DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44482-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38167874

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-02

يساعد التصوير الضوئي في تعزيز استجابة وسرعة الأنفاق غير المتجانسة

تم القبول: 14 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2024

الملخص

تأثير التصوير الضوئي هو الآلية السائدة في معظم كاشفات الضوء من المواد ثنائية الأبعاد (2D) ذات الاستجابة العالية. ومع ذلك، فإن الاستجابات الفائقة العالية في تلك الأجهزة تأتي بطبيعتها على حساب سرعة استجابة بطيئة جداً. في هذا العمل، نبلغ عن

الخطوط، والفرص الغنية التي توفرها الواجهات غير المتجانسة الحادة ذريًا

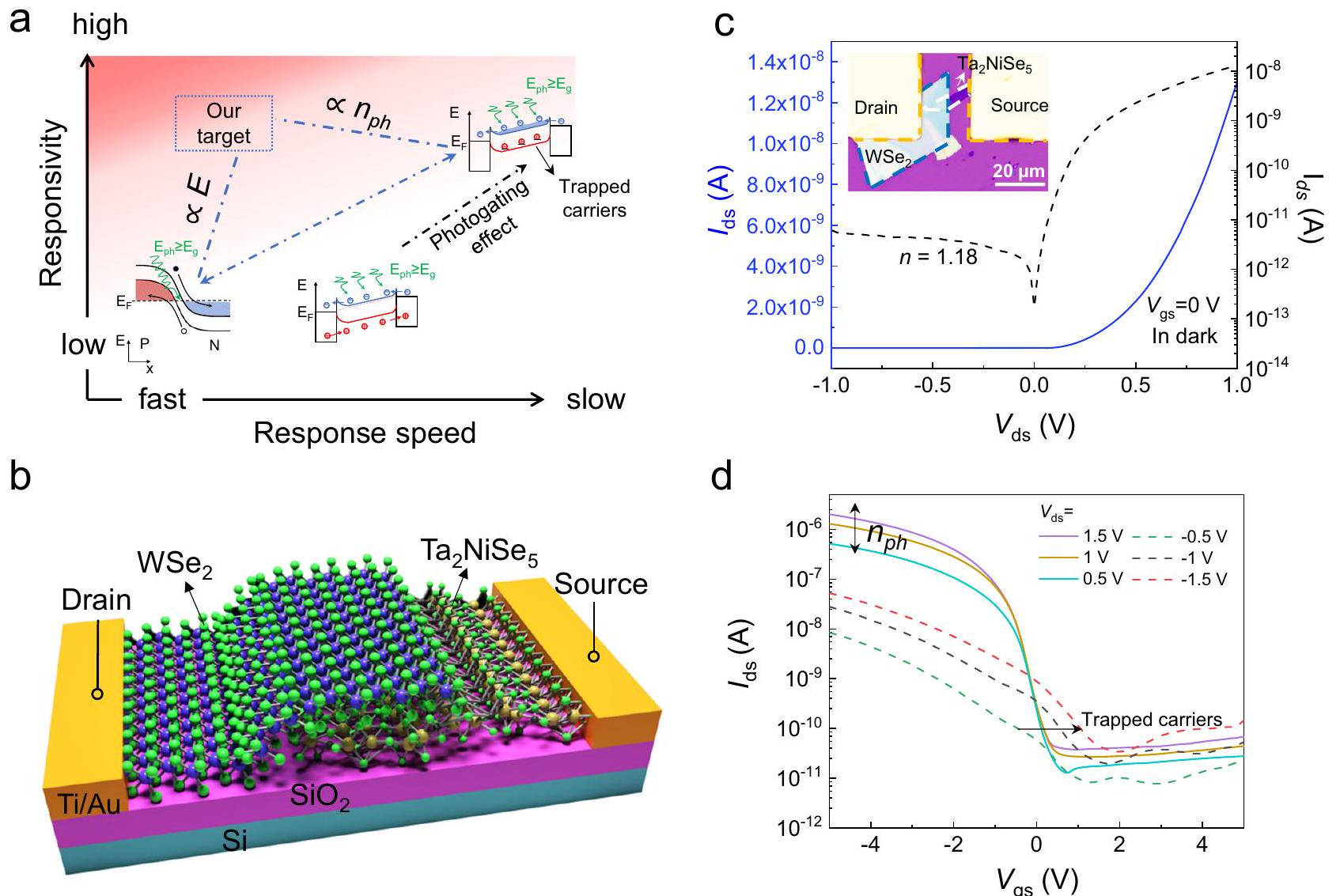

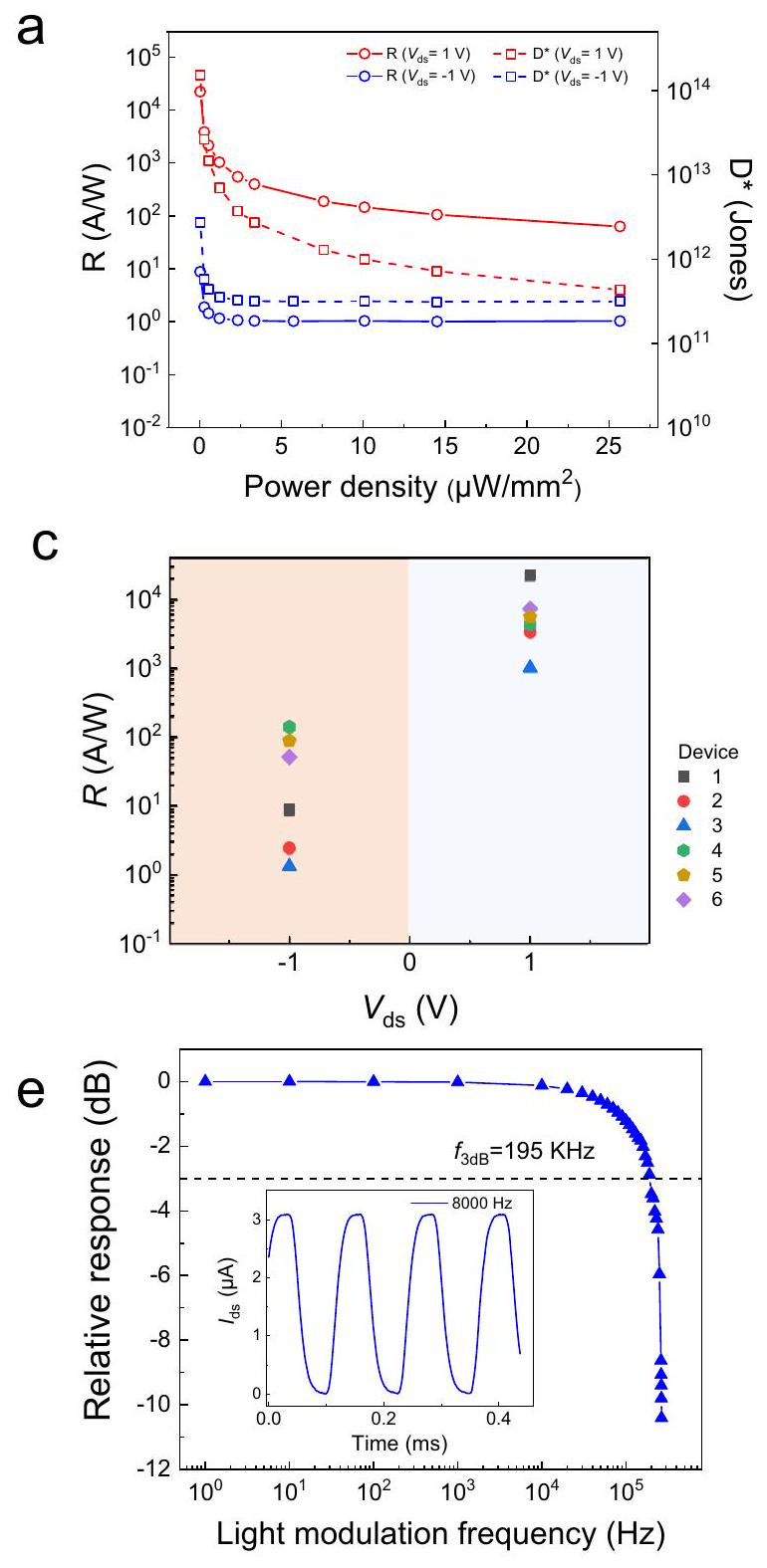

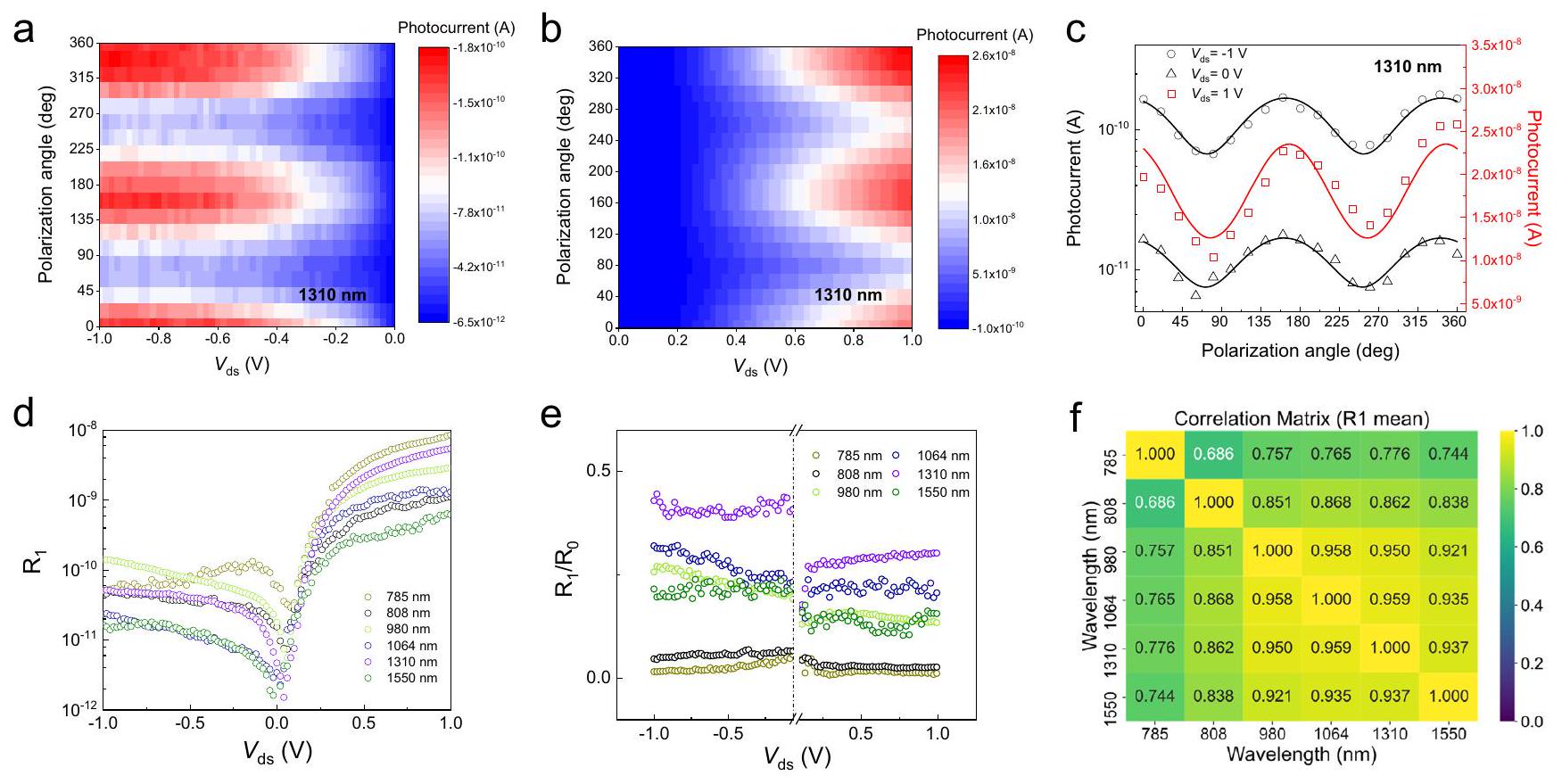

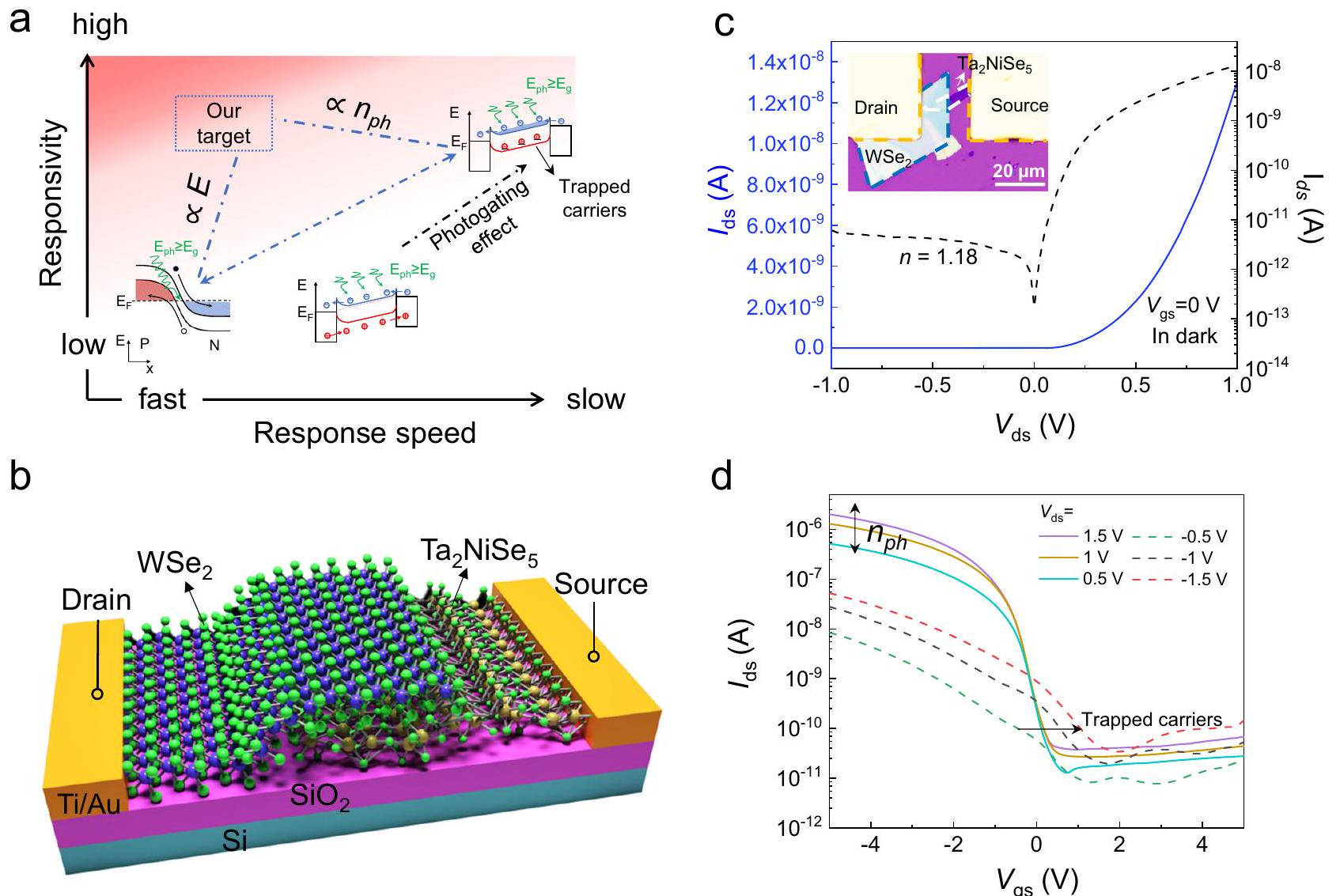

كاشف. توضيح للتوازن بين الاستجابة والسرعة في كواشف الضوء من المواد ثنائية الأبعاد. للتغلب على هذا التوازن والدخول إلى المنطقة العليا اليسرى، نحتاج تقليديًا إلى زيادة استهلاك الطاقة، المشار إليه باللون الأحمر. مخطط نطاق الطاقة في الجانب السفلي الأيسر هو وضع الخلايا الشمسية لكاشف الضوء، والوسط هو وضع التوصيل الضوئي، والجانب العلوي الأيمن ينتمي إلى وضع التحكم الضوئي.

بفضل زمن الانتقال القصير الممكن بفضل النفق، يتيح جهازنا استجابة عالية حتى في ظل عمر حامل قصير نسبيًا. تصل الاستجابة إلى أكثر من

النتائج

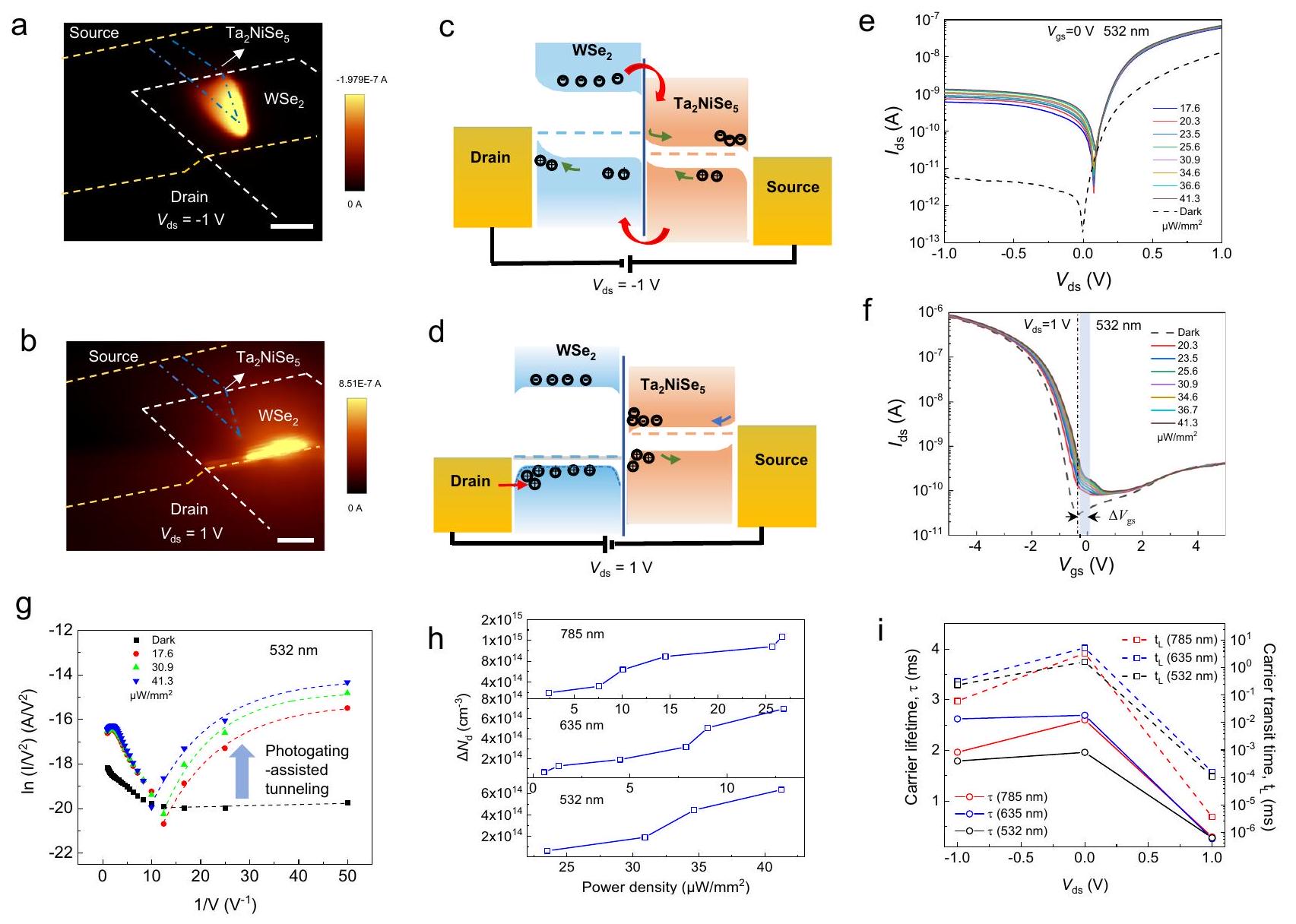

سلوك النقل القابل للتعديل حسب التحيز

الكالكوجينيدات الثلاثية،

التنقل المدعوم بالتصوير في

سمك، والذي يبلغ 60 نانومتر لـ

عمره. بالمقارنة، تلعب الفخاخ الداخلية للحاملين ذات مستويات الطاقة الضحلة والعميقة في المواد دورًا رئيسيًا تحت الجهد السالب، مما يتميز بعمر أطول نسبيًا. تقيس أوقات انتقال الحاملين وعمر الحاملين الضوئيين للجهاز تحت ظروف مختلفة.

علاقات سرعة الاستجابة

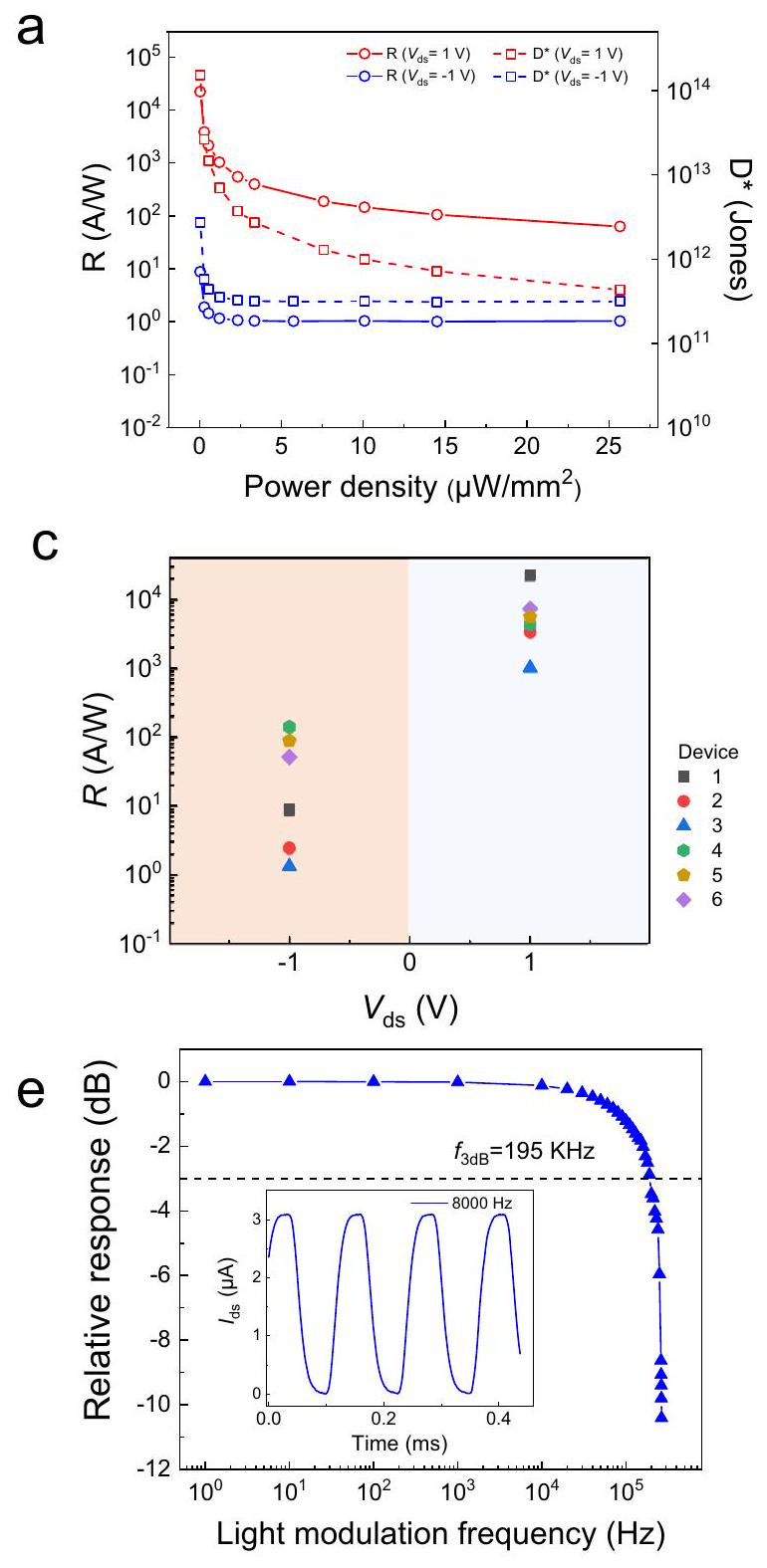

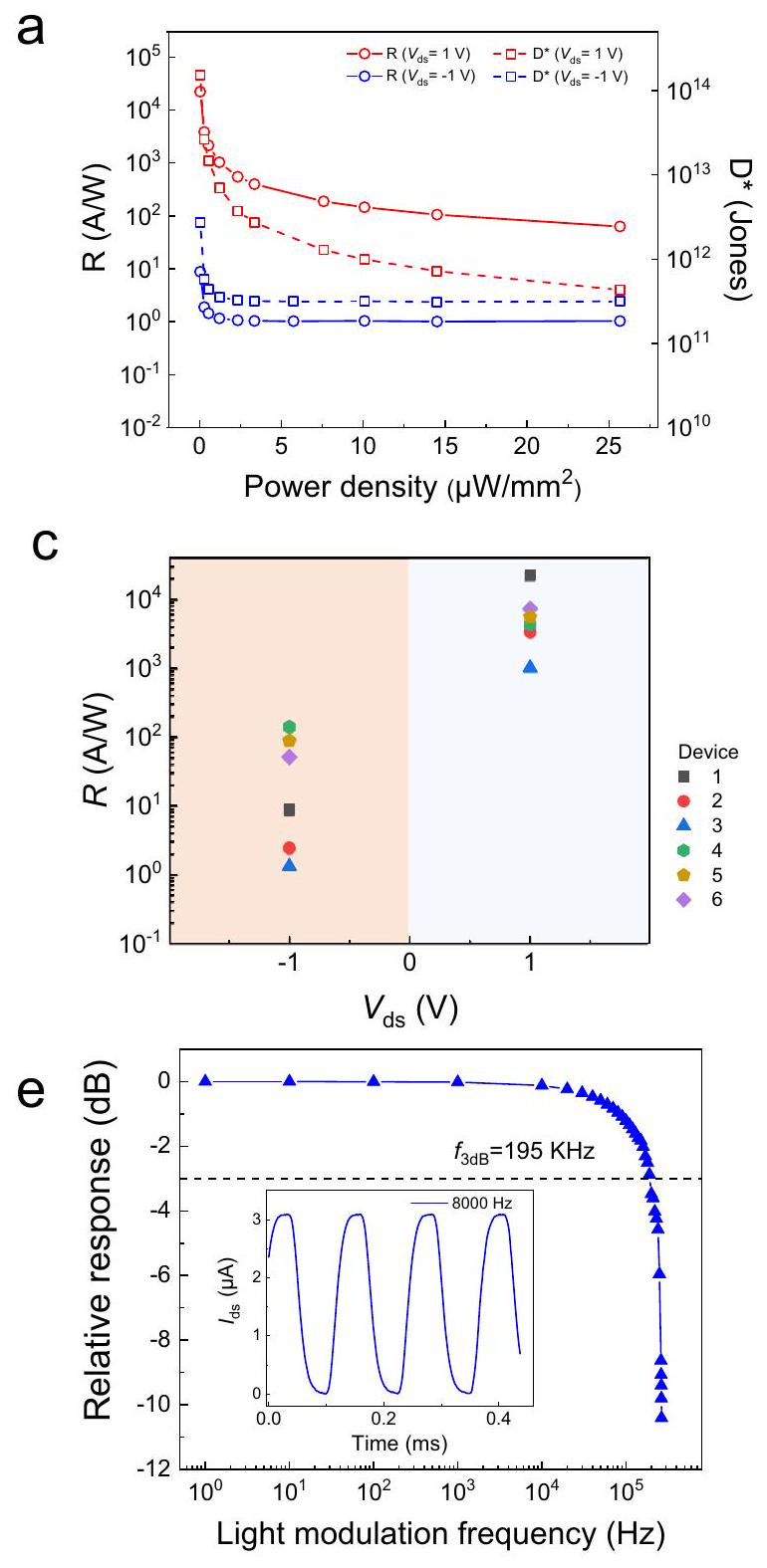

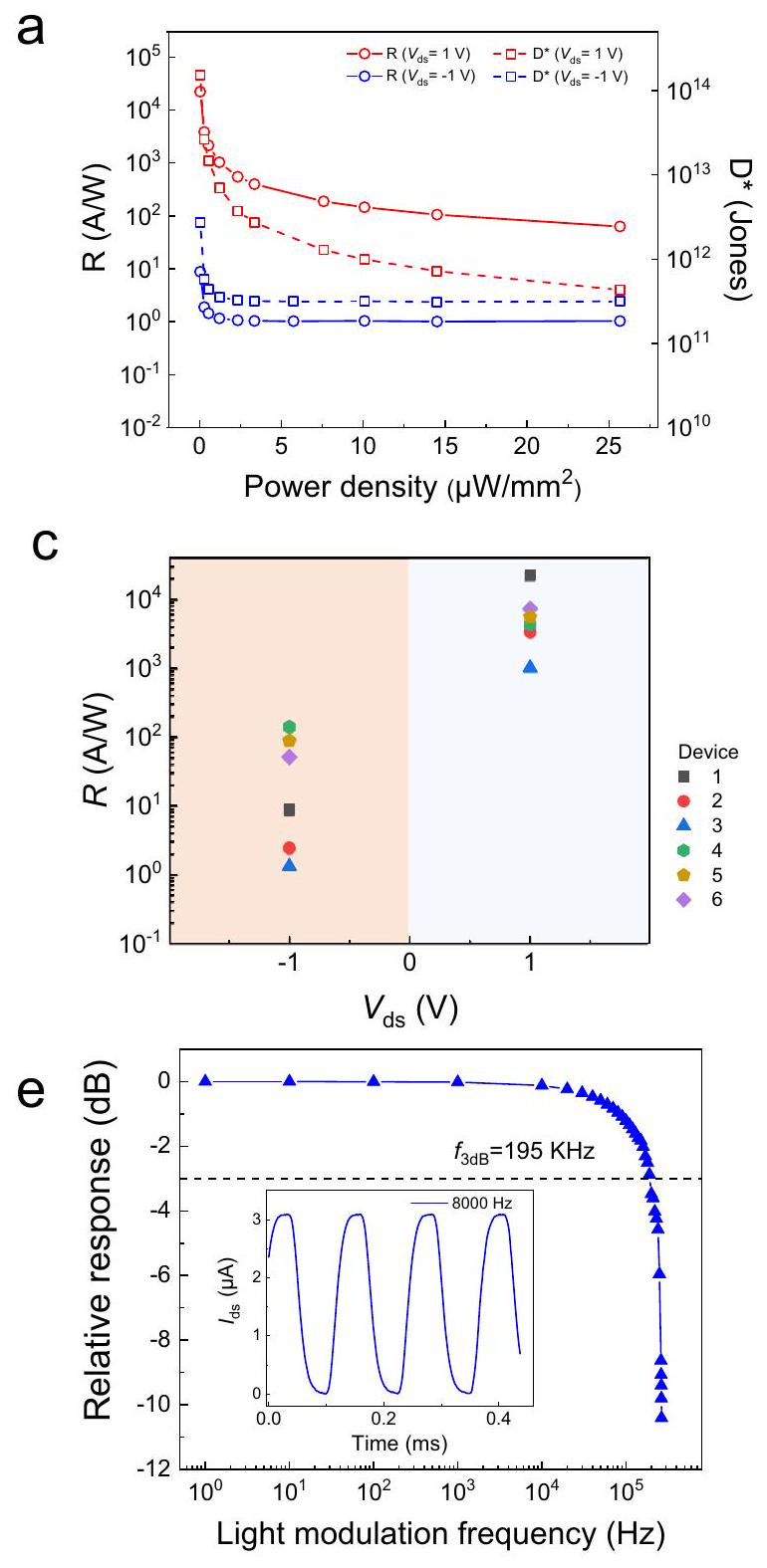

تم قياسه للجهاز 6. الإطار: التيار المعتمد على الزمن للجهاز.

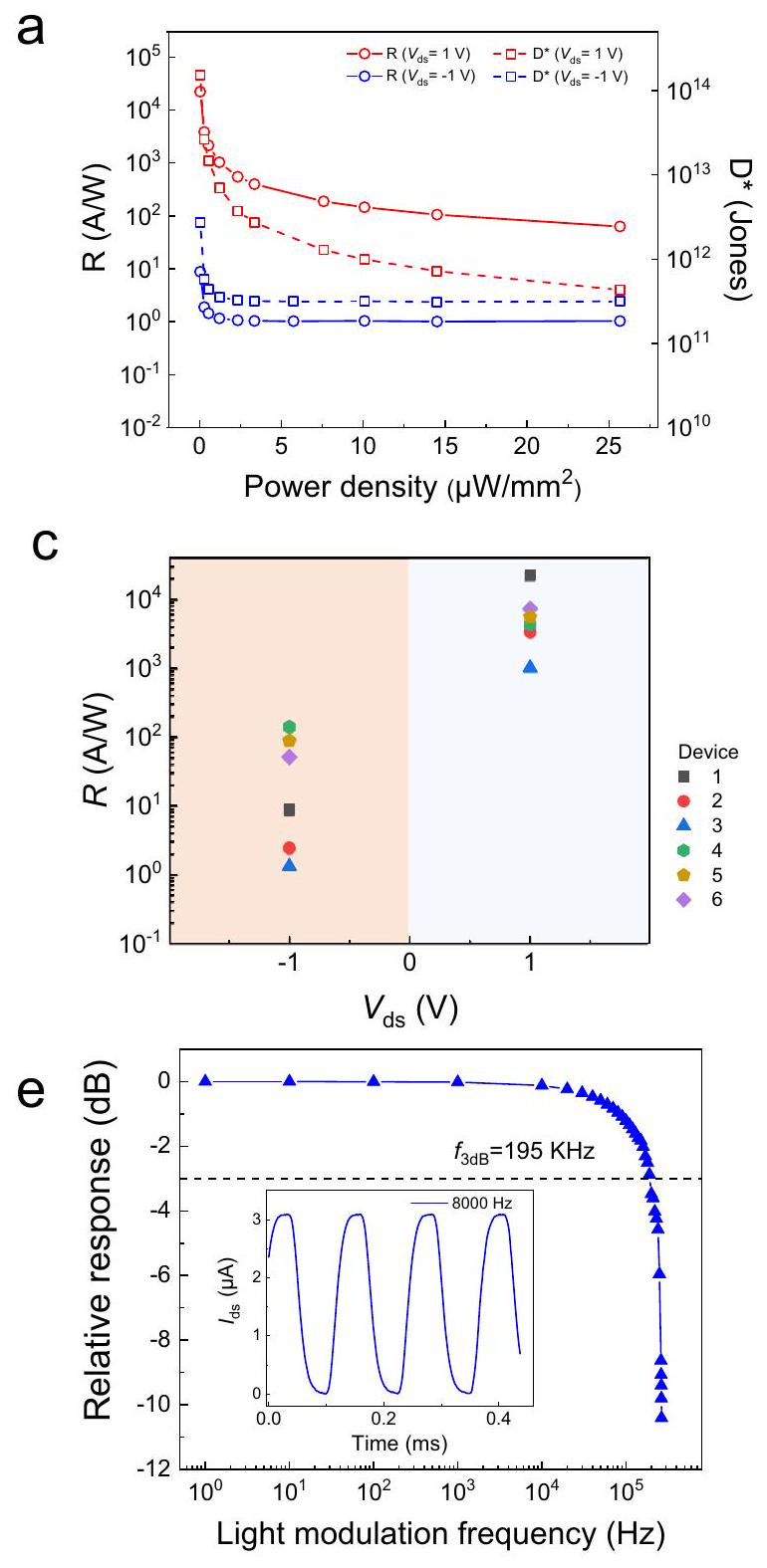

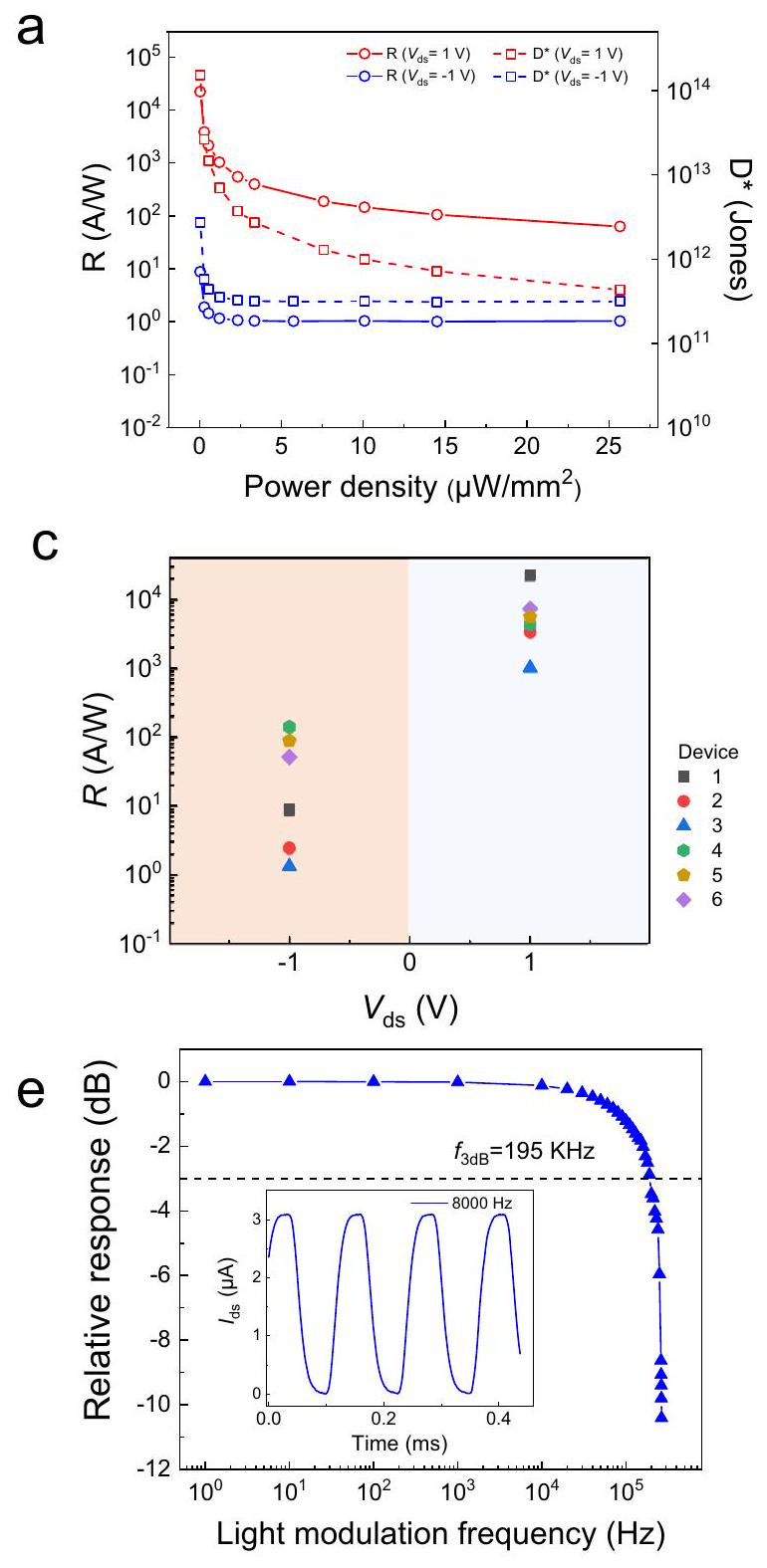

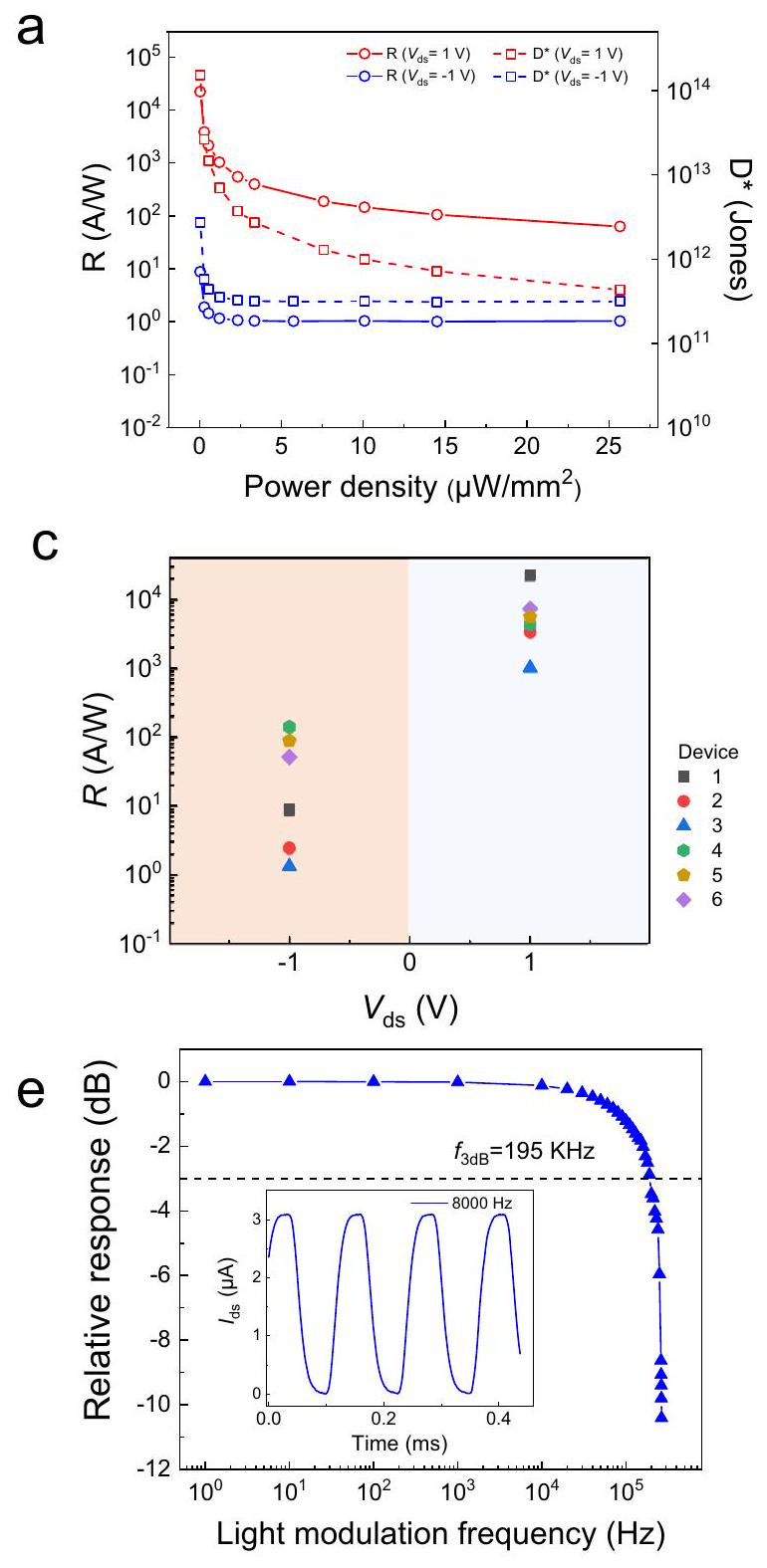

مستمدة من التيارات المظلمة ذات الزمن المحدد (الملاحظة التكميلية 11)، وتظهر نتائج الحساسية النوعية المقابلة اتجاهات مماثلة كما

تحسن الاستجابة بمقدار ثلاثة أوامر من حيث الحجم عند تطبيق جهد +1 فولت مقارنةً بجهد -1 فولت، كما يتحسن سرعة الاستجابة بمقدار أمر واحد (الشكل 3c، d) في الوقت نفسه. تكشف هذه الظواهر أن قيود السرعة في تأثير الفوتوغيت الناتج عن العيوب قد تم التخفيف منها عند الجهد الإيجابي.

(

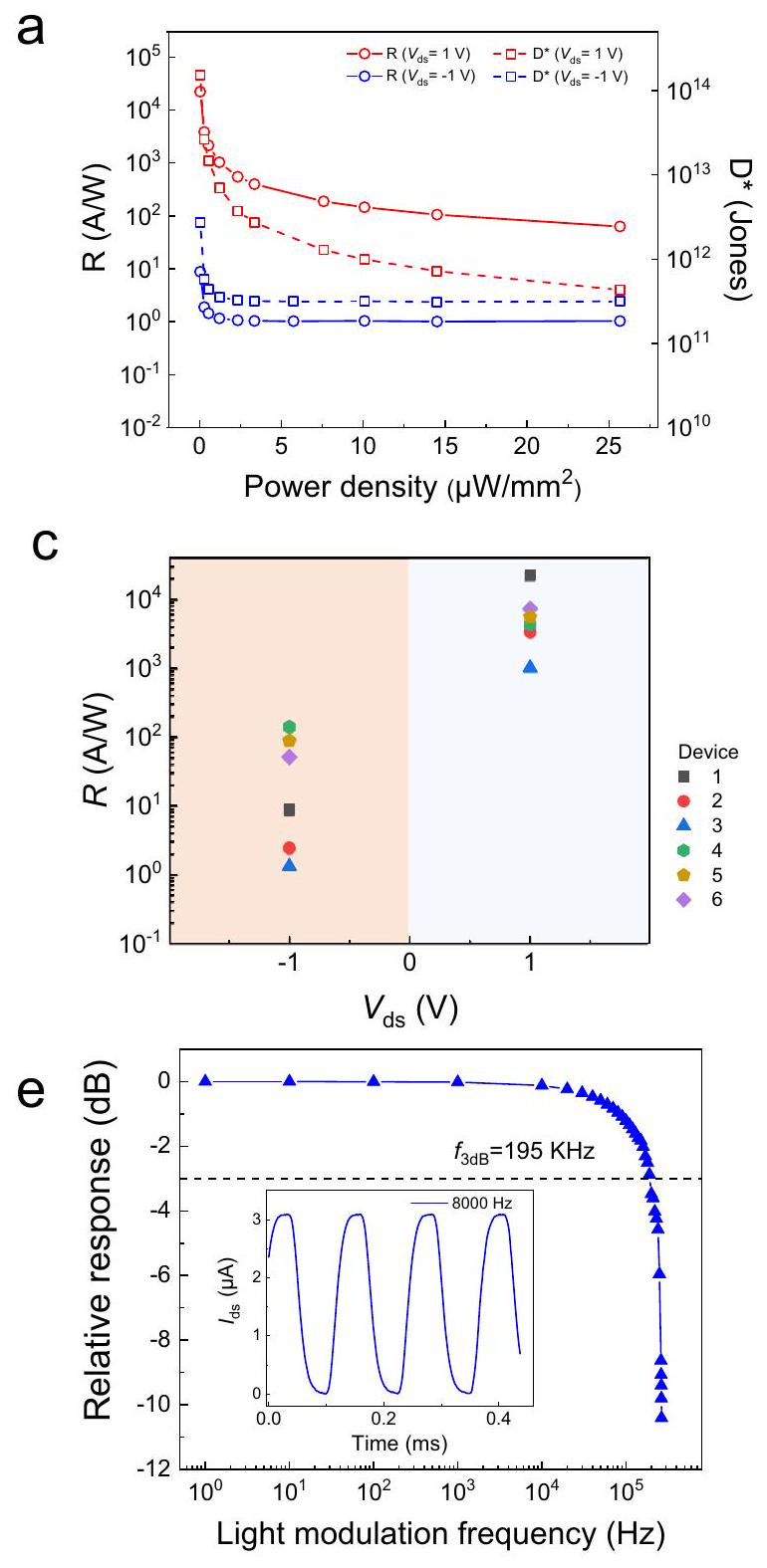

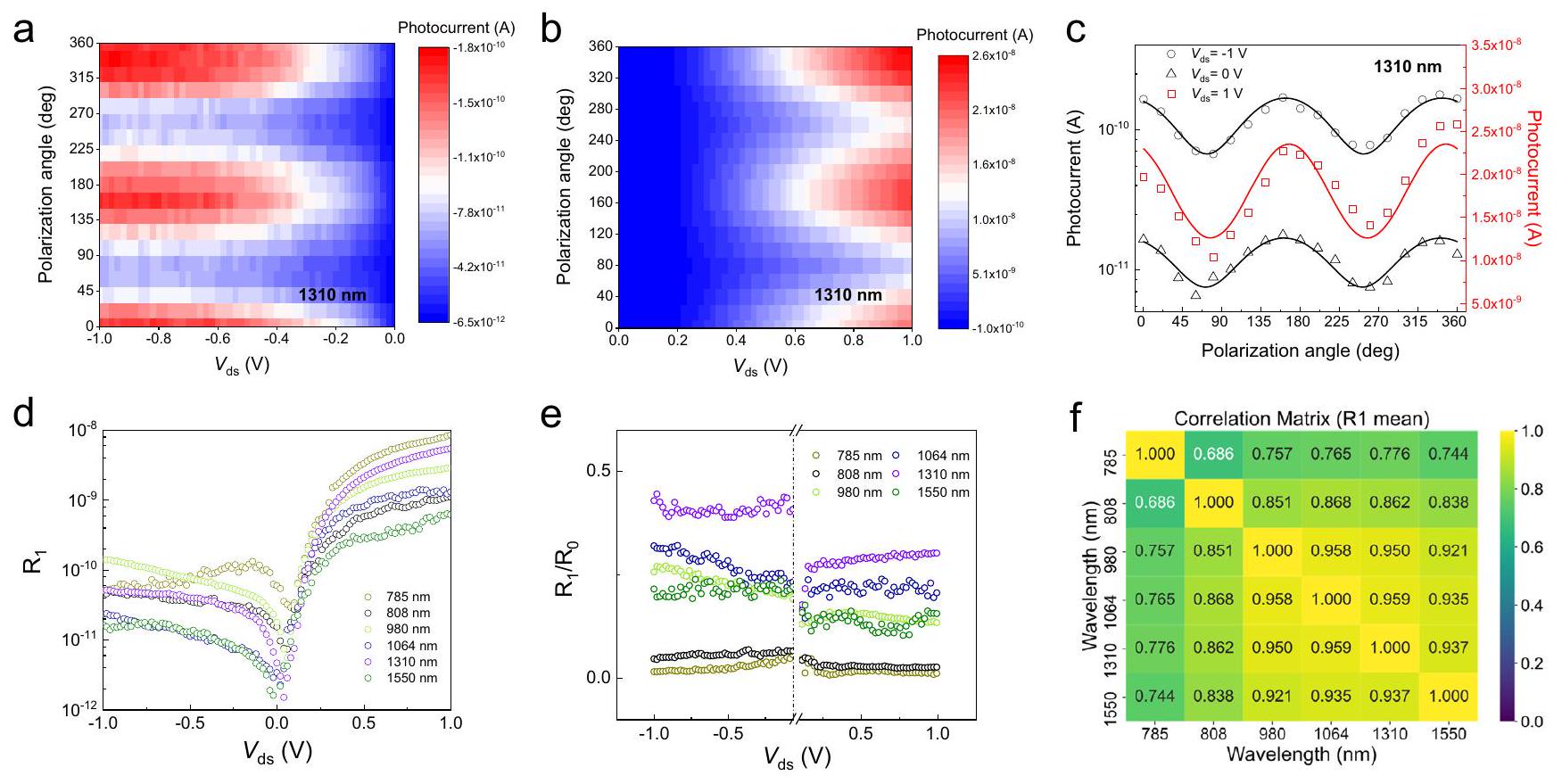

هناك طولان موجيان مختلفان. من الجدير بالذكر أن طريقتنا تتطلب فقط قطبين، وهو تكوين بسيط للتنفيذ العملي للبكسلات عالية الدقة.

نقاش

طرق

تصنيع الأجهزة

توصيف

القياسات البصرية الكهربائية

تم تأكيد منطقة بقعة الضوء الساقط استنادًا إلى مجهر بصري

رسم خرائط التيار الضوئي

توصيف حساس للاستقطاب

حسابات DFT

توفر البيانات

References

- Sun, C. et al. Single-chip microprocessor that communicates directly using light. Nature 528, 534-538(2015).

- Elshaari, A. W., Pernice, W., Srinivasan, K., Benson, O. & Zwiller, V. Hybrid integrated quantum photonic circuits. Nat. Photon. 14, 285-298 (2020).

- Maiti, R. et al. Strain-engineered high-responsivity

photodetector for silicon photonic integrated circuits. Nat. Photon. 14, 578-584 (2020). - Yang, Z., Albrow-Owen, T., Cai, W. & Hasan, T. Miniaturization of optical spectrometers. Science 371, eabeO722 (2021).

- Xu, X. et al. Self-calibrating programmable photonic integrated circuits. Nat. Photon. 16, 595-602 (2022).

- Tian, R. et al. Chip-integrated van der Waals PN heterojunction photodetector with low dark current and high responsivity. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 101 (2022).

- Hui, Y., Gomez-Diaz, J. S., Qian, Z., Alù, A. & Rinaldi, M. Plasmonic piezoelectric nanomechanical resonator for spectrally selective infrared sensing. Nat. Commun. 7, 11249 (2016).

- Qian, Z. et al. Zero-power infrared digitizers based on plasmonically enhanced micromechanical photoswitches. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 969-973 (2017).

- Wei, J. et al. Zero-bias mid-infrared graphene photodetectors with bulk photoresponse and calibration-free polarization detection. Nat. Commun. 11, 6404 (2020).

- Bullock, J. et al. Polarization-resolved black phosphorus/molybdenum disulfide mid-wave infrared photodiodes with high detectivity at room temperature. Nat. Photon. 12, 601-607 (2018).

- Akinwande, D. et al. Graphene and two-dimensional materials for silicon technology. Nature 573, 507-518 (2019).

- Romagnoli, M. et al. Graphene-based integrated photonics for nextgeneration datacom and telecom. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 392-414 (2018).

- Zhang, Z. et al. All-in-one two-dimensional retinomorphic hardware device for motion detection and recognition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 27-32 (2022).

- Lin, K.-T., Chen, H.-L., Lai, Y.-S. & Yu, C.-C. Silicon-based broadband antenna for high responsivity and polarization-insensitive photodetection at telecommunication wavelengths. Nat. Commun. 5, 3288 (2014).

- Lischke, S. et al. Ultra-fast germanium photodiode with 3-dB bandwidth of 265 GHz. Nat. Photon. 15, 925-931 (2021).

- Miyazaki, H. T. et al. Synchronously wired infrared antennas for resonant single-quantum-well photodetection up to room temperature. Nat. Commun. 11, 565 (2020).

- Novoselov, K. S., Mishchenko, A., Carvalho, A. & Castro Neto, A. H. 2D materials and van der Waals heterostructures. Science 353, aac9439 (2016).

- Guo, Z. et al. In-situ neutron-transmutation for substitutional doping in 2D layered indium selenide based phototransistor. eLight 2, 9 (2022).

- Lee, D. et al. Hyperbolic metamaterials: fusing artificial structures to natural 2D materials. eLight 2, 1 (2022).

- Konstantatos, G. et al. Hybrid graphene-quantum dot phototransistors with ultrahigh gain. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 363-368 (2012).

- Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer

. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497-501 (2013). - Huo, N. & Konstantatos, G. Ultrasensitive all-2D MoS

phototransistors enabled by an out-of-plane pn homojunction. Nat. Commun. 8, 572 (2017). - Lee, S.-J. et al. Lead halide perovskite sensitized

photodiodes with ultrahigh open circuit voltages. eLight 3, 8 (2023). - Buscema, M. et al. Photocurrent generation with two-dimensional van der Waals semiconductors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 3691-3718 (2015).

- Nikitskiy, I. et al. Integrating an electrically active colloidal quantum dot photodiode with a graphene phototransistor. Nat. Commun. 7, 11954 (2016).

- Ghosh, S., Varghese, A., Thakar, K., Dhara, S. & Lodha, S. Enhanced responsivity and detectivity of fast

phototransistor using electrostatically tunable in-plane lateral p-n homojunction. Nat. Commun. 12, 3336 (2021). - Flöry, N. et al. Waveguide-integrated van der Waals heterostructure photodetector at telecom wavelengths with high speed and high responsivity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 118-124 (2020).

- Jiang, H. et al. Ultrasensitive and fast photoresponse in graphene/ silicon-on-insulator hybrid structure by manipulating the photogating effect. Nanophotonics 9, 3663-3672 (2020).

- Cao, G., Chen, G. & Li, X. Core-shell single-nanowire photodetector with radial carrier transport: an opportunity to break the

responsivity-speed trade-off. Adv. Electron. Mater. 7, 2000920 (2021). - Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562, 101-104 (2018).

- International technology roadmap for semiconductors. http:// www.itrs.net/.

- Wei, J., Xu, C., Dong, B., Qiu, C.-W. & Lee, C. Mid-infrared semimetal polarization detectors with configurable polarity transition. Nat. Photon. 15, 614-621 (2021).

- Ni, Y. et al. Computational spectropolarimetry with a tunable liquid crystal metasurface. eLight 2, 23 (2022).

- Nakano, A. et al. Antiferroelectric distortion with anomalous phonon softening in the excitonic insulator

. Phys. Rev. B. 98, 045139 (2018). - Di Salvo, F. J. et al. Physical and structural properties of the new layered compounds

and . J. Less Common Met. 116, 51-61 (1986). - Watson, M. D. et al. Band hybridization at the semimetalsemiconductor transition of

enabled by mirror-symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013236 (2020). - Qiao, J. et al. Highly in-plane anisotropic two-dimensional ternary

for polarization-sensitive photodetectors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 17948-17956 (2021). - Jog, H., Harnagea, L., Mele Eugene, J. & Agarwal, R. Exchange coupling-mediated broken symmetries in

revealed from quadrupolar circular photogalvanic effect. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl9020 (2022). - Lu, Y. F. et al. Zero-gap semiconductor to excitonic insulator transition in

. Nat. Commun. 8, 14408 (2017). - Qiao, J. et al. Perovskite quantum dot-

mixed-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures for high-performance near-infrared photodetection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2110706 (2022). - Zhou, H. et al. Large area growth and electrical properties of p-type

atomic layers. Nano Lett. 15, 709-713 (2015). - Jung, Y. et al. Transferred via contacts as a platform for ideal twodimensional transistors. Nat. Electron. 2, 187-194 (2019).

- Hong,

. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer in atomically thin heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 682-686 (2014). - Li, L. et al. Ternary

flakes for a high-performance infrared photodetector. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 8281-8289 (2016). - Zhou, X. et al. Tunneling diode based on

heterostructure incorporating high detectivity and responsivity. Adv. Mater. 30, 1703286 (2018). - Liu, C.-H., Chang, Y.-C., Norris, T. B. & Zhong, Z. Graphene photodetectors with ultra-broadband and high responsivity at room temperature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 273-278 (2014).

- Wang, Q. et al. Nonvolatile infrared memory in

van der Waals heterostructures. Sci. Adv. 4, eaap7916 (2018). - Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin

: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phy. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010). - Zhu, X., Li, F., Wang, Y., Qiao, M. & Li, Y.

monolayer: a novel two-dimensional material with excellent electronic, transport, and optical properties. J. Mater. Chem. C. 6, 4494-4500 (2018). - McDonnell, S. et al. Hole contacts on transition metal dichalcogenides: interface chemistry and band alignments. ACS Nano 8, 6265-6272 (2014).

- Nassiri Nazif, K. et al. High-specific-power flexible transition metal dichalcogenide solar cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 7034 (2021).

- Zhang, Y. et al. Ultra-broadband photodetection based on twodimensional layered

with strong anisotropy and high responsivity. Mater. Des. 208, 109894 (2021). - Tao, L., Chen, Z., Li, X., Yan, K. & Xu, J.-B. Hybrid graphene tunneling photoconductor with interface engineering towards fast photoresponse and high responsivity. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 1, 19 (2017).

- Wu, F. et al. AsP/InSe van der Waals tunneling heterojunctions with ultrahigh reverse rectification ratio and high photosensitivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1900314 (2019).

- Sze, S. M., Li, Y., Ng, K. K. Physics of semiconductor devices (John Wiley & Sons, 2021).

- Seeger K. Semiconductor physics (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

- Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Photodetectors based on graphene, other two-dimensional materials and hybrid systems. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 780-793 (2014).

- Feng, S. et al. An ultrasensitive molybdenum-based double-heterojunction phototransistor. Nat. Commun. 12, 4094 (2021).

- Liu, Y., Stradins, P., Wei, S.-H. Van der Waals metal-semiconductor junction: weak Fermi level pinning enables effective tuning of Schottky barrier. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600069 (2016).

- Kong, L. et al. Doping-free complementary

circuit via van der Waals metal integration. Nat. Commun. 11, 1866 (2020). - Yang, Z. et al. Single-nanowire spectrometers. Science 365, 1017-1020 (2019).

- Yuan, S., Naveh, D., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Xia, F. A wavelength-scale black phosphorus spectrometer. Nat. Photon. 15, 601-607 (2021).

- Ma, C. et al. Intelligent infrared sensing enabled by tunable moiré quantum geometry. Nature 604, 266-272 (2022).

- Wang, F., Zhang, T., Xie, R., Wang, Z. & Hu, W. How to characterize figures of merit of two-dimensional photodetectors. Nat. Commun. 14, 2224 (2023).

- Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 59, 1758-1775 (1999).

- Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

- Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phy. Rev. Lett. 78, 1396-1396 (1997).

- Fox, M. Optical properties of solids. Am. J. Phys. 70, 1269-1270 (2002).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44482-7.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

المختبر الوطني الرئيسي للتألق والتطبيقات، معهد تشانغتشون للبصريات والميكانيكا الدقيقة والفيزياء، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، جيلين 130033 تشانغتشون، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. جامعة الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم (UCAS)، 100049 بكين، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. قسم الهندسة الكهربائية وهندسة الحاسوب، الجامعة الوطنية في سنغافورة، سنغافورة 117583، سنغافورة. مدرسة علوم وهندسة البصريات الإلكترونية، جامعة علوم وتكنولوجيا الإلكترونيات في الصين، 611731 تشنغدو، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. معهد المواد الذكية الوظيفية، الجامعة الوطنية في سنغافورة، سنغافورة 117544، سنغافورة. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: مينغشيو ليو، جينغشوان وي، ليوجيان تشي. البريد الإلكتروني:lidb@ciomp.ac.cn; chengwei.qiu@nus.edu.sg; lishaojuan@ciomp.ac.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44482-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38167874

Publication Date: 2024-01-02

Photogating-assisted tunneling boosts the responsivity and speed of heterogeneous

Accepted: 14 December 2023

Published online: 02 January 2024

Abstract

Photogating effect is the dominant mechanism of most high-responsivity twodimensional (2D) material photodetectors. However, the ultrahigh responsivities in those devices are intrinsically at the cost of very slow response speed. In this work, we report a

lines, and the rich opportunities provided by atomically sharp heterointerfaces

detector. a Illustration of the trade-off between the responsivity and speed in 2D materials photodetectors. To overcome the trade-off and enter the upper left area, we conventionally need to increase the power consumption, denoted by the red shade. The energy band diagram on the lower left side is the photovoltaic mode of photodetector, the middle is the photoconductive mode, and the upper right side belongs to photogating mode. Where

to the tunneling enabled short transit time, our device allows high responsivity even at a relatively short carrier lifetime. The responsivity reaches above

Results

Bias-tunable transport behavior of

ternary chalcogenides,

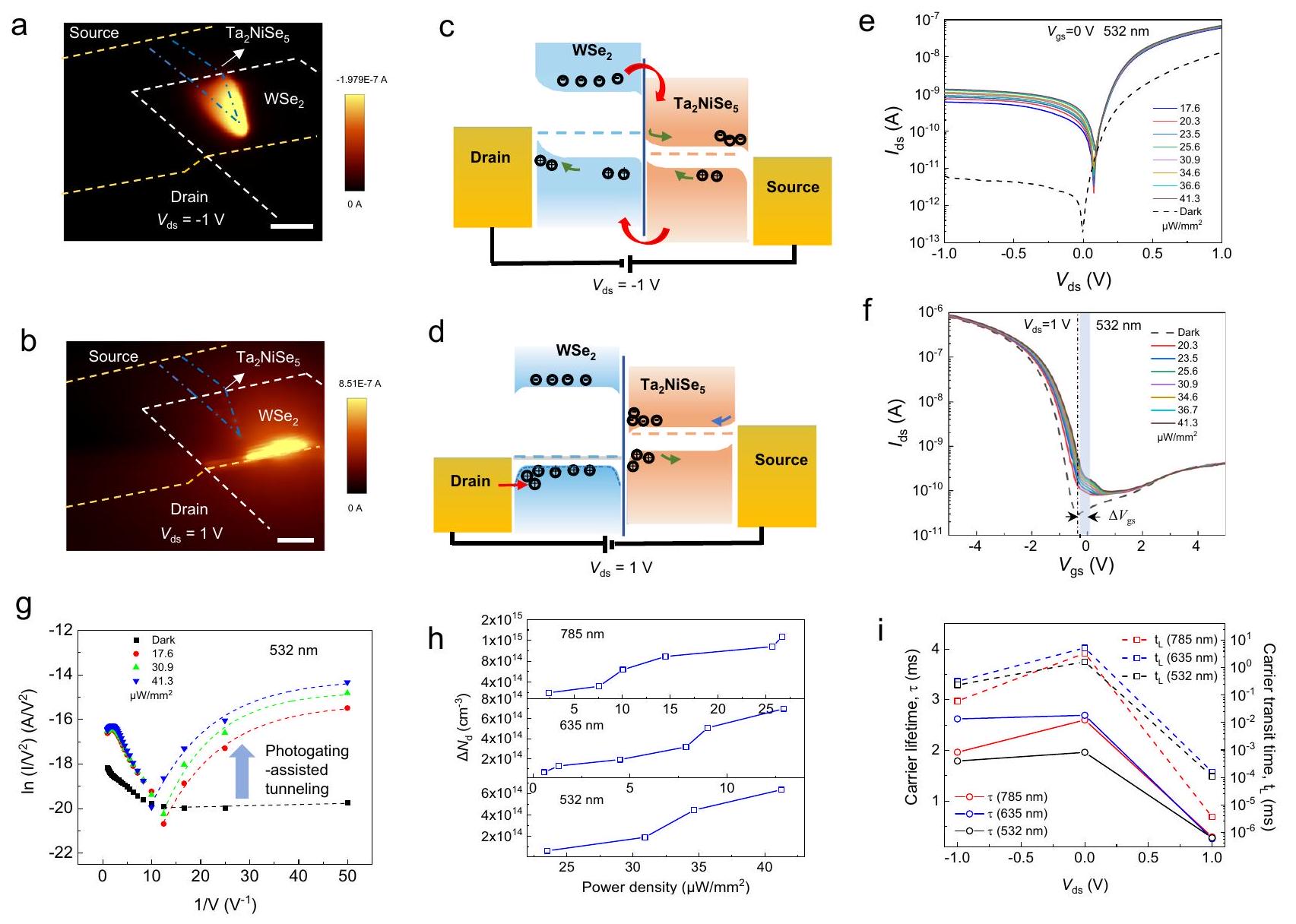

Photogating-assisted tunneling in

thickness, which is 60 nm for

lifetime. In comparison, the intrinsic carrier traps with both shallow and deep energy levels in the materials plays a dominant role under negative bias, featuring a relatively longer lifetime. The measurements of the carrier transit time and photocarrier lifetime of the device under different

Responsivity-speed relations of

measured for Device 6. Inset: The time-dependent current of the device. The

derived from the time-resolved dark currents (Supplementary Note 11), and the corresponding specific detectivity results display similar trends as

responsivity improves by three orders of magnitude when +1 V bias is applied compared to -1 V bias, the response speed also improves by an order of magnitude (Fig. 3c, d), simultaneously. These phenomena reveal that the speed constrains in defects-induced photogating effect is mitigated at positive

(

are two different wavelengths. It is worth noting that our method only requires two electrodes, a simple configuration for practical implementation of high-resolution pixels.

Discussion

Methods

Device fabrication

Characterization of

Optoelectrical measurements

spot area of incident light was confirmed based on an optical microscope

Photocurrent mapping

Polarization-sensitive characterization

DFT calculations

Data availability

References

- Sun, C. et al. Single-chip microprocessor that communicates directly using light. Nature 528, 534-538(2015).

- Elshaari, A. W., Pernice, W., Srinivasan, K., Benson, O. & Zwiller, V. Hybrid integrated quantum photonic circuits. Nat. Photon. 14, 285-298 (2020).

- Maiti, R. et al. Strain-engineered high-responsivity

photodetector for silicon photonic integrated circuits. Nat. Photon. 14, 578-584 (2020). - Yang, Z., Albrow-Owen, T., Cai, W. & Hasan, T. Miniaturization of optical spectrometers. Science 371, eabeO722 (2021).

- Xu, X. et al. Self-calibrating programmable photonic integrated circuits. Nat. Photon. 16, 595-602 (2022).

- Tian, R. et al. Chip-integrated van der Waals PN heterojunction photodetector with low dark current and high responsivity. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 101 (2022).

- Hui, Y., Gomez-Diaz, J. S., Qian, Z., Alù, A. & Rinaldi, M. Plasmonic piezoelectric nanomechanical resonator for spectrally selective infrared sensing. Nat. Commun. 7, 11249 (2016).

- Qian, Z. et al. Zero-power infrared digitizers based on plasmonically enhanced micromechanical photoswitches. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 969-973 (2017).

- Wei, J. et al. Zero-bias mid-infrared graphene photodetectors with bulk photoresponse and calibration-free polarization detection. Nat. Commun. 11, 6404 (2020).

- Bullock, J. et al. Polarization-resolved black phosphorus/molybdenum disulfide mid-wave infrared photodiodes with high detectivity at room temperature. Nat. Photon. 12, 601-607 (2018).

- Akinwande, D. et al. Graphene and two-dimensional materials for silicon technology. Nature 573, 507-518 (2019).

- Romagnoli, M. et al. Graphene-based integrated photonics for nextgeneration datacom and telecom. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 392-414 (2018).

- Zhang, Z. et al. All-in-one two-dimensional retinomorphic hardware device for motion detection and recognition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 27-32 (2022).

- Lin, K.-T., Chen, H.-L., Lai, Y.-S. & Yu, C.-C. Silicon-based broadband antenna for high responsivity and polarization-insensitive photodetection at telecommunication wavelengths. Nat. Commun. 5, 3288 (2014).

- Lischke, S. et al. Ultra-fast germanium photodiode with 3-dB bandwidth of 265 GHz. Nat. Photon. 15, 925-931 (2021).

- Miyazaki, H. T. et al. Synchronously wired infrared antennas for resonant single-quantum-well photodetection up to room temperature. Nat. Commun. 11, 565 (2020).

- Novoselov, K. S., Mishchenko, A., Carvalho, A. & Castro Neto, A. H. 2D materials and van der Waals heterostructures. Science 353, aac9439 (2016).

- Guo, Z. et al. In-situ neutron-transmutation for substitutional doping in 2D layered indium selenide based phototransistor. eLight 2, 9 (2022).

- Lee, D. et al. Hyperbolic metamaterials: fusing artificial structures to natural 2D materials. eLight 2, 1 (2022).

- Konstantatos, G. et al. Hybrid graphene-quantum dot phototransistors with ultrahigh gain. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 363-368 (2012).

- Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer

. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497-501 (2013). - Huo, N. & Konstantatos, G. Ultrasensitive all-2D MoS

phototransistors enabled by an out-of-plane pn homojunction. Nat. Commun. 8, 572 (2017). - Lee, S.-J. et al. Lead halide perovskite sensitized

photodiodes with ultrahigh open circuit voltages. eLight 3, 8 (2023). - Buscema, M. et al. Photocurrent generation with two-dimensional van der Waals semiconductors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 3691-3718 (2015).

- Nikitskiy, I. et al. Integrating an electrically active colloidal quantum dot photodiode with a graphene phototransistor. Nat. Commun. 7, 11954 (2016).

- Ghosh, S., Varghese, A., Thakar, K., Dhara, S. & Lodha, S. Enhanced responsivity and detectivity of fast

phototransistor using electrostatically tunable in-plane lateral p-n homojunction. Nat. Commun. 12, 3336 (2021). - Flöry, N. et al. Waveguide-integrated van der Waals heterostructure photodetector at telecom wavelengths with high speed and high responsivity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 118-124 (2020).

- Jiang, H. et al. Ultrasensitive and fast photoresponse in graphene/ silicon-on-insulator hybrid structure by manipulating the photogating effect. Nanophotonics 9, 3663-3672 (2020).

- Cao, G., Chen, G. & Li, X. Core-shell single-nanowire photodetector with radial carrier transport: an opportunity to break the

responsivity-speed trade-off. Adv. Electron. Mater. 7, 2000920 (2021). - Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562, 101-104 (2018).

- International technology roadmap for semiconductors. http:// www.itrs.net/.

- Wei, J., Xu, C., Dong, B., Qiu, C.-W. & Lee, C. Mid-infrared semimetal polarization detectors with configurable polarity transition. Nat. Photon. 15, 614-621 (2021).

- Ni, Y. et al. Computational spectropolarimetry with a tunable liquid crystal metasurface. eLight 2, 23 (2022).

- Nakano, A. et al. Antiferroelectric distortion with anomalous phonon softening in the excitonic insulator

. Phys. Rev. B. 98, 045139 (2018). - Di Salvo, F. J. et al. Physical and structural properties of the new layered compounds

and . J. Less Common Met. 116, 51-61 (1986). - Watson, M. D. et al. Band hybridization at the semimetalsemiconductor transition of

enabled by mirror-symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013236 (2020). - Qiao, J. et al. Highly in-plane anisotropic two-dimensional ternary

for polarization-sensitive photodetectors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 17948-17956 (2021). - Jog, H., Harnagea, L., Mele Eugene, J. & Agarwal, R. Exchange coupling-mediated broken symmetries in

revealed from quadrupolar circular photogalvanic effect. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl9020 (2022). - Lu, Y. F. et al. Zero-gap semiconductor to excitonic insulator transition in

. Nat. Commun. 8, 14408 (2017). - Qiao, J. et al. Perovskite quantum dot-

mixed-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures for high-performance near-infrared photodetection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2110706 (2022). - Zhou, H. et al. Large area growth and electrical properties of p-type

atomic layers. Nano Lett. 15, 709-713 (2015). - Jung, Y. et al. Transferred via contacts as a platform for ideal twodimensional transistors. Nat. Electron. 2, 187-194 (2019).

- Hong,

. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer in atomically thin heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 682-686 (2014). - Li, L. et al. Ternary

flakes for a high-performance infrared photodetector. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 8281-8289 (2016). - Zhou, X. et al. Tunneling diode based on

heterostructure incorporating high detectivity and responsivity. Adv. Mater. 30, 1703286 (2018). - Liu, C.-H., Chang, Y.-C., Norris, T. B. & Zhong, Z. Graphene photodetectors with ultra-broadband and high responsivity at room temperature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 273-278 (2014).

- Wang, Q. et al. Nonvolatile infrared memory in

van der Waals heterostructures. Sci. Adv. 4, eaap7916 (2018). - Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin

: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phy. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010). - Zhu, X., Li, F., Wang, Y., Qiao, M. & Li, Y.

monolayer: a novel two-dimensional material with excellent electronic, transport, and optical properties. J. Mater. Chem. C. 6, 4494-4500 (2018). - McDonnell, S. et al. Hole contacts on transition metal dichalcogenides: interface chemistry and band alignments. ACS Nano 8, 6265-6272 (2014).

- Nassiri Nazif, K. et al. High-specific-power flexible transition metal dichalcogenide solar cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 7034 (2021).

- Zhang, Y. et al. Ultra-broadband photodetection based on twodimensional layered

with strong anisotropy and high responsivity. Mater. Des. 208, 109894 (2021). - Tao, L., Chen, Z., Li, X., Yan, K. & Xu, J.-B. Hybrid graphene tunneling photoconductor with interface engineering towards fast photoresponse and high responsivity. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 1, 19 (2017).

- Wu, F. et al. AsP/InSe van der Waals tunneling heterojunctions with ultrahigh reverse rectification ratio and high photosensitivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1900314 (2019).

- Sze, S. M., Li, Y., Ng, K. K. Physics of semiconductor devices (John Wiley & Sons, 2021).

- Seeger K. Semiconductor physics (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

- Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Photodetectors based on graphene, other two-dimensional materials and hybrid systems. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 780-793 (2014).

- Feng, S. et al. An ultrasensitive molybdenum-based double-heterojunction phototransistor. Nat. Commun. 12, 4094 (2021).

- Liu, Y., Stradins, P., Wei, S.-H. Van der Waals metal-semiconductor junction: weak Fermi level pinning enables effective tuning of Schottky barrier. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600069 (2016).

- Kong, L. et al. Doping-free complementary

circuit via van der Waals metal integration. Nat. Commun. 11, 1866 (2020). - Yang, Z. et al. Single-nanowire spectrometers. Science 365, 1017-1020 (2019).

- Yuan, S., Naveh, D., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Xia, F. A wavelength-scale black phosphorus spectrometer. Nat. Photon. 15, 601-607 (2021).

- Ma, C. et al. Intelligent infrared sensing enabled by tunable moiré quantum geometry. Nature 604, 266-272 (2022).

- Wang, F., Zhang, T., Xie, R., Wang, Z. & Hu, W. How to characterize figures of merit of two-dimensional photodetectors. Nat. Commun. 14, 2224 (2023).

- Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 59, 1758-1775 (1999).

- Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

- Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phy. Rev. Lett. 78, 1396-1396 (1997).

- Fox, M. Optical properties of solids. Am. J. Phys. 70, 1269-1270 (2002).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44482-7.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© The Author(s) 2024

State Key Laboratory of Luminescence and Applications, Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Jilin 130033 Changchun, PR China. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (UCAS), 100049 Beijing, PR China. Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117583, Singapore. School of Optoelectronic Science and Engineering, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, 611731 Chengdu, PR China. Institute for Functional Intelligent Materials, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117544, Singapore. These authors contributed equally: Mingxiu Liu, Jingxuan Wei, Liujian Qi. e-mail: lidb@ciomp.ac.cn; chengwei.qiu@nus.edu.sg; lishaojuan@ciomp.ac.cn