DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44359-024-00009-x

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-15

تكنولوجيا التبخر الواجهاتي المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية للغذاء والطاقة والمياه

الملخص

تستخدم تقنيات التبخر الواجهية المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية الطاقة الشمسية لتسخين المواد التي تدفع تبخر المياه. هذه التقنيات متعددة الاستخدامات ولا تتطلب الكهرباء، مما يمكّن من تطبيقها المحتمل عبر الربط بين الغذاء والطاقة والمياه. في هذه المراجعة، نقيم إمكانيات تقنيات التبخر الواجهية المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية في إنتاج الغذاء والطاقة والمياه النظيفة، في معالجة مياه الصرف، وفي استعادة الموارد. يمكن لتقنيات التبخر الواجهية إنتاج ما يصل إلى

إنتاج المياه ومعالجتها

إنتاج الغذاء

الطاقة

الملخص ووجهات النظر المستقبلية

النقاط الرئيسية

- تستخدم أجهزة تنقية التبخر-التكثيف (تصميم شائع لجهاز تنقية التبخر الواجهية الشمسية) الطاقة الشمسية لتوليد المياه العذبة عند

، ولكنها محدودة بإنثالبي تبخر المياه . تقلل تحلية الأغشية المدفوعة بالبخار الشمسي من طاقة فصل الماء المالح إلى ، مما ينتج مياه عذبة تصل إلى تحت إضاءة شمسية تبلغ 12 شمس. - من خلال تنفيذ تدابير مختلفة لمكافحة التلوث، تظهر أجهزة التبخر الشمسية المصممة مقاومة قوية للملح، والتلوث البيولوجي، والتلوث العضوي، مع استقرار لمدة شهر في المختبر. يجب توسيع الأنظمة من الجيل التالي ومراقبتها في الميدان على مدى عدة أشهر لتقييم جدواها في العالم الحقيقي.

- يمكن أن توفر تقنيات التبخر الشمسية مياه عذبة عالية الجودة للري وإصلاح التربة، مما يساعد الزراعة في المناطق الساحلية.

- يمكن حصاد الطاقة من تبخر المياه من خلال توليد الطاقة الحرارية الكهربائية، والطاقة الحرارية الكهربائية، وتدرج الملوحة، وتوليد الطاقة الهيدروفولتائية، مما ينتج

. أنظمة الهجين من التبخر الكهروضوئي الشمسي أكثر ملاءمة للتطبيقات على نطاق واسع، حيث تولد حوالي من الكهرباء. - يمكن لمبخرات استخراج الموارد الحرجة المخففة من مصفوفات المياه المعقدة. يمكن أن تعزز التوليد المشترك لموارد متعددة من خلال التبخر الواجهية كفاءة الطاقة للعمليات، ولكنها تتطلب مزيدًا من الدراسة والتطوير.

- تم اختبار الأنظمة الصغيرة النطاق بشكل جيد على نطاق المختبر وهي مناسبة للاستخدام الشخصي أو المنزلي، ولكن الأنظمة الكبيرة النطاق ضرورية للتطبيقات الصناعية. سيتطلب النجاح التجاري لتقنيات التبخر الشمسية توسيع النطاق، وتقليل التكاليف، والامتثال للمعايير التنظيمية.

المقدمة

من مصادر مياه متنوعة (بما في ذلك مياه البحر

إنتاج المياه ومعالجتها

إنتاج المياه النظيفة

الملخص

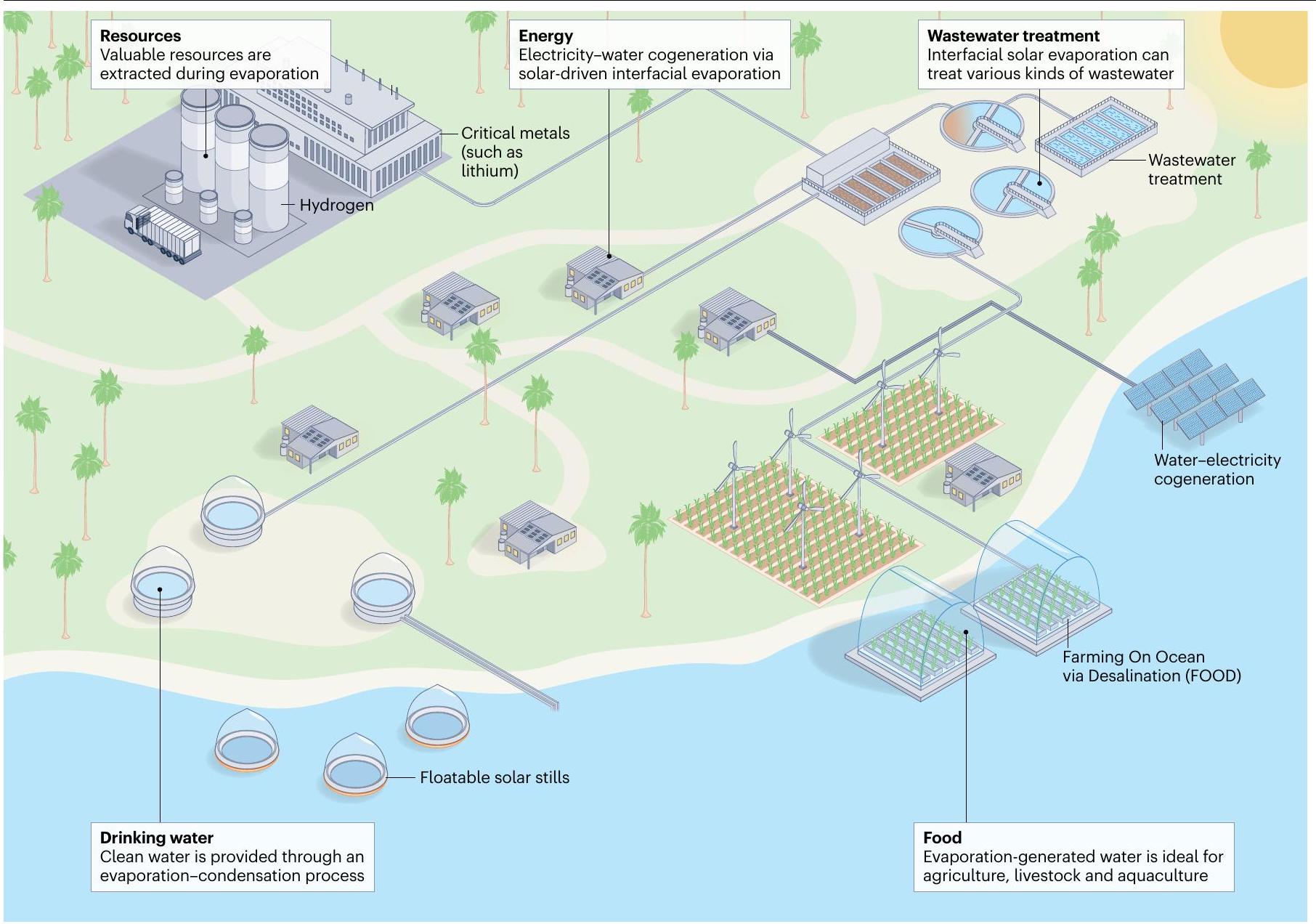

يمكن أيضًا تصميمها لإنتاج مياه عذبة للزراعة على اليابسة وفي المحيط: نظام الزراعة على المحيط عبر التحلية (FOOD). يمكن استرداد الموارد من الماء باستخدام التبخر الشمسي الواجهية لاستخراج المعادن، مثل الليثيوم، أو بالاشتراك مع أنظمة تحفيزية لإنتاج غاز الهيدروجين من الماء. تصاميم جديدة تدمج التبخر الشمسي الواجهية مع تقنيات الطاقة المتجددة مثل الألواح الكهروضوئية وتوربينات الرياح، مما يمكّن من توليد الكهرباء والموارد الأخرى في وقت واحد.

وتشتت ضوء الشمس، مما يؤدي إلى فقدان كبير للضوء يصل إلى

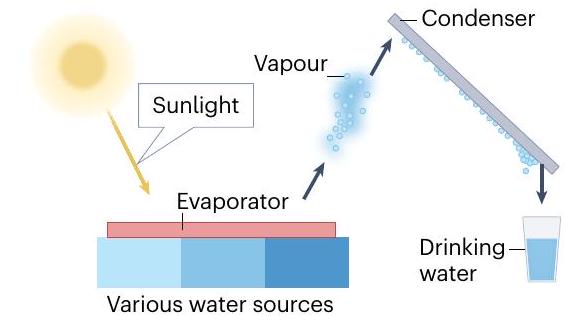

مما يفصل بين امتصاص الضوء والتكثيف (الشكل 2ج). وبالتالي، لا يتطلب سطح التكثيف نفاذية ضوئية عالية

من إمكانية استخدام مواد ذات موصلية حرارية عالية وخصائص كارهة للماء مثل النحاس

د منقيات التبخر-التكثيف – الهيكل متعدد المراحل

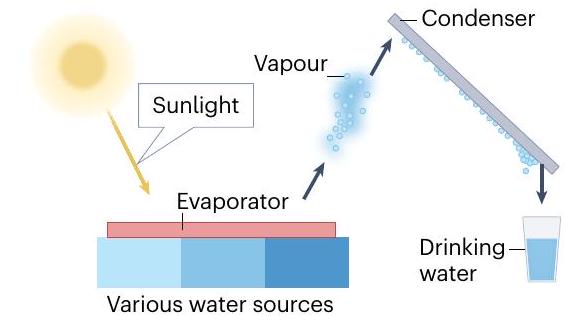

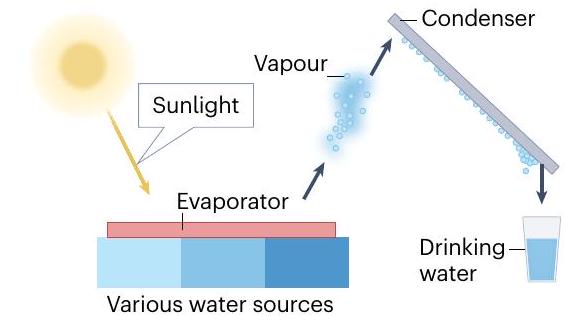

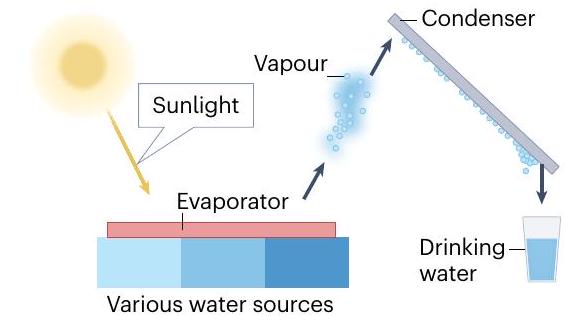

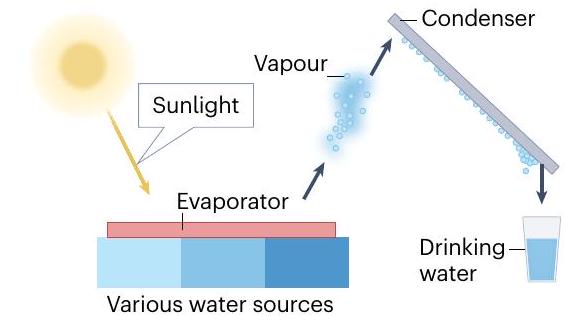

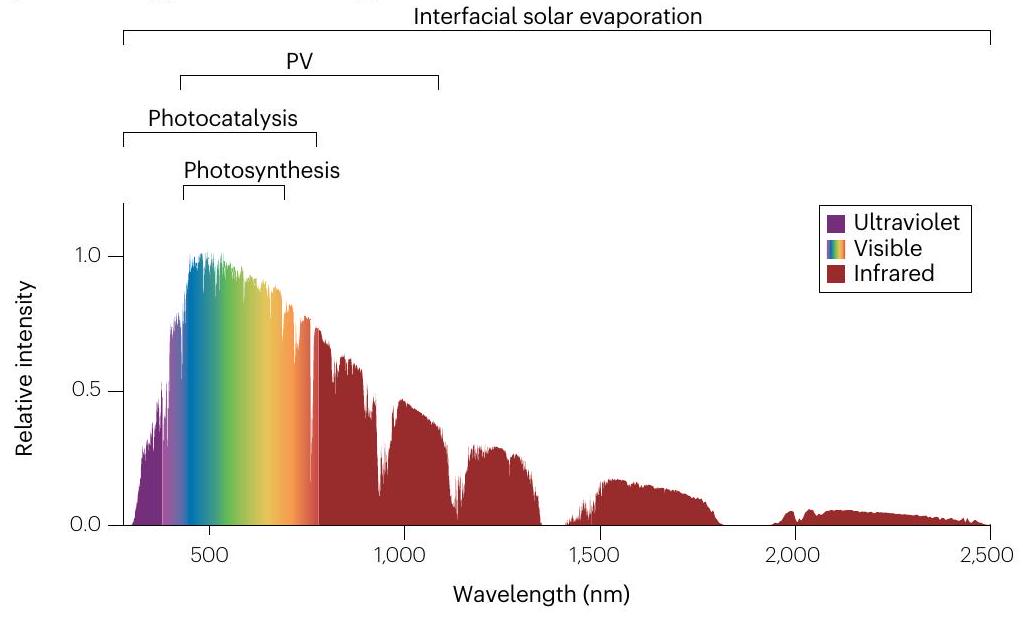

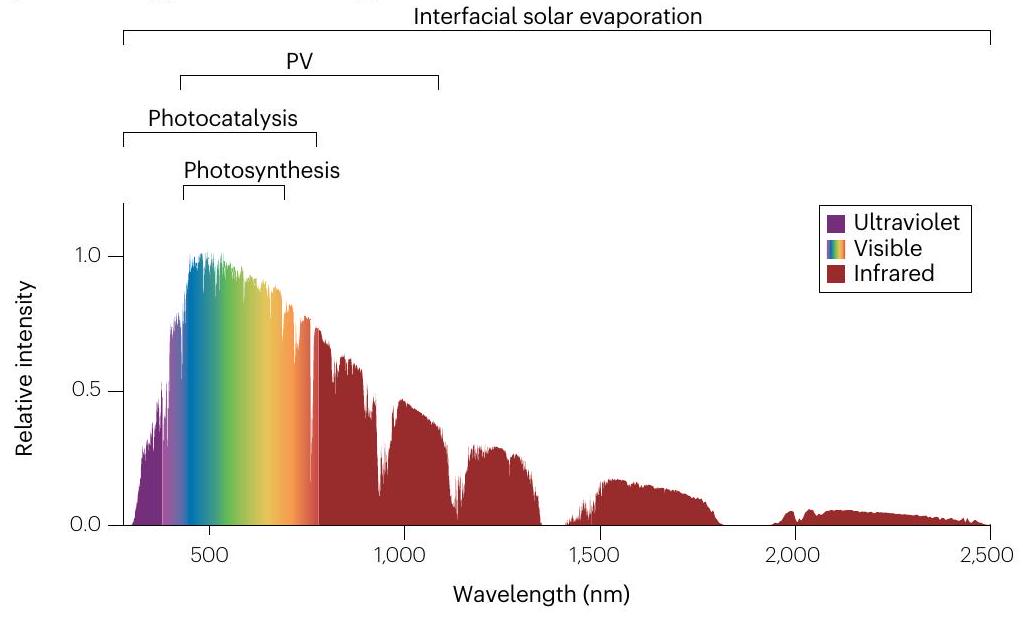

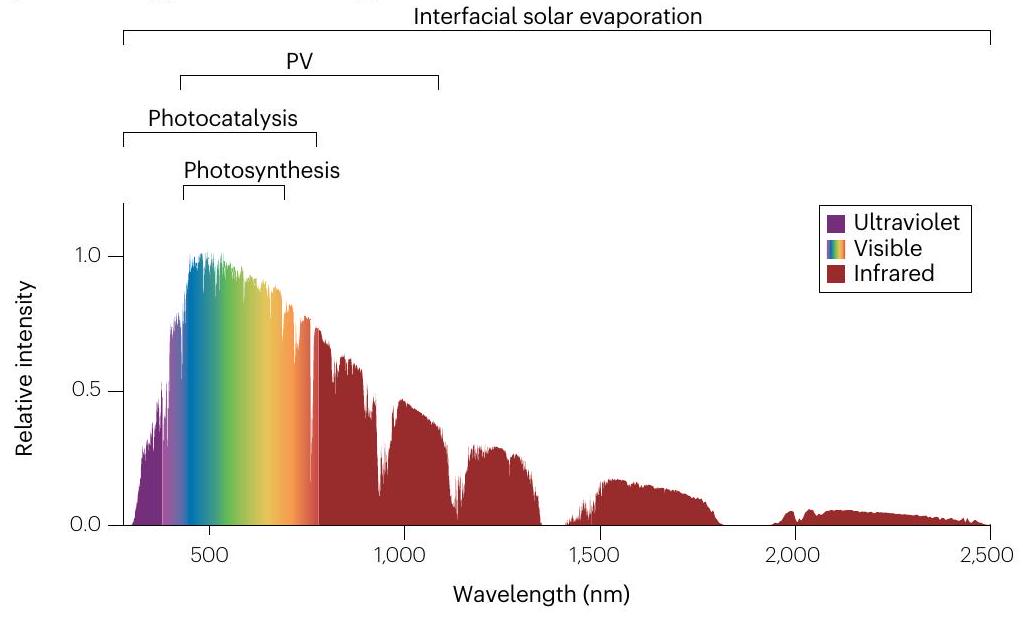

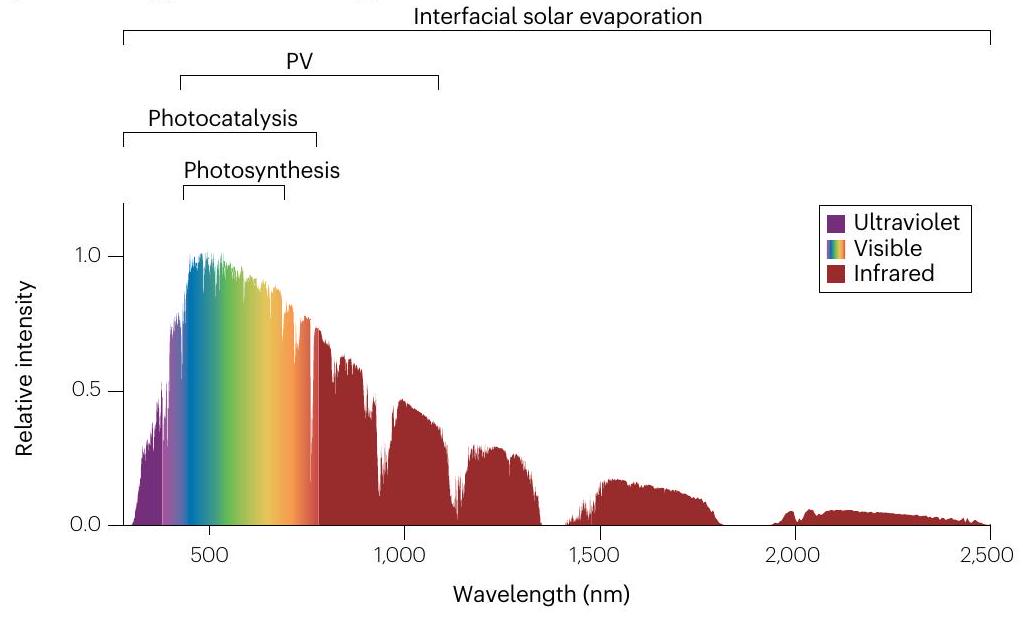

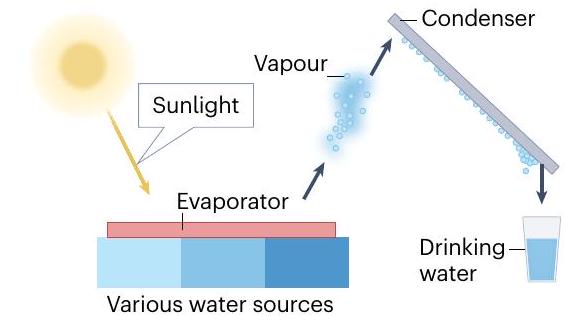

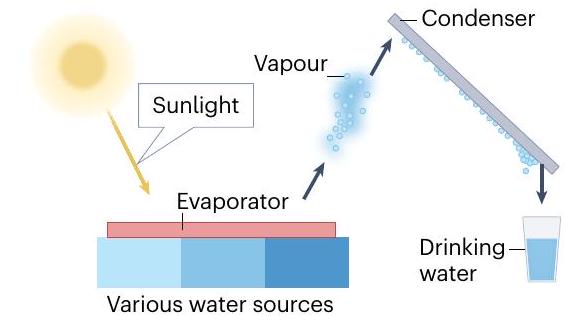

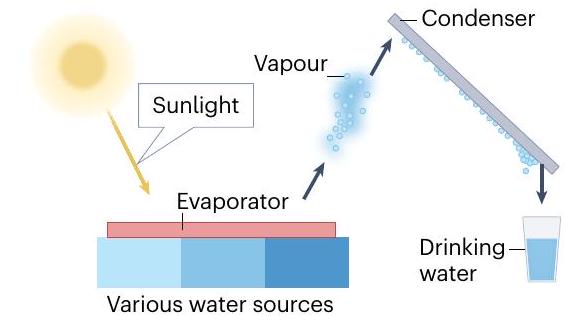

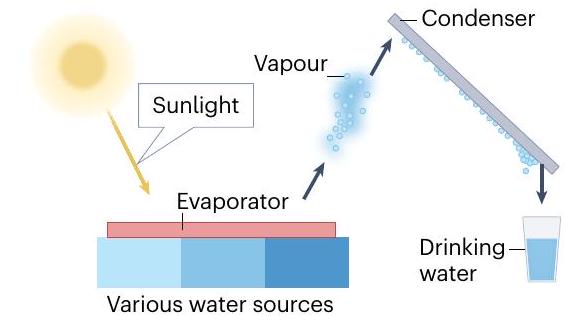

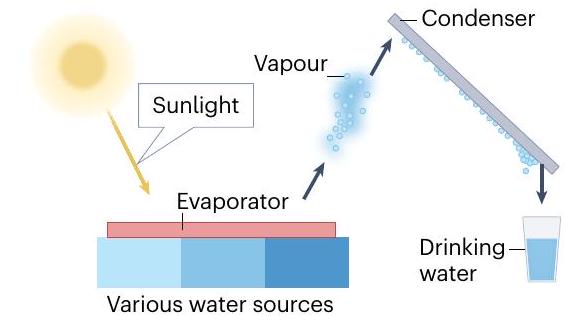

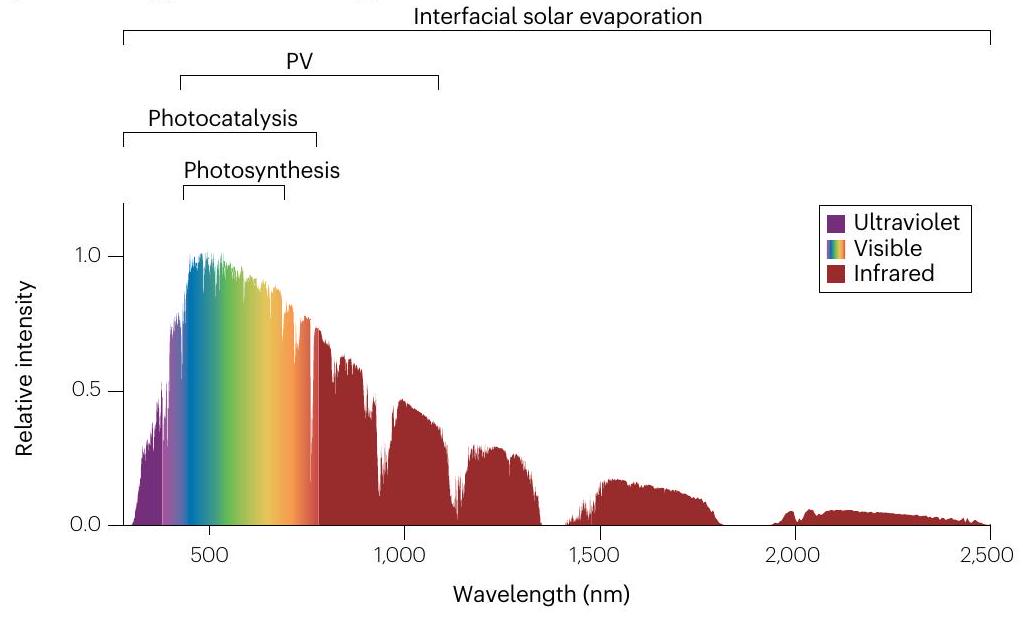

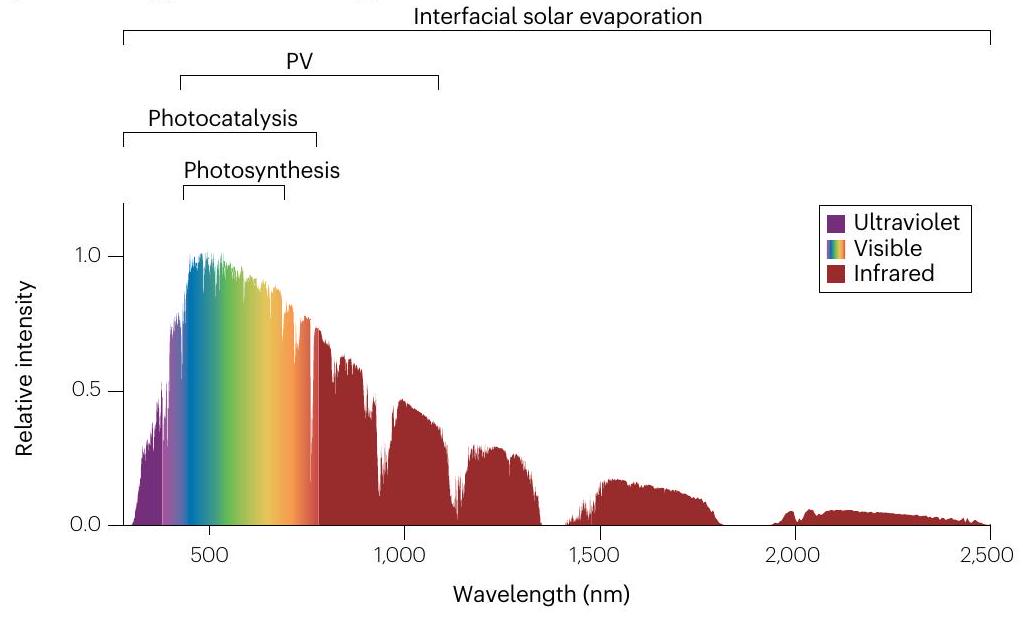

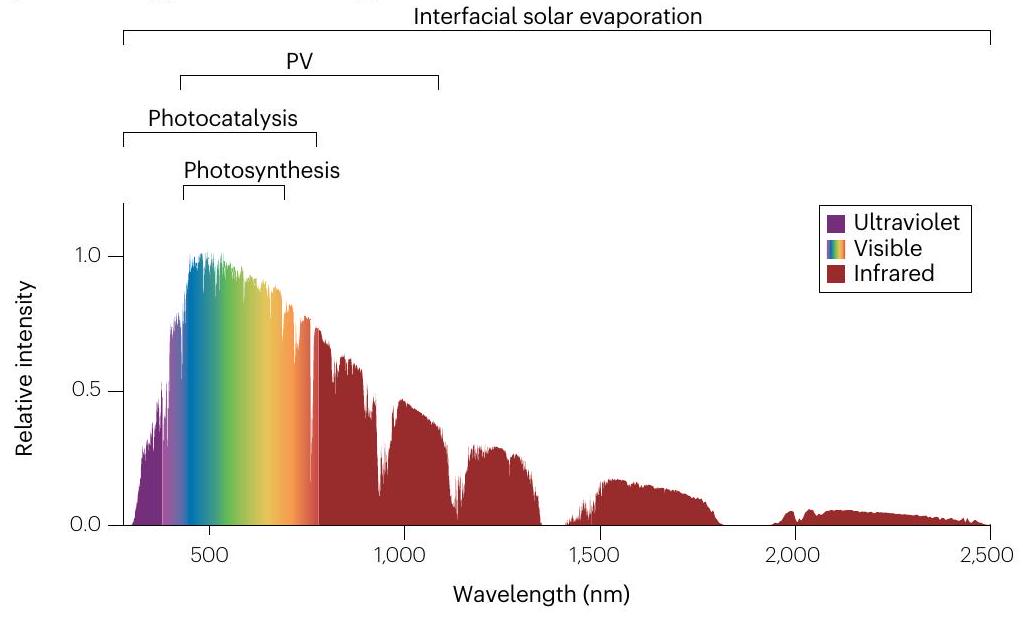

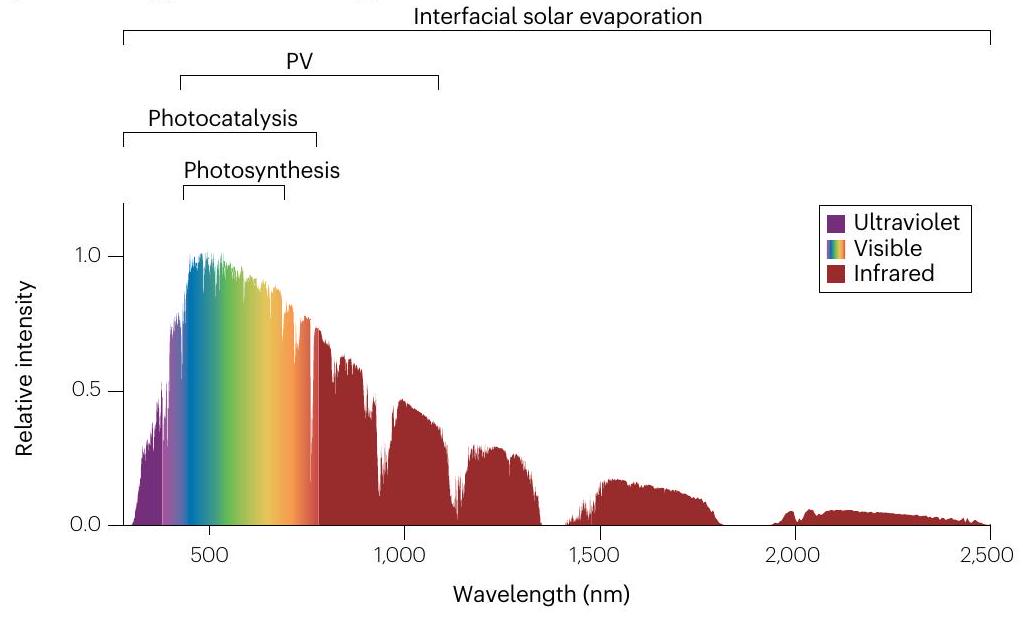

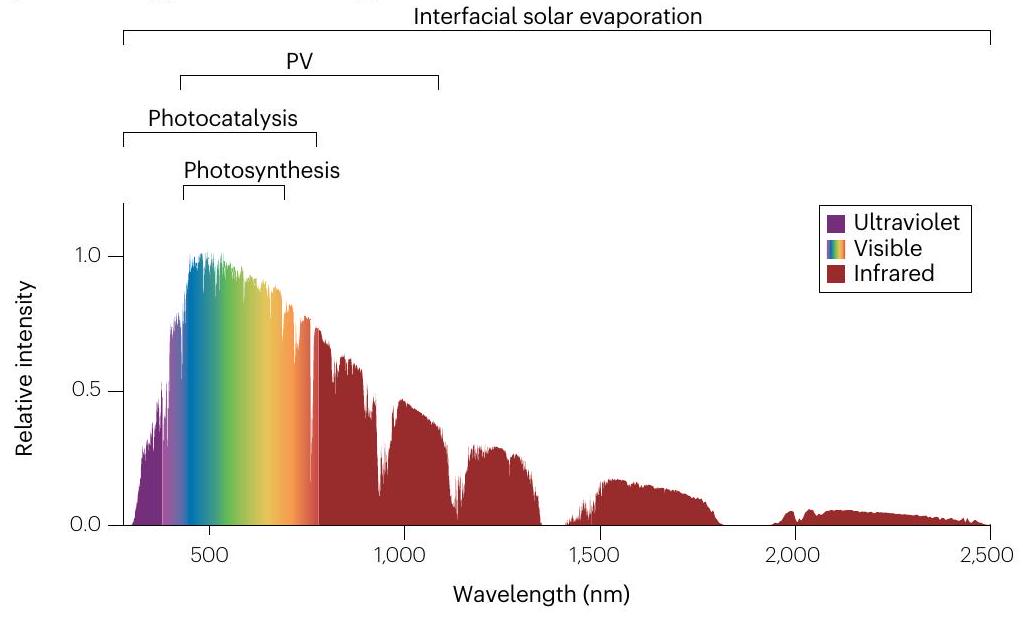

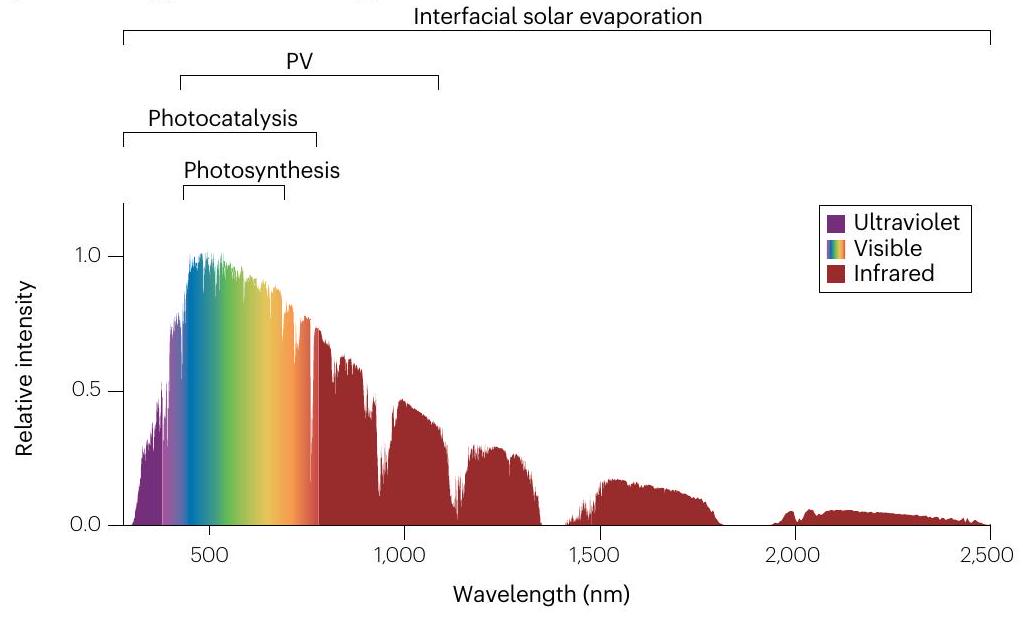

أ، في التبخر الشمسي الواجهية، يتم امتصاص الطاقة الشمسية بواسطة مبخر، مما يسخن ويولد بخار الماء. يتكثف البخار إلى ماء عند ملامسته للمكثف. ب، تستخدم مولدات المياه الشمسية التقليدية غطاء شفاف للتكثيف. يمكن تعزيز التكثيف عن طريق ضبط محبة السطح للماء وكراهيته لتعزيز التكثيف على شكل فيلم لتجنب تشتت الضوء (يسار) والتكثيف على شكل قطرات لمعامل نقل حرارة مرتفع (يمين).

طبقات إمداد مائية محبة للماء وطبقات تكثيف مفصولة بفجوات هوائية لإعادة تدوير إنثالبي التكثيف. هـ، تستخدم تقنية الأغشية المدفوعة بالبخار الشمسي لإنتاج مياه عذبة الطاقة الشمسية لتوليد بخار عالي الطاقة، والذي يولد الضغط لدفع مياه البحر عبر غشاء التناضح العكسي أو الترشيح النانوي، مما ينتج مياه نظيفة. و، تستخدم مولدات المياه الجوية المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية السوائل الأيونية لجمع الرطوبة الجوية، والتي تستخدم بعد ذلك في التبخر الشمسي الواجهية لإنتاج مياه نظيفة. ز، معدلات إنتاج المياه لأنواع مختلفة من تقنيات التبخر الشمسي الواجهية (البيانات من المراجع 10، 23، 40، 50-54، 57، 195-201 ومفصلة في الجدول التكميلي 1). ح، منقي شمسي عائم تجاري. تم تعديل اللوحة د بإذن من المرجع 50، RSC. تم تعديل اللوحة هـ من المرجع 10، Springer Nature Limited. تم تعديل اللوحة و بإذن من المرجع 58، Wiley. اللوحة

مقالة مراجعة

تمت مراقبته وصيانته على مدى عدة أشهر في الميدان. يجب تتبع عوامل مثل جودة المياه، وخاصة محتوى المواد العضوية، حيث يمكن أن تتبخر المركبات العضوية المتطايرة مع الماء، مما يؤدي إلى تلوث المنتج المقطر ويعرض سلامة مياه الشرب للخطر. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يجب تقييم تكاليف الاستثمار والصيانة بدقة لتقييم جاهزية التكنولوجيا للتشغيل الميداني على المدى الطويل.

مطبق على

معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي

تقل فعالية مقاومة الملح المستندة إلى تأثير دونان في المياه عالية الملوحة التي تزيد ملوحتها عن

الموارد من الماء

المعادن الحرجة

المعادن الحرجة

تم تطويره لاستعادة الليثيوم المستدام من المحاليل الملحية

C بلورة مفصولة مكانياً

(مثل NaCl) عند ارتفاعات أقل من بلورة الألياف. تتساقط الأملاح ذات التركيزات الأقل والذوبانية الأعلى (مثل LiCl) بالقرب من القمة. د، نموذج أولي لمصفوفة استخراج الليثيوم تحتوي على

غشاء التناضح

الهيدروجين

؛ ويتطلب التحفيز الضوئي في الطور الغازي طاقة أقل لتفكيك الماء بسبب انخفاض الطاقة الحرة القياسية لجيس في تكوين الماء الغازي مقارنة بالسائل (

تحتاج إلى توسيع نطاق واستعادة متعددة المنتجات

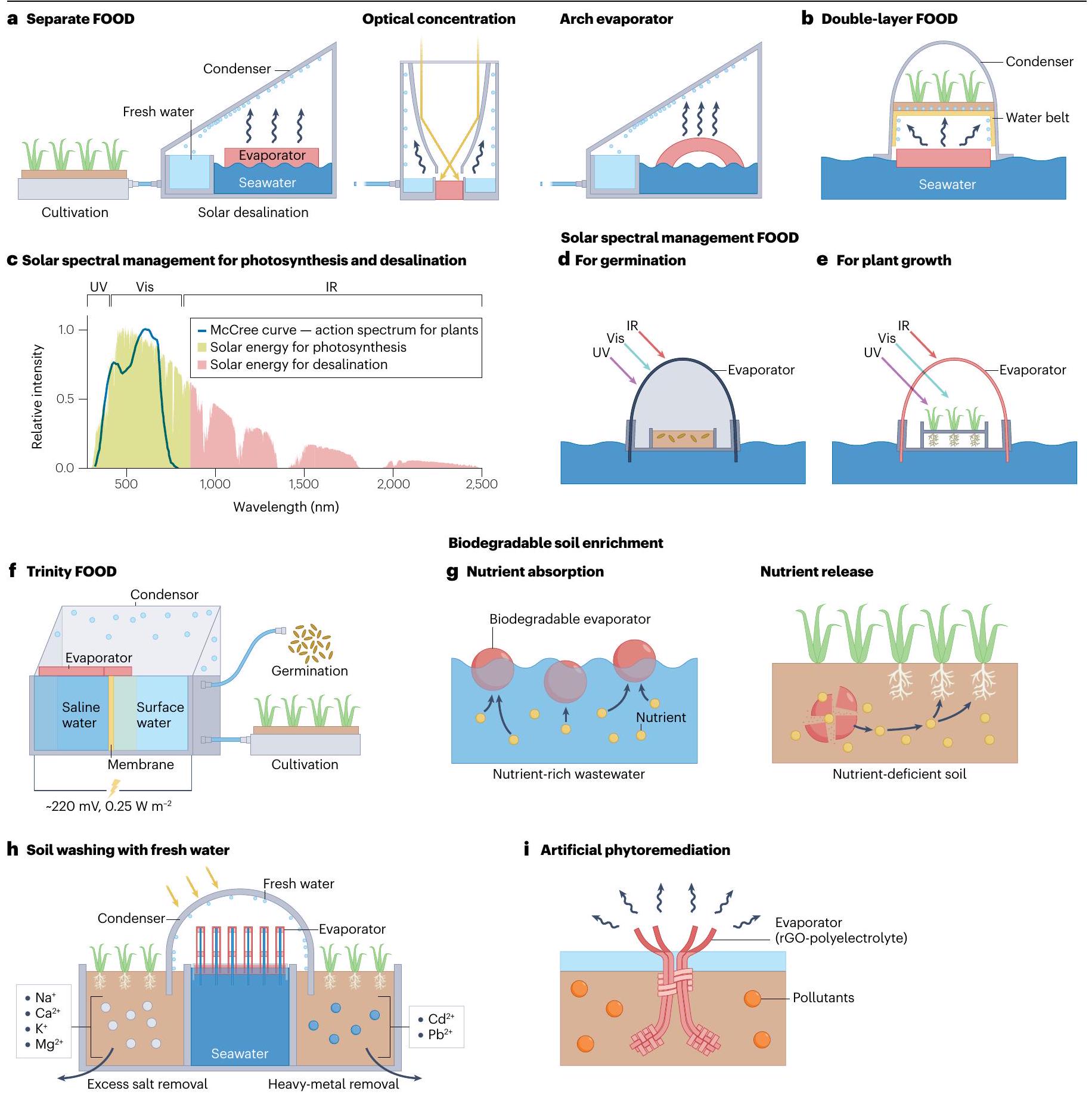

إنتاج الغذاء

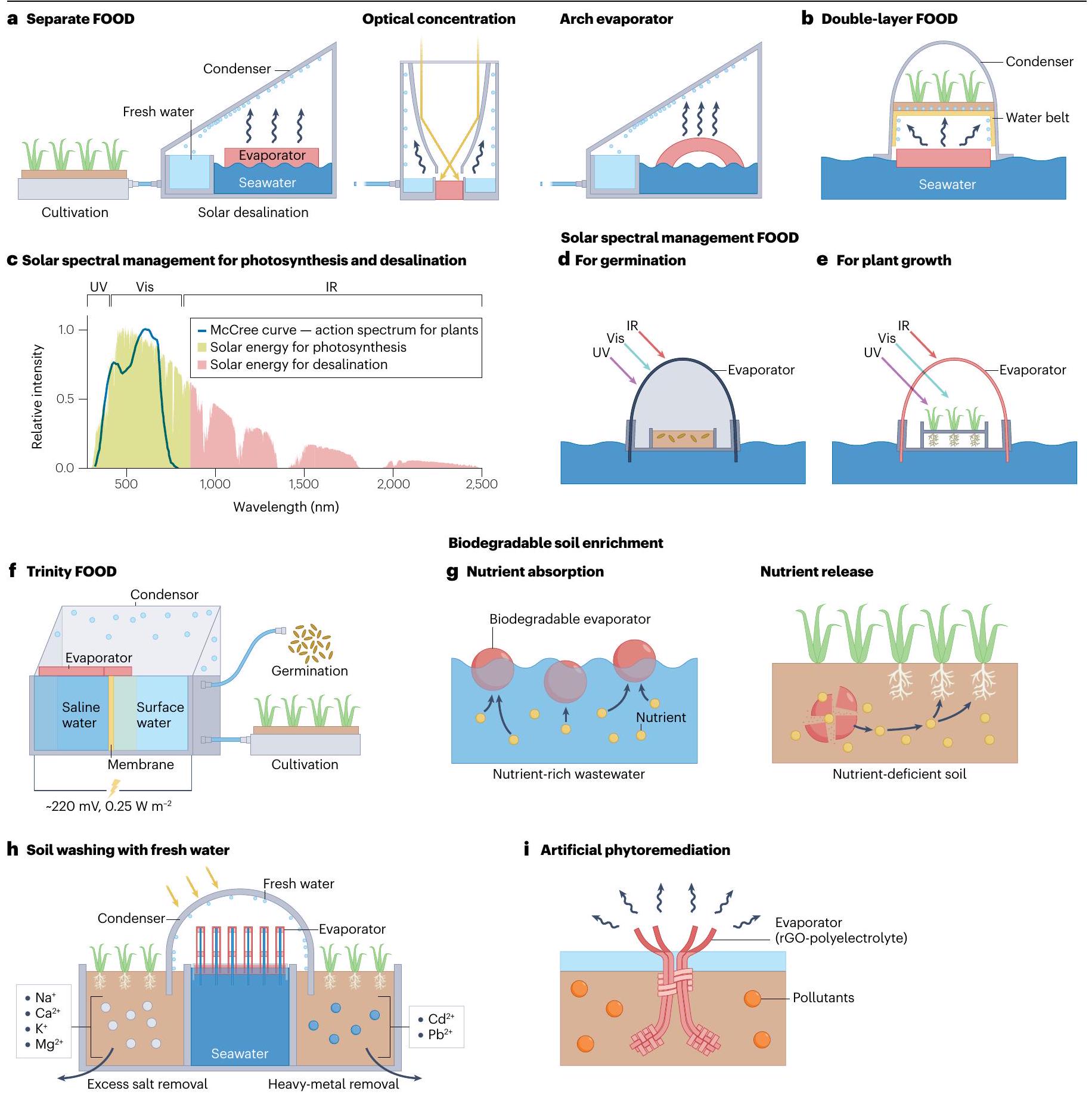

الزراعة. يمكن أن تكون أنظمة تحلية المياه الشمسية الواجهات-الزراعة مفيدة بشكل خاص في المناطق الساحلية حيث تكون المياه العذبة والتربة الخصبة نادرة. غالبًا ما تعتمد الزراعة الساحلية على طرق تحلية مكلفة ومرتفعة الطاقة

الزراعة على المحيط عبر التحلية

تسمح بمرور الضوء فوق البنفسجي والمرئي. تتيح هذه التكوينات للضوء فوق البنفسجي والمرئي الوصول إلى النباتات لعملية التمثيل الضوئي، بينما يتم امتصاص الضوء تحت الأحمر بواسطة الغلاف الخارجي للتحلية (الشكل 5e). وبالتالي، تعمل هذه الاستراتيجية على تحسين كفاءة استخدام كل من الأرض والطاقة الشمسية.

إصلاح التربة

غرفة (الشكل 5 ج). تمر أشعة الشمس من خلال الغطاء الشفاف ويتم امتصاصها وتحويلها إلى حرارة بواسطة مبخر ضوئي حراري. تسهل هذه الحرارة تبخر مياه البحر ويتكثف البخار الناتج إلى مياه عذبة تتساقط إلى التربة. تظهر الاختبارات الميدانية أن هذه الطريقة تزيل الملوثات الخطرة بمعدل أسرع بثلاث مرات من التقطير الشمسي، استنادًا إلى التبخر الطبيعي، مما يكمل العملية في 16 يومًا بدلاً من 50 يومًا

مخصصة للزراعة

(Vis) للنمو النباتي (اللوحة هـ). و، أنظمة FOOD المتكاملة تقوم بتحلية المياه، وتوليد الطاقة وري المحاصيل. يتضمن النظام غرفة لتحلية المياه وتوليد الطاقة وغرفة زراعة. يتم استخراج طاقة تدرج الملوحة بين مياه البحر عالية الملوحة ومياه السطح بواسطة تقنية التحليل الكهربائي العكسي لإنتاج الكهرباء. ز، في معالجة التربة المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية، يتم نقل المياه العذبة الناتجة من خلال التبخر الشمسي السطحي مباشرة إلى التربة، حيث يمكن استخدامها في غسل التربة و/أو الري الزراعي. ح، تمتص المبخرات الشمسية القابلة للتحلل البيولوجي العناصر الغذائية من مياه الصرف الصحي وتُنقل إلى التربة، حيث تتحلل وتحرر العناصر الغذائية. ط، تستخدم التنظيف الاصطناعي للنباتات مبخرات مصممة مثل النباتات. تستخدم هذه المبخرات عملية التبخر السطحي الشمسي لتسريع تثبيت الملوثات في التربة أو الماء، مما يعزز عمليات المعالجة. IR، الأشعة تحت الحمراء؛ rGO، أكسيد الجرافين المخفض. الجزء و تم تعديله من المرجع 153، Springer Nature Limited. تم تعديل الجزء من المرجع 146، Elsevier.

على التربة الملوثة لاستخراج أيونات المعادن الثقيلة من خلال النتح

الطاقة

توليد الطاقة من تدرج الملوحة

توليد الطاقة من تدرج الحرارة

الصندوق 1 | التوليد المشترك للغذاء والطاقة والمياه

الكهرباء والماء والحرارة

عن

الكهرباء والماء والتبريد

(مستمر من الصفحة السابقة)

الكهرباء، الطعام والماء

الماء، الكهرباء و الفحم الحيوي

توليد الطاقة المائية والكهربائية

غاز التخليق والماء

الماء والحرارة

طبقة تداخل حرارية في المنتصف لنقل حرارة التهيئة من خلية الطاقة الشمسية إلى جهاز تنقية المياه، وجهاز تنقية مياه شمسية واجهية في الأسفل لتوليد مياه نظيفة.

التطبيق والجدوى

ملخص وآفاق المستقبل

هذه الأنظمة في ظروف العالم الحقيقي. علاوة على ذلك، نوصي بشدة بإجراء تقييمات شاملة لدورة الحياة لتقييم الآثار البيئية قبل التنفيذ لتوجيه التطبيق والاستخدام الأكثر كفاءة واستدامة. أخيرًا، ستكون التقدمات في تصميم الأجهزة والإنتاج الضخم حاسمة في خفض التكاليف وجعل هذه التقنيات متاحة على نطاق واسع، مما يضمن الوصول العالمي إلى حلول FEW.

References

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition. United Nations https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/ (2023).

- Kalogirou, S. A. Solar Thermal Energy: History (Springer, 2022).

- Li, X. et al. Graphene oxide-based efficient and scalable solar desalination under one sun with a confined 2D water path. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 13953-13958 (2016).

- Zhou, L. et al. 3D self-assembly of aluminium nanoparticles for plasmon-enhanced solar desalination. Nat. Photon. 10, 393-398 (2016).

- Xu, N. et al. Going beyond efficiency for solar evaporation. Nat. Water 1, 494-501 (2023).

- Tao, P. et al. Solar-driven interfacial evaporation. Nat. Energy 3, 1031-1041 (2018).

- Zhao, F., Guo, Y., Zhou, X., Shi, W. & Yu, G. Materials for solar-powered water evaporation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 388-401 (2020).

- Dang, C. et al. Structure integration and architecture of solar-driven interfacial desalination from miniaturization designs to industrial applications. Nat. Water 2, 115-126 (2024).

- Wu, X. et al. Interfacial solar evaporation: from fundamental research to applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313090 (2024).

- Wang, X. et al. Solar steam-driven membrane filtration for high flux water purification. Nat. Water 1, 391-398 (2023).

- Xia, Y. et al. Spatially isolating salt crystallisation from water evaporation for continuous solar steam generation and salt harvesting. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1840-1847 (2019).

- Thakur, A. K. et al. Exploring the potential of MXene-based advanced solar-absorber in improving the performance and efficiency of a solar-desalination unit for brackish water purification. Desalination 526, 115521 (2022).

- Xu, N. et al. A scalable fish-school inspired self-assembled particle system for solar-powered water-solute separation. Natl Sci. Rev. 8, nwab065 (2021).

- Bian, Y. et al. Farming On the Ocean via Desalination (FOOD). Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 21104-21112 (2023).

- Yang, T. et al. Efficient solar domestic and industrial sewage purification via polymer wastewater collector. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 131199 (2022).

- Lin, S., Qi, H., Hou, P. & Liu, K. Resource recovery from textile wastewater: dye, salt, and water regeneration using solar-driven interfacial evaporation. J. Clean. Prod. 391, 136148 (2023).

- Shang, Y., Li, B., Xu, C., Zhang, R. & Wang, Y. Biomimetic Janus photothermal membrane for efficient interfacial solar evaporation and simultaneous water decontamination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 298, 121597 (2022).

- Li, J. et al. Interfacial solar steam generation enables fast-responsive, energy-efficient, and low-cost off-grid sterilization. Adv. Mater. 30, 1805159 (2018).

- Zhao, L. et al. A passive high-temperature high-pressure solar steam generator for medical sterilization. Joule 4, 2733-2745 (2020).

- Shi, P., Li, J., Song, Y., Xu, N. & Zhu, J. Cogeneration of clean water and valuable energy/resources via interfacial solar evaporation. Nano Lett. 24, 5673-5682 (2024).

- Xu, N. et al. A water lily-inspired hierarchical design for stable and efficient solar evaporation of high-salinity brine. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw7013 (2019).

- Menon, A. K., Haechler, I., Kaur, S., Lubner, S. & Prasher, R. S. Enhanced solar evaporation using a photo-thermal umbrella for wastewater management. Nat. Sustain. 3, 144-151 (2020).

- Ni, G. et al. A salt-rejecting floating solar still for low-cost desalination. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 1510-1519 (2018).

- Geng, Y. et al. Bioinspired fractal design of waste biomass-derived solar-thermal materials for highly efficient solar evaporation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2007648 (2021).

- Chen, L. et al. Low-cost and reusable carbon black based solar evaporator for effective water desalination. Desalination 483, 114412 (2020).

- Zhou, H., Xue, C., Chang, Q., Yang, J. & Hu, S. Assembling carbon dots on vertically aligned acetate fibers as ideal salt-rejecting evaporators for solar water purification. Chem. Eng. J. 421, 129822 (2021).

- Dang, C. et al. Ultra salt-resistant solar desalination system via large-scale easy assembly of microstructural units. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 5405-5414 (2022).

- Ibrahim, S., Bari, M. & Miles, L. Water resources management in Maldives with an emphasis on desalination. Maldives Water and Sanitation Authority http://pacificwater.org/ userfiles/file/Case Study B THEME 1 Maldives on Desalination.pdf (2002).

- Ahmed, F. E., Hashaikeh, R. & Hilal, N. Solar powered desalination-technology, energy and future outlook. Desalination 453, 54-76 (2019).

- Chen, C., Kuang, Y. & Hu, L. Challenges and opportunities for solar evaporation. Joule 3, 683-718 (2019).

مقالة مراجعة

- زو، ل.، قاو، م.، بيه، سي. كيه. إن. & هو، ج. و. التقدم الأخير في تبخر الماء على الواجهة المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية: تصاميم متقدمة وتطبيقات. الطاقة النانوية 57، 507-518 (2019).

- تشو، ل. وآخرون. التجميع الذاتي لممتصات بلازمونية عالية الكفاءة وعريضة النطاق لتوليد بخار الشمس. Sci. Adv. 2، e1501227 (2016).

- تشو، هـ. ج.، بريستون، د. ج.، زو، ي. ووانغ، إ. ن. مواد نانوية مصممة لهندسة نقل الحرارة في تغيير الطور من السائل إلى البخار. مراجعات الطبيعة للمواد 2، 16092 (2016).

- تشانغ، س. وآخرون. تأثير الطاقة السطحية الحرة والميكروهيكل على آلية تكثف بخار الماء. تقدم العلوم الطبيعية. المواد. الدولية 33، 37-46 (2023).

- غسيمي، ح. وآخرون. توليد بخار الشمس من خلال تركيز الحرارة. نات. كوميونيك. 5، 4449 (2014).

- ني، ج. وآخرون. توليد البخار تحت شمس واحدة ممكن بفضل هيكل عائم مع تركيز حراري. نات. إنرجي 1، 16126 (2016).

-

. وآخرون. الفطر كأجهزة فعالة لتوليد البخار الشمسي. مواد متقدمة. 29، 1606762 (2017). - لي، إكس. وآخرون. التبخر الاصطناعي ثلاثي الأبعاد لمعالجة مياه الصرف الصحي بالطاقة الشمسية بكفاءة. مراجعة العلوم الطبيعية 5، 70-77 (2017).

- شي، ي. وآخرون. هيكل ضوئي حراري ثلاثي الأبعاد نحو تحسين كفاءة الطاقة في توليد بخار الشمس. جول 2، 1171-1186 (2018).

- وانغ، ف. وآخرون. جهاز تنقية المياه الشمسية ذو الهيكل المقلوب عالي الأداء من مرحلة واحدة من خلال تحسين الامتصاص والتكثيف. جول 5، 1602-1612 (2021).

- زو، ل.، قاو، م.، بيه، س. ك. ن.، وانغ، إكس. و هو، ج. و. إسفنجات كربونية أحادية الكتلة ذاتية الاحتواء للتقطير بالتبخر المائي المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية وتوليد الكهرباء. مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 8، 1702149 (2018).

- سينغ، س. س. وآخرون. لوحة معدنية سوداء فائقة الامتصاص وقابلة للتتبع الشمسي لمعالجة المياه بالحرارة الشمسية. نات. سستين. 3، 938-946 (2020).

- جاني، هـ. ك. ومودي، ك. ف. تقييم الأداء التجريبي لمكثف شمسي ذو حوض واحد وميول مزدوجة مع زعانف مجوفة دائرية ومربعة المقطع العرضي. طاقة شمسية 179، 186-194 (2019).

- ليو، ز. وآخرون. توليد بخار شمسي فعال للغاية ومنخفض التكلفة تحت إضاءة غير مركزة باستخدام ورق أسود معزول حرارياً. التحديات العالمية 1، 1600003 (2017).

- تشانغ، ل. وآخرون. تحلية المياه الشمسية السلبية عالية الكفاءة والمحددة حرارياً. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 14، 1771-1793 (2021).

- تشانغ، ي. وتان، س. ج. أفضل الممارسات لتقنيات إنتاج المياه الشمسية. نات. سستين. 5، 554-556 (2022).

- أونغووارسيتو، سي. وآخرون. منظور محدث حول تطبيق توليد البخار الشمسي. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 17، 2088-2099 (2024).

- أوه، ج. وآخرون. تكثف الفيلم الرقيق على الأسطح النانوية. مواد وظيفية متقدمة. 28، 1707000 (2018).

- وانغ، ز.، إليمليش، م. ولين، س. التطبيقات البيئية للمواد السطحية ذات القابلية الخاصة للبلل. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 50، 2132-2150 (2016).

- شو، ز. وآخرون. تحلية مياه فائقة الكفاءة عبر جهاز تبخير شمسي متعدد المراحل موضعي حرارياً. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 13، 830-839 (2020).

- شيافازو، إ.، مورسيانو، م.، فيجلينو، ف.، فاسانو، م. وأسيناري، ب. تحلية مياه البحر بالطاقة الشمسية السلبية ذات العائد العالي بواسطة التقطير المعياري ومنخفض التكلفة. نات. سستين. 1، 763-772 (2018).

- مورسيانو، م.، فاسانو، م.، بوريسكينا، س. ف.، شيفازو، إ. وأسيناري، ب. مكثف شمسي سلبي ذو إنتاجية عالية وطرد ملح مدفوع بتأثير مارانغوني. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 13، 3646-3655 (2020).

- وانغ، و. وآخرون. تكامل تبريد الطاقة الشمسية الكهروضوئية وتحلية مياه البحر مع عدم تصريف السوائل. جول 5، 1873-1887 (2021).

- وانغ، و. وآخرون. الإنتاج المتزامن للمياه العذبة والكهرباء عبر تقطير الأغشية الشمسية الفوتوفولطية متعددة المراحل. نات. كوميونيك. 10، 3012 (2019).

- Zhang، ل. وآخرون. نمذجة وتحليل أداء الألواح الشمسية متعددة المراحل ذات الكفاءة الحرارية العالية. الطاقة التطبيقية 266، 114864 (2020).

- نواز، ف. وآخرون. هل يمكن أن تكون أداء توليد بخار الشمس عند الواجهة حقًا “ما وراء” الحد النظري؟ مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 14، 2400135 (2024).

- جينغ، هـ. وآخرون. جهاز تنقية مستوحى من أوراق النباتات يعمل بالطاقة الشمسية لإنتاج مياه نظيفة بكفاءة عالية. نات. كوميونيك. 10، 1512 (2019).

- Qi، هـ. وآخرون. مولد مياه جوية مدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية على الواجهة يعتمد على مادة ماصة سائلة مع امتصاص وإطلاق متزامنين. مواد متقدمة 31، 1903378 (2019).

- وانغ، إكس. وآخرون. مولد مياه جوية بمساعدة تسخين شمسي على الواجهة باستخدام مادة ماصة سائلة. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إد. 131، 12182-12186 (2019).

- شو، و. وياغي، أ. م. الإطارات المعدنية العضوية لجمع المياه من الهواء، في أي مكان، في أي وقت. ACS Cent. Sci. 6، 1348-1354 (2020).

- اللورد، ج. وآخرون. الإمكانية العالمية لجمع مياه الشرب من الهواء باستخدام الطاقة الشمسية. ناتشر 598، 611-617 (2021).

- هانكل، ن.، بريفو، م. س. وياغي، أ. م. حصادات المياه من MOF. نات. نانو تكنولوجي. 15، 348-355 (2020).

- ما، ج. وآخرون. نظام تبخر شمسي كهربائي حراري مع إنتاج مياه مرتفع يعتمد على مبخر متكامل سهل. ج. مواد. كيمياء. أ 8، 21771-21779 (2020).

- قو، ق.، يي، هـ.، جيا، ف. وسونغ، س. تصميم

الهلام الهوائي ذو الطبقتين المدمج مع مواد تغيير الطور للتناضح الشمسي المستدام والفعال. التحلية 541، 116028 (2022). - شو، ج. وآخرون. إنتاج المياه من الغلاف الجوي المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية بشكل فائق من خلال جامع مياه سريع الدورة قابل للتوسع مع مادة ماصة نانوية مصفوفة عمودياً. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 14، 5979-5994 (2021).

- سونغ، ي. وآخرون. الهندسة الهرمية لجمع المياه الجوية القائم على الامتصاص. مواد متقدمة. 36، 2209134 (2024).

- تشو، م. وآخرون. تكثف البخار مع التبريد الإشعاعي خلال النهار. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 118، e2019292118 (2021).

- هايشلر، إ. وآخرون. استغلال التبريد الإشعاعي لجمع المياه من الغلاف الجوي على مدار 24 ساعة دون انقطاع. ساينس أدفانس. 7، eabf3978 (2021).

- شو، ج. وآخرون. جمع المياه الهجينة الشاملة من الغلاف الجوي لإنتاج المياه على مدار اليوم بواسطة ضوء الشمس الطبيعي والتبريد الإشعاعي. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 17، 4988-5001 (2024).

- شان، هـ. وآخرون. إنتاج استثنائي للمياه تم تمكينه بواسطة جامع مياه محمول مُعالج على دفعات في مناخ شبه جاف. نات. كوميونيك. 13، 5406 (2022).

- جرينلي، ل. ف.، لولر، د. ف.، فريمان، ب. د.، ماروت، ب. ومولين، ب. تحلية المياه بالتناضح العكسي: مصادر المياه، التكنولوجيا، وتحديات اليوم. أبحاث المياه. 43، 2317-2348 (2009).

- وانغ، ي.، تشي، ك.، فان، ج.، وانغ، و. ويو، د. أقمشة MXene/أنابيب الكربون/القطن بسيطة وقوية لتنقية مياه الصرف الصحي النسيجية عبر تبخر الماء على الواجهة المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية. فصل. تقنية التنقية. 254، 117615 (2021).

- تونغ، ت. وإليميلخ، م. الارتفاع العالمي لتقنية عدم تصريف السوائل: الدوافع، والتقنيات، والاتجاهات المستقبلية. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 50، 6846-6855 (2016).

- شي، ي. وآخرون. مبخر شمسي مع ترسيب ملح محكوم لإزالة الملح بدون تصريف سائل. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 52، 11822-11830 (2018).

- بينغ، ب. وآخرون. هيدروجيلات فوتوحرارية كاتيونية ذات قدرة على تثبيط البكتيريا لإنتاج المياه العذبة من خلال توليد البخار المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية. مواد ACS التطبيقيه. واجهات. 13، 37724-37733 (2021).

- شيا، ق. وآخرون. مبخر شمسي ميكروي متكامل عائم للتنظيف الذاتي وإزالة الملح وتحلل المواد العضوية. مواد متقدمة ذات وظائف 33، 2214769 (2023).

- هاو، إكس. وآخرون. جامع مياه شمسية متعدد الوظائف مع قدرة عالية على اختيار النقل ورفض التلوث. نات. ووتر 1، 982-991 (2023).

- مي، ب. مبخر شمسي على الواجهة لمعالجة المحلول الملحي: أهمية القدرة على التحمل لدرجات الملوحة العالية. مراجعة العلوم الطبيعية 8، nwab118 (2021).

- شينغ، م. وآخرون. تقنيات حديثة متقدمة لمنع الملح ذاتية الدفع لأنظمة تحلية المياه بالتبخر الواجهوي المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية السلبية. نانو إنرجي 89، 106468 (2021).

- شو، و. وآخرون. ماصات جانوس مرنة ومقاومة للملح بواسطة تقنية النسيج الكهربائي للتناضح الشمسي المستقر والفعال. مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 8، 1702884 (2018).

- كووانغ، ي. وآخرون. مبخر شمسي ذاتي التجديد عالي الأداء لإزالة الملح من الماء بشكل مستمر. مواد متقدمة. 31، 1900498 (2019).

- زينغ، ج.، وانغ، ق.، شي، ي.، ليو، ب. & تشين، ر. الضخ الأسموزي ورفض الملح بواسطة هيدروجيل البوليمر الكهربائي للتن desalination الشمسي المستمر. مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 9، 1900552 (2019).

- تشاو، و. وآخرون. مبخر شمسي مقاوم للملح مصمم بشكل هرمي يعتمد على تأثير دونان لمعالجة المياه المالحة بشكل مستقر وعالي الأداء. مواد وظيفية متقدمة 31، 2100025 (2021).

- وو، ل. وآخرون. مبخر شمسي ثلاثي الأبعاد عالي الكفاءة لإزالة الملح من المياه عالية الملوحة عن طريق التبلور المحلي. نات. كوميونيك. 11، 521 (2020).

- تشانغ، ق. وآخرون. هلامات هوائية قائمة عمودياً تعتمد على جانوس MXene للتناضح الشمسي بكفاءة عالية ومقاومة للملح. ACS Nano 13، 13196-13207 (2019).

- تشين، إكس. وآخرون. التحلية المستدامة للمياه عالية الملوحة خارج الشبكة باستخدام مبخرات الخشب جانوس. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 14، 5347-5357 (2021).

- يانغ، ي. وآخرون. تصميم عام لطبقة مزدوجة نانوية هيدروفيلية/هيدروفوبية مقاومة للملح من أجل تقطير مياه الشمس بكفاءة واستقرار. مواد. أفق. 5، 1143-1150 (2018).

- يوسف، إ. & حداد، ر. التحلل الضوئي والتثبيت الضوئي للبوليمرات، وخاصة البولي ستيرين: مراجعة. سبرينجر بلس 2، 398 (2013).

- أسماتولو، ر.، محمود، ج. أ.، هيل، ج. & ميساك، هـ. إ. تأثيرات تدهور الأشعة فوق البنفسجية على الكارهية السطحية، الشقوق، وسمك الطلاءات النانوية المعتمدة على MWCNT. تقدم. طلاءات عضوية. 72، 553-561 (2011).

- هو، س. وآخرون. مبخر شمسي مسامي ثنائي النمط مقاوم للملح مستوحى من الطبيعة من أجل تحلية المياه بكفاءة واستقرار. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 12، 1558-1567 (2019).

- ليو، إكس. وآخرون. مبخر هيدروجيل ثلاثي الأبعاد مع أوعية إشعاعية عمودية يكسر التوازن بين التوضع الحراري ومقاومة الملح لتحلية المياه المالحة. مواد متقدمة. 34، e2203137 (2022).

- يانغ، ي. وآخرون. مبخر شمسي غير متماثل قابل للتوسع يشبه الصمام الثنائي مع مقاومة ملح فائقة. مواد متقدمة ووظيفية 33، 2210972 (2023).

- يانغ، ك.، بان، ت.، دانغ، س.، غان، ق. وهان، ي. هندسة معمارية ثلاثية الأبعاد مفتوحة تمكّن من أجهزة التبخر الشمسية ذات الرفض الملحي مع زيادة كفاءة إنتاج المياه. نات. كوميونيك. 13، 6653 (2022).

- Zhang، L. وآخرون. تبخر شمسي عالي الكفاءة ورفض الملح عبر طبقة ماء محصورة بدون فتيل. نات. كوميونيك. 13، 849 (2022).

- تشانغ، سي. وآخرون. تصميم بلورة شمسية من الجيل التالي لمعالجة مياه البحر المالحة الحقيقية مع عدم تصريف سائل. نات. كوميونيك. 12، 998 (2021).

- كوبر، ت. أ. وآخرون. توليد البخار بدون تلامس والتسخين الفائق تحت إضاءة الشمس الواحدة. نات. كوميونيك. 9، 5086 (2018).

- بانيرجي، I.، بانغولي، R. C. وكين، R. S. الطلاءات المضادة للتلوث: التطورات الأخيرة في تصميم الأسطح التي تمنع التلوث بواسطة البروتينات والبكتيريا والكائنات البحرية. مواد متقدمة. 23، 690-718 (2011).

- زينغ، إكس.، مكارثي، د. ت.، دليتيك، أ. وزانغ، إكس. هيدروجيل أكسيد الجرافين المخفض/الفضي كمرشح مضاد للبكتيريا جديد لتعقيم المياه عند نقطة الاستخدام. مواد متقدمة ووظيفية 25، 4344-4351 (2015).

مقالة مراجعة

- شو، ي. وآخرون. استراتيجية بسيطة وعالمية لترسيب Ag/بوليبيرول على ركائز متنوعة لتعزيز تبخر الشمس عند الواجهة والنشاط المضاد للبكتيريا. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 384، 123379 (2020).

- لي، ي. وآخرون. نظام ذاتي الضخ قائم على الهيدروجيل المركب مع مقاومة للملح والبكتيريا لتبخر المياه المدعوم بالطاقة الشمسية بكفاءة فائقة. تحلية 515، 115192 (2021).

- رسول، ك. وآخرون. غشاء مضاد للبكتيريا فعال يعتمد على ثنائي الأبعاد

أوراق نانوية (MXene). Sci. Rep. 7، 1598 (2017). - زا، إكس. جي. وآخرون. غشاء ليفي مرن مضاد للتلوث البيولوجي من الماكسين/السليلوز لتنقية المياه المستدامة المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 11، 36589-36597 (2019).

- قو، ي.، دونداس، س. م.، تشو، إكس.، جونستون، ك. ب. & يو، ج. الهندسة الجزيئية للهلاميات المائية للتعقيم السريع للمياه وتوليد بخار شمسي مستدام. مواد متقدمة. 33، e2102994 (2021).

- لي، ي. وآخرون. التلاعب في احتجاز الضوء وحرارة تبخر الماء من خلال الهيدروجيل الهجين المسامي من أجل تعزيز تبخر الماء على الواجهة المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية مع القدرة المضادة للبكتيريا. ج. مواد. كيمياء. أ 7، 26769-26775 (2019).

- سالكي، أ. م.، إيفان، م. ن. أ. س.، أحمد، س. وتسانغ، ي. هـ. نسيج هيدروجيل حابس للضوء بخصائص مضادة للتلوث البيولوجي ومضادة للبكتيريا للتن desalination الشمسي الفعال. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 458، 141430 (2023).

- كوي، ل. وآخرون. التبخر المائي على الواجهة المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية لتنقية المياه العادمة: التقدمات والتحديات الأخيرة. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 477، 147158 (2023).

- زوه، ي. وآخرون. هلام السليلوز المملوء بالبوليدوبامين المستوحى من المحار لمعالجة المياه المدعومة بالطاقة الشمسية. مواد ACS التطبيقيه. واجهات 13، 7617-7624 (2021).

- أبيلسون، ب. هـ. تلوث المياه الجوفية. العلوم 224، 673-673 (1984).

- ما، ج.، شو، ي.، صن، ف.، تشن، إكس. ووانغ، و. منظور لإزالة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة أثناء تبخر الماء المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية نحو إنتاج الماء. إيكومات 3، e12147 (2021).

- تشانغ، ب. وآخرون. هلامات فائقة لاستخراج المياه لإدارة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة المدعومة بالطاقة الشمسية في الدورة الهيدرولوجية. مواد متقدمة. 34، e2110548 (2022).

- دينغ، ج. وآخرون. ميكرو رياكتور حراري ضوئي معلق ذاتيًا لتحلية المياه وإزالة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة المدمجة. مواد ACS تطبيقيه. واجهات 12، 51537-51545 (2020).

- سونغ، سي. وآخرون. تقطير شمسي معتمد على غشاء نانوي ذو مسام مزدوجة الحجم لالتقاط المركبات العضوية المتطايرة بواسطة التأثير الضوئي الحراري/التحفيزي الضوئي. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 54، 9025-9033 (2020).

- تشانغ، ب.، وونغ، ب. وآن، أ. ك. غشاء هيدروجيل MXene المدعوم حرارياً مع تبخر مدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية وتفكك ضوئي لتنقية المياه بكفاءة. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 430، 133054 (2022).

- يانغ، ي. وآخرون. رغوة ضوئية قابلة للتجديد وقابلة للتوسع صناعيًا. أنف. سست. سيست. 7، 2300041 (2023).

- يان، س. وآخرون. هيدروجيل هجين من أكسيد الجرافين المخفض والبوليبيرول المتكامل للتطهير الضوئي المتزامن وتبخر الماء. تطبيقات الحفز ب 301، 120820 (2022).

- تشاو، و. وآخرون. مراجعة نقدية حول تطبيق المحفزات النانوية المعدلة سطحياً في التحلل الضوئي للمركبات العضوية المتطايرة. علوم البيئة. نانو 9، 61-80 (2022).

- بينغ، ي. وآخرون. غشاء مركب من إطار معدني عضوي للتصوير الحراري لإزالة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة عالية التركيز من الماء عبر الغربلة الجزيئية. ACS Nano 16، 8329-8337 (2022).

- Qi، د. وآخرون. أغشية بوليمرية ذات انتشار انتقائي للحل لاعتراض المركبات العضوية المتطايرة أثناء معالجة المياه المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية. مواد متقدمة. 32، e2004401 (2020).

- سونغ، ي. وآخرون. استخراج وتخزين الليثيوم المدعوم بالتبخر الشمسي. ساينس 385، 1444-1449 (2024).

- ليانغ، هـ.، مو، ي.، ين، م.، هي، ب.-ب. & قوه، و. تحلية مياه البحر بكفاءة عالية واستخراج مستهدف عالي التحديد باستخدام هيدروجيلات الحمض النووي الذكية المعتمدة على الطاقة الشمسية. ساينس أدف. 9، eadj1677 (2023).

- بورنرونغروج، س. وآخرون. أوراق هجينة من الفوتوحرارية والفوتوكاتاليست لتقسيم الماء الشامل المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية المرتبطة بتنقية المياه. نات. ووتر 1، 952-960 (2023).

- لي، و. هـ. وآخرون. هلامات نانوية فوتوكاتاليتيكية قابلة للطفو لإنتاج الهيدروجين الشمسي على نطاق واسع. نات. نانو تكنولوج. 18، 754-762 (2023).

- Guo, S.، Li, X.، Li, J. & Wei, B. تعزيز إنتاج الهيدروجين الضوئي التحفيزي من الماء بواسطة أنظمة ثنائية الطور مستحثة حرارياً بالضوء. Nat. Commun. 12، 1343 (2021).

- غاو، م.، بيه، س. ك.، زو، ل.، يلماظ، ج. و هو، ج. و. هلام محفز ضوئي حراري يتميز بإدارة طيفية وحرارية لإنتاج المياه العذبة والهيدروجين بشكل متوازي. مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 10، 2000925 (2020).

- تشو، ي. وآخرون. توزيع المياه غير المتجانس والتحكم في التبخر نحو تعزيز إنتاج الكهرباء والماء والهيدروجين بالحرارة الضوئية. طاقة نانو 77، 105102 (2020).

- فيرا، م. ل.، توريس، و. ر.، غالي، س. إ.، شاجنيس، أ. وفليكس، ف. تأثير البيئة لاستخراج الليثيوم المباشر من المحاليل الملحية. مراجعة الطبيعة: الأرض والبيئة 4، 149-165 (2023).

- Zhang، س. وآخرون. الفصل بين الأغشية المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية لاستخراج الليثيوم مباشرة من محلول ملحي صناعي. نات. كوميونيك. 15، 238 (2024).

- وانغ، ي.، لي، ج.، ويربر، ج. ر. وإليميلخ، م. التحلية المدفوعة بالشعيرات في غابة مانغروف صناعية. ساينس أدفانس 6، eaax5253 (2020).

- كورنيش، ج. أ. وآخرون. زجاجة مياه تحلية تعمل بالطاقة الناتجة عن النتح. مادة ناعمة 18، 1287-1293 (2022).

- تشين، إكس. وآخرون. استخراج الليثيوم المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية بواسطة شعيرة عائمة. مواد وظيفية متقدمة 34، 2316178 (2024).

- شيا، ق. وآخرون. استخراج الليثيوم المعزز بالطاقة الشمسية مع إعادة تدوير المياه المستدامة ذاتيًا من مياه البحيرات المالحة. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 121، e2400159121 (2024).

- وانغ، ن. وآخرون. الديناميكا الحرارية الكيميائية المعجلة لاستخراج اليورانيوم من مياه البحر بواسطة التبخر الشبيه بالنبات. علوم متقدمة 8، 2102250 (2021).

- لي، ت. وآخرون. استخراج اليورانيوم المعزز بالحرارة الضوئية من مياه البحر: جامع حراري شمسي من الكتلة الحيوية مع شبكات نقل أيونات ثلاثية الأبعاد. مواد متقدمة وظيفية 33، 2212819 (2023).

- كوي، و.-ر.، تشانغ، ج.-ر.، ليانغ، ر.-ب.، ليو، ج. & تشيو، ج.-د. إسفنجات الإطار العضوي التساهمي للتناضح الشمسي الفعال واستعادة اليورانيوم الانتقائية. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 13، 31561-31568 (2021).

- شان، هـ. وآخرون. مواد مركبة مدمجة بأملاح هيدروسكوبية لجمع المياه من الغلاف الجوي بناءً على الامتصاص. مراجعة طبيعية للمواد 9، 699-721 (2024).

- تشين، إكس. وآخرون. التبلور المنفصل مكانيًا لاستخراج الليثيوم الانتقائي من المياه المالحة. نات. ووتر 1، 808-817 (2023).

- فينيرتي، سي. تي. كيه. وآخرون. التبخر الشمسي الواجهاتي بواسطة ساق من أكسيد الجرافين ثلاثي الأبعاد لمعالجة المحاليل الملحية المركزة للغاية. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 55، 15435-15445 (2021).

- سبيرجون، ج. م. ولويس، ن. س. التحليل الكهربائي لغشاء تبادل البروتون المدعوم ببخار الماء. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 4، 2993-2998 (2011).

- زان، إكس. وآخرون. محفزات ضوئية فعالة من مصفوفة أسلاك نانوية CoO لـ

جيل. رسائل الفيزياء التطبيقية 105، 153903 (2014). - لو، ي. وآخرون. التبخر الواجهاتي المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية يسرع من التحليل الكهربائي للماء على هيكل هجين من أكسيد البيروفسكايت ثنائي الأبعاد/الميكسي. مواد وظيفية متقدمة 33، 2215061 (2023).

- برن، س. وآخرون. تقنيات التحلية – مراجعة للفرص المتاحة للتحلية في الزراعة. التحلية 364، 2-16 (2015).

- مارتينيز-ألفاريز، ف.، مارتن-غوريس، ب. وسوتو-غارثيا، م. تحلية مياه البحر لري المحاصيل – مراجعة للتجارب الحالية والقضايا الرئيسية التي تم الكشف عنها. تحلية 381، 58-70 (2016).

- شارون، هـ. و ريدي، ك. س. مراجعة لتقنيات التحلية المدفوعة بالطاقة الشمسية. مراجعات الطاقة المتجددة والمستدامة 41، 1080-1118 (2015).

- دسيلفا وينفريد روفوس، د.، إينيان، س.، سوغانثي، ل. وديفيز، ب. مراجعة شاملة لتصاميم وأداء وتطورات المواد في أجهزة التقطير الشمسي. مراجعات الطاقة المتجددة والمستدامة 63، 464-496 (2016).

- دسيلفا وينفريد روفوس، د.، راج كومار، ف.، سوغانثي، ل.، إينيان، س. وديفيز، ب. تحليل تقني اقتصادي للآبار الشمسية باستخدام عملية التحليل الهرمي الضبابي المتكاملة وتحليل الانحدار البياني. طاقة شمسية 159، 820-833 (2018).

- وو، ب.، وو، إكس.، وانغ، واي.، شو، إتش. وأوينز، ج. نحو الزراعة المالحة المستدامة: التبخر الشمسي على الواجهة من أجل تحلية مياه البحر وإصلاح التربة المالحة في آن واحد. أبحاث المياه. 212، 118099 (2022).

- وانغ، ق.، تشو، ز.، وو، ج.، تشانغ، إكس. وزينغ، هـ. تحليل الطاقة والتحقق التجريبي لفيلم بيئي ذاتي الإنتاج من المياه العذبة الشمسية يطفو على البحر. الطاقة التطبيقية 224، 510-526 (2018).

- وانغ، ل.، هي، ق.، يو، هـ.، جين، ر. وزينغ، هـ. نظام زراعة عائم يعتمد على عملية تقطير الفيلم المتصاعد متعدد المراحل بالطاقة الشمسية المركزة. إدارة تحويل الطاقة 254، 115227 (2022).

- زوه، م. وآخرون. طباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد لمبخر شمسي على شكل قوس جسر يحاكي الطبيعة للقضاء على تراكم الملح مع تطبيقات التحلية والزراعة. مواد متقدمة 33، 2102443 (2021).

- تشانغ، س.-ي.، تشينغ، ب.، لي، ج. ويانغ، ي. الخلايا الشمسية البوليمرية الشفافة لجمع الطاقة الشمسية وما بعدها. جول 2، 1039-1054 (2018).

- شين، ل. وآخرون. زيادة إنتاج البيوت المحمية من خلال تغيير الطيف والفوتونيكس لاستخراج الضوء في اتجاه واحد. نات. فود 2، 434-441 (2021).

- وو، ب. وآخرون. مزرعة شمسية بحرية عائمة مزدوجة الطبقات ذاتية التشغيل مدعومة بالتبخر الشمسي على الواجهة. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 473، 145452 (2023).

- وانغ، م. وآخرون. نظام متكامل يحتوي على وظائف تحلية المياه بالطاقة الشمسية، وتوليد الطاقة، وري المحاصيل. نات. ووتر 1، 716-724 (2023).

- جاكوبسون، م. ز. مراجعة للحلول المتعلقة بالاحترار العالمي، وتلوث الهواء، وأمن الطاقة. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 2، 148-173 (2009).

- بيسواس، ك. وآخرون. مواد حرارية كهربائية ذات أداء عالي مع هياكل هرمية على جميع المقاييس. ناتشر 489، 414-418 (2012).

- فان، ف.-ر.، تيان، ز.-كيو. و لين وانغ، ز. مولد تريبوإلكتريك مرن. نانو إنرجي 1، 328-334 (2012).

- ستورر، د. ب. وآخرون. هلامات هوائية ثلاثية الأبعاد قائمة على الجرافين وألياف قش الأرز للتبخر الشمسي عالي الكفاءة. مواد ACS التطبيقة. واجهات. 12، 15279-15287 (2020).

- فانغ، ق. وآخرون. مكثفات شمسية كاملة مشتقة من الكتلة الحيوية للتبخر القوي والمستقر لجمع المياه النظيفة من وسائط حاملة للمياه متنوعة. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 11، 10672-10679 (2019).

- هو، ج. وآخرون. مبخر شمسي واجهي ثلاثي الأبعاد قائم على عرانيس الذرة معزز بالطاقة البيئية مع رفض الملح ومقاومة التآكل لتقطير مياه البحر. طاقة شمسية 252، 39-49 (2023).

- يوكيرت، ت.، بيشلر، س. م.، شوبيرت، ت. ورايزنر، إ. الإصلاح المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية للنفايات الصلبة من أجل مستقبل مستدام. نات. سستين. 4، 383-391 (2021).

- لي، ج. وآخرون. كرات الهلام الهوائي الضوئي الحراري المستندة إلى البوليسكاريد: تصنيع محكوم وتطبيقات هجينة في التبخر الواجهاتي المدعوم بالطاقة الشمسية، معالجة المياه، وإثراء التربة. مواد ACS. واجهات. 14، 50266-50279 (2022).

- تشين، ي. وآخرون. مبخر لإفراز الملح البيوميمي المدفوع بمارانغوني. تحلية المياه 548، 116287 (2023).

مقالة مراجعة

- وو، ب.، وو، إكس.، شو، إتش. وأوينز، ج. إزالة الرصاص المدفوعة بالتبخر الشمسي الواجهاتي من التربة الملوثة. إيكومات 3، e12140 (2021).

- وو، ب. وآخرون. تعزيز استخراج الرصاص من التربة الملوثة عبر التبخر الشمسي على الواجهة باستخدام إسفنجة متعددة الوظائف. الطاقة الخضراء والبيئة. 8، 1459-1468 (2023).

- شو، ي. وآخرون. جهاز تبخير واجهة الطاقة الشمسية للتنظيف النباتي الاصطناعي لفصل أملاح المعادن الثقيلة بكفاءة وإصلاح التربة المالحة. مجلة هندسة الكيمياء البيئية 12، 113114 (2024).

- وو، ب.، وو، إكس.، وانغ، ي.، شو، إتش. وأوينز، ج. مبخر شمسي واجهي محاكي حيوي لإصلاح التربة الملوثة بالمعادن الثقيلة. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 435، 134793 (2022).

- ليو، ك. وآخرون. مبخر ضوئي حراري على شكل شجرة بيونية مصنوعة من القطن لاستخراج المعادن الثقيلة من رواسب الأنهار. مجلة هندسة الكيمياء البيئية 11، 111063 (2023).

- ليو، ك. وآخرون. إزالة الكادميوم من الرواسب الملوثة المدفوعة بالتبخر الشمسي السطحي. مجلة هندسة الكيمياء البيئية 12، 112920 (2024).

- جيلوسيتش، م.، فودنيك، د.، ماسيك، إ. ولستان، د. تأثير غسل EDTA للتربة الملوثة بالمعادن في الحدائق. الجزء الثاني: هل يمكن استخدام التربة المعالجة كركيزة للنباتات؟ العلوم. البيئة الكاملة. 475، 142-152 (2014).

- يانغ، ب. وآخرون. إنتاج البخار وتوليد الكهرباء المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية من الملوحة. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 10، 1923-1927 (2017).

- هو، ن. وآخرون. هندسة التأين للهيدروجيل تتيح تبخر الشمس بكفاءة عالية مع وجود الملح وجمع الكهرباء في الليل. نانو-ميكرو ليت. 16، 8 (2023).

- Wani، ت. أ.، كايث، ب.، غارغ، ب. & بيرا، أ. إنتاج الكهرباء على مدار اليوم الناتج عن تدرج الملوحة في الميكروفلويديات في توليد بخار الشمس. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 14، 35802-35808 (2022).

- غاو، ج. وآخرون. غشاء ثنائي الأيونات عالي الأداء لتوليد الطاقة من تدرج الملوحة. مجلة الجمعية الكيميائية الأمريكية 136، 12265-12272 (2014).

- تشين، سي. & هو، ل. تنظيم الأيونات على النانو في الهياكل القائمة على الخشب وتطبيقاتها في الأجهزة. مواد متقدمة 33، 2002890 (2021).

- وو، ق.-ي. وآخرون. توليد الطاقة من تدرج الملوحة باستخدام أغشية الخشب المؤين. مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 10، 1902590 (2020).

- زو، ل.، دينغ، ت.، قاو، م.، بيه، س. ك. ن. & هو، ج. و. إسفنجة ماصة شمسية عضوية متوافقة الشكل وعازلة حرارية للتبخر المائي الفوتوحراري وتوليد الطاقة الحرارية الكهربائية. مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 9، 1900250 (2019).

-

. وآخرون. تخزين وإعادة تدوير حرارة بخار الشمس الواجهة. جول 2، 2477-2484 (2018). - كوي، ي. وآخرون. مادة عضوية صغيرة الحجم من نوع المانح-المستقبل لامتصاص الطاقة الشمسية من أجل تبخر الماء بكفاءة عالية وتوليد الطاقة الحرارية الكهربائية. مواد متقدمة وظيفية 31، 2106247 (2021).

- تشاو، ج. وآخرون. خلايا حرارية كهربائية قائمة على الهلام الهوائي القابل للتجديد لجمع الحرارة المنخفضة بكفاءة من الإشعاع الشمسي وأنظمة تبخر الشمس عند الواجهة. إيكومات 5، e12302 (2023).

- شين، ق. وآخرون. خلية حرارية كهربائية مفتوحة ممكنة من خلال التبخر الواجهاتي. مجلة مواد الكيمياء A 7، 6514-6521 (2019).

- غاو، ف.، لي، و.، وانغ، إكس.، فانغ، إكس. وما، م. مولد نانو حراري كهربائي ذاتي الاستدامة مدفوع ببخار الماء. طاقة نانو 22، 19-26 (2016).

- جيانغ، م. وآخرون. تنظيم درجة الحرارة المستوحى من الطبيعة في التبخر الواجهاتي. مواد وظيفية متقدمة 30، 1910481 (2020).

- هو، ج. وتريت، ت. م. التقدم في أبحاث المواد الكهروحرارية: النظر إلى الوراء والمضي قدماً. العلوم 357، eaak9997 (2017).

- دوان، ج. وآخرون. خلايا حرارية في الحالة السائلة: الفرص والتحديات لجمع الحرارة منخفضة الدرجة. جول 5، 768-779 (2021).

- برميستروف، إ. وآخرون. التقدم في أداء خلايا الحرارة الكهربائية (TEC) لجمع الطاقة الحرارية منخفضة الدرجة: مراجعة. الاستدامة 14، 9483 (2022).

- واتمور، ر. و. أجهزة ومواد الكهروحرارية. تقرير. تقدم. الفيزياء 49، 1335 (1986).

- شو، ي. وآخرون. مركب إسفنجي بوليمري شامل ثلاثي الأبعاد لمبخرات لتقنية التحلية الشمسية الحرارية عالية التدفق وتوليد الكهرباء في آن واحد. طاقة نانو 93، 106882 (2022).

- شيو، ج. وآخرون. الكهرباء الناتجة عن تبخر الماء باستخدام مواد كربونية نانوية. نات. نانو تكنولوجي. 12، 317-321 (2017).

- شو، ن. وآخرون. مولدات الكهرباء الشمسية والمياه المتزامنة التآزرية. جول 4، 347-358 (2020).

- جي، ك. وآخرون. توليد الماء والكهرباء بالطاقة الشمسية بشكل متكامل من خلال الدمج العقلاني للألواح الشمسية شبه الشفافة ومولدات البخار الواجهة. مجلة مواد الكيمياء A 9، 21197-21208 (2021).

- جوي، ج. وآخرون. نظام تبخر شمسي هجين لتوليد الماء والكهرباء: الاستخدام الشامل للطاقة الشمسية ومياه. طاقة نانو 107، 108155 (2023).

- Zhang، Z. وآخرون. تكنولوجيا الهيدروفولتيك الناشئة. نات. نانو تكنولوج. 13، 1109-1119 (2018).

- الميدا، ر. م. وآخرون. الطاقة الشمسية العائمة: تقييم الموازنة. ناتشر 606، 246-249 (2022).

- دجالب، أ. وآخرون. مراجعة شاملة لأنظمة الطاقة الشمسية العائمة: التقدم التكنولوجي، التأثيرات البيئية البحرية على أنظمة الطاقة الشمسية البحرية، وتحليل الجدوى الاقتصادية. طاقة شمسية 277، 112711 (2024).

- جافيد، م. وآخرون. نظام كامل لتوليد مياه نظيفة من جسم مائي ملوث بواسطة ماص ضوء يدوي على شكل زهرة. ACS أوميغا 6، 35104-35111 (2021).

- كاو، ب. وآخرون. تأثير التسخين المتدرج المعدل بواسطة هياكل شبكة أنابيب الكربون النانوية الكارهة للماء/المحبة للماء لتوليد بخار الشمس بسرعة فائقة. مواد ACS التطبيقيه. واجهات. 13، 19109-19116 (2021).

- جونغ، ف. وآخرون. مولدات بخار شمسية سريعة للغاية وصديقة للبيئة وقابلة للتوسع تعتمد على إسفنجات الكربون المشتقة من الميلاتونين من خطوة واحدة نحو تنقية المياه. طاقة نانو 58، 322-330 (2019).

- ني، ف. وآخرون. التحكم المتناغم ميكروسكوبياً/ماكروسكوبياً في تنقية المياه الضوئية القابلة للتبديل 2D/3D المدعومة بأوراق السليلوز القوية، المحمولة، والفعالة من حيث التكلفة. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 11، 15498-15506 (2019).

- جين، ب. وآخرون. مولد المياه الشمسي المستوحى من الجبال الجليدية لإنتاج الكهرباء الحرارية المتزايدة والمياه العذبة بشكل متزامن. Chem. Eng. J. 469، 143906 (2023).

- ياو، هـ. وآخرون. هندسة واجهة جانوس لتعزيز البخار الشمسي نحو جمع المياه بكفاءة عالية. Energy Environ. Sci. 14، 5330-5338 (2021).

- تشو، ز.، تشنغ، هـ.، كونغ، هـ.، ما، إكس. & شيونغ، ج. التحلية الشمسية السلبية نحو كفاءة عالية وطرد الملح عبر طبقة مياه متبخرة عكسية بسماكة مليمترية. Nat. Water 1، 790-799 (2023).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© Springer Nature Limited 2025

- ¹المختبر الوطني للهياكل الدقيقة للحالة الصلبة، كلية الطاقة المستدامة والموارد، كلية الهندسة والعلوم التطبيقية، مركز العلوم الأمامية لدورة المواد الأرضية الحرجة، مركز أبحاث العلوم الفيزيائية في جيانغسو، جامعة نانجينغ، نانجينغ، جمهورية الصين الشعبية.

ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: يان سونغ، شيكي فانغ. □ البريد الإلكتروني: nxu@nju.edu.cn; jiazhu@nju.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44359-024-00009-x

Publication Date: 2025-01-15

Solar-driven interfacial evaporation technologies for food, energy and water

Abstract

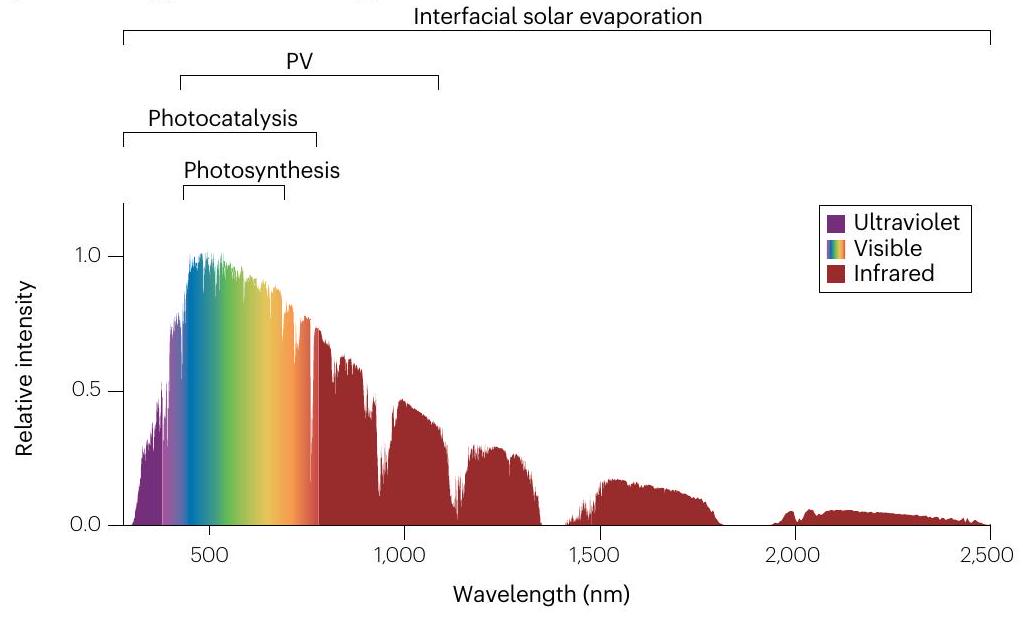

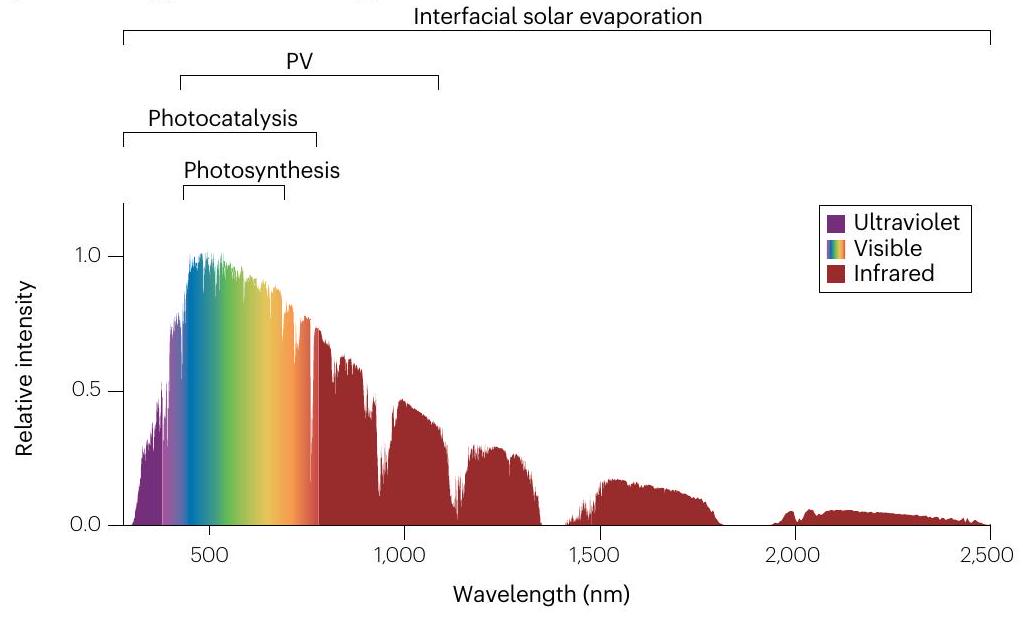

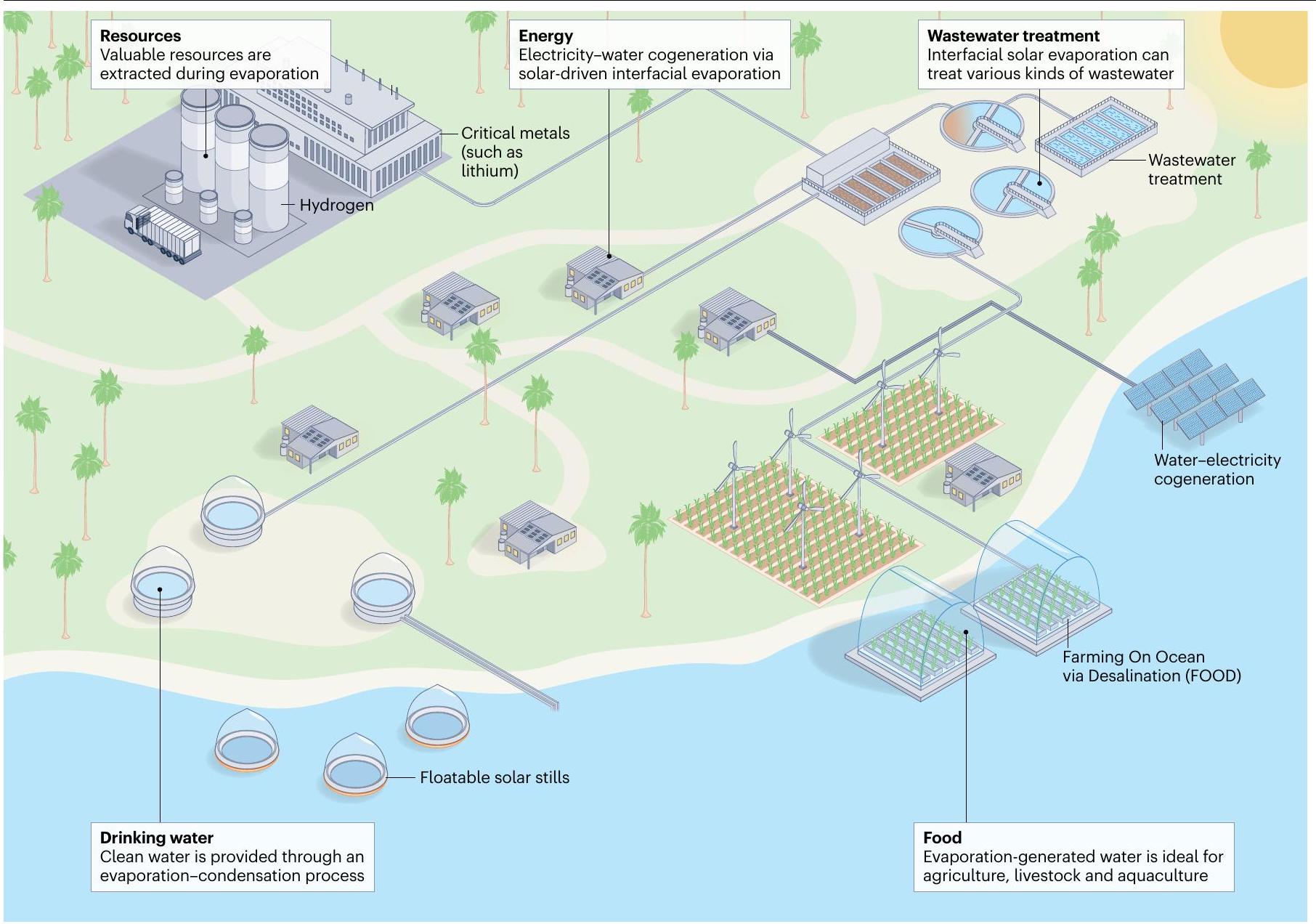

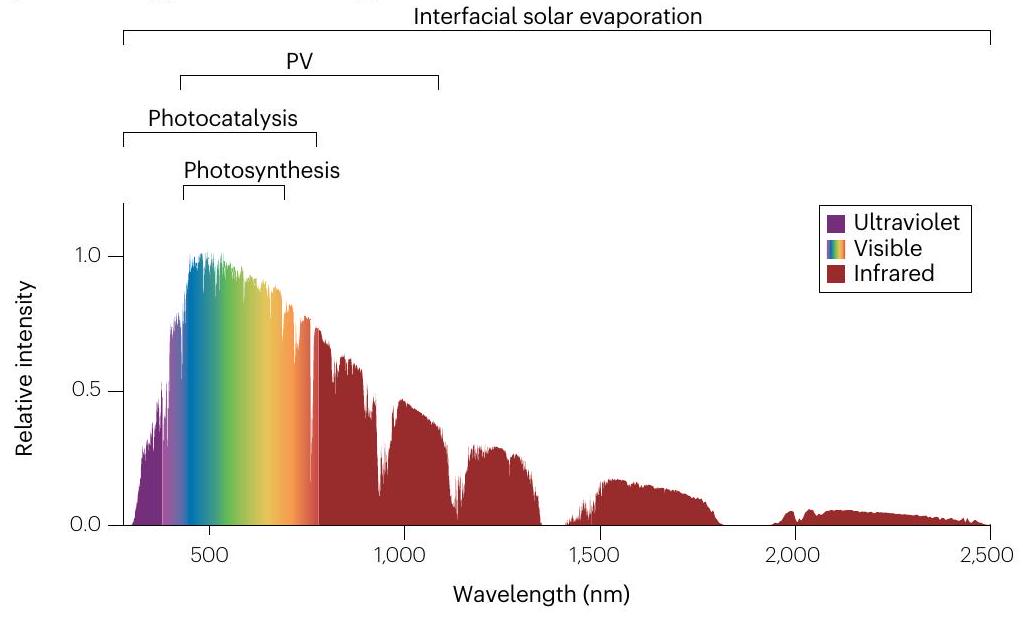

Solar-driven interfacial evaporation technologies use solar energy to heat materials that drive water evaporation. These technologies are versatile and do not require electricity, which enables their potential application across the food, energy and water nexus. In this Review, we assess the potential of solar-driven interfacial evaporation technologies in food, energy and clean-water production, in wastewater treatment, and in resource recovery. Interfacial evaporation technologies can produce up to

Water production and treatment

Food production

Energy

Summary and future perspectives

Key points

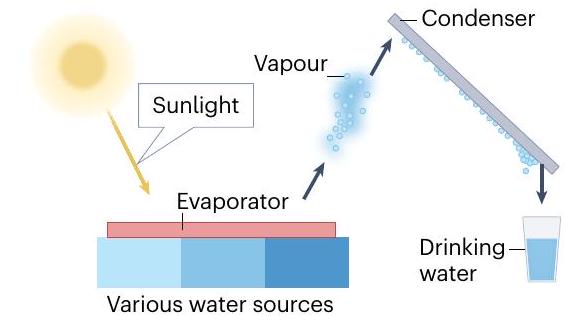

- Evaporation-condensation purifiers (a common solar interfacial evaporation purifier design) use solar energy to generate fresh water at

, but are limited by water’s vaporization enthalpy . Solar steam-driven membrane desalination lowers the salt-water separation energy to , producing fresh water at up to under 12-sun illumination. - Through the implementation of various anti-fouling measures, engineered solar evaporators show strong resistance to salt, biofouling and organic contamination, with month-long stability in the laboratory. Next-generation systems should be scaled up and monitored in the field over several months to assess real-world viability.

- Solar evaporation technologies could supply high-quality fresh water for irrigation and soil remediation, aiding agriculture in coastal areas.

- Energy can be harvested from water evaporation through thermoelectric, pyroelectric, salinity gradient and hydrovoltaic power generation, producing

. Solar photovoltaic-evaporation hybrid systems are better suited to large-scale applications, generating around of electricity. - Evaporators can extract dilute critical resources from complex water matrices. Co-generation of multiple resources through interfacial evaporation could enhance the energy efficiency of the processes, but require further study and development.

- Small-scale systems are well tested at the laboratory scale and are suitable for personal or household use, but large-scale systems are essential for industrial applications. Successful commercialization of solar evaporation technologies will require scaling up, reducing costs and meeting regulatory standards.

Introduction

from various water sources (including seawater

Water production and treatment

Clean water production

Abstract

They can also be designed to produce fresh water for agriculture on land and on the ocean: the Farming On Ocean via Desalination (FOOD) system. Resources can be recovered from water by using interfacial solar evaporation to extract metals, such as lithium, or in combination with catalytic systems to produce hydrogen gas from water. Emerging designs integrate interfacial solar evaporation with renewable energy technologies like photovoltaic panels and wind turbines, enabling the simultaneous generation of electricity and other resources.

barrier and scatter sunlight, resulting in substantial light loss of up to

thereby decoupling the light absorption and condensation (Fig. 2c). As such, the condensation surface does not require high light transmittance

allows for the use of materials with high thermal conductivity and hydrophophic properties such as copper

d Evaporation-condensation purifiers – multistage structure

a, In interfacial solar evaporation, solar energy is absorbed by an evaporator, which warms and generates water vapour. The vapour condenses into water upon contact with the condenser.b, Traditional solar water generators use a transparent cover for condensation. Condensation can be enhanced by adjusting the surface hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity to promote filmwise condensation to avoid light scattering (left) and dropwise condensation for a high heat transfer coefficient (right).

hydrophilic water supply layers and condensation layers separated by air gaps to recycle the enthalpy of condensation. e, A solar steam-driven membrane technology for fresh water production uses solar energy to generate high-power steam, which generates the pressure to push saltwater through a reverse osmosis nanofiltration (RO/NF) membrane, producing clean water.f, Interfacial solar-driven atmospheric water generators use ionic liquids to harvest atmospheric moisture, which is then used in interfacial solar evaporation to produce clean water.g, Water production rates for different types of solar-driven interfacial evaporation technology (data from refs.10,23,40,50-54,57,195-201 and detailed in Supplementary Table 1). h, A commercial floatable solar still. Panel d adapted with permission from ref. 50 , RSC. Panel e adapted from ref.10, Springer Nature Limited. Panel f adapted with permission from ref.58, Wiley. Panel

Review article

monitored and maintained over several months in the field. Factors such as water quality, especially organic matter content, must be tracked, as volatile organic compounds can evaporate with water, contaminating the distillate and compromising drinking water safety. Additionally, investment and maintenance costs must be thoroughly evaluated to assess the technology’s readiness for long-term field operation.

applied to a

Wastewater treatment

effectiveness of Donnan-effect-based salt resistance is reduced in high-salinity water with salinity greater than

Resources from water

as critical metals

Critical metals

been developed for sustainable lithium recovery from brines

C Spatially separated crystallization

(like NaCl ) crystallize at lower heights of the fibre crystallizer. Salts with lower concentrations and higher solubilities (like LiCl ) precipitate near the top. d, Prototype Li extraction array containing

osmosis membrane

Hydrogen

product; and vapor-phase photocatalysis demands less energy for water splitting due to the lower standard Gibbs free energy of formation of gaseous water compared with liquid (

Scale and multi-product recovery are needed

Food production

agriculture. Interfacial solar desalination-agriculture systems could be particularly useful in coastal areas where fresh water and fertile soils are scarce. Coastal farming often relies on costly and energy-intensive desalination methods

Farming on ocean via desalination

allowing ultraviolet and visible light to pass through. This configuration enables ultraviolet and visible light to reach the plants for photosynthesis, while near-infrared light is absorbed by the outer cover for desalination (Fig.5e). Consequently, this strategy optimizes both land and solar energy utilization efficiency.

Soil remediation

chamber (Fig. 5 g ). Sunlight transmits through the transparent cover and is absorbed and converted into heat by a photothermal evaporator. This heat facilitates seawater evaporation and the resulting vapour condenses into fresh water that drips down into the soil. Field tests demonstrate that this method removes hazardous contaminants at a rate three times faster than solar distillation, based on natural evaporation, completing the process in 16 days instead of 50 days

intended for agriculture

(Vis) light to pass through for plant growth (panel e). f, Integrated trinity FOOD systems desalinate water, generate power and irrigate crops. The system includes a desalination-power-generation chamber and a cultivation chamber. The energy of the salinity gradient between high-salinity seawater and surface water is extracted by the reverse electrodialysis technique to produce electricity.g, In solar-driven soil remediation, fresh water produced through interfacial solar evaporation is directly transferred into the soil, where it can be used for soil washing and/or agricultural irrigation.h, Biodegradable solar evaporators adsorb nutrients from wastewater and are transferred to soils, where they degrade and release nutrients. i, Artificial phytoremediation uses evaporators that are structured like plants. These evaporators use the solar interfacial process to accelerate the immobilization of pollutants in soil or water, enhancing remediation processes. IR, infrared;rGO, reduced graphene oxide. Part f adapted from ref. 153, Springer Nature Limited. Parth adapted with permission from ref.146, Elsevier.

on contaminated soil to extract heavy-metal ions through transpiration

Energy

Salinity-gradient energy generation

Thermal-gradient energy generation

Box 1 | Food, energy and water co-generation

Electricity, water and heat

(about

Electricity, water and cooling

(continued from previous page)

Electricity, food and water

Water, electricity and biochar

Water-electricity co-generation

Syngas and water

Water and heat

a thermal interconnecting layer in the middle to transfer the thermalization heat from the PV cell to the water purifier, and an interfacial solar water purifier at the bottom to generate clean water

Application and viability

Summary and future perspectives

these systems in real-world conditions. Moreover, we strongly recommend comprehensive life-cycle assessments to evaluate environmental impacts before implementation to guide application and more efficient and sustainable use. Finally, advances in hardware design and mass production will be crucial to reducing costs and making these technologies widely accessible, ensuring global access to FEW solutions.

References

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition. United Nations https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/ (2023).

- Kalogirou, S. A. Solar Thermal Energy: History (Springer, 2022).

- Li, X. et al. Graphene oxide-based efficient and scalable solar desalination under one sun with a confined 2D water path. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 13953-13958 (2016).

- Zhou, L. et al. 3D self-assembly of aluminium nanoparticles for plasmon-enhanced solar desalination. Nat. Photon. 10, 393-398 (2016).

- Xu, N. et al. Going beyond efficiency for solar evaporation. Nat. Water 1, 494-501 (2023).

- Tao, P. et al. Solar-driven interfacial evaporation. Nat. Energy 3, 1031-1041 (2018).

- Zhao, F., Guo, Y., Zhou, X., Shi, W. & Yu, G. Materials for solar-powered water evaporation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 388-401 (2020).

- Dang, C. et al. Structure integration and architecture of solar-driven interfacial desalination from miniaturization designs to industrial applications. Nat. Water 2, 115-126 (2024).

- Wu, X. et al. Interfacial solar evaporation: from fundamental research to applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313090 (2024).

- Wang, X. et al. Solar steam-driven membrane filtration for high flux water purification. Nat. Water 1, 391-398 (2023).

- Xia, Y. et al. Spatially isolating salt crystallisation from water evaporation for continuous solar steam generation and salt harvesting. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1840-1847 (2019).

- Thakur, A. K. et al. Exploring the potential of MXene-based advanced solar-absorber in improving the performance and efficiency of a solar-desalination unit for brackish water purification. Desalination 526, 115521 (2022).

- Xu, N. et al. A scalable fish-school inspired self-assembled particle system for solar-powered water-solute separation. Natl Sci. Rev. 8, nwab065 (2021).

- Bian, Y. et al. Farming On the Ocean via Desalination (FOOD). Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 21104-21112 (2023).

- Yang, T. et al. Efficient solar domestic and industrial sewage purification via polymer wastewater collector. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 131199 (2022).

- Lin, S., Qi, H., Hou, P. & Liu, K. Resource recovery from textile wastewater: dye, salt, and water regeneration using solar-driven interfacial evaporation. J. Clean. Prod. 391, 136148 (2023).

- Shang, Y., Li, B., Xu, C., Zhang, R. & Wang, Y. Biomimetic Janus photothermal membrane for efficient interfacial solar evaporation and simultaneous water decontamination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 298, 121597 (2022).

- Li, J. et al. Interfacial solar steam generation enables fast-responsive, energy-efficient, and low-cost off-grid sterilization. Adv. Mater. 30, 1805159 (2018).

- Zhao, L. et al. A passive high-temperature high-pressure solar steam generator for medical sterilization. Joule 4, 2733-2745 (2020).

- Shi, P., Li, J., Song, Y., Xu, N. & Zhu, J. Cogeneration of clean water and valuable energy/resources via interfacial solar evaporation. Nano Lett. 24, 5673-5682 (2024).

- Xu, N. et al. A water lily-inspired hierarchical design for stable and efficient solar evaporation of high-salinity brine. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw7013 (2019).

- Menon, A. K., Haechler, I., Kaur, S., Lubner, S. & Prasher, R. S. Enhanced solar evaporation using a photo-thermal umbrella for wastewater management. Nat. Sustain. 3, 144-151 (2020).

- Ni, G. et al. A salt-rejecting floating solar still for low-cost desalination. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 1510-1519 (2018).

- Geng, Y. et al. Bioinspired fractal design of waste biomass-derived solar-thermal materials for highly efficient solar evaporation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2007648 (2021).

- Chen, L. et al. Low-cost and reusable carbon black based solar evaporator for effective water desalination. Desalination 483, 114412 (2020).

- Zhou, H., Xue, C., Chang, Q., Yang, J. & Hu, S. Assembling carbon dots on vertically aligned acetate fibers as ideal salt-rejecting evaporators for solar water purification. Chem. Eng. J. 421, 129822 (2021).

- Dang, C. et al. Ultra salt-resistant solar desalination system via large-scale easy assembly of microstructural units. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 5405-5414 (2022).

- Ibrahim, S., Bari, M. & Miles, L. Water resources management in Maldives with an emphasis on desalination. Maldives Water and Sanitation Authority http://pacificwater.org/ userfiles/file/Case Study B THEME 1 Maldives on Desalination.pdf (2002).

- Ahmed, F. E., Hashaikeh, R. & Hilal, N. Solar powered desalination-technology, energy and future outlook. Desalination 453, 54-76 (2019).

- Chen, C., Kuang, Y. & Hu, L. Challenges and opportunities for solar evaporation. Joule 3, 683-718 (2019).

Review article

- Zhu, L., Gao, M., Peh, C. K. N. & Ho, G. W. Recent progress in solar-driven interfacial water evaporation: advanced designs and applications. Nano Energy 57, 507-518 (2019).

- Zhou, L. et al. Self-assembly of highly efficient, broadband plasmonic absorbers for solar steam generation. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501227 (2016).

- Cho, H. J., Preston, D. J., Zhu, Y. & Wang, E. N. Nanoengineered materials for liquid-vapour phase-change heat transfer. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16092 (2016).

- Zhang, S. et al. The effect of surface-free energy and microstructure on the condensation mechanism of water vapor. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 33, 37-46 (2023).

- Ghasemi, H. et al. Solar steam generation by heat localization. Nat. Commun. 5, 4449 (2014).

- Ni, G. et al. Steam generation under one sun enabled by a floating structure with thermal concentration. Nat. Energy 1, 16126 (2016).

-

. et al. Mushrooms as efficient solar steam-generation devices. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606762 (2017). - Li, X. et al. Three-dimensional artificial transpiration for efficient solar waste-water treatment. Nat. Sci. Rev. 5, 70-77 (2017).

- Shi, Y. et al. A 3D photothermal structure toward improved energy efficiency in solar steam generation. Joule 2, 1171-1186 (2018).

- Wang, F. et al. A high-performing single-stage invert-structured solar water purifier through enhanced absorption and condensation. Joule 5, 1602-1612 (2021).

- Zhu, L., Gao, M., Peh, C. K. N., Wang, X. & Ho, G. W. Self-contained monolithic carbon sponges for solar-driven interfacial water evaporation distillation and electricity generation. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702149 (2018).

- Singh, S. C. et al. Solar-trackable super-wicking black metal panel for photothermal water sanitation. Nat. Sustain. 3, 938-946 (2020).

- Jani, H. K. & Modi, K. V. Experimental performance evaluation of single basin dual slope solar still with circular and square cross-sectional hollow fins. Sol. Energy 179, 186-194 (2019).

- Liu, Z. et al. Extremely cost-effective and efficient solar vapor generation under nonconcentrated illumination using thermally isolated black paper. Global Challenges 1, 1600003 (2017).

- Zhang, L. et al. Passive, high-efficiency thermally-localized solar desalination. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 1771-1793 (2021).

- Zhang, Y. & Tan, S. C. Best practices for solar water production technologies. Nat. Sustain. 5, 554-556 (2022).

- Onggowarsito, C. et al. Updated perspective on solar steam generation application. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 2088-2099 (2024).

- Oh, J. et al. Thin film condensation on nanostructured surfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1707000 (2018).

- Wang, Z., Elimelech, M. & Lin, S. Environmental applications of interfacial materials with special wettability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 2132-2150 (2016).

- Xu, Z. et al. Ultrahigh-efficiency desalination via a thermally-localized multistage solar still. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 830-839 (2020).

- Chiavazzo, E., Morciano, M., Viglino, F., Fasano, M. & Asinari, P. Passive solar high-yield seawater desalination by modular and low-cost distillation. Nat. Sustain. 1, 763-772 (2018).

- Morciano, M., Fasano, M., Boriskina, S. V., Chiavazzo, E. & Asinari, P. Solar passive distiller with high productivity and Marangoni effect-driven salt rejection. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 3646-3655 (2020).

- Wang, W. et al. Integrated solar-driven PV cooling and seawater desalination with zero liquid discharge. Joule 5, 1873-1887 (2021).

- Wang, W. et al. Simultaneous production of fresh water and electricity via multistage solar photovoltaic membrane distillation. Nat. Commun. 10, 3012 (2019).

- Zhang, L. et al. Modeling and performance analysis of high-efficiency thermally-localized multistage solar stills. Appl. Energy 266, 114864 (2020).

- Nawaz, F. et al. Can the interfacial solar vapor generation performance be really “beyond” theoretical limit? Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400135 (2024).

- Geng, H. et al. Plant leaves inspired sunlight-driven purifier for high-efficiency clean water production. Nat. Commun. 10, 1512 (2019).

- Qi, H. et al. An interfacial solar-driven atmospheric water generator based on a liquid sorbent with simultaneous adsorption-desorption. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903378 (2019).

- Wang, X. et al. An interfacial solar heating assisted liquid sorbent atmospheric water generator. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 131, 12182-12186 (2019).

- Xu, W. & Yaghi, O. M. Metal-organic frameworks for water harvesting from air, anywhere, anytime. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 1348-1354(2020).

- Lord, J. et al. Global potential for harvesting drinking water from air using solar energy. Nature 598, 611-617 (2021).

- Hanikel, N., Prévot, M. S. & Yaghi, O. M. MOF water harvesters. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 348-355 (2020).

- Ma, J. et al. A solar-electro-thermal evaporation system with high water-production based on a facile integrated evaporator. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 21771-21779 (2020).

- Guo, Q., Yi, H., Jia, F. & Song, S. Design of

bi-layered aerogels integrated with phase change materials for sustained and efficient solar desalination. Desalination 541, 116028 (2022). - Xu, J. et al. Ultrahigh solar-driven atmospheric water production enabled by scalable rapid-cycling water harvester with vertically aligned nanocomposite sorbent. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5979-5994 (2021).

- Song, Y. et al. Hierarchical engineering of sorption-based atmospheric water harvesters. Adv. Mater. 36, 2209134 (2024).

- Zhou, M. et al. Vapor condensation with daytime radiative cooling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2019292118 (2021).

- Haechler, I. et al. Exploiting radiative cooling for uninterrupted 24 -hour water harvesting from the atmosphere. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf3978 (2021).

- Xu, J. et al. All-in-one hybrid atmospheric water harvesting for all-day water production by natural sunlight and radiative cooling. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 4988-5001 (2024).

- Shan, H. et al. Exceptional water production yield enabled by batch-processed portable water harvester in semi-arid climate. Nat. Commun. 13, 5406 (2022).

- Greenlee, L. F., Lawler, D. F., Freeman, B. D., Marrot, B. & Moulin, P. Reverse osmosis desalination: water sources, technology, and today’s challenges. Water Res. 43, 2317-2348 (2009).

- Wang, Y., Qi, Q., Fan, J., Wang, W. & Yu, D. Simple and robust MXene/carbon nanotubes/cotton fabrics for textile wastewater purification via solar-driven interfacial water evaporation. Separ. Purif. Technol. 254, 117615 (2021).

- Tong, T. & Elimelech, M. The global rise of zero liquid discharge for wastewater management: drivers, technologies, and future directions. Env. Sci. Technol. 50, 6846-6855 (2016).

- Shi, Y. et al. Solar evaporator with controlled salt precipitation for zero liquid discharge desalination. Env. Sci. Technol. 52, 11822-11830 (2018).

- Peng, B. et al. Cationic photothermal hydrogels with bacteria-inhibiting capability for freshwater production via solar-driven steam generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 13, 37724-37733 (2021).

- Xia, Q. et al. A floating integrated solar micro-evaporator for self-cleaning desalination and organic degradation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214769 (2023).

- Hao, X. et al. Multifunctional solar water harvester with high transport selectivity and fouling rejection capacity. Nat. Water 1, 982-991 (2023).

- Mi, B. Interfacial solar evaporator for brine treatment: the importance of resilience to high salinity. Nat. Sci. Rev. 8, nwab118 (2021).

- Sheng, M. et al. Recent advanced self-propelling salt-blocking technologies for passive solar-driven interfacial evaporation desalination systems. Nano Energy 89, 106468 (2021).

- Xu, W. et al. Flexible and salt resistant Janus absorbers by electrospinning for stable and efficient solar desalination. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702884 (2018).

- Kuang, Y. et al. A high-performance self-regenerating solar evaporator for continuous water desalination. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900498 (2019).

- Zeng, J., Wang, Q., Shi, Y., Liu, P. & Chen, R. Osmotic pumping and salt rejection by polyelectrolyte hydrogel for continuous solar desalination. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1900552 (2019).

- Zhao, W. et al. Hierarchically designed salt-resistant solar evaporator based on donnan effect for stable and high-performance brine treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100025 (2021).

- Wu, L. et al. Highly efficient three-dimensional solar evaporator for high salinity desalination by localized crystallization. Nat. Commun. 11, 521 (2020).

- Zhang, Q. et al. Vertically aligned Janus MXene-based aerogels for solar desalination with high efficiency and salt resistance. ACS Nano 13, 13196-13207 (2019).

- Chen, X. et al. Sustainable off-grid desalination of hypersaline waters using Janus wood evaporators. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5347-5357 (2021).

- Yang, Y. et al. A general salt-resistant hydrophilic/hydrophobic nanoporous double layer design for efficient and stable solar water evaporation distillation. Mater. Horiz. 5, 1143-1150 (2018).

- Yousif, E. & Haddad, R. Photodegradation and photostabilization of polymers, especially polystyrene: review. SpringerPlus 2, 398 (2013).

- Asmatulu, R., Mahmud, G. A., Hille, C. & Misak, H. E. Effects of UV degradation on surface hydrophobicity, crack, and thickness of MWCNT-based nanocomposite coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 72, 553-561 (2011).

- He, S. et al. Nature-inspired salt resistant bimodal porous solar evaporator for efficient and stable water desalination. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1558-1567 (2019).

- Liu, X. et al. 3D hydrogel evaporator with vertical radiant vessels breaking the trade-off between thermal localization and salt resistance for solar desalination of high-salinity. Adv. Mater. 34, e2203137 (2022).

- Yang, Y. et al. A diode-like scalable asymmetric solar evaporator with ultra-high salt resistance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2210972 (2023).

- Yang, K., Pan, T., Dang, S., Gan, Q. & Han, Y. Three-dimensional open architecture enabling salt-rejection solar evaporators with boosted water production efficiency. Nat. Commun. 13, 6653 (2022).

- Zhang, L. et al. Highly efficient and salt rejecting solar evaporation via a wick-free confined water layer. Nat. Commun. 13, 849 (2022).

- Zhang, C. et al. Designing a next generation solar crystallizer for real seawater brine treatment with zero liquid discharge. Nat. Commun. 12, 998 (2021).

- Cooper, T. A. et al. Contactless steam generation and superheating under one sun illumination. Nat. Commun. 9, 5086 (2018).

- Banerjee, I., Pangule, R. C. & Kane, R. S. Antifouling coatings: recent developments in the design of surfaces that prevent fouling by proteins, bacteria, and marine organisms. Adv. Mater. 23, 690-718 (2011).

- Zeng, X., McCarthy, D. T., Deletic, A. & Zhang, X. Silver/reduced graphene oxide hydrogel as novel bactericidal filter for point-of-use water disinfection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 4344-4351 (2015).

Review article

- Xu, Y. et al. A simple and universal strategy to deposit Ag/polypyrrole on various substrates for enhanced interfacial solar evaporation and antibacterial activity. Chem. Eng. J. 384, 123379 (2020).

- Li, Y. et al. Composite hydrogel-based photothermal self-pumping system with salt and bacteria resistance for super-efficient solar-powered water evaporation. Desalination 515, 115192 (2021).

- Rasool, K. et al. Efficient antibacterial membrane based on two-dimensional

(MXene) nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 7, 1598 (2017). - Zha, X. J. et al. Flexible anti-biofouling mxene/cellulose fibrous membrane for sustainable solar-driven water purification. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 11, 36589-36597 (2019).

- Guo, Y., Dundas, C. M., Zhou, X., Johnston, K. P. & Yu, G. Molecular engineering of hydrogels for rapid water disinfection and sustainable solar vapor generation. Adv. Mater. 33, e2102994 (2021).

- Li, Y. et al. Manipulating light trapping and water vaporization enthalpy via porous hybrid nanohydrogels for enhanced solar-driven interfacial water evaporation with antibacterial ability. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 26769-26775 (2019).

- Saleque, A. M., Ivan, M. N. A. S., Ahmed, S. & Tsang, Y. H. Light-trapping texture bio-hydrogel with anti-biofouling and antibacterial properties for efficient solar desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 458, 141430 (2023).

- Cui, L. et al. Solar-driven interfacial water evaporation for wastewater purification: Recent advances and challenges. Chem. Eng. J. 477, 147158 (2023).

- Zou, Y. et al. A mussel-inspired polydopamine-filled cellulose aerogel for solar-enabled water remediation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 13, 7617-7624 (2021).

- Abelson, P. H. Groundwater contamination. Science 224, 673-673 (1984).

- Ma, J., Xu, Y., Sun, F., Chen, X. & Wang, W. Perspective for removing volatile organic compounds during solar-driven water evaporation toward water production. EcoMat 3, e12147 (2021).

- Zhang, P. et al. Super water-extracting gels for solar-powered volatile organic compounds management in the hydrological cycle. Adv. Mater. 34, e2110548 (2022).

- Deng, J. et al. Self-suspended photothermal microreactor for water desalination and integrated volatile organic compound removal. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 12, 51537-51545 (2020).

- Song, C. et al. Volatile-organic-compound-intercepting solar distillation enabled by a photothermal/photocatalytic nanofibrous membrane with dual-scale pores. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 9025-9033 (2020).

- Zhang, B., Wong, P. W. & An, A. K. Photothermally enabled MXene hydrogel membrane with integrated solar-driven evaporation and photodegradation for efficient water purification. Chem. Eng. J. 430, 133054 (2022).

- Yang, Y. et al. Industrially scalable and refreshable photocatalytic foam. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 7, 2300041 (2023).

- Yan, S. et al. Integrated reduced graphene oxide/polypyrrole hybrid aerogels for simultaneous photocatalytic decontamination and water evaporation. Appl. Catal. B 301, 120820 (2022).

- Zhao, W. et al. A critical review on surface-modified nano-catalyst application for the photocatalytic degradation of volatile organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Nano 9, 61-80 (2022).

- Peng, Y. et al. Metal-organic framework composite photothermal membrane for removal of high-concentration volatile organic compounds from water via molecular sieving. ACS Nano 16, 8329-8337 (2022).

- Qi, D. et al. Polymeric membranes with selective solution-diffusion for intercepting volatile organic compounds during solar-driven water remediation. Adv. Mater. 32, e2004401 (2020).

- Song, Y. et al. Solar transpiration-powered lithium extraction and storage. Science 385, 1444-1449 (2024).

- Liang, H., Mu, Y., Yin, M., He, P.-P. & Guo, W. Solar-powered simultaneous highly efficient seawater desalination and highly specific target extraction with smart DNA hydrogels. Sci. Adv. 9, eadj1677 (2023).

- Pornrungroj, C. et al. Hybrid photothermal-photocatalyst sheets for solar-driven overall water splitting coupled to water purification. Nat. Water 1, 952-960 (2023).

- Lee, W. H. et al. Floatable photocatalytic hydrogel nanocomposites for large-scale solar hydrogen production. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 754-762 (2023).

- Guo, S., Li, X., Li, J. & Wei, B. Boosting photocatalytic hydrogen production from water by photothermally induced biphase systems. Nat. Commun. 12, 1343 (2021).

- Gao, M., Peh, C. K., Zhu, L., Yilmaz, G. & Ho, G. W. Photothermal catalytic gel featuring spectral and thermal management for parallel freshwater and hydrogen production. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2000925 (2020).

- Zhou, Y. et al. Controlled heterogeneous water distribution and evaporation towards enhanced photothermal water-electricity-hydrogen production. Nano Energy 77, 105102 (2020).

- Vera, M. L., Torres, W. R., Galli, C. I., Chagnes, A. & Flexer, V. Environmental impact of direct lithium extraction from brines. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 149-165 (2023).

- Zhang, S. et al. Solar-driven membrane separation for direct lithium extraction from artificial salt-lake brine. Nat. Commun. 15, 238 (2024).

- Wang, Y., Lee, J., Werber, J. R. & Elimelech, M. Capillary-driven desalination in a synthetic mangrove. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax5253 (2020).

- Cornish, G. A. et al. Transpiration-powered desalination water bottle. Soft Matter 18, 1287-1293 (2022).

- Chen, X. et al. Solar-driven lithium extraction by a floating felt. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2316178 (2024).

- Xia, Q. et al. Solar-enhanced lithium extraction with self-sustaining water recycling from salt-lake brines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2400159121 (2024).

- Wang, N. et al. Accelerated chemical thermodynamics of uranium extraction from seawater by plant-mimetic transpiration. Adv. Sci. 8, 2102250 (2021).

- Li, T. et al. Photothermal-enhanced uranium extraction from seawater: a biomass solar thermal collector with 3D ion-transport networks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212819 (2023).

- Cui, W.-R., Zhang, C.-R., Liang, R.-P., Liu, J. & Qiu, J.-D. Covalent organic framework sponges for efficient solar desalination and selective uranium recovery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 13, 31561-31568 (2021).

- Shan, H. et al. Hygroscopic salt-embedded composite materials for sorption-based atmospheric water harvesting. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 699-721 (2024).

- Chen, X. et al. Spatially separated crystallization for selective lithium extraction from saline water. Nat. Water 1, 808-817(2023).

- Finnerty, C. T. K. et al. Interfacial solar evaporation by a 3D graphene oxide stalk for highly concentrated brine treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15435-15445 (2021).

- Spurgeon, J. M. & Lewis, N. S. Proton exchange membrane electrolysis sustained by water vapor. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 2993-2998 (2011).

- Zhan, X. et al. Efficient CoO nanowire array photocatalysts for

generation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 153903 (2014). - Lu, Y. et al. Solar-driven interfacial evaporation accelerated electrocatalytic water splitting on 2D perovskite oxide/mxene heterostructure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2215061 (2023).

- Burn, S. et al. Desalination techniques-a review of the opportunities for desalination in agriculture. Desalination 364, 2-16 (2015).

- Martínez-Alvarez, V., Martin-Gorriz, B. & Soto-García, M. Seawater desalination for crop irrigation-a review of current experiences and revealed key issues. Desalination 381, 58-70 (2016).

- Sharon, H. & Reddy, K. S. A review of solar energy driven desalination technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 41, 1080-1118 (2015).

- Dsilva Winfred Rufuss, D., Iniyan, S., Suganthi, L. & Davies, P. A. Solar stills: a comprehensive review of designs, performance and material advances. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 63, 464-496 (2016).

- Dsilva Winfred Rufuss, D., Raj Kumar, V., Suganthi, L., Iniyan, S. & Davies, P. A. Techno-economic analysis of solar stills using integrated fuzzy analytical hierarchy process and data envelopment analysis. Sol. Energy 159, 820-833 (2018).

- Wu, P., Wu, X., Wang, Y., Xu, H. & Owens, G. Towards sustainable saline agriculture: interfacial solar evaporation for simultaneous seawater desalination and saline soil remediation. Water Res. 212, 118099 (2022).

- Wang, Q., Zhu, Z., Wu, G., Zhang, X. & Zheng, H. Energy analysis and experimental verification of a solar freshwater self-produced ecological film floating on the sea. Appl. Energy 224, 510-526 (2018).

- Wang, L., He, Q., Yu, H., Jin, R. & Zheng, H. A floating planting system based on concentrated solar multi-stage rising film distillation process. Energy Conv. Manag. 254, 115227 (2022).

- Zou, M. et al. 3D printing a biomimetic bridge-arch solar evaporator for eliminating salt accumulation with desalination and agricultural applications. Adv. Mater. 33, 2102443 (2021).

- Chang, S.-Y., Cheng, P., Li, G. & Yang, Y. Transparent polymer photovoltaics for solar energy harvesting and beyond. Joule 2, 1039-1054 (2018).

- Shen, L. et al. Increasing greenhouse production by spectral-shifting and unidirectional light-extracting photonics. Nat. Food 2, 434-441(2021).

- Wu, P. et al. An interfacial solar evaporation enabled autonomous double-layered vertical floating solar sea farm. Chem. Eng. J. 473, 145452 (2023).

- Wang, M. et al. An integrated system with functions of solar desalination, power generation and crop irrigation. Nat. Water 1, 716-724 (2023).

- Jacobson, M. Z. Review of solutions to global warming, air pollution, and energy security. Energy Environ. Sci. 2, 148-173 (2009).

- Biswas, K. et al. High-performance bulk thermoelectrics with all-scale hierarchical architectures. Nature 489, 414-418 (2012).

- Fan, F.-R., Tian, Z.-Q. & Lin Wang, Z. Flexible triboelectric generator. Nano Energy 1, 328-334 (2012).

- Storer, D. P. et al. Graphene and rice-straw-fiber-based 3D photothermal aerogels for highly efficient solar evaporation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 12, 15279-15287(2020).

- Fang, Q. et al. Full biomass-derived solar stills for robust and stable evaporation to collect clean water from various water-bearing media. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 11, 10672-10679 (2019).

- He, J. et al. A 3D corncob-based interfacial solar evaporator enhanced by environment energy with salt-rejecting and anti-corrosion for seawater distillation. Sol. Energy 252, 39-49 (2023).

- Uekert, T., Pichler, C. M., Schubert, T. & Reisner, E. Solar-driven reforming of solid waste for a sustainable future. Nat. Sustain. 4, 383-391 (2021).

- Li, J. et al. Photothermal aerogel beads based on polysaccharides: controlled fabrication and hybrid applications in solar-powered interfacial evaporation, water remediation, and soil enrichment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 14, 50266-50279 (2022).

- Chen, Y. et al. Marangoni-driven biomimetic salt secretion evaporator. Desalination 548, 116287 (2023).

Review article

- Wu, P., Wu, X., Xu, H. & Owens, G. Interfacial solar evaporation driven lead removal from a contaminated soil. EcoMat 3, e12140 (2021).

- Wu, P. et al. Boosting extraction of Pb in contaminated soil via interfacial solar evaporation of multifunctional sponge. Green Energy Environ. 8, 1459-1468 (2023).

- Xu, Y. et al. Artificial phytoremediation solar interface evaporator for efficient heavy metal salt separation and saline soil remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 113114 (2024).

- Wu, P., Wu, X., Wang, Y., Xu, H. & Owens, G. A biomimetic interfacial solar evaporator for heavy metal soil remediation. Chem. Eng. J. 435, 134793 (2022).

- Liu, K. et al. Cotton-based bionic tree-shaped photothermal evaporator for extraction of heavy metals from river sediment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 111063 (2023).

- Liu, K. et al. Interfacial solar evaporation driven Cd removal from contaminated sediments. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 112920 (2024).

- Jelusic, M., Vodnik, D., Macek, I. & Lestan, D. Effect of EDTA washing of metal polluted garden soils. Part II: Can remediated soil be used as a plant substrate? Sci. Total. Environ. 475, 142-152 (2014).

- Yang, P. et al. Solar-driven simultaneous steam production and electricity generation from salinity. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 1923-1927 (2017).

- He, N. et al. Ionization engineering of hydrogels enables highly efficient salt-impeded solar evaporation and night-time electricity harvesting. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 8 (2023).

- Wani, T. A., Kaith, P., Garg, P. & Bera, A. Microfluidic salinity gradient-induced all-day electricity production in solar steam generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 14, 35802-35808 (2022).

- Gao, J. et al. High-performance ionic diode membrane for salinity gradient power generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12265-12272 (2014).

- Chen, C. & Hu, L. Nanoscale ion regulation in wood-based structures and their device applications. Adv. Mater. 33, 2002890 (2021).

- Wu, Q.-Y. et al. Salinity-gradient power generation with ionized wood membranes. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1902590 (2020).

- Zhu, L., Ding, T., Gao, M., Peh, C. K. N. & Ho, G. W. Shape conformal and thermal insulative organic solar absorber sponge for photothermal water evaporation and thermoelectric power generation. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1900250 (2019).

-