المجلة: Eurosurveillance، المجلد: 29، العدد: 11

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2024.29.11.2400106

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38487886

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-14

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2024.29.11.2400106

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38487886

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-14

تفشي مرض المونكي بوكس المستمر في كامتوجا، محافظة جنوب كيفو، المرتبط بفيروس المونكي بوكس من سلالة فرعية جديدة من الفصيلة الأولى، جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية، 2024

المراسلات: لياندري مورهولا (leandremurhula@gmail.com)

أسلوب الاقتباس لهذه المقالة:

ماسيريكا لياندري مورهولا، أوداهيموكا جان كلود، شولي ليونارد، نديشيميي باكفيك، أوتاني ساريا، مبيريبيندي جاستين بينغيهيا، ماريكاني جان م.، مامبو لياندري موتيمبا، بوبالا نادين ماليامونغو، بوتير مارجان، نيفنهاويز ديفيد ف.، لانغ ترودي، كلاليزي إرنست باليهموابو، موسابييمانا جان بيير، أريستروب فرانك م.، كوبمانز ماريون، أود مونيك باس ب.، سيانغولي فريدي بيلسي. تفشي مرض المونكيبوكس المستمر في كامتوجا، مقاطعة جنوب كيفو، المرتبط بفيروس المونكيبوكس من سلالة فرعية جديدة من مجموعة I، جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية، 2024. يورو سيرفيل. 2024؛29(11): pii=2400106.https://doi.org/10.2807/15607917.ES.2024.29.11.2400106

ماسيريكا لياندري مورهولا، أوداهيموكا جان كلود، شولي ليونارد، نديشيميي باكفيك، أوتاني ساريا، مبيريبيندي جاستين بينغيهيا، ماريكاني جان م.، مامبو لياندري موتيمبا، بوبالا نادين ماليامونغو، بوتير مارجان، نيفنهاويز ديفيد ف.، لانغ ترودي، كلاليزي إرنست باليهموابو، موسابييمانا جان بيير، أريستروب فرانك م.، كوبمانز ماريون، أود مونيك باس ب.، سيانغولي فريدي بيلسي. تفشي مرض المونكيبوكس المستمر في كامتوجا، مقاطعة جنوب كيفو، المرتبط بفيروس المونكيبوكس من سلالة فرعية جديدة من مجموعة I، جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية، 2024. يورو سيرفيل. 2024؛29(11): pii=2400106.https://doi.org/10.2807/15607917.ES.2024.29.11.2400106

تم تقديم المقال في 14 فبراير 2024 / تم قبوله في 13 مارس 2024 / تم نشره في 14 مارس 2024

منذ بداية عام 2023، زاد عدد الأشخاص الذين يُشتبه في إصابتهم بفيروس جدري القردة (MPXV) بشكل حاد في جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية (DRC). نحن نبلغ عن تسلسل الجينوم الخاص بـ MPXV الذي تم الحصول عليه من ست حالات من محافظة جنوب كيفو. تكشف التحليلات النشوء والتطور أن MPXV الذي يؤثر على الحالات ينتمي إلى سلالة فرعية جديدة من الفصيلة I. يفتقر جينوم سلالة التفشي إلى تسلسل الهدف الخاص بالاستشعار والمبادئ التوجيهية لبروتينات PCR في الوقت الحقيقي الخاصة بالفصيلة I والتي تُستخدم بشكل شائع.

في جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية، زادت أعداد الأشخاص الذين يُشتبه في إصابتهم بفيروس جدري القردة منذ بداية عام 2023. تم الإبلاغ عن إجمالي 12,569 حالة مشبوهة من جدري القردة حتى 12 نوفمبر، وهو أعلى عدد من الحالات السنوية المسجلة على الإطلاق. وقد تم تقدير معدل الوفيات بين الحالات بـ

محافظة كيفو [1،2]. على الرغم من هذه الحالة المقلقة، هناك معلومات جينومية محدودة فقط متاحة عن الفيروسات المتداولة، مما يشير إلى أنها تنتمي إلى المجموعة الأولى [3]. للحصول على مزيد من الفهم حول خصائص السلالات التي تسبب الوباء، بالإضافة إلى التأكد من أن الاختبارات الجزيئية الحالية والشائعة الاستخدام لتشخيص عدوى فيروس جدري القرود يمكن أن تكشف عن هذه السلالات، قمنا بتسلسل الجينومات الفيروسية لجدري القرود من حالات تم تشخيصها مؤخرًا في جنوب كيفو، جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية.

تعريفات الحالة وخصائص المرضى

تم تصنيف الحالة على أنها ‘مشتبه بها’ إذا كانت تعاني من مرض حاد مع حمى، صداع شديد، ألم عضلي، وألم في الظهر، تليها 1 إلى 3 أيام من طفح جلدي يتطور بشكل تدريجي وغالبًا ما يبدأ على الوجه وينتشر على الجسم. كانت حالة جدري القرود المؤكدة تحتوي على عدوى فيروس جدري القرود التي تم تأكيدها مختبريًا بواسطة PCR. تم تصنيف الحالة على أنها ‘مرجحة’ عند استيفائها التعريف السريري للحالة المشتبه بها ووجود رابط وبائي بحالة مؤكدة أو

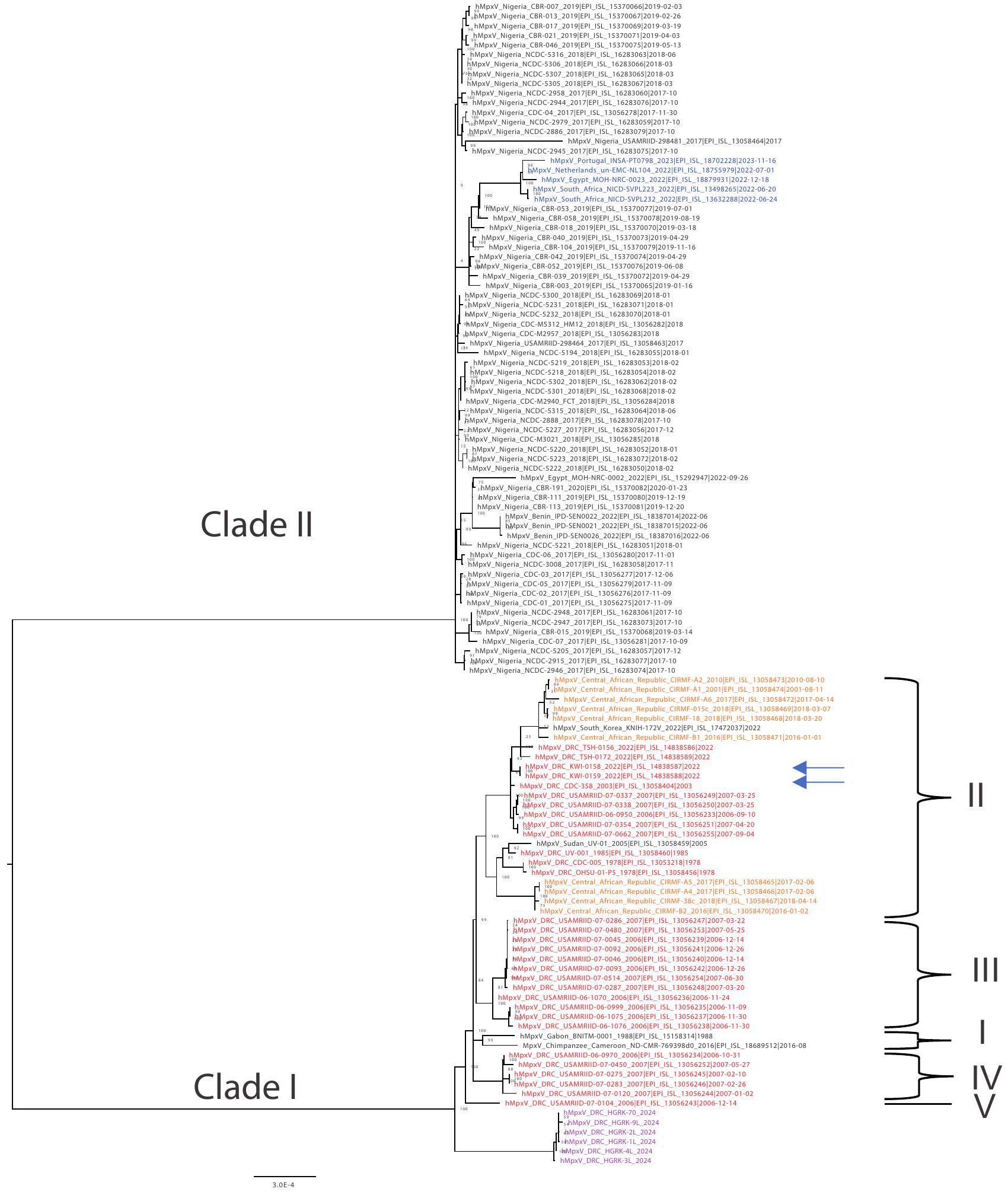

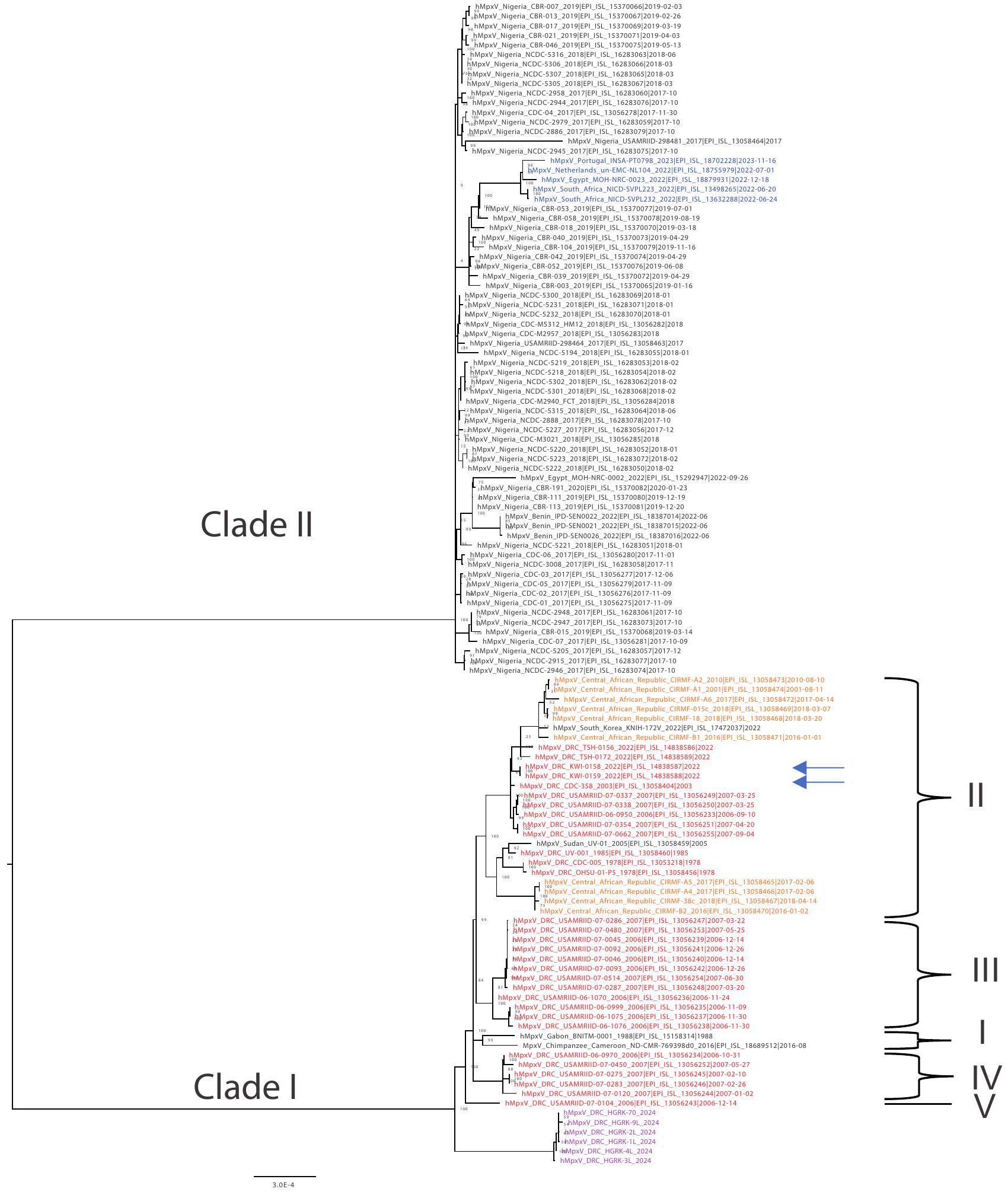

الشكل 1

تحليل النشوء والتطور لجميع تسلسلات الجينوم شبه الكاملة لفيروس المبوك المتاحة من إفريقيا على GISAID و NCBI بما في ذلك تسلسلات 2024 من كاميتيغا، جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية

تحليل النشوء والتطور لجميع تسلسلات الجينوم شبه الكاملة لفيروس المبوك المتاحة من إفريقيا على GISAID و NCBI بما في ذلك تسلسلات 2024 من كاميتيغا، جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية

جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية: جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية؛ NCBI: المركز الوطني لمعلومات التكنولوجيا الحيوية.

المقياس تحت الشجرة يمثل عدد الاستبدالات لكل موقع. تم تقديم التسلسلات من كاميتيغا باللون الأرجواني، والتسلسلات السابقة من جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية باللون الأحمر، والتسلسلات من تفشي عام 2022 باللون الأزرق [14]. تشير الأسهم إلى التسلسلات التي تم إظهارها في منشور سابق لتتجمع مع التسلسلات السابقة من تفشي فيروس MPXV في عام 2023 من مقاطعة كويلو بالقرب من كينشاسا [3]. يتم الإشارة إلى السلالات كما اقترحها ناكازاوا وآخرون [19] وبيرتيه وآخرون [20].

المقياس تحت الشجرة يمثل عدد الاستبدالات لكل موقع. تم تقديم التسلسلات من كاميتيغا باللون الأرجواني، والتسلسلات السابقة من جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية باللون الأحمر، والتسلسلات من تفشي عام 2022 باللون الأزرق [14]. تشير الأسهم إلى التسلسلات التي تم إظهارها في منشور سابق لتتجمع مع التسلسلات السابقة من تفشي فيروس MPXV في عام 2023 من مقاطعة كويلو بالقرب من كينشاسا [3]. يتم الإشارة إلى السلالات كما اقترحها ناكازاوا وآخرون [19] وبيرتيه وآخرون [20].

نحن نُعبر عن امتناننا لجميع المساهمين في البيانات، أي المؤلفين والمختبرات الأصلية المسؤولة عن الحصول على العينات، والمختبرات المقدمة التي قامت بتوليد التسلسل الجيني والبيانات الوصفية ومشاركتها عبر مبادرة GISAID، التي تستند إليها هذه البحث.

حالة محتملة؛ لم يتم تأكيد حالة محتملة في المختبر [4].

حالة محتملة؛ لم يتم تأكيد حالة محتملة في المختبر [4].

شملت الدراسة مرضى من محافظة جنوب كيفو في إقليم موينغا، الذين تم إدخالهم إلى مستشفى كاميتيغا، الذي يقع في منطقة كاميتيغا الصحية. تم الإبلاغ عن أول حالات جدري القردة في هذه المنطقة اعتبارًا من سبتمبر 2023.

تم تضمين 10 مرضى في الدراسة. جميعهم كانوا من البالغين الشباب في أواخر المراهقة حتى منتصف العشرينات، وكان خمسة منهم ذكورًا وخمسة إناث. فيما يتعلق بالمهن، كان معظم الأفراد المعنيين من العاملين في مجال الجنس. بالنسبة لهؤلاء المرضى، كانت الإقامة في مستشفى كاميتيغا قائمة على التشخيص السريري لمرض الميموكس من قبل موظفي المستشفى. وفقًا للإجراءات الروتينية، تم إرسال عينات من الآفات الجلدية ومسحات البلعوم من المرضى إلى المعهد الوطني للبحوث الطبية في جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية (المعهد الوطني للبحث البيولوجي؛ INRB) في غومًا لتأكيد الإصابة بفيروس MPXV بواسطة PCR، وقد كانت جميع الفحوصات إيجابية للفيروس.

تحضير مكتبة الحمض النووي، التسلسل والتحليل النشوي

تم جمع العينات من 10 مرضى على مدار شهر يناير 2024، وتم تخزينها في وسط نقل الفيروسات وتجميدها عند

تمت معالجة قراءات التسلسل باستخدام dorado v.7.2.13 مع نموذج استدعاء القواعد الفائق الدقة (ONT). تمت إزالة تسلسلات البرايمر باستخدام cutadapt v4.6 [6] وتم محاذاتها ضد مرجع MXPV (رقم الوصول في GenBank: OQ729808) في MinKNOW v23.11.5 (ONT). تم إنشاء الإجماع من ملف bam الناتج باستخدام samtools v1.19.2 كما هو موضح [7,8]. تم استخدام NextClade v3.1.0 لتعيين الفصائل وإجراء فحوصات الجودة [9].

تم محاذاة التسلسلات باستخدام MAFFT v7.520 [10]، وتم تنسيق المحاذاة يدويًا. تم إجراء تحليل النشوء والتطور باستخدام IQ-TREE v2.2.6 [11]، وتم تصويره باستخدام FigTree v1.4.4 [12]، ولتأكيد النتائج بشكل إضافي، تم أيضًا إجراء تحليل النشوء والتطور باستخدام NextStrain CLI v8.2.0 وتم تصويره في auspice.

تحديد فيروسات جدري القرود التي تنتمي إلى سلالة فرعية جديدة من المجموعة I

في وقت كتابة هذا التقرير، لم تكن هناك تسلسلات شبه كاملة من MPXV المتداولة في جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية من تفشي عام 2023 متاحة على قواعد البيانات العامة عبر الإنترنت. سمح تسلسل الأمبليكون المستهدف الذي تم إجراؤه لتوصيف تسلسلات MPXV في 10 مرضى تم إدخالهم إلى المستشفى بتوليد تسلسلات شبه كاملة من MPXV لستة منهم؛ جميعها تم تصنيفها على أنها من المجموعة I. تراوحت تغطية الجينوم بين

تم إجراء تحليل النشوء والتطور بما في ذلك 113 تسلسل جينوم مرجعي شبه كامل من mpox من إفريقيا متاحة من GISAID [13]، والتي تشمل جميع التسلسلات المتاحة في المركز الوطني لمعلومات التكنولوجيا الحيوية (NCBI) في 8 فبراير 2024 واثنين من التسلسلات الأوروبية من تفشي mpox العالمي الأخير في 2022 [14]. تم تجميع التسلسلات الستة من الدراسة الحالية مع التسلسلات المنشورة من المجموعة I، ولكن في سلالة فرعية متميزة عن جميع التسلسلات الأخرى من المجموعة I، مما يشير إلى أن التفشي المستمر في جنوب كيفو ناتج عن إدخال منفصل (الشكل 1 والشكل التكميلية 1 و 2). تحتوي التسلسلات الستة على عدة اختلافات في تعدد أشكال النوكليوتيدات المفردة (SNP) بينها، مما يشير إلى استمرار تداول سلالة التفشي هذه لبعض الوقت بالفعل.

تفتقر سلالة فيروس جدري القرود في جنوب كيفو إلى تسلسل الهدف المستخدم لتحديد فيروسات المجموعة I

للتحقق مما إذا كانت السلالات التي تم الحصول عليها في الدراسة الحالية يمكن اكتشافها بواسطة الفحوصات الجزيئية الشائعة المستخدمة لتشخيص عدوى MPXV، تم محاذاة تسلسلاتها مع تسلسل المجموعة I المرتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا EPI_ISL_13056243. يتطابق هذا التسلسل مع تسلسلات البرايمر والمسبار الموصى بها من قبل مراكز السيطرة على الأمراض والوقاية منها (CDC) في الولايات المتحدة لتشخيص MPXV [15]. تم تقييم المحاذاة باستخدام أداة فحص البرايمر الداخلية (https://viro-science-emc.shinyapps.io/primer-check/). بينما لا تزال البرايمرات والمسبار العامة تبدو فعالة مع وجود طفرة واحدة فقط في البرايمر العكسي، فإن الهدف المحدد لفيروس المجموعة I في PCR في الوقت الحقيقي، الموصى به من قبل CDC الأمريكي، غائب في جينومات سلالات MPXV الجديدة (الشكل 2 والشكل التكميلية 3). الحجم الملحوظ للحذف هو

نقاش

MPXV هو فيروس زونوتي ناشئ ينتمي إلى عائلة Poxviridae وجنس Orthopoxvirus. في الماضي، تم اكتشاف MPXV بشكل أساسي في غرب ووسط إفريقيا، ومع ذلك، في عام 2022، أعلنت منظمة الصحة العالمية

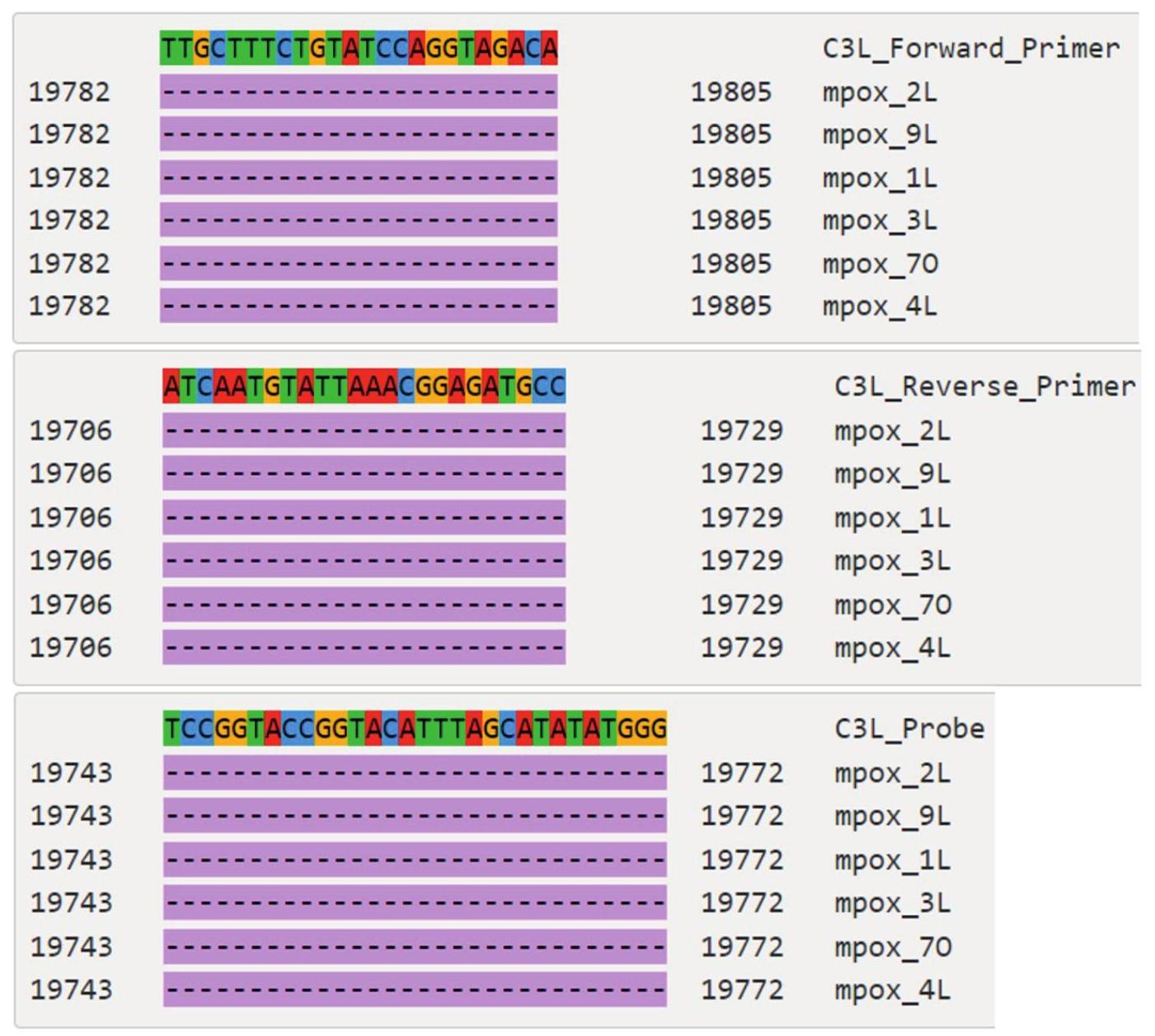

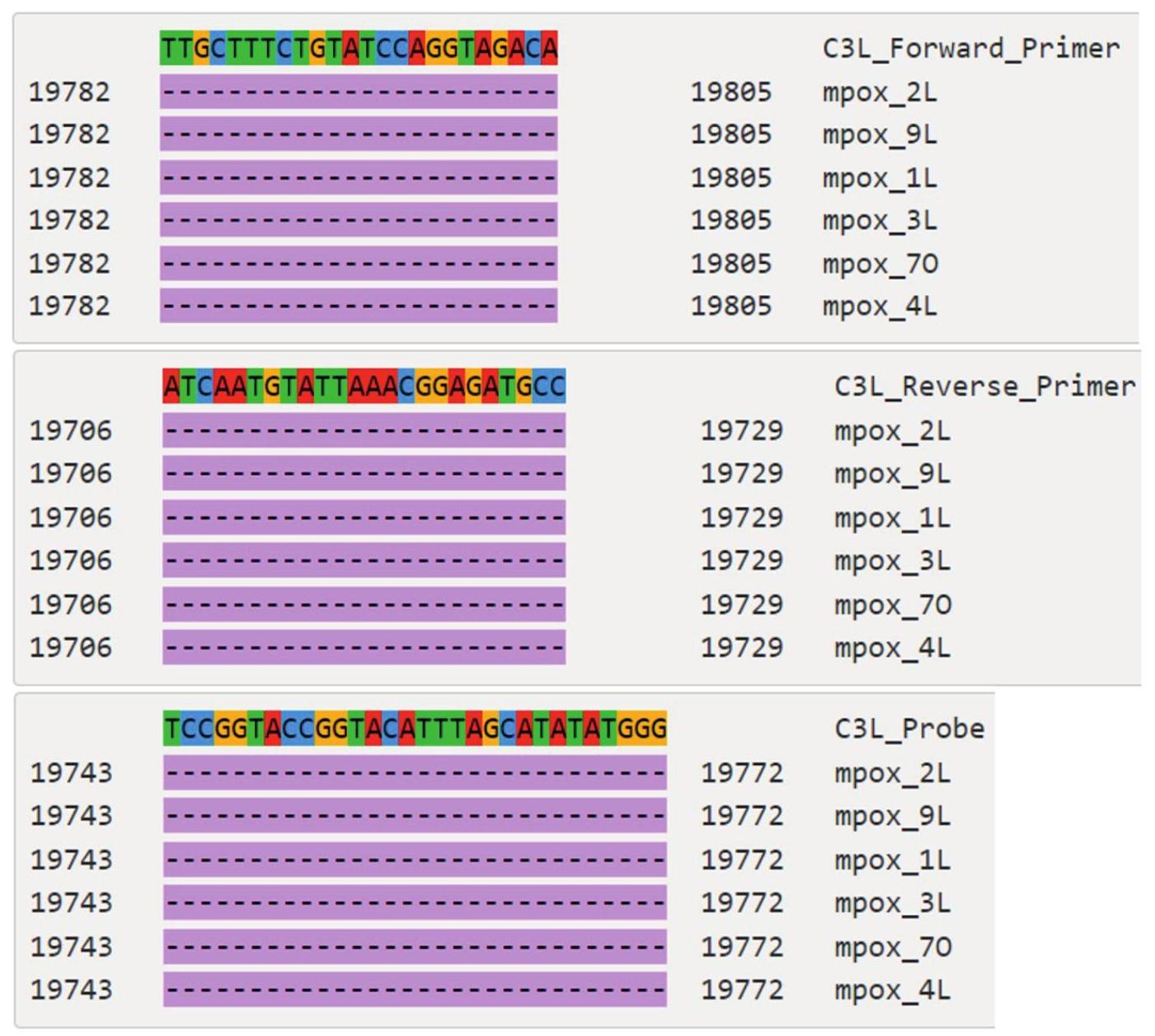

الشكل 2

تسلسلات المحاذاة التي تبرز ميزات التسلسل الجيني لـ MPXV المكتشف في كامتوجا مما يؤدي إلى (A) عدم تطابق nt واحد مع البرايمر العكسي العام الموصى به من قبل CDC (G2R_G البرايمر العكسي) و (B) غياب موقع الهدف المحدد للمجموعة I الموصى به من قبل CDC (C3L)، جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية، 2024

A. عدم تطابق nt واحد مع البرايمر العكسي العام الموصى به من قبل CDC

| GCTATCACATAATCTGGAAGCGTA | G2R_G_البرايمر_العكسي | ||

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_2L |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_9L |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_1L |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_3L |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_70 |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_4L |

B. غياب تسلسل الهدف ل PCR في الوقت الحقيقي المحدد للمجموعة I الموصى به من قبل CDC

CDC الأمريكية: مراكز السيطرة على الأمراض والوقاية منها في الولايات المتحدة؛ MPXV: فيروس جدري القرود.

التسلسل الذي يتطابق مع البرايمرات أو مواقع التحام المسبار الموصى بها من قبل CDC موجود في السطر العلوي، حيث يتم تمييز كل nt بلون مختلف. تمثل الخطوط الموجودة تحت السطر العلوي كل منها تسلسلات MPXV التي تم تحديدها في الدراسة الحالية، والتي تم محاذاتها مع التسلسل الموجود في السطر العلوي. في كل موضع من تسلسل الدراسة، يتم تمثيل الهوية مع التسلسل العلوي بنقطة. عندما يكون الاختلاف استبدالًا، يتم الإشارة إلى nt الموجود في كل تسلسل دراسة، وعندما يكون الاختلاف حذفًا، يتم تمثيله بشرطة مميزة باللون الأرجواني.

التسلسل الذي يتطابق مع البرايمرات أو مواقع التحام المسبار الموصى بها من قبل CDC موجود في السطر العلوي، حيث يتم تمييز كل nt بلون مختلف. تمثل الخطوط الموجودة تحت السطر العلوي كل منها تسلسلات MPXV التي تم تحديدها في الدراسة الحالية، والتي تم محاذاتها مع التسلسل الموجود في السطر العلوي. في كل موضع من تسلسل الدراسة، يتم تمثيل الهوية مع التسلسل العلوي بنقطة. عندما يكون الاختلاف استبدالًا، يتم الإشارة إلى nt الموجود في كل تسلسل دراسة، وعندما يكون الاختلاف حذفًا، يتم تمثيله بشرطة مميزة باللون الأرجواني.

تم تصويره بواسطة أداة فحص البرايمر: https://viroscience-emc.shinyapps.io/primer-check/.

أعلنت منظمة الصحة العالمية عن تفشي عالمي متعدد البلدان لفيروس MPXV من المجموعة IIb [14،16]. تم وصف هذا التفشي بشكل أساسي على أنه يؤثر على مجتمعات الرجال الذين يمارسون الجنس مع الرجال (MSM)، على الرغم من أنه تم الإبلاغ عن إصابات أيضًا في عدد محدود من الأشخاص الذين لا يمارسون الاتصال الجنسي مع الأفراد المصابين.

في جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية، حيث تم التعرف على العدوى البشرية بفيروس MPXV لأول مرة في عام 1970، تم الإبلاغ عن تفشي sporadic من mpox منذ ذلك الحين، مع زيادة التكرار بمرور الوقت [17]. تشير الزيادة الخاصة في عدد حالات MPXV المشتبه بها المسجلة في البلاد في عام 2023، وظهورها في مناطق جغرافية غير عادية [2] إلى احتمال حدوث تغيير في خصائص الفيروس وعلم الأوبئة للمرض. لذلك، يعتبر الحصول على معلومات التسلسل حول السلالة (السلالات) المتداولة أمرًا حاسمًا وقد تم توفير تدريب على تسلسل الجينوم الكامل لفيروس MPXV باستخدام تقنية نانو بور مؤخرًا للعلماء المحليين من رواندا وجمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية لأداء كل من تسلسل المختبر الرطب وتحليل تسلسل المختبر الجاف.

من تفشي mpox في كامتوجا، جنوب كيفو، تم الحصول على ستة تسلسلات شبه كاملة من MPXV مشتقة من مرضى محليين تم إدخالهم إلى المستشفى بسبب mpox. وضعت تحليلات النشوء والتطور لهذه التسلسلات مع تلك المتاحة لفيروسات المجموعة I و II الأخرى، في سلالة فرعية جديدة بالقرب من جذر المجموعة I، مما يشير إلى أن التفشي في هذه المنطقة ناتج عن إدخال جديد، على الأرجح من خزان زونوتي. على الرغم من أن التسلسلات من تفشي صغير في كينشاسا في عام 2023 غير متاحة للجمهور، فإن وضع تلك التسلسلات في شجرة النشوء والتطور المنشورة [3] يشير إلى أن تفشي كامتوجا ليس مرتبطًا بالتفشي في كينشاسا. وبالتالي، تشير نتائجنا إلى أن هناك على الأقل تفشيين مستقلين مستمرين في جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية.

من المRemarkably، كان هناك جزء كبير من التسلسل في الجينومات التي تنتمي إلى سلالة MPXV الجديدة غائبًا مقارنةً بجينومات المجموعة I الأخرى، مما قد يؤدي إلى فشل PCR المحدد للمجموعة I الموصى به من قبل CDC الأمريكي [15]. تم أيضًا ملاحظة حذف في نفس المنطقة في MPXV من المجموعة II، وكان هذا هو الأساس لتعيين المجموعة باستخدام PCR من CDC. لذلك، إذا انتشرت الفيروسات من السلالة الجديدة دوليًا، فلا يمكن استخدام هذه الأداة للمراقبة الجزيئية بسرعة لتحديد هذه العدوى بفيروس المجموعة I بينما يستمر التفشي العالمي للمجموعة IIb.

تم تطوير وتطبيق العديد من الفحوصات المعتمدة على الأمبليكون التي تستهدف MPXV من المجموعة IIb منذ تفشي mpox العالمي في عام 2022 [5،18]. في العمل الحالي، أدى تطبيق فحص كبير من الأمبليكون الذي تم تصميمه في الأصل لاستهداف المجموعة IIb إلى تغطية جينومية متوسطة قدرها

إنشاء التوافق باستخدام محاذاة قائمة على المرجع باستخدام بيانات نانو بور. قد تكون هناك حاجة إلى تسلسل نانو بور أو إيلومينا الميتاجينومي بالاقتران مع أساليب التجميع de novo لاستدعاء توافق مصقول، ومع ذلك، لم يكن ذلك ممكنًا هنا، مما يجعل هذا قيدًا على العمل الحالي. هناك حاجة إلى دراسات إضافية لتقييم قابلية الانتقال وشدة السريرية المرتبطة بالسلالة الجديدة.

إنشاء التوافق باستخدام محاذاة قائمة على المرجع باستخدام بيانات نانو بور. قد تكون هناك حاجة إلى تسلسل نانو بور أو إيلومينا الميتاجينومي بالاقتران مع أساليب التجميع de novo لاستدعاء توافق مصقول، ومع ذلك، لم يكن ذلك ممكنًا هنا، مما يجعل هذا قيدًا على العمل الحالي. هناك حاجة إلى دراسات إضافية لتقييم قابلية الانتقال وشدة السريرية المرتبطة بالسلالة الجديدة.

استنتاج

بشكل عام، تشير نتائج هذه الدراسة بقوة إلى أن تسلسل الجينوم الكامل لمجموعة أكبر من MPXV التي تسبب حاليًا حالات mpox في جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية، بالإضافة إلى مشاركة البيانات العامة، أمران أساسيان لفهم الوباء المستمر. الدراسات الإضافية، والتسلسل، والتحليلات جارية، ولكن وفقًا للبيان أعلاه نعتقد أن المشاركة السريعة لجميع المعلومات المتاحة أمر ضروري للمساعدة في فهم واحتواء ظهور mpox الحالي بشكل أفضل.

عند نشر المقال، كانت بعض أرقام الانتماء في قائمة المؤلفين غير صحيحة بالنسبة للمؤلفين التاليين: جاستين بنغيهيا مبيريبيندي، جان بيير موسابييمانا وفريدي بيلسي سيانغولي. تم تصحيح أرقام الانتماء بناءً على طلب المؤلفين في 18 مارس 2024.

عند نشر المقال، كانت بعض أرقام الانتماء في قائمة المؤلفين غير صحيحة بالنسبة للمؤلفين التاليين: جاستين بنغيهيا مبيريبيندي، جان بيير موسابييمانا وفريدي بيلسي سيانغولي. تم تصحيح أرقام الانتماء بناءً على طلب المؤلفين في 18 مارس 2024.

بيان أخلاقي

تم الحصول على الموافقة الأخلاقية لإجراء هذه الدراسة من لجنة المراجعة الأخلاقية في الجامعة الكاثوليكية في بوكافو (رقم UCB/CIES/NC/022/2023).

تم الحصول على الموافقة الأخلاقية لإجراء هذه الدراسة من لجنة المراجعة الأخلاقية في الجامعة الكاثوليكية في بوكافو (رقم UCB/CIES/NC/022/2023).

توفر البيانات

تم تحميل تسلسلات الإجماع على GISAID مع أرقام الوصول: EPI_ISL_18886301، EPI_ISL_18886588، EPI_ISL_18886467، EPI_ISL_18886467، EPI_ISL_18886588 و EPI_ISL_18886301. تم تحميل بيانات التسلسل الخام إلى ENA تحت معرف الدراسة: ERP157439.

تم تحميل تسلسلات الإجماع على GISAID مع أرقام الوصول: EPI_ISL_18886301، EPI_ISL_18886588، EPI_ISL_18886467، EPI_ISL_18886467، EPI_ISL_18886588 و EPI_ISL_18886301. تم تحميل بيانات التسلسل الخام إلى ENA تحت معرف الدراسة: ERP157439.

الشكر والتقدير

تم تمويل هذا العمل من قبل منح الاتحاد الأوروبي Horizon 2020 VEO (874735) وبرنامج Global Health EDCTP3 Joint Undertaking (Global Health EDCTP3) بموجب اتفاقية المنحة رقم 101103059 (GREATLIFE). نشكر بشدة جامعة دالهوزي، كندا على دعمها للأعمال الميدانية، والمعهد الوطني للبحوث البيولوجية (INRB) في غومه لتشخيص PCR.

نود أن نشكر قسم الصحة الإقليمي (DPS) في جنوب كيفو ومنطقة صحة كاميتيغا (KHZ) على تعاونهم خلال الدراسة. نشكر بشدة شبكة الحفاظ على الحياة البرية (WCN) وشبكة أبحاث العمل للحفاظ على البيئة (CARN) على المنح الدراسية ودعم الأبحاث التي قدموها للمؤلف الأول.

نحن نقدر جميع المساهمين في البيانات، أي المؤلفين ومختبراتهم الأصلية المسؤولة عن الحصول على العينات، ومختبراتهم المقدمة التي تولت إنتاج التسلسل الجيني والبيانات الوصفية ومشاركتها عبر مبادرة GISAID، التي تستند إليها هذه الأبحاث.

تعارض المصالح

لا يوجد ما يُعلن عنه.

مساهمات المؤلفين

LMM، JCU، PN، MK، BBOM، FMA، FBS، JPM قاموا بتصميم الدراسة، LMM، MB، JCU، PN، LS، DFN، SO، FMA، BBOM، FBS ساهموا في جمع البيانات وتفسيرها، وصاغوا، وراجعوا المخطوطة. JBM، JMM، LMM، NMB، TL، EBK، كانوا متورطين في جمع العينات والتحقيق. جميع المؤلفين وافقوا على النسخة النهائية.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mpox (monkeypox) Democratic Republic of the Congo. Geneva: WHO; 23 Nov 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/ disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON493

- Multi-country outbreak of mpox. External situation report#30 – 25 November 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Accessed 14 Feb 2024]. Available from: https://www.who. int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-mpox–external-situation-report-30—25-november-2023

- Kibungu EM, Vakaniaki EH, Kinganda-Lusamaki E, KalonjiMukendi T, Pukuta E, Hoff NA, et al. , International Mpox Research Consortium. Clade I-Associated Mpox Cases Associated with Sexual Contact, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30(1):172-6. https://doi. org/10.3201/eid3001.231164 PMID: 38019211

- Murhula LM, Udahemuka JC, Ndishimye P, Sganzerla Martinez G, Kelvin P, Bubala Nadine M, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and transmission patterns of a novel Mpox (Monkeypox) outbreak in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): an observational, cross-sectional cohort study. medRxiv. 2024.03.05.24303395. Preprint. https://doi. org/10.1038/S41598-021-92315-8 PMID: 34158533

- Welkers M, Jonges M, Van Den Ouden A. Monkeypox virus whole genome sequencing using combination of NextGenPCR and Oxford Nanopore. protocols.io. 12 Jul 2022. Available from: https://protocols.io/view/monkeypox-virus-whole-genome-sequencing-using-comb-ccc7sszn

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from highthroughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011;17(1):10. https:// doi.org/10.14806/ej.17.1.200

- Schuele L, Boter M, Nieuwenhuijse DF, Götz H, Fanoy E, de Vries H, et al. Circulation, viral diversity and genomic rearrangement in mpox virus in the Netherlands during the 2022 outbreak and beyond. J Med Virol. 2024;96(1):e29397. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv. 29397 PMID: 38235923

- Nieuwenhuijse DF, van der Linden A, Kohl RHG, Sikkema RS, Koopmans MPG, Oude Munnink BB. Towards reliable whole genome sequencing for outbreak preparedness and response. BMC Genomics. 2022;23(1):569. https://doi.org/10.1186/ S12864-022-08749-5 PMID: 35945497

- Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, Huddleston J, Potter B, Callender C, et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(23):4121-3. https://doi.org/10.1093/ bioinformatics/bty407 PMID: 29790939

- Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(14):3059-66. https:// doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkf436 PMID: 12136088

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37(5):1530-4. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/ msaao15 PMID: 32011700

- Rambaut A. FigTree. 2016. Available from: http://tree.bio. ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

- Elbe S, Buckland-Merrett G. Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID’s innovative contribution to global health. Glob Chall. 2017;1(1):33-46. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.1018 PMID: 31565258

- World Health Organization (WHO). Multi-country monkeypox outbreak in non-endemic countries. Geneva: WHO; 21 May 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/ disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON385

- Li Y, Zhao H, Wilkins K, Hughes C, Damon IK. Real-time PCR assays for the specific detection of monkeypox

virus West African and Congo Basin strain DNA. J Virol Methods. 2010;169(1):223-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jviromet.2010.07.012 PMID: 20643162 - World Health Organization (WHO). Monkeypox: experts give virus variants new names. Geneva: WHO; 12 August 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/12-08-2022-monkeypox–experts-give-virus-variants-new-names

- Ladnyj ID, Ziegler P, Kima E. A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46(5):593-7. PMID: 4340218

- Brinkmann A, Pape K, Uddin S, Woelk N, Förster S, Jessen H, et al. Genome sequencing of the mpox virus 2022 outbreak with amplicon-based Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencing. J Virol Methods. 2024;325:114888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jviromet.2024.114888 PMID: 38246565

- Nakazawa Y, Mauldin MR, Emerson GL, Reynolds MG, Lash RR, Gao J, et al. A phylogeographic investigation of African monkeypox. Viruses. 2015;7(4):2168-84. https://doi. org/10.3390/v7042168 PMID: 25912718

- Berthet N, Descorps-Declère S, Besombes C, Curaudeau M, Nkili Meyong AA, Selekon B, et al. Genomic history of human monkey pox infections in the Central African Republic between 2001 and 2018. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13085. https://doi. org/10.1038/S41598-021-92315-8 PMID: 34158533

الرخصة، المواد التكميلية وحقوق الطبع والنشر

هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول موزعة بموجب شروط رخصة المشاع الإبداعي (CC BY 4.0). يمكنك مشاركة وتكييف المادة، ولكن يجب أن تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمصدر، وتوفير رابط للرخصة والإشارة إذا تم إجراء تغييرات.

يمكن العثور على أي مواد تكميلية تم الإشارة إليها في المقال في النسخة الإلكترونية.

هذه المقالة هي حقوق الطبع والنشر للمؤلفين أو مؤسساتهم المرتبطة، 2024.

Journal: Eurosurveillance, Volume: 29, Issue: 11

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2024.29.11.2400106

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38487886

Publication Date: 2024-03-14

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2024.29.11.2400106

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38487886

Publication Date: 2024-03-14

Ongoing mpox outbreak in Kamituga, South Kivu province, associated with monkeypox virus of a novel Clade I sub-lineage, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2024

Correspondence: Leandre Murhula (leandremurhula@gmail.com)

Citation style for this article:

Masirika Leandre Murhula, Udahemuka Jean Claude, Schuele Leonard, Ndishimye Pacifique, Otani Saria, Mbiribindi Justin Bengehya, Marekani Jean M., Mambo Léandre Mutimbwa, Bubala Nadine Malyamungu, Boter Marjan, Nieuwenhuijse David F., Lang Trudie, Kalalizi Ernest Balyahamwabo, Musabyimana Jean Pierre, Aarestrup Frank M., Koopmans Marion, Oude Munnink Bas B., Siangoli Freddy Belesi. Ongoing mpox outbreak in Kamituga, South Kivu province, associated with monkeypox virus of a novel Clade I sub-lineage, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2024. Euro Surveill. 2024;29(11):pii=2400106. https://doi.org/10.2807/15607917.ES.2024.29.11.2400106

Masirika Leandre Murhula, Udahemuka Jean Claude, Schuele Leonard, Ndishimye Pacifique, Otani Saria, Mbiribindi Justin Bengehya, Marekani Jean M., Mambo Léandre Mutimbwa, Bubala Nadine Malyamungu, Boter Marjan, Nieuwenhuijse David F., Lang Trudie, Kalalizi Ernest Balyahamwabo, Musabyimana Jean Pierre, Aarestrup Frank M., Koopmans Marion, Oude Munnink Bas B., Siangoli Freddy Belesi. Ongoing mpox outbreak in Kamituga, South Kivu province, associated with monkeypox virus of a novel Clade I sub-lineage, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2024. Euro Surveill. 2024;29(11):pii=2400106. https://doi.org/10.2807/15607917.ES.2024.29.11.2400106

Article submitted on 14 Feb 2024 / accepted on 13 Mar 2024 / published on 14 Mar 2024

Since the beginning of 2023, the number of people with suspected monkeypox virus (MPXV) infection have sharply increased in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). We report near-to-complete MPXV genome sequences derived from six cases from the South Kivu province. Phylogenetic analyses reveal that the MPXV affecting the cases belongs to a novel Clade I sub-lineage. The outbreak strain genome lacks the target sequence of the probe and primers of a commonly used Clade I-specific real-time PCR.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the numbers of people with suspected infection with monkeypox virus (MPXV), the virus that causes mpox, have increased since the start of 2023. A total of 12,569 suspected mpox cases have been reported up to 12 November, the highest number of annual cases ever recorded [1]. The case fatality rate has been estimated at

Kivu province [ 1,2 ]. Despite this concerning situation, there is only limited genomic information available on the circulating viruses, which suggests that they belong to Clade I [3]. To gain more insight into the characteristics of the strains causing the epidemic, as well as assurance that current and commonly used molecular assays to diagnose MPXV infections can detect these strains, we sequenced monkeypox viral genomes from recently diagnosed cases in South Kivu, DRC.

Case definitions and patient characteristics

A case was listed as ‘suspect’ if presenting with an acute illness with fever, intense headache, myalgia, and back pain, followed by 1 to 3 days of a progressively developing rash often starting on the face and spreading on the body. A confirmed mpox case had a monkeypox virus infection which was laboratory-confirmed by PCR. A case was listed as ‘probable’ when satisfying the clinical definition of a suspected case and having an epidemiological link to a confirmed or

Figure 1

Phylogenetic analysis of all near-to-complete genome mpox sequences from Africa available on GISAID and the NCBI including the 2024 sequences from Kamituga, Democratic Republic of the Congo (

Phylogenetic analysis of all near-to-complete genome mpox sequences from Africa available on GISAID and the NCBI including the 2024 sequences from Kamituga, Democratic Republic of the Congo (

DRC: Democratic Republic of the Congo; NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information.

The scale under the tree represents the number of substitutions per site. Sequences from Kamituga are presented in magenta, previous sequences from DRC in red and sequences from the 2022 outbreak in blue [14]. Arrows indicate sequences which have been shown in a prior publication to cluster with the previous sequences from a 2023 MPXV outbreak from Kwilu Province near Kinshasa [3]. Lineages are indicated as proposed by Nakazawa et al. [19] and Berthet et al. [20].

The scale under the tree represents the number of substitutions per site. Sequences from Kamituga are presented in magenta, previous sequences from DRC in red and sequences from the 2022 outbreak in blue [14]. Arrows indicate sequences which have been shown in a prior publication to cluster with the previous sequences from a 2023 MPXV outbreak from Kwilu Province near Kinshasa [3]. Lineages are indicated as proposed by Nakazawa et al. [19] and Berthet et al. [20].

We gratefully acknowledge all data contributors, i.e., the authors and their originating laboratories responsible for obtaining the specimens, and their submitting laboratories for generating the genetic sequence and metadata and sharing via the GISAID Initiative, on which this research is based.

probable case; a probable case was not laboratoryconfirmed [4].

probable case; a probable case was not laboratoryconfirmed [4].

The study involved patients from South Kivu province in the territory of Mwenga, who were hospitalised in the Kamituga hospital, which is in the Kamituga health zone. The first mpox cases in this area were reported from September 2023 onwards.

A total of 10 patients were included in the study. All were young adults in their late teenage up to the age of mid-20 years and five were male and five females. Regarding professions comprised, the majority of the concerned individuals were sex workers. For these patients, admission to the Kamituga Hospital had been based on clinical diagnosis of mpox by hospital staff. According to routines, skin lesion and oropharyngeal swabs collected from the patients had been sent to the national medical research institute of the DRC (Institut National de la Recherche Biomédicale; INRB) in Goma for MPXV infection confirmation by PCR, and all patients had tested positive for the virus.

DNA library preparation, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

The samples from the 10 patients had been collected throughout the month of January 2024, stored in virus transport medium and frozen at

Sequencing reads were basecalled using dorado v.7.2.13 with the super-accurate base calling model (ONT). Primer sequences were removed using cutadapt v4.6 [6] and aligned against a MXPV reference (GenBank accession: OQ729808) in MinKNOW v23.11.5 (ONT). The consensus was created from the resulting bam file using samtools v1.19.2 as described [7,8]. NextClade v3.1.0 was used for clade assignment and quality checks [9].

Sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.520 [10], and the alignment manually curated. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using IQ-TREE v2.2.6 [11], visualised with FigTree v1.4.4 [12], and for additional confirmation of the results, phylogenetic analysis was also performed using NextStrain CLI v8.2.0 and visualised in auspice.

Identification of monkeypox viruses belonging to novel Clade I sub-lineage

At the time of writing, no near-complete sequences of MPXV circulating in DRC from the 2023 outbreak were available on (public) online databases. The targeted amplicon sequencing conducted to characterise MPXV sequences in the 10 hospitalised study patients allowed to generate near-complete MPXV sequences for six of them; all were classified as Clade I. The genome coverage ranged between

Phylogenetic analysis was done including 113 near-to-complete genome reference mpox sequences from Africa available from GISAID [13], which include all sequences available on the National Center for Biotechnological Information (NCBI) on 8 February 2024 and two European sequences from the recent 2022 global mpox outbreak [14]. The six sequences from the current study grouped with published Clade I sequences, but in a distinct sub-lineage from all other Clade I sequences, suggesting that the ongoing outbreak in South Kivu results from a separate introduction ( Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1 and 2 ). The six sequences have several single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) differences between them, which suggests ongoing circulation of this outbreak strain for some time already.

The monkeypox virus outbreak strain in South Kivu lacks the target sequence used for identifying Clade I viruses

To check if the strains obtained in the current study could be detected by commonly used molecular assays to diagnose MPXV infections, their sequences were aligned to the closely related Clade I sequence EPI_ISL_13056243. This sequence matches primer and probe sequences recommended by the United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to diagnose MPXV [15]. The alignment was assessed using an in-house Primer Check Tool (https://viro-science-emc.shinyapps.io/primer-check/). While the generic primers and probe still seem to be functional with only one mutation in the reverse primer, the specific Clade I virus real-time PCR target, recommended by the US CDC, is absent in the genomes of the novel MPXV strains ( Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 3). The observed deletion is

Discussion

MPXV is an emerging zoonotic virus belonging to the Poxviridae family and the genus Orthopoxvirus. In the past, MPXV has been primarily detected in West and Central Africa, however, in 2022 the World Health

Figure 2

Sequence alignments highlighting genetic sequence features of the MPXV detected in Kamituga resulting in (A) a single nt mismatch with US CDC recommended generic reverse primer (G2R_G reverse primer) and (B) absence of the US CDC recommended clade I specific forward, reverse, and probe target location (C3L), Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2024

A. Single nt mismatch with CDC-recommended generic reverse primer

| GCTATCACATAATCTGGAAGCGTA | G2R_G_Reverse_Primer | ||

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_2L |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_9L |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_1L |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_3L |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_70 |

| 194834 |

|

194857 | mpox_4L |

B. Absence of target sequence for CDC-recommended Clade-I-specific real-time PCR

US CDC: United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; MPXV: monkeypox virus.

The sequence matching the US CDC primers or probe annealing sites is on the top line, where each nt is highlighted in a different colour. The lines underneath the top line each represent sequences of the MPXV identified in the current study, which are aligned to the sequence on the top line. At each position of a study sequence, identity to the top sequence is represented by a dot. When a difference is a substitution, the nt present in each study sequences is indicated, when a difference is a deletion, this is represented by a dash highlighted in purple.

The sequence matching the US CDC primers or probe annealing sites is on the top line, where each nt is highlighted in a different colour. The lines underneath the top line each represent sequences of the MPXV identified in the current study, which are aligned to the sequence on the top line. At each position of a study sequence, identity to the top sequence is represented by a dot. When a difference is a substitution, the nt present in each study sequences is indicated, when a difference is a deletion, this is represented by a dash highlighted in purple.

Visualised by primer-check tool: https://viroscience-emc.shinyapps.io/primer-check/.

Organization (WHO) declared a multi-country global outbreak of MPXV of Clade IIb [14,16]. This outbreak was predominantly described as affecting communities of men having sex with men (MSM), although infections were also reported in a limited number of people not engaging in sexual contact with infected individuals.

In DRC, where human infection with MPXV was first ever recognised in 1970, sporadic mpox outbreaks have been reported since, with increasing frequency over time [17]. The particular rise in the number of suspected MPXV cases recorded in the country in 2023, and their occurrence in unusual geographic areas [2] suggests a possible change in the characteristics of the virus and the epidemiology of the disease. Therefore, obtaining sequence information on the circulating strain(s) is considered crucial and MPXV whole genome Nanopore sequencing training has been provided recently to local scientists from Rwanda and DRC to perform both wetlaboratory sequencing and dry-laboratory sequence analysis.

From the mpox outbreak in Kamituga, South Kivu, six near-to-complete MPXV sequences derived from local patients hospitalised with mpox were obtained. Phylogenetic analyses of these sequences together with those available for other Clade I and II viruses, placed them in a new sub-lineage near the root of Clade I, which suggests that the outbreak in this region results from a new introduction, most likely from a zoonotic reservoir. Although sequences from a small 2023 Kinshasa outbreak are not publicly available, the placement of those sequences in a published phylogenetic tree [3] suggests that the Kamituga outbreak is not related to the outbreak in Kinshasa. Our findings therefore suggest that there are at least two independent outbreaks ongoing in DRC.

Remarkably, a large stretch of sequence in the genomes belonging to the novel MPXV sub-lineage was absent compared to other Clade I genomes, which would lead to failure of the Clade I-specific real-time PCR recommended by the US CDC [15]. A deletion in the same region is also observed in Clade II MPXV, and this was the basis for clade assignment using the CDC PCR. Therefore, if the viruses from the new lineage were to spread internationally, this molecular surveillance tool can no longer be used to rapidly identify these Clade I virus infections while the global Clade IIb outbreak is ongoing.

Multiple amplicon-based assays targeting Clade IIb MPXV have been developed and applied since the global mpox outbreak in 2022 [5,18]. In the current work, the application of a large amplicon assay which was originally designed to target Clade llb resulted in an average genome coverage of

generated using a reference-based alignment using Nanopore data. Metagenomic Nanopore or Illumina sequencing might be needed in combination with de novo assembly approaches for refined consensus calling, however, this was not possible here, making this a limitation of the current work. Further studies are needed/ongoing to assess transmissibility and clinical severity associated with the new lineage.

generated using a reference-based alignment using Nanopore data. Metagenomic Nanopore or Illumina sequencing might be needed in combination with de novo assembly approaches for refined consensus calling, however, this was not possible here, making this a limitation of the current work. Further studies are needed/ongoing to assess transmissibility and clinical severity associated with the new lineage.

Conclusion

Altogether, the findings of this study strongly suggest that whole genome sequencing of a larger subset of MPXV currently causing mpox cases in DRC, as well as public data sharing, are essential to understand the ongoing epidemic. Further studies, sequencing and analyses are ongoing, but in accordance with the above statement we believe that rapid public sharing of all available information is essential to help to better understand and contain the current mpox emergence.

Upon publication of the article, some affiliation numbers in the authors’ list were incorrect for the following authors: Justin Bengehya Mbiribindi, Jean Pierre Musabyimana and Freddy Belesi Siangoli. Affiliation numbers were corrected at the request of the authors on 18 March 2024.

Upon publication of the article, some affiliation numbers in the authors’ list were incorrect for the following authors: Justin Bengehya Mbiribindi, Jean Pierre Musabyimana and Freddy Belesi Siangoli. Affiliation numbers were corrected at the request of the authors on 18 March 2024.

Ethical statement

Ethical clearance to conduct this study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Catholic University of Bukavu (Number UCB/CIES/NC/022/2023).

Ethical clearance to conduct this study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Catholic University of Bukavu (Number UCB/CIES/NC/022/2023).

Data availability

Consensus sequences were uploaded on GISAID with the accession numbers: EPI_ISL_18886301, EPI_ISL_18886588, EPI_ISL_18886467, EPI_ISL_18886467, EPI_ISL_18886588 and EPI_ISL_18886301. Raw sequence data was uploaded to the ENA under the study ID: ERP157439.

Consensus sequences were uploaded on GISAID with the accession numbers: EPI_ISL_18886301, EPI_ISL_18886588, EPI_ISL_18886467, EPI_ISL_18886467, EPI_ISL_18886588 and EPI_ISL_18886301. Raw sequence data was uploaded to the ENA under the study ID: ERP157439.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the EU Horizon 2020 grants VEO (874735) and the Global Health EDCTP3 Joint Undertaking (Global Health EDCTP3) programme under grant agreement No. 101103059 (GREATLIFE). We greatly thank the University of Dalhousie, Canada for supporting the field works, and the Institut National de Recherche Biomedicale (INRB) Goma for PCR diagnostics.

We would like to thank the Provincial Division of Health (DPS) of South-Kivu and Kamituga Health Zone (KHZ) for their collaboration during the study. We greatly thank Wildlife Conservation Network (WCN) and Conservation Action Research Network (CARN) for the scholarship and research supports they awarded to the first author.

We gratefully acknowledge all data contributors, i.e., the Authors and their Originating laboratories responsible for obtaining the specimens, and their Submitting laboratories for generating the genetic sequence and metadata and sharing via the GISAID Initiative, on which this research is based.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Authors’ contributions

LMM, JCU, PN, MK, BBOM, FMA, FBS, JPM conceptualised and designed the study, LMM, MB, JCU, PN, LS, DFN, SO, FMA, BBOM, FBS contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, drafted, cross-reviewed the manuscript. JBM, JMM, LMM, NMB, TL, EBK, were involved in sample collection and investigation. All authors approved the final version.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mpox (monkeypox) Democratic Republic of the Congo. Geneva: WHO; 23 Nov 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/ disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON493

- Multi-country outbreak of mpox. External situation report#30 – 25 November 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Accessed 14 Feb 2024]. Available from: https://www.who. int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-mpox–external-situation-report-30—25-november-2023

- Kibungu EM, Vakaniaki EH, Kinganda-Lusamaki E, KalonjiMukendi T, Pukuta E, Hoff NA, et al. , International Mpox Research Consortium. Clade I-Associated Mpox Cases Associated with Sexual Contact, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30(1):172-6. https://doi. org/10.3201/eid3001.231164 PMID: 38019211

- Murhula LM, Udahemuka JC, Ndishimye P, Sganzerla Martinez G, Kelvin P, Bubala Nadine M, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and transmission patterns of a novel Mpox (Monkeypox) outbreak in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): an observational, cross-sectional cohort study. medRxiv. 2024.03.05.24303395. Preprint. https://doi. org/10.1038/S41598-021-92315-8 PMID: 34158533

- Welkers M, Jonges M, Van Den Ouden A. Monkeypox virus whole genome sequencing using combination of NextGenPCR and Oxford Nanopore. protocols.io. 12 Jul 2022. Available from: https://protocols.io/view/monkeypox-virus-whole-genome-sequencing-using-comb-ccc7sszn

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from highthroughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011;17(1):10. https:// doi.org/10.14806/ej.17.1.200

- Schuele L, Boter M, Nieuwenhuijse DF, Götz H, Fanoy E, de Vries H, et al. Circulation, viral diversity and genomic rearrangement in mpox virus in the Netherlands during the 2022 outbreak and beyond. J Med Virol. 2024;96(1):e29397. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv. 29397 PMID: 38235923

- Nieuwenhuijse DF, van der Linden A, Kohl RHG, Sikkema RS, Koopmans MPG, Oude Munnink BB. Towards reliable whole genome sequencing for outbreak preparedness and response. BMC Genomics. 2022;23(1):569. https://doi.org/10.1186/ S12864-022-08749-5 PMID: 35945497

- Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, Huddleston J, Potter B, Callender C, et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(23):4121-3. https://doi.org/10.1093/ bioinformatics/bty407 PMID: 29790939

- Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(14):3059-66. https:// doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkf436 PMID: 12136088

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37(5):1530-4. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/ msaao15 PMID: 32011700

- Rambaut A. FigTree. 2016. Available from: http://tree.bio. ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

- Elbe S, Buckland-Merrett G. Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID’s innovative contribution to global health. Glob Chall. 2017;1(1):33-46. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.1018 PMID: 31565258

- World Health Organization (WHO). Multi-country monkeypox outbreak in non-endemic countries. Geneva: WHO; 21 May 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/ disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON385

- Li Y, Zhao H, Wilkins K, Hughes C, Damon IK. Real-time PCR assays for the specific detection of monkeypox

virus West African and Congo Basin strain DNA. J Virol Methods. 2010;169(1):223-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jviromet.2010.07.012 PMID: 20643162 - World Health Organization (WHO). Monkeypox: experts give virus variants new names. Geneva: WHO; 12 August 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/12-08-2022-monkeypox–experts-give-virus-variants-new-names

- Ladnyj ID, Ziegler P, Kima E. A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46(5):593-7. PMID: 4340218

- Brinkmann A, Pape K, Uddin S, Woelk N, Förster S, Jessen H, et al. Genome sequencing of the mpox virus 2022 outbreak with amplicon-based Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencing. J Virol Methods. 2024;325:114888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jviromet.2024.114888 PMID: 38246565

- Nakazawa Y, Mauldin MR, Emerson GL, Reynolds MG, Lash RR, Gao J, et al. A phylogeographic investigation of African monkeypox. Viruses. 2015;7(4):2168-84. https://doi. org/10.3390/v7042168 PMID: 25912718

- Berthet N, Descorps-Declère S, Besombes C, Curaudeau M, Nkili Meyong AA, Selekon B, et al. Genomic history of human monkey pox infections in the Central African Republic between 2001 and 2018. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13085. https://doi. org/10.1038/S41598-021-92315-8 PMID: 34158533

License, supplementary material and copyright

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) Licence. You may share and adapt the material, but must give appropriate credit to the source, provide a link to the licence and indicate if changes were made.

Any supplementary material referenced in the article can be found in the online version.

This article is copyright of the authors or their affiliated institutions, 2024.