DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-024-02838-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39849504

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-23

تعزيز التواصل بين الطبيب والمريض باستخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة لتفسير تقارير الأمراض

الملخص

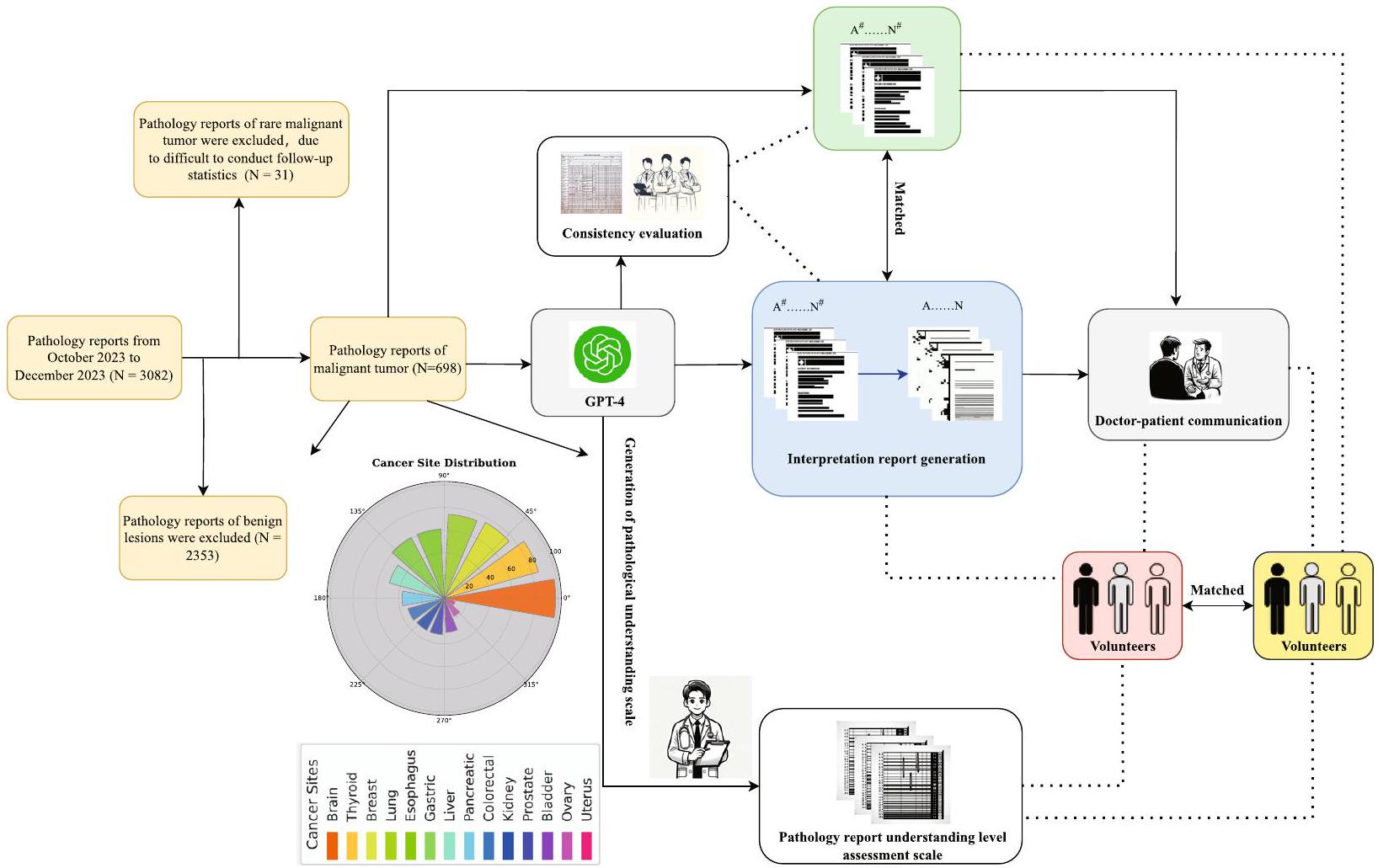

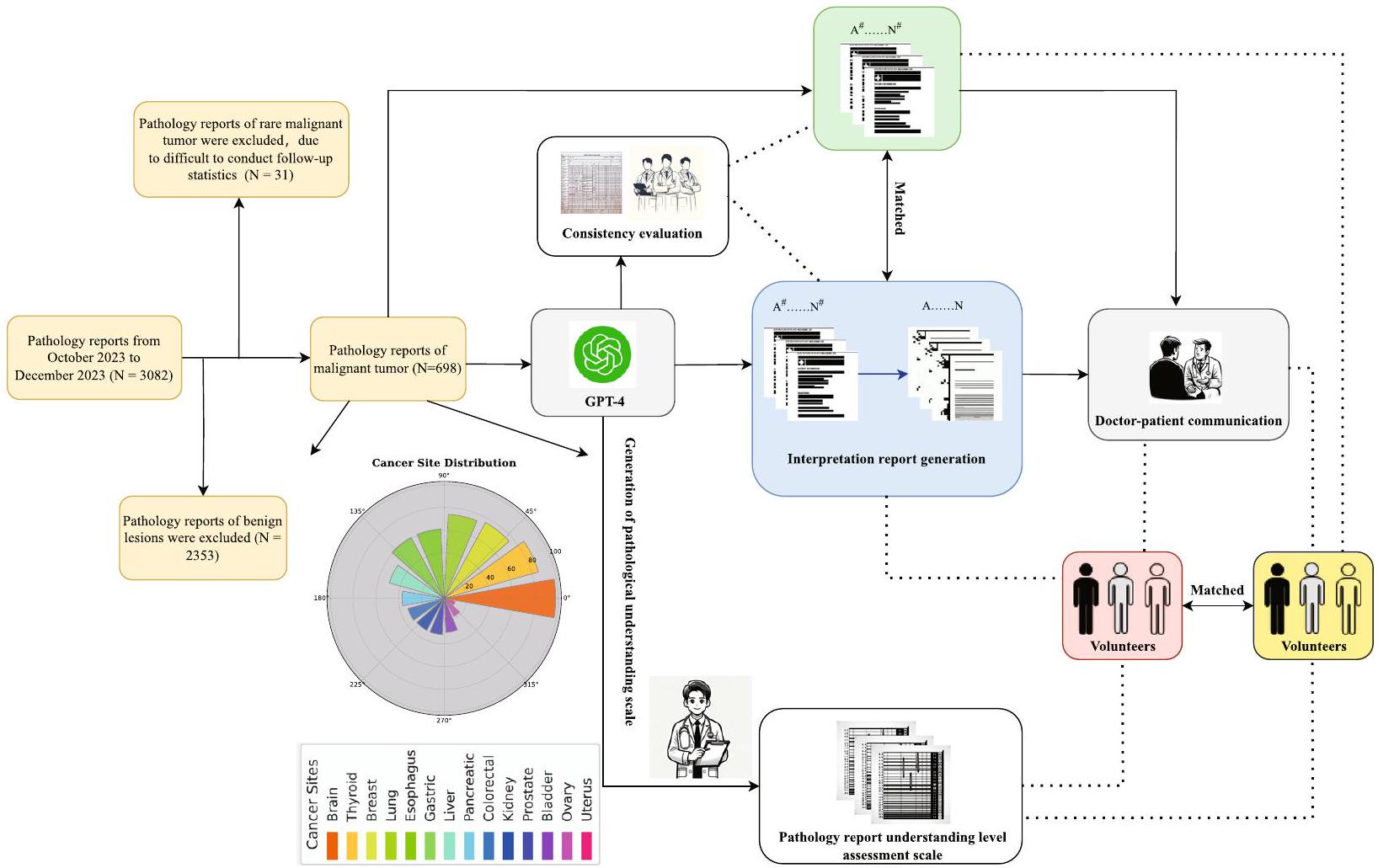

الخلفية: تُستخدم نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) بشكل متزايد في بيئات الرعاية الصحية. تقارير علم الأمراض بعد الجراحة، التي تعتبر ضرورية لتشخيص وتحديد استراتيجيات العلاج للمرضى الجراحيين، غالبًا ما تتضمن بيانات معقدة قد تكون صعبة الفهم للمرضى. يمكن أن تؤثر هذه التعقيدات سلبًا على جودة التواصل بين الأطباء والمرضى حول تشخيصهم وخيارات العلاج، مما قد يؤثر على نتائج المرضى مثل فهمهم لحالتهم، والامتثال للعلاج، والرضا العام. المواد والأساليب: قامت هذه الدراسة بتحليل تقارير علم الأمراض النصية من أربعة مستشفيات بين أكتوبر وديسمبر 2023، مع التركيز على الأورام الخبيثة. باستخدام GPT-4، قمنا بتطوير قوالب لتقارير علم الأمراض التفسيرية (IPRs) لتبسيط المصطلحات الطبية لغير المتخصصين. قمنا باختيار 70 تقريرًا بشكل عشوائي لتوليد هذه القوالب وقيمنا 628 تقريرًا المتبقية من حيث الاتساق وقابلية القراءة. تم قياس فهم المرضى باستخدام مقياس تقييم مستوى فهم تقارير علم الأمراض المصمم خصيصًا، والذي تم تقييمه من قبل متطوعين ليس لديهم خلفية طبية. كما سجلت الدراسة وقت التواصل بين الطبيب والمريض ومستويات فهم المرضى قبل وبعد استخدام IPRs. النتائج: من بين 698 تقريرًا لعلم الأمراض تم تحليلها، حسنت الترجمة من خلال LLMs بشكل كبير من قابلية القراءة وفهم المرضى. انخفض متوسط وقت التواصل بين الأطباء والمرضى بأكثر من 70%، من 35 إلى

المقدمة

في السنوات الأخيرة، حققت LLMs تقدمًا كبيرًا في فهم وتوليد اللغة الطبيعية، مما يظهر قدرتها على تحليل وإعادة كتابة النصوص الطبية بطريقة أكثر فهمًا لغير المتخصصين [7، 8]. على سبيل المثال، أظهر ستايميتز وآخرون (2024) أن روبوتات الدردشة LLM يمكن أن تحسن بشكل كبير من قابلية قراءة تقارير علم الأمراض بينما تسلط الضوء أيضًا على بعض القيود مثل عدم الدقة والهلاوس في التقارير المولدة [9]. تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى استكشاف إمكانية استخدام LLMs لتعزيز كفاءة التواصل بين الطبيب والمريض، خاصة من خلال أتمتة ترجمة محتوى تقارير علم الأمراض إلى لغة صديقة للمرضى. تهدف هذه الطريقة إلى تقليل الحواجز المعرفية أمام المعلومات الطبية وتعزيز فهم أفضل للمرضى لحالاتهم الصحية.

باستخدام تقارير علم الأمراض الروتينية بعد الجراحة في الأورام، صممت هذه الدراسة إطار عمل عالمي لتفسير تقارير علم الأمراض من خلال LLMs ووضعت مقياس تقييم مستوى فهم تقارير علم الأمراض المقابل. تم ذلك لاستكشاف الإمكانيات والتأثيرات الفعلية لـ LLMs في تعزيز كفاءة التواصل بين الطبيب والمريض.

لذلك، استجابةً لهذه التحديات، تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى استكشاف إمكانية استخدام LLMs لتعزيز التواصل بين الطبيب والمريض، خاصة

من خلال تبسيط محتوى تقارير علم الأمراض إلى لغة صديقة للمرضى، وتقديم رؤى حول كيفية دمج LLMs في الممارسة السريرية لتحسين كفاءة التواصل [10، 11].

من خلال تحسين قابلية قراءة تقارير علم الأمراض، نأمل في تعزيز فهم أفضل للمرضى لحالاتهم الصحية، وتعزيز الثقة والتواصل بين الأطباء والمرضى، وفي النهاية تحسين الجودة العامة للخدمات الطبية ورضا المرضى. تلعب الثقة في الأطباء، التي تعززها التواصل الفعال، دورًا محوريًا في الالتزام بالعلاج. تشير الأبحاث إلى أن المرضى الذين يثقون بمقدمي الرعاية الصحية لديهم هم أكثر عرضة لاتباع العلاجات الموصوفة، وهو أمر ضروري لتحقيق نتائج صحية أفضل [12، 13].

المواد والأساليب

تصميم الدراسة

من بين 698 تقريرًا نصيًا مؤهلاً لعلم الأمراض عن الأورام الخبيثة، تم اختيار 70 تقريرًا (5 تقارير لكل عضو لـ 14 عضوًا) بشكل عشوائي لتطوير قوالب للتقارير التفسيرية ومقاييس الدرجات المقابلة. تم استخدام هذه القوالب لتمكين LLMs من توليد تقارير تفسيرية مماثلة بشكل موثوق، بالإضافة إلى إنتاج مخرجات متطابقة من 628 تقريرًا المتبقية. قام الأطباء بتقييم كل تقرير من حيث الاتساق من خلال مقارنة تقرير علم الأمراض الأصلي (OPR) مع التقرير المبسط الذي تم إنشاؤه بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي (تقرير علم الأمراض التفسيري، IPR). ركز التقييم على ما إذا كانت المعلومات التشخيصية الرئيسية، مثل نوع الورم (مثل، سرطان، لمفوما)، مرحلة الورم (مثل، تصنيف TNM)، الميزات النسيجية (مثل، تمايز الخلايا)، وجود النقائل، وغيرها من النتائج السريرية الهامة (مثل، العلامات الجزيئية، الهوامش، ومشاركة العقد اللمفاوية)، تم تمثيلها بدقة في النسخة المبسطة. شارك أطباء من تخصصات متعددة، بما في ذلك علم الأمراض، والأورام، والجراحة، في هذه العملية التقييمية. كل

تم تقييم مستويات المعرفة الصحية الأساسية للمتطوعين باستخدام استبيان المعرفة الصحية (HLQ)، مما يضمن تقييم فهمهم للمصطلحات الطبية قبل الدراسة. ساعدتنا هذه التقييمات في التحكم في التباينات في المعرفة الصحية بين المتطوعين. تم تلخيص نتائج تقييمات HLQ في الجدول 1. في الدراسة، كان هناك ثلاثة متطوعين (

مقاييس التقييم (الشكل 2) ووقت القراءة المسجل. أخيرًا، الأطباء (مع

توليد المقياس والقالب

تم تقديم مقياس تقييم مستوى فهم تقرير الأمراض في الشكل 2A. يهدف هذا المقياس إلى تقييم مستوى فهم الأفراد غير ذوي الخلفية الطبية بشأن تقارير الأمراض بشكل شامل. تم قياس فهم المرضى باستخدام مقياس تقييم مستوى فهم تقرير الأمراض المصمم خصيصًا، والذي تم تطويره بناءً على معايير صحية معتمدة.

مقياس تقييم مستوى فهم تقرير علم الأمراض

معايير التقييم (مقياس من عشرة نقاط)*:

1. فهم هيكل التقرير.

- غير قادر على تحديد الهيكل الأساسي والأجزاء المختلفة من التقرير (0 نقاط).

- يمكنه تحديد بعض أجزاء الهيكل (مثل، التشخيص، معلومات المريض) لكنه لا يفهمها بالكامل (1 نقطة).

- يفهم تمامًا هيكل التقرير ومحتوى ووظيفة كل قسم رئيسي (2 نقاط).

2. التعرف على المصطلحات وفهمها.

- لا يمكنه التعرف على المصطلحات المهنية أو يفهم المصطلحات بشكل خاطئ تمامًا.

نقاط). - يمكنه التعرف على بعض المصطلحات الطبية الأساسية ولكنه يفهم بشكل محدود (1 نقطة).

- يتعرف بدقة ويفهم أساسياً معظم المصطلحات (نقطتان).

3. تفسير النتائج.

- غير قادر على تفسير نتائج التقرير (0 نقاط).

- يمكنه تفسير النتائج جزئيًا، ولكن توجد سوء فهم (1 نقطة).

- يفسر بشكل صحيح المعلومات الأساسية لنتائج التقرير (نقطتان).

4. استخراج المعلومات الرئيسية.

- غير قادر على استخراج المعلومات الرئيسية من التقرير (0 نقطة).

- يمكنه استخراج بعض المعلومات الرئيسية ولكنه يفوت تفاصيل مهمة (1 نقطة).

- يستخرج ويفهم بدقة جميع المعلومات الرئيسية من التقرير (نقطتان).

- فهم شامل وتطبيق.

- غير قادر على فهم محتوى التقرير بشكل شامل أو ربطه بالحالات الصحية (0 نقاط).

- لديه فهم شامل أساسي ولكن قدرة محدودة على ربط محتوى التقرير بالحالات الصحية (1 نقطة).

- لا يفهم محتوى التقرير بشكل كامل فحسب، بل يمكنه أيضًا ربطه بفعالية بحالات الصحة الشخصية أو حالات صحة الآخرين (نقطتان).

دليل التقييم:

المستوى ب (5-7 نقاط): مستوى أساسي من الفهم، قادر على استيعاب بعض النقاط الرئيسية في التقرير ولكنه لا يزال بحاجة إلى تعزيز فهم المصطلحات المهنية وبنية التقرير.

المستوى A (8-10 نقاط): مستوى عالٍ من الفهم، قادر على تفسير المعلومات من تقارير الأمراض بدقة وتطبيقها.

- تهدف هذه المقياس إلى تقييم مستوى الفهم للأفراد ذوي الخلفية غير الطبية فيما يتعلق بتقارير الأمراض.

C

مؤشر جودة الذكاء الاصطناعي في علم الأمراض

| 1. الدقة (ما إذا كانت المعلومات في تقرير GPT-4 دقيقة ومتوافقة مع المعرفة الطبية الحالية والمحتوى الفعلي لتقرير الأمراض.) | |||||

|

|||||

| 2. عمق التفسير (كيف يفسر GPT-4 تفاصيل تقرير الأمراض وما إذا كان يمكنه تقديم تفسيرات معمقة لنتائج الأمراض.) | |||||

|

|||||

| 3. قابلية القراءة (قابلية قراءة التقرير، بما في ذلك سلاسة وفهم اللغة.) | |||||

|

|||||

| 4. الأهمية السريرية (أهمية وفائدة معلومات التقرير في الممارسة السريرية.) | |||||

|

|||||

| 5. التقييم العام (بالنظر إلى جميع الجوانب المذكورة أعلاه، رضا الطبيب العام عن التقرير الذي تم إنشاؤه بواسطة GPT-4.) | |||||

|

- باستخدام هذه المقياس، يمكن للأطباء تقييم جودة تقارير تفسير الأمراض التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-4 بشكل شامل. من خلال تلخيص الدرجات، من الممكن تحديد مستوى فهم GPT-4 وتفسيره لتقارير الأمراض، بالإضافة إلى قيمته المحتملة في التطبيقات السريرية.

نموذج تفسير تقرير علم الأمراض*

1. نظرة عامة على التقرير

معلومات الحالة: تلخيص موجز للمعلومات الأساسية عن المريض، مثل العمر والجنس.

2. معلومات العينة

3. النتائج الكلية والميكروسكوبية

4. نتائج التشخيص

5. التوصيات والتفسيرات

إرشادات صحية: تقديم نصائح متعلقة بنمط الحياة أو النظام الغذائي للمساعدة في فهم كيفية إدارة أو تحسين الحالة.

6. الأسئلة الشائعة

ملاحظات:

2) استخدم لغة بسيطة ومباشرة، مع تجنب الكثير من المصطلحات الطبية.

3) حيثما أمكن، استخدم الاستعارات أو التشبيهات لشرح المفاهيم الطبية المعقدة، مما يجعلها أسهل للفهم.

* هذه القالب مخصص كإطار عمل عام؛ يجب ملء المحتوى المحدد وتعديله وفقًا للتفاصيل الفعلية لكل تقرير علم الأمراض. يهدف ذلك إلى مساعدة الأفراد الذين ليس لديهم خلفية طبية في فهم محتوى وأهمية تقارير علم الأمراض.

| بعد معرفة الصحة | الدرجة المتوسطة |

| الشعور بالفهم والدعم من مقدمي الرعاية الصحية | 3.92 |

| امتلاك معلومات كافية لإدارة صحتي | 3.83 |

| إدارة صحتي بنشاط | 3.58 |

| الدعم الاجتماعي للصحة | 3.58 |

| تقييم المعلومات الصحية | 3.83 |

| القدرة على التفاعل بنشاط مع مقدمي الرعاية الصحية | 3.83 |

| التنقل في نظام الرعاية الصحية | 3.42 |

| القدرة على العثور على معلومات صحية جيدة | 3.75 |

| فهم المعلومات الصحية بشكل كافٍ لمعرفة ما يجب القيام به | 3.92 |

مبادئ المعرفة. استندت المقياس إلى استبيان معرفة الصحة (HLQ) وأبحاث رئيسية أخرى حول معرفة الصحة [15-18]. تم تصميمه لتقييم وضوح وملاءمة وسهولة فهم المعلومات الرئيسية في تقارير علم الأمراض، خاصة للأفراد الذين ليس لديهم خلفية طبية. تم تحسين المقياس من خلال اختبار تجريبي لضمان قابليته للتطبيق على عينة الدراسة.

تم تصوير قالب تفسير تقرير علم الأمراض في الشكل 2B. هذا القالب مخصص كإطار عمل عام؛ يجب ملء المحتوى المحدد وتعديله وفقًا للتفاصيل الفعلية لكل تقرير علم الأمراض. يهدف ذلك إلى مساعدة الأفراد الذين ليس لديهم خلفية طبية في فهم محتوى وأهمية تقارير علم الأمراض. شمل هندسة التحفيز التكرارية عدة خطوات: التحفيز الأول: “تلخيص تقرير علم الأمراض لشخص غير متخصص.” التحسين: “تلخيص تقرير علم الأمراض بلغة بسيطة، موضحًا التشخيص والأهمية والخطوات التالية.” التحفيز النهائي: “ترجمة تقرير علم الأمراض إلى لغة سهلة الفهم، تشمل التشخيص والأهمية السريرية وخيارات العلاج وتوصيات المتابعة.” تم إنشاء OPRs باستخدام القوالب المحسنة. تم ملء كل قسم من القالب بتفاصيل محددة من تقارير علم الأمراض، مما يضمن الاتساق والفهم. تم توضيح أمثلة على هذه القوالب والتقارير المملوءة في الأشكال 2B و3.

تم عرض مؤشر جودة الذكاء الاصطناعي لعلم الأمراض في الشكل 2C. تم تطوير هذا المؤشر باستخدام GPT-4 وتم تحسينه من خلال المناقشات مع أخصائيي علم الأمراض، الذين أنهوا المحتوى ومعايير التقييم. باستخدام هذا المقياس، يمكن للأطباء تقييم جودة تقارير تفسير علم الأمراض التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-4 بشكل شامل. من خلال تلخيص الدرجات، من الممكن تحديد مستوى فهم GPT-4 وتفسيره لتقارير علم الأمراض، فضلاً عن قيمته المحتملة في التطبيقات السريرية. تم تصميم هذه الطريقة لمقارنة OPRs التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-4 بدقة مع المعايير المحددة

من قبل OPRs. تم إجراء التقييم عبر خمسة أبعاد رئيسية من قبل ثلاثة أخصائيين في علم الأمراض، كل منهم لديه أكثر من عقد من الخبرة المهنية: الدقة (البعد A)، عمق التفسير (البعد B)، قابلية القراءة (البعد C)، الأهمية السريرية (البعد D)، والتقييم العام (البعد E). أخصائي علم الأمراض X هو أخصائي علم الأمراض العام يعمل في مستشفى جامعي ولديه خبرة في علم الأمراض الأورام؛ أخصائي علم الأمراض Y هو أخصائي علم الأمراض الصدري متخصص في تشخيص سرطان الرئة، يعمل في مركز سرطان غير جامعي؛ وأخصائي علم الأمراض Z هو خبير في علم الأمراض الهضمي مرتبط بمركز طبي أكاديمي رائد. جميع أخصائيي علم الأمراض لديهم خبرة واسعة في تحليل تقارير علم الأمراض المعقدة والمساهمة في نماذج التشخيص المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. ضمنت خلفياتهم المتنوعة تقييمًا شاملاً لتقارير علم الأمراض من وجهات نظر مختلفة. كان الهدف من هذا الاستعراض الشامل هو تحديد مدى جودة التقارير التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-4 في التقاط جوهر OPRs. النتائج، كما تم الحكم عليها من قبل أخصائيي علم الأمراض – المشار إليهم بأخصائي علم الأمراض X، أخصائي علم الأمراض Y، وأخصائي علم الأمراض Z.

لتقييم تعقيد النص لكل من OPRs وIPRs، قمنا بحساب عدد الكلمات باستخدام ميزة عدد الكلمات في Microsoft Office 365 (شركة Microsoft، ريدموند، واشنطن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). قدمت هذه الطريقة مقياسًا كميًا لطول التقرير، مما يسمح لنا بمقارنة عدد الكلمات عبر أنواع مختلفة من الأورام وبين OPRs وIPRs.

إخفاء بيانات المرضى وأمانها

تقارير علم الأمراض الأصلية

النتائج الكلية:

التشخيص المرضي: قسم مجمد والأنسجة المتبقية المدمجة في البارافين:

حجم الورم:

تصنيف IASLC الجديد: الدرجة 3. غزو الغشاء الجنبي: PL0. انتشار الهواء (STAS): لم يُرَ. غزو الأوعية الدموية: موجود. غزو الأعصاب: موجود.

هامش القصبة الهوائية: سلبي. المسافة من الورم إلى هامش القصبة الهوائية: 2.5 سم. انتشار العقد اللمفاوية: لا توجد نقائل سرطانية في العقد اللمفاوية المحيطة بالقصبة الهوائية

نتائج المناعية الكيميائية (الشريحة 3): TTF-1 (+)، CK7 (+)، NapsinA (+)، P63 (قليل +)، CK5/6 (-)، P40 (-)، Ki67 (حوالي 5% +).

البقع الخاصة (الشريحة 3): الألياف المرنة (+).

نتائج العقد اللمفاوية الكلية: قسم مجمد:

المجموعة 2: قطعة نسيج رمادي-بني واحدة، قياس

المجموعة 7: قطعة نسيج رمادية-بنية، قياسها

المجموعة 10: قطعة نسيج رمادية-بنية، قياسها

النتائج المجهرية: التشخيص المرضي:

القسم المجمد: (المجموعة 7) انتشار السرطان في العقد اللمفاوية (1/1)؛ لا يوجد انتشار للسرطان في العقد اللمفاوية الأخرى: (المجموعة 2) 0/1، (المجموعة 4) 0/1، (المجموعة 9) 0/1، (المجموعة 10) 0/1، (المجموعة 11)

تقارير علم الأمراض التفسيرية

1. نظرة عامة على التقرير

معلومات الحالة: المريض ذكر يبلغ من العمر 54 عامًا.

2. معلومات العينة

نوع العينة: العينة هي قطعة من نسيج الرئة.

3. النتائج الكلية والميكروسكوبية

الفحص الإجمالي: تم فحص جزء من نسيج الرئة يبلغ قياسه 19×10.5×3 سم. القصبة الهوائية (المجرى الهوائي) طولها 0.5 سم وقطرها 2 سم. داخل نسيج الرئة، يوجد ورم رمادي-أبيض يبلغ قياسه

الفحص المجهري: تم تحديد الورم على أنه أدينوكارسينوما غازية، وهو نوع من سرطان الرئة. يتم تصنيف الورم على أنه نوع غير مخاطي مع أنماط متنوعة: حويصلي (

علم المناعة النسيجية:

علامات سلبية: CK5/6 و P40.

علامة التكاثر Ki67 تظهر حوالي

الألياف المرنة موجودة في العينة.

نتائج العقد اللمفاوية:

4. نتائج التشخيص

المريض يعاني من سرطان غدي غازٍ في الفص السفلي الأيمن من الرئة.

يتم تصنيف الورم على أنه منخفض الدرجة، مما يشير إلى أنه أكثر عدوانية وأقل تمايزًا.

لقد انتشرت خلايا السرطان إلى العقد اللمفاوية القريبة في مجموعة واحدة ولكن ليس في المجموعات الأخرى.

نتائج الكيمياء النسيجية المناعية تدعم تشخيص سرطان الغدة الرئوية.

الهامش الجراحي الواضح يشير إلى أن الورم قد تم إزالته بهامش أمان جيد.

5. التوصيات والتفسيرات

مواعيد متابعة مع أخصائي الأورام لمزيد من التقييم وتخطيط العلاج.

تشمل العلاجات المحتملة الجراحة، والعلاج الكيميائي، والعلاج الإشعاعي، أو العلاج المستهدف، وذلك اعتمادًا على مرحلة السرطان والصحة العامة للمريض.

إرشادات صحية:

حافظ على نظام غذائي صحي ونمط حياة لدعم الرفاهية العامة.

تجنب التدخين والتعرض لمهيجات الرئة لتحسين صحة الرئة.

متابعات منتظمة ودراسات تصويرية كما أوصى بها مقدم الرعاية الصحية.

6. الأسئلة المتكررة

س: ما هو السرطان الغدي؟

س: ماذا يعني ورم منخفض الدرجة؟

س: ما هي أهمية تورط العقد اللمفاوية؟

س: ما هي الخطوات التالية بعد هذا التشخيص؟

تأكدت هذه التدابير من عدم تعرض أي بيانات حساسة للمرضى أو إمكانية الوصول إليها خارج الدراسة، مما يحمي سرية المرضى مع السماح بتحليل دقيق لتقارير علم الأمراض التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي.

التحليلات الإحصائية

النتائج

خصائص العينة

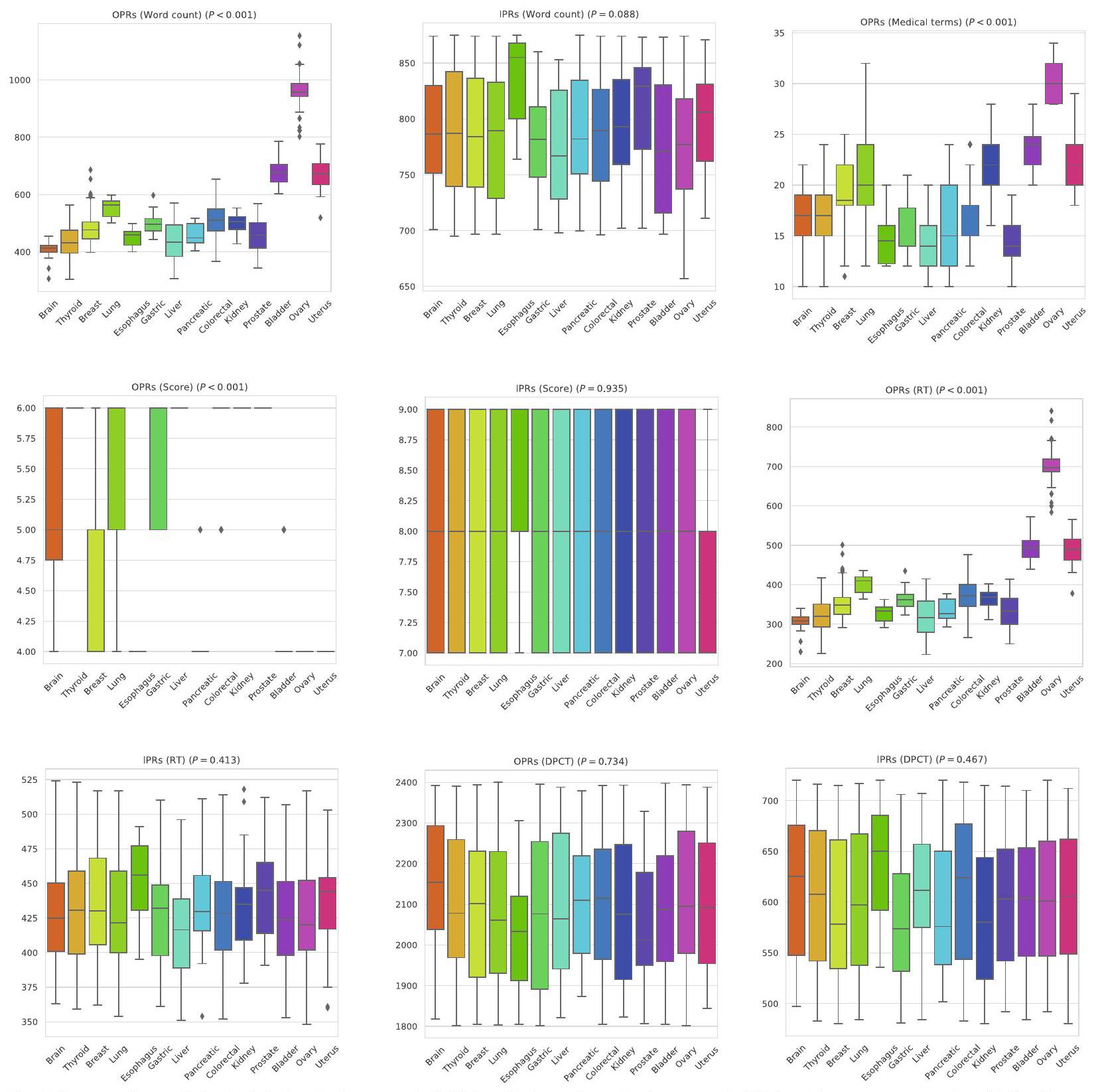

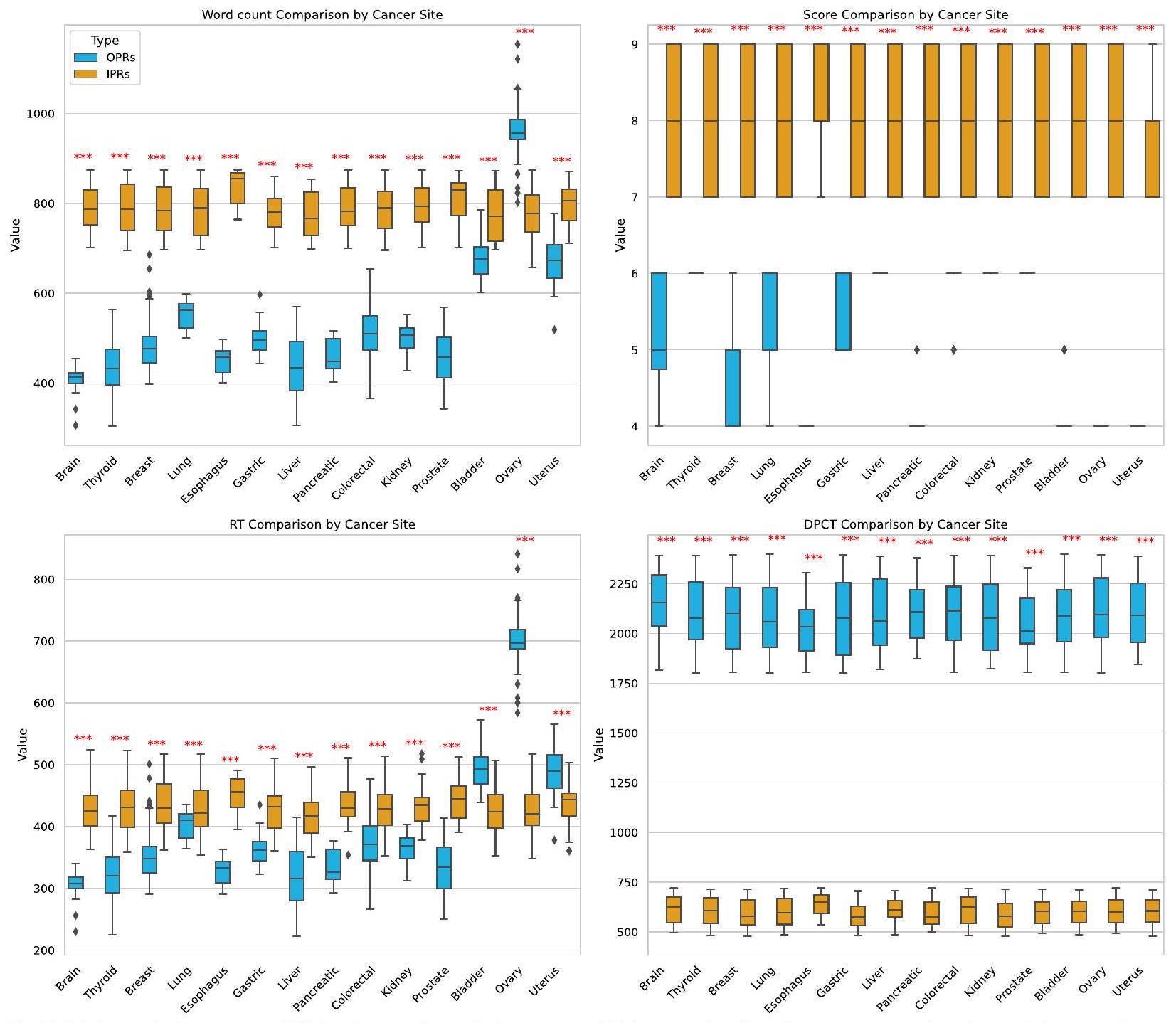

استخراج بيانات النص

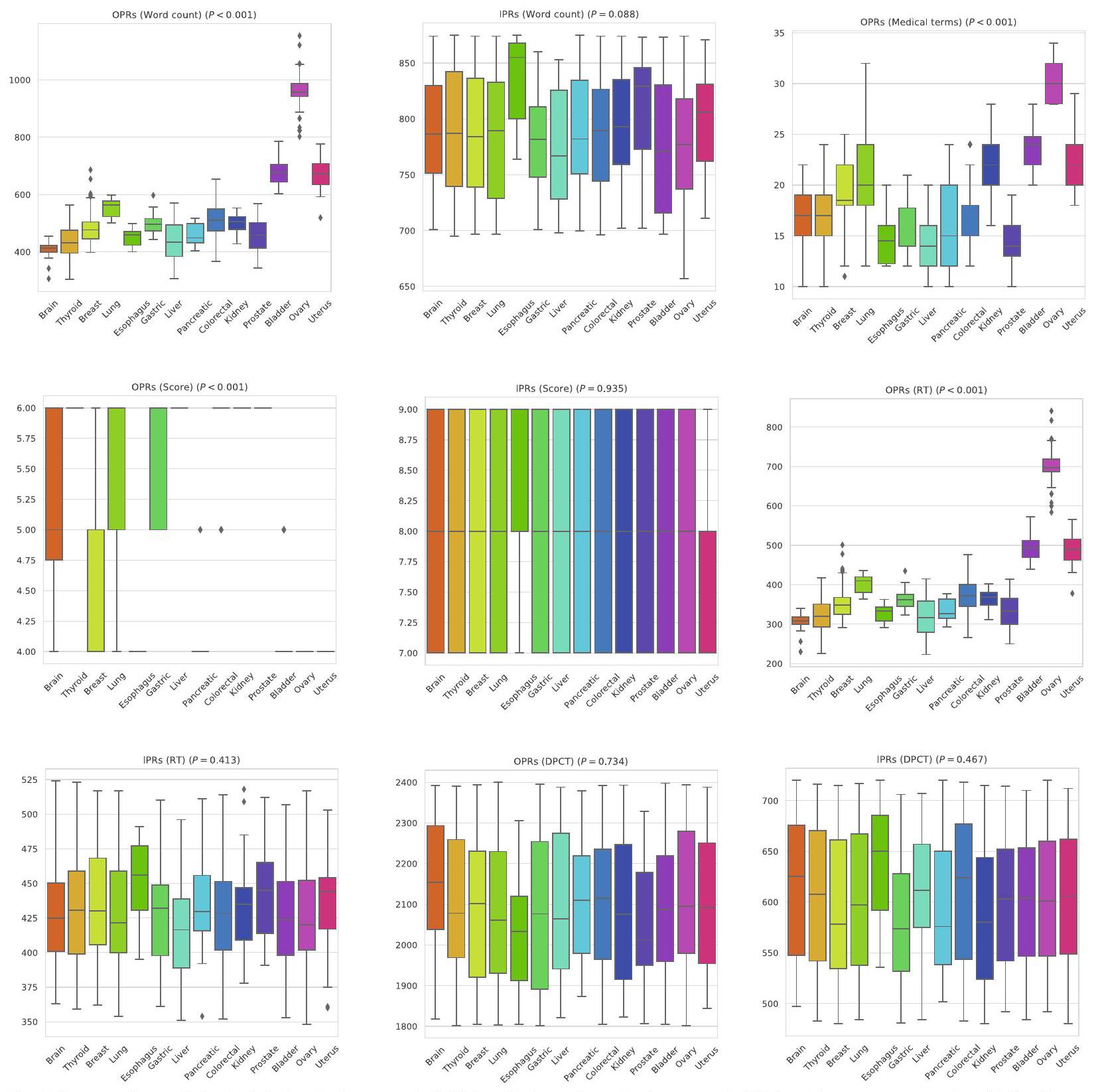

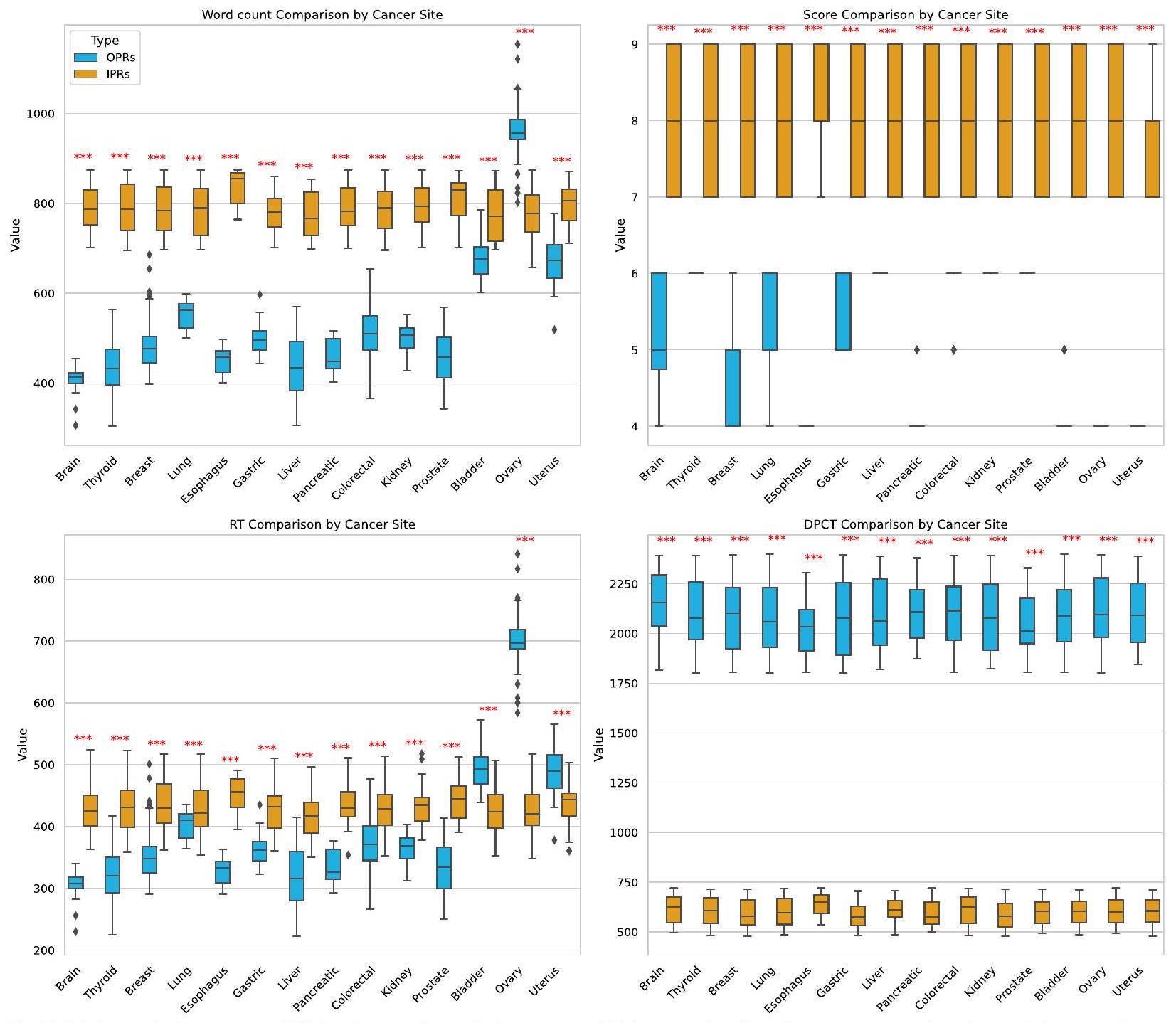

لقد لاحظنا أن متوسط عدد الكلمات في تقارير OPRs عبر جميع أنواع الأورام الخبيثة كان 549.98، بينما كان متوسط عدد الكلمات في تقارير IPRs أعلى بكثير عند 787.44. كانت الأورام الخبيثة في الكبد هي الأقل في متوسط عدد الكلمات لتقارير OPRs (441.41) و IPRs (775.25). في المقابل، كانت الأورام الخبيثة في المبيض هي الأعلى في متوسط عدد الكلمات لتقارير OPRs (961.21)، بينما كانت أورام المريء…

| مواقع السرطان | المرضى | العمر (بالسنوات)

|

الجنس (ذكر، أنثى) |

| جميع المواقع | 698 |

|

290 (41.55%)، 408 (58.45%) |

| دماغ | 32 |

|

13 (40.62%)، 19 (59.38%) |

| الغدة الدرقية | 76 |

|

32 (42.11%)، 44 (57.89%) |

| ثدي | 86 |

|

0 (0.00%)، 86 (100.00%) |

| رئة | 98 |

|

49 (50.00%)، 49 (50.00%) |

| المريء | 10 |

|

7 (70.00%)، 3 (30.00%) |

| معدي | 30 |

|

18 (60.00%)، 12 (40.00%) |

| كبد | 32 |

|

24 (75.00%)، 8 (25.00%) |

| بانكرياسي | 18 |

|

15 (83.33%)، 3 (16.67%) |

| قولون مستقيم | 74 |

|

31 (41.89%)، 43 (58.11%) |

| كلى | 61 |

|

31 (50.82%)، 30 (49.18%) |

| بروستاتا | 37 |

|

37 (100.00%)، 0 (0.00%) |

| المثانة | 50 |

|

33 (66.00%)، 17 (34.00%) |

| مبيض | 61 |

|

0 (0.00%)، 61 (100.00%) |

| رحم | ٣٣ |

|

0 (0.00%)، 33 (100.00%) |

كان لديها أعلى متوسط لعدد الكلمات في تقارير الملكية الفكرية (833.80). وهذا يشير إلى أنه على الرغم من وجود تباين كبير في عدد الكلمات في تقارير الملكية الفكرية بين مختلف الأورام الخبيثة (

علاوة على ذلك، كان عدد الكلمات في تقارير العمليات الجراحية للأورام الخبيثة المبيضية أعلى من ذلك في تقارير العمليات الجراحية الداخلية.

تقييم اتساق محتوى التعبير

وقت قراءة تقرير علم الأمراض

| مواقع السرطان | تقارير علم الأمراض | عدد الكلمات (OPRs)* | OPRs (مصطلحات طبية)* | حقوق الملكية الفكرية (عدد الكلمات)* |

|

| جميع المواقع | 698 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| دماغ | 32 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| الغدة الدرقية | 76 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| ثدي | 86 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| رئة | 98 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| المريء | 10 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| معدي | 30 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| كبد | 32 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| بانكرياسي | ١٨ |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| قولون مستقيم | 74 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| كلى | 61 |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

| بروستاتا | 37 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| المثانة | 50 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| مبيض | 61 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| رحم | ٣٣ |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

- البيانات هي المتوسطات ± الانحرافات المعيارية، مع النطاقات بين قوسين

تم تحليل معدلات البقاء على قيد الحياة (OPRs) ومعدلات الإصابة (IPRs) لمواقع السرطان المختلفة إحصائيًا.

اختلافات ذات دلالة إحصائية في أوقات القراءة لمؤشرات الأداء الرئيسية عبر أنواع الأورام (). بالمقابل، كان متوسط وقت القراءة لتقارير IPRs هو 430.67 ثانية، مع أقصر وقت للأورام الخبيثة في الكبد عند 418.88 ثانية، وأطول وقت لأورام المريء عند 452.10 ثانية. لم تُلاحظ فروق ذات دلالة إحصائية في أوقات القراءة لتقارير IPRs عبر أنواع الأورام ( ).

أظهر مقارنة أوقات القراءة بين OPRs و IPRs لجميع أنواع الأورام الخبيثة أن OPRs كانت تُقرأ عمومًا بشكل أسرع من IPRs، مع وجود فرق ذو دلالة إحصائية.ومع ذلك، بالنسبة لسرطانات المثانة والمبيض والرحم، كانت أوقات القراءة

أطول بالنسبة لـ OPRs مقارنةً بـ IPRs، مع كون هذه الفروقات أيضًا ذات دلالة إحصائيةلكل منها).

تقييم مستوى الفهم

التواصل بين الطبيب والمريض

كان الأقصر عند 2062.03 ثانية. أظهرت التحليلات الإحصائية عدم وجود فروق ذات دلالة إحصائية في أوقات التواصل عبر أنواع الأورام المختلفة.

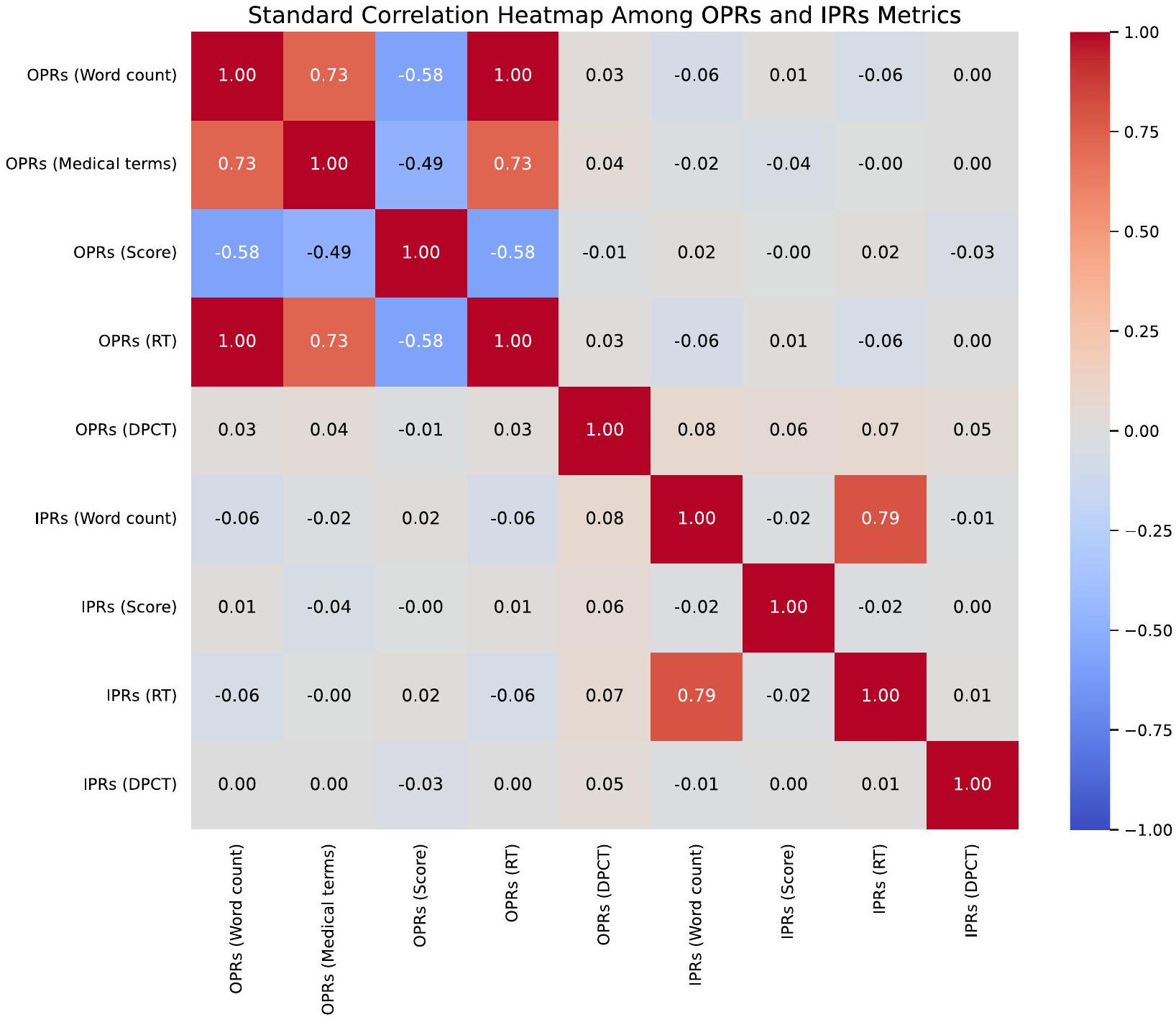

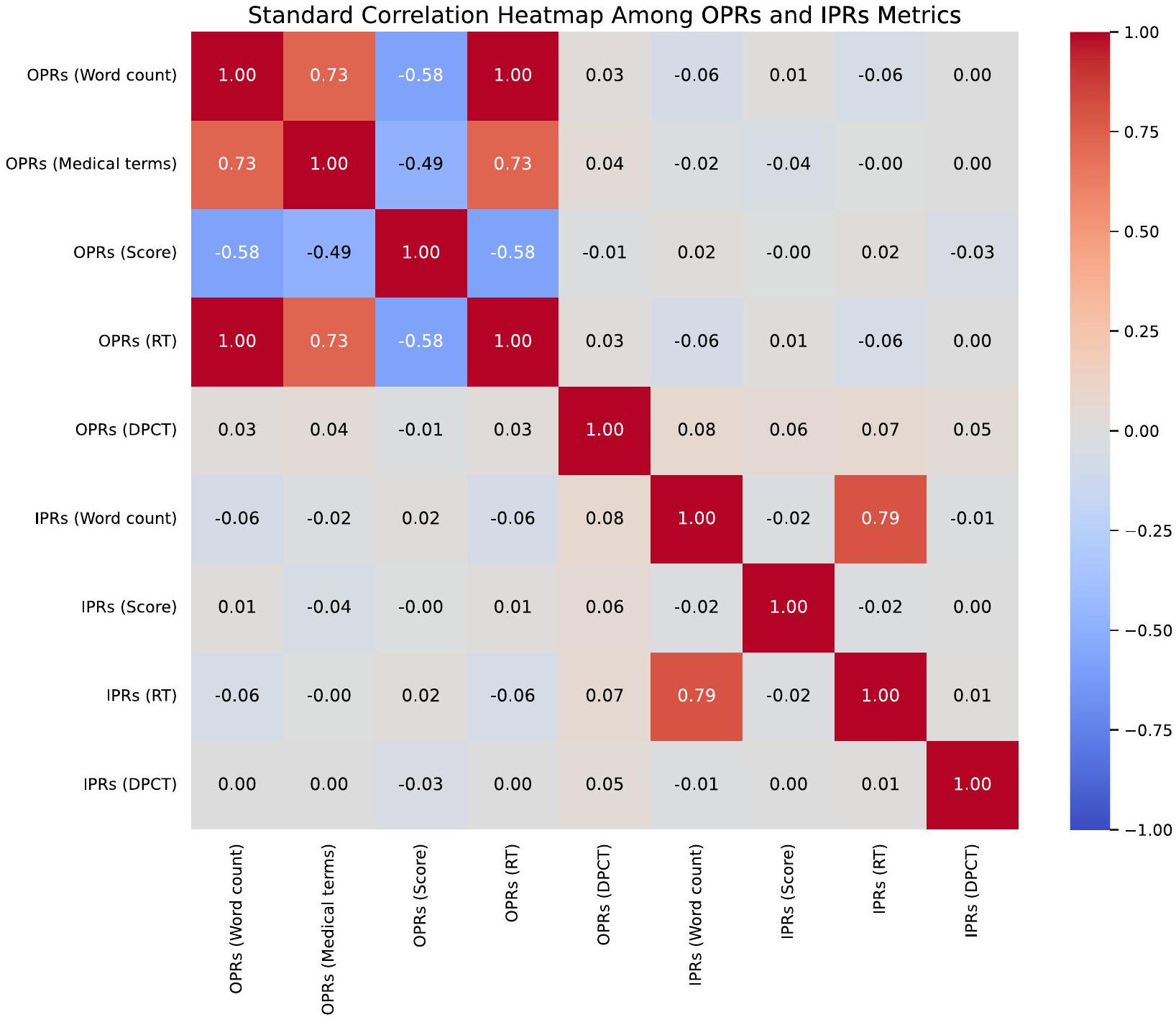

ارتباط مقاييس OPRs و IPRs

بين تسعة مقاييس رئيسية ضمن OPRs و IPRs. يكشف عن وجود علاقة قوية بين عدد الكلمات، والمصطلحات الطبية، والدرجة، ووقت القراءة لـ OPRs. تعتبر الصورة أداة بصرية بديهية لتحديد كل من قوة واتجاه العلاقات بين هذه المقاييس.

نقاش

| موقع السرطان | البعد A (الدقة) | البعد ب (عمق التفسير) | البعد C (قابلية القراءة) | البعد د (الأهمية السريرية) | البعد E (التقييم العام) |

| جميع المواقع | ٤.٩٥ | ٤.٩٥ | ٥ | ٤.٩٢ | ٤.٨٤ |

| دماغ | ٥ | ٤.٩٧ | ٥ | ٤.٩١ | ٤.٩١ |

| الغدة الدرقية | ٤.٩٣ | ٤.٩٦ | ٥ | ٤.٨٣ | ٤.٨٣ |

| ثدي | ٤.٩٤ | ٤.٩٤ | ٥ | ٤.٩١ | ٤.٨ |

| رئة | ٤.٩٥ | ٤.٩٤ | ٥ | ٤.٩٣ | ٤.٨٣ |

| المريء | ٥ | ٥ | ٥ | ٤.٩ | ٤.٩ |

| معدي | ٤.٩٧ | ٤.٩٧ | ٥ | ٤.٩ | ٤.٨٣ |

| كبد | ٥ | ٤.٩٤ | ٥ | ٤.٩٧ | ٤.٩١ |

| بانكرياسي | ٤.٨٩ | ٤.٨٩ | ٥ | ٤.٨٩ | ٤.٦٧ |

| قولون مستقيم | ٤.٩٦ | ٤.٩٧ | ٥ | ٤.٩٥ | ٤.٨٨ |

| كلى | ٤.٩٣ | ٤.٩٥ | ٥ | ٤.٩٧ | ٤.٨٥ |

| بروستاتا | ٤.٩٥ | ٤.٩٥ | ٥ | ٤.٩٥ | ٤.٨٤ |

| المثانة | ٤.٩٦ | ٤.٩٢ | ٥ | ٤.٩٦ | ٤.٨٦ |

| مبيض | ٤.٩٣ | ٤.٩٥ | ٥ | ٤.٩٣ | ٤.٨٢ |

| رحم | ٤.٩٤ | ٤.٩٧ | ٥ | ٤.٨٨ | ٤.٧٩ |

عبر جميع أنواع الأورام الخبيثة، أدى استخدام تقارير المعلومات الشخصية (IPRs) إلى تحقيق درجات فهم أعلى بكثير للمرضى مقارنة بتقارير المعلومات التقليدية (OPRs)، مع تحسن متوسط من 5.23 إلى 7.98 على مقياس تقييم مستوى فهم تقرير علم الأمراض. علاوة على ذلك، وجدت الدراسة انخفاضًا كبيرًا في وقت التواصل بين الطبيب والمريض عند استخدام تقارير المعلومات الشخصية، حيث انخفض من متوسط 2091.25 ثانية إلى 599.15 ثانية، مما يبرز الفوائد المحتملة لتوفير الوقت لتقارير المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن التقارير التي يتم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي يمكن أن تعزز التواصل بين الطبيب والمريض بينما تحسن أيضًا كفاءة الرعاية الصحية بشكل عام.

بالإضافة إلى تحسين وقت التواصل والفهم، أظهرت تقييمات الاتساق التي أجراها أطباء الأمراض أن التقارير الأولية التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-4 كانت دقيقة للغاية، حيث حصلت على درجات متسقة عبر أبعاد مثل الدقة، وعمق التفسير، وقابلية القراءة. يدعم هذا الاتساق في التقييم عبر أنواع الأورام المختلفة قوة التقارير التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي، مما يشير إلى إمكانياتها للتطبيق السريري على نطاق واسع. كما أن العلاقة القوية الملحوظة بين مقاييس التقارير الأولية والتقارير الأولية تعزز فعالية نموذج الذكاء الاصطناعي في الحفاظ على الصلة السريرية مع تبسيط محتوى التقرير لفهم المرضى. هذا الفهم المعزز أمر حاسم لأنه يؤثر بشكل مباشر على مشاركة المرضى وتمكينهم. المرضى الذين يفهمون حالتهم الطبية

تكون الظروف والمنطق وراء خيارات العلاج أكثر ميلاً للالتزام بالعلاجات الموصى بها والانخراط في إدارة الصحة بشكل استباقي. هذه العلاقة بين الفهم والامتثال موثقة جيدًا في أدبيات الرعاية الصحية، حيث توفر بياناتنا دليلًا قويًا على الدور المحوري للذكاء الاصطناعي في تعزيز هذا الفهم [19-22].

علاوة على ذلك، اعترفت الدراسات الحديثة بشكل متزايد بقدرة الذكاء الاصطناعي على تعزيز إمكانية الوصول وفهم الوثائق الطبية. على سبيل المثال، استخدم أمين وآخرون ثلاثة نماذج لغوية كبيرة بارزة – ChatGPT وGoogle Bard وMicrosoft Bing – لتبسيط تقارير الأشعة [23]. بعد ذلك، طلبوا تقييمات من الممارسين السريريين المعنيين بشأن دقة مخرجات كل نموذج. ومع ذلك، لم تتناول الدراسة قابلية فهم هذه التقارير المبسطة للأشعة للأفراد الذين يفتقرون إلى خلفية طبية. وبالتالي، فإن قابلية تطبيق نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في جعل المعلومات الإشعاعية متاحة لجمهور أوسع غير متخصص لا تزال غير مؤكدة [23]. استخدم ترون وآخرون GPT-4 لإنشاء تقارير مرضية منظمة، مما يدل على أن التقارير المنظمة التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة تتوافق مع تلك التي ينتجها أطباء الأمراض [24]. وهذا يشير إلى أن نماذج اللغة الكبيرة يمكن أن تُستخدم بشكل روتيني لاستخراج بيانات الحقيقة الأساسية للتعلم الآلي من تقارير الأمراض غير المنظمة في المستقبل. ومع ذلك، ركزت هذه الدراسة فقط على تقييمات المهنيين وتفتقر إلى تقييم قابلية استخدام التقارير التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي في سيناريوهات أوسع. وبالمثل، درس ستايميتز وآخرون طرقًا لـ

| مواقع السرطان | V

|

V (D، E، F)

|

|

V (A، B، C) تقارير الأمراض الأصلية (الدرجة) | V (D، E، F) تقارير الأمراض التفسيرية (الدرجة) |

|

V (A، B، C) تقارير الأمراض الأصلية (DPCT) | V (D، E، F) تقارير الأمراض التفسيرية (DPCT) |

|

| جميع المواقع |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

| الدماغ |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| الغدة الدرقية |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| الثدي |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| الرئة |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| المريء |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| المعدة |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| الكبد |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| البنكرياس |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| القولون والمستقيم |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| الكلى |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| البروستاتا |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| المثانة |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| المبيض |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| الرحم |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

تبسيط الوثائق الطبية لتحسين فهم المرضى، حيث وجدت أن تعزيز قابلية القراءة يؤثر بشكل مباشر على تفاعل المرضى ورضاهم [9]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهر سينغال وآخرون أن نماذج اللغة الكبيرة تشفر المعرفة السريرية بفعالية، مما يعزز إمكاناتها في تحسين التواصل في الرعاية الصحية [8]. يناقش هارر المزيد من الاعتبارات الأخلاقية والتعقيدات المتعلقة بدمج نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في الأنظمة الطبية، مؤكدًا على أهمية تقييم تطبيقاتها في العالم الحقيقي لضمان سلامة المرضى ودقتها [11].

أساسي في البيئات ذات الطلب العالي مثل وحدات الجراحة. تؤكد ندرة الموارد الطبية عالميًا على أهمية هذه النتائج، مما يشير إلى أن نماذج اللغة الكبيرة يمكن أن تخفف بشكل كبير من الضغط على موارد الرعاية الصحية.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تظهر دراستنا أن التقارير التفسيرية التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-4 تظهر درجة عالية من التوافق مع التقارير الأصلية، كما تم تقييمها عبر أبعاد رئيسية مثل الدقة، وعمق التفسير، وقابلية القراءة. تؤكد هذه النتائج على قوة الإطار التقييمي في التحقق من أن التقارير التفسيرية تمثل بدقة الرؤى الرئيسية للتقارير الأصلية. لا يضمن هذا الإطار فقط أن التقارير التي تم إنشاؤها تتوافق مع البيانات الطبية الأصلية، ولكنه يلعب أيضًا دورًا حيويًا في

الحفاظ على نزاهة وموثوقية عملية تفسير الأمراض. من خلال مقارنة منهجية لعدة أبعاد، يوفر الإطار تقييمًا شاملاً يساعد في تحديد التباينات المحتملة ويضمن الصلة السريرية للتقارير. يسمح هذا النهج الدقيق باستخدام التقارير التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي بثقة أكبر في البيئات الطبية الواقعية، مما يسهم في تحسين التواصل بين الأطباء والمرضى ونتائج الرعاية الصحية. مع التدريب المناسب وتعديلات النموذج، يمكن لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة مثل GPT-4 تحقيق مستويات عالية من الدقة والموثوقية في تفسير وتبسيط تقارير الأمراض الجراحية المعقدة، وهو أمر حيوي لتعافي المرضى وفهمهم بعد الجراحة.

تعتبر تداعيات هذه النتائج على الممارسة السريرية عميقة. يمكن تحقيق دمج التقارير التفسيرية التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي في أنظمة الرعاية الصحية من خلال عدة خطوات عملية. أولاً، يمكن للمستشفيات والعيادات تنفيذ نماذج الذكاء الاصطناعي مثل GPT-4 لإنشاء تقارير مرضية مبسطة وصديقة للمرضى تلقائيًا جنبًا إلى جنب مع التقارير التقليدية. يمكن مشاركة هذه التقارير التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي مع المرضى عبر بوابات المرضى أو خلال الاستشارات وجهًا لوجه. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن يعزز تدريب مقدمي الرعاية الصحية على استخدام التقارير التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي كأدوات تواصل خلال الاستشارات من فهم المرضى. من خلال تقديم ملخصات سهلة الفهم، من المرجح أن يشارك المرضى في خطط رعايتهم، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة الرضا وامتثال أفضل للعلاج، مما يسهم في تحسين نتائج الصحة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن يؤدي تقليل الوقت المستغرق في الشروحات الروتينية إلى تخفيف الضغوط على عبء العمل على المهنيين الصحيين، مما قد يعزز من رضاهم الوظيفي ويقلل من الإرهاق.

ومع ذلك، من المهم أن نلاحظ أن هذه الدراسة أجريت في منطقة ناطقة بالصينية، وأن جميع التقارير المرضية، سواء كانت أصلية أو تفسيرية، كانت مكتوبة باللغة الصينية. قد تؤثر اللغة والخلفية الثقافية على قابلية تعميم نتائجنا. خلال عملية إنشاء القالب والتقييم، أخذنا بعين الاعتبار بعناية استخدام مصطلحات الطب الصيني التقليدي (TCM) والبنية المحددة للتقارير المرضية الصينية. لذلك، في التطبيقات الواقعية، من الضروري أخذ السياقات الثقافية واللغوية في الاعتبار عند تطبيق استنتاجات هذه الدراسة.

بينما استخدمت دراستنا متطوعين لمحاكاة تفاعلات المرضى، نعترف بالاختلافات المحتملة بين المتطوعين والمرضى الحقيقيين. غالبًا ما يواجه المرضى الحقيقيون في البيئات السريرية مجموعة من المشاعر، مثل القلق والخوف والضيق، والتي يمكن أن تؤثر على سلوكهم، واتخاذ القرارات، وكفاءة التواصل. أظهرت الدراسات أن المرضى الذين يعانون من ضغوط عاطفية قد يواجهون صعوبة في فهم المعلومات الطبية والاحتفاظ بها، مما قد يؤثر على

قدرتهم على الانخراط في تواصل فعال مع مقدمي الرعاية الصحية [25]. بالمقابل، لم يواجه المتطوعون في دراستنا، الذين كانوا على دراية بالطبيعة غير المهددة للبيئة، هذه الضغوط العاطفية. لذلك، يجب أن تهدف الأبحاث المستقبلية إلى تضمين المرضى الحقيقيين لالتقاط تعقيد التفاعلات السريرية بشكل أفضل وتأثير الحالات العاطفية على نتائج التواصل.

على الرغم من النتائج الواعدة، تعترف دراستنا بعدة قيود رئيسية تستدعي الاعتبار الدقيق. تبرز هذه القيود مجالات للتفسير الحذر للنتائج وتقترح طرقًا محتملة للأبحاث المستقبلية لمعالجة هذه الفجوات. أولاً، الاعتماد الكبير لدراستنا على قدرات GPT-4، وهو إصدار محدد من نماذج اللغة الكبيرة التي طورتها OpenAI، يثير تساؤلات حول قابلية تعميم نتائجنا. بينما يُعرف GPT-4 بقدراته المتطورة في معالجة اللغة الطبيعية، فإنه يمثل مجرد مثال واحد على هذه التقنيات. قد تظهر نماذج اللغة الكبيرة المختلفة فعالية متفاوتة بناءً على بيانات التدريب والخوارزميات الأساسية. يمكن أن تستكشف الأبحاث المستقبلية أداء نماذج لغة كبيرة أخرى في مهام مماثلة للتحقق مما إذا كانت الفوائد الملحوظة قابلة للتكرار عبر منصات الذكاء الاصطناعي المختلفة. ثانيًا، كانت التنوع الديموغرافي والجغرافي لعينة مرضانا مقصورًا على مستشفيات محددة ضمن منطقة محدودة، مما قد يقيد قابلية تطبيق نتائجنا على إعدادات أخرى حيث تختلف مجموعات المرضى بشكل كبير من حيث اللغة والثقافة وممارسات الرعاية الصحية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد لا تعكس حجم العينة، على الرغم من كفايتها للتحليل الإحصائي، التباين والتعقيد الكامل لتجارب المرضى عبر مجموعات سكانية أوسع. قد يوفر توسيع حجم العينة وتضمين مجموعة مرضى أكثر تنوعًا في الدراسات المستقبلية رؤى حول كيفية تفاعل مجموعات سكانية مختلفة مع التقارير التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي والاستفادة منها. ثالثًا، توفر الطبيعة الكمية بشكل أساسي لدراستنا أساسًا إحصائيًا قويًا لتقييم فعالية الذكاء الاصطناعي في تحسين فهم المرضى وكفاءة التواصل. ومع ذلك، قد يتجاهل هذا النهج الجوانب الإنسانية الدقيقة لتفاعلات الطبيب والمريض التي يتم التقاطها بشكل أفضل من خلال الأساليب النوعية. قد تتضمن الدراسات المستقبلية تقنيات البحث النوعي، مثل المقابلات المتعمقة أو مجموعات التركيز، لجمع رؤى أكثر شمولاً حول كيفية إدراك المرضى ومقدمي الرعاية الصحية وتقديرهم للتقارير التفسيرية التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي. رابعًا، إحدى قيود هذه الدراسة هي استبعاد الهلوسات، وهو خطأ يتم الإبلاغ عنه بشكل شائع في نماذج اللغة الكبيرة/ GPT، من التقييم. تشير الهلوسات إلى الحالات التي ينتج فيها النموذج معلومات غير صحيحة من الناحية الواقعية أو مختلقة، مما قد يؤثر على تفسير تقارير الأمراض التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي. ومع ذلك، في هذه الدراسة، كان تركيزنا الأساسي هو

تقييم الدقة والاتساق وقابلية القراءة لتقارير الأمراض، تحديدًا فيما يتعلق بالمحتوى التشخيصي. لذلك، لم يتم تضمين الهلوسات في نطاق هذا التقييم. يجب أن تهدف الأبحاث المستقبلية إلى التحقيق في حدوث الهلوسات في توليد النصوص الطبية وتأثيراتها المحتملة على الممارسة السريرية، خاصة عند استخدام نماذج الذكاء الاصطناعي في بيئات اتخاذ القرار عالية المخاطر. خامسًا، نعترف بعدد المتطوعين القليل وتأثيره المحتمل على الخصائص الأساسية. تم اختيار مجموعات مختلفة لتجنب التحيز الناتج عن الألفة مع تنسيق التقرير. ومع ذلك، فإن التحكم في الخصائص الأساسية أمر بالغ الأهمية. تم تقييم مستويات معرفة الصحة لدى المتطوعين وأخذها في الاعتبار في التحليل. لذلك، تبرز هذه القيود الحاجة إلى تفسير حذر لنتائج دراستنا وتسلط الضوء على أهمية معالجة هذه المجالات في الأبحاث المستقبلية. من خلال توسيع نطاق البحث وتنوعه وعمقه في استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الصحية، يمكننا فهم قدرات هذه التقنيات وقيودها بشكل أفضل والعمل نحو تعظيم فوائدها مع تقليل العيوب المحتملة.

الخاتمة

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر على الإنترنت: 23 يناير 2025

References

- Yang X, Chen A, PourNejatian N, Shin HC, Smith KE, Parisien C, Compas C, Martin C, Costa AB, Flores MG, et al. A large language model for electronic health records. NPJ Digital Med. 2022;5(1):194.

- Thirunavukarasu AJ, Ting DSJ, Elangovan K, Gutierrez L, Tan TF, Ting DSW. Large language models in medicine. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):1930-40.

- Yang X, Chu XP, Huang S, Xiao Y, Li D, Su X, Qi YF, Qiu ZB, Wang Y, Tang WF, et al. A novel image deep learning-based sub-centimeter pulmonary nodule management algorithm to expedite resection of the malignant and avoid over-diagnosis of the benign. Eur Radiol. 2024;34(3):2048-61.

- Mossanen M, True LD, Wright JL, Vakar-Lopez F, Lavallee D, Gore JL. Surgical pathology and the patient: a systematic review evaluating the primary audience of pathology reports. Hum Pathol. 2014;45(11):2192-201.

- Dunsch F, Evans DK, Macis M, Wang Q. Bias in patient satisfaction surveys: a threat to measuring healthcare quality. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(2):e000694.

- Farley H, Enguidanos ER, Coletti CM, Honigman L, Mazzeo A, Pinson TB, Reed K, Wiler JL. Patient Satisfaction Surveys and Quality of Care: An Information Paper. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(4):351-7.

- Shah NH, Entwistle D, Pfeffer MA. Creation and Adoption of Large Language Models in Medicine. JAMA. 2023;330(9):866-9.

- Singhal K, Azizi S, Tu T, Mahdavi SS, Wei J, Chung HW, Scales N, Tanwani A, Cole-Lewis H, Pfohl S, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature. 2023;620(7972):172-80.

- Steimetz E, Minkowitz J, Gabutan EC, Ngichabe J, Attia H, Hershkop M, Ozay F, Hanna MG, Gupta R. Use of Artificial Intelligence

10. Winograd A. Loose-lipped large language models spill your secrets: The privacy implications of large language models. Harvard J Law Technol. 2023;36(2):615.

11. Harrer S. Attention is not all you need: the complicated case of ethically using large language models in healthcare and medicine. EBioMedicine. 2023;90: 104512.

12. Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, Hasler S, Krummenacher P, Werner C, Gerger H. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0170988.

13. Haskard Zolnierek KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician Communication and Patient Adherence to Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826.

14. Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (<em>Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence)</ em>: revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Safety. 2016;25(12):986-92.

15. Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, Hawkins M, Buchbinder R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):658.

16. Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228-39.

17. Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(Suppl 1):S19-26.

18. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97-107.

19. Kravitz RL, Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, DiMatteo MR, Rogers WH, Ordway L , Greenfield S . Recall of recommendations and adherence to advice among patients with chronic medical conditions. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(16):1869-78.

20. McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2868-79.

21. Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, Wang F, Wilson C, Daher C, LeongGrotz K, Castro C, Bindman AB. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83-90.

22. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):207-14.

23. Amin KS, Davis MA, Doshi R, Haims AH, Khosla P, Forman HP. Accuracy of ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing for Simplifying Radiology Reports. Radiology. 2023;309(2):e232561.

24. Truhn D, Loeffler CM, Müller-Franzes G, Nebelung S, Hewitt KJ, Brandner S, Bressem KK, Foersch S, Kather JN. Extracting structured information from unstructured histopathology reports using generative pre-trained transformer 4 (GPT-4). J Pathol. 2024;262(3):310-9.

25. Oben P. Understanding the Patient Experience: A Conceptual Framework. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(6):906-10.

ملاحظة الناشر

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-024-02838-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39849504

Publication Date: 2025-01-23

Enhancing doctor-patient communication using large language models for pathology report interpretation

Abstract

Background Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly utilized in healthcare settings. Postoperative pathology reports, which are essential for diagnosing and determining treatment strategies for surgical patients, frequently include complex data that can be challenging for patients to comprehend. This complexity can adversely affect the quality of communication between doctors and patients about their diagnosis and treatment options, potentially impacting patient outcomes such as understanding of their condition, treatment adherence, and overall satisfaction. Materials and methods This study analyzed text pathology reports from four hospitals between October and December 2023, focusing on malignant tumors. Using GPT-4, we developed templates for interpretive pathology reports (IPRs) to simplify medical terminology for non-professionals. We randomly selected 70 reports to generate these templates and evaluated the remaining 628 reports for consistency and readability. Patient understanding was measured using a custom-designed pathology report understanding level assessment scale, scored by volunteers with no medical background. The study also recorded doctor-patient communication time and patient comprehension levels before and after using IPRs. Results Among 698 pathology reports analyzed, the interpretation through LLMs significantly improved readability and patient understanding. The average communication time between doctors and patients decreased by over 70%, from 35 to

Introduction

In recent years, LLMs have made significant progress in understanding and generating natural language, demonstrating their ability to analyze and rewrite medical texts in a manner more understandable to non-professionals [7, 8]. For instance, Steimetz et al. (2024) demonstrated that LLM chatbots can significantly improve the readability of pathology reports while also highlighting some of the limitations such as inaccuracies and hallucinations in the generated reports [9]. This study aims to explore the possibility of using LLMs to enhance the efficiency of doctor-patient communication, particularly by automating the translation of pathology report content into patient-friendly language. This approach aims to reduce cognitive barriers to medical information and promote better patient understanding of their health conditions.

Using routine post-operative pathology reports in oncology, this study designed a universal pathology report interpretation framework through LLMs and developed a corresponding pathology report understanding level assessment scale. This was done to explore the potential and actual effects of LLMs in enhancing doctorpatient communication efficiency.

Therefore, in response to these challenges, this study aims to explore the potential of using LLMs to enhance doctor-patient communication, particularly

by simplifying pathology report content into patientfriendly language, and to provide insights on how LLMs can be integrated into clinical practice to improve communication efficiency [10, 11].

By improving the readability of pathology reports, we hope to promote better patient understanding of their health conditions, strengthen trust and communication between doctors and patients, and ultimately enhance the overall quality of medical services and patient satisfaction. Trust in physicians, fostered by effective communication, plays a pivotal role in treatment adherence. Research indicates that patients who trust their healthcare providers are more likely to follow prescribed treatments, which is essential for better health outcomes [12, 13].

Materials and methods

Study design

Among the 698 eligible text pathology reports on malignant tumors, 70 reports ( 5 reports per organ for 14 organs) were randomly selected to develop templates for interpretive reports and corresponding scoring scales. These were used to enable LLMs to reliably generate similar interpretive reports, as well as to produce identical outputs from the remaining 628 reports. Doctors evaluated each report for consistency by comparing the original pathology report (OPR) with the AI-generated simplified report (Interpretive pathology report, IPR). The evaluation focused on whether key diagnostic information, such as tumor type (e.g., carcinoma, lymphoma), tumor stage (e.g., TNM classification), histological features (e.g., cell differentiation), presence of metastasis, and other clinically significant findings (e.g., molecular markers, margins, and lymph node involvement), were accurately represented in the simplified version. Doctors from multiple specialisms, including pathology, oncology, and surgery, participated in this evaluation process. Each

The baseline health literacy levels of the volunteers were assessed using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ), ensuring that their understanding of medical terminology was evaluated prior to the study [15]. This assessment helped us control for variations in health literacy among the volunteers. The results of the HLQ assessments are summarized in Table 1. In the study, three volunteers (

scoring scales (Fig. 2) and recorded reading time. Lastly, doctors (with

Scale and template generation

A pathology report understanding level assessment scale is presented in Fig. 2A. This scale aims to comprehensively assess the understanding level of non-medical background individuals regarding pathology reports. Patient understanding was measured using a customdesigned pathology report understanding level assessment scale, developed based on established health

Pathology Report Understanding Level Assessment Scale

Scoring Criteria (Ten-point scale)*:

1. Understanding of Report Structure.

- Unable to identify the basic structure and various parts of the report (0 points).

- Can identify some parts of the structure (e.g., diagnosis, patient information) but does not fully understand them (1 point).

- Fully understands the report’s structure and the content and function of each major section (2 points).

2. Terminology Recognition and Understanding.

- Cannot recognize professional terminology or completely misunderstands the terms (

points). - Can recognize some basic medical terms but has limited understanding (1 point).

- Accurately recognizes and fundamentally understands most terms (2 points).

3. Interpretation of Results.

- Unable to interpret the report’s results (0 points).

- Can partially interpret results, but misunderstandings exist (1 point).

- Correctly interprets the basic information of the report’s results (2 points).

4. Extraction of Key Information.

- Unable to extract key information from the report (0 points).

- Can extract some key information but misses important details (1 point).

- Accurately extracts and understands all key information from the report (2 points).

- Comprehensive Understanding and Application.

- Unable to comprehensively understand the report content or relate it to health conditions (0 points).

- Has a basic comprehensive understanding but limited ability to relate the report content to health conditions (1 point).

- Not only fully understands the report content but also can effectively relate it to personal or others’ health conditions (2 points).

Scoring Guide:

Level B (5-7 points): Basic level of understanding, capable of grasping some key points of the report but still needs to enhance understanding of professional terminology and report structure.

Level A (8-10 points): High level of understanding, able to accurately interpret and apply information from the pathology reports.

- This scale aims to comprehensively assess the understanding level of non-medical background individuals regarding pathology reports.

C

Pathology Artificial Intelligence Quality Index

| 1. Accuracy (Whether the information in the GPT-4 report is accurate and consistent with current medical knowledge and the actual content of the pathology report.) | |||||

|

|||||

| 2. Interpretation Depth (How GPT-4 interprets the details of the pathology report and whether it can provide in-depth explanations of the pathology results.) | |||||

|

|||||

| 3. Readability (The readability of the report, including the fluency and comprehensibility of the language.) | |||||

|

|||||

| 4. Clinical Relevance (The relevance and usefulness of the report’s information to clinical practice.) | |||||

|

|||||

| 5. Overall Evaluation (Considering all the above aspects, the overall satisfaction of the doctor with the GPT-4 generated report.) | |||||

|

- Using this scale, doctors can comprehensively evaluate the quality of pathology interpretation reports generated by GPT-4. By summarizing the scores, it’s possible to roughly determine GPT-4’s level of understanding and interpreting pathology reports, as well as its potential value in clinical applications.

Pathology Report Interpretation Template*

1. Report Overview

Case Information: Briefly summarize the patient’s basic information, such as age and gender.

2. Sample Information

3. Gross and Microscopic Findings

4. Diagnosis Results

5. Recommendations and Explanations

Health Guidance: Offer related lifestyle or dietary advice to help understand how to manage or improve the condition.

6. Frequently Asked Questions

Notes:

2)Use simple and direct language, avoiding too many medical jargon terms.

3)Where possible, use metaphors or analogies to explain complex medical concepts, making them easier to understand.

*This template is intended as a general framework; specific content needs to be filled in and adjusted according to the actual details of each pathology report. This aims to assist individuals without a medical background in understanding the content and importance of pathology reports.

| Health Literacy Dimension | Average Score |

| Feeling Understood and Supported by Healthcare Providers | 3.92 |

| Having Sufficient Information to Manage My Health | 3.83 |

| Actively Managing My Health | 3.58 |

| Social Support for Health | 3.58 |

| Appraisal of Health Information | 3.83 |

| Ability to Actively Engage with Healthcare Providers | 3.83 |

| Navigating the Healthcare System | 3.42 |

| Ability to Find Good Health Information | 3.75 |

| Understanding Health Information Well Enough to Know What to Do | 3.92 |

literacy principles. The scale drew from the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) and other key research on health literacy [15-18]. It was designed to assess the clarity, relevance, and ease of understanding of key information in pathology reports, specifically for individuals with no medical background. The scale was refined through pilot testing to ensure its applicability for the study population.

A pathology report interpretation template is depicted in Fig. 2B. This template is intended as a general framework; specific content needs to be filled in and adjusted according to the actual details of each pathology report. This aims to assist individuals without a medical background in understanding the content and importance of pathology reports. The iterative prompt engineering involved multiple steps: First Prompt: “Summarize the pathology report for a layperson.” Refinement: “Summarize the pathology report in simple language, explaining the diagnosis, significance, and next steps.” Final Prompt: “Translate the pathology report into easy-to-understand language, include diagnosis, clinical significance, treatment options, and follow-up recommendations.” The OPRs were generated using the refined templates. Each section of the template was filled with specific details from the pathology reports, ensuring consistency and comprehensibility. Examples of these templates and filled reports are illustrated in Figs. 2B and 3.

A pathology AI quality index is shown in Fig. 2C. This index was developed using GPT-4 and further refined through discussions with pathologists, who finalized the content and scoring criteria. Using this scale, doctors can comprehensively evaluate the quality of pathology interpretation reports generated by GPT-4. By summarizing the scores, it is possible to roughly determine GPT-4’s level of understanding and interpreting pathology reports, as well as its potential value in clinical applications. This method was designed to rigorously compare the IPRs generated by GPT-4 against the standards set

by the OPRs. The evaluation was conducted across five key dimensions by three pathologists, each with over a decade of professional experience: Accuracy (Dimension A), Interpretative Depth (Dimension B), Readability (Dimension C), Clinical Relevance (Dimension D), and Overall Evaluation (Dimension E). Pathologist X is a general pathologist working in a university hospital with expertise in oncologic pathology; Pathologist Y is a thoracic pathologist with specialization in lung cancer diagnostics, working at a non-university cancer center; and Pathologist Z is a gastrointestinal pathology expert affiliated with a leading academic medical center. All pathologists have extensive experience in analyzing complex pathology reports and contributing to AI-assisted diagnostic models. Their diverse backgrounds ensured a comprehensive evaluation of the pathology reports from different perspectives. This comprehensive review aimed to determine how well the GPT-4-generated reports captured the essence of the OPRs. The results, as adjudicated by the pathologists-referred to as Pathologist X, Pathologist Y, and Pathologist Z.

To evaluate the text complexity of both OPRs and IPRs, we calculated the word count using the word count feature in Microsoft Office 365 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). This method provided a quantitative measure of report length, allowing us to compare word counts across different types of malignancies and between OPRs and IPRs.

Patient data anonymization and security

Original Pathology Reports

Gross Findings:

Pathological Diagnosis: Frozen section and paraffin-embedded remaining tissue:

Tumor Size:

IASLC New Classification: Grade 3. Pleural Invasion: PL0. Airway Spread (STAS): Not seen. Vascular Invasion: Present. Nerve Invasion: Present.

Bronchial Margin: Negative. Distance from Tumor to Bronchial Margin: 2.5 cm . Lymph Node Metastasis: No cancer metastasis in the peribronchial lymph node

Immunohistochemistry Results (Slide 3): TTF-1 (+), CK7 (+), NapsinA (+), P63 (few +), CK5/6 (-), P40 (-), Ki67 (about 5% +).

Special Stains (Slide 3): Elastic fibers (+).

Lymph Node Gross Findings: Frozen Section:

Group 2: One gray-brown tissue piece, measuring

Group 7: One gray-brown tissue piece, measuring

Group 10: One gray-brown tissue piece, measuring

Microscopic Findings: Pathological Diagnosis:

Frozen Section: (Group 7) Cancer metastasis in the lymph node (1/1); No cancer metastasis in the other lymph nodes: (Group 2) 0/1, (Group 4) 0/1, (Group 9) 0/1, (Group 10) 0/1, (Group 11)

Interpretive Pathology Reports

1. Report Overview

Case Information: The patient is a 54-year-old male.

2. Sample Information

Sample Type: The sample is a piece of lung tissue.

3. Gross and Microscopic Findings

Gross Examination: A portion of lung tissue measuring 19×10.5×3 cm was examined. The bronchus (airway) is 0.5 cm long and 2 cm in diameter. Inside the lung tissue, a gray-white tumor measuring

Microscopic Examination: The tumor is identified as an invasive adenocarcinoma, a type of lung cancer. The tumor is classified as a non-mucinous type with various patterns: acinar (

Immunohistochemistry:

Negative markers: CK5/6 and P40.

Proliferation marker Ki67 shows about

Elastic fibers are present in the sample.

Lymph Node Findings:

4. Diagnosis Results

The patient has invasive adenocarcinoma in the right lower lobe of the lung.

The tumor is classified as low-grade, indicating it is more aggressive and less differentiated.

Cancer cells have spread to nearby lymph nodes in one group but not in others.

Immunohistochemistry results support the diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma.

The clear surgical margin suggests the tumor has been removed with a good safety margin.

5. Recommendations and Explanations

Follow-up appointments with an oncologist for further evaluation and treatment planning.

Potential treatments include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or targeted therapy, depending on the cancer stage and overall health of the patient.

Health Guidance:

Maintain a healthy diet and lifestyle to support overall well-being.

Avoid smoking and exposure to lung irritants to improve lung health.

Regular follow-ups and imaging studies as recommended by the healthcare provider.

6. Frequently Asked Questions

Q : What is adenocarcinoma?

Q: What does low-grade tumor mean?

Q: What is the significance of lymph node involvement?

Q: What are the next steps after this diagnosis?

or HIPAA]. These measures ensured that no sensitive patient data was exposed or accessible outside the study, safeguarding patient confidentiality while allowing for accurate AI-generated pathology report analysis.

Statistical analyses

Results

Characteristics of sample

Text data extractions

We observed that the average word count for OPRs across all types of malignant tumors was 549.98, while the average word count for IPRs was significantly higher at 787.44. Liver malignancies had the lowest average word count for OPRs (441.41) and IPRs (775.25). In contrast, ovarian malignancies had the highest average word count for OPRs (961.21), while esophagus malignancies

| Cancer Sites | Patients | Age (years)

|

Sex (M, F) |

| All sites | 698 |

|

290 (41.55%), 408 (58.45%) |

| Brain | 32 |

|

13 (40.62%), 19 (59.38%) |

| Thyroid | 76 |

|

32 (42.11%), 44 (57.89%) |

| Breast | 86 |

|

0 (0.00%), 86 (100.00%) |

| Lung | 98 |

|

49 (50.00%), 49 (50.00%) |

| Esophagus | 10 |

|

7 (70.00%), 3 (30.00%) |

| Gastric | 30 |

|

18 (60.00%), 12 (40.00%) |

| Liver | 32 |

|

24 (75.00%), 8 (25.00%) |

| Pancreatic | 18 |

|

15 (83.33%), 3 (16.67%) |

| Colorectal | 74 |

|

31 (41.89%), 43 (58.11%) |

| Kidney | 61 |

|

31 (50.82%), 30 (49.18%) |

| Prostate | 37 |

|

37 (100.00%), 0 (0.00%) |

| Bladder | 50 |

|

33 (66.00%), 17 (34.00%) |

| Ovary | 61 |

|

0 (0.00%), 61(100.00%) |

| Uterus | 33 |

|

0 (0.00%), 33 (100.00%) |

had the highest average word count for IPRs (833.80). This suggests that although there is significant variation in the word count of OPRs among different malignancies (

Moreover, the word count for the OPRs of ovarian malignant tumors was higher than that for the IPRs (

Consistency evaluation of expression content

Pathology report reading time

| Cancer Sites | Pathology reports | OPRs (Word count)* | OPRs (medical terms)* | IPRs (Word count)* |

|

| All sites | 698 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Brain | 32 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Thyroid | 76 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Breast | 86 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Lung | 98 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Esophagus | 10 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Gastric | 30 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Liver | 32 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Pancreatic | 18 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Colorectal | 74 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Kidney | 61 |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

| Prostate | 37 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Bladder | 50 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Ovary | 61 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Uterus | 33 |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

- Data are means ± SDs, with ranges in parentheses

** The OPRs and IPRs of different cancer sites were analyzed statistically

statistically significant differences in reading times for OPRs across tumor types (). In contrast, the average reading time for IPRs was 430.67 s , with the shortest for liver malignancies at 418.88 s , and the longest for esophagus tumors at 452.10 s . No significant differences were observed in the reading times for IPRs across the tumor types ( ).

A comparison of the reading times between OPRs and IPRs for all types of malignant tumors revealed that OPRs were generally read faster than IPRs, with a statistically significant difference (). However, for bladder, ovarian, and uterus malignancies, the reading times were

longer for OPRs compared to IPRs, with these differences also being statistically significant (for each).

Understanding level assessment

Doctor-patient communication

had the shortest at 2062.03 s. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in communication times across the different tumor types

Correlation of OPRs and IPRs metrics

among nine key metrics within OPRs and IPRs. It reveals a strong correlation between word count, medical terms, score, and reading time for OPRs. The figure serves as a visually intuitive tool to identify both the strength and the direction of relationships between these metrics.

Discussion

| Cancer Site | Dimension A (Accuracy) | Dimension B (Interpretation Depth) | Dimension C (Readability) | Dimension D (Clinical Relevance) | Dimension E (Overall Evaluation) |

| All sites | 4.95 | 4.95 | 5 | 4.92 | 4.84 |

| Brain | 5 | 4.97 | 5 | 4.91 | 4.91 |

| Thyroid | 4.93 | 4.96 | 5 | 4.83 | 4.83 |

| Breast | 4.94 | 4.94 | 5 | 4.91 | 4.8 |

| Lung | 4.95 | 4.94 | 5 | 4.93 | 4.83 |

| Esophagus | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4.9 | 4.9 |

| Gastric | 4.97 | 4.97 | 5 | 4.9 | 4.83 |

| Liver | 5 | 4.94 | 5 | 4.97 | 4.91 |

| Pancreatic | 4.89 | 4.89 | 5 | 4.89 | 4.67 |

| Colorectal | 4.96 | 4.97 | 5 | 4.95 | 4.88 |

| Kidney | 4.93 | 4.95 | 5 | 4.97 | 4.85 |

| Prostate | 4.95 | 4.95 | 5 | 4.95 | 4.84 |

| Bladder | 4.96 | 4.92 | 5 | 4.96 | 4.86 |

| Ovary | 4.93 | 4.95 | 5 | 4.93 | 4.82 |

| Uterus | 4.94 | 4.97 | 5 | 4.88 | 4.79 |

Across all types of malignant tumors, the use of IPRs resulted in significantly higher patient understanding scores compared to traditional OPRs, with an average improvement from 5.23 to 7.98 on the Pathology Report Understanding Level Assessment Scale. Furthermore, the study found a substantial reduction in doctor-patient communication time when using IPRs, decreasing from an average of 2091.25 s to 599.15 s , underscoring the potential time-saving benefits of AI-assisted reports. These findings suggest that AI-generated reports can enhance doctor-patient communication while also improving overall healthcare efficiency.

In addition to improving communication time and comprehension, the consistency evaluation conducted by pathologists highlighted that the IPRs generated by GPT-4 were highly accurate, scoring consistently across dimensions such as Accuracy, Interpretative Depth, and Readability. This consistency in evaluation across different tumor types supports the robustness of the AI-generated reports, indicating their potential for widespread clinical application. The strong correlation observed between OPR and IPR metrics further emphasizes the effectiveness of the AI model in maintaining clinical relevance while simplifying report content for patient understanding. This enhanced understanding is critical as it directly influences patient engagement and empowerment. Patients who grasp their medical

conditions and the logic behind their treatment options are more inclined to adhere to recommended treatments and engage in proactive health management. This link between comprehension and compliance is well-documented in healthcare literature, with our data providing robust evidence of AI’s pivotal role in fostering this understanding [19-22].

Moreover, recent studies have increasingly acknowledged AI’s capability to enhance the accessibility and comprehensibility of medical documentation. For instance, Amin et al. employed three prominent large language models-ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing-to simplify radiology reports [23]. Subsequently, they solicited assessments from pertinent clinical practitioners concerning the accuracy of each model’s output. Nevertheless, the research did not address the comprehensibility of these simplified radiology reports for individuals lacking a medical background. Consequently, the applicability of large language models in making radiological information accessible to a broader, nonspecialist audience remains unverified [23]. Truhn et al. utilized GPT-4 to generate structured pathology reports, demonstrating that structured reports generated by large language models are consistent with those produced by pathologists [24]. This indicates that LLMs could potentially be employed routinely to extract ground truth data for machine learning from unstructured pathology reports in the future. However, this study focused only on evaluations by professionals and lacks an assessment of the usability of AI-generated reports in broader scenarios. Similarly, Steimetz et al. examined methods for

| Cancer Sites | V

|

V (D, E, F)

|

|

V (A, B, C) OPRs (Score) | V (D, E, F) IPRs (Score) |

|

V (A, B, C) OPRs (DPCT) | V (D, E, F) IPRs (DPCT) |

|

| All sites |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

| Brain |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Thyroid |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Breast |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Lung |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Esophagus |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Gastric |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Liver |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Pancreatic |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Colorectal |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Kidney |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Prostate |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Bladder |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Ovary |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

| Uterus |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

<0.001 |

simplifying medical documents to improve patient comprehension, finding that enhancing readability directly impacts patient engagement and satisfaction [9]. In addition, Singhal et al. showed that LLMs effectively encode clinical knowledge, reinforcing their potential in improving healthcare communication [8]. Harrer further discusses the ethical considerations and complexities of integrating large language models into medical systems, emphasizing the importance of thoroughly evaluating their real-world applications to ensure both patient safety and accuracy [11].

essential in high-demand environments like surgical units. The scarcity of medical resources globally further underscores the importance of these findings, suggesting that large language models can significantly alleviate the strain on healthcare resources.

Additionally, our study demonstrates that the IPRs generated by GPT-4 show a high degree of consistency with the OPRs, as evaluated across key dimensions such as accuracy, interpretative depth, and readability. These findings underscore the robustness of the evaluative framework in verifying that the IPRs accurately represent the key insights of the OPRs. This framework not only ensures that the generated reports are consistent with the original medical data, but also plays a crucial role in

maintaining the integrity and reliability of the pathology interpretation process. By systematically comparing multiple dimensions, the framework provides a comprehensive assessment that helps to identify potential discrepancies and ensures the clinical relevance of the reports. This rigorous approach allows for the use of AIgenerated reports with greater confidence in real-world medical settings, ultimately contributing to more efficient doctor-patient communication and improved healthcare outcomes. With proper training and model adjustments, LLMs like GPT-4 can achieve high levels of accuracy and reliability in interpreting and simplifying complex surgical pathology reports, vital for patient recovery and comprehension post-surgery.

The implications of these findings for clinical practice are profound. Integrating AI-generated IPRs into healthcare systems can be achieved through several practical steps. First, hospitals and clinics can implement AI models like GPT-4 to automatically generate simplified, patient-friendly pathology reports alongside traditional reports. These AI-generated reports can be shared with patients via patient portals or during face-to-face consultations. Additionally, training healthcare providers to utilize AI-generated reports as communication tools during consultations can further enhance patient understanding. By offering easy-to-understand summaries, patients are more likely to engage with their care plans, leading to greater satisfaction and better adherence to treatment, ultimately contributing to improved health outcomes. Additionally, reducing the time spent on routine explanations can alleviate workload pressures on healthcare professionals, potentially enhancing job satisfaction and reducing burnout.

However, it is important to note that this study was conducted in a Chinese-speaking region, and all pathology reports, whether original or interpretive, were written in Chinese. The language and cultural background may influence the generalizability of our findings. During the template generation and evaluation process, we carefully considered the use of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) terminology and the specific structure of Chinese pathology reports. Therefore, in real-world applications, it is crucial to take cultural and linguistic contexts into account when applying the conclusions of this study.

While our study utilized volunteers to simulate patient interactions, we acknowledge the potential differences between volunteers and real patients. Real patients in clinical settings often experience a range of emotions, such as anxiety, fear, and distress, which can influence their behavior, decision-making, and communication efficiency. Studies have shown that patients under emotional distress may struggle with comprehension and retention of medical information, potentially impacting

their ability to engage in effective communication with healthcare providers [25]. In contrast, volunteers in our study, who were aware of the non-threatening nature of the environment, did not experience these emotional stressors. As such, future research should aim to include real patients to better capture the complexity of clinical interactions and the impact of emotional states on communication outcomes.

Despite the promising results, our study acknowledges several key limitations that warrant careful consideration. These limitations highlight areas for cautious interpretation of the results and suggest potential avenues for future research to address these gaps. First, our study’s heavy reliance on the capabilities of GPT-4, a specific version of Large Language Models developed by OpenAI, raises questions about the generalizability of our findings. While GPT-4 is renowned for its sophisticated natural language processing capabilities, it represents only one example of such technologies. Different LLMs may exhibit varying effectiveness based on their training data and underlying algorithms. Future research could explore the performance of other LLMs in similar tasks to verify if the observed benefits are replicable across different AI platforms. Second, the demographic and geographic diversity of our patient sample was confined to specific hospitals within a limited region, which may restrict the applicability of our results to other settings where patient populations differ significantly in terms of language, culture, and healthcare practices. Additionally, the sample size, while sufficient for statistical analysis, may not fully capture the variability and complexity of patient experiences across broader populations. Expanding the sample size and including a more diverse patient group in future studies could provide insights into how different populations interact with and benefit from AI-generated reports. Third, the primarily quantitative nature of our study provides a robust statistical foundation for evaluating the effectiveness of AI in improving patient understanding and communication efficiency. However, this approach may overlook the nuanced human aspects of doctor-patient interactions that are better captured through qualitative methods. Future studies might incorporate qualitative research techniques, such as in-depth interviews or focus groups, to gather more comprehensive insights into how patients and healthcare providers perceive and value the AI-generated interpretive reports. Fourth, one limitation of this study is the exclusion of hallucinations, a commonly reported error in LLM/ GPT models, from the evaluation. Hallucinations refer to instances where the model generates information that is factually incorrect or fabricated, which could potentially affect the interpretation of AI-generated pathology reports. However, in this study, our primary focus was

on evaluating the accuracy, consistency, and readability of the pathology reports, specifically in relation to diagnostic content. As such, hallucinations were not included in the scope of this assessment. Future research should aim to investigate the occurrence of hallucinations in medical text generation and their potential implications for clinical practice, especially when using AI models in high-stakes decision-making environments. Fifth, we acknowledge the small number of volunteers and the potential impact on baseline characteristics. Different groups were chosen to avoid bias introduced by familiarity with the report format. However, controlling for baseline characteristics is crucial. The health literacy levels of the volunteers were assessed and considered in the analysis. Therefore, these limitations underscore the need for cautious interpretation of our study results and highlight the importance of addressing these areas in future research. By expanding the scope, diversity, and depth of research into the use of AI in healthcare, we can better understand the capabilities and limitations of these technologies and work towards maximizing their benefits while minimizing potential drawbacks.

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 23 January 2025

References

- Yang X, Chen A, PourNejatian N, Shin HC, Smith KE, Parisien C, Compas C, Martin C, Costa AB, Flores MG, et al. A large language model for electronic health records. NPJ Digital Med. 2022;5(1):194.

- Thirunavukarasu AJ, Ting DSJ, Elangovan K, Gutierrez L, Tan TF, Ting DSW. Large language models in medicine. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):1930-40.

- Yang X, Chu XP, Huang S, Xiao Y, Li D, Su X, Qi YF, Qiu ZB, Wang Y, Tang WF, et al. A novel image deep learning-based sub-centimeter pulmonary nodule management algorithm to expedite resection of the malignant and avoid over-diagnosis of the benign. Eur Radiol. 2024;34(3):2048-61.

- Mossanen M, True LD, Wright JL, Vakar-Lopez F, Lavallee D, Gore JL. Surgical pathology and the patient: a systematic review evaluating the primary audience of pathology reports. Hum Pathol. 2014;45(11):2192-201.

- Dunsch F, Evans DK, Macis M, Wang Q. Bias in patient satisfaction surveys: a threat to measuring healthcare quality. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(2):e000694.

- Farley H, Enguidanos ER, Coletti CM, Honigman L, Mazzeo A, Pinson TB, Reed K, Wiler JL. Patient Satisfaction Surveys and Quality of Care: An Information Paper. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(4):351-7.

- Shah NH, Entwistle D, Pfeffer MA. Creation and Adoption of Large Language Models in Medicine. JAMA. 2023;330(9):866-9.

- Singhal K, Azizi S, Tu T, Mahdavi SS, Wei J, Chung HW, Scales N, Tanwani A, Cole-Lewis H, Pfohl S, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature. 2023;620(7972):172-80.

- Steimetz E, Minkowitz J, Gabutan EC, Ngichabe J, Attia H, Hershkop M, Ozay F, Hanna MG, Gupta R. Use of Artificial Intelligence

10. Winograd A. Loose-lipped large language models spill your secrets: The privacy implications of large language models. Harvard J Law Technol. 2023;36(2):615.

11. Harrer S. Attention is not all you need: the complicated case of ethically using large language models in healthcare and medicine. EBioMedicine. 2023;90: 104512.

12. Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, Hasler S, Krummenacher P, Werner C, Gerger H. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0170988.

13. Haskard Zolnierek KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician Communication and Patient Adherence to Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826.

14. Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (<em>Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence)</ em>: revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Safety. 2016;25(12):986-92.

15. Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, Hawkins M, Buchbinder R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):658.

16. Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228-39.

17. Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(Suppl 1):S19-26.

18. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97-107.

19. Kravitz RL, Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, DiMatteo MR, Rogers WH, Ordway L , Greenfield S . Recall of recommendations and adherence to advice among patients with chronic medical conditions. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(16):1869-78.

20. McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2868-79.

21. Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, Wang F, Wilson C, Daher C, LeongGrotz K, Castro C, Bindman AB. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83-90.

22. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):207-14.

23. Amin KS, Davis MA, Doshi R, Haims AH, Khosla P, Forman HP. Accuracy of ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Microsoft Bing for Simplifying Radiology Reports. Radiology. 2023;309(2):e232561.

24. Truhn D, Loeffler CM, Müller-Franzes G, Nebelung S, Hewitt KJ, Brandner S, Bressem KK, Foersch S, Kather JN. Extracting structured information from unstructured histopathology reports using generative pre-trained transformer 4 (GPT-4). J Pathol. 2024;262(3):310-9.

25. Oben P. Understanding the Patient Experience: A Conceptual Framework. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(6):906-10.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Chuan Xu

xuchuan89757@163.com

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article