DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08818-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40307520

تاريخ النشر: 2025-04-30

توزيع الميكروبلاستيك تحت السطح في المحيط

تاريخ الاستلام: 28 سبتمبر 2023

تم القبول: 20 فبراير 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 30 أبريل 2025

الوصول المفتوح

تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

تلوث البلاستيك البحري هو قضية عالمية، مع وجود جزيئات البلاستيك الدقيقة (

يعمل كمصرف رئيسي لثاني أكسيد الكربون الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية

الصندوق 1

تعقيد الميكروبلاستيك في البيئة الطبيعية

التحولات البيولوجية (على سبيل المثال، التجزئة عن طريق العض، الابتلاع والتلوث البيولوجي)

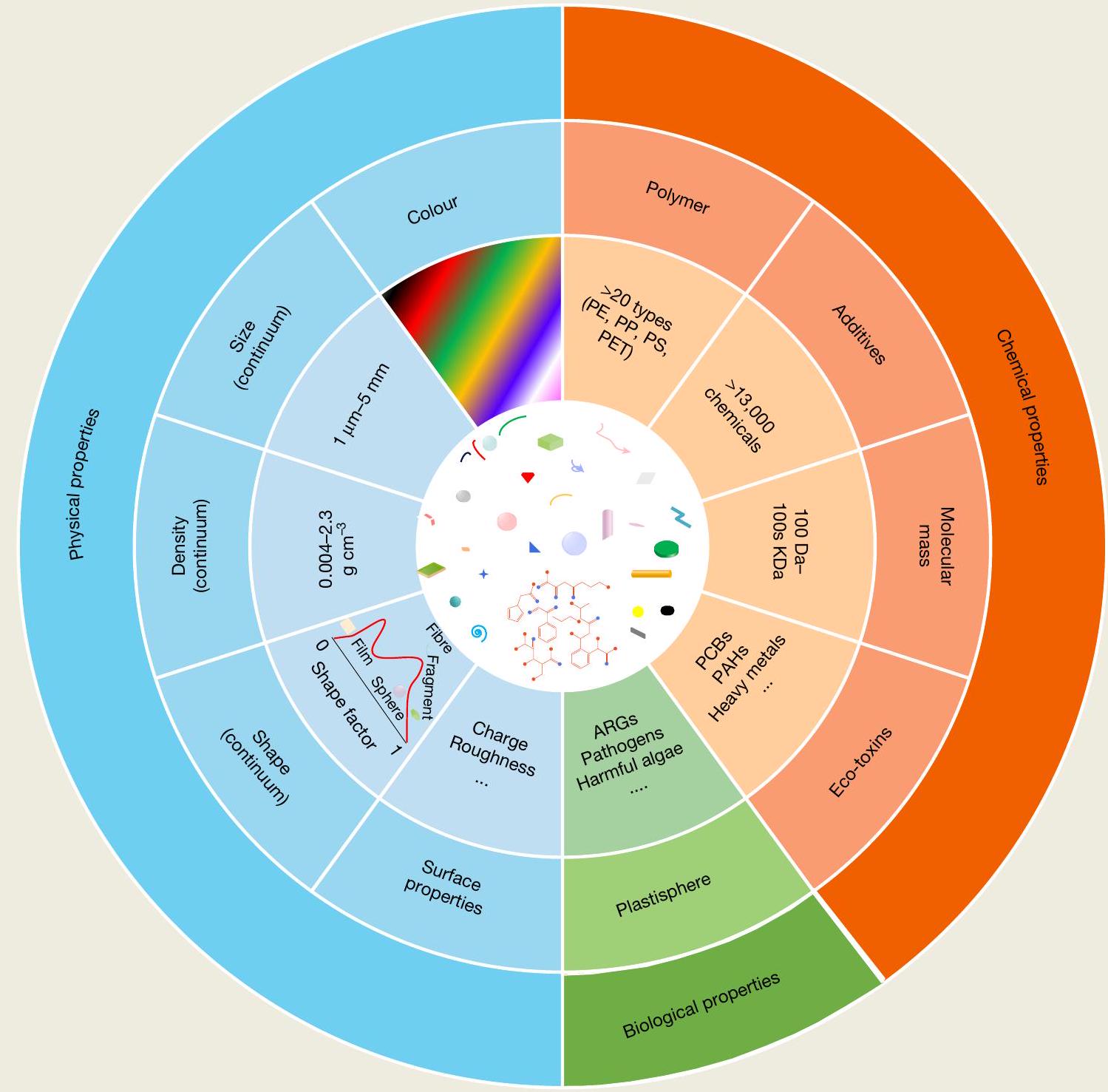

تعقيد قياسات الميكروبلاستيك وتأثيرها على البيئة. ARGs، جينات مقاومة المضادات الحيوية؛ PAHs، الهيدروكربونات العطرية متعددة الحلقات؛ PCBs، ثنائي الفينيل متعدد الكلور؛ PE، بولي إيثيلين؛ PP، بولي بروبيلين؛ PS، بولي ستيرين؛ PET، بولي إيثيلين تيريفثاليت.

عدم اليقين في طرق قياس الميكروبلاستيك

تشير المناطق الملونة المظللة إلى

as كل فئة بلاستيكية تتطلب أساليب أخذ عينات وتحليل مخصصة

تحليل

| المعرفة الحالية ومستوى الثقة | رؤى العملية | الفجوات الرئيسية ومستوى الأولوية | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

الميكروبلاستيك يتخلل مياه المحيط

الميكروبلاستيك. تم ملاحظة وفرة عالية باستمرار في المياه العميقة، بما في ذلك أكثر من 1,100 جزيء لكل

أنماط توزيع الميكروبلاستيك تحت السطح

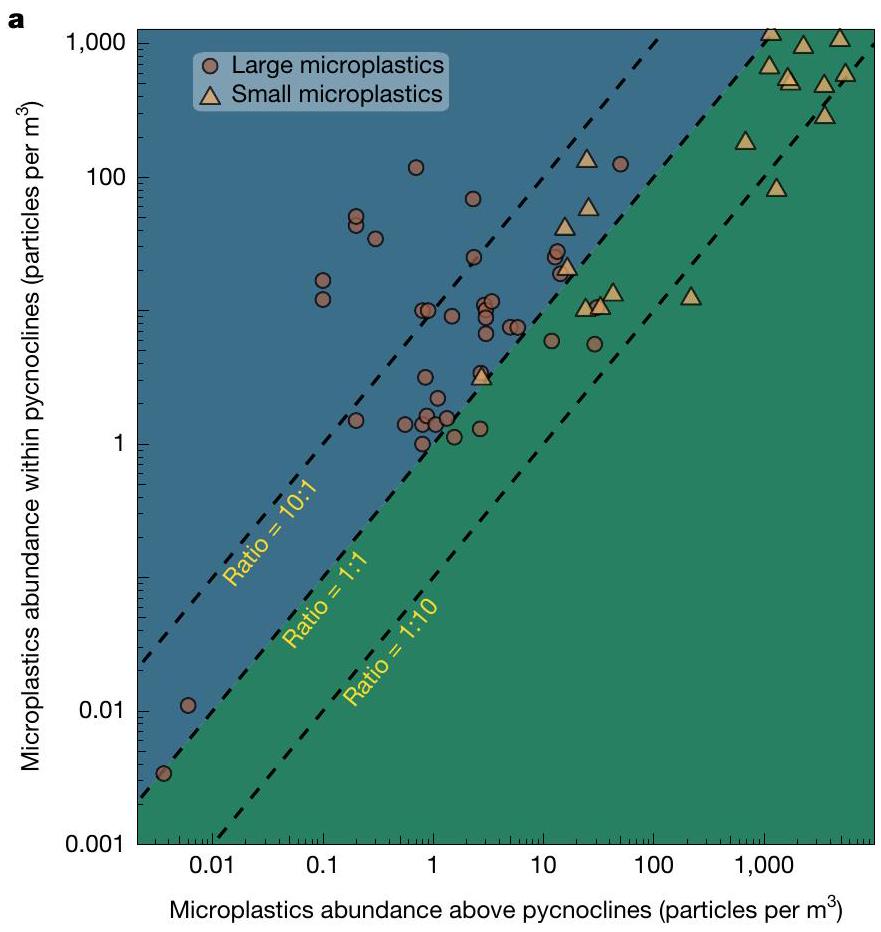

تراص الكثافة المحتفظة بالميكروبلاستيك الكبيرة

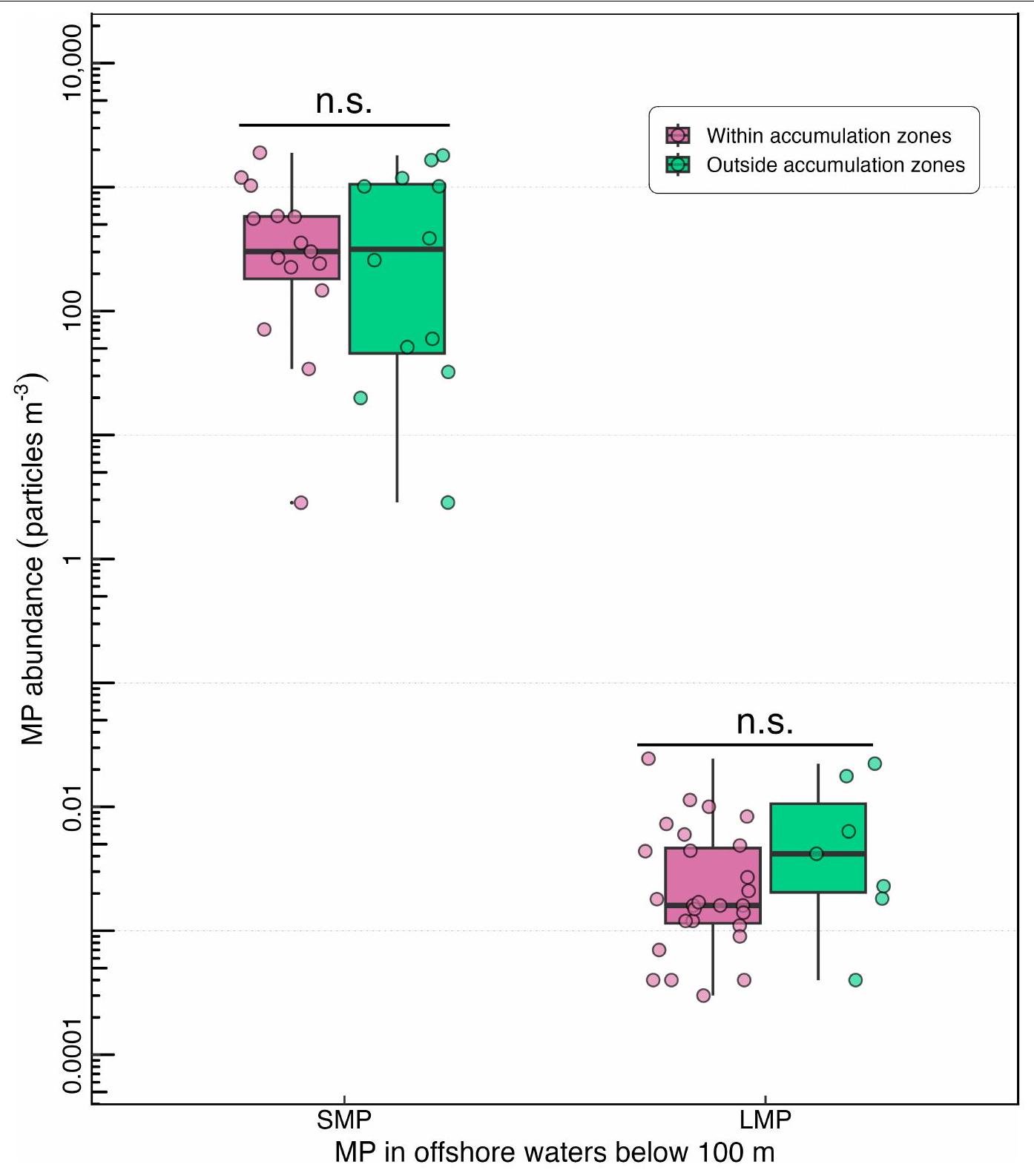

التمديد العمودي لمناطق تراكم الميكروبلاستيك

داخل وخارج مناطق التراكم المعروفة في أعلى 100 متر من عمود الماء (الطرق). مجموعات البيانات مأخوذة من المراجع.

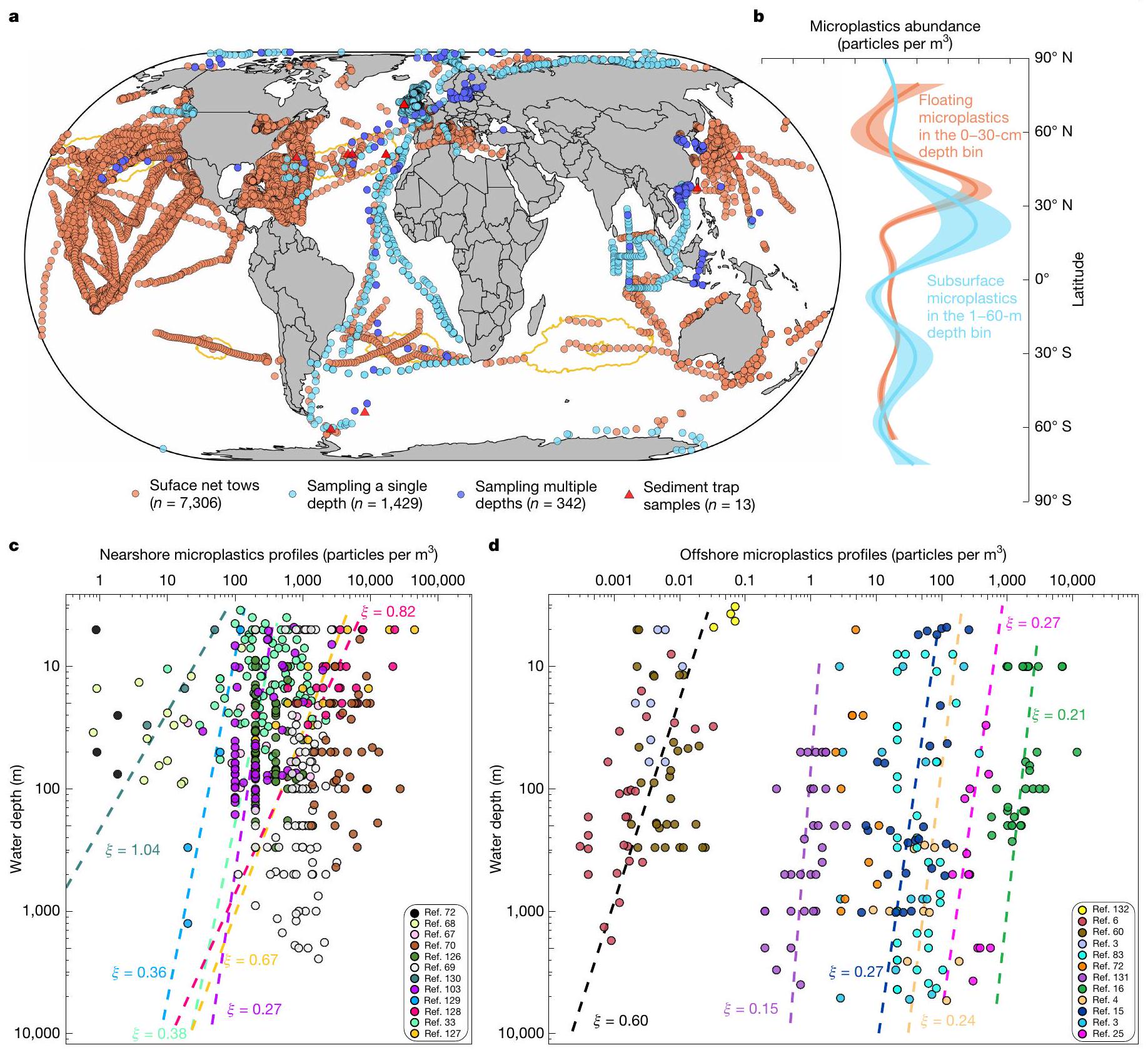

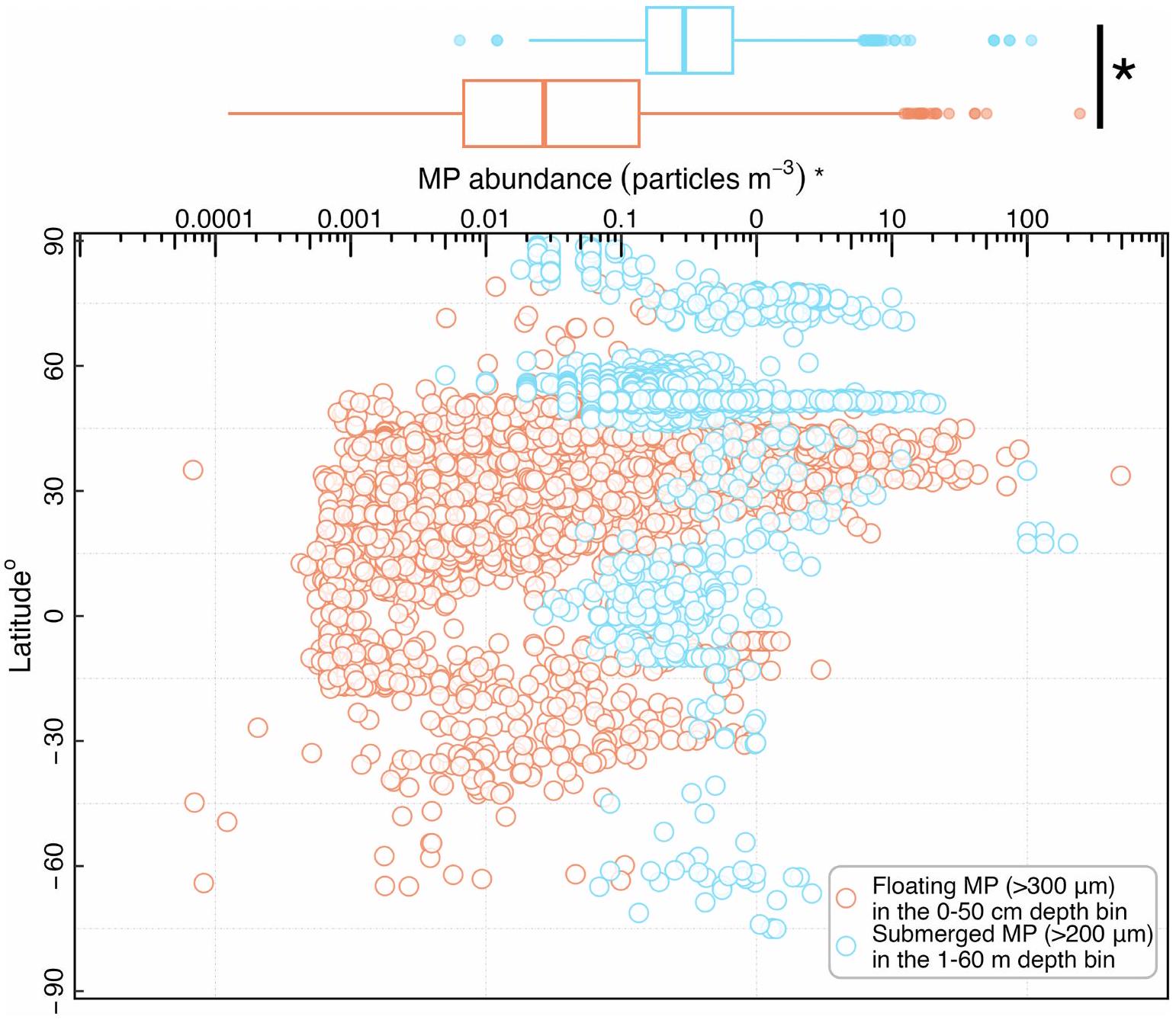

تتبع الجزيئات البلاستيكية العائمة في أعلى 10 أمتار من عمود الماء نمط السطح، مع تركيزات عالية في دوامات المحيط الوسطى.

الكربون البلاستيكي يدخل حوض الكربون الجزيئي البحري

من المتوقع أن يؤدي تسرب المواد إلى المحيط إلى إضافة كبيرة وطويلة الأمد من الكربون الميكرو بلاستيكي إلى مجموعة الكتلة العضوية القابلة للاستخدام في المحيط. يتم استخدام الكربون الميكرو بلاستيكي بواسطة الميكروبات البحرية جنبًا إلى جنب مع المستقلبات والحطام العضوي الذي تطلقه العمليات الميكروبية.

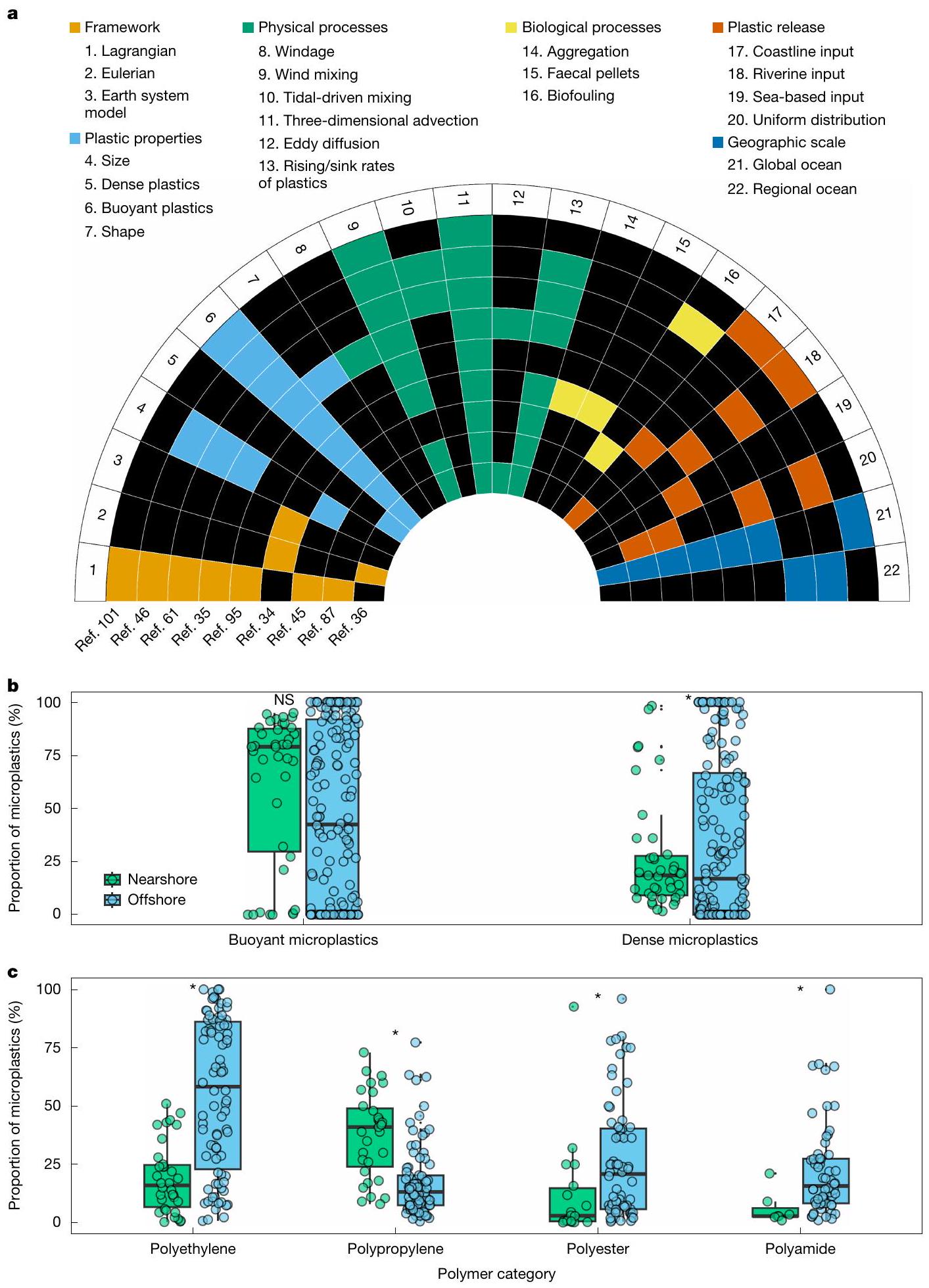

مقارنة النماذج بالملاحظات

قياسات الوفرة والخصائص، ومعدلات الغرق ذات الصلة البيئية، ومعدلات التلوث البيولوجي، ومعدلات الدمج والانفصال من الكتل، وسلامة الهيكل ومعدلات التحلل للكتل المحملة بالبلاستيك. ستكون البيانات حول اختيار وابتلاع جزيئات الميكروبلاستيك من العوالق، المصنفة حسب استراتيجية الرعي، ذات قيمة كبيرة لتحسين تقديرات نقل كريات البراز.

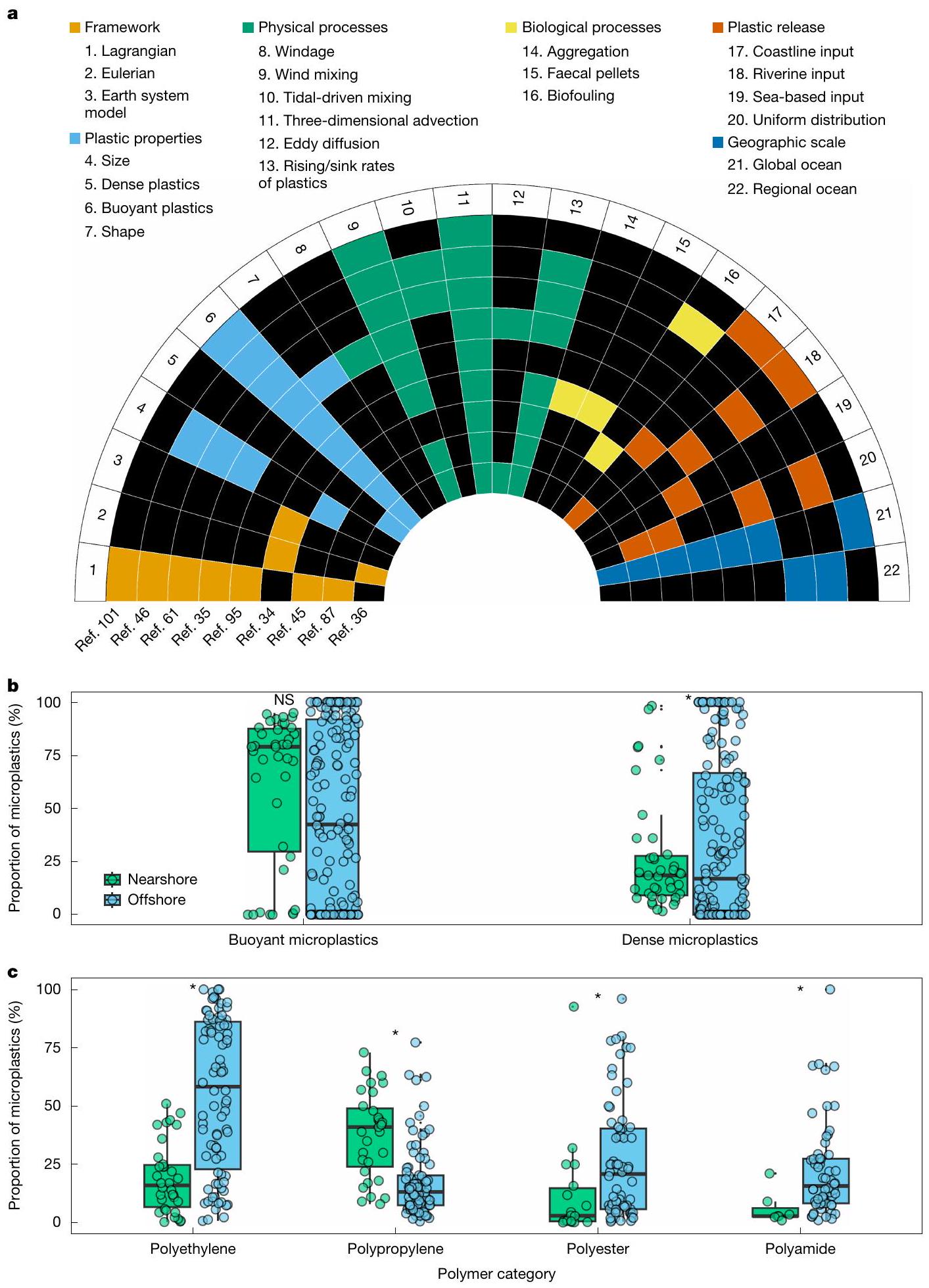

تركيب البوليمر للميكروبلاستيك تحت السطح

وجد آخر ملحوظ هو الانخفاض الواضح في أجزاء البولي بروبيلين العائم المغمور في عمود الماء مقارنةً بالزيادة الواضحة في البولي إيثيلين في المياه البعيدة عن الشاطئ (

مصادر عدم اليقين واستراتيجيات التحسين

من 18 ورقة مراجعة من الأقران حول الميكروبلاستيك في عمود الماء التي قدمت تركيبات البوليمر

الخاتمة

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- تومسون، ر. س. وآخرون. عشرون عامًا من أبحاث تلوث الميكروبلاستيك – ماذا تعلمنا؟ العلوم 386، eadl2746 (2024).

- إريكسن، م. وآخرون. ضباب بلاستيكي متزايد، يُقدّر الآن بأكثر من 170 تريليون جزيء بلاستيكي عائم في محيطات العالم – حلول عاجلة مطلوبة. PLoS ONE 18، e0281596 (2023).

- تشاو، س. وآخرون. كميات كبيرة من الميكروبلاستيك الصغيرة تتخلل المحيط السطحي إلى أعماق الهاوية في دوامة المحيط الأطلسي الجنوبي. تغيرات عالمية في البيولوجيا 28، 2991-3006 (2022).

- تيكمان، م. ب. وآخرون. ربط الأطراف المفقودة لتلوث الميكروبلاستيك في القطب الشمالي: التوزيع من سطح البحر عبر عمود الماء إلى رواسب أعماق البحر في مرصد هاوسغارتن. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 54، 4079-4090 (2020).

- إيزوبي، أ. وآخرون. مجموعة بيانات متعددة المستويات عن وفرة الميكروبلاستيك في المحيط العلوي للعالم وبحيرات لورينتيان العظمى. ميكروبلاست. نانوبلاست. 1، 16 (2021).

- إيجر، م.، سولو-غامباري، ف. وليبرتون، ل. أول دليل على تساقط البلاستيك من بقعة القمامة في شمال المحيط الهادئ. تقارير العلوم 10، 7495 (2020).

- فيلاروبيا-غوميز، ب.، كورنيل، س. إ. وفابريس، ج. تلوث البلاستيك البحري كتهديد لحدود الكوكب – القطعة العائمة في لغز الاستدامة. سياسة بحرية 96، 213-220 (2018).

- ريدي، س. ولاؤ، و. كسر موجة البلاستيك: تقييم شامل للطرق نحو وقف تلوث المحيطات بالبلاستيك (مؤسسة بيو الخيرية، 2020).

- لو، ك. ل. البلاستيك في البيئة البحرية. مراجعة سنوية لعلوم البحار 9، 205-229 (2017).

- ماكلويد، م.، أarp، هـ. ب. هـ.، تيكمان، م. ب. وجاهنكي، أ. التهديد العالمي من تلوث البلاستيك. ساينس 373، 61-65 (2021).

- أندرايدي، أ. ل. البلاستيك في الميكروبلاستيك: مراجعة. مجلة تلوث البحر. 119، 12-22 (2017).

- روتشمان، سي. إم. وآخرون. إعادة التفكير في الميكروبلاستيك كأحد أنواع الملوثات المتنوعة. الكيمياء البيئية والسمية 38، 703-711 (2019).

- فان سيبيل، إ. وآخرون. علم المحيطات الفيزيائية لنقل الحطام البحري العائم. رسائل البحث البيئي 15، 023003 (2020).

- كين، إ. أ. وآخرون. بؤر الميكروبلاستيك في قاع البحر التي تتحكم بها الدورة الدموية في أعماق البحار. ساينس 368، 1140-1145 (2020).

- روس، ب. س. وآخرون. التوزيع الواسع لألياف البوليستر في المحيط القطبي مدفوع بإدخالات الأطلسي. نات. كوميونيك. 12، 106 (2021).

- بابورتسافا، ك. ولامبيتي، ر. س. تركيزات عالية من البلاستيك مخفية تحت سطح المحيط الأطلسي. نات. كوم. 11، 4073 (2020).

- لال، د. الميكروكوزم المحيطي للجسيمات: تلعب المادة العالقة، حوالي 1 جرام في 100 طن من مياه البحر، دورًا حيويًا في كيمياء المحيطات. العلوم 198، 997-1009 (1977).

- الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ: ملخص لصانعي السياسات. في تغير المناخ 2021: الأساس العلمي الفيزيائي (تحرير ماسون-ديلموتي، ف. وآخرون) (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2021).

- بويد، ب. و.، كلستري، هـ.، ليفي، م.، سيجل، د. أ. وويبر، ت. مضخات الجسيمات متعددة الأوجه تدفع احتجاز الكربون في المحيط. ناتشر 568، 327-335 (2019).

- جالووي، ت. س.، كول، م. وليwis، س. تفاعلات حطام الميكروبلاستيك في جميع أنحاء النظام البيئي البحري. نات. إيكول. إيفول. 1، 0116 (2017).

- زييرفوجل، ك. وآخرون. التفاعلات الميكروبية مع الميكروبلاستيك: رؤى حول دورة الكربون البلاستيكي في المحيط. الكيمياء البحرية 262، 104395 (2024).

- غالغاني، ل. وآخرون. الترحال إلى الأعماق: كيف يتم تصدير جزيئات الميكروبلاستيك من خلال مضخة الكربون البيولوجية في المحيط الأطلسي الشمالي. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 56، 15638-15649 (2022).

- لو، ك. ل. وروخمان، س. م. تكشف التعاونيات واسعة النطاق عن مدى تلوث البلاستيك على مستوى العالم. ناتشر 169، 254-255 (2023).

- Koelmans، أ. أ. وآخرون. تقييم مخاطر جزيئات الميكروبلاستيك. نات. ريف. ماتير. 7، 138-152 (2022).

- تشاو، س.، مينسر، ت. ج.، ليبرتون، ل. وإيجر، م. الميكروبلاستيك العائم في دوامة شمال المحيط الهادئ شبه الاستوائية: مكون إنساني شائع من حوض الكربون العضوي الجزيئي. PNAS Nexus 2، pgadO7O (2023).

- برمبك، س. وآخرون. تقييم نقدي للطرق التحليلية لتحليل الميكروبلاستيك بشكل موحد وبتكلفة فعالة. تطبيقات الطيفية 74، 1012-1047 (2020).

- بيكن، I. وآخرون. الجليد البحري في القطب الشمالي هو مصب زمني مهم ووسيلة نقل للميكروبلاستيك. نات. كوم. 9، 1505 (2018).

- أوبارد، ر. و. وآخرون. الاحتباس الحراري يحرر إرث الميكروبلاستيك المجمد في جليد البحر القطبي. مستقبل الأرض 2، 315-320 (2014).

- روشر، ل. وآخرون. تلوث الميكروبلاستيك في مصب نهر فيزر والبحر الشمالي الألماني. التلوث البيئي. 288، 117681 (2021).

- أبل، س. م.، برمبك، س.، إنت-فين، إ.، براندت، أ. وجيردتس، ج. التعرف المنهجي على الميكروبلاستيك في الرواسب العميقة والهادلة لخندق كوريل كامتشاتكا. تلوث البيئة 269، 116095 (2021).

- كورتيين-جونز، و.، فان جينيب، س.، بينيكود، ج.، بن، إ. وتومسون، ر. س. وفرة وتركيب الميكروبلاستيك الاصطناعي على طول تدرج طولي يمر عبر الدوامة شبه الاستوائية في المحيط الأطلسي الشمالي. مجلة تلوث البحر. 185، 114371 (2022).

- مولازاده، م. وآخرون. دور الاضطراب في ترسيب الجسيمات الدقيقة العائمة بشكل طبيعي. العلوم. البيئة الكاملة 911، 168540 (2024).

- سونغ، ي. ك. وآخرون. التوزيع الأفقي والرأسي للميكروبلاستيك في المياه الساحلية الكورية. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 52، 12188-12197 (2018).

- كفالي، ك.، بروي، أ. ف.، تشين، س.-ت.، لاندولفي، أ. وأوشليز، أ. المصيدة العالمية لجزيئات الميكروبلاستيك البيولوجية. ساي ريب. 10، 16670-1 (2020).

- كلينك، د.، بييتافين، أ. وليبرتون، ل. النقل المعتمد على الحجم للبلاستيك العائم المودل في المحيط العالمي. Front. Mar. Sci. 9، 903134 (2022).

- ماونتفورد، أ. وموراليس ماكيدا، م. النمذجة الأويلرية للتوزيع ثلاثي الأبعاد لسبعة أنواع شائعة من الميكروبلاستيك في المحيط العالمي. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. المحيطات 124، 8558-8573 (2019).

- فان سيبيل، إ. وآخرون. جرد عالمي للقطع البلاستيكية الصغيرة العائمة. رسائل البحث البيئي 10، 124006 (2015).

- أمينبار، م. وآخرون. التوزيع المكاني للميكروبلاستيك في منطقة الارتفاع الساحلي: الانتشار في عرض البحر من المصادر الحضرية في نظام تيار هومبولت. تلوث البيئة. 343، 123157 (2024).

- كايل، ب.، كافان، إ. ل. وبريتن، ج. ل. التوفيق بين اعتماد سرعة غرق الجسيمات البحرية على الحجم. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 48، e2020GL091771 (2021).

- أرمبروست، إ. ف. حياة الدياتومات في محيطات العالم. الطبيعة 459، 185-192 (2009).

- أمارال-زيتلر، ل. أ.، زيتلر، إ. ر. & مينسر، ت. ج. علم البيئة للبلستسفير. نات. ريف. ميكروبيول. 18، 139-151 (2020).

- أمارال-زيتلر، ل. أ.، زيتلر، إ. ر.، مينسر، ت. ج.، كلاسن، م. أ. وغاليجر، س. م. تأثيرات التلوث البيولوجي على كثافة البولي إيثيلين وغرقه في المياه الساحلية: نقطة تحول ماكرو/ميكرو؟ مياه البحث. 201، 117289 (2021).

- سون، إكس.-إف.، تشانغ، واي.، شيا، إم.-واي.، ماي، إل. وزينغ، إي. واي. كربونات الكالسيت تغمر الحطام البلاستيكي منخفض الكثافة في المحيطات المفتوحة. نات. كوميونيك. 15، 4837 (2024).

- إيجر، م. وآخرون. ندرة متغيرة مكانيًا من الميكروبلاستيك العائم في شمال المحيط الهادئ الشرقي. رسائل البحث البيئي 15، 114056 (2020).

- لوبيل، د. وآخرون. الخصائص العالمية لنزول البلاستيك الدقيق المتأثر بالتلوث البيولوجي. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء: المحيطات 126، e2020JC017098 (2021).

- فيشر، ر. وآخرون. نمذجة الميكروبلاستيك المتسخ تحت الماء ومساراته الرأسية. علوم الأحياء الجيولوجية 19، 2211-2234 (2022).

- راينكيوس، ج. ووانيك، ج. ج. أول دليل طويل الأمد على تلوث الميكروبلاستيك في شمال المحيط الأطلسي الاستوائي العميق. تلوث البيئة 305، 119302 (2022).

- راينكيوس، ج. وآخرون. وفرة وخصائص الألياف الدقيقة المكتشفة في مواد فخ الرواسب من المحيط الأطلسي الشمالي العميق شبه الاستوائي. العلوم. البيئة الكاملة 738، 140354 (2020).

- ألورالد، ج. وآخرون. تدفق الألياف الدقيقة الناتجة عن الأنشطة البشرية في نظام بيئي ساحلي في القارة القطبية الجنوبية: هل هي قمة جبل الجليد؟ مجلة تلوث البحر. 175، 113388 (2022).

- روولاندز، إ. وآخرون. التدفق العمودي للميكروبلاستيك، دراسة حالة في المحيط الجنوبي، جورجيا الجنوبية. مجلة تلوث البحر. 193، 115117 (2023).

- ماتيوس-كارديناس، أ.، ويلر، أ. ج. & ليم، أ. الميكروبلاستيك والميكروكريات السليلوزية في أعماق شمال الأطلسي وفي الشعاب المرجانية الباردة لوفيليا بيرتوسا. مجلة تلوث البحر. 206، 116741 (2024).

- تشانغ، إكس، ليو، زد، لي، دي، تشاو، واي وزانغ، واي. التيارات العكرة تنظم نقل واستقرار الميكروبلاستيك في وادٍ تحت البحر في أعماق المحيط. الجيولوجيا 52، 646-650 (2024).

- إيكنوي، ت.، ناكاجيما، ر.، أوسافوني، س.، سيسوانتو، إ. وهوندا، م. ج. تدفق عمودي للميكروبلاستيك في المحيط الهادئ العميق شبه الاستوائي: ملاحظات فخ الرواسب المثبتة ضمن دوامة إعادة تدوير كوروشي. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا. 58، 16121-16130 (2024).

- لام، ب. ج.، دوني، س. ج. & بيشوب، ج. ك. المضخة البيولوجية الديناميكية للمحيط: رؤى من تجميع عالمي للكربون العضوي الجسيمي،

، وملفات تركيز الأوبال من الطبقة المتوسطة. الدورات البيوجيوكيميائية العالمية 25، GB3009 (2011). - إندرس، ك.، لنتز، ر.، ستيدمون، ك. أ. ونيلسن، ت. ج. وفرة وحجم وتركيب البوليمر للميكروبلاستيك البحري

في المحيط الأطلسي وتوزيعها العمودي المودل. مجلة تلوث البحر. 100، 70-81 (2015). - غونالان، ك. وآخرون. هل يؤثر تدرج عمود الماء على التوزيع العمودي للميكروبلاستيك؟ التلوث البيئي. 340، 122865 (2024).

- كوي، م.، نيس، إ. هـ. ف.، شيفر، م. وكويلمانس، أ. أ. التقلبات في المحيط: آثار التلوث البيولوجي على النقل العمودي للميكروبلاستيك. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 51، 7963-7971 (2017).

- ديتمار، س.، روله، أ. س.، ألتمن، ك. وجيكل، م. سرعات الاستقرار لقطع الألياف والميكروبلاستيك الصغيرة. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 58، 6359-6369 (2024).

- كايسر، د.، إستلمان، أ.، كوالسكي، ن.، غلوكزين، م. ووانيك، ج. ج. سرعة غرق الميكروبلاستيك دون المليمتر. مجلة تلوث البحر 139، 214-220 (2019).

- إيجر، م. وآخرون. التوزيع العائم للمواد البلاستيكية

) والأنظمة البحرية في الطبقة العليا من المحيط الأطلسي الشمالي. Sci. Rep. 12، 13465 (2022). - أونيك، ف.، كاندورب، م. ل.، فان سيبيل، إ. ولوافكوتير، س. تأثير حجم الجسيمات والتفتت على نقل الميكروبلاستيك على نطاق واسع في البحر الأبيض المتوسط. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 56، 15528-15540 (2022).

- هيدالغو-روز، ف.، غوتو، ل.، طومسون، ر. س. و ثيل، م. الميكروبلاستيك في البيئة البحرية: مراجعة للطرق المستخدمة للتعرف عليها وقياس كميتها. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 46، 3060-3075 (2012).

- رايت، ر. ج.، إيرني-كاسولا، ج.، زادجيلوفيتش، ف.، لاتفا، م. وكريستي-أوليزا، ج. أ. الحطام البلاستيكي البحري: سطح جديد لاستعمار الميكروبات. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 54، 11657-11672 (2020).

- تشاو، س.، زتلر، إ. ر.، أمارال-زتلر، ل. أ. و مينسر، ت. ج. السعة الاستيعابية الميكروبية وكتلة الكربون الحيوية للفضلات البلاستيكية البحرية. مجلة ISME 15، 67-77 (2021).

- دوست محمدي، أ.، ستوكير، ر. وأردكاني، أ. م. السباحة عند أعداد رينولدز المنخفضة في خطوط الكثافة. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 109، 3856-3861 (2012).

- ماكنتاير، س.، ألدرج، أ. ل. & غوتشالك، س. س. تراكم الكائنات البحرية الآن عند انقطاع الكثافة في عمود الماء. ليمنول. أوشنوجراف. 40، 449-468 (1995).

- أوراسجارفي، إ.، باككونن، م.، سيتالا، أ.، كويستينن، أ. وليهتينيمي، م. تتجمع الجسيمات البلاستيكية الدقيقة في طبقات رقيقة في بحر البلطيق المتمايز. تلوث البيئة 268، 115700 (2021).

- زوبكوف، م.، إسيوكوفا، إ.، زيوبين، أ. وساموسيف، إ. تباين محتوى الميكروبلاستيك في عمود الماء: الملاحظات باستخدام أداة أخذ عينات جديدة في بحر البلطيق المتمايز. مجلة تلوث البحر 138، 193-205 (2019).

- مانولانغ، سي. وا. وآخرون. التوزيع العمودي للميكروبلاستيك على طول البوابة الرئيسية لمسارات التدفق الإندونيسي. مجلة تلوث البحر. 199، 115954 (2024).

- تشو، ق. وآخرون. احتجاز الميكروبلاستيك في طبقات الهالوكلاين والعتامة في بحر البلطيق شبه المغلق. Front. Mar. Sci. 8، 761566 (2021).

- كارلوتي، ف. وآخرون. الميكروبلاستيك في طبقة الكلوروفيل القصوى على طول مقطع عرضي شمال-جنوب في البحر الأبيض المتوسط مقارنة بتركيزات العوالق الحيوانية. مجلة تلوث البحر. 196، 115614 (2023).

- تشوي، سي. أ. وآخرون. التوزيع العمودي والنقل البيولوجي للميكروبلاستيك البحري عبر عمود الماء الإبيبالاجي والميزوبالاجي. تقارير العلوم 9، 7843 (2019).

- أردكاني، أ. وستوكر، ر. ستراتليتس: حلول القوة النقطية عند أعداد رينولدز المنخفضة في سائل متدرج. فيز. ريف. ليتر. 105، 084502 (2010).

- ييك، ك. ي.، توريس، س. ر.، بيكوك، ت. و ستوكير، ر. زيادة سحب كرة تستقر في سائل متدرج عند أعداد رينولدز الصغيرة. مجلة ميكانيكا السوائل 632، 49-68 (2009).

- مروكوسكا، م. م. تأثير الطبقة الكثيفة على سلوك استقرار الجسيمات غير الكروية وتطور الذيل. تقارير علمية 10، 20595 (2020).

- تشانغ، م.، شو، د.، ليو، ل.، وي، ي. وغاو، ب. التمايز العمودي للميكروبلاستيك المتأثر بالتدرج الحراري في خزان عميق. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 57، 6999-7008 (2023).

- لي، سي.، زو، إل.، وانغ، إكس.، ليو، ك. ولي، دي. التوزيع عبر المحيطات وأصل الميكروبلاستيك في المياه تحت السطحية لبحر الصين الجنوبي والمحيط الهندي الشرقي. العلوم. البيئة الكاملة 805، 150243 (2022).

- زدانوف، إ. وآخرون. اختلافات في مصير الميكروبلاستيك السطحي وتحت السطحي: دراسة حالة في المحيط الأطلسي المركزي. مجلة علوم البحار والهندسة 11، 210 (2023).

- تشانغ، س. وآخرون. خصائص توزيع الميكروبلاستيك في مياه البحر السطحية وتحت السطحية في القارة القطبية الجنوبية. العلوم. البيئة الكاملة 838، 156051 (2022).

- مورغانا، س. وآخرون. الميكروبلاستيك في القطب الشمالي: دراسة حالة مع عينات من المياه تحت السطحية والأسماك قبالة شمال شرق غرينلاند. تلوث البيئة. 242، 1078-1086 (2018).

- باخوموفا، س. وآخرون. تباين الميكروبلاستيك في المياه تحت السطحية من القطب الشمالي إلى القطب الجنوبي. تلوث البيئة. 298، 118808 (2022).

- لوشر، أ. ل.، تيريللي، ف.، أوكونور، آي. وأوفيسر، ر. الميكروبلاستيك في المياه القطبية في القطب الشمالي: القيم المبلغ عنها لأول مرة للجسيمات في عينات السطح وتحت السطح. ساي. ريب. 5، 14947 (2015).

- كانهاي، ل. د. ك. وآخرون. الميكروبلاستيك في المياه تحت السطحية لحوض القطب الشمالي المركزي. مجلة تلوث البحر. 130، 8-18 (2018).

- كانهاي، ل. د. ك.، أوفيسر، ر.، ليشيفسكا، أ.، طومسون، ر. سي. وأوكونور، آي. وفرة الميكروبلاستيك، التوزيع والتركيب على طول تدرج عرضي في المحيط الأطلسي. مجلة تلوث البحر. 115، 307-314 (2017).

- لوشر، أ. ل.، بيرك، أ.، أوكونور، I. وأوفيسر، R. تلوث الميكروبلاستيك في شمال شرق المحيط الأطلسي: أخذ عينات موثوقة وعشوائية. مجلة تلوث البحر. 88، 325-333 (2014).

- ياكوشيف، إ. وآخرون. توزيع الميكروبلاستيك في القطب الشمالي الأوراسي يتأثر بالمياه الأطلسية والأنهار السيبيرية. اتصالات. الأرض والبيئة. 2، 23 (2021).

- Wichmann، د.، Delandmeter، ب. و van Sebille، إ. تأثير التيارات القريبة من السطح على الانتشار العالمي للميكروبلاستيك البحري. J.Geophys. Res. Oceans 124، 6086-6096 (2019).

- برغمان، م. وآخرون. تلوث البلاستيك في القطب الشمالي. مراجعة الطبيعة: الأرض والبيئة 3، 323-337 (2022).

- إريكسن، م. وآخرون. تلوث البلاستيك في محيطات العالم: أكثر من 5 تريليون قطعة بلاستيك تزن أكثر من 250,000 طن عائمة في البحر. PLoS ONE 9، e111913 (2014).

- كوزار، أ. وآخرون. الحطام البلاستيكي في المحيط المفتوح. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 111، 10239-10244 (2014).

- لو، ك. ل. وآخرون. تراكم البلاستيك في دوامة شمال الأطلسي شبه الاستوائية. ساينس 329، 1185-1188 (2010).

- ليبريتون، ل.-م.، غرير، س. وبوريرو، ج. س. النمذجة العددية للحطام العائم في محيطات العالم. مجلة تلوث البحر 64، 653-661 (2012).

- ماكسيمينكو، ن.، هافنر، ج. ونييلر، ب. مسارات الحطام البحري المستمد من مسارات العوامات لاغرانجيان. مجلة تلوث البحر 65، 51-62 (2012).

- فان سيبيل، إ.، إنجلاند، م. هـ. وفرويدلاند، ج. أصل وديناميات وتطور بقع النفايات البحرية من العوامات السطحية الملاحظة. رسائل البحث البيئي 7، 044040 (2012).

- هاك، ت. وآخرون. التشتت ثلاثي الأبعاد لجزيئات “بلاستيكية” محايدة في نموذج عالمي للمحيط. Front. Anal. Sci. 2، 868515 (2022).

- كارل، د. م.، كناور، ج. أ. ومارتن، ج. هـ. تدفق الجسيمات العضوية في المحيط: مفارقة تحلل الجسيمات. ناتشر 332، 438-441 (1988).

- فكسما، أ. وآخرون. تحلل البولي إيثيلين وامتصاصه بواسطة الخميرة البحرية رودوتورولا موكيلاجينوزا. ISME Commun. 3، 68 (2023).

- سيلي، م. إ.، سونغ، ب.، باسي، ر. و هيل، ر. س. تؤثر الجسيمات البلاستيكية الدقيقة على المجتمعات الميكروبية الرسوبية ودورة النيتروجين. نات. كوميونيك. 11، 2372 (2020).

- ليبي، و. ف. تأريخ الكربون المشع: الطريقة تزداد استخدامًا من قبل علماء الآثار، وعلماء الجيولوجيا، وعلماء الأرصاد الجوية، وعلماء المحيطات. العلوم 133، 621-629 (1961).

- هيتون، ت. ج. وآخرون. الكربون المشع: مؤشر رئيسي لدراسة دينامو الأرض، نظام المناخ، دورة الكربون، والشمس. العلوم 374، eabd7096 (2021).

- باجون، ر. وآخرون. تأثير الأمواج على التوزيع ثلاثي الأبعاد للبلاستيك في المحيط. نشرة تلوث البحر. 187، 114533 (2023).

- ليما، I. D.، لام، P. J. ودوني، S. C. ديناميات تدفق الكربون العضوي الجزيئي في نموذج المحيط العالمي. علوم الأحياء الجيولوجية 11، 1177-1198 (2014).

- باجايف، أ.، خاتمولينا، ل. وتشوبارينكو، إ. الميكرو-نفايات البشرية في عمود مياه بحر البلطيق. مجلة تلوث البحر 129، 918-923 (2018).

- جاير، ر.، جامبيك، ج. ر. & لو، ك. ل. إنتاج واستخدام ومصير جميع البلاستيكات التي تم تصنيعها على الإطلاق. ساي. أدف. 3، e1700782 (2017).

- مين، ك.، كويفي، ج. د. وماثرز، ر. ت. تصنيف اتجاهات تدهور البيئة للنفايات البلاستيكية البحرية بناءً على الخصائص الفيزيائية والبنية الجزيئية. نات. كوميونيك. 11، 727 (2020).

- ماكسيمينكو، ن.، هافنر، ج.، كاماتشي، م. وماكفادين، أ. محاكاة عددية لانجراف الحطام الناتج عن تسونامي اليابان الكبير عام 2011 والتحقق منها مع التقارير الملاحظة. نشرة تلوث البحر. 132، 5-25 (2018).

- جينيب، س. ج. ف. وآخرون. في البحث عن مصادر النفايات البلاستيكية البحرية التي تلوث منطقة إيكو ريجون في جزيرة الفصح. ساي. ريب. 9، 19662 (2019).

- ليبريتون، ل. وآخرون. تساهم الدول الصناعية في صيد الأسماك بشكل كبير في تلوث البلاستيك العائم في دوامة شمال المحيط الهادئ الاستوائية. تقارير العلوم 12، 12666 (2022).

- ألين، د. وآخرون. الميكروبلاستيك والنانو بلاستيك في بيئة المحيط-الجو. مراجعة الطبيعة: الأرض والبيئة 3، 393-405 (2022).

- أورتيغا، د. إ. وكورتيس-أريا غادا، د. الميكروبلاستيك والنانو بلاستيك في الغلاف الجوي كناقلات للملوثات الهوائية الأولية – دراسة نظرية حول حالة بولي إيثيلين تيريفثاليت (PET). تلوث البيئة. 318، 120860 (2023).

- جيويرت، ب.، بلاسيمان، م. م. وماكلود، م. مسارات تحلل البوليمرات البلاستيكية العائمة في البيئة البحرية. علوم البيئة. العمليات. التأثيرات 17، 1513-1521 (2015).

- زو، ل.، تشاو، س.، بيطار، ت. ب.، ستوبينز، أ. ولي، د. الذوبان الضوئي للبلاستيكات الدقيقة العائمة إلى الكربون العضوي المذاب: المعدلات والتأثيرات الميكروبية. ج. مواد خطرة. 383، 121065 (2020).

- دلري، أ. وآخرون. التحلل الضوئي للبلاستيك تحت ظروف بحرية محاكاة. نشرة تلوث البحر. 187، 114544 (2023).

- دي فروند، هـ. وآخرون. ما الذي يحدد دقة التعرف على المواد الكيميائية عند استخدام الميكروسبيكتروسكوبي لتحليل الميكروبلاستيك؟ كيموسفير 313، 137300 (2023).

- بينهيرو، هـ. ت. وآخرون. تلوث البلاستيك في شعاب العالم المرجانية. ناتشر 619، 311-316 (2023).

- نفا، ف. وآخرون. الحطام البلاستيكي في البحيرات والخزانات. الطبيعة 619، 317-322 (2023).

- هارد، د. س. وسبنسر، د. و. (محرران) الجسيمات البحرية: التحليل والتوصيف سلسلة المونوغراف الجيولوجية المجلد 63 (AGU، 1991).

- برمبك، س.، لورينز، س.، راشر-فريزنهاوزن، ر. & جيردتس، ج. نهج آلي لتحليل الميكروبلاستيك باستخدام مجهر FTIR مع مصفوفة الطائرة البؤرية (FPA) وتحليل الصور. طرق التحليل 9، 1499-1511 (2017).

- كوغر، و. وآخرون. تصنيف الطيف للميكروبلاستيك يحتاج إلى مجتمع مفتوح المصدر: أوبن سبيسي لإنقاذ الموقف! تحليل. كيمياء. 93، 7543-7548 (2021).

- برمبك، س. وآخرون. نحو التعرف المنهجي على الميكروبلاستيك في البيئة: تقييم أداة برمجية جديدة مستقلة (siMPle) للتحليل الطيفي. تطبيقات الطيفية 74، 1127-1138 (2020).

- Materić، د.، هولزينجر، ر. ونيمان، هـ. النانو بلاستيك والميكروبلاستيك الفائق الدقة في بحر وادن الهولندي – الحطام البلاستيكي المخفي؟ Sci. Total Environ. 846، 157371 (2022).

- كوكولكا، ت.، بروسكوروسكي، ج.، موريه-فيرغسون، س.، ماير، د. و. & لو، ك. ل. تأثير خلط الرياح على التوزيع العمودي للحطام البلاستيكي العائم. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 39، L07601 (2012).

- كول، م. وآخرون. تؤثر الجسيمات البلاستيكية الدقيقة على خصائص ومعدلات غرق كريات براز العوالق. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 50، 3239-3246 (2016).

- بودان، ك. تقدير وفرة الميكروبلاستيك السطحي البحري العالمي: مراجعة منهجية للأدبيات. Sci. Total Environ. 832، 155064 (2022).

- ليبريتون، ل. حالة ومصير بقع النفايات المحيطية. مراجعة طبيعة الأرض والبيئة 3، 730-732 (2022).

- وانغ، إكس.، زو، إل.، ليو، ك. ولي، دي. انتشار ألياف الميكروبلاستيك في عمود المياه البحرية الهامشية قبالة جنوب شرق الصين. العلوم. البيئة الكاملة 804، 150138 (2022).

- دينغ، ج. وآخرون. الميكروبلاستيك في أنظمة الشعاب المرجانية من جزر شيشا في بحر الصين الجنوبي. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 53، 8036-8046 (2019).

- داي، ز. وآخرون. حدوث الميكروبلاستيك في عمود الماء والرواسب في بحر داخلي تأثر بالأنشطة البشرية المكثفة. تلوث البيئة. 242، 1557-1565 (2018).

- كوردوفا، م. & هيرناوان، أ. الميكروبلاستيك في مياه سومبا، شرق نوسا تنغارا. في سلسلة مؤتمرات IOP: علوم الأرض والبيئة المجلد 162، 012023 (IOP، 2018).

- أوزتيكين، أ. وبات، ل. تلوث الميكرو بلاستيك في مياه البحر: دراسة أولية من ساحل ساركوم في سينوب على البحر الأسود الجنوبي. المجلة التركية لعلوم الأسماك والموارد المائية 17، 1431-1440 (2017).

- لي، د. وآخرون. تحليل النقل العمودي للميكروبلاستيك في المحيط الهادئ الغربي والمحيط الهندي الشرقي باستخدام تقنية ترشيح جديدة في الموقع. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 54، 12979-12988 (2020).

- رايسر، ج. وآخرون. التوزيع العمودي للبلاستيك العائم في البحر: دراسة رصدية في دوامة شمال الأطلسي. علوم الأحياء الجيولوجية 12، 1249-1256 (2015).

- ويزينجر، هـ.، وانغ، ز. وهيلويغ، س. غوص عميق في المونومرات البلاستيكية، والإضافات، ومواد المعالجة. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 55، 9339-9351 (2021).

(ج) المؤلفون 2025

طرق

التصنيف

جمع البيانات

تنسيق البيانات لمقارنة الميكروبلاستيك عند أعماق 1-60 م مع تلك العائمة عند سطح البحر

بناء نماذج توزيع وفرة الميكروبلاستيك

دالة القوة للقيم الميكروبلاستيكية تحت السطح

مقارنة بين الميكروبلاستيك-ك إلى إجمالي POC

التحليل الإحصائي

لتناسب نموذج GAM، وتشغيل محاكاة مونت كارلو وإجراء تحليل البوتستراب. تم إجراء جميع التحليلات الإحصائية والتصورات باستخدام

توفر البيانات

134. بويسلر، ك. أ.، بوي، ب. و.، بلاك، إ. إ. وسجل، د. أ. مقاييس مهمة لتقييم مضخة الكربون البيولوجية في المحيط. بروك. ناتل أكاد. ساي. الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 117، 9679-9687 (2020).

135. سوبهاس، أ. ف.، أديكنز، ج. ف.، دونغ، س.، رولينز، ن. إ. وبيرلسون، و. م. نشاط أنزيم الكربونيك أنهيدراز للجسيمات الغارقة والمعلقة في شمال المحيط الهادئ. ليمنول. أوشنوجراف. 65، 637-651 (2020).

136. أومهاو، ب. ب. وآخرون. التغيرات الموسمية والمكانية في تدفقات الكربون والنيتروجين المقدرة باستخدام

137. تشاو، س. مجموعات البيانات للميكروبلاستيك المغمور في المحيط. فيغشير https://doi.org/ 10.6084/m9.figshare. 28157324 (2025).

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات وطلبات المواد إلى شيي زهاو.

معلومات مراجعة الأقران الطبيعة تشكر المراجعين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة الأقران لهذا العمل.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على http://www.nature.com/reprints.

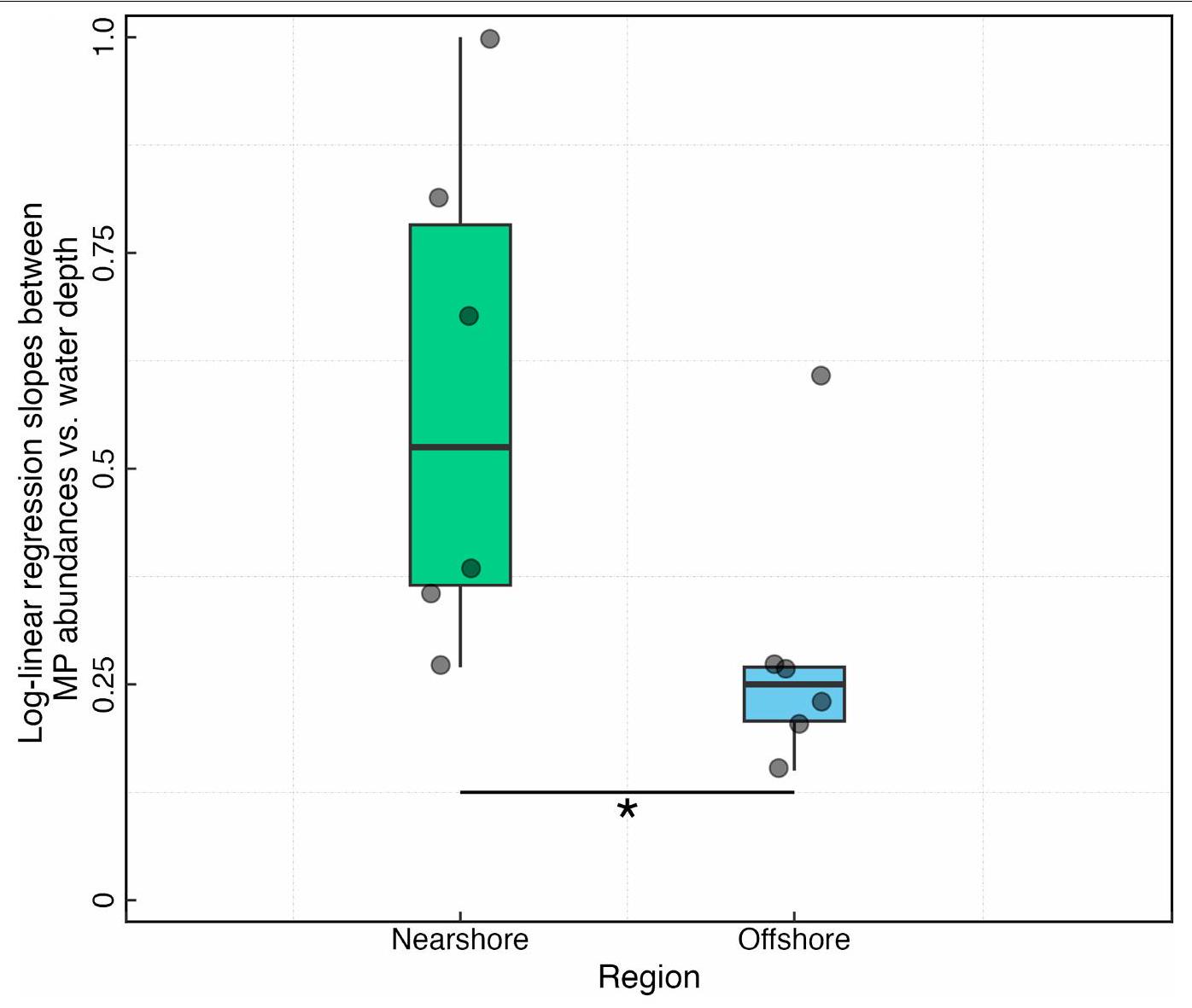

من الصندوق. تشير النجوم إلى الفروق ذات الدلالة الإحصائية بين فئتين (اختبار مان-ويتني-ويلكوك، p <.05). تتكون مجموعة البيانات المكررة للميكروبلاستيك في

قيم مقاسة ضمن 1.5 نطاق ربعي من الصندوق. تشير النجوم إلى الفروق ذات الدلالة الإحصائية بين مجموعتين (اختبار مان-ويتني ويلكوكسون،

تمثل النسب المئوية 25 و75 على التوالي. تشير الخطوط إلى أكبر وأصغر القيم المقاسة ضمن 1.5 من نطاقات الربع من الصندوق. مجموعات البيانات مأخوذة من المراجع.

تحليل

يمثل الخط الأسود ملاءمة الانحدار الخطي والمنطقة المظللة تمثل

| الوصف في الأدبيات | المزايا | العيوب | |||||||||||

| معدات أخذ العينات | |||||||||||||

| مضخة في الموقع | مضخة مكلاين، مضخة ISP، مضخة البلانكتون

|

|

|

||||||||||

| مضخة غاطسة، مضخة بئر عميق، مضخة أثناء سير السفينة |

|

|

|||||||||||

| شبكة العوالق | MOCNESS

|

|

|

||||||||||

| جهاز أخذ عينات المياه بالجملة | زجاجة نيسكين، جهاز أخذ عينات المياه ليمنوس، جهاز أخذ عينات المياه من الأكريليك |

|

-حجم عينة محدود | ||||||||||

| أنواع الفلاتر/الشبكات | |||||||||||||

| فلتر الشاشة

|

أنوديسك، فلتر بولي كربونات، فلتر نايلون، شبكة فولاذية مقاومة للصدأ، فلتر نيتروسيليلوز |

|

|

||||||||||

| مرشح العمق

|

GF/A، GF/C، فلاتر الكوارتز |

|

-تُحتجز الجسيمات داخل الهيكل | ||||||||||

| التعرف الكيميائي | |||||||||||||

| التصوير الكيميائي | كاشف تلوريد الزئبق والكادميوم ذو العنصر الواحد، كاشف مصفوفة مستوى البؤرة |

|

|

||||||||||

| فحص مدعوم بالمجهر يتبعه

|

تقنيات FTIR: الانعكاس الكلي المخفف – FTIR

|

-سهولة إعداد العينات والتحليل |

|

||||||||||

| فحص مجهرى | تحديد جزيئات البلاستيك من خلال الفحص البصري تحت المجهر |

|

-لم يتم توفير معلومات عن البوليمر | ||||||||||

وكالة اليابان لعلوم البحار والأرض، يوكوسوكا، اليابان. أوتياروا أبحاث المحيط الأزرق، لور هوت، نيوزيلندا. المختبر الوطني الرئيسي لأبحاث المصبات والسواحل، جامعة شرق الصين العادية، شنغهاي، الصين. قسم العلوم البحرية والبيئية، جامعة نورث إيسترن، بوسطن، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. معهد نيدرلاند الملكي لأبحاث البحر، دين بورغ، هولندا. تنظيف المحيط، روتردام، هولندا. إمباكتيفي، سانت غالن، سويسرا. كلية هارriet ويلكس الشرفية، جامعة فلوريدا أتلانتيك، بوكا راتون، فلوريدا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علم البيئة للمياه العذبة والبحرية، معهد التنوع البيولوجي وديناميات النظام البيئي، جامعة أمستردام، أمستردام، هولندا. قسم علوم الأرض، كلية علوم الأرض، جامعة أوترخت، أوترخت، هولندا. كلية علوم البحر، الجامعة الكاثوليكية الشمالية، كوكيمبو، تشيلي. برنامج MarineGEO، مركز سميثسونيان للبحوث البيئية، إدج ووتر، ماريلاند، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز علم البيئة والإدارة المستدامة للجزر المحيطية (ESMOI)، كوكيمبو، تشيلي. قسم البيولوجيا العضوية والتطورية، جامعة هارفارد، كامبريدج، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم التكنولوجيا الحيوية والكيمياء والصيدلة، جامعة سيينا، سيينا، إيطاليا. المركز الوطني لمستقبل التنوع البيولوجي (NBFC)، باليرمو، إيطاليا. قسم الكيمياء وعلم الأحياء الكيميائي، جامعة نورث إيسترن، بوسطن، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الهندسة المدنية والبيئية، جامعة نورث إيسترن، بوسطن، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: szhao@jamstec.go.jp

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08818-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40307520

Publication Date: 2025-04-30

The distribution of subsurface microplastics in the ocean

Received: 28 September 2023

Accepted: 20 February 2025

Published online: 30 April 2025

Open access

Check for updates

Abstract

Marine plastic pollution is a global issue, with microplastics (

serves as a major sink for anthropogenic carbon dioxide

Box 1

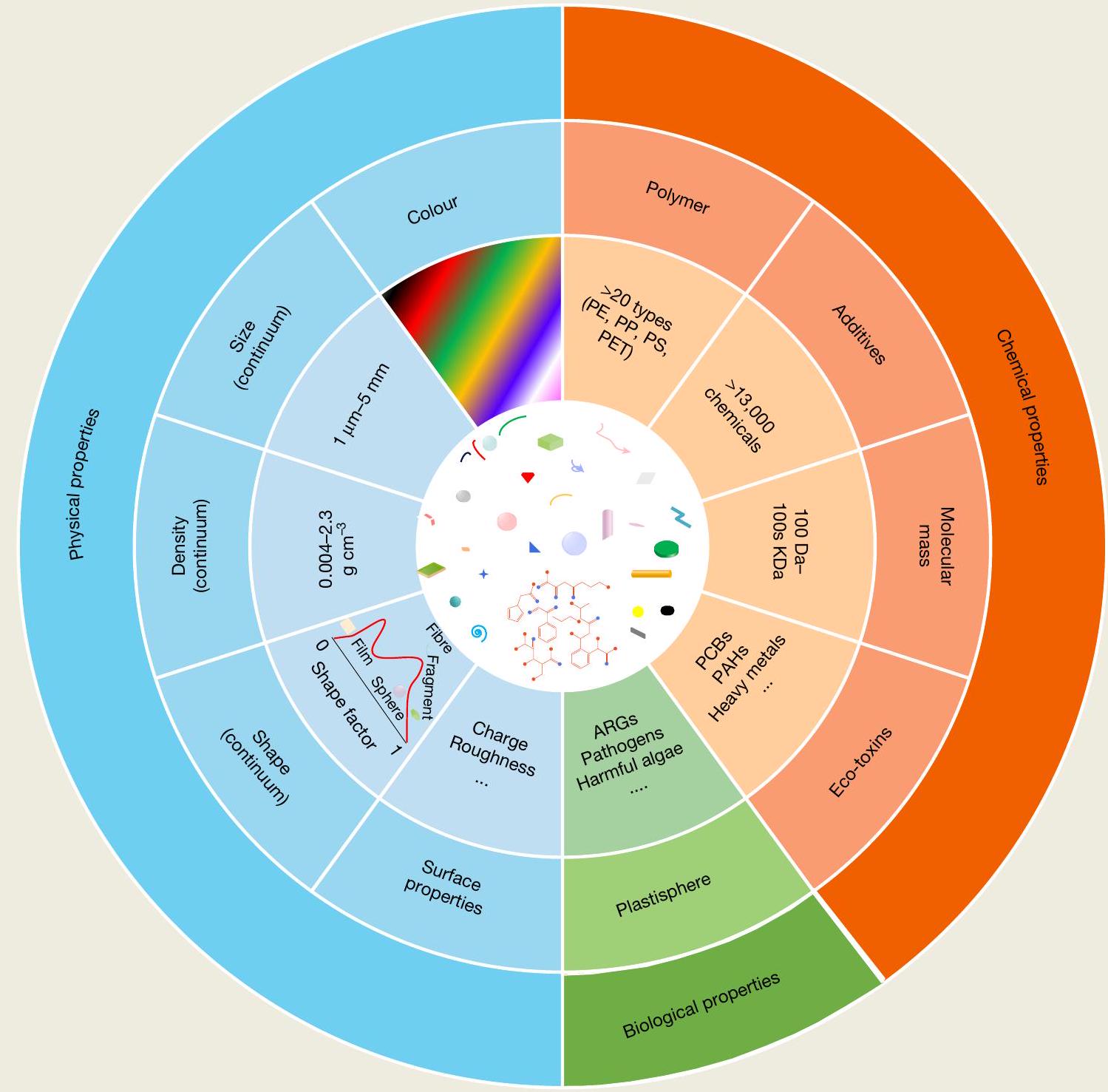

Complexity of microplastics in the natural environment

biological (for example, fragmentation via biting, ingestion and biofouling) transformations

complicate the measurements of microplastics and influence their ecological impact.ARGs, antibiotic-resistant genes;PAHs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; PCBs, polychlorinated biphenyls; PE, polyethylene; PP, polypropylene; PS, polystyrene; PET, polyethylene terephthalate.

Uncertainties in microplastic measurement methods

refer to Supplementary Fig.1). The coloured shaded areas denote

as each plastic category demands customized sampling and analysis approaches

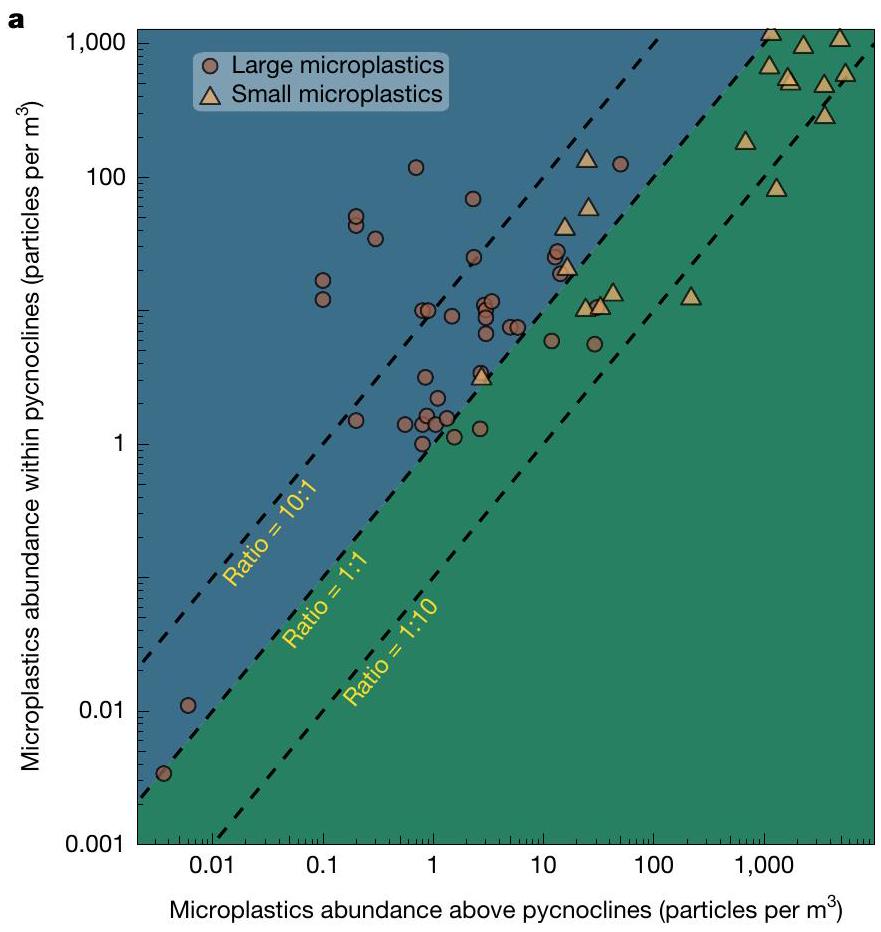

Analysis

| Current knowledge and confidence level | Process insights | Major gaps and priority level | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

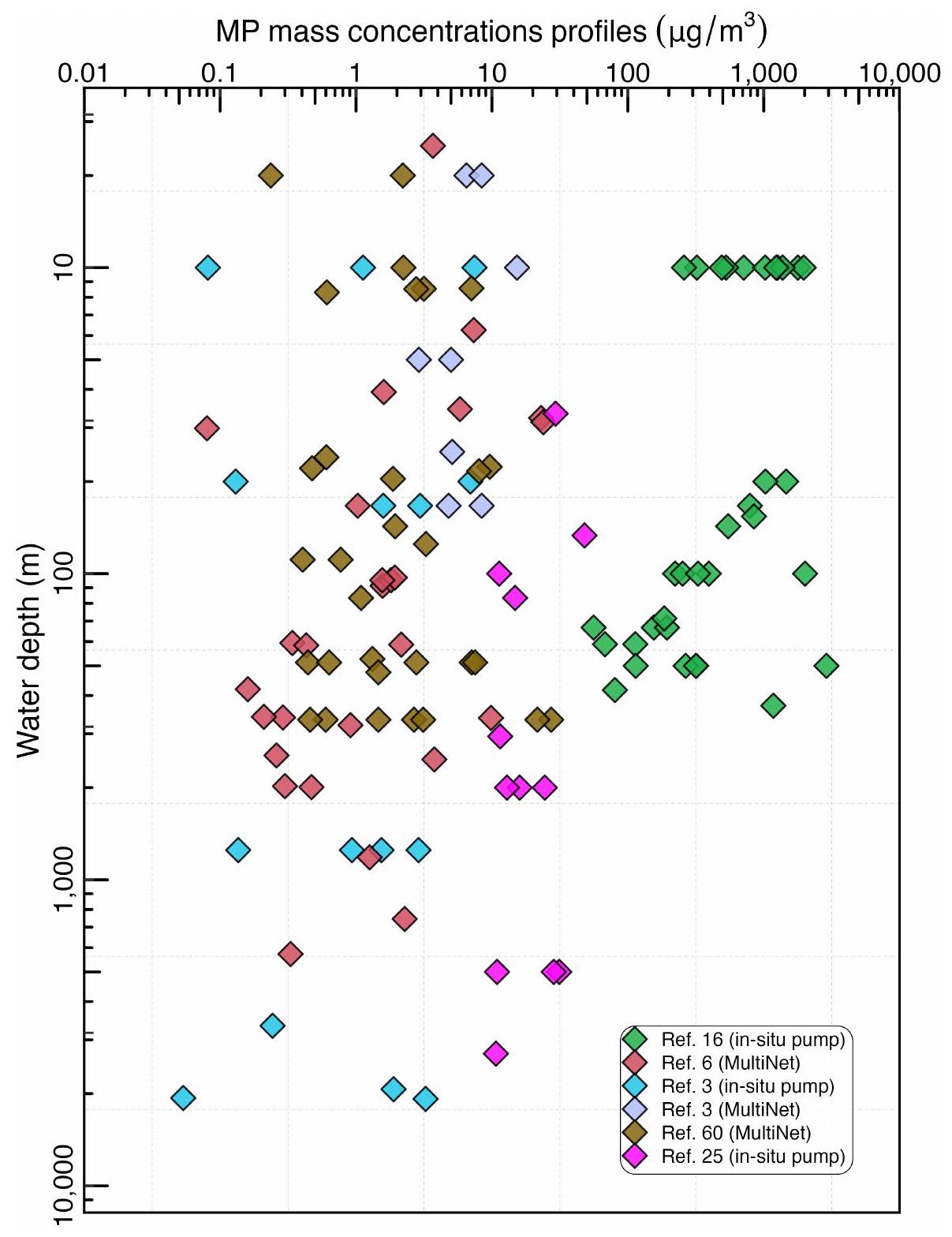

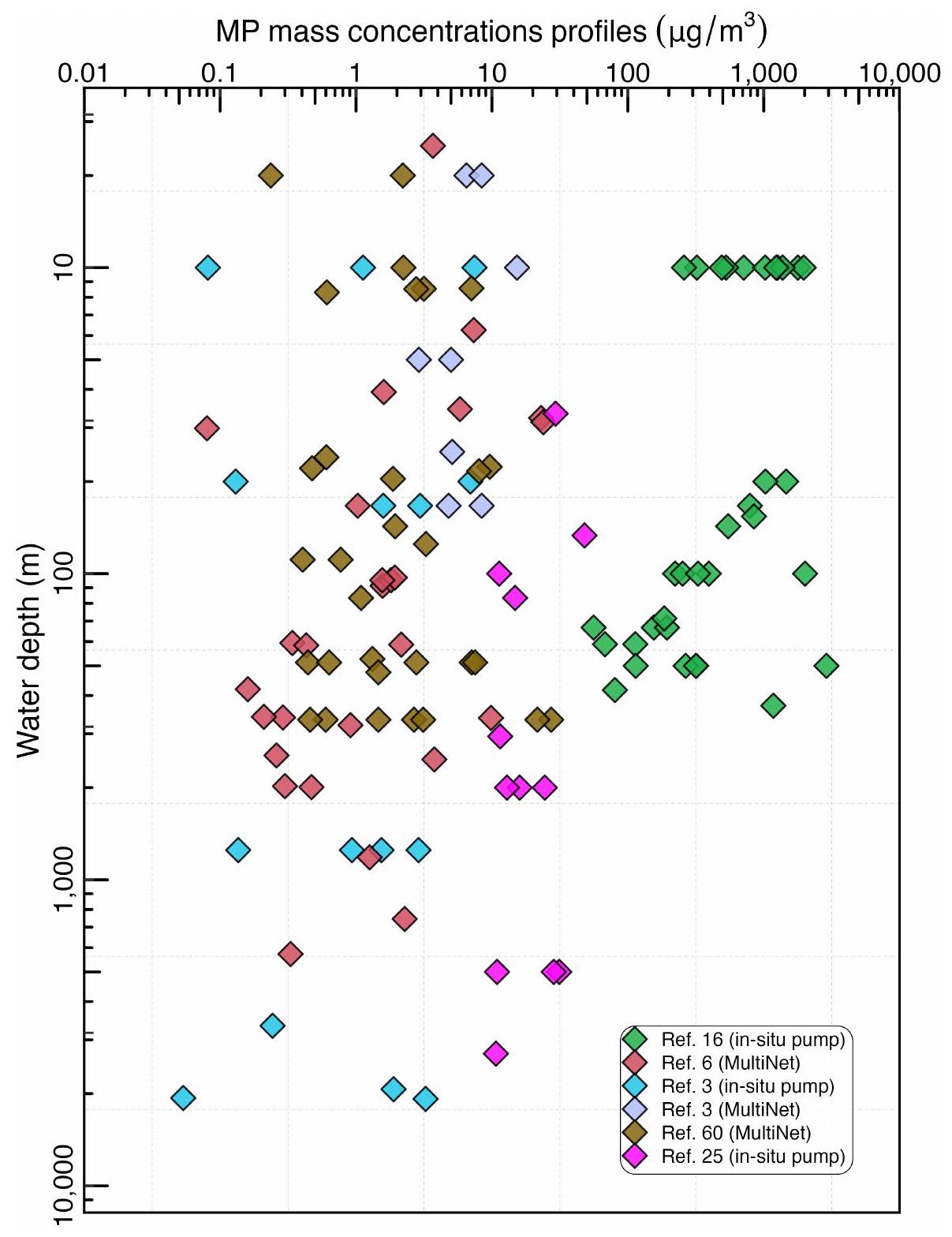

Microplastics permeating ocean waters

microplastics. High abundances have been consistently observed in deep waters, including over 1,100 particles per

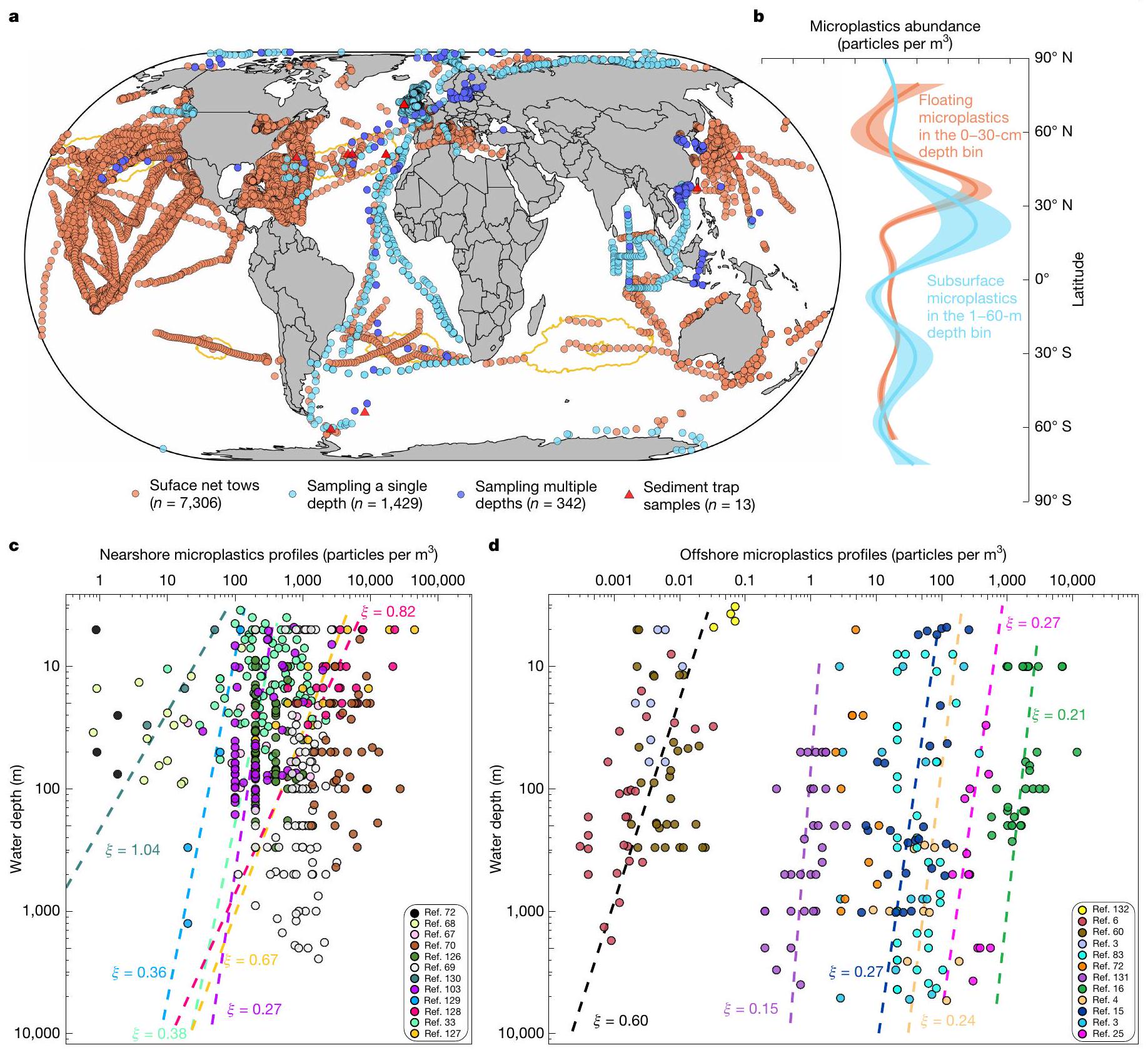

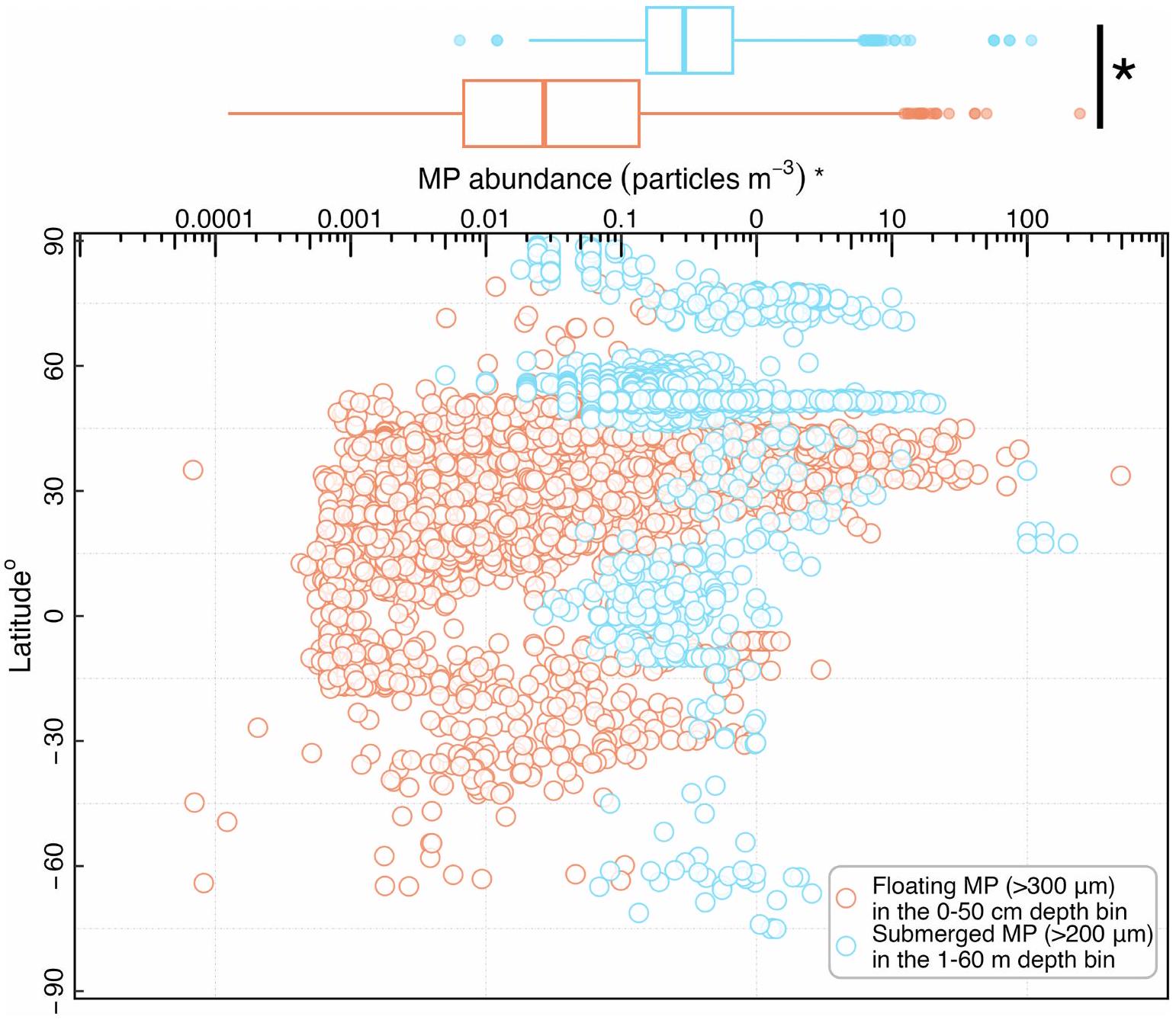

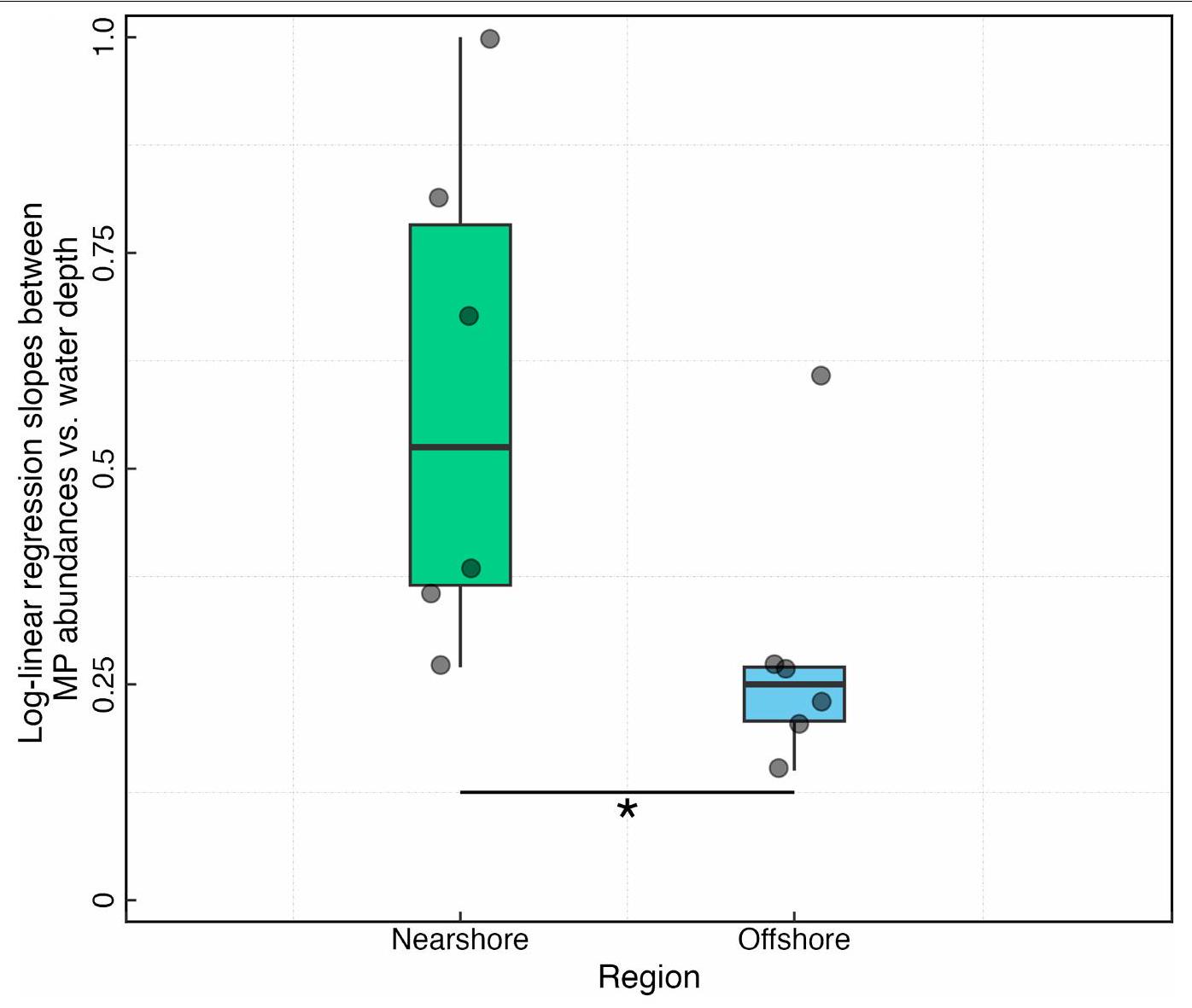

Subsurface microplastic distribution patterns

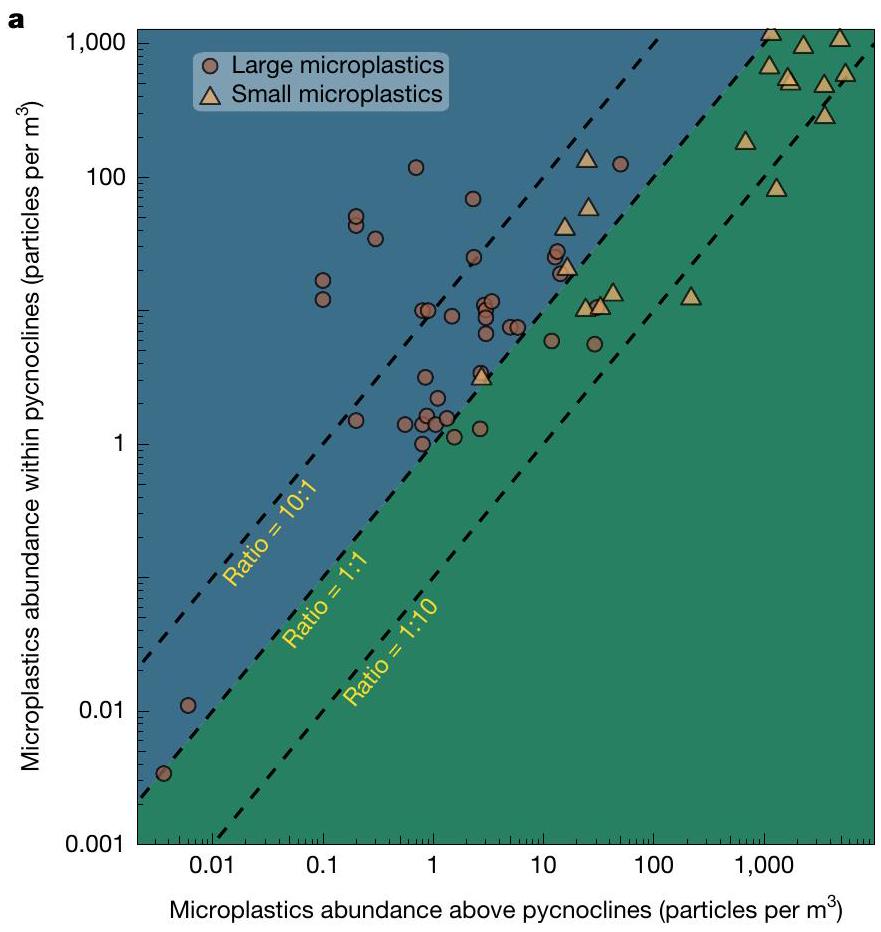

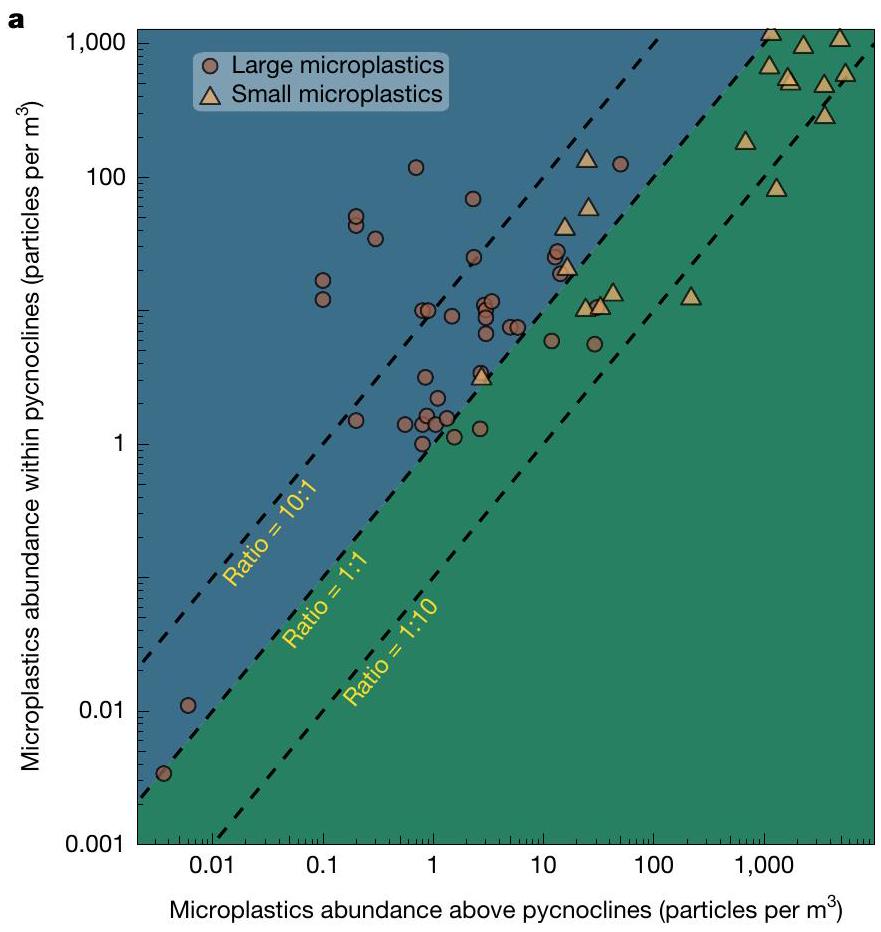

Density stratification retaining large microplastics

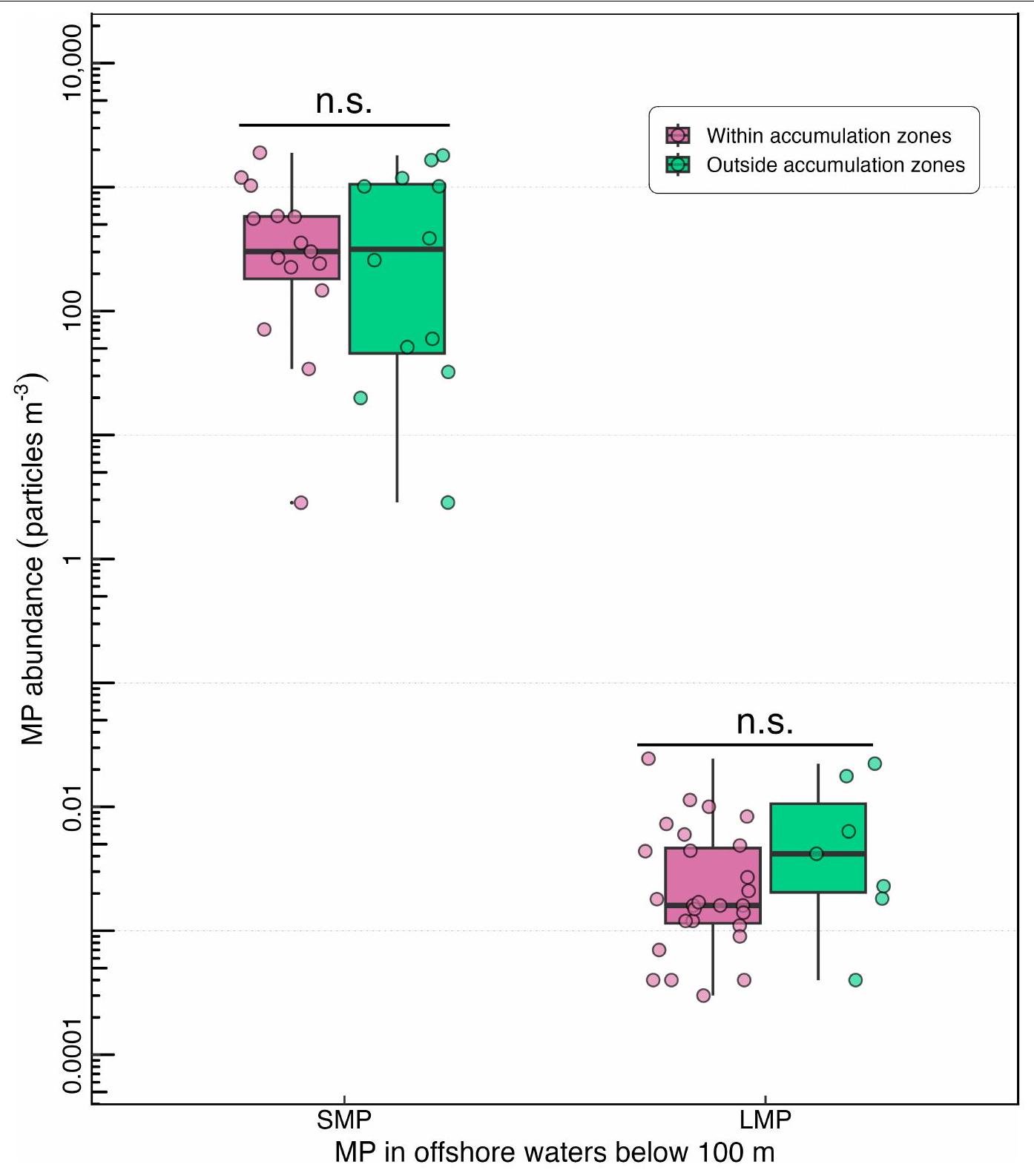

Vertical extension of microplastic accumulation zones

within and outside the well-known accumulation zones in the top 100 m of the water column (Methods). The datasets are from refs.

buoyant microplastics in the top 10 m of the water column follow the surface pattern, with high concentrations in mid-ocean gyres

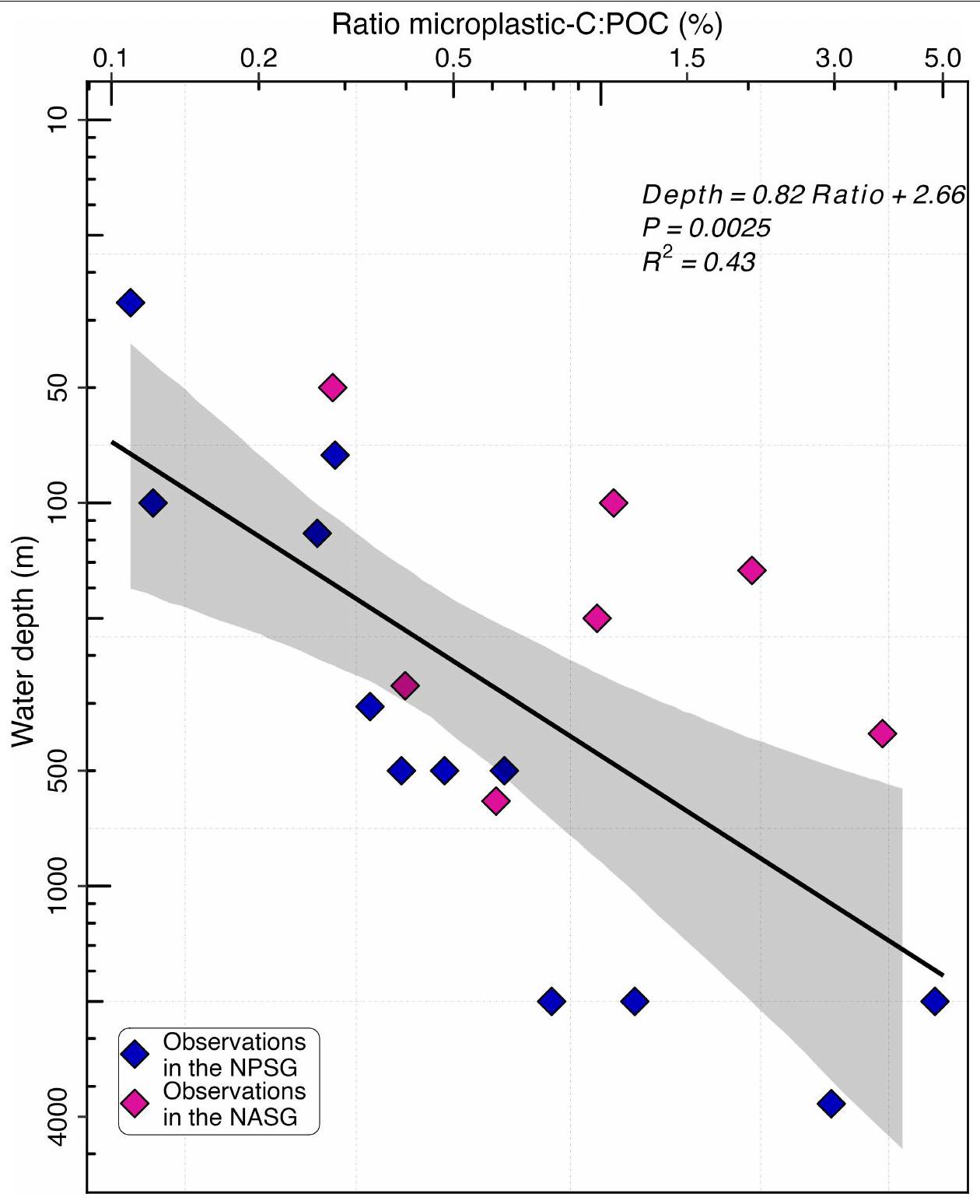

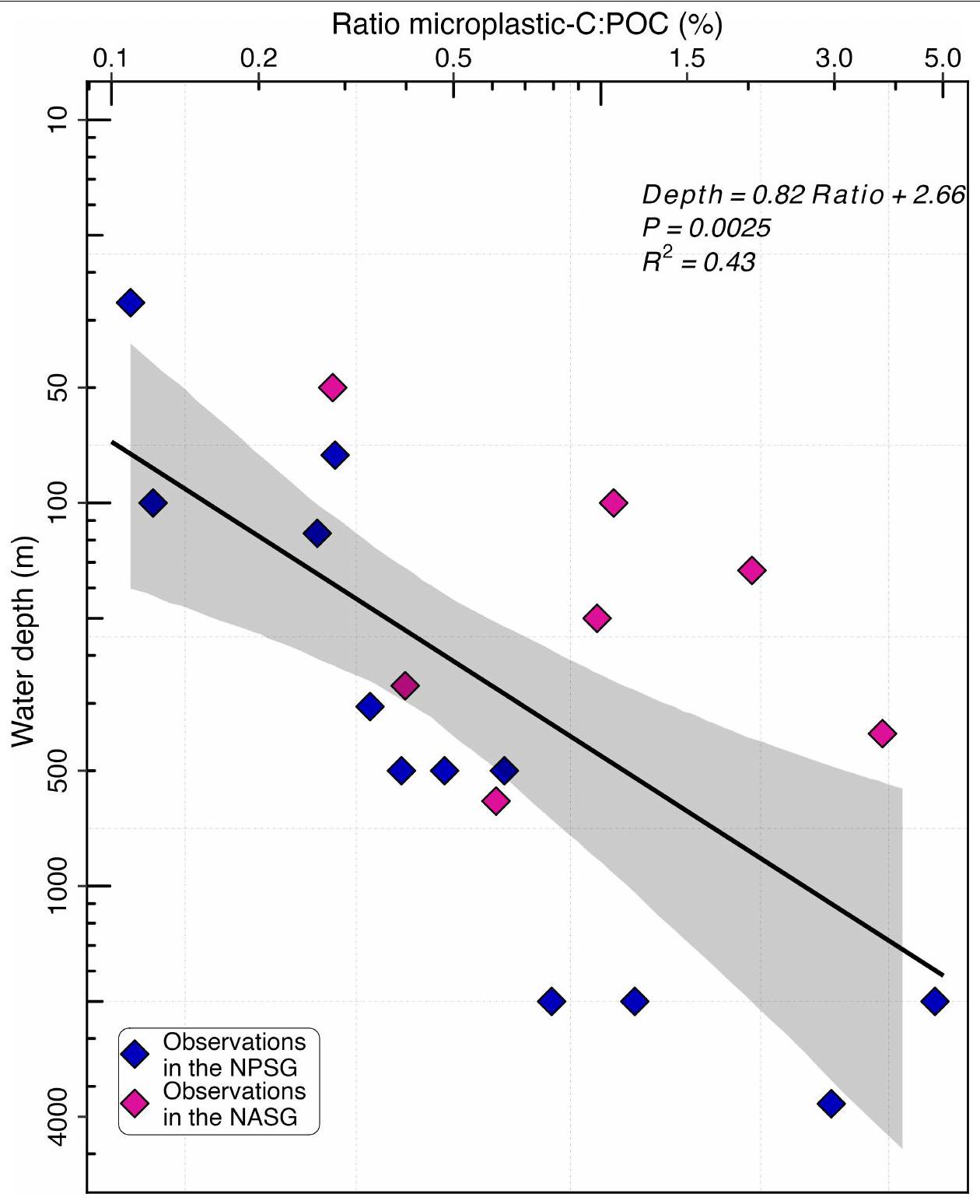

Plastic-carbon entering marine particulate carbon pool

leakage into the ocean, substantial long-term addition of microplastic-C to the marine POC pool is anticipated. Microplastic-C, utilized by marine microbes alongside metabolites and organic debris released by microbial processes

A comparison of models with observations

measurements of abundance and characteristics, environmentally relevant sinking rates, biofouling rates, incorporation-detachment rates from aggregates, and the structural integrity and degradation rates of plastic-laden aggregates. Data on zooplankton microplastic particle selection and ingestion, categorized by grazing strategy, would also be invaluable to improving estimates of faecal pellet transport.

Polymer composition of subsurface microplastics

Another notable finding is the apparent decline in the portions of buoyant polypropylene submerged in the water column compared with the apparent increase in polyethylene offshore (

Uncertainty sources and improvement strategies

from 18 peer-reviewed papers on water-column microplastics that provided polymer compositions

Conclusion

Online content

- Thompson, R. C. et al. Twenty years of microplastic pollution research-what have we learned? Science 386, eadl2746 (2024).

- Eriksen, M. et al. A growing plastic smog, now estimated to be over 170 trillion plastic particles afloat in the world’s oceans-urgent solutions required. PLoS ONE 18, e0281596 (2023).

- Zhao, S. et al. Large quantities of small microplastics permeate the surface ocean to abyssal depths in the South Atlantic Gyre. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 2991-3006 (2022).

- Tekman, M. B. et al. Tying up loose ends of microplastic pollution in the Arctic: distribution from the sea surface through the water column to deep-sea sediments at the HAUSGARTEN observatory. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 4079-4090 (2020).

- Isobe, A. et al. A multilevel dataset of microplastic abundance in the world’s upper ocean and the Laurentian Great Lakes. Microplast. Nanoplast. 1, 16 (2021).

- Egger, M., Sulu-Gambari, F. & Lebreton, L. First evidence of plastic fallout from the North Pacific Garbage Patch. Sci. Rep. 10, 7495 (2020).

- Villarrubia-Gómez, P., Cornell, S. E. & Fabres, J. Marine plastic pollution as a planetary boundary threat-the drifting piece in the sustainability puzzle. Mar. Policy 96, 213-220 (2018).

- Reddy, S. & Lau, W. Breaking the Plastic Wave: A Comprehensive Assessment of Pathways Towards Stopping Ocean Plastic Pollution (PEW Charitable Trusts, 2020).

- Law, K. L. Plastics in the marine environment. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 9, 205-229 (2017).

- MacLeod, M., Arp, H. P. H., Tekman, M. B. & Jahnke, A. The global threat from plastic pollution. Science 373, 61-65 (2021).

- Andrady, A. L. The plastic in microplastics: a review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 119, 12-22 (2017).

- Rochman, C. M. et al. Rethinking microplastics as a diverse contaminant suite. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 38, 703-711 (2019).

- Van Sebille, E. et al. The physical oceanography of the transport of floating marine debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 023003 (2020).

- Kane, I. A. et al. Seafloor microplastic hotspots controlled by deep-sea circulation. Science 368, 1140-1145 (2020).

- Ross, P. S. et al. Pervasive distribution of polyester fibres in the Arctic Ocean is driven by Atlantic inputs. Nat. Commun. 12, 106 (2021).

- Pabortsava, K. & Lampitt, R. S. High concentrations of plastic hidden beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. Nat. Commun. 11, 4073 (2020).

- Lal, D. The oceanic microcosm of particles: suspended particulate matter, about 1 gram in 100 tons of seawater, plays a vital role in ocean chemistry. Science 198, 997-1009 (1977).

- IPCC: Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

- Boyd, P. W., Claustre, H., Levy, M., Siegel, D. A. & Weber, T. Multi-faceted particle pumps drive carbon sequestration in the ocean. Nature 568, 327-335 (2019).

- Galloway, T. S., Cole, M. & Lewis, C. Interactions of microplastic debris throughout the marine ecosystem. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0116 (2017).

- Ziervogel, K. et al. Microbial interactions with microplastics: Insights into the plastic carbon cycle in the ocean. Mar. Chem. 262, 104395 (2024).

- Galgani, L. et al. Hitchhiking into the deep: how microplastic particles are exported through the biological carbon pump in the North Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 15638-15649 (2022).

- Law, K. L. & Rochman, C. M. Large-scale collaborations uncover global extent of plastic pollution. Nature 169, 254-255 (2023).

- Koelmans, A. A. et al. Risk assessment of microplastic particles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 138-152 (2022).

- Zhao, S., Mincer, T. J., Lebreton, L. & Egger, M. Pelagic microplastics in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre: a prevalent anthropogenic component of the particulate organic carbon pool. PNAS Nexus 2, pgadO7O (2023).

- Primpke, S. et al. Critical assessment of analytical methods for the harmonized and cost-efficient analysis of microplastics. Appl. Spectrosc. 74, 1012-1047 (2020).

- Peeken, I. et al. Arctic sea ice is an important temporal sink and means of transport for microplastic. Nat. Commun. 9, 1505 (2018).

- Obbard, R. W. et al. Global warming releases microplastic legacy frozen in Arctic Sea ice. Earths Future 2, 315-320 (2014).

- Roscher, L. et al. Microplastic pollution in the Weser Estuary and the German North Sea. Environ. Pollut. 288, 117681 (2021).

- Abel, S. M., Primpke, S., Int-Veen, I., Brandt, A. & Gerdts, G. Systematic identification of microplastics in abyssal and hadal sediments of the Kuril Kamchatka Trench. Environ. Pollut. 269, 116095 (2021).

- Courtene-Jones, W., van Gennip, S., Penicaud, J., Penn, E. & Thompson, R. C. Synthetic microplastic abundance and composition along a longitudinal gradient traversing the subtropical gyre in the North Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 185, 114371 (2022).

- Molazadeh, M. et al. The role of turbulence in the deposition of intrinsically buoyant MPs. Sci. Total Environ. 911, 168540 (2024).

- Song, Y. K. et al. Horizontal and vertical distribution of microplastics in Korean coastal waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 12188-12197 (2018).

- Kvale, K., Prowe, A. F., Chien, C.-T., Landolfi, A. & Oschlies, A. The global biological microplastic particle sink. Sci Rep. 10, 16670-1 (2020).

- Klink, D., Peytavin, A. & Lebreton, L. Size dependent transport of floating plastics modeled in the global ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 903134 (2022).

- Mountford, A. & Morales Maqueda, M. Eulerian modeling of the three-dimensional distribution of seven popular microplastic types in the global ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 8558-8573 (2019).

- Van Sebille, E. et al. A global inventory of small floating plastic debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 124006 (2015).

- Amenábar, M. et al. Spatial distribution of microplastics in a coastal upwelling region: offshore dispersal from urban sources in the Humboldt Current System. Environ. Pollut. 343, 123157 (2024).

- Cael, B., Cavan, E. L. & Britten, G. L. Reconciling the size-dependence of marine particle sinking speed. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091771 (2021).

- Armbrust, E. V. The life of diatoms in the world’s oceans. Nature 459, 185-192 (2009).

- Amaral-Zettler, L. A., Zettler, E. R. & Mincer, T. J. Ecology of the plastisphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 139-151 (2020).

- Amaral-Zettler, L. A., Zettler, E. R., Mincer, T. J., Klaassen, M. A. & Gallager, S. M. Biofouling impacts on polyethylene density and sinking in coastal waters: a macro/micro tipping point? Water Res. 201, 117289 (2021).

- Sun, X.-F., Zhang, Y., Xie, M.-Y., Mai, L. & Zeng, E. Y. Calcite carbonate sinks low-density plastic debris in open oceans. Nat. Commun. 15, 4837 (2024).

- Egger, M. et al. A spatially variable scarcity of floating microplastics in the eastern North Pacific Ocean. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 114056 (2020).

- Lobelle, D. et al. Global modeled sinking characteristics of biofouled microplastic. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, e2020JC017098 (2021).

- Fischer, R. et al. Modelling submerged biofouled microplastics and their vertical trajectories. Biogeosciences 19, 2211-2234 (2022).

- Reineccius, J. & Waniek, J. J. First long-term evidence of microplastic pollution in the deep subtropical Northeast Atlantic. Environ. Pollut. 305, 119302 (2022).

- Reineccius, J. et al. Abundance and characteristics of microfibers detected in sediment trap material from the deep subtropical North Atlantic Ocean. Sci. Total Environ. 738, 140354 (2020).

- Alurralde, G. et al. Anthropogenic microfibres flux in an Antarctic coastal ecosystem: the tip of an iceberg? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 175, 113388 (2022).

- Rowlands, E. et al. Vertical flux of microplastic, a case study in the Southern Ocean, South Georgia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 193, 115117 (2023).

- Mateos-Cárdenas, A., Wheeler, A. J. & Lim, A. Microplastics and cellulosic microparticles in North Atlantic deep waters and in the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 206, 116741 (2024).

- Zhang, X., Liu, Z., Li, D., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, Y. Turbidity currents regulate the transport and settling of microplastics in a deep-sea submarine canyon. Geology 52, 646-650 (2024).

- Ikenoue, T., Nakajima, R., Osafune, S., Siswanto, E. & Honda, M. C. Vertical flux of microplastics in the deep subtropical Pacific Ocean: moored sediment-trap observations within the Kuroshio Extension Recirculation Gyre. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 16121-16130 (2024).

- Lam, P. J., Doney, S. C. & Bishop, J. K. The dynamic ocean biological pump: Insights from a global compilation of particulate organic carbon,

, and opal concentration profiles from the mesopelagic. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 25, GB3009 (2011). - Enders, K., Lenz, R., Stedmon, C. A. & Nielsen, T. G. Abundance, size and polymer composition of marine microplastics

in the Atlantic Ocean and their modelled vertical distribution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 100, 70-81 (2015). - Gunaalan, K. et al. Does water column stratification influence the vertical distribution of microplastics? Environ. Pollut. 340, 122865 (2024).

- Kooi, M., Nes, E. H. V., Scheffer, M. & Koelmans, A. A. Ups and downs in the ocean: effects of biofouling on vertical transport of microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 7963-7971 (2017).

- Dittmar, S., Ruhl, A. S., Altmann, K. & Jekel, M. Settling velocities of small microplastic fragments and fibers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 6359-6369 (2024).

- Kaiser, D., Estelmann, A., Kowalski, N., Glockzin, M. & Waniek, J. J. Sinking velocity of sub-millimeter microplastic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 139, 214-220 (2019).

- Egger, M. et al. Pelagic distribution of plastic debris (

) and marine organisms in the upper layer of the North Atlantic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 12, 13465 (2022). - Onink, V., Kaandorp, M. L., van Sebille, E. & Laufkötter, C. Influence of particle size and fragmentation on large-scale microplastic transport in the Mediterranean Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 15528-15540 (2022).

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V., Gutow, L., Thompson, R. C. & Thiel, M. Microplastics in the marine environment: a review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 3060-3075 (2012).

- Wright, R. J., Erni-Cassola, G., Zadjelovic, V., Latva, M. & Christie-Oleza, J. A. Marine plastic debris: a new surface for microbial colonization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 11657-11672 (2020).

- Zhao, S., Zettler, E. R., Amaral-Zettler, L. A. & Mincer, T. J. Microbial carrying capacity and carbon biomass of plastic marine debris. ISME J. 15, 67-77 (2021).

- Doostmohammadi, A., Stocker, R. & Ardekani, A. M. Low-Reynolds-number swimming at pycnoclines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 3856-3861 (2012).

- MacIntyre, S., Alldredge, A. L. & Gotschalk, C. C. Accumulation of marines now at density discontinuities in the water column. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40, 449-468 (1995).

- Uurasjärvi, E., Pääkkönen, M., Setälä, O., Koistinen, A. & Lehtiniemi, M. Microplastics accumulate to thin layers in the stratified Baltic Sea. Environ. Pollut. 268, 115700 (2021).

- Zobkov, M., Esiukova, E., Zyubin, A. & Samusev, I. Microplastic content variation in water column: the observations employing a novel sampling tool in stratified Baltic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 138, 193-205 (2019).

- Manullang, C. Y. et al. Vertical distribution of microplastic along the main gate of Indonesian Throughflow pathways. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 199, 115954 (2024).

- Zhou, Q. et al. Trapping of microplastics in halocline and turbidity layers of the semienclosed Baltic Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 761566 (2021).

- Carlotti, F. et al. Microplastics in the maximum chlorophyll layer along a north-south transect in the Mediterranean Sea in comparison with zooplankton concentrations. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 196, 115614 (2023).

- Choy, C. A. et al. The vertical distribution and biological transport of marine microplastics across the epipelagic and mesopelagic water column. Sci. Rep. 9, 7843 (2019).

- Ardekani, A. & Stocker, R. Stratlets: low Reynolds number point-force solutions in a stratified fluid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 084502 (2010).

- Yick, K. Y., Torres, C. R., Peacock, T. & Stocker, R. Enhanced drag of a sphere settling in a stratified fluid at small Reynolds numbers. J. Fluid Mech. 632, 49-68 (2009).

- Mrokowska, M. M. Influence of pycnocline on settling behaviour of non-spherical particle and wake evolution. Sci. Rep. 10, 20595 (2020).

- Zhang, M., Xu, D., Liu, L., Wei, Y. & Gao, B. Vertical differentiation of microplastics influenced by thermal stratification in a deep reservoir. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 6999-7008 (2023).

- Li, C., Zhu, L., Wang, X., Liu, K. & Li, D. Cross-oceanic distribution and origin of microplastics in the subsurface water of the South China Sea and Eastern Indian Ocean. Sci. Total Environ. 805, 150243 (2022).

- Zhdanov, I. et al. Differences in the fate of surface and subsurface microplastics: a case study in the Central Atlantic. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 210 (2023).

- Zhang, S. et al. Distribution characteristics of microplastics in surface and subsurface Antarctic seawater. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 156051 (2022).

- Morgana, S. et al. Microplastics in the Arctic: a case study with sub-surface water and fish samples off Northeast Greenland. Environ. Pollut. 242, 1078-1086 (2018).

- Pakhomova, S. et al. Microplastic variability in subsurface water from the Arctic to Antarctica. Environ. Pollut. 298, 118808 (2022).

- Lusher, A. L., Tirelli, V., O’Connor, I. & Officer, R. Microplastics in Arctic polar waters: the first reported values of particles in surface and sub-surface samples. Sci. Rep. 5, 14947 (2015).

- Kanhai, L. D. K. et al. Microplastics in sub-surface waters of the Arctic Central Basin. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 130, 8-18 (2018).

- Kanhai, L. D. K., Officer, R., Lyashevska, O., Thompson, R. C. & O’Connor, I. Microplastic abundance, distribution and composition along a latitudinal gradient in the Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 115, 307-314 (2017).

- Lusher, A. L., Burke, A., O’Connor, I. & Officer, R. Microplastic pollution in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean: validated and opportunistic sampling. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 88, 325-333 (2014).

- Yakushev, E. et al. Microplastics distribution in the Eurasian Arctic is affected by Atlantic waters and Siberian rivers. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 23 (2021).

- Wichmann, D., Delandmeter, P. & van Sebille, E. Influence of near-surface currents on the global dispersal of marine microplastic. J.Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 6086-6096 (2019).

- Bergmann, M. et al. Plastic pollution in the Arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 323-337 (2022).

- Eriksen, M. et al. Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans: more than 5 trillion plastic pieces weighing over 250,000 tons afloat at sea. PLoS ONE 9, e111913 (2014).

- Cózar, A. et al. Plastic debris in the open ocean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10239-10244 (2014).

- Law, K. L. et al. Plastic accumulation in the North Atlantic subtropical gyre. Science 329, 1185-1188 (2010).

- Lebreton, L.-M., Greer, S. & Borrero, J. C. Numerical modelling of floating debris in the world’s oceans. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 64, 653-661(2012).

- Maximenko, N., Hafner, J. & Niiler, P. Pathways of marine debris derived from trajectories of Lagrangian drifters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 65, 51-62 (2012).

- Van Sebille, E., England, M. H. & Froyland, G. Origin, dynamics and evolution of ocean garbage patches from observed surface drifters. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 044040 (2012).

- Huck, T. et al. Three-dimensional dispersion of neutral “plastic” particles in a global ocean model. Front. Anal. Sci. 2, 868515 (2022).

- Karl, D. M., Knauer, G. A. & Martin, J. H. Downward flux of particulate organic matter in the ocean: a particle decomposition paradox. Nature 332, 438-441 (1988).

- Vaksmaa, A. et al. Polyethylene degradation and assimilation by the marine yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. ISME Commun. 3, 68 (2023).

- Seeley, M. E., Song, B., Passie, R. & Hale, R. C. Microplastics affect sedimentary microbial communities and nitrogen cycling. Nat. Commun. 11, 2372 (2020).

- Libby, W. F. Radiocarbon dating: the method is of increasing use to the archeologist, the geologist, the meteorologist, and the oceanographer. Science 133, 621-629 (1961).

- Heaton, T. J. et al. Radiocarbon: a key tracer for studying Earth’s dynamo, climate system, carbon cycle, and Sun. Science 374, eabd7096 (2021).

- Bajon, R. et al. Influence of waves on the three-dimensional distribution of plastic in the ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 187, 114533 (2023).

- Lima, I. D., Lam, P. J. & Doney, S. C. Dynamics of particulate organic carbon flux in a global ocean model. Biogeosciences 11, 1177-1198 (2014).

- Bagaev, A., Khatmullina, L. & Chubarenko, I. Anthropogenic microlitter in the Baltic Sea water column. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 129, 918-923 (2018).

- Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R. & Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700782 (2017).

- Min, K., Cuiffi, J. D. & Mathers, R. T. Ranking environmental degradation trends of plastic marine debris based on physical properties and molecular structure. Nat. Commun. 11, 727 (2020).

- Maximenko, N., Hafner, J., Kamachi, M. & MacFadyen, A. Numerical simulations of debris drift from the Great Japan Tsunami of 2011 and their verification with observational reports. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 132, 5-25 (2018).

- Gennip, S. J. V. et al. In search for the sources of plastic marine litter that contaminates the Easter Island ecoregion. Sci. Rep. 9, 19662 (2019).

- Lebreton, L. et al. Industrialised fishing nations largely contribute to floating plastic pollution in the North Pacific subtropical gyre. Sci. Rep. 12, 12666 (2022).

- Allen, D. et al. Microplastics and nanoplastics in the marine-atmosphere environment. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 393-405 (2022).

- Ortega, D. E. & Cortés-Arriagada, D. Atmospheric microplastics and nanoplastics as vectors of primary air pollutants-a theoretical study on the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) case. Environ. Pollut. 318, 120860 (2023).

- Gewert, B., Plassmann, M. M. & MacLeod, M. Pathways for degradation of plastic polymers floating in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 17, 1513-1521 (2015).

- Zhu, L., Zhao, S., Bittar, T. B., Stubbins, A. & Li, D. Photochemical dissolution of buoyant microplastics to dissolved organic carbon: rates and microbial impacts. J. Hazard. Mater. 383, 121065 (2020).

- Delre, A. et al. Plastic photodegradation under simulated marine conditions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 187, 114544 (2023).

- De Frond, H. et al. What determines accuracy of chemical identification when using microspectroscopy for the analysis of microplastics? Chemosphere 313, 137300 (2023).

- Pinheiro, H. T. et al. Plastic pollution on the world’s coral reefs. Nature 619, 311-316 (2023).

- Nava, V. et al. Plastic debris in lakes and reservoirs. Nature 619, 317-322 (2023).

- Hurd, D. C. & Spencer, D. W. (eds) Marine Particles: Analysis and Characterization Geophysical Monograph Series Vol. 63 (AGU, 1991).

- Primpke, S., Lorenz, C., Rascher-Friesenhausen, R. & Gerdts, G. An automated approach for microplastics analysis using focal plane array (FPA) FTIR microscopy and image analysis. Anal. Methods 9, 1499-1511 (2017).

- Cowger, W. et al. Microplastic spectral classification needs an open source community: open specy to the rescue! Anal. Chem. 93, 7543-7548 (2021).

- Primpke, S. et al. Toward the systematic identification of microplastics in the environment: evaluation of a new independent software tool (siMPle) for spectroscopic analysis. Appl. Spectrosc. 74, 1127-1138 (2020).

- Materić, D., Holzinger, R. & Niemann, H. Nanoplastics and ultrafine microplastic in the Dutch Wadden Sea-the hidden plastics debris? Sci. Total Environ. 846, 157371 (2022).

- Kukulka, T., Proskurowski, G., Morét-Ferguson, S., Meyer, D. W. & Law, K. L. The effect of wind mixing on the vertical distribution of buoyant plastic debris. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L07601 (2012).

- Cole, M. et al. Microplastics alter the properties and sinking rates of zooplankton faecal pellets. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 3239-3246 (2016).

- Bohdan, K. Estimating global marine surface microplastic abundance: systematic literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 832, 155064 (2022).

- Lebreton, L. The status and fate of oceanic garbage patches. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 730-732 (2022).

- Wang, X., Zhu, L., Liu, K. & Li, D. Prevalence of microplastic fibers in the marginal sea water column off southeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 804, 150138 (2022).

- Ding, J. et al. Microplastics in the coral reef systems from Xisha Islands of South China Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 8036-8046 (2019).

- Dai, Z. et al. Occurrence of microplastics in the water column and sediment in an inland sea affected by intensive anthropogenic activities. Environ. Pollut. 242, 1557-1565 (2018).

- Cordova, M. & Hernawan, U. Microplastics in Sumba waters, East Nusa Tenggara. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science Vol. 162, 012023 (IOP, 2018).

- Oztekin, A. & Bat, L. Microlitter pollution in sea water: a preliminary study from Sinop Sarikum coast of the southern Black Sea. Turkish J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 17, 1431-1440 (2017).

- Li, D. et al. Profiling the vertical transport of microplastics in the West Pacific Ocean and the East Indian Ocean with a novel in situ filtration technique. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 12979-12988 (2020).

- Reisser, J. et al. The vertical distribution of buoyant plastics at sea: an observational study in the North Atlantic Gyre. Biogeosciences 12, 1249-1256 (2015).

- Wiesinger, H., Wang, Z. & Hellweg, S. Deep dive into plastic monomers, additives, and processing aids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 9339-9351(2021).

(c) The Author(s) 2025

Methods

Categorization

Data collection

Curating data to compare microplastics at depths of 1-60 m with those floating at the sea surface

Building microplastic abundance distribution models

Power-law function for subsurface microplastic abundance profiles

Comparison of microplastic-C to total POC

Statistical analysis

to fit the GAM, run the Monte Carlo simulations and do the bootstrap analysis. All statistical analyses and visualizations were performed using

Data availability

134. Buesseler, K. O., Boyd, P. W., Black, E. E. & Siegel, D. A. Metrics that matter for assessing the ocean biological carbon pump. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9679-9687 (2020).

135. Subhas, A. V., Adkins, J. F., Dong, S., Rollins, N. E. & Berelson, W. M. The carbonic anhydrase activity of sinking and suspended particles in the North Pacific Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 65, 637-651 (2020).

136. Umhau, B. P. et al. Seasonal and spatial changes in carbon and nitrogen fluxes estimated using

137. Zhao, S. Datasets for submerged microplastics in the ocean. figshare https://doi.org/ 10.6084/m9.figshare. 28157324 (2025).

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Shiye Zhao.

Peer review information Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

ranges from the box. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between two categories (Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test, p <.05). This refined dataset of microplastics in the

measured values within 1.5 interquartile ranges from the box. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between two groups (Mann-WhitneyWilcoxon test,

represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers indicate the largest and smallest measured values within 1.5 interquartile ranges from the box. The datasets are from refs.

Analysis

The black line represents the linear regression fit and the shade area represents the

| Description in the literature | Advantages | Disadvantages | |||||||||||

| Sampling equipment | |||||||||||||

| In-situ pump | McLane pump, ISP pump, Plankton pump

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Submersible pump, Borehole deepwell pump, Ship underway pump |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Plankton Net | MOCNESS

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Bulk water sampler | Niskin bottle, Limnos water sampler, Plexiglass water sampler |

|

-Limited sample volume | ||||||||||

| Filter/mesh types | |||||||||||||

| Screen filter

|

Anodisc, Polycarbonate filter, Nylon filter, Stainless steel mesh, Cellulose nitrate filter) |

|

|

||||||||||

| Depth filter

|

GF/A, GF/C, Quartz filters |

|

-Particle are entrapped within the structure | ||||||||||

| Chemical identification | |||||||||||||

| Chemical imaging | Single-element mercury cadmium telluride detector, Focal plane array detector |

|

|

||||||||||

| Microscopy-aided inspection following by

|

FTIR techniques : Attenuated total reflection-FTIR,

|

-Ease of sample preparation and analysis |

|

||||||||||

| Microscopic inspection | Identifying plastic particles by visual inspection under microscopy |

|

-No polymer information provided | ||||||||||

Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, Yokosuka, Japan. Aotearoa Blue Ocean Research, Lower Hutt, New Zealand. State Key Laboratory of Estuarine and Coastal Research, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China. Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA. NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, Den Burg, The Netherlands. The Ocean Cleanup, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Empaqtify, St Gallen, Switzerland. Harriet Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL, USA. Department of Freshwater and Marine Ecology, Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Department of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Facultad Ciencias del Mar, Universidad Catolica del Norte, Coquimbo, Chile. MarineGEO Program, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Edgewater, MD, USA. Centre for Ecology and Sustainable Management of Oceanic Island (ESMOI), Coquimbo, Chile. Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Department of Biotechnology, Chemistry and Pharmacy, University of Siena, Siena, Italy. National Biodiversity Future Center (NBFC), Palermo, Italy. Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA. e-mail: szhao@jamstec.go.jp