DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140728

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-19

تنوع الجنس في مجالس الإدارة وأداء ESG: الدور الوسيط للتوجه الزمني في سياق جنوب أفريقيا

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

ESG

التوجه قصير الأجل

مدة عمل المديرات

الشركات العائلية

الملخص

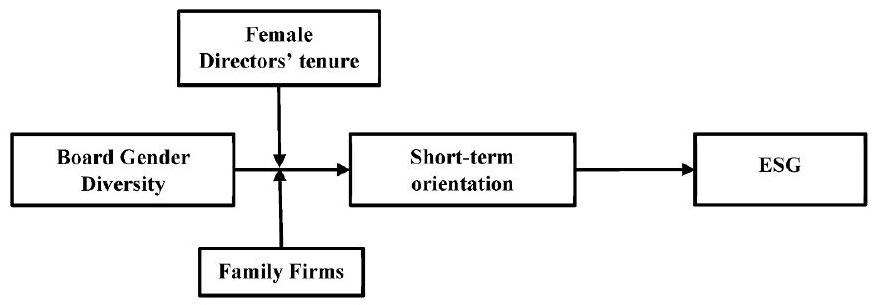

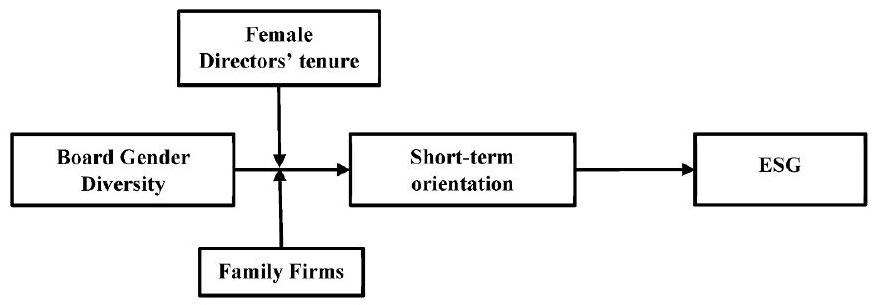

تقدم الأبحاث السائدة حول التفاعل بين تنوع الجنس في مجلس الإدارة (BGD) وأداء البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة (ESG) نتائج متناقضة، خاصة في سياق الدول النامية. تتناول هذه الدراسة فحصًا استكشافيًا لهذه العلاقة، في السياق الاجتماعي والثقافي لجنوب أفريقيا، وهي منطقة حيث يؤدي الوضع الاجتماعي المنخفض للنساء غالبًا إلى تحيز نحو وجهات نظر قصيرة الأجل. استنادًا إلى نظرية توافق الدور في التحيز تجاه القائدات، تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى التحقيق في الدور الوسيط للتوجه قصير الأجل (SHRT) في العلاقة بين BGD وESG. نستكشف أيضًا كيف يختلف تفضيل المديرات للتوجه قصير الأجل حسب مدة عملهن في المجلس وعبر الشركات العائلية وغير العائلية. تشير النتائج التجريبية، المستمدة من فحص الشركات غير المالية المدرجة في البورصة في جوهانسبرغ (JSE) من 2015 إلى 2020، إلى وجود علاقة سلبية بين BGD وESG، مع كون SHRT يتوسط هذه العلاقة بشكل رئيسي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تقلل مدة عمل المديرات من تفضيلهن للتوجه قصير الأجل. ومن الجدير بالذكر أننا وجدنا أن تأثير BGD على SHRT أقل وضوحًا في الشركات العائلية، حيث تتماشى اختيارات المديرات بشكل أكبر مع التوجه طويل الأجل للشركة العائلية. تسهم نتائجنا في كل من النظرية والممارسة من خلال تعزيز فهمنا لعلاقة BGD وESG وتقديم تداعيات عملية للمنظمات والقادة وصانعي السياسات.

1. المقدمة

الاقتصادات النامية صورة أكثر تفتتًا وعدم اتساق. بينما تشير بعض الأبحاث إلى وجود علاقة إيجابية (Wasiuzzaman and Subramaniam, 2023; Al-Mamun and Seamer, 2021; Katmon et al., 2019)، تشير أخرى إلى وجود علاقة سلبية أو غير ذات دلالة إحصائية (Gallego-Álvarez and Pucheta-Martínez, 2020; Hussain et al., 2018; Zaid et al., 2020; Yadav and Prashar, 2022). تشير هذه التناقضات الظاهرة إلى الحاجة الملحة لإجراء تحقيق أعمق في ديناميات BGD وESG. وبالتالي، تهدف أبحاثنا إلى إعادة تصور العلاقة بين BGD وESG، مع وضع هذا الفحص في السياق الاجتماعي والثقافي الفريد لجنوب أفريقيا – وهو بيئة لم يتم استكشافها حتى الآن في هذا الخطاب الأكاديمي.

من غير المرجح أن تظهر الصور النمطية السلبية القائمة على الجنس في مثل هذه البيئات، مما يؤثر بالتالي على نتائج الأعمال. لذلك، نقدم الشركات العائلية كعامل محتمل للتعديل في العلاقة بين التحيز الجنسي والتوجه قصير الأجل، بما يتماشى مع الاقتراح بأن سلوك المديرات يتماشى مع التوجه طويل الأجل المتأصل في ثقافة الشركات العائلية.

2. نظرية وتطوير الفرضيات

2.1. تنوع الجنس في مجالس الإدارة و ESG

والدليل التجريبي إلى أن فوائد المديرات تتحقق بشكل أساسي في الدول المتقدمة حيث يكون التوازن بين الجنسين أكثر انتشارًا. على سبيل المثال، أظهرت دراسة مقارنة بين الدول المتقدمة والنامية أن المديرات يزيدن بشكل كبير من ESG في الدول المتقدمة، بينما لا ينطبق نفس الشيء على الدول النامية (وزيوازمان وسوبارامانيام، 2023). هذه الملاحظة تجعل دور المديرات تجاه ESG في الدول النامية موضع تساؤل. تشمل العوامل التي تسهم في هذا التأثير المحدود على ESG عدم كفاية تمثيل النساء في المجالس، والتمييز الجنسي، والصور النمطية السلبية المنتشرة في الدول النامية (هوستد وسوزا-فيليو، 2019؛ زيد وآخرون، 2020). يجادل يارام وآدابا (2021) بأن وجود مديرة واحدة فقط في المجلس قد لا يؤثر بشكل كبير على المسؤولية الاجتماعية للشركات (CSR) بسبب تصورات الرمزية.

2.2. الدور الوسيط للتوجه قصير الأجل

(2019) وجدت أن الرؤساء التنفيذيين الذين لديهم قيم مصلحة ذاتية يميلون إلى توجيه شركاتهم بعيدًا عن التوجهات طويلة الأجل. وبالمثل، لاحظ غالبراث (2017) أن المديرين الداخليين أكثر عرضة للتفكير قصير الأجل مقارنة بنظرائهم. كما تدعم الأدبيات فكرة أن التوجه الزمني للشركة يمكن أن يؤثر على انخراطها في قضايا البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة (ESG). على سبيل المثال، أفاد تشوي وآخرون (2023) أن الشركات التي لديها توجه طويل الأجل تميل أكثر للاستثمار في مبادرات ESG. بناءً على الحجج المذكورة أعلاه، نقترح فرضيتنا الثانية كما يلي.

2.3. الدور الوسيط لفترة ولاية المديرات الإناث

2.4. الدور الوسيط للشركات العائلية

تُلاحظ الشركات أنها تأخذ نظرة أطول، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار العواقب طويلة الأجل للأفعال الحالية (دو وآخرون، 2019). وبالتالي، فهي أكثر توجهاً نحو المدى الطويل من نظرائها غير العائلية (لومبكين وبريغهام، 2011؛ زهراء وآخرون، 2004). وغالباً ما تنبع هذه النظرة طويلة الأجل من اعتقاد مالكي العائلة أن ملكيتهم ستنتقل إلى الأجيال القادمة، مما يشجع على وجهة نظر متعددة الأجيال (أندرسون وريب، 2003؛ تسينغ، 2020). وهذا يدفع الشركات العائلية للحفاظ على سمعتها الاجتماعية (لومبكين وبريغهام، 2011). لذلك، عند اتخاذ القرارات، تميل الشركات العائلية إلى إعطاء الأولوية للثروة الاجتماعية والعاطفية كنقطة مرجعية استراتيجية رئيسية (غوميز-ميخيا وآخرون، 2007). جادل بيروني وآخرون (2010) بأن الشركات التي تسيطر عليها العائلات تحمي ثروتها الاجتماعية والعاطفية من خلال أداء بيئي متفوق. تدعم العديد من الدراسات هذا الادعاء، موثقة الالتزام المعزز للشركات العائلية تجاه المسؤولية الاجتماعية (كورديرو وآخرون، 2018؛ لامب وباتلر، 2016؛ لوبيز-غونزاليس وآخرون، 2019؛ ساهاسرانامام وآخرون، 2020) لضمان بقاء الشركة. ونتيجة لذلك، تميل الشركات العائلية إلى أن تكون أكثر توجهاً اجتماعياً من الشركات غير العائلية (غارسيا-سانشيز وآخرون، 2021).

3. المنهج

3.1. العينة وجمع البيانات

3.2. قياسات المتغيرات

3.2.1. المتغير التابع: ESG

3.2.2. المتغير المستقل: تنوع الجنس في المجلس (BGD)

3.2.3. المتغير الوسيط: التوجه قصير الأجل (SHRT)

لإنتاج مؤشر SHRT، استخدمنا برنامج NVivo لتحليل التقارير المتكاملة للشركات في عينتنا. للتحقق من صحة هذا النهج، قمنا بعد الكلمات الرئيسية ذات الصلة يدوياً في 20 تقريراً مختاراً عشوائياً وقارننا هذه النتائج مع نتائج NVivo. وُجد أن مجموعتي النتائج متطابقتان.

3.2.4. المتغيرات المعدلة

3.2.5. متغيرات التحكم

3.3. تحديد النموذج

4. النتائج

4.1. الإحصائيات الوصفية

4.2. تحليل الانحدار المتعدد

الإحصائيات الوصفية.

| متغير | ملاحظة | معنى | الوسيط | الانحراف المعياري | دقيقة | ماكس. |

| البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة | 432 | 0.498 | 0.497 | 0.178 | 0.091 | 0.910 |

| بي جي دي | 432 | 0.256 | 0.250 | 0.121 | 0.000 | 0.667 |

| SHRT | 432 | 0.320 | 0.320 | 0.111 | 0.031 | 0.592 |

| فترة الخدمة | 432 | ٤.٨١٠ | ٤٫٥٠٠ | ٢.٩٣٠ | 0.000 | 16.00 |

| ف.ن.ف | 432 | 0.110 | 0.000 | 0.314 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| حجم | 432 | ٢٣.٦٠ | ٢٣.٥٠ | 1.120 | ٢٠.٤٠ | ٢٦.٨٠ |

| العائد على الأصول | 432 | 0.067 | 0.060 | 0.118 | -0.522 | 0.499 |

| ليف | 432 | 0.223 | 0.218 | 0.143 | 0.001 | 0.761 |

| فاج | 432 | 3.790 | ٣.٩١٠ | 0.822 | 0.000 | ٥.١٣٠ |

| بي سايز | 432 | 11.20 | 11.00 | ٢.٦١٠ | ٥٫٠٠٠ | ٢٠.٠٠ |

| IND | 432 | 0.723 | 0.750 | 0.105 | 0.167 | 0.917 |

| ميت | 432 | ٤.٩٣٢ | ٥٫٠٠٠ | 1.316 | ٢٫٠٠٠ | 10.00 |

| FCEO | 432 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.143 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| المتغيرات | VIF. | 1 | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ١٣ |

| (1) الحوكمة البيئية والاجتماعية والمؤسسية | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| (2) بي جي دي | 1.23 | 0.068 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (3) شورت | 1.11 | -0.193*** | 0.016 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (4) ف.ن.ف | 1.10 | -0.281*** | -0.215*** | 0.131*** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (5) فترة العمل | 1.12 | -0.068 | -0.210*** | -0.007 | -0.018 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (6) الحجم | 1.26 | 0.324*** | -0.018 | -0.173*** | -0.065 | 0.002 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (7) العائد على الأصول | 1.09 | -0.007 | -0.102** | 0.033 | 0.008 | 0.121** | -0.050 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (8) ليف | 1.06 | -0.025 | 0.025 | -0.025 | 0.022 | 0.096** | 0.069 | -0.159*** | 1.000 | |||||

| (9) فاج | 1.08 | 0.040 | 0.034 | 0.232*** | -0.040 | 0.037 | -0.116** | -0.033 | -0.024 | 1.000 | ||||

| (10) حجم | 1.22 | 0.241*** | 0.022 | -0.042 | -0.117** | -0.057 | 0.354*** | 0.005 | -0.004 | -0.056 | 1.000 | |||

| (11) إند | 1.18 | 0.176*** | 0.013 | -0.072 | -0.110** | -0.146*** | 0.255*** | -0.033 | 0.009 | -0.102** | 0.295*** | 1.000 | ||

| (12) ميت | 1.04 | 0.149*** | -0.064 | -0.040 | -0.003 | -0.064 | 0.088* | 0.122** | 0.012 | -0.040 | -0.031 | 0.020 | 1.000 | |

| (13) FCEO | 1.17 | -0.066 | 0.297 | 0.002 | -0.052 | -0.018 | -0.166*** | -0.103** | -0.084* | 0.000 | -0.074 | -0.134*** | -0.042 | 1.000 |

جي إم إم: التأثير الوسيط على المدى القصير بين BGD و ESG.

| المتغيرات | النموذج 1-ESG

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

موديل 3 – ESG

|

|||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| ESG (t-1) | 0.844 | 0.000*** | 0.859 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.660 | 0.000*** | ||||

| SHRT | -0.172 | 0.000*** | ||||

| بي جي دي | -0.184 | 0.002*** | 0.172 | 0.002*** | -0.151 | 0.002*** |

| حجم | 0.077 | 0.000*** | -0.002 | 0.349 | 0.013 | 0.007*** |

| ROA | -0.007 | 0.682 | 0.006 | 0.771 | -0.004 | 0.863 |

| ليف | 0.002 | 0.785 | 0.003 | 0.225 | 0.003 | 0.103 |

| فاج | 0.077 | 0.033** | 0.007 | 0.066* | 0.003 | 0.646 |

| بي سايز | -0.087 | 0.000*** | 0.006 | 0.001*** | -0.001 | 0.444 |

| الهند | 0.082 | 0.235 | -0.072 | 0.190 | 0.219 | 0.001*** |

| ميت | -0.005 | 0.001*** | 0.003 | 0.050** | -0.003 | 0.133 |

| FCEO | 0.048 | 0.164 | 0.061 | 0.387 | -0.030 | 0.350 |

| نموذج صناعي | نعم | لا | نعم | |||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | نعم | |||

| AR (1) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.948 | 0.224 | 0.908 | |||

| اختبار هانسن | 0.364 | 0.245 | 0.268 | |||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | |||

انخفاض في الاستثمارات طويلة الأجل، مثل تلك المتعلقة بمبادرات البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة (ESG)، مما يؤثر سلبًا على قرارات ESG في النهاية.

جميع النماذج: الدور الوسيط لفترة عمل المديرات الإناث والشركات العائلية على المدى القصير.

| المتغيرات | موديل 1-شيرت

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.602 | 0.000*** | 0.566 | 0.000*** |

| بي جي دي | 0.149 | 0.061* | 0.179 | 0.011** |

| فترة | 0.003 | 0.465 | ||

| ف.ن.ف | 0.214 | 0.005*** | ||

| BGD* فترة | -0.028 | 0.030** | ||

| بي جي دي* إف.إن إف | -0.634 | 0.039** | ||

| حجم | -0.002 | 0.422 | -0.014 | 0.062* |

| العائد على الأصول | 0.007 | 0.817 | 0.020 | 0.533 |

| ليف | 0.008 | 0.025** | 0.004 | 0.474 |

| فاج | 0.045 | 0.000** | 0.018 | 0.097* |

| بي سايز | 0.003 | 0.110 | 0.006 | 0.057* |

| IND | -0.056 | 0.355 | -0.010 | 0.903 |

| ميت | 0.003 | 0.159 | 0.003 | 0.087* |

| FCEO | 0.023 | 0.778 | -0.080 | 0.295 |

| نموذج صناعي | لا | نعم | ||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | ||

| AR (1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| AR (2) | 0.160 | 0.152 | ||

| اختبار هانسن | 0.364 | 0.331 | ||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | ||

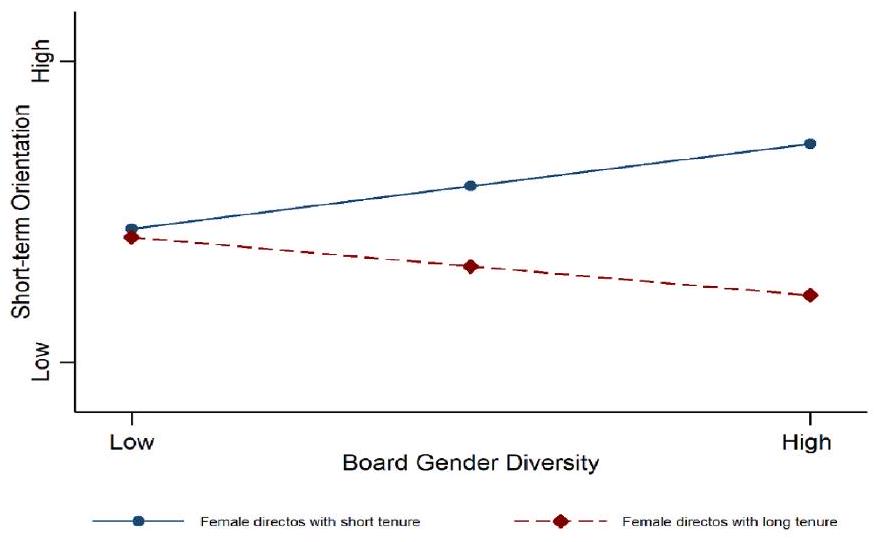

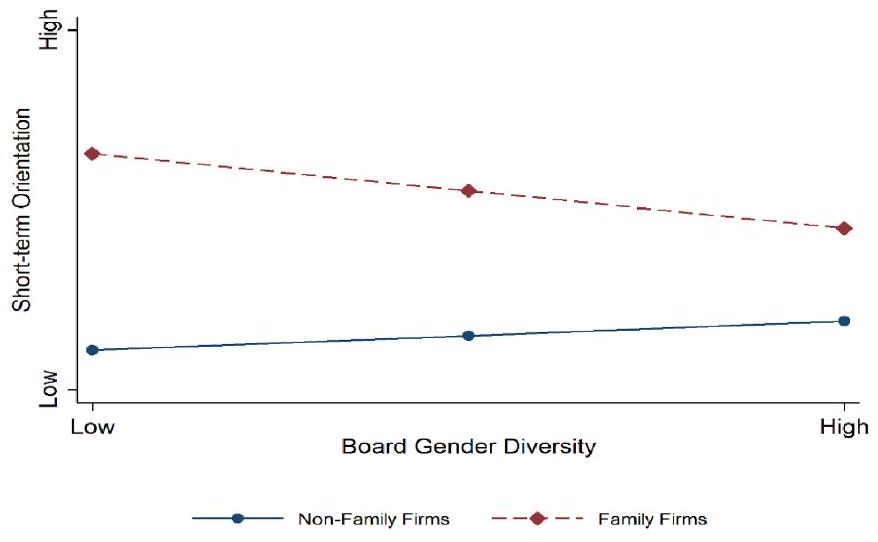

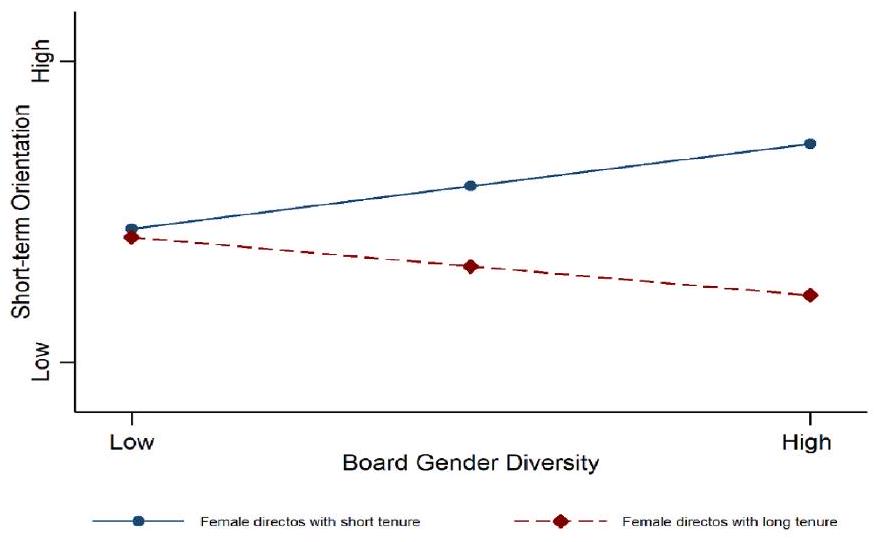

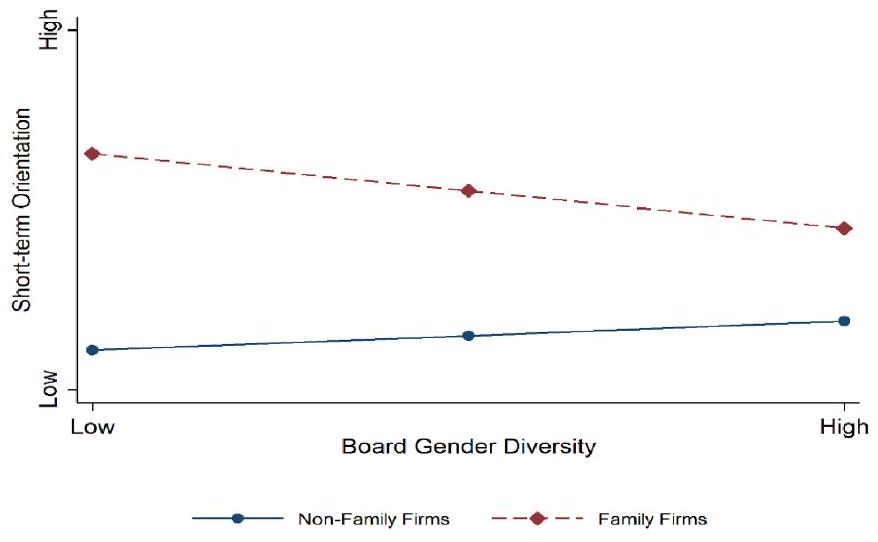

تقلل الصور النمطية، مما يقلل الضغط للتركيز على النتائج قصيرة المدى. يساعد طول مدة الخدمة المديرات الإناث في تأسيس الشرعية، مما يمكّنهن بدوره من إدخال قيمهن ووجهات نظرهن في عمليات اتخاذ القرارات الاستراتيجية (دو وآخرون، 2015). وبالمثل، يظهر النموذج 2 أن الشركات العائلية تؤثر سلبًا على العلاقة بين BGD و SHRT.

4.3. تحليل إضافي

5. المناقشة

5.1. المساهمة النظرية

5.2. الآثار العملية

2SLS: التأثير الوسيط على المدى القصير بين BGD و ESG.

| المتغيرات | النموذج 1-ESG

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

موديل 3 – ESG

|

|||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| SHRT | -0.294 | 0.000*** | ||||

| بي جي دي | -0.589 | 0.017** | 0.614 | 0.017** | -0.407 | 0.513 |

| حجم | 0.039 | 0.000*** | -0.028 | 0.001*** | 0.030 | 0.001*** |

| العائد على الأصول | 0.008 | 0.959 | 0.074 | 0.130 | 0.141 | 0.077* |

| ليف | -0.008 | 0.196 | 0.001 | 0.850 | -0.007 | 0.618 |

| فاج | 0.019 | 0.000*** | 0.023 | 0.000*** | 0.027 | 0.023** |

| بي سايز | 0.010 | 0.000*** | 0.001 | 0.683 | 0.010 | 0.009*** |

| IND | 0.178 | 0.003*** | -0.046 | 0.145 | 0.186 | 0.053* |

| ميت | 0.039 | 0.476 | -0.023 | 0.229 | -0.007 | 0.846 |

| FCEO | 0.146 | 0.044** | -0.183 | 0.036** | 0.078 | 0.628 |

| نموذج صناعي | لا | نعم | لا | |||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | نعم | |||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٣٦٠ | ٣٦٠ | ٣٦٠ | |||

2SLS: الدور الوسيط لفترة عمل المديرات الإناث والشركات العائلية على المدى القصير.

| المتغيرات | موديل 1-شيرت

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| بي جي دي | 0.639 | 0.004*** | 0.416 | 0.018** |

| فترة | 0.020 | 0.002*** | ||

| ف.ن.ف | 0.194 | 0.010** | ||

| BGD* فترة | -0.100 | 0.001*** | ||

| بي جي دي* إف.إن إف | -0.603 | 0.019** | ||

| حجم | -0.021 | 0.000*** | -0.024 | 0.000*** |

| العائد على الأصول | 0.032 | 0.301 | 0.080 | 0.001*** |

| ليف | -0.001 | 0.946 | 0.010 | 0.144 |

| فاج | 0.027 | 0.000*** | 0.031 | 0.000*** |

| بي سايز | 0.001 | 0.798 | 0.001 | 0.632 |

| IND | -0.126 | 0.001*** | -0.004 | 0.878 |

| ميت | -0.002 | 0.469 | -0.003 | 0.385 |

| FCEO | -0.054 | 0.130 | -0.116 | 0.098* |

| نموذج صناعي | نعم | نعم | ||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | ||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٣٦٠ | ٣٦٠ | ||

تعيق مساهمات النساء في معايير البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة، لا سيما التمييز الناجم عن تمثيل الأقليات القائمة على الجنس في الدول النامية. التأثير السلبي للصور النمطية على أداء وقدرات اتخاذ القرار للمديرين، وخاصة أولئك في المناصب الأقلية مثل المديرات، موثق جيدًا. نظرًا للافتقار المستمر لتمثيل المديرات في مجالس الإدارة في الدول النامية، هناك حالة قوية تدعو صانعي السياسات إلى سن تشريعات تعالج هذه الصور النمطية. يمكن أن تشمل هذه التدابير

يشمل ذلك فرض نسبة أعلى من النساء في مجالس الإدارة، مما يعزز المساواة بين الجنسين وقد يخفف من التحيزات التي تعيق فعالية المديرات. علاوة على ذلك، تسلط نتائجنا الضوء على الدور المؤثر لفترة خدمة المديرة في المجلس في تقليل الصور النمطية السلبية المتعلقة بالجنس. تعزز فترة الخدمة الطويلة في المجلس من الفطنة التجارية والخبرة لدى المديرات من الأقليات، مما يسهل بدوره مشاركتهن الفعالة في اتخاذ القرارات الاستراتيجية. ونتيجة لذلك، من غير المرجح أن يتم تجاهل وجهات نظرهن من قبل الأغلبية، مما يمكّن من اتباع نهج أكثر شمولية في الحوكمة. وبالتالي، يجب النظر في تشريعات لمنع التمييز القائم على الجنس المتعلق بفترة الخدمة في المجلس. يجب على المستثمرين أيضًا تقييم المدراء بناءً على أدائهم بدلاً من الصور النمطية المسبقة حولهم.

تحليل الاعتدال باستخدام Fexe بدلاً من BGD.

| المتغيرات | موديل 1-شيرت

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.661 | 0.000*** | 0.616 | 0.000*** |

| فكسي | 0.322 | 0.027** | 0.092 | 0.274 |

| فكست | 0.008 | 0.264 | ||

| ف.ن.ف | 0.14 | 0.000*** | ||

| فكسي* فكسيT | -0.159 | 0.040** | ||

| فكسي* ف.ن.ف | -0.734 | 0.032** | ||

| تحكم | مضمن | مضمن | ||

| نموذج صناعي | لا | نعم | ||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | ||

| AR (1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| AR (2) | 0.135 | 0.184 | ||

| هانسن | 0.162 | 0.387 | ||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | ||

تحليل الوساطة باستخدام المديرات التنفيذيات (Fexe) كمتغير مستقل.

| المتغيرات | نموذج 1-ESG

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

موديل 3 – ESG

|

|||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| ESG (t-1) | 0.869 | 0.000*** | 0.732 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.708 | 0.000 | ||||

| SHRT | -0.272 | 0.003*** | ||||

| فكسي | -0.310 | 0.043** | 0.466 | 0.010** | -0.197 | 0.198 |

| تحكم | مضمن | مضمن | مضمن | |||

| نموذج صناعي | نعم | نعم | نعم | |||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | نعم | |||

| AR (1) | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.002 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.790 | 0.342 | 0.705 | |||

| اختبار هانسن | 0.242 | 0.224 | 0.412 | |||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | |||

تحليل الوساطة باستخدام مؤشر بلاو كقياس بديل لـ BGD.

| المتغيرات | نموذج 1-ES

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

النموذج 3-

|

|||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| ES (t-1) | 0.855 | 0.000*** | 0.855 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.677 | 0.000*** | ||||

| SHRT | -0.171 | 0.001*** | ||||

| أزرق | -0.178 | 0.000*** | 0.086 | 0.006*** | -0.161 | 0.003*** |

| تحكم | مضمن | مضمن | مضمن | |||

| نموذج صناعي | نعم | لا | نعم | |||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | نعم | |||

| AR (1) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.685 | 0.249 | 0.849 | |||

| اختبار هانسن | 0.516 | 0.452 | 0.660 | |||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | |||

تحليل الاعتدال باستخدام مؤشر بلاو كقياس بديل لـ BGD.

| المتغيرات | موديل 1-شيرت

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.595 | 0.000*** | 0.553 | 0.000*** |

| أزرق | 0.178 | 0.010** | 0.191 | 0.035** |

| فترة | 0.005 | 0.324 | ||

| ف.ن.ف | 0.304 | 0.009*** | ||

| بلوا * فتنور | -0.027 | 0.006*** | ||

| بلau * F.NF | -0.761 | 0.019** | ||

| تحكم | مضمن | مضمن | ||

| نموذج صناعي | لا | نعم | ||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | ||

| AR (1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| AR (2) | 0.170 | 0.231 | ||

| هانسن | 0.450 | 0.337 | ||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | ||

النساء، تخفيف الضغوط للتركيز فقط على النتائج قصيرة الأجل بدلاً من النتائج طويلة الأجل مثل ESG. بشكل عام، توفر دراستنا فهماً دقيقاً للعلاقة المعقدة بين التنوع الجنسي، والتوجه الزمني، ونتائج ESG، مما يقدم رؤى قيمة للباحثين والممارسين على حد سواء.

5.3. القيود والاقتراحات للدراسات المستقبلية

وقارنّا نتائجنا بشأن تأثير المديرات على التوجه الزمني للشركة في الدول النامية مقابل الدول المتقدمة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، اعتمدنا على بيانات ثانوية لتأكيد حججنا. يمكن أن تستخدم الأبحاث المستقبلية بيانات أولية ونوعية (مثل المقابلات أو الاستطلاعات) للحصول على فهم أعمق للتحديات التي تواجهها المديرات في المجلس، والتي قد تعيق مساهمتهن في قرارات ESG. علاوة على ذلك، لم تؤكد نتائج تحليلاتنا الإضافية نظرية الكتلة الحرجة. يمكن أن توضح الأبحاث المستقبلية تأثير الصور النمطية من خلال مقارنة قابلية تطبيق نظرية الكتلة الحرجة عبر الدول المتقدمة والنامية. قد تدرس الدراسات المستقبلية أيضًا الفروق بين المديرات والمديرين الذكور من حيث الخصائص والتجارب، مثل مقارنة مدة خدمة المديرين الذكور والإناث في المجلس وكيف تؤثر هذه على قرارات ESG.

6. الخاتمة

تحليل الوساطة باستخدام درجة البيئة (E) كمتغير تابع.

| المتغيرات | النموذج 1-هـ

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

النموذج 3-

|

|||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| E (t-1) | 0.934 | 0.000*** | 0.786 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.659 | 0.000*** | ||||

| SHRT | -0.270 | 0.001*** | ||||

| بي جي دي | -0.233 | 0.002*** | 0.172 | 0.002*** | -0.062 | 0.301 |

| تحكم | مضمن | مضمن | مضمن | |||

| نموذج صناعي | نعم | لا | نعم | |||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | نعم | |||

| AR (1) | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.014 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.319 | 0.224 | 0.183 | |||

| اختبار هانسن | 0.469 | 0.245 | 0.311 | |||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | |||

تحليل الوساطة باستخدام الدرجة الاجتماعية (S) كمتغير تابع.

| المتغيرات | موديل 1-S

|

موديل 2-شيرت

|

النموذج 3-

|

|||

|

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P |

|

قيمة P | |

| س (ت-1) | 0.942 | 0.000*** | 0.942 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.659 | 0.000*** | ||||

| SHRT | -0.089 | 0.049** | ||||

| بي جي دي | -0.154 | 0.018*** | 0.172 |

|

-0.133 | 0.066* |

| تحكم | مضمن | مضمن | مضمن | |||

| نموذج صناعي | نعم | لا | نعم | |||

| متغير السنة | نعم | نعم | نعم | |||

| AR (1) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.180 | 0.224 | 0.141 | |||

| اختبار هانسن | 0.464 | 0.245 | 0.682 | |||

| عدد الملاحظات | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | ٢٨٨ | |||

تكتسب فترات العضوية في المجالس شرعية متزايدة وخبرة، مما يقلل من الصور النمطية السلبية ويمكنها من المساهمة بشكل أكثر فعالية في مبادرات الحوكمة البيئية والاجتماعية والإدارية. في سياق الشركات العائلية، التي تتميز بتوجهها طويل الأجل وتركيزها على الثروة الاجتماعية والعاطفية، يتم خلق بيئة داعمة. تسهل هذه البيئة على المديرات التوافق بين قراراتهن وقيم الأسرة وتفضيل السمعة طويلة الأجل على المكاسب قصيرة الأجل. يتم تأكيد قوة نتائجنا من خلال استخدام تقنيات بديلة وقياسات متنوعة للمتغيرات المستقلة والتابعة.

بيان التمويل

بيان موافقة الأخلاقيات

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

توفر البيانات

| متغير | اختصار | قياس |

| البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة | البيئة والمجتمع والحوكمة | درجة ESG المستمدة من قاعدة بيانات Refinitiv Eikon. |

| تنوع الجنس في مجالس الإدارة | بي جي دي | نسبة المديرات الإناث في المجلس. |

| تنفيذية أنثوية | فكسي | نسبة المديرات التنفيذيات الإناث في مجلس الإدارة |

| مؤشر بلوا للتنوع | أزرق |

|

| أين: | ||

|

|

||

| توجه قصير الأجل | SHRT | تم بناؤه عن طريق حساب نسبة الكلمات الرئيسية القصيرة المدة بالنسبة لمجموع الكلمات الرئيسية القصيرة والطويلة المدة. |

| مدة ولاية المديرات | التمكين | متوسط مدة الوقت التي قضتها المديرات في مجلس الإدارة. |

| مدة تولي النساء المناصب التنفيذية | فكست | متوسط مدة الوقت التي قضتها المديرات التنفيذيات في مجلس الإدارة. |

| الشركات العائلية | ف.ن.ف | تأخذ المتغير الوهمي القيمة 1 إذا كانت الشركة مملوكة لعائلة، و0 خلاف ذلك. |

| حجم الشركة | حجم | اللوغاريتم الطبيعي (ln) لإجمالي أصول الشركة. |

| العائد على الأصول | العائد على الأصول | الأرباح قبل الفوائد والضرائب مقسومة على إجمالي الأصول. |

| الرافعة | ليف | نسبة إجمالي الدين إلى إجمالي الأصول. |

| عمر الشركة | فاج | اللوغاريتم الطبيعي (ln) لعدد السنوات منذ تأسيس الشركة. |

| حجم المجلس | بي سايز | إجمالي عدد أعضاء مجلس إدارة الشركة. |

| استقلالية المجلس | الهند | عدد المديرين المستقلين/إجمالي عدد مديري المجلس. |

| اجتماع مجلس الإدارة | ميت | إجمالي عدد الاجتماعات التي تعقد سنويًا. |

| المديرة التنفيذية | FCEO | متغير وهمي يساوي 1 إذا كانت المديرة التنفيذية للشركة امرأة و0 خلاف ذلك |

References

Abdou, H.A., Ellelly, N.N., Elamer, A.A., Hussainey, K., Yazdifar, H., 2021. Corporate governance and earnings management nexus: evidence from the UK and Egypt using

neural networks. Int. J. Finance Econ. 26 (4), 6281-6311. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ijfe. 2120.

Abdullah, S.N., 2014. The causes of gender diversity in Malaysian large firms. J. Manag. Govern. 18 (4), 1137-1159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-013-9279-0.

Al-Mamun, A., Seamer, M., 2021. Board of director attributes and CSR engagement in emerging economy firms: evidence from across Asia. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 46 https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2020.100749.

Alshbili, I., Elamer, A.A., 2020. The influence of institutional context on corporate social responsibility disclosure: a case of a developing country. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 10 (3), 269-293. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2019.1677440.

Alshbili, I., Elamer, A.A., Beddewela, E., 2019. Ownership types, corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures. Account. Res. J. 33 (1), 148-166. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-03-2018-0060.

Amin, A., Ali, R., ur Rehman, R., Elamer, A.A., 2023. Gender diversity in the board room and sustainable growth rate: the moderating role of family ownership. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 13 (4), 1577-1599. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 20430795.2022.2138695.

Baron, R.M., Kenny, D.A., 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173-1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Bătae, O.M., Dragomir, V.D., Feleagă, L., 2021. The relationship between environmental, social, and financial performance in the banking sector: a European study. J. Clean. Prod. 290 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.125791.

Beji, R., Yousfi, O., Loukil, N., Omri, A., 2021. Board diversity and corporate social responsibility: empirical evidence from France. J. Bus. Ethics 173 (1), 133-155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04522-4.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L.R., Larraza-Kintana, M.J. A.s. q., 2010. Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: do familycontrolled firms pollute less? Adm. Sci. Q. 55 (1), 82-113.

Bettinelli, Cristina, Bosco, B.D., Giachino, C., 2019. Women on boards in family firms: what we know and what we need to know. In: Memili, E., Dibrell, C. (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Heterogeneity Among Family Firms, pp. 201-228.

Bonini, S., Deng, J., Ferrari, M., John, K., 2017. On Long-Tenured Independent Directors. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13164.36480.

Bose, S., Hossain, S., Sobhan, A., Handley, K., 2022. Does female participation in strategic decision-making roles matter for corporate social responsibility performance? Account. Finance. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12918.

Boulhaga, M., Bouri, A., Elamer, A.A., Ibrahim, B.A., 2023. Environmental, social and governance ratings and firm performance: the moderating role of internal control quality. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 30 (1), 134-145. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/CSR. 2343.

Brown, J.A., Anderson, A., Salas, J.M., Ward, A.J., 2017. Do investors care about director tenure? Insights from executive cognition and social capital theories. Organ. Sci. 28 (3), 471-494. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1123.

Buertey, S., 2021. Board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility assurance: the moderating effect of ownership concentration. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 28 (6), 1579-1590. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr. 2121.

Bufarwa, I.M., Elamer, A.A., Ntim, C.G., AlHares, A., 2020. Gender diversity, corporate governance and financial risk disclosure in the UK. International Journal of Law and Management 62 (6), 521-538. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-10-2018-0245.

Byron, K., Post, C., 2016. Women on boards of directors and corporate social performance: a meta-analysis. Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 24 (4), 428-442. https://doi. org/10.1111/corg.12165.

Cambrea, D.R., Paolone, F., Cucari, N., 2023. Advisory or Monitoring Role in ESG Scenario: Which Women Directors Are More Influential in the Italian Context? Business Strategy and the Environment. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3366.

Campbell, T.S., Marino, A.M., 1994. Myopic investment decisions and competitive labor markets. Int. Econ. Rev. 855-875.

Campbell, K., Mínguez-Vera, A., 2008. Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics 83 (3), 435-451. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10551-007-9630-y.

Campopiano, G., Gabaldón, P., Gimenez-Jimenez, D., 2022. Women directors and corporate social performance: an integrative review of the literature and a future research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04999-7.

Carr, P.B., Steele, C.M., 2010. Stereotype threat affects financial decision making. Psychol. Sci. 21 (10), 1411-1416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610384146.

Carter, D.A., Simkins, B.J., Simpson, W.G., 2003. Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financ. Rev. 38 (1), 33-53.

Cassell, C., 1997. The business case for equal opportunities: implications for women in management. Women Manag. Rev. 12 (1), 11-16.

Chen, C.J.P., Jaggi, B., 2000. Association between independent nonexecutive directors, family control and financial disclosures in Hong Kong. J. Account. Publ. Pol. 19 (4-5), 285-310.

Choi, J.J., Kim, J., Shenkar, O., 2023. Temporal orientation and corporate social responsibility: global evidence. J. Manag. Stud. 60 (1), 82-119. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/joms.12861.

Cordeiro, J.J., Profumo, G., Tutore, I., 2020. Board gender diversity and corporate environmental performance: the moderating role of family and dual-class majority

ownership structures. Bus. Strat. Environ. 29 (3), 1127-1144. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/bse.2421.

Dou, J., Su, E., Wang, S., 2019. When does family ownership promote proactive environmental strategy? The role of the firm’s long-term orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 158 (1), 81-95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3642-z.

Eagly, A.H., Karau, S.J., 2002. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 109 (3), 573-598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573.

Elmagrhi, M.H., Ntim, C.G., Elamer, A.A., Zhang, Q., 2019. A study of environmental policies and regulations, governance structures, and environmental performance: the role of female directors. Bus. Strat. Environ. 28 (1), 206-220. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/bse.2250.

Fiegenbaum, A.V.I., Hart, S., Schendel, D.A.N., 1996. Strategic reference point theory. Strat. Manag. J. 17 (3), 219-235. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(199603) 17:3<219::Aid-smj806>3.0.Co;2-n.

Flammer, C., Bansal, P., 2017. Does a long-term orientation create value? Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strat. Manag. J. 38 https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.

Flammer, C., Hong, B., Minor, D., 2019. Corporate governance and the rise of integrating corporate social responsibility criteria in executive compensation: effectiveness and implications for firm outcomes. Strat. Manag. J. 40 (7), 1097-1122. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/smj. 3018.

Francoeur, C., Labelle, R., Balti, S., El Bouzaidi, S., 2019. To what extent do gender diverse boards enhance corporate social performance? J. Bus. Ethics 155 (2), 343-357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3529-z.

Frijat, Y. S. Al, Albawwat, I.E., Elamer, A.A., 2023. Exploring the mediating role of corporate social responsibility in the connection between board competence and corporate financial performance amidst global uncertainties. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1002/CSR.2623.

Galbreath, J., 2011. Are there gender-related influences on corporate sustainability? A study of women on boards of directors. J. Manag. Organ. 17 (1), 17-38.

Galbreath, J., 2017. The impact of board structure on corporate social responsibility: a temporal view. Bus. Strat. Environ. 26 (3), 358-370. https://doi.org/10.1002/ bse. 1922.

Gallego-Álvarez, I., Pucheta-Martínez, M.C., 2020. Corporate social responsibility reporting and corporate governance mechanisms: an international outlook from emerging countries. Busin. Strat. Dev. 3 (1), 77-97. https://doi.org/10.1002/ bsd2.80.

Gangadharan, L., Jain, T., Maitra, P., Vecci, J., 2016. Social identity and governance: the behavioral response to female leaders. Eur. Econ. Rev. 90, 302-325. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.01.003.

Glass, C., Cook, A., 2016. Leading at the top: understanding women’s challenges above the glass ceiling. Leader. Q. 27 (1), 51-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. leaqua.2015.09.003.

Gómez-Mejía, L.R., Haynes, K.T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K.J., Moyano-Fuentes, J.J. A.s. q., 2007. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 52 (1), 106-137.

Goyal, R., Kakabadse, N., Kakabadse, A., Talbot, D., 2023. Female board directors’ resilience against gender discrimination. Gend. Work. Organ. 30 (1), 197-222. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12669.

Graafland, J., Noorderhaven, N., 2020. Culture and institutions: how economic freedom and long-term orientation interactively influence corporate social responsibility. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 51 (6), 1034-1043. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00301-0.

Gull, A.A., Nekhili, M., Nagati, H., Chtioui, T., 2018. Beyond gender diversity: how specific attributes of female directors affect earnings management. Br. Account. Rev. 50 (3), 255-274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2017.09.001.

Gupta, V.K., Han, S., Mortal, S.C., Silveri, S.D., Turban, D.B., 2018. Do women CEOs face greater threat of shareholder activism compared to male CEOs? A role congruity perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 103 (2), 228-236. https://doi.org/10.1037/ apl0000269.

Gyapong, E., Monem, R.M., Hu, F., 2016. Do women and ethnic minority directors influence firm value? Evidence from post-apartheid South Africa. J. Bus. Finance Account. 43 (3-4), 370-413. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa. 12175.

Hoyt, C.L., Murphy, S.E., 2016. Managing to clear the air: stereotype threat, women, and leadership. Leader. Q. 27 (3), 387-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. leaqua.2015.11.002.

Hussain, N., Rigoni, U., Orij, R.P., 2018. Corporate governance and sustainability performance: analysis of triple bottom line performance. J. Bus. Ethics 149 (2), 411-432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3099-5.

Husted, B.W., Sousa-Filho, J.M.d., 2019. Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 102, 220-227. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.017.

Jizi, M., 2017. The influence of board composition on sustainable development disclosure. Bus. Strat. Environ. 26 (5), 640-655. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse. 1943.

Jorissen, A., Laveren, E., Martens, R., Reheul, A.-M., 2005. Real versus sample-based differences in comparative family business research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 18 (3).

Jouber, H., 2020. Is the effect of board diversity on CSR diverse? New insights from onetier vs two-tier corporate board models. Corp. Govern.: The Int. J. Busin. Soc. 21 (1), 23-61. https://doi.org/10.1108/cg-07-2020-0277.

Katmon, N., Mohamad, Z.Z., Norwani, N.M., Farooque, O.A., 2019. Comprehensive board diversity and quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure: evidence from an emerging market. J. Bus. Ethics 157 (2), 447-481. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10551-017-3672-6.

Kazemi, M.Z., Elamer, A.A., Theodosopoulos, G., Khatib, S.F.A., 2023. Reinvigorating research on sustainability reporting in the construction industry: a systematic review and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 167, 114145 https://doi.org/10.1016/J. JBUSRES.2023.114145.

Kesner, I.F., 1988. Directors’ characteristics and committee membership: an investigation of type, occupation, tenure, and gender. Acad. Manag. J. 31 (1), 66-84.

Ketokivi, M., McIntosh, C.N., 2017. Addressing the endogeneity dilemma in operations management research: theoretical, empirical, and pragmatic considerations. J. Oper. Manag. 52 (1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2017.05.001.

Khatib, S.F.A., Abdullah, D.F., Elamer, A.A., Abueid, R., 2021. Nudging toward diversity in the boardroom: a systematic literature review of board diversity of financial institutions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 30 (2), 985-1002. https://doi.org/10.1002/ bse. 2665.

Lamb, N.H., Butler, F.C., 2016. The influence of family firms and institutional owners on corporate social responsibility performance. Bus. Soc. 57 (7), 1374-1406. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0007650316648443.

Lee, P.M., James, E.H., 2007. She’-e-os: gender effects and investor reactions to the announcements of top executive appointments. Strat. Manag. J. 28 (3), 227-241. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.575.

Lin, Y., Shi, W., Prescott, J.E., Yang, H., 2018. In the eye of the beholder: top managers’ long-term orientation, industry context, and decision-making processes. J. Manag. 45 (8), 3114-3145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318777589.

Livnat, J., Smith, G., Suslava, K., Tarlie, M., 2021. Board tenure and firm performance. Global Finance J. 47 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2020.100535.

López-González, E., Martínez-Ferrero, J., García-Meca, E., 2019. Corporate social responsibility in family firms: a contingency approach. J. Clean. Prod. 211, 1044-1064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.251.

Loy, T.R., Rupertus, H., 2022. How does the stock market value female directors? International evidence. Bus. Soc. 61 (1), 117-154. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0007650320949839.

Main, B.G.M., Gregory-Smith, I., 2018. Symbolic management and the glass cliff: evidence from the boardroom careers of female and male directors. Br. J. Manag. 29 (1), 136-155. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12208.

Manuel, A., Bond, S., 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 58 (2), 277-297.

Marano, V., Sauerwald, S., Van Essen, M., 2022. The influence of culture on the relationship between women directors and corporate social performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 53 (7), 1315-1342. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-022-00503-z.

Markóczy, L., Sun, S.L., Zhu, J., 2021. The glass pyramid: informal gender status hierarchy on boards. J. Bus. Ethics 168 (4), 827-845. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10551-019-04247-z.

Mathur-Helm, B., 2005. Equal opportunity and affirmative action for South African women: a benefit or barrier? Women Manag. Rev. 20 (1), 56-71. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/09649420510579577.

Mosomi, J., 2019. An empirical analysis of trends in female labour force participation and the gender wage gap in South Africa. Agenda 33 (4), 29-43. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/10130950.2019.1656090.

Narayanan, M.P., 1985. Managerial incentives for short-term results. J. Finance 40 (5), 1469-1484.

Natarajan, V., 1989. Strategic orientation of business enterprises: the construct, dimensionality, and measurement. Manag. Sci. 35 (8), 942-962.

Nekhili, M., Chakroun, H., Chtioui, T., 2018. Women’s leadership and firm performance: family versus nonfamily firms. J. Bus. Ethics 153 (2), 291-316. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10551-016-3340-2.

Nielsen, S., Huse, M., 2010. Women directors’ contribution to board decision-making and strategic involvement: the role of equality perception. Eur. Manag. Rev. 7 (1), 16-29. https://doi.org/10.1057/emr.2009.27.

Ntim, C.G., Soobaroyen, T., 2013. Black economic empowerment disclosures by South African listed corporations: the influence of ownership and board characteristics. J. Bus. Ethics 116 (1), 121-138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1446-8.

Pacelli, V., Pampurini, F., Quaranta, A.G., 2022. Environmental, social and governance investing: does rating matter? Bus. Strat. Environ. 32 (1), 30-41. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/bse.3116.

Post, C., Byron, K., 2015. Women on boards and firm financial performance: a metaanalysis. Acad. Manag. J. 58 (5), 1546-1571. https://doi.org/10.5465/ amj.2013.0319.

Preacher, K.J., Rucker, D.D., Hayes, A.F., 2007. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav. Res. 42 (1), 185-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316.

Pronin, E., Steele, C.M., Ross, L., 2004. Identity bifurcation in response to stereotype threat: women and mathematics. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 40 (2), 152-168. https://doi. org/10.1016/s0022-1031(03)00088-x.

Qian, C., Crilly, D., Lin, Y., Zhang, K., Zhang, R., 2023. Short-selling pressure and workplace safety: curbing short-termism through stakeholder interdependencies. Organ. Sci. 34 (1), 358-379. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2022.1576.

Rajesh, R., 2020. Exploring the sustainability performances of firms using environmental, social, and governance scores. J. Clean. Prod. 247 https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119600.

Reguera-Alvarado, N., Bravo, F., 2017. The effect of independent directors’ characteristics on firm performance: tenure and multiple directorships. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 41, 590-599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.04.045.

Richard, B., Bond, S., 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 87 (1), 115-143.

Roberts, L., Hassan, A., Elamer, A., Nandy, M., 2021. Biodiversity and extinction accounting for sustainable development: a systematic literature review and future research directions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 30 (1), 705-720. https://doi.org/10.1002/ bse. 2649.

Rodríguez-Ariza, L., Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B., Martínez-Ferrero, J., García-Sánchez, I.M., 2017. The role of female directors in promoting CSR practices: an international comparison between family and non-family businesses. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 26 (2), 162-174. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12140.

Roodman, D., 2009. How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. STATA J. 9 (1), 86-136.

Ruigrok, W., Peck, S., Tacheva, S., 2007. Nationality and gender diversity on Swiss corporate boards. Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 15 (4), 546-557.

Ryan, M.K., Haslam, S.A., 2007. The glass cliff: exploring the dynamics surrounding the appointment of women to precarious leadership positions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 32 (2), 549-572. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24351856.

Saeed, A., Riaz, H., Liedong, T.A., Rajwani, T., 2022. The impact of TMT gender diversity on corporate environmental strategy in emerging economies. J. Bus. Res. 141, 536-551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.057.

Sahasranamam, S., Arya, B., Sud, M., 2020. Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility in an emerging market. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 37 (4), 1165-1192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-019-09649-1.

Sarkar, J., Selarka, E., 2021. Women on board and performance of family firms: evidence from India. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 46 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2020.100770.

Sidhu, J.S., Feng, Y., Volberda, H.W., Bosch, F.A.J.V.D., 2021. In the Shadow of Social Stereotypes: gender diversity on corporate boards, board chair’s gender and strategic change. Organ. Stud. 42 (11), 1677-1698. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0170840620944560.

Steyn, M., 2014. Organisational benefits and implementation challenges of mandatory integrated reporting. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 5 (4), 476-503. https://doi. org/10.1108/sampj-11-2013-0052.

Sun, X.S., Bhuiyan, M.B.U., 2020. Board tenure: a review. J. Corp. Account. Finance 31 (4), 178-196. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcaf. 22464.

Ullah, F., Jiang, P., Mu, W., Elamer, A.A., 2023. Rookie directors and corporate innovation: evidence from Chinese listed firms. Appl. Econ. Lett. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/13504851.2023.2209308.

Wang, Y., Wilson, C., Li, Y., 2021b. Gender attitudes and the effect of board gender diversity on corporate environmental responsibility. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 47 https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2020.100744.

Wasiuzzaman, S., Subramaniam, V., 2023. Board gender diversity and environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure: is it different for developed and developing nations? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2475.

Weck, M.K., Veltrop, D.B., Oehmichen, J., Rink, F., 2022. Why and when female directors are less engaged in their board duties: an interface perspective. Long. Range Plan. 55 (3) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2021.102123.

Wilson, N., Wright, M., Scholes, L., 2013. Family business survival and the role of boards. Entrep. Theory Pract. 37 (6), 1369-1389. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12071.

Yadav, P., Prashar, A., 2022. Board gender diversity: implications for environment, social, and governance (ESG) performance of Indian firms. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijppm-12-2021-0689.

Yarram, S.R., Adapa, S., 2021. Board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility: is there a case for critical mass? J. Clean. Prod. 278 https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jclepro.2020.123319.

Yarram, S.R., Adapa, S., 2022. Women on boards, CSR and risk-taking: an investigation of the interaction effects of gender diversity and CSR on business risk. J. Clean. Prod. 378 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134493.

Zahra, S.A., Hayton, J.C., Salvato, C.J. E.t., Practice, 2004. Entrepreneurship in family vs. non-family firms: a resource-based analysis of the effect of organizational culture. Entrep. Theory Pract. 28 (4), 363-381.

Zaid, M.A.A., Wang, M., Adib, M., Sahyouni, A., Abuhijleh, S.T.F., 2020. Boardroom nationality and gender diversity: implications for corporate sustainability performance. J. Clean. Prod. 251 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119652.

Zheng, W., Shen, R., Zhong, W., Lu, J., 2019. CEO values, firm long-term orientation, and firm innovation: evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Manag. Organ. Rev. 16 (1), 69-106. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2019.43.

- School of Management, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Hubei, Wuhan, China

E-mail addresses: mohamedgamal@mans.edu.eg (M.G. Abdelkader), yqgao@hust.edu.cn (Y. Gao), ahmed.elamer@brunel.ac.uk (A.A. Elamer).We test our hypothesis using the ESG score and find support for it; however, we only provide the results of using the ES score to avoid the endogeneity issue. - Notes: *,

, and refer to the significance of correlation is at , and 0.01 levels, respectively. , and refer to the significance is at , and 0.01 levels, respectively. - *, **, and *** refer to the significance is at

, and 0.01 levels, respectively.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140728

Publication Date: 2024-01-19

Board gender diversity and ESG performance: The mediating role of temporal orientation in South Africa context

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

ESG

Short-term orientation

Female director tenure

Family firms

Abstract

Prevailing research on the interaction between board gender diversity (BGD) and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance presents equivocal findings, particularly in the context of developing countries. This study ventures into an exploratory examination of this association, situated in the socio-cultural milieu of South Africa, a region where the lower social status of women often leads to a bias towards short-term perspectives. Drawing on the role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders, this study aims to investigate the mediating role of short-term orientation (SHRT) in the BGD-ESG relationship. We further explore how the preference of female directors toward SHRT varies depending on their tenure on the board and across family and non-family firms. The empirical findings, drawn from an examination of publicly listed non-financial firms on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) from 2015 to 2020, indicate a negative relationship between BGD and ESG, with SHRT predominantly mediating this association. Additionally, the tenure of female directors attenuates their preference for SHRT. Notably, we found the effect of BGD on SHRT is less pronounced in family firms, where the choices of female directors are more aligned with the family firm’s long-term orientation. Our findings contribute to both theory and practice by advancing our understanding of the BGD-ESG relationship and providing practical implications for organizations, leaders, and policymakers.

1. Introduction

developing economies present a more fragmented and inconsistent picture. While some research suggests a positive relation (Wasiuzzaman and Subramaniam, 2023; Al-Mamun and Seamer, 2021; Katmon et al., 2019), others report a negative or statistically insignificant relationship (Gallego-Álvarez and Pucheta-Martínez, 2020; Hussain et al., 2018; Zaid et al., 2020; Yadav and Prashar, 2022). This apparent contradiction signals an exigent need for a deeper investigation into the dynamics of BGD and ESG. Thus, our research aims to reconceptualize the relationship between BGD and ESG, placing this examination within the unique socio-cultural context of South Africa-an environment hitherto underexplored in this scholarly discourse.

negative gender-based stereotypes are less likely to appear in such environments, consequently influencing business outcomes. We, therefore, introduce family firms as a potential moderating factor in the relationship between BGD and short-term orientation, keeping in line with the proposition that female directors’ behavior aligns with the long-term orientation inherent to family firms’ culture.

2. Theory and hypotheses development

2.1. Board gender diversity and ESG

and empirical evidence suggests that the benefits of female directors are primarily realized in developed countries where gender parity is more prevalent. For instance, a comparative study between developed and developing countries demonstrated that female directors significantly increase ESG in developed countries, while the same is not valid for developing countries (Wasiuzzaman and Subramaniam, 2023). This observation renders the role of female directors toward ESG in developing countries questionable. Factors contributing to this limited impact on ESG include inadequate representation of women on boards, gender discrimination, and pervasive negative gender stereotypes in developing countries (Husted and Sousa-Filho, 2019; Zaid et al., 2020). Yarram and Adapa (2021) contend that having just one female director on a board may not significantly affect corporate social responsibility (CSR) due to perceptions of tokenism.

2.2. The mediating role of short-term orientation

(2019) found that CEOs who have self-interest values tend to steer their companies away from long-term orientations. Similarly, Galbreath (2017) observed that insider directors are more prone to short-term thinking compared to their counterparts. The literature also supports the notion that a firm’s temporal orientation can affect its engagement with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. For instance, Choi et al. (2023) reported that firms with a long-term orientation are more inclined to invest in ESG initiatives. Following the above arguments, we propose our second hypothesis as follows.

2.3. The moderating role of female directors’ tenure

2.4. The moderating role of family firms

firms are noted to take a longer view, considering the long-term consequences of current actions (Dou et al., 2019). As such, they are more long-term oriented than their non-family counterparts (Lumpkin and Brigham, 2011; Zahra et al., 2004). This long-term perspective often stems from the belief of family owners that their ownership will pass on to future generations, encouraging a multigenerational viewpoint (Anderson and Reeb, 2003; Tseng, 2020). This drives family firms to maintain their societal reputation (Lumpkin and Brigham, 2011). Therefore, when making decisions, family firms tend to prioritize socioemotional wealth as the main strategic reference point (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). Berrone et al. (2010) argued that family-controlled firms protect their socioemotional wealth through superior environmental performance. Many studies corroborate this claim, documenting the enhanced commitment of family firms towards social responsibility (Cordeiro et al., 2018; Lamb and Butler, 2016; López-González et al., 2019; Sahasranamam et al., 2020) to ensure firm survival. As a result, family firms tend to be more socially oriented than non-family firms (García-Sánchez et al., 2021).

3. Method

3.1. Sample and data collection

3.2. Variables measurements

3.2.1. The dependent variable:ESG

3.2.2. The independent variable: board gender diversity (BGD)

3.2.3. The mediator variable: short-term orientation (SHRT)

To produce the SHRT index, we used NVivo software to analyze the integrated reports of the firms in our sample. To validate this approach, we manually counted the relevant keywords in 20 randomly selected reports and compared these findings with the NVivo results. The two sets of findings were found to be identical.

3.2.4. The moderator variables

3.2.5. Control variables

3.3. Model specification

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

4.2. Multivariate regression analysis

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Observation | Mean | Median | Standard deviation | Min. | Max. |

| ESG | 432 | 0.498 | 0.497 | 0.178 | 0.091 | 0.910 |

| BGD | 432 | 0.256 | 0.250 | 0.121 | 0.000 | 0.667 |

| SHRT | 432 | 0.320 | 0.320 | 0.111 | 0.031 | 0.592 |

| FTenure | 432 | 4.810 | 4.500 | 2.930 | 0.000 | 16.00 |

| F.NF | 432 | 0.110 | 0.000 | 0.314 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| SIZE | 432 | 23.60 | 23.50 | 1.120 | 20.40 | 26.80 |

| ROA | 432 | 0.067 | 0.060 | 0.118 | -0.522 | 0.499 |

| LEV | 432 | 0.223 | 0.218 | 0.143 | 0.001 | 0.761 |

| FAGE | 432 | 3.790 | 3.910 | 0.822 | 0.000 | 5.130 |

| BSIZE | 432 | 11.20 | 11.00 | 2.610 | 5.000 | 20.00 |

| IND | 432 | 0.723 | 0.750 | 0.105 | 0.167 | 0.917 |

| MET | 432 | 4.932 | 5.000 | 1.316 | 2.000 | 10.00 |

| FCEO | 432 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.143 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Variables | VIF. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| (1) ESG | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| (2) BGD | 1.23 | 0.068 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (3) SHRT | 1.11 | -0.193*** | 0.016 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (4) F.NF | 1.10 | -0.281*** | -0.215*** | 0.131*** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (5) FTenure | 1.12 | -0.068 | -0.210*** | -0.007 | -0.018 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (6) SIZE | 1.26 | 0.324*** | -0.018 | -0.173*** | -0.065 | 0.002 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (7) ROA | 1.09 | -0.007 | -0.102** | 0.033 | 0.008 | 0.121** | -0.050 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (8) LEV | 1.06 | -0.025 | 0.025 | -0.025 | 0.022 | 0.096** | 0.069 | -0.159*** | 1.000 | |||||

| (9) FAGE | 1.08 | 0.040 | 0.034 | 0.232*** | -0.040 | 0.037 | -0.116** | -0.033 | -0.024 | 1.000 | ||||

| (10) Bsize | 1.22 | 0.241*** | 0.022 | -0.042 | -0.117** | -0.057 | 0.354*** | 0.005 | -0.004 | -0.056 | 1.000 | |||

| (11) IND | 1.18 | 0.176*** | 0.013 | -0.072 | -0.110** | -0.146*** | 0.255*** | -0.033 | 0.009 | -0.102** | 0.295*** | 1.000 | ||

| (12) MET | 1.04 | 0.149*** | -0.064 | -0.040 | -0.003 | -0.064 | 0.088* | 0.122** | 0.012 | -0.040 | -0.031 | 0.020 | 1.000 | |

| (13) FCEO | 1.17 | -0.066 | 0.297 | 0.002 | -0.052 | -0.018 | -0.166*** | -0.103** | -0.084* | 0.000 | -0.074 | -0.134*** | -0.042 | 1.000 |

GMM: The mediating effect of short-term between BGD and ESG.

| Variables | Model 1-ESG

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

Model 3- ESG

|

|||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| ESG (t-1) | 0.844 | 0.000*** | 0.859 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.660 | 0.000*** | ||||

| SHRT | -0.172 | 0.000*** | ||||

| BGD | -0.184 | 0.002*** | 0.172 | 0.002*** | -0.151 | 0.002*** |

| SIZE | 0.077 | 0.000*** | -0.002 | 0.349 | 0.013 | 0.007*** |

| ROA | -0.007 | 0.682 | 0.006 | 0.771 | -0.004 | 0.863 |

| LEV | 0.002 | 0.785 | 0.003 | 0.225 | 0.003 | 0.103 |

| FAGE | 0.077 | 0.033** | 0.007 | 0.066* | 0.003 | 0.646 |

| BSIZE | -0.087 | 0.000*** | 0.006 | 0.001*** | -0.001 | 0.444 |

| IND | 0.082 | 0.235 | -0.072 | 0.190 | 0.219 | 0.001*** |

| MET | -0.005 | 0.001*** | 0.003 | 0.050** | -0.003 | 0.133 |

| FCEO | 0.048 | 0.164 | 0.061 | 0.387 | -0.030 | 0.350 |

| Industry dummy | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| AR (1) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.948 | 0.224 | 0.908 | |||

| Hansen test | 0.364 | 0.245 | 0.268 | |||

| Number of observations | 288 | 288 | 288 | |||

decrease in long-term investments, such as those related to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) initiatives, ultimately impacting ESG decisions negatively.

GMM: The moderating role of female directors’ tenure and Family firms on short term.

| Variables | Model 1-SHRT

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.602 | 0.000*** | 0.566 | 0.000*** |

| BGD | 0.149 | 0.061* | 0.179 | 0.011** |

| FTENURE | 0.003 | 0.465 | ||

| F.NF | 0.214 | 0.005*** | ||

| BGD* FTENURE | -0.028 | 0.030** | ||

| BGD* F.NF | -0.634 | 0.039** | ||

| SIZE | -0.002 | 0.422 | -0.014 | 0.062* |

| ROA | 0.007 | 0.817 | 0.020 | 0.533 |

| LEV | 0.008 | 0.025** | 0.004 | 0.474 |

| FAGE | 0.045 | 0.000** | 0.018 | 0.097* |

| BSIZE | 0.003 | 0.110 | 0.006 | 0.057* |

| IND | -0.056 | 0.355 | -0.010 | 0.903 |

| MET | 0.003 | 0.159 | 0.003 | 0.087* |

| FCEO | 0.023 | 0.778 | -0.080 | 0.295 |

| Industry dummy | No | Yes | ||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| AR (1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| AR (2) | 0.160 | 0.152 | ||

| Hansen test | 0.364 | 0.331 | ||

| Number of observations | 288 | 288 | ||

stereotypes decreases, thereby reducing the pressure to focus on short-term outcomes. Prolonged tenure aids female directors in establishing legitimacy, which, in turn, empowers them to infuse their values and perspectives into strategic decision-making processes (Dou et al., 2015). Similarly, Model 2 shows that family firms negatively moderate the relationship between BGD and SHRT (

4.3. Additional analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical contribution

5.2. Practical implications

2SLS: The mediating effect of short-term between BGD and ESG.

| Variables | Model 1-ESG

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

Model 3- ESG

|

|||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| SHRT | -0.294 | 0.000*** | ||||

| BGD | -0.589 | 0.017** | 0.614 | 0.017** | -0.407 | 0.513 |

| SIZE | 0.039 | 0.000*** | -0.028 | 0.001*** | 0.030 | 0.001*** |

| ROA | 0.008 | 0.959 | 0.074 | 0.130 | 0.141 | 0.077* |

| LEV | -0.008 | 0.196 | 0.001 | 0.850 | -0.007 | 0.618 |

| FAGE | 0.019 | 0.000*** | 0.023 | 0.000*** | 0.027 | 0.023** |

| BSIZE | 0.010 | 0.000*** | 0.001 | 0.683 | 0.010 | 0.009*** |

| IND | 0.178 | 0.003*** | -0.046 | 0.145 | 0.186 | 0.053* |

| MET | 0.039 | 0.476 | -0.023 | 0.229 | -0.007 | 0.846 |

| FCEO | 0.146 | 0.044** | -0.183 | 0.036** | 0.078 | 0.628 |

| Industry dummy | No | Yes | No | |||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Number of observations | 360 | 360 | 360 | |||

2SLS: The moderating role of female directors’ tenure and Family firms on short term.

| Variables | Model 1-SHRT

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| BGD | 0.639 | 0.004*** | 0.416 | 0.018** |

| FTENURE | 0.020 | 0.002*** | ||

| F.NF | 0.194 | 0.010** | ||

| BGD* FTENURE | -0.100 | 0.001*** | ||

| BGD* F.NF | -0.603 | 0.019** | ||

| SIZE | -0.021 | 0.000*** | -0.024 | 0.000*** |

| ROA | 0.032 | 0.301 | 0.080 | 0.001*** |

| LEV | -0.001 | 0.946 | 0.010 | 0.144 |

| FAGE | 0.027 | 0.000*** | 0.031 | 0.000*** |

| BSIZE | 0.001 | 0.798 | 0.001 | 0.632 |

| IND | -0.126 | 0.001*** | -0.004 | 0.878 |

| MET | -0.002 | 0.469 | -0.003 | 0.385 |

| FCEO | -0.054 | 0.130 | -0.116 | 0.098* |

| Industry dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| Number of observations | 360 | 360 | ||

impeding women’s contributions to ESG, particularly discrimination stemming from gender-based minority representation in developing countries. The effect of negative stereotypes on the performance and decision-making capabilities of directors, particularly those in minority positions such as female directors, is well documented. Given the persistent underrepresentation of female directors on corporate boards in developing countries, there is a compelling case for policymakers to enact legislation that addresses these stereotypes. Such measures could

include mandating a higher proportion of women on boards, thereby advancing gender parity and potentially mitigating the biases that hinder female directors’ effectiveness. Furthermore, our results highlight the impactful role of a female director’s board tenure in reducing negative gender stereotypes. Long tenure on the board enhances the business acumen and experience of minority directors, which, in turn, facilitates their effective participation in strategic decision-making. As a result, their perspectives are less likely to be overlooked by the majority, enabling a more inclusive approach to governance. Thus, considerations should be made for legislation to prevent gender-based discrimination related to board tenure. Investors should also evaluate directors based on their performance rather than preconceived stereotypes about

GMM: the moderation analysis using Fexe instead of BGD.

| Variables | Model 1-SHRT

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.661 | 0.000*** | 0.616 | 0.000*** |

| Fexe | 0.322 | 0.027** | 0.092 | 0.274 |

| FexeT | 0.008 | 0.264 | ||

| F.NF | 0.14 | 0.000*** | ||

| Fexe* FexeT | -0.159 | 0.040** | ||

| Fexe* F.NF | -0.734 | 0.032** | ||

| Control | Included | Included | ||

| Industry dummy | No | Yes | ||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| AR (1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| AR (2) | 0.135 | 0.184 | ||

| Hansen | 0.162 | 0.387 | ||

| Number of observations | 288 | 288 | ||

GMM: the mediation analysis using female executive directors (Fexe) as independent variable.

| Variables | Model 1-ESG

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

Model 3- ESG

|

|||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| ESG (t-1) | 0.869 | 0.000*** | 0.732 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.708 | 0.000 | ||||

| SHRT | -0.272 | 0.003*** | ||||

| Fexe | -0.310 | 0.043** | 0.466 | 0.010** | -0.197 | 0.198 |

| Control | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Industry dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| AR (1) | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.002 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.790 | 0.342 | 0.705 | |||

| Hansen test | 0.242 | 0.224 | 0.412 | |||

| Number of observations | 288 | 288 | 288 | |||

GMM: the mediation analysis using Blau index as alternative measurement of BGD.

| Variables | Model 1-ES

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

Model 3-

|

|||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| ES (t-1) | 0.855 | 0.000*** | 0.855 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.677 | 0.000*** | ||||

| SHRT | -0.171 | 0.001*** | ||||

| Blau | -0.178 | 0.000*** | 0.086 | 0.006*** | -0.161 | 0.003*** |

| Control | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Industry dummy | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| AR (1) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.685 | 0.249 | 0.849 | |||

| Hansen test | 0.516 | 0.452 | 0.660 | |||

| Number of observations | 288 | 288 | 288 | |||

GMM: the moderation analysis using Blau index as alternative measurement of BGD.

| Variables | Model 1-SHRT

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.595 | 0.000*** | 0.553 | 0.000*** |

| Blau | 0.178 | 0.010** | 0.191 | 0.035** |

| FTENURE | 0.005 | 0.324 | ||

| F.NF | 0.304 | 0.009*** | ||

| Blau * FTENURE | -0.027 | 0.006*** | ||

| Blau * F.NF | -0.761 | 0.019** | ||

| Control | Included | Included | ||

| Industry dummy | No | Yes | ||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| AR (1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| AR (2) | 0.170 | 0.231 | ||

| Hansen | 0.450 | 0.337 | ||

| Number of observations | 288 | 288 | ||

women, alleviating pressures to focus solely on short-term results over long-term outcomes such as ESG. Overall, our study provides a nuanced understanding of the intricate relationship between gender diversity, temporal orientation, and ESG outcomes, offering valuable insights for researchers and practitioners alike.

5.3. Limitations and suggestions for future studies

and compare our findings regarding the influence of female directors on a firm’s temporal orientation in developing versus developed countries. Additionally, we relied on secondary data to validate our arguments. Future research could utilize primary and qualitative data (i.e., interviews or surveys) to gain a deeper understanding of the challenges that female directors encounter on the board, which could inhibit their contribution to ESG decisions. Moreover, the results of our additional analyses did not corroborate the critical mass theory. Future research could elucidate the influence of stereotypes by comparing the applicability of the critical mass theory across developed and developing countries. Future studies may also examine differences between male and female directors in terms of characteristics and experiences, such as comparing the board tenures of male and female directors and how these affect ESG decisions.

6. Conclusion

GMM: the mediation analysis using environmental score (E) as a dependent variable.

| Variables | Model 1-E

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

Model 3-

|

|||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| E (t-1) | 0.934 | 0.000*** | 0.786 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.659 | 0.000*** | ||||

| SHRT | -0.270 | 0.001*** | ||||

| BGD | -0.233 | 0.002*** | 0.172 | 0.002*** | -0.062 | 0.301 |

| Control | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Industry dummy | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| AR (1) | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.014 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.319 | 0.224 | 0.183 | |||

| Hansen test | 0.469 | 0.245 | 0.311 | |||

| Number of observations | 288 | 288 | 288 | |||

GMM: the mediation analysis using social score ( S ) as a dependent variable.

| Variables | Model 1-S

|

Model 2-SHRT

|

Model 3-

|

|||

|

|

P.value |

|

P.value |

|

P.value | |

| S (t-1) | 0.942 | 0.000*** | 0.942 | 0.000*** | ||

| SHRT (t-1) | 0.659 | 0.000*** | ||||

| SHRT | -0.089 | 0.049** | ||||

| BGD | -0.154 | 0.018*** | 0.172 |

|

-0.133 | 0.066* |

| Control | Included | Included | Included | |||

| Industry dummy | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Year dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| AR (1) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |||

| AR (2) | 0.180 | 0.224 | 0.141 | |||

| Hansen test | 0.464 | 0.245 | 0.682 | |||

| Number of observations | 288 | 288 | 288 | |||

tenures on boards gain increased legitimacy and experience, which mitigates the negative stereotypes and enables them to contribute more effectively to ESG initiatives. In the context of family firms, characterized by their long-term orientation and focus on socioemotional wealth, a supportive environment is created. This environment facilitates female directors in aligning their decisions with family values and prioritizing long-term reputation over short-term gains. The robustness of our results is confirmed through the utilization of alternative techniques and varied measurements of independent and dependent variables.

Funding statement

Ethics approval statement

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Data availability

| Variable | Abbreviation | Measurement |

| ESG | ESG | ESG score obtained from the Refinitiv Eikon database. |

| Board gender diversity | BGD | The ratio of female directors on the board. |

| Female executive | Fexe | The ratio of female executive directors on board |

| Blau index for diversity | Blau |

|

| Where: | ||

|

|

||

| Short-term orientation | SHRT | Constructed by calculating the percentage of total short-term keywords relative to the sum of both short- and long-term keywords. |

| Female directors’ tenure | FTENURE | The average length of time that female directors have served on the board. |

| Female executive tenure | FexeT | The average length of time that female executive directors have served on the board. |

| Family firms | F.NF | Dummy variable takes 1 if the firm owed by family 0 otherwise. |

| Firm size | SIZE | Natural logarithm (ln) of the firm’s total assets. |

| Return on assets | ROA | Earnings before interest and tax divided by total assets. |

| Leverage | LEV | The ratio of total debt to total assets. |

| Firm age | FAGE | The natural logarithm (ln) of the number of years since the firm’s foundation. |

| Board size | BSIZE | Total number of board members of the firm. |

| Board independence | IND | Number of independent directors/total number of board directors. |

| Board meeting | MET | Total number of meetings held annually. |

| Female CEO | FCEO | Dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm’s CEO is a woman and 0 otherwise |

References

Abdou, H.A., Ellelly, N.N., Elamer, A.A., Hussainey, K., Yazdifar, H., 2021. Corporate governance and earnings management nexus: evidence from the UK and Egypt using

neural networks. Int. J. Finance Econ. 26 (4), 6281-6311. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ijfe. 2120.

Abdullah, S.N., 2014. The causes of gender diversity in Malaysian large firms. J. Manag. Govern. 18 (4), 1137-1159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-013-9279-0.

Al-Mamun, A., Seamer, M., 2021. Board of director attributes and CSR engagement in emerging economy firms: evidence from across Asia. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 46 https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2020.100749.

Alshbili, I., Elamer, A.A., 2020. The influence of institutional context on corporate social responsibility disclosure: a case of a developing country. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 10 (3), 269-293. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2019.1677440.

Alshbili, I., Elamer, A.A., Beddewela, E., 2019. Ownership types, corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures. Account. Res. J. 33 (1), 148-166. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-03-2018-0060.

Amin, A., Ali, R., ur Rehman, R., Elamer, A.A., 2023. Gender diversity in the board room and sustainable growth rate: the moderating role of family ownership. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 13 (4), 1577-1599. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 20430795.2022.2138695.

Baron, R.M., Kenny, D.A., 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173-1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Bătae, O.M., Dragomir, V.D., Feleagă, L., 2021. The relationship between environmental, social, and financial performance in the banking sector: a European study. J. Clean. Prod. 290 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.125791.

Beji, R., Yousfi, O., Loukil, N., Omri, A., 2021. Board diversity and corporate social responsibility: empirical evidence from France. J. Bus. Ethics 173 (1), 133-155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04522-4.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L.R., Larraza-Kintana, M.J. A.s. q., 2010. Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: do familycontrolled firms pollute less? Adm. Sci. Q. 55 (1), 82-113.

Bettinelli, Cristina, Bosco, B.D., Giachino, C., 2019. Women on boards in family firms: what we know and what we need to know. In: Memili, E., Dibrell, C. (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Heterogeneity Among Family Firms, pp. 201-228.

Bonini, S., Deng, J., Ferrari, M., John, K., 2017. On Long-Tenured Independent Directors. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13164.36480.

Bose, S., Hossain, S., Sobhan, A., Handley, K., 2022. Does female participation in strategic decision-making roles matter for corporate social responsibility performance? Account. Finance. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12918.

Boulhaga, M., Bouri, A., Elamer, A.A., Ibrahim, B.A., 2023. Environmental, social and governance ratings and firm performance: the moderating role of internal control quality. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 30 (1), 134-145. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/CSR. 2343.

Brown, J.A., Anderson, A., Salas, J.M., Ward, A.J., 2017. Do investors care about director tenure? Insights from executive cognition and social capital theories. Organ. Sci. 28 (3), 471-494. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1123.

Buertey, S., 2021. Board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility assurance: the moderating effect of ownership concentration. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 28 (6), 1579-1590. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr. 2121.

Bufarwa, I.M., Elamer, A.A., Ntim, C.G., AlHares, A., 2020. Gender diversity, corporate governance and financial risk disclosure in the UK. International Journal of Law and Management 62 (6), 521-538. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-10-2018-0245.

Byron, K., Post, C., 2016. Women on boards of directors and corporate social performance: a meta-analysis. Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 24 (4), 428-442. https://doi. org/10.1111/corg.12165.

Cambrea, D.R., Paolone, F., Cucari, N., 2023. Advisory or Monitoring Role in ESG Scenario: Which Women Directors Are More Influential in the Italian Context? Business Strategy and the Environment. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3366.

Campbell, T.S., Marino, A.M., 1994. Myopic investment decisions and competitive labor markets. Int. Econ. Rev. 855-875.

Campbell, K., Mínguez-Vera, A., 2008. Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics 83 (3), 435-451. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10551-007-9630-y.

Campopiano, G., Gabaldón, P., Gimenez-Jimenez, D., 2022. Women directors and corporate social performance: an integrative review of the literature and a future research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04999-7.

Carr, P.B., Steele, C.M., 2010. Stereotype threat affects financial decision making. Psychol. Sci. 21 (10), 1411-1416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610384146.

Carter, D.A., Simkins, B.J., Simpson, W.G., 2003. Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financ. Rev. 38 (1), 33-53.

Cassell, C., 1997. The business case for equal opportunities: implications for women in management. Women Manag. Rev. 12 (1), 11-16.

Chen, C.J.P., Jaggi, B., 2000. Association between independent nonexecutive directors, family control and financial disclosures in Hong Kong. J. Account. Publ. Pol. 19 (4-5), 285-310.

Choi, J.J., Kim, J., Shenkar, O., 2023. Temporal orientation and corporate social responsibility: global evidence. J. Manag. Stud. 60 (1), 82-119. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/joms.12861.

Cordeiro, J.J., Profumo, G., Tutore, I., 2020. Board gender diversity and corporate environmental performance: the moderating role of family and dual-class majority

ownership structures. Bus. Strat. Environ. 29 (3), 1127-1144. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/bse.2421.

Dou, J., Su, E., Wang, S., 2019. When does family ownership promote proactive environmental strategy? The role of the firm’s long-term orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 158 (1), 81-95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3642-z.

Eagly, A.H., Karau, S.J., 2002. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 109 (3), 573-598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573.

Elmagrhi, M.H., Ntim, C.G., Elamer, A.A., Zhang, Q., 2019. A study of environmental policies and regulations, governance structures, and environmental performance: the role of female directors. Bus. Strat. Environ. 28 (1), 206-220. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/bse.2250.

Fiegenbaum, A.V.I., Hart, S., Schendel, D.A.N., 1996. Strategic reference point theory. Strat. Manag. J. 17 (3), 219-235. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(199603) 17:3<219::Aid-smj806>3.0.Co;2-n.

Flammer, C., Bansal, P., 2017. Does a long-term orientation create value? Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strat. Manag. J. 38 https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.

Flammer, C., Hong, B., Minor, D., 2019. Corporate governance and the rise of integrating corporate social responsibility criteria in executive compensation: effectiveness and implications for firm outcomes. Strat. Manag. J. 40 (7), 1097-1122. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/smj. 3018.

Francoeur, C., Labelle, R., Balti, S., El Bouzaidi, S., 2019. To what extent do gender diverse boards enhance corporate social performance? J. Bus. Ethics 155 (2), 343-357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3529-z.

Frijat, Y. S. Al, Albawwat, I.E., Elamer, A.A., 2023. Exploring the mediating role of corporate social responsibility in the connection between board competence and corporate financial performance amidst global uncertainties. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1002/CSR.2623.

Galbreath, J., 2011. Are there gender-related influences on corporate sustainability? A study of women on boards of directors. J. Manag. Organ. 17 (1), 17-38.

Galbreath, J., 2017. The impact of board structure on corporate social responsibility: a temporal view. Bus. Strat. Environ. 26 (3), 358-370. https://doi.org/10.1002/ bse. 1922.

Gallego-Álvarez, I., Pucheta-Martínez, M.C., 2020. Corporate social responsibility reporting and corporate governance mechanisms: an international outlook from emerging countries. Busin. Strat. Dev. 3 (1), 77-97. https://doi.org/10.1002/ bsd2.80.

Gangadharan, L., Jain, T., Maitra, P., Vecci, J., 2016. Social identity and governance: the behavioral response to female leaders. Eur. Econ. Rev. 90, 302-325. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.01.003.

Glass, C., Cook, A., 2016. Leading at the top: understanding women’s challenges above the glass ceiling. Leader. Q. 27 (1), 51-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. leaqua.2015.09.003.

Gómez-Mejía, L.R., Haynes, K.T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K.J., Moyano-Fuentes, J.J. A.s. q., 2007. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 52 (1), 106-137.

Goyal, R., Kakabadse, N., Kakabadse, A., Talbot, D., 2023. Female board directors’ resilience against gender discrimination. Gend. Work. Organ. 30 (1), 197-222. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12669.

Graafland, J., Noorderhaven, N., 2020. Culture and institutions: how economic freedom and long-term orientation interactively influence corporate social responsibility. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 51 (6), 1034-1043. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00301-0.

Gull, A.A., Nekhili, M., Nagati, H., Chtioui, T., 2018. Beyond gender diversity: how specific attributes of female directors affect earnings management. Br. Account. Rev. 50 (3), 255-274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2017.09.001.

Gupta, V.K., Han, S., Mortal, S.C., Silveri, S.D., Turban, D.B., 2018. Do women CEOs face greater threat of shareholder activism compared to male CEOs? A role congruity perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 103 (2), 228-236. https://doi.org/10.1037/ apl0000269.

Gyapong, E., Monem, R.M., Hu, F., 2016. Do women and ethnic minority directors influence firm value? Evidence from post-apartheid South Africa. J. Bus. Finance Account. 43 (3-4), 370-413. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa. 12175.

Hoyt, C.L., Murphy, S.E., 2016. Managing to clear the air: stereotype threat, women, and leadership. Leader. Q. 27 (3), 387-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. leaqua.2015.11.002.

Hussain, N., Rigoni, U., Orij, R.P., 2018. Corporate governance and sustainability performance: analysis of triple bottom line performance. J. Bus. Ethics 149 (2), 411-432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3099-5.

Husted, B.W., Sousa-Filho, J.M.d., 2019. Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 102, 220-227. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.017.