية مختلفة قادرة على دمج استخدام ChatGPT وأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدية الأخرى ضمن المنهج التعليمي بطرق تسعى لتحقيق الأهداف الأساسية للتعليم. على سبيل المثال، قد يرغب المعلمون في تطوير المعرفة الميتامعرفية للطلاب، والفضائل الفكرية، ومهارات التفكير النقدي، من خلال طلب من الطلاب كتابة وتحليل نص باستخدام ChatGPT. يمكن استخدام الدردشة كأداة معرفية استبدالية لأداء المهمة الفرعية المتمثلة في اختراع قصة وكأداة معرفية تكميلية لممارسة القدرات المعرفية العليا والفضائل الفكرية. يمكن استخدام ChatGPT كأداة معرفية تأسيسية في مراحل التعلم، تعمل كدعامة مؤقتة من خلال تحويل دورها تدريجياً من تأسيسية إلى تكميلية. وهذا يعني أنه يجب أن يكون الطلاب قادرين على اختراع قصة أو إنشاء حجة دون أي دعم تكنولوجي؛ تماماً كما يجب أن يكون الطيار قادراً على قيادة الطائرة دون مساعدة تكنولوجية (Bliszczyk, 2023).

5 نظرية المعرفة الفضيلة السياقية في العمل

5.1 استخدامات معرفية فضيلة لـ ChatGPT في البيئات التعليمية

|

|||

| تساهم الأداة في المهمة من خلال تقديم أمثلة مختلفة يتم فيها تطبيق المفهوم A. | يمارس الوكيل البشري درجة عالية من الوكالة المعرفية القائمة على الدماغ المعنية بالفهم: القدرات المعرفية (الإدراك، الذاكرة العاملة…)، القدرات المعرفية والفضائل الفكرية (الاستقلال الفكري، العناية الفكرية، الانتباه…). | ||

|

|||

| أقصى تفويض للعمل المعرفي للأداة. | أدنى ممارسة للوكالة المعرفية القائمة على الدماغ في توليد الطلب. | ||

6 الخاتمة

تمويل تم توفير تمويل الوصول المفتوح من قبل مدرسة سانت آنا العليا ضمن اتفاقية CRUI-CARE.

إعلانات

الموافقة على النشر غير متاح.

References

Arango-Muñoz, S. (2013). Scaffolded memory and metacognitive feelings. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 4(1), 135-152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-012-0124-1

Atlas, S (2023). ChatGPT for higher education and professional development: A guide to conversational AI. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cba_facp (Accessed 20/4/2023).

Baehr, J. (2011). The Inquiring Mind: On Intellectual Virtues and Virtue Epistemology. Oxford University Press.

Baehr, J. (2013). Educating for Intellectual Virtues: From Theory to Practice. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 47(2), 248-262. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12023

Baehr, J. (2019). ‘Intellectual Virtues, Critical Thinking, and the Aims of Education’, Routledge Handbook of Social Epistemology, (eds.) P. Graham, M. Fricker, D. Henderson, N. Pedersen & J. Wyatt, 447-57. Routledge.

Baehr, J. (2015). Cultivating Good Minds: A Philosophical & Practical Guide to Educating for Intellectual Virtues. Retrieved March 15, 2023, from https://intellectualvirtues.org/why-should-we-educa te-for-intellectual-virtues2-2/

Baehr, J. (2016). The Four Dimensions of an Intellectual Virtue. Moral and Intellectual Virtues in Western and Chinese Philosophy, eds. Chienkuo Mi, Michael Slote, and Ernest Sosa Routledge: 86-98.

Baidoo-Anu, D., & Owusu Ansah, L. (2023). Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. https:// doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4337484

Barker, M. J. (2010). From cognition’s location to the epistemology of its nature. Cognitive Systems Research, 11, 357-366.

Barr, N., Pennycook, G., Stolz, J. A., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2015). The brain in your pocket: Evidence that smartphones are used to supplant thinking. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 473-480.

Barsalou, L. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, 577-609.

Barsalou, L. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617-645.

Barsalou, L. (2016). Situated conceptualization: Theory and applications. In Y. Coello & M. Fischer (Eds.), Perceptual and Emotional Embodiment: Foundations of Embodied Cognition (Vol. 1, pp. 18-47). Routledge.

Battaly, H. (2006). Teaching Intellectual Virtues: Applying Virtue Epistemology in the Classroom. Teaching Philosophy, 29, 191-222.

Battaly, H. (2008). Virtue Epistemology”. Philosophy Compass, 3(4), 639-663.

Bliszczyk, A. (2023) AI Writing Tools Like ChatGPT Are the Future of Learning & No, It’s Not Cheating. Vice. Retrieved March 16, 2023, from https://www.vice.com/en/article/xgyjm4/ai-writing-tools-like-chatgpt-are-the-future-of-learning-and-no-its-not-cheating

Boyle, C. (2016). Writing and rhetoric and/as posthuman practice. College English, 78(6), 532-554.

Byerly, T. R. (2019). Teaching for Intellectual Virtue in Logic and Critical Thinking Classes: Why and How. Teaching Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil201911599

Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies. Cambridge University Press.

Casati, R. (2017). Two, then four modes of functioning of the mind: Towards an unification of “dual” theories of reasoning and theories of cognitive artifacts. In J. Zacks & H. Taylor (Eds.), Representations in Mind and World, 7-23. Essays Inspired by Barbara Tversky.

Casner, S. M., Geven, R. W., Recker, M. P., & Schooler, J. W. (2014). The retention of manual flying skills in the automated cockpit. Human Factors, 56(8), 1506-1516. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187 20814535628

Cassinadri, G. (2022). Moral Reasons Not to posit Extended Cognitive Systems: A reply to Farina and Lavazza. Philosophy and Technology, 35, 64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-022-00560-0

Cassinadri, G., & Fasoli, M. (2023). Rejecting the extended cognition moral narrative: A critique of two normative arguments for extended cognition. Synthese, 202, 155. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11229-023-04397-8

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7-19.

Christodoulou, D. (2023). If we are setting assessments that a robot can complete, what does that say about our assessments? The No More Marking Blog. Retrieved March 16, 2023, from https://blog. nomoremarking.com/if-we-are-setting-assessments-that-a-robot-can-complete-what-does-that-say-about-our-assessments-cbc1871f502

Clowes, R. W. (2013). The cognitive integration of E-memory. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 4, 107-133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-013-0130-y

Clowes, R.W. (2020). The internet extended person: exoself or doppelganger? Límite. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Filosofía y Psicología, 15(22), 1-23. https://research.unl.pt/ws/portalfiles/portal/29762 990/document_8_.pdf

Clowes, R. W., Smart, P. R., & Heersmink, R. (2023). The ethics of the extended mind: Mental privacy, manipulation and agency. In B. Beck, O. Friedrich, & J. Heinrichs (Eds.), Neuroprosthetics. Ethics of applied situated cognition.

Colombo, M., Irvine, E., & Stapleton, M. (Eds.). (2019). Andy Clark and His Critics, Oxford. University Press.

Cotton, D., Cotton, A., & Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 14703297.2023.2190148

Deng, J., & Lin, Y. (2023). The Benefits and Challenges of ChatGPT: An Overview. Frontiers in Computing and Intelligent Systems, 2(2), 81-83. https://doi.org/10.54097/fcis.v2i2.4465

Digital Learning Institute (2023). Should Instructional Designers use Chat GPT? Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://www.digitallearninginstitute.com/learning-design-chat-gpt/

Dragga, S., & Gong, G. (1989). Editing: The design of rhetoric. Routledge.

Ebbatson, M., Harris, M., Huddlestone, D. J., & Sears, R. (2010). The relationship between manual handling performance and recent flying experience in air transport pilots. Ergonomics, 53(2), 268277. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130903342349

Facchin, M. (2023). Why can’t we say what cognition is (at least for the time being). Philosophy and the Mind Sciences, 4. https://doi.org/10.33735/phimisci.2023.9664

Farina, M., & Lavazza, A. (2022). Incorporation, transparency, and cognitive extension. Why the distinction between embedded or extended might be more important to ethics than to metaphysics. Philosophy and Technology, 35, 10.

Fasoli, M. (2016). Neuroethics of cognitive artifacts. In A. Lavazza (Ed.), Frontiers in neuroethics: Conceptual and empirical advancements (pp. 63-75). Cambridge scholars publishing.

Fasoli, M. (2017). Substitutive, Complementary and Constitutive Cognitive Artifacts: Developing an Interaction-Centered Approach. In Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 9, 671-687. https://doi. org/10.1007/s13164-017-0363-2

Ferlazzo, L (2023a). 19 Ways to Use ChatGPT in Your Classroom. EducationWeek. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-19-ways-to-use-chatgpt-in-yourclassroom/2023/01

Ferlazzo, L (2023b). Educators Need to Get With the AI Program. ChatGPT, More Specifically. EduWeek.Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-educa tors-need-to-get-with-the-ai-program-chatgpt-more-specifically/2023/01

Floridi, L., & Chiriatti, M. (2020). GPT-3: Its Nature, Scope, Limits, and Consequences. Minds & Machines, 30, 681-694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09548-1

Fyfe, P. (2022). How to cheat on your final paper: Assigning AI for student writing. AI & SOCIETY. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01397-z

Gimpel, H., Hall, K., Decker, S., Eymann, T., Lämmermann, L., Mädche, A., Röglinger, R., Ruiner, C., Schoch, M., Schoop, M., Urbach, N., Vandirk, S. (2023). Unlocking the Power of Generative AI Models and Systems such as GPT-4 and ChatGPT for Higher Education: A Guide for Students and Lecturers. University of Hohenheim https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.20710.09287/2

Glenberg, A. (2008). Embodiment for education. In P. Calvo & A. Gomila (Eds.), Handbook of Cognitive Science: An Embodied Approach (pp. 355-371). Elsevier Science.

Glenberg, A. (2010). Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. Wires Cognitive Science, 1, 586-596.

Gravel, J. D’Amours-Gravel, M. Osmanlliu, E. (2023 preprint) Learning to fake it: limited responses and fabricated references provided by ChatGPT for medical questions. medRxiv: 2023.03.16.23286914; https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.16.23286914

Heersmink, R. (2013). A taxonomy of cognitive artifacts: Function, information, and categories. Review of Philosphy and Psychology, 4, 465-481.

Heersmink, R. (2014). The metaphysics of cognitive artifacts. Philosophical Explorations, 19(1), 1-16.

Heersmink, R. (2015). Dimensions of Integration in Embedded and Extended Cognitive Systems. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 14(3), 577-598.

Heersmink, R. (2017). Distributed cognition and distributed morality: Agency, artifacts and systems. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(2), 431-448.

Heersmink, R. (2018). A virtue epistemology of the Internet: Search engines, intellectual virtues and education. Social Epistemology, 32(1), 1-12.

Heersmink, R., & Knight, S. (2018). Distributed learning: Educating and assessing extended cognitive systems. Philosophical Psychology, 31(6), 969-990. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2018.14691 22

Hernández-Orallo, J. and Vold, K. (2019). AI Extenders: The Ethical and Societal Implications of Humans Cognitively Extended by AI. In Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 507513. https://doi.org/10.1145/3306618.3314238

Hutchins, E. (1999). Cognitive artifacts. In R. A. Wilson & F. C. Keil (Eds.), The MIT encyclopaedia of the cognitive sciences (pp. 126-128). MIT Press.

Hutchins, E. (2010). Cognitive Ecology. Topics in Cognitive. Science, 2, 705-715. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.1756-8765.2010.01089.x

Hyslop-Margison, E. (2003). The Failure of Critical Thinking: Considering Virtue Epistemology as a Pedagogical Alternative. Philosophy of Education Society Yearbook, 2003, 319-326.

Kasneci, E., et al. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif. 2023.102274

King, C. (2016). Learning Disability and the Extended Mind. Essays in Philosophy, 17(2), 38-68.

Klein, A. (2023) Outsmart ChatGPT: 8 Tips for Creating Assignments It Can’t Do. EducationWeek. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.edweek.org/technology/outsmart-chatgpt-8-tips-for-creating-assignments-it-cant-do/2023/02

Konya, C., Lyons, D., Fischer, S., et al. (2015). Physical experience enhances science learning. Psychological Science, 26(6), 737-749.

Kuhn, D. (2000). Metacognitive development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(5), 178181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00088

Lipman, M. (1998). Philosophy goes to school. Temple University Press.

MacAllister, J. (2012). Virtue Epistemology and the Philosophy of Education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 46, 251-270.

Malafouris, L. (2013). How things shape the mind. MIT press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9476. 001.0001

McCormack, G (2023). Chat GPT Is here! – 5 alternative ways to assess your class! Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://gavinmccormack.com.au/chat-gpt-is-here-5-alter native-ways-to-assess-your-class/

Mhlanga, D. (2023). Open AI in Education, the Responsible and Ethical Use of ChatGPT Towards Lifelong Learning. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4354422

Mill, J. S. (1985). On Liberty. Penguin Classics.

Miller, J. (2022). ChatGPT, Chatbots and Artificial Intelligence in Education. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://ditchthattextbook.com/ai#tve-jump-18606008967

Moe, M (2022). EIEIO… Poetry in Motion. Medium. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://medium. com/the-eieio-newsletter/eieio-poetry-in-motion-1b9c0061bf63

Mollick, E. R., & Mollick, L. (2022). New Modes of Learning Enabled by AI Chatbots: Three Methods and Assignments. SSRN Electronic Journal https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4300783

Newen, A, L. De Bruin, and S. Gallagher (eds) (2018). The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition, Oxford Library of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198735410.001.0001

Norman, D. (1991). Cognitive artifacts. In J. M. Carroll (Ed.), Designing interaction: Psychology at the human-computer interface (pp. 17-38). Cambridge University Press.

Palermos, S. O. (2016). The Dynamics of Group Cognition. Minds & Machines, 26, 409-440. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11023-016-9402-5

Palermos, S. O. (2022a). Epistemic Collaborations: Distributed Cognition and Virtue Reliabilism. Erkenn, 87, 1481-1500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-020-00258-9

Palermos, S. O. (2022b). Collaborative knowledge: Where the distributed and commitment models merge. Synthese, 200, 54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03459-7

Piredda, G. (2020). What is an affective artifact? A further development in situated affectivity. Phenom Cogn Sci, 19, 549-567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-019-09628-3

Price, M. (2022). Beyond ‘gotcha!’: Situating plagiarism in policy and pedagogy. College Composition and Communication, 54(1), 88-115. https://doi.org/10.2307/1512103

Pritchard, D. (2013). Epistemic Virtue and the Epistemology of Education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 47, 236-247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12022

Pritchard, D. (2014). Virtue Epistemology, Extended Cognition, and the Epistemology of Education. Universitas: Monthly Review of Philosophy and Culture, 478, 47-66. https://www.pure.ed.ac.uk/ws/ portalfiles/portal/16633349/Virtue_Epistemology_Extended_Cognition_and_the_Epistemology_ of_Education.pdf

Pritchard, D. H. (2016). Intellectual Virtue, Extended Cognition, and the Epistemology of Education”. In J. Baehr (Ed.), Intellectual Virtues and Education: Essays in Applied Virtue Epistemology (pp. 113-127). Routledge.

Pritchard, D. H. (2018). Neuromedia and the Epistemology of Education. Metaphilosophy, 49, 328-349.

Pritchard, D. H. (2019). Philosophy in Prisons: Intellectual Virtue and the Community of Philosophical Inquiry. Teaching Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil201985108

Pritchard, D. H. (2020). Educating For Intellectual Humility and Conviction. Journal of Philosophy of Education., 54, 398-409.

Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y. ChatGPT for Education and Research: Opportunities, Threats, and Strategies. Preprints.org 2023, 2023030473. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202303.0473.v1

Robertson, E. (2009). ‘The Epistemic Aims of Education’, Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Education, (ed.) H. Siegel, 11-34. Oxford University Press.

Rudolph. J. Tan, S. Tan, S. (2023). ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education? ED-TECH REVIEWS Vol. 6 No. 1 https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2023.6.1.9

Rupert, R. D. (2004). Challenges to the Hypothesis of Extended Cognition. The Journal of Philosophy, 101(8), 389-428. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3655517

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037/ 0003-066X.55.1.68

Shapiro, L., & Stoltz, S. (2019). Embodied Cognition and its Significance for Education”, with Steven Stolz. Theory and Research in Education, 17, 19-39.

Shen-Berro, J. (2023). New York City schools blocked ChatGPT. Here’s what other large districts are doing. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.chalkbeat.org/2023/1/6/23543039/chatgpt-school-districts-ban-block-artificial-intelligence-open-ai

Shiri, A. (2023). ChatGPT and Academic Integrity (February 2, 2023). Information Matters, 3 (2), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4360052

Siegel, H. (1988). Educating Reason: Rationality, Critical Thinking, and Education. Routledge.

Siegel, H. (1997). Rationality Redeemed? Routledge.

Siegel, H. (2017). Education’s Epistemology: Rationality, Diversity, and Critical Thinking. Oxford University Press.

Sockett, H. (2012). Knowledge and Virtue in Teaching and Learning: The Primacy of Dispositions. Routledge.

Sok, S., & Heng, K. (2023). ChatGPT for Education and Research: A Review of Benefits and Risks. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4378735

Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science, 333(6043), 776-778.

Sprevak, M. (2010). Inference to the hypothesis of extended cognition. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 41, 353-362.

Sterelny, K. (2004). Externalism, Epistemic Artefacts and The Extended Mind. In R. Schantz (Ed.), The Externalist Challenge (pp. 239-255). Berlin.

Stratachery (2022). AI homework. Retrieved March 12, 2023, from https://stratechery.com/2022/aihomework/

Teubner, T., Flath, C. M., Weinhardt, C., van der Aalst, W., & Hinz, O. (2023). Welcome to the Era of ChatGPT et al. Business & Information Systems Engineering, https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12599-023-00795-x

Theiner, G., Allen, C., & Goldstone, R. L. (2010). Recognizing group cognition. Cognitive Systems Research, 11(4), 378-395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2010.07.002

Toppo, G (2023). How ChatGPT will reshape the future of the high school essay. FastCompany. Retrieved 1/4/2023, from https://www.fastcompany.com/90841387/gpt-3-chatgpt-high-school-schoolwork

Varga, S. (2017). Demarcating the Realm of Cognition. Journal for General Philosophy of Science, 49, 435-450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-017-9375-y

Vold, K. (2018). Overcoming Deadlock: Scientific and Ethical Reasons to Embrace the Extended Mind Thesis. In PHILOSOPHY AND SOCIETY., 29(4), 471-646.

Wei, J. Y. Tay, R. Bommasani, et al. (2022). Emergent abilities of large language models, CoRR, vol. abs/2206.07682. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.07682

Zagzebski, L. (1996). Virtues of the Mind: An Inquiry into the Nature of Virtue and the Ethical Foundations of Knowledge. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174763

Zhai, X. (2022). ChatGPT: Artificial Intelligence for Education. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.35971. 37920

- Guido Cassinadri

guido.cassinadri@santannapisa.it

Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Piazza Martiri Della Libertà, 33, 56127 Pisa, Italy This tool may prove beneficial by offering 1) efficient and time-saving creation of learning assessments (Zhai 2022; 2023; Baidoo-Anu and Owusu Ansah, 2023); 2) enhancement of pedagogical practices by assisting teachers’ production of quizzes, exams, syllabuses, and lesson plans (Rudolf 2023; Atlas 2023); 3) easily available personalized tutoring and feedback for students (Mhlanga 2023); 4) creation of outlines for organizing ideas (Kasneci et al., 2023) and 5) facilitation of brainstorming. In this treatment the label ‘tool-use’ refers only to the use of representational cognitive artifacts (Fasoli 2017), leaving out other forms of tool-use.

Baehr (2016, p. 2) defines personal excellences as qualities that “make their possessor good or admirable qua person”. For an account of the development of intellectual virtues in education see Hyslop-Margison (2003), Battaly (2006), MacAllister (2012), Sockett (2012), Pritchard (2013, 2018, 2020), Byerly (2019), Baehr (2015). Along with other virtue responsibilists, Pritchard (2013; 2014; 2016) considers the development of intellectual virtues as the fundamental goal of education, given the special role they play in relation to the cognitive economy of the subject. The analysis of distributed cognition frameworks and of socially distributed epistemology applied in educational contexts goes beyond the scope of this work, although I will briefly mention this field of research in Sect. 5.1. In Sect. 4.2 I will define these transformations as “cognitive trade-offs”.

Fifth, cognitive integration with AI system, either they are EMB or EXT cases, may have transformative and detrimental effects on an affective, motivational, and existential level, potentially undermining the self and autonomy of the embedded/extended agent (Cassinadri 2022; Clowes 2020; Clowes et al., - Footnote 7 (Continued)

2023; Hernández-Orallo and Vold 2019). This issue is out of the scope of this treatment but is worth mentioning if we want to educate students not simply as epistemic agents but as whole human beings. Although this tool can also be used as an affective and emotional artifact by contributing to regulating and influencing the affective states of the user (Piredda 2020), in this paper I will characterize it only as a cognitive artifact that supports cognitive tasks.

A task is “any activity in which a person engages, given an appropriate setting, in order to achieve a specifiable class of objectives, final results, or terminal states of affairs” (Carroll 1993, p. 8). Carroll defined a cognitive task as “any task in which correct or appropriate processing of mental information is critical to successful performance” (Carroll 1993, p. 10). So, it is a linguistic simplification to say that “an artifact is used in a substitutive, constitutive, and complementary way”, given the multiple levels of interaction and the potential division of each task into subtasks. However, in the rest of this treatment, when I say that an artifact is used in one of these three ways without further specification, I will refer to the higher-level task ( X ) to which it contributes. I leave for EXT theorists to define whether and how the latter cases may be genuine instances of EXT. According to Pritchard (2014; 2016) cognitive extension requires a great degree of cognitive agency, so it would be unlikely to admit a substitutive extended cognitive system. See Marconi (2005) for an argument against the possibility of substitutive extended cognitive systems. Cognitive extension does not solve per se complex moral problems inherent to human-AI interaction such as manipulation, given that there might be AI systems that extend cognition but undermine the agent’s self and autonomy (Cassinadri 2022; Clowes 2020; Clowes et al., 2023; Hernández-Orallo and Vold 2019). While I have no space to develop this pressing issue here, it is worth mentioning within educational research since we should not treat students simply as epistemic cognitive agents, but rather as whole human beings. See Robert and Wood, (2007) for an account of the fundamental elements of the cognitive character that contribute to human flourishing. If we consider the task as ‘not being deceived by the AI tool,’ then such a tool performs a constitutive contribution to the task. However, since we are interested in developing students’ abilities in different contexts, it is more useful to consider the task in more general terms such that the tool simply performs a complementary contribution. In this case, the artefactual contribution is constitutive since the task consists in an epistemically virtuous use of the artifact itself. The framework I presented here is limited to representational cognitive artifacts.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-024-00701-7

Publication Date: 2024-01-27

ChatGPT and the Technology-Education Tension: Applying Contextual Virtue Epistemology to a Cognitive Artifact

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

According to virtue epistemology, the main aim of education is the development of the cognitive character of students (Pritchard, 2014, 2016). Given the proliferation of technological tools such as ChatGPT and other LLMs for solving cognitive tasks, how should educational practices incorporate the use of such tools without undermining the cognitive character of students? Pritchard

1 Introduction

1.1 Virtue Epistemology in Education and the Technology-Education Tension

2 Pritchard’s solution to the ‘technology-education tension’

anti-individualism.’ The former considers subjects’ cognitive processes as entirely internal and non-extendible by technological resources, while the latter considers them as potentially extended by social

3 The limitations of Pritchard’s solution

(Pritchard, 2013, 2016, p. 117-118). Thus, an educator committed to extended virtue epistemology would require her students to critically engage in tool-use deploying a set of critical skills and epistemic virtues, rather than passively relying on the tool exerting a limited degree of cognitive agency. Therefore, even if the conditions for cognitive extension are not always met, this educational approach pushes toward epistemically virtuous uses of technology.

these issues and that is applicable to the forms of tool-use (EMB) left out by Pritchard’s solution. This framework will consider EXT as a special case of tool-use that can apply in some conditions and will offer a fine-grained characterization of different kinds of cognitive systems (embedded and extended) that explain the inner dynamics between brain-based and tech-based components of the cognitive character.

4 Contextual Virtue Epistemology applied to ChatGPT as a Cognitive Artifact

4.1 ChatGPT as a Cognitive artifact

physical objects that have been created or modified to contribute to the completion of a cognitive task, providing us with representations that we employ for substituting, constituting, or complementing our cognitive processes, thus modifying the original cognitive task or creating a new one. (Fasoli, 2017, p. 681)

- ‘Constitutive cognitive artifacts’ offer a necessary contribution to the completion of the cognitive task, which could not be completed solely by brain-based cognitive processes without the artefact’s contribution.

- ‘Complementary cognitive artifacts’ complement a brain-based cognitive process

in such a way that 1 ) the agent exerts a great degree of brain-based cognitive agency, delegating to the artifact only a limited component of the work to complete the cognitive task; and 2) the cognitive task may be performed by the brain-based cognitive process X independently of the artifact’s contribution. - ‘Substitutive cognitive artifacts’ complement a brain-based cognitive process X in such a way that 1) the agent exerts a minimal degree of brain-based cognitive agency, delegating to the artifact most of the work to complete the cognitive task; and 2) the cognitive task may be performed by brain-based process

independently of the artifact’s contribution.

artificial device, then it would work as a constitutive cognitive artifact for spatial orientation. However, the use of an artifact can involve different kinds of relations simultaneously.

| GPS’s substitutive contribution to the task of ‘spatial orientation’ | |

| Maximum delegation of cognitive work to the artifact. | Exercise of minimum degree of brain-based cognitive agency required for reading information for mapping the artifact’s indications in the external environment. |

| GPS’s constitutive contribution to the sub-task of ‘reading text’ | |

| Necessary artifactual contribution for completing the cognitive task. | Exercise of the brain-based cognitive agency required for completing the cognitive task. |

- Constitutive-EXT: an extended cognitive system that performs at least the extended cognitive process

and in which the agent cannot perform and display the brain-based cognitive agency for completing the cognitive process X independently of the artifact’s contribution. - Complementary-EXT: an extended cognitive system that performs at least the extended cognitive process

in such a way that

- the agent performs a great degree of brain-based cognitive agency for completing the cognitive process X , using the technological resource for performing only a partial component of the cognitive work necessary for X ;

- the agent can perform and display the brain-based cognitive process

independently of the artifact’s contribution.

- Substitutive-EXT: an extended cognitive system that performs at least the extended cognitive process

in such a way that

- the agent performs only a minimal degree of brain-based cognitive agency for performing the cognitive process

, using the technological resource for performing most of the cognitive work necessary for X . - the agent can perform and display the brain-based cognitive process

independently of the artifact’s contribution.

4.2 Contextual Virtue Epistemology, Cognitive Trade-offs, and Cognitive Artifacts

of cognitive extensions met by this tool, do not seem satisfactory solutions. The first option is inadequate because we should train students to face real-world circumstances that involve the use of generative AI systems in epistemically virtuous ways. On the other hand, specific uses of ChatGPT may respect EXT conditions for a specific set of cognitive abilities preventing the development of intellectual virtues. Thus, educators need to evaluate, experiment, and distribute different educational strategies and activities capable of incorporating the use of ChatGPT and other generative AI systems within the educational curriculum in ways that pursue the fundamental aims of education. For example, educators may want to develop the students’ metacognitive knowledge, intellectual virtues, and critical thinking skills, by asking students to write and analyze a text using ChatGPT. The chatbot may be used as a substitutive cognitive artifact for performing the sub-cognitive task of inventing a story and as a complementary cognitive artifact for exercising higher-level cognitive abilities and intellectual virtues. ChatGPT may be used as a constitutive cognitive artifact in learning phases, acting as a temporary scaffolding by gradually shifting its role from a constitutive to a complementary one. This means that students should still be able to invent a story or create an argument without any technological support; just as a pilot should still be able to fly a plane without technological assistance (Bliszczyk, 2023).

5 Contextual Virtue Epistemology in Action

5.1 Epistemically Virtuous uses of ChatGPT in Educational Settings

|

|||

| The artefact contributes to the task by providing different examples in which concept A is applied. | The human agent exercises a high degree of brain-based cognitive agency involved in understanding: cognitive faculties (perception, working memory…), cognitive abilities and intellectual virtues (intellectual autonomy, intellectual carefulness, attentiveness…). | ||

|

|||

| Maximum delegation of cognitive work to the artifact. | Minimal exercise of brain-based cognitive agency in generating the prompt. | ||

6 Conclusion

Funding Open access funding provided by Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Declarations

Consent for publication N/a.

References

Arango-Muñoz, S. (2013). Scaffolded memory and metacognitive feelings. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 4(1), 135-152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-012-0124-1

Atlas, S (2023). ChatGPT for higher education and professional development: A guide to conversational AI. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cba_facp (Accessed 20/4/2023).

Baehr, J. (2011). The Inquiring Mind: On Intellectual Virtues and Virtue Epistemology. Oxford University Press.

Baehr, J. (2013). Educating for Intellectual Virtues: From Theory to Practice. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 47(2), 248-262. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12023

Baehr, J. (2019). ‘Intellectual Virtues, Critical Thinking, and the Aims of Education’, Routledge Handbook of Social Epistemology, (eds.) P. Graham, M. Fricker, D. Henderson, N. Pedersen & J. Wyatt, 447-57. Routledge.

Baehr, J. (2015). Cultivating Good Minds: A Philosophical & Practical Guide to Educating for Intellectual Virtues. Retrieved March 15, 2023, from https://intellectualvirtues.org/why-should-we-educa te-for-intellectual-virtues2-2/

Baehr, J. (2016). The Four Dimensions of an Intellectual Virtue. Moral and Intellectual Virtues in Western and Chinese Philosophy, eds. Chienkuo Mi, Michael Slote, and Ernest Sosa Routledge: 86-98.

Baidoo-Anu, D., & Owusu Ansah, L. (2023). Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. https:// doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4337484

Barker, M. J. (2010). From cognition’s location to the epistemology of its nature. Cognitive Systems Research, 11, 357-366.

Barr, N., Pennycook, G., Stolz, J. A., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2015). The brain in your pocket: Evidence that smartphones are used to supplant thinking. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 473-480.

Barsalou, L. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, 577-609.

Barsalou, L. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617-645.

Barsalou, L. (2016). Situated conceptualization: Theory and applications. In Y. Coello & M. Fischer (Eds.), Perceptual and Emotional Embodiment: Foundations of Embodied Cognition (Vol. 1, pp. 18-47). Routledge.

Battaly, H. (2006). Teaching Intellectual Virtues: Applying Virtue Epistemology in the Classroom. Teaching Philosophy, 29, 191-222.

Battaly, H. (2008). Virtue Epistemology”. Philosophy Compass, 3(4), 639-663.

Bliszczyk, A. (2023) AI Writing Tools Like ChatGPT Are the Future of Learning & No, It’s Not Cheating. Vice. Retrieved March 16, 2023, from https://www.vice.com/en/article/xgyjm4/ai-writing-tools-like-chatgpt-are-the-future-of-learning-and-no-its-not-cheating

Boyle, C. (2016). Writing and rhetoric and/as posthuman practice. College English, 78(6), 532-554.

Byerly, T. R. (2019). Teaching for Intellectual Virtue in Logic and Critical Thinking Classes: Why and How. Teaching Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil201911599

Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies. Cambridge University Press.

Casati, R. (2017). Two, then four modes of functioning of the mind: Towards an unification of “dual” theories of reasoning and theories of cognitive artifacts. In J. Zacks & H. Taylor (Eds.), Representations in Mind and World, 7-23. Essays Inspired by Barbara Tversky.

Casner, S. M., Geven, R. W., Recker, M. P., & Schooler, J. W. (2014). The retention of manual flying skills in the automated cockpit. Human Factors, 56(8), 1506-1516. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187 20814535628

Cassinadri, G. (2022). Moral Reasons Not to posit Extended Cognitive Systems: A reply to Farina and Lavazza. Philosophy and Technology, 35, 64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-022-00560-0

Cassinadri, G., & Fasoli, M. (2023). Rejecting the extended cognition moral narrative: A critique of two normative arguments for extended cognition. Synthese, 202, 155. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11229-023-04397-8

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7-19.

Christodoulou, D. (2023). If we are setting assessments that a robot can complete, what does that say about our assessments? The No More Marking Blog. Retrieved March 16, 2023, from https://blog. nomoremarking.com/if-we-are-setting-assessments-that-a-robot-can-complete-what-does-that-say-about-our-assessments-cbc1871f502

Clowes, R. W. (2013). The cognitive integration of E-memory. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 4, 107-133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-013-0130-y

Clowes, R.W. (2020). The internet extended person: exoself or doppelganger? Límite. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Filosofía y Psicología, 15(22), 1-23. https://research.unl.pt/ws/portalfiles/portal/29762 990/document_8_.pdf

Clowes, R. W., Smart, P. R., & Heersmink, R. (2023). The ethics of the extended mind: Mental privacy, manipulation and agency. In B. Beck, O. Friedrich, & J. Heinrichs (Eds.), Neuroprosthetics. Ethics of applied situated cognition.

Colombo, M., Irvine, E., & Stapleton, M. (Eds.). (2019). Andy Clark and His Critics, Oxford. University Press.

Cotton, D., Cotton, A., & Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 14703297.2023.2190148

Deng, J., & Lin, Y. (2023). The Benefits and Challenges of ChatGPT: An Overview. Frontiers in Computing and Intelligent Systems, 2(2), 81-83. https://doi.org/10.54097/fcis.v2i2.4465

Digital Learning Institute (2023). Should Instructional Designers use Chat GPT? Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://www.digitallearninginstitute.com/learning-design-chat-gpt/

Dragga, S., & Gong, G. (1989). Editing: The design of rhetoric. Routledge.

Ebbatson, M., Harris, M., Huddlestone, D. J., & Sears, R. (2010). The relationship between manual handling performance and recent flying experience in air transport pilots. Ergonomics, 53(2), 268277. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130903342349

Facchin, M. (2023). Why can’t we say what cognition is (at least for the time being). Philosophy and the Mind Sciences, 4. https://doi.org/10.33735/phimisci.2023.9664

Farina, M., & Lavazza, A. (2022). Incorporation, transparency, and cognitive extension. Why the distinction between embedded or extended might be more important to ethics than to metaphysics. Philosophy and Technology, 35, 10.

Fasoli, M. (2016). Neuroethics of cognitive artifacts. In A. Lavazza (Ed.), Frontiers in neuroethics: Conceptual and empirical advancements (pp. 63-75). Cambridge scholars publishing.

Fasoli, M. (2017). Substitutive, Complementary and Constitutive Cognitive Artifacts: Developing an Interaction-Centered Approach. In Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 9, 671-687. https://doi. org/10.1007/s13164-017-0363-2

Ferlazzo, L (2023a). 19 Ways to Use ChatGPT in Your Classroom. EducationWeek. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-19-ways-to-use-chatgpt-in-yourclassroom/2023/01

Ferlazzo, L (2023b). Educators Need to Get With the AI Program. ChatGPT, More Specifically. EduWeek.Retrieved March 17, 2023, from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-educa tors-need-to-get-with-the-ai-program-chatgpt-more-specifically/2023/01

Floridi, L., & Chiriatti, M. (2020). GPT-3: Its Nature, Scope, Limits, and Consequences. Minds & Machines, 30, 681-694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09548-1

Fyfe, P. (2022). How to cheat on your final paper: Assigning AI for student writing. AI & SOCIETY. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01397-z

Gimpel, H., Hall, K., Decker, S., Eymann, T., Lämmermann, L., Mädche, A., Röglinger, R., Ruiner, C., Schoch, M., Schoop, M., Urbach, N., Vandirk, S. (2023). Unlocking the Power of Generative AI Models and Systems such as GPT-4 and ChatGPT for Higher Education: A Guide for Students and Lecturers. University of Hohenheim https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.20710.09287/2

Glenberg, A. (2008). Embodiment for education. In P. Calvo & A. Gomila (Eds.), Handbook of Cognitive Science: An Embodied Approach (pp. 355-371). Elsevier Science.

Glenberg, A. (2010). Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. Wires Cognitive Science, 1, 586-596.

Gravel, J. D’Amours-Gravel, M. Osmanlliu, E. (2023 preprint) Learning to fake it: limited responses and fabricated references provided by ChatGPT for medical questions. medRxiv: 2023.03.16.23286914; https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.16.23286914

Heersmink, R. (2013). A taxonomy of cognitive artifacts: Function, information, and categories. Review of Philosphy and Psychology, 4, 465-481.

Heersmink, R. (2014). The metaphysics of cognitive artifacts. Philosophical Explorations, 19(1), 1-16.

Heersmink, R. (2015). Dimensions of Integration in Embedded and Extended Cognitive Systems. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 14(3), 577-598.

Heersmink, R. (2017). Distributed cognition and distributed morality: Agency, artifacts and systems. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(2), 431-448.

Heersmink, R. (2018). A virtue epistemology of the Internet: Search engines, intellectual virtues and education. Social Epistemology, 32(1), 1-12.

Heersmink, R., & Knight, S. (2018). Distributed learning: Educating and assessing extended cognitive systems. Philosophical Psychology, 31(6), 969-990. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2018.14691 22

Hernández-Orallo, J. and Vold, K. (2019). AI Extenders: The Ethical and Societal Implications of Humans Cognitively Extended by AI. In Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 507513. https://doi.org/10.1145/3306618.3314238

Hutchins, E. (1999). Cognitive artifacts. In R. A. Wilson & F. C. Keil (Eds.), The MIT encyclopaedia of the cognitive sciences (pp. 126-128). MIT Press.

Hutchins, E. (2010). Cognitive Ecology. Topics in Cognitive. Science, 2, 705-715. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.1756-8765.2010.01089.x

Hyslop-Margison, E. (2003). The Failure of Critical Thinking: Considering Virtue Epistemology as a Pedagogical Alternative. Philosophy of Education Society Yearbook, 2003, 319-326.

Kasneci, E., et al. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif. 2023.102274

King, C. (2016). Learning Disability and the Extended Mind. Essays in Philosophy, 17(2), 38-68.

Klein, A. (2023) Outsmart ChatGPT: 8 Tips for Creating Assignments It Can’t Do. EducationWeek. Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.edweek.org/technology/outsmart-chatgpt-8-tips-for-creating-assignments-it-cant-do/2023/02

Konya, C., Lyons, D., Fischer, S., et al. (2015). Physical experience enhances science learning. Psychological Science, 26(6), 737-749.

Kuhn, D. (2000). Metacognitive development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(5), 178181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00088

Lipman, M. (1998). Philosophy goes to school. Temple University Press.

MacAllister, J. (2012). Virtue Epistemology and the Philosophy of Education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 46, 251-270.

Malafouris, L. (2013). How things shape the mind. MIT press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9476. 001.0001

McCormack, G (2023). Chat GPT Is here! – 5 alternative ways to assess your class! Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://gavinmccormack.com.au/chat-gpt-is-here-5-alter native-ways-to-assess-your-class/

Mhlanga, D. (2023). Open AI in Education, the Responsible and Ethical Use of ChatGPT Towards Lifelong Learning. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4354422

Mill, J. S. (1985). On Liberty. Penguin Classics.

Miller, J. (2022). ChatGPT, Chatbots and Artificial Intelligence in Education. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://ditchthattextbook.com/ai#tve-jump-18606008967

Moe, M (2022). EIEIO… Poetry in Motion. Medium. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://medium. com/the-eieio-newsletter/eieio-poetry-in-motion-1b9c0061bf63

Mollick, E. R., & Mollick, L. (2022). New Modes of Learning Enabled by AI Chatbots: Three Methods and Assignments. SSRN Electronic Journal https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4300783

Newen, A, L. De Bruin, and S. Gallagher (eds) (2018). The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition, Oxford Library of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198735410.001.0001

Norman, D. (1991). Cognitive artifacts. In J. M. Carroll (Ed.), Designing interaction: Psychology at the human-computer interface (pp. 17-38). Cambridge University Press.

Palermos, S. O. (2016). The Dynamics of Group Cognition. Minds & Machines, 26, 409-440. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11023-016-9402-5

Palermos, S. O. (2022a). Epistemic Collaborations: Distributed Cognition and Virtue Reliabilism. Erkenn, 87, 1481-1500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-020-00258-9

Palermos, S. O. (2022b). Collaborative knowledge: Where the distributed and commitment models merge. Synthese, 200, 54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03459-7

Piredda, G. (2020). What is an affective artifact? A further development in situated affectivity. Phenom Cogn Sci, 19, 549-567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-019-09628-3

Price, M. (2022). Beyond ‘gotcha!’: Situating plagiarism in policy and pedagogy. College Composition and Communication, 54(1), 88-115. https://doi.org/10.2307/1512103

Pritchard, D. (2013). Epistemic Virtue and the Epistemology of Education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 47, 236-247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12022

Pritchard, D. (2014). Virtue Epistemology, Extended Cognition, and the Epistemology of Education. Universitas: Monthly Review of Philosophy and Culture, 478, 47-66. https://www.pure.ed.ac.uk/ws/ portalfiles/portal/16633349/Virtue_Epistemology_Extended_Cognition_and_the_Epistemology_ of_Education.pdf

Pritchard, D. H. (2016). Intellectual Virtue, Extended Cognition, and the Epistemology of Education”. In J. Baehr (Ed.), Intellectual Virtues and Education: Essays in Applied Virtue Epistemology (pp. 113-127). Routledge.

Pritchard, D. H. (2018). Neuromedia and the Epistemology of Education. Metaphilosophy, 49, 328-349.

Pritchard, D. H. (2019). Philosophy in Prisons: Intellectual Virtue and the Community of Philosophical Inquiry. Teaching Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil201985108

Pritchard, D. H. (2020). Educating For Intellectual Humility and Conviction. Journal of Philosophy of Education., 54, 398-409.

Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y. ChatGPT for Education and Research: Opportunities, Threats, and Strategies. Preprints.org 2023, 2023030473. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202303.0473.v1

Robertson, E. (2009). ‘The Epistemic Aims of Education’, Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Education, (ed.) H. Siegel, 11-34. Oxford University Press.

Rudolph. J. Tan, S. Tan, S. (2023). ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education? ED-TECH REVIEWS Vol. 6 No. 1 https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2023.6.1.9

Rupert, R. D. (2004). Challenges to the Hypothesis of Extended Cognition. The Journal of Philosophy, 101(8), 389-428. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3655517

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037/ 0003-066X.55.1.68

Shapiro, L., & Stoltz, S. (2019). Embodied Cognition and its Significance for Education”, with Steven Stolz. Theory and Research in Education, 17, 19-39.

Shen-Berro, J. (2023). New York City schools blocked ChatGPT. Here’s what other large districts are doing. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.chalkbeat.org/2023/1/6/23543039/chatgpt-school-districts-ban-block-artificial-intelligence-open-ai

Shiri, A. (2023). ChatGPT and Academic Integrity (February 2, 2023). Information Matters, 3 (2), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4360052

Siegel, H. (1988). Educating Reason: Rationality, Critical Thinking, and Education. Routledge.

Siegel, H. (1997). Rationality Redeemed? Routledge.

Siegel, H. (2017). Education’s Epistemology: Rationality, Diversity, and Critical Thinking. Oxford University Press.

Sockett, H. (2012). Knowledge and Virtue in Teaching and Learning: The Primacy of Dispositions. Routledge.

Sok, S., & Heng, K. (2023). ChatGPT for Education and Research: A Review of Benefits and Risks. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4378735

Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science, 333(6043), 776-778.

Sprevak, M. (2010). Inference to the hypothesis of extended cognition. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 41, 353-362.

Sterelny, K. (2004). Externalism, Epistemic Artefacts and The Extended Mind. In R. Schantz (Ed.), The Externalist Challenge (pp. 239-255). Berlin.

Stratachery (2022). AI homework. Retrieved March 12, 2023, from https://stratechery.com/2022/aihomework/

Teubner, T., Flath, C. M., Weinhardt, C., van der Aalst, W., & Hinz, O. (2023). Welcome to the Era of ChatGPT et al. Business & Information Systems Engineering, https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12599-023-00795-x

Theiner, G., Allen, C., & Goldstone, R. L. (2010). Recognizing group cognition. Cognitive Systems Research, 11(4), 378-395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2010.07.002

Toppo, G (2023). How ChatGPT will reshape the future of the high school essay. FastCompany. Retrieved 1/4/2023, from https://www.fastcompany.com/90841387/gpt-3-chatgpt-high-school-schoolwork

Varga, S. (2017). Demarcating the Realm of Cognition. Journal for General Philosophy of Science, 49, 435-450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-017-9375-y

Vold, K. (2018). Overcoming Deadlock: Scientific and Ethical Reasons to Embrace the Extended Mind Thesis. In PHILOSOPHY AND SOCIETY., 29(4), 471-646.

Wei, J. Y. Tay, R. Bommasani, et al. (2022). Emergent abilities of large language models, CoRR, vol. abs/2206.07682. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.07682

Zagzebski, L. (1996). Virtues of the Mind: An Inquiry into the Nature of Virtue and the Ethical Foundations of Knowledge. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174763

Zhai, X. (2022). ChatGPT: Artificial Intelligence for Education. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.35971. 37920

- Guido Cassinadri

guido.cassinadri@santannapisa.it

Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Piazza Martiri Della Libertà, 33, 56127 Pisa, Italy This tool may prove beneficial by offering 1) efficient and time-saving creation of learning assessments (Zhai 2022; 2023; Baidoo-Anu and Owusu Ansah, 2023); 2) enhancement of pedagogical practices by assisting teachers’ production of quizzes, exams, syllabuses, and lesson plans (Rudolf 2023; Atlas 2023); 3) easily available personalized tutoring and feedback for students (Mhlanga 2023); 4) creation of outlines for organizing ideas (Kasneci et al., 2023) and 5) facilitation of brainstorming. In this treatment the label ‘tool-use’ refers only to the use of representational cognitive artifacts (Fasoli 2017), leaving out other forms of tool-use.

Baehr (2016, p. 2) defines personal excellences as qualities that “make their possessor good or admirable qua person”. For an account of the development of intellectual virtues in education see Hyslop-Margison (2003), Battaly (2006), MacAllister (2012), Sockett (2012), Pritchard (2013, 2018, 2020), Byerly (2019), Baehr (2015). Along with other virtue responsibilists, Pritchard (2013; 2014; 2016) considers the development of intellectual virtues as the fundamental goal of education, given the special role they play in relation to the cognitive economy of the subject. The analysis of distributed cognition frameworks and of socially distributed epistemology applied in educational contexts goes beyond the scope of this work, although I will briefly mention this field of research in Sect. 5.1. In Sect. 4.2 I will define these transformations as “cognitive trade-offs”.

Fifth, cognitive integration with AI system, either they are EMB or EXT cases, may have transformative and detrimental effects on an affective, motivational, and existential level, potentially undermining the self and autonomy of the embedded/extended agent (Cassinadri 2022; Clowes 2020; Clowes et al., - Footnote 7 (Continued)

2023; Hernández-Orallo and Vold 2019). This issue is out of the scope of this treatment but is worth mentioning if we want to educate students not simply as epistemic agents but as whole human beings. Although this tool can also be used as an affective and emotional artifact by contributing to regulating and influencing the affective states of the user (Piredda 2020), in this paper I will characterize it only as a cognitive artifact that supports cognitive tasks.

A task is “any activity in which a person engages, given an appropriate setting, in order to achieve a specifiable class of objectives, final results, or terminal states of affairs” (Carroll 1993, p. 8). Carroll defined a cognitive task as “any task in which correct or appropriate processing of mental information is critical to successful performance” (Carroll 1993, p. 10). So, it is a linguistic simplification to say that “an artifact is used in a substitutive, constitutive, and complementary way”, given the multiple levels of interaction and the potential division of each task into subtasks. However, in the rest of this treatment, when I say that an artifact is used in one of these three ways without further specification, I will refer to the higher-level task ( X ) to which it contributes. I leave for EXT theorists to define whether and how the latter cases may be genuine instances of EXT. According to Pritchard (2014; 2016) cognitive extension requires a great degree of cognitive agency, so it would be unlikely to admit a substitutive extended cognitive system. See Marconi (2005) for an argument against the possibility of substitutive extended cognitive systems. Cognitive extension does not solve per se complex moral problems inherent to human-AI interaction such as manipulation, given that there might be AI systems that extend cognition but undermine the agent’s self and autonomy (Cassinadri 2022; Clowes 2020; Clowes et al., 2023; Hernández-Orallo and Vold 2019). While I have no space to develop this pressing issue here, it is worth mentioning within educational research since we should not treat students simply as epistemic cognitive agents, but rather as whole human beings. See Robert and Wood, (2007) for an account of the fundamental elements of the cognitive character that contribute to human flourishing. If we consider the task as ‘not being deceived by the AI tool,’ then such a tool performs a constitutive contribution to the task. However, since we are interested in developing students’ abilities in different contexts, it is more useful to consider the task in more general terms such that the tool simply performs a complementary contribution. In this case, the artefactual contribution is constitutive since the task consists in an epistemically virtuous use of the artifact itself. The framework I presented here is limited to representational cognitive artifacts.