DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-023-01351-5

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-05

ثنائيات الباعث للضوء من البيروفسكايت الخالي من الرصاص ذات الأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة الساطعة والمستقرة

تم القبول: 17 نوفمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 5 يناير 2024

(د) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

تعتبر الصمامات الثنائية الباعثة للضوء في نطاق الأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة ذات الأطوال الموجية الطويلة (NIR LEDs) التي تتجاوز ذروة انبعاثها 900 نانومتر ذات أهمية حيوية لمجموعة متنوعة من التطبيقات بما في ذلك الرؤية الليلية، التصوير الطبي، الاستشعار والاتصالات البصرية. ومع ذلك، فإن الإشعاع المنخفض والاستقرار التشغيلي الضعيف لأحدث تقنيات الصمامات الثنائية الباعثة للضوء في نطاق الأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة ذات الأطوال الموجية الطويلة المستندة إلى المواد اللينة تظل من العوامل الأكثر أهمية التي تحد من تطبيقاتها العملية. هنا نقوم بتطوير صمامات ثنائية باحثة للضوء في نطاق الأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة التي تنبعث منها أشعة تتجاوز 900 نانومتر مع تحسين الأداء من خلال التلاعب العقلاني في عملية التخصيب الإيجابي في البيروفيسكيتات القصديرية غير العضوية بالكامل.

الهاليد بيروفسكايت (THPs)، وخاصةً الأسود الأورثورمبيك بالكامل غير العضوي

| فئة المواد وأمثلة | ذروة الانبعاث (نانومتر) | عرض النطاق الكامل عند نصف الحد الأقصى (نانومتر) | إشعاع

|

استقرار

|

مرجع | |

| الجزيئات العضوية | معقدات Pt(II) | 930 | >200 | ٤١.٦ | غير متوفر | 10 |

| نقاط الكم القائمة على الرصاص | PbS/PbS كوانتم دوت/ZnO | ١٤٠٠ | حوالي 200 | 9 | غير متوفر | 11 |

| كوانتوم دوت PbS/بيروفسكايت | 980 | حوالي 150 | 7.4 |

|

١٣ | |

| نقاط الكم القائمة على الفضة |

|

١,٣٩٧ | حوالي 75 | ٨٣.٩ | غير متوفر | 14 |

| هاليدات الرصاص والقصدير | FPMAI-MAPb

|

917 | حوالي 100 | ٢.٧ |

|

20 |

| هاليدات القصدير غير العضوية |

|

948 | 71 | 226 |

|

هذا العمل |

طيف عند فولتية تشغيل مختلفة. ج، د، كثافة التيار – الجهد – الإشعاع (ج) وتوزيعات الإشعاع الأقصى (د) لـ

لتحسين أداء LED، نعتقد أن الخصائص الداخلية للتطعيم الموجب في المواد شبه الموصلة ذات البنية غير العضوية يمكن أن تكون مفيدة لتحقيق LEDs عالية الأداء في نطاق الأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة من خلال التحكم الدقيق في كثافات التطعيم بالثقوب والفخاخ.

هيكل الجهاز والأداء

طبقة حقن الثقوب من بوليمر (3،4-إيثيلين ديوكسي ثيوفيني): بولي (ستايرين-سولفونات) (PEDOT:PSS)، نشطة

نمو مُراقب لـ

تحكم في نوعية الشوائب الموجبة وتقليل كثافة الفخاخ

عند

ومعلمة بـ

قد تحسن الثقوب الخلفية الناتجة عن التخصيب p من PLQY وتعزز إعادة التركيب الإشعاعي مع الإلكترونات الناتجة عن الضوء – وهذا صحيح لزيادة كثافات التخصيب حتى تصبح إعادة التركيب Auger هي السائدة؛ و (3) عندما تكون كثافة الفخاخ مشابهة أو أعلى من كثافة التخصيب، تهيمن عمليات إعادة التركيب المدفوعة بالفخاخ وتؤثر بشكل كبير على PLQY.

حسابات الهيكل الإلكتروني

مع كثافة الحالات الذاتية المتاحة لعملية الثلاثة أجسام في هيكل النطاق (الشكل 4a,b). تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن

المناقشات

الخاتمة

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

ومصالح متنافسة؛ وبيانات توفر البيانات والرموز متاحة على https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-023-01351-5.

References

- Medintz, I. L., Uyeda, H. T., Goldman, E. R. & Mattoussi, H. Quantum dot bioconjugates for imaging, labelling and sensing. Nat. Mater. 4, 435-446 (2005).

- Konstantatos, G. et al. Ultrasensitive solution-cast quantum dot photodetectors. Nature 442, 180-183 (2006).

- Kim, S. et al. Near-infrared fluorescent type II quantum dots for sentinel lymph node mapping. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 93-97 (2004).

- Sun, L. et al. Bright infrared quantum-dot light-emitting diodes through inter-dot spacing control. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 369-373 (2012).

- Yoon, J. et al. GaAs photovoltaics and optoelectronics using releasable multilayer epitaxial assemblies. Nature 465, 329-333 (2010).

- Walther, T., Cullis, A., Norris, D. & Hopkinson, M. Nature of the Stranski-Krastanow transition during epitaxy of InGaAs on GaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 2381 (2001).

- Tuong, Ly,K. et al. Near-infrared organic light-emitting diodes with very high external quantum efficiency and radiance. Nat. Photon. 11, 63-68 (2017).

- Cao, Y. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes based on spontaneously formed submicrometre-scale structures. Nature 562, 249-253 (2018).

- Xu, W. et al. Rational molecular passivation for high-performance perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 13, 418-424 (2019).

- Wei, Y. C. et al. Overcoming the energy gap law in near-infrared OLEDs by exciton-vibration decoupling. Nat. Photon. 14, 570-577 (2020).

- Gong, X. et al. Highly efficient quantum dot near-infrared light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 10, 253-257 (2016).

- Pradhan, S. et al. High-efficiency colloidal quantum dot infrared light-emitting diodes via engineering at the supra-nanocrystalline level. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 72-79 (2019).

- Gao, L. et al. Efficient near-infrared light-emitting diodes based on quantum dots in layered perovskite. Nat. Photon. 14, 227-233 (2020).

- Vasilopoulou, M. et al. Efficient colloidal quantum dot light-emitting diodes operating in the second near-infrared biological window. Nat. Photon. 14, 50-56 (2020).

- Dong, Y. et al. Bipolar-shell resurfacing for blue leds based on strongly confined perovskite quantum dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 668-674 (2020).

- Wang, Y.-K. et al. All-inorganic quantum-dot LEDs based on a phase-stabilized

perovskite. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 16164-16170 (2020). - Wang, Y.-K. et al. Chelating-agent-assisted control of

quantum well growth enables stable blue perovskite emitters. Nat. Commun. 11, 3674 (2020). - Zheng, X. et al. Chlorine vacancy passivation in mixed halide perovskite quantum dots by organic pseudohalides enables efficient Rec. 2020 blue light-emitting diodes. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 793-798 (2020).

- Wang, Z. et al. Multifunctional p-type carbon quantum dots: a novel hole injection layer for high-performance perovskite light-emitting diodes with significantly enhanced stability. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1901299 (2019).

- Qiu, W. et al. Mixed lead-tin halide perovskites for efficient and wavelength-tunable near-infrared light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806105 (2019).

- Yu, H. Q. et al. Alkalis-doping of mixed tin-lead perovskites for efficient near-infrared light-emitting diodes. Sci. Bull. 67, 54-60 (2022).

- Lu, J. X. et al. Dendritic

for efficient and flexible near-infrared perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104414 (2021). - Yuan, F. et al. Color-pure red light-emitting diodes based on two-dimensional lead-free perovskites. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb0253 (2020).

- Wang, K. et al. Lead-free organic-perovskite hybrid quantum wells for highly stable light-emitting diodes. ACS Nano 15, 6316-6325 (2021).

- Liang, H. et al. High color purity lead-free perovskite light-emitting diodes via Sn stabilization. Adv. Sci. 7, 1903213 (2020).

- Lin, R. et al. Monolithic all-perovskite tandem solar cells with 24.8% efficiency exploiting comproportionation to suppress

II oxidation in precursor ink. Nat. Energy. 4, 864-873 (2019). - Lin, J. et al. Harnessing dielectric confinement on tin perovskites to achieve emission quantum yield up to

. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 10324-10330 (2019). - Yakunin, S. et al. High-resolution remote thermometry and thermography using luminescent low-dimensional tin-halide perovskites. Nat. Mater. 18, 846-852 (2019).

- Hong, W. et al. Efficient low-temperature solution-processed lead-free perovskite infrared light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 28, 8029-8036 (2016).

- Xue, S. et al. Advances in electrically driven light-emitting diodes based on lead-free metal halides. Chem. Commun. 59, 1116-1124 (2023).

- Wei, Q. et al. Chances and challenges for tin perovskites. Trends Chem. 4, 1-4 (2022).

- Chung, I. et al.

: semiconductor or metal? High electrical conductivity and strong near-infrared photoluminescence from a single material. High hole mobility and phase-transitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8579-8587 (2012). - Ricciarelli, D. et al. Instability of tin iodide perovskites: bulk p-doping versus surface tin oxidation. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 2787-2795 (2020).

- Li, B. et al. Tin-based defects and passivation strategies in tin-related perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 3752-3772 (2020).

- Barrigón, E. et al. Synthesis and applications of III-V nanowires. Chem. Rev. 119, 9170-9220 (2019).

- Tsintzos, S. et al. A GaAs polariton light-emitting diode operating near room temperature. Nature 453, 372-375 (2008).

- Feldmann, S. et al. Photodoping through local charge carrier accumulation in alloyed hybrid perovskites for highly efficient luminescence. Nat. Photon. 14, 123-128 (2020).

- Treglia, A. et al. Effect of electronic doping and traps on carrier dynamics in tin halide perovskites. Mater. Horiz. 9, 1763-1773 (2022).

- Zhang, X. et al. First-principles simulation of carrier recombination mechanisms in halide perovskites. Adv. Eng. Mater. 10, 1902830 (2020).

- Meng, X. et al. Crystallization kinetics modulation of FASnI

films with pre-nucleation clusters for efficient lead-free perovskite solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3693-3698 (2021). - Wang, S. et al. High-performance perovskite solar cells with large grain-size obtained by using the Lewis acid-base adduct of thiourea. Sol. RRL 2, 1800034 (2018).

- Guo, Q. et al. Passivation of the grain boundaries of

using carbon quantum dots for highly efficient perovskite solar cells with excellent environmental stability. Nanoscale 11, 115-124 (2019). - Ye, T. et al. Ambient-air-stable lead-free

solar cells with greater than 7.5% efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4319-4328 (2021). - Milot, R. et al. The effects of doping density and temperature on the optoelectronic properties of formamidinium tin triiodide thin films. Adv. Mater. 30, 1804506 (2018).

- Bubnova, O. et al. Semi-metallic polymers. Nat. Mater. 13, 190-194 (2014).

- Shen, J. et al. Unexpectedly strong Auger recombination in halide perovskites. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1801027 (2018).

- Martani, S. et al. Defect engineering to achieve photostable wide bandgap metal halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 2801-2808 (2023).

© The Author(s) 2024

طرق

المواد

حسابات الهيكل الإلكتروني

تحضير محلول الأفلام البيروفيسكية

التحليل البصري

نظام عدّ الفوتونات المفردة (تذبذب التوقيت،

طيف الانبعاث الضوئي المعتمد على درجة الحرارة المنخفضة

قياس fs-TA

قياسات هول

الخصائص الهيكلية والشكلية والكيميائية

من خلال الإشارة إلى مستوى فيرمي وموقع قمة Au4f7/2 لـ

تصنيع الأجهزة وتوصيفها

توفر البيانات

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

قسم الفيزياء والكيمياء وعلم الأحياء (IFM)، جامعة لينشوبينغ، لينشوبينغ، السويد. المختبر الرئيسي للكيمياء الضوئية النظرية والحسابية بوزارة التعليم، كلية الكيمياء، جامعة بكين نورمال، بكين، الصين. مركز العلوم والتكنولوجيا النانوية@بوليمي، المعهد الإيطالي للتكنولوجيا، ميلانو، إيطاليا. قسم الفيزياء، بوليتكنيكو دي ميلانو، ميلانو، إيطاليا. قسم الفيزياء والفيزياء التطبيقية، مدرسة العلوم الفيزيائية والرياضية، جامعة نانيانغ التكنولوجية، سنغافورة، سنغافورة. قسم الفيزياء وعلم الفلك، جامعة أوبسالا، أوبسالا، السويد. البريد الإلكتروني: feng.gao@liu.se

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-023-01351-5

Publication Date: 2024-01-05

Bright and stable near-infrared lead-free perovskite light-emitting diodes

Accepted: 17 November 2023

Published online: 5 January 2024

(D) Check for updates

Abstract

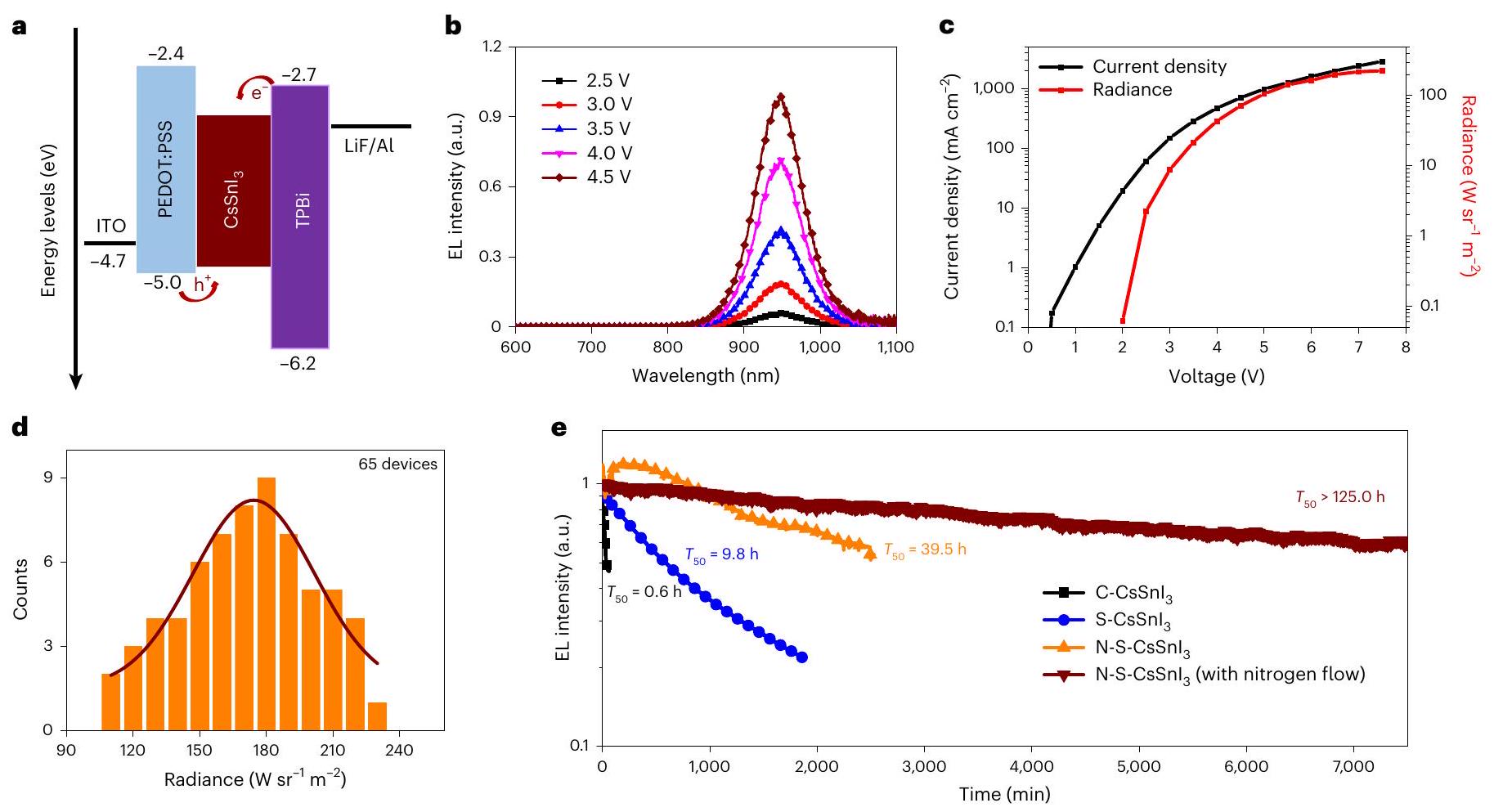

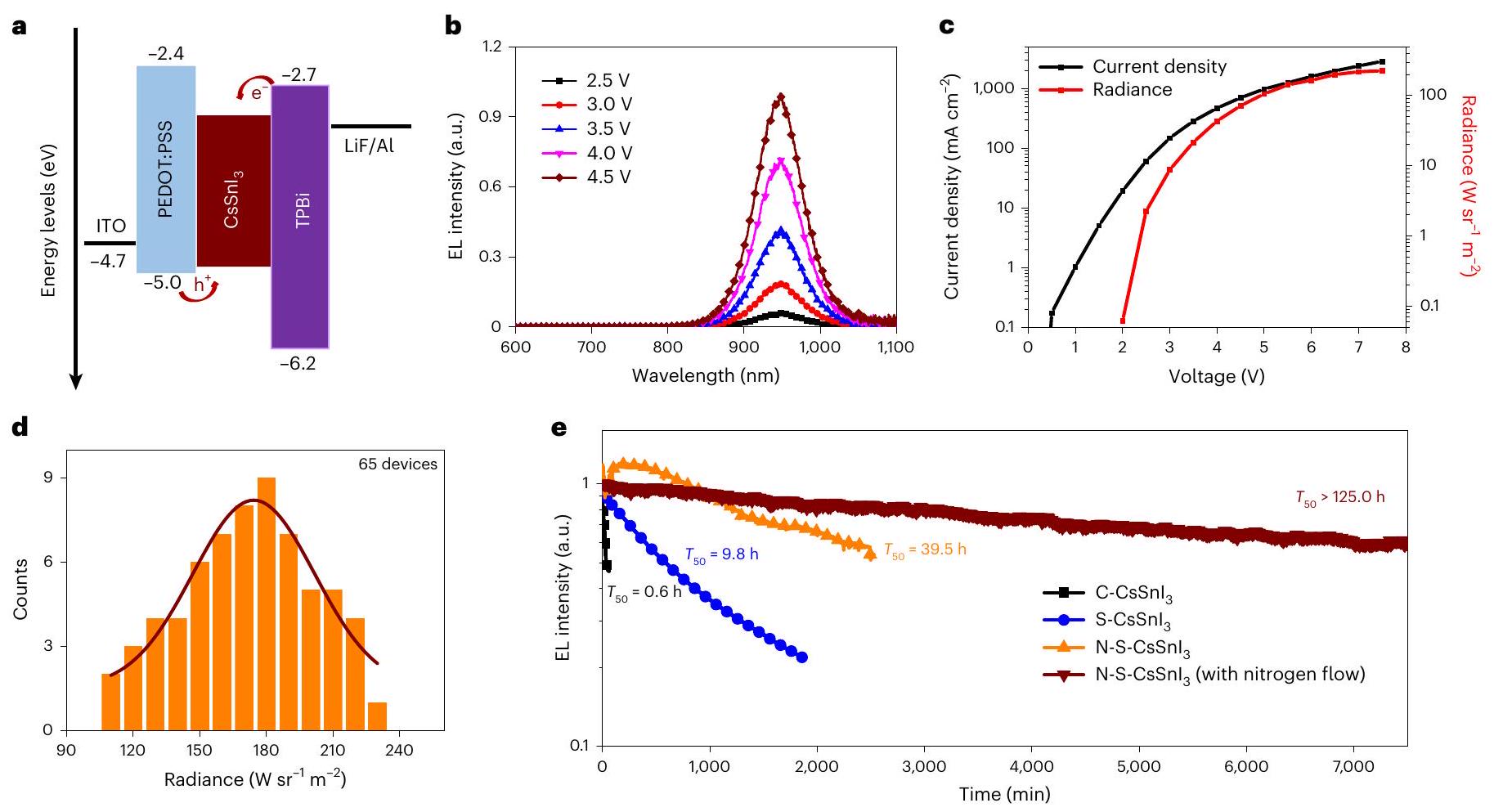

Long-wavelength near-infrared light-emitting diodes (NIR LEDs) with peak emission wavelengths beyond 900 nm are of critical importance for various applications including night vision, biomedical imaging, sensing and optical communications. However, the low radiance and poor operational stability of state-of-the-art long-wavelength NIR LEDs based on soft materials remain the most critical factors limiting their practical applications. Here we develop NIR LEDs emitting beyond 900 nm with improved performance through the rational manipulation of p doping in all-inorganic tin perovskites (

halide perovskites (THPs), especially all-inorganic black orthorhombic

| Materials category and examples | Emission peak (nm) | FWHM (nm) | Radiance (

|

Stability (

|

Ref. | |

| Organic molecules | Pt(II) complexes | 930 | >200 | 41.6 | NA | 10 |

| Pb-based QDs | PbS/PbS QD/ZnO | 1,400 | ~200 | 9 | NA | 11 |

| PbS QD/perovskite | 980 | ~150 | 7.4 |

|

13 | |

| Ag-based QDs |

|

1,397 | ~75 | 83.9 | NA | 14 |

| Lead-tin halides | FPMAI-MAPb

|

917 | ~100 | 2.7 |

|

20 |

| Inorganic tin halides |

|

948 | 71 | 226 |

|

This work |

spectra at different operating voltages. c,d, Current density-voltage-radiance (c) and histograms of maximum radiance (d) of

of electronic doping in inorganic semiconductors for improved LED performance, we, thus, believe that the intrinsic p-doping characteristic of THPs could be beneficial for achieving high-performance NIR LEDs through elaborately controlling the hole-doping and trap densities.

Device structure and performance

poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene-sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) hole injection layer, an active

Controlled growth of

Controlled p doping and reduced trap density

at

and are marked by

background holes due to p doping may improve the PLQY and boost the radiative recombination with photogenerated electrons-this is true for increasing doping densities until Auger recombination becomes dominant; and (3) when the trap density is comparable to or higher than the doping density, trap-mediated recombination processes dominate and mostly influence the PLQY.

Electronic structure calculations

with the density of available eigenstates for the three-body process in the band structure (Fig. 4a,b). These results imply that

Discussions

Conclusion

Online content

and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-023-01351-5.

References

- Medintz, I. L., Uyeda, H. T., Goldman, E. R. & Mattoussi, H. Quantum dot bioconjugates for imaging, labelling and sensing. Nat. Mater. 4, 435-446 (2005).

- Konstantatos, G. et al. Ultrasensitive solution-cast quantum dot photodetectors. Nature 442, 180-183 (2006).

- Kim, S. et al. Near-infrared fluorescent type II quantum dots for sentinel lymph node mapping. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 93-97 (2004).

- Sun, L. et al. Bright infrared quantum-dot light-emitting diodes through inter-dot spacing control. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 369-373 (2012).

- Yoon, J. et al. GaAs photovoltaics and optoelectronics using releasable multilayer epitaxial assemblies. Nature 465, 329-333 (2010).

- Walther, T., Cullis, A., Norris, D. & Hopkinson, M. Nature of the Stranski-Krastanow transition during epitaxy of InGaAs on GaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 2381 (2001).

- Tuong, Ly,K. et al. Near-infrared organic light-emitting diodes with very high external quantum efficiency and radiance. Nat. Photon. 11, 63-68 (2017).

- Cao, Y. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes based on spontaneously formed submicrometre-scale structures. Nature 562, 249-253 (2018).

- Xu, W. et al. Rational molecular passivation for high-performance perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 13, 418-424 (2019).

- Wei, Y. C. et al. Overcoming the energy gap law in near-infrared OLEDs by exciton-vibration decoupling. Nat. Photon. 14, 570-577 (2020).

- Gong, X. et al. Highly efficient quantum dot near-infrared light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 10, 253-257 (2016).

- Pradhan, S. et al. High-efficiency colloidal quantum dot infrared light-emitting diodes via engineering at the supra-nanocrystalline level. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 72-79 (2019).

- Gao, L. et al. Efficient near-infrared light-emitting diodes based on quantum dots in layered perovskite. Nat. Photon. 14, 227-233 (2020).

- Vasilopoulou, M. et al. Efficient colloidal quantum dot light-emitting diodes operating in the second near-infrared biological window. Nat. Photon. 14, 50-56 (2020).

- Dong, Y. et al. Bipolar-shell resurfacing for blue leds based on strongly confined perovskite quantum dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 668-674 (2020).

- Wang, Y.-K. et al. All-inorganic quantum-dot LEDs based on a phase-stabilized

perovskite. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 16164-16170 (2020). - Wang, Y.-K. et al. Chelating-agent-assisted control of

quantum well growth enables stable blue perovskite emitters. Nat. Commun. 11, 3674 (2020). - Zheng, X. et al. Chlorine vacancy passivation in mixed halide perovskite quantum dots by organic pseudohalides enables efficient Rec. 2020 blue light-emitting diodes. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 793-798 (2020).

- Wang, Z. et al. Multifunctional p-type carbon quantum dots: a novel hole injection layer for high-performance perovskite light-emitting diodes with significantly enhanced stability. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1901299 (2019).

- Qiu, W. et al. Mixed lead-tin halide perovskites for efficient and wavelength-tunable near-infrared light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806105 (2019).

- Yu, H. Q. et al. Alkalis-doping of mixed tin-lead perovskites for efficient near-infrared light-emitting diodes. Sci. Bull. 67, 54-60 (2022).

- Lu, J. X. et al. Dendritic

for efficient and flexible near-infrared perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104414 (2021). - Yuan, F. et al. Color-pure red light-emitting diodes based on two-dimensional lead-free perovskites. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb0253 (2020).

- Wang, K. et al. Lead-free organic-perovskite hybrid quantum wells for highly stable light-emitting diodes. ACS Nano 15, 6316-6325 (2021).

- Liang, H. et al. High color purity lead-free perovskite light-emitting diodes via Sn stabilization. Adv. Sci. 7, 1903213 (2020).

- Lin, R. et al. Monolithic all-perovskite tandem solar cells with 24.8% efficiency exploiting comproportionation to suppress

II oxidation in precursor ink. Nat. Energy. 4, 864-873 (2019). - Lin, J. et al. Harnessing dielectric confinement on tin perovskites to achieve emission quantum yield up to

. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 10324-10330 (2019). - Yakunin, S. et al. High-resolution remote thermometry and thermography using luminescent low-dimensional tin-halide perovskites. Nat. Mater. 18, 846-852 (2019).

- Hong, W. et al. Efficient low-temperature solution-processed lead-free perovskite infrared light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 28, 8029-8036 (2016).

- Xue, S. et al. Advances in electrically driven light-emitting diodes based on lead-free metal halides. Chem. Commun. 59, 1116-1124 (2023).

- Wei, Q. et al. Chances and challenges for tin perovskites. Trends Chem. 4, 1-4 (2022).

- Chung, I. et al.

: semiconductor or metal? High electrical conductivity and strong near-infrared photoluminescence from a single material. High hole mobility and phase-transitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8579-8587 (2012). - Ricciarelli, D. et al. Instability of tin iodide perovskites: bulk p-doping versus surface tin oxidation. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 2787-2795 (2020).

- Li, B. et al. Tin-based defects and passivation strategies in tin-related perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 3752-3772 (2020).

- Barrigón, E. et al. Synthesis and applications of III-V nanowires. Chem. Rev. 119, 9170-9220 (2019).

- Tsintzos, S. et al. A GaAs polariton light-emitting diode operating near room temperature. Nature 453, 372-375 (2008).

- Feldmann, S. et al. Photodoping through local charge carrier accumulation in alloyed hybrid perovskites for highly efficient luminescence. Nat. Photon. 14, 123-128 (2020).

- Treglia, A. et al. Effect of electronic doping and traps on carrier dynamics in tin halide perovskites. Mater. Horiz. 9, 1763-1773 (2022).

- Zhang, X. et al. First-principles simulation of carrier recombination mechanisms in halide perovskites. Adv. Eng. Mater. 10, 1902830 (2020).

- Meng, X. et al. Crystallization kinetics modulation of FASnI

films with pre-nucleation clusters for efficient lead-free perovskite solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3693-3698 (2021). - Wang, S. et al. High-performance perovskite solar cells with large grain-size obtained by using the Lewis acid-base adduct of thiourea. Sol. RRL 2, 1800034 (2018).

- Guo, Q. et al. Passivation of the grain boundaries of

using carbon quantum dots for highly efficient perovskite solar cells with excellent environmental stability. Nanoscale 11, 115-124 (2019). - Ye, T. et al. Ambient-air-stable lead-free

solar cells with greater than 7.5% efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4319-4328 (2021). - Milot, R. et al. The effects of doping density and temperature on the optoelectronic properties of formamidinium tin triiodide thin films. Adv. Mater. 30, 1804506 (2018).

- Bubnova, O. et al. Semi-metallic polymers. Nat. Mater. 13, 190-194 (2014).

- Shen, J. et al. Unexpectedly strong Auger recombination in halide perovskites. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1801027 (2018).

- Martani, S. et al. Defect engineering to achieve photostable wide bandgap metal halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 2801-2808 (2023).

© The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Materials

Electronic structure calculations

Preparation of perovskite solution and films

Optical characterization

single-photon counting system (timing jitter,

Low-temperature-dependent PL spectra

fs-TA measurement

Hall measurements

Structural, morphological and chemical characterizations

by referencing to the Fermi level and Au4f7/2 peak position of the

Device fabrication and characterization

Data availability

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

Department of Physics, Chemistry, and Biology (IFM), Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden. Key Laboratory of Theoretical and Computational Photochemistry of Ministry of Education, College of Chemistry, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China. Center for Nano Science and Technology@PoliMi, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Milan, Italy. Physics Department, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy. Division of Physics and Applied Physics, School of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore. Department of Physics and Astronomy, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. e-mail: feng.gao@liu.se