DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-024-00136-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38331952

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-08

تكلفة الرعاية لمرض الزهايمر والخرف المرتبط به في الولايات المتحدة: من 2016 إلى 2060

الملخص

يمكن أن تفرض الرعاية الطبية ورعاية طويلة الأمد لمرض الزهايمر والخرف المرتبط به (ADRDs) عبئًا اقتصاديًا كبيرًا على الأفراد والمجتمعات. قمنا بتقدير تكلفة الرعاية لكل فرد من ADRDs في الولايات المتحدة في عام 2016 وتوقعنا التكاليف الإجمالية المستقبلية للرعاية خلال الفترة من 2020 إلى 2060. استنادًا إلى منهجية تم نشرها سابقًا، استخدمنا بيانات المسح الصحي والتقاعد الأمريكي (2010-2016) لتقدير تكاليف الرعاية الرسمية وغير الرسمية. في عام 2016، كانت التكلفة المقدرة لكل مريض من الرعاية الرسمية هي

مقدمة

النتائج

| نوع الإنفاق | تكلفة رعاية الأمراض التنكسية العصبية في الولايات المتحدة (2020 دولار أمريكي) | ||

| تقدير | فترة الثقة 95% | ||

| من جيبك | |||

| الرعاية الصحية المنزلية | 185 | ١٠٨ | ٢٧١ |

| دار رعاية المسنين | 7203 | 6155 | 8263 |

| الإجمالي (أ) | 7943 | 6878 | 9078 |

| إنفاق ميديكير: | |||

| وكالات الرعاية الصحية المنزلية | 964 | 759 | 1191 |

| دار رعاية المسنين | 1505 | ١٣٩٥ | 1618 |

| الإجمالي (ب) | ٤٣٦٥ | ٣٩٧٤ | 4794 |

| الرعاية المنزلية الرسمية: | |||

| إجمالي | 7220 | 5687 | 8917 |

| أقل: ميديكير والنفقات الشخصية | 1149 | 935 | 1381 |

| الإجمالي الصافي (ج) | 6071 | ٤٧٤٤ | 7554 |

| رعاية دور المسنين: | |||

| إجمالي | 18,406 | ١٧,٠٥٧ | 19,791 |

| أقل: ميديكير والنفقات الشخصية | 8708 | 7587 | 9825 |

| الإجمالي الصافي (د) | 9698 | 8453 | 10,912 |

| إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة في السوق (

|

٢٨٠٧٨ | ٢٥,٨٩٣ | ٣٠,٤٣٣ |

| الرعاية غير الرسمية: تكلفة الاستبدال (E) | ٣٦,٦٦٧ | ٣٤٠٢٥ | ٣٩,٤٧٣ |

| إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة في السوق بالإضافة إلى وقت الرعاية المقدر وفقًا لتكلفة الاستبدال

|

٦٤٧٤٥ | 61,740 | 67,909 |

| الرعاية غير الرسمية: تكلفة الأجر المفقود (F) | 15,792 | ١٢٩٨٠ | 18,713 |

| إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة في السوق بالإضافة إلى وقت الرعاية الذي يتم تقييمه بتكلفة الأجر المفقود

|

٤٣,٨٦٩ | ٤٠٢٤٦ | ٤٧,٥٩١ |

نقاش

الولايات المتحدة ضرورية لتعبئة الاستثمارات اللازمة لتجنب الأعباء الإنسانية والاقتصادية للأمراض التنكسية العصبية.

| الجدول 2. التكلفة المستقبلية المتوقعة لرعاية اضطرابات الخرف الرسمية وغير الرسمية في الولايات المتحدة. | |||

| سنة | إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة في السوق (مليارات دولار أمريكي 2020) | إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة في السوق بالإضافة إلى وقت الرعاية المقدر وفقًا لتكلفة الاستبدال (مليارات الدولارات الأمريكية لعام 2020) | إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة في السوق بالإضافة إلى وقت الرعاية المقدر بتكاليف الأجور المفقودة (مليارات دولار أمريكي لعام 2020) |

| حالة الأساس (3% تضخم سنوي في التكاليف) | |||

| ٢٠٢٠ | 196 (179-213) | 450 (424-478) | 305 (278-333) |

| ٢٠٢٥ | 252 (184-326) | 580 (430-740) | 393 (288-508) |

| ٢٠٣٠ | ٣٢٥ (٢٣٣-٤٣٠) | 746 (542-979) | 506 (363-671) |

| ٢٠٣٥ | 417 (293-566) | 959 (677-1292) | 650 (456-878) |

| 2040 | 535 (364-748) | 1229 (842-1699) | 833 (567-1160) |

| 2045 | 683 (450-988) | 1570 (1046-2247) | 1064 (702-1532) |

| ٢٠٥٠ | 875 (558-1295) | 2010 (1293-2945) | 1362 (867-2009) |

| ٢٠٥٥ | 1115 (677-1714) | 2562 (1571-3911) | 1736 (1055-2664) |

| ٢٠٦٠ | 1424 (837-2238) | 3271 (1936-5120) | ٢٢١٧ (١٣١١-٣٤٨٧) |

| مع تضخم سنوي في التكاليف بنسبة 2% | |||

| ٢٠٢٠ | 189 (173-204) | 433 (410-457) | ٢٩٤ (٢٦٩-٣١٩) |

| ٢٠٢٥ | 231 (170-296) | 531 (398-672) | 360 (265-463) |

| ٢٠٣٠ | ٢٨٣ (٢٠٦-٣٦٩) | 651 (480-838) | ٤٤١ (٣٢٢-٥٧٦) |

| ٢٠٣٥ | 346 (249-457) | 796 (579-1043) | 539 (387-712) |

| 2040 | 422 (297-570) | 971 (692-1296) | 658 (464-886) |

| 2045 | ٥١٣ (٣٥٥-٧١٣) | 1179 (822-1622) | 799 (553-1105) |

| ٢٠٥٠ | 625 (422-879) | 1436 (978-1998) | 973 (655-1364) |

| ٢٠٥٥ | 757 (494-1099) | 1740 (1142-2503) | 1179 (769-1707) |

| ٢٠٦٠ | 919 (586-1352) | 2113 (1355-3094) | 1432 (915-2105) |

| مع تضخم سنوي في التكاليف بنسبة 4% | |||

| ٢٠٢٠ | 204 (185-223) | ٤٦٨ (٤٣٧-٥٠١) | 317 (287-349) |

| 2025 | 275 (199-359) | 632 (464-815) | 429 (311-558) |

| ٢٠٣٠ | 372 (262-503) | 855 (608-1147) | 580 (408-783) |

| ٢٠٣٥ | ٥٠٢ (٣٤٢-٧٠٢) | 1154 (793-1602) | 782 (532-1088) |

| 2040 | 677 (441-980) | 1555 (1022-2234) | 1054 (689-1520) |

| 2045 | 908 (568-1370) | 2087 (1318-3131) | 1414 (883-2130) |

| ٢٠٥٠ | 1223 (731-1905) | 2810 (1691-4343) | 1904 (1137-2955) |

| ٢٠٥٥ | 1640 (923-2668) | 3768 (2134-6117) | 2553 (1439-4144) |

| ٢٠٦٠ | 2203 (1184-3709) | 5062 (2738-8450) | ٣٤٣٠ (١٨٥٤-٥٧٧٢) |

| نطاقات عدم اليقين بنسبة 95% موجودة بين قوسين. | |||

الطرق

بيانات

| سنة | رعاية شاملة | إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة | إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة |

| تم شراؤه في | في السوق | في السوق | |

| سوق | وقت رعاية إضافي | بالإضافة إلى وقت الرعاية | |

| (مليارات 2020 | مُقدَّر وفقًا لـ | مُقدَّر بالتخلي | |

| دولار أمريكي | تكلفة الاستبدال | تكاليف الأجور (مليارات) | |

| (مليارات من دولارات الولايات المتحدة 2020) | من عام 2020 (دولار أمريكي) |

| الحالة الأساسية مع نمو عبء أقل بنسبة 40% | |||

| ٢٠٢٠ | 195 (178-212) | 448 (421-475) | 303 (276-331) |

| ٢٠٢٥ | 243 (177-314) | 559 (415-712) | 378 (277-489) |

| ٢٠٣٠ | 303 (218-401) | 697 (508-913) | 473 (340-624) |

| ٢٠٣٥ | 378 (267-511) | 869 (618-1165) | ٥٨٩ (٤١٥-٧٩٢) |

| 2040 | 470 (322-651) | 1080 (746-1482) | 732 (502-1011) |

| 2045 | 581 (387-831) | 1336 (898-1892) | 905 (606-1292) |

| ٢٠٥٠ | 722 (466-1053) | 1658 (1083-2397) | 1124 (724-1634) |

| ٢٠٥٥ | 891 (555-1345) | 2048 (1283-3073) | 1388 (863-2087) |

| ٢٠٦٠ | 1103 (662-1702) | 2535 (1538-3878) | 1718 (1039-2646) |

| ٢٠٢٠ | 187 (172-203) | 431 (408-454) | 292 (267-317) |

| 2025 | ٢٢٣ (١٦٤-٢٨٥) | 511 (383-646) | 347 (255-445) |

| ٢٠٣٠ | 265 (193-343) | 608 (451-781) | 412 (301-536) |

| ٢٠٣٥ | 314 (227-412) | 721 (527-937) | ٤٨٨ (٣٥٣-٦٤٠) |

| 2040 | 371 (263-496) | 852 (612-1125) | 578 (411-771) |

| 2045 | 437 (306-597) | 1004 (710-1356) | 680 (477-929) |

| ٢٠٥٠ | 515 (353-713) | 1184 (822-1621) | 803 (547-1107) |

| ٢٠٥٥ | 605 (405-859) | 1391 (938-1958) | 943 (630-1337) |

| ٢٠٦٠ | 712 (467-1025) | 1637 (1081-2333) | 1109 (730-1595) |

| ٢٠٢٠ | 202 (183-222) | 465 (435-497) | 315 (285-346) |

| 2025 | 265 (192-346) | 609 (447-786) | 413 (300-538) |

| ٢٠٣٠ | 348 (245-469) | 799 (570-1071) | 542 (382-730) |

| ٢٠٣٥ | 455 (311-633) | 1046 (721-1445) | 709 (484-982) |

| 2040 | 594 (390-856) | 1366 (906-1953) | 925 (609-1326) |

| 2045 | 773 (489-1156) | 1777 (1132-2636) | 1204 (763-1798) |

| ٢٠٥٠ | 1009 (610-1553) | 2318 (1414-3543) | 1571 (950-2414) |

| ٢٠٥٥ | 1311 (755-2107) | 3012 (1744-4802) | 2041 (1176-3273) |

| ٢٠٦٠ | 1707 (932-2822) | ٣٩٢٣ (٢١٦٦-٦٤١٤) | 2658 (1466-4389) |

(HRS). بدأت الاستطلاعات في عام 1992 وتغطي حوالي 20,000 فرد يتم مقابلتهم مرة كل عامين. يجمع HRS بيانات حول جوانب مختلفة من الشيخوخة، بما في ذلك الصحة والإعاقة، والوصول إلى الرعاية الصحية والإنفاق، والإسكان، والأصول، والتوظيف. تشكل مجموعة فرعية من 856 من المشاركين في HRS الذين كانوا في سن 70 وما فوق في 2000-2002 دراسة الشيخوخة والديموغرافيات والذاكرة (ADAMS). جمعت ADAMS بيانات سريرية متعمقة حول الحالة الإدراكية والخرف للمشاركين في أربع موجات من 2001 إلى

احتمالية الأمراض التنكسية العصبية و تكلفة الرعاية

أ. ناندي وآخرون

| الجدول 4. تحليل الحساسية مع تكاليف دور رعاية المسنين المرتفعة. | |||

| سنة | إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة في السوق (مليارات دولار أمريكي 2020) | إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة في السوق بالإضافة إلى وقت الرعاية المقدر وفقًا لتكلفة الاستبدال (مليارات الدولارات الأمريكية لعام 2020) | إجمالي الرعاية المشتراة في السوق بالإضافة إلى وقت الرعاية الذي يُقدّر بتكاليف الأجور المفقودة (مليارات الدولارات الأمريكية لعام 2020) |

| الحالة الأساسية مع تكاليف دور رعاية المسنين المرتفعة | |||

| ٢٠٢٠ | 318 (286-351) | 573 (520-628) | 428 (377-480) |

| ٢٠٢٥ | 410 (296-534) | 737 (538-959) | ٥٥١ (٣٩٥-٧٢٥) |

| ٢٠٣٠ | 527 (375-704) | 950 (679-1265) | 709 (501-956) |

| ٢٠٣٥ | 678 (473-924) | 1220 (852-1665) | 911 (630-1252) |

| 2040 | 869 (587-1222) | 1564 (1063-2184) | 1168 (783-1645) |

| 2045 | 1109 (726-1613) | 1997 (1316-2895) | 1491 (974-2179) |

| ٢٠٥٠ | 1420 (901-2110) | 2557 (1632-3784) | 1910 (1199-2850) |

| ٢٠٥٥ | 1810 (1094-2793) | 3259 (1975-5011) | 2434 (1465-3773) |

| ٢٠٦٠ | 2312 (1351-3648) | 4162 (2440-6537) | 3108 (1820-4916) |

| مع ارتفاع تكاليف دور رعاية المسنين وارتفاع التضخم السنوي بنسبة 2% | |||

| ٢٠٢٠ | 306 (276-336) | ٥٥١ (٥٠٣-٦٠٠) | 412 (364-460) |

| ٢٠٢٥ | 375 (273-485) | 675 (496-871) | 504 (364-662) |

| ٢٠٣٠ | 460 (333-602) | 828 (601-1085) | 618 (442-822) |

| ٢٠٣٥ | 562 (402-748) | 1012 (725-1344) | 756 (535-1014) |

| 2040 | 686 (479-932) | 1235 (869-1665) | 922 (639-1260) |

| 2045 | 833 (572-1163) | 1500 (1034-2085) | 1120 (765-1570) |

| ٢٠٥٠ | 1014 (681-1432) | 1826 (1230-2567) | 1364 (905-1934) |

| ٢٠٥٥ | 1230 (797-1794) | ٢٢١٤ (١٤٣٨-٣٢١٣) | 1653 (1065-2424) |

| ٢٠٦٠ | 1493 (948-2206) | ٢٦٨٨ (١٧٠٦-٣٩٦٤) | 2007 (1264-2974) |

| مع ارتفاع تكاليف دور رعاية المسنين وارتفاع التضخم السنوي بنسبة 4% | |||

| ٢٠٢٠ | ٣٣١ (٢٩٥-٣٦٧) | 596 (538-657) | 445 (389-502) |

| ٢٠٢٥ | 447 (320-588) | 805 (582-1056) | 601 (428-798) |

| ٢٠٣٠ | 604 (422-823) | 1088 (764-1477) | 813 (564-1114) |

| ٢٠٣٥ | 816 (553-1145) | 1469 (996-2060) | ١٠٩٧ (٧٣٦-١٥٤٦) |

| 2040 | 1099 (714-1603) | 1978 (1291-2866) | 1477 (954-2153) |

| 2045 | 1475 (917-2236) | 2656 (1664-4005) | 1983 (1228-3028) |

| ٢٠٥٠ | 1986 (1183-3110) | 3575 (2141-5573) | 2670 (1572-4191) |

| ٢٠٥٥ | 2663 (1494-4350) | 4793 (2697-7804) | 3579 (1994-5869) |

| ٢٠٦٠ | 3578 (1909-6053) | 6440 (3456-10810) | 4809 (2584-8135) |

| نطاقات عدم اليقين بنسبة 95% موجودة بين قوسين. | |||

التكلفة الرسمية للرعاية المشتراة في السوق

تكلفة الرعاية غير الرسمية، أو تكلفة مقدمي الرعاية

التوقعات المستقبلية

تحليل الحساسية

النشاط، التدخين، استهلاك الكحول المفرط، والتعرض لتلوث الهواء

توفر البيانات

توافر الشيفرة

تاريخ الاستلام: 9 أكتوبر 2023؛ تاريخ القبول: 9 يناير 2024؛

نُشر على الإنترنت: 08 فبراير 2024

REFERENCES

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects. 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/ (accessed April 6, 2022).

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures: 2022. https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf (accessed April 22, 2022).

- Rajan, K. B. et al. Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020-2060). Alzheimers Dement 17, 1966-1975 (2021).

- Tarawneh, R. & Holtzman, D. M. The clinical problem of symptomatic Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a006148 (2012).

- Deb, A., Thornton, J. D., Sambamoorthi, U. & Innes, K. Direct and indirect cost of managing alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States. Expert. Rev. Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 17, 189-202 (2017).

- Hurd, M. D., Martorell, P., Delavande, A., Mullen, K. J. & Langa, K. M. Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1326-1334 (2013).

- Hurd, M. D., Martorell, P. & Langa, K. Future Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States under Alternative Dementia Prevalence Scenarios. J. Popul. Ageing 8, 101-112 (2015).

- Zissimopoulos, J., Crimmins, E. & St Clair, P. The Value of Delaying Alzheimer’s Disease Onset. Forum Health Econ. Policy 18, 25-39 (2014).

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer Dementia 16, 391-460 (2020).

- Alzheimer’s Association. Changing the Trajectory of Alzheimer’s Disease: How a Treatment by 2025 Saves Lives and Dollars (Alzheimer’s Association, 2015).

- Burke, L. G., Burke, R. C., Epstein, S. K., Orav, E. J. & Jha, A. K. Trends in Costs of Care for Medicare Beneficiaries Treated in the Emergency Department From 2011 to 2016. JAMA Network Open 3, e208229 (2020).

- Pyenson, B. et al. The Real-World Medicare Costs of Alzheimer Disease: Considerations for Policy and Care. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 25, 800-809 (2019).

- Rattinger, G. B. et al. Dementia severity and the longitudinal costs of informal care in the Cache County population. Alzheimers Dement 11, 946-954 (2015).

- Yang, Z. & Levey, A. Gender Differences: A Lifetime Analysis of the Economic Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease. Womens Health Issues 25, 436-440 (2015).

- Zhu, C. W. et al. Health-care use and cost in dementia caregivers: Longitudinal results from the Predictors Caregiver Study. Alzheimers Dement 11, 444-454 (2015).

- Joyce, A. T. et al. Burden of illness among commercially insured patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 3, 204-210 (2007).

- Kuo, T.-C., Zhao, Y., Weir, S., Kramer, M. S. & Ash, A. S. Implications of comorbidity on costs for patients with Alzheimer disease. Med. Care 46, 839-846 (2008).

- Goldfeld, K. S., Stevenson, D. G., Hamel, M. B. & Mitchell, S. L. Medicare expenditures among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Arch. Intern. Med. 171, 824-830 (2011).

- Bharmal, M. F. et al. Incremental Dementia-Related Expenditures in a Medicaid Population. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 20, 73-83 (2012).

- Suehs, B. T. et al. The clinical and economic burden of newly diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease in a medicare advantage population. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 28, 384-392 (2013).

- Kelley, A. S., McGarry, K., Gorges, R. & Skinner, J. S. The Burden of Health Care Costs in the Last 5 Years of Life. Ann Intern. Med. 163, 729-736 (2015).

- Zhu, C. W. et al. Medicare Utilization and Expenditures Around Incident Dementia in a Multiethnic Cohort. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 70, 1448-1453 (2015).

- Lin, P.-J., Zhong, Y., Fillit, H. M., Chen, E. & Neumann, P. J. Medicare Expenditures of Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias or Mild Cognitive Impairment Before and After Diagnosis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64, 1549-1557 (2016).

- Yang, Z., Zhang, K., Lin, P.-J., Clevenger, C. & Atherly, A. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Lifetime Cost of Dementia. Health Serv. Res. 47, 1660-1678 (2012).

- Deb, A., Sambamoorthi, U., Thornton, J. D., Schreurs, B. & Innes, K. Direct medical expenditures associated with Alzheimer’s and related dementias (ADRD) in a nationally representative sample of older adults – an excess cost approach. Aging Ment Health 22, 619-624 (2018).

- Fishman, P. et al. Cost of Dementia in Medicare Managed Care: A Systematic Literature Review. Am. J. Manag. Care 25, e247-e253 (2019).

- David, K., Guterman, S.& Bandeali, F. The Affordable Care Act and Medicare: How the Law Is Changing the Program and the Challenges That Remain (Commonwealth Fund, 2015).

- Oney, M., White, L. & Coe, N. B. Out-of-pocket costs attributable to dementia: A longitudinal analysis. J. Am. Geriatrics Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs. 17746 (2022).

- Bloom, D. E., Counts, N., Nandi, A., Tortorice, D.& Vigo, D. How to address Alzheimer’s disease and support healthier ageing (World Economic Forum, 2022). https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/this-is-how-to-address-a-global-alzheimers-disease/ (accessed March 25, 2022).

- Bloom, D. et al. Addressing Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias to realise the promise of the UN’s ‘Decade of Healthy Ageing’ (VoxEU, 2021). https://voxeu.org/ article/alzheimer-s-and-un-s-decade-healthy-ageing (accessed May 14, 2021).

- Counts, N., Nandi, A., Seligman, B. & Tortorice, D. Dementia Storm on the Horizon: The rising incidence of dementia around the world calls for global collaboration and decisive financing. Finance Dev. 58, 54-57 (2021).

- Hartman, M., Martin, A. B., Washington, B., Catlin, A. & The, N. H. E. A. T. National Health Care Spending In 2020: Growth Driven By Federal Spending In Response To The COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Affairs 41, 13-25 (2022).

- Zafari, Z., Li, S., Eakin, M. N., Bellanger, M. & Reed, R. M. Projecting Long-term Health and Economic Burden of COPD in the United States. Chest 159, 1400-1410 (2021).

- Dall, T. M. et al. The Economic Burden of Elevated Blood Glucose Levels in 2017: Diagnosed and Undiagnosed Diabetes, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, and Prediabetes. Diabetes Care 42, 1661-1668 (2019).

- Nandi, A. et al. Global and regional projections of the economic burden of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias from 2019 to 2050: A value of statistical life approach. eClinicalMedicine 51, 101580 (2022).

- Jia, J. et al. The cost of Alzheimer’s disease in China and re-estimation of costs worldwide. Alzheimers Dement 14, 483-491 (2018).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI Inflation Calculator. 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ data/inflation_calculator.htm (accessed April 23, 2022).

- Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 396, 413-446 (2020).

- Chen, C. & Zissimopoulos, J. M. Racial and ethnic differences in trends in dementia prevalence and risk factors in the United States. Alzheimer Dementia 4, 510-520 (2018).

- Matthews, K. A. et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged

years. Alzheimers Dement 15, 17-24 (2019). - Alzheimer’s Association. Women and Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. 2022. https://alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/women-and-alzheimer-s (accessed April 23, 2022).

- Mikton, C., de la Fuente-Núñez, V., Officer, A. & Krug, E. Ageism: a social determinant of health that has come of age. Lancet 397, 1333-1334 (2021).

- Chen, S., Kuhn, M., Prettner, K. & Bloom, D. E. The global macroeconomic burden of road injuries: estimates and projections for 166 countries. Lancet Planet. Health 3, e390-e398 (2019).

- Langa, K. M. et al. The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study: study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology 25, 181-191 (2005).

- Okura, T. & Langa, K. M. Caregiver Burden and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment: The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS). Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 25, 116-121 (2011).

- Crimmins, E. M., Kim, J. K., Langa, K. M. & Weir, D. R. Assessment of Cognition Using Surveys and Neuropsychological Assessment: The Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 66B, i162-i171 (2011).

- Brookmeyer, R. et al. National estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimer Dementia 7, 61-73 (2011).

- Sonnega, A. et al. Cohort Profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 576-585 (2014).

- Genworth. Cost of Long Term Care by State. 2022. https://www.genworth.com/ aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html (accessed April 22, 2022).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index (CPI) Databases: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2022. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm (accessed June 9, 2022).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Diseases Results Tool. GBD Results Tool. 2019. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

- US Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States. 2022. https:// www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221 (accessed April 22, 2022).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Medical care in U.S. city average, all urban consumers, not seasonally adjusted. 2022. https://data.bls.gov/ (accessed May 10, 2023).

- Nianogo, R. A. et al. Risk Factors Associated With Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias by Sex and Race and Ethnicity in the US. JAMA Neurol. 79, 584-591 (2022).

- Lima, J. C., Ogarek, J. & Mor, V. Untapped Potential – Using the HRS-Medicare Linked Files to Study the Changing Nursing Home Population. Med. Care 56, 216-219 (2018).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing Home Data Compendium 2015 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2015).

- US Census Bureau. The Older Population: 2010 (US Department of Commerce, 2011).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

لا تمثل هذه المنشورة آراء وزارة شؤون المحاربين القدامى أو الحكومة الأمريكية.

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والإذن متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/إعادة طباعة

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

مجلس السكان، 1 ساحة داغ همرشولد، نيويورك، NY 10017، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ثقة الصحة الواحدة، واشنطن العاصمة، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مكتب مفوض الصحة والصحة العقلية لمدينة نيويورك، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مؤسسة بروكينغز، واشنطن العاصمة، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. بيانات للقرارات، ذ.م.م، وaltham، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. جامعة هايدلبرغ، هايدلبرغ، ألمانيا. قسم البيولوجيا الجزيئية والخلوية ومركز علوم الدماغ، جامعة هارفارد، كامبريدج، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الطب الشيخوخي، قسم الطب، كلية ديفيد غيفن للطب، جامعة كاليفورنيا، لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز أبحاث وتعليم ورعاية المسنين، نظام الرعاية الصحية في إدارة المحاربين القدامى في لوس أنجلوس الكبرى، لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. كلية الصليب المقدس، ووستر، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. جامعة كولومبيا البريطانية، فانكوفر، كولومبيا البريطانية V6T 1Z4، كندا. مدرسة هارفارد تي. إتش. تشان للصحة العامة، بوسطن، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني:anandi@popcouncil.org

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-024-00136-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38331952

Publication Date: 2024-02-08

Cost of care for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States: 2016 to 2060

Abstract

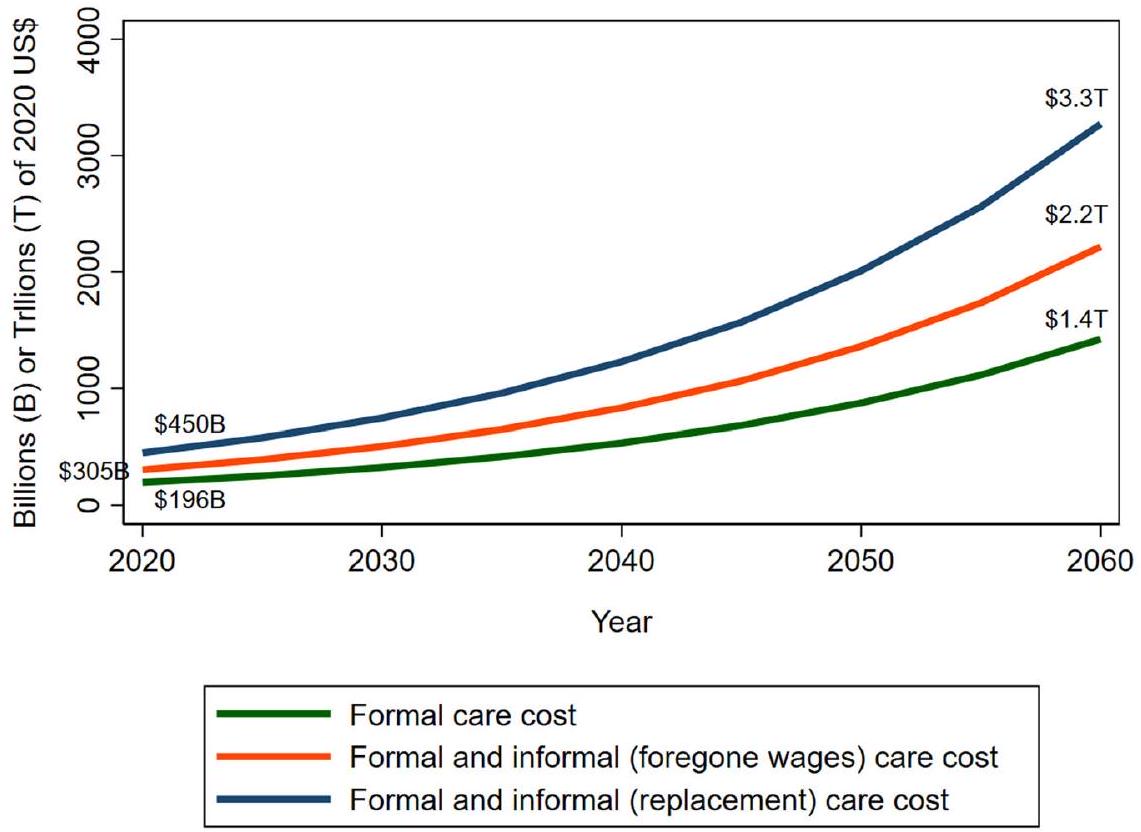

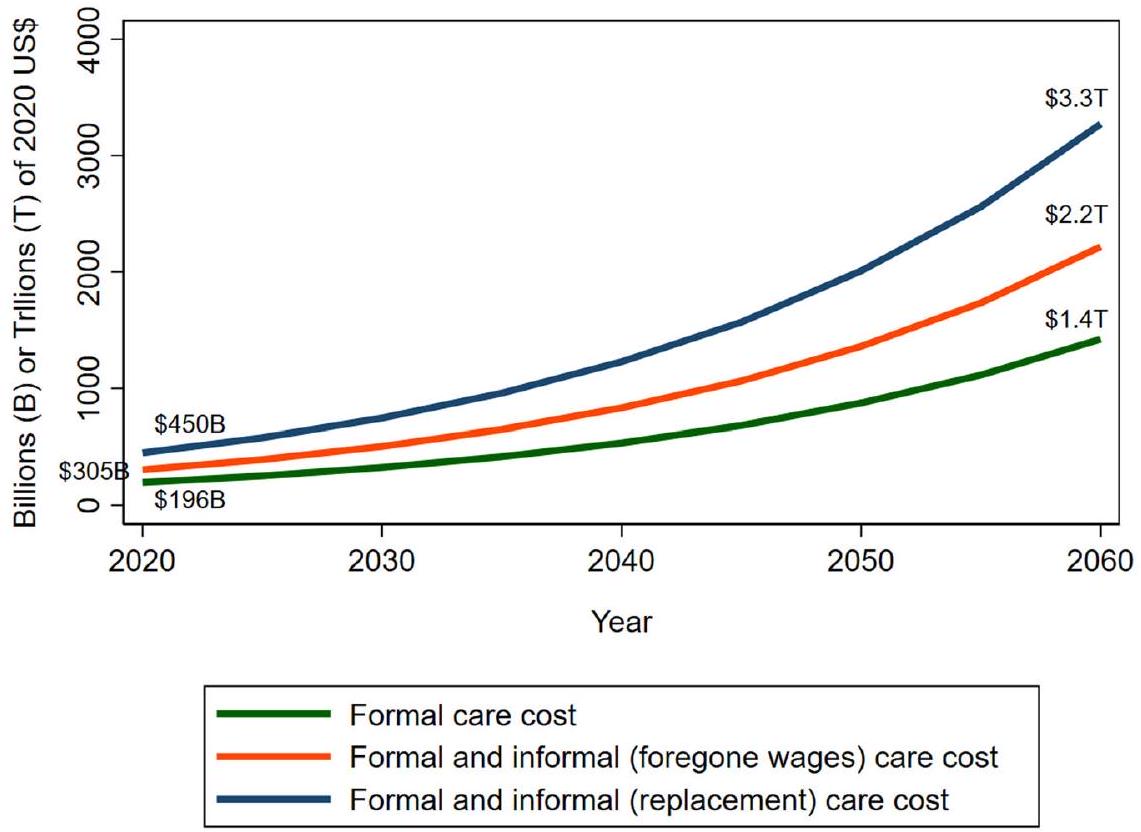

Medical and long-term care for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRDs) can impose a large economic burden on individuals and societies. We estimated the per capita cost of ADRDs care in the in the United States in 2016 and projected future aggregate care costs during 2020-2060. Based on a previously published methodology, we used U.S. Health and Retirement Survey (2010-2016) longitudinal data to estimate formal and informal care costs. In 2016, the estimated per patient cost of formal care was

INTRODUCTION

RESULTS

| Spending type | Cost of ADRDs care in the United States (2020 US$) | ||

| Estimate | 95% confidence interval | ||

| Out-of-pocket: | |||

| Home health care | 185 | 108 | 271 |

| Nursing home | 7203 | 6155 | 8263 |

| Total (A) | 7943 | 6878 | 9078 |

| Medicare spending: | |||

| Home health care agencies | 964 | 759 | 1191 |

| Nursing home | 1505 | 1395 | 1618 |

| Total (B) | 4365 | 3974 | 4794 |

| Formal home care: | |||

| Total | 7220 | 5687 | 8917 |

| Less: Medicare and OOP | 1149 | 935 | 1381 |

| Net total (C) | 6071 | 4744 | 7554 |

| Nursing home care: | |||

| Total | 18,406 | 17,057 | 19,791 |

| Less: Medicare and OOP | 8708 | 7587 | 9825 |

| Net total (D) | 9698 | 8453 | 10,912 |

| Total care purchased in the marketplace (

|

28,078 | 25,893 | 30,433 |

| Informal care: replacement cost (E) | 36,667 | 34,025 | 39,473 |

| Total care purchased in the marketplace plus caregiving time valued according to replacement cost (

|

64,745 | 61,740 | 67,909 |

| Informal care: Foregone wage cost (F) | 15,792 | 12,980 | 18,713 |

| Total care purchased in the marketplace plus caregiving time valued at foregone wage cost (

|

43,869 | 40,246 | 47,591 |

DISCUSSION

the United States is necessary to mobilize the necessary investment to avert the human and economic tolls of ADRDs

| Table 2. Projected future cost of ADRDs formal and informal care in the United States. | |||

| Year | Total care purchased in the marketplace (billions of 2020 US$) | Total care purchased in the marketplace plus caregiving time valued according to replacement cost (billions of 2020 US$) | Total care purchased in the marketplace plus caregiving time valued at foregone wage costs (billions of 2020 US$) |

| Base case (3% annual cost inflation) | |||

| 2020 | 196 (179-213) | 450 (424-478) | 305 (278-333) |

| 2025 | 252 (184-326) | 580 (430-740) | 393 (288-508) |

| 2030 | 325 (233-430) | 746 (542-979) | 506 (363-671) |

| 2035 | 417 (293-566) | 959 (677-1292) | 650 (456-878) |

| 2040 | 535 (364-748) | 1229 (842-1699) | 833 (567-1160) |

| 2045 | 683 (450-988) | 1570 (1046-2247) | 1064 (702-1532) |

| 2050 | 875 (558-1295) | 2010 (1293-2945) | 1362 (867-2009) |

| 2055 | 1115 (677-1714) | 2562 (1571-3911) | 1736 (1055-2664) |

| 2060 | 1424 (837-2238) | 3271 (1936-5120) | 2217 (1311-3487) |

| With 2% annual cost inflation | |||

| 2020 | 189 (173-204) | 433 (410-457) | 294 (269-319) |

| 2025 | 231 (170-296) | 531 (398-672) | 360 (265-463) |

| 2030 | 283 (206-369) | 651 (480-838) | 441 (322-576) |

| 2035 | 346 (249-457) | 796 (579-1043) | 539 (387-712) |

| 2040 | 422 (297-570) | 971 (692-1296) | 658 (464-886) |

| 2045 | 513 (355-713) | 1179 (822-1622) | 799 (553-1105) |

| 2050 | 625 (422-879) | 1436 (978-1998) | 973 (655-1364) |

| 2055 | 757 (494-1099) | 1740 (1142-2503) | 1179 (769-1707) |

| 2060 | 919 (586-1352) | 2113 (1355-3094) | 1432 (915-2105) |

| With 4% annual cost inflation | |||

| 2020 | 204 (185-223) | 468 (437-501) | 317 (287-349) |

| 2025 | 275 (199-359) | 632 (464-815) | 429 (311-558) |

| 2030 | 372 (262-503) | 855 (608-1147) | 580 (408-783) |

| 2035 | 502 (342-702) | 1154 (793-1602) | 782 (532-1088) |

| 2040 | 677 (441-980) | 1555 (1022-2234) | 1054 (689-1520) |

| 2045 | 908 (568-1370) | 2087 (1318-3131) | 1414 (883-2130) |

| 2050 | 1223 (731-1905) | 2810 (1691-4343) | 1904 (1137-2955) |

| 2055 | 1640 (923-2668) | 3768 (2134-6117) | 2553 (1439-4144) |

| 2060 | 2203 (1184-3709) | 5062 (2738-8450) | 3430 (1854-5772) |

| 95% uncertainty ranges are in parentheses. | |||

METHODS

Data

| Year | Total care | Total care purchased | Total care purchased |

| purchased in the | in the marketplace | in the marketplace | |

| marketplace | plus caregiving time | plus caregiving time | |

| (billions of 2020 | valued according to | valued at foregone | |

| US$) | replacement cost | wage costs (billions | |

| (billions of 2020 US$) | of 2020 US$) |

| Base case with 40% lower burden growth | |||

| 2020 | 195 (178-212) | 448 (421-475) | 303 (276-331) |

| 2025 | 243 (177-314) | 559 (415-712) | 378 (277-489) |

| 2030 | 303 (218-401) | 697 (508-913) | 473 (340-624) |

| 2035 | 378 (267-511) | 869 (618-1165) | 589 (415-792) |

| 2040 | 470 (322-651) | 1080 (746-1482) | 732 (502-1011) |

| 2045 | 581 (387-831) | 1336 (898-1892) | 905 (606-1292) |

| 2050 | 722 (466-1053) | 1658 (1083-2397) | 1124 (724-1634) |

| 2055 | 891 (555-1345) | 2048 (1283-3073) | 1388 (863-2087) |

| 2060 | 1103 (662-1702) | 2535 (1538-3878) | 1718 (1039-2646) |

| 2020 | 187 (172-203) | 431 (408-454) | 292 (267-317) |

| 2025 | 223 (164-285) | 511 (383-646) | 347 (255-445) |

| 2030 | 265 (193-343) | 608 (451-781) | 412 (301-536) |

| 2035 | 314 (227-412) | 721 (527-937) | 488 (353-640) |

| 2040 | 371 (263-496) | 852 (612-1125) | 578 (411-771) |

| 2045 | 437 (306-597) | 1004 (710-1356) | 680 (477-929) |

| 2050 | 515 (353-713) | 1184 (822-1621) | 803 (547-1107) |

| 2055 | 605 (405-859) | 1391 (938-1958) | 943 (630-1337) |

| 2060 | 712 (467-1025) | 1637 (1081-2333) | 1109 (730-1595) |

| 2020 | 202 (183-222) | 465 (435-497) | 315 (285-346) |

| 2025 | 265 (192-346) | 609 (447-786) | 413 (300-538) |

| 2030 | 348 (245-469) | 799 (570-1071) | 542 (382-730) |

| 2035 | 455 (311-633) | 1046 (721-1445) | 709 (484-982) |

| 2040 | 594 (390-856) | 1366 (906-1953) | 925 (609-1326) |

| 2045 | 773 (489-1156) | 1777 (1132-2636) | 1204 (763-1798) |

| 2050 | 1009 (610-1553) | 2318 (1414-3543) | 1571 (950-2414) |

| 2055 | 1311 (755-2107) | 3012 (1744-4802) | 2041 (1176-3273) |

| 2060 | 1707 (932-2822) | 3923 (2166-6414) | 2658 (1466-4389) |

(HRS). The surveys started in 1992 and cover approximately 20,000 individuals who are interviewed once every two years. The HRS collects data on various aspects of aging, including health and disability, health care access and spending, housing, assets, and employment. A subset of 856 HRS respondents who were age 70 and older in 2000-2002 form the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS). ADAMS collected in-depth clinical data on cognitive status and dementia of the participants in four waves from 2001 to

The probability of ADRDs and cost of care

A. Nandi et al.

| Table 4. Sensitivity analysis with higher nursing home costs. | |||

| Year | Total care purchased in the marketplace (billions of 2020 US$) | Total care purchased in the marketplace plus caregiving time valued according to replacement cost (billions of 2020 US$) | Total care purchased in the marketplace plus caregiving time valued at foregone wage costs (billions of 2020 US$) |

| Base case with higher nursing home costs | |||

| 2020 | 318 (286-351) | 573 (520-628) | 428 (377-480) |

| 2025 | 410 (296-534) | 737 (538-959) | 551 (395-725) |

| 2030 | 527 (375-704) | 950 (679-1265) | 709 (501-956) |

| 2035 | 678 (473-924) | 1220 (852-1665) | 911 (630-1252) |

| 2040 | 869 (587-1222) | 1564 (1063-2184) | 1168 (783-1645) |

| 2045 | 1109 (726-1613) | 1997 (1316-2895) | 1491 (974-2179) |

| 2050 | 1420 (901-2110) | 2557 (1632-3784) | 1910 (1199-2850) |

| 2055 | 1810 (1094-2793) | 3259 (1975-5011) | 2434 (1465-3773) |

| 2060 | 2312 (1351-3648) | 4162 (2440-6537) | 3108 (1820-4916) |

| With higher nursing home costs and 2% annual cost inflation | |||

| 2020 | 306 (276-336) | 551 (503-600) | 412 (364-460) |

| 2025 | 375 (273-485) | 675 (496-871) | 504 (364-662) |

| 2030 | 460 (333-602) | 828 (601-1085) | 618 (442-822) |

| 2035 | 562 (402-748) | 1012 (725-1344) | 756 (535-1014) |

| 2040 | 686 (479-932) | 1235 (869-1665) | 922 (639-1260) |

| 2045 | 833 (572-1163) | 1500 (1034-2085) | 1120 (765-1570) |

| 2050 | 1014 (681-1432) | 1826 (1230-2567) | 1364 (905-1934) |

| 2055 | 1230 (797-1794) | 2214 (1438-3213) | 1653 (1065-2424) |

| 2060 | 1493 (948-2206) | 2688 (1706-3964) | 2007 (1264-2974) |

| With higher nursing home costs and 4% annual cost inflation | |||

| 2020 | 331 (295-367) | 596 (538-657) | 445 (389-502) |

| 2025 | 447 (320-588) | 805 (582-1056) | 601 (428-798) |

| 2030 | 604 (422-823) | 1088 (764-1477) | 813 (564-1114) |

| 2035 | 816 (553-1145) | 1469 (996-2060) | 1097 (736-1546) |

| 2040 | 1099 (714-1603) | 1978 (1291-2866) | 1477 (954-2153) |

| 2045 | 1475 (917-2236) | 2656 (1664-4005) | 1983 (1228-3028) |

| 2050 | 1986 (1183-3110) | 3575 (2141-5573) | 2670 (1572-4191) |

| 2055 | 2663 (1494-4350) | 4793 (2697-7804) | 3579 (1994-5869) |

| 2060 | 3578 (1909-6053) | 6440 (3456-10810) | 4809 (2584-8135) |

| 95% uncertainty ranges are in parentheses. | |||

Formal cost of care purchased in the market

Informal cost of care, or the caregiver cost

Future projections

Sensitivity analysis

activity, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and exposure to air pollution

DATA AVAILABILITY

CODE AVAILABILITY

Received: 9 October 2023; Accepted: 9 January 2024;

Published online: 08 February 2024

REFERENCES

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects. 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/ (accessed April 6, 2022).

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures: 2022. https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf (accessed April 22, 2022).

- Rajan, K. B. et al. Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020-2060). Alzheimers Dement 17, 1966-1975 (2021).

- Tarawneh, R. & Holtzman, D. M. The clinical problem of symptomatic Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a006148 (2012).

- Deb, A., Thornton, J. D., Sambamoorthi, U. & Innes, K. Direct and indirect cost of managing alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States. Expert. Rev. Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 17, 189-202 (2017).

- Hurd, M. D., Martorell, P., Delavande, A., Mullen, K. J. & Langa, K. M. Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1326-1334 (2013).

- Hurd, M. D., Martorell, P. & Langa, K. Future Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States under Alternative Dementia Prevalence Scenarios. J. Popul. Ageing 8, 101-112 (2015).

- Zissimopoulos, J., Crimmins, E. & St Clair, P. The Value of Delaying Alzheimer’s Disease Onset. Forum Health Econ. Policy 18, 25-39 (2014).

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer Dementia 16, 391-460 (2020).

- Alzheimer’s Association. Changing the Trajectory of Alzheimer’s Disease: How a Treatment by 2025 Saves Lives and Dollars (Alzheimer’s Association, 2015).

- Burke, L. G., Burke, R. C., Epstein, S. K., Orav, E. J. & Jha, A. K. Trends in Costs of Care for Medicare Beneficiaries Treated in the Emergency Department From 2011 to 2016. JAMA Network Open 3, e208229 (2020).

- Pyenson, B. et al. The Real-World Medicare Costs of Alzheimer Disease: Considerations for Policy and Care. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 25, 800-809 (2019).

- Rattinger, G. B. et al. Dementia severity and the longitudinal costs of informal care in the Cache County population. Alzheimers Dement 11, 946-954 (2015).

- Yang, Z. & Levey, A. Gender Differences: A Lifetime Analysis of the Economic Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease. Womens Health Issues 25, 436-440 (2015).

- Zhu, C. W. et al. Health-care use and cost in dementia caregivers: Longitudinal results from the Predictors Caregiver Study. Alzheimers Dement 11, 444-454 (2015).

- Joyce, A. T. et al. Burden of illness among commercially insured patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 3, 204-210 (2007).

- Kuo, T.-C., Zhao, Y., Weir, S., Kramer, M. S. & Ash, A. S. Implications of comorbidity on costs for patients with Alzheimer disease. Med. Care 46, 839-846 (2008).

- Goldfeld, K. S., Stevenson, D. G., Hamel, M. B. & Mitchell, S. L. Medicare expenditures among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Arch. Intern. Med. 171, 824-830 (2011).

- Bharmal, M. F. et al. Incremental Dementia-Related Expenditures in a Medicaid Population. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 20, 73-83 (2012).

- Suehs, B. T. et al. The clinical and economic burden of newly diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease in a medicare advantage population. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 28, 384-392 (2013).

- Kelley, A. S., McGarry, K., Gorges, R. & Skinner, J. S. The Burden of Health Care Costs in the Last 5 Years of Life. Ann Intern. Med. 163, 729-736 (2015).

- Zhu, C. W. et al. Medicare Utilization and Expenditures Around Incident Dementia in a Multiethnic Cohort. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 70, 1448-1453 (2015).

- Lin, P.-J., Zhong, Y., Fillit, H. M., Chen, E. & Neumann, P. J. Medicare Expenditures of Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias or Mild Cognitive Impairment Before and After Diagnosis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64, 1549-1557 (2016).

- Yang, Z., Zhang, K., Lin, P.-J., Clevenger, C. & Atherly, A. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Lifetime Cost of Dementia. Health Serv. Res. 47, 1660-1678 (2012).

- Deb, A., Sambamoorthi, U., Thornton, J. D., Schreurs, B. & Innes, K. Direct medical expenditures associated with Alzheimer’s and related dementias (ADRD) in a nationally representative sample of older adults – an excess cost approach. Aging Ment Health 22, 619-624 (2018).

- Fishman, P. et al. Cost of Dementia in Medicare Managed Care: A Systematic Literature Review. Am. J. Manag. Care 25, e247-e253 (2019).

- David, K., Guterman, S.& Bandeali, F. The Affordable Care Act and Medicare: How the Law Is Changing the Program and the Challenges That Remain (Commonwealth Fund, 2015).

- Oney, M., White, L. & Coe, N. B. Out-of-pocket costs attributable to dementia: A longitudinal analysis. J. Am. Geriatrics Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs. 17746 (2022).

- Bloom, D. E., Counts, N., Nandi, A., Tortorice, D.& Vigo, D. How to address Alzheimer’s disease and support healthier ageing (World Economic Forum, 2022). https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/this-is-how-to-address-a-global-alzheimers-disease/ (accessed March 25, 2022).

- Bloom, D. et al. Addressing Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias to realise the promise of the UN’s ‘Decade of Healthy Ageing’ (VoxEU, 2021). https://voxeu.org/ article/alzheimer-s-and-un-s-decade-healthy-ageing (accessed May 14, 2021).

- Counts, N., Nandi, A., Seligman, B. & Tortorice, D. Dementia Storm on the Horizon: The rising incidence of dementia around the world calls for global collaboration and decisive financing. Finance Dev. 58, 54-57 (2021).

- Hartman, M., Martin, A. B., Washington, B., Catlin, A. & The, N. H. E. A. T. National Health Care Spending In 2020: Growth Driven By Federal Spending In Response To The COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Affairs 41, 13-25 (2022).

- Zafari, Z., Li, S., Eakin, M. N., Bellanger, M. & Reed, R. M. Projecting Long-term Health and Economic Burden of COPD in the United States. Chest 159, 1400-1410 (2021).

- Dall, T. M. et al. The Economic Burden of Elevated Blood Glucose Levels in 2017: Diagnosed and Undiagnosed Diabetes, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, and Prediabetes. Diabetes Care 42, 1661-1668 (2019).

- Nandi, A. et al. Global and regional projections of the economic burden of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias from 2019 to 2050: A value of statistical life approach. eClinicalMedicine 51, 101580 (2022).

- Jia, J. et al. The cost of Alzheimer’s disease in China and re-estimation of costs worldwide. Alzheimers Dement 14, 483-491 (2018).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI Inflation Calculator. 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ data/inflation_calculator.htm (accessed April 23, 2022).

- Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 396, 413-446 (2020).

- Chen, C. & Zissimopoulos, J. M. Racial and ethnic differences in trends in dementia prevalence and risk factors in the United States. Alzheimer Dementia 4, 510-520 (2018).

- Matthews, K. A. et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged

years. Alzheimers Dement 15, 17-24 (2019). - Alzheimer’s Association. Women and Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. 2022. https://alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/women-and-alzheimer-s (accessed April 23, 2022).

- Mikton, C., de la Fuente-Núñez, V., Officer, A. & Krug, E. Ageism: a social determinant of health that has come of age. Lancet 397, 1333-1334 (2021).

- Chen, S., Kuhn, M., Prettner, K. & Bloom, D. E. The global macroeconomic burden of road injuries: estimates and projections for 166 countries. Lancet Planet. Health 3, e390-e398 (2019).

- Langa, K. M. et al. The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study: study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology 25, 181-191 (2005).

- Okura, T. & Langa, K. M. Caregiver Burden and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment: The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS). Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 25, 116-121 (2011).

- Crimmins, E. M., Kim, J. K., Langa, K. M. & Weir, D. R. Assessment of Cognition Using Surveys and Neuropsychological Assessment: The Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 66B, i162-i171 (2011).

- Brookmeyer, R. et al. National estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimer Dementia 7, 61-73 (2011).

- Sonnega, A. et al. Cohort Profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 576-585 (2014).

- Genworth. Cost of Long Term Care by State. 2022. https://www.genworth.com/ aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html (accessed April 22, 2022).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index (CPI) Databases: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2022. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm (accessed June 9, 2022).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Diseases Results Tool. GBD Results Tool. 2019. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

- US Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States. 2022. https:// www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221 (accessed April 22, 2022).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Medical care in U.S. city average, all urban consumers, not seasonally adjusted. 2022. https://data.bls.gov/ (accessed May 10, 2023).

- Nianogo, R. A. et al. Risk Factors Associated With Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias by Sex and Race and Ethnicity in the US. JAMA Neurol. 79, 584-591 (2022).

- Lima, J. C., Ogarek, J. & Mor, V. Untapped Potential – Using the HRS-Medicare Linked Files to Study the Changing Nursing Home Population. Med. Care 56, 216-219 (2018).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing Home Data Compendium 2015 (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2015).

- US Census Bureau. The Older Population: 2010 (US Department of Commerce, 2011).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

COMPETING INTERESTS

interest. This publication does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Reprints and permission information is available at http://www.nature.com/ reprints

© The Author(s) 2024

The Population Council, 1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA. One Health Trust, Washington, DC, USA. Office of the Commissioner of Health & Mental Hygiene for the City of New York, New York, NY, USA. The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, USA. Data for Decisions, LLC, Waltham, MA, USA. University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology and The Center for Brain Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Division of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System, Los Angeles, CA, USA. College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, MA, USA. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA. email: anandi@popcouncil.org