DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44653-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38199996

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-10

تنشيط رابطة C-F يمكّن من تخليق ثنائي فلوروميثيل أريلي ثنائي الحلقة كبدائل حيوية من نوع بنزوفينون

تم القبول: 22 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 10 يناير 2024

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

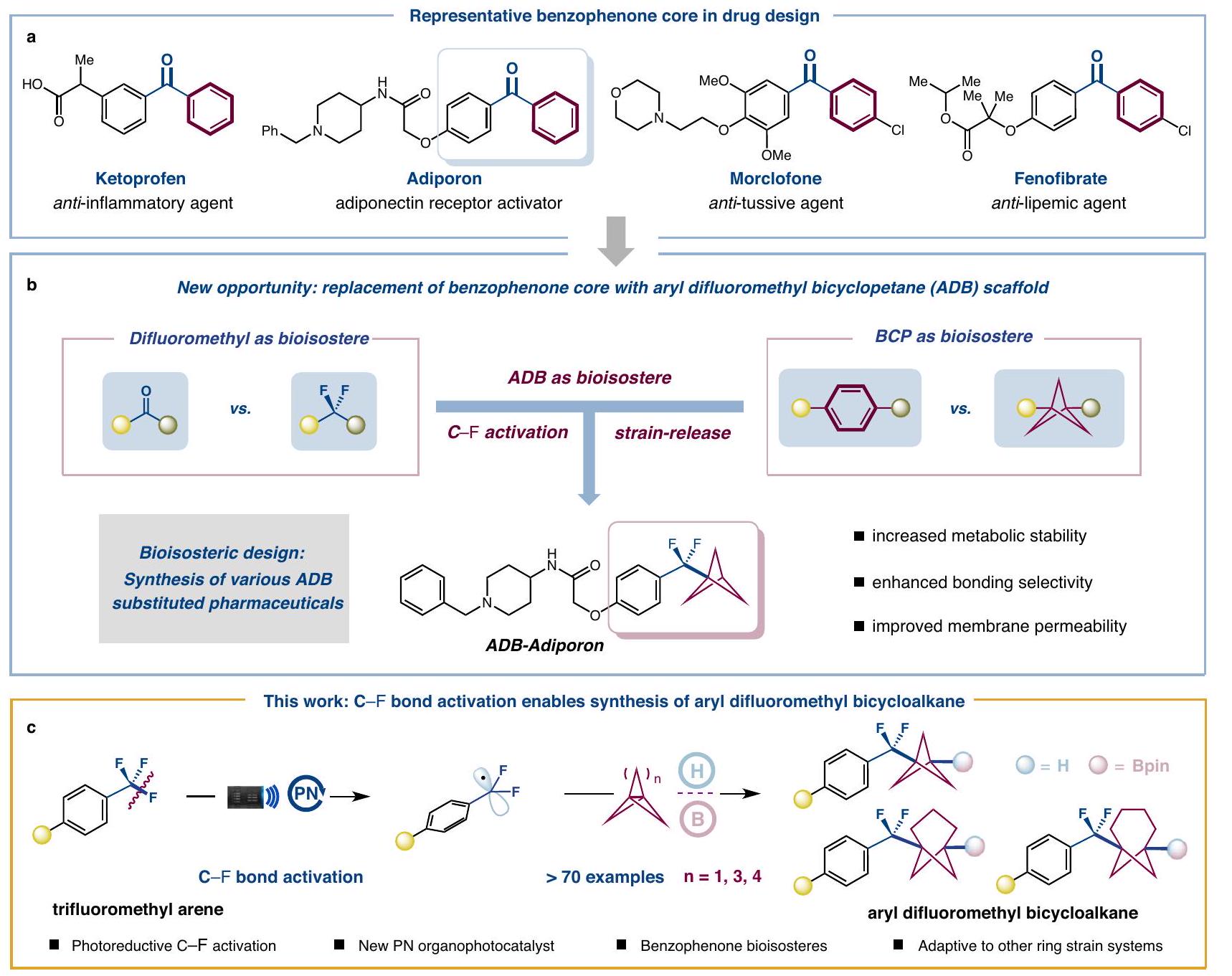

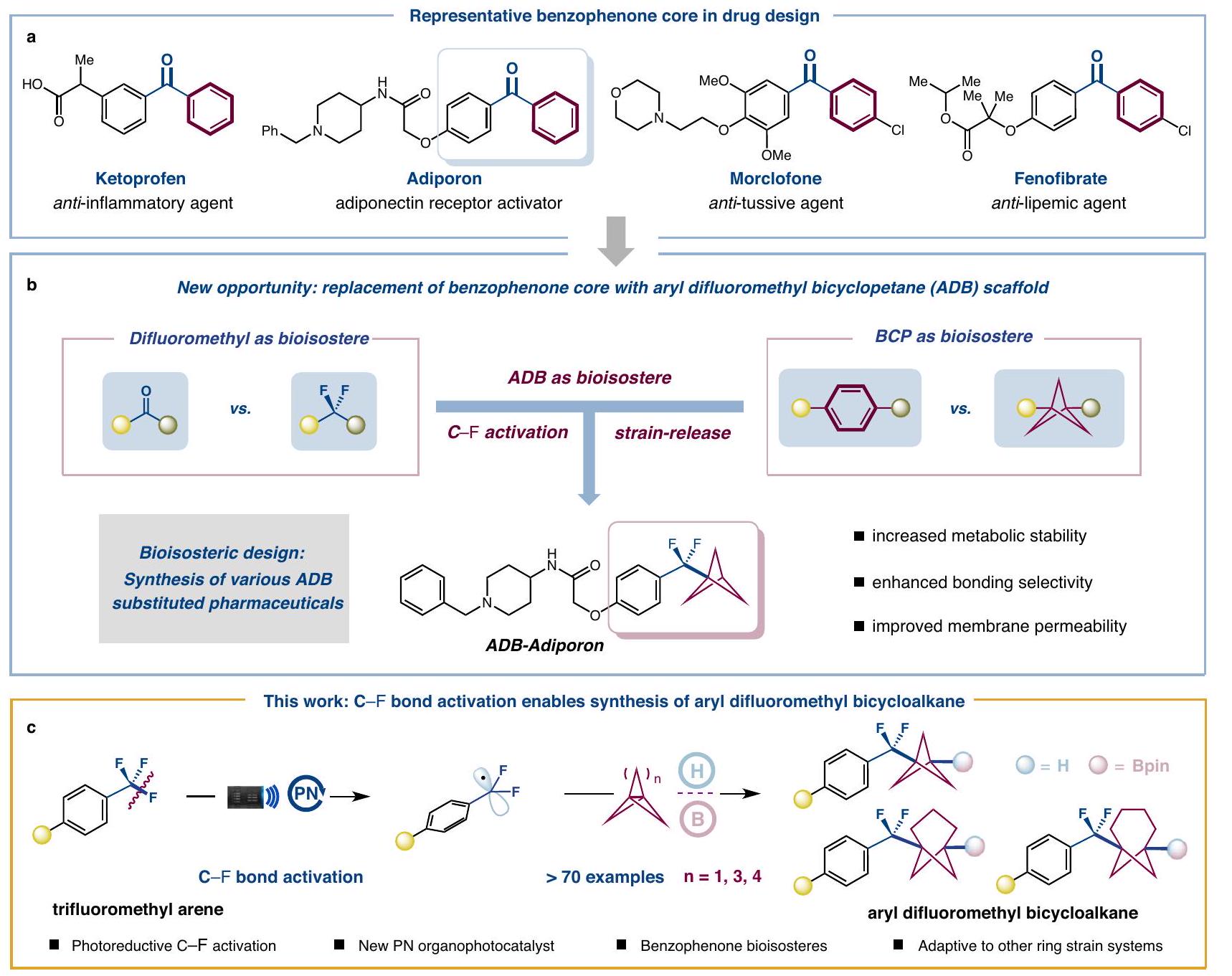

لقد أصبح التصميم البيوإيزوستيري نهجًا أساسيًا في تطوير جزيئات الأدوية. لقد مكنت التقدمات الأخيرة في المنهجيات الاصطناعية من التبني السريع لهذه الاستراتيجية في برامج اكتشاف الأدوية. وبالتالي، ستُقدَّر الممارسات الابتكارية المفاهيمية من قبل مجتمع الكيمياء الطبية. هنا نبلغ عن طريقة اصطناعية سريعة لتخليق ثنائي فلوروميثيل أريلي (ADB) كبيوإيزوستير لنواة البنزوفيكون. تتضمن هذه الطريقة دمج تنشيط رابطة C-F المدفوعة بالضوء وكيمياء تحرير الضغط تحت تحفيز تصميم جديد.

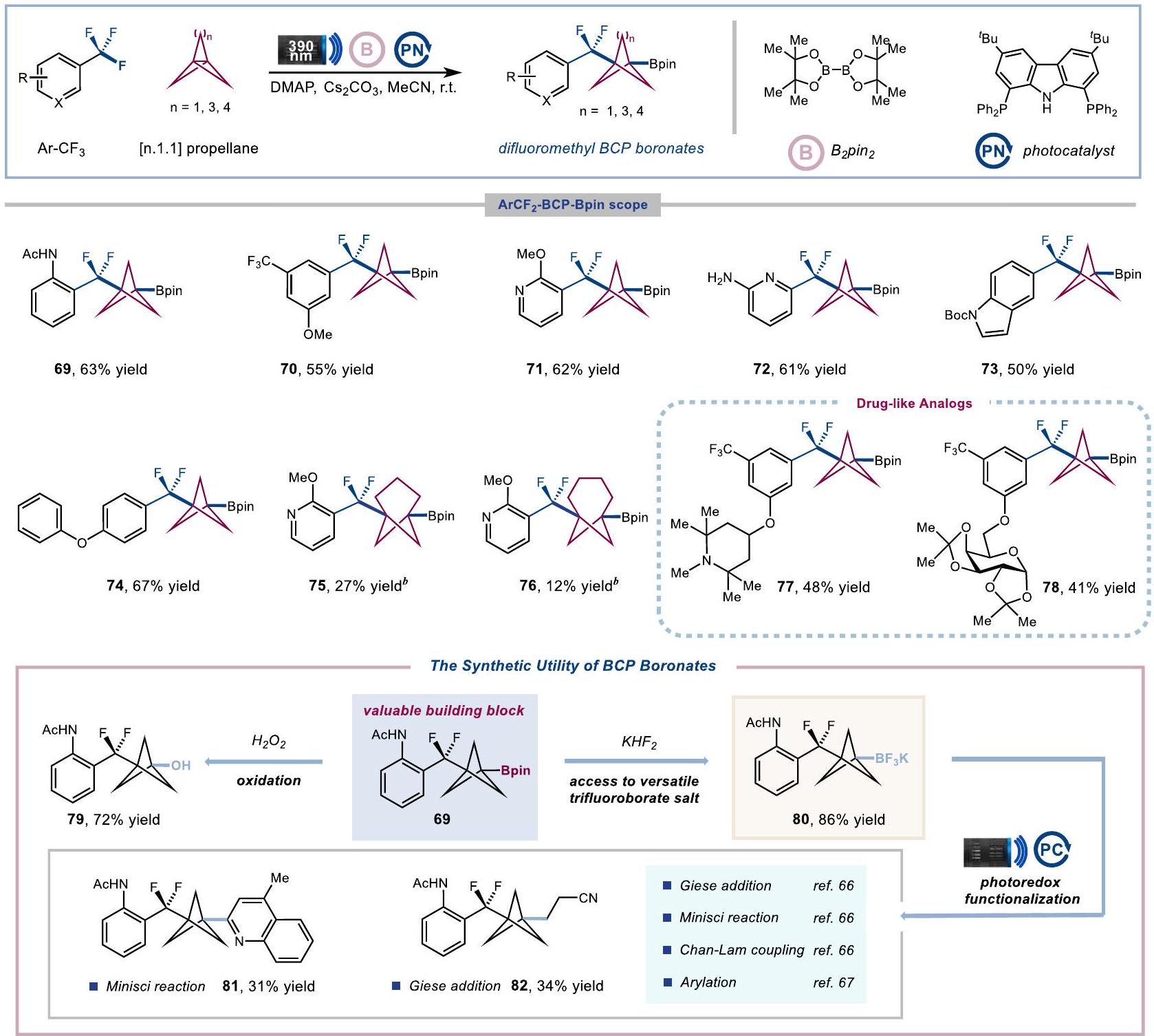

تركيب ثنائي فلوروميثيل BCP أرين كبديل جديد لمجموعة البنزويل والتقييم اللاحق لخصائصها الدوائية لا يزال غير مستكشف إلى حد كبير (الشكل 1ب)

(الشكل 1ج). بشكل محدد، يمكن أن يبدأ اختزال الإلكترون الواحد تفعيلًا انتقائيًا للثلاثي فلوروميثيل أرينات باستخدام محفز ضوئي مثير مختزل. ستُحبس الجذور الديفلورو بنزيل الناتجة بعد ذلك بواسطة [1.1.1] بروبلين، مما يؤدي إلى جذور BCP، التي يمكن أن تشارك في نقل ذرة الهيدروجين أو البوريل، مما ينتج الهياكل المطلوبة من BCP أرين ديفلورو ميثيل / بورونات BCP ديفلورو ميثيل.

النتائج

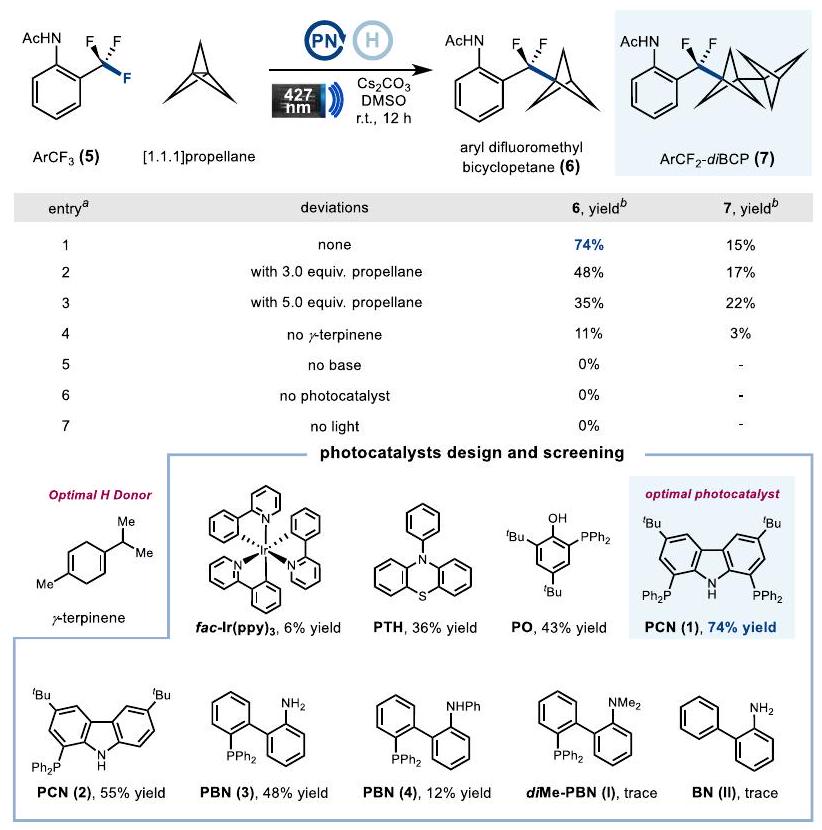

تحسين التفاعل

المحفز الضوئي والقاعدة انظر المعلومات التكميلية.

لمدة 12 ساعة. اختيار المحفز الضوئي والقاعدة انظر المعلومات التكميلية.

إلى 3.0 أو 5.0 مكافئ أدى إلى انخفاض كبير في كفاءات التفاعل بسبب تفاعل الديميراز غير المنتج الذي يؤدي إلى الديمير 7 (المدخلات 2-3). أخيرًا، كشفت تجارب التحكم أن المحفز الضوئي، والقاعدة، والضوء المرئي كانت جميعها ضرورية لنجاح هذا التحول (المدخلات 5-7). تم تنفيذ التفاعل بشكل سيء في غياب

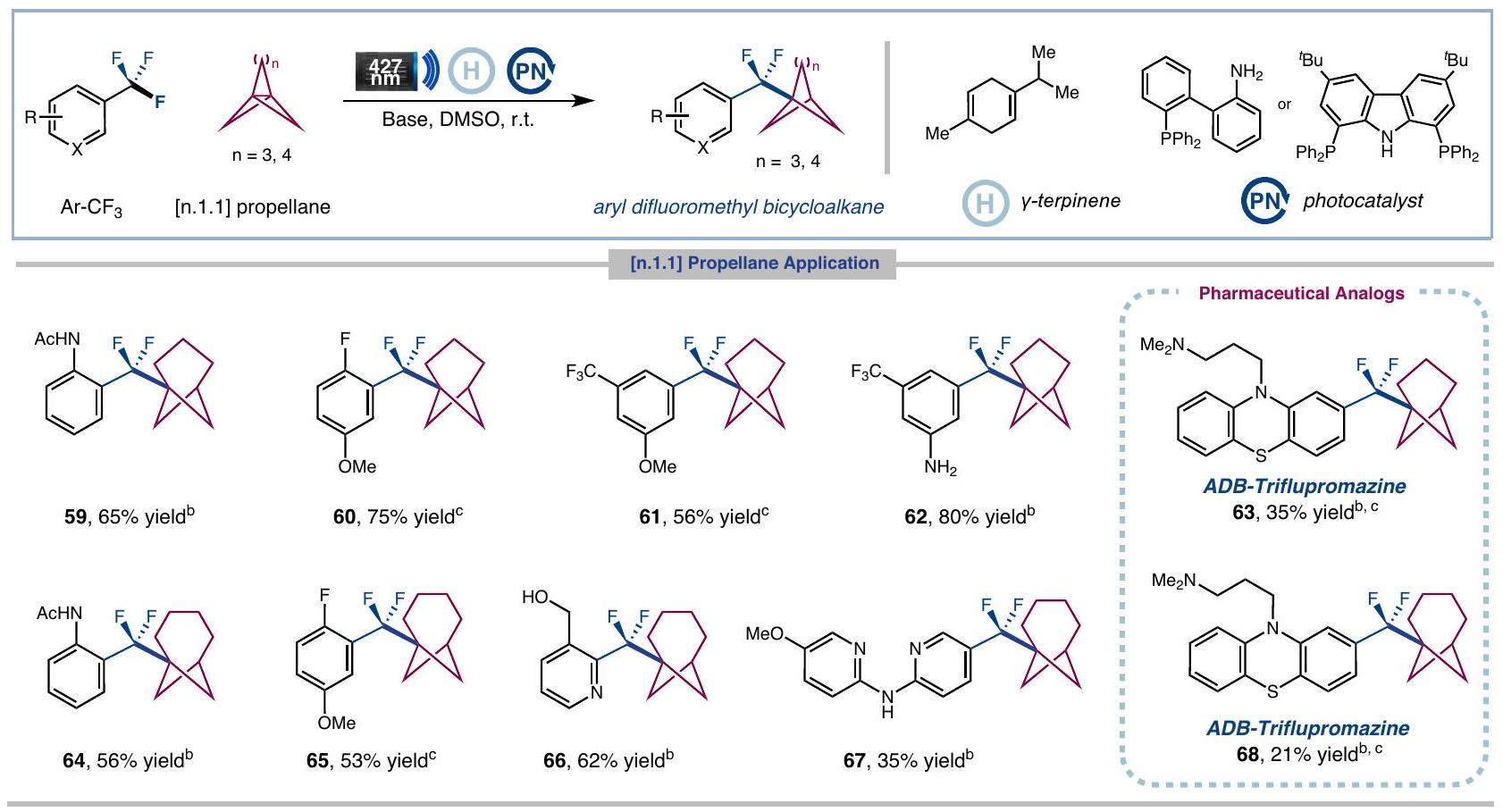

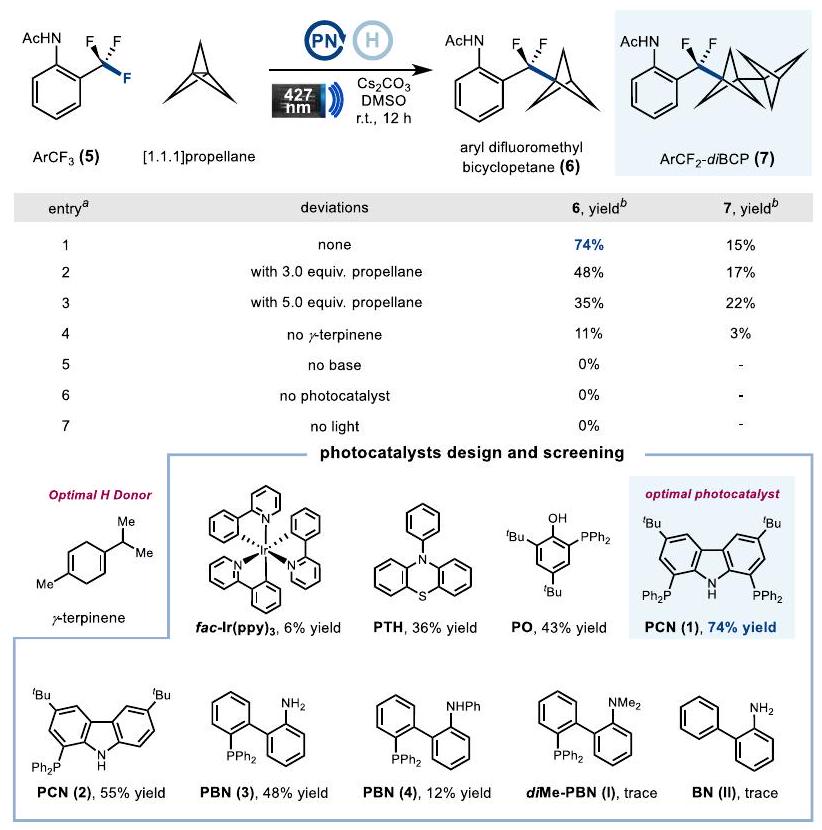

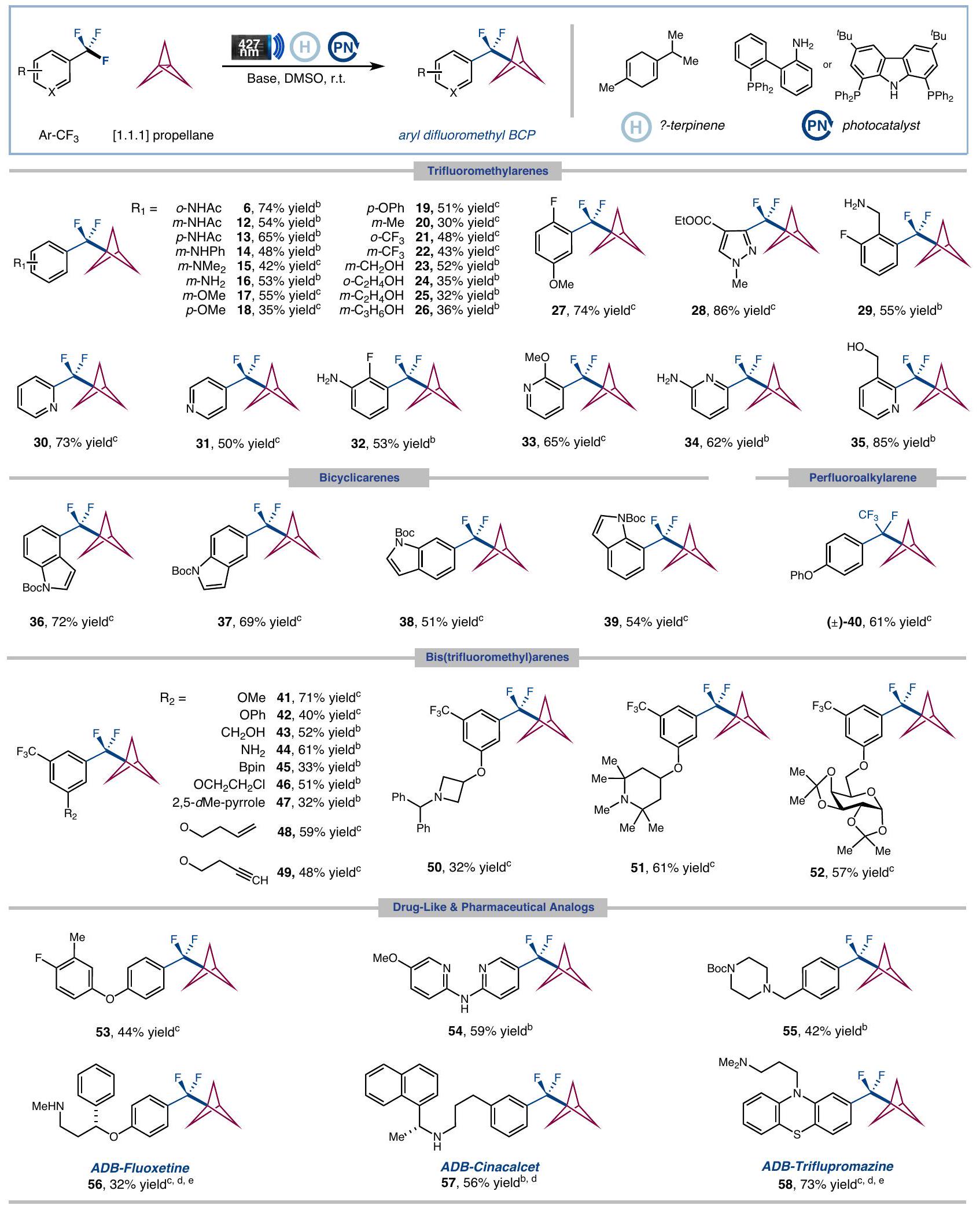

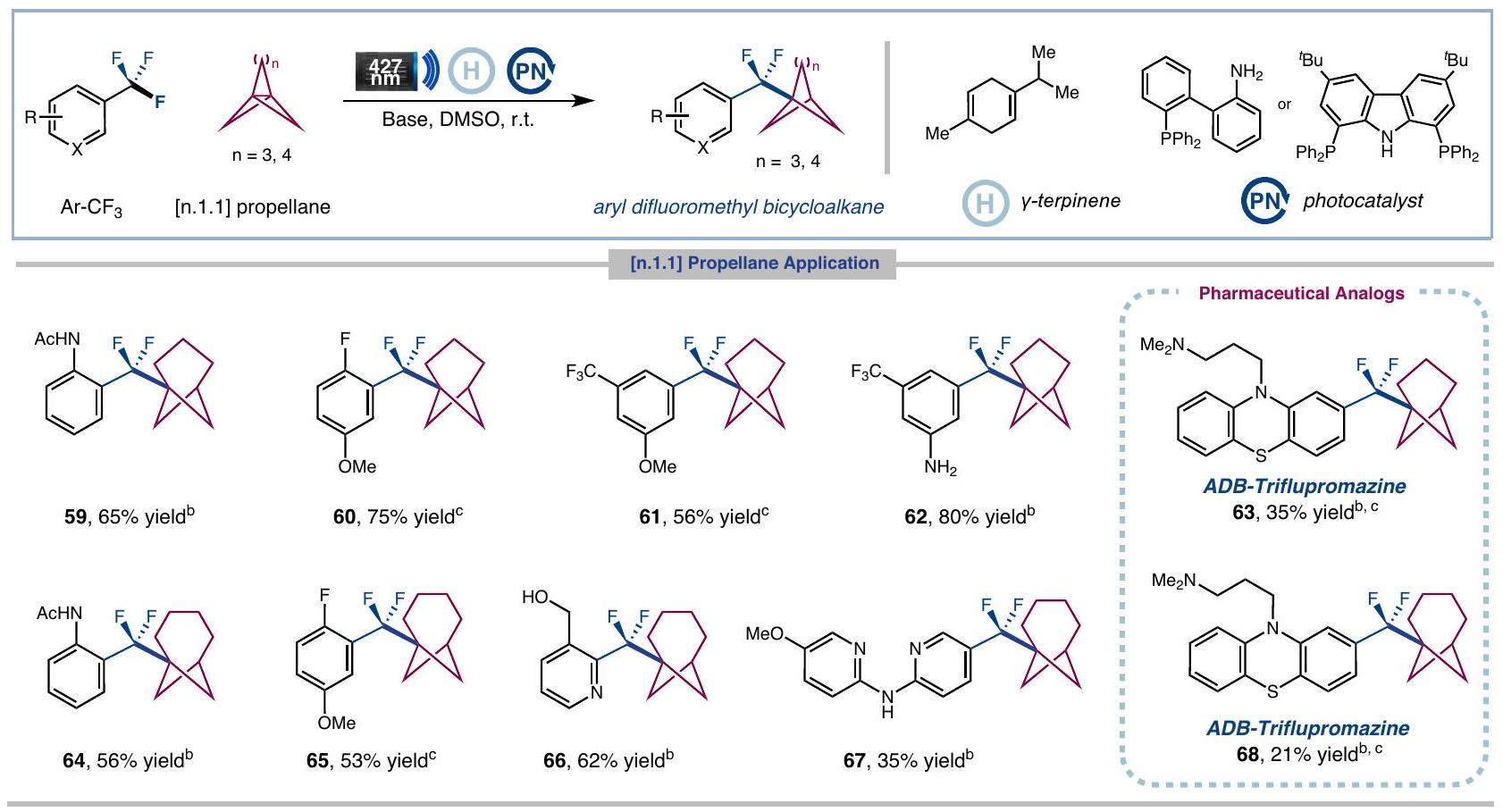

نطاق ركيزة التفاعل

(

لركائز البيريدين مع مجموعات ثلاثي فلوروميثيل في

تُبرز النتائج بشكل أكبر الفائدة العملية لهذه التقنية في الربط الخالية من الفلور.

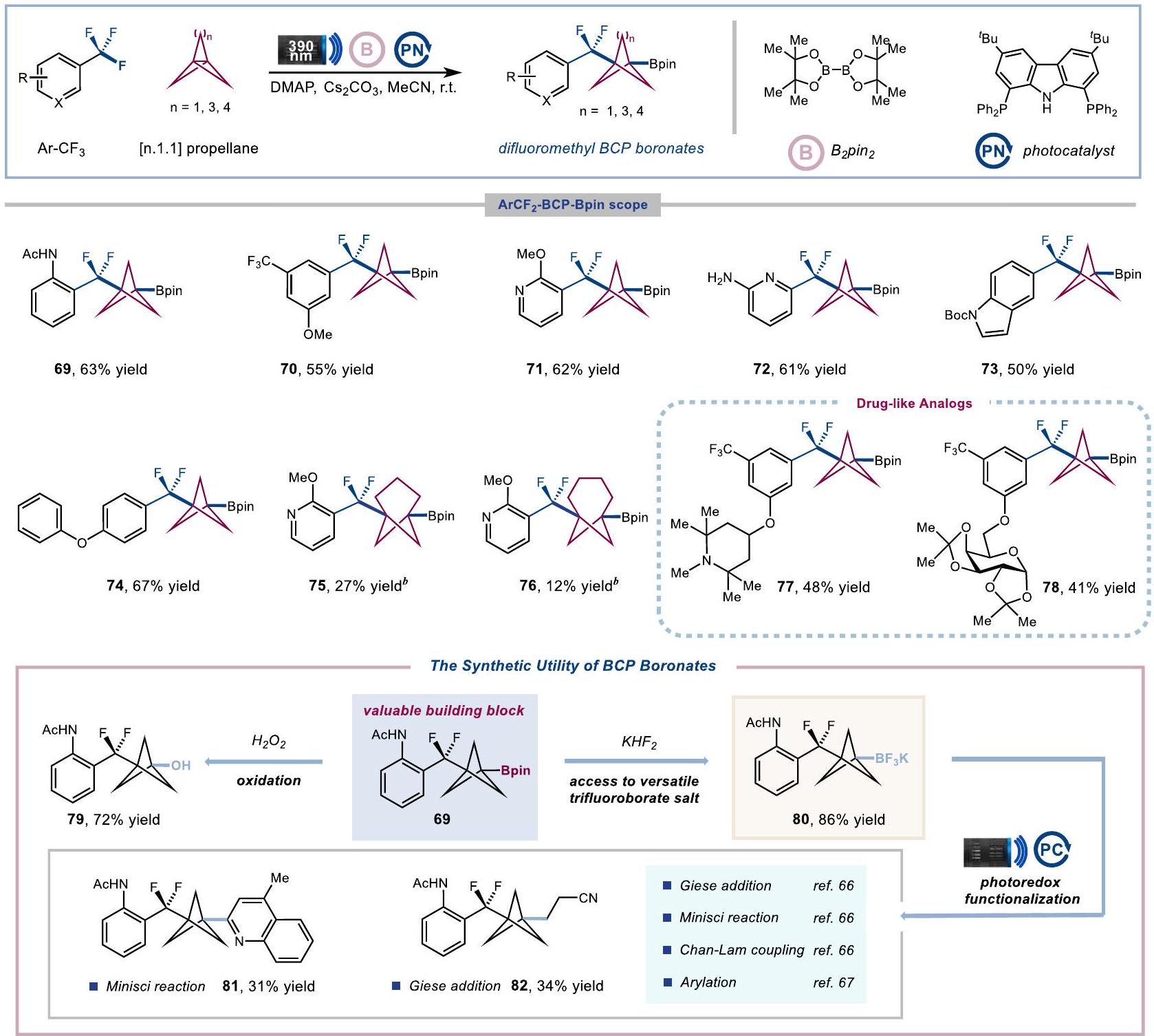

نطاق الربط ثلاثي المكونات

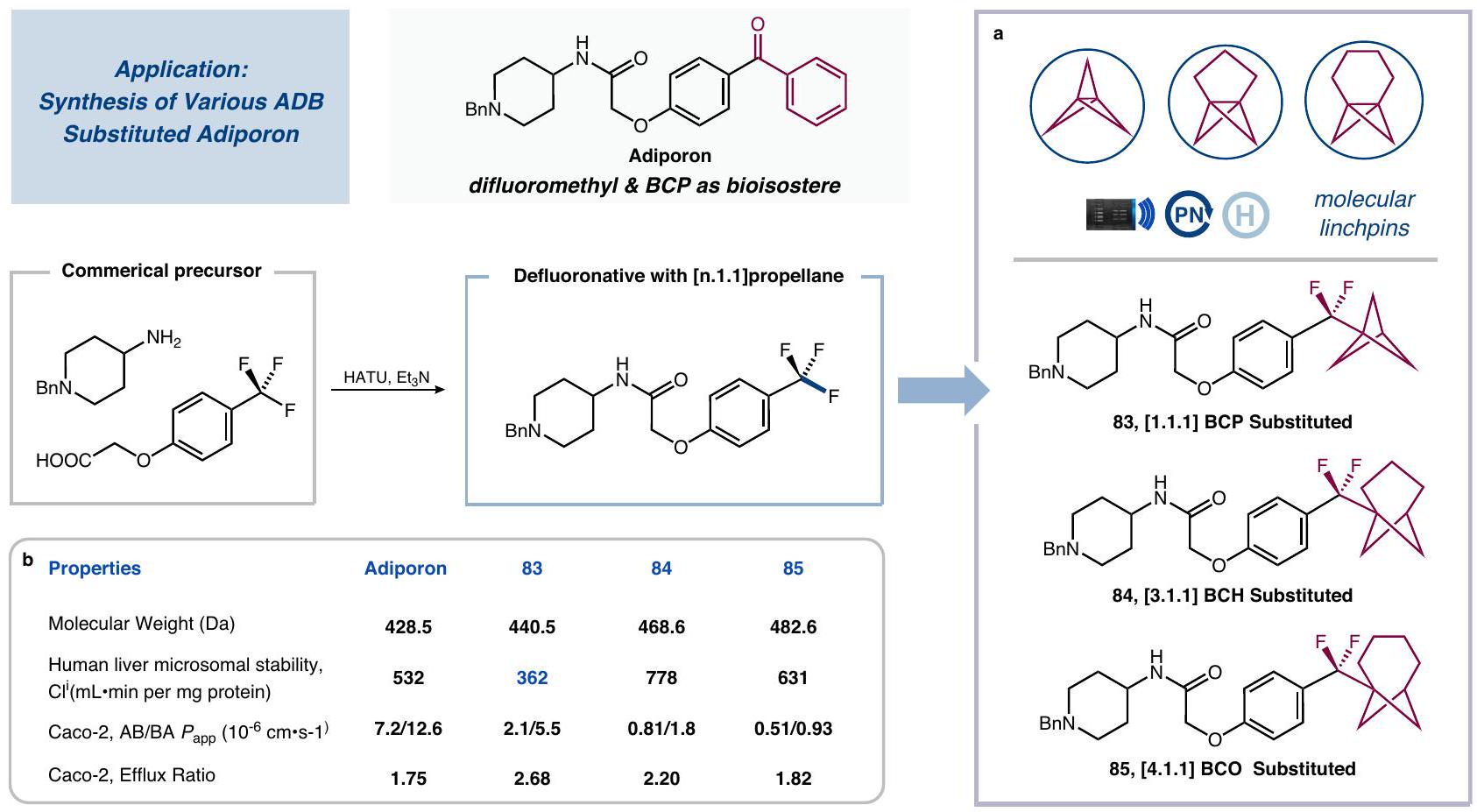

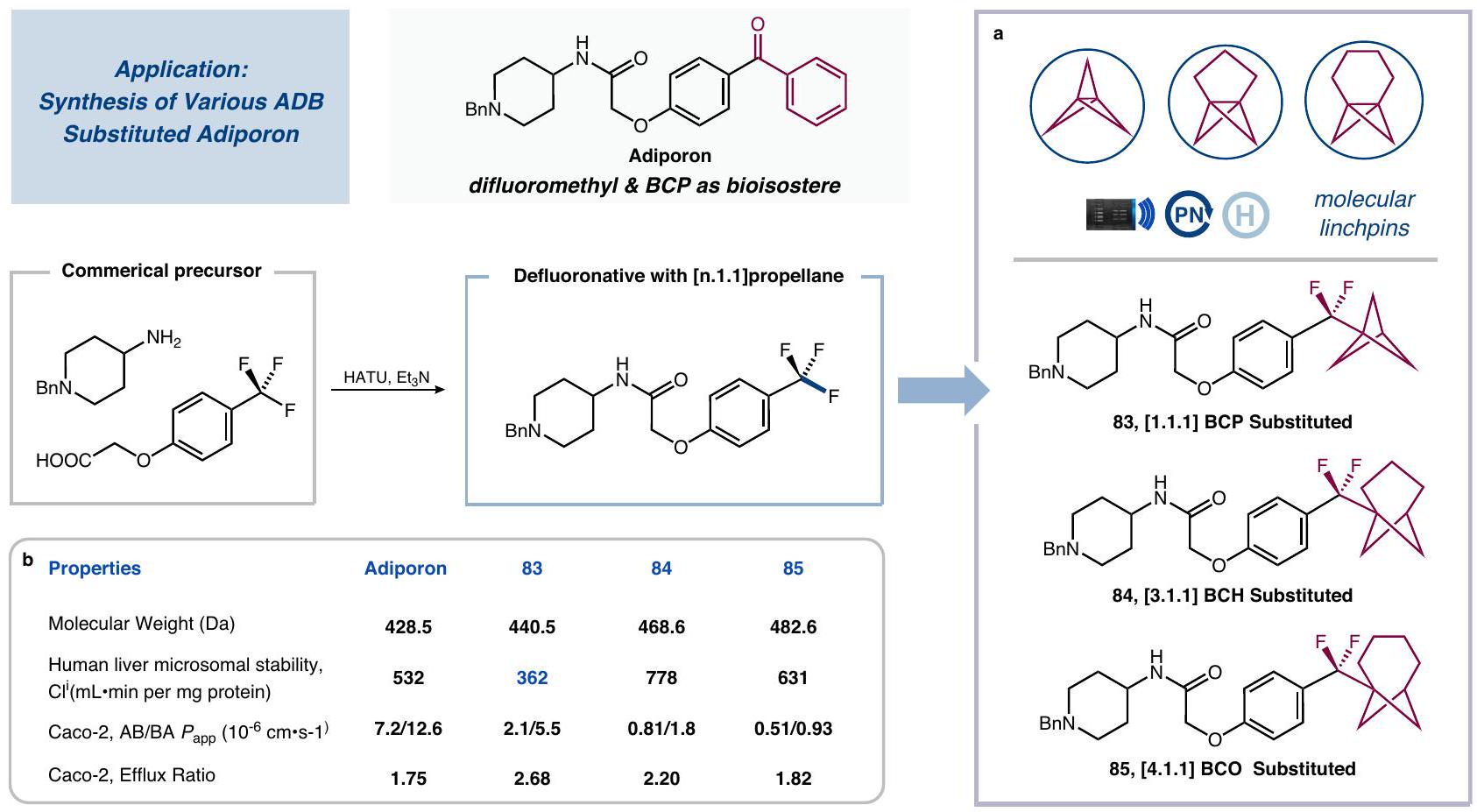

تحضير النظائر الصيدلانية

-أديبورون و 85 [4.1.1]BCO-أديبورون). ثم قمنا باختبار هذه النظائر الدوائية ADB مقارنةً بنظائرها التي تحتوي على البنزوفيكون. ومن المثير للاهتمام أن النظير 83 المستبدل بـ [1.1.1]BCP وُجد أنه مستقر من الناحية الأيضية، مع معدلات تصفية منخفضة في الميكروسومات الكبدية البشرية، على الرغم من أن نفاذيته عبر الغشاء (Caco-2) كانت منخفضة قليلاً مقارنةً بالدواء الأصلي. تؤكد هذه النتائج على إمكانيات هيكل ADB كعنصر مفيد لتعزيز الخصائص الصيدلانية لمرشحي الأدوية التي تحتوي على نواة البنزوفيكون.

طرق

الإجراء العام للربط بدون فلور

تفاعل في درجة حرارة الغرفة) لمدة 12 ساعة. تم إزالة خليط التفاعل من الضوء، وتبريده إلى درجة حرارة الغرفة، وتم إيقاف التفاعل بالتعرض للهواء. تم تخفيفه بالماء وEA، وتم استخراج الطبقة المائية بثلاثة أجزاء من EA. تم غسل الطبقات العضوية المجمعة بمحلول ملحي، وتجفيفها.

الإجراء العام للتوصيل الثلاثي غير الفلوري

توفر البيانات

References

- Meanwell, N. A. Improving drug design: an update on recent applications of efficiency metrics, strategies for replacing problematic elements, and compounds in nontraditional drug space. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 29, 564-616 (2016).

- Thornber, C. W. Isosterism and molecular modification in drug design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 8, 563-580 (1979).

- Wermuth, C. G. Similarity in drugs: reflections on analogue design. Drug Discov. Today 11, 348-354 (2006).

- Lovering, F., Bikker, J. & Humblet, C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 52, 6752-6756 (2009).

- Kumari, S., Carmona, A. V., Tiwari, A. K. & Trippier, P. C. Amide bond bioisosteres: strategies, synthesis, and successes. J. Med. Chem. 63, 12290-12358 (2020).

- Meanwell, N. A. Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 54, 2529-2591 (2011).

- Subbaiah, M. A. M. & Meanwell, N. A. Bioisosteres of the phenyl ring: recent strategic applications in lead optimization and drug design. J. Med. Chem. 64, 14046-14128 (2021).

- Measom, N. D. et al. Investigation of a bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane as a phenyl replacement within an LpPLA

inhibitor. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 8, 43-48 (2017). - Stepan, A. F. et al. Application of the bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane motif as a nonclassical phenyl ring bioisostere in the design of a potent and orally active

-secretase inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 55, 3414-3424 (2012). - Pu, Q. et al. Discovery of potent and orally available bicyclo[1.1.1] Pentane-derived Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 1548-1554 (2020).

- Shire, B. R. & Anderson, E. A. Conquering the synthesis and functionalization of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes. JACS Au 3, 1539-1553 (2023).

- Zhang, X. et al. Copper-mediated synthesis of drug-like bicyclopentanes. Nature 580, 220-226 (2020).

- Nugent, J. et al. A general route to bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes through photoredox catalysis. ACS Catal. 9, 9568-9574 (2019).

- Kraemer, Y. et al. Strain-release pentafluorosulfanylation and tetrafluoro(aryl)sulfanylation of [1.1.1]propellane: reactivity and structural insight. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211892 (2022).

- Wu, S.-B., Long, C. & Kennelly, E. J. Structural diversity and bioactivities of natural benzophenones. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 1158-1174 (2014).

- Rentería-Gómez, A. et al. General and practical route to diverse 1-(difluoro)alkyl-3-aryl Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes enabled by an Fecatalyzed multicomponent radical cross-coupling reaction. ACS Catal. 12, 11547-11556 (2022).

- Cuadros, S. et al. A general organophotoredox strategy to difluoroalkyl bicycloalkane (CF2-BCA) Hybrid Bioisosteres. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303585 (2023).

- Mandal, D., Gupta, R., Jaiswal, A. K. & Young, R. D. Frustrated Lewis-Pair-meditated selective single fluoride substitution in trifluoromethyl groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2572-2578 (2020).

- Yang, R.-Y. et al. Synthesis of

and via cleavage of the trifluoromethylsulfonyl group. Org. Lett. 24, 164-168 (2022). - Santos, L. et al. Deprotonative functionalization of the difluoromethyl group. Org. Lett. 22, 8741-8745 (2020).

- Acuna, U. M., Jancovski, N. & Kennelly, E. J. Polyisoprenylated benzophenones from clusiaceae: potential drugs and lead compounds. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 9, 1560-1580 (2009).

- Surana, K., Chaudhary, B., Diwaker, M. & Sharma, S. Benzophenone: a ubiquitous scaffold in medicinal chemistry. MedChemComm 9, 1803-1817 (2018).

- Wang, G. et al. Design, synthesis, and anticancer evaluation of benzophenone derivatives bearing naphthalene moiety as novel tubulin polymerization inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 104, 104265 (2020).

- Simur, T. T., Ye, T., Yu, Y.-J., Zhang, F.-L. & Wang, Y.-F. C-F bond functionalizations of trifluoromethyl groups via radical intermediates. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 1193-1198 (2022).

- Yoshida, S., Shimomori, K., Kim, Y. & Hosoya, T. Single C-F bond cleavage of trifluoromethylarenes with an ortho-silyl group. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 10406-10409 (2016).

- Mandal, D., Gupta, R. & Young, R. D. Selective monodefluorination and Wittig functionalization of gem-difluoromethyl groups to generate monofluoroalkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10682-10686 (2018).

- Idogawa, R., Kim, Y., Shimomori, K., Hosoya, T. & Yoshida, S. Single C-F transformations of o-hydrosilyl benzotrifluorides with trityl compounds as all-in-one reagents. Org. Lett. 22, 9292-9297 (2020).

- Utsumi, S., Katagiri, T. & Uneyama, K. Cu-deposits on Mg metal surfaces promote electron transfer reactions. Tetrahedron 68, 1085-1091 (2012).

- Dang, H., Whittaker, A. M. & Lalic, G. Catalytic activation of a single C-F bond in trifluoromethyl arenes. Chem. Sci. 7, 505-509 (2016).

- Munoz, S. B. et al. Selective late-stage hydrodefluorination of trifluoromethylarenes: a facile access to difluoromethylarenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2322-2326 (2017).

- Wright, S. E. & Bandar, J. S. A base-promoted reductive coupling platform for the divergent defluorofunctionalization of trifluoromethylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 13032-13038 (2022).

- Zhou, F.-Y. & Jiao, L. Asymmetric defluoroallylation of 4-trifluoromethylpyridines enabled by umpolung C-F bond activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201102 (2022).

- Shen, Z.-J. et al. Organoboron reagent-controlled selective (deutero)hydrodefluorination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217244 (2023).

- Box, J. R., Avanthay, M. E., Poole, D. L. & Lennox, A. J. J. Electronically ambivalent hydrodefluorination of aryl-CF3 groups enabled by electrochemical deep-reduction on a Ni cathode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218195 (2023).

- Yu, Y.-J. et al. Sequential C-F bond functionalizations of trifluoroacetamides and acetates via spin-center shifts. Science 371, 1232-1240 (2021).

- Zhang, X. et al. A carbene strategy for progressive (Deutero) hydrodefluorination of fluoroalkyl ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202116190 (2022).

- Li, L. et al. Carbodefluorination of fluoroalkyl ketones via a carbeneinitiated rearrangement strategy. Nat. Commun. 13, 4280 (2022).

- Chen, K., Berg, N., Gschwind, R. & König, B. Selective single

bond cleavage in trifluoromethylarenes: merging visible-light catalysis with lewis acid activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18444-18447 (2017). - Wang, H. & Jui, N. T. Catalytic defluoroalkylation of trifluoromethylaromatics with unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 163-166 (2018).

- Vogt, D. B., Seath, C. P., Wang, H. & Jui, N. T. Selective C-F functionalization of unactivated trifluoromethylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13203-13211 (2019).

- Sap, J. B. I. et al. Organophotoredox hydrodefluorination of trifluoromethylarenes with translational applicability to drug discovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 9181-9187 (2020).

- Campbell, M. W. et al. Photochemical C-F activation enables defluorinative alkylation of trifluoroacetates and -acetamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 19648-19654 (2021).

- Shreiber, S. T. et al. Visible-light-induced C-F bond activation for the difluoroalkylation of indoles. Org. Lett. 24, 8542-8546 (2022).

- Ye, J.-H., Bellotti, P., Heusel, C. & Glorius, F. Photoredox-catalyzed defluorinative functionalizations of polyfluorinated aliphatic amides and esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202115456 (2022).

- Luo, Y.-C., Tong, F.-F., Zhang, Y., He, C.-Y. & Zhang, X. Visible-lightinduced palladium-catalyzed selective defluoroarylation of trifluoromethylarenes with arylboronic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 13971-13979 (2021).

- Sugihara, N., Suzuki, K., Nishimoto, Y. & Yasuda, M. Photoredoxcatalyzed C-F bond allylation of perfluoroalkylarenes at the benzylic position. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 9308-9313 (2021).

- Yan, S.-S. et al. Visible-light photoredox-catalyzed selective carboxylation of C(sp3)-F bonds with CO2. Chem 7, 3099-3113 (2021).

- Ghosh, S. et al. HFIP-assisted single C-F bond activation of trifluoromethyl ketones using visible-light photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202115272 (2022).

- Liu, C., Li, K. & Shang, R. Arenethiolate as a dual function catalyst for photocatalytic defluoroalkylation and hydrodefluorination of trifluoromethyls. ACS Catal. 12, 4103-4109 (2022).

- Liu, C., Shen, N. & Shang, R. Photocatalytic defluoroalkylation and hydrodefluorination of trifluoromethyls using o-phosphinophenolate. Nat. Commun. 13, 354 (2022).

- Wang, J. et al. Late-stage modification of drugs via alkene formal insertion into benzylic C-F bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202215062 (2023).

- Xu, J. et al. Construction of C-X (

) bonds via Lewis acidpromoted functionalization of trifluoromethylarenes. ACS Catal. 13, 7339-7346 (2023). - Xu, P. et al. Defluorinative alkylation of trifluoromethylbenzimidazoles enabled by spin-center shift: a

synergistic photocatalysis/thiol catalysis process with. Org. Lett. 24, 4075-4080 (2022). - Wiberg, K. B. & Waddell, S. T. Reactions of [1.1.1]propellane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 2194-2216 (1990).

- Li, M. et al. Transition-metal-free radical

and coupling enabled by 2 -azaallyls as super-electron-donors and coupling-partners. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16327-16333 (2017). - Bortolato, T. et al. The rational design of reducing organophotoredox catalysts unlocks proton-coupled electron-transfer and atom transfer radical polymerization mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 1835-1846 (2023).

- Schweitzer-Chaput, B., Horwitz, M. A., de Pedro Beato, E. & Melchiorre, P. Photochemical generation of radicals from alkyl electrophiles using a nucleophilic organic catalyst. Nat. Chem. 11, 129-135 (2019).

- Mykhailiuk, P. K. Saturated bioisosteres of benzene: where to go next? Org. Biomol. Chem. 17, 2839-2849 (2019).

- Frank, N. et al. Synthesis of meta-substituted arene bioisosteres from [3.1.1]propellane. Nature 611, 721-726 (2022).

- lida, T. et al. Practical and facile access to bicyclo[3.1.1]heptanes: potent bioisosteres of meta -substituted benzenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21848-21852 (2022).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Photochemical intermolecular

-cycloaddition for the construction of aminobicyclo[3.1.1]heptanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 23685-23690 (2022). - Kleinmans, R. et al. ortho -Selective dearomative [

] photocycloadditions of bicyclic aza-arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12324-12332 (2023). - Fuchs, J. & Szeimies, G. Synthese von [

.1.1]propellanen ( ). Chem. Ber. 125, 2517-2522 (1992). - Kondo, M. et al. Silaboration of [1.1.1]propellane: a storable feedstock for bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 1970-1974 (2020).

- Shelp, R. A. et al. Strain-release 2-azaallyl anion addition/borylation of [1.1.1]propellane: synthesis and functionalization of benzylamine bicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl boronates. Chem. Sci. 12, 7066-7072 (2021).

- Dong, W. et al. Exploiting the sp2 character of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl radicals in the transition-metal-free multi-component difunctionalization of [1.1.1]propellane. Nat. Chem. 14, 1068-1077 (2022).

- VanHeyst, M. D. et al. Continuous flow-enabled synthesis of benchstable Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane trifluoroborate salts and their utilization in metallaphotoredox cross-couplings. Org. Lett. 22, 1648-1654 (2020).

- Yang, Y. et al. An intramolecular coupling approach to alkyl bioisosteres for the synthesis of multisubstituted bicycloalkyl boronates. Nat. Chem. 13, 950-955 (2021).

- Nicolas, S. et al. Adiporon, an adiponectin receptor agonist acts as an antidepressant and metabolic regulator in a mouse model of depression. Transl. Psychiatry 8, 159 (2018).

- Manley, S. J. et al. Synthetic adiponectin-receptor agonist, AdipoRon, induces glycolytic dependence in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 13, 114 (2022).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44653-6.

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى شياهينغ تشانغ.

© المؤلفون 2024

مدرسة الكيمياء وعلوم المواد، معهد هانغتشو للدراسات المتقدمة، جامعة الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، 1 زقاق فرعي شيانغشان، 310024 هانغتشو، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. قسم الكيمياء، جامعة طوكيو، طوكيو 113-0033، اليابان. البريد الإلكتروني: xiahengz@ucas.ac.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44653-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38199996

Publication Date: 2024-01-10

C-F bond activation enables synthesis of aryl difluoromethyl bicyclopentanes as benzophenone-type bioisosteres

Accepted: 22 December 2023

Published online: 10 January 2024

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

Bioisosteric design has become an essential approach in the development of drug molecules. Recent advancements in synthetic methodologies have enabled the rapid adoption of this strategy into drug discovery programs. Consequently, conceptionally innovative practices would be appreciated by the medicinal chemistry community. Here we report an expeditous synthetic method for synthesizing aryl difluoromethyl bicyclopentane (ADB) as a bioisostere of the benzophenone core. This approach involves the merger of lightdriven C-F bond activation and strain-release chemistry under the catalysis of a newly designed

synthesis of difluoromethyl BCP arene as a new surrogate of the benzoyl group and the subsequent evaluation of their pharmacokinetic properties remain largely underexplored (Fig. 1b)

(Fig. 1c). Specifically, a single-electron reduction can initiate the selective activation of trifluoromethylarenes by using a reducing excited photocatalyst. The resulting difluorobenzylic radicals would then be trapped by [1.1.1]propellane leading to BCP radicals, which could be engaged in hydrogen atom transfer or borylation generating the desired difluoromethyl BCP arene/difluoromethyl BCP boronate scaffolds.

Results

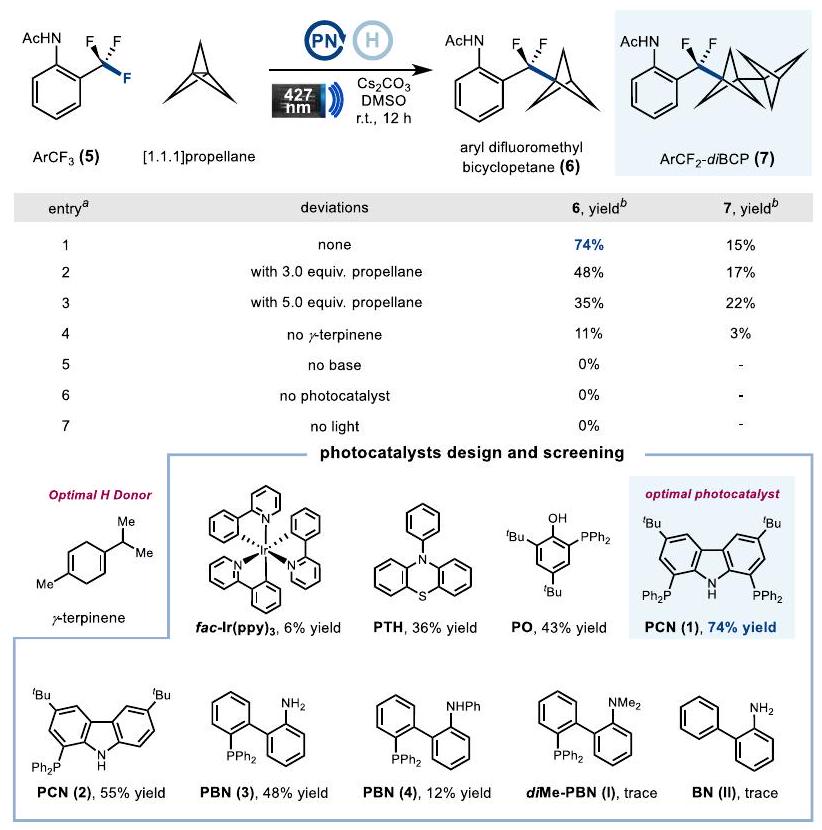

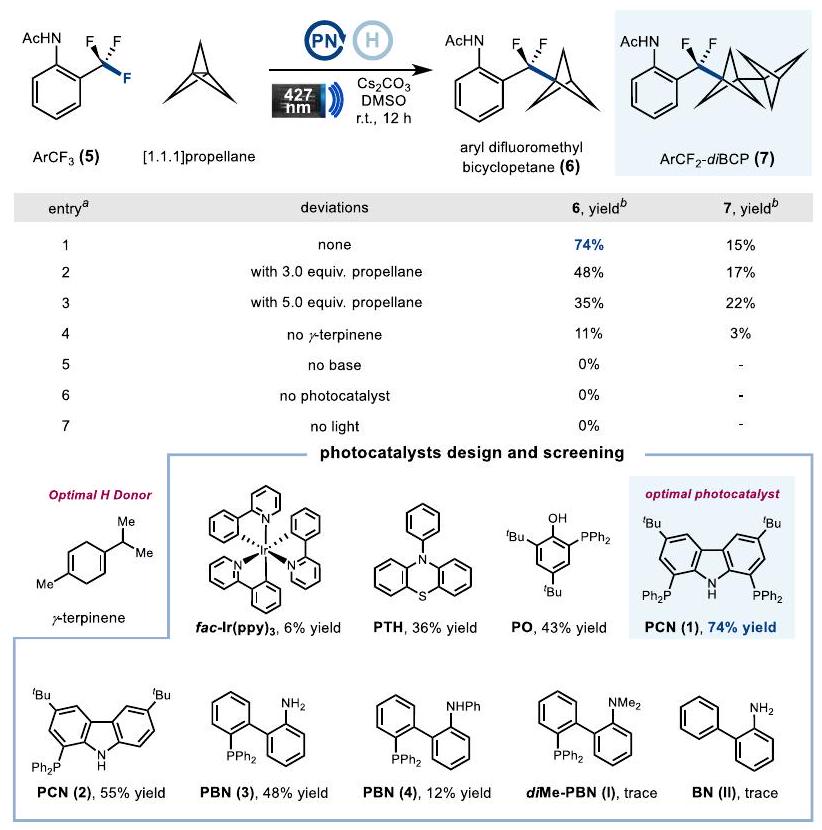

Reaction optimization

photocatalyst & base see Supplementary Information.

for 12 h . Selection of photocatalyst & base see Supplementary Information.

to 3.0 or 5.0 equiv. resulted in a significant decrease in reaction efficiencies due to the unproductive propellane dimerization leading to dimer 7(entries 2-3). Finally, control experiments revealed that the photocatalyst, base and visible-light were all essential for the success of this transformation (entries 5-7). The reaction proceeded poorly in the absence of

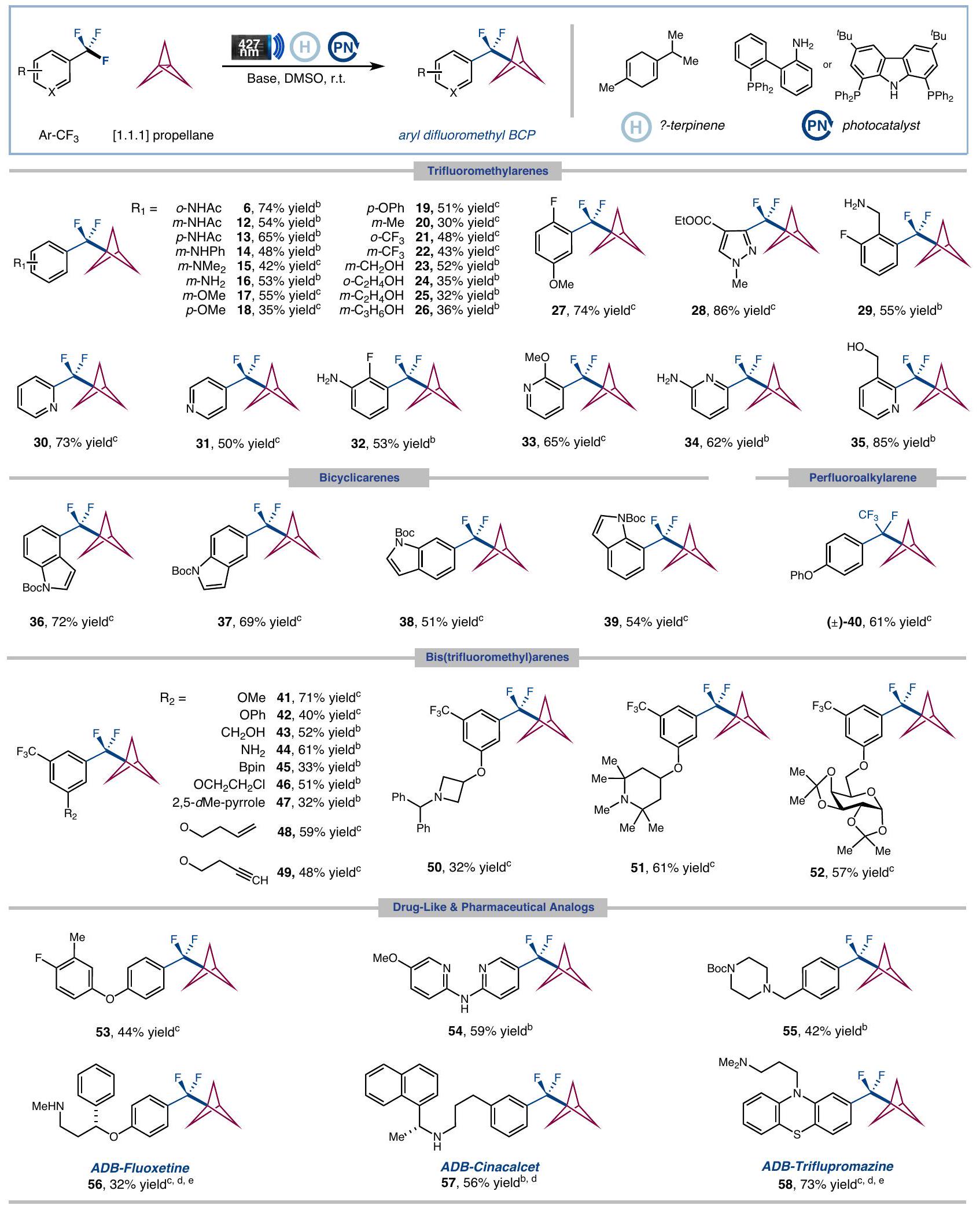

Reaction substrate scope

(

of pyridine substrates with trifluoromethyl groups at

results further highlight the real-world utility of this defluorinative coupling technology.

Scope for three-component coupling

Preparation of pharmaceutical analogs

-Adiporon and 85 [4.1.1]BCO-Adiporon). We then tested these ADB pharmaceutical analogs in comparison to their benzophenonecontaining counterparts. Interestingly, [1.1.1]BCP substituted analog 83 was found to be metabolically stable, with reduced clearance rates in human liver microsomes, although its membrane permeability (Caco-2) was slightly decreased compared to its parent drug. These findings underline the potential of the ADB scaffold as a beneficial motif for enhancing the pharmacological properties of drug candidates containing a benzophenone core.

Methods

General procedure for defluorinative coupling of

reaction at room temperature) for 12 hours. The reaction mixture was removed from the light, cooled to ambient temperature, and quenched by exposure to air. diluted with water and EA , and the aqueous layer was extracted with three portions of EA . The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over

General procedure for defluorinative three-component coupling

Data availability

References

- Meanwell, N. A. Improving drug design: an update on recent applications of efficiency metrics, strategies for replacing problematic elements, and compounds in nontraditional drug space. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 29, 564-616 (2016).

- Thornber, C. W. Isosterism and molecular modification in drug design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 8, 563-580 (1979).

- Wermuth, C. G. Similarity in drugs: reflections on analogue design. Drug Discov. Today 11, 348-354 (2006).

- Lovering, F., Bikker, J. & Humblet, C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 52, 6752-6756 (2009).

- Kumari, S., Carmona, A. V., Tiwari, A. K. & Trippier, P. C. Amide bond bioisosteres: strategies, synthesis, and successes. J. Med. Chem. 63, 12290-12358 (2020).

- Meanwell, N. A. Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 54, 2529-2591 (2011).

- Subbaiah, M. A. M. & Meanwell, N. A. Bioisosteres of the phenyl ring: recent strategic applications in lead optimization and drug design. J. Med. Chem. 64, 14046-14128 (2021).

- Measom, N. D. et al. Investigation of a bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane as a phenyl replacement within an LpPLA

inhibitor. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 8, 43-48 (2017). - Stepan, A. F. et al. Application of the bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane motif as a nonclassical phenyl ring bioisostere in the design of a potent and orally active

-secretase inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 55, 3414-3424 (2012). - Pu, Q. et al. Discovery of potent and orally available bicyclo[1.1.1] Pentane-derived Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 1548-1554 (2020).

- Shire, B. R. & Anderson, E. A. Conquering the synthesis and functionalization of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes. JACS Au 3, 1539-1553 (2023).

- Zhang, X. et al. Copper-mediated synthesis of drug-like bicyclopentanes. Nature 580, 220-226 (2020).

- Nugent, J. et al. A general route to bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes through photoredox catalysis. ACS Catal. 9, 9568-9574 (2019).

- Kraemer, Y. et al. Strain-release pentafluorosulfanylation and tetrafluoro(aryl)sulfanylation of [1.1.1]propellane: reactivity and structural insight. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211892 (2022).

- Wu, S.-B., Long, C. & Kennelly, E. J. Structural diversity and bioactivities of natural benzophenones. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 1158-1174 (2014).

- Rentería-Gómez, A. et al. General and practical route to diverse 1-(difluoro)alkyl-3-aryl Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes enabled by an Fecatalyzed multicomponent radical cross-coupling reaction. ACS Catal. 12, 11547-11556 (2022).

- Cuadros, S. et al. A general organophotoredox strategy to difluoroalkyl bicycloalkane (CF2-BCA) Hybrid Bioisosteres. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303585 (2023).

- Mandal, D., Gupta, R., Jaiswal, A. K. & Young, R. D. Frustrated Lewis-Pair-meditated selective single fluoride substitution in trifluoromethyl groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2572-2578 (2020).

- Yang, R.-Y. et al. Synthesis of

and via cleavage of the trifluoromethylsulfonyl group. Org. Lett. 24, 164-168 (2022). - Santos, L. et al. Deprotonative functionalization of the difluoromethyl group. Org. Lett. 22, 8741-8745 (2020).

- Acuna, U. M., Jancovski, N. & Kennelly, E. J. Polyisoprenylated benzophenones from clusiaceae: potential drugs and lead compounds. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 9, 1560-1580 (2009).

- Surana, K., Chaudhary, B., Diwaker, M. & Sharma, S. Benzophenone: a ubiquitous scaffold in medicinal chemistry. MedChemComm 9, 1803-1817 (2018).

- Wang, G. et al. Design, synthesis, and anticancer evaluation of benzophenone derivatives bearing naphthalene moiety as novel tubulin polymerization inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 104, 104265 (2020).

- Simur, T. T., Ye, T., Yu, Y.-J., Zhang, F.-L. & Wang, Y.-F. C-F bond functionalizations of trifluoromethyl groups via radical intermediates. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 1193-1198 (2022).

- Yoshida, S., Shimomori, K., Kim, Y. & Hosoya, T. Single C-F bond cleavage of trifluoromethylarenes with an ortho-silyl group. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 10406-10409 (2016).

- Mandal, D., Gupta, R. & Young, R. D. Selective monodefluorination and Wittig functionalization of gem-difluoromethyl groups to generate monofluoroalkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10682-10686 (2018).

- Idogawa, R., Kim, Y., Shimomori, K., Hosoya, T. & Yoshida, S. Single C-F transformations of o-hydrosilyl benzotrifluorides with trityl compounds as all-in-one reagents. Org. Lett. 22, 9292-9297 (2020).

- Utsumi, S., Katagiri, T. & Uneyama, K. Cu-deposits on Mg metal surfaces promote electron transfer reactions. Tetrahedron 68, 1085-1091 (2012).

- Dang, H., Whittaker, A. M. & Lalic, G. Catalytic activation of a single C-F bond in trifluoromethyl arenes. Chem. Sci. 7, 505-509 (2016).

- Munoz, S. B. et al. Selective late-stage hydrodefluorination of trifluoromethylarenes: a facile access to difluoromethylarenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2322-2326 (2017).

- Wright, S. E. & Bandar, J. S. A base-promoted reductive coupling platform for the divergent defluorofunctionalization of trifluoromethylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 13032-13038 (2022).

- Zhou, F.-Y. & Jiao, L. Asymmetric defluoroallylation of 4-trifluoromethylpyridines enabled by umpolung C-F bond activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201102 (2022).

- Shen, Z.-J. et al. Organoboron reagent-controlled selective (deutero)hydrodefluorination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217244 (2023).

- Box, J. R., Avanthay, M. E., Poole, D. L. & Lennox, A. J. J. Electronically ambivalent hydrodefluorination of aryl-CF3 groups enabled by electrochemical deep-reduction on a Ni cathode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218195 (2023).

- Yu, Y.-J. et al. Sequential C-F bond functionalizations of trifluoroacetamides and acetates via spin-center shifts. Science 371, 1232-1240 (2021).

- Zhang, X. et al. A carbene strategy for progressive (Deutero) hydrodefluorination of fluoroalkyl ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202116190 (2022).

- Li, L. et al. Carbodefluorination of fluoroalkyl ketones via a carbeneinitiated rearrangement strategy. Nat. Commun. 13, 4280 (2022).

- Chen, K., Berg, N., Gschwind, R. & König, B. Selective single

bond cleavage in trifluoromethylarenes: merging visible-light catalysis with lewis acid activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18444-18447 (2017). - Wang, H. & Jui, N. T. Catalytic defluoroalkylation of trifluoromethylaromatics with unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 163-166 (2018).

- Vogt, D. B., Seath, C. P., Wang, H. & Jui, N. T. Selective C-F functionalization of unactivated trifluoromethylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13203-13211 (2019).

- Sap, J. B. I. et al. Organophotoredox hydrodefluorination of trifluoromethylarenes with translational applicability to drug discovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 9181-9187 (2020).

- Campbell, M. W. et al. Photochemical C-F activation enables defluorinative alkylation of trifluoroacetates and -acetamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 19648-19654 (2021).

- Shreiber, S. T. et al. Visible-light-induced C-F bond activation for the difluoroalkylation of indoles. Org. Lett. 24, 8542-8546 (2022).

- Ye, J.-H., Bellotti, P., Heusel, C. & Glorius, F. Photoredox-catalyzed defluorinative functionalizations of polyfluorinated aliphatic amides and esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202115456 (2022).

- Luo, Y.-C., Tong, F.-F., Zhang, Y., He, C.-Y. & Zhang, X. Visible-lightinduced palladium-catalyzed selective defluoroarylation of trifluoromethylarenes with arylboronic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 13971-13979 (2021).

- Sugihara, N., Suzuki, K., Nishimoto, Y. & Yasuda, M. Photoredoxcatalyzed C-F bond allylation of perfluoroalkylarenes at the benzylic position. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 9308-9313 (2021).

- Yan, S.-S. et al. Visible-light photoredox-catalyzed selective carboxylation of C(sp3)-F bonds with CO2. Chem 7, 3099-3113 (2021).

- Ghosh, S. et al. HFIP-assisted single C-F bond activation of trifluoromethyl ketones using visible-light photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202115272 (2022).

- Liu, C., Li, K. & Shang, R. Arenethiolate as a dual function catalyst for photocatalytic defluoroalkylation and hydrodefluorination of trifluoromethyls. ACS Catal. 12, 4103-4109 (2022).

- Liu, C., Shen, N. & Shang, R. Photocatalytic defluoroalkylation and hydrodefluorination of trifluoromethyls using o-phosphinophenolate. Nat. Commun. 13, 354 (2022).

- Wang, J. et al. Late-stage modification of drugs via alkene formal insertion into benzylic C-F bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202215062 (2023).

- Xu, J. et al. Construction of C-X (

) bonds via Lewis acidpromoted functionalization of trifluoromethylarenes. ACS Catal. 13, 7339-7346 (2023). - Xu, P. et al. Defluorinative alkylation of trifluoromethylbenzimidazoles enabled by spin-center shift: a

synergistic photocatalysis/thiol catalysis process with. Org. Lett. 24, 4075-4080 (2022). - Wiberg, K. B. & Waddell, S. T. Reactions of [1.1.1]propellane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 2194-2216 (1990).

- Li, M. et al. Transition-metal-free radical

and coupling enabled by 2 -azaallyls as super-electron-donors and coupling-partners. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16327-16333 (2017). - Bortolato, T. et al. The rational design of reducing organophotoredox catalysts unlocks proton-coupled electron-transfer and atom transfer radical polymerization mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 1835-1846 (2023).

- Schweitzer-Chaput, B., Horwitz, M. A., de Pedro Beato, E. & Melchiorre, P. Photochemical generation of radicals from alkyl electrophiles using a nucleophilic organic catalyst. Nat. Chem. 11, 129-135 (2019).

- Mykhailiuk, P. K. Saturated bioisosteres of benzene: where to go next? Org. Biomol. Chem. 17, 2839-2849 (2019).

- Frank, N. et al. Synthesis of meta-substituted arene bioisosteres from [3.1.1]propellane. Nature 611, 721-726 (2022).

- lida, T. et al. Practical and facile access to bicyclo[3.1.1]heptanes: potent bioisosteres of meta -substituted benzenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21848-21852 (2022).

- Zheng, Y. et al. Photochemical intermolecular

-cycloaddition for the construction of aminobicyclo[3.1.1]heptanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 23685-23690 (2022). - Kleinmans, R. et al. ortho -Selective dearomative [

] photocycloadditions of bicyclic aza-arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12324-12332 (2023). - Fuchs, J. & Szeimies, G. Synthese von [

.1.1]propellanen ( ). Chem. Ber. 125, 2517-2522 (1992). - Kondo, M. et al. Silaboration of [1.1.1]propellane: a storable feedstock for bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 1970-1974 (2020).

- Shelp, R. A. et al. Strain-release 2-azaallyl anion addition/borylation of [1.1.1]propellane: synthesis and functionalization of benzylamine bicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl boronates. Chem. Sci. 12, 7066-7072 (2021).

- Dong, W. et al. Exploiting the sp2 character of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl radicals in the transition-metal-free multi-component difunctionalization of [1.1.1]propellane. Nat. Chem. 14, 1068-1077 (2022).

- VanHeyst, M. D. et al. Continuous flow-enabled synthesis of benchstable Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane trifluoroborate salts and their utilization in metallaphotoredox cross-couplings. Org. Lett. 22, 1648-1654 (2020).

- Yang, Y. et al. An intramolecular coupling approach to alkyl bioisosteres for the synthesis of multisubstituted bicycloalkyl boronates. Nat. Chem. 13, 950-955 (2021).

- Nicolas, S. et al. Adiporon, an adiponectin receptor agonist acts as an antidepressant and metabolic regulator in a mouse model of depression. Transl. Psychiatry 8, 159 (2018).

- Manley, S. J. et al. Synthetic adiponectin-receptor agonist, AdipoRon, induces glycolytic dependence in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 13, 114 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44653-6.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Xiaheng Zhang.

© The Author(s) 2024

School of Chemistry and Materials Science, Hangzhou Institute for Advanced Study, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1 Sub-lane Xiangshan, 310024 Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China. Department of Chemistry, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan. e-mail: xiahengz@ucas.ac.cn