DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-024-01991-z

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-18

توزيع الانزلاق لزلزال شبه جزيرة نوتو 2024 (MJMA 7.6) المقدر من أشكال موجات تسونامي وبيانات نظام تحديد المواقع العالمي (GNSS)

الملخص

زلزال نوتو-هانتو (شبه جزيرة نوتو) في 1 يناير 2024

مقدمة

في منطقة شبه جزيرة نوتو، بدأت مجموعة من الزلازل حوالي ديسمبر 2020، مع أكبر حجم لـ

محصور في منطقة صغيرة (

على طول الهامش الشرقي لبحر اليابان، تم تحديد سلسلة من الفوالق النشطة. في عام 2014، قامت لجنة حكومية مدعومة بشكل مشترك من وزارة الأراضي والبنية التحتية والنقل والسياحة (MLIT) ووزارة التعليم والثقافة والرياضة والعلوم والتكنولوجيا (MEXT) ومكتب مجلس الوزراء الياباني بتجميع الدراسات السابقة واقترحت 60 سيناريو للتمزق لفوالق تحت البحر (المشار إليها فيما بعد بنماذج فوالق MLIT) (الشكل 1 أ، ب). قامت MLIT (2014) بإجراء محاكاة تسونامي باستخدام نماذج انزلاق غير متجانسة، والتي تضمنت بقع انزلاق كبيرة محاطة ببقع خلفية أصغر. قام موليا وآخرون (2020) بإجراء تحليل احتمالي لمخاطر تسونامي لساحل بحر اليابان بافتراض أن نماذج فوالق MLIT الستين هي مصادر محتملة للتسونامي. تم تقديم معلمات الفالق بالإضافة إلى منحنيات مخاطر التسونامي لكل بلدية في موليا وآخرون (2020).

مؤخراً، تم تنفيذ مشروع زلزال تسونامي بحر اليابان، والذي سيشار إليه فيما بعد بـ JSPJ، (من 2013 إلى 2020) بدعم من وزارة التعليم والثقافة والرياضة والعلوم والتكنولوجيا اليابانية (MEXT)، وتم تطوير نماذج الفوالق تحت البحر والساحلية على طول بحر اليابان من خلال المسوحات الزلزالية والجيوولوجية (ساتو وآخرون 2020). اختار ساتاكي وآخرون (2022) 172 فالقاً بحرياً وساحلياً بطول 20 كم أو أكثر، بالإضافة إلى 177 مجموعة من القطاعات بما في ذلك 28 فالقاً أقصر، وقدروا كميات الانزلاق باستخدام علاقات قياس متعددة، وحسبوا ارتفاعات تسونامي الساحل (جداولهم S1، S2).

عدة كبيرة (

زلزال أكيتا عام 1983

وأدى ذلك إلى 100 ضحية. كما تسبب هذا التسونامي في ثلاث ضحايا في كوريا. استخدم ساتاكي (1985) أشكال موجات التسونامي لتقدير نموذج الخطأ.

بيانات تسونامي ونظام تحديد المواقع العالمي

كانت الإزاحات أكثر من 0.8 متر في اتجاه الغرب إلى الجنوب الغربي في الجزء الشمالي من شبه جزيرة نوتو، مع تسجيل أقصى إزاحة تبلغ 2 متر في واجيما. في وسط شبه جزيرة نوتو ومحافظة توياما، الواقعتين أبعد جنوبًا من منطقة المصدر، كانت الإزاحة الأفقية موجهة نحو الشمال الغربي، و

طرق الانعكاس

لم يتم اعتبار انتشار التمزق على الفوالق، وتم الافتراض أن جميع الفوالق الفرعية تمزقت في وقت واحد. الطول الإجمالي للفوالق الفرعية المذكورة هو حوالي 150 كم، ومركز الزلزال يقع تقريبًا في وسط منطقة الفالق (الشكل 1ب). زمن تأخير التمزق من المركز إلى أقرب حافة من كل فالق فرعي أقل من بضع عشرات من الثواني، بينما فترة أخذ العينات لموجة تسونامي هي 60 ثانية، وبالتالي يمكن أن يؤثر تأخير الانزلاق بسبب تمزق الفالق

يتم تجاهله. تم افتراض زمن الارتفاع لجميع العيوب الفرعية ليكون 10 ثوانٍ.

تم إجراء حسابات انتشار تسونامي من كل شق فرعي إلى محطات WG و TG. منطقة الحساب (

| # | خط العرض (درجة) | خط الطول (درجة) | الطول (كم) | العرض (كم) | العمق (كم) | ضرب (درجة) | انحدار (درجة) | زاوية الميل (درجات) | انزلاق (م) | ||

| مشترك | تسونامي | نظام تحديد المواقع العالمي | |||||||||

| NT2* | ٣٧.٩٩٢٨ | 137.9269 | ٣٦.٦ | 16.3 | ٢.٥ | ٢٠١ | 50 | 78 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| NT3* | ٣٧.٦٨٩٥ | 137.764 | 20 | 16.6 | 2.3 | 242 | 50 | ١١٧ | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| NT4 | ٣٧.٦٨٠٨ | 137.3973 | 19.8 | 16.5 | 0.7 | 61 | 60 | ١٢٢ | ٣.٤٥ | 3.31 | 1.99 |

| إن تي 5 | ٣٧.٥٢٧٨ | ١٣٧.٢٠٧٥ | 21.6 | 17.1 | 0.2 | 52 | 60 | ١٠٨ | 3.19 | ٤.٠٧ | 2.79 |

| NT6 |

|

|

|

16.7 | 0.5 | 66 | 60 | ١٢٤ | 3.17 | ٢.٢٤ | ٥.٥٩ |

| NT8 | ٣٧.٢٥٦٩ | ١٣٦.٦١٠٦ | 15.1 | 16.7 | 0.5 | 69 | 60 | 128 | 0.99 | 1.13 | 2.00 |

| إن تي 9 | ٣٧.١٠٠٢ | ١٣٦.٥٣٥٤ | 18.4 | 16.7 | 0.5 | ٣٤ | 60 | 94 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 15.14 |

| مو (نيوتن متر) |

|

|

|

||||||||

| م | ٧.٥ | ٧.٤ | ٧.٧ | ||||||||

فترات الشبكة، لذا كانت أعداد نقاط الشبكة 9600 و 9000 في اتجاه الطول والعرض، على التوالي. بينما تتوفر بيانات قاع البحر الأكثر دقة حول محطات TG اليابانية، فإن بيانات GEBCO توفر أفضل دقة لمحطات WG البحرية ومحطات TG الكورية والروسية. تم حل معادلات المياه الضحلة الخطية (ساتاكي 1995) عددياً في إحداثيات كروية لـ

النتائج

تمت أيضًا إجراء تحليلات الانعكاس باستخدام هندسة نموذج العطل MLIT مع نفس مجموعات البيانات وأوزان البيانات، وكانت النتائج مشابهة لتلك الخاصة بنموذج JSPJ (الملف الإضافي 1: الجدول S1، الأشكال S2، S3، S4). تقتصر انزلاقات العطل الناتجة عن الانعكاس المشترك على قطاع F43، مع أقصى انزلاق يبلغ 3.5 متر شرق المركز الزلزالي، وانزلاق 2.1 متر غرب المركز الزلزالي. القطاع F42 في البحر إلى الشرق، بعيد عن

مركز الزلزال، بالكاد ينزلق على الإطلاق. كانت لحظات الزلزال المحسوبة

نقاش

يبدو أنه يبالغ في تقدير مقدار الانزلاق، كما اقترح ساتاكي وآخرون (2022).

قدرت MLIT (2014) أيضًا كميات الانزلاق على الفوالق F42 وF43، وتوقعت ارتفاعات تسونامي على طول ساحل بحر اليابان. اعتمدوا أساسًا على علاقة إيريكورا وميياكي (2001)، لكنهم زادوا كمية الانزلاق بمقدار 1.5 متر نظرًا للاختلافات. كانت متوسطات الانزلاق لديهم 3.1 متر و4.5 متر، وكانت لحظات الزلزال المقابلة Mw هي 7.3 و7.6 على F42 وF43، على التوالي. كان الانزلاق المقدر على فالق F43 من خلال الانعكاس المشترك (2.1 متر و3.5 متر على شقين) ، بالإضافة إلى لحظة الزلزال المقدرة لعام 2024، أقل قليلاً من توقعات MLIT. كانت تقديراتهم لزلازل محتملة على F42 مشابهة لتلك التي تم توقعها على NT2-NT3 من قبل JSPJ.

الخاتمة

الاختصارات

| سي إف إل | كورانت-فريدريش-لووي |

| CMT | موتر لحظة المركز |

| كودا | معمارية الجهاز الموحد للحوسبة |

| جيبيكو | الخريطة العامة لعمق المحيطات |

| نظام تحديد المواقع العالمي | نظام الملاحة عبر الأقمار الصناعية العالمي |

| توقيت غرينتش | أدوات رسم الخرائط العامة |

| جي بي جي بي يو | الحوسبة العامة على وحدات معالجة الرسوميات |

| جي إس آي | الهيئة اليابانية للمعلومات الجغرافية |

| اللجنة الأولمبية الدولية | اللجنة الحكومية الدولية لعلوم المحيطات |

| جمعية | وكالة الأرصاد الجوية اليابانية |

| JSPJ | مشروع بحث زلزال تسونامي بحر اليابان |

| خوة | الوكالة الكورية للمسح الهيدروغرافي والمحيطات |

| وزارة التعليم والثقافة والرياضة والعلوم والتكنولوجيا | وزارة التعليم والثقافة والرياضة والعلوم والتكنولوجيا |

| MLIT | وزارة الأراضي والبنية التحتية والنقل والسياحة |

| نوفاس | شبكة معلومات أمواج المحيط على مستوى البلاد للموانئ والمرافئ |

| تي جي | مقياس المد |

| اليونسكو | منظمة الأمم المتحدة للتربية والعلم والثقافة |

| USGS | المسح الجيولوجي للولايات المتحدة |

| WG | مقياس الموج |

معلومات إضافية

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نُشر على الإنترنت: 18 مارس 2024

References

Abe K (1978) Determination of the fault model consistent with the tsunami generation of the 1964 Niigata earthquake. Mar Geodesy 1(4):313-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490417809387978

Abe I, Goto K, Imamura F, Shimizu K (2008) Numerical simulation of the tsunami generated by the 2007 Noto Hanto earthquake and implications for unusual tidal surges observed in Toyama Bay. Earth Planets Space 60:133-138. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03352774

Abe K, Okada M (1995) Source model of Noto-Hanto-Oki earthquake tsunami of 7 February 1993. Pure Appl Geophys 144:621-631. https://doi. org/10.1007/BF00874386

Dziewonski AM, Chou TA, Woodhouse JH (1981) Determination of earthquake source parameters from waveform data for studies of global and regional seismicity. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 86(B4):2825-2852

Ekström G, Nettles M, Dziewoński A (2012) The global CMT project 2004-2010: Centroid-moment tensors for 13,017 earthquakes. Phys Earth Planet Inter 200:1-9

Fujii Y, Satake K (2007) Tsunami source of the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake inferred from tide gauge and satellite data. Bull Seism Soc Am 97(1A):S192-S207

GEBCO Compilation Group (2023) GEBCO 2023. Grid. https://doi.org/10. 5285/f98b053b-0cbc-6c23-e053-6c86abc0af7b

Irikura K, Miyake H (2001) Prediction of strong ground motions for scenario earthquakes. J Geogr (Chigaku Zasshi) 110(6):849-875 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Lawson CL, Hanson RJ (1974) Solving least squares problems. Prentice -Hall Inc, Englewood

Matsuda T (1975) Magnitude and recurrence interval of earthquakes from a fault. J Seismol Soc Jpn (Zisin) 2nd Ser 28:269-283 (in Japanese with English abstract)

MLIT (2014) Investigation for large earthquakes occurring in the Sea of Japan. https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/daikibojishinch ousa/.

Mulia IE, Ishibe T, Satake K, Gusman AR, Murotani S (2020) Regional probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment associated with active faults along the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan. Earth Planets Space 72:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01256-5

Murotani S, Satake K, Ishibe T, Harada T (2022) Reexamination of tsunami source models for the twentieth century earthquakes off Hokkaido and Tohoku along the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan. Earth Planets Space 74(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-022-01607-4

Namegaya Y, Satake K (2008) Tsunami generated by the 2007 Noto Hanto earthquake. Earth Planets Space 60:127-132. https://doi.org/10.1186/ BF03352773

Nishimura T, Hiramatsu Y, Ohta Y (2023) Episodic transient deformation revealed by the analysis of multiple GNSS networks in the Noto Peninsula, central Japan. Sci Rep 13(1):8381. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-023-35459-z

Okada Y (1985) Surface deformation due to shear and tensile faults in a halfspace. Bull Seismol Soc Am 75(4):1135-1154

Okamura Y, Satake K, Ikehara K, Takeuchi A, Arai K (2005) Paleoseismology of deep-sea faults based on marine surveys of northern Okushiri ridge in the Japan Sea. J Geophys Res Solid Earth. https://doi.org/10.1029/ 2004JB003135

Satake K (1985) The mechanism of the 1983 Japan Sea earthquake as inferred from long-period surface waves and tsunamis. Phys Earth Planet Inter 37(4):249-260. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9201(85) 90012-3

Satake K (1986) Re-examination of the 1940 Shakotan-oki earthquake and the fault parameters of the earthquakes along the eastern margin of the Japan Sea. Phys Earth Planet Inter 43(2):137-147. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9201(86)90081-6

Satake K (1995) Linear and nonlinear computations of the 1992 Nicaragua earthquake tsunami. Pure Appl Geophys 144(3-4):455-470

Satake K, Abe K (1983) A fault model for the Niigata, Japan, earthquake of June 16, 1964. J Phys Earth 31(3):217-223. https://doi.org/10.4294/ jpe1952.31.217

Satake K, Fujii Y, Yamaki S (2017) Different depths of near-trench slips of the 1896 Sanriku and 2011 Tohoku earthquakes. Geosci Lett 4(1):33

Satake K, Ishibe T, Murotani S, Mulia IE, Gusman AR (2022) Effects of uncertainty in fault parameters on deterministic tsunami hazard assessment: examples for active faults along the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan. Earth, Planets and Space 74(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40623-022-01594-6

Sato H, Ishiyama T, Hashima A, Kato N, Van-Horne A, Claringbould J, No T, Ishikawa M, Matsubara M, Koshiya S, Toyoshima TK, K, Kosuga M (2020) Development of active fault model. Annual progress reports of the integrated research project on seismic and tsunami hazards around the Sea of Japan (FY2019).

Takemura M (1998) Scaling law for Japanese intraplate earthquakes in special relations to the surface faults and the damages. J Seismol Soc Jpn (Zisin) 2nd Ser 51:211-228 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Tanioka Y, Satake K (1996) Tsunami generation by horizontal displacement of ocean bottom. Geophys Res Lett 23(8):861-864

Tanioka Y, Satake K, Ruff L (1995) Total analysis of the 1993 Hokkaido Nanseioki earthquake using seismic wave, tsunami, and geodetic data. Geophys Res Lett 22(1):9-12

Wessel P, Smith WH (1998) New, improved version of generic mapping tools released. EOS Trans Am Geophys Union 79(47):579-579

ملاحظة الناشر

- (انظر الشكل في الصفحة التالية.)

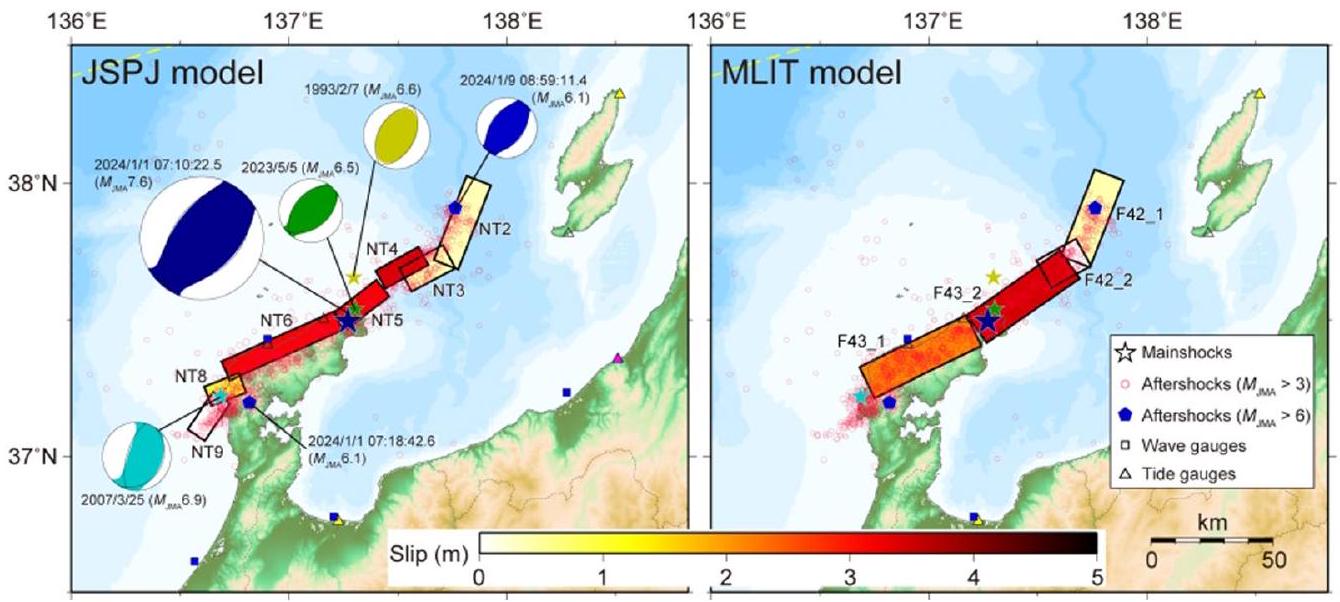

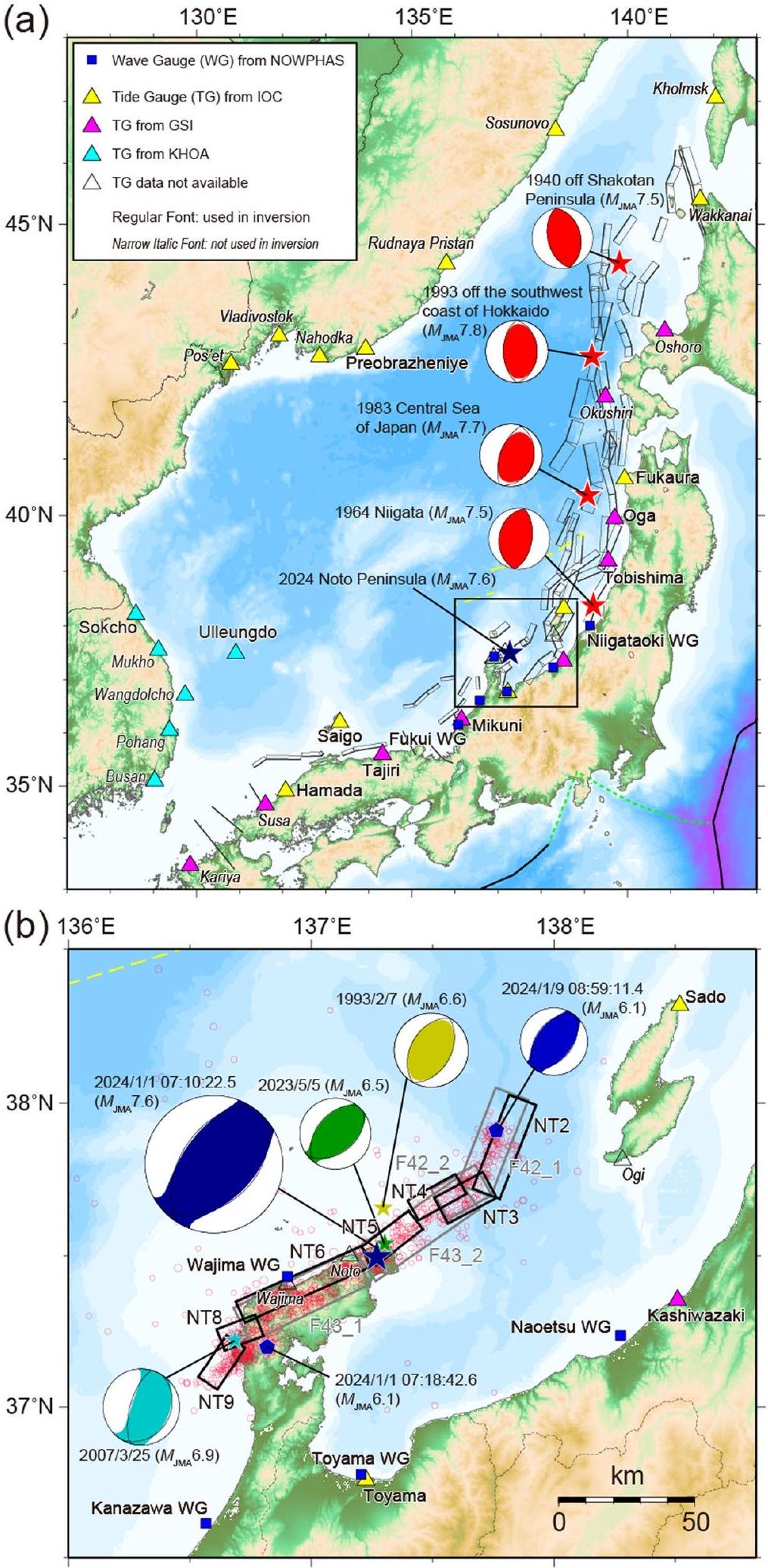

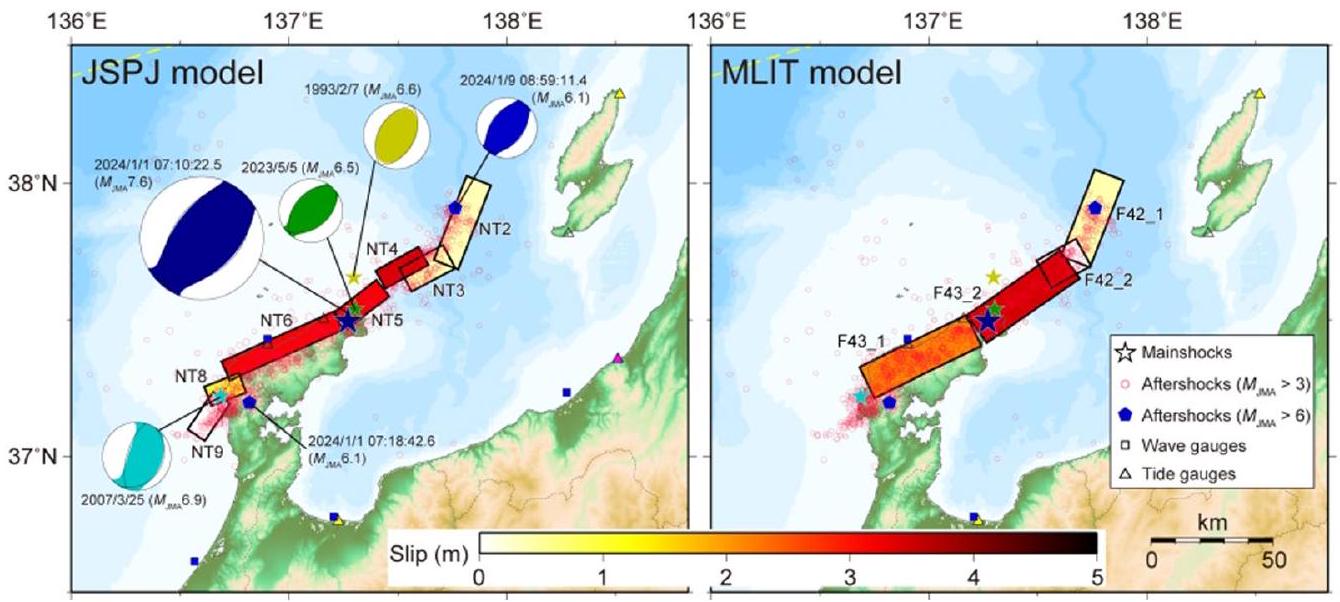

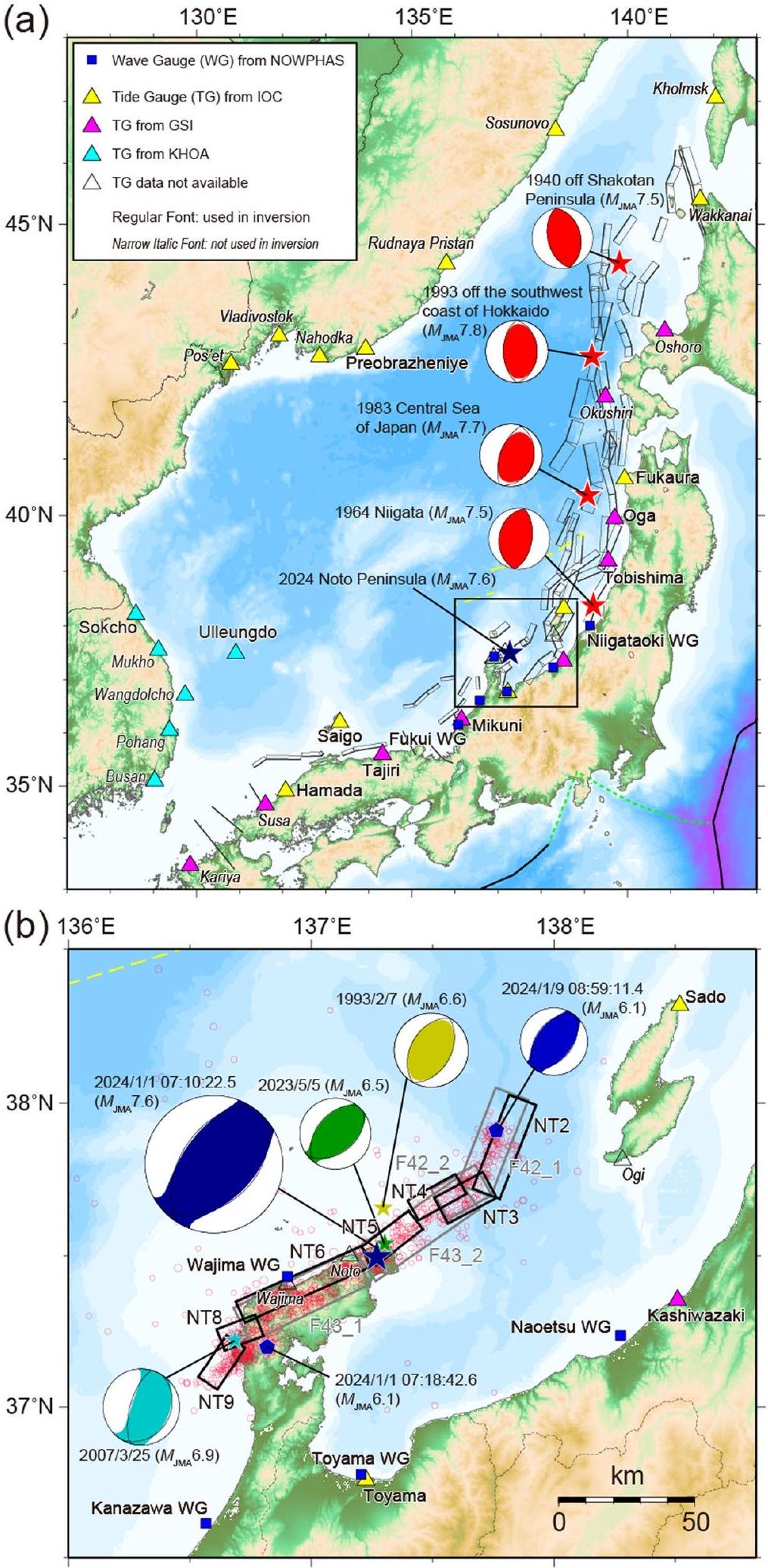

الشكل 1 خريطة بحر اليابان. تشير النجوم الزرقاء والحمراء إلى مراكز الزلازل في زلزال شبه جزيرة نوتو 2024 والزلازل الكبرى السابقة، على التوالي. آليات التركيز للزلازل في 1940 و1964 مأخوذة من ساتاكي (1986) وآبي (1975)، على التوالي، وتلك الخاصة بالزلازل في 1983 و1993 مأخوذة من CMT العالمية. تشير المستطيلات الرمادية الرفيعة وأقسام الخطوط إلى 60 نموذجًا للصدع من MLIT. موقع أجهزة قياس الأمواج NOWPHAS (WG، مربعات زرقاء) وأجهزة قياس المد (TG، مثلثات) التي تم جمع سجلات تسونامي منها من زلزال شبه جزيرة نوتو 2024. الأصفر يتوافق مع اليونسكو/IOC، والبنفسجي مع GSI، والأزرق الفاتح مع محطات المد KHOA. تشير المثلثات عديمة اللون إلى محطات المد التي لم يتم الحصول على بيانات منها. الخط العادي يتوافق مع اسم المحطة المستخدمة في الانعكاسات، والخط المائل الضيق يتوافق مع اسم المحطة غير المستخدمة في الانعكاسات. المستطيل الأسود يظهر مدى المنطقة المكبرة فيالمنطقة المكبرة حول شبه جزيرة نوتو. تظهر المستطيلات السوداء 7 نماذج للصدع من JSPJ (تم تعديل NT6 قليلاً في هذه الدراسة)، وتظهر المستطيلات الرمادية 4 نماذج للصدع من MLIT. تشير الخماسيات الزرقاء إلى الهزات الارتدادية بين 1 و31 يناير مع . تشير النجوم الصفراء الداكنة، والزرقاء الفاتحة، والخضراء إلى مراكز الزلازل السابقة التي حدثت بالقرب من شبه جزيرة نوتو. الهزات الارتدادية من أو أعلى (الفترة: 2024/1/1-1/17) من JMA تشير إليها الدوائر الحمراء. آلية التركيز لزلزال 1993 مأخوذة من CMT العالمية، والزلازل الأخرى، بما في ذلك الزلزال الرئيسي في 2024، مأخوذة من حلول W-phase من USGS

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-024-01991-z

Publication Date: 2024-03-18

Slip distribution of the 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake (

Abstract

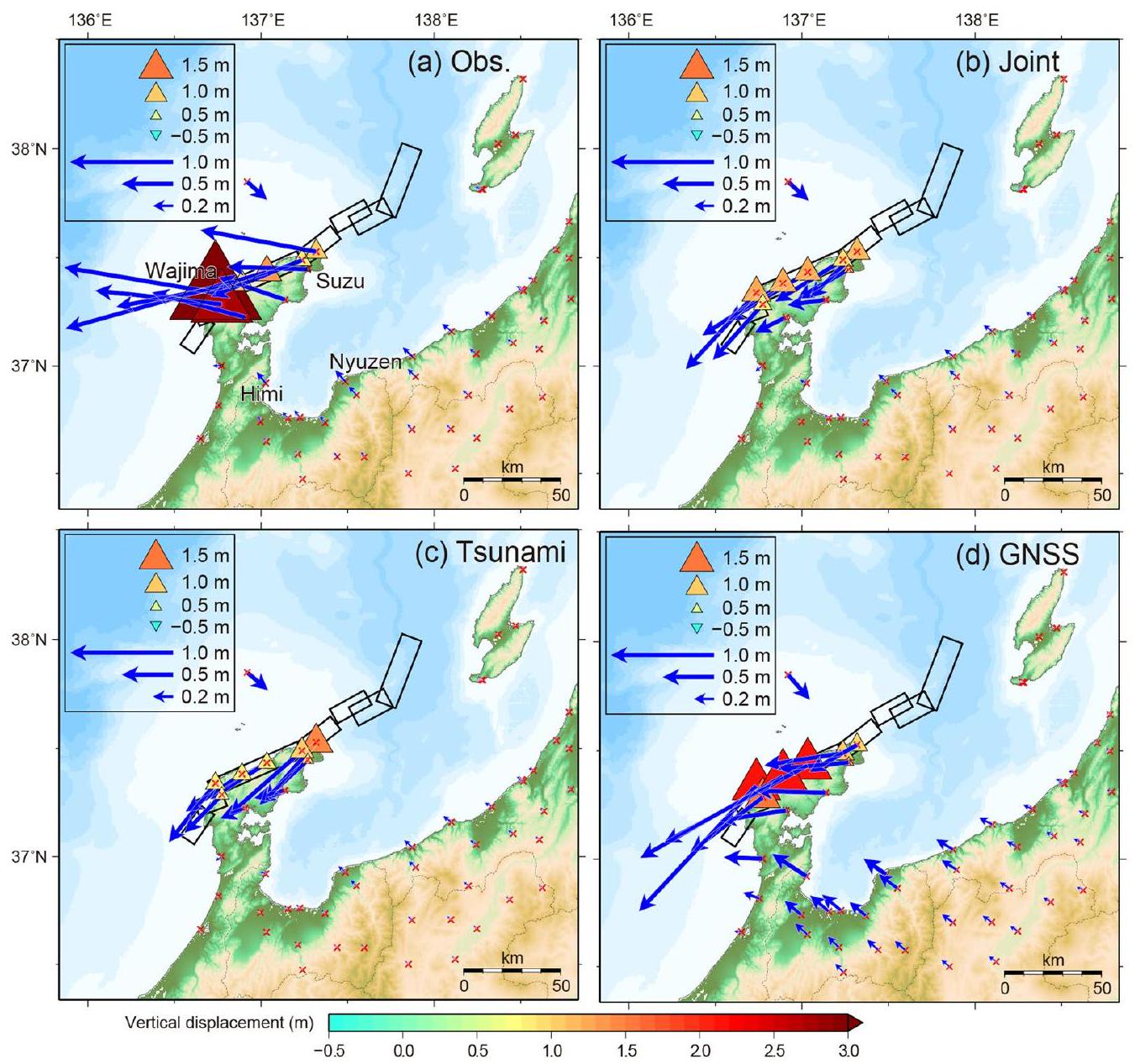

The 1 January 2024 Noto-Hanto (Noto Peninsula) earthquake (

Introduction

In the Noto Peninsula region, a swarm of earthquakes started around December 2020, with the largest size of

confined in a small region (

Along the eastern margin of Sea of Japan, series of active faults have been identified. In 2014, a government committee jointly supported by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), and the Cabinet Office of Japan compiled previous studies and proposed 60 rupture scenarios for submarine active faults (hereafter referred to as MLIT fault models) (Fig. 1a, b). MLIT (2014) conducted tsunami simulations using heterogeneous slip models, which included large slip patches surrounded by smaller background patches. Mulia et al. (2020) conducted a probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis for the coast of Sea of Japan assuming the 60 MLIT fault models as the potential tsunami sources. The fault parameters as well as the tsunami hazard curves for each municipality were provided in Mulia et al. (2020).

More recently, the Japan Sea earthquake and tsunami project, hereafter called JSPJ, was conducted (from 2013 to 2020) with support from the MEXT, and the submarine and coastal fault models along Sea of Japan were developed through seismic and geological surveys (Sato et al. 2020). Satake et al. (2022) selected 172 offshore and coastal faults with length of 20 km or greater, as well as 177 combinations of segments including 28 shorter faults, estimated the slip amounts using multiple scaling relations, and computed coastal tsunami heights (their Tables S1, S2).

Several large (

The 1983 off Akita earthquake (

and resulted in 100 casualties. This tsunami also caused three casualties in Korea. Satake (1985) used the tsunami waveforms to estimate the fault model.

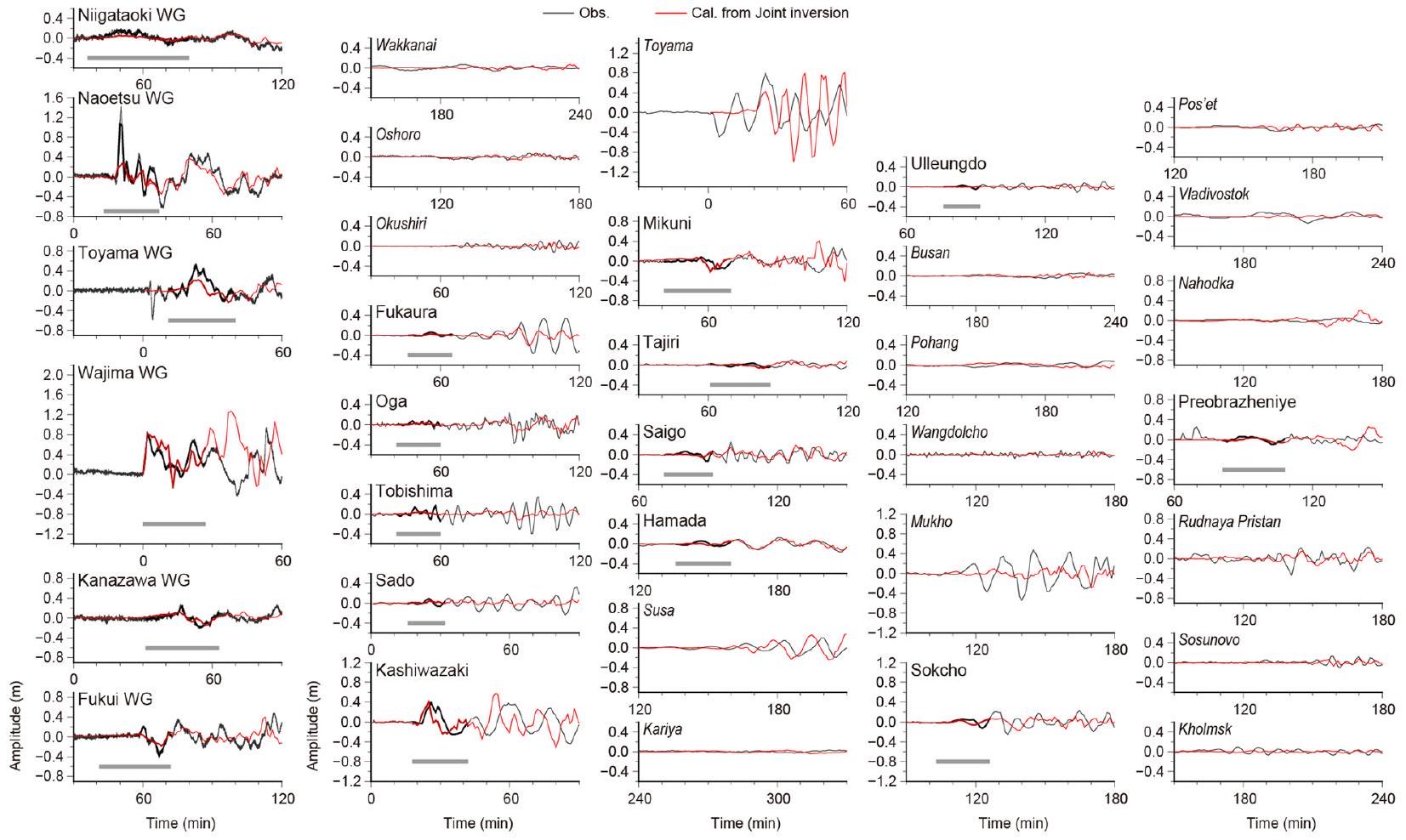

Tsunami and GNSS data

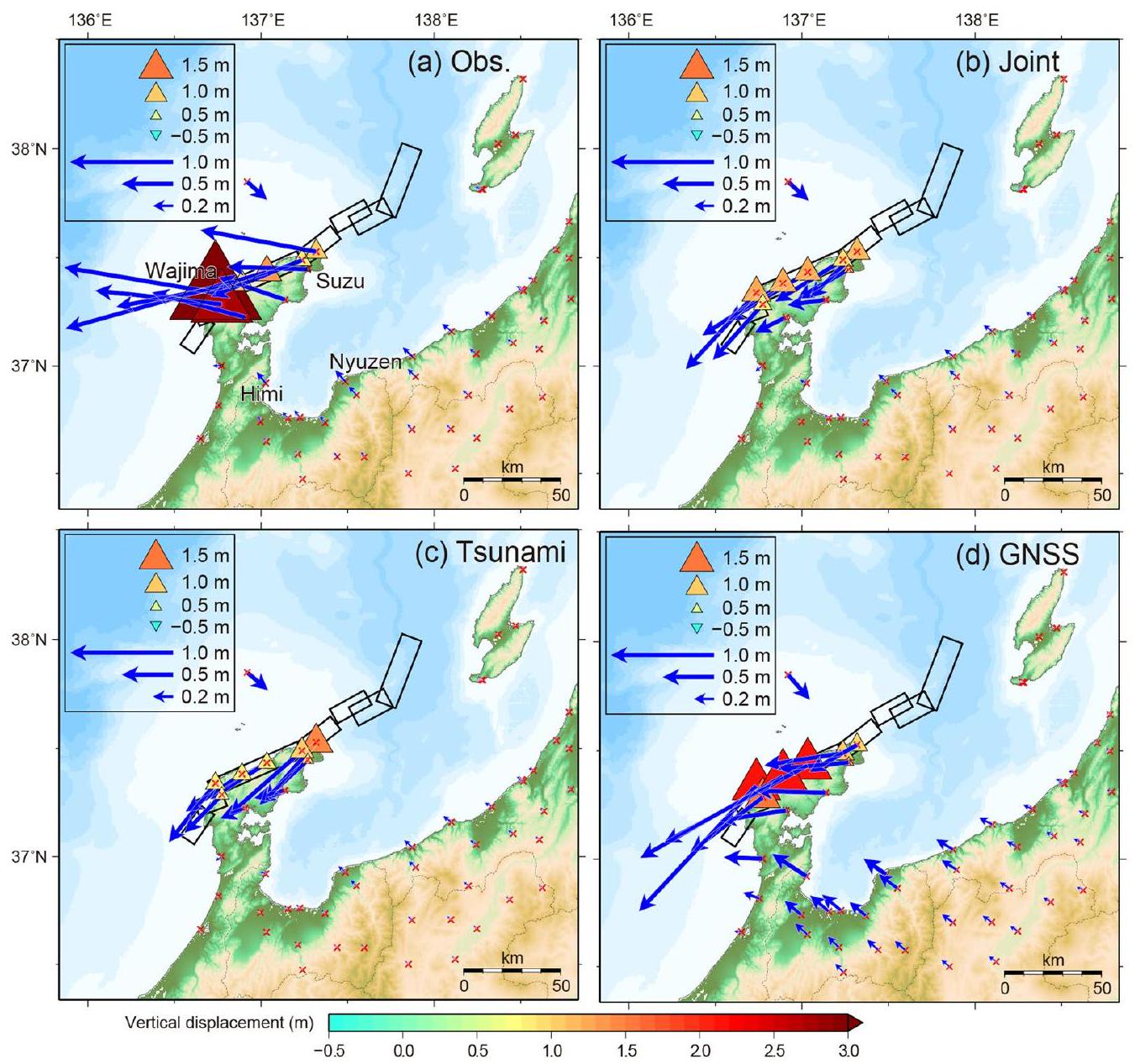

displacements were more than 0.8 m in a west to westsouthwest direction in the northern part of Noto Peninsula, with a maximum of 2 m recorded at Wajima. In the central Noto Peninsula and Toyama Prefecture, located farther south from the source area, the horizontal displacement is oriented to the northwest, and

Inversion methods

The rupture propagation on the faults was not considered, and it was assumed that all subfaults ruptured simultaneously. The total length of the above subfaults is approximately 150 km , and the mainshock epicenter is located almost at the center of the fault area (Fig. 1b). The rupture delay time from the epicenter to the nearest edge of each subfault is less than a few tens of seconds, while the sampling interval of the tsunami waveform is 60 s , hence the effect of slip delay due to the fault rupture can

be ignored. The rise time of all subfaults was assumed to be 10 s .

Tsunami propagation calculations were performed from each subfault to the WG and TG stations. The computation area (

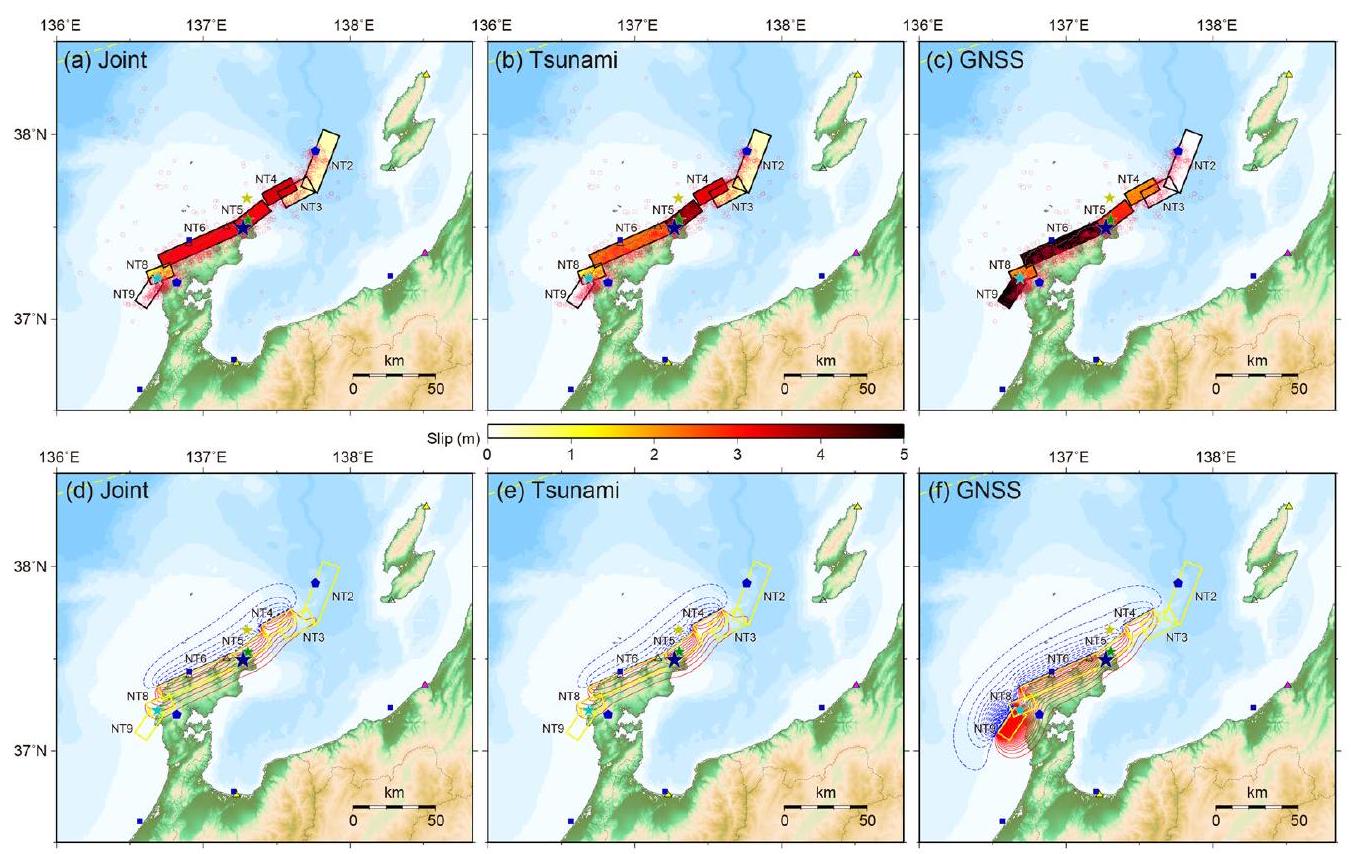

| # | Lat. (deg) | Lon. (deg) | Length (km) | Width (km) | Depth (km) | Strike (deg) | Dip (deg) | Rake (deg) | Slip (m) | ||

| Joint | Tsunami | GNSS | |||||||||

| NT2* | 37.9928 | 137.9269 | 36.6 | 16.3 | 2.5 | 201 | 50 | 78 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| NT3* | 37.6895 | 137.764 | 20 | 16.6 | 2.3 | 242 | 50 | 117 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| NT4 | 37.6808 | 137.3973 | 19.8 | 16.5 | 0.7 | 61 | 60 | 122 | 3.45 | 3.31 | 1.99 |

| NT5 | 37.5278 | 137.2075 | 21.6 | 17.1 | 0.2 | 52 | 60 | 108 | 3.19 | 4.07 | 2.79 |

| NT6 |

|

|

|

16.7 | 0.5 | 66 | 60 | 124 | 3.17 | 2.24 | 5.59 |

| NT8 | 37.2569 | 136.6106 | 15.1 | 16.7 | 0.5 | 69 | 60 | 128 | 0.99 | 1.13 | 2.00 |

| NT9 | 37.1002 | 136.5354 | 18.4 | 16.7 | 0.5 | 34 | 60 | 94 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 15.14 |

| Mo (Nm) |

|

|

|

||||||||

| Mw | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.7 | ||||||||

grid intervals, so the numbers of grid points were 9600 and 9000 in the longitude and latitude direction, respectively. While finer bathymetry data are available around the Japanese TG stations, for the offshore WG stations and Korean and Russian TG stations, the GEBCO data provides the best resolution. The linear shallow-water equations (Satake 1995) were solved numerically in spherical coordinates for the

Results

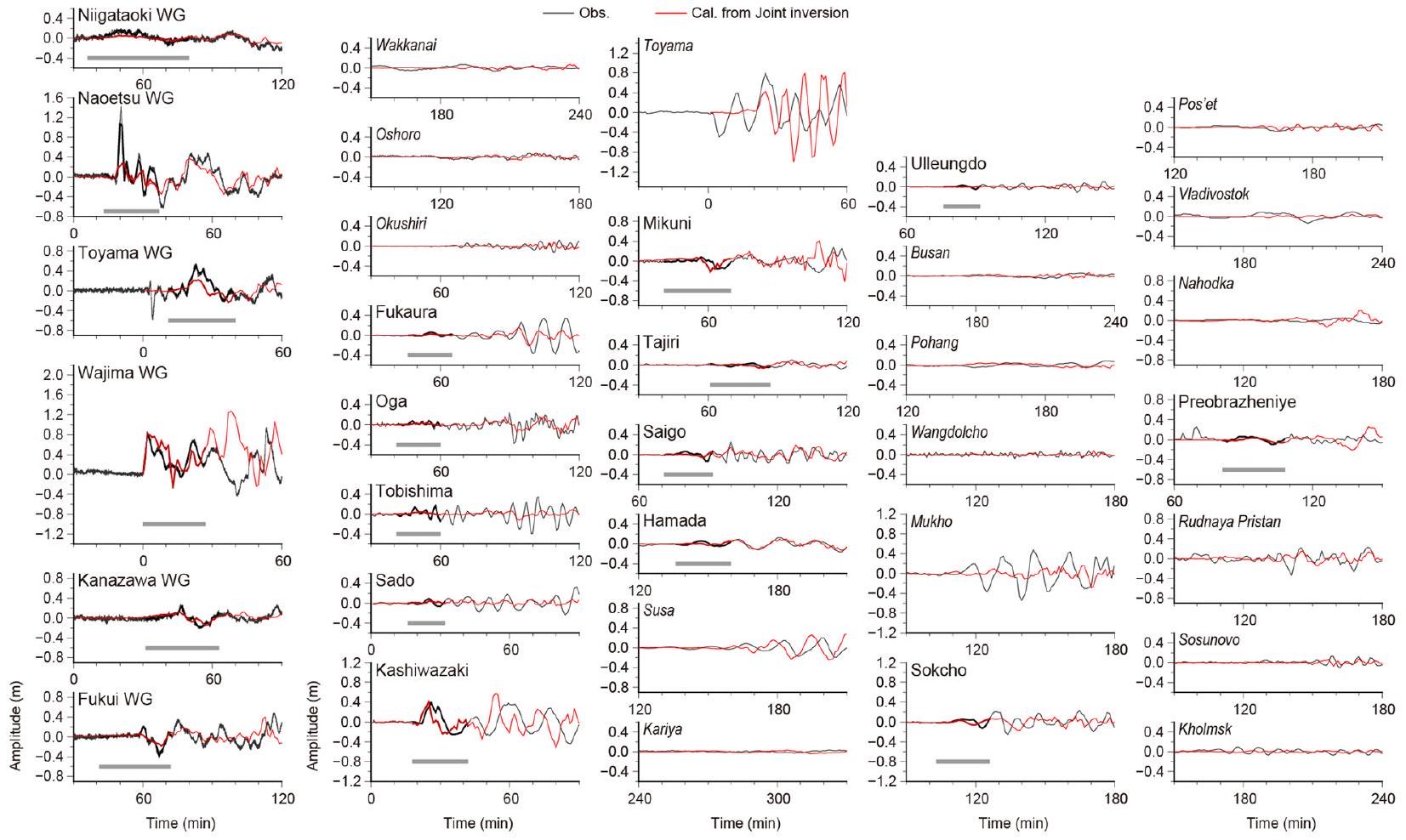

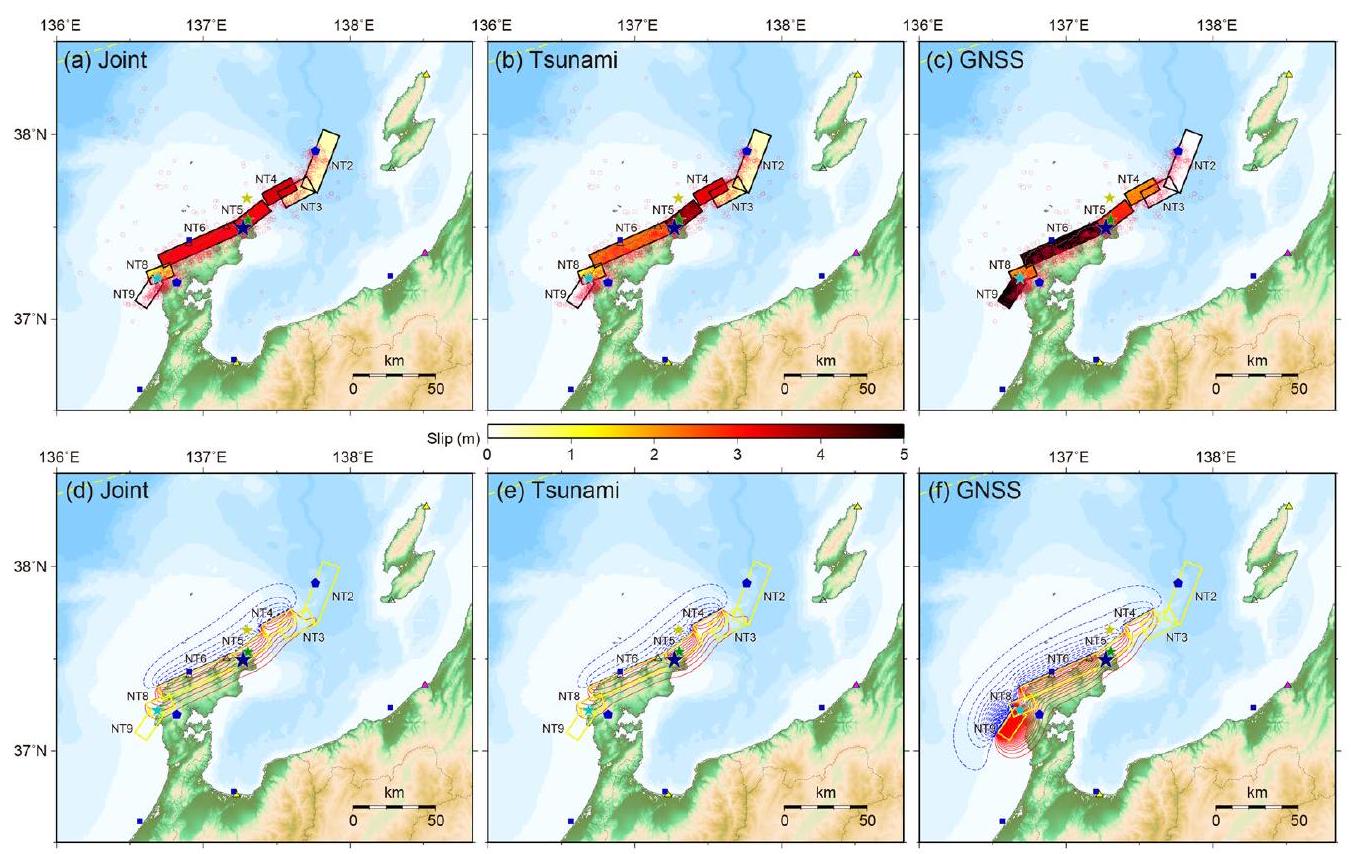

The inversion analyses were also performed adopting the MLIT fault model geometries using the same data sets and data weights, and the results were similar to those for the JSPJ model (Additional file 1: Table S1, Figs. S2, S3, S4). Fault slips due to joint inversion is limited to the F43 segment, with the maximum slip of 3.5 m east of the epicenter, and the 2.1 m slip west of the epicenter. The F42 segment offshore to the east, far from

the epicenter, hardly slips at all. The calculated seismic moments were

Discussion

seems to overestimate the slip amount, as suggested by Satake et al. (2022).

MLIT (2014) also estimated the slip amounts on faults F42 and F43, and forecasted the tsunami heights along the Sea of Japa coast. They basically adopted the Irikura and Miyake (2001) relation, but increased the slip amount by 1.5 m considering the uncertainty. Their average slips are 3.1 m and 4.5 m , and the corresponding moment magnitudes Mw are 7.3 and 7.6 on F42 and F43, respectively. The estimated slip on F43 fault by the joint inversion ( 2.1 m and 3.5 m on two segments), as well as the 2024 moment magnitude, was slightly smaller than the MLIT forecast. Their forecasted magnitude of potential earthquake on F42 is similar to that on NT2-NT3 forecasted by JSPJ.

Conclusion

Abbreviations

| CFL | Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy |

| CMT | Centroid moment tensor |

| CUDA | Compute Unified Device Architecture |

| GEBCO | General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GMT | Generic Mapping Tools |

| GPGPU | General-Purpose Computing on Graphics Processing Units |

| GSI | Geospatial Information Authority of Japan |

| IOC | Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission |

| JMA | Japan Meteorological Agency |

| JSPJ | Japan Sea Earthquake and Tsunami Research Project |

| KHOA | Korea Hydrographic and Oceanographic Agency |

| MEXT | Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology |

| MLIT | Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism |

| NOWPHAS | Nationwide Ocean Wave information network for Ports and HArbourS |

| TG | Tide gauge |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| WG | Wave gauge |

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 18 March 2024

References

Abe K (1978) Determination of the fault model consistent with the tsunami generation of the 1964 Niigata earthquake. Mar Geodesy 1(4):313-330. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490417809387978

Abe I, Goto K, Imamura F, Shimizu K (2008) Numerical simulation of the tsunami generated by the 2007 Noto Hanto earthquake and implications for unusual tidal surges observed in Toyama Bay. Earth Planets Space 60:133-138. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03352774

Abe K, Okada M (1995) Source model of Noto-Hanto-Oki earthquake tsunami of 7 February 1993. Pure Appl Geophys 144:621-631. https://doi. org/10.1007/BF00874386

Dziewonski AM, Chou TA, Woodhouse JH (1981) Determination of earthquake source parameters from waveform data for studies of global and regional seismicity. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 86(B4):2825-2852

Ekström G, Nettles M, Dziewoński A (2012) The global CMT project 2004-2010: Centroid-moment tensors for 13,017 earthquakes. Phys Earth Planet Inter 200:1-9

Fujii Y, Satake K (2007) Tsunami source of the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake inferred from tide gauge and satellite data. Bull Seism Soc Am 97(1A):S192-S207

GEBCO Compilation Group (2023) GEBCO 2023. Grid. https://doi.org/10. 5285/f98b053b-0cbc-6c23-e053-6c86abc0af7b

Irikura K, Miyake H (2001) Prediction of strong ground motions for scenario earthquakes. J Geogr (Chigaku Zasshi) 110(6):849-875 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Lawson CL, Hanson RJ (1974) Solving least squares problems. Prentice -Hall Inc, Englewood

Matsuda T (1975) Magnitude and recurrence interval of earthquakes from a fault. J Seismol Soc Jpn (Zisin) 2nd Ser 28:269-283 (in Japanese with English abstract)

MLIT (2014) Investigation for large earthquakes occurring in the Sea of Japan. https://www.mlit.go.jp/river/shinngikai_blog/daikibojishinch ousa/.

Mulia IE, Ishibe T, Satake K, Gusman AR, Murotani S (2020) Regional probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment associated with active faults along the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan. Earth Planets Space 72:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01256-5

Murotani S, Satake K, Ishibe T, Harada T (2022) Reexamination of tsunami source models for the twentieth century earthquakes off Hokkaido and Tohoku along the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan. Earth Planets Space 74(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-022-01607-4

Namegaya Y, Satake K (2008) Tsunami generated by the 2007 Noto Hanto earthquake. Earth Planets Space 60:127-132. https://doi.org/10.1186/ BF03352773

Nishimura T, Hiramatsu Y, Ohta Y (2023) Episodic transient deformation revealed by the analysis of multiple GNSS networks in the Noto Peninsula, central Japan. Sci Rep 13(1):8381. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-023-35459-z

Okada Y (1985) Surface deformation due to shear and tensile faults in a halfspace. Bull Seismol Soc Am 75(4):1135-1154

Okamura Y, Satake K, Ikehara K, Takeuchi A, Arai K (2005) Paleoseismology of deep-sea faults based on marine surveys of northern Okushiri ridge in the Japan Sea. J Geophys Res Solid Earth. https://doi.org/10.1029/ 2004JB003135

Satake K (1985) The mechanism of the 1983 Japan Sea earthquake as inferred from long-period surface waves and tsunamis. Phys Earth Planet Inter 37(4):249-260. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9201(85) 90012-3

Satake K (1986) Re-examination of the 1940 Shakotan-oki earthquake and the fault parameters of the earthquakes along the eastern margin of the Japan Sea. Phys Earth Planet Inter 43(2):137-147. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9201(86)90081-6

Satake K (1995) Linear and nonlinear computations of the 1992 Nicaragua earthquake tsunami. Pure Appl Geophys 144(3-4):455-470

Satake K, Abe K (1983) A fault model for the Niigata, Japan, earthquake of June 16, 1964. J Phys Earth 31(3):217-223. https://doi.org/10.4294/ jpe1952.31.217

Satake K, Fujii Y, Yamaki S (2017) Different depths of near-trench slips of the 1896 Sanriku and 2011 Tohoku earthquakes. Geosci Lett 4(1):33

Satake K, Ishibe T, Murotani S, Mulia IE, Gusman AR (2022) Effects of uncertainty in fault parameters on deterministic tsunami hazard assessment: examples for active faults along the eastern margin of the Sea of Japan. Earth, Planets and Space 74(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40623-022-01594-6

Sato H, Ishiyama T, Hashima A, Kato N, Van-Horne A, Claringbould J, No T, Ishikawa M, Matsubara M, Koshiya S, Toyoshima TK, K, Kosuga M (2020) Development of active fault model. Annual progress reports of the integrated research project on seismic and tsunami hazards around the Sea of Japan (FY2019).

Takemura M (1998) Scaling law for Japanese intraplate earthquakes in special relations to the surface faults and the damages. J Seismol Soc Jpn (Zisin) 2nd Ser 51:211-228 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Tanioka Y, Satake K (1996) Tsunami generation by horizontal displacement of ocean bottom. Geophys Res Lett 23(8):861-864

Tanioka Y, Satake K, Ruff L (1995) Total analysis of the 1993 Hokkaido Nanseioki earthquake using seismic wave, tsunami, and geodetic data. Geophys Res Lett 22(1):9-12

Wessel P, Smith WH (1998) New, improved version of generic mapping tools released. EOS Trans Am Geophys Union 79(47):579-579

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Yushiro Fujii

fujii@kenken.go.jp

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article - (See figure on next page.)

Fig. 1 a Map of Sea of Japan. Blue and red stars indicate the epicenters of the 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake and past major earthquakes, respectively. The focal mechanisms for the 1940 and the 1964 earthquakes are from Satake (1986) and Abe (1975), respectively, and the ones for the 1983 and the 1993 earthquakes are from the Global CMT. The thin gray rectangles and line segments indicate the 60 fault models by MLIT. Location of NOWPHAS wave gauges (WG, blue squares) and tide gauges (TG, triangles) at which tsunami records from the 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake were collected. Yellow corresponds to UNESCO/IOC, purple to GSI, and light blue to KHOA tide stations. Colorless triangles indicate tide stations for which no data were obtained. Regular font corresponds to the station name used in the inversions, and narrow italic corresponds to the station name not used in the inversions. The black rectangle shows the extent of the magnified area inenlarged area around Noto Peninsula. The black rectangles show 7 fault models by JSPJ (NT6 was slightly modified in this study), and the gray rectangles show 4 fault models by MLIT. Blue pentagons indicate the aftershocks between January 1 and 31 with . Dark yellow, light blue, and green stars indicate the epicenters of the past earthquakes that occurred near Noto Peninsula. Aftershocks of or higher (period: 2024/1/1-1/17) by JMA are indicated by red circles. The focal mechanism of the 1993 earthquake is from the Global CMT, and the other earthquakes, including the 2024 mainshock, are from the USGS W-phase solutions