المجلة: Nature Communications، المجلد: 15، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44424-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38168057

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-02

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44424-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38168057

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-02

تغيير انتقائية التعرف الجزيئي بواسطة درجة الحرارة في مادة مسامية تنظيم الانتشار

تاريخ الاستلام: 10 مايو 2023

تم القبول: 13 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2024

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

تم القبول: 13 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2024

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

على مدى التاريخ الطويل للتطور، طورت الطبيعة مجموعة متنوعة من الأنظمة البيولوجية ذات وظائف التعرف القابلة للتبديل، مثل قابلية نقل الأيونات في الأغشية البيولوجية، التي يمكن أن تغير انتقائيتها للأيونات استجابةً لمؤثرات متنوعة. ومع ذلك، فإن تطوير طريقة في نظام مضيف-ضيف صناعي للتعرف القابل للتبديل على ضيوف محددين عند تغيير المؤثرات الخارجية يمثل تحديًا أساسيًا في الكيمياء، لأن الترتيب في تقارب المضيف-الضيف لنظام معين نادرًا ما يتغير مع الظروف البيئية. هنا، نبلغ عن التعرف القابل للاستجابة لدرجات الحرارة على ضيفين غازيين متشابهين،

تلعب التعرف الجزيئي دورًا حيويًا في الكيمياء فوق الجزيئية.

تمكن الكيميائيون من تغيير الألفة بين المضيف والضيف باستخدام ضيوف استجابة للتحفيز، مما يسمح بالتعرف المحدد القابل للتبديل بين ضيوف مختلفين.

تمكن الكيميائيون من تغيير الألفة بين المضيف والضيف باستخدام ضيوف استجابة للتحفيز، مما يسمح بالتعرف المحدد القابل للتبديل بين ضيوف مختلفين.

بوليمرات التنسيق المسامية (PCPs)

الاعتراف. على الرغم من التقدم الأخير، فإن معظم التعرف الجزيئي في PCPs يعتمد على الامتصاص الديناميكي الحراري، وهو ما لا يمكن الوصول إليه للتعرف القابل للتبديل. من ناحية أخرى، فإن السيطرة على حركية نقل الضيوف تتيح تمييزًا دقيقًا بين الضيوف المتشابهين.

النتائج

تحضير PCP والتحليلات الهيكلية

قمنا بتصميم ربيطة من نوع النحل تتكون من [

امتصاص الغاز

FDC-3a الممتص

أنظمة المسام التنظيمية للاختراق في PCPs

أنظمة المسام التنظيمية للاختراق في PCPs

على الرغم من أن منحنيات الامتصاص المذكورة أعلاه قد كشفت بالفعل عن اختلاف واضح في كميات الامتصاص لـ

اختيارات IAST ومعدلات الانتشار

استخدمنا نظرية المحلول الممتص المثالي (IAST) للتنبؤ بالانتقائية لـ

لكشف جوهر الامتزاز المعتمد على درجة الحرارة، استخدمنا نظرية كرانك لتحديد معدل الانتشار لكل

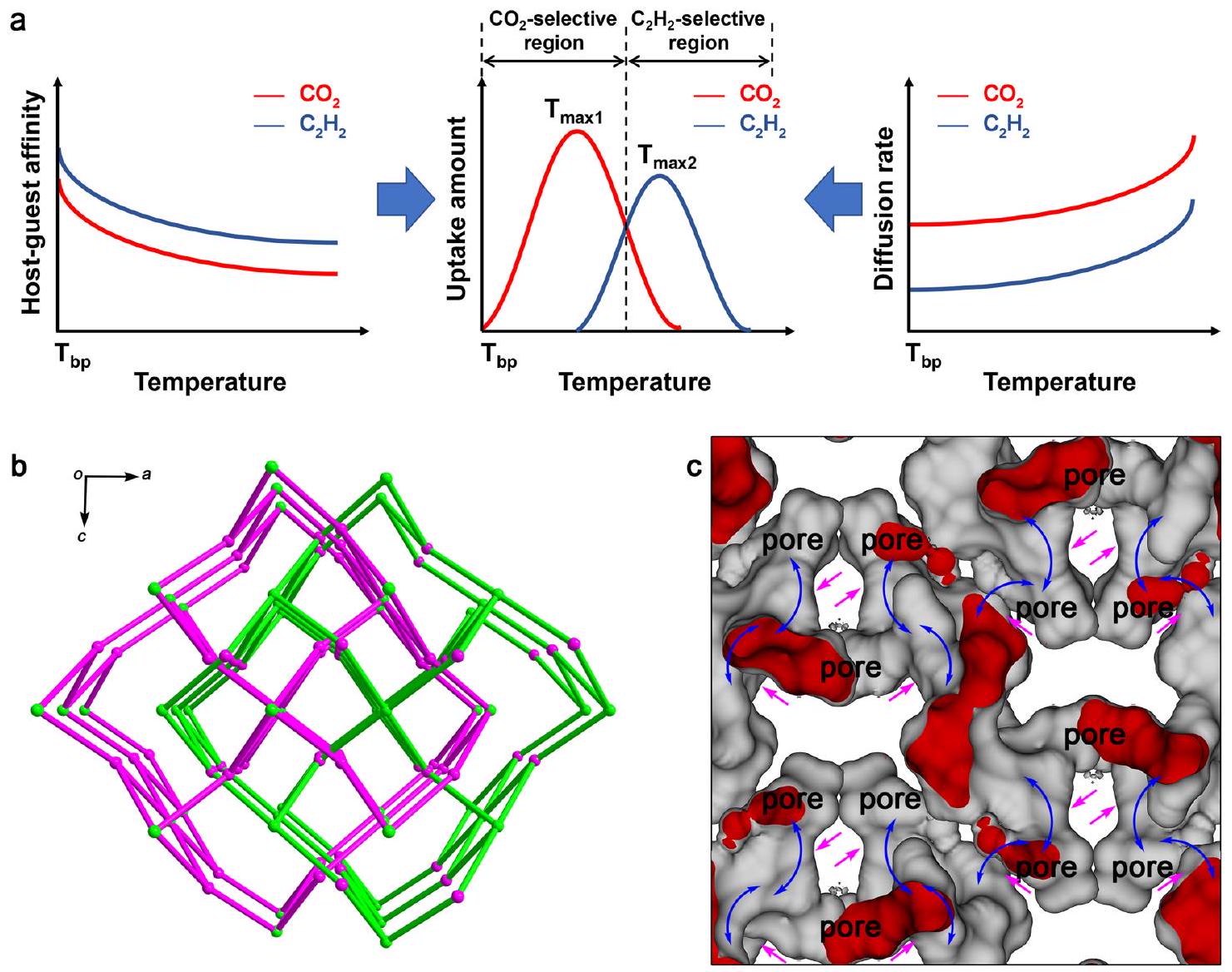

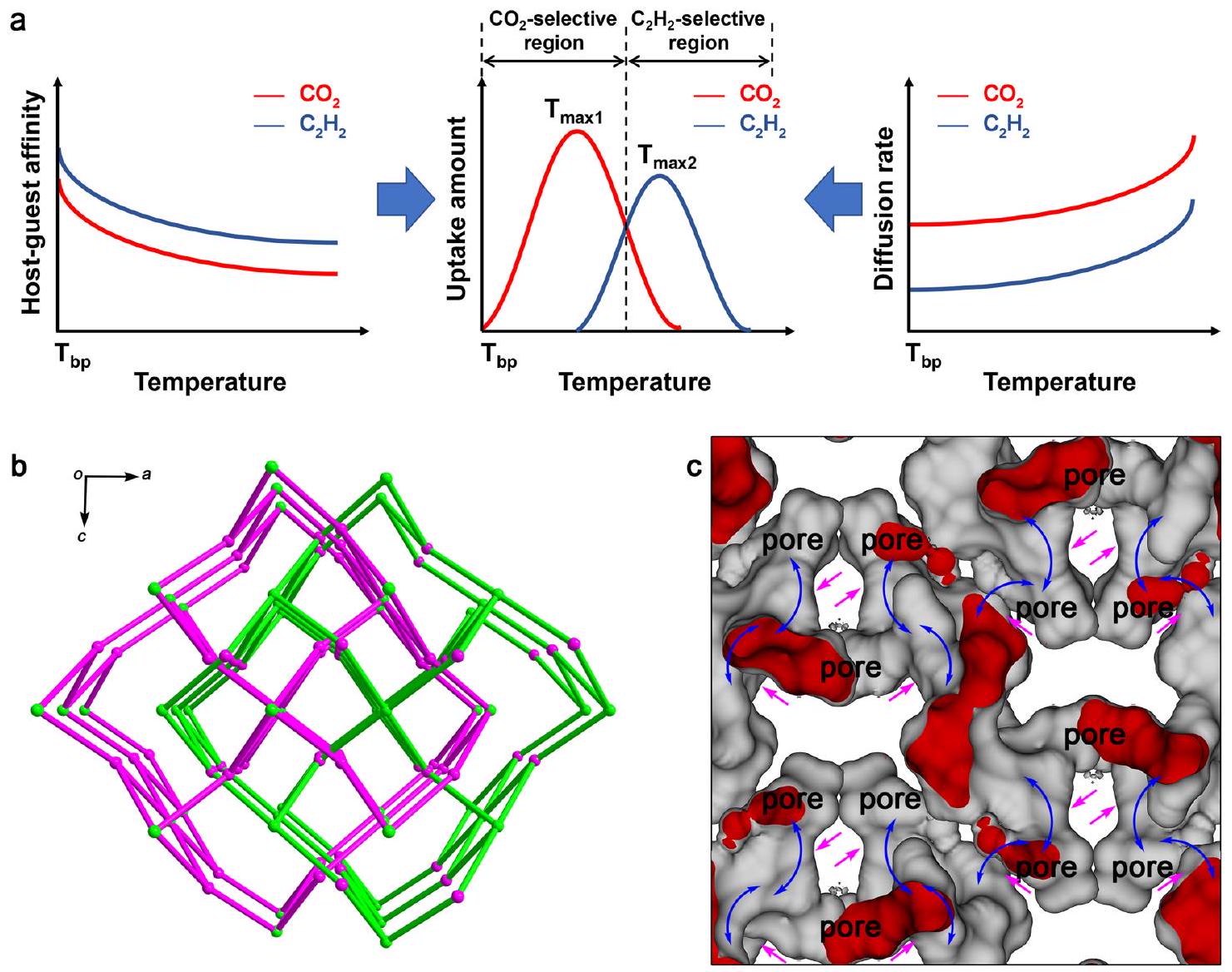

الشكل 1 | آلية تنظيم الانتشار للتعرف المعتمد على درجة الحرارة

لكن يتم امتصاص الألفة العالية بشكل انتقائي عند درجات حرارة أعلى.

على التوالي، في حين أن معدلات الانتشار لـ

على التوالي، في حين أن معدلات الانتشار لـ

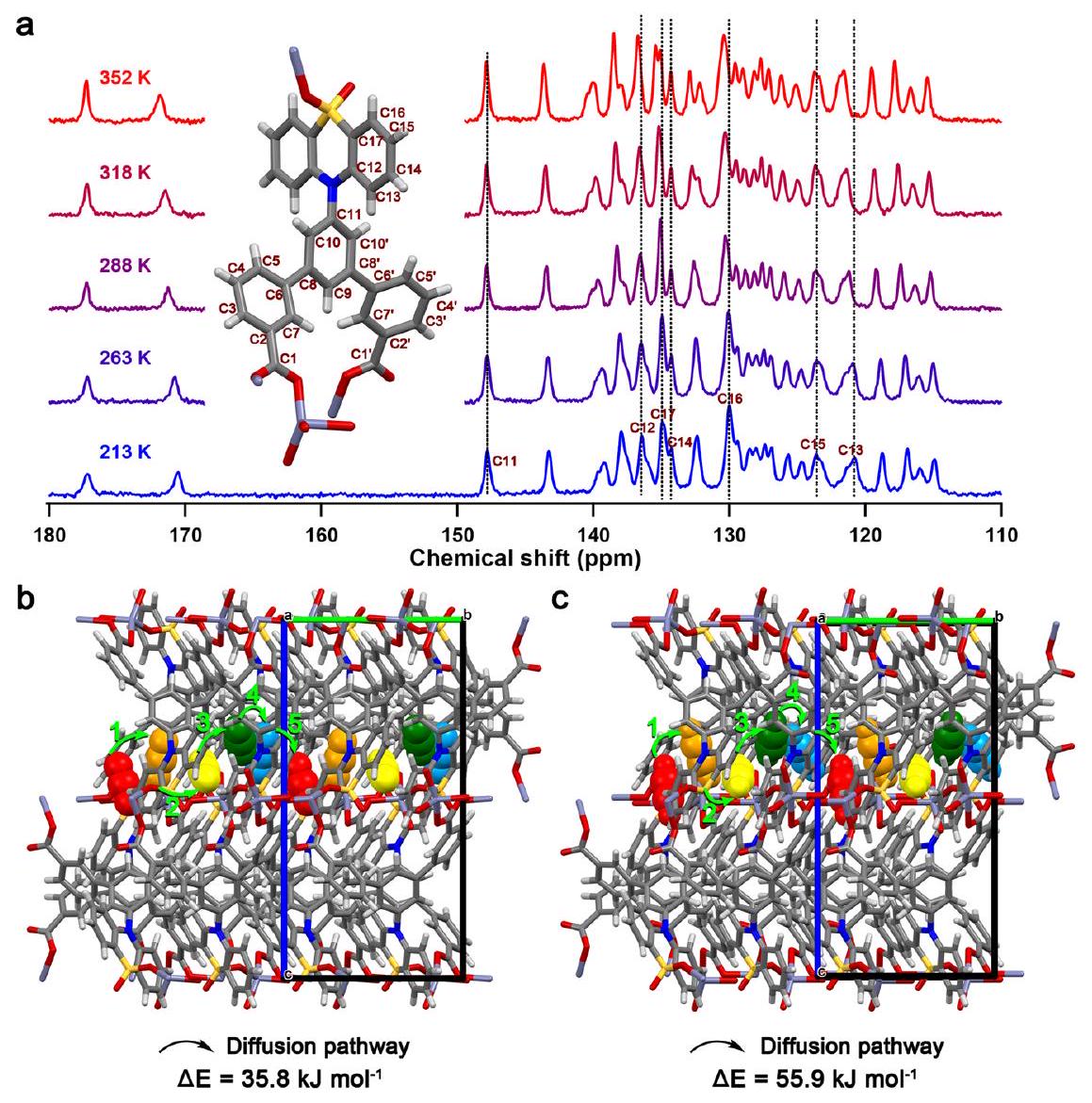

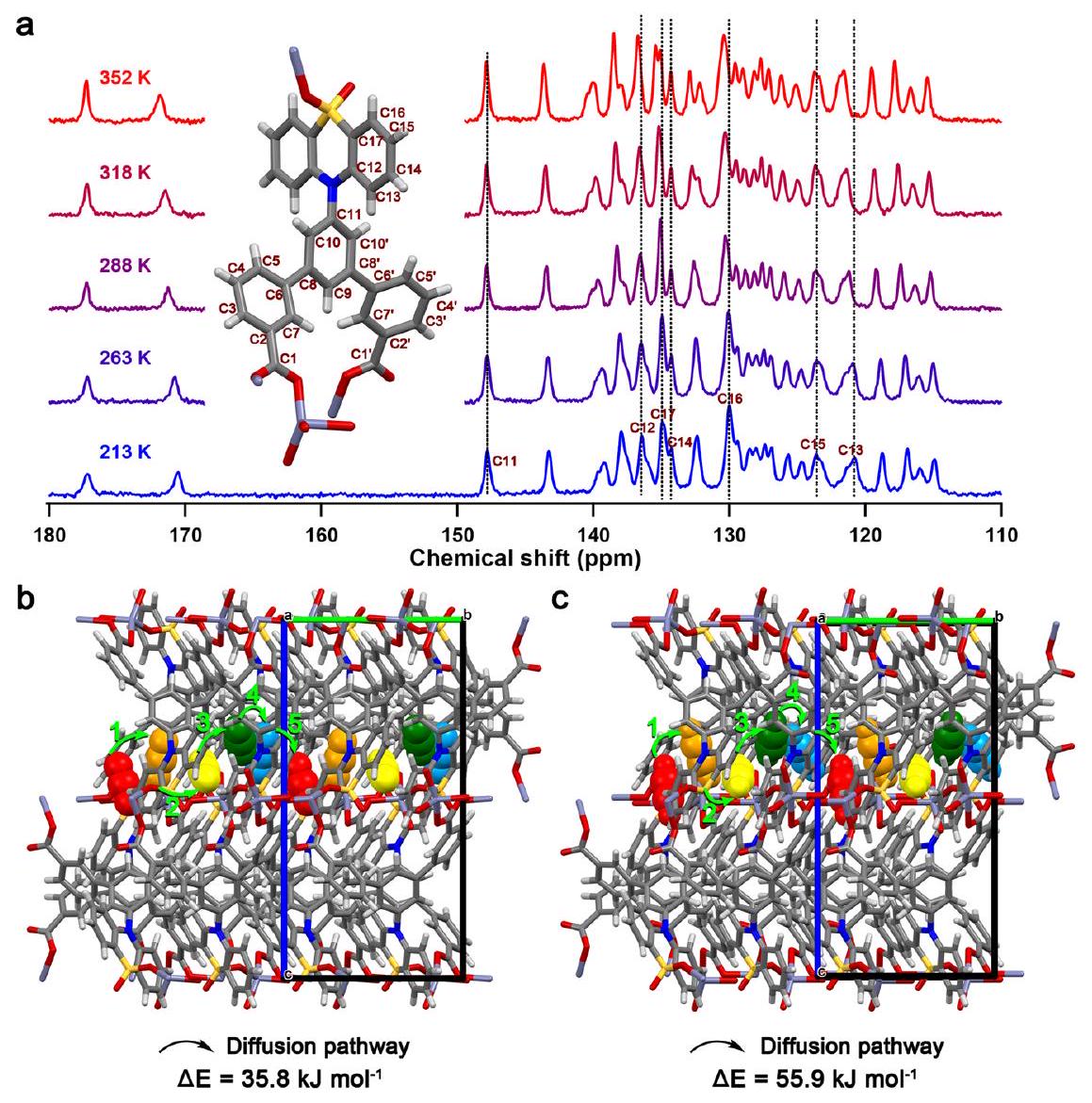

تحليلات PXRD و NMR الحالة الصلبة

لفهم الآلية من الجانب الهيكلي بشكل أفضل، تم جمع أنماط PXRD في الموقع خلال عملية الامتزاز. الأنماط التي تم الحصول عليها خلال عمليات الامتزاز لـ

الذي كشف عن تمدد محور [111]. لأن جزءًا واحدًا من OPTz كان موجهًا بالتوازي مع مستوى (111) (الشكل التكميلي 21)، يمكن أن يكون هذا التمدد الطفيف مرتبطًا بمدى التبديل الحراري، الذي وسع البوابات للسماح بانتشار الغاز والتحكم في معدل الانتشار.

الذي كشف عن تمدد محور [111]. لأن جزءًا واحدًا من OPTz كان موجهًا بالتوازي مع مستوى (111) (الشكل التكميلي 21)، يمكن أن يكون هذا التمدد الطفيف مرتبطًا بمدى التبديل الحراري، الذي وسع البوابات للسماح بانتشار الغاز والتحكم في معدل الانتشار.

على الرغم من أن تحليل PXRD يمكن أن يميز التغير في الشبكة عند درجات حرارة مختلفة في FDC-3a، إلا أنه لم يتمكن من إظهار الحركات المحلية على المستوى الجزيئي. لكشف الحركة المتبادلة بدقة في FDC-3a، قمنا بإجراء

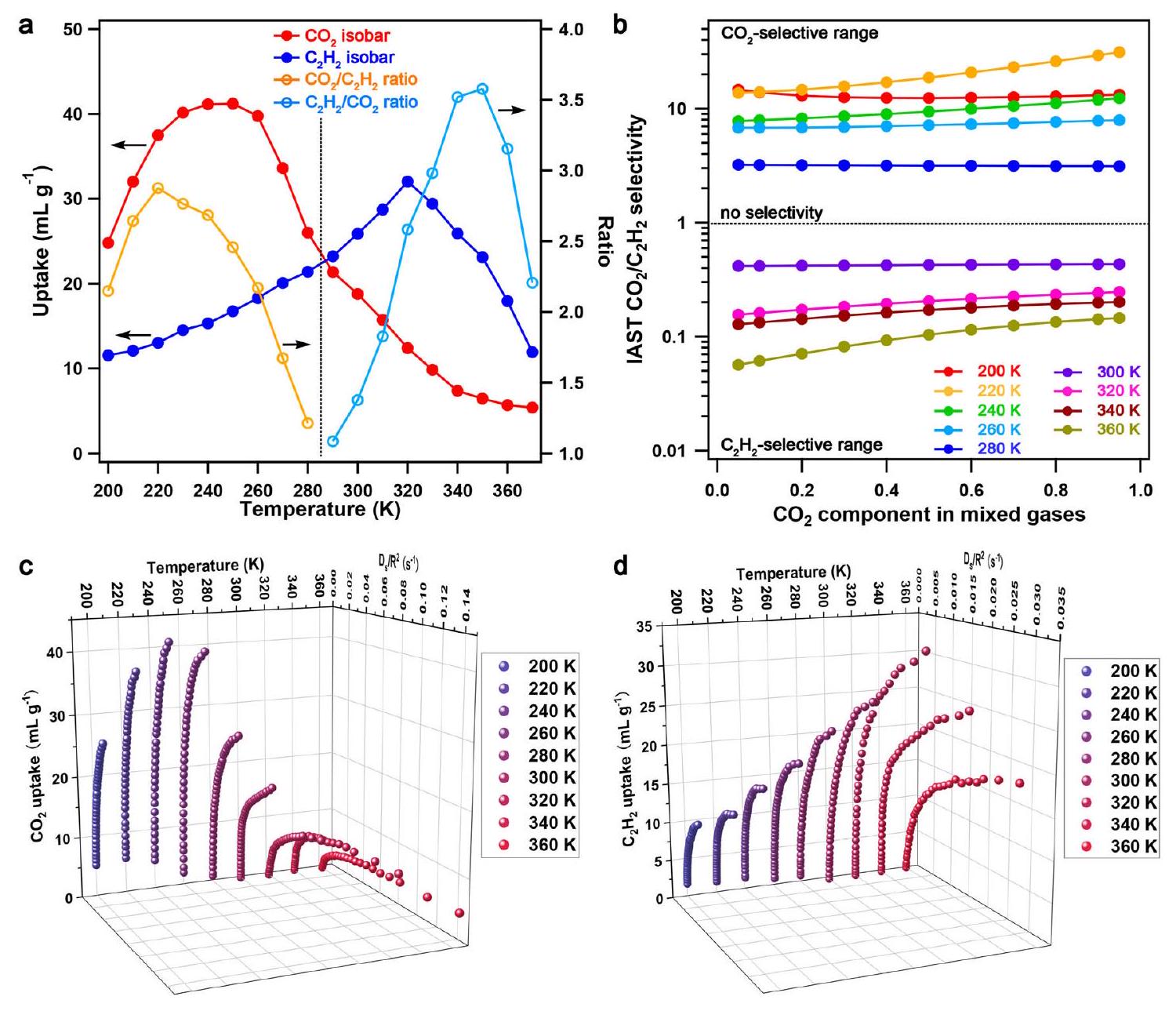

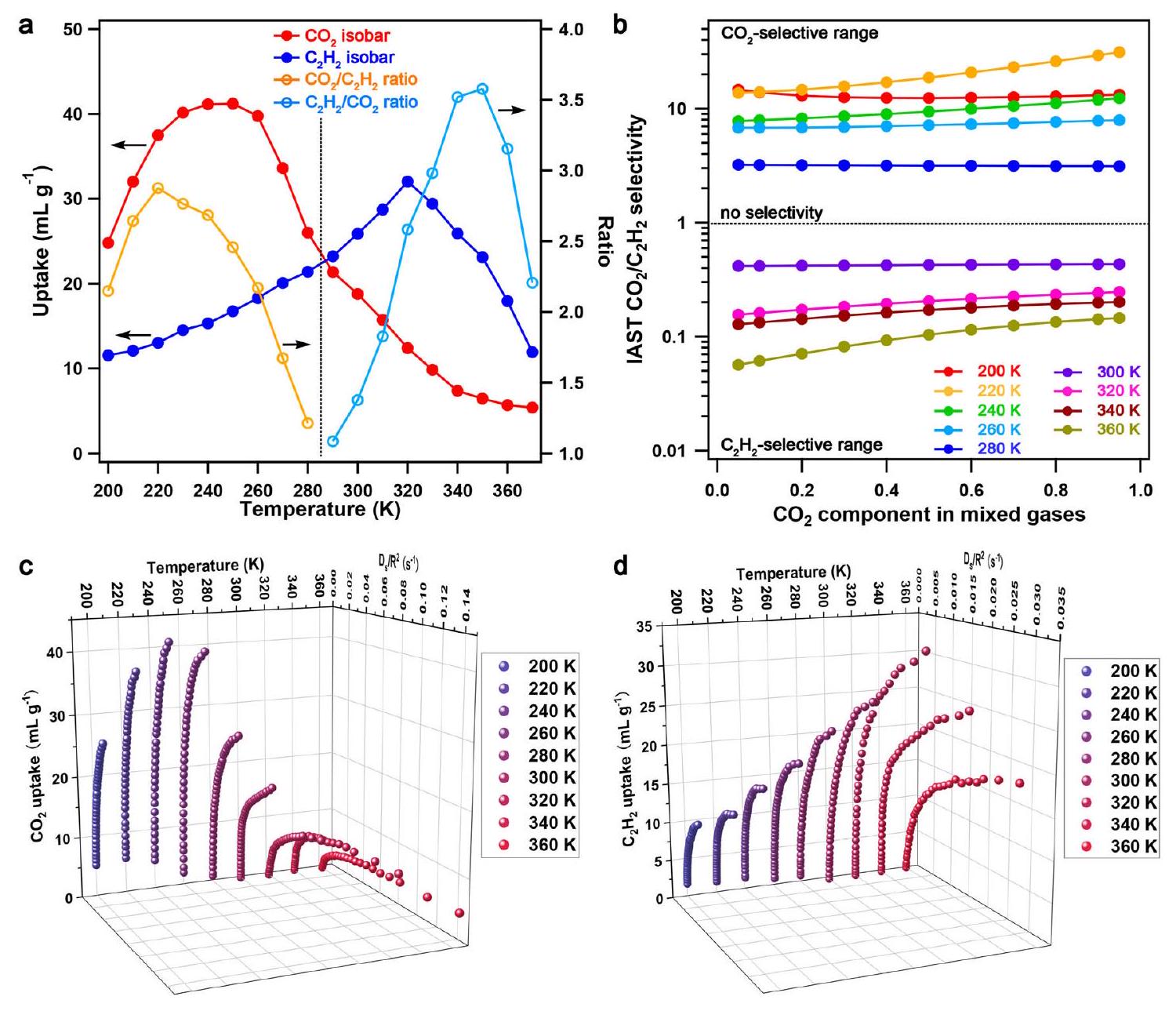

الشكل 2 | سلوك امتصاص الغاز، انتقائيات IAST، ومعدلات الانتشار بين 200 و 370 كلفن. أ

معدل كمية الامتصاص

الترددات لـ C1-C7)، بينما الحلقات الاثنين لـ OPTz متقاربة تقريبًا (تردد واحد أو اثنان قريبان لكل من

الترددات لـ C1-C7)، بينما الحلقات الاثنين لـ OPTz متقاربة تقريبًا (تردد واحد أو اثنان قريبان لكل من

الحسابات النظرية

للحصول على رؤى حول عملية الانتشار والامتزاز، تم استخدام محاكاة مونت كارلو وحسابات نظرية الكثافة (DFT) في البداية لتحسين مواقع الامتزاز لـ

من

من

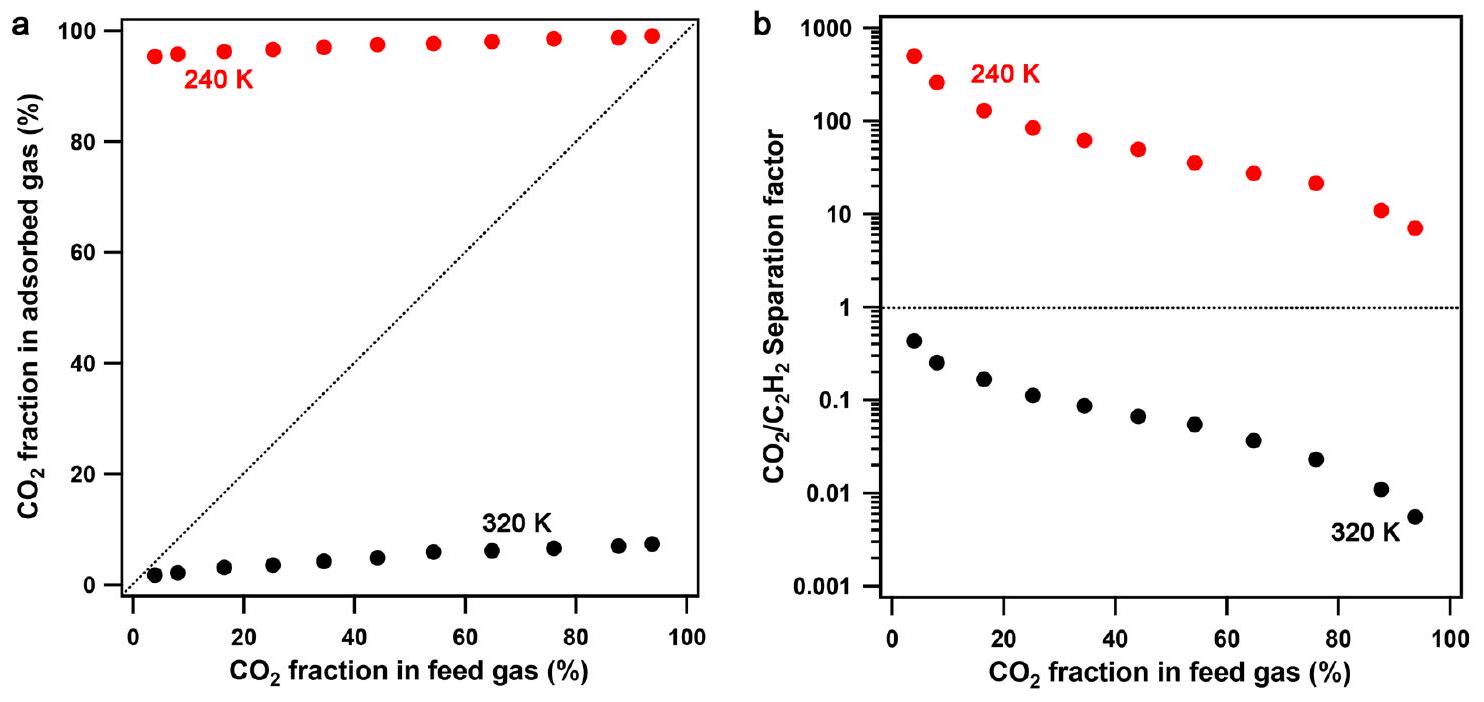

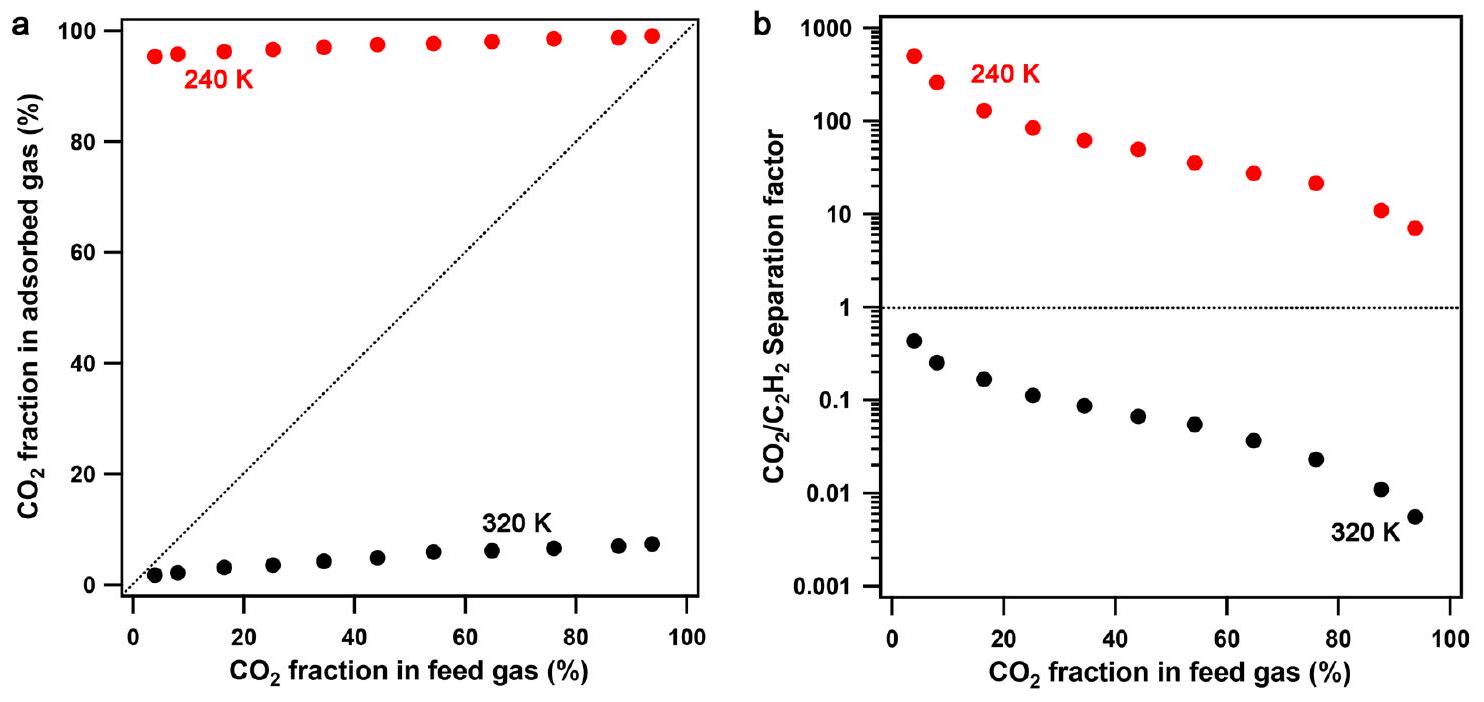

فصل الغاز المختلط

سلوك الامتزاز المعتمد على درجة الحرارة وآلية تنظيم الانتشار في FDC-3 ألهمتنا لإجراء تجارب فصل الغاز المختلط الديناميكية؛ وقد تم تنفيذ هذه التجارب مع

الشكل 3 | دراسة الرنين المغناطيسي النووي في الحالة الصلبة عند درجات حرارة متغيرة والدراسة النظرية. أ VT

مسارات.

بروتوكول إزالة الحرارة المبرمجة (TPD) (الأشكال التكميلية 28، 29)

كان مواتياً ديناميكياً حرارياً لـ

بروتوكول إزالة الحرارة المبرمجة (TPD) (الأشكال التكميلية 28، 29)

كان مواتياً ديناميكياً حرارياً لـ

نقاش

تقدم نتائجنا التعرف المعتمد على درجة الحرارة لـ

الشكل 4 | فصل الغاز المختلط. أ رسم بياني لمكابي-ثيلي لـ

الفضل يعود إلى الآلية الأساسية، التي يتم تنفيذها من خلال التعاون بين فتحات المسام الصغيرة جداً والديناميات المحلية لمكونات البوابة. يمكن أن يكون هذا المبدأ التصميمي قابلاً للتكيف بشكل واسع مع أنظمة المضيف-الضيف المختلفة لتحقيق اتجاهات انتقائية قابلة للتلاعب بواسطة المحفزات الخارجية للتعرف على الضيوف المتشابهين.

طرق

تركيب FDC-3

أولاً، تم إذابة 50 ملغ (0.09 مليمول) من OPTz-t3da في 2 مل من DMA في درجة حرارة الغرفة. محلول الميثانول

تبادل المذيب وتنشيط FDC-3

لقياس خاصية الامتزاز لـ FDC-3، قمنا بتبادل المذيب الضيف ومذيبات التنسيق (DMA) مع الميثانول عن طريق نقع FDC-3 في الميثانول في

أظهرت منحنى TG أن إطار FDC-3 المتبادل كان مستقرًا حراريًا حتى

توفر البيانات

البيانات التي تدعم الرسوم البيانية داخل هذه الورقة وغيرها من نتائج هذه الدراسة متاحة من المؤلفين المقابلين عند الطلب المعقول. تم توفير بيانات المصدر في هذه الورقة. تم إيداع إحداثيات البلورات بالأشعة السينية للهياكل المبلغ عنها في هذه الدراسة في مركز بيانات البلورات كامبريدج (CCDC)، تحت أرقام الإيداع 2236266-2236267. يمكن لهذه البيانات

يمكن الحصول عليها مجانًا من مركز كامبريدج لبيانات البلورات عبرwww.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cifتم توفير بيانات المصدر مع هذه الورقة.

يمكن الحصول عليها مجانًا من مركز كامبريدج لبيانات البلورات عبرwww.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cifتم توفير بيانات المصدر مع هذه الورقة.

References

- Lehn, J.-M. From supramolecular chemistry towards constitutional dynamic chemistry and adaptive chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 36, 151-160 (2007).

- Descalzo, A. B., Martínez-Máñez, R., Sancenón, F., Hoffmann, K. & Rurack, K. The supramolecular chemistry of organic-inorganic hybrid materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 5924-5948 (2006).

- Huang, F. & Anslyn, E. V. Introduction: supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Rev. 115, 6999-7000 (2015).

- Kolesnichenko, I. V. & Anslyn, E. V. Practical applications of supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 2385-2390 (2017).

- Balzani, V., Credi, A., Raymo, F. M. & Stoddart, J. F. Artificial molecular machines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 3348-3391 (2000).

- Schwartz, G., Hananel, U., Avram, L., Goldbourt, A. & Markovich, G. A kinetic isotope effect in the formation of lanthanide phosphate nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 9451-9457 (2022).

- Gu, Y. et al. Host-guest interaction modulation in porous coordination polymers for inverse selective

separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11688-11694 (2021). - Yi, S. et al. Controlled drug release from cyclodextrin-gated mesoporous silica nanoparticles based on switchable host-guest interactions. Bioconjug. Chem. 29, 2884-2891 (2018).

- Angelos, S., Yang, Y.-W., Patel, K., Stoddart, J. F. & Zink, J. I. pHresponsive supramolecular nanovalves based on cucurbit[6]uril pseudorotaxanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 2222-2226 (2008).

- Wang, D. & Wu, S. Red-light-responsive supramolecular valves for photocontrolled drug release from mesoporous nanoparticles. Langmuir 32, 632-636 (2016).

- Yu, G. et al. Pillar[6]arene-based photoresponsive host-guest complexation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8711-8717 (2012).

- Meng, H. et al. Autonomous in vitro anticancer drug release from mesoporous silica nanoparticles by pH-sensitive nanovalves. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 12690-12697 (2010).

- Xiao, Y. et al. Enzyme and voltage stimuli-responsive controlled release system based on

-cyclodextrin-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Dalton. Trans. 44, 4355-4361 (2015). - Horike, S., Shimomura, S. & Kitagawa, S. Soft porous crystals. Nat. Chem. 1, 695-704 (2009).

- Wilmer, C. E. et al. Large-scale screening of hypothetical metalorganic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 4, 83-89 (2012).

- Horike, S. & Kitagawa, S. The development of molecule-based porous material families and their future prospects. Nat. Mater. 21, 983-985 (2022).

- Zhang, Z. et al. Temperature-dependent rearrangement of gas molecules in ultramicroporous materials for tunable adsorption of

and . Nat. Commun. 14, 3789 (2023). - Gu, C. et al. Design and control of gas diffusion process in a nanoporous soft crystal. Science 363, 387-391 (2019).

- Su, Y. et al. Separating water isotopologues using diffusionregulatory porous materials. Nature 611, 289-294 (2022).

- Li, J.-R., Kuppler, R. J. & Zhou, H.-C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477-1504 (2009).

- Martineau, C., Senker, J. & Taulelle, F. Chapter One – NMR crystallography. Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 82, 1-57 (2014).

شكر وتقدير

تم دعم هذا العمل من قبل المؤسسة الوطنية للعلوم الطبيعية في الصين (21975078)، وصناديق البحث الأساسية للجامعات المركزية، وصندوق بدء التشغيل لجامعة سيتشوان، ومنحة KAKENHI للدعم الخاص للبحث (JP25000007)، والبحث العلمي (S) (JP18H05262) من جمعية اليابان لتعزيز العلوم (JSPS). نشكر مركز تحليل iCeMS على الوصول إلى الأجهزة التحليلية.

مساهمات المؤلفين

قام Y.S. بإجراء تجارب مرتبطة بالتركيب الجزيئي، ونمو البلورات، وامتصاص الغاز، وفصل الغاز. قام K.O. وP.W. بإجراء دراسات الأشعة السينية أحادية البلورة والمسحوق وتحليل الهياكل. قام J.Z. وH.X. بإجراء دراسات حسابية. قام Q.W. وH.L. بإجراء قياسات NMR في الحالة الصلبة. قام F.H. بإجراء قياسات cRED وحل هيكل المرحلة المنشطة. قام C.G. وS.K. بتصميم المشروع وتوجيه البحث. ساهم جميع المؤلفين في كتابة وتحرير المخطوطة.

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إضافية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44424-3.

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44424-3.

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى سوسومو كيتاجاوا أو تشينغ غو.

معلومات مراجعة الأقران تشكر مجلة Nature Communications المراجع(ين) المجهول(ين) على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذا العمل. يتوفر ملف مراجعة الأقران.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينغر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي النسب 4.0 الدولية، التي تسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج بأي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح إذا ما تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمواد. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فسيتعين عليك الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/رخصة/بواسطة/4.0/.

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

المختبر الوطني الرئيسي لمواد وأجهزة الإضاءة، معهد مواد وأجهزة البوليمر البصرية، جامعة جنوب الصين للتكنولوجيا، قوانغتشو 510640، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. معهد علوم الخلايا والمواد المتكاملة، جامعة كيوتو، كيوتو 606-8501، اليابان. مختبر العلوم النانوية النظرية والحاسوبية، المركز الوطني للعلوم النانوية والتكنولوجيا، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، بكين 100190، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. معهد التكنولوجيا النووية والطاقة الجديدة، جامعة تسينغhua، بكين 100084، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. مدرسة العلوم الفيزيائية والتكنولوجيا، جامعة شانغهاي للتكنولوجيا، شانغهاي 201210، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. شركة ريد كريستال للتكنولوجيا الحيوية، سوتشو 215505، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. كلية علوم البوليمرات والهندسة، المختبر الوطني الرئيسي لهندسة مواد البوليمرات، جامعة سيتشوان، تشنغدو 610065، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. البريد الإلكتروني:kitagawa@icems.kyoto-u.ac.jp; gucheng@scu.edu.cn

Journal: Nature Communications, Volume: 15, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44424-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38168057

Publication Date: 2024-01-02

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44424-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38168057

Publication Date: 2024-01-02

Switching molecular recognition selectivities by temperature in a diffusion-regulatory porous material

Received: 10 May 2023

Accepted: 13 December 2023

Published online: 02 January 2024

(A) Check for updates

Accepted: 13 December 2023

Published online: 02 January 2024

(A) Check for updates

Over the long history of evolution, nature has developed a variety of biological systems with switchable recognition functions, such as the ion transmissibility of biological membranes, which can switch their ion selectivities in response to diverse stimuli. However, developing a method in an artificial host-guest system for switchable recognition of specific guests upon the change of external stimuli is a fundamental challenge in chemistry because the order in the hostguest affinity of a given system hardly varies along with environmental conditions. Herein, we report temperature-responsive recognition of two similar gaseous guests,

Molecular recognition plays a vital role in supramolecular chemistry

specific recognition switchable to different guests, chemists attempted to change the host-guest affinity using stimuli-responsive guests

specific recognition switchable to different guests, chemists attempted to change the host-guest affinity using stimuli-responsive guests

Porous coordination polymers (PCPs)

recognition. Despite the recent progress, most of the molecular recognition in PCPs is based on thermodynamic adsorption, which is inaccessible for switchable recognition. On the other hand, the control over guest-transport kinetics allows precise discrimination of similar guests

Results

PCP synthesis and structural analyses

We designed a bee-type ligand comprising [

Gas sorption

FDC-3a adsorbed

diffusion-regulatory pore systems in PCPs

diffusion-regulatory pore systems in PCPs

Although the above-mentioned sorption curves already revealed an apparent difference in the adsorption amounts of

IAST selectivities and diffusion rates

We employed the ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) to predict the selectivity of a

To uncover the essence of the temperature-switched adsorption, we employed the Crank theory to quantify the diffusion rate for every

Fig. 1 | The diffusion-regulatory mechanism for the temperature-switched recognition of

but a high affinity is selectively adsorbed at higher temperatures.

respectively, whereas the diffusion rates for

respectively, whereas the diffusion rates for

PXRD and solid-state NMR analyses

To further understand the mechanism from a structural aspect, in-situ PXRD patterns were collected during the adsorption process. Patterns obtained during the adsorptions of

which revealed the expansion of the [111] axis. Because one OPTz moiety was oriented parallel to the (111) plane (Supplementary Fig. 21), this slight expansion could be related to the extent of thermal flipping, which enlarged the gates to allow gas diffusion and controlled the diffusion rate.

which revealed the expansion of the [111] axis. Because one OPTz moiety was oriented parallel to the (111) plane (Supplementary Fig. 21), this slight expansion could be related to the extent of thermal flipping, which enlarged the gates to allow gas diffusion and controlled the diffusion rate.

Although the PXRD analysis could characterize the lattice change at different temperatures in FDC-3a, it could not show the local motions at the molecular level. To precisely reveal the flip-flop motion in FDC-3a, we performed

Fig. 2 | Gas adsorption behavior, IAST selectivities, and diffusion rates between 200 and 370 K . a

rate-adsorption amount (

resonances for C1-C7), while the two rings of OPTz are nearly symmetric (single or two close resonances for each of

resonances for C1-C7), while the two rings of OPTz are nearly symmetric (single or two close resonances for each of

Theoretical calculations

To get insight into the diffusion and adsorption process, Monte Carlo simulations and density functional theory (DFT) calculations were initially employed to optimize the adsorption positions of

of

of

Mixed gas separation

The temperature-switched adsorption behavior and its diffusionregulatory mechanism in FDC-3a inspired us to perform dynamic mixed gas separation experiments; these were carried out with

Fig. 3 | Variable-temperature solid-state NMR and theoretical study. a VT

pathways.

temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) protocol (Supplementary Figs. 28, 29)

was thermodynamically favorable to

temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) protocol (Supplementary Figs. 28, 29)

was thermodynamically favorable to

Discussion

Our findings provide temperature-switched recognition of the

Fig. 4 | Mixed gas separation. a McCabe-Thiele diagram for

the credit to the underlying mechanism, which is implemented by the cooperation of ultrasmall pore apertures and local dynamics of gate constituents. This design principle can be extensively adaptable with various host-guest systems for manipulatable selectivity trends by external stimuli for recognizing similar guests.

Methods

Synthesis of FDC-3

Firstly, 50 mg ( 0.09 mmol ) OPTz-t3da was dissolved in 2 mL DMA at room temperature. A methanol solution

Solvent exchange and activation of FDC-3

To measure the adsorption property of FDC-3, we exchanged the guest and coordination solvents (DMA) with methanol by soaking FDC-3 in methanol at

TG curve showed that the framework of the exchanged FDC-3 was thermally stable until

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other finding of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided in this paper. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2236266-2236267. These data can

be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Source data are provided with this paper.

be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

- Lehn, J.-M. From supramolecular chemistry towards constitutional dynamic chemistry and adaptive chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 36, 151-160 (2007).

- Descalzo, A. B., Martínez-Máñez, R., Sancenón, F., Hoffmann, K. & Rurack, K. The supramolecular chemistry of organic-inorganic hybrid materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 5924-5948 (2006).

- Huang, F. & Anslyn, E. V. Introduction: supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Rev. 115, 6999-7000 (2015).

- Kolesnichenko, I. V. & Anslyn, E. V. Practical applications of supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 2385-2390 (2017).

- Balzani, V., Credi, A., Raymo, F. M. & Stoddart, J. F. Artificial molecular machines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 3348-3391 (2000).

- Schwartz, G., Hananel, U., Avram, L., Goldbourt, A. & Markovich, G. A kinetic isotope effect in the formation of lanthanide phosphate nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 9451-9457 (2022).

- Gu, Y. et al. Host-guest interaction modulation in porous coordination polymers for inverse selective

separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11688-11694 (2021). - Yi, S. et al. Controlled drug release from cyclodextrin-gated mesoporous silica nanoparticles based on switchable host-guest interactions. Bioconjug. Chem. 29, 2884-2891 (2018).

- Angelos, S., Yang, Y.-W., Patel, K., Stoddart, J. F. & Zink, J. I. pHresponsive supramolecular nanovalves based on cucurbit[6]uril pseudorotaxanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 2222-2226 (2008).

- Wang, D. & Wu, S. Red-light-responsive supramolecular valves for photocontrolled drug release from mesoporous nanoparticles. Langmuir 32, 632-636 (2016).

- Yu, G. et al. Pillar[6]arene-based photoresponsive host-guest complexation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8711-8717 (2012).

- Meng, H. et al. Autonomous in vitro anticancer drug release from mesoporous silica nanoparticles by pH-sensitive nanovalves. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 12690-12697 (2010).

- Xiao, Y. et al. Enzyme and voltage stimuli-responsive controlled release system based on

-cyclodextrin-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Dalton. Trans. 44, 4355-4361 (2015). - Horike, S., Shimomura, S. & Kitagawa, S. Soft porous crystals. Nat. Chem. 1, 695-704 (2009).

- Wilmer, C. E. et al. Large-scale screening of hypothetical metalorganic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 4, 83-89 (2012).

- Horike, S. & Kitagawa, S. The development of molecule-based porous material families and their future prospects. Nat. Mater. 21, 983-985 (2022).

- Zhang, Z. et al. Temperature-dependent rearrangement of gas molecules in ultramicroporous materials for tunable adsorption of

and . Nat. Commun. 14, 3789 (2023). - Gu, C. et al. Design and control of gas diffusion process in a nanoporous soft crystal. Science 363, 387-391 (2019).

- Su, Y. et al. Separating water isotopologues using diffusionregulatory porous materials. Nature 611, 289-294 (2022).

- Li, J.-R., Kuppler, R. J. & Zhou, H.-C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477-1504 (2009).

- Martineau, C., Senker, J. & Taulelle, F. Chapter One – NMR crystallography. Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 82, 1-57 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21975078), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the start-up foundation of Sichuan University, the KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (JP25000007), and Scientific Research (S) (JP18H05262) from the Japan Society of the Promotion of Science (JSPS). We thank the iCeMS analysis center for access to the analytical instruments.

Author contributions

Y.S. performed experiments associated with molecular synthesis, crystal growth, gas sorption, and gas separation. K.O. and P.W. conducted single-crystal and powder XRD studies and structure analyses. J.Z. and H.X. carried out calculation studies. Q.W. and H.L. conducted solid-state NMR measurements. F.H. performed cRED measurements and solved the structure of the activated phase. C.G. and S.K. conceived the project and directed the research. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information The online version contains

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44424-3.

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44424-3.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Susumu Kitagawa or Cheng Gu.

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2024

© The Author(s) 2024

State Key Laboratory of Luminescent Materials and Devices, Institute of Polymer Optoelectronic Materials and Devices, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510640, P. R. China. Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan. Laboratory of Theoretical and Computational Nanoscience, National Center for Nanoscience and Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, P. R. China. Institute of Nuclear and New Energy Technology, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, P. R. China. School of Physical Science and Technology, ShanghaiTech University, Shanghai 201210, P. R. China. ReadCrystal Biotech Co., Ltd., Suzhou 215505, P. R. China. College of Polymer Science and Engineering, State Key Laboratory of Polymer Materials Engineering, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, P. R. China. e-mail: kitagawa@icems.kyoto-u.ac.jp; gucheng@scu.edu.cn