DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47773-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38664402

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-25

تغني البيورينات بكتيريا الزائفة المرتبطة بالجذور وتحسن نمو فول الصويا البري تحت ضغط الملح

تاريخ القبول: 12 أبريل 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 25 أبريل 2024

تشينغ-شينغ تشانغ

الملخص

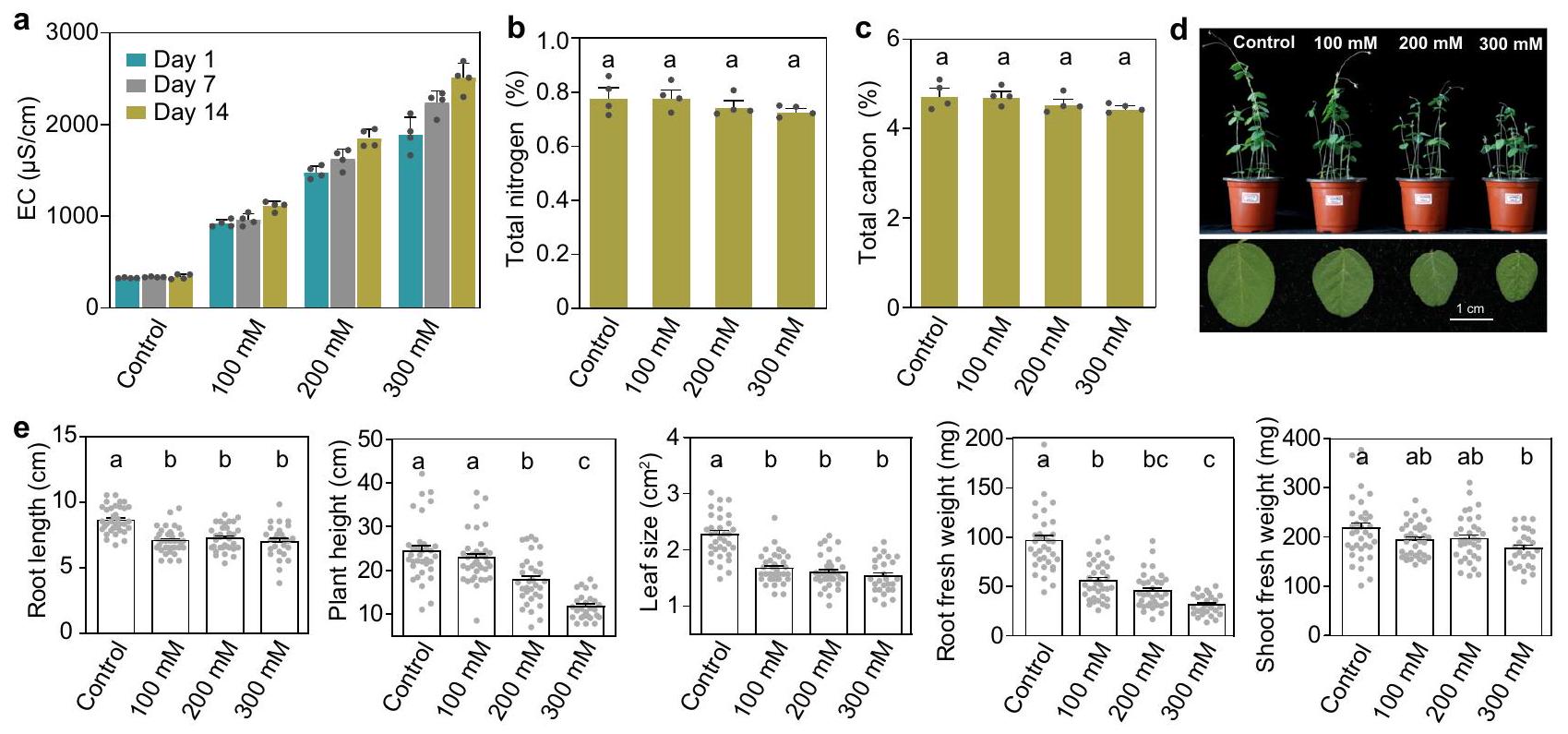

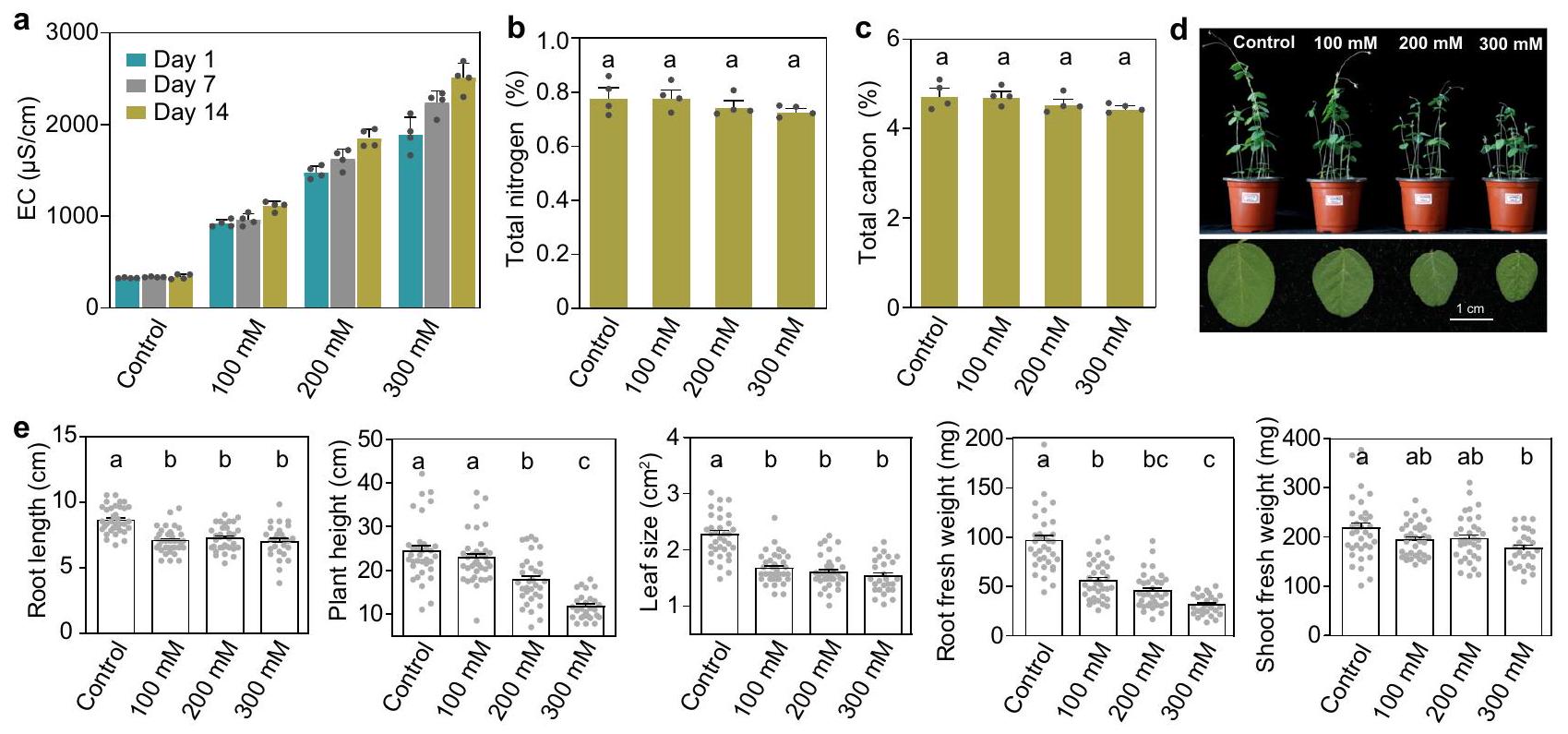

تحت المجموعة الضابطة ومعالجات الملح المختلفة. هـ طول الجذر، ارتفاع النبات، حجم الورقة، وزن الجذر ووزن الساق لفول الصويا البري في المجموعة الضابطة ومعالجات الملح المختلفة. عدد العينات لكل معالجة في (هـ) هو كما يلي: المجموعة الضابطة (

المستقلبات

والوظيفة للميكروبات المرتبطة بالجذور تحت ظروف ضغط الملح باستخدام تسلسل جين 16S rRNA، والميتاجينوم والميتاترنسكريبتوم. تم تحديد الميكروبات المستجيبة للضغط، وتم تقييم دورها في تعزيز نمو النباتات. أخيرًا، تم توضيح الأسباب الأساسية لتغيرات المجتمع المتأثرة بالملح بناءً على الخصائص الجينية للميكروبات المتزايدة والمستقلبات الجذرية في فول الصويا البري.

النتائج

تأثر نمو فول الصويا البري بضغط الملح

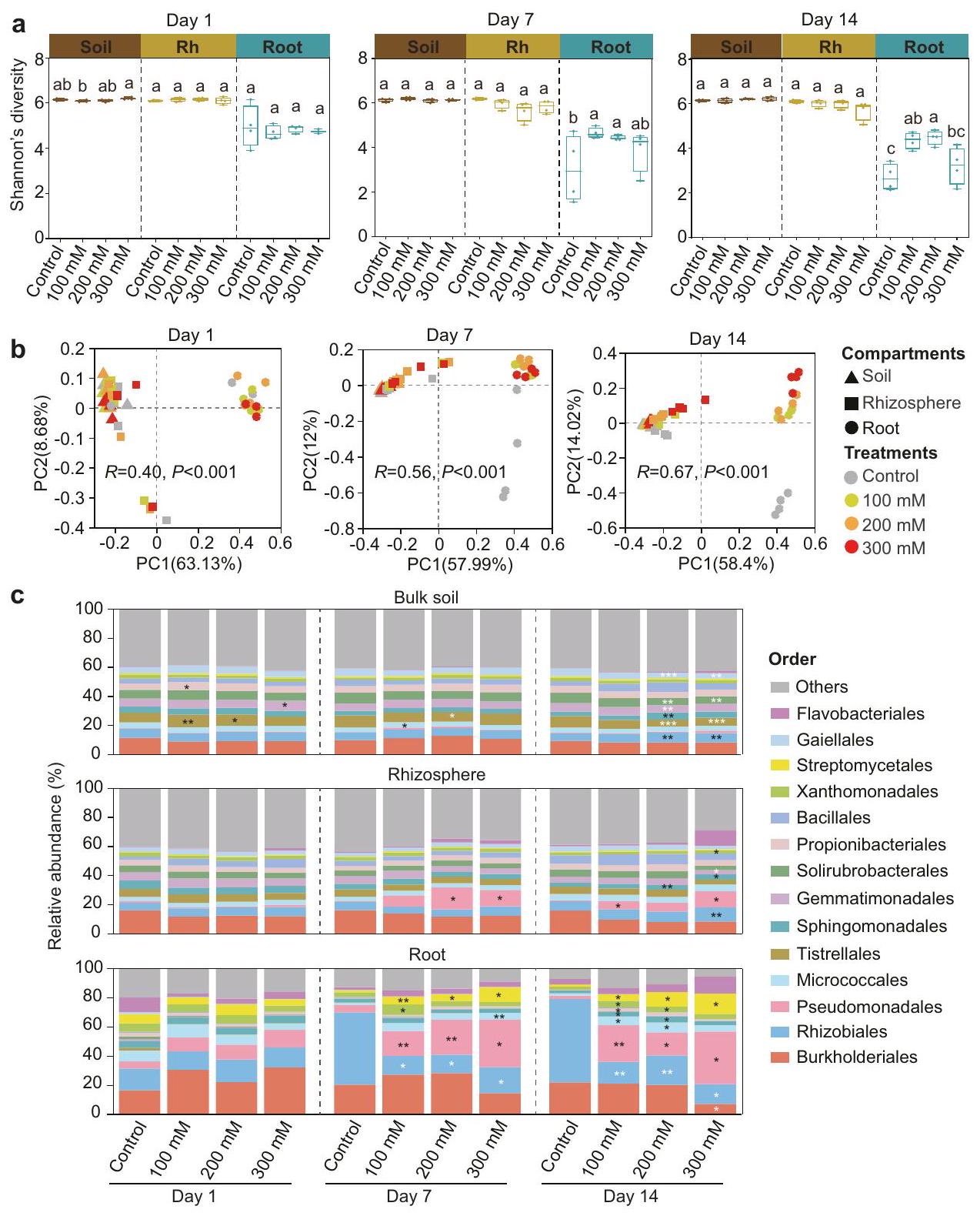

يؤدي ضغط الملح إلى استجابات مميزة في تنوع البكتيريا والأنواع السائدة بين الأقسام

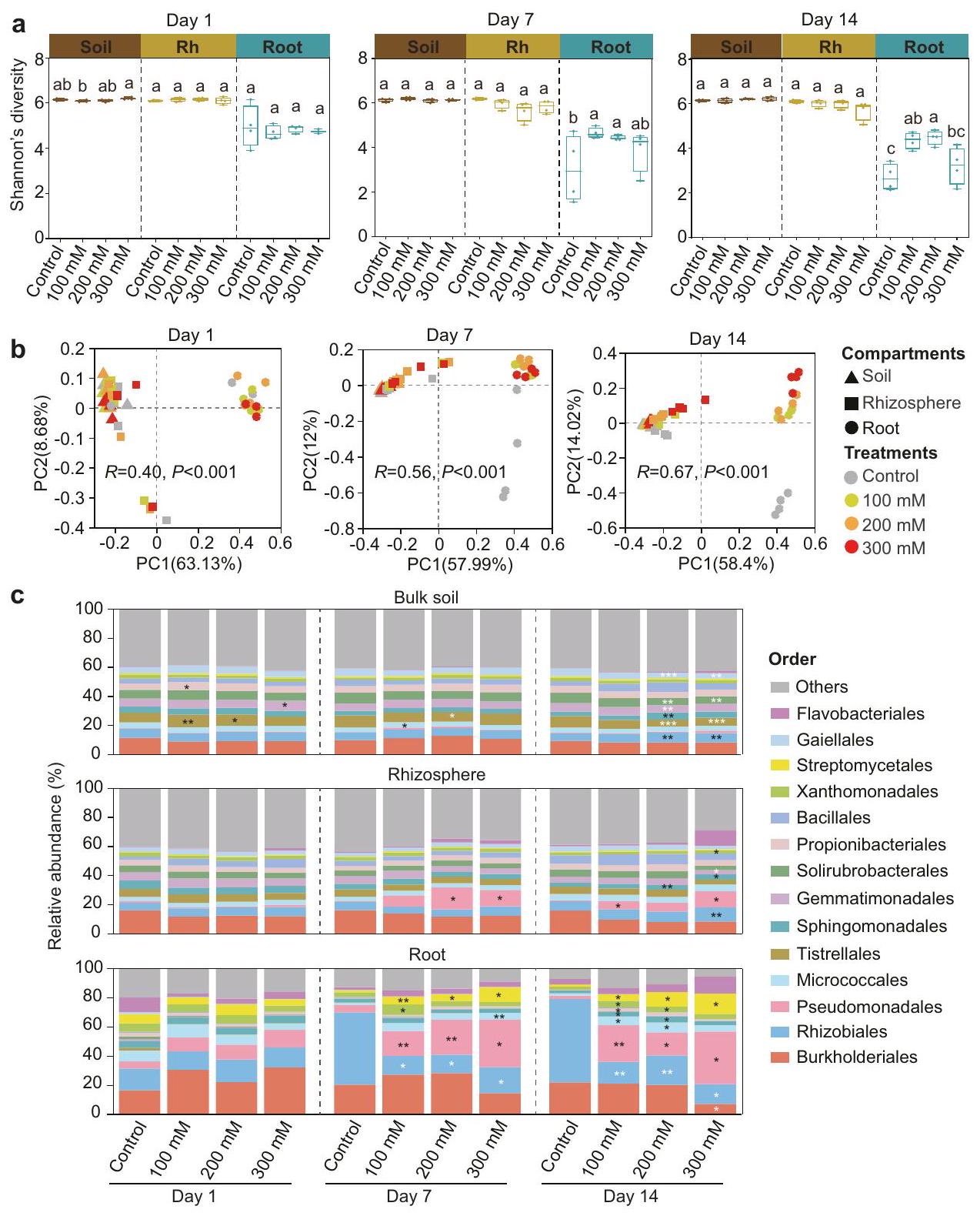

وفرة أعلى 15 ترتيبًا الأكثر وفرة للتربة السائبة، وتربة الجذور، والجذور عبر التحكم ومستويات مختلفة من إجهاد الملح. يتم تمييز مستويات الأهمية المختلفة بين التحكم وكل معالجة ملحية بالنجوم.

نقطة وعلاج (الجدول التكميلي 1). مجتمع الجذور (تحليل التشابه [ANOSIM])؛

في تربة منطقة الجذور استنادًا إلى بيانات الميتا ترانسكروم. القيم هي المتوسطات

تمت ملاحظة زيادة في الوفرة النسبية لجماعات Gammaproteobacteria وActinobacteriota في مجتمع الجذور تحت ضغط الملح (الشكل التوضيحي 2). لم يتم العثور على تغييرات تصنيفية ملحوظة بين المعالجة الضابطة ومعالجة الملح سواء في تربة الجذور أو التربة الكلية. على مستوى الرتبة، زادت الوفرة النسبية لجماعات Pseudomonadales وStreptomycetales بشكل ملحوظ في جميع عينات الجذور المعالجة بالملح في اليوم السابع واليوم الرابع عشر، مقارنة بتلك في المجموعة الضابطة (الشكل 2c). كما لوحظت زيادة في وفرة Pseudomonadales في مجتمعات تربة الجذور ولكن ليس في التربة الكلية (الشكل 2c).

أظهرت الوفرة بعض التقلبات بين العلاجات الملحية الثلاثة، لكن التغيرات لم تكن ذات دلالة إحصائية سواء في تربة الجذور أو عينات الجذور (الشكل التوضيحي التكميلي 4)، مما يشير إلى أن زيادة الأكتينوبكتيريا والغامما بروتيوبكتيريا لم تكن نتيجة لزيادة في الوفرة المطلقة للبكتيريا الكلية، بل كانت نتيجة لانخفاض في وفرة مجتمعات أخرى. بشكل عام، تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن ميكروبيوتا جذور فول الصويا البري، وتربة الجذور، وتربة الكتلة تستجيب بشكل مختلف لضغط الملح عبر الملف التصنيفي.

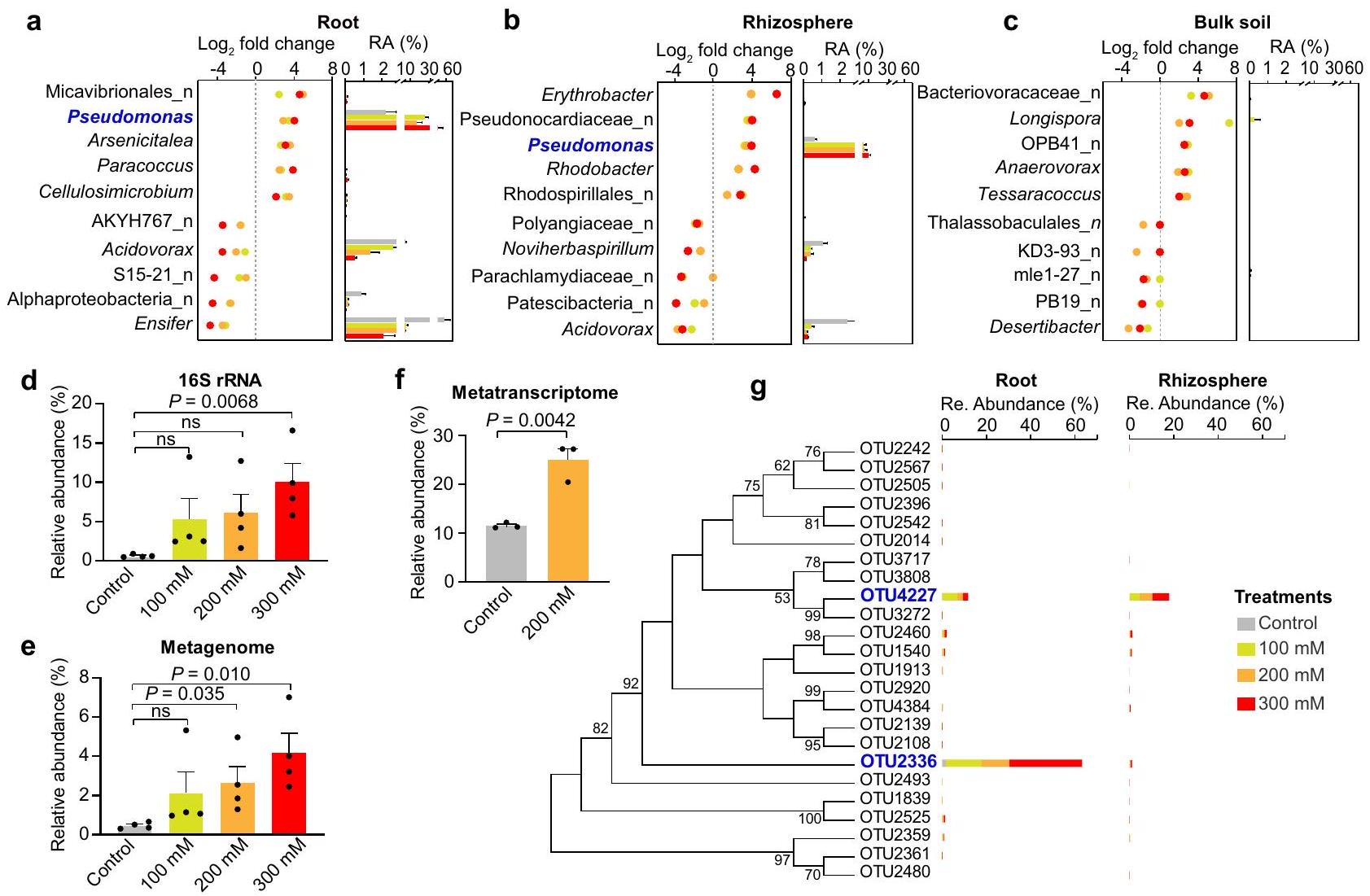

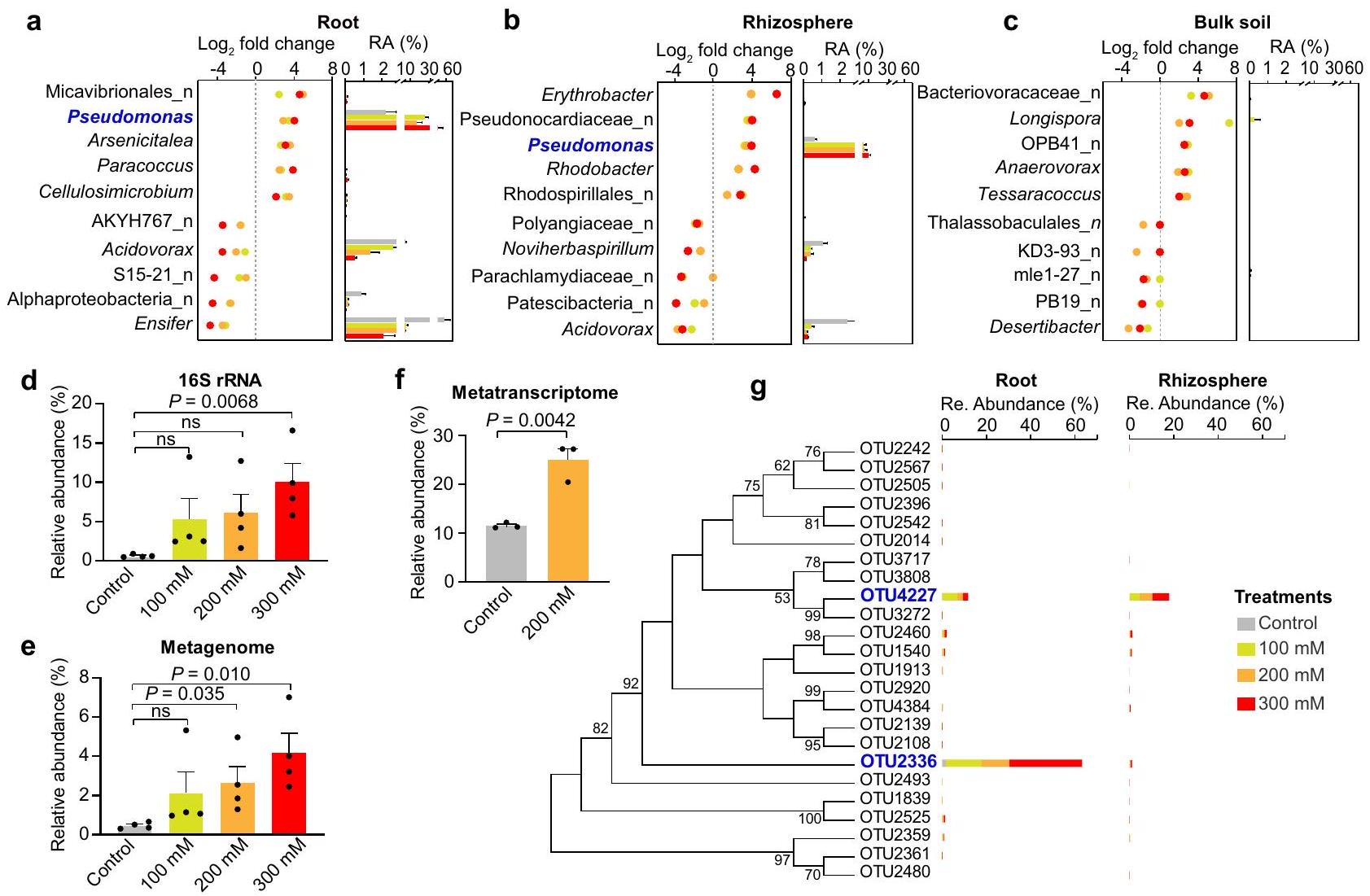

يزداد وفرة البكتيريا الزائفة بشكل كبير في الجذور المعالجة بالملح وتربة الجذور.

على التوالي. تشير القضبان الأفقية داخل الصناديق إلى الوسيط، وتمثل الشعيرات العليا والسفلى نطاق قيم البيانات غير الشاذة. جميع الرسوم البيانية تمثل المتوسط

أن البكتيريا الزائفة لم تكن فقط العضو الأكثر وفرة (الشكل 3e) ولكنها كانت نشطة أيضًا مع وفرة نسبية من النسخ

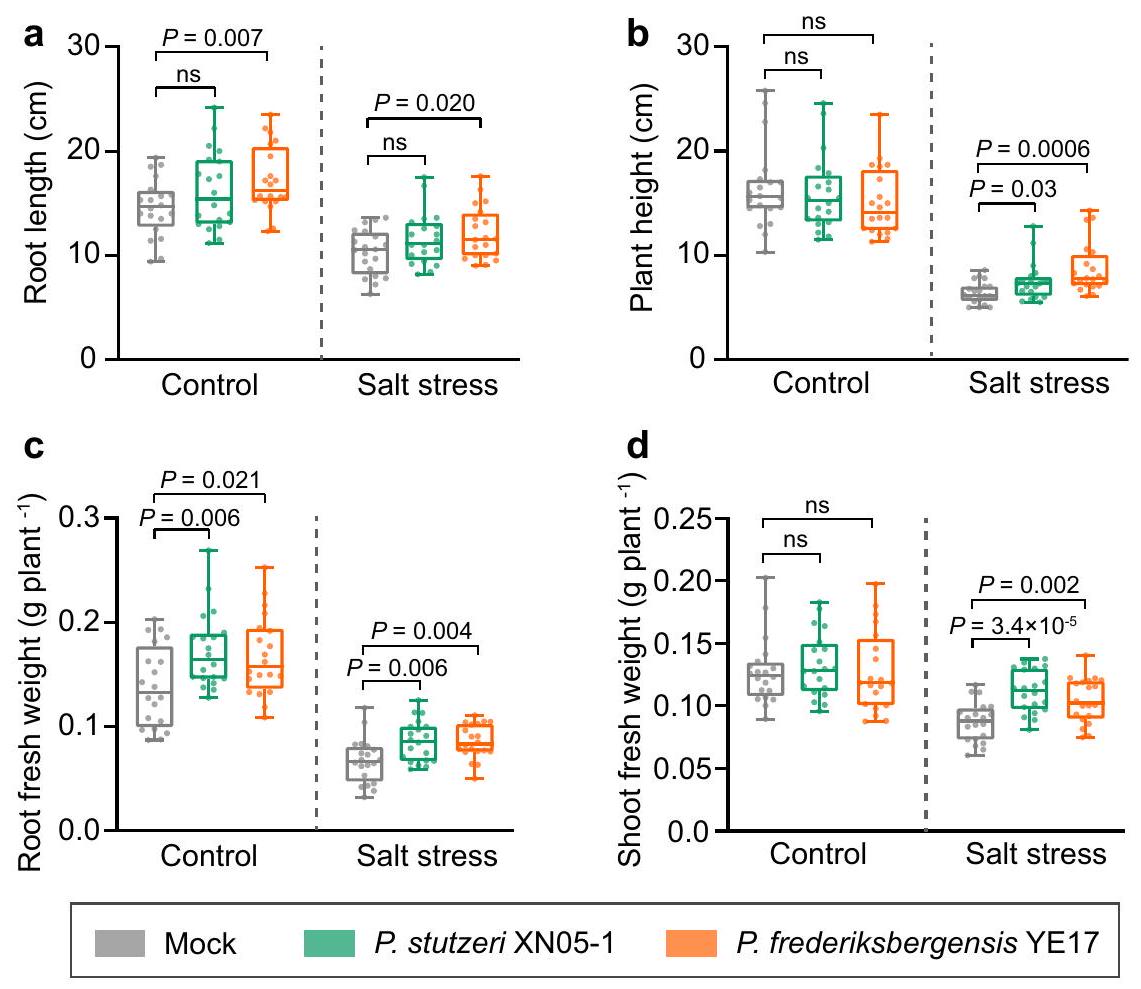

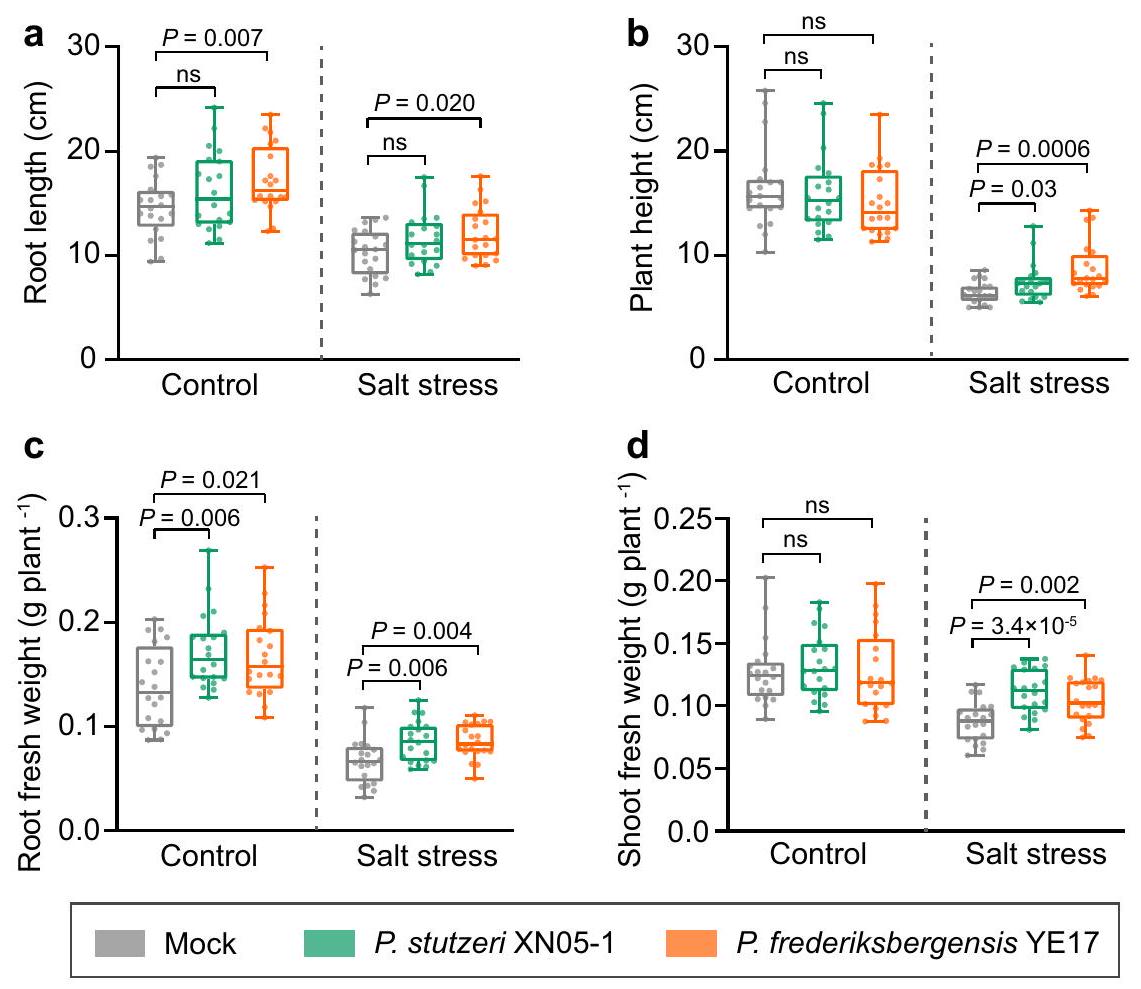

عزلتان من بكتيريا الزائفة أنقذتا نمو فول الصويا البري تحت ضغط الملح

ولم يتم عرض الهيكل النووي (COG Y).

كان وفرة بكتيريا الزائفة أعلى تحت ضغط الملح مقارنةً بالظروف غير المالحة (الشكل التوضيحي 9)، وهو ما يتماشى مع الاكتشاف الذي يشير إلى أن ضغط الملح يزيد من وفرة الزائفة.

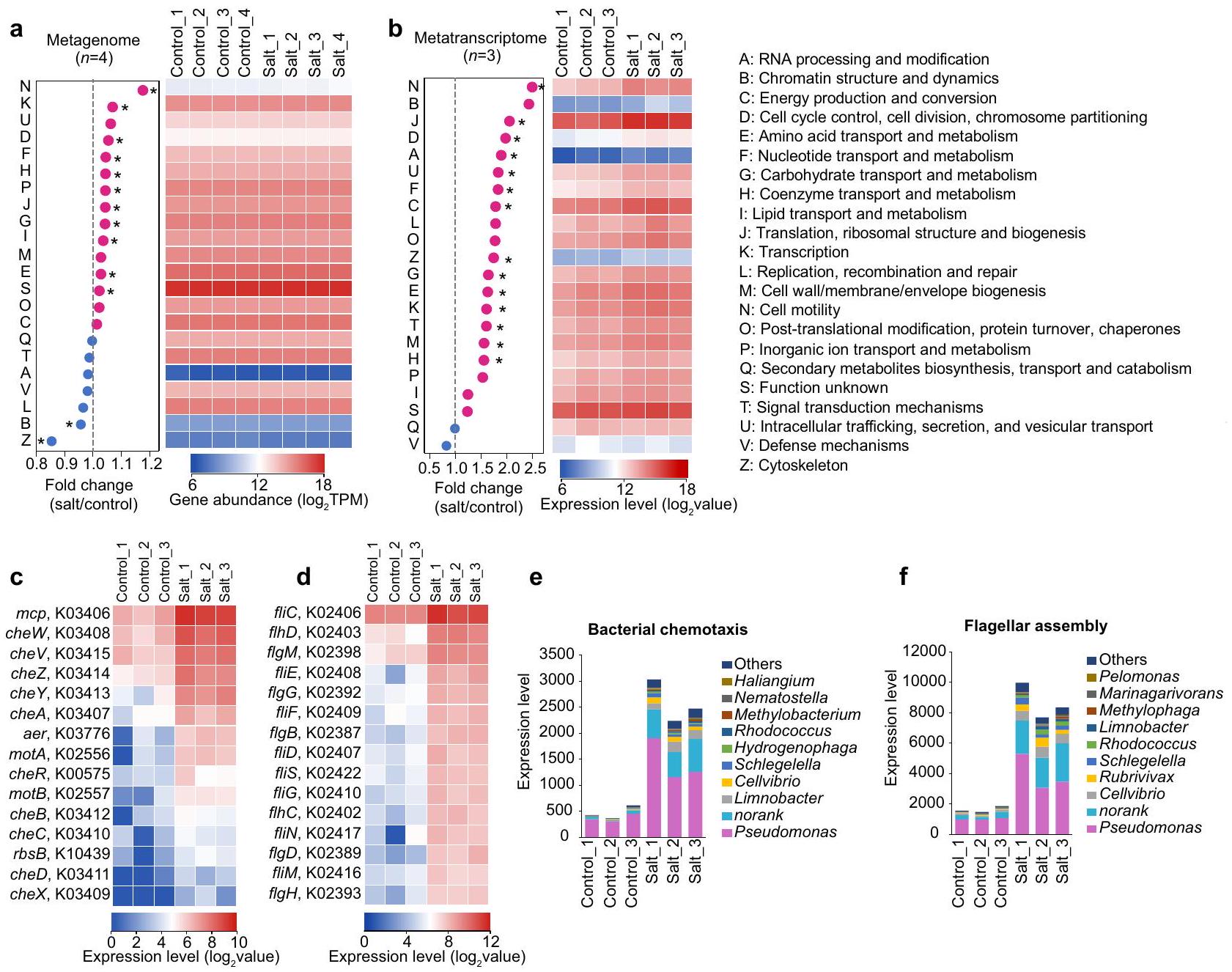

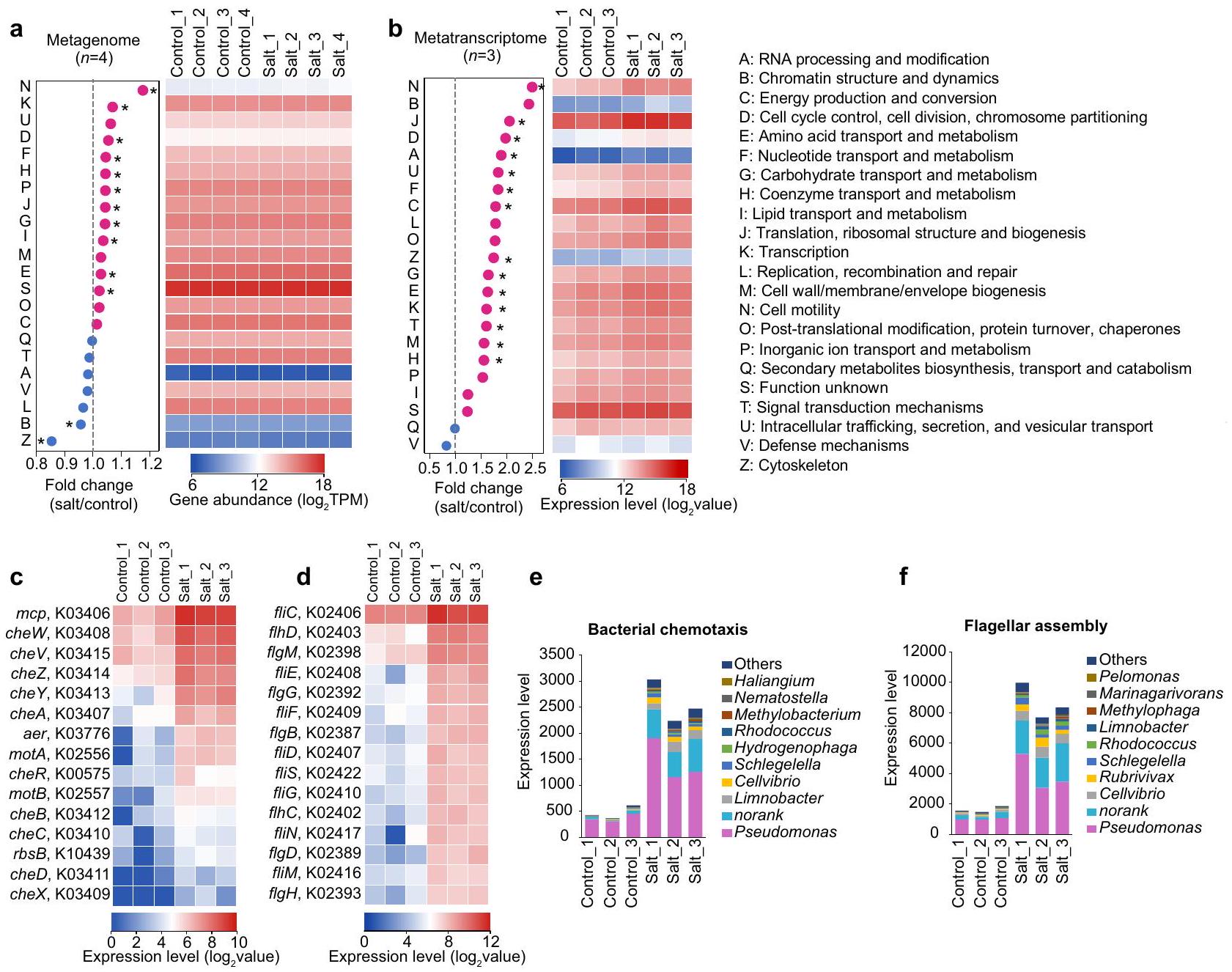

زادت جينات وحمض نووي خلوية الحركة في منطقة الجذور المعالجة بالملح

تربة منطقة الجذور (الشكل 5أ). ومن الجدير بالذكر أن التغير النسبي في الجينات المرتبطة بحركة الخلايا كان الأعلى بين جميع فئات COG.

الجينات التي تعبر عن بروتينات قبول الميثيل (MCP؛ تغيير في الطي = 6.14) وبروتين كيميائي جذب مرتبط بالبيورين CheW (تغيير في الطي

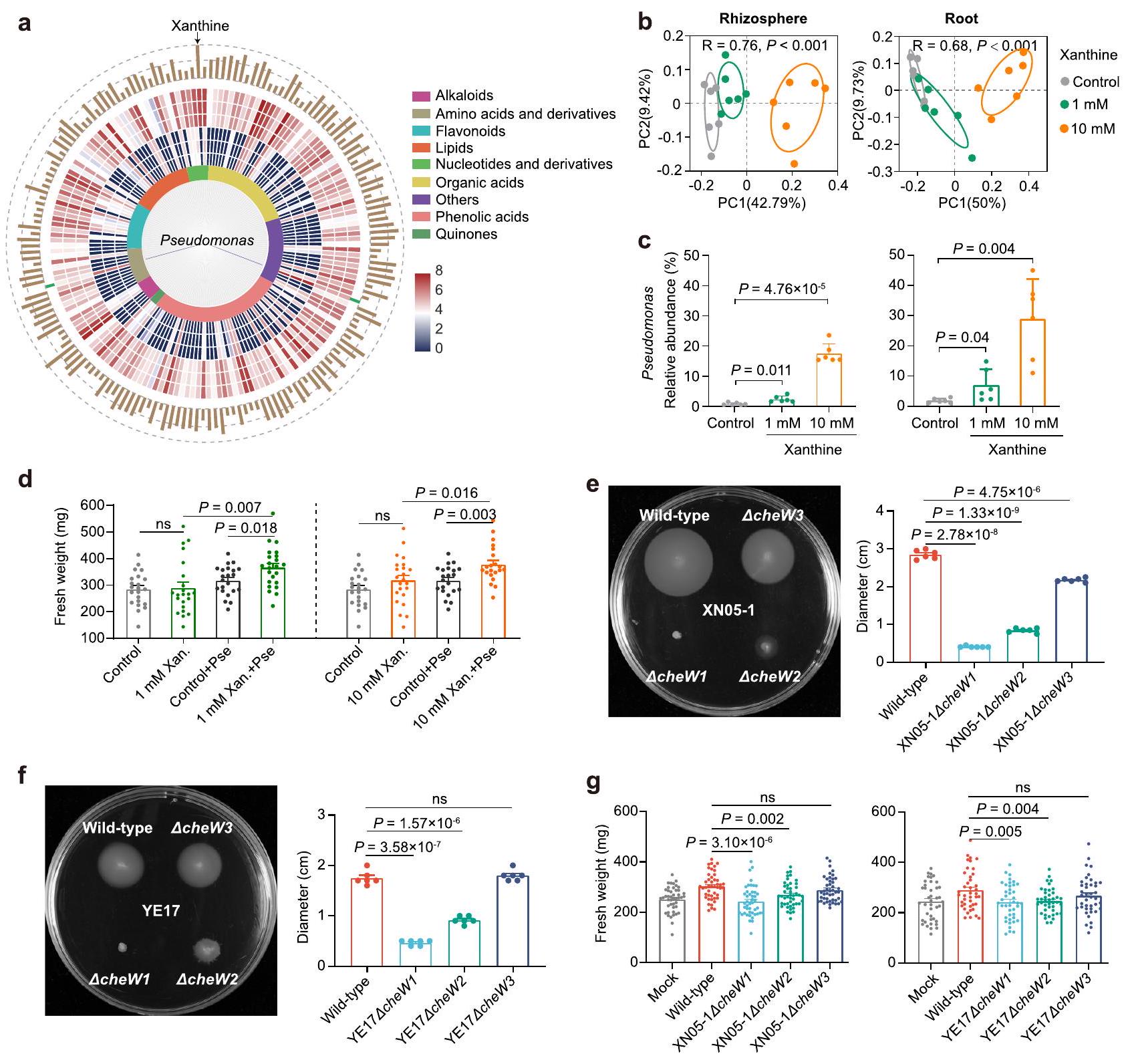

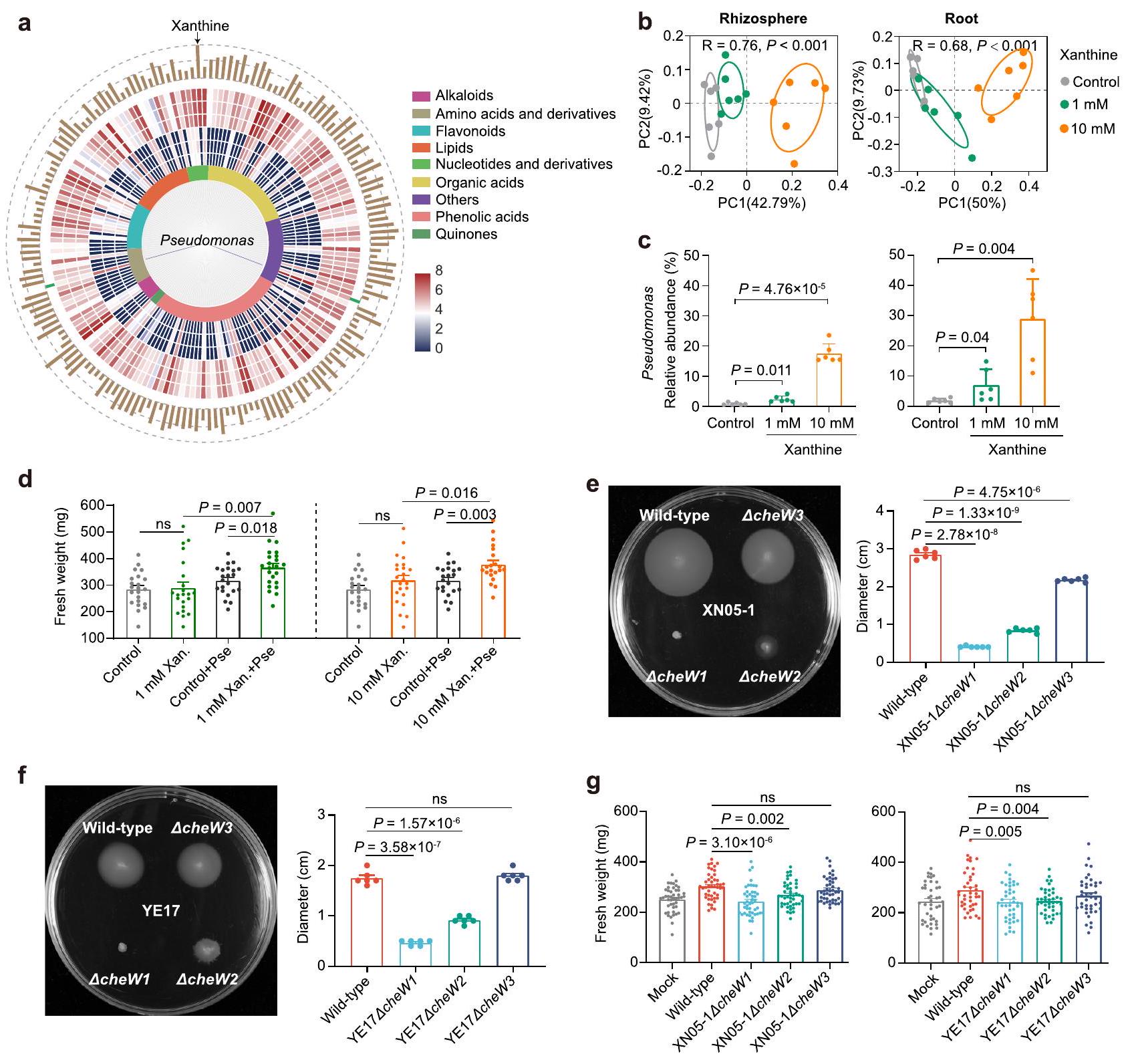

مكون إفراز الجذور زانثين أعاد إنتاج إثراء بكتيريا الزائفة

التربة المعالجة في منطقة الجذور (نسبة الوفرة 17.47%) كانت أعلى من تلك في المجموعة الضابطة (0.81%) (الشكل 6c والشكل التكميلي 17). تشير النتائج إلى أن زيادة البكتيريا الناتجة عن الزانثين محددة إلى حد كبير لجنس بseudomonas. كما تشير النتائج السابقة إلى أن إضافة الزانثين الخارجي أعادت إنتاج نتيجة زيادة بseudomonas داخل جذر فول الصويا البري الذي لوحظ تحت ظروف إجهاد الملح، مما يدعم بشكل أكبر أن الزانثين المفرز من الجذر يلعب دورًا مهمًا في استقطاب بseudomonas.

دور الجين المرتبط بالحركة تشيو في الكيمياء الجذبية نحو البيورين وتحمل ملح النباتات

نقاش

وفرة جنس البكتيريا الزائفة في جذور التربة والتربة المحيطة بالجذور بين تطبيقات التحكم و تطبيقات الزانثين (1 و 10 مللي مول).

الوزن الطازج بين التحكم، تطبيق الزانثين بمفرده، تلقيح البسودوموناس بمفرده وتطبيقات الزانثين في وجود البسودوموناس.

زاد مع مستويات مختلفة من إجهاد الملح (الأشكال 2 و 3). وبالمثل، أظهرت بياناتنا الميتاجينومية والميتا ترانسكرپتومية زيادة في الوفرة النسبية لبسودوموناس تحت إجهاد الملح (الشكل 3e، f). كما لوحظت زيادة في بسودوموناس في فول الصويا المستأنس (الشكل التوضيحي 6)، والنباتات الحساسة للملح وتلك المقاومة للملح التي تنتمي إلى عائلة القرعيات تحت إجهاد الملح.

إفرازات فول الصويا (G. max) والفاصوليا الشائعة (Phaseolus vulgaris) المزروعة تحت ظروف إجهاد الملح

بيانات متعددة الأوميات. تظهر نتائجنا أن الملح يسبب تحولًا أقوى بكثير في الميكروبيوم المرتبط بالجذور مقارنةً بميكروبيوم التربة الكلية. بكتيريا pseudomonas هي النوع السائد المستجيب للإجهاد، وعزلاتها المقابلة يمكن أن تعزز نمو فول الصويا البري تحت ضغط الملح، مما يدعم النظرية السابقة المعروفة باسم “نداء للمساعدة”.

طرق

تصميم التجربة

أخذ العينات

قياس خصائص التربة

استخراج الحمض النووي، تسلسل جين 16S rRNA ومعالجة البيانات

تمت التوصيات والتسلسل على منصة Illumina MiSeq PE300 في شركة Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology. تم إجراء تحليل تسلسلات جين 16S rRNA كما هو موصوف في دراستنا السابقة.

تسلسل الميتاجينوم

استخراج RNA وتسلسل الميتا ترانسكريبتوم

جمع إفرازات الجذور وتسلسل الميتابولوم

الحطام والميكروبات. تم إجراء ثلاث تكرارات لكل علاج. نظرًا لأن الإفرازات الجذرية تم جمعها من الشتلات التي تنمو في نظام مائي معقم، يمكن استبعاد إمكانية أن تكون المركبات مشتقة من الميكروبات. تم تحليل الإفرازات الجذرية المجمعة باستخدام نظام UPLC-ESI-MS/MS ونظام مطياف الكتلة المت tandem في شركة ووهان ميت وير للتكنولوجيا الحيوية المحدودة (الصين). تم تحديد المستقلبات باستخدام كل من طيف الكتلة ووقت الاحتفاظ. لمقارنة محتوى كل مستقلب بين المجموعة الضابطة والعلاجات، تم معايرة قمة طيف الكتلة لكل مستقلب في عينات مختلفة وفقًا لتكامل منطقة القمة.

qPCR للبكتيريا الكلية وPseudomonas

عزل البكتيريا وتجربة الدفيئة

استعمار Pseudomonas

تسلسل الجينوم

بناء طفرات cheW من Pseudomonas

اختبارات كيميائية كمية

تطبيق الزانثين الخارجي

تم استخدام النباتات بدون تلقيح بكتيريا الزائفة كتحكم لدراسة تأثير الزانثين على نمو النبات. تم زراعة شتلات فول الصويا البري التي تبلغ من العمر ثلاثة أيام في وعاء بلاستيكي يحتوي على 50 جرامًا من التربة أعلاه. بعد عشرة أيام، تم إضافة 5 مل من تركيزين (1 و 10 مللي مول) من محلول الزانثين إلى التربة المحيطة بالجذور، وتم تزويد المحلول مرة واحدة كل يوم لمدة ثلاثة أيام. نمت هذه النباتات في غرفة نمو تحت

التحليلات الإحصائية

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Golldack, D., Li, C., Mohan, H. & Probst, N. Tolerance to drought and salt stress in plants: unraveling the signaling networks. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 151 (2014).

- Yuan, F., Leng, B. & Wang, B. Progress in studying salt secretion from the salt glands in recretohalophytes: how do plants secrete salt? Front. Plant Sci. 7, 977 (2016).

- Zhou, H. et al. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J. Genet. Genomic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgg.2023.08. 007 (2023).

- Wang, Z. & Song, Y. Toward understanding the genetic bases underlying plant-mediated “cry for help” to the microbiota. iMeta 1, e8 (2022).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Patterns in the microbial community of salt-tolerant plants and the functional genes associated with salt stress alleviation. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e00767-00721 (2021).

- Yuan, Z. et al. Specialized microbiome of a halophyte and its role in helping non-host plants to withstand salinity. Sci. Rep. 6, 32467 (2016).

- Xiong, Y. W. et al. Root exudates-driven rhizosphere recruitment of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Bacillus flexus KLBMP 4941 and its growth-promoting effect on the coastal halophyte Limonium sinense under salt stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 194, 110374 (2020).

- Pan, X., Qin, Y. & Yuan, Z. Potential of a halophyte-associated endophytic fungus for sustaining Chinese white poplar growth under salinity. Symbiosis 76, 109-116 (2018).

- Vaishnav, A., Shukla, A. K., Sharma, A., Kumar, R. & Choudhary, D. K. Endophytic bacteria in plant salt stress tolerance: current and future prospects. J. Plant Growth Regul. 38, 650-668 (2018).

- Qin, Y., Druzhinina, I. S., Pan, X. & Yuan, Z. Microbially mediated plant salt tolerance and microbiome-based solutions for saline agriculture. Biotechnol. Adv. 34, 1245-1259 (2016).

- Berg, G. et al. Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome 8, 1-22 (2020).

- Qi, M. et al. Identification of beneficial and detrimental bacteria impacting sorghum responses to drought using multi-scale and multi-system microbiome comparisons. ISME J. 16, 1957-1969 (2022).

- Hou, S. et al. A microbiota-root-shoot circuit favours Arabidopsis growth over defence under suboptimal light. Nat. Plants 7, 1078-1092 (2021).

- Santos-Medellín, C. et al. Prolonged drought imparts lasting compositional changes to the rice root microbiome. Nat. Plants 7, 1065-1077 (2021).

- Li, H., La, S., Zhang, X., Gao, L. & Tian, Y. Salt-induced recruitment of specific root-associated bacterial consortium capable of enhancing plant adaptability to salt stress. ISME J. 15, 2865-2882 (2021).

-

. et al. Drought delays development of the sorghum root microbiome and enriches for monoderm bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E4284-E4293 (2018). - Abbasi, S., Sadeghi, A. & Safaie, N. Streptomyces alleviate drought stress in tomato plants and modulate the expression of transcription factors ERF1 and WRKY70 genes. Sci. Hortic. 265, 109206 (2020).

-

. et al. Genome-resolved metagenomics reveals role of iron metabolism in drought-induced rhizosphere microbiome dynamics. Nat. Commun. 12, 3209 (2021). - Kherfi-Nacer, A. et al. High salt levels reduced dissimilarities in rootassociated microbiomes of two barley genotypes. Mol. Plant Microbe. 35, 592-603 (2022).

- Cui, M. H. et al. Hybridization affects the structure and function of root microbiome by altering gene expression in roots of wheat introgression line under saline-alkali stress. Sci. Total Environ. 835, 155467 (2022).

- Santos, S. S. et al. Specialized microbiomes facilitate natural rhizosphere microbiome interactions counteracting high salinity stress in plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 186, 104430 (2021).

- Yaish, M. W., Al-Lawati, A., Jana, G. A., Vishwas Patankar, H. & Glick, B. R. Impact of soil salinity on the structure of the bacterial endophytic community identified from the roots of caliph medic (Medicago truncatula). PLoS One 11, e0159007 (2016).

- Yaish, M. W., Al-Harrasi, I., Alansari, A. S., Al-Yahyai, R. & Glick, B. R. The use of high throughput DNA sequence analysis to assess the endophytic microbiome of date palm roots grown under different levels of salt stress. Int. Microbiol. 19, 143-155 (2016).

- Hong, Y., Zhou, Q., Hao, Y. & Huang, A. C. Crafting the plant root metabolome for improved microbe-assisted stress resilience. N. Phytol. 234, 1945-1950 (2022).

- Sasse, J., Martinoia, E. & Northen, T. Feed your friends: Do plant exudates shape the root microbiome? Trends Plant Sci. 23, 25-41 (2018).

- Liu, H., Brettell, L. E., Qiu, Z. & Singh, B. K. Microbiome-mediated stress resistance in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 25, 733-743 (2020).

- Koprivova, A. & Kopriva, S. Plant secondary metabolites altering root microbiome composition and function. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 67, 102227 (2022).

- Yu, P. et al. Plant flavones enrich rhizosphere Oxalobacteraceae to improve maize performance under nitrogen deprivation. Nat. Plants 7, 481-499 (2021).

- Harbort, C. J. et al. Root-secreted coumarins and the microbiota interact to improve iron nutrition in Arabidopsis. Cell Host Microbe 28, 825-837 (2020).

- Hiruma, K. et al. Root endophyte Colletotrichum tofieldiae confers plant fitness benefits that are phosphate status dependent. Cell 165, 464-474 (2016).

- Kapulnik, Y. & Koltai, H. Fine-tuning by strigolactones of root response to low phosphate. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 58, 203-212 (2016).

- Zhao, X. et al. Comparative metabolite profiling of two rice genotypes with contrasting salt stress tolerance at the seedling stage. PloS one 9, e108020 (2014).

- Cui, G. et al. Response of carbon and nitrogen metabolism and secondary metabolites to drought stress and salt stress in plants. J. Plant Biol. 62, 387-399 (2019).

- Fitzpatrick, C. R. et al. Assembly and ecological function of the root microbiome across angiosperm plant species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E1157-E1165 (2018).

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P., Quaiser, A., Duhamel, M., Le Van, A. & Dufresne, A. The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. N. Phytol. 206, 1196-1206 (2015).

- Kasotia, A., Varma, A. & Choudhary, D. K. Pseudomonas-mediated mitigation of salt stress and growth promotion in Glycine max. Agr. Res. 4, 31-41 (2015).

- Ahmad, M., Zahir, Z. A., Asghar, H. N. & Arshad, M. The combined application of rhizobial strains and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria improves growth and productivity of mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) under salt-stressed conditions. Ann. Microbiol. 62, 1321-1330 (2012).

- Lami, M. et al. Pseudomonas stutzeri MJL19, a rhizosphere-colonizing bacterium that promotes plant growth under saline stress. J. Appl. Microbiol. 129, 1321-1336 (2020).

- Costa-Gutierrez, S. B. et al. Plant growth promotion by Pseudomonas putida KT2440 under saline stress: role of eptA. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 104, 4577-4592 (2020).

- Sandhya, V., Ali, S. Z., Grover, M., Reddy, G. & Venkateswarlu, B. Effect of plant growth promoting Pseudomonas spp. on compatible solutes, antioxidant status and plant growth of maize under drought stress. Plant Growth Regul. 62, 21-30 (2010).

- Bano, A. & Fatima, M. Salt tolerance in Zea mays (L). following inoculation with Rhizobium and Pseudomonas. Biol. Fert. Soils 45, 405-413 (2009).

- Gomila, M., Mulet, M., García-Valdés, E. & Lalucat, J. Genomebased taxonomy of the genus Stutzerimonas and proposal of

. frequens sp. nov. and S. degradans sp. nov. and emended descriptions of S. perfectomarina S. chloritidismutans. Microorg. 10, 1363 (2022). - Lalucat, J., Gomila, M., Mulet, M., Zaruma, A. & García-Valdés, E. Past, present and future of the boundaries of the Pseudomonas genus: Proposal of Stutzerimonas gen. Nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 45, 126289 (2022).

- Liu, Y. et al. Root colonization by beneficial rhizobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 48, fuad066 (2024).

- Gao, M. et al. Disease-induced changes in plant microbiome assembly and functional adaptation. Microbiome 9, 187 (2021).

- Salah Ud-Din, A. I. M. & Roujeinikova, A. Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins: a core sensing element in prokaryotes and archaea. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74, 3293-3303 (2017).

- Wadhams, G. H. & Armitage, J. P. Making sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 5, 1024-1037 (2004).

- Badri, D. V. & Vivanco, J. M. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 666-681 (2009).

- Vives-Peris, V., de Ollas, C., Gomez-Cadenas, A. & Perez-Clemente, R. M. Root exudates: from plant to rhizosphere and beyond. Plant Cell Rep. 39, 3-17 (2020).

- Dardanelli, M. S. et al. Effect of the presence of the plant growth promoting rhizobacterium (PGPR) Chryseobacterium balustinum Aur9 and salt stress in the pattern of flavonoids exuded by soybean roots. Plant Soil 328, 483-493 (2010).

- Dardanelli, M. S. et al. Changes in flavonoids secreted by Phaseolus vulgaris roots in the presence of salt and the plant growthpromoting rhizobacterium Chryseobacterium balustinum. Appl. Soil Ecol. 57, 31-38 (2012).

- Vives-Peris, V., Molina, L., Segura, A., Gómez-Cadenas, A. & PérezClemente, R. M. Root exudates from citrus plants subjected to abiotic stress conditions have a positive effect on rhizobacteria. J. Plant Physiol. 228, 208-217 (2018).

- Vives-Peris, V., Gómez-Cadenas, A. & Pérez-Clemente, R. M. Citrus plants exude proline and phytohormones under abiotic stress conditions. Plant Cell Rep. 36, 1971-1984 (2017).

- Sato, S., Sakaguchi, S., Furukawa, H. & Ikeda, H. Effects of NaCl application to hydroponic nutrient solution on fruit characteristics of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Sci. Hortic. 109, 248-253 (2006).

- Abbas, G. et al. Relationship between rhizosphere acidification and phytoremediation in two acacia species. J. Soils Sediment. 16, 1392-1399 (2016).

- D’Agostino, I. B. & Kieber, J. J. Molecular mechanisms of cytokinin action. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2, 359-364 (1999).

- Boldt, R. & Zrenner, R. Purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis in higher plants. Physiol. Plant. 117, 297-304 (2003).

- Rosniawaty, S., Anjarsari, I., Sudirja, R., Harjanti, S. & Mubarok, S. Application of coconut water and benzyl amino purine on the plant growth at second centering of tea (Camellia sinensis) in lowlands area of Indonesia. Res. Crop. 21, 817-822 (2020).

- Smith, P. M. & Atkins, C. A. Purine biosynthesis. Big in cell division, even bigger in nitrogen assimilation. Plant Physiol. 128, 793-802 (2002).

- Brychkova, G., Fluhr, R. & Sagi, M. Formation of xanthine and the use of purine metabolites as a nitrogen source in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 3, 999-1001 (2008).

- Fernandez, M., Morel, B., Corral-Lugo, A. & Krell, T. Identification of a chemoreceptor that specifically mediates chemotaxis toward metabolizable purine derivatives. Mol. Microbiol. 99, 34-42 (2016).

- Lopez-Farfan, D., Reyes-Darias, J. A. & Krell, T. The expression of many chemoreceptor genes depends on the cognate chemoeffector as well as on the growth medium and phase. Curr. Genet. 63, 457-470 (2017).

- He, D. et al. Flavonoid-attracted Aeromonas sp. from the Arabidopsis root microbiome enhances plant dehydration resistance. ISME J. 16, 2622-2632 (2022).

- Bulgarelli, D. et al. Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature 488, 91-95 (2012).

- Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996 (2013).

- Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261-5267 (2007).

- Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150-3152 (2012).

- Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59-60 (2015).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114-2120 (2014).

- Muyzer, G., de Waal, E. C. & Uitterlinden, A. G. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16 S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 695-700 (1993).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Exploring biocontrol agents from microbial keystone taxa associated to suppressive soil: a new attempt for a biocontrol strategy. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 655673 (2021).

- Johnsen, K., Enger, Ø., Jacobsen, C. S., Thirup, L. & Torsvik, V. Quantitative selective PCR of 16 S ribosomal DNA correlates well with selective agar plating in describing population dynamics of indigenous Pseudomonas spp. in soil hot spots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 1786-1788 (1999).

- Weisburg, W. G., Barns, S. M., Pelletier, D. A. & Lane, D. J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173, 697-703 (1991).

- Yoon, S.-H. et al. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16 S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67, 1613 (2017).

- Lim, H., Lee, E. H., Yoon, Y., Chua, B. & Son, A. Portable lysis apparatus for rapid single-step DNA extraction of Bacillus subtilis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 120, 379-387 (2016).

- Berlin, K. et al. Assembling large genomes with single-molecule sequencing and locality-sensitive hashing. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 623-630 (2015).

- Schäfer, A. et al. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145, 69-73 (1994).

- Figurski, D. H. & Helinski, D. R. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 76, 1648-1652 (1979).

- Sampedro, I., Parales, R. E., Krell, T. & Hill, J. E. Pseudomonas chemotaxis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 17-46 (2015).

- Oksanen, J. et al. The vegan package. Community Ecol. Package 10, 719 (2007).

- Chen, C. et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194-1202 (2020).

شكر وتقدير

تم دعمها من خلال منحة من المؤسسة الوطنية للعلوم الطبيعية في الصين (32171948). تم دعم C.-S.Z. أيضًا من خلال منحة من برنامج الابتكار في العلوم والتكنولوجيا الزراعية في الصين (ASTIP-TRIC-ZDO4).

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47773-9.

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2024

- ¹مركز أبحاث الزراعة البحرية، معهد أبحاث التبغ التابع للأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم الزراعية، تشينغداو 266101، الصين.

معهد علوم وتكنولوجيا البحار، جامعة شاندونغ، كينغداو 266200، الصين. المختبر الوطني للهندسة للاستخدام الفعال لموارد التربة والأسمدة، كلية الموارد والبيئة بجامعة شاندونغ الزراعية، تايآن 271018، الصين. هؤلاء المؤلفون ساهموا بالتساوي: يانفن تشنغ، شيوين كاو. البريد الإلكتروني:zhangchengsheng@caas.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47773-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38664402

Publication Date: 2024-04-25

Purines enrich root-associated Pseudomonas and improve wild soybean growth under salt stress

Accepted: 12 April 2024

Published online: 25 April 2024

Abstract

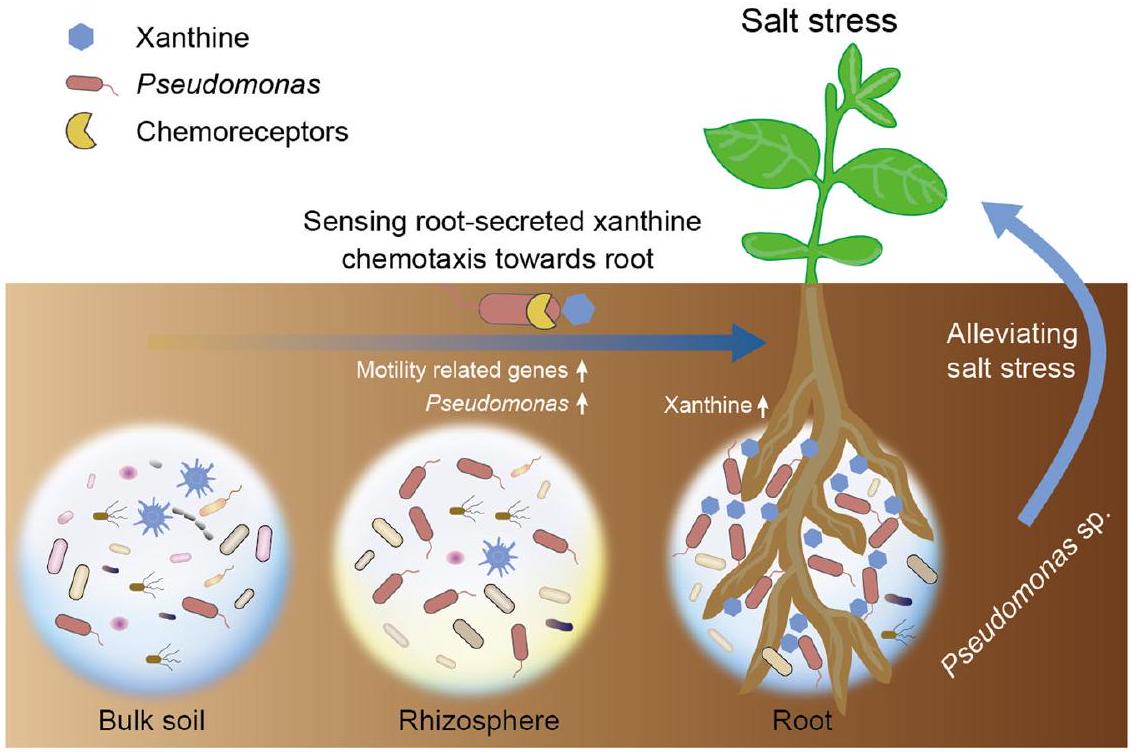

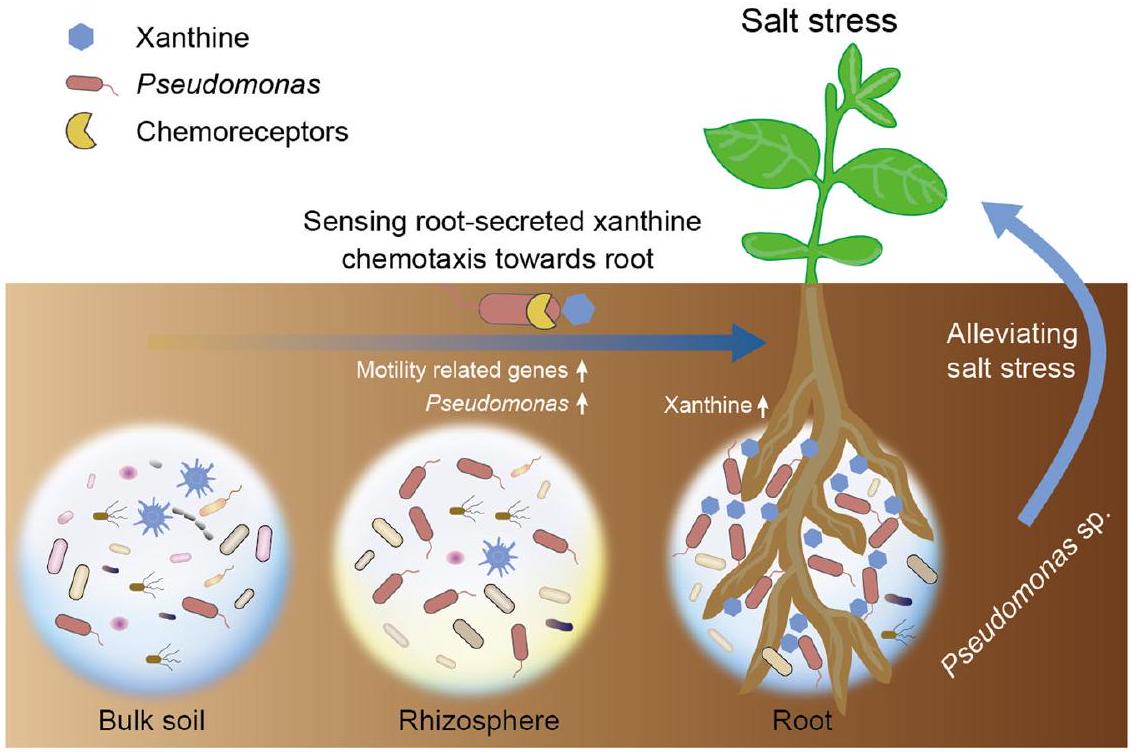

The root-associated microbiota plays an important role in the response to environmental stress. However, the underlying mechanisms controlling the interaction between salt-stressed plants and microbiota are poorly understood. Here, by focusing on a salt-tolerant plant wild soybean (Glycine soja), we demonstrate that highly conserved microbes dominated by Pseudomonas are enriched in the root and rhizosphere microbiota of salt-stressed plant. Two corresponding Pseudomonas isolates are confirmed to enhance the salt tolerance of wild soybean. Shotgun metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing reveal that motility-associated genes, mainly chemotaxis and flagellar assembly, are significantly enriched and expressed in salt-treated samples. We further find that roots of salt stressed plants secreted purines, especially xanthine, which induce motility of the Pseudomonas isolates. Moreover, exogenous application for xanthine to non-stressed plants results in Pseudomonas enrichment, reproducing the microbiota shift in salt-stressed root. Finally, Pseudomonas mutant analysis shows that the motility related gene che

under control and different salt treatments. e Root length, plant height, leaf size, root weight and shoot weight of wild soybean in control and different salt treatments. The number of samples per treatment in (e) is as follows: control (

metabolites

and function of root-associated microbiota under salt stress condition using 16S rRNA gene amplicon, and metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing. The stress-responsive microbiota was identified, and their role in promoting plant growth were assessed. Finally, the underlying causes of salt-stressed community changes were elucidated based on the genetic properties of the enriched microbes and root metabolites in wild soybean.

Results

Wild soybean growth is affected by salt stress

Salt stress induces distinct responses in bacterial diversity and dominant taxa among compartments

abundance of the top 15 most abundant orders for bulk soil, rhizosphere soil, and root across control and different levels of salt stress. Different significance levels between control and each salt treatment are marked with asterisks (

point and treatment (Supplementary Table 1). The root community (analysis of similarity [ANOSIM];

in the rhizosphere soil based on metatranscriptomic data. Values are means

salt stress, an increase in the relative abundances of Gammaproteobacteria and Actinobacteriota was observed in the root community (Supplementary Fig. 2). No discernible taxonomic changes were found between the control and salt treatments in either the rhizosphere soil or bulk soil. At the order level, the relative abundances of Pseudomonadales and Streptomycetales increased significantly in all salttreated root samples at Day 7 and Day 14, compared with those in the control group (Fig. 2c). An increase in Pseudomonadales abundance was also observed in the rhizosphere soil communities but not in the bulk soil (Fig. 2c).

abundances showed some fluctuations among the three salt treatments, but the changes were not significant in either the rhizosphere soil or root samples (Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that the enrichment of Actinobacteriota and Gammaproteobacteria was not the result of an increase in total bacterial absolute abundances but a decrease in the abundances of other communities. Overall, these results indicate that wild soybean root, rhizosphere soil, and bulk soil microbiota respond differently to salt stress across the taxonomic profile.

Pseudomonas abundance increases dramatically in salt-treated roots and rhizosphere soils

respectively. Horizontal bars within boxes denote medians, and the upper and lower whiskers represent the range of non-outlier data values. All plots are mean

that Pseudomonas was not only the most abundant member (Fig. 3e) but also was active with a relative abundance of transcripts of

Two Pseudomonas isolates rescued wild soybean growth under salt stress

and nuclear structure (COG Y), were not shown.

abundance of Pseudomonas was higher under salt stress compared with non-salt condition (Supplementary Fig. 9), which is consistent with the finding that salt stress enriches Pseudomonas.

Cell motility genes and transcripts increased in salt-treated rhizosphere

rhizosphere soil (Fig. 5a). Notably, the fold change of genes affiliated to cell motility was highest among all COG categories.

genes expressing methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCP; fold change = 6.14) and purine-binding chemotaxis protein CheW (fold change

Root exudate component xanthine reproduced Pseudomonas enrichment

treated rhizosphere soil (relative abundance of 17.47%) than that in the control (0.81%) (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 17). The results indicate that xanthine-induced bacterial enrichment is largely specific to Pseudomonas genus. Above findings also indicate that exogenous xanthine addition reproduced the result of Pseudomonas enrichment within wild soybean root observed under salt stress condition, further supporting that root-secreted xanthine plays an important role in Pseudomonas recruitment.

The role of motility related gene chew in the chemotaxis toward purine and plant salt tolerance

Discussion

abundance of Pseudomonas genus in root and rhizosphere soil between control and xanthine applications ( 1 and 10 mM ).

d Fresh weight between control, xanthine application alone, Pseudomonas inoculation alone and xanthine applications in presence of Pseudomonas.

increased with different salt stress levels (Figs. 2 and 3). Similarly, our metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data both showed an increase in the relative abundance of Pseudomonas under salt stress (Fig. 3e, f). Pseudomonas enrichment was also observed in domesticated soybeans (Supplementary Fig. 6), and salt-sensitive and salt-tolerant plants belonging to the family Curcurbitaceae under salt stress

exudates of G. max (soybean) and Phaseolus vulgaris (common bean) grown under salt stress condition

multiomics data. Our results show that salt induces a much stronger shift in the root-associated microbiota than in the bulk soil microbiota. Pseudomonas is the dominant stress-responsive taxon, and its corresponding isolates could promote wild soybean growth under salt stress, which supports the previously reported “cry for help” theory

Methods

Experiment design

Sampling

Measurement of the soil properties

DNA extraction, 16 S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and data processing

recommendations and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform at the Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology. Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequences was performed as described in our previous study

Metagenomic sequencing

RNA extraction and metatranscriptomic sequencing

Root exudates collection and metabolomic sequencing

debris and microorganisms. Three replicates were conducted for each treatment. Since the root exudates were collected from seedlings growing in sterile hydroponic system, the possibility that compounds derived from microorganisms could be excluded. The collected root exudates were analyzed using an UPLC-ESI-MS/MS system and Tandem mass spectrometry system at Wuhan MetWare Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (China). Metabolites were identified using both mass spectrum and retention time. To compare the content of each metabolite between the control and treatments, the mass spectrum peak of each metabolite in different samples was calibrated according to integration of the peak area.

qPCR for total bacteria and Pseudomonas

Bacterial isolation and greenhouse experiment

Pseudomonas colonization

Genome sequencing

cheW mutants construction of Pseudomonas

Quantitative chemotaxis assays

Exogenous xanthine application

without Pseudomonas inoculation was used as control to study the effect of xanthine on plant growth. Three days old wild soybean seedlings were transplanted to a plastic pot containing 50 g of above soil. After ten days, 5 ml of two concentrations ( 1 and 10 mM ) of xanthine solution were added in root surrounding soil, and the solution supplied once every day for three days. These plants grew in a growth chamber under

Statistical analyses

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Golldack, D., Li, C., Mohan, H. & Probst, N. Tolerance to drought and salt stress in plants: unraveling the signaling networks. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 151 (2014).

- Yuan, F., Leng, B. & Wang, B. Progress in studying salt secretion from the salt glands in recretohalophytes: how do plants secrete salt? Front. Plant Sci. 7, 977 (2016).

- Zhou, H. et al. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J. Genet. Genomic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgg.2023.08. 007 (2023).

- Wang, Z. & Song, Y. Toward understanding the genetic bases underlying plant-mediated “cry for help” to the microbiota. iMeta 1, e8 (2022).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Patterns in the microbial community of salt-tolerant plants and the functional genes associated with salt stress alleviation. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e00767-00721 (2021).

- Yuan, Z. et al. Specialized microbiome of a halophyte and its role in helping non-host plants to withstand salinity. Sci. Rep. 6, 32467 (2016).

- Xiong, Y. W. et al. Root exudates-driven rhizosphere recruitment of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Bacillus flexus KLBMP 4941 and its growth-promoting effect on the coastal halophyte Limonium sinense under salt stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 194, 110374 (2020).

- Pan, X., Qin, Y. & Yuan, Z. Potential of a halophyte-associated endophytic fungus for sustaining Chinese white poplar growth under salinity. Symbiosis 76, 109-116 (2018).

- Vaishnav, A., Shukla, A. K., Sharma, A., Kumar, R. & Choudhary, D. K. Endophytic bacteria in plant salt stress tolerance: current and future prospects. J. Plant Growth Regul. 38, 650-668 (2018).

- Qin, Y., Druzhinina, I. S., Pan, X. & Yuan, Z. Microbially mediated plant salt tolerance and microbiome-based solutions for saline agriculture. Biotechnol. Adv. 34, 1245-1259 (2016).

- Berg, G. et al. Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome 8, 1-22 (2020).

- Qi, M. et al. Identification of beneficial and detrimental bacteria impacting sorghum responses to drought using multi-scale and multi-system microbiome comparisons. ISME J. 16, 1957-1969 (2022).

- Hou, S. et al. A microbiota-root-shoot circuit favours Arabidopsis growth over defence under suboptimal light. Nat. Plants 7, 1078-1092 (2021).

- Santos-Medellín, C. et al. Prolonged drought imparts lasting compositional changes to the rice root microbiome. Nat. Plants 7, 1065-1077 (2021).

- Li, H., La, S., Zhang, X., Gao, L. & Tian, Y. Salt-induced recruitment of specific root-associated bacterial consortium capable of enhancing plant adaptability to salt stress. ISME J. 15, 2865-2882 (2021).

-

. et al. Drought delays development of the sorghum root microbiome and enriches for monoderm bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E4284-E4293 (2018). - Abbasi, S., Sadeghi, A. & Safaie, N. Streptomyces alleviate drought stress in tomato plants and modulate the expression of transcription factors ERF1 and WRKY70 genes. Sci. Hortic. 265, 109206 (2020).

-

. et al. Genome-resolved metagenomics reveals role of iron metabolism in drought-induced rhizosphere microbiome dynamics. Nat. Commun. 12, 3209 (2021). - Kherfi-Nacer, A. et al. High salt levels reduced dissimilarities in rootassociated microbiomes of two barley genotypes. Mol. Plant Microbe. 35, 592-603 (2022).

- Cui, M. H. et al. Hybridization affects the structure and function of root microbiome by altering gene expression in roots of wheat introgression line under saline-alkali stress. Sci. Total Environ. 835, 155467 (2022).

- Santos, S. S. et al. Specialized microbiomes facilitate natural rhizosphere microbiome interactions counteracting high salinity stress in plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 186, 104430 (2021).

- Yaish, M. W., Al-Lawati, A., Jana, G. A., Vishwas Patankar, H. & Glick, B. R. Impact of soil salinity on the structure of the bacterial endophytic community identified from the roots of caliph medic (Medicago truncatula). PLoS One 11, e0159007 (2016).

- Yaish, M. W., Al-Harrasi, I., Alansari, A. S., Al-Yahyai, R. & Glick, B. R. The use of high throughput DNA sequence analysis to assess the endophytic microbiome of date palm roots grown under different levels of salt stress. Int. Microbiol. 19, 143-155 (2016).

- Hong, Y., Zhou, Q., Hao, Y. & Huang, A. C. Crafting the plant root metabolome for improved microbe-assisted stress resilience. N. Phytol. 234, 1945-1950 (2022).

- Sasse, J., Martinoia, E. & Northen, T. Feed your friends: Do plant exudates shape the root microbiome? Trends Plant Sci. 23, 25-41 (2018).

- Liu, H., Brettell, L. E., Qiu, Z. & Singh, B. K. Microbiome-mediated stress resistance in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 25, 733-743 (2020).

- Koprivova, A. & Kopriva, S. Plant secondary metabolites altering root microbiome composition and function. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 67, 102227 (2022).

- Yu, P. et al. Plant flavones enrich rhizosphere Oxalobacteraceae to improve maize performance under nitrogen deprivation. Nat. Plants 7, 481-499 (2021).

- Harbort, C. J. et al. Root-secreted coumarins and the microbiota interact to improve iron nutrition in Arabidopsis. Cell Host Microbe 28, 825-837 (2020).

- Hiruma, K. et al. Root endophyte Colletotrichum tofieldiae confers plant fitness benefits that are phosphate status dependent. Cell 165, 464-474 (2016).

- Kapulnik, Y. & Koltai, H. Fine-tuning by strigolactones of root response to low phosphate. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 58, 203-212 (2016).

- Zhao, X. et al. Comparative metabolite profiling of two rice genotypes with contrasting salt stress tolerance at the seedling stage. PloS one 9, e108020 (2014).

- Cui, G. et al. Response of carbon and nitrogen metabolism and secondary metabolites to drought stress and salt stress in plants. J. Plant Biol. 62, 387-399 (2019).

- Fitzpatrick, C. R. et al. Assembly and ecological function of the root microbiome across angiosperm plant species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E1157-E1165 (2018).

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P., Quaiser, A., Duhamel, M., Le Van, A. & Dufresne, A. The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. N. Phytol. 206, 1196-1206 (2015).

- Kasotia, A., Varma, A. & Choudhary, D. K. Pseudomonas-mediated mitigation of salt stress and growth promotion in Glycine max. Agr. Res. 4, 31-41 (2015).

- Ahmad, M., Zahir, Z. A., Asghar, H. N. & Arshad, M. The combined application of rhizobial strains and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria improves growth and productivity of mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) under salt-stressed conditions. Ann. Microbiol. 62, 1321-1330 (2012).

- Lami, M. et al. Pseudomonas stutzeri MJL19, a rhizosphere-colonizing bacterium that promotes plant growth under saline stress. J. Appl. Microbiol. 129, 1321-1336 (2020).

- Costa-Gutierrez, S. B. et al. Plant growth promotion by Pseudomonas putida KT2440 under saline stress: role of eptA. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 104, 4577-4592 (2020).

- Sandhya, V., Ali, S. Z., Grover, M., Reddy, G. & Venkateswarlu, B. Effect of plant growth promoting Pseudomonas spp. on compatible solutes, antioxidant status and plant growth of maize under drought stress. Plant Growth Regul. 62, 21-30 (2010).

- Bano, A. & Fatima, M. Salt tolerance in Zea mays (L). following inoculation with Rhizobium and Pseudomonas. Biol. Fert. Soils 45, 405-413 (2009).

- Gomila, M., Mulet, M., García-Valdés, E. & Lalucat, J. Genomebased taxonomy of the genus Stutzerimonas and proposal of

. frequens sp. nov. and S. degradans sp. nov. and emended descriptions of S. perfectomarina S. chloritidismutans. Microorg. 10, 1363 (2022). - Lalucat, J., Gomila, M., Mulet, M., Zaruma, A. & García-Valdés, E. Past, present and future of the boundaries of the Pseudomonas genus: Proposal of Stutzerimonas gen. Nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 45, 126289 (2022).

- Liu, Y. et al. Root colonization by beneficial rhizobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 48, fuad066 (2024).

- Gao, M. et al. Disease-induced changes in plant microbiome assembly and functional adaptation. Microbiome 9, 187 (2021).

- Salah Ud-Din, A. I. M. & Roujeinikova, A. Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins: a core sensing element in prokaryotes and archaea. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74, 3293-3303 (2017).

- Wadhams, G. H. & Armitage, J. P. Making sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 5, 1024-1037 (2004).

- Badri, D. V. & Vivanco, J. M. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 666-681 (2009).

- Vives-Peris, V., de Ollas, C., Gomez-Cadenas, A. & Perez-Clemente, R. M. Root exudates: from plant to rhizosphere and beyond. Plant Cell Rep. 39, 3-17 (2020).

- Dardanelli, M. S. et al. Effect of the presence of the plant growth promoting rhizobacterium (PGPR) Chryseobacterium balustinum Aur9 and salt stress in the pattern of flavonoids exuded by soybean roots. Plant Soil 328, 483-493 (2010).

- Dardanelli, M. S. et al. Changes in flavonoids secreted by Phaseolus vulgaris roots in the presence of salt and the plant growthpromoting rhizobacterium Chryseobacterium balustinum. Appl. Soil Ecol. 57, 31-38 (2012).

- Vives-Peris, V., Molina, L., Segura, A., Gómez-Cadenas, A. & PérezClemente, R. M. Root exudates from citrus plants subjected to abiotic stress conditions have a positive effect on rhizobacteria. J. Plant Physiol. 228, 208-217 (2018).

- Vives-Peris, V., Gómez-Cadenas, A. & Pérez-Clemente, R. M. Citrus plants exude proline and phytohormones under abiotic stress conditions. Plant Cell Rep. 36, 1971-1984 (2017).

- Sato, S., Sakaguchi, S., Furukawa, H. & Ikeda, H. Effects of NaCl application to hydroponic nutrient solution on fruit characteristics of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Sci. Hortic. 109, 248-253 (2006).

- Abbas, G. et al. Relationship between rhizosphere acidification and phytoremediation in two acacia species. J. Soils Sediment. 16, 1392-1399 (2016).

- D’Agostino, I. B. & Kieber, J. J. Molecular mechanisms of cytokinin action. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2, 359-364 (1999).

- Boldt, R. & Zrenner, R. Purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis in higher plants. Physiol. Plant. 117, 297-304 (2003).

- Rosniawaty, S., Anjarsari, I., Sudirja, R., Harjanti, S. & Mubarok, S. Application of coconut water and benzyl amino purine on the plant growth at second centering of tea (Camellia sinensis) in lowlands area of Indonesia. Res. Crop. 21, 817-822 (2020).

- Smith, P. M. & Atkins, C. A. Purine biosynthesis. Big in cell division, even bigger in nitrogen assimilation. Plant Physiol. 128, 793-802 (2002).

- Brychkova, G., Fluhr, R. & Sagi, M. Formation of xanthine and the use of purine metabolites as a nitrogen source in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 3, 999-1001 (2008).

- Fernandez, M., Morel, B., Corral-Lugo, A. & Krell, T. Identification of a chemoreceptor that specifically mediates chemotaxis toward metabolizable purine derivatives. Mol. Microbiol. 99, 34-42 (2016).

- Lopez-Farfan, D., Reyes-Darias, J. A. & Krell, T. The expression of many chemoreceptor genes depends on the cognate chemoeffector as well as on the growth medium and phase. Curr. Genet. 63, 457-470 (2017).

- He, D. et al. Flavonoid-attracted Aeromonas sp. from the Arabidopsis root microbiome enhances plant dehydration resistance. ISME J. 16, 2622-2632 (2022).

- Bulgarelli, D. et al. Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature 488, 91-95 (2012).

- Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996 (2013).

- Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261-5267 (2007).

- Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150-3152 (2012).

- Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59-60 (2015).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114-2120 (2014).

- Muyzer, G., de Waal, E. C. & Uitterlinden, A. G. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16 S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 695-700 (1993).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Exploring biocontrol agents from microbial keystone taxa associated to suppressive soil: a new attempt for a biocontrol strategy. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 655673 (2021).

- Johnsen, K., Enger, Ø., Jacobsen, C. S., Thirup, L. & Torsvik, V. Quantitative selective PCR of 16 S ribosomal DNA correlates well with selective agar plating in describing population dynamics of indigenous Pseudomonas spp. in soil hot spots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 1786-1788 (1999).

- Weisburg, W. G., Barns, S. M., Pelletier, D. A. & Lane, D. J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173, 697-703 (1991).

- Yoon, S.-H. et al. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16 S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67, 1613 (2017).

- Lim, H., Lee, E. H., Yoon, Y., Chua, B. & Son, A. Portable lysis apparatus for rapid single-step DNA extraction of Bacillus subtilis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 120, 379-387 (2016).

- Berlin, K. et al. Assembling large genomes with single-molecule sequencing and locality-sensitive hashing. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 623-630 (2015).

- Schäfer, A. et al. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145, 69-73 (1994).

- Figurski, D. H. & Helinski, D. R. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 76, 1648-1652 (1979).

- Sampedro, I., Parales, R. E., Krell, T. & Hill, J. E. Pseudomonas chemotaxis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 17-46 (2015).

- Oksanen, J. et al. The vegan package. Community Ecol. Package 10, 719 (2007).

- Chen, C. et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194-1202 (2020).

Acknowledgements

was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171948). C.-S.Z. was additionally supported by a grant from the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of China (ASTIP-TRIC-ZDO4).

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47773-9.

(c) The Author(s) 2024

- ¹Marine Agriculture Research Center, Tobacco Research Institute of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Qingdao 266101, China.

Institute of Marine Science and Technology, Shandong University, Qingdao 266200, China. National Engineering Laboratory for Efficient Utilization of Soil and Fertilizer Resources, College of Resources and Environment of Shandong Agricultural University, Taian 271018, China. These authors contributed equally: Yanfen Zheng, Xuwen Cao. e-mail: zhangchengsheng@caas.cn