DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-023-01398-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38167159

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-02

التفاعل بين الإجهاد التأكسدي، التواصل الخلوي ومسارات الإشارة في السرطان

الملخص

لا يزال السرطان يمثل مصدر قلق كبير للصحة العامة على مستوى العالم، مع زيادة معدلات الإصابة والوفيات في جميع أنحاء العالم. يلعب الإجهاد التأكسدي، الذي يتميز بإنتاج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) داخل الخلايا، دورًا حاسمًا في تطور السرطان من خلال التأثير على استقرار الجينوم ومسارات الإشارة داخل البيئة الخلوية الدقيقة. تؤدي المستويات المرتفعة من ROS إلى اضطراب التوازن الخلوي والمساهمة في فقدان الوظائف الخلوية الطبيعية، والتي ترتبط ببدء وتقدم أنواع مختلفة من السرطان. في هذا الاستعراض، ركزنا على توضيح مسارات الإشارة اللاحقة التي تتأثر بالإجهاد التأكسدي وتساهم في التسرطن. تشمل هذه المسارات p53، Keap1-NRF2، RB1، p21، APC، جينات كابحة للأورام، وانتقالات نوع الخلية. يمكن أن يؤدي خلل تنظيم هذه المسارات إلى نمو خلوي غير مسيطر عليه، وضعف آليات إصلاح الحمض النووي، وتجنب موت الخلايا، وكلها سمات مميزة لتطور السرطان. ظهرت الاستراتيجيات العلاجية التي تستهدف الإجهاد التأكسدي كمجال حيوي للتحقيق لدى علماء الأحياء الجزيئية. الهدف هو تقليل وقت الاستجابة لأنواع مختلفة من السرطان، بما في ذلك سرطانات الكبد والثدي والبروستاتا والمبيض والرئة. من خلال تعديل التوازن التأكسدي وإعادة التوازن الخلوي، قد يكون من الممكن التخفيف من الآثار الضارة للإجهاد التأكسدي وتعزيز فعالية علاجات السرطان. يحمل تطوير العلاجات المستهدفة والتدخلات التي تعالج بشكل خاص تأثير الإجهاد التأكسدي على بدء وتقدم السرطان وعدًا كبيرًا في تحسين نتائج المرضى. قد تشمل هذه الأساليب علاجات قائمة على مضادات الأكسدة، وعوامل تعديل التوازن التأكسدي، وتدخلات تعيد الوظيفة الخلوية الطبيعية ومسارات الإشارة المتأثرة بالإجهاد التأكسدي. خلاصة القول، إن فهم دور الإجهاد التأكسدي في التسرطن واستهداف هذه العملية من خلال التدخلات العلاجية أمر في غاية الأهمية لمكافحة أنواع مختلفة من السرطان. هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من البحث لكشف الآليات المعقدة التي تكمن وراء مسارات الإجهاد التأكسدي وتطوير استراتيجيات فعالة يمكن ترجمتها إلى تطبيقات سريرية لإدارة وعلاج السرطان.

مقدمة

بالإضافة إلى أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS)، تلعب أنواع النيتروجين التفاعلية (RNS) دورًا هامًا في الإجهاد التأكسدي [5]. تساهم أنواع النيتروجين التفاعلية، مثل أكسيد النيتريك (NO) والبروكسينيتريت (ONOO-)، في تلف الخلايا وتشارك في مسارات إشارية مختلفة مرتبطة بتقدم السرطان. وبالمثل لأنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية، يمكن لأنواع النيتروجين التفاعلية تعديل بقاء الخلايا، وإحداث تلف في الحمض النووي، والتأثير على وظائف الميتوكوندريا [6]. يزيد التفاعل بين أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية وأنواع النيتروجين التفاعلية من تعقيد مشهد الإجهاد التأكسدي، مما يبرز الحاجة إلى استراتيجيات علاجية تستهدف كلا النوعين [5، 6].

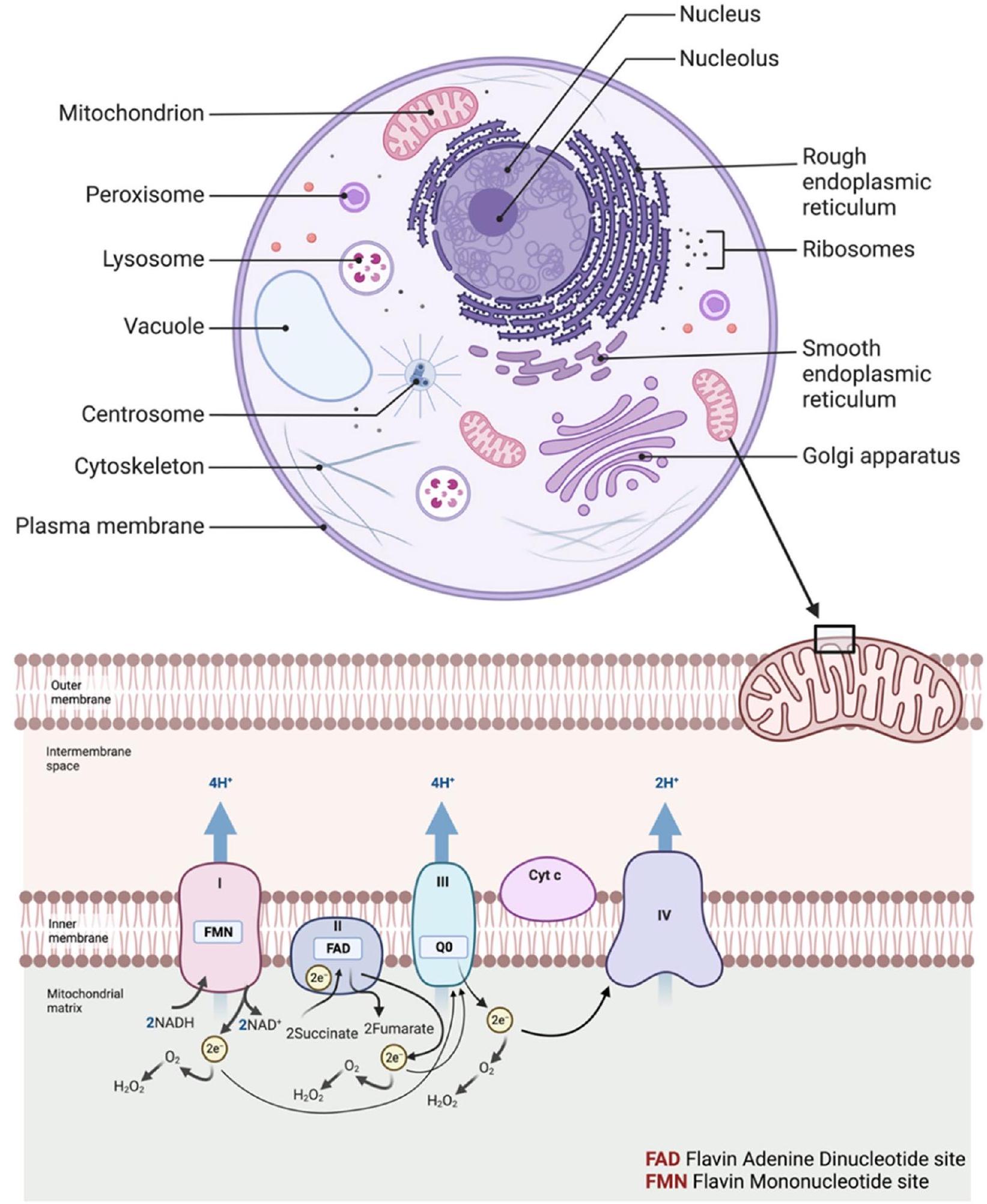

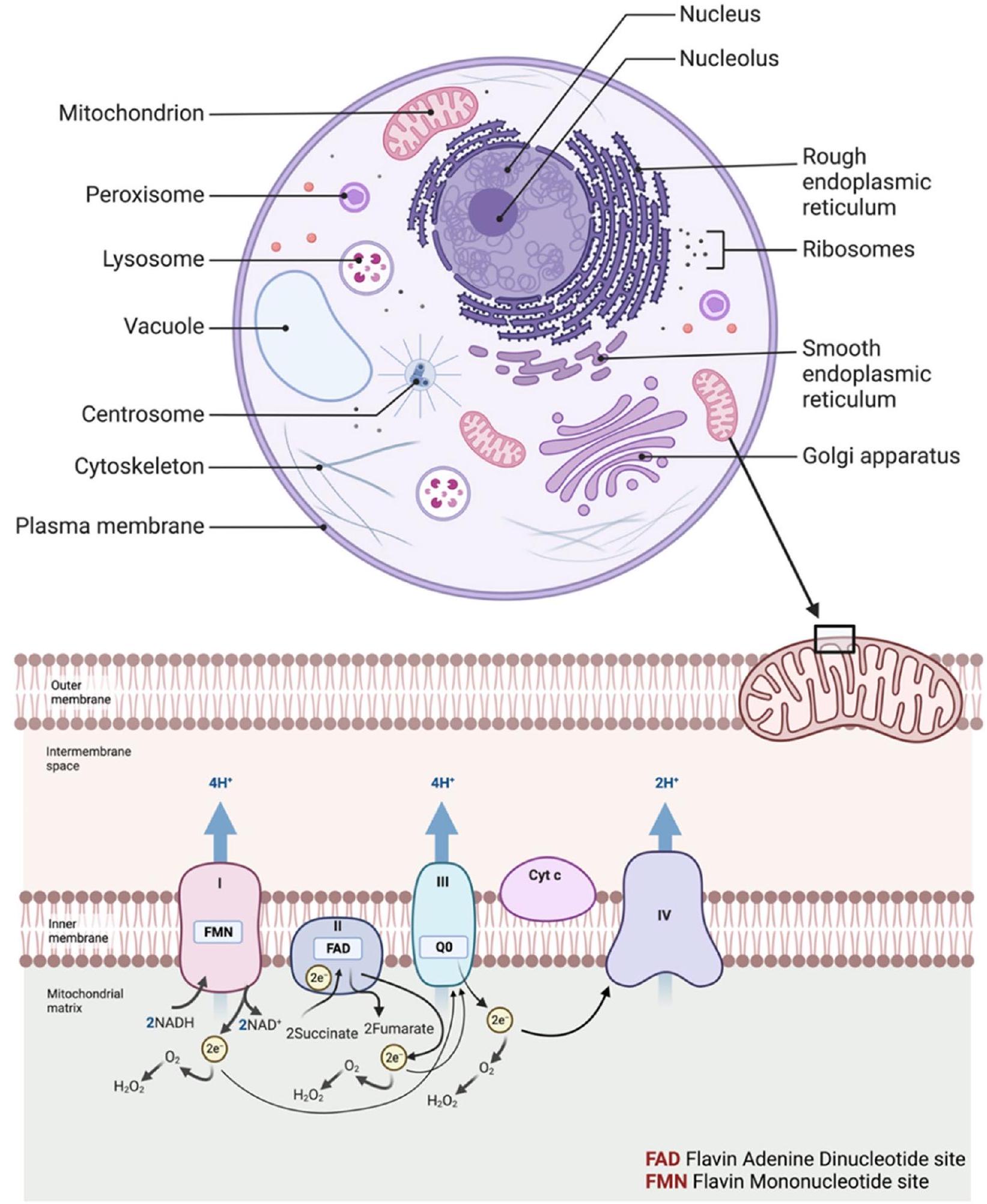

الإجهاد التأكسدي يتفاعل مع الجزيئات الكبيرة الخلوية مثل الحمض النووي DNA، والحمض النووي الريبوزي RNA، والبروتينات. على وجه التحديد، يمكن لأنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) أن تسبب طفرات في الحمض النووي، وكسور في السلاسل، وحتى شذوذات كروموسومية من خلال التفاعل مع القواعد النيتروجينية والعمود الفقري من السكر والفوسفات. تؤدي هذه التغيرات الجينية إلى اضطراب التنظيم الطبيعي لدورة الخلية، والبرمجة الخلوية للموت (الاستماتة)، وآليات إصلاح الحمض النووي. يؤدي تدهور سلامة الجينوم إلى تنشيط الجينات المسرطنة وإلغاء تنشيط جينات كابحة للأورام، مما يهيئ بيئة ملائمة لتكاثر الخلايا غير المنضبط وتكوين الأورام [7-10]. لوحظ في دراسات متعددة أن الإجهاد التأكسدي يشارك في بدء وتقدم أنواع مختلفة من السرطانات، بما في ذلك الميلانوما، واللوكيميا، واللمفوما، وسرطان الفم، والبنكرياس، والمبيض، والمثانة، والثدي، وعنق الرحم، والدماغ، والمعدة، والكبد، والرئة، والبروستاتا [11-14]. تُنتج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) بشكل كبير في الميتوكوندريا داخل الخلايا (الشكل 1) [14]، وتُعتبر المساهم الرئيسي المحتمل في الإجهاد التأكسدي والسرطان [15]. تُعد ROS جزيئات إشارة داخل الخلوية تساهم بشكل كبير في مسارات الإشارة المختلفة، بما في ذلك مسار إشارة عامل النمو الشبيه بالأنسولين، ومسار إشارة الكاتيونات الذي يتوسطه قناة المستقبلات العابرة للتيار [16]. في مسار إشارة عامل النمو، ROS، بشكل رئيسي…

الإجهاد التأكسدي، ارتفاع مستوى أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية وتكوّن السرطان: ربط النقاط

التحول الطلائي-الميزنكيمي (EMT)

تم الإبلاغ عن أن إشارات Notch وإشارات Hedgehog تحفز حدث الانتقال الطلائي اللحمي (EMT) [29]. العوامل النسخية، بما في ذلك Snail1 وE12/E47 وZeb1/2 وFOXC2 وSlug وSIP1 وTwist وGoosecoid، والتعديلات اللاجينية مثل مثيلة الحمض النووي وإعادة تشكيل النوكليوزومات تشارك أيضًا في تحفيز وبدء EMT [29]. خلال عملية EMT، تم الإبلاغ عن زيادة التعبير عن علامات اللحمة مثل الفبرونيكتين وN-cadherin وSnail وSlug وTwist وFOXC2 وSOX10 والفيمنتين وMMP-2 وMMP-3 وMMP-9 في الخلايا الطلائية. في حين تم الإبلاغ عن انخفاض التعبير عن علامات الطلائية مثل E-cadherin والسيتوكيراتين والديسموبلاكين والأوككلودين، مما يسبب فقدان القطبية، وإعادة تنظيم الهيكل الخلوي، وتوليد النمط الظاهري الغازي في الخلايا ويسهل تقدم السرطان [28].

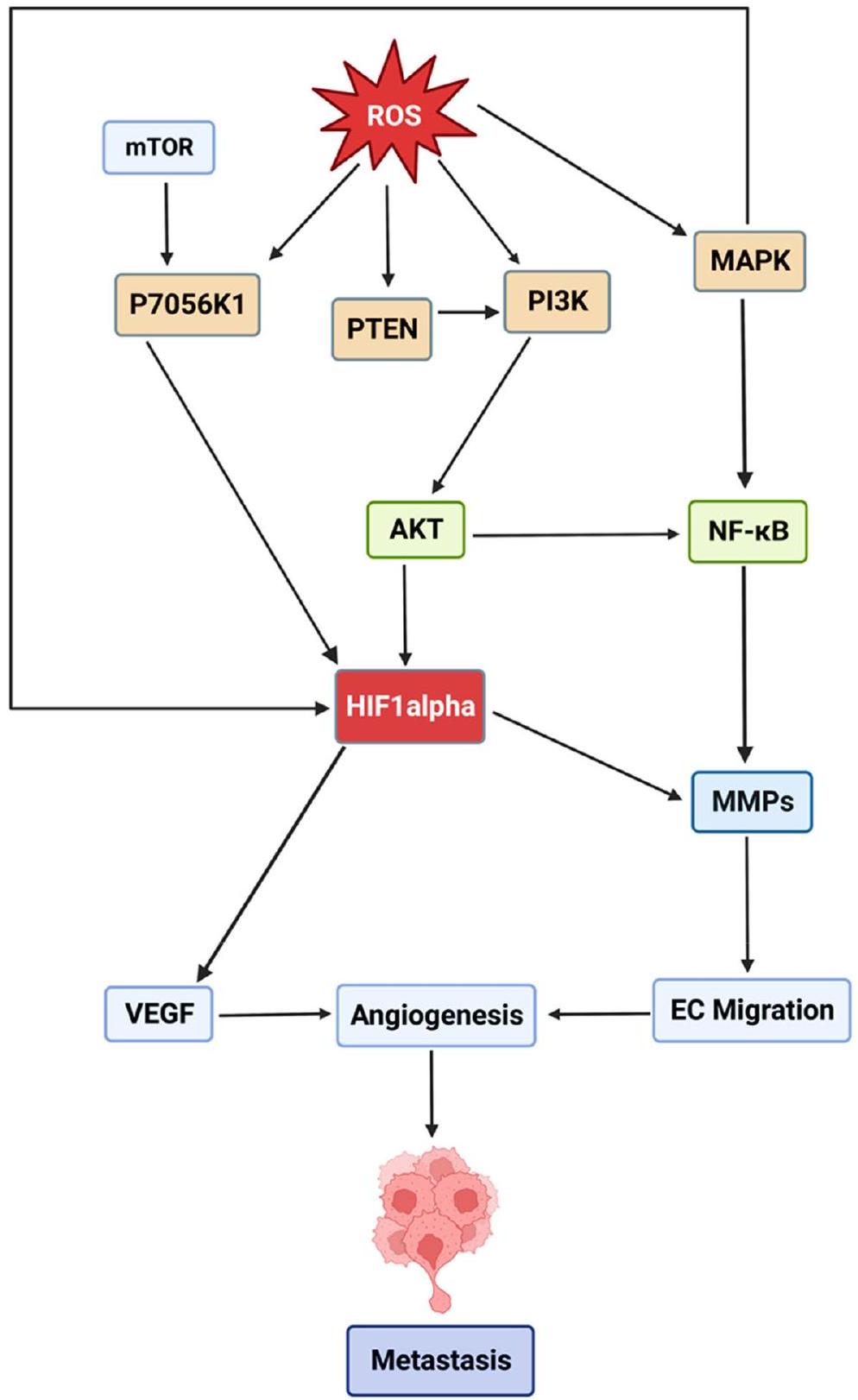

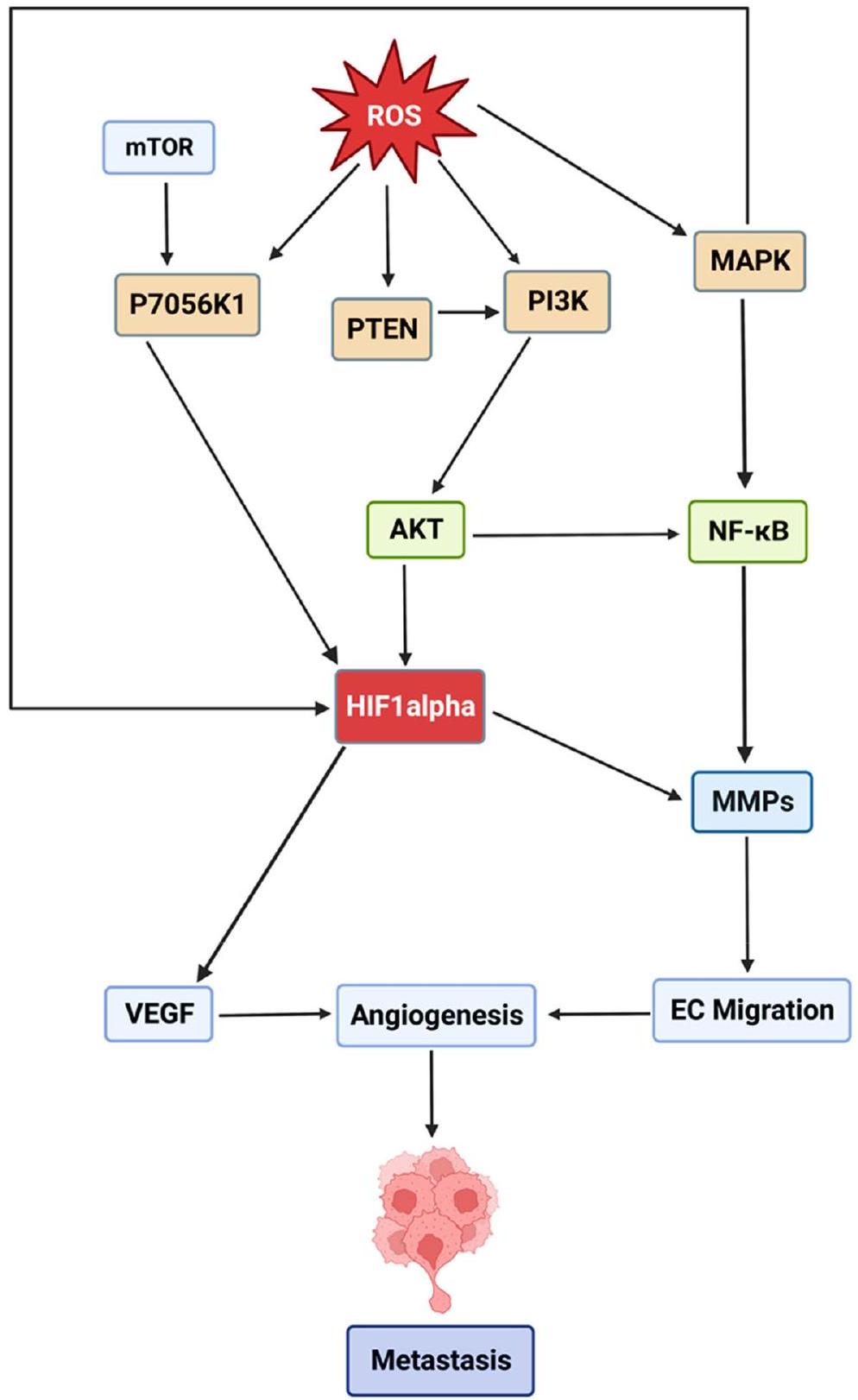

تكوّن الأوعية الدموية الجديدة

مسارات الإشارة في الإجهاد التأكسدي والسرطان مسار MAPK

تنظيم تعبير الجينات المشاركة في بقاء الخلايا، وتكاثرها، والموت المبرمج [34].

مسار PI3K/AKT

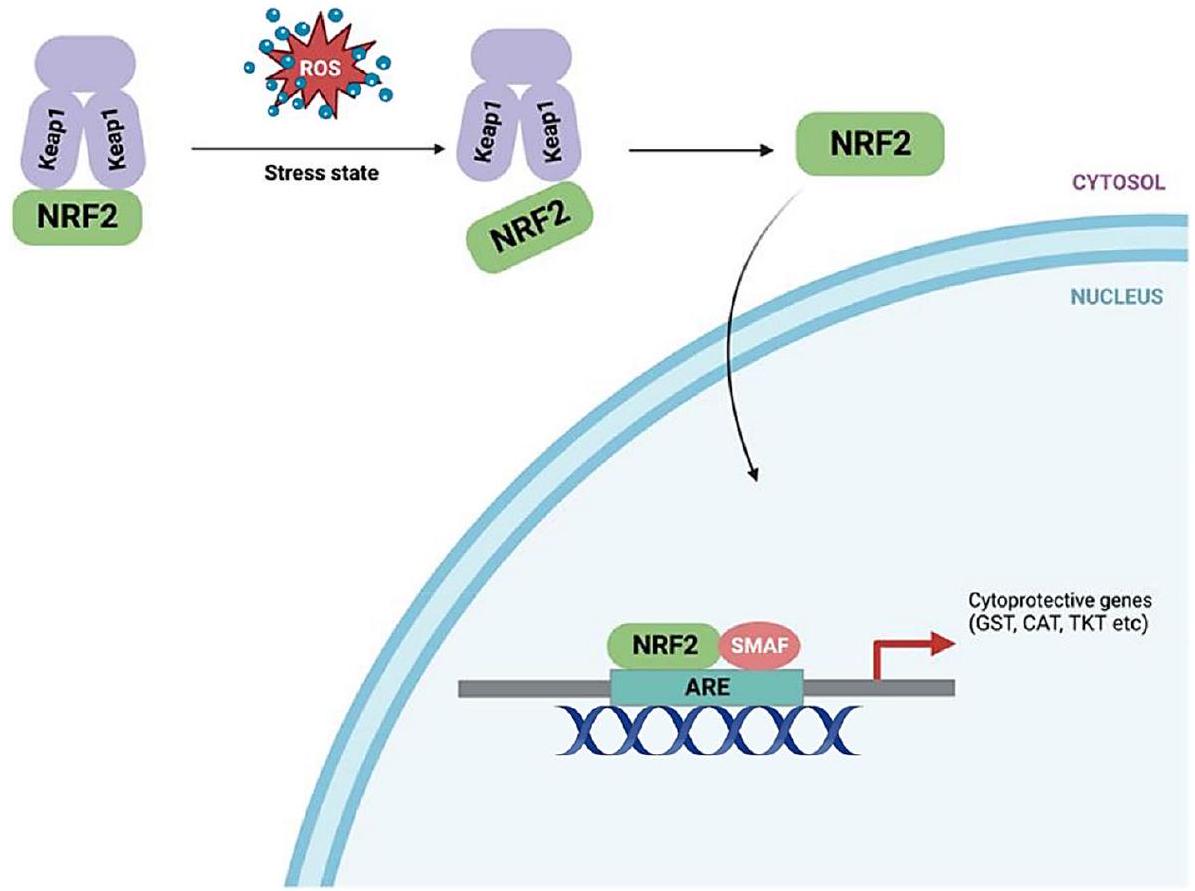

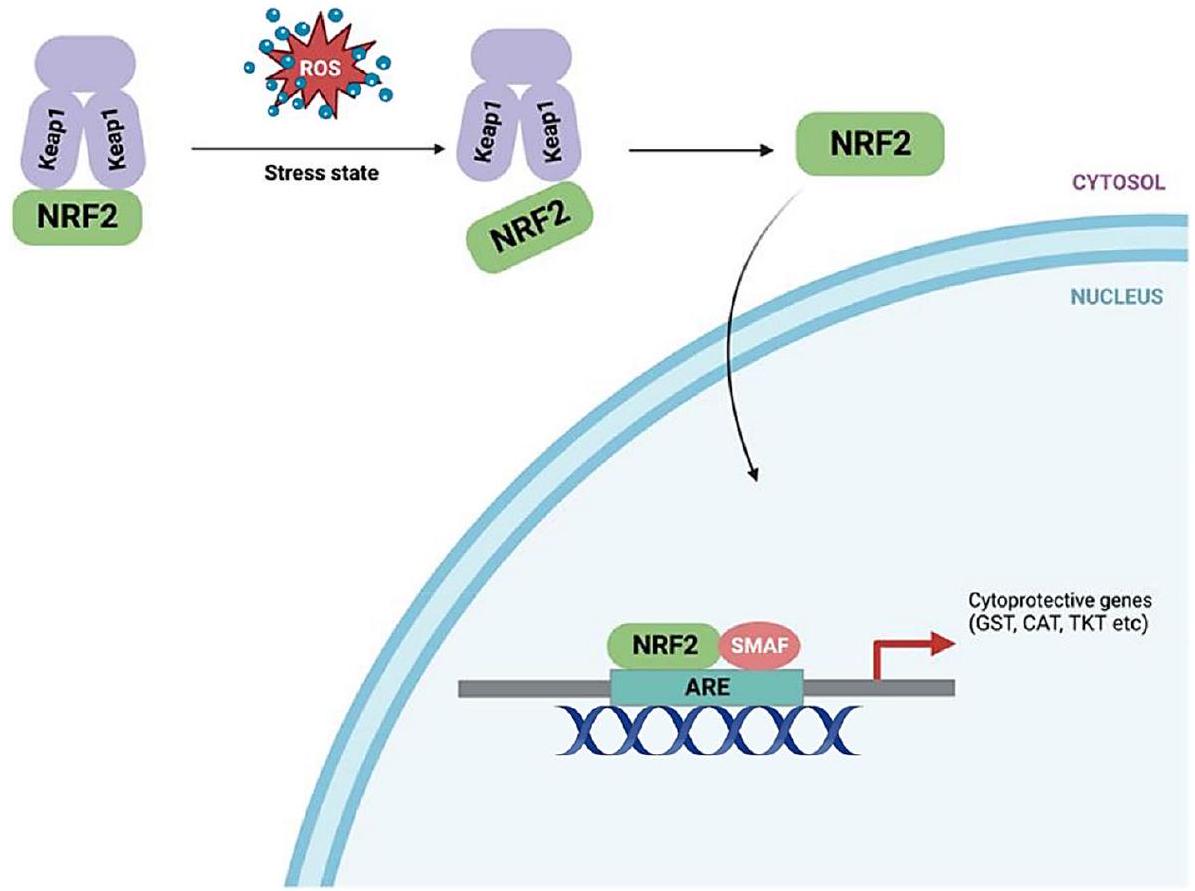

مسار Keap1-Nrf2

مسار JAK/STAT

ونت/

مسار p53

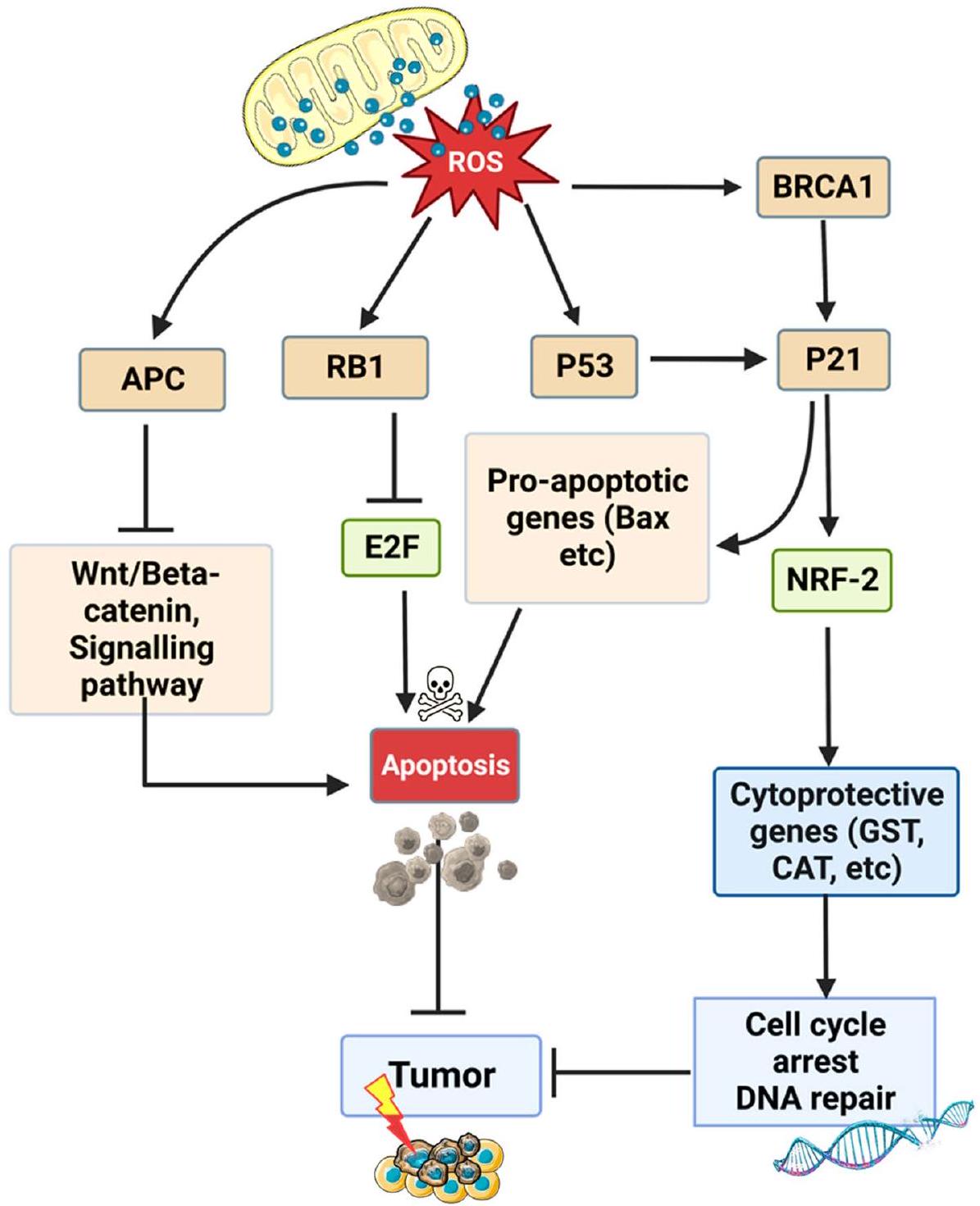

جينات كابحة للأورام والإجهاد التأكسدي: تفاعل متبادل في التسرطن

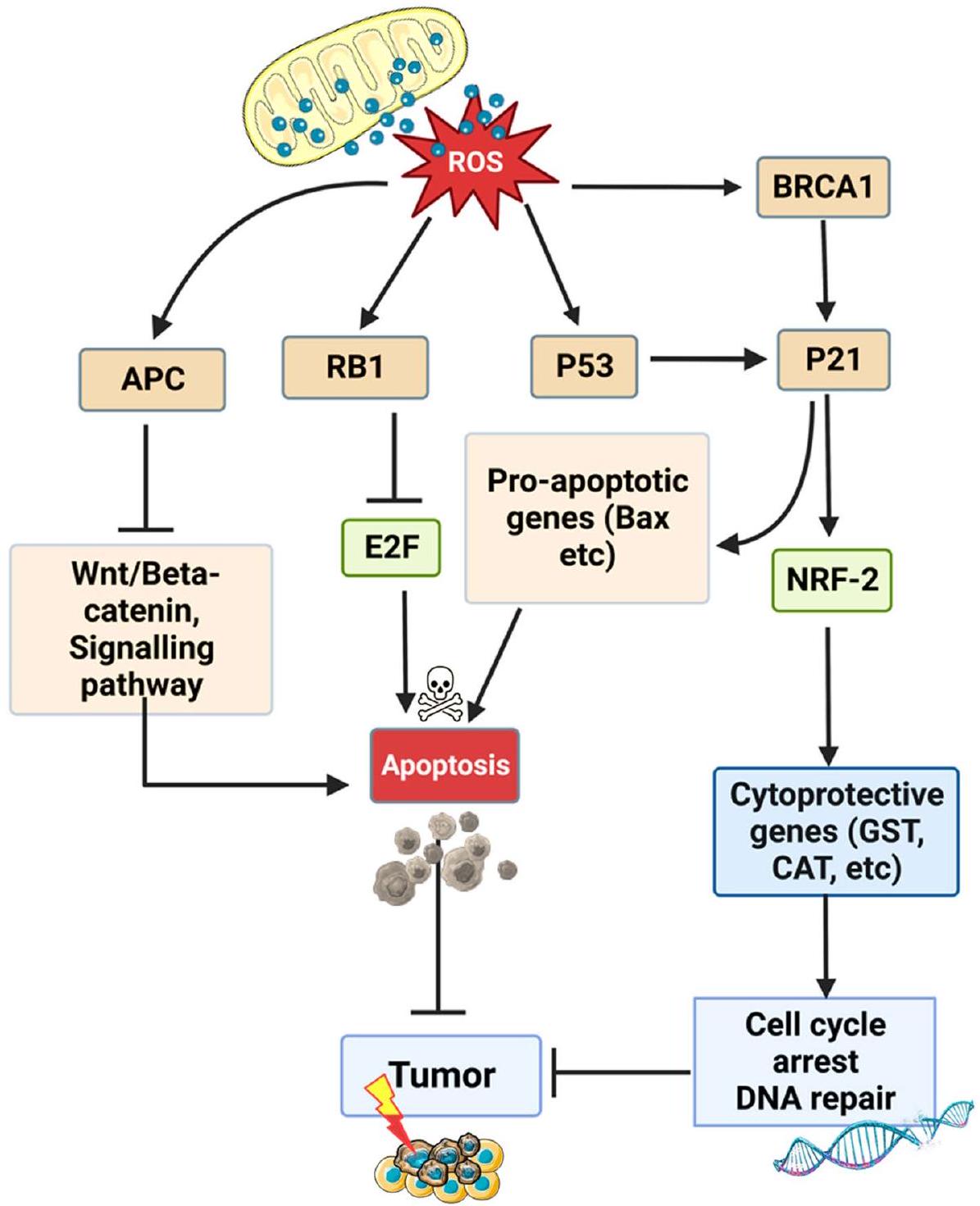

بي53

p53 هو المنظم الرئيسي للموت الخلوي المبرمج ويمنع تكون الأورام من خلال تسهيل تنظيم الإجهاد التأكسدي في الخلايا. عند مستوى منخفض من الإجهاد التأكسدي، يعزز p53 بقاء الخلية عن طريق تحفيز تعبير جينات مضادات الأكسدة، بما في ذلك Parkin وsestrins.

تم الإبلاغ عن أن p53 مسؤول عن الورم الأرومي الدبقي، ورم الشبكية، ورم العصب، الورم النخاعي، اللمفوما، سرطان المثانة، البنكرياس، الثدي، البروستاتا، الرئة، الرحم، ورم الرأس والعنق [48-50].

BRCA1 و BRCA2

NRF2

آر بي 1

يُذكر أنه يشارك في تحفيز وتقدم سرطان الشبكية، الورم الأرومي الدبقي، سرطان الثدي، البروستاتا، الرئة، والمثانة [61، 63].

P21

الحزب الأفريقي الوطني

طرق تحليل الإجهاد التأكسدي في علم الأورام

| جين مثبط للورم | عمل منخفض الإجهاد التأكسدي | نشاط الإجهاد التأكسدي العالي | السرطانات المرتبطة | المراجع |

| p53 | يعزز بقاء الخلايا من خلال تحفيز جينات مضادات الأكسدة: باركين، سيسترينز 1/2، GLS2، ALDH4، GPX1، TIGER | يعزز موت الخلايا عن طريق تحفيز الجينات المؤيدة للأكسدة: PIG3، PIG6، FDRX، Bax، Puma | الورم الأرومي الدبقي، ورم الشبكية، ورم العصب، ورم النخاع، اللمفوما، المثانة، البنكرياس، الثدي، البروستاتا، الرئتين، الرحم، الرأس والعنق | [47] [45]; [46] [40]; ;[48] [50]; ;[49]; |

| BRCA1/BRCA2 | ينظم الإجهاد التأكسدي عن طريق تنشيط الجينات: PON2، KL، UCHL1، GST، GPX3، ADH5، ME2 | يحمي الحمض النووي من انكسارات السلسلتين المزدوجتين | الثدي، المبيض، المريء، الرحم، البنكرياس، القولون والمستقيم، عنق الرحم، المعدة، البروستاتا، والكبد | [51] [54]; [52]; [53] [55] [56];;; |

| إن آر إف 2 | يبدأ آليات الحماية الخلوية عن طريق الارتباط ببروتينات sMAF وARE في النواة | ينشط تعبير الجينات الواقية للخلايا | القولون والمستقيم، الثدي، الكبد، المرارة، البروستاتا، المعدة، المبيض، والرئة | [57] [7] [58] [60]; ;,[59]; |

| آر بي 1 | يحافظ على سلامة الجينوم استجابة للإجهاد التأكسدي | يحفز السكون الخلوي عن طريق تثبيط تعبير E2f1 و E2f2 و E2f3 | ورم الشبكية، الورم الأرومي الدبقي، الثدي، البروستاتا، الرئتين، والمثانة | [61] [62] [63]; ;[61]; |

| P21 | يحفز استجابة وقائية خلوية تعتمد على NRF2 لمنع تلف الخلايا | يحفز استحثاث الاستجابة المسببة للموت الخلوي المبرمج | سرطان المعدة، وسرطان الخلايا الحرشفية للمريء | [64] [65] [66];; |

| APC | يحافظ على استقرار الجينوم من خلال آليات إصلاح الحمض النووي | يعيق آلية إصلاح الإزالة القاعدية ويسهل موت الخلايا المبرمج | سرطان البروستاتا، المعدة، البنكرياس، والقولون والمستقيم | [68] [67]; [69]; [70]; [71] [72]; ;[74] [73];; |

| نوع الطريقة | الوصف | أمثلة على الفحوصات/الطرق | مرجع |

| القياس المباشر لأنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية | تحديد كمية أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية الخلوية في العينات السريرية. | 5-6-كربوكسي-2,7-ديكلوروديهيدروفلوريسين دايأسيتات، ديهيدروإيثيديوم، اختبار d-ROMs | [75]. |

| الضرر التأكسدي وحالة مضادات الأكسدة | تقييم الضرر التأكسدي وحالة مضادات الأكسدة. | اختبار 2،4-داينيتروفينيل هيدرازين (DNPH)، اختبار اختزال 2،2-ثنائي فينيل-1-بيكريل هيدرازيل (DPPH) | |

| التحاليل الجزيئية والكيميائية الحيوية | تحديد كمية الضرر التأكسدي للحمض النووي. | 8-أوكسو-2′-ديوكسيغوانوزين (8-أوكسو-dG) | [76] |

| اختبارات تأكسد الدهون | تقييم الضرر التأكسدي لدهون الخلايا. | مالونديالدهيد (MDA)، 4-هيدروكسينونينال (4-HNE) | [77]. |

| الجينومية والنصوصية | تحديد الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف المرتبطة بالإجهاد التأكسدي. | تسلسل الحمض النووي الريبي (RNA-Seq)، فحوصات CRISPR/Cas9 | [78] [79] |

| النهج البروتينية | تحديد البروتينات التي تخضع لتعديلات أكسدة. | البروتيوميات التأكسدية | [80] |

| الفوسفوبروتيوميات | تحديد التغيرات في الفسفرة الناتجة عن الإجهاد التأكسدي. | [81] | |

| تقنيات الأيض | تحديد كمية المستقلبات المحددة مثل الجلوتاثيون. | التحليل الطيفي الكتلي LC-MS/MS المستهدف، التحليل الأيضى غير المستهدف | [82] [83]; |

| تقنيات التصوير | التصوير الحي والمراقبة الفورية لمستويات أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS). | التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي الحساس للجذور الحرة للأكسجين، التصوير البصري باستخدام مجسات حساسة للجذور الحرة للأكسجين | [84] |

| تقنيات الخلايا والأنسجة | قياس مستويات الجذور الحرة أو مضادات الأكسدة داخل الخلايا. | التحليل المناعي النسيجي (IHC)، التحليل السيتوفلوري المتري | [75] |

| الطرق الحاسوبية والمحاكاة الحاسوبية | رؤى حول سلاسل الإشارات التي يسببها الجذور الحرة التفاعلية والتغيرات الهيكلية في الجزيئات الحيوية. | تحليل المسارات، محاكاة الديناميكيات الجزيئية | [85] |

| الخزعة السائلة | المؤشرات الحيوية غير الغازية للإجهاد التأكسدي. | المايكرو RNA المتداولة (miRNAs)، الحمض النووي الحر الخلوي (cfDNA) | [86] |

لقياس الضرر التأكسدي للحمض النووي، وهو سمة شائعة في العديد من أنواع السرطان [76]. تُستخدم اختبارات تأكسد الدهون مثل مالونديالديهيد (MDA) و4-هيدروكسينونينال (4-HNE) لتقييم الضرر التأكسدي للدهون الخلوية، والذي يشارك في تطور السرطان [77]. كما تقدم الأساليب الجينومية والنسخية رؤى قيمة. يحدد تسلسل الحمض النووي الريبي (RNA-Seq) الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف والتي تشكل جزءًا من استجابة الإجهاد التأكسدي في خلايا السرطان [78]. يمكن لشاشات كريسبر/كاس9 (CRISPR/Cas9) تحديد الجينات التي تعدل الحساسية أو المقاومة للإجهاد التأكسدي، وهو أمر حاسم لتطوير العلاج المستهدف [79].

تحدد الأساليب البروتينية مثل البروتيوميات التأكسدية البروتينات التي تخضع لتعديلات أكسدة بشكل خاص، مما يوفر رؤى في علم أمراض السرطان [80]. تحدد تقنيات الفوسفوبروتيوميات التغيرات في الفسفرة الناتجة عن الإجهاد التأكسدي، وهي ضرورية في مسارات الإشارات المسببة للسرطان [81]. تُستخدم تقنيات الأيض مثل الكروماتوغرافيا السائلة المستهدفة مع مطياف الكتلة المتسلسل (LC-MS/MS) لقياس كميات محددة من المستقلبات مثل الجلوتاثيون، الذي يشارك مباشرة في توازن الأكسدة والاختزال [82]. غير المستهدفة

| النهج العلاجي | نوع الوكيل | أمثلة | آلية | المراجع |

| التقاط الجذور الحرة | مثبطات أوكسيداز NADPH | ديفينيلين يودونيوم، أبوسينين | تثبيط أوكسيداز NADPH، مما يقلل من إنتاج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) | [90]، [91] |

| فيتامينات مضادة للأكسدة | فيتامين هـ، فيتامين ج، فيتامين أ | تحييد الجذور الحرة عن طريق التبرع بالإلكترونات | ||

| مركبات السيلينيوم | سيلينوميثيونين، إبسلين | تفعيل السيلينوبروتينات التي تعمل كمضادات للأكسدة | ||

| المركبات الطبيعية | الكيرسيتين، الريسفيراترول، الكركمين، إي جي سي جي | تثبيط الإنزيمات المولدة للأكسجين التفاعلي واحتجاز أيونات المعادن | ||

| المحاكيات الإنزيمية | بورفيرينات المنغنيز، EUK-134 | تحاكي إنزيمات مضادات الأكسدة الطبيعية | ||

| البوليامينات | سبيرمين، سبيرميدين | تعديل الحالة المؤكسدة الخلوية عن طريق ترسيب أيونات المعادن أو تحفيز تعبير إنزيمات مضادات الأكسدة | ||

| متفرقات | إيدارافون، ترو لوكس، تمبول | آليات مختلفة تشمل التقاط الجذور الحرة واحتجاز المعادن | ||

| تعزيز ROS | مشتقات النتروكسيد | تمبول، تمبوني | توليد ROS لتحفيز الإجهاد التأكسدي | [92]، [93] |

| الأدوية المؤكسدة | ثلاثي أكسيد الزرنيخ، دوكسوروبيسين، ميناديون، إليسكولمول | تُحدث خللاً في التوازن التأكسدي والاختزالي، وترفع مستويات أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية مما يؤدي إلى الاستماتة | ||

| عوامل العلاج الضوئي الديناميكي | حمض الأمينوليفولينك، الميثيلين الأزرق، روز بيلجان | تنتج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية عند تنشيطها بواسطة الضوء | ||

| العوامل المؤكسدة الطبيعية | بيتا-لاباخون، بارتينوليد، كابسيسين | تحفيز توليد أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية مما يخل بتوازن الأكسدة والاختزال | ||

| مُخلِّبات المعادن | ديفيروكسامين، ترايابين، إل1 | تأينات المعادن الانتقالية المخلبية التي تحفز تكوين أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية | ||

| مضادات الأكسدة الثيولية | N-أسيتيل سيستئين، الجلوتاثيون، ثيوريدوكسين | يتبرع بالإلكترونات لتحييد الجذور الحرة | ||

| الأدوية المعتمدة على دورة الأكسدة والاختزال | بلومباجين، جوجلون، ثيوسيميكاربازونات | التناوب بين الأشكال المؤكسدة والمختزلة، مولدًا أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) |

الأساليب العلاجية لاستهداف الإجهاد التأكسدي والسرطان

الأساليب العلاجية المعدلة بواسطة ROS

تركيز مشتقات النيتروكسيد (أي الجذور الحرة المشتقة من النيتروكسيد والنيتروكسيدات الحلقية)، أو زيادة التعبير عن إنزيمات غلوتاثيون S-ترانسفيراز، وإنزيمات سوبر أكسيد ديسموتاز (SODs)، والكاتالازات يُذكر أنها تُستخدم لاستهداف الإجهاد التأكسدي الخلوي والسرطان [87-89].

طُرُق علاجية لالتقاط أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) [90، 91]

- مثبطات أوكسيداز NADPH (مثل دي فينيل يودونيوم، أبوسين) – تثبط نشاط أوكسيداز NADPH، مما يقلل من إنتاج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS).

- الفيتامينات المضادة للأكسدة (مثل فيتامين هـ، فيتامين ج، فيتامين أ) – تقوم بتحييد الجذور الحرة عن طريق التبرع بالإلكترونات، مما يقلل من الإجهاد التأكسدي.

- مركبات السيلينيوم (مثل سيلينوميثيونين، إبسلين) – تنشط السيلينوبروتينات التي تعمل كمضادات للأكسدة.

- المركبات الطبيعية (مثل الكيرسيتين، الريسفيراترول، الكركمين، EGCG) – تمارس هذه المركبات النباتية تأثيرات مضادة للأكسدة من خلال تثبيط الإنزيمات المولدة لأنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية وربط أيونات المعادن.

- المحاكيات الإنزيمية (مثل بورفيرينات المنغنيز، EUK-134) – هي مركبات صناعية تحاكي الإنزيمات المضادة للأكسدة الطبيعية.

- البوليامينات (مثل السبيرمين، السبيرميدين) – تعدل الحالة التأكسدية الخلوية عن طريق معقدة أيونات المعادن أو تحفيز تعبير إنزيمات مضادات الأكسدة.

- متفرقات (مثل إيدارافون، ترو لوكس، تمبول) – تعمل هذه العوامل من خلال آليات مختلفة، بما في ذلك التقاط الجذور الحرة واحتجاز المعادن.

ii) الأساليب العلاجية المعززة للجذور الحرة للأكسجين [92، 93] - مشتقات النيتروكسيد (مثل تمبول، تمبون) تولد أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية لإحداث الإجهاد التأكسدي في خلايا السرطان.

- الأدوية المؤيدة للأكسدة (مثل أكسيد الزرنيخ، دوكسوروبيسين، ميناديون، إليسكولمول) – تخلق خللاً في التوازن التأكسدي المختزل، مما يؤدي إلى ارتفاع مستويات أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) والموت الخلوي المبرمج اللاحق.

- عوامل العلاج الضوئي الديناميكي (مثل حمض الأمينوليفولينك، الميثيلين الأزرق، روز بEngal) – تنتج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية عند تنشيطها بالضوء، مما يؤدي إلى تلف تأكسدي.

- المؤكسدات الطبيعية (مثل بيتا-لاباشون، بارتينوليد، الكابسيسين) – هذه المركبات الطبيعية تحفز توليد أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية، مما يعطل توازن الأكسدة والاختزال ويؤدي إلى موت الخلايا.

- الميلاتونين: يعمل كعامل مباشر لالتقاط الجذور الحرة ويحفز أيضًا إنزيمات مضادة للأكسدة.

- المُخلِّبات المعدنية (مثل ديفيروكسامين، تريابين، L1) تخلب أيونات المعادن الانتقالية التي تحفز تكوين أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS).

- مضادات الأكسدة الثيولية (مثل N-أسيتيل سيستئين، الجلوتاثيون، الثيوريدوكسين) – تتبرع بالإلكترونات لتحييد الجذور الحرة.

- الأدوية التي تمر بدورة الأكسدة والاختزال (مثل البلومباجين، الجوجلُون، الثيوسيميكاربازونات) – هذه العوامل تتنقل بين الأشكال المؤكسدة والمختزلة، مولدة أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) في العملية.

- زيادة التعبير أو إعطاء إنزيمات مضادة للأكسدة (مثل SODs، الكاتالازات، جلوتاثيون S-ترانسفيرازات، بيروكسيردوكسينات) – تتضمن هذه الأساليب استخدام العلاج الجيني أو إعطاء الإنزيمات مباشرة لرفع مستويات إنزيمات مضادة للأكسدة، مما يؤدي بشكل متناقض إلى توليد أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) في خلايا السرطان.

- الأيونوفورات (مثل جراميسيدين، فالينوميسين) – تعطل تدرجات الأيونات عبر الأغشية، مما يؤدي بشكل غير مباشر إلى توليد أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS).

- متفرقات (مثل بيبرلونجومين، بي إي آي تي سي، داتس) – لها آليات فريدة، غالبًا ما تنطوي على تعديل مسارات الإشارة الحساسة للأكسدة.

الأساليب العلاجية القائمة على تكنولوجيا النانو

ناقلات نانوية لالتقاط الجذور الحرة

ثانيًا. الناقلات النانوية المولدة للأكسيد النيتري

ثالثًا. الناقلات النانوية ذات الوظيفة المزدوجة

رابعًا. استراتيجيات علاجية تآزرية

تطوير التدخلات العلاجية في الإجهاد التأكسدي والسرطان

ثانيًا. المعدلات اللاجينية: تعمل الأدوية اللاجينية مثل 5-أزاسيتيدين وفورينوسات عن طريق تثبيط الإنزيمات المسؤولة عن مثيلة الحمض النووي وإزالة أسيتيل الهيستونات على التوالي [105، 106]. تؤدي هذه الإجراءات إلى إعادة التعبير عن الجينات التي ترمز لمضادات الأكسدة مثل الجلوتاثيون وإنزيمات سوبر أكسيد ديسميوتاز (SOD)، مما يغير حالة الأكسدة والاختزال الخلوية ويجعل خلايا السرطان أكثر عرضة للاستمواتة الناتجة عن الإجهاد التأكسدي [105].

ثالثًا. استراتيجيات تثبيط الإنزيمات: تستهدف مثبطات محددة مثل ألوبورينول إنزيم زانثين أوكسيداز، وهو إنزيم يشارك في تحويل الهيبوكساثين إلى زانثين ثم إلى حمض اليوريك، وهي عملية تولد أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية [107]. من خلال تثبيط هذا الإنزيم، تنخفض مستويات أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية الخلوية، مما يمكن أن يثبط مسارات الإشارات الناتجة عن الإجهاد التأكسدي التي تعزز تكاثر خلايا السرطان [107].

رابعًا. العلاجات المناعية: تعمل مثبطات نقاط التفتيش مثل الأجسام المضادة المضادة لـ PD-1 عن طريق حجب التفاعل بين مستقبلات PD-1 على الخلايا التائية و PD-L1 على خلايا السرطان [108]. يعزز هذا الحجب النشاط السمي للخلايا التائية وينتج السيتوكينات التي يمكن أن تحفز الإجهاد التأكسدي في خلايا السرطان، مما يؤدي إلى الاستماتة؛ وهذا يضيف بعدًا جديدًا لكيفية تعديل العلاجات المناعية لحالة الأكسدة والاختزال داخل بيئة الورم الدقيقة [108].

خامسًا. العلاجات المركبة: يمكن لمضادات الأكسدة مثل N-أسيتيل سيستئين (NAC) التخفيف من الآثار الجانبية للعلاج الكيميائي عن طريق التبرع بالإلكترونات للجذور الحرة التي تولدها الأدوية، مما يعادلها [109، 110]. عند استخدامها مع العلاج الكيميائي، يمكن أن تحمي الخلايا الطبيعية من الضرر التأكسدي وتعزز فعالية العلاج الكيميائي من خلال السماح بجرعات أعلى محتملة التحمل [109، 110].

الاستنتاجات

أدوات تشخيصية وعلاجية أكثر فعالية. يجب أن تركز الأبحاث المستقبلية على فك التفاعلات المعقدة بين الإجهاد التأكسدي والمسارات الخلوية، بهدف ترجمة هذه النتائج إلى استراتيجيات قابلة للتطبيق سريريًا لإدارة السرطان. يقدم هذا الاستنتاج المعدل ملخصًا أكثر قوة لمحتوى المخطوطة، مع وضع اتجاهات مستقبلية للبحث في هذا المجال. لا تتردد في دمج هذا في مخطوطتك.

توفر البيانات والمواد

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

الإعلانات

الموافقة الأخلاقية والموافقة على المشاركة

تضارب المصالح

تفاصيل المؤلفين

نشر إلكترونيًا: 02 يناير 2024

References

- GBD 2019 Colorectal Cancer Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(7):627-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2468-1253(22)00044-9.

- Gupte A, Mumper RJ. Elevated copper and oxidative stress in cancer cells as a target for cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:32-46.

- Rizvi A, Farhan M, Nabi F, Khan RH, Adil M, Ahmad A. Transcriptional control of the oxidative stress response and implications of using plant derived molecules for therapeutic interventions in Cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28:8480-95.

- Gyurászová

, Gurecká , Bábíčková J, Tóthová Ľ. Oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of kidney disease: implications for noninvasive monitoring and identification of biomarkers. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:5478708. - Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, Alwasel SH, Nepovimova E, Kuca K, Valko M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch Toxicol. 2023;97:2499-574.

- Zaric BL, Macvanin MT, Isenovic ER. Free radicals: relationship to human diseases and potential therapeutic applications. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2023;154:106346.

- Baird L , Yamamoto M . The molecular mechanisms regulating the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2020;40:e00099-20.

- Deshmukh P, Unni S, Krishnappa G, Padmanabhan B. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: promising therapeutic target to counteract ROS-mediated damage in cancers and neurodegenerative diseases. Biophys Rev. 2017;9:41-56.

- Klaunig JE. Oxidative stress and cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24:4771-8.

- Klaunig JE, Wang Z. Oxidative stress in carcinogenesis. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2018;7:116-21.

- di Meo S, Reed TT, Venditti P, Victor VM. Role of ROS and RNS sources in physiological and pathological conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016.

- Navarro-Yepes J, Burns M, Anandhan A, Khalimonchuk O, del Razo LM, Quintanilla-Vega B, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI, Franco R. Oxidative stress, redox signaling, and autophagy: cell death versus survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21:66-85.

- Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1603-16.

- Zelickson BR, Ballinger SW, Dell’Italia LJ, Zhang J, Darley-Usmar VM. Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species: Interactions with Mitochondria and Pathophysiology. William J. Lennarz, M. Daniel Lane, Editors. Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry. 2nd Ed. Academic Press; 2013. p. 17-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-378630-2.00414-X.

- Fu Y, Chung F-L. Oxidative stress and hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatoma Res. 2018;4.

- Hayes JD, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Tew KD. Oxidative stress in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:167-97.

- Rhee SG, Woo HA, Kil IS, Bae SH. Peroxiredoxin functions as a peroxidase and a regulator and sensor of local peroxides. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4403-10.

- Mititelu RR, Padureanu R, Bacanoiu M, Padureanu V, Docea AO, Calina D, Barbulescu AL, Buga AM. Inflammatory and oxidative stress markersMirror tools in rheumatoid arthritis. Biomedicines. 2020;8.

- Zhang X, Hu M, Yang Y, Xu H. Organellar TRP channels. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:1009-18.

- Saretzki G. Telomerase, mitochondria and oxidative stress. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44:485-92.

- Loreto Palacio P, Godoy JR, Aktas O, Hanschmann EM. Changing perspectives from oxidative stress to redox signaling-extracellular redox control in translational medicine. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11.

- Rudrapal M, Khairnar SJ, Khan J, Dukhyil AB, Ansari MA, Alomary MN, Alshabrmi FM, Palai S, Deb PK, Devi R. Dietary polyphenols and their role in oxidative stress-induced human diseases: insights into protective effects, antioxidant potentials and mechanism(s) of action. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:806470.

- Chaitanya M, Ramanunny AK, Babu MR, Gulati M, Vishwas S, Singh TG, Chellappan DK, Adams J, Dua K, Singh SK. Journey of Rosmarinic acid as biomedicine to Nano-biomedicine for treating Cancer: current strategies and future perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14.

- Garzoli S, Alarcón-Zapata P, Seitimova G, Alarcón-Zapata B, Martorell M, Sharopov F, Fokou PVT, Dize D, Yamthe LRT, Les F, Cásedas G, López V, Iriti M, Rad JS, Gürer ES, Calina D, Pezzani R, Vitalini S. Natural essential oils as a new therapeutic tool in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22:407.

- Moloney JN, Cotter TG. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. Elsevier; 2018. p. 50-64.

- Reczek CR, Chandel NS. The two faces of reactive oxygen species in cancer. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 2017;1:79-98. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-cancerbio-041916-065808.

- Sosa V, Moliné T, Somoza R, Paciucci R, Kondoh H, Lleonart ME. Oxidative stress and cancer: an overview. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:376-90.

- Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: a historical overview. Transl Oncol. 2020;13:100773.

- Mego M, Reuben J, Mani SA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stem cells (CSCs): the traveling metastasis. In: Liquid biopsies in solid tumors. Springer; 2017.

31.Pagano K,Carminati L,Tomaselli S,Molinari H,Taraboletti G,Ragona L. Molecular basis of the antiangiogenic action of Rosmarinic acid,a natu- ral compound targeting fibroblast growth Factor-2/FGFR interactions. Chembiochem.2021;22:160-9.

32.Lugano R,Ramachandran M,Dimberg A.Tumor angiogenesis:causes, consequences,challenges and opportunities.Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77:1745-70.

33.Aggarwal V,Tuli HS,Varol A,Thakral F,Yerer MB,Sak K,Varol M,Jain A, Khan M,Sethi G.Role of reactive oxygen species in cancer progres- sion:molecular mechanisms and recent advancements.Biomolecules. 2019;9:735.

34.Son Y,Cheong YK,Kim NH,Chung HT,Kang DG,Pae HO.Mitogen- activated protein kinases and reactive oxygen species:how can ROS activate MAPK pathways?J Signal Transduct.2011;2011:792639.https:// doi.org/10.1155/2011/792639.

35.Koundouros N,Poulogiannis G.Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Akt Signal- ing and Redox Metabolism in Cancer.Front Oncol.2018;8:160.https:// doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00160.

36.Ngo V,Duennwald ML.Nrf2 and oxidative stress:A general overview of mechanisms and implications in human disease.Antioxidants. 2022;11:2345.

37.Hu Q,Bian Q,Rong D,Wang L,Song J,Huang H-S,Zeng J,Mei J,Wang P-Y.JAK/STAT pathway:extracellular signals,diseases,immunity,and therapeutic regimens.Front Bioeng Biotechnol.2023;11.

38.Lin L,Wu Q,Lu F,Lei J,Zhou Y,Liu Y,Zhu N,Yu Y,Ning Z,She T,Hu M. Nrf2 signaling pathway:current status and potential therapeutic targ- etable role in human cancers.Front Oncol.2023;13:1184079.

39.Chen Y,Chen M,Deng K.Blocking the Wnt/

40.Shi T,Dansen TB.Reactive oxygen species induced p53 activation: DNA damage,redox signaling,or both?Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020a;33:839-59.

41.Xing F,Hu Q,Qin Y,Xu J,Zhang B,Yu X,Wang W.The relationship of redox with hallmarks of Cancer:the importance of homeostasis and context.Front Oncol.2022;12:862743.

42.Vurusaner B,Poli G,Basaga H.Tumor suppressor genes and ROS:com- plex networks of interactions.Free Radic Biol Med.2012;52:7-18.

43.Shaw P,Kumar N,Sahun M,Smits E,Bogaerts A,Privat-Maldonado A. Modulating the antioxidant response for better oxidative stress-induc- ing therapies:how to take advantage of two sides of the same medal? Biomedicines.2022;10.

44.Pisoschi AM,Pop A,lordache F,Stanca L,Predoi G,Serban Al.Oxidative stress mitigation by antioxidants-an overview on their chemistry and influences on health status.Eur J Med Chem.2021;209:112891.

45.Bieging KT,Mello SS,Attardi LD.Unravelling mechanisms of p53-medi- ated tumour suppression.Nat Rev Cancer.2014;14:359-70.

46.Liang Y,Liu J,Feng Z.The regulation of cellular metabolism by tumor suppressor p53.Cell Biosci.2013;3:1-10.

47.Srinivas US,Tan BW,Vellayappan BA,Jeyasekharan AD.ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer.Redox Biol.2019;25:101084.

48.Maxwell KN,Cheng HH,Powers J,Gulati R,Ledet EM,Morrison C,LE A,Hausler R,Stopfer J,Hyman S.Inherited TP53 variants and risk of prostate Cancer.Eur Urol.2021;81.

49.Morris LG,Chan TA.Therapeutic targeting of tumor suppressor genes. Cancer.2015;121:1357-68.

50.Puzio-Kuter AM,Castillo-Martin M,Kinkade CW,Wang X,Shen TH,Matos T,Shen MM,Cordon-Cardo C,Abate-Shen C.Inactivation of p53 and Pten promotes invasive bladder cancer.Genes Dev.2009;23:675-80.

51.Wang B.BRCA1 tumor suppressor network:focusing on its tail.Cell Biosci.2012;2:1-10.

52.Bae I,Fan S,Meng Q,Rih JK,Kim HJ,Kang HJ,Xu J,Goldberg ID,Jaiswal AK,Rosen EM.BRCA1 induces antioxidant gene expression and resist- ance to oxidative stress.Cancer Res.2004;64:7893-909.

53.Sundararajan S, Ahmed A, Goodman OB Jr.The relevance of BRCA genetics to prostate cancer pathogenesis and treatment.Clin Adv Hematol Oncol.2011;9:748-55.

54.Yi YW,Kang HJ,Bae I.BRCA1 and oxidative stress.Cancers. 2014;6:771-95.

56.Mersch J,Jackson MA,Park M,Nebgen D,Peterson SK,Singletary C, Arun BK,Litton JK.Cancers associated with BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 muta- tions other than breast and ovarian.Cancer.2015;121:269-75.

57.Menegon S,Columbano A,Giordano S.The dual roles of NRF2 in can- cer.Trends Mol Med.2016;22:578-93.

58.de La Vega MR,Chapman E,Zhang DD.NRF2 and the hallmarks of cancer.Cancer Cell.2018;34:21-43.

59.Choi B-H,Kwak M-K.Shadows of NRF2 in cancer:resistance to chemo- therapy.Curr Opin Toxicol.2016;1:20-8.

60.Jung B-J,Yoo H-S,Shin S,Park Y-J,Jeon S-M.Dysregulation of NRF2 in cancer:from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Biomol Ther.2018;26:57.

61.Indovina P,Pentimalli F,Casini N,Vocca I,Giordano A.RB1 dual role in proliferation and apoptosis:cell fate control and implications for cancer therapy.Oncotarget.2015;6:17873.

62.Macleod KF.The role of the RB tumour suppressor pathway in oxida- tive stress responses in the haematopoietic system.Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:769-81.

63.di Fiore R,D'Anneo A,Tesoriere G,Vento R.RB1 in cancer:different mechanisms of RB1 inactivation and alterations of pRb pathway in tumorigenesis.J Cell Physiol.2013;228:1676-87.

64.Villeneuve NF,Sun Z,Chen W,Zhang DD.Nrf2 and p21 regulate the fine balance between life and death by controlling ROS levels.Taylor & Francis; 2009.

65.He S,Liu M,Zhang W,Xu N,Zhu H.Over expression of p21-activated kinase 7 associates with lymph node metastasis in esophageal squa- mous cell cancers.Cancer Biomarkers.2016;16:203-9.

66.Jing Z,You-Hong J,Wei Z.Expression of p21 and p15 in gastric cancer patients.中国公共卫生.2009;25:549-50.

67.Aceto GM,Catalano T,Curia MC.Molecular aspects of colorectal adeno- mas:the interplay among microenvironment,oxidative stress,and predisposition.BioMed Res Int.2020;2020.

68.Qin R-F,Zhang J,Huo H-R,Yuan Z-J,Xue J-D.MiR-205 mediated APC regulation contributes to pancreatic cancer cell proliferation.World J Gastroenterol.2019;25:3775.

69.Donkena KV,Young CY,Tindall DJ.Oxidative stress and DNA methyla- tion in prostate cancer.Obstet Gynecol Int.2010;2010.

70.Fang Z,Xiong Y,Li J,Liu L,Zhang W,Zhang C,Wan J.APC gene dele- tions in gastric adenocarcinomas in a Chinese population:a correlation with tumour progression.Clin Transl Oncol.2012;14:60-5.

71.Davee T,Coronel E,Papafragkakis C,Thaiudom S,Lanke G,Chakinala RC,González GMN,Bhutani MS,Ross WA,Weston BR.Pancreatic cancer screening in high-risk individuals with germline genetic mutations. Gastrointest Endosc.2018;87:1443-50.

72.Aghabozorgi AS,Bahreyni A,Soleimani A,Bahrami A,Khazaei M,Ferns GA,Avan A,Hassanian SM.Role of adenomatous polyposis coli(APC) gene mutations in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer;current status and perspectives.Biochimie.2019;157:64-71.

73.Hankey W,Frankel WL,Groden J.Functions of the APC tumor suppres- sor protein dependent and independent of canonical WNT signal- ing:implications for therapeutic targeting.Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018;37:159-72.

74.Narayan S,Sharma R.Molecular mechanism of adenomatous polyposis coli-induced blockade of base excision repair pathway in colorectal carcinogenesis.Life Sci.2015;139:145-52.

75.Katerji M,Filippova M,Duerksen-Hughes P.Approaches and methods to measure oxidative stress in clinical samples:research applications in the Cancer field.Oxidative Med Cell Longev.2019;2019:1279250.

76.Chiorcea-Paquim A-M.8-oxoguanine and 8-oxodeoxyguanosine bio- markers of oxidative DNA damage:A review on HPLC-ECD determina- tion.Molecules.2022;27:1620.

77.Milkovic L,Zarkovic N,Marusic Z,Zarkovic K,Jaganjac M.The 4-Hydrox- ynonenal-protein adducts and their biological relevance:are some proteins preferred targets?Antioxidants(Basel).2023;12.

78.Liu Y,Al-Adra DP,Lan R,Jung G,Li H,Yeh MM,Liu YZ.RNA sequencing analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma identified oxidative phosphoryla- tion as a major pathologic feature.Hepatol Commun.2022;6:2170-81.

79. Jiang C, Qian M, Gocho Y, Yang W, Du G, Shen S, Yang JJ, Zhang H. Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screening identifies determinant of panobinostat sensitivity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2022;6:2496-509.

80. Pimkova K, Jassinskaja M, Munita R, Ciesla M, Guzzi N, Cao Thi Ngoc P, Vajrychova M, Johansson E, Bellodi C, Hansson J. Quantitative analysis of redox proteome reveals oxidation-sensitive protein thiols acting in fundamental processes of developmental hematopoiesis. Redox Biol. 2022;53:102343.

81. Higgins L, Gerdes H, Cutillas PR. Principles of phosphoproteomics and applications in cancer research. Biochem J. 2023;480:403-20.

82. Serafimov K, Aydin Y, Lämmerhofer M. Quantitative analysis of the glutathione pathway cellular metabolites by targeted liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry. J Sep Sci. 2023;e2300780.

83. Wang Z, Ma P, Wang Y, Hou B, Zhou C, Tian H, Li B, Shui G, Yang X, Qiang G, Yin C, Du G. Untargeted metabolomics and transcriptomics identified glutathione metabolism disturbance and PCS and TMAO as potential biomarkers for ER stress in lung. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14680.

84. Greenwood HE, Witney TH. Latest advances in imaging oxidative stress in Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:1506-10.

85. Ghasemitarei M, Ghorbi T, Yusupov M, Zhang Y, Zhao T, Shali P, Bogaerts A. Effects of nitro-oxidative stress on biomolecules: part 1-non-reactive molecular dynamics simulations. Biomolecules. 2023;13.

86. Wang W, Rong Z, Wang G, Hou Y, Yang F, Qiu M. Cancer metabolites: promising biomarkers for cancer liquid biopsy. Biomarker Res. 2023;11:66.

87. Perillo B, di Donato M, Pezone A, di Zazzo E, Giovannelli P, Galasso G, Castoria G, Migliaccio A. ROS in cancer therapy: the bright side of the moon. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:192-203.

88. Raza MH, Siraj S, Arshad A, Waheed U, Aldakheel F, Alduraywish S, Arshad M. ROS-modulated therapeutic approaches in cancer treatment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:1789-809.

89. Somu P, Mohanty S, Paul S. A detailed overview of ROS-modulating approaches in Cancer treatment: Nano-based system to improve its future clinical perspective. Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects; 2021. p. 1-22.

90. Sofiullah SSM, Murugan DD, Muid SA, Seng WY, Kadir SZSA, Abas R, Ridzuan NRA, Zamakshshari NH, Woon CK. Natural bioactive compounds targeting NADPH oxidase pathway in cardiovascular diseases. Molecules. 2023;28:1047.

91. Forman HJ, Zhang H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:689-709.

92. Nizami ZN, Aburawi HE, Semlali A, Muhammad K, Iratni R. Oxidative stress inducers in Cancer therapy: preclinical and clinical evidence. Antioxidants. 2023;12:1159.

93. Li Y, Zhang X, Wang Z, Li B, Zhu H. Modulation of redox homeostasis: A strategy to overcome cancer drug resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14.

94. Anwanwan D, Singh SK, Singh S, Saikam V, Singh R. Challenges in liver cancer and possible treatment approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Rev Cancer. 2020;1873:188314.

95. Chehelgerdi

96. Wu C, Mao J, Wang X, Yang R, Wang C, Li C, Zhou X. Advances in treatment strategies based on scavenging reactive oxygen species of nanoparticles for atherosclerosis. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21:271.

97. Iqbal MJ, Ali S, Rashid U, Kamran M, Malik MF, Sughra K, Zeeshan N, Afroz A, Saleem J, Saghir M. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of Litchi chinensis and its dynamic biological impact on microbial cells and human cancer cell lines. Cell Mol Biol. 2018;64:42-7.

98. Rejinold NS, Muthunarayanan M, Divyarani V, Sreerekha P, Chennazhi K, Nair S, Tamura H, Jayakumar R. Curcumin-loaded biocompatible thermoresponsive polymeric nanoparticles for cancer drug delivery. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;360:39-51.

99. Javid H, Hashemy SI, Heidari MF, Esparham A, Gorgani-Firuzjaee S. The anticancer role of cerium oxide nanoparticles by inducing antioxidant

activity in esophageal Cancer and Cancer stem-like ESCC spheres. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:3268197.

100. Bonet-Aleta J, Calzada-Funes J, Hueso JL. Manganese oxide nanoplatforms in cancer therapy: recent advances on the development of synergistic strategies targeting the tumor microenvironment. Appl Mater Today. 2022;29:101628.

101. Chasara RS, Ajayi TO, Leshilo DM, Poka MS, Witika BA. Exploring novel strategies to improve anti-tumour efficiency: the potential for targeting reactive oxygen species. Heliyon. 2023;9:e19896.

102. Čapek J, Roušar T. Detection of oxidative stress induced by nanomaterials in cells-the roles of reactive oxygen species and glutathione. Molecules. 2021;26:4710.

103. Bigham A, Raucci MG. Multi-responsive materials: properties, design, and applications. In: Stimuli-Responsive Materials for Biomedical Applications. American Chemical Society; 2023.

104. Teixeira PV, Fernandes E, Soares TB, Adega F, Lopes CM, Lúcio M. Natural compounds: co-delivery strategies with chemotherapeutic agents or nucleic acids using lipid-based Nanocarriers. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15.

105. Craddock CF, Houlton AE, Quek LS, Ferguson P, Gbandi E, Roberts C, Metzner M, Garcia-Martin N, Kennedy A, Hamblin A, Raghavan M, Nagra S, Dudley L, Wheatley K, Mcmullin MF, Pillai SP, Kelly RJ, Siddique S, Dennis M , Cavenagh JD, Vyas P. Outcome of Azacitidine therapy in acute myeloid leukemia is not improved by concurrent Vorinostat therapy but is predicted by a diagnostic molecular signature. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6430-40.

106. Patnaik E, Madu C, Lu Y. Epigenetic modulators as therapeutic agents in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24.

107. Rullo R, Cerchia C, Nasso R, Romanelli V, Vendittis E, Masullo M, Lavecchia A. Novel reversible inhibitors of xanthine oxidase targeting the active site of the enzyme. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12.

108. Liu J, Chen Z, Li Y, Zhao W, Wu J, Zhang Z. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in tumor immunotherapy. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:731798.

109. Singh K, Bhori M, Kasu YA, Bhat G, Marar T. Antioxidants as precision weapons in war against cancer chemotherapy induced toxicity exploring the armoury of obscurity. Saudi Pharm J. 2018;26:177-90.

110. Tenório M, Graciliano NG, Moura FA, Oliveira ACM, Goulart MOF. N -acetylcysteine (NAC): impacts on human health. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10.

ملاحظة الناشر

هل أنت مستعد لتقديم بحثك؟ اختر BMC واستفد من:

- تقديم إلكتروني سريع ومريح

- مراجعة دقيقة من قبل باحثين ذوي خبرة في مجالك

- نشر سريع عند القبول

- دعم لبيانات البحث، بما في ذلك أنواع البيانات الكبيرة والمعقدة

- الوصول المفتوح الذهبي الذي يعزز التعاون الأوسع وزيادة الاقتباسات

- أقصى قدر من الرؤية لبحثك: أكثر من 100 مليون مشاهدة للموقع سنويًا

في BMC، البحث دائمًا في تقدم.

BMC

- *للتواصل:

دانييلا كالينا

calinadaniela@gmail.com

جواد شريفي-راد

javad.sharifirad@gmail.com

ويليام سي. تشو

chocs@ha.org.hk

قائمة كاملة بمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقالة

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-023-01398-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38167159

Publication Date: 2024-01-02

Interplay of oxidative stress, cellular communication and signaling pathways in cancer

Abstract

Cancer remains a significant global public health concern, with increasing incidence and mortality rates worldwide. Oxidative stress, characterized by the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within cells, plays a critical role in the development of cancer by affecting genomic stability and signaling pathways within the cellular microenvironment. Elevated levels of ROS disrupt cellular homeostasis and contribute to the loss of normal cellular functions, which are associated with the initiation and progression of various types of cancer. In this review, we have focused on elucidating the downstream signaling pathways that are influenced by oxidative stress and contribute to carcinogenesis. These pathways include p53, Keap1-NRF2, RB1, p21, APC, tumor suppressor genes, and cell type transitions. Dysregulation of these pathways can lead to uncontrolled cell growth, impaired DNA repair mechanisms, and evasion of cell death, all of which are hallmark features of cancer development. Therapeutic strategies aimed at targeting oxidative stress have emerged as a critical area of investigation for molecular biologists. The objective is to limit the response time of various types of cancer, including liver, breast, prostate, ovarian, and lung cancers. By modulating the redox balance and restoring cellular homeostasis, it may be possible to mitigate the damaging effects of oxidative stress and enhance the efficacy of cancer treatments. The development of targeted therapies and interventions that specifically address the impact of oxidative stress on cancer initiation and progression holds great promise in improving patient outcomes. These approaches may include antioxidant-based treatments, redox-modulating agents, and interventions that restore normal cellular function and signaling pathways affected by oxidative stress. In summary, understanding the role of oxidative stress in carcinogenesis and targeting this process through therapeutic interventions are of utmost importance in combating various types of cancer. Further research is needed to unravel the complex mechanisms underlying oxidative stress-related pathways and to develop effective strategies that can be translated into clinical applications for the management and treatment of cancer.

Introduction

In addition to Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) also play a significant role in oxidative stress [5]. RNS, such as nitric oxide (NO) and peroxynitrite (ONOO-), contribute to cellular damage and are involved in various signaling pathways related to cancer progression. Similar to ROS, RNS can modulate cell survival, induce DNA damage, and affect mitochondrial functions [6]. The interplay between ROS and RNS further complicates the oxidative stress landscape, highlighting the need for therapeutic strategies that target both species [5, 6].

oxidative stress, interact with cellular macromolecules like DNA, RNA, and proteins. Specifically, ROS can induce DNA mutations, strand breaks, and even chromosomal aberrations by interacting with the nitrogenous bases and the sugar-phosphate backbone. Such genetic alterations disrupt the normal regulation of cell cycle, apoptosis, and DNA repair mechanisms. The compromised genomic integrity leads to the activation of oncogenes and the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, thereby fostering an environment conducive for uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumorigenesis [7-10]. It is observed in various studies that oxidative stress is involved in the initiation and progression of various cancers, including melanoma, leukemia, lymphoma, oral, pancreatic, ovarian, bladder, breast, cervical, brain, gastric, liver, lung, and prostate cancer [11-14]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), greatly produced in the mitochondria of cells (Fig. 1) [14], are observed as the main potential contributors to oxidative stress and cancer [15]. ROS are intracellular signaling molecules that contribute significantly to various signaling pathways, including insulin-like growth factor signaling pathway, and transient receptor potential channel-mediated cation signaling pathway [16]. In the growth factor signaling pathway, ROS, mainly

Oxidative stress, elevated ROS level and carcinogenesis: connecting the dots

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

signaling, Notch signaling, and Hedgehog signaling are reported to stimulate EMT event [29]. Transcription factors, including Snail1, E12/E47, Zeb1/2, FOXC2, Slug, SIP1, Twist, Goosecoid, and epigenetic modifications like DNA methylation and remodeling of nucleosomes are also involved in the induction and initiation of EMT [29]. During the EMT process, mesenchymal markers that include fibronectin, N-cadherin, Snail, Slug, Twist, FOX C2, SOX 10, vimentin, MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 in epithelial cells are reported to be upregulated. Whereas, epithelial markers like E-cadherin, cytokeratin, desmoplakin, and occludin are reported to be downregulated, causing polarity loss, cytoskeletal reorganization, and generation of invasive phenotype in cells and facilitate the progression of cancer [28].

Angiogenesis

Signaling pathways in oxidative stress and cancer MAPK pathway

regulate the expression of genes involved in cell survival, proliferation, and apoptosis [34].

PI3K/AKT pathway

Keap1-Nrf2 pathway

JAK/STAT pathway

Wnt/

p53 pathway

Tumor suppressor genes and oxidative stress: a mutual interplay in carcinogenesis

p53

p53 is the chief regulator of programmed cell death and prevents tumorigenesis by facilitating the regulation of oxidative stress in cells. At low oxidative stress level, p53 promotes cell survival by stimulating the expression of antioxidant genes, including Parkin, sestrins

of p53 is reported to be responsible for glioblastoma, retinoblastoma, neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, lymphoma, bladder, pancreatic, breast, prostate, lungs, uterine, head and neck cancer [48-50].

BRCA1 and BRCA2

NRF2

RB1

is reported to be involved in the induction and progression of retinoblastoma, glioblastoma, breast, prostate, lungs, and bladder cancer [61, 63].

P21

APC

Methods for oxidative stress profiling in oncology

| Tumor Suppressor Gene | Low Oxidative Stress Action | High Oxidative Stress Action | Associated Cancers | References |

| p53 | Promotes cell survival by stimulating antioxidant genes: Parkin, sestrins 1/2, GLS2, ALDH4, GPX1, TIGER | Promotes cell death by inducing prooxidative genes: PIG3, PIG6, FDRX, Bax, Puma | Glioblastoma, Retinoblastoma, Neuroblastoma, Medulloblastoma, Lymphoma, Bladder, Pancreatic, Breast, Prostate, Lungs, Uterine, Head and Neck | [47] [45]; [46] [40]; ;[48] [50]; ;[49]; |

| BRCA1/BRCA2 | Regulates oxidative stress by activating genes: PON2, KL, UCHL1, GST, GPX3, ADH5, ME2 | Protects DNA from double-strand breaks | Breast, Ovarian, Esophageal, Uterine, Pancreatic, Colorectal, Cervical, Stomach, Prostate, and Liver | [51] [54]; [52]; [53] [55] [56];;; |

| NRF2 | Initiates cytoprotective mechanisms by binding with sMAF proteins and ARE in the nucleus | Activates expression of cytoprotective genes | Colorectal, Breast, Liver, Gall Bladder, Prostate, Gastric, Ovarian, and Lung | [57] [7] [58] [60]; ;,[59]; |

| RB1 | Maintains genomic integrity in response to oxidative stress | Triggers cell quiescence by inhibiting expression of E2f1, E2f2, and E2f3 | Retinoblastoma, Glioblastoma, Breast, Prostate, Lungs, and Bladder | [61] [62] [63]; ;[61]; |

| P21 | Induces NRF2-dependent cytoprotective response to prevent cell damage | Triggers induction of pro-apoptotic response | Gastric cancer, and Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | [64] [65] [66];; |

| APC | Maintains genomic stability through DNA repair mechanisms | Hinders base excision repair mechanism and facilitates apoptotic cell death | Prostate, Gastric, Pancreatic, and Colorectal cancer | [68] [67]; [69]; [70]; [71] [72]; ;[74] [73];; |

| Method Type | Description | Example Assays/Approaches | Reference |

| Direct measurement of ROS | Quantification of cellular ROS in clinical samples. | 5-6-carboxy-2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, dihydroethidium, d-ROMs test | [75]. |

| Oxidative Damage & Antioxidant Status | Assessment of oxidative damage and antioxidant status. | 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) assay, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) reduction assay | |

| Molecular & Biochemical Assays | Quantification of oxidative damage to DNA. | 8-Oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-Oxo-dG) | [76] |

| Lipid Peroxidation Assays | Assessment of oxidative damage to cellular lipids. | Malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) | [77]. |

| Genomic & Transcriptomic | Identification of differentially expressed genes related to oxidative stress. | RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq), CRISPR/Cas9 screenings | [78] [79] |

| Proteomic Approaches | Identification of proteins undergoing oxidative modifications. | Redox Proteomics | [80] |

| Phosphoproteomics | Identification of oxidative stress-induced phosphorylation changes. | [81] | |

| Metabolomic Techniques | Quantification of specific metabolites like glutathione. | Targeted LC-MS/MS, Untargeted Metabolomics | [82] [83]; |

| Imaging Techniques | In vivo visualization and real-time monitoring of ROS levels. | ROS-sensitive MRI, Optical Imaging with ROS-sensitive probes | [84] |

| Cellular & Tissue Techniques | Quantifying intracellular levels of ROS or antioxidants. | Immunohistochemistry (IHC), Cytofluorometric Analysis | [75] |

| In Silico & Computational Methods | Insights into ROS-induced signaling cascades and structural changes in biomolecules. | Pathway Analysis, Molecular Dynamics Simulations | [85] |

| Liquid Biopsy | Non-invasive biomarkers for oxidative stress. | Circulating microRNAs (miRNAs), cell-free DNA (cfDNA) | [86] |

quantify oxidative damage to DNA, a common feature in many cancer types [76]. Lipid Peroxidation Assays like Malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) are used to assess oxidative damage to cellular lipids, which is implicated in cancer progression [77]. Genomic and transcriptomic approaches also offer valuable insights. RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) identifies differentially expressed genes that are part of the oxidative stress response in cancer cells [78]. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 screenings can identify genes that modulate sensitivity or resistance to oxidative stress, which is crucial for targeted therapy development [79].

Proteomic approaches like Redox Proteomics specifically identify proteins that undergo oxidative modifications, providing insights into cancer pathology [80]. Phosphoproteomics techniques identify oxidative stress-induced phosphorylation changes, crucial in oncogenic signaling pathways [81]. Metabolomic techniques such as targeted Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) are used for the quantification of specific metabolites like glutathione, directly involved in redox homeostasis [82]. Untargeted

| Therapeutic Approach | Agent Type | Examples | Mechanism | References |

| ROS-Scavenging | NADPH oxidase inhibitors | Diphenylene iodonium, Apocynin | inhibit NADPH oxidase, reducing ROS production | [90], [91] |

| Antioxidant vitamins | Vitamin E, Vitamin C, Vitamin A | neutralize free radicals by donating electrons | ||

| Selenium compounds | Selenomethionine, Ebselen | activate selenoproteins functioning as antioxidants | ||

| Natural compounds | Quercetin, Resveratrol, Curcumin, EGCG | inhibit ROS-generating enzymes and chelate metal ions | ||

| Enzyme mimetics | Manganese Porphyrins, EUK-134 | mimic natural antioxidant enzymes | ||

| Polyamines | Spermine, Spermidine | modulate cellular redox status by chelating metal ions or inducing expression of antioxidant enzymes | ||

| Miscellaneous | Edaravone, Trolox, Tempol | various mechanisms including free radical scavenging and metal chelation | ||

| ROS-Boosting | Nitroxide derivatives | Tempol, Tempone | generate ros to induce oxidative stress | [92], [93] |

| Pro-oxidant drugs | Arsenic trioxide, Doxorubicin, Menadione, Elesclomol | create redox imbalance, elevate ros levels leading to apoptosis | ||

| Photodynamic therapy agents | Aminolevulinic acid, Methylene blue, Rose Bengal | produce ROS when activated by light | ||

| Natural pro-oxidants | Beta-Lapachone, Parthenolide, Capsaicin | induce ROS generation disrupting redox balance | ||

| Metal chelators | Deferoxamine, Triapine, L1 | chelate transition metal ions catalyzing ROS formation | ||

| Thiol antioxidants | N-Acetylcysteine, Glutathione, Thioredoxin | donate electrons to neutralize free radicals | ||

| Redox-cycling drugs | Plumbagin, Juglone, Thiosemicarbazones | cycle between oxidized and reduced forms, generating ros |

Treatment approaches to target oxidative stress and cancer

ROS modulated therapeutic approaches

concentration of nitroxide derivatives (i.e., nitroxide derived free radicals and cyclic nitroxides), or increased expression of glutathione S-transferases, superoxide dismutases (SODs), and catalases are reported to be utilized to target cellular oxidative stress and cancer [87-89].

i) ROS-Scavenging therapeutic -approaches [90, 91]

- NADPH oxidase inhibitors (e.g., Diphenylene iodonium, Apocynin) – inhibit the activity of NADPH oxidase, reducing the production of ROS.

- Antioxidant vitamins (e.g., Vitamin E, Vitamin C, Vitamin A) – neutralize free radicals by donating electrons, thereby reducing oxidative stress.

- Selenium compounds (e.g., Selenomethionine, Ebselen) – activate selenoproteins that function as antioxidants.

- Natural compounds (e.g., Quercetin, Resveratrol, Curcumin, EGCG) – these phytochemicals exert antioxidant effects by inhibiting ROS-generating enzymes and chelating metal ions.

- Enzyme mimetics (e.g., Manganese Porphyrins, EUK-134) – are synthetic compounds mimic natural antioxidant enzymes.

- Polyamines (e.g., Spermine, Spermidine) – modulate cellular redox status by chelating metal ions or inducing expression of antioxidant enzymes.

- Miscellaneous (e.g., Edaravone, Trolox, Tempol) – these agents work through various mechanisms, including free radical scavenging and metal chelation.

ii) ROS-Boosting therapeutic approaches [92, 93] - Nitroxide derivatives (e.g., Tempol, Tempone) generate ROS to induce oxidative stress in cancer cells.

- Pro-oxidant drugs (e.g., Arsenic trioxide, Doxorubicin, Menadione, Elesclomol) – create an imbalance in redox homeostasis, leading to elevated ROS levels and subsequent apoptosis.

- Photodynamic therapy agents (e.g., Aminolevulinic acid, Methylene blue, Rose Bengal) – produce ROS when activated by light, leading to oxidative damage.

- Natural pro-oxidants (e.g., Beta-Lapachone, Parthenolide, Capsaicin) – these natural compounds induce ROS generation, disrupting redox balance and leading to cell death.

- Melatonin: acts as a direct free radical scavenger and also stimulates antioxidant enzymes.

- Metal chelators (e.g., Deferoxamine, Triapine, L1) chelate transition metal ions that catalyze ROS formation.

- Thiol antioxidants (e.g., N-Acetylcysteine, Glutathione, Thioredoxin) – donate electrons to neutralize free radicals.

- Redox-cycling drugs (e.g., Plumbagin, Juglone, Thiosemicarbazones) – these agents cycle between oxidized and reduced forms, generating ROS in the process.

- Increased expression or administration of antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SODs, Catalases, Glutathione S-Transferases, Peroxiredoxins) – these approaches involve the use of gene therapy or direct enzyme administration to elevate antioxidant enzyme levels, paradoxically generating ROS in cancer cells.

- Ionophores (e.g., Gramicidin, Valinomycin) – disrupt ion gradients across membranes, indirectly leading to ROS generation.

- Miscellaneous (e.g., Piperlongumine, PEITC, DATS) – have unique mechanisms, often involving modulation of redox-sensitive signaling pathways.}

Nanotechnology based treatment approaches

i. ROS-scavenging nanocarriers

ii. ROS-generating nanocarriers

iii. Dual-function nanocarriers

iv. Synergistic therapeutic strategies

Advancing therapeutic interventions in oxidative stress and cancer

ii. Epigenetic modulators: epigenetic drugs like 5-Azacitidine and Vorinostat act by inhibiting enzymes responsible for DNA methylation and histone deacetylation, respectively [105, 106]. These actions lead to the re-expression of genes that encode for antioxidants like glutathione and superoxide dismutases (SOD), thus altering the cellular redox state and making cancer cells more susceptible to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis [105].

iii. Enzyme inhibition strategies: specific inhibitors such as Allopurinol target xanthine oxidase, an enzyme involved in the conversion of hypoxanthine to xanthine and subsequently to uric acid, a process that generates ROS [107]. By inhibiting this enzyme, the cellular levels of ROS are reduced, which can inhibit the oxidative stress-induced signaling pathways that promote cancer cell proliferation [107].

iv. Immunotherapies: checkpoint inhibitors like anti-PD-1 antibodies function by blocking the interaction between PD-1 receptors on T cells and PD-L1 on cancer cells [108]. This blockage enhances the cytotoxic activity of T cells and produces cytokines that can induce oxidative stress in cancer cells, leading to apoptosis; this adds a new dimension to how immunotherapies can modulate the redox state within the tumor microenvironment [108].

v. Combination therapies: antioxidants such as N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) can mitigate the side effects of chemotherapy by donating electrons to free radicals generated by the drugs, neutralizing them [109, 110]. When used in conjunction with chemotherapy, this can both protect normal cells from oxidative damage and enhance the efficacy of the chemotherapy by allowing for higher tolerable doses [109, 110].

Conclusions

effective diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions. Future research should focus on deciphering the complex interactions between oxidative stress and cellular pathways, with the aim of translating these findings into clinically applicable strategies for cancer management. This revised conclusion offers a more robust summary of the manuscript’s content, while laying out future directions for research in this area. Feel free to incorporate this into your manuscript.

Availability of data and material

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 02 January 2024

References

- GBD 2019 Colorectal Cancer Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(7):627-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2468-1253(22)00044-9.

- Gupte A, Mumper RJ. Elevated copper and oxidative stress in cancer cells as a target for cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:32-46.

- Rizvi A, Farhan M, Nabi F, Khan RH, Adil M, Ahmad A. Transcriptional control of the oxidative stress response and implications of using plant derived molecules for therapeutic interventions in Cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28:8480-95.

- Gyurászová

, Gurecká , Bábíčková J, Tóthová Ľ. Oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of kidney disease: implications for noninvasive monitoring and identification of biomarkers. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:5478708. - Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar SY, Alwasel SH, Nepovimova E, Kuca K, Valko M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch Toxicol. 2023;97:2499-574.

- Zaric BL, Macvanin MT, Isenovic ER. Free radicals: relationship to human diseases and potential therapeutic applications. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2023;154:106346.

- Baird L , Yamamoto M . The molecular mechanisms regulating the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2020;40:e00099-20.

- Deshmukh P, Unni S, Krishnappa G, Padmanabhan B. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: promising therapeutic target to counteract ROS-mediated damage in cancers and neurodegenerative diseases. Biophys Rev. 2017;9:41-56.

- Klaunig JE. Oxidative stress and cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24:4771-8.

- Klaunig JE, Wang Z. Oxidative stress in carcinogenesis. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2018;7:116-21.

- di Meo S, Reed TT, Venditti P, Victor VM. Role of ROS and RNS sources in physiological and pathological conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016.

- Navarro-Yepes J, Burns M, Anandhan A, Khalimonchuk O, del Razo LM, Quintanilla-Vega B, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI, Franco R. Oxidative stress, redox signaling, and autophagy: cell death versus survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21:66-85.

- Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1603-16.

- Zelickson BR, Ballinger SW, Dell’Italia LJ, Zhang J, Darley-Usmar VM. Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species: Interactions with Mitochondria and Pathophysiology. William J. Lennarz, M. Daniel Lane, Editors. Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry. 2nd Ed. Academic Press; 2013. p. 17-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-378630-2.00414-X.

- Fu Y, Chung F-L. Oxidative stress and hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatoma Res. 2018;4.

- Hayes JD, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Tew KD. Oxidative stress in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:167-97.

- Rhee SG, Woo HA, Kil IS, Bae SH. Peroxiredoxin functions as a peroxidase and a regulator and sensor of local peroxides. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4403-10.

- Mititelu RR, Padureanu R, Bacanoiu M, Padureanu V, Docea AO, Calina D, Barbulescu AL, Buga AM. Inflammatory and oxidative stress markersMirror tools in rheumatoid arthritis. Biomedicines. 2020;8.

- Zhang X, Hu M, Yang Y, Xu H. Organellar TRP channels. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:1009-18.

- Saretzki G. Telomerase, mitochondria and oxidative stress. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44:485-92.

- Loreto Palacio P, Godoy JR, Aktas O, Hanschmann EM. Changing perspectives from oxidative stress to redox signaling-extracellular redox control in translational medicine. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11.

- Rudrapal M, Khairnar SJ, Khan J, Dukhyil AB, Ansari MA, Alomary MN, Alshabrmi FM, Palai S, Deb PK, Devi R. Dietary polyphenols and their role in oxidative stress-induced human diseases: insights into protective effects, antioxidant potentials and mechanism(s) of action. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:806470.

- Chaitanya M, Ramanunny AK, Babu MR, Gulati M, Vishwas S, Singh TG, Chellappan DK, Adams J, Dua K, Singh SK. Journey of Rosmarinic acid as biomedicine to Nano-biomedicine for treating Cancer: current strategies and future perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14.

- Garzoli S, Alarcón-Zapata P, Seitimova G, Alarcón-Zapata B, Martorell M, Sharopov F, Fokou PVT, Dize D, Yamthe LRT, Les F, Cásedas G, López V, Iriti M, Rad JS, Gürer ES, Calina D, Pezzani R, Vitalini S. Natural essential oils as a new therapeutic tool in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22:407.

- Moloney JN, Cotter TG. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. Elsevier; 2018. p. 50-64.

- Reczek CR, Chandel NS. The two faces of reactive oxygen species in cancer. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 2017;1:79-98. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-cancerbio-041916-065808.

- Sosa V, Moliné T, Somoza R, Paciucci R, Kondoh H, Lleonart ME. Oxidative stress and cancer: an overview. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:376-90.

- Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: a historical overview. Transl Oncol. 2020;13:100773.

- Mego M, Reuben J, Mani SA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stem cells (CSCs): the traveling metastasis. In: Liquid biopsies in solid tumors. Springer; 2017.

31.Pagano K,Carminati L,Tomaselli S,Molinari H,Taraboletti G,Ragona L. Molecular basis of the antiangiogenic action of Rosmarinic acid,a natu- ral compound targeting fibroblast growth Factor-2/FGFR interactions. Chembiochem.2021;22:160-9.

32.Lugano R,Ramachandran M,Dimberg A.Tumor angiogenesis:causes, consequences,challenges and opportunities.Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77:1745-70.

33.Aggarwal V,Tuli HS,Varol A,Thakral F,Yerer MB,Sak K,Varol M,Jain A, Khan M,Sethi G.Role of reactive oxygen species in cancer progres- sion:molecular mechanisms and recent advancements.Biomolecules. 2019;9:735.

34.Son Y,Cheong YK,Kim NH,Chung HT,Kang DG,Pae HO.Mitogen- activated protein kinases and reactive oxygen species:how can ROS activate MAPK pathways?J Signal Transduct.2011;2011:792639.https:// doi.org/10.1155/2011/792639.

35.Koundouros N,Poulogiannis G.Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Akt Signal- ing and Redox Metabolism in Cancer.Front Oncol.2018;8:160.https:// doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00160.

36.Ngo V,Duennwald ML.Nrf2 and oxidative stress:A general overview of mechanisms and implications in human disease.Antioxidants. 2022;11:2345.

37.Hu Q,Bian Q,Rong D,Wang L,Song J,Huang H-S,Zeng J,Mei J,Wang P-Y.JAK/STAT pathway:extracellular signals,diseases,immunity,and therapeutic regimens.Front Bioeng Biotechnol.2023;11.

38.Lin L,Wu Q,Lu F,Lei J,Zhou Y,Liu Y,Zhu N,Yu Y,Ning Z,She T,Hu M. Nrf2 signaling pathway:current status and potential therapeutic targ- etable role in human cancers.Front Oncol.2023;13:1184079.

39.Chen Y,Chen M,Deng K.Blocking the Wnt/

40.Shi T,Dansen TB.Reactive oxygen species induced p53 activation: DNA damage,redox signaling,or both?Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020a;33:839-59.

41.Xing F,Hu Q,Qin Y,Xu J,Zhang B,Yu X,Wang W.The relationship of redox with hallmarks of Cancer:the importance of homeostasis and context.Front Oncol.2022;12:862743.

42.Vurusaner B,Poli G,Basaga H.Tumor suppressor genes and ROS:com- plex networks of interactions.Free Radic Biol Med.2012;52:7-18.

43.Shaw P,Kumar N,Sahun M,Smits E,Bogaerts A,Privat-Maldonado A. Modulating the antioxidant response for better oxidative stress-induc- ing therapies:how to take advantage of two sides of the same medal? Biomedicines.2022;10.

44.Pisoschi AM,Pop A,lordache F,Stanca L,Predoi G,Serban Al.Oxidative stress mitigation by antioxidants-an overview on their chemistry and influences on health status.Eur J Med Chem.2021;209:112891.

45.Bieging KT,Mello SS,Attardi LD.Unravelling mechanisms of p53-medi- ated tumour suppression.Nat Rev Cancer.2014;14:359-70.

46.Liang Y,Liu J,Feng Z.The regulation of cellular metabolism by tumor suppressor p53.Cell Biosci.2013;3:1-10.

47.Srinivas US,Tan BW,Vellayappan BA,Jeyasekharan AD.ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer.Redox Biol.2019;25:101084.

48.Maxwell KN,Cheng HH,Powers J,Gulati R,Ledet EM,Morrison C,LE A,Hausler R,Stopfer J,Hyman S.Inherited TP53 variants and risk of prostate Cancer.Eur Urol.2021;81.

49.Morris LG,Chan TA.Therapeutic targeting of tumor suppressor genes. Cancer.2015;121:1357-68.

50.Puzio-Kuter AM,Castillo-Martin M,Kinkade CW,Wang X,Shen TH,Matos T,Shen MM,Cordon-Cardo C,Abate-Shen C.Inactivation of p53 and Pten promotes invasive bladder cancer.Genes Dev.2009;23:675-80.

51.Wang B.BRCA1 tumor suppressor network:focusing on its tail.Cell Biosci.2012;2:1-10.

52.Bae I,Fan S,Meng Q,Rih JK,Kim HJ,Kang HJ,Xu J,Goldberg ID,Jaiswal AK,Rosen EM.BRCA1 induces antioxidant gene expression and resist- ance to oxidative stress.Cancer Res.2004;64:7893-909.

53.Sundararajan S, Ahmed A, Goodman OB Jr.The relevance of BRCA genetics to prostate cancer pathogenesis and treatment.Clin Adv Hematol Oncol.2011;9:748-55.

54.Yi YW,Kang HJ,Bae I.BRCA1 and oxidative stress.Cancers. 2014;6:771-95.

56.Mersch J,Jackson MA,Park M,Nebgen D,Peterson SK,Singletary C, Arun BK,Litton JK.Cancers associated with BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 muta- tions other than breast and ovarian.Cancer.2015;121:269-75.

57.Menegon S,Columbano A,Giordano S.The dual roles of NRF2 in can- cer.Trends Mol Med.2016;22:578-93.

58.de La Vega MR,Chapman E,Zhang DD.NRF2 and the hallmarks of cancer.Cancer Cell.2018;34:21-43.

59.Choi B-H,Kwak M-K.Shadows of NRF2 in cancer:resistance to chemo- therapy.Curr Opin Toxicol.2016;1:20-8.

60.Jung B-J,Yoo H-S,Shin S,Park Y-J,Jeon S-M.Dysregulation of NRF2 in cancer:from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Biomol Ther.2018;26:57.

61.Indovina P,Pentimalli F,Casini N,Vocca I,Giordano A.RB1 dual role in proliferation and apoptosis:cell fate control and implications for cancer therapy.Oncotarget.2015;6:17873.

62.Macleod KF.The role of the RB tumour suppressor pathway in oxida- tive stress responses in the haematopoietic system.Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:769-81.

63.di Fiore R,D'Anneo A,Tesoriere G,Vento R.RB1 in cancer:different mechanisms of RB1 inactivation and alterations of pRb pathway in tumorigenesis.J Cell Physiol.2013;228:1676-87.

64.Villeneuve NF,Sun Z,Chen W,Zhang DD.Nrf2 and p21 regulate the fine balance between life and death by controlling ROS levels.Taylor & Francis; 2009.

65.He S,Liu M,Zhang W,Xu N,Zhu H.Over expression of p21-activated kinase 7 associates with lymph node metastasis in esophageal squa- mous cell cancers.Cancer Biomarkers.2016;16:203-9.

66.Jing Z,You-Hong J,Wei Z.Expression of p21 and p15 in gastric cancer patients.中国公共卫生.2009;25:549-50.

67.Aceto GM,Catalano T,Curia MC.Molecular aspects of colorectal adeno- mas:the interplay among microenvironment,oxidative stress,and predisposition.BioMed Res Int.2020;2020.

68.Qin R-F,Zhang J,Huo H-R,Yuan Z-J,Xue J-D.MiR-205 mediated APC regulation contributes to pancreatic cancer cell proliferation.World J Gastroenterol.2019;25:3775.

69.Donkena KV,Young CY,Tindall DJ.Oxidative stress and DNA methyla- tion in prostate cancer.Obstet Gynecol Int.2010;2010.

70.Fang Z,Xiong Y,Li J,Liu L,Zhang W,Zhang C,Wan J.APC gene dele- tions in gastric adenocarcinomas in a Chinese population:a correlation with tumour progression.Clin Transl Oncol.2012;14:60-5.

71.Davee T,Coronel E,Papafragkakis C,Thaiudom S,Lanke G,Chakinala RC,González GMN,Bhutani MS,Ross WA,Weston BR.Pancreatic cancer screening in high-risk individuals with germline genetic mutations. Gastrointest Endosc.2018;87:1443-50.

72.Aghabozorgi AS,Bahreyni A,Soleimani A,Bahrami A,Khazaei M,Ferns GA,Avan A,Hassanian SM.Role of adenomatous polyposis coli(APC) gene mutations in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer;current status and perspectives.Biochimie.2019;157:64-71.

73.Hankey W,Frankel WL,Groden J.Functions of the APC tumor suppres- sor protein dependent and independent of canonical WNT signal- ing:implications for therapeutic targeting.Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018;37:159-72.

74.Narayan S,Sharma R.Molecular mechanism of adenomatous polyposis coli-induced blockade of base excision repair pathway in colorectal carcinogenesis.Life Sci.2015;139:145-52.

75.Katerji M,Filippova M,Duerksen-Hughes P.Approaches and methods to measure oxidative stress in clinical samples:research applications in the Cancer field.Oxidative Med Cell Longev.2019;2019:1279250.

76.Chiorcea-Paquim A-M.8-oxoguanine and 8-oxodeoxyguanosine bio- markers of oxidative DNA damage:A review on HPLC-ECD determina- tion.Molecules.2022;27:1620.

77.Milkovic L,Zarkovic N,Marusic Z,Zarkovic K,Jaganjac M.The 4-Hydrox- ynonenal-protein adducts and their biological relevance:are some proteins preferred targets?Antioxidants(Basel).2023;12.

78.Liu Y,Al-Adra DP,Lan R,Jung G,Li H,Yeh MM,Liu YZ.RNA sequencing analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma identified oxidative phosphoryla- tion as a major pathologic feature.Hepatol Commun.2022;6:2170-81.

79. Jiang C, Qian M, Gocho Y, Yang W, Du G, Shen S, Yang JJ, Zhang H. Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screening identifies determinant of panobinostat sensitivity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2022;6:2496-509.

80. Pimkova K, Jassinskaja M, Munita R, Ciesla M, Guzzi N, Cao Thi Ngoc P, Vajrychova M, Johansson E, Bellodi C, Hansson J. Quantitative analysis of redox proteome reveals oxidation-sensitive protein thiols acting in fundamental processes of developmental hematopoiesis. Redox Biol. 2022;53:102343.

81. Higgins L, Gerdes H, Cutillas PR. Principles of phosphoproteomics and applications in cancer research. Biochem J. 2023;480:403-20.

82. Serafimov K, Aydin Y, Lämmerhofer M. Quantitative analysis of the glutathione pathway cellular metabolites by targeted liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry. J Sep Sci. 2023;e2300780.

83. Wang Z, Ma P, Wang Y, Hou B, Zhou C, Tian H, Li B, Shui G, Yang X, Qiang G, Yin C, Du G. Untargeted metabolomics and transcriptomics identified glutathione metabolism disturbance and PCS and TMAO as potential biomarkers for ER stress in lung. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14680.

84. Greenwood HE, Witney TH. Latest advances in imaging oxidative stress in Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:1506-10.

85. Ghasemitarei M, Ghorbi T, Yusupov M, Zhang Y, Zhao T, Shali P, Bogaerts A. Effects of nitro-oxidative stress on biomolecules: part 1-non-reactive molecular dynamics simulations. Biomolecules. 2023;13.

86. Wang W, Rong Z, Wang G, Hou Y, Yang F, Qiu M. Cancer metabolites: promising biomarkers for cancer liquid biopsy. Biomarker Res. 2023;11:66.

87. Perillo B, di Donato M, Pezone A, di Zazzo E, Giovannelli P, Galasso G, Castoria G, Migliaccio A. ROS in cancer therapy: the bright side of the moon. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:192-203.

88. Raza MH, Siraj S, Arshad A, Waheed U, Aldakheel F, Alduraywish S, Arshad M. ROS-modulated therapeutic approaches in cancer treatment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:1789-809.

89. Somu P, Mohanty S, Paul S. A detailed overview of ROS-modulating approaches in Cancer treatment: Nano-based system to improve its future clinical perspective. Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects; 2021. p. 1-22.

90. Sofiullah SSM, Murugan DD, Muid SA, Seng WY, Kadir SZSA, Abas R, Ridzuan NRA, Zamakshshari NH, Woon CK. Natural bioactive compounds targeting NADPH oxidase pathway in cardiovascular diseases. Molecules. 2023;28:1047.

91. Forman HJ, Zhang H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:689-709.

92. Nizami ZN, Aburawi HE, Semlali A, Muhammad K, Iratni R. Oxidative stress inducers in Cancer therapy: preclinical and clinical evidence. Antioxidants. 2023;12:1159.

93. Li Y, Zhang X, Wang Z, Li B, Zhu H. Modulation of redox homeostasis: A strategy to overcome cancer drug resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14.

94. Anwanwan D, Singh SK, Singh S, Saikam V, Singh R. Challenges in liver cancer and possible treatment approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Rev Cancer. 2020;1873:188314.

95. Chehelgerdi

96. Wu C, Mao J, Wang X, Yang R, Wang C, Li C, Zhou X. Advances in treatment strategies based on scavenging reactive oxygen species of nanoparticles for atherosclerosis. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21:271.

97. Iqbal MJ, Ali S, Rashid U, Kamran M, Malik MF, Sughra K, Zeeshan N, Afroz A, Saleem J, Saghir M. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of Litchi chinensis and its dynamic biological impact on microbial cells and human cancer cell lines. Cell Mol Biol. 2018;64:42-7.

98. Rejinold NS, Muthunarayanan M, Divyarani V, Sreerekha P, Chennazhi K, Nair S, Tamura H, Jayakumar R. Curcumin-loaded biocompatible thermoresponsive polymeric nanoparticles for cancer drug delivery. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;360:39-51.

99. Javid H, Hashemy SI, Heidari MF, Esparham A, Gorgani-Firuzjaee S. The anticancer role of cerium oxide nanoparticles by inducing antioxidant

activity in esophageal Cancer and Cancer stem-like ESCC spheres. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:3268197.

100. Bonet-Aleta J, Calzada-Funes J, Hueso JL. Manganese oxide nanoplatforms in cancer therapy: recent advances on the development of synergistic strategies targeting the tumor microenvironment. Appl Mater Today. 2022;29:101628.

101. Chasara RS, Ajayi TO, Leshilo DM, Poka MS, Witika BA. Exploring novel strategies to improve anti-tumour efficiency: the potential for targeting reactive oxygen species. Heliyon. 2023;9:e19896.

102. Čapek J, Roušar T. Detection of oxidative stress induced by nanomaterials in cells-the roles of reactive oxygen species and glutathione. Molecules. 2021;26:4710.

103. Bigham A, Raucci MG. Multi-responsive materials: properties, design, and applications. In: Stimuli-Responsive Materials for Biomedical Applications. American Chemical Society; 2023.

104. Teixeira PV, Fernandes E, Soares TB, Adega F, Lopes CM, Lúcio M. Natural compounds: co-delivery strategies with chemotherapeutic agents or nucleic acids using lipid-based Nanocarriers. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15.

105. Craddock CF, Houlton AE, Quek LS, Ferguson P, Gbandi E, Roberts C, Metzner M, Garcia-Martin N, Kennedy A, Hamblin A, Raghavan M, Nagra S, Dudley L, Wheatley K, Mcmullin MF, Pillai SP, Kelly RJ, Siddique S, Dennis M , Cavenagh JD, Vyas P. Outcome of Azacitidine therapy in acute myeloid leukemia is not improved by concurrent Vorinostat therapy but is predicted by a diagnostic molecular signature. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6430-40.

106. Patnaik E, Madu C, Lu Y. Epigenetic modulators as therapeutic agents in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24.

107. Rullo R, Cerchia C, Nasso R, Romanelli V, Vendittis E, Masullo M, Lavecchia A. Novel reversible inhibitors of xanthine oxidase targeting the active site of the enzyme. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12.

108. Liu J, Chen Z, Li Y, Zhao W, Wu J, Zhang Z. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in tumor immunotherapy. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:731798.

109. Singh K, Bhori M, Kasu YA, Bhat G, Marar T. Antioxidants as precision weapons in war against cancer chemotherapy induced toxicity exploring the armoury of obscurity. Saudi Pharm J. 2018;26:177-90.

110. Tenório M, Graciliano NG, Moura FA, Oliveira ACM, Goulart MOF. N -acetylcysteine (NAC): impacts on human health. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10.

Publisher’s Note

Ready to submit your research? Choose BMC and benefit from:

- fast, convenient online submission

- thorough peer review by experienced researchers in your field

- rapid publication on acceptance

- support for research data, including large and complex data types

- gold Open Access which fosters wider collaboration and increased citations

- maximum visibility for your research: over 100 M website views per year

At BMC, research is always in progress.

BMC

- *Correspondence:

Daniela Calina

calinadaniela@gmail.com

Javad Sharifi-Rad

javad.sharifirad@gmail.com

William C. Cho

chocs@ha.org.hk

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article