DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-02078-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38191664

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-08

جزيئات فيروسية مصممة للتوصيل المؤقت لمجمعات ريبونوكليوبروتين المحرر الرئيسي في الجسم الحي

تاريخ القبول: 30 نوفمبر 2023

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 8 يناير 2024

الملخص

يمكن التحرير الرئيسي من تثبيت دقيق للتبديلات الجينومية والإدخالات والحذف في الأنظمة الحية. ومع ذلك، لا يزال توصيل مكونات التحرير الرئيسي بكفاءة في المختبر وفي الجسم الحي يمثل تحديًا. هنا نبلغ عن جزيئات فيروسية مصممة (PE-eVLPs) تقوم بتوصيل بروتينات المحرر الرئيسي، وأدلة RNA للتحرير الرئيسي وRNA أحادي الدليل المقطوع كمجمعات ريبونوكليوبروتين مؤقتة. لقد قمنا بتصميم PE-eVLPs من النوع v3 وv3b بكفاءة تحرير أعلى من 65 إلى 170 مرة في خلايا الإنسان مقارنةً ببناء PE-eVLP استنادًا إلى بنية eVLP للمحرر الأساسي التي أبلغنا عنها سابقًا. في نموذجين من الفئران للعمى الجيني، أدت الحقن الفردية لـ v3 PE-eVLPs إلى مستويات ذات صلة علاجية من التحرير الرئيسي في الشبكية، واستعادة التعبير البروتيني وإنقاذ جزئي لوظيفة الرؤية. تدعم PE-eVLPs المحسنة التوصيل المؤقت في الجسم الحي للريبونوكليوبروتينات المحرر الرئيسي، مما يعزز السلامة المحتملة للتحرير الرئيسي من خلال تقليل التحرير غير المستهدف وإلغاء إمكانية دمج الجينات المسرطنة.

ثلاث أحداث تزاوج مستقلة للأحماض النووية قبل أن يمكن أن يحدث التحرير ولا يعتمد على كسر DNA مزدوج الشريط أو قوالب DNA المتبرع. نتيجةً لهذه الآلية، فإن التحرير الرئيسي مقاوم بطبيعته للتحرير غير المستهدف أو التحرير الجانبي، ويمكن أن يستمر مع عدد قليل من المنتجات الجانبية أو العواقب غير المرغوب فيها لكسر DNA مزدوج الشريط

النتائج

توصيل PE: pegRNA RNPs عبر eVLPs في خلايا مزروعة

الهندسة المنهجية لبنية PE وeVLP

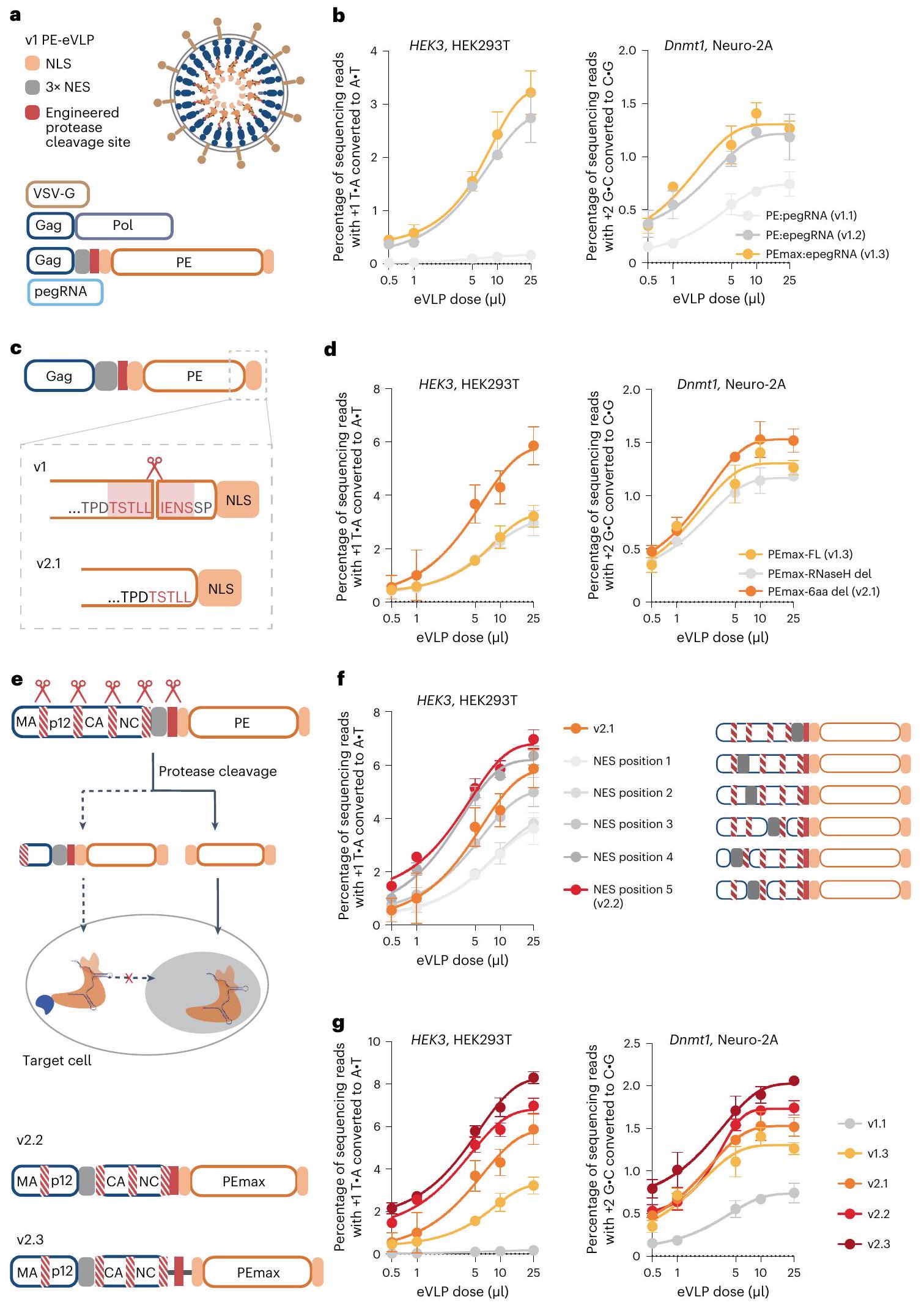

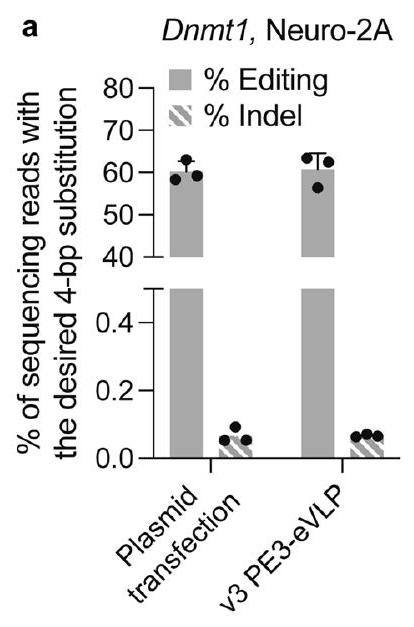

(موقع NES 1-5) من نطاق Gag. أظهر موقع NES 5 (الإصدار 2.2) تحسينًا في التحرير مقارنةً بـ PE-eVLPs الإصدار 2.1. ز، مقارنة كفاءات التحرير الأساسي مع PE-eVLPs الإصدار 1، 2.1، 2.2 و2.3 عند موضع HEK3 في خلايا HEK293T وموضع Dnmt1 في خلايا N2A. القيم المعروضة في جميع الرسوم البيانية تمثل متوسط كفاءات التحرير الأساسي

أحجام متغيرة في BE-eVLPs بواسطة البقعة الغربية

المواقع المختبرة، دعم إدخال

(الشكل 1e) التي تحتوي على تقصير MMLV RT، وتحسين NES وتحسين الروابط متوسط تحسين بمقدار 2.6 مرة و1.6 مرة في كفاءة التحرير الأساسي مقارنةً ببنية PE-eVLP الإصدار 1.3 عند أعلى جرعة تم اختبارها عند موضع HEK3 في خلايا HEK293T وموضع Dnmt1 في خلايا N2A، على التوالي (الشكل 1g).

اعتماد أداء PE-eVLP على نوع التحرير

تقييد تعبئة epegRNA يحد من كفاءة PE-eVLP

PE3 يحسن بشكل أكبر التحرير الأساسي باستخدام PE-eVLPs

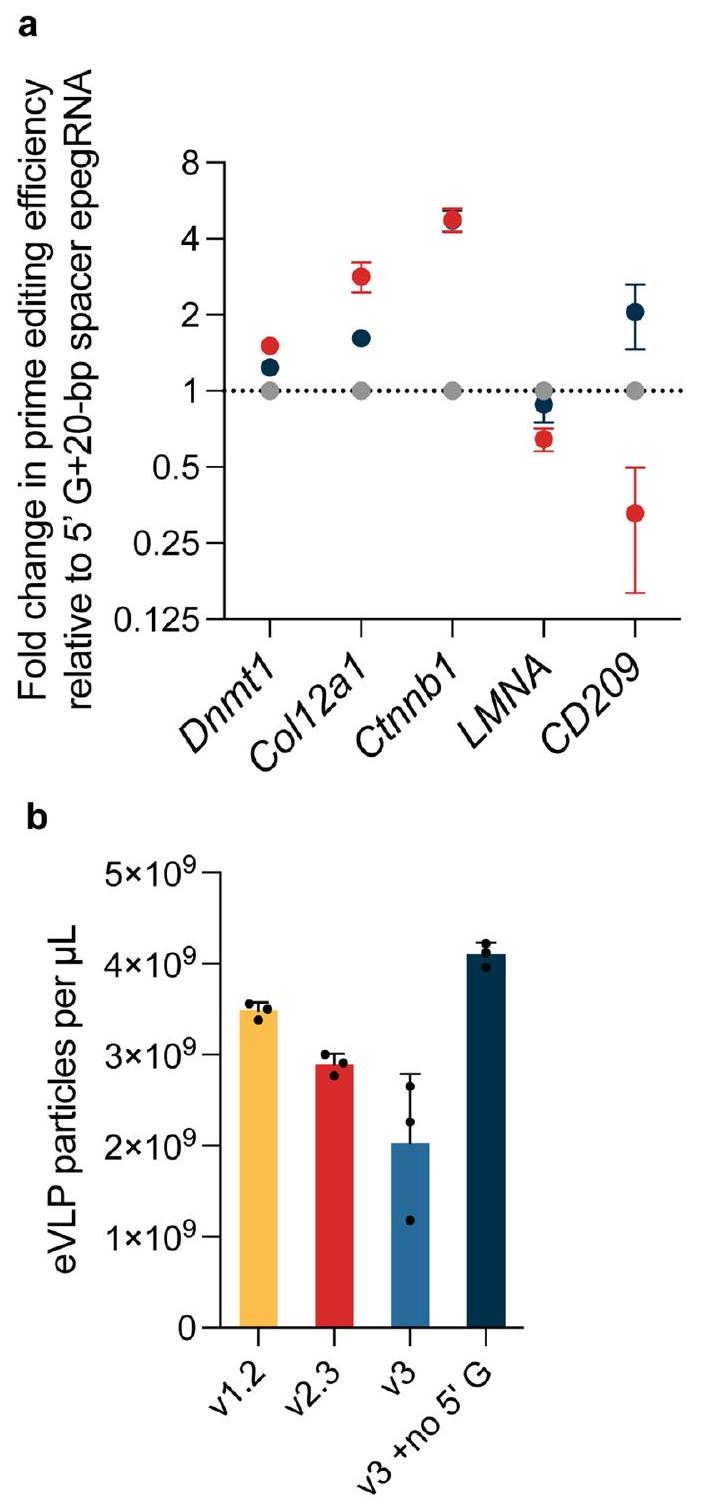

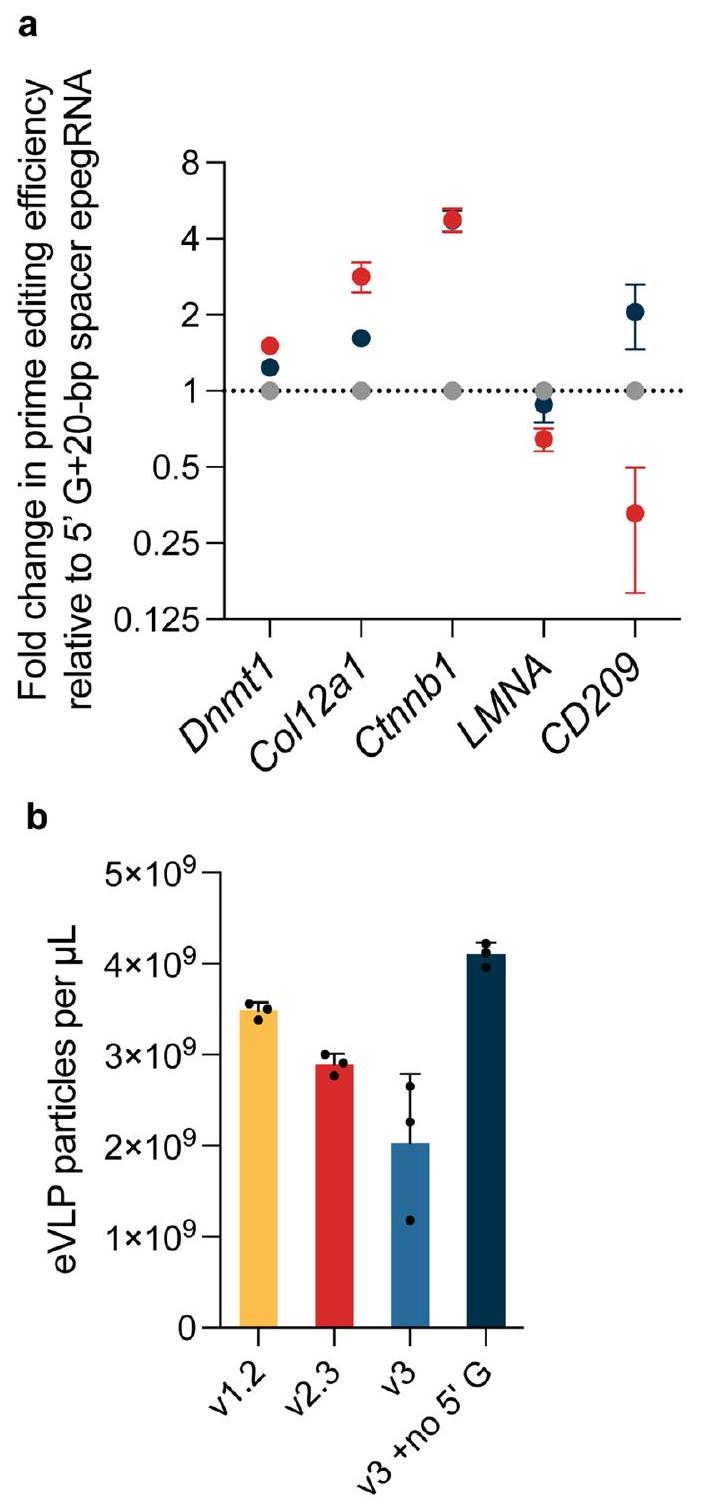

إزالة امتداد 5′-G تعزز التحرير باستخدام بعض epegRNAs

لجميع الظروف، تم معالجة 30,000-35,000 خلية باستخدام eVLPs التي تحتوي على

توصيف تحميل شحنة PE-eVLP

توظيف PE من خلال ارتباط الببتيد الحلزوني

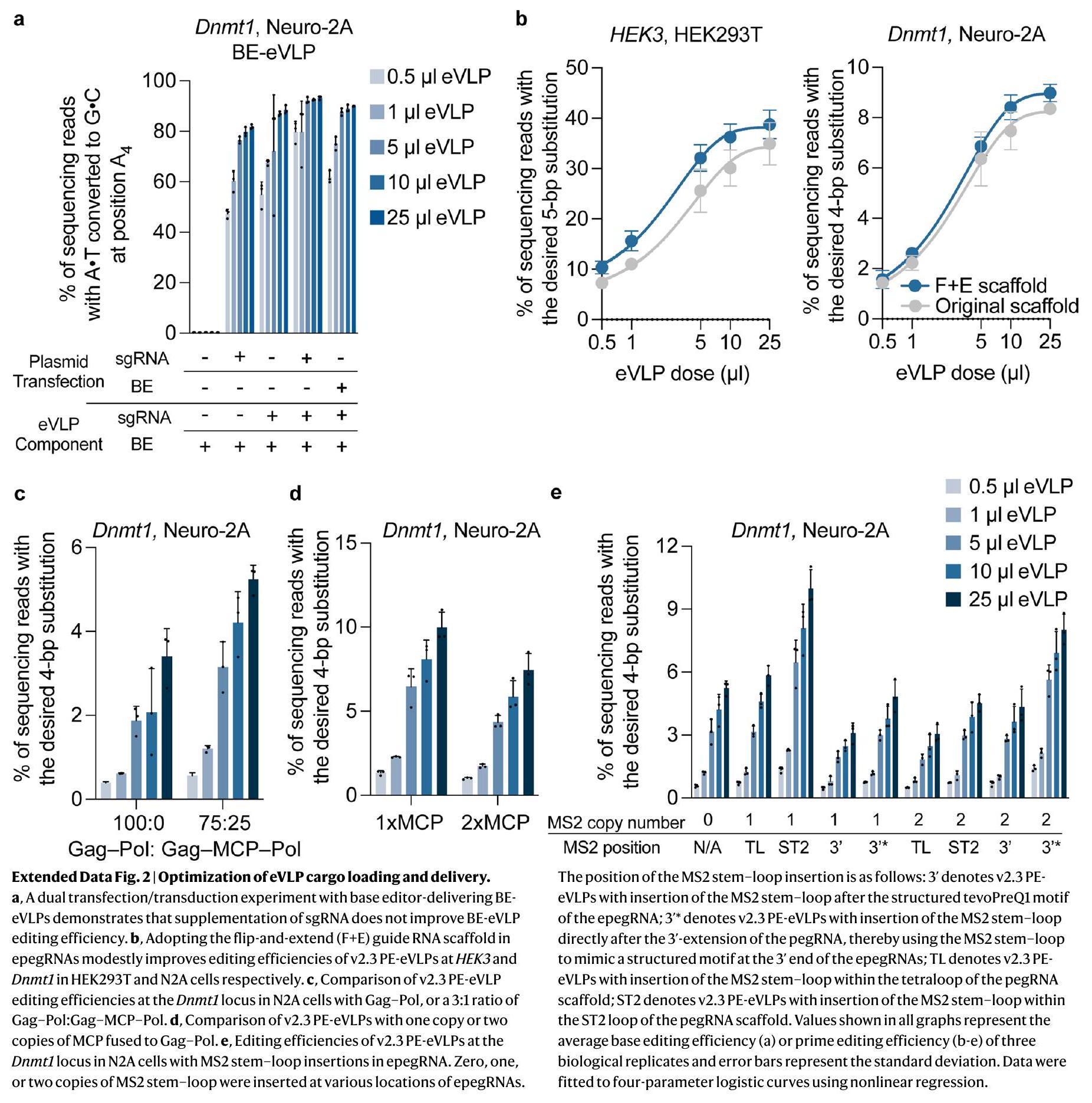

تستفيد BE-eVLPs من هندسة هيكل PE-eVLPs

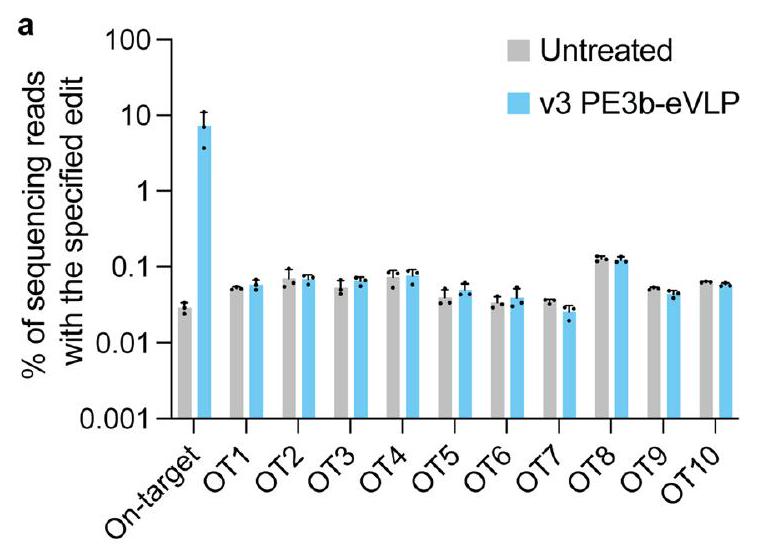

التوصيل العابر لـ PE بواسطة eVLPs يقلل من التحرير غير المستهدف

إلى متطلبات ثلاث خطوات متميزة من تفاعل الحمض النووي الهجين من أجل تحرير منتج.

تقوم PE-eVLPs بوساطة تحرير رئيسي قوي في الدماغ في الجسم الحي

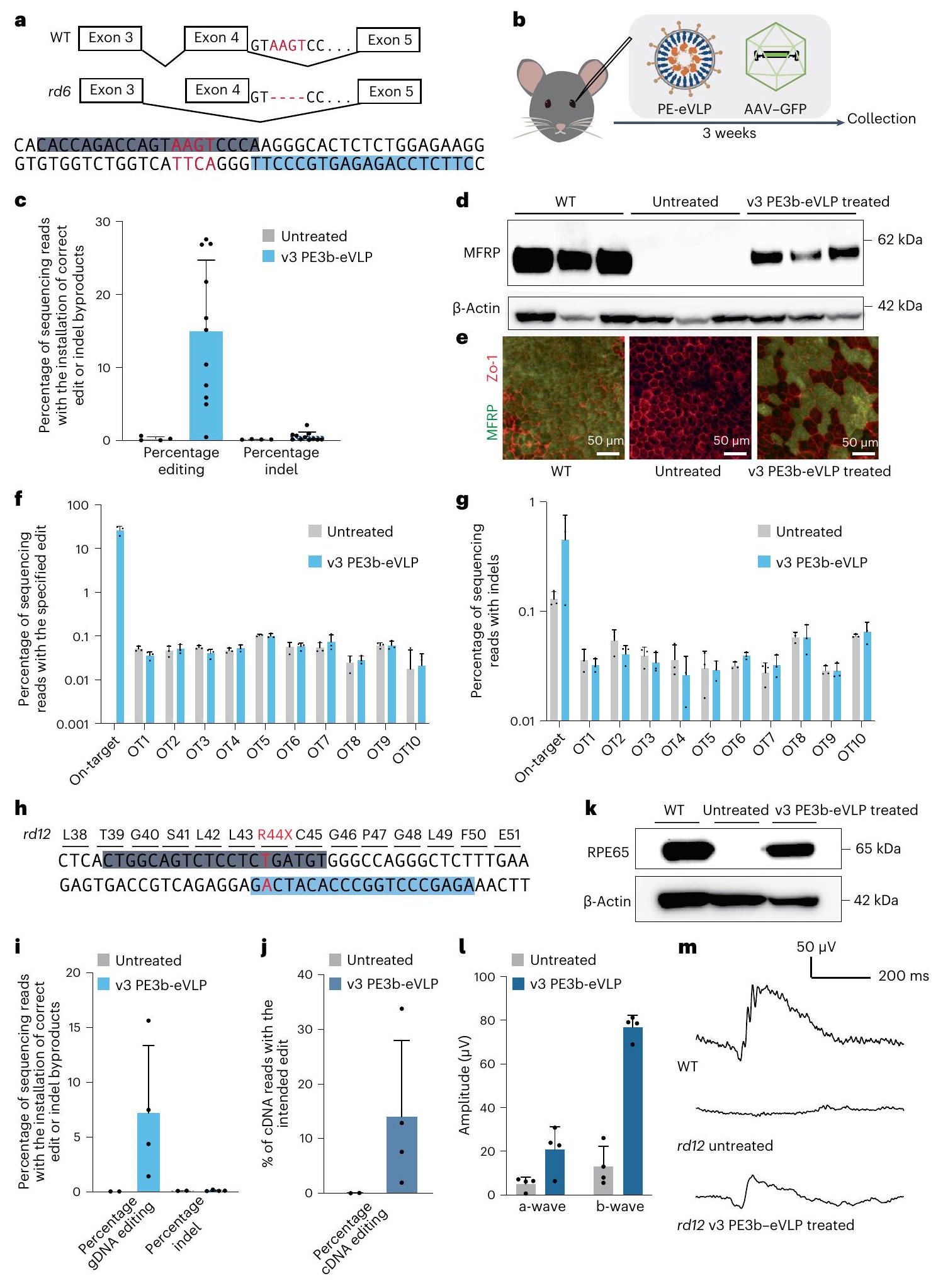

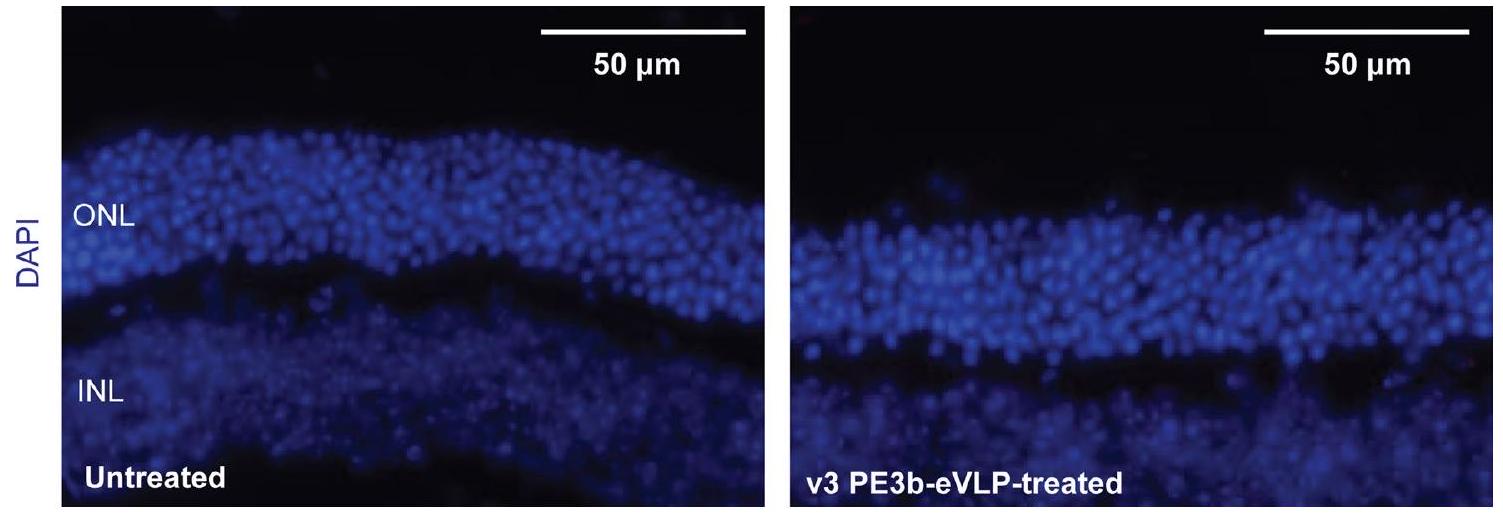

PE-eVLP يصحح الطفرات المسببة لأمراض الشبكية في الجسم الحي

الطفرة المقابلة في البشر في الشكل المتماثل تسبب عمى ليبر الخلقي

(

يمكن مقارنتها بتلك التي تم تحقيقها من خلال توصيل PE بواسطة AAV مزدوج الناقل بجرعات عالية

نقاش

تحرير الترددات وخطر دمج الحمض النووي المسبب للسرطان

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

References

- Anzalone, A. V. et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149-157 (2019).

- Chen, P. J. et al. Enhanced prime editing systems by manipulating cellular determinants of editing outcomes. Cell 184, 5635-5652 e5629 (2021).

- Newby, G. A. & Liu, D. R. In vivo somatic cell base editing and prime editing. Mol. Ther. 29, 3107-3124 (2021).

- Nelson, J. W. et al. Engineered pegRNAs improve prime editing efficiency. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 402-410 (2022).

- Anzalone, A. V. et al. Programmable deletion, replacement, integration and inversion of large DNA sequences with twin prime editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 731-740 (2022).

- Choi, J. et al. Precise genomic deletions using paired prime editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 218-226 (2022).

- Doman, J. L., Sousa, A. A., Randolph, P. B., Chen, P. J. & Liu, D. R. Designing and executing prime editing experiments in mammalian cells. Nat. Protoc. 17, 2431-2468 (2022).

- Bock, D. et al. In vivo prime editing of a metabolic liver disease in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabl9238 (2022).

- Zheng, C. et al. A flexible split prime editor using truncated reverse transcriptase improves dual-AAV delivery in mouse liver. Mol. Ther. 30, 1343-1351 (2022).

- Zhi, S. et al. Dual-AAV delivering split prime editor system for in vivo genome editing. Mol. Ther. 30, 283-294 (2022).

- Qin, H. et al. Vision rescue via unconstrained in vivo prime editing in degenerating neural retinas. J. Exp. Med. https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem. 20220776 (2023).

- Gao, R. et al. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of prime editing guide RNA-independent off-target effects by prime editors. CRISPR J. 5, 276-293 (2022).

- Kim, D. Y., Moon, S. B., Ko, J. H., Kim, Y. S. & Kim, D. Unbiased investigation of specificities of prime editing systems in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 10576-10589 (2020).

- Liu, Y. et al. Efficient generation of mouse models with the prime editing system. Cell Discov. 6, 27 (2020).

- Schene, I. F. et al. Prime editing for functional repair in patient-derived disease models. Nat. Commun. 11, 5352 (2020).

- Geurts, M. H. et al. Evaluating CRISPR-based prime editing for cancer modeling and CFTR repair in organoids. Life Sci. Alliance https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa. 202000940 (2021).

- Park, S. J. et al. Targeted mutagenesis in mouse cells and embryos using an enhanced prime editor. Genome Biol. 22, 170 (2021).

- Gao, P. et al. Prime editing in mice reveals the essentiality of a single base in driving tissue-specific gene expression. Genome Biol. 22, 83 (2021).

- Lin, J. et al. Modeling a cataract disorder in mice with prime editing. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 25, 494-501 (2021).

- Jin, S. et al. Genome-wide specificity of prime editors in plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1292-1299 (2021).

- Habib, O., Habib, G., Hwang, G. H. & Bae, S. Comprehensive analysis of prime editing outcomes in human embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 1187-1197 (2022).

- She, K. et al. Dual-AAV split prime editor corrects the mutation and phenotype in mice with inherited retinal degeneration. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 8, 57 (2023).

- Jang, H. et al. Application of prime editing to the correction of mutations and phenotypes in adult mice with liver and eye diseases. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 181-194 (2022).

- Liu, B. et al. A split prime editor with untethered reverse transcriptase and circular RNA template. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1388-1393 (2022).

- Davis, J. R. et al. Efficient prime editing in mouse brain, liver and heart with dual AAVs. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41587-023-01758-z (2023).

- Wu, Z., Yang, H. & Colosi, P. Effect of genome size on AAV vector packaging. Mol. Ther. 18, 80-86 (2010).

- Davis, J. R. et al. Efficient in vivo base editing via single adeno-associated viruses with size-optimized genomes encoding compact adenine base editors. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 1272-1283 (2022).

- Taha, E. A., Lee, J. & Hotta, A. Delivery of CRISPR-Cas tools for in vivo genome editing therapy: trends and challenges. J. Control. Release 342, 345-361 (2022).

- Chandler, R. J., Sands, M. S. & Venditti, C. P. Recombinant adeno-associated viral integration and genotoxicity: insights from animal models. Hum. Gene Ther. 28, 314-322 (2017).

- Kazemian, P. et al. Lipid-nanoparticle-based delivery of CRISPR/ Cas9 genome-editing components. Mol. Pharm. 19, 1669-1686 (2022).

- Loughrey, D. & Dahlman, J. E. Non-liver mRNA delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 13-23 (2022).

- Breda, L. et al. In vivo hematopoietic stem cell modification by mRNA delivery. Science 381, 436-443 (2023).

- Raguram, A., Banskota, S. & Liu, D. R. Therapeutic in vivo delivery of gene editing agents. Cell 185, 2806-2827 (2022).

- Lyu, P., Wang, L. & Lu, B. Virus-like particle mediated CRISPR/Cas9 delivery for efficient and safe genome editing. Life https://doi.org/ 10.3390/life10120366 (2020).

- Garnier, L., Wills, J. W., Verderame, M. F. & Sudol, M. WW domains and retrovirus budding. Nature 381, 744-745 (1996).

- Choi, J. G. et al. Lentivirus pre-packed with Cas9 protein for safer gene editing. Gene Ther. 23, 627-633 (2016).

- Campbell, L. A. et al. Gesicle-mediated delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex for inactivating the HIV provirus. Mol. Ther. 27, 151-163 (2019).

- Lyu, P., Javidi-Parsijani, P., Atala, A. & Lu, B. Delivering Cas9/ sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) by lentiviral capsid-based bionanoparticles for efficient ‘hit-and-run’ genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, e99 (2019).

- Mangeot, P. E. et al. Genome editing in primary cells and in vivo using viral-derived Nanoblades loaded with Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoproteins. Nat. Commun. 10, 45 (2019).

- Gee, P. et al. Extracellular nanovesicles for packaging of CRISPRCas9 protein and sgRNA to induce therapeutic exon skipping. Nat. Commun. 11, 1334 (2020).

- Indikova, I. & Indik, S. Highly efficient ‘hit-and-run’ genome editing with unconcentrated lentivectors carrying Vpr.Prot.Cas9 protein produced from RRE-containing transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 8178-8187 (2020).

- Hamilton, J. R. et al. Targeted delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 and transgenes enables complex immune cell engineering. Cell Rep. 35, 109207 (2021).

- Yao, X. et al. Engineered extracellular vesicles as versatile ribonucleoprotein delivery vehicles for efficient and safe CRISPR genome editing. J. Extracell. Vesicles 10, e12076 (2021).

- Banskota, S. et al. Engineered virus-like particles for efficient in vivo delivery of therapeutic proteins. Cell 185, 250-265 e216 (2022).

- Zuris, J. A. et al. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 73-80 (2015).

- Rees, H. A. et al. Improving the DNA specificity and applicability of base editing through protein engineering and protein delivery. Nat. Commun. 8, 15790 (2017).

- Tozser, J. Comparative studies on retroviral proteases: substrate specificity. Viruses 2, 147-165 (2010).

- Lim, K. I., Klimczak, R., Yu, J. H. & Schaffer, D. V. Specific insertions of zinc finger domains into Gag-Pol yield engineered retroviral vectors with selective integration properties. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12475-12480 (2010).

- Dhindsa, R. S. et al. A minimal role for synonymous variation in human disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 109, 2105-2109 (2022).

- Kruglyak, L. et al. Insufficient evidence for non-neutrality of synonymous mutations. Nature 616, E8-E9 (2023).

- Chen, B. et al. Dynamic imaging of genomic loci in living human cells by an optimized CRISPR/Cas system. Cell 155, 1479-1491 (2013).

- Bernardi, A. & Spahr, P. F. Nucleotide sequence at the binding site for coat protein on RNA of bacteriophage R17. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 69, 3033-3037 (1972).

- Lu, Z. et al. Lentiviral capsid-mediated Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 ribonucleoprotein delivery for efficient and safe multiplex genome editing. CRISPR J. 4, 914-928 (2021).

- Lyu, P. et al. Adenine base editor ribonucleoproteins delivered by lentivirus-like particles show high on-target base editing and undetectable RNA off-target activities. CRISPR J. 4, 69-81 (2021).

- Feng, Y. et al. Enhancing prime editing efficiency and flexibility with tethered and split pegRNAs. Protein Cell 14, 304-308 (2023).

- Chen, R. et al. Enhancement of a prime editing system via optimal recruitment of the pioneer transcription factor P65. Nat. Commun. 14, 257 (2023).

- Ma, H. et al. Pol III promoters to express small RNAs: delineation of transcription initiation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 3, e161 (2014).

- Kulcsar, P. I. et al. Blackjack mutations improve the on-target activities of increased fidelity variants of SpCas9 with 5’G-extended sgRNAs. Nat. Commun. 11, 1223 (2020).

- Mullally, G. et al. 5′ modifications to CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA can change the dynamics and size of R-loops and inhibit DNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 6811-6823 (2020).

- Mason, J. M. & Arndt, K. M. Coiled coil domains: stability, specificity, and biological implications. ChemBioChem 5, 170-176 (2004).

- Lebar, T., Lainscek, D., Merljak, E., Aupic, J. & Jerala, R. A tunable orthogonal coiled-coil interaction toolbox for engineering mammalian cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 513-519 (2020).

- Richter, M. F. et al. Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 883-891 (2020).

- Gaudelli, N. M. et al. Programmable base editing of

to in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464-471 (2017). - Neugebauer, M. E. et al. Evolution of an adenine base editor into a small, efficient cytosine base editor with low off-target activity. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01533-6 (2022).

- Cameron, P. et al. Mapping the genomic landscape of CRISPRCas9 cleavage. Nat. Methods 14, 600-606 (2017).

- Liang, S. Q. et al. Genome-wide profiling of prime editor off-target sites in vitro and in vivo using PE-tag. Nat. Methods https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-023-01859-2 (2023).

- Farhy-Tselnicker, I. & Allen, N. J. Astrocytes, neurons, synapses: a tripartite view on cortical circuit development. Neural Dev. 13, 7 (2018).

- Semple, B. D., Blomgren, K., Gimlin, K., Ferriero, D. M. & Noble-Haeusslein, L. J. Brain development in rodents and humans: Identifying benchmarks of maturation and vulnerability to injury across species. Prog. Neurobiol. 106-107, 1-16 (2013).

- Gusel’nikova, V. V. & Korzhevskiy, D. E. NeuN as a neuronal nuclear antigen and neuron differentiation marker. Acta Naturae 7, 42-47 (2015).

- Kato, S. et al. Selective neural pathway targeting reveals key roles of thalamostriatal projection in the control of visual discrimination. J. Neurosci. 31, 17169-17179 (2011).

- Kameya, S. et al. Mfrp, a gene encoding a frizzled related protein, is mutated in the mouse retinal degeneration 6. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 1879-1886 (2002).

- Ayala-Ramirez, R. et al. A new autosomal recessive syndrome consisting of posterior microphthalmos, retinitis pigmentosa,

foveoschisis, and optic disc drusen is caused by a MFRP gene mutation. Mol. Vis. 12, 1483-1489 (2006). - Yan, A. L., Du, S. W. & Palczewski, K. Genome editing, a superior therapy for inherited retinal diseases. Vision Res. 206, 108192 (2023).

- Puppo, A. et al. Retinal transduction profiles by high-capacity viral vectors. Gene Ther. 21, 855-865 (2014).

- Suh, S. et al. Restoration of visual function in adult mice with an inherited retinal disease via adenine base editing. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 169-178 (2021).

- Tsai, S. Q. et al. CIRCLE-seq: a highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat. Methods 14, 607-614 (2017).

- Pang, J. J. et al. Retinal degeneration 12 (rd12): a new, spontaneously arising mouse model for human Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). Mol. Vis. 11, 152-162 (2005).

- Zhong, Z. et al. Seven novel variants expand the spectrum of RPE65-related Leber congenital amaurosis in the Chinese population. Mol. Vis. 25, 204-214 (2019).

- Dong, W. & Kantor, B. Lentiviral vectors for delivery of gene-editing systems based on CRISPR/Cas: current state and perspectives. Viruses https://doi.org/10.3390/v13071288 (2021).

- Schellekens, H. Bioequivalence and the immunogenicity of biopharmaceuticals. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1, 457-462 (2002).

© The Author(s) 2024

طرق

الاستنساخ الجزيئي

زراعة الخلايا

إنتاج PE-eVLP

نقل PE-eVLP في الخلايا المزروعة وجمع الحمض النووي الجيني

تم جمع الحمض النووي الجيني الخلوي بعد 72 ساعة من النقل كما هو موصوف سابقًا

HTS لعينات الحمض النووي الجينومي

تحليل بيانات HTS

نقل البلازميد

تحديد محتوى بروتين PE-eVLP بواسطة ELISA

تم تركيزها عبر الطرد المركزي الفائق كما هو موصوف أعلاه للكشف الأمثل عن البروتين. تم خلط إجمالي

تحديد محتوى pegRNA في PE-eVLP بواسطة RT-qPCR

DLS

تحليل Western blot لمحتوى بروتين lysate الخلايا المنتجة

حمض الديوكسيكوليك، 1 مليمول EDTA، 1% Triton X-100،

تحليل Western blot لمحتوى بروتين PE-eVLP

تحليل الأهداف الجانبية في الخلايا المزروعة

أو تم قياس الحذف في مواقع النيك غير المستهدفة لـ Cas9 كنسبة مئوية من (القراءات المهملة)/(إجمالي القراءات المتوافقة مع المرجع). يتم حساب إجمالي التحرير غير المستهدف كـ (تكرار التحرير غير المستهدف المدعوم من pegRNA) + (تكرار الإنديل في موقع نيك Cas9).

إنتاج الفيروسات القهقرية

الحيوانات

حقن POICV وجمع الأنسجة

العزل النووي والفرز

حقن تحت الشبكية

تخطيط كهربائية الشبكية

فصل RPE وتحضير الحمض النووي الجيني والحمض النووي الريبي

تحليل البقعة الغربية لاستخراج أنسجة RPE من الفئران

التلوين المناعي النسجي لشرائح RPE المسطحة والشرائح المجمدة

ترشيح مواقع غير مستهدفة بواسطة CIRCLE-seq لـ

الإحصائيات وإمكانية التكرار

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

تم توفير تفاصيل بنية PE-eVLP في المعلومات التكميلية. تم إيداع البلازميدات الرئيسية التالية من هذا العمل في Addgene للتوزيع: Gag-MCP-Pol (Addgene #211370)، Gag-PE (Addgene #211371)، MS2-epegRNA-Dnmt1 (Addgene #211372)، Gag-COM-Pol (Addgene #211373)، Gag-PE3-Pol (#211374)، P4-PE (#211375)، COM-epegRNA-Dnmt1 (#211376). البلازميدات الأخرى والبيانات الخام متاحة من المؤلف المراسل عند الطلب. تم توفير صورة غير معدلة للبلات الغربية المعروضة في الشكل 5d، k كبيانات مصدر. تم توفير بيانات المصدر مع هذه الورقة.

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Renner, T. M., Tang, V. A., Burger, D. & Langlois, M. A. Intact viral particle counts measured by flow virometry provide insight into the infectivity and genome packaging efficiency of Moloney Murine Leukemia virus. J. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01600-19 (2020).

- Levy, J. M. et al. Cytosine and adenine base editing of the brain, liver, retina, heart and skeletal muscle of mice via adeno-associated viruses. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 97-110 (2020).

- Golczak, M., Kiser, P. D., Lodowski, D. T., Maeda, A. & Palczewski, K. Importance of membrane structural integrity for RPE65 retinoid isomerization activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9667-9682 (2010).

- Lazzarotto, C. R. et al. CHANGE-seq reveals genetic and epigenetic effects on CRISPR-Cas9 genome-wide activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1317-1327 (2020).

- circleseq. GitHub https://github.com/tsailabSJ/circleseq (2018)

- An, M. et al. Engineered virus-like particles for transient delivery of prime editor ribonucleoprotein complexes in vivo. NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA980181 (2023).

شكر وتقدير

نصائح ومساعدة في رعاية الفئران. نشكر J. Doman و S. DeCarlo و P. Randolph و A. Yan و A. Tworak على المناقشات المفيدة. هذه المقالة تخضع لسياسة الوصول المفتوح إلى المنشورات الخاصة بـ HHMI. لقد منح رؤساء مختبرات HHMI سابقًا ترخيصًا غير حصري CC BY 4.0 للجمهور وترخيصًا قابلًا للتراخيص الفرعية لـ HHMI في مقالاتهم البحثية. وفقًا لتلك التراخيص، يمكن أن يتوفر المخطوط المعتمد من المؤلف لهذه المقالة مجانًا بموجب ترخيص CC BY 4.0 فور نشرها.

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-02078-y.

معلومات إضافية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على مواد إضافية متاحة فيhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-02078-y.

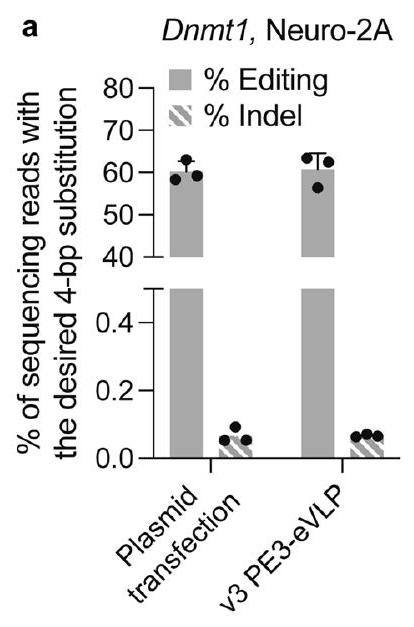

كفاءة التحرير لثلاث نسخ بيولوجية وتمثل أشرطة الخطأ الانحراف المعياري. تم ملاءمة البيانات لمنحنيات لوجستية بأربعة معلمات باستخدام الانحدار غير الخطي.

- 5′ G+20-bp GTGACTTCCATGGTTCCACAA

- 20-زوج قاعدي TGACTTCCATGGTTCCACAA

- 5 ‘ G+19-bp GGACTTCCATGGTTCCACAA

تجارب لتحديد عدد جزيئات بروتين محرر الأحماض النووية epegRNA و eVLP كما هو موضح في الشكل 2g، h. ج، نسبة تكوين epegRNA و ngRNA في v3 PE2-eVLPs و v3 PE3-eVLPs. تمثل البيانات القيمة المتوسطة لثلاث تكرارات فنية وتمثل أشرطة الخطأ الانحراف المعياري.

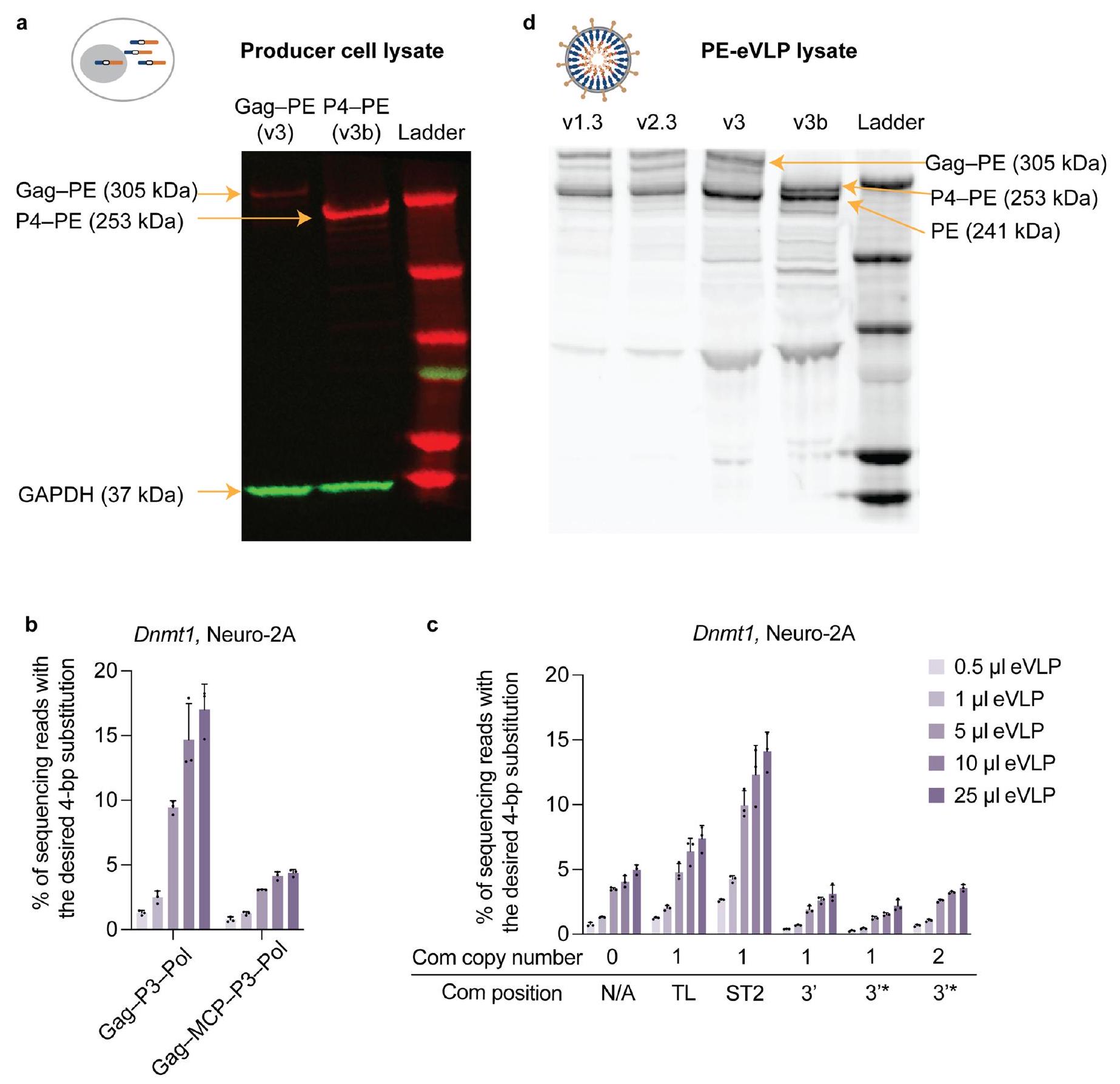

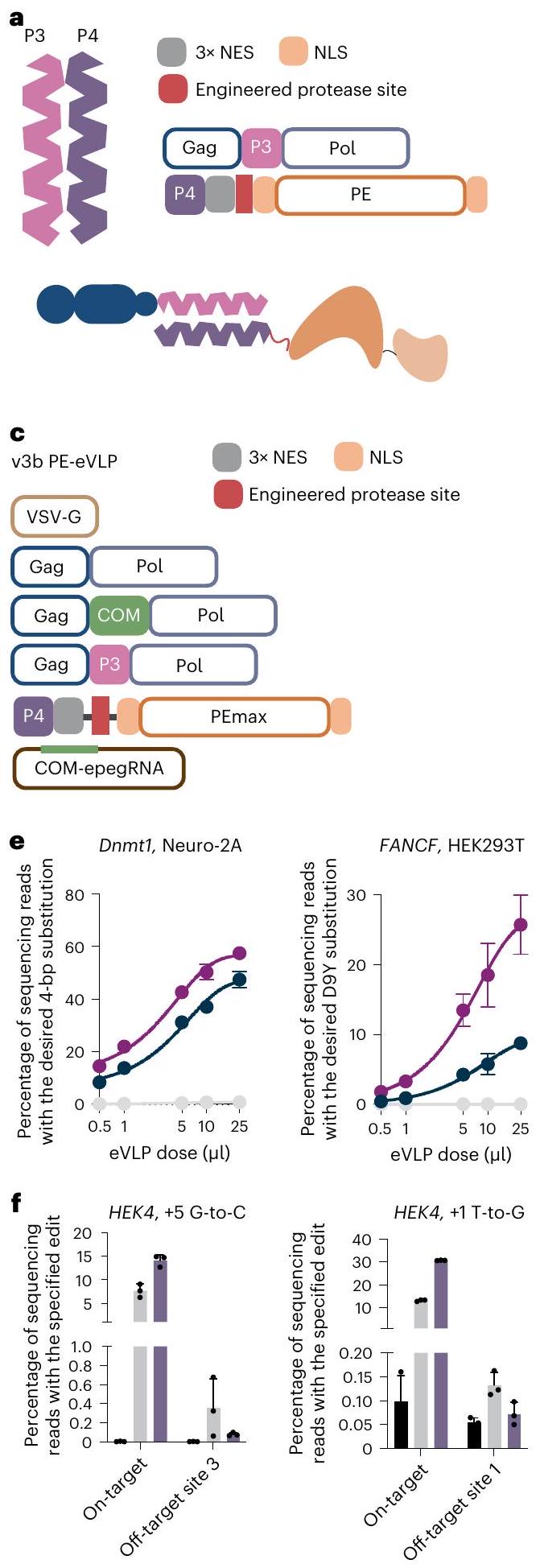

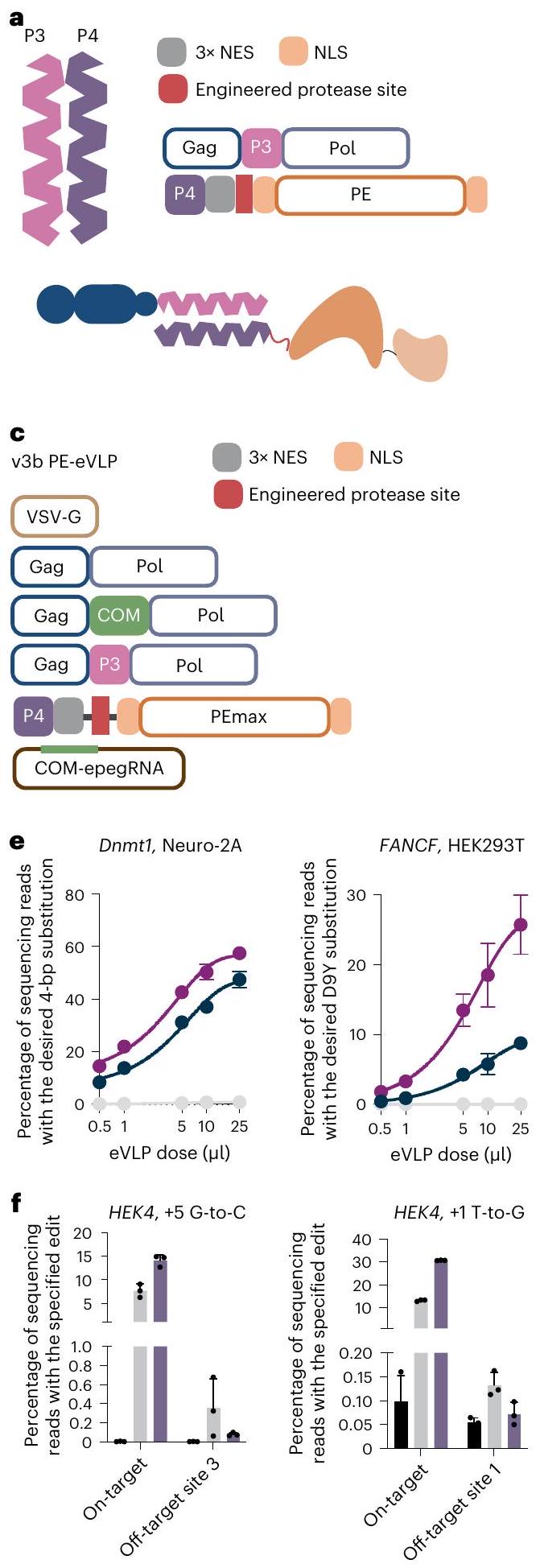

a، تمثيل غربي يقارن تعبير بروتين الاندماج gag-PE من v3 PE-eVLPs مقابل بروتين الاندماج P4-PE من v3b PE-eVLPs في خلايا المنتج التي تم نقلها بالبروتينات الاندماجية المقابلة. ب، كفاءات التحرير الأولي لـ v3b PE-eVLPs مع Gag-P3-Pol أو Gag-MCP-P3-Pol. بناء الاندماج Gag-MCP-P3-Pol غير متوافق مع الإنتاج الفعال لـ PE-eVLPs. ج، كفاءات التحرير لـ v3b PE-eVLPs عند موضع Dnmt1 في خلايا N2A مع إدخال الأبتامر Com في مواقع مختلفة في epegRNAs. موضع إدخال الأبتامر Com هو كما يلي:

epegRNA؛ 3 * تشير إلى v3b PE-eVLPs مع إدخال الأبتامر Com مباشرة بعد الامتداد 3′ من pegRNA، مما يستخدم الأبتامر Com لمحاكاة نمط هيكلي في الطرف 3′ من epegRNAs؛ TL تشير إلى v3b PE-eVLPs مع إدخال الأبتامر Com داخل الحلقة الرباعية من هيكل pegRNA؛ ST2 تشير إلى v3b PE-eVLPs مع إدخال الأبتامر Com داخل حلقة ST2 من هيكل pegRNA. د، تمثيل غربي يقيّم كمية الحمولة PE المعبأة في v1.3 و v2.3 و v3 و v3b PE-eVLPs. الأشكال المعروضة في (أ) و (د) هي صور تمثيلية من تجربتين مكررتين بشكل مستقل. القيم المعروضة في (ب) و (ج) تمثل متوسط كفاءة التحرير الأساسي لثلاث نسخ بيولوجية والأشرطة الخطأ تمثل الانحراف المعياري.

b

| بروتينات ملحقة | بروتينات الشحن | ARNs الموجهة | تحسينات من النسخة السابقة | |||

| الإصدار 1.1 | غير متوفر |  |

pegRNA | |||

| الإصدار 1.2 | غير متوفر |  |

epegRNA | epegRNA | ||

| الإصدار 1.3 | غير متوفر |  |

epegRNA | PEmax | ||

| الإصدار 2.1 | غير متوفر |  |

epegRNA | قصّ MMLV RT | ||

| الإصدار 2.2 | غير متوفر |  |

تحسين NES | |||

| الإصدار 2.3 | غير متوفر |  |

epegRNA | تحسين الرابط | ||

| v3 |  |

|

|

تجنيد gRNA عبر تفاعل MCP:MS2 | ||

| v3b |  |

|

|

توظيف الشحن عبر تفاعل P3-P4؛ توظيف gRNA عبر تفاعل COM:Com |

*المخططات الموضحة في الجدول تمثل PE2-eVLPs. بالنسبة لـ PE3-eVLPs، يتم تعبئة ngRNAs إضافية.

تم استبعاد جميع نسخ PE-eVLPs من الجدول. المخططات المعروضة في الجدول تمثل PE2-eVLPs. بالنسبة لـ PE3-eVLPs، يتم تعبئة ngRNAs إضافية بنسبة 4:1 للـ pegRNAs و ngRNAs مع تعديل السقالة المناسب وإدخال الأبتامر.

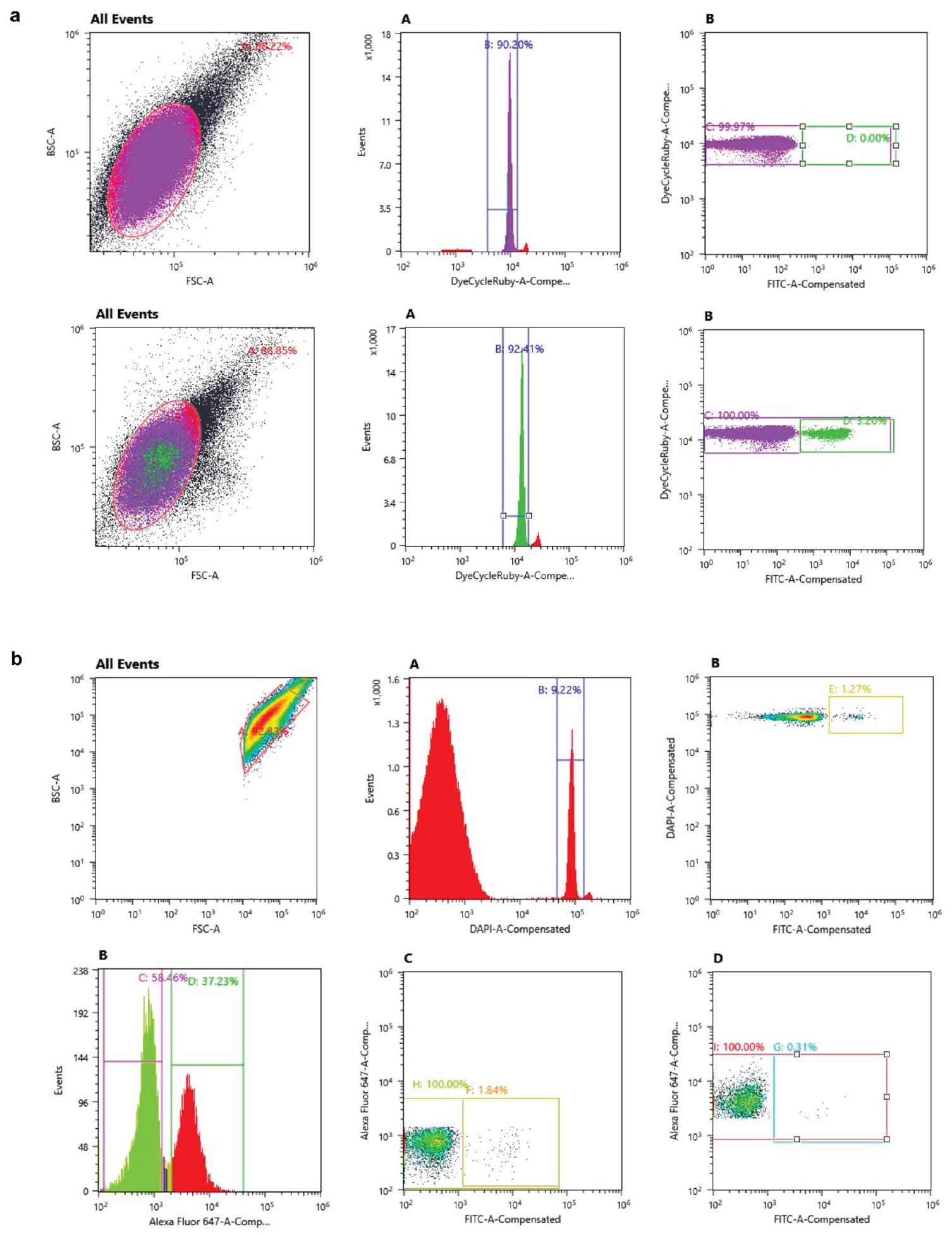

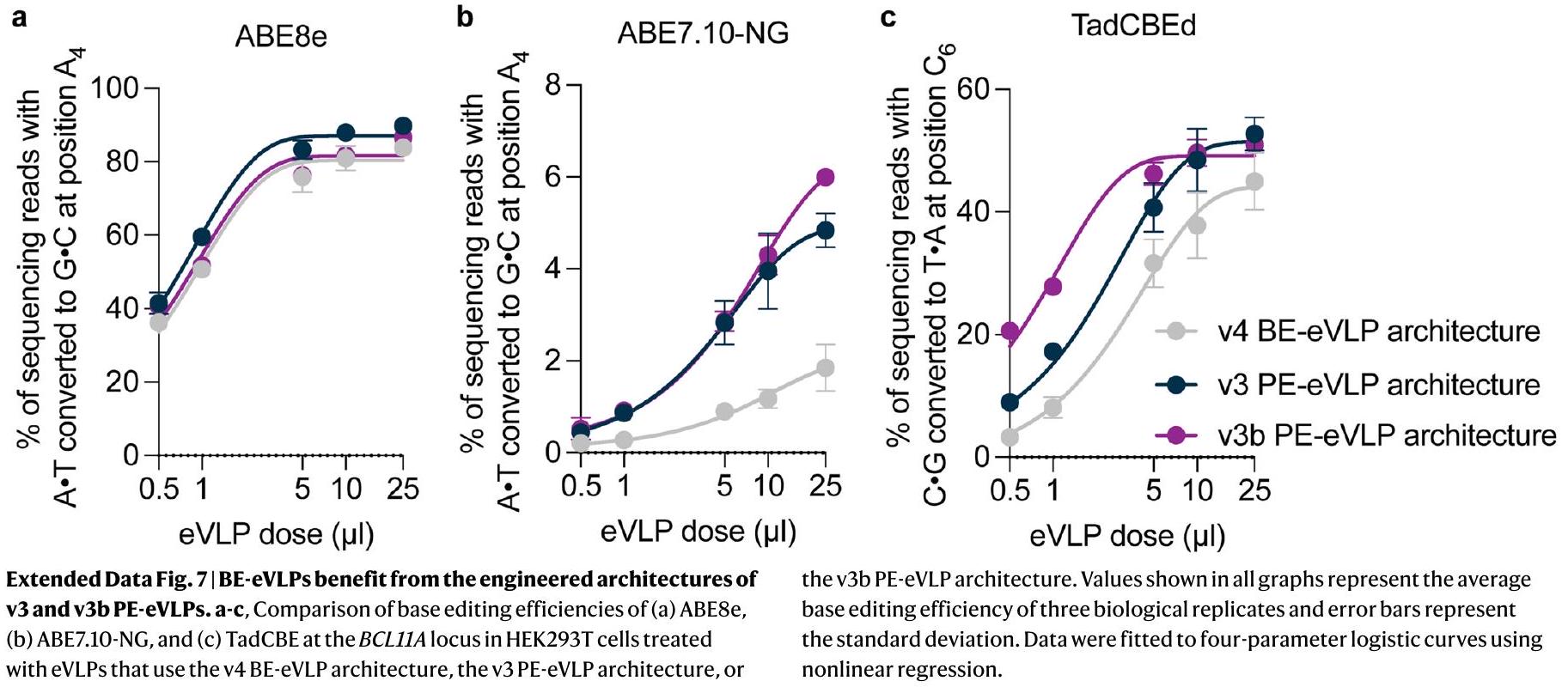

تم تحديد نواة واحدة بناءً على نسب التشتت الأمامي (FSC-A) والتشتت الخلفي (BCS-A) وإشارة DyeCycle Ruby. تم تحديد النوى الإيجابية لـ GFP بناءً على إشارة FITC. يعرض الصف الأول بيانات FACS التمثيلية للعينات غير المعالجة، بينما يعرض الصف الثاني بيانات FACS التمثيلية لعينات القشرة المجمعة من الفئران حديثة الولادة التي تم حقنها معاً بـ

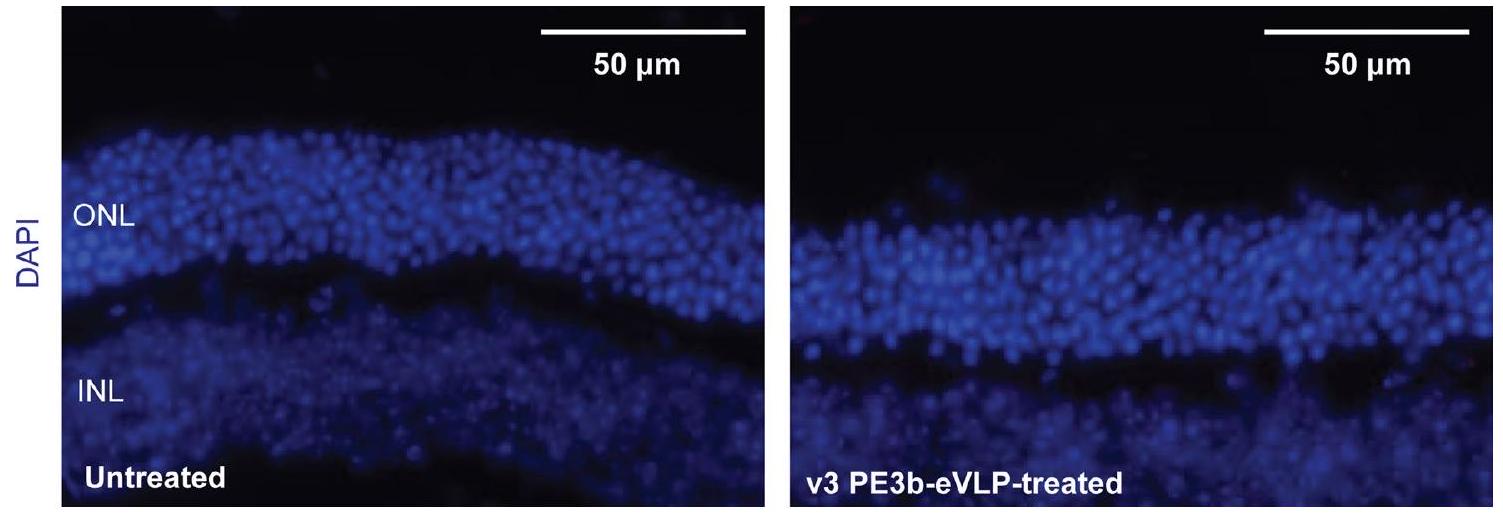

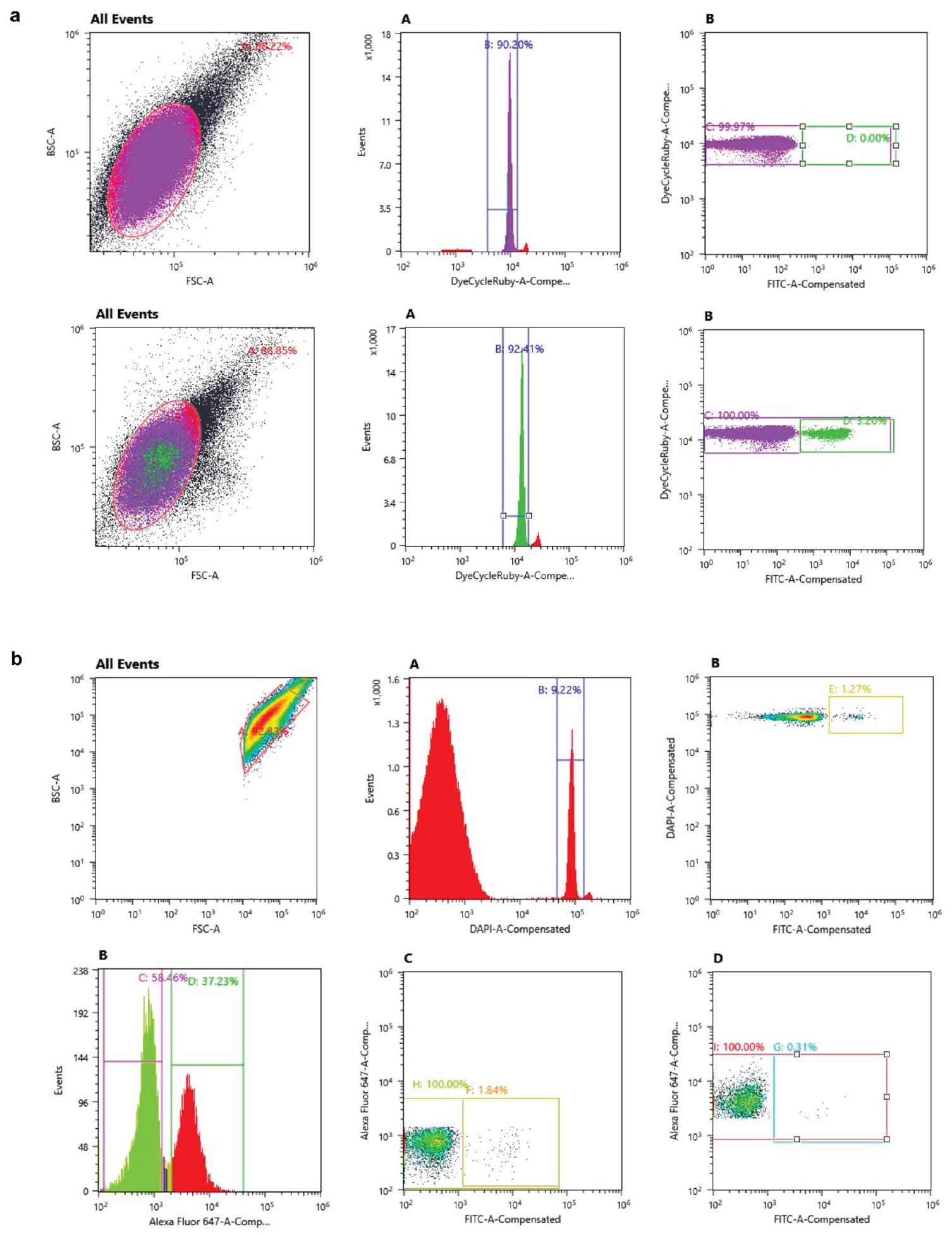

فرز. تم تحديد نواة واحدة بناءً على نسب التشتت الأمامي (FSC-A) والتشتت الخلفي (BCS-A) وإشارة DAPI. تميز الإشارة من جسم مضاد NeuN المرتبط بـ Alexa 647 بين السكان الإيجابيين لـ NeuN والسكان السلبيين لـ NeuN. تم تحديد النوى الإيجابية لـ GFP بناءً على إشارة FITC في كل من السكان الإيجابيين والسكان السلبيين لـ NeuN. تمثل الأبواب المعروضة بيانات FACS لعينات الدماغ الأوسط التي تم جمعها من فئران حديثي الولادة التي تم حقنها معاً بـ

b

مرتبطة بتسلسل rd12ngRNA. تمثل الأعمدة القيم المتوسطة لـ

محفظة الطبيعة

آخر تحديث من المؤلف(ين): 16 نوفمبر 2023

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

حجم العينة بالضبط (

اختبار(ات) الإحصاء المستخدمة وما إذا كانت أحادية الجانب أو ثنائية الجانب

يجب أن تُوصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ واصفًا التقنيات الأكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

وصف لجميع المتغيرات المشتركة التي تم اختبارها

“凶” translates to “شر” in Arabic.

وصف كامل للمعلمات الإحصائية بما في ذلك الاتجاه المركزي (مثل المتوسطات) أو تقديرات أساسية أخرى (مثل معامل الانحدار) والتباين (مثل الانحراف المعياري) أو تقديرات عدم اليقين المرتبطة (مثل فترات الثقة)

لتحليل بايزي، معلومات حول اختيار القيم الأولية وإعدادات سلسلة ماركوف مونت كارلو

للتصاميم الهرمية والمعقدة، تحديد المستوى المناسب للاختبارات والتقارير الكاملة عن النتائج

تقديرات أحجام التأثير (مثل حجم تأثير كوهين)

تحتوي مجموعتنا على الإنترنت حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات تتناول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

البرمجيات والشيفرة

معلومات السياسة حول توفر كود الكمبيوتر

جمع البيانات

تحليل البيانات

بيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الانضمام، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا

البحث الذي يتضمن مشاركين بشريين، بياناتهم، أو مواد بيولوجية

التوظيف

غير متوفر

غير متوفر

التقارير المتخصصة في المجال

علوم الحياة العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

تصميم دراسة العلوم الحياتية

| حجم العينة | أحجام العينات كانت

|

| استبعاد البيانات | للتصحيح في نموذج rd6 و rd12، تم حقن الفئران مع PE-eVLPs و AAV1-GFP. تم فحص إشارة GFP كعلامة على نجاح الحقن. تم أخذ عينات من العيون التي أظهرت أقل من

|

| التكرار | تم تكرار جميع التجارب أكثر من مرة. كانت جميع محاولات التكرار ناجحة. |

| التوزيع العشوائي | تم تعيين جميع ظروف التحكم والاختبار عشوائيًا. على سبيل المثال، بالنسبة لجميع تجارب الزراعة الخلوية/الأنسجة، تم تعيين الظروف عشوائيًا إلى آبار عبر ألواح تحتوي على 96 أو 48 بئرًا، ولا يُتوقع أن تؤثر موضع الألواح على نتيجة التجربة. بالنسبة لتجارب in vivo، تم تعيين الفئران عشوائيًا إلى مجموعات. |

| مُعَمي | تم تحليل جميع بيانات HTS باستخدام برنامج نصي آلي من CRISPResso2 لا يسمح بتدخل الباحث، لذلك لم يكن الباحث معصوب العينين. تم تحليل بيانات تحرير الحقن تحت الشبكية بواسطة باحث معصوب العينين. لم يكن التعمية ضرورية للتجارب الأخرى لأن ظروف التحكم والاختبار تمت معالجتها بشكل متطابق. |

التقارير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | طرق | ||

| غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة | غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

علم الحفريات وعلم الآثار |  |

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

||

| إكس | |||

الأجسام المضادة

| الأجسام المضادة المستخدمة | أجسام مضادة لـ Mouse Cas9 (Thermo Fisher Scientific، #MA5-23519)؛ أجسام مضادة لـ Rabbit GAPDH (Cell signaling Technology، #2118)؛ أجسام مضادة لـ Goat anti-mouse MFRP (R&D Systems #AF3445)؛ أجسام مضادة لـ Mouse anti-mouse RPE65 (إنتاج داخلي؛ تم الحصول عليها من مختبر الدكتور كريستوف بالتشوفسكي، جامعة كاليفورنيا إيرفين؛ غولتشاك وآخرون، 2010)؛ أجسام مضادة متعددة النسائل لـ Rabbit anti-beta-actin (Cell Signaling Technology؛ 4970S)؛ أجسام مضادة لـ Anti-NeuN (Abcam، ab190565)؛ أجسام مضادة ثانوية لـ Goat anti-mouse (LI-COR IRDye 680RD، 926-68070)؛ أجسام مضادة لـ Goat anti-rabbit (LI-COR IRDye 800RD، 926-32211)؛ أجسام مضادة لـ Donkey anti-goat IgG-HRP (Abcam، ab97110)؛ أجسام مضادة لـ Goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Cell Signaling Technology، 7076S)؛ أجسام مضادة لـ Goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Cell signaling Technology، 7074S)؛ أجسام مضادة متعددة النسائل لـ Rabbit anti-ZO-1 (Invitrogen، #61-7300)؛ أليكسا فلور 594 المرتبطة بـ donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher؛ A21207)؛ أليكسا فلور 647 المرتبطة بـ donkey anti-goat IgG (Thermo Fisher، A32849)؛ |

| التحقق | تم التحقق من جميع الأجسام المضادة التجارية من قبل الشركات المصنعة لاختبار الويسترن بلوت. بالنسبة للأجسام المضادة المنتجة داخليًا، قمنا بتأكيد وجود خطوط واضحة عند الوزن الجزيئي المتوقع مع وجود التحكم الإيجابي في التجارب. |

خطوط خلايا حقيقية النواة

معلومات السياسة حول خطوط الخلايا والجنس والنوع في البحث

الخطوط التي يتم التعرف عليها بشكل خاطئ بشكل شائع

(انظر سجل ICLAC)

لا شيء مستخدم.

الحيوانات وغيرها من الكائنات البحثية

| الحيوانات المخبرية | تم شراء إناث الفئران الحوامل من سلالة C57BL/6J (027) من مختبرات تشارلز ريفر لدراسات P0. لم يتم تحديد عمر الفئران الحوامل. تم استخدام الصغار للحقن في يوم الولادة. تم شراء نماذج الفئران المصابة بالتنكس الشبكي rd6 (003684) و rd12 (005379) من مختبر جاكسون. تم إجراء الحقن تحت الشبكية على فئران rd6 و rd12 التي تبلغ من العمر 5 أسابيع. تم الحفاظ على مرافق سكن الفئران على نظام إضاءة لمدة 12 ساعة.

|

| الحيوانات البرية | هذه الدراسة لا تشمل الحيوانات البرية. |

| التقارير عن الجنس | تم استخدام كل من ذكور وإناث الفئران لكل حالة. |

| عينات تم جمعها من الميدان | هذه الدراسة لا تتضمن عينات تم جمعها من الميدان. |

| رقابة الأخلاقيات | قدمت لجنة IACUC في معهد برود (D16-00903؛ 0048-04-15-2) ولجنة IACUC في جامعة كاليفورنيا، إيرفين (D16-00259؛ AUP-21-096) الأخلاقيات على مدار الليل لجميع التجارب التي تشمل الحيوانات الحية. |

| مخزونات البذور | غير متوفر | ||

| أنماط جينية نباتية جديدة |

|

||

| المصادقة |

|

تدفق الخلايا

المؤامرات

توضح تسميات المحاور العلامة والفلوركروم المستخدم (مثل CD4-FITC).

المقاييس على المحاور مرئية بوضوح. قم بتضمين الأرقام على المحاور فقط للرسم البياني في أسفل اليسار من المجموعة (المجموعة هي تحليل للعلامات المتطابقة).

جميع الرسوم البيانية هي رسوم بيانية متساوية الارتفاع مع نقاط شاذة أو رسوم بيانية بالألوان الزائفة.

تم توفير قيمة عددية لعدد الخلايا أو النسبة المئوية (مع الإحصائيات).

المنهجية

آلة

برمجيات

وفرة تجمع الخلايا

فرز الخلايا سوني MA900

برنامج فرز الخلايا MA900 الإصدار 3.1

في المتوسط

معهد ميركين للتقنيات التحويلية في الرعاية الصحية، معهد برود التابع لمعهد ماساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا وجامعة هارفارد، كامبريدج، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الكيمياء وعلم الأحياء الكيميائي، جامعة هارفارد، كامبريدج، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. معهد هوارد هيوز الطبي، جامعة هارفارد، كامبريدج، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. معهد غافين هيربرت لطب العيون، مركز أبحاث الرؤية الانتقالية، قسم طب العيون، جامعة كاليفورنيا، إيرفين، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الفسيولوجيا والبيوفيزيكس، جامعة كاليفورنيا، إيرفين، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الكيمياء، جامعة كاليفورنيا، إيرفين، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم البيولوجيا الجزيئية والكيمياء الحيوية، جامعة كاليفورنيا، إيرفين، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: drliu@fas.harvard.edu - بالنسبة للمخطوطات التي تستخدم خوارزميات أو برامج مخصصة تكون مركزية في البحث ولكن لم يتم وصفها بعد في الأدبيات المنشورة، يجب أن تكون البرمجيات متاحة للمحررين والمراجعين. نحن نشجع بشدة على إيداع الشيفرة في مستودع مجتمعي (مثل GitHub). راجع إرشادات مجموعة Nature لتقديم الشيفرة والبرمجيات لمزيد من المعلومات.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-02078-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38191664

Publication Date: 2024-01-08

Engineered virus-like particles for transient delivery of prime editor ribonucleoprotein complexes in vivo

Accepted: 30 November 2023

Published online: 8 January 2024

Abstract

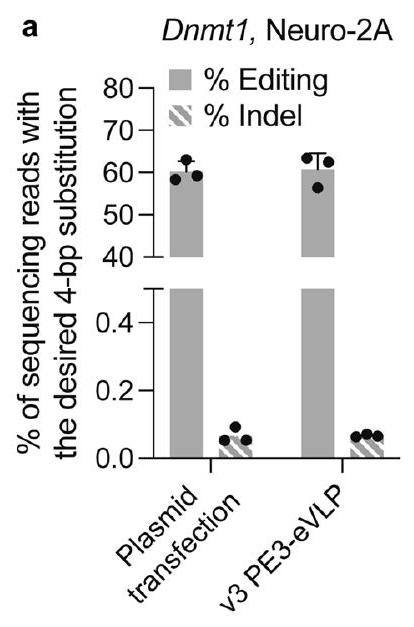

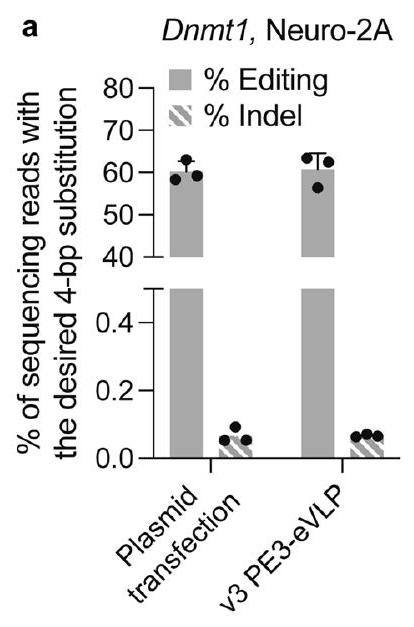

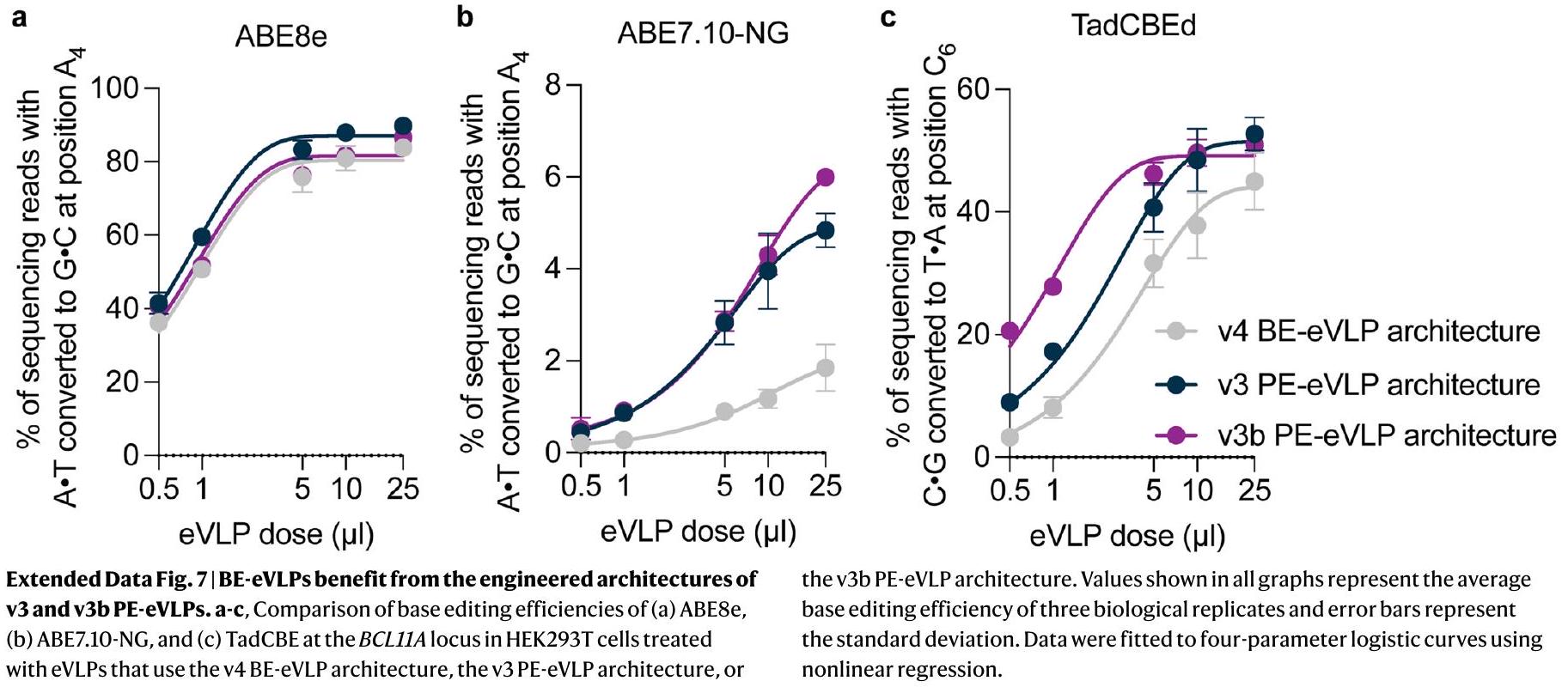

Prime editing enables precise installation of genomic substitutions, insertions and deletions in living systems. Efficient in vitro and in vivo delivery of prime editing components, however, remains a challenge. Here we report prime editor engineered virus-like particles (PE-eVLPs) that deliver prime editor proteins, prime editing guide RNAs and nicking single guide RNAs as transient ribonucleoprotein complexes. We systematically engineered v3 and v3b PE-eVLPs with 65- to 170-fold higher editing efficiency in human cells compared to a PE-eVLP construct based on our previously reported base editor eVLP architecture. In two mouse models of genetic blindness, single injections of v3 PE-eVLPs resulted in therapeutically relevant levels of prime editing in the retina, protein expression restoration and partial visual function rescue. Optimized PE-eVLPs support transient in vivo delivery of prime editor ribonucleoproteins, enhancing the potential safety of prime editing by reducing off-target editing and obviating the possibility of oncogenic transgene integration.

requires three independent nucleic acid hybridization events before editing can take place and does not rely on double-strand DNA breaks or donor DNA templates. As a result of this mechanism, prime editing is inherently resistant to off-target editing or bystander editing, and can proceed with few indel byproducts or other undesired consequences of double-strand DNA breaks

Results

Delivery of PE:pegRNA RNPs via eVLPs in cultured cells

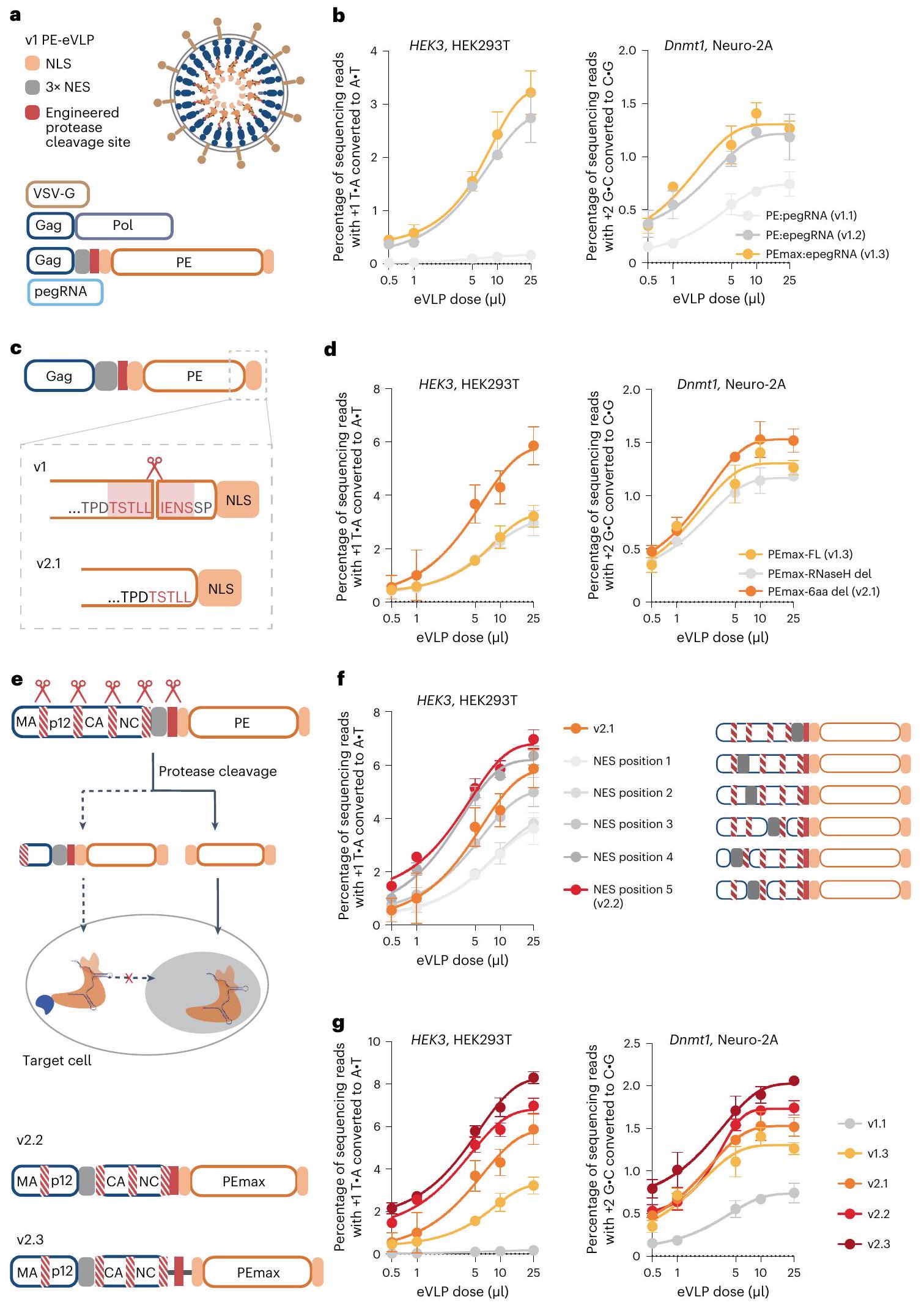

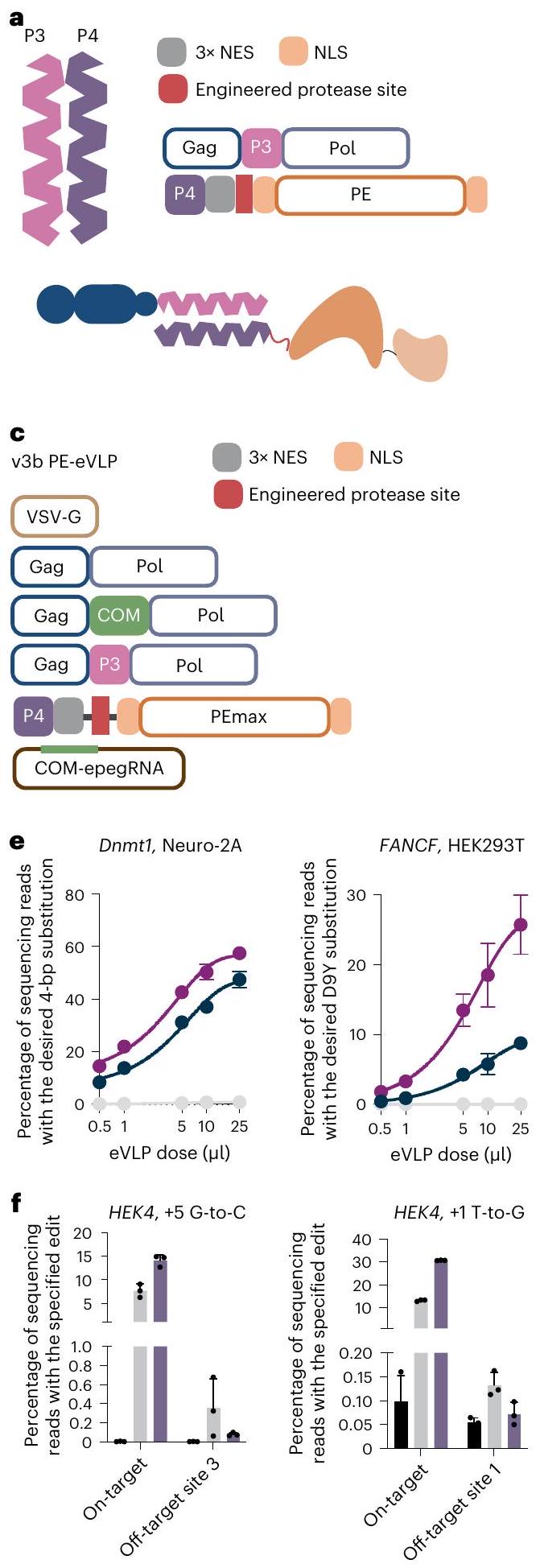

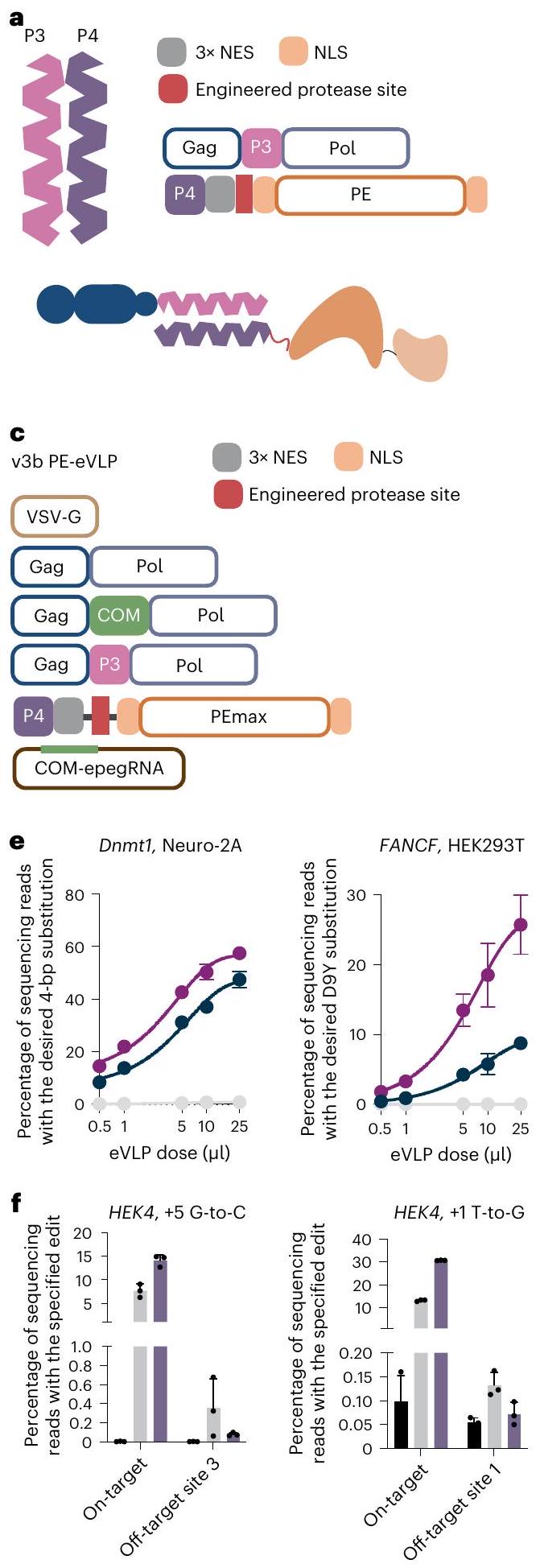

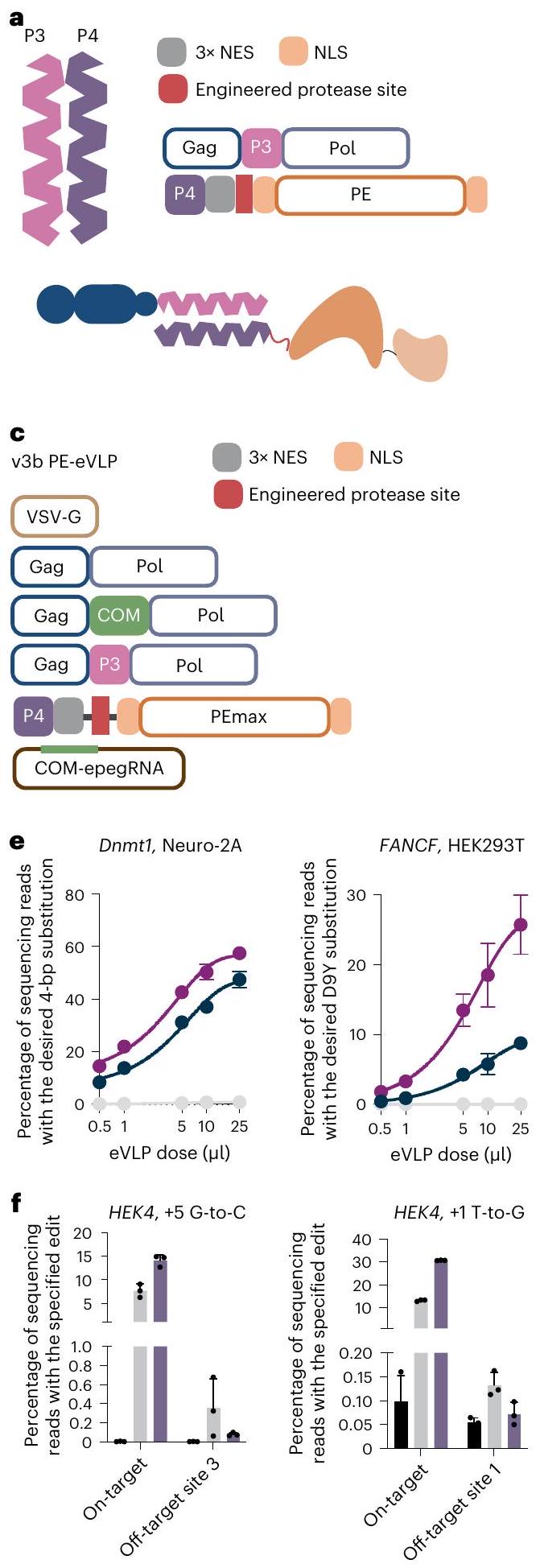

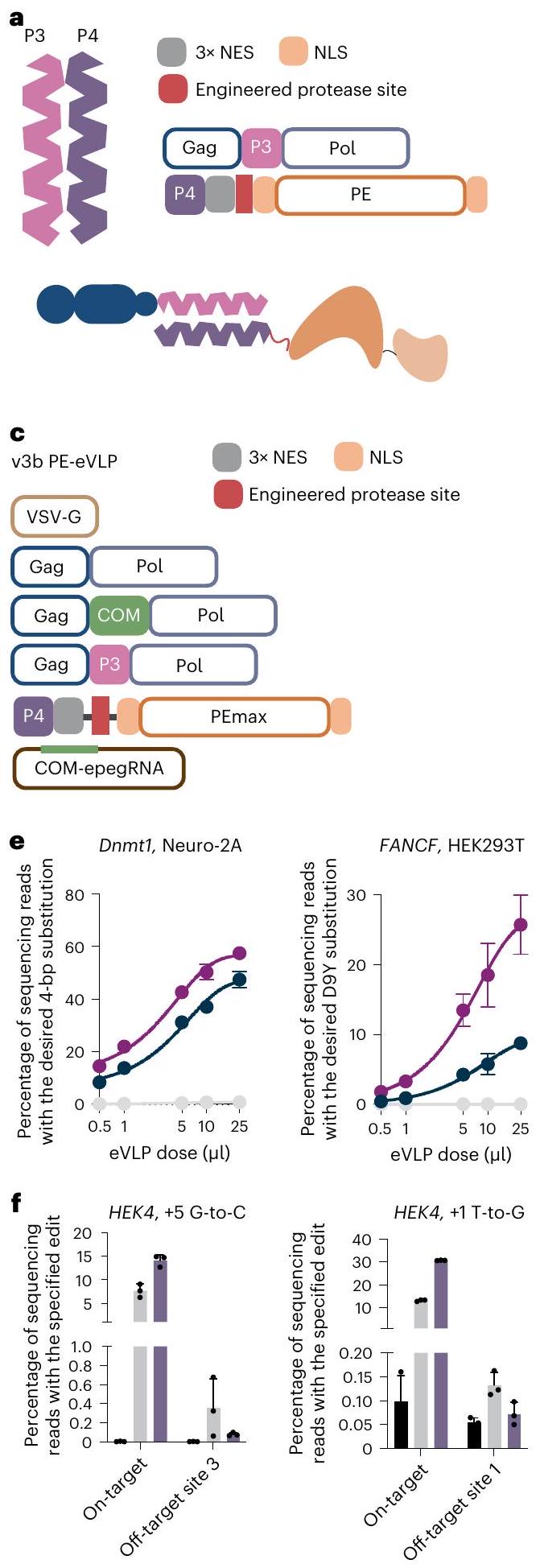

Systematic engineering of PE and eVLP architecture

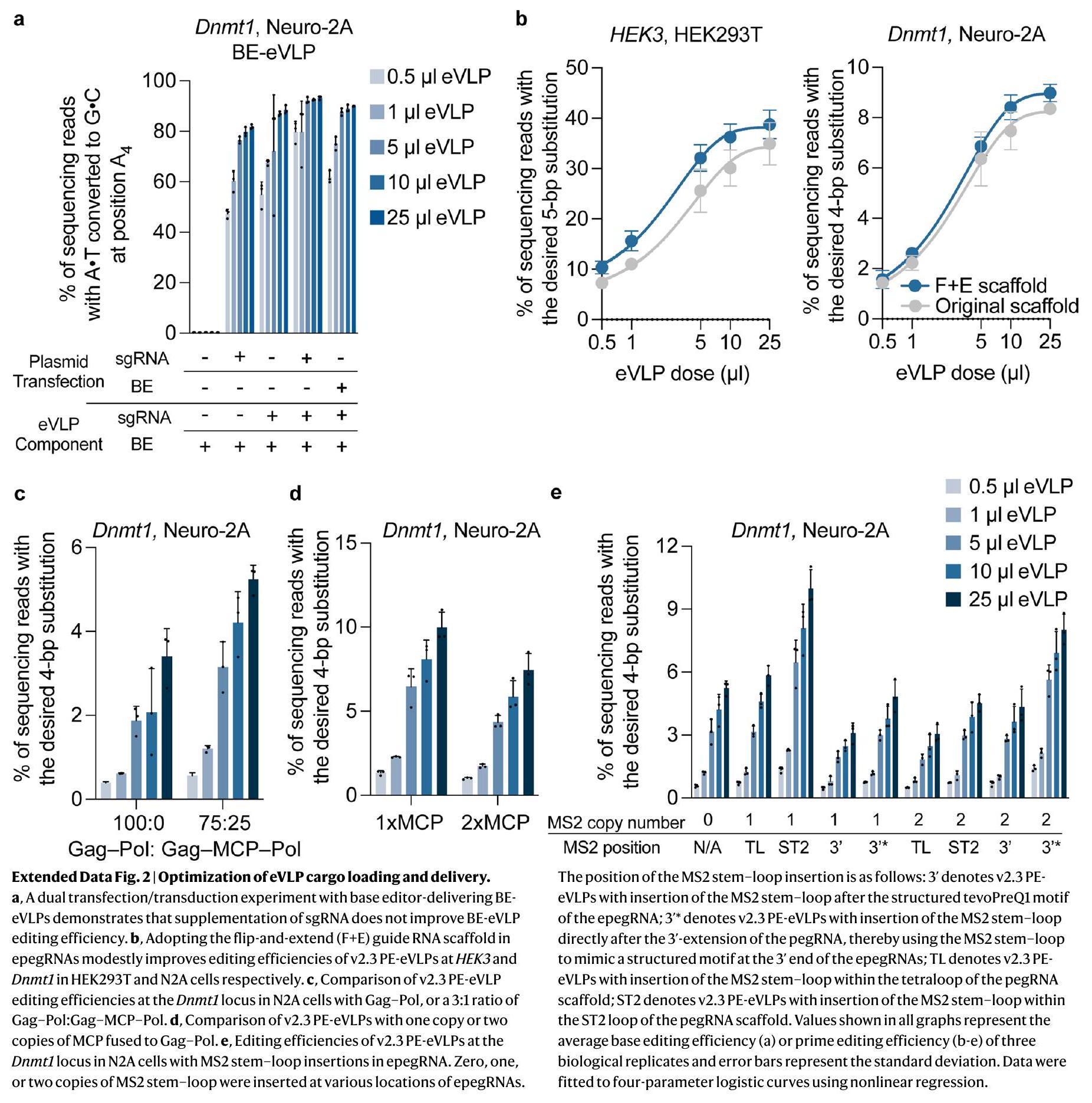

(NES position 1-5) of the Gag domain. NES position 5 (v2.2) showed improved editing compared to that of v2.1PE-eVLPs. g, Comparison of prime editing efficiencies with v1, v2.1, v2.2 and v2.3 PE-eVLPs at the HEK3 locus in HEK293T cells and Dnmt1 locus in N2A cells. Values shown in all graphs represent the mean prime editing efficiencies

varying sizes in BE-eVLPs by western blot

tested sites, inserting

(Fig. 1e) containing MMLV RT truncation, NES optimization and linker optimization showed an average 2.6 -fold and 1.6 -fold improvement in prime editing efficiency over the v1.3PE-eVLP architecture at the highest dose tested at the HEK3 locus in HEK293T cells and Dnmt1 locus in N2A cells, respectively (Fig. 1g).

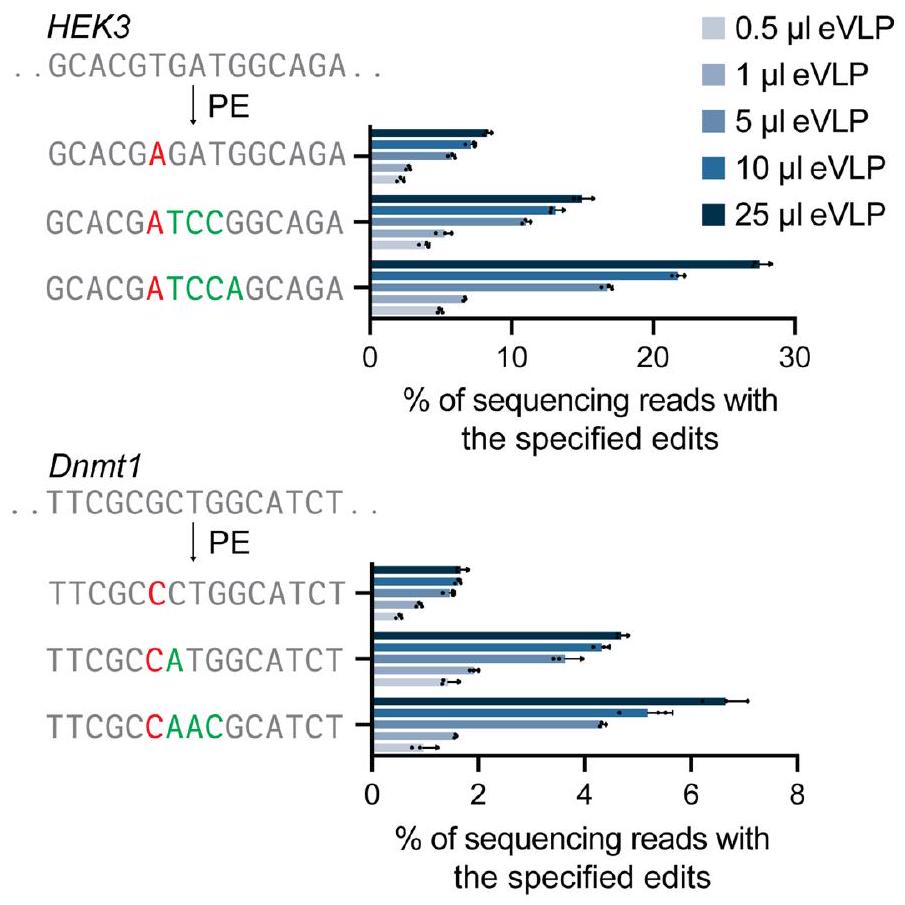

Dependence of PE-eVLP performance on edit type

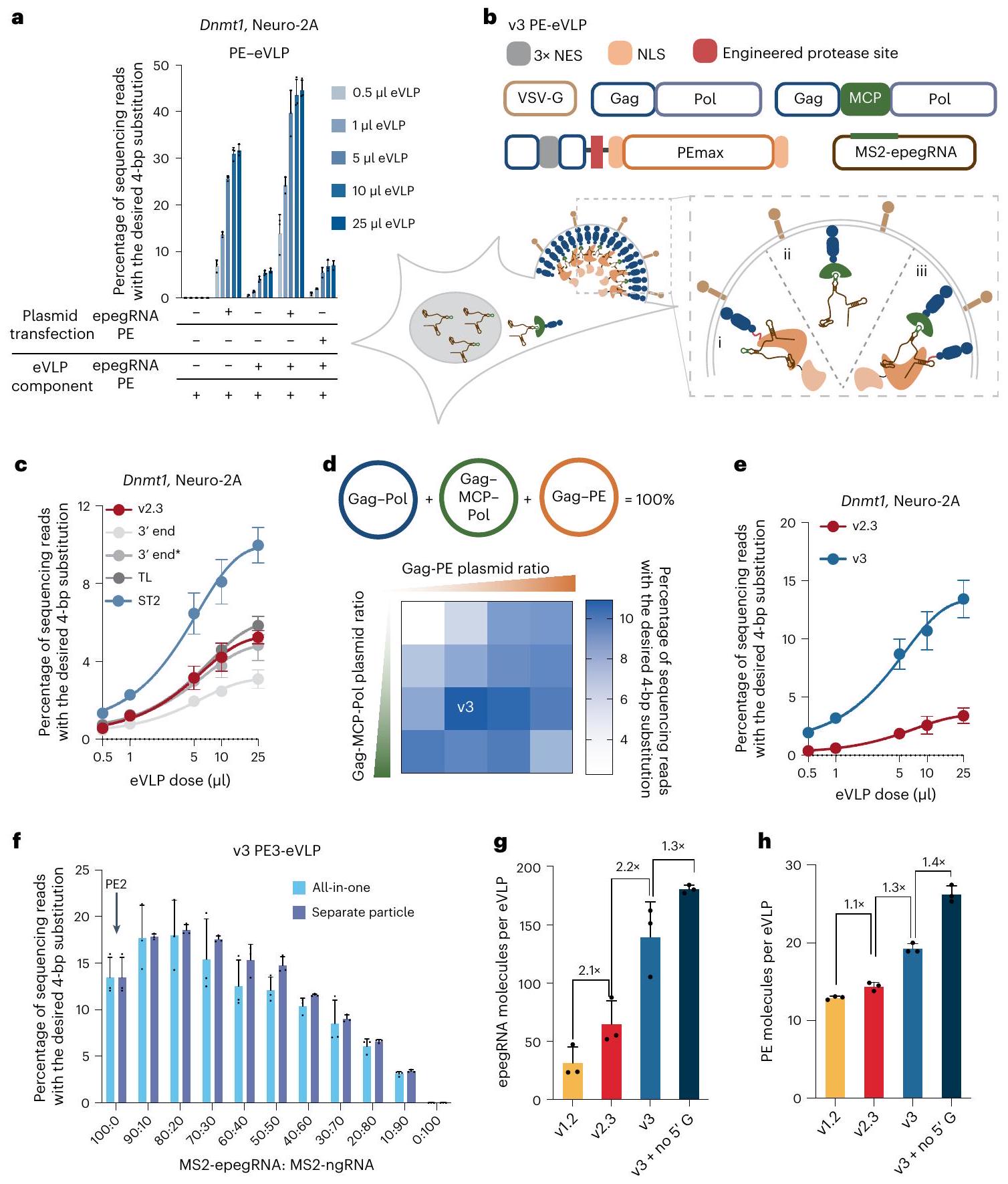

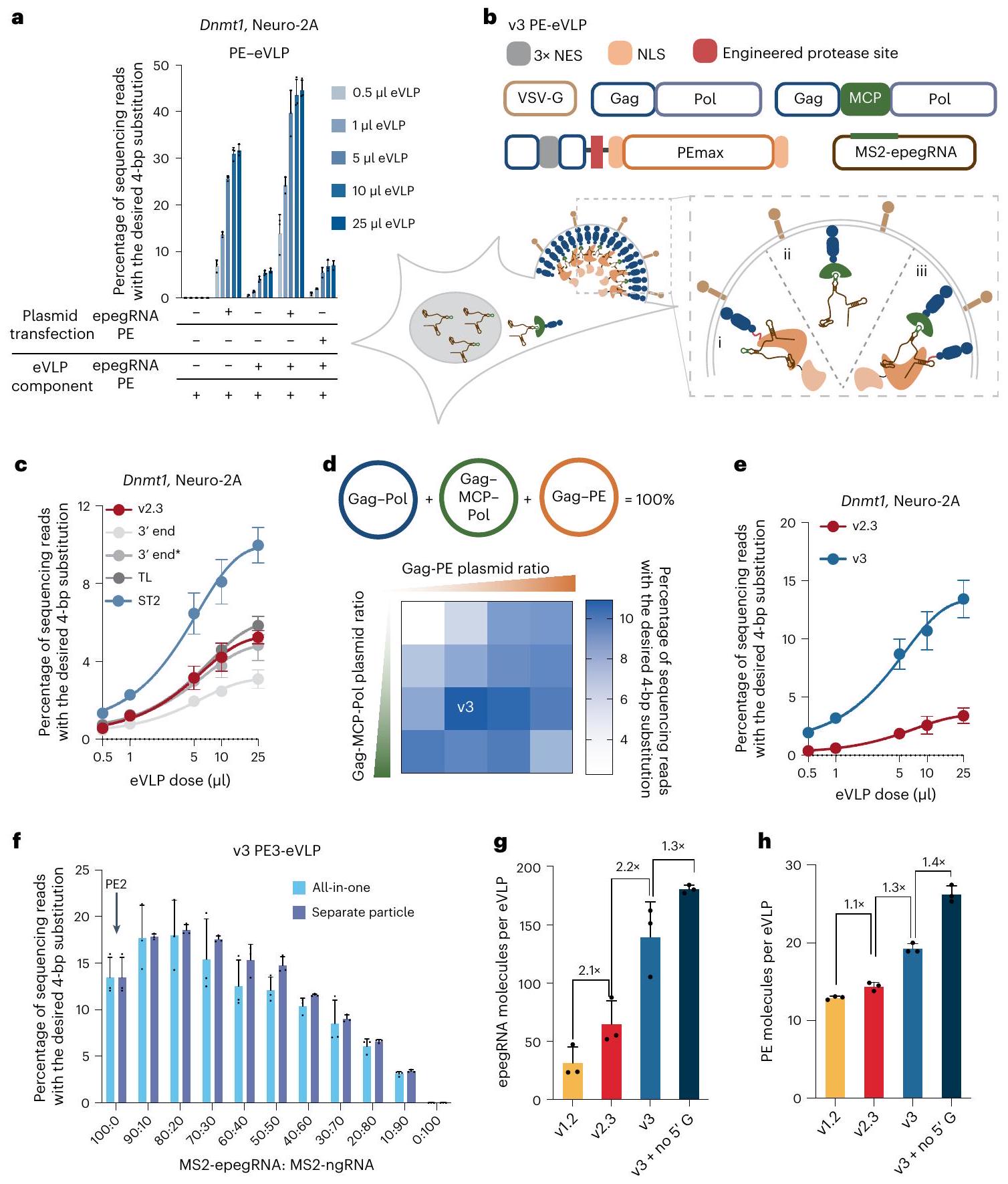

Insufficient epegRNA packaging limits PE-eVLP efficiency

PE3 further improves prime editing with PE-eVLPs

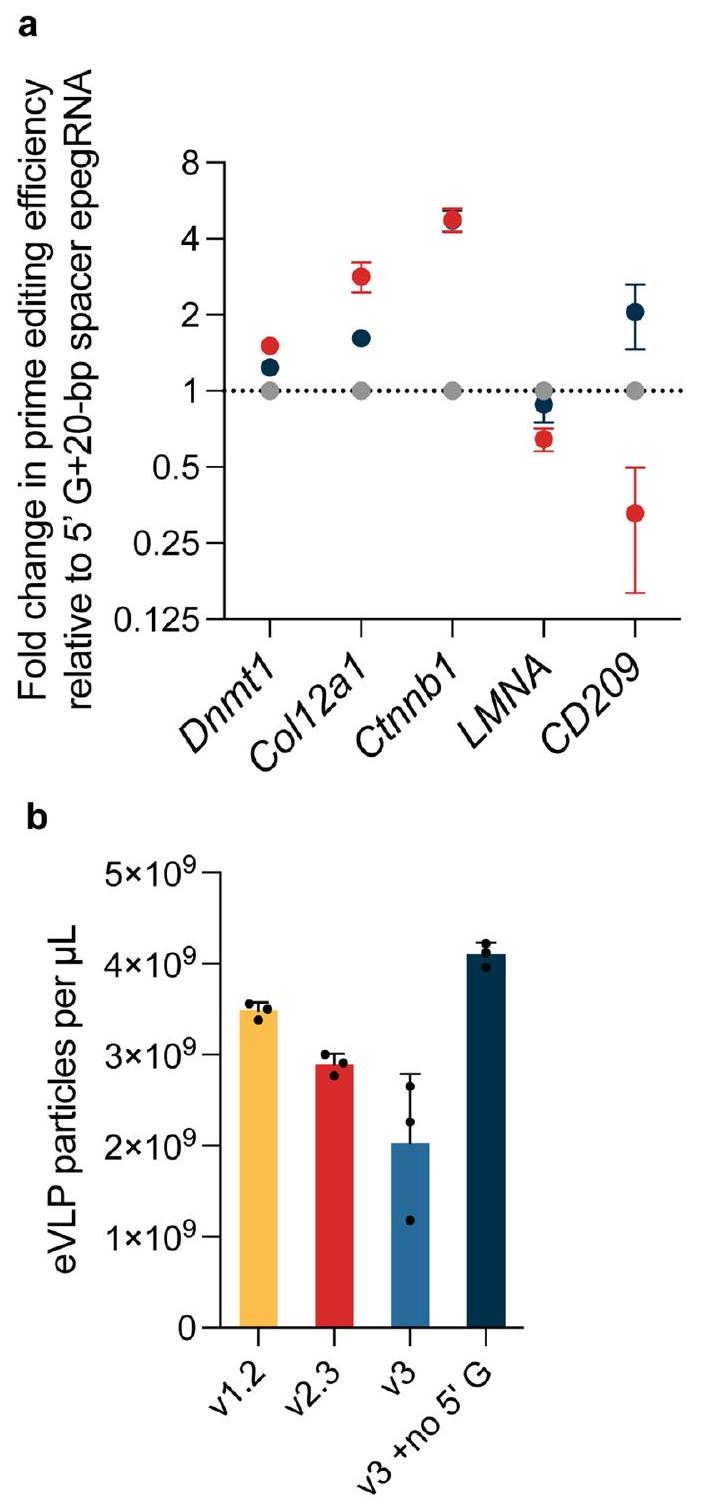

5′-G extension removal enhances editing with certain epegRNAs

For all conditions, 30,000-35,000 cells were treated with eVLPs containing

Characterization of PE-eVLP cargo loading

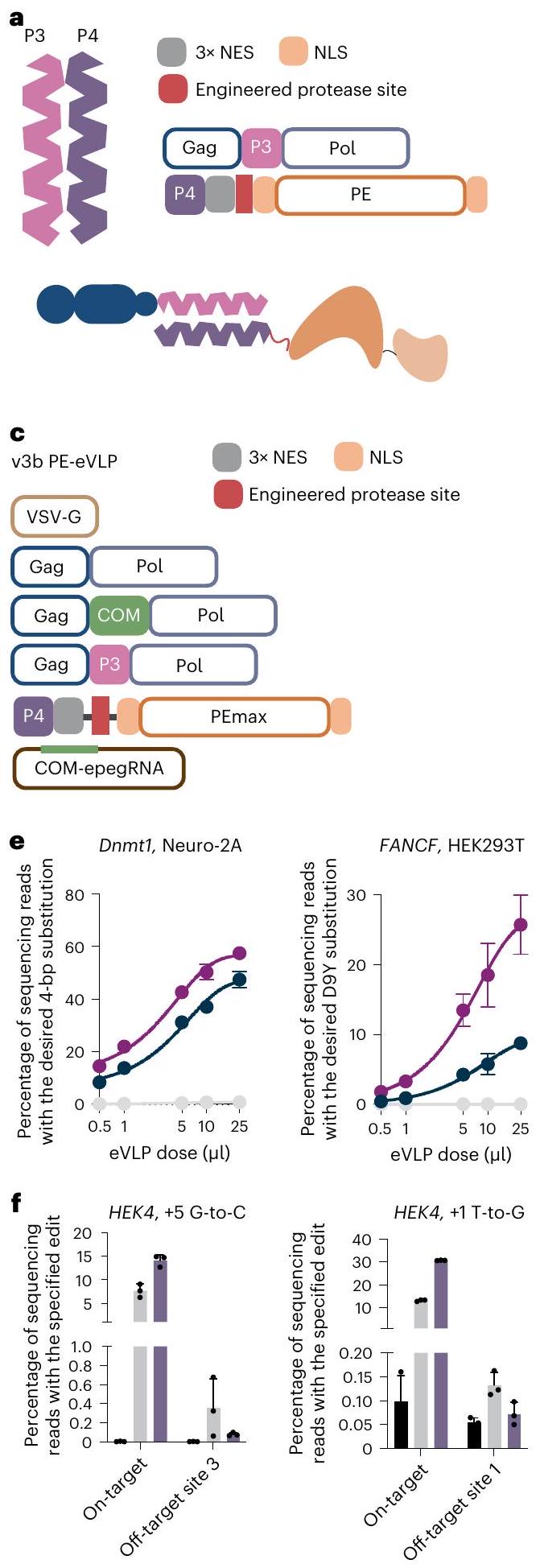

PE recruitment via coiled-coil peptide association

BE-eVLPs benefit from the engineered PE-eVLPs architecture

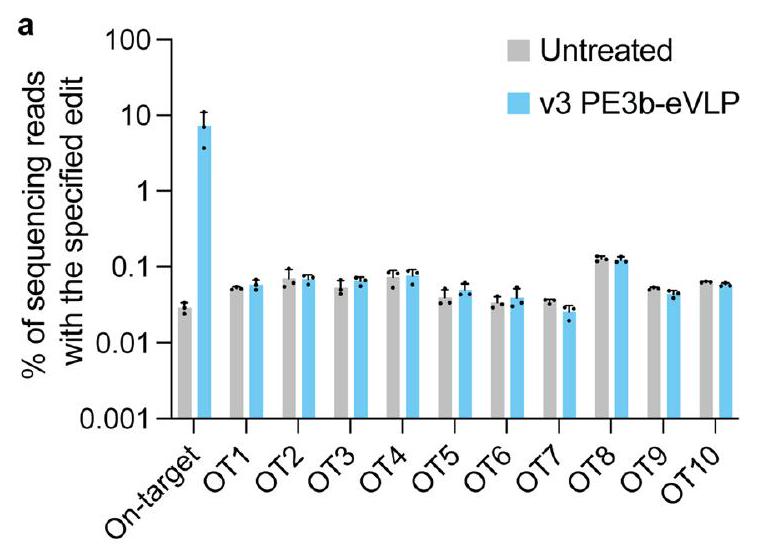

Transient delivery of PE by eVLPs reduces off-target editing

to the requirement of three distinct DNA hybridization steps for productive editing

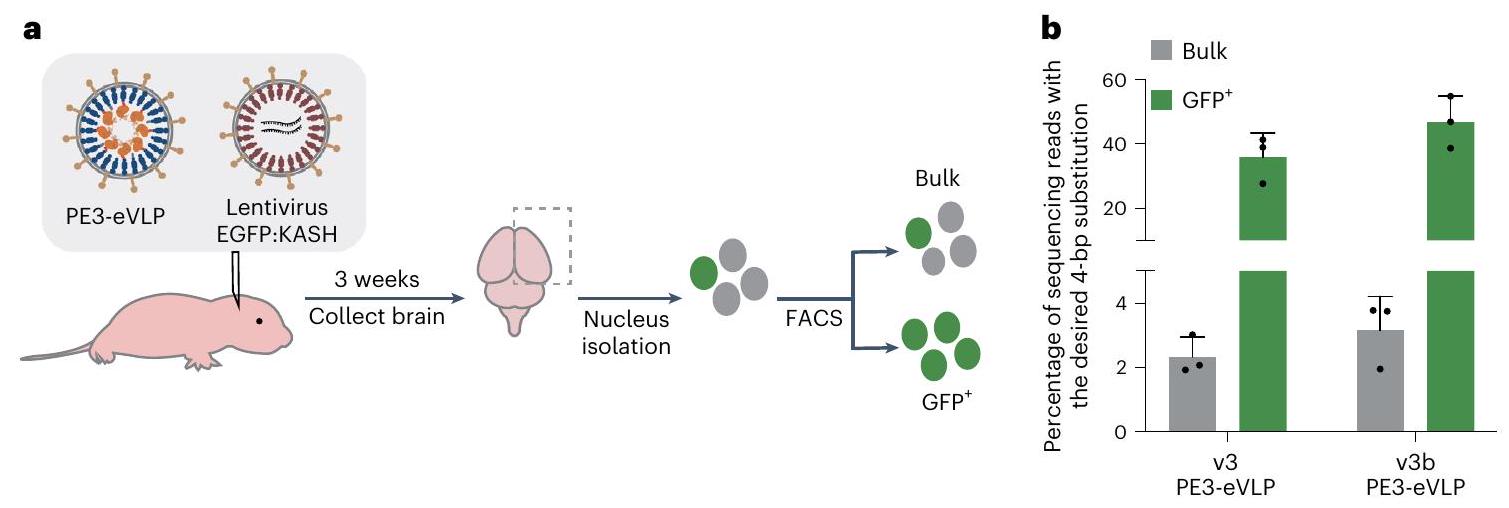

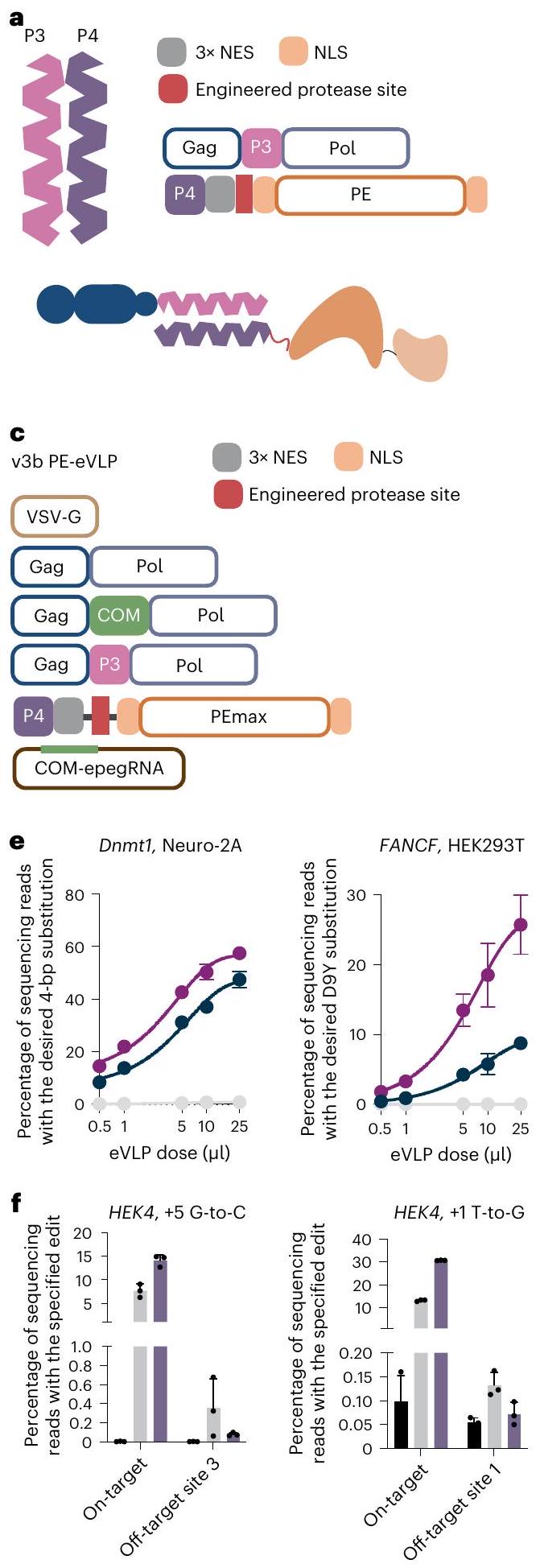

PE-eVLPs mediate potent in vivo prime editing in the brain

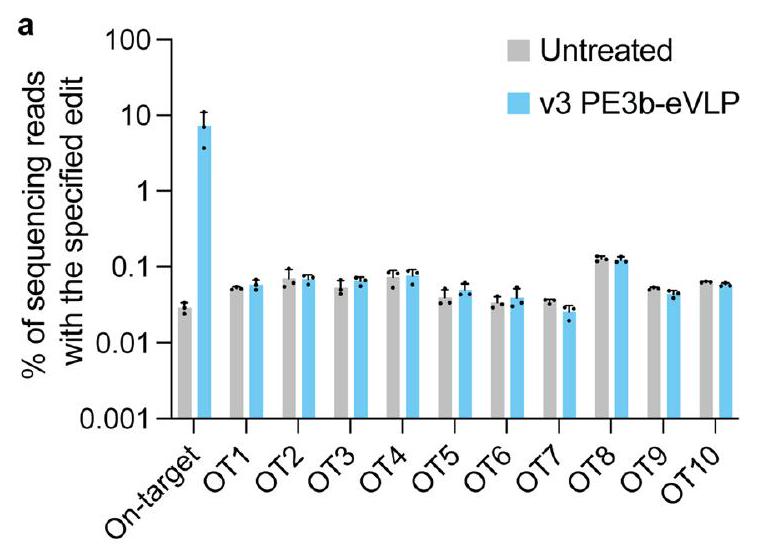

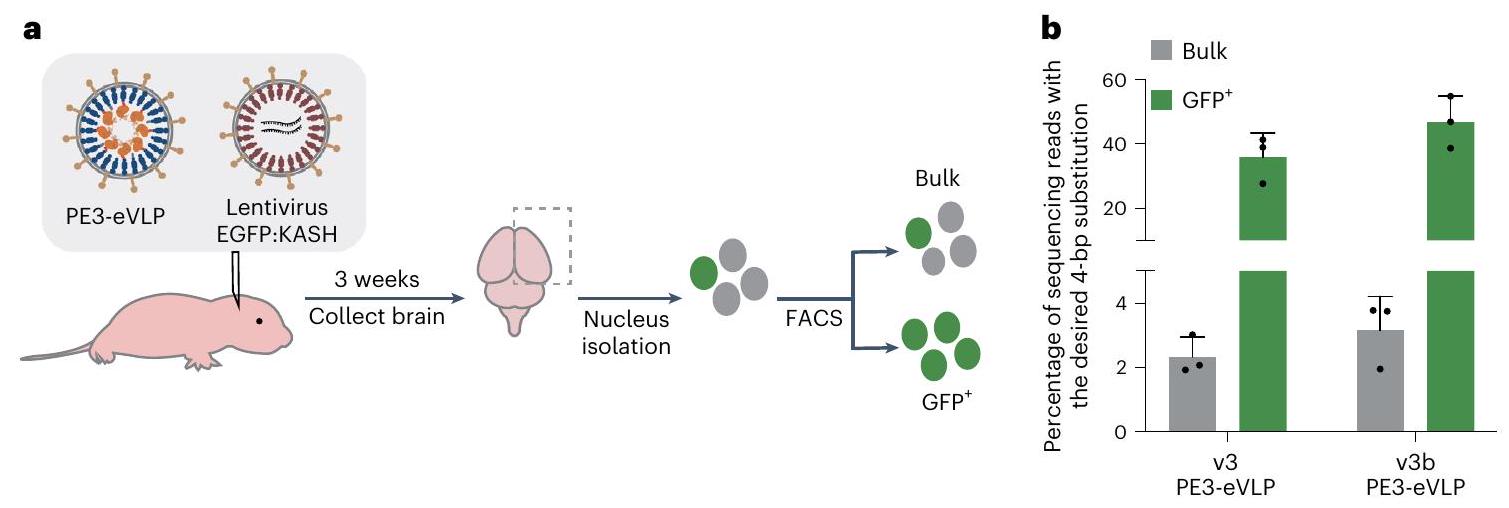

PE-eVLP corrects mutations causing retinal diseases in vivo

corresponding mutation in humans in homozygous form causes Leber congenital amaurosis

(

comparable to that achieved by high-dose dual-vector AAV-mediated PE delivery

Discussion

editing frequencies and the risk of oncogenic DNA integration

Online content

References

- Anzalone, A. V. et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149-157 (2019).

- Chen, P. J. et al. Enhanced prime editing systems by manipulating cellular determinants of editing outcomes. Cell 184, 5635-5652 e5629 (2021).

- Newby, G. A. & Liu, D. R. In vivo somatic cell base editing and prime editing. Mol. Ther. 29, 3107-3124 (2021).

- Nelson, J. W. et al. Engineered pegRNAs improve prime editing efficiency. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 402-410 (2022).

- Anzalone, A. V. et al. Programmable deletion, replacement, integration and inversion of large DNA sequences with twin prime editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 731-740 (2022).

- Choi, J. et al. Precise genomic deletions using paired prime editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 218-226 (2022).

- Doman, J. L., Sousa, A. A., Randolph, P. B., Chen, P. J. & Liu, D. R. Designing and executing prime editing experiments in mammalian cells. Nat. Protoc. 17, 2431-2468 (2022).

- Bock, D. et al. In vivo prime editing of a metabolic liver disease in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabl9238 (2022).

- Zheng, C. et al. A flexible split prime editor using truncated reverse transcriptase improves dual-AAV delivery in mouse liver. Mol. Ther. 30, 1343-1351 (2022).

- Zhi, S. et al. Dual-AAV delivering split prime editor system for in vivo genome editing. Mol. Ther. 30, 283-294 (2022).

- Qin, H. et al. Vision rescue via unconstrained in vivo prime editing in degenerating neural retinas. J. Exp. Med. https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem. 20220776 (2023).

- Gao, R. et al. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of prime editing guide RNA-independent off-target effects by prime editors. CRISPR J. 5, 276-293 (2022).

- Kim, D. Y., Moon, S. B., Ko, J. H., Kim, Y. S. & Kim, D. Unbiased investigation of specificities of prime editing systems in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 10576-10589 (2020).

- Liu, Y. et al. Efficient generation of mouse models with the prime editing system. Cell Discov. 6, 27 (2020).

- Schene, I. F. et al. Prime editing for functional repair in patient-derived disease models. Nat. Commun. 11, 5352 (2020).

- Geurts, M. H. et al. Evaluating CRISPR-based prime editing for cancer modeling and CFTR repair in organoids. Life Sci. Alliance https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa. 202000940 (2021).

- Park, S. J. et al. Targeted mutagenesis in mouse cells and embryos using an enhanced prime editor. Genome Biol. 22, 170 (2021).

- Gao, P. et al. Prime editing in mice reveals the essentiality of a single base in driving tissue-specific gene expression. Genome Biol. 22, 83 (2021).

- Lin, J. et al. Modeling a cataract disorder in mice with prime editing. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 25, 494-501 (2021).

- Jin, S. et al. Genome-wide specificity of prime editors in plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1292-1299 (2021).

- Habib, O., Habib, G., Hwang, G. H. & Bae, S. Comprehensive analysis of prime editing outcomes in human embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 1187-1197 (2022).

- She, K. et al. Dual-AAV split prime editor corrects the mutation and phenotype in mice with inherited retinal degeneration. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 8, 57 (2023).

- Jang, H. et al. Application of prime editing to the correction of mutations and phenotypes in adult mice with liver and eye diseases. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 181-194 (2022).

- Liu, B. et al. A split prime editor with untethered reverse transcriptase and circular RNA template. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1388-1393 (2022).

- Davis, J. R. et al. Efficient prime editing in mouse brain, liver and heart with dual AAVs. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41587-023-01758-z (2023).

- Wu, Z., Yang, H. & Colosi, P. Effect of genome size on AAV vector packaging. Mol. Ther. 18, 80-86 (2010).

- Davis, J. R. et al. Efficient in vivo base editing via single adeno-associated viruses with size-optimized genomes encoding compact adenine base editors. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 1272-1283 (2022).

- Taha, E. A., Lee, J. & Hotta, A. Delivery of CRISPR-Cas tools for in vivo genome editing therapy: trends and challenges. J. Control. Release 342, 345-361 (2022).

- Chandler, R. J., Sands, M. S. & Venditti, C. P. Recombinant adeno-associated viral integration and genotoxicity: insights from animal models. Hum. Gene Ther. 28, 314-322 (2017).

- Kazemian, P. et al. Lipid-nanoparticle-based delivery of CRISPR/ Cas9 genome-editing components. Mol. Pharm. 19, 1669-1686 (2022).

- Loughrey, D. & Dahlman, J. E. Non-liver mRNA delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 13-23 (2022).

- Breda, L. et al. In vivo hematopoietic stem cell modification by mRNA delivery. Science 381, 436-443 (2023).

- Raguram, A., Banskota, S. & Liu, D. R. Therapeutic in vivo delivery of gene editing agents. Cell 185, 2806-2827 (2022).

- Lyu, P., Wang, L. & Lu, B. Virus-like particle mediated CRISPR/Cas9 delivery for efficient and safe genome editing. Life https://doi.org/ 10.3390/life10120366 (2020).

- Garnier, L., Wills, J. W., Verderame, M. F. & Sudol, M. WW domains and retrovirus budding. Nature 381, 744-745 (1996).

- Choi, J. G. et al. Lentivirus pre-packed with Cas9 protein for safer gene editing. Gene Ther. 23, 627-633 (2016).

- Campbell, L. A. et al. Gesicle-mediated delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex for inactivating the HIV provirus. Mol. Ther. 27, 151-163 (2019).

- Lyu, P., Javidi-Parsijani, P., Atala, A. & Lu, B. Delivering Cas9/ sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) by lentiviral capsid-based bionanoparticles for efficient ‘hit-and-run’ genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, e99 (2019).

- Mangeot, P. E. et al. Genome editing in primary cells and in vivo using viral-derived Nanoblades loaded with Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoproteins. Nat. Commun. 10, 45 (2019).

- Gee, P. et al. Extracellular nanovesicles for packaging of CRISPRCas9 protein and sgRNA to induce therapeutic exon skipping. Nat. Commun. 11, 1334 (2020).

- Indikova, I. & Indik, S. Highly efficient ‘hit-and-run’ genome editing with unconcentrated lentivectors carrying Vpr.Prot.Cas9 protein produced from RRE-containing transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 8178-8187 (2020).

- Hamilton, J. R. et al. Targeted delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 and transgenes enables complex immune cell engineering. Cell Rep. 35, 109207 (2021).

- Yao, X. et al. Engineered extracellular vesicles as versatile ribonucleoprotein delivery vehicles for efficient and safe CRISPR genome editing. J. Extracell. Vesicles 10, e12076 (2021).

- Banskota, S. et al. Engineered virus-like particles for efficient in vivo delivery of therapeutic proteins. Cell 185, 250-265 e216 (2022).

- Zuris, J. A. et al. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 73-80 (2015).

- Rees, H. A. et al. Improving the DNA specificity and applicability of base editing through protein engineering and protein delivery. Nat. Commun. 8, 15790 (2017).

- Tozser, J. Comparative studies on retroviral proteases: substrate specificity. Viruses 2, 147-165 (2010).

- Lim, K. I., Klimczak, R., Yu, J. H. & Schaffer, D. V. Specific insertions of zinc finger domains into Gag-Pol yield engineered retroviral vectors with selective integration properties. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12475-12480 (2010).

- Dhindsa, R. S. et al. A minimal role for synonymous variation in human disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 109, 2105-2109 (2022).

- Kruglyak, L. et al. Insufficient evidence for non-neutrality of synonymous mutations. Nature 616, E8-E9 (2023).

- Chen, B. et al. Dynamic imaging of genomic loci in living human cells by an optimized CRISPR/Cas system. Cell 155, 1479-1491 (2013).

- Bernardi, A. & Spahr, P. F. Nucleotide sequence at the binding site for coat protein on RNA of bacteriophage R17. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 69, 3033-3037 (1972).

- Lu, Z. et al. Lentiviral capsid-mediated Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 ribonucleoprotein delivery for efficient and safe multiplex genome editing. CRISPR J. 4, 914-928 (2021).

- Lyu, P. et al. Adenine base editor ribonucleoproteins delivered by lentivirus-like particles show high on-target base editing and undetectable RNA off-target activities. CRISPR J. 4, 69-81 (2021).

- Feng, Y. et al. Enhancing prime editing efficiency and flexibility with tethered and split pegRNAs. Protein Cell 14, 304-308 (2023).

- Chen, R. et al. Enhancement of a prime editing system via optimal recruitment of the pioneer transcription factor P65. Nat. Commun. 14, 257 (2023).

- Ma, H. et al. Pol III promoters to express small RNAs: delineation of transcription initiation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 3, e161 (2014).

- Kulcsar, P. I. et al. Blackjack mutations improve the on-target activities of increased fidelity variants of SpCas9 with 5’G-extended sgRNAs. Nat. Commun. 11, 1223 (2020).

- Mullally, G. et al. 5′ modifications to CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA can change the dynamics and size of R-loops and inhibit DNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 6811-6823 (2020).

- Mason, J. M. & Arndt, K. M. Coiled coil domains: stability, specificity, and biological implications. ChemBioChem 5, 170-176 (2004).

- Lebar, T., Lainscek, D., Merljak, E., Aupic, J. & Jerala, R. A tunable orthogonal coiled-coil interaction toolbox for engineering mammalian cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 513-519 (2020).

- Richter, M. F. et al. Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 883-891 (2020).

- Gaudelli, N. M. et al. Programmable base editing of

to in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464-471 (2017). - Neugebauer, M. E. et al. Evolution of an adenine base editor into a small, efficient cytosine base editor with low off-target activity. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01533-6 (2022).

- Cameron, P. et al. Mapping the genomic landscape of CRISPRCas9 cleavage. Nat. Methods 14, 600-606 (2017).

- Liang, S. Q. et al. Genome-wide profiling of prime editor off-target sites in vitro and in vivo using PE-tag. Nat. Methods https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-023-01859-2 (2023).

- Farhy-Tselnicker, I. & Allen, N. J. Astrocytes, neurons, synapses: a tripartite view on cortical circuit development. Neural Dev. 13, 7 (2018).

- Semple, B. D., Blomgren, K., Gimlin, K., Ferriero, D. M. & Noble-Haeusslein, L. J. Brain development in rodents and humans: Identifying benchmarks of maturation and vulnerability to injury across species. Prog. Neurobiol. 106-107, 1-16 (2013).

- Gusel’nikova, V. V. & Korzhevskiy, D. E. NeuN as a neuronal nuclear antigen and neuron differentiation marker. Acta Naturae 7, 42-47 (2015).

- Kato, S. et al. Selective neural pathway targeting reveals key roles of thalamostriatal projection in the control of visual discrimination. J. Neurosci. 31, 17169-17179 (2011).

- Kameya, S. et al. Mfrp, a gene encoding a frizzled related protein, is mutated in the mouse retinal degeneration 6. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 1879-1886 (2002).

- Ayala-Ramirez, R. et al. A new autosomal recessive syndrome consisting of posterior microphthalmos, retinitis pigmentosa,

foveoschisis, and optic disc drusen is caused by a MFRP gene mutation. Mol. Vis. 12, 1483-1489 (2006). - Yan, A. L., Du, S. W. & Palczewski, K. Genome editing, a superior therapy for inherited retinal diseases. Vision Res. 206, 108192 (2023).

- Puppo, A. et al. Retinal transduction profiles by high-capacity viral vectors. Gene Ther. 21, 855-865 (2014).

- Suh, S. et al. Restoration of visual function in adult mice with an inherited retinal disease via adenine base editing. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 169-178 (2021).

- Tsai, S. Q. et al. CIRCLE-seq: a highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat. Methods 14, 607-614 (2017).

- Pang, J. J. et al. Retinal degeneration 12 (rd12): a new, spontaneously arising mouse model for human Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). Mol. Vis. 11, 152-162 (2005).

- Zhong, Z. et al. Seven novel variants expand the spectrum of RPE65-related Leber congenital amaurosis in the Chinese population. Mol. Vis. 25, 204-214 (2019).

- Dong, W. & Kantor, B. Lentiviral vectors for delivery of gene-editing systems based on CRISPR/Cas: current state and perspectives. Viruses https://doi.org/10.3390/v13071288 (2021).

- Schellekens, H. Bioequivalence and the immunogenicity of biopharmaceuticals. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1, 457-462 (2002).

© The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Molecular cloning

Cell culture

PE-eVLP production

PE-eVLP transduction in cultured cells and genomic DNA collection

cellular genomic DNA was collected 72 h after transduction as previously described

HTS of genomic DNA samples

HTS data analysis

Plasmid transfection

PE-eVLP protein content quantification by ELISA

concentrated via ultracentrifugation as described above for optimal detection of protein. A total of

PE-eVLP pegRNA content quantification by RT-qPCR

DLS

Western blot analysis of producer cell lysate protein content

deoxycholic acid, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100,

Western blot analysis of PE-eVLP protein content

Off-target analysis in cultured cells

or deletions at the off-target Cas9 nick sites were quantified as a percentage of (discarded reads)/(the total reference-aligned reads). Total off-target editing is calculated as (pegRNA-mediated off-target editing frequency) + (indel frequency at the Cas9 nick site).

Lentivirus production

Animals

POICV injections and tissue collection

Nuclear isolation and sorting

Subretinal injection

Electroretinography

RPE dissociation and genomic DNA and RNA preparation

Western blot analysis of mouse RPE tissue extracts

Immunohistochemistry of RPE flatmounts and cryosections

CIRCLE-seq nomination of off-target sites for the

Statistics and reproducibility

Reporting summary

Data availability

of the PE-eVLP architecture are provided in Supplementary Information. The following key plasmids from this work are deposited to Addgene for distribution: Gag-MCP-Pol (Addgene #211370), Gag-PE (Addgene #211371), MS2-epegRNA-Dnmt1 (Addgene #211372), Gag-COM-Pol (Addgene #211373), Gag-PE3-Pol (#211374), P4-PE (#211375), COM-epegRNA-Dnmt1 (#211376). Other plasmids and raw data are available from the corresponding author on request. Unmodified image of the western blots shown in Fig. 5d,k are provided as Source data. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

References

- Renner, T. M., Tang, V. A., Burger, D. & Langlois, M. A. Intact viral particle counts measured by flow virometry provide insight into the infectivity and genome packaging efficiency of Moloney Murine Leukemia virus. J. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01600-19 (2020).

- Levy, J. M. et al. Cytosine and adenine base editing of the brain, liver, retina, heart and skeletal muscle of mice via adeno-associated viruses. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 97-110 (2020).

- Golczak, M., Kiser, P. D., Lodowski, D. T., Maeda, A. & Palczewski, K. Importance of membrane structural integrity for RPE65 retinoid isomerization activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9667-9682 (2010).

- Lazzarotto, C. R. et al. CHANGE-seq reveals genetic and epigenetic effects on CRISPR-Cas9 genome-wide activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1317-1327 (2020).

- circleseq. GitHub https://github.com/tsailabSJ/circleseq (2018)

- An, M. et al. Engineered virus-like particles for transient delivery of prime editor ribonucleoprotein complexes in vivo. NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA980181 (2023).

Acknowledgements

advice and assistance with mouse husbandry. We thank J. Doman, S. DeCarlo, P. Randolph, A. Yan and A. Tworak for helpful discussions. This article is subject to HHMI’s Open Access to Publications policy. HHMI lab heads have previously granted a nonexclusive CC BY 4.0 license to the public and a sublicensable license to HHMI in their research articles. Pursuant to those licenses, the author-accepted manuscript of this article can be made freely available under a CC BY 4.0 license immediately upon publication.

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-02078-y.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-02078-y.

editing efficiency of three biological replicates and error bars represent the standard deviation. Data were fitted to four-parameter logistic curves using nonlinear regression.

- 5′ G+20-bp GTGACTTCCATGGTTCCACAA

- 20-bp TGACTTCCATGGTTCCACAA

- 5 ‘ G+19-bp GGACTTCCATGGTTCCACAA

experiments to determine the number of prime editor protein and epegRNA molecules per eVLP shown in Fig. 2g,h. c, Percentage of epegRNA and ngRNA composition in v3 PE2-eVLPs and v3 PE3-eVLPs. Data represent the average value of three technical replicates and error bars represent the standard deviation.

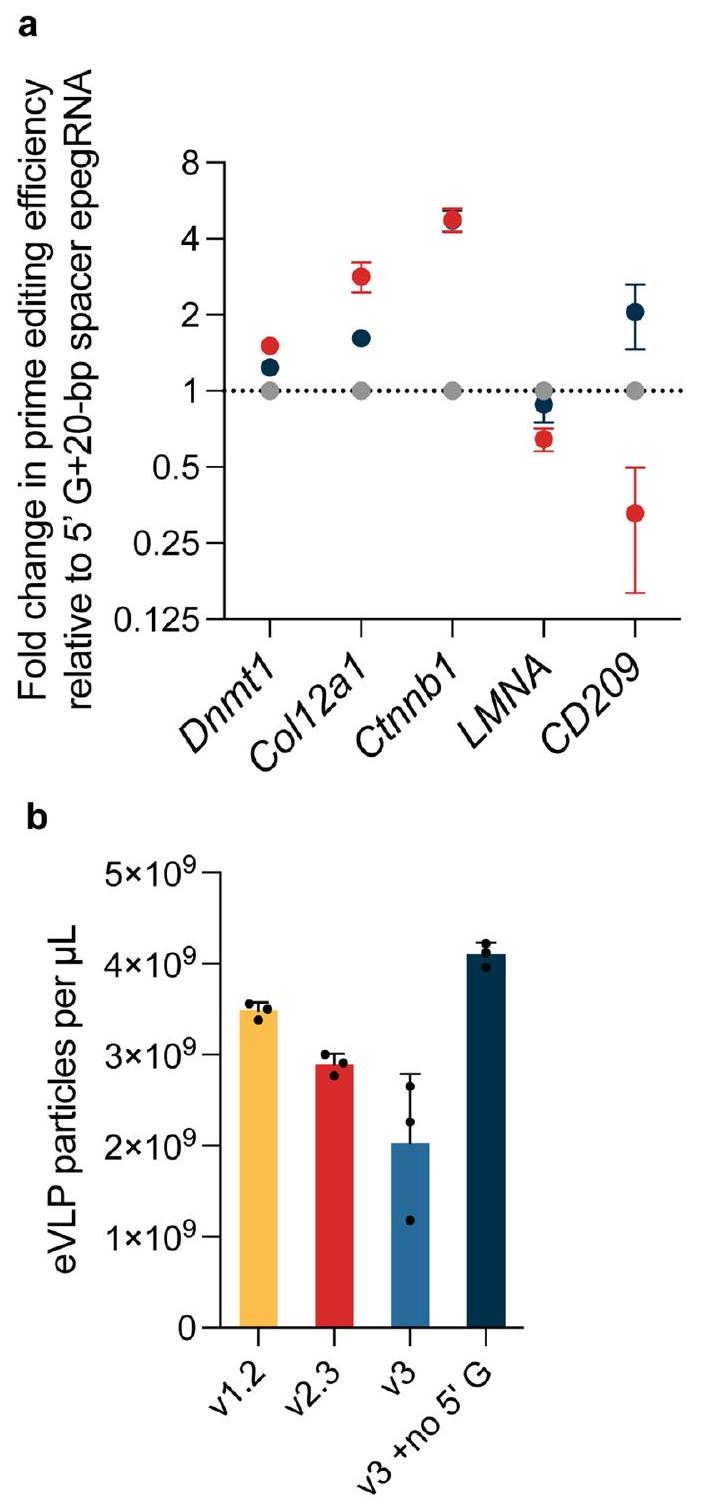

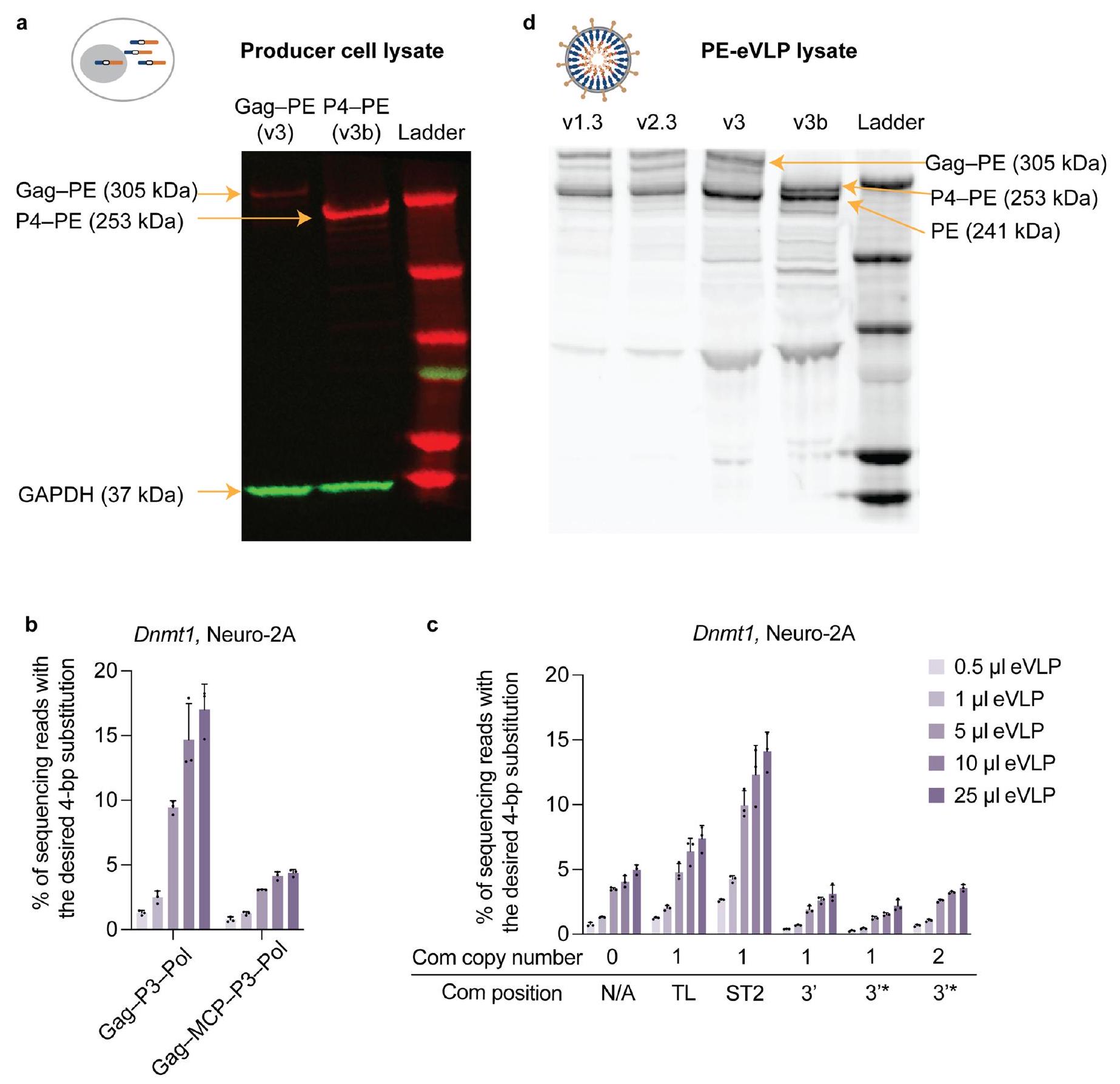

a, Representative western blot comparing expression of the gag-PE fusion protein from v3 PE-eVLPs versus the P4-PE fusion protein from v3b PE-eVLPs in producer cells transfected with the corresponding fusion proteins. b, Prime editing efficiencies of v3b PE-eVLPs with Gag-P3-Pol or Gag-MCP-P3-Pol. The Gag-MCP-P3-Pol fusion construct is not compatible with the efficient production of PE-eVLPs. c, Editing efficiencies of v3b PE-eVLPs at the Dnmt1 locus in N2A cells with the Com aptamer inserted at various locations in the epegRNAs. The position of the Com aptamer insertion is as follows:

epegRNA; 3 * denotes v3b PE-eVLPs with insertion of the Com aptamer directly after the 3′-extension of the pegRNA, thereby using the Com aptamer to mimic a structured motif at the 3 ‘ end of epegRNAs; TL denotes v3b PE-eVLPs with insertion of the Com aptamer within the tetraloop of the pegRNA scaffold; ST2 denotes v3b PE-eVLPs with insertion of the Com aptamer within the ST2 loop of the pegRNA scaffold. d, Representative western blot evaluating the amount of PE cargo packaged in v1.3, v2.3, v3 and v3b PE-eVLPs. Figures shown in (a) and (d) are representative images from two independently repeated experiments. Values shown in (b) and (c) represent the average prime editing efficiency of three biological replicates and error bars represent the standard deviation.

b

| Accessory proteins | Cargo proteins | Guide RNAs | Improvements from the previous version | |||

| v1.1 | N/A |  |

pegRNA | |||

| v1.2 | N/A |  |

epegRNA | epegRNA | ||

| v1.3 | N/A |  |

epegRNA | PEmax | ||

| v2.1 | N/A |  |

epegRNA | MMLV RT truncation | ||

| v2.2 | N/A |  |

NES optimization | |||

| v2.3 | N/A |  |

epegRNA | Linker optimization | ||

| v3 |  |

|

|

gRNA recruitment via MCP:MS2 interaction | ||

| v3b |  |

|

|

Cargo recruitment via P3-P4 interaction; gRNA recruitment via COM:Com interaction |

*Schematics shown in the table represent PE2-eVLPs. For PE3-eVLPs, additional ngRNAs are pacakged.

all versions of PE-eVLPs are omitted from the table. Schematics shown in the table represent PE2-eVLPs. For PE3-eVLPs, additional ngRNAs are packaged at a ratio of 4:1 for pegRNAs and ngRNAs with corresponding scaffold modification and aptamer insertion.

a, Single nucleus was gated based on forward scatter (FSC-A) and back scatter (BCS-A) ratios and DyeCycle Ruby signal. GFP-positive nuclei were gated based on the FITC signal. The first row displays representative FACS data for untreated samples and the second row displays representative FACS data for cortex samples harvested from neonatal mice co-injected with

sorting. Single nucleus was gated based on forward scatter (FSC-A) and back scatter (BCS-A) ratios and DAPI signal. The signal from Alexa 647-conjugated NeuN antibody distinguishes NeuN-positive and NeuN-negative populations. GFP-positive nuclei were gated based on FITC signal in both NeuN-positive and NeuN-negative populations. Gates displayed represent FACS data for midbrain samples harvested from neonatal mice co-injected with

b

associated with the rd12ngRNA sequence. Bars represent average values for

natureportfolio

Last updated by author(s): Nov 16, 2023

Reporting Summary

Statistics

X The exact sample size (

X The statistical test(s) used AND whether they are one- or two-sided

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

X A description of all covariates tested

凶

A full description of the statistical parameters including central tendency (e.g. means) or other basic estimates (e.g. regression coefficient) AND variation (e.g. standard deviation) or associated estimates of uncertainty (e.g. confidence intervals)

For Bayesian analysis, information on the choice of priors and Markov chain Monte Carlo settings

For hierarchical and complex designs, identification of the appropriate level for tests and full reporting of outcomes

Estimates of effect sizes (e.g. Cohen’s

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

Policy information about availability of computer code

Data collection

Data analysis

Data

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

Research involving human participants, their data, or biological material

Recruitment

N/A

N/A

Field-specific reporting

Life sciences Behavioural & social sciences Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

Life sciences study design

| Sample size | Sample sizes were

|

| Data exclusions | For the rd6 and rd12 model correction, mice were co-injected with PE-eVLPs and AAV1-GFP. GFP signal was examined as a marker for successful injection. Samples from the eyes that showed less than

|

| Replication | All experiments were repeated more than once. All attempts at replication were successful. |

| Randomization | All control and test conditions were assigned randomly. For example, for all in vitro/tissue culture experiments, conditions were assigned randomly to wells across 96 – or 48 -well plates and plate positioning is not expected to affect experimental outcome. For in vivo experiments, mice were assigned randomly into groups. |

| Blinding | All HTS data were analyzed using an automated CRISPResso2 script that does not allow experimenter intervention, therefore experimenter was not blinded. Subretinal injection editing data were analyzed by blinded investigator. Blinding was not necessary for other experiments because control and test conditions were processed identically. |

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | ||

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a | Involved in the study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Palaeontology and archaeology |  |

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

||

| X | |||

Antibodies

| Antibodies used | Mouse Cas9 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #MA5-23519); Rabbit GAPDH antibody (Cell signaling Technology, #2118); Goat anti-mouse MFRP antibody (R&D Systems #AF3445); Mouse anti-mouse RPE65 antibody (in house production; obtained from the laboratory of Dr. Krzysztof Palczewski, UC Irvine ; Golczak et al, 2010); Rabbit anti-beta-actin polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology; 4970S); Anti-NeuN antibody (Abcam, ab190565); Goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (LI-COR IRDye 680RD, 926-68070); Goat anti-rabbit antibody (LI-COR IRDye 800RD, 926-32211); Donkey anti-goat IgG-HRP antibody (Abcam, ab97110); Goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 7076S); Goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP antibody (Cell signaling Technology, 7074S); Rabbit anti-ZO-1 polyclonal antibody (Invitrogen, #61-7300); Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher; A21207); Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (Thermo Fisher, A32849); |

| Validation | All commercial antibodies were validated by the manufacturers for western blot. For in-house produced antibody, we confirmed clear bands at the expected molecular weight with positive control included in the experiments. |

Eukaryotic cell lines

Policy information about cell lines and Sex and Gender in Research

Commonly misidentified lines

(See ICLAC register)

None used.

Animals and other research organisms

| Laboratory animals | Time pregnant C57BL/6J mice (027) for P0 studies were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Age of the pregnant mice was not specified. Litters were used for injection on the day of birth. Reitnal degenration mice models rd6 (003684) and rd12 (005379) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Subretinal injections were performed on 5 -week-old rd6 and rd12 mice. Mouse housing facilities were maintained on a 12 h light

|

| Wild animals | This study does not involve wild animals. |

| Reporting on sex | Both male and female mice were used for each condition. |

| Field-collected samples | This study does not involve samples collected from the field. |

| Ethics oversight | Broad Institute IACUC committee (D16-00903; 0048-04-15-2) and University of California, Irvine IACUC committee (D16-00259; AUP-21-096) provided ethics overnight for all experiments involving live animals. |

| Seed stocks | N/A | ||

| Novel plant genotypes |

|

||

| Authentication |

|

Flow Cytometry

Plots

The axis labels state the marker and fluorochrome used (e.g. CD4-FITC).

The axis scales are clearly visible. Include numbers along axes only for bottom left plot of group (a ‘group’ is an analysis of identical markers).

All plots are contour plots with outliers or pseudocolor plots.

A numerical value for number of cells or percentage (with statistics) is provided.

Methodology

Instrument

Software

Cell population abundance

Sony MA900 Cell Sorter

MA900 Cell Sorter software v3.1

On average

Merkin Institute of Transformative Technologies in Healthcare, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA. Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Gavin Herbert Eye Institute, Center for Translational Vision Research, Department of Ophthalmology, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA. Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA. Department of Chemistry, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA. Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA. e-mail: drliu@fas.harvard.edu - For manuscripts utilizing custom algorithms or software that are central to the research but not yet described in published literature, software must be made available to editors and reviewers. We strongly encourage code deposition in a community repository (e.g. GitHub). See the Nature Portfolio guidelines for submitting code & software for further information.