DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68906-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39085577

تاريخ النشر: 2024-07-31

تنبؤ المناخ الشهري باستخدام الشبكة العصبية التلافيفية العميقة وذاكرة المدى القصير والطويل

الملخص

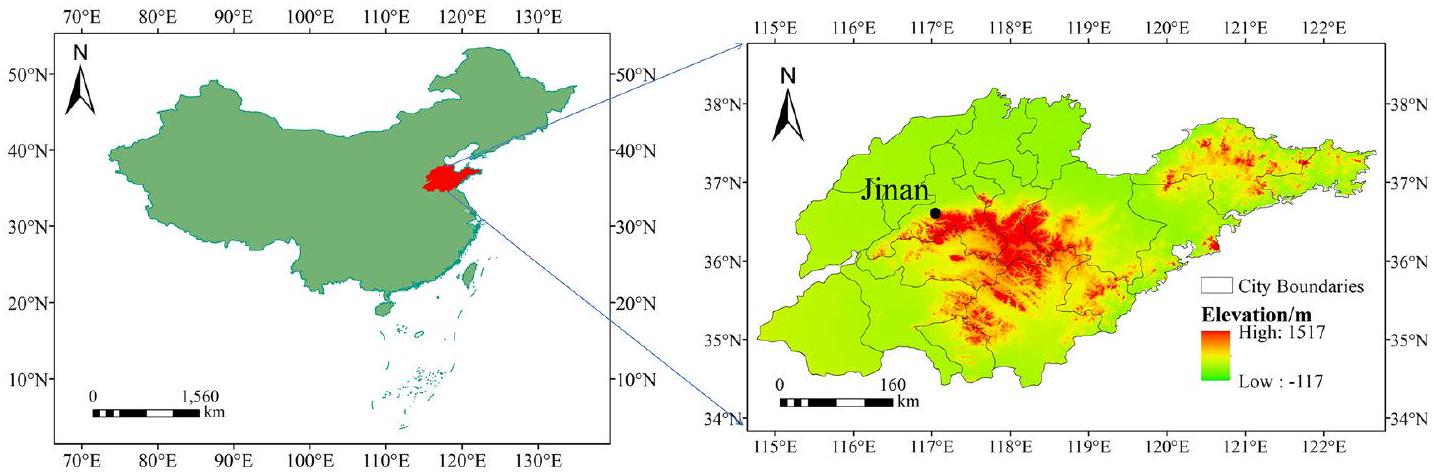

تؤثر تغيرات المناخ على نمو النباتات وإنتاج الغذاء والأنظمة البيئية والتنمية الاجتماعية والاقتصادية المستدامة وصحة الإنسان. تم اقتراح نماذج الذكاء الاصطناعي المختلفة لمحاكاة معلمات المناخ في مدينة جينان في الصين، بما في ذلك الشبكة العصبية الاصطناعية (ANN) والشبكة العصبية المتكررة (RNN) والشبكة العصبية للذاكرة القصيرة والطويلة (LSTM) والشبكة العصبية التلافيفية العميقة (CNN) وCNN-LSTM. تُستخدم هذه النماذج للتنبؤ بستة عوامل مناخية على أساس شهري. تشمل بيانات المناخ لمدة 72 عامًا (من 1 يناير 1951 إلى 31 ديسمبر 2022) المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة متوسط درجة الحرارة الجوية الشهرية ودرجة الحرارة الجوية القصوى الدنيا ودرجة الحرارة الجوية القصوى العليا وهطول الأمطار ومتوسط الرطوبة النسبية وساعات الشمس. تُستخدم سلسلة زمنية من بيانات متأخرة لمدة 12 شهرًا كإشارات إدخال للنماذج. يتم فحص كفاءة النماذج المقترحة باستخدام معايير تقييم متنوعة وهي متوسط الخطأ المطلق وجذر متوسط مربع الخطأ (RMSE) ومعامل الارتباط (R). تشير نتائج النمذجة إلى أن نموذج CNN-LSTM الهجين المقترح يحقق دقة أكبر من النماذج المقارنة الأخرى. يقلل نموذج CNN-LSTM الهجين بشكل كبير من خطأ التنبؤ مقارنة بالنماذج للخطوة الزمنية لشهر واحد. على سبيل المثال، فإن قيم RMSE لنماذج ANN وRNN وLSTM وCNN وCNN-LSTM لدرجة الحرارة الجوية الشهرية المتوسطة في مرحلة التنبؤ هي

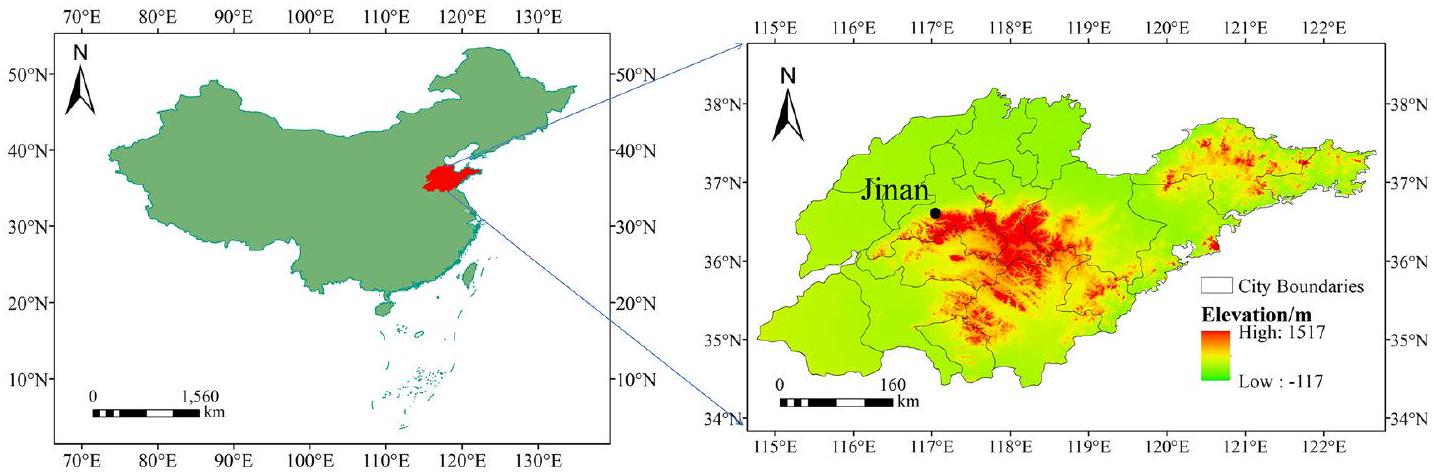

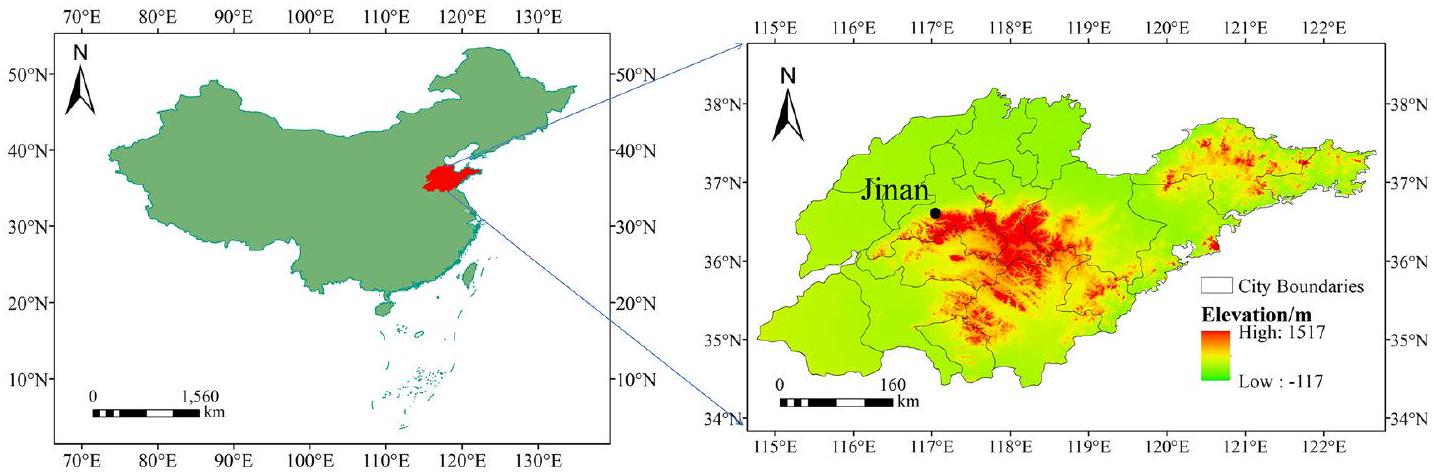

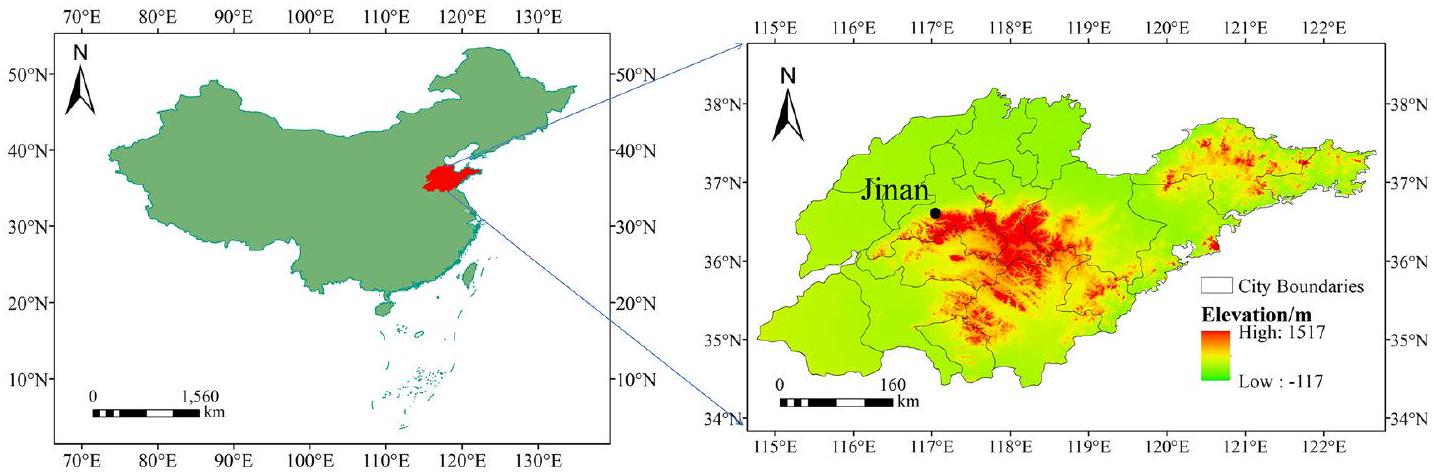

منطقة الدراسة والبيانات

section*{منطقة الدراسة}

البيانات وتوحيد البيانات

المنهجية

الشبكة العصبية الاصطناعية (ANN)

الشبكة العصبية التكرارية (RNN)

وبالمثل، يتم تعيين معلمات النموذج. المتغيرات المدخلة هي 12، المتغير الناتج هو 1، وعدد خلايا الطبقة المخفية هو 8. دوال التنشيط هي tansig للطبقة المخفية و purelin لطبقة الإخراج. وظيفة التدريب هي trainlm. وظيفة التعلم هي learngdm. وظيفة الأداء mse هي

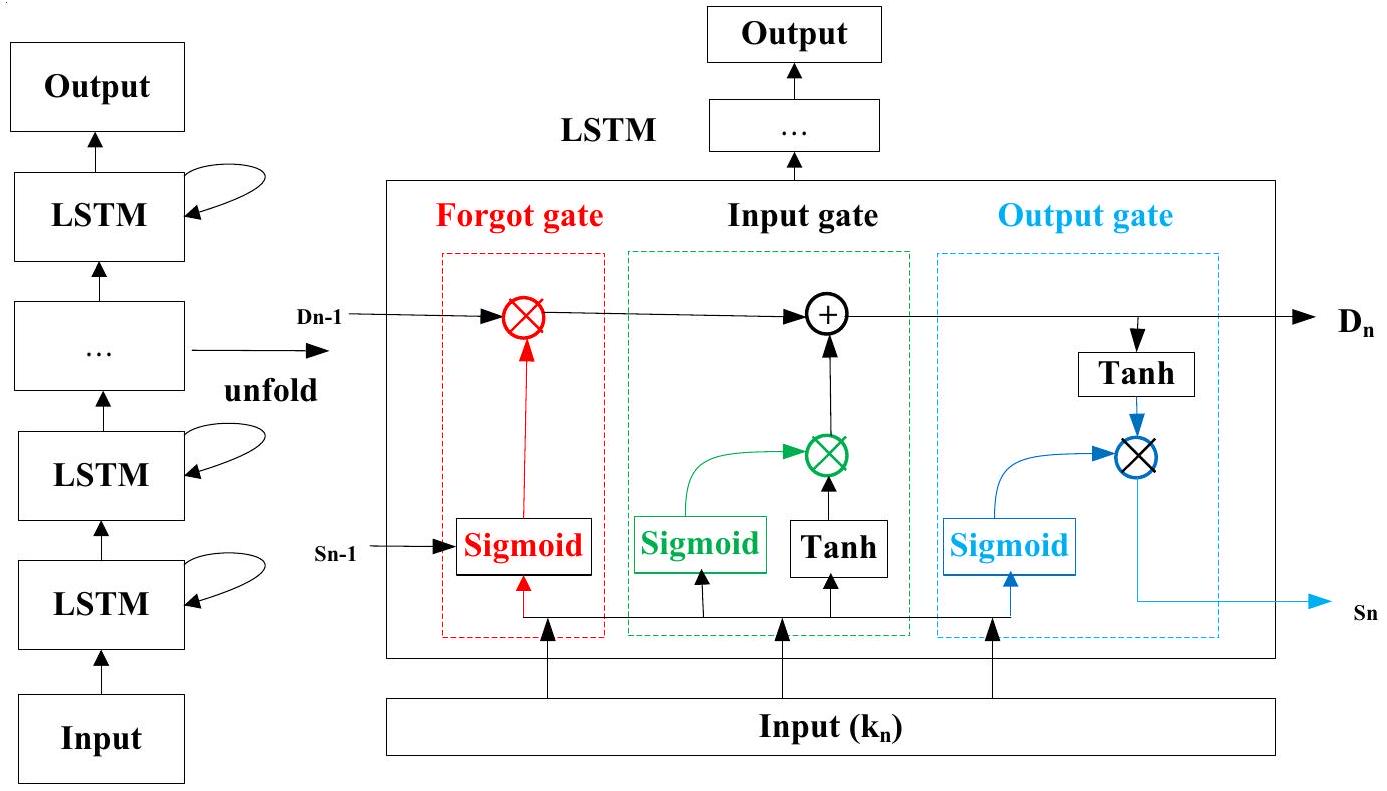

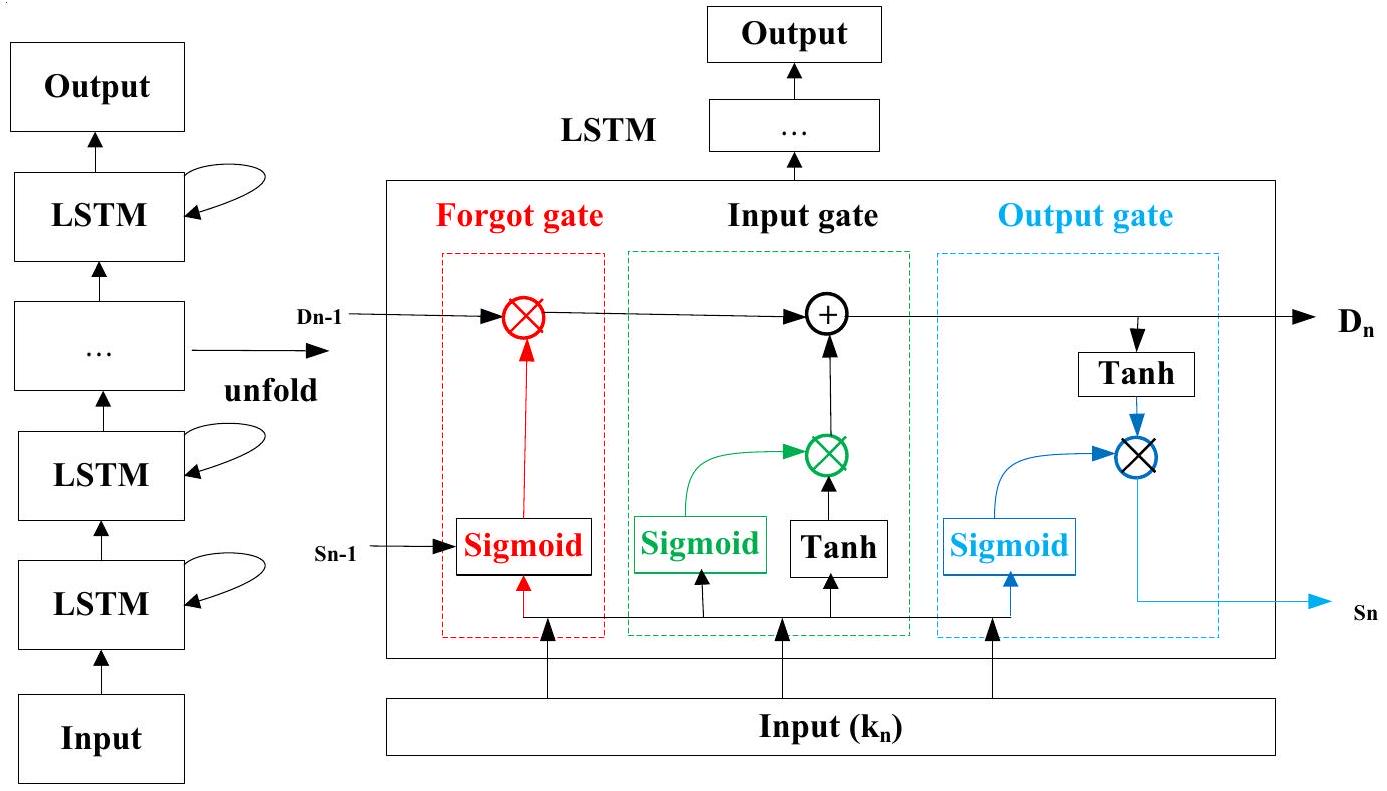

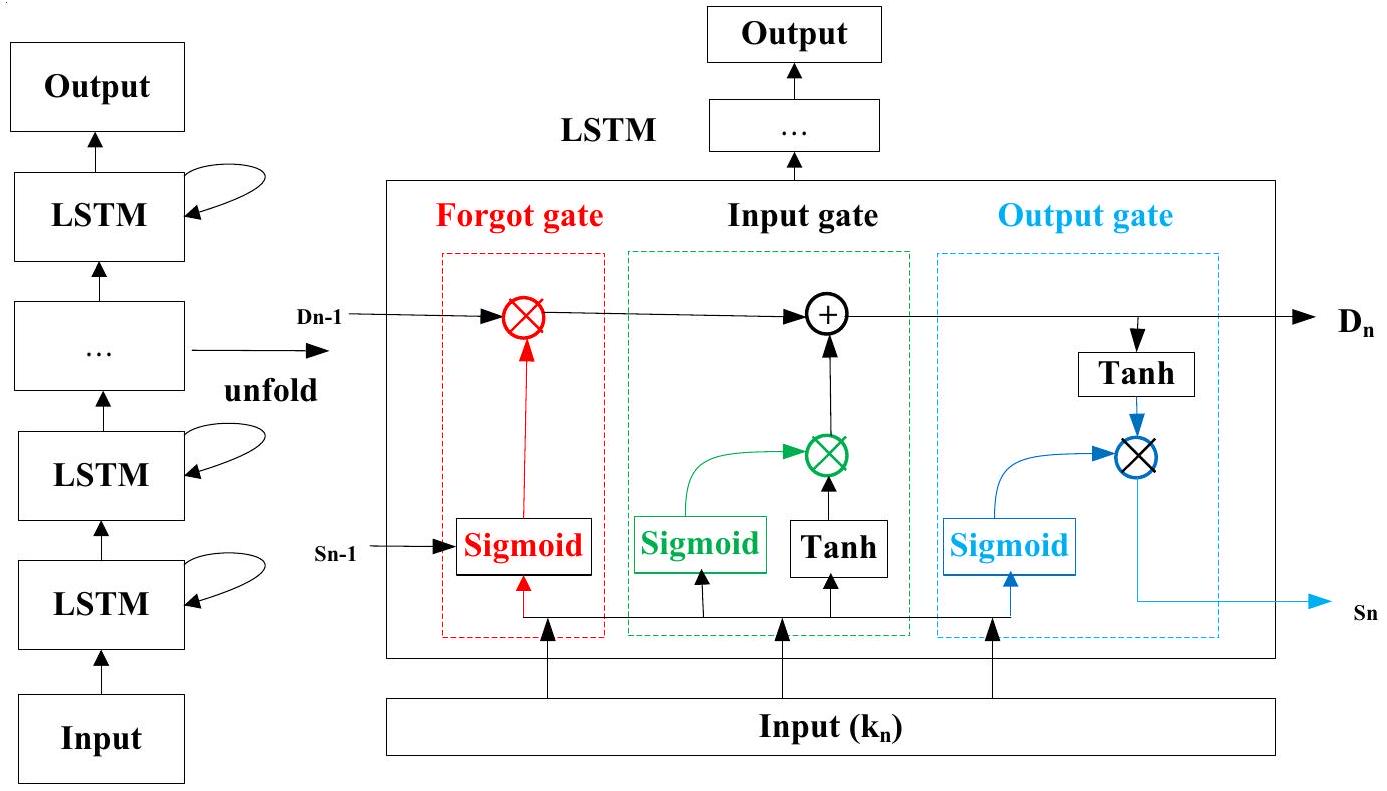

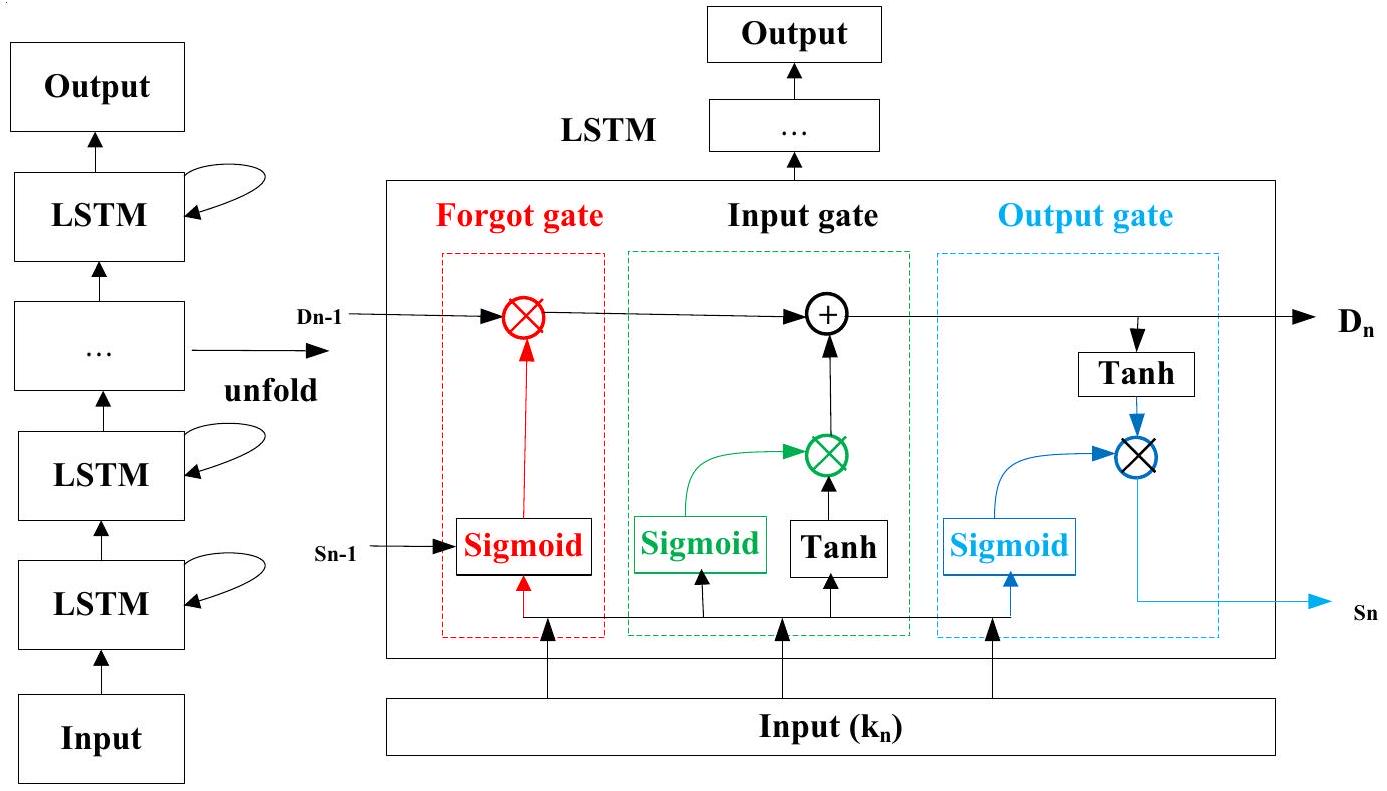

شبكة الذاكرة طويلة وقصيرة المدى (LSTM)

وبالمثل، يتم تعيين المعلمات الفائقة للنموذج. حجم المدخلات هو 12، وعدد المخرجات هو 1، وعدد الوحدات المخفية هو 100. دوال التنشيط هي tanh و sigmoid. يتم استخدام محسن آدم ومعدل التعلم محدد إلى 0.001. الهدف هو

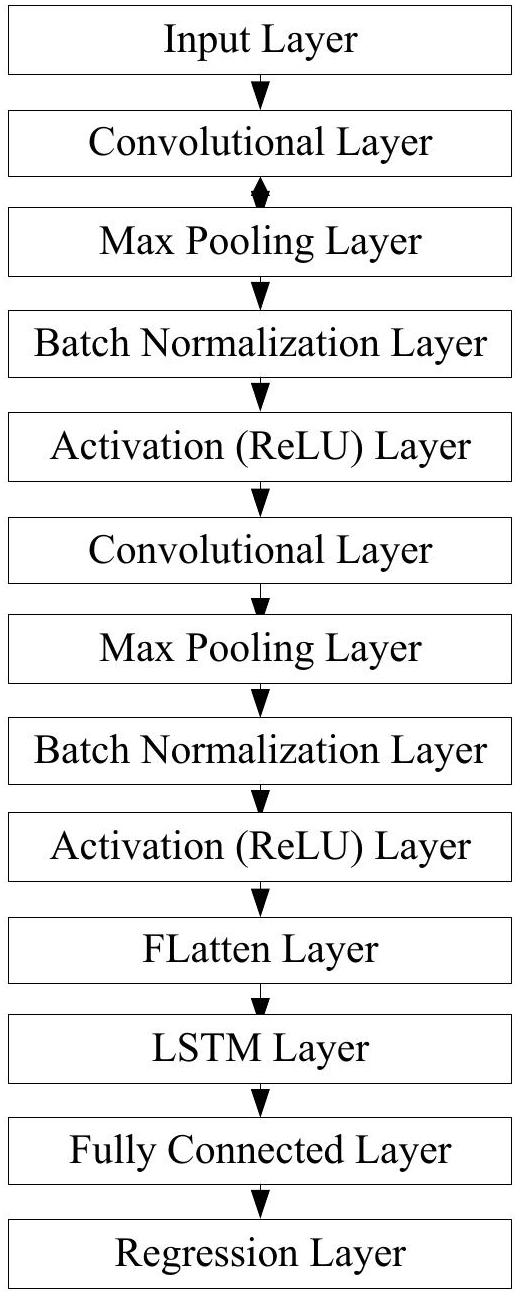

الشبكة العصبية التلافيفية (CNN)

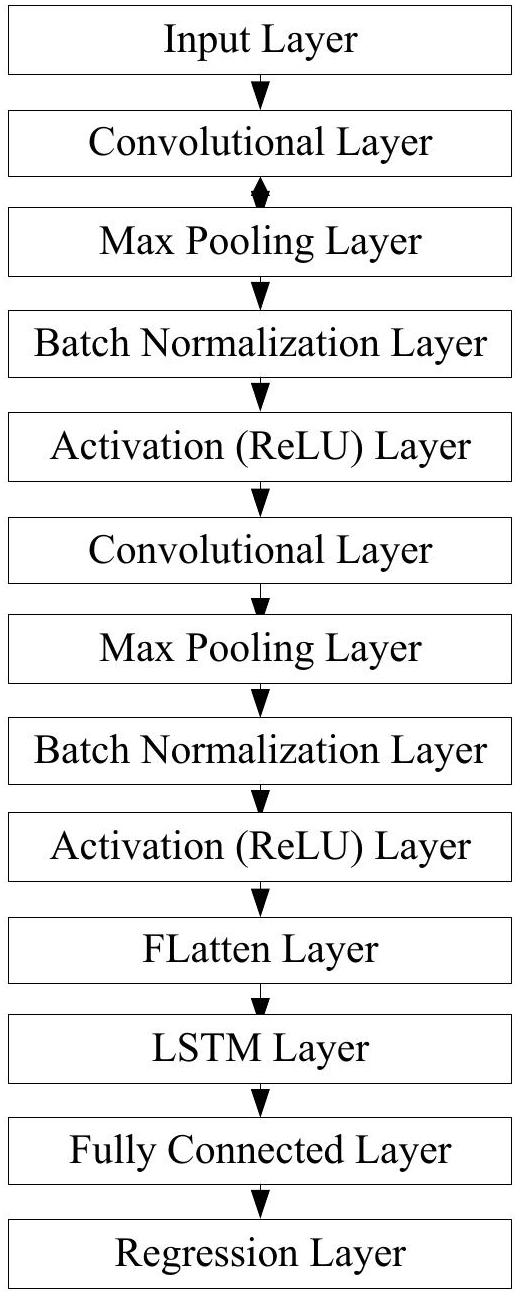

CNN-LSTM

تجربة

التحقق المتقاطع

معايير التقييم

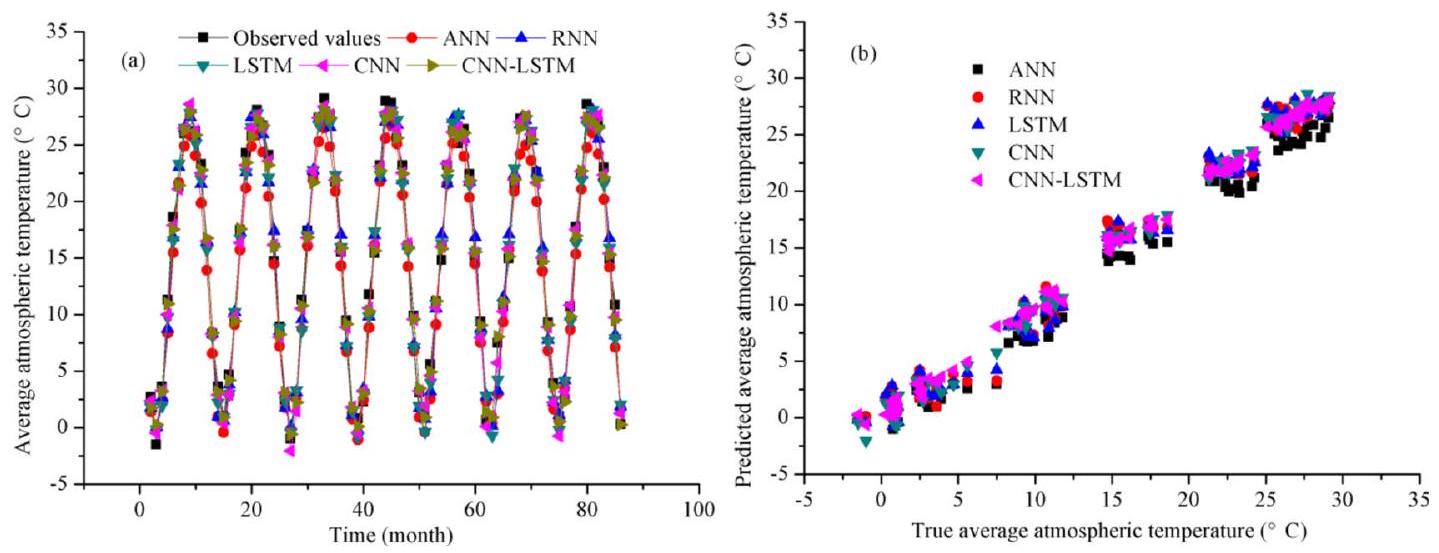

محاكاة متوسط درجة حرارة الغلاف الجوي الشهري

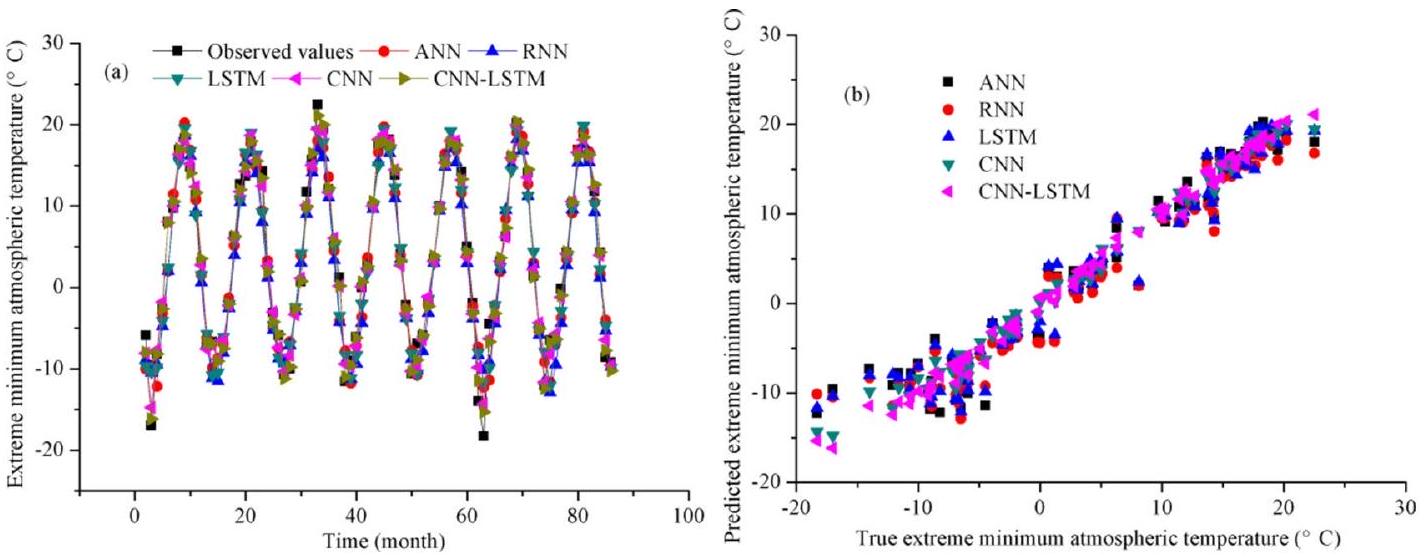

مقارنة بين درجات الحرارة الجوية القصوى الدنيا الشهرية الملاحظة والمحاكاة

| وظائف التدريب | ر | جذر متوسط مربع الخطأ (RMSE)

|

ماي

|

||||||

| تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | |

| ترينبر | 0.9894 | 0.9870 | 0.9907 | 1.8199 | 1.9923 | 2.0669 | 1.4787 | 1.6352 | 1.8042 |

| تدريب | 0.9891 | 0.9865 | 0.9903 | 1.8280 | 1.9947 | ٢.٢٠٥٥ | 1.5286 | 1.6417 | 1.8223 |

| تراينغديكس | 0.9848 | 0.9831 | 0.9865 | ٢.٥٨٦٥ | ٢.٦٠٣٢ | ٢.٦٢٣٢ | 2.0750 | 2.1694 | ٢.٢٨٨٤ |

| تدريب | 0.9843 | 0.9829 | 0.9863 | 3.3718 | 3.3298 | 3.2961 | 2.7721 | ٢.٨٣٣٢ | 2.8319 |

| ترينغدم | 0.9869 | 0.9845 | 0.9875 | ٢.٥٣٣٥ | ٢.٥٧٠١ | ٢.٥٣٩٥ | ٢.٠٥٠٩ | ٢.١٤٥٤ | 2.1707 |

| ترينغدا | 0.9857 | 0.9839 | 0.9867 | ٢.٢٢٧٠ | 2.3107 | ٢.٤٩١٢ | 1.8536 | 1.9816 | 2.1897 |

| تدريب | 0.9871 | 0.9856 | 0.9890 | 1.8872 | 1.9955 | ٢.٤٠٧١ | 1.6493 | 1.6761 | 1.8887 |

| ترين سي جي بي | 0.9888 | 0.9853 | 0.9804 | 1.8347 | 1.9958 | ٢.٥٢٥٥ | 1.6806 | 1.6718 | 1.8886 |

| تدريب | 0.9887 | 0.9857 | 0.9802 | 1.8494 | 1.9955 | ٢.٤١٦٦ | 1.6243 | 1.6572 | 1.8801 |

| ترين سي جي بي | 0.9797 | 0.9777 | 0.9808 | 2.1680 | ٢.١٥٧٧ | 2.9158 | 1.7103 | 1.7804 | 1.8576 |

| تدريب | 0.9876 | 0.9852 | 0.9802 | 1.8518 | 1.9958 | 2.4130 | 1.6286 | 1.6853 | 1.8755 |

| تدريب بي إف جي | 0.9878 | 0.9853 | 0.9880 | 1.8462 | 1.9946 | ٢.٤٠٨٦ | 1.6244 | 1.6922 | 1.8613 |

| ترينوس | 0.9880 | 0.9854 | 0.9889 | 1.8350 | 1.9957 | ٢.٥٣٦٦ | 1.6653 | 1.6671 | 1.8932 |

| دوال النقل | ر | جذر متوسط مربع الخطأ (RMSE)

|

ماي

|

||||||

| تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | |

| تي-بيو | 0.9889 | 0.9859 | 0.9904 | 1.8382 | 1.9949 | ٢.١٣٧٣ | 1.5046 | 1.6413 | 1.8125 |

| تي-أل | 0.9879 | 0.9848 | 0.9902 | 1.8355 | 1.9950 | ٢.٢٩١٠ | 1.5057 | 1.6517 | 1.8210 |

| تي-تي | 0.9869 | 0.9839 | 0.9901 | 1.8351 | 1.9959 | ٢.٢٨٧٣ | 1.5060 | 1.6516 | 1.8193 |

| L-PU | 0.9894 | 0.9870 | 0.9907 | 1.8199 | 1.9923 | 2.0669 | 1.4787 | 1.6352 | 1.8042 |

| ل-ت | 0.9859 | 0.9829 | 0.9898 | 1.8353 | 1.9949 | ٢.٢٨٧٣ | 1.5056 | 1.6416 | 1.8142 |

| ل-ل | 0.9849 | 0.9818 | 0.9903 | 1.8354 | 1.9950 | 2.2829 | 1.5056 | 1.6621 | 1.8309 |

| بي يو – تي | 0.9878 | 0.9827 | 0.9883 | 1.8575 | 1.9962 | ٢.٥٧٧١ | 1.5228 | 1.6723 | 1.8228 |

| PU-L | 0.9877 | 0.9855 | 0.9873 | 1.8780 | 1.9986 | ٢.٨٣٣٩ | 1.5411 | 1.6646 | 1.8557 |

| بيو-بيو | 0.9886 | 0.9856 | 0.9886 | 1.8524 | 1.9968 | ٢.٥٠٢٨ | 1.5191 | 1.6829 | 1.8258 |

| تي-بو | 0.9839 | 0.9828 | 0.9902 | 1.8373 | 1.9951 | ٢.٢٩٣٤ | 1.5070 | 1.6916 | 1.8309 |

| ال-بو | 0.9829 | 0.9882 | 0.9898 | 1.8356 | 1.9952 | 2.3004 | 1.5063 | 1.6519 | 1.8211 |

| بو-بو | 0.9819 | 0.9818 | 0.9892 | 1.8440 | 1.9954 | ٢.٤٥٨٤ | 1.5120 | 1.6514 | 1.8281 |

| PU-PO | 0.9886 | 0.9856 | 0.9886 | 1.8690 | 1.9985 | 2.8205 | 1.5344 | 1.6648 | 1.8544 |

| PO-L | 0.9885 | 0.9857 | 0.9868 | 1.8527 | 1.9959 | 2.6051 | 1.5186 | 1.6721 | 1.8304 |

| بو-بو | 0.9850 | 0.9848 | 0.9892 | 1.8439 | 1.9953 | ٢.٤٥٩٣ | 1.5120 | 1.6814 | 1.8209 |

| بو-تي | 0.9879 | 0.9827 | 0.9900 | 1.8396 | 1.9957 | ٢.٤٢٤٩ | 1.5081 | 1.6519 | 1.8218 |

| نماذج | ر | جذر متوسط مربع الخطأ (RMSE)

|

ماي

|

||||||

| تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | |

| إيه إن إن | 0.9894 | 0.9870 | 0.9907 | 1.8199 | 1.9923 | 2.0669 | 1.4787 | 1.6352 | 1.8042 |

| شبكة عصبية متكررة | 0.9905 | 0.9881 | 0.9895 | 1.3891 | 1.5245 | 1.4416 | 1.0836 | 1.1594 | 1.1917 |

| LSTM | 0.9906 | 0.9870 | 0.9914 | 1.3819 | 1.5965 | 1.3482 | 1.0710 | 1.2278 | 1.1485 |

| سي إن إن | 0.9968 | 0.9965 | 0.9969 | 0.8148 | 0.8249 | 0.8015 | 0.6387 | 0.6290 | 0.6680 |

| سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم | 0.9982 | 0.9982 | 0.9981 | 0.6422 | 0.6270 | 0.6292 | 0.5043 | 0.4726 | 0.5048 |

| نماذج | ر | جذر متوسط مربع الخطأ (RMSE)

|

ماي

|

||||||

| تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | |

| إعلان | 0.9790 | 0.9741 | 0.9696 | ٢.١٨٧٤ | 2.3985 | ٢.٦٢٣٨ | 1.7348 | 1.8691 | 1.9254 |

| شبكة عصبية متكررة | 0.9782 | 0.9733 | 0.9709 | 2.3703 | ٢.٥٩٥١ | 2.8135 | 1.9171 | ٢.٠٦٥١ | ٢.٢٣٧٢ |

| LSTM | 0.9806 | 0.9769 | 0.9719 | 2.1011 | ٢.٢٥٨٧ | ٢.٥٣٢٠ | 1.6674 | 1.6604 | 1.9572 |

| سي إن إن | 0.9942 | 0.9936 | 0.9942 | 1.1576 | 1.1977 | 1.1528 | 0.9102 | 0.9197 | 0.8200 |

| سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم | 0.9971 | 0.9973 | 0.9970 | 0.8350 | 0.7785 | 0.8287 | 0.6583 | 0.5809 | 0.5979 |

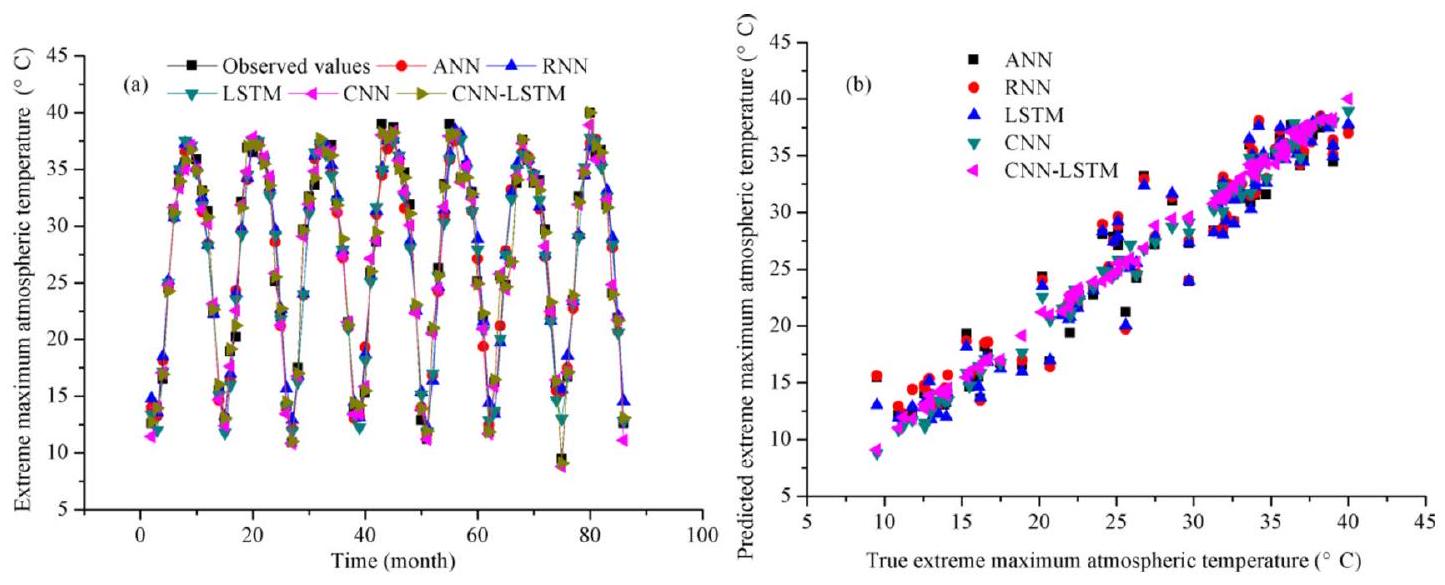

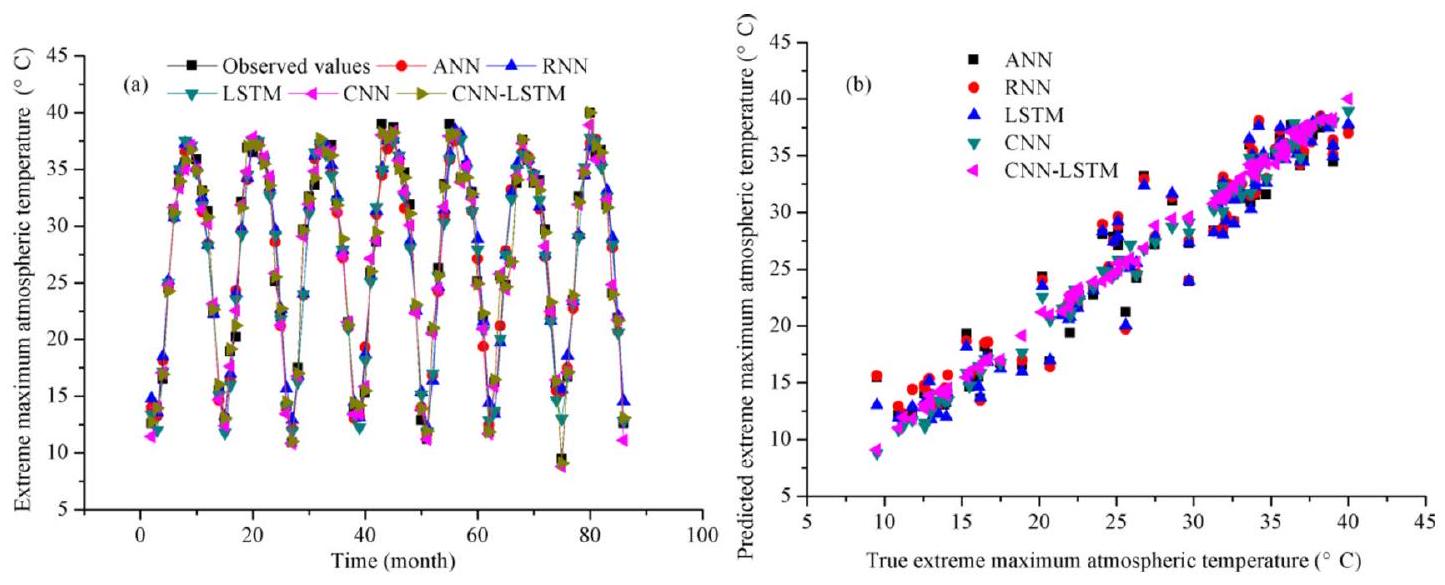

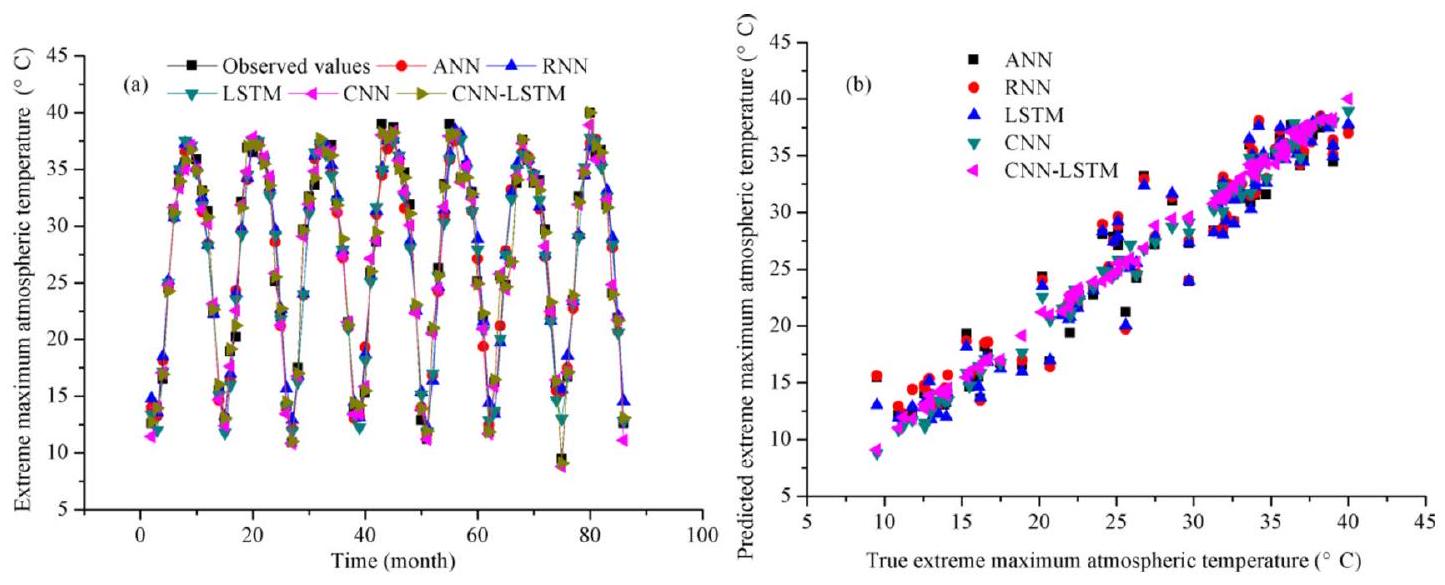

مقارنة بين درجات الحرارة القصوى الشهرية الملاحظة والمحاكاة

| نماذج | ر | جذر متوسط مربع الخطأ (RMSE)

|

ماي

|

||||||

| تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | |

| إيه إن إن | 0.9647 | 0.9621 | 0.9689 | ٢.٤٢٦٩ | ٢.٥١٣٢ | ٢.٢٣٤٥ | 1.8372 | 1.9768 | 1.6627 |

| شبكة عصبية متكررة | 0.9643 | 0.9611 | 0.9666 | ٢.٤٨٠٦ | ٢.٥٧٦٢ | 2.2979 | 1.9156 | ٢.٠٤٨١ | 1.6812 |

| LSTM | 0.9668 | 0.9591 | 0.9709 | ٢.٣٤٥٢ | 2.6012 | ٢.١٦٦٦ | 1.8163 | 2.0398 | 1.6583 |

| سي إن إن | 0.9948 | 0.9950 | 0.9962 | 0.9446 | 0.9604 | 0.8212 | 0.7346 | 0.7354 | 0.6202 |

| سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم | 0.9987 | 0.9982 | 0.9987 | 0.5339 | 0.6213 | 0.4932 | 0.4216 | 0.4848 | 0.3931 |

مقارنة بين هطول الأمطار الشهري المرصود والمحاكى

| نماذج | ر | جذر متوسط مربع الخطأ (مم) | MAE (مم) | ||||||

| تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | |

| إيه إن إن | 0.6853 | 0.6823 | 0.7092 | ٥٨٫٧٧٣٦ | ٥٦.٣٧٦٧ | 67.4976 | ٣٩.٨٨٩١ | ٣٤.٤٨٠١ | 42.5787 |

| شبكة عصبية متكررة | 0.7412 | 0.7452 | 0.7590 | 53.0472 | 50.2847 | 62.1261 | ٣٣.١٣٥٥ | ٢٩.٣٨٨٣ | ٣٧.٧٥٦٥ |

| LSTM | 0.7685 | 0.7246 | 0.7672 | 50.6978 | 52.4807 | 60.5523 | ٣٢.٥٠٧٩ | 31.4153 | ٣٦.٠٧٤٨ |

| سي إن إن | 0.9691 | 0.9629 | 0.9857 | ٢٠٫٢٤٣٢ | ٢٢.٥٧٧٧ | 16.8436 | 13.8417 | 13.8229 | 11.8683 |

| سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم | 0.9952 | 0.9930 | 0.9962 | 7.8252 | 8.8947 | 8.1762 | 6.0644 | 6.7083 | 6.7051 |

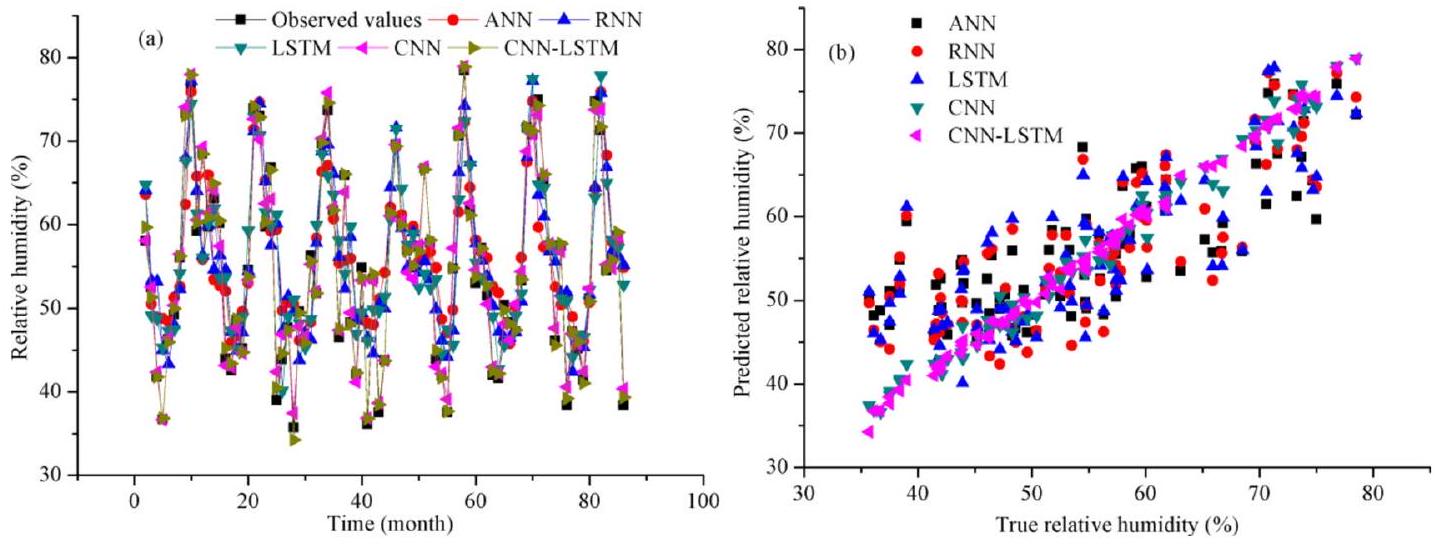

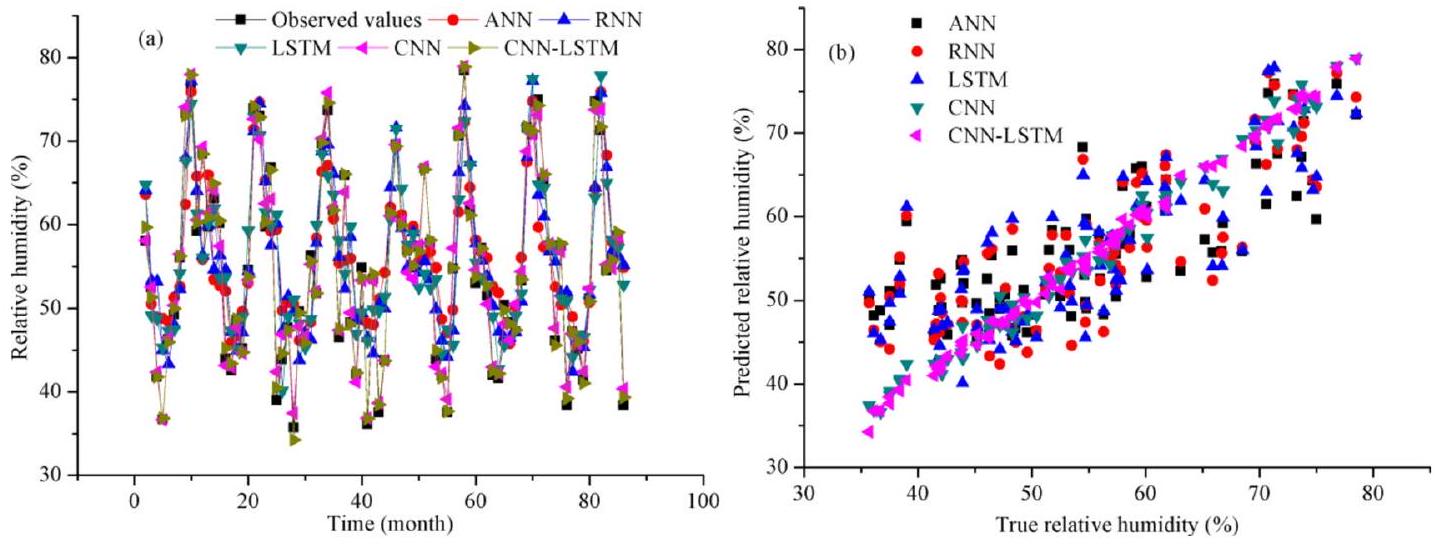

مقارنة بين الرطوبة النسبية الشهرية المتوسطة المرصودة والمحاكاة

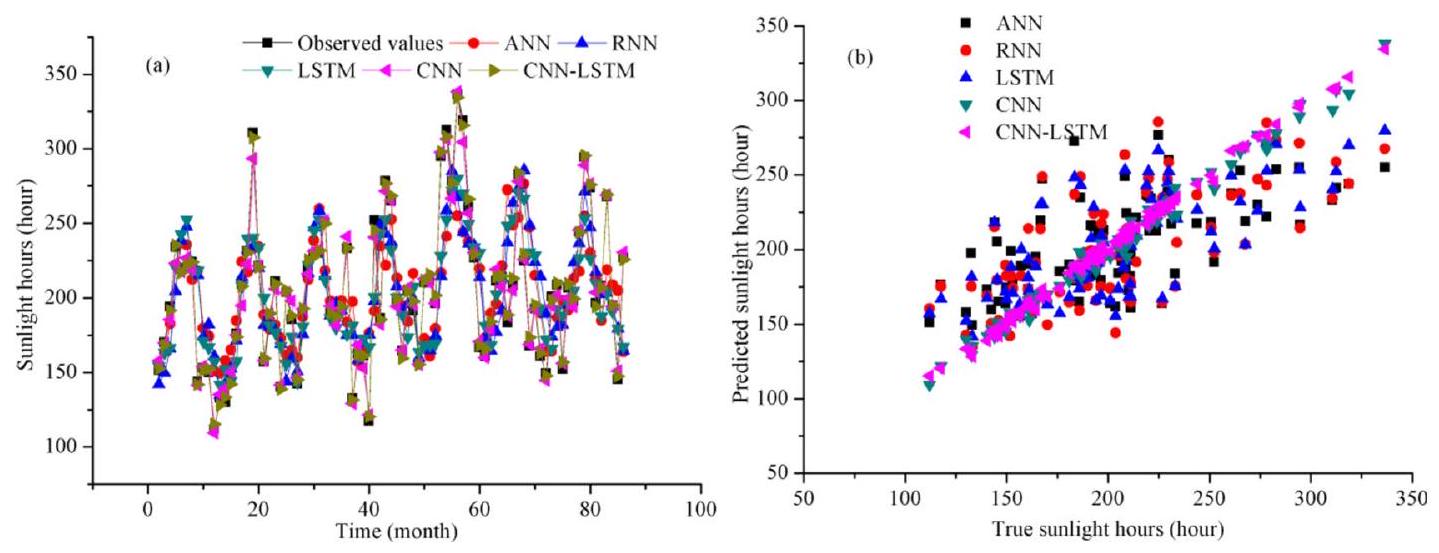

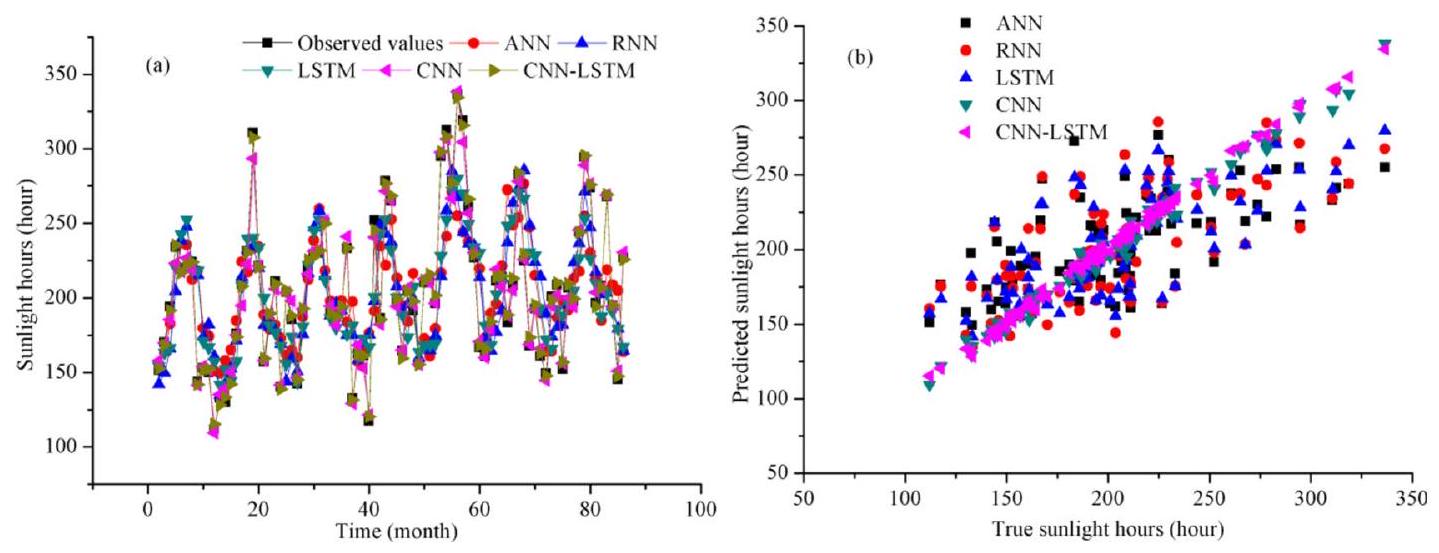

مقارنة بين ساعات ضوء الشمس الشهرية المرصودة والمحاكاة

| نماذج | ر | جذر متوسط مربع الخطأ (%) | MAE (%) | ||||||

| تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | |

| إيه إن إن | 0.7444 | 0.7452 | 0.7672 | 7.9631 | 8.6807 | 7.4171 | 6.3622 | 6.9138 | 5.9593 |

| شبكة عصبية متكررة | 0.7693 | 0.7549 | 0.7874 | 7.6236 | 8.3876 | 7.0419 | 6.0314 | 6.5664 | 5.6321 |

| LSTM | 0.7779 | 0.7862 | 0.7934 | 7.4957 | 7.8915 | 6.9580 | 6.0077 | 6.0309 | 5.4739 |

| سي إن إن | 0.9935 | 0.9943 | 0.9919 | 1.4208 | 1.4384 | 1.4513 | 1.0988 | 1.0889 | 1.1419 |

| سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم | 0.9988 | 0.9987 | 0.9984 | 0.6222 | 0.7171 | 0.6615 | 0.4991 | 0.5546 | 0.5093 |

| نماذج | ر | RMSE (ساعة) | MAE (ساعة) | ||||||

| تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | تدريب | التحقق | التنبؤ | |

| إيه إن إن | 0.7095 | 0.5295 | 0.6413 | ٣٤.٩٤٣٦ | 41.8596 | 37.4016 | ٢٧.٩٥٧٠ | 32.7740 | ٢٩.٧٧٧٨ |

| شبكة عصبية متكررة | 0.7468 | 0.6156 | 0.6752 | ٣٢.٩٧٠٤ | ٣٨.٧٣١٤ | ٣٦.١٨٩٦ | ٢٦.٧٠٩٧ | 30.6143 | ٢٨.٦٥١٩ |

| LSTM | 0.7515 | 0.5801 | 0.7192 | ٣٢.٦٥٥٠ | ٣٩.٩٨٨٥ | 33.9022 | ٢٦.٣٩٩٦ | 30.9942 | ٢٧.٠٢٦٩ |

| سي إن إن | 0.9903 | 0.9940 | 0.9939 | 7.0557 | ٥.٧٥٢٠ | 5.6467 | 5.5325 | ٤.٥٩٣٧ | ٤.٣٧٤٢ |

| سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم | 0.9984 | 0.9988 | 0.9984 | 2.9650 | ٢.٥٨٢٤ | 2.9058 | ٢.٣٤٩١ | 2.0115 | 2.3794 |

مقارنة مع أدبيات أخرى

| نماذج | إيه إن إن | شبكة عصبية متكررة | LSTM | سي إن إن | سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم |

| متوسط الوقت المنقضي | 17 | ١٨ | 19 | 40 | 89 |

الخاتمة

(2) تم مقارنة CNN-LSTM مع ANN و RNN و LSTM و CNN باستخدام نفس بيانات المناخ الشهرية. تم اشتقاق أوقات تأخر المتغيرات المدخلة من دورة بيانات المناخ الشهرية. الأداء الذي حققه نموذج CNN-LSTM أكبر من النماذج الأخرى المقارنة من الذكاء الاصطناعي (ANN و RNN و LSTM و CNN). نتائج التنبؤ لنموذج CNN-LSTM متفوقة على النماذج الأخرى من حيث القدرة على التعميم والدقة. وهذا يدل على فعالية نموذج CNN-LSTM المقترح مقارنة بالنماذج الأخرى الموجودة. وهذا يعني أنه مقارنة بالنماذج الأخرى، فإن CNN-LSTM لديه أدنى قيم RMSE و MAE وأعلى قيمة R.

(3) في مراقبة تغير المناخ، المناخ المتطرف له أهمية استثنائية، ونموذج CNN-LSTM لديه أيضًا كفاءة أعلى من النماذج الأربعة الأخرى في توقع المناخ المتطرف. تظهر الاستطلاعات أن درجة الحرارة الجوية المتطرفة المتوقعة أكثر دقة من هطول الأمطار المتوقع. نموذج CNN قريب من نموذج CNN-LSTM في بعض المعاملات الفردية ولكن الأخطاء تظهر أن CNN-LSTM لديه أداء أكثر استقرارًا. يمكن لـ CNN-LSTM التنبؤ بشكل معقول بحجم وتغيرات المناخ الشهرية، والتقاط قمم بيانات المناخ، وتلبية معايير تقييم أداء النموذج. يعد CNN-LSTM نهجًا واعدًا لمحاكاة المناخ.

القيود والاقتراحات

(2) في المستقبل، ستتم مقارنة دقة التنبؤ لـ CNN-LSTM أيضًا مع النماذج الديناميكية الحالية المعتمدة على الفيزياء. يمكن توسيع النماذج بشكل أكبر من خلال تطبيق تقنيات التحليل (WT و TVF-EMD و CEEMD) و LSTM ثنائي الاتجاه (BiLSTM) والتعلم الانتقالي و GRU ثنائي الاتجاه (BiGRU) وأخذ المكونات المتبقية من بيانات المناخ كمدخلات لتطوير النماذج. سيتم تحسين أداء نمذجة المناخ بشكل أكبر من خلال استكشاف المقاييس الزمنية المتعددة والميزات المكانية وعوامل أخرى مثل الإشعاع الشمسي ودرجة حرارة الدفيئة والتضاريس والنباتات و ظاهرة النينيو والتذبذب الجنوبي، إلخ. يمكن استخدام هذه الاستراتيجية لأي تطبيق تنبؤي لوضع خطط تشغيلية قصيرة ومتوسطة وطويلة الأجل. لذلك، يمكن الاستفادة من قوة النماذج للتنبؤ بعناصر المناخ متعددة المقاييس الزمنية. في محاكاة وتنبؤ المناخات المتطرفة المختلفة، سنقوم بدمج بيانات متعددة مثل الاستشعار عن بعد والملاحظات الأرضية لنمذجة المناخ متعددة المقاييس الزمانية والمكانية. في عملية نمذجة المناخ، سنقوم بدمج الآليات الفيزيائية في نماذج التعلم الآلي لتحسين قابلية التفسير والقدرة على التعميم للنماذج. يوفر ذلك نهجًا تكنولوجيًا جديدًا لدمج النماذج الفيزيائية التقليدية وخوارزميات الذكاء الاصطناعي المتقدمة.

توفر البيانات

تاريخ الاستلام: 27 مايو 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 29 يوليو 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 31 يوليو 2024

References

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Change in air quality during 2014-2021 in Jinan City in China and its influencing factors. Toxics 11, 210 (2023).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Long-term projection of future climate change over the twenty-first century in the Sahara region in Africa under four Shared Socio-Economic Pathways scenarios. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 22319-22329. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11356-022-23813-z (2023).

- Guo, Q. et al. Changes in air quality from the COVID to the post-COVID era in the Beijing-Tianjin-Tangshan region in China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 21, 210270. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr. 210270 (2021).

- Zhao, R. et al. Assessing resilience of sustainability to climate change in China’s cities. Sci. Total Environ. 898, 165568. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165568 (2023).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Assessing the impacts of climate variables on long-term air quality trends in Peninsular Malaysia. Sci. Total Environ. 901, 166430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166430 (2023).

- Zhou, S., Yu, B. & Zhang, Y. Global concurrent climate extremes exacerbated by anthropogenic climate change. Sci. Adv. 9, eabo1638. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo1638 (2023).

- Zurek, M., Hebinck, A. & Selomane, O. Climate change and the urgency to transform food systems. Science 376, 1416-1421. https:// doi.org/10.1126/science.abo2364 (2022).

- Klisz, M. et al. Local site conditions reduce interspecific differences in climate sensitivity between native and non-native pines. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet. 2023.109694 (2023).

- Li, X. et al. Attribution of runoff and hydrological drought changes in an ecologically vulnerable basin in semi-arid regions of China. Hydrol. Process. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp. 15003 (2023).

- Xue, B. et al. Divergent hydrological responses to forest expansion in dry and wet basins of China: Implications for future afforestation planning. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR031856. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR031856 (2022).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. The characteristics of air quality changes in Hohhot City in China and their relationship with meteorological and socio-economic factors. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 24, 230274. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr. 230274 (2024).

- Wang, Y., Hu, K., Huang, G. & Tao, W. Asymmetric impacts of El Niño and La Niña on the Pacific-North American teleconnection pattern: The role of subtropical jet stream. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114040. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac31ed (2021).

- Abbas, G. et al. Modeling the potential impact of climate change on maize-maize cropping system in semi-arid environment and designing of adaptation options. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109674 (2023).

- Mangani, R., Gunn, K. M. & Creux, N. M. Projecting the effect of climate change on planting date and cultivar choice for South African dryland maize production. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109695 (2023).

- Liang, R., Sun, Y., Qiu, S., Wang, B. & Xie, Y. Relative effects of climate, stand environment and tree characteristics on annual tree growth in subtropical Cunninghamia lanceolata forests. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 342, 109711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet. 2023.109711 (2023).

- Kumar, A., Chen, M. & Wang, W. An analysis of prediction skill of monthly mean climate variability. Clim. Dyn. 37, 1119-1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-010-0901-4 (2011).

- Chen, Y. et al. Improving the heavy rainfall forecasting using a weighted deep learning model. Front. Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1116672 (2023).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Predicting of daily PM2.5 concentration employing wavelet artificial neural networks based on meteorological elements in Shanghai, China. Toxics 11, 51 (2023).

- He, Z., Guo, Q., Wang, Z. & Li, X. Prediction of monthly PM2.5 concentration in Liaocheng in China employing artificial neural network. Atmosphere 13, 1221 (2022).

- Guo, Q. & He, Z. Prediction of the confirmed cases and deaths of global COVID-19 using artificial intelligence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 11672-11682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11930-6 (2021).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Simulating daily PM2.5 concentrations using wavelet analysis and artificial neural network with remote sensing and surface observation data. Chemosphere 340, 139886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139886 (2023).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Prediction of hourly PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations in Chongqing City in China based on artificial neural network. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 23, 220448. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr. 220448 (2023).

- Fang, S. et al. MS-Net: Multi-source spatio-temporal network for traffic flow prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 7142-7155. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2021.3067024 (2022).

- Rajasundrapandiyanleebanon, T., Kumaresan, K., Murugan, S., Subathra, M. S. P. & Sivakumar, M. Solar energy forecasting using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 30, 3059-3079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-023-09893-1 (2023).

- Han, Y. et al. Novel economy and carbon emissions prediction model of different countries or regions in the world for energy optimization using improved residual neural network. Sci. Total Environ. 860, 160410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022. 160410 (2023).

- Wang, H. et al. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature 620, 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06221-2 (2023).

- Nathvani, R. et al. Beyond here and now: Evaluating pollution estimation across space and time from street view images with deep learning. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166168 (2023).

- Faraji, M., Nadi, S., Ghaffarpasand, O., Homayoni, S. & Downey, K. An integrated 3D CNN-GRU deep learning method for shortterm prediction of PM2.5 concentration in urban environment. Sci. Total Environ. 834, 155324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv. 2022.155324 (2022).

- Hu, T. et al. Crop yield prediction via explainable AI and interpretable machine learning: Dangers of black box models for evaluating climate change impacts on crop yield. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 336, 109458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109458 (2023).

- Priyatikanto, R., Lu, Y., Dash, J. & Sheffield, J. Improving generalisability and transferability of machine-learning-based maize yield prediction model through domain adaptation. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023. 109652 (2023).

- von Bloh, M. et al. Machine learning for soybean yield forecasting in Brazil. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109670. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109670 (2023).

- Liu, N. et al. Meshless surface wind speed field reconstruction based on machine learning. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 39, 1721-1733. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-1343-8 (2022).

- Li, Y. et al. Convective storm VIL and lightning nowcasting using satellite and weather radar measurements based on multi-task learning models. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 887-899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-2082-6 (2023).

- Yang, D. et al. Predictor selection for CNN-based statistical downscaling of monthly precipitation. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1117-1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-2119-x (2023).

- Wang, T. & Huang, P. Superiority of a convolutional neural network model over dynamical models in predicting central pacific ENSO. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-023-3001-1 (2023).

- Zou, H., Wu, S. & Tian, M. Radar quantitative precipitation estimation based on the gated recurrent unit neural network and echo-top data. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1043-1057. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-2127-x (2023).

- Bi, K. et al. Accurate medium-range global weather forecasting with 3D neural networks. Nature 619, 533-538. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41586-023-06185-3 (2023).

- Zhang, Y. et al. Skilful nowcasting of extreme precipitation with NowcastNet. Nature 619, 526-532. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-023-06184-4 (2023).

- Ham, Y.-G. et al. Anthropogenic fingerprints in daily precipitation revealed by deep learning. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-023-06474-x (2023).

- Shamekh, S., Lamb, K. D., Huang, Y. & Gentine, P. Implicit learning of convective organization explains precipitation stochasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2216158120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 2216158120 (2023).

- Pinheiro Gomes, E., Progênio, M. F. & da Silva Holanda, P. Modeling with artificial neural networks to estimate daily precipitation in the Brazilian Legal Amazon. Clim. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-024-07200-7 (2024).

- Papantoniou, S. & Kolokotsa, D.-D. Prediction of outdoor air temperature using neural networks: Application in 4 European cities. Energy Build. 114, 72-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.06.054 (2016).

- Roebber, P. Toward an adaptive artificial neural network-based postprocessor. Mon. Weather Rev. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-21-0089.1 (2021).

- Chen, Y. et al. Prediction of ENSO using multivariable deep learning. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 16, 100350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. aosl.2023.100350 (2023).

- Baño-Medina, J., Manzanas, R. & Gutiérrez, J. M. Configuration and intercomparison of deep learning neural models for statistical downscaling. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 2109-2124. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-2109-2020 (2020).

- Zhong, H. et al. Prediction of instantaneous yield of bio-oil in fluidized biomass pyrolysis using long short-term memory network based on computational fluid dynamics data. J. Clean. Prod. 391, 136192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136192 (2023).

- Jiang, N., Yu, X. & Alam, M. A hybrid carbon price prediction model based-combinational estimation strategies of quantile regression and long short-term memory. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139508 (2023).

- Guo, Y. et al. Stabilization temperature prediction in carbon fiber production using empirical mode decomposition and long short-term memory network. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139345 (2023).

- Yang, C.-H., Chen, P.-H., Wu, C.-H., Yang, C.-S. & Chuang, L.-Y. Deep learning-based air pollution analysis on carbon monoxide in Taiwan. Ecol. Inform. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102477 (2024).

- Yang, X. et al. A spatio-temporal graph-guided convolutional LSTM for tropical cyclones precipitation nowcasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 124, 109003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2022.109003 (2022).

- Ham, Y.-G., Kim, J.-H. & Luo, J.-J. Deep learning for multi-year ENSO forecasts. Nature 573, 568-572. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-019-1559-7 (2019).

- Xie, W., Xu, G., Zhang, H. & Dong, C. Developing a deep learning-based storm surge forecasting model. Ocean Model. 182, 102179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocemod.2023.102179 (2023).

- Hu, W. et al. Deep learning forecast uncertainty for precipitation over the Western United States. Mon. Weather Rev. 151, 13671385. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-22-0268.1 (2023).

- Wang, C. & Li, X. A deep learning model for estimating tropical cyclone wind radius from geostationary satellite infrared imagery. Mon. Weather Rev. 151, 403-417. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-22-0166.1 (2023).

- Ling, F. et al. Multi-task machine learning improves multi-seasonal prediction of the Indian Ocean Dipole. Nat. Commun. 13, 7681. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35412-0 (2022).

- Sun, W. et al. Artificial intelligence forecasting of marine heatwaves in the south China sea using a combined U-Net and ConvLSTM system. Remote Sens. 15, 4068 (2023).

- Sun, X. et al. PN-HGNN: Precipitation nowcasting network via hypergraph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3407157 (2024).

- Harnist, B., Pulkkinen, S. & Mäkinen, T. DEUCE v1.0: A neural network for probabilistic precipitation nowcasting with aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties. Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 3839-3866. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-3839-2024 (2024).

- Beucler, T. et al. Climate-invariant machine learning. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj7250. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adj7250 (2024).

- Kontolati, K., Goswami, S., Em Karniadakis, G. & Shields, M. D. Learning nonlinear operators in latent spaces for real-time predictions of complex dynamics in physical systems. Nat. Commun. 15, 5101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49411-w (2024).

- Chen, H. et al. Visibility forecast in Jiangsu province based on the GCN-GRU model. Sci. Rep. 14, 12599. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-024-61572-8 (2024).

- Pan, S. et al. Oil well production prediction based on CNN-LSTM model with self-attention mechanism. Energy 284, 128701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.128701 (2023).

- Dehghani, A. et al. Comparative evaluation of LSTM, CNN, and ConvLSTM for hourly short-term streamflow forecasting using deep learning approaches. Ecol. Inform. 75, 102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102119 (2023).

- Boulila, W., Ghandorh, H., Khan, M. A., Ahmed, F. & Ahmad, J. A novel CNN-LSTM-based approach to predict urban expansion. Ecol. Inform. 64, 101325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101325 (2021).

- Lima, F. T. & Souza, V. M. A. A large comparison of normalization methods on time series. Big Data Res. 34, 100407. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.bdr.2023.100407 (2023).

- Liu, K. et al. New methods based on a genetic algorithm back propagation (GABP) neural network and general regression neural network (GRNN) for predicting the occurrence of trihalomethanes in tap water. Sci. Total Environ. 870, 161976. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161976 (2023).

- Khaldi, R., El Afia, A., Chiheb, R. & Tabik, S. What is the best RNN-cell structure to forecast each time series behavior?. Expert Syst. Appl. 215, 119140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119140 (2023).

- Chandrasekar, A., Zhang, S. & Mhaskar, P. A hybrid Hubspace-RNN based approach for modelling of non-linear batch processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 281, 119118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2023.119118 (2023).

- Al Mehedi, M. A. et al. Predicting the performance of green stormwater infrastructure using multivariate long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network. J. Hydrol. 625, 130076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130076 (2023).

- Ma, J., Ding, Y., Cheng, J. C. P., Jiang, F. & Wan, Z. A temporal-spatial interpolation and extrapolation method based on geographic Long Short-Term Memory neural network for PM2.5. J. Clean. Prod. 237, 117729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117729 (2019).

- Sejuti, Z. A. & Islam, M. S. A hybrid CNN-KNN approach for identification of COVID-19 with 5-fold cross validation. Sensors Int. 4, 100229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2023.100229 (2023).

- Guo, Q. et al. Air pollution forecasting using artificial and wavelet neural networks with meteorological conditions. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 20, 1429-1439. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2020.03.0097 (2020).

- Bilgili, M., Ozbek, A., Yildirim, A. & Simsek, E. Artificial neural network approach for monthly air temperature estimations and maps. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 242, 106000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jastp. 2022.106000 (2023).

- Hrisko, J., Ramamurthy, P., Yu, Y., Yu, P. & Melecio-Vázquez, D. Urban air temperature model using GOES-16 LST and a diurnal regressive neural network algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 237, 111495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111495 (2020).

- Yu, X., Shi, S. & Xu, L. A spatial-temporal graph attention network approach for air temperature forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 113, 107888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107888 (2021).

- Zhang, X., Xiao, Y., Zhu, G. & Shi, J. A coupled CEEMD-BiLSTM model for regional monthly temperature prediction. Environ. Monitor. Assess. 195, 379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-023-10977-5 (2023).

- Zhang, X., Ren, H., Liu, J., Zhang, Y. & Cheng, W. A monthly temperature prediction based on the CEEMDAN-BO-BiLSTM coupled model. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51524-7 (2024).

- Song, C., Chen, X., Wu, P. & Jin, H. Combining time varying filtering based empirical mode decomposition and machine learning to predict precipitation from nonlinear series. J. Hydrol. 603, 126914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126914 (2021).

- Priestly, S. E., Raimond, K., Cohen, Y., Brema, J. & Hemanth, D. J. Evaluation of a novel hybrid lion swarm optimization-AdaBoostRegressor model for forecasting monthly precipitation. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 39, 100884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. suscom.2023.100884 (2023).

- Tao, L., He, X., Li, J. & Yang, D. A multiscale long short-term memory model with attention mechanism for improving monthly precipitation prediction. J. Hydrol. 602, 126815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126815 (2021).

- Rajendra, P., Murthy, K. V. N., Subbarao, A. & Boadh, R. Use of ANN models in the prediction of meteorological data. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 5, 1051-1058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-019-00590-2 (2019).

- Hanoon, M. S. et al. Developing machine learning algorithms for meteorological temperature and humidity forecasting at Terengganu state in Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 11, 18935. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96872-w (2021).

- Gurlek, C. Artificial neural networks approach for forecasting of monthly relative humidity in Sivas, Turkey. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 37, 4391-4400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-023-0753-6 (2023).

- Shad, M., Sharma, Y. D. & Singh, A. Forecasting of monthly relative humidity in Delhi, India, using SARIMA and ANN models. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 4843-4851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-022-01385-8 (2022).

- Ozbek, A., Unal, Ş& Bilgili, M. Daily average relative humidity forecasting with LSTM neural network and ANFIS approaches. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 150, 697-714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-022-04181-7 (2022).

- Rahimikhoob, A. Estimating sunshine duration from other climatic data by artificial neural network for ET0 estimation in an arid environment. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 118, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-013-1047-1 (2014).

- Kandirmaz, H. M., Kaba, K. & Avci, M. Estimation of monthly sunshine duration in Turkey using artificial neural networks. Int. J. Photoenergy 2014, 680596. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/680596 (2014).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

© المؤلفون 2024

كلية الجغرافيا والبيئة، جامعة لياوتشينغ، لياوتشينغ 252000، الصين. معهد دراسات هوانغهي، جامعة لياوتشينغ، لياوتشينغ 252000، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي للكيمياء الجوية، الإدارة الوطنية للأرصاد الجوية، بكين 100081، الصين. المختبر الوطني الرئيسي للتربة والجيولوجيا الرباعية، معهد بيئة الأرض، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، شيآن 710061، الصين. مركز بيانات علوم النظام البيئي الوطني، المختبر الرئيسي لمراقبة الشبكات البيئية والنمذجة، معهد العلوم الجغرافية وبحوث الموارد الطبيعية، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، بكين 100101، الصين. البريد الإلكتروني: guogingchun@Icu.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68906-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39085577

Publication Date: 2024-07-31

Monthly climate prediction using deep convolutional neural network and long short-term memory

Abstract

Climate change affects plant growth, food production, ecosystems, sustainable socio-economic development, and human health. The different artificial intelligence models are proposed to simulate climate parameters of Jinan city in China, include artificial neural network (ANN), recurrent NN (RNN), long short-term memory neural network (LSTM), deep convolutional NN (CNN), and CNN-LSTM. These models are used to forecast six climatic factors on a monthly ahead. The climate data for 72 years (1 January 1951-31 December 2022) used in this study include monthly average atmospheric temperature, extreme minimum atmospheric temperature, extreme maximum atmospheric temperature, precipitation, average relative humidity, and sunlight hours. The time series of 12 month delayed data are used as input signals to the models. The efficiency of the proposed models are examined utilizing diverse evaluation criteria namely mean absolute error, root mean square error (RMSE), and correlation coefficient (R). The modeling result inherits that the proposed hybrid CNNLSTM model achieves a greater accuracy than other compared models. The hybrid CNN-LSTM model significantly reduces the forecasting error compared to the models for the one month time step ahead. For instance, the RMSE values of the ANN, RNN, LSTM, CNN, and CNN-LSTM models for monthly average atmospheric temperature in the forecasting stage are

Study area and data

section*{Study area}

Data and data standardization

Methodology

Artificial neural network (ANN)

Recurrent neural network (RNN)

Similarly, the parameters of the model are set. The input variables are 12, the output variable is 1 , and the neurons of hidden layer are 8. The activation functions are tansig for hidden layer and purelin for output layer. training function is trainlm. learning function is learngdm. Performance function mse is

Long short-term memory neural network (LSTM)

Similarly, the hyperparameters of the model are set. The input size is 12 , the number of output is 1 , and the number of hidden units is 100 . The activation functions are tanh and sigmoid. The Adam Optimizer is used and the learning rate is set to 0.001 . The goal is

Convolutional neural network (CNN)

CNN-LSTM

Experiment

Cross-validation

Evaluation criteria

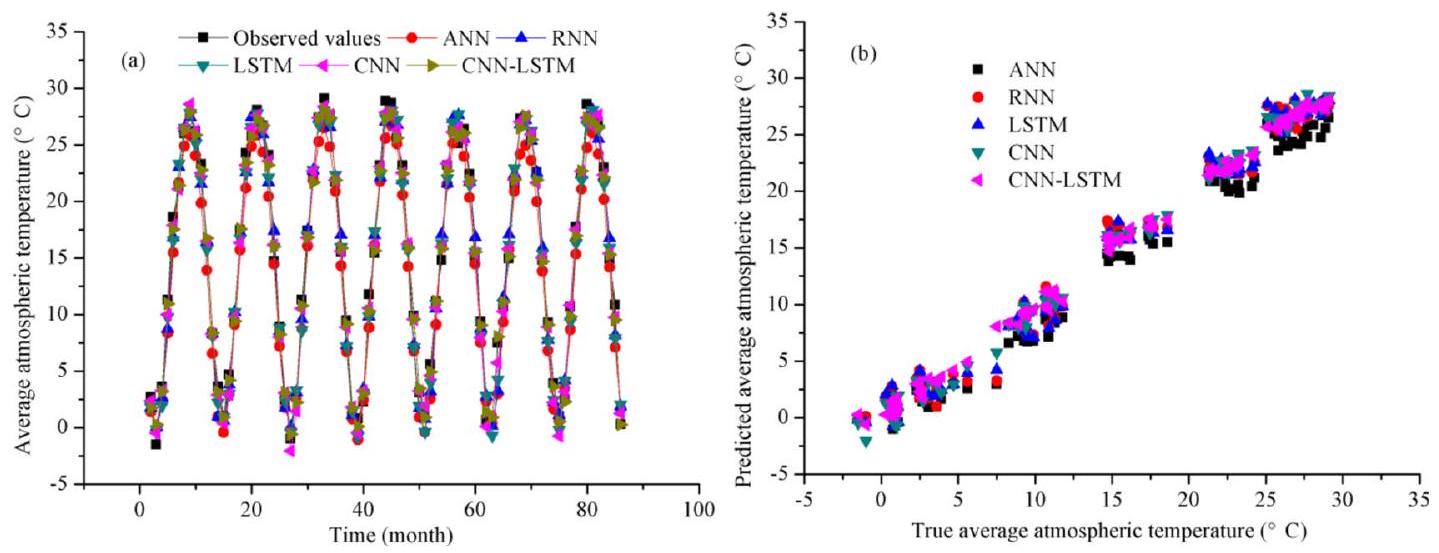

Simulating monthly average atmospheric temperature

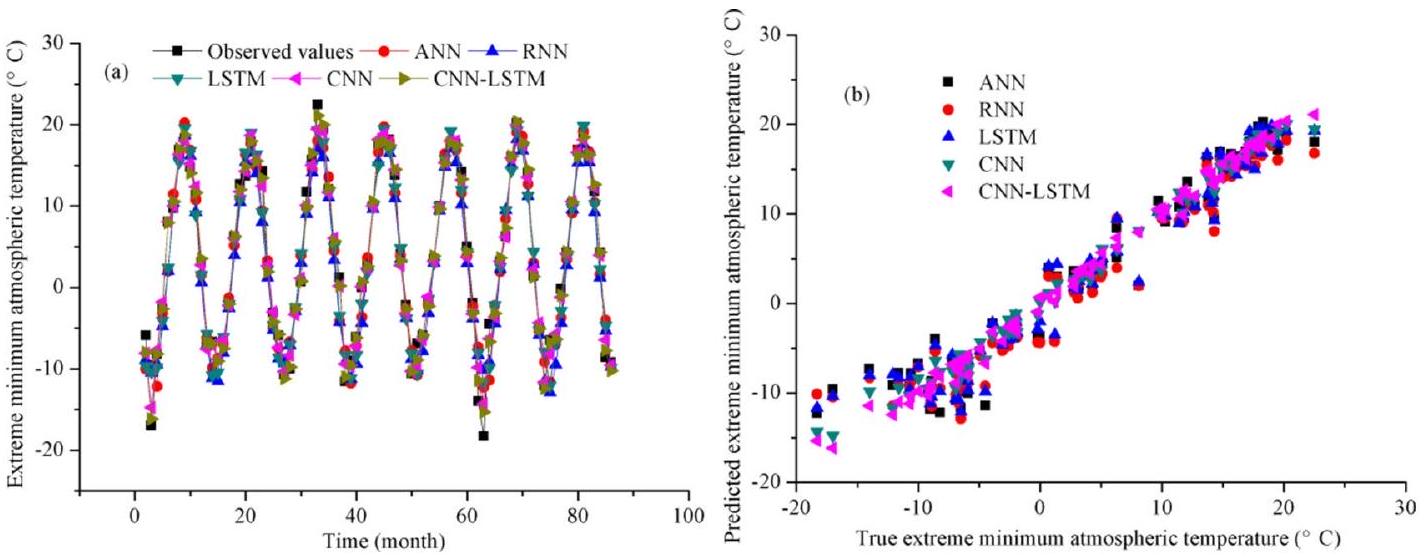

Comparison of observed and simulated monthly extreme minimum atmospheric temperature

| Training functions | R | RMSE (

|

MAE (

|

||||||

| Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | |

| Trainbr | 0.9894 | 0.9870 | 0.9907 | 1.8199 | 1.9923 | 2.0669 | 1.4787 | 1.6352 | 1.8042 |

| Trainlm | 0.9891 | 0.9865 | 0.9903 | 1.8280 | 1.9947 | 2.2055 | 1.5286 | 1.6417 | 1.8223 |

| Traingdx | 0.9848 | 0.9831 | 0.9865 | 2.5865 | 2.6032 | 2.6232 | 2.0750 | 2.1694 | 2.2884 |

| Traingd | 0.9843 | 0.9829 | 0.9863 | 3.3718 | 3.3298 | 3.2961 | 2.7721 | 2.8332 | 2.8319 |

| Traingdm | 0.9869 | 0.9845 | 0.9875 | 2.5335 | 2.5701 | 2.5395 | 2.0509 | 2.1454 | 2.1707 |

| Traingda | 0.9857 | 0.9839 | 0.9867 | 2.2270 | 2.3107 | 2.4912 | 1.8536 | 1.9816 | 2.1897 |

| Trainrp | 0.9871 | 0.9856 | 0.9890 | 1.8872 | 1.9955 | 2.4071 | 1.6493 | 1.6761 | 1.8887 |

| Traincgp | 0.9888 | 0.9853 | 0.9804 | 1.8347 | 1.9958 | 2.5255 | 1.6806 | 1.6718 | 1.8886 |

| Traincgf | 0.9887 | 0.9857 | 0.9802 | 1.8494 | 1.9955 | 2.4166 | 1.6243 | 1.6572 | 1.8801 |

| Traincgb | 0.9797 | 0.9777 | 0.9808 | 2.1680 | 2.1577 | 2.9158 | 1.7103 | 1.7804 | 1.8576 |

| Trainscg | 0.9876 | 0.9852 | 0.9802 | 1.8518 | 1.9958 | 2.4130 | 1.6286 | 1.6853 | 1.8755 |

| Trainbfg | 0.9878 | 0.9853 | 0.9880 | 1.8462 | 1.9946 | 2.4086 | 1.6244 | 1.6922 | 1.8613 |

| Trainoss | 0.9880 | 0.9854 | 0.9889 | 1.8350 | 1.9957 | 2.5366 | 1.6653 | 1.6671 | 1.8932 |

| Transfer functions | R | RMSE (

|

MAE (

|

||||||

| Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | |

| T-PU | 0.9889 | 0.9859 | 0.9904 | 1.8382 | 1.9949 | 2.1373 | 1.5046 | 1.6413 | 1.8125 |

| T-L | 0.9879 | 0.9848 | 0.9902 | 1.8355 | 1.9950 | 2.2910 | 1.5057 | 1.6517 | 1.8210 |

| T-T | 0.9869 | 0.9839 | 0.9901 | 1.8351 | 1.9959 | 2.2873 | 1.5060 | 1.6516 | 1.8193 |

| L-PU | 0.9894 | 0.9870 | 0.9907 | 1.8199 | 1.9923 | 2.0669 | 1.4787 | 1.6352 | 1.8042 |

| L-T | 0.9859 | 0.9829 | 0.9898 | 1.8353 | 1.9949 | 2.2873 | 1.5056 | 1.6416 | 1.8142 |

| L-L | 0.9849 | 0.9818 | 0.9903 | 1.8354 | 1.9950 | 2.2829 | 1.5056 | 1.6621 | 1.8309 |

| PU-T | 0.9878 | 0.9827 | 0.9883 | 1.8575 | 1.9962 | 2.5771 | 1.5228 | 1.6723 | 1.8228 |

| PU-L | 0.9877 | 0.9855 | 0.9873 | 1.8780 | 1.9986 | 2.8339 | 1.5411 | 1.6646 | 1.8557 |

| PU-PU | 0.9886 | 0.9856 | 0.9886 | 1.8524 | 1.9968 | 2.5028 | 1.5191 | 1.6829 | 1.8258 |

| T-PO | 0.9839 | 0.9828 | 0.9902 | 1.8373 | 1.9951 | 2.2934 | 1.5070 | 1.6916 | 1.8309 |

| L-PO | 0.9829 | 0.9882 | 0.9898 | 1.8356 | 1.9952 | 2.3004 | 1.5063 | 1.6519 | 1.8211 |

| PO-PO | 0.9819 | 0.9818 | 0.9892 | 1.8440 | 1.9954 | 2.4584 | 1.5120 | 1.6514 | 1.8281 |

| PU-PO | 0.9886 | 0.9856 | 0.9886 | 1.8690 | 1.9985 | 2.8205 | 1.5344 | 1.6648 | 1.8544 |

| PO-L | 0.9885 | 0.9857 | 0.9868 | 1.8527 | 1.9959 | 2.6051 | 1.5186 | 1.6721 | 1.8304 |

| PO-PU | 0.9850 | 0.9848 | 0.9892 | 1.8439 | 1.9953 | 2.4593 | 1.5120 | 1.6814 | 1.8209 |

| PO-T | 0.9879 | 0.9827 | 0.9900 | 1.8396 | 1.9957 | 2.4249 | 1.5081 | 1.6519 | 1.8218 |

| Models | R | RMSE (

|

MAE (

|

||||||

| Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | |

| ANN | 0.9894 | 0.9870 | 0.9907 | 1.8199 | 1.9923 | 2.0669 | 1.4787 | 1.6352 | 1.8042 |

| RNN | 0.9905 | 0.9881 | 0.9895 | 1.3891 | 1.5245 | 1.4416 | 1.0836 | 1.1594 | 1.1917 |

| LSTM | 0.9906 | 0.9870 | 0.9914 | 1.3819 | 1.5965 | 1.3482 | 1.0710 | 1.2278 | 1.1485 |

| CNN | 0.9968 | 0.9965 | 0.9969 | 0.8148 | 0.8249 | 0.8015 | 0.6387 | 0.6290 | 0.6680 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.9982 | 0.9982 | 0.9981 | 0.6422 | 0.6270 | 0.6292 | 0.5043 | 0.4726 | 0.5048 |

| Models | R | RMSE (

|

MAE (

|

||||||

| Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | |

| ANN | 0.9790 | 0.9741 | 0.9696 | 2.1874 | 2.3985 | 2.6238 | 1.7348 | 1.8691 | 1.9254 |

| RNN | 0.9782 | 0.9733 | 0.9709 | 2.3703 | 2.5951 | 2.8135 | 1.9171 | 2.0651 | 2.2372 |

| LSTM | 0.9806 | 0.9769 | 0.9719 | 2.1011 | 2.2587 | 2.5320 | 1.6674 | 1.6604 | 1.9572 |

| CNN | 0.9942 | 0.9936 | 0.9942 | 1.1576 | 1.1977 | 1.1528 | 0.9102 | 0.9197 | 0.8200 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.9971 | 0.9973 | 0.9970 | 0.8350 | 0.7785 | 0.8287 | 0.6583 | 0.5809 | 0.5979 |

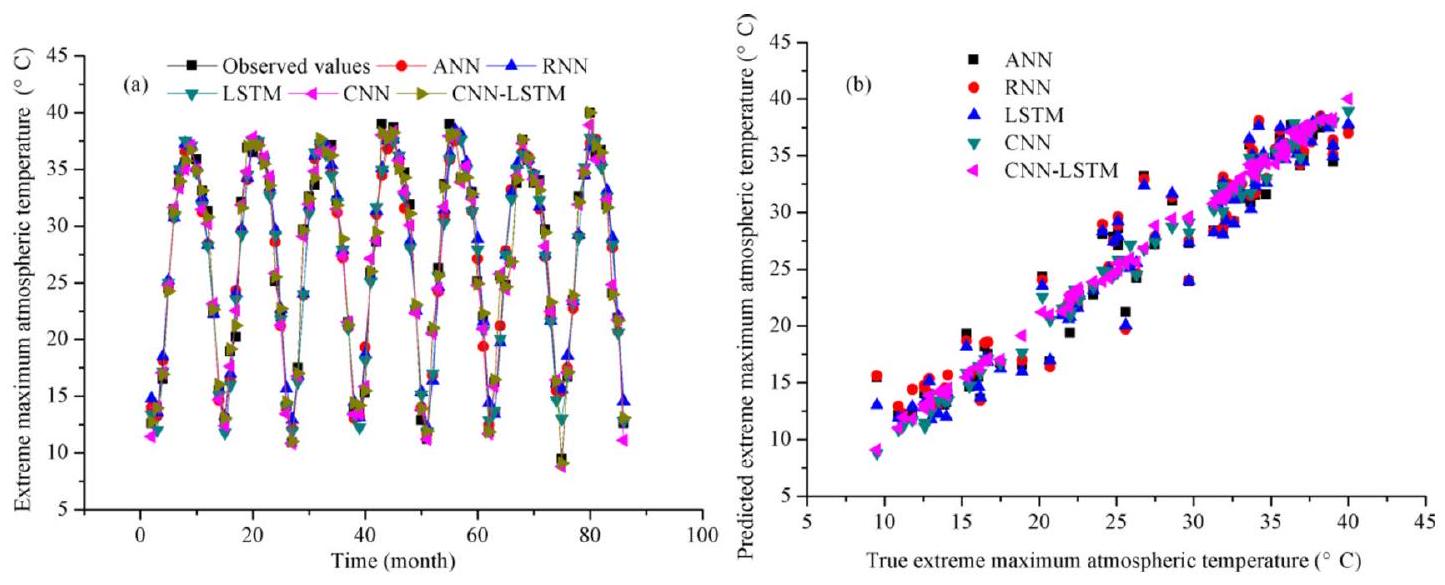

Comparison of observed and simulated monthly extreme maximum atmospheric temperature

| Models | R | RMSE (

|

MAE (

|

||||||

| Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | |

| ANN | 0.9647 | 0.9621 | 0.9689 | 2.4269 | 2.5132 | 2.2345 | 1.8372 | 1.9768 | 1.6627 |

| RNN | 0.9643 | 0.9611 | 0.9666 | 2.4806 | 2.5762 | 2.2979 | 1.9156 | 2.0481 | 1.6812 |

| LSTM | 0.9668 | 0.9591 | 0.9709 | 2.3452 | 2.6012 | 2.1666 | 1.8163 | 2.0398 | 1.6583 |

| CNN | 0.9948 | 0.9950 | 0.9962 | 0.9446 | 0.9604 | 0.8212 | 0.7346 | 0.7354 | 0.6202 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.9987 | 0.9982 | 0.9987 | 0.5339 | 0.6213 | 0.4932 | 0.4216 | 0.4848 | 0.3931 |

Comparison of observed and simulated monthly precipitation

| Models | R | RMSE (mm) | MAE (mm) | ||||||

| Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | |

| ANN | 0.6853 | 0.6823 | 0.7092 | 58.7736 | 56.3767 | 67.4976 | 39.8891 | 34.4801 | 42.5787 |

| RNN | 0.7412 | 0.7452 | 0.7590 | 53.0472 | 50.2847 | 62.1261 | 33.1355 | 29.3883 | 37.7565 |

| LSTM | 0.7685 | 0.7246 | 0.7672 | 50.6978 | 52.4807 | 60.5523 | 32.5079 | 31.4153 | 36.0748 |

| CNN | 0.9691 | 0.9629 | 0.9857 | 20.2432 | 22.5777 | 16.8436 | 13.8417 | 13.8229 | 11.8683 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.9952 | 0.9930 | 0.9962 | 7.8252 | 8.8947 | 8.1762 | 6.0644 | 6.7083 | 6.7051 |

Comparison of observed and simulated monthly average relative humidity

Comparison of observed and simulated monthly sunlight hours

| Models | R | RMSE (%) | MAE (%) | ||||||

| Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | |

| ANN | 0.7444 | 0.7452 | 0.7672 | 7.9631 | 8.6807 | 7.4171 | 6.3622 | 6.9138 | 5.9593 |

| RNN | 0.7693 | 0.7549 | 0.7874 | 7.6236 | 8.3876 | 7.0419 | 6.0314 | 6.5664 | 5.6321 |

| LSTM | 0.7779 | 0.7862 | 0.7934 | 7.4957 | 7.8915 | 6.9580 | 6.0077 | 6.0309 | 5.4739 |

| CNN | 0.9935 | 0.9943 | 0.9919 | 1.4208 | 1.4384 | 1.4513 | 1.0988 | 1.0889 | 1.1419 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.9988 | 0.9987 | 0.9984 | 0.6222 | 0.7171 | 0.6615 | 0.4991 | 0.5546 | 0.5093 |

| Models | R | RMSE (hour) | MAE (hour) | ||||||

| Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | Training | Verification | Predicting | |

| ANN | 0.7095 | 0.5295 | 0.6413 | 34.9436 | 41.8596 | 37.4016 | 27.9570 | 32.7740 | 29.7778 |

| RNN | 0.7468 | 0.6156 | 0.6752 | 32.9704 | 38.7314 | 36.1896 | 26.7097 | 30.6143 | 28.6519 |

| LSTM | 0.7515 | 0.5801 | 0.7192 | 32.6550 | 39.9885 | 33.9022 | 26.3996 | 30.9942 | 27.0269 |

| CNN | 0.9903 | 0.9940 | 0.9939 | 7.0557 | 5.7520 | 5.6467 | 5.5325 | 4.5937 | 4.3742 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.9984 | 0.9988 | 0.9984 | 2.9650 | 2.5824 | 2.9058 | 2.3491 | 2.0115 | 2.3794 |

Comparison with other literatures

| Models | ANN | RNN | LSTM | CNN | CNN-LSTM |

| Average elapsed time | 17 | 18 | 19 | 40 | 89 |

Conclusion

(2) The CNN-LSTM is compared with ANN, RNN, LSTM, and CNN utilizing the same monthly climate data. The input variables lag times are derived from the cycle of monthly climate data. The performance achieved by the CNN-LSTM model is greater than other compared artificial intelligence models (ANN, RNN, LSTM, CNN). The prediction results of CNN-LSTM model is superior to other models in generalization ability and precision. This indicates the effectiveness of the proposed CNN-LSTM model over other existing artificial intelligence models. This means that compared to other models, the CNN-LSTM has the lowest RMSE and MAE values and the highest R value.

(3) In climate change monitoring, extreme climate is of extraordinary importance, and the CNN-LSTM model also has higher efficiency than other four models in extreme climate prediction. The surveys show that predicted extreme air temperature is more accurate than predicted precipitation. The CNN model is close to CNN-LSTM model in some single coefficients but the errors demonstrate that the CNN-LSTM has more stable performance. The CNN-LSTM can reasonably predict the magnitude and monthly variations in climate elements, capture the peaks of the climate data, and meet the evaluation criteria of model performance. The CNN-LSTM is a promising approach for climate simulation.

Limitations and suggestions

(2) In future, the prediction accuracy of CNN-LSTM will also compare with current physics-based dynamical models. The models can be further extended by applying the decomposition techniques (WT, TVF-EMD, and CEEMD), bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM), transfer learning, bidirectional GRU (BiGRU), and considering the residual components of climate data as input for the models development. The performance of climate modeling will be further improved by exploring multi-time scales, spatial features and other factors such as solar radiation, greenhouse temperature, terrain, vegetation, El Niño-Southern Oscillation, etc. This strategy can be utilized for any prediction application to make short-term, medium-term, and longterm operational plans. Therefore, the robustness of the models can be utilized to forecast multi-time scale climatic elements. In the simulation and prediction of different extreme climates, we will integrate multiple data such as remote sensing and ground observations for spatiotemporal multi-scale climate modeling. In the process of climate modeling, we will integrate physical mechanisms into machine learning models to improve the interpretability and generalization ability of the models. It provides a new technological approach for the combination of traditional physical models and advanced artificial intelligence algorithms.

Data availability

Received: 27 May 2024; Accepted: 29 July 2024

Published online: 31 July 2024

References

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Change in air quality during 2014-2021 in Jinan City in China and its influencing factors. Toxics 11, 210 (2023).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Long-term projection of future climate change over the twenty-first century in the Sahara region in Africa under four Shared Socio-Economic Pathways scenarios. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 22319-22329. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11356-022-23813-z (2023).

- Guo, Q. et al. Changes in air quality from the COVID to the post-COVID era in the Beijing-Tianjin-Tangshan region in China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 21, 210270. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr. 210270 (2021).

- Zhao, R. et al. Assessing resilience of sustainability to climate change in China’s cities. Sci. Total Environ. 898, 165568. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165568 (2023).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Assessing the impacts of climate variables on long-term air quality trends in Peninsular Malaysia. Sci. Total Environ. 901, 166430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166430 (2023).

- Zhou, S., Yu, B. & Zhang, Y. Global concurrent climate extremes exacerbated by anthropogenic climate change. Sci. Adv. 9, eabo1638. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo1638 (2023).

- Zurek, M., Hebinck, A. & Selomane, O. Climate change and the urgency to transform food systems. Science 376, 1416-1421. https:// doi.org/10.1126/science.abo2364 (2022).

- Klisz, M. et al. Local site conditions reduce interspecific differences in climate sensitivity between native and non-native pines. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet. 2023.109694 (2023).

- Li, X. et al. Attribution of runoff and hydrological drought changes in an ecologically vulnerable basin in semi-arid regions of China. Hydrol. Process. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp. 15003 (2023).

- Xue, B. et al. Divergent hydrological responses to forest expansion in dry and wet basins of China: Implications for future afforestation planning. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR031856. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR031856 (2022).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. The characteristics of air quality changes in Hohhot City in China and their relationship with meteorological and socio-economic factors. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 24, 230274. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr. 230274 (2024).

- Wang, Y., Hu, K., Huang, G. & Tao, W. Asymmetric impacts of El Niño and La Niña on the Pacific-North American teleconnection pattern: The role of subtropical jet stream. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114040. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac31ed (2021).

- Abbas, G. et al. Modeling the potential impact of climate change on maize-maize cropping system in semi-arid environment and designing of adaptation options. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109674 (2023).

- Mangani, R., Gunn, K. M. & Creux, N. M. Projecting the effect of climate change on planting date and cultivar choice for South African dryland maize production. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109695 (2023).

- Liang, R., Sun, Y., Qiu, S., Wang, B. & Xie, Y. Relative effects of climate, stand environment and tree characteristics on annual tree growth in subtropical Cunninghamia lanceolata forests. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 342, 109711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet. 2023.109711 (2023).

- Kumar, A., Chen, M. & Wang, W. An analysis of prediction skill of monthly mean climate variability. Clim. Dyn. 37, 1119-1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-010-0901-4 (2011).

- Chen, Y. et al. Improving the heavy rainfall forecasting using a weighted deep learning model. Front. Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1116672 (2023).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Predicting of daily PM2.5 concentration employing wavelet artificial neural networks based on meteorological elements in Shanghai, China. Toxics 11, 51 (2023).

- He, Z., Guo, Q., Wang, Z. & Li, X. Prediction of monthly PM2.5 concentration in Liaocheng in China employing artificial neural network. Atmosphere 13, 1221 (2022).

- Guo, Q. & He, Z. Prediction of the confirmed cases and deaths of global COVID-19 using artificial intelligence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 11672-11682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11930-6 (2021).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Simulating daily PM2.5 concentrations using wavelet analysis and artificial neural network with remote sensing and surface observation data. Chemosphere 340, 139886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139886 (2023).

- Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Prediction of hourly PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations in Chongqing City in China based on artificial neural network. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 23, 220448. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr. 220448 (2023).

- Fang, S. et al. MS-Net: Multi-source spatio-temporal network for traffic flow prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 7142-7155. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2021.3067024 (2022).

- Rajasundrapandiyanleebanon, T., Kumaresan, K., Murugan, S., Subathra, M. S. P. & Sivakumar, M. Solar energy forecasting using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 30, 3059-3079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-023-09893-1 (2023).

- Han, Y. et al. Novel economy and carbon emissions prediction model of different countries or regions in the world for energy optimization using improved residual neural network. Sci. Total Environ. 860, 160410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022. 160410 (2023).

- Wang, H. et al. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature 620, 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06221-2 (2023).

- Nathvani, R. et al. Beyond here and now: Evaluating pollution estimation across space and time from street view images with deep learning. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166168 (2023).

- Faraji, M., Nadi, S., Ghaffarpasand, O., Homayoni, S. & Downey, K. An integrated 3D CNN-GRU deep learning method for shortterm prediction of PM2.5 concentration in urban environment. Sci. Total Environ. 834, 155324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv. 2022.155324 (2022).

- Hu, T. et al. Crop yield prediction via explainable AI and interpretable machine learning: Dangers of black box models for evaluating climate change impacts on crop yield. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 336, 109458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109458 (2023).

- Priyatikanto, R., Lu, Y., Dash, J. & Sheffield, J. Improving generalisability and transferability of machine-learning-based maize yield prediction model through domain adaptation. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2023. 109652 (2023).

- von Bloh, M. et al. Machine learning for soybean yield forecasting in Brazil. Agricult. For. Meteorol. 341, 109670. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109670 (2023).

- Liu, N. et al. Meshless surface wind speed field reconstruction based on machine learning. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 39, 1721-1733. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-1343-8 (2022).

- Li, Y. et al. Convective storm VIL and lightning nowcasting using satellite and weather radar measurements based on multi-task learning models. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 887-899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-2082-6 (2023).

- Yang, D. et al. Predictor selection for CNN-based statistical downscaling of monthly precipitation. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1117-1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-2119-x (2023).

- Wang, T. & Huang, P. Superiority of a convolutional neural network model over dynamical models in predicting central pacific ENSO. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-023-3001-1 (2023).

- Zou, H., Wu, S. & Tian, M. Radar quantitative precipitation estimation based on the gated recurrent unit neural network and echo-top data. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1043-1057. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-2127-x (2023).

- Bi, K. et al. Accurate medium-range global weather forecasting with 3D neural networks. Nature 619, 533-538. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41586-023-06185-3 (2023).

- Zhang, Y. et al. Skilful nowcasting of extreme precipitation with NowcastNet. Nature 619, 526-532. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-023-06184-4 (2023).

- Ham, Y.-G. et al. Anthropogenic fingerprints in daily precipitation revealed by deep learning. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-023-06474-x (2023).

- Shamekh, S., Lamb, K. D., Huang, Y. & Gentine, P. Implicit learning of convective organization explains precipitation stochasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2216158120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 2216158120 (2023).

- Pinheiro Gomes, E., Progênio, M. F. & da Silva Holanda, P. Modeling with artificial neural networks to estimate daily precipitation in the Brazilian Legal Amazon. Clim. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-024-07200-7 (2024).

- Papantoniou, S. & Kolokotsa, D.-D. Prediction of outdoor air temperature using neural networks: Application in 4 European cities. Energy Build. 114, 72-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.06.054 (2016).

- Roebber, P. Toward an adaptive artificial neural network-based postprocessor. Mon. Weather Rev. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-21-0089.1 (2021).

- Chen, Y. et al. Prediction of ENSO using multivariable deep learning. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 16, 100350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. aosl.2023.100350 (2023).

- Baño-Medina, J., Manzanas, R. & Gutiérrez, J. M. Configuration and intercomparison of deep learning neural models for statistical downscaling. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 2109-2124. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-2109-2020 (2020).

- Zhong, H. et al. Prediction of instantaneous yield of bio-oil in fluidized biomass pyrolysis using long short-term memory network based on computational fluid dynamics data. J. Clean. Prod. 391, 136192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136192 (2023).

- Jiang, N., Yu, X. & Alam, M. A hybrid carbon price prediction model based-combinational estimation strategies of quantile regression and long short-term memory. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139508 (2023).

- Guo, Y. et al. Stabilization temperature prediction in carbon fiber production using empirical mode decomposition and long short-term memory network. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139345 (2023).

- Yang, C.-H., Chen, P.-H., Wu, C.-H., Yang, C.-S. & Chuang, L.-Y. Deep learning-based air pollution analysis on carbon monoxide in Taiwan. Ecol. Inform. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102477 (2024).

- Yang, X. et al. A spatio-temporal graph-guided convolutional LSTM for tropical cyclones precipitation nowcasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 124, 109003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2022.109003 (2022).

- Ham, Y.-G., Kim, J.-H. & Luo, J.-J. Deep learning for multi-year ENSO forecasts. Nature 573, 568-572. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-019-1559-7 (2019).

- Xie, W., Xu, G., Zhang, H. & Dong, C. Developing a deep learning-based storm surge forecasting model. Ocean Model. 182, 102179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocemod.2023.102179 (2023).

- Hu, W. et al. Deep learning forecast uncertainty for precipitation over the Western United States. Mon. Weather Rev. 151, 13671385. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-22-0268.1 (2023).

- Wang, C. & Li, X. A deep learning model for estimating tropical cyclone wind radius from geostationary satellite infrared imagery. Mon. Weather Rev. 151, 403-417. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-22-0166.1 (2023).

- Ling, F. et al. Multi-task machine learning improves multi-seasonal prediction of the Indian Ocean Dipole. Nat. Commun. 13, 7681. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35412-0 (2022).

- Sun, W. et al. Artificial intelligence forecasting of marine heatwaves in the south China sea using a combined U-Net and ConvLSTM system. Remote Sens. 15, 4068 (2023).

- Sun, X. et al. PN-HGNN: Precipitation nowcasting network via hypergraph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3407157 (2024).

- Harnist, B., Pulkkinen, S. & Mäkinen, T. DEUCE v1.0: A neural network for probabilistic precipitation nowcasting with aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties. Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 3839-3866. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-3839-2024 (2024).

- Beucler, T. et al. Climate-invariant machine learning. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj7250. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adj7250 (2024).

- Kontolati, K., Goswami, S., Em Karniadakis, G. & Shields, M. D. Learning nonlinear operators in latent spaces for real-time predictions of complex dynamics in physical systems. Nat. Commun. 15, 5101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49411-w (2024).

- Chen, H. et al. Visibility forecast in Jiangsu province based on the GCN-GRU model. Sci. Rep. 14, 12599. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-024-61572-8 (2024).

- Pan, S. et al. Oil well production prediction based on CNN-LSTM model with self-attention mechanism. Energy 284, 128701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.128701 (2023).

- Dehghani, A. et al. Comparative evaluation of LSTM, CNN, and ConvLSTM for hourly short-term streamflow forecasting using deep learning approaches. Ecol. Inform. 75, 102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102119 (2023).

- Boulila, W., Ghandorh, H., Khan, M. A., Ahmed, F. & Ahmad, J. A novel CNN-LSTM-based approach to predict urban expansion. Ecol. Inform. 64, 101325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101325 (2021).

- Lima, F. T. & Souza, V. M. A. A large comparison of normalization methods on time series. Big Data Res. 34, 100407. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.bdr.2023.100407 (2023).

- Liu, K. et al. New methods based on a genetic algorithm back propagation (GABP) neural network and general regression neural network (GRNN) for predicting the occurrence of trihalomethanes in tap water. Sci. Total Environ. 870, 161976. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161976 (2023).

- Khaldi, R., El Afia, A., Chiheb, R. & Tabik, S. What is the best RNN-cell structure to forecast each time series behavior?. Expert Syst. Appl. 215, 119140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119140 (2023).

- Chandrasekar, A., Zhang, S. & Mhaskar, P. A hybrid Hubspace-RNN based approach for modelling of non-linear batch processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 281, 119118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2023.119118 (2023).

- Al Mehedi, M. A. et al. Predicting the performance of green stormwater infrastructure using multivariate long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network. J. Hydrol. 625, 130076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130076 (2023).

- Ma, J., Ding, Y., Cheng, J. C. P., Jiang, F. & Wan, Z. A temporal-spatial interpolation and extrapolation method based on geographic Long Short-Term Memory neural network for PM2.5. J. Clean. Prod. 237, 117729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117729 (2019).

- Sejuti, Z. A. & Islam, M. S. A hybrid CNN-KNN approach for identification of COVID-19 with 5-fold cross validation. Sensors Int. 4, 100229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2023.100229 (2023).

- Guo, Q. et al. Air pollution forecasting using artificial and wavelet neural networks with meteorological conditions. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 20, 1429-1439. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2020.03.0097 (2020).

- Bilgili, M., Ozbek, A., Yildirim, A. & Simsek, E. Artificial neural network approach for monthly air temperature estimations and maps. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 242, 106000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jastp. 2022.106000 (2023).

- Hrisko, J., Ramamurthy, P., Yu, Y., Yu, P. & Melecio-Vázquez, D. Urban air temperature model using GOES-16 LST and a diurnal regressive neural network algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 237, 111495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111495 (2020).

- Yu, X., Shi, S. & Xu, L. A spatial-temporal graph attention network approach for air temperature forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 113, 107888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107888 (2021).

- Zhang, X., Xiao, Y., Zhu, G. & Shi, J. A coupled CEEMD-BiLSTM model for regional monthly temperature prediction. Environ. Monitor. Assess. 195, 379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-023-10977-5 (2023).

- Zhang, X., Ren, H., Liu, J., Zhang, Y. & Cheng, W. A monthly temperature prediction based on the CEEMDAN-BO-BiLSTM coupled model. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51524-7 (2024).

- Song, C., Chen, X., Wu, P. & Jin, H. Combining time varying filtering based empirical mode decomposition and machine learning to predict precipitation from nonlinear series. J. Hydrol. 603, 126914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126914 (2021).

- Priestly, S. E., Raimond, K., Cohen, Y., Brema, J. & Hemanth, D. J. Evaluation of a novel hybrid lion swarm optimization-AdaBoostRegressor model for forecasting monthly precipitation. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 39, 100884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. suscom.2023.100884 (2023).

- Tao, L., He, X., Li, J. & Yang, D. A multiscale long short-term memory model with attention mechanism for improving monthly precipitation prediction. J. Hydrol. 602, 126815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126815 (2021).

- Rajendra, P., Murthy, K. V. N., Subbarao, A. & Boadh, R. Use of ANN models in the prediction of meteorological data. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 5, 1051-1058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-019-00590-2 (2019).

- Hanoon, M. S. et al. Developing machine learning algorithms for meteorological temperature and humidity forecasting at Terengganu state in Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 11, 18935. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96872-w (2021).

- Gurlek, C. Artificial neural networks approach for forecasting of monthly relative humidity in Sivas, Turkey. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 37, 4391-4400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-023-0753-6 (2023).

- Shad, M., Sharma, Y. D. & Singh, A. Forecasting of monthly relative humidity in Delhi, India, using SARIMA and ANN models. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 4843-4851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-022-01385-8 (2022).

- Ozbek, A., Unal, Ş& Bilgili, M. Daily average relative humidity forecasting with LSTM neural network and ANFIS approaches. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 150, 697-714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-022-04181-7 (2022).

- Rahimikhoob, A. Estimating sunshine duration from other climatic data by artificial neural network for ET0 estimation in an arid environment. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 118, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-013-1047-1 (2014).

- Kandirmaz, H. M., Kaba, K. & Avci, M. Estimation of monthly sunshine duration in Turkey using artificial neural networks. Int. J. Photoenergy 2014, 680596. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/680596 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

© The Author(s) 2024

School of Geography and Environment, Liaocheng University, Liaocheng 252000, China. Institute of Huanghe Studies, Liaocheng University, Liaocheng 252000, China. Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Chemistry, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing 100081, China. State Key Laboratory of Loess and Quaternary Geology, Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710061, China. National Ecosystem Science Data Center, Key Laboratory of Ecosystem Network Observation and Modeling, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China. email: guogingchun@ Icu.edu.cn