DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-024-01160-1

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-07

تفاعل الربط بين الكربون والذرات غير المعدنية مع الأريل الغني بالإلكترونات بفضل تحفيز النيكل والضوء

تم القبول: 9 أبريل 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 7 مايو 2024

(د) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

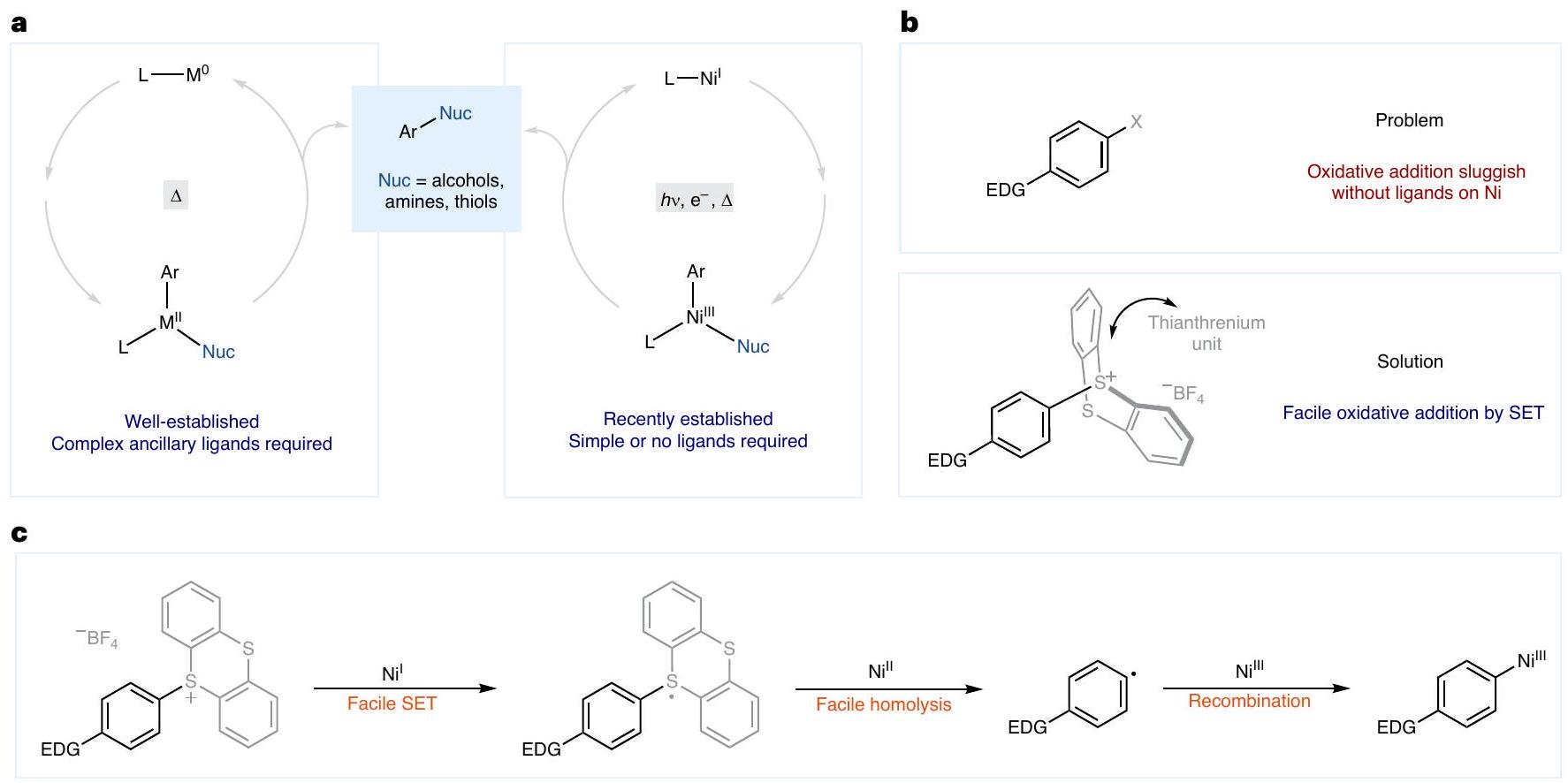

لقد أدى التحفيز الضوئي بالنيكل إلى تطوير غني للتحولات التي يتم تحفيزها بواسطة المعادن الانتقالية لتكوين روابط الكربون-الهيدروجين. من خلال استغلال طاقة الضوء، يمكن للمعادن الانتقالية أن تصل إلى حالات أكسدة يصعب تحقيقها من خلال الكيمياء الحرارية في نظام تحفيزي. على سبيل المثال، تم الإبلاغ عن تفاعلات التحفيز الضوئي بالنيكل لكل من تخليق الأنيلينات والإيثرات العطرية من الهاليدات العطرية (الزائفة). ومع ذلك، فإن الإضافة المؤكسدة إلى أنظمة النيكل البسيطة غالبًا ما تكون بطيئة في غياب روابط خاصة غنية بالإلكترونات، مما يؤدي إلى تحلل المحفز. لذلك، فإن الكواشف العطرية الغنية بالإلكترونات تقع حاليًا خارج نطاق العديد من التحولات في هذا المجال. هنا نقدم حلاً مفاهيميًا لهذه المشكلة ونظهر تفاعلات تكوين روابط الكربون-الهيدروجين المحفزة بالنيكل لأملاح الثيانثرينيوم العطرية، بما في ذلك الأمينية، والأكسدة، والكبريت، والهالوجين. نظرًا لأن خصائص الأكسدة والاختزال لأملاح الثيانثرينيوم العطرية تحددها بشكل أساسي الثيانثرينيوم، يمكن فتح الإضافة المؤكسدة للمانحين العطريين الغنيين بالإلكترونات باستخدام بسيطة.

الكحوليات

النتائج

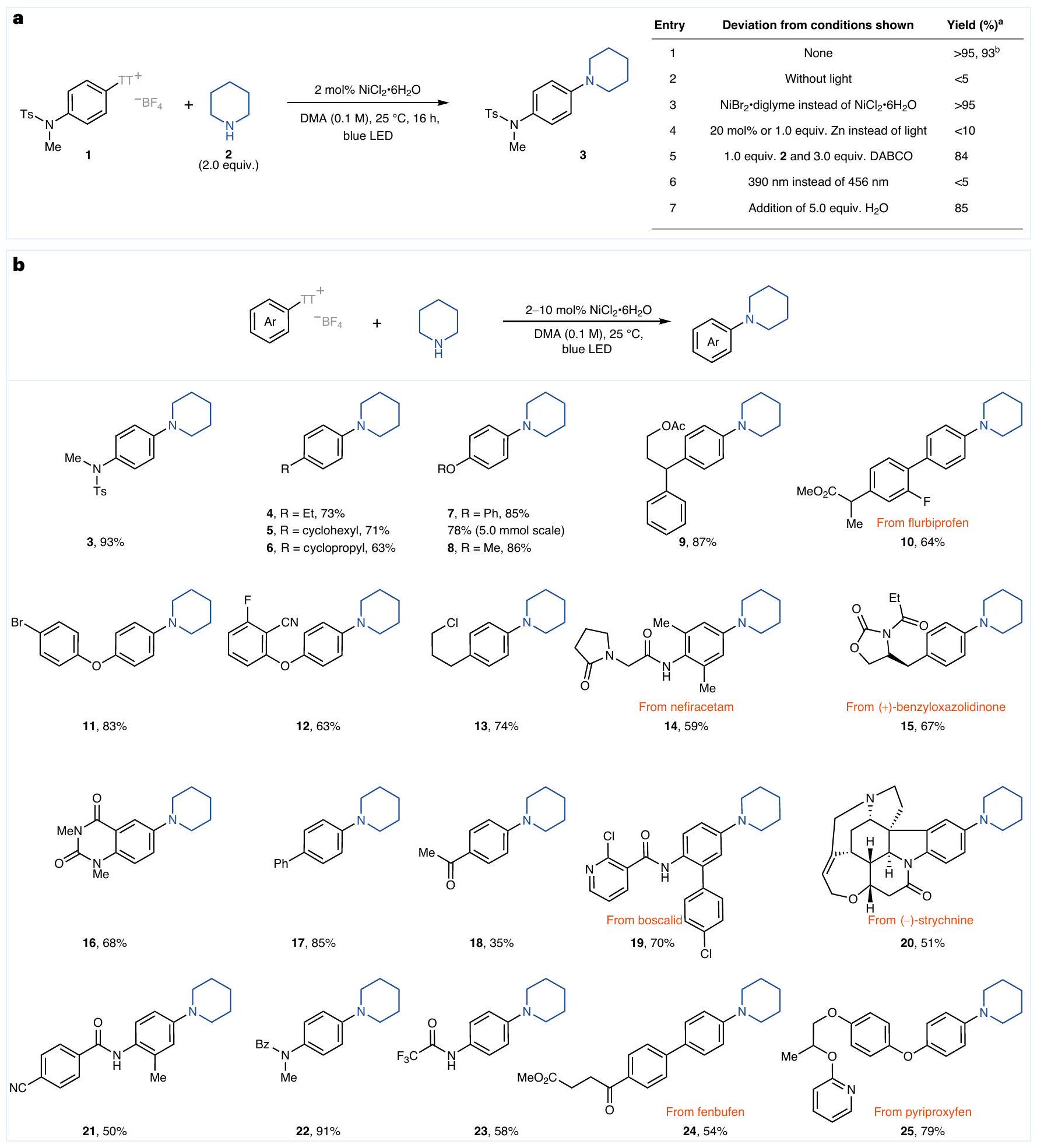

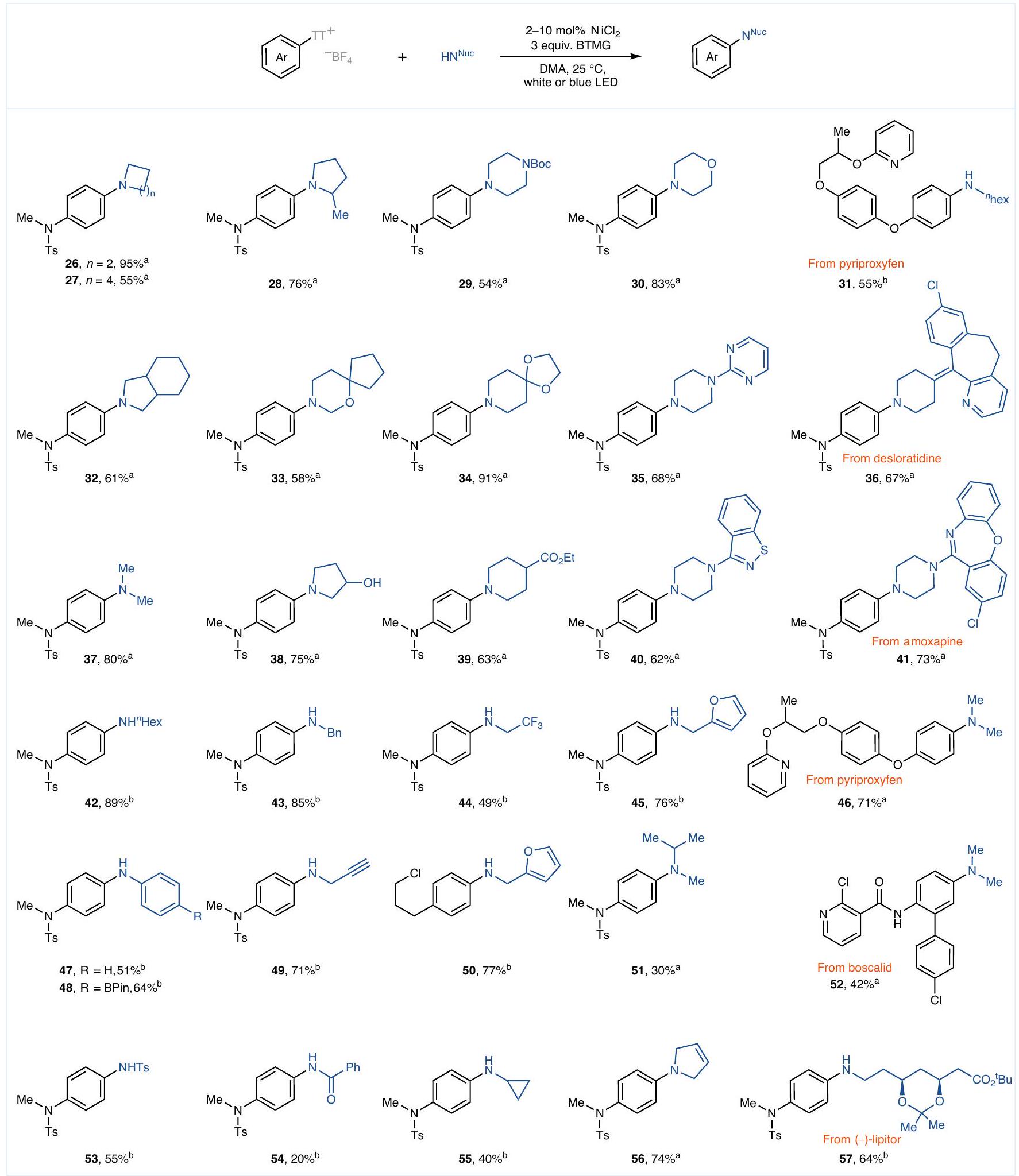

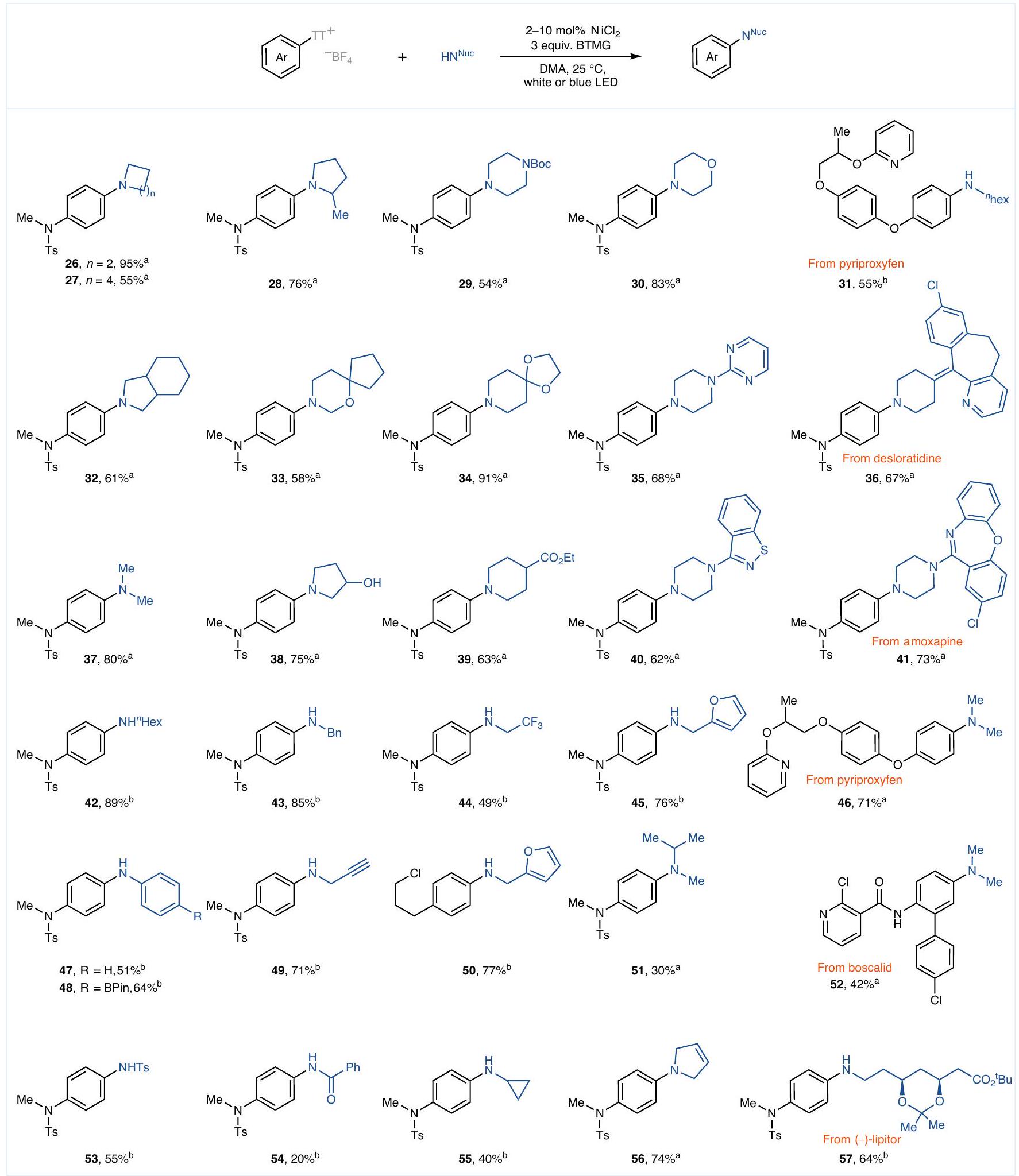

تكوين رابطة C-N

تتم عملية الأرينات الفقيرة بالإلكترونات بشكل أسرع (انظر أدناه)، ولكن العوائد أقل بسبب التفاعل الجانبي المتنافس الملحوظ لإزالة الوظائف الهيدروجينية. لم يتم تحديد الأسباب التفصيلية لهذا التفاعل الجانبي، إلى حد كبير لأن تحليل الأنواع الأريليكية النيكل في غياب الروابط المساعدة يمثل تحديًا، ولكن قد يكون

نتيجة لنقل ذرة الهيدروجين (HAT) من

يمكن تحويل الفلوريبيروفين (10) ، النيفيراسيتام (14) ، البنزيلوكازوليدينون (15) ، البوسكاليد (19) ، الستريكنين (20) ، الفينبوفين (24) و البيريبروكسي فين (25) إلى المنتجات الأمينية المقابلة، مما يوفر

بروتوكول مفيد للتعديل في المراحل المتأخرة. يمكن أن تشارك الركائز ذات الاستبدال بارا وميتا في التفاعل أيضًا. أما أملاح ArTT المستبدلة في الوضع ortho فتقع خارج نطاق البروتوكول.

ويسفر عن منتجات ثانوية غير وظيفية مائية بالإضافة إلى المواد الأولية غير المتفاعلة.

المنتجات في

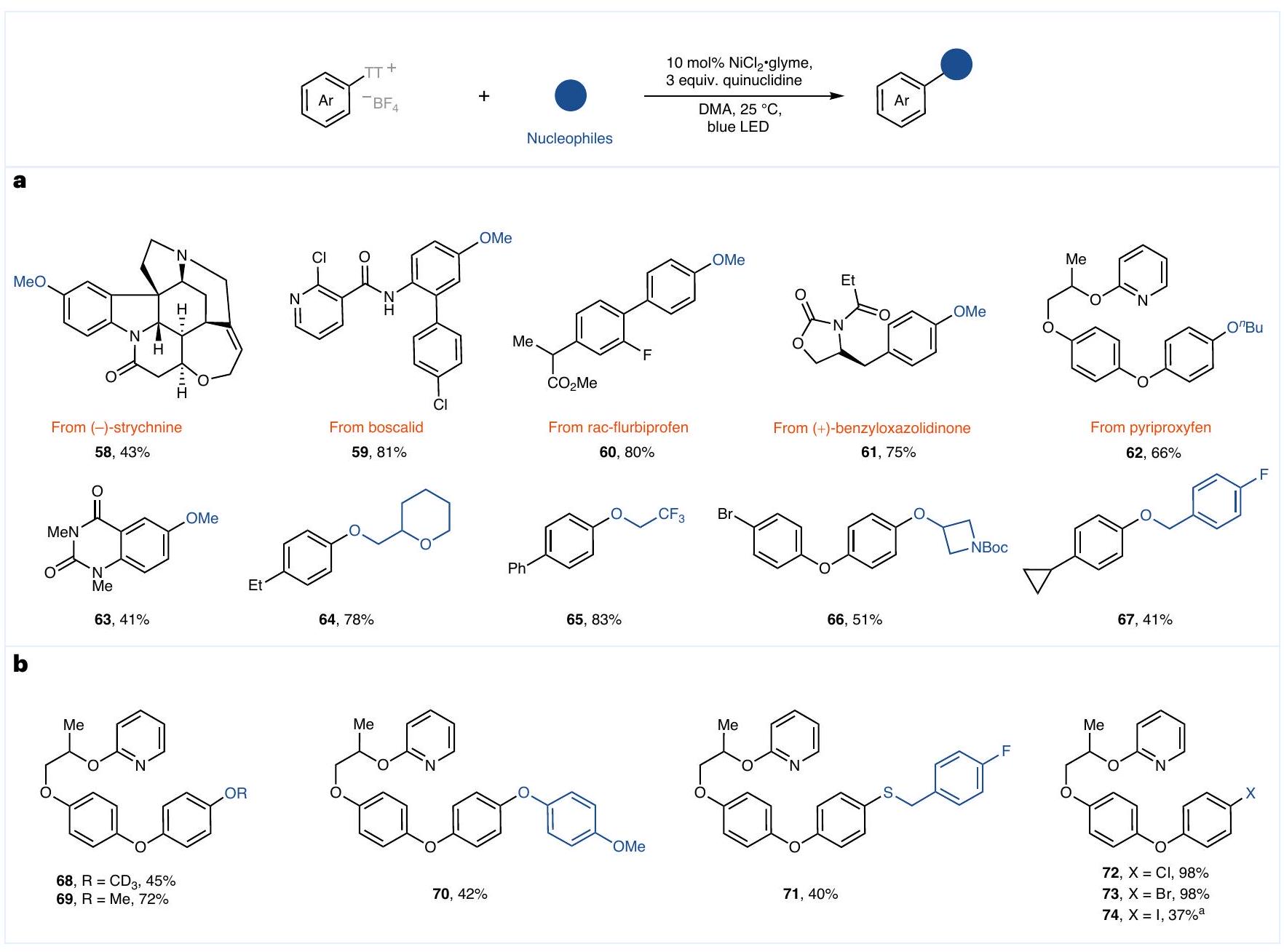

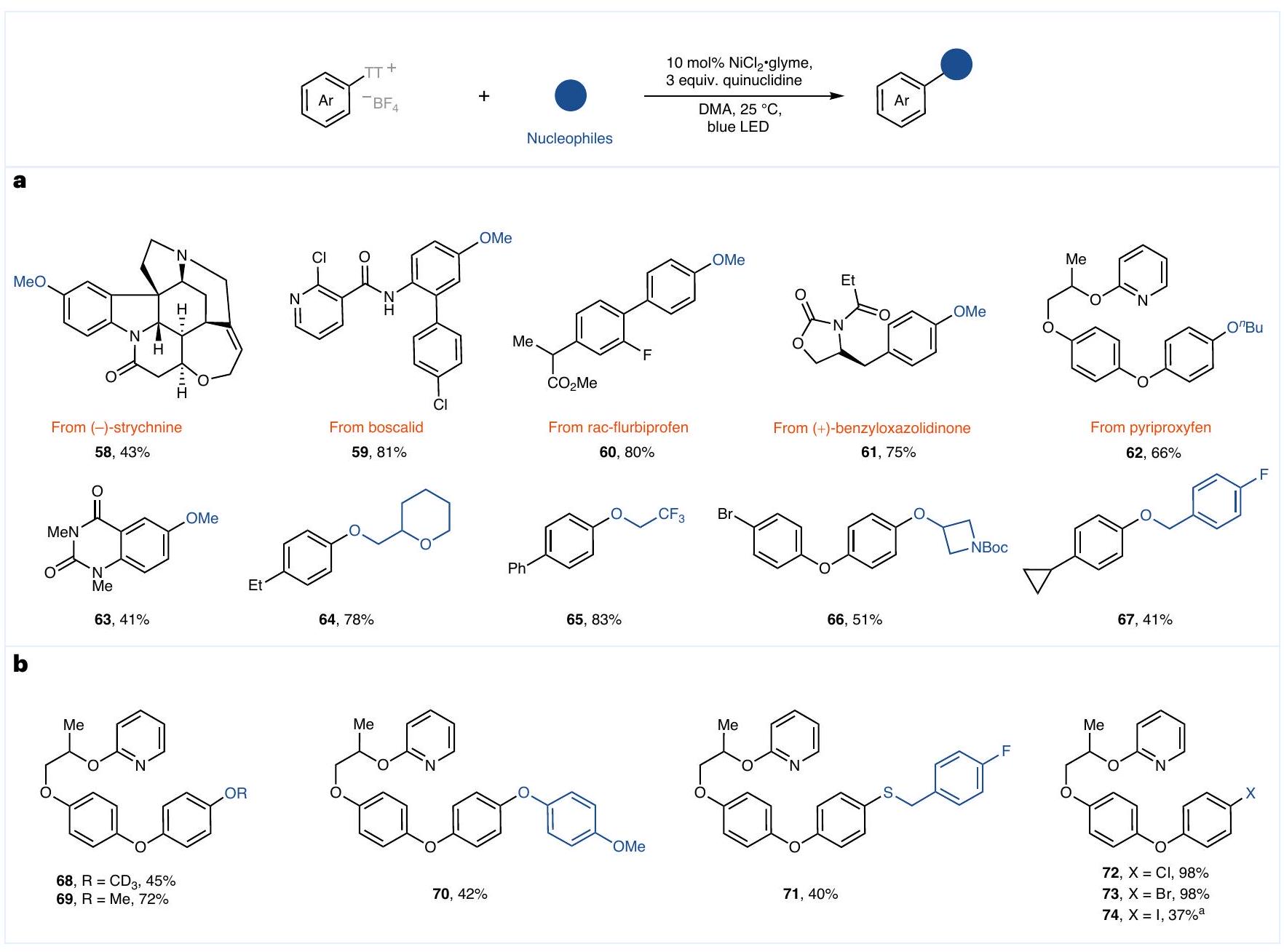

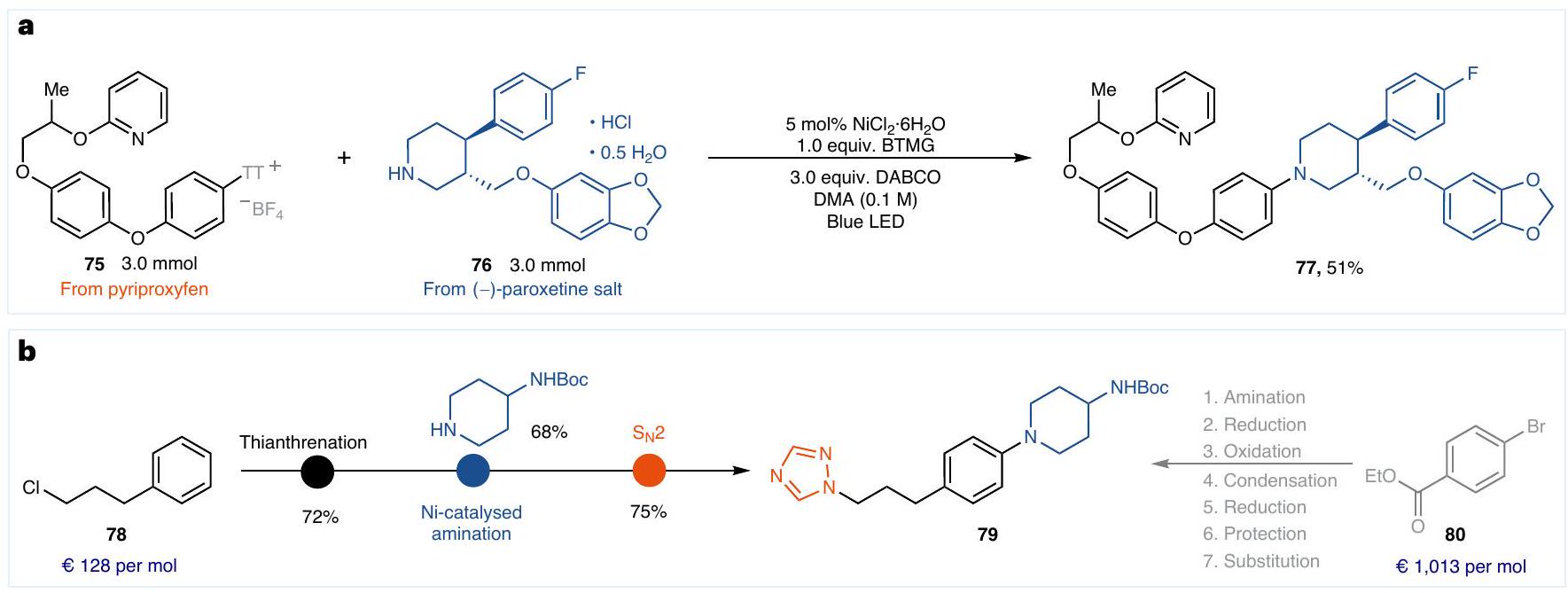

تمديد لتكوين روابط C-X الأخرى

الخاتمة

طرق

الإجراء العام لتأمين أملاح ArTT (الأمينات الثانوية الألكيلية)

من صندوق القفازات، وتم إضافة الأمين (إذا كان سائلًا، 0.40 مللي مول، 2.0 مكافئ) عبر ميكروسيرينج في

الإجراء العام لتأمين أملاح ArTT (الأمينات الألكيلية الأولية، الأنيلينات، الأميدات والسلفوناميدات)

الإجراء العام لتكوين روابط C-heteroatom الحفزية لأملاح ArTT (الكحوليات، الثيولات، الفينولات والهالوجينات)

توفر البيانات

References

- Hartwig, J. F. Evolution of a fourth generation catalyst for the amination and thioetherification of aryl halides. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1534-1544 (2008).

- Ruiz-Castillo, P. & Buchwald, S. L. Applications of palladium-catalyzed

cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 116, 12564-12649 (2016). - Dorel, R., Grugel, C. P. & Haydl, A. M. The Buchwald-Hartwig amination after 25 years. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 17118-17129 (2019).

- Hughes, E. C., Veatch, F. & Elersich, V. N-methylaniline from chlorobenzene and methylamine. Ind. Eng. Chem. 42, 787-790 (1950).

- Cramer, R. & Coulson, D. R. Nickel-catalyzed displacement reactions of aryl halides. J. Org. Chem. 40, 2267-2273 (1975).

- Ullmann, F. Ueber eine neue Bildungsweise von Diphenylaminderivaten. Chem. Ber. 36, 2382-2384 (1903).

- Cristau, H.-J. & Desmurs, J.-R. in Industrial Chemistry Library Vol. 7 (eds Desmurs, J.-R. et al.) 240-263 (Elsevier, 1995).

- Marín, M., Rama, R. J. & Nicasio, M. C. Ni-catalyzed amination reactions: an overview. Chem. Rec. 16, 1819-1832 (2016).

- Ma, D. & Cai, Q. Copper/amino acid catalyzed cross-couplings of aryl and vinyl halides with nucleophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1450-1460 (2008).

- Creutz, S. E., Lotito, K. J., Fu, G. C. & Peters, J. C. Photoinduced Ullmann C-N coupling: demonstrating the viability of a radical pathway. Science 338, 647-651 (2012).

- Ziegler, D. T. et al. A versatile approach to Ullmann C-N couplings at room temperature: new families of nucleophiles and electrophiles for photoinduced, copper-catalyzed processes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13107-13112 (2013).

- Morrison, K. M., Yeung, C. S. & Stradiotto, M. Nickel-catalyzed chemoselective arylation of amino alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202300686 (2023).

- Reichert, E. C., Feng, K., Sather, A. C. & Buchwald, S. L. Pd-catalyzed amination of base-sensitive five-membered heteroaryl halides with aliphatic amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3323-3329 (2023).

- Gowrisankar, S. et al. A general and efficient catalyst for palladium-catalyzed C-O coupling reactions of aryl halides with primary alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11592-11598 (2010).

- Tassone, J. P., England, E. V., MacQueen, P. M., Ferguson, M. J. & Stradiotto, M. PhPAd-DalPhos: ligand-enabled, nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of (hetero)aryl electrophiles with bulky primary alkylamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2485-2489 (2019).

- Newman-Stonebraker, S. H., Wang, J. Y., Jeffrey, P. D. & Doyle, A. G. Structure-reactivity relationships of Buchwald-type phosphines in nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19635-19648 (2022).

- Marion, N. et al. Modified (NHC)Pd(allyl)Cl (NHC=N-heterocyclic carbene) complexes for room-temperature Suzuki-Miyaura and Buchwald-Hartwig reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 4101-4111 (2006).

- Rull, S. G. et al. Elucidating the mechanism of aryl aminations mediated by NHC-supported nickel complexes: evidence for a nonradical

pathway. ACS Catal. 8, 3733-3742 (2018). - Corcoran, E. B. et al. Aryl amination using ligand-free

salts and photoredox catalysis. Science 353, 279-283 (2016). - Barker, T. J. & Jarvo, E. R. Umpolung amination: nickel-catalyzed coupling reactions of

-dialkyl- -chloroamines with diorganozinc reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 15598-15599 (2009). - Koo, K. & Hillhouse, G. L. Carbon-nitrogen bond formation by reductive elimination from nickel(II) amido alkyl complexes. Organometallics 14, 4421-4423 (1995).

- Terrett, J. A., Cuthbertson, J. D., Shurtleff, V. W. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Switching on elusive organometallic mechanisms with photoredox catalysis. Nature 524, 330-334 (2015).

- Till, N. A., Tian, L., Dong, Z., Scholes, G. D. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Mechanistic analysis of metallaphotoredox C-N coupling: photocatalysis initiates and perpetuates

coupling activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15830-15841 (2020). - Bradley, R. D., McManus, B. D., Yam, J. G., Carta, V. & Bahamonde, A. Mechanistic evidence of a

cycle for nickel photoredox amide arylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310753 (2023). - Chan, A. Y. et al. Metallaphotoredox: the merger of photoredox and transition metal catalysis. Chem. Rev. 122, 1485-1542 (2022).

- Li, C. et al. Electrochemically enabled, nickel-catalyzed amination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13088-13093 (2017).

- Kawamata, Y. et al. Electrochemically driven, Ni-catalyzed aryl amination: scope, mechanism and applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6392-6402 (2019).

- Kudisch, M., Lim, C.-H., Thordarson, P. & Miyake, G. M. Energy transfer to Ni-amine complexes in dual catalytic, light-driven C-N cross-coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 19479-19486 (2019).

- Sun, R., Qin, Y. & Nocera, D. G. General paradigm in photoredox nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling allows for light-free access to reactivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9527-9533 (2020).

- Gisbertz, S., Reischauer, S. & Pieber, B. Overcoming limitations in dual photoredox/nickel-catalysed C-N cross-couplings due to catalyst deactivation. Nat. Catal. 3, 611-620 (2020).

- Tang, T. et al. Interrogating the mechanistic features of

-mediated aryl iodide oxidative addition using electroanalytical and statistical modeling techniques. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8689-8699 (2023). - Portnoy, M. & Milstein, D. Mechanism of aryl chloride oxidative addition to chelated palladium(0) complexes. Organometallics 12, 1665-1673 (1993).

- Tsou, T. T. & Kochi, J. K. Mechanism of oxidative addition. Reaction of nickel(0) complexes with aromatic halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 6319-6332 (1979).

- Amatore, C. & Pfluger, F. Mechanism of oxidative addition of palladium(0) with aromatic iodides in toluene, monitored at ultramicroelectrodes. Organometallics 9, 2276-2282 (1990).

- Biscoe, M. R., Fors, B. P. & Buchwald, S. L. A new class of easily activated palladium precatalysts for facile C -N cross-coupling reactions and the low temperature oxidative addition of aryl chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6686-6687 (2008).

- Berger, F. et al. Site-selective and versatile aromatic C-H functionalization by thianthrenation. Nature 567, 223-228 (2019).

- Li, J. et al. Photoredox catalysis with aryl sulfonium salts enables site-selective late-stage fluorination. Nat. Chem. 12, 56-62 (2020).

- Ni, S. et al. Nickel meets aryl thianthrenium salts: Ni(I)-catalyzed halogenation of arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9988-9993 (2023).

- Ghosh, I. et al. General cross-coupling reactions with adaptive dynamic homogeneous catalysis. Nature 619, 87-93 (2023).

- Lim, C.-H., Kudisch, M., Liu, B. & Miyake, G. M. C-N cross-coupling via photoexcitation of nickel-amine complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7667-7673 (2018).

- Shields, B. J., Kudisch, B., Scholes, G. D. & Doyle, A. G. Long-lived charge-transfer states of nickel(II) aryl halide complexes facilitate bimolecular photoinduced electron transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3035-3039 (2018).

- Engl, P. S. et al. C-N cross-couplings for site-selective late-stage diversification via aryl sulfonium salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13346-13351 (2019).

- Sang, R. et al. Site-selective C-H oxygenation via aryl sulfonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 16161-16166 (2019).

- Cabrera-Afonso, M. J., Granados, A. & Molander, G. A. Sustainable thioetherification via electron donor-acceptor photoactivation using thianthrenium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202706 (2022).

- Zhu, J., Ye, Y., Yan, Y., Sun, J. & Huang, Y. Highly regioselective dichalcogenation of alkenyl sulfonium salts to access 1,1-dichalcogenalkenes. Org. Lett. 25, 5324-5328 (2023).

- Urade, Y. et al. Preparation of 4-((pyrrol-2-yl)carbonyl)-N-(piperidin-4-yl)-1-piperazinecarboxamide compounds having a prostaglandin D synthase (PGDS) inhibitory effect. PCT patent WO2011090062 (2011).

- Till, N. A., Oh, S., MacMillan, D. W. C. & Bird, M. J. The application of pulse radiolysis to the study of

intermediates in Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 9332-9337 (2021). - Ting, S. I., Williams, W. L. & Doyle, A. G. Oxidative addition of aryl halides to a Ni(I)-bipyridine complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5575-5582 (2022).

- Pierson, C. N. & Hartwig, J. F. Mapping the mechanisms of oxidative addition in cross-coupling reactions catalysed by phosphine-ligated Ni(0). Nat. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41557-024-01451-x (2024).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

(ج) المؤلفون 2024

معهد ماكس بلانك لبحوث الفحم، مولهيم على نهر الرور، ألمانيا. معهد الكيمياء العضوية، جامعة RWTH آخن، آخن، ألمانيا.

معهد ماكس بلانك لتحويل الطاقة الكيميائية، مولهيم على نهر الرور، ألمانيا. البريد الإلكتروني: cornella@kofo.mpg.de; ritter@kofo.mpg.de

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-024-01160-1

Publication Date: 2024-05-07

C-heteroatom coupling with electron-rich aryls enabled by nickel catalysis and light

Accepted: 9 April 2024

Published online: 7 May 2024

(D) Check for updates

Abstract

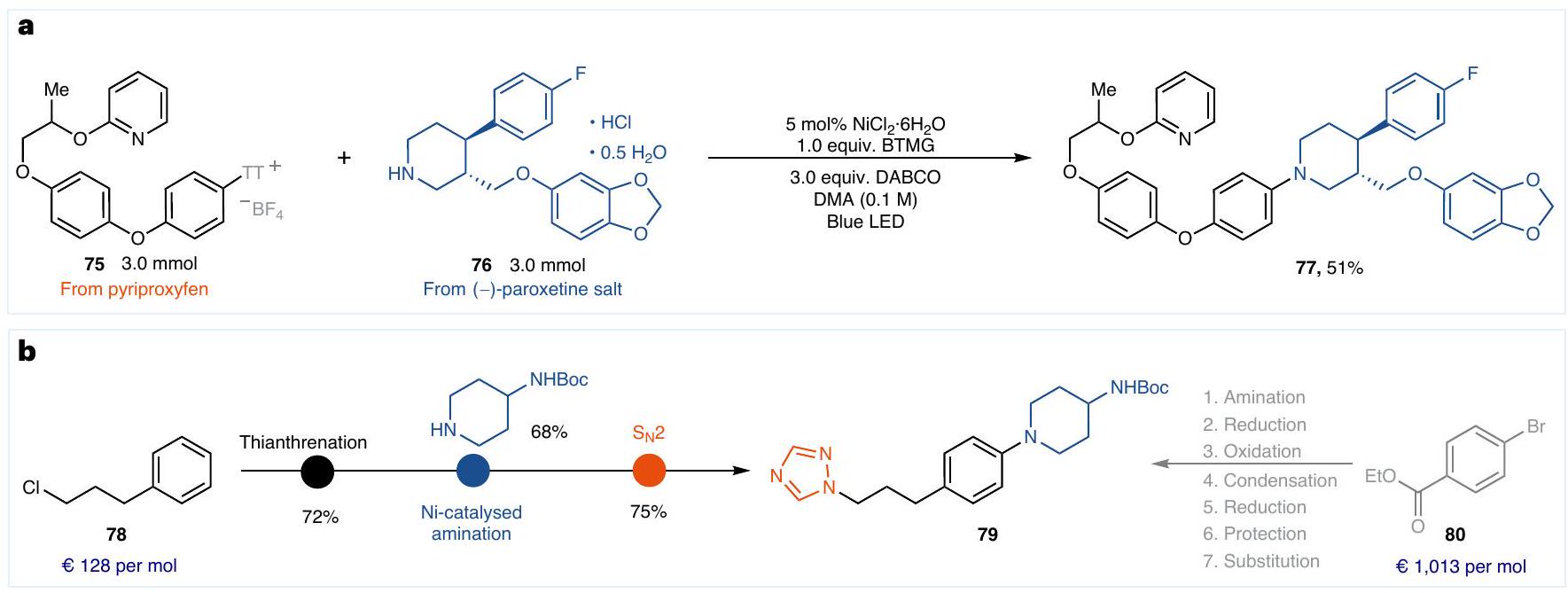

Nickel photoredox catalysis has resulted in a rich development of transition-metal-catalysed transformations for carbon-heteroatom bond formation. By harnessing light energy, the transition metal can attain oxidation states that are difficult to achieve through thermal chemistry in a catalytic manifold. For example, nickel photoredox reactions have been reported for both the synthesis of anilines and aryl ethers from aryl(pseudo) halides. However, oxidative addition to simple nickel systems is often sluggish in the absence of special, electron-rich ligands, leading to catalyst decomposition. Electron-rich aryl electrophiles therefore currently fall outside the scope of many transformations in the field. Here we provide a conceptual solution to this problem and demonstrate nickel-catalysed C-heteroatom bond-forming reactions of arylthianthrenium salts, including amination, oxygenation, sulfuration and halogenation. Because the redox properties of arylthianthrenium salts are primarily dictated by the thianthrenium, oxidative addition of highly electron-rich aryl donors can be unlocked using simple

alcohols

Results

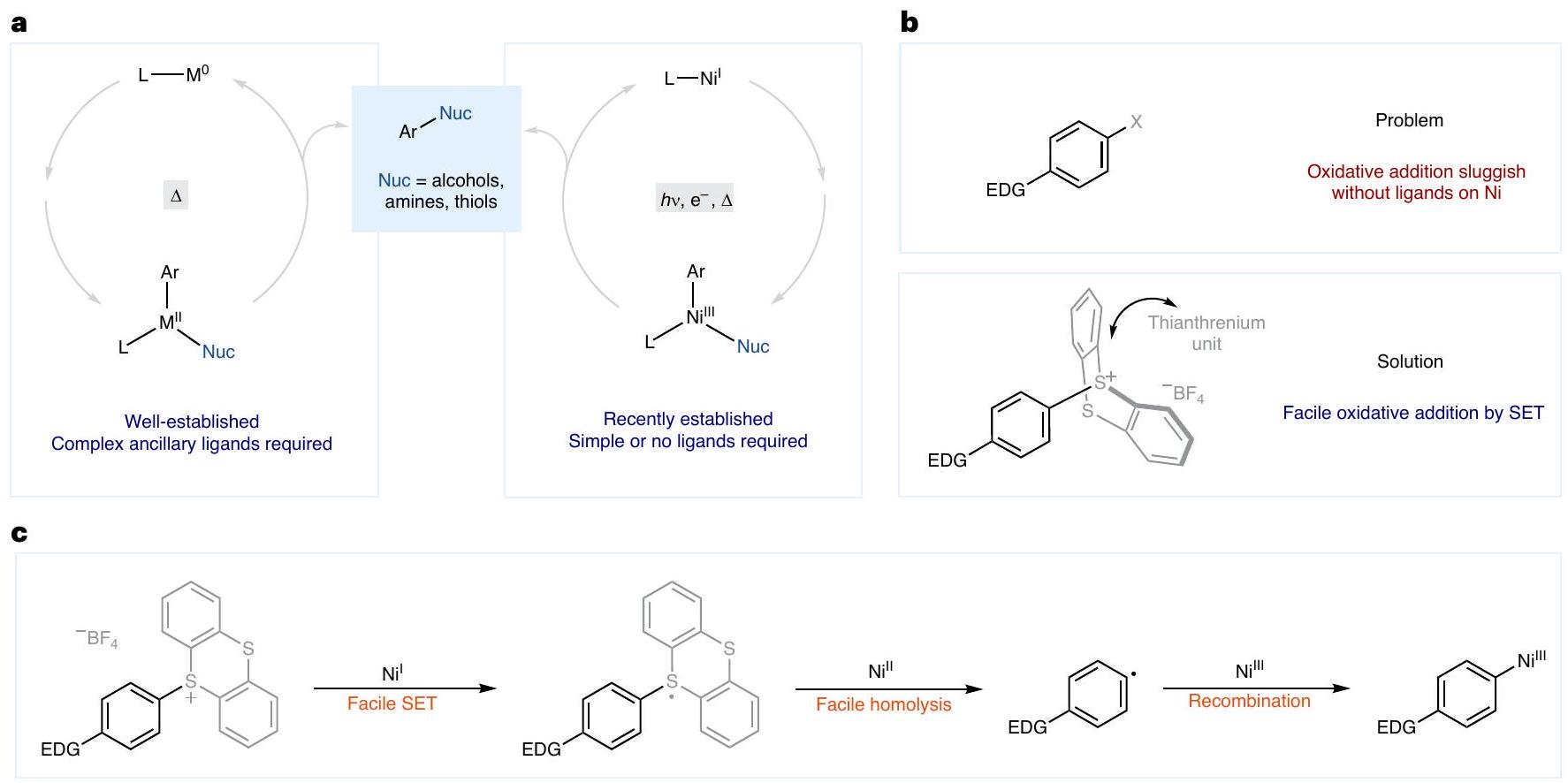

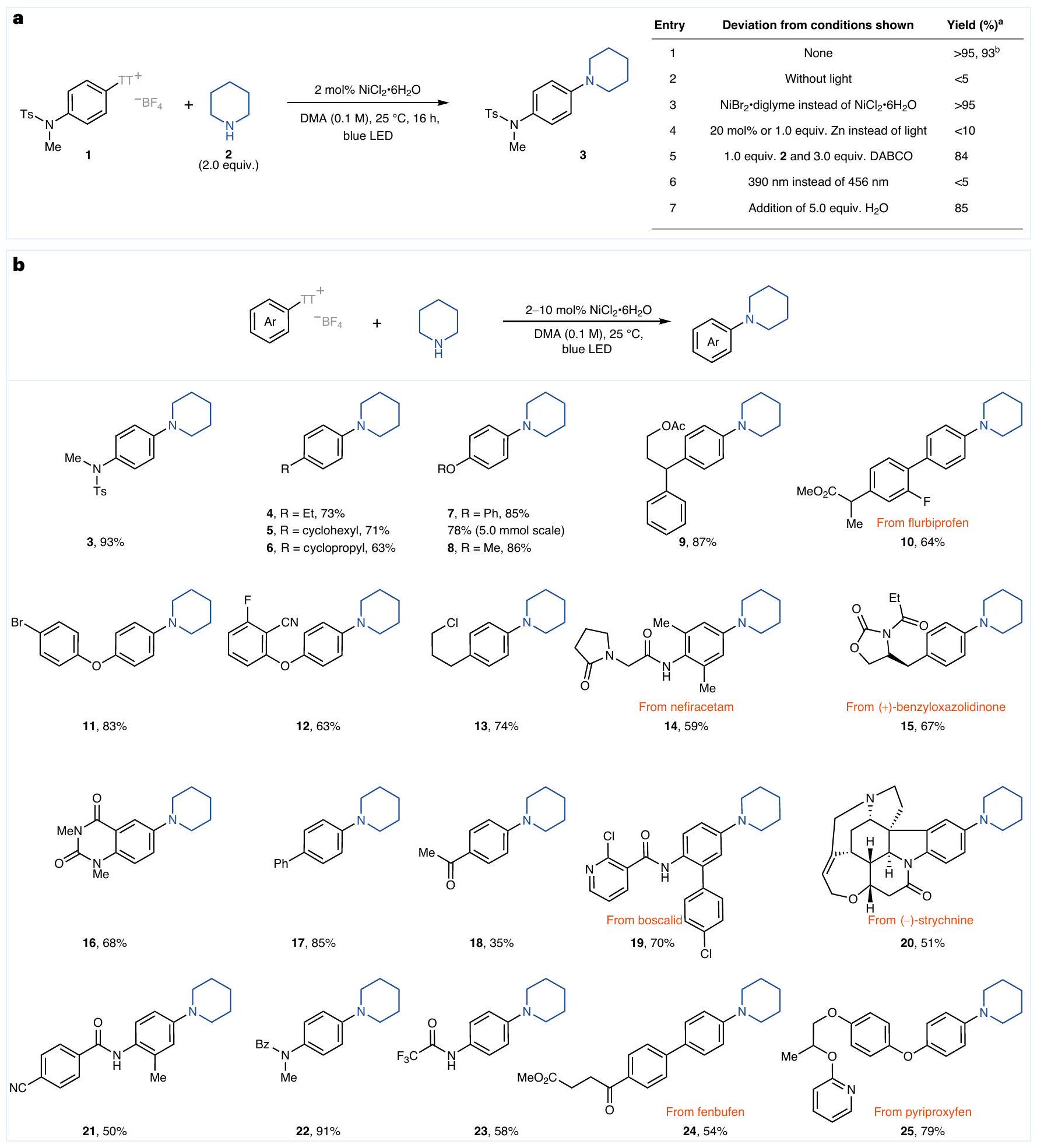

C-N bond formation

of electron-poor arenes proceeds faster (vide infra), but the yields are lower due to the observed competing side reaction of hydrodefunctionalization. The detailed reasons for this side reaction were not established, in large part because analysis of the arylnickel species in the absence of ancillary ligands is challenging, but it may be

a consequence of hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from the

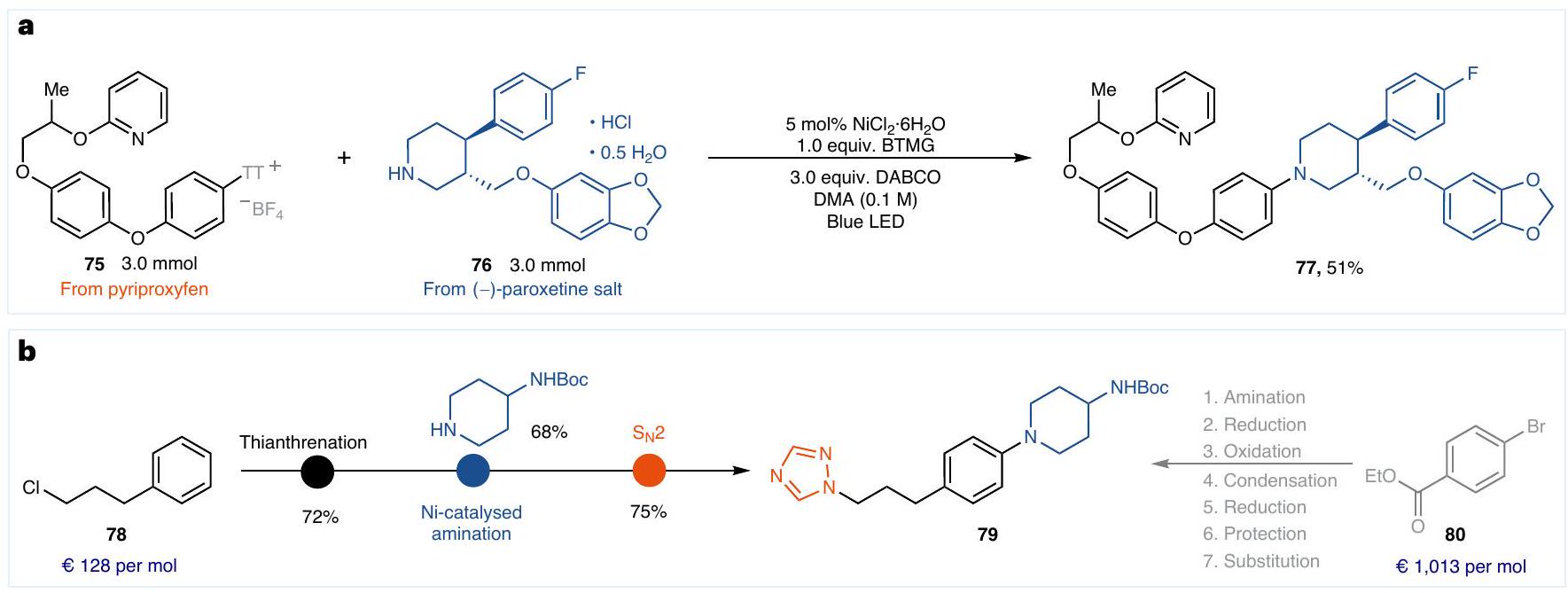

flurbiprofen (10), nefiracetam (14), benzyloxazolidinone (15), boscalid (19), strychnine (20), fenbufen (24) and pyriproxyfen (25) can be converted into the corresponding aminated products, providing

a useful protocol for late-stage modification. Substrates with paraand meta-substitution can participate in the reaction as well. The ortho-substituted ArTT salts fall beyond the scope of the protocol,

and result in hydrodefunctionalized by-products as well as unreacted starting materials.

products in

Extension to other C-X bond formation

Conclusion

Methods

General procedure for amination of ArTT salts (secondary alkyl amines)

out of the glovebox, and amine (if liquid, 0.40 mmol , 2.0 equiv.) was added via a microsyringe at

General procedure for amination of ArTT salts (primary alkyl amines, anilines, amides and sulfonamides)

General procedure for catalytic C-heteroatom bond formation of ArTT salts (alcohols, thiols, phenols and halogens)

Data availability

References

- Hartwig, J. F. Evolution of a fourth generation catalyst for the amination and thioetherification of aryl halides. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1534-1544 (2008).

- Ruiz-Castillo, P. & Buchwald, S. L. Applications of palladium-catalyzed

cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 116, 12564-12649 (2016). - Dorel, R., Grugel, C. P. & Haydl, A. M. The Buchwald-Hartwig amination after 25 years. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 17118-17129 (2019).

- Hughes, E. C., Veatch, F. & Elersich, V. N-methylaniline from chlorobenzene and methylamine. Ind. Eng. Chem. 42, 787-790 (1950).

- Cramer, R. & Coulson, D. R. Nickel-catalyzed displacement reactions of aryl halides. J. Org. Chem. 40, 2267-2273 (1975).

- Ullmann, F. Ueber eine neue Bildungsweise von Diphenylaminderivaten. Chem. Ber. 36, 2382-2384 (1903).

- Cristau, H.-J. & Desmurs, J.-R. in Industrial Chemistry Library Vol. 7 (eds Desmurs, J.-R. et al.) 240-263 (Elsevier, 1995).

- Marín, M., Rama, R. J. & Nicasio, M. C. Ni-catalyzed amination reactions: an overview. Chem. Rec. 16, 1819-1832 (2016).

- Ma, D. & Cai, Q. Copper/amino acid catalyzed cross-couplings of aryl and vinyl halides with nucleophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1450-1460 (2008).

- Creutz, S. E., Lotito, K. J., Fu, G. C. & Peters, J. C. Photoinduced Ullmann C-N coupling: demonstrating the viability of a radical pathway. Science 338, 647-651 (2012).

- Ziegler, D. T. et al. A versatile approach to Ullmann C-N couplings at room temperature: new families of nucleophiles and electrophiles for photoinduced, copper-catalyzed processes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13107-13112 (2013).

- Morrison, K. M., Yeung, C. S. & Stradiotto, M. Nickel-catalyzed chemoselective arylation of amino alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202300686 (2023).

- Reichert, E. C., Feng, K., Sather, A. C. & Buchwald, S. L. Pd-catalyzed amination of base-sensitive five-membered heteroaryl halides with aliphatic amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3323-3329 (2023).

- Gowrisankar, S. et al. A general and efficient catalyst for palladium-catalyzed C-O coupling reactions of aryl halides with primary alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11592-11598 (2010).

- Tassone, J. P., England, E. V., MacQueen, P. M., Ferguson, M. J. & Stradiotto, M. PhPAd-DalPhos: ligand-enabled, nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of (hetero)aryl electrophiles with bulky primary alkylamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2485-2489 (2019).

- Newman-Stonebraker, S. H., Wang, J. Y., Jeffrey, P. D. & Doyle, A. G. Structure-reactivity relationships of Buchwald-type phosphines in nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19635-19648 (2022).

- Marion, N. et al. Modified (NHC)Pd(allyl)Cl (NHC=N-heterocyclic carbene) complexes for room-temperature Suzuki-Miyaura and Buchwald-Hartwig reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 4101-4111 (2006).

- Rull, S. G. et al. Elucidating the mechanism of aryl aminations mediated by NHC-supported nickel complexes: evidence for a nonradical

pathway. ACS Catal. 8, 3733-3742 (2018). - Corcoran, E. B. et al. Aryl amination using ligand-free

salts and photoredox catalysis. Science 353, 279-283 (2016). - Barker, T. J. & Jarvo, E. R. Umpolung amination: nickel-catalyzed coupling reactions of

-dialkyl- -chloroamines with diorganozinc reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 15598-15599 (2009). - Koo, K. & Hillhouse, G. L. Carbon-nitrogen bond formation by reductive elimination from nickel(II) amido alkyl complexes. Organometallics 14, 4421-4423 (1995).

- Terrett, J. A., Cuthbertson, J. D., Shurtleff, V. W. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Switching on elusive organometallic mechanisms with photoredox catalysis. Nature 524, 330-334 (2015).

- Till, N. A., Tian, L., Dong, Z., Scholes, G. D. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Mechanistic analysis of metallaphotoredox C-N coupling: photocatalysis initiates and perpetuates

coupling activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15830-15841 (2020). - Bradley, R. D., McManus, B. D., Yam, J. G., Carta, V. & Bahamonde, A. Mechanistic evidence of a

cycle for nickel photoredox amide arylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310753 (2023). - Chan, A. Y. et al. Metallaphotoredox: the merger of photoredox and transition metal catalysis. Chem. Rev. 122, 1485-1542 (2022).

- Li, C. et al. Electrochemically enabled, nickel-catalyzed amination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13088-13093 (2017).

- Kawamata, Y. et al. Electrochemically driven, Ni-catalyzed aryl amination: scope, mechanism and applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6392-6402 (2019).

- Kudisch, M., Lim, C.-H., Thordarson, P. & Miyake, G. M. Energy transfer to Ni-amine complexes in dual catalytic, light-driven C-N cross-coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 19479-19486 (2019).

- Sun, R., Qin, Y. & Nocera, D. G. General paradigm in photoredox nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling allows for light-free access to reactivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9527-9533 (2020).

- Gisbertz, S., Reischauer, S. & Pieber, B. Overcoming limitations in dual photoredox/nickel-catalysed C-N cross-couplings due to catalyst deactivation. Nat. Catal. 3, 611-620 (2020).

- Tang, T. et al. Interrogating the mechanistic features of

-mediated aryl iodide oxidative addition using electroanalytical and statistical modeling techniques. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8689-8699 (2023). - Portnoy, M. & Milstein, D. Mechanism of aryl chloride oxidative addition to chelated palladium(0) complexes. Organometallics 12, 1665-1673 (1993).

- Tsou, T. T. & Kochi, J. K. Mechanism of oxidative addition. Reaction of nickel(0) complexes with aromatic halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 6319-6332 (1979).

- Amatore, C. & Pfluger, F. Mechanism of oxidative addition of palladium(0) with aromatic iodides in toluene, monitored at ultramicroelectrodes. Organometallics 9, 2276-2282 (1990).

- Biscoe, M. R., Fors, B. P. & Buchwald, S. L. A new class of easily activated palladium precatalysts for facile C -N cross-coupling reactions and the low temperature oxidative addition of aryl chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6686-6687 (2008).

- Berger, F. et al. Site-selective and versatile aromatic C-H functionalization by thianthrenation. Nature 567, 223-228 (2019).

- Li, J. et al. Photoredox catalysis with aryl sulfonium salts enables site-selective late-stage fluorination. Nat. Chem. 12, 56-62 (2020).

- Ni, S. et al. Nickel meets aryl thianthrenium salts: Ni(I)-catalyzed halogenation of arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9988-9993 (2023).

- Ghosh, I. et al. General cross-coupling reactions with adaptive dynamic homogeneous catalysis. Nature 619, 87-93 (2023).

- Lim, C.-H., Kudisch, M., Liu, B. & Miyake, G. M. C-N cross-coupling via photoexcitation of nickel-amine complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7667-7673 (2018).

- Shields, B. J., Kudisch, B., Scholes, G. D. & Doyle, A. G. Long-lived charge-transfer states of nickel(II) aryl halide complexes facilitate bimolecular photoinduced electron transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3035-3039 (2018).

- Engl, P. S. et al. C-N cross-couplings for site-selective late-stage diversification via aryl sulfonium salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13346-13351 (2019).

- Sang, R. et al. Site-selective C-H oxygenation via aryl sulfonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 16161-16166 (2019).

- Cabrera-Afonso, M. J., Granados, A. & Molander, G. A. Sustainable thioetherification via electron donor-acceptor photoactivation using thianthrenium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202706 (2022).

- Zhu, J., Ye, Y., Yan, Y., Sun, J. & Huang, Y. Highly regioselective dichalcogenation of alkenyl sulfonium salts to access 1,1-dichalcogenalkenes. Org. Lett. 25, 5324-5328 (2023).

- Urade, Y. et al. Preparation of 4-((pyrrol-2-yl)carbonyl)-N-(piperidin-4-yl)-1-piperazinecarboxamide compounds having a prostaglandin D synthase (PGDS) inhibitory effect. PCT patent WO2011090062 (2011).

- Till, N. A., Oh, S., MacMillan, D. W. C. & Bird, M. J. The application of pulse radiolysis to the study of

intermediates in Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 9332-9337 (2021). - Ting, S. I., Williams, W. L. & Doyle, A. G. Oxidative addition of aryl halides to a Ni(I)-bipyridine complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5575-5582 (2022).

- Pierson, C. N. & Hartwig, J. F. Mapping the mechanisms of oxidative addition in cross-coupling reactions catalysed by phosphine-ligated Ni(0). Nat. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41557-024-01451-x (2024).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany. Institute of Organic Chemistry, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany.

Max Planck Institut for Chemical Energy Conversion, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany. e-mail: cornella@kofo.mpg.de; ritter@kofo.mpg.de