تصورات محترفي تصميم تجربة المستخدم حول الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي

الملخص

بين المحترفين المبدعين، أثار الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (GenAI) حماسًا بشأن قدراته وخوفًا من العواقب غير المتوقعة. كيف يؤثر GenAI على ممارسة تصميم تجربة المستخدم (UXD)، وهل هذه المخاوف مبررة؟ قمنا بإجراء مقابلات مع 20 مصمم تجربة مستخدم، بتجارب متنوعة ومن شركات مختلفة (من الشركات الناشئة إلى المؤسسات الكبيرة). استفسرنا منهم لتوصيف ممارساتهم، وعينة من مواقفهم واهتماماتهم وتوقعاتهم. وجدنا أن المصممين ذوي الخبرة واثقون من أصالتهم وإبداعهم ومهاراتهم التعاطفية، ويعتبرون دور GenAI مساعدًا. وأكدوا على العوامل البشرية الفريدة مثل “الاستمتاع” و”الوكالة”، حيث يبقى البشر هم الحكام على “محاذاة الذكاء الاصطناعي”. ومع ذلك، يمكن أن تؤثر تدهور المهارات، واستبدال الوظائف، واستنفاد الإبداع سلبًا على المصممين المبتدئين. نناقش الآثار المترتبة على التعاون بين البشر وGenAI، وبشكل خاص حقوق الطبع والنشر والملكية، والإبداع البشري والوكالة، ومعرفة الذكاء الاصطناعي والوصول إليه. من خلال عدسة الذكاء الاصطناعي المسؤول والمشارك، نساهم في فهم أعمق لمخاوف GenAI والفرص المتاحة لتصميم تجربة المستخدم.

الكلمات والعبارات الرئيسية الإضافية: الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، مصممو تجربة المستخدم، الذكاء الاصطناعي المسؤول، تجربة المستخدم، التعاون بين الإنسان والذكاء الاصطناعي

تنسيق مرجع ACM:

1 المقدمة

2 أسئلة البحث والمساهمات

قد تتناسب أو تغير هذه التدفقات المختلفة. ثانياً، نسعى لفهم تصورات مصممي تجربة المستخدم تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي – نعتزم استكشاف كيف يمكن لمصممي تجربة المستخدم الاستفادة من إمكانيات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي لتجاوز القيود الحالية في الأدوات والتحديات في التدفقات، مما يسمح لهم في النهاية بخلق تجارب مستخدم مؤثرة وذات مغزى الآن وفي المستقبل. أخيراً، نسعى لفهم كيف وبأي شكل قد يؤثر الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي على ممارسة تصميم تجربة المستخدم، وما إذا كانت المخاوف التي قد تنشأ مبررة. لهذا الغرض، نطرح الأسئلة البحثية التالية:

- RQ1: كيف يرى مصممو تجربة المستخدم أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، وما هو رأيهم في إمكانية دمج هذه الأدوات في سير العمل الحالي لديهم؟

- RQ2: ما الفرص والمخاطر التي يتصورها مصممو تجربة المستخدم لمستقبل التعاون بين الإنسان والذكاء الاصطناعي في ممارسة تصميم تجربة المستخدم؟

3 الخلفية والأعمال ذات الصلة

3.1 تأثير الذكاء الاصطناعي على العمل (الإبداعي)

3.2 التعاون بين الإنسان والذكاء الاصطناعي لتمكين الإنسان

3.3 استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في تصميم وتجربة المستخدم

مساحة أنظمة التعاون الإبداعي المختلط حيث يمكن للبشر وأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التواصل مع بعضهم البعض حول النوايا الإبداعية.

4 الطريقة

| خصائص | مصممي تجربة المستخدم | |

| خبرة العمل | >5 سنوات | ب1، ب5، ب6، ب8، ب10، ب11، ب12، ب14، ب16، ب17، ب18 |

| 3-5 سنوات | ب2، ب7 | |

| <3 سنوات | P3، P4، P9، P13، P15، P19، P20 | |

| حجم الشركة | >10,000 | P5، P6، P7، P8، P9، P11، P14، P15، P16، P17 |

| 1,000-10,000 | ب1، ب2، ب10، ب13، ب18 | |

| 500-1,000 | P20 | |

| <50 | P3، P4، P12، P19 | |

| عروض فيديو GenAI | تشمل أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي | تاريخ النشر على يوتيوب |

| تصميم واجهة موبايل

|

ميدجورني (V4)، ملحق استقرار فوتوشوب (0.7.0) وChatGPT (نسخة 30 يناير 2023) | 20 فبراير 2023 |

| صياغة اقتراح تصميم (استخدمت فقط جزء من Notion AI:

|

نوتيون AI (2.21) | 15 مارس 2023 |

| إنشاء مكونات واجهة المستخدم

|

برومبت2ديزاين (الإصدار 3) | 6 مايو 2023 |

| تنظيم ملاحظات الأفكار

|

ميرو إيه آي (بيتا) | 8 مارس 2023 |

4.1 المشاركون

4.2 أسئلة المقابلة والإجراءات

- الخطوة 1 (5 دقائق): مقدمة يقدمها ميسر المقابلة لضمان فهم المشاركين لغرض المقابلة، وأنهم قد قرأوا وفهموا ووقعوا على نموذج الموافقة المستنيرة؛

- الخطوة 2 (

أسئلة عامة حول الخلفية، سير العمل، وممارسة تجربة المستخدم؛ - الخطوة 3 (20 دقيقة): المواقف والمخاوف والتوقعات من أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي العام؛

- الخطوة 4 (20 دقيقة): تصور دور الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في التعاون بين الإنسان والذكاء الاصطناعي (بما في ذلك مشاهدة عرض فيديو لعينة من أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي الحالية);

- الخطوة 5 (5 دقائق): أسئلة ختامية.

4.3 تحليل البيانات

5 نتائج

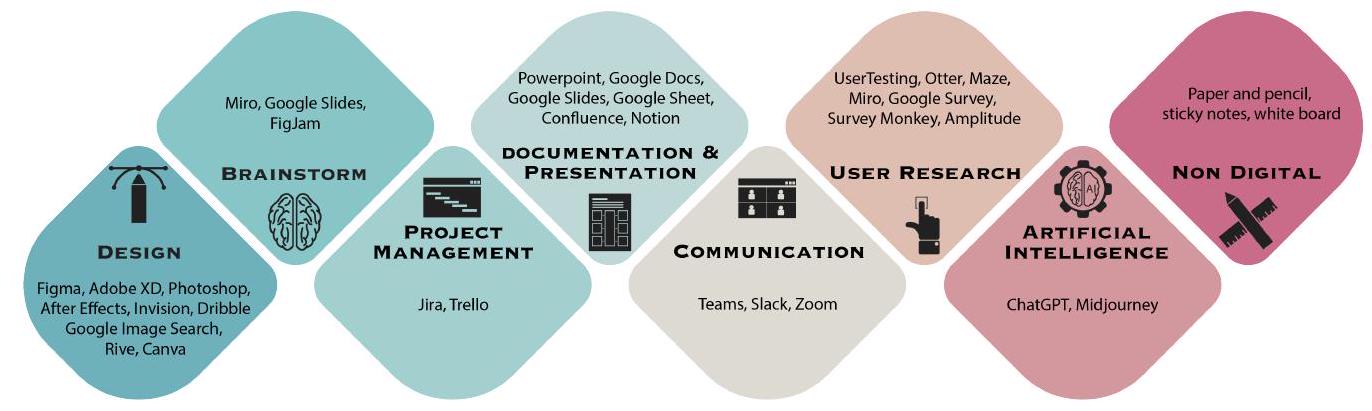

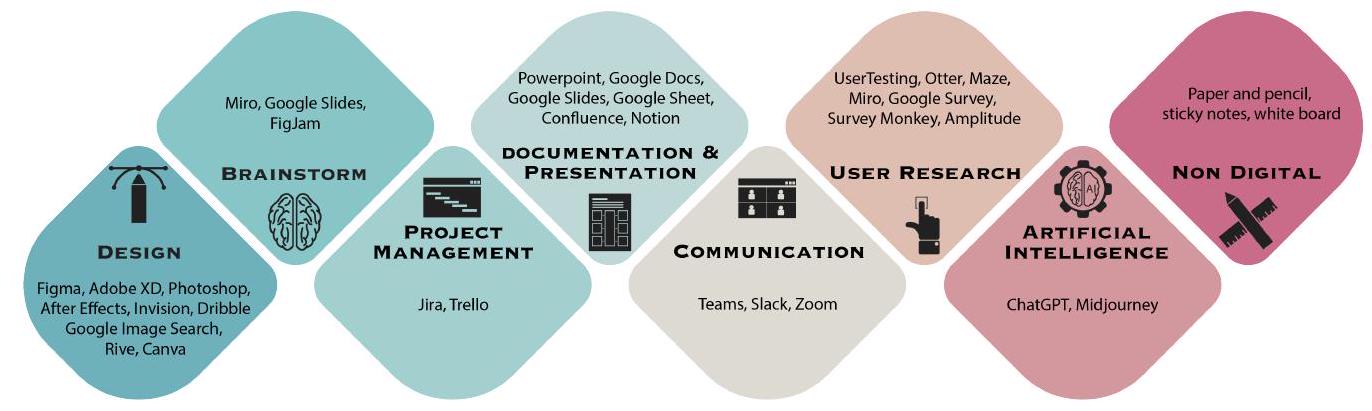

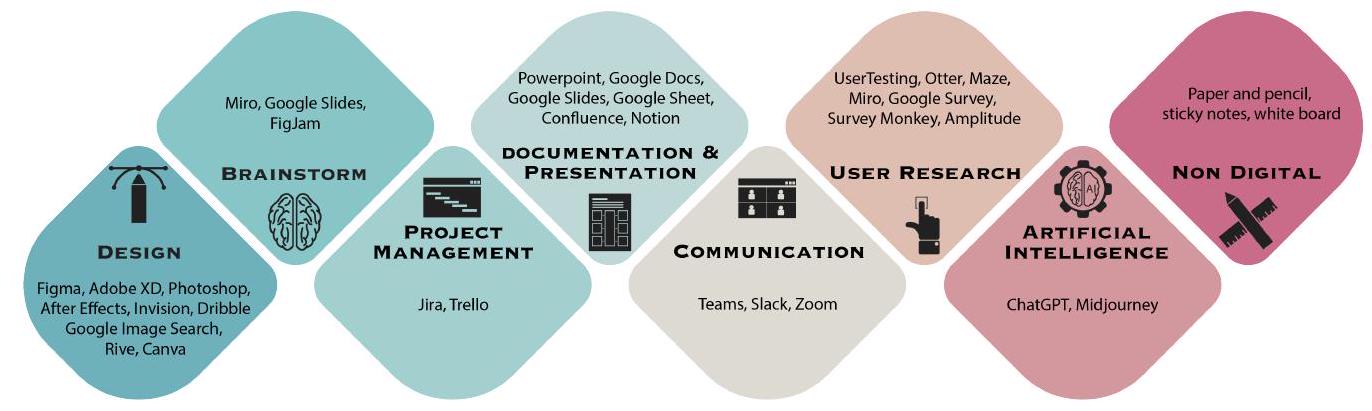

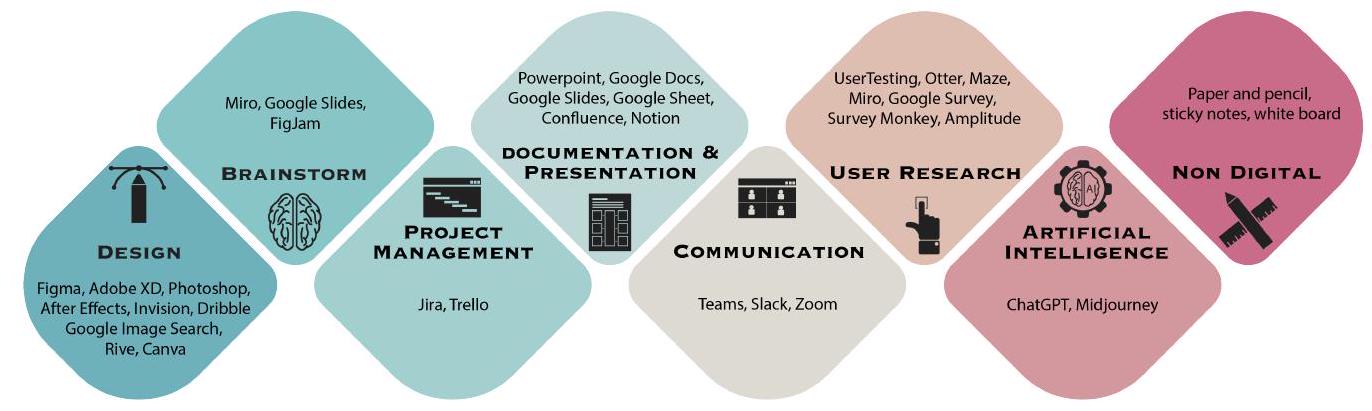

5.1 أدوات تصميم تجربة المستخدم الحالية وسير العمل

| خطوات | الأنشطة الرئيسية | أدوات | |||

| 1 متطلبات العمل |

|

عصف ذهني | |||

| 2 متطلبات المستخدم |

|

العصف الذهني وبحث المستخدم | |||

| ٣ |

|

العصف الذهني، التوثيق والعرض | |||

| 4 النمذجة |

|

تصميم | |||

| ٥ |

|

الاتصال وبحوث المستخدمين | |||

| 6 تكرار |

|

التصميم وغير الرقمي | |||

| 7 حل | – التعاون مع أصحاب المصلحة لضمان أن التصميم يلبي احتياجات المستخدم ويتماشى مع أهداف العمل. | التوثيق والعرض | |||

| 8 تسليم التصميم |

|

التوثيق، العرض والتصميم |

5.2 الموضوع 1: قيود أدوات تصميم تجربة المستخدم الحالية

5.2.2 القيد 2: الأدوات المجزأة. أكد المشاركون أن أدوات تصميم تجربة المستخدم الحالية متفرقة. كل أداة لها نقاط قوة أو وظائف محددة، لكن الانتقال بسلاسة بينها يمثل تحديًا: “نستخدم ميرو للعصف الذهني وإنشاء نماذج أولية منخفضة الدقة، وفigma للنماذج عالية الدقة. ومع ذلك، فإن نقل الإطارات السلكية من ميرو إلى Figma ليس بالأمر السهل.” [P10] أشار بعض المشاركين بشكل خاص إلى أن أدوات التصميم الحالية تفتقر إلى الدعم لأبحاث المستخدم: “شيء ذو قيمة سيكون القدرة على إجراء اختبارات قابلية الاستخدام وتوليد البيانات داخل أداة التصميم نفسها.” [P17].

5.2.3 القيود 3: نقص الدعم المتقدم في التصميم. أعرب المشاركون عن عدم رضاهم عن أدوات التصميم الحالية بسبب نقص الدعم المتقدم للرسوم المتحركة المعقدة، والتصاميم متعددة المنصات، وتصميم الجرافيك، وأنظمة التصميم الأكثر ذكاءً: “هناك أشياء من نوع الرسوم المتحركة الدقيقة التي لا تحصل عليها من Figma، مثل الجداول الزمنية التي ستستخدمها في After Effects أو Principle لضبط الرسوم المتحركة الخاصة بك.” [P17] “تفتقر أنظمة التصميم إلى الذكاء. سأكون ممتنًا لنظام تصميم يوصي بمكونات تصميم مناسبة ويضبط هذه المكونات تلقائيًا لتناسب الشاشات المختلفة.” [P5].

5.3 الموضوع 2: التحديات في تصميم تجربة المستخدم الحالي

5.3.2 التحدي 2: فهم المستخدمين النهائيين. ذكر المشاركون أن إجراء أبحاث لفهم احتياجات المستخدمين يمثل تحديًا من حيث اكتشاف النقاط المؤلمة الصحيحة للمستخدمين وبناء المنتجات الصحيحة: “أعتقد أن التحدي يكمن دائمًا في محاولة فهم من أصمم له، وما هي احتياجاتهم، وأهدافهم، ومشاكلهم، وما إذا كان المنتج أو الخدمة التي أعمل عليها تتناسب مع المشهد الأوسع.”[P17]. يكمن مثل هذا التحدي في قلب

5.3.3 التحدي 3: تصميم حلول تلبي كل من قيمة الأعمال واحتياجات المستخدمين. أشار المشاركون إلى أن التوصل إلى حلول تصميم جيدة توازن بين احتياجات العملاء، واحتياجات المستخدمين، وقيمة الأعمال، والجدة البصرية يمثل تحديًا: “مجال تجربة المستخدم ناضج تمامًا، مع وجود مراجع تصميم وأنظمة تصميم قائمة تساعد في العمل. التحدي هو التوصل إلى أفكار جديدة باستمرار وإيجاد توازن عند النظر في كل من مراجع التصميم المعتمدة، وتوقعات أصحاب المصلحة الداخليين، واحتياجات المستخدمين، ودمجها في التصميم الجديد.”[P18] يمكن أن تحمل تلبية احتياجات الأعمال تداعيات على الأصالة، وحقوق الطبع والنشر، والملكية، وكلها تؤثر على التبني (انظر، القسم 5.6.1).

5.3.4 التحدي 4: نقص المعرفة والموارد في المجال. ذكر المشاركون أن نقص الخبرة في المجال والموارد للوصول إلى المعرفة يمثل تحديًا كبيرًا: “أحد التحديات لمصممي تجربة المستخدم هو اكتساب معرفة واسعة في المجال، مثل إنشاء تصاميم مخصصة لمجالات متخصصة مثل الطب، والسيارات، والتكنولوجيا المالية، وما إلى ذلك.”[P1]; “في شركة ناشئة، غالبًا ما نواجه قيودًا في الموارد تحد من وصولنا إلى الخبراء، وإجراء أبحاث المستخدم أو اختبارات القابلية للاستخدام على نطاق أوسع، وهو أمر حاسم لضمان جدوى وجاذبية المنتجات.”[P6]. نعتقد أن هذه قد تكون طريقًا واعدًا يمكن أن تمكّن فيه أدوات GenAI، وخاصة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة المعتمدة على النص مثل ChatGPT، المصممين. على الرغم من الهلاوس الحالية للنموذج (انظر، [46])، يمكن للمصممين الوصول الفوري والواسع والسهل إلى المعلومات والموارد الخاصة بالمجال.

5.4 الموضوع 3: مواقف مصممي تجربة المستخدم تجاه GenAI

5.4.1 العيوب المتصورة لأدوات GenAI التي تم عرضها في العرض التقديمي. كانت هناك عيبان يُعتبران رئيسيين بين المشاركين:

(1) العملية والكفاءة. أشار المشاركون إلى أن أدوات GenAI المعروضة في العروض التقديمية عامة جدًا، ولا يزال يتطلب عملية التصميم قدرًا كبيرًا من العمل اليدوي. يشمل ذلك مهامًا مثل إعادة رسم الرموز والأزرار وإدخال نصوص دقيقة. “تم تدريب المصممين على التفكير بصريًا. تتضمن عملية التصميم لدينا

تجربة وخطأ على دفاتر الرسم. تظهر التصاميم من العديد من تجارب الرسم، وليس من النصوص. [في العرض التقديمي]، يُطلب منك التبديل بين أدوات GenAI المختلفة، وإضافات Photoshop، وأداء قدر كبير من العمل اليدوي، بما في ذلك إعادة الرسم وإعادة توليد الصور عالية الدقة. أشك في ما إذا كانت هذه الأدوات GenAI تعزز حقًا سير العمل في التصميم.”[P12]

(2) الدقة والموثوقية. تساءل المشاركون عن الدقة العامة والموثوقية للنتائج التي تنتجها أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي. يعتقدون أن المدخلات البشرية ضرورية للتحقق من النتائج التي ينتجها الذكاء الاصطناعي. شارك P16: “بالنسبة للتصميم البصري، لا تزال أدوات GenAI محدودة جدًا في التقاط الفروق الدقيقة والتفاصيل المعقدة. فيما يتعلق بتوليد الأفكار، قد تفشل أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي مثل Miro AI في تمثيل رؤى أصحاب المصلحة الذين يمتلكون خبرة واسعة، لنقل، 20 عامًا في مجال متخصص مثل الرعاية الصحية.” [P16]. وصفت P19 تجربتها السلبية في استخدام أدوات GenAI: “بالنسبة لـ Midjourney، وجدت نفسي غالبًا أقضي ساعات في تعديل نصوصي، ومع ذلك لم أتمكن من تحقيق النتائج المتوقعة. أما بالنسبة لـ Miro، فإن البطاقات تتجمع فقط بناءً على الكلمات الرئيسية، مما يتطلب جهدًا يدويًا لإنشاء تجمعات متماسكة.” [P19]. علاوة على ذلك، أعرب P3 عن شكوكه بشأن موثوقية قدرة الذكاء الاصطناعي على توليد الشفرات: “لقد حاولت فعليًا أن أجعل ChatGPT يولد شفرات لبعض الميزات أو الوظائف، لكنه لم ينتج النتائج التي كنت أبحث عنها.”[P3].

5.5 الموضوع 4: التعاون بين البشر والذكاء الاصطناعي

5.5.1 تصورات التهديدات والتعاون مع GenAI. أعرب المشاركون عن مستويات متفاوتة من القلق بشأن التهديدات المحتملة لـ GenAI. شعر البعض أنه إذا ظلت GenAI أداة عامة تحت سيطرتهم، فلن تكون مصدر قلق، بينما كان الآخرون قلقين بشأن قدرتها على محاكاة تفكير المصممين. شملت التوصيات التعامل مع GenAI كعضو في الفريق، مع التأكيد من بعض المشاركين على أهمية احتفاظ البشر بسلطة اتخاذ القرار النهائية في التعاون بين البشر والذكاء الاصطناعي. علق P18: “إذا وصلت التكنولوجيا في النهاية إلى نقطة يمكنها فيها محاكاة مبررات المصممين بدقة، فقد أبدأ في القلق بشأنها.” [P18]. أوصى P19 بمعاملة GenAI كعضو في الفريق: “أتصور الذكاء الاصطناعي كجزء من الفريق، يساهم في العملية العامة، ولكن ليس مسؤولاً وحده عن النتيجة النهائية.” [P19]. أكد P8 على أنه يجب أن يكون للبشر السلطة النهائية في اتخاذ القرار في التعاون بين البشر والذكاء الاصطناعي: “يجب أن يعتمد الأمر على الناس لاختيار الجزء الذي أريد فيه مساعدة الذكاء الاصطناعي، بغرض تسريع المهام. لا أحب كلمة ‘استبدال’. أستمتع كثيرًا بتصميم واجهة المستخدم وتجربة المستخدم… أريد أن يكون الذكاء الاصطناعي متدربي. يقوم البشر بالأجزاء الإبداعية والمعقدة، ويملأ متدربو الذكاء الاصطناعي الألوان أو يرسمون الخطوط.” [P8].

5.5.2 يمكن استبدال العمل العام والمتكرر بـ GenAI. شارك جميع المشاركين الاعتقاد بأن GenAI لديها القدرة على استبدال المهام المتكررة، مثل إنشاء نصوص “لوريم إيبسوم” لنماذج التصميم، وتلخيص موجزات التصميم والوثائق الفنية، وصياغة مكونات تصميم متكررة، وإنشاء تصميمات استجابة لشاشات مختلفة، وتوثيق عناصر التصميم المرئية تلقائيًا في أنظمة التصميم، وإنشاء نماذج أولية منخفضة الدقة، وتوليد تنويعات تصميمية للإلهام (انظر الشكل 3: “يمكن لـ GenAI”). كما قال P8، “أتصور الذكاء الاصطناعي كأداة إنتاجية تساعدني بسرعة في المهام المحددة. على سبيل المثال، يمكن للذكاء الاصطناعي تلخيص PRDs [وثائق متطلبات المنتج] أو شرح الخلفيات الفنية بلغة بسيطة. حاليًا، تتطلب هذه الجوانب جهدًا كبيرًا من مديري المنتجات والمهندسين لنقلها لنا كمصممين.” [P8]. أعرب P12 عن أمله في تصميم استجابة مدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي، “آمل أن تساعد GenAI في مهام مثل التصميم الاستجابي لشاشات مختلفة واقتراح تدفقات المستخدم عبر الصفحات، وليس فقط على صفحة واحدة.” [P12] أعرب العديد من المشاركين الآخرين عن رغبتهم في دعم GenAI في مهام متنوعة، بما في ذلك توفير الإلهام التصميمي (P2 وP4 وP8)، بالإضافة إلى تسهيل الكتابة الفعالة لتجربة المستخدم (P18 وP19).

5.5.3 لا يمكن استبدال عمل تصميم تجربة المستخدم بـ GenAI. أوضح العديد من المشاركين أن الكثير من عمل تصميم تجربة المستخدم لا يمكن ببساطة استبداله بالذكاء الاصطناعي، بما في ذلك العمل الذي يتطلب التواصل بين أصحاب المصلحة البشريين، والتعاطف مع احتياجات المستخدمين، وتصميم وظائف تركز على المستخدم. وأكدوا على أهمية كون البشر هم المبدعون الأصليون والمحققون لنتائج الذكاء الاصطناعي (انظر الشكل 3: “لا يمكن لـ GenAI”).

(1) مدخلات المستخدمين والتواصل أو التعاون بين البشر. أعرب المشاركون بثقة عن أنهم لا يرون حاليًا GenAI كمنافس، حيث يعمل المصممون البشر كوسطاء لاحتياجات المستخدمين ويستمرون في كونهم صانعي القرار النهائيين ووسطاء توافق الذكاء الاصطناعي. وأكدوا أن GenAI لا يمكن أن تحل محل العمل الذي يتطلب مدخلات المستخدم، والتعاون بين البشر: “قد تكون GenAI قادرة على تولي المهام الأساسية والمتكررة والمباشرة، لكنها لا يمكن أن تحل محل تصميم الخدمة والجهود التعاونية التي تتطلب تفكيرًا أكثر نظامية وتجريديًا.” [P6]. أشار P14 أيضًا إلى أن “تصميم تجربة المستخدم ليس مجرد جمالية، بل أيضًا قابلية الاستخدام والوصول إلى العناصر. المستخدمون الحقيقيون ضروريون لتحسين التصميمات من خلال البحث الفعلي واختبار المستخدمين.” [P14]. اعتقد P16 أن التواصل البشري لا يمكن استبداله بالذكاء الاصطناعي، قائلاً “أقدر الأفكار من زملائي البشر، وتجاربهم، وأفكارهم، والمعرفة التي يجلبونها إلى الطاولة. لا يجب أن تكون هذه مثالية، لكنها تساعدنا في رسم الاتجاهات معًا. لا أعتقد أن الذكاء الاصطناعي يمكنه أداء هذا الجانب من العمل.” [P16].

(2) الإبداع البشري واتخاذ القرار. أشار بعض المشاركين إلى أن الإبداع البشري والأصالة هما صفات بشرية قوية يصعب استبدالها بالذكاء الاصطناعي. تعتمد نتائج الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل كبير على البيانات السابقة، مما قد يؤدي إلى نتائج متكررة بسبب محدودية مجموعة البيانات. لا يزال المصممون البشر هم القوة الدافعة القادرة على فهم سياقات التصميم بعمق، والتعاطف مع المستخدمين، والابتكار بناءً على أحدث المعرفة: “يجب ألا يتم استبدال العمل الإبداعي الذي يستمتع البشر بالقيام به بالذكاء الاصطناعي. الذكاء الاصطناعي هو نموذج مدرب يعتمد على الماضي، بينما الإبداع البشري والأصالة أكثر توجهاً نحو المستقبل.” [P8]; “يمكن دعم الإبداع بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي، حيث يمكنه إعادة مزج وتجديد بناءً على البيانات الإبداعية المدخلة من البشر، لكن البشر يمتلكون الأصالة.” [P4].

5.6 الموضوع 5: المخاوف الأخلاقية والملكية

5.6.1 الأصالة وحقوق الطبع والنشر والملكية. أكد المشاركون على أهمية منح الفضل للمبدعين الأصليين للأعمال الفنية أو أنماط الفن المستخدمة في عمل تجربة المستخدم. اقترح P3 وP4 أن تقنية البلوكشين قد تكون مفيدة في ضمان نسب الملكية المباشرة للمبدعين الأصليين، بغض النظر عن مدى تعديل العمل الأصلي. قال P4: “يجب أن تظل الملكية قابلة للتتبع بغض النظر عن مدى تعديل أو اشتقاق أو إعادة إنتاج مخرجات الذكاء الاصطناعي من الأعمال الأصلية. ربما يمكن أن توفر تقنية البلوكشين حلاً هنا.” أعربت P14 عن مخاوفها بشأن سرقة التصميم، “من وجهة نظر السرية، ما البيانات التي يمكن وضعها في أدوات GenAI، وكيف يمكننا التأكد من أننا نستخدم مصادر قانونية وأننا لا ننتهك لوائح GDPR. هناك بالفعل حالات يقوم فيها المصممون بنسخ أعمال الآخرين لبناء محافظهم الخاصة. يمكن أن تجعل GenAI السرقة في التصميم أسوأ بكثير.” [P14].

5.6.2 تدهور المهارات والبطالة. أشار العديد من المشاركين إلى قلقهم من أن العمل البشري في تصميم تجربة المستخدم قد لا يُقدَّر كما ينبغي، مما قد يؤدي إلى شعور المصممين بالرضا عن النفس وتراجع مهاراتهم. وهم يخشون أن يؤدي استحواذ الذكاء الاصطناعي على المهام التي كانت تُعتبر أساسية للمصممين إلى تدهور المهارات. هذه المخاوف، التي ذُكرت بشكل أساسي من قبل المصممين الكبار (انظر الجدول 1)، ذات صلة خاصة بالمصممين المبتدئين، الذين قد يفوتون فرص تطوير مهاراتهم بشكل أكبر. وبالتالي، قد ينتقل المصممون البشريون إلى أدوار إدارية أو عامة أكثر. تصور P16 (مصمم كبير) هذا، حيث قال: “قد يقع المصممون في فخ الرضا عن النفس. قد يكون لدى المصممين المبتدئين فرص أقل لتعلم عملية التصميم، ولكن بدلاً من ذلك، قد يركزون على إتقان أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي. ونتيجة لذلك، قد يتطور المصممون إلى مصممين عامين.” [P16]

5.6.3 الخصوصية والشفافية والوصول المتساوي إلى GenAI. أشار المشاركون إلى أن الخصوصية تمثل مصدر قلق كبير في مجال GenAI. حيث إن هذه النماذج الذكية تستوعب كميات كبيرة من البيانات لتتعلم الأنماط وتولد المحتوى، هناك احتمال للتعرض غير المقصود لمعلومات حساسة، مثل التفاصيل الشخصية أو السرية التي لم يقصد المستخدمون مشاركتها: “إذا كنت أرغب في استخدام ChatGPT لاستخراج المعلومات من الوثائق التقنية، لا أعرف كيف يمكنني منع تسرب المعلومات الحساسة. بالنسبة لحياتي الشخصية أيضًا، ليس من الواضح كم من بياناتي الشخصية ستظل محفوظة لتدريب نماذج الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل أكبر.”[P19]

“قد تكتسب الدول المتقدمة السيطرة على البيانات المدخلة في الذكاء الاصطناعي. كما أنه من الأسهل لها الوصول إلى أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي مقارنة ببعض الدول النامية.” [P6]. أضاف P2، “من المهم ضمان أن الأفراد الذين لديهم مستوى تعليمي أقل ولديهم معرفة محدودة بالذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي يمكنهم استخدام هذه الأدوات لتعزيز عملهم وحياتهم اليومية.” [P2].

5.7 الموضوع 6: مستقبل الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في تصميم تجربة المستخدم

5.7.1 تصور التصميم التعاوني مع GenAI. تخيل بعض المشاركين نظامًا مثلثيًا يتضمن التعاون ومدخلات من المستخدمين والمصممين وGenAI. تهدف هذه المقاربة إلى تقليل التحيزات وضمان عدم تجاهل الفروق الدقيقة الحاسمة، الضرورية للابتكارات التصميمية. كما ذكر P11، “قد يغفل المصممون البشر عن بعض الفروق الدقيقة التي قد تكون مهمة للمستخدمين. أتمنى أن يعزز GenAI هذا الجانب من خلال تقديم مدخلاته المستندة إلى بيانات ومعرفة واسعة من الماضي، مما قد يرفع تصميم تجربة المستخدم إلى المستوى التالي.” [P11].

5.7.2 تعزيز معرفة الذكاء الاصطناعي والوصول إليه للمصممين. أعرب عدد من المشاركين عن أملهم في زيادة معرفة الذكاء الاصطناعي من خلال التعليم، مما يعود بالفائدة على المصممين ذوي الخبرة والمبتدئين. أشار P13 (مصمم مبتدئ) إلى أن “الطلاب قد يشعرون بالقلق حيال هذه الثورة الكبيرة في الذكاء الاصطناعي. التعليم ضروري لإعداد المصممين المبتدئين والبارعين لتأثير الذكاء الاصطناعي وكيفية الاستفادة منه لتعزيز مهارات التصميم البشرية لدينا.” [P13]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يتصور عدد قليل من المشاركين أن أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي المستقبلية ستكون أكثر سهولة للمصممين. بعبارة أخرى، يرغبون في أدوات ذكاء اصطناعي تقدم قابلية استخدام بصرية وبديهية أكبر، متجاوزة الاعتماد الوحيد على المدخلات النصية. “سماعة Apple Vision Pro الأخيرة ملهمة. تصميمها البصري والبديهي يبدو واعدًا. وبالتالي، يجب أن يتطور الذكاء الاصطناعي أيضًا ليصبح أكثر بصرية وبديهية ومتاحة عالميًا لجميع المستخدمين.” [P12].

5.7.3 الدور المرغوب فيه لـ Al في تعزيز عمليات التصميم. أعرب العديد من المشاركين عن رغبتهم في أن تتطور GenAI أكثر، لدعمهم في مهام التصميم المختلفة. كانوا يأملون أن تتمكن GenAI من المساعدة في تصميم الرسوميات، وكتابة التعليمات، وتوليد المكونات الذكية، وتقديم أمثلة تصميم ناجحة، وأتمتة نقل التصاميم إلى فرق التطوير. أشار P4 إلى: “أتوقع طرقًا أسهل لكتابة التعليمات أو توليد المكونات تلقائيًا التي تتكيف مع الشاشات المختلفة، وتوصي بانتقالات الرسوم المتحركة الذكية، وحتى توليد محتوى ثلاثي الأبعاد لبيئات غامرة في المستقبل.” [P4]. كما أعرب العديد من المشاركين الآخرين عن رغباتهم في دعم GenAI المحدد في مهام مختلفة في المستقبل. على سبيل المثال، كانوا يأملون أن تتمكن الذكاء الاصطناعي من تلخيص المعرفة المتطورة للبحث والاستراتيجية (P10 وP18 وP19)، وأن تعمل كمستخدم اصطناعي لتسريع السبرينت (P1 وP18)، وتقديم إرشادات مهنية في تصميم الوصول (P12)، ومساعدة المصممين على إتقان والتبديل بسرعة بين أدوات التصميم المختلفة (P18)، والمساعدة في تصنيف وتجميع البيانات الخام النوعية من دراسات المستخدمين (P5 وP9 وP10 وP12 وP18)، وترجمة التصاميم بسلاسة إلى التطوير (P5 وP18 وP19).

5.7.4 تحدي تعريف مقاييس نتائج GenAI. وفقًا لعدة مشاركين، فإن رؤية مستقبلية أخرى لـ GenAI تتضمن تحدي تعريف مقاييس لقياس جودة المخرجات التي تنتجها الذكاء الاصطناعي. كما علق P17، “إذا استخدمت العديد من الشركات نفس أدوات GenAI، فقد يؤدي ذلك إلى تصميمات مشابهة ويفتقر إلى التنوع والابتكار. أيضًا، يمكن أن يؤدي الذكاء الاصطناعي إلى توليد العديد من المخرجات ويترك التحدي لنا، البشر، لاختيار من بينها.” [P17]. “إنه بالفعل تحدٍ لاختيار وتحسين نتائج الذكاء الاصطناعي. نحن بحاجة إلى إرشادات حول كيفية قياس أو التحقق من مخرجات الذكاء الاصطناعي.” [P18]

6 المناقشة

6.1 المتعة والقدرة على اتخاذ القرار في التعاون بين البشر وGenAI

6.2 GenAI يتداخل، البشر يستنتجون، وإرهاق الإبداع

6.3 محو الأمية في الذكاء الاصطناعي والذكاء الاصطناعي التشاركي في تصميم تجربة المستخدم

المفاهيم، بما في ذلك كيفية عمل التعلم الآلي، وأنواع أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي، وقدراتها، وقيودها، وآثارها. هذا الفهم ضروري لمصممي تجربة المستخدم للاستفادة من قوة الذكاء الاصطناعي، وضمان الوصول المتساوي إلى التعليم والأدوات المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، والمشاركة بنشاط في تشكيل وتطوير تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي، خاصة تلك المستخدمة في عمليات التصميم الخاصة بهم. من خلال اعتماد نهج الذكاء الاصطناعي التشاركي، يصبح مصممو تجربة المستخدم جزءًا لا يتجزأ من الحوار حول مستقبل تطوير الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي – مما يمكّن مصممي تجربة المستخدم من تعزيز ملاحظاتهم وخبراتهم، وضمان توافق أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل فعال مع النوايا البشرية وممارسات تصميم تجربة المستخدم.

6.4 حقوق الطبع والنشر والملكية لنتائج الذكاء الاصطناعي في تصميم تجربة المستخدم وما بعده

6.5 مستقبل تصميم تجربة المستخدم المدعوم بالذكاء الاصطناعي: المخاوف والفرص

6.6 قيود الدراسة والعمل المستقبلي

7 الخاتمة

شكر وتقدير

REFERENCES

[2] Saleema Amershi, Dan Weld, Mihaela Vorvoreanu, Adam Fourney, Besmira Nushi, Penny Collisson, Jina Suh, Shamsi Iqbal, Paul N. Bennett, Kori Inkpen, Jaime Teevan, Ruth Kikin-Gil, and Eric Horvitz. 2019. Guidelines for Human-AI Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Glasgow, Scotland Uk) (CHI ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300233

[3] Kareem Ayoub and Kenneth Payne. 2016. Strategy in the age of artificial intelligence. 7ournal of strategic studies 39, 5-6 (2016), 793-819.

[4] Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. 2021. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (Virtual Event, Canada) (FAccT ’21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 610-623. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922

[5] Abeba Birhane, William Isaac, Vinodkumar Prabhakaran, Mark Diaz, Madeleine Clare Elish, Iason Gabriel, and Shakir Mohamed. 2022. Power to the People? Opportunities and Challenges for Participatory AI. In Equity and Access in Algorithms, Mechanisms, and Optimization (Arlington, VA, USA) (EAAMO ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 6, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3551624.3555290

[6] Rishi Bommasani, Drew A. Hudson, Ehsan Adeli, Russ Altman, Simran Arora, Sydney von Arx, Michael S. Bernstein, Jeannette Bohg, Antoine Bosselut, Emma Brunskill, Erik Brynjolfsson, Shyamal Buch, Dallas Card, Rodrigo Castellon, Niladri Chatterji, Annie Chen, Kathleen Creel, Jared Quincy Davis, Dora Demszky, Chris Donahue, Moussa Doumbouya, Esin Durmus, Stefano Ermon, John Etchemendy, Kawin Ethayarajh, Li Fei-Fei, Chelsea Finn, Trevor Gale, Lauren Gillespie, Karan Goel, Noah Goodman, Shelby Grossman, Neel Guha, Tatsunori Hashimoto, Peter Henderson, John Hewitt, Daniel E. Ho, Jenny Hong, Kyle Hsu, Jing Huang, Thomas Icard, Saahil Jain, Dan Jurafsky, Pratyusha Kalluri, Siddharth Karamcheti, Geoff Keeling, Fereshte Khani, Omar Khattab, Pang Wei Koh, Mark Krass, Ranjay Krishna, Rohith Kuditipudi, Ananya Kumar, Faisal Ladhak, Mina Lee, Tony Lee, Jure Leskovec, Isabelle Levent, Xiang Lisa Li, Xuechen Li, Tengyu Ma, Ali Malik, Christopher D. Manning, Suvir Mirchandani, Eric Mitchell, Zanele Munyikwa, Suraj Nair, Avanika Narayan, Deepak Narayanan, Ben Newman, Allen Nie, Juan Carlos Niebles, Hamed Nilforoshan, Julian Nyarko, Giray Ogut, Laurel Orr, Isabel Papadimitriou, Joon Sung Park, Chris Piech, Eva Portelance, Christopher Potts, Aditi Raghunathan, Rob Reich, Hongyu Ren, Frieda Rong, Yusuf Roohani, Camilo Ruiz, Jack Ryan, Christopher Ré, Dorsa Sadigh, Shiori Sagawa, Keshav Santhanam, Andy Shih, Krishnan Srinivasan, Alex Tamkin, Rohan Taori, Armin W. Thomas, Florian Tramèr, Rose E. Wang, William Wang, Bohan Wu, Jiajun Wu, Yuhuai Wu, Sang Michael Xie, Michihiro Yasunaga, Jiaxuan You, Matei Zaharia, Michael Zhang, Tianyi Zhang, Xikun Zhang, Yuhui Zhang, Lucia Zheng, Kaitlyn Zhou, and Percy Liang. 2022. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. arXiv:2108.07258 [cs.LG]

[7] Zalán Borsos, Raphaël Marinier, Damien Vincent, Eugene Kharitonov, Olivier Pietquin, Matt Sharifi, Olivier Teboul, David Grangier, Marco Tagliasacchi, and Neil Zeghidour. 2022. AudioLM: a Language Modeling Approach to Audio Generation. arXiv:2209.03143 [cs.SD]

[8] Petter Bae Brandtzæg, Asbjørn Følstad, and Jan Heim. 2018. Enjoyment: Lessons from Karasek. Springer International Publishing, Cham, 331-341. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68213-6_21

[9] Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke. 2012. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Vol. 2. Research Designs. American Psychological Association, 750 First St. NE, Washington, DC 20002-4242, 57-71.

[10] Lizzy Burnam. 2023. We Surveyed 1093 Researchers About How They Use AI-Here’s What We Learned. https://www.userinterviews.com/blog/ai-in-ux-research-report

[11] Patrick Butlin. 2021. AI Alignment and Human Reward. In Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (Virtual Event, USA) (AIES ’21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 437-445. https://doi.org/10.1145/3461702.3462570

[12] Bill Buxton. 2010. Sketching user experiences: getting the design right and the right design. Morgan kaufmann, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA.

[13] Kelly Caine. 2016. Local Standards for Sample Size at CHI. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (San Jose, California, USA) (CHI ’16). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 981-992. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858498

[14] Tara Capel and Margot Brereton. 2023. What is Human-Centered about Human-Centered AI? A Map of the Research Landscape. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Hamburg, Germany) (CHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 359, 23 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3580959

[15] Minsuk Chang, Stefania Druga, Alexander J. Fiannaca, Pedro Vergani, Chinmay Kulkarni, Carrie J Cai, and Michael Terry. 2023. The Prompt Artists. In Proceedings of the 15th Conference on Creativity and Cognition (, Virtual Event, USA,) (C&C’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 75-87. https://doi.org/10.1145/3591196.3593515

[16] Li-Yuan Chiou, Peng-Kai Hung, Rung-Huei Liang, and Chun-Teng Wang. 2023. Designing with AI: An Exploration of Co-Ideation with Image Generators. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) (DIS ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1941-1954. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596001

[17] Victoria Clarke, Virginia Braun, and Nikki Hayfield. 2015. Thematic analysis. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods 222, 2015 (2015), 248.

[18] Tiago Silva Da Silva, Milene Selbach Silveira, Frank Maurer, and Theodore Hellmann. 2012. User experience design and agile development: From theory to practice. Fournal of Software Engineering and Applications 5, 10 (2012), 743-751. https://doi.org/10.4236/jsea.2012.510087

[19] Smit Desai, Tanusree Sharma, and Pratyasha Saha. 2023. Using ChatGPT in HCI Research-A Trioethnography. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Conversational User Interfaces (Eindhoven, Netherlands) (CUI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 8, 6 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3571884.3603755

[20] Fiona Draxler, Anna Werner, Florian Lehmann, Matthias Hoppe, Albrecht Schmidt, Daniel Buschek, and Robin Welsch. 2024. The AI Ghostwriter Effect: When Users do not Perceive Ownership of AI-Generated Text but Self-Declare as Authors. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 31, 2 (Feb. 2024), 1-40. https://doi.org/10.1145/3637875

[21] Upol Ehsan and Mark O. Riedl. 2020. Human-Centered Explainable AI: Towards a Reflective Sociotechnical Approach. In HCI International 2020 Late Breaking Papers: Multimodality and Intelligence, Constantine Stephanidis, Masaaki Kurosu, Helmut Degen, and Lauren Reinerman-Jones (Eds.).

[22] Damian Okaibedi Eke. 2023. ChatGPT and the rise of generative AI: Threat to academic integrity? Journal of Responsible Technology 13 (2023), 100060.

[23] Tyna Eloundou, Sam Manning, Pamela Mishkin, and Daniel Rock. 2023. GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models. arXiv:2303.10130 [econ.GN]

[24] Chris Elsden, Arthi Manohar, Jo Briggs, Mike Harding, Chris Speed, and John Vines. 2018. Making Sense of Blockchain Applications: A Typology for HCI. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Montreal QC, Canada) (CHI ’18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3174032

[25] Ziv Epstein, Aaron Hertzmann, Investigators of Human Creativity, Memo Akten, Hany Farid, Jessica Fjeld, Morgan R Frank, Matthew Groh, Laura Herman, Neil Leach, et al. 2023. Art and the science of generative AI. Science 380, 6650 (2023), 1110-1111.

[26] Rosanna Fanni, Valerie Steinkogler, Giulia Zampedri, and Jo Pierson. 2022. Enhancing human agency through redress in Artificial Intelligence Systems. AI & SOCIETY 38 (06 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01454-7

[27] Ed Felten, Manav Raj, and Robert Seamans. 2023. How will Language Modelers like ChatGPT Affect Occupations and Industries? arXiv:2303.01157 [econ.GN]

[28] K. J. Kevin Feng, Maxwell James Coppock, and David W. McDonald. 2023. How Do UX Practitioners Communicate AI as a Design Material? Artifacts, Conceptions, and Propositions. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (, Pittsburgh, PA, USA,) (DIS ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2263-2280. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596101

[29] Jennifer Fereday and Eimear Muir-Cochrane. 2006. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5, 1 (2006), 80-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107 arXiv:https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

[30] Giorgio Franceschelli and Mirco Musolesi. 2023. Reinforcement Learning for Generative AI: State of the Art, Opportunities and Open Research Challenges. arXiv:2308.00031 [cs.LG]

[31] Michael C. Frank. 2023. Bridging the data gap between children and large language models. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 27, 11 (2023), 990-992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2023.08.007

[32] Jonas Frich, Lindsay MacDonald Vermeulen, Christian Remy, Michael Mose Biskjaer, and Peter Dalsgaard. 2019. Mapping the Landscape of Creativity Support Tools in HCI. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Glasgow, Scotland Uk) (CHI ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300619

[33] Batya Friedman. 1996. Value-Sensitive Design. Interactions 3, 6 (dec 1996), 16-23. https://doi.org/10.1145/242485.242493

[34] Ozlem Ozmen Garibay, Brent Winslow, Salvatore Andolina, Margherita Antona, Anja Bodenschatz, Constantinos Coursaris, Gregory Falco, Stephen M. Fiore, Ivan Garibay, Keri Grieman, John C. Havens, Marina Jirotka, Hernisa Kacorri, Waldemar Karwowski, Joe Kider, Joseph Konstan, Sean Koon, Monica Lopez-Gonzalez, Iliana Maifeld-Carucci, Sean McGregor, Gavriel Salvendy, Ben Shneiderman, Constantine Stephanidis, Christina Strobel, Carolyn Ten Holter, and Wei Xu. 2023. Six Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Grand Challenges. International fournal of Human Computer Interaction 39, 3 (2023), 391-437. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2153320 arXiv:https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2153320

[35] Frederic Gmeiner, Humphrey Yang, Lining Yao, Kenneth Holstein, and Nikolas Martelaro. 2023. Exploring Challenges and Opportunities to Support Designers in Learning to Co-create with AI-based Manufacturing Design Tools. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (, Hamburg, Germany, ) (CHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 226, 20 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3580999

[36] Abid Haleem, Mohd Javaid, and Ravi Pratap Singh. 2022. An era of ChatGPT as a significant futuristic support tool: A study on features, abilities, and challenges. BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations 2, 4 (2022), 100089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbench.2023.100089

[37] Perttu Hämäläinen, Mikke Tavast, and Anton Kunnari. 2023. Evaluating Large Language Models in Generating Synthetic HCI Research Data: a Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (, Hamburg, Germany, ) (CHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 433, 19 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3580688

[38] Ariel Han and Zhenyao Cai. 2023. Design Implications of Generative AI Systems for Visual Storytelling for Young Learners. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual ACM Interaction Design and Children Conference (Chicago, IL, USA) (IDC ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 470-474. https://doi.org/10.1145/3585088.3593867

[39] Gunnar Harboe and Elaine M. Huang. 2015. Real-World Affinity Diagramming Practices: Bridging the Paper-Digital Gap. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Seoul, Republic of Korea) (CHI ’15). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 95-104. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702561

[40] Rex Hartson and Pardha Pyla. 2018. The UX Book: Process and Guidelines for Ensuring a Quality User Experience (2st ed.). Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA.

[41] Monique Hennink and Bonnie N. Kaiser. 2022. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine 292 (2022), 114523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

[42] Jonathan Ho, William Chan, Chitwan Saharia, Jay Whang, Ruiqi Gao, Alexey Gritsenko, Diederik P. Kingma, Ben Poole, Mohammad Norouzi, David J. Fleet, and Tim Salimans. 2022. Imagen Video: High Definition Video Generation with Diffusion Models. arXiv:2210.02303 [cs.CV]

[43] Matthew K. Hong, Shabnam Hakimi, Yan-Ying Chen, Heishiro Toyoda, Charlene Wu, and Matt Klenk. 2023. Generative AI for Product Design: Getting the Right Design and the Design Right. arXiv:2306.01217 [cs.HC]

[44] Eric Horvitz. 1999. Principles of mixed-initiative user interfaces. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA) (CHI ’99). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 159-166. https://doi.org/10.1145/302979. 303030

[45] Stephanie Houde, Steven I Ross, Michael Muller, Mayank Agarwal, Fernando Martinez, John Richards, Kartik Talamadupula, and Justin D Weisz. 2022. Opportunities for Generative AI in UX Modernization. In 7oint Proceedings of the ACM IUI Workshops 2022, March 2022, Helsinki, Finland. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA.

[46] Lei Huang, Weijiang Yu, Weitao Ma, Weihong Zhong, Zhangyin Feng, Haotian Wang, Qianglong Chen, Weihua Peng, Xiaocheng Feng, Bing Qin, and Ting Liu. 2023. A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions. arXiv:2311.05232 [cs.CL]

[47] Nanna Inie, Jeanette Falk, and Steve Tanimoto. 2023. Designing Participatory AI: Creative Professionals’ Worries and Expectations about Generative AI. In Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (, Hamburg, Germany, ) (CHI EA ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 82, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544549.3585657

[48] Alice M Isen and Johnmarshall Reeve. 2005. The influence of positive affect on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Facilitating enjoyment of play, responsible work behavior, and self-control. Motivation and emotion 29 (2005), 295-323.

[49] Maurice Jakesch, Zana Buçinca, Saleema Amershi, and Alexandra Olteanu. 2022. How Different Groups Prioritize Ethical Values for Responsible AI. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (Seoul, Republic of Korea) (FAccT ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 310-323. https://doi.org/10.1145/3531146.3533097

[50] Harry H. Jiang, Lauren Brown, Jessica Cheng, Mehtab Khan, Abhishek Gupta, Deja Workman, Alex Hanna, Johnathan Flowers, and Timnit Gebru. 2023. AI Art and Its Impact on Artists. In Proceedings of the 2023 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (Montréal, QC, Canada) (AIES ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 363-374. https://doi.org/10.1145/3600211.3604681

[51] Zachary Kaiser. 2019. Creativity as computation: Teaching design in the age of automation. Design and Culture 11, 2 (2019), 173-192.

[52] Taenyun Kim, Maria D Molina, Minjin Rheu, Emily S Zhan, and Wei Peng. 2023. One AI Does Not Fit All: A Cluster Analysis of the Laypeople’s Perception of AI Roles. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 29, 1-20 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581340

[53] Joke Kort, APOS Vermeeren, and Jenneke E Fokker. 2007. Conceptualizing and measuring user experience. , 57-64 pages.

[54] Thomas S. Kuhn. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

[55] Chinmay Kulkarni, Stefania Druga, Minsuk Chang, Alex Fiannaca, Carrie Cai, and Michael Terry. 2023. A Word is Worth a Thousand Pictures: Prompts as AI Design Material. arXiv:2303.12647 [cs.HC]

[56] Tomas Lawton, Kazjon Grace, and Francisco J Ibarrola. 2023. When is a Tool a Tool? User Perceptions of System Agency in Human-AI Co-Creative Drawing. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) (DIS ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1978-1996. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3595977

[57] Mina Lee, Megha Srivastava, Amelia Hardy, John Thickstun, Esin Durmus, Ashwin Paranjape, Ines Gerard-Ursin, Xiang Lisa Li, Faisal Ladhak, Frieda Rong, Rose E. Wang, Minae Kwon, Joon Sung Park, Hancheng Cao, Tony Lee, Rishi Bommasani, Michael Bernstein, and Percy Liang. 2024. Evaluating Human-Language Model Interaction. arXiv:2212.09746 [cs.CL]

[58] Florian Lehmann. 2023. Mixed-Initiative Interaction with Computational Generative Systems. In Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Hamburg, Germany) (CHIEA ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 501, 6 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544549.3577061

[59] Robert W Lent and Steven D Brown. 2006. Integrating person and situation perspectives on work satisfaction: A social-cognitive view. 7ournal of vocational behavior 69, 2 (2006), 236-247.

[60] Joseph CR Licklider. 1960. Man-Computer Symbiosis. IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics HFE-1, 1(1960), 4-11.

[61] Lassi A. Liikkanen. 2019. It AIn’t Nuttin’ New – Interaction Design Practice After the AI Hype. In Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2019, David Lamas, Fernando Loizides, Lennart Nacke, Helen Petrie, Marco Winckler, and Panayiotis Zaphiris (Eds.). Springer International Publishing, Cham, 600-604.

[62] Zhiyu Lin, Upol Ehsan, Rohan Agarwal, Samihan Dani, Vidushi Vashishth, and Mark Riedl. 2023. Beyond Prompts: Exploring the Design Space of Mixed-Initiative Co-Creativity Systems. arXiv:2305.07465 [cs.AI]

[63] Duri Long and Brian Magerko. 2020. What is AI Literacy? Competencies and Design Considerations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Honolulu, HI, USA) (CHI ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376727

[64] Robyn Longhurst. 2003. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Key methods in geography 3, 2 (2003), 143-156.

[65] Yuwen Lu, Chengzhi Zhang, Iris Zhang, and Toby Jia-Jun Li. 2022. Bridging the Gap Between UX Practitioners’ Work Practices and AI-Enabled Design Support Tools. In Extended Abstracts of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New Orleans, LA, USA) (CHI EA ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 268, 7 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491101.3519809

[66] Henrietta Lyons, Eduardo Velloso, and Tim Miller. 2021. Conceptualising Contestability: Perspectives on Contesting Algorithmic Decisions. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 5, CSCW1, Article 106 (apr 2021), 25 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449180

[67] Nora McDonald, Sarita Schoenebeck, and Andrea Forte. 2019. Reliability and Inter-rater Reliability in Qualitative Research: Norms and Guidelines for CSCW and HCI Practice. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 3 (11 2019), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359174

[68] Kobe Millet, Florian Buehler, Guanzhong Du, and Michail D. Kokkoris. 2023. Defending humankind: Anthropocentric bias in the appreciation of AI art. Computers in Human Behavior 143 (2023), 107707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107707

[69] Bin Ning, Fang Liu, and Zhixiong Liu. 2023. Creativity Support in AI Co-creative Tools: Current Research, Challenges and Opportunities. In 2023 26th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD). IEEE, New York, NY, USA, 5-10. https: //doi.org/10.1109/CSCWD57460.2023.10152832

[70] Lorelli S. Nowell, Jill M. Norris, Deborah E. White, and Nancy J. Moules. 2017. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International fournal of Qualitative Methods 16, 1 (2017), 1609406917733847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847 arXiv:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

[71] Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang. 2023. Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence. Available at SSRN 4375283 381, 6654 (2023), 187-192. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh2586

[72] OpenAI, Josh Achiam, Steven Adler, and Sandhini Agarwal et al. 2023. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv:2303.08774 [cs.CL]

[73] Antti Oulasvirta, Niraj Ramesh Dayama, Morteza Shiripour, Maximilian John, and Andreas Karrenbauer. 2020. Combinatorial optimization of graphical user interface designs. Proc. IEEE 108, 3 (2020), 434-464.

[74] Joon Sung Park, Lindsay Popowski, Carrie Cai, Meredith Ringel Morris, Percy Liang, and Michael S. Bernstein. 2022. Social Simulacra: Creating Populated Prototypes for Social Computing Systems. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (Bend, OR, USA) (UIST ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 74, 18 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3526113.3545616

[75] John V Pavlik. 2023. Collaborating with ChatGPT: Considering the implications of generative artificial intelligence for journalism and media education. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 78, 1 (2023), 84-93.

[76] Andrew Pearson. 2023. The rise of CreAltives: Using AI to enable and speed up the creative process. Journal of AI, Robotics & Workplace Automation 2, 2 (2023), 101-114.

[77] Sida Peng, Eirini Kalliamvakou, Peter Cihon, and Mert Demirer. 2023. The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity: Evidence from GitHub Copilot. arXiv:2302.06590 [cs.SE]

[78] Bogdana Rakova, Jingying Yang, Henriette Cramer, and Rumman Chowdhury. 2021. Where Responsible AI Meets Reality: Practitioner Perspectives on Enablers for Shifting Organizational Practices. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 5, CSCW1, Article 7 (apr 2021), 23 pages. https://doi.org/10. 1145/3449081

[79] Kevin Roose. 2022. The brilliance and weirdness of ChatGPT. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/05/technology/chatgpt-ai-twitter.html

[80] S. Russell. 2019. Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control. Penguin Publishing Group, New York, NY, USA. https: //books.google.nl/books?id=M1eFDwAAQBAJ

[81] Jana I Saadi and Maria C Yang. 2023. Generative Design: Reframing the Role of the Designer in Early-Stage Design Process. 7ournal of Mechanical Design 145, 4 (2023), 041411.

[82] Chitwan Saharia, William Chan, Saurabh Saxena, Lala Li, Jay Whang, Emily L Denton, Kamyar Ghasemipour, Raphael Gontijo Lopes, Burcu Karagol Ayan, Tim Salimans, et al. 2022. Photorealistic text-to-image diffusion models with deep language understanding. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (2022), 36479-36494.

[83] NANNA SANDBERG, TOM HOY, and MARTIN ORTLIEB. 2019. My AI versus the company AI: how knowledge workers conceptualize forms of AI assistance in the workplace. In Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, Vol. 2019. Wiley Online Library, American Anthropological Association, Arlington, Virginia, USA, 125-143.

[84] Ava Elizabeth Scott, Daniel Neumann, Jasmin Niess, and Paweł W. Woźniak. 2023. Do You Mind? User Perceptions of Machine Consciousness. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (, Hamburg, Germany, ) (CHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 374, 19 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581296

[85] Ben Shneiderman. 2020. Human-centered artificial intelligence: Reliable, safe & trustworthy. International fournal of Human-Computer Interaction 36, 6 (2020), 495-504.

[86] Ben Shneiderman. 2020. Human-centered artificial intelligence: Three fresh ideas. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction 12, 3 (2020), 109-124.

[87] D.K. Simonton. 1999. Origins of Genius: Darwinian Perspectives on Creativity. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. https://books.google.li/books? id=a2LnBwAAQBAJ

[88] Marita Skjuve, Asbjørn Følstad, and Petter Bae Brandtzaeg. 2023. The User Experience of ChatGPT: Findings from a Questionnaire Study of Early Users. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Conversational User Interfaces (Eindhoven, Netherlands) (CUI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 2, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3571884.3597144

[89] Irene Solaiman, Zeerak Talat, William Agnew, Lama Ahmad, Dylan Baker, Su Lin Blodgett, Hal Daumé III au2, Jesse Dodge, Ellie Evans, Sara Hooker, Yacine Jernite, Alexandra Sasha Luccioni, Alberto Lusoli, Margaret Mitchell, Jessica Newman, Marie-Therese Png, Andrew Strait, and Apostol Vassilev. 2023. Evaluating the Social Impact of Generative AI Systems in Systems and Society. arXiv:2306.05949 [cs.CY]

[90] Åsne Stige, Efpraxia D Zamani, Patrick Mikalef, and Yuzhen Zhu. 2023. Artificial intelligence (AI) for user experience (UX) design: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-07-2022-0519

[91] S Shyam Sundar. 2020. Rise of machine agency: A framework for studying the psychology of human-AI interaction (HAII). Fournal of ComputerMediated Communication 25, 1 (2020), 74-88.

[92] Jakob Tholander and Martin Jonsson. 2023. Design Ideation with AI – Sketching, Thinking and Talking with Generative Machine Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) (DIS ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1930-1940. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596014

[93] Katja Thoring, Sebastian Huettemann, and Roland M Mueller. 2023. THE AUGMENTED DESIGNER: A RESEARCH AGENDA FOR GENERATIVE AI-ENABLED DESIGN. Proceedings of the Design Society 3 (2023), 3345-3354.

[94] Joel E Tohline et al. 2008. Computational provenance. Computing in Science & Engineering 10, 03 (2008), 9-10.

[95] Steven Umbrello and Ibo Poel. 2021. Mapping value sensitive design onto AI for social good principles. AI and Ethics 1 (08 2021), 3. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00038-3

[96] Russ Unger and Carolyn Chandler. 2012. A Project Guide to UX Design: For user experience designers in the field or in the making. New Riders, Nora, Indianapolis, USA.

[97] Michael Veale and Frederik Zuiderveen Borgesius. 2021. Demystifying the Draft EU Artificial Intelligence Act – Analysing the good, the bad, and the unclear elements of the proposed approach. Computer Law Review International 22, 4 (Aug. 2021), 97-112. https://doi.org/10.9785/cri-2021-220402

[98] Florent Vinchon, Todd Lubart, Sabrina Bartolotta, Valentin Gironnay, Marion Botella, Samira Bourgeois-Bougrine, Jean-Marie Burkhardt, Nathalie Bonnardel, Giovanni Emanuele Corazza, Vlad Glăveanu, et al. 2023. Artificial Intelligence & Creativity: A manifesto for collaboration. The Journal of Creative Behavior 57, 4 (2023), 472-484.

[99] Qian Wan and Zhicong Lu. 2023. GANCollage: A GAN-Driven Digital Mood Board to Facilitate Ideation in Creativity Support. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) (DIS ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 136-146. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596072

[100] Norbert Wiener. 1960. Some Moral and Technical Consequences of Automation. Science 131, 3410 (1960), 1355-1358. https://doi.org/10.1126/ science.131.3410.1355 arXiv:https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/science.131.3410.1355

[101] Wen Xu and Katina Zammit. 2020. Applying Thematic Analysis to Education: A Hybrid Approach to Interpreting Data in Practitioner Research. International Fournal of Qualitative Methods 19 (2020), 1609406920918810. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920918810 arXiv:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920918810

[102] Bin Yang, Long Wei, and Zihan Pu. 2020. Measuring and improving user experience through artificial intelligence-aided design. Frontiers in Psychology 11 (2020), 595374.

[103] Qian Yang, Aaron Steinfeld, Carolyn Rosé, and John Zimmerman. 2020. Re-examining Whether, Why, and How Human-AI Interaction Is Uniquely Difficult to Design. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (, Honolulu, HI, USA, ) (CHI ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1-13. https: //doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376301

[104] Yang Yuan. 2023. On the Power of Foundation Models. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vol. 202), Andreas Krause, Emma Brunskill, Kyunghyun Cho, Barbara Engelhardt, Sivan Sabato, and Jonathan Scarlett (Eds.). PMLR, USA, 40519-40530. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v202/yuan23b.html

[105] Xiao Zhan, Yifan Xu, and Stefan Sarkadi. 2023. Deceptive AI Ecosystems: The Case of ChatGPT. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Conversational User Interfaces (Eindhoven, Netherlands) (CUI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 3, 6 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3571884.3603754

[106] Chengzhi Zhang, Weijie Wang, Paul Pangaro, Nikolas Martelaro, and Daragh Byrne. 2023. Generative Image AI Using Design Sketches as Input: Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 15th Conference on Creativity and Cognition (Virtual Event, USA) (C&C ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 254-261. https://doi.org/10.1145/3591196.3596820

[107] Haonan Zhong, Jiamin Chang, Ziyue Yang, Tingmin Wu, Pathum Chamikara Mahawaga Arachchige, Chehara Pathmabandu, and Minhui Xue. 2023. Copyright Protection and Accountability of Generative AI: Attack, Watermarking and Attribution. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023 (Austin, TX, USA) (WWW’23 Companion). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 94-98. https://doi.org/10.1145/3543873.3587321

[108] Simon Zhuang and Dylan Hadfield-Menell. 2020. Consequences of Misaligned AI. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, H. Larochelle, M. Ranzato, R. Hadsell, M.F. Balcan, and H. Lin (Eds.), Vol. 33. Curran Associates, Inc., Red Hook, New York, USA, 15763-15773.

ChatGPT: https://chat.openai.com

DALL-E 2: https://openai.com/dall-e-2

Stable Diffusion: https://stablediffusionweb.com

Midjourney: https://www.midjourney.com

Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for third-party components of this work must be honored. For all other uses, contact the owner/author(s).

© 2024 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).

Manuscript submitted to ACMMiro: https://miro.com

User Experience Design Professionals’ Perceptions of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Abstract

Among creative professionals, Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) has sparked excitement over its capabilities and fear over unanticipated consequences. How does GenAI impact User Experience Design (UXD) practice, and are fears warranted? We interviewed 20 UX Designers, with diverse experience and across companies (startups to large enterprises). We probed them to characterize their practices, and sample their attitudes, concerns, and expectations. We found that experienced designers are confident in their originality, creativity, and empathic skills, and find GenAI’s role as assistive. They emphasized the unique human factors of “enjoyment” and “agency”, where humans remain the arbiters of “AI alignment”. However, skill degradation, job replacement, and creativity exhaustion can adversely impact junior designers. We discuss implications for human-GenAI collaboration, specifically copyright and ownership, human creativity and agency, and AI literacy and access. Through the lens of responsible and participatory AI, we contribute a deeper understanding of GenAI fears and opportunities for UXD.

Additional Key Words and Phrases: Generative AI, UX Designers, Responsible AI, User Experience, Human-AI Collaboration

ACM Reference Format:

1 INTRODUCTION

2 RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND CONTRIBUTIONS

might fit into or potentially alter these various workflows. Second, we seek to comprehend UX Designers’ perceptions toward GenAI – we intend to explore how UX Designers can leverage the potential of GenAI to overcome the existing limitations in tools and challenges in workflows, allowing them to ultimately craft impactful and meaningful user experiences now and in the future. Lastly, we seek to understand how and in what capacity GenAI may impact User Experience Design (UXD) practice, and whether fears that may arise are warranted. To this end, we pose the following research questions (RQs):

- RQ1: How do UX Designers perceive GenAI tools, and what is their view on the potential for incorporating these tools into their current workflows?

- RQ2: What opportunities and risks do UX Designers envision for the future of human-AI collaboration in UX Design practice?

3 BACKGROUND AND RELATED WORK

3.1 Al’s Impact on (Creative) Work

3.2 Human-AI Collaboration for Human Empowerment

3.3 Use of AI in UX Design and Research

space of mixed-initiative co-creativity systems where humans and AI systems could communicate creative intent to each other.

4 METHOD

| Characteristics | UX Designers | |

| Work experience | >5 years | P1, P5, P6, P8, P10, P11, P12, P14, P16, P17, P18 |

| 3-5 years | P2, P7 | |

| <3 years | P3, P4, P9, P13, P15, P19, P20 | |

| Company size | >10,000 | P5, P6, P7, P8, P9, P11, P14, P15, P16, P17 |

| 1,000-10,000 | P1, P2, P10, P13, P18 | |

| 500-1,000 | P20 | |

| <50 | P3, P4, P12, P19 | |

| GenAI video demos | GenAI tools included | Date posted on YouTube |

| Crafting a mobile interface

|

Midjourney (V4), Stability Photoshop Plugin (0.7.0) & ChatGPT (Jan. 30, 2023 version) | Feb. 20, 2023 |

| Drafting a design proposal (only used the part of Notion AI:

|

Notion AI (2.21) | Mar. 15, 2023 |

| Creating UI components

|

Prompt2Design (V3) | May. 6, 2023 |

| Organizing ideation notes

|

MiroAI (Beta) | Mar. 8, 2023 |

4.1 Participants

4.2 Interview questions and procedure

- Step 1 ( 5 mins ): Introduction given by the interview facilitator to ensure participants understand the purpose of the interview, have read, comprehended, and signed the informed consent form;

- Step 2 (

: General questions about background, workflows, and UX practice; - Step 3 ( 20 mins): Attitudes, concerns, and expectations of GenAI Systems;

- Step 4 ( 20 mins): Envisioning GenAI’s role in human-AI collaboration (including watching a video demonstration of a sample of current GenAI tools);

- Step 5 ( 5 mins): Concluding questions.

4.3 Data Analysis

5 FINDINGS

5.1 Current UX Design Tools and Workflow

| Steps | Main Activities | Tools | |||

| 1 Business Requirements |

|

Brainstorm | |||

| 2 User Requirements |

|

Brainstorm & User Research | |||

| 3 |

|

Brainstorm, Documentation & Presentation | |||

| 4 Prototyping |

|

Design | |||

| 5 |

|

Communication & User Research | |||

| 6 Iteration |

|

Design & Non Digital | |||

| 7 Solution | – Collaborate with stakeholders to ensure the design addresses user needs and aligns with the business goals. | Documentation & Presentation | |||

| 8 Design Handoff |

|

Documentation, Presentation & Design |

5.2 Theme 1: Limitations of Current UX Design Tools

5.2.2 Limitation 2: Fragmented Tools. Participants emphasized that the current UX Design tools are scattered. Each tool has specific strengths or functionalities, but transitioning seamlessly between them is challenging: “We use Miro for brainstorming and creating low-fidelity prototypes, and Figma for high-fidelity ones. However, transferring wireframes from Miro to Figma isn’t straightforward.”[P10] Some participants specifically noted that the current design tools lack support for user research: “Something valuable would be the ability to conduct usability testing and generate data within the design tool itself.” [P17].

5.2.3 Limitation 3: Lack of Advanced Design Support. Participants expressed dissatisfaction with the current design tools due to their lack of advanced support for complex animations, cross-platform designs, graphic design, and more intelligent design systems: “There are micro animation-type things that you don’t get from Figma, like the timelines that you would use in After Effects or Principle to fine-tune your animations.” [P17] “Design systems lack intelligence. I’d appreciate a design system that recommends suitable design components and automatically adjusts these components to fit various screens.” [P5].

5.3 Theme 2: Challenges in Current UX Design

5.3.2 Challenge 2: Understanding end-users. Participants mentioned that conducting research to understand user needs is challenging in terms of finding out the right pain points of users and building the right products: “I think the challenge always lies in trying to understand who I’m designing for, what their needs, goals, and problems are, and whether the product or service that I’m working on fits into the broader landscape.”[P17]. Such a challenge lies at the heart of

5.3.3 Challenge 3: Designing solutions that satisfy both business value and user needs. Participants pointed out that coming up with good design solutions that balance clients’ needs, users’ needs, business value, and visual novelty is challenging: “The UX field is quite mature, with existing design references and design systems aiding the work. The challenge is to come up with new ideas constantly and find a balance when considering both established design references, internal stakeholders’ expectations, user needs, and incorporating them into the new design.”[P18] Satisfying business needs can carry implications for originality, copyright, and ownership, all of which impact adoption (cf., Sec 5.6.1).

5.3.4 Challenge 4: Lacking domain knowledge and resources. Participants mentioned that lacking domain expertise and resources to access knowledge poses a significant challenge: “One of the challenges for UX Designers is acquiring extensive domain knowledge, such as creating designs customized for specialized fields like medical, automotive, fintech, and so on.”[P1]; “In a startup, we often face resource constraints that limit our access to experts, conducting user research or usability testing on a larger scale, which is crucial to ensure the feasibility and desirability of the products.”[P6]. We believe this may be a promising avenue by which GenAI tools, specifically text-based large language models such as ChatGPT, can empower designers. Despite current model hallucinations (cf., [46]), designers can have immediate, vast, and easy access to domain-specific information and resources.

5.4 Theme 3: UX Designers’ Attitudes toward GenAI

5.4.1 Perceived shortcomings of GenAI tools shown in the demo. There were two shortcomings perceived to be key amongst participants:

(1) Practicality and efficiency. Participants highlighted that the GenAI tools showcased in the demos are quite generic, and the design process still requires a substantial amount of manual work. This includes tasks such as redrawing icons and buttons and inputting accurate text-based prompts. “Designers are trained to think visually. Our design process

involves trial and error on sketchbooks. Designs emerge from numerous sketch trials, not from text-based prompts. [In the demo], you’re required to switch between various GenAI tools, Photoshop plugins, and perform a substantial amount of manual work, including redrawing and regenerating high-resolution images. I question whether these GenAI tools truly enhance the design workflow.”[P12]

(2) Accuracy and reliability. Participants questioned the overall accuracy and reliability of outcomes generated by AI tools. They hold the belief that human inputs are necessary to validate the AI-generated outcomes. P16 shared: “For visual design, GenAI tools are still quite limited in capturing nuances and intricate details. Regarding ideation, AI tools like Miro AI may fall short in adequately representing the insights of stakeholders who possess extensive experience, say, 20 years in a specialized field like healthcare.” [P16]. P19 described her negative experience using GenAI tools: “For Midjourney, I often found myself spending hours adjusting my prompts, yet still unable to achieve the envisioned results. As for Miro, the cards are only clustered based on keywords, requiring manual effort to create coherent clusters.” [P19]. Furthermore, P3 expressed doubts about the reliability of AI’s code generation capability: “I’ve actually attempted to have ChatGPT generate code for certain features or functionalities, but it didn’t quite produce the results I was looking for.”[P3].

5.5 Theme 4: Human-AI Collaboration

5.5.1 Perceptions of threats and collaboration with GenAI. Participants expressed varying levels of concern regarding the potential threats of GenAI. Some felt that if GenAI remained a generic tool under their control, it wouldn’t be a source of concern, while others worried about its ability to simulate designers’ reasoning. Recommendations included treating GenAI as a team member, with some participants emphasizing the importance of humans retaining ultimate decision-making power in human-AI collaboration. P18 commented: “If the technology does eventually reach a point where it can accurately simulate designers’ rationales, then I might start worrying about it.” [P18]. P19 recommended treating GenAI as a team member: “I would envision AI as part of the team, contributing to the overall process, but not solely responsible for the final outcome.”[P19]. P8 stressed that humans should have the ultimate decision-making power in human-AI collaboration: “It should depend on people to choose which part I want AI assistance, for the purpose of expediting tasks. I don’t like the word ‘replace’. I very much enjoy the UI and UX Design…I want AI to be my apprentices. Humans do the creative and complex parts, and AI apprentices fill in the colors or draw lines.”[P8].

5.5.2 General and repetitive work can be replaced by GenAI. All participants shared the belief that GenAI has the potential to replace repetitive tasks, such as generating “lorem ipsum” texts for design mockups, condensing design briefs and technical documentation, crafting repetitive design components, creating responsive designs for various screens, automatically documenting visual design elements into design systems, generating low-fidelity prototypes, and generating design variations for inspiration (see Fig. 3: “GenAI Can”). As P8 said, “I envision AI functioning as a productivity tool that quickly aids me in concrete tasks. For instance, AI could summarize PRDs [Product Requirement Documents] or explain technical backgrounds in plain language. Currently, these aspects require substantial effort from PMs [Product Managers] and engineers to convey to us designers.”[P8]. P12 expressed their wish for AI-supported responsive design, “I’m hopeful that GenAI can assist with tasks like responsive design for different screens and suggesting user flows across pages, not just on a single page.” [P12] Many other participants expressed their desire for GenAI support in various tasks, including providing design inspiration (P2, P4, and P8), as well as facilitating efficient UX writing (P18 and P19).

5.5.3 UX Design work cannot be replaced by GenAI. Many participants made it clear that much UX Design work simply cannot be replaced by AI, including the work that requires communicating between human stakeholders, being empathetic towards user needs, and designing user-centered functionalities. They stressed the importance of humans being the original creator and validator of the AI outcomes (see Fig. 3: “GenAI Cannot”).

(1) User inputs and human-human communication or collaboration. Participants confidently expressed that they do not currently perceive GenAI as a competitor, since human designers serve as ambassadors for user needs and continue to be the ultimate decision-makers and arbiters of AI alignment. They emphasized that GenAI cannot replace work that requires user inputs, and human-human collaborations: “GenAI might be capable of taking over basic, repetitive, and straightforward tasks, but it cannot replace service design and collaborative efforts that demand more systematic and abstract thinking.”[P6]. P14 additionally pointed out, “UX Design is not just about aesthetics, but also usability and the accessibility of elements. Real human users are essential for improving designs through actual user research and testing.” [P14]. P16 believed that human communication is not replaceable by AI, stating “I value insights from human colleagues, their experiences, ideas, and the knowledge they bring to the table. These do not have to be flawless, but they aid us in charting directions together. I do not believe AI can perform this aspect of work.”[P16].

(2) Human creativity and decision making. Some participants pointed out that human creativity and originality are strong human qualities that are difficult to be replaced by AI. AI outcomes heavily rely on past data, potentially leading to recurring results due to the limited data pool. Human designers remain the driving force capable of deeply comprehending design contexts, empathizing with users, and innovating based on the latest knowledge: “The creative work that humans enjoy doing should not be replaced by AI. AI is a trained model that is based on the past, while human creativity and originality are more future-oriented.” [P8]; “Creativity can be supported by AI, as it can remix and regenerate based on human-inputted creative data, but humans possess the originality.”[P4].

5.6 Theme 5: Ethical Concerns and Ownership

5.6.1 Originality, copyright, and ownership. Participants emphasized the significance of crediting the original creators of artworks or art styles utilized in UX work. P3 and P4 suggested that blockchain technology could be useful in ensuring direct ownership attribution to the original creators, regardless of the extent to which the original work has been modified. P4 stated, “Ownership must remain traceable regardless of how extensively the AI outputs have been modified, derived, or reproduced from the originals. Perhaps blockchain can provide a solution here.” P14 expressed her concerns over design plagiarism, “From the confidentiality point of view, what data can be placed into GenAI tools, how we can make sure that we are using legal sources and we are not violating GDPR regulations. There are already cases that designers copy others’ work to build their own portfolios. GenAI can make plagiarism in design much worse.”[P14].

5.6.2 Skill degradation and unemployment. Several participants highlighted their concern that human UX Design work might be less appreciated, potentially leading to complacency among human designers and a decline in their skills. They worry that AI taking over tasks previously considered essential for designers could contribute to skill degradation. These concerns, mentioned primarily by senior designers (refer to Table 1), are particularly relevant for junior designers, who could miss out on opportunities to further develop their skills. As such, human designers might transition into more managerial or generalist roles. P16 (a senior designer) envisioned this, stating, “Designers may fall into the trap of becoming complacent. Junior designers might have fewer chances to learn the design process but, instead, they may focus on mastering AI systems. Consequently, designers could evolve into generalists.”[P16]

5.6.3 Privacy, transparency, and equal access to GenAI. Participants pointed out that privacy is a significant concern within the realm of GenAI. As these AI models ingest large amounts of data to learn patterns and generate content, there is potential for the unintentional exposure of sensitive information, such as personal or confidential details that users did not intend to share: “If I want to use ChatGPT to extract information from technical documents, I don’t know how I should prevent sensitive information from being leaked. For my personal life as well, it is not clear how much of my personal data will be retained to further train the AI models.”[P19]

developed countries may gain control over the data fed into AI. It’s also easier for them to access GenAI tools compared to some developing countries.” [P6]. P2 added, “It is important to ensure that individuals who are relatively less educated and have limited knowledge of GenAI can still use these tools to enhance their work and daily lives.”[P2].

5.7 Theme 6: The Future of GenAI in UX Design

5.7.1 Envisioning collaborative design with GenAI. Some participants envisioned a triangulated system that involves collaboration and input from users, designers, and GenAI. This approach aims to minimize biases and ensure that crucial nuances, essential for design innovations, are not overlooked. As P11 mentioned, “Human designers may overlook certain nuances that could hold importance for users. I wish for GenAI to enhance this aspect by providing its input grounded in vast past data and knowledge, potentially elevating user experience design to the next level.”[P11].

5.7.2 Promoting AI literacy and access for designers. Several participants expressed a hope for increased AI literacy through education, benefiting both experienced and junior designers. P13 (a junior designer) noted, “Students may feel apprehensive about this significant AI revolution. Education is essential to prepare both junior and senior designers for the impact of AI and how to leverage it to enhance our human design skills.”[P13]. Additionally, a few participants envision future AI tools to be more accessible for designers. In other words, they desire AI tools that offer greater visual and intuitive usability, moving beyond sole reliance on text-based inputs. “The recent Apple Vision Pro headset is inspiring. Its visual and intuitive design appears promising. Thus, AI should also evolve to become more visual, intuitive, and universally accessible to all users.” [P12].

5.7.3 Al’s desired role in enhancing design processes. Many participants expressed their desire for GenAI to mature further, supporting them in various design tasks. They hoped that GenAI could assist in designing graphics, writing prompts, generating smart components, providing successful design examples, and automating the handoff of designs to development teams. P4 noted, “I am anticipating easier ways to write prompts or automatically generate components that adapt to different screens, recommend smart animation transitions, and even generate 3D content for immersive environments in the future.” [P4]. Many other participants also voiced their desires for specific GenAI support in various tasks in the future. For instance, they hoped AI could summarize state-of-the-art knowledge for research and strategy (P10, P18, and P19), serve as a synthetic user to expedite sprints (P1 and P18), offer professional guidance in accessibility design (P12), help designers quickly master and switch between different design tools (P18), aid in labeling and clustering qualitative raw data from user studies (P5, P9, P10, P12, and P18), and seamlessly translate designs into development (P5, P18, and P19).

5.7.4 The challenge of defining GenAI outcome metrics. According to several participants, another envisioned future for GenAI involves the challenge of defining metrics to measure the quality of AI-generated output. As P17 commented, “If many businesses use the same GenAI tools, it may result in similar designs and lacking diversity and innovation. Also, AI can lead to generating numerous outputs and leave the challenge to us, humans, to choose among them.”[P17]. “It is already a challenge to select and fine-tune AI outcomes. We need guidelines on how to measure or validate AI’s output.” [P18]

6 DISCUSSION

6.1 Enjoyment and Agency in Human-GenAI Collaboration

6.2 GenAI Interpolating, Humans Extrapolating, and Creativity Exhaustion

6.3 AI Literacy and Participatory AI in UX Design

concepts, including how machine learning works, the types of AI systems, their capabilities, limitations, and implications. This understanding is crucial for UX designers to harness AI’s power, ensure equal access to AI education and tools, and actively participate in shaping and refining AI technologies, especially those used in their design processes. By adopting a participatory AI approach, UX Designers are part and parcel of the conversation around the future of GenAI development – this enables UX designers to strengthen their feedback and expertise, ensuring that AI tools align effectively with human intentions and UX design practices [57, 63].

6.4 Copyright and Ownership for GenAI Output in and beyond UX Design

6.5 The Future of GenAI-infused UX Design: Fears and Opportunities

6.6 Study Limitations and Future Work

7 CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

REFERENCES

[2] Saleema Amershi, Dan Weld, Mihaela Vorvoreanu, Adam Fourney, Besmira Nushi, Penny Collisson, Jina Suh, Shamsi Iqbal, Paul N. Bennett, Kori Inkpen, Jaime Teevan, Ruth Kikin-Gil, and Eric Horvitz. 2019. Guidelines for Human-AI Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Glasgow, Scotland Uk) (CHI ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300233

[3] Kareem Ayoub and Kenneth Payne. 2016. Strategy in the age of artificial intelligence. 7ournal of strategic studies 39, 5-6 (2016), 793-819.

[4] Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. 2021. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (Virtual Event, Canada) (FAccT ’21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 610-623. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922

[5] Abeba Birhane, William Isaac, Vinodkumar Prabhakaran, Mark Diaz, Madeleine Clare Elish, Iason Gabriel, and Shakir Mohamed. 2022. Power to the People? Opportunities and Challenges for Participatory AI. In Equity and Access in Algorithms, Mechanisms, and Optimization (Arlington, VA, USA) (EAAMO ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 6, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3551624.3555290

[6] Rishi Bommasani, Drew A. Hudson, Ehsan Adeli, Russ Altman, Simran Arora, Sydney von Arx, Michael S. Bernstein, Jeannette Bohg, Antoine Bosselut, Emma Brunskill, Erik Brynjolfsson, Shyamal Buch, Dallas Card, Rodrigo Castellon, Niladri Chatterji, Annie Chen, Kathleen Creel, Jared Quincy Davis, Dora Demszky, Chris Donahue, Moussa Doumbouya, Esin Durmus, Stefano Ermon, John Etchemendy, Kawin Ethayarajh, Li Fei-Fei, Chelsea Finn, Trevor Gale, Lauren Gillespie, Karan Goel, Noah Goodman, Shelby Grossman, Neel Guha, Tatsunori Hashimoto, Peter Henderson, John Hewitt, Daniel E. Ho, Jenny Hong, Kyle Hsu, Jing Huang, Thomas Icard, Saahil Jain, Dan Jurafsky, Pratyusha Kalluri, Siddharth Karamcheti, Geoff Keeling, Fereshte Khani, Omar Khattab, Pang Wei Koh, Mark Krass, Ranjay Krishna, Rohith Kuditipudi, Ananya Kumar, Faisal Ladhak, Mina Lee, Tony Lee, Jure Leskovec, Isabelle Levent, Xiang Lisa Li, Xuechen Li, Tengyu Ma, Ali Malik, Christopher D. Manning, Suvir Mirchandani, Eric Mitchell, Zanele Munyikwa, Suraj Nair, Avanika Narayan, Deepak Narayanan, Ben Newman, Allen Nie, Juan Carlos Niebles, Hamed Nilforoshan, Julian Nyarko, Giray Ogut, Laurel Orr, Isabel Papadimitriou, Joon Sung Park, Chris Piech, Eva Portelance, Christopher Potts, Aditi Raghunathan, Rob Reich, Hongyu Ren, Frieda Rong, Yusuf Roohani, Camilo Ruiz, Jack Ryan, Christopher Ré, Dorsa Sadigh, Shiori Sagawa, Keshav Santhanam, Andy Shih, Krishnan Srinivasan, Alex Tamkin, Rohan Taori, Armin W. Thomas, Florian Tramèr, Rose E. Wang, William Wang, Bohan Wu, Jiajun Wu, Yuhuai Wu, Sang Michael Xie, Michihiro Yasunaga, Jiaxuan You, Matei Zaharia, Michael Zhang, Tianyi Zhang, Xikun Zhang, Yuhui Zhang, Lucia Zheng, Kaitlyn Zhou, and Percy Liang. 2022. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. arXiv:2108.07258 [cs.LG]

[7] Zalán Borsos, Raphaël Marinier, Damien Vincent, Eugene Kharitonov, Olivier Pietquin, Matt Sharifi, Olivier Teboul, David Grangier, Marco Tagliasacchi, and Neil Zeghidour. 2022. AudioLM: a Language Modeling Approach to Audio Generation. arXiv:2209.03143 [cs.SD]

[8] Petter Bae Brandtzæg, Asbjørn Følstad, and Jan Heim. 2018. Enjoyment: Lessons from Karasek. Springer International Publishing, Cham, 331-341. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68213-6_21

[9] Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke. 2012. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Vol. 2. Research Designs. American Psychological Association, 750 First St. NE, Washington, DC 20002-4242, 57-71.