المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 14، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48612-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195778

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-09

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48612-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195778

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-09

تقييم ضعف السواحل في غرب أفريقيا تجاه الفيضانات والتآكل

تتعرض المناطق الساحلية العالمية للخطر بسبب القضايا الجيومورفولوجية، وارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر الناتج عن تغير المناخ، وزيادة عدد السكان، والمستوطنات، والأنشطة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية. هنا، تدرس الدراسة ضعف الساحل الغربي الأفريقي باستخدام ستة متغيرات جيوفيزيائية مستمدة من الأقمار الصناعية واثنين من المعايير الاجتماعية والاقتصادية الرئيسية كمؤشرات لمؤشر ضعف الساحل (CVI). يتم دمج هذه المتغيرات الجيوفيزيائية والاجتماعية والاقتصادية لتطوير مؤشر CVI لساحل WA. ثم يتم تحديد النقاط الساخنة الإقليمية للضعف مع المؤشرات الرئيسية التي يمكن أن تؤثر على كيفية تصرف الساحل الغربي الأفريقي وكيفية إدارته. تشير النتائج إلى أن 64,17 و

السواحل أنظمة ديناميكية ومعقدة تستجيب للأحداث الجوية القاسية، وتتأثر بالسكان البشريين، والمستوطنات، والأنشطة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية.

كونها مناطق انتقالية بين العمليات البناءة والهدامة للأرض والمحيطات، تتمتع المناطق الساحلية بتعقيد كبير وحركة فيزيائية عالية.

في غرب أفريقيا،

تغيير الساحل

إعدادات منطقة الدراسة والحالة الحالية

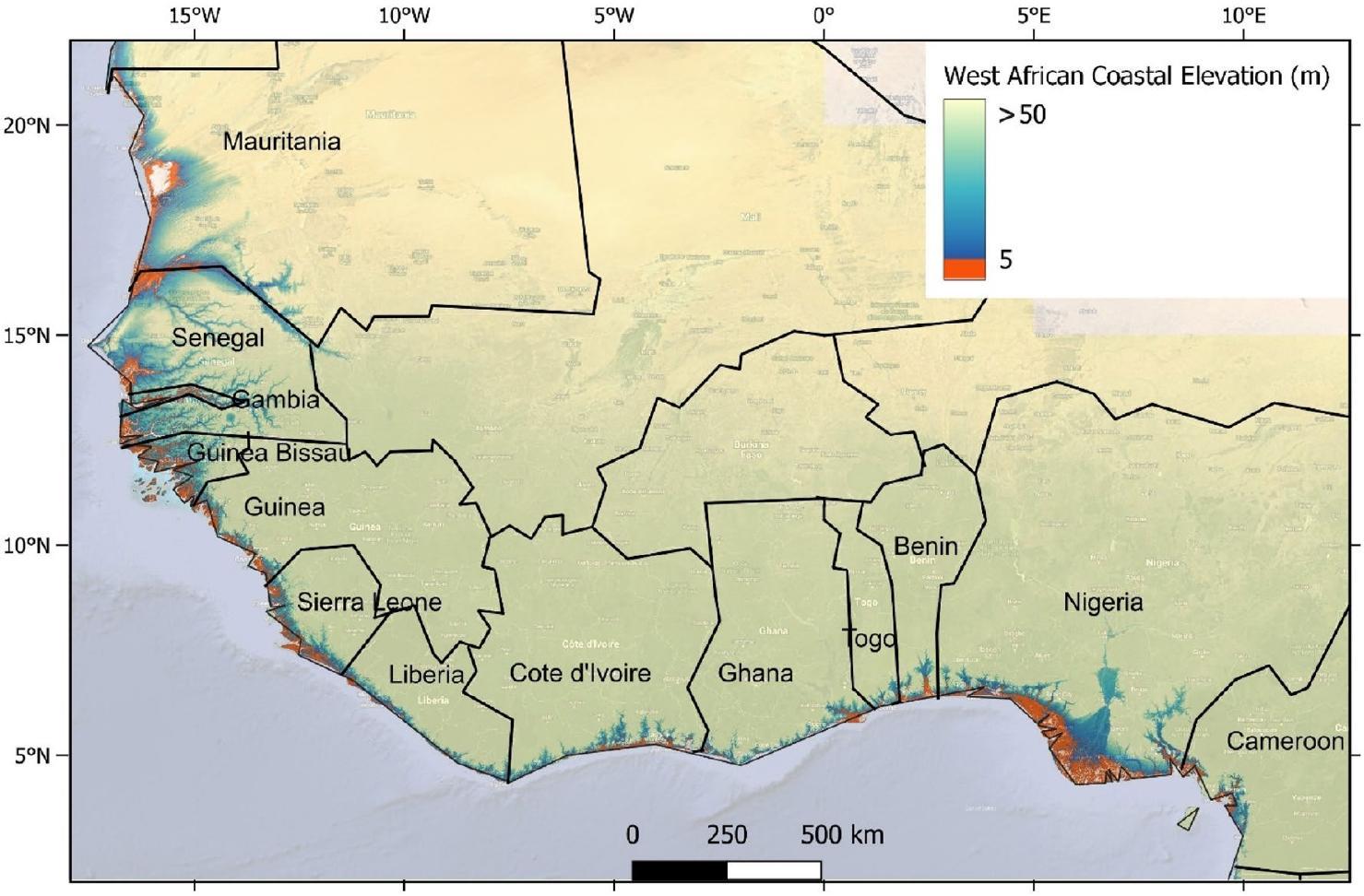

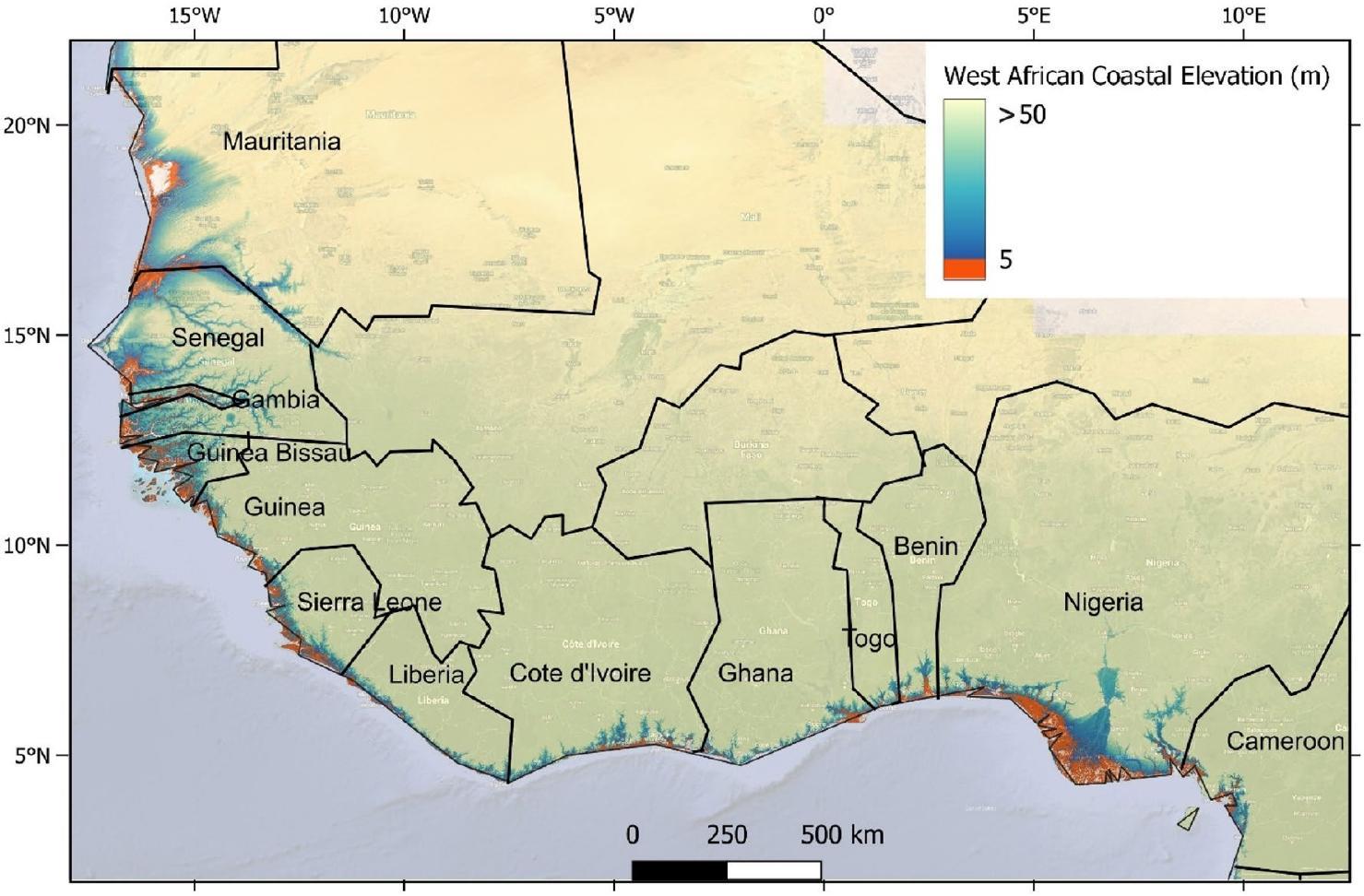

تغطي منطقة الدراسة، التي تشمل دول الساحل الغربي الأفريقي من موريتانيا إلى نيجيريا والكاميرون (الشكل 1)، تنوعًا فريدًا في الجيومورفولوجيا الساحلية. يعد ساحل غرب أفريقيا موطنًا لمجموعة متنوعة من النظم البيئية والموائل. تتأثر التنوع البيولوجي في هذه المنطقة بوفرة المصبات، والدلتا، والبحيرات الساحلية، وصعود المياه الباردة الغنية بالمغذيات. توفر هذه الموائل الأساسية للطيور المهاجرة، وسلاحف البحر، ونظم بيئية أخرى. حاليًا، تؤثر الأنشطة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية بشكل متزايد على البيئة الساحلية والبحرية.

يمثل الاتجاه طويل الأمد لانتقال الناس إلى المناطق الساحلية، وخاصة المدن الساحلية، تحديًا كبيرًا في إدارة الموارد الساحلية. تشهد المنطقة اتجاهًا متزايدًا للاستغلال المفرط للموارد والأنظمة البيئية الساحلية. بسبب الضغوط السكانية المتزايدة ونقص الموارد البديلة لدعم السكان، أصبح استغلال الموارد غير مستدام. تتعرض الأنظمة البيئية الساحلية الحيوية للتلف أو التدمير على طول السواحل لإفساح المجال للنمو الحضري والزراعة وتربية الأحياء المائية وتطوير الموانئ والمرافئ والسدود الكهرومائية.

التحضر السريع في غرب إفريقيا يمثل مصدر قلق كبير بسبب الضغط المتزايد على النظام البيئي وموارده. على سبيل المثال، تمتلك غامبيا وغانا وموريتانيا وليبيريا ونيجيريا وساحل العاج مستويات من التحضر تبلغ

النتائج والمناقشة

النتائج

يتم تقييم ضعف ساحل غرب إفريقيا بناءً على ثلاثة مكونات: PVI و SVI و CVI (الشكل 2).

الشكل 1. ارتفاع الساحل الغربي الأفريقي (م). الارتفاع الساحلي أقل من 5 م باللون الأحمر (مصدر البيانات: MERIT DEM). تم إنشاء الخريطة في الشكل 1 باستخدام بيانات تم الحصول عليها من MERIT DEM (http://hydro.iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~yamadai/MERIT_DEM/) في بيئة QGIS v.3.24.0 (https://www.qgis.org/).

الشكل 2. تقييم ضعف السواحل في غرب أفريقيا استنادًا إلى مؤشر الضعف الساحلي (CVI) ومؤشر الضعف البيئي (PVI) ومؤشر الضعف الاجتماعي (SVI).

مؤشر الضعف الجسدي (PVI)

توجد اختلافات كبيرة في مؤشرات قيمة الممتلكات (PVI) على طول ساحل واشنطن. في المتوسط، يقع ساحل واشنطن بأكمله ضمن فئة PVI المعتدلة. حوالي

الشكل 3. مؤشر الضعف الفيزيائي في غرب إفريقيا (PVI). (تم إنتاج صورة الخريطة المستخدمة في إنتاج الشكل باستخدام مكون Google Satellite Hybrid في بيئة QGIS v.3.24.0، https://www.qgis.org/).

(

الضعف الاجتماعي الاقتصادي (SVI)

حوالي

مؤشر الضعف الساحلي العام (CVI)

تم حساب CVI من خلال دمج PVI وSVI باستخدام المعادلة 3. حوالي

المواقع الضعيفة في غرب إفريقيا

وصف أكثر تفصيلاً للمواقع التي تتعرض للضعف بسبب تآكل السواحل ومخاطر الفيضانات على طول ساحل WA.

المناطق الضعيفة جدًا

استنادًا إلى CVI، فإن بعض المناطق تعتبر ضعيفة جدًا، ومعظم هذه المناطق تقع على طول القسم الشمالي من ساحل WA، من موريتانيا إلى السنغال، في القسم الغربي من WA، من غينيا بيساو إلى ليبيريا وفي خليج غينيا، من كوت ديفوار إلى الكاميرون. كما هو موضح في الشكل 7، فإن الجزء المركزي من موريتانيا والجوانب المركزية والجنوبية من ساحل السنغال، وساحل غامبيا، والجزء الجنوبي من غينيا بيساو وغينيا الجنوبية إلى الساحل الشمالي لسيراليون أظهرت ضعفًا عاليًا إلى مرتفع جدًا. مناطق أخرى على طول ساحل WA تحمل سمة مشابهة هي موقع في الجزء الشرقي من كوت ديفوار، من وسط غانا

الشكل 4. ترتيب (%) لمتغيرات جيولوجية مختلفة على المستوى (أ) الإقليمي؛ و(ب) مستوى الدولة.

نحو الساحل الشمالي للكاميرون. معظم هذه المواقع لديها شواطئ رملية طويلة غير منقطعة وتركيبة غير مواتية من الجيومورفولوجيا الساحلية، والانحدار، واتجاه التآكل، تحت تأثير قوي للأمواج وربما ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر النسبي

توجد مستويات عالية إلى مرتفعة جدًا من SVI في الأجزاء المركزية والجنوبية من السنغال، والجزء المركزي من غينيا بيساو، من ساحل غينيا المركزي إلى الجزء الشمالي من ساحل سيراليون. أيضًا، في بعض المواقع في وسط ليبيريا والساحل الشرقي لكوت ديفوار نحو الحدود مع غانا. ثم، تمتد من ساحل غانا المركزي إلى الجزء الشمالي من ساحل الكاميرون (الشكل 5).

من المدهش أن هذه المناطق ذات CVI المرتفع إلى المرتفع جدًا (الشكل 7) هي أيضًا مناطق ذات SVI مرتفع إلى مرتفع جدًا (الشكل 5). وهذا يعني أن العوامل الاجتماعية الاقتصادية لها تأثير أكبر على الضعف الساحلي على طول ساحل WA. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، من المعروف أن هذه المناطق كانت تاريخيًا عرضة للفيضانات الساحلية

المناطق الضعيفة معتدلة

استنادًا إلى CVI، فإن سواحل شمال السنغال، شمال غينيا بيساو، غينيا الوسطى، وسط وجنوب سيراليون، شمال ليبيريا، غرب كوت ديفوار، وجنوب الكاميرون تعتبر ذات درجة معتدلة من الضعف (الشكل 7) بسبب عوامل فيزيائية مثل الجيومورفولوجيا الساحلية، والانحدار، وطاقة الأمواج، وارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر النسبي (الشكل 4). استنادًا إلى SVI، فإن ساحل غامبيا، وسط موريتانيا، الأجزاء الشمالية والجنوبية من ساحل غينيا بيساو، والجزء المركزي من سواحل غينيا وسيراليون وكوت ديفوار، شمال ليبيريا، غرب غانا وجنوب الكاميرون تقع تحت المناطق الضعيفة معتدلة (الشكل 5).

الشكل 5. مؤشر الضعف الاجتماعي الاقتصادي في غرب إفريقيا (SVI). (تم إنتاج صورة الخريطة المستخدمة في إنتاج الشكل باستخدام مكون Google Satellite Hybrid في بيئة QGIS v.3.24.0، https://www.qgis.org/).

VL = ضعف منخفض جدًا؛ L = ضعف منخفض؛ M = ضعف معتدل؛

H = ضعف مرتفع؛ VH = ضعف مرتفع جدًا

H = ضعف مرتفع؛ VH = ضعف مرتفع جدًا

الشكل 6. مؤشر الضعف الساحلي في غرب إفريقيا لكل دولة.

المناطق الأقل ضعفًا

يمكن اعتبار جميع أجزاء ساحل WA التي لم يتم ذكرها في الفئتين السابقتين أقل ضعفًا. استنادًا إلى CVI، فإن ساحل شمال موريتانيا، الحدود الشمالية للسنغال، بالإضافة إلى السواحل الجنوبية لسيراليون وليبيريا هي أقل أجزاء الساحل ضعفًا في WA (الأشكال 7). قد يكون ضعف هذه السواحل المنخفض بسبب أنها سواحل ذات طاقة منخفضة مع شواطئ مسطحة وعريضة مدعومة بالبحيرات الساحلية

الشكل 7. مؤشر الضعف الساحلي العام في غرب إفريقيا (CVI). (تم إنتاج صورة الخريطة المستخدمة في إنتاج الشكل باستخدام مكون Google Satellite Hybrid في بيئة QGIS v.3.24.0، https://www.qgis.org/).

المؤشر الرئيسي للضعف

تسمح المقارنة بين PVI وSVI بتقييم أفضل لمستويات الضعف العامة للمواقع المختلفة. لتقييم الروابط المحتملة بين PVI وSVI، وللحصول على فهم أفضل لكل من مقادير التغيير والعواقب الاقتصادية، يوضح الجدول 1 نسبة PVI وSVI لكل دولة ساحلية في WA. يمثل الشكل 8 الدول الساحلية باستخدام أرباع رسومية وفقًا لأربع فئات: PVI منخفض/SVI منخفض، PVI منخفض/SVI مرتفع، PVI مرتفع/SVI منخفض وفئات PVI مرتفع/SVI مرتفع. أعطت متوسطات درجات PVI وSVI نتائج مثيرة للاهتمام (الجدول 1؛ الشكل 8). بينما كانت PVIs لموريتانيا وغينيا بيساو أعلى من SVIs الخاصة بهما، كانت SVIs للدول الساحلية الأخرى في WA أعلى من PVIs الخاصة بها. كانت SVI أعلى بكثير من PVI في مواقع الدراسة في بنين، غانا، نيجيريا، توغو (

تحديد العامل الرئيسي (الفيزيائي أو الاجتماعي-الاقتصادي) الذي يحكم ضعف ساحل WA مهم عند النظر في تدابير التكيف. كما هو موضح في الشكل 8، فإن ضعف ساحل WA يهيمن عليه عوامل اجتماعية-اقتصادية تفوق قيمتها 1 (الشكل 8). تظهر التحليلات الإضافية أنه يهيمن عليه نشاط التنمية البشرية (الجدول 1). درجة الضعف المرتبطة بالمتغيرات الاجتماعية-الاقتصادية، وخاصة نشاط التنمية البشرية، مقارنة بالمتغيرات الفيزيائية مرتفعة لمعظم الدول (الجدول 1؛ الشكل 8). لذلك يجب أن تركز حلول التكيف أكثر على العوامل الاجتماعية-الاقتصادية. يمكن استخدام التمثيل الرسومي على مقاييس مختلفة لمقارنة المناطق الساحلية، مما قد يساعد صانعي القرار في تحديد أولويات الموارد المحدودة لحماية المناطق الأكثر ضعفًا.

نقاش

آثار العمليات الفيزيائية على ضعف الساحل الغربي

تتأثر التغيرات في مؤشر التعرض للتآكل والفيضانات على ساحل واشنطن بعوامل (جيو)فيزيائية مختلفة (الشكل 7). بناءً على تصنيفنا، فإن العوامل الفيزيائية التي لها أكبر تأثيرات سائدة على هشاشة ساحل واشنطن هي الجيومورفولوجيا، ومعدل تغير الشاطئ، وانحدار الساحل، ومناخ الأمواج، وارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر (الشكل 7؛ الأشكال التكميلية 1-6). عادةً ما تكون المناطق ذات الهشاشة العالية إلى العالية جدًا هي مناطق ذات انحدار ساحلي منخفض، وأنواع تضاريس معرضة للخطر (دلتا، شواطئ رملية وطينية)، وسواحل ذات طاقة أمواج عالية، وارتفاع نسبي كبير في مستوى سطح البحر (الأشكال التكميلية 1-3). بينما تعتبر طاقة الأمواج هي العامل الفيزيائي الرئيسي الذي يتحكم في العمليات الساحلية على ساحل واشنطن، فإن تأثير المد والجزر يكون أكثر وضوحًا على سواحل سيراليون وغينيا وغينيا بيساو والكاميرون (الشكل 7؛ الأشكال التكميلية 5-6)، ربما بسبب تضعيف الأمواج (حماية الأمواج) بواسطة الجزر البحرية.

تتأثر العمليات الساحلية على ساحل واشنطن بين غينيا الجنوبية وسيراليون الشمالية بطاقة الأمواج والتيارات المدية، وتتعرض لطاقة منخفضة إلى متوسطة، وأمواج طويلة المدة (الأشكال التكميلية 5-6). أظهرت دراسة سابقة أن أعلى سعات مدية (عادةً

| بلد | نسبة PVI (%) | SVI (%) | نسبة PVI-SVI (%) | ||

| بوب | SETT | بوب-سيت | |||

| بنين | – | 100 | – | ||

| – | – | 100 | |||

| ساحل العاج | ٢٥ | 75 | – | ||

| ٢٥ | 50 | ٢٥ | |||

| الكاميرون | ٢٥ | ٥٨.٣ | 16.7 | ||

| – | 54.5 | ٤٥.٥ | |||

| غينيا بيساو | ٥٢.٩ | ٤٧.١ | – | ||

| 11.8 | 82.4 | 5.8 | |||

| غامبيا | – | ٨٣.٣ | 16.7 | ||

| – | 66.7 | ٣٣.٣ | |||

| غانا | – | 100 | – | ||

| 27.3 | 18.2 | 54.5 | |||

| غينيا | 44.4 | ٥٥.٦ | – | ||

| ٤٣.٨ | ٣٣.٣ | ٢٧.٧ | |||

| ليبيريا | 42.9 | ٥٧.١ | – | ||

| ٥٦.٩ | 42.9 | 7.2 | |||

| موريتانيا | 69.6 | 30.4 | – | ||

| 10.5 | 89.5 | ||||

| نيجيريا | – | 100 | – | ||

| ٤٣.٨ | 12.4 | ٤٣.٨ | |||

| سيراليون | ٢٦.٧ | 66.7 | ٦.٧ | ||

| ٤٦.٧ | ٤٦.٧ | 6.6 | |||

| السنغال | 7.1 | 86.8 | 7.1 | ||

| 7.1 | ٥٧.١ | ٣٥.٨ | |||

| توغو | – | 100 | – | ||

| – | – | 100 | |||

الجدول 1. متوسط مؤشر الضعف الجسدي (PVI) ومؤشر الضعف الاجتماعي والاقتصادي (SVI) بالنسب. القيم المهمة بالخط العريض.

نتيجتنا الحالية تتماشى مع الدراسات السابقة. على سبيل المثال، لوبيس وآخرون.

في موريتانيا، تكون الجيومورفولوجيا عمومًا منخفضة في عدة أماكن تحت مستوى سطح البحر، وهي محمية بواسطة سلسلة رملية رقيقة وهشة يمكن عبورها في بعض الأماكن خلال العواصف القوية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن مرافق الموانئ وغيرها من الأنشطة البشرية على الساحل تزيد من ضعف المنطقة الساحلية في موريتانيا.

تتميز سواحل السنغال وغامبيا بأنظمة بيئية متنوعة، بما في ذلك الشواطئ الرملية، والتكوينات الصخرية البركانية، والمساحات الواسعة من المصبات بالقرب من مصبات أنهار السنغال وسالوم وغامبيا وكازامانس. تتأثر السواحل المنخفضة في السنغال وغامبيا بشكل خاص بالظاهرة الواسعة الانتشار للتآكل الساحلي.

في كوت ديفوار، تم تصنيف المنطقة الساحلية الإيفوارية بالكامل على أنها ذات مستوى ضعف معتدل بواسطة تانو وآخرين.

الشكل 8. توضيح بياني لمؤشر الضعف الاجتماعي والاقتصادي (PVI) ومؤشر الضعف الاجتماعي (SVI). يُظهر أن التنمية الاجتماعية والاقتصادية المتزايدة على طول ساحل غرب إفريقيا هي عامل رئيسي في ضعف الساحل الغربي.

قطاع أكرا من ساحل غانا كمخاطر معتدلة، بواتينغ وآخرون.

الشريط الساحلي بين دلتا نهر فولتا وأقصى غرب بنين مأهول بكثافة (مثل لومي، كوتونو) وعرضة بشدة بسبب الهجرة من المناطق الداخلية، والتطوير المستمر قد يؤثر بشكل كبير على الظروف الاجتماعية والاقتصادية والنظم البيئية الطبيعية في المنطقة.

تداعيات زيادة التنمية الاجتماعية والاقتصادية على تآكل السواحل، والانخفاض، وارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر النسبي

تشهد سواحل غرب أستراليا زيادة سريعة في عدد السكان وما يتبعها من تطوير (الشكل 9؛ الأشكال التكميلية 7-8). بلغ متوسط الناتج المحلي الإجمالي للفرد في المجموعة الاقتصادية لدول غرب أفريقيا (ECOWAS) من الولايات المتحدة

مع هذا النمو الاقتصادي المتزايد والتوسع الحضري المتسارع، شهد ساحل WA تطويرًا مكثفًا للأراضي واستصلاحًا واسع النطاق في العقود الأخيرة. لقد كان لهذا التوسع الحضري تأثير على كل من المدن والبلدات الساحلية في المنطقة. لقد زاد الطلب على الأراضي والمياه والموارد الطبيعية الأخرى؛ وقد ساهمت البنية التحتية من صنع الإنسان واستخراج الرمال في تآكل ساحلي كبير

كما هو موضح في الشكل 9، زادت اتجاهات السكان الحضريين في WA من 125 تجمعًا حضريًا و4 ملايين ساكن حضري في 1950 إلى 992 تجمعًا حضريًا (حوالي

الشكل 9. اتجاهات السكان الحضريين في غرب أفريقيا من 1950 إلى

الأهم من ذلك، أن المناطق المبنية غير المخطط لها، وخاصة بالقرب من المدن والبلدات الساحلية، تشكل تهديدًا للأنظمة الاجتماعية والبيئية في المنطقة

لقد حظيت المصادفة الأخيرة بين الهبوط وارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر في المدن الساحلية باهتمام أكبر بسبب الإمكانية المتزايدة لحدوث مخاطر الفيضانات المستقبلية الناتجة عن ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر النسبي

قيود الدراسة

على الرغم من أن النهج المستخدم في هذه الدراسة يقدم تقييمًا مفيدًا لضعف الساحل على المستوى الإقليمي والوطني، إلا أن النتائج تحتوي على قدر كبير من عدم اليقين لأن البيانات ذات الدقة الخشنة تم استخدامها. لذلك سيكون من الحكمة إجراء دراسات أكثر شمولاً على المستوى المحلي للأماكن التي أشارت إليها الدراسة الحالية على أنها ضعيفة للغاية، خاصة إذا كان الخطر المحتمل على المجتمعات أو التطورات كبيرًا أيضًا في مثل هذه المناطق. بخلاف كثافة السكان، فإن قاعدة بيانات الدراسة تفتقر إلى معلومات حول مؤشرات اجتماعية واقتصادية أخرى مثل استخدام الأراضي. قد يؤدي إضافة هذه العوامل الإضافية إلى تحسين تصنيف الضعف على مجموعة المعايير الحالية.

الاستنتاجات والتوصيات

تتبنى هذه الدراسة تحليل بيانات الاستشعار عن بعد لتوصيف ضعف ساحل WA بشكل كمي تجاه القوى (الجيو)فيزيائية والعوامل الاجتماعية والاقتصادية. تستخدم الدراسة ستة متغيرات جيوفيزيائية لتقييم مخاطر الفيضانات أو التآكل الساحلي مع دمجها مع متغيرين رئيسيين اجتماعيين واقتصاديين لفهم ضعف ساحل WA، من خلال تعيينها مرتبة تتراوح من 1 إلى 5، بناءً على عامل ضعفها النسبي. تشير النتائج إلى ضعف معتدل على طول ساحل WA بأكمله، مع ضعف مرتفع في القطاع الشمالي الغربي (بين موريتانيا وغينيا بيساو) وساحل خليج غينيا (بين كوت ديفوار والكاميرون). ترتبط هذه المناطق الضعيفة بشدة بطبيعة الأشكال الأرضية الجيومورفولوجية، والمنحدرات الساحلية التي أدت إلى التآكل والفيضانات بسبب ارتفاع الأمواج وارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر. يتعقد هذا أكثر بسبب ارتفاع إلى مرتفع جدًا من مؤشر الضعف الاجتماعي (كثافة السكان والأنشطة التنموية البشرية) في المناطق الساحلية من المنطقة. توضح الدراسة درجة المناطق الضعيفة التي قد تزداد بسبب تغير المناخ وتأثير زيادة الوجود البشري.

لذلك من الضروري أن يقوم مدراء السواحل وصناع السياسات في المنطقة بوضع أفضل استراتيجيات التكيف باستخدام طرق مختلفة. يجب أن تحل استراتيجية التنمية “استدامة السواحل أولاً” محل “التنمية الاقتصادية أولاً”. بناءً على الضعف الوطني والإقليمي، يجب على صناع القرار والباحثين وأصحاب المصلحة الساحليين في المنطقة النظر في خيارات التكيف المناسبة. يمكن دمج الحلول الهندسية في مجموعة من استراتيجيات التكيف الساحلي. تشمل هذه الإجراءات حماية الأراضي الرطبة الساحلية، وتثبيت الكثبان الرملية، وتجديد الشواطئ بانتظام، وتعزيز وتوسيع أنظمة السدود في مواقع محددة مثل الموانئ والسواحل الحضرية الكثيفة، وتعزيز أنظمة التنبؤ والتحذير ونشر المعلومات، وبناء ملاجئ للاجئين، والمزيد.

الطرق

تقدم هذه القسم الإجراء المستخدم لتقييم الضعف بسبب التآكل الساحلي والفيضانات على طول المناطق الساحلية في غرب أفريقيا.

مؤشر الضعف الساحلي ومكوناته

يتم تعريف مؤشر الضعف الساحلي العام (CVI) على أنه مزيج من مؤشر الضعف (الجيو)فيزيائي (PVI) ومؤشر الضعف الاجتماعي والاقتصادي (SVI)، باستخدام المعادلة 2. يفحص PVI وSVI، على التوالي، المتغيرات الفيزيائية والعوامل الاجتماعية والاقتصادية المسؤولة عن ضعف ساحل WA

تم إنشاء قاعدة بيانات تضم متغيرات فيزيائية ومعلمات اجتماعية واقتصادية تمثل بقوة العمليات الدافعة الهامة للتآكل الساحلي والفيضانات في غرب أفريقيا. المتغيرات الفيزيائية الستة هي الجيومورفولوجيا (GEO)، ومعدلات تغيير الشاطئ التاريخية (SCR)، والمنحدر الساحلي الإقليمي (CS)، وتغيير مستوى سطح البحر النسبي (RSLC)، ومتوسط تدفق طاقة الأمواج (WE) ومتوسط نطاق المد والجزر الفلكي (TR). تعتبر GEO وSCR وCS متغيرات جيولوجية تفسر مقاومة الشاطئ للتآكل، والاتجاه طويل الأجل للتآكل/الاستصلاح، والضعف تجاه الفيضانات. WE وTR وRSLC هي متغيرات عمليات فيزيائية يمكن أن تسبب مناطق متآكلة ومغمورة على مدى فترات زمنية

الحصول على البيانات، التصنيف والتطبيع

المتغيرات الفيزيائية

تم الحصول على بيانات هذه المتغيرات من دراسات سابقة، والتي تستند إلى تحليل الملاحظات الساتلية وإعادة تحليل النماذج على مدى 23 عامًا بين 1993 و2015، تم استخراجها من 204 مواقع ساحلية تقع على طول السواحل المفتوحة في غرب أفريقيا. الدقة الخشنة نسبيًا لمجموعة بياناتنا هي

تم الحصول على بيانات هذه المتغيرات من دراسات سابقة، والتي تستند إلى تحليل الملاحظات الساتلية وإعادة تحليل النماذج على مدى 23 عامًا بين 1993 و2015، تم استخراجها من 204 مواقع ساحلية تقع على طول السواحل المفتوحة في غرب أفريقيا. الدقة الخشنة نسبيًا لمجموعة بياناتنا هي

المتغيرات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية

تم الحصول على مجموعات البيانات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية، التي تتضمن كثافة السكان (POP) والاستيطان البشري (SETT) من مركز معلومات علوم الأرض الدولية (CIESIN) بجامعة كولومبيا على (https:// sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/gpw-v4-population-density-rev11) و (https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/بيانات/مجموعة/تقديرات سكان GHSL المبنية على درجة التحضر SMOD/تحميل البيانات). هذه البيانات بتنسيق Geo TIFF بدقة مكانية

التصنيف والوزن

اعتمادًا على القيم المقاسة، تمتلك الأنظمة المختلفة تصنيفات ونطاقات متغيرة مختلفة.

تشير هذه الترتيب إلى درجة الضعف، حيث تساهم 5 بأعلى درجة (ضعف شديد – VH) وتساهم 1 بأقل درجة (ضعف منخفض جداً – VL).

وفقًا لدينر وآخرون

حسابات مؤشر الضعف الساحلي (CVI)

تم تقييم مؤشرات التعرض للتآكل والفيضانات لـ 204 مواقع استنادًا إلى مؤشر التعرض الفيزيائي ومؤشر التعرض الاجتماعي (الجدول التكميلي 1). تم تحديد مؤشر التعرض الفيزيائي من خلال دمج القيم العادية للمتغيرات الفيزيائية باستخدام المعادلة (1).

أين

أين

لتحديد المكون الرئيسي (الفيزيائي أو الاجتماعي الاقتصادي) الذي له تأثير كبير على ضعف المنطقة المعنية، تم حساب نسبة مؤشر الضعف المعياري إلى مؤشر القيمة المعيارية المقابل. عندما تكون النسبة أقل من 1، فإن ضعف الجزء المعني يعتمد بشكل كبير على المتغيرات الفيزيائية. عندما تساوي 1، يتأثر القسم الساحلي بالتساوي بالقوى الفيزيائية والاجتماعية الاقتصادية. عندما تكون النسبة أكبر من 1، تكون المتغيرات الاجتماعية الاقتصادية هي العوامل الرئيسية للضعف.

يتم تقدير مؤشر الضعف الساحلي العام (CVI) من خلال دمج كل من مؤشر الضعف الفيزيائي (PVI) ومؤشر الضعف الاجتماعي (SVI)، باستخدام المعادلة (3):

بعد ذلك، تم تصنيف مؤشر القيمة المعرضة للخطر (CVI) المقدر إلى خمس فئات من الضعف (منخفض جداً، منخفض، معتدل، مرتفع، ومرتفع جداً) استناداً إلى طريقة التصنيف الطبيعي لجينكس.

توفر البيانات

البيانات الخام التي تدعم نتائج هذه الدراسة متاحة بالفعل على الإنترنت، مجانًا. استخدمنا ملاحظات مستوى البحر من AVISOhttps://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/ar/data/products/auxiliary-products/dynamic-atmospheric-correction/description-atmospheric-corrections.htmlتدفق من أطلس المد والجزر العالمي FES2014

تاريخ الاستلام: 27 يونيو 2023؛ تاريخ القبول: 28 نوفمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 09 يناير 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 09 يناير 2024

References

- Balica, S. F., Wright, N. G. & van der Meulen, F. A flood vulnerability index for coastal cities and its use in assessing climate change impacts. Nat. Hazards 64, 73-105 (2012).

- Neumann, B., Vafeidis, A. T., Zimmermann, J. & Nicholls, R. J. B. Future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding-A global assessment. PLoS ONE 10, e0118571 (2015).

- Nguyen, Q. H. Impact of investment in tourism infrastructure development on attracting international visitors: A nonlinear panel ARDL approach using Vietnam’s data. Economies 9(3), 131 (2021).

- Stanchev, H., Stancheva, M. & Young, R. Implications of population and tourism development growth for Bulgarian coastal zone. J. Coast. Conserv. 19, 59-72 (2015).

- Abir, L. M. Impact of tourism in coastal areas: Need of sustainable tourism strategy. Available from http://www.coastalwiki.org/ wiki/Impact_of_tourism_in_coastal_areas:_Need_of_sustainable_tourism_strategy (2023).

- Nicholls, R. J. & Hoozemans, F. M. J. The Mediterranean: Vulnerability to coastal implications of climate change. Ocean Coast. Manag. 31(2-3), 105-132 (1996).

- Masselink, G. & Gehrels, R. (eds) Coastal Environments & Global Change 448 (Wiley-Blackwell, New York, 2014).

- Bonetti, J. & Woodroffe, C. D. Spatial analysis techniques and methodological approaches for coastal vulnerability assessment. In Geoinformatics for Marine and Coastal Management (eds Bartlett, D. & Celliers, L.) 367-395 (CRC Press, 2017).

- Hummell, B. M. L., Cutter, S. L. & Emrich, C. Social vulnerability to natural hazards in Brazil. Int. J. Disast. Risk Sci. 7(2), 111-122 (2016).

- Kantamaneni, K. Counting the cost of coastal vulnerability. Ocean Coast. Manag. 132, 155-169 (2016).

- IPCC. Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (eds Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E. S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., Okem, A. & Rama, B.) 3056 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022).

- World Bank Group. A partnership for saving West Africa’s coastal areas. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/622041448394069174/ 1606426-WACA-Brochure.pdf (2016).

- Appeaning Addo, K. Assessing coastal vulnerability index to climate change: The case of Accra-Ghana. J. Coast. Res. 65, 1892-1897 (2013).

- Nyadzi, E., Bessah, E. & Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G. Taking stock of climate change induced sea level rise across the West African coast. Environ. Claims J. 33(1), 77-90 (2021).

- Tano, R. et al. Development of an integrated coastal vulnerability index for the Ivorian coast in West Africa. J. Environ. Prot. 9, 1171-1184 (2018).

- Lopes, N. D. R. et al. Coastal vulnerability assessment based on multi-hazards and bio-geophysical parameters. Case studynorthwestern coastline of Guinea-Bissau. Nat. Hazards 114, 989-1013 (2022).

- Abessolo, G. O. et al. African coastal camera network efforts at monitoring ocean, climate, and human impacts. Sci. Rep. 13, 1514. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28815-6 (2023).

- Almar, R. et al. Coastal zone changes in West Africa: Challenges and opportunities for satellite earth observations. Surv. Geophys. 44, 249-275 (2022).

- Almar, R. et al. Influence of El Niño on the variability of global shoreline position. Nat. Commun. 14, 3133. https://doi.org/10. 1038/s41467-023-38742-9 (2023).

- Anthony, E. J. Patterns of sand spit development and their management implications on deltaic, drift-aligned coasts: The cases of the Senegal and Volta River delta spits, West Africa. In Sand and Gravel Spits (eds Randazzo, G. et al.) 21-36 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

- Anthony, E. J., Almar, R. & Aagaard, T. Recent shoreline changes in the Volta River delta, West Africa: The roles of natural processes and human impacts. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 41(1), 81-87 (2016).

- Anthony, E. J. et al. Response of the Bight of Benin (Gulf of Guinea, West Africa) coastline to anthropogenic and natural forcing, part 2: Sources and patterns of sediment supply, sediment cells, and recent shoreline change. Cont. Shelf Res. 173, 93-103 (2019).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Evolutionary trends of the Niger Delta shoreline during the last 100 years: Responses to rainfall and river discharge. Mar. Geol. 367, 202-211 (2015).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Seasonal shoreline behaviours along the arcuate Niger Delta coast: Complex interaction between fluvial and marine processes. Cont. Shelf Res. 122, 51-67 (2016).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Recent Niger Delta shoreline response to Niger River hydrology: Conflict between force of Nature and Humans. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 139(03), 222-231 (2018).

- Dada, O. A., Agbaje, A. O., Adesina, R. B. & Asiwaju-Bello, Y. A. Effect of coastal land use change on coastline dynamics along the Nigerian transgressive Mahin mud coast. J. Ocean Coast. Manag. 168, 251-264 (2019).

- Dada, O., Almar, R., Morand, P. & Menard, F. Towards West African coastal social-ecosystems sustainability: Interdisciplinary approaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 211, 105746 (2021).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Future socioeconomic development along the West African coast forms a larger hazard than sea level rise. Nat. Commun. Earth Environ. 4(1), 1-12 (2023).

- Diop, S. et al. The western and central Africa land-sea interface: A vulnerable, threatened, and important coastal zone within a changing environment. In The Land/Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone of West and Central Africa. Estuaries of the World (eds Diop, S. et al.) (Springer, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06388-1_1.

- Ly, C. K. The role of the Akosombo Dam on the Volta River in causing coastal erosion in central and eastern Ghana (West Africa). Mar. Geol. 37(3-4), 323-332 (1980).

- Diop, S. et al. The coastal and marine environment of Eastern and Western Africa: Challenges to sustainable management and socioeconomic development. In Treatise on Estuarine and Coastal Science Vol. 11 (eds Wolanski, E. & McLusky, D. S.) 315-335 (Academic Press, 2011).

- OECD. Development at a Glance: Statistics by Region-Africa. 2020. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataS etCode=Table2A (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Croitoru, L., Miranda, J. J., Sarraf, M. The cost of coastal zone degradation in West Africa, World Bank Group Report. 2019. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/31428/135269-Cost-of-Coastal-Degradation-in-West-Africa-March-2019.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- World Bank. Effects of climate change on coastal erosion and flooding in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania, Senegal, and Togo. World Bank Technical Report, 127 (2020).

- Marti, F., Cazenave, A., Birol, F., Marcello Passaro, P., Fabien Le ‘ger, F., Niño, F., Almar, R., Benveniste, J. & Legeais, J. F. Altimetrybased sea level trends along the coasts of Western Africa. Adv. Space Res. (2019).

- Appeaning, A. K. Monitoring sea level rise-induced hazards along the coast of Accra in Ghana. Nat. Hazards 78(2), 1293-1307 (2015).

- Appeaning Addo, K., Larbi, L., Amisigo, B. & Ofori-Danson, P. K. Impacts of coastal inundation due to climate change in a cluster of urban coastal communities in Ghana, West Africa. Remote Sens. 3(9), 2029-2050 (2011).

- Dada, O. A., Almar, R. & Oladapo, M. I. Recent coastal sea-level variations and flooding events in the Nigerian Transgressive Mud coast of Gulf of Guinea. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 161, 103668 (2020).

- Failler, P., Touron-Gardic, G., Drakeford, B., Sadio, O. & Traoré, M.-S. Perception of threats and related management measures: The case of 32 marine protected areas in West Africa. Mar. Policy 117, 103936 (2020).

- Almar, R., Kestenare, E. & Boucharel, J. On the key influence of remote climate variability from Tropical Cyclones, North and South Atlantic mid-latitude storms on the Senegalese coast (West Africa). Environ. Res. Commun. 1(7), 071001 (2019).

- Alves, B., Angnuureng, D. B., Morand, P. & Almar, R. A review on coastal erosion and flooding risks and best management practices in West Africa: What has been done and should be done. J. Coast. Conserv. 24(3), 38 (2020).

- Angnuureng, D. B., Addo, K. A., Almar, R. & Dieng, H. Influence of sea level variability on a micro-tidal beach. Nat. Hazards 68, 1611-1628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3370-4 (2018).

- Brown, S., Kebede, A. S. & Nicholls, R. J. Sea-level rise and impacts in Africa, 2000-2100 (2011) https://research.fit.edu/media/ site-specific/researchfitedu/coast-climate-adaptation-library/africa/regional—africa/Brown-et-al.–2009.–SLR–Impact-in-Africa. pdf (Accessed online on 08 November 2023).

- Tano, R. A. et al. Assessment of the Ivorian coastal vulnerability. J. Coast. Res. 32, 1495-1503. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOAS TRES-D-15-00228.1 (2016).

- Vousdoukas, M. I. et al. African heritage sites threatened as sea-level rise accelerates. Nat. Clim. Change 12(3), 256-262 (2022).

- Abessolo, O. G., Hoan, L. X., Larson, M. & Almar, R. Modeling the Bight of Benin (Gulf of Guinea, West Africa) coastline response to natural and anthropogenic forcing. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 48, 101995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2021.101995 (2021).

- Almar, R. et al. Response of the Bight of Benin (Gulf of Guinea, West Africa) coastline to anthropogenic and natural forcing, Part1: Wave climate variability and impacts on the longshore sediment transport. Cont. Shelf Res. 110, 48-59 (2015).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Response of wave and coastline evolution to global climate change off the Niger Delta during the past 110 years. Mar. Syst. 160, 64-80 (2016).

- Aman, A. et al. Physical forcing induced coastal vulnerability along the Gulf of Guinea. J. Environ. Prot. 10, 1194-1211 (2019).

- de Ponce León, S. & Guedes Soares, C. The sheltering effect of the Balearic Islands in the hindcast wave field. Ocean Eng. 37(7), 603-610 (2010).

- Soares, C. G. On the sheltering effect of islands in ocean wave models. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JC0026 82 (2005).

- Anthony, E. J. The muddy tropical coast of West Africa from Sierra Leone to Guinea-Bissau: Geological heritage, geomorphology and sediment dynamics. Afr. Geosci. Rev. 13, 227-237 (2006).

- Anthony, E. J. Beach-ridge development and sediment supply: Examples from West Africa. Mar. Geol. 129, 175-186 (1995).

- Niang, A. J. Remote sensing and GIS application for natural hazards assessment of the Mauritanian coastal zone. In Applications of Space Techniques on the Natural Hazards in the MENA Region (ed. Al Saud, M. M.) (Springer, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-3-030-88874-9_9.

- Thior, M. et al. Coastline dynamics of the northern lower Casamance (Senegal) and southern Gambia littoral from 1968 to 2017. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 160, 103611 (2019).

- Mendoza, E. et al. Coastal flood vulnerability assessment, a satellite remote sensing and modeling approach. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 29, 100923 (2023).

- Meur-Férec, C., Deboudt, P. & Morel, V. Coastal risks in France: An integrated method for evaluating vulnerability. J. Coast. Res. 24(2B), 178-189 (2008).

- Mclaughlin, S. & Cooper, J. A. G. A multi-scale coastal vulnerability index: A tool for coastal managers?. Environ. Hazards 9(3), 233-248 (2010).

- Oloyede, M. O., Williams, A. B., Ode, G. O. & Benson, N. U. Coastal vulnerability assessment: A case study of the Nigerian coastline. Sustainability 14(4), 2097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042097 (2022).

- Boateng, I., Wiafe, G. & Jayson-Quashigah, P.-N. Mapping vulnerability and risk of Ghana’s coastline to sea level rise. Mar. Geodesy 40, 23-39 (2017).

- Charuka, B., Angnuureng, D. B., Brempong, E. K., Agblorti, S. K. & Antwi Agyakwa, K. T. Assessment of the integrated coastal vulnerability index of Ghana toward future coastal infrastructure investment plans. Ocean Coast. Manag. 244, 106804. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106804 (2023).

- Guerrera, F., Tramontana, M., Nimon, B. & Essotina Kpémoua, K. Shoreline changes and coastal erosion: The case study of the coast of Togo (Bight of Benin, West Africa Margin). Geosciences 11(2), 40 (2021).

- Aikins, E. R. ECOWAS/West Africa. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/geogr aphic/regions/ecowas/ (2023) [Accessed online 08 November 2023].

- Hitimana, L., Heinrigs, P. & Tremolieres, M. West African urbanisation trends. West African Futures 01 (2011). https://www.oecd. org/swac/publications/48231121.pdf

- Cian, F., Blasco, J. M. D. & Carrera, L. Sentinel-1 for monitoring land subsidence of coastal cities in Africa using PSInSAR: A methodology based on the integration of SNAP and StaMPS. Geosciences 9(124), 1-32 (2019).

- Ohenhen, L. O. & Shirzaei, M. Land subsidence hazard and building collapse risk in the coastal city of Lagos, West Africa. Earth’s Future 10(12), e2022EF003219 (2022).

- Ikuemonisan, F. E. & Ozebo, V. C. Characterisation and mapping of land subsidence based on geodetic observations in Lagos, Nigeria. Geodesy Geodyn. 11(2), 151-162 (2020).

- Nicholls, R. J. et al. A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change and coastal flood exposure. Nat. Clim. Change 11(4), 338-342 (2021).

- Restrepo-Ángel, J. D. et al. Coastal subsidence increases vulnerability to sea level rise over twenty first century in Cartagena, Caribbean Colombia. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1-13 (2021).

- Shirzaei, M. et al. Measuring, modelling and projecting coastal land subsidence. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2(1), 40-58 (2021).

- Wu, T. & Barrett, J. Coastal land use management methodologies under pressure from climate change and population growth. Environ. Manag. 70, 827-839 (2022).

- Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD). In: Hitimana, L., Heinrigs, P., and Tremolieres, M. West African urbanisation trends. West African Futures 01. https://www.oecd.org/swac/publications/48231121.pdf (2011)

- Kantamanenia, K., Phillip, M., Thomas, T. & Jenkins, R. Assessing coastal vulnerability: Development of a combined physical and economic index. Ocean Coast. Manag. 158, 164-217 (2018).

- Pendleton, E. A., Thieler, E. R., Williams, S. J. & Beavers, R. S. Coastal vulnerability assessment of Padre Island National Seashore (PAIS) to Sea-level rise. USGS report No 2004-1090 (2004). Available from: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2004/1090/a.

- Pendleton, E. A., Barras, J. A., Williams, S. J. & Twichell, D. C. Coastal vulnerability assessment of the Northern Gulf of Mexico to sea-level rise and coastal change: U.S. geological survey open-file report 2010-1146. http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2010/1146/ (2010).

- Joint Research Centre – JRC – European Commission and Center for International Earth Science Information Network – CIESIN – Columbia University. Global Human Settlement Layer: Population and Built-Up Estimates, and Degree of Urbanization Settlement Model Grid. Palisades, New York: NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC). https://doi.org/10.7927/ h4154f0w (2021). (Accessed online on 08 November 2023).

- Florczyk A. J., Corbane, C., Ehrlich, D., Freire, S., Kemper, T., Maffenini, L., Melchiorri, M., Pesaresi, M., Politis, P., Schiavina, M., Sabo, F. & Zanchetta, L. GHSL data package 2019, EUR 29788 EN. ISBN 978-92-76-13186-1, JRC 117104. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/290498 (2019).

- Almar, R. et al. A global analysis of extreme coastal water levels with implications for potential coastal overtopping. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 3775 (2021).

- Hayden, B., Vincent, M., Resio, D., Biscoe, C. & Dolan, R. Classification of the Coastal Environments of the World: Part II—Africa (Office of Naval Research, 1973).

- Allersma, E. & Tilmans, W. M. Coastal conditions in West Africa-A review. Ocean Coast. Manag. 19(3), 199-240 (1993).

- Musa, Z. N., Popescu, I. & Mynett, A. The Niger Delta’s vulnerability to river floods due to sea level rise. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 3317-3329 (2014).

- El-Shahat, S. et al. Vulnerability assessment of African coasts to sea level rise using GIS and remote sensing. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 2827-2845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00639-8 (2021).

- Kumar, T. & Kunte, P. Coastal vulnerability assessment for Chennai, east coast of india using geospatial techniques. J. Nat. Hazards 64, 853-872 (2012).

- Yin, J., Yin, Z., Wang, J. & Xu, S. National assessment of coastal vulnerability to sea-level rise for the Chinese coast. J. Coast. Conserv. 16, 123-133 (2012).

- Dinh, Q., Balica, S., Popescu, I. & Jonoski, A. Climate change impact on flood hazard, vulnerability and risk of the Long Xuyen Quadrangle in the Mekong Delta. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 10, 103-120 (2012).

- Thieler, E. R. & Hammar-Klose, E. S. National assessment of coastal vulnerability to sea-level rise, U.S. Atlantic Coast. US Geological Survey, Open-File Report, 99-593 (1999).

- Gornitz, V. Global coastal hazards from future sea level rise. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 89, 379-398 (1991).

- Koroglua, A., Ranasinghe, R., Iméneze, J. A. & Dastghei, A. Comparison of coastal vulnerability index applications for Barcelona province. Ocean Coast. Manag. 178, 104799 (2019).

- Gornitz, V. M., Daniels, R. C., White, T. W. & Birdwell, K. R. The development of a coastal risk assessment database: Vulnerability to sea-level rise in the U.S. southeast. J. Coast. Res. 12, 327-338 (1994).

- Szlafsztein, C. & Sterr, H. A GIS-based vulnerability assessment of coastal natural hazards, state of Pará, Brazil. J. Coast. Conserv. 11, 53-66 (2007).

- Denner, K., Phillips, M., Jenkins, R. & Thomas, T. A coastal vulnerability and environmental risk assessment of Loughor Estuary, South Wales. Ocean Coast. Manag. 116, 478-490 (2015).

- Carrere, L., Lyard, F. H., Cancet, M. & Guillot, A. Finite element solution fes2014, a new tidal model – validation results and perspectives for improvements. In ESA Living Planet Conference 2016 (2016).

- Adono, T. et al. Generation of the 30 M-MESH global digital surface model by ALOS prism. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci.- ISPRS Arch. 41, 157-162 (2016).

- Zhang, K. et al. Accuracy assessment of ASTER, SRTM, ALOS, and TDX DEMs for Hispaniola and implications for mapping vulnerability to coastal flooding. Remote Sens. Environ. 225, 290-306 (2019).

شكر وتقدير

تم إجراء هذه الدراسة في إطار مشروع تحديد الضعف والقدرة على التكيف والمرونة في منطقة الساحل الغربي لأفريقيا (WACAVAR)، الذي ترعاه المعهد الفرنسي للبحث من أجل التنمية (IRD). تعرب OAD عن امتنانها لقيادة المعهد لدعمها زمالتها ما بعد الدكتوراه.

يود المؤلفون أيضًا أن يعربوا عن امتنانهم للمراجعين المجهولين الاثنين على مساهماتهم القيمة في المسودة السابقة من المخطوطة.

مساهمات المؤلفين

قام O.A.D. بتصميم الدراسة بالتعاون مع R.A.. قام R.A. بإنتاج مجموعات البيانات، بينما قام O.A.D. بإنتاج الأشكال وصياغة المخطوطة. قام O.A.D. وR.A. وP.M. بمراجعة المخطوطة.

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إضافية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على مواد إضافية متاحة علىhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48612-5.

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى O.A.D. أو R.A.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينغر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينغر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي النسب 4.0 الدولية، التي تسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج بأي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمواد. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© المؤلفون 2023

© المؤلفون 2023

ليغو (IRD/CNRS/CNES/جامعة تولوز)، تولوز، فرنسا. قسم علوم البحار والتكنولوجيا، الجامعة الفيدرالية للتكنولوجيا أكور، أكور، نيجيريا. مصدر UMI (IRD – UVSQ / باريس ساكلاي) ، غويانكور ، فرنسا. البريد الإلكتروني: oadada@futa.edu.ng; rafael.almar@ird.fr

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 14, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48612-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195778

Publication Date: 2024-01-09

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48612-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195778

Publication Date: 2024-01-09

Coastal vulnerability assessment of the West African coast to flooding and erosion

Global coastal areas are at risk due to geomorphological issues, climate change-induced sea-level rise, and increasing human population, settlements, and socioeconomic activities. Here, the study examines the vulnerability of the West African (WA) coast using six satellite-derived geophysical variables and two key socioeconomic parameters as indicators of coastal vulnerability index (CVI). These geophysical and socioeconomic variables are integrated to develop a CVI for the WA coast. Then, the regional hotspots of vulnerability with the main indicators that could influence how the WA coast behaves and can be managed are identified. The results indicate that 64,17 and

Coasts are dynamic, complex systems responding to extreme weather events, influenced by the human population, settlements, and socioeconomic activities

Being transition areas between both constructive and destructive processes of land and oceans, coastal zones hold significant complexity and high physical mobility

In West Africa,

coastal change

The study area settings and present status

The study area, covering the mainland West African (WA) coastal countries from Mauritania to Nigeria, and Cameroon (Fig. 1), presents a unique coastal geomorphic variability. The coast of West Africa is home to a diverse range of ecosystems and habitats. The biodiversity in this area is influenced by the abundance of estuaries, deltas, coastal lagoons, and nutrient-rich cold-water upwelling. These provide essential habitats for migratory birds, sea turtles, and other ecosystems. Presently, socio-economic activities are increasingly affecting the coastal and marine environment of

The long-term trend of people migrating to coastal areas, particularly coastal cities, poses a significant challenge to managing coastal resources. The region is experiencing a rising trend of overexploitation of coastal resources and ecosystems. Due to growing population pressures and a lack of alternative resources to support populations, resource exploitation is becoming unsustainable. Critical coastal ecosystems are damaged or destroyed along coastlines to make room for urban growth, agriculture, aquaculture, port and harbour development, and hydropower dams

Rapid urbanization in West Africa is a significant concern due to its increasing pressure on the ecosystem and its resources. For instance, the Gambia, Ghana, Mauritania, Liberia, Nigeria, and Cote d’Ivoire have urbanization levels of

Results and Discussion

Results

The vulnerability of the West African coast is assessed based on three components: PVI, SVI and CVI (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. West African coastal elevation (m). Coastal elevation below 5 m is in red (Data source: MERIT DEM). The map in Fig. 1 is generated using data acquired from MERIT DEM (http://hydro.iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ ~yamadai/MERIT_DEM/) in QGIS v.3.24.0 environment (https://www.qgis.org/).

Figure 2. West African coastal vulnerability assessment based on CVI, PVI, and SVI.

Physical vulnerability index (PVI)

There are significant variations in PVIs along the WA coast. On average, the entire WA coast falls under the moderate PVI category. About

Figure 3. West African physical vulnerability index (PVI). (The map image used in producing the figure was generated using the Google Satellite Hybrid plugin in QGIS v.3.24.0 environment, https://www.qgis.org/).

(

Socioeconomic vulnerability (SVI)

About

Overall coastal vulnerability index (CVI)

The CVI was calculated by integrating the PVI and SVI using Eq. 3. About

West Africa vulnerable locations

A more detailed description of the locations that are vulnerable to coastal erosion and flooding hazards along the WA coast is given.

Very vulnerable zones

Based on the CVI, some areas are very vulnerable, and most of these areas are located along the northern section of the WA coast, from Mauritania to Senegal, in the western section of WA, from Guinea Bissau to Liberia and in the Gulf of Guinea Coast, from Cote d’Ivoire to Cameroon. As shown in Fig. 7, the central part of Mauritania and central and southern flanks of Senegal coast, the Gambia coast, the southern part of Guinea Bissau and southern Guinea to the northern coast of Sierra Leone displayed a high to very high vulnerability. Other areas along the WA coast with a similar attribute are a location in the eastern part of Cote d’Ivoire, from central Ghana

Figure 4. Ranking (%) of various geophysical variables at (a) regional level; and (b) country level.

towards the northern Cameroonian coast. Most of these locations have long uninterrupted sand beaches and an unfavourable combination of coastal geomorphology, slope, and erosion trend, mostly under the influence of energetic wave actions and possibly relative sea level rise

High to very high SVI are found in the central and southern parts of Senegal, the central part of Guinea Bissau, from the central Guinea coast to the northern part of the Sierra Leone coast. Also, at some locations in central Liberia and the eastern coast of Cote d’Ivoire towards the boundary with Ghana. Then, it extends from the central Ghana coast to the northern part of the Cameroon coast (Fig. 5).

Surprisingly, these high to very high CVI areas (Fig. 7) are equally areas of high to very SVI (Fig. 5). This implies socioeconomic factors have a greater influence on the coastal vulnerability along the WA coast. In addition, these areas are known to be historically vulnerable to coastal flooding

Moderately vulnerable zones

Based on CVI, the coasts of northern Senegal, northern Guinea Bissau, Central Guinea, Central and southern Sierra Leone, northern Liberia, western Cote d’Ivoire, and southern Cameroon are found to have a moderate degree of vulnerability (Fig. 7) owing to physical factors such as coastal geomorphology, slope, wave energy, and relative sea level rise (Fig. 4). Based on SVI, the Gambian coast, central Mauritania, northern and southern sections of the Guinea Bissau coast, and the central part of the Guinea Sierra Leone and Cote d’Ivoire coasts, northern Liberia, western Ghana and southern Cameroon fall under moderately vulnerable areas (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. West African socioeconomic vulnerability index (SVI). (The map image used in producing the figure was generated using the Google Satellite Hybrid plugin in QGIS v.3.24.0 environment, https://www.qgis.org/).

VL = Very Low Vulnerability; L = Low Vulnerability; M = Moderate Vulnerability;

H = High Vulnerability; VH = Very High Vulnerability

H = High Vulnerability; VH = Very High Vulnerability

Figure 6. West African coastal vulnerability index per country.

Less vulnerable zones

All parts of the WA coastline that have not been mentioned in the previous two categories can be considered less vulnerable. Based on CVI, the northern Mauritania coast, the northern boundary of Senegal, in addition the southern coasts of Sierra Leone and Liberia are the least vulnerable stretches of coastline in WA (Figs. 7). The low vulnerability of these coasts could be because they are low-energy coasts with flat and wide beaches backed by coastal lagoons

Figure 7. West African overall coastal vulnerability index (CVI). (The map image used in producing the figure was generated using the Google Satellite Hybrid plugin in QGIS v.3.24.0 environment, https://www.qgis.org/).

The main vulnerability indicator

Comparison between the PVI and SVI allows for a better assessment of the overall levels of vulnerability of the different sites. To assess potential links between the PVI and the SVI, and to obtain a better understanding of both the magnitudes of change and the economic consequences, Table 1 shows the percentage of PVI and SVI for every WA coastal country. Figure 8 represents the coastal countries using graphical quadrants according to four categories: low PVI/low SVI, low PVI/high SVI, high PVI/low SVI and high PVI/high SVI categories. The average PVI and SVI scores gave interesting results (Table 1; Fig. 8). While Mauritania and Guinea Bissau’s PVIs are higher than their SVIs, the SVIs for other WA coastal countries are higher than their PVIs. The SVI is much higher than the PVI at study sites in Benin, Ghana, Nigeria, Togo (

The identification of the main factor (physical or socio-economic) that governs the vulnerability of the WA coast is important when adaptation measures are considered. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the vulnerability of the WA coast is dominated by socio-economic factors which are greater than 1 (Fig. 8). Further analysis shows that it is dominated by human development activity (Table 1). The degree of vulnerability associated with socioeconomic variables, especially human development activity, compared with physical variables is high for most countries (Table 1; Fig. 8). Hence adaptation solutions should focus more on socioeconomic factors. The graphic representation can be used at different scales to compare coastal areas, which could help decision-makers prioritize limited resources to protect the most vulnerable areas.

Discussion

Impacts of physical processes on WA coastal vulnerability

The variability in the CVI to erosion and flooding along the WA coast is influenced by different (geo)physical variables (Fig. 7). Based on our categorization, the physical variables with the highest dominant impacts on the vulnerabilities of the WA coastline are geomorphology, shoreline change rate, coastal slope, wave climate and sea level rise (Fig. 7; Supplementary Figs. 1-6). The high to very-high vulnerability areas are typically areas of a low coastal slope, vulnerable landform types (deltas, sandy, and muddy beaches), high wave energy coastlines, and a high relative sea-level rise (Supplementary Figs. 1-3). While wave energy is the main physical variable controlling the coastal processes along the WA coastline, the influence of tides is more prominent along the Sierra Leone, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, and Cameroon coasts (Fig. 7; Supplementary Figs. 5-6), possibly due to attenuation of waves (wave sheltering) by offshore islands

The coastal processes along the WA coast between southern Guinea and northern Sierra Leone are influenced by wave energy and tidal currents and are exposed to low to moderate energy, long-period swells (Supplementary Figs. 5-6). A previous study revealed that the highest tidal amplitudes (typically

| Country | PVI (%) | SVI (%) | PVI-SVI (%) | ||

| POP | SETT | POP-SETT | |||

| Benin | – | 100 | – | ||

| – | – | 100 | |||

| Cote d’Ivoire | 25 | 75 | – | ||

| 25 | 50 | 25 | |||

| Cameroon | 25 | 58.3 | 16.7 | ||

| – | 54.5 | 45.5 | |||

| Guinea Bissau | 52.9 | 47.1 | – | ||

| 11.8 | 82.4 | 5.8 | |||

| Gambia | – | 83.3 | 16.7 | ||

| – | 66.7 | 33.3 | |||

| Ghana | – | 100 | – | ||

| 27.3 | 18.2 | 54.5 | |||

| Guinea | 44.4 | 55.6 | – | ||

| 43.8 | 33.3 | 27.7 | |||

| Liberia | 42.9 | 57.1 | – | ||

| 56.9 | 42.9 | 7.2 | |||

| Mauritania | 69.6 | 30.4 | – | ||

| 10.5 | 89.5 | ||||

| Nigeria | – | 100 | – | ||

| 43.8 | 12.4 | 43.8 | |||

| Sierra Leone | 26.7 | 66.7 | 6.7 | ||

| 46.7 | 46.7 | 6.6 | |||

| Senegal | 7.1 | 86.8 | 7.1 | ||

| 7.1 | 57.1 | 35.8 | |||

| Togo | – | 100 | – | ||

| – | – | 100 | |||

Table 1. Average physical vulnerability index (PVI) and socioeconomic vulnerability index (SVI) in % Significant values are in bold.

Our current finding is consistent with the previous studies. For instance, Lopes et al.

In Mauritania, geomorphology is generally low in several places below sea level, and it is protected by a thin and fragile dune ridge which can be crossed in some places during strong storms. Aside, port facilities and other human activities at the coastline are exacerbating the vulnerability of the Mauritania coastal area

Senegal and Gambia’s coasts feature diverse ecosystems, including sandy beaches, volcanic rocky outcrops, and large estuary expanses near the mouths of Senegal, Saloum, Gambia, and Casamance Rivers. The low coasts of Senegal and Gambia are particularly affected by the widespread phenomena of coastal erosion

In Cote d’Ivoire, the entire Ivorian coastal zone is classified as having a moderate vulnerability level by Tano et al.

Figure 8. Graphical illustration of PVI and SVI. It shows that the increasing socioeconomic development along the West African coast is a major factor in the WA coastal vulnerability.

the Accra sector of Ghana’s coast as moderate risk, Boateng et al.

The coastal strip between the Volta River delta and the far westernmost part of Benin is densely inhabited (e.g., Lomé, Cotonou) and extremely vulnerable due to migration from inland areas and ongoing development could have a severe impact on the region’s socioeconomic conditions and natural ecosystems

Implications of increasing socioeconomic development on coastal erosion, subsidence and relative sea level rise

The WA coast is experiencing a fast-growing population and its attendant development (Fig. 9; Supplementary Figs. 7-8). The average GDP per capita of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) went from US

With this increased economic growth and accelerated urbanization, the WA coast has seen high-intensity land development and large-scale reclamation in recent decades. This urbanization has had an impact on both the region’s coastal towns and cities. It has raised the demand for land, water, and other natural resources; manmade infrastructure and sand mining have contributed to major coastal erosion

As shown in Fig. 9, WA urban population trends increased from 125 urban agglomerations and 4 million urban inhabitants in 1950-992 urban agglomerations (about

Figure 9. West African urban population trends from 1950 to

Most crucially, unplanned built-up areas, particularly near coastal cities and towns, pose a threat to the region’s socio-ecosystems

The recent co-incidence of subsidence and sea-level rise in coastal cities has garnered greater attention due to the potential for increased future inundation hazards resulting from relative sea level rise

Limitations of the study

Although the approach used in this study offers a helpful assessment of coastal vulnerability at the regionalnational scale, the results do contain a significant amount of uncertainty because coarse-resolution data were used. It would therefore be wise to do more thorough, local-scale studies for the places that the present study indicated as being extremely vulnerable, especially if the potential risk to communities or developments is likewise significant in such areas. Apart from population density, the study database is deficient in information on other socioeconomic indicators such as land use. The addition of these extra risk factors may improve the vulnerability rating over the current set of criteria.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study adopts analysis of remote-sensing data to quantitatively characterize the WA coast’s vulnerability to (geo)physical forcing and socioeconomic factors. The study uses six geophysical variables to assess coastal inundation or erosion hazards combined with two key socioeconomic variables to understand the vulnerability of the WA coast, by assigning them a rank ranging from 1 to 5 , based on their relative vulnerability factor. Results indicate shows moderate vulnerability on the entire WA coast, with high vulnerability in the northwestern sector (between Mauritania and Guinea Bissau) and the Gulf of Guinea coast (between Cote d’Ivoire and Cameroon). These highly vulnerable areas are linked to the nature of geomorphological landforms, and coastal slopes which resulted in erosion and inundation due to wave heights and sea level rise. This is further complicated by high to very high SVI (population density and human development activities) in the coastal zones of the region. The study illustrates the degree of vulnerable areas which could increase owing to climate change and the impact of increasing human presence.

It is therefore necessary for coastal managers and policymakers in the region to devise the best adaptation strategies using different methods. The development strategy of “coastal sustainability first” should replace “economic development first”. Based on national and regional vulnerabilities, decision-makers, researchers, and coastal stakeholders in the region should consider appropriate adaptation options. Engineering solutions can be incorporated into a portfolio of coastal adaptation strategies. These actions include safeguarding coastal wetlands, stabilizing dunes, replenishing beaches regularly, strengthening and expanding dike systems in specific locations such as harbours and densely urbanized seafronts, enhancing forecasting, warning, and informationdissemination systems, building refugee shelters, and more.

Methods

This Section presents the procedure used to evaluate the vulnerability due to coastal erosion and flooding along the West African coastal areas.

The CVI and its components

The overall coastal vulnerability index (CVI) is defined as the combination of the (geo)physical vulnerability index (PVI) and socioeconomic vulnerability index (SVI), using Eq. 2. The PVI and SVI, respectively, examine the physical variables and socioeconomic factors that are responsible for the vulnerability of the WA coast

A database comprising physical variables and socioeconomic parameters that strongly represent significant driving processes of coastal erosion and flooding in West Africa was created. The six physical variables are geomorphology (GEO), historical shoreline change rates (SCR), regional coastal slope (CS), relative sea-level change (RSLC), mean wave energy flux (WE) and mean astronomical tidal range (TR). GEO, SCR, and CS are geologic variables that explain shoreline resistance to erosion, long-term erosion/accretion tendency, and susceptibility to flooding. WE, TR, and RSLC are physical process variables that can cause eroded and flooded areas over timescales

Data acquisition, ranking and normalization

Physical variables

Data on these variables are derived from previous studies, which are based on an analysis of satellite observation and model reanalysis over 23 years between 1993 and 2015, extracted at 204 coastal sites situated along the open coasts of West Africa. The relatively coarse resolution of our dataset is

Data on these variables are derived from previous studies, which are based on an analysis of satellite observation and model reanalysis over 23 years between 1993 and 2015, extracted at 204 coastal sites situated along the open coasts of West Africa. The relatively coarse resolution of our dataset is

Socioeconomic variables

The socioeconomic datasets, comprising population density (POP) and human settlement (SETT) were obtained from the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University at (https:// sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/gpw-v4-population-density-rev11) and (https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/ data/set/ghsl-population-built-up-estimates-degree-urban-smod/data-download). These data are in Geo TIFF format at a spatial resolution of

Ranking and weighting

Depending on the measured values, different systems have different rankings and ranges of variables

This ranking indicates the degree of vulnerability, with 5 contributing the most strongly (very high-VH) vulnerability and 1 contributing the least (very low-VL) vulnerability. The

According to Denner et al.

Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) calculations

The CVIs to erosion and flooding were evaluated for 204 sites based on the PVI and SVI (Supplementary Table 1). The PVI was determined by integrating the normalized values of the physical variables using Eq. (1).

where

where

To identify the primary component (physical or socioeconomic) that has a substantial impact on the vulnerability of the corresponding area, the ratio of the normalized SVI to the corresponding normalized CVI was calculated. When the ratio is less than 1 , the vulnerability of the corresponding portion is heavily dependent on physical variables. When it equals 1 , the coastal section is influenced equally by physical and socioeconomic forces. When the ratio is greater than 1 , the socioeconomic variables are the dominant vulnerability factors.

The overall coastal vulnerability index (CVI) is estimated by combining both the PVI and SVI, using Eq. (3):

Subsequently, the estimated CVI was classified into five vulnerability classes (very low, low, moderate, high, and very high) based on the Jenks natural classification method

Data availability

The raw data that support the findings of this study are already available online, freely. We used sea level observation from AVISO (https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/en/data/products/auxiliary-products/dynamic-atmospheric-correction/description-atmospheric-corrections.html), tide from FES2014 tide global atlas

Received: 27 June 2023; Accepted: 28 November 2023

Published online: 09 January 2024

Published online: 09 January 2024

References

- Balica, S. F., Wright, N. G. & van der Meulen, F. A flood vulnerability index for coastal cities and its use in assessing climate change impacts. Nat. Hazards 64, 73-105 (2012).

- Neumann, B., Vafeidis, A. T., Zimmermann, J. & Nicholls, R. J. B. Future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding-A global assessment. PLoS ONE 10, e0118571 (2015).

- Nguyen, Q. H. Impact of investment in tourism infrastructure development on attracting international visitors: A nonlinear panel ARDL approach using Vietnam’s data. Economies 9(3), 131 (2021).

- Stanchev, H., Stancheva, M. & Young, R. Implications of population and tourism development growth for Bulgarian coastal zone. J. Coast. Conserv. 19, 59-72 (2015).

- Abir, L. M. Impact of tourism in coastal areas: Need of sustainable tourism strategy. Available from http://www.coastalwiki.org/ wiki/Impact_of_tourism_in_coastal_areas:_Need_of_sustainable_tourism_strategy (2023).

- Nicholls, R. J. & Hoozemans, F. M. J. The Mediterranean: Vulnerability to coastal implications of climate change. Ocean Coast. Manag. 31(2-3), 105-132 (1996).

- Masselink, G. & Gehrels, R. (eds) Coastal Environments & Global Change 448 (Wiley-Blackwell, New York, 2014).

- Bonetti, J. & Woodroffe, C. D. Spatial analysis techniques and methodological approaches for coastal vulnerability assessment. In Geoinformatics for Marine and Coastal Management (eds Bartlett, D. & Celliers, L.) 367-395 (CRC Press, 2017).

- Hummell, B. M. L., Cutter, S. L. & Emrich, C. Social vulnerability to natural hazards in Brazil. Int. J. Disast. Risk Sci. 7(2), 111-122 (2016).

- Kantamaneni, K. Counting the cost of coastal vulnerability. Ocean Coast. Manag. 132, 155-169 (2016).

- IPCC. Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (eds Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E. S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., Okem, A. & Rama, B.) 3056 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022).

- World Bank Group. A partnership for saving West Africa’s coastal areas. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/622041448394069174/ 1606426-WACA-Brochure.pdf (2016).

- Appeaning Addo, K. Assessing coastal vulnerability index to climate change: The case of Accra-Ghana. J. Coast. Res. 65, 1892-1897 (2013).

- Nyadzi, E., Bessah, E. & Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G. Taking stock of climate change induced sea level rise across the West African coast. Environ. Claims J. 33(1), 77-90 (2021).

- Tano, R. et al. Development of an integrated coastal vulnerability index for the Ivorian coast in West Africa. J. Environ. Prot. 9, 1171-1184 (2018).

- Lopes, N. D. R. et al. Coastal vulnerability assessment based on multi-hazards and bio-geophysical parameters. Case studynorthwestern coastline of Guinea-Bissau. Nat. Hazards 114, 989-1013 (2022).

- Abessolo, G. O. et al. African coastal camera network efforts at monitoring ocean, climate, and human impacts. Sci. Rep. 13, 1514. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28815-6 (2023).

- Almar, R. et al. Coastal zone changes in West Africa: Challenges and opportunities for satellite earth observations. Surv. Geophys. 44, 249-275 (2022).

- Almar, R. et al. Influence of El Niño on the variability of global shoreline position. Nat. Commun. 14, 3133. https://doi.org/10. 1038/s41467-023-38742-9 (2023).

- Anthony, E. J. Patterns of sand spit development and their management implications on deltaic, drift-aligned coasts: The cases of the Senegal and Volta River delta spits, West Africa. In Sand and Gravel Spits (eds Randazzo, G. et al.) 21-36 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

- Anthony, E. J., Almar, R. & Aagaard, T. Recent shoreline changes in the Volta River delta, West Africa: The roles of natural processes and human impacts. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 41(1), 81-87 (2016).

- Anthony, E. J. et al. Response of the Bight of Benin (Gulf of Guinea, West Africa) coastline to anthropogenic and natural forcing, part 2: Sources and patterns of sediment supply, sediment cells, and recent shoreline change. Cont. Shelf Res. 173, 93-103 (2019).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Evolutionary trends of the Niger Delta shoreline during the last 100 years: Responses to rainfall and river discharge. Mar. Geol. 367, 202-211 (2015).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Seasonal shoreline behaviours along the arcuate Niger Delta coast: Complex interaction between fluvial and marine processes. Cont. Shelf Res. 122, 51-67 (2016).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Recent Niger Delta shoreline response to Niger River hydrology: Conflict between force of Nature and Humans. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 139(03), 222-231 (2018).

- Dada, O. A., Agbaje, A. O., Adesina, R. B. & Asiwaju-Bello, Y. A. Effect of coastal land use change on coastline dynamics along the Nigerian transgressive Mahin mud coast. J. Ocean Coast. Manag. 168, 251-264 (2019).

- Dada, O., Almar, R., Morand, P. & Menard, F. Towards West African coastal social-ecosystems sustainability: Interdisciplinary approaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 211, 105746 (2021).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Future socioeconomic development along the West African coast forms a larger hazard than sea level rise. Nat. Commun. Earth Environ. 4(1), 1-12 (2023).

- Diop, S. et al. The western and central Africa land-sea interface: A vulnerable, threatened, and important coastal zone within a changing environment. In The Land/Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone of West and Central Africa. Estuaries of the World (eds Diop, S. et al.) (Springer, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06388-1_1.

- Ly, C. K. The role of the Akosombo Dam on the Volta River in causing coastal erosion in central and eastern Ghana (West Africa). Mar. Geol. 37(3-4), 323-332 (1980).

- Diop, S. et al. The coastal and marine environment of Eastern and Western Africa: Challenges to sustainable management and socioeconomic development. In Treatise on Estuarine and Coastal Science Vol. 11 (eds Wolanski, E. & McLusky, D. S.) 315-335 (Academic Press, 2011).

- OECD. Development at a Glance: Statistics by Region-Africa. 2020. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataS etCode=Table2A (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Croitoru, L., Miranda, J. J., Sarraf, M. The cost of coastal zone degradation in West Africa, World Bank Group Report. 2019. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/31428/135269-Cost-of-Coastal-Degradation-in-West-Africa-March-2019.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- World Bank. Effects of climate change on coastal erosion and flooding in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania, Senegal, and Togo. World Bank Technical Report, 127 (2020).

- Marti, F., Cazenave, A., Birol, F., Marcello Passaro, P., Fabien Le ‘ger, F., Niño, F., Almar, R., Benveniste, J. & Legeais, J. F. Altimetrybased sea level trends along the coasts of Western Africa. Adv. Space Res. (2019).

- Appeaning, A. K. Monitoring sea level rise-induced hazards along the coast of Accra in Ghana. Nat. Hazards 78(2), 1293-1307 (2015).

- Appeaning Addo, K., Larbi, L., Amisigo, B. & Ofori-Danson, P. K. Impacts of coastal inundation due to climate change in a cluster of urban coastal communities in Ghana, West Africa. Remote Sens. 3(9), 2029-2050 (2011).

- Dada, O. A., Almar, R. & Oladapo, M. I. Recent coastal sea-level variations and flooding events in the Nigerian Transgressive Mud coast of Gulf of Guinea. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 161, 103668 (2020).

- Failler, P., Touron-Gardic, G., Drakeford, B., Sadio, O. & Traoré, M.-S. Perception of threats and related management measures: The case of 32 marine protected areas in West Africa. Mar. Policy 117, 103936 (2020).

- Almar, R., Kestenare, E. & Boucharel, J. On the key influence of remote climate variability from Tropical Cyclones, North and South Atlantic mid-latitude storms on the Senegalese coast (West Africa). Environ. Res. Commun. 1(7), 071001 (2019).

- Alves, B., Angnuureng, D. B., Morand, P. & Almar, R. A review on coastal erosion and flooding risks and best management practices in West Africa: What has been done and should be done. J. Coast. Conserv. 24(3), 38 (2020).

- Angnuureng, D. B., Addo, K. A., Almar, R. & Dieng, H. Influence of sea level variability on a micro-tidal beach. Nat. Hazards 68, 1611-1628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3370-4 (2018).

- Brown, S., Kebede, A. S. & Nicholls, R. J. Sea-level rise and impacts in Africa, 2000-2100 (2011) https://research.fit.edu/media/ site-specific/researchfitedu/coast-climate-adaptation-library/africa/regional—africa/Brown-et-al.–2009.–SLR–Impact-in-Africa. pdf (Accessed online on 08 November 2023).

- Tano, R. A. et al. Assessment of the Ivorian coastal vulnerability. J. Coast. Res. 32, 1495-1503. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOAS TRES-D-15-00228.1 (2016).

- Vousdoukas, M. I. et al. African heritage sites threatened as sea-level rise accelerates. Nat. Clim. Change 12(3), 256-262 (2022).

- Abessolo, O. G., Hoan, L. X., Larson, M. & Almar, R. Modeling the Bight of Benin (Gulf of Guinea, West Africa) coastline response to natural and anthropogenic forcing. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 48, 101995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2021.101995 (2021).

- Almar, R. et al. Response of the Bight of Benin (Gulf of Guinea, West Africa) coastline to anthropogenic and natural forcing, Part1: Wave climate variability and impacts on the longshore sediment transport. Cont. Shelf Res. 110, 48-59 (2015).

- Dada, O. A. et al. Response of wave and coastline evolution to global climate change off the Niger Delta during the past 110 years. Mar. Syst. 160, 64-80 (2016).

- Aman, A. et al. Physical forcing induced coastal vulnerability along the Gulf of Guinea. J. Environ. Prot. 10, 1194-1211 (2019).

- de Ponce León, S. & Guedes Soares, C. The sheltering effect of the Balearic Islands in the hindcast wave field. Ocean Eng. 37(7), 603-610 (2010).

- Soares, C. G. On the sheltering effect of islands in ocean wave models. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JC0026 82 (2005).

- Anthony, E. J. The muddy tropical coast of West Africa from Sierra Leone to Guinea-Bissau: Geological heritage, geomorphology and sediment dynamics. Afr. Geosci. Rev. 13, 227-237 (2006).

- Anthony, E. J. Beach-ridge development and sediment supply: Examples from West Africa. Mar. Geol. 129, 175-186 (1995).

- Niang, A. J. Remote sensing and GIS application for natural hazards assessment of the Mauritanian coastal zone. In Applications of Space Techniques on the Natural Hazards in the MENA Region (ed. Al Saud, M. M.) (Springer, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-3-030-88874-9_9.

- Thior, M. et al. Coastline dynamics of the northern lower Casamance (Senegal) and southern Gambia littoral from 1968 to 2017. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 160, 103611 (2019).

- Mendoza, E. et al. Coastal flood vulnerability assessment, a satellite remote sensing and modeling approach. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 29, 100923 (2023).

- Meur-Férec, C., Deboudt, P. & Morel, V. Coastal risks in France: An integrated method for evaluating vulnerability. J. Coast. Res. 24(2B), 178-189 (2008).

- Mclaughlin, S. & Cooper, J. A. G. A multi-scale coastal vulnerability index: A tool for coastal managers?. Environ. Hazards 9(3), 233-248 (2010).

- Oloyede, M. O., Williams, A. B., Ode, G. O. & Benson, N. U. Coastal vulnerability assessment: A case study of the Nigerian coastline. Sustainability 14(4), 2097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042097 (2022).

- Boateng, I., Wiafe, G. & Jayson-Quashigah, P.-N. Mapping vulnerability and risk of Ghana’s coastline to sea level rise. Mar. Geodesy 40, 23-39 (2017).

- Charuka, B., Angnuureng, D. B., Brempong, E. K., Agblorti, S. K. & Antwi Agyakwa, K. T. Assessment of the integrated coastal vulnerability index of Ghana toward future coastal infrastructure investment plans. Ocean Coast. Manag. 244, 106804. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106804 (2023).

- Guerrera, F., Tramontana, M., Nimon, B. & Essotina Kpémoua, K. Shoreline changes and coastal erosion: The case study of the coast of Togo (Bight of Benin, West Africa Margin). Geosciences 11(2), 40 (2021).

- Aikins, E. R. ECOWAS/West Africa. Published online at futures.issafrica.org. Retrieved from https://futures.issafrica.org/geogr aphic/regions/ecowas/ (2023) [Accessed online 08 November 2023].

- Hitimana, L., Heinrigs, P. & Tremolieres, M. West African urbanisation trends. West African Futures 01 (2011). https://www.oecd. org/swac/publications/48231121.pdf

- Cian, F., Blasco, J. M. D. & Carrera, L. Sentinel-1 for monitoring land subsidence of coastal cities in Africa using PSInSAR: A methodology based on the integration of SNAP and StaMPS. Geosciences 9(124), 1-32 (2019).

- Ohenhen, L. O. & Shirzaei, M. Land subsidence hazard and building collapse risk in the coastal city of Lagos, West Africa. Earth’s Future 10(12), e2022EF003219 (2022).

- Ikuemonisan, F. E. & Ozebo, V. C. Characterisation and mapping of land subsidence based on geodetic observations in Lagos, Nigeria. Geodesy Geodyn. 11(2), 151-162 (2020).

- Nicholls, R. J. et al. A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change and coastal flood exposure. Nat. Clim. Change 11(4), 338-342 (2021).

- Restrepo-Ángel, J. D. et al. Coastal subsidence increases vulnerability to sea level rise over twenty first century in Cartagena, Caribbean Colombia. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1-13 (2021).

- Shirzaei, M. et al. Measuring, modelling and projecting coastal land subsidence. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2(1), 40-58 (2021).

- Wu, T. & Barrett, J. Coastal land use management methodologies under pressure from climate change and population growth. Environ. Manag. 70, 827-839 (2022).

- Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD). In: Hitimana, L., Heinrigs, P., and Tremolieres, M. West African urbanisation trends. West African Futures 01. https://www.oecd.org/swac/publications/48231121.pdf (2011)

- Kantamanenia, K., Phillip, M., Thomas, T. & Jenkins, R. Assessing coastal vulnerability: Development of a combined physical and economic index. Ocean Coast. Manag. 158, 164-217 (2018).

- Pendleton, E. A., Thieler, E. R., Williams, S. J. & Beavers, R. S. Coastal vulnerability assessment of Padre Island National Seashore (PAIS) to Sea-level rise. USGS report No 2004-1090 (2004). Available from: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2004/1090/a.

- Pendleton, E. A., Barras, J. A., Williams, S. J. & Twichell, D. C. Coastal vulnerability assessment of the Northern Gulf of Mexico to sea-level rise and coastal change: U.S. geological survey open-file report 2010-1146. http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2010/1146/ (2010).

- Joint Research Centre – JRC – European Commission and Center for International Earth Science Information Network – CIESIN – Columbia University. Global Human Settlement Layer: Population and Built-Up Estimates, and Degree of Urbanization Settlement Model Grid. Palisades, New York: NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC). https://doi.org/10.7927/ h4154f0w (2021). (Accessed online on 08 November 2023).

- Florczyk A. J., Corbane, C., Ehrlich, D., Freire, S., Kemper, T., Maffenini, L., Melchiorri, M., Pesaresi, M., Politis, P., Schiavina, M., Sabo, F. & Zanchetta, L. GHSL data package 2019, EUR 29788 EN. ISBN 978-92-76-13186-1, JRC 117104. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/290498 (2019).

- Almar, R. et al. A global analysis of extreme coastal water levels with implications for potential coastal overtopping. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 3775 (2021).

- Hayden, B., Vincent, M., Resio, D., Biscoe, C. & Dolan, R. Classification of the Coastal Environments of the World: Part II—Africa (Office of Naval Research, 1973).

- Allersma, E. & Tilmans, W. M. Coastal conditions in West Africa-A review. Ocean Coast. Manag. 19(3), 199-240 (1993).

- Musa, Z. N., Popescu, I. & Mynett, A. The Niger Delta’s vulnerability to river floods due to sea level rise. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 3317-3329 (2014).

- El-Shahat, S. et al. Vulnerability assessment of African coasts to sea level rise using GIS and remote sensing. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 2827-2845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00639-8 (2021).

- Kumar, T. & Kunte, P. Coastal vulnerability assessment for Chennai, east coast of india using geospatial techniques. J. Nat. Hazards 64, 853-872 (2012).

- Yin, J., Yin, Z., Wang, J. & Xu, S. National assessment of coastal vulnerability to sea-level rise for the Chinese coast. J. Coast. Conserv. 16, 123-133 (2012).

- Dinh, Q., Balica, S., Popescu, I. & Jonoski, A. Climate change impact on flood hazard, vulnerability and risk of the Long Xuyen Quadrangle in the Mekong Delta. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 10, 103-120 (2012).

- Thieler, E. R. & Hammar-Klose, E. S. National assessment of coastal vulnerability to sea-level rise, U.S. Atlantic Coast. US Geological Survey, Open-File Report, 99-593 (1999).

- Gornitz, V. Global coastal hazards from future sea level rise. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 89, 379-398 (1991).