DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49605-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38906879

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-22

توجيه الانتقال في المسار غير الجذري من خلال النانو احتجاز في التحفيز الشبيه بفنتون للذرات المفردة لتحسين استخدام المؤكسدات

تم القبول: 6 يونيو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 22 يونيو 2024

الملخص

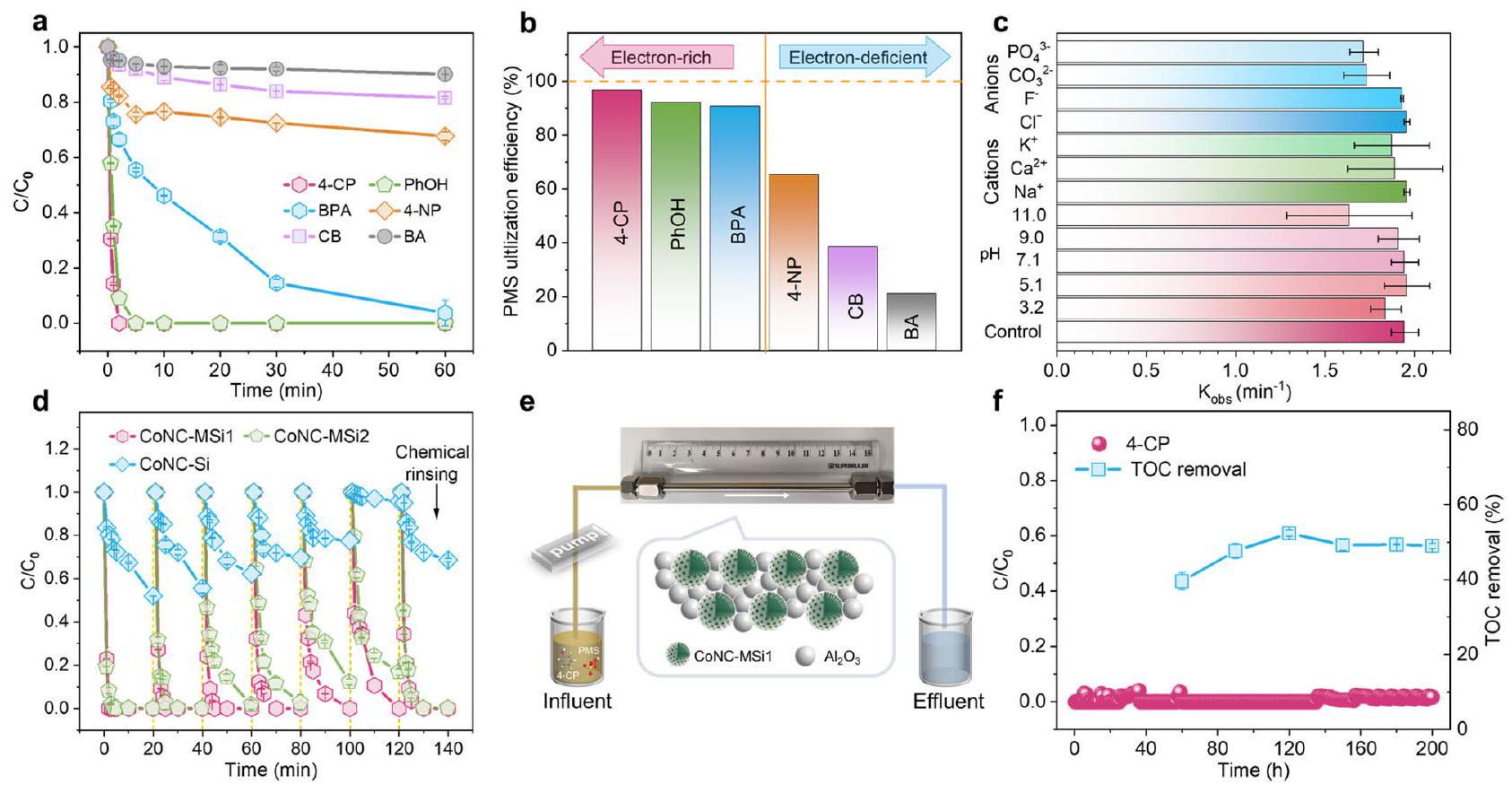

إن إدخال المحفزات ذات الذرة الواحدة (SACs) في الأكسدة الشبيهة بفنتون يعد بإزالة ملوثات المياه بسرعة فائقة، ولكن الوصول المحدود إلى الملوثات والأكسيد من قبل مواقع التحفيز السطحية والاستهلاك المكثف للأكسيد لا يزال يقيد بشدة أداء إزالة التلوث. بينما يسمح حصر SACs في النانو بتحسين كبير في حركية تفاعل إزالة التلوث، تظل الآليات التنظيمية التفصيلية غامضة. هنا، نكشف أنه، بالإضافة إلى التركيز المحلي للمتفاعلات، فإن تغيير مسار التحفيز هو أيضًا سبب مهم لتعزيز التفاعل في SACs المحصورة في النانو. يتم تغيير الهيكل الإلكتروني السطحي لموقع الكوبالت من خلال حصره داخل المسام النانوية لجزيئات السيليكا ذات البنية المتوسطة، مما يؤدي إلى انتقال أساسي من الأكسجين الأحادي إلى مسار نقل الإلكترون لأكسدة 4-كلوروفينول. إن المسار المتغير وتسريع نقل الكتلة بين السطحين يجعل النظام المحصور في النانو يصل إلى معدل تحلل ملوثات أعلى بمقدار 34.7 مرة وكفاءة استخدام بيروكسيمونوكبريتات مرتفعة بشكل كبير (من

الاهتمام في توليد الأنواع غير الجذرية بشكل تفضيلي بما في ذلك الأكسجين المفرد

النتائج

خصائص SACs من الكوبالت المحصور نانوياً

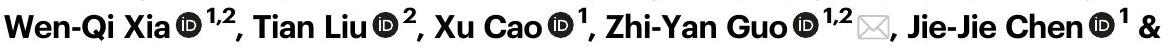

أنتجت قشرة CoNC-MSil مساحة سطح محددة أكبر بمقدار 6.8 مرة من CoNC-Si غير المسامي (الجدول التكميلي 1).

تحلل الملوثات وأداء استخدام PMS

صور توضح توزيع ذرات الكوبالت الفردية (المعلمة بالدوائر الصفراء، كانت SACs تقع بشكل رئيسي داخل مسام غلاف المحفز).

يدعم زيادة عميقة في التفاعل الذاتي لذرات الكوبالت تحت القيود النانوية. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن تفاعل تحلل 4-CP لـ CoNCMSi 2 قد تم تعزيزه أيضًا بالنسبة إلى

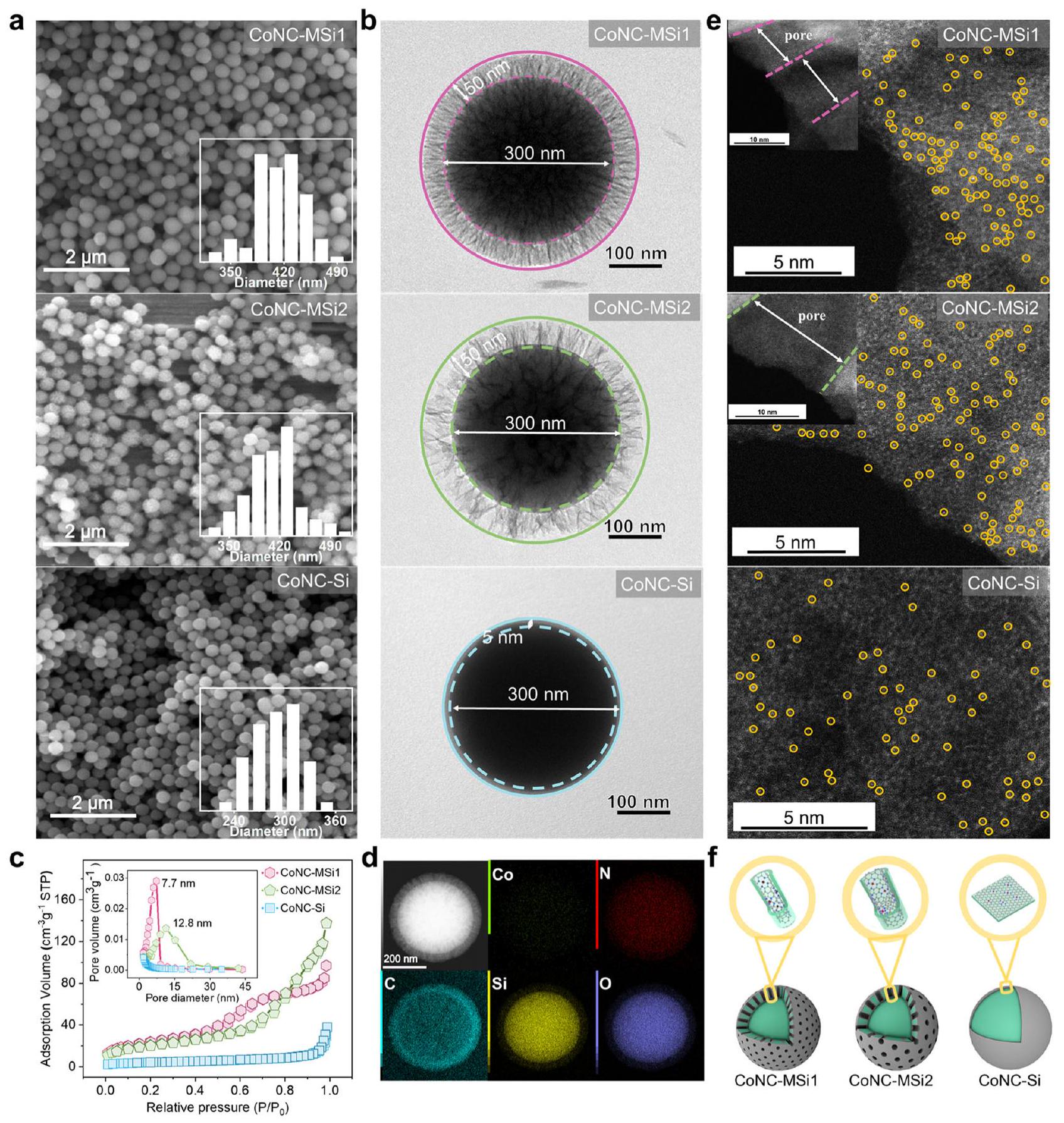

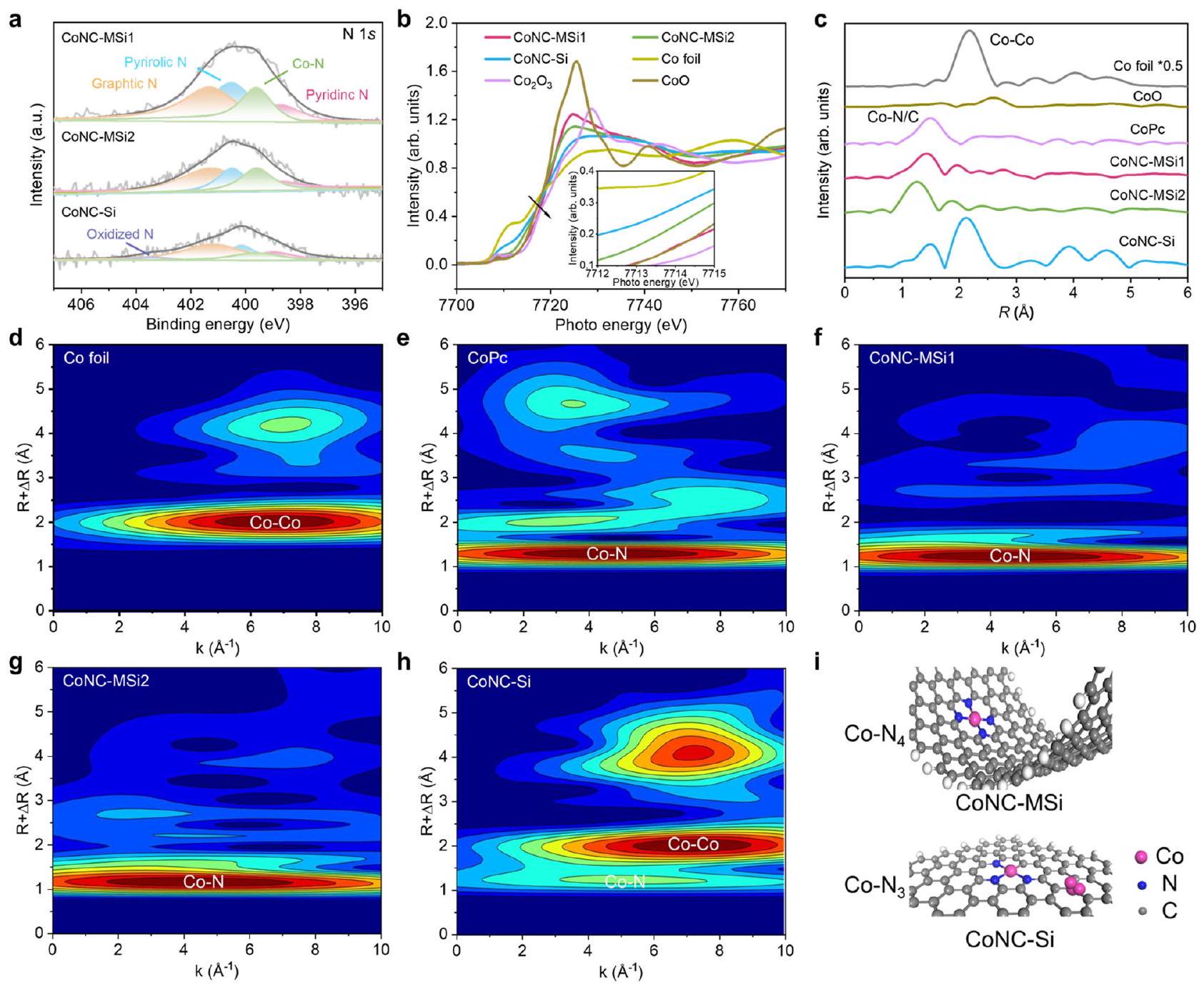

طيف SACs الكوبالت وعينات المرجع (رقائق الكوبالت، CoO، وCoPc). مخططات WTEXAFS للدوافع المختلفة. رسم تخطيطي لتنسيقات التنسيق لـ SACs الكوبالت.

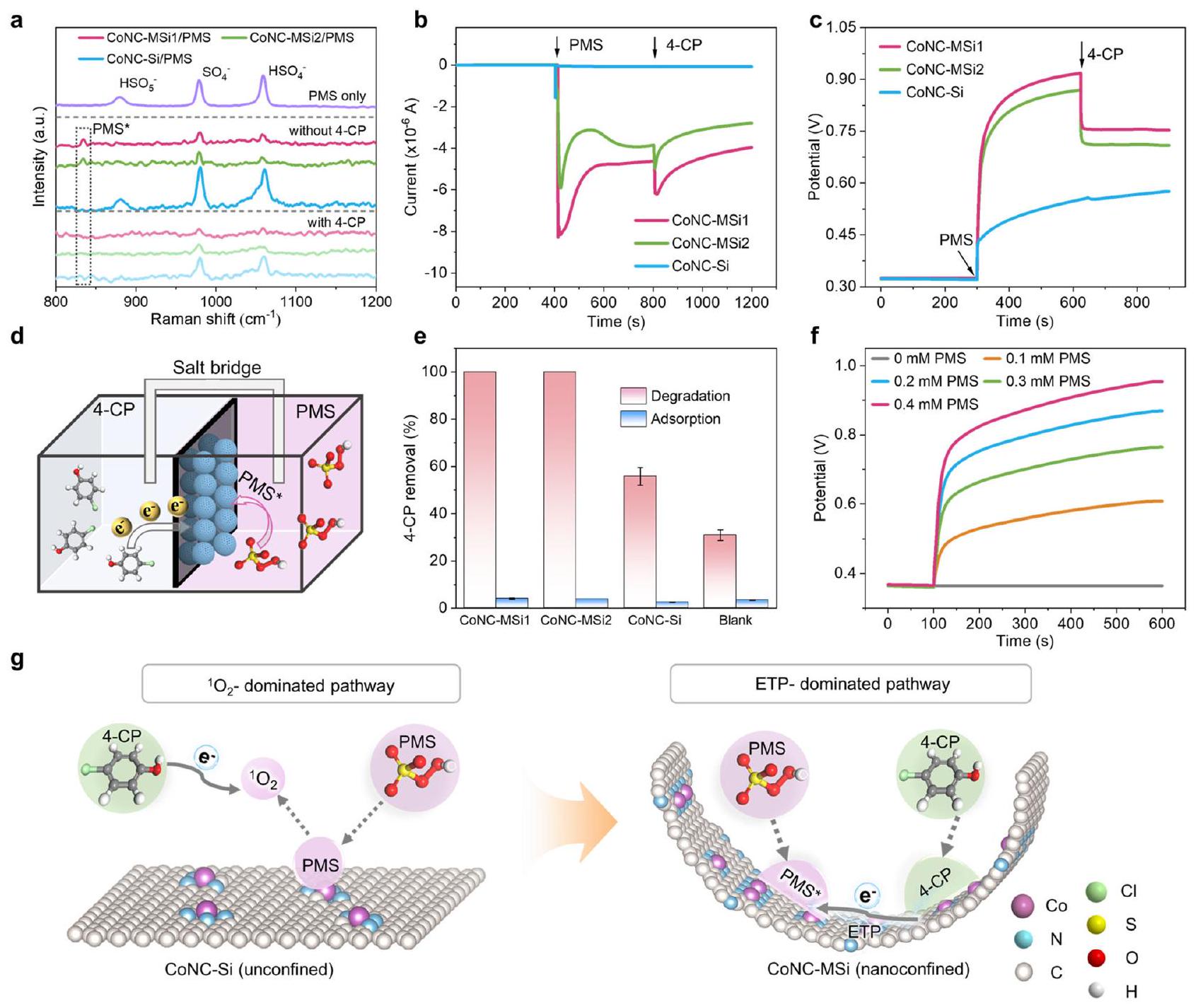

تحول مسارات التحفيز الناتج عن الحصر النانوي

نشاط محدد أكثر من CoNC-Si ولكن فقط حتى زيادة تركيز المتفاعل المحلي بمقدار 4.3 مرة، مما يشير إلى أن بعض العوامل الأخرى قد تساهم أيضًا في تحسين الأداء تحت النانو احتجاز.

كشف

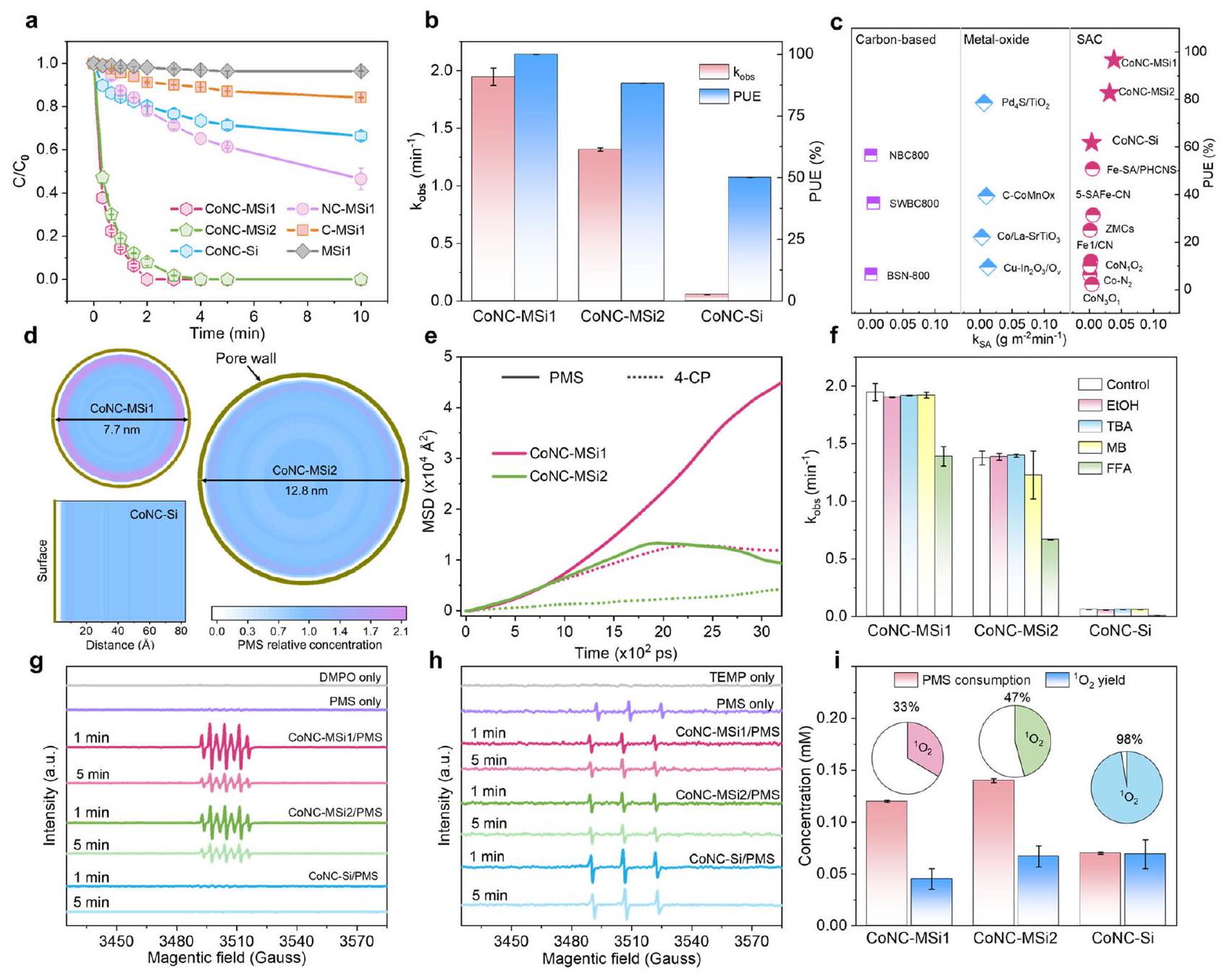

الاحتجاز النانوي، وبالتالي يساهم بشكل كبير في زيادة النشاط و PUE لـ CoNC-MSi1.

بين الغرفتين. تمثل أشرطة الخطأ الانحراف المعياري، الذي تم الحصول عليه من خلال تكرار التجربة مرتين.

تم تفعيل المسار من خلال ارتباط الجزيئات الداخلية لكل من الملوث وPMS بواسطة المحفز المحصور نانو، كما يتضح من مقاومته العالية لـ

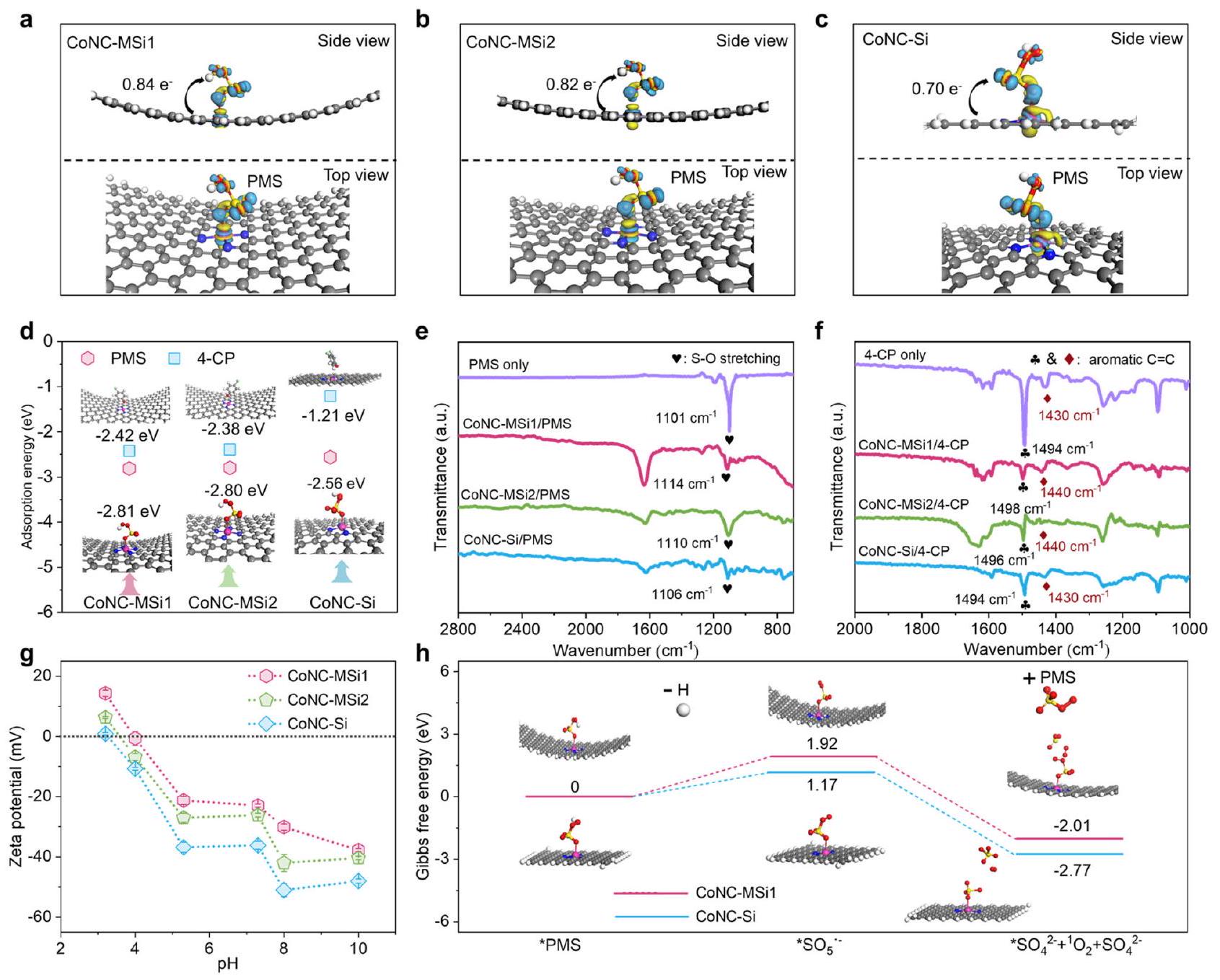

آليات تغيير مسار التحفيز الناتج عن النانو confinement

عدد أكبر من التحكم غير المقيد لتسهيل تشكيل PMS* (الشكل 5 أ-د والجدول التكميلي 7). تكشف هذه النتائج عن مسار ETP معزز لـ Co SACs المحصورة نانوياً مع زيادة تنسيق النيتروجين وتبرز إمكانيات تأثيرات النانو الأخرى في إعادة توجيه المسارات التحفيزية.

لعلاج مياه البحيرة الملوثة بـ 4-CP (TOC الأولي

تظل العلاقة بين تأثيرات النانو احتجاز وحجم المسام في نظام التحفيز SAC غامضة.

أداء إزالة التلوث لمركبات الكوبالت المدعمة بالنانو في مصفوفة المياه المعقدة

نظام CoNC-MSi1/PMS حقق فقط تحلل معتدل لـ 4-CP

من

نقاش

طرق

مواد كيميائية

تخليق جزيئات السيليكا المسامية

تخليق المحفزات أحادية الذرة المقيدة نانو على MSi

توصيف المحفز وتحليله

تقييم أداء إزالة التلوث للمحفز في تجارب الدفعة

تجربة التدفق المستمر لمعالجة المياه

محاكاة الديناميكا الجزيئية

حسابات DFT المعتمدة على الاستقطاب الدوراني

لتمثيل CoNC-Si لتقييم تأثير بيئة التنسيق على السلوك التحفيزي. تم حساب الطاقات الحرة للأنواع على النحو التالي:

توفر البيانات

References

- Hodges, B. C., Cates, E. L. & Kim, J.-H. Challenges and prospects of advanced oxidation water treatment processes using catalytic nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 642-650 (2018).

- Zhang, S., Zheng, H. & Tratnyek, P. G. Advanced redox processes for sustainable water treatment. Nat. Water 1, 666-681 (2023).

- Peydayesh, M. & Mezzenga, R. Protein nanofibrils for next generation sustainable water purification. Nat. Commun. 12, 3248 (2021).

- Li, J. et al. Mesoporous bimetallic Fe/Co as highly active heterogeneous Fenton catalyst for the degradation of tetracycline hydrochlorides. Sci. Rep. 9, 15820 (2019).

- Liang, Z. et al. Effective green treatment of sewage sludge from Fenton reactions: utilizing

for sustainable resource recovery. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2317394121 (2024). - Zhang, Y.-J. et al. Simultaneous nanocatalytic surface activation of pollutants and oxidants for highly efficient water decontamination. Nat. Commun. 13, 3005 (2022).

- Thomas, N., Dionysiou, D. D. & Pillai, S. C. Heterogeneous Fenton catalysts: a review of recent advances. J. Hazard. Mater. 404, 124082 (2021).

- Li, F. et al. Efficient removal of antibiotic resistance genes through 4f-2p-3d gradient orbital coupling mediated Fenton-like redox processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313298 (2023).

- Jiang, J. et al. Nitrogen vacancy-modulated peroxymonosulfate nonradical activation for organic contaminant removal via highvalent cobalt-oxo species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 5611-5619 (2022).

- Liu, H.-Z. et al. Tailoring d-band center of high-valent metal-oxo species for pollutant removal via complete polymerization. Nat. Commun. 15, 2327 (2024).

- Yang, Z. et al. Toward selective oxidation of contaminants in aqueous systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 14494-14514 (2021).

- Ren, W. et al. Origins of electron-transfer regime in persulfatebased nonradical oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 78-97 (2022).

- Weng, Z. et al. Site engineering of covalent organic frameworks for regulating peroxymonosulfate activation to generate singlet oxygen with 100 % selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310934 (2023).

- Xin, S. et al. Electron delocalization realizes speedy fenton-like catalysis over a high-loading and low-valence zinc single-atom catalyst. Adv. Sci. 10, 2304088 (2023).

- Liu, T. et al. Water decontamination via nonradical process by nanoconfined Fenton-like catalysts. Nat. Commun. 14, 2881 (2023).

- Wang, Y., Lin, Y., He, S., Wu, S. & Yang, C. Singlet oxygen: properties, generation, detection, and environmental applications. J. Hazard. Mater. 461, 132538 (2024).

- Wu, Q.-Y., Yang, Z.-W., Wang, Z.-W. & Wang, W.-L. Oxygen doping of cobalt-single-atom coordination enhances peroxymonosulfate activation and high-valent cobalt-oxo species formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2219923120 (2023).

- Wu, L. et al. Oxygen vacancy-induced nonradical degradation of organics: critical trigger of oxygen (

) in the Fe-Co LDH/peroxymonosulfate system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15400-15411 (2021). - Zhang, S., Hedtke, T., Zhou, X., Elimelech, M. & Kim, J.-H. Environmental applications of engineered materials with nanoconfinement. ACS EST Eng. 1, 706-724 (2021).

- Qian, J., Gao, X. & Pan, B. Nanoconfinement-mediated water treatment: from fundamental to application. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 8509-8526 (2020).

- Meng, C. et al. Angstrom-confined catalytic water purification within Co -TiOx laminar membrane nanochannels. Nat. Commun. 13, 4010 (2022).

- Grommet, A. B., Feller, M. & Klajn, R. Chemical reactivity under nanoconfinement. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 256-271 (2020).

- Yang, Z., Qian, J., Yu, A. & Pan, B. Singlet oxygen mediated ironbased Fenton-like catalysis under nanoconfinement. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 6659-6664 (2019).

- Liu, C. et al. Nanoconfinement engineering over hollow multi-shell structured copper towards efficient electrocatalytical C-C coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202113498 (2022).

- Zhang, X. et al. Nanoconfinement-triggered oligomerization pathway for efficient removal of phenolic pollutants via a Fenton-like reaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 917 (2024).

- Li, X. et al. Single cobalt atoms anchored on porous N-doped graphene with dual reaction sites for efficient fenton-like catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12469-12475 (2018).

- Sheng, X. et al. N-doped ordered mesoporous carbons prepared by a two-step nanocasting strategy as highly active and selective electrocatalysts for the reduction of

to . Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 176, 212-224 (2015). - Kumar, P. et al. High-density cobalt single-atom catalysts for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8052-8063 (2023).

- Wan, W. et al. Mechanistic insight into the active centers of single/ dual-atom Ni/Fe-based oxygen electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 12, 5589 (2021).

- Wang, X. et al. Insight into dynamic and steady-state active sites for nitrogen activation to ammonia by cobalt-based catalyst. Nat. Commun. 11, 653 (2020).

- Jung, E. et al. Atomic-level tuning of Co-N-C catalyst for highperformance electrochemical

production. Nat. Mater. 19, 436-442 (2020). - Hu, J. et al. Uncovering dynamic edge-sites in atomic Co-N-C electrocatalyst for selective hydrogen peroxide production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202304754 (2023).

- Chen, S . et al. Identification of the highly active

coordination motif for selective oxygen reduction to hydrogen peroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14505-14516 (2022). - Yu, P. et al. Co nanoislands rooted on Co-N-C nanosheets as efficient oxygen electrocatalyst for Zn-Air batteries. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901666 (2019).

- Gu, C.-H. et al. Slow-release synthesis of Cu single-atom catalysts with the optimized geometric structure and density of state distribution for Fenton-like catalysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2311585120 (2023).

- Zeng, Z. et al. Single-atom platinum confined by the interlayer nanospace of carbon nitride for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nano Energy 69, 104409 (2020).

- Wordsworth, J. et al. The influence of nanoconfinement on electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200755 (2022).

- Wei, Y. et al. Ultrahigh peroxymonosulfate utilization efficiency over CuO nanosheets via heterogeneous

formation and preferential electron transfer during degradation of phenols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 8984-8992 (2022). - Ren, Q. et al. Extreme phonon anharmonicity underpins superionic diffusion and ultralow thermal conductivity in argyrodite Ag8SnSe6. Nat. Mater. 22, 999-1006 (2023).

- Guo, Z.-Y. et al. Crystallinity engineering for overcoming the activity-stability tradeoff of spinel oxide in Fenton-like catalysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2220608120 (2023).

- Yun, E.-T., Lee, J. H., Kim, J., Park, H.-D. & Lee, J. Identifying the nonradical mechanism in the peroxymonosulfate activation process: singlet oxygenation versus mediated electron transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7032-7042 (2018).

- Zhao, Y. et al. Janus electrocatalytic flow-through membrane enables highly selective singlet oxygen production. Nat. Commun. 11, 6228 (2020).

- Liu, C. et al. An open source and reduce expenditure ROS generation strategy for chemodynamic/photodynamic synergistic therapy. Nat. Commun. 11, 1735 (2020).

- Yao, Y. et al. Rational regulation of

coordination for highefficiency generation of toward nearly selective degradation of organic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 8833-8843 (2022). - Song, J. et al. Unsaturated single-atom

sites for improved fenton-like reaction towards high-valent metal species. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 325, 122368 (2023). - Song, J. et al. Asymmetrically coordinated

moieties for selective generation of high-valence Co -Oxo species via coupled electron-proton transfer in fenton-like reactions. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209552 (2023). - Li, H., Shan, C. & Pan, B. Fe(III)-doped g-C

mediated peroxymonosulfate activation for selective degradation of phenolic compounds via high-valent iron-oxo species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2197-2205 (2018). - Shao, P. et al. Revisiting the graphitized nanodiamond-mediated activation of peroxymonosulfate: singlet oxygenation versus electron transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 16078-16087 (2021).

- Zhao, Y. et al. Selective activation of peroxymonosulfate govern by B-site metal in delafossite for efficient pollutants degradation: pivotal role of d orbital electronic configuration. Water Res. 236, 119957 (2023).

- Peng, J. et al. Insights into the electron-transfer mechanism of permanganate activation by graphite for enhanced oxidation of sulfamethoxazole. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 9189-9198 (2021).

- Miao, J. et al. Spin-state-dependent peroxymonosulfate activation of single-atom M-N moieties via a radical-free pathway. ACS Catal. 11, 9569-9577 (2021).

- Wang, L. et al. Effective activation of peroxymonosulfate with natural manganese-containing minerals through a nonradical pathway and the application for the removal of bisphenols. J. Hazard. Mater. 417, 126152 (2021).

- Zhao, Y. et al.

@nitrogen doped CNT arrays aligned on nitrogen functionalized carbon nanofibers as highly efficient catalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 19672-19679 (2017). - Yan, Y. et al. Merits and limitations of radical vs. nonradical pathways in persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 12153-12179 (2023).

- Gong, F. et al. Universal sub-nanoreactor strategy for synthesis of yolk-shell

supported single atom electrocatalysts toward robust hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202308091 (2023). - Huang, M. et al. In situ-formed phenoxyl radical on the CuO surface triggers efficient persulfate activation for phenol degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15361-15370 (2021).

- Huang, K. Z. & Zhang, H. Direct electron-transfer-based peroxymonosulfate activation by iron-doped manganese oxide (

) and the development of galvanic oxidation processes (GOPs). Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12610-12620 (2019). - Yang, Y. et al. Crystallinity and valence states of manganese oxides in Fenton-like polymerization of phenolic pollutants for carbon recycling against degradation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 315, 121593 (2022).

- Wang, F. et al. Insights into the transformations of Mn species for peroxymonosulfate activation by tuning the

shapes. Chem. Eng. J. 404, 127097 (2021). - Gao, Y., Chen, Z., Zhu, Y., Li, T. & Hu, C. New insights into the generation of singlet oxygen in the metal-free peroxymonosulfate activation process: important role of electron-deficient carbon atoms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 1232-1241 (2020).

- Wang, B. et al. Nanocurvature-induced field effects enable control over the activity of single-atom electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 15, 1719 (2024).

- Zhang, S. et al. Mechanism of heterogeneous fenton reaction kinetics enhancement under nanoscale spatial confinement. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 10868-10875 (2020).

- Zhong, Y. et al. Adjusting local CO confinement in porous-shell Ag@Cu catalysts for enhancing C-C coupling toward CO2 eletroreduction. Nano Lett. 22, 2554-2560 (2022).

- Zhao, Y. et al. Selective degradation of electron-rich organic pollutants induced by CuO@Biochar: the key role of outer-sphere interaction and singlet oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 10710-10720 (2022).

- Wu, B., Li, Z. L., Zu, Y. X., Lai, B. & Wang, A. J. Polar electric fieldmodulated peroxymonosulfate selective activation for removal of organic contaminants via non-radical electron transfer process. Water Res. 246, 120678 (2023).

- Liang, X. et al. Coordination number dependent catalytic activity of single-atom cobalt catalysts for fenton-like reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2203001 (2022).

- Yu, Z. et al. Decoupled oxidation process enabled by atomically dispersed copper electrodes for in-situ chemical water treatment. Nat. Commun. 15, 1186 (2024).

- Yue, Q. et al. An interface coassembly in biliquid phase: toward core-shell magnetic mesoporous silica microspheres with tunable pore size. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13282-13289 (2015).

- Zhang, L. L. et al. Co-N-C catalyst for C-C coupling reactions: on the catalytic performance and active sites. ACS Catal. 5, 6563-6572 (2015).

- Martyna, G. J., Klein, M. L. & Tuckerman, M. Nosé-Hoover chains: the canonical ensemble via continuous dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 2635-2643 (1992).

- Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS All-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225-11236 (1996).

- Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1-19 (1995).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169-11186 (1996).

- Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865-3868 (1996).

- Entwistle, M. T. et al. Local density approximations from finite systems. Phys. Rev. B 94, 205134 (2016).

- Sheppard, D., Terrell, R. & Henkelman, G. Optimization methods for finding minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 134106 (2008).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

مختبر المفاتيح لعلوم تحويل الملوثات الحضرية، قسم علوم البيئة والهندسة، جامعة العلوم والتكنولوجيا في الصين، هيفي، الصين. مركز الابتكار في الطاقة المستدامة ومواد البيئة، معهد سوزهو للبحوث المتقدمة، جامعة العلوم والتكنولوجيا في الصين، سوزهو، الصين. مختبر الإشعاع السنكروتروني الوطني، جامعة العلوم والتكنولوجيا في الصين، هيفي، الصين. معهد كونمينغ للفيزياء، كونمينغ، الصين. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: يان مينغ، يو-تشين ليو، تشاو وانغ. البريد الإلكتروني: gzy2018@ustc.edu.cn; wwli@ustc.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49605-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38906879

Publication Date: 2024-06-22

Nanoconfinement steers nonradical pathway transition in single atom fenton-like catalysis for improving oxidant utilization

Accepted: 6 June 2024

Published online: 22 June 2024

Abstract

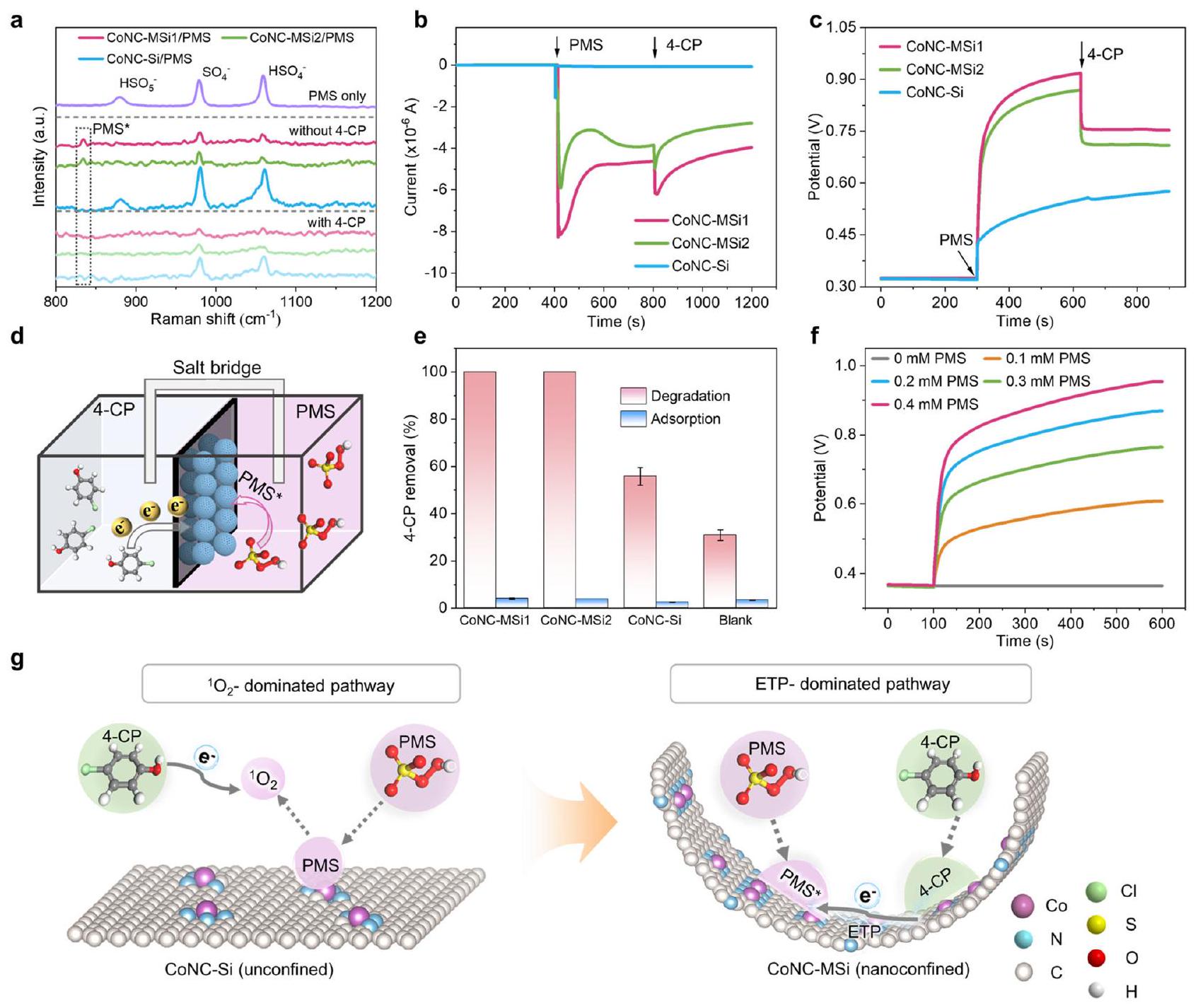

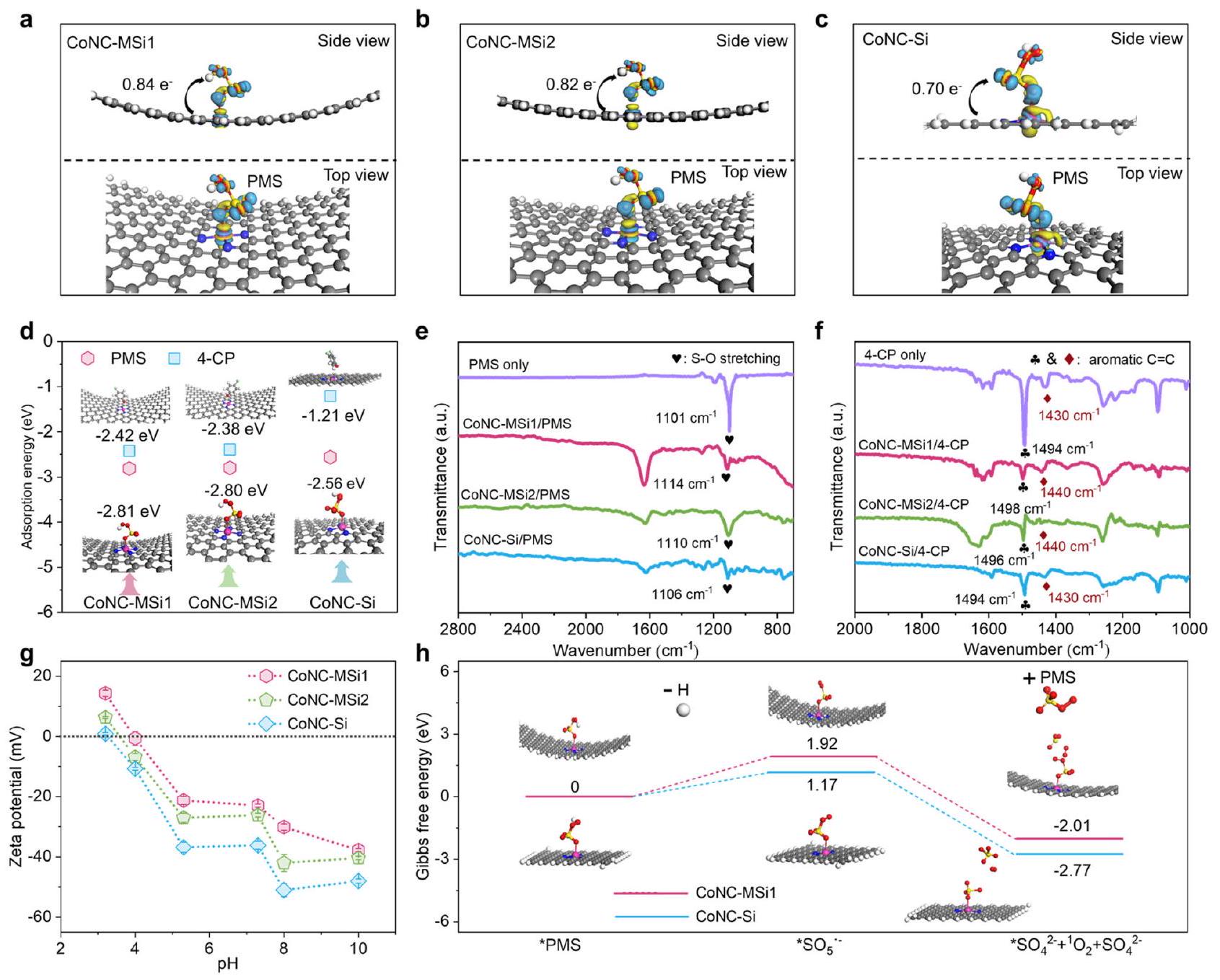

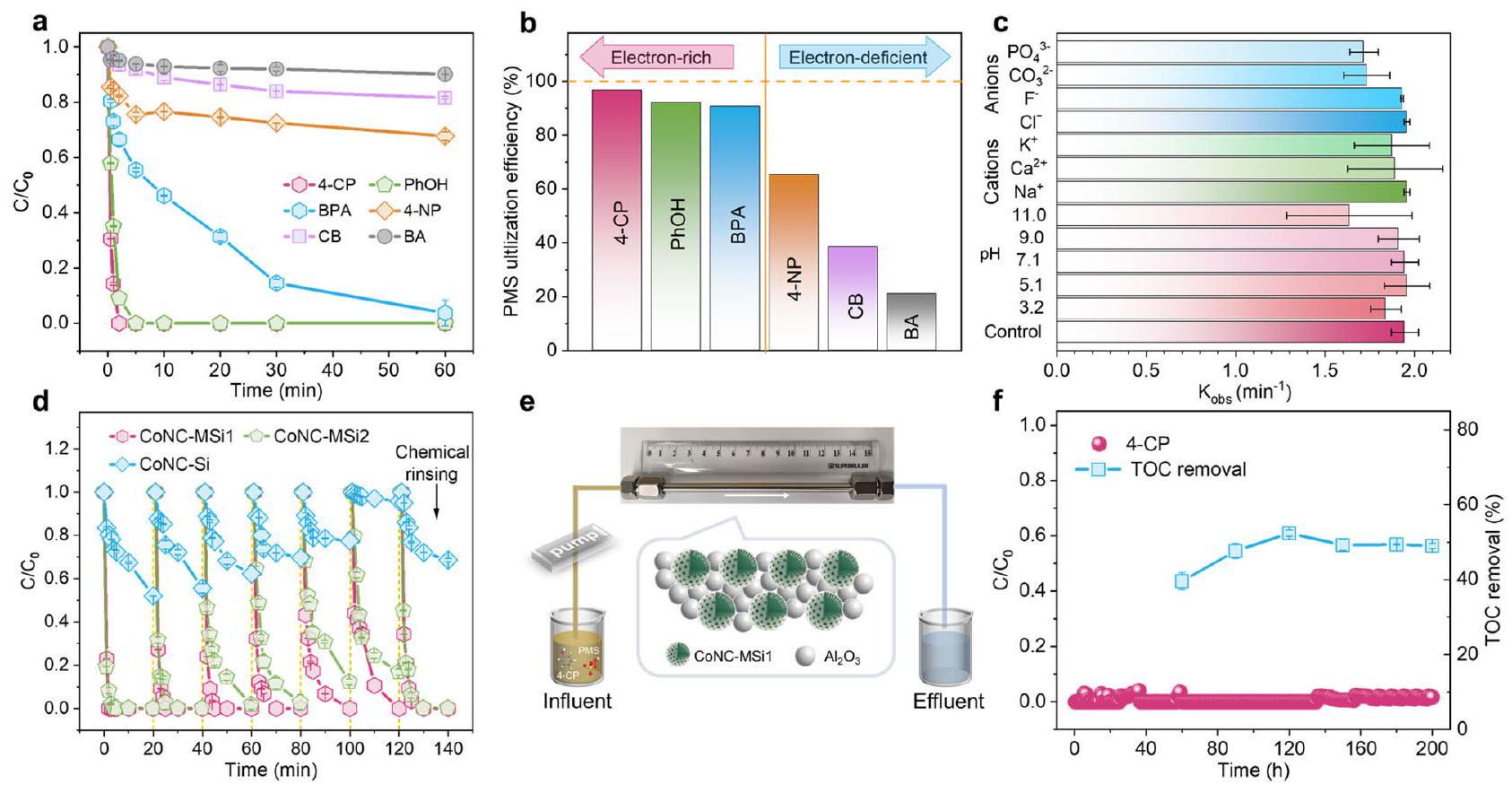

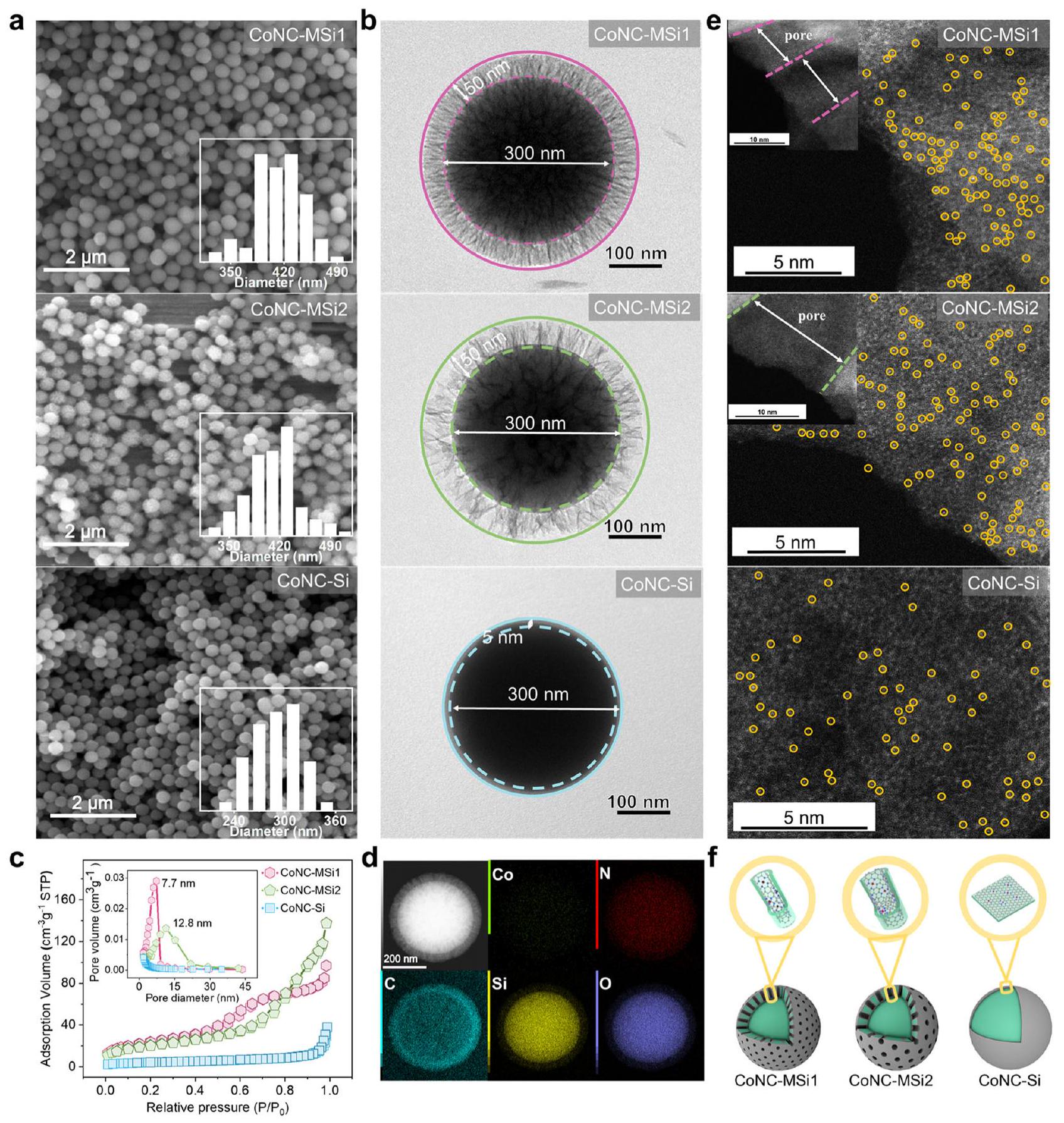

The introduction of single-atom catalysts (SACs) into Fenton-like oxidation promises ultrafast water pollutant elimination, but the limited access to pollutants and oxidant by surface catalytic sites and the intensive oxidant consumption still severely restrict the decontamination performance. While nanoconfinement of SACs allows drastically enhanced decontamination reaction kinetics, the detailed regulatory mechanisms remain elusive. Here, we unveil that, apart from local enrichment of reactants, the catalytic pathway shift is also an important cause for the reactivity enhancement of nanoconfined SACs. The surface electronic structure of cobalt site is altered by confining it within the nanopores of mesostructured silica particles, which triggers a fundamental transition from singlet oxygen to electron transfer pathway for 4-chlorophenol oxidation. The changed pathway and accelerated interfacial mass transfer render the nanoconfined system up to 34.7-fold higher pollutant degradation rate and drastically raised peroxymonosulfate utilization efficiency (from

interest in preferentially generating nonradical species including singlet oxygen (

Results

Characteristics of nanoconfined Co SACs

shell rendered the CoNC-MSil 6.8-fold larger specific surface area than the nonporous CoNC-Si (Supplementary Table 1).

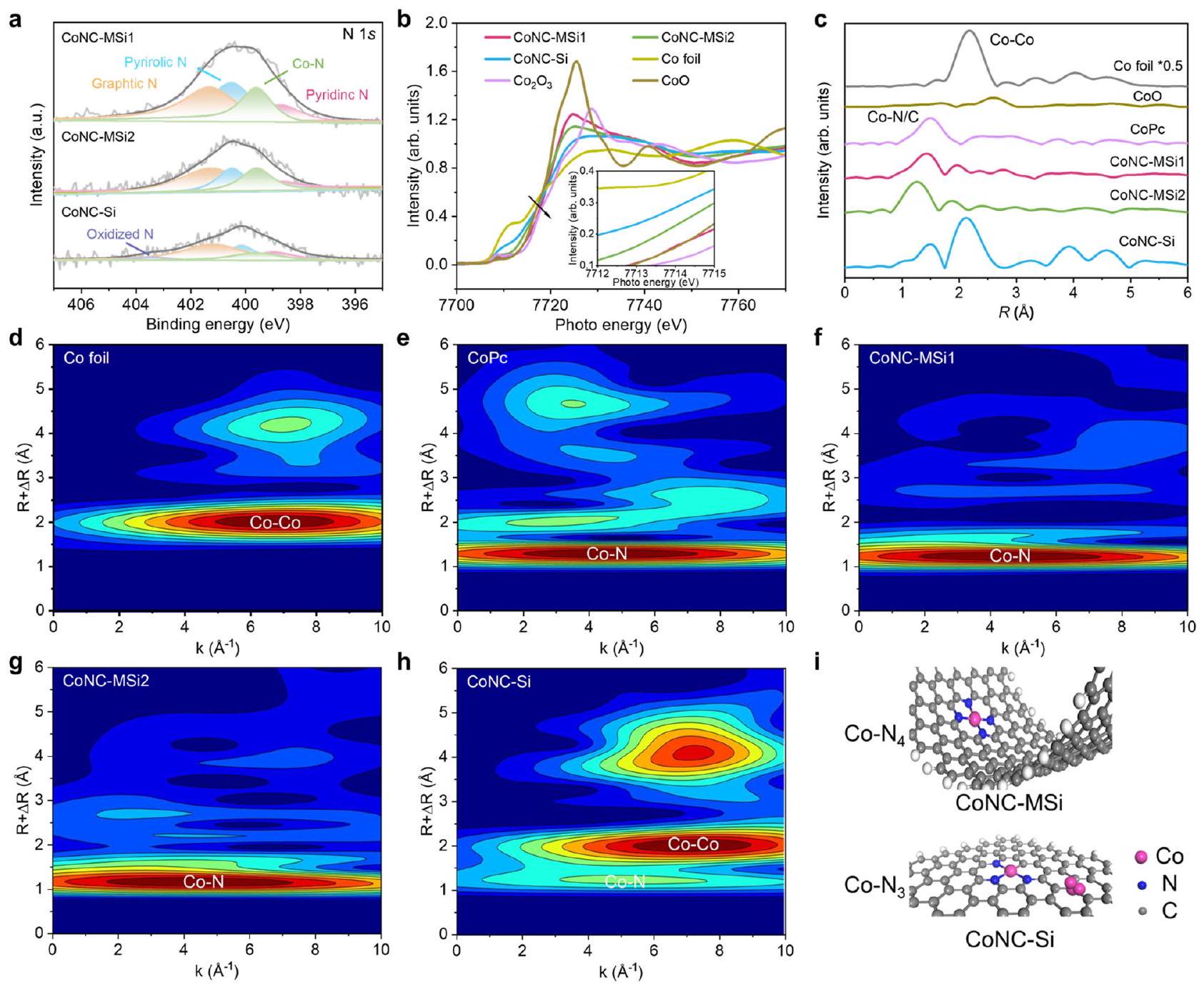

Pollutant degradation and PMS utilization performances

images showing the distribution of single-atom Co (marked with the yellow circles, SACs were mainly located inside the pores of the catalyst shell).

support a profoundly raised intrinsic reactivity of the Co atoms under nanoconfinement. Notably, the 4-CP degradation reactivity of CoNCMSi 2 was also enhanced relative to

spectra of the Co SACs and reference samples (Co foil, CoO, and CoPc). d-h WTEXAFS plots of different catalysts. i Schematic diagram of coordination configurations of the Co SACs.

Catalytic pathways transition triggered by nanoconfinement

specific activity than the CoNC-Si but only up to 4.3 -fold raised local reactant concentration, indicating that some other factors might also account for the performance improvement under nanoconfinement.

detect

nanoconfinement, thus also contribute considerably to the raised activity and PUE of CoNC-MSi1.

between the two chambers. Error bars represent the standard deviation, obtained by repeating the experiment twice.

pathway was enabled by the inner-sphere binding of both the pollutant and PMS by the nanoconfined catalyst, as evidenced by its high resistance to

Mechanisms of nanoconfinement-induced catalytic pathway change

number than the unconfined control to facilitate the PMS* formation (Fig. 5a-d and Supplementary Table 7). These results reveal an enhanced ETP pathway for nanoconfined Co SACs with increased N coordination and underline the potential of other nanoconfinement effects in redirecting the catalytic pathways.

for treating lake water spiked with 4-CP (initial TOC

correlation between the nanoconfinement effects and pore size in the SAC catalytic system remains elusive.

Decontamination performances of the nanoconfined Co SACs in complicated water matrix

the CoNC-MSi1/PMS system achieved only moderate 4-CP mineralization (

of

Discussion

Methods

Chemicals

Synthesis of mesoporous silica particles

Synthesis of nanoconfined single-atom catalysts on MSi

Catalyst characterization and analysis

Evaluation of catalyst decontamination performance in batch experiments

Continuous-flow experiment for water treatment

Molecular dynamics simulations

Spin-polarized DFT calculations

to simulate the CoNC-Si for evaluating the effect of the coordination environment on catalytic behavior. The free energies of the species were calculated as:

Data availability

References

- Hodges, B. C., Cates, E. L. & Kim, J.-H. Challenges and prospects of advanced oxidation water treatment processes using catalytic nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 642-650 (2018).

- Zhang, S., Zheng, H. & Tratnyek, P. G. Advanced redox processes for sustainable water treatment. Nat. Water 1, 666-681 (2023).

- Peydayesh, M. & Mezzenga, R. Protein nanofibrils for next generation sustainable water purification. Nat. Commun. 12, 3248 (2021).

- Li, J. et al. Mesoporous bimetallic Fe/Co as highly active heterogeneous Fenton catalyst for the degradation of tetracycline hydrochlorides. Sci. Rep. 9, 15820 (2019).

- Liang, Z. et al. Effective green treatment of sewage sludge from Fenton reactions: utilizing

for sustainable resource recovery. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2317394121 (2024). - Zhang, Y.-J. et al. Simultaneous nanocatalytic surface activation of pollutants and oxidants for highly efficient water decontamination. Nat. Commun. 13, 3005 (2022).

- Thomas, N., Dionysiou, D. D. & Pillai, S. C. Heterogeneous Fenton catalysts: a review of recent advances. J. Hazard. Mater. 404, 124082 (2021).

- Li, F. et al. Efficient removal of antibiotic resistance genes through 4f-2p-3d gradient orbital coupling mediated Fenton-like redox processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313298 (2023).

- Jiang, J. et al. Nitrogen vacancy-modulated peroxymonosulfate nonradical activation for organic contaminant removal via highvalent cobalt-oxo species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 5611-5619 (2022).

- Liu, H.-Z. et al. Tailoring d-band center of high-valent metal-oxo species for pollutant removal via complete polymerization. Nat. Commun. 15, 2327 (2024).

- Yang, Z. et al. Toward selective oxidation of contaminants in aqueous systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 14494-14514 (2021).

- Ren, W. et al. Origins of electron-transfer regime in persulfatebased nonradical oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 78-97 (2022).

- Weng, Z. et al. Site engineering of covalent organic frameworks for regulating peroxymonosulfate activation to generate singlet oxygen with 100 % selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310934 (2023).

- Xin, S. et al. Electron delocalization realizes speedy fenton-like catalysis over a high-loading and low-valence zinc single-atom catalyst. Adv. Sci. 10, 2304088 (2023).

- Liu, T. et al. Water decontamination via nonradical process by nanoconfined Fenton-like catalysts. Nat. Commun. 14, 2881 (2023).

- Wang, Y., Lin, Y., He, S., Wu, S. & Yang, C. Singlet oxygen: properties, generation, detection, and environmental applications. J. Hazard. Mater. 461, 132538 (2024).

- Wu, Q.-Y., Yang, Z.-W., Wang, Z.-W. & Wang, W.-L. Oxygen doping of cobalt-single-atom coordination enhances peroxymonosulfate activation and high-valent cobalt-oxo species formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2219923120 (2023).

- Wu, L. et al. Oxygen vacancy-induced nonradical degradation of organics: critical trigger of oxygen (

) in the Fe-Co LDH/peroxymonosulfate system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15400-15411 (2021). - Zhang, S., Hedtke, T., Zhou, X., Elimelech, M. & Kim, J.-H. Environmental applications of engineered materials with nanoconfinement. ACS EST Eng. 1, 706-724 (2021).

- Qian, J., Gao, X. & Pan, B. Nanoconfinement-mediated water treatment: from fundamental to application. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 8509-8526 (2020).

- Meng, C. et al. Angstrom-confined catalytic water purification within Co -TiOx laminar membrane nanochannels. Nat. Commun. 13, 4010 (2022).

- Grommet, A. B., Feller, M. & Klajn, R. Chemical reactivity under nanoconfinement. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 256-271 (2020).

- Yang, Z., Qian, J., Yu, A. & Pan, B. Singlet oxygen mediated ironbased Fenton-like catalysis under nanoconfinement. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 6659-6664 (2019).

- Liu, C. et al. Nanoconfinement engineering over hollow multi-shell structured copper towards efficient electrocatalytical C-C coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202113498 (2022).

- Zhang, X. et al. Nanoconfinement-triggered oligomerization pathway for efficient removal of phenolic pollutants via a Fenton-like reaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 917 (2024).

- Li, X. et al. Single cobalt atoms anchored on porous N-doped graphene with dual reaction sites for efficient fenton-like catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12469-12475 (2018).

- Sheng, X. et al. N-doped ordered mesoporous carbons prepared by a two-step nanocasting strategy as highly active and selective electrocatalysts for the reduction of

to . Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 176, 212-224 (2015). - Kumar, P. et al. High-density cobalt single-atom catalysts for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8052-8063 (2023).

- Wan, W. et al. Mechanistic insight into the active centers of single/ dual-atom Ni/Fe-based oxygen electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 12, 5589 (2021).

- Wang, X. et al. Insight into dynamic and steady-state active sites for nitrogen activation to ammonia by cobalt-based catalyst. Nat. Commun. 11, 653 (2020).

- Jung, E. et al. Atomic-level tuning of Co-N-C catalyst for highperformance electrochemical

production. Nat. Mater. 19, 436-442 (2020). - Hu, J. et al. Uncovering dynamic edge-sites in atomic Co-N-C electrocatalyst for selective hydrogen peroxide production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202304754 (2023).

- Chen, S . et al. Identification of the highly active

coordination motif for selective oxygen reduction to hydrogen peroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14505-14516 (2022). - Yu, P. et al. Co nanoislands rooted on Co-N-C nanosheets as efficient oxygen electrocatalyst for Zn-Air batteries. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901666 (2019).

- Gu, C.-H. et al. Slow-release synthesis of Cu single-atom catalysts with the optimized geometric structure and density of state distribution for Fenton-like catalysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2311585120 (2023).

- Zeng, Z. et al. Single-atom platinum confined by the interlayer nanospace of carbon nitride for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nano Energy 69, 104409 (2020).

- Wordsworth, J. et al. The influence of nanoconfinement on electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200755 (2022).

- Wei, Y. et al. Ultrahigh peroxymonosulfate utilization efficiency over CuO nanosheets via heterogeneous

formation and preferential electron transfer during degradation of phenols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 8984-8992 (2022). - Ren, Q. et al. Extreme phonon anharmonicity underpins superionic diffusion and ultralow thermal conductivity in argyrodite Ag8SnSe6. Nat. Mater. 22, 999-1006 (2023).

- Guo, Z.-Y. et al. Crystallinity engineering for overcoming the activity-stability tradeoff of spinel oxide in Fenton-like catalysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2220608120 (2023).

- Yun, E.-T., Lee, J. H., Kim, J., Park, H.-D. & Lee, J. Identifying the nonradical mechanism in the peroxymonosulfate activation process: singlet oxygenation versus mediated electron transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7032-7042 (2018).

- Zhao, Y. et al. Janus electrocatalytic flow-through membrane enables highly selective singlet oxygen production. Nat. Commun. 11, 6228 (2020).

- Liu, C. et al. An open source and reduce expenditure ROS generation strategy for chemodynamic/photodynamic synergistic therapy. Nat. Commun. 11, 1735 (2020).

- Yao, Y. et al. Rational regulation of

coordination for highefficiency generation of toward nearly selective degradation of organic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 8833-8843 (2022). - Song, J. et al. Unsaturated single-atom

sites for improved fenton-like reaction towards high-valent metal species. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 325, 122368 (2023). - Song, J. et al. Asymmetrically coordinated

moieties for selective generation of high-valence Co -Oxo species via coupled electron-proton transfer in fenton-like reactions. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209552 (2023). - Li, H., Shan, C. & Pan, B. Fe(III)-doped g-C

mediated peroxymonosulfate activation for selective degradation of phenolic compounds via high-valent iron-oxo species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2197-2205 (2018). - Shao, P. et al. Revisiting the graphitized nanodiamond-mediated activation of peroxymonosulfate: singlet oxygenation versus electron transfer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 16078-16087 (2021).

- Zhao, Y. et al. Selective activation of peroxymonosulfate govern by B-site metal in delafossite for efficient pollutants degradation: pivotal role of d orbital electronic configuration. Water Res. 236, 119957 (2023).

- Peng, J. et al. Insights into the electron-transfer mechanism of permanganate activation by graphite for enhanced oxidation of sulfamethoxazole. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 9189-9198 (2021).

- Miao, J. et al. Spin-state-dependent peroxymonosulfate activation of single-atom M-N moieties via a radical-free pathway. ACS Catal. 11, 9569-9577 (2021).

- Wang, L. et al. Effective activation of peroxymonosulfate with natural manganese-containing minerals through a nonradical pathway and the application for the removal of bisphenols. J. Hazard. Mater. 417, 126152 (2021).

- Zhao, Y. et al.

@nitrogen doped CNT arrays aligned on nitrogen functionalized carbon nanofibers as highly efficient catalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 19672-19679 (2017). - Yan, Y. et al. Merits and limitations of radical vs. nonradical pathways in persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 12153-12179 (2023).

- Gong, F. et al. Universal sub-nanoreactor strategy for synthesis of yolk-shell

supported single atom electrocatalysts toward robust hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202308091 (2023). - Huang, M. et al. In situ-formed phenoxyl radical on the CuO surface triggers efficient persulfate activation for phenol degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15361-15370 (2021).

- Huang, K. Z. & Zhang, H. Direct electron-transfer-based peroxymonosulfate activation by iron-doped manganese oxide (

) and the development of galvanic oxidation processes (GOPs). Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12610-12620 (2019). - Yang, Y. et al. Crystallinity and valence states of manganese oxides in Fenton-like polymerization of phenolic pollutants for carbon recycling against degradation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 315, 121593 (2022).

- Wang, F. et al. Insights into the transformations of Mn species for peroxymonosulfate activation by tuning the

shapes. Chem. Eng. J. 404, 127097 (2021). - Gao, Y., Chen, Z., Zhu, Y., Li, T. & Hu, C. New insights into the generation of singlet oxygen in the metal-free peroxymonosulfate activation process: important role of electron-deficient carbon atoms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 1232-1241 (2020).

- Wang, B. et al. Nanocurvature-induced field effects enable control over the activity of single-atom electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 15, 1719 (2024).

- Zhang, S. et al. Mechanism of heterogeneous fenton reaction kinetics enhancement under nanoscale spatial confinement. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 10868-10875 (2020).

- Zhong, Y. et al. Adjusting local CO confinement in porous-shell Ag@Cu catalysts for enhancing C-C coupling toward CO2 eletroreduction. Nano Lett. 22, 2554-2560 (2022).

- Zhao, Y. et al. Selective degradation of electron-rich organic pollutants induced by CuO@Biochar: the key role of outer-sphere interaction and singlet oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 10710-10720 (2022).

- Wu, B., Li, Z. L., Zu, Y. X., Lai, B. & Wang, A. J. Polar electric fieldmodulated peroxymonosulfate selective activation for removal of organic contaminants via non-radical electron transfer process. Water Res. 246, 120678 (2023).

- Liang, X. et al. Coordination number dependent catalytic activity of single-atom cobalt catalysts for fenton-like reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2203001 (2022).

- Yu, Z. et al. Decoupled oxidation process enabled by atomically dispersed copper electrodes for in-situ chemical water treatment. Nat. Commun. 15, 1186 (2024).

- Yue, Q. et al. An interface coassembly in biliquid phase: toward core-shell magnetic mesoporous silica microspheres with tunable pore size. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13282-13289 (2015).

- Zhang, L. L. et al. Co-N-C catalyst for C-C coupling reactions: on the catalytic performance and active sites. ACS Catal. 5, 6563-6572 (2015).

- Martyna, G. J., Klein, M. L. & Tuckerman, M. Nosé-Hoover chains: the canonical ensemble via continuous dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 2635-2643 (1992).

- Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS All-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225-11236 (1996).

- Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1-19 (1995).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169-11186 (1996).

- Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865-3868 (1996).

- Entwistle, M. T. et al. Local density approximations from finite systems. Phys. Rev. B 94, 205134 (2016).

- Sheppard, D., Terrell, R. & Henkelman, G. Optimization methods for finding minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 134106 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024

CAS Key Laboratory of Urban Pollutant Conversion, Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei, China. Sustainable Energy and Environmental Materials Innovation Center, Suzhou Institute for Advanced Research, University of Science & Technology of China, Suzhou, China. National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei, China. Kunming Institute of Physics, Kunming, China. These authors contributed equally: Yan Meng, Yu-Qin Liu, Chao Wang. e-mail: gzy2018@ustc.edu.cn; wwli@ustc.edu.cn